Новый Орлеан

Новый Орлеан Новый Орлеан ( французский ) Новый Орлеан ( луизианский креольский ) | |

|---|---|

| Nicknames: "The Crescent City", "The Big Easy", "The City That Care Forgot", "NOLA", "The City of Yes", "Hollywood South", "The Creole City" | |

Location within the U.S. state of Louisiana | |

| Coordinates: 29°58′34″N 90°4′42″W / 29.97611°N 90.07833°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Louisiana |

| Parish | Orleans |

| Founded | 1718 |

| Founded by | Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville |

| Named for | Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (1674–1723) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | LaToya Cantrell (D) |

| • Council | New Orleans City Council |

| Area | |

| • Consolidated city-parish | 349.85 sq mi (906.10 km2) |

| • Land | 169.42 sq mi (438.80 km2) |

| • Water | 180.43 sq mi (467.30 km2) |

| • Metro | 3,755.2 sq mi (9,726.6 km2) |

| Elevation | −6.5 to 20 ft (−2 to 6 m) |

| Population | |

| • Consolidated city-parish | 383,997 |

| • Density | 2,267/sq mi (875/km2) |

| • Urban | 963,212 (US: 49th) |

| • Urban density | 3,563.8/sq mi (1,376.0/km2) |

| • Metro | 1,270,530 (US: 45th) |

| Demonym | New Orleanian |

| GDP | |

| • Consolidated city-parish | $27.333 billion (2022) |

| • Metro | $94.031 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Area code | 504 |

| FIPS code | 22-55000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1629985 |

| Website | nola |

Новый Орлеан [а] (широко известный как NOLA или Big Easy среди других прозвищ) — объединенный город-приход, расположенный вдоль реки Миссисипи в юго-восточном регионе штата американского Луизиана . По данным переписи населения США 2020 года, население составляет 383 997 человек. [8] это самый густонаселенный город Луизианы и Луизиана ; французского региона [9] третий по численности населения город на Глубоком Юге ; и двенадцатый по численности населения город на юго-востоке США . Являясь крупным портом , Новый Орлеан считается экономическим и торговым центром всего региона побережья Мексиканского залива в Соединенных Штатах .

New Orleans is world-renowned for its distinctive music, Creole cuisine, unique dialects, and its annual celebrations and festivals, most notably Mardi Gras. The historic heart of the city is the French Quarter, known for its French and Spanish Creole architecture and vibrant nightlife along Bourbon Street. The city has been described as the "most unique" in the United States,[10][11][12][13] owing in large part to its cross-cultural and multilingual heritage.[14] Additionally, New Orleans has increasingly been known as "Hollywood South" due to its prominent role in the film industry and in pop culture.[15][16]

Founded in 1718 by French colonists, New Orleans was once the territorial capital of French Louisiana before becoming part of the United States in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. New Orleans in 1840 was the third most populous city in the United States,[17] and it was the largest city in the American South from the Antebellum era until after World War II. The city has historically been very vulnerable to flooding, due to its high rainfall, low lying elevation, poor natural drainage, and proximity to multiple bodies of water. State and federal authorities have installed a complex system of levees and drainage pumps in an effort to protect the city.[18][19]

New Orleans was severely affected by Hurricane Katrina in late August 2005, which flooded more than 80% of the city, killed more than 1,800 people, and displaced thousands of residents, causing a population decline of over 50%.[20] Since Katrina, major redevelopment efforts have led to a rebound in the city's population. Concerns have been expressed about gentrification, new residents buying property in formerly close-knit communities, and displacement of longtime residents.[21][22][23][24] Additionally, high rates of violent crime continue to plague the city with New Orleans experiencing 280 murders in 2022, resulting in the highest per capita homicide rate in the United States.[25][26]

The city and Orleans Parish (French: paroisse d'Orléans) are coterminous.[27] As of 2017, Orleans Parish is the third most populous parish in Louisiana, behind East Baton Rouge Parish and neighboring Jefferson Parish.[28] The city and parish are bounded by St. Tammany Parish and Lake Pontchartrain to the north, St. Bernard Parish and Lake Borgne to the east, Plaquemines Parish to the south, and Jefferson Parish to the south and west.

The city anchors the larger Greater New Orleans metropolitan area, which had a population of 1,271,845 in 2020.[29] Greater New Orleans is the most populous metropolitan statistical area (MSA) in Louisiana and, since the 2020 census, has been the 46th most populous MSA in the United States.[30]

Etymology and nicknames

The name of New Orleans derives from the original French name (La Nouvelle-Orléans), which was given to the city in honor of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, who served as Louis XV's regent from 1715 to 1723.[31] The French city of Orléans itself is named after the Roman emperor Aurelian, originally being known as Aurelianum. Thus, by extension, since New Orleans is also named after Aurelian, its name in Latin would translate to Nova Aurelia.

Following France's defeat in the Seven Years' War and the Treaty of Paris, which was signed in 1763, France transferred possession of Louisiana to Spain. The Spanish renamed the city to Nueva Orleans (pronounced [ˌnweβa oɾleˈans]), which was used until 1800.[32] When the United States acquired possession from France in 1803, the French name was adopted and anglicized to become the modern name, which is still in use today.

New Orleans has several nicknames, including these:

- Crescent City, alluding to the course of the Lower Mississippi River around and through the city.[33]

- The Big Easy, possibly a reference by musicians in the early 20th century to the relative ease of finding work there.[34][35]

- The City that Care Forgot, used since at least 1938,[36] referring to the outwardly easygoing, carefree nature of the residents.[35]

- NOLA, the acronym for New Orleans, Louisiana.

History

French–Spanish colonial era

Kingdom of France 1718–1763

Kingdom of Spain 1763–1802

French First Republic 1802–1803

United States of America 1803–1861

State of Louisiana 1861

Confederate States of America 1861–1862

United States of America 1862–present

La Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans) was founded in the spring of 1718 (May 7 has become the traditional date to mark the anniversary, but the actual day is unknown)[37] by the French Mississippi Company, under the direction of Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, on land inhabited by the Chitimacha. It was named for Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, who was regent of the Kingdom of France at the time.[31] His title came from the French city of Orléans. The French colony of Louisiana was ceded to the Spanish Empire in the 1763 Treaty of Paris, following France's defeat by Great Britain in the Seven Years' War. During the American Revolutionary War, New Orleans was an important port for smuggling aid to the American revolutionaries, and transporting military equipment and supplies up the Mississippi River. Beginning in the 1760s, Filipinos began to settle in and around New Orleans.[38] Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, Count of Gálvez successfully directed a southern campaign against the British from the city in 1779.[39] Nueva Orleans (the name of New Orleans in Spanish)[40] remained under Spanish control until 1803, when it reverted briefly to French rule. Nearly all of the surviving 18th-century architecture of the Vieux Carré (French Quarter) dates from the Spanish period, notably excepting the Old Ursuline Convent.[41]

As a French colony, Louisiana faced struggles with numerous Native American tribes, who were navigating the competing interests of France, Spain, and England, as well as traditional rivals. Notably, the Natchez, whose traditional lands were along the Mississippi near the modern city of Natchez, Mississippi, had a series of wars culminating in the Natchez Revolt that began in 1729 with the Natchez overrunning Fort Rosalie. Approximately 230 French colonists were killed and the Natchez settlement destroyed, causing fear and concern in New Orleans and the rest of the territory.[42] In retaliation, then-governor Étienne Perier launched a campaign to completely destroy the Natchez nation and its Native allies.[43] By 1731, the Natchez people had been killed, enslaved, or dispersed among other tribes, but the campaign soured relations between France and the territory's Native Americans leading directly into the Chickasaw Wars of the 1730s.[44]

Relations with Louisiana's Native American population remained a concern into the 1740s for governor Marquis de Vaudreuil. In the early 1740s traders from the Thirteen Colonies crossed into the Appalachian Mountains. The Native American tribes would now operate dependent on which of various European colonists would most benefit them. Several of these tribes and especially the Chickasaw and Choctaw would trade goods and gifts for their loyalty.[45] The economic issue in the colony, which continued under Vaudreuil, resulted in many raids by Native American tribes, taking advantage of the French weakness. In 1747 and 1748, the Chickasaw would raid along the east bank of the Mississippi all the way south to Baton Rouge. These raids would often force residents of French Louisiana to take refuge in New Orleans proper.

