Мальта

Республика Мальта Республика Мальта ( мальтийский ) | |

|---|---|

| Девиз: Сила и постоянство ( лат .) «Сила и настойчивость» | |

| Гимн: Гимн Мальты ( мальтийский ) «Мальтийский гимн» | |

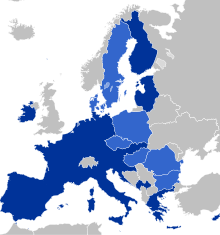

![Расположение Мальты (зеленый кружок) – в Европе (светло-зеленый и темно-серый) – в Европейском Союзе (светло-зеленый) – [Легенда]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/63/EU-Malta.svg/250px-EU-Malta.svg.png) Location of Malta (green circle) – in Europe (light green & dark grey) | |

| Capital | Valletta 35°54′N 14°31′E / 35.900°N 14.517°E |

| Largest administrative unit | St. Paul's Bay[1] |

| Official languages | |

| Other languages | Maltese Sign Language[3] Italian |

| Ethnic groups (2021[4]) | |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Maltese |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Myriam Spiteri Debono | |

| Robert Abela | |

| Legislature | Parliament of Malta |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 21 September 1964 | |

• Republic | 13 December 1974 |

| 1 May 2004 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 316[7] km2 (122 sq mi) (187th) |

• Water (%) | 0.001 |

| Population | |

• 2021 census | 542,051[8] |

• Density | 1,649/km2 (4,270.9/sq mi) (8th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2019) | low |

| HDI (2022) | very high (25th) |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (Central European Time) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (Central European Summer Time) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy[b] |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +356 |

| ISO 3166 code | MT |

| Internet TLD | .mt[b] |

Мальта ( / ˈ m ɒ l t ə / MOL к , / ˈ m ɔː l t ə / MAWL к , Мальтийский: [ˈmɐːltɐ] ), официально Республика Мальта , [14] островное государство в Южной Европе, расположенное в Средиземном море . Он состоит из архипелага , расположенного в 80 км (50 миль) к югу от Италии, в 284 км (176 миль) к востоку от Туниса. [15] и в 333 км (207 миль) к северу от Ливии. [16] [17] Двумя официальными языками являются мальтийский (единственный семитский язык, имеющий официальный статус в европейской стране и Европейском Союзе (ЕС)), и английский . Столица страны — Валлетта , которая является самой маленькой столицей ЕС как по площади, так и по населению.

С населением около 542 000 человек. [8] на площади 316 км 2 (122 квадратных миль), [7] в мире по площади. Мальта является десятой самой маленькой страной [18] [19] и пятый по густонаселенности . Различные источники считают, что страна состоит из единого городского региона, [20] [21] из-за чего его часто называют городом-государством . [22] [23] [24]

Мальта была заселена примерно с 5900 г. до н. э. [25] Its location in the centre of the Mediterranean has historically given it great geostrategic importance, with a succession of powers having ruled the islands and shaped its culture and society.[26] These include the Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Greeks, and Romans in antiquity; the Arabs, Normans, and Aragonese during the Middle Ages; and the Knights Hospitaller, French, and British in the modern era.[27][28] Malta came under British rule in the early 19th century and served as the headquarters for the British Mediterranean Fleet. It was besieged by the Axis powers during World War II and was an important Allied base for North Africa and the Mediterranean.[29][30] Malta achieved independence in 1964,[31] и основал свою нынешнюю парламентскую республику в 1974 году. С момента обретения независимости он был государством-членом Содружества Наций и Организации Объединенных Наций; он вступил в Европейский Союз в 2004 году и в валютный союз еврозоны в 2008 году.

Malta's long history of foreign rule and close proximity to both Europe and North Africa have influenced its art, music, cuisine, and architecture. Malta has close historical and cultural ties to Italy and especially Sicily; between 62 and 66 percent of Maltese people speak or have significant knowledge of the Italian language, which had official status from 1530 to 1934.[32][33] Malta was an early centre of Christianity, and Catholicism is the state religion, although the country's constitution guarantees freedom of conscience and religious worship.[34][35]

Malta is a developed country with an advanced high-income economy. It is heavily reliant on tourism, attracting both travelers and a growing expatriate community with its warm climate, numerous recreational areas, and architectural and historical monuments, including three UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum,[36] Valletta,[37] and seven megalithic temples which are some of the oldest free-standing structures in the world.[38][39][40]

Name

[edit]The English name Malta derives from Italian and Maltese Malta, from medieval Arabic Māliṭā (مَالِطَا), from classical Latin Melita,[41] from latinised or Doric forms[42] of the ancient Greek Melítē (Μελίτη) of uncertain origin. The name Melítē—shared by the Croatian island Mljet in antiquity—literally means "place of honey" or "sweetness", derived from the combining form of méli (μέλι, "honey" or any similarly sweet thing)[43] and the suffix -ē (-η). The ancient Greeks may have given the island this name after Malta's endemic subspecies of bees.[44] Alternatively, other scholars argue for derivation of the Greek name from an original Phoenician or Punic Maleth (𐤌𐤋𐤈, mlṭ), meaning "haven"[45] or "port"[46] in reference to the Grand Harbour and its primary settlement at Cospicua following the sea level rise that separated the Maltese islands and flooded its original coastal settlements in the 10th century BC.[47] The name was then applied to all of Malta by the Greeks and to its ancient capital at Mdina by the Romans.[47]

Malta and its demonym Maltese are attested in English from the late 16th century.[48] The Greek name appears in the Book of Acts in the Bible's New Testament.[49] English translations including the 1611 King James Version long used the Vulgate Latin form Melita, although William Tyndale's 1525 translation from Greek sources used the transliteration Melite instead. Malta is widely used in more recent versions. The name is attested earlier in other languages, however, including some medieval manuscripts of the Latin Antonine Itinerary.[50]

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]Malta has been inhabited from circa 5900 BC,[51] since the arrival of settlers originating from European Neolithic agriculturalists.[52] Pottery found by archaeologists at the Skorba Temples resembles that found in Italy, and suggests that the Maltese islands were first settled in 5200 BC by Stone Age hunters or farmers who had arrived from Sicily, possibly the Sicani. The extinction of the dwarf hippos, giant swans and dwarf elephants has been linked to the earliest arrival of humans on Malta.[53] Prehistoric farming settlements dating to the Early Neolithic include Għar Dalam.[54] The population on Malta grew cereals, raised livestock and, in common with other ancient Mediterranean cultures, worshipped a fertility figure.[55]

A culture of megalithic temple builders then either supplanted or arose from this early period. Around 3500 BC, these people built some of the oldest existing free-standing structures in the world in the form of the megalithic Ġgantija temples on Gozo;[56] other early temples include those at Ħaġar Qim and Mnajdra.[40][57][58] The temples have distinctive architecture, typically a complex trefoil design, and were used from 4000 to 2500 BC. Tentative information suggests that animal sacrifices were made to the goddess of fertility, whose statue is now in the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta.[59] Another archaeological feature of the Maltese Islands often attributed to these ancient builders is equidistant uniform grooves dubbed "cart tracks" or "cart ruts" which can be found in several locations throughout the islands, with the most prominent being those found in Misraħ Għar il-Kbir. These may have been caused by wooden-wheeled carts eroding soft limestone.[60][61] The culture apparently disappeared from the islands around 2500 BC, possibly due to famine or disease.

