Эпилепсия

| Эпилепсия | |

|---|---|

| Другие имена | Судорожное расстройствоНеврологическая инвалидность |

| |

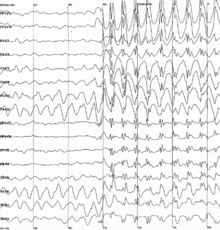

| Генерализованные разряды частотой 3 Гц спайк-волновые на электроэнцефалограмме | |

| Специальность | Неврология |

| Symptoms | Periods of loss of consciousness, abnormal shaking, staring, change in vision, mood changes and/or other cognitive disturbances [1] |

| Duration | Long term[1] |

| Causes | Unknown, brain injury, stroke, brain tumors, infections of the brain, birth defects[1][2][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Electroencephalogram, ruling out other possible causes[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Fainting, alcohol withdrawal, electrolyte problems[4] |

| Treatment | Medication, surgery, neurostimulation, dietary changes[5][6] |

| Prognosis | Controllable in 69%[7] |

| Frequency | 51.7 million/0.68% (2021)[8] |

| Deaths | 140,000 (2021)[9] |

Эпилепсия — группа неинфекционных неврологических заболеваний, характеризующихся повторяющимися эпилептическими припадками . [10] Эпилептический припадок — это клиническое проявление аномального, чрезмерного и синхронизированного электрического разряда в нейронах . [1] Возникновение двух и более неспровоцированных приступов определяет эпилепсию. [11] Возникновение всего лишь одного приступа может служить основанием для определения (установленного Международной лигой борьбы с эпилепсией ) в более клиническом использовании, где рецидив можно предсказать заранее. [10] Эпилептические припадки могут варьироваться от коротких и почти незаметных периодов до длительных периодов сильной тряски из-за аномальной электрической активности в мозге. [1] Эти эпизоды могут привести к физическим травмам, как непосредственно, например, переломам костей, так и в результате несчастных случаев. [1] При эпилепсии припадки имеют тенденцию повторяться и могут не иметь видимой основной причины. [11] Изолированные припадки, вызванные определенной причиной, например отравлением, не считаются эпилепсией. [12] В разных регионах мира к людям, страдающим эпилепсией, могут относиться по-разному, и они испытывают разную степень социальной стигмы из-за тревожного характера их симптомов. [11]

The underlying mechanism of an epileptic seizure is excessive and abnormal neuronal activity in the cortex of the brain,[12] which can be observed in the electroencephalogram (EEG) of an individual. The reason this occurs in most cases of epilepsy is unknown (cryptogenic);[1] some cases occur as the result of brain injury, stroke, brain tumors, infections of the brain, or birth defects through a process known as epileptogenesis.[1][2][3] Known genetic mutations are directly linked to a small proportion of cases.[4][13] The diagnosis involves ruling out other conditions that might cause similar symptoms, such as fainting, and determining if another cause of seizures is present, such as alcohol withdrawal or electrolyte problems.[4] This may be partly done by imaging the brain and performing blood tests.[4] Epilepsy can often be confirmed with an EEG, but a normal reading does not rule out the condition.[4]

Epilepsy that occurs as a result of other issues may be preventable.[1] Seizures are controllable with medication in about 69% of cases;[7] inexpensive anti-seizure medications are often available.[1] In those whose seizures do not respond to medication; surgery, neurostimulation or dietary changes may be considered.[5][6] Not all cases of epilepsy are lifelong, and many people improve to the point that treatment is no longer needed.[1]

As of 2021[update], about 51 million people have epilepsy. Nearly 80% of cases occur in the developing world.[1][8] In 2021, it resulted in 140,000 deaths, an increase from 125,000 in 1990.[9][14][15] Epilepsy is more common in children and older people.[16][17] In the developed world, onset of new cases occurs most frequently in babies and the elderly.[18] In the developing world, onset is more common at the extremes of age – in younger children and in older children and young adults due to differences in the frequency of the underlying causes.[19] About 5–10% of people will have an unprovoked seizure by the age of 80.[20] The chance of experiencing a second seizure within two years after the first is around 40%.[21][22] In many areas of the world, those with epilepsy either have restrictions placed on their ability to drive or are not permitted to drive until they are free of seizures for a specific length of time.[23] The word epilepsy is from Ancient Greek ἐπιλαμβάνειν, 'to seize, possess, or afflict'.[24]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

Epilepsy is characterized by a long-term risk of recurrent epileptic seizures.[25] These seizures may present in several ways depending on the parts of the brain involved and the person's age.[25][26]

Seizures

[edit]The most common type (60%) of seizures are convulsive which involve involuntary muscle contractions.[26] Of these, one-third begin as generalized seizures from the start, affecting both hemispheres of the brain and impairing consciousness.[26] Two-thirds begin as focal seizures (which affect one hemisphere of the brain) which may progress to generalized seizures.[26] The remaining 40% of seizures are non-convulsive. An example of this type is the absence seizure, which presents as a decreased level of consciousness and usually lasts about 10 seconds.[2][27]

Certain experiences, known as auras often precede focal seizures.[28] The seizures can include sensory (visual, hearing, or smell), psychic, autonomic, and motor phenomena depending on which part of the brain is involved.[2] Muscle jerks may start in a specific muscle group and spread to surrounding muscle groups in which case it is known as a Jacksonian march.[29] Automatisms may occur, which are non-consciously generated activities and mostly simple repetitive movements like smacking the lips or more complex activities such as attempts to pick up something.[29]

There are six main types of generalized seizures:

They all involve loss of consciousness and typically happen without warning.

Tonic-clonic seizures occur with a contraction of the limbs followed by their extension and arching of the back which lasts 10–30 seconds (the tonic phase). A cry may be heard due to contraction of the chest muscles, followed by a shaking of the limbs in unison (clonic phase). Tonic seizures produce constant contractions of the muscles. A person often turns blue as breathing is stopped. In clonic seizures there is shaking of the limbs in unison. After the shaking has stopped it may take 10–30 minutes for the person to return to normal; this period is called the "postictal state" or "postictal phase." Loss of bowel or bladder control may occur during a seizure.[31] People experiencing a seizure may bite their tongue, either the tip or on the sides;[32] in tonic-clonic seizure, bites to the sides are more common.[32] Tongue bites are also relatively common in psychogenic non-epileptic seizures.[32] Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures are seizure like behavior without an associated synchronised electrical discharge on EEG and are considered a dissociative disorder.[32]

Myoclonic seizures involve very brief muscle spasms in either a few areas or all over.[33][34] These sometimes cause the person to fall, which can cause injury.[33] Absence seizures can be subtle with only a slight turn of the head or eye blinking with impaired consciousness;[2] typically, the person does not fall over and returns to normal right after it ends.[2] Atonic seizures involve losing muscle activity for greater than one second,[29] typically occurring on both sides of the body.[29] Rarer seizure types can cause involuntary unnatural laughter (gelastic), crying (dyscrastic), or more complex experiences such as déjà vu.[34]

About 6% of those with epilepsy have seizures that are often triggered by specific events and are known as reflex seizures.[35] Those with reflex epilepsy have seizures that are only triggered by specific stimuli.[36] Common triggers include flashing lights and sudden noises.[35] In certain types of epilepsy, seizures happen more often during sleep,[37] and in other types they occur almost only when sleeping.[38] In 2017, the International League Against Epilepsy published new uniform guidelines for the classification of seizures as well as epilepsies along with their cause and comorbidities.[39]

Seizure clusters

[edit]Patients with epilepsy may experience seizure clusters which may be broadly defined as an acute deterioration in seizure control.[40] The prevalence of seizure clusters is uncertain given that studies have used different definitions to define them.[41] However, estimates suggest that the prevalence may range from 5% to 50% of epilepsy patients.[42] Refractory epilepsy patients who have a high seizure frequency are at the greatest risk for having seizure clusters.[43][44][45] Seizure clusters are associated with increased healthcare use, worse quality of life, impaired psychosocial functioning, and possibly increased mortality.[41][46] Benzodiazepines are used as an acute treatment for seizure clusters.[47]

Post-ictal

[edit]After the active portion of a seizure (the ictal state) there is typically a period of recovery during which there is confusion, referred to as the postictal period, before a normal level of consciousness returns.[28] It usually lasts 3 to 15 minutes[48] but may last for hours.[49] Other common symptoms include feeling tired, headache, difficulty speaking, and abnormal behavior.[49] Psychosis after a seizure is relatively common, occurring in 6–10% of people.[50] Often people do not remember what happened during this time.[49] Localized weakness, known as Todd's paralysis, may also occur after a focal seizure. It would typically last for seconds to minutes but may rarely last for a day or two.[51]

