Синьцзян

Синьцзян | |

|---|---|

| Синьцзян-Уйгурский автономный район | |

| Транскрипция(и) имени | |

| • китайский | Синьцзян-Уйгурский автономный район ( Синьцзян Вейвуер Зижику ) |

| • уйгурский | Синьцзян-Уйгурский автономный район ( Синьцзян-Уйгурский автономный район ) |

| • Аббревиатура | XJ / 新 ( Синь ) |

Clockwise from top: | |

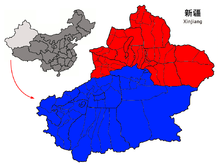

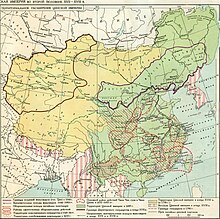

Location of Xinjiang within China | |

| Coordinates: 41°N 85°E / 41°N 85°E | |

| Country | China |

| Capital and largest city | Ürümqi |

| Divisions – Prefecture-level – County-level – Township-level | 14 prefectures 95 counties 1142 towns and subdistricts |

| Government | |

| • Type | Autonomous region |

| • Body | Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Regional People's Congress |

| • CCP Secretary | Ma Xingrui |

| • Congress Chairwoman | Zumret Obul |

| • Government Chairman | Erkin Tuniyaz |

| • Regional CPPCC Chairman | Nurlan Abilmazhinuly |

| • National People's Congress Representation | 60 deputies |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,664,897 km2 (642,820 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 1st |

| Highest elevation (Mount K2) | 8,611 m (28,251 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | −154 m (−505 ft) |

| Population (2021)[3] | |

| • Total | 25,890,000 |

| • Rank | 21st |

| • Density | 16/km2 (40/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 29th |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic composition (2020 census) | |

| • Languages | 44 languages;[5] including the two lingua francas, Chinese and Uyghur[6] |

| GDP (2023)[7] | |

| • Total | CN¥ 1,913 billion (23th) US$ 271 billion |

| • Per capita | CN¥ 73,774 (16h) US$ 10,469 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-XJ |

| HDI (2021) | 0.738[8] (24th) – high |

| Website | www Uyghur version |

Синьцзян , [а] официально Синьцзян-Уйгурский автономный район , [11] [12] — автономный район ( Китайской Народной Республики КНР), расположенный на северо-западе страны на стыке Центральной и Восточной Азии . Являясь крупнейшим по площади провинциальным подразделением Китая и восьмым по величине подразделением страны в мире, Синьцзян занимает площадь более 1,6 миллиона квадратных километров (620 000 квадратных миль) и насчитывает около 25 миллионов жителей. [1] [13] Синьцзян граничит со странами Афганистана , Казахстана , Кыргызстана , Монголии , Пакистана , России , Таджикистана и Индии . Скалистые горные хребты Каракорум , Куньлунь и Тянь-Шань занимают большую часть границ Синьцзяна, а также его западные и южные районы. На регионы Аксай -Чин и Транс-Каракорумский тракт претендует Индия, но они находятся под управлением Китая. [14] [15] [16] Синьцзян также граничит с Тибетским автономным районом и провинциями Ганьсу и Цинхай . Самый известный маршрут исторического Шелкового пути пролегал через территорию с востока до ее северо-западной границы.

Xinjiang is divided into the Dzungarian Basin (Dzungaria) in the north and the Tarim Basin in the south by a mountain range and only about 9.7 percent of Xinjiang's land area is fit for human habitation.[17][unreliable source?] It is home to a number of ethnic groups, including the Chinese Tajiks (Pamiris), Han Chinese, Hui, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Mongols, Russians, Sibe, Tibetans, and Uyghurs.[18] There are more than a dozen autonomous prefectures and counties for minorities in Xinjiang. Older English-language reference works often refer to the area as Chinese Turkestan,[19][20] Chinese Turkistan,[21] East Turkestan[22] and East Turkistan.[23]

With a documented history of at least 2,500 years, a succession of people and empires have vied for control over all or parts of this territory. The territory came under the rule of the Qing dynasty in the 18th century, which was later replaced by the Republic of China. Since 1949 and the Chinese Civil War, it has been part of the People's Republic of China. In 1954, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) established the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC) to strengthen border defense against the Soviet Union and promote the local economy by settling soldiers into the region.[24] In 1955, Xinjiang was administratively changed from a province into an autonomous region. In recent decades, abundant oil and mineral reserves have been found in Xinjiang and it is currently China's largest natural-gas-producing region.

From the 1990s to the 2010s, the East Turkestan independence movement, separatist conflict and the influence of radical Islam have resulted in unrest in the region with occasional terrorist attacks and clashes between separatist and government forces.[25][26] These conflicts prompted the Chinese government to commit a series of ongoing human rights abuses against Uyghurs and other ethnic and religious minorities in the province including, according to some, genocide.[27][28]

Names

| Xinjiang | |||

|---|---|---|---|

"Xīnjiāng" in Chinese characters | |||

| Chinese name | |||

| Chinese | 新疆 | ||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Xīnjiāng | ||

| Postal | Sinkiang | ||

| Literal meaning | "New Frontier" | ||

| |||

| Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region | |||

| Simplified Chinese | 新疆维吾尔自治区 | ||

| Traditional Chinese | 新疆維吾爾自治區 | ||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Xīnjiāng Wéiwú'ěr Zìzhìqū | ||

| |||

| Mongolian name | |||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Шиньжян Уйгурын өөртөө засах орон | ||

| Mongolian script | ᠰᠢᠨᠵᠢᠶᠠᠩ ᠤᠶᠢᠭᠤᠷ ᠤᠨ ᠥᠪᠡᠷᠲᠡᠭᠡᠨ ᠵᠠᠰᠠᠬᠤ ᠣᠷᠤᠨ | ||

| |||

| Uyghur name | |||

| Uyghur | شىنجاڭ ئۇيغۇر ئاپتونوم رايونى | ||

| |||

| Manchu name | |||

| Manchu script | ᡳᠴᡝ ᠵᡝᠴᡝᠨ ᡠᡳᡤᡠᡵ ᠪᡝᠶᡝ ᡩᠠᠰᠠᠩᡤᠠ ᡤᠣᠯᠣ | ||

| Möllendorff | Ice Jecen Uigur beye dasangga golo | ||

| Kazakh name | |||

| Kazakh | شينجياڭ ۇيعۇر اۆتونوميالىق رايونى Шыңжаң Ұйғыр автономиялық ауданы Shyńjań Uıǵyr aýtonomııalyq aýdany | ||

| Kyrgyz name | |||

| Kyrgyz | شئنجاڭ ۇيعۇر اپتونوم رايونۇ Шинжаң-Уйгур автоном району Şincañ-Uyğur avtonom rayonu | ||

| Oirat name | |||

| Oirat | ᠱᡅᠨᡓᡅᡕᠠᡊ ᡇᡕᡅᡎᡇᠷ ᡅᠨ ᡄᡋᡄᠷᡄᡃᠨ ᠴᠠᠰᠠᡍᡇ ᡆᠷᡇᠨ Šinǰiyang Uyiγur-in ebereen zasaqu orun | ||

| Xibe name | |||

| Xibe | ᠰᡞᠨᡪᠶᠠᡢ ᡠᡞᡤᡠᠷ ᠪᡝᠶᡝ ᡩᠠᠰᠠᡢᡤᠠ ᡤᠣᠯᠣ Sinjyang Uigur beye dasangga golo | ||

| Sarikoli name | |||

| Sarikoli | شىنجاڭ ئۈيغۈر ئافتۇنۇم رەيۇن Xinjong Üighür Oftunum Rayun[b] | ||

The general region of Xinjiang has been known by many different names throughout time. These names include Altishahr, the historical Uyghur name for the southern half of the region referring to "the six cities" of the Tarim Basin, as well as Khotan, Khotay, Chinese Tartary, High Tartary, East Chagatay (it was the eastern part of the Chagatai Khanate), Moghulistan ("land of the Mongols"), Kashgaria, Little Bokhara, Serindia (due to Indian cultural influence)[30] and, in Chinese, Xiyu (西域), meaning "Western Regions".[31]

Between the 2nd century BCE and 2nd century CE, the Han Empire established the Protectorate of the Western Regions or Xiyu Protectorate (西域都護府) in an effort to secure the profitable routes of the Silk Road.[32] The Western Regions during the Tang era were known as Qixi (磧西). Qi refers to the Gobi Desert while Xi refers to the west. The Tang Empire had established the Protectorate General to Pacify the West or Anxi Protectorate (安西都護府) in 640 to control the region.

