Питтсбург

Питтсбург | |

|---|---|

| Nicknames: | |

| Motto: Benigno Numine ("With the benevolent deity") | |

Interactive map of Pittsburgh | |

| Coordinates: 40°26′23″N 79°58′35″W / 40.43972°N 79.97639°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| County | Allegheny |

| Founded | November 27, 1758 (fort) |

| Municipal incorporation |

|

| Founded by | John Forbes |

| Named for | William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council |

| • Mayor | Ed Gainey (D) |

| • City Council | List |

| Area | |

| • City | 58.35 sq mi (151.12 km2) |

| • Land | 55.38 sq mi (143.42 km2) |

| • Water | 2.97 sq mi (7.70 km2) |

| Highest elevation | 1,370 ft (420 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 710 ft (220 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 302,971 |

| • Rank | 68th in the United States 2nd in Pennsylvania |

| • Density | 5,471.26/sq mi (2,112.47/km2) |

| • Urban | 1,745,039 (US: 30th) |

| • Urban density | 1,924.7/sq mi (743.1/km2) |

| • Metro | 2,457,000 (US: 26th) |

| Demonym(s) | Pittsburgher, Yinzer |

| GDP | |

| • Pittsburgh (MSA) | $153.3 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern Standard Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern Daylight Time) |

| ZIP Code | 35 total ZIP codes: |

| Area codes | 412, 724, 878 |

| FIPS code | 42-61000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1213644 |

| Website | pittsburghpa |

| Designated | 1946[6] |

Питтсбург ( / ˈ p ɪ t s b ɜːr ɡ / PITS -burg ) — город и административный центр округа Аллегейни, штат Пенсильвания , США. Это второй по численности населения город Пенсильвании после Филадельфии и 68-й по численности населения город США с населением 302 971 человек по данным переписи 2020 года . Город расположен на юго-западе Пенсильвании, в месте слияния рек Аллегейни и Мононгахела , которые в совокупности образуют реку Огайо . [ 7 ] Он образует агломерацию Питтсбурга с населением 2,457 миллиона жителей и является крупнейшей агломерацией как в долине Огайо , так и в Аппалачах , второй по величине в Пенсильвании и 26-й по величине в США. Питтсбург – главный город большая объединенная статистическая территория Питтсбург-Вейртон-Стьюбенвилл, которая включает части Огайо и Западной Вирджинии .

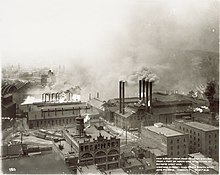

Pittsburgh is known as "the Steel City" for its dominant role in the history of the U.S. steel industry.[8] It developed as a vital link of the Atlantic coast and Midwest, as the mineral-rich Allegheny Mountains led to the region being contested by the French and British Empires, Virginians, Whiskey Rebels, and Civil War raiders.[9] For part of the 20th century, Pittsburgh was behind only New York City and Chicago in corporate headquarters employment; it had the most U.S. stockholders per capita.[10] Deindustrialization in the late 20th century resulted in massive layoffs among blue-collar workers as steel and other heavy industries declined, coinciding with several Pittsburgh-based corporations moving out of the city.[11] However, the city divested from steel and, since the 1990s, Pittsburgh has focused its energies on the healthcare, education, and technology industries.[12][13]

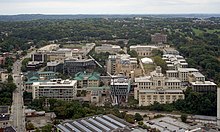

Pittsburgh is home to large medical providers, including the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Allegheny Health Network, and 68 colleges and universities, including research and development leaders Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh.[14] The area has served as the federal agency headquarters for cyber defense, software engineering, robotics, energy research, and the nuclear navy.[15] In the private sector, Pittsburgh-based PNC is the nation's fifth-largest bank, and the city is home to eight Fortune 500 companies and seven of the largest 300 U.S. law firms. Other corporations that have regional headquarters and offices have helped Pittsburgh become the sixth-best area for U.S. job growth.[16] Furthermore, the region is a hub for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design and energy extraction.[17]

Pittsburgh is sometimes called the "City of Bridges" for its 446 bridges.[8] Its rich industrial history left the area with renowned cultural institutions, including the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, Pittsburgh Zoo & Aquarium, Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens, the National Aviary, and a diverse cultural district.[18] The city's major league professional sports teams include the Pittsburgh Steelers, Pittsburgh Penguins, and Pittsburgh Pirates. Pittsburgh is additionally where Jehovah's Witnesses traces its earliest origins, and was the host of the 2009 G20 Pittsburgh summit.

Etymology

[edit]Pittsburgh was named in 1758, by General John Forbes, in honor of British statesman William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham. As Forbes was a Scotsman, he probably pronounced the name /ˈpɪtsbərə/ PITS-bər-ə (similar to Edinburgh).[19][20]

Pittsburgh was incorporated as a borough on April 22, 1794, with the following Act:[21] "Be it enacted by the Pennsylvania State Senate and Pennsylvania House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania ... by the authority of the same, that the said town of Pittsburgh shall be ... erected into a borough, which shall be called the borough of Pittsburgh for ever."[22]

From 1891 to 1911, the city's name was federally recognized as "Pittsburg", though use of the final h was retained during this period by the city government and other local organizations.[23][19] After a public campaign, the federal decision to drop the h was reversed.[19] The Pittsburg Press continued spelling the city without an h until 1921.[24]

History

[edit]

Kingdom of France 1690s–1763

Great Britain 1681–1781

United States 1776–present

Native Americans

[edit]The area of the Ohio headwaters was long inhabited by the Shawnee and several other settled groups of Native Americans.[25] Shannopin's Town was an 18th-century Lenape (Delaware) town located roughly from where Penn Avenue is today, below the mouth of Two Mile Run, from 30th Street to 39th Street. According to George Croghan, the town was situated on the south bank of the Allegheny, nearly opposite what is now known as Washington's Landing, formerly Herr's Island, in what is now the Lawrenceville neighborhood.[26]: 289

18th century

[edit]

The first known European to enter the region was the French explorer Robert de La Salle from Quebec during his 1669 expedition down the Ohio River.[27][better source needed] European pioneers, primarily Dutch, followed in the early 18th century. Michael Bezallion was the first to describe the forks of the Ohio in a 1717 manuscript, and later that year European fur traders established area posts and settlements.[28]

In 1749, French soldiers from Quebec launched an expedition to the forks to unite Canada with French Louisiana via the rivers.[28] During 1753–1754, the British hastily built Fort Prince George before a larger French force drove them off. The French built Fort Duquesne based on LaSalle's 1669 claims. The French and Indian War, the North American front of the Seven Years' War, began with the future Pittsburgh as its center. British General Edward Braddock was dispatched with Major George Washington as his aide to take Fort Duquesne.[29] The British and colonial force were defeated at Braddock's Field. General John Forbes finally took the forks in 1758. He began construction on Fort Pitt, named after William Pitt the Elder, while the settlement was named "Pittsborough".[30]

During Pontiac's War, a loose confederation of Native American tribes laid siege to Fort Pitt in 1763; the siege was eventually lifted after Colonel Henry Bouquet defeated a portion of the besieging force at the Battle of Bushy Run. Bouquet strengthened the defenses of Fort Pitt the next year.[31][32][33][34]

During this period, the powerful nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, based in New York, had maintained control of much of the Ohio Valley as hunting grounds by right of conquest after defeating other tribes. By the terms of the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the Penns were allowed to purchase the modern region from the Iroquois. A 1769 survey referenced the future city as the "Manor of Pittsburgh".[35] Both the Colony of Virginia and the Province of Pennsylvania claimed the region under their colonial charters until 1780, when they agreed under a federal initiative to extend the Mason–Dixon line westward, placing Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. On March 8, 1771, Bedford County, Pennsylvania was created to govern the frontier.

On April 16, 1771, the city's first civilian local government was created as Pitt Township.[36][37] William Teagarden was the first constable, and William Troop was the first clerk.[38]

Following the American Revolution, the village of Pittsburgh continued to grow. One of its earliest industries was boat building for settlers of the Ohio Country. In 1784, Thomas Vickroy completed a town plan which was approved by the Penn family attorney. Pittsburgh became a possession of Pennsylvania in 1785. The following year, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette was started, and in 1787, the Pittsburgh Academy was chartered. Unrest during the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 resulted in federal troops being sent to the area. By 1797, glass manufacture began, while the population grew to around 1,400. Settlers arrived after crossing the Appalachian Mountains or through the Great Lakes. Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh) at the source of the Ohio River became the main base for settlers moving into the Northwest Territory.

