Экономика

| Часть серии о |

| Экономика |

|---|

Экономика ( / ˌ ɛ k ə ˈ n ɒ m ɪ k s , ˌ iː k ə - / ) [ 1 ] [ 2 ] — это социальная наука , изучающая производство , распределение и потребление товаров и услуг . [ 3 ] [ 4 ]

Экономика фокусируется на поведении и взаимодействии экономических агентов , а также на том, как работает экономика . Микроэкономика анализирует то, что рассматривается как базовые элементы внутри экономики , включая отдельных агентов и рынки , их взаимодействие и результаты взаимодействия. Отдельные агенты могут включать, например, домашние хозяйства, фирмы, покупателей и продавцов. Макроэкономика анализирует экономику как систему, в которой взаимодействуют производство, распределение, потребление, сбережения и инвестиционные расходы , а также факторы, влияющие на это: факторы производства , такие как труд , капитал , земля и предпринимательство , инфляция , экономический рост и государственная политика , оказывающая влияние. на этих элементах . Он также стремится проанализировать и описать мировую экономику .

Other broad distinctions within economics include those between positive economics, describing "what is", and normative economics, advocating "what ought to be";[5] between economic theory and applied economics; between rational and behavioural economics; and between mainstream economics and heterodox economics.[6]

Economic analysis can be applied throughout society, including business,[7] finance, cybersecurity,[8] health care,[9] engineering[10] and government.[11] It is also applied to such diverse subjects as crime,[12] education,[13] the family,[14] feminism,[15] law,[16] philosophy,[17] politics, religion,[18] social institutions, war,[19] science,[20] and the environment.[21]

Definitions of economics

The earlier term for the discipline was "political economy", but since the late 19th century, it has commonly been called "economics".[22] The term is ultimately derived from Ancient Greek οἰκονομία (oikonomia) which is a term for the "way (nomos) to run a household (oikos)", or in other words the know-how of an οἰκονομικός (oikonomikos), or "household or homestead manager". Derived terms such as "economy" can therefore often mean "frugal" or "thrifty".[23][24][25][26] By extension then, "political economy" was the way to manage a polis or state.

There are a variety of modern definitions of economics; some reflect evolving views of the subject or different views among economists.[27][28] Scottish philosopher Adam Smith (1776) defined what was then called political economy as "an inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations", in particular as:

a branch of the science of a statesman or legislator [with the twofold objectives of providing] a plentiful revenue or subsistence for the people ... [and] to supply the state or commonwealth with a revenue for the publick services.[29]

Jean-Baptiste Say (1803), distinguishing the subject matter from its public-policy uses, defined it as the science of production, distribution, and consumption of wealth.[30] On the satirical side, Thomas Carlyle (1849) coined "the dismal science" as an epithet for classical economics, in this context, commonly linked to the pessimistic analysis of Malthus (1798).[31] John Stuart Mill (1844) delimited the subject matter further:

The science which traces the laws of such of the phenomena of society as arise from the combined operations of mankind for the production of wealth, in so far as those phenomena are not modified by the pursuit of any other object.[32]

Alfred Marshall provided a still widely cited definition in his textbook Principles of Economics (1890) that extended analysis beyond wealth and from the societal to the microeconomic level:

Economics is a study of man in the ordinary business of life. It enquires how he gets his income and how he uses it. Thus, it is on the one side, the study of wealth and on the other and more important side, a part of the study of man.[33]

Lionel Robbins (1932) developed implications of what has been termed "[p]erhaps the most commonly accepted current definition of the subject":[28]

Economics is the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.[34]

Robbins described the definition as not classificatory in "pick[ing] out certain kinds of behaviour" but rather analytical in "focus[ing] attention on a particular aspect of behaviour, the form imposed by the influence of scarcity."[35] He affirmed that previous economists have usually centred their studies on the analysis of wealth: how wealth is created (production), distributed, and consumed; and how wealth can grow.[36] But he said that economics can be used to study other things, such as war, that are outside its usual focus. This is because war has as the goal winning it (as a sought after end), generates both cost and benefits; and, resources (human life and other costs) are used to attain the goal. If the war is not winnable or if the expected costs outweigh the benefits, the deciding actors (assuming they are rational) may never go to war (a decision) but rather explore other alternatives. Economics cannot be defined as the science that studies wealth, war, crime, education, and any other field economic analysis can be applied to; but, as the science that studies a particular common aspect of each of those subjects (they all use scarce resources to attain a sought after end).

Some subsequent comments criticised the definition as overly broad in failing to limit its subject matter to analysis of markets. From the 1960s, however, such comments abated as the economic theory of maximizing behaviour and rational-choice modelling expanded the domain of the subject to areas previously treated in other fields.[37] There are other criticisms as well, such as in scarcity not accounting for the macroeconomics of high unemployment.[38]

Gary Becker, a contributor to the expansion of economics into new areas, described the approach he favoured as "combin[ing the] assumptions of maximizing behaviour, stable preferences, and market equilibrium, used relentlessly and unflinchingly."[39] One commentary characterises the remark as making economics an approach rather than a subject matter but with great specificity as to the "choice process and the type of social interaction that [such] analysis involves." The same source reviews a range of definitions included in principles of economics textbooks and concludes that the lack of agreement need not affect the subject-matter that the texts treat. Among economists more generally, it argues that a particular definition presented may reflect the direction toward which the author believes economics is evolving, or should evolve.[28]

Many economists including nobel prize winners James M. Buchanan and Ronald Coase reject the method-based definition of Robbins and continue to prefer definitions like those of Say, in terms of its subject matter.[37] Ha-Joon Chang has for example argued that the definition of Robbins would make economics very peculiar because all other sciences define themselves in terms of the area of inquiry or object of inquiry rather than the methodology. In the biology department, they do not say that all biology should be studied with DNA analysis. People study living organisms in many different ways, so some people will do DNA analysis, others might do anatomy, and still others might build game theoretic models of animal behaviour. But they are all called biology because they all study living organisms. According to Ha Joon Chang, this view that the economy can and should be studied in only one way (for example by studying only rational choices), and going even one step further and basically redefining economics as a theory of everything, is very peculiar.[40]

History of economic thought

This section is missing information about information and behavioural economics, contemporary microeconomics. (September 2020) |

From antiquity through the physiocrats

Questions regarding distribution of resources are found throughout the writings of the Boeotian poet Hesiod and several economic historians have described Hesiod himself as the "first economist".[41] However, the word Oikos, the Greek word from which the word economy derives, was used for issues regarding how to manage a household (which was understood to be the landowner, his family, and his slaves[42]) rather than to refer to some normative societal system of distribution of resources, which is a much more recent phenomenon.[43][44][45] Xenophon, the author of the Oeconomicus, is credited by philologues for being the source of the word economy.[46] Joseph Schumpeter described 16th and 17th century scholastic writers, including Tomás de Mercado, Luis de Molina, and Juan de Lugo, as "coming nearer than any other group to being the 'founders' of scientific economics" as to monetary, interest, and value theory within a natural-law perspective.[47]

Two groups, who later were called "mercantilists" and "physiocrats", more directly influenced the subsequent development of the subject. Both groups were associated with the rise of economic nationalism and modern capitalism in Europe. Mercantilism was an economic doctrine that flourished from the 16th to 18th century in a prolific pamphlet literature, whether of merchants or statesmen. It held that a nation's wealth depended on its accumulation of gold and silver. Nations without access to mines could obtain gold and silver from trade only by selling goods abroad and restricting imports other than of gold and silver. The doctrine called for importing cheap raw materials to be used in manufacturing goods, which could be exported, and for state regulation to impose protective tariffs on foreign manufactured goods and prohibit manufacturing in the colonies.[48]

Physiocrats, a group of 18th-century French thinkers and writers, developed the idea of the economy as a circular flow of income and output. Physiocrats believed that only agricultural production generated a clear surplus over cost, so that agriculture was the basis of all wealth.[49] Thus, they opposed the mercantilist policy of promoting manufacturing and trade at the expense of agriculture, including import tariffs. Physiocrats advocated replacing administratively costly tax collections with a single tax on income of land owners. In reaction against copious mercantilist trade regulations, the physiocrats advocated a policy of laissez-faire, which called for minimal government intervention in the economy.[50]

Adam Smith (1723–1790) was an early economic theorist.[51] Smith was harshly critical of the mercantilists but described the physiocratic system "with all its imperfections" as "perhaps the purest approximation to the truth that has yet been published" on the subject.[52]

Classical political economy

The publication of Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations in 1776, has been described as "the effective birth of economics as a separate discipline."[53] The book identified land, labour, and capital as the three factors of production and the major contributors to a nation's wealth, as distinct from the physiocratic idea that only agriculture was productive.

