Сотрудничество с нацистской Германией и фашистской Италией.

| Хронология Второй мировой войны |

|---|

| хронологический |

| Прелюдия |

| По теме |

| По театру |

Во время Второй мировой войны многие правительства, организации и отдельные лица сотрудничали с державами Оси «по убеждению, отчаянию или по принуждению». [ 1 ] Националисты иногда приветствовали немецкие или итальянские войска, которые, по их мнению, освободили их страны от колонизации. Правительства Дании, Бельгии и Франции Виши пытались умиротворить и договориться с захватчиками в надежде смягчить ущерб своим гражданам и экономике.

Лидеры некоторых стран сотрудничали с Италией и Германией, потому что они хотели вернуть территории, утраченные во время и после Первой мировой войны или которых просто жаждали их националистически настроенные граждане. В других странах, таких как Франция, уже существовали свои собственные фашистские движения и/или антисемитские настроения, и оккупанты подтвердили и усилили это. Такие люди, как Хендрик Зейффардт в Нидерландах и Теодорос Пангалос в Греции, рассматривали сотрудничество как путь к личной власти в политике своей страны. Другие верили, что Германия победит, и либо хотели оказаться на стороне победителей, либо боялись оказаться на стороне проигравших.

Axis military forces recruited many volunteers, sometimes at gunpoint, more often with promises that they later broke, or from among POWs trying to escape appalling and frequently lethal conditions in their detention camps. Other volunteers willingly enlisted because they shared Nazi or fascist ideologies.

Terminology

Stanley Hoffman in 1968 used the term collaborationist to describe those who collaborated for ideological reasons.[2] Bertram Gordon, a professor of modern history, also used the terms collaborationist and collaborator for ideological and non-ideological collaboration.[3] Collaboration described cooperation, sometimes passive, with a victorious power.[4]

Stanley Hoffmann saw collaboration as either involuntary, a reluctant recognition of necessity, or voluntary, opportunistic, or greedy. He also categorized collaborationism as "servile", attempting to be useful, or "ideological", full-throated advocacy of the occupier's ideology.[citation needed]

Collaboration in Western Europe

Belgium

Belgium was invaded by Nazi Germany in May 1940[5] and occupied until the end of 1944.

Political collaboration took separate forms across the Belgian language divide. In Dutch-speaking Flanders, the Vlaamsch Nationaal Verbond (Flemish National Union or VNV), clearly authoritarian, anti-democratic and influenced by fascist ideas,[6] became a major player in the German occupation strategy as part of the pre-war Flemish Movement. VNV politicians were promoted to positions in the Belgian civil administration.[7] VNV and its comparatively moderate stance was increasingly eclipsed later in the war by the more radical and pro-German DeVlag movement.[8]

In French-speaking Wallonia, Léon Degrelle's Rexist Party, a pre-war authoritarian and Catholic Fascist political party,[9] became the VNV's Walloon equivalent, although Rex's Belgian nationalism put it at odds with the Flemish nationalism of VNV and the German Flamenpolitik. Rex became increasingly radical after 1941 and declared itself part of the Waffen-SS.

Although the pre-war Belgian government went into exile in 1940, the Belgian civil service remained in place for much of the occupation. The Committee of Secretaries-General, an administrative panel of civil servants, although conceived as a purely technocratic institution, has been accused of helping to implement German occupation policies. Despite its intention of mitigating harm to Belgians, it enabled but could not moderate German policies such as the persecution of Jews and deportation of workers to Germany. It did manage to delay the latter to October 1942.[10] Encouraging the Germans to delegate tasks to the Committee made their implementation much more efficient than the Germans could have achieved by force.[11] Belgium depended on Germany for food imports, so the committee was always at a disadvantage in negotiations.[11]

The Belgian government in exile criticized the committee for helping the Germans.[12][13] The Secretaries-General were also unpopular in Belgium itself. In 1942, journalist Paul Struye described them as "the object of growing and almost unanimous unpopularity."[14] As the face of the German occupation authority, they became unpopular with the public, which blamed them for the German demands they implemented.[12]

After the war, several of the Secretaries-General were tried for collaboration. Most were quickly acquitted. Gérard Romsée, the former secretary-general for internal affairs, was sentenced to twenty years imprisonment, and Gaston Schuind, Judicial Police of Brussels,[15][unreliable source?] was sentenced to five.[16] Many former secretaries-general had careers in politics after the war. Victor Leemans served as a senator from the centre-right Christian Social Party (PSC-CVP) and became president of the European Parliament.[17]

Belgian police have also been accused of collaborating, especially in the Holocaust.[8]

Towards the end of the war, militias of collaborationist parties actively carried out reprisals for resistance attacks or even assassinations.[18] Those assassinations included leading figures suspected of resistance involvement or sympathy,[19] such as Alexandre Galopin, head of the Société Générale, assassinated in February 1944. Among the retaliatory massacres of civilians[18] were the Courcelles massacre, in which 20 civilians were killed by the Rexist paramilitary for the assassination of a Burgomaster, and a massacre at Meensel-Kiezegem, where 67 were killed.[20]

British Channel Islands

The Channel Islands were the only British territory in Europe occupied by Nazi Germany. The policy of the islands' governments was what they called "correct relations" with the German occupiers. There was no armed or violent resistance by islanders to the occupation.[21] After 1945 allegations of collaboration were investigated.[clarification needed] In November 1946, the UK Home Secretary informed the UK House of Commons[22] that most allegations lacked substance. Only twelve cases of collaboration were considered for prosecution, and the Director of Public Prosecutions ruled them out for insufficient grounds. In particular, it was decided that there were no legal grounds for proceeding against those alleged to have informed the occupying authorities against their fellow citizens.[23][page needed]

On the islands of Jersey and Guernsey, laws[24][25] were passed to retrospectively confiscate the financial gains made by war profiteers and black marketeers.

After liberation, British soldiers had to intervene to prevent revenge attacks on women thought to have fraternized with German soldiers.[26]

Denmark

When on 9 April 1940, German forces invaded neutral Denmark, they violated a treaty of non-aggression signed the year before, but claimed they would "respect Danish sovereignty and territorial integrity, and neutrality."[27] The Danish government quickly surrendered and remained intact. The parliament maintained control over domestic policy.[28] Danish public opinion generally backed the new government, particularly after the Fall of France in June 1940.[29]

Denmark's government cooperated with the German occupiers until 1943,[30] and helped organize sales of industrial and agricultural products to Germany.[31] The Danish government enacted a number of policies to satisfy Germany and retain the social order. Newspaper articles and news reports "which might jeopardize German-Danish relations" were outlawed[citation needed] and on 25 November 1941, Denmark joined the Anti-Comintern Pact.[32] The Danish government and King Christian X repeatedly discouraged sabotage and encouraged informing on the resistance movement. Resistance fighters were imprisoned or executed; after the war informants were sentenced to death.[33][34][35]

Prior to, during and after the war, Denmark enforced a restrictive refugee policy; it handed over to German authorities at least 21 Jewish refugees who managed to cross the border;[31] 18 of them died in concentration camps, including a woman and her three children.[36] In 2005 prime minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen officially apologized for these policies.[37]

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, German authorities demanded the arrest of Danish communists. The Danish government complied, directing the police to arrest 339 communists listed on secret registers. Of these, 246, including the three communist members of the Danish parliament, were imprisoned in the Horserød camp, in violation of the Danish constitution. On 22 August 1941, the Danish parliament passed the Communist Law, outlawing the Communist Party of Denmark and also communist activities, in another violation of the Danish constitution. In 1943, about half of the imprisoned communists were transferred to Stutthof concentration camp, where 22 of them died.

Industrial production and trade were, partly due to geopolitical reality and economic necessity, redirected towards Germany. Many government officials saw expanded trade with Germany as vital to maintaining social order in Denmark[38] and feared that higher unemployment and poverty could lead to civil unrest, resulting in a crackdown by the Germans.[39] Unemployment benefits could be denied if jobs were available in Germany, so an average of 20,000 Danes worked in German factories through the five years of the war.[40]

The Danish cabinet, however, rejected German demands for legislation discriminating against Denmark's Jewish minority. Demands for a death penalty were likewise rebuffed and so were demands to give German military courts jurisdiction over Danish citizens and for the transfer of Danish army units to the German military.[citation needed]

France

Vichy France

World War I hero Marshal Philippe Pétain became the head of the post-democratic French State (État Français), governed not from Paris but from Vichy, when the French Third Republic collapsed after the Battle of France.[41] Prime minister Paul Reynaud resigned rather than sign the resulting armistice agreement. The National Assembly then gave Pétain absolute power to call a constituent assembly (constitutional convention) to write a new constitution. Instead Pétain used his plenary powers to establish the authoritarian French State.[42]

Pierre Laval and other Vichy ministers initially prioritized saving French lives and repatriating French prisoners of war.[43] The illusion of autonomy was important to Vichy, which wanted to avoid direct rule by the German military government.

