Ecofascism

| Part of a series on |

| Fascism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Green politics |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Neo-fascism |

|---|

|

Ecofascism (sometimes spelled eco-fascism[1]) is a term used to describe individuals and groups which combine environmentalism with fascism.[2]

Philosopher André Gorz characterized eco-fascism as hypothetical forms of totalitarianism based on an ecological orientation of politics.[3] Similar definitions have been used by others in older academic literature in accusations of ecofascism of "environmental fascism".[4] However, since the 2010s, a number of individuals and groups have emerged that either self-identify as "ecofascist" or have been labelled as "ecofascist" by academic or journalistic sources.[5] These individuals and groups synthesise radical far-right politics with environmentalism,[6][7] and will typically argue that overpopulation is the primary threat to the environment and that the only solution is a complete halt to immigration or, at their most extreme, genocide against non-White groups and ethnicities.[8] Many far-right political parties have added green politics to their platforms.[9][1][10] Through the 2010s ecofascism has seen increasing support.[11]

Definition

[edit]In 2005, environmental historian Michael E. Zimmerman defined "ecofascism" as "a totalitarian government that requires individuals to sacrifice their interests to the well-being of the 'land', understood as the splendid web of life, or the organic whole of nature, including peoples and their states".[2] This was supported by philosopher Patrick Hassan’s work analysing historical accusations of ecofascism in academic literature.[12] Zimmerman argued that while no ecofascist government has existed so far, "important aspects of it can be found in German National Socialism, one of whose central slogans was "Blood and Soil".[2][13] Other political agendas, instead of environmental protection and prevention of climate change, are nationalist approaches to climate such as national economic environmentalism, securitization of climate change, and ecobordering.[14]

Ecofascists often believe there is a symbiotic relationship between a nation-group and its homeland.[15] They often blame the global south for ecological problems,[16][17] with their proposed solutions often entailing extreme population control measures based on racial categorisations,[18] and advocating for the accelerated collapse of current society to be replaced by fascist societies.[19] This latter belief is often accompanied with vocal support for terrorist actions.[20][21][22]

Vice has defined ecofascism as an ideology "which blames the demise of the environment on overpopulation, immigration, and over-industrialization, problems that followers think could be partly remedied through the mass murder of refugees in Western countries."[9] Environmentalist author Naomi Klein has suggested that ecofascists' primary objectives are to close borders to immigrants and, on the more extreme end, to embrace the idea of climate change as a divinely-ordained signal to begin a mass purge of sections of the human race. Ecofascism is "environmentalism through genocide", opined Klein.[1] Political researcher Alex Amend defined ecofascist belief as "The devaluing of human life—particularly of populations seen as inferior—in order to protect the environment viewed as essential to White identity."[23]

Terrorism researcher Kristy Campion defined ecofascism as "a reactionary and revolutionary ideology that champions the regeneration of an imagined community through a return to a romanticised, ethnopluralist vision of the natural order."[24]

The European Commission describes ecofascism as the "weaponization of climate change by far right populist political parties and white supremacist groups".[25] Tactics of this weaponization include the use of language and equating actors in population and migration discourses to components of the climate crisis. As said in a policy brief for The International Center for Counter-Terrorism, this "linguistic violence"[25] entails that "the invasion of non-native species that threaten the environment becomes synonymous with the invasion of immigrants, the protection of the environment with the protection of borders, trash with people, and environmental cleansing with ethnic cleaning."[25]

Helen Cawood and Xany Jansen Van Vuuren have criticised previous attempts to define ecofascism as focusing too heavily on environmental and ecological conservationism in historical fascist movements, and the subsequent definitions being too broad and encompassing many ontologically different ideologies.[26] In their criticism they summarise the current definition of ecofascism as used in the academic literature as "a movement that uses environmental and ecological conservationist talking points to push an ideology of ethnic or racial separatism".[27] This is supported by Blair Taylor statement that ecofascism refers to "groups and ideologies that offer authoritarian, hierarchical, and racist analyses and solutions to environmental problems".[28] Similarly, extremism researchers Brian Hughes, Dave Jones, and Amarnath Amarasingam state how ecofascism is less a coherent ideology and more a cultural expression of mystical, anti-humanist romanticism.[29] This is further supported by Maria Darwish in her research into the Nordic Resistance Movement where while there is concern for environmental issues they are "a concern for Neo-Nazis only in so far as it supports and popularizes the backstage mission of the NRM", that is the implementation of a fascist regime,[30] and Jacob Blumenfeld stating "ecofascism names a specific far-right ideology that rationalizes white supremacist violence by invoking imminent ecological collapse and scarce natural resources".[31]

Borrowing from the "watermelon" analogy of eco-socialism, Berggruen Institute scholar Nils Gilman has coined the term "avocado politics" for eco-fascism, being "green on the outside but brown(shirt) at the core".[32][33][34]

Ideological origins

[edit]Madison Grant

[edit]Sometimes dubbed the "founding father" of ecofascism,[35][36] Madison Grant was a pioneer of conservationism in America in the late 19th and early 20th century. Grant is credited as a founder of modern wildlife management. Grant built the Bronx River Parkway, was a co-founder of the American Bison Society, and helped create Glacier National Park, Olympic National Park, Everglades National Park and Denali National Park. As president of the New York Zoological Society, he founded the Bronx Zoo in 1899.[37]

In addition to his conservationist work, Grant was a trenchant racist.[38][39] In 1906, Grant supported the placement of Ota Benga, a member of the Mbuti people who was kidnapped, removed from his home in the Congo, and put on display in the Bronx Zoo as an exhibit in the Monkey House.[35][36] In 1916, Grant wrote The Passing of the Great Race, a work of pseudoscientific literature which claimed to give an account of the anthropological history of Europe.[40] The book divides Europeans into three races; Alpines, Mediterraneans and Nordics, and it also claims that the first two races are inferior to the superior Nordic race, which is the only race which is fit to rule the earth. Adolf Hitler would later describe Grant's book as "his bible" and Grant's "Nordic theory" became the bedrock of Nazi racial theories.[41] Additionally, Grant was a eugenicist: He cofounded and was the director of the American Eugenics Society and he also advocated the culling of the unfit from the human population.[42][43][44] Grant concocted a 100-year plan to perfect the human race, a plan in which one ethnic group after another would be killed off until racial purity would be obtained.[35] Grant campaigned for the passage of the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and he also campaigned for the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, which drastically reduced the number of immigrants from eastern Europe and Asia who were allowed to enter the United States.[45][43]

In the modern era, Grant's ideas have been cited by advocates of far-right politics such as Richard Spencer[37] and Anders Breivik.[36][46][47]

Nazism

[edit]The authors Janet Biehl and Peter Staudenmaier suggest that the synthesis of fascism and environmentalism began with Nazism, stating that 19th and 20th century Germany was an early center of ecofascist thought, finding its antecedents in many prominent natural scientists and environmentalists, including Ernst Moritz Arndt, Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl, and Ernst Haeckel.[48] With the works and ideas of such individuals being later established as policies in the Nazi regime.[49] This is supported by other researchers who identify the Völkisch movement as an ideological originator of later ecofascism.[50][51] In Biehl and Staudenmaier's book Ecofascism: Lessons from the German Experience, they note the Nazi Party's interest in ecology, and suggest their interest was "linked with traditional agrarian romanticism and hostility to urban civilization".[52][53][54] With Zimmerman pointing to the works of conservationist and Nazi Walther Schoenichen as having pertinence to later ecofascism and similarities to developments in deep ecological understanding.[55] During the Nazi rise to power, there was strong support for the Nazis among German environmentalists and conservationists.[56] Richard Walther Darré, a leading Nazi ideologist and Reich Minister of Food and Agriculture who invented the term "Blood and Soil", developed a concept of the nation having a mystic connection with their homeland, and as such, the nation was dutybound to take care of the land.[57] This was supported by other Nazi theorists such as Alfred Rosenberg who wrote of how society's move from agricultural systems to industrialised systems broke their connection to nature and contributed to the death of the Volk.[52] Similar sentiments are found in speeches from Fascist Italy’s Minister of Agriculture Giuseppe Tassinari.[58] Because of this, modern ecofascists cite the Nazi Party as an origin point of ecofascism.[59][60][61] Beyond Darré, Rudolf Hess and Fritz Todt are viewed as representatives of environmentalism within the Nazi party.[62][63] Roger Griffin has also pointed to the glorification of wildlife in Nazi art and ruralism in the novels of the fascist sympathizers Knut Hamsun and Henry Williamson as examples.[64]

After the outlawing of the neo-nazi Socialist Reich Party, one of its members August Haußleiter moved towards organising within the environmental and anti-nuclear movements, going on to become a founding member of the German Green Party. When green activists later uncovered his past activities in the neo-nazi movement, Haußleiter was forced to step down as the party's chairman, although he continued to hold a central role in the party newspaper.[65] As efforts to expel nationalist elements within the party continued, a conservative faction split off and founded the Ecological Democratic Party, which became noted for persistent holocaust denial, rejection of social justice and opposition to immigration.[66]

Savitri Devi

[edit]