Psychosocial

[edit]Epilepsy can have adverse effects on social and psychological well-being.[26] These effects may include social isolation, stigmatization, or disability.[26] They may result in lower educational achievement and worse employment outcomes.[26] Learning disabilities are common in those with the condition, and especially among children with epilepsy.[26] The stigma of epilepsy can also affect the families of those with the disorder.[31]

Certain disorders occur more often in people with epilepsy, depending partly on the epilepsy syndrome present. These include depression, anxiety, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD),[52] and migraine.[53] Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) affects three to five times more children with epilepsy than children without the condition.[54] ADHD and epilepsy have significant consequences on a child's behavioral, learning, and social development.[55] Epilepsy is also more common in children with autism.[56]

Approximately, one-in-three people with epilepsy have a lifetime history of a psychiatric disorder.[57] There are believed to be multiple causes for this including pathophysiological changes related to the epilepsy itself as well as adverse experiences related to living with epilepsy (e.g., stigma, discrimination).[58] In addition, it is thought that the relationship between epilepsy and psychiatric disorders is not unilateral but rather bidirectional. For example, patients with depression have an increased risk for developing new-onset epilepsy.[59]

The presence of comorbid depression or anxiety in patients with epilepsy is associated with a poorer quality of life, increased mortality, increased healthcare use and a worse response to treatment (including surgical).[60][61][62][63] Anxiety disorders and depression may explain more variability in quality of life than seizure type or frequency.[64] There is evidence that both depression and anxiety disorders are underdiagnosed and undertreated in patients with epilepsy.[65]

Causes

[edit]Epilepsy can have both genetic and acquired causes, with the interaction of these factors in many cases.[66][67] Established acquired causes include serious brain trauma, stroke, tumours, and brain problems resulting from a previous infection.[66] In about 60% of cases, the cause is unknown.[26][31] Epilepsies caused by genetic, congenital, or developmental conditions are more common among younger people, while brain tumors and strokes are more likely in older people.[26]

Seizures may also occur as a consequence of other health problems;[30] if they occur right around a specific cause, such as a stroke, head injury, toxic ingestion, or metabolic problem, they are known as acute symptomatic seizures and are in the broader classification of seizure-related disorders rather than epilepsy itself.[68][69]

Genetics

[edit]Genetics is believed to be involved in the majority of cases, either directly or indirectly.[13][70] Some epilepsies are due to a single gene defect (1–2%); most are due to the interaction of multiple genes and environmental factors.[13] Each of the single gene defects is rare, with more than 200 in all described.[71] Most genes involved affect ion channels, either directly or indirectly.[66] These include genes for ion channels, enzymes, GABA, and G protein-coupled receptors.[33]

In identical twins, if one is affected, there is a 50–60% chance that the other will also be affected.[13] In non-identical twins, the risk is 15%.[13] These risks are greater in those with generalized rather than focal seizures.[13] If both twins are affected, most of the time they have the same epileptic syndrome (70–90%).[13] Other close relatives of a person with epilepsy have a risk five times that of the general population.[72] Between 1 and 10% of those with Down syndrome and 90% of those with Angelman syndrome have epilepsy.[72]

Phakomatoses

[edit]Phakomatoses, also known as neurocutaneous disorders, are a group of multisystemic diseases that most prominently affect the skin and central nervous system. They are caused by defective development of the embryonic ectodermal tissue that is most often due to a single genetic mutation. The brain, as well as other neural tissue and the skin, are all derived from the ectoderm and thus defective development may result in epilepsy as well as other manifestations such as autism and intellectual disability. Some types of phakomatoses such as tuberous sclerosis complex and Sturge-Weber syndrome have a higher prevalence of epilepsy relative to others such as neurofibromatosis type 1.[73]

Tuberous sclerosis complex is an autosomal dominant disorder that is caused by mutations in either the TSC1 or TSC2 gene and it affects approximately 1 in 6,000–10,000 live births.[74][75] These mutations result in the upregulation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway which leads to the growth of tumors in many organs including the brain, skin, heart, eyes and kidneys.[75] In addition, abnormal mTOR activity is believed to alter neural excitability.[76] The prevalence of epilepsy is estimated to be 80-90%.[73][76] The majority of cases of epilepsy present within the first 3 years of life and are medically refractory.[77] Relatively recent developments for the treatment of epilepsy in TSC patients include mTOR inhibitors, cannabidiol and vigabatrin. Epilepsy surgery is often pursued.

Sturge-Weber syndrome is caused by an activating somatic mutation in the GNAQ gene and it affects approximately 1 in 20,000–50,000 live births.[78] The mutation results in vascular malformations affecting the brain, skin and eyes. The typical presentation includes a facial port-wine birthmark, ocular angiomas and cerebral vascular malformations which are most often unilateral but are bilateral in 15% of cases.[79] The prevalence of epilepsy is 75-100% and is higher in those with bilateral involvement.[79] Seizures typically occur within the first two years of life and are refractory in nearly half of cases.[80] However, high rates of seizure freedom with surgery have been reported in as many as 83%.[81]

Neurofibromatosis type 1 is the most common phakomatoses and occurs in approximately 1 in 3,000 live births.[82] It is caused by autosomal dominant mutations in the Neurofibromin 1 gene. Clinical manifestations are variable but may include hyperpigmented skin marks, hamartomas of the iris called Lisch nodules, neurofibromas, optic pathway gliomas and cognitive impairment. The prevalence of epilepsy is estimated to be 4–7%.[83] Seizures are typically easier to control with anti-seizure medications relative to other phakomatoses but in some refractory cases surgery may need to be pursued.[84]

Acquired

[edit]Epilepsy may occur as a result of several other conditions, including tumors, strokes, head trauma, previous infections of the central nervous system, genetic abnormalities, and as a result of brain damage around the time of birth.[30][31] Of those with brain tumors, almost 30% have epilepsy, making them the cause of about 4% of cases.[72] The risk is greatest for tumors in the temporal lobe and those that grow slowly.[72] Other mass lesions such as cerebral cavernous malformations and arteriovenous malformations have risks as high as 40–60%.[72] Of those who have had a stroke, 6–10% develop epilepsy.[85][86] Risk factors for post-stroke epilepsy include stroke severity, cortical involvement, hemorrhage and early seizures.[87][88] Between 6 and 20% of epilepsy is believed to be due to head trauma.[72] Mild brain injury increases the risk about two-fold while severe brain injury increases the risk seven-fold.[72] In those who have experienced a high-powered gunshot wound to the head, the risk is about 50%.[72]

Some evidence links epilepsy and celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity, while other evidence does not. There appears to be a specific syndrome that includes coeliac disease, epilepsy, and calcifications in the brain.[89][90] A 2012 review estimates that between 1% and 6% of people with epilepsy have coeliac disease while 1% of the general population has the condition.[90]

The risk of epilepsy following meningitis is less than 10%; it more commonly causes seizures during the infection itself.[72] In herpes simplex encephalitis the risk of a seizure is around 50%[72] with a high risk of epilepsy following (up to 25%).[91][92] A form of an infection with the pork tapeworm (cysticercosis), in the brain, is known as neurocysticercosis, and is the cause of up to half of epilepsy cases in areas of the world where the parasite is common.[72] Epilepsy may also occur after other brain infections such as cerebral malaria, toxoplasmosis, and toxocariasis.[72] Chronic alcohol use increases the risk of epilepsy: those who drink six units of alcohol per day have a 2.5-fold increase in risk.[72] Other risks include Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, and autoimmune encephalitis.[72] Getting vaccinated does not increase the risk of epilepsy.[72] Malnutrition is a risk factor seen mostly in the developing world, although it is unclear however if it is a direct cause or an association.[19] People with cerebral palsy have an increased risk of epilepsy, with half of people with spastic quadriplegia and spastic hemiplegia having the disease.[93]

Mechanism

[edit]Normally brain electrical activity is non-synchronous, as large numbers of neurons do not normally fire at the same time, but rather fire in order as signals travel throughout the brain.[2] Neuron activity is regulated by various factors both within the cell and the cellular environment. Factors within the neuron include the type, number and distribution of ion channels, changes to receptors and changes of gene expression.[94] Factors around the neuron include ion concentrations, synaptic plasticity and regulation of transmitter breakdown by glial cells.[94][95]

Epilepsy

[edit]The exact mechanism of epilepsy is unknown,[96] but a little is known about its cellular and network mechanisms. However, it is unknown under which circumstances the brain shifts into the activity of a seizure with its excessive synchronization.[97][98] .[99][100]

