Карл III

| Карл III | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Глава Содружества [ а ] | |||||

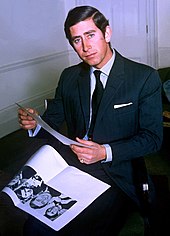

Карл III в 2023 году | |||||

| Король Соединенного Королевства и другие сферы Содружества [ б ] | |||||

| Царствование | 8 сентября 2022 г. – настоящее время | ||||

| Коронация | 6 мая 2023 г. | ||||

| Предшественник | Елизавета II | ||||

| Наследник | Уильям, принц Уэльский | ||||

| Рожденный | Принц Чарльз Эдинбургский 14 ноября 1948 г. Букингемский дворец , Лондон, Англия | ||||

| Супруги | |||||

| Проблема Деталь | |||||

| |||||

| Дом | Виндзор | ||||

| Отец | Принц Филипп, герцог Эдинбургский | ||||

| Мать | Елизавета II | ||||

| Религия | протестант [ д ] | ||||

| Подпись |  | ||||

| Образование | Школа Гордонстоун | ||||

| Альма-матер | Тринити-колледж, Кембридж ( Массачусетс ) | ||||

| Военная карьера | |||||

| Верность | Великобритания | ||||

| Услуга/ | |||||

| Лет активной службы | 1971–1976 | ||||

| Классифицировать | Полный список | ||||

| Команды удержаны | HMS Бронингтон | ||||

| Королевская семья Соединенное Королевство и другие сферы Содружества |

|---|

Чарльз III (Чарльз Филип Артур Джордж; родился 14 ноября 1948 года) — король Соединенного Королевства и 14 других королевств Содружества . [ б ]

Чарльз родился в Букингемском дворце во время правления своего деда по материнской линии, короля Георга VI , и стал прямым наследником, когда его мать, королева Елизавета II , взошла на престол в 1952 году. он был провозглашен принцем Уэльским В 1958 году его инвеститура. , и была проведена в 1969 году. Он получил образование в школах Чим и Гордонстоун , а затем провел шесть месяцев в Тимбертоп кампусе гимназии Джилонга в Виктории, Австралия. После получения степени по истории в Кембриджском университете Чарльз служил в Королевских ВВС и Королевском флоте с 1971 по 1976 год. В 1981 году он женился на леди Диане Спенсер . У них было два сына, Уильям и Гарри . Чарльз и Диана развелись в 1996 году, после того как каждый из них вступил в широко разрекламированные внебрачные связи. Диана умерла в результате травм, полученных в автокатастрофе в следующем году. В 2005 году Чарльз женился на своей давней партнерше Камилле Паркер-Боулз .

Как наследник, Чарльз взял на себя официальные обязанности и обязательства от имени своей матери. Он основал Фонд принца в 1976 году, спонсировал благотворительные организации принца и стал покровителем или президентом более чем 800 других благотворительных организаций и организаций. Он выступал за сохранение исторических зданий и важность архитектуры в обществе. В этом духе он создал экспериментальный новый город Паундбери . Защитник окружающей среды, Чарльз поддерживал органическое сельское хозяйство и действия по предотвращению изменения климата во время своего пребывания на посту управляющего поместьями герцогства Корнуолл , что принесло ему награды и признание, а также критику; он также является известным критиком использования генетически модифицированных продуктов питания , в то время как его поддержка альтернативной медицины подвергалась критике. Он является автором или соавтором 17 книг .

Чарльз стал королем после смерти своей матери в 2022 году. В возрасте 73 лет он был самым старым человеком, вступившим на британский престол, после того как он был наследником и принцем Уэльским в британской истории дольше всех. Важными событиями в его правление стали его коронация в 2023 году и диагноз рака в следующем году, последнее из которых временно приостановило запланированные публичные мероприятия.

Ранняя жизнь, семья и образование

Чарльз родился в 21:14 ( GMT ) 14 ноября 1948 года. [ 3 ] во время правления его деда по материнской линии, короля Георга VI , как первого ребенка принцессы Елизаветы, герцогини Эдинбургской (впоследствии королевы Елизаветы II) и Филиппа, герцога Эдинбургского . [ 4 ] Он был доставлен с помощью кесарева сечения в Букингемском дворце. [ 5 ] У его родителей было еще трое детей: Энн (1950 г.р.), Эндрю (1960 г.р.) и Эдвард (1964 г.р.). Он был крещен Чарльзом Филипом Артуром Джорджем 15 декабря 1948 года в Музыкальном зале Букингемского дворца архиепископом Кентерберийским Фишером Джеффри . [ и ] [ ж ] [ 9 ] [ 10 ]

Георг VI умер 6 февраля 1952 года, и мать Чарльза взошла на престол как Елизавета II; Чарльз немедленно стал наследником . Согласно хартии Эдуарда III в 1337 году, как старший сын монарха, он автоматически принял традиционные титулы герцога Корнуолла , а в шотландском пэрстве — титулы герцога Ротсейского , графа Каррика , барона Ренфрю , лорда Острова , а также принц и великий управляющий Шотландии . [ 11 ] В следующем году Чарльз присутствовал на коронации своей матери в Вестминстерском аббатстве . [ 12 ]

Когда Чарльзу исполнилось пять лет, гувернантка, известная как Кэтрин Пиблс, была назначена курировать его образование в Букингемском дворце. [ 13 ] Затем в ноябре 1956 года он начал занятия в школе Hill House в западном Лондоне . [ 14 ] Чарльз был первым наследником, который посещал школу, а не получал образование у частного репетитора. [ 15 ] Он не пользовался привилегиями со стороны основателя и директора школы Стюарта Тауненда , который посоветовал королеве тренировать Чарльза футболом , потому что мальчики никогда не проявляли почтительности ни к кому на футбольном поле. [ 16 ] Впоследствии Чарльз посещал две бывшие школы своего отца: Cheam School в Хэмпшире, [ 17 ] с 1958 года, [ 18 ] за ним последовал Гордонстоун на северо-востоке Шотландии, где занятия начались в апреле 1962 года. [ 18 ] [ 19 ] Позже он стал покровителем Гордонстоуна в мае 2024 года. [ 20 ]

В его официальной биографии Джонатана Димблби 1994 года родители Чарльза были описаны как физически и эмоционально далекие, а Филиппа обвиняли в игнорировании чувствительной натуры Чарльза, включая принуждение его посещать Гордонстоун, где над ним издевались. [ 21 ] Хотя Чарльз, как сообщается, охарактеризовал Гордонстоун, известный своей особенно строгой учебной программой, как « Кольдиц в килтах », [ 17 ] Позже он похвалил школу, заявив, что она научила его «многому обо мне, моих собственных способностях и недостатках». В интервью 1975 года он сказал, что «рад», что посетил Гордонстоун, и что «крутость этого места» была «сильно преувеличена». [ 22 ] В 1966 году Чарльз провел два семестра в Тимбертоп кампусе гимназии Джилонга в Виктории, Австралия, во время которых он посетил Папуа-Новую Гвинею во время школьной поездки со своим учителем истории Майклом Коллинзом Перссом. [ 23 ] [ 24 ] В 1973 году Чарльз описал время, проведенное в Тимбертопе, как самую приятную часть всего своего образования. [ 25 ] По возвращении в Гордонстоун он подражал своему отцу, став старостой , и ушел в 1967 году, получив шесть уровней GCE O и два уровня A по истории и французскому языку, на оценки B и C соответственно. [ 23 ] [ 26 ] On his education, Charles later remarked, "I didn't enjoy school as much as I might have; but, that was only because I'm happier at home than anywhere else".[22]

Charles broke royal tradition when he proceeded straight to university after his A-levels, rather than joining the British Armed Forces.[17] In October 1967, he was admitted to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied archaeology and anthropology for the first part of the Tripos and then switched to history for the second part.[9][23][27] During his second year, he attended the University College of Wales in Aberystwyth, studying Welsh history and the Welsh language for one term.[23] Charles became the first British heir apparent to earn a university degree, graduating in June 1970 from the University of Cambridge with a 2:2 Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree.[23][28] Following standard practice, in August 1975, his Bachelor of Arts was promoted to a Master of Arts (MA Cantab) degree.[23]

