Программа Аполлон

| |

| Обзор программы | |

|---|---|

| Страна | Соединенные Штаты |

| Организация | НАСА |

| Цель | Пилотируемая посадка на Луну |

| Статус | Завершенный |

| История программы | |

| Расходы |

|

| Продолжительность | 1961–1972 |

| Первый полет |

|

| Первый полет с экипажем |

|

| Последний рейс |

|

| Успехи | 32 |

| Неудачи | 2 ( Аполлон 1 и 13 ) |

| Частичные отказы | 1 ( Аполлон 6 ) |

| Сайт(ы) запуска | |

| Информация об автомобиле | |

| Транспортное средство(а) с экипажем | |

| Ракета-носитель (и) | |

| Часть серии о |

| Космическая программа США |

|---|

|

Программа «Аполлон» , также известная как «Проект Аполлон» США, , — это программа пилотируемых космических полетов осуществляемая Национальным управлением по аэронавтике и исследованию космического пространства (НАСА), в рамках которой удалось подготовить и высадить первых людей. [2] на Луне с 1968 по 1972 год . Впервые он был задуман в 1960 году во время правления президента Дуайта Д. Эйзенхауэра как космический корабль для трех человек, последовавший за одноместным проектом «Меркурий» , который отправил первых американцев в космос. Аполлон» был посвящен национальной цели президента Джона Ф. Кеннеди на 1960-е годы «высадить человека на Луну и благополучно вернуть его на Землю». Позже в обращении к Конгрессу 25 мая 1961 года « для двух человек, Программа космических полетов, которой предшествовал проект «Близнецы» задуманный в 1961 году для расширения возможностей космических полетов в поддержку Аполлона.

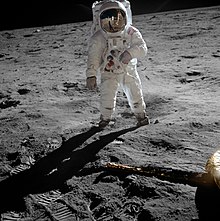

Цель Кеннеди была достигнута во время миссии «Аполлон-11», когда астронавты Нил Армстронг и Базз Олдрин 20 июля 1969 года приземлили свой лунный модуль «Аполлон» (LM) и прошли по поверхности Луны, в то время как Майкл Коллинз остался на лунной орбите в командно-служебном модуле. (CSM), и все трое благополучно приземлились на Земле в Тихом океане 24 июля. Пять последующих миссий Аполлона также высадили астронавтов на Луну, последняя, Аполлон-17 , в декабре 1972 года. В этих шести космических полетах двенадцать человек прошли по Луне. Луна .

«Аполлон» эксплуатировался с 1961 по 1972 год, а первый полет с экипажем состоялся в 1968 году. Серьезную неудачу он потерпел в 1967 году, когда в результате пожара в кабине «Аполлона-1» погиб весь экипаж во время предстартовых испытаний. После первой успешной посадки осталось достаточно летной техники для девяти последующих посадок с планом расширенных геологических и астрофизических исследований Луны. Сокращение бюджета привело к отмене трех из них. Пять из оставшихся шести миссий завершились успешными приземлениями, но посадку «Аполлона-13» пришлось прервать после того, как на пути к Луне взорвался кислородный баллон, что повредило CSM. Экипажу с трудом удалось благополучно вернуться на Землю, используя лунный модуль в качестве «спасательной шлюпки» на обратном пути. «Аполлон» использовал семейство ракет «Сатурн» в качестве ракет-носителей, которые также использовались для программы «Аполлон» , которая состояла из «Скайлэб» , космической станции , которая поддерживала три миссии с экипажем в 1973–1974 годах, и испытательного проекта «Аполлон-Союз» , совместного проекта Соединенных Штатов. Штаты - Миссия Советского Союза на околоземной орбите в 1975 году.

Аполлон установил несколько важных вех пилотируемых космических полетов . Он стоит особняком в отправке пилотируемых миссий за пределы низкой околоземной орбиты . «Аполлон-8» был первым космическим кораблем с экипажем, вышедшим на орбиту другого небесного тела, а «Аполлон-11» был первым космическим кораблем с экипажем, на который высадились люди.

В целом программа «Аполлон» вернула на Землю 842 фунта (382 кг) лунных камней и почвы, что внесло большой вклад в понимание состава и геологической истории Луны. Программа заложила основу для последующих пилотируемых космических полетов НАСА и профинансировала строительство Космического центра Джонсона и Космического центра Кеннеди . Аполлон также стимулировал развитие во многих областях технологий, связанных с ракетной техникой и пилотируемыми космическими полетами, включая авионику , телекоммуникации и компьютеры.

Name

[edit]The program was named after Apollo, the Greek god of light, music, and the Sun, by NASA manager Abe Silverstein, who later said, "I was naming the spacecraft like I'd name my baby."[3] Silverstein chose the name at home one evening, early in 1960, because he felt "Apollo riding his chariot across the Sun was appropriate to the grand scale of the proposed program".[4]

The context of this was that the program focused at its beginning mainly on developing an advanced crewed spacecraft, the Apollo command and service module, succeeding the Mercury program. A lunar landing became the focus of the program only in 1961.[5] Thereafter Project Gemini instead followed the Mercury program to test and study advanced crewed spaceflight technology.

Background

[edit]Origin and spacecraft feasibility studies

[edit]The Apollo program was conceived during the Eisenhower administration in early 1960, as a follow-up to Project Mercury. While the Mercury capsule could support only one astronaut on a limited Earth orbital mission, Apollo would carry three. Possible missions included ferrying crews to a space station, circumlunar flights, and eventual crewed lunar landings.

In July 1960, NASA Deputy Administrator Hugh L. Dryden announced the Apollo program to industry representatives at a series of Space Task Group conferences. Preliminary specifications were laid out for a spacecraft with a mission module cabin separate from the command module (piloting and reentry cabin), and a propulsion and equipment module. On August 30, a feasibility study competition was announced, and on October 25, three study contracts were awarded to General Dynamics/Convair, General Electric, and the Glenn L. Martin Company. Meanwhile, NASA performed its own in-house spacecraft design studies led by Maxime Faget, to serve as a gauge to judge and monitor the three industry designs.[6]

Political pressure builds

[edit]In November 1960, John F. Kennedy was elected president after a campaign that promised American superiority over the Soviet Union in the fields of space exploration and missile defense. Up to the election of 1960, Kennedy had been speaking out against the "missile gap" that he and many other senators said had developed between the Soviet Union and the United States due to the inaction of President Eisenhower.[7] Beyond military power, Kennedy used aerospace technology as a symbol of national prestige, pledging to make the US not "first but, first and, first if, but first period".[8] Despite Kennedy's rhetoric, he did not immediately come to a decision on the status of the Apollo program once he became president. He knew little about the technical details of the space program, and was put off by the massive financial commitment required by a crewed Moon landing.[9] When Kennedy's newly appointed NASA Administrator James E. Webb requested a 30 percent budget increase for his agency, Kennedy supported an acceleration of NASA's large booster program but deferred a decision on the broader issue.[10]

On April 12, 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person to fly in space, reinforcing American fears about being left behind in a technological competition with the Soviet Union. At a meeting of the US House Committee on Science and Astronautics one day after Gagarin's flight, many congressmen pledged their support for a crash program aimed at ensuring that America would catch up.[11] Kennedy was circumspect in his response to the news, refusing to make a commitment on America's response to the Soviets.[12]

On April 20, Kennedy sent a memo to Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, asking Johnson to look into the status of America's space program, and into programs that could offer NASA the opportunity to catch up.[13][14] Johnson responded approximately one week later, concluding that "we are neither making maximum effort nor achieving results necessary if this country is to reach a position of leadership."[15][16] His memo concluded that a crewed Moon landing was far enough in the future that it was likely the United States would achieve it first.[15]

On May 25, 1961, twenty days after the first US crewed spaceflight Freedom 7, Kennedy proposed the crewed Moon landing in a Special Message to the Congress on Urgent National Needs:

Now it is time to take longer strides—time for a great new American enterprise—time for this nation to take a clearly leading role in space achievement, which in many ways may hold the key to our future on Earth.

