Вирджиния

Вирджиния | |

|---|---|

| Содружество Вирджинии | |

| Прозвища : Старый Доминион, мать президентов | |

| Девиз (ы) : | |

| Гимн: « Наша великая Вирджиния » | |

Карта Соединенных Штатов с Вирджинией выделена | |

| Страна | Соединенные Штаты |

| До государственности | Колония Вирджинии |

| Допущен в профсоюз | 25 июня 1788 г. (10 -е место) |

| Капитал | Ричмонд |

| Крупнейший город | Вирджиния Бич |

| Крупнейшие метро и городские районы | Вашингтон (Метро и Урбан) |

| Правительство | |

| • Губернатор | Гленн Янгкин ( R ) |

| • Губернатор -лейтенант | Winsome Sears (R) |

| Законодательный орган | Генеральная Ассамблея |

| • Верхний дом | Сенат |

| • Нижний дом | Дом делегатов |

| Судебная власть | Верховный суд Вирджинии |

| США сенаторы |

|

| Делегация США | 6 демократов 5 республиканцев ( список ) |

| Область | |

| • Общий | 42 774,2 кв. Миль (110 785,67 км 2 ) |

| • Классифицировать | 35 -й |

| Размеры | |

| • Длина | 430 миль (690 л.с.) |

| • Ширина | 200 миль (320 км) |

| Возвышение | 950 футов (290 м) |

| Высокая высота ( Гора Роджерс [ 2 ] ) | 5729 футов (1746 м) |

| Самая низкая высота | 0 футов (0 м) |

| Население (2023) | |

| • Общий | 8,715,698 [ 3 ] |

| • Классифицировать | 12 -й |

| • Плотность | 219,3/кв. Миль (84,7/км 2 ) |

| • Классифицировать | 14 -е |

| • Средний доход домохозяйства | $80,615 |

| • Ранг дохода | 10 -е место |

| Демон | Вирджинец |

| Язык | |

| • Официальный язык | Английский |

| • разговорной язык |

|

| Часовой пояс | UTC-05: 00 ( восточная ) |

| • Лето ( DST ) | UTC-04: 00 ( EDT ) |

| USPS аббревиатура | И |

| ISO 3166 Код | US-VA |

| Традиционная аббревиатура | И. |

| Широта | 36 ° 32 ′ с N до 39 ° 28 ′ N |

| Долготу | 75 ° 15 ′ w составляет 83 ° 41 ′ w |

| Веб -сайт | Вирджиния |

Вирджиния , официально Содружество Вирджинии , [ А ] является государством в юго-восточных и средних атлантических регионах Соединенных Штатов между Атлантическим побережье и Аппалачскими горами . штата Столицей является Ричмонд , а его самый густонаселенный город - Вирджиния -Бич . Его наиболее густонаселенным подразделением является округ Фэрфакс , часть Северной Вирджинии , где в прямом эфире жителя Вирджинии составляет 8,7 миллиона человек.

Восточная Вирджиния является частью Атлантической равнины , а Средний полуостров образует устье Чесапикского залива . Центральная Вирджиния лежит преимущественно в Пьемонте , в районе предгорья горов Голубого хребта , которая пересекает западные и юго -западные части штата. Плодородная долина Шенандоа способствует наиболее продуктивным сельскохозяйственным округам штата, в то время как экономика в Северной Вирджинии обусловлена технологическими компаниями и федеральными правительственными учреждениями США, включая Министерство обороны США и центральное разведывательное управление . Hampton Roads также является местом главного морского порта региона и военно -морской станции Норфолк , крупнейшей военно -морской базы в мире.

История Вирджинии начинается с нескольких коренных групп , включая Паухатан . В 1607 году лондонская компания основала колонию Вирджинии как первую постоянную английскую колонию в Новом Свете , что привело к прозвищу Вирджинии как старого Доминиона . Рабы из Африки и земли из перемещенных местных племен питали растущую экономику плантаций, но также питали конфликты как внутри, так и за пределами колонии. Вирджинцы боролись за независимость тринадцати колоний в американской революции и помогли создать новое национальное правительство. Во время гражданской войны в американской гражданской войне правительство штата в Ричмонде присоединилось к Конфедерации , в то время как многие северо -западные округа оставались верными Союзу , что привело к разделению Западной Вирджинии в 1863 году.

Хотя государство находилось под одним партийным правлением в течение почти столетия после эпохи реконструкции , обе основные политические партии были конкурентоспособны в Вирджинии с момента отмены законов Джима Кроу в 1970-х годах. Законодательным органом штата Вирджинии является Генеральная Ассамблея Вирджинии , которая была основана в июле 1619 года, что делает его самым старым нынешним законодательным органом в Северной Америке . В отличие от других штатов, города и округа Вирджиния функционируют как равные, но правительство штата управляет большинством местных дорог внутри каждого. Это также единственное государство, в котором губернаторам запрещено отбывать последовательные условия.

История

Самые ранние жители

По оценкам, охотники за кочевым образом прибыли в Вирджинию около 17 000 лет назад. Доказательства из пещеры Догерти в округе Рассел показывают, что он регулярно использовался в качестве приюта для рок -приюта 9800 лет назад. [ 5 ] В течение позднего периода леса (500–1000 н.э. ) начались племена соавсированы, и сельское хозяйство, сначала из кукурузы и тыквы, с бобами и табаком, прибывающими с юго -запада и Мексики к концу периода. Палисадские города стали построить около 1200 года, а коренное население в нынешних границах Вирджинии достигло около 50 000 в 1500 -х годах. [ 6 ] В то время крупные группы в этом районе включали Алгонкиан в регионе Тидеотер , который они называли Ценакоммакой , ирокеанским говорящим Ноттоуэем и Мехеррином на севере и юге, а также Тутело , который говорил Сиуан , на Западе. [ 7 ]

В ответ на угрозы со стороны этих других групп в их торговую сеть, тридцать или около того Вирджинии Алгонкианские племена консолидировались в течение 1570 -х годов под руководством Вахунсенакава, известного на английском языке как главный Похатан . [ 7 ] Паухатан контролировал более 150 поселений, в которых население составило около 15 000 человек в 1607 году. [ 8 ] Три четверти местного населения в Вирджинии, однако, умерли от оспы и других болезней Старого Света в течение этого столетия, [ 9 ] нарушение их устных традиций и усложнение исследований в более ранних периодах. [ 10 ] Кроме того, многие первичные источники, в том числе те, которые упоминают дочь Паухатана, Покахонтас , были созданы европейцами, которые, возможно, имели предубеждения или неправильно поняли местные социальные структуры и обычаи. [ 4 ] [ 11 ]

Колония

Несколько европейских экспедиций, в том числе группа испанских иезуитов , исследовали Чесапикский залив в течение 16 -го века. [ 12 ] Чтобы помочь противодействовать колониям Испании в Карибском бассейне , королева Елизавета I из Англии поддержала экспедицию Уолтера Роли 1584 года на Атлантическое побережье Северной Америки . [ 13 ] [ 14 ] Название «Вирджиния» использовалось капитаном Артуром Барлоу в отчете экспедиции, и, возможно, было предложено в этом году Роли или Элизабет, возможно, отметив ее статус «королевы девственницы» или что они рассматривали землю как нетронутую, и может Также связаны с фразой алгонкина , Wingandacoa или Windgancon , или именем лидера, Wingina , как слышна экспедиция. [ 15 ] [ 16 ] Первоначально название применялось ко всему прибрежному региону от Южной Каролины на юге до Мэна на севере, наряду с островом Бермудские острова . [ 17 ] Колония Роли потерпела неудачу, но потенциальные финансовые и стратегические выгоды все еще очаровали многих английских политиков, и в 1606 году король Джеймс I выпустил хартию для новой колонии в лондонскую компанию Вирджинии . Группа финансировала экспедицию при Кристофере Ньюпорте , которая пересекла Атлантику и установила урегулирование под названием Джеймстаун в мае 1607 года. [ 18 ]

Хотя вскоре присоединились к большему количеству поселенцев, многие были плохо подготовлены к опасностям нового поселения. Как президент колонии, Джон Смит получил еду для колонистов из близлежащих племен, но после того, как он уехал в 1609 году, эта сделка прекратилась, и серия убийств в стиле засады между колонистами и местными жителями под руководством вождя Паухатана и его брата началась, что привело к массовому голоду В колонии той зимой. [ 19 ] К концу первых четырнадцати лет колонии, более восьмидесяти процентов из примерно восьми тысяч поселенцев, перевезенных там. [ 20 ] Однако спрос на экспортированный табак вызвал необходимость большего количества работников. [ 21 ] Начиная с 1618 года, система Headright попыталась решить это, предоставив колонистам сельскохозяйственные угодья за их помощь привлечении слуг . [ 22 ] Порабощенные африканцы были впервые проданы в Вирджинии в 1619 году. Несмотря на то, что другие африканцы прибыли в соответствии с правилами солевого рабства и могли быть освобождены через четыре -семь лет, основа для рабства на протяжении всей жизни была разработана в юридических случаях, таких как Джона Панча в 1640 году и Джона. Касор в 1655 году. [ 23 ] Законы, принятые в Джеймстауне, определили рабство как расовое в 1661 году, как унаследованные материнские жители в 1662 году, и как и принудительно применяется смертью в 1669 году. [ 24 ]