The French-born Greek fascist Savitri Devi (born Maximiani Julia Portas) was a prominent proponent of Esoteric Nazism and deep ecology.[68] A fanatical supporter of Hitler and the Nazi Party from the 1930s onwards, she also supported animal rights activism and was a vegetarian from a young age. In her works, she espoused ecologist views, such as the Impeachment of Man (1959), in which she espoused her views on animal rights and nature.[69][70] In accordance with her ecologist views, human beings do not stand above the animals; instead, humans are a part of the ecosystem and as a result, they should respect all forms of life, including animals and the whole of nature. Because of her dual devotion to Nazism and deep ecology, she is considered an influential figure in ecofascist circles.[71][72]

Malthusianism

[edit]Malthusian ideas of overpopulation have been adopted by ecofascists,[73] using Malthusian rationale in anti-immigration arguments[74] and seeking to resolve the perceived global issue by enforcing population control measures on the global south and racial minorities in white majority countries.[75] Such Malthusian ideas are often paired with Social Darwinist and eugenicist views.[76][44][77]

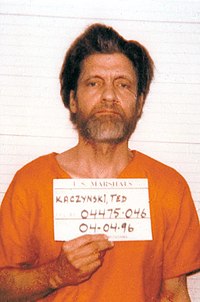

Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber

[edit]

Ted Kaczynski, better known as "The Unabomber", is cited as a figure who was highly influential in the development of ecofascist thought, and features prominently in contemporary ecofascist propaganda.[78] Between 1978 and 1995 Kaczynski instigated a terrorist bombing campaign aimed at inciting a revolution against modern industrial society,[79] in the name of returning humanity to a primitive state he suggested offered humanity more freedom while protecting the environment. In 1995 Kaczynski offered to end his bombing campaign if The Washington Post or The New York Times would publish his 35,000-word Unabomber manifesto. Both newspapers agreed to those terms. The manifesto railed not only against modern industrial society but also against "modern leftists", whom Kaczynski defined as "mainly socialists, collectivists, 'politically correct' types, feminists, gay and disability activists, animal rights activists and the like".[80][81]

Because of Kaczynski's intelligence and because of his ability to write in a high-level academic tone, his manifesto was given serious consideration upon its release and it became highly influential, even amongst those who severely disagreed with his use of violence. Kaczynski's staunchly radical pro-green, anti-left work was quickly absorbed into ecofascist thought.[82][83]

Kaczynski also criticized right-wing activists who complained about the erosion of traditional social mores because they supported technological and economic progress, a view which he opposed. He stated that technology erodes traditional social mores that conservatives and right wingers want to protect, and he referred to conservatives as fools.[84]

Although Kaczynski and his manifesto have been embraced by ecofascists,[82] he rejected "fascism",[85] including specifically "the 'ecofascists'", describing 'ecofascism' itself as 'an aberrant branch of leftism':[86][87]

The true anti-tech movement rejects every form of racism or ethnocentrism. This has nothing to do with "tolerance," "diversity," "pluralism," "multiculturalism," "equality," or "social justice." The rejection of racism and ethnocentrism is - purely and simply - a cardinal point of strategy.[86]

In his manifesto, Kaczynski wrote that he considered fascism a "kook ideology" and he also wrote that he considered Nazism "evil".[85] Kaczynski never tried to align himself with the far-right at any point before or after his arrest.[85]

In 2017, Netflix released a dramatisation of Kaczynski's life, titled Manhunt: Unabomber. Once again, the popularity of the show thrust Kaczynski and his manifesto into the public's mind and it also raised the profile of ecofascism.[88][60][85]

Garrett Hardin, Pentti Linkola, and "Lifeboat Ethics"

[edit]

Two figures influential in ecofascism are Garrett Hardin[89] and Pentti Linkola,[90][91] both of whom were proponents of what they refer to as "Lifeboat Ethics".[92] Hardin was a professor of Human Ecology at the University of California often described as a white nationalist.[93][94][95] His work was focused on the ethics of overpopulation and population control and suggested different methods like "birth control, abortion, and sterilization". Not only did he have medical suggestions but also stood against immigration and the end of foreign aid.[96]

Linkola was a Finnish ecologist and radical Malthusian[97] accused of being an active ecofascist[98] who actively advocated ending democracy and replacing it with dictatorships that would use totalitarian and even genocidal tactics[99] to end climate change.[46][100][101] Both men used versions of the following analogy to illustrate their viewpoint:

What to do, when a ship carrying a hundred passengers suddenly capsizes and there is only one lifeboat? When the lifeboat is full, those who hate life will try to load it with more people and sink the lot. Those who love and respect life will take the ship's axe and sever the extra hands that cling to the sides.[88][60]

Renaud Camus

[edit]Renaud Camus' conspiracy theory, the Great Replacement, has been influential on ecofascism, being referenced explicitly in multiple manifestos and had its ideas relayed in others.[102] In the conspiracy theory, the "native" white populations of western countries are being replaced by non-white populations as a directed political effort.[103][104]

Association with violence

[edit]Ecofascist violence has occurred since the 21st century,[105][106] with academics and researchers warning that as ecological crises worsen and remain unaddressed, support for ecofascism and violence in the name of ecofascism will increase.[107]

In December 2020, the Swedish Defence Research Agency released a report on ecofascism. The paper argued that ecofascism is intimately tied to the ideology of accelerationism, and ecofascists nearly exclusively choose terror tactics over the political approach.[105] Further, the SDRA argues not all ecofascist mass shooters have been recognized as such: Pekka-Eric Auvinen who shot eight people in Finland in 2007 before killing himself adhered to the ideology according to his manifesto titled "The Natural Selector's Manifesto".[108][109] He advocated "total war against humanity" due to the threat humanity posed to other species. He wrote that death and killing is not a tragedy, as it constantly happens in nature between all species. Auvinen also wrote that the modern society hinders "natural justice" and that all inferior "subhumans" should be killed and only the elite of humanity be spared. In one of his YouTube videos Auvinen paid tribute to the prominent deep ecologist Pentti Linkola.[105]

2010s

[edit]James Jay Lee, the eco-terrorist who took several hostages at the Discovery Communications headquarters on 1 September 2010, was described as an ecofascist by Mark Potok of the Southern Poverty Law Center.[110]

Anders Breivik committed the 2011 Norway attacks on 22 July 2011, in which he killed eight people by detonating a van bomb at Regjeringskvartalet in Oslo, and then killed 69 participants of a Workers' Youth League (AUF) summer camp, in a mass shooting on the island of Utøya.[111][112][113]While dismissive of climate change, Breivik's manifesto was concerned with the carrying capacity of the planet,[114] taking inspiration from Kaczynski[115] and Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race.[47] Breivik’s solution to this perceived problem was to cap the global population at 2.5 billion people, with the reduction in the global population being forced upon the global south.[114] Through his actions he sought to inspire other terrorist attacks,[116] and was an inspiration for later ecofascist terrorists.[117]

William H. Stoetzer, a member of the Atomwaffen Division, an organisation responsible for at least eight murders, was active in the Earth Liberation Front as late as 2008 and joined Atomwaffen in 2016.[118]

Brenton Tarrant, the Australian-born perpetrator of the Christchurch mosque shootings in New Zealand described himself as an ecofascist,[119] ethno-nationalist, and racist[120][121] in his manifesto The Great Replacement, named after a far-right conspiracy theory[122] originating in France. In the manifesto Tarrant specifically mentions Breivik as an ideological and operational influence.[123] Researchers point to Tarrant's terrorist attack as the moment when discussion of ecofascism moved from academic and specialist circles into the mainstream.[124][125] Jordan Weissmann, writing for Slate, describes the perpetrator's version of ecofascism as "an established, if somewhat obscure, brand of neo-Nazi"[126] and quotes Sarah Manavis of New Statesman as saying, "[Eco-fascists] believe that living in the original regions a race is meant to have originated in and shunning multiculturalism is the only way to save the planet they prioritise above all else".[126][127] Similarly, Luke Darby clarifies it as: "eco-fascism is not the fringe hippie movement usually associated with ecoterrorism. It's a belief that the only way to deal with climate change is through eugenics and the brutal suppression of migrants."[36]

Patrick Crusius, the perpetrator of the 2019 El Paso shooting wrote a similar manifesto, professing support for Tarrant.[128] Posted to the online message board 8chan,[129] it blames immigration to the United States for environmental destruction,[130][28] saying that American lifestyles were "destroying the environment",[131] invoking an ecological burden to be borne by future generations,[132][36] and concluding that the solution was to "decrease the number of people in America using resources".[131] Crusius outlined how he took inspiration from Tarrant and Breivik in his manifesto.[133][134][135] Crusius and Tarrant also inspired Philip Manshaus who attacked a mosque in Norway in 2019.[136][137]

2020s

[edit]The Swedish self-identified ecofascist Green Brigade is an eco-terrorist group linked to The Base that is responsible for multiple mass murder plots.[140][141][125] The Green Brigade has been responsible for arson attacks against targets deemed to be enemies of nature,[9][142] like an attack on a mink farm that caused multi-million-dollar damages.[141][143] Two members were arrested by Swedish police, allegedly planning assassinating judges and bombings.[144][145]