Smith discusses potential benefits of specialisation by division of labour, including increased labour productivity and gains from trade, whether between town and country or across countries.[54] His "theorem" that "the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market" has been described as the "core of a theory of the functions of firm and industry" and a "fundamental principle of economic organization."[55] To Smith has also been ascribed "the most important substantive proposition in all of economics" and foundation of resource-allocation theory—that, under competition, resource owners (of labour, land, and capital) seek their most profitable uses, resulting in an equal rate of return for all uses in equilibrium (adjusted for apparent differences arising from such factors as training and unemployment).[56]

In an argument that includes "one of the most famous passages in all economics,"[57] Smith represents every individual as trying to employ any capital they might command for their own advantage, not that of the society,[a] and for the sake of profit, which is necessary at some level for employing capital in domestic industry, and positively related to the value of produce.[59] In this:

He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.[60]

The Rev. Thomas Robert Malthus (1798) used the concept of diminishing returns to explain low living standards. Human population, he argued, tended to increase geometrically, outstripping the production of food, which increased arithmetically. The force of a rapidly growing population against a limited amount of land meant diminishing returns to labour. The result, he claimed, was chronically low wages, which prevented the standard of living for most of the population from rising above the subsistence level.[61][non-primary source needed] Economist Julian Simon has criticised Malthus's conclusions.[62]

While Adam Smith emphasised production and income, David Ricardo (1817) focused on the distribution of income among landowners, workers, and capitalists. Ricardo saw an inherent conflict between landowners on the one hand and labour and capital on the other. He posited that the growth of population and capital, pressing against a fixed supply of land, pushes up rents and holds down wages and profits. Ricardo was also the first to state and prove the principle of comparative advantage, according to which each country should specialise in producing and exporting goods in that it has a lower relative cost of production, rather relying only on its own production.[63] It has been termed a "fundamental analytical explanation" for gains from trade.[64]

Coming at the end of the classical tradition, John Stuart Mill (1848) parted company with the earlier classical economists on the inevitability of the distribution of income produced by the market system. Mill pointed to a distinct difference between the market's two roles: allocation of resources and distribution of income. The market might be efficient in allocating resources but not in distributing income, he wrote, making it necessary for society to intervene.[65]

Value theory was important in classical theory. Smith wrote that the "real price of every thing ... is the toil and trouble of acquiring it". Smith maintained that, with rent and profit, other costs besides wages also enter the price of a commodity.[66] Other classical economists presented variations on Smith, termed the 'labour theory of value'. Classical economics focused on the tendency of any market economy to settle in a final stationary state made up of a constant stock of physical wealth (capital) and a constant population size.

Marxian economics

Marxist (later, Marxian) economics descends from classical economics and it derives from the work of Karl Marx. The first volume of Marx's major work, Das Kapital, was published in 1867. Marx focused on the labour theory of value and theory of surplus value. Marx wrote that they were mechanisms used by capital to exploit labour.[67] The labour theory of value held that the value of an exchanged commodity was determined by the labour that went into its production, and the theory of surplus value demonstrated how workers were only paid a proportion of the value their work had created.[68]

Marxian economics was further developed by Karl Kautsky (1854–1938)'s The Economic Doctrines of Karl Marx and The Class Struggle (Erfurt Program), Rudolf Hilferding's (1877–1941) Finance Capital, Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924)'s The Development of Capitalism in Russia and Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, and Rosa Luxemburg (1871–1919)'s The Accumulation of Capital.

Neoclassical economics

At its inception as a social science, economics was defined and discussed at length as the study of production, distribution, and consumption of wealth by Jean-Baptiste Say in his Treatise on Political Economy or, The Production, Distribution, and Consumption of Wealth (1803). These three items were considered only in relation to the increase or diminution of wealth, and not in reference to their processes of execution.[b] Say's definition has survived in part up to the present, modified by substituting the word "wealth" for "goods and services" meaning that wealth may include non-material objects as well. One hundred and thirty years later, Lionel Robbins noticed that this definition no longer sufficed,[c] because many economists were making theoretical and philosophical inroads in other areas of human activity. In his Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science, he proposed a definition of economics as a study of human behaviour, subject to and constrained by scarcity,[d] which forces people to choose, allocate scarce resources to competing ends, and economise (seeking the greatest welfare while avoiding the wasting of scarce resources). According to Robbins: "Economics is the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses".[35] Robbins' definition eventually became widely accepted by mainstream economists, and found its way into current textbooks.[69] Although far from unanimous, most mainstream economists would accept some version of Robbins' definition, even though many have raised serious objections to the scope and method of economics, emanating from that definition.[70]

A body of theory later termed "neoclassical economics" formed from about 1870 to 1910. The term "economics" was popularised by such neoclassical economists as Alfred Marshall and Mary Paley Marshall as a concise synonym for "economic science" and a substitute for the earlier "political economy".[25][26] This corresponded to the influence on the subject of mathematical methods used in the natural sciences.[71]

Neoclassical economics systematically integrated supply and demand as joint determinants of both price and quantity in market equilibrium, influencing the allocation of output and income distribution. It rejected the classical economics' labour theory of value in favour of a marginal utility theory of value on the demand side and a more comprehensive theory of costs on the supply side.[72] In the 20th century, neoclassical theorists departed from an earlier idea that suggested measuring total utility for a society, opting instead for ordinal utility, which posits behaviour-based relations across individuals.[73][74]

In microeconomics, neoclassical economics represents incentives and costs as playing a pervasive role in shaping decision making. An immediate example of this is the consumer theory of individual demand, which isolates how prices (as costs) and income affect quantity demanded.[73] In macroeconomics it is reflected in an early and lasting neoclassical synthesis with Keynesian macroeconomics.[75][73]

Neoclassical economics is occasionally referred as orthodox economics whether by its critics or sympathisers. Modern mainstream economics builds on neoclassical economics but with many refinements that either supplement or generalise earlier analysis, such as econometrics, game theory, analysis of market failure and imperfect competition, and the neoclassical model of economic growth for analysing long-run variables affecting national income.