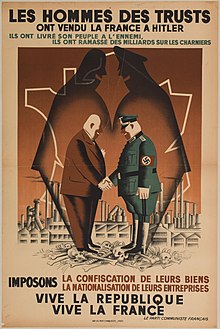

German authorities implicitly threatened to replace the Vichy administration with unreservedly pro-Nazi leaders such as Marcel Déat, Joseph Darnand and Jacques Doriot, who were permitted to operate, publish and criticise Vichy for insufficiently cooperation with Nazi Germany.

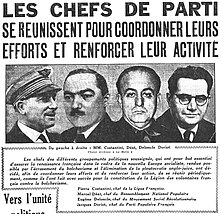

Collaborationist movements

The four main political factions which emerged as leading proponents of radical collaborationism in France were Marcel Déat's National Popular Rally (Rassemblement National Populaire, RNP), Jacques Doriot's French Popular Party (Parti Populaire Français, PPF), Eugène Deloncle's Social Revolutionary Movement (Mouvement Social Révolutionnaire, MSR), and Pierre Costantini's French League (Ligue Française).[44] These groups were small in size, between 1940 and 1944 fewer than 220,000 French people (including in North Africa) joined collaborationist movements.[45][46] In the last six months of the occupation, Déat, Darnand and Doriot became members of the government.[47]

Uniformed collaboration

The collaboration of the French police was decisive for the implementation of the Holocaust in occupied France. Germany used French police to maintain order and repress the resistance. The French police were responsible for the census of Jews, their arrest and their assembly in camps from where they were sent abroad to extermination camps. To do this the police requisitioned buses and used the rail network of SNCF trains.[48] In January 1943, Laval established the Milice, a paramilitary police force led by Joseph Darnand that assisted the Gestapo in fighting the Resistance and persecuting Jews, it counted 30,000 members both male and female.[47]

In July 1941, the collaborationist parties cooperated in organising and recruiting the Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism (LVF), to fight alongside German forces on the Eastern Front. From July 1941, a total of 5,800 French volunteers served with the LVF until its disbanding in November 1944. In February 1945, French volunteers, either from the LVF or the Milice, were incorporated into the 33rd Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Charlemagne, which had a strength of 7,340 men at the time of its deployment in eastern Europe and Berlin.[49] According to French historian Pierre Giolitto about 30,000 Frenchmen served in German military units (including non-combatants), during the course of the war.[47]

Communist party

Until the German invasion of Russia on 21 June 1941, the national leadership of the French Communist Party (PCF) remained close to the line defined by the Comintern and the Soviet Union, claiming that “the only legitimate struggle is the revolutionary struggle and not the pseudo-resistance of the Gaullists, pawns of British capitalism".[50][51] Following this logic, relations with the occupier were ambiguous. Ronald Tiersky has described the actions of the French communists during that period as "actively collaborating in certain respects".[52]

During the early days of the German occupation, the clandestine edition of newspaper L’Humanité called on French workers to fraternise with German soldiers, presenting them not as enemies of the nation but as "class brothers".[53] In June 1940, under instructions from the party leadership, French communist leaders contacted the German authorities[54] and were received by Otto Abetz, the German ambassador in Paris.[55] They requested the permission to republish L'Humanité, which had been suspended in August 1939 by the Daladier government because of its support for the German-Soviet Pact;[56] They also demanded the legalisation of the French Communist Party, dissolved in September 1939.[57] The negotiations were not successful due to the hostility of the German military command and the visceral anti-communism of the Pétain government.[54] Throughout that summer, L’Humanité and the entire communist underground press continued to publish articles preaching “Franco-German brotherhood,” denouncing “British imperialism,” and depicting de Gaulle as a reactionary and war-mongering soldier.[54]

Following the Wehrmacht invasion of Russia a year later, the PCF completely changed its stance and became one of the key players of the French Resistance.[58][59]

French workers for Germany

Vichy initially agreed, for every repatriated French prisoner-of-war, to send three French volunteers to work in German factories. When this program (known as la relève) didn't draw enough workers to please the Reich, Vichy began in February 1943 to conscript young Frenchmen, ages 18—20 into the Service du travail obligatoire (STO; English: compulsory labour service), a compulsory two-year labour draft that resulted in the deportation to German labor camps of 800,000 Frenchmen.[60]

Very unpopular, the STO provoked growing hostility towards the policy of collaboration and led to a great number of young men joining the French Resistance rather than report for it. People began to disappear into forests and mountain wildernesses to join the maquis (rural Resistance).[61][62]

Vichy collaboration in the Holocaust

Long before the Occupation, France had had a history of native anti-Semitism and philo-Semitism, as seen in the controversy over the guilt of Alfred Dreyfus (from 1894 to 1906). Historians differ how much of Vichy's anti-Semitic campaigns came from native French roots, how much from willing collaboration with the German occupiers and how much from simple (and sometimes reluctant) cooperation with Nazi instructions.

Pierre Laval was an important decision-maker in the extermination of Jews, the Romani Holocaust, and of other "undesirables." Following an increasingly restrictive series of anti-Semitic and anti-Masonic measures, such as the Second law on the status of Jews, Vichy opened a series of internment camps in France — such as one at Drancy — where Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, and political opponents were interned.[63] The French police directed by René Bousquet, under increasing German pressure, helped to deport 76,000 Jews (both directly and via the French camps) to Nazi concentration and extermination camps.[64]

In 1995, President Jacques Chirac officially recognized the responsibility of the French state for the deportation of Jews during the war, in particular, the more than 13,000 victims, of whom only 2,500 survived, of the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup of July 1942, in which Laval decided, of his own volition, to deport children along with their parents.[65] Bousquet also organized the French police to work with the Gestapo in the massive Marseille roundup (rafle) that decimated a whole neighbourhood in the Old Port.

Estimates of how many of France's Jews (about 300,000 at the start of the Occupation) died in the Holocaust range from about 60,000 (≅ 20%) to about 130,000 (≅ 43%).[66] According to Serge Klarsfeld’s study of the records kept at the Drancy internment camp, out of the 75,721 jews deported from France to death camps in Poland, only 2,567 survived.[47]

Aftermath

As the Liberation spread across France in 1944–45, so did the so-called Wild Purges (Épuration sauvage). Resistance groups took summary reprisals, especially against suspected informers and members of Vichy's anti-partisan paramilitary, the Milice. Unofficial courts tried and punished thousands of people accused (sometimes unjustly) of collaborating and consorting with the enemy. Estimates of the numbers of victims differ, but historians agree that the number will never be fully known.[67]

As a formal legal order returned to France, the informal purges were replaced by l'Épuration légale (legal purge). The most notable, and most demanded, convictions were those of Pierre Laval, tried and executed in October 1945, and Marshal Philippe Pétain, whose 1945 death sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment on the Bréton Yeu, where he died in 1951.

Several decades later, a few surviving ex-collaborators such as Paul Touvier were tried for crimes against humanity. René Bousquet was rehabilitated and regained some influence in French politics, finance and journalism, but was nonetheless investigated in 1991 for deporting Jews. He was assassinated in 1993 just before his trial would have begun. Maurice Papon served as prefect of the Paris police under President de Gaulle (thus bearing ultimate responsibility for the Paris massacre of 1961) and, 20 years later, as Budget Minister under President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, before Papon's 1998 conviction and imprisonment for crimes against humanity in organizing the deportation of 1,560 Jews from the Bordeaux region to the French internment camp at Drancy.

Other collaborators such as Émile Dewoitine also managed to have important roles after the war. Dewoitine was eventually named head of Aérospatiale, which created the Concorde airplane.

Luxembourg

Luxembourg was invaded by Nazi Germany in May 1940 and remained under German occupation until early 1945. Initially, the country was governed as a distinct region as the Germans prepared to assimilate its Germanic population into Germany itself. The Volksdeutsche Bewegung (VdB) was founded in Luxembourg in 1941 under the leadership of Damian Kratzenberg, a German teacher at the Athénée de Luxembourg.[68] It aimed to encourage the population towards a pro-German position, prior to outright annexation, using the slogan Heim ins Reich. In August 1942, Luxembourg was annexed into Nazi Germany, and Luxembourgish men were drafted into the German military.