After 2500 BC, the Maltese Islands were depopulated for several decades until an influx of Bronze Age immigrants, a culture that cremated its dead and introduced smaller megalithic structures called dolmens.[62] They are claimed to belong to a population certainly different from that which built the previous megalithic temples. It is presumed the population arrived from Sicily because of the similarity of Maltese dolmens to some small constructions found there.[63]

Phoenicians, Carthaginians and Romans

[edit]

Phoenician traders[64] colonised the islands under the name Ann (𐤀𐤍𐤍, ʾNN)[65][66][47] sometime after 1000 BC[15] as a stop on their trade routes from the eastern Mediterranean to Cornwall.[67] Their seat of government was apparently at Mdina, which shared the island's name;[65][66] the primary port was at Cospicua on the Grand Harbour, which they called Maleth.[47] After the fall of Phoenicia in 332 BC, the area came under the control of Carthage.[15][68] During this time, the people on Malta mainly cultivated olives and carob and produced textiles.[68]

During the First Punic War, the island was conquered after harsh fighting by Marcus Atilius Regulus.[69] After the failure of his expedition, the island fell back in the hands of Carthage, only to be conquered again during the Second Punic War in 218 BC by the Roman consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus.[69] After that, Malta became a Foederata Civitas, a designation that meant it was exempt from paying tribute or the rule of Roman law, and fell within the jurisdiction of the province of Sicily.[44] Its capital at Mdina was renamed Melita after the Greek and Roman name for the island. Punic influence, however, remained vibrant on the islands with the famous Cippi of Melqart, pivotal in deciphering the Punic language, dedicated in the second century BC.[70][71] Local Roman coinage, which ceased in the first century BC,[72] indicates the slow pace of the island's Romanisation: the last locally minted coins still bear inscriptions in Ancient Greek and Punic motifs, showing the resistance of the Greek and Punic cultures.[73]

In the second century, Emperor Hadrian (r. 117–38) upgraded the status of Malta to a municipium or free town: the island's local affairs were administered by four quattuorviri iuri dicundo and a municipal senate, while a Roman procurator living in Mdina represented the proconsul of Sicily.[69] In AD 58, Paul the Apostle and Luke the Evangelist were shipwrecked on the islands.[69] Paul remained for three months, preaching the Christian faith.[69] The island is mentioned at the Acts of the Apostles as Melitene (Greek: Μελιτήνη).[74]

In 395, when the Roman Empire was divided for the last time at the death of Theodosius I, Malta, following Sicily, fell under the control of the Western Roman Empire.[75] During the Migration Period as the Western Roman Empire declined, Malta was conquered or occupied a number of times.[72] From 454 to 464 the islands were subdued by the Vandals, and after 464 by the Ostrogoths.[69] In 533, Belisarius, on his way to conquer the Vandal Kingdom in North Africa, reunited the islands under Imperial (Eastern) rule.[69] Little is known about the Byzantine rule in Malta: the island depended on the theme of Sicily and had Greek Governors and a small Greek garrison.[69] While the bulk of population continued to be constituted by the old, Latinized dwellers, during this period its religious allegiance oscillated between the Pope and the Patriarch of Constantinople.[69] The Byzantine rule introduced Greek families to the Maltese collective.[76] Malta remained under the Byzantine Empire until 870, when it was conquered by the Arabs.[69][77]

Arab period and the Middle Ages

[edit]Malta became involved in the Arab–Byzantine wars, and the conquest of Malta is closely linked with that of Sicily that began in 827 after Admiral Euphemius' betrayal of his fellow Byzantines, requesting that the Aghlabids invade the island.[78] The Muslim chronicler and geographer al-Himyari recounts that in 870, following a violent struggle against the defending Byzantines, the Arab invaders, first led by Halaf al-Hadim, and later by Sawada ibn Muhammad,[79] pillaged the island, destroying the most important buildings, and leaving it practically uninhabited until it was recolonised by the Arabs from Sicily in 1048–1049.[79] It is uncertain whether this new settlement resulted from demographic expansion in Sicily, a higher standard of living in Sicily (in which case the recolonisation may have taken place a few decades earlier), or a civil war which broke out among the Arab rulers of Sicily in 1038.[80] The Arab Agricultural Revolution introduced new irrigation, cotton, and some fruits. The Siculo-Arabic language was adopted on the island from Sicily; it would eventually evolve into the Maltese language.[81]

Norman conquest

[edit]

The Normans attacked Malta in 1091, as part of their conquest of Sicily.[82] The Norman leader, Roger I of Sicily, was welcomed by Christian captives.[44] The notion that Count Roger I reportedly tore off a portion of his checkered red-and-white banner and presented it to the Maltese in gratitude for having fought on his behalf, forming the basis of the modern flag of Malta, is founded in myth.[44][83]

Malta became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Sicily, which also covered the island of Sicily and the southern half of the Italian Peninsula.[44] The Catholic Church was reinstated as the state religion, with Malta under the See of Palermo, and some Norman architecture sprang up around Malta, especially in its ancient capital Mdina.[44] King Tancred made Malta a fief of the kingdom and installed a Count of Malta in 1192. As the islands were much desired due to their strategic importance, it was during this time that the men of Malta were militarised to fend off attempted conquest; early Counts were skilled Genoese privateers.[44]

The kingdom passed on to the Hohenstaufen dynasty from 1194 until 1266. As Emperor Frederick II began to reorganise his Sicilian kingdom, Western culture and religion started to exert their influence more intensely.[84] Malta was declared a county and a marquisate, but its trade was totally ruined. For a long time it remained solely a fortified garrison.[85]

A mass expulsion of Arabs occurred in 1224, and the entire Christian male population of Celano in Abruzzo was deported to Malta in the same year.[44] In 1249 Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, decreed that all remaining Muslims be expelled from Malta[86] or compelled to convert.[87][88]

For a brief period, the kingdom passed to the Capetian House of Anjou,[89] but high taxes made the dynasty unpopular in Malta, due in part to Charles of Anjou's war against the Republic of Genoa, and the island of Gozo was sacked in 1275.[44]

Crown of Aragon, the Knights of Malta and Portuguese Rule

[edit]

Malta was ruled by the House of Barcelona, the ruling dynasty of the Crown of Aragon, from 1282 to 1409,[90] with the Aragonese aiding the Maltese insurgents in the Sicilian Vespers in the naval battle in Grand Harbour in 1283.[91]

Relatives of the kings of Aragon ruled the island until 1409 when it formally passed to the Crown of Aragon. Early on in the Aragonese ascendancy, the sons of the monarchs received the title Count of Malta. During this time much of the local nobility was created. By 1397, however, the bearing of the comital title reverted to a feudal basis, with two families fighting over the distinction. This led King Martin I of Sicily to abolish the title. The dispute over the title returned when the title was reinstated a few years later and the Maltese, led by the local nobility, rose up against Count Gonsalvo Monroy.[44] Although they opposed the Count, the Maltese voiced their loyalty to the Sicilian Crown, which so impressed King Alfonso that he did not punish the people for their rebellion. Instead, he promised never to grant the title to a third party and incorporated it back into the crown. The city of Mdina was given the title of Città Notabile.[44]

On 23 March 1530,[92] Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, gave the islands to the Knights Hospitaller under the leadership of Frenchman Philippe Villiers de L'Isle-Adam,[93][94] in perpetual lease for which they had to pay an annual tribute of a single Maltese Falcon.[95][96][97][98][99][100][101] These knights, a military religious order also known as the Order of St John and later as the Knights of Malta, had been driven out of Rhodes by the Ottoman Empire in 1522.[102]

The Knights Hospitaller ruled Malta and Gozo between 1530 and 1798.[103] During this period, the strategic and military importance of the island grew greatly as the small yet efficient fleet of the Order of Saint John launched their attacks from this new base targeting the shipping lanes of the Ottoman territories around the Mediterranean Sea.[103][104]

In 1551, the population of the island of Gozo (around 5,000 people) were enslaved by Barbary pirates and taken to the Barbary Coast in North Africa.[105]

The knights, led by Frenchman Jean Parisot de Valette, withstood the Great Siege of Malta by the Ottomans in 1565.[94] The knights, with the help of Portuguese, Spanish and Maltese forces, repelled the attack.[106][107] After the siege they decided to increase Malta's fortifications, particularly in the inner-harbour area, where the new city of Valletta, named in honour of Valette, was built. They also established watchtowers along the coasts – the Wignacourt, Lascaris and De Redin towers – named after the Grand Masters who ordered the work. The Knights' presence on the island saw the completion of many architectural and cultural projects, including the embellishment of Città Vittoriosa (modern Birgu) and the construction of new cities including Città Rohan (modern Ħaż-Żebbuġ). However, by the late 1700s the power of the Knights had declined and the Order had become unpopular.