Neoclassical economics studies the behaviour of individuals, households, and organisations (called economic actors, players, or agents), when they manage or use scarce resources, which have alternative uses, to achieve desired ends. Agents are assumed to act rationally, have multiple desirable ends in sight, limited resources to obtain these ends, a set of stable preferences, a definite overall guiding objective, and the capability of making a choice. There exists an economic problem, subject to study by economic science, when a decision (choice) is made by one or more players to attain the best possible outcome.[76]

Keynesian economics

Keynesian economics derives from John Maynard Keynes, in particular his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936), which ushered in contemporary macroeconomics as a distinct field.[77] The book focused on determinants of national income in the short run when prices are relatively inflexible. Keynes attempted to explain in broad theoretical detail why high labour-market unemployment might not be self-correcting due to low "effective demand" and why even price flexibility and monetary policy might be unavailing. The term "revolutionary" has been applied to the book in its impact on economic analysis.[78]

During the following decades, many economists followed Keynes' ideas and expanded on his works. John Hicks and Alvin Hansen developed the IS–LM model which was a simple formalisation of some of Keynes' insights on the economy's short-run equilibrium. Franco Modigliani and James Tobin developed important theories of private consumption and investment, respectively, two major components of aggregate demand. Lawrence Klein built the first large-scale macroeconometric model, applying the Keynesian thinking systematically to the US economy.[79]

Post-WWII economics

Immediately after World War II, Keynesian was the dominant economic view of the United States establishment and its allies, Marxian economics was the dominant economic view of the Soviet Union nomenklatura and its allies.

Monetarism

Monetarism appeared in the 1950s and 1960s, its intellectual leader being Milton Friedman. Monetarists contended that monetary policy and other monetary shocks, as represented by the growth in the money stock, was an important cause of economic fluctuations, and consequently that monetary policy was more important than fiscal policy for purposes of stabilisation.[80][81] Friedman was also skeptical about the ability of central banks to conduct a sensible active monetary policy in practice, advocating instead using simple rules such as a steady rate of money growth.[82]

Monetarism rose to prominence in the 1970s and 1980s, when several major central banks followed a monetarist-inspired policy, but was later abandoned again because the results turned out to be unsatisfactory.[83][84]

New classical economics

A more fundamental challenge to the prevailing Keynesian paradigm came in the 1970s from new classical economists like Robert Lucas, Thomas Sargent and Edward Prescott. They introduced the notion of rational expectations in economics, which had profound implications for many economic discussions, among which were the so-called Lucas critique and the presentation of real business cycle models.[85]

New Keynesians

During the 1980s, a group of researchers appeared being called New Keynesian economists, including among others George Akerlof, Janet Yellen, Gregory Mankiw and Olivier Blanchard. They adopted the principle of rational expectations and other monetarist or new classical ideas such as building upon models employing micro foundations and optimizing behaviour, but simultaneously emphasised the importance of various market failures for the functioning of the economy, as had Keynes.[86] Not least, they proposed various reasons that potentially explained the empirically observed features of price and wage rigidity, usually made to be endogenous features of the models, rather than simply assumed as in older Keynesian-style ones.

New neoclassical synthesis

After decades of often heated discussions between Keynesians, monetarists, new classical and new Keynesian economists, a synthesis emerged by the 2000s, often given the name the new neoclassical synthesis. It integrated the rational expectations and optimizing framework of the new classical theory with a new Keynesian role for nominal rigidities and other market imperfections like imperfect information in goods, labour and credit markets. The monetarist importance of monetary policy in stabilizing[87] the economy and in particular controlling inflation was recognised as well as the traditional Keynesian insistence that fiscal policy could also play an influential role in affecting aggregate demand. Methodologically, the synthesis led to a new class of applied models, known as dynamic stochastic general equilibrium or DSGE models, descending from real business cycles models, but extended with several new Keynesian and other features. These models proved very useful and influential in the design of modern monetary policy and are now standard workhorses in most central banks.[88]

After the financial crisis

After the 2007–2008 financial crisis, macroeconomic research has put greater emphasis on understanding and integrating the financial system into models of the general economy and shedding light on the ways in which problems in the financial sector can turn into major macroeconomic recessions. In this and other research branches, inspiration from behavioural economics has started playing a more important role in mainstream economic theory.[89] Also, heterogeneity among the economic agents, e.g. differences in income, plays an increasing role in recent economic research.[90]

Other schools and approaches

Other schools or trends of thought referring to a particular style of economics practised at and disseminated from well-defined groups of academicians that have become known worldwide, include the Freiburg School, the School of Lausanne, the Stockholm school and the Chicago school of economics. During the 1970s and 1980s mainstream economics was sometimes separated into the Saltwater approach of those universities along the Eastern and Western coasts of the US, and the Freshwater, or Chicago school approach.[91]

Within macroeconomics there is, in general order of their historical appearance in the literature; classical economics, neoclassical economics, Keynesian economics, the neoclassical synthesis, monetarism, new classical economics, New Keynesian economics[92] and the new neoclassical synthesis.[93]

Beside the mainstream development of economic thought, various alternative or heterodox economic theories have evolved over time, positioning themselves in contrast to mainstream theory.[94] These include:[94]

- Austrian School, emphasizing human action, property rights and the freedom to contract and transact to have a thriving and successful economy.[95] It also emphasises that the state should play as small role as possible (if any role) in the regulation of economic activity between two transacting parties.[96] Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises are the two most prominent representatives of the Austrian school.

- Post-Keynesian economics concentrates on macroeconomic rigidities and adjustment processes. It is generally associated with the University of Cambridge and the work of Joan Robinson.[97]

- Ecological economics like environmental economics studies the interactions between human economies and the ecosystems in which they are embedded,[98] but in contrast to environmental economics takes an oppositional position towards general mainstream economic principles. A major difference between the two subdisciplines is their assumptions about the substitution possibilities between man-made and natural capital.[99]

Additionally, alternative developments include Marxian economics, constitutional economics, institutional economics, evolutionary economics, dependency theory, structuralist economics, world systems theory, econophysics, econodynamics, feminist economics and biophysical economics.[100]

Feminist economics emphasises the role that gender plays in economies, challenging analyses that render gender invisible or support gender-oppressive economic systems.[101] The goal is to create economic research and policy analysis that is inclusive and gender-aware to encourage gender equality and improve the well-being of marginalised groups.

Methodology

Theoretical research

Mainstream economic theory relies upon analytical economic models. When creating theories, the objective is to find assumptions which are at least as simple in information requirements, more precise in predictions, and more fruitful in generating additional research than prior theories.[102] While neoclassical economic theory constitutes both the dominant or orthodox theoretical as well as methodological framework, economic theory can also take the form of other schools of thought such as in heterodox economic theories.

In microeconomics, principal concepts include supply and demand, marginalism, rational choice theory, opportunity cost, budget constraints, utility, and the theory of the firm.[103] Early macroeconomic models focused on modelling the relationships between aggregate variables, but as the relationships appeared to change over time macroeconomists, including new Keynesians, reformulated their models with microfoundations,[104] in which microeconomic concepts play a major part.

Sometimes an economic hypothesis is only qualitative, not quantitative.[105]

Expositions of economic reasoning often use two-dimensional graphs to illustrate theoretical relationships. At a higher level of generality, mathematical economics is the application of mathematical methods to represent theories and analyse problems in economics. Paul Samuelson's treatise Foundations of Economic Analysis (1947) exemplifies the method, particularly as to maximizing behavioural relations of agents reaching equilibrium. The book focused on examining the class of statements called operationally meaningful theorems in economics, which are theorems that can conceivably be refuted by empirical data.[106]

Empirical research

Economic theories are frequently tested empirically, largely through the use of econometrics using economic data.[107] The controlled experiments common to the physical sciences are difficult and uncommon in economics,[108] and instead broad data is observationally studied; this type of testing is typically regarded as less rigorous than controlled experimentation, and the conclusions typically more tentative. However, the field of experimental economics is growing, and increasing use is being made of natural experiments.