In epilepsy, the resistance of excitatory neurons to fire during this period is decreased.[2] This may occur due to changes in ion channels or inhibitory neurons not functioning properly.[2] This then results in a specific area from which seizures may develop, known as a "seizure focus".[2] Another mechanism of epilepsy may be the up-regulation of excitatory circuits or down-regulation of inhibitory circuits following an injury to the brain.[2][3] These secondary epilepsies occur through processes known as epileptogenesis.[2][3] Failure of the blood–brain barrier may also be a causal mechanism as it would allow substances in the blood to enter the brain.[101]

Seizures

[edit]There is evidence that epileptic seizures are usually not a random event. Seizures are often brought on by factors (also known as triggers) such as stress, excessive alcohol use, flickering light, or a lack of sleep, among others. The term seizure threshold is used to indicate the amount of stimulus necessary to bring about a seizure; this threshold is lowered in epilepsy.[97]

In epileptic seizures a group of neurons begin firing in an abnormal, excessive,[26] and synchronized manner.[2] This results in a wave of depolarization known as a paroxysmal depolarizing shift.[102] Normally, after an excitatory neuron fires it becomes more resistant to firing for a period of time.[2] This is due in part to the effect of inhibitory neurons, electrical changes within the excitatory neuron, and the negative effects of adenosine.[2]

Focal seizures begin in one area of the brain while generalized seizures begin in both hemispheres.[30] Some types of seizures may change brain structure, while others appear to have little effect.[103] Gliosis, neuronal loss, and atrophy of specific areas of the brain are linked to epilepsy but it is unclear if epilepsy causes these changes or if these changes result in epilepsy.[103]

The seizures can be described on different scales, from the cellular level[104] to the whole brain.[105] These are several concomitant factor, which on different scale can "drive" the brain to pathological states and trigger a seizure.

Diagnosis

[edit]

The diagnosis of epilepsy is typically made based on observation of the seizure onset and the underlying cause.[26] An electroencephalogram (EEG) to look for abnormal patterns of brain waves and neuroimaging (CT scan or MRI) to look at the structure of the brain are also usually part of the initial investigations.[26] While figuring out a specific epileptic syndrome is often attempted, it is not always possible.[26] Video and EEG monitoring may be useful in difficult cases.[106]

Definition

[edit]Epilepsy is a disorder of the brain defined by any of the following conditions:[10]

- At least two unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring more than 24 hours apart

- One unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) after two unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years

- Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome

Furthermore, epilepsy is considered to be resolved for individuals who had an age-dependent epilepsy syndrome but are now past that age or those who have remained seizure-free for the last 10 years, with no seizure medicines for the last 5 years.[10]

This 2014 definition of the International League Against Epilepsy[10] (ILAE) is a clarification of the ILAE 2005 conceptual definition, according to which epilepsy is "a disorder of the brain characterized by an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizures and by the neurobiologic, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences of this condition. The definition of epilepsy requires the occurrence of at least one epileptic seizure."[107][108]

It is, therefore, possible to outgrow epilepsy or to undergo treatment that causes epilepsy to be resolved, but with no guarantee that it will not return. In the definition, epilepsy is now called a disease, rather than a disorder. This was a decision of the executive committee of the ILAE, taken because the word disorder, while perhaps having less stigma than does disease, also does not express the degree of seriousness that epilepsy deserves.[10]

The definition is practical in nature and is designed for clinical use. In particular, it aims to clarify when an "enduring predisposition" according to the 2005 conceptual definition is present. Researchers, statistically minded epidemiologists, and other specialized groups may choose to use the older definition or a definition of their own devising. The ILAE considers doing so is perfectly allowable, so long as it is clear what definition is being used.[10]

The ILAE definition for one seizure needs an understanding of projecting an enduring predisposition to the generation of epileptic seizures.[10] WHO, for instance, chooses to just use the traditional definition of two unprovoked seizures.[11]

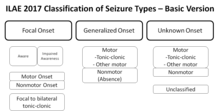

Classification

[edit]

In contrast to the classification of seizures which focuses on what happens during a seizure, the classification of epilepsies focuses on the underlying causes. When a person is admitted to hospital after an epileptic seizure the diagnostic workup results preferably in the seizure itself being classified (e.g. tonic-clonic) and in the underlying disease being identified (e.g. hippocampal sclerosis).[106] The name of the diagnosis finally made depends on the available diagnostic results and the applied definitions and classifications (of seizures and epilepsies) and its respective terminology.

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) provided a classification of the epilepsies and epileptic syndromes in 1989 as follows:[109]

- Localization-related epilepsies and syndromes

- Unknown cause (e.g. benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes)

- Symptomatic/cryptogenic (e.g. temporal lobe epilepsy)

- Generalized

- Unknown cause (e.g. childhood absence epilepsy)

- Cryptogenic or symptomatic (e.g. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome)

- Symptomatic (e.g. early infantile epileptic encephalopathy with burst suppression)

- Epilepsies and syndromes undetermined whether focal or generalized

- With both generalized and focal seizures (e.g. epilepsy with continuous spike-waves during slow wave sleep)

- Special syndromes (with situation-related seizures)

- Localization-related epilepsies and syndromes

This classification was widely accepted but has also been criticized mainly because the underlying causes of epilepsy (which are a major determinant of clinical course and prognosis) were not covered in detail.[110] In 2010 the ILAE Commission for Classification of the Epilepsies addressed this issue and divided epilepsies into three categories (genetic, structural/metabolic, unknown cause)[111] which were refined in their 2011 recommendation into four categories and a number of subcategories reflecting recent technological and scientific advances.[112]

A revised, operational classification of seizure types has been introduced by the ILAE.[113] It allows more clearly understood terms and clearly defines focal and generalized onset dichotomy, when possible, even without observing the seizures based on description by patient or observers.[114] The essential changes in terminology are that "partial" is called "focal" with awareness used as a classifier for focal seizures -based on description focal seizures are now defined as behavioral arrest, automatisms, cognitive, autonomic, emotional or hyperkinetic variants while atonic, myoclonic, clonic, infantile spasms, and tonic seizures may be either focal or generalized based on their onset.[114] Several terms that were not clear or consistent in the description were removed such as dyscognitive, psychic, simple, and complex partial, while "secondarily generalized" is replaced by a clearer term "focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizure".[114] New seizure types now believed to be generalized are eyelid myoclonia, myoclonic atonic, myoclonic absence, and myoclonic tonic-clonic.[114] Sometimes it is possible to classify seizures as focal or generalized based on presenting features even though onset in not known.[114] This system is based on the 1981 seizure classification modified in 2010 and principally is the same with an effort to improve the flexibility and clarity of use to understand seizure types better in keeping with current knowledge.[114]- Unknown cause (mostly genetic or presumed genetic origin)

- Pure epilepsies due to single gene disorders

- Pure epilepsies with complex inheritance

- Symptomatic (associated with gross anatomic or pathologic abnormalities)

- Mostly genetic or developmental causation

- Childhood epilepsy syndromes

- Progressive myoclonic epilepsies

- Neurocutaneous syndromes

- Other neurologic single gene disorders

- Disorders of chromosome function

- Developmental anomalies of cerebral structure

- Mostly acquired causes

- Hippocampal sclerosis

- Perinatal and infantile causes

- Cerebral trauma, tumor or infection

- Cerebrovascular disorders

- Cerebral immunologic disorders

- Degenerative and other neurologic conditions

- Mostly genetic or developmental causation

- Provoked (a specific systemic or environmental factor is the predominant cause of the seizures)

- Provoking factors

- Reflex epilepsies

- Cryptogenic (presumed symptomatic nature in which the cause has not been identified)[112]

- Unknown cause (mostly genetic or presumed genetic origin)

Syndromes

[edit]Cases of epilepsy may be organized into epilepsy syndromes by the specific features that are present. These features include the age that seizure begin, the seizure types, EEG findings, among others. Identifying an epilepsy syndrome is useful as it helps determine the underlying causes as well as what anti-seizure medication should be tried.[30][115]

The ability to categorize a case of epilepsy into a specific syndrome occurs more often with children since the onset of seizures is commonly early.[69] Less serious examples are benign rolandic epilepsy (2.8 per 100,000), childhood absence epilepsy (0.8 per 100,000) and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (0.7 per 100,000).[69] Severe syndromes with diffuse brain dysfunction caused, at least partly, by some aspect of epilepsy, are also referred to as developmental and epileptic encephalopathies. These are associated with frequent seizures that are resistant to treatment and cognitive dysfunction, for instance Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (1–2% of all persons with epilepsy),[116] Dravet syndrome(1: 15000-40000 worldwide[117]), and West syndrome(1–9: 100000[118]).[119] Genetics is believed to play an important role in epilepsies by a number of mechanisms. Simple and complex modes of inheritance have been identified for some of them. However, extensive screening have failed to identify many single gene variants of large effect.[120] More recent exome and genome sequencing studies have begun to reveal a number of de novo gene mutations that are responsible for some epileptic encephalopathies, including CHD2 and SYNGAP1[121][122][123] and DNM1, GABBR2, FASN and RYR3.[124]

