неандерталец

| неандерталец Временной диапазон: от среднего до позднего плейстоцена | |

|---|---|

| |

| Примерная реконструкция скелета неандертальца. Центральная грудная клетка (включая грудину) и части таза принадлежат современному человеку. | |

| Научная классификация | |

| Домен: | Эукариоты |

| Королевство: | животное |

| Тип: | Хордовые |

| Сорт: | Млекопитающие |

| Заказ: | Приматы |

| Подотряд: | Хаплорини |

| Инфрапорядок: | Симииформы |

| Семья: | Гоминиды |

| Подсемейство: | Люди |

| Племя: | Люди |

| Род: | гомо |

| Разновидность: | † H. neanderthalensis |

| Биномиальное имя | |

| † Человек неандертальский Кинг , 1864 г. | |

| |

| Известный ареал неандертальцев в Европе (синий), Юго-Западной Азии (оранжевый), Узбекистане (зеленый) и Горном Алтае (фиолетовый). | |

| Синонимы [6] | |

гомо Палеоантроп Протантроп Акантроп | |

Неандертальцы ( / n i ˈ æ n d ər ˌ t ɑː l , n eɪ -, - ˌ θ ɑː l / nee- AN -də(r)- TAHL , nay-, - THAHL ; [7] Homo neanderthalensis или H. sapiens neanderthalensis ) — вымершая группа архаичных людей (обычно рассматриваемых как отдельный вид, хотя некоторые считают ее подвидом Homo sapiens ), живших в Евразии примерно 40 000 лет назад. [8] [9] [10] [11] Типовой экземпляр , Neanderthal 1 , был найден в 1856 году в долине Неандер на территории современной Германии .

Неясно, когда линия неандертальцев отделилась от линии современных людей ; исследования дали в разное время от 315 000 [12] до более чем 800 000 лет назад. [13] дата отделения неандертальцев от их предка H. heidelbergensis Неясна и . Самые старые потенциальные кости неандертальцев датируются 430 000 лет назад, но классификация остается неопределенной. [14] Неандертальцы известны по многочисленным окаменелостям, особенно датированным 130 000 лет назад. [15]

Причины вымирания неандертальцев спорны. [16] [17] Теории их исчезновения включают демографические факторы, такие как небольшой размер популяции и инбридинг, конкурентное замещение, [18] скрещивание и ассимиляция с современным человеком, [19] изменение климата, [20] [21] [22] болезнь, [23] [24] или сочетание этих факторов. [22]

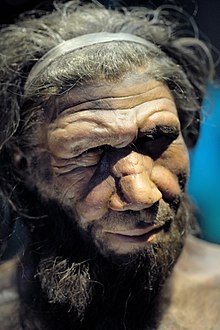

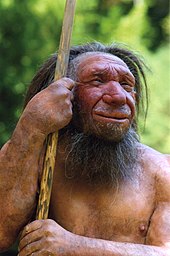

На протяжении большей части начала 20 века европейские исследователи изображали неандертальцев примитивными, неразумными и жестокими. Хотя с тех пор знания и восприятие их в научном сообществе заметно изменились, образ неразвитого архетипа пещерного человека по-прежнему преобладает в массовой культуре. [25] [26] По правде говоря, технология неандертальцев была весьма сложной. Включает мустьерскую каменно-орудийную промышленность. [27] [28] а также способности создавать огонь , [29] [30] строить пещерные очаги [31] [32] (готовить еду, согреваться, защищаться от животных, размещая ее в центре своего жилища), [33] сделать клей из бересты , [34] смастерите хотя бы простую одежду, похожую на одеяла и пончо, [35] ткать, [36] отправиться в мореплавание по Средиземному морю, [37] [38] использовать лекарственные растения , [39] [40] [41] лечить тяжелые травмы, [42] хранить еду, [43] и использовать различные методы приготовления, такие как запекание , варка , [44] и курение . [45] Неандертальцы потребляли разнообразную пищу, в основном копытных млекопитающих . [46] но и мегафауна , [25] [47] растения, [48] [49] [50] мелкие млекопитающие, птицы, а также водные и морские ресурсы. [51] Хотя они, вероятно, были высшими хищниками , они все же конкурировали с пещерными львами , пещерными гиенами и другими крупными хищниками. [52] Ряд примеров символической мысли и палеолитического искусства были безрезультатно изучены. [53] приписывают неандертальцам, а именно возможные украшения из птичьих когтей и перьев, [54] [55] ракушки, [56] коллекции необычных предметов, включая кристаллы и окаменелости, [57] гравюры, [58] музыкальное производство (возможно, обозначено флейтой Дивье Бабе ), [59] и испанские наскальные рисунки вызывают споры [60] датируется примерно 65 000 лет назад. [61] [62] Были сделаны некоторые заявления о религиозных убеждениях. [63] Неандертальцы, вероятно, были способны к речи, возможно, членораздельной, хотя сложность их языка неизвестна. [64] [65]

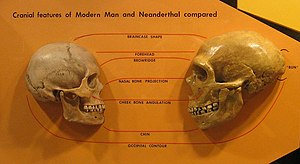

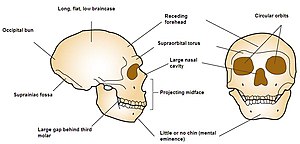

По сравнению с современными людьми неандертальцы имели более крепкое телосложение и пропорционально более короткие конечности. Исследователи часто объясняют эти особенности адаптацией к сохранению тепла в холодном климате, но они также могли быть адаптацией к бегу на короткие дистанции в более теплом лесном ландшафте, который часто населяли неандертальцы. [66] У них были приспособления, специфичные для холода, такие как специализированное накопление жира в организме. [67] и увеличенный нос для теплого воздуха [68] (хотя нос мог быть вызван генетическим дрейфом [69] ). Средний рост мужчин-неандертальцев составлял около 165 см (5 футов 5 дюймов), а женщин — 153 см (5 футов 0 дюймов), что соответствовало доиндустриальным современным европейцам. [70] Размер черепной коробки неандертальцев, мужчин и женщин, составлял в среднем около 1600 см. 3 (98 куб. Дюймов) и 1300 см 3 (79 у.е. дюймов) соответственно [71] [72] [73] что значительно больше, чем в среднем у современного человека (1260 см). 3 (77 куб. Дюймов) и 1130 см. 3 (69 у.е. дюймов) соответственно). [74] Череп неандертальца был более вытянутым, а теменные доли мозга были меньше. [75] [76] [77] и мозжечок, [78] [79] но более крупные височные, затылочные и орбитофронтальные области. [80] [81]

Общая популяция неандертальцев оставалась низкой, распространяя слабовредные варианты генов. [82] и препятствуют созданию эффективных сетей дальней связи. Несмотря на это, есть свидетельства существования региональных культур и регулярного общения между сообществами. [83] [84] Возможно, они часто посещали пещеры и перемещались между ними сезонно. [85] Неандертальцы жили в условиях сильного стресса с высоким уровнем травматизма, и около 80% из них умерли в возрасте до 40 лет. [86]

2010 года В проекте отчета проекта генома неандертальца представлены доказательства скрещивания неандертальцев и современных людей . [87] [88] [89] Возможно, это произошло от 316 000 до 219 000 лет назад. [90] но более вероятно 100 000 лет назад и снова 65 000 лет назад. [91] Неандертальцы также, по-видимому, скрещивались с денисовцами , другой группой архаичных людей, в Сибири. [92] [93] Около 1–4% геномов евразийцев , коренных австралийцев , меланезийцев , коренных американцев и жителей Северной Африки имеют неандертальское происхождение, в то время как большинство жителей стран Африки к югу от Сахары имеют около 0,3% генов неандертальцев, за исключением возможных следов от ранних сапиенсов до Поток генов неандертальцев и/или недавняя обратная миграция евразийцев в Африку. В целом около 20% явно неандертальских вариантов генов выживают у современных людей. [94] Хотя многие из вариантов генов, унаследованных от неандертальцев, возможно, были вредными и были исключены, [82] неандертальцев, Интрогрессия по-видимому, повлияла на иммунную систему современного человека . [95] [96] [97] [98] а также участвует в ряде других биологических функций и структур, [99] но большая часть, по-видимому, представляет собой некодирующую ДНК . [100]

Таксономия

[ редактировать ]Этимология

[ редактировать ]

Неандертальцы названы в честь долины Неандер , в которой был найден первый идентифицированный экземпляр. Долина называлась Neanderthal назывался Neanderthaler , а вид на немецком языке до реформы правописания 1901 года . [б] Написание этого вида «неандерталец» иногда встречается в английском языке, даже в научных публикациях, но научное название H. neanderthalensis всегда пишется через th в соответствии с принципом приоритета . Народное название вида на немецком языке всегда Neandertaler («обитатель долины Неандер»), тогда как неандерталец всегда относится к долине. [с] Сама долина была названа в честь немецкого теолога и автора гимнов конца 17 века Иоахима Неандера , который часто посещал этот район. [101] Его имя, в свою очередь, означает «новый человек», являясь учёной грецизацией немецкой фамилии Нойман .