French period and British conquest

[edit]

The Knights' reign ended when Napoleon captured Malta on his way to Egypt during the French Revolutionary Wars in 1798. During 12–18 June 1798, Napoleon resided at the Palazzo Parisio in Valletta.[108][109][110] He reformed national administration with the creation of a Government Commission, twelve municipalities, a public finance administration, the abolition of all feudal rights and privileges, the abolition of slavery and the granting of freedom to all Turkish and Jewish slaves.[111][112] On the judicial level, a family code was framed and twelve judges were nominated. Public education was organised along principles laid down by Bonaparte himself, providing for primary and secondary education.[112][113] He then sailed for Egypt, leaving a substantial garrison in Malta.[114]

The French forces left behind became unpopular with the Maltese, due particularly to the French forces' hostility towards Catholicism and pillaging of local churches to fund war efforts. French financial and religious policies so angered the Maltese that they rebelled, forcing the French to depart. Great Britain, along with the Kingdom of Naples and the Kingdom of Sicily, sent ammunition and aid to the Maltese, and Britain also sent its navy, which blockaded the islands.[112]

On 28 October 1798, Captain Sir Alexander Ball successfully completed negotiations with the French garrison on Gozo for a surrender and transfer of the island to the British. The British transferred the island to the locals that day, and it was administered by Archpriest Saverio Cassar on behalf of Ferdinand III of Sicily. Gozo remained independent until Cassar was removed by the British in 1801.[115]

General Claude-Henri Belgrand de Vaubois surrendered his French forces in 1800.[112] Maltese leaders presented the main island to Sir Alexander Ball, asking that the island become a British Dominion. The Maltese people created a Declaration of Rights in which they agreed to come "under the protection and sovereignty of the King of the free people, His Majesty the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland". The Declaration also stated that "his Majesty has no right to cede these Islands to any power...if he chooses to withdraw his protection, and abandon his sovereignty, the right of electing another sovereign, or of the governing of these Islands, belongs to us, the inhabitants and aborigines alone, and without control."[112][116]

British Empire and the Second World War

[edit]

In 1814, as part of the Treaty of Paris,[112][117] Malta officially became a part of the British Empire and was used as a shipping way-station and fleet headquarters. After the Suez Canal opened in 1869, Malta's position halfway between the Strait of Gibraltar and Egypt proved to be its main asset, and it was considered an important stop on the way to India, a central trade route for the British.

A Turkish Military Cemetery was commissioned by Sultan Abdul Aziz and built between 1873 and 1874 for the fallen Ottoman soldiers of the Great Siege of Malta.

Between 1915 and 1918, during the First World War, Malta became known as the Nurse of the Mediterranean due to the large number of wounded soldiers who were accommodated there.[118] In 1919, British troops fired into a crowd protesting against new taxes, killing four. The event, known as Sette Giugno ("7 June"), is commemorated every year and is one of five National Days.[119][120] Until the Second World War, Maltese politics was dominated by the Language Question fought out by Italophone and Anglophone parties.[121]

Before the Second World War, Valletta was the location of the Royal Navy's Mediterranean fleet headquarters; however, despite Winston Churchill's objections,[122] the command was moved to Alexandria, Egypt, in 1937 out of fear that it was too susceptible to air attacks from Europe.[122][123][124] During the war Malta played an important role for the Allies; being a British colony, situated close to Sicily and the Axis shipping lanes, Malta was bombarded by the Italian and German air forces. Malta was used by the British to launch attacks on the Italian Navy and had a submarine base. It was also used as a listening post, intercepting German radio messages including Enigma traffic.[125] The bravery of the Maltese people during the second siege of Malta moved King George VI to award the George Cross to Malta on a collective basis on 15 April 1942. Some historians argue that the award caused Britain to incur disproportionate losses in defending Malta, as British credibility would have suffered if Malta had surrendered, as British forces in Singapore had done.[126] A depiction of the George Cross now appears on the Flag of Malta and the country's arms.

Independence and Republic

[edit]

Malta achieved its independence as the State of Malta on 21 September 1964 (Independence Day). Under its 1964 constitution, Malta initially retained Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Malta and thus head of state, with a governor-general exercising executive authority on her behalf. In 1971, the Malta Labour Party led by Dom Mintoff won the general elections, resulting in Malta declaring itself a republic on 13 December 1974 (Republic Day) within the Commonwealth. A defence agreement was signed soon after independence, and after being re-negotiated in 1972, expired on 31 March 1979 (Freedom Day).[127] Upon its expiry, the British base closed and lands formerly controlled by the British were given to the Maltese government.[128]

In the aftermath of the departure of the remaining British troops in 1979, the country intensified its participation in the Non-Aligned Movement. Malta adopted a policy of neutrality in 1980.[129] In that same year, three of Malta's sites, including the capital Valletta, were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. In 1989, Malta was the venue of a summit between US President George H. W. Bush and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, their first face-to-face encounter, which signalled the end of the Cold War.[130] Malta International Airport was inaugurated and became fully operational on 25 March 1992, boosting the local aircraft and tourism industry. A referendum on joining the European Union was held on 8 March 2003, with 53.65% in favour.[131] Malta joined the European Union on 1 May 2004[132] and the eurozone on 1 January 2008.[133]

Politics

[edit]

Malta is a republic[34] whose parliamentary system and public administration are closely modelled on the Westminster system.

The unicameral Parliament is made up of the President of Malta and the House of Representatives (Maltese: Kamra tad-Deputati). The President of Malta, a largely ceremonial position, is appointed for a five-year term by a resolution of the House of Representatives carried by a simple majority. The House of Representatives has 65 members, elected for a five-year term in 13 five-seat electoral divisions, called distretti elettorali, with constitutional amendments that allow for mechanisms to establish strict proportionality amongst seats and votes of political parliamentary groups. Members of the House of Representatives are elected by direct universal suffrage through single transferable vote every five years, unless the House is dissolved earlier by the president either on the advice of the prime minister or through a motion of no confidence. Malta had the second-highest voter turnout in the world (and the highest for nations without mandatory voting), based on election turnout in national lower house elections from 1960 to 1995.[134]Since Malta is a republic, the head of state in Malta is the President of the Republic. The current President of the Republic is Myriam Spiteri Debono, who was elected on 27 March, 2024 by members of parliament in an indirect election.[135] The 80th article of the Constitution of Malta provides that the president appoint as prime minister "the member of the House of Representatives who, in his judgment, is best able to command the support of a majority of the members of that House".[34] Maltese politics is a two-party system dominated by the Labour Party (Maltese: Partit Laburista), a centre-left social democratic party, and the Nationalist Party (Maltese: Partit Nazzjonalista), a centre-right Christian democratic party. The Labour Party has been the governing party since 2013 and is currently led by Prime Minister Robert Abela, who has been in office since 13 January 2020. There are a number of small political parties in Malta which have no parliamentary representation.

Administrative divisions

[edit]

Malta has had a system of local government since 1993,[136] based on the European Charter of Local Self-Government. The country is divided into six regions (one of them being Gozo), with each region having its own Regional Council, serving as the intermediate level between local government and national government.[137] The regions are divided into local councils, of which there are currently 68 (54 in Malta and 14 in Gozo). The six districts (five on Malta and the sixth being Gozo) serve primarily statistical purposes.[138]

Each council is made up of a number of councillors (from 5 to 13, depending on and relative to the population they represent). A mayor and a deputy mayor are elected by and from the councillors. The executive secretary, who is appointed by the council, is the executive, administrative and financial head of the council. Councillors are elected every four years through the single transferable vote. Due to system reforms, no elections were held before 2012. Since then, elections have been held every two years for an alternating half of the councils.

Local councils are responsible for the general upkeep and embellishment of the locality (including repairs to non-arterial roads), allocation of local wardens, and refuse collection; they also carry out general administrative duties for the central government such as the collection of government rents and funds and answer government-related public inquiries. Additionally, a number of individual towns and villages in the Republic of Malta have sister cities.

Military

[edit]

The objectives of the Armed Forces of Malta (AFM) are to maintain a military organisation with the primary aim of defending the islands' integrity according to the defence roles as set by the government in an efficient and cost-effective manner. This is achieved by emphasising the maintenance of Malta's territorial waters and airspace integrity.[139]

The AFM also engages in combating terrorism, fighting against illicit drug trafficking, conducting anti-illegal immigrant operations and patrols, and anti-illegal fishing operations, operating search and rescue (SAR) services, and physical or electronic security and surveillance of sensitive locations. Malta's search-and-rescue area extends from east of Tunisia to west of Crete, an area of around 250,000 km2 (97,000 sq mi).[140]

As a military organisation, the AFM provides backup support to the Malta Police Force (MPF) and other government departments/agencies in situations as required in an organised, disciplined manner in the event of national emergencies (such as natural disasters) or internal security and bomb disposal.[141]

In 2020, Malta signed and ratified the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[142][143]

Human rights

[edit]Malta is regarded as one of the most LGBT-supportive countries in the world,[144][145] and was the first nation in the European Union to prohibit conversion therapy.[146] Malta also constitutionally bans discrimination based on disability.[147]Maltese legislation recognises both civil and canonical (ecclesiastical) marriages. Annulments by the ecclesiastical and civil courts are unrelated and are not necessarily mutually endorsed. Malta voted in favour of divorce legislation in a referendum held on 28 May 2011.[148]

