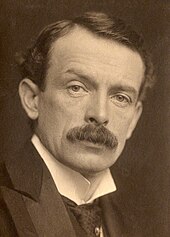

Джон Мейнард Кейнс

Лорд Кейнс | |

|---|---|

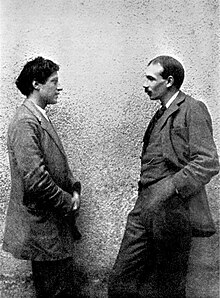

Кейнс в 1933 году | |

| Рожденный | 5 июня 1883 г. Кембридж , Англия |

| Умер | 21 апреля 1946 г. (62 года) Тилтон, недалеко от Фирла в Сассексе, Англия. |

| Образование | |

| Политическая партия | Либеральный |

| Супруг | |

| Родители |

|

| Академическая карьера | |

| учреждение | Королевский колледж, Кембридж |

| Поле | |

| Школа или традиция | Кейнсианская экономика |

| Влияния | |

| Взносы | |

| Часть серии о |

| Макроэкономика |

|---|

|

Джон Мейнард Кейнс, первый барон Кейнс , [3] CB , FBA ( / k eɪ n z / KAYNZ ; 5 июня 1883 — 21 апреля 1946), английский экономист и философ, чьи идеи фундаментально изменили теорию и практику макроэкономики , а также экономическую политику правительств. Первоначально получив образование в области математики, он развил и значительно усовершенствовал более ранние работы о причинах деловых циклов . [4] Один из самых влиятельных экономистов ХХ века, [5] [6] [7] он написал труды, которые легли в основу школы мысли, известной как кейнсианская экономика , и ее различных ответвлений. [8] Его идеи, переформулированные как новое кейнсианство , имеют фундаментальное значение для основной макроэкономики . Он известен как «отец макроэкономики». [9]

Во время Великой депрессии 1930-х годов Кейнс возглавил революцию в экономическом мышлении , бросив вызов идеям неоклассической экономики , которая утверждала, что свободный рынок в краткосрочной и среднесрочной перспективе автоматически обеспечит полную занятость, пока рабочие будут гибкими в своей заработной плате. требования. Он утверждал, что совокупный спрос (общие расходы в экономике) определяет общий уровень экономической активности и что неадекватный совокупный спрос может привести к длительным периодам высокой безработицы, а поскольку заработная плата и затраты на рабочую силу жестко снижаются, экономика не вернется автоматически к снижению. полная занятость. [10] Кейнс выступал за использование налогово-бюджетной и денежно-кредитной политики для смягчения неблагоприятных последствий экономических спадов и депрессий . Он подробно изложил эти идеи в своем выдающемся труде « Общая теория занятости, процента и денег» , опубликованном в начале 1936 года. К концу 1930-х годов ведущие западные экономики начали принимать политические рекомендации Кейнса. Почти все капиталистические правительства сделали это к концу двух десятилетий после смерти Кейнса в 1946 году. Будучи руководителем британской делегации, Кейнс участвовал в разработке международных экономических институтов, созданных после окончания Второй мировой войны , но его решение было отменено Американская делегация по нескольким аспектам.

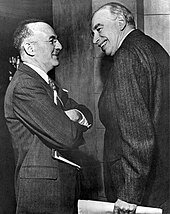

Влияние Кейнса начало ослабевать в 1970-е годы, отчасти в результате стагфляции , поразившей англо - американскую экономику в течение этого десятилетия, а отчасти из-за критики кейнсианской политики со стороны Милтона Фридмана и других монетаристов . [11] который оспаривал способность правительства благоприятно регулировать деловой цикл с помощью налогово-бюджетной политики . [12] Наступление мирового финансового кризиса 2007–2008 годов вызвало возрождение кейнсианской мысли . Кейнсианская экономика обеспечила теоретическую основу для экономической политики, предпринятой в ответ на финансовый кризис 2007–2008 годов президентом Бараком Обамой США Гордоном Брауном и другими главами правительств. , премьер-министром Соединенного Королевства [13]

Когда журнал Time включил Кейнса в список « Самых важных людей века» в 1999 году, он сообщил, что «его радикальная идея о том, что правительства должны тратить деньги, которых у них нет, возможно, спасла капитализм». [14] The Economist назвал Кейнса «самым известным британским экономистом ХХ века». [15] Помимо того, что Кейнс был экономистом, он также был государственным служащим , директором Банка Англии и членом Блумсбери . группы интеллектуалов [16]

Молодость образование и

Джон Мейнард Кейнс родился в Кембридже , Англия, в июне 1883 года в семье, принадлежащей к высшему среднему классу. Его отец, Джон Невилл Кейнс , был экономистом и преподавателем моральных наук в Кембриджском университете, а мать, Флоренс Ада Кейнс , была местным социальным реформатором. Кейнс был первенцем, за ним последовали еще двое детей — Маргарет Невилл Кейнс в 1885 году и Джеффри Кейнс в 1887 году. Джеффри стал хирургом, а Маргарет вышла замуж за физиолога, лауреата Нобелевской премии Арчибальда Хилла .

По словам экономического историка и биографа Роберта Скидельски , родители Кейнса были любящими и внимательными. Они посещали конгрегационалистскую церковь [17] и оставались в одном доме на протяжении всей своей жизни, куда дети всегда могли вернуться. Кейнс получил значительную поддержку от своего отца, в том числе профессиональное обучение, которое помогло ему сдать экзамены на стипендию, а также финансовую помощь как в молодости, так и когда его активы были почти уничтожены в начале Великой депрессии в 1929 году. Мать Кейнса сделала интересы своих детей своими интересами. собственная, и, по словам Скидельского, «поскольку она могла расти вместе со своими детьми, они никогда не перерастали дом». [18]

В январе 1889 года, в возрасте пяти с половиной лет, Кейнс начал ходить в детский сад школы для девочек Персе пять утра в неделю. Он быстро проявил талант к арифметике, но его здоровье было плохим, что привело к нескольким длительным отсутствиям. Дома его обучали гувернантка Беатрис Макинтош и его мать. В январе 1892 года, в восемь с половиной лет, он пошел дневным учеником в Святой Фейт подготовительную школу . К 1894 году Кейнс был лучшим учеником в классе и преуспел в математике. В 1896 году директор школы Сент-Фейт Ральф Гудчайлд написал, что Кейнс «на голову выше всех остальных мальчиков в школе» и был уверен, что Кейнс сможет получить стипендию для обучения в Итоне. [19]

В 1897 году Кейнс получил королевскую стипендию для обучения в Итонском колледже , где он проявил талант в широком спектре предметов, особенно в математике, классической литературе и истории: в 1901 году он был удостоен премии Томлина по математике. В Итоне Кейнс испытал первую «любовь всей своей жизни» в лице Дэна Макмиллана, старшего брата будущего премьер-министра Гарольда Макмиллана . [20] Несмотря на свое происхождение из среднего класса, Кейнс легко общался с учениками из высших слоев общества.

В 1902 году Кейнс покинул Итон и поступил в Королевский колледж в Кембридже , получив стипендию и за это, чтобы изучать математику. Альфред Маршалл умолял Кейнса стать экономистом, [21] хотя собственные склонности Кейнса влекли его к философии, особенно к этической системе Дж. Э. Мура . Кейнс был избран в университетский клуб Питта. [22] и был активным членом полусекретного общества Кембриджских апостолов , дискуссионного клуба, в основном предназначенного для самых способных студентов. Как и многие его члены, Кейнс сохранил связь с клубом после окончания учебы и продолжал время от времени посещать собрания на протяжении всей своей жизни. Прежде чем покинуть Кембридж, Кейнс стал президентом Общества Кембриджского союза и Либерального клуба Кембриджского университета . Говорили, что он атеист. [23] [24]

первой степени В мае 1904 года он получил степень бакалавра математики . Помимо нескольких месяцев, проведенных в отпуске с семьей и друзьями, Кейнс продолжал заниматься университетом в течение следующих двух лет. Он принимал участие в дебатах, далее изучал философию и неофициально посещал лекции по экономике в качестве аспиранта в течение одного семестра, что было его единственным формальным образованием по этому предмету. В 1906 году он сдал экзамены на государственную службу.

