Post-classical history

| Part of a series on |

| Human history |

|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Stone Age) (Pleistocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future |

In world history, post-classical history refers to the period from about 500 CE to 1500 CE, roughly corresponding to the European Middle Ages. The period is characterized by the expansion of civilizations geographically and the development of trade networks between civilizations.[1][2][3][A] This period is also called the medieval era, post-antiquity era, post-ancient era, pre-modernity era, or pre-modern era.

In Asia, the spread of Islam created a series of caliphates and inaugurated the Islamic Golden Age, leading to advances in science in the medieval Islamic world and trade among the Asian, African, and European continents. East Asia experienced the full establishment of the power of Imperial China, which established several dynasties influencing Japan, Korea and Vietnam. Religions such as Buddhism and neo-Confucianism spread in the region.[5] Gunpowder was developed in China during the post-classical era. The Mongol Empire connected Europe and Asia, creating safe trade and stability between the two regions.[6] In total, the population of the world doubled in the time period, from approximately 210 million in 500 CE to 461 million in 1500 CE.[7] The population generally grew steadily throughout the period but endured some incidental declines due to events including the Plague of Justinian, the Mongol invasions, and the Black Death.[8][9]

Historiography

[edit]Terminology and periodization

[edit]

Post-classical history is a periodization used by historians employing a world history approach to history, specifically the school developed during the late 20th and early 21st centuries.[3] Outside of world history, the term is also sometimes used to avoid erroneous pre-conceptions around the terms Middle Ages, Medieval Period, and the Dark Ages (see medievalism), though the application of the term post-classical on a global scale is also problematic, and may likewise be Eurocentric.[10] Academic publications sometimes use the terms post-classical and late antiquity synomously to describe the history of Western Eurasia between 250 and 800 CE.[11][12]

The post-classical period corresponds roughly to the period from 500 CE to 1450 CE.[1][13][3] Beginning and ending dates might vary depending on the region, with the period beginning at the end of the previous classical period: Han China (ending in 220 CE), the Western Roman Empire (in 476 CE), the Gupta Empire (in 543 CE), and the Sasanian Empire (in 651 CE).[14]

The post-classical period is one of the five or six major periods world historians use:

- early civilization,

- classical societies,

- post-classical

- early modern,

- long nineteenth century, and

- contemporary or modern era.[3] (Sometimes the nineteenth century and modern are combined.[3])

Although post-classical is synonymous with the Middle Ages of Western Europe, the term post-classical is not necessarily a member of the traditional tripartite periodization of Western European history into classical, middle, and modern.

Approaches

[edit]The historical field of world history, which looks at common themes occurring across multiple cultures and regions, has enjoyed extensive development since the 1980s.[15] However, World History research has tended to focus on early modern globalization (beginning around 1500) and subsequent developments, and views post-classical history as mainly pertaining to Afro-Eurasia.[3] Historians recognize the difficulties of creating a periodization and identifying common themes that include not only this region but also, for example, the Americas, since they had little contact with Afro-Eurasia before the Columbian exchange.[3] Thus researchers around the year 2020 emphasized that "a global history of the period between 500 and 1500 is still wanting" and that "historians have only just begun to embark on a global history of the Middle Ages".[16][17]

For many regions of the world, there are well established histories. Although medieval studies in Europe tended in the 19th century to focus on creating histories for individual nation-states, much 20th-century research focused, successfully, on creating an integrated history of medieval Europe.[18][19][20][16] The Islamic World likewise has a rich regional historiography, ranging from the 14th-century Ibn Khaldun to the 20th-century Marshall Hodgson and beyond.[21] Correspondingly, research into the network of commercial hubs which enabled goods and ideas to move between China in the East and the Atlantic islands in the West—which can be called the early history of globalization—is fairly advanced; one key historian in this field is Janet Abu-Lughod.[16] Understanding of communication within sub-Saharan Africa or the Americas is, by contrast, far more limited.[16]

Around the 2010s, therefore, researchers began to explore the possibilities of writing history covering the Old World, where human activities were fairly interconnected, and establish its relationship with other cultural spheres, such as the Americas and Oceania. In the assessment of James Belich, John Darwin, Margret Frenz, and Chris Wickham,

Global history may be boundless, but global historians are not. Global history cannot usefully mean the history of everything, everywhere, all the time. [...] Three approaches [...] seem to us to have real promise. One is global history as the pursuit of significant historical problems across time, space, and specialism. This can sometimes be characterized as 'comparative' history. [...] Another is connectedness, including transnational relationships. [...] The third approach is the study of globalization [...]. Globalization is a term that needs to be rescued from the present, and salvaged for the past. To define it as always encompassing the whole planet is to mistake the current outcome for a very ancient process.[22]

A number of commentators have pointed to the history of the Earth's climate as a useful approach to World History in the Middle Ages, noting that certain climate events had effects on all human populations.[23][24][25][26][27][28]

Global trends

[edit]The post-classical era saw several common developments or themes. There was the expansion and growth of civilization into new geographic areas; the rise and/or spread of the three major world, or missionary, religions; and a period of rapidly expanding trade and trade networks. While scholastic emphasis has remained on Eurasia there is a growing effort to examine the effects of these global trends on other places.[1] In describing geographic zones historians have identified three large self contained world regions, Afro-Eurasia, the Americas, and Oceania.[10][B]

Growth of civilization

[edit]

First was the expansion and growth of civilization into new geographic areas across Asia, Africa, Europe, Mesoamerica, and western South America. However, as noted by world historian Peter N. Stearns, there were no common global political trends during the post-classical period, rather it was a period of loosely organized states and other developments, but no common political patterns emerged.[3] In Asia, China continued its historic dynastic cycle and became more complex, improving its bureaucracy. The creation of the Islamic empires established a new power in the Middle East, North Africa, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. The Mali and Songhai Empires were formed in West Africa. The fall of Roman civilization not only left a power vacuum for the Mediterranean and Europe, but forced certain areas to build what some historians might call new civilizations entirely.[30] An entirely different political system was applied in Western Europe (i.e. feudalism), as well as a different society (i.e. manorialism). However, the once Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) retained many features of old Rome, as well as Greek and Persian similarities. Kievan Rus' and subsequently Russia began development in Eastern Europe as well. In the isolated Americas, Mesoamerica saw the building of the Aztec Empire, while the Andean region of South America saw the establishment of the Wari Empire first and the Inca Empire later.[31] In Oceania, ancestors of modern Polynesians were established in village communities by the 6th century, a gradual intensification of complexity took place. In the 13th century, complex states were established, most notably the Tuʻi Tonga Empire which collected tribute from many island chains in the greater region.[32]

Spread of universal religions

[edit]

Religion that envisaged the possibility that all humans could be included in a universal order had emerged already in the first millennium BCE, particularly with Buddhism. In the following millennium, Buddhism was joined by two other major, universalizing, missionary religions, both developing from Judaism: Christianity and Islam. By the end of the period, these three religions were between them widespread, and often politically dominant, across the Old World.[33]

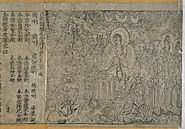

- Buddhism spread from India into China and flourished there briefly before using it as a hub to spread to Japan, Korea, and Vietnam;[34] a similar effect occurred with Confucian revivalism in the later centuries.[33]

- Christianity had become the state church of the Roman Empire in 380, and continued spreading into northern and eastern Europe during the post-classical period at the expense of belief systems that Christians labelled pagan.[35] An attempt was even made to incur upon the Middle East during the Crusades. The split of the Catholic Church in Western Europe and the Eastern Orthodox Church in Eastern Europe encouraged religious and cultural diversity in Eurasia.[36]

- Islam began between 610 and 632, with a series of revelations to Muhammad. It helped unify the warring Bedouin clans of the Arabian Peninsula and, through a rapid series of Muslim conquests, became established to the west across North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and parts of West Africa, and to the east across Persia, Central Asia, India, and Indonesia.[37]

Outside of Eurasia, religion or otherwise a veneration of the supernatural was also used to reinforce power structures, articulate world views and create foundational myths for society. Mesoamerican cosmological narratives are an example of this.[10]

Trade and communication

[edit]

Finally, communication and trade across Afro-Eurasia increased rapidly. The Silk Road continued to spread cultures and ideas through trade. Communication spread throughout Europe, Asia, and Africa. Trade networks were established between western Europe, Byzantium, early Russia, the Islamic Empires, and the Far Eastern civilizations.[38] In Africa, the earlier introduction of the camel allowed for a new and eventually large trans-Saharan trade, which connected Sub-Saharan West Africa to Eurasia. The Islamic Empires adopted many Greek, Roman, and Indian advances and spread them through the Islamic sphere of influence, allowing these developments to reach Europe, North and West Africa, and Central Asia. Islamic sea trade helped connect these areas, including those in the Indian Ocean and in the Mediterranean, replacing Byzantium in the latter region. The Christian Crusades into the Middle East (as well as Muslim Spain and Sicily) brought Islamic science, technology, and goods to Western Europe.[35] Western trade into East Asia was pioneered by Marco Polo. Importantly, China began to influence regions like Japan,[34] Korea, and Vietnam through trade and conquest. Finally, the growth of the Mongol Empire in Central Asia established safe trade which allowed goods, cultures, ideas, and disease to spread between Asia, Europe, and Africa.