Syndromes in which causes are not clearly identified are difficult to match with categories of the current classification of epilepsy. Categorization for these cases was made somewhat arbitrarily.[112] The idiopathic (unknown cause) category of the 2011 classification includes syndromes in which the general clinical features and/or age specificity strongly point to a presumed genetic cause.[112] Some childhood epilepsy syndromes are included in the unknown cause category in which the cause is presumed genetic, for instance benign rolandic epilepsy.[112] Clinical syndromes in which epilepsy is not the main feature (e.g. Angelman syndrome) were categorized symptomatic but it was argued to include these within the category idiopathic.[112] Classification of epilepsies and particularly of epilepsy syndromes will change with advances in research.[112]

Tests

[edit]An electroencephalogram (EEG) can assist in showing brain activity suggestive of an increased risk of seizures. It is only recommended for those who are likely to have had an epileptic seizure on the basis of symptoms. In the diagnosis of epilepsy, electroencephalography may help distinguish the type of seizure or syndrome present.[125] In children it is typically only needed after a second seizure unless specified by a specialist. It cannot be used to rule out the diagnosis and may be falsely positive in those without the disease.[125] In certain situations it may be useful to perform the EEG while the affected individual is sleeping or sleep deprived.[106]

Diagnostic imaging by CT scan and MRI is recommended after a first non-febrile seizure to detect structural problems in and around the brain.[106] MRI is generally a better imaging test except when bleeding is suspected, for which CT is more sensitive and more easily available.[20] If someone attends the emergency room with a seizure but returns to normal quickly, imaging tests may be done at a later point.[20] If a person has a previous diagnosis of epilepsy with previous imaging, repeating the imaging is usually not needed even if there are subsequent seizures.[106][126]

For adults, the testing of electrolyte, blood glucose and calcium levels is important to rule out problems with these as causes.[106] An electrocardiogram can rule out problems with the rhythm of the heart.[106] A lumbar puncture may be useful to diagnose a central nervous system infection but is not routinely needed.[20] In children additional tests may be required such as urine biochemistry and blood testing looking for metabolic disorders.[106][127] Together with EEG and neuroimaging, genetic testing is becoming one of the most important diagnostic technique for epilepsy, as a diagnosis might be achieved in a relevant proportion of cases with severe epilepsies, both in children and adults.[128] For those with negative genetic testing, in some it might be important to repeat or re-analyze previous genetic studies after 2–3 years.[129]

A high blood prolactin level within the first 20 minutes following a seizure may be useful to help confirm an epileptic seizure as opposed to psychogenic non-epileptic seizure.[130][131] Serum prolactin level is less useful for detecting focal seizures.[132] If it is normal an epileptic seizure is still possible[131] and a serum prolactin does not separate epileptic seizures from syncope.[133] It is not recommended as a routine part of the diagnosis of epilepsy.[106]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]Diagnosis of epilepsy can be difficult. A number of other conditions may present very similar signs and symptoms to seizures, including syncope, hyperventilation, migraines, narcolepsy, panic attacks and psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES).[134][135] In particular, syncope can be accompanied by a short episode of convulsions.[136] Nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy, often misdiagnosed as nightmares, was considered to be a parasomnia but later identified to be an epilepsy syndrome.[137] Attacks of the movement disorder paroxysmal dyskinesia may be taken for epileptic seizures.[138] The cause of a drop attack can be, among many others, an atonic seizure.[135]

Children may have behaviors that are easily mistaken for epileptic seizures but are not. These include breath-holding spells, bedwetting, night terrors, tics and shudder attacks.[135] Gastroesophageal reflux may cause arching of the back and twisting of the head to the side in infants, which may be mistaken for tonic-clonic seizures.[135]

Misdiagnosis is frequent (occurring in about 5 to 30% of cases).[26] Different studies showed that in many cases seizure-like attacks in apparent treatment-resistant epilepsy have a cardiovascular cause.[136][139] Approximately 20% of the people seen at epilepsy clinics have PNES[20] and of those who have PNES about 10% also have epilepsy;[140] separating the two based on the seizure episode alone without further testing is often difficult.[140]

Prevention

[edit]While many cases are not preventable, efforts to reduce head injuries,[7] provide good care around the time of birth, and reduce environmental parasites such as the pork tapeworm may be effective.[31] Efforts in one part of Central America to decrease rates of pork tapeworm resulted in a 50% decrease in new cases of epilepsy.[19] Yoga-based Nadi Shodhana Pranayama, also known as Alternate Nostril Breathing, may positively impact the nervous system and help manage seizure disorders. Regular exercise helps balance brain function by providing the body with oxygen and removing carbon dioxide and toxins from the blood.[141]

Complications

[edit]Epilepsy can be dangerous when seizure occurs at certain times. The risk of drowning or being involved in a motor vehicle collision is higher. It is also found that people with epilepsy are more likely to have psychological problems.[142] Other complications include aspiration pneumonia and difficulty learning.[143]

Management

[edit]

Epilepsy is usually treated with daily medication once a second seizure has occurred,[26][106] while medication may be started after the first seizure in those at high risk for subsequent seizures.[106] Supporting people's self-management of their condition may be useful.[144] In drug-resistant cases different management options may be considered, including special diets, the implantation of a neurostimulator, or neurosurgery.

First aid

[edit]Rolling people with an active tonic-clonic seizure onto their side and into the recovery position helps prevent fluids from getting into the lungs.[145] Putting fingers, a bite block or tongue depressor in the mouth is not recommended as it might make the person vomit or result in the rescuer being bitten.[28][145] Efforts should be taken to prevent further self-injury.[28] Spinal precautions are generally not needed.[145]

If a seizure lasts longer than 5 minutes or if there are more than two seizures in 5 minutes without a return to a normal level of consciousness between them, it is considered a medical emergency known as status epilepticus.[106][146] This may require medical help to keep the airway open and protected;[106] a nasopharyngeal airway may be useful for this.[145] At home the recommended initial medication for seizure of a long duration is midazolam placed in the nose or mouth.[147] Diazepam may also be used rectally.[147] In hospital, intravenous lorazepam is preferred.[106]

If two doses of benzodiazepines are not effective, other medications such as phenytoin are recommended.[106] Convulsive status epilepticus that does not respond to initial treatment typically requires admission to the intensive care unit and treatment with stronger agents such as midazolam infusion, ketamine, thiopentone or propofol.[106] Most institutions have a preferred pathway or protocol to be used in a seizure emergency like status epilepticus.[106] These protocols have been found to be effective in reducing time to delivery of treatment.[106]

Medications

[edit]

The mainstay treatment of epilepsy is anticonvulsant medications, possibly for the person's entire life.[26] The choice of anticonvulsant is based on seizure type, epilepsy syndrome, other medications used, other health problems, and the person's age and lifestyle.[147] A single medication is recommended initially;[148] if this is not effective, switching to a single other medication is recommended.[106] Two medications at once is recommended only if a single medication does not work.[106] In about half, the first agent is effective; a second single agent helps in about 13% and a third or two agents at the same time may help an additional 4%.[149] About 30% of people continue to have seizures despite anticonvulsant treatment.[7]

There are a number of medications available including phenytoin, carbamazepine and valproate. Evidence suggests that phenytoin, carbamazepine, and valproate may be equally effective in both focal and generalized seizures.[150][151] Controlled release carbamazepine appears to work as well as immediate release carbamazepine, and may have fewer side effects.[152][153]In the United Kingdom, carbamazepine or lamotrigine are recommended as first-line treatment for focal seizures, with levetiracetam and valproate as second-line due to issues of cost and side effects.[106][154] Valproate is recommended first-line for generalized seizures with lamotrigine being second-line.[106] In those with absence seizures, ethosuximide or valproate are recommended; valproate is particularly effective in myoclonic seizures and tonic or atonic seizures.[106] If seizures are well-controlled on a particular treatment, it is not usually necessary to routinely check the medication levels in the blood.[106]

The least expensive anticonvulsant is phenobarbital at around US$5 a year.[19] The World Health Organization gives it a first-line recommendation in the developing world and it is commonly used there.[155][156] Access, however, may be difficult as some countries label it as a controlled drug.[19]