Экономист Гарри Джонсон писал, что оптимизм, вызванный ранней жизнью Кейнса, является ключом к пониманию его более позднего мышления. [25] Кейнс всегда был уверен, что сможет найти решение любой проблемы, на которую обращал свое внимание, и сохранял прочную веру в способность правительственных чиновников творить добро. [26] Оптимизм Кейнса был также культурным в двух смыслах: он принадлежал к последнему поколению, воспитанному империей, все еще находившейся на пике своего могущества, а также к последнему поколению, которое чувствовало себя вправе управлять посредством культуры, а не опыта. По мнению Скидельского , чувство культурного единства, существовавшее в Британии с XIX века до конца Первой мировой войны, обеспечило основу, с помощью которой хорошо образованные люди могли ставить различные сферы знаний по отношению друг к другу и к жизни, позволяя им уверенно использовать знания из разных областей при решении практических задач. [18]

Карьера [ править ]

В октябре 1906 года Кейнс начал свою карьеру на государственной службе в качестве клерка в индийском офисе . [27] Поначалу ему нравилась его работа, но к 1908 году ему стало скучно, и он оставил свою должность, чтобы вернуться в Кембридж и работать над теорией вероятностей , читая лекции по экономике, сначала финансируемые лично экономистами Альфредом Маршаллом и Артуром Пигу ; он стал научным сотрудником Королевского колледжа в 1909 году. [28]

К 1909 году Кейнс также опубликовал свою первую профессиональную статью по экономике в The Economic Journal о влиянии недавнего глобального экономического спада на Индию. [29] Он основал Клуб политической экономии , еженедельную дискуссионную группу. Заработки Кейнса еще больше выросли, когда он начал брать учеников на частное обучение.

В 1911 году Кейнс стал редактором «Экономического журнала» . К 1913 году он опубликовал свою первую книгу « Индийская валюта и финансы» . [30] Затем он был назначен членом Королевской комиссии по индийской валюте и финансам. [31] – та же тема, что и его книга, – где Кейнс продемонстрировал значительный талант в применении экономической теории к практическим проблемам. Его письменные работы были опубликованы под именем «Дж. М. Кейнс», хотя семье и друзьям он был известен как Мейнард. (Его отец, Джон Невилл Кейнс, также всегда был известен под вторым именем). [32]

Первая мировая война [ править ]

Британское правительство воспользовалось опытом Кейнса во время Первой мировой войны . Хотя он формально не вернулся на государственную службу в 1914 году, Кейнс отправился в Лондон по просьбе правительства за несколько дней до начала военных действий. Банкиры настаивали на приостановке платежей звонкой монетой – золотым эквивалентом банкнот – но с помощью Кейнса канцлер казначейства (тогда Ллойд Джордж ) был убежден, что это была бы плохая идея, поскольку это нанесло бы ущерб будущей репутации банка. города, если выплаты были приостановлены раньше, чем это было необходимо.

В январе 1915 года Кейнс занял официальную правительственную должность в Министерстве финансов . Среди его обязанностей была разработка условий кредита между Великобританией и ее континентальными союзниками во время войны и приобретение дефицитной валюты. По словам экономиста Роберта Лекачмана , «нервность и мастерство Кейнса стали легендарными» благодаря выполнению им этих обязанностей, как в случае, когда ему удалось собрать запас испанских песет .

Министр финансов был рад услышать, что Кейнс накопил достаточно средств, чтобы обеспечить временное решение для британского правительства. Но Кейнс не отдал песеты, решив вместо этого продать их все, чтобы сломать рынок: его смелость окупилась, поскольку песеты стали гораздо менее редкими и дорогими. [33]

После введения воинской повинности в 1916 году он подал заявление об освобождении от военной службы по соображениям совести , что фактически было предоставлено при условии продолжения его государственной работы.

короля В 1917 году на церемонии чествования дня рождения Кейнс был назначен кавалером Ордена Бани за свою работу во время войны. [34] и его успех привел к назначению, которое оказало огромное влияние на жизнь и карьеру Кейнса; Кейнс был назначен финансовым представителем Казначейства на Версальской мирной конференции 1919 года . Он также был назначен кавалером бельгийского ордена Леопольда . [35]

Версальская мирная конференция [ править ]

Опыт Кейнса в Версале повлиял на формирование его взглядов на будущее, но не был успешным. Главный интерес Кейнса заключался в том, чтобы попытаться не допустить, чтобы компенсационные выплаты Германии были установлены настолько высокими, что это травмировало бы ни в чем не повинный немецкий народ, нанесло бы ущерб платежеспособности нации и резко ограничило бы ее способность покупать экспортные товары из других стран – тем самым нанося ущерб не только экономике Германии, но и экономике Германии. более широкий мир.

К несчастью для Кейнса, консервативные силы в коалиции, возникшей в результате купонных выборов 1918 года , смогли добиться того, чтобы как сам Кейнс, так и Казначейство были в значительной степени исключены из официальных переговоров на высоком уровне относительно репараций. Их место заняли Небесные близнецы — судья лорд Самнер и банкир лорд Канлифф , чье прозвище произошло от «астрономически» высокой военной компенсации, которую они хотели потребовать от Германии. Кейнс был вынужден пытаться оказывать влияние преимущественно из-за кулис.

Тремя основными игроками на парижских конференциях были британский Ллойд Джордж, французский Жорж Клемансо и американский президент Вудро Вильсон . [36] Только Ллойд Джордж имел прямой доступ к Кейнсу; до выборов 1918 года он в некоторой степени симпатизировал точке зрения Кейнса, но во время предвыборной кампании обнаружил, что его речи были хорошо приняты общественностью только в том случае, если он пообещал сурово наказать Германию, и поэтому обязал свою делегацию добиваться высоких выплат.

Ллойд Джордж, однако, заслужил некоторую лояльность со стороны Кейнса своими действиями на Парижской конференции, вмешавшись против французов, чтобы обеспечить доставку столь необходимых продовольствия немецкому гражданскому населению. Клемансо также настаивал на существенных репарациях, хотя и не таких высоких, как предложенные Великобританией, в то время как по соображениям безопасности Франция выступала за еще более суровое урегулирование, чем Великобритания.

Первоначально Вильсон выступал за относительно мягкое отношение к Германии – он опасался, что слишком суровые условия могут спровоцировать рост экстремизма, и хотел, чтобы Германии был оставлен достаточный капитал для оплаты импорта. К разочарованию Кейнса, Ллойд Джордж и Клемансо смогли оказать давление на Вильсона, чтобы тот согласился включить пенсии в законопроект о репарациях.

Ближе к концу конференции Кейнс предложил план, который, как он утверждал, не только поможет Германии и другим обедневшим центральноевропейским державам, но и принесет пользу мировой экономике в целом. Оно включало радикальное списание военных долгов, что могло бы привести к увеличению международной торговли во всех отношениях, но в то же время переложить более двух третей стоимости восстановления Европы на Соединенные Штаты. [37]

Ллойд Джордж согласился, что это может быть приемлемо для британского электората. Однако Америка была против этого плана; США были тогда крупнейшим кредитором, и к этому времени Вильсон начал верить в преимущества сурового мира и считал, что его страна уже пошла на чрезмерные жертвы. Таким образом, несмотря на все его усилия, результатом конференции стал договор, который вызвал отвращение Кейнса как с моральной, так и с экономической точки зрения и привел к его отставке из Министерства финансов. [38]

В июне 1919 года он отклонил предложение стать председателем Британского банка Северной торговли , должность, которая обещала зарплату в размере 2000 фунтов стерлингов в обмен на одно утро в неделю работы. [ нужна ссылка ]

Анализ Кейнса предсказанных разрушительных последствий договора появился в весьма влиятельной книге « Экономические последствия мира» , опубликованной в 1919 году. [39] Эту работу называют лучшей книгой Кейнса, в которой он смог применить все свои способности – свою страсть, а также свои навыки экономиста. Помимо экономического анализа, в книге содержались призывы к чувству сострадания читателя :

Я не могу оставить эту тему так, как будто ее справедливое рассмотрение полностью зависело либо от наших обещаний, либо от экономических фактов. Политика обращения Германии в рабство на целое поколение, унижения жизни миллионов людей и лишения целой нации счастья должна быть отвратительной и отвратительной, — отвратительной и отвратительной, даже если бы это было возможно, даже если бы она обогатила себя, даже если это не сеяло упадок всей цивилизованной жизни Европы.