The Americas had their own trade network, but here trade was restricted by range and scope. The Mayan network spread across Mesoamerica but lacked direct connections to the complex societies of South and North America, and these zones remained separate from one another.[39]

In Oceania, some of the island chains of Polynesia engaged in trade with one another.[40] For instance, with outrigger canoes long-distance communication of over 2,300 miles between Hawaii and Tahiti was maintained for centuries before its disruption and separation.[41] Meanwhile, in Melanesia there is evidence of exchanges between mainland Papua New Guinea and the Trobriand Islands off its coast, most likely for obsidian. Populations moved westward until 1200, after which the network dissolved into much smaller economies.[42]

Climate

[edit]During post-classical times, there is evidence that many regions of the world were affected similarly by global climate conditions; however, direct effects in temperature and precipitation varied by region. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, changes did not all occur at once. Generally however, studies found that temperatures were relatively warmer in the 11th century, but colder by the early 17th century. The degree of climate change which occurred in all regions across the world is uncertain, as is whether such changes were all part of a global trend.[43] Climate trends appear to be more recognizable in the Northern than in the Southern Hemisphere however, there are instances where climate in areas without written records have been estimated, historians now believe the Southern Hemisphere became colder between 950 and 1250.[44]

There are shorter climate periods that could be said roughly to account for large scale climate trends in the post-classical period. These include the Late Antique Little Ice Age, the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age. The extreme weather events of 536–537 were likely initiated by the eruption of the Lake Ilopango caldera in El Salvador. Sulfate emitted into the air initiated global cooling, migrations and crop failures worldwide, possibly intensifying an already cooler time period.[45] Records show that the world's average temperature remained colder for at least a century afterwards.

The Medieval Warm Period from 950 to 1250 occurred mostly in the Northern Hemisphere, causing warmer summers in many areas; the high temperatures would only be surpassed by the global warming of the 20th/21st centuries. It has been hypothesized that the warmer temperatures allowed the Norse to colonize Greenland, due to ice-free waters. Outside of Europe there is evidence of warming conditions, including higher temperatures in China and major North American droughts which adversely affected numerous cultures.[46]

After 1250, glaciers began to expand in Greenland, affecting its thermohaline circulation, and cooling the entire North Atlantic. In the 14th century, the growing season in Europe became unreliable; meanwhile in China the cultivation of oranges was driven southward by colder temperatures. Especially in Europe, the Little Ice Age had great cultural ramifications.[47] It persisted until the Industrial Revolution, long after the post-classical period.[48] Its causes are unclear: possible explanations include sunspots, orbital cycles of the Earth, volcanic activity, ocean circulation, and man-made population decline.[49]

Timeline

[edit]This timetable gives a basic overview of states, cultures and events which transpired roughly between the years 200 and 1500. Sections are broken by political and geographic location.[50][51]

- Dates are approximate range (based upon influence), consult particular article for details

- Middle Ages Divisions, Middle Ages Themes Other themes

Eurasian trends

[edit]This section explains events and trends which affected the geographic area of Eurasia. The civilizations within this area were distinct from one another but still endured shared experiences and some development patterns.[52][53][54]

Feudalism

[edit]

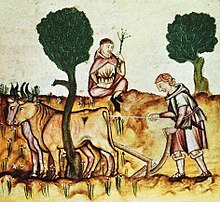

In the context of global history, the label of feudalism has been used to describe any agricultural society where central authority broke down to be replaced by a warrior aristocracy. Feudal societies are characterized by reliance on personal relationships with military elites, rather than a bureaucracy with a state-supported professional standing army.[55] The label of feudalism has thus been used to describe many areas of Eurasia including medieval Europe, the Islamic iqta' system, Indian feudalism, and Heian Japan.[56] Some world historians generalize that societies can be called feudal if authority was fragmented, with a set of obligations between vassal and lord. After the 8th century, feudalism became more common across Europe. Even Byzantium, which had inherited the government of the Roman Empire, chose to devolve its military obligations into themes to increase the number of soldiers and ships available for military service during times of crisis.[57] There were similarities between European feudalism and the Islamic iqta', as both featured landed classes of mounted warriors whose titles were granted by a monarch or sultan.[58] Because of these similarities, it was common for societal structures to be preserved in the face of religious upheaval; for instance, after the Islamic Delhi Sultanate conquered large portions of India, it imposed higher taxes but otherwise left local feudal structures in place.[59]

Though most of Eurasia adopted feudalism and similar systems during this era, China employed a centralized bureaucracy throughout much of the post classical period, particularly after 1000.[60] A major factor that distinguished China from other regions was that local leaders were reluctant to self-identify by their current location; instead, they typically displayed an ambition to unite the country in times of disunity.[61]

Beyond a broad generalization, the usefulness of the term "feudalism" is debated by contemporary historians, as the daily functions of feudalism sometimes differed greatly between world regions.[55] Comparisons between feudal Europe and post-classical Japan have been particularly controversial. Throughout the 20th century, historians often compared medieval Europe to post-classical Japan.[62] More recently, it has been argued that, until roughly 1400, Japan balanced its decentralized military power with more centralized forms of imperial (governmental) and monastic (religious) authority. Only in the Sengoku period did there come to be fully decentralized power dominated by private military leaders.[63] Still other historians reject the term feudalism outright, challenging its ability to usefully describe societies either within or outside of medieval Europe.[64]

Mongol Empire

[edit]

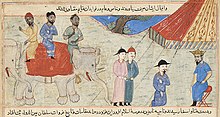

The Mongol Empire, which existed during the 13th and 14th centuries, was the largest continuous land empire in history.[65] Originating in the steppes of Central Asia, the Mongol Empire eventually stretched from Central Europe to the Sea of Japan, extending northwards into Siberia, eastwards and southwards into the Indian subcontinent, Indochina, and the Iranian Plateau, and westwards as far as the Levant and Arabia.[66]

The Mongol Empire emerged from the unification of nomadic tribes in the Mongolia homeland under the leadership of Genghis Khan, who was proclaimed ruler of all Mongols in 1206. The empire grew rapidly under his rule and then under his descendants, who sent invasions in every direction.[67][68][69][70][71][72] The vast transcontinental empire connected east and west with an enforced Pax Mongolica allowing trade, technologies, commodities, and ideologies to be disseminated and exchanged across Eurasia.[73][74]

The empire began to split due to wars over succession, as the grandchildren of Genghis Khan disputed whether the royal line should follow from his son and initial heir Ögedei, or one of his other sons such as Tolui, Chagatai, or Jochi. After Möngke Khan died, rival kurultai councils simultaneously elected different successors, the brothers Ariq Böke and Kublai Khan, who then not only fought each other in the Toluid Civil War, but also dealt with challenges from descendants of other sons of Genghis.[75] Kublai successfully took power, but civil war ensued as Kublai sought unsuccessfully to regain control of the Chagatayid and Ögedeid families.[76]

The Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260 marked the high-water point of the Mongol conquests and was the first time a Mongol advance had ever been beaten back in direct combat on the battlefield.[76] Though the Mongols launched many more invasions into the Levant, briefly occupying it and raiding as far as Gaza after a decisive victory at the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar in 1299, they withdrew due to various geopolitical factors.