In Malta, life from conception is protected, and as such abortion in Malta is illegal. It is the only European Union member state with a total ban on the procedure. There are no exceptions for rape or incest.[149] On 21 November 2022, the government led by the Labour Party proposed a bill that "introduces a new clause into the country's criminal code allowing for the termination of a pregnancy if the mother's life is at risk or if her health is in serious jeopardy".[150] As of 2023, an exception was added to allow abortion only if the mother's life is at risk.[151]

Geography

[edit]

Malta is an archipelago in the central Mediterranean (in its eastern basin), some 80 km (50 mi) from southern Italy across the Malta Channel. Only the three largest islands—Malta (Maltese: Malta), Gozo (Għawdex), and Comino (Kemmuna)—are inhabited. The islands of the archipelago lie on the Malta plateau, a shallow shelf formed from the high points of a land bridge between Sicily and North Africa that became isolated as sea levels rose after the last ice age.[152] The archipelago is located on the African tectonic plate.[153][154] Malta was considered an island of North Africa for centuries.[155]

Numerous bays along the indented coastline of the islands provide good harbours. The landscape consists of low hills with terraced fields. The highest point in Malta is Ta' Dmejrek, at 253 m (830 ft), near Dingli. Although there are some small rivers at times of high rainfall, there are no permanent rivers or lakes on Malta. However, some watercourses have fresh water running all year round at Baħrija near Ras ir-Raħeb, at l-Imtaħleb and San Martin, and at Lunzjata Valley in Gozo.

Phytogeographically, Malta belongs to the Liguro-Tyrrhenian province of the Mediterranean region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, the territory of Malta belongs to the terrestrial ecoregion of Tyrrhenian-Adriatic sclerophyllous and mixed forests.[156]

The following uninhabited minor islands are part of the archipelago:

- Barbaġanni Rock (Gozo)

- Cominotto (Kemmunett)

- Dellimara Island (Marsaxlokk)

- Filfla (Żurrieq)/(Siġġiewi)

- Fessej Rock

- Fungus Rock (Il-Ġebla tal-Ġeneral), (Gozo)

- Għallis Rock (Naxxar)

- Ħalfa Rock (Gozo)

- Large Blue Lagoon Rocks (Comino)

- Islands of St. Paul/Selmunett Island (Mellieħa)

- Manoel Island, which connects to the town of Gżira, on the mainland via a bridge

- Mistra Rocks (San Pawl il-Baħar)

- Taċ-Ċawl Rock (Gozo)

- Qawra Point/Ta' Fraben Island (San Pawl il-Baħar)

- Small Blue Lagoon Rocks (Comino)

- Sala Rock (Żabbar)

- Xrobb l-Għaġin Rock (Marsaxlokk)

- Ta' taħt il-Mazz Rock

Climate

[edit]Malta has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa),[35][157] with mild winters and hot summers, hotter in the inland areas. Rain occurs mainly in autumn and winter, with summer being generally dry.

The average yearly temperature is around 23 °C (73 °F) during the day and 15.5 °C (59.9 °F) at night. In the coldest month – January – the typical maximum temperature ranges from 12 to 18 °C (54 to 64 °F) during the day and minimum 6 to 12 °C (43 to 54 °F) at night. In the warmest month – August – the typical maximum temperature ranges from 28 to 34 °C (82 to 93 °F) during the day and minimum 20 to 24 °C (68 to 75 °F) at night. Amongst all capitals in the continent of Europe, Valletta – the capital of Malta has the warmest winters, with average temperatures of around 15 to 16 °C (59 to 61 °F) during the day and 9 to 10 °C (48 to 50 °F) at night in the period January–February. In March and December average temperatures are around 17 °C (63 °F) during the day and 11 °C (52 °F) at night.[158] Large fluctuations in temperature are rare. Snow is very rare, although snowfalls have been recorded in the last century, the last one in 2014.[159]

The average annual sea temperature is 20 °C (68 °F), from 15–16 °C (59–61 °F) in February to 26 °C (79 °F) in August. In the 6 months – from June to November – the average sea temperature exceeds 20 °C (68 °F).[160][161][162]

The annual average relative humidity is high, averaging 75%, ranging from 65% in July (morning: 78% evening: 53%) to 80% in December (morning: 83% evening: 73%).[163]

Sunshine duration hours total around 3,000 per year, from an average 5.2 hours of sunshine duration per day in December to an average above 12 hours in July.[161][164] This is about double that of cities in the northern half of Europe,[original research?] for comparison: London – 1,461;[165] however, in winter it has up to four times more sunshine; for comparison: in December, London has 37 hours of sunshine[165] whereas Malta has above 160.

| Climate data for Malta (Luqa in the south-east part of main island, 1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 15.7 (60.3) | 15.7 (60.3) | 17.4 (63.3) | 20.0 (68.0) | 24.2 (75.6) | 28.7 (83.7) | 31.7 (89.1) | 32.0 (89.6) | 28.6 (83.5) | 25.0 (77.0) | 20.8 (69.4) | 17.2 (63.0) | 23.1 (73.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.2) | 12.6 (54.7) | 14.1 (57.4) | 16.4 (61.5) | 20.1 (68.2) | 24.2 (75.6) | 26.9 (80.4) | 27.5 (81.5) | 24.9 (76.8) | 21.8 (71.2) | 17.9 (64.2) | 14.5 (58.1) | 19.5 (67.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 10.1 (50.2) | 9.5 (49.1) | 10.9 (51.6) | 12.8 (55.0) | 15.8 (60.4) | 19.6 (67.3) | 22.1 (71.8) | 23.0 (73.4) | 21.2 (70.2) | 18.4 (65.1) | 14.9 (58.8) | 11.8 (53.2) | 15.9 (60.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 79.3 (3.12) | 73.2 (2.88) | 45.3 (1.78) | 20.7 (0.81) | 11.0 (0.43) | 6.2 (0.24) | 0.2 (0.01) | 17.0 (0.67) | 60.7 (2.39) | 81.8 (3.22) | 91.0 (3.58) | 93.7 (3.69) | 580.7 (22.86) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.0 | 8.2 | 6.1 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 4.3 | 6.6 | 8.7 | 10.0 | 61 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 169.3 | 178.1 | 227.2 | 253.8 | 309.7 | 336.9 | 376.7 | 352.2 | 270.0 | 223.8 | 195.0 | 161.2 | 3,054 |

| Source: Meteo Climate (1991–2020 Data),[166] MaltaWeather.com (Sun data)[167] | |||||||||||||

Urbanisation

[edit]

According to Eurostat, Malta is composed of two larger urban zones nominally referred to as "Valletta" (the main island of Malta) and "Gozo". The main urban area covers the entire main island, with a population of around 400,000.[168][169] The core of the urban area, the greater city of Valletta, has a population of 205,768.[170] According to the data from 2020 by Eurostat, the Functional Urban Area and metropolitan region covered the whole island and has a population of 480,134.[171][172] According to the United Nations, about 95 percent of the area of Malta is urban and the number grows every year.[20] According to ESPON and EU Commission studies, "the whole territory of Malta constitutes a single urban region".[21]

Malta, with area of 316 km2 (122 sq mi) and population of over 0.5 million, is one of the most densely populated countries worldwide. It is in some sources[22][23][24][173][174] referred to as a city-state. Sometimes Malta is listed in rankings concerning cities[175] or metropolitan areas.[176]

Flora

[edit]

The Maltese islands are home to a wide diversity of indigenous, sub-endemic and endemic plants.[177] They feature many traits typical of a Mediterranean climate, such as drought resistance. The most common indigenous trees on the islands are olive (Olea europaea), carob (Ceratonia siliqua), fig (Ficus carica), holm oak (Quericus ilex) and Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis), while the most common non-native trees are eucalyptus, acacia and opuntia. Endemic plants include the national flower widnet il-baħar (Cheirolophus crassifolius), sempreviva ta' Malta (Helichrysum panormitanum subsp. melitense), żigland t' Għawdex (Hyoseris frutescens) and ġiżi ta' Malta (Matthiola incana subsp. melitensis) while sub-endemics include kromb il-baħar (Jacobaea maritima subsp. sicula) and xkattapietra (Micromeria microphylla).[178] The biodiversity of Malta is severely endangered by habitat loss, invasive species and human intervention.[179]

Economy

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (December 2019) |

Malta is classified as an advanced economy according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[180] Malta's major resources are limestone, a favourable geographic location and a productive labour force. Malta produces only about 20 percent of its food needs, has limited fresh water supplies because of the drought in the summer, and has no domestic energy sources, aside from the potential for solar energy from its plentiful sunlight. The economy is dependent on foreign trade (serving as a freight trans-shipment point), manufacturing (especially electronics and textiles), and tourism.[181] Film production has contributed to the Maltese economy.[182]

