Смертная казнь

| Уголовный процесс |

|---|

| Уголовные процессы и приговоры |

| Права обвиняемого |

| Вердикт |

| Приговор |

|

| Post-sentencing |

| Related areas of law |

| Portals |

|

Смертная казнь , также известная как смертная казнь и ранее называемая судебным убийством , [1] [2] Это санкционированное государством убийство человека в качестве наказания за фактическое или предполагаемое проступок. [3] Приговор , предусматривающий наказание преступника таким образом, известен как смертный приговор , а сам акт исполнения приговора называется казнью . Заключенный, приговоренный к смертной казни и ожидающий казни, осуждается , и его обычно называют «находящимся в камере смертников ». Этимологически термин «капитал » ( букв. « головы » , происходящий от латинского «caputis» от caput , «голова») относится к казни путем обезглавливания . [4] но казни осуществляются многими методами , включая повешение , расстрел , смертельную инъекцию , забивание камнями , казнь на электрическом стуле и отравление газом .

Crimes that are punishable by death are known as capital crimes, capital offences, or capital felonies, and vary depending on the jurisdiction, but commonly include serious crimes against a person, such as murder, assassination, mass murder, child murder, aggravated rape, terrorism, aircraft hijacking, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide, along with crimes against the state such as attempting to overthrow government, treason, espionage, sedition, and piracy. Also, in some cases, acts of recidivism, aggravated robbery, and kidnapping, in addition to drug trafficking, drug dealing, and drug possession, are capital crimes or enhancements. However, states have also imposed punitive executions, for an expansive range of conduct, for political or religious beliefs and practices, for a status beyond one's control, or without employing any significant due process procedures.[3] Judicial murder is the intentional and premeditated killing of an innocent person by means of capital punishment.[5] Например, казни после показательных процессов в Советском Союзе во время Великой чистки 1936–1938 годов были инструментом политических репрессий.

As of 2023, only 2 out of 38 OECD member countries (the United States and Japan) allow capital punishment.[6] As of 2021, 56 countries retain capital punishment, 111 countries have completely abolished it de jure for all crimes, seven have abolished it for ordinary crimes (while maintaining it for special circumstances such as war crimes), and 24 are abolitionist in practice.[7] The top 3 countries by the number of executions are China, Iran and Saudi Arabia.[8]

Capital punishment is controversial, with many people, organisations, and religious groups holding differing views on whether it is ethically permissible. Amnesty International declares that the death penalty breaches human rights, specifically "the right to life and the right to live free from torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment."[9] These rights are protected under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations in 1948.[9] In the European Union (EU), Article 2 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union prohibits the use of capital punishment.[10] The Council of Europe, which has 46 member states, has worked to end the death penalty and no execution has taken place its current member states since 1997. The United Nations General Assembly has adopted, throughout the years from 2007 to 2020,[11] eight non-binding resolutions calling for a global moratorium on executions, with a view to eventual abolition.[12]

History

Execution of criminals and dissidents has been used by nearly all societies since the beginning of civilisations on Earth.[13] Until the nineteenth century, without developed prison systems, there was frequently no workable alternative to ensure deterrence and incapacitation of criminals.[14] In pre-modern times the executions themselves often involved torture with painful methods, such as the breaking wheel, keelhauling, sawing, hanging, drawing and quartering, burning at the stake, crucifixion, flaying, slow slicing, boiling alive, impalement, mazzatello, blowing from a gun, schwedentrunk, and scaphism. Other methods which appear only in legend include the blood eagle and brazen bull.

The use of formal execution extends to the beginning of recorded history. Most historical records and various primitive tribal practices indicate that the death penalty was a part of their justice system. Communal punishments for wrongdoing generally included blood money compensation by the wrongdoer, corporal punishment, shunning, banishment and execution. In tribal societies, compensation and shunning were often considered enough as a form of justice.[15] The response to crimes committed by neighbouring tribes, clans or communities included a formal apology, compensation, blood feuds, and tribal warfare.

A blood feud or vendetta occurs when arbitration between families or tribes fails, or an arbitration system is non-existent. This form of justice was common before the emergence of an arbitration system based on state or organized religion. It may result from crime, land disputes or a code of honour. "Acts of retaliation underscore the ability of the social collective to defend itself and demonstrate to enemies (as well as potential allies) that injury to property, rights, or the person will not go unpunished."[16]

In most countries that practice capital punishment, it is now reserved for murder, terrorism, war crimes, espionage, treason, or as part of military justice. In some countries, sexual crimes, such as rape, fornication, adultery, incest, sodomy, and bestiality carry the death penalty, as do religious crimes such as Hudud, Zina, and Qisas crimes, such as apostasy (formal renunciation of the state religion), blasphemy, moharebeh, hirabah, Fasad, Mofsed-e-filarz and witchcraft. In many countries that use the death penalty, drug trafficking and often drug possession is also a capital offence. In China, human trafficking and serious cases of corruption and financial crimes are punished by the death penalty. In militaries around the world, courts-martial have imposed death sentences for offences such as cowardice, desertion, insubordination, and mutiny.[17]

Ancient history

Elaborations of tribal arbitration of feuds included peace settlements often done in a religious context and compensation system. Compensation was based on the principle of substitution which might include material (for example, cattle, slaves, land) compensation, exchange of brides or grooms, or payment of the blood debt. Settlement rules could allow for animal blood to replace human blood, or transfers of property or blood money or in some case an offer of a person for execution. The person offered for execution did not have to be an original perpetrator of the crime because the social system was based on tribes and clans, not individuals. Blood feuds could be regulated at meetings, such as the Norsemen things.[18] Systems deriving from blood feuds may survive alongside more advanced legal systems or be given recognition by courts (for example, trial by combat or blood money). One of the more modern refinements of the blood feud is the duel.

In certain parts of the world, nations in the form of ancient republics, monarchies or tribal oligarchies emerged. These nations were often united by common linguistic, religious or family ties. Moreover, expansion of these nations often occurred by conquest of neighbouring tribes or nations. Consequently, various classes of royalty, nobility, various commoners and slaves emerged. Accordingly, the systems of tribal arbitration were submerged into a more unified system of justice which formalized the relation between the different "social classes" rather than "tribes". The earliest and most famous example is Code of Hammurabi which set the different punishment and compensation, according to the different class or group of victims and perpetrators. The Torah/Old Testament lays down the death penalty for murder,[19] kidnapping, practicing magic, violation of the Sabbath, blasphemy, and a wide range of sexual crimes, although evidence[specify] suggests that actual executions were exceedingly rare, if they occurred at all.[20][page needed]

A further example comes from Ancient Greece, where the Athenian legal system replacing customary oral law was first written down by Draco in about 621 BC: the death penalty was applied for a particularly wide range of crimes, though Solon later repealed Draco's code and published new laws, retaining capital punishment only for intentional homicide, and only with victim's family permission.[21] The word draconian derives from Draco's laws. The Romans also used the death penalty for a wide range of offences.[22]

Ancient Greece

Protagoras (whose thought is reported by Plato) criticised the principle of revenge, because once the damage is done it cannot be cancelled by any action. So, if the death penalty is to be imposed by society, it is only to protect the latter against the criminal or for a dissuasive purpose.[23] "The only right that Protagoras knows is therefore human right, which, established and sanctioned by a sovereign collectivity, identifies itself with positive or the law in force of the city. In fact, it finds its guarantee in the death penalty which threatens all those who do not respect it."[24][25]

Plato saw the death penalty as a means of purification, because crimes are a "defilement". Thus, in the Laws, he considered necessary the execution of the animal or the destruction of the object which caused the death of a man by accident. For the murderers, he considered that the act of homicide is not natural and is not fully consented by the criminal. Homicide is thus a disease of the soul, which must be reeducated as much as possible, and, as a last resort, sentence to death if no rehabilitation is possible.[26]