Prince of Wales

Charles was created Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester on 26 July 1958,[29] though his investiture was not held until 1 July 1969, when he was crowned by his mother in a televised ceremony held at Caernarfon Castle;[30] the investiture was controversial in Wales owing to growing Welsh nationalist sentiment.[31] He took his seat in the House of Lords the following year[32] and he delivered his maiden speech on 13 June 1974,[33] the first royal to speak from the floor since the future Edward VII in 1884.[34] He spoke again in 1975.[35]

Charles began to take on more public duties, founding the Prince's Trust in 1976[36] and travelling to the United States in 1981.[37] In the mid-1970s, he expressed an interest in serving as governor-general of Australia, at the suggestion of Australian prime minister Malcolm Fraser; however, because of a lack of public enthusiasm, nothing came of the proposal.[38] In reaction, Charles commented, "so, what are you supposed to think when you are prepared to do something to help and you are just told you're not wanted?"[39]

Military training and career

Charles served in the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Royal Navy. During his second year at Cambridge, he received Royal Air Force training, learning to fly the Chipmunk aircraft with the Cambridge University Air Squadron,[40][41] and was presented with his RAF wings in August 1971.[42]

After the passing-out parade that September, Charles embarked on a naval career and enrolled in a six-week course at the Royal Naval College Dartmouth. He then served from 1971 to 1972 on the guided-missile destroyer HMS Norfolk and the frigates HMS Minerva, from 1972 to 1973, and HMS Jupiter in 1974. That same year, he also qualified as a helicopter pilot at RNAS Yeovilton and subsequently joined 845 Naval Air Squadron, operating from HMS Hermes.[43] Charles spent his last 10 months of active service in the Navy commanding the coastal minehunter HMS Bronington, beginning on 9 February 1976.[43] He took part in a parachute training course at RAF Brize Norton two years later, after being appointed colonel-in-chief of the Parachute Regiment in 1977.[44] Charles gave up flying after crash-landing a BAe 146 in Islay in 1994, as a passenger who was invited to fly the aircraft; the crew was found negligent by a board of inquiry.[45]

Relationships and marriages

Bachelorhood

In his youth, Charles was amorously linked to a number of women. His girlfriends included Georgiana Russell, the daughter of Sir John Russell, who was the British ambassador to Spain;[46] Lady Jane Wellesley, the daughter of the 8th Duke of Wellington;[47] Davina Sheffield;[48] Lady Sarah Spencer;[49] and Camilla Shand, who later became his second wife.[50]

Charles's great-uncle Lord Mountbatten advised him to "sow his wild oats and have as many affairs as he can before settling down", but, for a wife, he "should choose a suitable, attractive, and sweet-charactered girl before she has met anyone else she might fall for ... It is disturbing for women to have experiences if they have to remain on a pedestal after marriage".[51] Early in 1974, Mountbatten began corresponding with 25-year-old Charles about a potential marriage to Amanda Knatchbull, Mountbatten's granddaughter.[52] Charles wrote to Amanda's mother, Lady Brabourne, who was also his godmother, expressing interest in her daughter. Lady Brabourne replied approvingly, but suggested that a courtship with a 16-year-old was premature.[53] Four years later, Mountbatten arranged for Amanda and himself to accompany Charles on his 1980 visit to India. Both fathers, however, objected; Prince Philip feared that his famous uncle[g] would eclipse Charles, while Lord Brabourne warned that a joint visit would concentrate media attention on the cousins before they could decide on becoming a couple.[54]

In August 1979, before Charles would depart alone for India, Mountbatten was assassinated by the Irish Republican Army. When Charles returned, he proposed to Amanda. But in addition to her grandfather, she had lost her paternal grandmother and younger brother in the bomb attack and was now reluctant to join the royal family.[54]

Lady Diana Spencer

Charles first met Lady Diana Spencer in 1977, while he was visiting her home, Althorp. He was then the companion of her elder sister Sarah and did not consider Diana romantically until mid-1980. While Charles and Diana were sitting together on a bale of hay at a friend's barbecue in July, she mentioned that he had looked forlorn and in need of care at the funeral of his great-uncle Lord Mountbatten. Soon, according to Dimbleby, "without any apparent surge in feeling, he began to think seriously of her as a potential bride" and she accompanied Charles on visits to Balmoral Castle and Sandringham House.[55]

Charles's cousin Norton Knatchbull and his wife told Charles that Diana appeared awestruck by his position and that he did not seem to be in love with her.[56] Meanwhile, the couple's continuing courtship attracted intense attention from the press and paparazzi. When Charles's father told him that the media speculation would injure Diana's reputation if Charles did not come to a decision about marrying her soon, and realising that she was a suitable royal bride (according to Mountbatten's criteria), Charles construed his father's advice as a warning to proceed without further delay.[57] He proposed to Diana in February 1981, with their engagement becoming official on 24 February; the wedding took place in St Paul's Cathedral on 29 July. Upon his marriage, Charles reduced his voluntary tax contribution from the profits of the Duchy of Cornwall from 50 per cent to 25 per cent.[58] The couple lived at Kensington Palace and Highgrove House, near Tetbury, and had two children: William, in 1982, and Harry, in 1984.[15]

Within five years, the marriage was in trouble due to the couple's incompatibility and near 13-year age difference.[59][60] In 1986, Charles had fully resumed his affair with Camilla Parker Bowles.[61] In a videotape recorded by Peter Settelen in 1992, Diana admitted that, from 1985 to 1986, she had been "deeply in love with someone who worked in this environment."[62][63] It was assumed that she was referring to Barry Mannakee,[64] who had been transferred to the Diplomatic Protection Squad in 1986, after his managers determined his relationship with Diana had been inappropriate.[63][65] Diana later commenced a relationship with Major James Hewitt, the family's former riding instructor.[66]

Charles and Diana's evident discomfort in each other's company led to them being dubbed "The Glums" by the press.[67] Diana exposed Charles's affair with Parker Bowles in a book by Andrew Morton, Diana: Her True Story. Audio tapes of her own extramarital flirtations also surfaced,[67] as did persistent suggestions that Hewitt is Prince Harry's father, based on a physical similarity between Hewitt and Harry. However, Harry had already been born by the time Diana's affair with Hewitt began.[68]

In December 1992, John Major announced the couple's legal separation in the House of Commons. Early the following year, the British press published transcripts of a passionate, bugged telephone conversation between Charles and Parker Bowles that had taken place in 1989, which was dubbed "Camillagate" and "Tampongate".[69] Charles subsequently sought public understanding in a television film with Dimbleby, Charles: The Private Man, the Public Role, broadcast in June 1994. In an interview in the film, Charles confirmed his own extramarital affair with Parker Bowles, saying that he had rekindled their association in 1986, only after his marriage to Diana had "irretrievably broken down".[70][71] This was followed by Diana's own admission of marital troubles in an interview on the BBC current affairs show Panorama, broadcast in November 1995.[72] Referring to Charles's relationship with Parker Bowles, she said, "well, there were three of us in this marriage. So, it was a bit crowded." She also expressed doubt about her husband's suitability for kingship.[73] Charles and Diana divorced on 28 August 1996,[74] after being advised by the Queen in December 1995 to end the marriage.[75] The couple shared custody of their children.[76]

Diana was killed in a car crash in Paris on 31 August 1997. Charles flew to Paris with Diana's sisters to accompany her body back to Britain.[77] In 2003 Diana's butler Paul Burrell published a note that he claimed had been written by Diana in 1995, in which there were allegations that Charles was "planning 'an accident' in [Diana's] car, brake failure and serious head injury", so that he could remarry.[78] When questioned by the Metropolitan Police inquiry team as a part of Operation Paget, Charles told the authorities that he did not know about his former wife's note from 1995 and could not understand why she had those feelings.[79]

