Щелочной металл

| Щелочные металлы | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| ↓ Период | |||||||||||

| 2 | Литий (Li) 3 | ||||||||||

| 3 | Sodium (Na) 11 | ||||||||||

| 4 | Калий (К) 19 | ||||||||||

| 5 | Рубидий (Rb) 37 | ||||||||||

| 6 | Цезий (Cs) 55 | ||||||||||

| 7 | Франций (фр.) 87 | ||||||||||

Легенда

| |||||||||||

Щелочные металлы состоят из химических элементов: лития (Li), натрия (Na), калия (K), [примечание 1] рубидий (Rb), цезий (Cs), [примечание 2] и франций (фр.). Вместе с водородом они составляют группу 1 , [примечание 3] который лежит в s-блоке таблицы Менделеева . У всех щелочных металлов самый внешний электрон находится на s-орбитали : эта общая электронная конфигурация приводит к тому, что они имеют очень схожие характеристические свойства. [примечание 4] Действительно, щелочные металлы представляют собой лучший пример групповых тенденций свойств в периодической таблице, при этом элементы демонстрируют хорошо охарактеризованное гомологическое поведение. [5] Это семейство элементов также известно как семейство лития по названию его ведущего элемента.

Все щелочные металлы являются блестящими, мягкими , высокореактивными металлами при стандартной температуре и давлении и легко теряют свой внешний электрон , образуя катионы с зарядом +1. Все их можно легко разрезать ножом из-за их мягкости, обнажая блестящую поверхность, которая быстро тускнеет на воздухе из-за окисления атмосферной влагой и кислородом (а в случае лития - азотом ). Из-за их высокой реакционной способности их необходимо хранить под маслом, чтобы предотвратить реакцию с воздухом, и в природе они встречаются только в солях и никогда в виде свободных элементов. Цезий, пятый щелочной металл, является наиболее реакционноспособным из всех металлов. Все щелочные металлы реагируют с водой, причем более тяжелые щелочные металлы реагируют более энергично, чем более легкие.

Все открытые щелочные металлы встречаются в природе в виде их соединений: по распространенности наиболее распространен натрий, за ним следуют калий, литий, рубидий, цезий и, наконец, франций, который из-за чрезвычайно высокой радиоактивности встречается очень редко ; Франций встречается в природе лишь в незначительных следах как промежуточный этап в некоторых неясных побочных ветвях цепочек естественного распада . Были проведены эксперименты с целью синтеза элемента 119 , который, вероятно, станет следующим членом группы; ни один из них не увенчался успехом. Однако унунений не может быть щелочным металлом из-за релятивистских эффектов , которые, по прогнозам, окажут большое влияние на химические свойства сверхтяжелых элементов ; даже если он действительно окажется щелочным металлом, по прогнозам, он будет иметь некоторые отличия по физическим и химическим свойствам от своих более легких гомологов.

Большинство щелочных металлов имеют множество различных применений. Одним из наиболее известных применений чистых элементов является использование рубидия и цезия в атомных часах , из которых цезиевые атомные часы составляют основу вторых. Распространенным применением соединений натрия являются натриевые лампы , которые очень эффективно излучают свет. Поваренная соль , или хлорид натрия, использовалась с древности. Литий находит применение в качестве психиатрического лекарства и в качестве анода в литиевых батареях . Натрий, калий и, возможно, литий являются важными элементами , играющими важную биологическую роль в качестве электролитов , и хотя другие щелочные металлы не являются незаменимыми, они также оказывают различное воздействие на организм, как полезное, так и вредное.

История [ править ]

Соединения натрия известны с древних времен; соль ( хлорид натрия ) была важным товаром в человеческой деятельности, о чем свидетельствует английское слово «зарплата» , обозначающее «зарплату» — деньги, выплачиваемые римским солдатам за покупку соли. [6] [ нужен лучший источник ] Хотя поташ использовался с древних времен, на протяжении большей части его истории не считалось, что он является веществом, принципиально отличающимся от минеральных солей натрия. Георг Эрнст Шталь получил экспериментальные данные, которые позволили ему предположить фундаментальное различие солей натрия и калия в 1702 году. [7] и Анри-Луи Дюамель дю Монсо смог доказать это различие в 1736 году. [8] Точный химический состав соединений калия и натрия, а также статус калия и натрия как химического элемента тогда не был известен, и поэтому Антуан Лавуазье не включил ни одну из щелочей в свой список химических элементов в 1789 году. [9] [10]

Чистый калий был впервые выделен в 1807 году в Англии Хамфри Дэви , который получил его из едкого поташа (KOH, гидроксид калия) путем электролиза расплавленной соли с помощью недавно изобретенной гальванической батареи . Предыдущие попытки электролиза водной соли не увенчались успехом из-за чрезвычайной реакционной способности калия. [11] : 68 Калий был первым металлом, выделенным электролизом. [12] Позже в том же году Дэви сообщил об экстракции натрия из аналогичного вещества каустической соды (NaOH, щелок) с помощью аналогичного метода, продемонстрировав, что элементы и, следовательно, соли различны. [9] [10] [13] [14]

Петалит ( Li Al Si 4 O 10 ) был открыт в 1800 году бразильским химиком Хосе Бонифасио де Андрада в шахте на острове Утё, Швеция . [15] [16] [17] Однако только в 1817 году Йохан Август Арфведсон , работавший тогда в лаборатории химика Йонса Якоба Берцелиуса , обнаружил присутствие нового элемента при анализе петалитовой руды . [18] [19] Он отметил, что этот новый элемент образует соединения, подобные соединениям натрия и калия, хотя его карбонат и гидроксид были менее растворимы в воде и более щелочными , чем другие щелочные металлы. [20] Берцелиус дал неизвестному материалу название литион / литина , от греческого слова λιθoς (транслитерируемого как литос , что означает «камень»), чтобы отразить его открытие в твердом минерале, в отличие от калия, который был обнаружен в растительной золе, и натрий, который был известен отчасти своим высоким содержанием в крови животных. Он назвал металл внутри материала литием . [21] [16] [19] Литий, натрий и калий были частью открытия периодичности , поскольку они входят в серию триад элементов одной группы , которые были отмечены Иоганном Вольфгангом Дёберейнером в 1850 году как имеющие схожие свойства. [22]

Рубидий и цезий были первыми элементами, открытыми с помощью спектроскопа , изобретенного в 1859 году Робертом Бунзеном и Густавом Кирхгофом . [23] В следующем году они обнаружили цезий в минеральной воде из Бад-Дюркхайма , Германия. Открытие рубидия произошло в следующем году в Гейдельберге , Германия, в минерале лепидолите . [24] Названия рубидия и цезия происходят от наиболее заметных линий в их спектрах излучения : ярко-красной линии рубидия (от латинского слова Rubidus , означающего темно-красный или ярко-красный) и небесно-голубой линии цезия (происходящего от Латинское слово caesius , что означает небесно-голубой). [25] [26]

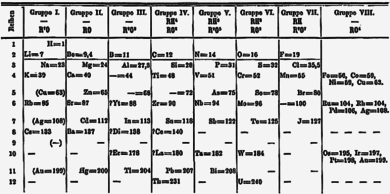

Примерно в 1865 году Джон Ньюлендс опубликовал серию статей, в которых перечислил элементы в порядке увеличения атомного веса и аналогичных физических и химических свойств, которые повторялись с интервалом в восемь; он сравнил такую периодичность с октавами музыки, где ноты, отстоящие друг от друга на октаву, имеют схожие музыкальные функции. [27] [28] В его версии все известные тогда щелочные металлы (от лития до цезия), а также медь, серебро и таллий (которые имеют степень окисления +1, характерную для щелочных металлов) были объединены в группу. В его таблице водород помещался рядом с галогенами . [22]

После 1869 года Дмитрий Менделеев предложил свою периодическую таблицу, поместив литий во главе группы с натрием, калием, рубидием, цезием и таллием. [29] Два года спустя Менделеев пересмотрел свою таблицу, поместив водород в группу 1 выше лития, а также переместив таллий в группу бора . В этой версии 1871 года медь, серебро и золото были помещены дважды: один раз как часть группы IB и один раз как часть «группы VIII», охватывающей сегодняшние группы с 8 по 11. [30] [примечание 5] После введения таблицы из 18 столбцов элементы группы IB были перемещены на свое нынешнее положение в d-блоке , а щелочные металлы остались в группе IA . Позже в 1988 году название группы было изменено на группу 1 . [4] Тривиальное название «щелочные металлы» происходит от того, что все гидроксиды элементов 1 группы при растворении в воде являются сильными щелочами . [5]

