Центральный парк

| Центральный парк | |

|---|---|

Вид с воздуха на южную часть Центрального парка в сентябре 2014 г. | |

| |

| Тип | Городской парк |

| Расположение | Манхэттен , Нью-Йорк, Нью-Йорк, США |

| Координаты | 40 ° 46'56 "с.ш. 73 ° 57'55" з.д. / 40,78222 ° с.ш. 73,96528 ° з.д. |

| Область | 843 акра (341 га; 1317 квадратных миль; 3,41 км ) 2 ) |

| Созданный | 1857–1876 |

| Владелец | Парки Нью-Йорка |

| Управляется | Охрана Центрального парка |

| Посетители | около 42 миллионов ежегодно |

| Открыть | с 6:00 до 1:00 утра |

| Доступ к общественному транспорту | Метро и автобус; см. «Общественный транспорт» |

| Архитектор | Фредерик Лоу Олмстед (1822–1903), Калверт Во (1824–1895) |

| Номер ссылки NRHP . | 66000538 |

| NYSRHP . Номер | 06101.000663 |

| Значимые даты | |

| Добавлено в НРХП | 15 октября 1966 г. [3] |

| Назначен НХЛ | 23 мая 1963 г. |

| Назначен NYSRHP | 23 июня 1980 г. [1] |

| Назначен NYCL | 26 марта 1974 г. [2] |

Центральный парк — городской парк между Верхний Вест-Сайд и Верхний Ист-Сайд районами на Манхэттене в Нью-Йорке , который был первым ландшафтным парком в Соединенных Штатах. Это шестой по величине парк в городе , занимающий 843 акра (341 га), и самый посещаемый городской парк в Соединенных Штатах, который, по оценкам, по состоянию на 2016 год посещают 42 миллиона человек ежегодно. [update].

Создание большого парка на Манхэттене было впервые предложено в 1840-х годах, а парк площадью 778 акров (315 га) был одобрен в 1853 году. В 1858 году ландшафтные архитекторы Фредерик Лоу Олмстед и Калверт Во выиграли конкурс на дизайн парка со своей « План Гринсворда». Строительство началось в 1857 году; -Виллидж, в котором преобладают чернокожие существующие постройки, в том числе поселение Сенека , были захвачены через выдающиеся владения и снесены. Первые территории парка были открыты для публики в конце 1858 года. Дополнительная земля в северной части Центрального парка была куплена в 1859 году, а строительство парка было завершено в 1876 году. После периода упадка в начале 20 века парки Нью-Йорка комиссар Роберт Мозес начал программу по очистке Центрального парка в 1930-х годах. Организация по охране Центрального парка , созданная в 1980 году для борьбы с дальнейшим ухудшением состояния парка в конце 20-го века, начиная с 1980-х годов отремонтировала многие части парка.

Основные достопримечательности парка включают Рамбл и озеро , природный заповедник Халлетт , водохранилище Жаклин Кеннеди Онассис и Овечий луг ; развлекательные аттракционы, такие как каток Wollman Rink , карусель Центрального парка и зоопарк Центрального парка ; формальные помещения, такие как торговый центр Central Park и терраса Bethesda ; и Театр Делакорта . экосистема Биологически разнообразная насчитывает несколько сотен видов флоры и фауны. Развлекательные мероприятия включают конные и велосипедные туры, езду на велосипеде, спортивные сооружения, а также концерты и мероприятия, такие как «Шекспир в парке» . Центральный парк пересекается системой дорог и пешеходных дорожек и обслуживается общественным транспортом.

Его размер и культурное положение делают его образцом городских парков мира. Его влияние принесло Центральному парку статус Национальной исторической достопримечательности в 1963 году и живописной достопримечательности Нью-Йорка в 1974 году. Центральный парк принадлежит Департаменту парков и отдыха Нью-Йорка , но с 1998 года находится под управлением Управления охраны природы Центрального парка под управлением договор с муниципальным самоуправлением в рамках государственно-частного партнерства . Некоммерческая организация Conservancy увеличивает годовой операционный бюджет Центрального парка и отвечает за весь базовый уход за парком.

Описание

[ редактировать ]Центральный парк граничит с Северным Центральным парком на 110-й улице; Южный Центральный парк на 59-й улице; Западный Центральный парк на Восьмой авеню; и Пятая авеню на востоке. Парк примыкает к районам Гарлема на севере, Мидтауна Манхэттена на юге, Верхнего Вест-Сайда на западе и Верхнего Ист-Сайда на востоке. Его длина составляет 2,5 мили (4,0 км) с севера на юг и 0,5 мили (0,80 км) с запада на восток. [4]

Дизайн и верстка

[ редактировать ]Центральный парк разделен на три части: «Норт-Энд», простирающийся над водохранилищем Жаклин Кеннеди-Онассис ; «Мид-Парк», между водохранилищем на севере и озером и зимним садом на юге; и «Саут-Энд» ниже озера и воды в зимнем саду. [5] В парке есть пять центров для посетителей: Центр открытий Чарльза А. Даны , Замок Бельведер , Дом шахмат и шашек, Молочная ферма и Columbus Circle . [6] [7]

Парк называют первым ландшафтным парком в Соединенных Штатах. [8] Он имеет естественные насаждения и формы рельефа , почти полностью благоустроенный при строительстве в 1850-х и 1860-х годах. [9][10] It has eight lakes and ponds that were created artificially by damming natural seeps and flows.[11] There are several wooded sections, lawns, meadows, and minor grassy areas. There are 21 children's playgrounds,[12] and 6.1 miles (9.8 km) of drives.[4][13]

Central Park is the sixth-largest park in New York City, behind Pelham Bay Park, the Staten Island Greenbelt, Freshkills Park, Van Cortlandt Park, and Flushing Meadows–Corona Park,[14] with an area of 843 acres (341 ha; 1.317 sq mi; 3.41 km2).[15][16] Central Park constitutes its own United States census tract, numbered 143. According to American Community Survey five-year estimates, the park was home to four females with a median age of 19.8.[17] Though the 2010 United States Census recorded 25 residents within the census tract, park officials have rejected the claim of anyone permanently living there.[18]

Visitors

[edit]Central Park is the most visited urban park in the United States[19] and one of the most visited tourist attractions worldwide,[20] with 42 million visitors in 2016.[21] The number of unique visitors is much lower; a Central Park Conservancy report conducted in 2011 found that between eight and nine million people visited Central Park, with 37 to 38 million visits between them.[22] By comparison, there were 25 million visitors in 2009,[23] and 12.3 million in 1973.[24]

The number of tourists as a proportion of total visitors is much lower: in 2009, one-fifth of the 25 million park visitors recorded that year were estimated to be tourists.[23] The 2011 Conservancy report gave a similar ratio of park usage: only 14% of visits are by people visiting Central Park for the first time. According to the report, nearly two-thirds of visitors are regular park users who enter the park at least once weekly, and about 70% of visitors live in New York City. Moreover, peak visitation occurred during summer weekends, and most visitors used the park for passive recreational activities such as walking or sightseeing, rather than for active sport.[22]

Governance

[edit]The park is managed and maintained by the Central Park Conservancy, a private, not-for-profit organization, under contract with the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation (NYC Parks).[15] The president of the Conservancy is the ex officio administrator of Central Park who effectively oversees the work of both the park's private and public employees under the authority of the publicly appointed Central Park Administrator, who reports to both the parks commissioner and the Conservancy's president.[15] The Central Park Conservancy was founded in 1980 as a nonprofit organization with a citizen board to assist with the city's initiatives to clean up and rehabilitate the park.[25][26] The Conservancy took over the park's management duties from NYC Parks in 1998, though NYC Parks retained ownership of Central Park.[27] The conservancy provides maintenance support and staff training programs for other public parks in New York City, and has assisted with the development of new parks such as the High Line and Brooklyn Bridge Park.[28]

Central Park is patrolled by its own New York City Police Department precinct, the 22nd (Central Park) Precinct,[a] at the 86th Street transverse. The precinct employs both regular police and auxiliary officers.[30] The 22nd Precinct has a lower crime rate than in the 1990s, with crimes across all categories having decreased by 81.2% between 1990 and 2023. The precinct saw no murders, three rapes, 23 robberies, nine felony assaults, five burglaries, 48 grand larcenies, and no grand larcenies auto in 2023.[31] The citywide New York City Parks Enforcement Patrol patrols Central Park, and the Central Park Conservancy sometimes hires seasonal Parks Enforcement Patrol officers to protect certain features such as the Conservatory Garden.[32]

A free volunteer medical emergency service, the Central Park Medical Unit, operates within Central Park. The unit operates a rapid-response patrol with bicycles, ambulances, and an all-terrain vehicle. Before the unit was established in 1975, municipal EMS often took over 30 minutes to respond to incidents in the park.[33]