Camilla Parker Bowles

In 1999 Charles and Parker Bowles made their first public appearance as a couple at the Ritz London Hotel, and she moved into Charles’s official residence, Clarence House, in 2003.[80][81] Their engagement was announced on 10 February 2005.[82] The Queen's consent to the marriage – as required by the Royal Marriages Act 1772 – was recorded in a Privy Council meeting on 2 March.[83] In Canada, the Department of Justice determined the consent of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada was not required, as the union would not produce any heirs to the Canadian throne.[84]

Charles was the only member of the royal family to have a civil, rather than a church, wedding in England. British government documents from the 1950s and 1960s, published by the BBC, stated that such a marriage was illegal; these claims were dismissed by Charles's spokesman[85] and explained by the sitting government to have been repealed by the Registration Service Act 1953.[86]

The union was scheduled to take place in a civil ceremony at Windsor Castle, with a subsequent religious blessing at the castle's St George's Chapel. The wedding venue was changed to Windsor Guildhall after it was realised a civil marriage at Windsor Castle would oblige the venue to be available to anyone who wished to be married there. Four days before the event, it was postponed from the originally scheduled date of 8 April until the following day in order to allow Charles and some of the invited dignitaries to attend the funeral of Pope John Paul II.[87]

Charles's parents did not attend the marriage ceremony; the Queen's reluctance to attend possibly arose from her position as Supreme Governor of the Church of England.[88] However, his parents did attend the service of blessing and held a reception for the newlyweds at Windsor Castle.[89] The blessing by Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams was televised.[90]

Official duties

In 1965 Charles undertook his first public engagement by attending a student garden party at the Palace of Holyroodhouse.[91] During his time as Prince of Wales, he undertook official duties on behalf of the Queen,[92] completing 10,934 engagements between 2002 and 2022.[93] He officiated at investitures and attended the funerals of foreign dignitaries.[94] Charles made regular tours of Wales, fulfilling a week of engagements each summer, and attending important national occasions, such as opening the Senedd.[95] The six trustees of the Royal Collection Trust met three times a year under his chairmanship.[96] Charles also represented his mother at the independence celebrations in Fiji in 1970,[97] The Bahamas in 1973,[98] Papua New Guinea in 1975,[99] Zimbabwe in 1980,[100] and Brunei in 1984.[101]

In 1983 Christopher John Lewis, who had fired a shot with a .22 rifle at the Queen in 1981, attempted to escape a psychiatric hospital in order to assassinate Charles, who was visiting New Zealand with Diana and William.[102] While Charles was visiting Australia on Australia Day in January 1994, David Kang fired two shots at him from a starting pistol in protest of the treatment of several hundred Cambodian asylum seekers held in detention camps.[103] In 1995, Charles became the first member of the royal family to visit the Republic of Ireland in an official capacity.[104] In 1997, he represented the Queen at the Hong Kong handover ceremony.[105][106]

At the funeral of Pope John Paul II in 2005, Charles caused controversy when he shook hands with the president of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, who had been seated next to him. Charles's office subsequently released a statement saying that he could not avoid shaking Mugabe's hand and that he "finds the current Zimbabwean regime abhorrent".[107]

Charles represented the Queen at the opening ceremony of the 2010 Commonwealth Games in Delhi, India.[108] In November 2010, he and Camilla were indirectly involved in student protests when their car was attacked by protesters.[109] In November 2013, he represented the Queen for the first time at a Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, in Colombo, Sri Lanka.[110]

Charles and Camilla made their first joint trip to the Republic of Ireland in May 2015. The British Embassy called the trip an important step in "promoting peace and reconciliation".[111] During the trip, he shook hands in Galway with Gerry Adams, leader of Sinn Féin and widely believed to be the leader of the IRA, the militant group that had assassinated Lord Mountbatten in 1979. The event was described by the media as a "historic handshake" and a "significant moment for Anglo-Irish relations".[112]

Commonwealth heads of government decided at their 2018 meeting that Charles would be the next Head of the Commonwealth after the Queen.[113] The head is chosen and therefore not hereditary.[114] In March 2019, at the request of the British government, Charles and Camilla went on an official tour of Cuba, making them the first British royals to visit the country. The tour was seen as an effort to form a closer relationship between Cuba and the United Kingdom.[115]

Charles contracted COVID-19 during the pandemic in March 2020.[116][117] Several newspapers were critical that Charles and Camilla were tested promptly at a time when many NHS doctors, nurses and patients had been unable to be tested expeditiously.[118] He tested positive for COVID-19 for a second time in February 2022.[119] He and Camilla, who also tested positive, had received doses of a COVID-19 vaccine in February 2021.[120]

Charles attended the November 2021 ceremonies to mark Barbados's transition into a parliamentary republic, abolishing the position of monarch of Barbados.[121] He was invited by Prime Minister Mia Mottley as the future Head of the Commonwealth;[122] it was the first time that a member of the royal family attended the transition of a realm to a republic.[123] In May of the following year, Charles attended the State Opening of the British Parliament, delivering the Queen's Speech on behalf of his mother, as a counsellor of state.[124]

Reign

Charles acceded to the British throne on his mother's death on 8 September 2022. He was the longest-serving British heir apparent, having surpassed Edward VII's record of 59 years on 20 April 2011.[125] Charles was the oldest person to succeed to the British throne, at the age of 73. The previous record holder, William IV, was 64 when he became king in 1830.[126]

Charles gave his first speech to the nation at 6 pm on 9 September, in which he paid tribute to his mother and announced the appointment of his elder son, William, as Prince of Wales.[127] The following day, the Accession Council publicly proclaimed Charles as king, the ceremony being televised for the first time.[128][113] Attendees included Queen Camilla, Prince William, and the British prime minister, Liz Truss, along with her six living predecessors.[129] The proclamation was also read out by local authorities around the United Kingdom. Other realms signed and read their own proclamations, as did Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, British Overseas Territories, Crown Dependencies, Canadian provinces, and Australian states.[130]

In 2023, the King asked for the profits from Britain's growing fleet of offshore windfarms to be used for the "wider public good" rather than as extra funding for the monarchy and it was also announced that the funding of the monarchy would be reduced to 12% of the Crown Estate's net profits.[131][132]

Charles and Camilla's coronation took place at Westminster Abbey on 6 May 2023.[133] Plans had been made for many years, under the code name Operation Golden Orb.[134][135] Reports before his accession suggested that Charles's coronation would be simpler than his mother's in 1953,[136] with the ceremony expected to be "shorter, smaller, less expensive, and more representative of different faiths and community groups – falling in line with the King's wish to reflect the ethnic diversity of modern Britain".[137] Nonetheless, the coronation was a Church of England rite, including the coronation oath, the anointment, delivery of the orb, and enthronement.[138] In July that year, they attended a national service of thanksgiving where Charles was presented with the Honours of Scotland in St Giles' Cathedral.[139]

Charles and Camilla have engaged in three state visits and received three. In November 2022 they hosted the South African president, Cyril Ramaphosa, during the first official state visit to Britain of Charles's reign.[140] In March the following year, the King and Queen embarked on a state visit to Germany; Charles became the first British monarch to address the Bundestag.[141] Similarly, in September, he became the first British monarch to give a speech from France's Senate chamber during his state visit to the country.[142] The following month, the King visited Kenya where he faced pressure to apologise for British colonial actions. In a speech at the state banquet, he acknowledged "abhorrent and unjustifiable acts of violence", but did not formally apologise.[143]

In May 2024, the British prime minister Rishi Sunak asked the King to call a general election; subsequently royal engagements which could divert attention from the election campaign were postponed.[144] In June 2024, Charles and Camilla travelled to Normandy to attend the 80th anniversary commemorations of D-Day.[145] The same month, he received Emperor Naruhito of Japan during the latter's state visit to the United Kingdom.[146] In July the annual Holyrood Week, which is usually spent in Scotland, was shortened so that Charles could return to London and appoint a new prime minister following the general election.[147] After Sunak's Conservatives lost the election to the Labour Party led by Sir Keir Starmer, Charles appointed Starmer as prime minister.[148]