Было как минимум четыре ошибочных и неполных открытия. [31] [32] [33] [34] До того, как Маргарита Перей из Института Кюри в Париже, Франция открыла франций в 1939 году, очистив образец актиния-227 , энергия распада которого, как сообщалось, составляла 220 кэВ . Однако Перей заметил частицы распада с уровнем энергии ниже 80 кэВ. Перей предположил, что эта активность распада могла быть вызвана ранее неопознанным продуктом распада, который был выделен во время очистки, но снова появился из чистого актиния -227. Различные тесты исключили возможность того, что неизвестным элементом является торий , радий , свинец, висмут или таллий . Новый продукт проявлял химические свойства щелочного металла (например, соосаждение с солями цезия), что заставило Перея предположить, что это элемент 87, возникший в результате альфа-распада актиния-227. [35] Затем Перей попытался определить соотношение бета-распада и альфа-распада актиния-227. Ее первый тест показал, что альфа-ветвление составило 0,6%, но позже она пересмотрела эту цифру до 1%. [36]

- 227

89 Ак

223

87 Пт

223

88 Ра

219

86 рн

Следующим элементом после франция ( эка -франций) в периодической таблице будет унунений (Uue), элемент 119. [37] : 1729–1730 Синтез унунения был впервые предпринят в 1985 году путем бомбардировки мишени из эйнштейния -254 ионами кальция -48 на ускорителе superHILAC в Национальной лаборатории Лоуренса Беркли в Беркли, Калифорния. Атомы не были идентифицированы, что привело к предельному выходу 300 нб . [38] [39]

- 254

99 Эс

+ 48

20 Калифорния

→ 302

119 Ууэ

* → нет атомов [примечание 6]

Это крайне маловероятно [38] что эта реакция сможет создать любые атомы унунения в ближайшем будущем, учитывая чрезвычайно сложную задачу получения достаточного количества эйнштейния-254, который предпочтителен для производства сверхтяжелых элементов из-за его большой массы и относительно длительного периода полураспада. 270 дней и наличие в значительных количествах нескольких микрограммов, [40] сделать мишень достаточно крупной, чтобы повысить чувствительность эксперимента до необходимого уровня; Эйнштейний не обнаружен в природе и производится только в лабораториях и в количествах, меньших, чем те, которые необходимы для эффективного синтеза сверхтяжелых элементов. Однако, учитывая, что унунений является лишь первым элементом 8-го периода , расширенной таблицы Менделеева он вполне может быть открыт в ближайшем будущем посредством других реакций, и действительно, в настоящее время в Японии предпринимаются попытки его синтеза. [41] В настоящее время ни один из элементов периода 8 еще не обнаружен, и также возможно, что из-за капельной нестабильности физически возможны только элементы нижнего периода 8, примерно до элемента 128. [42] [43] Никаких попыток синтеза более тяжелых щелочных металлов не предпринималось: из-за их чрезвычайно высокого атомного номера для их производства потребуются новые, более мощные методы и технологии. [37] : 1737–1739

Происшествие [ править ]

В Солнечной системе [ править ]

Правило Оддо-Харкинса гласит, что элементы с четными атомными номерами встречаются чаще, чем элементы с нечетными атомными номерами, за исключением водорода. Это правило утверждает, что элементы с нечетными атомными номерами имеют один неспаренный протон и с большей вероятностью захватят другой, тем самым увеличивая свой атомный номер. В элементах с четными атомными номерами протоны спарены, причем каждый член пары компенсирует спин другого, повышая стабильность. [45] [46] [47] Все щелочные металлы имеют нечетные атомные номера и они не так распространены, как соседние с ними элементы с четными атомными номерами ( благородные газы и щелочноземельные металлы ) в Солнечной системе. Более тяжелые щелочные металлы также менее распространены, чем более легкие, поскольку щелочные металлы, начиная с рубидия, могут быть синтезированы только в сверхновых , а не в ходе звездного нуклеосинтеза . Литий также гораздо менее распространен, чем натрий и калий, поскольку он плохо синтезируется как в ходе нуклеосинтеза Большого взрыва , так и в звездах: Большой взрыв мог произвести лишь следовые количества лития, бериллия и бора из-за отсутствия стабильного ядра с 5 или 8 атомами углерода. нуклонов , и звездный нуклеосинтез мог преодолеть это узкое место только с помощью процесса тройного альфа , соединяя три ядра гелия с образованием углерода и пропуская эти три элемента. [44]

На Земле [ править ]

Земля образовалась из того же облака материи, из которого образовалось Солнце, но планеты приобрели разный состав в ходе формирования и эволюции Солнечной системы . В свою очередь, естественная история Земли привела к тому, что некоторые части этой планеты имели разную концентрацию элементов. Масса Земли составляет примерно 5,98 × 10 24 кг. Он состоит в основном из железа (32,1%), кислорода (30,1%), кремния (15,1%), магния (13,9%), серы (2,9%), никеля (1,8%), кальция (1,5%) и алюминия ( 1,4%); остальные 1,2% состоят из следовых количеств других элементов. Считается, что из-за планетарной дифференциации область ядра в основном состоит из железа (88,8%), с меньшим количеством никеля (5,8%), серы (4,5%) и менее 1% микроэлементов. [48]

Щелочные металлы из-за своей высокой реакционной способности не встречаются в природе в чистом виде. Они являются литофилами и поэтому остаются близко к поверхности Земли, поскольку легко соединяются с кислородом и, таким образом, прочно связываются с кремнеземом , образуя минералы относительно низкой плотности, которые не опускаются в ядро Земли. Калий, рубидий и цезий также являются несовместимыми элементами из-за большого ионного радиуса . [49]

Натрий и калий очень распространены на Земле, и оба входят в десятку наиболее распространенных элементов земной коры ; [50] [51] натрий составляет примерно 2,6% земной коры по весу, что делает его шестым по распространенности элементом в целом. [52] и самый распространенный щелочной металл. Калий составляет примерно 1,5% земной коры и является седьмым по распространенности элементом. [52] Натрий содержится во многих различных минералах, из которых наиболее распространена обыкновенная соль (хлорид натрия), которая в огромных количествах растворяется в морской воде. Другие твердые месторождения включают галит , амфибол , криолит , нитратин и цеолит . [52] Многие из этих твердых отложений образовались в результате испарения древних морей, которое до сих пор происходит в таких местах, как Юта штата Большое Соленое озеро и Мертвое море . [11] : 69 Несмотря на почти одинаковое содержание натрия в земной коре, натрий встречается гораздо чаще, чем калий в океане, как потому, что больший размер калия делает его соли менее растворимыми, так и потому, что калий связывается силикатами в почве, и то, что выщелачивает калий, усваивается гораздо легче. растительной жизнью, чем натрий. [11] : 69

Несмотря на химическое сходство, литий обычно не встречается вместе с натрием или калием из-за его меньшего размера. [11] : 69 Из-за относительно низкой реакционной способности его можно найти в морской воде в больших количествах; по оценкам, концентрация лития в морской воде составляет примерно от 0,14 до 0,25 частей на миллион (ppm). [53] [54] или 25 микромолярных . [55] Его диагональное расположение с магнием часто позволяет ему замещать магний в ферромагниевых минералах, где его концентрация в коре составляет около 18 частей на миллион , что сравнимо с концентрацией галлия и ниобия . В коммерческом отношении наиболее важным минералом лития является сподумен , который встречается в крупных месторождениях по всему миру. [11]: 69

Rubidium is approximately as abundant as zinc and more abundant than copper. It occurs naturally in the minerals leucite, pollucite, carnallite, zinnwaldite, and lepidolite,[56] although none of these contain only rubidium and no other alkali metals.[11]: 70 Caesium is more abundant than some commonly known elements, such as antimony, cadmium, tin, and tungsten, but is much less abundant than rubidium.[57]

Francium-223, the only naturally occurring isotope of francium,[58][59] is the product of the alpha decay of actinium-227 and can be found in trace amounts in uranium minerals.[60] In a given sample of uranium, there is estimated to be only one francium atom for every 1018 uranium atoms.[61][62] It has been calculated that there are at most 30 grams of francium in the earth's crust at any time, due to its extremely short half-life of 22 minutes.[63][64]

Properties[edit]

Physical and chemical[edit]