Monaco

During the Nazi occupation of Monaco, the police arrested and turned over 42 Central European Jewish refugees to the Nazis while also protecting Monaco's own Jews.[69]

Netherlands

The Germans re-organized the pre-war Dutch police and established a new Communal Police, which helped Germans fight the country's resistance and to deport Jews. The National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands (NSB) had militia units, whose members were transferred to other paramilitaries like the Netherlands Landstorm or the Control Commando. A small number of people greatly assisted the German in their hunt for Jews, including some policemen and the Henneicke Column. Many of them were members of the NSB.[70] The column alone was responsible for the arrest of about 900 Jews.[71][72]

Norway

In Norway, the national government, headed by Vidkun Quisling, was installed by the Germans as a puppet regime during the German occupation, while king Haakon VII and the legally elected Norwegian government fled into exile.[73] Quisling encouraged Norwegians to volunteer for service in the Waffen-SS, collaborated in the deportation of Jews, and was responsible for the executions of members of the Norwegian resistance movement.

About 45,000 Norwegian collaborators joined the fascist party Nasjonal Samling (National Union), and about 8,500 of them enlisted in the Hirden collaborationist paramilitary organization. About 15,000 Norwegians volunteered on the Nazi side and 6,000 joined the Germanic SS. In addition, Norwegian police units like the Statspolitiet helped arrest many of Jews in Norway. All but 23 of the 742 Jews deported to concentration camps and death camps were murdered or died before the end of the war. Knut Rød, the Norwegian police officer most responsible for the arrest, detention and transfer of Jewish men, women and children to SS troops at Oslo harbour, was later acquitted during the legal purge in Norway after World War II in two highly publicized trials that remain controversial.[74]

Nasjonal Samling had very little support among the population at large[75] and Norway was one of few countries where resistance during World War II was widespread before the turning point of the war in 1942–43.[citation needed]

After the war, Quisling was executed by firing squad.[76] His name became an international eponym for "traitor".[77]

Collaboration in Eastern Europe

Albania

After the Italian invasion of Albania, the Royal Albanian Army, police and gendarmerie were amalgamated into the Italian armed forces in the newly created Italian protectorate of Albania.

The Albanian Fascist Militia formed after the Italian invasion of Albania in April 1939. In the Yugoslav part of Kosovo, it established the Vulnetari (or Kosovars), a volunteer militia of Kosovo Albanians. Vulnetari units often attacked ethnic Serbs and carried out raids against civilian targets.[78][79] They burned down hundreds of Serbian and Montenegrin villages, killed many people, and plundered the Kosovo and neighboring regions.[80]

Baltic states

The three Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, first invaded by the Soviet Union, were later occupied by Germany and incorporated, together with what had been the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic of the U.S.S.R. (Belarus, see below), into Reichskommissariat Ostland.[81]

Estonia

In German plans, Estonia was to become an area for future German settlements, as Estonians themselves were considered high on the Nazi racial scale, with potential for Germanization.[82] Unlike the other Baltic states, the seizure of Estonian territory by German troops was relatively long, from July 7 to December 2, 1941. This period was used by the Soviets to carry out a wave of repression against Estonians. It is estimated that the NKVD's subordinate Destruction battalions killed some 2,000 Estonian civilians,[83] and 50–60,000 people were deported deep into the USSR.[84] 10,000 of them died in the GULAG system within a year.[84] Many Estonians fought against Soviet troops on the German side, hoping to liberate their country. Some 12,000 Estonian partisans took part in the fighting.[85] Of great importance were the 57 Finnish-trained members of the Erna group, who operated behind enemy lines.[85]

Resistance groups were organised by Germans in August 1941 into the Omakaitse (lit. 'Self-defence'), which had between 34,000[86] and 40,000 members,[87] mainly based on the Kaitseliit, dissolved by the Soviets.[86] Omakaitse was in charge of clearing the German army's rear of Red Army soldiers, NKVD members, and Communist activists. Within a year its members killed 5,500 Estonian residents.[88] Later, they performed guard duty and fought Soviet partisans flown into Estonia.[88] From among Omakaitse members were recruited Estonian policemen, members of the Estonian Auxiliary Police and officers of the Estonian 20th Waffen-SS Division.[89]

The Germans formed a puppet government, the Estonian Self-Administration, headed by Hjalmar Mäe. This government had considerable autonomy in internal affairs, such as filling police posts.[89] The Security Police in Estonia (SiPo) had a mixed Estonian-German structure (139 Germans and 873 Estonians) and was formally under the Estonian Self-Administration.[90] Estonian police cooperated with Germans in rounding up Jews, Roma, communists and those deemed enemies of existing order or asocial elements. The police also helped to conscript Estonians for forced labor and military service under German command.[91] Most of the small population of Estonian Jews fled before the Germans arrived, with only about a thousand remaining. All of them were arrested by Estonian police and executed by Omakaitse.[92] Members of the Estonian Auxiliary Police and 20th Waffen-SS Division also executed Jewish prisoners sent to concentration and labor camps established by the Germans on Estonian territory.[93]

Immediately after entering Estonia, the Germans began forming volunteer Estonian units the size of a battalion. By January 1942, six Security Groups (battalions No. 181-186, about 4,000 men) had been formed and were subordinate to the Wehrmacht 18th Army.[94] After the one-year contract expired, some volunteers transferred to the Waffen-SS or returned to civilian life, and three Eastern Battalions (No. 658-660) were formed from those who remained.[94] They fought until early 1944, after which their members transferred to the 20th Waffen-SS Division.[94]

Beginning in September 1941, the SS and police command created four Infantry Defence Battalions (No. 37-40) and a reserve and sapper battalion (No. 41-42), which were operationally subordinate to the Wehrmacht. From 1943 they were called Police Battalions, with 3,000 serving in them.[94] In 1944 they were transformed into two infantry battalions and evacuated to Germany in the fall of 1944, where they were incorporated into the 20th Waffen-SS Division.[94]

In the fall of 1941, the Germans also formed eight police battalions (No. 29-36), of which only Battalion No. 36 had a typically military purpose. However, due to shortages, most of them were sent to the front near Leningrad,[95] and were mostly disbanded in 1943. That same year, the SS and police command created five new Security and Defense Battalions (they inherited No. 29-33 and had more than 2,600 men).[96] In the spring of 1943, five Defence Battalions (No. 286-290) were established as compulsory military service units. The 290th Battalion consisted of Estonian Russians. Battalions No. 286, 288 and 289 were used to fight partisans in Belarus.[97]

On Aug. 28, 1942, the Germans formed the volunteer Estonian Waffen-SS Legion. Of the approximately 1,000 volunteers, 800 were incorporated into Battalion Narva and sent to Ukraine in the spring of 1943.[98] Due to the shrinking number of volunteers, in February 1943 the Germans introduced compulsory conscription in Estonia. Born between 1919 and 1924 faced the choice of going to work in Germany, joining the Waffen-SS or Estonian auxiliary battalions. 5,000 joined the Estonian Waffen-SS Legion, which was reorganized into the 3rd Estonian Waffen-SS Brigade.[97]

As the Red Army advanced, a general mobilization was announced, officially supported by Estonia's last Prime Minister Jüri Uluots. By April 1944, 38,000 Estonians had been drafted. Some went into the 3rd Waffen-SS Brigade, which was enlarged to division size (20th Waffen-SS Division: 10 battalions, more than 15,000 men in the summer of 1944) and also incorporated most of the already existing Estonian units (mostly Eastern Battalions).[99] Younger men were conscripted into other Waffen-SS units. From the rest, six Border Defense Regiments and four Police Fusilier Battalions (Nos. 286, 288, 291, and 292).[100]

The Estonian Security Police and SD,[101] the 286th, 287th and 288th Estonian Auxiliary Police battalions, and 2.5–3% of the Estonian Omakaitse (Home Guard) militia units (between 1,000 and 1,200 men) took part in rounding up, guarding or killing of 400–1,000 Roma and 6,000 Jews in concentration camps in the Pskov region of Russia and the Jägala, Vaivara, Klooga and Lagedi concentration camps in Estonia.