According to Aristotle, for whom free will is proper to man, a person is responsible for their actions. If there was a crime, a judge must define the penalty allowing the crime to be annulled by compensating it. This is how pecuniary compensation appeared for criminals the least recalcitrant and whose rehabilitation is deemed possible. However, for others, he argued, the death penalty is necessary.[27]

This philosophy aims on the one hand to protect society and on the other hand to compensate to cancel the consequences of the crime committed. It inspired Western criminal law until the 17th century, a time when the first reflections on the abolition of the death penalty appeared.[28]

Ancient Rome

The Twelve Tables, the body of laws handed down from archaic Rome, prescribe the death penalty for a variety of crimes including libel, arson and theft.[29] During the Late Republic, there was consensus among the public and legislators to reduce the incidence of capital punishment. This opinion led to voluntary exile being prescribed in place of the death penalty, whereby a convict could either choose to leave in exile or face execution.[30]

A historic debate, followed by a vote, took place in the Roman Senate to decide the fate of Catiline's allies when he attempted to seize power in December, 63 BC. Cicero, then Roman consul, argued in support of the killing of conspirators without judgment by decision of the Senate (Senatus consultum ultimum) and was supported by the majority of senators; among the minority voices opposed to the execution, the most notable was Julius Caesar.[31] The custom was different for foreigners who did not hold rights as Roman citizens, and especially for slaves, who were transferrable property.

Crucifixion was a form of punishment first employed by the Romans against slaves who rebelled, and throughout the Republican era was reserved for slaves, bandits, and traitors. Intended to be a punishment, a humiliation, and a deterrent, the condemned could take up to a few days to die. Corpses of the crucified were typically left on the crosses to decompose and to be eaten by animals.[32]

China

There was a time in the Tang dynasty (618–907) when the death penalty was abolished.[33] This was in the year 747, enacted by Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (r. 712–756). When abolishing the death penalty, Xuanzong ordered his officials to refer to the nearest regulation by analogy when sentencing those found guilty of crimes for which the prescribed punishment was execution. Thus, depending on the severity of the crime a punishment of severe scourging with the thick rod or of exile to the remote Lingnan region might take the place of capital punishment. However, the death penalty was restored only 12 years later in 759 in response to the An Lushan Rebellion.[34] At this time in the Tang dynasty only the emperor had the authority to sentence criminals to execution. Under Xuanzong capital punishment was relatively infrequent, with only 24 executions in the year 730 and 58 executions in the year 736.[33]

The two most common forms of execution in the Tang dynasty were strangulation and decapitation, which were the prescribed methods of execution for 144 and 89 offences respectively. Strangulation was the prescribed sentence for lodging an accusation against one's parents or grandparents with a magistrate, scheming to kidnap a person and sell them into slavery and opening a coffin while desecrating a tomb. Decapitation was the method of execution prescribed for more serious crimes such as treason and sedition. Despite the great discomfort involved, most of the Tang Chinese preferred strangulation to decapitation, as a result of the traditional Tang Chinese belief that the body is a gift from the parents and that it is, therefore, disrespectful to one's ancestors to die without returning one's body to the grave intact.

Some further forms of capital punishment were practiced in the Tang dynasty, of which the first two that follow at least were extralegal.[clarification needed] The first of these was scourging to death with the thick rod[clarification needed] which was common throughout the Tang dynasty especially in cases of gross corruption. The second was truncation, in which the convicted person was cut in two at the waist with a fodder knife and then left to bleed to death.[35] A further form of execution called Ling Chi (slow slicing), or death by/of a thousand cuts, was used from the close of the Tang dynasty (around 900) to its abolition in 1905.

When a minister of the fifth grade or above received a death sentence the emperor might grant him a special dispensation allowing him to commit suicide in lieu of execution. Even when this privilege was not granted, the law required that the condemned minister be provided with food and ale by his keepers and transported to the execution ground in a cart rather than having to walk there.

Nearly all executions under the Tang dynasty took place in public as a warning to the population. The heads of the executed were displayed on poles or spears. When local authorities decapitated a convicted criminal, the head was boxed and sent to the capital as proof of identity and that the execution had taken place.[35]

Middle Ages

In medieval and early modern Europe, before the development of modern prison systems, the death penalty was also used as a generalised form of punishment for even minor offences.[36]

In early modern Europe, a mass panic regarding witchcraft swept across Europe and later the European colonies in North America. During this period, there were widespread claims that malevolent Satanic witches were operating as an organised threat to Christendom. As a result, tens of thousands of women were prosecuted for witchcraft and executed through the witch trials of the early modern period (between the 15th and 18th centuries).

The death penalty also targeted sexual offences such as sodomy. In the early history of Islam (7th–11th centuries), there is a number of "purported (but mutually inconsistent) reports" (athar) regarding the punishments of sodomy ordered by some of the early caliphs.[37][38] Abu Bakr, the first caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, apparently recommended toppling a wall on the culprit, or else burning him alive,[38] while Ali ibn Abi Talib is said to have ordered death by stoning for one sodomite and had another thrown head-first from the top of the highest building in the town; according to Ibn Abbas, the latter punishment must be followed by stoning.[38][39] Other medieval Muslim leaders, such as the Abbasid caliphs in Baghdad (most notably al-Mu'tadid), were often cruel in their punishments.[40][page needed] In early modern England, the Buggery Act 1533 stipulated hanging as punishment for "buggery". James Pratt and John Smith were the last two Englishmen to be executed for sodomy in 1835.[41] In 1636 the laws of Puritan governed Plymouth Colony included a sentence of death for sodomy and buggery.[42] The Massachusetts Bay Colony followed in 1641. Throughout the 19th century, U.S. states repealed death sentences from their sodomy laws, with South Carolina being the last to do so in 1873.[43]

Historians recognise that during the Early Middle Ages, the Christian populations living in the lands invaded by the Arab Muslim armies between the 7th and 10th centuries suffered religious discrimination, religious persecution, religious violence, and martyrdom multiple times at the hands of Arab Muslim officials and rulers.[44][45] As People of the Book, Christians under Muslim rule were subjected to dhimmi status (along with Jews, Samaritans, Gnostics, Mandeans, and Zoroastrians), which was inferior to the status of Muslims.[45][46] Christians and other religious minorities thus faced religious discrimination and religious persecution in that they were banned from proselytising (for Christians, it was forbidden to evangelise or spread Christianity) in the lands invaded by the Arab Muslims on pain of death, they were banned from bearing arms, undertaking certain professions, and were obligated to dress differently in order to distinguish themselves from Arabs.[46] Under sharia, Non-Muslims were obligated to pay jizya and kharaj taxes,[45][46] together with periodic heavy ransom levied upon Christian communities by Muslim rulers in order to fund military campaigns, all of which contributed a significant proportion of income to the Islamic states while conversely reducing many Christians to poverty, and these financial and social hardships forced many Christians to convert to Islam.[46] Christians unable to pay these taxes were forced to surrender their children to the Muslim rulers as payment who would sell them as slaves to Muslim households where they were forced to convert to Islam.[46] Many Christian martyrs were executed under the Islamic death penalty for defending their Christian faith through dramatic acts of resistance such as refusing to convert to Islam, repudiation of the Islamic religion and subsequent reconversion to Christianity, and blasphemy towards Muslim beliefs.[44]

Despite the wide use of the death penalty, calls for reform were not unknown. The 12th-century Jewish legal scholar Moses Maimonides wrote: "It is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty persons than to put a single innocent man to death." He argued that executing an accused criminal on anything less than absolute certainty would lead to a slippery slope of decreasing burdens of proof, until we would be convicting merely "according to the judge's caprice". Maimonides's concern was maintaining popular respect for law, and he saw errors of commission as much more threatening than errors of omission.[47]

Enlightenment philosophy

While during the Middle Ages the expiatory aspect of the death penalty was taken into account, this is no longer the case under the Lumières. These define the place of man within society no longer according to a divine rule, but as a contract established at birth between the citizen and the society, it is the social contract. From that moment on, capital punishment should be seen as useful to society through its dissuasive effect, but also as a means of protection of the latter vis-à-vis criminals.[48]

Modern era

In the last several centuries, with the emergence of modern nation states, justice came to be increasingly associated with the concept of natural and legal rights. The period saw an increase in standing police forces and permanent penitential institutions. Rational choice theory, a utilitarian approach to criminology which justifies punishment as a form of deterrence as opposed to retribution, can be traced back to Cesare Beccaria, whose influential treatise On Crimes and Punishments (1764) was the first detailed analysis of capital punishment to demand the abolition of the death penalty.[49] In England, Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), the founder of modern utilitarianism, called for the abolition of the death penalty.[50] Beccaria, and later Charles Dickens and Karl Marx noted the incidence of increased violent criminality at the times and places of executions. Official recognition of this phenomenon led to executions being carried out inside prisons, away from public view.