19th century

[edit]

The federal government recognizes Pittsburgh as the starting point for the Lewis and Clark Expedition.[39] Preparations began in Pittsburgh in 1803 when Meriwether Lewis purchased a keelboat that would later be used to ascend the Missouri River.[40]

The War of 1812 cut off the supply of British goods, stimulating American industry. By 1815, Pittsburgh was producing significant quantities of iron, brass, tin, and glass. On March 18, 1816, the 46-year-old local government became a city. It was served by numerous river steamboats that increased trading traffic on the rivers.

In the 1830s, many Welsh people from the Merthyr steelworks immigrated to the city following the aftermath of the Merthyr Rising. By the 1840s, Pittsburgh was one of the largest cities west of the Allegheny Mountains. The Great Fire of Pittsburgh destroyed over a thousand buildings in 1845. The city rebuilt with the aid of Irish immigrants who came to escape the Great Famine. By 1857, Pittsburgh's 1,000 factories were consuming 22 million coal bushels yearly. Coal mining and iron manufacturing attracted waves of European immigrants to the area, with the most coming from Germany.

Because Pennsylvania had been established as a free state after the Revolution, enslaved African Americans sought freedom here through escape as refugees from the South, or occasionally fleeing from travelers they were serving who stayed in the city. There were active stations of the Underground Railroad in the city, and numerous refugees were documented as getting help from station agents and African-American workers in city hotels. The Drennen Slave Girl walked out of the Monongahela House in 1850, apparently to freedom.[41] The Merchant's Hotel was also a place where African-American workers would advise slaves the state was free and aid them in getting to nearby stations of the Underground Railroad.[42] Sometimes refugee slaves from the South stayed in Pittsburgh, but other times they continued North, including into Canada. Many slaves left the city and county for Canada after Congress passed the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, as it required cooperation from law enforcement even in free states and increased penalties. From 1850 to 1860, the black population in Allegheny County dropped from 3,431 to 2,725 as people headed to more safety in Canada.[41]

The American Civil War boosted the city's economy with increased iron and armament demand by the Union. Andrew Carnegie began steel production in 1875 at the Edgar Thomson Steel Works in North Braddock, Pennsylvania, which evolved into the Carnegie Steel Company. He adopted the Bessemer process to increase production. Manufacturing was key to growth of Pittsburgh and the surrounding region. Railroad lines were built into the city along both rivers, increasing transportation access to important markets.

20th century

[edit]

In 1901, J. P. Morgan and attorney Elbert H. Gary merged Carnegie Steel Company and several other companies into U.S. Steel. By 1910, Pittsburgh was the nation's eighth-largest city, accounting for between one-third and one-half of national steel output.

The Pittsburgh Agreement was subscribed in May 1918 between the Czech and Slovak nationalities, as envisioned by T. G. Masaryk, concerning the future foundation of Czechoslovakia.[44]

The city suffered severe flooding in March 1936.

The city's population swelled to more than a half million, attracting numerous European immigrants to its industrial jobs. By 1940, non-Hispanic whites were 90.6% of the city's population.[45] Pittsburgh also became a main destination of the African-American Great Migration from the rural South during the first half of the 20th century.[46] Limited initially by discrimination, some 95% percent of the men became unskilled steel workers.[47]

During World War II, demand for steel increased and area mills operated 24 hours a day to produce 95 million tons of steel for the war effort.[30] This resulted in the highest levels of air pollution in the city's almost century of industry. The city's reputation as the "arsenal of democracy"[48][49] was being overshadowed by James Parton's 1868 observation of Pittsburgh being "hell with the lid off."[50]

Following World War II, the city launched a clean air and civic revitalization project known as the "Renaissance," cleaning up the air and the rivers. The "Renaissance II" project followed in 1977, focused on cultural and neighborhood development. The industrial base continued to expand through the 1970s, but beginning in the early 1980s both the area's steel and electronics industries imploded during national industrial restructuring. There were massive layoffs from mill and plant closures.[11]

In the later 20th century, the area shifted its economic base to education, tourism, and services, largely based on healthcare/medicine, finance, and high technology such as robotics. Although Pittsburgh successfully shifted its economy and remained viable, the city's population has never rebounded to its industrial-era highs. While 680,000 people lived in the city proper in 1950, a combination of suburbanization and economic turbulence resulted in a decrease in city population, even as the metropolitan area population increased again.

21st century

[edit]During the late 2000s recession, Pittsburgh was economically strong, adding jobs when most cities were losing them. It was one of the few cities in the United States to see housing property values rise. Between 2006 and 2011, the Pittsburgh metropolitan statistical area (MSA) experienced over 10% appreciation in housing prices, the highest appreciation of the largest 25 metropolitan statistical areas in the United States, with 22 of the largest 25 metropolitan statistical areas experiencing depreciations in housing values.[51]

In September 2009, the 2009 G20 Pittsburgh summit was held in Pittsburgh.[52]

Geography

[edit]

Pittsburgh has an area of 58.3 square miles (151 km2), of which 55.6 square miles (144 km2) is land and 2.8 square miles (7.3 km2), or 4.75%, is water. The 80th meridian west passes directly through the city's downtown.

The city is on the Allegheny Plateau, within the ecoregion of the Western Allegheny Plateau.[53] The Downtown area (also known as the Golden Triangle) sits where the Allegheny River flows from the northeast and the Monongahela River from the southeast to form the Ohio River. The convergence is at Point State Park and is referred to as "the Point." The city extends east to include the Oakland and Shadyside sections, which are home to the University of Pittsburgh, Carnegie Mellon University, Chatham University, Carnegie Museum and Library, and many other educational, medical, and cultural institutions. The southern, western, and northern areas of the city are primarily residential.

Many Pittsburgh neighborhoods are steeply sloped with two-lane roads. More than a quarter of neighborhood names make reference to "hills," "heights," or similar features.[a]

The steps of Pittsburgh consist of 800 sets of outdoor public stairways with 44,645 treads and 24,090 vertical feet. They include hundreds of streets composed entirely of stairs, and many other steep streets with stairs for sidewalks.[54] Many provide vistas of the Pittsburgh area while attracting hikers and fitness walkers.[55]

Bike and walking trails have been built to border many of the city's rivers and hollows. The Great Allegheny Passage and Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Towpath connect the city directly to downtown Washington, D.C. (some 335 miles [539 km] away) with a continuous bike/running trail.

Cityscape

[edit]Areas

[edit]

The city consists of the Downtown area, called the Golden Triangle,[56] and four main areas surrounding it. These surrounding areas are subdivided into distinct neighborhoods (Pittsburgh has 90 neighborhoods).[57] Relative to downtown, these areas are known as the Central, North Side/North Hills, South Side/South Hills, East End, and West End.

Golden Triangle

[edit]Downtown Pittsburgh has 30 skyscrapers, nine of which top 500 feet (150 m). The U.S. Steel Tower is the tallest, at 841 ft (256 m).[58] The Cultural District consists of a 14-block area of downtown along the Allegheny River. This district contains many theaters and arts venues and is home to a growing residential segment. Most significantly, the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust is embarking on RiverParc, a four-block mixed-use "green" community, featuring 700 residential units and multiple towers of between 20 and 30 stories. The Firstside portion of Downtown borders the Monongahela River, the historic Mon Wharf and hosts the distinctive PPG Place Gothic-style glass skyscraper complex. New condo towers have been constructed and historic office towers are converted to residential use, increasing 24-hour residents. Downtown is served by the Port Authority's light rail system and multiple bridges leading north and south.[59] It is also home to Point Park University and Duquesne University which borders Uptown.

North Side

[edit]

The North Side is home to various neighborhoods in transition. The area was once known as Allegheny City and operated as its own independent city until 1907, when it was merged with Pittsburgh despite great protest from its citizens. The North Side is primarily composed of residential neighborhoods and is noteworthy for its well-constructed and architecturally interesting homes. Many buildings date from the 19th century and are constructed of brick or stone and adorned with decorative woodwork, ceramic tile, slate roofs and stained glass. The North Side is also home to attractions such as Acrisure Stadium, PNC Park, Kamin Science Center, National Aviary, Andy Warhol Museum, Mattress Factory art museum, Children's Museum of Pittsburgh, Randyland, Penn Brewery, Allegheny Observatory, and Allegheny General Hospital.[60]

South Side

[edit]

The South Side was once the site of railyards and associated dense, inexpensive housing for mill and railroad workers. Starting in the late 20th century, the city undertook a Main Street program in cooperation with the National Trust for Historic Preservation, encouraging design and landscape improvements on East Carson Street, and supporting new retail. The area has become a local Pittsburgher destination, and the value of homes in the South Side had increased in value by about 10% annually for the 10 years leading up to 2014.[61] East Carson Street has developed as one of the most vibrant areas of the city, packed with diverse shopping, ethnic eateries, vibrant nightlife, and live music venues.

