Иллинойс

Иллинойс | |

|---|---|

| штат Иллинойс | |

| Псевдоним(а) : Земля Линкольна, Штат Прери, Внутренний Имперский штат | |

| Девиз(ы) : Государственный суверенитет, Национальный союз | |

| Гимн: « Иллинойс ». | |

Map of the United States with Illinois highlighted | |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Illinois Territory |

| Admitted to the Union | December 3, 1818 (21st) |

| Capital | Springfield |

| Largest city | Chicago |

| Largest county or equivalent | Cook |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Chicagoland |

| Government | |

| • Governor | J. B. Pritzker (D) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Juliana Stratton (D) |

| Legislature | General Assembly |

| • Upper house | Illinois Senate |

| • Lower house | Illinois House of Representatives |

| Judiciary | Supreme Court of Illinois |

| U.S. senators | Dick Durbin (D) Tammy Duckworth (D) |

| U.S. House delegation | 14 Democrats 3 Republicans (list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 57,915 sq mi (149,997 km2) |

| • Land | 55,593 sq mi (143,969 km2) |

| • Water | 2,320 sq mi (5,981 km2) 3.99% |

| • Rank | 25th |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 390 mi (628 km) |

| • Width | 210 mi (338 km) |

| Elevation | 600 ft (180 m) |

| Highest elevation | 1,235 ft (376.4 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 280 ft (85 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 12,812,508[3] |

| • Rank | 6th |

| • Density | 232/sq mi (89.4/km2) |

| • Rank | 12th |

| • Median household income | $65,030[4] |

| • Income rank | 17th |

| Demonyms | Illinoisan |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English[5] |

| • Spoken language | English (80.8%) Spanish (14.9%) Other (5.1%) |

| Time zone | UTC−06:00 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−05:00 (CDT) |

| USPS abbreviation | IL |

| ISO 3166 code | US-IL |

| Traditional abbreviation | Ill. |

| Latitude | 36° 58′ N to 42° 30′ N |

| Longitude | 87° 30′ W to 91° 31′ W |

| Website | illinois |

Иллинойс ( / ˌ ɪ l ɪ ˈ n ɔɪ / IL -in- OY ) — штат в Среднего Запада регионе США . Он граничит с озером Мичиган на северо-востоке, рекой Миссисипи на западе и реками Вабаш и Огайо на юге. [б] Из пятидесяти штатов США Иллинойс занимает пятое место по величине валового внутреннего продукта (ВВП) , шестое место по численности населения и 25-е место по площади территории . Его крупнейшие городские районы включают Чикаго и метро к востоку от Большого Сент-Луиса , а также Пеорию , Рокфорд , Шампейн-Урбану и Спрингфилд , столицу штата.

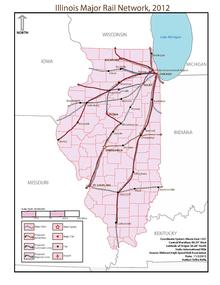

Illinois has a highly diverse economy, with the global city of Chicago in the northeast, major industrial and agricultural hubs in the north and center, and natural resources such as coal, timber, and petroleum in the south. Owing to its central location and favorable geography, the state is a major transportation hub: the Port of Chicago has access to the Atlantic Ocean through the Great Lakes and Saint Lawrence Seaway and to the Gulf of Mexico from the Mississippi River via the Illinois Waterway. Chicago has been the nation's railroad hub since the 1860s,[6] and its O'Hare International Airport has been among the world's busiest airports for decades. Illinois has long been considered a microcosm of the United States and a bellwether in American culture, exemplified by the phrase Will it play in Peoria?.[7]

Present-day Illinois was inhabited by various indigenous cultures for thousands of years, including the advanced civilization centered in the Cahokia region. The French were the first Europeans to arrive, settling near the Mississippi and Illinois River in the 17th century in the region they called Illinois Country, as part of the sprawling colony of New France. Following U.S. independence in 1783, American settlers began arriving from Kentucky via the Ohio River, and the population grew from south to north. Illinois was part of the United States' oldest territory, the Northwest Territory, and in 1818 it achieved statehood. The Erie Canal brought increased commercial activity in the Great Lakes, and the small settlement of Chicago became one of the fastest growing cities in the world, benefiting from its location as one of the few natural harbors in southwestern Lake Michigan.[8] The invention of the self-scouring steel plow by Illinoisan John Deere turned the state's rich prairie into some of the world's most productive and valuable farmland, attracting immigrant farmers from Germany and Sweden. In the mid-19th century, the Illinois and Michigan Canal and a sprawling railroad network greatly facilitated trade, commerce, and settlement, making the state a transportation hub for the nation.[9]

By 1900, the growth of industrial jobs in the northern cities and coal mining in the central and southern areas attracted immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe. Illinois became one of America's most industrialized states and remains a major manufacturing center.[10] The Great Migration from the South established a large community of African Americans, particularly in Chicago, who founded the city's famous jazz and blues cultures.[11][12] Chicago became a leading cultural, economic, and population center and is today one of the world's major commercial centers; its metropolitan area, informally referred to as Chicagoland, holds about 65% of the state's 12.8 million residents.

Two World Heritage Sites are in Illinois, the ancient Cahokia Mounds, and part of the Wright architecture site. Major centers of learning include the University of Chicago, University of Illinois, and Northwestern University. A wide variety of protected areas seek to conserve Illinois' natural and cultural resources. Historically, three U.S. presidents have been elected while residents of Illinois: Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, and Barack Obama; additionally, Ronald Reagan was born and raised in the state. Illinois honors Lincoln with its official state slogan Land of Lincoln.[13][14] The state is the site of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield and the future home of the Barack Obama Presidential Center in Chicago.

Etymology

"Illinois" is the modern spelling for the early French Catholic missionaries and explorers' name for the Illinois Native Americans, a name that was spelled in many different ways in the early records.[15]

American scholars previously thought the name Illinois meant 'man' or 'men' in the Miami-Illinois language, with the original iliniwek transformed via French into Illinois.[16][17] This etymology is not supported by the Illinois language,[citation needed] as the word for "man" is ireniwa, and plural of "man" is ireniwaki. The name Illiniwek has also been said to mean 'tribe of superior men',[18] which is a false etymology. The name Illinois derives from the Miami-Illinois verb irenwe·wa 'he speaks the regular way'. This was taken into the Ojibwe language, perhaps in the Ottawa dialect, and modified into ilinwe· (pluralized as ilinwe·k). The French borrowed these forms, spelling the /we/ ending as -ois, a transliteration of that sound in the French of that time. The current spelling form, Illinois, began to appear in the early 1670s, when French colonists had settled in the western area. The Illinois's name for themselves, as attested in all three of the French missionary-period dictionaries of Illinois, was Inoka, of unknown meaning and unrelated to the other terms.[19][20]

History

Pre-European

American Indians of successive cultures lived along the waterways of the Illinois area for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans. The Koster Site has been excavated and demonstrates 7,000 years of continuous habitation. Cahokia, the largest regional chiefdom and Urban Center of the Pre-Columbian Mississippian culture, was located near present-day Collinsville, Illinois. They built an urban complex of more than 100 platform and burial mounds, a 50-acre (20 ha) plaza larger than 35 football fields,[21] and a woodhenge of sacred cedar, all in a planned design expressing the culture's cosmology. Monks Mound, the center of the site, is the largest Pre-Columbian structure north of the Valley of Mexico. It is 100 ft (30 m) high, 951 ft (290 m) long, 836 ft (255 m) wide, and covers 13.8 acres (5.6 ha).[22] It contains about 814,000 cu yd (622,000 m3) of earth.[23] It was topped by a structure thought to have measured about 105 ft (32 m) in length and 48 ft (15 m) in width, covered an area 5,000 sq ft (460 m2), and been as much as 50 ft (15 m) high, making its peak 150 ft (46 m) above the level of the plaza. The finely crafted ornaments and tools recovered by archaeologists at Cahokia include elaborate ceramics, finely sculptured stonework, carefully embossed and engraved copper and mica sheets, and one funeral blanket for an important chief fashioned from 20,000 shell beads. These artifacts indicate that Cahokia was truly an urban center, with clustered housing, markets, and specialists in toolmaking, hide dressing, potting, jewelry making, shell engraving, weaving and salt making.[24]

The civilization vanished in the 15th century for unknown reasons, but historians and archeologists have speculated that the people depleted the area of resources. Many indigenous tribes engaged in constant warfare. According to Suzanne Austin Alchon, "At one site in the central Illinois River valley, one third of all adults died as a result of violent injuries."[25] The next major power in the region was the Illinois Confederation or Illini, a political alliance.[26] Around the time of European contact in 1673, the Illinois confederation had an estimated population of over 10,000 people.[27] As the Illini declined during the Beaver Wars era, members of the Algonquian-speaking Potawatomi, Miami, Sauk, and other tribes including the Fox (Meskwaki), Iowa, Kickapoo, Mascouten, Piankeshaw, Shawnee, Wea, and Winnebago (Ho-Chunk) came into the area from the east and north around the Great Lakes.[28][29]

European exploration and settlement prior to 1800

French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet explored the Illinois River in 1673. Marquette soon after founded a mission at the Grand Village of the Illinois in Illinois Country. In 1680, French explorers under René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle and Henri de Tonti constructed a fort at the site of present-day Peoria, and in 1682, a fort atop Starved Rock in today's Starved Rock State Park. French Empire Canadiens came south to settle particularly along the Mississippi River, and Illinois was part of first New France, and then of La Louisiane until 1763, when it passed to the British with their defeat of France in the Seven Years' War. The small French settlements continued, although many French migrated west to Ste. Genevieve and St. Louis, Missouri, to evade British rule.[31]

A few British soldiers were posted in Illinois, but few British or American settlers moved there, as the Crown made it part of the territory reserved for Indians west of the Appalachians, and then part of the British Province of Quebec. In 1778, George Rogers Clark claimed Illinois County for Virginia. In a compromise, Virginia (and other states that made various claims) ceded the area to the new United States in the 1780s and it became part of the Northwest Territory, administered by the federal government and later organized as states.[31]

19th century

Prior to statehood

The Illinois-Wabash Company was an early claimant to much of Illinois. The Illinois Territory was created on February 3, 1809, with its capital at Kaskaskia, an early French settlement.