Statistical methods such as regression analysis are common. Practitioners use such methods to estimate the size, economic significance, and statistical significance ("signal strength") of the hypothesised relation(s) and to adjust for noise from other variables. By such means, a hypothesis may gain acceptance, although in a probabilistic, rather than certain, sense. Acceptance is dependent upon the falsifiable hypothesis surviving tests. Use of commonly accepted methods need not produce a final conclusion or even a consensus on a particular question, given different tests, data sets, and prior beliefs.

Experimental economics has promoted the use of scientifically controlled experiments. This has reduced the long-noted distinction of economics from natural sciences because it allows direct tests of what were previously taken as axioms.[109] In some cases these have found that the axioms are not entirely correct.

In behavioural economics, psychologist Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in economics in 2002 for his and Amos Tversky's empirical discovery of several cognitive biases and heuristics. Similar empirical testing occurs in neuroeconomics. Another example is the assumption of narrowly selfish preferences versus a model that tests for selfish, altruistic, and cooperative preferences.[110] These techniques have led some to argue that economics is a "genuine science".[111]

Microeconomics

Microeconomics examines how entities, forming a market structure, interact within a market to create a market system. These entities include private and public players with various classifications, typically operating under scarcity of tradable units and regulation. The item traded may be a tangible product such as apples or a service such as repair services, legal counsel, or entertainment.

Various market structures exist. In perfectly competitive markets, no participants are large enough to have the market power to set the price of a homogeneous product. In other words, every participant is a "price taker" as no participant influences the price of a product. In the real world, markets often experience imperfect competition.

Forms of imperfect competition include monopoly (in which there is only one seller of a good), duopoly (in which there are only two sellers of a good), oligopoly (in which there are few sellers of a good), monopolistic competition (in which there are many sellers producing highly differentiated goods), monopsony (in which there is only one buyer of a good), and oligopsony (in which there are few buyers of a good). Firms under imperfect competition have the potential to be "price makers", which means that they can influence the prices of their products.

In partial equilibrium method of analysis, it is assumed that activity in the market being analysed does not affect other markets. This method aggregates (the sum of all activity) in only one market. General-equilibrium theory studies various markets and their behaviour. It aggregates (the sum of all activity) across all markets. This method studies both changes in markets and their interactions leading towards equilibrium.[112]

Production, cost, and efficiency

In microeconomics, production is the conversion of inputs into outputs. It is an economic process that uses inputs to create a commodity or a service for exchange or direct use. Production is a flow and thus a rate of output per period of time. Distinctions include such production alternatives as for consumption (food, haircuts, etc.) vs. investment goods (new tractors, buildings, roads, etc.), public goods (national defence, smallpox vaccinations, etc.) or private goods, and "guns" vs "butter".

Inputs used in the production process include such primary factors of production as labour services, capital (durable produced goods used in production, such as an existing factory), and land (including natural resources). Other inputs may include intermediate goods used in production of final goods, such as the steel in a new car.

Economic efficiency measures how well a system generates desired output with a given set of inputs and available technology. Efficiency is improved if more output is generated without changing inputs. A widely accepted general standard is Pareto efficiency, which is reached when no further change can make someone better off without making someone else worse off.

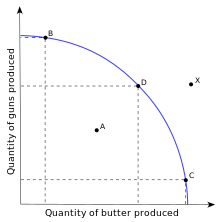

The production–possibility frontier (PPF) is an expository figure for representing scarcity, cost, and efficiency. In the simplest case an economy can produce just two goods (say "guns" and "butter"). The PPF is a table or graph (as at the right) showing the different quantity combinations of the two goods producible with a given technology and total factor inputs, which limit feasible total output. Each point on the curve shows potential total output for the economy, which is the maximum feasible output of one good, given a feasible output quantity of the other good.

Scarcity is represented in the figure by people being willing but unable in the aggregate to consume beyond the PPF (such as at X) and by the negative slope of the curve.[113] If production of one good increases along the curve, production of the other good decreases, an inverse relationship. This is because increasing output of one good requires transferring inputs to it from production of the other good, decreasing the latter.

The slope of the curve at a point on it gives the trade-off between the two goods. It measures what an additional unit of one good costs in units forgone of the other good, an example of a real opportunity cost. Thus, if one more Gun costs 100 units of butter, the opportunity cost of one Gun is 100 Butter. Along the PPF, scarcity implies that choosing more of one good in the aggregate entails doing with less of the other good. Still, in a market economy, movement along the curve may indicate that the choice of the increased output is anticipated to be worth the cost to the agents.

By construction, each point on the curve shows productive efficiency in maximizing output for given total inputs. A point inside the curve (as at A), is feasible but represents production inefficiency (wasteful use of inputs), in that output of one or both goods could increase by moving in a northeast direction to a point on the curve. Examples cited of such inefficiency include high unemployment during a business-cycle recession or economic organisation of a country that discourages full use of resources. Being on the curve might still not fully satisfy allocative efficiency (also called Pareto efficiency) if it does not produce a mix of goods that consumers prefer over other points.

Much applied economics in public policy is concerned with determining how the efficiency of an economy can be improved. Recognizing the reality of scarcity and then figuring out how to organise society for the most efficient use of resources has been described as the "essence of economics", where the subject "makes its unique contribution."[114]

Specialisation

Specialisation is considered key to economic efficiency based on theoretical and empirical considerations. Different individuals or nations may have different real opportunity costs of production, say from differences in stocks of human capital per worker or capital/labour ratios. According to theory, this may give a comparative advantage in production of goods that make more intensive use of the relatively more abundant, thus relatively cheaper, input.

Even if one region has an absolute advantage as to the ratio of its outputs to inputs in every type of output, it may still specialise in the output in which it has a comparative advantage and thereby gain from trading with a region that lacks any absolute advantage but has a comparative advantage in producing something else.

It has been observed that a high volume of trade occurs among regions even with access to a similar technology and mix of factor inputs, including high-income countries. This has led to investigation of economies of scale and agglomeration to explain specialisation in similar but differentiated product lines, to the overall benefit of respective trading parties or regions.[115][116]

The general theory of specialisation applies to trade among individuals, farms, manufacturers, service providers, and economies. Among each of these production systems, there may be a corresponding division of labour with different work groups specializing, or correspondingly different types of capital equipment and differentiated land uses.[117]

An example that combines features above is a country that specialises in the production of high-tech knowledge products, as developed countries do, and trades with developing nations for goods produced in factories where labour is relatively cheap and plentiful, resulting in different in opportunity costs of production. More total output and utility thereby results from specializing in production and trading than if each country produced its own high-tech and low-tech products.

Theory and observation set out the conditions such that market prices of outputs and productive inputs select an allocation of factor inputs by comparative advantage, so that (relatively) low-cost inputs go to producing low-cost outputs. In the process, aggregate output may increase as a by-product or by design.[118] Such specialisation of production creates opportunities for gains from trade whereby resource owners benefit from trade in the sale of one type of output for other, more highly valued goods. A measure of gains from trade is the increased income levels that trade may facilitate.[119]

Supply and demand

Prices and quantities have been described as the most directly observable attributes of goods produced and exchanged in a market economy.[120] The theory of supply and demand is an organizing principle for explaining how prices coordinate the amounts produced and consumed. In microeconomics, it applies to price and output determination for a market with perfect competition, which includes the condition of no buyers or sellers large enough to have price-setting power.

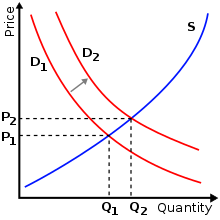

For a given market of a commodity, demand is the relation of the quantity that all buyers would be prepared to purchase at each unit price of the good. Demand is often represented by a table or a graph showing price and quantity demanded (as in the figure). Demand theory describes individual consumers as rationally choosing the most preferred quantity of each good, given income, prices, tastes, etc. A term for this is "constrained utility maximisation" (with income and wealth as the constraints on demand). Here, utility refers to the hypothesised relation of each individual consumer for ranking different commodity bundles as more or less preferred.

