Западная Бенгалия

Bigrien ( / Batal 8 ˈ - âk / betalm : , bonim ossshim произносится [ˈpoʃtʃim ˈbɔŋo] , abbr. WB является государством в восточной части Индии ) . Он расположен вдоль Бенгальского залива , наряду с населением более 91 миллиона жителей в районе 88 752 км 2 (34 267 кв. МИ) по состоянию на 2011 год. Оценка населения по состоянию на 2023 год составляет 102 552 787. [ 12 ] Западная Бенгалия является четвертым по численным густонаселенным и тринадцатым по величине штатом по районам в Индии, а также восьмым по численным численным страновым подразделениям мира. В рамках бенгальского региона индийского субконтинента он граничит с Бангладеш на востоке, а также Непал и Бутан на севере. Это также граничит с индийскими штатами Джаркханд , Одиша , Бихар , Сикким и Ассам . Столицей штата является Калькутта , третий по величине мегаполис , и седьмой по величине город по населению Индии. Западная Бенгалия включает в себя область Дарджилинг Гималайского холма , Дельта Ганг , регион Рарх , прибрежные сундарбаны и Бенгальский залив . Основная этническая группа штата - бенгальцы , а бенгальские индусы образуют демографическое большинство.

The area's early history featured a succession of Indian empires, internal squabbling, and a tussle between Hinduism and Buddhism for dominance. Ancient Bengal was the site of several major Janapadas, while the earliest cities date back to the Vedic period. The region was part of several ancient pan−Indian empires, including the Vangas, Mauryans, and the Guptas. The citadel of Gauḍa served as the capital of the Gauḍa Kingdom, the Pala Empire, and the Sena Empire. Islam was introduced through trade with the Abbasid Caliphate, but following the Ghurid conquests led by Bakhtiyar Khalji and the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate, the Muslim faith spread across the entire Bengal region. During the Bengal Sultanate, the territory was a major trading nation in the world, and was often referred by the Europeans as the "richest country to trade with". It was absorbed into the Mughal Empire in 1576. Simultaneously, some parts of the region were ruled by several Hindu states, and Baro-Bhuyan landlords, and part of it was briefly overrun by the Suri Empire. Following the death of Emperor Aurangzeb in the early 1700s, the proto-industrialised Mughal Bengal became a semi-independent state under the Nawabs of Bengal, and showed signs of the first Industrial Revolution.[13][14] The region was later annexed into the Bengal Presidency by the British East India Company after the Battle of Buxar in 1764.[15][16] From 1772 to 1911, Calcutta was the capital of all of East India Company's territories and then the capital of the entirety of India after the establishment of the Viceroyalty.[17] From 1912 to India's Independence in 1947, it was the capital of the Bengal Province.[18]

The region was a hotbed of the Indian independence movement and has remained one of India's great artistic and intellectual centres.[19] Following widespread religious violence, the Bengal Legislative Council and the Bengal Legislative Assembly voted on the Partition of Bengal in 1947 along religious lines into two independent dominions: West Bengal, a Hindu-majority Indian state, and East Bengal, a Muslim-majority province of Pakistan which later became the independent Bangladesh. The state was also flooded with Hindu refugees from East Bengal (present-day Bangladesh) in the decades following the 1947 partition of India, transforming its landscape and shaping its politics.[20][21] The early and prolonged exposure to British administration resulted in an expansion of Western education, culminating in developments in science, institutional education, and social reforms in the region, including what became known as the Bengali Renaissance. Several regional and pan−Indian empires throughout Bengal's history have shaped its culture, cuisine, and architecture.

Post-Indian independence, as a welfare state, West Bengal's economy is based on agricultural production and small and medium-sized enterprises.[22] The state's cultural heritage, besides varied folk traditions, ranges from stalwarts in literature including Nobel-laureate Rabindranath Tagore to scores of musicians, film-makers and artists. For several decades, the state underwent political violence and economic stagnation after the beginning of communist rule in 1977 before it rebounded.[23] In 2023–24, the economy of West Bengal is the sixth-largest state economy in India with a gross state domestic product (GSDP) of ₹17.19 lakh crore (US$210 billion),[5] and has the country's 20th-highest GSDP per capita of ₹121,267 (US$1,500)[24] as of 2020–21. Despite being one of the fastest-growing major economies, West Bengal has struggled to attract foreign direct investment due to adverse land acquisition policies, poor infrastructure, and red tape.[25][26] It also has the 26th-highest ranking among Indian states in human development index, with the index value being lower than the Indian average.[8][22] The state government debt of ₹6.47 lakh crore (US$78 billion), or 37.67% of GSDP, has dropped from 40.65% since 2010–11.[27][5] West Bengal has three World Heritage sites and ranks as the eight-most visited tourist destination in India and third-most visited state of India globally.[28][29]

Etymology

The origin of the name Bengal (Bangla and Bongo in Bengali) is unknown. One theory suggests the word derives from "Bang", the name of a Dravidian tribe that settled the region around 1000 BCE.[30] The Bengali word Bongo might have been derived from the ancient kingdom of Vanga (or Banga). Although some early Sanskrit literature mentions the name Vanga, the region's early history is obscure.[31]

In 1947, at the end of British rule over the Indian subcontinent the Bengal Legislative Council and the Bengal Legislative Assembly voted on the Partition of Bengal along religious lines into two separate entities: West Bengal, which continued as an Indian state and East Bengal, a province of Pakistan, which came to be known be as East Pakistan and later became the independent Bangladesh.[11][32]

In 2011 the Government of West Bengal proposed a change in the official name of the state to Paschim Banga (Bengali: পশ্চিমবঙ্গ Pôshchimbônggô).[33] This is the native name of the state, literally meaning "western Bengal" in the native Bengali language. In August 2016 the West Bengal Legislative Assembly passed another resolution to change the name of West Bengal to "Bengal" in English and "Bangla" in Bengali. Despite the Trinamool Congress government's efforts to forge a consensus on the name change resolution, the Indian National Congress, the Left Front and the Bharatiya Janata Party opposed the resolution.[34] However, the central government has turned down the proposal maintaining the state should have one single name for all languages instead of three and it should not be the same as that of any other territory (pointing out that the name 'Bangla' may create confusion with neighbouring Bangladesh).[34][35][36]

History

Ancient and classical period

Stone Age tools dating back 20,000 years have been excavated in the state, showing human occupation 8,000 years earlier than scholars had thought.[37] According to the Indian epic Mahabharata the region was part of the Vanga Kingdom.[38] Several Vedic realms were present in the Bengal region, including Vanga, Rarh, Pundravardhana and the Suhma Kingdom. One of the earliest foreign references to Bengal is a mention by the Ancient Greeks around 100 BCE of a land named Gangaridai located at the mouths of the Ganges.[39] Bengal had overseas trade relations with Suvarnabhumi (Burma, Lower Thailand, the Lower Malay Peninsula and Sumatra).[40] According to the Sri Lankan chronicle Mahavamsa, Prince Vijaya (c. 543 – c. 505 BCE), a Vanga Kingdom prince, conquered Lanka (modern-day Sri Lanka) and named the country Sinhala Kingdom.[41]

The kingdom of Magadha was formed in the 7th century BCE, consisting of the regions now comprising Bihar and Bengal. It was one of the four main kingdoms of India at the time of the lives of Mahavira, the principal figure of Jainism and Gautama Buddha, founder of Buddhism. It consisted of several janapadas, or kingdoms.[42] Under Ashoka, the Maurya Empire of Magadha in the 3rd century BCE extended over nearly all of South Asia, including Afghanistan and parts of Balochistan. From the 3rd to the 6th centuries CE, the kingdom of Magadha served as the seat of the Gupta Empire.[43]

Two kingdoms—Vanga or Samatata, and Gauda—are said in some texts to have appeared after the end of the Gupta Empire although details of their ascendancy are uncertain.[44] The first recorded independent king of Bengal was Shashanka, who reigned in the early 7th century.[45] Shashanka is often recorded in Buddhist annals as an intolerant Hindu ruler noted for his persecution of the Buddhists. He murdered Rajyavardhana, the Buddhist king of Thanesar, and is noted for destroying the Bodhi tree at Bodhgaya, and replacing Buddha statues with Shiva lingams.[46] After a period of anarchy,[47]: 36 the Pala dynasty ruled the region for four hundred years beginning in the 8th century. A shorter reign of the Hindu Sena dynasty followed.[48]

Rajendra Chola I of the Chola dynasty invaded some areas of Bengal between 1021 and 1023.[49]

Islam was introduced through trade with the Abbasid Caliphate.[50] Following the Ghurid conquests led by Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji and the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate, it spread across the entire Bengal region. Mosques, madrasas and khanqahs were built throughout these stages. During the Islamic Bengal Sultanate, founded in 1352, Bengal was a major world trading nation and was often referred by the Europeans as the richest country with which to trade.[51] Later, in 1576, it was absorbed into the Mughal Empire.[52]