By the time of Kublai's death in 1294, the Mongol Empire had fractured into four separate khanates or empires, each pursuing its own separate interests and objectives: the Golden Horde khanate in the northwest; the Chagatai Khanate in the west; the Ilkhanate in the southwest; and the Yuan dynasty based in modern-day Beijing.[77] In 1304, the three western khanates briefly accepted the nominal suzerainty of the Yuan dynasty,[78][79] but it was later overthrown by the Han Chinese Ming dynasty in 1368.[80] The Genghisid rulers returned to Mongolia homeland and continued rule in the Northern Yuan dynasty.[80] All of the original Mongol Khanates collapsed by 1500, but smaller successor states remained independent until the 1700s. Descendants of Chagatai Khan created the Mughal Empire that ruled much of India in early modern times.[80]

The conquests and the interactions the Mongol Empire had with western Eurasia are one of the more comprehensively researched areas for historians looking to define a globalized Middle Ages.[17]

Silk Road

[edit]

The Silk Road was a Eurasian trade route that played a large role in global communication and interaction. It stimulated cultural exchange; encouraged the learning of new languages; resulted in the trade of many goods, such as silk, gold, and spices; and also spread religion and disease.[81] It is even claimed by some historians – such as Andre Gunder Frank, William Hardy McNeill, Jerry H. Bentley, and Marshall Hodgson – that the Afro-Eurasian world was loosely united culturally, and that the Silk Road was fundamental to this unity.[81] This major trade route began with the Han dynasty of China, connecting it to the Roman Empire and any regions in between or nearby. At this time, Central Asia exported horses, wool, and jade into China for the latter's silk; the Romans would trade for the Chinese commodity as well, offering wine in return.[82] The Silk Road would often decline and rise again in trade from the Iron Age to the post-classical era. Following one such decline, it was reopened in Central Asia by Han dynasty general Ban Chao during the 1st century.[83]

There were vulnerabilities as well to changing political situations. The rise of Islam changed the Silk Road, because Muslim rulers generally closed the Silk Road to Christian Europe to an extent that Europe would be cut off from Asia for centuries. Specifically, the political developments that affected the Silk Road included the emergence of the Turks, the political movements of the Byzatine and Sasanian Empires, and the rise of the Arabs, among others.[84]

The Silk Road flourished again in the 13th century during the reign of the Mongol Empire, which through conquest had brought stability in Central Asia comparable to the Pax Romana.[85] It was claimed by a Muslim historian that Central Asia was peaceful and safe to transverse.

"(Central Asia) enjoyed such a peace that a man might have journeyed from the land of sunrise to the land of sunset with a golden platter upon his head without suffering the least violence from anyone."[86]

As such, trade and communication between Europe, East Asia, South Asia, and West Asia required little effort. Handicraft production, art, and scholarship prospered, and wealthy merchants enjoyed cosmopolitan cities. Notable Travelers including Ibn Battuta, Rabban Bar Sauma, and Marco Polo traveled across North Africa and Eurasia freely, those that left accounts of their experiences inspired future adventurers.[86] The Silk Road was also a major factor in spreading religion across Afro-Eurasia. Muslim teachings from Arabia and Persia reached East Asia. Buddhism spread from India, to China, to Central Asia. One significant development in the spread of Buddhism was the carving of the Gandhara School in the cities of ancient Taxila and the Peshwar, allegedly in the mid 1st century.[83] In addition to commercial travel was the esteem of pilgrimage that existed across all of Afro-Eurasia, in the words of world historian R. I. Moore "if any single institution 'made' the Eurasian Middle Ages it was pilgrimage."[54][87][88]

Nevertheless, after the 15th century, the Silk Road disappeared from regular use.[85] This was primarily a result from the growing sea travel pioneered by Europeans, which allowed the trade of goods by sailing around the southern tip of Africa and into the Indian Ocean.[85]

The route was vulnerable to spreading plague. The Plague of Justinian originated in East Africa and had a major outbreak in Europe in 542 causing the deaths of a quarter of the Mediterranean's population. Trade between Europe, Africa, and Asia along the route was at least partially responsible for spreading the plague.[89] Eight centuries later, the Silk Road trade played a role in spreading the infamous Black Death. The disease, spread by rats, was carried by merchant ships sailing across the Mediterranean that brought the plague back to Sicily, causing an epidemic in 1347.[90]

Plague and disease

[edit]In the Eurasian world, disease was an inescapable part of daily life. Europe in particular suffered minor outbreaks of disease every decade during the period. Using both land and sea routes, devastating pandemics could spread far beyond their initial focal point.[91] Tracking the origin of massive bubonic plagues and their potential spread between Eastern and Western Eurasia has been academically contentious.[92] Besides bubonic plague, other diseases including smallpox also spread across cultural regions.[93]

The first plague

[edit]The first plague pandemic caused by Yersinia pestis began with the 541–549 Plague of Justinian. The origin of the plague appears to have been the Tian Shan mountains in Kyrgyzstan.[94] But the origin of the 541–549 epidemic remains uncertain: some historians postulate East Africa as a possible geographical origin.[95]

There is no record of a disease with the characteristics of Yersinia pestis breaking out in China before its appearance in Pelusium Egypt. The plague spread to Europe and West Asia, with a possible spread into East Asia.[C] Established urban civilizations were massively depopulated; the economies and social fabric of established empires were severely destabilized.[97] Rural societies, while still facing horrific death tolls, saw fewer socioeconomic effects.[98] In addition, no evidence has been found of bubonic plague in India before 1600.[97] Nevertheless, it is likely that the trauma of disease (and other natural disasters) was a major cause of profound religious and political changes in Eurasia. Different authorities reacted to disease outbreaks with strategies that they believed would best protect their power. The Catholic Church in France spoke of healing miracles; Confucian bureaucrats asserted that sudden deaths of Chinese emperors represented the loss of a dynasty's Mandate of Heaven, shifting blame away from themselves. The severe loss of manpower in the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires contributed to early Muslim conquests in the region.[96] In the long term, overland trade in Eurasia diminshed, as coastal Indian Ocean trade became more frequent. There were recurrent aftershocks of the Plague of Justinian until around 750, after which many nations saw an economic recovery.[99]

Second plague pandemic until 1500

[edit]

Six centuries later, a relative (but not a direct descendant) of Yersinia Pestis rose to afflict Eurasia: the Black Death. The first instance of the second plague pandemic was between 1347 and 1351. It killed variously between 25% and 50% of populations.[100] Traditionally many historians believed the Black Death started in China and was then spread westward by invading Mongols who inadvertently carried infected fleas and rats with them.[92] Although there is no concrete historical evidence for this theory, the plague is considered endemic on the steppe.[101] Currently there is extensive historiography of the Black Death's effects in Europe and the Islamic world, but beyond Western Eurasia direct evidence for Black Death's presence is lacking.[102][103] The Bulletin of the History of Medicine explored the potential linking of known 14th century epidemics in Asia with the plague. One example is the Deccan Plateau, where much of the Delhi Sultanate's army suddenly died of a sickness in 1334. As this was 15 years before Europe's Black Death but little detail about the symptoms, it is unlikely that this was an instance of bubonic plague. Meanwhile, Yuan China suffered from major epidemics in the mid-14th century, including a recorded 90% death rate in Hebei Province.[92] As with the Deccan event, surviving accounts do not describe symptoms; so historians are left to speculate.[92] Perhaps these outbreaks were not the Black Death but instead some other disease already common to East Asia at the time, such as typhus, smallpox, or dysentery.[92][104] Compared to Western reactions to the Black Death, Chinese records that do mention the epidemics are relatively muted, indicating that epidemics were a routine occurrence. Historians consider the hypothesis of a Chinese origin of a westward-moving plague unlikely given the fragmentation of the Mongol Empire and the 5,000-mile journey between China proper and Crimea through sparsely populated Central Asia.[92]

The aftershocks of the plague continued to affect populations well into the early modern period. In Western Europe, the devastating loss of people created lasting changes. Wage labor began to rise in Western Europe and there was more emphasis on labor-saving machines and mechanisms. Slavery, which had almost vanished from medieval Europe, returned and was one of the reasons for early Portuguese exploration after 1400. The adoption of Arabic numerals may have been partially caused by the plague.[105] Importantly, many economies became specialist, producing only certain goods, seeking expansion elsewhere for exotic resources and slave labor. While typically Western European expansion as a result of the Black Death is most discussed, Islamic countries including the Ottoman Empire also partook in land-based expansionism and used their own slave trade.[106]

Science

[edit]

The term post-classical science is often used in academic circles and in college courses to combine the study of medieval European science and medieval Islamic science due to their interactions with one another.[107] However scientific knowledge also spread westward by trade and war from Eastern Eurasia, particularly from China by Arabs. The Islamic world also took medical knowledge from South Asia.[108]