... I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important in the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.[17][a]

NASA expansion

[edit]At the time of Kennedy's proposal, only one American had flown in space—less than a month earlier—and NASA had not yet sent an astronaut into orbit. Even some NASA employees doubted whether Kennedy's ambitious goal could be met.[18] By 1963, Kennedy even came close to agreeing to a joint US-USSR Moon mission, to eliminate duplication of effort.[19]

With the clear goal of a crewed landing replacing the more nebulous goals of space stations and circumlunar flights, NASA decided that, in order to make progress quickly, it would discard the feasibility study designs of Convair, GE, and Martin, and proceed with Faget's command and service module design. The mission module was determined to be useful only as an extra room, and therefore unnecessary.[20] They used Faget's design as the specification for another competition for spacecraft procurement bids in October 1961. On November 28, 1961, it was announced that North American Aviation had won the contract, although its bid was not rated as good as the Martin proposal. Webb, Dryden and Robert Seamans chose it in preference due to North American's longer association with NASA and its predecessor.[21]

Landing humans on the Moon by the end of 1969 required the most sudden burst of technological creativity, and the largest commitment of resources ($25 billion; $182 billion in 2023 US dollars)[22] ever made by any nation in peacetime. At its peak, the Apollo program employed 400,000 people and required the support of over 20,000 industrial firms and universities.[23]

On July 1, 1960, NASA established the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Alabama. MSFC designed the heavy lift-class Saturn launch vehicles, which would be required for Apollo.[24]

Manned Spacecraft Center

[edit]It became clear that managing the Apollo program would exceed the capabilities of Robert R. Gilruth's Space Task Group, which had been directing the nation's crewed space program from NASA's Langley Research Center. So Gilruth was given authority to grow his organization into a new NASA center, the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC). A site was chosen in Houston, Texas, on land donated by Rice University, and Administrator Webb announced the conversion on September 19, 1961.[25] It was also clear NASA would soon outgrow its practice of controlling missions from its Cape Canaveral Air Force Station launch facilities in Florida, so a new Mission Control Center would be included in the MSC.[26]

In September 1962, by which time two Project Mercury astronauts had orbited the Earth, Gilruth had moved his organization to rented space in Houston, and construction of the MSC facility was under way, Kennedy visited Rice to reiterate his challenge in a famous speech:

But why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? ...We choose to go to the Moon. We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills; because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win ...[27][b]

The MSC was completed in September 1963. It was renamed by the US Congress in honor of Lyndon Johnson soon after his death in 1973.[28]

Launch Operations Center

[edit]It also became clear that Apollo would outgrow the Canaveral launch facilities in Florida. The two newest launch complexes were already being built for the Saturn I and IB rockets at the northernmost end: LC-34 and LC-37. But an even bigger facility would be needed for the mammoth rocket required for the crewed lunar mission, so land acquisition was started in July 1961 for a Launch Operations Center (LOC) immediately north of Canaveral at Merritt Island. The design, development and construction of the center was conducted by Kurt H. Debus, a member of Wernher von Braun's original V-2 rocket engineering team. Debus was named the LOC's first Director.[29] Construction began in November 1962. Following Kennedy's death, President Johnson issued an executive order on November 29, 1963, to rename the LOC and Cape Canaveral in honor of Kennedy.[30]

The LOC included Launch Complex 39, a Launch Control Center, and a 130-million-cubic-foot (3,700,000 m3) Vertical Assembly Building (VAB).[31] in which the space vehicle (launch vehicle and spacecraft) would be assembled on a mobile launcher platform and then moved by a crawler-transporter to one of several launch pads. Although at least three pads were planned, only two, designated A and B, were completed in October 1965. The LOC also included an Operations and Checkout Building (OCB) to which Gemini and Apollo spacecraft were initially received prior to being mated to their launch vehicles. The Apollo spacecraft could be tested in two vacuum chambers capable of simulating atmospheric pressure at altitudes up to 250,000 feet (76 km), which is nearly a vacuum.[32][33]

Organization

[edit]Administrator Webb realized that in order to keep Apollo costs under control, he had to develop greater project management skills in his organization, so he recruited George E. Mueller for a high management job. Mueller accepted, on the condition that he have a say in NASA reorganization necessary to effectively administer Apollo. Webb then worked with Associate Administrator (later Deputy Administrator) Seamans to reorganize the Office of Manned Space Flight (OMSF).[34] On July 23, 1963, Webb announced Mueller's appointment as Deputy Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, to replace then Associate Administrator D. Brainerd Holmes on his retirement effective September 1. Under Webb's reorganization, the directors of the Manned Spacecraft Center (Gilruth), Marshall Space Flight Center (von Braun), and the Launch Operations Center (Debus) reported to Mueller.[35]

Based on his industry experience on Air Force missile projects, Mueller realized some skilled managers could be found among high-ranking officers in the U.S. Air Force, so he got Webb's permission to recruit General Samuel C. Phillips, who gained a reputation for his effective management of the Minuteman program, as OMSF program controller. Phillips's superior officer Bernard A. Schriever agreed to loan Phillips to NASA, along with a staff of officers under him, on the condition that Phillips be made Apollo Program Director. Mueller agreed, and Phillips managed Apollo from January 1964, until it achieved the first human landing in July 1969, after which he returned to Air Force duty.[36]

Charles Fishman, in One Giant Leap, estimated the number of people and organizations involved into the Apollo program as "410,000 men and women at some 20,000 different companies contributed to the effort".[37]

Choosing a mission mode

[edit]

Once Kennedy had defined a goal, the Apollo mission planners were faced with the challenge of designing a spacecraft that could meet it while minimizing risk to human life, limiting cost, and not exceeding limits in possible technology and astronaut skill. Four possible mission modes were considered:

- Direct Ascent: The spacecraft would be launched as a unit and travel directly to the lunar surface, without first going into lunar orbit. A 50,000-pound (23,000 kg) Earth return ship would land all three astronauts atop a 113,000-pound (51,000 kg) descent propulsion stage,[38] which would be left on the Moon. This design would have required development of the extremely powerful Saturn C-8 or Nova launch vehicle to carry a 163,000-pound (74,000 kg) payload to the Moon.[39]

- Earth Orbit Rendezvous (EOR): Multiple rocket launches (up to 15 in some plans) would carry parts of the Direct Ascent spacecraft and propulsion units for translunar injection (TLI). These would be assembled into a single spacecraft in Earth orbit.

- Lunar Surface Rendezvous: Two spacecraft would be launched in succession. The first, an automated vehicle carrying propellant for the return to Earth, would land on the Moon, to be followed some time later by the crewed vehicle. Propellant would have to be transferred from the automated vehicle to the crewed vehicle.[40]

- Lunar Orbit Rendezvous (LOR): This turned out to be the winning configuration, which achieved the goal with Apollo 11 on July 20, 1969: a single Saturn V launched a 96,886-pound (43,947 kg) spacecraft that was composed of a 63,608-pound (28,852 kg) Apollo command and service module which remained in orbit around the Moon and a 33,278-pound (15,095 kg) two-stage Apollo Lunar Module spacecraft which was flown by two astronauts to the surface, flown back to dock with the command module and was then discarded.[41] Landing the smaller spacecraft on the Moon, and returning an even smaller part (10,042 pounds or 4,555 kilograms) to lunar orbit, minimized the total mass to be launched from Earth, but this was the last method initially considered because of the perceived risk of rendezvous and docking.

In early 1961, direct ascent was generally the mission mode in favor at NASA. Many engineers feared that rendezvous and docking, maneuvers that had not been attempted in Earth orbit, would be nearly impossible in lunar orbit. LOR advocates including John Houbolt at Langley Research Center emphasized the important weight reductions that were offered by the LOR approach. Throughout 1960 and 1961, Houbolt campaigned for the recognition of LOR as a viable and practical option. Bypassing the NASA hierarchy, he sent a series of memos and reports on the issue to Associate Administrator Robert Seamans; while acknowledging that he spoke "somewhat as a voice in the wilderness", Houbolt pleaded that LOR should not be discounted in studies of the question.[42]

Seamans's establishment of an ad hoc committee headed by his special technical assistant Nicholas E. Golovin in July 1961, to recommend a launch vehicle to be used in the Apollo program, represented a turning point in NASA's mission mode decision.[43] This committee recognized that the chosen mode was an important part of the launch vehicle choice, and recommended in favor of a hybrid EOR-LOR mode. Its consideration of LOR—as well as Houbolt's ceaseless work—played an important role in publicizing the workability of the approach. In late 1961 and early 1962, members of the Manned Spacecraft Center began to come around to support LOR, including the newly hired deputy director of the Office of Manned Space Flight, Joseph Shea, who became a champion of LOR.[44] The engineers at Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), who were heavily invested in direct ascent, took longer to become convinced of its merits, but their conversion was announced by Wernher von Braun at a briefing on June 7, 1962.[45]

But even after NASA reached internal agreement, it was far from smooth sailing. Kennedy's science advisor Jerome Wiesner, who had expressed his opposition to human spaceflight to Kennedy before the President took office,[46] and had opposed the decision to land people on the Moon, hired Golovin, who had left NASA, to chair his own "Space Vehicle Panel", ostensibly to monitor, but actually to second-guess NASA's decisions on the Saturn V launch vehicle and LOR by forcing Shea, Seamans, and even Webb to defend themselves, delaying its formal announcement to the press on July 11, 1962, and forcing Webb to still hedge the decision as "tentative".[47]

Wiesner kept up the pressure, even making the disagreement public during a two-day September visit by the President to Marshall Space Flight Center. Wiesner blurted out "No, that's no good" in front of the press, during a presentation by von Braun. Webb jumped in and defended von Braun, until Kennedy ended the squabble by stating that the matter was "still subject to final review". Webb held firm and issued a request for proposal to candidate Lunar Excursion Module (LEM) contractors. Wiesner finally relented, unwilling to settle the dispute once and for all in Kennedy's office, because of the President's involvement with the October Cuban Missile Crisis, and fear of Kennedy's support for Webb. NASA announced the selection of Grumman as the LEM contractor in November 1962.[48]

Space historian James Hansen concludes that:

Without NASA's adoption of this stubbornly held minority opinion in 1962, the United States may still have reached the Moon, but almost certainly it would not have been accomplished by the end of the 1960s, President Kennedy's target date.[49]