The physical and chemical properties of the alkali metals can be readily explained by their having an ns1 valence electron configuration, which results in weak metallic bonding. Hence, all the alkali metals are soft and have low densities,[5] melting[5] and boiling points,[5] as well as heats of sublimation, vaporisation, and dissociation.[11]: 74 They all crystallise in the body-centered cubic crystal structure,[11]: 73 and have distinctive flame colours because their outer s electron is very easily excited.[11]: 75 Indeed, these flame test colours are the most common way of identifying them since all their salts with common ions are soluble.[11]: 75 The ns1 configuration also results in the alkali metals having very large atomic and ionic radii, as well as very high thermal and electrical conductivity.[11]: 75 Their chemistry is dominated by the loss of their lone valence electron in the outermost s-orbital to form the +1 oxidation state, due to the ease of ionising this electron and the very high second ionisation energy.[11]: 76 Most of the chemistry has been observed only for the first five members of the group. The chemistry of francium is not well established due to its extreme radioactivity;[5] thus, the presentation of its properties here is limited. What little is known about francium shows that it is very close in behaviour to caesium, as expected. The physical properties of francium are even sketchier because the bulk element has never been observed; hence any data that may be found in the literature are certainly speculative extrapolations.[65]

| Name | Lithium | Sodium | Potassium | Rubidium | Caesium | Francium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic number | 3 | 11 | 19 | 37 | 55 | 87 |

| Standard atomic weight[note 7][58][59] | 6.94(1)[note 8] | 22.98976928(2) | 39.0983(1) | 85.4678(3) | 132.9054519(2) | [223][note 9] |

| Electron configuration | [He] 2s1 | [Ne] 3s1 | [Ar] 4s1 | [Kr] 5s1 | [Xe] 6s1 | [Rn] 7s1 |

| Melting point (°C) | 180.54 | 97.72 | 63.38 | 39.31 | 28.44 | ? |

| Boiling point (°C) | 1342 | 883 | 759 | 688 | 671 | ? |

| Density (g·cm−3) | 0.534 | 0.968 | 0.89 | 1.532 | 1.93 | ? |

| Heat of fusion (kJ·mol−1) | 3.00 | 2.60 | 2.321 | 2.19 | 2.09 | ? |

| Heat of vaporisation (kJ·mol−1) | 136 | 97.42 | 79.1 | 69 | 66.1 | ? |

| Heat of formation of monatomic gas (kJ·mol−1) | 162 | 108 | 89.6 | 82.0 | 78.2 | ? |

| Electrical resistivity at 25 °C (nΩ·cm) | 94.7 | 48.8 | 73.9 | 131 | 208 | ? |

| Atomic radius (pm) | 152 | 186 | 227 | 248 | 265 | ? |

| Ionic radius of hexacoordinate M+ ion (pm) | 76 | 102 | 138 | 152 | 167 | ? |

| First ionisation energy (kJ·mol−1) | 520.2 | 495.8 | 418.8 | 403.0 | 375.7 | 392.8[68] |

| Electron affinity (kJ·mol−1) | 59.62 | 52.87 | 48.38 | 46.89 | 45.51 | ? |

| Enthalpy of dissociation of M2 (kJ·mol−1) | 106.5 | 73.6 | 57.3 | 45.6 | 44.77 | ? |

| Pauling electronegativity | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.79 | ?[note 10] |

| Allen electronegativity | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.67 |

| Standard electrode potential (E°(M+→M0); V)[71] | −3.04 | −2.71 | −2.93 | −2.98 | −3.03 | ? |

| Flame test colour Principal emission/absorption wavelength (nm) | Crimson 670.8 | Yellow 589.2 | Violet 766.5 | Red-violet 780.0 | Blue 455.5 | ? |

The alkali metals are more similar to each other than the elements in any other group are to each other.[5] Indeed, the similarity is so great that it is quite difficult to separate potassium, rubidium, and caesium, due to their similar ionic radii; lithium and sodium are more distinct. For instance, when moving down the table, all known alkali metals show increasing atomic radius,[72] decreasing electronegativity,[72] increasing reactivity,[5] and decreasing melting and boiling points[72] as well as heats of fusion and vaporisation.[11]: 75 In general, their densities increase when moving down the table, with the exception that potassium is less dense than sodium.[72] One of the very few properties of the alkali metals that does not display a very smooth trend is their reduction potentials: lithium's value is anomalous, being more negative than the others.[11]: 75 This is because the Li+ ion has a very high hydration energy in the gas phase: though the lithium ion disrupts the structure of water significantly, causing a higher change in entropy, this high hydration energy is enough to make the reduction potentials indicate it as being the most electropositive alkali metal, despite the difficulty of ionising it in the gas phase.[11]: 75

The stable alkali metals are all silver-coloured metals except for caesium, which has a pale golden tint:[73] it is one of only three metals that are clearly coloured (the other two being copper and gold).[11]: 74 Additionally, the heavy alkaline earth metals calcium, strontium, and barium, as well as the divalent lanthanides europium and ytterbium, are pale yellow, though the colour is much less prominent than it is for caesium.[11]: 74 Their lustre tarnishes rapidly in air due to oxidation.[5]

All the alkali metals are highly reactive and are never found in elemental forms in nature.[21] Because of this, they are usually stored in mineral oil or kerosene (paraffin oil).[74] They react aggressively with the halogens to form the alkali metal halides, which are white ionic crystalline compounds that are all soluble in water except lithium fluoride (LiF).[5] The alkali metals also react with water to form strongly alkaline hydroxides and thus should be handled with great care. The heavier alkali metals react more vigorously than the lighter ones; for example, when dropped into water, caesium produces a larger explosion than potassium if the same number of moles of each metal is used.[5][75][57] The alkali metals have the lowest first ionisation energies in their respective periods of the periodic table[65] because of their low effective nuclear charge[5] and the ability to attain a noble gas configuration by losing just one electron.[5] Not only do the alkali metals react with water, but also with proton donors like alcohols and phenols, gaseous ammonia, and alkynes, the last demonstrating the phenomenal degree of their reactivity. Their great power as reducing agents makes them very useful in liberating other metals from their oxides or halides.[11]: 76

The second ionisation energy of all of the alkali metals is very high[5][65] as it is in a full shell that is also closer to the nucleus;[5] thus, they almost always lose a single electron, forming cations.[11]: 28 The alkalides are an exception: they are unstable compounds which contain alkali metals in a −1 oxidation state, which is very unusual as before the discovery of the alkalides, the alkali metals were not expected to be able to form anions and were thought to be able to appear in salts only as cations. The alkalide anions have filled s-subshells, which gives them enough stability to exist. All the stable alkali metals except lithium are known to be able to form alkalides,[76][77][78] and the alkalides have much theoretical interest due to their unusual stoichiometry and low ionisation potentials. Alkalides are chemically similar to the electrides, which are salts with trapped electrons acting as anions.[79] A particularly striking example of an alkalide is "inverse sodium hydride", H+Na− (both ions being complexed), as opposed to the usual sodium hydride, Na+H−:[80] it is unstable in isolation, due to its high energy resulting from the displacement of two electrons from hydrogen to sodium, although several derivatives are predicted to be metastable or stable.[80][81]

In aqueous solution, the alkali metal ions form aqua ions of the formula [M(H2O)n]+, where n is the solvation number. Their coordination numbers and shapes agree well with those expected from their ionic radii. In aqueous solution the water molecules directly attached to the metal ion are said to belong to the first coordination sphere, also known as the first, or primary, solvation shell. The bond between a water molecule and the metal ion is a dative covalent bond, with the oxygen atom donating both electrons to the bond. Each coordinated water molecule may be attached by hydrogen bonds to other water molecules. The latter are said to reside in the second coordination sphere. However, for the alkali metal cations, the second coordination sphere is not well-defined as the +1 charge on the cation is not high enough to polarise the water molecules in the primary solvation shell enough for them to form strong hydrogen bonds with those in the second coordination sphere, producing a more stable entity.[82][83]: 25 The solvation number for Li+ has been experimentally determined to be 4, forming the tetrahedral [Li(H2O)4]+: while solvation numbers of 3 to 6 have been found for lithium aqua ions, solvation numbers less than 4 may be the result of the formation of contact ion pairs, and the higher solvation numbers may be interpreted in terms of water molecules that approach [Li(H2O)4]+ through a face of the tetrahedron, though molecular dynamic simulations may indicate the existence of an octahedral hexaaqua ion. There are also probably six water molecules in the primary solvation sphere of the sodium ion, forming the octahedral [Na(H2O)6]+ ion.[66][83]: 126–127 While it was previously thought that the heavier alkali metals also formed octahedral hexaaqua ions, it has since been found that potassium and rubidium probably form the [K(H2O)8]+ and [Rb(H2O)8]+ ions, which have the square antiprismatic structure, and that caesium forms the 12-coordinate [Cs(H2O)12]+ ion.[84]

Lithium[edit]

The chemistry of lithium shows several differences from that of the rest of the group as the small Li+ cation polarises anions and gives its compounds a more covalent character.[5] Lithium and magnesium have a diagonal relationship due to their similar atomic radii,[5] so that they show some similarities. For example, lithium forms a stable nitride, a property common among all the alkaline earth metals (magnesium's group) but unique among the alkali metals.[85] In addition, among their respective groups, only lithium and magnesium form organometallic compounds with significant covalent character (e.g. LiMe and MgMe2).[86]

Lithium fluoride is the only alkali metal halide that is poorly soluble in water,[5] and lithium hydroxide is the only alkali metal hydroxide that is not deliquescent.[5] Conversely, lithium perchlorate and other lithium salts with large anions that cannot be polarised are much more stable than the analogous compounds of the other alkali metals, probably because Li+ has a high solvation energy.[11]: 76 This effect also means that most simple lithium salts are commonly encountered in hydrated form, because the anhydrous forms are extremely hygroscopic: this allows salts like lithium chloride and lithium bromide to be used in dehumidifiers and air-conditioners.[11]: 76

Francium[edit]