In June 2021, the Telegram-based Terrorgram collective published an online guide with incitements for attacks on infrastructure and violence against minorities, police, public figures, journalists, and other perceived enemies. In December 2021, they published a second document containing ideological sections on accelerationism, white supremacy, and ecofascism.[146][147][148]

During 2021, several neo-Nazi groups and individuals who espoused ecofascist rhetoric were arrested and charged by French authorities for planning terrorist attacks.[21] These include the group Recolonisons la France, and two "accelerationists" in Occitania.[21][149]

In an interview with a blog Maldición Eco-Extremista a leader of the anarchist eco-extremist group Individualists Tending to the Wild (ITS) claimed to have taken organisational influence from the fascist accelerationist terrorist group Order of Nine Angles. The Foundation for Defense of Democracies characterized ITS as ecofascist.[150][151]

Payton S. Gendron, the instigator of the 2022 Buffalo shooting, also wrote a manifesto self-describing as "an ethno-nationalist eco-fascist national socialist" within it and also professing support for far-right shooters from Tarrant[152] and Dylann Roof to Breivik and Robert Bowers.[153][154] Later in 2022, the Terrorgram collective released another publication, with analysts believing it would likely inspire further "Buffalo shootings".[155]

In Finland on 15 March 2024, the anniversary of Christchurch mosque shooting, a Finnish army Non-commissioned officer was arrested for allegedly planning a mass shooting in a university in Vaasa that day. As her motivation she said the world needed "a mass culling" to put an end to "selfish individualism", "human degeneration", global warming and conspicuous consumption.[156][157] The Finnish police described her as ecofascist and that she had read books by Nietzsche, Linkola and Kaczynski. Additionally she had praised Pekka-Eric Auvinen in internet conversations and had visited Jokela school where he perpetrated the mass shooting.[158]

Criticism

[edit]The deep ecologic activist and "left biocentrism" advocate David Orton stated in 2000 that the term is pejorative in nature and it has "social ecology roots, against the deep ecology movement and its supporters plus, more generally, the environmental movement. Thus, 'ecofascist' and 'ecofascism', are used not to enlighten but to smear." Orton argued that "it is a strange term/concept to really have any conceptual validity" as there has not "yet been a country that has had an "eco-fascist" government or, to my knowledge, a political organization which has declared itself publicly as organized on an ecofascist basis."[159][a]

Accusations of ecofascism have often been made but are usually strenuously denied.[159][162] Left wing critiques view ecofascism as an assault on human rights, as in social ecologist Murray Bookchin's use of the term.[163]

Deep ecology

[edit]Deep ecology is an environmental philosophy that promotes the inherent worth of all living beings regardless of their instrumental utility to human needs. It has long been linked to fascist ideologies, both by critics and fascist proponents.[55][164] In certain texts, the Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss, a leading voice of the "deep ecology" movement, opposes environmentalism and humanism, even proclaiming, in imitation of a famous phrase of the Marquis de Sade, "Écologistes, encore un effort pour devenir anti-humanistes" ("Ecologists, another effort to become anti-humanists!").[165] Luc Ferry, in his anti-environmentalist book Le Nouvel Ordre écologique published in 1992, particularly incriminated deep ecology as being an anti-humanist ideology bordering on Nazism.[166][167] Modern ecofascism has been described as a deep ecological philosophy combined with antihumanism and an accelerationist stance.[168]

Bookchin's critique of deep ecology

[edit]Murray Bookchin criticizes the political position of deep ecologists[169] such as David Foreman:

There are barely disguised racists, survivalists, macho Daniel Boones, and outright social reactionaries who use the word ecology to express their views, just as there are deeply concerned naturalists, communitarians, social radicals, and feminists who use the word ecology to express theirs... It was out of this former kind of crude eco-brutalism that Hitler, in the name of "population control," with a racial orientation, fashioned theories of blood and soil...

The same eco-brutalism now reappears a half-century later among self-professed deep ecologists who believe that Third World peoples should be permitted to starve to death and that desperate Indian immigrants from Latin America should be excluded by the border cops from the United States lest they burden "our" ecological resources.[163]

Sakai on "natural purity"

[edit]Such observations among the left are not exclusive to Bookchin. In his review of Anna Bramwell's biography of Richard Walther Darré, political writer J. Sakai and author of Settlers: The Mythology of the White Proletariat, observes the fascist ideological undertones of natural purity.[170] Prior to the Russian Revolution, the tsarist intelligentsia was divided on the one hand between liberal "utilitarian naturalists", who were "taken with the idea of creating a paradise on earth through scientific mastery of nature" and influenced by nihilism as well as Russian zoologists such as Anatoli Petrovich Bogdanov; and, on the other, "cultural-aesthetic" conservationists such as Ivan Parfenevich Borodin, who were influenced in turn by German Romantic and idealist concepts such as Landschaftspflege and Naturdenkmal.[171]

Narrowness of the label

[edit]Political scientist Balša Lubarda has criticised the use of the term "ecofascism" as not sufficiently covering and describing the wider network of ideologies and systems that feed into ecofascist action, suggesting the term "far-right ecologism" (FRE) instead.[172][173][174] Lubarda is supported by researcher Bernhard Forchtner who emphasises ecofascism's existence as a fringe ideology that has had little impact on the wider far-right's interaction with environmentalism.[175][176]

Disavowment

[edit]As ecofascism has become more prevalent various environmental groups and organisations have publicly disavowed the ideology and those who subscribe to it.[177]

Far-right green movements

[edit]In recent years there has been a greater proliferation in ecofascist groups globally in line with the proliferation of ecofascist rhetoric.[178][179]

Australia

[edit]Australia has seen an increasing prominence of ecofascism among its far-right groups in recent years.[180][181]

Austria

[edit]The Greens of Austria (DGÖ) had been founded in 1982 by the former NDP official Alfred Bayer to use the popularity of the green movement at the time for the purposes of the NDP. The party managed to win a number of municipal seats in the mid-1980s but in 1988 the Constitutional Court banned the party on grounds of Neo-Nazism alongside a parallel ban on the NDP.[182]

Finland

[edit]The neo-fascist Blue-and-Black Movement includes ecofascist policy goals, stating that they aim to protect the nature and biodiversity of Finland, and to live in harmony with nature, ending ritual slaughter, fur-farming and animal testing.[183]

France

[edit]Nouvelle Droite movement

[edit]The European Nouvelle Droite movement, developed by Alain de Benoist and other individuals involved with the GRECE think tank, have also combined various left-wing ideas, including green politics, with right-wing ideas such as European ethnonationalism.[64][21][184] Various other far-right figures have taken the lead from de Benoist, providing an appeal to nature in their politics, including: Guillaume Faye, Renaud Camus, and Hervé Juvin.[21]

Génération identitaire

[edit]In 2020, following articles from self-described ecofascist Piero San Giorgio, a spokesperson for Génération identitaire, Clément Martin, advocated for zones identitaires à défendre, ethnically homogenous zones to be violently defended in order to protect the environment.[21]

National Rally

[edit]Marine Le Pen, leader of the far-right National Rally (Rassemblement National, or RN) has shown an ecofascist approach towards climate change issue and has incorporated environmental issues into her platform, although her policies regarding the climate often reflect a nationalist and protectionist stance to address it.[185][186][187] Le Pen has stated that concern for the climate is inherently nationalist, and that immigrants "do not care about the environment".[188][186]

Jordan Bardella, President of National Rally, embraces similar beliefs and has stated "Borders are the environment’s greatest ally; it is through them we will save the planet."".[186]

Solutions for climate change proposed for Le Pen also align with right-wing conservative economics. She has disregarded liberal free trade economics, under her belief that it "kills the planet" and creates "suffering for animals". Rather than supporting mass production of international commerce, she designed a localist project for "economic patriotism" to boost French products.[189]

Climate change was not in the RN's party platform until around 2019, when the issue began to be capitalized electorally by both leftist and center parties alike. In response to this rising awareness regarding environmental issues, Le Pen designed an energy plan focused on fossil fuels, opposing wind and solar energy,[185] and emphasizing expanding nuclear power wherein she delineated a party policy where 70% of France's electricity was to come from nuclear energy by 2050. Additionally, Le Pen supports maintaining oil heating systems and reducing taxes on fossil fuels, which contradicts climate experts' recommendations, and could increase France's dependence on fossil fuels.[190]

Germany

[edit]Staudenmaier points to how from the post-war period in Germany an ecofascist section has always been present in the German far-right, though as a minor peripheral section,[191][192] with others pointing out a long history of right-wing individuals and groups being present in the environmental and green movement in Germany.[193]

Die Heimat

[edit]

Die Heimat (The Homeland), previously known as the National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD), a German Nationalist far-right party, has long sought to utilise the green movement.[194] This is one of many strategies the party has used to try to gain supporters.[195]