Medieval and early modern periods

Subsequent Muslim conquests helped spread Islam throughout the region.[53] It was ruled by dynasties of the Bengal Sultanate and feudal lords under the Delhi Sultanate for the next few hundred years. The Bengal Sultanate was interrupted for twenty years by a Hindu uprising under Raja Ganesha. In the 16th century, Mughal general Islam Khan conquered Bengal. Administration by governors appointed by the court of the Mughal Empire gave way to semi-independence under the Nawabs of Murshidabad, who nominally respected the sovereignty of the Mughals in Delhi. Several independent Hindu states were established in Bengal during the Mughal period, including those of Pratapaditya of Jessore District and Raja Sitaram Ray of Bardhaman. Following the death of Emperor Aurangzeb and the Governor of Bengal, Shaista Khan, the proto-industrialised Mughal Bengal became a semi-independent state under the Nawabs of Bengal, and showed signs of the world's first Industrial Revolution.[13][14] The Koch dynasty in northern Bengal flourished during the 16th and 17th centuries; it weathered the Mughals and survived until the advent of the British colonial era.[54][55]

Colonial period

Several European traders reached this area in the late 15th century. The British East India Company defeated Siraj ud-Daulah, the last independent Nawab, in the Battle of Plassey in 1757. The company gained the right to collect revenue in Bengal subah (province) in 1765 with the signing of the treaty between the East India company and the Mughal emperor following the Battle of Buxar in 1764.[56] The Bengal Presidency was established in 1765; it later incorporated all British-controlled territory north of the Central Provinces (now Madhya Pradesh), from the mouths of the Ganges and the Brahmaputra to the Himalayas and the Punjab. The Bengal famine of 1770 claimed millions of lives due to tax policies enacted by the British company.[57] Calcutta, the headquarters of the East India company, was named the capital of British-held territories in India in 1773.[58] The failed Indian rebellion of 1857 started near Calcutta and resulted in a transfer of authority to the British Crown,[59] administered by the Viceroy of India.[60]

The Bengal Renaissance and the Brahmo Samaj socio-cultural reform movements significantly influenced the cultural and economic life of Bengal.[61] Between 1905 and 1911 an abortive attempt was made to divide the province of Bengal into two zones.[62] Bengal suffered from the Great Bengal famine in 1943, which claimed three million lives during World War II.[63] Bengalis played a major role in the Indian independence movement, in which revolutionary groups such as Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar were dominant.[19] Armed attempts against the British Raj from Bengal reached a climax when news of Subhas Chandra Bose leading the Indian National Army against the British reached Bengal. The Indian National Army was subsequently routed by the British.[64]

Indian independence and afterwards

When India gained independence in 1947, Bengal was partitioned along religious lines. The western part went to the Dominion of India and was named West Bengal. The eastern part went to the Dominion of Pakistan as a province called East Bengal (later renamed East Pakistan in 1956), becoming the independent nation of Bangladesh in 1971.[65] In 1950 the Princely State of Cooch Behar merged with West Bengal.[66] In 1955 the former French enclave of Chandannagar, which had passed into Indian control after 1950, was integrated into West Bengal; portions of Bihar were also subsequently merged with West Bengal. Both West and East Bengal experienced large influxes of refugees during and after the partition in 1947. Refugee resettlement and related issues continued to play a significant role in the politics and socio-economic condition of the state.[66]

During the 1970s and 1980s, severe power shortages, strikes and a violent Marxist–Maoist movement by groups known as the Naxalites damaged much of the city's infrastructure, leading to a period of economic stagnation and deindustrialisation.[23] The Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971 resulted in an influx of millions of refugees to West Bengal, causing significant strains on its infrastructure.[67] The 1974 smallpox epidemic killed thousands. West Bengal politics underwent a major change when the Left Front won the 1977 assembly election, defeating the incumbent Indian National Congress. The Left Front, led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist), governed the state for the next three decades.[68]

The state's economic recovery gathered momentum after the central government introduced economic liberalisations in the mid-1990s. This was aided by the advent of information technology and IT-enabled services. Beginning in the mid-2000s, armed activists conducted minor terrorist attacks in some parts of the state.[69][70] Clashes with the administration took place at several controversial locations over the issue of industrial land acquisition.[71][72] This became a decisive reason behind the defeat of the ruling Left Front government in the 2011 assembly election.[73] Although the economy was severely damaged during the unrest in the 1970s, the state has managed to revive its economy steadily throughout the years.[74][75][76] The state has shown improvement regarding bandhs (strikes)[77][78][79] and educational infrastructure.[80] Significant strides have been made in reducing unemployment,[81] though the state suffers from substandard healthcare services,[82][83] a lack of socio-economic development,[84] poor infrastructure,[85] unemployment and civil violence.[86][87] In 2006 the state's healthcare system was severely criticised in the aftermath of the West Bengal blood test kit scam.[88][89]

Geography

West Bengal is on the eastern bottleneck of India, stretching from the Himalayas in the north to the Bay of Bengal in the south. The state has a total area of 88,752 square kilometres (34,267 sq mi).[3] The Darjeeling Himalayan hill region in the northern extreme of the state is a part of the eastern Himalayas mountain range. In this region is Sandakfu, which, at 3,636 m (11,929 ft), is the highest peak in the state.[90] The narrow Terai region separates the hills from the North Bengal plains, which in turn transitions into the Ganges delta towards the south. The Rarh region intervenes between the Ganges delta in the east and the western plateau and high lands. A small coastal region is in the extreme south, while the Sundarbans mangrove forests form a geographical landmark at the Ganges delta.[91]

The main river in West Bengal is the Ganges, which divides into two branches. One branch enters Bangladesh as the Padma, or Pôdda, while the other flows through West Bengal as the Bhagirathi River and Hooghly River. The Farakka barrage over the Ganges feeds the Hooghly branch of the river by a feeder canal. Its water flow management has been a source of lingering dispute between India and Bangladesh.[92] The Teesta, Torsa, Jaldhaka and Mahananda rivers are in the northern hilly region. The western plateau region has rivers like the Damodar, Ajay and Kangsabati. The Ganges delta and the Sundarbans area have numerous rivers and creeks. Pollution of the Ganges from indiscriminate waste dumped into the river is a major problem.[93] Damodar, another tributary of the Ganges and once known as the "Sorrow of Bengal" (due to its frequent floods), has several dams under the Damodar Valley Project. At least nine districts in the state suffer from arsenic contamination of groundwater, and as of 2017 an estimated 1.04 crore people were afflicted by arsenic poisoning.[94]

West Bengal's climate varies from tropical savanna in the southern portions to humid subtropical in the north. The main seasons are summer, the rainy season, a short autumn and winter. While the summer in the delta region is noted for excessive humidity, the western highlands experience a dry summer like northern India. The highest daytime temperatures range from 38 to 45 °C (100 to 113 °F).[95] At night, a cool southerly breeze carries moisture from the Bay of Bengal. In early summer, brief squalls and thunderstorms known as Kalbaisakhi, or Nor'westers, often occur.[96] West Bengal receives the Bay of Bengal branch of the Indian Ocean monsoon that moves in a southeast to northwest direction. Monsoons bring rain to the whole state from June to September. Heavy rainfall of above 250 centimetres (98 in) is observed in the Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, and Cooch Behar district. During the arrival of the monsoons, low pressure in the Bay of Bengal region often leads to the formation of storms in the coastal areas. Winter (December–January) is mild over the plains with average minimum temperatures of 15 °C (59 °F).[95] A cold and dry northern wind blows in the winter, substantially lowering the humidity level. The Darjeeling Himalayan Hill region experiences a harsh winter, with occasional snowfall.[97]

Flora and fauna

The "India State of Forest Report 2017", recorded forest area in the state is 16,847 km2 (6,505 sq mi),[98][99] while in 2013, forest area was 16,805 km2 (6,488 sq mi), which was 18.93% of the state's geographical area, compared to the then national average of 21.23%.[100] Reserves and protected and unclassed forests constitute 59.4%, 31.8% and 8.9%, respectively, of forested areas, as of 2009.[101] Part of the world's largest mangrove forest, the Sundarbans in southern West Bengal.[102]

From a phytogeographic viewpoint, the southern part of West Bengal can be divided into two regions: the Gangetic plain and the littoral mangrove forests of the Sundarbans.[103] The alluvial soil of the Gangetic plain, combined with favourable rainfall, makes this region especially fertile.[103] Much of the vegetation of the western part of the state has similar species composition with the plants of the Chota Nagpur plateau in the adjoining state of Jharkhand.[103] The predominant commercial tree species is Shorea robusta, commonly known as the sal tree. The coastal region of Purba Medinipur exhibits coastal vegetation; the predominant tree is the Casuarina. A notable tree from the Sundarbans is the ubiquitous sundari (Heritiera fomes), from which the forest gets its name.[104]

The distribution of vegetation in northern West Bengal is dictated by elevation and precipitation. For example, the foothills of the Himalayas, the Dooars, are densely wooded with sal and other tropical evergreen trees.[105] Above an elevation of 1,000 metres (3,300 ft), the forest becomes predominantly subtropical. In Darjeeling, which is above 1,500 metres (4,900 ft), temperate forest trees like oaks, conifers and rhododendrons predominate.[105]

3.26% of the geographical area of West Bengal is protected land, comprising fifteen wildlife sanctuaries and five national parks—Sundarbans National Park, Buxa Tiger Reserve, Gorumara National Park, Neora Valley National Park and Singalila National Park.[101] Extant wildlife includes Indian rhinoceros, Indian elephant, deer, leopard, gaur, tiger and crocodiles, as well as many bird species. Migratory birds come to the state during the winter.[106] The high-altitude forests of Singalila National Park shelter barking deer, red panda, chinkara, takin, serow, pangolin, minivet and kalij pheasants. The Sundarbans are noted for a reserve project devoted to conserving the endangered Bengal tiger, although the forest hosts many other endangered species such as the Gangetic dolphin, river terrapin and estuarine crocodile.[107] The mangrove forest also acts as a natural fish nursery, supporting coastal fishes along the Bay of Bengal.[107] Recognising its special conservation value, the Sundarbans area has been declared a Biosphere Reserve.[101]