History

[edit]

Planning

[edit]Between 1821 and 1855, New York City's population nearly quadrupled. As the city expanded northward up Manhattan, people were drawn to the few existing open spaces, mainly cemeteries, for passive recreation. These were seen as escapes from the noise and chaotic life in the city, which at the time was almost entirely centered on Lower Manhattan.[34] The Commissioners' Plan of 1811, the outline for Manhattan's modern street grid, included several smaller open spaces but not Central Park.[35] As such, John Randel Jr. had surveyed the grounds for the construction of intersections within the modern-day park site. The only remaining surveying bolt from his survey is embedded in a rock north of the present Dairy and the 66th Street transverse, marking the location where West 65th Street would have intersected Sixth Avenue.[36][37]

Site

[edit]

By the 1840s, members of the city's elite were publicly calling for the construction of a new large park in Manhattan.[34][38] At the time, Manhattan's seventeen squares comprised a combined 165 acres (67 ha) of land, the largest of which was the 10-acre (4 ha) Battery Park at Manhattan island's southern tip.[39] These plans were endorsed in 1844 by New York Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant, and in 1851 by Andrew Jackson Downing, one of the first American landscape designers.[38][40][41]

Mayor Ambrose Kingsland, in a message to the New York City Common Council on May 5, 1851, set forth the necessity and benefits of a large new park and proposed the council move to create such a park. Kingsland's proposal was referred to the council's Committee of Lands, which endorsed the proposal. The committee chose Jones's Wood, a 160-acre (65 ha) tract of land between 66th and 75th streets on the Upper East Side, as the park's site, as Bryant had advocated for Jones Wood. The acquisition was controversial because of its location, small size relative to other potential uptown tracts, and cost.[42][43][44] A bill to acquire Jones's Wood was invalidated as unconstitutional,[45][46] so attention turned to a second site: a 750-acre (300 ha) area known as "Central Park", bounded by 59th and 106th streets between Fifth and Eighth avenues.[45][47] Croton Aqueduct Board president Nicholas Dean, who proposed the Central Park site, chose it because the Croton Aqueduct's 35-acre (14 ha), 150-million-US-gallon (570×106 L) collecting reservoir would be in the geographical center.[45][47] In July 1853, the New York State Legislature passed the Central Park Act, authorizing the purchase of the present-day site of Central Park.[48][49]

The board of land commissioners conducted property assessments on more than 34,000 lots in the area,[50] completing them by July 1855.[51] While the assessments were ongoing, proposals to downsize the plans were vetoed by mayor Fernando Wood.[51][52][53] At the time, the site was occupied by free black people and Irish immigrants who had developed a property-owning community there since 1825.[54][55] Most of the Central Park site's residents lived in small villages, such as Pigtown;[56][57] Seneca Village;[58] or in the school and convent at Mount St. Vincent's Academy.[59] Clearing began shortly after the land commission's report was released in October 1855,[50][60] and approximately 1,600 residents were evicted under eminent domain.[58][61][62] Though supporters claimed that the park would cost just $1.7 million,[63] the total cost of the land ended up being $7.39 million (equivalent to $242 million in 2023), more than the price that the United States would pay for Alaska a few years later.[64][65][66]

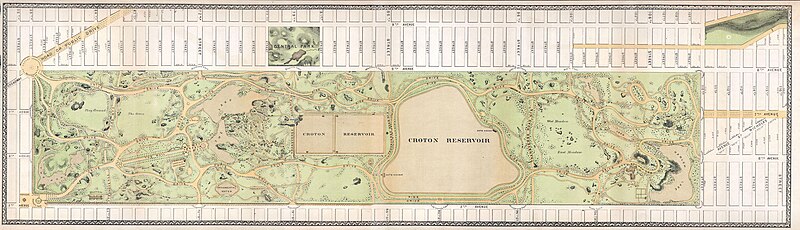

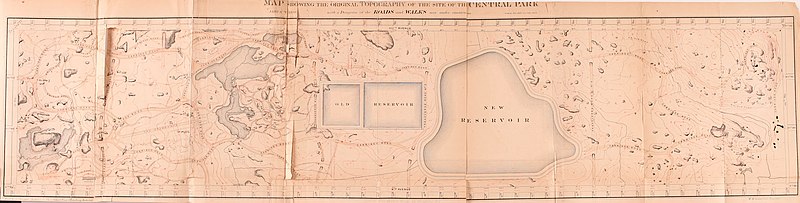

Design contest

[edit]In June 1856, Fernando Wood appointed a "consulting board" of seven people, headed by author Washington Irving, to inspire public confidence in the proposed development.[67][68] Wood hired military engineer Egbert Ludovicus Viele as the park's chief engineer, tasking him with a topographical survey of the site.[69][70][71] The following April, the state legislature passed a bill to authorize the appointment of four Democratic and seven Republican commissioners,[67][72] who had exclusive control over the planning and construction process.[73][74][75] Though Viele had already devised a plan for the park,[76] the commissioners disregarded it and retained him to complete only the topographical surveys.[77][78] The Central Park Commission began hosting a landscape design contest shortly after its creation.[78][79][80] The commission specified that each entry contain extremely detailed specifications, as mandated by the consulting board.[80][81][82] Thirty-three firms or organizations submitted plans.[80][81]

In April 1858, the park commissioners selected Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux's "Greensward Plan" as the winning design.[83][84][85] Three other plans were designated as runners-up and featured in a city exhibit.[84][86] Unlike many of the other designs, which effectively integrated Central Park with the surrounding city, Olmsted and Vaux's proposal introduced clear separations with sunken transverse roadways.[87][88] The plan eschewed symmetry, instead opting for a more picturesque design.[87][89] It was influenced by the pastoral ideals of landscaped cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Green-Wood in Brooklyn.[88][90] The design was also inspired by Olmsted's 1850 visit to Birkenhead Park in Birkenhead, England,[91] which is generally acknowledged as the first publicly funded civil park in the world.[92][93][94] According to Olmsted, the park was "of great importance as the first real Park made in this country—a democratic development of the highest significance".[89][95]

Construction

[edit]Construction of Central Park's design was executed by a gamut of professionals. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux were the primary designers, assisted by board member Andrew Haswell Green, architect Jacob Wrey Mould, master gardener Ignaz Anton Pilat, and engineer George E. Waring Jr.[96][97] Olmsted was responsible for the overall plan, while Vaux designed some of the finer details. Mould, who worked frequently with Vaux, designed the Central Park Esplanade and the Tavern on the Green building.[98] Pilat was the park's chief landscape architect, whose primary responsibility was the importation and placement of plants within the park.[98][99] A "corps" of construction engineers and foremen, managed by superintending engineer William H. Grant, were tasked with the measuring and constructing architectural features such as paths, roads, and buildings.[100][101] Waring was one of the engineers working under Grant's leadership and was in charge of land drainage.[102][103]

Central Park was difficult to construct because of the generally rocky and swampy landscape.[9] Around five million cubic feet (140,000 m3) of soil and rocks had to be transported out of the park, and more gunpowder was used to clear the area than was used at the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War.[10] More than 18,500 cubic yards (14,100 m3) of topsoil were transported from Long Island and New Jersey, because the original soil was neither fertile nor sufficiently substantial to sustain the flora specified in the Greensward Plan.[9][10] Modern steam-powered equipment and custom tree-moving machines augmented the work of unskilled laborers.[10] In total, over 20,000 individuals helped construct Central Park.[10] Because of extreme precautions taken to minimize collateral damage, five laborers died during the project, at a time when fatality rates were generally much higher.[104]

During the development of Central Park, Superintendent Olmsted hired several dozen mounted police officers, who were classified into two types of "keepers": park keepers and gate keepers.[9][105][106] The mounted police were viewed favorably by park patrons and were later incorporated into a permanent patrol.[9] The regulations were sometimes strict.[106] For instance, prohibited actions included games of chance, speech-making, large congregations such as picnics, or picking flowers or other parts of plants.[106][107][108] These ordinances were effective: by 1866, there had been nearly eight million visits and only 110 arrests in the park's history.[109]

Late 1850s

[edit]

In late August 1857, workers began building fences, clearing vegetation, draining the land, and leveling uneven terrain.[110][111] By the following month, chief engineer Viele reported that the project employed nearly 700 workers.[111] Olmsted employed workers using day labor, hiring men directly without any contracts and paying them by the day.[100] Many of the laborers were Irish immigrants or first-or-second generation Irish Americans, and some Germans and Italians;[112] there were no black or female laborers.[113][114] The workers were often underpaid,[114][115] and workers would often take jobs at other construction projects to supplement their income.[116] A pattern of seasonal hiring was established, wherein more workers would be hired and paid at higher rates during the summers.[114]

