Биоразнообразие

Биоразнообразие (или биологическое разнообразие ) — это разнообразие и изменчивость жизни на Земле . Его можно измерить на разных уровнях. Например, существует генетическая изменчивость , разнообразие видов , разнообразие экосистем и филогенетическое разнообразие. [1] неравномерно Разнообразие распределено на Земле . она выше В тропиках из-за теплого климата и высокой первичной продуктивности в районе экватора . Экосистемы тропических лесов покрывают менее одной пятой земной площади и содержат около 50% мировых видов. [2] Существуют широтные градиенты видового разнообразия как морских, так и наземных таксонов. [3]

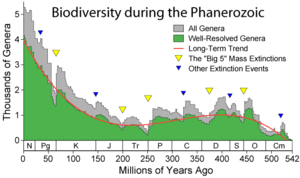

С момента зарождения жизни на Земле шесть крупных массовых вымираний и несколько незначительных событий привели к значительному и внезапному сокращению биоразнообразия. Фанерозойский период (последние 540 миллионов лет) ознаменовал быстрый рост биоразнообразия в результате кембрийского взрыва . большинство многоклеточных типов В этот период впервые появилось . Следующие 400 миллионов лет сопровождались неоднократными масштабными потерями биоразнообразия. Эти события были классифицированы как события массового вымирания . В каменноугольном периоде разрушение тропических лесов могло привести к огромным потерям растительного и животного мира. Пермско -триасовое вымирание , произошедшее 251 миллион лет назад, было самым страшным; Восстановление позвоночных заняло 30 миллионов лет.

Human activities have led to an ongoing biodiversity loss and an accompanying loss of genetic diversity. This process is often referred to as Holocene extinction, or sixth mass extinction. For example, it was estimated in 2007 that up to 30% of all species will be extinct by 2050.[4] Destroying habitats for farming is a key reason why biodiversity is decreasing today. Climate change also plays a role.[5][6] This can be seen for example in the effects of climate change on biomes. This anthropogenic extinction may have started toward the end of the Pleistocene, as some studies suggest that the megafaunal extinction event that took place around the end of the last ice age partly resulted from overhunting.[7]

Definitions

[edit]

Biologists most often define biodiversity as the "totality of genes, species and ecosystems of a region".[8][9] An advantage of this definition is that it presents a unified view of the traditional types of biological variety previously identified:

- taxonomic diversity (usually measured at the species diversity level)[10]

- ecological diversity (often viewed from the perspective of ecosystem diversity)[10]

- morphological diversity (which stems from genetic diversity and molecular diversity[11])

- functional diversity (which is a measure of the number of functionally disparate species within a population (e.g. different feeding mechanism, different motility, predator vs prey, etc.)[12])

Biodiversity is most commonly used to replace the more clearly-defined and long-established terms, species diversity and species richness.[13] However, there is no concrete definition for biodiversity, as its definition continues to be defined. Other definitions include (in chronological order):

- An explicit definition consistent with this interpretation was first given in a paper by Bruce A. Wilcox commissioned by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) for the 1982 World National Parks Conference.[14] Wilcox's definition was "Biological diversity is the variety of life forms...at all levels of biological systems (i.e., molecular, organismic, population, species and ecosystem)...".[14]

- A publication by Wilcox in 1984: Biodiversity can be defined genetically as the diversity of alleles, genes and organisms. They study processes such as mutation and gene transfer that drive evolution.[14]

- The 1992 United Nations Earth Summit defined biological diversity as "the variability among living organisms from all sources, including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part: this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems".[15] This definition is used in the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity.[15]

- Gaston and Spicer's definition in their book "Biodiversity: an introduction" in 2004 is "variation of life at all levels of biological organization".[16]

- The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) defined biodiversity in 2019 as "the variability that exists among living organisms (both within and between species) and the ecosystems of which they are part."[17]

Number of species

[edit]

According to Mora and her colleagues' estimation, there are approximately 8.7 million terrestrial species and 2.2 million oceanic species. The authors note that these estimates are strongest for eukaryotic organisms and likely represent the lower bound of prokaryote diversity.[18] Other estimates include:

- 220,000 vascular plants, estimated using the species-area relation method[19]

- 0.7-1 million marine species[20]

- 10–30 million insects;[21] (of some 0.9 million we know today)[22]

- 5–10 million bacteria;[23]

- 1.5-3 million fungi, estimates based on data from the tropics, long-term non-tropical sites and molecular studies that have revealed cryptic speciation.[24] Some 0.075 million species of fungi had been documented by 2001;[25]

- 1 million mites[26]

- The number of microbial species is not reliably known, but the Global Ocean Sampling Expedition dramatically increased the estimates of genetic diversity by identifying an enormous number of new genes from near-surface plankton samples at various marine locations, initially over the 2004–2006 period.[27] The findings may eventually cause a significant change in the way science defines species and other taxonomic categories.[28][29]

Since the rate of extinction has increased, many extant species may become extinct before they are described.[30] Not surprisingly, in the animalia the most studied groups are birds and mammals, whereas fishes and arthropods are the least studied animals groups.[31]

Current biodiversity loss

[edit]

During the last century, decreases in biodiversity have been increasingly observed. It was estimated in 2007 that up to 30% of all species will be extinct by 2050.[4] Of these, about one eighth of known plant species are threatened with extinction.[35] Estimates reach as high as 140,000 species per year (based on Species-area theory).[36] This figure indicates unsustainable ecological practices, because few species emerge each year.[37] The rate of species loss is greater now than at any time in human history, with extinctions occurring at rates hundreds of times higher than background extinction rates.[35][38][39] and expected to still grow in the upcoming years.[39][40][41] As of 2012, some studies suggest that 25% of all mammal species could be extinct in 20 years.[42]

In absolute terms, the planet has lost 58% of its biodiversity since 1970 according to a 2016 study by the World Wildlife Fund.[43] The Living Planet Report 2014 claims that "the number of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish across the globe is, on average, about half the size it was 40 years ago". Of that number, 39% accounts for the terrestrial wildlife gone, 39% for the marine wildlife gone and 76% for the freshwater wildlife gone. Biodiversity took the biggest hit in Latin America, plummeting 83 percent. High-income countries showed a 10% increase in biodiversity, which was canceled out by a loss in low-income countries. This is despite the fact that high-income countries use five times the ecological resources of low-income countries, which was explained as a result of a process whereby wealthy nations are outsourcing resource depletion to poorer nations, which are suffering the greatest ecosystem losses.[44]

A 2017 study published in PLOS One found that the biomass of insect life in Germany had declined by three-quarters in the last 25 years.[45] Dave Goulson of Sussex University stated that their study suggested that humans "appear to be making vast tracts of land inhospitable to most forms of life, and are currently on course for ecological Armageddon. If we lose the insects then everything is going to collapse."[46]

In 2020 the World Wildlife Foundation published a report saying that "biodiversity is being destroyed at a rate unprecedented in human history". The report claims that 68% of the population of the examined species were destroyed in the years 1970 – 2016.[47]

Of 70,000 monitored species, around 48% are experiencing population declines from human activity (in 2023), whereas only 3% have increasing populations.[48][49][50]

Rates of decline in biodiversity in the current sixth mass extinction match or exceed rates of loss in the five previous mass extinction events in the fossil record.[60] Biodiversity loss is in fact "one of the most critical manifestations of the Anthropocene" (since around the 1950s); the continued decline of biodiversity constitutes "an unprecedented threat" to the continued existence of human civilization.[61] The reduction is caused primarily by human impacts, particularly habitat destruction.

Since the Stone Age, species loss has accelerated above the average basal rate, driven by human activity. Estimates of species losses are at a rate 100–10,000 times as fast as is typical in the fossil record.[62]

Loss of biodiversity results in the loss of natural capital that supplies ecosystem goods and services. Species today are being wiped out at a rate 100 to 1,000 times higher than baseline, and the rate of extinctions is increasing. This process destroys the resilience and adaptability of life on Earth.[63]

In 2006, many species were formally classified as rare or endangered or threatened; moreover, scientists have estimated that millions more species are at risk which have not been formally recognized. About 40 percent of the 40,177 species assessed using the IUCN Red List criteria are now listed as threatened with extinction—a total of 16,119.[64] As of late 2022 9251 species were considered part of the IUCN's critically endangered.[65]

Numerous scientists and the IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services assert that human population growth and overconsumption are the primary factors in this decline.[66][67][68][69][70] However, other scientists have criticized this finding and say that loss of habitat caused by "the growth of commodities for export" is the main driver.[71]

Some studies have however pointed out that habitat destruction for the expansion of agriculture and the overexploitation of wildlife are the more significant drivers of contemporary biodiversity loss, not climate change.[5][6]

Distribution

[edit]

Biodiversity is not evenly distributed, rather it varies greatly across the globe as well as within regions and seasons. Among other factors, the diversity of all living things (biota) depends on temperature, precipitation, altitude, soils, geography and the interactions between other species.[72] The study of the spatial distribution of organisms, species and ecosystems, is the science of biogeography.[73][74]