The German far-right has published the magazine Umwelt & Aktiv, that masquerades as a garden and nature publication but intertwines garden tips with extremist political ideology.[196][197][198] This is known as a "camouflage publication" in which the NPD has spread its mission and ideologies through a discrete source and made its way into homes they otherwise wouldn’t.[195] Right-wing environmentalists are settling in the northern regions of rural Germany and are forming nationalistic and authoritarian communities which produce honey, fresh produce, baked goods, and other such farm goods for profit. Their ideology is centered around "blood and soil" ruralism in which they humanely raise produce and animals for profit and sustenance. Through their support of this operation, and the backing of many others, it’s reported that the NPD is trying to wrestle the green movement, which has been dominated by the left since the 1980s, back from the left through these avenues.[199]

It's difficult to know if when one is buying local produce or farm fresh eggs from a farmer at their stand, they're supporting a right-wing agenda. Various efforts are being made to halt or slow the infiltration of right-wing ecologists into the community of organic farmers such as brochures about their communities and common practices. However, as the organic cultivation organisation, Biopark, demonstrates with their vetting process, it's difficult to keep people out of communities because of their ideologies. Biopark specifies that they vet based on cultivation habits, not opinions or doctrines, especially when they're not explicitly stated.[195]

AfD

[edit]Prominent Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany) politician, Björn Höcke, has stated his desire to "reclaim" natural conservation from the left.[200] Höcke believes that nature conservation is not correctly executed under climate justice politics, and is quoted stating that the AfD has "to take the issue of nature conservation back from the Greens"[201] However, Höcke recognizes that a socially conservative position that strongly values environmental protection is not the majority position of the AfD. Regardless, Höcke sees the work of far-right ecological magazine, Die Kehre, as laying a theoretical standpoint for the AfD to later draw from.[201]

Collegium Humanum

[edit]Other groups

[edit]The term is also used to a limited extent within the Neue Rechte.[204]The neo-Artamans have been identified as ecofascists in their attempts to revive the agrarian and völkisch traditions of the Artaman League in communes that they have built up since the 1990s.[205][195]

Hungary

[edit]

Following the fall of Communism in Hungary at the end of the 1980s, one of the new political parties that emerged in the country was the Green Party of Hungary. Initially having a moderate centre-right green outlook, after 1993 the party adopted a radical anti-liberal, anti-communist, anti-Semitic and pro-fascist stance, paired with the creation of a paramilitary wing.[206] This ideological swing resulted in many members breaking off from the party to form new green parties, first with Green Alternative in 1993 and secondly with Hungarian Social Green Party in 1995. Each green party remained on the political fringe of Hungarian politics and petered out over time.[207] It was not until the formation of LMP – Hungary's Green Party in the 2010s that green politics in Hungary consolidated around a single green party.

The far-right Hungarian political party Our Homeland Movement has adopted some elements of environmentalism, and commonly refers to itself as the only true green party;[208] for example, the party has called on Hungarians to show patriotism by supporting the removal of pollution from the Tisza River while simultaneously placing the blame on the pollution on Romania and Ukraine.[209] Similarly, elements of the far-right Sixty-Four Counties Youth Movement proscribe themselves to the "Eco-Nationalist" label, with one member stating "no real nationalist is a climate denialist".[210]

India

[edit]Narendra Modi's leadership of India with the Bharatiya Janata Party seeks to install a complete system of Hindutva,[211] with repression of racial and religious minorities and caste discrimination.[212] Since 2018 Modi has been increasingly viewed as an environmental champion and used rhetoric about protecting the environment to greenwash his image and the image of his party.[213][214][215]

International

[edit]Greenline Front is an international network of ecofascists which originated in Eastern Europe, with chapters in a variety of countries such as Argentina, Belarus, Chile, Germany, Italy, Poland, Russia, Serbia, Spain and Switzerland.[216]

Serbia

[edit]Leviathan Movement promotes ecology and protects animals from cruelty by, among other things, saving them from abusers. Leviathan has been reported as an ideologically neo-fascist[217] and neo-nazi group.[218] They used to share an office with the Serbian Right, a far-right political party, and Leviathan ’s leader, Pavle Bihali, is seen in pictures on his social media accounts posing with neo-Nazis.[219]

Sweden

[edit]The Nordic Resistance Movement, a pan-Nordic[220][221] neo-Nazi[222] movement in the Nordic countries and a political party in Sweden has been continually described as ecofascist,[223][224] and have declared themselves as the "new green party" of the Nordics.[225]

Switzerland

[edit]In Switzerland, the initiators of the Ecopop initiative were accused of eco-fascism by FDFA State Secretary Yves Rossier at a Christian Democratic People's Party of Switzerland event on 11 January 2013.[226] However, after threatening to sue, Rossier apologized for the allegation.[227]

United Kingdom

[edit]There is also a historic tradition between the far-right and environmentalism in the UK.[228][229] Throughout its history, the far-right British National Party has flirted on and off with environmentalism. During the 1970s the party's first leader John Bean expressed support for the emerging environmentalist movement in the pages of the party's newspaper and suggested the primary cause of pollution as overpopulation, and therefore immigration into Britain must be halted.[230][47] During the 2000s the BNP sought to position itself as the "only 'true' green party in the United Kingdom, dedicating a significant portion of their manifestos to green issues. During an appearance on BBC One's Question Time in October 2009, then-leader Nick Griffin proclaimed:

Unlike the fake "Greens" who are merely a front for the far left of the Labour regime, the BNP is the only party to recognise that overpopulation – whose primary driver is immigration, as revealed by the government's own figures – is the cause of the destruction of our environment. Furthermore, the BNP's manifesto states that a BNP government will make it a priority to stop building on green land. New housing should wherever possible be built on derelict "brown land".[231]

The Guardian criticised Griffin's claims that himself and the BNP were truly environmentalists at heart, suggesting it was merely a smokescreen for anti-immigrant rhetoric and pointed to previous statements by Griffin in which he suggested that climate change was a hoax.[231] These suspicions seemed to be proven correct when in December 2009 the BNP released a 40-page document denying that global warming is a "man-made" phenomenon.[232] The party reiterated this stance in 2011, as well as making claims that wind farms were causing the deaths of "thousands of Scottish pensioners from hypothermia".[233]John Bean a far-right activist and politician, the first leader of the BNP and latterly a leader within the National Front, wrote regularly in the National Front’s magazine about the problems of pollution and environmental degradation tying them to ideas of overpopulation and immigration.[230]

In 2024 it was reported by Searchlight that the fascist groups Patriotic Alternative and Homeland party has also started to make claims that the countryside was being destroyed by immigration.[234]

In Scotland, former UKIP candidate and activist Alistair McConnachie, who has questioned the Holocaust, founded the Independent Green Voice in 2003,[235] and multiple ex-BNP members and activists have stood as candidates for the party.[236]

United States

[edit]During the 1990s a highly militant environmentalist subculture called Hardline emerged from the straight edge hardcore punk music scene and established itself in a number of cities across the US. Adherents to the Hardline lifestyle combined the straight edge belief in no alcohol, no drugs, no tobacco with militant veganism and advocacy for animal rights. Hardline touted a biocentric worldview that claimed to value all life, and therefore opposed abortion, contraceptives, and sex for any purpose other than procreation. On this same line, Hardline opposed homosexuality as "unnatural" and "deviant”.[237] Hardline groups were highly militant; In 1999 Salt Lake City grouped Hardliners as a criminal gang and suggested they were behind dozens of assaults in the metro area.[238] That same year CBS News reported that Hardliners were behind the firebombing of fast food outlets and clothing stores selling leather items, and attributed 30 attacks to Hardliners.[239] The Hardline subculture dissolved after the 1990s.

White supremacist John Tanton and the network of organisations he created, dubbed the Tanton network, have been described as ecofascist.[240][241] Tanton and his organisations spent decades linking immigration to environmental concerns.[242][243][244]

Political researchers Blair Taylor and Eszter Szenes have identified multiple threads in alt-right discourse and ideology that align with far-right ecologism and ecofascism.[245][246]

The Green Party of the United States has also long been the target of various far-right figures, such as anti-Semitic conspiracy theorists, who have tried to shift the party drastically to the far-right.[5]

In 1994, so-called "Takings" bills were introduced by the U.S. Congress to financially compensate wetlands owners who were unable to develop their land for profit due to environmental protection policies. These bills were met with resistance by "anthropocentric market liberals", who oppose any sort of market regulation or intervention of the state into private ownership. Hence, these "takings" bills were deemed ecofascist and proponents of the bills were "disparaged" and viewed as "'nature-loving' romantics for having reactionary tendencies that may be consistent with fascism". The journal Social Theory and Practice uses this instance to exemplify how growing public frustration with complex federal environmental regulations leads to rapidly polarizing opinions on environmental regulations in the United States: one is either a citizen who supports people, private property, and the U.S. Constitution, or a radical environmentalist who supports nature, communal ownership, and ecofascism.[247]

Pejorative

[edit]Detractors on the political right tend to use the term "ecofascism" as a hyperbolic general pejorative against all environmental activists,[248][249] including more mainstream groups such as Greenpeace, prominent activists such as Greta Thunberg, and government agencies tasked with protecting environmental resources.[162][250] Such detractors include Rush Limbaugh and other conservative and wise use movement commentators.[251][252] The term as a pejorative has been used in multiple countries.[253]

See also

[edit]- Adolf Hitler and vegetarianism

- Animal welfare in Nazi Germany

- ATWA

- Conspirituality

- Definitions of fascism

- Ecoauthoritarianism

- Ecocapitalism

- Eco-nationalism

- Eco-socialism

- Eco-terrorism

- Environmental movement

- Environmental racism

- Green Imperialism

- Hardline (subculture)

- Neo-Luddism

- Pastel QAnon

- Radical environmentalism

- Red-green-brown alliance

Notes

[edit]- ^ Since 2000, multiple individuals and groups have self described as ecofascists, including:

References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c Corcione 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Zimmerman 2008, p. 531.