In the Western world and in Islamic realms, much emphasis was placed on preserving the rationalist Greek tradition of figures such as Aristotle. In the context of science within Islam there are questions as to whether Islamic scientists simply preserved accomplishments from classical antiquity or built upon earlier Greek advances.[109][110] Regardless, classical European science was brought back to the Christian kingdoms due to the experience of the Crusades.[111]

As a result of Persian trade in China, and the battle of the Talas River, Chinese innovations entered the Islamic intellectual world.[112] These include advances in astronomy and in papermaking.[113][114] Paper-making spread through the Islamic world as far west as Islamic Spain, before paper-making was acquired for Europe by the Reconquista.[115] There is debate about transmission of gunpowder regarding whether the Mongols introduced Chinese gunpowder weapons to Europe or whether gunpowder weapons were independently invented in Europe.[116][117] In the Mongol Empire, information from diverse cultures was brought together for large projects: for instance in 1303 the Mongol Yuan dynasty combined Chinese and Islamic cartography to make a map that likely included all of Eurasia including western Europe. This "Eurasia map" is now lost, but it influenced Chinese and Korean geographical knowledge centuries later.[104] It is apparent that within Eurasia transfer of information between world cultures did occur, usually through translations of written documents.[52]

Literature and the arts

[edit]

Within Eurasia, there were four major civilization groups that had literate cultures and created literature and arts, including Europe, West Asia, South Asia, and East Asia. Southeast Asia could be a possible fifth category but was influenced heavily from both South and East Asia literal cultures. All four cultures in post-classical times used poetry, drama, and prose. Throughout the period and until the 19th century poetry was the dominant form of literary expression. In West Asia, South Asia, Europe, and China, great poetic works often used figurative language. Examples include, the Sanskrit Shakuntala, the Arabic Thousand and one nights, Old English Beowulf and works by the Chinese Du Fu and the Persian Rumi. In Japan, prose uniquely thrived more than in other geographic areas. The Tale of Genji is considered the world's first realistic novel written in the 9th century.[118]

Musically, most regions of the world only used monophonic melodies as opposed to harmony. Medieval Europe was the lone exception to this rule, developing harmonic music in the 14th/15th century as musical culture transitioned form sacred music (meant for the church) to secular music.[119] South Asian and West Asian music were similar to each other for their use of microtone. East Asian music shared some similarities with European music by using twelve tones and employing scales, but differed in the number of scales used- 5 for the former and seven for the latter[120]

History by region

[edit]Africa

[edit]

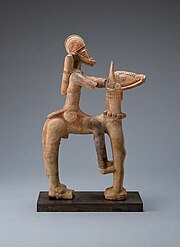

During the post-classical era, Africa was both culturally and politically affected by the introduction of Islam and the Arab empires.[121] This was especially true in the north, the Sudan, and the east coast. However, this conversion was not complete nor uniform among different areas, and the low-level classes hardly changed their beliefs at all.[122] Prior to the migration and conquest of Muslims into Africa, much of the continent was dominated by diverse societies of varying sizes and complexities. These were ruled by kings or councils of elders who would control their constituents in a variety of ways. Most of these peoples practiced spiritual, animistic religions. Africa was culturally separated between Saharan Africa (which consisted of North Africa and the Sahara Desert) and sub-Saharan Africa (everything south of the Sahara). Sub-Saharan Africa was further divided into the Sudan, which covered everything north of Central Africa, including West Africa. The area south of the Sudan was primarily occupied by the Bantu peoples who spoke the Bantu language. From 1100 onward, Christian Europe and the Islamic world became dependent on Africa for gold.[123]

After approximately 650 urbanization expanded for the first time beyond the ancient kingdoms Aksum and Nubia. African civilizations can be divided into three categories based on religion:[124][125]

- Christian civilizations on the Horn of Africa

- Islamic civilizations which formed in the Niger River Valley and on the Swahili Coast

- Traditional societies which adhered to native African religions

Sub-Saharan Africa was part of two large, separate trading networks, the trans-Saharan trade that bridged commerce between West and North Africa. Due to the huge profits from trade native African Islamic empires arose, including those of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai.[126] In the 14th century, Mansa Musa of Mali may have been the wealthiest person of his time.[127] Within Mali, the city of Timbuktu was an international center of science and well known throughout the Islamic world, particularly from the University of Sankoré. East Africa was part of the Indian Ocean trade network, which included both Arab ruled Islamic cities on the East African Coast such as Mombasa and traditional cities such as Great Zimbabwe which exported gold, copper and ivory to markets in the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia.[123]

Europe

[edit]

In Europe, Western civilization reconstituted after the fall of the Western Roman Empire into the period now known as the Early Middle Ages (500–1000). The Early Middle Ages saw a continuation of trends begun in late antiquity: depopulation, deurbanization, and increased barbarian invasion.[128]

From the 7th until the 11th centuries, Arabs, Magyars, and Norse were all threats to the Christian Kingdoms that killed thousands of people over centuries.[129] Raiders however, also created new trading networks.[130] In Western Europe, the Frankish king Charlemagne attempted to kindle the rise of culture and science in the Carolingian Renaissance.[131] In 800, Charlemagne founded the Holy Roman Empire in attempt to resurrect ancient Rome.[132] The reign of Charlemagne attempted to kindle a rise of learning and literacy in what has become known as the Carolingian Renaissance.[133]

In Eastern Europe, the Eastern Roman Empire survived in what is now called the Byzantine Empire, which created the Code of Justinian that inspired the legal structures of modern European states.[134] Overseen by Eastern Orthodox emperors, in the 9th–10th centuries the Byzantine Eastern Orthodox Church Christianized the First Bulgarian Empire and Kievan Rus', the cultural and political ancestors to modern-day Bulgaria and North Macedonia, on the one hand, and Russia and Ukraine, on the other.[135][136] Byzantium flourished as the leading power and trade center in its region in the Macedonian Renaissance until it was overshadowed by Italian city-states and the Islamic Ottoman Empire near the end of the Middle Ages.[137][138]

Later in the period, the creation of the feudal system allowed greater degrees of military and agricultural organization. There was sustained urbanization in northern and western Europe.[58] Later developments were marked by manorialism and feudalism, and evolved into the prosperous High Middle Ages.[58] After 1000 the Christian kingdoms that had emerged from Rome's collapse changed dramatically in their cultural and societal character.[130]

During the High Middle Ages (c. 1000–1300), Christian-oriented art and architecture flourished and the Crusades were mounted to recapture the Holy Land from Muslim control.[139] The influence of the emerging nation-state was tempered by the ideal of an international Christendom and the presence of the Catholic Church in all western kingdoms.[140] The codes of chivalry and courtly love set rules for proper behavior, while the Scholastic philosophers attempted to reconcile faith and reason.[111] The age of Feudalism would be dramatically transformed by the cataclysm of the Black Death and its aftermath.[141] This time would be a major underlying cause for the Renaissance. By the turn of the 16th century European or Western civilization would be engaging in the Age of Discovery.[142]

The term "Middle Ages" first appears in Latin in the 15th century and reflects the view that this period was a deviation from the path of classical learning, a path supposedly reconnected by Renaissance scholarship.[143]

West and Central Asia

[edit]The Arabian Peninsula and the surrounding Middle East and Near East regions saw dramatic change during the post-classical era caused primarily by the spread of Islam and the establishment of the Arab caliphates.[144]

In the 5th century, the Middle East was separated by empires and their spheres of influence; the two most prominent were the Persian Sasanian Empire, centered in what is now Iran, and the Byzantine Empire in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). The Byzantines and Sasanians fought with each other continually, a reflection of the rivalry between the Roman Empire and the Persian Empire seen during the previous five hundred years.[145] The fighting weakened both states, leaving the stage open to a new power.[146] Meanwhile, the nomadic Bedouin tribes who dominated the Arabian desert saw a period of tribal warfare for scarce resources and a familiarity with Abrahamic religions or monotheism.[147]

While the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires were both weakened by the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, a new power in the form of Islam grew in the Middle East under Muhammad in Medina. In a series of rapid Muslim conquests, the Rashidun army, led by the caliphs and skilled military commanders such as Khalid ibn al-Walid, swept through most of the Middle East, taking more than half of Byzantine territory in the Arab–Byzantine wars and completely engulfing Persia in the Muslim conquest of Persia.[148] It would be the Arab caliphates of the Middle Ages that would first unify the entire Middle East as a distinct region and create the dominant ethnic identity that persists today. These caliphates included the Rashidun, Umayyad, and Abbasid Caliphates, along with the later Turkic-based Seljuk Empire.[149]