During the Qing dynasty, the northern part of Xinjiang, Dzungaria was known as Zhunbu (準部, "Dzungar region") and the Southern Tarim Basin was known as Huijiang (回疆, "Muslim Frontier"). Both regions merged after Qing dynasty suppressed the Revolt of the Altishahr Khojas in 1759 and became the region of "Xiyu Xinjiang" (西域新疆, literally "Western Regions' New Frontier"), later simplified as "Xinjiang" (新疆; formerly romanized as "Sinkiang"). The official name was given during the reign of the Guangxu Emperor in 1878.[33] It can be translated as "new frontier" or "new territory".[34] In fact, the term "Xinjiang" was used in many other places conquered, but never were ruled by Chinese empires directly until the gradual Gaitu Guiliu administrative reform, including regions in Southern China.[35] For instance, present-day Jinchuan County in Sichuan was then known as "Jinchuan Xinjiang", Zhaotong in Yunnan was named directly as "Xinjiang", Qiandongnan region, Anshun and Zhenning were named as "Liangyou Xinjiang" etc.[36]

In 1955, Xinjiang Province was renamed "Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region". The name that was originally proposed was simply "Xinjiang Autonomous Region" because that was the name for the imperial territory. This proposal was not well-received by Uyghurs in the Communist Party, who found the name colonialist in nature since it meant "new territory". Saifuddin Azizi, the first chairman of Xinjiang, registered his strong objections to the proposed name with Mao Zedong, arguing that "autonomy is not given to mountains and rivers. It is given to particular nationalities." Some Uyghur Communists proposed the name "Tian Shan Uyghur Autonomous Region" instead. The Han Communists in the central government denied the name Xinjiang was colonialist and denied that the central government could be colonialists both because they were communists and because China was a victim of colonialism. However, due to the Uyghur complaints, the administrative region would be named "Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region".[37][34]

Description

Xinjiang consists of two main geographically, historically and ethnically distinct regions with different historical names, Dzungaria north of the Tianshan Mountains and the Tarim Basin south of the Tianshan Mountains, before Qing China unified them into one political entity called Xinjiang Province in 1884. At the time of the Qing conquest in 1759, Dzungaria was inhabited by steppe dwelling, nomadic Tibetan Buddhist Dzungar people, while the Tarim Basin was inhabited by sedentary, oasis dwelling, Turkic-speaking Muslim farmers, now known as the Uyghurs, who were governed separately until 1884.

The Qing dynasty was well aware of the differences between the former Buddhist Mongol area to the north of the Tian Shan and the Turkic Muslim area south of the Tian Shan and ruled them in separate administrative units at first.[38] However, Qing people began to think of both areas as part of one distinct region called Xinjiang.[39] The very concept of Xinjiang as one distinct geographic identity was created by the Qing.[40] During the Qing rule, no sense of "regional identity" was held by ordinary Xinjiang people; rather, Xinjiang's distinct identity was given to the region by the Qing, since it had distinct geography, history and culture, while at the same time it was created by the Chinese, multicultural, settled by Han and Hui and separated from Central Asia for over a century and a half.[41]

In the late 19th century, it was still being proposed by some people that two separate regions be created out of Xinjiang, the area north of the Tianshan and the area south of the Tianshan, while it was being argued over whether to turn Xinjiang into a province.[42]

Xinjiang is a large, sparsely populated area, spanning over 1.6 million km2 (comparable in size to Iran), which takes up about one sixth of the country's territory. Xinjiang borders the Tibet Autonomous Region and India's Leh district in Ladakh to the south, Qinghai and Gansu provinces to the east, Mongolia (Bayan-Ölgii, Govi-Altai and Khovd Provinces) to the east, Russia's Altai Republic to the north and Kazakhstan (Almaty and East Kazakhstan Regions), Kyrgyzstan (Issyk-Kul, Naryn and Osh Regions), Tajikistan's Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region, Afghanistan's Badakhshan Province and Pakistan's Gilgit-Baltistan to the west.

The east-west chain of the Tian Shan separate Dzungaria in the north from the Tarim Basin in the south. Dzungaria is a dry steppe and the Tarim Basin contains the massive Taklamakan Desert, surrounded by oases. In the east is the Turpan Depression. In the west, the Tian Shan split, forming the Ili River valley.

History

Early history

| History of Xinjiang |

|---|

|

The earliest inhabitants of the region encompassing modern day Xinjiang were genetically of Ancient North Eurasian and Northeast Asian origin, with later geneflow from during the Bronze Age linked to the expansion of early Indo-Europeans. These population dynamics gave rise to a heterogeneous demographic makeup. Iron Age samples from Xinjiang show intensified levels of admixture between Steppe pastoralists and northeast Asians, with northern and eastern Xinjiang showing more affinities with northeast Asians, and southern Xinjiang showing more affinity with central Asians.[43][44]

Between 2009 and 2015, the remains of 92 individuals in the Xiaohe Cemetery were analyzed for Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA markers. Genetic analyses of the mummies showed that the paternal lineages of the Xiaohe people were of almost all European[45] origin, while the maternal lineages of the early population were diverse, featuring both East Eurasian and West Eurasian lineages, as well as a smaller number of Indian / South Asian lineages. lineages. Over time, the west Eurasian maternal lineages were gradually replaced by east Eurasian maternal lineages. Outmarriage to women from Siberian communities, led to the loss of the original diversity of mtDNA lineages observed in the earlier Xiaohe population.[46][47][48]

The Tarim population was therefore always notably diverse, reflecting a complex history of admixture between people of Ancient North Eurasian, South Asian and Northeast Asian descent. The Tarim mummies have been found in various locations in the Western Tarim Basin such as Loulan, the Xiaohe Tomb complex and Qäwrighul. These mummies have been previously suggested to have been Tocharian or Indo-European speakers, but recent evidence suggest that the earliest mummies belonged to a distinct population unrelated to Indo-European pastoralists and spoke an unknown language, probably a language isolate.[49]

Although many of the Tarim mummies were classified as Caucasoid by anthropologists, Tarim Basin sites also contain both "Caucasoid" and "Mongoloid" remains, indicating contact between newly arrived western nomads and agricultural communities in the east.[50] Mummies have been found in various locations in the Western Tarim Basin such as Loulan, the Xiaohe Tomb complex and Qäwrighul.

Nomadic tribes such as the Yuezhi, Saka and Wusun were probably part of the migration of Indo-European speakers who had settled in Tarim Basin of Xinjiang long before the Xiongnu and Han Chinese. By the time the Han dynasty under Emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BC) wrested the western Tarim Basin away from its previous overlords (the Xiongnu), it was inhabited by various peoples who included the Indo-European-speaking Tocharians in Turfan and Kucha, the Saka peoples centered in the Shule Kingdom and the Kingdom of Khotan, the various Tibeto-Burmese groups (especially people related to the Qiang) as well as the Han Chinese people.[51] Some linguists posit that the Tocharian language had high amounts of influence from Paleosiberian languages,[52] such as Uralic and Yeniseian languages.

Yuezhi culture is documented in the region. The first known reference to the Yuezhi was in 645 BC by the Chinese chancellor Guan Zhong in his work, Guanzi (管子, Guanzi Essays: 73: 78: 80: 81). He described the Yúshì, 禺氏 (or Niúshì, 牛氏), as a people from the north-west who supplied jade to the Chinese from the nearby mountains (also known as Yushi) in Gansu.[53] The longtime jade supply[54] from the Tarim Basin is well-documented archaeologically: "It is well known that ancient Chinese rulers had a strong attachment to jade. All of the jade items excavated from the tomb of Fuhao of the Shang dynasty, more than 750 pieces, were from Khotan in modern Xinjiang. As early as the mid-first millennium BC, the Yuezhi engaged in the jade trade, of which the major consumers were the rulers of agricultural China."[55]

Crossed by the Northern Silk Road,[56] the Tarim and Dzungaria regions were known as the Western Regions. At the beginning of the Han dynasty the region was ruled by the Xiongnu, a powerful nomadic people.[57]: 148 During the 2nd century BC, the Han dynasty prepared for war against Xiongnu when Emperor Wu of Han dispatched Zhang Qian to explore the mysterious kingdoms to the west and form an alliance with the Yuezhi against the Xiongnu. As a result of the war, the Chinese controlled the strategic region from the Ordos and Gansu corridor to Lop Nor. They separated the Xiongnu from the Qiang people on the south and gained direct access to the Western Regions. Han China sent Zhang Qian as an envoy to the states of the region, beginning several decades of struggle between the Xiongnu and Han China in which China eventually prevailed. During the 100s BCE, the Silk Road brought increasing Chinese economic and cultural influence to the region.[57]: 148 In 60 BCE, Han China established the Protectorate of the Western Regions (西域都護府) at Wulei (烏壘, near modern Luntai), to oversee the region as far west as the Pamir Mountains. The protectorate was seized during the civil war against Wang Mang (r. AD 9–23), returning to Han control in 91 due to the efforts of general Ban Chao.

The Western Jin dynasty succumbed to successive waves of invasions by nomads from the north at the beginning of the 4th century. The short-lived kingdoms that ruled northwestern China one after the other, including Former Liang, Former Qin, Later Liang and Western Liáng, all attempted to maintain the protectorate, with varying degrees of success. After the final reunification of Northern China under the Northern Wei empire, its protectorate controlled what is now the southeastern region of Xinjiang. Local states such as Shule, Yutian, Guizi and Qiemo controlled the western region, while the central region around Turpan was controlled by Gaochang, remnants of a state (Northern Liang) that once ruled part of what is now Gansu province in northwestern China.

During the Tang dynasty, a series of expeditions were conducted against the Western Turkic Khaganate and their vassals: the oasis states of southern Xinjiang.[58] Campaigns against the oasis states began under Emperor Taizong with the annexation of Gaochang in 640.[59] The nearby kingdom of Karasahr was captured by the Tang in 644 and the kingdom of Kucha was conquered in 649.[60] The Tang Dynasty then established the Protectorate General to Pacify the West (安西都護府) or Anxi Protectorate, in 640 to control the region.

During the Anshi Rebellion, which nearly destroyed the Tang dynasty, Tibet invaded the Tang on a broad front from Xinjiang to Yunnan. It occupied the Tang capital of Chang'an in 763 for 16 days, and controlled southern Xinjiang by the end of the century. The Uyghur Khaganate took control of Northern Xinjiang, much of Central Asia and Mongolia at the same time.