- ^ Gorz, André (1977). Ökologie und Politik [Ecology and Politics] (in German). Rowohlt: Reinbek. p. 75.

- ^ Hassan 2021, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Phelan 2018.

- ^ Jahn, Thomas; Wehling, Peter (1991). Ökologie von rechts. Nationalismus und Umweltschutz bei der Neuen Rechten und den Republikanern [Ecology from the right. Nationalism and environmentalism among the New Right and Republicans] (in German). Campus, Frankfurt/Main, New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ditfurth 1992, pp. 278, 324.

- ^ Kamel, Lamoureux & Makuch 2020; Corcione 2020; Oksa 2005; Taylor 2020, pp. 277–278; Harris 2022, pp. 458–459; Staudenmaier 2004, p. 520

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kamel, Lamoureux & Makuch 2020.

- ^ Ross & Bevensee 2020, pp. 4–9.

- ^ Protopapadakis 2014, p. 587; Dyett & Thomas 2019, p. 220; Kaati et al. 2020; Harris 2022, p. 452; Tynan 2023, pp. 90–91; Chalecki 2023, p. 1

- ^ Hassan 2021, p. 53.

- ^ Macklin 2022, p. 982: "Instead, this article highlights an emerging strain of "eco-fascism" within sections of the contemporary extreme right that takes "Blood and Soil" as its ideological baseline and fuses it with a particularly virulent form of misanthropic ecological nihilism that views violence and terrorism against the current social, political, and economic order, as the only means of restoring man to a state of pristine pastoral purity."

- ^ Huq & Mochida 2018, p. 4; Yakushko & De Francisco 2022, pp. 471–472; Lynch 2022, pp. 17–18: "Similar to other critical perspectives of the greening of hate, the authors critique what they call 'ecobordering,' which represents 'the consolidation and sanitization of a constellation of 19th and 20th century Malthusian, conservative, and ecofascist ideas, as well as Romantic-era notions of nature and belonging.'"; Saltmarsh 2022: "Moore and Roberts describe the contemporary far-right's approach to climate change, despite historical nods at 'nature protection', as a combination of denialism and securitisation, with the first undermining mitigation and promoting continued extraction, and the second redirecting security complexes toward expanding and protecting sites of extraction from resistance."

- ^ Forchtner & Lubarda 2023; Yakushko & De Francisco 2022, p. 472; Farrell-Molloy & Macklin 2022; Hancock 2022; Chalecki 2023, p. 6: "Ecofascists believe that race and nationality are literally tied to the natural environment of the country and that "blood and soil" determines who belongs in a country and who doesn't."; Armiero & von Hardenberg 2013, p. 291: "Nevertheless, in Fascist discourses and politics, reclamation was not only about land and water; it also included humans, who needed to be redeemed as well. The blend of soil and people in a racist and nationalistic fusion gave the Fascist environmental narrative its distinctive character."

- ^ Kitch, Sally L. (2023). "Reproductive Rights and Ecofeminism". Humanities. 12 (2): 34. doi:10.3390/h12020034.

- ^ Lynch 2022, pp. 6–8.

- ^ Thomas & Gosink 2021, pp. 40–43; Lynch 2022, pp. 17–18; Walsh 2022: "They are often radicalized online, as the latest alleged shooter claims to have been, and many believe that white people, along with the environment, are threatened by non-white overpopulation. They often call for a halt to immigration, or the eradication of non-white populations."}}; Tilley & Ajl 2022, p. 13; Anantharaman 2022

- ^ Richards, Jones & Brinn 2022, p. 1: "Expressions of eco-fascism often entail extreme population control measures advocated by right-wing activists and ethnonationalist governments, and accelerationist propaganda hastening the collapse of societies worldwide."; Manavis 2018; Yakushko & De Francisco 2022, pp. 457–458, 472; Farrell-Molloy & Macklin 2022: "The co-opting of Kaczynski provides eco-fascists with a 'green accelerationist' pathway as the use of violent tactics to increase tensions can easily be applied to his ideas, elevating him as 'an obvious sage of violence.'"; Kaati et al. 2020, p. 3: "Ett drag som ekofascimen delar med många av de nyare radikalnationalistiska rörelserna, som exempelvis the Base eller Atomwaffen Division, är accelerationism. Accelerationismen hos dessa grupper går ut på att försöka påskynda det moderna samhällets undergång genom upprepade aktioner som skapar kaos och splittring. Strategierna innefattar bland annat sabotage, mord och masskjutningar." ["A trait that eco-fascism shares with many of the newer radical nationalist movements, such as the Base or Atomwaffen Division, is accelerationism. The accelerationism of these groups consists of trying to hasten the demise of modern society through repeated actions that create chaos and division. The strategies include sabotage, murder and mass shootings."]; Molloy 2022: "The fusion between militant accelerationism and eco-fascism produced a distinctly high level of content promoting sabotage and infrastructural attack"

- ^ Dannemann 2023, p. 5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f d'Allens 2022a.

- ^ Macklin 2022, p. 982.

- ^ Amend, Alex (9 July 2020). "Blood and Vanishing Topsoil: American Ecofascism Past, Present, and in the Coming Climate Crisis". Political Research Associates. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Campion 2021, pp. 933–934.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Investigating the role of disinformation in the rise of eco-fascism". CORDIS. European Commission. Archived from the original on 6 July 2024. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ Cawood & Vuuren 2022, pp. 90–92.

- ^ Cawood & Vuuren 2022, pp. 89–91.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Arvin 2021.

- ^ Hughes, Jones & Amarasingam 2022, p. 998.

- ^ Darwish 2018, p. 90.

- ^ Blumenfeld 2022, p. 173.

- ^ Gilman, Nils (7 February 2020). "The Coming Avocado Politics: What Happens When the Ethno-Nationalist Right Gets Serious about the Climate Emergency". Breakthrough Institute. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023.

- ^ Sargent, Greg (26 August 2021). "Opinion: The dark future of far-right Trumpist politics is coming into view". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022.

- ^ Chalecki 2023, p. 6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Tucker 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Darby 2019a.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Patin 2021.

- ^ "Madison Grant (U.S. National Park Service)". U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Purdy 2015; Frazier 2019; Alexander 1962

- ^ Spiro, Jonathan Peter (2009). "Creating the Refuge". Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant. University of Vermont Press, University Press of New England. pp. 225–226. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1xx9bzb.13. ISBN 978-1-58465-715-6. JSTOR j.ctv1xx9bzb.13. S2CID 239426317.

- ^ Patin 2021; Weymouth 2021; Sparrow 2019; Hoff 2021

- ^ Yakushko & De Francisco 2022, pp. 467–469.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hoff 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hussein 2022.

- ^ Sparrow 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Adler-Bell, Sam (24 September 2019). "Why White Supremacists Are Hooked on Green Living". The New Republic. Archived from the original on 14 November 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Knights 2020.

- ^ Biehl & Staudenmaier 1996, pp. 6–7; Macklin 2022, p. 979: "Indeed, it was the German nationalist, zoologist, and naturalist, Ernest Haeckel, who coined the term ökologie in 1866."; Naustdalslid 2023, pp. 49–52; Tynan 2023, p. 101; Szenes 2023, p. 3: "German zoologist and eugenicist Ernst Haeckel, who, by stressing the connection between the purity of nature and the purity of race, paved the way for German National Socialism."

- ^ Dyett & Thomas 2019, pp. 217–219.

- ^ Ross & Bevensee 2020, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Szenes 2023, p. 3: "White supremacist environmentalism is not a new phenomenon but one with a long and troubled history, whose roots can be traced back to the 19th century German Völkisch movement, German Romanticism, and anti-Enlightenment nationalism."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Biehl & Staudenmaier 1996, p. 12.

- ^ Smith, Kev. "Ecofascism: Deep Ecology and Right-Wing Co-optation". Environment and Ecology. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ Olsen, Jonathan (1999). Nature and Nationalism: Right-Wing Ecology and the Politics of Identity. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zimmerman 2004.

- ^ Brüggemeier, Franz-Josef; Cioc, Mark; Zeller, Thomas (2005). How Green Were the Nazis?: Nature, Environment, and Nation in the Third Reich. Ohio University Press.