Inability to find labor was the most pressing issue in the young colony. The colonists turned to sub-Saharan African slaves to make their investments in Louisiana profitable. In the late 1710s the transatlantic slave trade imported enslaved Africans into the colony. This led to the biggest shipment in 1716 where several trading ships appeared with slaves as cargo to the local residents in a one-year span.

By 1724, the large number of blacks in Louisiana prompted the institutionalizing of laws governing slavery within the colony.[46] These laws required that slaves be baptized in the Roman Catholic faith, slaves be married in the church; the slave law formed in the 1720s is known as the Code Noir, which would bleed into the antebellum period of the American South as well. Louisiana slave culture had its own distinct Afro-Creole society that called on past cultures and the situation for slaves in the New World. Afro-Creole was present in religious beliefs and the Louisiana Creole language. The religion most associated with this period was called Voodoo.[47][48]

In the city of New Orleans an inspiring mixture of foreign influences created a melting pot of culture that is still celebrated today. By the end of French colonization in Louisiana, New Orleans was recognized commercially in the Atlantic world. Its inhabitants traded across the French commercial system. New Orleans was a hub for this trade both physically and culturally because it served as the exit point to the rest of the globe for the interior of the North American continent.

In one instance the French government established a chapter house of sisters in New Orleans. The Ursuline sisters after being sponsored by the Company of the Indies, founded a convent in the city in 1727.[49] At the end of the colonial era, the Ursuline Academy maintained a house of 70 boarding and 100 day students. Today numerous schools in New Orleans can trace their lineage from this academy.

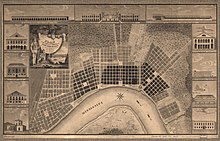

Another notable example is the street plan and architecture still distinguishing New Orleans today. French Louisiana had early architects in the province who were trained as military engineers and were now assigned to design government buildings. Pierre Le Blond de Tour and Adrien de Pauger, for example, planned many early fortifications, along with the street plan for the city of New Orleans.[50] After them in the 1740s, Ignace François Broutin, as engineer-in-chief of Louisiana, reworked the architecture of New Orleans with an extensive public works program.

French policy-makers in Paris attempted to set political and economic norms for New Orleans. It acted autonomously in much of its cultural and physical aspects, but also stayed in communication with the foreign trends as well.

After the French relinquished West Louisiana to the Spanish, New Orleans merchants attempted to ignore Spanish rule and even re-institute French control on the colony. The citizens of New Orleans held a series of public meetings during 1765 to keep the populace in opposition of the establishment of Spanish rule. Anti-Spanish passions in New Orleans reached their highest level after two years of Spanish administration in Louisiana. On October 27, 1768, a mob of local residents, spiked the guns guarding New Orleans and took control of the city from the Spanish.[51] The rebellion organized a group to sail for Paris, where it met with officials of the French government. This group brought with them a long memorial to summarize the abuses the colony had endured from the Spanish. King Louis XV and his ministers reaffirmed Spain's sovereignty over Louisiana.

United States territorial era

The Third Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1800 restored French control of New Orleans and Louisiana, but Napoleon sold both to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.[52] Thereafter, the city grew rapidly with influxes of Americans, French, Creoles and Africans. Later immigrants were Irish, Germans, Poles and Italians. Major commodity crops of sugar and cotton were cultivated with slave labor on nearby large plantations.

Between 1791 and 1810, thousands of St. Dominican refugees from the Haitian Revolution, both whites and free people of color (affranchis or gens de couleur libres), arrived in New Orleans; a number brought their slaves with them, many of whom were native Africans or of full-blood descent.[53] While Governor Claiborne and other officials wanted to keep out additional free black people, the French Creoles wanted to increase the French-speaking population. In addition to bolstering the territory's French-speaking population, these refugees had a significant impact on the culture of Louisiana, including developing its sugar industry and cultural institutions.[54]

As more refugees were allowed into the Territory of Orleans, St. Dominican refugees who had first gone to Cuba also arrived.[55] Many of the white Francophones had been deported by officials in Cuba in 1809 as retaliation for Bonapartist schemes.[56] Nearly 90 percent of these immigrants settled in New Orleans. The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites, 3,102 free people of color (of mixed-race European and African descent), and 3,226 slaves of primarily African descent, doubling the city's population. The city became 63 percent black, a greater proportion than Charleston, South Carolina's 53 percent at that time.[55]

Battle of New Orleans

During the final campaign of the War of 1812, the British sent a force of 11,000 in an attempt to capture New Orleans. Despite great challenges, General Andrew Jackson, with support from the U.S. Navy, successfully cobbled together a force of militia from Louisiana and Mississippi, U.S. Army regulars, a large contingent of Tennessee state militia, Kentucky frontiersmen and local privateers (the latter led by the pirate Jean Lafitte), to decisively defeat the British, led by Sir Edward Pakenham, in the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815.[58]

The armies had not learned of the Treaty of Ghent, which had been signed on December 24, 1814 (however, the treaty did not call for cessation of hostilities until after both governments had ratified it. The U.S. government ratified it on February 16, 1815). The fighting in Louisiana began in December 1814 and did not end until late January, after the Americans held off the Royal Navy during a ten-day siege of Fort St. Philip (the Royal Navy went on to capture Fort Bowyer near Mobile, before the commanders received news of the peace treaty).[58]

Port

As a port, New Orleans played a major role during the antebellum period in the Atlantic slave trade. The port handled commodities for export from the interior and imported goods from other countries, which were warehoused and transferred in New Orleans to smaller vessels and distributed along the Mississippi River watershed. The river was filled with steamboats, flatboats and sailing ships. Despite its role in the slave trade, New Orleans at the time also had the largest and most prosperous community of free persons of color in the nation, who were often educated, middle-class property owners.[59][60]

Dwarfing the other cities in the Antebellum South, New Orleans had the U.S.' largest slave market. The market expanded after the United States ended the international trade in 1808. Two-thirds of the more than one million slaves brought to the Deep South arrived via forced migration in the domestic slave trade. The money generated by the sale of slaves in the Upper South has been estimated at 15 percent of the value of the staple crop economy. The slaves were collectively valued at half a billion dollars. The trade spawned an ancillary economy—transportation, housing and clothing, fees, etc., estimated at 13.5 percent of the price per person, amounting to tens of billions of dollars (2005 dollars, adjusted for inflation) during the antebellum period, with New Orleans as a prime beneficiary.[61]

According to historian Paul Lachance,

the addition of white immigrants [from Saint-Domingue] to the white creole population enabled French-speakers to remain a majority of the white population until almost 1830. If a substantial proportion of free persons of color and slaves had not also spoken French, however, the Gallic community would have become a minority of the total population as early as 1820.[62]

After the Louisiana Purchase, numerous Anglo-Americans migrated to the city. The population doubled in the 1830s and by 1840, New Orleans had become the nation's wealthiest and the third-most populous city, after New York and Baltimore.[63] German and Irish immigrants began arriving in the 1840s, working as port laborers. In this period, the state legislature passed more restrictions on manumissions of slaves and virtually ended it in 1852.[64]

In the 1850s, white Francophones remained an intact and vibrant community in New Orleans. They maintained instruction in French in two of the city's four school districts (all served white students).[65] In 1860, the city had 13,000 free people of color (gens de couleur libres), the class of free, mostly mixed-race people that expanded in number during French and Spanish rule. They set up some private schools for their children. The census recorded 81 percent of the free people of color as mulatto, a term used to cover all degrees of mixed race.[64][page needed] Mostly part of the Francophone group, they constituted the artisan, educated and professional class of African Americans. The mass of blacks were still enslaved, working at the port, in domestic service, in crafts, and mostly on the many large, surrounding sugarcane plantations.