Неандерталец можно произносить с помощью /t/ (как в / n i ˈ æ n d ər t ɑː l / ) [104] или стандартное английское произношение th с фрикативным звуком / θ / (as / n i ˈ æ n d ər θ ɔː l / ). [105] [106]

Неандерталец 1 , типовой экземпляр , был известен в антропологической литературе как «череп неандертальца» или «череп неандертальца», а человека, реконструированного на основе черепа, иногда называли «неандертальцем». [107] Биномиальное название Homo neanderthalensis , расширяющее название «неандерталец» от отдельного экземпляра до всего вида и формально признающее его отличие от человека, было впервые предложено ирландским геологом Уильямом Кингом в статье, прочитанной на 33-й сессии Британской научной ассоциации в 1863. [108] [109] [110] Однако в 1864 году он рекомендовал отнести неандертальцев и современных людей к разным родам, сравнивая черепную коробку неандертальцев с черепной коробкой шимпанзе и утверждая, что они «неспособны к моральным и [ теистическим [д] ] концепции». [111]

История исследований

[ редактировать ]

Первые останки неандертальца — Энжис 2 (череп) — были обнаружены в 1829 году голландско-бельгийским доисториком Филиппом-Шарлем Шмерлингом в Грот-д'Энгис , Бельгия. Он пришел к выводу, что эти «слабо развитые» человеческие останки, должно быть, были захоронены в то же время и по тем же причинам, что и сосуществовавшие останки вымерших видов животных. [112] В 1848 году Гибралтар 1 из карьера Форбса был подарен Научному обществу Гибралтара его секретарем лейтенантом Эдмундом Генри Рене Флинтом, но считался черепом современного человека. [113] В 1856 году местный школьный учитель Иоганн Карл Фульротт распознал кости из Кляйне Фельдхофер Гротте в долине Неандер — неандертальца 1 ( образец голотипа ) — в отличие от костей современных людей. [и] и передал их немецкому антропологу Герману Шаафхаузену для изучения в 1857 году. Он включал череп, бедренные кости, правую руку, левую плечевую и локтевую кости , левую подвздошную кость (тазовую кость), часть правой лопатки и части ребер . [111] [114] Следуя Чарльза Дарвина книге «Происхождение видов» , Фульротт и Шаафхаузен утверждали, что кости представляют собой древнюю современную человеческую форму; [26] [111] [115] [116] Шаафхаузен, социальный дарвинист , полагал, что люди линейно эволюционировали от дикарей к цивилизованным, и поэтому пришел к выводу, что неандертальцы были варварскими пещерными жителями. [26] Фульротт и Шаафхаузен встретили сопротивление, в частности, со стороны выдающегося патологоанатома Рудольфа Вирхова , который выступал против определения новых видов на основе только одной находки. В 1872 году Вирхов ошибочно истолковал характеристики неандертальцев как свидетельство старости , болезней и уродств, а не архаичности. [117] что остановило исследования неандертальцев до конца века. [26] [115]

К началу 20 века было сделано множество других открытий неандертальцев, сделавших H. neanderthalensis законным видом. Самым влиятельным экземпляром был La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 («Старик») из Ла-Шапель-о-Сент , Франция. Французский палеонтолог Марселлен Буль является автором нескольких публикаций, одной из первых, кто утвердил палеонтологию как науку, подробно описав образец, но реконструировал его как сутулого, обезьяноподобного и лишь отдаленно связанного с современными людьми. «Открытие» пилтдаунского человека в 1912 году (мистификация), который выглядел гораздо более похожим на современных людей, чем на неандертальцев, было использовано в качестве доказательства существования множества различных и не связанных друг с другом ветвей примитивных людей, и поддержало реконструкцию Буля H. neanderthalensis как очень далекого вида. относительный и эволюционный тупик . [26] [118] [119] [120] Он способствовал распространению популярного образа неандертальцев как варварских, сутулящихся, владеющих дубинками примитивов; этот образ воспроизводился в течение нескольких десятилетий и популяризировался в научно-фантастических произведениях, таких как « В поисках огня» года Ж.-Х. 1911 Росни Айне и «Ужасный народ» Герберта Уэллса 1927 года , в котором они изображены в виде монстров. [26] В 1911 году шотландский антрополог Артур Кейт реконструировал Ла-Шапель-о-Сент-1 как непосредственного предшественника современных людей, сидящих рядом с огнем, производящих инструменты, носящих ожерелье и имеющих более человеческую позу, но это не помогло собрать много научных данных. взаимопонимание, и Кейт позже отказался от своей диссертации в 1915 году. [26] [115] [121]

К середине столетия, основываясь на разоблачении Пилтдаунского человека как мистификации, а также на повторном обследовании Ла Шапель-о-Сент-1 (у которого был остеоартрит , из-за которого он сутулился в жизни) и новых открытиях, научное сообщество начало перерабатывать его понимание неандертальцев. Обсуждались такие идеи, как поведение, интеллект и культура неандертальцев, и возник их более человеческий образ. В 1939 году американский антрополог Карлтон Кун реконструировал неандертальца в современном деловом костюме и шляпе, чтобы подчеркнуть, что они были бы более или менее неотличимы от современных людей, если бы дожили до наших дней. В романе Уильяма Голдинга » 1955 года «Наследники неандертальцы изображены гораздо более эмоциональными и цивилизованными. [25] [26] [120] Однако образ Буля продолжал влиять на произведения вплоть до 1960-х годов. В наши дни реконструкции неандертальцев часто очень похожи на человеческие. [115] [120]

−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — | ( О. praegens ) ( О. тугененсис ) ( Ар. кадабба ) ( Ар. ramidus ) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Гибридизация между неандертальцами и ранними современными людьми была предложена еще раньше. [122] например, английский антрополог Томас Хаксли в 1890 году, [123] Датский этнограф Ганс Педер Стенсби в 1907 году. [124] и Кун в 1962 году. [125] В начале 2000-х годов были обнаружены предполагаемые гибридные экземпляры: Lagar Velho 1. [126] [127] [128] [129] и Муиерии 1 . [130] Однако подобная анатомия могла быть вызвана адаптацией к сходной среде, а не скрещиванием. [100] Примесь неандертальцев была обнаружена в современных популяциях в 2010 году при картировании первой последовательности генома неандертальца. [87] Это было основано на трех образцах из пещеры Виндия в Хорватии, которые содержали почти 4% архаичной ДНК (что позволяет почти полностью секвенировать геном). ) приходилось примерно 1 ошибка Однако на каждые 200 букв ( пар оснований из-за невероятно высокой частоты мутаций, вероятно, из-за сохранности образца. В 2012 году британско-американский генетик Грэм Куп выдвинул гипотезу, что вместо этого они обнаружили доказательства скрещивания различных архаичных видов человека с современными людьми, что было опровергнуто в 2013 году секвенированием высококачественного генома неандертальца, сохранившегося в кости пальца ноги из Денисовой пещеры. Сибирь. [100]

Классификация

[ редактировать ]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Филогения 2019 г. основана на сравнении древних протеомов и геномов с протеомами и геномами современных видов. [131] |

Неандертальцы — гоминиды рода Homo Homo , люди, и обычно классифицируются как отдельный вид , H. neanderthalensis , хотя иногда и как подвид современного человека, как sapiens neanderthalensis . Это потребовало бы классификации современных людей как H. sapiens sapiens . [132]

Большая часть разногласий проистекает из расплывчатости термина «вид», поскольку он обычно используется для различения двух генетически изолированных популяций, но известно, что смешение между современными людьми и неандертальцами имело место. [132] [133] Однако отсутствие отцовской Y-хромосомы и матрилинейной митохондриальной ДНК (мтДНК) неандертальского происхождения у современных людей, а также недостаточная представленность ДНК Х-хромосомы неандертальцев может означать снижение плодовитости или частую стерильность некоторых гибридных скрещиваний. [89] [134] [135] [136] представляющий собой частичный биологический репродуктивный барьер между группами и, следовательно, видовое различие. [89] В 2014 году генетик Сванте Пэабо резюмировал противоречие, назвав такие « таксономические войны» неразрешимыми, «поскольку не существует определения вида, идеально описывающего этот случай». [132]

Считается, что неандертальцы были более тесно связаны с денисовцами, чем с современными людьми. Точно так же неандертальцы и денисовцы имеют более позднего последнего общего предка (LCA), чем современные люди, на основе ядерной ДНК (нДНК). Однако неандертальцы и современные люди имеют общий более поздний митохондриальный LCA (наблюдаемый при изучении мтДНК) и LCA Y-хромосомы. [137] Вероятно, это произошло в результате скрещивания, последовавшего за расколом неандертальцев и денисовцев. Это включало либо интрогрессию неизвестного архаичного человека в денисовцев, [92] [93] [131] [138] [139] или интрогрессия более ранней неопознанной современной человеческой волны из Африки в неандертальцев. [137] [140] [141] Тот факт, что мтДНК раннего архаического человека неандертальской линии возрастом около 430 000 лет из Сима-де-лос-Уэсос в Испании более тесно связана с мтДНК денисовцев, чем с другими неандертальцами или современными людьми, был приведен в качестве доказательства в пользу последней гипотезы. . [137] [14] [140]

