Алюминий

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Алюминий | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Произношение |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative name | Aluminum (U.S., Canada) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | Silvery gray metallic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Al) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aluminium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 13 (boron group) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ne] 3s2 3p1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 933.47 K (660.32 °C, 1220.58 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2743[4] K (2470 °C, 4478 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (at 20 °C) | 2.699 g/cm3[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 2.375 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 10.71 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 284 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.20 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, −1, 0,[6] +1,[7] +2,[8] +3 (an amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.61 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 143 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 121±4 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 184 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc) (cF4) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lattice constant | a = 404.93 pm (at 20 °C)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 22.87×10−6/K (at 20 °C)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 237 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 26.5 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic[9] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +16.5×10−6 cm3/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 70 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 26 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 76 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | (rolled) 5000 m/s (at r.t.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.35 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 2.75 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 160–350 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 160–550 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7429-90-5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | from alumine, obsolete name for alumina | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prediction | Antoine Lavoisier (1782) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Hans Christian Ørsted (1824) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Named by | Humphry Davy (1812[a]) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of aluminium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

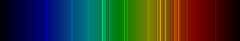

Алюминий (или алюминий на североамериканском английском ) является химическим элементом ; Он имеет символ и металлов атомный номер 13. Алюминий имеет плотность ниже, чем у других общих , примерно на треть стали . Он имеет большое сродство к кислороду , образуя защитный слой на оксида поверхности при воздействии воздуха. Алюминиевый визуально напоминает серебро , как по его цвету, так и в своей великой способности отражать свет. Он мягкий, немагнитный и пластичный . У него один стабильный изотоп, 27 AL, который очень распространен, делает алюминий двенадцатым общим элементом во вселенной. Радиоактивность 26 AL , более нестабильный изотоп, приводит к тому, что он используется в радиометрическом датировании .

Химически алюминий-это металл после трансляции в группе борона ; Как обычно для группы, алюминиевые формируют соединения, прежде всего, в состоянии окисления +3 . Алюминиевый катион al 3+ маленький и сильно заряженный ; Таким образом, он обладает большей поляризационной силой , а связи, образованные алюминием, имеют более ковалентный характер. Сильное сродство алюминия к кислороду приводит к общему появлению его оксидов в природе. Алюминий встречается на Земле в основном в скалах в коре , где он является третьим самым распространенным элементом , после кислорода и кремния , а не в мантии , и практически никогда не является свободным металлом . Он получается в промышленности с помощью горнодобывающего боксита , осадочной породы, богатой алюминиевыми минералами.

The discovery of aluminium was announced in 1825 by Danish physicist Hans Christian Ørsted. The first industrial production of aluminium was initiated by French chemist Henri Étienne Sainte-Claire Deville in 1856. Aluminium became much more available to the public with the Hall–Héroult process developed independently by French engineer Paul Héroult and American engineer Charles Martin Hall in 1886, and the mass production of aluminium led to its extensive use in industry and everyday life. In the First and Second World Wars, aluminium was a crucial strategic resource for aviation. In 1954, aluminium became the most produced non-ferrous metal, surpassing copper. In the 21st century, most aluminium was consumed in transportation, engineering, construction, and packaging in the United States, Western Europe, and Japan.

Despite its prevalence in the environment, no living organism is known to metabolize aluminium salts, but this aluminium is well tolerated by plants and animals. Because of the abundance of these salts, the potential for a biological role for them is of interest, and studies are ongoing.

Physical characteristics

Isotopes

Of aluminium isotopes, only 27

Al

is stable. This situation is common for elements with an odd atomic number.[b] It is the only primordial aluminium isotope, i.e. the only one that has existed on Earth in its current form since the formation of the planet. It is therefore a mononuclidic element and its standard atomic weight is virtually the same as that of the isotope. This makes aluminium very useful in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), as its single stable isotope has a high NMR sensitivity.[13] The standard atomic weight of aluminium is low in comparison with many other metals.[c]

All other isotopes of aluminium are radioactive. The most stable of these is 26Al: while it was present along with stable 27Al in the interstellar medium from which the Solar System formed, having been produced by stellar nucleosynthesis as well, its half-life is only 717,000 years and therefore a detectable amount has not survived since the formation of the planet.[14] However, minute traces of 26Al are produced from argon in the atmosphere by spallation caused by cosmic ray protons. The ratio of 26Al to 10Be has been used for radiodating of geological processes over 105 to 106 year time scales, in particular transport, deposition, sediment storage, burial times, and erosion.[15] Most meteorite scientists believe that the energy released by the decay of 26Al was responsible for the melting and differentiation of some asteroids after their formation 4.55 billion years ago.[16]

The remaining isotopes of aluminium, with mass numbers ranging from 21 to 43, all have half-lives well under an hour. Three metastable states are known, all with half-lives under a minute.[12]

Electron shell

An aluminium atom has 13 electrons, arranged in an electron configuration of [Ne] 3s2 3p1,[17] with three electrons beyond a stable noble gas configuration. Accordingly, the combined first three ionization energies of aluminium are far lower than the fourth ionization energy alone.[18] Such an electron configuration is shared with the other well-characterized members of its group, boron, gallium, indium, and thallium; it is also expected for nihonium. Aluminium can surrender its three outermost electrons in many chemical reactions (see below). The electronegativity of aluminium is 1.61 (Pauling scale).[19]

A free aluminium atom has a radius of 143 pm.[20] With the three outermost electrons removed, the radius shrinks to 39 pm for a 4-coordinated atom or 53.5 pm for a 6-coordinated atom.[20] At standard temperature and pressure, aluminium atoms (when not affected by atoms of other elements) form a face-centered cubic crystal system bound by metallic bonding provided by atoms' outermost electrons; hence aluminium (at these conditions) is a metal.[21] This crystal system is shared by many other metals, such as lead and copper; the size of a unit cell of aluminium is comparable to that of those other metals.[21] The system, however, is not shared by the other members of its group: boron has ionization energies too high to allow metallization, thallium has a hexagonal close-packed structure, and gallium and indium have unusual structures that are not close-packed like those of aluminium and thallium. The few electrons that are available for metallic bonding in aluminium are a probable cause for it being soft with a low melting point and low electrical resistivity.[22]

Bulk

Aluminium metal has an appearance ranging from silvery white to dull gray depending on its surface roughness.[d] Aluminium mirrors are the most reflective of all metal mirrors for near ultraviolet and far infrared light. It is also one of the most reflective for light in the visible spectrum, nearly on par with silver in this respect, and the two therefore look similar. Aluminium is also good at reflecting solar radiation, although prolonged exposure to sunlight in air adds wear to the surface of the metal; this may be prevented if aluminium is anodized, which adds a protective layer of oxide on the surface.

The density of aluminium is 2.70 g/cm3, about 1/3 that of steel, much lower than other commonly encountered metals, making aluminium parts easily identifiable through their lightness.[25] Aluminium's low density compared to most other metals arises from the fact that its nuclei are much lighter, while difference in the unit cell size does not compensate for this difference. The only lighter metals are the metals of groups 1 and 2, which apart from beryllium and magnesium are too reactive for structural use (and beryllium is very toxic).[26] Aluminium is not as strong or stiff as steel, but the low density makes up for this in the aerospace industry and for many other applications where light weight and relatively high strength are crucial.[27]

Pure aluminium is quite soft and lacking in strength. In most applications various aluminium alloys are used instead because of their higher strength and hardness.[28] The yield strength of pure aluminium is 7–11 MPa, while aluminium alloys have yield strengths ranging from 200 MPa to 600 MPa.[29] Aluminium is ductile, with a percent elongation of 50-70%,[30] and malleable allowing it to be easily drawn and extruded.[31] It is also easily machined and cast.[31]

Aluminium is an excellent thermal and electrical conductor, having around 60% the conductivity of copper, both thermal and electrical, while having only 30% of copper's density.[32] Aluminium is capable of superconductivity, with a superconducting critical temperature of 1.2 kelvin and a critical magnetic field of about 100 gauss (10 milliteslas).[33] It is paramagnetic and thus essentially unaffected by static magnetic fields.[34] The high electrical conductivity, however, means that it is strongly affected by alternating magnetic fields through the induction of eddy currents.[35]

Chemistry

Aluminium combines characteristics of pre- and post-transition metals. Since it has few available electrons for metallic bonding, like its heavier group 13 congeners, it has the characteristic physical properties of a post-transition metal, with longer-than-expected interatomic distances.[22] Furthermore, as Al3+ is a small and highly charged cation, it is strongly polarizing and bonding in aluminium compounds tends towards covalency;[36] this behavior is similar to that of beryllium (Be2+), and the two display an example of a diagonal relationship.[37]

The underlying core under aluminium's valence shell is that of the preceding noble gas, whereas those of its heavier congeners gallium, indium, thallium, and nihonium also include a filled d-subshell and in some cases a filled f-subshell. Hence, the inner electrons of aluminium shield the valence electrons almost completely, unlike those of aluminium's heavier congeners. As such, aluminium is the most electropositive metal in its group, and its hydroxide is in fact more basic than that of gallium.[36][e] Aluminium also bears minor similarities to the metalloid boron in the same group: AlX3 compounds are valence isoelectronic to BX3 compounds (they have the same valence electronic structure), and both behave as Lewis acids and readily form adducts.[38] Additionally, one of the main motifs of boron chemistry is regular icosahedral structures, and aluminium forms an important part of many icosahedral quasicrystal alloys, including the Al–Zn–Mg class.[39]