Government and politics

West Bengal is governed through a parliamentary system of representative democracy, a feature the state shares with other Indian states. Universal suffrage is granted to residents. There are two branches of government. The legislature, the West Bengal Legislative Assembly, consists of elected members and special office bearers such as the Speaker and Deputy Speaker, who are elected by the members. Assembly meetings are presided over by the Speaker or the Deputy Speaker in the Speaker's absence. The judiciary is composed of the Calcutta High Court and a system of lower courts. Executive authority is vested in the Council of Ministers headed by the Chief Minister although the titular head of government is the Governor. The Governor is the Head of State appointed by the President of India. The leader of the party or coalition with a majority in the Legislative Assembly is appointed as the Chief Minister by the Governor. The Council of Ministers is appointed by the Governor on the advice of the Chief Minister. The Council of Ministers reports to the Legislative Assembly. The Assembly is unicameral with 295 members, or MLAs,[108] including one nominated from the Anglo-Indian community. Terms of office run for five years unless the Assembly is dissolved before the completion of the term. Auxiliary authorities known as panchayats, for which local body elections are regularly held, govern local affairs. The state contributes 42 seats to the Lok Sabha[109] and 16 seats to the Rajya Sabha of the Indian Parliament.[110]

Politics in West Bengal is dominated by the All India Trinamool Congress (AITC), Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Indian National Congress (INC), and the Left Front alliance (led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) or CPI(M)). Following the West Bengal State Assembly Election in 2011, the All India Trinamool Congress and Indian National Congress coalition under Mamata Banerjee of the All India Trinamool Congress was elected to power with 225 seats in the legislature.[111]

Prior to this, West Bengal was ruled by the Left Front for 34 years (1977–2011), making it the world's longest-running democratically elected communist government.[68] Banerjee was re-elected twice as Chief Minister in the 2016 West Bengal Legislative Assembly election and 2021 West Bengal Legislative Assembly election with 211 and 215 seats respectively, an absolute majority by the Trinamool Congress.[112] The state has one autonomous region, the Gorkhaland Territorial Administration.[113]

Districts and cities

Districts

As of 1 November 2023,[update] West Bengal is divided into 23 districts.[114]

| District | Population | Growth rate | Sex ratio | Literacy | Density per square Kilometer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North 24 Parganas | 10,009,781 | 12.04 | 955 | 84.06 | 2445 |

| South 24 Parganas | 8,161,961 | 18.17 | 956 | 77.51 | 819 |

| Purba Bardhaman | 4,835,432 | – | 945 | 74.73 | 890 |

| Paschim Bardhaman | 2,882,031 | – | 922 | 78.75 | 1800 |

| Murshidabad | 7,103,807 | 21.09 | 958 | 66.59 | 1334 |

| West Midnapore | 5,913,457 | 13.86 | 966 | 78.00 | 631 |

| Hooghly | 5,519,145 | 9.46 | 961 | 81.80 | 1753 |

| Nadia | 5,167,600 | 12.22 | 947 | 74.97 | 1316 |

| East Midnapore | 5,095,875 | 15.36 | 938 | 87.02 | 1081 |

| Howrah | 4,850,029 | 13.50 | 939 | 83.31 | 3306 |

| Kolkata | 4,496,694 | −1.67 | 908 | 86.31 | 24306 |

| Maldah | 3,988,845 | 21.22 | 944 | 61.73 | 1069 |

| Jalpaiguri | 3,872,846 | 13.87 | 953 | 73.25 | 622 |

| Alipurduar[a] | 1,700,000 | – | – | – | 400 |

| Bankura | 3,596,292 | 12.64 | 954 | 70.95 | 523 |

| Birbhum | 3,502,404 | 16.15 | 956 | 70.68 | 771 |

| North Dinajpur | 3,007,134 | 23.15 | 939 | 59.07 | 958 |

| Purulia | 2,930,115 | 15.52 | 957 | 64.48 | 468 |

| Cooch Behar | 2,819,086 | 13.71 | 942 | 74.78 | 832 |

| Darjeeling | 1,846,823 | 14.77 | 970 | 79.56 | 586 |

| Dakshin Dinajpur | 1,676,276 | 11.52 | 956 | 72.82 | 755 |

| Kalimpong[a] | 202,239 | – | – | – | 270 |

| Jhargram[a] | 1,136,548 | – | – | – | 374 |

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Was created after the 2011 Census

Each district is governed by a district collector or district magistrate, appointed by either the Indian Administrative Service or the West Bengal Civil Service.[115] Each district is subdivided into sub-divisions, governed by a Sub-Divisional Magistrate, and again into blocks. Blocks consists of panchayats (village councils) and town municipalities.[116]

Cities

The capital and largest city of the state is Kolkata—the third-largest urban agglomeration[117] and the seventh-largest city[118] in India. Asansol is the second-largest city and urban agglomeration in West Bengal.[117]

Major planned cities of West Bengal include Bidhannagar, New Town, Kalyani, Haldia, Durgapur and Kharagpur. Kolkata has some planned neighbourhoods like New Garia, Tollygunge, and Lake Town. Siliguri is an economically important city, strategically located in the northeastern Siliguri Corridor (Chicken's Neck) of India.[119] Other larger cities and towns in West Bengal are Howrah, Chandannagar, Bardhaman, Baharampur, Jalpaiguri, and Purulia etc.[120]

Economy

| Net State Domestic Product at Factor Cost at Current Prices (2004–05 Base)[121] (figures in crores of Indian rupees) | |

| Year | Net State Domestic Product |

|---|---|

| 2004–2005 | 190,073 |

| 2005–2006 | 209,642 |

| 2006–2007 | 238,625 |

| 2007–2008 | 272,166 |

| 2008–2009 | 309,799 |

| 2009–2010 | 366,318 |

As of 2015[update], West Bengal has the sixth-highest GSDP in India. GSDP at current prices (base 2004–2005) has increased from Rs 2,086.56 billion in 2004–05 to Rs 8,00,868 crores in 2014–2015,[122] reaching Rs 10,21,000 crores in 2017–18.[123] GSDP per cent growth at current prices varied from a low of 10.3% in 2010–2011 to a high of 17.11% in 2013–2014. The growth rate was 13.35% in 2014–2015.[124] The state's per capita income has lagged the all India average for over two decades. As of 2014–2015, per capita NSDP at current prices was Rs 78,903.[124] Per-capita NSDP growth rate at current prices varied from 9.4% in 2010–2011 to a high of 16.15% in 2013–2014. The growth rate was 12.62% in 2014–2015.[125]

In 2015–2016, the percentage share of Gross Value Added (GVA) at factor cost by economic activity at the constant price (the base year 2011–2012) was Agriculture-Forestry and Fishery—4.84%, Industry 18.51% and Services 66.65%. It has been observed that there has been a slow but steady decline in the percentage share of industry and agriculture over the years.[126] Agriculture is the leading economic sector in West Bengal. Rice is the state's principal food crop. Rice, potato, jute, sugarcane and wheat are the state's top five crops.[127]: 14 Tea is produced commercially in northern districts; the region is well known for Darjeeling and other high-quality teas.[127]: 14 State industries are localised in the Kolkata region, the mineral-rich western highlands, and the Haldia Port region.[128] The Durgapur-Asansol colliery belt is home to a number of steel plants.[128] Important manufacturing industries include: engineering products, electronics, electrical equipment, cables, steel, leather, textiles, jewellery, frigates, automobiles, railway coaches and wagons. The Durgapur centre has established several industries in the areas of tea, sugar, chemicals and fertilisers. Natural resources like tea and jute in nearby areas have made West Bengal a major centre for the jute and tea industries.[129]

Years after independence, West Bengal is dependent on the central government for help in meeting its demands for food; food production remained stagnant, and the Indian green revolution bypassed the state. However, there has been a significant increase in food production since the 1980s and the state now has a surplus of grains.[130] The state's share of total industrial output in India was 9.8% in 1980–1981, declining to 5% by 1997–1998. In contrast, the service sector has grown at a rate higher than the national rate.[130] The state's total financial debt stood at ₹1,918,350 million (US$23 billion) as of 2011.[131]

In the period 2004–2010, the average gross state domestic product (GSDP) growth rate was 13.9% (calculated in Indian rupee terms) lower than 15.5%, the average for all states of the country.[127]: 4

The economy of West Bengal has witnessed many surprising changes in direction. The agricultural sector in particular rose to 8.33% in 2010–11 before tumbling to −4.01% in 2012–13.[132] Many major industries such as the Uttarpara Hindustan Motors car manufacturing unit, the jute industry, and the Haldia Petrochemicals unit experienced shutdowns in 2014. In the same year, plans for a 300 billion Jindal Steel project was mothballed. The tea industry of West Bengal has also witnessed shutdowns for financial and political reasons.[133] The tourism industry of West Bengal was negatively impacted in 2017 because of the Gorkhaland agitation.[134]

However, over the years due to effective changes in the stance towards industrialisation, ease of doing business has improved in West Bengal.[135][136][137] Steps are being taken to remedy this situation by promoting West Bengal as an investment destination. A leather complex has been built in Kolkata. Smart cities are being planned close to Kolkata, and major roadway projects are in the offing to revive the economy.[138] West Bengal has been able to attract 2% of the foreign direct investment in the last decade.[139]

Transport

-

Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose International Airport is a hub for flights to and from Bangladesh, East Asia, Nepal, Bhutan and north-east India.