As Tibet and the Uyghur Khaganate declined in the mid-9th century, the Kara-Khanid Khanate (a confederation of Turkic tribes including the Karluks, Chigils and Yaghmas)[61] controlled Western Xinjiang during the 10th and 11th centuries. After the Uyghur Khaganate in Mongolia was destroyed by the Kirghiz in 840, branches of the Uyghurs established themselves in Qocha (Karakhoja) and Beshbalik (near present-day Turfan and Ürümqi). The Uyghur state remained in eastern Xinjiang until the 13th century, although it was ruled by foreign overlords. The Kara-Khanids converted to Islam. The Uyghur state in Eastern Xinjiang, initially Manichean, later converted to Buddhism.

Remnants of the Liao dynasty from Manchuria entered Xinjiang in 1132, fleeing rebellion by the neighboring Jurchens. They established a new empire, the Qara Khitai (Western Liao), which ruled the Kara-Khanid and Uyghur-held parts of the Tarim Basin for the next century. Although Khitan and Chinese were the primary administrative languages, Persian and Uyghur were also used.[62]

Islamization

| Part of a series on Islam in China |

|---|

|

Present-day Xinjiang consisted of the Tarim Basin and Dzungaria and was originally inhabited by Indo-European Tocharians and Iranian Sakas who practiced Buddhism and Zoroastrianism. The Turfan and Tarim Basins were inhabited by speakers of Tocharian languages,[63] with Caucasian mummies found in the region.[64] The area became Islamified during the 10th century with the conversion of the Kara-Khanid Khanate, who occupied Kashgar. During the mid-10th century, the Saka Buddhist Kingdom of Khotan was attacked by the Turkic Muslim Karakhanid ruler Musa; the Karakhanid leader Yusuf Qadir Khan conquered Khotan around 1006.[65]

Mongol period

After Genghis Khan unified Mongolia and began his advance west the Uyghur state in the Turpan-Urumchi region offered its allegiance to the Mongols in 1209, contributing taxes and troops to the Mongol imperial effort. In return, the Uyghur rulers retained control of their kingdom; Genghis Khan's Mongol Empire conquered the Qara Khitai in 1218. Xinjiang was a stronghold of Ögedei Khan and later came under the control of his descendant, Kaidu. This branch of the Mongol family kept the Yuan dynasty at bay until their rule ended.

During the Mongol Empire era the Yuan dynasty vied with the Chagatai Khanate for rule of the region and the latter controlled most of it. After the Chagatai Khanate divided into smaller khanates during the mid-14th century, the politically-fractured region was ruled by a number of Persianized Mongol Khans, including those from Moghulistan (with the assistance of local Dughlat emirs), Uigurstan (later Turpan) and Kashgaria. These leaders warred with each other and the Timurids of Transoxiana to the west and the Oirats to the east: the successor Chagatai regime based in Mongolia and China. During the 17th century, the Dzungars established an empire over much of the region.

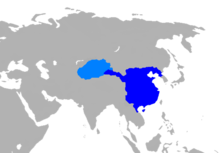

The Mongolian Dzungars were the collective identity of several Oirat tribes which formed and maintained, one of the last nomadic empires. The Dzungar Khanate covered Dzungaria, extending from the western Great Wall of China to present-day Eastern Kazakhstan and from present-day Northern Kyrgyzstan to Southern Siberia. Most of the region was renamed "Xinjiang" by the Chinese after the fall of the Dzungar Empire, which existed from the early 17th to the mid-18th century.[66]

The sedentary Turkic Muslims of the Tarim Basin were originally ruled by the Chagatai Khanate and the nomadic Buddhist Oirat Mongols in Dzungaria ruled the Dzungar Khanate. The Naqshbandi Sufi Khojas, descendants of Muhammad, had replaced the Chagatayid Khans as rulers of the Tarim Basin during the early 17th century. There was a struggle between two Khoja factions: the Afaqi (White Mountain) and the Ishaqi (Black Mountain). The Ishaqi defeated the Afaqi and the Afaq Khoja invited the 5th Dalai Lama (the leader of the Tibetans) to intervene on his behalf in 1677. The Dalai Lama then called on his Dzungar Buddhist followers in the Dzungar Khanate to act on the invitation. The Dzungar Khanate conquered the Tarim Basin in 1680, setting up the Afaqi Khoja as their puppet ruler. After converting to Islam, the descendants of the previously-Buddhist Uyghurs in Turfan believed that the "infidel Kalmuks" (Dzungars) built Buddhist monuments in their region.[67]

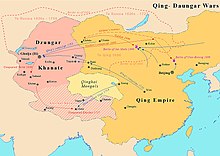

Qing dynasty

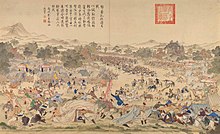

The Turkic Muslims of the Turfan and Kumul oases then submitted to the Qing dynasty and asked China to free them from the Dzungars; the Qing accepted their rulers as vassals. They warred against the Dzungars for decades before defeating them; Qing Manchu Bannermen then conducted the Dzungar genocide, nearly eradicating them and depopulating Dzungaria. The Qing freed the Afaqi Khoja leader Burhan-ud-din and his brother, Khoja Jihan, from Dzungar imprisonment and appointed them to rule the Tarim Basin as Qing vassals. The Khoja brothers reneged on the agreement, declaring themselves independent leaders of the Tarim Basin. The Qing and the Turfan leader Emin Khoja crushed their revolt, and by 1759 China controlled Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin.[68]

The Manchu Qing dynasty gained control of eastern Xinjiang as a result of a long struggle with the Dzungars which began during the 17th century. In 1755, with the help of the Oirat noble Amursana, the Qing attacked Ghulja and captured the Dzungar khan. After Amursana's request to be declared Dzungar khan went unanswered, he led a revolt against the Qing. Qing armies destroyed the remnants of the Dzungar Khanate over the next two years, and many Han Chinese and Hui moved into the pacified areas.[69]

The native Dzungar Oirat Mongols suffered greatly from the brutal campaigns and a simultaneous smallpox epidemic. Writer Wei Yuan described the resulting desolation in present-day northern Xinjiang as "an empty plain for several thousand li, with no Oirat yurt except those surrendered."[70] It has been estimated that 80 percent of the 600,000 (or more) Dzungars died from a combination of disease and warfare,[71] and recovery took generations.[72]

Han and Hui merchants were initially only allowed to trade in the Tarim Basin; their settlement in the Tarim Basin was banned until the 1830 Muhammad Yusuf Khoja invasion, when the Qing rewarded merchants for fighting off Khoja by allowing them to settle in the basin.[73] The Uyghur Muslim Sayyid and Naqshbandi Sufi rebel of the Afaqi suborder, Jahangir Khoja was sliced to death (Lingchi) in 1828 by the Manchus for leading a rebellion against the Qing. According to Robert Montgomery Martin, many Chinese with a variety of occupations were settled in Dzungaria in 1870; in Turkestan (the Tarim Basin), however, only a few Chinese merchants and garrison soldiers were interspersed with the Muslim population.[74]

The 1765 Ush rebellion by the Uyghurs against the Manchu began after Uyghur women were raped by the servants and son of Manchu official Su-cheng.[75] It was said that "Ush Muslims had long wanted to sleep on [Sucheng and son's] hides and eat their flesh" because of the months-long abuse.[76] The Manchu emperor ordered the massacre of the Uyghur rebel town; Qing forces enslaved the Uyghur children and women, and killed the Uyghur men.[77] Sexual abuse of Uyghur women by Manchu soldiers and officials triggered deep Uyghur hostility against Manchu rule.[78]

Yettishar

By the 1860s, Xinjiang had been under Qing rule for a century. The region was captured in 1759 from the Dzungar Khanate,[79] whose population (the Oirats) became the targets of genocide. Xinjiang was primarily semi-arid or desert and unattractive to non-trading Han settlers, and others (including the Uyghurs) settled there.

The Dungan Revolt by the Muslim Hui and other Muslim ethnic groups was fought in China's Shaanxi, Ningxia and Gansu provinces and in Xinjiang from 1862 to 1877. The conflict led to a reported 20.77 million deaths due to migration and war, with many refugees dying of starvation.[80][failed verification] Thousands of Muslim refugees from Shaanxi fled to Gansu; some formed battalions in eastern Gansu, intending to reconquer their lands in Shaanxi. While the Hui rebels were preparing to attack Gansu and Shaanxi, Yaqub Beg (an Uzbek or Tajik commander of the Kokand Khanate) fled from the khanate in 1865 after losing Tashkent to the Russians. Beg settled in Kashgar, and soon controlled Xinjiang. Although he encouraged trade, built caravansareis, canals and other irrigation systems, his regime was considered harsh. The Chinese took decisive action against Yettishar; an army under General Zuo Zongtang rapidly approached Kashgaria, reconquering it on 16 May 1877.[81]

After reconquering Xinjiang in the late 1870s from Yaqub Beg,[82] the Qing dynasty established Xinjiang ("new frontier") as a province in 1884[83] – making it part of China, and dropping the old names of Zhunbu (準部, Dzungar Region) and Huijiang (Muslimland).[84][85]

After Xinjiang became a Chinese province, the Qing government encouraged the Uyghurs to migrate from southern Xinjiang to other areas of the province (such as the region between Qitai and the capital, largely inhabited by Han Chinese, and Ürümqi, Tacheng (Tabarghatai), Yili, Jinghe, Kur Kara Usu, Ruoqiang, Lop Nor and the lower Tarim River.[86]

Republic of China

In 1912, the Qing dynasty was replaced by the Republic of China. The ROC continued to treat the Qing territory as its own, including Xinjiang.[87]: 69 Yuan Dahua, the last Qing governor of Xinjiang, fled. One of his subordinates, Yang Zengxin, took control of the province and acceded in name to the Republic of China in March of that year. Balancing mixed ethnic constituencies, Yang controlled Xinjiang until his 1928 assassination after the Northern Expedition of the Kuomintang.[88]