After Muhammad introduced Islam, it jump-started Middle Eastern culture into an Islamic Golden Age, inspiring achievements in architecture, the revival of old advances in science and technology, and the formation of a distinct way of life.[150] Muslims saved and spread Greek advances in medicine, algebra, geometry, astronomy, anatomy, and ethics that would later find their way back to Western Europe.[151]

The dominance of the Arabs came to a sudden end in the mid-11th century with the arrival of the Seljuk Turks, migrating south from the Turkic homelands in Central Asia. They conquered Persia, Iraq (capturing Baghdad in 1055), Syria, Palestine, and the Hejaz.[152] This was followed by a series of Christian Western Europe invasions. The fragmentation of the Middle East allowed joint European forces mainly from England, France, and the emerging Holy Roman Empire, to enter the region.[153] In 1099 the knights of the First Crusade captured Jerusalem and founded the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which survived until 1187, when Saladin retook the city. Smaller crusader fiefdoms survived until 1291.[154] In the early 13th century, a new wave of invaders, the armies of the Mongol Empire, swept through the region, sacking Baghdad in the siege of Baghdad and advancing as far south as the border of Egypt in what became known as the Mongol conquests.[155] The Mongols eventually retreated in 1335, but the chaos that ensued throughout the empire deposed the Seljuk Turks. In 1401, the region was further plagued by the Turko-Mongol, Timur, and his ferocious raids. By then, another group of Turks had arisen as well, the Ottomans.[156]

South Asia

[edit]There has been difficulty applying the word "medieval" or "post-classical" to the history of South Asia. This section follows historian Stein Burton's definition that corresponds from the 8th century to the 16th century, more or less following the same time frame of the post-classical period and the European Middle Ages.[157]

Until the 13th century, there was no less than 20 to 40 different states on the Indian subcontinent which hosted a variety of cultures, languages, writing systems and religions.[158] At the beginning of the time period Buddhism was predominant throughout the area with the short-lived Pala Empire on the Indo-Gangetic Plain sponsoring the faith's institutions. One such institution was the Buddhist Nalanda mahavihara in modern-day Bihar, a centre of scholarship that brought the divided South Asia onto the global intellectual stage. Another accomplishment was the invention of the Chaturanga game which later was exported to Europe and became chess.[159]

In South India, the Hindu kingdom of Chola gained prominence with an overseas empire that controlled parts of modern-day Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Indonesia as oversees territories and accelerated the spread of Hinduism into the historic culture of these places.[160] In this time period, neighboring areas such as Afghanistan, Tibet, and Myanmar were under South Asian influence.[161]

From 1206 onward, a series of Turkic invasions from modern-day Afghanistan and Iran conquered massive portions of North India, founding the Delhi Sultanate which remained supreme until the 16th century.[59] Buddhism declined in South Asia vanishing in many areas but Hinduism survived and reinforced itself in areas conquered by Muslims. In the far south, the Vijayanagara Empire was not conquered by any Muslim state in the period. The turn of the 16th century would see the rise of a new Islamic empire – the Mughals and the establishment of European trade posts by the Portuguese.[162]

Southeast Asia

[edit]

From the 8th century onward, Southeast Asia stood to benefit from the trade taking place between South Asia and East Asia, numerous kingdoms arose in the region due to the flow of wealth passing through the Strait of Malacca. While Southeast Asia had numerous outside influences including Indian and Chinese Civilization, local cultures strove to cement their own unique identities.[163] North Vietnam (known as Dai Viet) was culturally closer to China for centuries due to conquest.[164]

Since rule from the third century BCE, North Vietnam continued to be subjugated by Chinese states, although they continually resisted periodically. There were three periods of Chinese domination that spanned near 1100 years. The Vietnamese gained long lasting independence in the 10th century when China was divided with Tĩnh Hải quân and the successor Đại Việt. Nonetheless, even as an independent state a sort of begrudging Sinicization occurred. South Vietnam was governed by the ancient Hindu Champa Kingdom but was annexed by the Vietnamese in the 15th century.[165]

The spread of Hinduism, Buddhism, and maritime trade between China and South Asia created the foundation for Southeast Asia's first major empires; including the Khmer Empire from Cambodia and Srivijaya from Indonesia. During the Khmer Empire's height in the 12th century the city of Angkor Thom was among the largest of the pre-modern world due to its water management. King Jayavarman II constructed over a hundred hospitals throughout his realm.[166] Nearby rose the Pagan Empire in modern-day Burma, using elephants as military might.[167] The construction of the Buddhist Shwezigon Pagoda and its tolerance for believers of older polytheistic gods helped Theravada Buddhism become supreme in the region.[167] In Indonesia, Srivijaya from the 7th through 14th century was a thalassocracy that focused on maritime city states and trade. Controlling the vital choke points of the Sunda and Malacca Straits it became rich from trade ranging from Japan through Arabia.

Gold, ivory, and ceramics were all major commodities traveling through port cities. The empire was also responsible for the construction of wonders such as Borobudur. During this time Indonesian sailors crossed the Indian Ocean; evidence suggests that they may have colonized Madagascar.[168] Indian culture spread to the Philippines, likely through Indonesian trade resulting in the first documented use of writing in the archipelago and Indianized kingdoms.[169]

Over time, changing economic and political conditions elsewhere and wars weakened the traditional empires of Southeast Asia. While the Mongol invasions did not directly annex Southeast Asia, the war-time devastation paved way for the rise of new nations. In the 14th century the Khmer Empire was uprooted by persistent years of war - losing the functionality and engineering knowledge of its advanced water management system.[170] Srivijaya was overtaken by the Majapahit.[171] Islamic missionaries and merchants arrived eventually leading to Islamization in Indonesia.[172][D]

East Asia

[edit]

The time frame of 500–1500 in East Asia's history and China in particular has been proposed as a possible classification for the region's history within the context of global post-classical history.[174] Discussions within Columbia University's Association of Asian studies have postulated that similarities between China and other regions of Eurasia during post-classical times have often been overlooked.[175][E] Typically the English language histography of Japan postulates that its 'medieval period' began as late as 1185.[176][F]

During this period the Eastern empires continued to expand through trade, migration and conquests of neighboring areas. Japan and Korea went under the process of voluntary Sinicization, or the impression of Chinese cultural and political ideas.[177][178][179]

Korea and Japan sinicized because their ruling class were largely impressed by China's bureaucracy.[180] The major influences China had on these countries were the spread of Confucianism, the spread of Buddhism, and the establishment of centralized governance. Throughout East Asia, Buddhism was most visible in monasteries and local educational institutions and Confucianism remained the ideology of social cohesion and state power.[1]

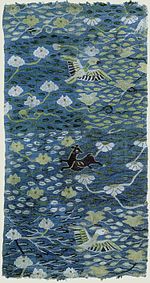

[181] In the times of the Sui, Tang, and Song dynasties (581–1279), China remained the world's largest economy and most technologically advanced society.[182][183] Inventions such as gunpowder, woodblock printing, and the magnetic compass were improved upon. China stood in contrast to other areas at the time as the imperial governments exhibited concentrated central authority instead of feudalism.[184]

China exhibited much interest in foreign affairs during the Tang and Song dynasties. From the 7th through the 10th centuries, Tang China was focused on securing the Silk Road as the selling of its goods westwards was central to the nation's economy.[180][185] For a time China successfully secured its frontiers by integrating their nomadic neighbors - the Göktürks - into their civilization.[186] The Tang dynasty expanded into Central Asia and received tribute from countries as distant as Eastern Iran.[180] Western expansion ended with wars with the Abbasid Caliphate and the deadly An Lushan Rebellion which resulted in a deadly but uncertain death toll of millions.[187] After the collapse of the Tang dynasty and subsequent civil wars came the second phase of Chinese interest in foreign relations. Unlike the Tang, the Song specialized in overseas trade and peacefully created a maritime network, and China's population became concentrated in the south.[188] Chinese merchant ships reached Indonesia, India, and Arabia. Southeast Asia's economy flourished from trade with Song China.[189]

With the country's emphasis on trade and economic growth. Song China's economy began to use machines to manufacture goods and coal as a source of energy.[190] The advances of the Song in the 11th/12th centuries have been considered an early industrial revolution.[191] Economic advancements came at the cost of military affairs and the Song became open to invasions from the north. China became divided as Song's northern lands were conquered by the Jurchen people.[192] By 1200, there were five Chinese kingdoms stretching from modern day Turkestan to the Sea of Japan including the Western Liao, Western Xia, Jin, Southern Song, and Dali.[193] Because these states competed with each other they all were eventually annexed by the rising Mongol Empire before 1279.[194] After seventy years of conquest, the Mongols proclaimed the Yuan dynasty and also annexed Korea; they failed to conquer Japan.[195] Mongol conquerors also made China accessible to European travelers such as Marco Polo.[196] The Mongol era was short lived due to plagues and famine.[197] After the revolution in 1368, the succeeding Ming dynasty ushered in a period of prosperity and brief foreign expeditions before isolating itself from global affairs for centuries.[198]

Korea and Japan however continued to have relations with China and with other Asian countries. In the 15th century Sejong the Great of Korea cemented his country's identity by creating the Hangul writing system to replace use of Chinese characters.[199] Meanwhile, Japan fell under military rule of the Kamakura and later Ashikaga Shogunate dominated by the samurai.[200]

Oceania

[edit]- Map of the Aboriginal regions in Australia.