-

An SBSTC bus in Karunamoyee

-

Kolkata Metro, India's first metro rail system

As of 2011, the total length of surface roads in West Bengal was over 92,023 kilometres (57,180 miles);[127]: 18 national highways comprise 2,578 km (1,602 mi)[140] and state highways 2,393 km (1,487 mi).[127]: 18 As of 2006, the road density of the state was 103.69 kilometres per square kilometre (166.87 miles per square mile), higher than the national average of 74.7 km/km2 (120.2 mi/sq mi).[141]

As of 2011, the total railway route length was around 4,481 km (2,784 mi).[127]: 20 Kolkata is the headquarters of three zones of the Indian Railways—Eastern Railway and South Eastern Railway and the Kolkata Metro, which is the newly formed 17th zone of the Indian Railways.[142][143] The Northeast Frontier Railway (NFR) serves the northern parts of the state. The Kolkata metro is the country's first underground railway.[144] The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, part of NFR, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[145]

Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose International Airport at Dum Dum, Kolkata, is the state's largest airport. Bagdogra Airport near Siliguri is a customs airport that offers international service to Bhutan and Thailand, besides regular domestic service. Kazi Nazrul Islam Airport, India's first private sector airport, serves the twin cities of Asansol-Durgapur at Andal, Paschim Bardhaman.[146][147]

Kolkata is a major river port in eastern India. The Kolkata Port Trust manages the Kolkata and the Haldia docks.[148] There is passenger service to Port Blair on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Cargo ship service operates to ports in India and abroad, operated by the Shipping Corporation of India. Ferries are a principal mode of transport in the southern part of the state, especially in the Sundarbans area. Kolkata is the only city in India to have trams as a mode of transport; these are operated by the Calcutta Tramways Company.[149]

Several government-owned organisations operate bus services in the state, including: the Calcutta State Transport Corporation, the North Bengal State Transport Corporation, the South Bengal State Transport Corporation, the West Bengal Surface Transport Corporation and the Calcutta Tramways Company.[150] There are also private bus companies. The railway system is a nationalised service without any private investment.[151] Hired forms of transport include metered taxis and auto rickshaws, which often ply specific routes in cities. In most of the state, cycle rickshaws and in Kolkata, hand-pulled rickshaws and electric rickshaws are used for short-distance travel.[152]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 16,940,088 | — |

| 1911 | 17,998,769 | +6.2% |

| 1921 | 17,474,348 | −2.9% |

| 1931 | 18,897,036 | +8.1% |

| 1941 | 23,229,552 | +22.9% |

| 1951 | 26,299,980 | +13.2% |

| 1961 | 34,926,279 | +32.8% |

| 1971 | 44,312,011 | +26.9% |

| 1981 | 54,580,647 | +23.2% |

| 1991 | 68,077,965 | +24.7% |

| 2001 | 80,176,197 | +17.8% |

| 2011 | 91,276,115 | +13.8% |

| 2022 est. | 98,604,000 | +8.0% |

| Source: Census of India[153] | ||

According to the provisional results of the 2011 national census, West Bengal is the fourth-most-populous state in India with a population of 91,347,736 (7.55% of India's population).[3] The state's 2001–2011 decennial population growth rate was 13.93%,[3] lower than the 1991–2001 growth rate of 17.8%[3] and lower than the national rate of 17.64%.[154] The gender ratio is 947 females per 1,000 males.[154] As of 2011, West Bengal had a population density of 1,029 inhabitants per square kilometre (2,670/sq mi) making it the second-most densely populated state in India, after Bihar.[154]

The literacy rate is 77.08%, higher than the national rate of 74.04%.[155] Data from 2010 to 2014 showed the life expectancy in the state was 70.2 years, higher than the national value of 67.9.[156][157] The proportion of people living below the poverty line in 2013 was 19.98%, a decline from 31.8% a decade ago.[158] Scheduled castes and tribes form 28.6% and 5.8% of the population, respectively, in rural areas and 19.9% and 1.5%, respectively, in urban areas.[130]

In September 2017, West Bengal achieved 100% electrification, after some remote villages in the Sunderbans became the last to be electrified.[159]

As of September 2017, of 125 towns and cities in Bengal, 76 have achieved open defecation free (ODF) status. All towns in the districts of: Nadia, North 24 Parganas, Hooghly, Bardhaman and East Medinipur are ODF zones, with Nadia becoming the first ODF district in the state in April 2015.[160][161]

A study conducted in three districts of West Bengal found that accessing private health services to treat illness had a catastrophic impact on households. This indicates the importance of the public provision of health services to mitigate poverty and the impact of illness on poor households.[162]

The latest Sample Registration System (SRS) statistical report shows that West Bengal has the lowest fertility rate among Indian states. West Bengal's total fertility rate was 1.6, lower than neighbouring Bihar's 3.4, which is the highest in the entire country. Bengal's TFR of 1.6 roughly equals that of Canada.[163]

Bengalis, consisting of Bengali Hindus, Bengali Muslims, Bengali Christians and a few Bengali Buddhists, comprise the majority of the population.[164] Marwari, Maithili and Bhojpuri speakers are scattered throughout the state; various indigenous ethnic Buddhist communities such as the Sherpas, Bhutias, Lepchas, Tamangs, Yolmos and ethnic Tibetans can be found in the Darjeeling Himalayan hill region. Native Khortha speakers are found in Malda district.[165]

Surjapuri, a language considered to be a mix of Maithili and Bengali, is spoken across northern parts of the state.[166] The Darjeeling Hills are mainly inhabited by various Gorkha communities who overwhelmingly speak Nepali (also known as Gorkhali), although there are some who retain their ancestral languages like Lepcha. West Bengal is also home to indigenous tribal Adivasis such as: Santhal, Munda, Oraon, Bhumij, Lodha, Kol and Toto.

There are a small number of ethnic minorities primarily in the state capital, including : Chinese, Tamils, Maharashtrians, Odias, Malayalis, Gujaratis, Anglo-Indians, Armenians, Jews, Punjabis and Parsis.[167] India's sole Chinatown is in eastern Kolkata.[168]

Languages

The state's official languages are Bengali and English;[4] Nepali has additional official status in the three subdivisions of Darjeeling district.[4] In 2012, the state government passed a bill granting additional official status to Hindi, Odia, Punjabi, Santali and Urdu in areas where speakers exceed 10% of the population.[4] In 2019, another bill was passed by the government to include Kamtapuri, Kurmali and Rajbanshi as additional official languages in blocks, divisions or districts where the speakers exceed 10% of the population.[4] On 24 December 2020, Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee announced Telugu as an additional official language.[4] As of the 2011 census, 86.22% of the population spoke Bengali, 5.00% Hindi, 2.66% Santali, 1.82% Urdu and 1.26% Nepali as their first language.[169]

Religion

Religion in West Bengal (2011)[170]

West Bengal is religiously diverse, with regional cultural and religious specificities. Although Hindus are the predominant community, the state has a large minority Muslim population. Christians, Buddhists and others form a minuscule part of the population. As of 2011, Hinduism is the most common religion, with adherents representing 70.54% of the total population.[171] Muslims, the second-largest community, comprise 27.01% of the total population,[172] Three of West Bengal's districts: Murshidabad, Malda and Uttar Dinajpur, are Muslim-majority. Sikhism, Christianity, Buddhism and other religions make up the remainder.[173] Buddhism remains a prominent religion in the Himalayan region of the Darjeeling hills; almost the entirety of West Bengal's Buddhist population is from this region.[174] Christianity is mainly found among the tea garden tribes at tea plantations scattered throughout the Dooars of Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri and Alipurduar districts.

The Hindu population of West Bengal is 64,385,546 while the Muslim population is 24,654,825, according to the 2011 census.[175]

Culture

Literature

The Bengali language boasts a rich literary heritage it shares with neighbouring Bangladesh. West Bengal has a long tradition of folk literature, evidenced by the Charyapada, a collection of Buddhist mystic songs dating back to the 10th and 11th centuries; Mangalkavya, a collection of Hindu narrative poetry composed around the 13th century; Shreekrishna Kirtana, a pastoral Vaishnava drama in verse composed by Boru Chandidas; Thakurmar Jhuli, a collection of Bengali folk and fairy tales compiled by Dakshinaranjan Mitra Majumder; and stories of Gopal Bhar, a court jester in medieval Bengal. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Bengali literature was modernised in the works of authors such as Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, whose works marked a departure from the traditional verse-oriented writings prevalent in that period;[178] Michael Madhusudan Dutt, a pioneer in Bengali drama who introduced the use of blank verse;[179] and Rabindranath Tagore, who reshaped Bengali literature and music. Indian art saw the introduction of Contextual Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[180] Other notable figures include Kazi Nazrul Islam, whose compositions form the avant-garde genre of Nazrul Sangeet,[181] Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, whose works on contemporary social practices in Bengal are widely acclaimed,[182] and Manik Bandyopadhyay, who is considered one of the leading lights of modern Bengali fiction.[183] In modern times, Jibanananda Das has been acknowledged as "the premier poet of the post-Tagore era in India".[184] Other writers include: Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay, best known for his work Pather Panchali; Tarashankar Bandopadhyay, well known for his portrayal of the lower strata of society;[185] Manik Bandopadhyay, a pioneering novelist; and Ashapurna Devi, Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay, Saradindu Bandopadhyay, Buddhadeb Guha, Mahashweta Devi, Samaresh Majumdar, Sanjeev Chattopadhyay, Shakti Chattopadhyay, Buddhadeb Basu,[186] Joy Goswami and Sunil Gangopadhyay.[187][188]