The law of demand states that, in general, price and quantity demanded in a given market are inversely related. That is, the higher the price of a product, the less of it people would be prepared to buy (other things unchanged). As the price of a commodity falls, consumers move toward it from relatively more expensive goods (the substitution effect). In addition, purchasing power from the price decline increases ability to buy (the income effect). Other factors can change demand; for example an increase in income will shift the demand curve for a normal good outward relative to the origin, as in the figure. All determinants are predominantly taken as constant factors of demand and supply.

Supply is the relation between the price of a good and the quantity available for sale at that price. It may be represented as a table or graph relating price and quantity supplied. Producers, for example business firms, are hypothesised to be profit maximisers, meaning that they attempt to produce and supply the amount of goods that will bring them the highest profit. Supply is typically represented as a function relating price and quantity, if other factors are unchanged.

That is, the higher the price at which the good can be sold, the more of it producers will supply, as in the figure. The higher price makes it profitable to increase production. Just as on the demand side, the position of the supply can shift, say from a change in the price of a productive input or a technical improvement. The "Law of Supply" states that, in general, a rise in price leads to an expansion in supply and a fall in price leads to a contraction in supply. Here as well, the determinants of supply, such as price of substitutes, cost of production, technology applied and various factors inputs of production are all taken to be constant for a specific time period of evaluation of supply.

Market equilibrium occurs where quantity supplied equals quantity demanded, the intersection of the supply and demand curves in the figure above. At a price below equilibrium, there is a shortage of quantity supplied compared to quantity demanded. This is posited to bid the price up. At a price above equilibrium, there is a surplus of quantity supplied compared to quantity demanded. This pushes the price down. The model of supply and demand predicts that for given supply and demand curves, price and quantity will stabilise at the price that makes quantity supplied equal to quantity demanded. Similarly, demand-and-supply theory predicts a new price-quantity combination from a shift in demand (as to the figure), or in supply.

Firms

People frequently do not trade directly on markets. Instead, on the supply side, they may work in and produce through firms. The most obvious kinds of firms are corporations, partnerships and trusts. According to Ronald Coase, people begin to organise their production in firms when the costs of doing business becomes lower than doing it on the market.[121] Firms combine labour and capital, and can achieve far greater economies of scale (when the average cost per unit declines as more units are produced) than individual market trading.

In perfectly competitive markets studied in the theory of supply and demand, there are many producers, none of which significantly influence price. Industrial organisation generalises from that special case to study the strategic behaviour of firms that do have significant control of price. It considers the structure of such markets and their interactions. Common market structures studied besides perfect competition include monopolistic competition, various forms of oligopoly, and monopoly.[122]

Managerial economics applies microeconomic analysis to specific decisions in business firms or other management units. It draws heavily from quantitative methods such as operations research and programming and from statistical methods such as regression analysis in the absence of certainty and perfect knowledge. A unifying theme is the attempt to optimise business decisions, including unit-cost minimisation and profit maximisation, given the firm's objectives and constraints imposed by technology and market conditions.[123]

Uncertainty and game theory

Uncertainty in economics is an unknown prospect of gain or loss, whether quantifiable as risk or not. Without it, household behaviour would be unaffected by uncertain employment and income prospects, financial and capital markets would reduce to exchange of a single instrument in each market period, and there would be no communications industry.[124] Given its different forms, there are various ways of representing uncertainty and modelling economic agents' responses to it.[125]

Game theory is a branch of applied mathematics that considers strategic interactions between agents, one kind of uncertainty. It provides a mathematical foundation of industrial organisation, discussed above, to model different types of firm behaviour, for example in a solipsistic industry (few sellers), but equally applicable to wage negotiations, bargaining, contract design, and any situation where individual agents are few enough to have perceptible effects on each other. In behavioural economics, it has been used to model the strategies agents choose when interacting with others whose interests are at least partially adverse to their own.[126]

In this, it generalises maximisation approaches developed to analyse market actors such as in the supply and demand model and allows for incomplete information of actors. The field dates from the 1944 classic Theory of Games and Economic Behavior by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern. It has significant applications seemingly outside of economics in such diverse subjects as the formulation of nuclear strategies, ethics, political science, and evolutionary biology.[127]

Risk aversion may stimulate activity that in well-functioning markets smooths out risk and communicates information about risk, as in markets for insurance, commodity futures contracts, and financial instruments. Financial economics or simply finance describes the allocation of financial resources. It also analyses the pricing of financial instruments, the financial structure of companies, the efficiency and fragility of financial markets,[128] financial crises, and related government policy or regulation.[129][130][131][132][133]

Some market organisations may give rise to inefficiencies associated with uncertainty. Based on George Akerlof's "Market for Lemons" article, the paradigm example is of a dodgy second-hand car market. Customers without knowledge of whether a car is a "lemon" depress its price below what a quality second-hand car would be.[134] Information asymmetry arises here, if the seller has more relevant information than the buyer but no incentive to disclose it. Related problems in insurance are adverse selection, such that those at most risk are most likely to insure (say reckless drivers), and moral hazard, such that insurance results in riskier behaviour (say more reckless driving).[135]

Both problems may raise insurance costs and reduce efficiency by driving otherwise willing transactors from the market ("incomplete markets"). Moreover, attempting to reduce one problem, say adverse selection by mandating insurance, may add to another, say moral hazard. Information economics, which studies such problems, has relevance in subjects such as insurance, contract law, mechanism design, monetary economics, and health care.[135] Applied subjects include market and legal remedies to spread or reduce risk, such as warranties, government-mandated partial insurance, restructuring or bankruptcy law, inspection, and regulation for quality and information disclosure.[136][137][138][139][140]

Market failure

The term "market failure" encompasses several problems which may undermine standard economic assumptions. Although economists categorise market failures differently, the following categories emerge in the main texts.[e]

Information asymmetries and incomplete markets may result in economic inefficiency but also a possibility of improving efficiency through market, legal, and regulatory remedies, as discussed above.

Natural monopoly, or the overlapping concepts of "practical" and "technical" monopoly, is an extreme case of failure of competition as a restraint on producers. Extreme economies of scale are one possible cause.

Public goods are goods which are under-supplied in a typical market. The defining features are that people can consume public goods without having to pay for them and that more than one person can consume the good at the same time.

Externalities occur where there are significant social costs or benefits from production or consumption that are not reflected in market prices. For example, air pollution may generate a negative externality, and education may generate a positive externality (less crime, etc.). Governments often tax and otherwise restrict the sale of goods that have negative externalities and subsidise or otherwise promote the purchase of goods that have positive externalities in an effort to correct the price distortions caused by these externalities.[141] Elementary demand-and-supply theory predicts equilibrium but not the speed of adjustment for changes of equilibrium due to a shift in demand or supply.[142]

In many areas, some form of price stickiness is postulated to account for quantities, rather than prices, adjusting in the short run to changes on the demand side or the supply side. This includes standard analysis of the business cycle in macroeconomics. Analysis often revolves around causes of such price stickiness and their implications for reaching a hypothesised long-run equilibrium. Examples of such price stickiness in particular markets include wage rates in labour markets and posted prices in markets deviating from perfect competition.

Some specialised fields of economics deal in market failure more than others. The economics of the public sector is one example. Much environmental economics concerns externalities or "public bads".

