Норвегия

Королевство Норвегия | |

|---|---|

| Гимн: Да, мы любим эту страну (Английский: «Да, мы любим эту страну» ) Королевский гимн : Королевская песня. (английский: «Королевская песня» ) | |

Location of the Kingdom of Norway (green) in Europe (green and dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Oslo 59°56′N 10°41′E / 59.933°N 10.683°E |

| Official languages | |

| Recognised national languages | |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Norwegian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Harald V |

| Jonas Gahr Støre | |

| Masud Gharahkhani | |

| Toril Marie Øie | |

| Legislature | Storting |

| History | |

| 872 | |

• Old Kingdom of Norway (Peak extent) | 1263 |

| 1397 | |

| 1524 | |

| 25 February 1814 | |

| 17 May 1814 | |

| 4 November 1814 | |

| 7 June 1905 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 385,207 km2 (148,729 sq mi)[12] (61stb) |

• Water (%) | 5.32 (2015)[13] |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• Density | 14.4/km2 (37.3/sq mi) (213th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2020) | low |

| HDI (2022) | very high (2nd) |

| Currency | Norwegian krone (NOK) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +47 |

| ISO 3166 code | NO |

| Internet TLD | .nod |

| |

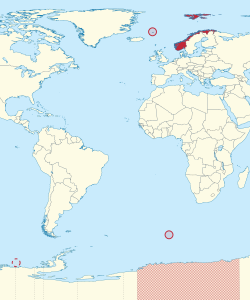

Норвегия ( букмол : Norge , Нюнорск : Noreg ), формально Королевство Норвегия , [а] Северная страна в Северной Европе , расположенная на Скандинавском полуострове . Отдаленный арктический остров Ян-Майен и архипелаг Шпицберген также входят в состав Норвегии. [примечание 5] Остров Буве , расположенный в Субантарктике , является зависимым ; Норвегия также претендует на антарктические территории острова Петра I и Земли Королевы Мод . Столица и крупнейший город Норвегии — Осло .

Общая площадь Норвегии составляет 385 207 квадратных километров (148 729 квадратных миль). [12] и имел население 5 488 984 человека в январе 2023 года. [14] Страна имеет протяженную восточную границу со Швецией . Граничит с Финляндией и Россией на северо-востоке и проливом Скагеррак на юге. Норвегия имеет обширную береговую линию, выходящую к северной части Атлантического океана и Баренцеву морю . Харальд V из дома Глюксбургов — нынешний король Норвегии . Йонас Гар Стёре является премьер-министром Норвегии с 2021 года. Будучи унитарным государством с конституционной монархией , Норвегия разделяет государственную власть между парламентом , кабинетом министров и верховным судом , как это определено конституцией 1814 года . Единое королевство Норвегия было создано в 872 году в результате слияния мелких королевств и просуществовало непрерывно 1151–1152 года. С 1537 по 1814 год Норвегия была частью Дании-Норвегии , а с 1814 по 1905 год находилась в личной унии со Швецией. Норвегия была нейтральной во время Первой мировой войны и во Второй мировой войне до апреля 1940 года, когда она была захвачена и оккупирована нацистской Германией до конца войны.

Norway has both administrative and political subdivisions on two levels: counties and municipalities. The Sámi people have a certain amount of self-determination and influence over traditional territories through the Sámi Parliament and the Finnmark Act. Norway maintains close ties with the European Union and the United States. Norway is a founding member of the United Nations, NATO, the European Free Trade Association, the Council of Europe, the Antarctic Treaty, and the Nordic Council; a member of the European Economic Area, the WTO, and the OECD; and a part of the Schengen Area. The Norwegian dialects share mutual intelligibility with Danish and Swedish.

Norway maintains the Nordic welfare model with universal health care and a comprehensive social security system, and its values are rooted in egalitarian ideals.[20] The Norwegian state has large ownership positions in key industrial sectors, having extensive reserves of petroleum, natural gas, minerals, lumber, seafood, and fresh water. The petroleum industry accounts for around a quarter of the country's gross domestic product (GDP).[21] On a per-capita basis, Norway is the world's largest producer of oil and natural gas outside of the Middle East.[22][23] The country has the fourth- and eighth-highest per-capita income in the world on the World Bank's and IMF's list, respectively.[24] It has the world's largest sovereign wealth fund, with a value of US$1.3 trillion.[25][26]

Etymology

Norway has two official names: Norge in Bokmål and Noreg in Nynorsk. The English name Norway comes from the Old English word Norþweg mentioned in 880, meaning "northern way" or "way leading to the north", which is how the Anglo-Saxons referred to the coastline of Atlantic Norway.[27][28][29] The Anglo-Saxons of Britain also referred to the kingdom of Norway in 880 as Norðmanna land.[27][28]

There is some disagreement about whether the native name of Norway originally had the same etymology as the English form. According to the traditional dominant view, the first component was originally norðr, a cognate of English north, so the full name was Norðr vegr, "the way northwards", referring to the sailing route along the Norwegian coast, and contrasting with suðrvegar "southern way" (from Old Norse suðr) for (Germany), and austrvegr "eastern way" (from austr) for the Baltic.[30]

History

Prehistory

The earliest traces of human occupation in Norway are found along the coast, where the huge ice shelf of the last ice age first melted between 11,000 and 8000 BC. The oldest finds are stone tools dating from 9500 to 6000 BC, discovered in Finnmark (Komsa culture) in the north and Rogaland (Fosna culture) in the southwest. Theories about the two cultures being separate were deemed obsolete in the 1970s.[31]

Between 3000 and 2500 BC, new settlers (Corded Ware culture) arrived in eastern Norway. They were Indo-European farmers who grew grain and kept livestock, and gradually replaced the hunting-fishing population of the west coast.

Metal Ages

From about 1500 BC, bronze was gradually introduced. Burial cairns built close to the sea as far north as Harstad and also inland in the south are characteristic of this period, with rock carving motifs that differ from those of the Stone Age, depicting ships resembling the Hjortspring boat, while large stone burial monuments known as stone ships were also erected.[32]

There is little archaeological evidence dating to the early Iron Age (the last 500 years BC). The dead were cremated, and their graves contained few goods. During the first four centuries AD, the people of Norway were in contact with Roman-occupied Gaul; about 70 Roman bronze cauldrons, often used as burial urns, have been found. Contact with countries farther south brought a knowledge of runes; the oldest known Norwegian runic inscription dates from the third century.

Viking Age

By the time of the first historical records of Scandinavia, about the 8th century, several small political entities existed in Norway. It has been estimated that there were nine petty realms in Western Norway during the early Viking Age.[33] Archaeologist Bergljot Solberg on this basis estimates that there would have been at least 20 in the whole country.[34]

In the Viking period, Norwegian Viking explorers discovered Iceland by accident in the ninth century when heading for the Faroe Islands, and eventually came across Vinland, known today as Newfoundland, in Canada. The Vikings from Norway were most active in the northern and western British Isles and eastern North America isles.[35]

According to tradition, Harald Fairhair unified them into one in 872 after the Battle of Hafrsfjord in Stavanger, thus becoming the first king of a united Norway.[36] Harald's realm was mainly a South Norwegian coastal state. Fairhair ruled with a strong hand and according to the sagas, many Norwegians left the country to live in Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and parts of Britain and Ireland.[37]

Haakon I the Good was Norway's first Christian king, in the mid-10th century, though his attempt to introduce the religion was rejected. Norse traditions were replaced slowly by Christian ones in the late 10th and early 11th centuries. This is largely attributed to the missionary kings Olaf I Tryggvasson and Olaf II Haraldsson (St. Olaf). Olaf Tryggvasson conducted raids in England, including attacking London. Arriving back in Norway in 995, Olaf landed in Moster where he built a church which became the first Christian church in Norway. From Moster, Olaf sailed north to Trondheim where he was proclaimed King of Norway by the Eyrathing in 995.[38] One of the most important sources for the history of the 11th century Vikings is the treaty between the Icelanders and Olaf II Haraldsson, king of Norway circa 1015 to 1028.[39]

Feudalism never really developed in Norway or Sweden, as it did in the rest of Europe. However, the administration of government took on a very conservative feudal character. The Hanseatic League forced royalty to cede to them greater and greater concessions over foreign trade and the economy, because of the loans the Hansa had made to the royals and the large debt the kings were carrying. The League's monopolistic control over the economy of Norway put pressure on all classes, especially the peasantry, to the degree that no real burgher class existed in Norway.[40]