Music and dance

A notable music tradition is the Baul music, practised by the Bauls, a sect of mystic minstrels.[189] Other folk music forms include Gombhira and Bhawaiya. Folk music in West Bengal is often accompanied by the ektara, a one-stringed instrument. Shyama Sangeet is a genre of devotional songs, praising the Hindu goddess Kali; kirtan is devotional group songs dedicated to the god Krishna.[190] Like other states in northern India, West Bengal also has a heritage in North Indian classical music. Rabindrasangeet, songs composed and set to words by Rabindranath Tagore, and Nazrul geeti (by Kazi Nazrul Islam) are popular. Also prominent are Dwijendralal, Atulprasad and Rajanikanta's songs, and adhunik or modern music from films and other composers.[191] From the early 1990s, new genres of music have emerged, including what has been called Bengali Jeebonmukhi Gaan (a modern genre based on realism). Bengali dance forms draw from folk traditions, especially those of the tribal groups, as well as the broader Indian dance traditions. Chhau dance of Purulia is a rare form of masked dance.[192]

Films

West Bengali films are shot mostly in studios in the Kolkata neighbourhood of Tollygunge; the name "Tollywood" (similar to Hollywood and Bollywood) is derived from that name. The Bengali film industry is well known for its art films, and has produced acclaimed directors like Satyajit Ray who is widely regarded as one of the greatest filmmakers of the 20th century,[193] Mrinal Sen whose films were known for their artistic depiction of social reality, Tapan Sinha,[194] and Ritwik Ghatak. Some contemporary directors include veterans such as: Buddhadeb Dasgupta, Tarun Majumdar, Goutam Ghose, Aparna Sen, and Rituparno Ghosh, and a newer pool of directors such as Kaushik Ganguly and Srijit Mukherji.[195][196][197] Uttam Kumar was the most popular lead actor for decades, and his romantic pairing with actress Suchitra Sen in films attained legendary status.[198] Soumitra Chatterjee, who acted in many Satyajit Ray-films, and Prosenjit Chatterjee are among other popular lead male actors. As of 2020[update], Bengali films have won India's annual National Film Award for Best Feature Film twenty-two times in sixty seven years, the highest among all Indian languages.

Fine arts

There are significant examples of fine arts in Bengal from earlier times, including the terracotta art of Hindu temples and the Kalighat paintings. Bengal has been in the vanguard of modernism in fine arts. Abanindranath Tagore, called the father of modern Indian art, started the Bengal School of Art, one of whose goals was to promote the development of styles of art outside the European realist tradition that had been taught in art colleges under the British colonial administration. The movement had many adherents, including: Gaganendranath Tagore, Ramkinkar Baij, Jamini Roy and Rabindranath Tagore. After Indian Independence, important groups such as the Calcutta Group and the Society of Contemporary Artists were formed in Bengal and came to dominate the art scene in India.[199][200]

Reformist heritage

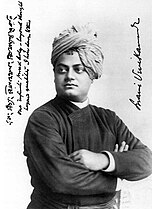

The capital, Kolkata, was the workplace of several social reformers, including Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar and Swami Vivekananda. Their social reforms eventually led to a cultural atmosphere that made it possible for practices like sati, dowry, and caste-based discrimination, or untouchability, to be abolished.[201] The region was also home to several religious teachers, such as Chaitanya, Ramakrishna, Prabhupada and Paramahansa Yogananda.[201]

Cuisine

Rice and fish are traditional favourite foods, leading to a saying in Bengali, "machhe bhate bangali", that translates as "fish and rice make a Bengali".[202] Bengal's vast repertoire of fish-based dishes includes hilsa preparations, a favourite among Bengalis. There are numerous ways of cooking fish depending on its texture, size, fat content and bones.[203] Most of the people also consume eggs, chicken, mutton, and shrimp. Panta bhat (rice soaked overnight in water) with onion and green chili is a traditional dish consumed in rural areas.[204] Common spices found in a Bengali kitchen include cumin, ajmoda (radhuni), bay leaf, mustard, ginger, green chillies and turmeric.[205] Sweets occupy an important place in the diet of Bengalis and at their social ceremonies. Bengalis make distinctive sweetmeats from milk products, including Rôshogolla, Chômchôm, Kalojam and several kinds of sondesh. Pitha, a kind of sweet cake, bread, or dim sum, are specialties of the winter season. Sweets such as narkol-naru, til-naru, moa and payesh are prepared during festivals such as Lakshmi puja.[206] Popular street foods include Aloor Chop, Beguni, Kati roll, biryani, and phuchka.[207][208]

Clothing

Bengali women commonly wear the sari, often distinctly designed according to local cultural customs. In urban areas, many women and men wear western attire. Among men, western dress has greater acceptance. Particularly on cultural occasions, men also wear traditional costumes such as the panjabi with dhuti while women wear salwar kameez or sari.[209]

West Bengal produces several varieties of cotton and silk saris in the country. Handlooms are a popular way for the state's rural population to earn a living through weaving. Every district has weaving clusters, which are home to artisan communities, each specialising in specific varieties of handloom weaving. Notable handloom saris include tant, jamdani, garad, korial, baluchari, tussar and muslin.[210]

Festivals

Durga Puja is the biggest, most popular and widely celebrated festival in West Bengal.[211] The five-day-long colourful Hindu festival includes intense celebration across the state. Pandals are erected in various cities, towns, and villages throughout West Bengal. The city of Kolkata transforms Durga Puja. It is decked up in lighting decorations and thousands of colourful pandals are set up where effigies of the goddess Durga and her four children are displayed and worshipped. The idols of the goddess are brought in from Kumortuli, where idol-makers work throughout the year fashioning clay models of the goddess. Since independence in 1947, Durga Puja has slowly changed into more of a glamorous carnival than a religious festival. Today people of diverse religious and ethnic backgrounds partake in the festivities.[212] On Vijayadashami, the last day of the festival, the effigies are paraded through the streets with riotous pageantry before being immersed into the rivers.[213]

Rath Yatra is a Hindu festival which celebrates Jagannath, a form of Krishna. It is celebrated with much fanfare in Kolkata as well as in rural Bengal. Images of Jagannath are set upon a chariot and pulled through the streets.[214]

Other major festivals of West Bengal include: Poila Baishakh the Bengali new year, Dolyatra or Holi the festival of lights, Poush Parbon, Kali Puja, Nabadwip Shakta Rash, Saraswati Puja, Deepavali, Lakshmi Puja, Janmashtami, Jagaddhatri Puja, Vishwakarma Puja, Bhai Phonta, Rakhi Bandhan, Kalpataru Day, Shivratri, Ganesh Chathurthi, Maghotsav, Karam festival, Kartik Puja, Akshay Tritiya, Raas Yatra, Guru Purnima, Annapurna Puja, Charak Puja, Gajan, Buddha Purnima, Christmas, Eid ul-Fitr, Eid ul-Adha and Muharram. Rabindra Jayanti, Kolkata Book Fair, Kolkata Film Festival, and Nazrul Jayanti. All are important cultural events.[214]

Eid al-Fitr is the most important Muslim festival in West Bengal. They celebrate the end of Ramadan with prayers, alms-giving, shopping, gift-giving, and feasting.[215]

Christmas, called Bôŗodin (Great day) is perhaps the next major festival celebrated in Kolkata, after Durga Puja. Although Hinduism is the major religion in the state, people show significant passion to the festival. Just like Durga Puja, Christmas in Kolkata is an occasion when all communities and people of every religion take part. Large masses of people go to parks, gardens, museums, parties, fairs, churches and other places to celebrate the day. A lot of Hindus go to Hindu-temples and the festival is celebrated there too with Hindu rituals.[216][217] The state tourism department organises a gala Christmas Festival every year in Park Street.[218] The whole of Park Street is hung with colourful lights, and food stalls sell cakes, chocolates, Chinese cuisine, momo, and various other items. The state invites musical groups from Darjeeling and other North East India states to perform choir recitals, carols, and jazz numbers.[219]

Buddha Purnima, which marks the birth of Gautama Buddha, is one of the most important Hindu/Buddhist festivals and is celebrated with much gusto in the Darjeeling hills. On this day, processions begin at the various Buddhist monasteries, or gumpas, and congregate at the Chowrasta (Darjeeling) Mall. The Lamas chant mantras and sound their bugles, and students, as well as people from every community, carry the holy books or pustaks on their heads. Besides Buddha Purnima, Dashain, or Dusshera, Holi, Diwali, Losar, Namsoong or the Lepcha New Year, and Losoong are the other major festivals of the Darjeeling Himalayan region.[215]

Each year between July and August at Tarakeswar Yatra held, nearly 10 million devotees come from various part of India bringing holy water of Ganga fin order to offer it to Lord Shiva.

