Вагина

| Вагина | |

|---|---|

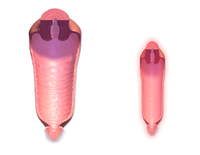

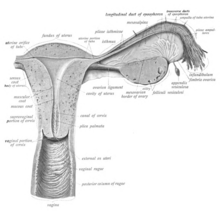

Человеческое влагалище; нормальный канал (слева) и канал во время менопаузы (справа) | |

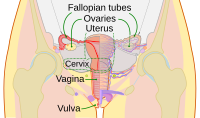

Схема женских репродуктивных путей и яичников человека | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Urogenital sinus and paramesonephric ducts |

| Artery | Superior part to uterine artery, middle and inferior parts to vaginal artery |

| Vein | Uterovaginal venous plexus, vaginal vein |

| Nerve |

|

| Lymph | Upper part to internal iliac lymph nodes, lower part to superficial inguinal lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vagina |

| MeSH | D014621 |

| TA98 | A09.1.04.001 |

| TA2 | 3523 |

| FMA | 19949 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

У млекопитающих и других животных влагалище ( мн. ч .: вагины или влагалища ) [ 1 ] — эластичный, мускулистый репродуктивный орган женских половых путей . У человека он простирается от преддверия влагалища до шейки матки (шейки матки ) . Вход во влагалище обычно частично покрыт тонким слоем слизистой оболочки, называемой девственной плевой . Влагалище позволяет совокупляться и рожать . Он также направляет менструальные выделения , которые происходят у людей и близкородственных приматов как часть менструального цикла .

Хотя исследования влагалища у разных животных особенно недостаточны, документально подтверждено, что его расположение, структура и размер различаются у разных видов. У самок млекопитающих обычно имеется два наружных отверстия вульвы ; это уретральное отверстие для мочевыводящих путей и вагинальное отверстие для половых путей. В этом отличие от самцов млекопитающих, у которых обычно имеется одно отверстие уретры как для мочеиспускания , так и для размножения . Отверстие влагалища намного больше, чем близлежащее отверстие уретры, и оба они защищены половыми губами у человека . У земноводных , птиц , рептилий и однопроходных клоака . является единственным наружным отверстием для желудочно-кишечного, мочевого и репродуктивного путей

To accommodate smoother penetration of the vagina during sexual intercourse or other sexual activity, vaginal moisture increases during sexual arousal in human females and other female mammals. This increase in moisture provides vaginal lubrication, which reduces friction. The texture of the vaginal walls creates friction for the penis during sexual intercourse and stimulates it toward ejaculation, enabling fertilization. Along with pleasure and bonding, women's sexual behavior with other people can result in sexually transmitted infections (STIs), the risk of which can be reduced by recommended safe sex practices. Other health issues may also affect the human vagina.

The vagina has evoked strong reactions in societies throughout history, including negative perceptions and language, cultural taboos, and their use as symbols for female sexuality, spirituality, or regeneration of life. In common speech, the word vagina is often used incorrectly to refer to the vulva or to the female genitals in general.

Etymology and definition

The term vagina is from Latin vāgīna, meaning "sheath" or "scabbard".[1] The vagina may also be referred to as the birth canal in the context of pregnancy and childbirth.[2][3] Although by its dictionary and anatomical definitions, the term vagina refers exclusively to the specific internal structure, it is colloquially used to refer to the vulva or to both the vagina and vulva.[4][5]

Using the term vagina to mean "vulva" can pose medical or legal confusion; for example, a person's interpretation of its location might not match another's interpretation of the location.[4][6] Medically, one description of the vagina is that it is the canal between the hymen (or remnants of the hymen) and the cervix, while a legal description is that it begins at the vulva (between the labia).[4] It may be that the incorrect use of the term vagina is due to not as much thought going into the anatomy of the female genitals as has gone into the study of male genitals, and that this has contributed to an absence of correct vocabulary for the external female genitalia among both the general public and health professionals. Because a better understanding of female genitalia can help combat sexual and psychological harm with regard to female development, researchers endorse correct terminology for the vulva.[6][7][8]

Structure

Gross anatomy

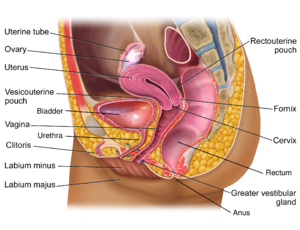

The human vagina is an elastic, muscular canal that extends from the vulva to the cervix.[9][10] The opening of the vagina lies in the urogenital triangle. The urogenital triangle is the front triangle of the perineum and also consists of the urethral opening and associated parts of the external genitalia.[11] The vaginal canal travels upwards and backwards, between the urethra at the front, and the rectum at the back. Near the upper vagina, the cervix protrudes into the vagina on its front surface at approximately a 90 degree angle.[12] The vaginal and urethral openings are protected by the labia.[13]

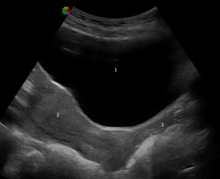

When not sexually aroused, the vagina is a collapsed tube, with the front and back walls placed together. The lateral walls, especially their middle area, are relatively more rigid. Because of this, the collapsed vagina has an H-shaped cross section.[10][14] Behind, the upper vagina is separated from the rectum by the recto-uterine pouch, the middle vagina by loose connective tissue, and the lower vagina by the perineal body.[15] Where the vaginal lumen surrounds the cervix of the uterus, it is divided into four continuous regions (vaginal fornices); these are the anterior, posterior, right lateral, and left lateral fornices.[9][10] The posterior fornix is deeper than the anterior fornix.[10]

Supporting the vagina are its upper, middle, and lower third muscles and ligaments. The upper third are the levator ani muscles, and the transcervical, pubocervical, and sacrocervical ligaments.[9][16] It is supported by the upper portions of the cardinal ligaments and the parametrium.[17] The middle third of the vagina involves the urogenital diaphragm.[9] It is supported by the levator ani muscles and the lower portion of the cardinal ligaments.[17] The lower third is supported by the perineal body,[9][18] or the urogenital and pelvic diaphragms.[19] The lower third may also be described as being supported by the perineal body and the pubovaginal part of the levator ani muscle.[16]

Vaginal opening and hymen

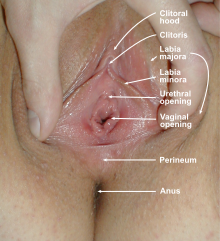

The vaginal opening (also known as the vaginal introitus and the Latin ostium vaginae)[20][21] is at the posterior end of the vulval vestibule, behind the urethral opening. The term introitus is more technically correct than "opening", since the vagina is usually collapsed, with the opening closed. The opening to the vagina is normally obscured by the labia minora (inner lips), but may be exposed after vaginal delivery.[10]

The hymen is a thin layer of mucosal tissue that surrounds or partially covers the vaginal opening.[10] The effects of intercourse and childbirth on the hymen vary. Where it is broken, it may completely disappear or remnants known as carunculae myrtiformes may persist. Otherwise, being very elastic, it may return to its normal position.[22] Additionally, the hymen may be lacerated by disease, injury, medical examination, masturbation or physical exercise. For these reasons, virginity cannot be definitively determined by examining the hymen.[22][23]

Variations and size

The length of the vagina varies among women of child-bearing age. Because of the presence of the cervix in the front wall of the vagina, there is a difference in length between the front wall, approximately 7.5 cm (2.5 to 3 in) long, and the back wall, approximately 9 cm (3.5 in) long.[10][24] During sexual arousal, the vagina expands both in length and width. If a woman stands upright, the vaginal canal points in an upward-backward direction and forms an angle of approximately 45 degrees with the uterus.[10][18] The vaginal opening and hymen also vary in size; in children, although the hymen commonly appears crescent-shaped, many shapes are possible.[10][25]

Development

The vaginal plate is the precursor to the vagina.[26] During development, the vaginal plate begins to grow where the fused ends of the paramesonephric ducts (Müllerian ducts) enter the back wall of the urogenital sinus as the sinus tubercle. As the plate grows, it significantly separates the cervix and the urogenital sinus; eventually, the central cells of the plate break down to form the vaginal lumen.[26] This usually occurs by the twenty to twenty-fourth week of development. If the lumen does not form, or is incomplete, membranes known as vaginal septa can form across or around the tract, causing obstruction of the outflow tract later in life.[26]

There are conflicting views on the embryologic origin of the vagina. The majority view is Koff's 1933 description, which posits that the upper two-thirds of the vagina originate from the caudal part of the Müllerian duct, while the lower part of the vagina develops from the urogenital sinus.[27][28] Other views are Bulmer's 1957 description that the vaginal epithelium derives solely from the urogenital sinus epithelium,[29] and Witschi's 1970 research, which reexamined Koff's description and concluded that the sinovaginal bulbs are the same as the lower portions of the Wolffian ducts.[28][30] Witschi's view is supported by research by Acién et al., Bok and Drews.[28][30] Robboy et al. reviewed Koff and Bulmer's theories, and support Bulmer's description in light of their own research.[29] The debates stem from the complexity of the interrelated tissues and the absence of an animal model that matches human vaginal development.[29][31] Because of this, study of human vaginal development is ongoing and may help resolve the conflicting data.[28]