Guarded by these units, 15,000 Soviet POWs died in Estonia: some through neglect and mistreatment and some by execution.[102]

Latvia

Deportations and murders of Latvians by the Soviet NKVD reached their peak in the days before the capture of Soviet-occupied Riga by German forces.[103] Those that the NKVD could not deport before the Germans arrived were shot at the Central Prison.[103] The RSHA's instructions to their agents to unleash pogroms fell on fertile ground.[103] After the Einsatzkommando 1a and part of Einsatzkommando 2 entered the Latvian capital,[104] Einsatzgruppe A's commander Franz Walter Stahlecker made contact with Viktors Arājs on 1 July and instructed him to set up a commando unit. It was later named Latvian Auxiliary Police or Arajs Kommandos.[105] The members, far-right students and former officers were all volunteers, and free to leave at any time.[105]

The next day, 2 July, Stahlecker instructed Arājs to have the Arājs Kommandos unleash pogroms that looked spontaneous,[103] before the German occupation authorities were properly established.[106] Einsatzkommando-influenced[107] mobs of former members of Pērkonkrusts and other extreme right-wing groups began pillaging and making mass arrests, and killed 300 to 400 Riga Jews. Killings continued under the supervision of SS Brigadeführer Walter Stahlecker, until more than 2,700 Jews had died.[103][106]

The activities of the Einsatzkommando were constrained after the full establishment of the German occupation authority, after which the SS made use of select units of native recruits.[104] German General Wilhelm Ullersperger and Voldemārs Veiss, a well known Latvian nationalist, appealed to the population in a radio address to attack "internal enemies". During the next few months, the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police primarily focused on killing Jews, Communists and Red Army stragglers in Latvia and in neighbouring Byelorussia.[105]

In February–March 1943, eight Latvian battalions took part in the punitive anti-partisan Operation Winterzauber near the Belarus–Latvia border, which resulted in 439 burned villages, 10,000 to 12,000 deaths, and over 7,000 taken for forced labor or imprisoned at the Salaspils concentration camp.[108] This group alone killed almost half of Latvia's Jewish population,[109] about 26,000 Jews, mainly in November and December 1941.[110]

The creation of the Arājs Kommando was "one of the most significant inventions of the early Holocaust",[109] and marked a transition from German-organised pogroms to systematic killing of Jews by local volunteers (former army officers, policemen, students, and Aizsargi).[106] This helped with a chronic German personnel shortage and provided the Germans with relief from the psychological stress of routinely murdering civilians.[106] By the autumn of 1941, the SS had deployed the Latvian Auxiliary Police battalions to Leningrad, where they were consolidated into the 2nd Latvian SS Infantry Brigade.[111] In 1943, this brigade, which later became the 19th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (2nd Latvian), was consolidated with the 15th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Latvian) to become the Latvian Legion.[111] Although the Latvian Legion was a formally volunteer Waffen-SS unit, it was voluntary only in name; approximately 80–85% of its men were conscripts.[112]

Lithuania

Prior to the German invasion, some leaders in Lithuania and in exile believed Germany would grant the country autonomy, as they had the Slovak Republic. The German intelligence service Abwehr believed that it controlled the Lithuanian Activist Front, a pro-German organization based at the Lithuanian embassy in Berlin.[113] Lithuanians formed the Provisional Government of Lithuania on their own initiative, but Germany did not recognize it diplomatically, or allow Lithuanian ambassador Kazys Škirpa to become prime minister, instead actively thwarting his activities. The provisional government disbanded, since it had no power and it had become clear that the Germans came as occupiers not liberators from Soviet occupation, as initially thought. By 1943, the German opinion of Lithuanians was that they had failed to show allegiance to them.[114] When the Germans called-up Lithuanians for military service in spring 1943, Lithuanians protested against it by making the call-up produce dismally low numbers, which angered the German occupiers.[114]

Units under Algirdas Klimaitis and supervised by SS Brigadeführer Walter Stahlecker started pogroms in and around Kaunas on 25 June 1941.[115][116] Lithuanian collaborators killed hundreds of thousands of Jews, Poles and Gypsies.[117] According to Lithuanian-American scholar Saulius Sužiedėlis, an increasingly antisemitic atmosphere clouded Lithuanian society, and antisemitic LAF émigrés "needed little prodding from 'foreign influences'".[118] He concluded that Lithuanian collaboration was "a significant help in facilitating all phases of the genocidal program . . . [and that] the local administration contributed, at times with zeal, to the destruction of Lithuanian Jewry".[119] Elsewhere, Sužiedėlis similarly emphasised that Lithuania's "moral and political leadership failed in 1941, and that thousands of Lithuanians participated in the Holocaust",[120] though he warned that "[u]ntil buttressed by reliable accounts providing time, place and at least an approximate number of victims, claims of large-scale pogroms before the advent of the German forces must be treated with caution".[121]

In 1941, the Lithuanian Security Police was created, subordinate to Nazi Germany's Security Police and Criminal Police.[122] Of the 26 Lithuanian Auxiliary Police Battalions, 10 were involved in the Holocaust.[clarification needed] On August 16, the head of the Lithuanian police, Vytautas Reivytis, ordered the arrest of Jewish men and women with Bolshevik activities: "In reality, it was a sign to kill everyone."[123] The Special SD and German Security Police Squad in Vilnius killed 70,000 Jews in Paneriai and other places.[122][clarification needed] In Minsk, the 2nd Battalion shot about 9,000 Soviet prisoners of war, and in Slutsk it massacred 5,000 Jews.

In March 1942, in Poland, the 2nd Lithuanian Battalion guarded the Majdanek concentration camp.[124] In July 1942, the 2nd Battalion participated in the deportation of Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto to Treblinka extermination camp.[125] In August–October 1942, some of the Lithuanian police battalions were in Belarus and Ukraine: the 3rd in Molodechno, the 4th in Donetsk, the 7th in Vinnytsa, the 11th in Korosten, the 16th in Dnepropetrovsk, the 254th in Poltava and the 255th in Mogilev (Belarus).[126][unreliable source?] One battalion was also used to put down the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943.[124]

The participation of the local populace was a key factor in the Holocaust in Nazi-occupied Lithuania[127] which resulted in the near total decimation of Lithuanian Jews living in the Nazi-occupied Lithuanian territories that would. From 25 July 1941, participation was under the Generalbezirk Litauen of Reichskommissariat Ostland. Out of approximately 210,000[128] Jews, (208,000 according to the Lithuanian pre-war statistical data)[129] an estimated 195,000–196,000 perished before the end of World War II (wider estimates are sometimes published); most from June to December 1941.[128][130] The events happening in the USSR's western regions occupied by Nazi Germany in the first weeks after the German invasion (including Lithuania – see map) marked the sharp intensification of the Holocaust.[131][132][133]

Bulgaria

Bulgaria was interested in acquiring Thessalonica and western Macedonia and hoped to gain the allegiance of the 80,000 Slavs who lived there at the time.[134] The appearance of Greek partisans there persuaded Axis forces to allow the formation of Ohrana collaborationist detachments.[134] The organization initially recruited 1,000 to 3,000 armed men from the Slavophone community in the west of Greek Macedonia.[135]

Czecho-Slovakia

Sudetenland

Konrad Henlein, a populist strongman who represented the sizable German minority of the Sudetenland border region, actively sought a Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia.[136] and his efforts arguably triggered the Munich Agreement[137] After the invasion he administered the Nazi deportations that sent Jews to Theresienstadt Ghetto, almost none of whom survived. For example, 42,000 people, mostly Czech Jews, were deported from Theresienstadt in 1942, of whom only 356 survivors are known.[138] Henlein also tried to expel all Czechs from the Sudetenland, but the neighbouring Protectorate of Bohemia-Moravia refused to accept them and he was informed that the need of the area's factories for labour outweighed such ethnic policies.[139]

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (the Czech lands)

When the Germans annexed Czechoslovakia in 1938 and 1939, they created the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia from the Czech part of pre-war Czechoslovakia[140] It had its own military forces, including a 12-battalion 'government army', police and gendarmerie. Most members of the 'government army' were sent to Northern Italy in 1944 as labourers and guards.[141][unreliable source?] Whether or not the government army was a collaborationist force has been debated. Its commanding officer, Jaroslav Eminger, was tried and acquitted on charges of collaboration following World War II.[142] Some members of the force engaged in active resistance operations while in the army, and, in the waning days of the conflict, elements of the army joined in the Prague uprising.[143]

Slovak Republic

The Slovak Republic (Slovenská Republika) was a quasi-independent ethnic Slovak state which existed from 14 March 1939 to 8 May 1945 as an ally and client state of Nazi Germany. The Slovak Republic existed on roughly the same territory as present-day Slovakia (except for the southern and eastern parts). It bordered Germany, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, German-occupied Poland, and Hungary.