Poush Mela is a popular winter festival of Shantiniketan, with performances of folk music, Baul songs, dance, and theatre taking place throughout the town.[215]

Ganga Sagar Mela coincides with the Makar Sankranti, and hundreds of thousands of Hindu pilgrims converge where the river Ganges meets the sea to bathe en masse during this fervent festival.[214]

Education

-

University of Calcutta, the oldest public university of India.

-

The front entrance to the academic block of NUJS, Kolkata.

-

Prajna Bhavan, housing the School of Mathematical Sciences and School of RKMVU.

West Bengal schools are run by the state government or private organisations, including religious institutions. Instruction is mainly in English or Bengali, though Urdu is also used, especially in Central Kolkata. Secondary schools are affiliated with the Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (CISCE), the Central Board for Secondary Education (CBSE), the National Institute of Open School (NIOS), West Bengal Board of Secondary Education, or the West Bengal Board of Madrasah Education.[220]

As of 2016 85% of children within the 6 to 17-year age group attend school (86% do so in urban areas and 84% in rural areas). School attendance is almost universal among the 6 to 14-year age group then drops to 70% with the 15 to 17-year age group. There is a gender disparity in school attendance in the 6 to 14-year age group, more girls than boys are attending school. In Bengal, 71% of women aged 15–49 years and 81% of men aged 15–49 years are literate. Only 14% of women aged 15–49 years in West Bengal have completed 12 or more years of schooling, compared with 22% of men. 22% of women and 14% of men aged 15–49 years have never attended school.[221]

Some of the notable schools in the city are: Ramakrishna Mission Narendrapur, Baranagore Ramakrishna Mission, Sister Nivedita Girls' School, Hindu School, Hare School, La Martiniere Calcutta, Calcutta Boys' School, St. James' School (Kolkata), South Point School, Techno India Group Public School, St. Xavier's Collegiate School, and Loreto House, Loreto Convent, Pearl Rosary School are some of which rank amongst the best schools in the country.[222] Many of the schools in Kolkata and Darjeeling are colonial-era establishments housed in buildings that are exemplars of neo-classical architecture. Darjeeling's schools include: St. Paul's, St. Joseph's North Point, Goethals Memorial School, and Dow Hill in Kurseong.[223]

West Bengal has eighteen universities.[224][225] Kolkata has played a pioneering role in the development of the modern education system in India. It was the gateway to the revolution of European education during the British Raj.[226] Sir William Jones established the Asiatic Society in 1794 to promote oriental studies. People such as Ram Mohan Roy, David Hare, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Alexander Duff and William Carey played leading roles in setting up modern schools and colleges in the city.[215]

The University of Calcutta, the oldest and one of the most prestigious public universities in India, has 136 affiliated colleges. Fort William College was established in 1810. The Hindu College was established in 1817. The Lady Brabourne College was established in 1939. The Scottish Church College, the oldest Christian liberal arts college in South Asia, started in 1830. The Vidyasagar College was established in 1872 and was the first purely Indian-run private college in India.[227] In 1855 the Hindu College was renamed the Presidency College.[228] The state government granted it university status in 2010 and it was renamed Presidency University. Kazi Nazrul University was established in 2012. The University of Calcutta and Jadavpur University are prestigious technical universities.[229] Visva-Bharati University at Santiniketan is a central university and an institution of national importance.[230]

Other higher education institutes of importance in West Bengal include: St. Xavier's College, Kolkata, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, Indian Institute of Management Calcutta (the first IIM), Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Kolkata, Indian Statistical Institute, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur (the first IIT), Indian Institute of Engineering Science and Technology, Shibpur (the first IIEST), Indian Institute of Information Technology, Kalyani, Medical College, Kolkata, National Institute of Technology, Durgapur, National Institute of Technical Teachers' Training and Research, Kolkata, National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, Kolkata, and West Bengal National University of Juridical Sciences. In 2003 the state government supported the creation of West Bengal University of Technology, West Bengal University of Health Sciences, West Bengal State University, and Gour Banga University.[231]

Jadavpur University (Focus area—Mobile Computing and Communication and Nano-science), and the University of Calcutta (Modern Biology) are among two of the fifteen universities selected under the "University with Potential for Excellence" scheme. University of Calcutta (Focus Area—Electro-Physiological and Neuro-imaging studies including mathematical modelling) has also been selected under the "Centre with Potential for Excellence in a Particular Area" scheme.[232]

In addition, the state is home to Kalyani University, The University of Burdwan, Vidyasagar University, and North Bengal University all well established and nationally renowned schools that cover education needs at the district level and the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Kolkata. Apart from this there is a Deemed university run by the Ramakrishna mission named Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda University at Belur Math.[233]

There are several research institutes in Kolkata. The Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science is the first research institute in Asia. C. V. Raman was awarded the Nobel Prize for his discovery (Raman Effect) done at the IACS. The Bose Institute, Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics, S. N. Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences, Indian Institute of Chemical Biology, Central Glass and Ceramic Research Institute, Central Mechanical Engineering Research Institute Durgapur, Central Research Institute for Jute and Allied Fibers, National Institute of Research on Jute and Allied Fibre Technology, Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute, National Institute of Biomedical Genomics (NIBMG), Kalyani, and the Variable Energy Cyclotron Centre are the most prominent.[231]

Notable scholars who were born, worked, or studied in the geographic area of the state include physicists: Satyendra Nath Bose, Meghnad Saha,[234] and Jagadish Chandra Bose;[235] chemist Prafulla Chandra Roy;[234] statisticians Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis and Anil Kumar Gain;[234] physician Upendranath Brahmachari;[234] educator Ashutosh Mukherjee;[236] and Nobel laureates Rabindranath Tagore,[237] C. V. Raman,[235] Amartya Sen,[238] and Abhijit Banerjee[239]

Media

In 2005 West Bengal had 505 published newspapers,[240] of which 389 were in Bengali.[240] Ananda Bazar Patrika, published in Kolkata with 1,277,801 daily copies, has the largest circulation for a single-edition, regional language newspaper in India.[240] Other major Bengali newspapers are: Bartaman, Ei Samay, Sangbad Pratidin, Aajkaal and Uttarbanga Sambad. Major English language newspapers include The Telegraph, The Times of India, Hindustan Times, The Hindu, The Statesman, The Indian Express and Asian Age. Some prominent financial dailies such as: The Economic Times, Financial Express, Business Line and Business Standard are widely circulated. Vernacular newspapers such as those in Hindi, Nepali, Gujarati, Odia, Urdu and Punjabi also exist.[241]

DD Bangla is the state-owned television broadcaster. Multi system operators provide a mix of Bengali, Nepali, Hindi, English and international channels via cable. Bengali 24-hour television news channels include ABP Ananda, News18 Bangla, Republic Bangla, Kolkata TV, News Time, Zee 24 Ghanta, TV9 Bangla, Calcutta News and Channel 10.[242][243] All India Radio is a public radio station.[243] Private FM stations are available only in cities like Kolkata, Siliguri, and Asansol.[243] Vodafone Idea, Airtel, BSNL, Jio are available cellular phone providers. Broadband Internet is available in select towns and cities and is provided by the state-run BSNL and by other private companies. Dial-up access is provided throughout the state by BSNL and other providers.[244]

Sports

Cricket and association football are popular. West Bengal, unlike most other states of India, is noted for its passion and patronage of football.[245][246][247] Kolkata is one of the major centres for football in India[248] and houses top national clubs such as Mohun Bagan Super Giant, East Bengal Club and Mohammedan Sporting Club.[249]

West Bengal has several large stadiums. Eden Gardens was one of only two 100,000-seat cricket stadiums in the world;[250] renovations before the 2011 Cricket World Cup reduced the capacity to 66,000.[251] The stadium is the home to various cricket teams such as the Kolkata Knight Riders, the Bengal cricket team and the East Zone. The 1987 Cricket World Cup final was hosted in Eden Gardens. The Calcutta Cricket and Football Club is the second-oldest cricket club in the world.[252]

Vivekananda Yuba Bharati Krirangan (VYBK), is a multipurpose stadium in Kolkata, with a current capacity of 85,000. It is the largest stadium in India by seating capacity.[253] Before its renovation in 2011, it was the second-largest football stadium in the world, having a seating capacity of 120,000. It has hosted many national and international sporting events like the SAF Games of 1987 and the 2011 FIFA friendly football match between Argentina and Venezuela featuring Lionel Messi.[254] In 2008 legendary German goalkeeper, Oliver Kahn played his farewell match on this ground.[255] The stadium hosted the final match of the 2017 FIFA U-17 World Cup.

Notable sports persons from West Bengal include former Indian national cricket team captain Sourav Ganguly, Pankaj Roy, Olympic tennis bronze medallist Leander Paes and chess grand master Dibyendu Barua.[245][246][247]

Смотрите также

- Бангал

- Бенгальские языковые движения в Индии

- Готте люди

- Список людей из Западной Бенгалии

- Список туристических достопримечательностей в Западной Бенгалии

- Схема Западной Бенгалии

Ссылки

- ^ «Западная Бенгальская Ассамблея проходит резолюцию, объявляющую композицию Рабиндраната Тагора как гимн штата» . Scroll.in . 7 сентября 2023 года . Получено 8 сентября 2023 года .