Microanatomy

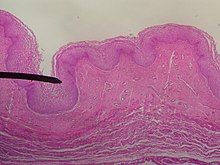

The vaginal wall from the lumen outwards consists firstly of a mucosa of stratified squamous epithelium that is not keratinized, with a lamina propria (a thin layer of connective tissue) underneath it. Secondly, there is a layer of smooth muscle with bundles of circular fibers internal to longitudinal fibers (those that run lengthwise). Lastly, is an outer layer of connective tissue called the adventitia. Some texts list four layers by counting the two sublayers of the mucosa (epithelium and lamina propria) separately.[32][33]

The smooth muscular layer within the vagina has a weak contractive force that can create some pressure in the lumen of the vagina; much stronger contractive force, such as during childbirth, comes from muscles in the pelvic floor that are attached to the adventitia around the vagina.[34]

The lamina propria is rich in blood vessels and lymphatic channels. The muscular layer is composed of smooth muscle fibers, with an outer layer of longitudinal muscle, an inner layer of circular muscle, and oblique muscle fibers between. The outer layer, the adventitia, is a thin dense layer of connective tissue and it blends with loose connective tissue containing blood vessels, lymphatic vessels and nerve fibers that are between pelvic organs.[12][33][24] The vaginal mucosa is absent of glands. It forms folds (transverse ridges or rugae), which are more prominent in the outer third of the vagina; their function is to provide the vagina with increased surface area for extension and stretching.[9][10]

The epithelium of the ectocervix (the portion the uterine cervix extending into the vagina) is an extension of, and shares a border with, the vaginal epithelium.[35] The vaginal epithelium is made up of layers of cells, including the basal cells, the parabasal cells, the superficial squamous flat cells, and the intermediate cells.[36] The basal layer of the epithelium is the most mitotically active and reproduces new cells.[37] The superficial cells shed continuously and basal cells replace them.[10][38][39] Estrogen induces the intermediate and superficial cells to fill with glycogen.[39][40] Cells from the lower basal layer transition from active metabolic activity to death (apoptosis). In these mid-layers of the epithelia, the cells begin to lose their mitochondria and other organelles.[37][41] The cells retain a usually high level of glycogen compared to other epithelial tissue in the body.[37]

Under the influence of maternal estrogen, the vagina of a newborn is lined by thick stratified squamous epithelium (or mucosa) for two to four weeks after birth. Between then to puberty, the epithelium remains thin with only a few layers of cuboidal cells without glycogen.[39][42] The epithelium also has few rugae and is red in color before puberty.[4] When puberty begins, the mucosa thickens and again becomes stratified squamous epithelium with glycogen containing cells, under the influence of the girl's rising estrogen levels.[39] Finally, the epithelium thins out from menopause onward and eventually ceases to contain glycogen, because of the lack of estrogen.[10][38][43]

Flattened squamous cells are more resistant to both abrasion and infection.[42] The permeability of the epithelium allows for an effective response from the immune system since antibodies and other immune components can easily reach the surface.[44] The vaginal epithelium differs from the similar tissue of the skin. The epidermis of the skin is relatively resistant to water because it contains high levels of lipids. The vaginal epithelium contains lower levels of lipids. This allows the passage of water and water-soluble substances through the tissue.[44]

Keratinization happens when the epithelium is exposed to the dry external atmosphere.[10] In abnormal circumstances, such as in pelvic organ prolapse, the mucosa may be exposed to air, becoming dry and keratinized.[45]

Blood and nerve supply

Blood is supplied to the vagina mainly via the vaginal artery, which emerges from a branch of the internal iliac artery or the uterine artery.[9][46] The vaginal arteries anastamose (are joined) along the side of the vagina with the cervical branch of the uterine artery; this forms the azygos artery,[46] which lies on the midline of the anterior and posterior vagina.[15] Other arteries which supply the vagina include the middle rectal artery and the internal pudendal artery,[10] all branches of the internal iliac artery.[15] Three groups of lymphatic vessels accompany these arteries; the upper group accompanies the vaginal branches of the uterine artery; a middle group accompanies the vaginal arteries; and the lower group, draining lymph from the area outside the hymen, drain to the inguinal lymph nodes.[15][47] Ninety-five percent of the lymphatic channels of the vagina are within 3 mm of the surface of the vagina.[48]

Two main veins drain blood from the vagina, one on the left and one on the right. These form a network of smaller veins, the vaginal venous plexus, on the sides of the vagina, connecting with similar venous plexuses of the uterus, bladder, and rectum. These ultimately drain into the internal iliac veins.[15]

The nerve supply of the upper vagina is provided by the sympathetic and parasympathetic areas of the pelvic plexus. The lower vagina is supplied by the pudendal nerve.[10][15]

Function

Secretions

Vaginal secretions are primarily from the uterus, cervix, and vaginal epithelium in addition to minuscule vaginal lubrication from the Bartholin's glands upon sexual arousal.[10] It takes little vaginal secretion to make the vagina moist; secretions may increase during sexual arousal, the middle of or a little prior to menstruation, or during pregnancy.[10] Menstruation (also known as a "period" or "monthly") is the regular discharge of blood and mucosal tissue (known as menses) from the inner lining of the uterus through the vagina.[49] The vaginal mucous membrane varies in thickness and composition during the menstrual cycle,[50] which is the regular, natural change that occurs in the female reproductive system (specifically the uterus and ovaries) that makes pregnancy possible.[51][52] Different hygiene products such as tampons, menstrual cups, and sanitary napkins are available to absorb or capture menstrual blood.[53]

The Bartholin's glands, located near the vaginal opening, were originally considered the primary source for vaginal lubrication, but further examination showed that they provide only a few drops of mucus.[54] Vaginal lubrication is mostly provided by plasma seepage known as transudate from the vaginal walls. This initially forms as sweat-like droplets, and is caused by increased fluid pressure in the tissue of the vagina (vasocongestion), resulting in the release of plasma as transudate from the capillaries through the vaginal epithelium.[54][55][56]

Before and during ovulation, the mucus glands within the cervix secrete different variations of mucus, which provides an alkaline, fertile environment in the vaginal canal that is favorable to the survival of sperm.[57] Following menopause, vaginal lubrication naturally decreases.[58]

Sexual stimulation

Nerve endings in the vagina can provide pleasurable sensations when the vagina is stimulated during sexual activity. Women may derive pleasure from one part of the vagina, or from a feeling of closeness and fullness during vaginal penetration.[59] Because the vagina is not rich in nerve endings, women often do not receive sufficient sexual stimulation, or orgasm, solely from vaginal penetration.[59][60][61] Although the literature commonly cites a greater concentration of nerve endings and therefore greater sensitivity near the vaginal entrance (the outer one-third or lower third),[60][61][62] some scientific examinations of vaginal wall innervation indicate no single area with a greater density of nerve endings.[63][64] Other research indicates that only some women have a greater density of nerve endings in the anterior vaginal wall.[63][65] Because of the fewer nerve endings in the vagina, childbirth pain is significantly more tolerable.[61][66][67]

Pleasure can be derived from the vagina in a variety of ways. In addition to penile penetration, pleasure can come from masturbation, fingering, or specific sex positions (such as the missionary position or the spoons sex position).[68] Heterosexual couples may engage in fingering as a form of foreplay to incite sexual arousal or as an accompanying act,[69][70] or as a type of birth control, or to preserve virginity.[71][72] Less commonly, they may use non penile-vaginal sexual acts as a primary means of sexual pleasure.[70] In contrast, lesbians and other women who have sex with women commonly engage in fingering as a main form of sexual activity.[73][74] Some women and couples use sex toys, such as a vibrator or dildo, for vaginal pleasure.[75]

Most women require direct stimulation of the clitoris to orgasm.[60][61] The clitoris plays a part in vaginal stimulation. It is a sex organ of multiplanar structure containing an abundance of nerve endings, with a broad attachment to the pubic arch and extensive supporting tissue to the labia. Research indicates that it forms a tissue cluster with the vagina. This tissue is perhaps more extensive in some women than in others, which may contribute to orgasms experienced vaginally.[60][76][77]

During sexual arousal, and particularly the stimulation of the clitoris, the walls of the vagina lubricate. This begins after ten to thirty seconds of sexual arousal, and increases in amount the longer the woman is aroused.[78] It reduces friction or injury that can be caused by insertion of the penis into the vagina or other penetration of the vagina during sexual activity. The vagina lengthens during the arousal, and can continue to lengthen in response to pressure; as the woman becomes fully aroused, the vagina expands in length and width, while the cervix retracts.[78][79] With the upper two-thirds of the vagina expanding and lengthening, the uterus rises into the greater pelvis, and the cervix is elevated above the vaginal floor, resulting in tenting of the mid-vaginal plane.[78] This is known as the tenting or ballooning effect.[80] As the elastic walls of the vagina stretch or contract, with support from the pelvic muscles, to wrap around the inserted penis (or other object),[62] this creates friction for the penis and helps to cause a man to experience orgasm and ejaculation, which in turn enables fertilization.[81]