During the discussions leading up to Illinois's admission to the Union, the proposed northern boundary of the state was moved twice.[32] The original provisions of the Northwest Ordinance had specified a boundary that would have been tangent to the southern tip of Lake Michigan. Such a boundary would have left Illinois with no shoreline on Lake Michigan at all. However, as Indiana had successfully been granted a 10 mi (16 km) northern extension of its boundary to provide it with a usable lakefront, the original bill for Illinois statehood, submitted to Congress on January 23, 1818, stipulated a northern border at the same latitude as Indiana's, which is defined as 10 miles north of the southernmost extremity of Lake Michigan. However, the Illinois delegate, Nathaniel Pope, wanted more, and lobbied to have the boundary moved further north. The final bill passed by Congress included an amendment to shift the border to 42° 30' north, which is approximately 51 mi (82 km) north of the Indiana northern border. This shift added 8,500 sq mi (22,000 km2) to the state, including the lead mining region near Galena. More importantly, it added nearly 50 miles of Lake Michigan shoreline and the Chicago River. Pope and others envisioned a canal that would connect the Chicago and Illinois rivers and thus connect the Great Lakes to the Mississippi.

The State of Illinois prior to the Civil War

In 1818, Illinois became the 21st U.S. state. The capital remained at Kaskaskia, headquartered in a small building rented by the state. In 1819, Vandalia became the capital, and over the next 18 years, three separate buildings were built to serve successively as the capitol building. In 1837, the state legislators representing Sangamon County, under the leadership of state representative Abraham Lincoln, succeeded in having the capital moved to Springfield,[33] where a fifth capitol building was constructed. A sixth capitol building was erected in 1867, which continues to serve as the Illinois capitol today.

Though it was ostensibly a "free state", there was nonetheless slavery in Illinois. The ethnic French had owned black slaves since the 1720s, and American settlers had already brought slaves into the area from Kentucky. Slavery was nominally banned by the Northwest Ordinance, but that was not enforced for those already holding slaves. When Illinois became a state in 1818, the Ordinance no longer applied, and about 900 slaves were held in the state. As the southern part of the state, later known as "Egypt" or "Little Egypt",[34][35] was largely settled by migrants from the South, the section was hostile to free blacks. Settlers were allowed to bring slaves with them for labor, but, in 1822, state residents voted against making slavery legal. Still, most residents opposed allowing free blacks as permanent residents. Some settlers brought in slaves seasonally or as house servants.[36] The Illinois Constitution of 1848 was written with a provision for exclusionary laws to be passed. In 1853, John A. Logan helped pass a law to prohibit all African Americans, including freedmen, from settling in the state.[37]

The winter of 1830–1831 is called the "Winter of the Deep Snow";[38] a sudden, deep snowfall blanketed the state, making travel impossible for the rest of the winter, and many travelers perished. Several severe winters followed, including the "Winter of the Sudden Freeze". On December 20, 1836, a fast-moving cold front passed through, freezing puddles in minutes and killing many travelers who could not reach shelter. The adverse weather resulted in crop failures in the northern part of the state. The southern part of the state shipped food north, and this may have contributed to its name, "Little Egypt", after the Biblical story of Joseph in Egypt supplying grain to his brothers.[39]

In 1832, the Black Hawk War was fought in Illinois and present-day Wisconsin between the United States and the Sauk, Fox (Meskwaki), and Kickapoo Indian tribes. It represents the end of Indian resistance to white settlement in the Chicago region.[40] The Indians had been forced to leave their homes and move to Iowa in 1831; when they attempted to return, they were attacked and eventually defeated by U.S. militia. The survivors were forced back to Iowa.[41] By 1832, when the last Indian lands in Illinois were ceded to the United States, the indigenous population of the state had been reduced by infectious diseases, warfare, and forced westward removal to only one village with fewer than 300 inhabitants.[27]

By 1839, the Latter Day Saints had founded a utopian city called Nauvoo, formerly called Commerce. Located in Hancock County along the Mississippi River, Nauvoo flourished and, by 1844, briefly surpassed Chicago for the position of the state's largest city.[42][43] But in that same year, the Latter Day Saint movement founder, Joseph Smith, was killed in the Carthage Jail, about 30 miles away from Nauvoo. Following a succession crisis, Brigham Young led most Latter Day Saints out of Illinois in a mass exodus to present-day Utah; after close to six years of rapid development, Nauvoo quickly declined afterward.

After it was established in 1833, Chicago gained prominence as a Great Lakes port, and then as an Illinois and Michigan Canal port after 1848, and as a rail hub soon afterward. By 1857, Chicago was Illinois's largest city.[31] With the tremendous growth of mines and factories in the state in the 19th century, Illinois was the ground for the formation of labor unions in the United States.

In 1847, after lobbying by Dorothea L. Dix, Illinois became one of the first states to establish a system of state-supported treatment of mental illness and disabilities, replacing local almshouses. Dix came into this effort after having met J. O. King, a Jacksonville, Illinois businessman, who invited her to Illinois, where he had been working to build an asylum for the insane. With the lobbying expertise of Dix, plans for the Jacksonville State Hospital (now known as the Jacksonville Developmental Center) were signed into law on March 1, 1847.[44]

Civil War and after

During the American Civil War, Illinois ranked fourth in soldiers who served (more than 250,000) in the Union Army, a figure surpassed by only New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. Beginning with President Abraham Lincoln's first call for troops and continuing throughout the war, Illinois mustered 150 infantry regiments, which were numbered from the 7th to the 156th regiments. Seventeen cavalry regiments were also gathered, as well as two light artillery regiments.[45] The town of Cairo, at the southern tip of the state at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, served as a strategically important supply base and training center for the Union army. For several months, both General Grant and Admiral Foote had headquarters in Cairo.

During the Civil War, and more so afterwards, Chicago's population skyrocketed, which increased its prominence. The Pullman Strike and Haymarket Riot, in particular, greatly influenced the development of the American labor movement. From Sunday, October 8, 1871, until Tuesday, October 10, 1871, the Great Chicago Fire burned in downtown Chicago, destroying four sq mi (10 km2).[46]

20th century

At the turn of the 20th century, Illinois had a population of nearly 5 million. Many people from other parts of the country were attracted to the state by employment caused by the expanding industrial base. Whites were 98% of the state's population.[47] Bolstered by continued immigration from southern and eastern Europe, and by the African-American Great Migration from the South, Illinois grew and emerged as one of the most important states in the union. By the end of the century, the population had reached 12.4 million.