Access to biocapacity in Malta is below the world average. In 2016, Malta had 0.6 global hectares of biocapacity per person within its territory, contrasted with a global average of 1.6 hectares per person.[183][184] Additionally, residents of Malta exhibited an ecological footprint of consumption of 5.8 global hectares of biocapacity per person, resulting in a sizable biocapacity deficit.[183]

In preparation for Malta's membership in the European Union, which it joined on 1 May 2004, it privatised some state-controlled firms and liberalised markets.[185][186][187][188] Malta has a financial regulator, the Malta Financial Services Authority (MFSA), with a strong business development mindset, and the country has been successful in attracting gaming businesses, aircraft and ship registration, credit-card issuing banking licences and also fund administration. Malta has made strong headway in implementing EU Financial Services Directives including UCITs IV and Alternative Investment Fund Managers (AIFMs). As a base for alternative asset managers who must comply with new directives, Malta has attracted a number of key players including IDS, Iconic Funds, Apex Fund Services and TMF/Customs House.[189]

As of 2015, Malta did not have a property tax. Its property market, especially around the harbour area, was booming, with the prices of apartments in some towns like St Julian's, Sliema and Gzira skyrocketing.[190]

According to Eurostat data, Maltese GDP per capita stood at 88 per cent of the EU average in 2015 with €21,000.[191]

The National Development and Social Fund from the Individual Investor Programme, a citizenship by investment programme also known as the "citizenship scheme", became a significant income source for the government of Malta, adding 432,000,000 euro to the budget in 2018.[192]

Banking and finance

[edit]

The two largest commercial banks are Bank of Valletta and HSBC Bank Malta. Digital banks such as Revolut have also increased in popularity.[193] The Central Bank of Malta (Bank Ċentrali ta' Malta) has two key areas of responsibility: the formulation and implementation of monetary policy and the promotion of a sound and efficient financial system. The Maltese government entered ERM II on 4 May 2005, and adopted the euro as the country's currency on 1 January 2008.[194]

Currency

[edit]Maltese euro coins feature the Maltese cross on €2 and €1 coins, the coat of arms of Malta on the €0.50, €0.20 and €0.10 coins, and the Mnajdra Temples on the €0.05, €0.02 and €0.01 coins.[195]

Malta has produced collectors' coins with face value ranging from 10 to 50 euros. These coins continue an existing national practice of minting of silver and gold commemorative coins. Unlike normal issues, these coins are not accepted in all the eurozone.

From its introduction in 1972 until the introduction of the Euro in 2008, the currency was the Maltese lira, which had replaced the Maltese pound. The pound replaced the Maltese scudo in 1825.

Tourism

[edit]

Malta is a popular tourist destination, with 1.6 million tourists per year.[196] Three times more tourists visit than there are residents. Tourism infrastructure has increased dramatically over the years and a number of hotels are present on the island, although overdevelopment and the destruction of traditional housing is of growing concern. In 2019, Malta had a record year in tourism, recording over 2.1 million tourists in one single year.[197]

In recent years, Malta has advertised itself as a medical tourism destination,[198] and a number of health tourism providers are developing the industry. However, no Maltese hospital has undergone independent international healthcare accreditation. Malta is popular with British medical tourists,[199] pointing Maltese hospitals towards seeking UK-sourced accreditation, such as with the Trent Accreditation Scheme.

Tourism in Malta contributes around 11.6 percent of the country's gross domestic product.[200]

Science and technology

[edit]Malta signed a co-operation agreement with the European Space Agency (ESA) for more-intensive co-operation in ESA projects.[201]The Malta Council for Science and Technology (MCST) is the civil body responsible for the development of science and technology on an educational and social level. Most science students in Malta graduate from the University of Malta and are represented by S-Cubed (Science Student's Society), UESA (University Engineering Students Association) and ICTSA (University of Malta ICT Students' Association).[202][203] Malta was ranked 25th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[204]

Demographics

[edit]As of the 2021 census, Maltese-born natives make up the majority of the island with 386,280 people out of a total population of 519,562.[206] However, there are minorities, the largest of which by birthplace were: 15,082 from the United Kingdom, Italy (13,361), India (7,946), Philippines (7,784) and Serbia (5,935). Among racial origins for the non-Maltese, 58.1% of all identified as Caucasian, 22.2% Asian, 6.3% Arab, 6.0% African, 4.5% Hispanic or Latino and 2.9% more than one race.[207]

As of 2005[update], 17 percent were aged 14 and under, 68 percent were within the 15–64 age bracket whilst the remaining 13 percent were 65 years and over. Malta's population density of 1,282 per square km (3,322/sq mi) is by far the highest in the EU and one of the highest in the world.

The Maltese-resident population for 2004 was estimated to make up 97.0 per cent of the total resident population.[208] All censuses since 1842 have shown a slight excess of females over males. Population growth has slowed down, from +9.5 per cent between the 1985 and 1995 censuses, to +6.9 per cent between the 1995 and 2005 censuses (a yearly average of +0.7 per cent). The birth rate stood at 3860 (a decrease of 21.8 per cent from the 1995 census) and the death rate stood at 3025. Thus, there was a natural population increase of 835 (compared to +888 for 2004, of which over a hundred were foreign residents).[209]The population's age composition is similar to the age structure prevalent in the EU. Malta's old-age-dependency-ratio rose from 17.2 percent in 1995 to 19.8 percent in 2005, reasonably lower than the EU's 24.9 percent average; 31.5 percent of the Maltese population is aged under 25 (compared to the EU's 29.1 percent); but the 50–64 age group constitutes 20.3 percent of the population, significantly higher than the EU's 17.9 percent. Malta's old-age-dependency-ratio is expected to continue rising steadily in the coming years.

In 2021, the population of the Maltese Islands stood at 519,562.[8]

The total fertility rate (TFR) as of 2016[update] was estimated at 1.45 children born/woman, which is below the replacement rate of 2.1.[210] In 2012, 25.8 per cent of births were to unmarried women.[211] The life expectancy in 2018 was estimated at 83.[212]

Languages

[edit]

The Maltese language (Maltese: Malti) is one of the two constitutional languages of Malta and is considered the national language. The second official language is English and hence laws are enacted both in Maltese and English. However, article 74 of the Constitution states that "if there is any conflict between the Maltese and the English texts of any law, the Maltese text shall prevail."[34]

Maltese is a Semitic language descended from the now extinct Sicilian-Arabic (Siculo-Arabic) dialect (from southern Italy) that developed during the Emirate of Sicily.[213] The Maltese alphabet consists of 30 letters based on the Latin alphabet.

In 2022, Malta National Statistics Office states that 90 percent of the Maltese population has at least a basic knowledge of Maltese, 96 percent of English, 62 percent of Italian, and 20 percent of French.[33] This widespread knowledge of second languages makes Malta one of the most multilingual countries in the European Union. A study collecting public opinion on what language was "preferred" discovered that 86 percent of the population preferred Maltese, 12 percent English, and 2 percent Italian.[214] Italian television channels from Italy-based broadcasters, such as Mediaset and RAI, reach Malta and remain popular.[214][215][216]

Maltese Sign Language is used by signers in Malta.[217]

Religion

[edit]Religion in Malta (2021 census)[5][6][218]

The predominant religion in Malta is Catholicism. The second article of the Constitution of Malta establishes Catholicism as the state religion and it is also reflected in various elements of Maltese culture, although there are entrenched provisions for the freedom of religion.[34] There are more than 360 churches in Malta, Gozo, and Comino, or one church for every 1,000 residents. The parish church (Maltese: "il-parroċċa", or "il-knisja parrokkjali") is the architectural and geographic focal point of every Maltese town and village.

Malta is an Apostolic See; the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 28) tells of how St. Paul was shipwrecked on the island of "Melite", which many Bible scholars identify with Malta, an episode dated around AD 60.[219] The Maltese saint, Saint Publius is said to have been made Malta's first bishop. Further evidence of Christian practices and beliefs during the period of Roman persecution appears in catacombs that lie beneath various sites around Malta, including St. Paul's Catacombs. There are also a number of cave churches, including the grotto at Mellieħa, which is a Shrine of the Nativity of Our Lady where, according to legend, St. Luke painted a picture of the Madonna. It has been a place of pilgrimage since the medieval period.