An area in the vagina that may be an erogenous zone is the G-spot. It is typically defined as being located at the anterior wall of the vagina, a couple or few inches in from the entrance, and some women experience intense pleasure, and sometimes an orgasm, if this area is stimulated during sexual activity.[63][65] A G-spot orgasm may be responsible for female ejaculation, leading some doctors and researchers to believe that G-spot pleasure comes from the Skene's glands, a female homologue of the prostate, rather than any particular spot on the vaginal wall; other researchers consider the connection between the Skene's glands and the G-spot area to be weak.[63][64][65] The G-spot's existence (and existence as a distinct structure) is still under dispute because reports of its location can vary from woman to woman, it appears to be nonexistent in some women, and it is hypothesized to be an extension of the clitoris and therefore the reason for orgasms experienced vaginally.[63][66][77]

Childbirth

The vagina is the birth canal for the delivery of a baby. When labor nears, several signs may occur, including vaginal discharge and the rupture of membranes (water breaking). The latter results in a gush or small stream of amniotic fluid from the vagina.[82] Water breaking most commonly happens at the beginning of labor. It happens before labor if there is a premature rupture of membranes, which occurs in 10% of cases.[83] Among women giving birth for the first time, Braxton Hicks contractions are mistaken for actual contractions,[84] but they are instead a way for the body to prepare for true labor. They do not signal the beginning of labor,[85] but they are usually very strong in the days leading up to labor.[84][85]

As the body prepares for childbirth, the cervix softens, thins, moves forward to face the front, and begins to open. This allows the fetus to settle into the pelvis, a process known as lightening.[86] As the fetus settles into the pelvis, pain from the sciatic nerves, increased vaginal discharge, and increased urinary frequency can occur.[86] While lightening is likelier to happen after labor has begun for women who have given birth before, it may happen ten to fourteen days before labor in women experiencing labor for the first time.[87]

The fetus begins to lose the support of the cervix when contractions begin. With cervical dilation reaching 10 cm to accommodate the head of the fetus, the head moves from the uterus to the vagina.[82][88] The elasticity of the vagina allows it to stretch to many times its normal diameter in order to deliver the child.[89]

Vaginal births are more common, but if there is a risk of complications a caesarean section (C-section) may be performed.[90] The vaginal mucosa has an abnormal accumulation of fluid (edematous) and is thin, with few rugae, a little after birth. The mucosa thickens and rugae return in approximately three weeks once the ovaries regain usual function and estrogen flow is restored. The vaginal opening gapes and is relaxed, until it returns to its approximate pre-pregnant state six to eight weeks after delivery, known as the postpartum period; however, the vagina will continue to be larger in size than it was previously.[91]

After giving birth, there is a phase of vaginal discharge called lochia that can vary significantly in the amount of loss and its duration but can go on for up to six weeks.[92]

Vaginal microbiota

The vaginal flora is a complex ecosystem that changes throughout life, from birth to menopause. The vaginal microbiota resides in and on the outermost layer of the vaginal epithelium.[44] This microbiome consists of species and genera, which typically do not cause symptoms or infections in women with normal immunity. The vaginal microbiome is dominated by Lactobacillus species.[93] These species metabolize glycogen, breaking it down into sugar. Lactobacilli metabolize the sugar into glucose and lactic acid.[94] Under the influence of hormones, such as estrogen, progesterone and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), the vaginal ecosystem undergoes cyclic or periodic changes.[94]

Clinical significance

Pelvic examinations

Vaginal health can be assessed during a pelvic examination, along with the health of most of the organs of the female reproductive system.[95][96][97] Such exams may include the Pap test (or cervical smear). In the United States, Pap test screening is recommended starting around 21 years of age until the age of 65.[98] However, other countries do not recommend pap testing in non-sexually active women.[99] Guidelines on frequency vary from every three to five years.[99][100][101] Routine pelvic examination on women who are not pregnant and lack symptoms may be more harmful than beneficial.[102] A normal finding during the pelvic exam of a pregnant woman is a bluish tinge to the vaginal wall.[95]

Pelvic exams are most often performed when there are unexplained symptoms of discharge, pain, unexpected bleeding or urinary problems.[95][103][104] During a pelvic exam, the vaginal opening is assessed for position, symmetry, presence of the hymen, and shape. The vagina is assessed internally by the examiner with gloved fingers, before the speculum is inserted, to note the presence of any weakness, lumps or nodules. Inflammation and discharge are noted if present. During this time, the Skene's and Bartolin's glands are palpated to identify abnormalities in these structures. After the digital examination of the vagina is complete, the speculum, an instrument to visualize internal structures, is carefully inserted to make the cervix visible.[95] Examination of the vagina may also be done during a cavity search.[105]

Lacerations or other injuries to the vagina can occur during sexual assault or other sexual abuse.[4][95] These can be tears, bruises, inflammation and abrasions. Sexual assault with objects can damage the vagina and X-ray examination may reveal the presence of foreign objects.[4] If consent is given, a pelvic examination is part of the assessment of sexual assault.[106] Pelvic exams are also performed during pregnancy, and women with high risk pregnancies have exams more often.[95][107]

Medications

Intravaginal administration is a route of administration where the medication is inserted into the vagina as a creme or tablet. Pharmacologically, this has the potential advantage of promoting therapeutic effects primarily in the vagina or nearby structures (such as the vaginal portion of cervix) with limited systemic adverse effects compared to other routes of administration.[108][109] Medications used to ripen the cervix and induce labor are commonly administered via this route, as are estrogens, contraceptive agents, propranolol, and antifungals. Vaginal rings can also be used to deliver medication, including birth control in contraceptive vaginal rings. These are inserted into the vagina and provide continuous, low dose and consistent drug levels in the vagina and throughout the body.[110][111]

Before the baby emerges from the womb, an injection for pain control during childbirth may be administered through the vaginal wall and near the pudendal nerve. Because the pudendal nerve carries motor and sensory fibers that innervate the pelvic muscles, a pudendal nerve block relieves birth pain. The medicine does not harm the child, and is without significant complications.[112]

Infections, diseases, and safe sex

Vaginal infections or diseases include yeast infection, vaginitis, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and cancer. Lactobacillus gasseri and other Lactobacillus species in the vaginal flora provide some protection from infections by their secretion of bacteriocins and hydrogen peroxide.[113] The healthy vagina of a woman of child-bearing age is acidic, with a pH normally ranging between 3.8 and 4.5.[94] The low pH prohibits growth of many strains of pathogenic microbes.[94] The acidic balance of the vagina may also be affected by semen,[114][115] pregnancy, menstruation, diabetes or other illness, birth control pills, certain antibiotics, poor diet, and stress.[116] Any of these changes to the acidic balance of the vagina may contribute to yeast infection.[117] An elevated pH (greater than 4.5) of the vaginal fluid can be caused by an overgrowth of bacteria as in bacterial vaginosis, or in the parasitic infection trichomoniasis, both of which have vaginitis as a symptom.[94][118] Vaginal flora populated by a number of different bacteria characteristic of bacterial vaginosis increases the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.[119] During a pelvic exam, samples of vaginal fluids may be taken to screen for sexually transmitted infections or other infections.[95][120]

Because the vagina is self-cleansing, it usually does not need special hygiene.[121] Clinicians generally discourage the practice of douching for maintaining vulvovaginal health.[121][122] Since the vaginal flora gives protection against disease, a disturbance of this balance may lead to infection and abnormal discharge.[121] Vaginal discharge may indicate a vaginal infection by color and odor, or the resulting symptoms of discharge, such as irritation or burning.[123][124] Abnormal vaginal discharge may be caused by STIs, diabetes, douches, fragranced soaps, bubble baths, birth control pills, yeast infection (commonly as a result of antibiotic use) or another form of vaginitis.[123] While vaginitis is an inflammation of the vagina, and is attributed to infection, hormonal issues, or irritants,[125][126] vaginismus is an involuntary tightening of the vagina muscles during vaginal penetration that is caused by a conditioned reflex or disease.[125] Vaginal discharge due to yeast infection is usually thick, creamy in color and odorless, while discharge due to bacterial vaginosis is gray-white in color, and discharge due to trichomoniasis is usually a gray color, thin in consistency, and has a fishy odor. Discharge in 25% of the trichomoniasis cases is yellow-green.[124]

HIV/AIDS, human papillomavirus (HPV), genital herpes and trichomoniasis are some STIs that may affect the vagina, and health sources recommend safe sex (or barrier method) practices to prevent the transmission of these and other STIs.[127][128] Safe sex commonly involves the use of condoms, and sometimes female condoms (which give women more control). Both types can help avert pregnancy by preventing semen from coming in contact with the vagina.[129][130] There is, however, little research on whether female condoms are as effective as male condoms at preventing STIs,[130] and they are slightly less effective than male condoms at preventing pregnancy, which may be because the female condom fits less tightly than the male condom or because it can slip into the vagina and spill semen.[131]