The Century of Progress World's fair was held at Chicago in 1933. Oil strikes in Marion County and Crawford County led to a boom in 1937, and by 1939, Illinois ranked fourth in U.S. oil production. Illinois manufactured 6.1 percent of total United States military armaments produced during World War II, ranking seventh among the 48 states.[48] Chicago became an ocean port with the opening of the Saint Lawrence Seaway in 1959. The seaway and the Illinois Waterway connected Chicago to both the Mississippi River and the Atlantic Ocean. In 1960, Ray Kroc opened the first McDonald's franchise in Des Plaines, which was demolished in 1984.[49] In 1985 a replica was built on the same site to recreate how the original one looked.[49] Though this replica was demolished in 2017, due to repeated flooding of the building.[50][51]

Illinois had a prominent role in the emergence of the nuclear age. In 1942, as part of the Manhattan Project, the University of Chicago conducted the first sustained nuclear chain reaction. In 1957, Argonne National Laboratory, near Chicago, activated the first experimental nuclear power generating system in the United States. By 1960, the first privately financed nuclear plant in the United States, Dresden 1, was dedicated near Morris. In 1967, Fermilab, a national nuclear research facility near Batavia, opened a particle accelerator, which was the world's largest for over 40 years. With eleven plants currently operating, Illinois leads all states in the amount of electricity generated from nuclear power.[52][53]

In 1961, Illinois became the first state in the nation to adopt the recommendation of the American Law Institute and pass a comprehensive criminal code revision that repealed the law against sodomy. The code also abrogated common law crimes and established an age of consent of 18.[54] The state's fourth constitution was adopted in 1970, replacing the 1870 document.[55]

The first Farm Aid concert was held in Champaign to benefit American farmers, in 1985. The worst upper Mississippi River flood of the century, the Great Flood of 1993, inundated many towns and thousands of acres of farmland.[31]

21st century

Illinois entered the 21st century under Republican Governor George Ryan. Near the end of his term in January 2003, following a string of high-profile exonerations, Ryan commuted all death sentences in the state.[56]

The 2002 election brought Democrat Rod Blagojevich to the governor's mansion. It also brought future president Barack Obama into a committee leadership position in the Illinois Senate, where he drafted the Health Care Justice Act, a forerunner of the Affordable Care Act.[57] Obama's election to the presidency in Blagojevich's second term set off a chain of events culminating in Blagojevich's impeachment, trial, and subsequent criminal conviction and imprisonment, making Blagojevich the second consecutive Illinois governor to be convicted on federal corruption charges.[58]

Blagojevich's replacement Pat Quinn was defeated by Republican Bruce Rauner in the 2014 election. Disagreements between the governor and legislature over budgetary policy led to the Illinois Budget Impasse, a 793-day period stretching from 2015 to 2018 in which the state had no budget and struggled to pay its bills.[59]

On August 28, 2017, Rauner signed a bill into law that prohibited state and local police from arresting anyone solely due to their immigration status or due to federal detainers.[60][61] Some fellow Republicans criticized Rauner for his action, claiming the bill made Illinois a sanctuary state.[62]

In the 2018 election, Rauner was replaced by J. B. Pritzker, returning the state government to a Democratic trifecta.[63] In January 2020 the state legalized marijuana.[64] On March 9, 2020, Pritzker issued a disaster proclamation due to the COVID-19 pandemic. He ended the state of emergency in May 2023.[65]

Geology

During the early part of the Paleozoic Era, the area that would one day become Illinois was submerged beneath a shallow sea and located near the Equator. Diverse marine life lived at this time, including trilobites, brachiopods, and crinoids. Changing environmental conditions led to the formation of large coal swamps in the Carboniferous.

Illinois was above sea level for at least part of the Mesozoic, but by its end was again submerged by the Western Interior Seaway. This receded by the Eocene Epoch.

During the Pleistocene Epoch, vast ice sheets covered much of Illinois, with only the Driftless Area remaining exposed. These glaciers carved the basin of Lake Michigan and left behind traces of ancient glacial lakes and moraines.[66]

Geography

Illinois is located in the Midwest region of the United States and is one of the eight states in the Great Lakes region of North America (which also includes Ontario, Canada).

Boundaries

Illinois's eastern border with Indiana consists of a north–south line at 87° 31′ 30″ west longitude in Lake Michigan at the north, to the Wabash River in the south above Post Vincennes. The Wabash River continues as the eastern/southeastern border with Indiana until the Wabash enters the Ohio River. This marks the beginning of Illinois's southern border with Kentucky, which runs along the northern shoreline of the Ohio River.[67] Most of the western border with Missouri and Iowa is the Mississippi River; Kaskaskia is an exclave of Illinois, lying west of the Mississippi and reachable only from Missouri. The state's northern border with Wisconsin is fixed at 42° 30′ north latitude. The northeastern border of Illinois lies in Lake Michigan, within which Illinois shares a water boundary with the state of Michigan, as well as Wisconsin and Indiana.[28]

Topography

Though Illinois lies entirely in the Interior Plains, it does have some minor variation in its elevation. In extreme northwestern Illinois, the Driftless Area, a region of unglaciated and therefore higher and more rugged topography, occupies a small part of the state. Southern Illinois includes the hilly areas around the Shawnee National Forest.

Charles Mound, located in the Driftless region, has the state's highest natural elevation above sea level at 1,235 ft (376 m). Other highlands include the Shawnee Hills in the south, and there is varying topography along its rivers; the Illinois River bisects the state northeast to southwest. The floodplain on the Mississippi River from Alton to the Kaskaskia River is known as the American Bottom.

Divisions

Illinois has three major geographical divisions. Northern Illinois is dominated by Chicago metropolitan area, or Chicagoland, which is the city of Chicago and its suburbs, and the adjoining exurban area into which the metropolis is expanding. As defined by the federal government, the Chicago metro area includes several counties in Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin, and has a population of over 9.8 million. Chicago itself is a cosmopolitan city, densely populated, industrialized, the transportation hub of the nation, and settled by a wide variety of ethnic groups. The city of Rockford, Illinois's third-largest city and center of the state's fourth largest metropolitan area, sits along Interstates 39 and 90 some 75 mi (121 km) northwest of Chicago. The Quad Cities region, located along the Mississippi River in northern Illinois, had a population of 381,342 in 2011.

The midsection of Illinois is the second major division, called Central Illinois. Historically prairie, it is now mainly agricultural and known as the Heart of Illinois. It is characterized by small towns and medium–small cities. The western section (west of the Illinois River) was originally part of the Military Tract of 1812 and forms the conspicuous western bulge of the state. Agriculture, particularly corn and soybeans, as well as educational institutions and manufacturing centers, figure prominently in Central Illinois. Cities include Peoria; Springfield, the state capital; Quincy; Decatur; Bloomington-Normal; and Champaign-Urbana.[28]

The third division is Southern Illinois, comprising the area south of U.S. Route 50, including Little Egypt, near the juncture of the Mississippi River and Ohio River. Southern Illinois is the site of the ancient city of Cahokia, as well as the site of the first state capital at Kaskaskia, which today is separated from the rest of the state by the Mississippi River.[28][69] This region has a somewhat warmer winter climate, different variety of crops (including some cotton farming in the past), more rugged topography (due to the area remaining unglaciated during the Illinoian Stage, unlike most of the rest of the state), as well as small-scale oil deposits and coal mining. The Illinois suburbs of St. Louis, such as East St. Louis, are located in this region, and collectively, they are known as the Metro-East. The other somewhat significant concentration of population in Southern Illinois is the Carbondale-Marion-Herrin, Illinois Combined Statistical Area centered on Carbondale and Marion, a two-county area that is home to 123,272 residents.[28] A portion of southeastern Illinois is part of the extended Evansville, Indiana, Metro Area, locally referred to as the Tri-State with Indiana and Kentucky. Seven Illinois counties are in the area.

In addition to these three, largely latitudinally defined divisions, all of the region outside the Chicago metropolitan area is often called "downstate" Illinois. This term is flexible, but is generally meant to mean everything outside the influence of the Chicago area. Thus, some cities in Northern Illinois, such as DeKalb, which is west of Chicago, and Rockford—which is actually north of Chicago—are sometimes incorrectly considered to be 'downstate'.

Climate

Illinois has a climate that varies widely throughout the year. Because of its nearly 400-mile distance between its northernmost and southernmost extremes, as well as its mid-continental situation, most of Illinois has a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa), with hot, humid summers and cold winters. The southern part of the state, from about Carbondale southward, has a humid subtropical climate (Koppen Cfa), with more moderate winters. Average yearly precipitation for Illinois varies from just over 48 in (1,219 mm) at the southern tip to around 35 in (889 mm) in the northern portion of the state. Normal annual snowfall exceeds 38 in (965 mm) in the Chicago area, while the southern portion of the state normally receives less than 14 in (356 mm).[70] The all-time high temperature was 117 °F (47 °C), recorded on July 14, 1954, at East St. Louis, and the all-time low temperature was −38 °F (−39 °C), recorded on January 31, 2019, during the January 2019 North American cold wave at a weather station near Mount Carroll,[71][72] and confirmed on March 5, 2019.[73] This followed the previous record of −36 °F (−38 °C) recorded on January 5, 1999, near Congerville.[73] Prior to the Mount Carroll record, a temperature of −37 °F (−38 °C) was recorded on January 15, 2009, at Rochelle, but at a weather station not subjected to the same quality control as official records.[74][75]