Эволюция

[ редактировать ]Принято считать, что H. heidelbergensis был последним общим предком неандертальцев, денисовцев и современных людей до того, как популяции были изолированы в Европе, Азии и Африке соответственно. [143] Таксономическое различие между H. heidelbergensis и неандертальцами в основном основано на разрыве в окаменелостях в Европе между 300 и 243 000 лет назад, во время 8-й стадии морских изотопов . «Неандертальцами» принято называть окаменелости, датируемые после этого разрыва. [12] [25] [142] ДНК архаичных людей из 430 000-летнего поселения Сима-де-лос-Уэсос в Испании указывает на то, что они более тесно связаны с неандертальцами, чем с денисовцами, а это указывает на то, что раскол между неандертальцами и денисовцами должен был произойти еще до этого времени. [14] [144] [145] возрастом 400 000 лет Череп Ароэйры 3 также может представлять собой одного из ранних представителей линии неандертальцев. [146] Вполне возможно, что поток генов между Западной Европой и Африкой во время среднего плейстоцена мог скрыть неандертальские характеристики у некоторых экземпляров европейских гомининов среднего плейстоцена, например, из Чепрано , Италия, и ущелья Сичево , Сербия. [14] Летопись окаменелостей гораздо более полна, начиная с 130 000 лет назад. [147] и экземпляры этого периода составляют основную часть известных скелетов неандертальцев. [148] [149] Остатки зубов из итальянских стоянок Висольяно и Фонтана-Рануччо указывают на то, что особенности зубов неандертальцев развились примерно 450–430 000 лет назад во время среднего плейстоцена . [150]

Существуют две основные гипотезы относительно эволюции неандертальцев после разделения неандертальцев и людей: двухфазная и аккреционная. Двухфазный утверждает, что одно-единственное крупное экологическое событие, такое как оледенение Заале , привело к быстрому увеличению размера и прочности тела европейского H. heidelbergensis , а также к удлинению головы (фаза 1), что затем привело к другим изменения анатомии черепа (2 этап). [128] Однако анатомия неандертальцев, возможно, не была полностью обусловлена адаптацией к холодной погоде. [66] что неандертальцы медленно эволюционировали с течением времени от предка H. heidelbergensis , разделенного на четыре стадии: ранние пренеандертальцы ( MIS 12 , Эльстерское оледенение ), пренеандертальцы (MIS 11–9 MIS Аккреция утверждает , , голштинское межледниковье ), ранние неандертальцы ( 7–5 ), и , оледенение Заале – эмское классические неандертальцы (МИС 4–3, оледенение Вюрма ). [142]

Было предложено множество дат разделения неандертальцев и людей. Дата около 250 000 лет назад указывает на то, что « H. Helmei » был последним общим предком (LCA), а раскол связан с леваллуазской техникой изготовления каменных орудий. Для даты около 400 000 лет назад используется H. heidelbergensis в качестве LCA . По оценкам, сделанным 600 000 лет назад, предполагается, что « H. rhodesiensis » был LCA, который разделился на современную человеческую линию и линию неандертальцев/ H. heidelbergensis . [151] Восемьсот тысяч лет назад в качестве LCA использовался H. antecessor , но различные варианты этой модели отодвинули бы дату на 1 миллион лет назад. [14] [151] Однако анализ H. antecessor, эмали протеомов проведенный в 2020 году, предполагает, что H. antecessor является родственным, но не прямым предком. [152] Исследования ДНК дали различные результаты для времени расхождения неандертальцев и человека, например, 538–315, [12] 553–321, [153] 565–503, [154] 654–475, [151] 690–550, [155] 765–550, [14] [92] 741–317, [156] и 800–520 000 лет назад; [157] и стоматологический анализ завершился более 800 000 лет назад. [13]

Неандертальцы и денисовцы более тесно связаны друг с другом, чем с современными людьми, а это означает, что раскол неандертальцев и денисовцев произошел после их раскола с современными людьми. [14] [92] [138] [158] Предполагая частоту мутаций 1 × 10 −9 или 0,5 × 10 −9 на пару оснований (п.н.) в год раскол неандертальцев и денисовцев произошел примерно 236–190 000 или 473–381 000 лет назад соответственно. [92] Использование 1,1 × 10 −8 на поколение, новое поколение каждые 29 лет, время — 744 000 лет назад. Использование 5 × 10 −10 нуклеотидных сайтов в год, это 616 000 лет назад. Если использовать последние даты, раскол, вероятно, уже произошел к тому времени, когда гоминиды распространились по Европе, а уникальные черты неандертальцев начали развиваться 600–500 000 лет назад. [138] Перед расколом неандертальцы/денисовцы (или «неандерсовцы»), мигрировавшие из Африки в Европу, по-видимому, скрещивались с неопознанным «суперархаичным» человеческим видом, который уже присутствовал там; эти суперархаики были потомками очень ранней миграции из Африки около 1,9 млн лет назад. [159]

Демография

[ редактировать ]Диапазон

[ редактировать ]

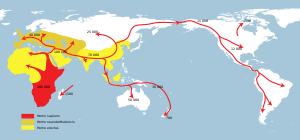

Пре- и ранние неандертальцы, жившие до эемского межледниковья (130 000 лет назад), мало известны и происходят в основном из западноевропейских стоянок. Начиная со 130 000 лет назад качество летописи окаменелостей резко возрастает с появлением классических неандертальцев, которые зарегистрированы в Западной, Центральной, Восточной и Средиземноморской Европе. [15] а также Юго-Западную , Центральную и Северную Азию до Горного Алтая на юге Сибири. С другой стороны, пре- и ранние неандертальцы, по-видимому, постоянно оккупировали только Францию, Испанию и Италию, хотя некоторые из них, по-видимому, покинули эту «основную территорию», чтобы сформировать временные поселения на востоке (хотя и не покидая Европу). Тем не менее, на юго-западе Франции самая высокая плотность стоянок до-, ранних и классических неандертальцев. [160] Неандертальцы были первым человеческим видом, постоянно населявшим Европу, поскольку более ранние люди на континенте были лишь время от времени. [161]

Самая южная находка была зафиксирована в пещере Шукба , Левант; [162] сообщения о неандертальцах из североафриканского Джебель-Ирхуда [163] и Хауа Фтеах [164] были повторно идентифицированы как H. sapiens . Их самое восточное присутствие зафиксировано в Денисовой пещере , Сибирь, 85° в.д .; Юго-восточный китайский человек Маба , череп, имеет некоторые общие физические признаки с неандертальцами, хотя они могут быть результатом конвергентной эволюции, а не расширения неандертальцами своего ареала до Тихого океана. [165] Самая северная граница обычно считается 55° с.ш. , а однозначные места известны между 50–53 , хотя это трудно оценить, поскольку наступление ледников разрушает большую часть ° с.ш. человеческих останков, а палеоантрополог Трине Келлберг Нильсен утверждает, что отсутствие доказательств Заселение южных скандинавов (по крайней мере, во время эемского межледниковья) связано с первым объяснением и отсутствием исследований в этом районе. [166] [167] Артефакты среднего палеолита обнаружены до 60° с.ш. на равнинах России. [168] [169] [170] но они, скорее всего, приписываются современным людям. [171] Исследование 2017 года показало присутствие Homo на 130 000-летнем калифорнийском участке мастодонта Черутти в Северной Америке. [172] но это во многом считается неправдоподобным. [173] [174] [175]

Неизвестно, как быстро меняющийся климат последнего ледникового периода ( события Дансгаарда-Эшгера ) повлиял на неандертальцев, поскольку периоды потепления приводили к более благоприятным температурам, но способствовали росту лесов и сдерживали мегафауну, тогда как холодные периоды приводили к противоположному результату. [176] Однако неандертальцы, возможно, предпочитали лесной ландшафт. [66] Стабильная среда с умеренными среднегодовыми температурами, возможно, была наиболее подходящей средой обитания для неандертальцев. [177] Пик численности популяций мог достигаться в холодные, но не экстремальные периоды, например, на 8-й и 6-й стадиях морских изотопов (соответственно 300 000 и 191 000 лет назад во время оледенения Заале). Возможно, их ареал расширялся и сужался по мере отступания и роста льда, соответственно, чтобы избежать зон вечной мерзлоты , находящихся в определенных зонах убежища во время максимумов ледников. [176] возрастом от 140 до 120 000 лет В 2021 году израильский антрополог Исраэль Гершковитц и его коллеги предположили, что останки израильского Нешера Рамлы , которые представляют собой смесь черт неандертальца и более древних H. erectus , представляют собой одну из таких исходных популяций, которые повторно заселили Европу после ледникового периода. . [178]

Население

[ редактировать ]Как и современные люди, неандертальцы, вероятно, произошли от очень небольшой популяции с эффективной популяцией (количеством особей, способных выносить или стать отцом детей) примерно от 3000 до 12 000 человек. Однако неандертальцы сохранили эту очень низкую популяцию, размножая слабо вредные гены из-за снижения эффективности естественного отбора . [82] [179] Различные исследования с использованием анализа мтДНК дают разные эффективные популяции. [176] например, от около 1000 до 5000; [179] от 5000 до 9000 остается постоянным; [180] или от 3000 до 25 000, которые постепенно увеличивались до 52 000 лет назад, а затем начали сокращаться вплоть до исчезновения. [84] Археологические данные свидетельствуют о десятикратном увеличении численности современного человека в Западной Европе в период перехода от неандертальцев к современному человеку. [181] а неандертальцы, возможно, находились в невыгодном демографическом положении из-за более низкого уровня рождаемости, более высокого уровня детской смертности или комбинации этих двух факторов. [182] По оценкам, общая численность населения превышает десятки тысяч человек. [138] оспариваются. [179] Постоянно низкую численность населения можно объяснить в контексте « ловушки Бозерупа популяции »: пропускная способность ограничена количеством пищи, которую она может получить, что, в свою очередь, ограничено ее технологией. Инновации растут вместе с населением, но если население слишком мало, инновации не будут происходить очень быстро, и население останется низким. Это согласуется с очевидным 150 000-летним застоем неандертальской каменной технологии. [176]