The vaginal lymph nodes often trap cancerous cells that originate in the vagina. These nodes can be assessed for the presence of disease. Selective surgical removal (rather than total and more invasive removal) of vaginal lymph nodes reduces the risk of complications that can accompany more radical surgeries. These selective nodes act as sentinel lymph nodes.[48] Instead of surgery, the lymph nodes of concern are sometimes treated with radiation therapy administered to the patient's pelvic, inguinal lymph nodes, or both.[132]

Vaginal cancer and vulvar cancer are very rare, and primarily affect older women.[133][134] Cervical cancer (which is relatively common) increases the risk of vaginal cancer,[135] which is why there is a significant chance for vaginal cancer to occur at the same time as, or after, cervical cancer. It may be that their causes are the same.[135][133][136] Cervical cancer may be prevented by pap smear screening and HPV vaccines, but HPV vaccines only cover HPV types 16 and 18, the cause of 70% of cervical cancers.[137][138] Some symptoms of cervical and vaginal cancer are dyspareunia, and abnormal vaginal bleeding or vaginal discharge, especially after sexual intercourse or menopause.[139][140] However, most cervical cancers are asymptomatic (present no symptoms).[139] Vaginal intracavity brachytherapy (VBT) is used to treat endometrial, vaginal and cervical cancer. An applicator is inserted into the vagina to allow the administration of radiation as close to the site of the cancer as possible.[141][142] Survival rates increase with VBT when compared to external beam radiation therapy.[141] By using the vagina to place the emitter as close to the cancerous growth as possible, the systemic effects of radiation therapy are reduced and cure rates for vaginal cancer are higher.[143] Research is unclear on whether treating cervical cancer with radiation therapy increases the risk of vaginal cancer.[135]

Effects of aging and childbirth

Age and hormone levels significantly correlate with the pH of the vagina.[144] Estrogen, glycogen and lactobacilli impact these levels.[145][146] At birth, the vagina is acidic with a pH of approximately 4.5,[144] and ceases to be acidic by three to six weeks of age,[147] becoming alkaline.[148] Average vaginal pH is 7.0 in pre-pubertal girls.[145] Although there is a high degree of variability in timing, girls who are approximately seven to twelve years of age will continue to have labial development as the hymen thickens and the vagina elongates to approximately 8 cm. The vaginal mucosa thickens and the vaginal pH becomes acidic again. Girls may also experience a thin, white vaginal discharge called leukorrhea.[148] The vaginal microbiota of adolescent girls aged 13 to 18 years is similar to women of reproductive age,[146] who have an average vaginal pH of 3.8–4.5,[94] but research is not as clear on whether this is the same for premenarcheal or perimenarcheal girls.[146] The vaginal pH during menopause is 6.5–7.0 (without hormone replacement therapy), or 4.5–5.0 with hormone replacement therapy.[146]

After menopause, the body produces less estrogen. This causes atrophic vaginitis (thinning and inflammation of the vaginal walls),[38][149] which can lead to vaginal itching, burning, bleeding, soreness, or vaginal dryness (a decrease in lubrication).[150] Vaginal dryness can cause discomfort on its own or discomfort or pain during sexual intercourse.[150][151] Hot flashes are also characteristic of menopause.[116][152] Menopause also affects the composition of vaginal support structures. The vascular structures become fewer with advancing age.[153] Specific collagens become altered in composition and ratios. It is thought that the weakening of the support structures of the vagina is due to the physiological changes in this connective tissue.[154]

Menopausal symptoms can be eased by estrogen-containing vaginal creams,[152] non-prescription, non-hormonal medications,[150] vaginal estrogen rings such as the Femring,[155] or other hormone replacement therapies,[152] but there are risks (including adverse effects) associated with hormone replacement therapy.[156][157] Vaginal creams and vaginal estrogen rings may not have the same risks as other hormone replacement treatments.[158] Hormone replacement therapy can treat vaginal dryness,[155] but a personal lubricant may be used to temporarily remedy vaginal dryness specifically for sexual intercourse.[151] Some women have an increase in sexual desire following menopause.[150] It may be that menopausal women who continue to engage in sexual activity regularly experience vaginal lubrication similar to levels in women who have not entered menopause, and can enjoy sexual intercourse fully.[150] They may have less vaginal atrophy and fewer problems concerning sexual intercourse.[159]

Vaginal changes that happen with aging and childbirth include mucosal redundancy, rounding of the posterior aspect of the vagina with shortening of the distance from the distal end of the anal canal to the vaginal opening, diastasis or disruption of the pubococcygeus muscles caused by poor repair of an episiotomy, and blebs that may protrude beyond the area of the vaginal opening.[160] Other vaginal changes related to aging and childbirth are stress urinary incontinence, rectocele, and cystocele.[160] Physical changes resulting from pregnancy, childbirth, and menopause often contribute to stress urinary incontinence. If a woman has weak pelvic floor muscle support and tissue damage from childbirth or pelvic surgery, a lack of estrogen can further weaken the pelvic muscles and contribute to stress urinary incontinence.[161] Pelvic organ prolapse, such as a rectocele or cystocele, is characterized by the descent of pelvic organs from their normal positions to impinge upon the vagina.[162][163] A reduction in estrogen does not cause rectocele, cystocele or uterine prolapse, but childbirth and weakness in pelvic support structures can.[159] Prolapse may also occur when the pelvic floor becomes injured during a hysterectomy, gynecological cancer treatment, or heavy lifting.[162][163] Pelvic floor exercises such as Kegel exercises can be used to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles,[164] preventing or arresting the progression of prolapse.[165] There is no evidence that doing Kegel exercises isotonically or with some form of weight is superior; there are greater risks with using weights since a foreign object is introduced into the vagina.[166]

During the third stage of labor, while the infant is being born, the vagina undergoes significant changes. A gush of blood from the vagina may be seen right before the baby is born. Lacerations to the vagina that can occur during birth vary in depth, severity and the amount of adjacent tissue involvement.[4][167] The laceration can be so extensive as to involve the rectum and anus. This event can be especially distressing to a new mother.[167][168] When this occurs, fecal incontinence develops and stool can leave through the vagina.[167] Close to 85% of spontaneous vaginal births develop some form of tearing. Out of these, 60–70% require suturing.[169][170] Lacerations from labor do not always occur.[44]

Surgery

The vagina, including the vaginal opening, may be altered as a result of surgeries such as an episiotomy, vaginectomy, vaginoplasty or labiaplasty.[160][171] Those who undergo vaginoplasty are usually older and have given birth.[160] A thorough examination of the vagina before a vaginoplasty is standard, as well as a referral to a urogynecologist to diagnose possible vaginal disorders.[160] With regard to labiaplasty, reduction of the labia minora is quick without hindrance, complications are minor and rare, and can be corrected. Any scarring from the procedure is minimal, and long-term problems have not been identified.[160]

During an episiotomy, a surgical incision is made during the second stage of labor to enlarge the vaginal opening for the baby to pass through.[44][141] Although its routine use is no longer recommended,[172] and not having an episiotomy is found to have better results than an episiotomy,[44] it is one of the most common medical procedures performed on women. The incision is made through the skin, vaginal epithelium, subcutaneous fat, perineal body and superficial transverse perineal muscle and extends from the vagina to the anus.[173][174] Episiotomies can be painful after delivery. Women often report pain during sexual intercourse up to three months after laceration repair or an episiotomy.[169][170] Some surgical techniques result in less pain than others.[169] The two types of episiotomies performed are the medial incision and the medio-lateral incision. The median incision is a perpendicular cut between the vagina and the anus and is the most common.[44][175] The medio-lateral incision is made between the vagina at an angle and is not as likely to tear through to the anus. The medio-lateral cut takes more time to heal than the median cut.[44]

Vaginectomy is surgery to remove all or part of the vagina, and is usually used to treat malignancy.[171] Removal of some or all of the sexual organs can result in damage to the nerves and leave behind scarring or adhesions.[176] Sexual function may also be impaired as a result, as in the case of some cervical cancer surgeries. These surgeries can impact pain, elasticity, vaginal lubrication and sexual arousal. This often resolves after one year but may take longer.[176]

Women, especially those who are older and have had multiple births, may choose to surgically correct vaginal laxity. This surgery has been described as vaginal tightening or rejuvenation.[177] While a woman may experience an improvement in self-image and sexual pleasure by undergoing vaginal tightening or rejuvenation,[177] there are risks associated with the procedures, including infection, narrowing of the vaginal opening, insufficient tightening, decreased sexual function (such as pain during sexual intercourse), and rectovaginal fistula. Women who undergo this procedure may unknowingly have a medical issue, such as a prolapse, and an attempt to correct this is also made during the surgery.[178]

Surgery on the vagina can be elective or cosmetic. Women who seek cosmetic surgery can have congenital conditions, physical discomfort or wish to alter the appearance of their genitals. Concerns over average genital appearance or measurements are largely unavailable and make defining a successful outcome for such surgery difficult.[179] A number of sex reassignment surgeries are available to transgender people. Although not all intersex conditions require surgical treatment, some choose genital surgery to correct atypical anatomical conditions.[180]