Illinois averages approximately 51 days of thunderstorm activity a year, which ranks somewhat above average in the number of thunderstorm days for the United States. Illinois is vulnerable to tornadoes, with an average of 35 occurring annually, which puts much of the state at around five tornadoes per 10,000 sq mi (30,000 km2) annually.[76] While tornadoes are no more powerful in Illinois than other states, some of Tornado Alley's deadliest tornadoes on record have occurred in the state. The Tri-State Tornado of 1925 killed 695 people in three states; 613 of the victims died in Illinois.[77]

| City | January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cairo[78] | 43/25 | 48/29 | 59/37 | 70/46 | 78/57 | 86/67 | 90/71 | 88/69 | 81/61 | 71/49 | 57/39 | 46/30 |

| Chicago[79] | 31/16 | 36/21 | 47/31 | 59/42 | 70/52 | 81/61 | 85/65 | 83/65 | 75/57 | 64/45 | 48/34 | 36/22 |

| Edwardsville[80] | 36/19 | 42/24 | 52/34 | 64/45 | 75/55 | 84/64 | 89/69 | 86/66 | 79/58 | 68/46 | 53/35 | 41/25 |

| Moline[81] | 30/12 | 36/18 | 48/29 | 62/39 | 73/50 | 83/60 | 86/64 | 84/62 | 76/53 | 64/42 | 48/30 | 34/18 |

| Peoria[82] | 31/14 | 37/20 | 49/30 | 62/40 | 73/51 | 82/60 | 86/65 | 84/63 | 77/54 | 64/42 | 49/31 | 36/20 |

| Rockford[83] | 27/11 | 33/16 | 46/27 | 59/37 | 71/48 | 80/58 | 83/63 | 81/61 | 74/52 | 62/40 | 46/29 | 32/17 |

| Springfield[84] | 33/17 | 39/22 | 51/32 | 63/42 | 74/53 | 83/62 | 86/66 | 84/64 | 78/55 | 67/44 | 51/34 | 38/23 |

Urban areas

Chicago is the largest city in the state and the third-most populous city in the United States, with a population of 2,746,388 in 2020. Furthermore, over 7 million residents of the Chicago metropolitan area reside in Illinois. The U.S. Census Bureau currently lists seven other cities with populations of over 100,000 within the state. This includes the Chicago satellite towns of Aurora, Joliet, Naperville, and Elgin, as well as the cities of Rockford, the most populous city in the state outside of the Chicago area; Springfield, the state's capital; and Peoria.

The most populated city in the state south of Springfield is Belleville, with 42,000 residents. It is located in the Metro East region of Greater St. Louis, the second-most populous urban area in Illinois with over 700,000 residents. Other major urban areas include the Peoria metropolitan area, Rockford metropolitan area, Champaign–Urbana metropolitan area (home to the University of Illinois), Springfield metropolitan area, the Illinois portion of the Quad Cities area, and the Bloomington–Normal metropolitan area.

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Chicago  Aurora | 1 | Chicago | Cook | 2,746,388 | 11 | Cicero | Cook | 85,268 |  Joliet  Naperville |

| 2 | Aurora | Kane | 180,542 | 12 | Schaumburg | Cook | 78,723 | ||

| 3 | Joliet | Will | 150,362 | 13 | Bloomington | McLean | 78,680 | ||

| 4 | Naperville | DuPage | 149,540 | 14 | Evanston | Cook | 78,110 | ||

| 5 | Rockford | Winnebago | 148,655 | 15 | Arlington Heights | Cook | 77,676 | ||

| 6 | Elgin | Kane, Cook | 114,797 | 16 | Bolingbrook | Will, DuPage | 73,922 | ||

| 7 | Springfield | Sangamon | 114,394 | 17 | Decatur | Macon | 70,522 | ||

| 8 | Peoria | Peoria | 113,150 | 18 | Palatine | Cook | 67,908 | ||

| 9 | Waukegan | Lake | 89,321 | 19 | Skokie | Cook | 67,824 | ||

| 10 | Champaign | Champaign | 88,302 | 20 | Des Plaines | Cook | 60,675 | ||

Demographics

The United States Census Bureau found that the population of Illinois was 12,812,508 in the 2020 United States census, moving from the fifth-largest state to the sixth-largest state (losing out to Pennsylvania). Illinois' population slightly declined in 2020 from the 2010 United States census by just over 18,000 residents and the overall population was quite higher than recent census estimates.[86]

Illinois is the most populous state in the Midwest region. Chicago, the third-most populous city in the United States, is the center of the Chicago metropolitan area or Chicagoland, as this area is nicknamed. Although the Chicago metropolitan area comprises only 9% of the land area of the state, it contains 65% of the state's residents, with 21.4% of Illinois' population living in the city of Chicago itself as of 2020.[87] The losses of population anticipated from the 2020 census results do not arise from the Chicago metro area; rather the declines are from the Downstate counties.[88] As of the 2020 census, the state's geographic mean center of population is located at 41° 18′ 43″N 88° 22 23″W in Grundy County, about six miles northwest of Coal City.[89]

Illinois is the most racially and ethnically diverse state in the Midwest. By several metrics, including racial and ethnic background, religious affiliation, and percentage of rural and urban divide, Illinois is the most representative of the larger demography of the United States.[90]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 2,458 | — | |

| 1810 | 12,282 | 399.7% | |

| 1820 | 55,211 | 349.5% | |

| 1830 | 157,445 | 185.2% | |

| 1840 | 476,183 | 202.4% | |

| 1850 | 851,470 | 78.8% | |

| 1860 | 1,711,951 | 101.1% | |

| 1870 | 2,539,891 | 48.4% | |

| 1880 | 3,077,871 | 21.2% | |

| 1890 | 3,826,352 | 24.3% | |

| 1900 | 4,821,550 | 26.0% | |

| 1910 | 5,638,591 | 16.9% | |

| 1920 | 6,485,280 | 15.0% | |

| 1930 | 7,630,654 | 17.7% | |

| 1940 | 7,897,241 | 3.5% | |

| 1950 | 8,712,176 | 10.3% | |

| 1960 | 10,081,158 | 15.7% | |

| 1970 | 11,113,976 | 10.2% | |

| 1980 | 11,426,518 | 2.8% | |

| 1990 | 11,430,602 | 0.0% | |

| 2000 | 12,419,293 | 8.6% | |

| 2010 | 12,830,632 | 3.3% | |

| 2020 | 12,812,508 | −0.1% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 12,549,689 | [91] | −2.1% |

| Source: 1910–2020) | |||

Race and ethnicity

2020 Census

| Race / Ethnicity | Pop 2000[92] | Pop 2010[93] | Pop 2020[94] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 8,424,140 | 8,167,753 | 7,472,751 | 67.83% | 63.66% | 58.32% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 1,856,152 | 1,832,924 | 1,775,612 | 14.95% | 14.29% | 13.86% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 18,232 | 18,849 | 16,561 | 0.15% | 0.15% | 0.13% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 419,916 | 580,586 | 747,280 | 3.38% | 4.52% | 5.83% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 3,116 | 2,977 | 2,959 | 0.03% | 0.02% | 0.02% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 13,479 | 16,008 | 45,080 | 0.11% | 0.12% | 0.35% |

| Mixed Race/Multi-Racial (NH) | 153,996 | 183,957 | 414,855 | 1.24% | 1.43% | 3.24% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 1,530,262 | 2,027,578 | 2,337,410 | 12.32% | 15.80% | 18.24% |

| Total | 12,419,293 | 12,830,632 | 12,812,508 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Race and ethnicity[95] | Alone | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 58.3% | 61.3% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino[c] | — | 18.2% | ||

| African American (non-Hispanic) | 13.9% | 15.0% | ||

| Asian | 5.8% | 6.7% | ||

| Native American | 0.1% | 1.1% | ||

| Pacific Islander | 0.02% | 0.1% | ||

| Other | 0.4% | 1.1% | ||

| Racial composition | 1950[96] | 1960[96] | 1970[96] | 1980[96] | 1990[97] | 2000[98] | 2010[99] | 2020[100] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 92.4% | 89.4% | 86.4% | 80.8% | 78.3% | 73.5% | 71.5% | 61.4% |

| Black | 7.4% | 10.3% | 12.8% | 14.7% | 14.8% | 15.1% | 14.5% | 14.1% |

| Asian | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 1.4% | 2.5% | 3.4% | 4.6% | 5.9% |

| Native | 0% | 0% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.8% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander | — | — | — | — | — | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Other race | — | — | 0.2% | 3% | 4.2% | 5.8% | 6.7% | 8.9% |

| Two or more races | — | — | — | — | — | 1.9% | 2.3% | 8.9% |

| Hispanic or Latino | — | — | 3.3% | 5.6% | 7.9% | 12.3% | 15.8% | 18.2% |

| Non-Hispanic white | — | — | 83.5% | 78% | 74.8% | 67.8% | 63.7% | 58.3% |

2022 American Community Survey

Racial Makeup of Illinois (2022)[101] White alone (61.07%) Black alone (13.43%) Native American alone (0.69%) Asian Alone (6.00%) Pacific Islander Alone (0.06%) Some other race alone (7.89%) Two or more races (10.87%) | Racial/Ethnic Makeup of Illinois excluding Hispanics from racial categories (2022)[101] White NH (58.47%) Black NH (13.20%) Native American NH (0.08%) Asian NH (5.94%) Pacific Islander NH (0.03%) Other NH (0.36%) Two or more races NH (3.64%) Hispanic Any Race (18.28%) | Racial Makeup of Hispanics in Illinois (2022)[101] White alone (14.23%) Black alone (1.27%) Native American alone (3.33%) Asian Alone (0.33%) Pacific Islander Alone (0.15%) Other race alone (41.17%) Two or more races (39.52%) |