— [ нужна ссылка ]

Также присутствовали поразительные образы, такие как «год за годом Германия должна оставаться бедной, а ее дети голодать и калечить», а также смелые предсказания, которые позже были оправданы событиями:

Если мы намеренно стремимся к обнищанию Центральной Европы, месть, я смею предсказать, не замедлится. Ничто не сможет тогда надолго задержать эту последнюю войну между силами Реакции и отчаянными конвульсиями Революции, перед которой ужасы поздней немецкой войны исчезнут в ничто.

— [ нужна ссылка ]

Keynes's followers assert that his predictions of disaster were borne out when the German economy suffered the hyperinflation of 1923, and again by the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the outbreak of the Second World War. However, historian Ruth Henig claims that "most historians of the Paris peace conference now take the view that, in economic terms, the treaty was not unduly harsh on Germany and that, while obligations and damages were inevitably much stressed in the debates at Paris to satisfy electors reading the daily newspapers, the intention was quietly to give Germany substantial help towards paying her bills, and to meet many of the German objections by amendments to the way the reparations schedule was in practice carried out".[40][41]

Only a small fraction of reparations was ever paid. In fact, historian Stephen A. Schuker demonstrates in American 'Reparations' to Germany, 1919–33, that the capital inflow from American loans substantially exceeded German out payments so that, on a net basis, Germany received support equal to four times the amount of the post-Second World War Marshall Plan.[citation needed]

Schuker also shows that, in the years after Versailles, Keynes became an informal reparations adviser to the German government, wrote one of the major German reparation notes, and supported the hyperinflation on political grounds. Nevertheless, The Economic Consequences of the Peace gained Keynes international fame, even though it also caused him to be regarded as anti-establishment – it was not until after the outbreak of the Second World War that Keynes was offered a directorship of a major British Bank, or an acceptable offer to return to government with a formal job. However, Keynes was still able to influence government policy making through his network of contacts, his published works and by serving on government committees; this included attending high-level policy meetings as a consultant.[38]

In the 1920s[edit]

Keynes had completed his A Treatise on Probability before the war but published it in 1921.[38] The work was a notable contribution to the philosophical and mathematical underpinnings of probability theory, championing the important view that probabilities were no more or less than truth values intermediate between simple truth and falsity. Keynes developed the first upper-lower probabilistic interval approach to probability in chapters 15 and 17 of this book, as well as having developed the first decision weight approach with his conventional coefficient of risk and weight, c, in chapter 26. In addition to his academic work, the 1920s saw Keynes active as a journalist selling his work internationally and working in London as a financial consultant. In 1924 Keynes wrote an obituary for his former tutor Alfred Marshall which Joseph Schumpeter called "the most brilliant life of a man of science I have ever read".[42] Mary Paley Marshall was "entranced" by the memorial, while Lytton Strachey rated it as one of Keynes's "best works".[38]

In 1922 Keynes continued to advocate reduction of German reparations with A Revision of the Treaty.[38] He attacked the post-World War I deflation policies with A Tract on Monetary Reform in 1923[38] – a trenchant argument that countries should target stability of domestic prices, avoiding deflation even at the cost of allowing their currency to depreciate. Britain suffered from high unemployment through most of the 1920s, leading Keynes to recommend the depreciation of sterling to boost jobs by making British exports more affordable. From 1924 he was also advocating a fiscal response, where the government could create jobs by spending on public works.[38] During the 1920s Keynes's pro stimulus views had only limited effect on policy makers and mainstream academic opinion – according to Hyman Minsky one reason was that at this time his theoretical justification was "muddled".[29] The Tract had also called for an end to the gold standard. Keynes advised it was no longer a net benefit for countries such as Britain to participate in the gold standard, as it ran counter to the need for domestic policy autonomy. It could force countries to pursue deflationary policies at exactly the time when expansionary measures were called for to address rising unemployment. The Treasury and Bank of England were still in favour of the gold standard and in 1925 they were able to convince the then Chancellor Winston Churchill to re-establish it, which had a depressing effect on British industry. Keynes responded by writing The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill and continued to argue against the gold standard until Britain finally abandoned it in 1931.[38]

During the Great Depression[edit]

Keynes had begun a theoretical work to examine the relationship between unemployment, money and prices back in the 1920s.[43] The work, Treatise on Money, was published in 1930 in two volumes. A central idea of the work was that if the amount of money being saved exceeds the amount being invested – which can happen if interest rates are too high – then unemployment will rise. This is in part a result of people not wanting to spend too high a proportion of what employers pay out, making it difficult, in aggregate, for employers to make a profit. Another key theme of the book is the unreliability of financial indices for representing an accurate – or indeed meaningful – indication of general shifts in purchasing power of currencies over time. In particular, he criticised the justification of Britain's return to the gold standard in 1925 at pre-war valuation by reference to the wholesale price index. He argued that the index understated the effects of changes in the costs of services and labour.

Keynes was deeply critical of the British government's austerity measures during the Great Depression. He believed that budget deficits during recessions were a good thing and a natural product of an economic slump. He wrote, "For Government borrowing of one kind or another is nature's remedy, so to speak, for preventing business losses from being, in so severe a slump as the present one, so great as to bring production altogether to a standstill."[44]

At the height of the Great Depression, in 1933, Keynes published The Means to Prosperity, which contained specific policy recommendations for tackling unemployment in a global recession, chiefly counter-cyclical public spending. The Means to Prosperity contains one of the first mentions of the multiplier effect. While it was addressed chiefly to the British Government, it also contained advice for other nations affected by the global recession. A copy was sent to the newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt and other world leaders. The work was taken seriously by both the American and British governments, and according to Robert Skidelsky, helped pave the way for the later acceptance of Keynesian ideas, though it had little immediate practical influence. In the 1933 London Economic Conference opinions remained too diverse for a unified course of action to be agreed upon.[45]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Keynesian-like policies were adopted by Sweden and Germany, but Sweden was seen as too small to command much attention, and Keynes was deliberately silent about the successful efforts of Germany as he was dismayed by its imperialist ambitions and its treatment of Jews.[45] Apart from Great Britain, Keynes's attention was primarily focused on the United States. In 1931, he received considerable support for his views on counter-cyclical public spending in Chicago, then America's foremost center for economic views alternative to the mainstream.[29][45] However, orthodox economic opinion remained generally hostile regarding fiscal intervention to mitigate the depression, until just before the outbreak of war.[29] In late 1933 Keynes was persuaded by Felix Frankfurter to address President Roosevelt directly, which he did by letters and face to face in 1934, after which the two men spoke highly of each other.[45] However, according to Skidelsky, the consensus is that Keynes's efforts began to have a more than marginal influence on US economic policy only after 1939.[45]

Keynes's magnum opus, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money was published in 1936.[10] It was researched and indexed by one of Keynes's favourite students, and later economist, David Bensusan-Butt.[46] The work served as a theoretical justification for the interventionist policies Keynes favoured for tackling a recession. Although Keynes stated in his preface that his General Theory was only secondarily concerned with the "applications of this theory to practice," the circumstances of its publication were such that his suggestions shaped the course of the 1930s.[47] In addition, Keynes introduced the world to a new interpretation of taxation: since the legal tender is now defined by the state, inflation becomes "taxation by currency depreciation". This hidden tax meant a) that the standard of value should be governed by deliberate decision; and (b) that it was possible to maintain a middle course between deflation and inflation.[48] This novel interpretation was inspired by the desperate search for control over the economy which permeated the academic world after the Depression. The General Theory challenged the earlier neoclassical economic paradigm, which had held that provided it was unfettered by government interference, the market would naturally establish full employment equilibrium. In doing so Keynes was partly setting himself against his former teachers Marshall and Pigou. Keynes believed the classical theory was a "special case" that applied only to the particular conditions present in the 19th century, his theory being the general one. Classical economists had believed in Say's law, which, simply put, states that "supply creates its demand", and that in a free-market workers would always be willing to lower their wages to a level where employers could profitably offer them jobs.[49]