Aluminium has a high chemical affinity to oxygen, which renders it suitable for use as a reducing agent in the thermite reaction. A fine powder of aluminium reacts explosively on contact with liquid oxygen; under normal conditions, however, aluminium forms a thin oxide layer (~5 nm at room temperature)[40] that protects the metal from further corrosion by oxygen, water, or dilute acid, a process termed passivation.[36][41] Because of its general resistance to corrosion, aluminium is one of the few metals that retains silvery reflectance in finely powdered form, making it an important component of silver-colored paints.[42] Aluminium is not attacked by oxidizing acids because of its passivation. This allows aluminium to be used to store reagents such as nitric acid, concentrated sulfuric acid, and some organic acids.[43]

In hot concentrated hydrochloric acid, aluminium reacts with water with evolution of hydrogen, and in aqueous sodium hydroxide or potassium hydroxide at room temperature to form aluminates—protective passivation under these conditions is negligible.[44] Aqua regia also dissolves aluminium.[43] Aluminium is corroded by dissolved chlorides, such as common sodium chloride, which is why household plumbing is never made from aluminium.[44] The oxide layer on aluminium is also destroyed by contact with mercury due to amalgamation or with salts of some electropositive metals.[36] As such, the strongest aluminium alloys are less corrosion-resistant due to galvanic reactions with alloyed copper,[29] and aluminium's corrosion resistance is greatly reduced by aqueous salts, particularly in the presence of dissimilar metals.[22]

Aluminium reacts with most nonmetals upon heating, forming compounds such as aluminium nitride (AlN), aluminium sulfide (Al2S3), and the aluminium halides (AlX3). It also forms a wide range of intermetallic compounds involving metals from every group on the periodic table.[36]

Inorganic compounds

The vast majority of compounds, including all aluminium-containing minerals and all commercially significant aluminium compounds, feature aluminium in the oxidation state 3+. The coordination number of such compounds varies, but generally Al3+ is either six- or four-coordinate. Almost all compounds of aluminium(III) are colorless.[36]

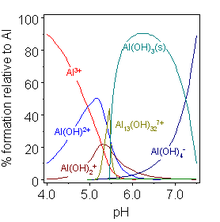

In aqueous solution, Al3+ exists as the hexaaqua cation [Al(H2O)6]3+, which has an approximate Ka of 10−5.[13] Such solutions are acidic as this cation can act as a proton donor and progressively hydrolyze until a precipitate of aluminium hydroxide, Al(OH)3, forms. This is useful for clarification of water, as the precipitate nucleates on suspended particles in the water, hence removing them. Increasing the pH even further leads to the hydroxide dissolving again as aluminate, [Al(H2O)2(OH)4]−, is formed.

Aluminium hydroxide forms both salts and aluminates and dissolves in acid and alkali, as well as on fusion with acidic and basic oxides.[36] This behavior of Al(OH)3 is termed amphoterism and is characteristic of weakly basic cations that form insoluble hydroxides and whose hydrated species can also donate their protons. One effect of this is that aluminium salts with weak acids are hydrolyzed in water to the aquated hydroxide and the corresponding nonmetal hydride: for example, aluminium sulfide yields hydrogen sulfide. However, some salts like aluminium carbonate exist in aqueous solution but are unstable as such; and only incomplete hydrolysis takes place for salts with strong acids, such as the halides, nitrate, and sulfate. For similar reasons, anhydrous aluminium salts cannot be made by heating their "hydrates": hydrated aluminium chloride is in fact not AlCl3·6H2O but [Al(H2O)6]Cl3, and the Al–O bonds are so strong that heating is not sufficient to break them and form Al–Cl bonds instead:[36]

- 2[Al(H2O)6]Cl3 Al2O3 + 6 HCl + 9 H2O

All four trihalides are well known. Unlike the structures of the three heavier trihalides, aluminium fluoride (AlF3) features six-coordinate aluminium, which explains its involatility and insolubility as well as high heat of formation. Each aluminium atom is surrounded by six fluorine atoms in a distorted octahedral arrangement, with each fluorine atom being shared between the corners of two octahedra. Such {AlF6} units also exist in complex fluorides such as cryolite, Na3AlF6.[f] AlF3 melts at 1,290 °C (2,354 °F) and is made by reaction of aluminium oxide with hydrogen fluoride gas at 700 °C (1,300 °F).[46]

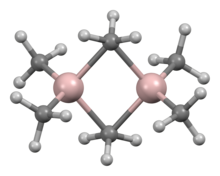

With heavier halides, the coordination numbers are lower. The other trihalides are dimeric or polymeric with tetrahedral four-coordinate aluminium centers.[g] Aluminium trichloride (AlCl3) has a layered polymeric structure below its melting point of 192.4 °C (378 °F) but transforms on melting to Al2Cl6 dimers. At higher temperatures those increasingly dissociate into trigonal planar AlCl3 monomers similar to the structure of BCl3. Aluminium tribromide and aluminium triiodide form Al2X6 dimers in all three phases and hence do not show such significant changes of properties upon phase change.[46] These materials are prepared by treating aluminium with the halogen. The aluminium trihalides form many addition compounds or complexes; their Lewis acidic nature makes them useful as catalysts for the Friedel–Crafts reactions. Aluminium trichloride has major industrial uses involving this reaction, such as in the manufacture of anthraquinones and styrene; it is also often used as the precursor for many other aluminium compounds and as a reagent for converting nonmetal fluorides into the corresponding chlorides (a transhalogenation reaction).[46]

Aluminium forms one stable oxide with the chemical formula Al2O3, commonly called alumina.[47] It can be found in nature in the mineral corundum, α-alumina;[48] there is also a γ-alumina phase.[13] Its crystalline form, corundum, is very hard (Mohs hardness 9), has a high melting point of 2,045 °C (3,713 °F), has very low volatility, is chemically inert, and a good electrical insulator, it is often used in abrasives (such as toothpaste), as a refractory material, and in ceramics, as well as being the starting material for the electrolytic production of aluminium. Sapphire and ruby are impure corundum contaminated with trace amounts of other metals.[13] The two main oxide-hydroxides, AlO(OH), are boehmite and diaspore. There are three main trihydroxides: bayerite, gibbsite, and nordstrandite, which differ in their crystalline structure (polymorphs). Many other intermediate and related structures are also known.[13] Most are produced from ores by a variety of wet processes using acid and base. Heating the hydroxides leads to formation of corundum. These materials are of central importance to the production of aluminium and are themselves extremely useful. Some mixed oxide phases are also very useful, such as spinel (MgAl2O4), Na-β-alumina (NaAl11O17), and tricalcium aluminate (Ca3Al2O6, an important mineral phase in Portland cement).[13]

The only stable chalcogenides under normal conditions are aluminium sulfide (Al2S3), selenide (Al2Se3), and telluride (Al2Te3). All three are prepared by direct reaction of their elements at about 1,000 °C (1,800 °F) and quickly hydrolyze completely in water to yield aluminium hydroxide and the respective hydrogen chalcogenide. As aluminium is a small atom relative to these chalcogens, these have four-coordinate tetrahedral aluminium with various polymorphs having structures related to wurtzite, with two-thirds of the possible metal sites occupied either in an orderly (α) or random (β) fashion; the sulfide also has a γ form related to γ-alumina, and an unusual high-temperature hexagonal form where half the aluminium atoms have tetrahedral four-coordination and the other half have trigonal bipyramidal five-coordination.[49]

Four pnictides – aluminium nitride (AlN), aluminium phosphide (AlP), aluminium arsenide (AlAs), and aluminium antimonide (AlSb) – are known. They are all III-V semiconductors isoelectronic to silicon and germanium, all of which but AlN have the zinc blende structure. All four can be made by high-temperature (and possibly high-pressure) direct reaction of their component elements.[49]

Aluminium alloys well with most other metals (with the exception of most alkali metals and group 13 metals) and over 150 intermetallics with other metals are known. Preparation involves heating fixed metals together in certain proportion, followed by gradual cooling and annealing. Bonding in them is predominantly metallic and the crystal structure primarily depends on efficiency of packing.[50]

There are few compounds with lower oxidation states. A few aluminium(I) compounds exist: AlF, AlCl, AlBr, and AlI exist in the gaseous phase when the respective trihalide is heated with aluminium, and at cryogenic temperatures.[46] A stable derivative of aluminium monoiodide is the cyclic adduct formed with triethylamine, Al4I4(NEt3)4. Al2O and Al2S also exist but are very unstable.[51] Very simple aluminium(II) compounds are invoked or observed in the reactions of Al metal with oxidants. For example, aluminium monoxide, AlO, has been detected in the gas phase after explosion[52] and in stellar absorption spectra.[53] More thoroughly investigated are compounds of the formula R4Al2 which contain an Al–Al bond and where R is a large organic ligand.[54]