Throughout New Orleans' history, until the early 20th century when medical and scientific advances ameliorated the situation, the city suffered repeated epidemics of yellow fever and other tropical and infectious diseases.[66] In the first half of the 19th century, yellow fever epidemics killed over 150,000 people in New Orleans.[67]

After growing by 45 percent in the 1850s, by 1860, the city had nearly 170,000 people.[68] It had grown in wealth, with a "per capita income [that] was second in the nation and the highest in the South."[68] The city had a role as the "primary commercial gateway for the nation's booming midsection."[68] The port was the nation's third largest in terms of tonnage of imported goods, after Boston and New York, handling 659,000 tons in 1859.[68]

Civil War–Reconstruction era

As the Creole elite feared, the American Civil War changed their world. In April 1862, following the city's occupation by the Union Navy after the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip, Gen. Benjamin F. Butler – a respected Massachusetts lawyer serving in that state's militia – was appointed military governor. New Orleans residents supportive of the Confederacy nicknamed him "Beast" Butler, because of an order he issued. After his troops had been assaulted and harassed in the streets by women still loyal to the Confederate cause, his order warned that such future occurrences would result in his men treating such women as those "plying their avocation in the streets", implying that they would treat the women like prostitutes. Accounts of this spread widely. He also came to be called "Spoons" Butler because of the alleged looting that his troops did while occupying the city, during which time he himself supposedly pilfered silver flatware.[69]

Significantly, Butler abolished French-language instruction in city schools. Statewide measures in 1864 and, after the war, 1868 further strengthened the English-only policy imposed by federal representatives. With the predominance of English speakers, that language had already become dominant in business and government.[65] By the end of the 19th century, French usage had faded. It was also under pressure from Irish, Italian and German immigrants.[70] However, as late as 1902 "one-fourth of the population of the city spoke French in ordinary daily intercourse, while another two-fourths was able to understand the language perfectly,"[71] and as late as 1945, many elderly Creole women spoke no English.[72] The last major French language newspaper, L'Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans Bee), ceased publication on December 27, 1923, after 96 years.[73] According to some sources, Le Courrier de la Nouvelle Orleans continued until 1955.[74]

As the city was captured and occupied early in the war, it was spared the destruction through warfare suffered by many other cities of the American South. The Union Army eventually extended its control north along the Mississippi River and along the coastal areas. As a result, most of the southern portion of Louisiana was originally exempted from the liberating provisions of the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln. Large numbers of rural ex-slaves and some free people of color from the city volunteered for the first regiments of Black troops in the War. Led by Brigadier General Daniel Ullman (1810–1892), of the 78th Regiment of New York State Volunteers Militia, they were known as the "Corps d'Afrique". While that name had been used by a militia before the war, that group was composed of free people of color. The new group was made up mostly of former slaves. They were supplemented in the last two years of the War by newly organized United States Colored Troops, who played an increasingly important part in the war.[75]

Violence throughout the South, especially the Memphis Riots of 1866 followed by the New Orleans Riot in the same year, led Congress to pass the Reconstruction Act and the Fourteenth Amendment, extending the protections of full citizenship to freedmen and free people of color. Louisiana and Texas were put under the authority of the "Fifth Military District" of the United States during Reconstruction. Louisiana was readmitted to the Union in 1868. Its Constitution of 1868 granted universal male suffrage and established universal public education. Both blacks and whites were elected to local and state offices. In 1872, lieutenant governor P.B.S. Pinchback, who was of mixed race, succeeded Henry Clay Warmouth for a brief period as Republican governor of Louisiana, becoming the first governor of African descent of a U.S. state (the next African American to serve as governor of a U.S. state was Douglas Wilder, elected in Virginia in 1989). New Orleans operated a racially integrated public school system during this period.

Wartime damage to levees and cities along the Mississippi River adversely affected southern crops and trade. The federal government contributed to restoring infrastructure. The nationwide financial recession and Panic of 1873 adversely affected businesses and slowed economic recovery.

From 1868, elections in Louisiana were marked by violence, as white insurgents tried to suppress black voting and disrupt Republican Party gatherings. The disputed 1872 gubernatorial election resulted in conflicts that ran for years. The "White League", an insurgent paramilitary group that supported the Democratic Party, was organized in 1874 and operated in the open, violently suppressing the black vote and running off Republican officeholders. In 1874, in the Battle of Liberty Place, 5,000 members of the White League fought with city police to take over the state offices for the Democratic candidate for governor, holding them for three days. By 1876, such tactics resulted in the white Democrats, the so-called Redeemers, regaining political control of the state legislature. The federal government gave up and withdrew its troops in 1877, ending Reconstruction.

In 1892 the racially integrated unions of New Orleans led a general strike in the city from November 8 to 12, shutting down the city & winning the vast majority of their demands.[76][77]

Jim Crow era

Dixiecrats passed Jim Crow laws, establishing racial segregation in public facilities. In 1889, the legislature passed a constitutional amendment incorporating a "grandfather clause" that effectively disfranchised freedmen as well as the propertied people of color manumitted before the war. Unable to vote, African Americans could not serve on juries or in local office, and were closed out of formal politics for generations. The Southern U.S. was ruled by a white Democratic Party. Public schools were racially segregated and remained so until 1960.

New Orleans' large community of well-educated, often French-speaking free persons of color (gens de couleur libres), who had been free prior to the Civil War, fought against Jim Crow. They organized the Comité des Citoyens (Citizens Committee) to work for civil rights. As part of their legal campaign, they recruited one of their own, Homer Plessy, to test whether Louisiana's newly enacted Separate Car Act was constitutional. Plessy boarded a commuter train departing New Orleans for Covington, Louisiana, sat in the car reserved for whites only, and was arrested. The case resulting from this incident, Plessy v. Ferguson, was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1896. The court ruled that "separate but equal" accommodations were constitutional, effectively upholding Jim Crow measures.

In practice, African American public schools and facilities were underfunded across the South. The Supreme Court ruling contributed to this period as the nadir of race relations in the United States. The rate of lynchings of black men was high across the South, as other states also disfranchised blacks and sought to impose Jim Crow. Nativist prejudices also surfaced. Anti-Italian sentiment in 1891 contributed to the lynchings of 11 Italians, some of whom had been acquitted of the murder of the police chief. Some were shot and killed in the jail where they were detained. It was the largest mass lynching in U.S. history.[78][79] In July 1900 the city was swept by white mobs rioting after Robert Charles, a young African American, killed a policeman and temporarily escaped. The mob killed him and an estimated 20 other blacks; seven whites died in the days-long conflict, until a state militia suppressed it.

20th century

New Orleans' economic and population zenith in relation to other American cities occurred in the antebellum period. It was the nation's fifth-largest city in 1860 (after New York, Philadelphia, Boston and Baltimore) and was significantly larger than all other southern cities.[80] From the mid-19th century onward rapid economic growth shifted to other areas, while New Orleans' relative importance steadily declined. The growth of railways and highways decreased river traffic, diverting goods to other transportation corridors and markets.[80] Thousands of the most ambitious people of color left the state in the Great Migration around World War II and after, many for West Coast destinations. From the late 1800s, most censuses recorded New Orleans slipping down the ranks in the list of largest American cities (New Orleans' population still continued to increase throughout the period, but at a slower rate than before the Civil War).

In 1929 the New Orleans streetcar strike during which serious unrest occurred.[81] It is also credited for the creation of the distinctly Louisianan Po' boy sandwich.[82][83]

By the mid-20th century, New Orleanians recognized that their city was no longer the leading urban area in the South. By 1950, Houston, Dallas, and Atlanta exceeded New Orleans in size, and in 1960 Miami eclipsed New Orleans, even as the latter's population reached its historic peak.[80] As with other older American cities, highway construction and suburban development drew residents from the center city to newer housing outside. The 1970 census recorded the first absolute decline in population since the city became part of the United States in 1803. The Greater New Orleans metropolitan area continued expanding in population, albeit more slowly than other major Sun Belt cities. While the port remained one of the nation's largest, automation and containerization cost many jobs. The city's former role as banker to the South was supplanted by larger peer cities. New Orleans' economy had always been based more on trade and financial services than on manufacturing, but the city's relatively small manufacturing sector also shrank after World War II. Despite some economic development successes under the administrations of DeLesseps "Chep" Morrison (1946–1961) and Victor "Vic" Schiro (1961–1970), metropolitan New Orleans' growth rate consistently lagged behind more vigorous cities.