High Middle Ages

From the 1040s to 1130, the country was at peace.[41] In 1130, the civil war era broke out on the basis of unclear succession laws, which allowed the king's sons to rule jointly. The Archdiocese of Nidaros was created in 1152 and attempted to control the appointment of kings.[42] The church inevitably had to take sides in the conflicts. The wars ended in 1217 with the appointment of Håkon IV Håkonsson, who introduced clear laws of succession.[43]

From 1000 to 1300, the population increased from 150,000 to 400,000, resulting both in more land being cleared and the subdivision of farms. While in the Viking Age farmers owned their own land, by 1300, seventy per cent of the land was owned by the king, the church, or the aristocracy, and about twenty per cent of yields went to these landowners.[44]

The 14th century is described as Norway's golden age, with peace and increase in trade, especially with the British Islands, although Germany became increasingly important towards the end of the century. Throughout the High Middle Ages, the king established Norway as a sovereign state with a central administration and local representatives.[45]

In 1349, the Black Death spread to Norway and within a year killed a third of the population. Later plagues reduced the population to half the starting point by 1400. Many communities were entirely wiped out, resulting in an abundance of land, allowing farmers to switch to more animal husbandry. The reduction in taxes weakened the king's position,[46] and many aristocrats lost the basis for their surplus. High tithes to church made it increasingly powerful and the archbishop became a member of the Council of State.[47]

The Hanseatic League took control over Norwegian trade during the 14th century and established a trading centre in Bergen. In 1380, Olaf Haakonsson inherited both the Norwegian (as Olaf IV) and Danish thrones (as Olaf II), creating a union between the two countries.[47] In 1397, under Margaret I, the Kalmar Union was created between the three Scandinavian countries. She waged war against the Germans, resulting in a trade blockade and higher taxation on Norwegian goods, which led to a rebellion. However, the Norwegian Council of State was too weak to pull out of the union.[48]

Margaret pursued a centralising policy which inevitably favoured Denmark because of its greater population.[49] Margaret also granted trade privileges to the Hanseatic merchants of Lübeck in Bergen in return for recognition of her rule, and these hurt the Norwegian economy. The Hanseatic merchants formed a state within a state in Bergen for generations.[50] The "Victual Brothers" launched three devastating pirate raids on the port (the last in 1427).[51]

Norway slipped ever more to the background under the Oldenburg dynasty (established 1448). There was one revolt under Knut Alvsson in 1502.[52] Norway took no part in the events which led to Swedish independence from Denmark in the 1520s.[53]

Kalmar Union

Upon the death of King Haakon V in 1319, Magnus Erikson, at just three years old, inherited the throne as King Magnus VII. A simultaneous movement to make Magnus King of Sweden proved successful (he was a grandson of King Magnus III of Sweden), and both the kings of Sweden and of Denmark were elected to the throne by their respective nobles. Thus Sweden and Norway were united under King Magnus VII.[54]

In 1349, the Black Death killed between 50% and 60% of Norway's population[55] and led to a period of social and economic decline.[56] Although the death rate was comparable with the rest of Europe, economic recovery took much longer because of the small, scattered population.[56] Even before the plague, the population was only about 500,000.[57] After the plague, many farms lay idle while the population slowly increased.[56] However, the few surviving farms' tenants found their bargaining positions with their landlords greatly strengthened.[56]

King Magnus VII ruled Norway until 1350, when his son, Haakon, was placed on the throne as Haakon VI.[58] In 1363, Haakon married Margaret, daughter of King Valdemar IV of Denmark.[56] Upon the death of Haakon in 1379, his 10-year-old son Olaf IV acceded to the throne.[56] As Olaf had already been elected to the throne of Denmark in 1376,[56] Denmark and Norway entered a personal union.[59] Olaf's mother and Haakon's widow, Queen Margaret, managed the foreign affairs of Denmark and Norway during Olaf's minority.[56]

Margaret was on the verge of achieving a union of Sweden with Denmark and Norway when Olaf IV suddenly died.[56] Denmark made Margaret temporary ruler on the death of Olaf. On 2 February 1388, Norway followed suit and crowned Margaret.[56] Queen Margaret knew that her power would be more secure if she were able to find a king to rule in her place. She settled on Eric of Pomerania, grandson of her sister. Thus at an all-Scandinavian meeting held at Kalmar, Erik of Pomerania was crowned king of all three Scandinavian countries, bringing the thrones of Norway, Denmark, and Sweden under the control of Queen Margaret when the country entered into the Kalmar Union.

Early modern period

After Sweden broke out of the Kalmar Union in 1521, Norway tried to follow suit,[citation needed] but the subsequent rebellion was defeated, and Norway remained in a union with Denmark until 1814. This period was by some referred to as the "400-Year Night", since all of the kingdom's intellectual and administrative power was centred in Copenhagen.

With the introduction of Protestantism in 1536, the archbishopric in Trondheim was dissolved; Norway lost its independence and effectually became a colony of Denmark. The Church's incomes and possessions were instead redirected to the court in Copenhagen. Norway lost the steady stream of pilgrims to the relics of St. Olav at the Nidaros shrine, and with them, much of the contact with cultural and economic life in the rest of Europe.

Eventually restored as a kingdom (albeit in legislative union with Denmark) in 1661, Norway saw its land area decrease in the 17th century with the loss of the provinces Båhuslen, Jemtland, and Herjedalen to Sweden, as the result of a number of disastrous wars with Sweden. In the north, its territory was increased by the acquisition of the northern provinces of Troms and Finnmark, at the expense of Sweden and Russia.

The famine of 1695–1696 killed roughly 10% of Norway's population.[60] The harvest failed in Scandinavia at least nine times between 1740 and 1800, with great loss of life.[61]

Later modern period

After Denmark–Norway was attacked by the United Kingdom at the 1807 Battle of Copenhagen, it entered into an alliance with Napoleon, with the war leading to dire conditions and mass starvation in 1812. As the Danish kingdom was on the losing side in 1814, it was forced by the Treaty of Kiel to cede Norway to Sweden, while the old Norwegian provinces of Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands remained with the Danish crown.[62] Norway took this opportunity to declare independence, adopted a constitution based on American and French models, and elected the Crown Prince of Denmark and Norway, Christian Frederick, as king on 17 May 1814 – celebrated as the Syttende mai (Seventeenth of May) holiday.

Norwegian opposition to the decision to link Norway with Sweden caused the Norwegian–Swedish War to break out as Sweden tried to subdue Norway by military means. As Sweden's military was not strong enough to defeat the Norwegian forces outright, and Norway's treasury was not large enough to support a protracted war, and as British and Russian navies blockaded the Norwegian coast,[63] the belligerents were forced to negotiate the Convention of Moss. Christian Frederik abdicated the Norwegian throne and authorised the Parliament of Norway to make the necessary constitutional amendments to allow for the personal union that Norway was forced to accept. On 4 November 1814, the Parliament (Storting) elected Charles XIII of Sweden as king of Norway, thereby establishing the union with Sweden.[64] Under this arrangement, Norway kept its liberal constitution and its own independent institutions, though it shared a monarch and foreign policy with Sweden. Following the recession caused by the Napoleonic Wars, economic development of Norway remained slow until 1830.[65]

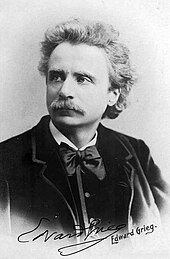

This period also saw the rise of Norwegian romantic nationalism, as Norwegians sought to define and express a distinct national character. The movement covered all branches of culture, including literature (Henrik Wergeland, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, Peter Christen Asbjørnsen, Jørgen Moe), painting (Hans Gude, Adolph Tidemand), music (Edvard Grieg), and even language policy, where attempts to define a native written language for Norway led to today's two official written forms for Norwegian: Bokmål and Nynorsk.