Francium is also predicted to show some differences due to its high atomic weight, causing its electrons to travel at considerable fractions of the speed of light and thus making relativistic effects more prominent. In contrast to the trend of decreasing electronegativities and ionisation energies of the alkali metals, francium's electronegativity and ionisation energy are predicted to be higher than caesium's due to the relativistic stabilisation of the 7s electrons; also, its atomic radius is expected to be abnormally low. Thus, contrary to expectation, caesium is the most reactive of the alkali metals, not francium.[68][37]: 1729 [87] All known physical properties of francium also deviate from the clear trends going from lithium to caesium, such as the first ionisation energy, electron affinity, and anion polarisability, though due to the paucity of known data about francium many sources give extrapolated values, ignoring that relativistic effects make the trend from lithium to caesium become inapplicable at francium.[87] Some of the few properties of francium that have been predicted taking relativity into account are the electron affinity (47.2 kJ/mol)[88] and the enthalpy of dissociation of the Fr2 molecule (42.1 kJ/mol).[89] The CsFr molecule is polarised as Cs+Fr−, showing that the 7s subshell of francium is much more strongly affected by relativistic effects than the 6s subshell of caesium.[87] Additionally, francium superoxide (FrO2) is expected to have significant covalent character, unlike the other alkali metal superoxides, because of bonding contributions from the 6p electrons of francium.[87]

Nuclear[edit]

| Z | Alkali metal | Stable | Decays | unstable: italics odd–odd isotopes coloured pink | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | lithium | 2 | — | 7 Li | 6 Li | |

| 11 | sodium | 1 | — | 23 Na | ||

| 19 | potassium | 2 | 1 | 39 K | 41 K | 40 K |

| 37 | rubidium | 1 | 1 | 85 Rb | 87 Rb | |

| 55 | caesium | 1 | — | 133 Cs | ||

| 87 | francium | — | — | No primordial isotopes (223 Fr is a radiogenic nuclide) | ||

| Radioactive: 40K, t1/2 1.25 × 109 years; 87Rb, t1/2 4.9 × 1010 years; 223Fr, t1/2 22.0 min. | ||||||

All the alkali metals have odd atomic numbers; hence, their isotopes must be either odd–odd (both proton and neutron number are odd) or odd–even (proton number is odd, but neutron number is even). Odd–odd nuclei have even mass numbers, whereas odd–even nuclei have odd mass numbers. Odd–odd primordial nuclides are rare because most odd–odd nuclei are highly unstable with respect to beta decay, because the decay products are even–even, and are therefore more strongly bound, due to nuclear pairing effects.[90]

Due to the great rarity of odd–odd nuclei, almost all the primordial isotopes of the alkali metals are odd–even (the exceptions being the light stable isotope lithium-6 and the long-lived radioisotope potassium-40). For a given odd mass number, there can be only a single beta-stable nuclide, since there is not a difference in binding energy between even–odd and odd–even comparable to that between even–even and odd–odd, leaving other nuclides of the same mass number (isobars) free to beta decay toward the lowest-mass nuclide. An effect of the instability of an odd number of either type of nucleons is that odd-numbered elements, such as the alkali metals, tend to have fewer stable isotopes than even-numbered elements. Of the 26 monoisotopic elements that have only a single stable isotope, all but one have an odd atomic number and all but one also have an even number of neutrons. Beryllium is the single exception to both rules, due to its low atomic number.[90]

All of the alkali metals except lithium and caesium have at least one naturally occurring radioisotope: sodium-22 and sodium-24 are trace radioisotopes produced cosmogenically,[91] potassium-40 and rubidium-87 have very long half-lives and thus occur naturally,[92] and all isotopes of francium are radioactive.[92] Caesium was also thought to be radioactive in the early 20th century,[93][94] although it has no naturally occurring radioisotopes.[92] (Francium had not been discovered yet at that time.) The natural long-lived radioisotope of potassium, potassium-40, makes up about 0.012% of natural potassium,[95] and thus natural potassium is weakly radioactive. This natural radioactivity became a basis for a mistaken claim of the discovery for element 87 (the next alkali metal after caesium) in 1925.[31][32] Natural rubidium is similarly slightly radioactive, with 27.83% being the long-lived radioisotope rubidium-87.[11]: 74

Caesium-137, with a half-life of 30.17 years, is one of the two principal medium-lived fission products, along with strontium-90, which are responsible for most of the radioactivity of spent nuclear fuel after several years of cooling, up to several hundred years after use. It constitutes most of the radioactivity still left from the Chernobyl accident. Caesium-137 undergoes high-energy beta decay and eventually becomes stable barium-137. It is a strong emitter of gamma radiation. Caesium-137 has a very low rate of neutron capture and cannot be feasibly disposed of in this way, but must be allowed to decay.[96] Caesium-137 has been used as a tracer in hydrologic studies, analogous to the use of tritium.[97] Small amounts of caesium-134 and caesium-137 were released into the environment during nearly all nuclear weapon tests and some nuclear accidents, most notably the Goiânia accident and the Chernobyl disaster. As of 2005, caesium-137 is the principal source of radiation in the zone of alienation around the Chernobyl nuclear power plant.[98] Its chemical properties as one of the alkali metals make it one of the most problematic of the short-to-medium-lifetime fission products because it easily moves and spreads in nature due to the high water solubility of its salts, and is taken up by the body, which mistakes it for its essential congeners sodium and potassium.[99]: 114

Periodic trends[edit]

The alkali metals are more similar to each other than the elements in any other group are to each other.[5] For instance, when moving down the table, all known alkali metals show increasing atomic radius,[72] decreasing electronegativity,[72] increasing reactivity,[5] and decreasing melting and boiling points[72] as well as heats of fusion and vaporisation.[11]: 75 In general, their densities increase when moving down the table, with the exception that potassium is less dense than sodium.[72]

Atomic and ionic radii[edit]

The atomic radii of the alkali metals increase going down the group.[72] Because of the shielding effect, when an atom has more than one electron shell, each electron feels electric repulsion from the other electrons as well as electric attraction from the nucleus.[100] In the alkali metals, the outermost electron only feels a net charge of +1, as some of the nuclear charge (which is equal to the atomic number) is cancelled by the inner electrons; the number of inner electrons of an alkali metal is always one less than the nuclear charge. Therefore, the only factor which affects the atomic radius of the alkali metals is the number of electron shells. Since this number increases down the group, the atomic radius must also increase down the group.[72]

The ionic radii of the alkali metals are much smaller than their atomic radii. This is because the outermost electron of the alkali metals is in a different electron shell than the inner electrons, and thus when it is removed the resulting atom has one fewer electron shell and is smaller. Additionally, the effective nuclear charge has increased, and thus the electrons are attracted more strongly towards the nucleus and the ionic radius decreases.[5]

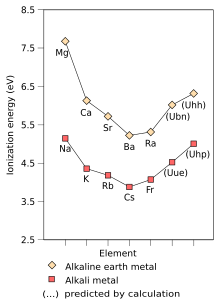

First ionisation energy[edit]

The first ionisation energy of an element or molecule is the energy required to move the most loosely held electron from one mole of gaseous atoms of the element or molecules to form one mole of gaseous ions with electric charge +1. The factors affecting the first ionisation energy are the nuclear charge, the amount of shielding by the inner electrons and the distance from the most loosely held electron from the nucleus, which is always an outer electron in main group elements. The first two factors change the effective nuclear charge the most loosely held electron feels. Since the outermost electron of alkali metals always feels the same effective nuclear charge (+1), the only factor which affects the first ionisation energy is the distance from the outermost electron to the nucleus. Since this distance increases down the group, the outermost electron feels less attraction from the nucleus and thus the first ionisation energy decreases.[72] This trend is broken in francium due to the relativistic stabilisation and contraction of the 7s orbital, bringing francium's valence electron closer to the nucleus than would be expected from non-relativistic calculations. This makes francium's outermost electron feel more attraction from the nucleus, increasing its first ionisation energy slightly beyond that of caesium.[37]: 1729

The second ionisation energy of the alkali metals is much higher than the first as the second-most loosely held electron is part of a fully filled electron shell and is thus difficult to remove.[5]

Reactivity[edit]

The reactivities of the alkali metals increase going down the group. This is the result of a combination of two factors: the first ionisation energies and atomisation energies of the alkali metals. Because the first ionisation energy of the alkali metals decreases down the group, it is easier for the outermost electron to be removed from the atom and participate in chemical reactions, thus increasing reactivity down the group. The atomisation energy measures the strength of the metallic bond of an element, which falls down the group as the atoms increase in radius and thus the metallic bond must increase in length, making the delocalised electrons further away from the attraction of the nuclei of the heavier alkali metals. Adding the atomisation and first ionisation energies gives a quantity closely related to (but not equal to) the activation energy of the reaction of an alkali metal with another substance. This quantity decreases going down the group, and so does the activation energy; thus, chemical reactions can occur faster and the reactivity increases down the group.[101]