Organoaluminium compounds and related hydrides

A variety of compounds of empirical formula AlR3 and AlR1.5Cl1.5 exist.[55] The aluminium trialkyls and triaryls are reactive, volatile, and colorless liquids or low-melting solids. They catch fire spontaneously in air and react with water, thus necessitating precautions when handling them. They often form dimers, unlike their boron analogues, but this tendency diminishes for branched-chain alkyls (e.g. Pri, Bui, Me3CCH2); for example, triisobutylaluminium exists as an equilibrium mixture of the monomer and dimer.[56][57] These dimers, such as trimethylaluminium (Al2Me6), usually feature tetrahedral Al centers formed by dimerization with some alkyl group bridging between both aluminium atoms. They are hard acids and react readily with ligands, forming adducts. In industry, they are mostly used in alkene insertion reactions, as discovered by Karl Ziegler, most importantly in "growth reactions" that form long-chain unbranched primary alkenes and alcohols, and in the low-pressure polymerization of ethene and propene. There are also some heterocyclic and cluster organoaluminium compounds involving Al–N bonds.[56]

The industrially most important aluminium hydride is lithium aluminium hydride (LiAlH4), which is used as a reducing agent in organic chemistry. It can be produced from lithium hydride and aluminium trichloride.[58] The simplest hydride, aluminium hydride or alane, is not as important. It is a polymer with the formula (AlH3)n, in contrast to the corresponding boron hydride that is a dimer with the formula (BH3)2.[58]

Natural occurrence

Space

Aluminium's per-particle abundance in the Solar System is 3.15 ppm (parts per million).[59][h] It is the twelfth most abundant of all elements and third most abundant among the elements that have odd atomic numbers, after hydrogen and nitrogen.[59] The only stable isotope of aluminium, 27Al, is the eighteenth most abundant nucleus in the universe. It is created almost entirely after fusion of carbon in massive stars that will later become Type II supernovas: this fusion creates 26Mg, which upon capturing free protons and neutrons, becomes aluminium. Some smaller quantities of 27Al are created in hydrogen burning shells of evolved stars, where 26Mg can capture free protons.[60] Essentially all aluminium now in existence is 27Al. 26Al was present in the early Solar System with abundance of 0.005% relative to 27Al but its half-life of 728,000 years is too short for any original nuclei to survive; 26Al is therefore extinct.[60] Unlike for 27Al, hydrogen burning is the primary source of 26Al, with the nuclide emerging after a nucleus of 25Mg catches a free proton. However, the trace quantities of 26Al that do exist are the most common gamma ray emitter in the interstellar gas;[60] if the original 26Al were still present, gamma ray maps of the Milky Way would be brighter.[60]

Earth

Overall, the Earth is about 1.59% aluminium by mass (seventh in abundance by mass).[61] Aluminium occurs in greater proportion in the Earth's crust than in the universe at large. This is because aluminium easily forms the oxide and becomes bound into rocks and stays in the Earth's crust, while less reactive metals sink to the core.[60] In the Earth's crust, aluminium is the most abundant metallic element (8.23% by mass[30]) and the third most abundant of all elements (after oxygen and silicon).[62] A large number of silicates in the Earth's crust contain aluminium.[63] In contrast, the Earth's mantle is only 2.38% aluminium by mass.[64] Aluminium also occurs in seawater at a concentration of 2 μg/kg.[30]

Because of its strong affinity for oxygen, aluminium is almost never found in the elemental state; instead it is found in oxides or silicates. Feldspars, the most common group of minerals in the Earth's crust, are aluminosilicates. Aluminium also occurs in the minerals beryl, cryolite, garnet, spinel, and turquoise.[65] Impurities in Al2O3, such as chromium and iron, yield the gemstones ruby and sapphire, respectively.[66] Native aluminium metal is extremely rare and can only be found as a minor phase in low oxygen fugacity environments, such as the interiors of certain volcanoes.[67] Native aluminium has been reported in cold seeps in the northeastern continental slope of the South China Sea. It is possible that these deposits resulted from bacterial reduction of tetrahydroxoaluminate Al(OH)4−.[68]

Although aluminium is a common and widespread element, not all aluminium minerals are economically viable sources of the metal. Almost all metallic aluminium is produced from the ore bauxite (AlOx(OH)3–2x). Bauxite occurs as a weathering product of low iron and silica bedrock in tropical climatic conditions.[69] In 2017, most bauxite was mined in Australia, China, Guinea, and India.[70]

History

The history of aluminium has been shaped by usage of alum. The first written record of alum, made by Greek historian Herodotus, dates back to the 5th century BCE.[71] The ancients are known to have used alum as a dyeing mordant and for city defense.[71] After the Crusades, alum, an indispensable good in the European fabric industry,[72] was a subject of international commerce;[73] it was imported to Europe from the eastern Mediterranean until the mid-15th century.[74]

The nature of alum remained unknown. Around 1530, Swiss physician Paracelsus suggested alum was a salt of an earth of alum.[75] In 1595, German doctor and chemist Andreas Libavius experimentally confirmed this.[76] In 1722, German chemist Friedrich Hoffmann announced his belief that the base of alum was a distinct earth.[77] In 1754, German chemist Andreas Sigismund Marggraf synthesized alumina by boiling clay in sulfuric acid and subsequently adding potash.[77]

Attempts to produce aluminium date back to 1760.[78] The first successful attempt, however, was completed in 1824 by Danish physicist and chemist Hans Christian Ørsted. He reacted anhydrous aluminium chloride with potassium amalgam, yielding a lump of metal looking similar to tin.[79][80][81] He presented his results and demonstrated a sample of the new metal in 1825.[82][83] In 1827, German chemist Friedrich Wöhler repeated Ørsted's experiments but did not identify any aluminium.[84] (The reason for this inconsistency was only discovered in 1921.)[85] He conducted a similar experiment in the same year by mixing anhydrous aluminium chloride with potassium and produced a powder of aluminium.[81] In 1845, he was able to produce small pieces of the metal and described some physical properties of this metal.[85] For many years thereafter, Wöhler was credited as the discoverer of aluminium.[86]

As Wöhler's method could not yield great quantities of aluminium, the metal remained rare; its cost exceeded that of gold.[84] The first industrial production of aluminium was established in 1856 by French chemist Henri Etienne Sainte-Claire Deville and companions.[87] Deville had discovered that aluminium trichloride could be reduced by sodium, which was more convenient and less expensive than potassium, which Wöhler had used.[88] Even then, aluminium was still not of great purity and produced aluminium differed in properties by sample.[89] Because of its electricity-conducting capacity, aluminium was used as the cap of the Washington Monument, completed in 1885. The tallest building in the world at the time, the non-corroding metal cap was intended to serve as a lightning rod peak.

The first industrial large-scale production method was independently developed in 1886 by French engineer Paul Héroult and American engineer Charles Martin Hall; it is now known as the Hall–Héroult process.[90] The Hall–Héroult process converts alumina into metal. Austrian chemist Carl Joseph Bayer discovered a way of purifying bauxite to yield alumina, now known as the Bayer process, in 1889.[91] Modern production of aluminium is based on the Bayer and Hall–Héroult processes.[92]

As large-scale production caused aluminium prices to drop, the metal became widely used in jewelry, eyeglass frames, optical instruments, tableware, and foil, and other everyday items in the 1890s and early 20th century. Aluminium's ability to form hard yet light alloys with other metals provided the metal with many uses at the time.[93] During World War I, major governments demanded large shipments of aluminium for light strong airframes;[94] during World War II, demand by major governments for aviation was even higher.[95][96][97]

By the mid-20th century, aluminium had become a part of everyday life and an essential component of housewares.[98] In 1954, production of aluminium surpassed that of copper,[i] historically second in production only to iron,[101] making it the most produced non-ferrous metal. During the mid-20th century, aluminium emerged as a civil engineering material, with building applications in both basic construction and interior finish work,[102] and increasingly being used in military engineering, for both airplanes and land armor vehicle engines.[103] Earth's first artificial satellite, launched in 1957, consisted of two separate aluminium semi-spheres joined and all subsequent space vehicles have used aluminium to some extent.[92] The aluminium can was invented in 1956 and employed as a storage for drinks in 1958.[104]

Throughout the 20th century, the production of aluminium rose rapidly: while the world production of aluminium in 1900 was 6,800 metric tons, the annual production first exceeded 100,000 metric tons in 1916; 1,000,000 tons in 1941; 10,000,000 tons in 1971.[99] In the 1970s, the increased demand for aluminium made it an exchange commodity; it entered the London Metal Exchange, the oldest industrial metal exchange in the world, in 1978.[92] The output continued to grow: the annual production of aluminium exceeded 50,000,000 metric tons in 2013.[99]

The real price for aluminium declined from $14,000 per metric ton in 1900 to $2,340 in 1948 (in 1998 United States dollars).[99] Extraction and processing costs were lowered over technological progress and the scale of the economies. However, the need to exploit lower-grade poorer quality deposits and the use of fast increasing input costs (above all, energy) increased the net cost of aluminium;[105] the real price began to grow in the 1970s with the rise of energy cost.[106] Production moved from the industrialized countries to countries where production was cheaper.[107] Production costs in the late 20th century changed because of advances in technology, lower energy prices, exchange rates of the United States dollar, and alumina prices.[108] The BRIC countries' combined share in primary production and primary consumption grew substantially in the first decade of the 21st century.[109] China is accumulating an especially large share of the world's production thanks to an abundance of resources, cheap energy, and governmental stimuli;[110] it also increased its consumption share from 2% in 1972 to 40% in 2010.[111] In the United States, Western Europe, and Japan, most aluminium was consumed in transportation, engineering, construction, and packaging.[112] In 2021, prices for industrial metals such as aluminium have soared to near-record levels as energy shortages in China drive up costs for electricity.[113]