King Charles III John came to the throne of Norway and Sweden in 1818 and reigned to 1844. He protected the constitution and liberties of Norway and Sweden during the age of Metternich.[neutrality is disputed] As such, he was regarded as a liberal monarch. However, he was ruthless in his use of paid informers, secret police and restrictions on the freedom of the press to put down public movements for reform—especially the Norwegian national independence movement.[66]

The Romantic Era that followed the reign of Charles III John brought some significant social and political reforms. In 1854, women won the right to inherit property. In 1863, the last trace of keeping unmarried women in the status of minors was removed. Furthermore, women were eligible for different occupations, particularly the common school teacher.[67] By mid-century, Norway's democracy was limited; voting was limited to officials, property owners, leaseholders and burghers of incorporated towns.[68]

Norway remained a conservative society. Life in Norway (especially economic life) was "dominated by the aristocracy of professional men who filled most of the important posts in the central government".[69] There was no strong bourgeois class to demand a breakdown of this aristocratic control.[70] Thus, even while revolution swept over most of the countries of Europe in 1848, Norway was largely unaffected.[70]

Marcus Thrane was a Utopian socialist who in 1848 organised a labour society in Drammen. In just a few months, this society had a membership of 500 and was publishing its own newspaper. Within two years, 300 societies had been organised all over Norway, with a total membership of 20,000 drawn from the lower classes of both urban and rural areas.[71] In the end, the revolt was easily crushed; Thrane was captured and jailed.[72]

In 1898, all men were granted universal suffrage, followed by all women in 1913.

Dissolution of the union and the First World War

Christian Michelsen, Prime Minister of Norway from 1905 to 1907, played a central role in the peaceful separation of Norway from Sweden on 7 June 1905. A national referendum confirmed the people's preference for a monarchy over a republic. However, no Norwegian could legitimately claim the throne, since none of Norway's noble families could claim royal descent.

The government then offered the throne of Norway to Prince Carl of Denmark, a prince of the Dano-German royal house of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg and a distant relative of Norway's medieval kings. Following the plebiscite, he was unanimously elected king by the Norwegian Parliament; he took the name Haakon VII.

Throughout the First World War, Norway remained neutral; however, diplomatic pressure from the British government meant that it heavily favoured the Allies. During the war, Norway exported fish to both Germany and Britain, until an ultimatum from the British government and anti-German sentiments as a result of German submarines targeting Norwegian merchantmen led to a termination of trade with Germany. 436 Norwegian merchantmen were sunk by the Kaiserliche Marine, with 1,150 Norwegian sailors killed.[73][disputed – discuss]

Second World War

Norway once more proclaimed its neutrality during the Second World War, but was invaded by German forces on 9 April 1940. Although Norway was unprepared for the German surprise attack (see: Battle of Drøbak Sound, Norwegian Campaign, and Invasion of Norway), military and naval resistance lasted for two months. Norwegian armed forces in the north launched an offensive against the German forces in the Battles of Narvik, but were forced to surrender on 10 June after losing British support which had been diverted to France during the German invasion of France.

King Haakon and the Norwegian government escaped to Rotherhithe in London. Throughout the war they sent radio speeches and supported clandestine military actions against the Germans. On the day of the invasion, the leader of the small National-Socialist party Nasjonal Samling, Vidkun Quisling, tried to seize power, but was forced by the German occupiers to step aside. Real power was wielded by the leader of the German occupation authority, Josef Terboven. Quisling, as minister president, later formed a collaborationist government under German control. Up to 15,000 Norwegians volunteered to fight in German units, including the Waffen-SS.[74]

Many Norwegians and persons of Norwegian descent joined the Allied forces as well as the Free Norwegian Forces. In June 1940, a small group had left Norway following their king to Britain. This group included 13 ships, five aircraft, and 500 men from the Royal Norwegian Navy. By the end of the war, the force had grown to 58 ships and 7,500 men in service in the Royal Norwegian Navy, 5 squadrons of aircraft in the newly formed Norwegian Air Force, and land forces including the Norwegian Independent Company 1 and 5 Troop as well as No. 10 Commandos.[citation needed]

During German occupation, Norwegians built a resistance movement which incorporated civil disobedience and armed resistance including the destruction of Norsk Hydro's heavy water plant and stockpile of heavy water at Vemork, which crippled the German nuclear programme. More important to the Allied war effort, however, was the role of the Norwegian Merchant Marine, the fourth-largest merchant marine fleet in the world. It was led by the Norwegian shipping company Nortraship under the Allies throughout the war and took part in every war operation from the evacuation of Dunkirk to the Normandy landings. Every December Norway gives a Christmas tree to the United Kingdom as thanks for the British assistance during the war.[75]

Svalbard was not occupied by German troops, but Germany secretly established a meteorological station there in 1944.[76]

Post–World War II history

From 1945 to 1962, the Labour Party held an absolute majority in the parliament. The government, led by prime minister Einar Gerhardsen, embarked on a programme inspired by Keynesian economics, emphasising state financed industrialisation and co-operation between trade unions and employers' organisations. Many measures of state control of the economy imposed during the war were continued, although the rationing of dairy products was lifted in 1949, while price controls and rationing of housing and cars continued until 1960.

The wartime alliance with the United Kingdom and the United States continued in the post-war years. Although pursuing the goal of a socialist economy, the Labour Party distanced itself from the Communists, especially after the Communists' seizure of power in Czechoslovakia in 1948, and strengthened its foreign policy and defence policy ties with the US. Norway received Marshall Plan aid from the United States starting in 1947, joined the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) one year later, and became a founding member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949.

Oil was discovered at the small Balder field in 1967, but production only began in 1999.[77] In 1969, the Phillips Petroleum Company discovered petroleum resources at the Ekofisk field west of Norway. In 1973, the Norwegian government founded the State oil company, Statoil (now Equinor). Oil production did not provide net income until the early 1980s because of the large capital investment required. Around 1975, both the proportion and absolute number of workers in industry peaked. Since then labour-intensive industries and services like factory mass production and shipping have largely been outsourced.

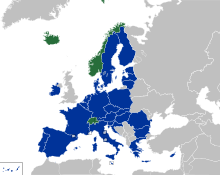

Norway was a founding member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). Norway was twice invited to join the European Union, but ultimately declined after referendums that failed by narrow margins in 1972 and 1994.[78]

In 1981, a Conservative Party government led by Kåre Willoch replaced the Labour Party with a policy of stimulating the stagflated economy with tax cuts, economic liberalisation, deregulation of markets, and measures to curb record-high inflation (13.6% in 1981).

Norway's first female prime minister Gro Harlem Brundtland of the Labour Party continued many of the reforms, while backing traditional Labour concerns such as social security, high taxes, the industrialisation of nature, and feminism. By the late 1990s, Norway had paid off its foreign debt and had started accumulating a sovereign wealth fund. Since the 1990s, a divisive question in politics has been how much of the income from petroleum production the government should spend, and how much it should save.

In 2011, Norway suffered two terrorist attacks by Anders Behring Breivik which struck the government quarter in Oslo and a summer camp of the Labour party's youth movement at Utøya island, resulting in 77 deaths and 319 wounded.[79]

Jens Stoltenberg led Norway as prime minister for eight years from 2005 to 2013.[80] The 2013 Norwegian parliamentary election brought a more conservative government to power, with the Conservative Party and the Progress Party winning 43% of the electorate's votes.[81] In the Norwegian parliamentary election 2017 the centre-right government of Prime Minister Erna Solberg won re-election.[82] The 2021 Norwegian parliamentary election saw a big win for the left-wing opposition in an election fought on climate change, inequality, and oil;[83] Labour leader Jonas Gahr Støre was sworn in as prime minister.[84]

Geography

Norway's core territory comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula; the remote island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard are also included.[note 5] The Antarctic Peter I Island and the sub-Antarctic Bouvet Island are dependent territories and thus not considered part of the Kingdom. Norway also claims a section of Antarctica known as Queen Maud Land.[85] Norwegian possessions in the North Atlantic, Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Iceland, remained Danish when Norway was passed to Sweden at the Treaty of Kiel.[86] Norway also comprised Bohuslän until 1658, Jämtland and Härjedalen until 1645,[85] Shetland and Orkney until 1468,[87] and the Hebrides and Isle of Man until the Treaty of Perth in 1266.[88]

Norway comprises the western and northernmost part of Scandinavia in Northern Europe,[89] between latitudes 57° and 81° N, and longitudes 4° and 32° E. Norway is the northernmost of the Nordic countries and if Svalbard is included also the easternmost.[90] Norway includes the northernmost point on the European mainland.[91] The rugged coastline is broken by huge fjords and thousands of islands. The coastal baseline is 2,532 kilometres (1,573 mi). The coastline of the mainland including fjords stretches 28,953 kilometres (17,991 mi), when islands are included the coastline has been estimated to 100,915 kilometres (62,706 mi).[92] Norway shares a 1,619-kilometre (1,006 mi) land border with Sweden, 727 kilometres (452 mi) with Finland, and 196 kilometres (122 mi) with Russia to the east. To the north, west and south, Norway is bordered by the Barents Sea, the Norwegian Sea, the North Sea, and Skagerrak.[93] The Scandinavian Mountains form much of the border with Sweden.