Greece

Germany put a collaborationist government in place in Greece. Prime ministers Georgios Tsolakoglou, Konstantinos Logothetopoulos and Ioannis Rallis[144] all cooperated with Axis authorities. Greece exported agricultural products, especially tobacco, to Germany, and Greek "volunteers" worked in German factories.[145]

While efforts by Major General Georgios Bakos to recruit a Greek volunteer legion to fight in the Eastern Front failed,[146] the collaborationist government of Ioannis Rallis created armed paramilitary forces such as the Security Battalions[147] to fight the EAM/ELAS resistance[148] Former dictator, General Theodoros Pangalos, saw the Security Battalions as a way to make a political comeback, and most of the Hellenic Army officers recruited in April 1943 were republicans in some way associated with Pangalos.[149]

Greek National-Socialist parties like George S. Mercouris' Greek National Socialist Party of the ESPO organization, or such openly anti-semitic organisations as the National Union of Greece, helped German authorities fight the Greek resistance, and identify and deport Greek Jews.[150] The BUND Organization and its leader Aginor Giannopoulos trained a battalion of Greek volunteers who fought in SS and Brandenburgers units.

During the Axis occupation, a number of Cham Albanians set up their own administration and militia in Thesprotia, Greece, under the Balli Kombëtar organization, and actively collaborated with first Italian and then German occupation forces, committing a number of atrocities.[151][better source needed] In one incident on 29 September 1943, Nuri and Mazzar Dino, Albanian paramilitary leaders, instigated the mass execution of all Greek officials and notables in Paramythia.[152]

An Aromanian political and paramilitary force, the Roman Legion, led by Aromanian nationalists Alcibiades Diamandi and Nicolaos Matussis, also collaborated with Italian forces.[citation needed]

Hungary

In April 1941, in order to regain territory and under German pressure, Hungary allowed the Wehrmacht across its territory in the invasion of Yugoslavia. Hungarian prime minister Pál Teleki wanted to maintain a pro-Allies neutral stance,[153] but could no longer stay out of the war. British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden threatened to break diplomatic relations if Hungary did not actively resist the passage of German troops across its territory. General Henrik Werth, chief of the Hungarian General Staff, made a private arrangement with the German High Command, unsanctioned by the Hungarian government, to transport German troops across Hungary. Teleki, unable to stop these events, committed suicide on April 3, 1941.[153] After the war the Hungarian People's Court sentenced Werth to death for war crimes.[154]

Hungary joined the war on April 11, after the proclamation of the Independent State of Croatia.[citation needed]

It is not clear whether the 10,000–20,000 Jewish refugees (from Poland and elsewhere) were counted in the January 1941 census. They, and about 20,000 people who could not prove legal residency since 1850, were deported to southern Poland. According to Nazi German reports, a total of 23,600 Jews were murdered, including 16,000 who had earlier been expelled from Hungary[155] between July 15 and August 12, 1941, and either abandoned there or handed over to the Germans. In practice, the Hungarians deported many people whose families had lived in the area for generations. In some cases, applications for residency permits were allowed to pile up without action by Hungarian officials until after the deportations had been carried out. The vast majority (16,000) of those deported were massacred in the Kamianets-Podilskyi massacre at the end of August.[156][a]

In the massacres in Újvidék (Novi Sad) and nearby villages, 2,550–2,850 Serbs, 700–1,250 Jews and 60–130 others were murdered by the Hungarian Army and "Csendőrség" (gendarmerie) in January 1942. Those responsible, Ferenc Feketehalmy-Czeydner, Márton Zöldy, József Grassy, László Deák and others, were later tried in Budapest in December 1943 and were sentenced, but some escaped to Germany.[citation needed]

During the war, Jews were called up to serve in unarmed "labour service" (munkaszolgálat) units which repaired bombed railroads, built airports or cleaned up minefields at the front barehanded. Approximately 42,000 Jewish labour service troops were killed on the Soviet front in 1942–43, of whom about 40% perished in Soviet POW camps.[citation needed] Many died as a result of harsh conditions on the Eastern Front and cruel treatment by their Hungarian sergeants and officers. Another 4,000 forced laborers died in the copper mine of Bor, Serbia. But Miklós Kállay, prime minister beginning on March 9, 1942, and Regent Miklós Horthy refused to allow the deportation of Hungarian Jews to German extermination camps in occupied Poland. This lasted until German troops occupied Hungary and forced Horthy to oust Kállay.[citation needed]

Following the German occupation of Hungary on March 19, 1944, Jews from the provinces were deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp; between May and July that year, 437,000 Jews were sent there from Hungary, most of them gassed on arrival.[160]

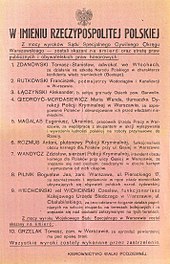

Poland

Unlike some other German-occupied European countries, occupied Poland did not have a government that collaborated with the Nazis.[161][162] The Polish government did not surrender,[163] but instead went into exile, first in France, then in London, while evacuating the armed forces via Romania and Hungary and by sea to allied France and Great Britain.[164][165][166] German-occupied Polish territory was either annexed outright by Nazi Germany or placed under German administration as the General Government.[167]

Shortly after the German Invasion of Poland in September 1939, the Nazi authorities ordered the mobilization of prewar Polish officials and Polish police (Blue Police), who were ordered to report for duty under threat of severe penalties.[168][169][170] Apart from serving as a regular police force dealing with criminal activities, the Blue Police was used by the Germans also to combat smuggling and resistance, to round up łapanka, random civilians, for forced labor, and to apprehend Jews (German: Judenjagd, "hunting Jews")[171] and participate in their extermination. Polish policemen were instrumental in implementing the Nazi policy of centralising Jews in ghettos and, from 1942 onwards, liquidating the ghettos.[172] In the late autumn and early winter of 1941, shooting Jews, including women and children, became one of their many activities at the orders of the German occupiers.[173] After an initial phase of hesitation, Polish policemen became familiar with Nazi brutality and, according to Jan Grabowski, sometimes "surpassed their German teachers."[174] While many officials and police followed German orders, some acted as agents for the Polish resistance.[175][176]

Some of the collaborators – szmalcowniks – blackmailed Jews and their Polish rescuers and acted as informers, turning in Jews and Poles who hid them, and reporting on the Polish resistance.[177] Many prewar Polish citizens of German descent voluntarily declared themselves Volksdeutsche ("ethnic Germans"), and some of them committed atrocities against the Polish population and organized large-scale looting of property.[178][179]

The Germans set up Jewish-run governing bodies in Jewish communities and ghettos – Judenrāte (Jewish councils) that served as self-enforcing intermediaries to manage Jewish communities and ghettos; and Jewish Ghetto Police (Jüdischer Ordnungsdienst), which functioned as auxiliary police to maintaining order and combating crime.[180]

The Polish Underground State's wartime underground courts investigated 17,000 Poles who collaborated with the Germans; about 3,500 were sentenced to death.[181][182]

Romania

- See also Responsibility for the Holocaust (Romania), Antonescu and the Holocaust, Porajmos#Persecution in other Axis countries.

According to an international commission report released by the Romanian government in 2004, between 280,000 and 380,000 Jews died on Romanian soil, in the war zones of Bessarabia, Bukovina, and in territories formerly occupied by Soviets that came under Romanian control (Transnistria Governorate). Of the 25,000 Romani deported to concentration camps in Transnistria, 11,000 died.[183]

Though much of the killing was committed in the war zone by Romanian and German troops, in the Iaşi pogrom of June 1941 over 13,000 Jews died in trains traveling back and forth across the countryside.[184]

Half of the estimated 270,000 to 320,000 Jews living in Bessarabia, Bukovina, and Dorohoi County were murdered or died between June 1941 and the spring of 1944. Of these, between 45,000 and 60,000 Jews were killed in Bessarabia and Bukovina by Romanian and German troops[185][186] within months of the entry of the country into the war during 1941. Even after the initial killings, Jews in Moldavia, Bukovina and Bessarabia were subject to frequent pogroms, and were concentrated into ghettos from which they were sent to camps in Transnistria built and run by the Romanian authorities.[citation needed]

Romanian soldiers and gendarmes also worked with the Einsatzkommandos, German killing squads, tasked with massacring Jews and Roma in conquered territories, the local Ukrainian militia, and the SS squads of local Ukrainian Germans (Sonderkommando Russland and Selbstschutz). Romanian troops were in large part responsible for the 1941 Odessa massacre, in which from October 18, 1941, to mid-March 1942 Romanian soldiers, gendarmes and police, killed up to 25,000 Jews and deported more than 35,000.[183]

The lowest respectable mortality estimates run to about 250,000 Jews and 11,000 Roma in these eastern regions.[citation needed]

Nonetheless, half of the Jews living within the pre-Barbarossa borders survived the war, although they were subject to a wide range of harsh conditions, including forced labor, financial penalties, and discriminatory laws. All Jewish property was nationalized.