Etymology

The names aluminium and aluminum are derived from the word alumine, an obsolete term for alumina,[j] the primary naturally occurring oxide of aluminium.[115] Alumine was borrowed from French, which in turn derived it from alumen, the classical Latin name for alum, the mineral from which it was collected.[116] The Latin word alumen stems from the Proto-Indo-European root *alu- meaning "bitter" or "beer".[117]

Origins

British chemist Humphry Davy, who performed a number of experiments aimed to isolate the metal, is credited as the person who named the element. The first name proposed for the metal to be isolated from alum was alumium, which Davy suggested in an 1808 article on his electrochemical research, published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.[118] It appeared that the name was created from the English word alum and the Latin suffix -ium; but it was customary then to give elements names originating in Latin, so this name was not adopted universally. This name was criticized by contemporary chemists from France, Germany, and Sweden, who insisted the metal should be named for the oxide, alumina, from which it would be isolated.[119] The English name alum does not come directly from Latin, whereas alumine/alumina obviously comes from the Latin word alumen (upon declension, alumen changes to alumin-).

One example was Essai sur la Nomenclature chimique (July 1811), written in French by a Swedish chemist, Jöns Jacob Berzelius, in which the name aluminium is given to the element that would be synthesized from alum.[120][k] (Another article in the same journal issue also refers to the metal whose oxide is the basis of sapphire, i.e. the same metal, as to aluminium.)[122] A January 1811 summary of one of Davy's lectures at the Royal Society mentioned the name aluminium as a possibility.[123] The next year, Davy published a chemistry textbook in which he used the spelling aluminum.[124] Both spellings have coexisted since. Their usage is currently regional: aluminum dominates in the United States and Canada; aluminium is prevalent in the rest of the English-speaking world.[125]

Spelling

In 1812, British scientist Thomas Young[126] wrote an anonymous review of Davy's book, in which he proposed the name aluminium instead of aluminum, which he thought had a "less classical sound".[127] This name persisted: although the -um spelling was occasionally used in Britain, the American scientific language used -ium from the start.[128] Most scientists throughout the world used -ium in the 19th century;[125] and it was entrenched in several other European languages, such as French, German, and Dutch.[l] In 1828, an American lexicographer, Noah Webster, entered only the aluminum spelling in his American Dictionary of the English Language.[129] In the 1830s, the -um spelling gained usage in the United States; by the 1860s, it had become the more common spelling there outside science.[128] In 1892, Hall used the -um spelling in his advertising handbill for his new electrolytic method of producing the metal, despite his constant use of the -ium spelling in all the patents he filed between 1886 and 1903. It is unknown whether this spelling was introduced by mistake or intentionally, but Hall preferred aluminum since its introduction because it resembled platinum, the name of a prestigious metal.[130] By 1890, both spellings had been common in the United States, the -ium spelling being slightly more common; by 1895, the situation had reversed; by 1900, aluminum had become twice as common as aluminium; in the next decade, the -um spelling dominated American usage. In 1925, the American Chemical Society adopted this spelling.[125]

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) adopted aluminium as the standard international name for the element in 1990.[131] In 1993, they recognized aluminum as an acceptable variant;[131] the most recent 2005 edition of the IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry also acknowledges this spelling.[132] IUPAC official publications use the -ium spelling as primary, and they list both where it is appropriate.[m]

Production and refinement

| Country | Output (thousand tons) |

|---|---|

| 36,000 | |

| 3,700 | |

| 3,600 | |

| 2,900 | |

| 2,700 | |

| 1,600 | |

| 1,400 | |

| 1,300 | |

| 1,100 | |

| 850 | |

| Other countries | 9,200 |

| Total | 64,000 |

The production of aluminium starts with the extraction of bauxite rock from the ground. The bauxite is processed and transformed using the Bayer process into alumina, which is then processed using the Hall–Héroult process, resulting in the final aluminium.

Aluminium production is highly energy-consuming, and so the producers tend to locate smelters in places where electric power is both plentiful and inexpensive.[135] Production of one kilogram of aluminium requires 7 kilograms of oil energy equivalent, as compared to 1.5 kilograms for steel and 2 kilograms for plastic.[136] As of 2019, the world's largest smelters of aluminium are located in China, India, Russia, Canada, and the United Arab Emirates,[134] while China is by far the top producer of aluminium with a world share of 55%.

According to the International Resource Panel's Metal Stocks in Society report, the global per capita stock of aluminium in use in society (i.e. in cars, buildings, electronics, etc.) is 80 kg (180 lb). Much of this is in more-developed countries (350–500 kg (770–1,100 lb) per capita) rather than less-developed countries (35 kg (77 lb) per capita).[137]

Bayer process

Bauxite is converted to alumina by the Bayer process. Bauxite is blended for uniform composition and then is ground. The resulting slurry is mixed with a hot solution of sodium hydroxide; the mixture is then treated in a digester vessel at a pressure well above atmospheric, dissolving the aluminium hydroxide in bauxite while converting impurities into relatively insoluble compounds:[138]

After this reaction, the slurry is at a temperature above its atmospheric boiling point. It is cooled by removing steam as pressure is reduced. The bauxite residue is separated from the solution and discarded. The solution, free of solids, is seeded with small crystals of aluminium hydroxide; this causes decomposition of the [Al(OH)4]− ions to aluminium hydroxide. After about half of aluminium has precipitated, the mixture is sent to classifiers. Small crystals of aluminium hydroxide are collected to serve as seeding agents; coarse particles are converted to alumina by heating; the excess solution is removed by evaporation, (if needed) purified, and recycled.[138]

Hall–Héroult process

The conversion of alumina to aluminium is achieved by the Hall–Héroult process. In this energy-intensive process, a solution of alumina in a molten (950 and 980 °C (1,740 and 1,800 °F)) mixture of cryolite (Na3AlF6) with calcium fluoride is electrolyzed to produce metallic aluminium. The liquid aluminium sinks to the bottom of the solution and is tapped off, and usually cast into large blocks called aluminium billets for further processing.[43]

Anodes of the electrolysis cell are made of carbon—the most resistant material against fluoride corrosion—and either bake at the process or are prebaked. The former, also called Söderberg anodes, are less power-efficient and fumes released during baking are costly to collect, which is why they are being replaced by prebaked anodes even though they save the power, energy, and labor to prebake the cathodes. Carbon for anodes should be preferably pure so that neither aluminium nor the electrolyte is contaminated with ash. Despite carbon's resistivity against corrosion, it is still consumed at a rate of 0.4–0.5 kg per each kilogram of produced aluminium. Cathodes are made of anthracite; high purity for them is not required because impurities leach only very slowly. The cathode is consumed at a rate of 0.02–0.04 kg per each kilogram of produced aluminium. A cell is usually terminated after 2–6 years following a failure of the cathode.[43]

The Hall–Heroult process produces aluminium with a purity of above 99%. Further purification can be done by the Hoopes process. This process involves the electrolysis of molten aluminium with a sodium, barium, and aluminium fluoride electrolyte. The resulting aluminium has a purity of 99.99%.[43][139]

Electric power represents about 20 to 40% of the cost of producing aluminium, depending on the location of the smelter. Aluminium production consumes roughly 5% of electricity generated in the United States.[131] Because of this, alternatives to the Hall–Héroult process have been researched, but none has turned out to be economically feasible.[43]

Recycling

Recovery of the metal through recycling has become an important task of the aluminium industry. Recycling was a low-profile activity until the late 1960s, when the growing use of aluminium beverage cans brought it to public awareness.[140] Recycling involves melting the scrap, a process that requires only 5% of the energy used to produce aluminium from ore, though a significant part (up to 15% of the input material) is lost as dross (ash-like oxide).[141] An aluminium stack melter produces significantly less dross, with values reported below 1%.[142]

White dross from primary aluminium production and from secondary recycling operations still contains useful quantities of aluminium that can be extracted industrially. The process produces aluminium billets, together with a highly complex waste material. This waste is difficult to manage. It reacts with water, releasing a mixture of gases (including, among others, hydrogen, acetylene, and ammonia), which spontaneously ignites on contact with air;[143] contact with damp air results in the release of copious quantities of ammonia gas. Despite these difficulties, the waste is used as a filler in asphalt and concrete.[144]

Applications

Metal

The global production of aluminium in 2016 was 58.8 million metric tons. It exceeded that of any other metal except iron (1,231 million metric tons).[145][146]

Aluminium is almost always alloyed, which markedly improves its mechanical properties, especially when tempered. For example, the common aluminium foils and beverage cans are alloys of 92% to 99% aluminium.[147] The main alloying agents are copper, zinc, magnesium, manganese, and silicon (e.g., duralumin) with the levels of other metals in a few percent by weight.[148] Aluminium, both wrought and cast, has been alloyed with: manganese, silicon, magnesium, copper and zinc among others.[149]

The major uses for aluminium are in:[150]

- Transportation (automobiles, aircraft, trucks, railway cars, marine vessels, bicycles, spacecraft, etc.). Aluminium is used because of its low density;

- Packaging (cans, foil, frame, etc.). Aluminium is used because it is non-toxic (see below), non-adsorptive, and splinter-proof;

- Building and construction (windows, doors, siding, building wire, sheathing, roofing, etc.). Since steel is cheaper, aluminium is used when lightness, corrosion resistance, or engineering features are important;

- Electricity-related uses (conductor alloys, motors, and generators, transformers, capacitors, etc.). Aluminium is used because it is relatively cheap, highly conductive, has adequate mechanical strength and low density, and resists corrosion;

- A wide range of household items, from cooking utensils to furniture. Low density, good appearance, ease of fabrication, and durability are the key factors of aluminium usage;

- Machinery and equipment (processing equipment, pipes, tools). Aluminium is used because of its corrosion resistance, non-pyrophoricity, and mechanical strength.