For several months, the park commissioners faced funding issues,[74][117] and a dedicated workforce and funding stream was not secured until June 1858.[74] The landscaped Upper Reservoir was the only part of the park that the commissioners were not responsible for constructing; instead, the Reservoir would be built by the Croton Aqueduct board. Work on the Reservoir started in April 1858.[118] The first major work in Central Park involved grading the driveways and draining the land in the park's southern section.[119][120] The Lake in Central Park's southwestern section was the first feature to open to the public, in December 1858,[121] followed by the Ramble in June 1859.[104][122] The same year, the New York State Legislature authorized the purchase of an additional 65 acres (26 ha) at the northern end of Central Park, from 106th to 110th Streets.[121][123] The section of Central Park south of 79th Street was mostly completed by 1860.[124]

The park commissioners reported in June 1860 that $4 million had been spent on the construction to date.[125] As a result of the sharply rising construction costs, the commissioners eliminated or downsized several features in the Greensward Plan.[126] Based on claims of cost mismanagement, the New York State Senate commissioned the Swiss engineer Julius Kellersberger to write a report on the park.[127] Kellersberger's report, submitted in 1861, stated that the commission's management of the park was a "triumphant success".[128][129]

1860s

[edit]

Olmsted often clashed with the park commissioners, notably with Chief Commissioner Green.[126][130] Olmsted resigned in June 1862, and Green was appointed to Olmsted's position.[131][132] Vaux resigned in 1863 because of what he saw as pressure from Green.[133] As superintendent of the park, Green accelerated construction, though having little experience in architecture.[131] He implemented a style of micromanagement, keeping records of the smallest transactions in an effort to reduce costs.[130][134] Green finalized the negotiations to purchase the northernmost 65 acres (26 ha) of the park which was later converted into a "rugged" woodland and the Harlem Meer waterway.[131][134]

When the American Civil War began in 1861, the park commissioners decided to continue building Central Park, since significant parts of the park had already been completed.[135] Only three major structures were completed during the Civil War: the Music Stand and the Casino restaurant, both later demolished, and the Bethesda Terrace and Fountain.[136] By late 1861, the park south of 72nd Street had been completed, except for various fences.[137] Work had begun on the northern section of the park but was complicated by a need to preserve the historic McGowan's Pass.[138] The Upper Reservoir was completed the following year.[139]

During this period Central Park began to gain popularity.[135] One of the main attractions was the "Carriage Parade", a daily display of horse-drawn carriages that traversed the park.[135][140][141] Park patronage grew steadily: by 1867, Central Park accommodated nearly three million pedestrians, 85,000 horses, and 1.38 million vehicles annually.[135] The park had activities for New Yorkers of all social classes. While the wealthy could ride horses on bridle paths or travel in horse-drawn carriages, almost everyone was able to participate in sports such as ice-skating or rowing, or listen to concerts at the Mall's bandstand.[142]

Olmsted and Vaux were re-hired in mid-1865.[143] Several structures were erected, including the Children's District, the Ballplayers House, and the Dairy in the southern part of Central Park. Construction commenced on Belvedere Castle, Harlem Meer, and structures on Conservatory Water and the Lake.[136][144]

1870–1876: completion

[edit]

The Tammany Hall political machine, which was the largest political force in New York at the time, was in control of Central Park for a brief period beginning in April 1870.[145] A new charter created by Tammany boss William M. Tweed abolished the old 11-member commission and replaced it with one with five men composed of Green and four other Tammany-connected figures.[145][146] Subsequently, Olmsted and Vaux resigned again from the project in November 1870.[145] After Tweed's embezzlement was publicly revealed in 1871, leading to his imprisonment, Olmsted and Vaux were re-hired, and the Central Park Commission appointed new members who were mostly in favor of Olmsted.[147]

One of the areas that remained relatively untouched was the underdeveloped western side of Central Park, though some large structures would be erected in the park's remaining empty plots.[148] By 1872, Manhattan Square had been reserved for the American Museum of Natural History, founded three years before at the Arsenal. A corresponding area on the East Side, originally intended as a playground, would later become the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[148][149] In the final years of Central Park's construction, Vaux and Mould designed several structures for Central Park. The park's sheepfold (now Tavern on the Green) and Ladies' Meadow were designed by Mould in 1870–1871, followed by the administrative offices on the 86th Street transverse in 1872.[150] Even though Olmsted and Vaux's partnership was dissolved by the end of 1872,[151] the park was not officially completed until 1876.[152]

Late 19th and early 20th centuries: first decline

[edit]

By the 1870s, the park's patrons increasingly came to include the middle and working class, and strict regulations were gradually eased, such as those against public gatherings.[153] Because of the heightened visitor count, neglect by the Tammany administration, and budget cuts demanded by taxpayers, the maintenance expenses for Central Park had reached a nadir by 1879.[107][154] Olmsted blamed politicians, real estate owners, and park workers for Central Park's decline, though high maintenance costs were also a factor.[155] By the 1890s, the park faced several challenges: cars were becoming commonplace, and with the proliferation of amusements and refreshment stands, people were beginning to see the park as a recreational attraction.[156][157] The 1904 opening of the New York City Subway displaced Central Park as the city's predominant leisure destination, as New Yorkers could travel to farther destinations such as Coney Island beaches or Broadway theaters for a five-cent fare.[158]

In the late 19th century the landscape architect Samuel Parsons took the position of New York City parks superintendent. A onetime apprentice of Calvert Vaux,[159] Parsons helped restore the nurseries of Central Park in 1886.[160] Parsons closely followed Olmsted's original vision for the park, restoring Central Park's trees while blocking the placement of several large statues in the park.[161] Under Parsons' leadership, two circles (now Duke Ellington and Frederick Douglass Circles) were constructed at the northern corners of the park.[162][163] He was removed in May 1911 following a lengthy dispute over whether an expense to replace the soil in the park was unnecessary.[161][164] A succession of Tammany-affiliated Democratic mayors were indifferent toward Central Park.[165]

Several park advocacy groups were formed in the early 20th century. To preserve the park's character, the citywide Parks and Playground Association, and a consortium of multiple Central Park civic groups operating under the Parks Conservation Association, were formed in the 1900s and 1910s.[166] These associations advocated against such changes to the park as the construction of a library,[167] sports stadium,[168] a cultural center,[169] and an underground parking lot.[170] A third group, the Central Park Association, was created in 1926.[166] The Central Park Association and the Parks and Playgrounds Association were merged into the Park Association of New York City two years later.[171]

The Heckscher Playground—named after philanthropist August Heckscher, who donated the play equipment—opened near its southern end in 1926,[172][173] and quickly became popular with poor immigrant families.[173] The following year, Mayor Jimmy Walker commissioned landscape designer Hermann W. Merkel to create a plan to improve Central Park.[165] Merkel's plans would combat vandalism and plant destruction, rehabilitate paths, and add eight new playgrounds, at a cost of $1 million.[174][175] One of the suggested modifications, underground irrigation pipes, were installed soon after Merkel's report was submitted.[165][176] The other improvements outlined in the report, such as fences to mitigate plant destruction, were postponed due to the Great Depression.[177]

1930s to 1950s: Moses rehabilitation

[edit]In 1934, Republican Fiorello La Guardia was elected mayor of New York City. He unified the five park-related departments then in existence. Newly appointed city parks commissioner Robert Moses was given the task of cleaning up the park, and he summarily fired many of the Tammany-era staff.[178] At the time, the lawns were filled with weeds and dust patches, while many trees were dying or already dead. Monuments had been vandalized, equipment and walkways were broken, and ironwork was rusted.[178][179] Moses's biographer Robert Caro later said, "The once beautiful Mall looked like a scene of a wild party the morning after. Benches lay on their backs, their legs jabbing at the sky..."[179]

During the following year, the city's parks department replanted lawns and flowers, replaced dead trees and bushes, sandblasted walls, repaired roads and bridges, and restored statues.[180][181][182] The park menagerie was transformed into the modern Central Park Zoo, and a rat extermination program was instituted within the zoo.[181] Another dramatic change was Moses' removal of the "Hoover valley" shantytown at the north end of Turtle Pond, which became the 30-acre (12 ha) Great Lawn.[180][182] The western part of the Pond at the park's southeast corner became an ice skating rink called Wollman Rink,[181] roads were improved or widened,[183] and twenty-one playgrounds were added.[182] These projects used funds from the New Deal program, and donations from the public.[182] Moses removed Sheep Meadow's sheep to make way for the Tavern on the Green restaurant.[183][184]