An innovation from Keynes was the concept of price stickiness – the recognition that in reality workers often refuse to lower their wage demands even in cases where a classical economist might argue that it is rational for them to do so. Due in part to price stickiness, it was established that the interaction of "aggregate demand" and "aggregate supply" may lead to stable unemployment equilibria – and in those cases, it is on the state, not the market, that economies must depend for their salvation. In contrast, Keynes argued that demand is what creates supply and not the other way around. He questioned Say's Law by asking what would happen if the money that is being given to individuals is not finding its way back into the economy and is saved instead. He suggested the result would be a recession. To tackle the fear of a recession Say's Law suggests government intervention. This government intervention can be used to prevent any further increase in savings in the form of a decreased interest rate. Decreasing the interest rate will encourage people to start spending and investing again, or so it is stated by Say's Law. The reason behind this is that when there is little investing, savings start to accumulate and reach a stopping point in the flow of money. During the normal economic activity, it would be justified to have savings because they can be given out as loans but in this case, there is little demand for them, so they are doing no good for the economy. The supply of savings then exceeds the demand for loans and the result is lower prices or lower interest rates. Thus, the idea is that the money that was once saved is now re-invested or spent, assuming lower interest rates appeal to consumers. To Keynes, however, this was not always the case, and it couldn't be assumed that lower interest rates would automatically encourage investment and spending again since there is no proven link between the two.[49]

The General Theory argues that demand, not supply, is the key variable governing the overall level of economic activity. Aggregate demand, which equals total un-hoarded income in a society, is defined by the sum of consumption and investment. In a state of unemployment and unused production capacity, one can enhance employment and total income only by first increasing expenditures for either consumption or investment. Without government intervention to increase expenditure, an economy can remain trapped in a low-employment equilibrium. The demonstration of this possibility has been described as the revolutionary formal achievement of the work.[50]The book advocated activist economic policy by government to stimulate demand in times of high unemployment, for example by spending on public works. "Let us be up and doing, using our idle resources to increase our wealth," he wrote in 1928. "With men and plants unemployed, it is ridiculous to say that we cannot afford these new developments. It is precisely with these plants and these men that we shall afford them."[44]

The General Theory is often viewed as the foundation of modern macroeconomics. Few senior American economists agreed with Keynes through most of the 1930s.[51]Yet his ideas were soon to achieve widespread acceptance, with eminent American professors such as Alvin Hansen agreeing with the General Theory before the outbreak of World War II.[52][53][54]

Keynes himself had only limited participation in the theoretical debates that followed the publication of the General Theory as he suffered a heart attack in 1937, requiring him to take long periods of rest. Among others, Hyman Minsky and Post-Keynesian economists have argued that as result, Keynes's ideas were diluted by those keen to compromise with classical economists or to render his concepts with mathematical models like the IS–LM model (which, they argue, distort Keynes's ideas).[29][54] Keynes began to recover in 1939, but for the rest of his life his professional energies were directed largely towards the practical side of economics: the problems of ensuring optimum allocation of resources for the war efforts, post-war negotiations with America, and the new international financial order that was presented at the Bretton Woods Conference.

In the General Theory and later, Keynes responded to the socialists who argued, especially during the Great Depression of the 1930s, that capitalism caused war. He argued that if capitalism were managed domestically and internationally (with coordinated international Keynesian policies, an international monetary system that did not pit the interests of countries against one another, and a high degree of freedom of trade), then this system of managed capitalism could promote peace rather than conflict between countries. His plans during World War II for post-war international economic institutions and policies (which contributed to the creation at Bretton Woods of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and later to the creation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and eventually the World Trade Organization) were aimed to give effect to this vision.[55]

Although Keynes has been widely criticised – especially by members of the Chicago school of economics – for advocating irresponsible government spending financed by borrowing, in fact he was a firm believer in balanced budgets and regarded the proposals for programmes of public works during the Great Depression as an exceptional measure to meet the needs of exceptional circumstances.[56]

Second World War[edit]

During the Second World War, Keynes argued in How to Pay for the War, published in 1940, that the war effort should be largely financed by higher taxation and especially by compulsory saving (essentially workers lending money to the government), rather than deficit spending, to avoid inflation. Compulsory saving would act to dampen domestic demand, assist in channelling additional output towards the war efforts, would be fairer than punitive taxation and would have the advantage of helping to avoid a post-war slump by boosting demand once workers were allowed to withdraw their savings. In September 1941 he was proposed to fill a vacancy in the Court of Directors of the Bank of England, and subsequently carried out a full term from the following April.[57] In June 1942, Keynes was rewarded for his service with a hereditary peerage in the King's Birthday Honours.[58] On 7 July his title was gazetted as "Baron Keynes, of Tilton, in the County of Sussex" and he took his seat in the House of Lords on the Liberal Party benches.[59]

By contrast, in his capacity as advisor on the Indian Financial and Monetary Affairs for the British Government, there is evidence that Keynes advocated "profit inflation" in order to finance war spending by the Allied forces in Bengal. This deliberate inflationary policy, which caused a sixfold increase in the price of rice, contributed to the 1943 Bengal famine.[60]

As the Allied victory began to look certain, Keynes was heavily involved, as leader of the British delegation and chairman of the World Bank commission, in the mid-1944 negotiations that established the Bretton Woods system. The Keynes plan, concerning an international clearing-union, argued for a radical system for the management of currencies. He proposed the creation of a common world unit of currency, the bancor and new global institutions – a world central bank and the International Clearing Union. Keynes envisaged these institutions managing an international trade and payments system with strong incentives for countries to avoid substantial trade deficits or surpluses.[61] The USA's greater negotiating strength, however, meant that the outcomes accorded more closely to the more conservative plans of Harry Dexter White. According to US economist J. Bradford DeLong, on almost every point where he was overruled by the Americans, Keynes was later proven correct by events.[62]

The two new institutions, later known as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), were founded as a compromise that primarily reflected the American vision. There would be no incentives for states to avoid a large trade surplus; instead, the burden for correcting a trade imbalance would continue to fall only on the deficit countries, which Keynes had argued were least able to address the problem without inflicting economic hardship on their populations. Yet, Keynes was still pleased when accepting the final agreement, saying that if the institutions stayed true to their founding principles, "the brotherhood of man will have become more than a phrase."[63][64]

Postwar[edit]

After the war, Keynes continued to represent the United Kingdom in international negotiations despite his deteriorating health. He succeeded in obtaining preferential terms from the United States for new and outstanding debts to facilitate the rebuilding of the British economy.[65]

Just before his death in 1946, Keynes told Henry Clay, a professor of social economics and advisor to the Bank of England,[66] of his hopes that Adam Smith's "invisible hand" could help Britain out of the economic hole it was in: "I find myself more and more relying for a solution of our problems on the invisible hand which I tried to eject from economic thinking twenty years ago."[67]

Influence and legacy[edit]

Keynesian ascendancy 1939–79[edit]

From the end of the Great Depression to the mid-1970s, Keynes provided the main inspiration for economic policymakers in Europe, America and much of the rest of the world.[54] While economists and policymakers had become increasingly won over to Keynes's way of thinking in the mid and late 1930s, it was only after the outbreak of World War II that governments started to borrow money for spending on a scale sufficient to eliminate unemployment. According to the economist John Kenneth Galbraith (then a US government official charged with controlling inflation), in the rebound of the economy from wartime spending, "one could not have had a better demonstration of the Keynesian ideas".[68]

The Keynesian Revolution was associated with the rise of modern liberalism in the West during the post-war period.[69] Keynesian ideas became so popular that some scholars point to Keynes as representing the ideals of modern liberalism, as Adam Smith represented the ideals of classical liberalism.[70] After the war, Winston Churchill attempted to check the rise of Keynesian policy-making in the United Kingdom and used rhetoric critical of the mixed economy in his 1945 election campaign. Despite his popularity as a war hero, Churchill suffered a landslide defeat to Clement Attlee, whose government's economic policy continued to be influenced by Keynes's ideas.[68]

Neo-Keynesian economics[edit]

In the late 1930s and 1940s, economists (notably John Hicks, Franco Modigliani and Paul Samuelson) attempted to interpret and formalise Keynes's writings in terms of formal mathematical models. In what had become known as the neoclassical synthesis, they combined Keynesian analysis with neoclassical economics to produce neo-Keynesian economics, which came to dominate mainstream macroeconomic thought for the next 40 years.