At 385,207 square kilometres (148,729 sq mi) (including Svalbard and Jan Mayen; 323,808 square kilometres (125,023 sq mi) without),[12] much of the country is dominated by mountainous or high terrain, with a great variety of natural features caused by prehistoric glaciers and varied topography. The most noticeable of these are the fjords. Sognefjorden is the world's second deepest fjord, and the world's longest at 204 kilometres (127 mi). Hornindalsvatnet is the deepest lake in Europe.[94] Norway has about 400,000 lakes[95][96] and 239,057 registered islands.[89] Permafrost can be found all year in the higher mountain areas and in the interior of Finnmark county. Numerous glaciers are found in Norway. The land is mostly made of hard granite and gneiss rock, but slate, sandstone, and limestone are also common, and the lowest elevations contain marine deposits.

Climate

Because of the Gulf Stream and prevailing westerlies, Norway experiences higher temperatures and more precipitation than expected at such northern latitudes, especially along the coast. The mainland experiences four distinct seasons, with colder winters and less precipitation inland. The northernmost part has a mostly maritime Subarctic climate, while Svalbard has an Arctic tundra climate. The southern and western parts of Norway, fully exposed to Atlantic storm fronts, experience more precipitation and have milder winters than the eastern and far northern parts. Areas to the east of the coastal mountains are in a rain shadow, and have lower rain and snow totals than the west. The lowlands around Oslo have the warmest summers, but also cold weather and snow in wintertime. The sunniest weather is along the south coast, but sometimes even the coast far north can be very sunny – the sunniest month with 430 sun hours was recorded in Tromsø.[97][98]

Because of Norway's high latitude, there are large seasonal variations in daylight. From late May to late July, the sun never completely descends beneath the horizon in areas north of the Arctic Circle, and the rest of the country experiences up to 20 hours of daylight per day. Conversely, from late November to late January, the sun never rises above the horizon in the north, and daylight hours are very short in the rest of the country.

Temperature anomalies found in coastal locations are exceptional, with southern Lofoten and Bø having all monthly means above freezing in spite of being north of the Arctic Circle. The very northernmost coast of Norway would be ice-covered in winter if not for the Gulf Stream.[99] The east of the country has a more continental climate, and the mountain ranges have subarctic and tundra climates. There is also higher rainfall in areas exposed to the Atlantic, especially the western slopes of the mountain ranges and areas close, such as Bergen. The valleys east of the mountain ranges are the driest; some of the valleys are sheltered by mountains in most directions. Saltdal (81 m) in Nordland is the driest place with 211 millimetres (8.3 inches) precipitation annually (1991–2020). In southern Norway, Skjåk in Innlandet get 295 millimetres (11.6 inches) precipitation. Finnmarksvidda and some interior valleys of Troms receive around 400 millimetres (16 inches) annually, and the high Arctic Longyearbyen 217 millimetres (8.5 inches).[100]

Parts of southeastern Norway including parts of Mjøsa have a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb), the southern and western coasts and also the coast north to Bodø have an oceanic climate (Cfb), and the outer coast further north almost to North Cape has a subpolar oceanic climate (Cfc). Further inland in the south and at higher altitudes, and also in much of Northern Norway, the subarctic climate (Dfc) dominates. A small strip of land along the coast east of North Cape (including Vardø) earlier had tundra/alpine/polar climate (ET), but this is mostly gone with the updated 1991–2020 climate normals, making this also subarctic. Large parts of Norway are covered by mountains and high altitude plateaus, and about one third of the land is above the treeline and thus exhibit tundra/alpine/polar climate (ET).[97][101][102][98][103]

Biodiversity

Norway has a larger number of different habitats than almost any other European country. There are approximately 60,000 species in Norway and adjacent waters (excluding bacteria and viruses). The Norwegian Shelf large marine ecosystem is considered highly productive.[104] The total number of species include 16,000 species of insects (probably 4,000 more species yet to be described), 20,000 species of algae, 1,800 species of lichen, 1,050 species of mosses, 2,800 species of vascular plants, up to 7,000 species of fungi, 450 species of birds (250 species nesting in Norway), 90 species of mammals, 45 fresh-water species of fish, 150 salt-water species of fish, 1,000 species of fresh-water invertebrates, and 3,500 species of salt-water invertebrates.[105] About 40,000 of these species have been described by science. The red list of 2010 encompasses 4,599 species.[106] Norway contains five terrestrial ecoregions: Sarmatic mixed forests, Scandinavian coastal conifer forests, Scandinavian and Russian taiga, Kola Peninsula tundra, and Scandinavian montane birch forest and grasslands.[107]

Seventeen species are listed mainly because they are endangered on a global scale, such as the European beaver, even if the population in Norway is not seen as endangered. The number of threatened and near-threatened species equals to 3,682; it includes 418 fungi species, many of which are closely associated with the small remaining old-growth forests,[108] 36 bird species, and 16 species of mammals. In 2010, 2,398 species were listed as endangered or vulnerable; of these 1,250 were listed as vulnerable (VU), 871 as endangered (EN), and 276 species as critically endangered (CR), among which were the grey wolf, the Arctic fox, and the pool frog.[106]

The largest predator in Norwegian waters is the sperm whale, and the largest fish is the basking shark. The largest predator on land is the polar bear, while the brown bear is the largest predator on the Norwegian mainland. The largest land animal on the mainland is the elk (American English: moose).

Environment

Attractive and dramatic scenery and landscape are found throughout Norway.[109] The west coast of southern Norway and the coast of northern Norway present some of the most visually impressive coastal sceneries in the world. National Geographic has listed the Norwegian fjords as the world's top tourist attraction.[110] The country is also home to the natural phenomena of the Midnight sun (during summer), as well as the Aurora borealis known also as the Northern lights.[111]

The 2016 Environmental Performance Index from Yale University, Columbia University and the World Economic Forum put Norway in seventeenth place, immediately below Croatia and Switzerland.[112] The index is based on environmental risks to human health, habitat loss, and changes in CO2 emissions. The index notes over-exploitation of fisheries, but not Norway's whaling or oil exports.[113] Norway had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.98/10, ranking it 60th globally out of 172 countries.[114]

Politics and government

(reigning since 17 January 1991)

(since 14 October 2021)

Norway is considered to be one of the most developed democracies and states of justice in the world. Since 2010, Norway has been classified as the world's most democratic country by the Democracy Index.[115][116][117]

According to the Constitution of Norway, which was adopted on 17 May 1814[118] and was inspired by the United States Declaration of Independence and French Revolution, Norway is a unitary constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system of government, wherein the King of Norway is the head of state and the prime minister is the head of government. Power is separated among the legislative, executive and judicial branches of government, as defined by the Constitution, which serves as the country's supreme legal document.

The monarch officially retains executive power. But following the introduction of a parliamentary system of government, the duties of the monarch became strictly representative and ceremonial.[119] The Monarch is commander-in-chief of the Norwegian Armed Forces, and serves as chief diplomatic official abroad and as a symbol of unity. Harald V of the House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg ascended to the Norwegian throne in 1991, the first since the 14th century who has been born in the country.[120] Haakon, Crown Prince of Norway, is the heir to the throne.

In practice, the Prime Minister exercises the executive powers. Constitutionally, legislative power is vested with both the government and the Parliament of Norway, but the latter is the supreme legislature and a unicameral body.[121] Norway is fundamentally structured as a representative democracy. The Parliament can pass a law by simple majority of the 169 representatives, of which 150 are elected directly from 19 constituencies, and an additional 19 seats ("levelling seats") are allocated on a nationwide basis to make the representation in parliament correspond better with the popular vote for the political parties. A 4% election threshold is required for a party to gain levelling seats in Parliament.[122]

The Parliament of Norway, called the Storting, ratifies national treaties developed by the executive branch. It can impeach members of the government if their acts are declared unconstitutional. If an indicted suspect is impeached, Parliament has the power to remove the person from office.