Anomalies and other health issues

Vaginal anomalies are defects that result in an abnormal or absent vagina.[181][182] The most common obstructive vaginal anomaly is an imperforate hymen, a condition in which the hymen obstructs menstrual flow or other vaginal secretions.[183][184] Another vaginal anomaly is a transverse vaginal septum, which partially or completely blocks the vaginal canal.[183] The precise cause of an obstruction must be determined before it is repaired, since corrective surgery differs depending on the cause.[185] In some cases, such as isolated vaginal agenesis, the external genitalia may appear normal.[186]

Abnormal openings known as fistulas can cause urine or feces to enter the vagina, resulting in incontinence.[187][188] The vagina is susceptible to fistula formation because of its proximity to the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts.[189] Specific causes are manifold and include obstructed labor, hysterectomy, malignancy, radiation, episiotomy, and bowel disorders.[190][191] A small number of vaginal fistulas are congenital.[192] Various surgical methods are employed to repair fistulas.[193][187] Untreated, fistulas can result in significant disability and have a profound impact on quality of life.[187]

Vaginal evisceration is a serious complication of a vaginal hysterectomy and occurs when the vaginal cuff ruptures, allowing the small intestine to protrude from the vagina.[106][194]

Cysts may also affect the vagina. Various types of vaginal cysts can develop on the surface of the vaginal epithelium or in deeper layers of the vagina and can grow to be as large as 7 cm.[195][196] Often, they are an incidental finding during a routine pelvic examination.[197] Vaginal cysts can mimic other structures that protrude from the vagina such as a rectocele and cystocele.[195] Cysts that can be present include Müllerian cysts, Gartner's duct cysts, and epidermoid cysts.[198][199] A vaginal cyst is most likely to develop in women between the ages of 30 and 40.[195] It is estimated that 1 out of 200 women has a vaginal cyst.[195][200] The Bartholin's cyst is of vulvar rather than vaginal origin,[201] but it presents as a lump at the vaginal opening.[202] It is more common in younger women and is usually without symptoms,[203] but it can cause pain if an abscess forms,[203] block the entrance to the vulval vestibule if large,[204] and impede walking or cause painful sexual intercourse.[203]

Society and culture

Perceptions, symbolism and vulgarity

Various perceptions of the vagina have existed throughout history, including the belief it is the center of sexual desire, a metaphor for life via birth, inferior to the penis, unappealing to sight or smell, or vulgar.[205][206][207] These views can largely be attributed to sex differences, and how they are interpreted. David Buss, an evolutionary psychologist, stated that because a penis is significantly larger than a clitoris and is readily visible while the vagina is not, and males urinate through the penis, boys are taught from childhood to touch their penises while girls are often taught that they should not touch their own genitalia, which implies that there is harm in doing so. Buss attributed this as the reason many women are not as familiar with their genitalia, and that researchers assume these sex differences explain why boys learn to masturbate before girls and do so more often.[208]

The word vagina is commonly avoided in conversation,[209] and many people are confused about the vagina's anatomy and may be unaware that it is not used for urination.[210][211][212] This is exacerbated by phrases such as "boys have a penis, girls have a vagina", which causes children to think that girls have one orifice in the pelvic area.[211] Author Hilda Hutcherson stated, "Because many [women] have been conditioned since childhood through verbal and nonverbal cues to think of [their] genitals as ugly, smelly and unclean, [they] aren't able to fully enjoy intimate encounters" because of fear that their partner will dislike the sight, smell, or taste of their genitals. She argued that women, unlike men, did not have locker room experiences in school where they compared each other's genitals, which is one reason so many women wonder if their genitals are normal.[206] Scholar Catherine Blackledge stated that having a vagina meant she would typically be treated less well than her vagina-less counterparts and subject to inequalities (such as job inequality), which she categorized as being treated like a second-class citizen.[209]

Negative views of the vagina are simultaneously contrasted by views that it is a powerful symbol of female sexuality, spirituality, or life. Author Denise Linn stated that the vagina "is a powerful symbol of womanliness, openness, acceptance, and receptivity. It is the inner valley spirit".[213] Sigmund Freud placed significant value on the vagina,[214] postulating the concept that vaginal orgasm is separate from clitoral orgasm, and that, upon reaching puberty, the proper response of mature women is a changeover to vaginal orgasms (meaning orgasms without any clitoral stimulation). This theory made many women feel inadequate, as the majority of women cannot achieve orgasm via vaginal intercourse alone.[215][216][217] Regarding religion, the womb represents a powerful symbol as the yoni in Hinduism, which represents "the feminine potency", and this may indicate the value that Hindu society has given female sexuality and the vagina's ability to deliver life;[218] however, yoni as a representation of "womb" is not the primary denotation.[219]

While, in ancient times, the vagina was often considered equivalent (homologous) to the penis, with anatomists Galen (129 AD – 200 AD) and Vesalius (1514–1564) regarding the organs as structurally the same except for the vagina being inverted, anatomical studies over latter centuries showed the clitoris to be the penile equivalent.[76][220] Another perception of the vagina was that the release of vaginal fluids would cure or remedy a number of ailments; various methods were used over the centuries to release "female seed" (via vaginal lubrication or female ejaculation) as a treatment for suffocatio ex semine retento (suffocation of the womb, lit. 'suffocation from retained seed'), green sickness, and possibly for female hysteria. Reported methods for treatment included a midwife rubbing the walls of the vagina or insertion of the penis or penis-shaped objects into the vagina. Symptoms of the female hysteria diagnosis – a concept that is no longer recognized by medical authorities as a medical disorder – included faintness, nervousness, insomnia, fluid retention, heaviness in abdomen, muscle spasm, shortness of breath, irritability, loss of appetite for food or sex, and a propensity for causing trouble.[221] It may be that women who were considered suffering from female hysteria condition would sometimes undergo "pelvic massage" – stimulation of the genitals by the doctor until the woman experienced "hysterical paroxysm" (i.e., orgasm). In this case, paroxysm was regarded as a medical treatment, and not a sexual release.[221]

The vagina has been given many vulgar names, three of which are pussy, twat, and cunt. Cunt is also used as a derogatory epithet referring to people of either sex. This usage is relatively recent, dating from the late nineteenth century.[222] Reflecting different national usages, cunt is described as "an unpleasant or stupid person" in the Compact Oxford English Dictionary,[223] whereas the Merriam-Webster has a usage of the term as "usually disparaging and obscene: woman",[224] noting that it is used in the United States as "an offensive way to refer to a woman".[225] Random House defines it as "a despicable, contemptible or foolish man".[222] Some feminists of the 1970s sought to eliminate disparaging terms such as cunt.[226] Twat is widely used as a derogatory epithet, especially in British English, referring to a person considered obnoxious or stupid.[227][228] Pussy can indicate "cowardice or weakness", and "the human vulva or vagina" or by extension "sexual intercourse with a woman".[229] In English, the use of the word pussy to refer to women is considered derogatory or demeaning, treating people as sexual objects.[230]

In literature and art

The vagina loquens, or "talking vagina", is a significant tradition in literature and art, dating back to the ancient folklore motifs of the "talking cunt".[231][232] These tales usually involve vaginas talking by the effect of magic or charms, and often admitting to their lack of chastity.[231] Other folk tales relate the vagina as having teeth – vagina dentata (Latin for "toothed vagina"). These carry the implication that sexual intercourse might result in injury, emasculation, or castration for the man involved. These stories were frequently told as cautionary tales warning of the dangers of unknown women and to discourage rape.[233]

In 1966, the French artist Niki de Saint Phalle collaborated with Dadaist artist Jean Tinguely and Per Olof Ultvedt on a large sculpture installation entitled "hon-en katedral" (also spelled "Hon-en-Katedrall", which means "she-a cathedral") for Moderna Museet, in Stockholm, Sweden. The outer form is a giant, reclining sculpture of a woman which visitors can enter through a door-sized vaginal opening between her spread legs.[234]

The Vagina Monologues, a 1996 episodic play by Eve Ensler, has contributed to making female sexuality a topic of public discourse. It is made up of a varying number of monologues read by a number of women. Initially, Ensler performed every monologue herself, with subsequent performances featuring three actresses; latter versions feature a different actress for every role. Each of the monologues deals with an aspect of the feminine experience, touching on matters such as sexual activity, love, rape, menstruation, female genital mutilation, masturbation, birth, orgasm, the various common names for the vagina, or simply as a physical aspect of the body. A recurring theme throughout the pieces is the vagina as a tool of female empowerment, and the ultimate embodiment of individuality.[235][236]