- ^ Hughes, Jones & Amarasingam 2022, p. 999; Macklin 2022, p. 982; Molloy 2022: "Neo-völkisch-’ism’, the revival of paganism and folklore traditions, aimed to denote a mystical connection between land and race, reinforcing the 'naturalness' of the in-group to the ecosystem"; Dannemann 2023, p. 6; Szenes 2023, p. 3: "The notorious Nazi slogan 'Blood and Soil', a symbol for the mystical-spiritual connection between race and nature, was coined by Walter Darré, the NSDAP's Minister for Food and Agriculture."; Staudenmaier 2004, p. 519

- ^ Armiero & von Hardenberg 2013, p. 292: "land and race are indissolubly bound; it is through the land that we make the history of our race; the race rules, develops, and fecundates the land"

- ^ Wilson 2019: "Nazism and a twisted version of ecological thinking are joined in the minds of a share of rightwing extremists."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bennett 2019.

- ^ Toulouse, Teresa A.; Zimmerman, Michael E. (2016). "Ecofascism". In Adamson, Joni; Gleason, William A.; Pellow, David N. (eds.). Keywords for Environmental Studies. New York University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-8147-6083-3.

- ^ Dahl, Göran (2006). Radikalare än Hitler?: de esoteriska och grona nazisterna, Inspirationskallor, Pionjarer, Forvaltare, Attlingarby [More radical than Hitler?: The esoteric and verdant Nazis, Pioneers, Trustees, Attlingarby] (in Swedish). Atlantis. pp. 136–145. ISBN 91-7353-122-7. OCLC 225237172.

- ^ Biehl & Staudenmaier 1996, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Griffin 2008.

- ^ "June 21–22: West German Greens Decide to Contest First Federal Elections". Global Green Party History Chronology – 1980. Global Greens, Brussels. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Lee, Martin A. (2000). The Beast Reawakens: Fascism's Resurgence from Hitler's Spymasters to Today's Neo-Nazi Groups and Right-Wing Extremists. New York City: Routledge. pp. 217–218. ISBN 0415925460. OCLC 1106702367.

- ^ Macklin 2022, p. 983: "Savitri Devi’s blend of Aryan supremacism, vitriolic anti-Semitism, Hinduism, animal rights and ecology, have served as the basis for a post-war redefinition of Nazism as a “religion of nature” in the more cultic corners of the extreme right."

- ^ Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas (2003). Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism, and the Politics of Identity. New York University Press. pp. 57, 88. ISBN 0-8147-3155-4. OCLC 47665567. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Greer, John Michael (2003). The new encyclopedia of the occult. Llewellyn Worldwide. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-1-56718-336-8. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Macklin 2022, pp. 982–984.

- ^ "Savitri Devi: The mystical fascist being resurrected by the alt-right". BBC. 29 October 2017. Archived from the original on 22 November 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ Manavis 2018: "The links between Devi’s views and eco-fascism are supported by the fact she’s enjoyed something of a renaissance amongst members of the alt-right in the last several years."

- ^ Фаррелл-Моллой и Маклин, 2022 : «Хотя большая часть того, что обсуждалось об экофашизме, сосредоточена на антииммиграционном «зеленом» национализме или крайне правых неомальтузианских аргументах о перенаселении»; Гюнтер 2023 , с. 16; Earthworks 2022b : «К ним относится расистская мальтузианская идея о том, что человеческое население достигнет несущей способности, которую земля не сможет выдержать, и которая неоднократно развенчалась, […] мы должны осознавать, что происхождение национальных парков и охраняемых территорий лежит в в явно евгенической идеологии и идеологии превосходства белой расы, которая насильственно вытеснила коренные народы с земель, которыми они управляли с незапамятных времен»; Тайнан, 2023 г. , стр. 101–102; Камель, Ламуре и Макуч 2020 ; Солтмарш 2022 : «его манифест связал изменение климата с обычной крайне правой мыслью, мальтузианской экологической политикой, пересекающейся с идеями расовой замены, кульминацией которой стало применение смертельного насилия против мусульманских «других»»; Форхтнер и Лубарда 2020 : «Экофашизм, который в основном ассоциируется с «зеленым крылом» исторического национал-социализма и неомальтузианскими авторитарными режимами 1960-70-х годов, представляет собой радужную концепцию, которая означает озабоченность крайне правых акторов экологическими проблемами. "; d'Allens 2022b

- ^ Линч 2022 , с. 11.

- ^ Дайетт и Томас 2019 , стр. 210–216; Уилкинсон 2020 ; Хьюз, Джонс и Амарасингам 2022 , с. 999; Томас и Госинк, 2021 г. , стр. 40–43; Фернандес и Харт, 2023 г. , стр. 5–6; Уолш, 2022 : «Они часто радикализируются в Интернете, как утверждает последний предполагаемый стрелок, и многие полагают, что белым людям, наряду с окружающей средой, угрожает перенаселение небелого населения. Они часто призывают остановить иммиграцию или искоренение цветного населения."}}; Маклин, 2022 , стр. 986–987.

- ^ Каати и др. 2020 , стр. 4-6.

- ^ Earthworks 2022b : «К ним относится расистская мальтузианская идея о том, что человеческое население достигнет несущей способности, которую земля не сможет выдержать, и которая неоднократно развенчалась, […] мы должны осознавать, что происхождение национальных парков и охраняемых территорий лежит в откровенно евгенической идеологии и идеологии превосходства белой расы, которая насильственно вытеснила коренные народы с земель, которыми они управляли с незапамятных времен».

- ^ Моллой 2022 : «Антитехнологический радикализм Качиньского представлял собой принятие и кооптацию идеологии Унабомбера Теда Качиньского и олицетворял самую сильную точку сплоченности субкультуры».

- ^ Маклин 2022 , с. 984.

- ^ Дидион, Джоан (23 апреля 1998 г.). «Разновидности безумия» . Нью-Йоркское обозрение книг . Архивировано из оригинала 13 августа 2017 года.

- ^ Маклин 2022 , стр. 984–985.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Wilson 2019 : «Современные экофашисты вдохновлены рядом ключевых фигур. Одной из них является «Унабомбер» Тед Качиньски, чья террористическая кампания против того, что он называл «индустриальным обществом», сочетала в себе насилие, человеконенавистничество и самодраматизирующий манифест».

- ^ Фаррелл-Моллой и Маклин, 2022 : «Этот взгляд на левые взгляды как на несовместимость с дикой природой отражается убеждением экофашистов, что они должны перехватить управление окружающей средой у левых»

- ^ «Суд над Унабомбером: Манифест» . Вашингтон Пост . 1997. Архивировано из оригинала 22 февраля 2021 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Ханрахан 2018 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Качиньский, Тед . «Экофашизм: аберрантная ветвь левых взглядов» . Анархическая библиотека . Архивировано из оригинала 21 февраля 2022 года . Проверено 21 февраля 2022 г.

- ^ Скауге-Монсен, Вильде (1 июня 2022 г.). «Спасите пчел, а не беженцев»: ультраправый энвайронментализм встречается с Интернетом (Сравнительный контент-анализ энвайронментализма нацистской Германии и четырех самопровозглашенных экофашистских каналов в Telegram) (PDF) (магистр). Университет Осло , факультет СМИ и коммуникации. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 11 декабря 2022 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уилсон 2019 .

- ^ Гюнтер 2023 , с. 16.

- ^ Окса 2005 , с. 75.

- ^ Маклин 2022 , с. 986.

- ^ Рыцари 2020 ; Тилли и Эйл 2022 , с. 3: «Этика спасательной шлюпки выступает за отказ от многонаселенной бедноты, чтобы спасти немногих богатых в ограниченной планетарной «спасательной шлюпке»»; Эллисон 2020 , с. 3; Протопападакис 2016 , стр. 227–228.

- ^ «Гаррет Хардин» . Южный юридический центр по борьбе с бедностью . Архивировано из оригинала 15 ноября 2021 года . Проверено 20 июля 2018 г.

- ^ Тилли и Эйл, 2022 , с. 2.

- ^ Бисс, Юла (8 июня 2022 г.). «Кража общины» . Житель Нью-Йорка . Архивировано из оригинала 11 августа 2022 года . Проверено 13 июня 2022 г.

- ^ «Путеводитель по документам Гаррета Хардина» . Интернет-архив Калифорнии . Архивировано из оригинала 7 июля 2022 года . Проверено 22 июня 2024 г.

- ^ Хьюз, Джонс и Амарасингам, 2022 г. , с. 1005.

- ^ Протопападакис 2014 , с. 590.

- ^ Маклин 2022 , стр. 986–987.

- ^ Анвар, Андре (13 ноября 2007 г.). «Пентти Линкола: «Стрелять товарищей не помогает» » [Пентти Линкола: «Стрелять товарищей не помогает»]. Тагесшпигель (на немецком языке). Архивировано из оригинала 20 января 2015 года.

- ^ Линкола, Пентти (2011). Может ли жизнь преобладать?: революционный подход к экологическому кризису (2-е изд. на английском языке). Арктос. ISBN 978-1-907166-63-1 . OCLC 780962580 .