The position of prime minister is allocated to the member of Parliament who can obtain the confidence of a majority in Parliament, usually the current leader of the largest political party or, more effectively, through a coalition of parties; Norway has often been ruled by minority governments. The prime minister nominates the cabinet, traditionally drawn from members of the same political party or parties in the Storting, making up the government. The PM organises the executive government and exercises its power as vested by the Constitution.[123]

Norway has a state church, the Lutheran Church of Norway, which has gradually been granted more internal autonomy in day-to-day affairs, but which still has a special constitutional status. Formerly, the PM had to have more than half the members of cabinet be members of the Church of Norway; this rule was removed in 2012. The issue of separation of church and state in Norway has been increasingly controversial. A part of this is the evolution of the public school subject Christianity, a required subject since 1739. Even the state's loss in a battle at the European Court of Human Rights at Strasbourg[124] in 2007 did not settle the matter. As of 1 January 2017, the Church of Norway is a separate legal entity, and no longer a branch of the civil service.[125]Through the Council of State, a privy council presided over by the monarch, the prime minister and the cabinet meet at the Royal Palace and formally consult the Monarch. All government bills need formal approval by the monarch before and after introduction to Parliament. The Council approves all of the monarch's actions as head of state.[120]

Members of the Storting are directly elected from party-list proportional representation in nineteen plural-member constituencies in a national multi-party system.[126] Historically, both the Norwegian Labour Party and Conservative Party have played leading political roles. In the early 21st century, the Labour Party has been in power since the 2005 election, in a Red–Green Coalition with the Socialist Left Party and the Centre Party.[127] Since 2005, both the Conservative Party and the Progress Party have won numerous seats in the Parliament.[128]

In national elections in September 2013, two political parties, Høyre and Fremskrittspartiet, were elected on promises of tax cuts, more spending on infrastructure and education, better services and stricter rules on immigration, formed a government. Erna Solberg became prime minister, the second female prime minister after Gro Harlem Brundtland and the first conservative prime minister since Jan P. Syse. Solberg said her win was "a historic election victory for the right-wing parties".[129] Her centre-right government won re-election in the 2017 Norwegian parliamentary election.[82] Norway's new centre-left cabinet under Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre, the leader the Labour Party, took office on 14 October 2021.[130]

Administrative divisions

Norway, a unitary state, is divided into fifteen first-level administrative counties (fylke).[131] The counties are administered through directly elected county assemblies who elect the County Governor. Additionally, the King and government are represented in every county by a fylkesmann, who effectively acts as a Governor.[132] The counties are then sub-divided into 357 second-level municipalities (Norwegian: kommuner), which in turn are administered by directly elected municipal council, headed by a mayor and a small executive cabinet. The capital of Oslo is considered both a county and a municipality. Norway has two integral overseas territories out of mainland: Jan Mayen and Svalbard, the only developed island in the archipelago of the same name, located far to the north of the Norwegian mainland.[133]

There are 108 settlements that have town/city status in Norway (the Norwegian word by is used to represent these places and that word can be translated as either town or city in English). Cities/towns in Norway were historically designated by the King and used to have special rules and privileges under the law. This was changed in the late 20th century, so now towns/cities have no special rights and a municipality can designate an urban settlement as a city/town. Towns and cities in Norway do not have to be large. Some cities have over a million residents such as Oslo, while others are much smaller such as Honningsvåg with about 2,200 residents. Usually, there is only one town within a municipality, but there are some municipalities that have more than one town within it (such as Larvik Municipality which has the town of Larvik and the town of Stavern.[134]

Dependencies of Norway

There are three Antarctic and Subantarctic dependencies: Bouvet Island, Peter I Island, and Queen Maud Land. On most maps, there was an unclaimed area between Queen Maud Land and the South Pole until 12 June 2015 when Norway formally annexed that area.[135]

Largest populated areas

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Oslo  Bergen | 1 | Oslo | Oslo | 1,000,467 | 11 | Moss | Østfold | 46,618 |  Stavanger/Sandnes  Trondheim |

| 2 | Bergen | Vestland | 255,464 | 12 | Haugesund | Rogaland | 44,830 | ||

| 3 | Stavanger/Sandnes | Rogaland | 222,697 | 13 | Sandefjord | Vestfold | 43,595 | ||

| 4 | Trondheim | Trøndelag | 183,378 | 14 | Arendal | Agder | 43,084 | ||

| 5 | Drammen | Buskerud | 117,510 | 15 | Bodø | Nordland | 40,705 | ||

| 6 | Fredrikstad/Sarpsborg | Østfold | 111,267 | 16 | Tromsø | Troms | 38,980 | ||

| 7 | Porsgrunn/Skien | Telemark | 92,753 | 17 | Hamar | Innlandet | 27,324 | ||

| 8 | Kristiansand | Agder | 61,536 | 18 | Halden | Østfold | 25,300 | ||

| 9 | Ålesund | Møre og Romsdal | 52,163 | 19 | Larvik | Vestfold | 24,208 | ||

| 10 | Tønsberg | Vestfold | 51,571 | 20 | Askøy | Vestland | 23,194 | ||

Judicial system and law enforcement

Norway uses a civil law system where laws are created and amended in Parliament and the system regulated through the Courts of justice of Norway. It consists of the Supreme Court of 20 permanent judges and a Chief Justice, appellate courts, city and district courts, and conciliation councils.[136] The judiciary is independent of executive and legislative branches. While the Prime Minister nominates Supreme Court Justices for office, their nomination must be approved by Parliament and formally confirmed by the Monarch. Usually, judges attached to regular courts are formally appointed by the Monarch on the advice of the Prime Minister.

The Courts' formal mission is to regulate the Norwegian judicial system, interpret the Constitution, and implement the legislation adopted by Parliament. In its judicial reviews, it monitors the legislative and executive branches to ensure that they comply with provisions of enacted legislation.[136]

The law is enforced in Norway by the Norwegian Police Service. It is a Unified National Police Service made up of 27 Police Districts and several specialist agencies, such as Norwegian National Authority for the Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime, known as Økokrim; and the National Criminal Investigation Service, known as Kripos, each headed by a chief of police. The Police Service is headed by the National Police Directorate, which reports to the Ministry of Justice and the Police. The Police Directorate is headed by a National Police Commissioner. The only exception is the Norwegian Police Security Agency, whose head answers directly to the Ministry of Justice and the Police.

Norway abolished the death penalty for regular criminal acts in 1902 and for high treason in war and war-crimes in 1979. Norwegian prisons are humane, rather than tough, with emphasis on rehabilitation. At 20%, Norway's re-conviction rate is among the lowest in the world.[137]Reporters Without Borders, in its 2023 World Press Freedom Index, ranked Norway in first place out of 180 countries.[138] In general, the legal and institutional framework in Norway is characterised by a high degree of transparency, accountability and integrity, and the perception and the occurrence of corruption are very low.[139]

Human rights

Norway has been considered a progressive country, which has adopted legislation and policies to support women's rights, minority rights, and LGBT rights. As early as 1884, 171 of the leading figures, among them five Prime Ministers, co-founded the Norwegian Association for Women's Rights.[140] They successfully campaigned for women's right to education, women's suffrage, the right to work, and other gender equality policies. From the 1970s, gender equality also came high on the state agenda, with the establishment of a public body to promote gender equality, which evolved into the Gender Equality and Anti-Discrimination Ombud. Civil society organisations also continue to play an important role; women's rights organisations are today organised in the Norwegian Women's Lobby umbrella organisation.

In 1990, the Norwegian constitution was amended to grant absolute primogeniture to the Norwegian throne, meaning that the eldest child, regardless of gender, takes precedence in the line of succession. As it was not retroactive, the current successor to the throne is the eldest son of the King, rather than his eldest child.[141]

The Sámi people have for centuries been the subject of discrimination and abuse by the dominant cultures in Scandinavia and Russia, those countries claiming possession of Sámi lands.[142] Norway has been greatly criticised by the international community for the politics of Norwegianization of and discrimination against the indigenous population of the country.[143] Nevertheless, Norway was, in 1990, the first country to recognise ILO-convention 169 on indigenous people recommended by the UN.