A report commissioned and accepted by the Romanian government in 2004 on the Holocaust concluded:[183]

Of all the allies of Nazi Germany, Romania bears responsibility for the deaths of more Jews than any country other than Germany itself. The murders committed in Iasi, Odessa, Bogdanovka, Domanovka, and Peciora, for example, were among the most hideous murders committed against Jews anywhere during the Holocaust. Romania committed genocide against the Jews. The survival of Jews in some parts of the country does not alter this reality.

Yugoslavia

On 25 March 1941, under considerable pressure, the Yugoslav government agreed to the signing of the Tripartite Pact with Nazi Germany, guaranteeing Yugoslavia's neutrality. The agreement was extremely unpopular in Serbia and led to massive street demonstrations.[187] Two days later, on 27 March, Serb military officers led by general Dušan Simović overthrew the regency and placed 17-year-old King Peter on the throne.[188] Furious at the temerity of the Serbs, Hitler ordered the invasion of Yugoslavia.[189] On 6 April 1941, without a declaration of war, combined German and Italian military armies invaded. Eleven days later Yugoslavia capitulated and was subsequently partitioned among the Axis states.[190]

The Central Serbia region and the Banat were subjected to German military occupation in the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia, Italian forces occupied the Dalmatian coast and Montenegro; Albania annexed the Kosovo region and part of Macedonia; Bulgaria received Vardar Macedonia (today's North Macedonia); Hungary occupied and annexed the Bačka and Baranya regions as well as Međimurje and Prekmurje; the rest of Drava Banovina (roughly present-day Slovenia) was divided between Germany and Italy; Croatia, Syrmia and Bosnia were combined into the Independent State of Croatia, a puppet state under the direction of Croatian fascist Ante Pavelić.[191]

Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia

Under German military occupation Serbia was at first directly administered by Nazis, then by a puppet government led by General Milan Nedić.[192] The main function of the government was to maintain internal order under the authority of the German Command with the use of local paramilitary units.[193] The Wehrmacht Operations Staff never considered raising a unit to serve in the German armed forces.[194] By mid 1943, the collaborationist forces in Serbia, (Serbian and ethnic Russian units), numbered between 25,000 and 30,000.[194][195]

Serbian units

Serbian collaborationist organizations the Serbian State Guard (SDS) and the Serbian Border Guard (SGS) reached a combined 21,000 men at their peak. The Serbian Volunteers Corps (SDK), the party militia of the fascist Yugoslav National Movement led by Dimitrije Ljotić, reached 9,886 men; its members helped guard and run concentration camps and fought the Yugoslav Partisans and the Chetniks alongside the Germans. In October 1941, the Serbian Volunteer Corps participated in the Kragujevac massacre, arresting and delivering hostages to the Wehrmacht.[196] The members of the Serbian Volunteer Corps had to take an oath stating that they would fight to death against both Communists and Chetniks.[194]

Collaborationist Belgrade Special Police helped German units round up Jewish citizens for deportation to concentration camps. By the summer of 1942, most Serbian Jews had been exterminated.[197] By the end of 1942 the Special Police had 240 agents and 878 police guards under the command of the Gestapo.[195] After the liberation of the country in October 1944, the collaborationist forces retreated with the German army and were later absorbed into the Waffen-SS.[198]

Almost from the start, two rival guerrilla movements, the Chetniks and the Partisans, engaged in a bloody civil war with each other, in addition to fighting against the occupying forces. Some Chetniks collaborated with the Axis occupation to fight the rival Partisan resistance, whom they viewed as their primary enemy, by establishing modus vivendi or operating as "legalised" auxiliary forces under Axis control.[199][200][201][202]

In August 1941 Kosta Pećanac put himself and his Chetniks at the disposal of Milan Nedić's government, becoming the occupation regime's ‘legal Chetniks'.[203] At the peak of their strength in mid-May 1942, the two legal Chetnik auxiliary forces numbered 13,400 men; these detachments were dissolved by the end of 1942.[194] Pećanac was captured and executed by forces loyal to his Chetnik rival Draža Mihailović in 1944. As no single Chetnik organization existed,[203] other Chetnik units engaged independently in marginal[204] resistance activities and avoided accommodations with the enemy.[199][205] Over a period of time, and in different parts of the country, some Chetnik groups were drawn progressively[204][206] into opportunist agreements: first with the Nedić forces in Serbia, then with the Italians in occupied Dalmatia and Montenegro, with some of the Ustaše forces in northern Bosnia, and after the Italian capitulation, also with the Germans directly.[207] In some regions Chetniks collaborated "extensively and systematically", which they called "using the enemy".[207][208][209]

Ethnic Russian units

The Auxiliary Police Troop and the Russian Protective Corps were paramilitary units raised in the German-occupied territory of Serbia, composed exclusively of anti-communist White émigrés or Volksdeutsche from Russia, under the command of General Mikhail Skorodumov (around 400 and 7,500 men respectively by December 1942).[210] The force reached a peak size of 11,197 by September 1944.[211] Unlike the Serbian units, the Russian Protective Corps was part of the German armed forces and its members took the Hitler Oath.[194]

Banat

Between April 1941 and October 1944, the Serbian half of the Banat was under German military occupation as an administrative unit of the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia. Its daily administration and security were left up to its 120,000 Volksdeutsche, who represented 20% of the local population. In the Banat, security, anti-partisan warfare, and border patrols, were exclusively carried out by the Volksdeutsche in the Deutsche Mannschaft. In 1941, the Banat Auxiliary Police force was created to serve in concentration camps. It had 1,552 members by February 1943.[212] It was affiliated with the Ordnungspolizei and included some 400 Hungarians. The Gestapo in the Banat employed local ethnic Germans as agents. Banat Jews were deported and exterminated with the full participation of the Banat German leadership, the Banat Police and many ethnic German civilians.[212]

According to German sources, as of 28 December 1943, the Volksdeutsche minority of the Banat had contributed 21,516 men to the Waffen SS, the auxiliary police, and the Banat police.[190]

The 700,000 Volksdeutsche who lived in Yugoslavia[213] were the basis for the 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division Prinz Eugen, which towards the war's end included other ethnicities. The division's soldiers brutally punished civilians accused of working with partisans in both occupied Serbia and the Independent State of Croatia, going so far as to raze entire villages.[214][failed verification]

Montenegro

The Italian governorate of Montenegro was established as an Italian protectorate with the support of Montenegrin separatists known as Greens. The Lovćen Brigade, the militia of the Greens, collaborated with the Italians. Other collaborationist units included local Chetniks, police, gendarmerie and Sandžak Muslim militia.[215]

Kosovo

Most of Kosovo and the western part of southern Serbia (Juzna Srbija, included in Zeta Banovina) was annexed to Albania by fascist Italy and Nazi Germany.[216] Kosovar Albanians were recruited into Albanian paramilitary groups known as the Vulnetari, set up to assist Italian fascists maintain order,[217] many Serbs and Jews were expelled from Kosovo and sent to internment camps in Albania.[218][page needed]

The Balli Kombëtar militias, or Ballistas, were volunteer Albanian nationalistic groups that started as a resistance movement, then collaborated with the Axis Powers in hopes of seeing Greater Albania created.[219] Military units were formed within the militias, among them the Kosovo Regiment, raised in Kosovska Mitrovica as a Nazi auxiliary military unit after Italian capitulation.[220][page needed] According to German reports, in early 1944 some 20,000 Albanian guerrillas led by Xhafer Deva fought the Partisans alongside the Wehrmacht in Albania and Kosovo.[190]

Macedonia

In Bulgaria-annexed Vardar Macedonia, the occupation authority organized the Ohrana into auxiliary security forces. On 11 March 1943, Skopje's entire Jewish population was deported to the gas chambers of Treblinka concentration camp.[221]

Slovene Lands

The Axis powers divided the Slovene Lands into three zones. Germany occupied the largest, northern part. Italy annexed the southern part, and Hungary annexed the northeast part, Prekmurje.[222] As in the rest of Yugoslavia, the Nazis used the Slovene Volksdeutsche to further their aims, in groups like the Deutsche Jugend (German Youth) which was used as an auxiliary military force for guard duty and fighting the partisans, and the Slovenian National Defense Corps.[222]