В выборке из 206 неандертальцев, исходя из численности молодых и зрелых взрослых по сравнению с представителями других возрастных групп, около 80% из них в возрасте старше 20 лет умерли, не дожив до 40 лет. Такой высокий уровень смертности, вероятно, был обусловлен их сильным стрессом. среда. [86] Однако было также подсчитано, что возрастные пирамиды неандертальцев и современных современных людей были одинаковыми. [176] По оценкам, детская смертность у неандертальцев была очень высокой - около 43% в Северной Евразии. [183]

Анатомия

[ редактировать ]Строить

[ редактировать ]Неандертальцы имели более крепкое и коренастое телосложение, чем типичные современные люди. [70] более широкие и бочкообразные грудные клетки; более широкий таз; [25] [184] и пропорционально более короткие предплечья и передние ноги. [66] [185]

На основе 45 длинных костей неандертальцев , взятых у 14 мужчин и 7 женщин, средний рост составлял от 164 до 168 см (от 5 футов 5 дюймов до 5 футов 6 дюймов) для мужчин и от 152 до 156 см (от 5 футов 0 дюймов до 5 футов 1 дюйм). для женщин. [70] Для сравнения, средний рост 20 мужчин и 10 женщин эпохи верхнего палеолита составляет соответственно 176,2 см (5 футов 9,4 дюйма) и 162,9 см (5 футов 4,1 дюйма), хотя ближе к концу он уменьшается на 10 см (4 дюйма). за период на основе 21 мужчины и 15 женщин; [186] а средний показатель в 1900 году составлял 163 см (5 футов 4 дюйма) и 152,7 см (5 футов 0 дюймов) соответственно. [187] Летопись окаменелостей показывает, что рост взрослых неандертальцев варьировался от 147,5 до 177 см (от 4 футов 10 дюймов до 5 футов 10 дюймов), хотя некоторые из них могли вырасти намного выше (от 73,8 до 184,8 см в зависимости от длины следа и от 65,8 до 189,3 см). в зависимости от ширины следа). [188] Что касается веса неандертальца, образцы из 26 экземпляров обнаружили в среднем 77,6 кг (171 фунт) для мужчин и 66,4 кг (146 фунтов) для женщин. [189] Используя 76 кг (168 фунтов), индекс массы тела мужчин-неандертальцев составил 26,9–28,2, что у современных людей коррелирует с избыточным весом . Это указывает на очень надежную конструкцию. [70] Ген неандертальского LEPR, отвечающий за накопление жира и выработку тепла телом, аналогичен гену шерстистого мамонта и поэтому, вероятно, был адаптацией к холодному климату. [67]

Шейные позвонки неандертальцев толще спереди назад и в поперечном направлении, чем у (большинства) современных людей, что приводит к стабильности и, возможно, позволяет приспособиться к другой форме и размеру головы. [190] неандертальцев Хотя грудная клетка (там, где находится грудная клетка ) по размеру была похожа на современных людей, более длинные и прямые ребра соответствовали расширению средней и нижней части грудной клетки и более сильному дыханию в нижней части грудной клетки, что указывает на большую диафрагму и, возможно, на более крупную диафрагму. большая емкость легких . [184] [191] [192] Емкость легких Кебары 2 оценивалась в 9,04 л (2,39 галлона США) по сравнению со средней емкостью легких человека 6 л (1,6 галлона США) для мужчин и 4,7 л (1,2 галлона США) для женщин. Грудь неандертальцев также была более выраженной (расширенной спереди назад или переднезадней). Крестец лордоз (там, где таз соединяется с позвоночником ) был более наклонен вертикально и располагался ниже по отношению к тазу, в результате чего позвоночник был менее изогнут (проявлялся меньший ) и несколько сгибался (чтобы быть инвагинированным). . В современных популяциях это состояние затрагивает лишь часть населения и известно как поясничный крестец. [193] Такие модификации позвоночника будут способствовать усилению бокового (медиолатерального) сгибания , что позволит лучше поддерживать более широкую нижнюю часть грудной клетки. Некоторые утверждают, что эта особенность была бы нормальной для всех Homo , даже адаптированных к тропическим условиям Homo ergaster или erectus , при этом более узкая грудная клетка у большинства современных людей является уникальной характеристикой. [184]

Пропорции тела обычно называют «гиперарктическими» как приспособление к холоду, поскольку они аналогичны пропорциям человеческих популяций, развившихся в холодном климате. [194] — телосложение неандертальцев наиболее похоже на телосложение инуитов и сибирских юпиков среди современных людей. [195] — а более короткие конечности приводят к более высокому сохранению тепла тела. [185] [194] [196] Тем не менее, неандертальцы из более умеренного климата, таких как Иберия, все еще сохраняют «гиперарктическое» телосложение. [197] В 2019 году английский антрополог Джон Стюарт и его коллеги предположили, что неандертальцы вместо этого были приспособлены к бегу на короткие дистанции из-за доказательств того, что неандертальцы предпочитают более теплые лесные районы более холодным гигантским степям , а также анализа ДНК, указывающего на более высокую долю быстросокращающихся мышечных волокон у неандертальцев, чем у современных. люди. Он объяснил их пропорции тела и большую мышечную массу адаптацией к спринтерскому бегу, в отличие от телосложения современного человека, ориентированного на выносливость . [66] поскольку настойчивая охота может быть эффективной только в жарком климате, где охотник может довести добычу до теплового истощения ( гипертермии ). У них были длиннее пяточные кости , [198] снижая их способность к бегу на выносливость, а их более короткие конечности имели бы уменьшенный момент силы в конечностях, что позволяло бы создавать большую чистую вращательную силу в запястьях и лодыжках, вызывая более быстрое ускорение. [66] В 1981 году американский палеоантрополог Эрик Тринкаус обратил внимание на это альтернативное объяснение, но посчитал его менее вероятным. [185] [199]

Лицо

[ редактировать ]

У неандертальцев были менее развитые подбородки, покатые лбы и более длинные, широкие и выступающие носы. Череп неандертальца обычно более удлиненный, но при этом более широкий и менее шаровидный, чем у большинства современных людей, и имеет гораздо больше сходства с затылочным бугорком . [200] или «шиньон», выступ на задней части черепа, хотя у современных людей он находится в пределах вариаций. Это вызвано тем, что основание черепа и височные кости расположены выше и ближе к передней части черепа, а также более плоской черепной коробкой . [201]

Лицо неандертальца характеризуется прогнатизмом средней части лица , при котором скуловые дуги расположены назад по сравнению с современными людьми, в то время как их верхнечелюстные кости и носовые кости, по сравнению с ними, расположены более вперед. [202] Глазные яблоки неандертальцев крупнее, чем у современного человека. В одном исследовании было высказано предположение, что это произошло из-за того, что у неандертальцев были улучшены зрительные способности за счет неокортикального и социального развития. [203] Однако это исследование было отвергнуто другими исследователями, которые пришли к выводу, что размер глазного яблока не является доказательством когнитивных способностей неандертальцев или современных людей. [204]

Проецируемый неандертальский нос и околоносовые пазухи обычно объяснялись тем, что воздух нагревался при попадании в легкие и сохранял влагу (гипотеза «носового радиатора»); [205] если бы их носы были шире, это отличалось бы от обычно суженной формы у существ, адаптированных к холоду, и это было бы вызвано генетическим дрейфом . Кроме того, широко реконструированные пазухи не очень велики и сравнимы по размеру с таковыми у современного человека. Однако если размер пазух не является важным фактором для дыхания холодным воздухом, то фактическая функция будет неясна, поэтому они не могут быть хорошим индикатором эволюционного давления, необходимого для развития такого носа. [206] Кроме того, компьютерная реконструкция носа неандертальца и предсказанные структуры мягких тканей показывают некоторое сходство с таковыми у современных арктических народов, что потенциально означает, что носы обеих популяций конвергентно эволюционировали для дыхания холодным и сухим воздухом. [68]

У неандертальцев была довольно большая челюсть, которая когда-то упоминалась как реакция на большую силу укуса , о чем свидетельствует сильное изнашивание передних зубов неандертальцев (гипотеза «передней нагрузки на зубы»), но аналогичные тенденции изнашивания наблюдаются и у современных людей. Он также мог бы эволюционировать, чтобы соответствовать более крупным зубам в челюсти, которые лучше сопротивлялись бы износу и истиранию. [205] [207] а повышенный износ передних зубов по сравнению с задними, вероятно, связан с повторяющимся использованием. Образцы износа зубов неандертальцев больше всего похожи на таковые у современных инуитов. [205] Резцы большие и имеют лопатообразную форму, и, по сравнению с современными людьми, наблюдается необычно высокая частота тауродонтизма — состояния, при котором коренные зубы становятся более объемными из-за увеличенной пульпы (сердцевины зуба). Когда-то считалось, что тауродонтизм был отличительной чертой неандертальцев, которая давала некоторые механические преимущества или возникала в результате повторяющегося использования, но, скорее всего, была просто продуктом генетического дрейфа. [208] Сейчас считается, что сила укуса неандертальцев и современных людей примерно одинакова. [205] около 285 Н (64 фунта-силы) и 255 Н (57 фунтов-силы) у современных мужчин и женщин соответственно. [209]