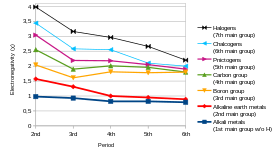

Electronegativity[edit]

Electronegativity is a chemical property that describes the tendency of an atom or a functional group to attract electrons (or electron density) towards itself.[102] If the bond between sodium and chlorine in sodium chloride were covalent, the pair of shared electrons would be attracted to the chlorine because the effective nuclear charge on the outer electrons is +7 in chlorine but is only +1 in sodium. The electron pair is attracted so close to the chlorine atom that they are practically transferred to the chlorine atom (an ionic bond). However, if the sodium atom was replaced by a lithium atom, the electrons will not be attracted as close to the chlorine atom as before because the lithium atom is smaller, making the electron pair more strongly attracted to the closer effective nuclear charge from lithium. Hence, the larger alkali metal atoms (further down the group) will be less electronegative as the bonding pair is less strongly attracted towards them. As mentioned previously, francium is expected to be an exception.[72]

Because of the higher electronegativity of lithium, some of its compounds have a more covalent character. For example, lithium iodide (LiI) will dissolve in organic solvents, a property of most covalent compounds.[72] Lithium fluoride (LiF) is the only alkali halide that is not soluble in water,[5] and lithium hydroxide (LiOH) is the only alkali metal hydroxide that is not deliquescent.[5]

Melting and boiling points[edit]

The melting point of a substance is the point where it changes state from solid to liquid while the boiling point of a substance (in liquid state) is the point where the vapour pressure of the liquid equals the environmental pressure surrounding the liquid[103][104] and all the liquid changes state to gas. As a metal is heated to its melting point, the metallic bonds keeping the atoms in place weaken so that the atoms can move around, and the metallic bonds eventually break completely at the metal's boiling point.[72][105] Therefore, the falling melting and boiling points of the alkali metals indicate that the strength of the metallic bonds of the alkali metals decreases down the group.[72] This is because metal atoms are held together by the electromagnetic attraction from the positive ions to the delocalised electrons.[72][105] As the atoms increase in size going down the group (because their atomic radius increases), the nuclei of the ions move further away from the delocalised electrons and hence the metallic bond becomes weaker so that the metal can more easily melt and boil, thus lowering the melting and boiling points.[72] The increased nuclear charge is not a relevant factor due to the shielding effect.[72]

Density[edit]

The alkali metals all have the same crystal structure (body-centred cubic)[11] and thus the only relevant factors are the number of atoms that can fit into a certain volume and the mass of one of the atoms, since density is defined as mass per unit volume. The first factor depends on the volume of the atom and thus the atomic radius, which increases going down the group; thus, the volume of an alkali metal atom increases going down the group. The mass of an alkali metal atom also increases going down the group. Thus, the trend for the densities of the alkali metals depends on their atomic weights and atomic radii; if figures for these two factors are known, the ratios between the densities of the alkali metals can then be calculated. The resultant trend is that the densities of the alkali metals increase down the table, with an exception at potassium. Due to having the lowest atomic weight and the largest atomic radius of all the elements in their periods, the alkali metals are the least dense metals in the periodic table.[72] Lithium, sodium, and potassium are the only three metals in the periodic table that are less dense than water:[5] in fact, lithium is the least dense known solid at room temperature.[11]: 75

Compounds[edit]

The alkali metals form complete series of compounds with all usually encountered anions, which well illustrate group trends. These compounds can be described as involving the alkali metals losing electrons to acceptor species and forming monopositive ions.[11]: 79 This description is most accurate for alkali halides and becomes less and less accurate as cationic and anionic charge increase, and as the anion becomes larger and more polarisable. For instance, ionic bonding gives way to metallic bonding along the series NaCl, Na2O, Na2S, Na3P, Na3As, Na3Sb, Na3Bi, Na.[11]: 81

Hydroxides[edit]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

All the alkali metals react vigorously or explosively with cold water, producing an aqueous solution of a strongly basic alkali metal hydroxide and releasing hydrogen gas.[101] This reaction becomes more vigorous going down the group: lithium reacts steadily with effervescence, but sodium and potassium can ignite, and rubidium and caesium sink in water and generate hydrogen gas so rapidly that shock waves form in the water that may shatter glass containers.[5] When an alkali metal is dropped into water, it produces an explosion, of which there are two separate stages. The metal reacts with the water first, breaking the hydrogen bonds in the water and producing hydrogen gas; this takes place faster for the more reactive heavier alkali metals. Second, the heat generated by the first part of the reaction often ignites the hydrogen gas, causing it to burn explosively into the surrounding air. This secondary hydrogen gas explosion produces the visible flame above the bowl of water, lake or other body of water, not the initial reaction of the metal with water (which tends to happen mostly under water).[75] The alkali metal hydroxides are the most basic known hydroxides.[11]: 87

Recent research has suggested that the explosive behavior of alkali metals in water is driven by a Coulomb explosion rather than solely by rapid generation of hydrogen itself.[106] All alkali metals melt as a part of the reaction with water. Water molecules ionise the bare metallic surface of the liquid metal, leaving a positively charged metal surface and negatively charged water ions. The attraction between the charged metal and water ions will rapidly increase the surface area, causing an exponential increase of ionisation. When the repulsive forces within the liquid metal surface exceeds the forces of the surface tension, it vigorously explodes.[106]

The hydroxides themselves are the most basic hydroxides known, reacting with acids to give salts and with alcohols to give oligomeric alkoxides. They easily react with carbon dioxide to form carbonates or bicarbonates, or with hydrogen sulfide to form sulfides or bisulfides, and may be used to separate thiols from petroleum. They react with amphoteric oxides: for example, the oxides of aluminium, zinc, tin, and lead react with the alkali metal hydroxides to give aluminates, zincates, stannates, and plumbates. Silicon dioxide is acidic, and thus the alkali metal hydroxides can also attack silicate glass.[11]: 87

Intermetallic compounds[edit]

The alkali metals form many intermetallic compounds with each other and the elements from groups 2 to 13 in the periodic table of varying stoichiometries,[11]: 81 such as the sodium amalgams with mercury, including Na5Hg8 and Na3Hg.[107] Some of these have ionic characteristics: taking the alloys with gold, the most electronegative of metals, as an example, NaAu and KAu are metallic, but RbAu and CsAu are semiconductors.[11]: 81 NaK is an alloy of sodium and potassium that is very useful because it is liquid at room temperature, although precautions must be taken due to its extreme reactivity towards water and air. The eutectic mixture melts at −12.6 °C.[108] An alloy of 41% caesium, 47% sodium, and 12% potassium has the lowest known melting point of any metal or alloy, −78 °C.[23]

Compounds with the group 13 elements[edit]

The intermetallic compounds of the alkali metals with the heavier group 13 elements (aluminium, gallium, indium, and thallium), such as NaTl, are poor conductors or semiconductors, unlike the normal alloys with the preceding elements, implying that the alkali metal involved has lost an electron to the Zintl anions involved.[109] Nevertheless, while the elements in group 14 and beyond tend to form discrete anionic clusters, group 13 elements tend to form polymeric ions with the alkali metal cations located between the giant ionic lattice. For example, NaTl consists of a polymeric anion (—Tl−—)n with a covalent diamond cubic structure with Na+ ions located between the anionic lattice. The larger alkali metals cannot fit similarly into an anionic lattice and tend to force the heavier group 13 elements to form anionic clusters.[110]

Boron is a special case, being the only nonmetal in group 13. The alkali metal borides tend to be boron-rich, involving appreciable boron–boron bonding involving deltahedral structures,[11]: 147–8 and are thermally unstable due to the alkali metals having a very high vapour pressure at elevated temperatures. This makes direct synthesis problematic because the alkali metals do not react with boron below 700 °C, and thus this must be accomplished in sealed containers with the alkali metal in excess. Furthermore, exceptionally in this group, reactivity with boron decreases down the group: lithium reacts completely at 700 °C, but sodium at 900 °C and potassium not until 1200 °C, and the reaction is instantaneous for lithium but takes hours for potassium. Rubidium and caesium borides have not even been characterised. Various phases are known, such as LiB10, NaB6, NaB15, and KB6.[111][112] Under high pressure the boron–boron bonding in the lithium borides changes from following Wade's rules to forming Zintl anions like the rest of group 13.[113]

Compounds with the group 14 elements[edit]