Diversity consistently measures higher in the tropics and in other localized regions such as the Cape Floristic Region and lower in polar regions generally. Rain forests that have had wet climates for a long time, such as Yasuní National Park in Ecuador, have particularly high biodiversity.[75][76]

There is local biodiversity, which directly impacts daily life, affecting the availability of fresh water, food choices, and fuel sources for humans. Regional biodiversity includes habitats and ecosystems that synergizes and either overlaps or differs on a regional scale. National biodiversity within a country determines the ability for a country to thrive according to its habitats and ecosystems on a national scale. Also, within a country, endangered species are initially supported on a national level then internationally. Ecotourism may be utilized to support the economy and encourages tourists to continue to visit and support species and ecosystems they visit, while they enjoy the available amenities provided. International biodiversity impacts global livelihood, food systems, and health. Problematic pollution, over consumption, and climate change can devastate international biodiversity. Nature-based solutions are a critical tool for a global resolution. Many species are in danger of becoming extinct and need world leaders to be proactive with the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

Terrestrial biodiversity is thought to be up to 25 times greater than ocean biodiversity.[77] Forests harbour most of Earth's terrestrial biodiversity. The conservation of the world's biodiversity is thus utterly dependent on the way in which we interact with and use the world's forests.[78] A new method used in 2011, put the total number of species on Earth at 8.7 million, of which 2.1 million were estimated to live in the ocean.[79] However, this estimate seems to under-represent the diversity of microorganisms.[80] Forests provide habitats for 80 percent of amphibian species, 75 percent of bird species and 68 percent of mammal species. About 60 percent of all vascular plants are found in tropical forests. Mangroves provide breeding grounds and nurseries for numerous species of fish and shellfish and help trap sediments that might otherwise adversely affect seagrass beds and coral reefs, which are habitats for many more marine species.[78] Forests span around 4 billion acres (nearly a third of the Earth's land mass) and are home to approximately 80% of the world's biodiversity. About 1 billion hectares are covered by primary forests. Over 700 million hectares of the world's woods are officially protected.[81][82]

The biodiversity of forests varies considerably according to factors such as forest type, geography, climate and soils – in addition to human use.[78] Most forest habitats in temperate regions support relatively few animal and plant species and species that tend to have large geographical distributions, while the montane forests of Africa, South America and Southeast Asia and lowland forests of Australia, coastal Brazil, the Caribbean islands, Central America and insular Southeast Asia have many species with small geographical distributions.[78] Areas with dense human populations and intense agricultural land use, such as Europe, parts of Bangladesh, China, India and North America, are less intact in terms of their biodiversity. Northern Africa, southern Australia, coastal Brazil, Madagascar and South Africa, are also identified as areas with striking losses in biodiversity intactness.[78] European forests in EU and non-EU nations comprise more than 30% of Europe's land mass (around 227 million hectares), representing an almost 10% growth since 1990.[83][84]

Latitudinal gradients

[edit]Generally, there is an increase in biodiversity from the poles to the tropics. Thus localities at lower latitudes have more species than localities at higher latitudes. This is often referred to as the latitudinal gradient in species diversity. Several ecological factors may contribute to the gradient, but the ultimate factor behind many of them is the greater mean temperature at the equator compared to that at the poles.[85]

Even though terrestrial biodiversity declines from the equator to the poles,[86] some studies claim that this characteristic is unverified in aquatic ecosystems, especially in marine ecosystems.[87] The latitudinal distribution of parasites does not appear to follow this rule.[73] Also, in terrestrial ecosystems the soil bacterial diversity has been shown to be highest in temperate climatic zones,[88] and has been attributed to carbon inputs and habitat connectivity.[89]

In 2016, an alternative hypothesis ("the fractal biodiversity") was proposed to explain the biodiversity latitudinal gradient.[90] In this study, the species pool size and the fractal nature of ecosystems were combined to clarify some general patterns of this gradient. This hypothesis considers temperature, moisture, and net primary production (NPP) as the main variables of an ecosystem niche and as the axis of the ecological hypervolume. In this way, it is possible to build fractal hyper volumes, whose fractal dimension rises to three moving towards the equator.[91]

Biodiversity Hotspots

[edit]A biodiversity hotspot is a region with a high level of endemic species that have experienced great habitat loss.[92] The term hotspot was introduced in 1988 by Norman Myers.[93][94][95][96] While hotspots are spread all over the world, the majority are forest areas and most are located in the tropics.[97]

Brazil's Atlantic Forest is considered one such hotspot, containing roughly 20,000 plant species, 1,350 vertebrates and millions of insects, about half of which occur nowhere else.[98][99] The island of Madagascar and India are also particularly notable. Colombia is characterized by high biodiversity, with the highest rate of species by area unit worldwide and it has the largest number of endemics (species that are not found naturally anywhere else) of any country. About 10% of the species of the Earth can be found in Colombia, including over 1,900 species of bird, more than in Europe and North America combined, Colombia has 10% of the world's mammals species, 14% of the amphibian species and 18% of the bird species of the world.[100] Madagascar dry deciduous forests and lowland rainforests possess a high ratio of endemism.[101][102] Since the island separated from mainland Africa 66 million years ago, many species and ecosystems have evolved independently.[103] Indonesia's 17,000 islands cover 735,355 square miles (1,904,560 km2) and contain 10% of the world's flowering plants, 12% of mammals and 17% of reptiles, amphibians and birds—along with nearly 240 million people.[104] Many regions of high biodiversity and/or endemism arise from specialized habitats which require unusual adaptations, for example, alpine environments in high mountains, or Northern European peat bogs.[102]

Accurately measuring differences in biodiversity can be difficult. Selection bias amongst researchers may contribute to biased empirical research for modern estimates of biodiversity. In 1768, Rev. Gilbert White succinctly observed of his Selborne, Hampshire "all nature is so full, that that district produces the most variety which is the most examined."[105]

Evolution over geologic timeframes

[edit]Biodiversity is the result of 3.5 billion years of evolution.[106] The origin of life has not been established by science, however, some evidence suggests that life may already have been well-established only a few hundred million years after the formation of the Earth. Until approximately 2.5 billion years ago, all life consisted of microorganisms – archaea, bacteria, and single-celled protozoans and protists.[80]

−4500 — – — – −4000 — – — – −3500 — – — – −3000 — – — – −2500 — – — – −2000 — – — – −1500 — – — – −1000 — – — – −500 — – — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Biodiversity grew fast during the Phanerozoic (the last 540 million years), especially during the so-called Cambrian explosion—a period during which nearly every phylum of multicellular organisms first appeared.[108] However, recent studies suggest that this diversification had started earlier, at least in the Ediacaran, and that it continued in the Ordovician.[109] Over the next 400 million years or so, invertebrate diversity showed little overall trend and vertebrate diversity shows an overall exponential trend.[10] This dramatic rise in diversity was marked by periodic, massive losses of diversity classified as mass extinction events.[10] A significant loss occurred in anamniotic limbed vertebrates when rainforests collapsed in the Carboniferous,[110] but amniotes seem to have been little affected by this event; their diversification slowed down later, around the Asselian/Sakmarian boundary, in the early Cisuralian (Early Permian), about 293 Ma ago.[111] The worst was the Permian-Triassic extinction event, 251 million years ago.[112][113] Vertebrates took 30 million years to recover from this event.[114]

The most recent major mass extinction event, the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, occurred 66 million years ago. This period has attracted more attention than others because it resulted in the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs, which were represented by many lineages at the end of the Maastrichtian, just before that extinction event. However, many other taxa were affected by this crisis, which affected even marine taxa, such as ammonites, which also became extinct around that time.[115]

The biodiversity of the past is called Paleobiodiversity. The fossil record suggests that the last few million years featured the greatest biodiversity in history.[10] However, not all scientists support this view, since there is uncertainty as to how strongly the fossil record is biased by the greater availability and preservation of recent geologic sections.[116] Some scientists believe that corrected for sampling artifacts, modern biodiversity may not be much different from biodiversity 300 million years ago,[108] whereas others consider the fossil record reasonably reflective of the diversification of life.[117][10] Estimates of the present global macroscopic species diversity vary from 2 million to 100 million, with a best estimate of somewhere near 9 million,[79] the vast majority arthropods.[118] Diversity appears to increase continually in the absence of natural selection.[119]

Diversification

[edit]The existence of a global carrying capacity, limiting the amount of life that can live at once, is debated, as is the question of whether such a limit would also cap the number of species. While records of life in the sea show a logistic pattern of growth, life on land (insects, plants and tetrapods) shows an exponential rise in diversity.[10] As one author states, "Tetrapods have not yet invaded 64 percent of potentially habitable modes and it could be that without human influence the ecological and taxonomic diversity of tetrapods would continue to increase exponentially until most or all of the available eco-space is filled."[10]

It also appears that the diversity continues to increase over time, especially after mass extinctions.[120]