Influence on modification

Societal views, influenced by tradition, a lack of knowledge on anatomy, or sexism, can significantly impact a person's decision to alter their own or another person's genitalia.[178][237] Women may want to alter their genitalia (vagina or vulva) because they believe that its appearance, such as the length of the labia minora covering the vaginal opening, is not normal, or because they desire a smaller vaginal opening or tighter vagina. Women may want to remain youthful in appearance and sexual function. These views are often influenced by the media,[178][238] including pornography,[238] and women can have low self-esteem as a result.[178] They may be embarrassed to be naked in front of a sexual partner and may insist on having sex with the lights off.[178] When modification surgery is performed purely for cosmetic reasons, it is often viewed poorly,[178] and some doctors have compared such surgeries to female genital mutilation (FGM).[238]

Female genital mutilation, also known as female circumcision or female genital cutting, is genital modification with no health benefits.[239][240] The most severe form is Type III FGM, which is infibulation and involves removing all or part of the labia and the vagina being closed up. A small hole is left for the passage of urine and menstrual blood, and the vagina is opened up for sexual intercourse and childbirth.[240]

Significant controversy surrounds female genital mutilation,[239][240] with the World Health Organization (WHO) and other health organizations campaigning against the procedures on behalf of human rights, stating that it is "a violation of the human rights of girls and women" and "reflects deep-rooted inequality between the sexes".[240] Female genital mutilation has existed at one point or another in almost all human civilizations,[241] most commonly to exert control over the sexual behavior, including masturbation, of girls and women.[240][241] It is carried out in several countries, especially in Africa, and to a lesser extent in other parts of the Middle East and Southeast Asia, on girls from a few days old to mid-adolescent, often to reduce sexual desire in an effort to preserve vaginal virginity.[239][240][241] Comfort Momoh stated it may be that female genital mutilation was "practiced in ancient Egypt as a sign of distinction among the aristocracy"; there are reports that traces of infibulation are on Egyptian mummies.[241]

Custom and tradition are the most frequently cited reasons for the practice of female genital mutilation. Some cultures believe that female genital mutilation is part of a girl's initiation into adulthood and that not performing it can disrupt social and political cohesion.[240][241] In these societies, a girl is often not considered an adult unless she has undergone the procedure.[240]

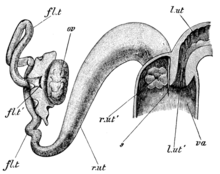

Other animals

Влагалище — это структура животных, у которых самка оплодотворяется изнутри , а не путем травматического оплодотворения, как у некоторых беспозвоночных. Форма влагалища различается у разных животных. У плацентарных млекопитающих и сумчатых влагалище ведет от матки к внешней стороне женского тела. У самок сумчатых есть два боковых влагалища , которые ведут к отдельным маткам, но оба открываются наружу через одно и то же отверстие; [ 242 ] третий канал, известный как срединное влагалище, может быть временным или постоянным, используется для родов. [ 243 ] У самки пятнистой гиены нет наружного влагалищного отверстия. Вместо этого влагалище выходит через клитор , позволяя женщинам мочиться, совокупляться и рожать через клитор. [ 244 ] Влагалище самки койота сжимается во время совокупления, образуя копулятивную связь . [ 245 ]

У птиц, однопроходных и некоторых рептилий имеется часть яйцевода , ведущая в клоаку . [ 246 ] [ 247 ] Куры имеют вагинальное отверстие, открывающееся из вертикальной вершины клоаки. Влагалище простирается вверх от отверстия и становится яйцевой железой. [ 247 ] У некоторых бесчелюстных рыб нет ни яйцевода, ни влагалища, и вместо этого яйцеклетка проходит непосредственно через полость тела (и оплодотворяется снаружи, как у большинства рыб и земноводных ). У насекомых и других беспозвоночных влагалище может быть частью яйцевода (см. Половая система насекомых ). [ 248 ] У птиц есть клоака, в которую опорожняются мочевые, половые пути (влагалище) и желудочно-кишечный тракт. [ 249 ] развились вагинальные структуры, называемые тупиковыми мешочками и кольцами, вращающимися по часовой стрелке У самок некоторых видов водоплавающих птиц для защиты от сексуального принуждения . [ 250 ]

Отсутствие исследований влагалища и других женских гениталий, особенно у различных животных, сдерживает знания о женской сексуальной анатомии. [ 251 ] [ 252 ] Одно из объяснений того, почему мужские гениталии изучаются больше, заключается в том, что пенисы значительно проще анализировать, чем женские половые органы, поскольку мужские гениталии обычно выступают вперед, и поэтому их легче оценить и измерить. Женские гениталии, напротив, чаще скрыты и требуют большего вскрытия, что, в свою очередь, требует больше времени. [ 251 ] Другое объяснение состоит в том, что основной функцией пениса является оплодотворение, в то время как женские гениталии могут менять форму при взаимодействии с мужскими органами, особенно для того, чтобы способствовать или препятствовать репродуктивному успеху . [ 251 ]

, кроме человека, Приматы являются оптимальными моделями для биомедицинских исследований человека, поскольку люди и приматы, кроме человека, имеют общие физиологические характеристики в результате эволюции . [ 253 ] Хотя менструация в значительной степени связана с человеческими самками, и у них она наиболее выражена, она также типична для обезьян родственников и обезьян . [ 254 ] [ 255 ] У самок макак менструация имеет продолжительность цикла в течение жизни, сравнимую с продолжительностью цикла у самок человека. Эстрогены и прогестагены в менструальных циклах , а также во время пременархе и постменопаузы также схожи у самок человека и макак; происходит ороговение эпителия однако только у макак во время фолликулярной фазы . [ 253 ] pH влагалища макак также различается: медианные значения от почти нейтральных до слегка щелочных, и он широко варьируется, что может быть связано с отсутствием лактобактерий во влагалищной флоре. [ 253 ] Это одна из причин, почему, хотя макаки используются для изучения передачи ВИЧ и тестирования микробицидов , [ 253 ] Животные модели не часто используются при изучении инфекций, передающихся половым путем, таких как трихомониаз. Другая причина заключается в том, что причины таких состояний неразрывно связаны с генетической структурой человека, поэтому результаты, полученные от других видов, трудно применить к людям. [ 256 ]

См. также

- Искусственное влагалище

- Стигма (ботаника)

- Надвлагалищная часть шейки матки

- Выворот матки

- Вагинальный расширитель

- Вагинальный фотоплетизмограф

Ссылки

- ^ Jump up to: а б Стивенсон А (2010). Оксфордский словарь английского языка . Издательство Оксфордского университета . п. 1962. ISBN 978-0-19-957112-3 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июня 2021 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Невид Дж., Ратус С., Рубинштейн Х. (1998). Здоровье в новом тысячелетии: Smart Electronic Edition (SEE) . Макмиллан . п. 297. ИСБН 978-1-57259-171-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июня 2021 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Липский М.С. (2006). Краткая медицинская энциклопедия Американской медицинской ассоциации . Случайный справочник по дому . п. 96. ИСБН 978-0-375-72180-9 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июня 2021 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г Далтон М. (2014). Судебная гинекология . Издательство Кембриджского университета . п. 65. ИСБН 978-1-107-06429-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 17 сентября 2020 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Джонс Т., Уир Д., Фридман Л.Д. (2014). Читатель по гуманитарным наукам в области здравоохранения . Издательство Университета Рутгерса . стр. 231–232. ISBN 978-0-8135-7367-0 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июня 2021 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Киркпатрик М (2012). Человеческая сексуальность: личность и социально-психологические перспективы . Springer Science & Business Media . п. 175. ИСБН 978-1-4684-3656-3 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 3 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ Хилл, Калифорния (2007). Человеческая сексуальность: личность и социально-психологические перспективы . Публикации SAGE . стр. 265–266. ISBN 978-1-5063-2012-0 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июня 2021 года . Проверено 3 февраля 2016 г.

Природе женских половых органов в целом, очевидно, уделяется мало внимания, что, вероятно, объясняет причину того, что большинство людей используют неправильные термины, говоря о женских наружных половых органах. Термин, обычно используемый для обозначения женских половых органов, — это влагалище , которое на самом деле представляет собой внутреннюю половую структуру, мышечный проход, ведущий наружу от матки. Правильный термин для обозначения женских наружных половых органов — вульва , как обсуждалось в главе 6, и включает клитор, большие и малые половые губы.

- ^ Саенс-Эрреро М (2014). Психопатология у женщин: включение гендерной перспективы в описательную психопатологию . Спрингер . п. 250. ИСБН 978-3-319-05870-2 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 3 февраля 2016 г.

Кроме того, в настоящее время отсутствует подходящая лексика для обозначения наружных женских половых органов, например, слова «влагалище» и «вульва» используются как синонимы, как будто неправильное использование этих терминов безвредно для сексуального и психологического состояния. развитие женщин».