Lithium and sodium react with carbon to form acetylides, Li2C2 and Na2C2, which can also be obtained by reaction of the metal with acetylene. Potassium, rubidium, and caesium react with graphite; their atoms are intercalated between the hexagonal graphite layers, forming graphite intercalation compounds of formulae MC60 (dark grey, almost black), MC48 (dark grey, almost black), MC36 (blue), MC24 (steel blue), and MC8 (bronze) (M = K, Rb, or Cs). These compounds are over 200 times more electrically conductive than pure graphite, suggesting that the valence electron of the alkali metal is transferred to the graphite layers (e.g. M+C−8).[66] Upon heating of KC8, the elimination of potassium atoms results in the conversion in sequence to KC24, KC36, KC48 and finally KC60. KC8 is a very strong reducing agent and is pyrophoric and explodes on contact with water.[114][115] While the larger alkali metals (K, Rb, and Cs) initially form MC8, the smaller ones initially form MC6, and indeed they require reaction of the metals with graphite at high temperatures around 500 °C to form.[116] Apart from this, the alkali metals are such strong reducing agents that they can even reduce buckminsterfullerene to produce solid fullerides MnC60; sodium, potassium, rubidium, and caesium can form fullerides where n = 2, 3, 4, or 6, and rubidium and caesium additionally can achieve n = 1.[11]: 285

When the alkali metals react with the heavier elements in the carbon group (silicon, germanium, tin, and lead), ionic substances with cage-like structures are formed, such as the silicides M4Si4 (M = K, Rb, or Cs), which contains M+ and tetrahedral Si4−4 ions.[66] The chemistry of alkali metal germanides, involving the germanide ion Ge4− and other cluster (Zintl) ions such as Ge2−4, Ge4−9, Ge2−9, and [(Ge9)2]6−, is largely analogous to that of the corresponding silicides.[11]: 393 Alkali metal stannides are mostly ionic, sometimes with the stannide ion (Sn4−),[110] and sometimes with more complex Zintl ions such as Sn4−9, which appears in tetrapotassium nonastannide (K4Sn9).[117] The monatomic plumbide ion (Pb4−) is unknown, and indeed its formation is predicted to be energetically unfavourable; alkali metal plumbides have complex Zintl ions, such as Pb4−9. These alkali metal germanides, stannides, and plumbides may be produced by reducing germanium, tin, and lead with sodium metal in liquid ammonia.[11]: 394

Nitrides and pnictides[edit]

Lithium, the lightest of the alkali metals, is the only alkali metal which reacts with nitrogen at standard conditions, and its nitride is the only stable alkali metal nitride. Nitrogen is an unreactive gas because breaking the strong triple bond in the dinitrogen molecule (N2) requires a lot of energy. The formation of an alkali metal nitride would consume the ionisation energy of the alkali metal (forming M+ ions), the energy required to break the triple bond in N2 and the formation of N3− ions, and all the energy released from the formation of an alkali metal nitride is from the lattice energy of the alkali metal nitride. The lattice energy is maximised with small, highly charged ions; the alkali metals do not form highly charged ions, only forming ions with a charge of +1, so only lithium, the smallest alkali metal, can release enough lattice energy to make the reaction with nitrogen exothermic, forming lithium nitride. The reactions of the other alkali metals with nitrogen would not release enough lattice energy and would thus be endothermic, so they do not form nitrides at standard conditions.[85] Sodium nitride (Na3N) and potassium nitride (K3N), while existing, are extremely unstable, being prone to decomposing back into their constituent elements, and cannot be produced by reacting the elements with each other at standard conditions.[119][120] Steric hindrance forbids the existence of rubidium or caesium nitride.[11]: 417 However, sodium and potassium form colourless azide salts involving the linear N−3 anion; due to the large size of the alkali metal cations, they are thermally stable enough to be able to melt before decomposing.[11]: 417

All the alkali metals react readily with phosphorus and arsenic to form phosphides and arsenides with the formula M3Pn (where M represents an alkali metal and Pn represents a pnictogen – phosphorus, arsenic, antimony, or bismuth). This is due to the greater size of the P3− and As3− ions, so that less lattice energy needs to be released for the salts to form.[66] These are not the only phosphides and arsenides of the alkali metals: for example, potassium has nine different known phosphides, with formulae K3P, K4P3, K5P4, KP, K4P6, K3P7, K3P11, KP10.3, and KP15.[121] While most metals form arsenides, only the alkali and alkaline earth metals form mostly ionic arsenides. The structure of Na3As is complex with unusually short Na–Na distances of 328–330 pm which are shorter than in sodium metal, and this indicates that even with these electropositive metals the bonding cannot be straightforwardly ionic.[11] Other alkali metal arsenides not conforming to the formula M3As are known, such as LiAs, which has a metallic lustre and electrical conductivity indicating the presence of some metallic bonding.[11] The antimonides are unstable and reactive as the Sb3− ion is a strong reducing agent; reaction of them with acids form the toxic and unstable gas stibine (SbH3).[122] Indeed, they have some metallic properties, and the alkali metal antimonides of stoichiometry MSb involve antimony atoms bonded in a spiral Zintl structure.[123] Bismuthides are not even wholly ionic; they are intermetallic compounds containing partially metallic and partially ionic bonds.[124]

Oxides and chalcogenides[edit]

All the alkali metals react vigorously with oxygen at standard conditions. They form various types of oxides, such as simple oxides (containing the O2− ion), peroxides (containing the O2−2 ion, where there is a single bond between the two oxygen atoms), superoxides (containing the O−2 ion), and many others. Lithium burns in air to form lithium oxide, but sodium reacts with oxygen to form a mixture of sodium oxide and sodium peroxide. Potassium forms a mixture of potassium peroxide and potassium superoxide, while rubidium and caesium form the superoxide exclusively. Their reactivity increases going down the group: while lithium, sodium and potassium merely burn in air, rubidium and caesium are pyrophoric (spontaneously catch fire in air).[85]

The smaller alkali metals tend to polarise the larger anions (the peroxide and superoxide) due to their small size. This attracts the electrons in the more complex anions towards one of its constituent oxygen atoms, forming an oxide ion and an oxygen atom. This causes lithium to form the oxide exclusively on reaction with oxygen at room temperature. This effect becomes drastically weaker for the larger sodium and potassium, allowing them to form the less stable peroxides. Rubidium and caesium, at the bottom of the group, are so large that even the least stable superoxides can form. Because the superoxide releases the most energy when formed, the superoxide is preferentially formed for the larger alkali metals where the more complex anions are not polarised. The oxides and peroxides for these alkali metals do exist, but do not form upon direct reaction of the metal with oxygen at standard conditions.[85] In addition, the small size of the Li+ and O2− ions contributes to their forming a stable ionic lattice structure. Under controlled conditions, however, all the alkali metals, with the exception of francium, are known to form their oxides, peroxides, and superoxides. The alkali metal peroxides and superoxides are powerful oxidising agents. Sodium peroxide and potassium superoxide react with carbon dioxide to form the alkali metal carbonate and oxygen gas, which allows them to be used in submarine air purifiers; the presence of water vapour, naturally present in breath, makes the removal of carbon dioxide by potassium superoxide even more efficient.[66][125] All the stable alkali metals except lithium can form red ozonides (MO3) through low-temperature reaction of the powdered anhydrous hydroxide with ozone: the ozonides may be then extracted using liquid ammonia. They slowly decompose at standard conditions to the superoxides and oxygen, and hydrolyse immediately to the hydroxides when in contact with water.[11]: 85 Potassium, rubidium, and caesium also form sesquioxides M2O3, which may be better considered peroxide disuperoxides, [(M+)4(O2−2)(O−2)2].[11]: 85

Rubidium and caesium can form a great variety of suboxides with the metals in formal oxidation states below +1.[11]: 85 Rubidium can form Rb6O and Rb9O2 (copper-coloured) upon oxidation in air, while caesium forms an immense variety of oxides, such as the ozonide CsO3[126][127] and several brightly coloured suboxides,[128] such as Cs7O (bronze), Cs4O (red-violet), Cs11O3 (violet), Cs3O (dark green),[129] CsO, Cs3O2,[130] as well as Cs7O2.[131][132] The last of these may be heated under vacuum to generate Cs2O.[57]

The alkali metals can also react analogously with the heavier chalcogens (sulfur, selenium, tellurium, and polonium), and all the alkali metal chalcogenides are known (with the exception of francium's). Reaction with an excess of the chalcogen can similarly result in lower chalcogenides, with chalcogen ions containing chains of the chalcogen atoms in question. For example, sodium can react with sulfur to form the sulfide (Na2S) and various polysulfides with the formula Na2Sx (x from 2 to 6), containing the S2−

x ions.[66] Due to the basicity of the Se2− and Te2− ions, the alkali metal selenides and tellurides are alkaline in solution; when reacted directly with selenium and tellurium, alkali metal polyselenides and polytellurides are formed along with the selenides and tellurides with the Se2−

x and Te2−

x ions.[133] They may be obtained directly from the elements in liquid ammonia or when air is not present, and are colourless, water-soluble compounds that air oxidises quickly back to selenium or tellurium.[11]: 766 The alkali metal polonides are all ionic compounds containing the Po2− ion; they are very chemically stable and can be produced by direct reaction of the elements at around 300–400 °C.[11]: 766 [134][135]

Halides, hydrides, and pseudohalides[edit]