On the other hand, changes through the Phanerozoic correlate much better with the hyperbolic model (widely used in population biology, demography and macrosociology, as well as fossil biodiversity) than with exponential and logistic models. The latter models imply that changes in diversity are guided by a first-order positive feedback (more ancestors, more descendants) and/or a negative feedback arising from resource limitation. Hyperbolic model implies a second-order positive feedback.[121] Differences in the strength of the second-order feedback due to different intensities of interspecific competition might explain the faster rediversification of ammonoids in comparison to bivalves after the end-Permian extinction.[121] The hyperbolic pattern of the world population growth arises from a second-order positive feedback between the population size and the rate of technological growth.[122] The hyperbolic character of biodiversity growth can be similarly accounted for by a feedback between diversity and community structure complexity.[122][123] The similarity between the curves of biodiversity and human population probably comes from the fact that both are derived from the interference of the hyperbolic trend with cyclical and stochastic dynamics.[122][123]

Most biologists agree however that the period since human emergence is part of a new mass extinction, named the Holocene extinction event, caused primarily by the impact humans are having on the environment.[124] It has been argued that the present rate of extinction is sufficient to eliminate most species on the planet Earth within 100 years.[125]

New species are regularly discovered (on average between 5–10,000 new species each year, most of them insects) and many, though discovered, are not yet classified (estimates are that nearly 90% of all arthropods are not yet classified).[118] Most of the terrestrial diversity is found in tropical forests and in general, the land has more species than the ocean; some 8.7 million species may exist on Earth, of which some 2.1 million live in the ocean.[79]

Species diversity in geologic time frames

[edit]It is estimated that 5 to 50 billion species have existed on the planet.[126] Assuming that there may be a maximum of about 50 million species currently alive,[127] it stands to reason that greater than 99% of the planet's species went extinct prior to the evolution of humans.[128] Estimates on the number of Earth's current species range from 10 million to 14 million, of which about 1.2 million have been documented and over 86% have not yet been described.[129] However, a May 2016 scientific report estimates that 1 trillion species are currently on Earth, with only one-thousandth of one percent described.[130] The total amount of related DNA base pairs on Earth is estimated at 5.0 x 1037 and weighs 50 billion tonnes. In comparison, the total mass of the biosphere has been estimated to be as much as four trillion tons of carbon.[131] In July 2016, scientists reported identifying a set of 355 genes from the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all organisms living on Earth.[132]

The age of Earth is about 4.54 billion years.[133][134][135] The earliest undisputed evidence of life dates at least from 3.7 billion years ago, during the Eoarchean era after a geological crust started to solidify following the earlier molten Hadean eon.[136][137][138] There are microbial mat fossils found in 3.48 billion-year-old sandstone discovered in Western Australia. Other early physical evidence of a biogenic substance is graphite in 3.7 billion-year-old meta-sedimentary rocks discovered in Western Greenland..[139][140] More recently, in 2015, "remains of biotic life" were found in 4.1 billion-year-old rocks in Western Australia. According to one of the researchers, "If life arose relatively quickly on Earth...then it could be common in the universe."[141]

Role and benefits of biodiversity

[edit]

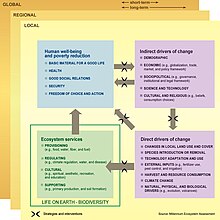

Ecosystem services

[edit]There have been many claims about biodiversity's effect on the ecosystem services, especially provisioning and regulating services.[142] Some of those claims have been validated, some are incorrect and some lack enough evidence to draw definitive conclusions.[142]

Ecosystem services have been grouped in three types:[142]

- Provisioning services which involve the production of renewable resources (e.g.: food, wood, fresh water)

- Regulating services which are those that lessen environmental change (e.g.: climate regulation, pest/disease control)

- Cultural services represent human value and enjoyment (e.g.: landscape aesthetics, cultural heritage, outdoor recreation and spiritual significance)[143]

Experiments with controlled environments have shown that humans cannot easily build ecosystems to support human needs;[144] for example insect pollination cannot be mimicked, though there have been attempts to create artificial pollinators using unmanned aerial vehicles.[145] The economic activity of pollination alone represented between $2.1–14.6 billion in 2003.[146] Other sources have reported somewhat conflicting results and in 1997 Robert Costanza and his colleagues reported the estimated global value of ecosystem services (not captured in traditional markets) at an average of $33 trillion annually.[147]

Provisioning services

[edit]With regards to provisioning services, greater species diversity has the following benefits:

- Greater species diversity of plants increases fodder yield (synthesis of 271 experimental studies).[74]

- Greater species diversity of plants (i.e. diversity within a single species) increases overall crop yield (synthesis of 575 experimental studies).[148] Although another review of 100 experimental studies reported mixed evidence.[149]

- Greater species diversity of trees increases overall wood production (synthesis of 53 experimental studies).[150] However, there is not enough data to draw a conclusion about the effect of tree trait diversity on wood production.[142]

Regulating services

[edit]With regards to regulating services, greater species diversity has the following benefits:

Greater species diversity

- of fish increases the stability of fisheries yield (synthesis of 8 observational studies)[142]

- of plants increases carbon sequestration, but note that this finding only relates to actual uptake of carbon dioxide and not long-term storage; synthesis of 479 experimental studies)[74]

- of plants increases soil nutrient remineralization (synthesis of 103 experimental studies), increases soil organic matter (synthesis of 85 experimental studies) and decreases disease prevalence on plants (synthesis of 107 experimental studies)[151]

- of natural pest enemies decreases herbivorous pest populations (data from two separate reviews; synthesis of 266 experimental and observational studies;[152] Synthesis of 18 observational studies.[153][154] Although another review of 38 experimental studies found mixed support for this claim, suggesting that in cases where mutual intraguild predation occurs, a single predatory species is often more effective[155]

Agriculture

[edit]

Agricultural diversity can be divided into two categories: intraspecific diversity, which includes the genetic variation within a single species, like the potato (Solanum tuberosum) that is composed of many different forms and types (e.g. in the U.S. they might compare russet potatoes with new potatoes or purple potatoes, all different, but all part of the same species, S. tuberosum). The other category of agricultural diversity is called interspecific diversity and refers to the number and types of different species.

Agricultural diversity can also be divided by whether it is 'planned' diversity or 'associated' diversity. This is a functional classification that we impose and not an intrinsic feature of life or diversity. Planned diversity includes the crops which a farmer has encouraged, planted or raised (e.g. crops, covers, symbionts, and livestock, among others), which can be contrasted with the associated diversity that arrives among the crops, uninvited (e.g. herbivores, weed species and pathogens, among others).[156]

Associated biodiversity can be damaging or beneficial. The beneficial associated biodiversity include for instance wild pollinators such as wild bees and syrphid flies that pollinate crops[157] and natural enemies and antagonists to pests and pathogens. Beneficial associated biodiversity occurs abundantly in crop fields and provide multiple ecosystem services such as pest control, nutrient cycling and pollination that support crop production.[158]

Although about 80 percent of humans' food supply comes from just 20 kinds of plants,[159] humans use at least 40,000 species.[160] Earth's surviving biodiversity provides resources for increasing the range of food and other products suitable for human use, although the present extinction rate shrinks that potential.[125]

Human health

[edit]

Biodiversity's relevance to human health is becoming an international political issue, as scientific evidence builds on the global health implications of biodiversity loss.[161][162][163] This issue is closely linked with the issue of climate change,[164] as many of the anticipated health risks of climate change are associated with changes in biodiversity (e.g. changes in populations and distribution of disease vectors, scarcity of fresh water, impacts on agricultural biodiversity and food resources etc.). This is because the species most likely to disappear are those that buffer against infectious disease transmission, while surviving species tend to be the ones that increase disease transmission, such as that of West Nile Virus, Lyme disease and Hantavirus, according to a study done co-authored by Felicia Keesing, an ecologist at Bard College and Drew Harvell, associate director for Environment of the Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future (ACSF) at Cornell University.[165]

Some of the health issues influenced by biodiversity include dietary health and nutrition security, infectious disease, medical science and medicinal resources, social and psychological health.[166] Biodiversity is also known to have an important role in reducing disaster risk and in post-disaster relief and recovery efforts.[167][168]

Biodiversity provides critical support for drug discovery and the availability of medicinal resources.[169][170] A significant proportion of drugs are derived, directly or indirectly, from biological sources: at least 50% of the pharmaceutical compounds on the US market are derived from plants, animals and microorganisms, while about 80% of the world population depends on medicines from nature (used in either modern or traditional medical practice) for primary healthcare.[162] Only a tiny fraction of wild species has been investigated for medical potential.