Adverse effects from medications are reported in 10% to 90% of people, depending on how and from whom the data is collected.[157] Most adverse effects are dose-related and mild.[157] Some examples include mood changes, sleepiness, or an unsteadiness in gait.[157] Certain medications have side effects that are not related to dose such as rashes, liver toxicity, or suppression of the bone marrow.[157] Up to a quarter of people stop treatment due to adverse effects.[157] Some medications are associated with birth defects when used in pregnancy.[106] Many of the common used medications, such as valproate, phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, and gabapentin have been reported to cause increased risk of birth defects,[158] especially when used during the first trimester.[159] Despite this, treatment is often continued once effective, because the risk of untreated epilepsy is believed to be greater than the risk of the medications.[159] Among the antiepileptic medications, levetiracetam and lamotrigine seem to carry the lowest risk of causing birth defects.[158]

Slowly stopping medications may be reasonable in some people who do not have a seizure for two to four years; however, around a third of people have a recurrence, most often during the first six months.[106][160] Stopping is possible in about 70% of children and 60% of adults.[31] Measuring medication levels is not generally needed in those whose seizures are well controlled.[126]

Surgery

[edit]Epilepsy surgery should be considered for any person with epilepsy who is medically refractory.[16] Patients are evaluated on a case-by-case basis in centres that are familiar with and have expertise in epilepsy surgery.[16] Epilepsy surgery may be an option for people with focal seizures that remain a problem despite other treatments.[161][162] These other treatments include at least a trial of two or three medications.[163] The goal of surgery has been total control of seizures.[164] However, most physicians believe that even palliative surgery where the burden of seizures is reduced significantly can help in achieving developmental progress or reversal of developmental stagnation in children with drug-resistant epilepsy and this may be achieved in 60–70% of cases.[163] Common procedures include cutting out the hippocampus via an anterior temporal lobe resection, removal of tumors, and removing parts of the neocortex.[163] Some procedures such as a corpus callosotomy are attempted in an effort to decrease the number of seizures rather than cure the condition.[163] Following surgery, medications may be slowly withdrawn in many cases.[163][161]

Neurostimulation

[edit]Neurostimulation via neuro-cybernetic prosthesis implantation may be another option in those who are not candidates for surgery, providing chronic, pulsatile electrical stimulation of specific nerve or brain regions, alongside standard care.[106] Three types have been used in those who do not respond to medications: vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), anterior thalamic stimulation, and closed-loop responsive stimulation (RNS).[5][165][166]

Vagus nerve stimulation

[edit]Non-pharmacological modulation of neurotransmitters via high-level VNS (h-VNS) may reduce seizure frequency in children and adults who do not respond to medical and/or surgical therapy, when compared with low-level VNS (l-VNS).[166] In a 2022 Cochrane review of four randomized controlled trials, with moderate certainty of evidence, people receiving h-VNS treatment were 73% more likely (13% more likely to 164% more likely) to experience a reduction in seizure frequency by at least 50% (the minimum threshold defined for individual clinical response).[166] Potentially 249 (163 to 380) per 1000 people with drug-resistant epilepsy may achieve a 50% reduction in seizures following h-VNS, benefiting an additional 105 per 1000 people compared with l-VNS.[166]

This outcome was limited by the number of studies available, and the quality of one trial in particular, wherein three people received l-VNS in error. A sensitivity analysis suggested that the best case scenario was that the likelihood of clinical response to h-VNS may be 91% (27% to 189%) higher than those receiving l-VNS. In the worst-case scenario, the likelihood of clinical response to h-VNS was still 61% higher (7% higher to 143% higher) than l-VNS.[166]

Despite the potential benefit for h-VNS treatment, the Cochrane review also found that the risk of several adverse-effects was greater than those receiving l-VNS. There was moderate certainty of evidence that voice alteration or hoarseness risk may be 2.17(1.49 to 3.17) fold higher than people receiving l-VNS. Dyspnoea risk was also 2.45 (1.07 to 5.60) times that of l-VNS recipients, although the low number of events and studies meant that the certainty of evidence was low. The risk of rebound-withdrawal symptoms, coughing, pain and paraesthesia was unclear.[166]

Diet

[edit]There is promising evidence that a ketogenic diet (high-fat, low-carbohydrate, adequate-protein) decreases the number of seizures and eliminates seizures in some; however, further research is necessary.[6] A 2022 systematic review of the literature has found some evidence to support that a ketogenic diet or modified Atkins diet can be helpful in the treatment of epilepsy in some infants.[167] These types of diets may be beneficial for children with drug-resistant epilepsy; the use for adults remains uncertain.[6] The most commonly reported adverse effects were vomiting, constipation and diarrhoea.[6] It is unclear why this diet works.[168] In people with coeliac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity and occipital calcifications, a gluten-free diet may decrease the frequency of seizures.[90]

Other

[edit]Avoidance therapy consists of minimizing or eliminating triggers. For example, those who are sensitive to light may have success with using a small television, avoiding video games, or wearing dark glasses.[169] Operant-based biofeedback based on the EEG waves has some support in those who do not respond to medications.[170] Psychological methods should not, however, be used to replace medications.[106]

Exercise has been proposed as possibly useful for preventing seizures,[171] with some data to support this claim.[172] Some dogs, commonly referred to as seizure dogs, may help during or after a seizure.[173][174] It is not clear if dogs have the ability to predict seizures before they occur.[175]

There is moderate-quality evidence supporting the use of psychological interventions along with other treatments in epilepsy.[176] This can improve quality of life, enhance emotional wellbeing, and reduce fatigue in adults and adolescents.[176] Psychological interventions may also improve seizure control for some individuals by promoting self-management and adherence.[176]

As an add-on therapy in those who are not well controlled with other medications, cannabidiol appears to be useful in some children.[177][178] In 2018 the FDA approved this product for Lennox–Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome.[179]

There are a few studies on the use of dexamethasone for the successful treatment of drug-resistant seizures in both adults and children.[180]

Alternative medicine

[edit]Alternative medicine, including acupuncture,[181] routine vitamins,[182] and yoga,[183] have no reliable evidence to support their use in epilepsy. Melatonin, as of 2016[update], is insufficiently supported by evidence.[184] The trials were of poor methodological quality and it was not possible to draw any definitive conclusions.[184]

Several supplements (with varied reliabilities of evidence) have been reported to be helpful for drug-resistant epilepsy. These include high-dose Omega-3, berberine, Manuka honey, reishi and lion's mane mushrooms, curcumin,[185] vitamin E, coenzyme Q-10, and resveratrol. The reason these can work (in theory) is that they reduce inflammation or oxidative stress, two of the major mechanism contributing to epilepsy.[186]

Contraception and pregnancy

[edit]Women of child-bearing age, including those with epilepsy, are at risk of unintended pregnancies if they are not using an effective form of contraception.[187] Women with epilepsy may experience a temporary increase in seizure frequency when they begin hormonal contraception.[187]

Some anti-seizure medications interact with enzymes in the liver and cause the drugs in hormonal contraception to be broken down more quickly. These enzyme inducing drugs make hormonal contraception less effective, and this is particularly hazardous if the anti-seizure medication is associated with birth defects.[188] Potent enzyme-inducing anti-seizure medications include carbamazepine, eslicarbazepine acetate, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, primidone, and rufinamide. The drugs perampanel and topiramate can be enzyme-inducing at higher doses.[189] Conversely, hormonal contraception can lower the amount of the anti-seizure medication lamotrigine circulating in the body, making it less effective.[187] The failure rate of oral contraceptives, when used correctly, is 1%, but this increases to between 3–6% in women with epilepsy.[188] Overall, intrauterine devices (IUDs) are preferred for women with epilepsy who are not intending to become pregnant.[187]

Women with epilepsy, especially if they have other medical conditions, may have a slightly lower, but still high, chance of becoming pregnant.[187] Women with infertility have about the same chance of success with in vitro fertilisation or other forms of assisted reproductive technology as women without epilepsy.[187] There may be a higher risk of pregnancy loss.[187]

Once pregnant, there are two main concerns related to pregnancy. The first concern is about the risk of seizures during pregnancy, and the second concern is that the anti-seizure medications may result in birth defects.[158] Most women with epilepsy must continue treatment with anti-seizure drugs, and the treatment goal is to balance the need to prevent seizures with the need to prevent drug-induced birth defects.[187][190]

Pregnancy does not seem to change seizure frequency very much.[187] When seizures happen, however, they can cause some pregnancy complications, such as pre-term births or the babies being smaller than usual when they are born.[187]