In 1993, the Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh purchased the South Side Works steel mill property. It collaborated with the community and various developers to create a master plan for a mixed-use development that included a riverfront park, office space, housing, health-care facilities, and indoor practice fields for the Pittsburgh Steelers and Pitt Panthers. Construction of the development began in 1998. The SouthSide Works has been open since 2005, featuring many stores, restaurants, offices, and the world headquarters for American Eagle Outfitters.[62]

East End

[edit]

The East End of Pittsburgh is home to the University of Pittsburgh, Carnegie Mellon University, Carlow University, Chatham University, The Carnegie Institute's Museums of Art and Natural History, Phipps Conservatory, and Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall. It is also home to many parks and public spaces including Mellon Park, Westinghouse Park, Schenley Park, Frick Park, The Frick Pittsburgh, Bakery Square, and the Pittsburgh Zoo and PPG Aquarium. The neighborhoods of Shadyside and Squirrel Hill are large, wealthy neighborhoods with some apartments and condos, and pedestrian-oriented shopping/business districts. Squirrel Hill is also known as the hub of Jewish life in Pittsburgh, home to approximately 20 synagogues.[63] Oakland, heavily populated by undergraduate and graduate students, is home to most of the universities, and the Petersen Events Center. The Strip District to the west along the Allegheny River is an open-air marketplace by day and a clubbing destination by night. Bloomfield is Pittsburgh's Little Italy and is known for its Italian restaurants and grocers. Lawrenceville is a revitalizing rowhouse neighborhood popular with artists and designers. The Hill District was home to photographer Charles Harris as well as various African-American jazz clubs.[64] Other East End neighborhoods include Point Breeze, Regent Square, Highland Park, Homewood, Lincoln-Lemington-Belmar, Larimer, East Hills, East Liberty, Polish Hill, Hazelwood, Garfield, Morningside, and Stanton Heights.

West End

[edit]The West End includes Mt. Washington, with its famous view of the downtown skyline, and numerous other residential neighborhoods such as Sheraden and Elliott.

Ethnicities

[edit]Many of Pittsburgh's patchwork of neighborhoods still retain ethnic characters reflecting the city's settlement history. These include:

- German: Troy Hill, Mt. Washington, and East Allegheny (Deutschtown)

- Italian: Brookline, Bloomfield, Morningside, Oakland

- Hispanic/Latino: Beechview/Brookline

- Polish, Austrian, Belgian, Czech, Slovak, German, Greek, Hungarian, Luxembourgish, Dutch, Romanian, Swiss, Slovenia and the northern marginal regions of Italy, Croatian, as well as northeastern France, Central European: South Side, Lawrenceville, and Polish Hill

- Lithuanian: South Side, Uptown

- African American/Multiracial African American: Hill District, Homewood, Lincoln-Lemington-Belmar, Larimer, East Hills, and Hazelwood

- Jewish (Ashkenazi): Squirrel Hill

- Irish: Mt. Washington, Carrick, Greenfield

- Ukrainian (Ruthenian): South Side

Population densities

[edit]Several neighborhoods on the edges of the city are less urban, featuring tree-lined streets, yards and garages, with a more suburban character. Oakland, the South Side, the North Side, and the Golden Triangle are characterized by more density of housing, walking neighborhoods, and a more diverse, urban feel.

Images

[edit]

Regional identity

[edit]

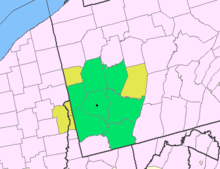

Pittsburgh falls within the borders of the Northeastern United States as defined by multiple US Government agencies. Pittsburgh is the principal city of the Pittsburgh Combined Statistical Area, a combined statistical area defined by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Pittsburgh falls within the borders of Appalachia as defined by the Appalachian Regional Commission, and has long been characterized as the "northern urban industrial anchor of Appalachia."[67] In its post-industrial state, Pittsburgh has been characterized as the "Paris of Appalachia",[68][69][70][71] recognizing the city's cultural, educational, healthcare, and technological resources, and is the largest city in Appalachia.

Climate

[edit]| Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Under the Köppen climate classification, Pittsburgh falls within either a hot-summer humid continental climate (Dfa) if the 0 °C (32 °F) isotherm is used or a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) if the −3 °C (27 °F) isotherm is used. Summers are hot and winters are moderately cold with wide variations in temperature. Despite this, it has one of the most pleasant summer climates between medium and large cities in the U.S.[72][73][74] The city lies in the USDA plant hardiness zone 6b except along the rivers where the zone is 7a.[75] The area has four distinct seasons: winters are cold and snowy, springs and falls are mild with moderate levels of sunshine, and summers are warm. As measured by percent possible sunshine, summer is by far the sunniest season, though annual sunshine is low among major US cities at well under 50%.[76]

The warmest month of the year in Pittsburgh is July, with a 24-hour average of 73.2 °F (22.9 °C). Conditions are often humid, and combined with highs reaching 90 °F (32 °C) on an average 9.5 days a year,[77] a considerable heat index arises. The coolest month is January, when the 24-hour average is 28.8 °F (−1.8 °C), and lows of 0 °F (−18 °C) or below can be expected on an average 2.6 nights per year.[77] Officially, record temperatures range from −22 °F (−30 °C), on January 19, 1994 to 103 °F (39 °C), which occurred three times, most recently on July 16, 1988; the record cold daily maximum is −3 °F (−19 °C), which occurred three times, most recently the day of the all-time record low, while, conversely, the record warm daily minimum is 82 °F (28 °C) on July 1, 1901.[77][b] Due to elevation and location on the windward side of the Appalachian Mountains, 100 °F (38 °C)+ readings are very rare, and were last seen on July 15, 1995.[77]

Average annual precipitation is 39.61 inches (1,006 mm) and precipitation is greatest in May while least in October; annual precipitation has historically ranged from 22.65 in (575 mm) in 1930 to 57.83 in (1,469 mm) in 2018.[78] On average, December and January have the greatest number of precipitation days. Snowfall averages 44.1 inches (112 cm) per season, but has historically ranged from 8.8 in (22 cm) in 1918–19 to 80 in (200 cm) in 1950–51.[79] There is an average of 59 clear days and 103 partly cloudy days per year, while 203 days are cloudy.[80] In terms of annual percent-average possible sunshine received, Pittsburgh (45%) is similar to Seattle (49%).

| Climate data for Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh International Airport), 1991–2020 normals,[c] extremes 1874–present[d] |

|---|

Air quality

[edit]The American Lung Association's (ALA) 2023 “State of the Air” report (which included data from 2019 to 2021) showed air quality in Pittsburgh improving. The city received a passing grade for ozone pollution, going from an F to a C grade, and improving from the 46th to 54th most polluted by ozone smog.[84]

According to daily ozone air quality data provided by the EPA, from 2021 to 2024, Pittsburgh had good or moderate air quality most of the time.[85][86] Then-Allegheny County executive Rich Fitzgerald said in December 2023 that they’d seen an “80 % drop in hazardous air pollutants” and that they made EPA attainment at all eight county air monitors for the first time in 2020, and then also achieved that goal in 2021, 2022, and were on track for better results in 2023.[87]

A past 2019 "State of the Air" report from the American Lung Association (ALA) found that air quality in the Pittsburgh-New Castle-Weirton, PA-OH-WV metro area worsened compared to previous reports, not only for ozone (smog), but also for the second year in a row for both the daily and long-term measures of fine particle pollution. In 2019, outside of California, Allegheny County was the only county in the United States that recorded failing grades for all three.[88]

In a 2013 ranking of 277 metropolitan areas in the United States, the American Lung Association ranked only six U.S. metro areas as having higher amounts of short-term particle pollution, and only seven U.S. metro areas having higher amounts of year-round particle pollution than Pittsburgh. For ozone (smog) pollution, Pittsburgh was ranked 24th among U.S. metro areas.[89][90] The area has improved its air quality with every annual survey. The ALA's rankings have been disputed by the Allegheny County Health Department (ACHD), since data from only the worst of the region's 20 air quality monitors is considered by the ALA, without any context or averaging. The lone monitor used is immediately downwind and adjacent to U.S. Steel's Clairton Coke Works, the nation's largest coke mill, and several municipalities outside the city's jurisdiction of pollution controls, leading to possible confusion that Pittsburgh is the source or center of the emissions cited in the survey.[91] The region's readings also reflect pollution swept in from Ohio and West Virginia.[92]