Compounds

The great majority (about 90%) of aluminium oxide is converted to metallic aluminium.[138] Being a very hard material (Mohs hardness 9),[151] alumina is widely used as an abrasive;[152] being extraordinarily chemically inert, it is useful in highly reactive environments such as high pressure sodium lamps.[153] Aluminium oxide is commonly used as a catalyst for industrial processes;[138] e.g. the Claus process to convert hydrogen sulfide to sulfur in refineries and to alkylate amines.[154][155] Many industrial catalysts are supported by alumina, meaning that the expensive catalyst material is dispersed over a surface of the inert alumina.[156] Another principal use is as a drying agent or absorbent.[138][157]

Несколько сульфатов алюминия имеют промышленное и коммерческое применение. Сульфат алюминия (в его гидратной форме) производится по годовой шкале нескольких миллионов метрических тонн. [158] About two-thirds is consumed in water treatment.[158] The next major application is in the manufacture of paper.[158] It is also used as a mordant in dyeing, in pickling seeds, deodorizing of mineral oils, in leather tanning, and in production of other aluminium compounds.[158] Two kinds of alum, ammonium alum and potassium alum, were formerly used as mordants and in leather tanning, but their use has significantly declined following availability of high-purity aluminium sulfate.[158] Anhydrous aluminium chloride is used as a catalyst in chemical and petrochemical industries, the dyeing industry, and in synthesis of various inorganic and organic compounds.[158] Алюминиевые гидроксихлориды используются в очищающей воде, в бумажной промышленности и в качестве антиперспирантов . [ 158 ] Алюминат натрия используется при обработке воды и в качестве ускорителя затвердевания цемента. [ 158 ]

Многие алюминиевые соединения имеют нишевые приложения, например:

- Алюминиевый ацетат в растворе используется в качестве вяжущего . [ 159 ]

- Алюминиевый фосфат используется при изготовлении стекла, керамики, целлюлозы и бумаги, косметики , красок, лаков и зубного цемента . [ 160 ]

- Гидроксид алюминия используется в качестве антацида и морданта; Он также используется в очистке воды , производстве стекла и керамики, а также гидроизоляции тканей в . [ 161 ] [ 162 ]

- Гидрад лития алюминия является мощным восстановительным агентом, используемым в органической химии . [ 163 ] [ 164 ]

- Оргауалуминия используются в качестве кислот и коатализаторов Льюиса. [ 165 ]

- Метилалуминоксан является со-катализатором для Ziegler-Natta полимеризации олефиновой полимеризации с образованием виниловых полимеров, таких как полиэтен . [ 166 ]

- Водные алюминиевые ионы (такие как водный алюминиевый сульфат) используются для лечения от паразитов рыб, таких как Gyrodactylus salaris . [ 167 ]

- Во многих вакцинах некоторые соли алюминия служат иммунным адъювантом (бустер иммунного ответа), чтобы позволить белке в вакцине достичь достаточной потенции в качестве иммунного стимулятора. [ 168 ] До 2004 года большинство адъювантов, используемых в вакцинах, были склонны к алюминиям. [ 169 ]

Биология

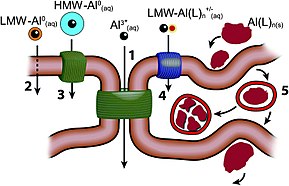

Несмотря на широкое распространение в коре Земли, алюминий не имеет известной функции в биологии. [ 43 ] При рН 6–9 (актуальном для большинства природных вод) алюминиевые осаждают из воды в качестве гидроксида и, следовательно, недоступны; Большинство элементов, которые ведут себя таким образом, не имеют биологической роли или являются токсичными. [ 171 ] Сульфат алюминия имеет LD 50 из 6207 мг/кг (оральный, мышь), который соответствует 435 граммам (около одного фунта) для мыши 70 кг (150 фунтов).

Токсичность

Алюминий классифицируется как некарциноген Министерством здравоохранения и социальных служб США . [ 172 ] [ n ] В обзоре, опубликованном в 1988 году, говорится, что было мало доказательств того, что нормальное воздействие алюминия представляет риск для здорового взрослого,. [ 175 ] А многоэлементный токсикологический обзор 2014 года не смог найти вредные эффекты алюминия, потребляемого в количествах не более 40 мг/день на кг массы тела . [ 172 ] Большинство потребляемых алюминия покинут тело в кале; Большая часть небольшой части, которая попадает в кровоток, будет выводиться с помощью мочи; [ 176 ] Тем не менее, какой-то алюминий проходит гематоэнцефалический барьер и проживает преимущественно в мозге пациентов с болезнью Альцгеймера. [ 177 ] [ 178 ] Данные, опубликованные в 1989 году, указывают на то, что для пациентов с болезнью Альцгеймера алюминий может действовать электростатически сшивающими белками, таким образом, понижали гены в верхней височной извилине . [ 179 ]

Эффекты

Алюминий, хотя и редко, может вызвать витамин D -устойчивую остеомаляцию , эритропоэтин -резистентную микроцитарную анемию и изменения центральной нервной системы. Люди с недостаточностью почек особенно подвержены риску. [ 172 ] Хроническое проглатывание гидратированных алюминиевых силикатов (для избыточного контроля кислотности желудка) может привести к связыванию алюминия с содержанием кишечника и увеличению устранения других металлов, таких как железо или цинк ; Достаточно высокие дозы (> 50 г/день) могут вызвать анемию. [ 172 ]

Во время инцидента с загрязнением воды в Камелфорде в Камелфорде их питьевая вода загрязнена сульфатом алюминия в течение нескольких недель. В окончательном отчете об инциденте в 2013 году показано, что маловероятно, что это вызвало долгосрочные проблемы со здоровьем. [ 180 ]

Алюминий подозревается в том, что является возможной причиной болезни Альцгеймера , [ 181 ] Но исследование этого на протяжении более 40 лет обнаружилось, по состоянию на 2018 год [update], нет хороших доказательств причинного эффекта. [ 182 ] [ 183 ]

Алюминий увеличивает эстрогеном, , связанную с экспрессию генов человека, в клетках рака молочной железы культивируемых в лаборатории. [ 184 ] В очень высоких дозах алюминий связан с измененной функцией барьеры крови -брейна. [ 185 ] Небольшой процент людей [ 186 ] иметь контактную аллергию на алюминий и испытывать зудящие красные сыпи, головную боль, боль в мышцах, боль в суставах, плохая память, бессонница, депрессия, астма, синдром раздраженного кишечника или другие симптомы при контакте с продуктами, содержащими алюминий. [ 187 ]

Воздействие порошкообразного алюминиевого или алюминиевого сварки может вызвать легочный фиброз . [ 188 ] Тонкий алюминиевый порошок может зажечь или взорваться, создавая другую опасность на рабочем месте. [ 189 ] [ 190 ]

Маршруты экспозиции

Еда является основным источником алюминия. Питьевая вода содержит больше алюминия, чем твердая пища; [ 172 ] Тем не менее, алюминий в пище может быть поглощен больше, чем алюминий из воды. [ 191 ] Основные источники воздействия полости рта на пероральные лица на человека включают пищу (из-за ее использования в пищевых добавках, пищевой упаковке и упаковке для напитков, а также для приготовления пищи), питьевой воды (из-за ее использования при лечении муниципальной воды) и алюминиевые препараты (особенно антацидные /противодействие и буферированные составы аспирина). [ 192 ] Диетическое воздействие у европейцев составляет в среднем до 0,2–1,5 мг/кг/неделя, но может достигать 2,3 мг/кг/неделя. [ 172 ] Более высокие уровни воздействия алюминия в основном ограничены шахтерами, работниками по производству алюминия и пациентами с диализом . [ 193 ]

Потребление антацид , антиперспирантов, вакцин и косметики обеспечивает возможные маршруты воздействия. [ 194 ] Потребление кислотных продуктов или жидкостей с алюминием усиливает поглощение алюминия, [ 195 ] и было показано, что Мальтол увеличивает накопление алюминия в нервных и костных тканях. [ 196 ]