The Slovene Home Guard (Domobranci) was a collaborationist force formed in September 1943 in the Province of Ljubljana (then a part of Italy). It was led by former general Leon Rupnik but had limited autonomy, and at first, functioned as an auxiliary police force that assisted the Germans in anti-partisan actions.[223] Later, it gained more autonomy and conducted most of the anti-partisan operations in Ljubljana. Much of the Guard's equipment was Italian (confiscated when Italy dropped out of the war in 1943), although German weapons and equipment were used as well, especially later in the war. Similar, but much smaller units, were also formed in the Littoral (Primorska) and Upper Carniola (Gorenjska). The Blue Guard, also known as the Slovene Chetniks, was an anti-communist militia led by Karl Novak and Ivan Prezelj.[224]

The Anti-Communist Volunteer Militia (MVAC), was under Italian authority. One of the biggest components of the MVAC was the Civic Guards (Vaške Straže),[223] a Slovene volunteer military organization formed by the Italian Fascist authorities to fight the partisans, as well as some collaborationist Chetniks units. The Legion of Death (Legija Smrti), was another Slovene anti-partisan armed unit formed after the Blue Guard joined the MVAC.[222]

Independent State of Croatia

On 10 April 1941, a few days before Yugoslavia's capitulation, Ante Pavelić's Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was established as an Axis-affiliated state, with Zagreb as capital.[225] Between 1941 and 1945, the fascist Ustaše regime collaborated with Nazi Germany, and engaged in independent persecution. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, this resulted in the deaths of approximately 30,000 Jews, between 25,000 and 30,000 Roma, and between 320,000 and 340,000 ethnic Serbs from Croatia and Bosnia,[226] in camps like the infamous Jasenovac concentration camp.[227][228]

The 13th Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Handschar (1st Croatian), created in February 1943, and the 23rd Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Kama (2nd Croatian), created in January 1944, were manned by Croats and Bosniaks as well as local Germans. Earlier in the war, Pavelić formed a Croatian Legion for the Eastern Front and attached it to the Wehrmacht. Volunteer pilots joined the Luftwaffe as Pavelić did not want to get his army directly involved for both propaganda reasons (Domobrans/Home Guards were a "chieftain of Croatian values, never attacking and only defending") and due to a safeguarding need for political flexibility with the Soviet Union.

Pavelić proclaimed that Croats were the descendants of Goths, to eliminate the leadership's inferiority complex and be better viewed by the Germans. The Poglavnik stated that "Croats are not Slavs, but Germanic by blood and race".[229] Nazi German leadership was indifferent to this claim.[citation needed]

Bosnia

In 1941 Bosnia became an integral part of the Independent State of Croatia. Bosnian Muslims were considered Croats of Islamic confession.[230]

Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa began on 22 June 1941 and, by November 1942, Nazi Germany had occupied around 750,000 sq mi (1,900,000 km2) of the Soviet Union.[231] By November 1944, the German forces had been forced out of the pre-World War II Soviet territory.[231]

According to the American historian Jeffrey Burds, out of the three million armed collaborators with Nazi Germany in Europe, as many as 2.5 million originated from the Soviet Union, and by 1945, every eighth German soldier had previously been a pre-war Soviet citizen.[232] Antony Beevor writes that 1 to 1.5 million men from the territory of the USSR served militarily under the Germans.[233] Regardless, the precise number will never be known.[234][dubious – discuss] The people from the Soviet Union served in the Wehrmacht under a wide array of units: Hiwi, Security units, Russian Liberation Army (ROA), KONR, Ukrainian Liberation Army, various independent Russian units (SS-Verband Drushina, RNNA, RONA, 1st Russian National Army) and the Eastern Legions.[231]

Toward's the war's end, the SS Main Office and the Ostministerium began conflicting over the Eastern Legions and Cossack units.[235] The former tried to control all non-German troops fighting in the Wehrmacht, while the latter had its own policy towards the military units, which was helped by the national committees whose patron it was.[235] Most national committees refused to subordinate themselves and the associated military units to Andrey Vlasov's Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia (KONR) and its armed forces (ROA), instead choosing to declare national armies, e.g. Caucasian Liberation Army and National Army of Turkestan.[235] However, through the help of his patrons in the SS Main Office, Vlasov became their ostensibly leader by April 1945 and all national committees and related troops were nominally subordinated to him.[235]

According to Antony Beevor, those serving under the Germans were "often extraordinarily naïve and ill-informed."[233] Many viewed their service under the Germans as just serving in another military service and a way to ensure food for themselves, which they preferred to being maltreated and starved in a prisoner-of-war camp.[233]

The Waffen-SS recruited from many nationalities living in the Soviet Union, and the German government attempted to enroll Soviet citizens voluntarily for the Ostarbeiter program. Originally this effort worked well, but the news of the terrible conditions faced by workers dried up the flow of new volunteers and the program became forcible.[236]

Hiwis

Already from the very first days, individual deserters and prisoners from the Red Army were offering their help to the Germans in auxiliary duties such as, but not limited to, cooking, driving, and medical assistance.[234] There were also Soviet civilians that joined supply units and construction battalions.[231] Both military and civilian auxiliaries were called Hiwis (German abbreviation for auxiliary volunteer) with the former Soviets soldiers frequently wearing their Red Army uniforms without any Soviet insignia.[231] After two months service, they were permitted to wear German uniforms with insignia and ranks, which made veteran Hiwis almost indistinguishable from the regular German soldiers, although their promotion up the ranks was very limited.[231]

Hitler reluctantly gave permission in September 1941 to recruit people from the Soviet Union as unarmed voluntary assistants, but in practice this was frequently ignored and many of them served in frontline units.[231] Sometimes many of the men of German units consisted of the Hiwis, for example, half of the 134th Infantry Division and a quarter of the 6th Army consisted of Hiwis in late 1942.[231] The Red Army authorities estimated that more than a million served in the Wehrmacht as Hiwis.[233]

Eastern Legions

The failure of the Axis powers to immediately defeat the Soviet Union in late 1941 led the Wehrmacht to resort to new sources of manpower necessary for a protracted war.[235] In November–December 1941, Hitler ordered the formation of four Eastern Legions: Turkestan, Georgian, Armenian and Caucasian Mohammedan.[235] In August 1942, the "Regulations on Local Auxiliary Formations in the East" singled out the Turkic peoples and the Cossacks as "equal allies fighting shoulder to shoulder with German soldiers against Bolshevism in composition of special combat units."[235] The incorporation of eastern battalions into German divisions guarding the Atlantic Wall in Western Europe caused problems as they were totally unfit to fight against the Western Allies and the battalions were actually a burden on the weakened divisions that they were supposed to replenish.[237] Between 275,000 and 350,000 "Muslim and Caucasian" volunteers and conscripts served in the Wehrmacht.[238]

| Ethnic groups from the USSR | Estimates of people that served in the Wehrmacht |

|---|---|

| Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Turkmens and other ethnic groups of Central Asia | ~70,000[235] |

| Azerbaijanis | <40,000[235] |

| North Caucasians | <30,000[235] |

| Georgians | 25,000[235] |

| Armenians | 20,000[235] |

| Volga Tatars | 12,500[235] |

| Crimean Tatars | 10,000[235] |

| Kalmyks | 7,000[235] |

| Cossacks | 70,000[235] |

| Total | 280,000[235] |

Between early 1942 and late 1943, the Kommando der Ostlegionen in Polen formed a total of 54 battalions, but this was not the only place where such units were being created:[239]

| Legion | No. of battalions formed |

|---|---|

| Turkestan | 15 |

| Armenian | 9 |

| Georgian | 8 |

| Azerbaijani | 8 |

| Idel-Ural (Volga Finns and Tartars) | 7 |

| North Caucasian | 7 |

| Total | 54 |

Russia

In Russia proper, ethnic Russians governed the semi-autonomous Lokot Autonomy in Nazi-occupied Russia.[240] On 22 June 1943, a parade of the Wehrmacht and Russian collaborationist forces was welcomed and positively received in Pskov. The entry of Germans into Pskov was labelled "Liberation day" by occupying authorities, and the old Russian tricolor flag was included in the parade.[241]

Kalmykians

The Kalmykian Cavalry Corps was composed of about 5,000 Kalmyks who chose to join the retreating Germans in 1942 rather than remain in Kalmykia as the German Army retreated before the Red Army.[242] Joseph Stalin subsequently declared the Kalmyk population as a whole to be German collaborators in 1943 and ordered mass deportations to Siberia, causing great loss of life.[243]

Belarus

In Byelorussia under German occupation, local pro-independence politicians attempted to use the Nazis to re-establish an independent Belarusian state, which was conquered by the Bolsheviks in 1919. A Belarusian representative body, the Belarusian Central Council, was created under German control in 1943 but had no real power and concentrated mainly on managing social issues and education. Belarusian national military units (the Byelorussian Home Defence) were only created a few months before the end of the German occupation.