Although the county was still below the "pass" threshold, the report showed substantial improvement over previous decades on every air quality measure. Fewer than 15 high ozone days were reported between 2007 and 2009, and just 10 between 2008 and 2010, compared to more than 40 between 1997 and 1999.[93] ACHD spokesman Guillermo Cole stated "It's the best it's been in the lifetime for virtually every resident in this county ... We've seen a steady decrease in pollution levels over the past decade and certainly over the past 20, 30, 40, 50 years, or more."[94]

As of 2005, the city includes 31,000 trees on 900 miles of streets. A 2011 analysis of Pittsburgh's tree cover, which involved sampling more than 200 small plots throughout the city, showed a value of between $10 and $13 million in annual benefits based on the urban forest contributions to aesthetics, energy use and air quality. Energy savings from shade, impact on city air and water quality, and the boost in property values were taken into account in the analysis. The city spends $850,000 annually on street tree planting and maintenance.[95]

Despite improvements, some studies still suggest that poor air quality in Pittsburgh is causing negative health effects. In a past study conducted between 2014 and 2016 researchers determined that children who lived in areas close to sources of pollution, such as industrial sites, experienced rates of asthma at almost 3 times the national average.[96] The study also found that 38% of students live in areas over USEPA's 12 micrograms per cubic meter standards, while 70% live in areas over the WHO's standard of 10 micrograms per cubic meter.[96] Several of the plants were located in or very near Pittsburgh.[96] The study also noted that most of the effected communities were minority communities.[96] This had led some residents in Pittsburgh to believe that the continuing effects of air pollution are a case of environmental racism.[97]

Groups such as Women for a Healthy Environment are working to address ongoing concerns surrounding air pollution in Pittsburgh.[98] WHE does work such as policy analysis, publishing reports, and community education.[98] In the summer of 2017, a crowd sourced air quality monitoring application, Smell PGH, was launched. As air quality is still a concern of many in the area, the app allows for users to report odd smells and informs local authorities.[99]

Water quality

[edit]The local rivers continue to have pollution levels exceeding EPA limits.[100] This is caused by frequently overflowing untreated sewage into local waterways, due to flood conditions and antiquated infrastructure. Pittsburgh has a combined sewer system, where its sewage pipes contain both stormwater and wastewater. The pipes were constructed in the early 1900s, and the sewage treatment plant was built in 1959.[101] Due to insufficient improvements over time, the city is faced with public health concerns regarding its water.[102] As little as a tenth of an inch of rain causes runoffs from the sewage system to drain into local rivers.[103] Nine billion gallons of untreated waste and stormwater flow into rivers, leading to health hazards and Clean Water Act violations.[104] The local sewage authority, Allegheny County Sanitary Authority, or ALCOSAN, is operating under Consent Decree from the EPA to come up with solutions.[105] In 2017, ALCOSAN proposed a $2 billion upgrade to the system which was approved by the EPA in 2019.[106][107]

Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority (PWSA) is the city's agency required to replace pipes and charge water rates. They have come under fire from both city and state authorities due to alleged mismanagement.[108] In 2017, Mayor William Peduto advocated for a restructuring of the PWSA and a partially privatized water authority.[109] Governor Wolf subsequently assigned the PWSA to be under the oversight of the Public Utilities Commission (PUC).[108]

PWSA has also been subject to criticism due to findings released in 2016 showing high levels of lead in Pittsburgh's drinking water.[110] Although Pittsburgh's drinking water had been high in lead levels, and steadily rising, for many years, many residents blame PWSA administrative changes for the spike in lead levels.[111] In the years prior, PWSA had hired Veolia, a Paris-based company, for consultation to help with mounting administrative difficulties.[112] By 2015, PWSA in consultation with Veolia had laid off 23 people, including halving the laboratory staff that was responsible for testing water safety and quality.[112] Simultaneously, PWSA in consultation with Veolia had changed what chemicals they were using to prevent metal corrosion in 2014,[111] from soda ash to caustic soda, without consulting with Department of Environmental Protection.[113] Anti-corrosive chemicals were being used because many of Pittsburgh's water pipes were made of lead, and adding anti-corrosive chemicals helped prevent lead from seeping into drinking water.[113]

In 2016 lead levels were as high as 27 ppb in some cases. The legal limit is 15 ppb, although there is not a safe amount of lead in drinking water.[113] Though lead levels had been rising in previous years, they had not exceeded the legal limit.[111] In late 2015 PWSA terminated its contracted with Veolia.[112] In response to the high lead levels PWSA began adding orthophosphate to the water.[114] Orthophosphate is meant to create a coating on the inside of pipes, creating a barrier to prevent lead from leaching into drinking water.[114] PWSA has also been working to replace lead pipes, and continuing to test water for lead.[114]

There remains concern among residents over the long-term effects of this lead, particularly for children, in whom lead causes permanent damage to the brain and nervous system.[115] Some people also believe that the high levels of lead reflect environmental racism, as black and Hispanic children in Pittsburgh experience elevated blood-lead levels at 4 times the rate of white children.[115] Water fountains in Langley k-8 school in Sheraden were found to have the highest levels of lead of any schools in the Pittsburgh area. These levels were about 11 times the legal limit. Some residents believe this is due to Langely being a predominantly black school, with 89% of the student body being eligible for the free lunch program.[116]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 1,565 | — | |

| 1810 | 4,768 | 204.7% | |

| 1820 | 7,248 | 52.0% | |

| 1830 | 12,568 | 73.4% | |

| 1840 | 21,115 | 68.0% | |

| 1850 | 46,601 | 120.7% | |

| 1860 | 49,221 | 5.6% | |

| 1870 | 86,076 | 74.9% | |

| 1880 | 156,389 | 81.7% | |

| 1890 | 238,617 | 52.6% | |

| 1900 | 321,616 | 34.8% | |

| 1910 | 533,905 | 66.0% | |

| 1920 | 588,343 | 10.2% | |

| 1930 | 669,817 | 13.8% | |

| 1940 | 671,659 | 0.3% | |

| 1950 | 676,806 | 0.8% | |

| 1960 | 604,332 | −10.7% | |

| 1970 | 520,117 | −13.9% | |

| 1980 | 423,938 | −18.5% | |

| 1990 | 369,879 | −12.8% | |

| 2000 | 334,563 | −9.5% | |

| 2010 | 305,704 | −8.6% | |

| 2020 | 302,971 | −0.9% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 303,255 | 0.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[117][118][2] | |||

| Historical Racial composition | 2020[119] | 2010[120] | 1990[121] | 1970[121] | 1950[121] |

|---|

2020 census

[edit]This section needs expansion with: examples with reliable citations. You can help by adding to it. (September 2021) |

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 1980[122] | Pop 1990[123] | Pop 2000[124] | Pop 2010[125] | Pop 2020[126] | % 1980 | % 1990 | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 316,262 | 264,722 | 223,982 | 198,186 | 187,099 | 74.60% | 71.57% | 66.95% | 64.83% | 61.75% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 100,734 | 94,743 | 90,183 | 78,847 | 68,314 | 23.76% | 25.61% | 26.96% | 25.79% | 22.55% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 552 | 583 | 561 | 505 | 475 | 0.13% | 0.16% | 0.17% | 0.17% | 0.16% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 2,778 | 5,865 | 9,160 | 13,393 | 19,745 | 0.66% | 1.59% | 2.74% | 4.38% | 6.52% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | N/A | N/A | 100 | 76 | 96 | N/A | N/A | 0.03% | 0.02% | 0.03% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 242 | 498 | 1,217 | 843 | 2,081 | 0.06% | 0.13% | 0.36% | 0.28% | 0.69% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | N/A | N/A | 4,935 | 6,890 | 13,541 | N/A | N/A | 1.48% | 2.25% | 4.47% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 3,370 | 3,468 | 4,425 | 6,964 | 11,620 | 0.79% | 0.94% | 1.32% | 2.28% | 3.84% |

| Total | 423,938 | 369,879 | 334,563 | 305,704 | 302,971 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

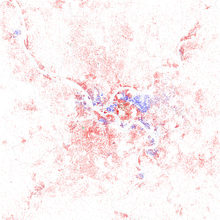

At the 2010 census, there were 305,704 people residing in Pittsburgh, a decrease of 8.6% since 2000; 66.0% of the population was White, 25.8% Black or African American, 0.2% American Indian and Alaska Native, 4.4% Asian, 0.3% Other, and 2.3% mixed; in 2020, 2.3% of Pittsburgh's population was of Hispanic or Latino American origin of any race. Non-Hispanic whites were 64.8% of the population in 2010,[120] compared to 78.7% in 1970.[121] By the 2020 census, the population slightly declined further to 302,971.[119] Its racial and ethnic makeup in 2020 was 64.7% non-Hispanic white, 23.0% Black or African American, 5.8% Asian, and 3.2% Hispanic or Latino American of any race.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the five largest European ethnic groups in Pittsburgh were German (19.7%), Irish (15.8%), Italian (11.8%), Polish (8.4%), and English (4.6%), while the metropolitan area is approximately 22% German-American, 15.4% Italian American and 11.6% Irish American. Pittsburgh has one of the largest Italian-American communities in the nation,[127] and the fifth-largest Ukrainian community per the 1990 census.[128] Pittsburgh has one of the most extensive Croatian communities in the United States.[129] Overall, the Pittsburgh metro area has one of the largest populations of Slavic Americans in the country.