The LOR method had the advantage of allowing the lander spacecraft to be used as a "lifeboat" in the event of a failure of the command ship. Some documents prove this theory was discussed before and after the method was chosen. In 1964 an MSC study concluded, "The LM [as lifeboat] ... was finally dropped, because no single reasonable CSM failure could be identified that would prohibit use of the SPS."[50] Ironically, just such a failure happened on Apollo 13 when an oxygen tank explosion left the CSM without electrical power. The lunar module provided propulsion, electrical power and life support to get the crew home safely.[51]

Spacecraft

[edit]

Faget's preliminary Apollo design employed a cone-shaped command module, supported by one of several service modules providing propulsion and electrical power, sized appropriately for the space station, cislunar, and lunar landing missions. Once Kennedy's Moon landing goal became official, detailed design began of a command and service module (CSM) in which the crew would spend the entire direct-ascent mission and lift off from the lunar surface for the return trip, after being soft-landed by a larger landing propulsion module. The final choice of lunar orbit rendezvous changed the CSM's role to the translunar ferry used to transport the crew, along with a new spacecraft, the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM, later shortened to LM (Lunar Module) but still pronounced /ˈlɛm/) which would take two individuals to the lunar surface and return them to the CSM.[52]

Command and service module

[edit]

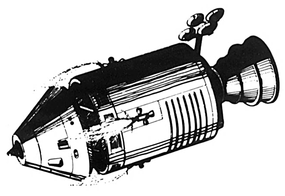

The command module (CM) was the conical crew cabin, designed to carry three astronauts from launch to lunar orbit and back to an Earth ocean landing. It was the only component of the Apollo spacecraft to survive without major configuration changes as the program evolved from the early Apollo study designs. Its exterior was covered with an ablative heat shield, and had its own reaction control system (RCS) engines to control its attitude and steer its atmospheric entry path. Parachutes were carried to slow its descent to splashdown. The module was 11.42 feet (3.48 m) tall, 12.83 feet (3.91 m) in diameter, and weighed approximately 12,250 pounds (5,560 kg).[53]

A cylindrical service module (SM) supported the command module, with a service propulsion engine and an RCS with propellants, and a fuel cell power generation system with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen reactants. A high-gain S-band antenna was used for long-distance communications on the lunar flights. On the extended lunar missions, an orbital scientific instrument package was carried. The service module was discarded just before reentry. The module was 24.6 feet (7.5 m) long and 12.83 feet (3.91 m) in diameter. The initial lunar flight version weighed approximately 51,300 pounds (23,300 kg) fully fueled, while a later version designed to carry a lunar orbit scientific instrument package weighed just over 54,000 pounds (24,000 kg).[53]

North American Aviation won the contract to build the CSM, and also the second stage of the Saturn V launch vehicle for NASA. Because the CSM design was started early before the selection of lunar orbit rendezvous, the service propulsion engine was sized to lift the CSM off the Moon, and thus was oversized to about twice the thrust required for translunar flight.[54] Also, there was no provision for docking with the lunar module. A 1964 program definition study concluded that the initial design should be continued as Block I which would be used for early testing, while Block II, the actual lunar spacecraft, would incorporate the docking equipment and take advantage of the lessons learned in Block I development.[52]

Apollo Lunar Module

[edit]

The Apollo Lunar Module (LM) was designed to descend from lunar orbit to land two astronauts on the Moon and take them back to orbit to rendezvous with the command module. Not designed to fly through the Earth's atmosphere or return to Earth, its fuselage was designed totally without aerodynamic considerations and was of an extremely lightweight construction. It consisted of separate descent and ascent stages, each with its own engine. The descent stage contained storage for the descent propellant, surface stay consumables, and surface exploration equipment. The ascent stage contained the crew cabin, ascent propellant, and a reaction control system. The initial LM model weighed approximately 33,300 pounds (15,100 kg), and allowed surface stays up to around 34 hours. An extended lunar module weighed over 36,200 pounds (16,400 kg), and allowed surface stays of more than three days.[53] The contract for design and construction of the lunar module was awarded to Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, and the project was overseen by Thomas J. Kelly.[55]

Launch vehicles

[edit]

Before the Apollo program began, Wernher von Braun and his team of rocket engineers had started work on plans for very large launch vehicles, the Saturn series, and the even larger Nova series. In the midst of these plans, von Braun was transferred from the Army to NASA and was made Director of the Marshall Space Flight Center. The initial direct ascent plan to send the three-person Apollo command and service module directly to the lunar surface, on top of a large descent rocket stage, would require a Nova-class launcher, with a lunar payload capability of over 180,000 pounds (82,000 kg).[56] The June 11, 1962, decision to use lunar orbit rendezvous enabled the Saturn V to replace the Nova, and the MSFC proceeded to develop the Saturn rocket family for Apollo.[57]

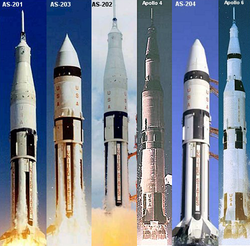

Since Apollo, like Mercury, used more than one launch vehicle for space missions, NASA used spacecraft-launch vehicle combination series numbers: AS-10x for Saturn I, AS-20x for Saturn IB, and AS-50x for Saturn V (compare Mercury-Redstone 3, Mercury-Atlas 6) to designate and plan all missions, rather than numbering them sequentially as in Project Gemini. This was changed by the time human flights began.[58]

Little Joe II

[edit]Since Apollo, like Mercury, would require a launch escape system (LES) in case of a launch failure, a relatively small rocket was required for qualification flight testing of this system. A rocket bigger than the Little Joe used by Mercury would be required, so the Little Joe II was built by General Dynamics/Convair. After an August 1963 qualification test flight,[59] four LES test flights (A-001 through 004) were made at the White Sands Missile Range between May 1964 and January 1966.[60]

Saturn I

[edit]

Saturn I, the first US heavy lift launch vehicle, was initially planned to launch partially equipped CSMs in low Earth orbit tests. The S-I first stage burned RP-1 with liquid oxygen (LOX) oxidizer in eight clustered Rocketdyne H-1 engines, to produce 1,500,000 pounds-force (6,670 kN) of thrust. The S-IV second stage used six liquid hydrogen-fueled Pratt & Whitney RL-10 engines with 90,000 pounds-force (400 kN) of thrust. The S-V third stage flew inactively on Saturn I four times.[61]

The first four Saturn I test flights were launched from LC-34, with only the first stage live, carrying dummy upper stages filled with water. The first flight with a live S-IV was launched from LC-37. This was followed by five launches of boilerplate CSMs (designated AS-101 through AS-105) into orbit in 1964 and 1965. The last three of these further supported the Apollo program by also carrying Pegasus satellites, which verified the safety of the translunar environment by measuring the frequency and severity of micrometeorite impacts.[62]

In September 1962, NASA planned to launch four crewed CSM flights on the Saturn I from late 1965 through 1966, concurrent with Project Gemini. The 22,500-pound (10,200 kg) payload capacity[63] would have severely limited the systems which could be included, so the decision was made in October 1963 to use the uprated Saturn IB for all crewed Earth orbital flights.[64]

Saturn IB

[edit]The Saturn IB was an upgraded version of the Saturn I. The S-IB first stage increased the thrust to 1,600,000 pounds-force (7,120 kN) by uprating the H-1 engine. The second stage replaced the S-IV with the S-IVB-200, powered by a single J-2 engine burning liquid hydrogen fuel with LOX, to produce 200,000 pounds-force (890 kN) of thrust.[65] A restartable version of the S-IVB was used as the third stage of the Saturn V. The Saturn IB could send over 40,000 pounds (18,100 kg) into low Earth orbit, sufficient for a partially fueled CSM or the LM.[66] Saturn IB launch vehicles and flights were designated with an AS-200 series number, "AS" indicating "Apollo Saturn" and the "2" indicating the second member of the Saturn rocket family.[67]

Saturn V

[edit]

Saturn V launch vehicles and flights were designated with an AS-500 series number, "AS" indicating "Apollo Saturn" and the "5" indicating Saturn V.[67] The three-stage Saturn V was designed to send a fully fueled CSM and LM to the Moon. It was 33 feet (10.1 m) in diameter and stood 363 feet (110.6 m) tall with its 96,800-pound (43,900 kg) lunar payload. Its capability grew to 103,600 pounds (47,000 kg) for the later advanced lunar landings. The S-IC first stage burned RP-1/LOX for a rated thrust of 7,500,000 pounds-force (33,400 kN), which was upgraded to 7,610,000 pounds-force (33,900 kN). The second and third stages burned liquid hydrogen; the third stage was a modified version of the S-IVB, with thrust increased to 230,000 pounds-force (1,020 kN) and capability to restart the engine for translunar injection after reaching a parking orbit.[68]

Astronauts

[edit]

NASA's director of flight crew operations during the Apollo program was Donald K. "Deke" Slayton, one of the original Mercury Seven astronauts who was medically grounded in September 1962 due to a heart murmur. Slayton was responsible for making all Gemini and Apollo crew assignments.[69]

Thirty-two astronauts were assigned to fly missions in the Apollo program. Twenty-four of these left Earth's orbit and flew around the Moon between December 1968 and December 1972 (three of them twice). Half of the 24 walked on the Moon's surface, though none of them returned to it after landing once. One of the moonwalkers was a trained geologist. Of the 32, Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee were killed during a ground test in preparation for the Apollo 1 mission.[58]