Many Belarusian collaborators retreated with German forces in the wake of the Red Army advance. In January 1945, the 30th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Belarusian) was formed from the remains of Belarusian military units. The division participated in a small number of battles in France but demonstrated active disloyalty to the Nazis and saw mass desertion.[citation needed]

Transcaucasia

Ethnic Armenian, Georgian, Turkic and Caucasian forces deployed by the Germans consisted primarily of Soviet Red Army POWs assembled into ill-trained legions.[citation needed] Among these battalions were 18,000 Armenians, 13,000 Azerbaijanis, 14,000 Georgians, and 10,000 men from the "North Caucasus."[244] American historian Alexander Dallin notes that the Armenian and Georgian Legions were sent to the Netherlands as a result of Hitler's distrust of them, and many later deserted.[245] Author Christopher Ailsby called the Turkic and Caucasian forces formed by the Germans "poorly armed, trained and motivated", and "unreliable and next to useless".[244]

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (the Dashnaks) was suppressed in Armenia when the First Republic of Armenia was conquered by the Russian Bolsheviks in the 1920 Red Army invasion of Armenia and thus ceased to exist. During World War II, some of the Dashnaks saw an opportunity to regain Armenia's independence. The Armenian Legion under Drastamat Kanayan participated in the occupation of the Crimean Peninsula and the Caucasus.[246] On 15 December 1942, the Armenian National Council was granted official recognition by Alfred Rosenberg, the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories. The president of the Council was Ardasher Abeghian, its vice-president was Abraham Guilkhandanian, and it numbered among its members Garegin Nzhdeh and Vahan Papazian. Until the end of 1944, the organization published a weekly journal, Armenian, edited by Viken Shantn, who also broadcast on Radio Berlin with the aid of Dr. Paul Rohrbach.[247]

Collaboration beyond Europe with the European Axis powers

Egypt and the Palestine mandate

The well-publicized Arab-Jewish clash in Mandatory Palestine from 1936 to 1939, and the rise of Nazi Germany, began to affect Jewish relations with Egyptian society, despite the fact that the number of active Zionists was small.[248] Local militant and nationalistic societies, like the Young Egypt Party and the Society of Muslim Brothers, circulated reports claiming that Jews and the British were destroying holy places in Jerusalem, and other false reports that hundreds of Arab women and children were being killed.[249][undue weight? – discuss] Some of this antisemitism was fueled by an association between Hitler's regime and anti-imperialist Arab activists. One activist, Haj Amin al-Husseini, received Nazi funds for the Muslim Brotherhood to print and distribute thousands of anti-Semitic propaganda pamphlets.[249]

In the 1940s the situation worsened. Sporadic pogroms began in 1942.[undue weight? – discuss][citation needed]

French colonial empire

France retained its colonial empire, and the terms of the armistice shifted the balance of power of France's reduced military resources away from metropolitan France and towards its overseas possessions, especially French North Africa. Although in 1940, most French colonies except for the French Equatorial Africa had rallied to Vichy France, this changed during the war. By 1943, all French colonies, except for Japanese-controlled French Indochina, were under the control of the Free French.[250] French Equatorial Africa in particular played a key role.[251]

French North Africa

Concerned that the French fleet might fall into German hands, the British Royal Navy sank or disabled most of it in the July 1940 attack on the Algerian naval port at Mers-el-Kébir, which poisoned Anglo-French relations and led to Vichy reprisals.[252] When Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of French North Africa, began on 8 November 1942 with landings in Morocco and Algeria, Vichy forces initially resisted, killing 479 and wounding 720. Admiral François Darlan appointed himself High Commissioner of France (head of civil government) for North and West Africa, then ordered Vichy forces there to stop resisting and co-operate with the Allies, which they did.[253][254][page needed]

Most Vichy figures were arrested, including Darlan and General Alphonse Juin,[255] chief commander in North Africa. Both were released, and US General Dwight D. Eisenhower accepted Darlan's self-appointment. This infuriated de Gaulle, who refused to recognise Darlan. Darlan was assassinated on Christmas Eve 1942 by a French monarchist. German Wehrmacht forces in North Africa established the Kommando Deutsch-Arabische Truppen, composed of two battalions of Arab volunteers of Tunisian origin, an Algerian battalion and a Moroccan battalion.[256] The four units had total of 3,000 men; with German cadres.[257]

Morocco

In 1940, Résident Général Charles Noguès implemented antisemitic decrees coming from Vichy excluding Moroccan Jews from working as doctors, lawyers or teachers.[258][259] [260] All Jews living elsewhere were required to move to the Jewish quarters, called mellahs,[258] Vichy anti-semitic propaganda encouraged boycotting Jews,[258] and pamphlets were pinned to Jewish shops.[258] These laws put Moroccan Jews in an uncomfortable position "between an indifferent Muslim majority and an antisemitic settler class."[259] Sultan Mohammed V reportedly refused to sign off on "Vichy's plan to ghettoize and deport Morocco's quarter of a million Jews to the killing factories of Europe," and, in an act of defiance, insisted on inviting all the rabbis of Morocco to the 1941 throne celebrations.[261]

Tunisia

Many Tunisians took satisfaction in France's defeat by Germany in June 1940,[262] but little else. Despite his commitment to ending the French protectorate, the pragmatic independence leader Habib Bourguiba abhorred the Axis state ideologies.[263] and feared any short-term benefit would come at the cost of long-term tragedy.[263] After the Second Armistice at Compiègne, Pétain sent a new Resident-General to Tunis, Admiral Jean-Pierre Esteva. Arrests followed of Taieb Slim and Habib Thameur, central figures in the Neo-Destour party. Bey Muhammad VII al-Munsif moved towards greater independence in 1942, but when the Free French forced out the Axis powers in 1943, they accused him of collaborating with Vichy and deposed him.

French Equatorial Africa

The federation of colonies in French Equatorial Africa (AEF or Afrique-Équatoriale française) rallied to the cause of De Gaulle after Félix Éboué of Chad joined him in August 1940. The exception was Gabon, which remained Vichy French until 12 November 1940, when it surrendered to the invading Free French. The federation became the strategic centre of Free French activities in Africa.

Syria and the Lebanon (League of Nations mandates)

The Vichy government's Armée du Levant (Army of the Levant) under General Henri Dentz had regular metropolitan colonial troops and troupes spéciales (special troops, indigenous Syrian and Lebanese soldiers).[264] Dentz had seven infantry battalions of regular French troops at his disposal, and eleven infantry battalions of "special troops", including at least 5,000 cavalry in horsed and motorized units, two artillery groups and supporting units.[264] The French had 90 tanks (according to British estimates), the Armée de l'air had 90 aircraft (increasing to 289 aircraft after reinforcement) and the Marine nationale (French Navy) had two destroyers,a sloop and three submarines.[265][266]

The Royal Air Force attacked the airfield at Palmyra, in central Syria, on 14 May 1941, after a reconnaissance mission spotted German and Italian aircraft. Attacks against German and Italian aircraft staging through Syria continued: Vichy French forces shot down a Blenheim bomber on 28 May, killing the crew, and forced down another on 2 June.[267] French Morane-Saulnier M.S.406 fighters also escorted German Junkers Ju 52 aircraft into Iraq on 28 May.[267] Germany permitted French aircraft en route from Algeria to Syria to fly over Axis-controlled territory and refuel at the German-controlled Eleusina air base in Greece.[268]

After the Armistice of Saint Jean d'Acre, on 14 July 1941, 37,736 Vichy French prisoners of war survived, who mostly chose to be repatriated rather than join the Free French.

Foreign volunteers

French military volunteers

French volunteers formed the Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism (LVF), Légion impériale, SS-Sturmbrigade Frankreich and finally in 1945 the 33rd Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Charlemagne (1st French), which was among the final defenders of Berlin.[269][270][271]

Volunteers from British India

The Indian Legion (Legion Freies Indien, Indische Freiwilligen Infanterie Regiment 950 or Indische Freiwilligen-Legion der Waffen-SS) was created in August 1942, recruiting chiefly from disaffected British Indian Army prisoners of war captured by Axis forces in the North African campaign. Most were supporters of the exiled nationalist and former president of the Indian National Congress Subhas Chandra Bose. The Royal Italian Army formed a similar unit of Indian prisoners of war, the Battaglione Azad Hindoustan. (A Japanese-supported puppet state, Azad Hind, was also established in far-eastern India with the Indian National Army as its military force.)[272][273]

Non-German units of the Waffen-SS