For centuries, the Church in Malta was subordinate to the Diocese of Palermo, except when it was under Charles of Anjou, who appointed bishops for Malta, as did – on rare occasions – the Spanish and later, the Knights. Since 1808 all bishops of Malta have been Maltese. The patron saints of Malta are Saint Paul, Saint Publius, and Saint Agatha. Although not a patron saint, St George Preca (San Ġorġ Preca) is greatly revered as the second canonised Maltese saint after St. Publius. Various Catholic religious orders are present in Malta, including the Jesuits, Franciscans, Dominicans, Carmelites and Little Sisters of the Poor.

Most congregants of the local Protestant churches are not Maltese; their congregations draw on vacationers and British retirees living in the country. There are also a Seventh-day Adventist church in Birkirkara, and a New Apostolic Church congregation founded in 1983 in Gwardamangia.[220] There are approximately 600 Jehovah's Witnesses.[221] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is also represented.

The Jewish population of Malta reached its peak in the Middle Ages under Norman rule. In 1479, Malta and Sicily came under Aragonese rule and the Alhambra Decree of 1492 forced all Jews to leave the country. Today, there are two Jewish congregations.[220] In 2019 the Jewish community in Malta gathered around 150 persons, slightly more than the 120 (of which 80 were active) estimated in 2003, and mostly elderly. Many among the newer generations decided to settle abroad, including in England and Israel. Most contemporary Maltese Jews are Sephardi, however, an Ashkenazi prayer book is used. In 2013 the Chabad Jewish Center in Malta was founded.

There is one Muslim mosque, the Mariam Al-Batool Mosque. Of the estimated 3,000 Muslims in Malta, approximately 2,250 are foreigners, approximately 600 are naturalised citizens, and approximately 150 are native-born Maltese.[222]Zen Buddhism and the Baháʼí Faith claim some 40 members.[220]

In a survey held by Malta Today, the overwhelming majority of the Maltese population adheres to Christianity (95.2%) with Catholicism as the main denomination (93.9%); 4.5% of the population declared themselves either atheist or agnostic, one of the lowest figures in Europe.[223] According to a 2019 Eurobarometer survey, 83% of the population identified as Catholic.[224] The number of atheists has doubled from 2014 to 2018. Non-religious people have a higher risk of suffering from discrimination. In the 2015 edition of the annual Freedom of Thought Report from the International Humanist and Ethical Union, Malta was in the category of "severe discrimination". In 2016, following the abolishment of blasphemy law, Malta was shifted to the category of "systematic discrimination" (same as most EU countries).[225]

Migration

[edit]| Foreign population in Malta | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | % total | |||||||||||||||||

| 2005 | 12,112 | 3.0% | |||||||||||||||||

| 2011 | 20,289 | 4.9% | |||||||||||||||||

| 2019 | 98,918 | 21.0% | |||||||||||||||||

| 2020 | 119,261 | 23.17% | |||||||||||||||||

Historically a land of emigration, since the early 21st century Malta has seen a significant increase in net migration; the foreign-born population has grown nearly eightfold between 2005 and 2020. Most of the foreign community in Malta consists of active or retired British nationals and their dependents, centred on Sliema and surrounding suburbs. Other smaller foreign groups include Italians, Libyans, and Serbians, many of whom have assimilated into the Maltese nation over the decades.[226]

Malta is also home to a large number of foreign workers who migrated to the island for economic opportunity. This migration was driven predominantly in the early 21st century, when the Maltese economy was steadily booming yet the cost and quality of living on the island remained relatively stable. In recent years however the local Maltese housing index has doubled[227] pushing property and rental prices to very high and almost unaffordable levels. Consequently, some expats in Malta have seen their relative financial fortunes decline, with others relocating to other European countries altogether.

Since the late 20th century, Malta has become a transit country for migration routes from Africa towards Europe.[228] As a member of the European Union and the Schengen Agreement, Malta is bound by the Dublin Regulation to process all claims for asylum by those asylum seekers that enter EU territory for the first time in Malta.[229] However, irregular migrants who land in Malta are subject to a compulsory detention policy, being held in several camps organised by the Armed Forces of Malta (AFM), including those near Ħal Far and Ħal Safi. The compulsory detention policy has been denounced by several NGOs, and in July 2010, the European Court of Human Rights found that Malta's detention of migrants was arbitrary, lacking in adequate procedures to challenge detention, and in breach of its obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights.[230][231] On 8 September 2020, Amnesty International criticized Malta for "illegal tactics" in the Mediterranean, against immigrants who were attempting to cross from North Africa. The reports claimed that the government's approach might have led to avoidable deaths.[232]

In January 2014, Malta started granting citizenship for a €650,000 contribution plus investments, contingent on residence and criminal background checks.[233] This "golden passport" citizenship scheme has been criticized as a fraudulent act by the Maltese Government.[clarification needed][234] Concerns as to whether the Maltese citizenship scheme is allowing an influx of such individuals into the greater European Union have been raised by both the public as well as the European Council on multiple occasions.[235]

In the 19th century, most emigration from Malta was to North Africa and the Middle East, although rates of return migration to Malta were high.[236] In the 20th century, most emigrants went to destinations in the New World, particularly to Australia, Canada, and the United States. Post Second World War, Malta's Emigration Department would assist emigrants with the cost of their travel. Between 1948 and 1967, 30 percent of the population emigrated.[236] Between 1946 and the late-1970s, over 140,000 people left Malta on the assisted passage scheme, with 57.6% migrating to Australia, 22% to the UK, 13% to Canada and 7% to the United States.[237] Emigration dropped dramatically after the mid-1970s and has since ceased to be a social phenomenon of significance. However, since Malta joined the EU in 2004 expatriate communities emerged in a number of European countries, particularly in Belgium and Luxembourg.

Education

[edit]

Primary schooling has been compulsory since 1946; secondary education up to the age of sixteen was made compulsory in 1971. The state and the Church provide education free of charge, both running a number of schools in Malta and Gozo. As of 2006[update], state schools are organised into networks known as Colleges and incorporate kindergarten schools, primary and secondary schools. A number of private schools are run in Malta. St. Catherine's High School, Pembroke offers an International Foundation Course for students wishing to learn English before entering mainstream education. As of 2008[update], there are two international schools, Verdala International School and QSI Malta. The state pays a portion of the teachers' salary in Church schools.[238]

Education in Malta is based on the British model. Primary school lasts six years. Pupils sit for SEC O-level examinations at the age of 16, with passes obligatory in mathematics, a minimum of one science subject, English and Maltese. Pupils may opt to continue studying at a sixth form college for two years, at the end of which students sit for the matriculation examination. Subject to their performance, students may then apply for an undergraduate degree or diploma.

The adult literacy rate is 99.5 per cent.[239]

Maltese and English are both used to teach pupils at the primary and secondary school level, and both languages are also compulsory subjects. Public schools tend to use both Maltese and English in a balanced manner. Private schools prefer to use English for teaching, as is also the case with most departments of the University of Malta; this has a limiting effect on the capacity and development of the Maltese language.[214] Most university courses are in English.[240][213] The College of Remote and Offshore Medicine based in Malta teaches exclusively in English.

Of the total number of pupils studying a first foreign language at secondary level, 51 per cent take Italian whilst 38 per cent take French. Other choices include German, Russian, Spanish, Latin, Chinese and Arabic.[214][241]

Malta is also a popular destination to study the English language, attracting over 83,000 students in 2019.[242]

Infrastructure

[edit]Transport

[edit]Owing to the British colonial rule, traffic in Malta drives on the left. Car ownership in Malta is exceedingly high, considering the very small size of the islands; it is the fourth-highest in the European Union. There were 182,254 registered cars in 1990, giving an automobile density of 577/km2 (1,494/sq mi).[243] Malta has 2,254 kilometres (1,401 miles) of road, 1,972 km (1,225 mi) (87.5 per cent) of which are paved (as of December 2003).[244]

Buses (xarabank or karozza tal-linja) are the primary method of public transport, established in 1905. Malta's vintage buses operated in the Maltese islands up to 2011 and became popular tourist attractions.[245] To this day they are depicted on many Maltese advertisements and merchandise for tourists.