Pittsburgh has a sizable Black and African American population, concentrated in various neighborhoods especially in the East End. There is also a small Asian community consisting of Indian immigrants, and a small Hispanic community consisting of Mexicans and Puerto Ricans.[130]

According to a 2010 Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) study, residents include 773,341 "Catholics"; 326,125 "Mainline Protestants"; 174,119 "Evangelical Protestants;" 20,976 "Black Protestants;" and 16,405 "Orthodox Christians," with 996,826 listed as "unclaimed" and 16,405 as "other" in the metro area.[130] A 2017 study by the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies at Brandeis University estimated the Jewish population of Greater Pittsburgh was 49,200.[131] Pittsburgh is also cited as the location where the earliest precursor to Jehovah's Witnesses was founded by Charles Taze Russell; today the denomination makes up approximately 1% of the population based on data from the Pew Research Center.[132][133]

According to a 2014 study by the Pew Research Center, 78% of the population of the city identified themselves as Christians, with 42% professing attendance at a variety of churches that could be considered Protestant, and 32% professing Catholic beliefs. while 18% claim no religious affiliation. The same study says that other religions (including Judaism, Buddhism, Islam, and Hinduism) collectively make up about 4% of the population.[134]

In 2010, there were 143,739 households, out of which 21.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 31.2% were married couples living together, 16.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 48.4% were non-families. 39.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.17 and the average family size was 2.95.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 19.9% under the age of 18, 14.8% from 18 to 24, 28.6% from 25 to 44, 20.3% from 45 to 64, and 16.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.8 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $28,588, and the median income for a family was $38,795. Males had a median income of $32,128 versus $25,500 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,816. About 15.0% of families and 20.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 27.5% of those under the age of 18 and 13.5% ages 65 or older. By the 2019 American Community Survey, the median income for a household increased to $53,799.[135] Families had a median income of $68,922; married-couple families had a median income of $93,500; and non-family households had a median income of $34,448. Pittsburgh's wealthiest suburbs within city limits are Squirrel Hill and Point Breeze, the only two areas of the city which have average household incomes over $100,000 a year. Outside of city limits, Sewickley Heights is by a wide margin the wealthiest suburb of Pittsburgh within Allegheny County, with an average yearly household income of just over $218,000. Sewickely Heights is seen as one of Pittsburgh's wealthiest suburbs culturally as well, titles which the suburbs of Upper St. Clair, Fox Chapel, Wexford, and Warrendale also have been bestowed.[136][137]

In a 2002 study, Pittsburgh ranked 22nd of 69 urban places in the U.S. in the number of residents 25 years or older who had completed a bachelor's degree, at 31%.[138] Pittsburgh ranked 15th of the 69 places in the number of residents 25 years or older who completed a high school degree, at 84.7%.[139]

The metro area has shown greater residential racial integration during the last 30 years. The 2010 census ranked 18 other U.S. metros as having greater black-white segregation, while 32 other U.S. metros rank higher for black-white isolation.[140]

As of 2018, much of Pittsburgh's population density was concentrated in the central, southern, and eastern areas. The city limits itself have a population density of 5,513 people per square mile; its most densely populated parts are North Oakland (at 21,200 per square mile) and Uptown Pittsburgh (at 19,869 per square mile). Outside of the city limits, Dormont and Mount Oliver are Pittsburgh's most densely-populated neighborhoods, with 11,167 and 9,902 people per square mile respectively.[141]

Most of Pittsburgh's immigrants are from China, India, Korea and Italy.[142]

Demographic changes

[edit]Since the 1940s, some demographic changes have sometimes been caused by city initiatives for redevelopment.

Throughout the 1950s Pittsburgh's Lower Hill District faced massive demographic changes when 1,551, majority black, residents and 413 businesses were forced to relocate when the city of Pittsburgh used eminent domain to make space for the construction of the Civic Arena.[13] This Civic Arena ultimately opened in 1961.[13] The Civic Arena was built as part of one of Pittsburgh's revitalization campaigns. An auditorium in this space was initially proposed in 1947 by the Regional Planning Association and Urban Redevelopment Authority. The idea of an auditorium with a retractable roof that would house the Pittsburgh Civic Light Opera was more specifically proposed in 1953 by the Allegheny Conference on Community Redevelopment. The following year the Public Auditorium Authority of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County was formed. The Lower Hill District had been approved by the City Planning Commission in 1950.[13] Partially as a result of the Civic arena, the whole Hill District is estimated to only have 12,000 residents now.[143] These governmental organizations caused demographic changes through creating a mass exodus from the lower hill district for the construction of the Civic Arena.[13]

In the 1960s the Urban Redevelopment Authority attempted to redevelop East Liberty with the goal of preserving its status as a market center. Penn Center Mall was the result of this effort. In the process of constructing this mall, approximately 3,800 people were forced to relocate. This proved to be another case of government intervention resulting in demographic changes.[144]

Later on, in the early 2000s, movement of businesses into East Liberty, such as Home Depot, Whole Foods, and Google, created another demographic shift. This era of redevelopment was led by private developers who catered to what one scholar described as “Florida’s creative class.” This change continued to be supported by the Urban Redevelopment Authority; particularly by the executive director Rob Stepney, who said of the redevelopment “We had an inspired and shared vision.” When describing the result of redevelopment he said “East Liberty went from blighted and ‘keep off the grass’ to the definition of what millennials are looking for.”[144]

The Pittsburgh government’s choices during redevelopment and the resulting demographic changes have resulted in criticism and led some residents to believe that displacement was purposeful. In one article published in Public Source, a resident explains their belief that redevelopment plans are part of “deconcentration,” an effort to spread out black and low-income residents in order to prevent them from being concentrated in one place.[143] Others worry that these demographic changes are part of government complicity in gentrification.[145] Gentrification is a process where wealthier residents move into an area, altering it by increasing housing / renting costs and changing the market for businesses in the area. This displaces current residents who are unable to afford living in the changed neighborhood. In East Liberty, for example, people frequently cite housing units being demolished and replaced by businesses as evidence of gentrification. For example, when the East Mall public housing unit was demolished in 2009, and a Target built in its place.[146]

Economy

[edit]Pittsburgh has adapted since the collapse of its century-long steel and electronics industries. The region has shifted to high technology, robotics, health care, nuclear engineering, tourism, biomedical technology, finance, education, and services. Annual payroll of the region's technology industries, when taken in aggregate, exceeded $10.8 billion in 2007,[147] and in 2010 there were 1,600 technology companies.[148] A National Bureau of Economic Research 2014 report named Pittsburgh the second-best U.S. city for intergenerational economic mobility[149] or the American Dream.[150] Reflecting the citywide shift from industry to technology, former factories have been renovated as modern office space. Google has research and technology offices in a refurbished 1918–1998 Nabisco factory, a complex known as Bakery Square.[151] Some of the factory's original equipment, such as a large dough mixer, were left standing in homage to the site's industrial roots.[152] Pittsburgh's transition from its industrial heritage has earned it praise as "the poster child for managing industrial transition".[153] Other major cities in the northeast and mid-west have increasingly borrowed from Pittsburgh's model in order to renew their industries and economic base.[154]