С самого начала колонии жители взволнованы для большего местного контроля, и в 1619 году некоторые колонисты -мужчины начали избрать представителей на собрание, впоследствии названную Палатой Берджесеса , которые договорились о вопросах с руководящим советом, назначенным лондонской компанией. [ 26 ] Несчастный с этой договоренностью, монархия отменила устав компании и начала непосредственно называть губернаторов и членов совета в 1624 году. В 1635 году колонисты арестовали губернатора, который проигнорировал собрание и отправила его обратно в Англию против его воли. [ 27 ] Уильям Беркли был назначен губернатором в 1642 году, так же, как суматоха Английской гражданской войны и межгнума позволила колонии большей автономии. [ 28 ] Как сторонник короля, Беркли приветствовал других так называемых кавалеров , которые бежали в Вирджинию. Он сдался парламентариям в 1652 году, но после того, как восстановление 1660 года снова сделало его губернатором, он заблокировал выборы в ассамблею и усугубил разрыв класса , лишая лишенность гражданских прав и ограничив движение заседавших слуг, которые составили около восьмидесяти процентов рабочей силы колонии. [ 29 ] На границе колонии Пьемонта племена , такие как Tutelo и Doeg, были сжаты Сенека Рейдерами с севера, что привело к большей конфронтации с колонистами. В 1676 году несколько сотен последователей рабочего класса Натаниэля Бэкона , расстроенные отказа Беркли отменять племен, пошли в Джеймстаун и сжигали его. [ 30 ]

Восстание Бэкона вызвало подписание законов Бэкона , которые восстановили некоторые права колонии и санкционировали как атаки на родные племена, так и порабощение их мужчин и женщин. [ 31 ] Договор 1677 года дополнительно уменьшил независимость племен, которые подписали его, и помог ассимиляции колонии их земли в последующие годы. [ 32 ] [ 33 ] Колонисты в 1700 -х годах подталкивали к западу в эту область, принадлежащую Seneca и их более крупной ирокезной нации , и в 1748 году группа богатых спекулянтов, поддерживаемая британской монархией, сформировала компанию Огайо для начала урегулирования английского языка и торговли в стране Огайо. к западу от Аппалачских гор . [ 34 ] Королевство Франция , которое претендовало на эту область как часть своей колонии Новой Франции , рассматривало это как угрозу, а в 1754 году военная война Франции и Индии охватила Англию, Францию, Ирокезы и другие союзные племена с обеих сторон. Милиции из нескольких британских колоний, называемых полком Вирджинии , возглавлял 21-летний майор Джордж Вашингтон , сам один из инвесторов в компании Огайо. [ 35 ]

Государственность

В течение десятилетия после французской и индийской войны британский парламент под руководством премьер -министров Гренвилл , Чатем и Север принял новые налоги на различные колониальные мероприятия. Они были глубоко непопулярны в колониях, и в доме Бурджессов противодействуют налогообложению без представительства Патриком Генри и Ричардом Генри Ли , среди прочего. [ 36 ] Вирджинцы начали координировать свои действия с другими колониями в 1773 году и отправили делегатов на континентальный конгресс в следующем году. [ 37 ] После того, как Палата Берджессов была распущена в 1774 году королевским губернатором , революционные лидеры Вирджинии продолжали управлять посредством конвенций Вирджинии . 15 мая 1776 года Конвенция объявила независимость Вирджинии от Британской империи и приняла Джорджа Мейсона в декларацию о правах Вирджинии , которая затем была включена в новую конституцию, которая назначила Вирджинию как Содружество, используя перевод латинского термина Res Publica Полем [ 38 ] Другой вирджинец, Томас Джефферсон , рассмотрел работу Мейсона по составлению национальной декларации независимости . [ 39 ]

После американской революционной войны начала Джордж Вашингтон был выбран вторым континентальным конгрессом в Филадельфии, чтобы возглавить континентальную армию , и многие вирджинии присоединились к армии и другим революционным ополченцам. Вирджиния была первой колонией, которая ратифицировала статьи Конфедерации в декабре 1777 года. [ 40 ] В апреле 1780 года столица была перенесена в Ричмонд по настоянию губернатора Томаса Джефферсона, который опасался, что прибрежное расположение Вильямсбурга сделает его уязвимым для британского нападения. [ 41 ] Британские войска действительно приземлились вокруг Портсмута в октябре 1780 года, и солдатам под руководством Бенедикта Арнольда удалось совершить набег на Ричмонда в январе 1781 года. [ 42 ] У британской армии было более семи тысяч солдат и двадцать пять военных кораблей, размещенных в Вирджинии в начале 1781 года, но генерал Чарльз Корнуоллис и его начальство были нерешительными, а маневрировали три тысячи солдат под Маркизом де Лафайеттом и двадцатью девять Военные корабли вместе смогли ограничить британцев в болотистую зону полуострова Вирджиния в сентябре. Около шестнадцати тысяч солдат под руководством Джорджа Вашингтона и Конт -де -Рошамбо быстро сблизились и победили Корнуоллиса в осаде Йорктауна . [ 43 ] Его сдача 19 октября 1781 года привела к мирным переговорам в Париже и обеспечила независимость колоний. [ 44 ]

Вирджинцы сыграли важную роль в первых годах новой страны и в письменной форме Конституции Соединенных Штатов . Джеймс Мэдисон составил план Вирджинии в 1787 году и Билль о правах в 1789 году. [ 39 ] Вирджиния ратифицировала Конституцию 25 июня 1788 года. Компромисс в три пятых гарантировал, что Вирджиния с большим количеством рабов первоначально имел самый большой блок в Палате представителей . Вместе с Вирджинии династией президентов это дало национальное значение Содружества. В 1790 году Вирджиния и Мэриленд уступили территорию, чтобы сформировать новую национальную столицу, которая переехала из Филадельфии в округ Колумбия десятилетие спустя, в 1800 году. В 1846 году был ретроцредактирован вирджинский район новой столицы . [ 45 ] Вирджиния называется «матери штатов» из -за своей роли в том, чтобы быть вырезанными в таких штатах, как Кентукки , который стал пятнадцатым штатом в 1792 году, и для числа американских пионеров, родившихся в Вирджинии. [ 46 ]

Гражданская война

В период с 1790 по 1860 год число рабов в Вирджинии выросло с 290 тысяч до более чем 490 тысяч, примерно одна треть населения штата за это время, а количество рабовладельцев выросло более чем на 50 тысяч. Оба этих числа представляли больше всего в США [ 48 ] [ 49 ] Бум в производстве хлопка по всему югу с использованием хлопковых джинов увеличил количество рабочей силы, необходимой для сбора хлопка , но новые федеральные законы запрещали импорт дополнительных рабов из -за рубежа. Десятилетия монокультурного табачного сельского хозяйства также ухудшило Вирджинии продуктивность сельского хозяйства . [ 50 ] Чтобы извлечь выгоду из этой ситуации, плантации Вирджинии все чаще обращались к экспортированию рабов , которые разбивали бесчисленные семьи и делали размножение рабов , часто благодаря изнасилованию, прибыльному бизнесу для своих владельцев. [ 51 ] [ 52 ] Рабы в районе Ричмонда также были вынуждены на промышленные рабочие места, включая добычу и судостроение. [ 53 ] Неудача рабовладельцев Габриэля Проссера в 1800 году, Джорджа Боксли в 1815 году и Нат Тернера в 1831 году, однако, ознаменовало растущее сопротивление системе рабства. Опасаясь дальнейших восстаний, правительство Вирджинии в 1830 -х годах поощряло свободных чернокожих мигрировать в Либерию . [ 50 ]

16 октября 1859 года аболиционист Джон Браун провел рейд на арсенал в Харперс -Ферри, штат Вирджиния , в попытке начать восстание рабов в южных штатах. Поляризованный национальный ответ на его рейд, захват, судебный процесс и казнь в Чарльз -Тауне , что декабрь ознаменовало переломный момент для многих, кто полагал, что конец рабства должен быть достигнут силой. [ 54 ] Выборы Авраама Линкольна в 1860 году еще больше убедили многих южных сторонников рабства в том, что его оппозиция его расширению в конечном итоге будет означать конец рабства по всей стране. В Южной Каролине первый штат, который отделился, чтобы сохранить институт рабства , полка, преданного недавно сформированным конфедеративным государствам Америки, изъяли Форт Самтер 14 апреля 1861 года, побудив президента Линкольна призвать федеральную армию из 75 000 человек из штата ополченцы на следующий день. [ 55 ]

В Вирджинии специальная конвенция , вызванная законодательным органом, проголосовала 17 апреля в соответствии с условиями, оно было одобрено на референдуме в следующем месяце. Затем Конвенция проголосовала за присоединение к Конфедерации, которая назвала Ричмонд своей столицей 20 мая. [ 46 ] Во время референдума 23 мая вооруженные проконтравтные группы предотвращали кастинг и подсчет голосов из областей, которые выступали против отделения. В этом месяце представители 27 из этих северо -западных округов начали конвенцию о колесных , которая организовала правительство, лояльное к Союзу и привело к разделению Западной Вирджинии в качестве нового штата. [ 56 ]

Армии Союза и Конфедерации впервые встретились 21 июля 1861 года, в битве при Булл -Ран недалеко от Манассаса, штат Вирджиния , где кровавая победа Конфедерации установила, что война не будет легко решена. Генерал профсоюза Джордж Б. Макклеллан организовал армию Потомака , которая приземлилась на полуострове Вирджиния в марте 1862 года и достиг окраины Ричмонда в июне в июне. В связи с тем, что генерал -конфедерат Джозеф Э. Джонстон ранен в борьбе за пределами города, командование его армией Северной Вирджинии упало на Роберта Э. Ли . В течение следующего месяца Ли поехал в армию Союза обратно , и начиная с сентября возглавлял первое из нескольких вторжений на территорию Союза. В течение следующих трех лет войны в Вирджинии сражались больше сражений, чем где -либо еще, включая битвы за Фредериксбург , Кансллорсвилл , Спотсильванию и заключительную битву при Аппоматтоксском суде , где Ли сдался 9 апреля 1865 года. [ 57 ] После захвата Ричмонда в этом месяце государственные лидеры, преданные конфедерации, переехали в Линчберг , [ 58 ] в то время как руководство Конфедерации бежало в Данвилл . [ 59 ] 32 751 вирджиния погибли в гражданской войне . [ 60 ]