According to 2022 U.S. Census Bureau estimates, Illinois' population was 61.1% White, 13.4% Black or African American, 0.1% Native American or Alaskan Native, 6.0% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 7.9% Some Other Race, and 10.9% from two or more races.[101] The white population continues to remain the largest racial category in Illinois. Hispanics are allocated amongst the various racial groups and primarily identify as Some Other Race (41.2%) or Multiracial (39.5%) with the remainder identifying as White (14.2%), Black (1.3%), American Indian and Alaskan Native (3.3), Asian (0.3%), and Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (0.2%).[101] By ethnicity, 18.3% of the total population is Hispanic-Latino (of any race) and 81.7% is Non-Hispanic (of any race). If treated as a separate category, Hispanics are the largest minority group in Illinois.[101]

As of 2022[update], 50% of Illinois's population younger than age 4 were minorities (Note: Children born to white Hispanics or to a sole full or partial minority parent are counted as minorities).[102]

The state's most populous ethnic group, non-Hispanic white, has declined from 83.5% in 1970[103] to 58.5% in 2022.[101] Almost 60% of Illinois' minority population, including over 67% of the black population, lives in Cook County, while the county includes around 40% of the state's total population.[104] Cook County, which is home to Chicago, is the only majority-minority county within Illinois, with non-Hispanic whites making up a plurality of 40.4% of the population.[105]

Ancestry

According to 2022 estimates from the American Community Survey, 16% of the population had German ancestry, 14% had Mexican ancestry, 10.4% had Irish ancestry, 7.1% had English ancestry, 6.2% had Polish ancestry, 5.2% had Italian ancestry, 3.4% listed themselves as American, 2.3% had Indian ancestry, 1.7% had Puerto Rican ancestry, 1.7% had Swedish ancestry, 1.4% had Filipino ancestry, 1.4% had French ancestry, and 1.2% had Chinese ancestry. The state also has a large population of African-Americans, making up 15.3% of the population alone or in combination.[106][107][108][109]This table displays all self-reported ancestries with over 50,000 members in Illinois, alone or in combination, according to estimates from the 2022 American Community Survey. Hispanic groups are not distinguished between total and partial ancestry:

| Ancestry | Number in 2022 (Alone)[110][111] | Number as of 2022 (Alone or in any combination)[112][113][114] | % Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| German | 649,997 | 2,014,297 | 16.0% |

| Black or African American (Including Afro-Caribbean & Sub-Saharan African) | 1,689,724 | 1,931,027 | 15.3% |

| Mexican | — | 1,759,842 | 14.0% |

| Irish | 338,198 | 1,312,888 | 10.4% |

| English | 278,564 | 891,189 | 7.1% |

| Polish | 336,810 | 780,152 | 6.2% |

| Italian | 205,189 | 657,830 | 5.2% |

| American (Mostly old-stock white Americans of British descent) | 345,772 | 428,431 | 3.4% |

| Indian | 270,311 | 287,101 | 2.3% |

| Puerto Rican | — | 214,835 | 1.7% |

| Swedish | 48,814 | 210,128 | 1.7% |

| Filipino | 131,433 | 175,619 | 1.4% |

| French | 27,025 | 174,964 | 1.4% |

| Chinese | 130,864 | 153,277 | 1.2% |

| Broadly "European" (No country specified) | 114,209 | 146,671 | 1.2% |

| Scottish | 33,638 | 136,636 | 1.1% |

| Norwegian | 33,099 | 133,538 | 1.1% |

| Dutch | 32,184 | 122,139 | 1.0% |

| Arab | 74,779 | 106,612 | 0.8% |

| Czech | 21,168 | 83,090 | 0.7% |

| Greek | 39,290 | 82,360 | 0.7% |

| Russian | 27,532 | 79,623 | 0.6% |

| Lithuanian | 27,001 | 73,207 | 0.6% |

| Korean | 55,515 | 71,709 | 0.6% |

| Scotch-Irish | 16,817 | 60,693 | 0.5% |

| Ukrainian | 37,306 | 60,623 | 0.5% |

Immigration

At the 2022 estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau, there were 1,810,100 foreign-born inhabitants of the state or 14.4% of the population, with 37.8% from Mexico or Central America, 31% from Asia, 20.2% from Europe, 4.3% from South America, 4.2% from Africa, 1% from Canada, and 0.2% from Oceania.[115][116] Of the foreign-born population, 53.5% were naturalized U.S. citizens, and 46.5% were not U.S. citizens.[117] The top countries of origin for immigrants in Illinois were Mexico, India, Poland, the Philippines and China in 2018.[118]

| Place of Birth | Population (2022)[119][120] | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 10,660,218 | 84.7% |

| Illinois | 8,379,091 | 66.6% |

| Other States or D.C. | 2,227,917 | 17.7% |

| Puerto Rico | 50,577 | 0.4% |

| Other US Territories | 2,633 | 0.0% |

| Born abroad to American parents | 111,714 | 0.9% |

| Mexico & Central America | 683,766 | 5.4% |

| Mexico | 621,541 | 4.9% |

| Guatemala | 22,886 | 0.2% |

| Honduras | 13,811 | 0.1% |

| El Salvador | 12,097 | 0.1% |

| Belize | 7,150 | 0.1% |

| Other Central American countries | 6,281 | 0.0% |

| Caribbean (Not including Puerto Rico) | 25,258 | 0.2% |

| Cuba | 6,955 | 0.1% |

| Jamaica | 6,873 | 0.1% |

| Haiti | 5,265 | 0.0% |

| Other Caribbean countries | 6,165 | 0.0% |

| South America | 76,944 | 0.7% |

| Colombia | 22,796 | 0.2% |

| Venezuela | 15,387 | 0.1% |

| Ecuador | 14,356 | 0.1% |

| Brazil | 9,164 | 0.1% |

| Peru | 6,426 | 0.1% |

| Other South American countries | 8,815 | 0.1% |

| Northern America | 17,775 | 0.1% |

| Canada | 17,632 | 0.1% |

| Other Northern American countries | 143 | 0.0% |

| Eastern Europe | 271,358 | 2.2% |

| Poland | 120,473 | 1.0% |

| Ukraine | 33,575 | 0.3% |

| Romania | 15,452 | 0.1% |

| Russia | 14,930 | 0.1% |

| Bulgaria | 13,464 | 0.1% |

| Bosnia & Herzegovina | 11,071 | 0.1% |

| Other Eastern European countries | 62,393 | 0.5% |

| Western Europe | 30,076 | 0.3% |

| Germany | 19,611 | 0.2% |

| Other Western European countries | 10,465 | 0.1% |

| Southern Europe | 34,997 | 0.3% |

| Italy | 18,660 | 0.1% |

| Greece | 12,463 | 0.1% |

| Other Southern European countries | 3,874 | 0.0% |

| Northern Europe | 27,573 | 0.2% |

| United Kingdom (Including overseas CrownDependencies) | 19,123 | 0.2% |

| Ireland | 5,465 | 0.0% |

| Other Northern European countries | 2,985 | 0.0% |

| Europe, unspecified country | 1,353 | 0.0% |

| East Asia | 137,098 | 1.1% |

| China | 77,933 | 0.7% |

| Korea (North & South) | 37,662 | 0.3% |

| Japan | 9,905 | 0.1% |

| Taiwan | 8,995 | 0.1% |

| Other East Asian countries | 2,603 | 0.0% |

| South or Central Asia | 231,775 | 1.8% |

| India | 173,578 | 1.4% |

| Pakistan | 29,823 | 0.2% |

| Bangladesh | 5,858 | 0.0% |

| Other South or Central Asian countries | 22,516 | 0.2% |

| Southeast Asia | 131,684 | 1.0% |

| Philippines | 92,569 | 0.7% |

| Vietnam | 18,559 | 0.1% |

| Thailand | 5,268 | 0.0% |

| Other Southeast Asian countries | 15,288 | 0.1% |

| West Asia | 52,352 | 0.4% |

| Iraq | 13,341 | 0.1% |

| Jordan | 8,240 | 0.1% |

| Syria | 8,130 | 0.1% |

| Turkey | 5,271 | 0.0% |

| Other West Asian countries | 17,370 | 0.1% |

| Asia, unspecified country | 8,366 | 0.1% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 63,590 | 0.6% |

| Nigeria | 22,648 | 0.2% |

| Ghana | 6,018 | 0.0% |

| Ethiopia | 5,069 | 0.0% |

| Other Sub-Saharan African countries | 29,855 | 0.3% |

| North Africa | 11,924 | 0.1% |

| Africa, unspecified country | 2,368 | 0.0% |

| Oceania | 4,211 | 0.0% |

| Total Population | 12,582,032 | 100% |

Age and sex

In 2022, 11.2% of Illinois's population was reported as being under the age of 9, 12.9% were between 10 and 19 years old, 13.4% were 20–29 years old, 13.6% were 30–39 years old, 12.6% were 40–49 years old, 12.7% were 50–59 years old, 11.9% were 60–69 years old, 7.7% were 70–79 years old, and 4% were over the age of 80.[121] The median age in Illinois is 39.1 years. Females made up approximately 50.5% of the population, while males made up 49.5%.[122] According to a 2022 study from the Williams Institute, an estimated 0.44% of adults in Illinois identify as transgender, a rate slighly lower than the national estimate of 0.52%.[123] According to a Gallup survey from 2019, 4.3% of adults in Illinois identify as LGBTQ.[124]

| Age Group | % of Total (2022) | Population (2022) |

|---|---|---|

| 0-9 | 11.2% | 1,409,553 |

| 10-19 | 12.9% | 1,628,658 |

| 20-29 | 13.4% | 1,683,823 |

| 30-39 | 13.6% | 1,709,929 |

| 40-49 | 12.6% | 1,579,665 |

| 50-59 | 12.7% | 1,596,049 |

| 60-69 | 11.9% | 1,501,221 |

| 70-79 | 7.7% | 970,961 |

| 80+ | 4% | 502,173 |

Socioeconomics

As of 2022, the per-capita income in Illinois is $43,317, and the median income for a household in the state is $76,708, slightly higher than the national average. 11.9% of the population lives below the poverty line, including 16% of children under 18 and 10% of those over the age of 65. There are 5,056,360 households in Illinois, with an average size of 2.4 people per household. 90.4% of the adult population has a high school diploma, and 37.7% of the population over 25 has a bachelor's degree or higher, compared to a national average of 35.7%.[121]