The Apollo astronauts were chosen from the Project Mercury and Gemini veterans, plus from two later astronaut groups. All missions were commanded by Gemini or Mercury veterans. Crews on all development flights (except the Earth orbit CSM development flights) through the first two landings on Apollo 11 and Apollo 12, included at least two (sometimes three) Gemini veterans. Harrison Schmitt, a geologist, was the first NASA scientist astronaut to fly in space, and landed on the Moon on the last mission, Apollo 17. Schmitt participated in the lunar geology training of all of the Apollo landing crews.[70]

NASA awarded all 32 of these astronauts its highest honor, the Distinguished Service Medal, given for "distinguished service, ability, or courage", and personal "contribution representing substantial progress to the NASA mission". The medals were awarded posthumously to Grissom, White, and Chaffee in 1969, then to the crews of all missions from Apollo 8 onward. The crew that flew the first Earth orbital test mission Apollo 7, Walter M. Schirra, Donn Eisele, and Walter Cunningham, were awarded the lesser NASA Exceptional Service Medal, because of discipline problems with the flight director's orders during their flight. In October 2008, the NASA Administrator decided to award them the Distinguished Service Medals. For Schirra and Eisele, this was posthumously.[71]

Lunar mission profile

[edit]The first lunar landing mission was planned to proceed:[72]

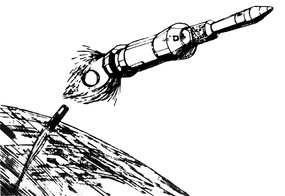

- Launch The three Saturn V stages burn for about 11 minutes to achieve a 100-nautical-mile (190 km) circular parking orbit. The third stage burns a small portion of its fuel to achieve orbit.

- Translunar injection After one to two orbits to verify readiness of spacecraft systems, the S-IVB third stage reignites for about six minutes to send the spacecraft to the Moon.

- Transposition and docking The Spacecraft Lunar Module Adapter (SLA) panels separate to free the CSM and expose the LM. The command module pilot (CMP) moves the CSM out a safe distance, and turns 180°.

- Extraction The CMP docks the CSM with the LM, and pulls the complete spacecraft away from the S-IVB. The lunar voyage takes between two and three days. Midcourse corrections are made as necessary using the SM engine.

- Lunar orbit insertion The spacecraft passes about 60 nautical miles (110 km) behind the Moon, and the SM engine is fired to slow the spacecraft and put it into a 60-by-170-nautical-mile (110 by 310 km) orbit, which is soon circularized at 60 nautical miles by a second burn.

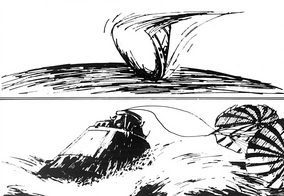

- After a rest period, the commander (CDR) and lunar module pilot (LMP) move to the LM, power up its systems, and deploy the landing gear. The CSM and LM separate; the CMP visually inspects the LM, then the LM crew move a safe distance away and fire the descent engine for Descent orbit insertion, which takes it to a perilune of about 50,000 feet (15 km).

- Powered descent At perilune, the descent engine fires again to start the descent. The CDR takes control after pitchover for a vertical landing.

- The CDR and LMP perform one or more EVAs exploring the lunar surface and collecting samples, alternating with rest periods.

- The ascent stage lifts off, using the descent stage as a launching pad.

- The LM rendezvouses and docks with the CSM.

- The CDR and LMP transfer back to the CM with their material samples, then the LM ascent stage is jettisoned, to eventually fall out of orbit and crash on the surface.

- Trans-Earth injection The SM engine fires to send the CSM back to Earth.

- The SM is jettisoned just before reentry, and the CM turns 180° to face its blunt end forward for reentry.

- Atmospheric drag slows the CM. Aerodynamic heating surrounds it with an envelope of ionized air which causes a communications blackout for several minutes.

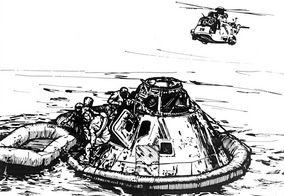

- Parachutes are deployed, slowing the CM for a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean. The astronauts are recovered and brought to an aircraft carrier.

Profile variations

[edit]- The first three lunar missions (Apollo 8, Apollo 10, and Apollo 11) used a free return trajectory, keeping a flight path coplanar with the lunar orbit, which would allow a return to Earth in case the SM engine failed to make lunar orbit insertion. Landing site lighting conditions on later missions dictated a lunar orbital plane change, which required a course change maneuver soon after TLI, and eliminated the free-return option.[73]

- After Apollo 12 placed the second of several seismometers on the Moon,[74] the jettisoned LM ascent stages on Apollo 12 and later missions were deliberately crashed on the Moon at known locations to induce vibrations in the Moon's structure. The only exceptions to this were the Apollo 13 LM which burned up in the Earth's atmosphere, and Apollo 16, where a loss of attitude control after jettison prevented making a targeted impact.[75]

- As another active seismic experiment, the S-IVBs on Apollo 13 and subsequent missions were deliberately crashed on the Moon instead of being sent to solar orbit.[76]

- Starting with Apollo 13, descent orbit insertion was to be performed using the service module engine instead of the LM engine, in order to allow a greater fuel reserve for landing. This was actually done for the first time on Apollo 14, since the Apollo 13 mission was aborted before landing.[77]

Development history

[edit]Uncrewed flight tests

[edit]

Two Block I CSMs were launched from LC-34 on suborbital flights in 1966 with the Saturn IB. The first, AS-201 launched on February 26, reached an altitude of 265.7 nautical miles (492.1 km) and splashed down 4,577 nautical miles (8,477 km) downrange in the Atlantic Ocean.[78] The second, AS-202 on August 25, reached 617.1 nautical miles (1,142.9 km) altitude and was recovered 13,900 nautical miles (25,700 km) downrange in the Pacific Ocean. These flights validated the service module engine and the command module heat shield.[79]

A third Saturn IB test, AS-203 launched from pad 37, went into orbit to support design of the S-IVB upper stage restart capability needed for the Saturn V. It carried a nose cone instead of the Apollo spacecraft, and its payload was the unburned liquid hydrogen fuel, the behavior of which engineers measured with temperature and pressure sensors, and a TV camera. This flight occurred on July 5, before AS-202, which was delayed because of problems getting the Apollo spacecraft ready for flight.[80]

Preparation for crewed flight

[edit]Two crewed orbital Block I CSM missions were planned: AS-204 and AS-205. The Block I crew positions were titled Command Pilot, Senior Pilot, and Pilot. The Senior Pilot would assume navigation duties, while the Pilot would function as a systems engineer.[81] The astronauts would wear a modified version of the Gemini spacesuit.[82]

After an uncrewed LM test flight AS-206, a crew would fly the first Block II CSM and LM in a dual mission known as AS-207/208, or AS-278 (each spacecraft would be launched on a separate Saturn IB).[83] The Block II crew positions were titled Commander, Command Module Pilot, and Lunar Module Pilot. The astronauts would begin wearing a new Apollo A6L spacesuit, designed to accommodate lunar extravehicular activity (EVA). The traditional visor helmet was replaced with a clear "fishbowl" type for greater visibility, and the lunar surface EVA suit would include a water-cooled undergarment.[84]

Deke Slayton, the grounded Mercury astronaut who became director of flight crew operations for the Gemini and Apollo programs, selected the first Apollo crew in January 1966, with Grissom as Command Pilot, White as Senior Pilot, and rookie Donn F. Eisele as Pilot. But Eisele dislocated his shoulder twice aboard the KC135 weightlessness training aircraft, and had to undergo surgery on January 27. Slayton replaced him with Chaffee.[85] NASA announced the final crew selection for AS-204 on March 21, 1966, with the backup crew consisting of Gemini veterans James McDivitt and David Scott, with rookie Russell L. "Rusty" Schweickart. Mercury/Gemini veteran Wally Schirra, Eisele, and rookie Walter Cunningham were announced on September 29 as the prime crew for AS-205.[85]

In December 1966, the AS-205 mission was canceled, since the validation of the CSM would be accomplished on the 14-day first flight, and AS-205 would have been devoted to space experiments and contribute no new engineering knowledge about the spacecraft. Its Saturn IB was allocated to the dual mission, now redesignated AS-205/208 or AS-258, planned for August 1967. McDivitt, Scott and Schweickart were promoted to the prime AS-258 crew, and Schirra, Eisele and Cunningham were reassigned as the Apollo 1 backup crew.[86]

Program delays

[edit]The spacecraft for the AS-202 and AS-204 missions were delivered by North American Aviation to the Kennedy Space Center with long lists of equipment problems which had to be corrected before flight; these delays caused the launch of AS-202 to slip behind AS-203, and eliminated hopes the first crewed mission might be ready to launch as soon as November 1966, concurrently with the last Gemini mission. Eventually, the planned AS-204 flight date was pushed to February 21, 1967.[87]

North American Aviation was prime contractor not only for the Apollo CSM, but for the Saturn V S-II second stage as well, and delays in this stage pushed the first uncrewed Saturn V flight AS-501 from late 1966 to November 1967. (The initial assembly of AS-501 had to use a dummy spacer spool in place of the stage.)[88]