Реконструкция и Джим Кроу

Вирджиния была официально восстановлена в Соединенных Штатах в 1870 году из -за работы комитета девяти . [ 62 ] Во время послевоенной эпохи реконструкции афроамериканцы смогли объединиться в общинах, особенно вокруг Ричмонда , Данвилла и региона Приливной воды , и играть большую роль в обществе Вирджинии, как многие достигли некоторых земель в 1870-х годах. [ 63 ] [ 64 ] Вирджиния приняла конституцию в 1868 году, которая гарантировала политические, гражданские права и права голоса , и предоставила бесплатные государственные школы. [ 65 ] Однако, поскольку многие железнодорожные линии и другие инвестиции в инфраструктуру были уничтожены во время гражданской войны, Содружество было глубоко в долгах, и в конце 1870 -х годов перенаправляли деньги в государственных школах для оплаты владельцев облигаций. Партия ReadJuster сформировалась в 1877 году и выиграла законодательную власть в 1879 году, объединив чернокожих и белых вирджинцев за общей оппозицией выплат долга и воспринимаемых элит плантации . [ 66 ]

Readjusters сосредоточились на создании школ, таких как Virginia Tech и Virginia State , и успешно вынудили Западную Вирджинию поделиться в предварительном долге. [ 67 ] Но в 1883 году они были разделены на предложенную отмену законов о борьбе с грифом , и за несколько дней до выборов этого года, бунта в Данвилле , с участием вооруженных полицейских, оставили четырех чернокожих мужчин и одного белого человека погибшего. [ 68 ] Эти события побуждали белых сторонников превосходства в захват политической власти посредством подавления избирателей , и сегреганисты в Демократической партии выиграли законодательный орган в этом году и сохранили контроль на протяжении десятилетий. [ 69 ] Они приняли законы Джима Кроу , которые установили расово сегрегированное общество , и в 1902 году переписали государственную конституцию , чтобы включить налог на опрос и другие меры регистрации избирателей, которые эффективно лишены гражданских прав большинства афроамериканцев и многих бедных белых. [ 70 ]

Тем временем новые экономические силы будут индустриализовать Содружество. Вирджинский Джеймс Альберт Бонсак изобрел табачную сигаретную машину в 1880 году, что привело к новому крупномасштабному производству, сосредоточенному на Ричмонде. Железнодорожный магнат Коллис Поттер Хантингтон основал Newport News Shipbuilding в 1886 году, который отвечал за строительство шести дредноутов , семи линейных кораблей и 25 эсминцев для военно -морского флота США в период с 1907 по 1923 год. [ 71 ] Во время мировой войны Первой немецкие подводные лодки, такие как U-151, атаковали суда за пределами порта, [ 72 ] который был основным местом для транспортировки как солдат, так и припасов. [ 61 ] После войны, парад возвращения в афроамериканцы, возвращающиеся с службы, был атакован в июле 1919 года полицией афроамериканцев в рамках обновленного движения белой супремии, которое было известно как красное лето . [ 73 ] Середина продолжала строить крейсеры и авианосцы во войне дозонные рабочие силы до 70 . Второй мировой и к 1943 году увеличила свои 000 [ 74 ] В то время как на турпедной фабрике в Александрии было более 5050 лет. [ 75 ] Многие из которых были афроамериканцами, поскольку президент Рузвельт приказал десегрегации оборонной промышленности в 1941 году. [ 76 ]

Гражданские права на представление

16-летняя Барбара Роуз Джонс начала удар в 1951 году против недофинансированных сегрегированных школ в округе Принс Эдвард . Протесты побудили коренных жителей Ричмонда Споттсвуд Робинсон и Оливер Хилл подать иск против округа . Их дело присоединилось к Браун против Совета по образованию в Верховном суде, которое отклонило доктрину « отдельного, но равного » в 1954 году. Сегрегационное учреждение, возглавляемое сенатором Гарри Ф. Бердом и его организацией Берда , отреагировало с стратегией под названием « Массивное Сопротивление », и Генеральная Ассамблея приняла пакет законов в 1956 году, который сокращал финансирование местных школ, которые десегрегировали . Это заставило школы начать закрытие в сентябре 1958 года. Государственные и районные суды затем правили стратегией неконституционной, и 2 февраля 1959 года чернокожие учащиеся интегрировали школы в Арлингтоне и Норфолке , где они были известны как Норфолк 17 . [ 77 ] Однако лидеры графства принца Эдварда все еще отказались подчиняться и вместо этого закрыли свою школьную систему в июне 1959 года. Он оставался закрытым в течение следующих пяти лет, пока судебные разбирательства против них не достигли Верховного суда, где округу было приказано вновь открыть и интегрировать их государственные школы, которые наконец произошли в сентябре 1964 года. [ 78 ] [ 79 ]

Федеральный принятие Закона о гражданских правах в июне 1964 года и Закон о правах голоса в августе 1965 года и их более позднее исполнение Министерства юстиции помогли положить конец расовой сегрегации в Вирджинии и опрокинуть законы штата Джима Кроу . [ 80 ] В июне 1967 года Верховный суд также отказался от запрета штата в межрасовом браке с Loving v. Virginia . В 1968 году губернатор Миллс Годвин назвал комиссию для переписывания государственной конституции. Новая конституция, которая запретила дискриминацию и удалила статьи, которые в настоящее время нарушили федеральный закон, приняли на референдуме с 71,8% поддержкой и вступили в силу в июне 1971 года. [ 81 ] В 1977 году черные члены стали большинством городского совета Ричмонда; В 1989 году Дуглас Уайлдер стал первым афроамериканцем, избранным губернатором в Соединенных Штатах; А в 1992 году Бобби Скотт стал первым черным конгрессменом из Вирджинии с 1888 года. [ 82 ] [ 83 ]

Расширение федеральных правительственных учреждений в пригород Северной Вирджинии во время холодной войны повысило население региона и экономику. [ 84 ] Центральное разведывательное агентство переворачивало свои офисы в туманном дне во время Корейской войны и переехали в Лэнгли в 1961 году, отчасти из -за решения Совета по национальной безопасности , которое агентство переехало за пределы округа Колумбия. [ 85 ] Агентство участвовало в различных событиях холодной войны , и его штаб -квартира была целью советской шпионской деятельности . Пентагон , построенный в Арлингтоне во время Второй мировой войны в качестве штаб -квартиры Министерства обороны, была одной из целей нападений 11 сентября 2001 года ; 189 человек погибли на месте, когда в здание влетело самолет реактивного пассажира. [ 86 ] Массовые расстрелы в Virginia Tech в 2007 году и в Вирджиния -Бич в 2019 году привели к принятию мер по борьбе с оружием в 2020 году. [ 87 ] Расовая несправедливость и присутствие памятников Конфедерации в Вирджинии также привели к крупным демонстрациям, в том числе в августе 2017 года, когда белый сторонник превосходства въехал на своей машине в протестующих , убив одну, и в июне 2020 года, когда протесты, которые были частью более крупных чернокожих. Matter Movement привело к удалению статуй на проспекте памятников в Ричмонде и в других местах. [ 88 ]

География

Вирджиния расположена в середине Атлантической и юго-восточной части Соединенных Штатов. [ 89 ] [ 90 ] Вирджиния имеет общую площадь 42 774,2 квадратных миль (110 784,7 км 2 ), включая 3180,13 квадратных миль (8 236,5 км 2 ) воды, что делает его 35-м по величине государством по площади. [ 91 ] Содружество граничит с Мэрилендом и Вашингтоном, округ Колумбия на севере и востоке; Атлантическим океаном на востоке; к Северной Каролине на юге; Теннесси ; на юго -запад Кентукки ; на западе и по Западной Вирджинии на севере и западе. Граница Вирджинии с Мэрилендом и Вашингтоном, округ Колумбия, распространяется на низкую отметку на южном берегу реки Потомак . [ 92 ]

Южная граница Вирджинии была определена в 1665 году как 36 ° 30 'северной широты . Группы, отмечающие границу с Северной Каролиной в 18 -м веке, однако, начали свою работу примерно в 3,5 милях (5,6 км) на севере и дрейфовали еще 3,5 мили по самой западной точке границы , вероятно, из -за проблем с оборудованием и инструкций по использованию природных ориентиров, когда это возможно, когда это возможно. Полем [ 93 ] После того, как Теннесси присоединился к США в 1796 году, новые геодезисты работали в 1802 и 1803 годах, чтобы сбросить свою границу с Вирджинией в качестве линии от вершины белой вершины горы до вершины вершины Три-Стейт в Камберлендских горах . Однако отклонения в этой границе были идентифицированы, когда она была пересмотрена в 1856 году, а Генеральная Ассамблея Вирджинии предложила новую комиссию по обследованиям в 1871 году. Представители Теннесси предпочли сохранить меньшую линию 1803 года, а в 1893 году- высшее США. Суд постановил их против Вирджинии . [ 94 ] [ 95 ] Одним из результатов является то, как город Бристоль разделен на два между штатами. [ 96 ]

Геология и местность

Чесапикский залив отделяет смежную часть Содружества от полуострова из двух округов восточного берега Вирджинии . Залив был сформирован из утонувшей долины реки древней реки Саскуэханна . [ 98 ] Многие из рек Вирджинии текут в Чесапикский залив, в том числе Потомак , Раппаханнок , Йорк и Джеймс , которые создают три полуострова в заливе, традиционно называемые «шеей», названные северной шеей , Средний полуостров и полуостров Вирджинии с севера к северу к северу к северу на север. юг. [ 99 ] Повышение уровня моря разрушило землю на островах Вирджинии, которая включает в себя остров Тангер в заливе и Чинкотигу , один из 23 барьеров на Атлантическом побережье. [ 100 ] [ 101 ]