Уход

В случае предполагаемого внезапного потребления большого количества алюминия единственным лечением является дефероксамин мезилат , который может быть предоставлен, чтобы помочь удалить алюминий из организма путем хелационной терапии . [ 197 ] [ 198 ] Тем не менее, это должно применяться с осторожностью, поскольку это снижает не только уровни алюминиевого тела, но и уровни других металлов, таких как медь или железо. [ 197 ]

Воздействие на окружающую среду

Высокий уровень алюминия встречается вблизи участков добычи; Небольшие количества алюминия выделяются в окружающую среду на угольных электростанциях или мусоросжигательных сетях . [ 176 ] Алюминий в воздухе промывается дождем или обычно оседает, но небольшие частицы алюминия в течение длительного времени остаются в воздухе. [ 176 ]

Кислотное осаждение является основным естественным фактором для мобилизации алюминия из природных источников [ 172 ] и основная причина воздействия алюминия на окружающую среду; [ 199 ] Однако основным фактором присутствия алюминия в соли и пресной воде являются промышленные процессы, которые также выпускают алюминий в воздух. [ 172 ]

В воде алюминий действует как агент -токсис на животных , таких как рыба, таких как рыба , когда вода кисла, в которой алюминий может осаждать на жабрах, [ 200 ] который вызывает потерю ионов плазмы и гемолимф, ведущих к осморегуляторной недостаточности. [ 199 ] Органические комплексы алюминия могут быть легко поглощены и мешать метаболизму у млекопитающих и птиц, даже если это редко происходит на практике. [ 199 ]

Алюминий является первичным среди факторов, которые снижают рост растений на кислых почвах. Хотя обычно это безвредно для роста растений в pH-нейтральных почвах, в кислотных почвах концентрация токсичного AL 3+ Катионы увеличиваются и нарушают рост и функцию корней. [ 201 ] [ 202 ] [ 203 ] [ 204 ] Пшеница разработала , толерантность к алюминию, высвобождая органические соединения которые связываются с вредными алюминиевыми катионами . сорго имеет тот же механизм толерантности. Считается, что [ 205 ]

Производство алюминия обладает своими собственными проблемами для окружающей среды на каждом этапе производственного процесса. Основной проблемой являются выбросы парниковых газов . [ 193 ] Эти газы возникают в результате потребления электрооборудования и побочных продуктов обработки. Наиболее мощными из этих газов являются перфторуруглероды от процесса плавки. [ 193 ] Выпущенный диоксид серы является одним из первичных предшественников кислотного дождя . [ 193 ]

Биодеградация металлического алюминия встречается чрезвычайно редко; Большинство алюминиевых организмов напрямую не нападают и не потребляют алюминий, а вместо этого производят коррозионные отходы. [ 206 ] [ 207 ] Гриб Geotrichum candidum может потреблять алюминий на компактных дисках . [ 208 ] [ 209 ] [ 210 ] Bacterium pseudomonas aeruginosa и грибковые Cladosporium Resinae обычно обнаруживаются в авиационных топливных баках, в которых используется керосина топливо на основе (не Avgas ), а лабораторные культуры могут ухудшить алюминий. [ 211 ]

Смотрите также

- Алюминиевые гранулы

- Алюминиевое соединение

- Алюминиевая батарея

- Алюминизированная сталь для коррозионной стойкости и других свойств

- Алюминизированный экран , для отображения устройств

- Алюминизированная ткань , чтобы отразить тепло

- Алюминизированный милар , чтобы отразить тепло

- Окрашивание краем панели

- Квантовые часы

Примечания

- ^ Письменное использование слова алюминия в 1812 году было предшествовало использованию алюминия других авторов . Тем не менее, Дэви часто упоминается как человек, который назвал элемент; Он был первым, кто снял имя для алюминия: он использовал алюмиум в 1808 году. Другие авторы не приняли это имя, вместо этого выбирая алюминий . Смотрите ниже для более подробной информации.

- ^ Нет элементов со странными атомными числами не имеют более двух стабильных изотопов; Увлежденные элементы имеют несколько стабильных изотопов, причем олово (элемент 50) имеет наибольшее количество стабильных изотопов всех элементов, десять. Единственным исключением является бериллий , который является равномерным, но имеет только один стабильный изотоп. [ 12 ] Смотрите даже и странные атомные ядра для более подробной информации.

- ^ Большинство других металлов имеют более высокие стандартные атомные веса: например, железо составляет 55,845 ; медь 63,546 ; Ведущий 207.2 . [ 3 ] который имеет последствия для свойств элемента (см. Ниже )

- ^ Две стороны алюминиевой фольги отличаются по их блеске: одна блестящая, а другая скучна. Разница связана с небольшим механическим повреждением на поверхности тусклой стороны, возникающей в результате технологического процесса производства алюминиевой фольги. [ 23 ] Обе стороны отражают одинаковые количества видимого света, но блестящая сторона отражает гораздо большую долю видимого света, тогда как тусая сторона почти исключительно диффундирует свет. Обе стороны алюминиевой фольги служат хорошими отражателями (приблизительно 86%) видимым светом и превосходным отражателем (до 97%) среднего и дальнего инфракрасного излучения. [ 24 ]

- ^ На самом деле, электропозитивное поведение алюминия, высокая аффинность к кислороду и очень отрицательный стандартный потенциал электрода лучше выровнены со скандами , иттрием , лантанами и актинием , которые, как и алюминий, имеют три валентные электроны вне благородного газа; Эта серия показывает непрерывные тенденции, тогда как в группе 13 разбита первая добавленная D-Subshell в галлиее и полученное сокращение D-блока и первое добавленное F-Subshell в таллие и полученное сжатие лантанида . [ 36 ]

- ^ Они не должны рассматриваться как [ALF 6 ] 3− Сложные анионы как связи Al -F существенно не отличаются по типу от других связей M - F. [ 46 ]

- ^ Такие различия в координации между фторидами и более тяжелыми галогениками не являются необычными, происходящие в SN IV и би Iii , например; Еще большие различия происходят между CO 2 и SIO 2 . [ 46 ]

- ^ Источники в источнике перечислены относительно кремния, а не в обозначениях для первой части. Сумма всех элементов на 10 6 Части кремния составляют 2,6682 × 10 10 части; Алюминий состоит из 8,410 × 10 4 части

- ^ Сравните годовую статистику алюминия [ 99 ] и медь [ 100 ] Производство USGS.

- ^ Правоцветный алюмин исходит от французского, тогда как орфографический глинозем из латыни. [ 114 ]

- ^ Дэви обнаружил несколько других элементов, в том числе тех, кого он назвал натрием и калием , после английских слов сода и калия . Берзелиус назвал их натриумом и калием . Предложение Берцелиуса было расширено в 1814 году [ 121 ] с его предложенной системой из одного или двухбуквенных химических символов , которые используются вплоть до сегодняшнего дня; Натрий и калий имеют символы NA и K , соответственно, после их латинских названий.

- ^ Некоторые европейские языки, такие как испанский или итальянский , используют другой суффикс от латинского -ум / -ум, чтобы сформировать название металла, у некоторых, таких польский или чешский как , как и русский или греческий , не используйте латинский сценарий вообще.

- ^ Например, см. Выпуск Chemistry International в ноябре по ноябрь 2013 года : в таблице (некоторых) элементов элемент указан как «алюминий (алюминий)». [ 133 ]

- ^ Хотя алюминий как таковой не является канцерогенным, выработка алюминия Сёдерберга, как отмечается Международным агентством по исследованиям рака , [ 173 ] Вероятно, из -за воздействия полициклических ароматических углеводородов. [ 174 ]

Ссылки

- ^ «Алюминий» . Оксфордский английский словарь (онлайн изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета . в учреждении или (Требуется членство участвующее учреждение .)

- ^ «Стандартные атомные веса: алюминий» . Ciaaw . 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Прохаска, Томас; Irrgeher, Johanna; Благосостояние, Жаклин; Böhlke, John K.; Чессон, Лесли А.; Коплен, Тайлер Б.; Ding, наконечник; Данн, Филипп Дж.Х.; Грёнинг, Манфред; Холден, Норман Э.; Meijer, Harro AJ (4 мая 2022 г.). «Стандартные атомные веса элементов 2021 (технический отчет IUPAC)» . Чистая и прикладная химия . doi : 10.1515/pac-2019-0603 . ISSN 1365-3075 .

- ^ Чжан, Йиминг; Эванс, Джулиан Р.Г.; Ян, Шуфенг (2011). «Исправленные значения для точек кипения и энтальпий испарения элементов в справочниках» . J. Chem. Англ. Данные . 56 (2): 328–337. doi : 10.1021/je1011086 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Arblaster, John W. (2018). Выбранные значения кристаллографических свойств элементов . Материал Парк, штат Огайо: ASM International. ISBN 978-1-62708-155-9 .

- ^ Нестабильный карбонил Al (0) был обнаружен в реакции Al 2 (Ch 3 ) 6 с окисью углерода; видеть Санчес, Рамиро; Аррингтон, Калеб; Аррингтон -младший, Калифорния (1 декабря 1989 г.). «Реакция триметилалуминия с окисью углерода в матрицах с низкой температурой» . Американское химическое общество . 111 (25): 9110-9111. doi : 10.1021/ja00207a023 . Ости 6973516 .