The Kumul Rebellion and others broke out throughout Xinjiang during the early 1930s against Jin Shuren, Yang's successor, involving Uyghurs, other Turkic groups and Hui (Muslim) Chinese. Jin enlisted White Russians to crush the revolts. In the Kashgar region on 12 November 1933, the short-lived First East Turkestan Republic was self-proclaimed after debate about whether it should be called "East Turkestan" or "Uyghuristan".[89][90] The region claimed by the ETR encompassed the Kashgar, Khotan and Aksu Prefectures in southwestern Xinjiang.[91] The Chinese Muslim Kuomintang 36th Division (National Revolutionary Army) defeated the army of the First East Turkestan Republic in the 1934 Battle of Kashgar, ending the republic after Chinese Muslims executed its two emirs: Abdullah Bughra and Nur Ahmad Jan Bughra. The Soviet Union invaded the province; it was brought under the control of northeast Han warlord Sheng Shicai after the 1937 Xinjiang War. Sheng ruled Xinjiang for the next decade with support from the Soviet Union, many of whose ethnic and security policies he instituted. The Soviet Union maintained a military base in the province and deployed several military and economic advisors. Sheng invited a group of Chinese Communists to Xinjiang (including Mao Zedong's brother, Mao Zemin),[92]: 111 but executed them all in 1943 in fear of a conspiracy. In 1944, President and Premier of China Chiang Kai-shek, informed by the Soviet Union of Shicai's intention to join it, transferred him to Chongqing as the Minister of Agriculture and Forestry the following year.[93] During the Ili Rebellion, the Soviet Union backed Uyghur separatists to form the Second East Turkestan Republic (ETR) in the Ili region while most of Xinjiang remained under Kuomintang control.[89]

People's Republic of China

The People's Liberation Army entered Xinjiang in 1949, when Kuomintang commander Tao Zhiyue and government chairman Burhan Shahidi surrendered the province to them.[90] Five ETR leaders who were to negotiate with the Chinese about ETR sovereignty died in an airplane crash that year in the outskirts of Kabansk in the Russian SFSR.[94] The PRC continued the system of settler colonialism and forced assimilation which had defined previous Chinese expansionism in Xinjiang.[95]

The PRC autonomous region was established on 1 October 1955, replacing the province;[90] that year (the first modern census in China was taken in 1953), Uyghurs were 73 percent of Xinjiang's total population of 5.11 million.[37] Although Xinjiang was designated a "Uygur Autonomous Region" since 1954, more than 50 percent of its area is designated autonomous areas for 13 native non-Uyghur groups.[96] Modern Uyghurs developed ethnogenesis in 1955, when the PRC recognized formerly separately self-identified oasis peoples.[97]

Southern Xinjiang is home to most of the Uyghur population, about nine million people, out of a total population of twenty million; fifty-five percent of Xinjiang's Han population, mainly urban, live in the north.[98][99] This created an economic imbalance, since the northern Junghar basin (Dzungaria) is more developed than the south.[100]

Land reform and collectivization occurred in Uyghur agricultural areas at the same general pace as in most of China.[101]: 134 Hunger in Xinjiang was not as great as elsewhere in China during the Great Leap Forward and a million Han Chinese fleeing famine resettled in Xinjiang.[101]: 134

In 1980, China allowed the United States to establish electronic listening stations in Xinjiang so the United States could monitor Soviet rocket launches in central Asia in exchange for the United States authorizing the sale of dual-use civilian and military technology and nonlethal military equipment to China.[102]

Since Chinese economic reform since the late 1970s has exacerbated uneven regional development, more Uyghurs have migrated to Xinjiang's cities and some Han have migrated to Xinjiang for economic advancement. Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping made a nine-day visit to Xinjiang in 1981 and described the region as "unsteady".[103] The Deng era reforms encouraged China's ethnic minorities, including Uyghurs, to establish small private companies for commodity transit, retail, and restaurants.[104] By the early 1990s, a total of 19 billion yuan had been spent building in Xinjiang on large and medium sized industrial projects, with an emphasis on developing modern transportation, communications infrastructure, and support for the oil and gas industries.[57]: 149

A brisk cross-border shuttle trade by Uyghurs further developed following the Soviet Union's perestroika.[104]

Increased ethnic contact and labor competition coincided with Uyghur terrorism since the 1990s, such as the 1997 Ürümqi bus bombings.[105]

In 2000, Uyghurs were 45 percent of Xinjiang's population and 13 percent of Ürümqi's population. With nine percent of Xinjiang's population, Ürümqi accounts for 25 percent of the region's GDP; many rural Uyghurs have migrated to the city for work in its light, heavy and petrochemical industries.[106] Han in Xinjiang are older, better-educated and work in higher-paying professions than their Uyghur counterparts. Han are more likely to cite business reasons for moving to Ürümqi, while some Uyghurs cite legal trouble at home and family reasons for moving to the city.[107] Han and Uyghurs are equally represented in Ürümqi's floating population, which works primarily in commerce. Auto-segregation in the city is widespread in residential concentration, employment relationships and endogamy.[108] In 2010, Uyghurs were a majority in the Tarim Basin and a plurality in Xinjiang as a whole.[109]

Xinjiang has 81 public libraries and 23 museums, compared to none in 1949. It has 98 newspapers in 44 languages, compared with four in 1952. According to official statistics, the ratio of doctors, medical workers, clinics and hospital beds to the general population surpasses the national average; the immunization rate has reached 85 percent.[5]

The ongoing Xinjiang conflict[110][111] includes the 2007 Xinjiang raid,[112] a thwarted 2008 suicide-bombing attempt on a China Southern Airlines flight,[113] the 2008 Kashgar attack which killed 16 police officers four days before the Beijing Olympics,[114][115] the August 2009 syringe attacks,[116] the 2011 Hotan attack,[117] the 2014 Kunming attack,[118] the April 2014 Ürümqi attack,[119] and the May 2014 Ürümqi attack.[120] Several of the attacks were orchestrated by the Turkistan Islamic Party (formerly the East Turkestan Islamic Movement), identified as a terrorist group by several entities (including Russia,[121] Turkey,[122][123] the United Kingdom,[124] the United States until October 2020,[125][126] and the United Nations).[127]

In 2014, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership in Xinjiang commenced a People's War against the "Three Evil Forces" of separatism, terrorism, and extremism. They deployed two hundred thousand party cadres to Xinjiang and the launched the Civil Servant-Family Pair Up program.[128][129] Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping was dissatisfied with the initial results of the People's War and replaced Zhang Chunxian with Chen Quanguo as Party Committee Secretary in 2016. Following his appointment Chen oversaw the recruitment of tens of thousands of additional police officers and the division of society into three categories: trusted, average, untrustworthy. He instructed his subordinated to "Take this crackdown as the top project," and "to preëmpt the enemy, to strike at the outset." Following a meeting with Xi in Beijing Chen Quanguo held a rally in Ürümqi with ten thousand troops, helicopters, and armored vehicles. As they paraded he announced a "smashing, obliterating offensive," and declared that they would "bury the corpses of terrorists and terror gangs in the vast sea of the People's War."[128]

Chinese authorities have operated internment camps to indoctrinate Uyghurs and other Muslims as part of the People's War since at least 2017.[130][27] The camps have been criticized by a number of governments and human-rights organizations for patterns of abuse and mistreatment, with various characterizations up to and including that of a genocide being perpetrated by the Chinese government.[131] In 2020, CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping said: "Practice has proven that the party's strategy for governing Xinjiang in the new era is completely correct."[132]

In 2021, authorities sentenced Sattar Sawut and Shirzat Bawudun—former heads of Xinjiang's education and justice departments respectively—both to death with a two-year reprieve on separatism and bribery charges.[133] Such a sentence is usually commuted to life imprisonment.[134] Officials said Sawut was found guilty of incorporating ethnic separatism, violence, and religious extremism content into Uyghur-language textbooks, which had influenced several people to participate in attacks in Urumqi. They said Bawudun was found guilty of colluding with ETIM and carrying out "illegal religious activities at his daughter's wedding".[133][135] Three other educators were sentenced to life in prison.[136] Chen was replaced as Community Party Secretary for Xinjiang by Ma Xingrui in December 2021.[137]

Xi Jinping made a four-day visit to Xinjiang in July 2022 where Kompas TV had documented groups of Uyghurs welcoming his arrival.[138] Xi called on local officials to do more in preserving ethnic minority culture[139] and following an inspection of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, he praised the organisation's "great progress" in reform and development.[140] During another visit to Xinjiang in August 2023, Xi said in a speech that the region should open up more for tourism to attract domestic and foreign visitors.[141][142]

Administrative divisions

Xinjiang is divided into thirteen prefecture-level divisions: four prefecture-level cities, six prefectures and five autonomous prefectures (including the sub-provincial autonomous prefecture of Ili, which in turn has two of the seven prefectures within its jurisdiction) for Mongol, Kazakh, Kyrgyz and Hui minorities.[143]

These are then divided into 13 districts, 29 county-level cities, 60 counties and 6 autonomous counties. Twelve of the county-level cities do not belong to any prefecture and are de facto administered by the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC). Sub-level divisions of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region is shown in the adjacent picture and described in the table below:

| Administrative divisions of Xinjiang | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