Separate from developments in Afro-Eurasia and the Americas the region of greater Oceania continued to develop independently of the outside world. In Australia, the society of Aboriginal Australians changed little through the post-classical Period since their arrival in the area from Africa around 50,000 BCE. The only evidence of outside contact were encounters with fishermen of Indonesian origin.[G][201]

Polynesian and Micronesian peoples are rooted from Taiwan and Southeast Asia and began their migration into the Pacific Ocean from 3000 to 1500 BCE.[202] After the 4th century, the Micronesians and Polynesians began to explore the South Pacific and later constructed cities in previously uninhabited areas including Nan Madol Muʻa and others.[H][203] Around 1200 CE the Tuʻi Tonga Empire spread its influence far and wide throughout the South Pacific Islands, being described by academics as a maritime chiefdom which used trade networks to keep power centralized around the king's capital.[204] Polynesians on outrigger canoes discovered and colonized some of the last uninhabited islands of earth.[202] Hawaii, New Zealand, and Easter Island were among the final places to be reached, settlers discovering pristine lands. Oral tradition claimed that navigator Ui-te-Rangiora discovered icebergs in the Southern Ocean.[205] In exploring and settling, Polynesian settlers did not strike at random but used their knowledge of wind and water currents to reach their destinations.[206]

On the settled islands some Polynesian groups became distinct from one another, a significant example being the Maori of New Zealand. Other island systems kept in contact with each other, including Hawaii and the Tahiti, goods in long-distance trade included basalt, and Pearl shell.[204] Ecologically, Polynesians had the challenge of sustaining themselves within limited environments. Some settlements caused mass extinctions of some native plant and animal species over time by hunting species such as the moa and introducing the Polynesian rat.[202] Easter Island settlers engaged in complete ecological destruction of their habtiat and their population crashed afterwards possibly due to the construction of the Easter Island Statues.[207][208][209][210][I] Other colonizing groups adapted to accommodate to the ecology of specific islands such as the Moriori of the Chatham Islands.

Europeans on their voyages visited many Pacific islands in the 16th and 17th century, but most areas of Oceania were not colonized until after the voyages of British explorer James Cook in the 1780s.[212]

Americas

[edit]The post-classical era of the Americas can be considered set at a different time span from that of Afro-Eurasia. As the developments of Mesoamerican and Andean civilization differ greatly from that of the Old World, as well as the speed at which it developed, the post-classical era in the traditional sense does not take place until near the end of the medieval age in Western Europe. [J]

As such, for the purposes of this article, the Woodland period and Classic stage of the Americas will be discussed here, which takes place from about 400 to 1400.[215] For the technical post-classical stage in American development which took place on the eve of European contact, see Post-Classic stage.

North America

[edit]As a continent there was little unified trade or communication. Advances in agriculture spread northward from Mesoamerica indirectly through trade. Major cultural areas however still developed independently of each other.

Norse contact and the polar regions

[edit]

While there was little regular contact between the Americas and the Old World, the Norse explored and even colonized Greenland and Canada as early as 1000. None of these settlements survived past medieval times. Outside of Scandinavia knowledge of the discovery of the Americas was interpreted as a remote island or the North Pole.[216]

Норвежцы, прибывшие из Исландии, заселили Гренландию примерно с 980 по 1450 год. [217] Норвежцы прибыли в южную Гренландию до прихода инуитов Туле в этот район в 13 веке. Степень взаимодействия между норвежцами и Туле неясна. [217] Гренландия была ценна для норвежцев благодаря торговле слоновой костью, полученной из бивней моржей. Малый ледниковый период отрицательно повлиял на колонии, и они исчезли. [217] Гренландия была потеряна для европейцев до датской колонизации в 18 веке. [218]

Норвежцы также исследовали и колонизировали южнее Ньюфаундленда , Канада, в Л'Анс-о-Медоуз, который норвежцы называют Винландом . Колония просуществовала самое большее двадцать лет и не привела к каким-либо известным случаям передачи болезней или технологий коренным народам . У скандинавов Винланд был известен обилием виноградных лоз, из которых производилось превосходное вино. Одной из причин неудачи колонии было постоянное насилие по отношению к коренному народу Беотук , которого норвежцы называли скрелингами .

После первоначальных экспедиций есть вероятность, что норвежцы продолжили посещать современную Канаду. Сохранившиеся записи из средневековой Исландии указывают на некоторые спорадические путешествия в землю под названием Маркланд , возможно, на побережье Лабрадора в Канаде, еще в 1347 году, предположительно, для сбора древесины для обезлесенной Гренландии. [219]

Северные районы

[ редактировать ]

В Северной Америке в этом разнообразном регионе процветали многие общества охотников-собирателей и земледельцев. Племена коренных американцев сильно различались по характеристикам; некоторые, в том числе строители курганов и оазиамериканские культуры, представляли собой сложные вождества. [220] Другие страны, населявшие штаты современных северных Соединенных Штатов и Канады, имели меньшую сложность и не так быстро следовали за технологическими изменениями. Примерно около 500 года, в период Вудленда , коренные американцы начали переходить на луки и стрелы из копий для охоты и ведения войны. [221] Примерно в этом году 1000 кукурузы стали широко использоваться в качестве основной культуры на востоке Соединенных Штатов . Кукуруза продолжала оставаться основной культурой коренных жителей восточной части Соединенных Штатов и Канады до Колумбийской биржи. [222] [223]

На востоке Соединенных Штатов реки были средством торговли и общения. Кахокия , расположенная в современном американском штате Иллинойс, была одним из самых значительных городов в культуре Миссисипи . [220] Археологические исследования, сосредоточенные вокруг Монахского кургана, показывают, что после 1000 года население увеличилось в геометрической прогрессии, поскольку здесь производились важные инструменты для сельского хозяйства и располагались культурные достопримечательности. [224] Около 1350 года Кахокия была заброшена, и были высказаны предположения, что экологические факторы привели к упадку города. [225]

В то же время предки пуэблоанцев построили группы зданий в каньоне Чако , расположенном в штате Нью-Мексико . В отдельных домах одновременно могло проживать более 600 жителей. Каньон Чако был единственным доколумбовым местом в Соединенных Штатах, где строились дороги с твердым покрытием. [226] Керамика указывает на то, что общество становилось все более сложным: впервые в континентальной части Соединенных Штатов были одомашнены индейки. Около 1150 года сооружения каньона Чако были заброшены, вероятно, из-за сильной засухи. [227] [228] [229] Были и другие комплексы пуэбло на юго-западе США, такие как Клифф Палас, расположенный в национальном парке Меса Верде . Достигнув кульминации, местные сложные общества в Соединенных Штатах пришли в упадок и не полностью восстановились до прибытия европейских исследователей. [228] [К]

Карибский бассейн

[ редактировать ]

Сосредоточив значительное количество островов, Карибский бассейн был ареной постоянных морских миграций на каноэ, начиная с каменного этапа , причем его первые жители достигли этого района примерно к 5000 году до нашей эры. [231]

После тысячелетних потоков населения различные народы Карибского бассейна вступили в постклассический период с заметным развитием многочисленных постоянных поселений и более сложных социальных организаций, которые стали результатом совершенствования методов ведения сельского хозяйства, а также значительного роста деревень. , которые стали крупными церемониальными и торговыми центрами под руководством разных касиков . Торговые товары, такие как ракушки, хлопок, золото, цветные камни и редкие перья, в основном экспортировались с острова на остров, от Малых до Больших Антильских островов. [232]

Примерно к 650 и 800 годам нашей эры произошли новые миграционные волны с карибского побережья современной Венесуэлы , и несколько человек начали процесс крупных культурных, социально-политических и ритуальных реформ, который привел к образованию первых вождеств и возникновению иерархии социальной . [233] Этот период также можно охарактеризовать изгнанием древних саладоидов с главных островов Карибского моря и их последующей заменой вновь прибывшим народом таино , который яростно конкурировал с другими аравакоязычными группами за пахотные земли и военных пленников. Несмотря на малое количество доказательств, некоторые ученые все еще утверждают, что таино, возможно, имели незначительное влияние со стороны цивилизации майя , поскольку некоторые обычаи, такие как практика бати , могли быть унаследованы от оригинальной мезоамериканской игры в мяч , которая также носила религиозный характер. [234]

Когда Христофор Колумб высадился на Багамах в 1492 году, он и его команда сначала поддерживали мирные контакты с местным народом таино, но вскоре после этого они были порабощены испанскими колонизаторами, в результате чего этот район перешел в период раннего Нового времени .