Policy options include regulations that reflect cost–benefit analysis or market solutions that change incentives, such as emission fees or redefinition of property rights.[143]

Welfare

Welfare economics uses microeconomics techniques to evaluate well-being from allocation of productive factors as to desirability and economic efficiency within an economy, often relative to competitive general equilibrium.[144] It analyses social welfare, however measured, in terms of economic activities of the individuals that compose the theoretical society considered. Accordingly, individuals, with associated economic activities, are the basic units for aggregating to social welfare, whether of a group, a community, or a society, and there is no "social welfare" apart from the "welfare" associated with its individual units.

Macroeconomics

Macroeconomics, another branch of economics, examines the economy as a whole to explain broad aggregates and their interactions "top down", that is, using a simplified form of general-equilibrium theory.[145] Such aggregates include national income and output, the unemployment rate, and price inflation and subaggregates like total consumption and investment spending and their components. It also studies effects of monetary policy and fiscal policy.

Since at least the 1960s, macroeconomics has been characterised by further integration as to micro-based modelling of sectors, including rationality of players, efficient use of market information, and imperfect competition.[146] This has addressed a long-standing concern about inconsistent developments of the same subject.[147]

Macroeconomic analysis also considers factors affecting the long-term level and growth of national income. Such factors include capital accumulation, technological change and labour force growth.[148]

Growth

Growth economics studies factors that explain economic growth – the increase in output per capita of a country over a long period of time. The same factors are used to explain differences in the level of output per capita between countries, in particular why some countries grow faster than others, and whether countries converge at the same rates of growth.

Much-studied factors include the rate of investment, population growth, and technological change. These are represented in theoretical and empirical forms (as in the neoclassical and endogenous growth models) and in growth accounting.[149]

Business cycle

The economics of a depression were the spur for the creation of "macroeconomics" as a separate discipline. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, John Maynard Keynes authored a book entitled The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money outlining the key theories of Keynesian economics. Keynes contended that aggregate demand for goods might be insufficient during economic downturns, leading to unnecessarily high unemployment and losses of potential output.

He therefore advocated active policy responses by the public sector, including monetary policy actions by the central bank and fiscal policy actions by the government to stabilise output over the business cycle.[150] Thus, a central conclusion of Keynesian economics is that, in some situations, no strong automatic mechanism moves output and employment towards full employment levels. John Hicks' IS/LM model has been the most influential interpretation of The General Theory.

Over the years, understanding of the business cycle has branched into various research programmes, mostly related to or distinct from Keynesianism. The neoclassical synthesis refers to the reconciliation of Keynesian economics with classical economics, stating that Keynesianism is correct in the short run but qualified by classical-like considerations in the intermediate and long run.[75]

New classical macroeconomics, as distinct from the Keynesian view of the business cycle, posits market clearing with imperfect information. It includes Friedman's permanent income hypothesis on consumption and "rational expectations" theory,[151] led by Robert Lucas, and real business cycle theory.[152]

In contrast, the new Keynesian approach retains the rational expectations assumption, however it assumes a variety of market failures. In particular, New Keynesians assume prices and wages are "sticky", which means they do not adjust instantaneously to changes in economic conditions.[104]

Thus, the new classicals assume that prices and wages adjust automatically to attain full employment, whereas the new Keynesians see full employment as being automatically achieved only in the long run, and hence government and central-bank policies are needed because the "long run" may be very long.

Unemployment

The amount of unemployment in an economy is measured by the unemployment rate, the percentage of workers without jobs in the labour force. The labour force only includes workers actively looking for jobs. People who are retired, pursuing education, or discouraged from seeking work by a lack of job prospects are excluded from the labour force. Unemployment can be generally broken down into several types that are related to different causes.[153]

Classical models of unemployment occurs when wages are too high for employers to be willing to hire more workers. Consistent with classical unemployment, frictional unemployment occurs when appropriate job vacancies exist for a worker, but the length of time needed to search for and find the job leads to a period of unemployment.[153]

Structural unemployment covers a variety of possible causes of unemployment including a mismatch between workers' skills and the skills required for open jobs.[154] Large amounts of structural unemployment can occur when an economy is transitioning industries and workers find their previous set of skills are no longer in demand. Structural unemployment is similar to frictional unemployment since both reflect the problem of matching workers with job vacancies, but structural unemployment covers the time needed to acquire new skills not just the short term search process.[155]

While some types of unemployment may occur regardless of the condition of the economy, cyclical unemployment occurs when growth stagnates. Okun's law represents the empirical relationship between unemployment and economic growth.[156] The original version of Okun's law states that a 3% increase in output would lead to a 1% decrease in unemployment.[157]

Money and monetary policy

Money is a means of final payment for goods in most price system economies, and is the unit of account in which prices are typically stated. Money has general acceptability, relative consistency in value, divisibility, durability, portability, elasticity in supply, and longevity with mass public confidence. It includes currency held by the nonbank public and checkable deposits. It has been described as a social convention, like language, useful to one largely because it is useful to others. In the words of Francis Amasa Walker, a well-known 19th-century economist, "Money is what money does" ("Money is that money does" in the original).[158]

As a medium of exchange, money facilitates trade. It is essentially a measure of value and more importantly, a store of value being a basis for credit creation. Its economic function can be contrasted with barter (non-monetary exchange). Given a diverse array of produced goods and specialised producers, barter may entail a hard-to-locate double coincidence of wants as to what is exchanged, say apples and a book. Money can reduce the transaction cost of exchange because of its ready acceptability. Then it is less costly for the seller to accept money in exchange, rather than what the buyer produces.[159]

Monetary policy is the policy that central banks conduct to accomplish their broader objectives. Most central banks in developed countries follow inflation targeting,[160] whereas the main objective for many central banks in development countries is to uphold a fixed exchange rate system.[161] The primary monetary tool is normally the adjustment of interest rates,[162] either directly via administratively changing the central bank's own interest rates or indirectly via open market operations.[163] Via the monetary transmission mechanism, interest rate changes affect investment, consumption and net export, and hence aggregate demand, output and employment, and ultimately the development of wages and inflation.

Fiscal policy

Governments implement fiscal policy to influence macroeconomic conditions by adjusting spending and taxation policies to alter aggregate demand. When aggregate demand falls below the potential output of the economy, there is an output gap where some productive capacity is left unemployed. Governments increase spending and cut taxes to boost aggregate demand. Resources that have been idled can be used by the government.

For example, unemployed home builders can be hired to expand highways. Tax cuts allow consumers to increase their spending, which boosts aggregate demand. Both tax cuts and spending have multiplier effects where the initial increase in demand from the policy percolates through the economy and generates additional economic activity.

The effects of fiscal policy can be limited by crowding out. When there is no output gap, the economy is producing at full capacity and there are no excess productive resources. If the government increases spending in this situation, the government uses resources that otherwise would have been used by the private sector, so there is no increase in overall output. Some economists think that crowding out is always an issue while others do not think it is a major issue when output is depressed.

Sceptics of fiscal policy also make the argument of Ricardian equivalence. They argue that an increase in debt will have to be paid for with future tax increases, which will cause people to reduce their consumption and save money to pay for the future tax increase. Under Ricardian equivalence, any boost in demand from tax cuts will be offset by the increased saving intended to pay for future higher taxes.

Inequality

Economic inequality includes income inequality, measured using the distribution of income (the amount of money people receive), and wealth inequality measured using the distribution of wealth (the amount of wealth people own), and other measures such as consumption, land ownership, and human capital. Inequality exists at different extents between countries or states, groups of people, and individuals.[164] There are many methods for measuring inequality,[165] the Gini coefficient being widely used for income differences among individuals. An example measure of inequality between countries is the Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index, a composite index that takes inequality into account.[166] Important concepts of equality include equity, equality of outcome, and equality of opportunity.