In England in the 18th century, when there was no police force, Parliament drastically increased the number of capital offences to more than 200. These were mainly property offences, for example cutting down a cherry tree in an orchard.[51] In 1820, there were 160, including crimes such as shoplifting, petty theft or stealing cattle.[52] The severity of the so-called Bloody Code was often tempered by juries who refused to convict, or judges, in the case of petty theft, who arbitrarily set the value stolen at below the statutory level for a capital crime.[53]

20th century

In Nazi Germany, there were three types of capital punishment; hanging, decapitation, and death by shooting.[54] Also, modern military organisations employed capital punishment as a means of maintaining military discipline. In the past, cowardice, absence without leave, desertion, insubordination, shirking under enemy fire and disobeying orders were often crimes punishable by death (see decimation and running the gauntlet). One method of execution, since firearms came into common use, has also been firing squad, although some countries use execution with a single shot to the head or neck.

Various authoritarian states employed the death penalty as a potent means of political oppression.[55] Anti-Soviet author Robert Conquest claimed that more than one million Soviet citizens were executed during the Great Purge of 1936 to 1938, almost all by a bullet to the back of the head.[56][57] Mao Zedong publicly stated that "800,000" people had been executed in China during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). Partly as a response to such excesses, civil rights organisations started to place increasing emphasis on the concept of human rights and an abolition of the death penalty.[citation needed]

Contemporary era

By continent, all European countries but one have abolished capital punishment;[note 1] many Oceanian countries have abolished it;[note 2] most countries in the Americas have abolished its use,[note 3] while a few actively retain it;[note 4] less than half of countries in Africa retain it;[note 5] and the majority of countries in Asia retain it, for example, China, Japan and India.[58]

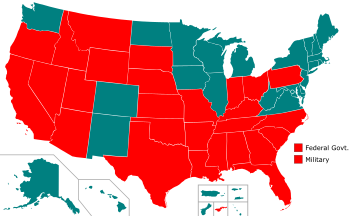

Abolition was often adopted due to political change, as when countries shifted from authoritarianism to democracy, or when it became an entry condition for the EU. The United States is a notable exception: some states have had bans on capital punishment for decades, the earliest being Michigan, where it was abolished in 1846, while other states still actively use it today. The death penalty in the United States remains a contentious issue which is hotly debated.

In retentionist countries, the debate is sometimes revived when a miscarriage of justice has occurred though this tends to cause legislative efforts to improve the judicial process rather than to abolish the death penalty. In abolitionist countries, the debate is sometimes revived by particularly brutal murders, though few countries have brought it back after abolishing it. However, a spike in serious, violent crimes, such as murders or terrorist attacks, has prompted some countries to effectively end the moratorium on the death penalty. One notable example is Pakistan which in December 2014 lifted a six-year moratorium on executions after the Peshawar school massacre during which 132 students and 9 members of staff of the Army Public School and Degree College Peshawar were killed by Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan terrorists, a group distinct from the Afghan Taliban, who condemned the attack.[59]Since then, Pakistan has executed over 400 convicts.[60]

In 2017, two major countries, Turkey and the Philippines, saw their executives making moves to reinstate the death penalty.[61] In the same year, passage of the law in the Philippines failed to obtain the Senate's approval.[62]

On 29 December 2021, after a 20-year moratorium, the Kazakhstan government enacted the 'On Amendments and Additions to Certain Legislative Acts of the Republic of Kazakhstan on the Abolition of the Death Penalty' signed by President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev as part of series of Omnibus reformations of the Kazak legal system 'Listening State' initiative.[63]

History of abolition

In 724 AD in Japan, the death penalty was banned during the reign of Emperor Shōmu but the abolition only lasted a few years.[64] In 818, Emperor Saga abolished the death penalty under the influence of Shinto and it lasted until 1156.[65][66] In China, the death penalty was banned by Emperor Xuanzong of Tang in 747, replacing it with exile or scourging. However, the ban only lasted 12 years.[64] Following his conversion to Christianity in 988, Vladimir the Great abolished the death penalty in Kievan Rus', along with torture and mutilation; corporal punishment was also seldom used.[67]

In England, a public statement of opposition was included in The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards, written in 1395.In the post-classical Republic of Poljica, life was ensured as a basic right in its Poljica Statute of 1440.Sir Thomas More's Utopia, published in 1516, debated the benefits of the death penalty in dialogue form, coming to no firm conclusion. More was himself executed for treason in 1535.

More recent opposition to the death penalty stemmed from the book of the Italian Cesare Beccaria Dei Delitti e Delle Pene ("On Crimes and Punishments"), published in 1764. In this book, Beccaria aimed to demonstrate not only the injustice, but even the futility from the point of view of social welfare, of torture and the death penalty. Influenced by the book, Grand Duke Leopold II of Habsburg, the future emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, abolished the death penalty in the then-independent Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the first abolition in modern times. On 30 November 1786, after having de facto blocked executions (the last was in 1769), Leopold promulgated the reform of the penal code that abolished the death penalty and ordered the destruction of all the instruments for capital execution in his land. In 2000, Tuscany's regional authorities instituted an annual holiday on 30 November to commemorate the event. The event is commemorated on this day by 300 cities around the world celebrating Cities for Life Day. Leopolds brother Joseph, the then emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, abolished in his immediate lands in 1787 capital punishment, which though only lasted until 1795, after both had died and Leopolds son Francis abolished it in his immediate lands. In Tuscany it was reintroduced in 1790 after Leopolds departure becoming emperor. Only after 1831 capital punishment was again at times stoped, though it took until 2007 to abolish capital punishment in Italy completely.

The Kingdom of Tahiti (when the island was independent) was the first legislative assembly in the world to abolish the death penalty in 1824. Tahiti commuted the death penalty to banishment.[68]

In the United States, Michigan was the first state to ban the death penalty, on 18 May 1846.[69]

The short-lived revolutionary Roman Republic banned capital punishment in 1849. Venezuela followed suit and abolished the death penalty in 1863[70][71] and San Marino did so in 1865. The last execution in San Marino had taken place in 1468. In Portugal, after legislative proposals in 1852 and 1863, the death penalty was abolished in 1867. The last execution in Brazil was 1876; from then on all the condemnations were commuted by the Emperor Pedro II until its abolition for civil offences and military offences in peacetime in 1891. The penalty for crimes committed in peacetime was then reinstated and abolished again twice (1938–1953 and 1969–1978), but on those occasions it was restricted to acts of terrorism or subversion considered "internal warfare" and all sentences were commuted and not carried out.