The largest employer in the city is the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, with 48,000 employees. All hospitals, outpatient clinics, and doctor's office positions combine for 116,000 jobs, approximately 10% of the jobs in the region. An analyst recently observed of the city's medical sector: "That's both more jobs and a higher share of the region's total employment than the steel industry represented in the 1970s."[155]

| Top publicly traded companies in the Pittsburgh region for 2022 (ranked by revenues) with metropolitan and U.S. ranks | |||||

| Metro | corporation | US | |||

| 1 | The Kraft Heinz Company | 139 | |||

| 2 | U.S. Steel | 172 | |||

| 3 | PNC Financial Services | 178 | |||

| 4 | Viatris | 204 | |||

| 5 | PPG Industries | 218 | |||

| 6 | Dick's Sporting Goods | 307 | |||

| 7 | Alcoa | 312 | |||

| 8 | WESCO International | 357 | |||

| 9 | Wabtec | 439 | |||

| 10 | Arconic | 452 | |||

Education is a major economic driver in the region. The largest single employer in education is the University of Pittsburgh, with 10,700 employees.[156]

Ten Fortune 500 companies call the Pittsburgh area home.[157] They are (in alphabetical order): Alcoa Corporation (NYSE: AA), Arconic Corporation (NYSE: ARNC), Dick's Sporting Goods (NYSE: DKS), The Kraft Heinz Company (NASDAQ: KHC), PNC Financial Services (NYSE: PNC), PPG Industries (NYSE: PPG), U.S. Steel Corporation (NYSE: X), Viatris (NASDAQ: VRTS), Wabtec Corporation (NYSE: WAB), and WESCO International (WYSE: WCC).[158]

The region is home to Aurora, Allegheny Technologies, American Eagle Outfitters, Duolingo, EQT Corporation, CONSOL Energy, Howmet Aerospace, Kennametal and II-VI headquarters. Other major employers include BNY Mellon, GlaxoSmithKline, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Lanxess. The Northeast U.S. regional headquarters for Chevron Corporation, Nova Chemicals, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, FedEx Ground, Ariba, and the RAND Corporation call the area home. 84 Lumber, Giant Eagle, Highmark, Rue 21, General Nutrition Center (GNC), CNX Gas (CXG), and Genco Supply Chain Solutions are major non-public companies headquartered in the region. The global impact of Pittsburgh technology and business was recently demonstrated in several key components of the Boeing 787 Dreamliner being manufactured and supplied by area companies.[159] Area retail is anchored by over 35 shopping malls and a healthy downtown retail sector, as well as boutique shops along Walnut Street, in Squirrel Hill, Lawrenceville and Station Square.

The nonprofit arts and cultural industry in Allegheny County generates $341 million in economic activity that supports over 10,000 full-time equivalent jobs with nearly $34 million in local and state taxes raised.[160]

A leader in environmental design, the city is home to 60 total and 10 of the world's first green buildings while billions have been invested in the area's Marcellus natural gas fields.[17] A renaissance of Pittsburgh's 116-year-old film industry—that boasts the world's first movie theater—has grown from the long-running Three Rivers Film Festival to an influx of major television and movie productions. including Disney and Paramount offices with the largest sound stage outside Los Angeles and New York City.[161]

Pittsburgh has hosted many conventions, including INPEX, the world's largest invention trade show, since 1984;[162] Tekko, a four-day anime convention, since 2003; Anthrocon, a furry convention, since 2006; and the DUG East energy trade show since 2009.

In 2015, Pittsburgh was listed among the "eleven most livable cities in the world" by Metropolis magazine.[163][164] The Economist's Global Liveability Ranking placed Pittsburgh as the most or second-most livable city in the United States in 2005, 2009, 2011, 2012, 2014, and 2018.[165][166]

Arts and culture

[edit]Entertainment

[edit]

Pittsburgh has a rich history in arts and culture dating from 19th century industrialists commissioning and donating public works, such as Heinz Hall for the Performing Arts and the Benedum Center, home to the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra and Pittsburgh Opera, respectively as well as such groups as the River City Brass Band and the Pittsburgh Youth Symphony Orchestra.

Pittsburgh has a number of small and mid-size arts organizations including the Pittsburgh Irish and Classical Theatre, Quantum Theatre, the Renaissance and Baroque Society of Pittsburgh, and the early music ensemble Chatham Baroque. Several choirs and singing groups are also present at the cities' universities; some of the most notable include the Pitt Men's Glee Club and the Heinz Chapel Choir.

Pittsburgh Dance Council and the Pittsburgh Ballet Theater host a variety of dance events. Polka, folk, square, and round dancing have a long history in the city and are celebrated by the Duquesne University Tamburitzans, a multicultural academy dedicated to the preservation and presentation of folk songs and dance.

Hundreds of major films have been shot partially or wholly in Pittsburgh. The Dark Knight Rises was largely filmed in Downtown, Oakland, and the North Shore. Pittsburgh is also considered as the birthplace of the modern zombie film genre after George A. Romero directed the 1968 film Night of the Living Dead.[167][168] Pittsburgh has also teamed up with a Los Angeles-based production company, and has built the largest and most advanced movie studio in the eastern United States.[161]

Pittsburgh's major art museums include the Andy Warhol Museum, the Carnegie Museum of Art, The Frick Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, the Mattress Factory, and the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, which has extensive dinosaur, mineral, animal, and Egyptian collections. The Kamin Science Center and associated SportsWorks has interactive technology and science exhibits. The Senator John Heinz History Center and Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum is a Smithsonian affiliated regional history museum in the Strip District and its associated Fort Pitt Museum is in Point State Park. Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall and Museum in Oakland houses Western Pennsylvania military exhibits from the Civil War to present. The Children's Museum of Pittsburgh on the North Side features interactive exhibits for children. The eclectic Bayernhof Music Museum is six miles (9 km) from downtown while The Clemente Museum is in the city's Lawrenceville section. The Cathedral of Learning's Nationality Rooms showcase pre-19th century learning environments from around the world. There are regular guided and self-guided architectural tours in numerous neighborhoods. Downtown's cultural district hosts quarterly Gallery Crawls and the annual Three Rivers Arts Festival. Pittsburgh is home to a number of art galleries and centers including the Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon University, University Art Gallery of the University of Pittsburgh, the American Jewish Museum, and the Wood Street Galleries.

The Pittsburgh Zoo & Aquarium, Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens, and the National Aviary have served the city for over a century. Pittsburgh is home to the amusement park Kennywood. Pittsburgh is home to one of the several state licensed casinos. The Rivers Casino is on the North Shore along the Ohio River, just west of Kamin Science Center and Acrisure Stadium.

Pittsburgh is home to the world's largest furry convention known as Anthrocon, which has been held annually at the David L. Lawrence Convention Center since 2006. In 2017, Anthrocon drew over 7,000 visitors and has had a cumulative economic impact of $53 million over the course of its 11 years of being hosted in Pittsburgh.[169]

Lifetime's reality show, Dance Moms, is filmed at Pittsburgh's Abby Lee Dance Company.

Music

[edit]Pittsburgh has a long tradition of jazz, blues, and bluegrass music. The National Negro Opera Company was founded in the city as the first all African-American opera company in the United States. This led to the prominence of African-American singers like Leontyne Price in the world of opera. One of the greatest American musicians and composers of the 20th century, Billy Strayhorn, grew up and was educated in Pittsburgh, as was pianist/composer-arranger Mary Lou Williams, who composed and recorded an eponymous tribute to her home town in 1966,[170] featuring vocalist Leon Thomas.[171]

Pittsburgh's Wiz Khalifa is a recent artist to have a number one record. His anthem "Black and Yellow" (a tribute to Pittsburgh's official colors) reached number one on Billboard's "Hot 100"[172] for the Week of February 19, 2011.[173] Perry Como and Christina Aguilera are from Pittsburgh suburbs. The city is also where the band Rusted Root was formed. Liz Berlin of Rusted Root owns Mr. Smalls, a popular music venue for touring national acts in Pittsburgh.[174] Hip hop artist Mac Miller was also a Pittsburgh native, with his debut album Blue Slide Park named after the local Frick Park.

Many punk rock and Hardcore punk acts, such as Aus Rotten and Anti-Flag, originated in Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh has also seen many metal bands gain prominence in recent years,[when?] most notably Code Orange, who were nominated for a Grammy. The city was also home to the highly influential math rock band Don Caballero.

Pittsburgh has emerged as a leading city in the United States' heavy metal music scene. Ranking as the third 'most metal city' in a study conducted by MetalSucks,[175] Pittsburgh has earned a reputation for its heavy metal community. Pittsburgh is home to over six-hundred heavy metal bands,[175] as well as heavy metal coffee shops[176] and bars. The city is noted for its doom metal, metalcore, and death metal scenes.