Norway was the first country in the world to enact an anti-discrimination law protecting the rights of gay men and lesbians. In 1993, Norway became the second country to legalise civil union partnerships for same-sex couples, and on 1 January 2009, Norway became the sixth country to legalise same-sex marriage.[144] As a promoter of human rights, Norway has held the annual Oslo Freedom Forum conference, a gathering described by The Economist as "on its way to becoming a human-rights equivalent of the Davos economic forum".[145]

Foreign relations

Norway maintains embassies in 82 countries.[146] 60 countries maintain an embassy in Norway, all of them in the capital, Oslo.

Norway is a founding member of the United Nations (UN), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the Council of Europe and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). Norway issued applications for accession to the European Union (EU) and its predecessors in 1962, 1967 and 1992, respectively. While Denmark, Sweden and Finland obtained membership, the Norwegian electorate rejected the treaties of accession in referendums in 1972 and 1994.

After the 1994 referendum, Norway maintained its membership in the European Economic Area (EEA), granting the country access to the internal market of the Union, on the condition that Norway implements the Union's pieces of legislation which are deemed relevant.[147] Successive Norwegian governments have, since 1994, requested participation in parts of the EU's co-operation that go beyond the provisions of the EEA agreement. Non-voting participation by Norway has been granted in, for instance, the Union's Common Security and Defence Policy, the Schengen Agreement, and the European Defence Agency, as well as 19 separate programmes.[148]

Norway participated in the 1990s brokering of the Oslo Accords, an unsuccessful attempt to resolve the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

Military

The Norwegian Armed Forces numbers about 25,000 personnel, including civilian employees. According to 2009 mobilisation plans, full mobilisation produces approximately 83,000 combatant personnel. Norway has conscription (including 6–12 months of training);[149] in 2013, the country became the first in Europe and NATO to draft women as well as men. However, due to less need for conscripts after the Cold War, few people have to serve if they are not motivated.[150] The Armed Forces are subordinate to the Norwegian Ministry of Defence. The Commander-in-Chief is King Harald V. The military of Norway is divided into the Norwegian Army, the Royal Norwegian Navy, the Royal Norwegian Air Force, the Norwegian Cyber Defence Force and the Home Guard.

The country was one of the founding nations of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on 4 April 1949. Norway contributed in the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan.[151] Additionally, Norway has contributed in several missions in contexts of the United Nations, NATO, and the Common Security and Defence Policy of the European Union.

Economy

Norwegians enjoy the second-highest GDP per capita among European countries (after Luxembourg), and the sixth-highest GDP (PPP) per capita in the world. Norway ranks as the second-wealthiest country in monetary value, with the largest capital reserve per capita of any nation.[152] According to the CIA World Factbook, Norway is a net external creditor of debt.[93] Norway reclaimed first place in the world in the UNDP Human Development Index (HDI) in 2009.[153] The standard of living in Norway is among the highest in the world. Foreign Policy magazine ranks Norway last in its Failed States Index for 2009 and 2023, judging Norway to be the world's most well-functioning and stable country. The OECD ranks Norway fourth in the 2013 equalised Better Life Index and third in intergenerational earnings elasticity according to a 2010 study.[154][155]

The Norwegian economy is an example of a mixed economy; a prosperous capitalist welfare state, it features a combination of free market activity and large state ownership in certain key sectors, influenced by both liberal governments from the late 19th century and later by social democratic governments in the postwar era.[citation needed] Public healthcare in Norway is free (after an annual charge of around 2000 kroner for those over 16), and parents have 46 weeks paid[156] parental leave. The state income derived from natural resources includes a significant contribution from petroleum production. As of 2016[update], Norway has an unemployment rate of 4.8%, with 68% of the population aged 15–74 employed.[157] People in the labour force are either employed or looking for work.[158] As of 2013[update], 9.5% of the population aged 18–66 receive a disability pension[159] and 30% of the labour force are employed by the government, the highest in the OECD.[160] The hourly productivity levels, as well as average hourly wages in Norway, are among the highest in the world.[161][162]

The egalitarian values of Norwegian society have kept the wage difference between the lowest paid worker and the CEO of most companies as much less than in comparable western economies.[163] This is also evident in Norway's low Gini coefficient.

The state has large ownership positions in key industrial sectors, such as the strategic petroleum sector (Equinor), hydroelectric energy production (Statkraft), aluminium production (Norsk Hydro), the largest Norwegian bank (DNB), and telecommunication provider (Telenor). Through these big companies, the government controls approximately 30% of the stock values at the Oslo Stock Exchange. [citation needed] When non-listed companies are included, the state has even higher share in ownership (mainly from direct oil licence ownership).[citation needed] Norway is a major shipping nation and has the world's sixth largest merchant fleet, with 1,412 Norwegian-owned merchant vessels.[citation needed]

By referendums in 1972 and 1994, Norwegians rejected proposals to join the European Union (EU). However, Norway, together with Iceland and Liechtenstein, participates in the European Union's single market through the European Economic Area (EEA) agreement. The EEA Treaty between the European Union countries and the EFTA countries—transposed into Norwegian law via "EØS-loven"[164]—describes the procedures for implementing European Union rules in Norway and the other EFTA countries. Norway is a highly integrated member of most sectors of the EU internal market. Some sectors, such as agriculture, oil and fish, are not wholly covered by the EEA Treaty. Norway has also acceded to the Schengen Agreement and several other intergovernmental agreements among the EU member states.

The country is richly endowed with natural resources including petroleum, hydropower, fish, forests, and minerals. Large reserves of petroleum and natural gas were discovered in the 1960s, which led to an economic boom.[citation needed] Norway has obtained one of the highest standards of living in the world in part by having a large amount of natural resources compared to the size of the population.[citation needed] In 2011, 28% of state revenues were generated from the petroleum industry.[165][failed verification]

Norway was the first country to ban deforestation, with a view to preventing its rain forests from vanishing. The country declared its intention at the UN Climate Summit in 2014 alongside Great Britain and Germany.[166]

Resources

Oil industry

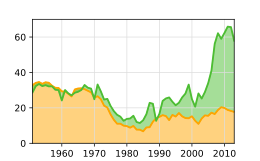

Export revenues from oil and gas have risen to over 40% of total exports and constitute almost 20% of the GDP.[167] Norway is the fifth-largest oil exporter and third-largest gas exporter in the world, but it is not a member of OPEC. In 1995, the Norwegian government established the sovereign wealth fund ("Government Pension Fund – Global") to be funded with oil revenues.

The government controls its petroleum resources through a combination of state ownership in major operators in the oil fields (with approximately 62% ownership in Equinor in 2007) and the fully state-owned Petoro, which has a market value of about twice Equinor, and SDFI. Finally, the government controls licensing of exploration and production of fields. The fund invests in developed financial markets outside Norway. Spending from the fund is constrained by the budgetary rule (Handlingsregelen), which limits spending over time to no more than the real value yield of the fund, lowered in 2017 to 3% of the fund's total value.[168]

Between 1966 and 2013, Norwegian companies drilled 5,085 oil wells, mostly in the North Sea.[169] Oil fields not yet in the production phase include: Wisting Central—calculated size in 2013 at 65–156 million barrels of oil and 10 to 40 billion cubic feet (0.28 to 1.13 billion cubic metres), (utvinnbar) of gas.[170] and the Castberg Oil Field (Castberg-feltet[170])—calculated size at 540 million barrels of oil, and 2 to 7 billion cubic feet (57 to 198 million cubic metres) (utvinnbar) of gas.[171] Both oil fields are located in the Barents Sea.