Marine ecosystems are particularly important,[171] although inappropriate bioprospecting can increase biodiversity loss, as well as violating the laws of the communities and states from which the resources are taken.[172][173][174]

Business and industry

[edit]Many industrial materials derive directly from biological sources. These include building materials, fibers, dyes, rubber, and oil. Biodiversity is also important to the security of resources such as water, timber, paper, fiber, and food.[175][176][177] As a result, biodiversity loss is a significant risk factor in business development and a threat to long-term economic sustainability.[178][179]

Cultural and aesthetic value

[edit]

Philosophically it could be argued that biodiversity has intrinsic aesthetic and spiritual value to mankind in and of itself. This idea can be used as a counterweight to the notion that tropical forests and other ecological realms are only worthy of conservation because of the services they provide.[180]

Biodiversity also affords many non-material benefits including spiritual and aesthetic values, knowledge systems and education.[62]

Measuring biodiversity

[edit]Analytical limits

[edit]Less than 1% of all species that have been described have been studied beyond noting their existence.[187] The vast majority of Earth's species are microbial. Contemporary biodiversity physics is "firmly fixated on the visible [macroscopic] world".[188] For example, microbial life is metabolically and environmentally more diverse than multicellular life (see e.g., extremophile). "On the tree of life, based on analyses of small-subunit ribosomal RNA, visible life consists of barely noticeable twigs. The inverse relationship of size and population recurs higher on the evolutionary ladder—to a first approximation, all multicellular species on Earth are insects".[189] Insect extinction rates are high—supporting the Holocene extinction hypothesis.[190][58]

Biodiversity changes (other than losses)

[edit]Natural seasonal variations

[edit]Biodiversity naturally varies due to seasonal shifts. Spring's arrival enhances biodiversity as numerous species breed and feed, while winter's onset temporarily reduces it as some insects perish and migrating animals leave. Additionally, the seasonal fluctuation in plant and invertebrate populations influences biodiversity.[191]

Introduced and invasive species

[edit]

Barriers such as large rivers, seas, oceans, mountains and deserts encourage diversity by enabling independent evolution on either side of the barrier, via the process of allopatric speciation. The term invasive species is applied to species that breach the natural barriers that would normally keep them constrained. Without barriers, such species occupy new territory, often supplanting native species by occupying their niches, or by using resources that would normally sustain native species.

Species are increasingly being moved by humans (on purpose and accidentally). Some studies say that diverse ecosystems are more resilient and resist invasive plants and animals.[192] Many studies cite effects of invasive species on natives,[193] but not extinctions.

Invasive species seem to increase local (alpha diversity) diversity, which decreases turnover of diversity (ibeta diversity). Overall gamma diversity may be lowered because species are going extinct because of other causes,[194] but even some of the most insidious invaders (e.g.: Dutch elm disease, emerald ash borer, chestnut blight in North America) have not caused their host species to become extinct. Extirpation, population decline and homogenization of regional biodiversity are much more common. Human activities have frequently been the cause of invasive species circumventing their barriers,[195] by introducing them for food and other purposes. Human activities therefore allow species to migrate to new areas (and thus become invasive) occurred on time scales much shorter than historically have been required for a species to extend its range.

At present, several countries have already imported so many exotic species, particularly agricultural and ornamental plants, that their indigenous fauna/flora may be outnumbered. For example, the introduction of kudzu from Southeast Asia to Canada and the United States has threatened biodiversity in certain areas.[196] Another example are pines, which have invaded forests, shrublands and grasslands in the southern hemisphere.[197]

Hybridization and genetic pollution

[edit]

Endemic species can be threatened with extinction[198] through the process of genetic pollution, i.e. uncontrolled hybridization, introgression and genetic swamping. Genetic pollution leads to homogenization or replacement of local genomes as a result of either a numerical and/or fitness advantage of an introduced species.[199]

Hybridization and introgression are side-effects of introduction and invasion. These phenomena can be especially detrimental to rare species that come into contact with more abundant ones. The abundant species can interbreed with the rare species, swamping its gene pool. This problem is not always apparent from morphological (outward appearance) observations alone. Some degree of gene flow is normal adaptation and not all gene and genotype constellations can be preserved. However, hybridization with or without introgression may, nevertheless, threaten a rare species' existence.[200][201]

Conservation

[edit]

Conservation biology matured in the mid-20th century as ecologists, naturalists and other scientists began to research and address issues pertaining to global biodiversity declines.[203][204][205]

The conservation ethic advocates management of natural resources for the purpose of sustaining biodiversity in species, ecosystems, the evolutionary process and human culture and society.[54][203][205][206][207]

Conservation biology is reforming around strategic plans to protect biodiversity.[203][208][209][210] Preserving global biodiversity is a priority in strategic conservation plans that are designed to engage public policy and concerns affecting local, regional and global scales of communities, ecosystems and cultures.[211] Action plans identify ways of sustaining human well-being, employing natural capital, market capital and ecosystem services.[212][213]

In the EU Directive 1999/22/EC zoos are described as having a role in the preservation of the biodiversity of wildlife animals by conducting research or participation in breeding programs.[214]

Protection and restoration techniques

[edit]Removal of exotic species will allow the species that they have negatively impacted to recover their ecological niches. Exotic species that have become pests can be identified taxonomically (e.g., with Digital Automated Identification SYstem (DAISY), using the barcode of life).[215][216] Removal is practical only given large groups of individuals due to the economic cost.

As sustainable populations of the remaining native species in an area become assured, "missing" species that are candidates for reintroduction can be identified using databases such as the Encyclopedia of Life and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility.

- Biodiversity banking places a monetary value on biodiversity. One example is the Australian Native Vegetation Management Framework.

- Gene banks are collections of specimens and genetic material. Some banks intend to reintroduce banked species to the ecosystem (e.g., via tree nurseries).[217]

- Reduction and better targeting of pesticides allows more species to survive in agricultural and urbanized areas.

- Location-specific approaches may be less useful for protecting migratory species. One approach is to create wildlife corridors that correspond to the animals' movements. National and other boundaries can complicate corridor creation.[218]

Protected areas

[edit]

Protected areas, including forest reserves and biosphere reserves, serve many functions including for affording protection to wild animals and their habitat.[219] Protected areas have been set up all over the world with the specific aim of protecting and conserving plants and animals. Some scientists have called on the global community to designate as protected areas of 30 percent of the planet by 2030, and 50 percent by 2050, in order to mitigate biodiversity loss from anthropogenic causes.[220][221] The target of protecting 30% of the area of the planet by the year 2030 (30 by 30) was adopted by almost 200 countries in the 2022 United Nations Biodiversity Conference. At the moment of adoption (December 2022) 17% of land territory and 10% of ocean territory were protected.[222] In a study published 4 September 2020 in Science Advances researchers mapped out regions that can help meet critical conservation and climate goals.[223]

Protected areas safeguard nature and cultural resources and contribute to livelihoods, particularly at local level. There are over 238 563 designated protected areas worldwide, equivalent to 14.9 percent of the earth's land surface, varying in their extension, level of protection, and type of management (IUCN, 2018).[224]

The benefits of protected areas extend beyond their immediate environment and time. In addition to conserving nature, protected areas are crucial for securing the long-term delivery of ecosystem services. They provide numerous benefits including the conservation of genetic resources for food and agriculture, the provision of medicine and health benefits, the provision of water, recreation and tourism, and for acting as a buffer against disaster. Increasingly, there is acknowledgement of the wider socioeconomic values of these natural ecosystems and of the ecosystem services they can provide.[225]

National parks and wildlife sanctuaries

[edit]A national park is a large natural or near natural area set aside to protect large-scale ecological processes, which also provide a foundation for environmentally and culturally compatible, spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational and visitor opportunities. These areas are selected by governments or private organizations to protect natural biodiversity along with its underlying ecological structure and supporting environmental processes, and to promote education and recreation. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and its World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA), has defined "National Park" as its Category II type of protected areas.[226] Wildlife sanctuaries aim only at the conservation of species

Forest protected areas

[edit]

Forest protected areas are a subset of all protected areas in which a significant portion of the area is forest.[78] This may be the whole or only a part of the protected area.[78] Globally, 18 percent of the world's forest area, or more than 700 million hectares, fall within legally established protected areas such as national parks, conservation areas and game reserves.[78]

There is an estimated 726 million ha of forest in protected areas worldwide. Of the six major world regions, South America has the highest share of forests in protected areas, 31 percent.[227] The forests play a vital role in harboring more than 45,000 floral and 81,000 faunal species of which 5150 floral and 1837 faunal species are endemic.[228] In addition, there are 60,065 different tree species in the world.[229] Plant and animal species confined to a specific geographical area are called endemic species.

In forest reserves, rights to activities like hunting and grazing are sometimes given to communities living on the fringes of the forest, who sustain their livelihood partially or wholly from forest resources or products.