Health

In March 1998, Charles had laser keyhole surgery on his right knee.[149] In March 2003 he underwent surgery at King Edward VII's Hospital to treat a hernia injury.[150] In 2008 a non-cancerous growth was removed from his nasal bridge.[149]

In January 2024, Charles underwent a "corrective procedure" at the London Clinic to treat benign prostate enlargement, which resulted in the postponement of some of his public engagements.[151] In February, Buckingham Palace announced that cancer had been discovered during the treatment, but that it was not prostate cancer. Although his public duties were postponed, it was reported Charles would continue to fulfil his constitutional functions during his outpatient treatment.[152] He released a statement espousing his support for cancer charities and that he "remain[ed] positive" on making a full recovery.[153] In March, Camilla deputised for him in his absence at the Commonwealth Day service at Westminster Abbey and at the Royal Maundy at Worcester Cathedral.[154][155] He made his first major public appearance since his cancer diagnosis at the Easter service held at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, on 31 March.[156] In April 2024, it was announced that he would resume public-facing duties after making progress in his cancer treatment.[157][158]

Diet

As early as 1985, Charles was questioning meat consumption. In the 1985 Royal Special television programme, he told host Alastair Burnet that "I actually now don't eat as much meat as I used to. I eat more fish." He also pointed out the societal double standard whereby eating meat is not questioned but eating less meat means "all hell seems to break loose."[159] In 2021, Charles spoke to the BBC about the environment and revealed that, two days per week, he eats no meat nor fish and, one day per week, he eats no dairy products.[160] In 2022, it was reported that he eats a breakfast of fruit salad, seeds, and tea. He does not eat lunch, but takes a break for tea at 5:00 p.m. and eats dinner at 8:30 p.m., returning to work until midnight or after.[161] Ahead of Christmas dinner in 2022, Charles confirmed to animal rights group PETA that foie gras would not be served at any royal residences; he had stopped the use of foie gras at his own properties for more than a decade before becoming king.[162] During a September 2023 state banquet at the Palace of Versailles, it was reported that Charles did not want foie gras or out-of-season asparagus on the menu. Instead he was served lobster. Charles does not like chocolate, coffee, or garlic.[163]

Charity work

Since founding the Prince's Trust in 1976, using his £7,500 of severance pay from the Navy,[164] Charles has established 16 more charitable organisations and now serves as president of each.[165][92] Together, they form a loose alliance, the Prince's Charities, which describes itself as "the largest multi-cause charitable enterprise in the United Kingdom, raising over £100 million annually ... [and is] active across a broad range of areas including education and young people, environmental sustainability, the built environment, responsible business and enterprise, and international".[165] As Prince of Wales, Charles became patron or president of over 800 other charities and organisations.[91]

The Prince's Charities Canada was established in 2010, in a similar fashion to its namesake in Britain.[166] Charles uses his tours of Canada as a way to help draw attention to youth, the disabled, the environment, the arts, medicine, the elderly, heritage conservation, and education.[167] He has also set up the Prince's Charities Australia, based in Melbourne, to provide a coordinating presence for his Australian and international charitable endeavours.[168]

Charles has supported humanitarian projects; for example, he and his sons took part in ceremonies that marked the 1998 International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.[167] Charles was one of the first public figures to express strong concerns about the human rights record of the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu, initiating objections in the international arena,[169] and subsequently supported the FARA Foundation,[9] a charity for Romanian orphans and abandoned children.[170]

Investigations of donations

Two of Charles's charities, the Prince's Foundation and the Prince of Wales's Charitable Fund (later renamed the King's Foundation and King Charles III Charitable Fund, respectively), came under scrutiny in 2021 and 2022 for accepting donations the media deemed inappropriate. In August 2021, it was announced that the Prince's Foundation was launching an investigation into the reports,[171] with Charles's support.[172] The Charity Commission also launched an investigation into allegations that the donations meant for the Prince's Foundation had been instead sent to the Mahfouz Foundation.[173] In February 2022, the Metropolitan Police launched an investigation into the cash-for-honours allegations linked to the foundation,[174] passing their evidence to the Crown Prosecution Service for deliberation in October.[175] In August 2023, the Metropolitan Police announced that they had concluded their investigations and no further actions would be taken.[176]

The Times reported in June 2022 that, between 2011 and 2015, Charles accepted €3 million in cash from Qatari prime minister Hamad bin Jassim bin Jaber Al Thani.[177][178] There was no evidence that the payments were illegal or that it was not intended for the money to go to the charity,[178] although, the Charity Commission stated it would review the information[179] and announced in July 2022 that there would be no further investigation.[180] In the same month, The Times reported that the Prince of Wales's Charitable Fund received a donation of £1 million from Bakr bin Laden and Shafiq bin Laden – both half-brothers of Osama bin Laden – during a private meeting in 2013.[181][182] The Charity Commission described the decision to accept donations as a "matter for trustees" and added that no investigation was required.[183]

Personal interests

From young adulthood, Charles encouraged understanding of Indigenous voices, claiming they held crucial messages about preservation of the land, respecting community and shared values, resolving conflict, and recognising and making good on past iniquities.[184] He dovetailed this view with his efforts against climate change,[185] as well as reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples and his charitable work in Canada.[186][187] At CHOGM 2022, Charles, who was representing his mother, raised that reconciliation process as an example for dealing with the history of slavery in the British Empire,[188] for which he expressed his sorrow.[189]

Letters sent by Charles to government ministers in 2004 and 2005 expressing his concerns over various policy issues – the so-called black spider memos – presented potential embarrassment following a challenge by The Guardian newspaper to release the letters under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. In March 2015, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom decided that Charles's letters must be released.[190] The Cabinet Office published the letters in May 2015.[191] The reaction was largely supportive of Charles, with little criticism of him;[192] the press variously described the memos as "underwhelming"[193] and "harmless",[194] and concluded that their release had "backfired on those who seek to belittle him".[195] It was revealed in the same year that Charles had access to confidential Cabinet papers.[196]

In October 2020, a letter sent by Charles to the governor-general of Australia, Sir John Kerr, after Kerr's dismissal of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam in 1975, was released as part of the collection of palace letters regarding the Australian constitutional crisis.[197] In the letter, Charles was supportive of Kerr's decision, writing that what Kerr "did last year was right and the courageous thing to do".[197]

The Times reported in June 2022 that Charles had privately described the British government's Rwanda asylum plan as "appalling" and he feared that it would overshadow the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Rwanda that same month.[198] It was later claimed that Cabinet ministers had warned Charles to avoid making political comments, as they feared a constitutional crisis could arise if he continued to make such statements once he became king.[199][200]

Built environment

Charles has openly expressed his views on architecture and urban planning; he fostered the advancement of New Classical architecture and asserted that he "care[s] deeply about issues such as the environment, architecture, inner-city renewal, and the quality of life."[201] In a speech given for the 150th anniversary of the Royal Institute of British Architects in May 1984, he described a proposed extension to the National Gallery in London as a "monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved friend" and deplored the "glass stumps and concrete towers" of modern architecture.[202] Charles called for local community involvement in architectural choices and asked, "why has everything got to be vertical, straight, unbending, only at right angles – and functional?"[202] Charles has "a deep understanding of Islamic art and architecture" and has been involved in the construction of a building and garden at the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, which combine Islamic and Oxford architectural styles.[203]

In Charles's 1989 book A Vision of Britain, and in speeches and essays, he has been critical of modern architecture, arguing that traditional designs and methods should guide contemporary ones.[204] He has continued to campaign for traditional urbanism, human scale, restoration of historic buildings, and sustainable design[205] despite criticism in the press.[206] Two of his charities – the Prince's Regeneration Trust and the Prince's Foundation for Building Community, which were later merged into one charity – promote his views. The village of Poundbury was built on land owned by the Duchy of Cornwall to a master plan by Léon Krier, under the guidance of Charles and in line with his philosophy.[201] In 2013 developments for the suburb of Nansledan began on the estate of the Duchy of Cornwall with Charles's endorsement.[207] Charles helped purchase Dumfries House and its complete collection of 18th century furnishings in 2007, taking a £20m loan from his charitable trust to contribute toward the £45m cost.[208] The house and gardens remain property of the Prince's Foundation and serve as a museum and community and skills training centre.[209][210] This led to the development of Knockroon, called the "Scottish Poundbury".[211][212]