The bus service underwent extensive reform in July 2011. The management structure changed from having self-employed drivers driving their own vehicles to a service being offered by a single company through a public tender.[246] The public tender was won by Arriva Malta, which introduced a fleet of brand new buses, built by King Long especially for service by Arriva Malta and including a smaller fleet of articulated buses brought in from Arriva London. It also operated two smaller buses for an intra-Valletta route only and 61 nine-metre buses, which were used to ease congestion on high-density routes. Overall Arriva Malta operated 264 buses. On 1 January 2014 Arriva ceased operations in Malta due to financial difficulties, having been nationalised as Malta Public Transport.[247][248] The government chose Autobuses Urbanos de León (Alsa subsidiary) as its preferred bus operator for the country in October 2014.[249] From October 2022, the bus system is free of charge for residents of Malta.[250]

As of 2021, an underground Malta Metro is being planned, with a projected total cost of €6.2 billion.[251]

Malta has three large natural harbours on its main island:

- The Grand Harbour (or Port il-Kbir), located at the eastern side of the capital city of Valletta, has been a harbour since Roman times. It has several extensive docks and wharves, as well as a cruise liner terminal. A terminal at the Grand Harbour serves ferries that connect Malta to Pozzallo & Catania in Sicily.

- Marsamxett Harbour, located on the western side of Valletta, accommodates a number of yacht marinas.

- Marsaxlokk Harbour (Malta Freeport), at Birżebbuġa on the south-eastern side of Malta, is the islands' main cargo terminal. Malta Freeport is the 11th busiest container ports in continent of Europe and 46th in the World with a trade volume of 2.3 million TEU's in 2008.[252]

There are also two human-made harbours that serve a passenger and car ferry service that connects Ċirkewwa Harbour on Malta and Mġarr Harbour on Gozo.

Malta International Airport (Ajruport Internazzjonali ta' Malta) is the only airport serving the Maltese islands. It is built on the land formerly occupied by the RAF Luqa air base. A heliport is also located there. The heliport in Gozo is at Xewkija. A former airfield at Ta' Qali houses a national park, stadium, the Crafts Village visitor attraction and the Malta Aviation Museum.

From 1 April 1974 to 30 March 2024, the national airline was Air Malta, which was based at Malta International Airport and operated services to 22 destinations in Europe and North Africa. The owners of Air Malta were the Government of Malta (98 percent) and private investors (2 percent).

On 31 March 2024, KM Malta Airlines took over as the national airline of Malta. All former Air Malta Airplanes and other assets were transferred to the new airline, together with the staff. KM Malta Airlines is based at Malta International Airport and operates services to 18 destinations in Europe.

In June 2019, Ryanair has invested into a fully-fledged airline subsidiary, called Malta Air, operating a low-cost model. The Government of Malta holds one share in the airline.[253]

Communications

[edit]The mobile penetration rate in Malta exceeded 100% by the end of 2009.[254] Malta uses the GSM900, UMTS(3G) and LTE(4G) mobile phone systems, which are compatible with the rest of the European countries, Australia and New Zealand.[citation needed]

In early 2012, the government called for a national Fibre to the Home (FttH) network to be built, with a minimum broadband service being upgraded from 4 Mbit/s to 100 Mbit/s.[255]

Healthcare

[edit]Malta has a long history of providing publicly funded health care. The first hospital recorded in the country was already functioning by 1372.[256]Today, Malta has both a public healthcare system, where healthcare is free at the point of delivery, and a private healthcare system.[257][258] Malta has a strong general practitioner-delivered primary care base and the public hospitals provide secondary and tertiary care. The Maltese Ministry of Health advises foreign residents to take out private medical insurance.[259]

Malta also boasts voluntary organisations such as Alpha Medical (Advanced Care), the Emergency Fire & Rescue Unit (E.F.R.U.), St John Ambulance and Red Cross Malta who provide first aid/nursing services during events involving crowds, Malta's primary hospital, opened in 2007. It has one of the largest medical buildings in Europe.

The University of Malta has a medical school and a Faculty of Health Sciences. The Medical Association of Malta represents practitioners of the medical profession. The Foundation Program followed in the UK has been introduced in Malta to stem the 'brain drain' of newly graduated physicians to the British Isles.

Culture

[edit]The culture of Malta reflects the various cultures, that have come into contact with the Maltese Islands throughout the centuries.[260]

Music

[edit]

While Maltese music today is largely Western, traditional Maltese music includes what is known as għana. This consists of background folk guitar music, while a few people, generally men, take it in turns to argue a point in a sing-song voice. Music plays an important part in Maltese culture as each locality parades its own band club, on various occasions these being multiple per locality, and function to establish the thematic musical background to the various village feasts. The Malta Philharmonic Orchestra is recognized as Malta's foremost musical institution and is notable for being called to participate in important state events.

Contemporary music in Malta spans a variety of styles and sports international classical talents such as Miriam Gauci and Joseph Calleja, as well as non-classical music bands such as Winter Moods, and Red Electric, and singers like Ira Losco, Fabrizio Faniello, Glen Vella, Kevin Borg, Kurt Calleja, Chiara Siracusa, and Thea Garrett.

Literature

[edit]Documented Maltese literature is over 200 years old. However, a recently unearthed love ballad testifies to literary activity in the local tongue from the Medieval period. Malta followed a Romantic literary tradition, culminating in the works of Dun Karm Psaila, Malta's national poet. Subsequent writers like Ruzar Briffa and Karmenu Vassallo tried to estrange themselves from the rigidity of formal themes and versification.[261]

The next generation of writers, including Karl Schembri and Immanuel Mifsud, widened the tracks further, especially in prose and poetry.[262]

Architecture

[edit]

Maltese architecture has been influenced by many different Mediterranean cultures and British architecture over its history.[263] The first settlers on the island constructed Ġgantija, one of the oldest manmade freestanding structures in the world. The Neolithic temple builders (3800–2500 BC) endowed the numerous temples of Malta and Gozo with intricate bas-relief designs.

The Roman period introduced highly decorative mosaic floors, marble colonnades, and classical statuary, remnants of which are beautifully preserved and presented in the Roman Domus, a country villa just outside the walls of Mdina. The early Christian frescoes that decorate the catacombs beneath Malta reveal a propensity for eastern, Byzantine tastes. These tastes continued to inform the endeavours of medieval Maltese artists, but they were increasingly influenced by the Romanesque and Southern Gothic movements.Malta is currently undergoing several large-scale building projects, while areas such as the Valletta Waterfront and Tigné Point have been or are being renovated.[264]

Art

[edit]Towards the end of the 15th century, Maltese artists, like their counterparts in Sicily, came under the influence of the School of Antonello da Messina, which introduced Renaissance ideals and concepts to the decorative arts in Malta.[265]

The artistic heritage of Malta blossomed under the Knights of St. John, who brought Italian and Flemish Mannerist painters to decorate their palaces and the churches of these islands, most notably, Matteo Perez d'Aleccio, whose works appear in the Magisterial Palace and in the Conventual Church of St. John in Valletta, and Filippo Paladini, who was active in Malta from 1590 to 1595. For many years, Mannerism continued to inform the tastes and ideals of local Maltese artists.[265]

The arrival in Malta of Caravaggio, who painted at least seven works during his 15-month stay on these islands, further revolutionised local art. Two of Caravaggio's most notable works, The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist and Saint Jerome Writing, are on display in the Conventual Church of St. John. His legacy is evident in the works of local artists Giulio Cassarino and Stefano Erardi. However, the Baroque movement that followed was destined to have the most enduring impact on Maltese art and architecture. The vault paintings of the Calabrese artist Mattia Preti transformed the Conventual Church St. John into a Baroque masterpiece. Melchior Gafà emerged as one of the top Baroque sculptors of the Roman School.[266]

During the 17th and 18th century, Neapolitan and Rococo influences emerged in the works of the Italian painters Luca Giordano and Francesco Solimena, and these developments can be seen in the work of their Maltese contemporaries such as Gio Nicola Buhagiar and Francesco Zahra. The Rococo movement was greatly enhanced by the relocation to Malta of Antoine de Favray, who assumed the position of court painter to Grand Master Pinto in 1744.[267]

Neo-classicism made some inroads among local Maltese artists in the late-18th century, but this trend was reversed in the early 19th century, as the local Church authorities – perhaps in an effort to strengthen Catholic resolve against the perceived threat of Protestantism during the early days of British rule in Malta – favoured and avidly promoted the religious themes embraced by the Nazarene movement. Romanticism, tempered by the naturalism introduced to Malta by Giuseppe Calì, informed the "salon" artists of the early 20th century, including Edward and Robert Caruana Dingli.[268]

Parliament established the National School of Art in the 1920s. During the reconstruction period that followed the Second World War, the emergence of the "Modern Art Group", whose members included Josef Kalleya, George Preca, Anton Inglott, Emvin Cremona, Frank Portelli, Antoine Camilleri, Gabriel Caruana and Esprit Barthet greatly enhanced the local art scene. This group came together forming an influential pressure group known as the Modern Art Group, which played a leading role in the renewal of Maltese art. Most of Malta's modern artists have in fact studied in Art institutions in England, or on the continent, leading to a diversity of artistic expression that has remained characteristic of contemporary Maltese art. In Valletta, the National Museum of Fine Arts featured work from artists such as H. Craig Hanna.[269] In 2018 the national collection of fine arts was put on display in the new National Museum of Art, MUŻA, at Auberge d'Italie in Valletta.[270]