Approximately 50 million hectares (or 24%) of European forest land is protected for biodiversity and landscape protection. Forests allocated for soil, water, and other ecosystem services encompass around 72 million hectares (32% of European forest area).[230][231]

Role of society

[edit]Transformative change

[edit]In 2019, a summary for policymakers of the largest, most comprehensive study to date of biodiversity and ecosystem services, the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, was published by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). It stated that "the state of nature has deteriorated at an unprecedented and accelerating rate". To fix the problem, humanity will need a transformative change, including sustainable agriculture, reductions in consumption and waste, fishing quotas and collaborative water management.[232][233]

The concept of nature-positive is playing a role in mainstreaming the goals of the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) for biodiversity.[234] The aim of mainstreaming is to embed biodiversity considerations into public and private practice to conserve and sustainably use biodiversity on global and local levels.[235] The concept of nature-positive refers to the societal goal to halt and reverse biodiversity loss, measured from a baseline of 2020 levels, and to achieve full so-called "nature recovery" by 2050.[236]

Citizen science

[edit]Citizen science, also known as public participation in scientific research, has been widely used in environmental sciences and is particularly popular in a biodiversity-related context. It has been used to enable scientists to involve the general public in biodiversity research, thereby enabling the scientists to collect data that they would otherwise not have been able to obtain.[237]

Volunteer observers have made significant contributions to on-the-ground knowledge about biodiversity, and recent improvements in technology have helped increase the flow and quality of occurrences from citizen sources. A 2016 study published in Biological Conservation[238] registers the massive contributions that citizen scientists already make to data mediated by the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). Despite some limitations of the dataset-level analysis, it is clear that nearly half of all occurrence records shared through the GBIF network come from datasets with significant volunteer contributions. Recording and sharing observations are enabled by several global-scale platforms, including iNaturalist and eBird.[239][240]

Legal status

[edit]

International

[edit]- United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (1992) and Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety;

- UN BBNJ (High Seas Treaty) 2023 Intergovernmental conference on an international legally binding instrument under the UNCLOS on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (GA resolution 72/249)

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES);

- Ramsar Convention (Wetlands);

- Bonn Convention on Migratory Species;

- UNESCO Convention concerning the Protection of the World's Cultural and Natural Heritage (indirectly by protecting biodiversity habitats)

- UNESCO Global Geoparks

- Regional Conventions such as the Apia Convention

- Bilateral agreements such as the Japan-Australia Migratory Bird Agreement.

Global agreements such as the Convention on Biological Diversity, give "sovereign national rights over biological resources" (not property). The agreements commit countries to "conserve biodiversity", "develop resources for sustainability" and "share the benefits" resulting from their use. Biodiverse countries that allow bioprospecting or collection of natural products, expect a share of the benefits rather than allowing the individual or institution that discovers/exploits the resource to capture them privately. Bioprospecting can become a type of biopiracy when such principles are not respected.[241]

Sovereignty principles can rely upon what is better known as Access and Benefit Sharing Agreements (ABAs). The Convention on Biodiversity implies informed consent between the source country and the collector, to establish which resource will be used and for what and to settle on a fair agreement on benefit sharing.

On the 19 of December 2022, during the 2022 United Nations Biodiversity Conference every country on earth, with the exception of the United States and the Holy See, signed onto the agreement which includes protecting 30% of land and oceans by 2030 (30 by 30) and 22 other targets intended to reduce biodiversity loss.[222][242][243] The agreement includes also recovering 30% of earth degraded ecosystems and increasing funding for biodiversity issues.[244]

European Union

[edit]In May 2020, the European Union published its Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. The biodiversity strategy is an essential part of the climate change mitigation strategy of the European Union. From the 25% of the European budget that will go to fight climate change, large part will go to restore biodiversity[210] and nature based solutions.

The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 include the next targets:

- Protect 30% of the sea territory and 30% of the land territory especially Old-growth forests.

- Plant 3 billion trees by 2030.

- Restore at least 25,000 kilometers of rivers, so they will become free flowing.

- Reduce the use of Pesticides by 50% by 2030.

- Increase Organic farming. In linked EU program From Farm to Fork it is said, that the target is making 25% of EU agriculture organic, by 2030.[245]

- Increase biodiversity in agriculture.

- Give €20 billion per year to the issue and make it part of the business practice.

Approximately half of the global GDP depend on nature. In Europe many parts of the economy that generate trillions of euros per year depend on nature. The benefits of Natura 2000 alone in Europe are €200 – €300 billion per year.[246]

National level laws

[edit]Biodiversity is taken into account in some political and judicial decisions:

- The relationship between law and ecosystems is very ancient and has consequences for biodiversity. It is related to private and public property rights. It can define protection for threatened ecosystems, but also some rights and duties (for example, fishing and hunting rights).[citation needed]

- Law regarding species is more recent. It defines species that must be protected because they may be threatened by extinction. The U.S. Endangered Species Act is an example of an attempt to address the "law and species" issue.

- Laws regarding gene pools are only about a century old.[247] Domestication and plant breeding methods are not new, but advances in genetic engineering have led to tighter laws covering distribution of genetically modified organisms, gene patents and process patents.[248] Governments struggle to decide whether to focus on for example, genes, genomes, or organisms and species.[citation needed]

Uniform approval for use of biodiversity as a legal standard has not been achieved, however. Bosselman argues that biodiversity should not be used as a legal standard, claiming that the remaining areas of scientific uncertainty cause unacceptable administrative waste and increase litigation without promoting preservation goals.[249]

India passed the Biological Diversity Act in 2002 for the conservation of biological diversity in India. The Act also provides mechanisms for equitable sharing of benefits from the use of traditional biological resources and knowledge.

History of the term

[edit]- 1916 – The term biological diversity was used first by J. Arthur Harris in "The Variable Desert", Scientific American: "The bare statement that the region contains a flora rich in genera and species and of diverse geographic origin or affinity is entirely inadequate as a description of its real biological diversity."[250]

- 1967 – Raymond F. Dasmann used the term biological diversity in reference to the richness of living nature that conservationists should protect in his book A Different Kind of Country.[251][252]

- 1974 – The term natural diversity was introduced by John Terborgh.[253]

- 1980 – Thomas Lovejoy introduced the term biological diversity to the scientific community in a book.[254] It rapidly became commonly used.[255]

- 1985 – According to Edward O. Wilson, the contracted form biodiversity was coined by W. G. Rosen: "The National Forum on BioDiversity ... was conceived by Walter G.Rosen ... Dr. Rosen represented the NRC/NAS throughout the planning stages of the project. Furthermore, he introduced the term biodiversity".[256]

- 1985 – The term "biodiversity" appears in the article, "A New Plan to Conserve the Earth's Biota" by Laura Tangley.[257]

- 1988 – The term biodiversity first appeared in publication.[258][259]

- С 1988 года по настоящее время – Специальная рабочая группа экспертов по биологическому разнообразию Программы Организации Объединенных Наций по окружающей среде (ЮНЕП) начала работу в ноябре 1988 года, что привело к публикации проекта Конвенции о биологическом разнообразии в мае 1992 года. 15 конференций сторон (КС) для обсуждения потенциальных глобальных политических мер реагирования на утрату биоразнообразия. Совсем недавно COP 15 прошла в Монреале, Канада, в 2022 году.

См. также

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Вера, Дэниел П. (1992). «Оценка сохранения и филогенетическое разнообразие» . Биологическая консервация . 61 (1): 1–10. Бибкод : 1992BCons..61....1F . дои : 10.1016/0006-3207(92)91201-3 . ISSN 0006-3207 .

- ^ Пиллэй, Раджив; Вентер, Мишель; Арагон-Осехо, Хосе; Гонсалес-дель-Плиего, Памела; Хансен, Эндрю Дж; Уотсон, Джеймс Э.М.; Вентер, Оскар (2022). «Тропические леса являются домом для более половины видов позвоночных животных в мире» . Границы в экологии и окружающей среде . 20 (1): 10–15. Бибкод : 2022FrEE...20...10P . дои : 10.1002/плата.2420 . ISSN 1540-9295 . ПМЦ 9293027 . ПМИД 35873358 .

- ^ Хиллебранд, Хельмут (2004). «Об общности градации широтного разнообразия» . Американский натуралист . 163 (2): 192–211. дои : 10.1086/381004 . ISSN 0003-0147 . ПМИД 14970922 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Габриэль, Зигмар (9 марта 2007 г.). «К 2050 году исчезнут 30% всех видов» . Новости Би-би-си .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кетчем, Кристофер (3 декабря 2022 г.). «Решение проблемы изменения климата не «спасет планету» » . Перехват . Проверено 8 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Каро, Тим; Роу, Зик; и др. (2022). «Неудобное заблуждение: изменение климата не является основной причиной утраты биоразнообразия» . Письма о сохранении . 15 (3): e12868. Бибкод : 2022ConL...15E2868C . дои : 10.1111/conl.12868 . S2CID 246172852 .

- ^ Брук, Барри В.; Боуман, Дэвид MJS (апрель 2004 г.). «Неопределенный блицкриг плейстоценовой мегафауны» . Журнал биогеографии . 31 (4): 517–523. Бибкод : 2004JBiog..31..517B . дои : 10.1046/j.1365-2699.2003.01028.x . ISSN 0305-0270 .