By the 1950s, Keynesian policies were adopted by almost the entire developed world and similar measures for a mixed economy were used by many developing nations. By then, Keynes's views on the economy had become mainstream in the world's universities. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the developed and emerging free capitalist economies enjoyed exceptionally high growth and low unemployment.[71][72] Professor Gordon Fletcher has written that the 1950s and 1960s, when Keynes's influence was at its peak, appear in retrospect as a golden age of capitalism.[54]

In late 1965 Time magazine ran a cover article with a title comment from Milton Friedman (later echoed by US President Richard Nixon), "We are all Keynesians now". The article described the exceptionally favourable economic conditions then prevailing and reported that "Washington's economic managers scaled these heights by their adherence to Keynes's central theme: the modern capitalist economy does not automatically work at top efficiency, but can be raised to that level by the intervention and influence of the government." The article also states that Keynes was one of the three most important economists who ever lived, and that his General Theory was more influential than the magna opera of other famous economists, such as Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations.[73]

Multiplier[edit]

The concept of the multiplier was first developed by R. F. Kahn[74] in his article "The relation of home investment to unemployment"[75] in The Economic Journal of June 1931. The Kahn multiplier was the employment multiplier; Keynes took the idea from Kahn and formulated the investment multiplier.[76]

Keynesian economics out of favour 1979–2007[edit]

Keynesian economics were officially discarded by the British Government in 1979, but forces had begun to gather against Keynes's ideas over 30 years earlier. Friedrich Hayek had formed the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947, with the explicit intention of nurturing intellectual currents to one day displace Keynesianism and other similar influences. Its members included the Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises along with the then young Milton Friedman. Initially the society had little impact on the wider world – according to Hayek it was as if Keynes had been raised to sainthood after his death and that people refused to allow his work to be questioned.[77][78]Friedman, however, began to emerge as a formidable critic of Keynesian economics from the mid-1950s, and especially after his 1963 publication of A Monetary History of the United States.

On the practical side of economic life, "big government" had appeared to be firmly entrenched in the 1950s, but the balance began to shift towards the power of private interests in the 1960s. Keynes had written against the folly of allowing "decadent and selfish" speculators and financiers the kind of influence they had enjoyed after World War I. For two decades after World War II public opinion was strongly against private speculators, the disparaging label "Gnomes of Zurich" being typical of how they were described during this period. International speculation was severely restricted by the capital controls in place after Bretton Woods. According to the journalists Larry Elliott and Dan Atkinson, 1968 was the pivotal year when power shifted in favour of private agents such as currency speculators. As the key 1968 event Elliott and Atkinson picked out America's suspension of the conversion of the dollar into gold except on request of foreign governments, which they identified as the beginning of the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system.[79]

Criticisms of Keynes's ideas had begun to gain significant acceptance by the early 1970s, as they were then able to make a credible case that Keynesian models no longer reflected economic reality. Keynes himself included few formulas and no explicit mathematical models in his General Theory. For economists such as Hyman Minsky, Keynes's limited use of mathematics was partly the result of his scepticism about whether phenomena as inherently uncertain as economic activity could ever be adequately captured by mathematical models. Nevertheless, many models were developed by Keynesian economists, with a famous example being the Phillips curve which predicted an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation. It implied that unemployment could be reduced by government stimulus with a calculable cost to inflation. In 1968, Milton Friedman published a paper arguing that the fixed relationship implied by the Philips curve did not exist.[80]Friedman suggested that sustained Keynesian policies could lead to both unemployment and inflation rising at once – a phenomenon that soon became known as stagflation. In the early 1970s stagflation appeared in both the US and Britain just as Friedman had predicted, with economic conditions deteriorating further after the 1973 oil crisis. Aided by the prestige gained from his successful forecast, Friedman led increasingly successful criticisms against the Keynesian consensus, convincing not only academics and politicians but also much of the general public with his radio and television broadcasts. The academic credibility of Keynesian economics was further undermined by additional criticism from other monetarists trained in the Chicago school of economics, by the Lucas critique and by criticisms from Hayek's Austrian School.[54] So successful were these criticisms that by 1980 Robert Lucas claimed economists would often take offence if described as Keynesians.[81]

Keynesian principles fared increasingly poorly on the practical side of economics – by 1979 they had been displaced by monetarism as the primary influence on Anglo-American economic policy.[54] However, many officials on both sides of the Atlantic retained a preference for Keynes, and in 1984 the Federal Reserve officially discarded monetarism, after which Keynesian principles made a partial comeback as an influence on policy making.[82]Not all academics accepted the criticism against Keynes – Minsky has argued that Keynesian economics had been debased by excessive mixing with neoclassical ideas from the 1950s, and that it was unfortunate that this branch of economics had even continued to be called "Keynesian".[29] Writing in The American Prospect, Robert Kuttner argued it was not so much excessive Keynesian activism that caused the economic problems of the 1970s but the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system of capital controls, which allowed capital flight from regulated economies into unregulated economies in a fashion similar to Gresham's law phenomenon (where weak currencies undermine strong ones).[83]Historian Peter Pugh has stated that a key cause of the economic problems afflicting America in the 1970s was the refusal to raise taxes to finance the Vietnam War, which was against Keynesian advice.[84]

A more typical response was to accept some elements of the criticisms while refining Keynesian economic theories to defend them against arguments that would invalidate the whole Keynesian framework – the resulting body of work largely composing New Keynesian economics. In 1992 Alan Blinder wrote about a "Keynesian Restoration", as work based on Keynes's ideas had to some extent become fashionable once again in academia, though in the mainstream it was highly synthesised with monetarism and other neoclassical thinking. In the world of policy making, free market influences broadly sympathetic to monetarism have remained very strong at government level – in powerful normative institutions like the World Bank, the IMF and US Treasury, and in prominent opinion-forming media such as the Financial Times and The Economist.[85]

Keynesian resurgence 2008–09[edit]

The global financial crisis of 2007–08 led to public skepticism about the free market consensus even from some on the economic right. In March 2008, Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator at the Financial Times, announced the death of the dream of global free-market capitalism.[87] In the same month macroeconomist James K. Galbraith used the 25th Annual Milton Friedman Distinguished Lecture to launch a sweeping attack against the consensus for monetarist economics and argued that Keynesian economics were far more relevant for tackling the emerging crises.[88]Economist Robert J. Shiller had begun advocating robust government intervention to tackle the financial crises, specifically citing Keynes.[89][90][91] Nobel laureate Paul Krugman also actively argued the case for vigorous Keynesian intervention in the economy in his columns for The New York Times.[92][93][94]Other prominent economic commentators who have argued for Keynesian government intervention to mitigate the financial crisis include George Akerlof,[95] J. Bradford DeLong,[96] Robert Reich[97] and Joseph Stiglitz.[98]Newspapers and other media have also cited work relating to Keynes by Hyman Minsky,[29] Robert Skidelsky,[18] Donald Markwell[99] and Axel Leijonhufvud.[100]

A series of major bailouts were pursued during the financial crisis, starting on 7 September with the announcement that the US Government was to nationalise the two government-sponsored enterprises which oversaw most of the US subprime mortgage market – Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. In October, Alistair Darling, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer, referred to Keynes as he announced plans for substantial fiscal stimulus to head off the worst effects of recession, in accordance with Keynesian economic thought.[101][102] Similar policies have been adopted by other governments worldwide.[103][104]This is in stark contrast to the action imposed on Indonesia during the Asian financial crisis of 1997, when it was forced by the IMF to close 16 banks at the same time, prompting a bank run.[105]Much of the post-crisis discussion reflected Keynes's advocacy of international coordination of fiscal or monetary stimulus, and of international economic institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank, which many had argued should be reformed as a "new Bretton Woods", and should have been even before the crises broke out.[106]The IMF and United Nations economists advocated a coordinated international approach to fiscal stimulus.[107] Donald Markwell argued that in the absence of such an international approach, there would be a risk of worsening international relations and possibly even world war arising from economic factors similar to those present during the depression of the 1930s.[99]

By the end of December 2008, the Financial Times reported that "the sudden resurgence of Keynesian policy is a stunning reversal of the orthodoxy of the past several decades."[108]In December 2008, Paul Krugman released his book The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008, arguing that economic conditions similar to those that existed during the earlier part of the 20th century had returned, making Keynesian policy prescriptions more relevant than ever. In February 2009 Robert J. Shiller and George Akerlof published Animal Spirits, a book where they argue the current US stimulus package is too small as it does not take into account Keynes's insight on the importance of confidence and expectations in determining the future behaviour of businesspeople and other economic agents.