Throughout the 1990s there was an electronic music subculture in Pittsburgh which likely traced its origins to similar Internet chatroom-based movements in Detroit, Cleveland, Minneapolis, and across the United States.[177][178][179] Pittsburgh promoters and DJs organized raves in warehouses, ice rinks, barns, and fields which eventually attracted thousands of attendees, some of whom were high school students or even younger.[178][180][181] As the events grew more popular, they drew internationally known DJs such as Adam Beyer and Richie Hawtin.[178] Pittsburgh rave culture itself spawned at least one well-known artist, the drum and bass DJ Dieselboy, who attended the University of Pittsburgh between 1990 and 1995.[177][182]

Since 2012, Pittsburgh has been the home of Hot Mass, an afterhours electronic music dance party which critics have compared favorably to European nightclubs and parties.[183][184] Electronic music artist and DJ Yaeji credits Hot Mass with her "indoctrination into nightlife"; she regularly attended the party while studying at Carnegie Mellon University.[185][186]

Theatre

[edit]

The city's first play was produced at the old courthouse in 1803[28] and the first theater built in 1812.[28] Collegiate companies include the University of Pittsburgh's Repertory Theatre and Kuntu Repertory Theatre, Point Park University's resident companies at its Pittsburgh Playhouse, and Carnegie Mellon University's School of Drama productions and Scotch'n'Soda organization. The Duquesne University Red Masquers, founded in 1912, are the oldest, continuously producing theater company in Pennsylvania.[citation needed] The city's longest-running theater show, Friday Nite Improvs, is an improv jam that has been performed in the Cathedral of Learning and other locations for 20 years. The Pittsburgh New Works Festival utilizes local theater companies to stage productions of original one-act plays by playwrights from all parts of the country. Similarly, Future Ten showcases new ten-minute plays. Saint Vincent Summer Theatre, Off the Wall Productions, Mountain Playhouse, The Theatre Factory, and Stage Right! in nearby Latrobe, Carnegie, Jennerstown, Trafford, and Greensburg, respectively, employ Pittsburgh actors and contribute to the culture of the region.

Pittsburgh is well known for being home to the late playwright August Wilson.[187] The August Wilson House now remains in Pittsburgh to celebrate the life and work of August Wilson, continue to produce his plays, and serve as an arts center for the Hill District, where Wilson was from.[187]

Literature

[edit]

Pittsburgh is the birthplace of Gertrude Stein and Rachel Carson, a Chatham University graduate from the suburb of Springdale, Pennsylvania.[188] Modern writers include Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright August Wilson[189] and Michael Chabon with his Pittsburgh-focused commentary on student and college life. Two-time Pulitzer Prize winner and recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, David McCullough was born and raised in Pittsburgh.[190] Annie Dillard, a Pulitzer Prize–winning writer, was born and raised in Pittsburgh. Much of her memoir An American Childhood takes place in post-World War II Pittsburgh. Award-winning author John Edgar Wideman grew up in Pittsburgh and has based several of his books, including the memoir Brothers and Keepers, in his hometown. Poet Terrance Hayes, winner of the 2010 National Book Award and a 2014 MacArthur Foundation Fellow, received his MFA from the University of Pittsburgh, where he is a faculty member. Poet Michael Simms, founder of Autumn House Press, resides in the Mount Washington neighborhood of Pittsburgh. Poet Samuel John Hazo, the first poet Laureate of Pennsylvania, resides in the city. Contemporary writers from Pittsburgh include Kathleen Tessaro, author of novels such as "Elegance," "The Perfume Collector," and "Rare Objects," whose works contribute to the city's rich literary tradition. New writers include Chris Kuzneski, who attended the University of Pittsburgh and mentions Pittsburgh in his works, and Pittsburgher Brian Celio, author of Catapult Soul, who captured the Pittsburgh 'Yinzer' dialect in his writing. Pittsburgh's unique literary style extends to playwrights,[191] as well as local graffiti and hip hop artists.

Pittsburgh's position as the birthplace for community owned television and networked commercial television helped spawn the modern children's show genres exemplified by Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?, Happy's Party, Cappelli & Company, and The Children's Corner, all nationally broadcast.

The Pittsburgh Dad series has showcased the Pittsburghese genre to a global YouTube audience since 2011.

The modern fantasy, macabre and science fiction genre was popularized by director George A. Romero, television's Bill Cardille and his Chiller Theatre,[192] director and writer Rusty Cundieff and makeup effects guru Tom Savini.[193] The genre continues today with the PARSEC science fiction organization,[194] The It's Alive Show, the annual "Zombie Fest",[195] and several writer's workshops including Write or Die,[196] Pittsburgh SouthWrites,[197] and Pittsburgh Worldwrights[198][199] with Barton Paul Levenson, Kenneth Chiacchia and Elizabeth Humphreys Penrose.

Food

[edit]

Pittsburgh is known for several specialties including pierogies, kielbasa, chipped chopped ham sandwiches, and Klondike bars.[200][201] In 2019, Pittsburgh was deemed "Food City of the Year" by the San Francisco-based restaurant and hospitality consulting firm af&co.[202] Many restaurants were favorably mentioned, among them were Superior Motors in Braddock, Driftwood Oven in Lawrenceville, Spork in Bloomfield, Fish nor Fowl in Garfield, Bitter Ends Garden & Luncheonette in Bloomfield, and Rolling Pepperoni in Lawrenceville.[203]

Pittsburgh is home to the annual pickle-themed festival Picklesburgh, which has been named the "best specialty food festival in America".[204]

Local dialect

[edit]The Pittsburgh English dialect, commonly called Pittsburghese, was influenced by Scots-Irish, German, and Eastern European immigrants and African Americans.[205] Locals who speak the dialect are sometimes referred to as "Yinzers" (from the local word "yinz" [var. yunz], a blended form of "you ones", similar to "y'all" and "you all" in the South). Common Pittsburghese terms are: "slippy" (slippery), "redd up" (clean up), "jagger bush" (thorn bush), and "gum bands" (rubber bands). The dialect is also notable for dropping the verb "to be". In Pittsburghese one would say "the car needs washed" instead of "needs to be washed", "needs washing", or "needs a wash." The dialect has some tonal similarities to other nearby regional dialects of Erie and Baltimore but is noted for its somewhat staccato rhythms. The staccato qualities of the dialect are thought to originate either from Welsh or other European languages. The many local peculiarities have prompted The New York Times to describe Pittsburgh as "the Galapagos Islands of American dialect".[206] The lexicon itself contains notable loans from Polish and other European languages; examples include babushka, pierogi, and halušky.[207]

Livability

[edit]

Pittsburgh has five city parks and several parks managed by the Nature Conservancy. The largest, Frick Park, provides 664 acres (269 ha) of woodland park with extensive hiking and biking trails throughout steep valleys and wooded slopes. Birding enthusiasts visit the Clayton Hill area of Frick Park, where over 100 species of birds have been recorded.[208]

Residents living in extremely low-lying areas near the rivers or one of the 1,400 creeks and streams may have occasional floods,[209] such as those caused when the remnants of Hurricane Ivan hit rainfall records in 2004.[210] River flooding is relatively rare due to federal flood control efforts extensively managing locks, dams, and reservoirs.[209][211][212] Residents living near smaller tributary streams are less protected from occasional flooding. The cost of a comprehensive flood control program for the region has been estimated at a prohibitive $50 billion.[209]

Pittsburgh has the greatest number of bars per capita in the nation.[18]

Sports

[edit]Pittsburgh hosted the first professional football game and the first World Series. In 2009, Pittsburgh won the Sporting News title of "Best Sports City" in the United States[213] and, in 2013, Sperling's Best Places "top 15 cities for baseball".[214] College sports also have large followings with the University of Pittsburgh in football and sharing Division I basketball fans with Robert Morris and Duquesne.

Pittsburgh has a long history with its major professional sports teams—the Steelers of the National Football League, the Penguins of the National Hockey League, and the Pirates of Major League Baseball—which all share the same team colors, the official city colors of black and gold.[f] Pittsburgh is the only city in the United States where this practice of sharing team colors in solidarity takes place.[215] The black-and-gold color scheme has since become widely associated with the city and personified in its famous Terrible Towel.[216]

The Pittsburgh Riverhounds are a professional soccer team who have been playing in Pittsburgh since they were established in 1999. They are a member of the USL Championship division, a second-tier league of US professional soccer and are in the league's Eastern Conference. The Riverhounds play their home matches at Highmark Stadium (Pennsylvania) a 5,000 seat soccer-specific stadium located in Pittsburgh's Station Square. In keeping with the uniformity of professional sports teams in Pittsburgh, the Riverhounds colors are black and gold.