- ^ Dohmeier, C.; Loos, D.; Schnöckel, H. (1996). «Соединения алюминия (I) и галлия (I): синтезы, структуры и реакции». Angewandte Chemie International Edition . 35 (2): 129–149. doi : 10.1002/anie.199601291 .

- ^ Tyte, DC (1964). «Красная (B2π - A2σ). Природа . 202 (4930): 383. Bibcode : 1964natur.202..383t . doi : 10.1038/202383a0 . S2CID 4163250 .

- ^ Lide, DR (2000). «Магнитная восприимчивость элементов и неорганических соединений» (PDF) . Справочник по химии и физике CRC (81 -е изд.). CRC Press . ISBN 0849304814 .

- ^ Kondev, FG; Ван, М.; Хуан, WJ; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). «Оценка ядерных свойств Nubase2020» (PDF) . Китайская физика c . 45 (3): 030001. DOI : 10.1088/1674-1137/Abddae .

- ^ Mougeot, X. (2019). «На пути к высокой рецептной расчету распадов электронов» . Прикладное излучение и изотопы . 154 (108884). doi : 10.1016/j.apradiso.2019.108884 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный МАГАТЭ - раздел ядерных данных (2017). «LiveChart - таблица нуклидов - ядерная структура и данные распада» . www-nds.iaea.org . Международное агентство по атомной энергии . Архивировано с оригинала 23 марта 2019 года . Получено 31 марта 2017 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997 , pp. 242–252.

- ^ «Алюминий» . Комиссия по изотопным численности и атомным весам. Архивировано из оригинала 23 сентября 2020 года . Получено 20 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Дикин, AP (2005). « in situ Космогенные изотопы » . Радиогенная изотопная геология . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-521-53017-0 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 6 декабря 2008 года . Получено 16 июля 2008 года .

- ^ Додд, RT (1986). Грозы и стреляющие звезды . Гарвардский университет издательство. С. 89–90 . ISBN 978-0-674-89137-1 .

- ^ Дин 1999 , с. 4.2.

- ^ Дин 1999 , с. 4.6

- ^ Дин 1999 , с. 4.29.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Дин 1999 , с. 4.30.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Enghag, per (2008). Энциклопедия элементов: технические данные - История - Обработка - Приложения . Джон Уайли и сыновья. с. 139, 819, 949. ISBN 978-3-527-61234-5 Полем Архивировано с оригинала 25 декабря 2019 года . Получено 7 декабря 2017 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Гринвуд и Эрншоу, с. 222–4

- ^ «Тяжелая фольга» . Рейнольдс Кухни . Архивировано из оригинала 23 сентября 2020 года . Получено 20 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ Pozzobon, v.; Levasseur, W.; Do, KH.-V.; и др. (2020). «Домохозяйственная алюминиевая фольга Матовую и яркую сторону измерения отражательной способности: применение к концентрации концентратора света фотобиореактора» . Биотехнологические отчеты . 25 : E00399. doi : 10.1016/j.btre.2019.e00399 . ISSN 2215-017X . PMC 6906702 . PMID 31867227 .

- ^ Lide 2004 , p.

- ^ Пучта, Ральф (2011). «Более яркий бериллий» . Природная химия . 3 (5): 416. Bibcode : 2011natch ... 3..416p . doi : 10.1038/nchem.1033 . PMID 21505503 .

- ^ Дэвис 1999 , стр. 1-3.

- ^ Дэвис 1999 , с. 2

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Polmear, IJ (1995). Световые сплавы: металлургия легких металлов (3 изд.). Баттерворт-Хейнеманн . ISBN 978-0-340-63207-9 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Кардарелли, Франсуа (2008). Справочник по материалам: краткая ссылка на рабочем столе (2 -е изд.). Лондон: Спрингер. С. 158–163. ISBN 978-1-84628-669-8 Полем OCLC 261324602 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Дэвис 1999 , с. 4

- ^ Дэвис 1999 , стр. 2-3.

- ^ Кокран, JF; Mapother, de (1958). «Сверхпроводящий переход в алюминиевом». Физический обзор . 111 (1): 132–142. Bibcode : 1958phrv..111..132c . doi : 10.1103/physrev.111.132 .

- ^ Schmitz 2006 , p. 6

- ^ Schmitz 2006 , p. 161.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997 , pp. 224–227.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997 , pp. 112–113.

- ^ Кинг 1995 , с. 241.

- ^ Кинг 1995 , с. 235–236.

- ^ Хэтч, Джон Э. (1984). Алюминий: свойства и физическая металлургия . Metals Park, штат Огайо: Американское общество металлов, алюминиевая ассоциация. п. 242. ISBN 978-1-61503-169-6 Полем OCLC 759213422 .

- ^ Варджел, Кристиан (2004) [Французское издание опубликовано 1999]. Коррозия алюминия . Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-044495-6 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 21 мая 2016 года.

- ^ Macleod, HA (2001). Тонкоплененные оптические фильтры . CRC Press. п. 158159. ISBN 978-0-7503-0688-1 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин Фрэнк, WB (2009). «Алюминий». Энциклопедия промышленной химии Уллмана . Wiley-Vch. doi : 10.1002/14356007.a01_459.pub2 . ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Бил, Рой Э. (1999). Тестирование охлаждающей жидкости двигателя: четвертый том . ASTM International. п. 90. ISBN 978-0-8031-2610-7 Полем Архивировано с оригинала 24 апреля 2016 года.

- ^ * Baes, CF; Mesmer, Re (1986) [1976]. Гидролиз катионов . Роберт Э. Кригер. ISBN 978-0-89874-892-5 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997 , pp. 233–237.

- ^ Исто, Николас; Уолш, Валентин; Чаплин, Трейси; Сиддалл, Рут (2008). Пигментный сборник . Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-37393-0 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 15 апреля 2021 года . Получено 1 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Роско, Генри Энфилд; Schorlemmer, Carl (1913). Трактат по химии . Макмиллан. Архивировано из оригинала 15 апреля 2021 года . Получено 1 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997 , pp. 252–257.

- ^ Даунс, AJ (1993). Химия алюминия, галлия, индия и таллий . Springer Science & Business Media. п. 218. ISBN 978-0-7514-0103-5 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 15 апреля 2021 года . Получено 1 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Dohmeier, C.; Loos, D.; Schnöckel, H. (1996). «Соединения алюминия (I) и галлия (I): синтезы, структуры и реакции». Angewandte Chemie International Edition . 35 (2): 129–149. doi : 10.1002/anie.199601291 .

- ^ Tyte, DC (1964). «Красная (B2π - A2σ). Природа . 202 (4930): 383–384. Bibcode : 1964natur.202..383t . doi : 10.1038/202383a0 . S2CID 4163250 .

- ^ Merrill, PW; Deutsch, AJ; Кинан, ПК (1962). «Спектры поглощения переменных MIRA M-типа». Астрофизический журнал . 136 : 21. Bibcode : 1962Apj ... 136 ... 21M . doi : 10.1086/147348 .

- ^ UHL, W. (2004). «Соединенные соединения, обладающие alal, gaga, inin и tltl отдельные связи». Достижения в области органометаллической химии Том 51 . Тол. 51. С. 53–108. doi : 10.1016/s0065-3055 (03) 51002-4 . ISBN 978-0-12-031151-4 .

- ^ Elschenbroich, C. (2006). Органометаллики . Wiley-Vch. ISBN 978-3-527-29390-2 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997 , pp. 257–67.

- ^ Смит, Мартин Б. (1970). «Мономер-димерные равновесия жидких алюминиевых алкил». Журнал органометаллической химии . 22 (2): 273–281. doi : 10.1016/s0022-328x (00) 86043-x .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997 , pp. 227–232.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Lodders, K. (2003). «Солнечная система численность и температура конденсации элементов» (PDF) . Астрофизический журнал . 591 (2): 1220–1247. Bibcode : 2003Apj ... 591.1220L . doi : 10.1086/375492 . ISSN 0004-637X . S2CID 42498829 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 12 апреля 2019 года . Получено 15 июня 2018 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Клейтон Д. (2003). Справочник по изотопам в космосе: водород до галлия . Лейден: издательство Кембриджского университета. С. 129–137. ISBN 978-0-511-67305-4 Полем OCLC 609856530 . Архивировано из оригинала 11 июня 2021 года . Получено 13 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ Уильям Ф. Макдоно, композиция Земли . Quake.mit.edu, архивировано интернет -архивной машиной.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу, с. 217–9

- ^ Уэйд, К.; Banister, AJ (2016). Химия алюминия, галлия, индия и таллий: комплексная неорганическая химия . Elsevier. п. 1049. ISBN 978-1-4831-5322-3 Полем Архивировано с оригинала 30 ноября 2019 года . Получено 17 июня 2018 года .

- ^ Palme, H.; O'Neill, Hugh St. C. (2005). «Космохимические оценки композиции мантии» (PDF) . В Карлсоне, Ричард В. (ред.). Мантия и ядро . Elseiver. п. 14. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 3 апреля 2021 года . Получено 11 июня 2021 года .