The alkali metals are among the most electropositive elements on the periodic table and thus tend to bond ionically to the most electronegative elements on the periodic table, the halogens (fluorine, chlorine, bromine, iodine, and astatine), forming salts known as the alkali metal halides. The reaction is very vigorous and can sometimes result in explosions.[11]: 76 All twenty stable alkali metal halides are known; the unstable ones are not known, with the exception of sodium astatide, because of the great instability and rarity of astatine and francium. The most well-known of the twenty is certainly sodium chloride, otherwise known as common salt. All of the stable alkali metal halides have the formula MX where M is an alkali metal and X is a halogen. They are all white ionic crystalline solids that have high melting points.[5][85] All the alkali metal halides are soluble in water except for lithium fluoride (LiF), which is insoluble in water due to its very high lattice enthalpy. The high lattice enthalpy of lithium fluoride is due to the small sizes of the Li+ and F− ions, causing the electrostatic interactions between them to be strong:[5] a similar effect occurs for magnesium fluoride, consistent with the diagonal relationship between lithium and magnesium.[11]: 76

The alkali metals also react similarly with hydrogen to form ionic alkali metal hydrides, where the hydride anion acts as a pseudohalide: these are often used as reducing agents, producing hydrides, complex metal hydrides, or hydrogen gas.[11]: 83 [66] Other pseudohalides are also known, notably the cyanides. These are isostructural to the respective halides except for lithium cyanide, indicating that the cyanide ions may rotate freely.[11]: 322 Ternary alkali metal halide oxides, such as Na3ClO, K3BrO (yellow), Na4Br2O, Na4I2O, and K4Br2O, are also known.[11]: 83 The polyhalides are rather unstable, although those of rubidium and caesium are greatly stabilised by the feeble polarising power of these extremely large cations.[11]: 835

Coordination complexes[edit]

Alkali metal cations do not usually form coordination complexes with simple Lewis bases due to their low charge of just +1 and their relatively large size; thus the Li+ ion forms most complexes and the heavier alkali metal ions form less and less (though exceptions occur for weak complexes).[11]: 90 Lithium in particular has a very rich coordination chemistry in which it exhibits coordination numbers from 1 to 12, although octahedral hexacoordination is its preferred mode.[11]: 90–1 In aqueous solution, the alkali metal ions exist as octahedral hexahydrate complexes [M(H2O)6]+, with the exception of the lithium ion, which due to its small size forms tetrahedral tetrahydrate complexes [Li(H2O)4]+; the alkali metals form these complexes because their ions are attracted by electrostatic forces of attraction to the polar water molecules. Because of this, anhydrous salts containing alkali metal cations are often used as desiccants.[66] Alkali metals also readily form complexes with crown ethers (e.g. 12-crown-4 for Li+, 15-crown-5 for Na+, 18-crown-6 for K+, and 21-crown-7 for Rb+) and cryptands due to electrostatic attraction.[66]

Ammonia solutions[edit]

The alkali metals dissolve slowly in liquid ammonia, forming ammoniacal solutions of solvated metal cation M+ and solvated electron e−, which react to form hydrogen gas and the alkali metal amide (MNH2, where M represents an alkali metal): this was first noted by Humphry Davy in 1809 and rediscovered by W. Weyl in 1864. The process may be speeded up by a catalyst. Similar solutions are formed by the heavy divalent alkaline earth metals calcium, strontium, barium, as well as the divalent lanthanides, europium and ytterbium. The amide salt is quite insoluble and readily precipitates out of solution, leaving intensely coloured ammonia solutions of the alkali metals. In 1907, Charles A. Kraus identified the colour as being due to the presence of solvated electrons, which contribute to the high electrical conductivity of these solutions. At low concentrations (below 3 M), the solution is dark blue and has ten times the conductivity of aqueous sodium chloride; at higher concentrations (above 3 M), the solution is copper-coloured and has approximately the conductivity of liquid metals like mercury.[11][66][137] In addition to the alkali metal amide salt and solvated electrons, such ammonia solutions also contain the alkali metal cation (M+), the neutral alkali metal atom (M), diatomic alkali metal molecules (M2) and alkali metal anions (M−). These are unstable and eventually become the more thermodynamically stable alkali metal amide and hydrogen gas. Solvated electrons are powerful reducing agents and are often used in chemical synthesis.[66]

Organometallic[edit]

Organolithium[edit]

Being the smallest alkali metal, lithium forms the widest variety of and most stable organometallic compounds, which are bonded covalently. Organolithium compounds are electrically non-conducting volatile solids or liquids that melt at low temperatures, and tend to form oligomers with the structure (RLi)x where R is the organic group. As the electropositive nature of lithium puts most of the charge density of the bond on the carbon atom, effectively creating a carbanion, organolithium compounds are extremely powerful bases and nucleophiles. For use as bases, butyllithiums are often used and are commercially available. An example of an organolithium compound is methyllithium ((CH3Li)x), which exists in tetrameric (x = 4, tetrahedral) and hexameric (x = 6, octahedral) forms.[66][141] Organolithium compounds, especially n-butyllithium, are useful reagents in organic synthesis, as might be expected given lithium's diagonal relationship with magnesium, which plays an important role in the Grignard reaction.[11]: 102 For example, alkyllithiums and aryllithiums may be used to synthesise aldehydes and ketones by reaction with metal carbonyls. The reaction with nickel tetracarbonyl, for example, proceeds through an unstable acyl nickel carbonyl complex which then undergoes electrophilic substitution to give the desired aldehyde (using H+ as the electrophile) or ketone (using an alkyl halide) product.[11]: 105

Alkyllithiums and aryllithiums may also react with N,N-disubstituted amides to give aldehydes and ketones, and symmetrical ketones by reacting with carbon monoxide. They thermally decompose to eliminate a β-hydrogen, producing alkenes and lithium hydride: another route is the reaction of ethers with alkyl- and aryllithiums that act as strong bases.[11]: 105 In non-polar solvents, aryllithiums react as the carbanions they effectively are, turning carbon dioxide to aromatic carboxylic acids (ArCO2H) and aryl ketones to tertiary carbinols (Ar'2C(Ar)OH). Finally, they may be used to synthesise other organometallic compounds through metal-halogen exchange.[11]: 106

Heavier alkali metals[edit]

Unlike the organolithium compounds, the organometallic compounds of the heavier alkali metals are predominantly ionic. The application of organosodium compounds in chemistry is limited in part due to competition from organolithium compounds, which are commercially available and exhibit more convenient reactivity. The principal organosodium compound of commercial importance is sodium cyclopentadienide. Sodium tetraphenylborate can also be classified as an organosodium compound since in the solid state sodium is bound to the aryl groups. Organometallic compounds of the higher alkali metals are even more reactive than organosodium compounds and of limited utility. A notable reagent is Schlosser's base, a mixture of n-butyllithium and potassium tert-butoxide. This reagent reacts with propene to form the compound allylpotassium (KCH2CHCH2). cis-2-Butene and trans-2-butene equilibrate when in contact with alkali metals. Whereas isomerisation is fast with lithium and sodium, it is slow with the heavier alkali metals. The heavier alkali metals also favour the sterically congested conformation.[142] Several crystal structures of organopotassium compounds have been reported, establishing that they, like the sodium compounds, are polymeric.[143] Organosodium, organopotassium, organorubidium and organocaesium compounds are all mostly ionic and are insoluble (or nearly so) in nonpolar solvents.[66]

Alkyl and aryl derivatives of sodium and potassium tend to react with air. They cause the cleavage of ethers, generating alkoxides. Unlike alkyllithium compounds, alkylsodiums and alkylpotassiums cannot be made by reacting the metals with alkyl halides because Wurtz coupling occurs:[123]: 265

- RM + R'X → R–R' + MX

As such, they have to be made by reacting alkylmercury compounds with sodium or potassium metal in inert hydrocarbon solvents. While methylsodium forms tetramers like methyllithium, methylpotassium is more ionic and has the nickel arsenide structure with discrete methyl anions and potassium cations.[123]: 265

The alkali metals and their hydrides react with acidic hydrocarbons, for example cyclopentadienes and terminal alkynes, to give salts. Liquid ammonia, ether, or hydrocarbon solvents are used, the most common of which being tetrahydrofuran. The most important of these compounds is sodium cyclopentadienide, NaC5H5, an important precursor to many transition metal cyclopentadienyl derivatives.[123]: 265 Similarly, the alkali metals react with cyclooctatetraene in tetrahydrofuran to give alkali metal cyclooctatetraenides; for example, dipotassium cyclooctatetraenide (K2C8H8) is an important precursor to many metal cyclooctatetraenyl derivatives, such as uranocene.[123]: 266 The large and very weakly polarising alkali metal cations can stabilise large, aromatic, polarisable radical anions, such as the dark-green sodium naphthalenide, Na+[C10H8•]−, a strong reducing agent.[123]: 266

Representative reactions of alkali metals[edit]

Reaction with oxygen[edit]

Upon reacting with oxygen, alkali metals form oxides, peroxides, superoxides and suboxides. However, the first three are more common. The table below[144] shows the types of compounds formed in reaction with oxygen. The compound in brackets represents the minor product of combustion.

| Alkali metal | Oxide | Peroxide | Superoxide |

| Li | Li2O | (Li2O2) | |

| Na | (Na2O) | Na2O2 | |

| K | KO2 | ||

| Rb | RbO2 | ||

| Cs | CsO2 |

The alkali metal peroxides are ionic compounds that are unstable in water. The peroxide anion is weakly bound to the cation, and it is hydrolysed, forming stronger covalent bonds.