- ^ Forchtner 2019 : «Убийство 51 человека в Крайстчерче, Новая Зеландия, в марте 2019 года привело, например, к принятию законопроекта о реформе оружия в Новой Зеландии и возобновлению интереса к идее «великой замены». […] Однако , идея «великой замены» действительно сыграла роль и в этом втором расстреле, который, несомненно, требует дальнейшего изучения»; О'Нил, 2022 г. , стр. 39–40; Ахенбах 2019 ; Руэда 2020 ; Tilley & Ajl 2022 , стр. 202–203: «Идеология манифеста часто восходит к работе Рено Камю 2011 года под названием Le Grand Remplacement и понимается как аналог заговоров белых о геноциде в США»; Anantharaman 2022 : «Например, подозреваемый в стрельбе в Буффало называет себя экофашистом, выступающим против перенаселения «захватчиков», чтобы спасти окружающую среду. Подобные рассуждения использовались во время массового расстрела в Крайстчерче в Новой Зеландии. В этих кругах население не находится на первом месте. на полях, но в самом центре (расовых) тревог. Ярким примером являются ночные проповеди о «великой теории замещения»; Rose 2022 : «Темы замены также поднимались массовыми стрелками в Утойе, Норвегия, в 2011 году, в синагоге «Древо жизни» в Питтсбурге, штат Пенсильвания, в 2018 году и в Эль-Пасо, штат Техас, в 2019 году. Однако каждый из этих стрелков – все белые люди – нацелены на другую группу людей. Стрельба в Буффало убила только чернокожих американцев. Стрельба в Крайстчерче терроризировала мусульман, покидающих пятничную молитву».

- ^ «Великая замена», кошмар крайне правых . Ле Темпс (на французском языке). 9 июля 2020 г. ISSN 1423-3967 . Архивировано из оригинала 21 сентября 2023 года.

Затем автор проводит различие между заменяемыми (европейская цивилизация и ее культура), замещающими (иммигранты, прибывающие в основном из Северной Африки и стран Африки к югу от Сахары) и замещающими (власть, которая не стремиться обратить вспять миграционные потоки, чтобы служить политическим интересам, особенно левым).

[Затем автор проводит различие между замещающими (европейская цивилизация и ее культура), замещающими (иммигранты, приезжающие в основном из Северной Африки и стран Африки к югу от Сахары) и замещающими (держава, которая не стремится повернуть вспять миграционные потоки, чтобы политические интересы, особенно левые).] - ^ Гуиди 2022 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Каати и др. 2020 .

- ^ Тайнан 2023 , стр. 101.

- ^ Дайетт и Томас 2019 , с. 220; Каати и др. 2020 ; Хасан 2021 , с. 52; Харрис 2022 , с. 452

- ^ Сван, Клас (10 ноября 2007 г.). «Среди друзей Аувинена крайности были нормой». Dagens Nyheter (на шведском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 10 марта 2016 года.

- ^ Маклин 2022 , с. 987.

- ^ Поток, Марк (1 сентября 2010 г.). «Предполагаемые экотеррористы держат заложников в здании телевидения» . Южный юридический центр по борьбе с бедностью . Архивировано из оригинала 10 апреля 2016 года . Проверено 20 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Льюис, Марк; Коуэлл, Алан (24 августа 2012 г.). «Норвежский убийца признан вменяемым и приговорен к 21 году тюремного заключения» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 24 августа 2012 г.

- ^ Пракон, Адриан (1 июня 2012 г.). «Утойя, история выжившего: «Нет!» Я закричал: «Не стреляйте!» " . Хранитель . Лондон . Проверено 24 августа 2012 г.

- ^ Дирден, Лиззи (20 апреля 2016 г.). «Андерс Брейвик: Правый экстремист, убивший 77 человек в резне в Норвегии, выиграл часть дела о правах человека» . Независимый . Лондон, Англия. Архивировано из оригинала 20 апреля 2016 года . Проверено 18 сентября 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Маклин 2022 , с. 981.

- ^ Шиффлетт 2021 , стр. 75–76; ван Гервен Оэй 2012 , стр. 88–94; Маклин 2022 , стр. 984–985; Пирс 2015 , стр. 460–462

- ^ Шиффлетт 2021 , стр. 76–79.

- ^ Хафез 2019 ; Маклин и Бьорго, 2021 г. , стр. 16–20; Маклин 2022 , стр. 981; Шиффлетт 2021 , стр. 90.

- ^ Тайер, Нейт (6 декабря 2019 г.). «Раскрыты тайные личности нацистской террористической группы США» . Архивировано из оригинала 7 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 25 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Козиол 2019 ; Ахенбах 2019 ; d'Allens 2022a : «Несколькими минутами ранее он опубликовал семидесятичетырехстраничный манифест, в котором подробно описал свой идеологический путь и открыто заявил, что является «экофашистом».» ["Несколькими минутами ранее он опубликовал 74-страничный манифест, в котором подробно описал свою идеологическую подоплеку и открыто заявил, что является "экофашистом"."]}}; Ричардс, Джонс и Бринн 2022

- ^ Фишер, Марк ; Ахенбах, Джоэл (15 марта 2019 г.). «Безграничный расизм, ноль раскаяния: манифест ненависти и 49 погибших в Новой Зеландии» . Вашингтон Пост . Архивировано из оригинала 11 декабря 2020 года . Проверено 16 сентября 2019 г.

- ^ Росс и Бевенси 2020 , с. 1.

- ^ Дарби, Люк (5 августа 2019b). «Как теория заговора «Великой замены» вдохновила убийц, сторонников превосходства белой расы» . «Дейли телеграф» . Лондон – через ProQuest .

- ^ Маклин и Бьёрго, 2021 , стр. 16–20.

- ^ Кэмпион 2021 , стр. 926–927.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Маклин 2022 , с. 990.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вайсманн 2019 .

- ^ Ноак 2019 : «Автор был последним из череды экстремистов, назвавших Крайстчерч пробным камнем для еще большей ненависти»; d'Allens 2022a ; Форхтнер и Лубарда 2020 ; Ричардс, Джонс и Бринн 2022

- ^ Аранго, Тим; Богель-Берроуз, Николас; Беннер, Кэти (3 августа 2019 г.). «За несколько минут до убийства в Эль-Пасо в сети появился полный ненависти манифест» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 30 сентября 2019 года.

- ^ Оуэн, Тесс (6 августа 2019 г.). «Эко-фашизм: расистская теория, вдохновившая стрелков в Эль-Пасо и Крайстчерче» . Вице-ньюс . Архивировано из оригинала 20 января 2021 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Леннард 2019 .

- ^ Ахенбах 2019 .

- ^ Хафез 2019 .

- ^ Узельтюзенци, Пинар (29 апреля 2020 г.). «Люди — не вирус: почему экофашизм вреден для вас» . Мангал Медиа . Архивировано из оригинала 26 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 30 сентября 2023 г.

- ^ Дариан-Смит, 2022 , стр. 91–92.

- ^ Росс и Бевенси 2020 , с. 3.

- ^ Берк, Джейсон (11 августа 2019 г.). «Подозреваемый в нападении на мечеть в Норвегии «вдохновлен расстрелами в Крайстчерче и Эль-Пасо» » . Хранитель . ISSN 0261-3077 . Архивировано из оригинала 17 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 11 августа 2019 г.

- ^ Шайковци, Адриан (27 сентября 2020 г.). «Экофашистская «Сосновая партия» становится угрозой насильственного экстремизма» . Национальная безопасность сегодня.us . Архивировано из оригинала 1 ноября 2020 года . Проверено 22 декабря 2021 г.

- ^ Манавис 2018 : «Эмодзи деревьев, земли или гор припаркованы рядом с именем почти каждого экофашиста в Твиттере, часто сопровождаемые скандинавской / протогерманской руной - чаще всего Альгиз, «ᛉ» или «ᛦ», известной как руна «жизни»; Каати и др. 2020 , стр. 12–13; Моллой 2022 : «Символы, используемые крайне правыми, такие как руна альгиз или сонненрад, сопровождали изображения природы, создавая особый экофашистский бренд, который легко распространялся по крайне правым сетям».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Смит, 2021 г. , стр. 100–102.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фаррелл-Моллой и Маклин, 2022 : «Одной группой, возникшей из этой среды, является недолговечная «Зеленая бригада», называющая себя «акселерационистскими экстремистами», группа действовала как экофашистское крыло неонацистов». The Base» и были ответственны за поджог шведской норковой фермы в 2020 году».

- ^ Fine & Love-Nichols 2021 , с. 308.

- ^ Маклин 2022 , с. 991.

- ^ Ламуре, Мак (25 декабря 2020 г.). «Неонацисты используют экофашизм для вербовки молодежи» . Вице-ньюс . Архивировано из оригинала 1 ноября 2020 года.

- ^ Ламуре, Мак (25 декабря 2020 г.). «Предполагаемые экотеррористы обсуждали взрыв в клинике абортов и убийство судьи: судебные документы» . Вице-ньюс . Архивировано из оригинала 8 января 2021 года.

- ^ «Отчет о террористической ситуации и тенденциях в ЕС на 2022 год» (PDF) . Европол . 23 ноября 2022 г. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 13 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Карлесс, Уилл (5 июля 2022 г.). «Наблюдатели за экстремистами: как сеть исследователей ищет следующую атаку на почве ненависти» . Физика.орг . Архивировано из оригинала 23 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 23 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Фаррелл-Моллой и Маклин, 2022 : «В сообществе «Terrorgram» в Telegram, которое предоставило цифровой дом осадной культуре после удаления неонацистских форумов Iron March и Fascist Forge, на произведения Качиньского часто ссылаются, и его почитают. как один из их «святой троицы» наряду с террористом в Оклахома-Сити Тимоти Маквеем и норвежским крайне правым террористом Андерсом Брейвиком».