- ^ Даунс, AJ (1993). Химия алюминия, галлия, индия и таллий . Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-7514-0103-5 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 25 июля 2020 года . Получено 14 июня 2017 года .

- ^ Котц, Джон С.; Трейхель, Пол М.; Таунсенд, Джон (2012). Химия и химическая реакционная способность . Cengage Learning. п. 300. ISBN 978-1-133-42007-1 Полем Архивировано с оригинала 22 декабря 2019 года . Получено 17 июня 2018 года .

- ^ Бартельми Д. "Алюминиевые минеральные данные" . База данных минералогии . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2008 года . Получено 9 июля 2008 года .

- ^ Chen, Z.; Хуан, Чи-Юэ; Чжао, Мейксан; Ян, Вэнь; Чиен, Чих-Вей; Чен, Мухон; Ян, Huaping; Мачияма, Хидиаки; Лин, Саулвуд (2011). «Характеристики и возможное происхождение местного алюминия в холодных отложениях от северо -восточного Южно -Китайского моря». Журнал азиатских наук о Земле . 40 (1): 363–370. Bibcode : 2011jaesc..40..363c . doi : 10.1016/j.jseaes.2010.06.006 .

- ^ Гилберт, JF; Парк, CF (1986). Геология депозитов руды . WH Freeman. С. 774–795. ISBN 978-0-7167-1456-9 .

- ^ Геологическая служба США (2018). «Боксит и глинозем» (PDF) . Резюме минеральных товаров. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 11 марта 2018 года . Получено 17 июня 2018 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Drozdov 2007 , p. 12.

- ^ Клэпхэм, Джон Гарольд; Власть, Эйлин Эдна (1941). Кембриджская экономическая история Европы: от упадка Римской империи . Кубок Архив. п. 207. ISBN 978-0-521-08710-0 .

- ^ Drozdov 2007 , p. 16.

- ^ Сеттон, Кеннет М. (1976). Папство и Левант: 1204-1571. 1 тринадцатый и четырнадцатый века . Американское философское общество. ISBN 978-0-87169-127-9 Полем OCLC 165383496 .

- ^ Drozdov 2007 , p. 25.

- ^ Недели, Мэри Эльвира (1968). Открытие элементов . Тол. 1 (7 изд.). Журнал химического образования. п. 187. ISBN 9780608300177 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ричардс 1896 , с. 2

- ^ Ричардс 1896 , с. 3

- ^ Örsted, HC (1825). Обзор Фордхадклингара Королевского датского общества наук и членов его членов, с 31 мая 1824 года по 31 мая 1825 года [ Обзор судебных разбирательств Королевского датского научного общества и работы его членов, с 31 мая 1824 года по 31 мая 1825 года ] (На датском). С. 15–16. Архивировано из оригинала 16 марта 2020 года . Получено 27 февраля 2020 года .

- ^ Королевская датская академия наук и писем (1827). Философские и исторические диссертации Королевского датского научного общества Датского научного общества [ философские и исторические диссертации Королевского датского научного общества ) (по датским). Попп С. XXV -XXVI. Архивировано с оригинала 24 марта 2017 года . Получено 11 марта 2016 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Вёлер, Фридрих (1827). «О алюминиевом» . Анналы физики и химии . 2. 11 (9): 146–161. Bibcode : 1828anp .... 87..146W . Doi : 10.1002/andp.18270870912 . S2CID 122170259 . Архивировано из оригинала 11 июня 2021 года . Получено 11 марта 2016 года .

- ^ Drozdov 2007 , p. 36.

- ^ Фонтани, Марко; Коста, Мариагразия; Орна, Мэри Вирджиния (2014). периодической стола Потерянные элементы: теневая сторона Издательство Оксфордского университета. П. 30. ISBN 978-0-19-938334-4 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Венецский С. (1969). « Серебро» из глины ». Металлург . 13 (7): 451–453. doi : 10.1007/bf00741130 . S2CID 137541986 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Drozdov 2007 , p. 38.

- ^ Холмс, Гарри Н. (1936). «Пятьдесят лет промышленного алюминия». Научный ежемесячный . 42 (3): 236–239. Bibcode : 1936scimo..42..236h . JSTOR 15938 .

- ^ Drozdov 2007 , p. 39.

- ^ Сент-Клэр Девиль, он (1859). Алюминий, его свойства, его производство . Париж: Маллет-МАКЛЕР. Архивировано с оригинала 30 апреля 2016 года.

- ^ Drozdov 2007 , p. 46.

- ^ Drozdov 2007 , pp. 55–61.

- ^ Drozdov 2007 , p. 74.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Алюминиевая история» . Все о алюминии . Архивировано с оригинала 7 ноября 2017 года . Получено 7 ноября 2017 года .

- ^ Drozdov 2007 , pp. 64–69.

- ^ Ingulstad, Mats (2012). « Мы хотим алюминия, никаких оправданий»: отношения с бизнесом в американской алюминиевой промышленности, 1917–1957 » . В Ingulstad, маты; Фрёланд, Ханс Отто (ред.). От войны до благосостояния: отношения с правительственными управлениями в алюминиевой промышленности . Тапирская академическая пресса. С. 33–68. ISBN 978-82-321-0049-1 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 25 июля 2020 года . Получено 7 мая 2020 года .

- ^ Селдес, Джордж (1943). Факты и фашизм (5 изд.). На самом деле, Inc. с. 261.

- ^ Торшайм, Питер (2015). Трата в оружие . Издательство Кембриджского университета. С. 66–69. ISBN 978-1-107-09935-7 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 6 апреля 2020 года . Получено 7 января 2021 года .

- ^ Недели, Альберт Лорен (2004). Российская спасение: помощь в аренде СССР во Второй мировой войне . Lexington Books . п. 135. ISBN 978-0-7391-0736-2 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 6 апреля 2020 года . Получено 7 января 2021 года .

- ^ Drozdov 2007 , pp. 69–70.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый «Алюминий» . Историческая статистика для минеральных товаров в Соединенных Штатах (отчет). Геологическая служба США . 2017. Архивировано с оригинала 8 марта 2018 года . Получено 9 ноября 2017 года .

- ^ «Медь. Статистика предложения поставки» . Историческая статистика для минеральных товаров в Соединенных Штатах (отчет). Геологическая служба США . 2017. Архивировано с оригинала 8 марта 2018 года . Получено 4 июня 2019 года .

- ^ Грегерсен, Эрик. "Медь" . Энциклопедия Британская . Архивировано с оригинала 22 июня 2019 года . Получено 4 июня 2019 года .

- ^ Drozdov 2007 , pp. 165–166.

- ^ Drozdov 2007 , p. 85.

- ^ Drozdov 2007 , p. 135.

- ^ Кнопка 2013 , с.

- ^ Подгузники 2013 , стр. 9-10.

- ^ Кнопка 2013 , с.

- ^ Подгузники 2013 , стр. 14-15.

- ^ Кнопка 2013 , с.

- ^ Кнопка 2013 , с.

- ^ Кнопка 2013 , с.

- ^ Кнопка 2013 , с.

- ^ «Алюминиевые цены достигли 13-летнего нехватки электроэнергии в Китае» . Nikkei Asia . 22 сентября 2021 года.

- ^ Black, J. (1806). Лекции по элементам химии: проведены в Университете Эдинбурга . Тол. 2. Грейвс, Б. с. 291.

Французские химики дали новое название этой чистой земле; алюмин на французском языке и глинозем на латыни. Признаюсь, мне не нравится этот глинозем.

- ^ «Алюминий, н». Оксфордский английский словарь, третье издание . Издательство Оксфордского университета. Декабрь 2011 года. Архивировано с оригинала 11 июня 2021 года . Получено 30 декабря 2020 года .

Происхождение: сформировано на английском языке, по деривации. Этимоны: Алюмин n . -Ium суффикс , алюминий н.

- ^ "Алюмине, н". Оксфордский английский словарь, третье издание . Издательство Оксфордского университета. Декабрь 2011 года. Архивировано с оригинала 11 июня 2021 года . Получено 30 декабря 2020 года .

Этимология: <Французский глинозем (LB Guyton de Morveau 1782, наблюдается на физике 19 378) <Классический латинский алумин- , алумен Квасцы н. 1 , после французского -Ин суффикс 4 .

- ^ Pokorny, Julius (1959). "Alu- (-d-, -t-)". Indogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch [ индоевропейский этимологический словарь (на немецком языке). А. Франке Верлаг. С. 33–34. Архивировано с оригинала 23 ноября 2017 года . Получено 13 ноября 2017 года .

- ^ Дэви, Хамфри (1808). «Электро -химические исследования, по разложению землей; с наблюдениями по металлам, полученным из щелочных земель, и на амальгаме, закупленной у аммиака» . Философские транзакции Королевского общества . 98 : 353. Bibcode : 1808rspt ... 98..333d . doi : 10.1098/rstl.1808.0023 . Архивировано из оригинала 15 апреля 2021 года . Получено 10 декабря 2009 года .

- ^ Ричардс 1896 , с. 3–4.

- ^ Berzelius, JJ (1811). «Эссе о химической номенклатуре» . Физический журнал . 73 : 253–286. Архивировано из оригинала 15 апреля 2021 года . Получено 27 декабря 2020 года . Полем