In the March 2009 speech entitled Reform the International Monetary System, Zhou Xiaochuan, the governor of the People's Bank of China, came out in favour of Keynes's idea of a centrally managed global reserve currency. Zhou argued that it was unfortunate that part of the reason for the Bretton Woods system breaking down was the failure to adopt Keynes's bancor. Zhou proposed a gradual move towards increased use of IMF special drawing rights (SDRs).[109][110]Although Zhou's ideas had not been broadly accepted, leaders meeting in April at the 2009 G-20 London summit agreed to allow $250 billion of special drawing rights to be created by the IMF, to be distributed globally. Stimulus plans were credited for contributing to a better-than-expected economic outlook by both the OECD[111]and the IMF,[112][113] in reports published in June and July 2009. Both organisations warned global leaders that recovery was likely to be slow, so counter recessionary measures ought not be rolled back too early.

While the need for stimulus measures was broadly accepted among policy makers, there had been much debate over how to fund the spending. Some leaders and institutions, such as Angela Merkel[114]and the European Central Bank,[115]expressed concern over the potential impact on inflation, national debt and the risk that a too large stimulus will create an unsustainable recovery.

Among professional economists the revival of Keynesian economics has been even more divisive. Although many economists, such as George Akerlof, Paul Krugman, Robert Shiller and Joseph Stiglitz, supported Keynesian stimulus, others did not believe higher government spending would help the United States economy recover from the Great Recession. Some economists, such as Robert Lucas, questioned the theoretical basis for stimulus packages.[116] Others, like Robert Barro and Gary Becker, say that empirical evidence for beneficial effects from Keynesian stimulus does not exist.[117] However, there is a growing academic literature that shows that fiscal expansion helps an economy grow in the near term, and that certain types of fiscal stimulus are particularly effective.[118][119]

New Keynesian economics[edit]

New Keynesian economics developed in the 1990s and early 2000s as a response to the critique that macroeconomics lacked microeconomic foundations. New Keynesianism developed models to provide microfoundations for Keynesian economics. It incorporated parts of new classical macroeconomics to develop the new neoclassical synthesis, which forms the basis for mainstream macroeconomics today.[120][121][122][123]

Two main assumptions define the New Keynesian approach to macroeconomics. Like the New Classical approach, New Keynesian macroeconomic analysis usually assumes that households and firms have rational expectations. However, the two schools differ in that New Keynesian analysis usually assumes a variety of market failures. In particular, New Keynesians assume that there is imperfect competition[124] in price and wage setting to help explain why prices and wages can become "sticky", which means they do not adjust instantaneously to changes in economic conditions.

Wage and price stickiness, and the other market failures present in New Keynesian models, imply that the economy may fail to attain full employment. Therefore, New Keynesians argue that macroeconomic stabilisation by the government (using fiscal policy) and the central bank (using monetary policy) can lead to a more efficient macroeconomic outcome than a laissez faire policy would.

Overall views[edit]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Liberalism in the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

Praise[edit]

On a personal level, Keynes's charm was such that he was generally well received wherever he went – even those who found themselves on the wrong side of his occasionally sharp tongue rarely bore a grudge.[125] Keynes's speech at the closing of the Bretton Woods negotiations was received with a lasting standing ovation, rare in international relations, as the delegates acknowledged the scale of his achievements made despite poor health.[26]

Austrian School economist Friedrich Hayek was Keynes's most prominent contemporary critic, with sharply opposing views on the economy.[50] Yet after Keynes's death, he wrote: "He was the one really great man I ever knew, and for whom I had unbounded admiration. The world will be a very much poorer place without him."[126] A colleague Nicholas Davenport recalled, "There were deep emotional forces about Maynard ... One could sense his humanity. There was nothing of the cold intellectual about him."[127]

Lionel Robbins, former head of the economics department at the London School of Economics, who engaged in many heated debates with Keynes in the 1930s, had this to say after observing Keynes in early negotiations with the Americans while drawing up plans for Bretton Woods:[50]

This went very well indeed. Keynes was in his most lucid and persuasive mood: and the effect was irresistible. At such moments, I often find myself thinking that Keynes must be one of the most remarkable men that have ever lived – the quick logic, the birdlike swoop of intuition, the vivid fancy, the wide vision, above all the incomparable sense of the fitness of words, all combine to make something several degrees beyond the limit of ordinary human achievement.

Douglas LePan, an official from the Canadian High Commission,[50] wrote:

I am spellbound. This is the most beautiful creature I have ever listened to. Does he belong to our species? Or is he from some other order? There is something mythic and fabulous about him. I sense in him something massive and sphinx like, and yet also a hint of wings.

Bertrand Russell named Keynes one of the most intelligent people he had ever known,[128] commenting:[129]

Keynes's intellect was the sharpest and clearest that I have ever known. When I argued with him, I felt that I took my life in my hands, and I seldom emerged without feeling something of a fool.

Keynes's obituary in The Times included the comment: "There is the man himself – radiant, brilliant, effervescent, gay, full of impish jokes ... He was a humane man genuinely devoted to the cause of the common good."[52]

Critiques[edit]

As a man of the centre described by some as having the greatest impact of any 20th-century economist,[43] Keynes attracted considerable criticism from both sides of the political spectrum. In the 1920s, Keynes was seen as anti-establishment and was mainly attacked from the right. In the "red 1930s", many young economists favoured Marxist views, even in Cambridge,[29] and while Keynes was engaging principally with the right to try to persuade them of the merits of more progressive policy, the most vociferous criticism against him came from the left, who saw him as a supporter of capitalism. From the 1950s and onwards, most of the attacks against Keynes have again been from the right.

In 1931, Friedrich Hayek extensively critiqued Keynes's 1930 Treatise on Money.[130] After reading Hayek's The Road to Serfdom, Keynes wrote to Hayek: "Morally and philosophically I find myself in agreement with virtually the whole of it."[131] He concluded the letter with the recommendation:

What we need therefore, in my opinion, is not a change in our economic programmes, which would only lead in practice to disillusion with the results of your philosophy; but perhaps even the contrary, namely, an enlargement of them. Your greatest danger is the probable practical failure of the application of your philosophy in the United States.

On the pressing issue of the time, whether deficit spending could lift a country from depression, Keynes replied to Hayek's criticism[132] in the following way:

I should... conclude rather differently. I should say that what we want is not no planning, or even less planning, indeed I should say we almost certainly want more. But the planning should take place in a community in which as many people as possible, both leaders and followers wholly share your moral position. Moderate planning will be safe enough if those carrying it out are rightly oriented in their minds and hearts to the moral issue.

Asked why Keynes expressed "moral and philosophical" agreement with Hayek's Road to Serfdom, Hayek stated:[133]

Because he believed that he was fundamentally still a classical English liberal and wasn't quite aware of how far he had moved away from it. His basic ideas were still those of individual freedom. He did not think systematically enough to see the conflicts. He was, in a sense, corrupted by political necessity.