After lamenting in 1996 the unbridled destruction of many of Canada's historic urban cores, Charles offered his assistance to the Department of Canadian Heritage in creating a trust modelled on Britain's National Trust, a plan that was implemented with the passage of the federal budget in 2007.[213] In 1999, Charles agreed to the use of his title for the Prince of Wales Prize for Municipal Heritage Leadership, awarded by the National Trust for Canada to municipal governments that have committed to the conservation of historic places.[214]

Whilst visiting the US and surveying the damage caused by Hurricane Katrina, Charles received the National Building Museum's Vincent Scully Prize in 2005 for his efforts in regard to architecture; he donated $25,000 of the prize money towards restoring storm-damaged communities.[215] For his work as patron of New Classical architecture, Charles was awarded the 2012 Driehaus Architecture Prize from the University of Notre Dame.[216] The Worshipful Company of Carpenters installed Charles as an Honorary Liveryman "in recognition of his interest in London's architecture."[217]

Charles has occasionally intervened in projects that employ architectural styles such as modernism and functionalism.[218][219] In 2009, Charles wrote to the Qatari royal family – the financier of the redevelopment of the Chelsea Barracks site – labelling Lord Rogers's design for the site "unsuitable". Rogers claimed that Charles had also intervened to block his designs for the Royal Opera House and Paternoster Square.[220] CPC Group, the project developer, took a case against Qatari Diar to the High Court.[221] After the suit was settled, the CPC Group apologised to Charles "for any offence caused ... during the course of the proceedings".[221]

Natural environment

Since the 1970s, Charles has promoted environmental awareness.[222] At the age of 21, he delivered his first speech on environmental issues in his capacity as the chairman of the Welsh Countryside Committee.[223] An avid gardener, Charles has also emphasised the importance of talking to plants, stating that "I happily talk to the plants and trees, and listen to them. I think it's absolutely crucial".[224] His interest in gardening began in 1980 when he took over the Highgrove estate.[225] His "healing garden", based on sacred geometry and ancient religious symbolism, went on display at the Chelsea Flower Show in 2002.[225]

Upon moving into Highgrove House, Charles developed an interest in organic farming, which culminated in the 1990 launch of his own organic brand, Duchy Originals,[226] which sells more than 200 different sustainably produced products; the profits (over £6 million by 2010) are donated to the Prince's Charities.[226][227] Charles became involved with farming and various industries within it, regularly meeting with farmers to discuss their trade. A prominent critic of the practice,[228] Charles has also spoken against the use of GM crops, and in a letter to Tony Blair in 1998, Charles criticised the development of genetically modified foods.[229]

The Sustainable Markets Initiative – a project that encourages putting sustainability at the centre of all activities – was launched by Charles at the World Economic Forum's annual meeting in Davos in January 2020.[230] In May of the same year, the initiative and the World Economic Forum initiated the Great Reset project, a five-point plan concerned with enhancing sustainable economic growth following the global recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.[231]

The holy chrism oil used at Charles's coronation was vegan, made from oils of olive, sesame, rose, jasmine, cinnamon, neroli, and benzoin, along with amber and orange blossom. His mother's chrism oil contained animal-based oils.[232]

Charles delivered a speech at the 2021 G20 Rome summit, describing COP26 as "the last chance saloon" for preventing climate change and asking for actions that would lead to a green-led, sustainable economy.[233] In his speech at the opening ceremony for COP26, he repeated his sentiments from the previous year, stating that "a vast military-style campaign" was needed "to marshal the strength of the global private sector" for tackling climate change.[234] In 2022, the media alleged that Liz Truss had advised Charles against attending COP27, to which advice he agreed.[235] Charles delivered the opening speech at COP28, saying among others he prayed "with all my heart that COP28 will be a critical turning point towards genuine transformational action."[236]

Charles, who is patron of the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership, introduced the Climate Action Scholarships for students from small island nations in partnership with University of Cambridge, University of Toronto, University of Melbourne, McMaster University, and University of Montreal in March 2022.[237] In 2010 he funded The Prince's Countryside Fund (renamed The Royal Countryside Fund in 2023), a charity which aims for a "confident, robust and sustainable agricultural and rural community".[238]

Alternative medicine

Charles has controversially championed alternative medicine, including homeopathy.[239][240] He first publicly expressed his interest in the topic in December 1982, in an address to the British Medical Association.[241][242] This speech was seen as "combative" and "critical" of modern medicine and was met with anger by some medical professionals.[240] Similarly, the Prince's Foundation for Integrated Health (FIH) attracted opposition from the scientific and medical community over its campaign encouraging general practitioners to offer herbal and other alternative treatments to NHS patients.[243][244]

In April 2008, The Times published a letter from Edzard Ernst, Professor of Complementary Medicine at the University of Exeter, which asked the FIH to recall two guides promoting alternative medicine. That year, Ernst published a book with Simon Singh called Trick or Treatment: Alternative Medicine on Trial and mockingly dedicated to "HRH the Prince of Wales". The last chapter is highly critical of Charles's advocacy of complementary and alternative treatments.[245]

Charles's Duchy Originals produced a variety of complementary medicinal products, including a "Detox Tincture" that Ernst denounced as "financially exploiting the vulnerable" and "outright quackery".[246] Charles personally wrote at least seven letters[247] to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency shortly before it relaxed the rules governing labelling of such herbal products, a move that was widely condemned by scientists and medical bodies.[248] It was reported in October 2009 that Charles had lobbied the health secretary, Andy Burnham, regarding greater provision of alternative treatments in the NHS.[246]

Following accounting irregularities, the FIH announced its closure in April 2010.[249][250] The FIH was re-branded and re-launched later in the year as the College of Medicine,[250][251] of which Charles became a patron in 2019.[252]

Sports

From his youth until 2005, Charles was an avid player of competitive polo.[253] Charles also frequently took part in fox hunting until the sport was banned in the United Kingdom, also in 2005.[254] By the late 1990s, opposition to the activity was growing when Charles's participation was viewed as a "political statement" by those who were opposed to it.[255] Charles suffered several polo and hunting-related injuries throughout the years, including a two-inch scar on his left cheek in 1980, a broken arm in 1990, a torn cartilage in his left knee in 1992, a broken rib in 1998, and a fractured shoulder in 2001.[149]

Charles has been a keen salmon angler since youth and supported Orri Vigfússon's efforts to protect the North Atlantic salmon. He frequently fishes the River Dee in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, and claims his most special angling memories are from his time spent in Vopnafjörður, Iceland.[256] Charles is a supporter of Burnley F.C.[257]

Apart from hunting, Charles has also participated in target rifle competitions, representing the House of Lords in the Vizianagram Match (Lords vs. Commons) at Bisley.[258] He became President of the British National Rifle Association in 1977.[259]

Visual, performing, and literary arts

Charles has been involved in performance since his youth, and appeared in sketches and revues while studying at Cambridge.[260]

Charles is president or patron of more than 20 performing arts organisations, including the Royal College of Music, Royal Opera, English Chamber Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, Welsh National Opera, Royal Shakespeare Company (attending performances in Stratford-Upon-Avon, supporting fundraising events, and attending the company's annual general meeting),[261] British Film Institute,[262] and Purcell School. In 2000, he revived the tradition of appointing an official harpist to the Prince of Wales, in order to foster Welsh talent at playing the national instrument of Wales.[263]

Charles is a keen watercolourist, having published books on the subject and exhibited and sold a number of his works to raise money for charity; in 2016, it was estimated that he had sold lithographs of his watercolours for a total of £2 million from a shop at his Highgrove House residence. For his 50th birthday, 50 of his watercolours were exhibited at Hampton Court Palace and, for his 70th birthday, his works were exhibited at the National Gallery of Australia.[264] In 2001, 20 lithographs of his watercolour paintings illustrating his country estates were exhibited at the Florence International Biennale of Contemporary Art[265] and 79 of his paintings were put on display in London in 2022. To mark the 25th anniversary of his investiture as Prince of Wales in 1994, the Royal Mail issued a series of postage stamps that featured his paintings.[264] Charles is Honorary President of the Royal Academy of Arts Development Trust[266] and, in 2015, 2022, and 2023, commissioned paintings of 12 D-Day veterans, seven Holocaust survivors, and ten members of the Windrush generation, respectively, which went on display at the Queen's Gallery in Buckingham Palace.[267][268][269]

Charles is the author of several books and has contributed a foreword or preface to numerous books by others. He has also been featured in a variety of documentary films.[270]

Religion and philosophy

Shortly after his accession to the throne, Charles publicly described himself as "a committed Anglican Christian";[271] at age 16, during Easter 1965, he had been confirmed into the Anglican communion by Archbishop of Canterbury Michael Ramsey in St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle.[272] The King is the Supreme Governor of the Church of England[273] and a member of the Church of Scotland; he swore an oath to uphold that church immediately after he was proclaimed king.[274] He attends services at various Anglican churches close to Highgrove[275] and attends the Church of Scotland's Crathie Kirk with the rest of the royal family when staying at Balmoral Castle.