Civil Rights movement

During the later years of Morrison's administration, and for the entirety of Schiro's, the city was a center of the Civil Rights movement. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference was founded in New Orleans, and lunch counter sit-ins were held in Canal Street department stores. A prominent and violent series of confrontations occurred in 1960 when the city attempted school desegregation, following the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). When six-year-old Ruby Bridges integrated William Frantz Elementary School in the Ninth Ward, she was the first child of color to attend a previously all-white school in the South. Much controversy preceded the 1956 Sugar Bowl at Tulane Stadium, when the Pitt Panthers, with African-American fullback Bobby Grier on the roster, met the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets.[84] There had been controversy over whether Grier should be allowed to play due to his race, and whether Georgia Tech should even play at all due to Georgia's Governor Marvin Griffin's opposition to racial integration.[85][86][87] After Griffin publicly sent a telegram to the state's Board Of Regents requesting Georgia Tech not to engage in racially integrated events, Georgia Tech's president Blake R. Van Leer rejected the request and threatened to resign. The game went on as planned.[88]

The Civil Rights movement's success in gaining federal passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 renewed constitutional rights, including voting for blacks. Together, these resulted in the most far-reaching changes in New Orleans' 20th century history.[89] Though legal and civil equality were re-established by the end of the 1960s, a large gap in income levels and educational attainment persisted between the city's White and African American communities.[90] As the middle class and wealthier members of both races left the center city, its population's income level dropped, and it became proportionately more African American. From 1980, the African American majority elected primarily officials from its own community. They struggled to narrow the gap by creating conditions conducive to the economic uplift of the African American community.

New Orleans became increasingly dependent on tourism as an economic mainstay during the administrations of Sidney Barthelemy (1986–1994) and Marc Morial (1994–2002). Relatively low levels of educational attainment, high rates of household poverty, and rising crime threatened the city's prosperity in the later decades of the century.[90] The negative effects of these socioeconomic conditions aligned poorly with the changes in the late-20th century to the economy of the United States, which reflected a post-industrial, knowledge-based paradigm in which mental skills and education were more important to advancement than manual skills.

Drainage and flood control

In the 20th century, New Orleans' government and business leaders believed they needed to drain and develop outlying areas to provide for the city's expansion. The most ambitious development during this period was a drainage plan devised by engineer and inventor A. Baldwin Wood, designed to break the surrounding swamp's stranglehold on the city's geographic expansion. Until then, urban development in New Orleans was largely limited to higher ground along the natural river levees and bayous.

Wood's pump system allowed the city to drain huge tracts of swamp and marshland and expand into low-lying areas. Over the 20th century, rapid subsidence, both natural and human-induced, resulted in these newly populated areas subsiding to several feet below sea level.[91][92]

New Orleans was vulnerable to flooding even before the city's footprint departed from the natural high ground near the Mississippi River. In the late 20th century, however, scientists and New Orleans residents gradually became aware of the city's increased vulnerability. In 1965, flooding from Hurricane Betsy killed dozens of residents, although the majority of the city remained dry. The rain-induced flood of May 8, 1995, demonstrated the weakness of the pumping system. After that event, measures were undertaken to dramatically upgrade pumping capacity. By the 1980s and 1990s, scientists observed that extensive, rapid, and ongoing erosion of the marshlands and swamp surrounding New Orleans, especially that related to the Mississippi River–Gulf Outlet Canal, had the unintended result of leaving the city more vulnerable than before to hurricane-induced catastrophic storm surges.[citation needed]

21st century

Hurricane Katrina

New Orleans was catastrophically affected by what Raymond B. Seed called "the worst engineering disaster in the world since Chernobyl", when the federal levee system failed during Hurricane Katrina on August 29, 2005.[93] By the time the hurricane approached the city on August 29, 2005, most residents had evacuated. As the hurricane passed through the Gulf Coast region that day, the city's federal flood protection system failed, resulting in the worst civil engineering disaster in American history at the time.[94] Floodwalls and levees constructed by the United States Army Corps of Engineers failed below design specifications and 80% of the city flooded. Tens of thousands of residents who had remained were rescued or otherwise made their way to shelters of last resort at the Louisiana Superdome or the New Orleans Morial Convention Center. More than 1,500 people were recorded as having died in Louisiana, most in New Orleans, while others remain unaccounted for.[95][96] Before Hurricane Katrina, the city called for the first mandatory evacuation in its history, to be followed by another mandatory evacuation three years later with Hurricane Gustav.[97]

Hurricane Rita

The city was declared off-limits to residents while efforts to clean up after Hurricane Katrina began. The approach of Hurricane Rita in September 2005 caused repopulation efforts to be postponed,[98] and the Lower Ninth Ward was reflooded by Rita's storm surge.[96]

Post-disaster recovery

Because of the scale of damage, many people resettled permanently outside the area. Federal, state, and local efforts supported recovery and rebuilding in severely damaged neighborhoods. The U.S. Census Bureau in July 2006 estimated the population to be 223,000; a subsequent study estimated that 32,000 additional residents had moved to the city as of March 2007, bringing the estimated population to 255,000, approximately 56% of the pre-Katrina population level. Another estimate, based on utility usage from July 2007, estimated the population to be approximately 274,000 or 60% of the pre-Katrina population. These estimates are somewhat smaller to a third estimate, based on mail delivery records, from the Greater New Orleans Community Data Center in June 2007, which indicated that the city had regained approximately two-thirds of its pre-Katrina population.[99] In 2008, the U.S. Census Bureau revised its population estimate for the city upward, to 336,644.[100] Most recently, by July 2015, the population was back up to 386,617—80% of what it was in 2000.[101]

Several major tourist events and other forms of revenue for the city have returned. Large conventions returned.[102][103] College bowl games returned for the 2006–2007 season. The New Orleans Saints returned that season. The New Orleans Hornets (now named the Pelicans) returned to the city for the 2007–2008 season. New Orleans hosted the 2008 NBA All-Star Game in addition to Super Bowl XLVII.

Major annual events such as Mardi Gras, Voodoo Experience, and the Jazz & Heritage Festival were never displaced or canceled. A new annual festival, "The Running of the Bulls New Orleans", was created in 2007.[104]

Hurricane Ida

On August 29, 2021, coincidentally the 16th anniversary of the landfall of Hurricane Katrina, Hurricane Ida, a category 4 hurricane, made landfall near Port Fourchon, where the Hurricane Ida tornado outbreak caused damage.[105]

Geography

New Orleans is located in the Mississippi River Delta, south of Lake Pontchartrain, on the banks of the Mississippi River, approximately 105 miles (169 km) upriver from the Gulf of Mexico. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city's area is 350 square miles (910 km2), of which 169 square miles (440 km2) is land and 181 square miles (470 km2) (52%) is water.[106] The area along the river is characterized by ridges and hollows.

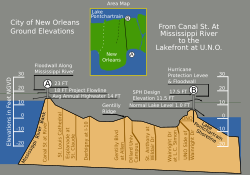

Elevation

New Orleans was originally settled on the river's natural levees or high ground. After the Flood Control Act of 1965, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built floodwalls and man-made levees around a much larger geographic footprint that included previous marshland and swamp. Over time, pumping of water from marshland allowed for development into lower elevation areas. Today, half of the city is at or below local mean sea level, while the other half is slightly above sea level. Evidence suggests that portions of the city may be dropping in elevation due to subsidence.[107]

A 2007 study by Tulane and Xavier University suggested that "51%... of the contiguous urbanized portions of Orleans, Jefferson, and St. Bernard parishes lie at or above sea level," with the more densely populated areas generally on higher ground. The average elevation of the city is currently between 1 and 2 feet (0.30 and 0.61 m) below sea level, with some portions of the city as high as 20 feet (6 m) at the base of the river levee in Uptown and others as low as 7 feet (2 m) below sea level in the farthest reaches of Eastern New Orleans.[108][109] A study published by the ASCE Journal of Hydrologic Engineering in 2016, however, stated:

...most of New Orleans proper—about 65%—is at or below mean sea level, as defined by the average elevation of Lake Pontchartrain[110]

The magnitude of subsidence potentially caused by the draining of natural marsh in the New Orleans area and southeast Louisiana is a topic of debate. A study published in Geology in 2006 by an associate professor at Tulane University claims:

While erosion and wetland loss are huge problems along Louisiana's coast, the basement 30 feet (9.1 m) to 50 feet (15 m) beneath much of the Mississippi Delta has been highly stable for the past 8,000 years with negligible subsidence rates.[111]