In 2021, Illinois scored 0.929 on the UN's Human Development Index, placing it in the category of "very high" Human Development and slighly higher than the US average of 0.921.[125]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 9,212 homeless people in Illinois.[126][127]

Birth data by race/ethnicity

Births do not add up, because Hispanics are counted both by ethnicity and by race.

| Race | 2013[128] | 2014[129] | 2015[130] | 2016[131] | 2017[132] | 2018[133] | 2019[134] | 2020[135] | 2021[136] | 2022[137] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White: | 119,157 (75.9%) | 119,995 (75.7%) | 119,630 (75.6%) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Non-Hispanic White | 85,866 (54.7%) | 86,227 (54.4%) | 85,424 (54.0%) | 82,318 (53.3%) | 78,925 (52.8%) | 77,244 (53.3%) | 74,434 (53.1%) | 70,550 (52.9%) | 71,482 (54.1%) | 68,107 (53.1%) |

| Black | 27,692 (17.6%) | 28,160 (17.8%) | 28,059 (17.7%) | 25,619 (16.6%) | 25,685 (17.2%) | 24,482 (16.9%) | 23,258 (16.6%) | 22,293 (16.7%) | 20,779 (15.7%) | 19,296 (15.0%) |

| Asian | 9,848 (6.3%) | 10,174 (6.4%) | 10,222 (6.5%) | 10,015 (6.5%) | 9,650 (6.5%) | 9,452 (6.5%) | 9,169 (6.5%) | 8,505 (6.4%) | 8,338 (6.3%) | 8,277 (6.4%) |

| American Indian | 234 (0.1%) | 227 (0.1%) | 205 (0.1%) | 110 (0.0%) | 133 (0.1%) | 129 (0.1%) | 119 (0.1%) | 79 (>0.1%) | 86 (>0.1%) | 126 (0.1%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 33,454 (21.3%) | 33,803 (21.3%) | 33,902 (21.4%) | 32,635 (21.1%) | 31,428 (21.0%) | 30,362 (21.0%) | 30,097 (21.5%) | 28,808 (21.6%) | 28,546 (21.6%) | 29,710 (23.1%) |

| Total Illinois | 156,931 (100%) | 158,556 (100%) | 158,116 (100%) | 154,445 (100%) | 149,390 (100%) | 144,815 (100%) | 140,128 (100%) | 133,298 (100%) | 132,189 (100%) | 128,350 (100%) |

- Since 2016, data for births of Hispanic origin are not collected by race, but included in one Hispanic group; persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

Languages

The official language of Illinois is English,[138] although between 1923 and 1969, state law gave official status to "the American language". Nearly 80% of people in Illinois speak English natively, and most of the rest speak it fluently as a second language.[139] A number of dialects of American English are spoken, ranging from Inland Northern American English and African-American English around Chicago, to Midland American English in Central Illinois, to Southern American English in the far south.

Over 23% of Illinoians speak a language other than English at home, of which Spanish is by far the most widespread, at more than 13% of the total population.[140] A sizeable number of Polish speakers is present in the Chicago Metropolitan Area. Illinois Country French has mostly gone extinct in Illinois, although it is still celebrated in the French Colonial Historic District.

| Language spoken at home | % of Total (2022)[141] | Population (2022) |

|---|---|---|

| English only | 76.1% | 9,067,296 |

| Spanish | 13.8% | 1,638,808 |

| Other Indo-European languages | 5.8% | 687,797 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander languages | 3.1% | 372,475 |

| Other languages | 1.2% | 141,445 |

| Total population aged 5+ | 100% | 11,907,821 |

Religion

Religion in Illinois (2014)[142][143]

Christianity

Roman Catholics constitute the single largest religious denomination in Illinois; they are heavily concentrated in and around Chicago and account for nearly 30% of the state's population.[144] However, taken together as a group, the various Protestant denominations comprise a greater percentage of the state's population than do Catholics. In 2010, Catholics in Illinois numbered 3,648,907. The largest Protestant denominations were the United Methodist Church with 314,461 members and the Southern Baptist Convention with 283,519. Illinois has one of the largest concentrations of Missouri Synod Lutherans in the United States.

Illinois played an important role in the early Latter Day Saint movement, with Nauvoo becoming a gathering place for Mormons in the early 1840s. Nauvoo was the location of the succession crisis, which led to the separation of the Mormon movement into several Latter Day Saint sects. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the largest of the sects to emerge from the Mormon schism, has more than 55,000 adherents in Illinois today.[145]

Other Abrahamic religious communities

A significant number of adherents of other Abrahamic faiths can be found in Illinois. Largely concentrated in the Chicago metropolitan area, followers of the Muslim, Baháʼí, and Jewish religions all call the state home.[146] Muslims constituted the largest non-Christian group, with 359,264 adherents.[147] Illinois has the largest concentration of Muslims by state in the country, with 2,800 Muslims per 100,000 citizens.[148]

The largest and oldest surviving Baháʼí House of Worship in the world is located on the shores of Lake Michigan in Wilmette, Illinois, one of eight continental Baháʼí House of Worship.[149] It serves as a space for people of all backgrounds and religions to gather, meditate, reflect, and pray, expressing the Baháʼí principle of the oneness of religions.[150] The Chicago area has a very large Jewish community, particularly in the suburbs of Skokie, Buffalo Grove, Highland Park, and surrounding suburbs. Former Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel was the Windy City's first Jewish mayor.

Other religions

Chicago is also home to a very large population of Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, and Buddhists.[146]

Economy

As of 2022, the gross state product for Illinois reached US$1.0 trillion.[151]

As of February 2019, the unemployment rate in Illinois reached 4.2%.[152]

Illinois's minimum wage will rise to $15 per hour by 2025, making it one of the highest in the nation.[153]

Agriculture

Illinois's major agricultural outputs are corn, soybeans, hogs, cattle, dairy products, and wheat. In most years, Illinois is either the first or second state for the highest production of soybeans, with a harvest of 427.7 million bushels (11.64 million metric tons) in 2008, after Iowa's production of 444.82 million bushels (12.11 million metric tons).[154] Illinois ranks second in U.S. corn production with more than 1.5 billion bushels produced annually.[155] With a production capacity of 1.5 billion gallons per year, Illinois is a top producer of ethanol, ranking third in the United States in 2011.[156] Illinois is a leader in food manufacturing and meat processing.[157] Although Chicago may no longer be "Hog Butcher for the World", the Chicago area remains a global center for food manufacture and meat processing,[157] with many plants, processing houses, and distribution facilities concentrated in the area of the former Union Stock Yards.[158] Illinois also produces wine, and the state is home to two American viticultural areas. In the area of The Meeting of the Great Rivers Scenic Byway, peaches and apples are grown. The German immigrants from agricultural backgrounds who settled in Illinois in the mid- to late 19th century are in part responsible for the profusion of fruit orchards in that area of Illinois.[159] Illinois's universities are actively researching alternative agricultural products as alternative crops.

Manufacturing

Illinois is one of the nation's manufacturing leaders, boasting annual value added productivity by manufacturing of over $107 billion in 2006. As of 2011[update], Illinois is ranked as the 4th-most productive manufacturing state in the country, behind California, Texas, and Ohio.[160] About three-quarters of the state's manufacturers are located in the Northeastern Opportunity Return Region, with 38 percent of Illinois's approximately 18,900 manufacturing plants located in Cook County. As of 2006, the leading manufacturing industries in Illinois, based upon value-added, were chemical manufacturing ($18.3 billion), machinery manufacturing ($13.4 billion), food manufacturing ($12.9 billion), fabricated metal products ($11.5 billion), transportation equipment ($7.4 billion), plastics and rubber products ($7.0 billion), and computer and electronic products ($6.1 billion).[161]

Services

By the early 2000s, Illinois's economy had moved toward a dependence on high-value-added services, such as financial trading, higher education, law, logistics, and medicine. In some cases, these services clustered around institutions that hearkened back to Illinois's earlier economies. For example, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, a trading exchange for global derivatives, had begun its life as an agricultural futures market. Other important non-manufacturing industries include publishing, tourism, and energy production and distribution.