Renovations in the 1940s and 1950s include a restoration of the Harlem Meer completed in 1943,[185] and a new boathouse completed in 1954.[186][187][188] Moses began construction on several other recreational features in Central Park, such as playgrounds and ball fields.[189] One of the more controversial projects proposed during this time was a 1956 dispute over a parking lot for Tavern in the Green. The controversy placed Moses, an urban planner known for displacing families for other large projects around the city, against a group of mothers who frequented a wooded hollow at the site of a parking lot.[189][190] Though opposed by the parents, Moses approved the destruction of part of the hollow. Demolition work commenced after Central Park was closed for the night and was only halted after the threat of a lawsuit.[189][191]

1960s and 1970s: "Events Era" and second decline

[edit]Moses left his position in May 1960. No park commissioner since then has been able to exercise the same degree of power, nor did NYC Parks remain in as stable a position in the aftermath of his departure. Eight commissioners held the office in the twenty years following his departure.[192] The city experienced economic and social changes, with some residents moving to the suburbs.[193][194] Interest in Central Park's landscape had long since declined, and it was now mostly being used for recreation.[195] Several unrealized additions were proposed for Central Park in that decade, such as a public housing development,[196] a golf course,[197] and a "revolving world's fair".[198]

The 1960s marked the beginning of an "Events Era" in Central Park that reflected the widespread cultural and political trends of the period.[199] The Public Theater's annual Shakespeare in the Park festival was settled in the Delacorte Theater,[200] and summer performances were instituted on the Sheep Meadow and the Great Lawn by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and the Metropolitan Opera.[201] During the late 1960s, the park became the venue for rallies and cultural events such as the "love-ins" and "be-ins" of the period.[202] The same year, Lasker Rink opened in the northern part of the park; the facility served as an ice rink in winter and Central Park's only swimming pool in summer.[203]

By the mid-1970s, managerial neglect resulted in a decline in park conditions. A 1973 report noted that the park suffered from severe erosion and tree decay, and that individual structures were being vandalized or neglected.[204] The Central Park Community Fund was subsequently created based on the recommendation of a report from a Columbia University professor.[205] The Fund then commissioned a study of the park's management and suggested the appointment of both a NYC Parks administrator and a board of citizens.[206] In 1979, Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis established the Office of Central Park Administrator and appointed Elizabeth Barlow, the executive director of the Central Park Task Force, to the position.[207][208] The Central Park Conservancy, a nonprofit organization with a citizen board, was founded the following year.[25][26]

1970s to 2000s: restoration

[edit]Under the leadership of the Central Park Conservancy, the park's reclamation began by addressing needs that could not be met within NYC Parks' existing resources. The Conservancy hired interns and a small restoration staff to reconstruct and repair unique rustic features, undertaking horticultural projects, and removing graffiti under the broken windows theory which advocated removing visible signs of decay.[209] The first structure to be renovated was the Dairy, which reopened as the park's first visitor center in 1979.[210] The Sheep Meadow, which reopened the following year, was the first landscape to be restored.[211] Bethesda Terrace and Fountain, the USS Maine National Monument, and the Bow Bridge were also rehabilitated.[212][213][214] By then, the Conservancy was engaged in design efforts and long-term restoration planning,[215] and in 1981, Davis and Barlow announced a 10-year, $100 million "Central Park Management and Restoration Plan".[214] The long-closed Belvedere Castle was renovated and reopened in 1983,[216][217] while the Central Park Zoo closed for a full reconstruction that year.[208][215] To reduce the maintenance effort, large gatherings such as free concerts were canceled.[218]

On completion of the planning stage in 1985, the Conservancy launched its first campaign[194] and mapped out a 15-year restoration plan.[219] Over the next several years, the campaign restored landmarks in the southern part of the park, such as Grand Army Plaza[220] and the police station at the 86th Street transverse;[221] while Conservatory Garden in the northeastern corner of the park was restored to a design by Lynden B. Miller.[222][223][224] Real estate developer Donald Trump renovated the Wollman Rink in 1987 after plans to renovate it were delayed repeatedly.[225] The following year, the Zoo reopened after a $35 million, four-year renovation.[226]

Work on the northern end of the park began in 1989.[227] A$51 million campaign, announced in 1993,[228] resulted in the restoration of bridle trails,[229] the Mall,[230] the Harlem Meer,[231] and the North Woods,[227] and the construction of the Dana Discovery Center on the Harlem Meer.[231] This was followed by the Conservancy's overhaul of the 55 acres (22 ha) near the Great Lawn and Turtle Pond, which was completed in 1997.[232] The Upper Reservoir was decommissioned as a part of the city's water supply system in 1993,[233][234] and was renamed after former U.S. first lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis the next year.[233][235] During the mid-1990s, the Conservancy hired additional volunteers and implemented a zone-based system of management throughout the park.[194] The Conservancy assumed much of the park's operations in early 1998.[27]

Renovations continued through the first decade of the 21st century, and a project to restore the pond was commenced in 2000.[236] Four years later, the Conservancy replaced a chain-link fence with a replica of the original cast-iron fence that surrounded the Upper Reservoir.[237] It started refurbishing the ceiling tiles of the Bethesda Arcade,[238] which was completed in 2007.[239] Soon after, the Central Park Conservancy began restoring the Ramble and Lake,[240] in a project that was completed in 2012.[241] Bank Rock Bridge was restored,[242][243] and the Gill, which empties into the lake, was reconstructed to approximate its dramatic original form.[244] The final feature to be restored was the East Meadow, which was rehabilitated in 2011.[245]

2010s to present

[edit]In 2014, the New York City Council proposed a study on the viability of banning vehicular traffic from the park's drives.[246] The next year, mayor Bill de Blasio announced that West and East drives north of 72nd Street would be closed to vehicular traffic, because the city's data showed that closing the roads did not adversely impact traffic flows.[247] Subsequently, in June 2018, the remaining drives south of 72nd Street were closed to vehicular traffic.[248][249]

Several structures were renovated. Belvedere Castle was closed in 2018 for an extensive renovation, reopening in June 2019.[250][251][252] Later in 2018, it was announced that the Delacorte Theater would be closed from 2020 to 2022 for a $110 million rebuild.[253] The Central Park Conservancy further announced that Lasker Rink would be closed for a $150 million renovation[254] between 2021 and 2024.[255][256][257]

In March 2020, in response to the coronavirus pandemic, temporary field hospitals were set up within the park to treat overflow patients from area hospitals.[258][259] By mid-2023, the New York City government was considering erecting tents in Central Park to temporarily house asylum seekers. This move came after the federal government repealed an order authorizing Title 42 expulsions of migrants, which had been implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic.[260][261] A renovation of the Chess and Checkers House was completed in June 2023.[262] In addition, pickleball courts were added to Wollman Rink in 2023 and became permanent the next year.[263][264] The Central Park Conservancy allocated $64 million in early 2024 to fix sidewalks on 108 blocks immediately surrounding the park.[265]

Landscape features

[edit]Geology

[edit]

There are four different types of bedrock in Manhattan. In Central Park, Manhattan schist and Hartland schist, which are both metamorphosed sedimentary rock, are exposed in various outcroppings. The other two types, Fordham gneiss (an older deeper layer) and Inwood marble (metamorphosed limestone which overlays the gneiss), do not surface in the park.[266][267][268] Fordham gneiss, which consists of metamorphosed igneous rocks, was formed a billion years ago, during the Grenville orogeny that occurred during the creation of an ancient super-continent. Manhattan schist and Hartland schist were formed in the Iapetus Ocean during the Taconic orogeny in the Paleozoic era, about 450 million years ago, when the tectonic plates began to merge to form the supercontinent Pangaea.[269] Cameron's Line, a fault zone that traverses Central Park on an east–west axis, divides the outcroppings of Hartland schist to the south and Manhattan schist to the north.[270]

Various glaciers have covered the area of Central Park in the past, with the most recent being the Wisconsin glacier which receded about 12,000 years ago. Evidence of past glaciers can be seen throughout the park in the form of glacial erratics (large boulders dropped by the receding glacier) and north–south glacial striations visible on stone outcroppings.[266][271][272] Alignments of glacial erratics, called "boulder trains", are present throughout Central Park.[273] The most notable of these outcroppings is Rat Rock (also known as Umpire Rock), a circular outcropping at the southwestern corner of the park.[271][274] It measures 55 feet (17 m) wide and 15 feet (4.6 m) tall with different east, west, and north faces.[274][275] Boulderers sometimes congregate there.[275] A single glacial pothole with yellow clay is near the southwest corner of the park.[276][277]