- ^ "Сандакфу" . 25 декабря 2008 года. Архивировано из оригинала 25 декабря 2008 года . Получено 24 марта 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и «Площадь, население, темпы роста в десятилетнем возрасте и плотность на 2001 и 2011 гг. С первого взгляда на Западной Бенгалии и округа: предварительное общее количество населения. Документ 1 от 2011 года: Западная Бенгалия» . Генеральный регистратор и комиссар по переписи, Индия. Архивировано из оригинала 7 января 2012 года . Получено 26 января 2012 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин — «Отчет Комиссара по лингвистическим меньшинствам: 52 -й отчет (июль 2014 года по июнь 2015 года)» (PDF) . Комиссар по лингвистическим меньшинствам, Министерство по делам меньшинств, правительство Индии. С. 85–86. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 15 ноября 2016 года . Получено 16 февраля 2016 года .

— Сингх, Шив Сахай (3 апреля 2012 г.). «Официальный языковой статус для урду в некоторых районах Западной Бенгалии» . Индус . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июня 2019 года . Получено 3 июня 2019 года .

— «Многоязычная Бенгалия» . Телеграф . 11 декабря 2012 года. Архивировано с оригинала 25 марта 2018 года . Получено 25 марта 2018 года .

— «Язык Курукх получил официальный статус правительством Бенгалии» . Outlook . 21 февраля 2017 года. Архивировано с оригинала 22 января 2021 года . Получено 12 октября 2020 года .

— Рой, Анирбан (28 февраля 2018 г.). «Камтапури, Раджбанши вошли в список официальных языков» . Индия сегодня . Архивировано с оригинала 30 марта 2018 года . Получено 30 марта 2018 года .

— «Западная Бенгалия показывает« мамата »на телугу» . Ганс Индия . 24 декабря 2020 года. Архивировано с оригинала 23 декабря 2020 года . Получено 31 декабря 2020 года . - ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Финансовая отчетность 2023-24, правительство Западной Бенгалии» (PDF) . Правительство Западной Бенгалии . 1 февраля 2023 г. с. 21. Архивировал (PDF) из оригинала 23 февраля 2023 года . Получено 1 февраля 2023 года .

- ^ «Справочник по статистике индийских штатов 2022-23» (PDF) . Резервный банк Индии . С. 11, 33 . Получено 15 сентября 2023 года .

- ^ «Государственные данные о доходе на душу населения» . Дели: Пиб Дели. 24 июля 2023 года . Получено 12 сентября 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Субнациональная база данных HDI-области» . Глобальная лаборатория данных . 15 июня 2021 года . Получено 7 марта 2023 года .

- ^ NSO (2018). «Соотношение полов, возрастное население 0–6, грамотность и уровень грамотности по полу за 2001 и 2011 годы с первого взгляда на Западную Бенгалии и округа: Временное население Итоговое общее количество 1 от 2011 года: Западная Бенгалия» (PDF) . Правительство Индии: Министерство внутренних дел. Архивировано из оригинала 7 января 2012 года.

- ^ «Соотношение полов, возрастное население 0–6, грамотность и уровень грамотности по полу за 2001 и 2011 годы с первого взгляда на Западную Бенгалии и округа: Временное население Итоговое общение 1 от 2011 года: Западная Бенгалия» . Правительство Индии: Министерство внутренних дел. Архивировано из оригинала 7 января 2012 года . Получено 29 января 2012 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Мукерджи 1987 , с. 230.

- ^ «Западная бенгальская население 2023 года» . Всемирный обзор населения . 13 июля 2023 года . Получено 13 июля 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Индраджит Рэй (2011). Бенгальская промышленность и Британская промышленная революция (1757-1857) . Routledge. с. 57, 90, 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 16 января 2023 года . Получено 7 февраля 2021 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Shombit Sengupta, Bengals Glunder подарили британскую промышленную революцию, архивную 1 августа 2017 года на The Wayback Machine , Financial Express , 8 февраля 2010 г.

- ^ Чаудхури, Сушил; Мохсин, К.М. (2012). "Сираджуддаула" . В исламе, Сираджул ; Джамал, Ахмед А. (ред.). Банглапедия: Национальная энциклопедия Бангладеш (второе изд.). Азиатское общество Бангладеш . Архивировано с оригинала 14 июня 2015 года.

- ^ Campbell & Watts 1760 .

- ^ Плетчер, Кеннет (15 августа 2010 г.). География Индии: священные и исторические места . The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. с. 17, 150. ISBN 978-1-61530-142-3 .

- ^ Chattopadhyay, Aparajita; Гош, Сасвата (1 мая 2020 года). Динамика населения в Восточной Индии и Бангладеш: демографические, проблемы со здоровьем и развитием . Спрингер Природа. п. 6. ISBN 978-981-15-3045-6 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Lochtefeld, James G (2001). Иллюстрированная энциклопедия индуизма, том 2 . Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. с. 771. ISBN 9780823931804 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 2 февраля 2023 года . Получено 12 августа 2020 года .

- ^ Талбот, Ян; Сингх, Гурхарпал (2009), Разделение Индии , издательство Кембриджского университета, с. 115–117, ISBN 978-0-521-67256-6

- ^ Тан, Тай Юн; Kudaisya, Ganesh (2002) [2000], последствия перегородки в Южной Азии , Тейлор и Фрэнсис, с. 172–175, ISBN 978-0-203-45060-4

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Индексы введения и развития человека для Западной Бенгалии» . Западная Бенгальская отчет о развитии человека 2004 года (PDF) . Департамент развития и планирования, правительство Западной Бенгалии. Май 2004 г. с. 4–6. ISBN 81-7955-030-3 Полем Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 27 мая 2006 года . Получено 26 августа 2006 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный — Banerjee, Partha Sarathi (5 февраля 2011 г.), «Партия, власть и политическое насилие в Западной Бенгалии», Экономический и политический еженедельный , 46 (6): 16–18, ISSN 0012-9976 , JSTOR 279181111111.

— Donner, Henrike (2004), Значение Naxalbari: рассказы о личном участии и политике в Западной Бенгалии (PDF) , Великобритания: Кембриджский университет , с. 14, архивировано (PDF) с оригинала 18 сентября 2020 года , извлечен 13 июля 2020 года.

— Banerjee, Debdas (20 февраля 1982 г.), «Промышленная стагнация в Восточной Индии: статистическое расследование», Экономический и политический еженедельный , 17 (8): 286–298, JSTOR 4370702

— Мукерджи, Рудрангшу (5 октября 2008 г.). «Убийство, самое грязное - народ Бенгалии создал тьму, которая их окутывает» . Телеграф . Калькутта. Архивировано из оригинала 18 января 2012 года . Получено 4 марта 2012 года . - ^ «Справочник по статистике индийских штатов 2021-22» (PDF) . Резервный банк Индии . С. 37–42. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 29 января 2022 года . Получено 11 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ «Инвестируйте в Западную Бенгалию - возможности для бизнеса, отрасли, ПИИ» . Архивировано из оригинала 14 ноября 2022 года . Получено 14 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ «ПИИ в Индии | Консультант по FDI | Компании FDI | FDI Opportunity 2022» . Архивировано из оригинала 14 ноября 2022 года . Получено 14 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ «Государственные финансы: анализ рисков» . Резервный банк Индии . 16 июня 2022 года . Получено 16 июня 2022 года .

- ^ ЮНЕСКО 2012 .

- ^ «Индийская статистика туризма с первого взгляда 2023 года» (PDF) . Правительство Индии : 21. Архивировал (PDF) от оригинала 18 декабря 2019 года . Получено 27 сентября 2023 года .

- ^ «Бангладеш: ранняя история, 1000 до н.э. - 1202» . Бангладеш: страновое исследование . Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Библиотека Конгресса . Сентябрь 1988 года. Архивировано с оригинала 15 июня 2017 года . Получено 2 марта 2012 года .

Историки считают, что Бенгалия, район, состоящий из современного Бангладеш и индийского штата Западная Бенгалия, была урегулирована примерно в 1000 г. до н.э. дравидийские говорящие народы, которые впоследствии были известны как взрыв. Их родина носила различные названия, которые отражали более ранние племенные имена, такие как Ванга, Банга, Бангала, Бангал и Бенгалия.

- ^ Маршмен, Джон Кларк (1865). Схема истории Бенгалии . Джон Кларк Маршмен . п. 1. Архивировано из оригинала 4 декабря 2017 года.

- ^ Чакрабарти 2004 , с. 142

- ^ «Западная Бенгалия может быть переименована в Пасхимбангу» . Индус . Ченнаи, Индия. 19 августа 2011 года. Архивировано с оригинала 21 января 2012 года . Получено 7 февраля 2012 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Ассамблея падает на запад, переименование государства как Бенгалия» . Индус . 29 августа 2016 года. ISSN 0971-751X . Архивировано с оригинала 25 декабря 2016 года . Получено 4 января 2018 года .

- ^ «Министерство иностранных дел выводит« Бангла »Маматы Банерджи для Западной Бенгалии» . Новый индийский экспресс . Архивировано с оригинала 22 декабря 2017 года . Получено 20 декабря 2017 года .

- ^ «Западная Бенгалия, чтобы отправить еще одно предложение, чтобы сосредоточиться на изменении своего названия» . Времена Hindustan . 8 сентября 2017 года. Архивировано с оригинала 22 декабря 2017 года . Получено 20 декабря 2017 года .

- ^ Саркар, Себанти (28 марта 2008 г.). «История Бенгалии стала намного старше» . Телеграф . Калькутта, Индия. Архивировано с оригинала 12 сентября 2011 года . Получено 13 сентября 2010 года .