The problems with North American were severe enough in late 1965 to cause Manned Space Flight Administrator George Mueller to appoint program director Samuel Phillips to head a "tiger team" to investigate North American's problems and identify corrections. Phillips documented his findings in a December 19 letter to NAA president Lee Atwood, with a strongly worded letter by Mueller, and also gave a presentation of the results to Mueller and Deputy Administrator Robert Seamans.[89] Meanwhile, Grumman was also encountering problems with the Lunar Module, eliminating hopes it would be ready for crewed flight in 1967, not long after the first crewed CSM flights.[90]

Apollo 1 fire

[edit]

Grissom, White, and Chaffee decided to name their flight Apollo 1 as a motivational focus on the first crewed flight. They trained and conducted tests of their spacecraft at North American, and in the altitude chamber at the Kennedy Space Center. A "plugs-out" test was planned for January, which would simulate a launch countdown on LC-34 with the spacecraft transferring from pad-supplied to internal power. If successful, this would be followed by a more rigorous countdown simulation test closer to the February 21 launch, with both spacecraft and launch vehicle fueled.[91]

The plugs-out test began on the morning of January 27, 1967, and immediately was plagued with problems. First, the crew noticed a strange odor in their spacesuits which delayed the sealing of the hatch. Then, communications problems frustrated the astronauts and forced a hold in the simulated countdown. During this hold, an electrical fire began in the cabin and spread quickly in the high pressure, 100% oxygen atmosphere. Pressure rose high enough from the fire that the cabin inner wall burst, allowing the fire to erupt onto the pad area and frustrating attempts to rescue the crew. The astronauts were asphyxiated before the hatch could be opened.[92]

NASA immediately convened an accident review board, overseen by both houses of Congress. While the determination of responsibility for the accident was complex, the review board concluded that "deficiencies existed in command module design, workmanship and quality control".[92] At the insistence of NASA Administrator Webb, North American removed Harrison Storms as command module program manager.[93] Webb also reassigned Apollo Spacecraft Program Office (ASPO) Manager Joseph Francis Shea, replacing him with George Low.[94]

To remedy the causes of the fire, changes were made in the Block II spacecraft and operational procedures, the most important of which were use of a nitrogen/oxygen mixture instead of pure oxygen before and during launch, and removal of flammable cabin and space suit materials.[95] The Block II design already called for replacement of the Block I plug-type hatch cover with a quick-release, outward opening door.[95] NASA discontinued the crewed Block I program, using the Block I spacecraft only for uncrewed Saturn V flights. Crew members would also exclusively wear modified, fire-resistant A7L Block II space suits, and would be designated by the Block II titles, regardless of whether a LM was present on the flight or not.[84]

Uncrewed Saturn V and LM tests

[edit]On April 24, 1967, Mueller published an official Apollo mission numbering scheme, using sequential numbers for all flights, crewed or uncrewed. The sequence would start with Apollo 4 to cover the first three uncrewed flights while retiring the Apollo 1 designation to honor the crew, per their widows' wishes.[58][96]

In September 1967, Mueller approved a sequence of mission types which had to be successfully accomplished in order to achieve the crewed lunar landing. Each step had to be successfully accomplished before the next ones could be performed, and it was unknown how many tries of each mission would be necessary; therefore letters were used instead of numbers. The A missions were uncrewed Saturn V validation; B was uncrewed LM validation using the Saturn IB; C was crewed CSM Earth orbit validation using the Saturn IB; D was the first crewed CSM/LM flight (this replaced AS-258, using a single Saturn V launch); E would be a higher Earth orbit CSM/LM flight; F would be the first lunar mission, testing the LM in lunar orbit but without landing (a "dress rehearsal"); and G would be the first crewed landing. The list of types covered follow-on lunar exploration to include H lunar landings, I for lunar orbital survey missions, and J for extended-stay lunar landings.[97]

The delay in the CSM caused by the fire enabled NASA to catch up on human-rating the LM and Saturn V. Apollo 4 (AS-501) was the first uncrewed flight of the Saturn V, carrying a Block I CSM on November 9, 1967. The capability of the command module's heat shield to survive a trans-lunar reentry was demonstrated by using the service module engine to ram it into the atmosphere at higher than the usual Earth-orbital reentry speed.

Apollo 5 (AS-204) was the first uncrewed test flight of the LM in Earth orbit, launched from pad 37 on January 22, 1968, by the Saturn IB that would have been used for Apollo 1. The LM engines were successfully test-fired and restarted, despite a computer programming error which cut short the first descent stage firing. The ascent engine was fired in abort mode, known as a "fire-in-the-hole" test, where it was lit simultaneously with jettison of the descent stage. Although Grumman wanted a second uncrewed test, George Low decided the next LM flight would be crewed.[98]

This was followed on April 4, 1968, by Apollo 6 (AS-502) which carried a CSM and a LM Test Article as ballast. The intent of this mission was to achieve trans-lunar injection, followed closely by a simulated direct-return abort, using the service module engine to achieve another high-speed reentry. The Saturn V experienced pogo oscillation, a problem caused by non-steady engine combustion, which damaged fuel lines in the second and third stages. Two S-II engines shut down prematurely, but the remaining engines were able to compensate. The damage to the third stage engine was more severe, preventing it from restarting for trans-lunar injection. Mission controllers were able to use the service module engine to essentially repeat the flight profile of Apollo 4. Based on the good performance of Apollo 6 and identification of satisfactory fixes to the Apollo 6 problems, NASA declared the Saturn V ready to fly crew, canceling a third uncrewed test.[99]

Crewed development missions

[edit]

Apollo 7, launched from LC-34 on October 11, 1968, was the C mission, crewed by Schirra, Eisele, and Cunningham. It was an 11-day Earth-orbital flight which tested the CSM systems.[100]

Apollo 8 was planned to be the D mission in December 1968, crewed by McDivitt, Scott and Schweickart, launched on a Saturn V instead of two Saturn IBs.[101] In the summer it had become clear that the LM would not be ready in time. Rather than waste the Saturn V on another simple Earth-orbiting mission, ASPO Manager George Low suggested the bold step of sending Apollo 8 to orbit the Moon instead, deferring the D mission to the next mission in March 1969, and eliminating the E mission. This would keep the program on track. The Soviet Union had sent two tortoises, mealworms, wine flies, and other lifeforms around the Moon on September 15, 1968, aboard Zond 5, and it was believed they might soon repeat the feat with human cosmonauts.[102][103] The decision was not announced publicly until successful completion of Apollo 7. Gemini veterans Frank Borman and Jim Lovell, and rookie William Anders captured the world's attention by making ten lunar orbits in 20 hours, transmitting television pictures of the lunar surface on Christmas Eve, and returning safely to Earth.[104]

The following March, LM flight, rendezvous and docking were successfully demonstrated in Earth orbit on Apollo 9, and Schweickart tested the full lunar EVA suit with its portable life support system (PLSS) outside the LM.[105] The F mission was successfully carried out on Apollo 10 in May 1969 by Gemini veterans Thomas P. Stafford, John Young and Eugene Cernan. Stafford and Cernan took the LM to within 50,000 feet (15 km) of the lunar surface.[106]

The G mission was achieved on Apollo 11 in July 1969 by an all-Gemini veteran crew consisting of Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin. Armstrong and Aldrin performed the first landing at the Sea of Tranquility at 20:17:40 UTC on July 20, 1969. They spent a total of 21 hours, 36 minutes on the surface, and spent 2 hours, 31 minutes outside the spacecraft,[107] walking on the surface, taking photographs, collecting material samples, and deploying automated scientific instruments, while continuously sending black-and-white television back to Earth. The astronauts returned safely on July 24.[108]

That's one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.

— Neil Armstrong, just after stepping onto the Moon's surface[109]

Production lunar landings

[edit]In November 1969, Charles "Pete" Conrad became the third person to step onto the Moon, which he did while speaking more informally than had Armstrong:

Whoopee! Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that's a long one for me.