Мозг

[ редактировать ]Размер черепной коробки неандертальца составляет в среднем 1640 см. 3 (100 у.е. дюймов) для мужчин и 1460 см. 3 (89 у.е. дюймов) для самок, [72] [73] что значительно превышает средние показатели для всех групп современного человека; [74] например, средний рост современных европейских мужчин составляет 1362 см. 3 (83,1 куб. Дюймов) и самки 1201 см. 3 (73,3 куб. Дюймов). [210] Для 28 современных человеческих экземпляров, живших от 190 000 до 25 000 лет назад, средний рост составлял около 1478 см. 3 (90,2 куб. Дюймов), независимо от пола, и предполагается, что размер мозга современного человека уменьшился со времен верхнего палеолита. [211] Самый большой мозг неандертальца, Амуд 1 , по расчетам, имел размер 1736 см. 3 (105,9 куб. Дюймов), один из крупнейших, когда-либо зарегистрированных у гоминид. [73] И неандертальцы, и человеческие младенцы имеют рост около 400 см. 3 (24 куб.дюйма). [212]

Если смотреть сзади, черепная коробка неандертальца выглядит ниже, шире и округлее, чем у анатомически современных людей. Эта характерная форма называется «en бомбе» (похожая на бомбу) и является уникальной для неандертальцев, при этом все другие виды гоминидов (включая большинство современных людей) обычно имеют узкие и относительно вертикальные своды черепа, если смотреть сзади. [213] [214] [215] [216] Мозг неандертальца характеризовался относительно меньшими теменными долями. [80] и больший мозжечок . [80] [217] Мозг неандертальцев также имеет более крупные затылочные доли (что связано с классическим появлением затылочного бугорка в анатомии черепа неандертальцев, а также с большей шириной их черепов), что подразумевает внутренние различия в пропорциональности внутренних областей мозга по сравнению с Homo sapiens. , что согласуется с внешними измерениями, полученными на ископаемых черепах. [203] [218] Их мозг также имеет более крупные полюса височных долей. [217] более широкая орбитофронтальная кора, [219] и более крупные обонятельные луковицы, [220] предполагая потенциальные различия в понимании языка и ассоциациях с эмоциями ( временные функции ), принятием решений ( орбитофронтальная кора ) и обонянием ( обонятельные луковицы ). Их мозг также демонстрирует разные темпы роста и развития. [221] Такие различия, хотя и незначительные, были бы заметны в ходе естественного отбора и могут лежать в основе и объяснять различия в материальных показателях в таких вещах, как социальное поведение, технологические инновации и художественные произведения. [18] [222]

Цвет волос и кожи

[ редактировать ]Недостаток солнечного света, скорее всего, привел к распространению более светлой кожи у неандертальцев. [223] хотя недавно утверждалось, что светлая кожа у современных европейцев не была особенно плодовитой, возможно, до бронзового века . [224] Генетически BNC2 присутствовал у неандертальцев, что связано со светлым цветом кожи; однако также присутствовал второй вариант BNC2, который в современных популяциях связан с более темным цветом кожи в Биобанке Великобритании . [223] Анализ ДНК трех женщин-неандертальцев из юго-восточной Европы показывает, что у них были карие глаза, темный цвет кожи и каштановые волосы, причем у одной из них были рыжие волосы. [225] [226]

У современных людей цвет кожи и волос регулируется меланоцитстимулирующим гормоном , который увеличивает соотношение эумеланина (черного пигмента) и феомеланина (красного пигмента), который кодируется геном MC1R. У современных людей известно пять вариантов этого гена, которые вызывают потерю функции и связаны со светлым цветом кожи и волос, а также еще один неизвестный вариант у неандертальцев (вариант R307G), который может быть связан с бледной кожей и рыжими волосами. Вариант R307G был идентифицирован у неандертальца из Монти Лессини , Италия, и, возможно, из Куэва-дель-Сидрон, Испания. [227] Однако, как и у современных людей, красный цвет волос, вероятно, не был очень распространенным, потому что этот вариант не присутствует у многих других секвенированных неандертальцев. [223]

Метаболизм

[ редактировать ]Максимальная естественная продолжительность жизни и сроки взросления, менопаузы и беременности, скорее всего, были очень похожи на современных людей. [176] была выдвинута гипотеза Однако на основе скорости роста зубов и зубной эмали : [228] [229] что неандертальцы взрослели быстрее современных людей, хотя это не подтверждается возрастными биомаркерами . [86] Основными различиями в созревании являются атлант шеи, а также средние грудные позвонки, сросшиеся у неандертальцев примерно на 2 года позже, чем у современных людей, но это, скорее, было вызвано различиями в анатомии, а не скоростью роста. [230] [231]

неандертальцев в Как правило, модели потребностей калориях сообщают о значительно более высоком потреблении калорий, чем у современных людей, поскольку они обычно предполагают, что у неандертальцев был более высокий уровень основного обмена (BMR) из-за более высокой мышечной массы, более высоких темпов роста и большего производства тепла телом в условиях холода; [232] [233] [234] и более высокие уровни ежедневной физической активности (PAL) из-за больших ежедневных путешествий во время поиска пищи. [233] [234] Однако, используя высокие показатели BMR и PAL, американский археолог Брайан Хокетт подсчитал, что беременная неандерталец потребляла бы 5500 калорий в день, что потребовало бы сильной зависимости от мяса крупной дичи; такая диета могла бы вызвать многочисленные недостатки или отравления питательными веществами, поэтому он пришел к выводу, что эти предположения необоснованны. [234]

Неандертальцы, возможно, были более активны в условиях слабого освещения, а не среди дневного света, потому что они жили в регионах с сокращенным световым днем зимой, охотились на крупную дичь (такие хищники обычно охотятся ночью, чтобы улучшить тактику засады) и имели большие глаза и зрительную обработку. нервные центры. Генетически дальтонизм (который может усиливать мезопическое зрение ) обычно коррелирует с популяциями северных широт, а у неандертальцев из пещеры Виндия в Хорватии были некоторые замены в генах опсина , которые могли повлиять на цветовое зрение. Однако функциональные последствия этих замен неубедительны. [235] Аллели неандертальского происхождения рядом с ASB1 и EXOC6 связаны с вечерним поведением , нарколепсией и дневным сном. [223]

Патология

[ редактировать ]Неандертальцы часто получали травматические повреждения: по оценкам, у 79–94% особей наблюдались признаки заживления серьезных травм, из которых 37–52% были серьезно ранены, а 13–19% получили травмы, не достигнув совершеннолетия. [236] Крайним примером является Шанидар 1 , у которого наблюдаются признаки ампутации правой руки, вероятно, из-за несращения после перелома кости в подростковом возрасте, остеомиелита (инфекции кости) левой ключицы , неправильной походки , проблем со зрением левого глаза. и возможная потеря слуха [237] (возможно, ухо пловца ). [238] В 1995 году Тринкаус подсчитал, что около 80% скончались от полученных травм и умерли, не дожив до 40 лет, и таким образом предположил, что неандертальцы использовали рискованную стратегию охоты (гипотеза «наездника на родео»). [86] Однако частота черепно-мозговых травм существенно не различается между неандертальцами и современными людьми среднего палеолита (хотя у неандертальцев, похоже, был более высокий риск смертности). [239] мало экземпляров как современных людей верхнего палеолита, так и неандертальцев, умерших после 40 лет, [182] и в целом между ними есть схожие модели травм. В 2012 году Тринкаус пришел к выводу, что неандертальцы наносили себе травмы так же, как и современные люди, например, в результате межличностного насилия. [240] Исследование, проведенное в 2016 году на 124 экземплярах неандертальцев, показало, что высокий уровень травм был вызван нападениями животных , и обнаружило, что около 36% выборки стали жертвами нападений медведей , 21% нападений больших кошек и 17% нападений волков (всего 92 положительных результата). случаев, 74%). Случаев нападения гиен не было, хотя гиены все же, вероятно, нападали на неандертальцев, по крайней мере, оппортунистически. [241] Такое интенсивное хищничество, вероятно, возникло из-за обычных конфронтаций из-за конкуренции за пищу и пространство в пещерах, а также из-за охоты неандертальцев на этих хищников. [241]

Низкая популяция вызвала низкое генетическое разнообразие и, возможно, инбридинг, что снизило способность популяции фильтровать вредные мутации ( инбредная депрессия ). Однако неизвестно, как это повлияло на генетическое бремя одного неандертальца и, следовательно, вызвало ли это более высокий уровень врожденных дефектов, чем у современных людей. [242] Однако известно, что у 13 жителей пещеры Сидрон в совокупности наблюдалось 17 различных врожденных дефектов, вероятно, связанных с инбридингом или рецессивными нарушениями . [243] Вероятно, из-за преклонного возраста (60 или 70 лет) у Ла Шапель-о-Сент 1 были признаки болезни Бааструпа , поражающей позвоночник, и остеоартрит. [244] У Шанидара 1, который, вероятно, умер примерно в 30 или 40 лет, был диагностирован самый древний случай диффузного идиопатического скелетного гиперостоза (DISH), дегенеративного заболевания, которое может ограничивать движения, что, если оно правильное, указывает на умеренно высокий уровень заболеваемости среди пожилых людей. Неандертальцы. [245]