- Приливная вода это прибрежная равнина между Атлантическим побережьем и линией осени . Он включает в себя восточный берег и основные устья Чесапикского залива. Piedmont представляет собой серию осадочных и магматических на основе предгорье горных пород к востоку от гор, которые были образованы в мезозойскую эпоху. [ 102 ] Регион, известный своей тяжелой глиняной почвой, включает в себя юго -западные горы вокруг Шарлоттсвилля . [ 103 ] Горы Голубого хребта являются физиографической провинцией Аппалачских гор с самыми высокими точками в Содружестве, самым высоким из которых была гора Роджерс на 5729 футов (1746 м). [ 2 ] Регион хребта и Valley находится к западу от гор, карбонатной скалы , и включает в себя горный хребет Массануттен и Великую Аппалачская долина , которая называется долиной Шенандоа в Вирджинии, названной в честь одноименной реки , которая течет через него Полем [ 104 ] Плато Камберленд и горы Камберленд находятся в юго -западном углу Вирджинии, к югу от плато Аллегейни . В этом регионе реки протекают на северо -запад с дендритной дренажной системой в бассейн реки Огайо . [ 105 ]

не Сейсмическая зона Вирджинии имела истории регулярной землетрясения . Землетрясения редко выше 4,5 в величине , потому что Вирджиния расположена вдали от краев североамериканской плиты . Самое большое землетрясение Содружества по крайней мере за столетие на уровне 5,8, поразившее Центральную Вирджинию 23 августа 2011 года , недалеко от Минерала . [ 106 ] Из -за геологических свойств района это землетрясение ощущалось от северной Флориды до южного Онтарио . [ 107 ] 35 миллионов лет назад болид повлиял на то, что сейчас является Восточной Вирджинии. Полученный в результате кратер Чесапик -Бей может объяснить, какие землетрясения и оседание испытывает регион. [ 108 ] Метеорный удар также теоретизируется как источник озера Драммонд , крупнейшего из двух натуральных озер в штате . [ 109 ]

Карбонатная порода Содружества заполнена более чем 4000 пещер из известняка , десять из которых открыты для туризма, включая популярные пещеры Luray и пещеры Skyline . [ 110 ] Вирджинии Знаменитый натуральный мост также является оставшейся крышей из рухнутой известняковой пещеры. [ 111 ] Угольная добыча проходит в трех горных регионах в 45 различных угольных руслах вблизи мезозойских бассейнов. [ 112 ] Более 72 миллионов тонн других нетоловых ресурсов, таких как Slate , Kyanite , Sand или Gravel, также были добыты в Вирджинии в 2020 году. [update]. [ 113 ] Крупнейшие известные месторождения урана в США находятся под Коулс -Хилл, штат Вирджиния . Несмотря на проблему, которая дважды достигла Верховного суда США , штат запрещал свою добычу с 1982 года из -за проблем с охраной окружающей среды и общественного здравоохранения. [ 114 ]

Климат

| В среднем штат Вирджиния 1895–2023 гг. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Климатическая карта ( объяснение ) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Вирджиния имеет влажный субтропический климат , который переходит к влажному континентальному западу от гор Голубого хребта . [ 115 ] Сезонные крайности варьируются от средних минимумов 25 ° F (-4 ° C) в январе до среднего максимума 86 ° F (30 ° C) в июле. [ 116 ] Атлантический океан и ручья океана оказывают сильное влияние на восточные и юго -восточные прибрежные районы Содружества, что делает климат там теплее, но также и более постоянным. Большая часть зарегистрированных крайностей Вирджинии в температуре и осадках произошла в горах Голубого хребта и в районах на запад. [ 117 ] Вирджиния ежегодно получает в среднем 43,47 дюйма (110 см) осадков, [ 116 ] С долиной Шенандоа является самой сухим регионом штата из -за гор с обеих сторон. [ 117 ]

Вирджиния имеет около 35–45 дней с грозами ежегодно, и штормы распространены в ближайшее время и вечера в период с апреля по сентябрь. [ 118 ] Эти месяцы также являются наиболее распространенными для торнадо , [ 119 ] восемь из которых приземлились в Содружестве в 2023 году. [ 120 ] Ураганы и тропические штормы могут происходить с августа по октябрь, и, хотя они обычно влияют на прибрежные регионы, самой смертоносной катастрофой в Вирджинии стало ураган Камиль , в результате которого в 1969 году погибли более 150 человек в округе Нельсон . [ 117 ] [ 121 ] В период с декабря по март, холодный атмосферный затухание , вызванное Аппалачскими горами, может привести к значительным снегопадам по всему штату, таким как Blizzard за январь 2016 года , которая создала самый высокий однодневный снегопад штата в 36,6 дюйма (93 см) возле Блюмонта . [ 122 ] [ 123 ] В среднем города Вирджинии могут ежегодно получать от 5,8–12,3 дюйма (15–31 см) снега, но недавние зимы наблюдались ниже среднего снегопада, и большая часть Вирджинии не смогла зарегистрировать какой-либо измеримый снег во время зимнего сезона 2022–2023 гг. Полем [ 124 ] [ 125 ]

Частично это связано с изменением климата в Вирджинии , что приводит к более высоким температурам круглый год, а также к большему дождю и наводнениям. [ 126 ] Городские острова тепло можно найти во многих городах Вирджинии и пригородах, особенно в районах, связанных с историческим красным линином . [ 127 ] [ 128 ] Воздух в Вирджинии статистически улучшился с 1998 года, когда в горах Голубого хребта [ 129 ] Как и количество дней Orange Days для высокого озона загрязнения в округе Фэрфакс , с 64,8. В 2023 году Fairfax, как и соседние округа Арлингтон и Лоудоун , записал всего три дня кода Orange. [ 130 ] Закрытие и преобразование угольных электростанций в Вирджинии и регионе долины Огайо помогли сократить количество твердых частиц в воздухе Вирджинии пополам, от 13,5 мкм на кубический метр в 2003 году, когда уголь обеспечил 49,3% электроэнергии Вирджинии , до 6,6 в. 2023, [ 131 ] Когда уголь обеспечил всего 1,5%, за возобновляемыми источниками энергии, такие как солнечная энергия и гидроэлектростанция . [ 132 ] [ 133 ] Текущие планы требуют, чтобы 30% электричества Содружества было возобновляемым к 2030 году, а к 2050 году-без углерода. [ 134 ]

Экосистема

Леса покрывают 62% Вирджинии по состоянию на 2021 год [update], из которых 80% считаются лиственными лесами, что означает, что деревья в Вирджинии в основном лиственные и широко оформленные . Остальные 20% - сосна, с ломболи и сосновой сосновой, доминирующей в большей части центральной и восточной Вирджинии. [ 136 ] В западных и горных частях Содружества дуб и гикори наиболее распространены, в то время как более низкие высоты с большей вероятностью имеют небольшие, но плотные стойки, любящих влагу, в изобилии. [ 117 ] Губчатая моль, заражения в дубах и упадок в каштановых деревьях, уменьшили оба их числа, оставив больше места для Гикори и инвазивного дерева небес . [ 137 ] [ 117 ] В низменной приливной воде и Пьемонте желтые сосны, как правило, доминируют, с лысыми водно -болотными лесами в великолепных мрачных и ноттовайских болотах. [ 136 ] Другие распространенные деревья включают красную ель, атлантический белый кедр , тюльпа-поплатор и цветущий кизил , государственное дерево и цветок , а также ивы, пепел и лавры. [ 138 ] Растения, такие как молочно -водоросли , одуванчики, ромашки, папоротники и вирджиния , которые представлены на государственном флаге , также распространены. [ 139 ] Район дикой природы Томпсона в Фокье известен тем, что имеет одну из крупнейших популяций полевых цветов Триллия во всей Северной Америке. [ 117 ]

Белый оленей , один из 75 видов млекопитающих, обнаруженный в Вирджинии, отскочил от приблизительно 25 000 человек в 1930-х годах до более миллиона к 2010-м годам. [ 140 ] [ 141 ] Среди местных карниворанов входят черные медведи , которые в штате составляют около пяти -шести тысяч. [ 142 ] Помимо рыб , койоты , серые и красные лисы , еноты , ласки и скунсы . Грызуны включают в себя сурок , нутрию , бобры , серые белки и белки лисы , бурундуки и Аллегейни Вуратс , в то время как семнадцать видов летучих мышей включают коричневые летучих мышей и бит-летучую мышь Вирджинии , государственное млекопитающее . [ 143 ] [ 141 ] Вирджиния Опоссум также является единственным уходным уроженцем Соединенных Штатов и Канады, [ 144 ] и местный аппалачский халат был признан в 1992 году как отдельный вид кролика, один из трех, найденных в штате. [ 145 ] Киты, дельфины и свинья также были зарегистрированы в прибрежных водах Вирджинии, причем аварийные дельфины являются наиболее частыми водными млекопитающими . [ 141 ]

Птичья фауна Вирджинии состоит из 422 подсчета видов, из которых 359 регулярно встречаются, а 214 разводятся в Вирджинии, в то время как остальные - в основном зимние жители или переходные процессы . [ 146 ] Водные птицы включают в себя песочницы, деревянные утки и железнодорожные железы Вирджинии , в то время как обычные примеры внутренних веществ включают камышевки, дятлы и кардиналы, государственная птица . Птицы добычи включают Osprey, широкие ястребы и зарешенные совы . [ 147 ] Нет никаких видов птиц, эндемичных для Содружества. [ 146 ] Одюбон признает 21 важные области птиц в штате. [ 148 ] Перегриновые соколы , чьи числа резко снизились из -за ДДТ отравления пестицидами в середине 20 -го века, являются центром усилий по сохранению в штате и программы реинтродукции в национальном парке Шенандоа . [ 149 ]