All pregnancies have a risk of birth defects, e.g., due to smoking during pregnancy.[187] In addition to this typical level of risk, some anti-seizure drugs significantly increase the risk of birth defects and intrauterine growth restriction, as well as developmental, neurocognitive, and behavioral disorders.[190] Most women with epilepsy receive safe and effective treatment and have typical, healthy children.[190] The highest risks are associated with specific anti-seizure drugs, such as valproic acid and carbamazepine, and with higher doses.[158][187] Folic acid supplementation, such as through prenatal vitamins, reduced the risk.[187] Planning pregnancies in advance gives women with epilepsy an opportunity to switch to a lower-risk treatment program and reduced drug doses.[187]

Although anti-seizure drugs can be found in breast milk, women with epilepsy can breastfeed their babies, and the benefits usually outweigh the risks.[187]

Prognosis

[edit]

Epilepsy cannot usually be cured, but medication can control seizures effectively in about 70% of cases.[7] Of those with generalized seizures, more than 80% can be well controlled with medications while this is true in only 50% of people with focal seizures.[5] One predictor of long-term outcome is the number of seizures that occur in the first six months.[26] Other factors increasing the risk of a poor outcome include little response to the initial treatment, generalized seizures, a family history of epilepsy, psychiatric problems, and waves on the EEG representing generalized epileptiform activity.[191] In the developing world, 75% of people are either untreated or not appropriately treated.[31] In Africa, 90% do not get treatment.[31] This is partly related to appropriate medications not being available or being too expensive.[31]

Mortality

[edit]People with epilepsy may have a higher risk of premature death compared to those without the condition.[192] This risk is estimated to be between 1.6 and 4.1 times greater than that of the general population.[193] The greatest increase in mortality from epilepsy is among the elderly.[193] Those with epilepsy due to an unknown cause have a relatively low increase in risk.[193]

Mortality is often related to the underlying cause of the seizures, status epilepticus, suicide, trauma, and sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP).[192] Death from status epilepticus is primarily due to an underlying problem rather than missing doses of medications.[192] The risk of suicide is between two and six times higher in those with epilepsy;[194][195] the cause of this is unclear.[194] SUDEP appears to be partly related to the frequency of generalized tonic-clonic seizures[196] and accounts for about 15% of epilepsy-related deaths;[191] it is unclear how to decrease its risk.[196]Risk factors for SUDEP include nocturnal generalized tonic-clonic seizures, seizures, sleeping alone and medically intractable epilepsy.[197]

In the United Kingdom, it is estimated that 40–60% of deaths are possibly preventable.[26] In the developing world, many deaths are due to untreated epilepsy leading to falls or status epilepticus.[19]

Epidemiology

[edit]Epilepsy is one of the most common serious neurological disorders[198] affecting about 50 million people as of 2021[update].[8][199] It affects 1% of the population by age 20 and 3% of the population by age 75.[17] It is more common in males than females with the overall difference being small.[19][69] Most of those with the disorder (80%) are in low income populations[200] or the developing world.[31]

The estimated prevalence of active epilepsy (as of 2012[update]) is in the range 3–10 per 1,000, with active epilepsy defined as someone with epilepsy who has had at least one unprovoked seizure in the last five years.[69][201] Epilepsy begins each year in 40–70 per 100,000 in developed countries and 80–140 per 100,000 in developing countries.[31] Poverty is a risk and includes both being from a poor country and being poor relative to others within one's country.[19] In the developed world epilepsy most commonly starts either in the young or in the old.[19] In the developing world its onset is more common in older children and young adults due to the higher rates of trauma and infectious diseases.[19] In developed countries the number of cases a year has decreased in children and increased among the elderly between the 1970s and 2003.[201] This has been attributed partly to better survival following strokes in the elderly.[69]

History

[edit]

The oldest medical records show that epilepsy has been affecting people at least since the beginning of recorded history.[202] Throughout ancient history, the disease was thought to be a spiritual condition.[202] The world's oldest description of an epileptic seizure comes from a text in Akkadian (a language used in ancient Mesopotamia) and was written around 2000 BC.[24] The person described in the text was diagnosed as being under the influence of a moon god, and underwent an exorcism.[24] Epileptic seizures are listed in the Code of Hammurabi (c. 1790 BC) as reason for which a purchased slave may be returned for a refund,[24] and the Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 1700 BC) describes cases of individuals with epileptic convulsions.[24]

The oldest known detailed record of the disease itself is in the Sakikku, a Babylonian cuneiform medical text from 1067–1046 BC.[202] This text gives signs and symptoms, details treatment and likely outcomes,[24] and describes many features of the different seizure types.[202] As the Babylonians had no biomedical understanding of the nature of disease, they attributed the seizures to possession by evil spirits and called for treating the condition through spiritual means.[202] Around 900 BC, Punarvasu Atreya described epilepsy as loss of consciousness;[203] this definition was carried forward into the Ayurvedic text of Charaka Samhita (c. 400 BC).[204]

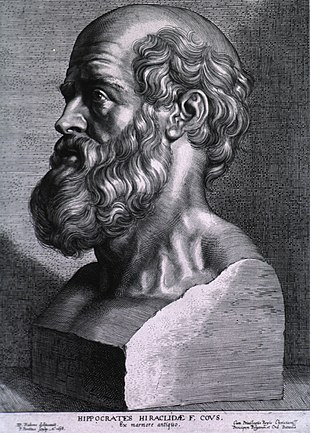

The ancient Greeks had contradictory views of the disease. They thought of epilepsy as a form of spiritual possession, but also associated the condition with genius and the divine. One of the names they gave to it was the sacred disease (Ancient Greek: ἠ ἱερὰ νόσος).[24][205] Epilepsy appears within Greek mythology: it is associated with the Moon goddesses Selene and Artemis, who afflicted those who upset them. The Greeks thought that important figures such as Julius Caesar and Hercules had the disease.[24] The notable exception to this divine and spiritual view was that of the school of Hippocrates. In the fifth century BC, Hippocrates rejected the idea that the disease was caused by spirits. In his landmark work On the Sacred Disease, he proposed that epilepsy was not divine in origin and instead was a medically treatable problem originating in the brain.[24][202] He accused those of attributing a sacred cause to the disease of spreading ignorance through a belief in superstitious magic.[24] Hippocrates proposed that heredity was important as a cause, described worse outcomes if the disease presents at an early age, and made note of the physical characteristics as well as the social shame associated with it.[24] Instead of referring to it as the sacred disease, he used the term great disease, giving rise to the modern term grand mal, used for tonic–clonic seizures.[24] Despite his work detailing the physical origins of the disease, his view was not accepted at the time.[202] Evil spirits continued to be blamed until at least the 17th century.[202]

In Ancient Rome people did not eat or drink with the same pottery as that used by someone who was affected.[206] People of the time would spit on their chest believing that this would keep the problem from affecting them.[206] According to Apuleius and other ancient physicians, to detect epilepsy, it was common to light a piece of gagates, whose smoke would trigger the seizure.[207] Occasionally a spinning potter's wheel was used, perhaps a reference to photosensitive epilepsy.[208]

In most cultures, persons with epilepsy have been stigmatized, shunned, or even imprisoned. As late as in the second half of the 20th century, in Tanzania and other parts of Africa epilepsy was associated with possession by evil spirits, witchcraft, or poisoning and was believed by many to be contagious.[209] In the Salpêtrière, the birthplace of modern neurology, Jean-Martin Charcot found people with epilepsy side by side with the mentally ill, those with chronic syphilis, and the criminally insane.[210] In Ancient Rome, epilepsy was known as the morbus comitialis or 'disease of the assembly hall' and was seen as a curse from the gods. In northern Italy, epilepsy was traditionally known as Saint Valentine's malady.[211] In at least the 1840s in the United States of America, epilepsy was known as the falling sickness or the falling fits, and was considered a form of medical insanity.[212] Around the same time period, epilepsy was known in France as the haut-mal lit. 'high evil', mal-de terre lit. 'earthen sickness', mal de Saint Jean lit. 'Saint John's sickness', mal des enfans lit. 'child sickness', and mal-caduc lit. 'falling sickness'.[212] Patients of epilepsy in France were also known as tombeurs lit. 'people who fall', due to the seizures and loss of consciousness in an epileptic episode.[212]

In the mid-19th century, the first effective anti-seizure medication, bromide, was introduced.[157] The first modern treatment, phenobarbital, was developed in 1912, with phenytoin coming into use in 1938.[213]

Society and culture

[edit]Stigma

[edit]Social stigma is commonly experienced, around the world, by those with epilepsy.[11][214] It can affect people economically, socially and culturally.[214] In India and China, epilepsy may be used as justification to deny marriage.[31] People in some areas still believe those with epilepsy to be cursed.[19] In parts of Africa, such as Tanzania and Uganda, epilepsy is claimed to be associated with possession by evil spirits, witchcraft, or poisoning and is incorrectly believed by many to be contagious.[209][19] Before 1971 in the United Kingdom, epilepsy was considered grounds for the annulment of marriage.[31] The stigma may result in some people with epilepsy denying that they have ever had seizures.[69]