Люди ходили по почве Бенгалии 20 000 лет назад, археологи выяснили, оттолкнув предварительную историю штата примерно на 8000 лет.

- ^ Sen, SN (1999). Древняя индийская история и цивилизация . New Age International. С. 273–274. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0 Полем Архивировано с оригинала 1 января 2016 года.

- ^ Чакрабарти, Дилип К. (2001). Археологическая география на равнине Ганга: Нижняя и Средняя Ганга . Дели: Постоянный черный. С. 154–155. ISBN 978-81-7824-016-9 .

- ^ Прасад, Пракаш Чандра (2003). Внешняя торговля и торговля в древней Индии . Нью -Дели: публикации Абхинад. п. 28. ISBN 978-81-7017-053-2 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 2 февраля 2023 года . Получено 21 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Гейгер, Вильгельм ; Хейнс Боде, Мейбл (2003) [1908]. «Глава VI: Пришествие Виджая» . Махавамса: Великая хроника Цейлона . Нью -Дели: Азиатские образовательные услуги . С. 51–54. ISBN 978-81-206-0218-2 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 2 февраля 2023 года . Получено 21 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Султана, Сабиха. «Урегулирование в Бенгалии (ранний период)» . Банглапедия . Азиатское общество Бангладеш . Архивировано с оригинала 14 июня 2015 года . Получено 12 июня 2015 года .

- ^ Мукерджи, Радхакумуд (1959). Империя Гупта . Motilal Banarsidass . Стр. 11, 113. ISBN 978-81-208-0440-1 .

- ^ Sen, Saileendra Nath (1 января 1999 г.). Древняя индийская история и цивилизация . New Age International. п. 275. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 31 декабря 2015 года.

- ^ "Шашанка" . Банглапедия . Азиатское общество Бангладеш . Архивировано с оригинала 14 июня 2015 года . Получено 12 июня 2015 года .

- ^ Джозеф, Тони (11 декабря 2015 г.). «Дискуссия о непереносимости: как некоторые исторические жестокости являются более особенными, чем другие» . Scroll.in . Архивировано с оригинала 25 декабря 2015 года . Получено 25 декабря 2015 года .

- ^ Bagchi, Jhunu (1993). История и культура палах Бенгалии и Бихара, Cir. 750 AD-Cir. 1200 г. н.э. ISBN 978-81-7017-301-4 Полем Архивировано с оригинала 23 апреля 2016 года.

- ^ Хан, Мухаммед Мойлум (21 октября 2013 г.). Мусульманское наследие Бенгалии: жизнь, мысли и достижения великих мусульманских ученых, писателей и реформаторов Бангладеш и Западной Бенгалии . Kube Publishing Limited. С. 15–16. ISBN 978-1-84774-062-5 Полем Архивировано с оригинала 26 января 2018 года.

- ^ Сенгупта, Нитиш К. (2011). Земля двух рек: история Бенгалии от Махабхараты до Муджиба . Пингвин книги Индия . п. 45. ISBN 978-0-14-341678-4 Полем Архивировано с оригинала 1 января 2016 года.

- ^ Радж Кумар (2003). Эссе о древней Индии . Discovery Publishing House. п. 199. ISBN 978-81-7141-682-0 .

- ^ Nanda, J. N (2005). Бенгалия: уникальное состояние . Концептуальная издательская компания. п. 10. 2005. ISBN 978-81-8069-149-2 Полем

Бенгалия [...] была богата производством и экспортом зерна, соли, фруктов, ликеров и вин, драгоценных металлов и украшений, помимо выхода его ручных работ в шелке и хлопке. Европа назвала Бенгалию самой богатой страной для торговли.

- ^ Бану, UAB Razia Akter (январь 1992 г.). Ислам в Бангладеш Брилль хлыст. 2, 17. ISBN 978-90-04-09497-0 Полем Архивировано с оригинала 1 января 2014 года.

- ^ «Ислам (в Бенгалии)» . Банглапедия . Азиатское общество Бангладеш. Архивировано из оригинала 23 июля 2015 года . Получено 26 октября 2006 года .

- ^ Льюис, Дэвид (31 октября 2011 г.). Бангладеш: политика, экономика и гражданское общество . Издательство Кембриджского университета . п. 44. ISBN 978-1-139-50257-3 .

- ^ Гангули, Дилип Кумар (1994). Древняя Индия, История и Археология . Абхинавские публикации. п. 41. ISBN 9788170173045 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 2 февраля 2023 года . Получено 12 августа 2020 года .

- ^ Chaudhury, S; Мохсин, км. "Сираджуддаула" . Банглапедия . Азиатское общество Бангладеш . Архивировано с оригинала 14 июня 2015 года . Получено 12 июня 2015 года .

- ^ Фиске, Джон. «Голод 1770 года в Бенгалии» . Невидимый мир и другие эссе . Аделаида: Университет Аделаиды библиотека, коллекция электронных текстов. Архивировано из оригинала 5 декабря 2006 года . Получено 26 октября 2006 года .

- ^ Арнольд-Бейкер 2015 , с. 504

- ^ Бакстер 1997 , с. 32

- ^ Bayly 1987 , с. 194–197

- ^ Саркар 1990 , с. 95

- ^ Baxter 1997 , с. 39–40

- ^ Wolpert, Stanley (1999). Индия Беркли, Калифорния, США: Университет Калифорнийской прессы . п. 14. ISBN 978-0-520-22172-7 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 9 мая 2013 года . Получено 2 марта 2012 года .

- ^ Chandra et al. 1989 , с. 26

- ^ Ислам, Сираджул. «Передел Бенгалии, 1947» . Банглапедия . Азиатское общество Бангладеш. Архивировано с оригинала 2 июля 2015 года . Получено 12 июня 2015 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Sailen Debnath, Западная Бенгалия в Doldrums ISBN 978-81-86860-34-2 ; & Sailen Debnath Ed. Социальная и политическая напряженность в Северной Бенгалии с 1947 года, ISBN 81-86860-23-1

- ^ Hindle 1996 , с. 63–70

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Бисвас, Сутик (16 апреля 2006 г.). «Бесцветная кампания Калькутты» . Би -би -си . Архивировано из оригинала 14 февраля 2012 года . Получено 15 февраля 2012 года .

- ^ Гош Рой, Парамазшиш (22 июля 2005 г.). «Маоист на подъеме в Западной Бенгалии» . VOA Bangla . Голос Америки . Архивировано из оригинала 12 декабря 2007 года . Получено 11 сентября 2006 года .

- ^ «Маоистский коммунистический центр (MCC)» . Левая экстремистская группа . Портал терроризма Южной Азии. Архивировано из оригинала 12 февраля 2012 года . Получено 11 сентября 2006 года .

- ^ «Несколько больно в столкновении Сингур» . Rediff.com . 28 января 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 11 декабря 2007 года . Получено 15 марта 2007 года .

- ^ «Красная рука Будда: 14 убито в предложении« Нандиграмм повторного входа » . Телеграф . Калькутта, Индия. 15 марта 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 17 марта 2007 года . Получено 15 марта 2007 года .

- ^ Бхамик, Субир (13 мая 2011 г.). «Победить скалы избранных индийских коммунистов» . Rediff India за границей. Архивировано с оригинала 4 апреля 2014 года . Получено 29 июля 2014 года .

- ^ «На самом деле возрождается ли экономика Западной Бенгалии при Мамате Банерджи?» Полем Scroll.in . Архивировано с оригинала 6 декабря 2016 года.

- ^ «Налоговые поступления в Западной Бенгалии выросли на 19% на большую эффективность» . Индийский экспресс . Архивировано с оригинала 4 сентября 2017 года.

- ^ «Сбор доходов: Западная Бенгальская Бенгалия Мамата Банерджи побеждает остальную часть Индии в росте» . Financial Express . Архивировано с оригинала 4 сентября 2017 года.

- ^ «Бхарат Бандх получает смешанный отклик из Индии, сюрпризы Западной Бенгалии с бизнесом, как обычно» . Индия сегодня . Архивировано с оригинала 30 ноября 2016 года . Получено 5 сентября 2017 года .

- ^ «Завтра Бенгалия нет: Мамата» . Бизнес -стандарт Индия . Бизнес -стандарт. Пресс доверие Индии. Сентябрь 2016 года. Архивировано с оригинала 4 сентября 2017 года.

- ^ «Культура работы с нулевым ударом не привела к потере дней: Молой Гатак» . Экономические времена . India Times . Архивировано с оригинала 10 сентября 2017 года.

- ^ «Тихое воскресение ~ я» . Государственный деятель . 24 августа 2017 года. Архивировано с оригинала 28 августа 2017 года.

- ^ «Отчет о пятом ежегодном опросе трудоустройства (2015–16)» (PDF) . Министерство труда и занятости . п. 120. Архивировал (PDF) из оригинала 25 ноября 2016 года . Получено 24 ноября 2016 года .

- ^ Шах, Манси (2007). «Ожидание здравоохранения: опрос государственной больницы в Калькутте» (PDF) . Центр гражданского общества . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 13 августа 2011 года . Получено 31 января 2012 года .

- ^ «Западная Бенгалия: Меморандум программы по развитию систем здравоохранения» (PDF) . Правительство Западной Бенгалии . 15 января 2005 г. Архивировал (PDF) из оригинала 13 марта 2012 года . Получено 4 марта 2012 года .