Вирджиния имеет 226 видов пресноводных рыб из 25 семей, разнообразие, связанного с разнообразным и влажным климатом, топографией, взаимосвязанной речной системой и отсутствием плейстоценовых ледников . Обычные примеры на плато Камберленд и регионов высшего уровня включают в себя восточную черную дэсу , скульптур , малый бас , Redhorse Sucker , Kanawha Darter и Brook Frout , государственная рыба . Вниз по склону в Пьемонте, полосатый сад и роанок, становятся обычными, как и болотные рыбы , блюзовые солнечные рыбы и пиратский окунь в приливной воде . [ 150 ] Чесапикский залив владеет моллюсками, устрицами и 350 видами соленой воды и устьевой рыбы , включая самые обильные рыбы залива, залив Анчоус , а также инвазивный голубой соп . [ 151 ] [ 152 ] По оценкам, 317 миллионов Чесапик -Голубые крабы живут в заливе с 2024 года [update]. [ 153 ] Есть 34 местных вида раков, таких как большой песчаный , который часто обитает в скалистых руслах. [ 154 ] [ 117 ] Амфибии, найденные в Вирджинии, включают Саламандре Камберлендского плато и Восточный Албендер , [ 155 ] в то время как северная водная змея является наиболее распространенным из 32 видов змей. [ 156 ]

Защищенные земли

По состоянию на 2019 год [update], примерно 16,2% земель в Содружестве защищены федеральными, государственными и местными органами власти и некоммерческими организациями. [ 158 ] Федеральные земли составляют большинство, с тридцатью подразделениями Службы национальных парков в штате, таких как Парк Грейт -Фолс и Аппалачская тропа , и один национальный парк, Шенандоа . [ 159 ] Шенандоа был основан в 1935 году и охватывает живописное горизонт . Почти сорок процентов от общего числа парка 199 173 акров (806 км 2 ) Район был обозначен как дикая местность в рамках Национальной системы сохранения дикой природы . [ 160 ] управляет Лесная служба США национальными лесами Джорджа Вашингтона и Джефферсона , которые охватывают более 1,6 миллиона акров (6500 км 2 ) в горах Вирджинии и продолжитесь в Западной Вирджинии и Кентукки . [ 161 ] Большой мрачный национальный заповедник дикой природы также распространяется на Северную Каролину, как и Национальный заповедник дикой природы Бэк -Бэй , который отмечает начало внешних банков . [ 162 ]

Государственные агентства контролируют около трети охраняемых земель в штате, [ 158 ] А Департамент сохранения и отдыха Вирджинии управляет более 75 900 акров (307,2 км 2 ) в сорок штатных парков Вирджинии и 59 222 акра (239,7 км 2 ) в 65 природных заповедниках плюс три неразвитых парка. [ 163 ] [ 164 ] Межгосударственный парк перерывает границу Кентукки и является одним из двух межгосударственных парков в Соединенных Штатах. [ 165 ] Устойчивые лесозаготовки разрешено в 26 государственных лесах, управляемых Департаментом лесного хозяйства Вирджинии на общую сумму 71 972 акра (291,3 км 2 ), [ 166 ] Как и охота в 44 районах управления дикой природой, управляемыми Департаментом дикой природы Вирджинии, охватывающим более 205 000 акров (829,6 км 2 ). [ 167 ] Чесапикский залив не является национальным парком, но защищен как государственным, так и федеральным законодательством и межгосударственной программой Чесапикского залива , которая проводит восстановление в заливе и его водоразделе. [ 168 ]

Города и города

Вирджиния разделена на 95 округов и 38 независимых городов , которые Бюро переписей США описывает как окружные эквиваленты . [ 169 ] Этот общий метод обработки городов и округов наравне друг с другом уникален для Вирджинии и возвращается к влиянию города Уильямсбург и Норфолк в колониальный период. [ 170 ] Только три других независимых города существуют в других частях Соединенных Штатов, каждый из которых в другом штате. [ 171 ] Различия между округами и городами в Вирджинии невелики и связаны с тем, как каждый оценивает новые налоги, необходимо ли референдум для выпуска облигаций, и с применением правления Диллона , что ограничивает полномочия городов и округов, чтобы противостоять действиям прямо разрешен Генеральной Ассамблеей . [ 172 ] [ 173 ] Округа также могут включать города , и, хотя нет никаких дополнительных административных подразделений , таких как деревни или поселки, Бюро переписей признает несколько сотен некорпоративных сообществ .

Более трех миллионов человек, 35% вирджинцев, живут в двадцати юрисдикциях, в совокупности, которые все вместе определяются как Северная Вирджиния , которая является частью более крупного столичного района Вашингтона и северо -восточного мегаполиса . [ 174 ] [ 175 ] Округ Фэрфакс с более чем 1,1 миллионами жителей является самой густонаселенной юрисдикцией Вирджинии, [ 176 ] и имеет крупный городской бизнес и торговый центр в Тайсоне , крупнейшем офисном рынке Вирджинии. [ 177 ] Соседний графство принца Уильям с более чем 450 000 жителей, является вторым по численным густонаселенным графством Вирджинии, а до дома на базе морской пехоты Квантико , Академии ФБР и Национальным парком битвы Манассас . Округ Арлингтон -самый маленький округ самоуправления в США по сухопутной площадке, [ 178 ] и местные политики предложили реорганизовать его как независимый город из -за его высокой плотности. [ 172 ] Округ Лоудоун , с его округом в Лисбурге , является самым быстрорастущим округом в штате. [ 176 ] [ 179 ] В Западной Вирджинии, городе Роаноке и округе Монтгомери , входящей в мегаполитен Блэксбург -христюргсбург , оба превысили население более 100 000 с 2018 года. [ 180 ]

На западном краю региона Tidewater находится столица Вирджинии, Ричмонд , которая насчитывает около 230 000 в своем собственном городе и более 1,3 миллиона человек в его столичном районе. На восточном краю находится столичный район Хэмптон -Роудс , где более 1,7 миллиона проживают в шести округах и девяти городах, в том числе три самых густонаселенных независимых города Содружества: Вирджиния -Бич , Чесапик и Норфолк . [ 174 ] [ 181 ] Соседний Саффолк , который включает в себя часть великого мрачного болота , является крупнейшим городом в районе площадью 429,1 квадратных миль (1111 км 2 ). [ 182 ] Одна из причин концентрации независимых городов в регионе приливной воды заключается в том, что несколько сельских округов, которые там были включены как города или консолидированы с существующими городами, чтобы попытаться удержать свои новые пригородные районы, которые начались в 1950-х годах , с таких городов, как Норфолк и и Портсмут смог аннексировать землю из соседних округов до моратория в 1987 году. [ 183 ] Другие, такие как Поккосон , стали городами, чтобы попытаться сохранить расовую сегрегацию в своих школах и районах в эпоху десегрегации 1970 -х годов. [ 184 ]

Крупнейшие столичные и микрополитические статистические районы в Вирджинии

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Классифицировать | Имя | Поп | Классифицировать | Имя | Поп | ||||

Северная Вирджиния  Хэмптон Роудс |

1 | Северная Вирджиния | 3,154,735 | 11 | Данвилл | 101,408 |  Ричмонд  Роанок | ||

| 2 | Хэмптон Роудс | 1,727,503 | 12 | Бристоль | 92,290 | ||||

| 3 | Ричмонд | 1,349,732 | 13 | Мартинсвилл | 63,465 | ||||

| 4 | Роанок | 314,314 | 14 | Тазевелл | 39,120 | ||||

| 5 | Линчберг | 264,590 | 15 | Озеро леса | 38,574 | ||||

| 6 | Шарлоттсвилль | 225,127 | |||||||

| 7 | Блэксбург -христиансбург | 181,428 | |||||||

| 8 | Харрисонбург | 137,650 | |||||||

| 9 | Стоунтон -Уэйнесборо | 127,344 | |||||||

| 10 | Винчестер | 123,611 | |||||||

Демография

| Перепись | Поп | Примечание | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 691,737 | — | |

| 1800 | 807,557 | 16.7% | |

| 1810 | 877,683 | 8.7% | |

| 1820 | 938,261 | 6.9% | |

| 1830 | 1,044,054 | 11.3% | |

| 1840 | 1,025,227 | −1.8% | |

| 1850 | 1,119,348 | 9.2% | |

| 1860 | 1,219,630 | 9.0% | |

| 1870 | 1,225,163 | 0.5% | |

| 1880 | 1,512,565 | 23.5% | |

| 1890 | 1,655,980 | 9.5% | |

| 1900 | 1,854,184 | 12.0% | |

| 1910 | 2,061,612 | 11.2% | |

| 1920 | 2,309,187 | 12.0% | |

| 1930 | 2,421,851 | 4.9% | |

| 1940 | 2,677,773 | 10.6% | |

| 1950 | 3,318,680 | 23.9% | |

| 1960 | 3,966,949 | 19.5% | |

| 1970 | 4,648,494 | 17.2% | |

| 1980 | 5,346,818 | 15.0% | |

| 1990 | 6,187,358 | 15.7% | |

| 2000 | 7,078,515 | 14.4% | |

| 2010 | 8,001,024 | 13.0% | |

| 2020 | 8,631,393 | 7.9% | |

| 2023 (есть.) | 8,715,698 | 1.0% | |

| 1790–2020, [ 185 ] [ 186 ] 2023 [ 3 ] | |||

Бюро переписей США обнаружило, что население штата составляет 8 631 393 1 апреля 2020 года, что на 7,9% больше, чем перепись 2010 года . Еще 23 149 вирджинцев живут за рубежом, что дает государству общую численность населения 8 654 542. Вирджиния имеет четвертое по величине зарубежное население штатов США из-за своих федеральных служащих и военнослужащих. [ 187 ] Уровень фертильности в Вирджинии с 2020 года [update] было 55,8 на 1000 женщин в возрасте от 15 до 44 лет, [ 188 ] и средний возраст с 2021 года [update] Был такой же, как в среднем по стране 38,8 года, с самым старым городом в среднем возрасте - Джеймс -Сити и самым молодым из которых был Линчберг , где проживают несколько университетов. [ 181 ] Географический центр населения расположен к северо -западу от Ричмонда в графстве Ганновер , по состоянию на 2020 год [update]. [ 189 ]