Many countries have abolished capital punishment either in law or in practice. Since World War II, there has been a trend toward abolishing capital punishment. Capital punishment has been completely abolished by 108 countries, a further seven have done so for all offences except under special circumstances and 26 more have abolished it in practice because they have not used it for at least 10 years and are believed to have a policy or established practice against carrying out executions.[72]

In the United States between 1972 and 1976 the death penalty was declared unconstitutional based on the Furman v. Georgia case, but the 1976 Gregg v. Georgia case once again permitted the death penalty under certain circumstances. Further limitations were placed on the death penalty in Atkins v. Virginia (2002; death penalty unconstitutional for people with an intellectual disability) and Roper v. Simmons (2005; death penalty unconstitutional if defendant was under age 18 at the time the crime was committed). In the United States, 23 of the 50 states and Washington, D.C. ban capital punishment.

In the United Kingdom, it was abolished for murder (leaving only treason, piracy with violence, arson in royal dockyards and a number of wartime military offences as capital crimes) for a five-year experiment in 1965 and permanently in 1969, the last execution having taken place in 1964. It was abolished for all offences in 1998.[73] Protocol 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights, first entering into force in 2003, prohibits the death penalty in all circumstances for those states that are party to it, including the United Kingdom from 2004.

Abolition occurred in Canada in 1976 (except for some military offences, with complete abolition in 1998); in France in 1981; and in Australia in 1973 (although the state of Western Australia retained the penalty until 1984). In South Australia, under the premiership of then-Premier Dunstan, the Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 (SA) was modified so that the death sentence was changed to life imprisonment in 1976.

In 1977, the United Nations General Assembly affirmed in a formal resolution that throughout the world, it is desirable to "progressively restrict the number of offences for which the death penalty might be imposed, with a view to the desirability of abolishing this punishment".[74]

Contemporary use

By country

Most nations, including almost all developed countries, have abolished capital punishment either in law or in practice; notable exceptions are the United States, Japan, Taiwan, and Singapore. Additionally, capital punishment is also carried out in China, India, and most Islamic states.[75][76][77][78][79][80]

Since World War II, there has been a trend toward abolishing the death penalty. 54 countries retain the death penalty in active use, 112 countries have abolished capital punishment altogether, 7 have done so for all offences except under special circumstances, and 22 more have abolished it in practice because they have not used it for at least 10 years and are believed to have a policy or established practice against carrying out executions.[81]

According to Amnesty International, 20 countries are known to have performed executions in 2022.[82] There are countries which do not publish information on the use of capital punishment, most significantly China and North Korea. According to Amnesty International, around 1,000 prisoners were executed in 2017.[83] Amnesty reported in 2004 and 2009 that Singapore and Iraq respectively had the world's highest per capita execution rate.[84][85] According to Al Jazeera and UN Special Rapporteur Ahmed Shaheed, Iran has had the world's highest per capita execution rate.[86][87] A 2012 EU report from the Directorate-General for External Relations' policy department pointed to Gaza as having the highest per capita execution rate in the MENA region.[88]

| Country | Total executed (2022) | |

|---|---|---|

| Capital Punishments UK [89] | Amnesty International [82] | |

| Unknown | >1,000 | |

| >596 | >576 | |

| 146 | 196 | |

| 13 | 24 | |

| 19 | >6 | |

| 18 | 18 | |

| 11 | 11 | |

| 4 | >11 | |

| 7 | 7 | |

| 5 | 5 | |

| 2 | >5 | |

| 4 | 4 | |

| 4 | 4 | |

| 1 | >4 | |

| 0 | 3 | |

| 1 | 1 | |

| 1 | Unknown | |

| 1 | 0 | |

| 0 | Unknown | |

| Unknown | Unknown | |

| Unknown | Unknown | |

The use of the death penalty is becoming increasingly restrained in some retentionist countries including Taiwan and Singapore.[90][better source needed] Indonesia carried out no executions between November 2008 and March 2013.[91] Singapore, Japan and the United States are the only developed countries that are classified by Amnesty International as 'retentionist' (South Korea is classified as 'abolitionist in practice').[92][93] Nearly all retentionist countries are situated in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean.[92] The only retentionist country in Europe is Belarus and in March 2023 Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko signed a law which allows to use capital punishment against officials and soldiers convicted of high treason.[94] During the 1980s, the democratisation of Latin America swelled the ranks of abolitionist countries.[95]

This was soon followed by the overthrow of the socialist states in Europe. Many of the these countries aspired to enter the EU, which strictly requires member states not to practice the death penalty, as does the Council of Europe (see Capital punishment in Europe). Public support for the death penalty in the EU varies.[96] The last execution in a member state of the present-day Council of Europe took place in 1997 in Ukraine.[97][98] In contrast, the rapid industrialisation in Asia has seen an increase in the number of developed countries which are also retentionist. In these countries, the death penalty retains strong public support, and the matter receives little attention from the government or the media; in China there is a small but significant and growing movement to abolish the death penalty altogether.[99] This trend has been followed by some African and Middle Eastern countries where support for the death penalty remains high.

Some countries have resumed practising the death penalty after having previously suspended the practice for long periods. The United States suspended executions in 1972 but resumed them in 1976; there was no execution in India between 1995 and 2004; and Sri Lanka declared an end to its moratorium on the death penalty on 20 November 2004,[100] although it has not yet performed any further executions. The Philippines re-introduced the death penalty in 1993 after abolishing it in 1987, but again abolished it in 2006.[101]

The United States and Japan are the only developed countries to have recently carried out executions. The U.S. federal government, the U.S. military, and 27 states have a valid death penalty statute, and over 1,400 executions have been carried in the United States since it reinstated the death penalty in 1976. Japan has 108 inmates with finalized death sentences as of February 2, 2024[update], after Yuki Endo, who was sentenced to death on 18 January, by the Kofu District Court for murdering the parents of his love interest and setting fire to their home in Yamanashi prefecture on 12 October 2021, when Endo was 19 years old at the time of the double murder,[102] withdrew the appeal to the High Court, which was filed by his attorney, thus Endo's death sentence was finalized.

The most recent country to abolish the death penalty was Kazakhstan on 2 January 2021 after a moratorium dating back 2 decades.[103][104]

According to an Amnesty International report released in April 2020, Egypt ranked regionally third and globally fifth among the countries that carried out most executions in 2019. The country increasingly ignored international human rights concerns and criticism. In March 2021, Egypt executed 11 prisoners in a jail, who were convicted in cases of "murder, theft, and shooting".[105]

According to Amnesty International's 2021 report, at least 483 people were executed in 2020 despite the COVID-19 pandemic. The figure excluded the countries that classify death penalty data as state secret. The top five executioners for 2020 were China, Iran, Egypt, Iraq and Saudi Arabia.[106]

Modern-day public opinion

The public opinion on the death penalty varies considerably by country and by the crime in question. Countries where a majority of people are against execution include Norway, where only 25% support it.[107] Most French, Finns, and Italians also oppose the death penalty.[108] In 2020, 55% of Americans supported the death penalty for an individual convicted of murder, down from 60% in 2016, 64% in 2010, 65% in 2006, and 68% in 2001.[109][110][111][112] In 2020, 43% of Italians expressed support for the death penalty.[113][114][115]

In Taiwan, polls and research have consistently shown strong support for the death penalty at 80%. This includes a survey conducted by the National Development Council of Taiwan in 2016, showing that 88% of Taiwanese people disagree with abolishing the death penalty.[116][117][118] Its continuation of the practice drew criticism from local rights groups.[119]

The support and sentencing of capital punishment has been growing in India in the 2010s[120] due to anger over several recent brutal cases of rape, even though actual executions are comparatively rare.[120] While support for the death penalty for murder is still high in China, executions have dropped precipitously, with 3,000 executed in 2012 versus 12,000 in 2002.[121] A poll in South Africa, where capital punishment is abolished, found that 76% of millennial South Africans support re-introduction of the death penalty due to increasing incidents of rape and murder.[122][123]A 2017 poll found younger Mexicans are more likely to support capital punishment than older ones.[124] 57% of Brazilians support the death penalty. The age group that shows the greatest support for execution of those condemned is the 25 to 34-year-old category, in which 61% say they support it.[125]