Laurens van der Post became a friend of Charles in 1977; he was dubbed Charles's "spiritual guru" and was godfather to Prince William.[276] From van der Post, Charles developed a focus on philosophy and an interest in other religions.[277] Charles expressed his philosophical views in his 2010 book, Harmony: A New Way of Looking at Our World,[278] which won a Nautilus Book Award.[279] He has also visited Eastern Orthodox monasteries on Mount Athos,[280] in Romania,[281] and in Serbia,[282] and met with Eastern Church leaders in Jerusalem in 2020, during a visit that culminated in an ecumenical service in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem and a walk through the city accompanied by Christian and Muslim dignitaries.[283] Charles also attended the consecration of Britain's first Syriac Orthodox cathedral, St Thomas Cathedral, Acton.[284] Charles is patron of the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies at the University of Oxford and attended the inauguration of the Markfield Institute of Higher Education, which is dedicated to Islamic studies in a multicultural context.[203][285]

In his 1994 documentary with Dimbleby, Charles said that, when king, he wished to be seen as a "defender of faith", rather than the British monarch's traditional title of Defender of the Faith, "preferr[ing] to embrace all religious traditions and 'the pattern of the divine, which I think is in all of us.'"[286] This attracted controversy at the time, as well as speculation that the coronation oath might be altered.[287] He stated in 2015 that he would retain the title of Defender of the Faith, whilst "ensuring that other people's faiths can also be practised", which he sees as a duty of the Church of England.[288] Charles reaffirmed this theme shortly after his accession and declared that his duties as sovereign included "the duty to protect the diversity of our country, including by protecting the space for faith itself and its practice through the religions, cultures, traditions, and beliefs to which our hearts and minds direct us as individuals."[271] His inclusive, multi-faith approach and his own Christian beliefs were expressed in his first Christmas message as king.[289]

Media image and public opinion

Since his birth, Charles has received close media attention, which increased as he matured. It has been an ambivalent relationship, largely impacted by his marriages to Diana and Camilla and their aftermath, but also centred on his future conduct as king.[290]

Described as the "world's most eligible bachelor" in the late 1970s,[291] Charles was subsequently overshadowed by Diana.[292] After her death, the media regularly breached Charles's privacy and printed exposés. Known for expressing his opinions, when asked during an interview to mark his 70th birthday whether this would continue in the same way once he is king, he responded "No. It won't. I'm not that stupid. I do realise that it is a separate exercise being sovereign. So, of course, you know, I understand entirely how that should operate."[293] In 2009 Charles was named the world's best-dressed man by Esquire magazine.[294] In 2023 the New Statesman named Charles as the fourth most powerful right-wing figure of the year, describing him as a "romantic traditionalist" and "the very last reactionary in public life" for his support of various traditionalist think-tanks and previous writings.[295]

A 2018 BMG Research poll found that 46 per cent of Britons wanted Charles to abdicate immediately on his mother's death, in favour of William.[296] However, a 2021 opinion poll reported that 60 per cent of the British public had a favourable opinion of him.[297] On his accession to the throne, The Statesman reported an opinion poll that put Charles's popularity with the British people at 42 per cent.[298] More recent polling suggested that his popularity increased sharply after he became king.[299] As of May 2024, Charles had an approval rating of 58 per cent, according to statistics and polling company YouGov.[300]

Reaction to press treatment

In 1994 German tabloid Bild published nude photos of Charles that were taken while he was vacationing in Le Barroux; they had reportedly been put up for sale for £30,000.[301] Buckingham Palace reacted by stating that it was "unjustifiable for anybody to suffer this sort of intrusion".[302]

Charles, "so often a target of the press, got his chance to return fire" in 2002, when addressing "scores of editors, publishers, and other media executives" gathered at St Bride's Fleet Street to celebrate 300 years of journalism.[h][303] Defending public servants from "the corrosive drip of constant criticism", he noted that the press had been "awkward, cantankerous, cynical, bloody-minded, at times intrusive, at times inaccurate, and at times deeply unfair and harmful to individuals and to institutions."[303] But, he concluded, regarding his own relations with the press, "from time to time we are probably both a bit hard on each other, exaggerating the downsides and ignoring the good points in each."[303]

In 2006 Charles filed a court case against The Mail on Sunday, after excerpts of his personal journals were published, revealing his opinions on matters such as the transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong to China in 1997, in which Charles described the Chinese government officials as "appalling old waxworks".[304][92] Charles and Camilla were named in 2011 as individuals whose confidential information was reportedly targeted or actually acquired in conjunction with the news media phone hacking scandal.[305]

The Independent noted in 2015 that Charles would only speak to broadcasters "on the condition they have signed a 15-page contract, demanding that Clarence House attends both the 'rough cut' and 'fine cut' edits of films and, if it is unhappy with the final product, can 'remove the contribution in its entirety from the programme'."[306] This contract stipulated that all questions directed at Charles must be pre-approved and vetted by his representatives.[306]

Residences and finance

In 2023, The Guardian estimated Charles's personal wealth at £1.8 billion.[307] This estimate includes the assets of the Duchy of Lancaster worth £653 million (and paying Charles an annual income of £20 million), jewels worth £533 million, real estate worth £330 million, shares and investments worth £142 million, a stamp collection worth at least £100 million, racehorses worth £27 million, artworks worth £24 million, and cars worth £6.3 million.[307] Most of this wealth which he inherited from his mother is exempt from inheritance tax.[307][308]

Clarence House, previously the residence of the Queen Mother, was Charles's official London residence from 2003, after being renovated at a cost of £6.1 million.[309] He previously shared apartments eight and nine at Kensington Palace with Diana before moving to York House at St James's Palace, which remained his principal residence until 2003.[310] Highgrove House in Gloucestershire is owned by the Duchy of Cornwall, having been purchased for Charles's use in 1980, and which he rented for £336,000 per annum.[311][312] Since William became Duke of Cornwall, Charles is expected to pay £700,000 per annum for use of the property.[313] Charles also owns a property near the village of Viscri in Romania.[314][315]

As Prince of Wales, Charles's primary source of income was generated from the Duchy of Cornwall, which owns 133,658 acres of land (around 54,090 hectares), including farming, residential, and commercial properties, as well as an investment portfolio. Since 1993, he has paid tax voluntarily under the Memorandum of Understanding on Royal Taxation, updated in 2013.[316] Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs were asked in December 2012 to investigate alleged tax avoidance by the Duchy of Cornwall.[317] The Duchy is named in the Paradise Papers, a set of confidential electronic documents relating to offshore investment that were leaked to the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung.[318][319]

Titles, styles, honours, and arms

Titles and styles

Charles has held many titles and honorary military positions throughout the Commonwealth, is sovereign of many orders in his own countries and has received honours and awards from around the world.[322][323][324][325][326] In each of his realms, he has a distinct title that follows a similar formula: King of Saint Lucia and of His other Realms and Territories in Saint Lucia, King of Australia and His other Realms and Territories in Australia, etc. In the Isle of Man, which is a Crown Dependency rather than a separate realm, he is known as Lord of Mann. Charles is also styled Defender of the Faith.