- ^ Тор-Бьорн Ларссон (2001). Инструменты оценки биоразнообразия европейских лесов . Уайли-Блэквелл. п. 178. ИСБН 978-87-16-16434-6 . Проверено 28 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Дэвис. Введение в Env Engg (Sie), 4E . McGraw-Hill Education (India) Pvt Ltd. с. 4. ISBN 978-0-07-067117-1 . Проверено 28 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Сахни, С.; Бентон, MJ; Ферри, Пол (2010). «Связь между глобальным таксономическим разнообразием, экологическим разнообразием и распространением позвоночных на суше» . Письма по биологии . 6 (4): 544–547. дои : 10.1098/rsbl.2009.1024 . ПМК 2936204 . ПМИД 20106856 .

- ^ Кэмпбелл, АК (2003). «Спасите эти молекулы: молекулярное биоразнообразие и жизнь» . Журнал прикладной экологии . 40 (2): 193–203. Бибкод : 2003JApEc..40..193C . дои : 10.1046/j.1365-2664.2003.00803.x .

- ^ Лефчек, Джон (20 октября 2014 г.). «Что такое функциональное разнообразие и почему нас это волнует?» . образец(ЭКОЛОГИЯ) . Проверено 22 декабря 2015 г.

- ^ Уокер, Брайан Х. (1992). «Биоразнообразие и экологическая избыточность». Биология сохранения . 6 (1): 18–23. Бибкод : 1992ConBi...6...18W . дои : 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1992.610018.x .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Уилкокс, Брюс А. 1984. Сохранение генетических ресурсов in situ: факторы, определяющие минимальные требования к площади. В книге «Национальные парки, охрана и развитие», Труды Всемирного конгресса по национальным паркам, Дж. А. Макнили и К. Р. Миллер , Smithsonian Institution Press, стр. 18–30.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Д.Л. Хоксворт (1996). «Биоразнообразие: измерение и оценка» . Философские труды Лондонского королевского общества. Серия Б, Биологические науки . 345 (1311). Спрингер: 6. doi : 10.1098/rstb.1994.0081 . ISBN 978-0-412-75220-9 . ПМИД 7972355 . Проверено 28 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Гастон, Кевин Дж.; Спайсер, Джон И. (13 февраля 2004 г.). Биоразнообразие: Введение . Уайли. ISBN 978-1-4051-1857-6 .

- ^ Беланжер, Ж.; Пиллинг, Д. (2019). Состояние биоразнообразия в мире для производства продовольствия и ведения сельского хозяйства (PDF) . Рим: ФАО. п. 4. ISBN 978-92-5-131270-4 .

- ^ Мора, Камило; Титтенсор, Дерек П.; Адл, Сина; Симпсон, Аластер ГБ; Червь, Борис; Мейс, Джорджина М. (23 августа 2011 г.). «Сколько видов существует на Земле и в океане?» . ПЛОС Биология . 9 (8): e1001127. дои : 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127 . ПМК 3160336 . ПМИД 21886479 .

- ^ Уилсон, Дж. Бастоу; Пит, Роберт К.; Денглер, Юрген; Пяртель, Меэлис (1 августа 2012 г.). «Видовое богатство растений: мировые рекорды» . Журнал науки о растительности . 23 (4): 796–802. Бибкод : 2012JVegS..23..796W . дои : 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2012.01400.x . S2CID 53548257 .

- ^ Аппельтанс, В.; Ахьонг, Северная Каролина; Андерсон, Дж; Ангел, МВ; Артуа, Т.; и др. (2012). «Масштабы глобального разнообразия морских видов» . Современная биология . 22 (23): 2189–2202. Бибкод : 2012CBio...22.2189A . дои : 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.036 . hdl : 1942/14524 . ПМИД 23159596 .

- ^ «Численность насекомых (видов и особей)» . Смитсоновский институт . Архивировано из оригинала 15 января 2024 года.

- ^ Галус, Кристина (5 марта 2007 г.). «Защита биоразнообразия: сложная инвентаризация» . Ле Монд (на французском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 1 апреля 2023 года.

- ^ Чунг, Луиза (31 июля 2006 г.). «Тысячи микробов залпом» . Новости Би-би-си . Архивировано из оригинала 23 декабря 2022 года.

- ^ Хоксворт, ДЛ (24 июля 2012 г.). «Глобальное количество видов грибов: способствуют ли тропические исследования и молекулярные подходы более надежной оценке?». Биоразнообразие и сохранение . 21 (9): 2425–2433. Бибкод : 2012BiCon..21.2425H . дои : 10.1007/s10531-012-0335-x . S2CID 15087855 .

- ^ Хоксворт, Д. (2001). «Масштабы разнообразия грибов: пересмотренная оценка в 1,5 миллиона видов». Микологические исследования . 105 (12): 1422–1432. дои : 10.1017/S0953756201004725 . S2CID 56122588 .

- ^ «Акари на веб-странице Зоологического музея Мичиганского университета» . Insects.ummz.lsa.umich.edu. 10 ноября 2003 года . Проверено 21 июня 2009 г.

- ^ «Информационный бюллетень – Обзор экспедиции» (PDF) . Институт Дж. Крейга Вентера . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 29 июня 2010 года . Проверено 29 августа 2010 г.

- ^ Мирский, Стив (21 марта 2007 г.). «Естественно говоря: поиск сокровищ природы с помощью глобальной экспедиции по отбору проб океана» . Научный американец . Проверено 4 мая 2011 г.

- ^ «Сборники статей, изданные Публичной научной библиотекой» . Коллекции PLoS. doi : 10.1371/issue.pcol.v06.i02 (неактивен 31 января 2024 г.). Архивировано из оригинала 12 сентября 2012 года . Проверено 24 сентября 2011 г.

{{cite journal}}: Для цитирования журнала требуется|journal=( помощь ) CS1 maint: DOI неактивен с января 2024 г. ( ссылка ) - ^ Маккай, Робин (25 сентября 2005 г.). «Открытие новых видов и их истребление быстрыми темпами» . Хранитель . Лондон.

- ^ Баутиста, Луис М.; Пантоха, Хуан Карлос (2005). «Какие виды нам следует изучить дальше?». Бюллетень Британского экологического общества . 36 (4): 27–28. hdl : 10261/43928 .

- ^ «Индекс живой планеты, мир» . Наш мир в данных. 13 октября 2022 года. Архивировано 8 октября 2023 года.

Источник данных: Всемирный фонд дикой природы (WWF) и Лондонское зоологическое общество.

- ^ Уайтинг, Кейт (17 октября 2022 г.). «6 диаграмм, показывающих состояние биоразнообразия и утраты природы, а также то, как мы можем стать «позитивными для природы» » . Всемирный экономический форум. Архивировано из оригинала 25 сентября 2023 года.

- ^ Региональные данные из «Как индекс живой планеты варьируется в зависимости от региона?» . Наш мир в данных. 13 октября 2022 г. Архивировано из оригинала 20 сентября 2023 г.

Источник данных: Living Planet Report (2022). Всемирный фонд дикой природы (WWF) и Лондонское зоологическое общество. –

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Рид, Уолтер В. (1995). «Обращение вспять утраты биоразнообразия: обзор международных мер» . Информационный бюллетень засушливых земель . Ag.arizona.edu.

- ^ Пимм, СЛ; Рассел, Дж.Дж.; Гиттлман, Дж.Л.; Брукс, ТМ (1995). «Будущее биоразнообразия» (PDF) . Наука . 269 (5222): 347–350. Бибкод : 1995Sci...269..347P . дои : 10.1126/science.269.5222.347 . ПМИД 17841251 . S2CID 35154695 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 15 июля 2011 года . Проверено 4 мая 2011 г.

- ^ «Статистика утраты биоразнообразия [Отчет WWF за 2020 год]» . Земля.Орг . Проверено 4 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Кэррингтон Д. (2 февраля 2021 г.). «Обзор экономики биоразнообразия: каковы рекомендации?» . Хранитель . Проверено 17 декабря 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дасгупта, Парта (2021). «Экономика биоразнообразия: основные сообщения обзора Дасгупты» (PDF) . Правительство Великобритании. п. 1 . Проверено 16 декабря 2021 г.

Биоразнообразие сокращается быстрее, чем когда-либо в истории человечества. Например, нынешние темпы вымирания примерно в 100–1000 раз превышают базовые темпы, и они растут.

- ^ Де Вос Дж. М., Джоппа Л. Н., Гиттлман Дж. Л., Стивенс П. Р., Пимм С. Л. (апрель 2015 г.). «Оценка нормальной фоновой скорости вымирания видов» (PDF) . Биология сохранения . 29 (2): 452–62. Бибкод : 2015ConBi..29..452D . дои : 10.1111/cobi.12380 . ПМИД 25159086 . S2CID 19121609 .

- ^ Себальос Дж., Эрлих П.Р., Рэйвен П.Х. (июнь 2020 г.). «Позвоночные животные на грани биологического уничтожения и шестого массового вымирания» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 117 (24): 13596–13602. Бибкод : 2020PNAS..11713596C . дои : 10.1073/pnas.1922686117 . ПМК 7306750 . ПМИД 32482862 .