Research has linked economic inequality to political and social instability, including revolution, democratic breakdown and civil conflict.[167][168][169][170] Research suggests that greater inequality hinders economic growth and macroeconomic stability, and that land and human capital inequality reduce growth more than inequality of income.[167][171] Inequality is at the centre stage of economic policy debate across the globe, as government tax and spending policies have significant effects on income distribution.[167] In advanced economies, taxes and transfers decrease income inequality by one-third, with most of this being achieved via public social spending (such as pensions and family benefits.)[167]

Other branches of economics

Public economics

Public economics is the field of economics that deals with economic activities of a public sector, usually government. The subject addresses such matters as tax incidence (who really pays a particular tax), cost–benefit analysis of government programmes, effects on economic efficiency and income distribution of different kinds of spending and taxes, and fiscal politics. The latter, an aspect of public choice theory, models public-sector behaviour analogously to microeconomics, involving interactions of self-interested voters, politicians, and bureaucrats.[172]

Much of economics is positive, seeking to describe and predict economic phenomena. Normative economics seeks to identify what economies ought to be like.

Welfare economics is a normative branch of economics that uses microeconomic techniques to simultaneously determine the allocative efficiency within an economy and the income distribution associated with it. It attempts to measure social welfare by examining the economic activities of the individuals that comprise society.[173]

International economics

International trade studies determinants of goods-and-services flows across international boundaries. It also concerns the size and distribution of gains from trade. Policy applications include estimating the effects of changing tariff rates and trade quotas. International finance is a macroeconomic field which examines the flow of capital across international borders, and the effects of these movements on exchange rates. Increased trade in goods, services and capital between countries is a major effect of contemporary globalisation.[174]

Labour economics

Экономика труда стремится понять функционирование и динамику рынков наемного труда . Рынки труда функционируют посредством взаимодействия работников и работодателей. Экономика труда рассматривает поставщиков трудовых услуг (работников), спрос на трудовые услуги (работодателей) и пытается понять результирующую структуру заработной платы, занятости и доходов. В экономике труд является мерой работы, выполняемой людьми. Его условно противопоставляют таким другим факторам производства , как земля и капитал . Существуют теории, которые разработали концепцию, называемую человеческим капиталом (имеющую в виду навыки, которыми обладают работники, а не обязательно их фактическую работу), хотя есть также противоположные теории макроэкономической системы, которые считают, что человеческий капитал является противоречивым в терминах. [ нужна ссылка ]

Экономика развития

Экономика развития исследует экономические аспекты процесса экономического развития в странах с относительно низкими доходами, уделяя особое внимание структурным изменениям , бедности и экономическому росту . Подходы в экономике развития часто включают социальные и политические факторы. [ 175 ]

Похожие темы

Экономика является одной из нескольких социальных наук и имеет области, граничащие с другими областями, включая экономическую географию , экономическую историю , общественный выбор , экономику энергетики , экономику культуры , семейную экономику и институциональную экономику .

Право и экономика, или экономический анализ права, — это подход к теории права, который применяет методы экономики к праву. Это включает в себя использование экономических концепций для объяснения последствий правовых норм, для оценки того, какие правовые нормы являются экономически эффективными , и для прогнозирования того, какими будут правовые нормы. [ 176 ] В плодотворной статье Рональда Коуза, опубликованной в 1961 году, говорилось, что четко определенные права собственности могут преодолеть проблемы внешних эффектов . [ 177 ]

Политическая экономия — это междисциплинарное исследование, которое объединяет экономику, право и политологию для объяснения того, как политические институты, политическая среда и экономическая система (капиталистическая, социалистическая , смешанная) влияют друг на друга. Он изучает такие вопросы, как монополия, стремление к получению ренты и внешние эффекты должны влиять на государственную политику. [ 178 ] [ 179 ] Историки использовали политическую экономию , чтобы изучить способы, которыми в прошлом люди и группы с общими экономическими интересами использовали политику для осуществления изменений, выгодных для их интересов. [ 180 ]

Экономика энергетики – это широкая научная предметная область, которая включает в себя темы, связанные с энергоснабжением и спросом на энергию . Джорджеску-Роген вновь ввел концепцию энтропии в отношении экономики и энергии из термодинамики , в отличие от того, что он считал механистической основой неоклассической экономики, взятой из ньютоновской физики. Его работа внесла значительный вклад в термоэкономику и экологическую экономику . Он также проделал фундаментальную работу, которая позже превратилась в эволюционную экономику . [ 181 ]

Социологическое современности подразделение экономической социологии возникло, прежде всего, благодаря работам Эмиля Дюркгейма , Макса Вебера и Георга Зиммеля , как подход к анализу воздействия экономических явлений по отношению к всеобъемлющей социальной парадигме (т.е. ) . [ 182 ] Классические работы включают Макса Вебера ( «Протестантскую этику и дух капитализма» 1905) и Георга Зиммеля » «Философию денег (1900). Совсем недавно появились работы Джеймса С. Коулмана , [ 183 ] Марк Грановеттер , Питер Хедстрем и Ричард Сведберг оказали влияние в этой области.

Гэри Беккер в 1974 году представил экономическую теорию социальных взаимодействий, приложения которой включали семью , благотворительность, блага и взаимодействия между людьми, а также зависть и ненависть. [ 184 ] В 2001 году он и Кевин Мерфи написали книгу, в которой анализируется поведение рынка в социальной среде. [ 185 ]

Профессия

Профессионализация экономики, отраженная в росте количества программ последипломного образования по этому предмету, была описана как «главное изменение в экономике примерно с 1900 года». [ 186 ] В большинстве крупных университетов и многих колледжей есть специализация, школа или факультет, на котором ученые степени присуждаются по данному предмету, будь то гуманитарные науки , бизнес или профессиональное обучение. См. Бакалавр экономики и Магистр экономики .

В частном секторе профессиональные экономисты работают консультантами, а также в промышленности, включая банковское дело и финансы . Экономисты также работают в различных правительственных ведомствах и агентствах, например, в национальном казначействе , центральном банке или Национальном бюро статистики . См. Экономический аналитик .

Ежегодно экономистам присуждаются десятки премий за выдающийся интеллектуальный вклад в эту область, наиболее заметной из которых является Нобелевская премия по экономическим наукам , хотя она и не является Нобелевской премией .

Современная экономика использует математику. Экономисты используют инструменты исчисления , линейной алгебры , статистики , теории игр и информатики . [ 187 ] Ожидается, что профессиональные экономисты знакомы с этими инструментами, в то время как меньшинство специализируются на эконометрике и математических методах.

Женщины в экономике

Гарриет Мартино (1802–1876) была широко читаемым популяризатором классической экономической мысли. Мэри Пейли Маршалл (1850–1944), первая женщина-преподаватель британского экономического факультета, написала «Экономику промышленности» вместе со своим мужем Альфредом Маршаллом . Джоан Робинсон (1903–1983) была важным посткейнсианским экономистом. Историк экономики Анна Шварц (1915–2012) написала «Монетарную историю Соединенных Штатов, 1867–1960» вместе с Милтоном Фридманом . [ 188 ] Три женщины получили Нобелевскую премию по экономике : Элинор Остром (2009 г.), Эстер Дюфло (2019 г.) и Клаудия Голдин (2023 г.). Пятеро получили медаль Джона Бейтса Кларка : Сьюзен Эйти (2007 г.), Эстер Дюфло (2010 г.), Эми Финкельштейн (2012 г.), Эми Накамура (2019 г.) и Мелисса Делл (2020 г.).