A 2023 poll by Research Co. found that 54% of Canadians support reinstating the death penalty for murder in their country.[126] In April 2021 a poll found that 54% of Britons said they would support reinstating the death penalty for those convicted of terrorism in the UK, while 23% of respondents said they would be opposed.[127] In 2020, an Ipsos/Sopra Steria survey showed that 55% of the French people support re-introduction of the death penalty; this was an increase from 44% in 2019.[128]

Juvenile offenders

The death penalty for juvenile offenders (criminals aged under 18 years at the time of their crime although the legal or accepted definition of juvenile offender may vary from one jurisdiction to another) has become increasingly rare. Considering the age of majority is not 18 in some countries or has not been clearly defined in law, since 1990 ten countries have executed offenders who were considered juveniles at the time of their crimes: China, Bangladesh, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iran, Iraq, Japan, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, the United States, and Yemen.[129] China, Pakistan, the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen have since raised the minimum age to 18.[130] Amnesty International has recorded 61 verified executions since then, in several countries, of both juveniles and adults who had been convicted of committing their offences as juveniles.[131] China does not allow for the execution of those under 18, but child executions have reportedly taken place.[132]

One of the youngest children ever to be executed was the infant son of Perotine Massey on or around 18 July 1556. His mother was one of the Guernsey Martyrs who was executed for heresy, and his father had previously fled the island. At less than one day old, he was ordered to be burned by Bailiff Hellier Gosselin, with the advice of priests nearby who said the boy should burn due to having inherited moral stain from his mother, who had given birth during her execution.[133]

Since 1642 in Colonial America and in the United States, an estimated 365[134] juvenile offenders were executed by various colonial authorities and (after the American Revolution) the federal government.[135] The U.S. Supreme Court abolished capital punishment for offenders under the age of 16 in Thompson v. Oklahoma (1988), and for all juveniles in Roper v. Simmons (2005).

In Prussia, children under the age of 14 were exempted from the death penalty in 1794.[136] Capital punishment was cancelled by the Electorate of Bavaria in 1751 for children under the age of 11[137] and by the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1813 for children and youth under 16 years.[138] In Prussia, the exemption was extended to youth under the age of 16 in 1851.[139] For the first time, all juveniles were excluded for the death penalty by the North German Confederation in 1871,[140] which was continued by the German Empire in 1872.[141] In Nazi Germany, capital punishment was reinstated for juveniles between 16 and 17 years in 1939.[142] This was broadened to children and youth from age 12 to 17 in 1943.[143] The death penalty for juveniles was abolished by West Germany, also generally, in 1949 and by East Germany in 1952.

In the Hereditary Lands, Austrian Silesia, Bohemia and Moravia within the Habsburg monarchy, capital punishment for children under the age of 11 was no longer foreseen by 1770.[144] The death penalty was, also for juveniles, nearly abolished in 1787 except for emergency or military law, which is unclear in regard of those. It was reintroduced for juveniles above 14 years by 1803,[145] and was raised by general criminal law to 20 years in 1852[146] and this exemption[147] and the alike one of military law in 1855,[148] which may have been up to 14 years in wartime,[149] were also introduced into all of the Austrian Empire.

In the Helvetic Republic, the death penalty for children and youth under the age of 16 was abolished in 1799[150] yet the country was already dissolved in 1803 whereas the law could remain in force if it was not replaced on cantonal level. In the canton of Bern, all juveniles were exempted from the death penalty at least in 1866.[151] In Fribourg, capital punishment was generally, including for juveniles, abolished by 1849. In Ticino, it was abolished for youth and young adults under the age of 20 in 1816.[152] In Zurich, the exclusion from the death penalty was extended for juveniles and young adults up to 19 years of age by 1835.[153] In 1942, the death penalty was almost deleted in criminal law, as well for juveniles, but since 1928 persisted in military law during wartime for youth above 14 years.[154] If no earlier change was made in the given subject, by 1979 juveniles could no longer be subject to the death penalty in military law during wartime.[155]

Between 2005 and May 2008, Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan and Yemen were reported to have executed child offenders, the largest number occurring in Iran.[156]

During Hassan Rouhani's tenure as president of Iran from 2013 until 2021, at least 3,602 death sentences have been carried out. This includes the executions of 34 juvenile offenders.[157][158]

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which forbids capital punishment for juveniles under article 37(a), has been signed by all countries and subsequently ratified by all signatories with the exception of the United States (despite the US Supreme Court decisions abolishing the practice).[159] The UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights maintains that the death penalty for juveniles has become contrary to a jus cogens of customary international law. A majority of countries are also party to the U.N. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (whose Article 6.5 also states that "Sentence of death shall not be imposed for crimes committed by persons below eighteen years of age...").

Iran, despite its ratification of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, was the world's largest executioner of juvenile offenders, for which it has been the subject of broad international condemnation; the country's record is the focus of the Stop Child Executions Campaign. But on 10 February 2012, Iran's parliament changed controversial laws relating to the execution of juveniles. In the new legislation the age of 18 (solar year) would be applied to accused of both genders and juvenile offenders must be sentenced pursuant to a separate law specifically dealing with juveniles.[160][161] Based on the Islamic law which now seems to have been revised, girls at the age of 9 and boys at 15 of lunar year (11 days shorter than a solar year) are deemed fully responsible for their crimes.[160] Iran accounted for two-thirds of the global total of such executions, and currently[needs update] has approximately 140 people considered as juveniles awaiting execution for crimes committed (up from 71 in 2007).[162][163] The past executions of Mahmoud Asgari, Ayaz Marhoni and Makwan Moloudzadeh became the focus of Iran's child capital punishment policy and the judicial system that hands down such sentences.[164][165] In 2023 Iran executed a minor who had knifed a man that fought him for following a girl in the street.[166]

Saudi Arabia also executes criminals who were minors at the time of the offence.[167][168] In 2013, Saudi Arabia was the center of an international controversy after it executed Rizana Nafeek, a Sri Lankan domestic worker, who was believed to have been 17 years old at the time of the crime.[169] Saudi Arabia banned execution for minors, except for terrorism cases, in April 2020.[170]

Japan has not executed juvenile criminals after August 1997, when they executed Norio Nagayama, a spree killer who had been convicted of shooting four people dead in the late 1960s. Nagayama's case created the eponymously named Nagayama standards, which take into account factors such as the number of victims, brutality and social impact of the crimes. The standards have been used in determining whether to apply the death sentence in murder cases. Teruhiko Seki, convicted of murdering four family members including a 4-year-old daughter and raping a 15-year-old daughter of a family in 1992, became the second inmate to be hanged for a crime committed as a minor in the first such execution in 20 years after Nagayama on 19 December 2017.[171] Takayuki Otsuki, who was convicted of raping and strangling a 23-year-old woman and subsequently strangling her 11-month-old daughter to death on 14 April 1999, when he was 18, is another inmate sentenced to death, and his request for retrial has been rejected by the Supreme Court of Japan.[172]

There is evidence that child executions are taking place in the parts of Somalia controlled by the Islamic Courts Union (ICU). In October 2008, a girl, Aisha Ibrahim Dhuhulow was buried up to her neck at a football stadium, then stoned to death in front of more than 1,000 people. Somalia's established Transitional Federal Government announced in November 2009 (reiterated in 2013)[173] that it plans to ratify the Convention on the Rights of the Child. This move was lauded by UNICEF as a welcome attempt to secure children's rights in the country.[174]

Methods

The following methods of execution have been used by various countries:[175][176][177][178][179]

- Hanging (Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Nigeria, Sudan, Pakistan, Palestinian National Authority, Israel, Yemen, Egypt, India, Myanmar, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Syria, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Liberia)

- Shooting (the People's Republic of China, Republic of China, Vietnam (until 2011), Belarus, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia, North Korea, Indonesia, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, Yemen, and in the US states of Oklahoma and Utah).