The underground geology of Central Park was altered by the construction of several subway lines underneath it, and by the New York City Water Tunnel No. 3 approximately 700 feet (210 m) underground. Excavations for the project have uncovered pegmatite, feldspar, quartz, biotite, and several metals.[278]

Wooded areas and lawns

[edit]

There are three wooded areas in Central Park: North Woods, the Ramble, and Hallett Nature Sanctuary.[279] North Woods, the largest of the woodlands, is at the northwestern corner of Central Park.[280][281][282] It covers about 90 acres (36 ha) adjacent to North Meadow.[283] The name sometimes applies to other attractions in the park's northern end; these adjacent features plus the area of North Woods can be 200 acres (81 ha).[227] North Woods contains the 55-acre (22 ha) Ravine, a forest with deciduous trees on its northwestern slope, and the Loch, a small stream that winds diagonally through North Woods.[282][284][285]

The Ramble is in the southern third of the park next to the Lake.[5][286][287] Covering 36 to 38 acres (15 to 15 ha), it contains a series of winding paths.[287] The area contains a diverse selection of vegetation and other flora, which attracts a plethora of birds.[286][287] At least 250 species of birds have been spotted in the Ramble over the years.[287][288] Historically, the Ramble was known as a place for private homosexual encounters due to its seclusion.[289]

The Hallett Nature Sanctuary is at the southeastern corner of Central Park.[5][290][291] It is the smallest wooded area at 4 acres (1.6 ha).[292] Originally known as the Promontory, it was renamed after civic activist and birder George Hervey Hallett Jr. in 1986.[291][292][293] The Hallett Sanctuary was closed to the public from 1934 to May 2016, when it was reopened allowing limited access.[294]

The Central Park Conservancy classifies its remaining green space into four types of lawns, labeled alphabetically based on usage and the amount of maintenance needed. There are seven high-priority "A Lawns", collectively covering 65 acres (26 ha), that are heavily used: Sheep Meadow, Great Lawn, North Meadow, East Meadow, Conservatory Garden, Heckscher Ballfields, and the Lawn Bowling and Croquet Greens near Sheep Meadow. These are permanently surrounded by fences, are constantly maintained, and are closed during the off-season. Another 16 lawns, covering 37 acres (15 ha), are classed as "B Lawns" and are fenced off only during off-seasons, while an additional 69 acres (28 ha) are "C Lawns" and are only occasionally fenced off. The lowest-prioritized type of turf, "D Lawns", cover 162 acres (66 ha) and are open year-round with few barriers or access restrictions.[295]

Watercourses

[edit]Central Park is home to numerous bodies of water.[11][87] The northernmost lake, Harlem Meer, is near the northeastern corner of the park and covers nearly 11 acres (4.5 ha).[296][297] Located in a wooded area of oak, cypress, and beech trees, it was named after Harlem, one of Manhattan's first suburban communities, and was built after the completion of the southern portion of the park. Harlem Meer allows catch and release fishing.[296] It is fed by two interconnected water features: the Pool, a pond within the North Woods fed by drinking water,[298] and the Loch, a small stream with three cascades that winds through the North Woods.[299][280] These are all adapted from a single watercourse called Montayne's Rivulet, originally fed from a natural spring but later replenished by the city's water system.[300][301] Lasker Rink is above the mouth of the Loch where it drains into the Harlem Meer.[302][303]

South of Harlem Meer and the Pool is Central Park's largest lake, the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir, known as the Central Park Reservoir before 1994.[304] It was constructed between 1858 and 1862. Covering an area of 106 acres (43 ha) between 86th and 96th streets, the reservoir reaches a depth of more than 40 feet (12 m) in places and contains about 1 billion U.S. gallons (3.8 billion liters) of water.[305][306] The Onassis Reservoir was created as a new, landscaped storage reservoir to the north of the Croton Aqueduct's rectangular receiving reservoir.[139] Because of the Onassis Reservoir's shape, East Drive was built as a straight path, with little clearance between the reservoir to the west and Fifth Avenue to the east.[307] It was decommissioned in 1993[233][234] and renamed after Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis the following year, after her death.[233][235]

The Turtle Pond is at the southern edge of the Great Lawn. The pond was originally part of the Croton receiving reservoir.[308][309] The receiving reservoir was drained starting in 1930,[310][311] and the dry reservoir bed was temporarily used as a homeless encampment when filling stopped during the Great Depression.[309][312][313] The Great Lawn was completed in 1937 on the site of the reservoir.[314] Until 1987, it was known as Belvedere Lake, after the castle at its southwestern corner.[308][309]

The Lake, south of the 79th Street transverse, covers nearly 18 acres (7.3 ha).[315] Originally, it was part of the Sawkill Creek, which flowed near the American Museum of Natural History.[316][317] The Lake was among the first features to be completed, opening to skaters in December 1858.[121] It was intended to accommodate boats in the summer and ice skaters in winter.[121][315] The Loeb Boathouse, on the eastern shore of the Lake, rents out rowboats, kayaks, and gondolas, and houses a restaurant.[187][188][318] The Lake is spanned by Bow Bridge at its center,[318] and its northern inlet, Bank Rock Bay, is spanned by the Bank Rock or Oak Bridge.[319][317] Ladies' Pond, spanned by two bridges on the western end of the Lake, was infilled in the 1930s.[317]

Directly east of the Lake is Conservatory Water,[5] on the site of an unbuilt formal garden.[320] The shore of Conservatory Water contains the Kerbs Memorial Boathouse,[321] where patrons can rent and navigate model boats.[320][322][323]

In the park's southeast corner is the Pond, with an area of 3.5 acres (1.4 ha).[324][325] The Pond was adapted from part of the former DeVoor's Mill Stream, which used to flow into the East River at the modern-day neighborhood of Turtle Bay.[11][326] The western section of the Pond was converted into Wollman Rink in 1950.[181][327][328]

Wildlife

[edit]Central Park is biologically diverse. A 2013 survey of park species by William E. Macaulay Honors College found 571 total species,[329][330] including 173 species that were not previously known to live there.[331]

Flora

[edit]According to a 2011 survey, Central Park had more than 20,000 trees,[332][333][334] representing a decrease from the 26,000 trees that were recorded in the park in 1993.[335] The majority of them are native to New York City, but there are several clusters of non-native species.[336] With few exceptions, the trees in Central Park were mostly planted or placed manually. Over four million trees, shrubs, and plants representing approximately 1,500 species were planted or imported to the park.[10] In Central Park's earliest years, two plant nurseries were maintained within the park boundaries: a demolished nursery near the Arsenal, and the still-extant Conservatory Garden.[337] Central Park Conservancy later took over regular maintenance of the park's flora, allocating gardeners to one of 49 "zones" for maintenance purposes.[338]

Central Park contains ten "great tree" clusters that are specially recognized by NYC Parks. These include four individual American elms and one American elm grove; the 600 pine trees in the Arthur Ross Pinetum; a black tupelo in the Ramble; 35 Yoshino cherries on the east side of the Onassis Reservoir; one of the park's oldest London plane trees at 96th Street; and an Euodia at Heckscher Playground.[336][339] The American elms in Central Park are the largest remaining stands in the Northeastern United States, protected by their isolation from the Dutch elm disease that devastated the tree throughout its native range.[335] There are several "tree walks" that run through Central Park.[334]

Fauna

[edit]

Central Park contains various migratory birds during their spring and fall migration on the Atlantic Flyway.[340] The first official list of birds observed in Central Park, which numbered 235 species, was published in Forest and Stream in 1886 by Augustus G. Paine Jr. and Lewis B. Woodruff.[341][342] Overall, 303 bird species have been seen in the park since the first official list of records was published,[340] and an estimated 200 species are spotted every season.[343] No single group is responsible for tracking Central Park's bird species.[344] Some of the more famous birds include a male red-tailed hawk called Pale Male, who made his perch on an apartment building overlooking Central Park in 1991.[345][346] A mandarin duck nicknamed Mandarin Patinkin received international media attention in late 2018 and early 2019[347] due to its colorful appearance and the species' presence outside its native range in East Asia.[348] Another bird, an Eurasian eagle-owl named Flaco, gained attention in 2023 when he escaped from the Central Park Zoo after his enclosure was vandalized.[349] More infamously, Eugene Schieffelin released 100 imported European starlings in Central Park in 1890–1891, which led to them becoming an invasive species across North America.[350][351]

Central Park has approximately ten species of mammals as of 2013[update].[330] Bats, a nocturnal order, have been found in dark crevices.[352] Because of the prevalence of raccoons, the Parks Department posts rabies advisories.[353] Eastern gray squirrels, eastern chipmunks, and Virginia opossums inhabit the park.[354] A 2019 squirrel census found there were 2,373 Eastern gray squirrels in Central Park.[355]