- ^ «Исследования показывают, что угроза утраты биоразнообразия равна угрозе изменения климата» . Виннипегская свободная пресса . 7 июня 2012 г.

- ^ Отчет «Живая планета» за 2016 год. Риски и устойчивость в новую эпоху (PDF) (Отчет). Международный Всемирный фонд дикой природы. 2016. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 7 августа 2021 года . Проверено 20 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Отчет о живой планете 2014 (PDF) , Всемирный фонд дикой природы, заархивировано из оригинала (PDF) 6 октября 2014 г. , получено 4 октября 2014 г.

- ^ Халлманн, Каспар А.; Сорг, Мартин; Йонгеянс, Элке; Сипель, Хенк; Хофланд, Ник; Шван, Хайнц; Стенманс, Вернер; Мюллер, Андреас; Самсер, Хьюберт; Хёррен, Томас; Гоулсон, Дэйв (18 октября 2017 г.). «За 27 лет общая биомасса летающих насекомых на охраняемых территориях снизилась более чем на 75 процентов» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 12 (10): e0185809. Бибкод : 2017PLoSO..1285809H . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0185809 . ISSN 1932-6203 . ПМЦ 5646769 . ПМИД 29045418 .

- ^ Кэррингтон, Дамиан (18 октября 2017 г.). «Предупреждение об «экологическом Армагеддоне» после резкого падения численности насекомых» . Хранитель . Архивировано из оригинала 11 июля 2022 года . Проверено 20 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Бриггс, Хелен (10 сентября 2020 г.). «Дикая природа находится в «катастрофическом упадке» из-за уничтожения человеком, предупреждают ученые» . Би-би-си . Проверено 3 декабря 2020 г.

- ^ «Биоразнообразие: исследования показывают, что почти половина животных вымирает» . Би-би-си . 23 мая 2023 г. Проверено 10 июня 2023 г.

- ^ Финн, Кэтрин; Граттарола, Флоренция; Пинчейра-Доносо, Даниэль (2023). «Больше проигравших, чем победителей: исследование антропоценовой дефауны через разнообразие демографических тенденций» . Биологические обзоры . 98 (5): 1732–1748. дои : 10.1111/brv.12974 . ПМИД 37189305 . S2CID 258717720 .

- ^ Пэддисон, Лаура (22 мая 2023 г.). «Согласно новому исследованию, глобальная утрата дикой природы «значительно более тревожна», чем считалось ранее» . CNN . Проверено 10 июня 2023 г.

- ^ Виньери, С. (25 июля 2014 г.). «Исчезающая фауна (Спецвыпуск)» . Наука . 345 (6195): 392–412. Бибкод : 2014Sci...345..392V . дои : 10.1126/science.345.6195.392 . ПМИД 25061199 .

- ^ «Убедительные доказательства показывают, что происходит шестое массовое вымирание глобального биоразнообразия» . ЭврекАлерт! . 13 января 2022 г. Проверено 17 февраля 2022 г.

- ^ Дирзо, Родольфо; Хиллари С. Янг; Мауро Галетти; Херардо Себальос; Ник Дж. Б. Исаак; Бен Коллен (2014). «Дефаунация в антропоцене» (PDF) . Наука . 345 (6195): 401–406. Бибкод : 2014Sci...345..401D . дои : 10.1126/science.1251817 . ПМИД 25061202 . S2CID 206555761 .

За последние 500 лет люди спровоцировали волну вымираний, угроз и сокращения местного населения, которая по темпам и масштабам может быть сопоставима с пятью предыдущими массовыми вымираниями в истории Земли.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пробуждение БД; Вреденбург В.Т. (2008). «Мы находимся в разгаре шестого массового вымирания? Взгляд из мира земноводных» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 105 (Приложение 1): 11466–11473. Бибкод : 2008PNAS..10511466W . дои : 10.1073/pnas.0801921105 . ПМК 2556420 . ПМИД 18695221 .

- ^ Кох, LP; Данн, Р.Р.; Содхи, Н.С.; Колвелл, РК; Проктор, ХК; Смит, В.С. (2004). «Сосуществование видов и кризис биоразнообразия» . Наука . 305 (5690): 1632–1634. Бибкод : 2004Sci...305.1632K . дои : 10.1126/science.1101101 . ПМИД 15361627 . S2CID 30713492 . [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ МакКаллум, Малкольм Л. (сентябрь 2007 г.). «Упадок или вымирание земноводных? Текущее снижение значительно превышает фоновые темпы вымирания». Журнал герпетологии . 41 (3): 483–491. doi : 10.1670/0022-1511(2007)41[483:ADOECD]2.0.CO;2 . S2CID 30162903 .

- ^ Джексон, JBC (2008). «Доклад коллоквиума: Экологическое вымирание и эволюция в дивном новом океане» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 105 (Приложение 1): 11458–11465. Бибкод : 2008PNAS..10511458J . дои : 10.1073/pnas.0802812105 . ПМК 2556419 . ПМИД 18695220 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Данн, Роберт Р. (август 2005 г.). «Современное вымирание насекомых: забытое большинство» (PDF) . Биология сохранения . 19 (4): 1030–1036. Бибкод : 2005ConBi..19.1030D . дои : 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00078.x . S2CID 38218672 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 8 августа 2017 года – через Калифорнийскую энергетическую комиссию.

- ^ Себальос, Херардо; Эрлих, Пол Р.; Барноски, Энтони Д .; Гарсиа, Андрес; Прингл, Роберт М.; Палмер, Тодд М. (2015). «Ускоренная гибель видов, вызванная деятельностью человека: на пороге шестого массового вымирания» . Достижения науки . 1 (5): e1400253. Бибкод : 2015SciA....1E0253C . дои : 10.1126/sciadv.1400253 . ПМК 4640606 . ПМИД 26601195 .

- ^ [51] [52] [53] [54] [55] [56] [57] [58] [59]

- ^ Дирзо, Родольфо; Себальос, Херардо; Эрлих, Пол Р. (2022). «По кругу стока: кризис вымирания и будущее человечества» . Философские труды Королевского общества Б. 377 (1857). дои : 10.1098/rstb.2021.0378 . ПМЦ 9237743 . ПМИД 35757873 . S2CID 250055843 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хасан, Рашид М.; и др. (2006). Экосистемы и благополучие человека: современное состояние и тенденции: выводы Рабочей группы по состоянию и тенденциям оценки экосистем на пороге тысячелетия . Остров Пресс. п. 105. ИСБН 978-1-55963-228-7 .

- ^ Официальные документы правительства Великобритании, февраль 2021 г., «Экономика биоразнообразия: основные сообщения обзора Dasgupta», стр. 1

- ^ Ловетт, Ричард А. (2 мая 2006 г.). «Список исчезающих видов расширен до 16 000» . Нэшнл Географик . Архивировано из оригинала 5 августа 2017 года.

- ^ «Красный список видов, находящихся под угрозой исчезновения МСОП» .

- ^ Стокстад, Эрик (6 мая 2019 г.). «Анализ ориентиров документирует тревожный глобальный упадок природы» . Наука . дои : 10.1126/science.aax9287 .

Впервые в глобальном масштабе в докладе ранжированы причины ущерба. Во главе списка стоят изменения в землепользовании (в основном в сельском хозяйстве), которые разрушили среду обитания. Во-вторых, охота и другие виды эксплуатации. За ними следуют изменение климата, загрязнение окружающей среды и инвазивные виды, которые распространяются в результате торговли и других видов деятельности. Авторы отмечают, что изменение климата, вероятно, опередит другие угрозы в ближайшие десятилетия. Движущей силой этих угроз являются растущее население, которое с 1970 года удвоилось до 7,6 миллиардов человек, а также потребление. (За последние 5 десятилетий использование материалов на душу населения выросло на 15%.)

- ^ Пимм С.Л., Дженкинс К.Н., Абелл Р., Брукс Т.М., Гиттлман Дж.Л., Джоппа Л.Н. и др. (май 2014 г.). «Биоразнообразие видов и темпы их исчезновения, распространения и защиты». Наука . 344 (6187): 1246752. doi : 10.1126/science.1246752 . ПМИД 24876501 . S2CID 206552746 .

Главной движущей силой вымирания видов является рост населения и увеличение потребления на душу населения.

- ^ Кафаро, Филип; Ханссон, Пернилла; Гётмарк, Франк (август 2022 г.). «Перенаселение является основной причиной утраты биоразнообразия, и для сохранения того, что осталось, необходимо меньшее население» (PDF) . Биологическая консервация . 272 . 109646. Бибкод : 2022BCons.27209646C . дои : 10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109646 . ISSN 0006-3207 . S2CID 250185617 .