"Rails to Trails", has converted miles of former rail tracks to recreational trails, including a Pittsburgh-Washington D.C. bike/walking trail.[217] Several mountain biking trails are within the city and suburbs, Frick Park has biking trails and Hartwood Acres Park has many miles of single track trails.[218][219]

Professional

[edit]Major league

| Team | Founded | League | Sport | Venue | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pittsburgh Pirates | 1882 | Major League Baseball (MLB) | Baseball | PNC Park | 7[o 1] |

| Pittsburgh Steelers | 1933 | National Football League (NFL) | Football | Acrisure Stadium | 6[o 2] |

| Pittsburgh Penguins | 1967 | National Hockey League (NHL) | Hockey | PPG Paints Arena | 5[o 3] |

Minor league/other

| Team | Founded | League | Sport | Venue | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pittsburgh Riverhounds | 1999 | USL Championship (USLC) | Soccer | Highmark Stadium | |

| Steel City Yellow Jackets | 2014 | ABA | Basketball | CCAC Allegheny Arena | 1 |

**Pittsburgh's ABA franchise won the 1968 title, but the Steel City Yellow Jackets franchise is heir to it only in location.

College

[edit]Power 5

| School | Prominent sports | Venues | Conference | National Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Pittsburgh | Pitt Football (FBS) | Acrisure Stadium | ACC | 9[o 1] |

| Pitt Basketball | Petersen Events Center | 1927–28 1929–30 |

Other

| School | Prominent sports | Venues | Conference | National Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duquesne University | Dukes Football (FCS) | Art Rooney Field | NEC | 1941, 1973, 2003 |

| Dukes Basketball | UPMC Cooper Fieldhouse | A10 | 1954–55 (NIT) | |

| Robert Morris University | Colonials Basketball | UPMC Events Center | NEC | |

| Colonials Hockey | Island Sports Center | AHA |

Baseball

[edit]

[t]his is the perfect blend of location, history, design, comfort and baseball ... The best stadium in baseball is in Pittsburgh.

ESPN

The Pittsburgh Pirates baseball team, often referred to as the Bucs or the Buccos (derived from buccaneer), is the city's oldest professional sports franchise, having been founded in 1881, and plays in the Central Division of the National League. The Pirates are nine-time Pennant winners and five-time World Series Champions, were in the first World Series (1903) and claim two pre-World Series titles in 1901 and 1902. The Pirates play in PNC Park.

Pittsburgh also has a rich Negro league history, with the former Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Homestead Grays credited with as many as 14 league titles and 11 Hall of Famers between them in the 1930s and 1940s, while the Keystones fielded teams in the 1920s. In addition, in 1971 the Pirates were the first Major League team to field an all-minority lineup. One sportswriter claimed, "No city is more synonymous with black baseball than Pittsburgh."[220]

Since the late 20th century, the Pirates had three consecutive National League Championship Series appearances (1990–92) (going 6, 7 and 7 games each), followed by setting the MLB record for most consecutive losing seasons, with 20 from 1993 until 2012. This era was followed by three consecutive postseason appearances: the 2013 National League Division Series and the 2014–2015 Wild Card games. Their September pennant race in 1997 featured the franchises' last no-hitter and last award for Sporting News' Executive of the Year.[221]

Football

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2017) |

The city's professional team, NFL's Pittsburgh Steelers, is named after the distribution company the Pittsburgh Steeling company established in 1927. News of the team has preempted news of elections and other events and are important to the region and its diaspora. The Steelers have been owned by the Rooney family since the team's founding in 1933, show consistency in coaching (only three coaches since the 1960s all with the same basic philosophy) and are noted as one of sports' most respectable franchises.[222] The Steelers have a long waiting list for season tickets, and have sold out every home game since 1972.[223] The team won four Super Bowls in a six-year span in the 1970s, a fifth Super Bowl in 2006, and a league record sixth Super Bowl in 2009. Since the AFL-NFL merger in 1970 they have qualified for the most NFL playoff berths (28) and have played in (15) and hosted (11) the most NFL conference championship games.[citation needed]

High school football routinely attract 10,000 fans per game and extensive press coverage.[citation needed] The Tom Cruise film All the Right Moves and ESPN's Bound for Glory with Dick Butkus both filmed in the area to capture the tradition and passion of local high school football.

College football in the city dates to 1889[224] with the Division I (FBS) Panthers of the University of Pittsburgh posting nine national championships, qualifying 37 total bowl games, appearing in the 2018 ACC Championship Game, and winning the 2020 ACC Championship Game which was the program's first conference title since leaving the Big East for the ACC between the 2012 and 2013 seasons.[225] Local universities Duquesne and Robert Morris have loyal fan bases that follow their lower (FCS) teams. Duquesne, Carnegie Mellon University, and Washington & Jefferson College all posted major bowl games and AP Poll rankings from the 1920s to the 1940s as that era's equivalent of Top 25 FBS programs.[citation needed]

Acrisure Stadium serves as home for the Steelers, Panthers, and both the suburban and city high school championships. Playoff franchises Pittsburgh Power and Pittsburgh Gladiators competed in the Arena Football League in the 1980s and 2010s respectively. The Gladiators hosted ArenaBowl I in the city, competing in two, but losing both before moving to Tampa, Florida and becoming the Storm.[226] The Pittsburgh Passion has been the city's professional women's football team since 2002 and plays its home games at Highmark Stadium. The Ed Debartolo owned Pittsburgh Maulers featured a Heisman Trophy winner in the mid-1980s, former superstar University of Nebraska running back Mike Rozier.

Hockey

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2015) |

The NHL's Pittsburgh Penguins have played in Pittsburgh since the team's founding in 1967. The team has won 6 Eastern Conference titles (1991, 1992, 2008, 2009, 2016 and 2017) and 5 Stanley Cup championships (1991, 1992, 2009, 2016 and 2017). Since 1999, Hall of Famer and back-to-back playoff MVP Mario Lemieux has served as Penguins owner. Until moving into the PPG Paints Arena in 2010 (when it was known as Consol Energy Center), the team played their home games at the world's first retractable domed stadium, the Civic Arena, or in local parlance "The Igloo".[227]

Ice hockey has had a regional fan base since the 1890s semi-pro Keystones. The city's first ice rink dates back to 1889, when there was an ice rink at the Casino in Schenley Park. From 1896 to 1956, the Exposition Building on the Allegheny River near The Point and Duquesne Gardens in Oakland offered indoor skating.[228]

The NHL awarded one of its first franchises to the city in 1924 on the strength of the back-to-back USAHA championship winning Pittsburgh Yellow Jackets featuring future Hall of Famers and a Stanley Cup winning coach. The NHL's Pittsburgh Pirates made several Stanley Cup playoff runs with a future Hall of Famer before folding from Great Depression financial pressures. Hockey survived with the Pittsburgh Hornets farm team (1936–1967) and their seven finals appearances and three championships in 18 playoff seasons.

Robert Morris University fields a Division I college hockey team at the Island Sports Center. Pittsburgh has semi-pro and amateur teams such as the Pittsburgh Penguins Elite.[229] Pro-grade ice rinks such as the Rostraver Ice Garden, Mt. Lebanon Recreation Center and Iceoplex at Southpointe have trained several native Pittsburgh players for NHL play. RMU hosted the city's first Frozen Four college championship in 2013 with the four PPG Paints Arena games televised by ESPN.

Basketball

[edit]

Professional basketball in Pittsburgh dates to the 1910s with teams "Monticello" and "Loendi" winning five national titles, the Pirates (1937–45 in the NBL), the Pittsburgh Ironmen (1947–48 NBA inaugural season), the Pittsburgh Rens (1961–63), the Pittsburgh Pipers (first American Basketball Association championship in 1968) led by Connie Hawkins (team then moved); the Pittsburgh Condors (ABA returned in 1970–72), the Pittsburgh Piranhas (CBA Finals in 1995), the Pittsburgh Xplosion (2004–08) and Phantoms (2009–10) both of the ABA. The city has hosted dozens of pre-season and 15 regular season "neutral site" NBA games, including Wilt Chamberlain's record setting performance in both consecutive field goals and field goal percentage on February 24, 1967, NBA records that still stand.[230]

The Duquesne University Dukes and the University of Pittsburgh Panthers have played college basketball in the city since 1914 and 1905 respectively. Pitt and Duquesne have played the annual City Game since 1932. Duquesne was the city's first team to appear in a Final Four (1940), obtain a number one AP Poll ranking (1954),[231] and to win a post-season national title, the 1955 National Invitation Tournament on its second straight trip to the NIT title game. Duquesne is the only college program to produce back-to-back NBA No. 1 overall draft picks with 1955's Dick Ricketts and 1956's Sihugo Green.[232] Duquesne's Chuck Cooper was the first African American drafted by an NBA team.[233]