There are 223 invertebrate species in Central Park.[330] Nannarrup hoffmani, a centipede species discovered in Central Park in 2002, is one of the smallest centipedes in the world at about 0.4 inches (10 mm) long.[356] The more prevalent Asian long-horned beetle is an invasive species that has infected trees in Long Island and Manhattan, including in Central Park.[357][358]

Turtles, fish, and frogs live in Central Park.[330] There are five turtle species: red-eared sliders, snapping turtles, painted turtles, musk turtles, and box turtles.[308] Most of the turtles live in Turtle Pond, and many of these are former pets that were released into the park.[329] The fish are scattered more widely, but they include several freshwater species,[359] such as the snakehead, an invasive species.[360] Catch and release fishing is allowed in the Lake, Pond, and Harlem Meer.[359][361] Central Park is a habitat for two amphibian species: the American bullfrog and the green frog.[362] The park contained snakes in the late 19th century,[363] though Marie Winn, who wrote about wildlife in Central Park, said in a 2008 interview that the snakes had died off.[364]

Landmarks and structures

[edit]Plazas and entrances

[edit]

Central Park is surrounded by a 29,025-foot-long (8,847 m), 3-foot-10-inch-high (117 cm) stone wall. It initially contained 18 unnamed gates.[365] In April 1862, the Central Park commissioners adopted a proposal to name each gate with "the vocations to which this city owes its metropolitan character", such as miners, scholars, artists, or hunters.[365][366] The park grew to contain 20 named gates by the late 20th century,[367][368] four of which are accessed from plazas at each corner of the park.[5][367] No named gates were added between 1862 and 2022,[369] when the Gate of the Exonerated at Lenox Avenue and Central Park North was dedicated in honor of the Central Park Five.[370]

Columbus Circle is a circular plaza at the southwestern corner, at the junction of Central Park West/Eighth Avenue, Broadway, and 59th Street (Central Park South).[5][371] Built in the 1860s,[371] it contains the Merchant's Gate entrance to the park.,[367] and its largest feature is the 1892 Columbus Monument[371][372] and was the subject of controversies in the 2010s.[373][374] The 1913 USS Maine National Monument is just outside the park entrance.[375]

The square Grand Army Plaza is on the southeastern corner, at the junction with Fifth Avenue and 59th Street.[5] Its largest feature is the Pulitzer Fountain, which was completed in 1916 along with the plaza itself.[376] The plaza contains the William Tecumseh Sherman statue, dedicated in 1903.[377]

Duke Ellington Circle, at the northeastern corner, forms the junction between Fifth Avenue and Central Park North/110th Street.[5] It contains the Duke Ellington Memorial, dedicated in 1997.[378] Duke Ellington Circle is adjacent to the Pioneers' Gate.[367]

Frederick Douglass Circle is on the northwestern corner, at the junction with Central Park West/Eighth Avenue and Central Park North/110th Street.[5] It was named for Douglass in 1950.[379] The center of the circle contains a memorial to Frederick Douglass, dedicated in 2011.[380]

Structures

[edit]

The Dana Discovery Center was built in 1993 at the northeast section of the park, on the north shore of the Harlem Meer.[5][281][302] Blockhouse No. 1, the oldest extant structure within Central Park, and built before the park's creation, sits in the northwest section of the park. It was erected as part of Fort Clinton during the War of 1812.[281][381][302] The Blockhouse is near McGowan's Pass, rocky outcroppings that also once contained Fort Fish and Nutter's Battery.[382] The Lasker Rink, a skating rink and swimming pool facility, formerly occupied the southwest corner of the Harlem Meer.[383] The Conservatory Garden, the park's only formal garden, is entered through the Vanderbilt Gate at Fifth Avenue and 105th Street.[5][384] The Tarr Family Playground, North Meadow Recreation Center, tennis courts, and East Meadow sit between the Loch to the north and the reservoir to the south.[5][385] The North Woods takes up the rest of the northern third of the park. The areas in the northern section of the park were developed later than the southern section and are not as heavily used, so there are several unnamed features.[386] The park's northern portion was intended as the "natural section" in contrast to the landscaped "pastoral section" to the south.[87]

The area between the 86th and 96th Street transverses is mostly occupied by the Onassis Reservoir. Directly south of the Reservoir is the Great Lawn and Turtle Pond. The Lawn is bordered by the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Fifth Avenue building to the east, Turtle Pond to the south, and Summit Rock to the west.[5] Summit Rock, the highest point in Central Park at 137.5 feet (41.9 m),[387][388] abuts Diana Ross Playground to the south and the Seneca Village site, occupied by the Toll Family playground, to the north.[5] Turtle Pond's western shore contains Belvedere Castle, Delacorte Theater, the Shakespeare Garden, and Marionette Theatre.[5] The section between the 79th Street transverse and Terrace Drive at 72nd Street contains three main natural features: the forested Ramble, the L-shaped Lake, and Conservatory Water. Cherry Hill is to the south of the Lake, while Cedar Hill is to the east.[5][281]

The southernmost part of Central Park, below Terrace Drive, contains several children's attractions and other flagship features.[5] It contains many of the structures built in Central Park's initial stage of construction, designed in the Victorian Gothic style.[389] Directly facing the southeastern shore of the Lake is a bi-level hall called Bethesda Terrace, which contains an elaborate fountain on its lower level.[389][390][391] Bethesda Terrace connects to Central Park Mall, a landscaped walkway and the only formal feature in the Greensward Plan.[5][389] Near the southwestern shore of the Lake is Strawberry Fields, a memorial to John Lennon who was murdered nearby;[5][392] Sheep Meadow, a lawn originally intended for use as a parade ground;[393] and Tavern on the Green, a restaurant.[5] The southern border of Central Park contains the "Children's District",[394] an area that includes Heckscher Playground, the Central Park Carousel, the Ballplayers House, and the Chess and Checkers House.[5][394] Wollman Rink/Victorian Gardens, the Central Park Zoo and Children's Zoo, the Arsenal, and the Pond and Hallett Nature Sanctuary are nearby.[5][281] The Arsenal, a red-brick building designed by Martin E. Thompson in 1851, has been NYC Parks' headquarters since 1934.[395][396]

There are 21 children's playgrounds in Central Park. The largest, at three acres (1.2 ha), is Heckscher Playground.[12] Central Park includes 36 ornamental bridges, each of a different design.[397][398][395] The bridges are generally designed in the Gothic Revival or Romanesque Revival styles and are made of wood, stone, or cast iron.[395] "Rustic" shelters and other structures were originally spread out through the park. Most have been demolished over the years, and several have been restored.[395][399][400] The park contains around 9,500 benches in three styles, of which nearly half have small engraved tablets of some kind, installed as part of Central Park's "Adopt-a-Bench" program. These engravings typically contain short personalized messages and can be installed for at least $10,000 apiece. "Handmade rustic benches" can cost more than half a million dollars and are only granted when the honoree underwrites a major park project.[401][402]

Art and monuments

[edit]Sculptures

[edit]

Twenty-nine sculptures have been erected within Central Park's boundaries.[389][403][404] Most of the sculptures were not part of the Greensward Plan, but were nevertheless included to placate wealthy donors when appreciation of art increased in the late 19th century.[159][405][406] Though Vaux and Mould proposed 26 statues in the Terrace in 1862, these were eliminated because they were too expensive.[405] More sculptures were added through the late 19th century, and by 1890s, there were 24 in the park.[407]

Several busts of authors and poets are on Literary Walk adjacent to the Central Park Mall.[389][408][409] Another cluster of sculptures, around the Zoo and Conservancy Water, are statues of characters from children's stories. A third sculpture grouping primarily depicts "subjects in nature" such as animals and hunters.[389]

Several sculptures stand out because of their geography and topography.[389] Alice in Wonderland Margaret Delacorte Memorial (1959), a sculpture of Alice, is at Conservatory Water.[410][411] Angel of the Waters (1873), by Emma Stebbins, is the centerpiece of Bethesda Fountain;[391][405] it was the first large public sculpture commission for an American woman[412] and the only statue included in the original park design.[405] Balto (1925), a statue of Balto, the sled dog who became famous during the 1925 serum run to Nome, is near East Drive and East 66th Street.[413] King Jagiello Monument (1939), a bronze monument installed in 1945, is at the east end of Turtle Pond.[414] Women's Rights Pioneers Monument (2020), a monument of Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton,[415] was the city's first statue to depict a female historical figure.[416][417]

Structures and exhibitions

[edit]