█ XPCC / Bingtuan administered county-level divisions █ Subordinate to Ili Kazakh A.P. ☐ Disputed areas claimed by India and administered by China (see Sino-Indian border dispute) | |||||||||||||

| Division code[144] | Division | Area in km2[145] | Population 2020[146][147] | Seat | Divisions[148] | ||||||||

| Districts | Counties | Aut. counties | CL cities | ||||||||||

| 650000 | Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region | 1,664,900.00 | 25,852,345 | Ürümqi city | 13 | 60 | 6 | 29 | |||||

| 650100 | Ürümqi city | 13,787.90 | 4,054,369 | Tianshan District | 7 | 1 | |||||||

| 650200 | Karamay city | 8,654.08 | 490,348 | Karamay District | 4 | ||||||||

| 650400 | Turpan city | 67,562.91 | 693,988 | Gaochang District | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| 650500 | Hami city | 142,094.88 | 673,383 | Yizhou District | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 652300 | Changji Hui Autonomous Prefecture | 73,139.75 | 1,613,585 | Changji city | 4 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| 652700 | Bortala Mongol Autonomous Prefecture | 24,934.33 | 488,198 | Bole city | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| 652800 | Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture | 470,954.25 | 1,613,979 | Korla city | 7 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 652900 | Aksu Prefecture | 127,144.91 | 2,714,422 | Aksu city | 7 | 2 | |||||||

| 653000 | Kizilsu Kyrgyz Autonomous Prefecture | 72,468.08 | 622,222 | Artux city | 3 | 1 | |||||||

| 653100 | Kashgar Prefecture | 137,578.51 | 4,496,377 | Kashi city | 10 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 653200 | Hotan Prefecture | 249,146.59 | 2,504,718 | Hotan city | 7 | 1 | |||||||

| 654000 | Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture | 56,381.53 * | 2,848,393 * | Yining city | 7 * | 1 * | 3 * | ||||||

| 654200 | Tacheng Prefecture* | 94,698.18 | 1,138,638 | Tacheng city | 4 | 1 | 3 | ||||||

| 654300 | Altay Prefecture* | 117,699.01 | 668,587 | Altay city | 6 | 1 | |||||||

| 659000 | Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps | 13,055.57 | 1,573,931 | Ürümqi city | 12 | ||||||||

| 659001 | Shihezi city (8th Division) | 456.84 | 498,587 | Hongshan Subdistrict | 1 | ||||||||

| 659002 | Aral city (1st Division) | 5,266.00 | 328,241 | Jinyinchuan Road Subdistrict | 1 | ||||||||

| 659003 | Tumxuk city (3rd Division) | 2,003.00 | 263,245 | Jinxiu Subdistrict | 1 | ||||||||

| 659004 | Wujiaqu city (6th Division) | 742.00 | 141,065 | Renmin Road Subdistrict | 1 | ||||||||

| 659005 | Beitun city (10th Division) | 910.50 | 20,414 | Beitun Town (Altay) | 1 | ||||||||

| 659006 | Tiemenguan city (2nd Division) | 590.27 | 104,746 | Xingjiang Road, 29th Regiment | 1 | ||||||||

| 659007 | Shuanghe city (5th Division) | 742.18 | 54,731 | Hongxing No.2 Road, 89th Regiment | 1 | ||||||||

| 659008 | Kokdala city (4th Division) | 979.71 | 69,524 | Xinfu Road, 66th Regiment | 1 | ||||||||

| 659009 | Kunyu city (14th Division) | 687.13 | 63,487 | Yuyuan Town | 1 | ||||||||

| 659010 | Huyanghe city (7th Division) | 677.94 | 29,891 | Gongqing town | 1 | ||||||||

| 659011 | Xinxing city (13th Division) | Huangtian Town | 1 | ||||||||||

| 659012 | Baiyang city (9th Division) | 163rd Regiment of the 9th Division | 1 | ||||||||||

| * – Altay Prefecture or Tacheng Prefecture are subordinate to Ili Prefecture. / The population or area figures of Ili do not include Altay Prefecture or Tacheng Prefecture which are subordinate to Ili Prefecture. | |||||||||||||

| Administrative divisions in Uyghur, Chinese and varieties of romanizations |

|---|

Urban areas

| Population by urban areas of prefecture & county cities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Cities | 2020 Urban area[149] | 2010 Urban area[150] | 2020 City proper |

| 1 | Ürümqi | 3,864,136 | 2,853,398 | 4,054,369 |

| 2 | Yining | 654,726 | 368,813 | part of Ili Prefecture |

| 3 | Korla | 490,961 | 425,182 | part of Bayingolin Prefecture |

| 4 | Karamay | 481,249 | 353,299 | 490,348 |

| 5 | Aksu | 470,601 | 284,872 | part of Aksu Prefecture |

| 6 | Shihezi | 461,663 | 313,768 | 498,587 |

| 7 | Changji | 451,234 | 303,938 | part of Changji Prefecture |

| 8 | Hami | 426,072 | 310,500[i] | 673,383 |

| 9 | Kashi | 392,730 | 310,448 | part of Kashi Prefecture |

| 10 | Hotan | 293,056 | 119,804 | part of Hotan Prefecture |

| 11 | Kuqa | 262,771 | [ii] | part of Aksu Prefecture |

| 12 | Aral | 239,647 | 65,175 | 328,241 |

| 13 | Kuytun | 224,471 | 20,805 | part of Ili Prefecture |

| 14 | Bole | 177,536 | 120,138 | part of Bortala Prefecture |

| 15 | Usu | 156,437 | 131,661 | part of Tacheng Prefecture |

| (16) | Shawan | 150,317[iii] | part of Tacheng Prefecture | |

| 17 | Altay | 147,301 | 112,711 | part of Altay Prefecture |

| 18 | Turpan | 143,456 | 89,719[iv] | 693,988 |

| 19 | Tumxuk | 128,056 | 34,808 | 263,245 |

| 20 | Fukang | 125,080 | 67,598 | part of Changji Prefecture |

| 21 | Tacheng | 122,447 | 75,122 | part of Tacheng Prefecture |

| 22 | Wujiaqu | 118,893 | 75,088 | 141,065 |

| 23 | Artux | 105,855 | 58,427 | part of Kizilsu Prefecture |

| (24) | Baiyang | 85,655[v] | 85,655 | |

| 25 | Tiemenguan | 77,969 | [vi] | 104,746 |

| 26 | Korgas | 44,701 | [vii] | part of Ili Prefecture |

| (27) | Xinxing | 44,700[viii] | 44,700 | |

| 28 | Shuanghe | 43,263 | [ix] | 54,731 |

| 29 | Kokdala | 39,257 | [x] | 69,524 |

| 30 | Kunyu | 32,591 | [xi] | 63,487 |

| 32 | Huyanghe | 24,769 | [xii] | 29,891 |

| 32 | Beitun | 13,874 | [xiii] | 20,414 |

| 33 | Alashankou | 11,097 | [xiv] | part of Bortala Prefecture |

- ^ Hami Prefecture is currently known as Hami PLC after 2010 census; Hami CLC is currently known as Yizhou after 2010 census.

- ^ Kuqa County is currently known as Kuqa CLC after 2010 census.

- ^ Shawan County is currently known as Shawan CLC after 2020 census.

- ^ Turpan Prefecture is currently known as Turpan PLC after 2010 census; Turpan CLC is currently known as Gaochang after 2010 census.

- ^ Baiyang CLC was established from parts of Tachang CLC after 2020 census.

- ^ Tiemenguan CLC was established from parts of Korla CLC after 2010 census.

- ^ Korgas CLC was established from parts of Huocheng County after 2010 census.

- ^ Xinxing CLC was established from parts of Yizhou District after 2020 census.

- ^ Shuanghe CLC was established from parts of Bole CLC after 2010 census.

- ^ Kokdala CLC was established from parts of Huocheng County after 2010 census.

- ^ Kunyu CLC was established from parts of Hotan County, Pishan County, Moyu County, & Qira County after 2010 census.

- ^ Huyanghe CLC was established from parts of Usu CLC after 2010 census.

- ^ Beitun CLC was established from parts of Altay CLC after 2010 census.

- ^ Alashankou CLC was established from parts of Bole CLC & Jinghe County after 2010 census.

Geography and geology

Xinjiang is the largest political subdivision of China, accounting for more than one sixth of China's total territory and a quarter of its boundary length. Xinjiang is mostly covered with uninhabitable deserts and dry grasslands, with dotted oases conducive to habitation accounting for 9.7 percent of Xinjiang's total area by 2015[17] at the foot of Tian Shan, Kunlun Mountains and Altai Mountains, respectively.

Mountain systems and basins

Xinjiang is split by the Tian Shan mountain range (تەڭرى تاغ, Tengri Tagh, Тәңри Тағ), which divides it into two large basins: the Dzungarian Basin in the north and the Tarim Basin in the south. A small V-shaped wedge between these two major basins, limited by the Tian Shan's main range in the south and the Borohoro Mountains in the north, is the basin of the Ili River, which flows into Kazakhstan's Lake Balkhash; an even smaller wedge farther north is the Emin Valley.

Other major mountain ranges of Xinjiang include the Pamir Mountains and Karakoram in the southwest, the Kunlun Mountains in the south (along the border with Tibet) and the Altai Mountains in the northeast (shared with Mongolia). The region's highest point is the mountain K2, an eight-thousander located 8,611 metres (28,251 ft) above sea level in the Karakoram Mountains on the border with Pakistan.

Much of the Tarim Basin is dominated by the Taklamakan Desert. North of it is the Turpan Depression, which contains the lowest point in Xinjiang and in the entire PRC, at 155 metres (509 ft) below sea level.

The Dzungarian Basin is slightly cooler, and receives somewhat more precipitation, than the Tarim Basin. Nonetheless, it, too, has a large Gurbantünggüt Desert (also known as Dzoosotoyn Elisen) in its center.

The Tian Shan mountain range marks the Xinjiang-Kyrgyzstan border at the Torugart Pass (3752 m). The Karakorum highway (KKH) links Islamabad, Pakistan with Kashgar over the Khunjerab Pass.