Неандертальцы были подвержены нескольким инфекционным заболеваниям и паразитам. Современные люди, вероятно, передали им болезни; Одним из возможных кандидатов является желудочная бактерия Helicobacter pylori . [246] Современный вариант вируса папилломы человека 16А может произойти от интрогрессии неандертальцев. [247] У неандертальца из Куэва-дель-Сидрон, Испания, обнаружены признаки желудочно-кишечной инфекции Enterocytozoon bieneusi . [248] Кости ног французского La Ferrassie 1 имеют поражения, которые соответствуют периоститу — воспалению ткани, окружающей кость, — вероятно, результату гипертрофической остеоартропатии , которая в первую очередь вызвана инфекцией грудной клетки или раком легких . [249] была ниже, У неандертальцев частота кариеса чем у современных людей, несмотря на то, что некоторые популяции потребляли в больших количествах продукты, обычно вызывающие кариес, что может указывать на отсутствие бактерий полости рта, вызывающих кариес, а именно Streptococcus mutans . [250]

Два 250 000-летних ребенка-неандерталоида из Пайре , Франция, представляют собой самые ранние известные случаи воздействия свинца на гомининов. Они подверглись воздействию в двух разных случаях: либо съели или выпили зараженную пищу или воду, либо вдыхали свинцовый дым от пожара. В радиусе 25 км (16 миль) от объекта находятся две свинцовые шахты. [251]

Культура

[ редактировать ]Социальная структура

[ редактировать ]Групповая динамика

[ редактировать ]

Neanderthals likely lived in more sparsely distributed groups than contemporary modern humans,[176] but group size is thought to have averaged 10 to 30 individuals, similar to modern hunter-gatherers.[31] Reliable evidence of Neanderthal group composition comes from Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, and the footprints at Le Rozel, France:[188] the former shows 7 adults, 3 adolescents, 2 juveniles and an infant;[252] whereas the latter, based on footprint size, shows a group of 10 to 13 members where juveniles and adolescents made up 90%.[188]

A Neanderthal child's teeth analysed in 2018 showed it was weaned after 2.5 years, similar to modern hunter gatherers, and was born in the spring, which is consistent with modern humans and other mammals whose birth cycles coincide with environmental cycles.[251] Indicated from various ailments resulting from high stress at a low age, such as stunted growth, British archaeologist Paul Pettitt hypothesised that children of both sexes were put to work directly after weaning;[183] and Trinkaus said that, upon reaching adolescence, an individual may have been expected to join in hunting large and dangerous game.[86] However, the bone trauma is comparable to modern Inuit, which could suggest a similar childhood between Neanderthals and contemporary modern humans.[253] Further, such stunting may have also resulted from harsh winters and bouts of low food resources.[251]

Sites showing evidence of no more than three individuals may have represented nuclear families or temporary camping sites for special task groups (such as a hunting party).[31] Bands likely moved between certain caves depending on the season, indicated by remains of seasonal materials such as certain foods, and returned to the same locations generation after generation. Some sites may have been used for over 100 years.[254] Cave bears may have greatly competed with Neanderthals for cave space,[255] and there is a decline in cave bear populations starting 50,000 years ago onwards (although their extinction occurred well after Neanderthals had died out).[256][257] Neanderthals also had a preference for caves whose openings faced towards the south.[258] Although Neanderthals are generally considered to have been cave dwellers, with 'home base' being a cave, open-air settlements near contemporaneously inhabited cave systems in the Levant could indicate mobility between cave and open-air bases in this area. Evidence for long-term open-air settlements is known from the 'Ein Qashish site in Israel,[259][260] and Moldova I in Ukraine. Although Neanderthals appear to have had the ability to inhabit a range of environments—including plains and plateaux—open-air Neanderthals sites are generally interpreted as having been used as slaughtering and butchering grounds rather than living spaces.[85]

In 2022, remains of the first-known Neanderthal family (six adults and five children) were excavated from Chagyrskaya Cave in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia in Russia. The family, which included a father, a daughter, and what appear to be cousins, most likely died together, presumably from starvation.[261][262]

Neanderthals, like contemporaneous modern humans, were most likely polygynous, based on their low second-to-fourth digit ratios, a biomarker for prenatal androgen effects that corresponds to high incidence of polygyny in haplorhine primates.[263]

Inter-group relations

[edit]

Canadian ethnoarchaeologist Brian Hayden calculated a self-sustaining population that avoids inbreeding to consist of about 450–500 individuals, which would necessitate these bands to interact with 8–53 other bands, but more likely the larger estimate given low population density.[31] Analysis of the mtDNA of the Neanderthals of Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, showed that the three adult men belonged to the same maternal lineage, while the three adult women belonged to different ones. This suggests a patrilocal residence (that a woman moved out of her group to live with her partner).[264] However, the DNA of a Neanderthal from Denisova Cave, Russia, shows that she had an inbreeding coefficient of 1⁄8 (her parents were either half-siblings with a common mother, double first cousins, an uncle and niece or aunt and nephew, or a grandfather and granddaughter or grandmother and grandson)[92] and the inhabitants of Cueva del Sidrón show several defects, which may have been caused by inbreeding or recessive disorders.[243]

Considering most Neanderthal artifacts were sourced no more than 5 km (3.1 mi) from the main settlement, Hayden considered it unlikely these bands interacted very often,[31] and mapping of the Neanderthal brain and their small group size and population density could indicate that they had a reduced ability for inter-group interaction and trade.[203] However, a few Neanderthal artefacts in a settlement could have originated 20, 30, 100 and 300 km (12.5, 18.5, 60 and 185 mi) away. Based on this, Hayden also speculated that macro-bands formed which functioned much like those of the low-density hunter-gatherer societies of the Western Desert of Australia. Macro-bands collectively encompass 13,000 km2 (5,000 sq mi), with each band claiming 1,200–2,800 km2 (460–1,080 sq mi), maintaining strong alliances for mating networks or to cope with leaner times and enemies.[31] Similarly, British anthropologist Eiluned Pearce and Cypriot archaeologist Theodora Moutsiou speculated that Neanderthals were possibly capable of forming geographically expansive ethnolinguistic tribes encompassing upwards of 800 people, based on the transport of obsidian up to 300 km (190 mi) from the source compared to trends seen in obsidian transfer distance and tribe size in modern hunter-gatherers. However, according to their model Neanderthals would not have been as efficient at maintaining long-distance networks as modern humans, probably due to a significantly lower population.[265] Hayden noted an apparent cemetery of six or seven individuals at La Ferrassie, France, which, in modern humans, is typically used as evidence of a corporate group which maintained a distinct social identity and controlled some resource, trading, manufacturing and so on. La Ferrassie is also located in one of the richest animal-migration routes of Pleistocene Europe.[31]

Genetic analysis indicates there were at least three distinct geographical groups—Western Europe, the Mediterranean coast, and east of the Caucasus—with some migration among these regions.[84] Post-Eemian Western European Mousterian lithics can also be broadly grouped into three distinct macro-regions: Acheulean-tradition Mousterian in the southwest, Micoquien in the northeast, and Mousterian with bifacial tools (MBT) in between the former two. MBT may actually represent the interactions and fusion of the two different cultures.[83] Southern Neanderthals exhibit regional anatomical differences from northern counterparts: a less protrusive jaw, a shorter gap behind the molars, and a vertically higher jawbone.[266] These all instead suggest Neanderthal communities regularly interacted with neighbouring communities within a region, but not as often beyond.[83]

Nonetheless, over long periods of time, there is evidence of large-scale cross-continental migration. Early specimens from Mezmaiskaya Cave in the Caucasus[139] and Denisova Cave in the Siberian Altai Mountains[90] differ genetically from those found in Western Europe, whereas later specimens from these caves both have genetic profiles more similar to Western European Neanderthal specimens than to the earlier specimens from the same locations, suggesting long-range migration and population replacement over time.[90][139] Similarly, artefacts and DNA from Chagyrskaya and Okladnikov Caves, also in the Altai Mountains, resemble those of eastern European Neanderthal sites about 3,000–4,000 km (1,900–2,500 mi) away more than they do artefacts and DNA of the older Neanderthals from Denisova Cave, suggesting two distinct migration events into Siberia.[267] Neanderthals seem to have suffered a major population decline during MIS 4 (71–57,000 years ago), and the distribution of the Micoquian tradition could indicate that Central Europe and the Caucasus were repopulated by communities from a refuge zone either in eastern France or Hungary (the fringes of the Micoquian tradition) who dispersed along the rivers Prut and Dniester.[268]

There is also evidence of inter-group conflict: a skeleton from La Roche à Pierrot, France, showing a healed fracture on top of the skull apparently caused by a deep blade wound,[269] and another from Shanidar Cave, Iraq, found to have a rib lesion characteristic of projectile weapon injuries.[270]

Social hierarchy

[edit]

It is sometimes suggested that, since they were hunters of challenging big game and lived in small groups, there was no sexual division of labour as seen in modern hunter-gatherer societies. That is, men, women and children all had to be involved in hunting, instead of men hunting with women and children foraging. However, with modern hunter-gatherers, the higher the meat dependency, the higher the division of labour.[31] Further, tooth-wearing patterns in Neanderthal men and women suggest they commonly used their teeth for carrying items, but men exhibit more wearing on the upper teeth, and women the lower, suggesting some cultural differences in tasks.[271]

It is controversially proposed that some Neanderthals wore decorative clothing or jewellery—such as a leopard skin or raptor feathers—to display elevated status in the group. Hayden postulated that the small number of Neanderthal graves found was because only high-ranking members would receive an elaborate burial, as is the case for some modern hunter-gatherers.[31] Trinkaus suggested that elderly Neanderthals were given special burial rites for lasting so long given the high mortality rates.[86] Alternatively, many more Neanderthals may have received burials, but the graves were infiltrated and destroyed by bears.[272] Given that 20 graves of Neanderthals aged under 4 have been found—over a third of all known graves—deceased children may have received greater care during burial than other age demographics.[253]