Cleopatra's Needle, a red granite obelisk west of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[5] is the oldest human-made structure in Central Park.[418] The needle in Central Park is one of three Cleopatra's Needles that were originally erected at the Temple of Ra in Heliopolis in Ancient Egypt around 1450 BC by the Pharaoh Thutmose III.[418][419][420] The hieroglyphs were inscribed about 200 years later by Pharaoh Rameses II to glorify his military victories. The needles are so named because they were later moved to in front of the Caesarium in Alexandria, a temple originally built by Cleopatra VII of Egypt in honor of Mark Antony.[421] The needle in Central Park arrived in late 1880 and was dedicated early the following year.[418][420]

The Strawberry Fields memorial, near Central Park West and 72nd Street,[5] is a memorial commemorating John Lennon, who was murdered outside the nearby Dakota apartment building. The city dedicated Strawberry Fields in Lennon's honor in April 1981,[422] and the memorial was completely rebuilt and rededicated on what would have been Lennon's 45th birthday, October 9, 1985.[423] Countries from all around the world contributed trees, and Italy donated the "Imagine" mosaic in the center of the memorial. It has since become the site of impromptu memorial gatherings for other notables.[424][425]

For 16 days in 2005, Central Park was the setting for Christo and Jeanne-Claude's installation The Gates, an exhibition that had been planned since 1979.[426] Although the project was the subject of mixed reactions, it was a major attraction for the park while it was open, drawing over a million people.[427]

Restaurants

[edit]Central Park contains two indoor restaurants. Tavern on the Green, at Central Park West and West 67th Street, was built in 1870 as a sheepfold and was converted into a restaurant in 1934.[181][183][184] The Tavern on the Green was expanded between 1974 and 1976;[428] it was closed in 2009 and reopened five years later after a renovation.[429] The Loeb Boathouse restaurant is at the Loeb Boathouse, on the Lake, near Fifth Avenue between 74th and 75th streets.[187][188] Though the boathouse was constructed in 1954,[188] its restaurant opened in 1983.[430]

Activities

[edit]Tours

[edit]

In the late 19th century, West and East Drives was a popular place for carriage rides, though only five percent of the city was able to afford a carriage. One of the main attractions in the park's early years was the introduction of the "Carriage Parade", a daily display of horse-drawn carriages that traversed the park.[135][431][141] The introduction of the automobile caused the carriage industry to die out by World War I,[431] though the carriage-horse tradition was revived in 1935.[432] The carriages have become a symbolic institution of the city; for instance, in a much-publicized event after the September 11 attacks, Mayor Rudy Giuliani went to the stables to ask the drivers to go back to work to help return a sense of normality.[432]

Some activists, celebrities, and politicians have questioned the ethics of the carriage-horse industry and called for its end.[433] The history of accidents involving spooked horses came under scrutiny in the 2000s and 2010s after reports of horses collapsing and even dying.[434][435] Supporters of the trade say it needs to be reformed rather than shut down.[436] Some replacements have been proposed, including electric vintage cars.[437] Bill de Blasio, in his successful 2013 mayoral campaign, pledged to eliminate horse carriage tours if he was elected;[438] as of August 2018[update], had only succeeded in relocating the carriage pick-up areas.[439]

Pedicabs operate mostly in the southern part of the park, as horse carriages do. The pedicabs have been criticized: there have been reports of pedicab drivers charging exorbitant fares of several hundred dollars.[440][441]

Recreation

[edit]The park's drives, which are 6.1 miles (9.8 km) long, are used heavily by runners, joggers, pedestrians, bicyclists, and inline skaters.[4][13] The park drives contain protected bike lanes[442] and are used as the home course for the racing series of the Century Road Club Association, a USA Cycling-sanctioned amateur cycling club.[443] In 2021, e-scooters were legalized in New York, including in Central Park.[444] The park is used for professional running, and the New York Road Runners designated a 5-mile (8.0 km) running loop within Central Park.[445] The New York City Marathon course uses several miles of drives within Central Park and finishes outside Tavern on the Green;[446] from 1970 through 1975, the race was held entirely in Central Park.[447]

There are 26 baseball fields in Central Park: eight on the Great Lawn, six at Heckscher Ballfields near Columbus Circle, and twelve in the North Meadow.[448][449][450] 12 tennis courts, six non-regulation soccer fields (which overlap with the North Meadow ball fields), four basketball courts, and a recreation center are in the North Meadow.[450][451] An additional soccer field and four basketball courts are at Great Lawn.[450] Four volleyball courts are in the southern part of the park.[452]

Central Park has two ice skating rinks: Wollman Rink in its southern portion and Lasker Rink in its northern portion.[453] During summer, the former is the site of Victorian Gardens seasonal amusement park,[454] and the latter converts to an outdoor swimming pool.[455][456]

Central Park's glaciated rock outcroppings attract climbers, especially boulderers, but the quality of the stone is poor, and the climbs present so little challenge that it has been called "one of America's most pathetic boulders".[274] The two most renowned spots for boulderers are Rat Rock and Cat Rock. Other rocks frequented by climbers, mostly at the south end of the park, include Dog Rock, Duck Rock, Rock N' Roll Rock, and Beaver Rock.[457]

Concerts and performances

[edit]

Central Park has been the site of concerts almost since its inception. Originally, they were hosted in the Ramble, but these were moved to the Concert Ground next to the Mall in the 1870s.[458] The weekend concerts hosted in the Mall drew tens of thousands of visitors from all social classes.[459] Since 1923, concerts have been held in Naumburg Bandshell, a bandshell of Indiana limestone on the Mall.[460] Named for banker Elkan Naumburg, who funded its construction, the bandshell has deteriorated over the years but has never been fully restored.[461] The oldest free classical music concert series in the United States—the Naumburg Orchestral Concerts, founded in 1905—is hosted in the bandshell.[462] Other large concerts include The Concert in Central Park, a benefit performance by Simon & Garfunkel in 1981,[463] and Garth: Live from Central Park, a free concert by Garth Brooks in 1997.[464]

Several arts groups are dedicated to performing in Central Park.[462] These include Central Park Brass, which performs concert series,[465] and the New York Classical Theatre, which produces an annual series of plays.[466]

There are several regular summer events. The Public Theater presents free open-air theater productions, such as Shakespeare in the Park, in the Delacorte Theater.[467][468] The City Parks Foundation offers Central Park Summerstage, a series of free performances including music, dance, spoken word, and film presentations, often featuring famous performers.[462][469] Additionally, the New York Philharmonic gives an open-air concert on the Great Lawn yearly during the summer,[462] and from 1967 until 2007, the Metropolitan Opera presented two operas in concert each year.[470] Every August since 2003, the Central Park Conservancy has hosted the Central Park Film Festival, a series of free film screenings.[471]

Transportation

[edit]Central Park incorporates a system of pedestrian walkways, scenic drives, bridle paths, and transverse roads to aid traffic circulation,[368] and it is easily accessible via several subway stations and bus routes.[472]

Public transport

[edit]

The New York City Subway's IND Eighth Avenue Line (A, B, C, and D trains) runs along the western edge of the park. Most of the Eighth Avenue Line stations on Central Park West serve only the local B and C trains, while the 59th Street–Columbus Circle station is additionally served by the express A and D trains and the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line (1 train). The IRT Lenox Avenue Line (2 and 3 trains) has a station at Central Park North. From there the line curves southwest under the park and heads west under 104th Street. On the southeastern corner of the park, the BMT Broadway Line (N, R, and W trains) has a station at Fifth Avenue and 59th Street.[473] The 63rd Street lines (F and <F> and Q trains) pass underneath without stopping,[473] and the line contains a single ventilation shaft within the park, west of Fifth Avenue and 63rd Street.[278]

Various bus routes pass through Central Park or stop along its boundaries. The M10 bus stops along Central Park West, while the M5 and part of the M7 runs along Central Park South, and the M2, M3 and M4 run along Central Park North. The M1, M2, M3, and M4 run southbound along Fifth Avenue with corresponding northbound bus service on Madison Avenue. The M66, M72, M79 SBS (Select Bus Service), M86 SBS, M96 and M106 buses use the transverse roads across Central Park. The M12, M20 and M104 only serve Columbus Circle on the south end of the park, and the M31 and M57 run on 57th Street two blocks from the park's south end but do not stop on the boundaries of the park.[472]

Some of the buses running on the edge of Central Park replaced former streetcar routes that formerly traveled across Manhattan. These streetcar routes included the Sixth Avenue line, which became the M5 bus, and the Eighth Avenue line, which became the M10.[474] Only one streetcar line traversed Central Park: the 86th Street Crosstown Line, the predecessor to the M86 bus.[475]

Transverse roads

[edit]