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г Снелл Р.С. (2004). Клиническая анатомия: иллюстрированный обзор с вопросами и пояснениями . Липпинкотт Уильямс и Уилкинс. п. 98. ИСБН 978-0-7817-4316-7 . Архивировано из оригинала 10 марта 2021 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот п д Датта, округ Колумбия (2014). Учебник гинекологии Д.К. Датты . JP Medical Ltd., стр. 2–7. ISBN 978-93-5152-068-9 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2019 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Дрейк Р., Фогль А.В., Митчелл А. (2016). Электронная книга «Основная анатомия Грея» . Elsevier Науки о здоровье . п. 246. ИСБН 978-0-323-50850-6 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июня 2021 года . Проверено 25 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Джинджер В.А., Ян CC (2011). «Функциональная анатомия женских половых органов» . В Малхолле Дж. П., Инкроччи Л., Гольдштейне И., Розене Р. (ред.). Рак и сексуальное здоровье . Спрингер . стр. 13, 20–21. ISBN 978-1-60761-915-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 16 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 20 августа 2020 г.

- ^ Рэнсонс А (15 мая 2009 г.). «Репродуктивный выбор» . Здоровье и благополучие на всю жизнь . Человеческая кинетика 10%. п. 221. ИСБН 978-0-7360-6850-5 . Архивировано из оригинала 6 мая 2016 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Бекманн CR (2010). Акушерство и гинекология . Липпинкотт Уильямс и Уилкинс . п. 37. ИСБН 978-0-7817-8807-6 . Архивировано из оригинала 15 февраля 2017 года . Проверено 31 января 2017 г.

Поскольку влагалище спалось, в поперечном сечении оно выглядит H-образным.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Стэндринг С., Борли Н.Р., ред. (2008). Анатомия Грея: анатомические основы клинической практики (40-е изд.). Лондон: Черчилль Ливингстон. стр. 1281–4. ISBN 978-0-8089-2371-8 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Баггиш М.С., Каррам М.М. (2011). Атлас анатомии таза и гинекологической хирургии — электронная книга . Elsevier Науки о здоровье . п. 582. ИСБН 978-1-4557-1068-3 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2019 года . Проверено 7 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Арулкумаран С., Риган Л., Папагеоргиу А., Монга А., Фаркухарсон Д. (2011). Оксфордский настольный справочник: акушерство и гинекология ОУП Оксфорд . п. 472. ИСБН 978-0-19-162087-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2019 года . Проверено 7 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Руководство по акушерству (3-е изд.). Эльзевир . 2011. стр. 1–16. ISBN 978-81-312-2556-1 .

- ^ Смит Р.П., Турек П. (2011). Коллекция медицинских иллюстраций Неттера: электронная книга о репродуктивной системе . Elsevier Науки о здоровье . п. 443. ИСБН 978-1-4377-3648-9 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2019 года . Проверено 7 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Риччи, Сьюзен Скотт; Кайл, Терри (2009). Родильный и детский уход . Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. п. 77. ИСБН 978-0-78178-055-1 . Проверено 7 января 2024 г.

- ^ Зинк, Кристофер (2011). Словарь акушерства и гинекологии . Де Грютер. п. 174. ИСБН 978-3-11085-727-6 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Найт Б (1997). Судебная медицина Симпсона (11-е изд.). Лондон: Арнольд. п. 114. ИСБН 978-0-7131-4452-9 .

- ^ Перлман С.Е., Накаджима С.Т., Хертвек С.П. (2004). Клинические протоколы в детской и подростковой гинекологии . Парфенон. п. 131. ИСБН 978-1-84214-199-1 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Уайли Л. (2005). Основная анатомия и физиология в охране материнства . Elsevier Науки о здоровье. стр. 157–158. ISBN 978-0-443-10041-3 . Архивировано из оригинала 5 мая 2016 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Эманс С.Дж. (2000). «Физикальный осмотр ребенка и подростка» . Оценка ребенка, подвергшегося сексуальному насилию: медицинский учебник и фотографический атлас (2-е изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета . стр. 61–65. ISBN 978-0-19-974782-5 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2019 года . Проверено 2 августа 2015 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Эдмондс К. (2012). Учебник Дьюхерста по акушерству и гинекологии . Джон Уайли и сыновья . п. 423. ИСБН 978-0-470-65457-6 . Архивировано из оригинала 6 мая 2016 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Херрингтон CS (2017). Патология шейки матки . Springer Science & Business Media . стр. 2–3. ISBN 978-3-319-51257-0 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2019 года . Проверено 21 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Вудрафф Т.Дж., Янссен С.Дж., Гийетт Л.Дж.-младший, Джудис Л.К. (2010). Воздействие окружающей среды на репродуктивное здоровье и фертильность . Издательство Кембриджского университета . п. 33. ISBN 978-1-139-48484-8 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2019 года . Проверено 21 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Роббой С., Курита Т., Баскин Л., Кунья Г.Р. (2017). «Новый взгляд на развитие женских репродуктивных путей» . Дифференциация . 97 : 9–22. дои : 10.1016/j.diff.2017.08.002 . ISSN 0301-4681 . ПМЦ 5712241 . ПМИД 28918284 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Гримбизис Г.Ф., Кампо Р., Тарлацис Б.К., Гордтс С. (2015). Врожденные пороки развития женских половых путей: классификация, диагностика и лечение . Springer Science & Business Media . п. 8. ISBN 978-1-4471-5146-3 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2019 года . Проверено 21 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Курман Р.Дж. (2013). Патология женских половых путей по Блаустейну . Springer Science & Business Media . п. 132. ИСБН 978-1-4757-3889-6 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2019 года . Проверено 21 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Браун Л. (2012). Патология вульвы и влагалища . Springer Science+Business Media . стр. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-85729-757-0 . Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2016 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Арулкумаран С., Риган Л., Папагеоргиу А., Монга А., Фаркухарсон Д. (2011). Оксфордский настольный справочник: акушерство и гинекология Издательство Оксфордского университета . п. 471. ИСБН 978-0-19-162087-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 6 мая 2016 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Битцер Дж., Липшульц Л., Пастушак А., Гольдштейн А., Джиральди А., Перельман М. (2016). «Женская сексуальная реакция: анатомия и физиология сексуального желания, возбуждения и оргазма у женщин». Управление сексуальной дисфункцией у мужчин и женщин . Спрингер Нью-Йорк. п. 202. дои : 10.1007/978-1-4939-3100-2_18 . ISBN 978-1-4939-3099-9 .

- ^ Компакт-диск Бласкевича, Падни Дж., Диджей Андерсон (июль 2011 г.). «Строение и функция межклеточных соединений эпителия слизистой оболочки шейки матки и влагалища человека» . Биология размножения . 85 (1): 97–104. doi : 10.1095/biolreprod.110.090423 . ПМК 3123383 . ПМИД 21471299 .

- ^ Мэйо Э.Дж., Кокс Дж.Т. (2011). Учебник и атлас «Современная кольпоскопия» . Липпинкотт Уильямс и Уилкинс . ISBN 978-1-4511-5383-5 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Курман Р.Дж., изд. (2002). Патология женских половых путей Блаустейна (5-е изд.). Спрингер. п. 154. ИСБН 978-0-387-95203-1 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2019 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Бекманн CR (2010). Акушерство и гинекология . Липпинкотт Уильямс и Уилкинс . стр. 241–245. ISBN 978-0-7817-8807-6 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2019 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Роббой С.Дж. (2009). Патология женских репродуктивных путей Роббоя . Elsevier Науки о здоровье . п. 111. ИСБН 978-0-443-07477-6 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2019 года . Проверено 15 декабря 2017 г.

- ^ Нанн К.Л., Форни LJ (сентябрь 2016 г.). «Разгадка динамики вагинального микробиома человека» . Йельский журнал биологии и медицины . 89 (3): 331–337. ISSN 0044-0086 . ПМК 5045142 . ПМИД 27698617 .

- ^ Гупта Р. (2011). Репродуктивная и онтотоксикология . Лондон: Академическая пресса. п. 1005. ИСБН 978-0-12-382032-7 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Холл Дж (2011). Учебник Гайтона и Холла по медицинской физиологии (12-е изд.). Филадельфия: Сондерс/Эльзевир. п. 993. ИСБН 978-1-4160-4574-8 .

- ^ Гад СК (2008). Справочник по фармацевтическому производству: Производство и процессы . Джон Уайли и сыновья . п. 817. ИСБН 978-0-470-25980-1 . Архивировано из оригинала 6 мая 2016 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час Андерсон DJ, Марат Дж, Падни Дж (июнь 2014 г.). «Строение рогового слоя влагалища человека и его роль в иммунной защите» . Американский журнал репродуктивной иммунологии . 71 (6): 618–623. дои : 10.1111/aji.12230 . ISSN 1600-0897 . ПМЦ 4024347 . ПМИД 24661416 .

- ^ Датта, округ Колумбия (2014). Учебник гинекологии Д.К. Датты . JP Medical Ltd. с. 206. ИСБН 978-93-5152-068-9 . Архивировано из оригинала 6 мая 2016 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Циммерн П.Е., Хааб Ф., Чаппл С.Р. (2007). Вагинальная хирургия при недержании и пролапсе . Springer Science & Business Media . п. 6. ISBN 978-1-84628-346-8 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2019 года . Проверено 3 декабря 2017 г.