— Pete Conrad[110]

Conrad and rookie Alan L. Bean made a precision landing of Apollo 12 within walking distance of the Surveyor 3 uncrewed lunar probe, which had landed in April 1967 on the Ocean of Storms. The command module pilot was Gemini veteran Richard F. Gordon Jr. Conrad and Bean carried the first lunar surface color television camera, but it was damaged when accidentally pointed into the Sun. They made two EVAs totaling 7 hours and 45 minutes.[107] On one, they walked to the Surveyor, photographed it, and removed some parts which they returned to Earth.[111]

The contracted batch of 15 Saturn Vs was enough for lunar landing missions through Apollo 20. Shortly after Apollo 11, NASA publicized a preliminary list of eight more planned landing sites after Apollo 12, with plans to increase the mass of the CSM and LM for the last five missions, along with the payload capacity of the Saturn V. These final missions would combine the I and J types in the 1967 list, allowing the CMP to operate a package of lunar orbital sensors and cameras while his companions were on the surface, and allowing them to stay on the Moon for over three days. These missions would also carry the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) increasing the exploration area and allowing televised liftoff of the LM. Also, the Block II spacesuit was revised for the extended missions to allow greater flexibility and visibility for driving the LRV.[112]

The success of the first two landings allowed the remaining missions to be crewed with a single veteran as commander, with two rookies. Apollo 13 launched Lovell, Jack Swigert, and Fred Haise in April 1970, headed for the Fra Mauro formation. But two days out, a liquid oxygen tank exploded, disabling the service module and forcing the crew to use the LM as a "lifeboat" to return to Earth. Another NASA review board was convened to determine the cause, which turned out to be a combination of damage of the tank in the factory, and a subcontractor not making a tank component according to updated design specifications.[51] Apollo was grounded again, for the remainder of 1970 while the oxygen tank was redesigned and an extra one was added.[113]

Mission cutbacks

[edit]About the time of the first landing in 1969, it was decided to use an existing Saturn V to launch the Skylab orbital laboratory pre-built on the ground, replacing the original plan to construct it in orbit from several Saturn IB launches; this eliminated Apollo 20. NASA's yearly budget also began to shrink in light of the successful landing, and NASA also had to make funds available for the development of the upcoming Space Shuttle. By 1971, the decision was made to also cancel missions 18 and 19.[114] The two unused Saturn Vs became museum exhibits at the John F. Kennedy Space Center on Merritt Island, Florida, George C. Marshall Space Center in Huntsville, Alabama, Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.[115]

The cutbacks forced mission planners to reassess the original planned landing sites in order to achieve the most effective geological sample and data collection from the remaining four missions. Apollo 15 had been planned to be the last of the H series missions, but since there would be only two subsequent missions left, it was changed to the first of three J missions.[116]

Apollo 13's Fra Mauro mission was reassigned to Apollo 14, commanded in February 1971 by Mercury veteran Alan Shepard, with Stuart Roosa and Edgar Mitchell.[117] This time the mission was successful. Shepard and Mitchell spent 33 hours and 31 minutes on the surface,[118] and completed two EVAs totalling 9 hours 24 minutes, which was a record for the longest EVA by a lunar crew at the time.[117]

In August 1971, just after conclusion of the Apollo 15 mission, President Richard Nixon proposed canceling the two remaining lunar landing missions, Apollo 16 and 17. Office of Management and Budget Deputy Director Caspar Weinberger was opposed to this, and persuaded Nixon to keep the remaining missions.[119]

Extended missions

[edit]

Apollo 15 was launched on July 26, 1971, with David Scott, Alfred Worden and James Irwin. Scott and Irwin landed on July 30 near Hadley Rille, and spent just under two days, 19 hours on the surface. In over 18 hours of EVA, they collected about 77 kilograms (170 lb) of lunar material.[120]

Apollo 16 landed in the Descartes Highlands on April 20, 1972. The crew was commanded by John Young, with Ken Mattingly and Charles Duke. Young and Duke spent just under three days on the surface, with a total of over 20 hours EVA.[121]

Apollo 17 was the last of the Apollo program, landing in the Taurus–Littrow region in December 1972. Eugene Cernan commanded Ronald E. Evans and NASA's first scientist-astronaut, geologist Harrison H. Schmitt.[122] Schmitt was originally scheduled for Apollo 18,[123] but the lunar geological community lobbied for his inclusion on the final lunar landing.[124] Cernan and Schmitt stayed on the surface for just over three days and spent just over 23 hours of total EVA.[122]

Canceled missions

[edit]Several missions were planned for but were canceled before details were finalized.

Mission summary

[edit]| Designation | Date | Launch vehicle | CSM | LM | Crew | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS-201 | Feb 26, 1966 | AS-201 | CSM-009 | None | None | First flight of Saturn IB and Block I CSM; suborbital to Atlantic Ocean; qualified heat shield to orbital reentry speed. |

| AS-203 | Jul 5, 1966 | AS-203 | None | None | None | No spacecraft; observations of liquid hydrogen fuel behavior in orbit, to support design of S-IVB restart capability. |

| AS-202 | Aug 25, 1966 | AS-202 | CSM-011 | None | None | Suborbital flight of CSM to Pacific Ocean. |

| Apollo 1 | Feb 21, 1967 | SA-204 | CSM-012 | None | Gus Grissom Ed White Roger B. Chaffee | Not flown. All crew members died in a fire during a launch pad test on January 27, 1967. |

| Apollo 4 | Nov 9, 1967 | SA-501 | CSM-017 | LTA-10R | None | First test flight of Saturn V, placed a CSM in a high Earth orbit; demonstrated S-IVB restart; qualified CM heat shield to lunar reentry speed. |

| Apollo 5 | Jan 22–23, 1968 | SA-204 | None | LM-1 | None | Earth orbital flight test of LM, launched on Saturn IB; demonstrated ascent and descent propulsion; human-rated the LM. |

| Apollo 6 | Apr 4, 1968 | SA-502 | CM-020 SM-014 | LTA-2R | None | Uncrewed, second flight of Saturn V, attempted demonstration of trans-lunar injection, and direct-return abort using SM engine; three engine failures, including failure of S-IVB restart. Flight controllers used SM engine to repeat Apollo 4's flight profile. Human-rated the Saturn V. |

| Apollo 7 | Oct 11–22, 1968 | SA-205 | CSM-101 | None | Wally Schirra Walt Cunningham Donn Eisele | First crewed Earth orbital demonstration of Block II CSM, launched on Saturn IB. First live television broadcast from a crewed mission. |

| Apollo 8 | Dec 21–27, 1968 | SA-503 | CSM-103 | LTA-B | Frank Borman James Lovell William Anders | First crewed flight of Saturn V; First crewed flight to Moon; CSM made 10 lunar orbits in 20 hours. |

| Apollo 9 | Mar 3–13, 1969 | SA-504 | CSM-104 Gumdrop | LM-3 Spider | James McDivitt David Scott Russell Schweickart | Second crewed flight of Saturn V; First crewed flight of CSM and LM in Earth orbit; demonstrated portable life support system to be used on the lunar surface. |

| Apollo 10 | May 18–26, 1969 | SA-505 | CSM-106 Charlie Brown | LM-4 Snoopy | Thomas Stafford John Young Eugene Cernan | Dress rehearsal for first lunar landing; flew LM down to 50,000 feet (15 km) from lunar surface. |

| Apollo 11 | Jul 16–24, 1969 | SA-506 | CSM-107 Columbia | LM-5 Eagle | Neil Armstrong Michael Collins Buzz Aldrin | First crewed landing, in Tranquility Base, Sea of Tranquility. Surface EVA time: 2:31 hr. Samples returned: 47.51 pounds (21.55 kg). |

| Apollo 12 | Nov 14–24, 1969 | SA-507 | CSM-108 Yankee Clipper | LM-6 Intrepid | C. "Pete" Conrad Richard Gordon Alan Bean | Second landing, in Ocean of Storms near Surveyor 3. Surface EVA time: 7:45 hr. Samples returned: 75.62 pounds (34.30 kg). |

| Apollo 13 | Apr 11–17, 1970 | SA-508 | CSM-109 Odyssey | LM-7 Aquarius | James Lovell Jack Swigert Fred Haise | Third landing attempt aborted in transit to the Moon, due to SM failure. Crew used LM as "lifeboat" to return to Earth. Mission labeled as a "successful failure".[125] |

| Apollo 14 | Jan 31 – Feb 9, 1971 | SA-509 | CSM-110 Kitty Hawk | LM-8 Antares | Alan Shepard Stuart Roosa Edgar Mitchell | Third landing, in Fra Mauro formation, located northeast of the Ocean of Storms. Surface EVA time: 9:21 hr. Samples returned: 94.35 pounds (42.80 kg). |

| Apollo 15 | Jul 26 – Aug 7, 1971 | SA-510 | CSM-112 Endeavour | LM-10 Falcon | David Scott Alfred Worden James Irwin | First Extended LM and rover, landed in Hadley-Apennine, located near the Sea of Showers/Rains. Surface EVA time: 18:33 hr. Samples returned: 169.10 pounds (76.70 kg). |

| Apollo 16 | Apr 16–27, 1972 | SA-511 | CSM-113 Casper | LM-11 Orion | John Young T. Kenneth Mattingly Charles Duke | Landed in Plain of Descartes. Rover on Moon. Surface EVA time: 20:14 hr. Samples returned: 207.89 pounds (94.30 kg). |

| Apollo 17 | Dec 7–19, 1972 | SA-512 | CSM-114 America | LM-12 Challenger | Eugene Cernan Ronald Evans Harrison Schmitt | Only Saturn V night launch. Landed in Taurus–Littrow. Rover on Moon. First geologist on the Moon. Apollo's last crewed Moon landing. Surface EVA time: 22:02 hr. Samples returned: 243.40 pounds (110.40 kg). |

Source: Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference (Orloff 2004)[126]

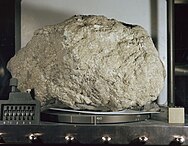

Samples returned

[edit]The Apollo program returned over 382 kg (842 lb) of lunar rocks and soil to the Lunar Receiving Laboratory in Houston.[127][126][128] Today, 75% of the samples are stored at the Lunar Sample Laboratory Facility built in 1979.[129]