The study noted, however, that the results did not necessarily apply to the Mississippi River Delta, nor the New Orleans metropolitan area proper. On the other hand, a report by the American Society of Civil Engineers claims that "New Orleans is subsiding (sinking)":[112]

Large portions of Orleans, St. Bernard, and Jefferson parishes are currently below sea level—and continue to sink. New Orleans is built on thousands of feet of soft sand, silt, and clay. Subsidence, or settling of the ground surface, occurs naturally due to the consolidation and oxidation of organic soils (called "marsh" in New Orleans) and local groundwater pumping. In the past, flooding and deposition of sediments from the Mississippi River counterbalanced the natural subsidence, leaving southeast Louisiana at or above sea level. However, due to major flood control structures being built upstream on the Mississippi River and levees being built around New Orleans, fresh layers of sediment are not replenishing the ground lost by subsidence.[112]

In May 2016, NASA published a study which suggested that most areas were, in fact, experiencing subsidence at a "highly variable rate" which was "generally consistent with, but somewhat higher than, previous studies."[113]

Cityscape

The Central Business District is located immediately north and west of the Mississippi and was historically called the "American Quarter" or "American Sector". It was developed after the heart of French and Spanish settlement. It includes Lafayette Square. Most streets in this area fan out from a central point. Major streets include Canal Street, Poydras Street, Tulane Avenue and Loyola Avenue. Canal Street divides the traditional "downtown" area from the "uptown" area.

Every street crossing Canal Street between the Mississippi River and Rampart Street, which is the northern edge of the French Quarter, has a different name for the "uptown" and "downtown" portions. For example, St. Charles Avenue, known for its street car line, is called Royal Street below Canal Street, though where it traverses the Central Business District between Canal and Lee Circle, it is properly called St. Charles Street.[114] Elsewhere in the city, Canal Street serves as the dividing point between the "South" and "North" portions of various streets. In the local parlance downtown means "downriver from Canal Street", while uptown means "upriver from Canal Street". Downtown neighborhoods include the French Quarter, Tremé, the 7th Ward, Faubourg Marigny, Bywater (the Upper Ninth Ward), and the Lower Ninth Ward. Uptown neighborhoods include the Warehouse District, the Lower Garden District, the Garden District, the Irish Channel, the University District, Carrollton, Gert Town, Fontainebleau and Broadmoor. However, the Warehouse and the Central Business District are frequently called "Downtown" as a specific region, as in the Downtown Development District.

Other major districts within the city include Bayou St. John, Mid-City, Gentilly, Lakeview, Lakefront, New Orleans East and Algiers.

Historic and residential architecture

New Orleans is world-famous for its abundance of architectural styles that reflect the city's multicultural heritage. Though New Orleans possesses numerous structures of national architectural significance, it is equally, if not more, revered for its enormous, largely intact (even post-Katrina) historic built environment. Twenty National Register Historic Districts have been established, and fourteen local historic districts aid in preservation. Thirteen of the districts are administered by the New Orleans Historic District Landmarks Commission (HDLC), while one—the French Quarter—is administered by the Vieux Carre Commission (VCC). Additionally, both the National Park Service, via the National Register of Historic Places, and the HDLC have landmarked individual buildings, many of which lie outside the boundaries of existing historic districts.[115]

Housing styles include the shotgun house and the bungalow style. Creole cottages and townhouses, notable for their large courtyards and intricate iron balconies, line the streets of the French Quarter. American townhouses, double-gallery houses, and Raised Center-Hall Cottages are notable. St. Charles Avenue is famed for its large antebellum homes. Its mansions are in various styles, such as Greek Revival, American Colonial and the Victorian styles of Queen Anne and Italianate architecture. New Orleans is also noted for its large, European-style Catholic cemeteries.

Tallest buildings

For much of its history, New Orleans' skyline displayed only low- and mid-rise structures. The soft soils are susceptible to subsidence, and there was doubt about the feasibility of constructing high rises. Developments in engineering throughout the 20th century eventually made it possible to build sturdy foundations in the foundations that underlie the structures. In the 1960s, the World Trade Center New Orleans and Plaza Tower demonstrated skyscrapers' viability. One Shell Square became the city's tallest building in 1972. The oil boom of the 1970s and early 1980s redefined New Orleans' skyline with the development of the Poydras Street corridor. Most are clustered along Canal Street and Poydras Street in the Central Business District.

| Name | Stories | Height |

|---|---|---|

| One Shell Square | 51 | 697 ft (212 m) |

| Place St. Charles | 53 | 645 ft (197 m) |

| Plaza Tower | 45 | 531 ft (162 m) |

| Energy Centre | 39 | 530 ft (160 m) |

| First Bank and Trust Tower | 36 | 481 ft (147 m) |

Climate

The climate of New Orleans is humid subtropical (Köppen: Cfa), with short, generally mild winters and hot, humid summers; in the 1991-2020 climate normals the USDA hardiness zone is 9b, with the coldest temperature in most years being about 27.6 °F (−2.4 °C). The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 54.3 °F (12.4 °C) in January to 84 °F (28.9 °C) in August. Officially, as measured at New Orleans International Airport, temperature records range from 11 to 105 °F (−12 to 41 °C) on December 23, 1989, and August 27, 2023, respectively; Audubon Park has recorded temperatures ranging from 6 °F (−14 °C) on February 13, 1899, up to 104 °F (40 °C) on June 24, 2009.[116] Dewpoints in the summer months (June–August) are relatively high, ranging from 71.1 to 73.4 °F (21.7 to 23.0 °C).[117]

The average precipitation is 62.5 inches (1,590 mm) annually; the summer months are the wettest, while October is the driest month.[116] Precipitation in winter usually accompanies the passing of a cold front. There are a median of over 80 days of 90 °F (32 °C)+ highs, 9 days per winter where the high does not exceed 50 °F (10 °C), and less than 8 nights with freezing lows annually, although it is not uncommon for entire winter seasons to pass with no freezing temperatures at all, such as the 2003-04 winter, the 2012-13 winter, the 2015-16 winter and the consecutive winters of 2018-19 and 2019–20. It is rare for the temperature to reach 20 or 100 °F (−7 or 38 °C), with the last occurrence of each being January 17, 2018, and August 27, 2023, respectively.[116][118]

New Orleans experiences snowfall only on rare occasions. A small amount of snow fell during the 2004 Christmas Eve Snowstorm and again on Christmas (December 25) when a combination of rain, sleet, and snow fell on the city, leaving some bridges icy. The New Year's Eve 1963 snowstorm affected New Orleans and brought 4.5 inches (11 cm). Snow fell again on December 22, 1989, during the December 1989 United States cold wave, when most of the city received 1–2 inches (2.5–5.1 cm).

The last significant snowfall in New Orleans was on the morning of December 11, 2008.[119]

| Climate data for Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport (1991–2020 normals,[b] extremes 1946–present)[c] |

|---|

| Climate data for Audubon Park, New Orleans (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present) |

|---|

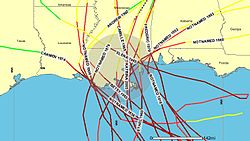

Threat from tropical cyclones

Hurricanes pose a severe threat to the area, and the city is particularly at risk due to its low elevation, the city being surrounded by water from the north, east, and south, and Louisiana's sinking coast.[123] According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency, New Orleans is the nation's most vulnerable city to hurricanes.[124] Indeed, portions of Greater New Orleans have been flooded by the Grand Isle Hurricane of 1909,[125] the New Orleans Hurricane of 1915,[125] 1947 Fort Lauderdale Hurricane,[125] Hurricane Flossy[126] in 1956, Hurricane Betsy in 1965, Hurricane Georges in 1998, Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, Hurricane Gustav in 2008, Hurricane Isaac in 2012, Hurricane Zeta in 2020 (Zeta was also the most intense hurricane to pass over New Orleans,) and Hurricane Ida in 2021. The flooding from Betsy was significant and in a few neighborhoods severe, and that from Katrina was disastrous for the majority of the city.[127][128][129]

On August 29, 2005, storm surge from Hurricane Katrina caused catastrophic failure of the federally designed and built levees, flooding 80% of the city.[130][131] A report by the American Society of Civil Engineers says that "had the levees and floodwalls not failed and had the pump stations operated, nearly two-thirds of the deaths would not have occurred".[112]

New Orleans has always had to consider the risk of hurricanes, but the risks are dramatically greater today due to coastal erosion from human interference.[132] Since the beginning of the 20th century, it has been estimated that Louisiana has lost 2,000 square miles (5,000 km2) of coast (including many of its barrier islands), which once protected New Orleans against storm surge. Following Hurricane Katrina, the Army Corps of Engineers has instituted massive levee repair and hurricane protection measures to protect the city.