Cuisine

[edit]

Maltese cuisine shows strong Sicilian and Italian influences as well as influences of English, Spanish, Maghrebin and Provençal cuisines. A number of regional variations can be noted as well as seasonal variations associated with the seasonal availability of produce and Christian feasts (such as Lent, Easter and Christmas). Food has been important historically in the development of a national identity in particular the traditional fenkata (i.e., the eating of stewed or fried rabbit). Potatoes are a staple of the Maltese diet as well.[271]

A number of grapes are endemic to Malta, including Girgentina and Ġellewża. There is a strong wine industry, with significant production of wines using these native grapes, as well as locally grown grapes of other more common varietals. A number of wines have achieved Protected Designation of Origin, with wines produced from grapes cultivated in Malta and Gozo designated as "DOK" wines, that is Denominazzjoni ta' l-Oriġini Kontrollata.[272]

Customs

[edit]A 2010 Charities Aid Foundation study found that the Maltese were the most generous people in the world, with 83% contributing to charity.[273]

Maltese folktales include various stories about mysterious creatures and supernatural events. These were most comprehensively compiled by the scholar (and pioneer in Maltese archaeology) Manwel Magri[274] in his core criticism "Ħrejjef Missirijietna" ("Fables from our Forefathers"). This collection of material inspired subsequent researchers and academics to gather traditional tales, fables and legends from all over the Archipelago.[264] While giants, witches, and dragons feature in many of the stories, some contain entirely Maltese creatures like the Kaw kaw, Il-Belliegħa and L-Imħalla among others.

Traditions

[edit]Traditional Maltese proverbs reveal cultural importance of childbearing and fertility: "iż-żwieġ mingħajr tarbija ma fihx tgawdija" (a childless marriage cannot be a happy one). This is a belief that Malta shares with many other Mediterranean cultures. In Maltese folktales the local variant of the classic closing formula, "and they all lived happily ever after" is "u għammru u tgħammru, u spiċċat" (and they lived together, and they had children together, and the tale is finished).[275]

Rural Malta shares in common with the Mediterranean society a number of superstitions regarding fertility, menstruation, and pregnancy, including the avoidance of cemeteries leading up to childbirth, and avoiding the preparation of certain foods during menses. Pregnant women are encouraged to satisfy their food cravings, out of fear that their unborn child will bear a representational birth mark (Maltese: xewqa, literally "desire" or "craving"). Maltese and Sicilian women also share certain traditions that are believed to predict the sex of an unborn child.[citation needed]

Traditionally, Maltese newborns were baptised as promptly as possible. Traditional Maltese delicacies served at a baptismal feast include biskuttini tal-magħmudija (almond macaroons), it-torta tal-marmorata (a spicy, heart-shaped tart of chocolate-flavoured almond paste), and a liqueur known as rożolin, made with rose petals, violets, and almonds.[citation needed]

On a child's first birthday, in a tradition that still survives today, Maltese parents would organise a game known as il-quċċija, where a variety of symbolic objects would be randomly placed around the seated child. These may include a hard-boiled egg, a Bible, crucifix or rosary beads, a book, and so on. Whichever object the child shows the most interest in is said to reveal the child's path and fortunes in adulthood.[276]

Traditional Maltese weddings featured the bridal party walking in procession beneath an ornate canopy, from the home of the bride's family to the parish church, with singers trailing behind (il-ġilwa). New wives would wear the għonnella, a traditional item of Maltese clothing. Today's couples are married in churches or chapels in the village or town of their choice, usually followed by a lavish wedding reception. Occasionally, couples will try to incorporate elements of the traditional Maltese wedding in their celebration. A resurgent interest in the traditional wedding was evident in May 2007, when thousands of Maltese and tourists attended a traditional Maltese wedding in the style of the 16th century, in Żurrieq.[citation needed]

Festivals and events

[edit]

Local festivals, similar to those in Southern Italy, are commonplace in Malta and Gozo, celebrating weddings, christenings and, most prominently, saints' days. On saints' days, in the morning, the festa reaches its apex with a High Mass featuring a sermon on the life and achievements of the patron saint. In the evening, a statue of the religious patron is taken around the local streets in solemn procession, with the faithful following in prayer. The atmosphere of religious devotion is preceded by several days of celebration and revelry: band marches, fireworks, and late-night parties.

Carnival (Maltese: il-karnival ta' Malta) has had an important place on the cultural calendar after Grand Master It is held during the week leading up to Ash Wednesday, and typically includes masked balls, fancy dress and grotesque mask competitions, lavish late-night parties, a colourful, ticker-tape parade of allegorical floats presided over by King Carnival (Maltese: ir-Re tal-Karnival), marching bands and costumed revellers.[277]

Holy Week (Maltese: il-Ġimgħa Mqaddsa) starts on Palm Sunday (Ħadd il-Palm) and ends on Easter Sunday (Ħadd il-Għid).

Mnarja, or l-Imnarja (pronounced lim-nar-ya) is one of the most important dates on the Maltese cultural calendar. Officially, it is a national festival dedicated to the feast of Saints Peter and Paul. Its roots can be traced back to the pagan Roman feast of Luminaria (literally, "the illumination"), when torches and bonfires lit up the early summer night of 29 June.[278] Празднования по-прежнему начинаются сегодня с чтения «банду» , официального правительственного объявления, которое читается в этот день на Мальте с 16 века. Говорят, что при рыцарях это был единственный день в году, когда мальтийцам разрешалось охотиться и есть дикого кролика , который в остальном предназначался для охотничьих удовольствий рыцарей. Тесная связь между Мнаржей и рагу из кролика (мальтийский: «фенката» ) остается сильной и сегодня. [279]

Isle of MTV — однодневный музыкальный фестиваль, ежегодно проводимый и транслируемый MTV. Фестиваль проводится на Мальте ежегодно с 2007 года, каждый год на нем выступают известные поп-исполнители. В 2012 году выступили всемирно известные артисты Рида , Нелли Фуртадо и Will.i.am. Фло На мероприятии присутствовало более 50 000 человек, что стало самым большим показателем посещаемости на данный момент. [280]

Мальтийский международный фестиваль фейерверков проводится ежегодно в Большой гавани Валлетты с 2003 года. [281]

СМИ

[ редактировать ]Наиболее читаемые и финансово сильные газеты издаются Allied Newspapers Ltd., в основном The Times of Malta (27 процентов) и ее воскресное издание The Sunday Times of Malta (51,6 процента). [ нужна ссылка ] Из-за двуязычия половина газет издается на английском языке, а другая половина – на мальтийском языке . Воскресная газета It-Torċa («Факел»), издаваемая дочерней компанией Профсоюза разнорабочих , является самой широкой газетой на мальтийском языке. Дочерняя газета L-Orizzont («Горизонт») — мальтийская ежедневная газета с самым большим тиражом. Существует большое количество ежедневных или еженедельных газет — одна на каждые 28 000 человек. Реклама, продажи и субсидии — три основных метода финансирования. [282]

На Мальте девять наземных телеканалов: TVM , TVMNews+ , Parliament TV , One , NET Television , Smash Television , F Living , TVMSport+ и Xejk . [283] Государство и политические партии субсидируют большую часть финансирования этих каналов. TVM, TVMNews+ и Парламентское телевидение управляются Службой общественного вещания , национальной телекомпанией и членами EBU . Media.link Communications Ltd., владелец NET Television, и One Productions Ltd. , владелец One, связаны с Националистической и Лейбористской партиями соответственно. Остальные находятся в частной собственности. Управление вещания Мальты имеет полномочия контролировать все местные радиовещательные станции и обеспечивает соблюдение ими юридических и лицензионных обязательств, а также сохранение должной беспристрастности. [284]

Управление связи Мальты сообщило, что на конец 2012 года насчитывалось 147 896 активных подписок на платное телевидение. [285] Для справки: последняя перепись населения на Мальте насчитала 139 583 домохозяйства. [286] Спутниковый прием доступен для приема других европейских телевизионных сетей. [287]

Спорт

[ редактировать ]Футбол (футбол) — один из самых популярных видов спорта на Мальте. Другие популярные виды спорта включают бочи , скачки, гостру , регату , водное поло , стрельбу по стендовым голубям и автоспорт. [288]