Economics

[edit]Seizures result in direct economic costs of about one billion dollars in the United States.[20] Epilepsy resulted in economic costs in Europe of around 15.5 billion euros in 2004.[26] In India epilepsy is estimated to result in costs of US$1.7 billion or 0.5% of the GDP.[31] It is the cause of about 1% of emergency department visits (2% for emergency departments for children) in the United States.[215]

Vehicles

[edit]Those with epilepsy are at about twice the risk of being involved in a motor vehicular collision and thus in many areas of the world are not allowed to drive or only able to drive if certain conditions are met.[23] Diagnostic delay has been suggested to be a cause of some potentially avoidable motor vehicle collisions since at least one study showed that most motor vehicle accidents occurred in those with undiagnosed non-motor seizures as opposed to those with motor seizures at epilepsy onset.[216] In some places physicians are required by law to report if a person has had a seizure to the licensing body while in others the requirement is only that they encourage the person in question to report it himself.[23] Countries that require physician reporting include Sweden, Austria, Denmark and Spain.[23] Countries that require the individual to report include the UK and New Zealand, and physicians may report if they believe the individual has not already.[23] In Canada, the United States and Australia the requirements around reporting vary by province or state.[23] If seizures are well controlled most feel allowing driving is reasonable.[217] The amount of time a person must be free from seizures before he can drive varies by country.[217] Many countries require one to three years without seizures.[217] In the United States the time needed without a seizure is determined by each state and is between three months and one year.[217]

Those with epilepsy or seizures are typically denied a pilot license.[218]

- In Canada if an individual has had no more than one seizure, they may be considered after five years for a limited license if all other testing is normal.[219] Those with febrile seizures and drug related seizures may also be considered.[219]

- In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration does not allow those with epilepsy to get a commercial pilot license.[220] Rarely, exceptions can be made for persons who have had an isolated seizure or febrile seizures and have remained free of seizures into adulthood without medication.[221]

- В Соединенном Королевстве полная национальная лицензия частного пилота требует тех же стандартов, что и лицензия профессионального водителя. [222] This requires a period of ten years without seizures while off medications.[223] Those who do not meet this requirement may acquire a restricted license if free from seizures for five years.[222]

Поддерживающие организации

[ редактировать ]Существуют организации, которые оказывают поддержку людям и семьям, страдающим эпилепсией. Кампания Out of the Shadows , совместная работа Всемирной организации здравоохранения, ILAE и Международного бюро по эпилепсии , оказывает помощь на международном уровне. [31] В Соединенных Штатах Фонд эпилепсии — это национальная организация, которая работает над повышением признания людей с этим расстройством, их способностью функционировать в обществе и продвигает исследования по лечению. [224] Фонд эпилепсии, некоторые больницы и отдельные лица также руководят группами поддержки в Соединенных Штатах. [225] В Австралии Фонд эпилепсии оказывает поддержку, проводит обучение и обучение, а также финансирует исследования для людей, живущих с эпилепсией.

Международный день эпилепсии (World Epilepsy Day) начался в 2015 году и отмечается во второй понедельник февраля. [226] [227]

Пурпурный день , еще один всемирный день осведомленности об эпилепсии, был инициирован девятилетней канадкой по имени Кэссиди Меган в 2008 году и проводится каждый год 26 марта. [228]

Исследовать

[ редактировать ]Прогнозирование и моделирование приступов

[ редактировать ]Прогнозирование припадков – это попытки прогнозировать эпилептические припадки на основе ЭЭГ до их возникновения. [229] По состоянию на 2011 год [update]Однако эффективный механизм прогнозирования приступов не разработан. [229] Хотя эффективного устройства, которое могло бы прогнозировать судороги, не существует, наука, лежащая в основе прогнозирования судорог и возможности предоставления такого инструмента, добилась прогресса.

Метод Kindling , при котором повторяющиеся воздействия событий, которые могут вызвать судороги, в конечном итоге вызывают их легче, использовался для создания моделей эпилепсии на животных. [230] У грызунов были охарактеризованы различные модели эпилепсии на животных , повторяющие ЭЭГ и поведенческие сопутствующие проявления различных форм эпилепсии, в частности возникновение рецидивирующих спонтанных припадков. [231] Поскольку у некоторых из этих животных в природе наблюдаются эпилептические припадки различного типа, линии мышей и крыс были выбраны для использования в качестве генетических моделей эпилепсии. В частности, несколько линий мышей и крыс демонстрируют спайк-волновые разряды при записи ЭЭГ, и их изучали для понимания абсанс-эпилепсии. [232] Среди этих моделей штамм GAERS (крысы с генетической абсансной эпилепсией из Страсбурга) был охарактеризован в 1980-х годах и помог понять механизмы, лежащие в основе детской абсансной эпилепсии. [233]

Срезы мозга крысы служат ценной моделью для оценки потенциала соединений в снижении эпилептиформной активности. Оценивая частоту эпилептиформных взрывов в сетях гиппокампа, исследователи могут определить многообещающих кандидатов на создание новых противосудорожных препаратов. [234]

Одна из гипотез, представленных в литературе, основана на воспалительных путях. Исследования, подтверждающие этот механизм, показали, что воспалительные, гликолипидные и окислительные факторы выше у пациентов с эпилепсией, особенно с генерализованной эпилепсией. [235]

Потенциальные будущие методы лечения

[ редактировать ]Генная терапия изучается при некоторых типах эпилепсии. [236] Лекарства, изменяющие иммунную функцию, такие как внутривенные иммуноглобулины , могут снизить частоту судорог при их включении в обычный уход в качестве дополнительной терапии; однако необходимы дальнейшие исследования, чтобы определить, хорошо ли переносятся эти лекарства детьми и взрослыми, страдающими эпилепсией. [237] Неинвазивная стереотаксическая радиохирургия по состоянию на 2012 г. [update], по сравнению со стандартной хирургией при определенных типах эпилепсии. [238]

Другие животные

[ редактировать ]Эпилепсия встречается у ряда других животных, включая собак и кошек; на самом деле это самое распространенное заболевание головного мозга у собак. [239] Обычно его лечат противосудорожными препаратами, такими как леветирацетам, фенобарбитал или бромид у собак и фенобарбитал у кошек. [239] Имепитоин также применяется у собак. [240] Хотя генерализованные припадки у лошадей диагностировать довольно легко, при негенерализованных припадках это может быть сложнее, поэтому ЭЭГ . может оказаться полезной [241]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л «Информационный бюллетень по эпилепсии» . ВОЗ . Февраль 2016. Архивировано из оригинала 11 марта 2016 года . Проверено 4 марта 2016 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот Хаммер Г.Д., Макфи С.Дж., ред. (2010). «7». Патофизиология заболеваний: введение в клиническую медицину (6-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-162167-0 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Голдберг Э.М., Коултер Д.А. (май 2013 г.). «Механизмы эпилептогенеза: конвергенция дисфункции нейронных цепей» . Обзоры природы. Нейронаука . 14 (5): 337–349. дои : 10.1038/nrn3482 . ПМЦ 3982383 . ПМИД 23595016 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Лонго Д.Л. (2012). «369 Судороги и эпилепсия». Принципы внутренней медицины Харрисона (18-е изд.). МакГроу-Хилл. п. 3258. ИСБН 978-0-07-174887-2 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Бергей ГК (июнь 2013 г.). «Нейростимуляция в лечении эпилепсии». Экспериментальная неврология . 244 : 87–95. дои : 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.04.004 . ПМИД 23583414 . S2CID 45244964 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Мартин-МакГилл К.Дж., Бреснахан Р., Леви Р.Г., Купер П.Н. (июнь 2020 г.). «Кетогенные диеты при лекарственно-устойчивой эпилепсии» . Кокрановская база данных систематических обзоров . 2020 (6): CD001903. дои : 10.1002/14651858.CD001903.pub5 . ПМЦ 7387249 . ПМИД 32588435 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Иди MJ (декабрь 2012 г.). «Недостатки современного лечения эпилепсии». Экспертный обзор нейротерапии . 12 (12): 1419–1427. дои : 10.1586/ern.12.129 . ПМИД 23237349 . S2CID 207221378 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Краткий обзор причин и рисков GBD 2021: ЭПИЛЕПСИЯ» . Институт показателей и оценки здоровья (IHME) . Сиэтл, США: Вашингтонский университет. 2021. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 19 июля 2024 года . Проверено 19 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Синмец Дж.Д., Зеехер К.М., Шисс Н., Николс Э., Цао Б., Сервили С. и др. (1 апреля 2024 г.). «Глобальное, региональное и национальное бремя расстройств, поражающих нервную систему, 1990–2021 гг.: систематический анализ для исследования глобального бремени болезней 2021 г.». Ланцет Неврология . 23 (4). Эльзевир: 344–381. дои : 10.1016/S1474-4422(24)00038-3 . hdl : 1959.4/102176 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Фишер Р.С., Асеведо С., Арзиманоглу А., Богач А., Кросс Дж.Х., Элгер С.Э. и др. (апрель 2014 г.). «Официальный отчет ILAE: практическое клиническое определение эпилепсии» . Эпилепсия . 55 (4): 475–482. дои : 10.1111/epi.12550 . ПМИД 24730690 . S2CID 35958237 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и «Эпилепсия» . www.who.int . Проверено 1 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фишер Р.С., ван Эмде Боас В., Блюм В., Элджер С., Гентон П., Ли П. и др. (апрель 2005 г.). «Эпилептические припадки и эпилепсия: определения, предложенные Международной лигой борьбы с эпилепсией (ILAE) и Международным бюро эпилепсии (IBE)» . Эпилепсия . 46 (4): 470–472. дои : 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.66104.x . ПМИД 15816939 . S2CID 21130724 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Пандольфо М. (ноябрь 2011 г.). «Генетика эпилепсии». Семинары по неврологии . 31 (5): 506–518. дои : 10.1055/s-0031-1299789 . ПМИД 22266888 . S2CID 260320566 .