In 2006, Louisiana voters overwhelmingly adopted an amendment to the state's constitution to dedicate all revenues from off-shore drilling to restore Louisiana's eroding coast line.[133] U.S. Congress has allocated $7 billion to bolster New Orleans' flood protection.[134]

According to a study by the National Academy of Engineering and the National Research Council, levees and floodwalls surrounding New Orleans—no matter how large or sturdy—cannot provide absolute protection against overtopping or failure in extreme events. Levees and floodwalls should be viewed as a way to reduce risks from hurricanes and storm surges, not as measures that eliminate risk. For structures in hazardous areas and residents who do not relocate, the committee recommended major floodproofing measures—such as elevating the first floor of buildings to at least the 100-year flood level.[135]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1769 | 3,190 | — |

| 1778 | 3,060 | −4.1% |

| 1791 | 5,497 | +79.6% |

| 1810 | 17,242 | +213.7% |

| 1820 | 27,176 | +57.6% |

| 1830 | 46,082 | +69.6% |

| 1840 | 102,193 | +121.8% |

| 1850 | 116,375 | +13.9% |

| 1860 | 168,675 | +44.9% |

| 1870 | 191,418 | +13.5% |

| 1880 | 216,090 | +12.9% |

| 1890 | 242,039 | +12.0% |

| 1900 | 287,104 | +18.6% |

| 1910 | 339,075 | +18.1% |

| 1920 | 387,219 | +14.2% |

| 1930 | 458,762 | +18.5% |

| 1940 | 494,537 | +7.8% |

| 1950 | 570,445 | +15.3% |

| 1960 | 627,525 | +10.0% |

| 1970 | 593,471 | −5.4% |

| 1980 | 557,515 | −6.1% |

| 1990 | 496,938 | −10.9% |

| 2000 | 484,674 | −2.5% |

| 2010 | 343,829 | −29.1% |

| 2020 | 383,997 | +11.7% |

| Population given for the City of New Orleans, not for Orleans Parish, before New Orleans absorbed suburbs and rural areas of Orleans Parish in 1874, since which time the city and parish have been coterminous. Population for Orleans Parish was 41,351 in 1820; 49,826 in 1830; 102,193 in 1840; 119,460 in 1850; 174,491 in 1860; and 191,418 in 1870. Source: U.S. Decennial Census[136] Historical Population Figures[100][137][138][139][140] 1790–1960[141] 1900–1990[142] 1990–2000[143] 2010–2013[144] 2020 estimate[145] | ||

From the 2010 U.S. census to 2014 census estimates the city grew by 12%, adding an average of more than 10,000 new residents each year following the official decennial census.[137] According to the 2020 United States census, there were 383,997 people, 151,753 households, and 69,370 families residing in the city. Prior to 1960, the population of New Orleans steadily increased to a historic 627,525.

Beginning in 1960, the population decreased due to factors such as the cycles of oil production and tourism,[146][147] and as suburbanization increased (as with many cities),[148] and jobs migrated to surrounding parishes.[149] This economic and population decline resulted in high levels of poverty in the city; in 1960 it had the fifth-highest poverty rate of all U.S. cities,[150] and was almost twice the national average in 2005, at 24.5%.[148] New Orleans experienced an increase in residential segregation from 1900 to 1980, leaving the disproportionately Black and African American poor in older, low-lying locations.[149] These areas were especially susceptible to flood and storm damage.[151]

The last population estimate before Hurricane Katrina was 454,865, as of July 1, 2005.[152] A population analysis released in August 2007 estimated the population to be 273,000, 60% of the pre-Katrina population and an increase of about 50,000 since July 2006.[153] A September 2007 report by The Greater New Orleans Community Data Center, which tracks population based on U.S. Postal Service figures, found that in August 2007, just over 137,000 households received mail. That compares with about 198,000 households in July 2005, representing about 70% of pre-Katrina population.[154] In 2010, the U.S. Census Bureau revised upward its 2008 population estimate for the city, to 336,644 inhabitants.[100] Estimates from 2010 showed that neighborhoods that did not flood were near or even greater than 100% of their pre-Katrina populations.[155]

Katrina displaced 800,000 people, contributing significantly to the decline.[156] Black and African Americans, renters, the elderly, and people with low income were disproportionately affected by Katrina, compared to affluent and White residents.[157][158] In Katrina's aftermath, city government commissioned groups such as Bring New Orleans Back Commission, the New Orleans Neighborhood Rebuilding Plan, the Unified New Orleans Plan, and the Office of Recovery Management to contribute to plans addressing depopulation. Their ideas included shrinking the city's footprint from before the storm, incorporating community voices into development plans, and creating green spaces,[157] some of which incited controversy.[159][160]

A 2006 study by researchers at Tulane University and the University of California, Berkeley determined that as many as 10,000 to 14,000 undocumented immigrants, many from Mexico, resided in New Orleans.[161] In 2016, the Pew Research Center estimated at least 35,000 undocumented immigrants lived in New Orleans and its metropolitan area.[162] The New Orleans Police Department began a new policy to "no longer cooperate with federal immigration enforcement" beginning on February 28, 2016.[163]

As of 2010[update], 90.3% of residents age 5 and older spoke English at home as a primary language, while 4.8% spoke Spanish, 1.9% Vietnamese, and 1.1% spoke French. In total, 9.7% population age 5 and older spoke a mother language other than English.[164]

Race and ethnicity

| Historic racial and ethnic composition | 2020[165] | 2010[166] | 1990[167] | 1970[167] | 1940[167] |

|---|

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[168] | Pop 2010[169] | Pop 2020[170] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 128,971 | 104,770 | 121,385 | 26.59% | 30.47% | 31.61% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 323,392 | 204,866 | 205,876 | 66.72% | 59.58% | 53.61% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 852 | 827 | 761 | 0.18% | 0.24% | 0.20% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 10,919 | 9,883 | 10,573 | 2.25% | 2.87% | 2.75% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 88 | 105 | 125 | 0.02% | 0.03% | 0.03% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 961 | 967 | 2,075 | 0.20% | 0.28% | 0.54% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 4,765 | 4,360 | 12,185 | 0.98% | 1.27% | 3.17% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 14,826 | 18,051 | 31,017 | 3.06% | 5.25% | 8.08% |

| Total | 484,674 | 343,829 | 373,977 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Growing into a predominantly Black and African American city by race and ethnicity since 1990,[167] in 2010 the racial and ethnic makeup of New Orleans was 60.2% Black and African American, 33.0% White, 2.9% Asian (1.7% Vietnamese, 0.3% Indian, 0.3% Chinese, 0.1% Filipino, 0.1% Korean), 0.0% Pacific Islander, and 1.7% people of two or more races.[171] People of Hispanic or Latino American origin made up 5.3% of the population; 1.3% were Mexican, 1.3% Honduran, 0.4% Cuban, 0.3% Puerto Rican, and 0.3% Nicaraguan. In 2020, the racial and ethnic makeup of the city was 53.61% Black or African American, 31.61% non-Hispanic white, 0.2% American Indian and Alaska Native, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 3.71% multiracial or of another race, and 8.08% Hispanic and Latino American of any race.[165] The growth of the Hispanic and Latino population in New Orleans proper from 2010 to 2020 reflected national demographic trends of diversification throughout regions once predominantly non-Hispanic white.[172] Additionally, the 2020 census revealed the city now has a more diverse population than it did before Katrina, yet 21% fewer people than it had in 2000.[173]

As of 2011[update], the Hispanic and Latino American population had also grown in the Greater New Orleans area alongside Black and African American residents, including in Kenner, central Metairie, and Terrytown in Jefferson Parish and Eastern New Orleans and Mid-City in New Orleans proper.[174] Janet Murguía, president and chief executive officer of the UnidosUS, stated that up to 120,000 Hispanic and Latino Americans workers lived in New Orleans. In June 2007, one study stated that the Hispanic and Latino American population had risen from 15,000, pre-Katrina, to over 50,000.[175]