- ^ «Два крайне правых активиста, призывающих к «насильственным действиям», арестованы за хранение оружия] . Освобождение (на французском языке). Агентство Франс-Пресс . 17 ноября 2021 года. Архивировано из оригинала 31 марта 2024 года.

- ^ «9 ИТС Интервью» . 12 марта 2021 г. Архивировано из оригинала 2 ноября 2021 г.

ITS никогда не признавал этого, хотя это правда, что мы переняли некоторый организационный опыт этих групп, не особо заботясь об их политической ориентации, не потому, что мы пишем или цитируем TOB, мы правы. Сатанисты-сатанисты, в какой-то момент мы также переняли опыт Парагвайской народной армии или мапуче, и это не означает, что мы левые или коренные народы, то же самое происходит, когда мы цитируем Первое столичное командование Бразилии или Группа Мальяна в Италии, не потому, что мы упоминаем о них, мы являемся частью этой мафии, НЕТ. ITS берет лучшее от каждой преступной группы и применяет это на практике, мы также видим их ошибки, чтобы не совершать их, именно так ITS взращивается и получает опыт из унаследованных эмпирических знаний.

- ^ Гартенштейн-Росс, Дэвид ; Чейс-Донаху, Эмели; Плант, Томас (23 июля 2023 г.). «Орден девяти углов: его мировоззрение и связь с насильственным экстремизмом» . Фонд защиты демократии . Архивировано из оригинала 26 июля 2023 года.

Предполагаемый лидер транснациональной воинственной группы «Люди, склоняющиеся к дикой природе» (ITS) — группы, чья литература посвящена анархистским и экофашистским темам, — заявил в интервью, опубликованном на анархистском веб-сайте Maldición Eco- Extremista утверждает, что группа «переняла некоторый организационный опыт» у O9A и Tempel ov Blood.

- ^ Ричардс, Джонс и Бринн 2022 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Старр 2022 .

- ^ Томпсон, Кэролайн; Коллинз, Дэйв (15 мая 2022 г.). «Стрелок на расовой почве указал на теракты в Крайстчерче в «манифесте» » . Сидней Морнинг Геральд . Архивировано из оригинала 1 июня 2022 года.

- ^ «Внезапное оповещение: высокий риск насилия из-за публикации «Жесткая перезагрузка: публикация Terrorgram» » . The Counterterrorism Group, Inc., 7 июля 2022 г. Архивировано из оригинала 11 августа 2022 г. . Проверено 23 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Карвинен, Эви (18 марта 2024 г.). «23-летняя женщина опубликовала в Интернете тревожный материал - Защита: «Нет намерения причинить вред» » [23-летняя женщина опубликовала в Интернете тревожный материал - Защита: «Нет намерения причинить вред»]. Илталехти (на финском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 18 марта 2024 года.

- ^ Харью, Юкка (7 июля 2024 г.). «Женщина, обвиняемая в подготовке нападения на школу, предстала перед судом, не закрыв лицо - Обвинение: Она готовила этот акт годами» [Женщина, обвиняемая в подготовке нападения на школу, предстала перед судом, не закрыв лицо - Обвинение: Она готовила акт для годы]. Helsingin Sanomat (на финском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 7 июля 2024 года.

- ^ Хямяляйнен, Вели-Пекка (28 мая 2024 г.). «КРП: Вот как тексты, найденные в доме молодой женщины, обвиняемой в планировании убийства школы, открывают ее мышление». Юлейсрадио (на финском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 1 июня 2024 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ортон 2000 .

- ^ Козиол 2019 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Смит, 2021 г. , стр. 29–30.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Штауденмайер 2003 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Букчин 1987 .

- ^ Хук и Мочида 2018 , стр. 5.

- ^ Нэсс, Арне (1989). Экология, общество и образ жизни . Перевод Ротенберга, Дэвида. Издательство Кембриджского университета . дои : 10.1017/CBO9780511525599 . ISBN 9780511525599 .

- ^ Флипо, Фабрис (2014). Природа и политика. Вклад в антропологию современности и глобализации [ Природа и политика. Вклад в антропологию современности и глобализации ] (на французском языке). Амстердам. ISBN 978-2354801342 .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: отсутствует местоположение издателя ( ссылка ) - ^ Тейлор и Циммерман 2008 , с. 458.

- ^ « Экофашизм с корнями в глубокой экологии». Ландец Фриа (на шведском языке). 9 марта 2021 года. Архивировано из оригинала 11 марта 2021 года . Проверено 28 марта 2021 г.

- ^ Окса 2005 , с. 85.

- ^ Сакаи, Дж. (2003). Зелёный нацист — расследование фашистской экологии . Керспледебеб. ISBN 978-0-9689503-9-5 .

- ^ Вайнер, Дуглас Р. (2000). Модели природы: экология, охрана и культурная революция в Советской России . Издательство Питтсбургского университета . ISBN 978-0-8229-5733-1 .

- ^ Лубарда, Бальша (декабрь 2020 г.). «За пределами экофашизма? Крайне правый экологизм (FRE) как основа для будущих исследований». Экологические ценности . 29 (6). White Horse Press : 713–732. дои : 10.3197/096327120X15752810323922 . S2CID 214075497 .

- ^ Фаррелл-Моллой и Маклин, 2022 : «Следует констатировать, что экофашизм сам по себе является маргинальным явлением и не оказал существенного влияния на основную или радикально правую политику. Вот почему термин крайне правый экологизм был предложен в качестве альтернативного ярлыка, чтобы не дать «экофашизму» с его более узким определением, изложенным выше, доминировать в нашем понимании более широкой природы политики радикальных правых».

- ^ Форхтнер и Лубарда, 2023 .

- ^ Форхтнер и Лубарда 2020 : «Учитывая это, кажется, что экофашизм не должен доминировать в нашем понимании более широких отношений радикальных правых с природой. Действительно, эти отношения многогранны из-за множества праворадикальных акторов, которые в них участвуют, от антилиберальных акторов до откровенно антидемократических».

- ^ Мур и Робертс 2022a , стр. 8–9, 12–13.

- ^ Ахенбах 2019 ; Земляные работы 2022а ; Гуиди 2022 ; Уолш, 2022 г .: «Основное экологическое движение, которое в значительной степени поддерживает социальную справедливость, неоднократно отвергало экофашистов, заявляя, что идеология «зеленых отмывок» ненавидит и больше ориентирована на превосходство белых, чем на защиту окружающей среды».}}; Шапиро, Озуг и Морелл, 2022 г .; Earthworks 2022b : «Экофашизм представляет реальную, реальную опасность почти для каждого человека на Земле, особенно для сообществ, наиболее пострадавших от климатического кризиса. Организации, активно участвующие в движениях за экологическую и климатическую справедливость, такие как Earthworks, должны внести свой вклад в признание и повышение осведомленности об этих проблемах, искоренение экофашистов в наших кругах и предотвращение их присоединения, а также работа в солидарности с теми, кто решительно выступает против экофашизма».

- ^ Уотер и Фрэнсис 2022 , стр. 107-1. 471–472.

- ^ Фернандес и Харт 2023 .

- ^ О'Нил 2022 .

- ^ Кэмпион и Филлипс, 2023 .

- ^ Крибернегг, Дэвид (2014). Коричневые пятна Зеленого движения: Исследование фолькиш-антимодернистских традиций экологического движения и влияние крайне правых на формирование зеленых партий в Австрии и ФРГ [ Коричневые пятна Зеленого движения: Исследование в völkisch-антимодернистские традиции экологического движения и влияние крайне правых на развитие зеленых партий в Австрии и ФРГ ] (магистр) (на немецком языке). Университет Граца . Архивировано из оригинала 2 августа 2021 года.

- ^ «Охельма» [Программа]. Сине-черное движение (на финском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 20 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 29 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Гриффин, Роджер (2000). «Между метаполитикой и аполитией : стратегия «Нового права» по сохранению фашистского видения в «междуцарствие» ». Современная и современная Франция . 8 (1): 35–53. дои : 10.1080/096394800113349 . S2CID 143890750 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Солончак 2022 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Аронофф, Кейт (15 апреля 2022 г.). «Климатическая политика Марин Ле Пен пахнет экофашизмом» . Новая Республика . Архивировано из оригинала 24 июня 2024 года . Проверено 29 июня 2024 г.

- ^ Уолш 2022 .

- ^ Сенеш 2023 , с. 2.

- ^ Гаррик, Одри (21 апреля 2022 г.). «Макрон и Ле Пен излагают совершенно разные взгляды на изменение климата» . Ле Монд . Архивировано из оригинала 24 июня 2024 года.

- ^ Гольдберг, Николас (11 апреля 2022 г.). «Энергетическая программа Марин Ле Пен: все для ископаемого топлива, ничего для климата» . Великий разговор (на французском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 24 июня 2024 года.