According to some observers,[who?] Hayek felt that the post-World War II "Keynesian orthodoxy" gave too much power to the state, and that such policies would lead toward socialism.[134]

While Milton Friedman described The General Theory as "a great book", he argues that its implicit separation of nominal from real magnitudes is neither possible nor desirable. Macroeconomic policy, Friedman argues, can reliably influence only the nominal.[135] He and other monetarists have consequently argued that Keynesian economics can result in stagflation, the combination of low growth and high inflation that developed economies suffered in the early 1970s. More to Friedman's taste was the Tract on Monetary Reform (1923), which he regarded as Keynes's best work because of its focus on maintaining domestic price stability.[135]

Joseph Schumpeter was an economist of the same age as Keynes and one of his main rivals. He was among the first reviewers to argue that Keynes's General Theory was not a general theory, but a special case.[136] He said the work expressed "the attitude of a decaying civilisation". After Keynes's death Schumpeter wrote a brief biographical piece Keynes the Economist – on a personal level he was very positive about Keynes as a man, praising his pleasant nature, courtesy and kindness. He assessed some of Keynes's biographical and editorial work as among the best he'd ever seen. Yet Schumpeter remained critical about Keynes's economics, linking Keynes's childlessness to what Schumpeter saw as an essentially short-term view. He considered Keynes to have a kind of unconscious patriotism that caused him to fail to understand the problems of other nations. For Schumpeter, "Practical Keynesianism is a seedling which cannot be transplanted into foreign soil: it dies there and becomes poisonous as it dies."[137] He "admired and envied Keynes, but when Keynes died in 1946, Schumpeter's obituary gave Keynes this same off-key, perfunctory treatment he would later give Adam Smith in the History of Economic Analysis, the "discredit of not adding a single innovation to the techniques of economic analysis."[138]

Ludwig von Mises, an Austrian economist, describes a Keynesian system as believing it can solve most problems with "more money and credit" which leads to a system of "inflationism" in which "prices (of goods) rise higher and higher."[139] Murray Rothbard wrote that Keynesian-style governmental regulation of money and credit created a "dismal monetary and banking situation," since it allows for the central bankers that have the exclusive ability to print money to be "unchecked and out of control."[140] Rothbard went on to say in an interview that, "There is one good thing about (Karl) Marx: he was not a Keynesian."[141]

President Harry S. Truman was sceptical of Keynesian theorising. He told Leon Keyserling, a Keynesian economist who chaired Truman's Council of Economic Advisers: "Nobody can ever convince me that government can spend a dollar that it's not got."[44]

Views on race[edit]

Some critics have sought to show that Keynes had sympathies towards Nazism, and a number of writers have described him as antisemitic. Keynes's private letters contain portraits and descriptions, some of which can be characterised as antisemitic, while others as philosemitic.[142][143]

Scholars have suggested that these reflect clichés current at the time that he accepted uncritically, rather than any racism.[144] On several occasions Keynes used his influence to help his Jewish friends, most notably when he successfully lobbied for Ludwig Wittgenstein to be allowed residency in the United Kingdom, explicitly to rescue him from being deported to Nazi-occupied Austria. Keynes was a supporter of Zionism, serving on committees supporting the cause.[144]

Allegations that he was racist or had totalitarian beliefs have been rejected by Robert Skidelsky and other biographers.[26] Professor Gordon Fletcher wrote that "the suggestion of a link between Keynes and any support of totalitarianism cannot be sustained".[54] Once the aggressive tendencies of the Nazis towards Jews and other minorities had become apparent, Keynes made clear his loathing of Nazism. As a lifelong pacifist he had initially favoured peaceful containment of Nazi Germany, yet he began to advocate a forceful resolution while many conservatives were still arguing for appeasement. After the war started, he roundly criticised the Left for losing their nerve to confront Adolf Hitler, saying:

The intelligentsia of the Left were the loudest in demanding that the Nazi aggression should be resisted at all costs. When it comes to a showdown, scarce four weeks have passed before they remember that they are pacifists and write defeatist letters to your columns, leaving the defence of freedom and civilisation to Colonel Blimp and the Old School Tie, for whom Three Cheers.[50]

Views on inflation[edit]

Keynes has been characterised as being indifferent or even positive about mild inflation.[145] He had expressed a preference for inflation over deflation, saying that if one has to choose between the two evils, it is "better to disappoint the rentier" than to inflict pain on working-class families.[146] Keynes was also aware of the dangers of inflation.[54][page range too broad] In The Economic Consequences of the Peace, he wrote:

Lenin is said to have declared that the best way to destroy the Capitalist System was to debauch the currency. By a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.[145]

Views on free trade and protectionism[edit]

Turning point of the Great Depression[edit]

At the beginning of his career, Keynes was an economist close to Alfred Marshall, deeply convinced of the benefits of free trade. From the crisis of 1929 onwards, noting the commitment of the British authorities to defend the gold parity of the pound sterling and the rigidity of nominal wages, he gradually adhered to protectionist measures.[147]

On 5 November 1929, when heard by the Macmillan Committee to bring the British economy out of the crisis, Keynes indicated that the introduction of tariffs on imports would help to rebalance the trade balance. The committee's report states in a section entitled "import control and export aid", that in an economy where there is not full employment, the introduction of tariffs can improve production and employment. Thus, the reduction of the trade deficit favours the country's growth.[147]

In January 1930, in the Economic Advisory Council, Keynes proposed the introduction of a system of protection to reduce imports. In the autumn of 1930, he proposed a uniform tariff of 10% on all imports and subsidies of the same rate for all exports.[147] In the Treatise on Money, published in the autumn of 1930, he took up the idea of tariffs or other trade restrictions with the aim of reducing the volume of imports and rebalancing the balance of trade.[147]

On 7 March 1931, in the New Statesman and Nation, he wrote an article entitled Proposal for a Tariff Revenue. He pointed out that the reduction of wages led to a reduction in national demand which constrained markets. Instead, he proposed the idea of an expansionary policy combined with a tariff system to neutralise the effects on the balance of trade. The application of customs tariffs seemed to him "unavoidable, whoever the Chancellor of the Exchequer might be". Thus, for Keynes, an economic recovery policy is only fully effective if the trade deficit is eliminated. He proposed a 15% tax on manufactured and semi-manufactured goods and 5% on certain foodstuffs and raw materials, with others needed for exports exempted (wool, cotton).[147]

In 1932, in an article entitled The Pro- and Anti-Tariffs, published in The Listener, he envisaged the protection of farmers and certain sectors such as the automobile and iron and steel industries, considering them indispensable to Britain.[147]

Critique of the theory of comparative advantage[edit]

In the post-crisis situation of 1929, Keynes judged the assumptions of the free trade model unrealistic. He criticised, for example, the neoclassical assumption of wage adjustment.[147][148]

As early as 1930, in a note to the Economic Advisory Council, he doubted the intensity of the gain from specialisation in the case of manufactured goods. While participating in the MacMillan Committee, he admitted that he no longer "believed in a very high degree of national specialisation" and refused to "abandon any industry which is unable, for the moment, to survive". He also criticised the static dimension of the theory of comparative advantage, which, in his view, by fixing comparative advantages definitively, led in practice to a waste of national resources.[147][148]

In the Daily Mail of 13 March 1931, he called the assumption of perfect sectoral labour mobility "nonsense" since it states that a person made unemployed contributes to a reduction in the wage rate until he finds a job. But for Keynes, this change of job may involve costs (job search, training) and is not always possible. Generally speaking, for Keynes, the assumptions of full employment and automatic return to equilibrium discredit the theory of comparative advantage.[147][148]

In July 1933, he published an article in the New Statesman and Nation entitled National Self-Sufficiency, in which he criticised the argument of the specialisation of economies, which is the basis of free trade. He thus proposed the search for a certain degree of self-sufficiency. Instead of the specialisation of economies advocated by the Ricardian theory of comparative advantage, he prefers the maintenance of a diversity of activities for nations.[148] In it he refutes the principle of peacemaking trade. His vision of trade became that of a system where foreign capitalists compete for new markets. He defends the idea of producing on national soil when possible and reasonable and expresses sympathy for the advocates of protectionism.[149] He notes in National Self-Sufficiency:[149][147]

A considerable degree of international specialization is necessary in a rational world in all cases where it is dictated by wide differences of climate, natural resources, native aptitudes, level of culture and density of population. But over an increasingly wide range of industrial products, and perhaps of agricultural products also, I have become doubtful whether the economic loss of national self-sufficiency is great enough to outweigh the other advantages of gradually bringing the product and the consumer within the ambit of the same national, economic, and financial organization. Experience accumulates to prove that most modern processes of mass production can be performed in most countries and climates with almost equal efficiency.