- Lethal injection (United States, Guatemala, Thailand, the People's Republic of China, Vietnam (after 2011))

- Beheading (Saudi Arabia)

- Stoning (Nigeria, Sudan)

- Electrocution and gas inhalation (some U.S. states, but only if the prisoner requests it or if lethal injection is unavailable)

- Inert gas asphyxiation (Some U.S. states, Oklahoma, Mississippi, Alabama)

Public execution

A public execution is a form of capital punishment which "members of the general public may voluntarily attend". This definition excludes the presence of a small number of witnesses randomly selected to assure executive accountability.[180] While today the great majority of the world considers public executions to be distasteful and most countries have outlawed the practice, throughout much of history executions were performed publicly as a means for the state to demonstrate "its power before those who fell under its jurisdiction be they criminals, enemies, or political opponents". Additionally, it afforded the public a chance to witness "what was considered a great spectacle".[181]

Social historians note that beginning in the 20th century in the U.S. and western Europe, death in general became increasingly shielded from public view, occurring more and more behind the closed doors of the hospital.[182] Executions were likewise moved behind the walls of the penitentiary.[182] The last formal public executions occurred in 1868 in Britain, in 1936 in the U.S. and in 1939 in France.[182]

According to Amnesty International, in 2012, "public executions were known to have been carried out in Iran, North Korea, Saudi Arabia and Somalia".[183] There have been reports of public executions carried out by state and non-state actors in Hamas-controlled Gaza, Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Yemen.[184][185][186] Executions which can be classified as public were also carried out in the U.S. states of Florida and Utah as of 1992[update].[180]

Capital crime

Crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity such as genocide are usually punishable by death in countries retaining capital punishment.[187] Death sentences for such crimes were handed down and carried out during the Nuremberg Trials in 1946 and the Tokyo Trials in 1948, but the current International Criminal Court does not use capital punishment. The maximum penalty available to the International Criminal Court is life imprisonment.[188]

Murder

Intentional homicide is punishable by death in most countries retaining capital punishment, but generally provided it involves an aggravating factor required by statute or judicial precedents.[citation needed]

Some countries, including Singapore and Malaysia, made the death penalty mandatory for murder, though Singapore later changed its laws since 2013 to reserve the mandatory death sentence for intentional murder while providing an alternative sentence of life imprisonment with/without caning for murder with no intention to cause death, which allowed some convicted murderers on death row in Singapore (including Kho Jabing) to apply for the reduction of their death sentences after the courts in Singapore confirmed that they committed murder without the intention to kill and thus eligible for re-sentencing under the new death penalty laws in Singapore.[189][190] In October 2018 the Malaysian Government imposed a moratorium on all executions until the passage of a new law that would abolish the death penalty.[191][192][193] In April 2023, legislation abolishing the mandatory death penalty was passed in Malaysia. The death penalty would be retained, but courts have the discretion to replace it with other punishments, including whipping and imprisonment of 30–40 years.[194]

Drug trafficking

In 2018, at least 35 countries retained the death penalty for drug trafficking, drug dealing, drug possession and related offences. People had been regularly sentenced to death and executed for drug-related offences in China, Indonesia, Iran, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore and Vietnam. Other countries may retain the death penalty for symbolic purposes.[195]

The death penalty was mandated for drug trafficking in Singapore and Malaysia. Since 2013, Singapore ruled that those who were certified to have diminished responsibility (e.g. major depressive disorder) or acting as drug couriers and had assisted the authorities in tackling drug-related activities, would be sentenced to life imprisonment instead of death, with the offender liable to at least 15 strokes of the cane if he was not sentenced to death and was simultaneously sentenced to caning as well.[189][190] Notably, drug couriers like Yong Vui Kong and Cheong Chun Yin successfully applied to have their death sentences replaced with life imprisonment and 15 strokes of the cane in 2013 and 2015 respectively.[196][197]

In April 2023, legislation abolishing the mandatory death penalty was passed in Malaysia.[194]

Other offences

Other crimes that are punishable by death in some countries include:

- Firearm offences (eg. Arms Offences Act of Singapore)

- Terrorism

- Treason (a capital crime in most countries that retain capital punishment)

- Espionage

- Crimes against the state, such as attempting to overthrow government (most countries with the death penalty)

- Political protests (Saudi Arabia)[198]

- Rape (China, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iran, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, Brunei, etc.)

- Economic crimes (China, Iran)

- Human trafficking (China)

- Corruption (China, Iran)

- Kidnapping (China, Singapore, Bangladesh, the US states of Georgia[199] and Idaho,[200] etc.)

- Separatism (China)[citation needed]

- Unlawful sexual behaviour (Saudi Arabia, Iran, Qatar, Brunei, Nigeria, etc.)

- Religious Hudud offences such as apostasy (Saudi Arabia, Iran, Afghanistan etc.)

- Blasphemy (Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan, certain states in Nigeria)

- Moharebeh (Iran)

- Drinking alcohol (Iran)

- Witchcraft and sorcery (Saudi Arabia)[201][202]

- Arson (Algeria, Tunisia, Mali, Mauritania, etc.)

- Hirabah; brigandage; armed or aggravated robbery (Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Kenya, Zambia, Ethiopia, the US state of Georgia[203] etc.)[204]

Controversy and debate

Death penalty opponents regard the death penalty as inhumane[205] and criticize it for its irreversibility.[206] They argue also that capital punishment lacks deterrent effect,[207][208][209] or has a brutalization effect,[210][211] discriminates against minorities and the poor, and that it encourages a "culture of violence".[212] There are many organizations worldwide, such as Amnesty International,[213] and country-specific, such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), whose main purpose includes abolition of the death penalty.[214][215]

Advocates of the death penalty argue that it deters crime,[216][217] is a good tool for police and prosecutors in plea bargaining,[218] makes sure that convicted criminals do not offend again, and that it ensures justice for crimes such as homicide, where other penalties will not inflict the desired retribution demanded by the crime itself. Capital punishment for non-lethal crimes is usually considerably more controversial, and abolished in many of the countries that retain it.[219][220]

Retribution

Supporters of the death penalty argued that death penalty is morally justified when applied in murder especially with aggravating elements such as for murder of police officers, child murder, torture murder, multiple homicide and mass killing such as terrorism, massacre and genocide. This argument is strongly defended by New York Law School's Professor Robert Blecker,[221] who says that the punishment must be painful in proportion to the crime. Eighteenth-century philosopher Immanuel Kant defended a more extreme position, according to which every murderer deserves to die on the grounds that loss of life is incomparable to any penalty that allows them to remain alive, including life imprisonment.[222]

Some abolitionists argue that retribution is simply revenge and cannot be condoned. Others while accepting retribution as an element of criminal justice nonetheless argue that life without parole is a sufficient substitute. It is also argued that the punishing of a killing with another death is a relatively unusual punishment for a violent act, because in general violent crimes are not punished by subjecting the perpetrator to a similar act (e.g. rapists are, typically, not punished by corporal punishment, although it may be inflicted in Singapore, for example).[223]

Human rights

Abolitionists believe capital punishment is the worst violation of human rights, because the right to life is the most important, and capital punishment violates it without necessity and inflicts to the condemned a psychological torture. Human rights activists oppose the death penalty, calling it "cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment". Amnesty International considers it to be "the ultimate irreversible denial of Human Rights".[224] Albert Camus wrote in a 1956 book called Reflections on the Guillotine, Resistance, Rebellion & Death:

An execution is not simply death. It is just as different from the privation of life as a concentration camp is from prison. [...] For there to be an equivalency, the death penalty would have to punish a criminal who had warned his victim of the date at which he would inflict a horrible death on him and who, from that moment onward, had confined him at his mercy for months. Such a monster is not encountered in private life.[225]