There had been speculation throughout Elizabeth II's reign as to what regnal name Charles would choose upon his accession; instead of Charles III, he could have chosen to reign as George VII or used one of his other given names.[327] It was reported that he might use George in honour of his grandfather George VI and to avoid associations with previous controversial kings named Charles.[i][328][329] Charles's office asserted in 2005 that no decision had yet been made.[330] Speculation continued for a few hours following his mother's death,[331] until Liz Truss announced and Clarence House confirmed that Charles had chosen the regnal name Charles III.[332][333]

Charles, who left active military service in 1976, was awarded the highest rank in all three armed services in 2012 by his mother: Admiral of the Fleet, Field Marshal, and Marshal of the Royal Air Force.[334]

Arms

As Prince of Wales, Charles's coat of arms was based on the arms of the United Kingdom, differenced with a white label and an inescutcheon of the Principality of Wales, surmounted by the heir apparent's crown, and with the motto Ich dien (German: [ɪç ˈdiːn], "I serve") instead of Dieu et mon droit.

When Charles became king, he inherited the royal coats of arms of the United Kingdom and of Canada.[335] The design of his royal cypher, featuring a depiction of the Tudor crown instead of St Edward's Crown, was revealed on 27 September 2022. The College of Arms envisages that the Tudor crown will be used in new arms, uniforms and crown badges as they are replaced.[336]

Banners, flags, and standards

As heir apparent

The banners used by Charles as Prince of Wales varied depending upon location. His personal standard for the United Kingdom was the Royal Standard of the United Kingdom differenced as in his arms, with a label of three points argent and the escutcheon of the arms of the Principality of Wales in the centre. It was used outside Wales, Scotland, Cornwall, and Canada, and throughout the entire United Kingdom when Charles was acting in an official capacity associated with the British Armed Forces.[337]

The personal flag for use in Wales was based upon the Royal Badge of Wales.[337] In Scotland, the personal banner used between 1974 and 2022 was based upon three ancient Scottish titles: Duke of Rothesay (heir apparent to the King of Scots), High Steward of Scotland, and Lord of the Isles. In Cornwall, the banner was the arms of the Duke of Cornwall.[337]

In 2011, the Canadian Heraldic Authority introduced a personal heraldic banner for the Prince of Wales for Canada, consisting of the shield of the Royal Coat of Arms of Canada defaced with both a blue roundel of the Prince of Wales's feathers surrounded by a wreath of gold maple leaves and a white label of three points.[338]

As sovereign

The royal standard of the United Kingdom is used to represent the King in the United Kingdom and on official visits overseas, except in Canada. It is the royal arms in banner form undifferentiated, having been used by successive British monarchs since 1702. The royal standard of Canada is used by the King in Canada and while acting on behalf of Canada overseas. It is the escutcheon of the Royal Coat of Arms of Canada in banner form undifferentiated.

Issue

| Name | Birth | Marriage | Children | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Spouse | |||

| William, Prince of Wales | 21 June 1982 | 29 April 2011 | Catherine Middleton | Prince George of Wales Princess Charlotte of Wales Prince Louis of Wales |

| Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex | 15 September 1984 | 19 May 2018 | Meghan Markle | |

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Charles III[339] |

|---|

See also

- List of current monarchs of sovereign states

- List of covers of Time magazine (1960s), (1970s), (1980s), (2010s), (2020s)

Notes

- ^ Ceremonial and non-hereditary title conferred by the Commonwealth heads of government to symbolise the voluntary association of nations in the Commonwealth. Charles was chosen to succeed Elizabeth II at the 2018 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting.[1]

- ^ Jump up to: a b In addition to the United Kingdom, the 14 other realms are Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, The Bahamas, Belize, Canada, Grenada, Jamaica, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, the Solomon Islands, and Tuvalu.

- ^ As the reigning monarch, Charles does not usually use a family name, but when one is needed, it is Mountbatten-Windsor.[2]

- ^ As monarch, Charles is Supreme Governor of the Church of England. He is also a member of the Church of Scotland.

- ^ He was reportedly named "Charles" after his godfather Haakon VII of Norway, who was called "Uncle Charles" by Elizabeth II.[6][7]

- ^ Prince Charles's godparents were: the King of the United Kingdom (his maternal grandfather); the King of Norway (his paternal cousin twice removed and maternal great-great-uncle by marriage, for whom Charles's great-great-uncle the Earl of Athlone stood proxy); Queen Mary (his maternal great-grandmother); Princess Margaret (his maternal aunt); Prince George of Greece and Denmark (his paternal great-uncle, for whom the Duke of Edinburgh stood proxy); the Dowager Marchioness of Milford Haven (his paternal great-grandmother); the Lady Brabourne (his cousin); and the Hon David Bowes-Lyon (his maternal great-uncle).[8]

- ^ Mountbatten had served as the last British viceroy and first governor-general of India.

- ^ London's first daily newspaper, the Daily Courant, was published in 1702.

- ^ Namely, the Stuart kings Charles I, who was beheaded, and Charles II, who was known for his promiscuous lifestyle. Charles Edward Stuart, once a Stuart pretender to the English and Scottish thrones, was called Charles III by his supporters.[328]

References

Citations

- ^ "Charles 'to be next Commonwealth head'". BBC News. 20 April 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ "The Royal Family name". Official website of the British monarchy. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- ^ "No. 38455". The London Gazette. 15 November 1948. p. 1.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 120.

- ^ Bland, Archie (1 May 2023). "King Charles: 71 facts about his long road to the throne". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 February 2024. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ Holden, Anthony (1980). Charles, Prince of Wales. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-330-26167-8.

- ^ "Close ties through the generations". The Royal House of Norway. 8 September 2022. Archived from the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ "The Christening of Prince Charles". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "HRH The Prince of Wales | Prince of Wales". Clarence House. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ "The Book of the Baptism Service of Prince Charles". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 127.

- ^ Elston, Laura (26 April 2023). "Charles made history when he watched the Queen's coronation aged four". The Independent. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Gordon, Peter; Lawton, Denis (2003). Royal Education: Past, Present, and Future. F. Cass. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-7146-8386-7. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Kirka, Danica (1 May 2023). "Name etched in gold, King Charles' school remembers him". The Independent. Archived from the original on 25 May 2023. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Johnson, Bonnie; Healy, Laura Sanderson; Thorpe-Tracey, Rosemary; Nolan, Cathy (25 April 1988). "Growing Up Royal". Time. Archived from the original on 31 March 2005. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- ^ "Lieutenant Colonel H. Stuart Townend". The Times. 30 October 2002. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "HRH The Prince of Wales". Debrett's. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "About the Prince of Wales". Royal Household. 26 December 2018. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 139.