Mountain passes

From south to north, the mountain passes bordering Xinjiang are:

| Mountain passes bordering Xinjiang |

|---|

Geology

Xinjiang is geologically young. Collision of the Indian and the Eurasian plates formed the Tian Shan, Kunlun Shan, and Pamir mountain ranges; said tectonics render it a very active earthquake zone. Older geological formations are located in the far north, where Kazakhstania is geologically part of Kazakhstan, and in the east, where is part of the North China Craton.[citation needed]

Center of the continent

Xinjiang has within its borders, in the Gurbantünggüt Desert, the location in Eurasia that is furthest from the sea in any direction (a continental pole of inaccessibility): 46°16.8′N 86°40.2′E / 46.2800°N 86.6700°E. It is at least 2,647 km (1,645 mi) (straight-line distance) from any coastline.

In 1992, local geographers determined another point within Xinjiang – 43°40′52″N 87°19′52″E / 43.68111°N 87.33111°E in the southwestern suburbs of Ürümqi, Ürümqi County – to be the "center point of Asia". A monument to this effect was then erected there and the site has become a local tourist attraction.[151]

Rivers and lakes

Having hot summer and low precipitation, most of Xinjiang is endorheic. Its rivers either disappear in the desert, or terminate in salt lakes (within Xinjiang itself, or in neighboring Kazakhstan), instead of running towards an ocean. The northernmost part of the region, with the Irtysh River rising in the Altai Mountains, that flows (via Kazakhstan and Russia) toward the Arctic Ocean, is the only exception. But even so, a significant part of the Irtysh's waters were artificially diverted via the Irtysh–Karamay–Ürümqi Canal to the drier regions of southern Dzungarian Basin.

Elsewhere, most of Xinjiang's rivers are comparatively short streams fed by the snows of the several ranges of the Tian Shan. Once they enter the populated areas in the mountains' foothills, their waters are extensively used for irrigation, so that the river often disappears in the desert instead of reaching the lake to whose basin it nominally belongs. This is the case even with the main river of the Tarim Basin, the Tarim, which has been dammed at a number of locations along its course, and whose waters have been completely diverted before they can reach the Lop Lake. In the Dzungarian basin, a similar situation occurs with most rivers that historically flowed into Lake Manas. Some of the salt lakes, having lost much of their fresh water inflow, are now extensively use for the production of mineral salts (used e.g., in the manufacturing of potassium fertilizers); this includes the Lop Lake and the Manas Lake.

Deserts

Deserts include:

- Gurbantünggüt Desert, also known as Dzoosotoyn Elisen

- Taklamakan Desert

- Kumtag Desert, east of Taklamakan

Major cities

Due to water scarcity, most of Xinjiang's population lives within fairly narrow belts that are stretched along the foothills of the region's mountain ranges in areas conducive to irrigated agriculture. It is in these belts where most of the region's cities are found.

Climate

A semiarid or desert climate (Köppen BSk or BWk, respectively) prevails in Xinjiang. The entire region has great seasonal differences in temperature with cold winters. The Turpan Depression often records some of the hottest temperatures nationwide in summer,[152] with air temperatures easily exceeding 40 °C (104 °F). Winter temperatures regularly fall below −20 °C (−4 °F) in the far north and highest mountain elevations. On 18 February 2024, a record low temperature for the region of −52.3 °C (−62.1 °F) was recorded.[153]

Continuous permafrost is typically found in the Tian Shan starting at the elevation of about 3,500–3,700 m above sea level. Discontinuous alpine permafrost usually occurs down to 2,700–3,300 m, but in certain locations, due to the peculiarity of the aspect and the microclimate, it can be found at elevations as low as 2,000 m.[154]

Time

Despite the province's easternmost point being more than 1,600 kilometres (990 mi) west of Beijing, Xinjiang, like the rest of China, is officially in the UTC+8 time zone, known by residents as Beijing Time. Despite this, some residents, local organizations and governments observe UTC+6 as the standard time and refer to this zone as Xinjiang Time.[155] Han people tend to use Beijing Time, while Uyghurs tend to use Xinjiang Time as a form of resistance to Beijing.[156] Time zones notwithstanding, most schools and businesses open and close two hours later than in the other regions of China.[157]

Politics

Structure

| Title | CCP Committee Secretary | People's Congress Chairwoman | Chairman | Xinjiang CPPCC Chairman |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Ma Xingrui | Zumret Obul | Erkin Tuniyaz | Nurlan Abilmazhinuly |

| Born | October 1959 (age 64) | August 1959 (age 64–65) | November 1961 (age 62) | December 1962 (age 61) |

| Assumed office | December 2021 | January 2023 | September 2021 | January 2023 |

Like all governing institutions in mainland China, Xinjiang has a parallel party-government system. The Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Regional Committee of the CCP acts as the top policy-formulation body, and exercises control over the Regional People's Government. The CCP Committee Secretary, generally a member of the Han ethnic group, outranks the Government Chairman, always an Uyghur. The Government Chairman typically serves as a Deputy Committee Secretary.[158]

- Chairmen of the Xinjiang Government

- 1949–1955: Burhan Shahidi (包尔汉·沙希迪; بۇرھان شەھىدى)

- 1955–1967: Saifuddin Azizi (赛福鼎·艾则孜; سەيپىدىن ئەزىزى)

- 1968–1972: Long Shujin (龙书金)

- 1972–1978: Saifuddin Azizi (赛福鼎·艾则孜; سەيپىدىن ئەزىزى)

- 1978–1979: Wang Feng (汪锋)

- 1979–1985: Ismail Amat (司马义·艾买提; ئىسمائىل ئەھمەد)

- 1985–1993: Tömür Dawamat (铁木尔·达瓦买提; تۆمۈر داۋامەت)

- 1993–2003: Abdul'ahat Abdulrixit (阿不来提·阿不都热西提; ئابلەت ئابدۇرىشىت)

- 2003–2007: Ismail Tiliwaldi (司马义·铁力瓦尔地; ئىسمائىل تىلىۋالدى)

- 2007–2015: Nur Bekri (努尔·白克力; نۇر بەكرى)

- 2015–2021: Shohrat Zakir (雪克来提·扎克尔; شۆھرەت زاكىر)

- Since 2021: Erkin Tuniyaz (艾尔肯·吐尼亚孜; ئەركىن تۇنىياز)

Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps

Xinjiang maintains the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC), an economic and paramilitary organization administered by the Chinese government and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It plays a critical role in the region's economy, owning or being otherwise connected to many companies in the region as well as dominating Xinjiang's agricultural output.[159] It additionally directly administers cities throughout Xinjiang, mainly concentrated in the northern parts. It is headed by the CCP secretary of Xinjiang, while the CCP secretary of the XPCC is considered the second most powerful person in the region.[159]

Human rights abuses

Human Rights Watch has documented the denial of due legal process and fair trials and failure to hold genuinely open trials as mandated by law e.g. to suspects arrested following ethnic violence in the city of Ürümqi's 2009 riots.[160]

The Chinese government, under Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping's administration,[27] launched the Strike Hard Campaign Against Violent Terrorism in 2014, which involved mass detention and surveillance of ethnic Uyghurs there;[161] the program was massively expanded by Chen Quanguo when he was appointed as CCP Xinjiang secretary in 2016.[162] The campaign included the detainment of 1.8 million people in internment camps, mostly Uyghurs, but also including other ethnic and religious minorities, by 2020.[162] An October 2018 exposé by BBC News claimed, based on analysis of satellite imagery collected over time, that hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs were likely interned in the camps, and they are rapidly being expanded.[163] In 2019, The Art Newspaper reported that "hundreds" of writers, artists, and academics had been imprisoned in (what the magazine qualified as) an attempt to "punish any form of religious or cultural expression" among Uyghurs.[164] China has also been accused of targeting Muslim religious figures, Mosques and tombs in the region. [165] This program has been called a genocide by some observers, while a report by the UN Human Rights Office said they may amount to crimes against humanity.[166][167]

On 28 June 2020, the Associated Press published a report which stated the Chinese government was taking draconian measures to slash birth rates among Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in Xinjiang, even as it encouraged some of the country's Han majority to have more children.[168] While individual women have spoken out before about forced birth control, the practice was far more widespread and systematic than previously known, according to an AP investigation based on government statistics, state documents and interviews with 30 ex-detainees, family members and a former detention camp instructor. The campaign over the past four years in Xinjiang has been labeled by some experts as a form of "demographic genocide."[168] The allegation of Uyghur birth rates being lower than those of Han Chinese have been disputed by pundits from Pakistan Observer,[169] Antara,[170] and Detik.com.[171]

East Turkestan independence movement

Some factions in Xinjiang, most prominently Uyghur nationalists, advocate establishing an independent country named East Turkestan (also sometimes called "Uyghuristan"),[172] which has led to tension, conflict,[173] and ethnic strife in the region.[174][175][176] Autonomous regions in China do not have a legal right to secede, and each one is considered to be an "inseparable part of the People's Republic of China" by the government.[177][178] The separatist movement claims that the region is not part of China, but was invaded by the CCP in 1949 and has been under occupation since then. The Chinese government asserts that the region has been part of China since ancient times,[179] and has engaged in "strike hard" campaigns targeted at separatists.[180] The movement has been supported by both militant Islamic extremist groups such as the Turkistan Islamic Party,[181] as well as advocacy groups with no connection to extremist groups.