After Katrina the small Brazilian American population expanded. Portuguese speakers were the second most numerous group to take English as a second language classes in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans, after Spanish speakers. Many Brazilians worked in skilled trades such as tile and flooring, although fewer worked as day laborers than other Hispanic and Latino Americans. Many had moved from Brazilian communities in the northeastern United States, and Florida and Georgia. Brazilians settled throughout the metropolitan area; most were undocumented. In January 2008, the New Orleans Brazilian population had a mid-range estimate of 3,000 people. By 2008, Brazilians had opened many small churches, shops and restaurants catering to their community.[176]

Among the growing Asian American community, the earliest Filipino Americans to live within the city arrived in the early 1800s.[177] The Vietnamese American community grew to become the largest by 2010 as many fled the aftermath of the Vietnam War in the 1970s.[178]

Sexual orientation and gender identity

New Orleans and its metropolitan area have historically been popular destinations for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender communities.[179][180] In 2015, a Gallup survey determined New Orleans was one of the largest cities in the American South with a significant LGBT population.[181][182] Much of the LGBT community in New Orleans lives near the Central Business District, Mid-City, and Uptown; several gay bars and nightclubs are present in those areas.[183]

Religion

New Orleans' colonial history of French and Spanish settlement generated a strong Roman Catholic tradition. Catholic missions ministered to slaves and free people of color and established schools for them. In addition, many late 19th and early 20th century European immigrants, such as the Irish, some Germans, and Italians were Catholic. Within the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans (which includes not only the city but the surrounding parishes as well), 40% percent of the population was Roman Catholic since 2016.[184] Catholicism is reflected in French and Spanish cultural traditions, including its many parochial schools, street names, architecture and festivals, including Mardi Gras. Within the city and metropolitan area, Catholicism is also reflected in the Black and African cultural traditions with Gospel Mass.[185]

Influenced by the Bible Belt's prominent Protestant population, New Orleans also has a sizable non-Catholic Christian demographic. Roughly the majority of Protestant Christians were Baptist, and the city proper's largest non-Catholic bodies were the Southern Baptist Convention, the National Missionary Baptist Convention of America, non-denominationals, the National Baptist Convention, the United Methodist Church, the Episcopal Church, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the National Baptist Convention of America, and the Church of God in Christ according to the Association of Religion Data Archives in 2020.[186]

New Orleans displays a distinctive variety of Louisiana Voodoo, due in part to syncretism with African and Afro-Caribbean Roman Catholic beliefs. The fame of voodoo practitioner Marie Laveau contributed to this, as did New Orleans' Caribbean cultural influences.[187][188][189] Although the tourism industry strongly associated Voodoo with the city, only a small number of people are serious adherents.

New Orleans was also home to the occultist Mary Oneida Toups, who was nicknamed the "Witch Queen of New Orleans". Toups' coven, The Religious Order of Witchcraft, was the first coven to be officially recognized as a religious institution by the state of Louisiana.[190] They would meet at Popp Fountain in City Park.[191]

Jewish settlers, primarily Sephardim, settled in New Orleans from the early nineteenth century. Some migrated from the communities established in the colonial years in Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia. The merchant Abraham Cohen Labatt helped found the first Jewish congregation in New Orleans in the 1830s, which became known as the Portuguese Jewish Nefutzot Yehudah congregation (he and some other members were Sephardic Jews, whose ancestors had lived in Portugal and Spain). Ashkenazi Jews from eastern Europe immigrated in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

By the beginning of the 21st century, 10,000 Jews lived in New Orleans. This number dropped to 7,000 after Hurricane Katrina, but rose again after efforts to incentivize the community's growth resulted in the arrival of about an additional 2,000 Jews.[192] New Orleans synagogues lost members, but most re-opened in their original locations. The exception was Congregation Beth Israel, the oldest and most prominent Orthodox synagogue in the New Orleans region. Beth Israel's building in Lakeview was destroyed by flooding. After seven years of holding services in temporary quarters, the congregation consecrated a new synagogue on land purchased from the Reform Congregation Gates of Prayer in Metairie.[193]

A visible religious minority,[194][195] Muslims constituted 0.6% of the religious population as of 2019 according to Sperling's BestPlaces.[196] The Association of Religion Data Archives in 2020 estimated that there were 6,150 Muslims in the city proper. The Islamic demographic in New Orleans and its metropolitan area have been mainly made up of Middle Eastern immigrants and African Americans.

Economy

New Orleans operates one of the world's largest and busiest ports and metropolitan New Orleans is a center of maritime industry.[197] The region accounts for a significant portion of the nation's oil refining and petrochemical production, and serves as a white-collar corporate base for onshore and offshore petroleum and natural gas production. Since the beginning of the 21st century, New Orleans has also grown into a technology hub.[198][199]

New Orleans is also a center for higher learning, with over 50,000 students enrolled in the region's eleven two- and four-year degree-granting institutions. Tulane University, a top-50 research university, is located in Uptown. Metropolitan New Orleans is a major regional hub for the health care industry and boasts a small, globally competitive manufacturing sector. The center city possesses a rapidly growing, entrepreneurial creative industries sector and is renowned for its cultural tourism. Greater New Orleans, Inc. (GNO, Inc.)[200] acts as the first point-of-contact for regional economic development, coordinating between Louisiana's Department of Economic Development and the various business development agencies.

Port

New Orleans began as a strategically located trading entrepôt and it remains, above all, a crucial transportation hub and distribution center for waterborne commerce. The Port of New Orleans is the fifth-largest in the United States based on cargo volume, and second-largest in the state after the Port of South Louisiana. It is the twelfth-largest in the U.S. based on cargo value. The Port of South Louisiana, also located in the New Orleans area, is the world's busiest in terms of bulk tonnage. When combined with Port of New Orleans, it forms the 4th-largest port system in volume. Many shipbuilding, shipping, logistics, freight forwarding and commodity brokerage firms either are based in metropolitan New Orleans or maintain a local presence. Examples include Intermarine,[201] Bisso Towboat,[202] Northrop Grumman Ship Systems,[203] Trinity Yachts, Expeditors International,[204] Bollinger Shipyards, IMTT, International Coffee Corp, Boasso America, Transoceanic Shipping, Transportation Consultants Inc., Dupuy Storage & Forwarding and Silocaf.[205] The largest coffee-roasting plant in the world, operated by Folgers, is located in New Orleans East.[206][207]

New Orleans is located near to the Gulf of Mexico and its many oil rigs. Louisiana ranks fifth among states in oil production and eighth in reserves. It has two of the four Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) storage facilities: West Hackberry in Cameron Parish and Bayou Choctaw in Iberville Parish. The area hosts 17 petroleum refineries, with a combined crude oil distillation capacity of nearly 2.8 million barrels per day (450,000 m3/d), the second highest after Texas. Louisiana's numerous ports include the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP), which is capable of receiving the largest oil tankers. Given the quantity of oil imports, Louisiana is home to many major pipelines: Crude Oil (Exxon, Chevron, BP, Texaco, Shell, Scurloch-Permian, Mid-Valley, Calumet, Conoco, Koch Industries, Unocal, U.S. Dept. of Energy, Locap); Product (TEPPCO Partners, Colonial, Plantation, Explorer, Texaco, Collins); and Liquefied Petroleum Gas (Dixie, TEPPCO, Black Lake, Koch, Chevron, Dynegy, Kinder Morgan Energy Partners, Dow Chemical Company, Bridgeline, FMP, Tejas, Texaco, UTP).[208] Several energy companies have regional headquarters in the area, including Shell plc, Eni and Chevron. Other energy producers and oilfield services companies are headquartered in the city or region, and the sector supports a large professional services base of specialized engineering and design firms, as well as a term office for the federal government's Minerals Management Service.