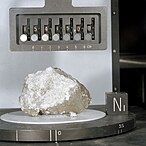

датирования , камни, собранные на Луне, чрезвычайно старые по сравнению с камнями, найденными на Земле По данным радиометрических методов . Их возраст варьируется от примерно 3,2 миллиарда лет для образцов базальта , полученных из лунных морей , до примерно 4,6 миллиардов лет для образцов, полученных из горной коры. [130] As such, they represent samples from a very early period in the development of the Solar System, that are largely absent on Earth. One important rock found during the Apollo Program is dubbed the Genesis Rock, retrieved by astronauts David Scott and James Irwin during the Apollo 15 mission.[131] Эта анортозитовая порода состоит почти исключительно из богатого кальцием минерала полевого шпата анортита и считается представителем горной коры. [132] Геохимический компонент под названием KREEP был обнаружен Аполлоном-12 и не имеет известных земных аналогов. [133] KREEP и образцы анортозита были использованы для вывода о том, что внешняя часть Луны когда-то была полностью расплавленной (см. Лунный океан магмы ). [134]

Почти все породы имеют следы воздействия ударного процесса. Многие образцы, по-видимому, изрыты ударными кратерами микрометеороидов , которые никогда не наблюдаются на земных породах из-за плотной атмосферы. Многие из них имеют признаки воздействия ударных волн высокого давления, возникающих во время ударов. Некоторые из возвращенных образцов представляют собой ударное расплавление (материалы, расплавленные вблизи ударного кратера). Все образцы, возвращенные с Луны, имеют сильную брекчию в результате многократного воздействия ударов. [135]

На основании анализа состава возвращенных лунных образцов теперь считается, что Луна была создана в результате столкновения большого астрономического тела с Землей. [136]

Затраты

[ редактировать ]Стоимость «Аполлона» составила 25,4 миллиарда долларов, или примерно 257 миллиардов долларов (2023 г.), если судить по улучшенному анализу затрат. [137]

Из этой суммы 20,2 миллиарда долларов (145 миллиардов долларов с учетом поправок) было потрачено на проектирование, разработку и производство семейства «Сатурн» ракет-носителей , космического корабля «Аполлон» , скафандров , научных экспериментов и операций миссии. Стоимость строительства и эксплуатации наземных объектов, связанных с Аполлоном, таких как центры пилотируемых космических полетов НАСА и глобальная сеть слежения и сбора данных , добавила дополнительные 5,2 миллиарда долларов (скорректированные 37,3 миллиарда долларов).

затраты на сопутствующие проекты, такие как Project Gemini и программы роботизированного рейнджера , Surveyor и Lunar Orbiter . Сумма вырастет до 28 миллиардов долларов (с учетом поправок на 280 миллиардов долларов), если включить [1]

Официальная структура расходов НАСА, представленная Конгрессу весной 1973 года, выглядит следующим образом:

| Проект Аполлон | Стоимость (исходная, млрд $) |

|---|---|

| Космический корабль Аполлон | 8.5 |

| Ракеты-носители Сатурна | 9.1 |

| Разработка двигателя ракеты-носителя | 0.9 |

| Операции | 1.7 |

| Всего НИОКР | 20.2 |

| Отслеживание и сбор данных | 0.9 |

| Наземные объекты | 1.8 |

| Эксплуатация установок | 2.5 |

| Общий | 25.4 |

Точная оценка затрат на пилотируемые космические полеты была затруднена в начале 1960-х годов, поскольку возможности были новыми, а опыта управления отсутствовало. Предварительный анализ стоимости НАСА оценил 7–12 миллиардов долларов на высадку экипажа на Луну. Администратор НАСА Джеймс Уэбб увеличил эту оценку до 20 миллиардов долларов, прежде чем сообщить об этом вице-президенту Джонсону в апреле 1961 года. [138]

Проект «Аполлон» был масштабным мероприятием, представляющим собой крупнейший научно-исследовательский проект в мирное время. На пике своего развития в нем работало более 400 000 сотрудников и подрядчиков по всей стране, и на его долю приходилось более половины общих расходов НАСА в 1960-х годах. [139] После первой высадки на Луну общественный и политический интерес ослабел, в том числе интерес президента Никсона, который хотел обуздать федеральные расходы. [140] Бюджет НАСА не мог поддерживать миссии «Аполлон», стоимость которых в среднем составляла 445 миллионов долларов (с учетом поправок на 2,66 миллиарда долларов). [141] каждый, одновременно разрабатывая космический шаттл . Последним финансовым годом финансирования Apollo стал 1973 год.

Программа приложений Apollo

[ редактировать ]Помимо высадки экипажа на Луну, НАСА исследовало несколько постлунных применений оборудования Аполлона. Серия расширения Apollo ( Apollo X ) предполагала до 30 полетов на околоземную орбиту с использованием пространства в адаптере лунного модуля космического корабля (SLA) для размещения небольшой орбитальной лаборатории (мастерской). Астронавты будут продолжать использовать CSM в качестве парома на станцию. За этим исследованием последовало проектирование более крупной орбитальной мастерской, которая будет построена на орбите из пустой верхней ступени S-IVB Saturn и перерастет в Программу приложений Apollo (AAP). Мастерскую должна была дополнить телескопическая установка «Аполлон» , которую можно было прикрепить к подъемной ступени лунного модуля через стойку. [142] Самый амбициозный план предусматривал использование пустого S-IVB в качестве межпланетного космического корабля для полета к Венере . [143]

Орбитальная мастерская S-IVB была единственным из этих планов, который еще не был реализован. Названный «Скайлэб» , он был собран на земле, а не в космосе, и запущен в 1973 году с использованием двух нижних ступеней «Сатурна-5». Он был оснащен телескопической монтировкой «Аполлон». Последний экипаж Скайлэба покинул станцию 8 февраля 1974 года, а сама станция вновь вошла в атмосферу в 1979 году после того, как разработка космического корабля "Шаттл" была отложена слишком надолго, чтобы его спасти. [144] [145]

Программа «Аполлон-Союз» также использовала оборудование «Аполлона» для первого совместного космического полета стран, открывая путь для будущего сотрудничества с другими странами в программах «Спейс Шаттл» и «Международная космическая станция» . [145] [146]

Недавние наблюдения

[ редактировать ]

В 2008 году аэрокосмических исследований Японского агентства зонд SELENE обнаружил следы гало, окружающего взрывной кратер лунного модуля Аполлона-15, когда он находился на орбите над поверхностью Луны. [147]

НАСА Начиная с 2009 года роботизированный лунный разведывательный орбитальный аппарат , находясь на высоте 50 километров (31 миль) над Луной, фотографировал остатки программы «Аполлон», оставленные на поверхности Луны, и каждое место, где приземлялись полеты «Аполлонов» с экипажем. [148] [149] Было обнаружено, что все флаги США, оставленные на Луне во время миссий «Аполлон», все еще стоят, за исключением флага, оставшегося во время миссии «Аполлон-11», который был унесен ветром во время отрыва этой миссии от лунной поверхности; степень, в которой эти флаги сохраняют свои первоначальные цвета, остается неизвестной. [150] Флаги невозможно увидеть в телескоп с Земли.

В редакционной статье The New York Times от 16 ноября 2009 г. высказывалось мнение:

[T] Есть что-то ужасно задумчивое в этих фотографиях мест посадки Аполлона. Детали таковы, что если бы Нил Армстронг шел сейчас там, мы могли бы его разглядеть, даже разглядеть его шаги, как тропу астронавта, хорошо видную на фотографиях места расположения Аполлона-14. Возможно, эта тоска вызвана чувством простого величия миссий Аполлона. Возможно, это также напоминание о риске, который мы все почувствовали после приземления «Орла» — о возможности того, что он не сможет снова взлететь, и астронавты окажутся на Луне. Но также возможно, что фотография, подобная этой, максимально близка к тому, чтобы заглянуть прямо в человеческое прошлое ...Там стоит лунный модуль [Аполлон-11], припаркованный именно там, где он приземлился 40 лет назад, как если бы он действительно находился 40 лет назад и все это время было просто воображаемым. [151]

Наследие

[ редактировать ]Наука и техника

[ редактировать ]Программу «Аполлон» называют величайшим технологическим достижением в истории человечества. [152] Apollo стимулировал многие области технологий, что привело к созданию более 1800 дополнительных продуктов по состоянию на 2015 год, включая достижения в разработке аккумуляторных электроинструментов, огнеупорных материалов , кардиомониторов , солнечных панелей , цифровых изображений и использования жидкого метана в качестве топлива. [153] [154] [155] Конструкция бортового компьютера, используемая как в лунном, так и в командном модулях, наряду с ракетными системами Polaris и Minuteman , стала движущей силой ранних исследований в области интегральных схем (ИС). К 1963 году Apollo использовала 60 процентов производства микросхем в США. Решающее различие между требованиями «Аполлона» и ракетными программами заключалось в гораздо большей потребности «Аполлона» в надежности. Хотя ВМС и ВВС могли решить проблемы с надежностью, развернув больше ракет, политические и финансовые издержки провала миссии «Аполлон» были неприемлемо высокими. [156]

Технологии и методы, необходимые для «Аполлона», были разработаны проектом «Близнецы». [157] Проект «Аполлон» стал возможным благодаря внедрению НАСА новых достижений в области полупроводниковых электронных технологий , включая полевые транзисторы металл-оксид-полупроводник (MOSFET) на Межпланетной платформе мониторинга (IMP). [158] [159] и кремниевые интегральные схемы в управляющем компьютере Apollo (AGC). [160]