- ^ Ван Х., Нагави М., Аллен С., Барбер Р.М., Бхутта З.А., Картер А. и др. (октябрь 2016 г.). «Глобальная, региональная и национальная продолжительность жизни, смертность от всех причин и смертность от конкретных причин по 249 причинам смерти, 1980-2015 гг.: систематический анализ для исследования глобального бремени болезней 2015 г.» . Ланцет . 388 (10053): 1459–1544. дои : 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1 . ПМЦ 5388903 . ПМИД 27733281 .

- ^ Нагави М., Ван Х., Лозано Р., Дэвис А., Лян Х., Чжоу М. и др. (GBD 2013 Смертность и причины смерти, сотрудники) (январь 2015 г.). «Глобальная, региональная и национальная смертность от всех причин и по конкретным причинам в разбивке по возрасту и по конкретным причинам по 240 причинам смерти, 1990-2013 гг.: систематический анализ для исследования глобального бремени болезней, 2013 г.» . Ланцет . 385 (9963): 117–171. дои : 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2 . hdl : 11655/15525 . ПМК 4340604 . ПМИД 25530442 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Броди М.Дж., старейшина А.Т., Кван П. (ноябрь 2009 г.). «Эпилепсия в дальнейшей жизни» . «Ланцет». Неврология . 8 (11): 1019–1030. дои : 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70240-6 . ПМИД 19800848 . S2CID 14318073 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Холмс Т.Р., Браун Г.Л. (2008). Справочник по эпилепсии (4-е изд.). Филадельфия: Липпинкотт Уильямс и Уилкинс. п. 7. ISBN 978-0-7817-7397-3 .

- ^ Лечение эпилепсии Уилли: принципы и практика (5-е изд.). Филадельфия: Уолтерс Клювер/Липпинкотт Уильямс и Уилкинс. 2010. ISBN 978-1-58255-937-7 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 июня 2016 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л Ньютон Ч.Р., Гарсия Х.Х. (сентябрь 2012 г.). «Эпилепсия в бедных регионах мира» . Ланцет . 380 (9848): 1193–1201. дои : 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61381-6 . ПМИД 23021288 . S2CID 13933909 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Уилден Дж. А., Коэн-Гадол А. А. (август 2012 г.). «Оценка первых нефебрильных судорог». Американский семейный врач . 86 (4): 334–340. ПМИД 22963022 .

- ^ Нелиган А., Адан Г., Невитт С.Дж., Пуллен А., Сандер Дж.В., Боннетт Л. и др. (Кокрейновская группа по эпилепсии) (январь 2023 г.). «Прогноз для взрослых и детей после первого неспровоцированного припадка» . Кокрановская база данных систематических обзоров . 1 (1): CD013847. дои : 10.1002/14651858.CD013847.pub2 . ПМЦ 9869434 . ПМИД 36688481 .

- ^ «Эпилепсия: какова вероятность повторного приступа?» . Доказательства НИХР . Национальный институт исследований в области здравоохранения и ухода. 16 августа 2023 г. doi : 10.3310/nihrevidence_59456 . S2CID 260965684 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Л. Девлин А., Оделл М., Л. Чарльтон Дж., Коппел С. (декабрь 2012 г.). «Эпилепсия и вождение: современное состояние исследований». Исследования эпилепсии . 102 (3): 135–152. doi : 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2012.08.003 . ПМИД 22981339 . S2CID 30673360 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л Магиоркинис Э., Сидиропулу К., Диамантис А. (январь 2010 г.). «Вехи в истории эпилепсии: эпилепсия в древности». Эпилепсия и поведение . 17 (1): 103–108. дои : 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.10.023 . ПМИД 19963440 . S2CID 26340115 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дункан Дж.С., Сандер Дж.В., Сисодия С.М., Уокер М.С. (апрель 2006 г.). «Эпилепсия у взрослых» (PDF) . Ланцет . 367 (9516): 1087–1100. дои : 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68477-8 . ПМИД 16581409 . S2CID 7361318 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 24 марта 2013 года . Проверено 10 января 2012 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот п д р с т Национальный центр клинических рекомендаций (январь 2012 г.). Эпилепсия: Диагностика и лечение эпилепсии у взрослых и детей в учреждениях первичной и вторичной медицинской помощи (PDF) . Национальный институт здравоохранения и клинического мастерства. стр. 21–28. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 16 декабря 2013 года.

- ^ Хьюз-младший (август 2009 г.). «Авансовые припадки: обзор недавних отчетов с новыми концепциями». Эпилепсия и поведение . 15 (4): 404–412. дои : 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.06.007 . ПМИД 19632158 . S2CID 22023692 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Ширер П. «Приступы и эпилептический статус: диагностика и лечение в отделении неотложной помощи» . Практика неотложной медицинской помощи . Архивировано из оригинала 30 декабря 2010 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Брэдли В.Г. (2012). «67». Неврология Брэдли в клинической практике (6-е изд.). Филадельфия, Пенсильвания: Эльзевир/Сондерс. ISBN 978-1-4377-0434-1 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Национальный центр клинических рекомендаций (январь 2012 г.). Эпилепсия: Диагностика и лечение эпилепсии у взрослых и детей в учреждениях первичной и вторичной медицинской помощи (PDF) . Национальный институт здравоохранения и клинического мастерства. стр. 119–129. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 16 декабря 2013 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот «Эпилепсия» . Информационные бюллетени. Всемирная организация здравоохранения . Октябрь 2012 года . Проверено 24 января 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Энгель Дж (2008). Эпилепсия: комплексный учебник (2-е изд.). Филадельфия: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. п. 2797. ИСБН 978-0-7817-5777-5 . Архивировано из оригинала 20 мая 2016 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Саймон Д.А., Гринберг М.Дж., Аминофф Р.П. (2012). «12». Клиническая неврология (8-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-175905-2 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Стивенсон Дж. Б. (1990). Припадки и обмороки . Лондон: Mac Keith Press. ISBN 0-632-02811-4 . ОСЛК 25711319 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Стивен С. Шахтер, изд. (2008). Поведенческие аспекты эпилепсии: принципы и практика ([Online-Ausg.]. Под ред.). Нью-Йорк: Демо. п. 125. ИСБН 978-1-933864-04-4 .

- ^ Сюэ Л.И., Ритаччо А.Л. (март 2006 г.). «Рефлекторные припадки и рефлекторная эпилепсия». Американский журнал электронейродиагностических технологий . 46 (1): 39–48. дои : 10.1080/1086508X.2006.11079556 . ПМИД 16605171 . S2CID 10098600 .

- ^ Малов Б.А. (ноябрь 2005 г.). «Сон и эпилепсия». Неврологические клиники . 23 (4): 1127–1147. дои : 10.1016/j.ncl.2005.07.002 . ПМИД 16243619 .

- ^ Тинупер П., Провини Ф., Бисулли Ф., Виньятелли Л., Плацци Г., Ветруньо Р. и др. (август 2007 г.). «Движительные расстройства во сне: рекомендации по дифференциации эпилептических и неэпилептических двигательных явлений, возникающих во сне». Обзоры медицины сна . 11 (4): 255–267. дои : 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.01.001 . ПМИД 17379548 .