Хотя с 2013 года все еще растут по мере того, как роды превышают смерть, негативная чистая миграция с 2013 года, причем на 8 995 человек покидают штат, чем переехали в него в 2021 году. Это в значительной степени приписывают высокие цены на жилье в Северной Вирджинии ,, чем [ 190 ] которые заставляют жителей переехать на юг, и хотя Роли является их главным пунктом назначения, миграция в штате из Северной Вирджинии в Ричмонд увеличилась на 36% в 2020 году и 2021 год по сравнению со среднегодовым в течение предыдущего десятилетия. [ 191 ] [ 192 ] Помимо Вирджинии, главным государством рождения вирджинцев является Нью -Йорк , обогнав Северную Каролину в 1990 -х годах, а на северо -востоке на северо -востоке наибольшее количество внутренних мигрантов в штат по региону. [ 193 ] Около двенадцати процентов жителей родились за пределами Соединенных Штатов по состоянию на 2020 год. [update]Полем Сальвадор является наиболее распространенной чужой стране рождения, с Индией , Мексикой , Южной Кореей , Филиппинами и Вьетнамом в качестве других распространенных мест рождения. [ 194 ]

Раса и этническая принадлежность

Самая густонаселенная расовая группа штата, неиспаноязычные белые , снизилась как доля населения с 76% в 1990 году до 58,6% в 2020 году, поскольку другие этнические группы увеличились. [ 195 ] [ 196 ] Иммигранты из острова Британия и Ирландия поселились по всему Содружеству в колониальный период, [ 197 ] Время, когда примерно три четверти иммигрантов стали наемными слугами . [ 198 ] Те, кто идентифицируется по переписи как « американская этническая принадлежность », преимущественно из английского происхождения, но у них есть предки, которые были в Северной Америке так долго, что они решили идентифицировать себя просто как американец. [ 199 ] [ 200 ] В Аппалачских горах и долине Шенандоа есть много поселений, которые были населены немецкими и шотландскими иммигрантами в 18-м и 19-м веках, часто следуя по Великой вагон-роуд . [ 201 ] [ 202 ] Более десяти процентов вирджинцев имеют немецкое происхождение с 2020 года [update]. [ 203 ]

Крупнейшей группой меньшинств в Вирджинии являются черные и афроамериканцы, которые включают около пятой численности населения. [ 196 ] Вирджиния была главным направлением атлантической работорговли , а первые поколения порабощенных мужчин, женщин и детей были доставлены в основном из Анголы и Бухта Биафры . Игбо была этническая группа того, что сейчас является южной Нигерии, крупнейшей африканской группой среди рабов в Вирджинии. [ 204 ] Чернокожие в Вирджинии также имеют больше европейского происхождения, чем в других южных штатах, и анализ ДНК показывает, что многие имеют асимметричный вклад мужского и женского происхождения до гражданской войны, свидетельствуя о европейских отцах и матерях афроамериканцев или коренных американцев во время рабства. [ 205 ] [ 206 ] Хотя чернокожие население было уменьшено благодаря великой миграции в северные промышленные города в первой половине 20 -го века, с 1965 года произошла обратная миграция чернокожих, возвращающихся на юг . [ 207 ] Содружество имеет самое большое количество черно-белых межрасовых браков в Соединенных Штатах , [ 208 ] и 8,2% вирджинцев описывают себя как многорасовые . [ 3 ]

Более поздняя иммиграция в конце 20 -го века и начале 21 -го века привела к новым общинам латиноамериканцев и азиатов. По состоянию на 2020 год [update]10,5% общей численности населения Вирджинии описывают себя как латиноамериканцев или латиноамериканцев и 8,8% азиатскими . [ 3 ] Латиноамериканское население штата выросло на 92% с 2000 по 2010 год, при этом две трети латиноамериканцев в штате проживают в Северной Вирджинии . [ 209 ] Северная Вирджиния также имеет значительную популяцию вьетнамских американцев , чья главная волна иммиграции последовала за войной во Вьетнаме . [ 210 ] Корейские американцы мигрировали там совсем недавно, привлеченной качественной школьной системой, [ 211 ] В то время как около 45 000 филиппинских американцев поселились в районе Хэмптон -Роудс, причем многие из них имеют связи с военно -морским флотом США и вооруженными силами. [ 212 ]

Членство в племени в Вирджинии осложняется наследием « геноцида карандаша » государства намеренно классифицировать коренных американцев и чернокожих вместе, и многие члены племени имеют африканское или европейское происхождение или оба. [ 214 ] В 2020 году Бюро переписей США обнаружило, что только 0,5% вирджинцев были исключительно американскими индейцами или уроженцами Аляски , хотя 2,1% были в некоторой комбинации с другими этническими группами. [ 196 ] Правительство штата расширило признание одиннадцать племен в Вирджинии. Семь племен также имеют федеральное признание, в том числе шесть, которые были признаны в 2018 году после принятия законопроекта, названного активистом Томасиной Джордан . [ 215 ] [ 216 ] Памунки воды и Маттапони имеют оговорки на притоки реки Йорк в регионе приливной . [ 217 ]

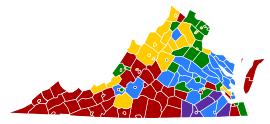

| Самая большая гонка округа или города | Раса и этническая принадлежность ( 2020 ) | Один | Общий |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Неиспаноязычный белый | 58.6% | 62.8% |

| Черный или афроамериканец | 18.3% | 20.1% | |

| Латиноамериканцы или латиноамериканцы (любой расы) | 10.5% | ||

| Азиатский | 7.1% | 8.6% | |

| Американский индейский и уроженец Аляски | 0.2% | 1.5% | |

| Другой | 0.6% | 1.5% | |

| Крупнейшая происхождение округа или города | Происхождение ( 2020 Est. ) | Общий | |

|

|

Ирландский или шотландский ирландский

|

10.4% | |

немецкий

|

10.3% | ||

Английский

|

9.8% | ||

Американец

|

9.4% | ||

Африканский африканский

|

2.3% | ||

Языки

В соответствии с данными переписи США по состоянию на 2022 год [update] На жителей Вирджинии в возрасте от пяти лет и старше 83% (6 805 548) говорят по -английски как на первом языке , а 17% (1 396 389) говорят что -то, кроме английского. Испанский язык является следующим наиболее распространенным языком: 7,5% (611 831) домохозяйств Вирджинии, хотя возраст является фактором, а 8,7% (120 560) вирджинии в возрасте до восемнадцати лет говорят по -испански. Из носителей испанского, 60,6% сообщили об английском «очень хорошо», но опять же, из тех, кто в возрасте до восемнадцати лет, 78,7% говорят по -английски «очень хорошо». Арабский язык был третьим наиболее распространенным языком с примерно 0,8% жителей, за которыми следуют китайские языки (включая стандартные мандаринские и кантонские ) и вьетнамцы с более чем 0,7%, а затем корейский и тагальский , чуть менее 0,7% и 0,6% соответственно. [ 218 ]

Английский был принят в качестве официального языка Содружества в 1981 году в 1981 году и снова в 1996 году, хотя статус не предписывается Конституцией Вирджинии . [ 219 ] В то время как более гомогенизированный американский английский находится в городских районах, а использование южных акцентов в целом наблюдается в снижении докладчиков, родившихся с 1960 -х годов, [220] various accents are still used around the commonwealth.[221] The Piedmont region is known for its non-rhotic dialect's strong influence on Southern American English, and a BBC America study in 2014 ranked it as one of the most identifiable accents in American English.[222] The Tidewater accent, sometimes described as a subset of the Old Virginia accent, evolved from the language that upper-class English typically spoke in the early Colonial period, while the Appalachian accent has much more influence from the English spoken by Scottish and Irish immigrants from that time.[221][223] The outward stereotypes of Appalachians has, however, led to some from the region code-switching to a less distinct English accent.[224] The English spoken on Tangier Island in the Chesapeake Bay, preserved by the island's isolation, contains many phrases and euphemisms not found anywhere else and retains elements of Early Modern English.[225][226]

Religion

Religious Tradition (2023)

Virginia enshrined religious freedom in 1786, in a statute written by Thomas Jefferson. Though the state is historically part of America's Bible Belt, the 2023 Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) survey estimated that 55% of Virginians either seldom or never attend religious services, ahead of the national average of 53.2%, and that the percent of Virginians unaffiliated with any particular religious body had increased from 21% in 2013 to 29% in 2023.[227] The 2020 U.S. Religion Census conducted by the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) similarly found that 55% of Virginians attend none of the state's 10,477 congregations.[228] Overall belief in God has also declined in the South region, of which Virginia is a part, from 93% of respondents in Gallup surveys from 2013 to 2017, to 86% in 2022.[229]