- ^ Richards, Bailey (25 May 2024). "King Charles becomes patron of his former Scottish school depicted in The Crown as 'absolute hell'". People. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Rocco, Fiammetta (18 October 1994). "Flawed Family: This week the Prince of Wales disclosed still powerful resentments against his mother and father". The Independent (UK). Independent Digital News & Media Ltd. ISSN 1741-9743. OCLC 185201487. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rudgard, Olivia (10 December 2017). "Colditz in kilts? Charles loved it, says old school as Gordonstoun hits back at The Crown". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. OCLC 49632006. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "The Prince of Wales – Education". Clarence House. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ "The New Boy at Timbertop". The Australian Women's Weekly. Vol. 33, no. 37. 9 February 1966. p. 7. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2018 – via National Library of Australia.; "Timbertop – Prince Charles Australia" (Video with audio, 1 min 28 secs). British Pathé. 1966. Archived from the original on 11 March 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Prince had happy time at Timbertop". Australian Associated Press. Vol. 47, no. 13, 346. The Canberra Times. 31 January 1973. p. 11. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 145.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 151

- ^ Holland, Fiona (10 September 2022). "God Save The King!". Trinity College Cambridge. Archived from the original on 14 September 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ "No. 41460". The London Gazette. 29 July 1958. p. 4733.; "The Prince of Wales – Previous Princes of Wales". Prince of Wales. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ "The Prince of Wales – Investiture". Clarence House. Archived from the original on 20 October 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ Jones, Craig Owen (2013). "Songs of Malice and Spite"?: Wales, Prince Charles, and an Anti-Investiture Ballad of Dafydd Iwan (PDF) (7th ed.). Michigan Publishing. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ "H.R.H. The Prince of Wales Introduced". Hansard. 11 February 1970. HL Deb vol 307 c871. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2019.; "The Prince of Wales – Biography". Prince of Wales. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ "Sport and Leisure". Hansard. 13 June 1974. HL Deb vol 352 cc624–630. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ Shuster, Alvin (14 June 1974). "Prince Charles Speaks in Lords". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ "Voluntary Service in the Community". Hansard. 25 June 1975. HL Deb vol 361 cc1418–1423. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ "The Prince's Trust". The Prince's Charities. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ Ferretti, Fred (18 June 1981). "Prince Charles pays a quick visit to city". The New York Times. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ Daley, Paul (9 November 2015). "Long to reign over Aus? Prince Charles and Australia go way back". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ David Murray (24 November 2009). "Next governor-general could be Prince Harry, William". The Australian. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, pp. 169–170

- ^ "Military Career of the Prince of Wales". Prince of Wales. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ Calvert, Alana (8 May 2023). "Vintage plane King learned to fly in takes to the sky for Coronation air show". The Independent. Archived from the original on 20 January 2024. Retrieved 27 May 2024.; "Prince Charles attends RAF Cranwell ceremony". BBC News. 16 July 2020. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brandreth 2007, p. 170.

- ^ "Prince Charles: Video shows 'upside down' parachute jump". BBC News. 15 July 2021. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ "Occurrence # 187927". Flight Safety Foundation. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2023.; Boggan, Steve (20 July 1995). "Prince gives up flying royal aircraft after Hebrides crash". The Independent (UK). Archived from the original on 24 March 2017.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 192.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 193.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 194.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 195.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, pp. 15–17, 178.

- ^ Junor 2005, p. 72.

- ^ Dimbleby 1994, pp. 204–206; Brandreth 2007, p. 200

- ^ Dimbleby 1994, p. 263.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dimbleby 1994, pp. 263–265.

- ^ Dimbleby 1994, p. 279.

- ^ Dimbleby 1994, pp. 280–282.

- ^ Dimbleby 1994, pp. 281–283.

- ^ "Royally Minted: What we give them and how they spend it". New Statesman. Vol. 138, no. 4956–4968. London. 13 July 2009. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ Brown 2007, p. 720.

- ^ Smith 2000, p. 561.

- ^ Griffiths, Eleanor Bley (1 January 2020). "The truth behind Charles and Camilla's affair storyline in The Crown". Radio Times. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ "Diana 'wanted to live with guard'". BBC News. 7 December 2004. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Langley, William (12 December 2004). "The Mannakee file". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Lawson, Mark (7 August 2017). "Diana: In Her Own Words – admirers have nothing to fear from the Channel 4 tapes". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ Milmo, Cahal (8 December 2004). "Conspiracy theorists feast on inquiry into death of Diana's minder". The Independent (UK). Independent Digital News & Media Ltd. ISSN 1741-9743. OCLC 185201487. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Duboff, Josh (13 March 2017). "Princess Diana's Former Lover Maintains He Is Not Prince Harry's Father". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Quest, Richard (3 June 2002). "Royals, Part 3: Troubled times". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 July 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Hewitt denies Prince Harry link". BBC News. 21 September 2002. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ "The Camillagate Tapes". Textfiles.com (phone transcript). Phone Phreaking. 18 December 1989. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010.; "Royals caught out by interceptions". BBC News. 29 November 2006. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2012.; Dockterman, Eliana (9 November 2022). "The True Story Behind Charles and Camilla's Phone Sex Leak on The Crown". Time. Archived from the original on 16 November 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "The Princess and the Press". PBS. Archived from the original on 10 March 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2017.; "Timeline: Charles and Camilla's romance". BBC. 6 April 2005. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ Dimbleby 1994, p. 395.

- ^ "1995: Diana admits adultery in TV interview". BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ "The Panorama Interview with the Princess of Wales". BBC News. 20 November 1995. Archived from the original on 4 March 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ^ "'Divorce': Queen to Charles and Diana". BBC News. 20 December 1995. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ "Charles and Diana to divorce". Associated Press. 21 December 1995. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Neville, Sarah (13 July 1996). "Charles and Diana Agree to Terms of Divorce". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Whitney, Craig R. (31 August 1997). "Prince Charles Arrives in Paris to Take Diana's Body Home". The New York Times. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ "Diana letter 'warned of car plot'". CNN. 20 October 2003. Archived from the original on 12 December 2003. Retrieved 14 April 2019.; Eleftheriou-Smith, Loulla-Mae (30 August 2017). "Princess Diana letter claims Prince Charles was 'planning an accident' in her car just 10 months before fatal crash". The Independent (UK). Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.; Rayner, Gordon (20 December 2007). "Princess Diana letter: 'Charles plans to kill me'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ Badshah, Nadeem (19 June 2021). "Police interviewed Prince Charles over 'plot to kill Diana'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ "Charles and Camilla go public". BBC News. 29 January 1999. Archived from the original on 5 May 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ "Prince Charles moves into Clarence House". The BBC. 2 August 2003. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ "Profile: Duchess of Cornwall". BBC News. 9 April 2012. Archived from the original on 3 May 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "Order in Council". The National Archives. 2 March 2005. Archived from the original on 3 November 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ Valpy, Michael (2 November 2005). "Scholars scurry to find implications of royal wedding". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ^ "Panorama Lawful impediment?". BBC News. 14 February 2005. Archived from the original on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ The Secretary of State for Constitutional Affairs and Lord Chancellor (Lord Falconer of Thoroton) (24 February 2005). "Royal Marriage; Lords Hansard Written Statements 24 Feb 2005 : Column WS87 (50224-51)". Publications.parliament.uk. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ "Pope funeral delays royal wedding". BBC News. 4 April 2005. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Q&A: Queen's wedding decision". BBC News. 23 February 2005. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ "Charles And Camilla Finally Wed, After 30 Years Of Waiting, Prince Charles Weds His True Love". CBS News. 9 April 2005. Archived from the original on 12 November 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ Oliver, Mark (9 April 2005). "Charles and Camilla wed". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "100 Coronation facts". Royal Household. Archived from the original on 1 May 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Landler, Mark (8 September 2022). "Long an Uneasy Prince, King Charles III Takes On a Role He Was Born To". The New York Times. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "King Charles averages 521 royal engagements per year, but Princess Anne does even more, according to a new report". The Guardian. 11 April 2023. Archived from the original on 26 March 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 325.

- ^ "Opening of the Senedd". National Assembly for Wales. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ "Administration". The Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ Trumbull, Robert (10 October 1970). "Fiji Raises the Flag of Independence After 96 Years of Rule by British". The New York Times. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "1973: Bahamas' sun sets on British Empire". BBC News. 9 July 1973. Archived from the original on 1 February 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ «Папуа-Новая Гвинея празднует независимость» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 16 сентября 1975 г. OCLC 1645522 . Архивировано из оригинала 10 сентября 2022 года . Проверено 3 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Росс, Джей (18 апреля 1980 г.). «Зимбабве обретает независимость» . Вашингтон Пост . Архивировано из оригинала 4 февраля 2021 года . Проверено 3 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Ведель, Пол (22 февраля 1984 г.). «В четверг Бруней отпраздновал свою независимость от Великобритании традиционным…» UPI . Архивировано из оригинала 19 февраля 2022 года . Проверено 3 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Эйндж Рой, Элеонора (13 января 2018 г.). « 'Черт... я промахнулась': невероятная история того дня, когда королеву чуть не застрелили» . Хранитель . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2018 года . Проверено 1 марта 2018 г.