Мезоамерика

[ редактировать ]

В начале глобального постклассического периода город Теотиуакан находился в зените своего развития, в нем проживало более 125 000 человек, а в 500 году нашей эры он был шестым по величине городом в мире того времени. [235] Жители города построили Пирамиду Солнца, третью по величине пирамиду мира, ориентированную на наблюдение за астрономическими событиями. Внезапно в VI и VII веках город внезапно пришел в упадок, возможно, в результате серьезного ущерба окружающей среде, вызванного экстремальными погодными явлениями 535–536 годов . Есть свидетельства того, что большая часть города была сожжена, возможно, в результате внутреннего восстания. [236] [Л] Наследие города будет вдохновлять все будущие цивилизации в регионе. [239]

В то же время классический век цивилизации майя был сосредоточен в десятках городов-государств на Юкатане и в современной Гватемале . [240] Самым значительным из этих городов был Чичен-Ица , который часто жестко конкурировал с 60-80 городами-государствами за доминирующее экономическое влияние в регионе. [241] Точно так же другие города майя, такие как Тикаль и Калакмуль, также инициировали серию полномасштабных конфликтов в этом районе из-за власти и престижа, кульминацией которых стали Тикаль-Калакмульские войны в VI веке. [242]

У майя была высшая каста жрецов, хорошо разбиравшихся в астрономии, математике и письменности. Майя разработали концепцию нуля и 365-дневный календарь, который, возможно, появился еще до его создания в обществах Старого Света. [243] После 900 года многие города майя внезапно пришли в упадок из-за экологической катастрофы, которая, вероятно, была вызвана сочетанием засухи и непрерывного цикла войн. Также было отмечено, что в классических городах майя не было помещений для хранения продуктов питания. [214]

Империя тольтеков возникла из культуры тольтеков и запомнилась как мудрые и доброжелательные лидеры. Один король-жрец по имени Се Акатль Топильцин выступал против человеческих жертвоприношений. [244] После его смерти в 947 году между сторонниками и противниками учения Топильцина вспыхнули гражданские войны религиозного характера. [244] Однако современные историки скептически относятся к масштабам и влиянию тольтеков и полагают, что большая часть информации, известной о тольтеках, была создана более поздними ацтеками как вдохновляющий миф. [245]

В 1300-х годах небольшая группа жестоких религиозных радикалов под названием ацтеки начала небольшие набеги по всей территории. [246] В конце концов они начали заявлять о своих связях с цивилизацией тольтеков и настаивали на том, что являются ее законными преемниками. [247] Они начали расти в численности и завоевывать большие территории. Фундаментальным для их завоевания было использование политического террора в том смысле, что ацтекские вожди и жрецы приказывали приносить человеческие жертвы своим порабощенным народам как средство смирения и принуждения. [246] Большая часть Мезоамериканского региона в конечном итоге попала под власть ацтекской империи. [246] На полуострове Юкатан большинство народов майя продолжали оставаться независимыми от ацтеков, но их традиционная цивилизация пришла в упадок. [248] Ацтекские разработки расширили земледелие, применив использование чинампас , ирригацию и террасное земледелие ; важными культурами были кукуруза , сладкий картофель и авокадо . [246]

В 1430 году город Теночтитлан объединился с другими могущественными на науатле городами, говорящими , Тескоко и Тлакопаном , чтобы создать Империю ацтеков, также известную как Тройственный союз. [248] Хотя ее называли империей, Империя ацтеков функционировала как система сбора дани с Теночтитланом в ее центре. На рубеже XVI века « цветочные войны » между ацтеками и конкурирующими государствами, такими как Тласкала, продолжались более пятидесяти лет. [249]

Южная Америка

[ редактировать ]Южноамериканская цивилизация была сосредоточена в Андском регионе, где уже с 2500 г. до н. э. существовали сложные культуры. К востоку от Андского региона общества в основном были полукочевыми. Открытия в бассейне реки Амазонки указывают на то, что до контакта в этом регионе, вероятно, проживало пять миллионов человек и существовали сложные общества. [250] По всему континенту многочисленные земледельческие народы от Колумбии до Аргентины неуклонно продвигались через многочисленные стадии развития, начиная с 500 г. н.э. до контактов с Европой. [251]

Анды

[ редактировать ]

В древние времена в Андах развивались цивилизации, независимые от внешних влияний, включая цивилизацию Мезоамерики. [252] В постклассическую эпоху цикл цивилизаций продолжался до контакта с испанцами . В целом андским обществам не хватало валюты, письменности и прочных тягловых животных, которыми пользовались цивилизации старого мира. Вместо этого жители Анд разработали другие методы, способствующие их росту, включая использование системы кипу для передачи сообщений, лам для перевозки небольших грузов и экономики, основанной на взаимности . [246] Общества часто основывались на строгой социальной иерархии и экономическом перераспределении правящего класса. [246]

В первой половине постклассического периода в Андах доминировали два почти одинаково могущественных государства. На севере Перу располагалась империя Вари , а на юге Перу и Боливии — империя Тиуанако , оба из которых были вдохновлены более ранним народом моче . [253] Хотя степень их взаимоотношений друг с другом неизвестна, считается, что они конкурировали друг с другом, но избегали прямого конфликта. Без войны было процветание, и около 700 года в городе Тиуанако проживало 1,4 миллиона человек. [254] После 8-го века оба государства пришли в упадок из-за изменения условий окружающей среды, заложив основу для того, чтобы инки и другие второстепенные королевства возникли как отдельные культуры столетия спустя. [255]

В 15 веке Империя инков выросла и аннексировала все остальные страны в этом районе. Под предводительством своего короля-бога солнца Сапа Инки они медленно завоевали территорию, которая сейчас является Перу , и построили свое общество по всему культурному региону Анд. Инки говорили на языках кечуа . Воспользовавшись древними достижениями, оставленными предыдущими андскими обществами, инки смогли создать самую развитую систему торговых путей Южной Америки, известную как система дорог инков , которая позволила расширить взаимосвязь между завоеванными провинциями. [256] Известно, что инки использовали счеты для математических вычислений. Империя инков известна своими великолепными сооружениями, такими как Мачу-Пикчу в регионе Куско . [257] Империя быстро расширилась на север до Эквадора и на юг до центрального Чили. К северу от Империи инков оставалась независимая Конфедерация Тайрона и Муиска, которая занималась сельским хозяйством и металлургией золота. [258] [259]

Конец периода

[ редактировать ]

Когда в 15 веке постклассическая эпоха подошла к концу, многие из империй, созданных в этот период, пришли в упадок. [260] Вскоре Византийскую империю в Средиземном море затмили как исламские, так и христианские соперники, включая Венецию , Геную и Османскую империю. [261] Византийцы столкнулись с неоднократными нападениями со стороны восточных и западных держав во время Четвертого крестового похода и продолжали приходить в упадок до потери Константинополя османами в 1453 году. [260]

Наибольшие изменения произошли в сфере торговли и технологий. Глобальное значение падения Византии заключалось в нарушении сухопутных путей между Азией и Европой. [262] Традиционное доминирование кочевничества в Евразии пришло в упадок, и Pax Mongolica , который позволял осуществлять взаимодействие между различными цивилизациями, больше не существовал. Западная и Южная Азия были завоеваны пороховыми империями , которые успешно использовали достижения военной техники, но закрыли Шелковый путь. [М] [263]