In the classic doctrine of natural rights as expounded by for instance Locke and Blackstone, on the other hand, it is an important idea that the right to life can be forfeited, as most other rights can be given due process is observed, such as the right to property and the right to freedom, including provisionally, in anticipation of an actual verdict.[226] As John Stuart Mill explained in a speech given in Parliament against an amendment to abolish capital punishment for murder in 1868:

And we may imagine somebody asking how we can teach people not to inflict suffering by ourselves inflicting it? But to this I should answer – all of us would answer – that to deter by suffering from inflicting suffering is not only possible, but the very purpose of penal justice. Does fining a criminal show want of respect for property, or imprisoning him, for personal freedom? Just as unreasonable is it to think that to take the life of a man who has taken that of another is to show want of regard for human life. We show, on the contrary, most emphatically our regard for it, by the adoption of a rule that he who violates that right in another forfeits it for himself, and that while no other crime that he can commit deprives him of his right to live, this shall.[227]

In one of the most recent cases relating to the death penalty in Singapore, activists like Jolovan Wham, Kirsten Han and Kokila Annamalai and even the international groups like the United Nations and European Union argued for Malaysian drug trafficker Nagaenthran K. Dharmalingam, who has been on death row at Singapore's Changi Prison since 2010, should not be executed due to an alleged intellectual disability, as they argued that Nagaenthran has low IQ of 69 and a psychiatrist has assessed him to be mentally impaired to an extent that he should not be held liable to his crime and execution. They also cited international law where a country should be prohibiting the execution of mentally and intellectually impaired people in order to push for Singapore to commute Nagaenthran's death penalty to life imprisonment based on protection of human rights. However, the Singapore government and both Singapore's High Court and Court of Appeal maintained their firm stance that despite his certified low IQ, it is confirmed that Nagaenthran is not mentally or intellectually disabled based on the joint opinion of three government psychiatrists as he is able to fully understand the magnitude of his actions and has no problem in his daily functioning of life.[228][229][230] Despite the international outcry, Nagaenthran was executed on 27 April 2022.[231]

Non-painful execution

Trends in most of the world have long been to move to private and less painful executions. France adopted the guillotine for this reason in the final years of the 18th century, while Britain banned hanging, drawing, and quartering in the early 19th century. Hanging by turning the victim off a ladder or by kicking a stool or a bucket, which causes death by strangulation, was replaced by long drop "hanging" where the subject is dropped a longer distance to dislocate the neck and sever the spinal cord. Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar, Shah of Persia (1896–1907) introduced throat-cutting and blowing from a gun (close-range cannon fire) as quick and relatively painless alternatives to more torturous methods of executions used at that time.[232] In the United States, electrocution and gas inhalation were introduced as more humane alternatives to hanging, but have been almost entirely superseded by lethal injection. A small number of countries, for example Iran and Saudi Arabia, still employ slow hanging methods, decapitation, and stoning.

A study of executions carried out in the United States between 1977 and 2001 indicated that at least 34 of the 749 executions, or 4.5%, involved "unanticipated problems or delays that caused, at least arguably, unnecessary agony for the prisoner or that reflect gross incompetence of the executioner". The rate of these "botched executions" remained steady over the period of the study.[233] A separate study published in The Lancet in 2005 found that in 43% of cases of lethal injection, the blood level of hypnotics was insufficient to guarantee unconsciousness.[234] However, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2008 (Baze v. Rees) and again in 2015 (Glossip v. Gross) that lethal injection does not constitute cruel and unusual punishment.[235] In Bucklew v. Precythe, the majority verdict – written by Judge Neil Gorsuch – further affirmed this principle, stating that while the ban on cruel and unusual punishment affirmatively bans penalties that deliberately inflict pain and degradation, it does in no sense limit the possible infliction of pain in the execution of a capital verdict.[236]

Wrongful execution

It is frequently argued that capital punishment leads to miscarriage of justice through the wrongful execution of innocent persons.[237] Many people have been proclaimed innocent victims of the death penalty.[238][239][240]

Some have claimed that as many as 39 executions have been carried out in the face of compelling evidence of innocence or serious doubt about guilt in the US from 1992 through 2004. Newly available DNA evidence prevented the pending execution of more than 15 death row inmates during the same period in the US,[241] but DNA evidence is only available in a fraction of capital cases.[242] As of 2017[update], 159 prisoners on death row have been exonerated by DNA or other evidence, which is seen as an indication that innocent prisoners have almost certainly been executed.[243][244] The National Coalition toAbolish the Death Penalty claims that between 1976 and 2015, 1,414 prisoners in the United States have been executed while 156 sentenced to death have had their death sentences vacated.[245] It is impossible to assess how many have been wrongly executed, since courts do not generally investigate the innocence of a dead defendant, and defense attorneys tend to concentrate their efforts on clients whose lives can still be saved; however, there is strong evidence of innocence in many cases.[246]

Improper procedure may also result in unfair executions. For example, Amnesty International argues that in Singapore "the Misuse of Drugs Act contains a series of presumptions which shift the burden of proof from the prosecution to the accused. This conflicts with the universally guaranteed right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty".[247] Singapore's Misuse of Drugs Act presumes one is guilty of possession of drugs if, as examples, one is found to be present or escaping from a location "proved or presumed to be used for the purpose of smoking or administering a controlled drug", if one is in possession of a key to a premises where drugs are present, if one is in the company of another person found to be in possession of illegal drugs, or if one tests positive after being given a mandatory urine drug screening. Urine drug screenings can be given at the discretion of police, without requiring a search warrant. The onus is on the accused in all of the above situations to prove that they were not in possession of or consumed illegal drugs.[248]

Volunteers

Some prisoners have volunteered or attempted to expedite capital punishment, often by waiving all appeals. Prisoners have made requests or committed further crimes in prison as well. In the United States, execution volunteers constitute approximately 11% of prisoners on death row. Volunteers often bypass legal procedures which are designed to designate the death penalty for the "worst of the worst" offenders. Opponents of execution volunteering cited the prevalence of mental illness among volunteers comparing it to suicide. Execution volunteers have received considerably less attention and effort at legal reform than those who were exonerated after execution.[249]

Racial, ethnic, and social class bias

Opponents of the death penalty argue that this punishment is being used more often against perpetrators from racial and ethnic minorities and from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, than against those criminals who come from a privileged background; and that the background of the victim also influences the outcome.[250][251][252] Researchers have shown that white Americans are more likely to support the death penalty when told that it is mostly applied to black Americans,[253] and that more stereotypically black-looking or dark-skinned defendants are more likely to be sentenced to death if the case involves a white victim.[254] However, a study published in 2018 failed to replicate the findings of earlier studies that had concluded that white Americans are more likely to support the death penalty if informed that it is largely applied to black Americans; according to the authors, their findings "may result from changes since 2001 in the effects of racial stimuli on white attitudes about the death penalty or their willingness to express those attitudes in a survey context."[255]

In Alabama in 2019, a death row inmate named Domineque Ray was denied his imam in the room during his execution, instead only offered a Christian chaplain.[256] After filing a complaint, a federal court of appeals ruled 5–4 against Ray's request. The majority cited the "last-minute" nature of the request, and the dissent stated that the treatment went against the core principle of denominational neutrality.[256]

In July 2019, two Shiite men, Ali Hakim al-Arab, 25, and Ahmad al-Malali, 24, were executed in Bahrain, despite the protests from the United Nations and rights group. Amnesty International stated that the executions were being carried out on confessions of "terrorism crimes" that were obtained through torture.[257]