Биологи-природоохранители обычно перечисляют пять основных прямых факторов утраты биоразнообразия: утрата среды обитания, чрезмерная эксплуатация видов, загрязнение окружающей среды, инвазивные виды и изменение климата. В докладе о глобальной оценке биоразнообразия и экосистемных услуг было установлено, что в последние десятилетия утрата среды обитания была основной причиной утраты наземного биоразнообразия, а чрезмерная эксплуатация (чрезмерный вылов рыбы) была наиболее важной причиной потерь морской среды (IPBES, 2019). Все пять прямых факторов важны, как на суше, так и на море, и все они усугубляются увеличением и плотностью населения.

- ^ Крист, Эйлин; Мора, Камило; Энгельман, Роберт (21 апреля 2017 г.). «Взаимодействие человеческой популяции, производства продуктов питания и защиты биоразнообразия» . Наука . 356 (6335): 260–264. Бибкод : 2017Sci...356..260C . doi : 10.1126/science.aal2011 . ПМИД 28428391 . S2CID 12770178 . Проверено 2 января 2023 г.

- ^ Себальос, Херардо; Эрлих, Пол Р. (2023). «Увечье древа жизни через массовое вымирание видов животных» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 120 (39): e2306987120. Бибкод : 2023PNAS..12006987C . дои : 10.1073/pnas.2306987120 . ПМЦ 10523489 . ПМИД 37722053 .

- ^ Хьюз, Элис К.; Тужерон, Кевин; Мартин, Доминик А.; Менга, Филиппо; Росадо, Бруно HP; Вилласанте, Себастьян; Мадгулкар, Света; Гонсалвеш, Фернандо; Дженелетти, Давиде; Диле-Вьегас, Луиза Мария; Бергер, Себастьян; Колла, Шейла Р.; де Андраде Камимура, Витор; Каджано, Холли; Мело, Фелипе (1 января 2023 г.). «Меньшая численность населения не является ни необходимым, ни достаточным условием для сохранения биоразнообразия» . Биологическая консервация . 277 : 109841. Бибкод : 2023BCons.27709841H . doi : 10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109841 . ISSN 0006-3207 .

Изучая причины утраты биоразнообразия в странах с высоким биоразнообразием, мы показываем, что не население приводит к потере среды обитания, а, скорее, рост экспорта товаров, особенно соевых бобов и пальмового масла, в первую очередь для корма для скота или потребления биотоплива в странах с более высоким уровнем биоразнообразия. экономики дохода.

- ^ Клей, Кейт; Хола, Дженни (10 сентября 1999 г.). «Грибной эндофитный симбиоз и разнообразие растений в сукцессионных полях» . Наука . 285 (5434): 1742–1744. дои : 10.1126/science.285.5434.1742 . ISSN 0036-8075 . ПМИД 10481011 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Моран, Серж; Краснов, Борис Р. (1 сентября 2010 г.). Биогеография взаимоотношений хозяина и паразита . Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 93–94. ISBN 978-0-19-956135-3 . Проверено 28 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Кардинале, Брэдли. Дж.; и др. (март 2011 г.). «Функциональная роль разнообразия производителей в экосистемах» . Американский журнал ботаники . 98 (3): 572–592. дои : 10.3732/ajb.1000364 . hdl : 2027.42/141994 . ПМИД 21613148 . S2CID 10801536 .

- ^ «Прочный, но уязвимый Эдем в Амазонии» . Блог Dot Earth, New York Times . 20 января 2010 г. Проверено 2 февраля 2013 г.

- ^ Марго С. Басс; Мэтт Файнер; Клинтон Н. Дженкинс; Хольгер Крефт; Диего Ф. Сиснерос-Эредиа; Шон Ф. Маккракен; Найджел К.А. Питман; Питер Х. Инглиш; Келли Свинг; Вилла Горького; Энтони Ди Фьоре; Кристиан К. Фойгт; Томас Х. Кунц (2010). «Глобальное значение сохранения эквадорского национального парка Ясуни» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 5 (1): е8767. Бибкод : 2010PLoSO...5.8767B . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0008767 . ПМК 2808245 . ПМИД 20098736 .

- ^ Бентон М.Дж. (2001). «Биоразнообразие на суше и в море». Геологический журнал . 36 (3–4): 211–230. Бибкод : 2001GeolJ..36..211B . дои : 10.1002/gj.877 . S2CID 140675489 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я Состояние лесов мира в 2020 году. Кратко – Леса, биоразнообразие и люди . Рим, Италия: ФАО и ЮНЕП. 2020. doi : 10.4060/ca8985en . ISBN 978-92-5-132707-4 . S2CID 241416114 . текст был добавлен из этого источника, который имеет заявление о лицензии , специфичное для Википедии.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Мора, К.; и др. (2011). «Сколько видов существует на Земле и в океане?» . ПЛОС Биология . 9 (8): e1001127. дои : 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127 . ПМК 3160336 . ПМИД 21886479 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Редакция «Микроорганизмы» (9 января 2019). «Благодарность рецензентам микроорганизмов в 2018 году» . Микроорганизмы . 7 (1): 13. doi : 10.3390/microorganisms7010013 . ПМК 6352028 .

- ^ «Глобальная оценка лесных ресурсов 2020» . Продовольственная и сельскохозяйственная организация . Проверено 30 января 2023 г.

- ^ «Состояние лесов мира в 2020 году: Леса, биоразнообразие и люди [EN/AR/RU] – World | ReliefWeb» . Reliefweb.int . Сентябрь 2020 года . Проверено 30 января 2023 г.

- ^ «39% территории ЕС покрыто лесами» . ec.europa.eu . Проверено 30 января 2023 г.

- ^ Каваллито, Маттео (8 апреля 2021 г.). «Европейские леса расширяются. Но их будущее не написано» . Фонд Re Soil . Проверено 30 января 2023 г.

- ^ Мора С., Робертсон Д.Р. (2005). «Причины широтных градиентов видового богатства: тест с рыбами тропической восточной части Тихого океана» (PDF) . Экология . 86 (7): 1771–1792. Бибкод : 2005Экол...86.1771М . дои : 10.1890/04-0883 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 4 марта 2016 года . Проверено 25 декабря 2012 г.

- ^ Хиллебранд Х (2004). «Об общности широтного градиента разнообразия» (PDF) . Американский натуралист . 163 (2): 192–211. дои : 10.1086/381004 . ПМИД 14970922 . S2CID 9886026 .

- ^ Каракассис, Иоаннис; Мустакас, Аристид (сентябрь 2005 г.). «Насколько разнообразны исследования водного биоразнообразия?». Водная экология . 39 (3): 367–375. Бибкод : 2005AqEco..39..367M . дои : 10.1007/s10452-005-6041-y . S2CID 23630051 .

- ^ Бахрам, Мохаммед; Хильдебранд, Фальк; Форслунд, София К.; Андерсон, Дженнифер Л.; Судзиловская, Надежда А.; Бодегом, Питер М.; Бенгтссон-Пальме, Йохан; Анслан, Стэн; Коэльо, Луис Педро; Харенд, Хелери; Уэрта-Сепас, Хайме; Медема, Марникс Х.; Мальц, Миа Р.; Мундра, Сунил; Олссон, Пол Аксель (август 2018 г.). «Структура и функции глобального микробиома верхнего слоя почвы» . Природа . 560 (7717): 233–237. Бибкод : 2018Nature.560..233B . дои : 10.1038/s41586-018-0386-6 . hdl : 1887/73861 . ISSN 1476-4687 . ПМИД 30069051 . S2CID 256768771 .

- ^ Бикель, Сэмюэл; Или Дэни (8 января 2020 г.). «Разнообразие почвенных бактерий, опосредованное микромасштабными процессами водной фазы в биомах» . Природные коммуникации . 11 (1): 116. Бибкод : 2020NatCo..11..116B . дои : 10.1038/s41467-019-13966-w . ISSN 2041-1723 . ПМЦ 6949233 . ПМИД 31913270 .

- ^ Каццолла Гатти, R (2016). «Фрактальная природа широтного градиента биоразнообразия». Биология . 71 (6): 669–672. Бибкод : 2016Биолг..71..669С . дои : 10.1515/биолог-2016-0077 . S2CID 199471847 .

- ^ Кожиторе, Клеман (1983–...). (январь 1988 г.), Гипотеза , ISBN 9780309037396 , OCLC 968249007

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: числовые имена: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ Биоразнообразие А–Я. «Горячие точки биоразнообразия» .

- ^ Майерс Н. (1988). «Биота, находящаяся под угрозой исчезновения: «горячие точки» в тропических лесах». Эколог . 8 (3): 187–208. дои : 10.1007/BF02240252 . ПМИД 12322582 . S2CID 2370659 .

- ^ Майерс Н. (1990). «Проблема биоразнообразия: расширенный анализ горячих точек» (PDF) . Эколог . 10 (4): 243–256. Бибкод : 1990ThEnv..10..243M . CiteSeerX 10.1.1.468.8666 . дои : 10.1007/BF02239720 . ПМИД 12322583 . S2CID 22995882 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 9 сентября 2022 года . Проверено 1 ноября 2017 г.