Европейцы, особенно португальцы и различные итальянские исследователи, намеревались заменить сухопутные путешествия морскими. [264] Первоначально европейские исследования просто искали новые маршруты для достижения известных мест назначения. [264] Португальский исследователь Васко да Гама отправился в Индию по морю в 1498 году, обогнув Африку вокруг мыса Доброй Надежды . [265] Индия и побережье Африки уже были известны европейцам, но до этого времени никто не предпринимал попыток совершить крупную торговую миссию. [265] Благодаря развитию мореплавания Португалия создала глобальную колониальную империю , начиная с завоевания Малакки в современной Малайзии в 1511 году. [266]

Другие исследователи, такие как спонсируемый Испанией итальянец Христофор Колумб, намеревались заняться торговлей, путешествуя по незнакомым маршрутам на запад от Европы. Последующее европейское открытие Америки в 1492 году привело к колумбийскому обмену и первой в мире панокеанической глобализации . [267] Испанский исследователь Фердинанд Магеллан совершил первое известное кругосветное плавание вокруг Земли в 1521 году. [268] Перенос товаров и болезней через океаны был беспрецедентным в создании более взаимосвязанного мира. [269] С развития мореплавания и торговли современная история . началась [267]

Пояснительные примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Постклассический часто используется для описания глобальной истории, которая происходила во времена европейского средневековья (масштаб которого полностью евроцентричен). Использование постклассического термина для обозначения этого периода иногда оспаривается, но все еще используется в академических кругах. [4] Такое использование постклассической «Всемирной истории» не следует путать с постклассическим периодом Мезоамерики.

- ^ Для дальнейшего расширения - Океания, Афро-Евразия и Америка были разделены жесткими океаническими барьерами, которые препятствовали глобальному взаимодействию между ними до конца 15 века. Существование этих трех «миров» не означает, что все части каждого мирового региона были связаны друг с другом. Например, в Афро-Евразии Южная и Центральная Африка, как и отдаленные районы Сибири, определенно были оторваны от крупных континентальных сетей. [29]

- ↑ Историки до 1980-х годов часто считали, что чума Юстиниана, разразившаяся в 541 году, имела азиатское происхождение. Хотя вполне возможно, что сама болезнь пришла из современного Таджикистана, теперь кажется, что все было наоборот: вместо этого чума распространилась с Запада на Восток. Мало упоминаний об эпидемиях VI века в Азии до того, как чума достигла Византийской империи. Вспышка 541 могла возникнуть в Аксуме (Эфиопия) или где-либо еще в Восточной Африке. Чума, очевидно, распространилась на восток из Византийского Египта. Персидские армии, вторгшиеся в Армению, были заражены в 543 году. В столице южного Китая произошла вспышка неизвестной болезни в 549 году. Сообщается, что в 585 году Центральная Азия поразила «голод и болезни». Вспышки болезней в Центральной и Восточной Азии Азия продолжалась и повторялась в течение следующих двух столетий. После длительного пребывания в Китае первые зарегистрированные эпидемии в Корее и Японии были зафиксированы в 698 году; вероятно, но не факт, что по крайней мере некоторые из эпидемий к востоку от Ирана были бубонными. [96]

- ^ Исламизация произошла в разных регионах Евразии. Однако исламизация, произошедшая в морской Юго-Восточной Азии, контрастирует с исламизацией Центральной Азии. В Юго-Восточной Азии подход ислама представлял собой восходящий процесс, когда определенные люди и группы начинали принимать ислам из-за осознанных преимуществ. Между тем преобразование Центральной Азии было процессом сверху вниз. [172]

- ^ В рамках этой модели наибольшее сходство Китая с Западной Азией и Европой имело место между 200–1000 гг. н.э. Сходства включали как распад центральной власти (во времена Троецарствия и раннего средневековья Европы), так и создание крупных децентрализованных многоэтнических империй (династия Тан и халифат Омейядов). [61]

- ↑ Это соответствует окончанию войны Гемпи и установлению титула «сёгун». Императорская династия и их гражданская администрация в Киото продолжали существовать, но не имели реальной власти. Япония будет находиться под военным контролем до 1868 года. [176]

- ↑ Люди Макассара прибыли в Австралию с сезонными миссиями в поисках морского огурца, впервые прибыв туда между 1500–1720 годами, после постклассического периода.

- ^ Рост полинезийских поселений был предложен в качестве возможной даты начала всей эпохи мировой истории. [203]

- ^ Упадок норвежской Гренландии сравнивают с упадком острова Пасхи, поскольку оба были изолированными островными обществами, практиковавшими вырубку лесов. [211]

- ^ Кроме того, использование этих терминов зависит от обсуждаемого местоположения в Америке. Например, позднеклассический период в Мезоамерике относится к 600–900 годам, а постклассический период начался после 900 года. Для континентальных Соединенных Штатов постклассическая история началась после 1200 года. [213] [214]

- ^ Обычно в североамериканской археологии постклассическая эра начинается в 1200 году, что отличается от использования этого термина в мировой истории, а также от мезоамериканского контекста. [230]

- ^ Это погодное явление произошло по всему миру, как было продемонстрировано дендроклиматологией, а также было задокументировано византийскими историками. [237] [238]

- ^ Использование слова «закрытый» может быть проблематичным, поскольку зачастую исламские режимы не полностью запрещали христианские поездки, а вместо этого взимали высокие тарифы. Хотя некоторые европейцы, в том числе Венеция , все еще принимали участие в торговле Восточного Средиземноморья, большинство европейцев не желали платить пошлины в долгосрочной перспективе. [263]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Кедар и Виснер-Хэнкс 2015 .

- ↑ Постклассическая эра. Архивировано 31 октября 2014 года в Wayback Machine Джоэлом Хермансеном.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Стернс, Питер Н. (2017). «Периодизация во всемирной истории: вызовы и возможности». В Р. Чарльзе Веллере (ред.). Нарративы всемирной истории XXI века: глобальные и междисциплинарные перспективы . Пэлгрейв. ISBN 978-3-319-62077-0 .

- ^ «Межкультурное взаимодействие и периодизация во всемирной истории». Американский исторический обзор . 1996. дои : 10.1086/ahr/101.3.749 . ISSN 1937-5239 .

- ^ Томпсон и др. 2009 , с. 82.

- ^ Times Books 1998 , с. 128.

- ^ Кляйн Голдевейк, Кес; Бойзен, Артур; Янссен, Питер (22 марта 2010 г.). «Долгосрочное динамическое моделирование глобального населения и застроенной территории в пространственном виде: HYDE 3.1». Голоцен . 20 (4): 565–573. Бибкод : 2010Holoc..20..565K . дои : 10.1177/0959683609356587 . ISSN 0959-6836 . S2CID 128905931 .

- ^ Хауб 1995 : «Средние годовые темпы роста были фактически ниже с 1 года нашей эры до 1650 года, чем предложенные выше темпы для периода с 8000 г. до н.э. по 1 год нашей эры. Одной из причин этого аномально медленного роста была Черная чума. Это ужасное бедствие не было ограничивается Европой 14 века. Эпидемия, возможно, началась около 542 года нашей эры в Западной Азии и распространилась оттуда. Считается, что половина Византийской империи была разрушена в 6 веке, всего погибло 100 миллионов человек.

- ^ Haub 1995 , стр. 5–6: «Средние годовые темпы роста на самом деле были намного выше с 1 года нашей эры до 1650 года, чем предложенные выше темпы для периода с 8000 г. до н.э. по 1 год нашей эры. Одной из причин этого аномально быстрого роста был коллапс Это страшное бедствие не ограничивалось Европой 14 века. Эпидемия, возможно, началась около 542 года нашей эры и распространилась оттуда. Считается, что в 6 веке была разрушена половина Византийской империи. 100 триллионов смертей».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Холмс и Стенден 2018 , с. 16.

- ^ Поздняя античность: Путеводитель по постклассическому миру . 1 апреля 2000 г.

- ^ Рэпп, Клаудия; Дрейк, ХА (ред.). Город в классическом и постклассическом мире . Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. xv – xvi. doi : 10.1017/cbo9781139507042.016 (неактивен 27 мая 2024 г.).

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI неактивен по состоянию на май 2024 г. ( ссылка ) - ^ Эвермон, Ванди. «Библиотека Стаффорда: Всемирная история до 1500 г. - Справочный справочник HIST 111: Часть 3 - от 500 до 1500 г.» . библиотека.ccis.edu . Архивировано из оригинала 6 октября 2022 года . Проверено 6 октября 2022 г.

- ^ «Всемирная история и география Pre-AP - Pre-AP | Совет колледжа» . pre-ap.collegeboard.org . Архивировано из оригинала 6 октября 2022 года . Проверено 6 октября 2022 г.