Business

The city is the home to a single Fortune 500 company: Entergy, a power generation utility and nuclear power plant operations specialist.[209] After Katrina, the city lost its other Fortune 500 company, Freeport-McMoRan, when it merged its copper and gold exploration unit with an Arizona company and relocated that division to Phoenix. Its McMoRan Exploration affiliate remains headquartered in New Orleans.[210]

Companies with significant operations or headquarters in New Orleans include: Pan American Life Insurance, Pool Corp, Rolls-Royce, Newpark Resources, AT&T, TurboSquid, iSeatz, IBM, Navtech, Superior Energy Services, Textron Marine & Land Systems, McDermott International, Pellerin Milnor, Lockheed Martin, Imperial Trading, Laitram, Harrah's Entertainment, Stewart Enterprises, Edison Chouest Offshore, Zatarain's, Waldemar S. Nelson & Co., Whitney National Bank, Capital One, Tidewater Marine, Popeyes Chicken & Biscuits, Parsons Brinckerhoff, MWH Global, CH2M Hill, Energy Partners Ltd, The Receivables Exchange, GE Capital, and Smoothie King.

Tourist and convention business

Tourism is a staple of the city's economy. Perhaps more visible than any other sector, New Orleans' tourist and convention industry is a $5.5 billion industry that accounts for 40 percent of city tax revenues. In 2004, the hospitality industry employed 85,000 people, making it the city's top economic sector as measured by employment.[211] New Orleans also hosts the World Cultural Economic Forum (WCEF). The forum, held annually at the New Orleans Morial Convention Center, is directed toward promoting cultural and economic development opportunities through the strategic convening of cultural ambassadors and leaders from around the world. The first WCEF took place in October 2008.[212]

Federal and military agencies

Federal agencies and the Armed forces operate significant facilities there. The U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals operates at the US. Courthouse downtown. NASA's Michoud Assembly Facility is located in New Orleans East and has multiple tenants including Lockheed Martin and Boeing. It is a huge manufacturing complex that produced the external fuel tanks for the Space Shuttles, the Saturn V first stage, the Integrated Truss Structure of the International Space Station, and is now used for the construction of NASA's Space Launch System. The rocket factory lies within the enormous New Orleans Regional Business Park, also home to the National Finance Center, operated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Crescent Crown distribution center. Other large governmental installations include the U.S. Navy's Space and Naval Warfare (SPAWAR) Systems Command, located within the University of New Orleans Research and Technology Park in Gentilly, Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base New Orleans; and the headquarters for the Marine Force Reserves in Federal City in Algiers.

Culture and contemporary life

Tourism

New Orleans has many visitor attractions, from the world-renowned French Quarter to St. Charles Avenue, (home of Tulane and Loyola universities, the historic Pontchartrain Hotel and many 19th-century mansions) to Magazine Street with its boutique stores and antique shops.

According to current travel guides, New Orleans is one of the top ten most-visited cities in the United States; 10.1 million visitors came to New Orleans in 2004.[211][213] Prior to Katrina, 265 hotels with 38,338 rooms operated in the Greater New Orleans Area. In May 2007, that had declined to some 140 hotels and motels with over 31,000 rooms.[214]

A 2009 Travel + Leisure poll of "America's Favorite Cities" ranked New Orleans first in ten categories, the most first-place rankings of the 30 cities included. According to the poll, New Orleans was the best U.S. city as a spring break destination and for "wild weekends", stylish boutique hotels, cocktail hours, singles/bar scenes, live music/concerts and bands, antique and vintage shops, cafés/coffee bars, neighborhood restaurants, and people watching. The city ranked second for: friendliness (behind Charleston, South Carolina), gay-friendliness (behind San Francisco), bed and breakfast hotels/inns, and ethnic food. However, the city placed near the bottom in cleanliness, safety and as a family destination.[215][216]

The French Quarter (known locally as "the Quarter" or Vieux Carré), which was the colonial-era city and is bounded by the Mississippi River, Rampart Street, Canal Street, and Esplanade Avenue, contains popular hotels, bars and nightclubs. Notable tourist attractions in the Quarter include Bourbon Street, Jackson Square, St. Louis Cathedral, the French Market (including Café du Monde, famous for café au lait and beignets) and Preservation Hall. Also in the French Quarter is the old New Orleans Mint, a former branch of the United States Mint which now operates as a museum, and The Historic New Orleans Collection, a museum and research center housing art and artifacts relating to the history and the Gulf South.

Close to the Quarter is the Tremé community, which contains the New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park and the New Orleans African American Museum—a site which is listed on the Louisiana African American Heritage Trail.

The Natchez is an authentic steamboat with a calliope that cruises the length of the city twice daily. Unlike most other places in the United States, New Orleans has become widely known for its elegant decay. The city's historic cemeteries and their distinct above-ground tombs are attractions in themselves, the oldest and most famous of which, Saint Louis Cemetery, greatly resembles Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

The National WWII Museum offers a multi-building odyssey through the history of the Pacific and European theaters. Nearby, Confederate Memorial Hall Museum, the oldest continually operating museum in Louisiana (although under renovation since Hurricane Katrina), contains the second-largest collection of Confederate memorabilia. Art museums include the Contemporary Arts Center, the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA) in City Park, and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art.

New Orleans is home to the Audubon Nature Institute (which consists of Audubon Park, the Audubon Zoo, the Aquarium of the Americas and the Audubon Insectarium), and home to gardens which include Longue Vue House and Gardens and the New Orleans Botanical Garden. City Park, one of the country's most expansive and visited urban parks, has one of the largest stands of oak trees in the world.

Other points of interest can be found in the surrounding areas. Many wetlands are found nearby, including Honey Island Swamp and Barataria Preserve. Chalmette Battlefield and National Cemetery, located just south of the city, is the site of the 1815 Battle of New Orleans.

Entertainment and performing arts

The New Orleans area is home to numerous annual celebrations. The most well known is Carnival, or Mardi Gras. Carnival officially begins on the Feast of the Epiphany, also known in some Christian traditions as the "Twelfth Night" of Christmas. Mardi Gras (French for "Fat Tuesday"), the final and grandest day of traditional Catholic festivities, is the last Tuesday before the Christian liturgical season of Lent, which commences on Ash Wednesday.

The largest of the city's many music festivals is the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. Commonly referred to simply as "Jazz Fest", it is one of the nation's largest music festivals. The festival features a variety of music, including both native Louisiana and international artists. Along with Jazz Fest, New Orleans' Voodoo Experience ("Voodoo Fest") and the Essence Music Festival also feature local and international artists.

Other major festivals include Southern Decadence, the French Quarter Festival, and the Tennessee Williams/New Orleans Literary Festival. The American playwright lived and wrote in New Orleans early in his career, and set his play, Streetcar Named Desire, there.

In 2002, Louisiana began offering tax incentives for film and television production. This has resulted in a substantial increase in activity and brought the nickname of "Hollywood South" for New Orleans. Films produced in and around the city include Ray, Runaway Jury, The Pelican Brief, Glory Road, All the King's Men, Déjà Vu, Last Holiday, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, 12 Years a Slave, and Project Power. In 2006, work began on the Louisiana Film & Television studio complex, based in the Tremé neighborhood.[217] Louisiana began to offer similar tax incentives for music and theater productions in 2007, and some commentators began to refer to New Orleans as "Broadway South".[218]

The first theatre in New Orleans was the French-language Theatre de la Rue Saint Pierre, which opened in 1792. The first opera in New Orleans was performed there in 1796. In the nineteenth century, the city was the home of two of America's most important venues for French opera, the Théâtre d'Orléans and later the French Opera House. Today, opera is performed by the New Orleans Opera. The Marigny Opera House is home to the Marigny Opera Ballet and also hosts opera, jazz, and classical music performances.

New Orleans has long been a significant center for music, showcasing its intertwined European, African and Latino American cultures. The city's unique musical heritage was born in its colonial and early American days from a unique blending of European musical instruments with African rhythms. As the only North American city to have allowed slaves to gather in public and play their native music (largely in Congo Square, now located within Louis Armstrong Park), New Orleans gave birth in the early 20th century to an epochal indigenous music: jazz. Soon, African American brass bands formed, beginning a century-long tradition. The Louis Armstrong Park area, near the French Quarter in Tremé, contains the New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park. The city's music was later also significantly influenced by Acadiana, home of Cajun and Zydeco music, and by Delta blues.

New Orleans' unique musical culture is on display in its traditional funerals. A spin on military funerals, New Orleans' traditional funerals feature sad music (mostly dirges and hymns) in processions on the way to the cemetery and happier music (hot jazz) on the way back. Until the 1990s, most locals preferred to call these "funerals with music". Visitors to the city have long dubbed them "jazz funerals".