Central Park contains four transverse roadways that carry crosstown traffic across the park.[5][88][368] From south to north, they are at 66th Street, 79th Street, 86th Street, and 97th Street; the transverse roads were originally numbered sequentially in that order. The 66th Street transverse connects the discontinuous sections of 65th and 66th streets on either side of the park. The 97th Street transverse likewise joins the disconnected segments of 96th and 97th streets. The 79th Street transverse links West 81st and East 79th streets, while the 86th Street transverse links West 86th Street with East 84th and 85th streets.[5] Each roadway carries two lanes, one in each direction, and is sunken below the level of the rest of the park to minimize the transverses' visual impact on it.[88][368] The transverse roadways are open even when the park is closed.[476]

The 66th Street transverse was the first to be finished, having opened in December 1859.[477] The 79th Street transverse—which passed under Vista Rock, Central Park's second-highest point—was completed by a railroad contractor because of their experience in drilling through hard rock;[478] it opened in December 1860. The 86th and 97th Street transverses opened in late 1862.[477] By the 1890s, maintenance had decreased to the point where the 86th Street transverse handled most crosstown traffic because the other transverse roads had been so poorly maintained.[163] Both ends of the 79th Street transverse were widened in 1964 to accommodate increased traffic.[479] Generally, the transverses were not maintained as frequently as the rest of the park, though being used more frequently than the park proper.[480]

Scenic drives

[edit]

The park has three scenic drives that travel through it vertically.[5] They have multiple traffic lights at the intersections with pedestrian paths, although there are some arches and bridges where pedestrian and drive traffic can cross without intersection.[368][397][398] To discourage park patrons from speeding, the designers incorporated extensive curves in the park drives.[481][482]

West Drive is the westernmost of the park's three vertical "drives". The road, which carries southbound bicycle and horse-carriage traffic, winds through the western part of Central Park, connecting Lenox Avenue/Central Park North with Seventh Avenue/Central Park South and Central Drive.[5]

Center Drive (also known as the "Central Park Lower Loop"[483]) connects northbound bicycle and carriage traffic from Midtown at Central Park South/Sixth Avenue to East Drive near the 66th Street transverse. The street generally goes east and then north, forming the bottom part of the Central Park loop. The attractions along Center Drive include Victorian Gardens, the Central Park Carousel, and the Central Park Mall.[5]

East Drive, the easternmost of the three drives, connects northbound bicycle and carriage traffic from Midtown to the Upper West Side at Lenox Avenue. The street is renowned for its country scenery and free concerts. It generally straddles the east side of the park along Fifth Avenue. The drive passes by the Central Park Zoo around 63rd Street and the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 80th to 84th Streets. Unlike the rest of the drive system, which is generally serpentine, East Drive is straight between the 86th and 96th Street transverses, because it is between Fifth Avenue and the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir.[5] East Drive is known as the "Elite Carriage Parade", because it was where the carriage procession occurred at the time of the park's opening, and because only five percent of the city was able to afford the carriage. In the late 19th century, West and East Drives were popular places for carriage rides.[141]

Two other scenic drives cross the park horizontally. Terrace Drive is at 72nd Street and connects West and East Drives, passing over Bethesda Terrace and Fountain. The 102nd Street Crossing, further north near the street of the same name, is a former carriage drive connecting West and East Drives.[5]

Modifications and closures

[edit]In Central Park's earliest years, the speed limits were set at 5 miles per hour (8.0 km/h) for carriages and 6 mph (9.7 km/h) for horses, which were later raised to 7 and 10 mph (11 and 16 km/h) respectively. Commercial vehicles and buses were banned from the park.[481] Automobiles became more common in Central Park during the 1900s and 1910s, and they often broke the speed limits, resulting in crashes. To increase safety, the gravel roads were paved in 1912, and the carriage speed limit was raised to 15 mph (24 km/h) two years later. With the proliferation of cars among the middle class in the 1920s, traffic increased on the drives, to as many as eight thousand cars per hour in 1929.[431] The roads were still dangerous; in the first ten months of 1929, eight people were killed and 249 were injured in 338 separate collisions.[484]

In November 1929, the scenic drives were converted from two-way traffic to unidirectional traffic.[485] Further improvements were made in 1932 when forty-two traffic lights were installed along the scenic drives, and the speed limit was lowered to 25 miles per hour (40 km/h). The signals were coordinated so that drivers could go through all of the green lights if they maintained a steady speed of 25 miles per hour (40 km/h).[431][486] The drives were experimentally closed to automotive traffic on weekends beginning in 1967, for exclusive use by pedestrians and bicyclists.[487] In subsequent years, the scenic drives were closed to automotive traffic for most of the day during the summer. By 1979, the drives were only open during rush hours and late evenings during the summer.[488]

Legislation was proposed in October 2014 to conduct a study to make the park car-free in summer 2015.[249] In 2015, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the permanent closure of West and East Drives north of 72nd Street to vehicular traffic as it was proven that closing the roads did not adversely impact traffic.[489] After most of the Central Park loop drives were closed to vehicular traffic, the city performed a follow-up study. The city found that West Drive was open for two hours during the morning rush period and was used by an average of 1,050 vehicles a day, while East Drive was open 12 hours a day and was used by an average of 3,400 vehicles daily.[490] Subsequently, all cars were banned from East Drive in January 2018.[491] In April 2018, de Blasio announced that the entirety of the three loop drives would be closed permanently to traffic.[490][492] The closure was put into effect in June 2018.[248][249]

During the early 21st century, there were numerous collisions in Central Park involving cyclists. The 2014 death of Jill Tarlov, after she was hit by a cyclist on West 63rd Street, called attention to the issue.[493] In 2011, residents of nearby communities unsuccessfully petitioned the NYPD to increase enforcement of cycling rules within the park.[494]

Issues

[edit]

Crime and neglect

[edit]In the mid-20th century, Central Park had a reputation for being very dangerous, especially after dark.[495] Such a viewpoint was reinforced following a 1941 incident when 12-year-old Jerome Dore fatally stabbed 15-year-old James O'Connell in the northern section of the park.[496][497] Local tabloids cited this incident and several other crimes as evidence of a highly exaggerated "crime wave". Though recorded crime had indeed increased since Central Park opened in the late 1850s, this was in line with crime trends seen in the rest of the city.[495] Central Park's reputation for crime was reinforced by its worldwide name recognition, and the fact that crimes in the park were covered disproportionately compared to crimes in the rest of the city. For instance, in 1973 The New York Times wrote stories about 20% of murders that occurred citywide but wrote about three of the four murders that took place in Central Park that year. By the 1970s and 1980s, the number of murders in the police precincts north of Central Park was 18 times higher than the number of murders within the park itself, and even in the precincts south of the park, the number of murders was three times as high.[498]

The park was the site of numerous high-profile crimes during the late 20th century. Of these, two particularly notable cases shaped public perception against the park.[498] In 1986, Robert Chambers murdered Jennifer Levin in what was later called the "preppy murder."[499][500] Three years later, an investment banker was raped and brutally beaten in what came to be known as the Central Park jogger case.[501][502] Conversely, other crimes such as the 1984 gang-rape of two homeless women were barely reported.[498] After World War II, it was feared that gay men perpetrated sex crimes and attracted violence.[503] Other problems in the 1970s and 1980s included a drug epidemic, a large homeless presence, vandalism, and neglect.[218][504][505]

As crime has declined in New York City, many of these negative perceptions have waned.[498] Safety measures keep the number of crimes in the park to fewer than 100 per year as of 2019[update], down from approximately 1,000 in the early 1980s.[31] Some well-publicized crimes have occurred since then: for instance, on June 11, 2000, following the Puerto Rican Day Parade, gangs of drunken men sexually assaulted women in the park.[506]

Other issues

[edit]Permission to hold issue-centered rallies in Central Park, similar to the be-ins of the 1960s, has been met with increasingly stiff resistance from the city. During some 2004 protests, the organization United for Peace and Justice wanted to hold a rally on the Great Lawn during the Republican National Convention. The city denied an application for a permit, stating that such a mass gathering would be harmful to the grass and the damage would make it harder to collect private donations to maintain the park.[507] A judge of the New York Supreme Court's New York County branch upheld the refusal.[508]

During the 2000s and 2010s, new supertall skyscrapers were constructed along the southern end of Central Park, in a corridor commonly known as Billionaires' Row. According to a Municipal Art Society report, such buildings cast long shadows over the southern end of the park.[509][510] A 2016 analysis by The New York Times found that some of the tallest and skinniest skyscrapers, such as One57, Central Park Tower, and 220 Central Park South, would cast shadows that can be as much as 1 mile (1.6 km) long during the winter, covering up to a third of the park's length.[511] In 2018, the New York City Council proposed a task force to study the effects of skyscrapers near city parks.[512]

Impact

[edit]Cultural significance

[edit]