Доля женского авторства в известных экономических журналах снизилась с 1940 по 1970-е годы, но впоследствии выросла, при этом наблюдались различные модели гендерного соавторства. [ 189 ] Женщины по-прежнему недостаточно представлены в профессии во всем мире (19% авторов в базе данных RePEc в 2018 году), с национальными различиями. [ 190 ]

См. также

- Асимметричная коинтеграция

- Теория критического момента

- Экономическая демократия

- Экономическая идеология

- Экономический союз

- Экономическая терминология, отличающаяся от общепринятого использования

- Свободная торговля

- Глоссарий экономики

- Экономика счастья

- Гуманистическая экономика

- Указатель статей по экономике

- Список академических областей § Экономика

- Список экономических наград

- Список фильмов по экономике

- Очерк экономики

- Социоэкономика

- Экономика солидарности

Примечания

- ^ «Капитал» в использовании Смита включает основной капитал и оборотный капитал . Последнее включает в себя заработную плату и содержание труда, деньги и ресурсы от земли, шахт и рыболовства, связанные с производством. [ 58 ]

- ^ «Эта наука указывает на случаи, в которых торговля действительно продуктивна, когда все, что приобретено одним, теряется другим и когда это выгодно всем; она также учит нас ценить отдельные ее процессы, но просто в их результатах, в Помимо этого знания, купец должен также понимать процессы своего искусства. Он должен быть знаком с товарами, которыми он торгует, их качествами и недостатками, странами, из которых они происходят, их рынками, средствами производства. их транспортировку, ценности, которые следует присвоить им в обмен и метод ведения счетов. То же самое замечание применимо и к земледельцу, и к фабриканту, и к практическому деловому человеку, чтобы приобрести глубокие знания о причинах и следствиях каждого явления, изучение политической экономии; существенно необходим им всем; и чтобы стать экспертом в своем конкретном деле, каждый должен добавить к этому знание его процессов». ( Скажем, 1803 г. , стр. XVI)

- ^ «И когда мы подвергаем рассматриваемое определение этому тесту, мы видим, что оно обладает недостатками, которые, будучи далеко не второстепенными и второстепенными, представляют собой не что иное, как полную неспособность продемонстрировать ни объем, ни значение наиболее центрального обобщения всего». ( Роббинс 2007 , стр. 5)

- ^ «Принятую нами концепцию можно охарактеризовать как аналитическую. Она не пытается выделить определенные виды поведения, а фокусирует внимание на определенном аспекте поведения, форме, навязанной влиянием дефицита. ( Роббинс 2007 , с. 17)

- ^ Сравните с Николасом Барром (2004), чей список провалов рынка смешан с провалами экономических предположений, согласно которым (1) производители являются получателями цен (т.е. наличие олигополии или монополии; но почему это не является продуктом следующего? ) (2) равные возможности потребителей (то, что юристы по труду называют дисбалансом переговорных сил) (3) полноценные рынки (4) общественные блага (5) внешние эффекты (т.е. внешние эффекты?) (6) возрастающая отдача от масштаба (т.е. практическая монополия) ) (7) совершенная информация (в Экономика государства всеобщего благосостояния (4-е изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета. 2004. стр. 72–79. ISBN 978-0-19-926497-1 . ).

• Джозеф Э. Стиглиц (2015) классифицирует провалы рынка как причины несостоятельности конкуренции (включая естественные монополии ), информационной асимметрии , несовершенства рынков , внешних эффектов , ситуации с общественным благом и макроэкономических нарушений (в «Глава 4: Провал рынка» . Экономика государственного сектора (4-е международное студенческое изд.). WW Нортон и компания. 2015. стр. 81–100. ISBN 978-0-393-93709-1 . ).

Ссылки

- ^ «экономика» . Оксфордский словарь английского языка (онлайн-изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета . (Требуется подписка или членство участвующей организации .)

- ^ «ЭКОНОМИКА | Значение и определение для британского английского языка» . Лексико.com . Архивировано из оригинала 24 августа 2022 года . Проверено 13 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Кругман, Пол ; Уэллс, Робин (2012). Экономика (3-е изд.). Стоит издательства. п. 2. ISBN 978-1464128738 .

- ^ Бэкхаус, Роджер (2002). История экономики Пингвина . Пингвин. ISBN 0-14-026042-0 . OCLC 59475581 .

Границы того, что представляет собой экономика, еще больше размываются из-за того, что экономические проблемы анализируются не только «экономистами», но также историками, географами, экологами, учеными-менеджерами и инженерами.

- ^ Фридман, Милтон (1953). « Методология позитивной экономики ». Очерки позитивной экономики . Издательство Чикагского университета. п. 5.

- ^ Кэплин, Эндрю; Шоттер, Эндрю, ред. (2008). Основы позитивной и нормативной экономики: Справочник . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-532831-8 .

- ^ Дилман, Терри Э. (2001). Прикладной регрессионный анализ для бизнеса и экономики . Даксбери/Томсон Обучение. ISBN 0-534-37955-9 . OCLC 44118027 .

- ^ Кианпур, Мазахер; Ковальски, Стюарт; Оверби, Харальд (2021). «Систематическое понимание экономики кибербезопасности: обзор» . Устойчивость . 13 (24): 13677. doi : 10.3390/su132413677 . HDL : 11250/2978306 .

- ^ Тарриконе, Розанна (2006). «Анализ стоимости болезни». Политика здравоохранения . 77 (1): 51–63. doi : 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.07.016 . ПМИД 16139925 .

- ^ Дхармарадж, Э. (2010). Инженерная экономика . Мумбаи: Издательство Гималаев. ISBN 978-9350432471 . OCLC 1058341272 .

- ^ Кинг, Дэвид (2018). Фискальные уровни: экономика многоуровневого правительства . Рутледж . ISBN 978-1-138-64813-5 . OCLC 1020440881 .

- ^ Беккер, Гэри С. (январь 1974 г.). «Преступление и наказание: экономический подход» (PDF) . В Беккере, Гэри С.; Ландес, Уильям М. (ред.). Очерки по экономике преступления и наказания . Национальное бюро экономических исследований . стр. 1–54. ISBN 0-87014-263-1 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 13 сентября 2021 года . Проверено 1 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Ханушек, Эрик А.; Вессманн, Людгер (2007). «Экономика образования» . Рабочие документы политических исследований. Всемирный банк . дои : 10.1596/1813-9450-4122 . hdl : 20.500.12323/2954 . S2CID 13912607 . Архивировано из оригинала 6 января 2022 года . Проверено 17 декабря 2020 г.

- ^ Беккер, Гэри С. (1991) [1981]. Трактат о семье (Расширенное изд.). Издательство Гарвардского университета. ISBN 0-674-90698-5 . Архивировано из оригинала 30 июля 2022 года . Проверено 1 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Нельсон, Джули А. (1995). «Феминизм и экономика» . Журнал экономических перспектив . 9 (2): 131–148. дои : 10.1257/jep.9.2.131 . Архивировано из оригинала 7 апреля 2022 года . Проверено 1 июля 2022 г. Фербер, Марианна А.; Нельсон, Джули А., ред. (октябрь 2003 г.) [1993]. Феминистская экономика сегодня: за пределами экономического человека . Издательство Чикагского университета. ISBN 978-0226242071 . Архивировано из оригинала 30 июля 2022 года . Проверено 1 июля 2022 г.

- ^

- Познер, Ричард А. (2007) [1972]. Экономический анализ права (7-е изд.). Уолтерс Клювер – Издательство Aspen. ISBN 978-0735563544 . Проверено 1 июля 2022 г.

- Познер, Ричард А. (1983). Экономика правосудия . Издательство Гарвардского университета. ISBN 978-0674235267 . Архивировано из оригинала 30 июля 2022 года . Проверено 1 июля 2022 г.

- ^