Of the 45% of Virginians who were associated with religious bodies in the 2020 ARDA census, Evangelical Protestants made up the largest overall grouping, with 20.3% of the state's population, while 8.1% and 2% were mainline and Black protestant respectively. Baptists, 84% of which are counted as Evangelical, included 9.4% of Virginians in that census.[230] Their major division is between the Baptist General Association of Virginia, which formed in 1823, and the Southern Baptist Conservatives of Virginia, which split off in 1996. Other Protestant branches with over one percent of Virginians included Pentecostalism (1.8%), Presbyterianism (1.3%), Anglicanism (1.2%), and Adventism (1%).[230] The 2023 PRRI survey estimated that 46% of Virginians were Protestants, with 14% each as White Evangelical, White Mainline, and Black, though these numbers include individuals who also report not attending services.[227]

Catholics accounted for 10.3% in the 2020 ARDA census,[230] and 16% in the 2023 PRRI survey, which divided them into 9% White Catholic, 6% Hispanic Catholic, and 1% other.[227] The Roman Catholic Diocese of Arlington includes most of Northern Virginia's Catholic churches, while the Diocese of Richmond covers the rest of the state. The Episcopal Diocese of Virginia, Southern Virginia, and Southwestern Virginia support the various Episcopal churches, while the Lutheran Church organizes under the Virginia Synod. Adherents of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints constitute just over one percent of the population, with 210 congregations in Virginia as of 2024[update].[232] While the state's Jewish population is small, organized Jewish sites date to 1789 with Congregation Beth Ahabah.[233]

Fairfax County is the state's most religiously diverse jurisdiction.[228] Fairfax Station is the site of the Ekoji Buddhist Temple, of the Jōdo Shinshū school, and the Hindu Durga Temple of Virginia. The All Dulles Area Muslim Society, on the county's border in Sterling, considers its eleven branches the country's second-largest Muslim mosque community.[234] McLean Bible Church, with around 16,500 weekly visitors, is among the top 25 largest megachurches in the U.S. and 8.4% of Virginians attend nondenomination Christian churches like it, according to the 2020 ARDA census.[235][230] Lynchburg and Roanoke ranked in that census as the two metropolitan areas with the highest rates of religious adherence, while the state-college-dominated Blacksburg–Christiansburg and Charlottesville were the lowest.[230] Two major Christian universities, Liberty University and the University of Lynchburg, are based in Lynchburg, while Regent University is in Virginia Beach.

Economy

Virginia's economy has diverse sources of income, including local and federal government, military, farming and high-tech. The state's average per capita income in 2022 was $68,211,[236] and the gross domestic product (GDP) was $654.5 billion, both ranking as 13th-highest among U.S. states.[237] The COVID-19 recession caused jobless claims due to soar over 10% in early April 2020,[238] before leaving off around 5% in November 2020 and returning to pre-pandemic levels in 2023.[239] In June 2024, the unemployment rate was 2.7%, which was the 6th-lowest nationwide.[240]

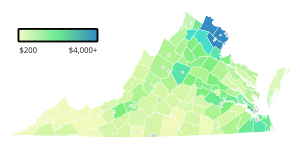

Virginia had a median household income of $80,615 in 2021, 11th-highest nationwide, and a poverty rate of 10.2%, 10th-lowest nationwide.[3] Montgomery County outside Blacksburg has the highest poverty rate in the state, with 28.5% falling below the U.S. Census poverty thresholds.[241] The Hampton Roads region has the state's highest per capita number of homeless individuals, with 11 per 10,000, as of 2020[update].[242] Loudoun County meanwhile has the highest median household income in the nation, and the wider Northern Virginia region is among the highest-income regions nationwide.[241] As of 2022[update], eighteen of the hundred highest-income counties in the United States, including the two highest, are located in Northern Virginia.[243] Though the Gini index shows Virginia has less income inequality than the national average,[244] the state's middle class is also smaller than the majority of states.[245]

Virginia's business environment has been ranked highly by various publications. CNBC ranked Virginia as their 2024 Top State for Business, with its deductions being mainly for the high cost of business and living,[246] while Forbes magazine ranked it as the sixteenth best to start a business in.[247] Additionally, in 2014 a survey of 12,000 small business owners found Virginia to be one of the most friendly states for small businesses.[248] Oxfam America however ranked Virginia in 2024[update] as only the 26th-best state to work in, with pluses for worker protections from sexual harassment and pregnancy discrimination, but negatives for laws on organized labor and the low tipped employee minimum wage of $2.13.[249] Virginia has been an employment-at-will state since 1906 and a "right to work" state since 1947,[250][251] and though state minimum wage increased to $12 in 2023, farm and tipped workers are specifically excluded.[252][249]

Government agencies

Government agencies directly employ around 714,100 Virginians as of 2022[update], almost 17% of all employees in the state.[253] Approximately 12% of all U.S. federal procurement money is spent in Virginia, the second-highest amount after California.[254][255] As of 2020[update], 125,648 active-duty personnel, 25,404 reservists, and 99,832 civilians work directly for the U.S. Department of Defense at the Pentagon or one of 27 military bases in the state, representing all major branches and covering 270,009 acres (1,092.69 km2).[256] Another 139,000 Virginians work for defense contracting firms,[257] which received $44.8 billion worth of contracts in the 2020 fiscal year.[256] Virginia has the second highest concentration of veterans of any state with 9.7% of the population, as many stay in the state and the Hampton Roads area in particular, which is home to the world's largest navy base and only NATO station on U.S. soil, Naval Station Norfolk.[258][256]

Other large federal agencies in Northern Virginia include the Central Intelligence Agency in Langley, the National Science Foundation and U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in Alexandria, the U.S. Geological Survey in Reston, and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service in Bailey's Crossroads. Virginia's state government employs over 106,000 public employees, who combined have a median income of $52,401 as of 2018[update],[259] with the Departments of Transportation and of Education the two largest state departments by expenditure.[260] K–12 teachers in Virginia make an annual average of $59,970, which is thirteen-lowest in the U.S. when adjusted for the state's cost of living as of the 2021–22 school year.[261]

Business

Based on data as of 2020[update], Virginia is home to 204,131 separate employers plus 644,341 sole proprietorships. Of the 144,431 registered non-farm businesses in 2017[update], 59.4% are majority male-owned, 22% are majority female-owned, 19.6% are majority minority-owned, and 8.9% are veteran-owned.[3] Twenty-four Fortune 500 companies are headquartered in Virginia as of 2024[update], with the largest companies by revenue being Freddie Mac, Boeing, RTX Corporation, Performance Food Group, and Capital One.[262] The two largest by number of employees are Dollar Tree in Chesapeake and Hilton Worldwide Holdings in McLean.[263]

Virginia has the third highest concentration of technology workers and the fifth highest overall number among U.S. states as of 2020[update], with the 451,268 tech jobs accounting for 11.1% of all jobs in the state and earning a median salary of $98,292.[264] Many of these jobs are in Northern Virginia, which hosts a large number of software, communications, and cybersecurity companies, particularly in the Dulles Technology Corridor and Tysons areas. Amazon additionally selected Crystal City for its HQ2 in 2018, while Google expanded their Reston offices in 2019.

Northern Virginia became the world's largest data center market in 2016, with over 47.7 million square feet (4.43 km2) as of 2023[update],[265] much of it in Loudoun County, which has branded itself "Data Center Alley".[266][267] Data centers in Virginia handled around one-third of all internet traffic and directly employed 13,500 Virginians in 2023 and supported 45,000 total jobs.[268] With 505.6 Mbit/s, Virginia boasted the second fastest average internet speed among U.S. states that year and ninth highest percent of households with broadband access, at 93.6%.[269][270] Computer chips first became the state's highest-grossing export in 2006,[271] and had an estimated export value of $740 million in 2022.[272] Though in the top quartile for diversity based on the Simpson index, only 26% of tech employees in Virginia are women, and only 13% are Black or African American.[264]

Tourists spent a record $33.3 billion in Virginia in 2023, an increase of 10% from the previous year, supporting an estimated 224,000 jobs, an increase of 13,000.[273] The state ranked as the eighth most visited based on data from 2022.[274] That year saw 745,000 international visitors, with 41% of those coming from Canada.[275]

Agriculture

As of 2021[update], agriculture occupies 30% of the land in Virginia with 7.7 million acres (12,031 sq mi; 31,161 km2) of farmland. Nearly 54,000 Virginians work on the state's 41,500 farms, which average 186 acres (0.29 sq mi; 0.75 km2). Though agriculture has declined significantly since 1960, when there were twice as many farms, it remains the largest industry in Virginia, providing for over 490,000 jobs.[277] Soybeans were the most profitable single crop in Virginia in 2022,[278] although the ongoing trade war with China has led many Virginia farmers to plant cotton instead of soybeans.[279] Other leading agricultural products include corn, cut flowers, and tobacco, where the state ranks third nationally in the production of the crop.[277][278]

Virginia is the country's third-largest producer of seafood as of 2021[update], with sea scallops, oysters, Chesapeake blue crabs, menhaden, and hardshell clams as the largest seafood harvests by value, and France, Canada, New Zealand, and Hong Kong as the top export destinations.[280] Commercial fishing supports 18,220 jobs as of 2020[update], while recreation fishing supports another 5,893.[281] The population of eastern oysters collapsed in the 1980s due to pollution and overharvesting, but has slowly rebounded, and the 2022–2023 season saw the largest harvest in 35 years with around 700,000 US bushels (25,000 kL).[282] A warm winter and a dry summer made the 2023 wine harvest one of the best for vineyards in the Northern Neck and along the Blue Ridge Mountains, which also attract 2.6 million tourists annually.[283][284] Virginia has the seventh-highest number of wineries in the nation, with 388 producing 1.1 million cases a year as of 2024[update].[285] Cabernet Franc and Chardonnay are the most grown varieties.[286] Breweries in Virginia also produced 460,315 barrels (54,017 kl) of craft beer in 2022, the 15th-most nationally.[287]