Investments

Venture capitalists funded a total of approximately $62 billion in the U.S. economy in 2016. Of this amount, Illinois-based companies received approximately $1.1 billion. Similarly, in FY 2016, the federal government spent $461 billion on contracts in the U.S. Of this amount, Illinois-based companies received approximately $8.7 billion.[citation needed]

Energy

Illinois is a net importer of fuels for energy, despite large coal resources and some minor oil production. Illinois exports electricity, ranking fifth among states in electricity production and seventh in electricity consumption.[162]

Coal

The coal industry of Illinois has its origins in the middle 19th century, when entrepreneurs such as Jacob Loose discovered coal in locations such as Sangamon County. Jacob Bunn contributed to the development of the Illinois coal industry and was a founder and owner of the Western Coal & Mining Company of Illinois. About 68% of Illinois has coal-bearing strata of the Pennsylvanian geologic period. According to the Illinois State Geological Survey, 211 billion tons of bituminous coal are estimated to lie under the surface, having a total heating value greater than the estimated oil deposits in the Arabian Peninsula.[163] However, this coal has a high sulfur content, which causes acid rain, unless special equipment is used to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions.[28][31][69] Many Illinois power plants are not equipped to burn high-sulfur coal. In 1999, Illinois produced 40.4 million tons of coal, but only 17 million tons (42%) of Illinois coal was consumed in Illinois. Most of the coal produced in Illinois is exported to other states and countries. In 2008, Illinois exported three million tons of coal and was projected to export nine million in 2011, as demand for energy grows in places such as China, India, and elsewhere in Asia and Europe.[164] As of 2010[update], Illinois was ranked third in recoverable coal reserves at producing mines in the nation.[156] Most of the coal produced in Illinois is exported to other states, while much of the coal burned for power in Illinois (21 million tons in 1998) is mined in the Powder River Basin of Wyoming.[162]

Mattoon was chosen as the site for the Department of Energy's FutureGen project, a 275-megawatt experimental zero emission coal-burning power plant that the DOE just gave a second round of funding. In 2010, after a number of setbacks, the city of Mattoon backed out of the project.[165]

Petroleum

Illinois is a leading refiner of petroleum in the American Midwest, with a combined crude oil distillation capacity of nearly 900,000 bbl/d (140,000 m3/d). However, Illinois has very limited crude oil proved reserves that account for less than 1% of the U.S. total reserves. Residential heating is 81% natural gas compared to less than 1% heating oil. Illinois is ranked 14th in oil production among states, with a daily output of approximately 28,000 bbl (4,500 m3) in 2005.[166][167]

Nuclear power

Nuclear power arguably began in Illinois with the Chicago Pile-1, the world's first artificial self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction in the world's first nuclear reactor, built on the University of Chicago campus. There are six operating nuclear power plants in Illinois: Braidwood, Byron, Clinton, Dresden, LaSalle, and Quad Cities.[168] With the exception of the single-unit Clinton plant, each of these facilities has two reactors. Three reactors have been permanently shut down and are in various stages of decommissioning: Dresden-1 and Zion-1 and 2. Illinois ranked first in the nation in 2010 in both nuclear capacity and nuclear generation. Generation from its nuclear power plants accounted for 12 percent of the nation's total.[156] In 2007, 48% of Illinois's electricity was generated using nuclear power.[169] The Morris Operation is the only de facto high-level radioactive waste storage site in the United States.

Wind power

Illinois has seen growing interest in the use of wind power for electrical generation.[170] Most of Illinois was rated in 2009 as "marginal or fair" for wind energy production by the U.S. Department of Energy, with some western sections rated "good" and parts of the south rated "poor".[171] These ratings are for wind turbines with 50 m (160 ft) hub heights; newer wind turbines are taller, enabling them to reach stronger winds farther from the ground. As a result, more areas of Illinois have become prospective wind farm sites. As of September 2009, Illinois had 1116.06 MW of installed wind power nameplate capacity with another 741.9 MW under construction.[172] Illinois ranked ninth among U.S. states in installed wind power capacity and sixteenth by potential capacity.[172] Large wind farms in Illinois include Twin Groves, Rail Splitter, EcoGrove, and Mendota Hills.[172]

As of 2007, wind energy represented only 1.7% of Illinois's energy production, and it was estimated that wind power could provide 5–10% of the state's energy needs.[173][174] Also, the Illinois General Assembly mandated in 2007 that by 2025, 25% of all electricity generated in Illinois is to come from renewable resources.[175]

Biofuels

Illinois is ranked second in corn production among U.S. states, and Illinois corn is used to produce 40% of the ethanol consumed in the United States.[155] The Archer Daniels Midland corporation in Decatur, Illinois, is the world's leading producer of ethanol from corn.

The National Corn-to-Ethanol Research Center (NCERC), the world's only facility dedicated to researching the ways and means of converting corn (maize) to ethanol is located on the campus of Southern Illinois University Edwardsville.[176][177]

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign is one of the partners in the Energy Biosciences Institute (EBI), a $500 million biofuels research project funded by petroleum giant BP.[178][179]

Taxes

Tax is collected by the Illinois Department of Revenue. State income tax is calculated by multiplying net income by a flat rate. In 1990, that rate was set at 3%, but in 2010, the General Assembly voted for a temporary increase in the rate to 5%; the new rate went into effect on January 1, 2011; the personal income rate partially sunset on January 1, 2015, to 3.75%, while the corporate income tax fell to 5.25%.[180][181] Illinois failed to pass a budget from 2015 to 2017, after the 736-day budget impasse, a budget was passed in Illinois after lawmakers overturned Governor Bruce Rauner's veto; this budget raised the personal income rate to 4.95% and the corporate rate to 7%.[182] There are two rates for state sales tax: 6.25% for general merchandise and 1% for qualifying food, drugs, and medical appliances.[183] The property tax is a major source of tax revenue for local government taxing districts. The property tax is a local—not state—tax imposed by local government taxing districts, which include counties, townships, municipalities, school districts, and special taxation districts. The property tax in Illinois is imposed only on real property.[28][31][69]

On May 1, 2019, the Illinois Senate voted to approve a constitutional amendment that would have stricken language from the Illinois Constitution requiring a flat state income tax, in a 73–44 vote. If approved, the amendment would have allowed the state legislature to impose a graduated income tax based on annual income. The governor, J. B. Pritzker, approved the bill on May 27, 2019. It was scheduled for a 2020 general election ballot vote[184][185] and required 60 percent voter approval to effectively amend the state constitution.[186] The amendment was not approved by Illinoisans, with 55.1% of voters voting "No" on approval and 44.9% voting "Yes".[187]

As of 2017 Chicago had the highest state and local sales tax rate for a U.S. city with a populations above 200,000, at 10.250%.[188] The state of Illinois has the second highest rate of real estate tax: 2.31%, which is second only to New Jersey at 2.44%.[189]

Toll roads are a de facto user tax on the citizens and visitors to the state of Illinois. Illinois ranks seventh out of the 11 states with the most miles of toll roads, at 282.1 miles. Chicago ranks fourth in most expensive toll roads in America by the mile, with the Chicago Skyway charging 51.2 cents per mile.[190] Illinois also has the 11th highest gasoline tax by state, at 37.5 cents per gallon.[191]

Culture

Museums

Illinois has numerous museums; the greatest concentration of these are in Chicago. Several museums in Chicago are ranked as some of the best in the world. These include the John G. Shedd Aquarium, the Field Museum of Natural History, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Adler Planetarium, and the Museum of Science and Industry.

The modern Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield is the largest and most attended presidential library in the country. The Illinois State Museum boasts a collection of 13.5 million objects that tell the story of Illinois life, land, people, and art. The ISM is among only 5% of the nation's museums that are accredited by the American Alliance of Museums. Other historical museums in the state include the Polish Museum of America in Chicago; Magnolia Manor in Cairo; Easley Pioneer Museum in Ipava; the Elihu Benjamin Washburne; Ulysses S. Grant Homes, both in Galena; and the Chanute Air Museum, located on the former Chanute Air Force Base in Rantoul.

The Chicago metropolitan area also hosts two zoos: The Brookfield Zoo, located about ten miles west of the city center in suburban Brookfield, contains more than 2,300 animals and covers 216 acres (87 ha). The Lincoln Park Zoo is located in Lincoln Park on Chicago's North Side, approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) north of the Loop. The zoo accounts for more than 35 acres (14 ha) of the park.

- Illinois Museums

- The Polish Museum of America in Chicago

Music

Illinois is a leader in music education, having hosted the Midwest Clinic International Band and Orchestra Conference since 1946, as well being home to the Illinois Music Educators Association (ILMEA, formerly IMEA), one of the largest professional music educator's organizations in the country. Each summer since 2004, Southern Illinois University Carbondale has played host to the Southern Illinois Music Festival, which presents dozens of performances throughout the region. Past featured artists include the Eroica Trio and violinist David Kim.