According to the Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, the two main sources for separatism in the Xinjiang Province are religion and ethnicity. Religiously, the most Uyghur peoples of Xinjiang follow Islam; in the rest of China, many are Buddhist, Taoist and Confucian, although many follow Islam as well, such as the Hui ethnic subgroup of the Han ethnicity, comprising some 10 million people. Thus, the major difference and source of friction with eastern China is ethnicity and religious doctrinal differences that differentiate them politically from other Muslim minorities elsewhere in the country.[180]

Economy

| Development of GDP | |

|---|---|

| Year | GDP in billions of Yuan |

| 1995 | 82 |

| 2000 | 136 |

| 2005 | 260 |

| 2010 | 544 |

| 2015 | 932 |

| 2020 | 1,380 |

| Source:[182] | |

The GDP of Xinjiang was about CN¥1.774 trillion (US$263 billion) as of 2022[update].[183] Economic growth has been fueled by to discovery of the abundant reserves of coal, oil, gas as well as the China Western Development policy introduced by the State Council to boost economic development in Western China.[184] Its per capita GDP for 2022 was CN¥68,552 (US$10,191). Southern Xinjiang, with 95 percent non-Han population, has an average per capita income half that of Xinjiang as a whole.[183] XPCC plays an outsized role in Xinjiang's economy, with the organization producing CN¥350 billion (US$52 billion), or around 19.7% of Xinjiang's economy, while the per capita GDP was CN¥98,748 (US$14,680).[185]

Economic development of Xinjiang is a priority for China.[186] In 1997, the 26,000 km Uzbek-Kyrgyz-Chinese highway became operational.[57]: 150 In 1998, the Turpan–Ürümqi–Dahuangshan Expressway was completed, linking several key areas in Xinjiang.[57]: 150 In 2000, the government articulated its strategy for developing the western regions of the country, and that plan made Xinjiang a major focus.[186] Accelerating development in Xinjiang is intended by China to achieve a number of objectives, including narrowing the economic gap between Xinjiang and the more developed eastern provinces, as well as alleviating political discontent and security problems by alleviating poverty and raising the standard of living in order to increase stability.[186] From 2014 to 2020, fiscal transfers from China's central government to Xinjiang grew by an average of 10.4% per year.[187]: 110

In July 2010, state media outlet China Daily reported that:

Local governments in China's 19 provinces and municipalities, including Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, Zhejiang and Liaoning, are engaged in the commitment of "pairing assistance" support projects in Xinjiang to promote the development of agriculture, industry, technology, education and health services in the region.[188]

Xinjiang has traditionally been an agricultural region, but is also rich in minerals and oil. Xinjiang is a major producer of solar panel components due to its large production of the base material polysilicon. In 2020 45 percent of global production of solar-grade polysilicon occurred in Xinjiang. Concerns have been raised both within the solar industry and outside it that forced labor may occur in the Xinjiang part of the supply chain.[189] The global solar panel industry are under pressure to move sourcing away from the region due to human rights and liability concerns.[190] China's solar association claimed the allegations were baseless and unfairly stigmatized firms with operations there.[191] A 2021 investigation in the United Kingdom found that 40 percent of solar farms in the UK had been built using panels from Chinese companies linked to forced labor in Xinjiang.[192]

Agriculture and fishing

Main area is of irrigated agriculture. By 2015, the agricultural land area of the region is 631 thousand km2 or 63.1 million ha, of which 6.1 million ha is arable land.[193] In 2016, the total cultivated land rose to 6.2 million ha, with the crop production reaching 15.1 million tons.[194] Agriculture in Xinjiang is dominated by the XPCC, which employs a majority of the organization's workforce.[195] Wheat was the main staple crop of the region, maize grown as well, millet found in the south, while only a few areas (in particular, Aksu) grew rice.[196]

Cotton became an important crop in several oases, notably Hotan, Yarkand and Turpan by the late 19th century.[196] Sericulture is also practiced.[197] The Xinjiang cotton industry is the world's largest cotton exporter, producing 84 percent of Chinese cotton while the country provides 26 percent of global cotton export.[198] Xinjiang also produces peppers and pepper pigments used in cosmetics such lipstick for export.[199]

Xinjiang is famous for its tomatoes, grapes and melons, particularly Hami melons and Turpan raisins.[200] The region is a leading source for tomato paste, which it supplies for international brands.[198]

The main livestock of the region have traditionally been sheep. Much of the region's pasture land is in its northern part, where more precipitation is available,[201] but there are mountain pastures throughout the region.[202]: 29

Due to the lack of access to the ocean and limited amount of inland water, Xinjiang's fish resources are somewhat limited. Nonetheless, there is a significant amount of fishing in Lake Ulungur and Lake Bosten and in the Irtysh River. A large number of fish ponds have been constructed since the 1970s, their total surface exceeding 10,000 hectares by the 1990s. In 2000, the total of 58,835 tons of fish was produced in Xinjiang, 85 percent of which came from aquaculture.[203] The Sayram Lake is both the largest alpine lake and highest altitude lake in Xinjiang, and is the location of a major cold-water fishery.[citation needed] Originally Sayram had no fish but in 1998, northern whitefish (Coregonus peled) from Russia were introduced and investment in breeding infrastructure and technology has consequently made Sayram into the country's largest exporter of northern whitefish with an annual output of over 400 metric tons.[204][better source needed]

Mining and minerals

Xinjiang was known for producing salt, soda, borax, gold, and jade in the 19th century.[205]

The Lop Lake was once a large brackish lake during the end of the Pleistocene but has slowly dried up in the Holocene where average annual precipitation in the area has declined to just 31.2 millimeters (1.2 inches), and experiences annual evaporation rate of 2,901 millimeters (114 inches). The area is rich in brine Potash, a key ingredient in fertilizer and is the second-largest source of potash in the country. Discovery of potash in the mid-1990s, has transformed Lop Nur into a major Potash mining industry.[206]

The oil and gas extraction industry in Aksu and Karamay is growing, with the West–East Gas Pipeline linking to Shanghai. The oil and petrochemical sector get up to 60 percent of Xinjiang's economy.[207] The region contains over a fifth of China's hydrocarbon resources and has the highest concentration of fossil fuel reserves of any region in the country.[208] The region is rich in coal and contains 40 percent of the country's coal reserves or around 2.2 trillion tonnes, which is enough to supply China's thermal coal demand for more than 100 years even if only 15 percent of the estimated coal reserve prove recoverable.[209][210]

Tarim basin is the largest oil and gas bearing area in the country with about 16 billion tonnes of oil and gas reserves discovered.[211] The area is still actively explored and in 2021, China National Petroleum Corporation found a new oil field reserve of 1 billion tons (about 907 million tonnes). That find is regarded as being the largest one in recent decades. As of 2021, the basin produces hydrocarbons at an annual rate of 2 million tons, up from 1.52 million tons from 2020.[212]

Foreign trade

Trade with Central Asian countries is crucial to Xinjiang's economy.[213] Most of the overall import/export volume in Xinjiang was directed to and from Kazakhstan through Ala Pass. China's first border free trade zone (Horgos Free Trade Zone) was located at the Xinjiang-Kazakhstan border city of Horgos.[214] Horgos is the largest "land port" in China's western region and it has easy access to the Central Asian market. Xinjiang also opened its second border trade market to Kazakhstan in March 2006, the Jeminay Border Trade Zone.[215]

Vietnam is a major importer of Xinjiang cotton.[216]: 45

Economic and Technological Development Zones

- Bole Border Economic Cooperation Area[217]

- Shihezi Border Economic Cooperation Area[218]

- Tacheng Border Economic Cooperation Area[219]

- Ürümqi Economic & Technological Development Zone is northwest of Ürümqi. It was approved in 1994 by the State Council as a national level economic and technological development zones. It is 1.5 km (0.93 mi) from the Ürümqi International Airport, 2 km (1.2 mi) from the North Railway Station and 10 km (6.2 mi) from the city center. Wu Chang Expressway and 312 National Road passes through the zone. The development has unique resources and geographical advantages. Xinjiang's vast land, rich in resources, borders eight countries. As the leading economic zone, it brings together the resources of Xinjiang's industrial development, capital, technology, information, personnel and other factors of production.[220]

- Ürümqi Export Processing Zone is in Urumuqi Economic and Technology Development Zone. It was established in 2007 as a state-level export processing zone.[221]

- Ürümqi New & Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone was established in 1992 and it is the only high-tech development zone in Xinjiang, China. There are more than 3470 enterprises in the zone, of which 23 are Fortune 500 companies. It has a planned area of 9.8 km2 (3.8 sq mi) and it is divided into four zones. There are plans to expand the zone.[222]

- Yining Border Economic Cooperation Area[223]

Culture

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2020) |

Media

The Xinjiang Networking Transmission Limited operates the Urumqi People's Broadcasting Station and the Xinjiang People Broadcasting Station, broadcasting in Mandarin, Uyghur, Kazakh and Mongolian.