- Na2O2 + 2H2O → 2NaOH + H2O2

The other oxygen compounds are also unstable in water.

- 2KO2 + 2H2O → 2KOH + H2O2 + O2[145]

- Li2O + H2O → 2LiOH

Reaction with sulfur[edit]

With sulfur, they form sulfides and polysulfides.[146]

- 2Na + 1/8S8 → Na2S + 1/8S8 → Na2S2...Na2S7

Because alkali metal sulfides are essentially salts of a weak acid and a strong base, they form basic solutions.

- S2- + H2O → HS− + HO−

- HS− + H2O → H2S + HO−

Reaction with nitrogen[edit]

Lithium is the only metal that combines directly with nitrogen at room temperature.

- 3Li + 1/2N2 → Li3N

Li3N can react with water to liberate ammonia.

- Li3N + 3H2O → 3LiOH + NH3

Reaction with hydrogen[edit]

With hydrogen, alkali metals form saline hydrides that hydrolyse in water.

Reaction with carbon[edit]

Lithium is the only metal that reacts directly with carbon to give dilithium acetylide. Na and K can react with acetylene to give acetylides.[147]

Reaction with water[edit]

On reaction with water, they generate hydroxide ions and hydrogen gas. This reaction is vigorous and highly exothermic and the hydrogen resulted may ignite in air or even explode in the case of Rb and Cs.[144]

- Na + H2O → NaOH + 1/2H2

Reaction with other salts[edit]

The alkali metals are very good reducing agents. They can reduce metal cations that are less electropositive. Titanium is produced industrially by the reduction of titanium tetrachloride with Na at 400 °C (van Arkel–de Boer process).

- TiCl4 + 4Na → 4NaCl + Ti

Reaction with organohalide compounds[edit]

Alkali metals react with halogen derivatives to generate hydrocarbon via the Wurtz reaction.

- 2CH3-Cl + 2Na → H3C-CH3 + 2NaCl

Alkali metals in liquid ammonia[edit]

Alkali metals dissolve in liquid ammonia or other donor solvents like aliphatic amines or hexamethylphosphoramide to give blue solutions. These solutions are believed to contain free electrons.[144]

- Na + xNH3 → Na+ + e(NH3)x−

Due to the presence of solvated electrons, these solutions are very powerful reducing agents used in organic synthesis.

Reaction 1) is known as Birch reduction.Other reductions[144] that can be carried by these solutions are:

- S8 + 2e− → S82-

- Fe(CO)5 + 2e− → Fe(CO)42- + CO

Extensions[edit]

Although francium is the heaviest alkali metal that has been discovered, there has been some theoretical work predicting the physical and chemical characteristics of hypothetical heavier alkali metals. Being the first period 8 element, the undiscovered element ununennium (element 119) is predicted to be the next alkali metal after francium and behave much like their lighter congeners; however, it is also predicted to differ from the lighter alkali metals in some properties.[37]: 1729–1730 Its chemistry is predicted to be closer to that of potassium[42] or rubidium[37]: 1729–1730 instead of caesium or francium. This is unusual as periodic trends, ignoring relativistic effects would predict ununennium to be even more reactive than caesium and francium. This lowered reactivity is due to the relativistic stabilisation of ununennium's valence electron, increasing ununennium's first ionisation energy and decreasing the metallic and ionic radii;[42] this effect is already seen for francium.[37]: 1729–1730 This assumes that ununennium will behave chemically as an alkali metal, which, although likely, may not be true due to relativistic effects.[149] The relativistic stabilisation of the 8s orbital also increases ununennium's electron affinity far beyond that of caesium and francium; indeed, ununennium is expected to have an electron affinity higher than all the alkali metals lighter than it. Relativistic effects also cause a very large drop in the polarisability of ununennium.[37]: 1729–1730 On the other hand, ununennium is predicted to continue the trend of melting points decreasing going down the group, being expected to have a melting point between 0 °C and 30 °C.[37]: 1724

The stabilisation of ununennium's valence electron and thus the contraction of the 8s orbital cause its atomic radius to be lowered to 240 pm,[37]: 1729–1730 very close to that of rubidium (247 pm),[5] so that the chemistry of ununennium in the +1 oxidation state should be more similar to the chemistry of rubidium than to that of francium. On the other hand, the ionic radius of the Uue+ ion is predicted to be larger than that of Rb+, because the 7p orbitals are destabilised and are thus larger than the p-orbitals of the lower shells. Ununennium may also show the +3[37]: 1729–1730 and +5 oxidation states,[150] which are not seen in any other alkali metal,[11]: 28 in addition to the +1 oxidation state that is characteristic of the other alkali metals and is also the main oxidation state of all the known alkali metals: this is because of the destabilisation and expansion of the 7p3/2 spinor, causing its outermost electrons to have a lower ionisation energy than what would otherwise be expected.[11]: 28 [37]: 1729–1730 Indeed, many ununennium compounds are expected to have a large covalent character, due to the involvement of the 7p3/2 electrons in the bonding.[87]

Not as much work has been done predicting the properties of the alkali metals beyond ununennium. Although a simple extrapolation of the periodic table (by the Aufbau principle) would put element 169, unhexennium, under ununennium, Dirac-Fock calculations predict that the next element after ununennium with alkali-metal-like properties may be element 165, unhexpentium, which is predicted to have the electron configuration [Og] 5g18 6f14 7d10 8s2 8p1/22 9s1.[37]: 1729–1730 [148] This element would be intermediate in properties between an alkali metal and a group 11 element, and while its physical and atomic properties would be closer to the former, its chemistry may be closer to that of the latter. Further calculations show that unhexpentium would follow the trend of increasing ionisation energy beyond caesium, having an ionisation energy comparable to that of sodium, and that it should also continue the trend of decreasing atomic radii beyond caesium, having an atomic radius comparable to that of potassium.[37]: 1729–1730 However, the 7d electrons of unhexpentium may also be able to participate in chemical reactions along with the 9s electron, possibly allowing oxidation states beyond +1, whence the likely transition metal behaviour of unhexpentium.[37]: 1732–1733 [151] Due to the alkali and alkaline earth metals both being s-block elements, these predictions for the trends and properties of ununennium and unhexpentium also mostly hold quite similarly for the corresponding alkaline earth metals unbinilium (Ubn) and unhexhexium (Uhh).[37]: 1729–1733 Unsepttrium, element 173, may be an even better heavier homologue of ununennium; with a predicted electron configuration of [Usb] 6g1, it returns to the alkali-metal-like situation of having one easily removed electron far above a closed p-shell in energy, and is expected to be even more reactive than caesium.[152][153]

The probable properties of further alkali metals beyond unsepttrium have not been explored yet as of 2019, and they may or may not be able to exist.[148] In periods 8 and above of the periodic table, relativistic and shell-structure effects become so strong that extrapolations from lighter congeners become completely inaccurate. In addition, the relativistic and shell-structure effects (which stabilise the s-orbitals and destabilise and expand the d-, f-, and g-orbitals of higher shells) have opposite effects, causing even larger difference between relativistic and non-relativistic calculations of the properties of elements with such high atomic numbers.[37]: 1732–1733 Interest in the chemical properties of ununennium, unhexpentium, and unsepttrium stems from the fact that they are located close to the expected locations of islands of stability, centered at elements 122 (306Ubb) and 164 (482Uhq).[154][155][156]

Pseudo-alkali metals[edit]

Many other substances are similar to the alkali metals in their tendency to form monopositive cations. Analogously to the pseudohalogens, they have sometimes been called "pseudo-alkali metals". These substances include some elements and many more polyatomic ions; the polyatomic ions are especially similar to the alkali metals in their large size and weak polarising power.[157]

Hydrogen[edit]

The element hydrogen, with one electron per neutral atom, is usually placed at the top of Group 1 of the periodic table because of its electron configuration. But hydrogen is not normally considered to be an alkali metal.[158] Metallic hydrogen, which only exists at very high pressures, is known for its electrical and magnetic properties, not its chemical properties.[159] Under typical conditions, pure hydrogen exists as a diatomic gas consisting of two atoms per molecule (H2);[160] however, the alkali metals form diatomic molecules (such as dilithium, Li2) only at high temperatures, when they are in the gaseous state.[161]

Hydrogen, like the alkali metals, has one valence electron[123] and reacts easily with the halogens,[123] but the similarities mostly end there because of the small size of a bare proton H+ compared to the alkali metal cations.[123] Its placement above lithium is primarily due to its electron configuration.[158] It is sometimes placed above fluorine due to their similar chemical properties, though the resemblance is likewise not absolute.[162]