Looking at Neanderthal skeletons recovered from several natural rock shelters, Trinkaus said that, although Neanderthals were recorded as bearing several trauma-related injuries, none of them had significant trauma to the legs that would debilitate movement. He suggested that self worth in Neanderthal culture derived from contributing food to the group; a debilitating injury would remove this self-worth and result in near-immediate death, and individuals who could not keep up with the group while moving from cave to cave were left behind.[86] However, there are examples of individuals with highly debilitating injuries being nursed for several years, and caring for the most vulnerable within the community dates even further back to H. heidelbergensis.[42][253] Especially given the high trauma rates, it is possible that such an altruistic strategy ensured their survival as a species for so long.[42]

Food

[edit]Hunting and gathering

[edit]

Neanderthals were once thought of as scavengers, but are now considered to have been apex predators.[273][274] In 1980, it was hypothesised that two piles of mammoth skulls at La Cotte de St Brelade, Jersey, at the base of a gulley were evidence of mammoth drive hunting (causing them to stampede off a ledge),[275] but this is contested.[276] Living in a forested environment, Neanderthals were likely ambush hunters, getting close to and attacking their target—a prime adult—in a short burst of speed, thrusting in a spear at close quarters.[66][277] Younger or wounded animals may have been hunted using traps, projectiles, or pursuit.[277] Some sites show evidence that Neanderthals slaughtered whole herds of animals in large, indiscriminate hunts and then carefully selected which carcasses to process.[278] Nonetheless, they were able to adapt to a variety of habitats.[51][276] They appear to have eaten predominantly what was abundant within their immediate surroundings,[53] with steppe-dwelling communities (generally outside of the Mediterranean) subsisting almost entirely on meat from large game, forest-dwelling communities consuming a wide array of plants and smaller animals, and waterside communities gathering aquatic resources, although even in more southerly, temperate areas such as the southeastern Iberian Peninsula, large game still featured prominently in Neanderthal diets.[279] Contemporary humans, in contrast, seem to have used more complex food extraction strategies and generally had a more diverse diet.[280] Nonetheless, Neanderthals still would have had to have eaten a varied enough diet to prevent nutrient deficiencies and protein poisoning, especially in the winter when they presumably ate mostly lean meat. Any food with high contents of other essential nutrients not provided by lean meat would have been vital components of their diet, such as fat-rich brains,[42] carbohydrate-rich and abundant underground storage organs (including roots and tubers),[281] or, like modern Inuit, the stomach contents of herbivorous prey items.[282]

For meat, they appear to have fed predominantly on hoofed mammals,[283] namely red deer and reindeer as these two were the most abundant game,[46][284] but also on other Pleistocene megafauna such as chamois,[285] ibex,[286] wild boar,[285] steppe wisent,[287] aurochs,[285] Irish elk,[288] woolly mammoth,[289] straight-tusked elephant,[290] woolly rhinoceros,[291] Merck's rhinoceros[292] the narrow-nosed rhinoceros,[293] wild horse,[284] and so on.[25][47][294] There is evidence of directed cave and brown bear hunting both in and out of hibernation, as well as butchering.[295] Analysis of Neanderthal bone collagen from Vindija Cave, Croatia, shows nearly all of their protein needs derived from animal meat.[47] Some caves show evidence of regular rabbit and tortoise consumption. At Gibraltar sites, there are remains of 143 different bird species, many ground-dwelling such as the common quail, corn crake, woodlark, and crested lark.[51] Scavenging birds such as corvids and eagles were commonly exploited.[296] Neanderthals also exploited marine resources on the Iberian, Italian and Peloponnesian Peninsulas, where they waded or dived for shellfish,[51][297][298] as early as 150,000 years ago at Cueva Bajondillo, Spain, similar to the fishing record of modern humans.[299] At Vanguard Cave, Gibraltar, the inhabitants consumed Mediterranean monk seal, short-beaked common dolphin, common bottlenose dolphin, Atlantic bluefin tuna, sea bream and purple sea urchin;[51][300] and at Gruta da Figueira Brava, Portugal, there is evidence of large-scale harvest of shellfish, crabs and fish.[301] Evidence of freshwater fishing was found in Grotte di Castelcivita, Italy, for trout, chub and eel;[298] Abri du Maras, France, for chub and European perch; Payré, France;[302] and Kudaro Cave, Russia, for Black Sea salmon.[303]

Edible plant and mushroom remains are recorded from several caves.[49] Neanderthals from Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, based on dental tartar, likely had a meatless diet of mushrooms, pine nuts and moss, indicating they were forest foragers.[248] Remnants from Amud Cave, Israel, indicates a diet of figs, palm tree fruits and various cereals and edible grasses.[50] Several bone traumas in the leg joints could possibly suggest habitual squatting, which, if the case, was likely done while gathering food.[304] Dental tartar from Grotte de Spy, Belgium, indicates the inhabitants had a meat-heavy diet including woolly rhinoceros and mouflon sheep, while also regularly consuming mushrooms.[248] Neanderthal faecal matter from El Salt, Spain, dated to 50,000 years ago—the oldest human faecal matter remains recorded—show a diet mainly of meat but with a significant component of plants.[305] Evidence of cooked plant foods—mainly legumes and, to a far lesser extent, acorns—was discovered at the Kebara Cave site in Israel, with its inhabitants possibly gathering plants in spring and fall and hunting in all seasons except fall, although the cave was probably abandoned in late summer to early fall.[40] At Shanidar Cave, Iraq, Neanderthals collected plants with various harvest seasons, indicating they scheduled returns to the area to harvest certain plants, and that they had complex food-gathering behaviours for both meat and plants.[48]

Food preparation

[edit]Neanderthals probably could employ a wide range of cooking techniques, such as roasting, and they may have been able to heat up or boil soup, stew, or animal stock.[44] The abundance of animal bone fragments at settlements may indicate the making of fat stocks from boiling bone marrow, possibly taken from animals that had already died of starvation. These methods would have substantially increased fat consumption, which was a major nutritional requirement of communities with low carbohydrate and high protein intake.[44][306] Neanderthal tooth size had a decreasing trend after 100,000 years ago, which could indicate an increased dependence on cooking or the advent of boiling, a technique that would have softened food.[307]

At Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, Neanderthals likely cooked and possibly smoked food,[45] as well as used certain plants—such as yarrow and camomile—as flavouring,[44] although these plants may have instead been used for their medicinal properties.[39] At Gorham's Cave, Gibraltar, Neanderthals may have been roasting pinecones to access pine nuts.[51]

At Grotte du Lazaret, France, a total of twenty-three red deer, six ibexes, three aurochs, and one roe deer appear to have been hunted in a single autumn hunting season, when strong male and female deer herds would group together for rut. The entire carcasses seem to have been transported to the cave and then butchered. Because this is such a large amount of food to consume before spoilage, it is possible these Neanderthals were curing and preserving it before winter set in. At 160,000 years old, it is the oldest potential evidence of food storage.[43] The great quantities of meat and fat which could have been gathered in general from typical prey items (namely mammoths) could also indicate food storage capability.[308] With shellfish, Neanderthals needed to eat, cook, or in some manner preserve them soon after collection, as shellfish spoils very quickly. At Cueva de los Aviones, Spain, the remains of edible, algae eating shellfish associated with the alga Jania rubens could indicate that, like some modern hunter gatherer societies, harvested shellfish were held in water-soaked algae to keep them alive and fresh until consumption.[309]

Competition

[edit]

Competition from large Ice Age predators was rather high. Cave lions likely targeted horses, large deer and wild cattle; and leopards primarily reindeer and roe deer; which heavily overlapped with Neanderthal diet. To defend a kill against such ferocious predators, Neanderthals may have engaged in a group display of yelling, arm waving, or stone throwing; or quickly gathered meat and abandoned the kill. However, at Grotte de Spy, Belgium, the remains of wolves, cave lions and cave bears—which were all major predators of the time—indicate Neanderthals hunted their competitors to some extent.[52]

Neanderthals and cave hyenas may have exemplified niche differentiation, and actively avoided competing with each other. Although they both mainly targeted the same groups of creatures—deer, horses and cattle—Neanderthals mainly hunted the former and cave hyenas the latter two. Further, animal remains from Neanderthal caves indicate they preferred to hunt prime individuals, whereas cave hyenas hunted weaker or younger prey, and cave hyena caves have a higher abundance of carnivore remains.[46] Nonetheless, there is evidence that cave hyenas stole food and leftovers from Neanderthal campsites and scavenged on dead Neanderthal bodies.[310]

Cannibalism

[edit]

There are several instances of Neanderthals practising cannibalism across their range.[312][313] The first example came from the Krapina, Croatia site, in 1899,[120] and other examples were found at Cueva del Sidrón[266] and Zafarraya in Spain; and the French Grotte de Moula-Guercy,[314] Les Pradelles, and La Quina. For the five cannibalised Neanderthals at the Grottes de Goyet, Belgium, there is evidence that the upper limbs were disarticulated, the lower limbs defleshed and also smashed (likely to extract bone marrow), the chest cavity disemboweled, and the jaw dismembered. There is also evidence that the butchers used some bones to retouch their tools. The processing of Neanderthal meat at Grottes de Goyet is similar to how they processed horse and reindeer.[312][313] About 35% of the Neanderthals at Marillac-le-Franc, France, show clear signs of butchery, and the presence of digested teeth indicates that the bodies were abandoned and eaten by scavengers, likely hyaenas.[315]