In 1995[update], there were 50 minority-language newspapers published in Xinjiang, including the Qapqal News, the world's only Xibe language newspaper.[224] The Xinjiang Economic Daily is considered one of China's most dynamic newspapers.[225]

For a time after the July 2009 riots, authorities placed restrictions on the internet and text messaging, gradually permitting access to state-controlled websites like Xinhua News Agency,[226] until restoring Internet to the same level as the rest of China on 14 May 2010.[227][228][229]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1912[230] | 2,098,000 | — |

| 1928[231] | 2,552,000 | +21.6% |

| 1936–37[232] | 4,360,000 | +70.8% |

| 1947[233] | 4,047,000 | −7.2% |

| 1954[234] | 4,873,608 | +20.4% |

| 1964[235] | 7,270,067 | +49.2% |

| 1982[236] | 13,081,681 | +79.9% |

| 1990[237] | 15,155,778 | +15.9% |

| 2000[238] | 18,459,511 | +21.8% |

| 2010[239] | 21,813,334 | +18.2% |

| 2020[240] | 25,852,345 | +18.5% |

The earliest Tarim mummies, dated to 1800 BC, are of a Caucasoid physical type.[241] East Asian migrants arrived in the eastern portions of the Tarim Basin about 3000 years ago and the Uyghur peoples appeared after the collapse of the Orkon Uyghur Kingdom, based in modern-day Mongolia, around 842 AD.[242][243]

The Islamization of Xinjiang started around 1000 AD. Xinjiang Muslim Turkic peoples contain Uyghurs, Kazaks, Kyrgyz, Tatars, Uzbeks; Muslim Iranian peoples comprise Tajiks, Sarikolis/Wakhis (often conflated as Tajiks); Muslim Sino-Tibetan peoples are such as the Hui. Other ethnic groups in the region are Hans, Mongols (Oirats, Daurs, Dongxiangs), Russians, Xibes, Manchus. Around 70,000 Russian immigrants were living in Xinjiang in 1945.[244]

The Han Chinese of Xinjiang arrived at different times from different directions and social backgrounds. There are now descendants of criminals and officials who had been exiled from China during the second half of the 18th and the first half of the 19th centuries; descendants of families of military and civil officers from Hunan, Yunnan, Gansu and Manchuria; descendants of merchants from Shanxi, Tianjin, Hubei and Hunan; and descendants of peasants who started immigrating into the region in 1776.[245]

Some Uyghur scholars claim descent from both the Turkic Uyghurs and the pre-Turkic Tocharians (or Tokharians, whose language was Indo-European); also, Uyghurs often have relatively-fair skin, hair and eyes and other Caucasoid physical traits.

In 2002, there were 9,632,600 males (growth rate of 1.0 percent) and 9,419,300 females (growth rate of 2.2 percent). The population overall growth rate was 1.09 percent, with 1.63 percent of birth rate and 0.54 percent mortality rate.

The Qing began a process of settling Han, Hui, and Uyghur settlers into Northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria) in the 18th century. At the start of the 19th century, 40 years after the Qing reconquest, there were around 155,000 Han and Hui Chinese in northern Xinjiang and somewhat more than twice that number of Uyghurs in Southern Xinjiang.[246] A census of Xinjiang under Qing rule in the early 19th century tabulated ethnic shares of the population as 30 percent Han and 60 percent Turkic and it dramatically shifted to 6 percent Han and 75 percent Uyghur in the 1953 census. However, a situation similar to the Qing era's demographics with a large number of Han had been restored by 2000, with 40.57 percent Han and 45.21 percent Uyghur.[247] Professor Stanley W. Toops noted that today's demographic situation is similar to that of the early Qing period in Xinjiang.[248] Before 1831, only a few hundred Chinese merchants lived in Southern Xinjiang oases (Tarim Basin), and only a few Uyghurs lived in Northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria).[249]

After 1831, the Qing encouraged Han Chinese migration into the Tarim Basin, in southern Xinjiang, but with very little success, and permanent troops were stationed on the land there as well.[250] Political killings and expulsions of non-Uyghur populations during the uprisings in the 1860s[250] and the 1930s saw them experience a sharp decline as a percentage of the total population[251] though they rose once again in the periods of stability from 1880, which saw Xinjiang increase its population from 1.2 million,[252][253] to 1949. From a low of 7 percent in 1953, the Han began to return to Xinjiang between then and 1964, where they comprised 33 percent of the population (54 percent Uyghur), like in Qing times. A decade later, at the beginning of the Chinese economic reform in 1978, the demographic balance was 46 percent Uyghur and 40 percent Han,[247] which did not change drastically until the 2000 Census, when the Uyghur population had reduced to 42 percent.[254] In 2010, the population of Xinjiang was 45.84 percent Uyghur and 40.48 percent Han. The 2020 Census showed the share of the Uyghur population decline slightly to 44.96 percent, and the Han population rise to 42.24 percent[255][256]

Military personnel are not counted and national minorities are undercounted in the Chinese census, as in some other censuses.[257] 3.6 million people reside in XPCC administered areas, around 14 percent of Xinjiang's population.[185] While some of the shift has been attributed to an increased Han presence,[18] Uyghurs have also emigrated to other parts of China, where their numbers have increased steadily. Uyghur independence activists express concern over the Han population changing the Uyghur character of the region though the Han and Hui Chinese mostly live in Northern Xinjiang Dzungaria and are separated from areas of historic Uyghur dominance south of the Tian Shan mountains (Southwestern Xinjiang), where Uyghurs account for about 90 percent of the population.[258]

In general, Uyghurs are the majority in Southwestern Xinjiang, including the prefectures of Kashgar, Khotan, Kizilsu and Aksu (about 80 percent of Xinjiang's Uyghurs live in those four prefectures) as well as Turpan Prefecture, in Eastern Xinjiang. The Han are the majority in Eastern and Northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria), including the cities of Ürümqi, Karamay, Shihezi and the prefectures of Changjyi, Bortala, Bayin'gholin, Ili (especially the cities of Kuitun) and Kumul. Kazakhs are mostly concentrated in Ili Prefecture in Northern Xinjiang. Kazakhs are the majority in the northernmost part of Xinjiang.

| Ethnic groups in Xinjiang | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2020 Chinese census[259] | ||

| Nationality | Population | Percentage |

| Uyghur | 11,624,257 | 44.96 percent |

| Han | 10,920,098 | 42.24 percent |

| Kazakh | 1,539,636 | 5.96 percent |

| Hui | 1,102,928 | 4.27 percent |

| Kirghiz | 199,264 | 0.77 percent |

| Mongols | 169,143 | 0.65 percent |

| Dongxiang | 72,036 | 0.28 percent |

| Tajiks | 50,238 | 0.19 percent |

| Xibe | 34,105 | 0.13 percent |

| Manchu | 20,915 | 0.080 percent |

| Tujia | 15,787 | 0.086 percent |

| Tibetan | 18,276 | 0.071 percent |

| Uzbek | 12,301 | 0.048 percent |

| Miao | 12,220 | 0.047 percent |

| Russian | 8,024 | 0.031 percent |

| Yi | 7,752 | 0.030 percent |

| Zhuang | 5,727 | 0.022 percent |

| Daur | 5,447 | 0.021 percent |

| Tatar | 5,183 | 0.024 percent |

| Tu | 3,827 | 0.015 percent |

| Salar | 3,266 | 0.013 percent |

| Other | 11,764 | 0.046 percent |

| Major ethnic groups in Xinjiang by region (2018 data)[I] P = Prefecture; AP = Autonomous prefecture; PLC = Prefecture-level city; DACLC = Directly administered county-level city.[260] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uyghurs (%) | Han (%) | Kazakhs (%) | others (%) | |

| Xinjiang | 51.14 | 34.41 | 6.90 | 7.55 |

| Ürümqi PLC | 12.85 | 71.21 | 2.77 | 13.16 |

| Karamay PLC | 15.59 | 74.67 | 4.05 | 5.69 |

| Turpan Prefecture | 76.96 | 16.84 | 0.05 | 6.15 |

| Kumul Prefecture | 20.01 | 65.49 | 10.04 | 4.46 |

| Changji AP | 4.89 | 72.28 | 10.34 | 12.49 |

| Bortala AP | 14.76 | 63.27 | 10.41 | 11.56 |

| Bayin'gholin AP | 36.38 | 53.31 | 0.11 | 10.20 |

| Aksu Prefecture | 80.08 | 18.56 | 0.01 | 1.36 |

| Kizilsu AP | 66.24 | 6.29 | 0.03 | 27.44 |

| Kashgar Prefecture | 92.56 | 6.01 | < 0.005 | 1.42 |

| Khotan Prefecture | 96.96 | 2.85 | < 0.005 | 0.19 |

| Ili AP[c] | 17.95 | 40.09 | 27.16 | 14.80 |

| – former Ili Prefecture | 26.30 | 35.21 | 21.57 | 16.91 |

| – Tacheng Prefecture | 4.25 | 54.66 | 26.66 | 14.43 |

| – Altay Prefecture | 1.42 | 39.85 | 52.76 | 5.97 |

| Shihezi DACLC | 1.09 | 94.13 | 0.63 | 4.15 |

| Aral DACLC | 3.66 | 91.96 | < 0.005 | 4.38 |

| Tumushuke DACLC | 67.49 | 31.73 | < 0.005 | 0.78 |

| Wujiaqu DACLC | 0.05 | 96.29 | 0.10 | 3.55 |

| Tiemenguan DACLC | 0.07 | 95.96 | 0.00 | 3.97 |

- ^ Does not include members of the People's Liberation Army in active service.

Vital statistics

| Year[261] | Population | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1000) | Crude death rate (per 1000) | Natural change (per 1000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 22,090,000 | 14.99 | 4.42 | 10.57 | |||

| 2012 | 22,330,000 | 15.32 | 4.48 | 10.84 | |||

| 2013 | 22,640,000 | 15.84 | 4.92 | 10.92 | |||

| 2014 | 22,980,000 | 16.44 | 4.97 | 11.47 | |||

| 2015 | 23,600,000 | 15.59 | 4.51 | 11.08 | |||

| 2016 | 23,980,000 | 15.34 | 4.26 | 11.08 | |||

| 2017 | 24,450,000 | 15.88 | 4.48 | 11.40 | |||

| 2018 | 24,870,000 | 10.69 | 4.56 | 6.13 | |||

| 2019 | 25,230,000 | 8.14 | 4.45 | 3.69 | |||

| 2020 | 25,852,000 | 7.01 | |||||

| 2021 | 25,890,000 | 6.16 | 5.60 | 0.56[262] |

Religion