He also writes in National Self-Sufficiency:[147]

I sympathize, therefore, with those who would minimize, rather than with those who would maximize, economic entanglement among nations. Ideas, knowledge, science, hospitality, travel – these are the things which should of their nature be international. But let goods be homespun whenever it is reasonably and conveniently possible, and, above all, let finance be primarily national.

Later, Keynes had a written correspondence with James Meade centred on the issue of import restrictions. Keynes and Meade discussed the best choice between quota and tariff. In March 1944 Keynes began a discussion with Marcus Fleming after the latter had written an article entitled Quotas versus depreciation. On this occasion, we see that he has definitely taken a protectionist stance after the Great Depression. He considered that quotas could be more effective than currency depreciation in dealing with external imbalances. Thus, for Keynes, currency depreciation was no longer sufficient and protectionist measures became necessary to avoid trade deficits. To avoid the return of crises due to a self-regulating economic system, it seemed essential to him to regulate trade and stop free trade (deregulation of foreign trade).[147]

He points out that countries that import more than they export weaken their economies. When the trade deficit increases, unemployment rises and gross domestic product (GDP) slows down. Furthermore, surplus countries exert a "negative externality" on their trading partners. They get richer at the expense of others and destroy the output of their trading partners. John Maynard Keynes believed that the products of surplus countries should be taxed to avoid trade imbalances.[150]

Views on trade imbalances[edit]

Keynes was the principal author of a proposal – the so-called Keynes Plan – for an International Clearing Union. The two governing principles of the plan were that the problem of settling outstanding balances should be solved by "creating" additional "international money", and that debtor and creditor should be treated almost alike as disturbers of equilibrium. In the event, though, the plans were rejected, in part because "American opinion was naturally reluctant to accept the principle of equality of treatment so novel in debtor-creditor relationships".[151]

The new system is not founded on free-trade (liberalisation[152] of foreign trade[153]) but rather on the regulation of international trade, to eliminate trade imbalances: the nations with a surplus would have an incentive to reduce it, and in doing so they would automatically clear other nations deficits.[154] He proposed a global bank that would issue its currency – the bancor – which was exchangeable with national currencies at fixed rates of exchange and would become the unit of account between nations, which means it would be used to measure a country's trade deficit or trade surplus. Every country would have an overdraft facility in its bancor account at the International Clearing Union. He pointed out that surpluses lead to weak global aggregate demand – countries running surpluses exert a "negative externality" on trading partners, and posed, far more than those in deficit, a threat to global prosperity.[155]

In his 1933 Yale Review article "National Self-Sufficiency",[156][157] he already highlighted the problems created by free trade. His view, supported by many economists and commentators at the time, was that creditor nations may be just as responsible as debtor nations for disequilibrium in exchanges and that both should be under an obligation to bring trade back into a state of balance. Failure for them to do so could have serious consequences. In the words of Geoffrey Crowther, then editor of The Economist, "If the economic relationships between nations are not, by one means or another, brought fairly close to balance, then there is no set of financial arrangements that can rescue the world from the impoverishing results of chaos."[158]

These ideas were informed by events prior to the Great Depression when – in the opinion of Keynes and others – international lending, primarily by the US, exceeded the capacity of sound investment and so got diverted into non-productive and speculative uses, which in turn invited default and a sudden stop to the process of lending.[159]

Influenced by Keynes, economics texts in the immediate post-war period put a significant emphasis on balance in trade. For example, the second edition of the popular introductory textbook, An Outline of Money,[160] devoted the last three of its ten chapters to questions of foreign exchange management and in particular the "problem of balance". However, in more recent years, since the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, with the increasing influence of monetarist schools of thought in the 1980s, and particularly in the face of large sustained trade imbalances, these concerns – and particularly concerns about the destabilising effects of large trade surpluses – have largely disappeared from mainstream economics discourse[161][page needed] and Keynes's insights have slipped from view.[162][page needed] They are receiving some attention again in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007–08.[163]

Personal life[edit]

Relationships[edit]

Keynes's early romantic and sexual relationships were exclusively with men.[164] Keynes had been in relationships while at Eton and Cambridge; significant among these early partners were Dilly Knox and Daniel Macmillan.[20][165] Keynes was open about his affairs, and from 1901 to 1915 kept separate diaries in which he tabulated his many sexual encounters.[166][167] Keynes's relationship and later close friendship with Macmillan was to be fortunate, as Macmillan's company first published his tract Economic Consequences of the Peace.[168]

Attitudes in the Bloomsbury Group, in which Keynes was avidly involved, were relaxed about homosexuality. Keynes, together with writer Lytton Strachey, had reshaped the Victorian attitudes of the Cambridge Apostles: "since [their] time, homosexual relations among the members were for a time common", wrote Bertrand Russell.[169] The artist Duncan Grant has been described as "the supreme male love of Keynes's life", and their sexual relationship lasted from 1908 to 1915.[170] Keynes was also involved with Lytton Strachey,[164] though they were, for the most part, love rivals rather than lovers. Keynes had won the affections of Arthur Hobhouse,[171] and as with Grant, fell out with a jealous Strachey over it.[172] Strachey had previously found himself put off by Keynes, not least because of his manner of "treat[ing] his love affairs statistically".[173]

Political opponents have used Keynes's sexuality to attack his academic work.[174] One line of attack held that he was uninterested in the long-term ramifications of his theories because he had no children.[174]

Keynes's friends in the Bloomsbury Group were initially surprised when, in his later years, he began pursuing affairs with women,[175] demonstrating himself to be bisexual.[176] Ray Costelloe (who later married Oliver Strachey) was an early heterosexual interest of Keynes.[177] In 1906, Keynes had written of this infatuation that, "I seem to have fallen in love with Ray a little bit, but as she isn't male I haven't [been] able to think of any suitable steps to take."[178]

Marriage[edit]

In 1921, Keynes wrote that he had fallen "very much in love" with Lydia Lopokova, a well-known Russian ballerina and one of the stars of Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes.[179] In the early years of his courtship, he maintained an affair with a younger man, Sebastian Sprott, in tandem with Lopokova, but eventually chose Lopokova exclusively.[180][181] They were married in 1925, with Keynes's former lover Duncan Grant as best man.[128][164] "What a marriage of beauty and brains, the fair Lopokova and John Maynard Keynes" was said at the time. Keynes later commented to Strachey that beauty and intelligence were rarely found in the same person, and that only in Duncan Grant had he found the combination.[182] The union was happy, with biographer Peter Clarke writing that the marriage gave Keynes "a new focus, a new emotional stability and a sheer delight of which he never wearied".[32][183] The couple hoped to have children but this did not happen.[32]

Among Keynes's Bloomsbury friends, Lopokova was, at least initially, subjected to criticism for her manners, mode of conversation and supposedly humble social origins – the last of the ostensible causes being particularly noted in the letters of Vanessa and Clive Bell, and Virginia Woolf.[184][185] In her novel Mrs Dalloway (1925), Woolf bases the character of Rezia Warren Smith on Lopokova.[186] E. M. Forster later wrote in contrition about "Lydia Keynes, every whose word should be recorded";[187] "How we all used to underestimate her".[184]

Keynes had no children, and his wife outlived him by 35 years, dying in 1981.

Support for the arts[edit]

Keynes thought that the pursuit of money for its own sake was a pathological condition, and that the proper aim of work is to provide leisure. He wanted shorter working hours and longer holidays for all.[56]

Keynes was interested in literature in general and drama in particular and supported the Cambridge Arts Theatre financially, which allowed the institution to become one of the major British stages outside London.[128]