Norway is also the world's second-largest exporter of fish (in value, after China).[172][173] Fish from fish farms and catch constitutes the second largest (behind oil/natural gas) export product measured in value.[174][175] Norway is the world's largest producer of salmon, followed by Chile.[176]

Hydroelectric plants generate roughly 98–99% of Norway's electric power, more than any other country in the world.[177]

Norway contains significant mineral resources, and in 2013, its mineral production was valued at US$1.5 billion (Norwegian Geological Survey data). The most valuable minerals are calcium carbonate (limestone), building stone, nepheline syenite, olivine, iron, titanium, and nickel.[178]

In 2017, the Government Pension Fund controlled assets surpassed a value of US$1 trillion (equal to US$190,000 per capita),[179] about 250% of Norway's 2017 GDP.[180] It is the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world.[181]

Other nations with economies based on natural resources, such as Russia, are trying to learn from Norway by establishing similar funds. The investment choices of the Norwegian fund are directed by ethical guidelines; for example, the fund is not allowed to invest in companies that produce parts for nuclear weapons. Norway's highly transparent investment scheme[182] is lauded by the international community.[183]

Transport

Due to the low population density, narrow shape and long coastlines of Norway, its public transport is less developed than in many European countries, especially outside the major cities. The country has long-standing water transport traditions, but the Norwegian Ministry of Transport and Communications has in recent years implemented rail, road, and air transport through numerous subsidiaries to develop the country's infrastructure.[184] Under discussion is development of a new high-speed rail system between the nation's largest cities.[185][186]

Norway's main railway network consists of 4,114 kilometres (2,556 mi) of standard gauge lines, of which 242 kilometres (150 mi) is double track and 64 kilometres (40 mi) high-speed rail (210 km/h) while 62% is electrified at 15 kV 16.7 Hz AC. The railways transported 56,827,000 passengers 2,956 million passenger-kilometres and 24,783,000 tonnes of cargo 3,414 million tonne-kilometres.[187] The entire network is owned by Bane NOR.[188] All domestic passenger trains except the Airport Express Train are operated by Norges Statsbaner (NSB).[189] Several companies operate freight trains.[190]Investment in new infrastructure and maintenance is financed through the state budget,[191] and subsidies are provided for passenger train operations.[192] NSB operates long-haul trains, including night trains, regional services and four commuter train systems, around Oslo, Trondheim, Bergen and Stavanger.[193]

Norway has approximately 92,946 kilometres (57,754 mi) of road network, of which 72,033 kilometres (44,759 mi) are paved and 664 kilometres (413 mi) are motorway.[93] The four tiers of road routes are national, county, municipal and private, with national and primary county roads numbered en route. The most important national routes are part of the European route scheme. The two most prominent are the European route E6 going north–south through the entire country, and the E39, which follows the West Coast. National and county roads are managed by the Norwegian Public Roads Administration.[194]

Norway has the world's largest registered stock of plug-in electric vehicles per capita.[195][196][197] In March 2014, Norway became the first country where over 1 in every 100 passenger cars on the roads is a plug-in electric.[198] The plug-in electric segment market share of new car sales is also the highest in the world.[199] According to a report by Dagens Næringsliv in June 2016, the country would like to ban sales of gasoline and diesel powered vehicles as early as 2025.[200]

Of the 98 airports in Norway,[93] 52 are public,[201] and 46 are operated by the state-owned Avinor.[202] Seven airports have more than one million passengers annually.[201] A total of 41,089,675 passengers passed through Norwegian airports in 2007, of whom 13,397,458 were international.[201]

The central gateway to Norway by air is Oslo Airport, Gardermoen.[201] Located about 35 kilometres (22 mi) northeast of Oslo, it is hub for the two major Norwegian airlines: Scandinavian Airlines[203] and Norwegian Air Shuttle,[204] and for regional aircraft from Western Norway.[205] There are departures to most European countries and some intercontinental destinations.[206][207] A direct high-speed train connects to Oslo Central Station every 10 minutes for a 20 min ride.

Research

Internationally recognised Norwegian scientists include the mathematicians Niels Henrik Abel and Sophus Lie. Caspar Wessel was the first to describe vectors and complex numbers in the complex plane. Ernst S. Selmer's advanced research lead to the modernisation of crypto-algorithms. Thoralf Skolem made revolutionary contributions to mathematical logic. Øystein Ore and Ludwig Sylow made important contributions in group theory. Atle Selberg was one of the most significant mathematicians of the 20th century, for which he was awarded a Fields Medal, Wolf Prize and Abel Prize.

Other scientists include the physicists Ægidius Elling, Ivar Giaever, Carl Anton Bjerknes, Christopher Hansteen, William Zachariasen and Kristian Birkeland, the neuroscientists May-Britt Moser and Edvard Moser, and the chemists Lars Onsager, Odd Hassel, Peter Waage, Erik Rotheim, and Cato Maximilian Guldberg. Mineralogist Victor Goldschmidt is considered to be one of two founders of modern geochemistry. The meteorologists Vilhelm Bjerknes and Ragnar Fjørtoft played a central role in the history of numerical weather prediction. Web pioneer Håkon Wium Lie developed Cascading Style Sheets. Pål Spilling participated in the development of the Internet Protocol and brought the Internet to Europe.[208] Computer scientists Ole-Johan Dahl and Kristen Nygaard are considered to be the fathers of the tremendously influential Simula and object-oriented programming, for which they were awarded a Turing Award.

In the 20th century, Norwegian academics have been pioneering in many social sciences, including criminology, sociology and peace and conflict studies. Prominent academics include Arne Næss, a philosopher and founder of deep ecology; Johan Galtung, the founder of peace studies; Nils Christie and Thomas Mathiesen, criminologists; Fredrik Barth, a social anthropologist; Vilhelm Aubert, Harriet Holter and Erik Grønseth, sociologists; Tove Stang Dahl, a pioneer of women's law; Stein Rokkan, a political scientist; and Ragnar Frisch, Trygve Haavelmo, and Finn E. Kydland, economists.

The Kingdom of Norway has produced thirteen Nobel laureates. Norway was ranked 19th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[209]

Tourism

In 2008, Norway ranked 17th in the World Economic Forum's Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report.[210] Tourism in Norway contributed to 4.2% of the gross domestic product as reported in 2016.[211] Every one in fifteen people throughout the country work in the tourism industry.[211] Tourism is seasonal in Norway, with more than half of total tourists visiting between the months of May and August.[211]

The main attractions of Norway are the varied landscapes that extend across the Arctic Circle. It is famous for its coastline and its mountains, ski resorts, lakes and woods. Popular tourist destinations in Norway include Oslo, Ålesund, Bergen, Stavanger, Trondheim, Kristiansand, Arendal, Tromsø, Fredrikstad and Tønsberg. Much of the nature of Norway remains unspoiled, and thus attracts numerous hikers and skiers. The fjords, mountains and waterfalls in Western and Northern Norway attract several hundred thousand foreign tourists each year. In the cities, cultural idiosyncrasies such as the Holmenkollen ski jump in Oslo and Saga Oseberg in Tønsberg attract many visitors, as do landmarks such as Bryggen in Bergen, Vigeland installation in Frogner Park in Oslo, Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim, Fredrikstad Fortress (Gamlebyen) in Fredrikstad and the ruin park of Tønsberg Fortress in Tønsberg.

Demographics

Population

Norway's population was 5,384,576 people in the third quarter of 2020.[212] Norwegians are an ethnic North Germanic people. The total fertility rate (TFR) in 2018 was estimated at 1.56 children born per woman,[213] below the replacement rate of 2.1, it remains considerably below the high of 4.69 children born per woman in 1877.[214] In 2018 the median age of the Norwegian population was 39.3 years.

In 2012, an official study showed that 86%[215] of the total population have at least one parent who was born in Norway. In 2020 approximately 980,000 individuals (18.2%) were immigrants and their descendants.[216] Among these approximately 189,000 are children of immigrants, born in Norway.[216]

Of these 980,000 immigrants and their descendants:

- 485,500 (49.5%)[217] have a Western background (Europe, US, Canada and Oceania).

- 493,700 (50.5%)[217] have a non-Western background (Asia, Africa, South and Central America).