Taxes

State income tax is collected from those with incomes above a filing threshold. There are five income brackets, with rates ranging from 2.0% to 5.75% of taxable income.[288][289] The state sales and use tax rate is 4.3%, though there is an additional 1% local tax, for a total of a 5.3% combined sales tax on most purchases. Three regions then have a higher sales tax: 6% in Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads, and 7% in the Historic Triangle.[290] Unlike the majority of states, Virginia does have a 1% sales tax on groceries.[291] This was lowered from 2.5% in January 2023, when the items covered by this lower rate were also extended to include essential personal hygiene goods.[290][292]

Virginia's property tax is set and collected at the local government level and varies throughout the Commonwealth. Real estate is also taxed at the local level based on one hundred percent of fair market value.[293] As of 2021[update], the overall median real estate tax rate per $100 of assessed taxable value was $0.96, though for 72 of the 95 counties this number was under $0.80 per $100. Northern Virginia has the highest property taxes in the state, with Manassas Park paying the highest effective tax rate at $1.31 per $100, while Powhatan and Lunenburg counties were tied for the lowest, at $0.30.[294] Of local government tax revenue, about 61% is generated from real property taxes while 24% is from tangible personal property, sales and use, and business license tax. The remaining 15% come from taxes on hotels, restaurant meals, public service corporation property, and consumer utilities.[293]

Culture

Modern Virginian culture has many sources and is part of the culture of the Southern United States.[295] The Smithsonian Institution divides Virginia into nine cultural regions, and in 2007 used their annual Folklife Festival to recognize the substantial contributions of England and Senegal on Virginian culture.[296] Virginia's culture was popularized and spread across America and the South by figures such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Robert E. Lee. Their homes in Virginia represent the birthplace of America and the South.[297]

Besides the general cuisine of the Southern United States, Virginians maintain their own particular traditions. Virginia wine is made in many parts of the Commonwealth.[284] Smithfield ham, sometimes called "Virginia ham", is a type of country ham which is protected by state law and can be produced only in the town of Smithfield.[298] Virginia furniture and architecture are typical of American colonial architecture. Thomas Jefferson and many of the Commonwealth's early leaders favored the Neoclassical architecture style, leading to its use for important state buildings. The Pennsylvania Dutch and their style can also be found in parts of the Commonwealth.[201]

Literature in Virginia often deals with the Commonwealth's extensive and sometimes troubled past. The works of Pulitzer Prize winner Ellen Glasgow often dealt with social inequalities and the role of women in her culture.[299] Glasgow's peer and close friend James Branch Cabell wrote extensively about the changing position of gentry in the Reconstruction era, and challenged its moral code with Jurgen, A Comedy of Justice.[300] William Styron approached history in works such as The Confessions of Nat Turner and Sophie's Choice.[301] Tom Wolfe has occasionally dealt with his southern heritage in bestsellers like I Am Charlotte Simmons.[302] Mount Vernon native Matt Bondurant received critical acclaim for his historic novel The Wettest County in the World about moonshiners in Franklin County during prohibition.[303] Virginia also names a state Poet Laureate.[304]

Fine and performing arts

Virginia ranks near the middle of U.S. states in terms of public spending on the arts as of 2021[update], at just over half of the national average.[305] The state government does fund some institutions, including the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and the Science Museum of Virginia. Other museums include the popular Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the National Air and Space Museum and the Chrysler Museum of Art.[306] Besides these sites, many open-air museums are located in the Commonwealth, such as Colonial Williamsburg, the Frontier Culture Museum, and various historic battlefields.[307] The Virginia Foundation for the Humanities works to improve the Commonwealth's civic, cultural, and intellectual life.[308]

Theaters and venues in Virginia are found both in the cities and in suburbs. The Harrison Opera House, in Norfolk, is home of the Virginia Opera. The Virginia Symphony Orchestra operates in and around Hampton Roads.[309] Resident and touring theater troupes operate from the American Shakespeare Center in Staunton.[310] The Barter Theatre in Abingdon, designated the State Theatre of Virginia, won the first Regional Theatre Tony Award in 1948, while the Signature Theatre in Arlington won it in 2009. There is also a Children's Theater of Virginia, Theatre IV, which is the second-largest touring troupe in the nation.[311] Notable music performance venues include The Birchmere, the Landmark Theater, and Jiffy Lube Live.[312] Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts is located in Vienna and is the only national park intended for use as a performing arts center.[313]

Virginia is known for its tradition in the music genres of old-time string and bluegrass, with groups such as the Carter Family and Stanley Brothers achieving national prominence during the 1940s.[314] The state's African tradition is found through gospel, blues, and shout bands, with both Ella Fitzgerald and Pearl Bailey coming from Newport News.[315] Contemporary Virginia is also known for folk rock artists like Dave Matthews and Jason Mraz, R&B artists Chris Brown, D'Angelo, and Kali Uchis, hip hop stars like Pharrell Williams, Timbaland, Missy Elliott and Pusha T, as well as thrash metal groups like GWAR and Lamb of God.[316] Several members of country music band Old Dominion grew up in the Roanoke area, and took their band name from Virginia's state nickname.[317]

Festivals

Many counties and localities host county fairs and festivals. The Virginia State Fair is held at the Meadow Event Park every September. Also in September is the Neptune Festival in Virginia Beach, which celebrates the city, the waterfront, and regional artists. Norfolk's Harborfest, in June, features boat racing and air shows.[319] Fairfax County also sponsors Celebrate Fairfax! with popular and traditional music performances.[320] The Virginia Lake Festival is held during the third weekend in July in Clarksville.[321] On the Eastern Shore island of Chincoteague the annual Pony Penning of feral Chincoteague ponies at the end of July is a unique local tradition expanded into a week-long carnival.[318] Every year on Thanksgiving in Richmond, the Mattaponi and Pamunkey tribes present Virginia's governor with a tribute of deer in a celebration honoring colonial treaties that enshrined their hunting rights.[213]

The Shenandoah Apple Blossom Festival is a two-week festival held annually in Winchester which includes parades and bluegrass concerts. The Old Time Fiddlers' Convention in Galax, begun in 1935, is one of the oldest and largest such events worldwide, and Wolf Trap hosts the Wolf Trap Opera Company, which produces an opera festival every summer.[313] The Blue Ridge Rock Festival has operated since 2017, and has brought as many as 33,000 concert-goers to the Blue Ridge Amphitheater in Pittsylvania County.[322] Two important film festivals, the Virginia Film Festival and the VCU French Film Festival, are held annually in Charlottesville and Richmond, respectively.[323]

Law and government

In 1619, the first Virginia General Assembly met at Jamestown Church, and included 22 locally elected representatives, making Virginia's legislature the oldest of its kind in North America.[324] The elected members became the House of Burgesses in 1642, and governed with the Governor's Council, which was appointed by the British monarchy, until Virginians declared their independence from Britain in 1776. The government today functions under the seventh Constitution of Virginia, which was approved by voters in 1970 and went into effect in July 1971.[81] It is similar to the federal structure in that it provides for three branches: a strong legislature, an executive, and a unified judicial system.[325]

Virginia's legislature is bicameral, with a 100-member House of Delegates and 40-member Senate, who together write the laws for the Commonwealth. Delegates serve two-year terms, while senators serve four-year terms, with the most recent elections for both taking place in November 2023. The executive department includes the governor, lieutenant governor, and attorney general, who are elected every four years in separate elections, with the next taking place in November 2025. The governor must be at least thirty years old and incumbent governors cannot run for re-election, however the lieutenant governor and attorney general can, and governors can and have served non-consecutive terms.[326] The lieutenant governor is the official head of the Senate and is responsible for breaking ties. The House elects a Speaker of the House and the Senate elects a President pro tempore, who presides when the lieutenant governor is not present, and both houses elect a clerk and majority and minority leaders.[327] The governor also nominates their 16 cabinet members and others who head various state departments.[328]

The legislature starts regular sessions on the second Wednesday of every year. They meet for up to 48 days in odd years, which are election years, or 60 days in even years, to allow more time for biennial state budgets, which governors propose.[327][329] After regular sessions end, special sessions can be called either by the governor or with agreement of two-thirds of both houses, and 21 special sessions have been called since 2000, typically for legislation on preselected issues.[330] Though not a full-time legislature, the Assembly is classified as a hybrid because special sessions are not limited by the state constitution and often last several months.[331] A one-day "veto session" is also automatically triggered when a governor chooses to veto or return legislation to the Assembly with amendments. Vetoes can then be overturned with approval of two-thirds of both the House and Senate.[332] A bill that passes with two-thirds approval can also become law without action from the governor,[333] and Virginia has no "pocket veto", so bills become law if the governor chooses to neither approve nor veto them.[334]

Legal system

The judges and justices who make up Virginia's judicial system, also the oldest in America, are elected by a majority vote in both the House and Senate without input from the governor, one way Virginia's legislature is stronger than its executive. The governor can make recess appointments, and when both branches are controlled by the same party, the assembly often confirms them. The judicial hierarchy starts with the General District Courts and Juvenile and Domestic Relations District Courts, with the Circuit Courts above them, then the Court of Appeals of Virginia, and the Supreme Court of Virginia on top.[335] The Supreme Court has seven justices who serve 12-year terms, with a mandatory retirement age of 73, and they select their own chief justice, who is informally limited to two four-year terms.[336] Virginia was the last state to guarantee an automatic right of appeal for all civil and criminal cases, and its Court of Appeals increased from 11 to 17 judges in 2021.[337][338]