- ^ О'Рахили Р. (2008). «Кровеносные сосуды, нервы и лимфодренаж малого таза» . В О'Рахилли Р., Мюллер Ф., Карпентер С., Свенсон Р. (ред.). Базовая анатомия человека: региональное исследование строения человека . Дартмутская медицинская школа. Архивировано из оригинала 2 декабря 2017 года . Проверено 13 декабря 2017 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Сабатер С, Андрес И, Лопес-Онрубия В, Беренгер Р, Севильяно М, Хименес-Хименес Е, Ровироса А, Аренас М (9 августа 2017 г.). «Вагинальная манжеточная брахитерапия при раке эндометрия – технически простой метод лечения?» . Управление раком и исследования . 9 : 351–362. дои : 10.2147/CMAR.S119125 . ISSN 1179-1322 . ПМЦ 5557121 . ПМИД 28848362 .

- ^ «Менструация и менструальный цикл» . Управление женского здоровья . 23 декабря 2014. Архивировано из оригинала 26 июня 2015 года . Проверено 25 июня 2015 г.

- ^ Вангикар П., Ахмед Т., Вангала С. (2011). «Токсикологическая патология репродуктивной системы». В Гупта RC (ред.). Репродуктивная и онтотоксикология . Лондон: Академическая пресса. п. 1005. ИСБН 978-0-12-382032-7 . OCLC 717387050 .

- ^ Сильверторн ДУ (2013). Физиология человека: комплексный подход (6-е изд.). Гленвью, Иллинойс: Pearson Education. стр. 850–890. ISBN 978-0-321-75007-5 .

- ^ Шервуд Л. (2013). Физиология человека: от клеток к системам (8-е изд.). Бельмонт, Калифорния: Сенгедж. стр. 735–794. ISBN 978-1-111-57743-8 .

- ^ Вострал С.Л. (2008). Под обертками: история технологии менструальной гигиены . Лексингтонские книги . стр. 1–181. ISBN 978-0-7391-1385-1 . Архивировано из оригинала 10 марта 2021 года . Проверено 22 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Слоан Э (2002). Биология женщин . Cengage Обучение . стр. 32, 41–42. ISBN 978-0-7668-1142-3 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 июня 2014 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Бурсье А., Макгуайр Э.Дж., Абрамс П. (2004). Заболевания тазового дна . Elsevier Науки о здоровье . п. 20. ISBN 978-0-7216-9194-7 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2019 года . Проверено 8 июня 2018 г.

- ^ Видерман М.В., Уитли Б.Е. младший (2012). Справочник по проведению исследований сексуальности человека . Психология Пресс . ISBN 978-1-135-66340-7 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2019 года . Проверено 8 июня 2018 г.

- ^ Каммингс М. (2006). Наследственность человека: принципы и проблемы (обновленное издание). Cengage Обучение . стр. 153–154. ISBN 978-0-495-11308-9 . Архивировано из оригинала 6 мая 2016 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Сирвен Дж.И., Маламут Б.Л. (2008). Клиническая неврология пожилых людей . Липпинкотт Уильямс и Уилкинс . стр. 230–232. ISBN 978-0-7817-6947-1 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2019 года . Проверено 8 июня 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Ли М.Т. (2013). Любовь, секс и все, что между ними . Маршалл Кавендиш Интернэшнл Азия Пте Лтд . п. 76. ИСБН 978-981-4516-78-5 . Архивировано из оригинала 6 мая 2016 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Секс и общество . Том. 2. Корпорация Маршалл Кавендиш . 2009. с. 590. ИСБН 978-0-7614-7907-9 . Архивировано из оригинала 12 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 20 августа 2020 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Вейтен В., Данн Д., Хаммер Э. (2011). Психология в применении к современной жизни: адаптация в XXI веке . Cengage Обучение . п. 386. ИСБН 978-1-111-18663-0 . Архивировано из оригинала 14 июня 2013 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Гринберг Дж.С., Брюсс К.Э., Конклин С.С. (2010). Исследование аспектов человеческой сексуальности . Издательство Джонс и Бартлетт . п. 126. ИСБН 978-981-4516-78-5 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 мая 2016 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Гринберг Дж.С., Брюсс К.Э., Освальт С.Б. (2014). Исследование аспектов человеческой сексуальности . Издательство Джонс и Бартлетт . стр. 102–104. ISBN 978-1-4496-4851-0 . Архивировано из оригинала 10 сентября 2015 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Хайнс Т. (август 2001 г.). «Точка G: современный гинекологический миф». Am J Obstet Gynecol . 185 (2): 359–62. дои : 10.1067/моб.2001.115995 . ПМИД 11518892 . S2CID 32381437 . [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Буллоу В.Л., Буллоу Б. (2014). Человеческая сексуальность: Энциклопедия . Рутледж . стр. 229–231. ISBN 978-1-135-82509-6 . Архивировано из оригинала 6 мая 2016 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Балон Р., Сегрейвс РТ (2009). Клиническое руководство по сексуальным расстройствам . Американский психиатрический паб . п. 258. ИСБН 978-1-58562-905-3 . Архивировано из оригинала 27 июня 2014 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Розенталь М (2012). Человеческая сексуальность: от клеток к обществу . Cengage Обучение . п. 76. ИСБН 978-0-618-75571-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 10 декабря 2020 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Кэрролл Дж (2012). Серия открытий: Человеческая сексуальность . Cengage Обучение . стр. 282–289. ISBN 978-1-111-84189-8 . Архивировано из оригинала 5 мая 2016 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Кэрролл Дж.Л. (2018). Сексуальность сейчас: признание разнообразия (1-е изд.). Cengage Обучение . п. 299. ИСБН 978-1-337-67206-1 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2019 года . Проверено 16 января 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Хейлз Д. (2012). Приглашение к здоровью (1-е изд.). Cengage Обучение . стр. 296–297. ISBN 978-1-111-82700-7 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2019 года . Проверено 16 января 2018 г.

- ^ Стронг Б., ДеВо С., Коэн Т.Ф. (2010). Опыт брака и семьи: интимные отношения в меняющемся обществе . Cengage Обучение . п. 186. ИСБН 978-0-534-62425-5 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 июля 2020 года . Проверено 20 августа 2020 г.

Большинство людей согласны с тем, что мы сохраняем девственность до тех пор, пока воздерживаемся от полового (вагинального) общения. Но иногда мы слышим, как люди говорят о «технической девственности» [...] Данные показывают, что «очень значительная часть подростков имела опыт орального секса, даже если у них не было полового акта, и они могут думать о себя как девственницы [...] Другие исследования, особенно исследования, посвященные потере девственности, сообщают, что 35% девственниц, определяемых как люди, которые никогда не вступали в вагинальный половой акт, тем не менее участвовали в одной или нескольких других формах гетеросексуальной сексуальной активности. (например, оральный секс, анальный секс, или взаимная мастурбация).

- ↑ См . 272. Архивировано 1 мая 2016 г. в Wayback Machine и стр. 301. Архивировано 7 мая 2016 г. в Wayback Machine , где приведены два разных определения внешнего курса (первая из страниц для определения запрета проникновения; вторая из страниц для запрета проникновения). определение проникновения полового члена). Розенталь М (2012). Человеческая сексуальность: от клеток к обществу (1-е изд.). Cengage Обучение . ISBN 978-0-618-75571-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 30 сентября 2015 года . Проверено 2 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Кэрролл Дж.Л. (2009). Сексуальность сегодня: признание разнообразия . Cengage Обучение. п. 272. ИСБН 978-0-495-60274-3 . Архивировано из оригинала 15 июня 2013 года . Проверено 20 августа 2020 г.

- ^ Зенилман Дж., Шахманеш М. (2011). Инфекции, передающиеся половым путем: диагностика, лечение и лечение . Издательство Джонс и Бартлетт . стр. 329–330. ISBN 978-0-495-81294-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 12 марта 2017 года . Проверено 20 августа 2020 г.

- ^ Таормино Т (2009). Большая книга секс-игрушек . Колчан. п. 52. ИСБН 978-1-59233-355-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 5 сентября 2015 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б О'Коннелл Х.Э., Сандживан К.В., Хатсон Дж.М. (октябрь 2005 г.). «Анатомия клитора». Журнал урологии . 174 (4, ч. 1): 1189–95. дои : 10.1097/01.ju.0000173639.38898.cd . ПМИД 16145367 . S2CID 26109805 .

- Шэрон Масколл (11 июня 2006 г.). «Время переосмыслить вопрос о клиторе» . Новости Би-би-си .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кильчевский А, Варди Ю, Ловенштейн Л, Грюнвальд I (январь 2012 г.). «Действительно ли женская точка G представляет собой отдельную анатомическую единицу?». Журнал сексуальной медицины . 9 (3): 719–26. дои : 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02623.x . ПМИД 22240236 .

- «Точка G не существует, «без сомнения», говорят исследователи» . Хаффингтон Пост . 19 января 2012 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Хеффнер LJ, Шуст DJ (2014). Репродуктивная система вкратце . Джон Уайли и сыновья . п. 39. ИСБН 978-1-118-60701-5 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 апреля 2016 года . Проверено 27 октября 2015 г.