In 2013, about 6% of the population are immigrants from EU, North America and Australia, and about 8.1% come from Asia, Africa and Latin America.[218] In 2012, of the total 660,000 with immigrant background, 407,262 had Norwegian citizenship (62.2%).[219]

Immigrants have settled in all Norwegian municipalities. The cities or municipalities with the highest share of immigrants in 2012 were Oslo (32%) and Drammen (27%).[220] According to Reuters, Oslo is the "fastest growing city in Europe because of increased immigration".[221] In recent years, immigration has accounted for most of Norway's population growth. In 2018, immigrants accounted for 14.1% of Norway's population.[222]

The Sámi people are indigenous to the Far North and have traditionally inhabited central and northern parts of Norway and Sweden, as well as areas in northern Finland and in Russia on the Kola Peninsula. Another national minority are the Kven people, descendants of Finnish-speaking people who migrated to northern Norway from the 18th up to the 20th century. From the 19th century up to the 1970s, the Norwegian government tried to assimilate both the Sámi and the Kven, encouraging them to adopt the majority language, culture and religion.[223] Because of this "Norwegianization process", many families of Sámi or Kven ancestry now identify as ethnic Norwegian.[224]

The national minorities of Norway are Kvens, Jews, Forest Finns, and Romani people.[225]

In 2017, the population of Norway ranked first on the World Happiness Report.[226]

Migration

Particularly in the 19th century, when economic conditions were difficult in Norway, tens of thousands of people migrated to the United States and Canada, where they could work and buy land in frontier areas. Many went to the Midwest and Pacific Northwest. In 2006, according to the US Census Bureau, almost 4.7 million persons identified as Norwegian Americans,[227] which was larger than the population of ethnic Norwegians in Norway itself.[228] In the 2011 Canadian census, 452,705 Canadian citizens identified as having Norwegian ancestry.[229]

On 1 January 2013[update], the number of immigrants or children of two immigrants residing in Norway was 710,465, or 14.1% of the total population,[218] up from 183,000 in 1992. Yearly immigration has increased since 2005. While yearly net immigration in 2001–2005 was on average 13,613, it increased to 37,541 between 2006 and 2010, and in 2011 net immigration reached 47,032.[230] This was mostly because of increased immigration by residents of the EU, by 2012 in particular from Poland and Sweden. Pakistan and Somalia were the two other most common countries of origin for immigrants during this period.[231]

Religion

Church of Norway

Separation of church and state happened significantly later in Norway than in most of Europe, and remains incomplete. In 2012, the Norwegian parliament voted to grant the Church of Norway greater autonomy,[232] a decision which was confirmed in a constitutional amendment on 21 May 2012.[233]

Until 2012 parliamentary officials were required to be members of the Evangelical-Lutheran Church of Norway, and at least half of all government ministers had to be a member of the state church. As state church, the Church of Norway's clergy were viewed as state employees, and the central and regional church administrations were part of the state administration. Members of the Royal family are required to be members of the Lutheran church. On 1 January 2017, Norway made the church independent of the state, but retained the Church's status as the "people's church".[234][235]

Most Norwegians are registered at baptism as members of the Church of Norway. Many remain in the church to participate in the community and practices such as baptism, confirmation, marriage and burial rites. About 70.6% of Norwegians were members of the Church of Norway in 2017. In 2017, about 53.6% of all newborns were baptised and about 57.9% of all 15-year-olds were confirmed in the church.[236]

Religious affiliation

Religions in Norway (31 December 2019):[237][238][239]

According to the 2010 Eurobarometer Poll, 22% of Norwegian citizens responded that "they believe there is a God", 44% responded that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force" and 29% responded that "they don't believe there is any sort of spirit, God or life force". Five per cent gave no response.[240] In the early 1990s, studies estimated that between 4.7% and 5.3% of Norwegians attended church on a weekly basis.[241] This figure has dropped to about 2%.[242][243]

In 2010, 10% of the population was religiously unaffiliated, while another 9% were members of religious communities outside the Church of Norway.[244] Other Christian denominations total about 4.9%[244] of the population, the largest of which is the Roman Catholic Church, with 83,000 members, according to 2009 government statistics.[245] The Aftenposten (Evening Post) in October 2012 reported there were about 115,234 registered Roman Catholics in Norway; the reporter estimated that the total number of people with a Roman Catholic background may be 170,000–200,000 or higher.[246]

Others include Pentecostals (39,600),[245] the Evangelical Lutheran Free Church of Norway (19,600),[245] the United Methodist Church in Norway (11,000),[245] Baptists (9,900),[245] Eastern Orthodox (9,900),[245] Brunstad Christian Church (6,800),[245] Seventh-day Adventists (5,100),[245] Assyrians and Chaldeans, and others. The Swedish, Finnish and Icelandic Lutheran congregations in Norway have about 27,500 members in total.[245] Other Christian denominations comprise less than 1% each, including 4,000 members in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and 12,000 Jehovah's Witnesses.[245]Among non-Christian religions, Islam is the largest, with 166,861 registered members (2018), and probably fewer than 200,000 in total.[247]

Other religions comprise less than 1% each, including 819 adherents of Judaism.[248] Indian immigrants introduced Hinduism to Norway, which in 2011 has slightly more than 5,900 adherents, or 1% of non-Lutheran Norwegians.[248] Sikhism has approximately 3,000 adherents, with most living in Oslo, which has two gurdwaras. Drammen also has a sizeable population of Sikhs; the largest gurdwara in north Europe was built in Lier. There are eleven Buddhist organisations, grouped under the Buddhistforbundet organisation, with slightly over 14,000 members,[248] which make up 0.2% of the population. The Baháʼí Faith religion has slightly more than 1,000 adherents.[248] Around 1.7% (84,500) of Norwegians belong to the secular Norwegian Humanist Association.

From 2006 to 2011, the fastest-growing religious communities in Norway were Eastern Orthodox Christianity and Oriental Orthodox Christianity, which grew in membership by 80%; however, their share of the total population remains small, at 0.2%. It is associated with the immigration from Eritrea and Ethiopia, and to a lesser extent from Central and Eastern European and Middle Eastern countries. Other fast-growing religions were Roman Catholicism (78.7%), Hinduism (59.6%), Islam (48.1%), and Buddhism (46.7%).[249]

Indigenous religions

As in other Scandinavian countries, the ancient Norse followed a form of Germanic paganism known as Norse paganism. By the end of the 11th century, when Norway had been Christianised, the indigenous Norse religion and practices were prohibited. Remnants of the native religion and beliefs of Norway survive today in the form of names, referential names of cities and locations, the days of the week, and everyday language. Modern interest in the old ways has led to a revival of pagan religious practices in the form of Åsatru. The Norwegian Åsatrufellesskapet Bifrost formed in 1996; in 2011, the fellowship had about 300 members. Foreningen Forn Sed was formed in 1999 and has been recognised by the Norwegian government.

The Sámi minority retained their shamanistic religion well into the 18th century, when most converted to Christianity under the influence of Dano-Norwegian Lutheran missionaries. Today there is a renewed appreciation for the Sámi traditional way of life, which has led to a revival of Noaidevuohta.[250] Some Norwegian and Sámi celebrities are reported to visit shamans for guidance.[251][252]

Health

Norway was awarded first place according to the UN's Human Development Index (HDI) for 2013.[253] From the 1900s, improvements in public health occurred as a result of development in several areas such as social and living conditions, changes in disease and medical outbreaks, establishment of the health care system, and emphasis on public health matters. Vaccination and increased treatment opportunities with antibiotics resulted in great improvements within the Norwegian population. Improved hygiene and better nutrition were factors that contributed to improved health.

The disease pattern in Norway changed from communicable diseases to non-communicable diseases and chronic diseases as cardiovascular disease. Inequalities and social differences are still present in public health in Norway.[254]

In 2013 the infant mortality rate was 2.5 per 1,000 live births among children under the age of one. For girls it was 2.7 and for boys 2.3, which is the lowest infant mortality rate for boys ever recorded in Norway.[255]

Education

Higher education in Norway is offered by a range of seven universities, five specialised colleges, 25 university colleges as well as a range of private colleges. Education follows the Bologna Process involving Bachelor (3 years), Master (2 years) and PhD (3 years) degrees.[256] Acceptance is offered after finishing upper secondary school with general study competence.

Public education is virtually free for citizens from EU/EEA and Switzerland, but other nationalities need to pay tuition fees.[257][258][259] Higher education has historically been free for everyone regardless of nationality, but tuition fees for all students from outside EU/EEA and Switzerland was implemented in 2023.[260][261]

The academic year has two semesters, from August to December and from January to June. The ultimate responsibility for the education lies with the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research.

Languages

Norwegian in its two forms, Bokmål and Nynorsk, is the main national official language of all of Norway. Sámi, a group which includes three separate languages, is recognised as a minority language on the national level and is a co-official language alongside Norwegian in the Sámi administrative linguistic area (Forvaltningsområdet for samisk språk) in Northern Norway.[1] Kven is a minority language and is a co-official language alongside Norwegian in one municipality, also in Northern Norway.[262][263][264]

Norwegian