Chicago, in the northeast corner of the state, is a major center for music[192] in the midwestern United States where distinctive forms of blues (greatly responsible for the future creation of rock and roll), and house music, a genre of electronic dance music, were developed.

The Great Migration of poor black workers from the South into the industrial cities brought traditional jazz and blues music to the city, resulting in Chicago blues and "Chicago-style" Dixieland jazz. Notable blues artists included Muddy Waters, Junior Wells, Howlin' Wolf and both Sonny Boy Williamsons; jazz greats included Nat King Cole, Gene Ammons, Benny Goodman, and Bud Freeman. Chicago is also well known for its soul music.

In the early 1930s, Gospel music began to gain popularity in Chicago due to Thomas A. Dorsey's contributions at Pilgrim Baptist Church.

In the 1980s and 1990s, heavy rock, punk, and hip hop also became popular in Chicago. Orchestras in Chicago include the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the Chicago Sinfonietta.[193]

Movies

John Hughes, who moved from Grosse Pointe to Northbrook, based many films of his in Chicago, and its suburbs. Ferris Bueller's Day Off, Home Alone, The Breakfast Club, and all his films take place in the fictional Shermer, Illinois (the original name of Northbrook was Shermerville, and Hughes's High School, Glenbrook North High School, is on Shermer Road). Most locations in his films include Glenbrook North, the former Maine North High School, the Ben Rose House in Highland Park, and the famous Home Alone house in Winnetka, Illinois.

Sports

Major league sports

As one of the United States' major metropolises, all major sports leagues have teams headquartered in Chicago.

- Two Major League Baseball teams are located in the state. The Chicago Cubs of the National League play in the second-oldest major league stadium, Wrigley Field, and went the longest length of time without a championship in all of major American sport, from 1908 to 2016, when they won the World Series.[194][195] The Chicago White Sox of the American League won the World Series in 2005, their first since 1917. They play on the city's south side at Guaranteed Rate Field.

- The Chicago Bears football team has won nine total NFL Championships, the last occurring in Super Bowl XX on January 26, 1986.

- The Chicago Bulls of the NBA is one of the most recognized basketball teams in the world, largely as a result of the efforts of Michael Jordan, who led the team to six NBA championships in eight seasons in the 1990s.

- The Chicago Blackhawks of the NHL began playing in 1926 and became a member of the Original Six once the NHL dropped to that number of teams during World War II. The Blackhawks have won six Stanley Cups, most recently in 2015.

- Chicago Fire FC is a member of MLS and has been one of the league's most successful and best-supported clubs since its founding in 1997, winning one league and four Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cups in that timespan. The team played in Bridgeview, adjacent to Chicago from 2006 to 2019. The team now plays at Soldier Field in Chicago.

- The Chicago Red Stars have played at the top level of U.S. women's soccer since their formation in 2009, except in the 2011 season. The team currently plays in the National Women's Soccer League, playing at SeatGeek Stadium, the Bridgeview venue it formerly shared with Fire FC.

- The Chicago Sky have played in the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA) since 2006. The Sky won their first WNBA Championship in 2021. They play at Wintrust Arena in Chicago.

- The Chicago Bandits of the NPF, a women's softball league, have won four league titles, most recently in 2016. They play at Parkway Bank Sports Complex in Rosemont, Illinois, in the Chicago area.

Minor league sports

Many minor league teams also call Illinois their home. They include:

- The Bloomington Edge of the Indoor Football League

- The Bloomington Flex of the Midwest Professional Basketball Association

- The Chicago Dogs of the American Association of Professional Baseball

- Chicago Fire FC II of MLS Next Pro

- The Chicago Wolves are an AHL team playing in the suburb of Rosemont

- The Gateway Grizzlies of the Frontier League in Sauget, Illinois

- The Kane County Cougars of the American Association

- The Joliet Slammers of the Frontier League

- The Peoria Chiefs of the Midwest League

- The Peoria Rivermen are an SPHL team

- The Rockford Aviators of the Frontier League

- The Rockford IceHogs of the AHL

- The Schaumburg Boomers of the Frontier League

- The Southern Illinois Miners based out of Marion in the Frontier League

- The Windy City Bulls, playing in the Chicago suburb of Hoffman Estates, of the NBA G League

- The Windy City ThunderBolts of the Frontier League

College sports

The state features 13 athletic programs that compete in NCAA Division I, the highest level of U.S. college sports.

The two most prominent are the Illinois Fighting Illini and Northwestern Wildcats, both members of the Big Ten Conference and the only ones competing in one of the so-called "Power Five conferences". The Fighting Illini football team has won five national championships and three Rose Bowl Games, whereas the men's basketball team has won 17 conference seasons and played five Final Fours. Meanwhile, the Wildcats have won eight football conference championships and one Rose Bowl Game.

The Northern Illinois Huskies from DeKalb, Illinois, compete in the Mid-American Conference, having won four conference championships and earning a bid in the Orange Bowl along with producing Heisman candidate Jordan Lynch at quarterback. The Huskies are the state's only other team competing in the Football Bowl Subdivision, the top level of NCAA football.

Four schools have football programs that compete in the second level of Division I football, the Football Championship Subdivision (FCS). The Illinois State Redbirds (Normal, adjacent to Bloomington) and Southern Illinois Salukis (representing Southern Illinois University's main campus in Carbondale) are members of the Missouri Valley Conference (MVC) for non-football sports and the Missouri Valley Football Conference (MVFC). The Western Illinois Leathernecks (Macomb) are full members of the Summit League, which does not sponsor football, and also compete in the MVFC. The Eastern Illinois Panthers (Charleston) are members of the Ohio Valley Conference (OVC).

The city of Chicago is home to four Division I programs that do not sponsor football. The DePaul Blue Demons, with main campuses in Lincoln Park and the Loop, are members of the Big East Conference. The Loyola Ramblers, with their main campus straddling the Edgewater and Rogers Park community areas on the city's far north side, compete in the Atlantic 10 Conference. The UIC Flames, from the Near West Side next to the Loop, are in the MVC. The Chicago State Cougars, from the city's south side, are one of only two all-sports independents in Division I after leaving the Western Athletic Conference in 2022.

Finally, two non-football Division I programs are located downstate. The Bradley Braves (Peoria) are MVC members, and the SIU Edwardsville Cougars (in the Metro East region across the Mississippi River from St. Louis) compete in the OVC.

Motor racing

Motor racing oval tracks at the Chicagoland Speedway in Joliet, the Chicago Motor Speedway in Cicero and the Gateway Motorsports Park in Madison, near St. Louis, have hosted NASCAR, CART, and IRL races, whereas the Sports Car Club of America, among other national and regional road racing clubs, have visited the Autobahn Country Club in Joliet, the Blackhawk Farms Raceway in South Beloit and the former Meadowdale International Raceway in Carpentersville. Illinois also has several short tracks and dragstrips. The dragstrip at Gateway International Raceway and the Route 66 Raceway, which sits on the same property as the Chicagoland Speedway, both host NHRA drag races.

Golf

Illinois features several golf courses, such as Olympia Fields, Medinah, Midlothian, Cog Hill, and Conway Farms, which have often hosted the BMW Championship, Western Open, and Women's Western Open.

Also, the state has hosted 13 editions of the U.S. Open (latest at Olympia Fields in 2003), six editions of the PGA Championship (latest at Medinah in 2006), three editions of the U.S. Women's Open (latest at The Merit Club), the 2009 Solheim Cup (at Rich Harvest Farms), and the 2012 Ryder Cup (at Medinah).

The John Deere Classic is a regular PGA Tour event played in the Quad Cities since 1971, whereas the Encompass Championship is a Champions Tour event since 2013. Previously, the LPGA State Farm Classic was an LPGA Tour event from 1976 to 2011.

Parks and recreation

The Illinois state parks system began in 1908 with what is now Fort Massac State Park, becoming the first park in a system encompassing more than 60 parks and about the same number of recreational and wildlife areas.

Areas under the protection of the National Park Service include: the Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage Corridor near Lockport,[196] the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, the Lincoln Home National Historic Site in Springfield, the Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail, the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, the American Discovery Trail,[197] the Pullman National Monument, and New Philadelphia Town Site. The federal government also manages the Shawnee National Forest and the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie.

Law and politics

In a 2020 study, Illinois was ranked as the 4th easiest state for citizens to vote in.[198]

State government

The government of Illinois, under the Constitution of Illinois, has three branches of government: executive, legislative, and judicial. The executive branch is split into several statewide elected offices, with the governor as chief executive. Legislative functions are granted to the Illinois General Assembly. The judiciary is composed of the Supreme Court and lower courts.

The executive branch is composed of six elected officers and their offices as well as numerous other departments.[199] The six elected officers are:[199] Governor, Lieutenant Governor, Attorney General, Secretary of State, Comptroller, and Treasurer. The government of Illinois has numerous departments, agencies, boards and commissions, but the so-called code departments provide most of the state's services.[199][200]