These cannibalistic tendencies have been explained as either ritual defleshing, pre-burial defleshing (to prevent scavengers or foul smell), an act of war, or simply for food. Due to a small number of cases, and the higher number of cut marks seen on cannibalised individuals than animals (indicating inexperience), cannibalism was probably not a very common practice, and it may have only been done in times of extreme food shortages as in some cases in recorded human history.[313]

The arts

[edit]Personal adornment

[edit]Neanderthals used ochre, a clay earth pigment. Ochre is well documented from 60 to 45,000 years ago in Neanderthal sites, with the earliest example dating to 250–200,000 years ago from Maastricht-Belvédère, the Netherlands (a similar timespan to the ochre record of H. sapiens).[316] It has been hypothesised to have functioned as body paint, and analyses of pigments from Pech de l'Azé, France, indicates they were applied to soft materials (such as a hide or human skin).[317] However, modern hunter gatherers, in addition to body paint, also use ochre for medicine, for tanning hides, as a food preservative, and as an insect repellent, so its use as decorative paint for Neanderthals is speculative.[316] Containers apparently used for mixing ochre pigments were found in Peștera Cioarei, Romania, which could indicate modification of ochre for solely aesthetic purposes.[318]

Neanderthals collected uniquely shaped objects and are suggested to have modified them into pendants, such as a fossil Aspa marginata sea snail shell possibly painted red from Grotta di Fumane, Italy, transported over 100 km (62 mi) to the site about 47,500 years ago;[319] three shells, dated to about 120–115,000 years ago, perforated through the umbo belonging to a rough cockle, a Glycymeris insubrica, and a Spondylus gaederopus from Cueva de los Aviones, Spain, the former two associated with red and yellow pigments, and the latter a red-to-black mix of hematite and pyrite; and a king scallop shell with traces of an orange mix of goethite and hematite from Cueva Antón, Spain. The discoverers of the latter two claim that pigment was applied to the exterior to make it match the naturally vibrant inside colouration.[56][309] Excavated from 1949 to 1963 from the French Grotte du Renne, Châtelperronian beads made from animal teeth, shells and ivory were found associated with Neanderthal bones, but the dating is uncertain and Châtelperronian artefacts may actually have been crafted by modern humans and simply redeposited with Neanderthal remains.[320][321][322][323]

Gibraltarian palaeoanthropologists Clive and Geraldine Finlayson suggested that Neanderthals used various bird parts as artistic media, specifically black feathers.[324] In 2012, the Finlaysons and colleagues examined 1,699 sites across Eurasia, and argued that raptors and corvids, species not typically consumed by any human species, were overrepresented and show processing of only the wing bones instead of the fleshier torso, and thus are evidence of feather plucking of specifically the large flight feathers for use as personal adornment. They specifically noted the cinereous vulture, red-billed chough, kestrel, lesser kestrel, alpine chough, rook, jackdaw and the white tailed eagle in Middle Palaeolithic sites.[325] Other birds claimed to present evidence of modifications by Neanderthals are the golden eagle, rock pigeon, common raven and the bearded vulture.[326] The earliest claim of bird bone jewellery is a number of 130,000-year-old white tailed eagle talons found in a cache near Krapina, Croatia, speculated, in 2015, to have been a necklace.[327][328] A similar 39,000-year-old Spanish imperial eagle talon necklace was reported in 2019 at Cova Foradà in Spain, though from the contentious Châtelperronian layer.[329] In 2017, 17 incision-decorated raven bones from the Zaskalnaya VI rock shelter, Ukraine, dated to 43–38,000 years ago were reported. Because the notches are more-or-less equidistant to each other, they are the first modified bird bones that cannot be explained by simple butchery, and for which the argument of design intent is based on direct evidence.[54]

Discovered in 1975, the so-called Mask of la Roche-Cotard, a mostly flat piece of flint with a bone pushed through a hole on the midsection—dated to 32, 40, or 75,000 years ago[330]—has been purported to resemble the upper half of a face, with the bone representing eyes.[331][332] It is contested whether it represents a face, or if it even counts as art.[333] In 1988, American archaeologist Alexander Marshack speculated that a Neanderthal at Grotte de L'Hortus, France, wore a leopard pelt as personal adornment to indicate elevated status in the group based on a recovered leopard skull, phalanges and tail vertebrae.[31][334]

Abstraction

[edit]

As of 2014, 63 purported engravings have been reported from 27 different European and Middle Eastern Lower-to-Middle Palaeolithic sites, of which 20 are on flint cortexes from 11 sites, 7 are on slabs from 7 sites, and 36 are on pebbles from 13 sites. It is debated whether or not these were made with symbolic intent.[58] In 2012, deep scratches on the floor of Gorham's Cave, Gibraltar, were discovered, dated to older than 39,000 years ago, which the discoverers have interpreted as Neanderthal abstract art.[335][336] The scratches could have also been produced by a bear.[272] In 2021, an Irish elk phalanx with five engraved offset chevrons stacked above each other was discovered at the entrance to the Einhornhöhle cave in Germany, dating to about 51,000 years ago.[337]

In 2018, some red-painted dots, disks, lines and hand stencils on the cave walls of the Spanish La Pasiega, Maltravieso, and Doña Trinidad were dated to be older than 66,000 years ago, at least 20,000 years prior to the arrival of modern humans in Western Europe. This would indicate Neanderthal authorship, and similar iconography recorded in other Western European sites—such as Les Merveilles, France, and Cueva del Castillo, Spain—could potentially also have Neanderthal origins.[61][62][338] However, the dating of these Spanish caves, and thus attribution to Neanderthals, is contested.[60]

Neanderthals are known to have collected a variety of unusual objects—such as crystals or fossils—without any real functional purpose or any indication of damage caused by use. It is unclear if these objects were simply picked up for their aesthetic qualities, or if some symbolic significance was applied to them. These items are mainly quartz crystals, but also other minerals such as cerussite, iron pyrite, calcite and galena. A few findings feature modifications, such as a mammoth tooth with an incision and a fossil nummulite shell with a cross etched in from Tata, Hungary; a large slab with 18 cupstones hollowed out from a grave in La Ferrassie, France;[57] and a geode from Peștera Cioarei, Romania, coated with red ochre.[339] A number of fossil shells are also known from French Neanderthals sites, such as a rhynchonellid and a Taraebratulina from Combe Grenal; a belemnite beak from Grottes des Canalettes; a polyp from Grotte de l'Hyène; a sea urchin from La Gonterie-Boulouneix; and a rhynchonella, feather star and belemnite beak from the contentious Châtelperronian layer of Grotte du Renne.[57]

Music

[edit]

Purported Neanderthal bone flute fragments made of bear long bones were reported from Potočka zijalka, Slovenia, in the 1920s, and Istállós-kői-barlang, Hungary,[340] and Mokriška jama, Slovenia, in 1985; but these are now attributed to modern human activities.[341][342]

The 43,000-year-old Divje Babe flute from Slovenia, found in 1995, has been attributed by some researchers to Neanderthals, though its status as a flute is heavily disputed. Many researchers consider it to be most likely the product of a carnivorous animal chewing the bone,[343][342][344] but its discoverer Ivan Turk and other researchers have maintained an argument that it was manufactured by Neanderthal as a musical instrument.[59]

Technology

[edit]Despite the apparent 150,000-year stagnation in Neanderthal lithic innovation,[176] there is evidence that Neanderthal technology was more sophisticated than was previously thought.[64] However, the high frequency of potentially debilitating injuries could have prevented very complex technologies from emerging, as a major injury would have impeded an expert's ability to effectively teach a novice.[236]

Stone tools

[edit]Neanderthals made stone tools, and are associated with the Mousterian industry.[27] The Mousterian is also associated with North African H. sapiens as early as 315,000 years ago[345] and was found in Northern China about 47–37,000 years ago in caves such as Jinsitai or Tongtiandong.[346] It evolved around 300,000 years ago with the Levallois technique which developed directly from the preceding Acheulean industry (invented by H. erectus about 1.8 mya). Levallois made it easier to control flake shape and size, and as a difficult-to-learn and unintuitive process, the Levallois technique may have been directly taught generation to generation rather than via purely observational learning.[28]

There are distinct regional variants of the Mousterian industry, such as: the Quina and La Ferrassie subtypes of the Charentian industry in southwestern France, Acheulean-tradition Mousterian subtypes A and B along the Atlantic and northwestern European coasts,[347] the Micoquien industry of Central and Eastern Europe and the related Sibiryachikha variant in the Siberian Altai Mountains,[267] the Denticulate Mousterian industry in Western Europe, the racloir industry around the Zagros Mountains, and the flake cleaver industry of Cantabria, Spain, and both sides of the Pyrenees. In the mid-20th century, French archaeologist François Bordes debated against American archaeologist Lewis Binford to explain this diversity (the "Bordes–Binford debate"), with Bordes arguing that these represent unique ethnic traditions and Binford that they were caused by varying environments (essentially, form vs. function).[347] The latter sentiment would indicate a lower degree of inventiveness compared to modern humans, adapting the same tools to different environments rather than creating new technologies.[53] A continuous sequence of occupation is well documented in Grotte du Renne, France, where the lithic tradition can be divided into the Levallois–Charentian, Discoid–Denticulate (43,300 ±929 – 40,900 ±719 years ago), Levallois Mousterian (40,200 ±1,500 – 38,400 ±1,300 years ago) and Châtelperronian (40,930 ±393 – 33,670 ±450 years ago).[348]