Культурное влияние

[ редактировать ]

экипаж «Аполлона-8» отправил на Землю первые телеизображения Земли и Луны в прямом эфире и зачитал историю сотворения мира из Книги Бытия . В канун Рождества 1968 года [161] По оценкам, четверть населения мира видела – в прямом эфире или с задержкой – передачу в канун Рождества во время девятого витка Луны. [162] и примерно одна пятая населения мира смотрела прямую трансляцию лунной прогулки Аполлона-11. [163]

Программа «Аполлон» также повлияла на экологическую активность в 1970-х годах благодаря фотографиям, сделанным астронавтами. Наиболее известные из них — «Восход Земли» , снятый Уильямом Андерсом на корабле «Аполлон-8», и «Голубой мрамор» , снятый астронавтами «Аполлона-17». «Голубой мрамор» был выпущен во время всплеска защиты окружающей среды и стал символом экологического движения как изображение хрупкости, уязвимости и изоляции Земли на фоне огромных космических просторов. [164]

По данным The Economist , «Аполлону» удалось достичь цели президента Кеннеди — сразиться с Советским Союзом в космической гонке , совершив уникальное и значительное достижение, продемонстрировав превосходство системы свободного рынка . Издание отметило иронию того, что для достижения цели программа потребовала организации огромных государственных ресурсов в рамках огромной централизованной правительственной бюрократии. [165]

Проект восстановления данных трансляции Аполлона-11

[ редактировать ]Перед 40-летием Аполлона-11 в 2009 году НАСА искало оригинальные видеозаписи лунной прогулки миссии, транслируемой в прямом эфире по телевидению. После изнурительных трехлетних поисков был сделан вывод, что записи, вероятно, были стерты и использованы повторно. Вместо этого была выпущена новая обновленная в цифровом формате версия лучших доступных телевизионных кадров. [166]

Изображения в фильме

[ редактировать ]Документальные фильмы

[ редактировать ]Многочисленные документальные фильмы посвящены программе «Аполлон» и космической гонке, в том числе:

- Следы на Луне (1969)

- Лунная походка-1 (1970) [167]

- Величайшее приключение (1978) [168]

- Для всего человечества (1989) [169]

- Лунный выстрел (мини-сериал, 1994)

- «Луна» из мини-сериала BBC «Планеты » (1999).

- Великолепное запустение: Прогулка по Луне 3D (2005)

- Чудо всего этого (2007)

- В тени луны (2007) [170]

- Когда мы покинули Землю: Миссии НАСА (мини-сериал, 2008 г.)

- Лунные машины (мини-сериал, 2008 г.)

- Джеймс Мэй на Луне (2009)

- История НАСА (мини-сериал, 2009 г.)

- Аполлон-11 (2019) [171] [172]

- В погоне за Луной (мини-сериал, 2019)

Документальные драмы

[ редактировать ]Некоторые миссии были драматизированы :

- Аполлон-13 (1995)

- Аполлон-11 (1996)

- С Земли на Луну (1998)

- Блюдо (2000)

- Космическая гонка (2005)

- Лунный выстрел (2009)

- Первый человек (2018)

Вымышленный

[ редактировать ]Программа «Аполлон» была в центре внимания нескольких художественных произведений, в том числе:

- Аполлон-18 (2011), фильм ужасов , получивший отрицательные отзывы.

- Люди в черном 3 (2012), научно-фантастический/комедия. Агент Джей , которого играет Уилл Смит, возвращается к запуску «Аполлона-11» в 1969 году, чтобы обеспечить запуск глобальной системы защиты в космос.

- Для всего человечества (2019), сериал, изображающий альтернативную историю , в которой Советский Союз был первой страной, успешно высадившей человека на Луну.

- «Индиана Джонс и циферблат судьбы» (2023), пятый фильм об Индиане Джонсе , в котором Юрген Феллер, член НАСА и бывший нацист, участвовавший в программе «Аполлон», хочет путешествовать во времени. В качестве сюжетной линии изображен парад экипажа Аполлона-11 в Нью-Йорке. [173]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Аполлон-11 в популярной культуре

- Пакет экспериментов «Аполлон» на лунной поверхности

- Исследование Луны

- Коллекция Лесли Кэнтуэлл

- Список искусственных объектов на Луне

- Список пилотируемых космических кораблей

- Список миссий на Луну

- Советские пилотируемые лунные программы

- Украденные и пропавшие лунные камни

- Программа Артемида

Примечания

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Сколько стоила программа «Аполлон»?» . Планетарное общество . Проверено 25 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «20 июля 1969 года: гигантский скачок для человечества — НАСА» . 20 июля 2019 г.

- ^ Мюррей и Кокс 1989 , с. 55

- ^ «Выпуск 69-36» (Пресс-релиз). Кливленд, Огайо: Исследовательский центр Льюиса . 14 июля 1969 года . Проверено 21 июня 2012 г.

- ^ «Проект Олимп (1962)» . ПРОВОДНОЙ . 2 сентября 2013 года . Проверено 12 октября 2023 г.

- ^ Брукс, Гримвуд и Свенсон 1979 , гл. 1.7: «ТЭО» . стр. 16–21.

- ^ Пребл, Кристофер А. (2003). « Кто когда-либо верил в« ракетный разрыв »?»: Джон Ф. Кеннеди и политика национальной безопасности». Ежеквартальный журнал президентских исследований . 33 (4): 813. doi : 10.1046/j.0360-4918.2003.00085.x . JSTOR 27552538 .

- ^ Решено в 1997 г.

- ^ Сиди 1963 , стр. 117–118

- ^ Решение 1997 г. , с. 55

- ^ 87-й Конгресс 1961 г.

- ^ Сиди 1963 , с. 114

- ^ Кеннеди, Джон Ф. (20 апреля 1961 г.). «Меморандум вице-президенту» . Белый дом (Меморандум). Бостон, Массачусетс: Президентская библиотека и музей Джона Ф. Кеннеди . Архивировано из оригинала 21 июля 2016 года . Проверено 1 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Лауниус, Роджер Д. (июль 1994 г.). «Записка президента Джона Ф. Кеннеди для вице-президента от 20 апреля 1961 года» (PDF) . Аполлон: ретроспективный анализ (PDF) . Монографии по истории аэрокосмической промышленности. Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: НАСА. OCLC 31825096 . Архивировано (PDF) оригинала 9 октября 2022 г. Проверено 1 августа 2013 г. Ключевые исходные документы Apollo, заархивированные 8 ноября 2020 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Джонсон, Линдон Б. (28 апреля 1961 г.). «Меморандум Президенту» . Канцелярия вице-президента (Меморандум). Бостон, Массачусетс: Президентская библиотека и музей Джона Ф. Кеннеди. Архивировано из оригинала 1 июля 2016 года . Проверено 1 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Лауниус, Роджер Д. (июль 1994 г.). «Линдон Б. Джонсон, вице-президент, Памятка президенту «Оценка космической программы», 28 апреля 1961 г.» (PDF) . Аполлон: ретроспективный анализ (PDF) . Монографии по истории аэрокосмической промышленности. Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: НАСА. OCLC 31825096 . Архивировано (PDF) оригинала 9 октября 2022 г. Проверено 1 августа 2013 г. Ключевые исходные документы Apollo, заархивированные 8 ноября 2020 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Кеннеди, Джон Ф. (25 мая 1961 г.). Специальное послание Конгрессу о неотложных национальных потребностях (Кинофильм (отрывок)). Бостон, Массачусетс: Президентская библиотека и музей Джона Ф. Кеннеди. Инвентарный номер: TNC:200; цифровой идентификатор: TNC-200-2 . Проверено 1 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Мюррей и Кокс 1989 , стр. 16–17.

- ^ Зитцен, Франк (2 октября 1997 г.). «Советы планировали принять предложение Джона Кеннеди о совместной лунной миссии» . СпейсДейли . Служба новостей SpaceCast . Проверено 1 августа 2013 г.

- ^ «Союз – Разработка космической станции; Аполлон – Путешествие на Луну» . Проверено 12 июня 2016 г.

- ^ Брукс, Гримвуд и Свенсон 1979 , гл. 2.5: «Заключение контракта на командный модуль» . стр. 41–44.

- ^ Джонстон, Луи; Уильямсон, Сэмюэл Х. (2023). «Какой тогда был ВВП США?» . Измерительная ценность . Проверено 30 ноября 2023 г. США Показатели дефлятора валового внутреннего продукта соответствуют серии MeasuringWorth .

- ^ Аллен, Боб (ред.). «Вклад Исследовательского центра НАСА в Лэнгли в программу Аполлон» . Исследовательский центр Лэнгли . НАСА . Проверено 1 августа 2013 г.

- ^ «Исторические факты» . Исторический офис MSFC . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июня 2016 года . Проверено 7 июня 2016 г.

- ^ Свенсон, Лойд С. младший; Гримвуд, Джеймс М.; Александр, Чарльз К. (1989) [первоначально опубликовано в 1966 году]. «Глава 12.3: Космическая оперативная группа получила новый дом и имя» . Этот новый океан: история проекта «Меркурий» . Серия историй НАСА. Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: НАСА. OCLC 569889 . НАСА SP-4201. Архивировано из оригинала 13 июля 2009 года . Проверено 1 августа 2013 г.