On 30 March 2022, despite the appeals by the United Nations and rights activists, 68-year-old Malay Singaporean Abdul Kahar Othman was hanged at Singapore's Changi Prison for illegally trafficking diamorphine, which marked the first execution in Singapore since 2019 as a result of an informal moratorium caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Earlier, there were appeals made to advocate for Abdul Kahar's death penalty be commuted to life imprisonment on humanitarian grounds, as Abdul Kahar came from a poor family and has struggled with drug addiction. He was also revealed to have been spending most of his life going in and out of prison, including a ten-year sentence of preventive detention from 1995 to 2005, and has not been given much time for rehabilitation, which made the activists and groups arguing that Abdul Kahar should be given a chance for rehabilitation instead of subjecting him to execution.[258][259][260] Both the European Union (EU) and Amnesty International criticised Singapore for finalizing and carrying out Abdul Kahar's execution, and about 400 Singaporeans protested against the government's use of the death penalty merely days after Abdul Kahar's death sentence was authorised.[261][262][263][229] Still, over 80% of the public supported the use of the death penalty in Singapore.[264]

International views

The United Nations introduced a resolution during the General Assembly's 62nd sessions in 2007 calling for a universal ban.[265][266] The approval of a draft resolution by the Assembly's third committee, which deals with human rights issues, voted 99 to 52, with 33 abstentions, in support of the resolution on 15 November 2007 and was put to a vote in the Assembly on 18 December.[267][268][269]

Again in 2008, a large majority of states from all regions adopted, on 20 November in the UN General Assembly (Third Committee), a second resolution calling for a moratorium on the use of the death penalty; 105 countries voted in support of the draft resolution, 48 voted against and 31 abstained.

The moratorium resolution has been presented for a vote each year since 2007. On December 15, 2022, 125 countries voted in support of the moratorium, with 37 countries opposing, and 22 abstentions. The countries voting against the moratorium included the United States, People's Republic of China, North Korea, and Iran.[270]

A range of amendments proposed by a small minority of pro-death penalty countries were overwhelmingly defeated. It had in 2007 passed a non-binding resolution (by 104 to 54, with 29 abstentions) by asking its member states for "a moratorium on executions with a view to abolishing the death penalty".[271]

A number of regional conventions prohibit the death penalty, most notably, the Protocol 6 (abolition in time of peace) and Protocol 13 (abolition in all circumstances) to the European Convention on Human Rights. The same is also stated under Protocol 2 in the American Convention on Human Rights, which, however, has not been ratified by all countries in the Americas, most notably Canada[272] and the United States. Most relevant operative international treaties do not require its prohibition for cases of serious crime, most notably, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This instead has, in common with several other treaties, an optional protocol prohibiting capital punishment and promoting its wider abolition.[273]

Several international organizations have made abolition of the death penalty (during time of peace, or in all circumstances) a requirement of membership, most notably the EU and the Council of Europe. The Council of Europe are willing to accept a moratorium as an interim measure. Thus, while Russia was a member of the Council of Europe, and the death penalty remains codified in its law, it has not made use of it since becoming a member of the council – Russia has not executed anyone since 1996. With the exception of Russia (abolitionist in practice) and Belarus (retentionist), all European countries are classified as abolitionist.[92]

Latvia abolished de jure the death penalty for war crimes in 2012, becoming the last EU member to do so.[274]

Protocol 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights calls for the abolition of the death penalty in all circumstances (including for war crimes). The majority of European countries have signed and ratified it. Some European countries have not done this, but all of them except Belarus have now abolished the death penalty in all circumstances (de jure, and Russia de facto). Poland is the most recent country to ratify the protocol, on 28 August 2013.[275]

Protocol 6, which prohibits the death penalty during peacetime, has been ratified by all members of the Council of Europe. It had been signed but not ratified by Russia at the time of its expulsion in 2022.

There are also other international abolitionist instruments, such as the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which has 90 parties;[276] and the Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights to Abolish the Death Penalty (for the Americas; ratified by 13 states).[277]

In Turkey, over 500 people were sentenced to death after the 1980 Turkish coup d'état. About 50 of them were executed, the last one 25 October 1984. Then there was a de facto moratorium on the death penalty in Turkey. As a move towards EU membership, Turkey made some legal changes. The death penalty was removed from peacetime law by the National Assembly in August 2002, and in May 2004 Turkey amended its constitution to remove capital punishment in all circumstances. It ratified Protocol 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights in February 2006.[278] As a result, Europe is a continent free of the death penalty in practice, all states, having ratified Protocol 6 to the European Convention on Human Rights, with the exceptions of Russia (which has entered a moratorium) and Belarus, which are not members of the Council of Europe.[citation needed] The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe has been lobbying for Council of Europe observer states who practice the death penalty, the U.S. and Japan, to abolish it or lose their observer status. In addition to banning capital punishment for EU member states, the EU has also banned detainee transfers in cases where the receiving party may seek the death penalty.[279]

Sub-Saharan African countries that have recently abolished the death penalty include Burundi, which abolished the death penalty for all crimes in 2009,[280] and Gabon which did the same in 2010.[281] On 5 July 2012, Benin became part of the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which prohibits the use of the death penalty.[282]

The newly created South Sudan is among the 111 UN member states that supported the resolution passed by the United Nations General Assembly that called for the removal of the death penalty, therefore affirming its opposition to the practice. South Sudan, however, has not yet abolished the death penalty and stated that it must first amend its Constitution, and until that happens it will continue to use the death penalty.[283]

Among non-governmental organizations (NGOs), Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch are noted for their opposition to capital punishment.[284][285] A number of such NGOs, as well as trade unions, local councils, and bar associations, formed a World Coalition Against the Death Penalty in 2002.[286]

An open letter led by Danish Member of the European Parliament, Karen Melchior was sent to the European Commission ahead of the 26 January 2021 meeting of the Bahraini Minister of Foreign Affairs, Abdullatif bin Rashid Al Zayani with the members of the European Union for the signing of a Cooperation Agreement. A total of 16 MEPs undersigned the letter expressing their grave concern towards the extended abuse of human rights in Bahrain following the arbitrary arrest and detention of activists and critics of the government. The attendees of the meeting were requested to demand from their Bahraini counterparts to take into consideration the concerns raised by the MEPs, particularly for the release of Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja and Sheikh Mohammed Habib Al-Muqdad, the two European-Bahraini dual citizens on death row.[287][288]

Religious views

The world's major faiths have differing views depending on the religion, denomination, sect and the individual adherent.[289][290] The Catholic Church considers the death penalty as "inadmissible" in any circumstance and denounces it as an "attack" on the "inviolability and dignity of the person."[291][292] Both the Baháʼí and Islamic faiths support capital punishment.[293][294]

See also

- Capital punishment for homosexuality

- Death in custody

- Execution chamber

- Executioner

- Judicial dissolution, sometimes referred to as the "corporate death penalty"

- The Death Penalty: Opposing Viewpoints (book)

- Shame culture

- Last meal

- Capital punishment in Judaism

- List of prisoners with whole life orders

Notes and references

Notes

Explanatory notes

- ^ Belarus

- ^ including Australia and New Zealand.

- ^ Most Latin American countries and Canada have completely abolished capital punishment, while a few such as Brazil and Guatemala allow for it only in exceptional situations (such as treason committed during wartime).

- ^ The United States and some Caribbean countries.

- ^ For example South Africa abolished the death penalty in 1995, while Botswana and Zambia retain it.

References

- ^ Shipley, Maynard (1906). "The Abolition of Capital Punishment in Italy and San Marino". American Law Review. 40 (2): 240–251 – via HeinOnline.

- ^ Grann, David (3 April 2018). Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI. Vintage Books. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-307-74248-3. OCLC 993996600.

- ^ Jump up to: a b 'Capital Punishment' in Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, access-date: December 4, 2022

- ^ Kronenwetter 2001, p. 202

- ^ Fowler, H. W. (14 October 2010). A Dictionary of Modern English Usage: The Classic First Edition. OUP Oxford. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-19-161511-5.