Елизавета II

| Елизавета II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Глава Содружества | |||||

Официальный портрет, 1959 год. | |||||

| Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms | |||||

| Reign | 6 February 1952 – 8 September 2022 | ||||

| Coronation | 2 June 1953 | ||||

| Predecessor | George VI | ||||

| Successor | Charles III | ||||

| Born | Princess Elizabeth of York 21 April 1926 Mayfair, London, England | ||||

| Died | 8 September 2022 (aged 96) Balmoral Castle, Aberdeenshire, Scotland | ||||

| Burial | 19 September 2022 King George VI Memorial Chapel, St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue Detail | |||||

| |||||

| House | Windsor | ||||

| Father | George VI | ||||

| Mother | Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon | ||||

| Religion | Protestant[a] | ||||

| Signature | |||||

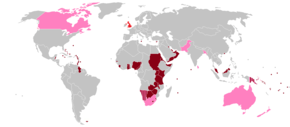

Елизавета II (Елизавета Александра Мария; 21 апреля 1926 г. - 8 сентября 2022 г.) была королевой Соединенного Королевства и других королевств Содружества с 6 февраля 1952 года до своей смерти в 2022 году. она была королевой 32 суверенных государств На протяжении своей жизни и к моменту своей смерти оставался монархом 15 королевств. Ее правление продолжительностью 70 лет и 214 дней является самым продолжительным из всех британских монархов или женщин-монархов и вторым по продолжительности подтвержденным правлением любого монарха суверенного государства в истории .

Элизабет родилась в Мейфэре , Лондон, во время правления ее деда по отцовской линии, короля Георга V. Она была первым ребенком герцога и герцогини Йоркских (впоследствии короля Георга VI и королевы Елизаветы, королевы-матери ). Ее отец взошел на престол в 1936 году после отречения своего брата Эдуарда VIII десятилетнюю принцессу Елизавету , сделав предполагаемой наследницей . Она получила частное домашнее образование и начала выполнять общественные обязанности во время Второй мировой войны, служа во вспомогательной территориальной службе . В ноябре 1947 года она вышла замуж за бывшего принца Греции и Дании Филиппа , который отказался от своих иностранных титулов и натурализовался как гражданин Великобритании. Их брак продлился 73 года до его смерти в 2021 году . У них было четверо детей: Чарльз , Энн , Эндрю и Эдвард .

When her father died in February 1952, Elizabeth—then 25 years old—became queen of seven independent Commonwealth countries: the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Pakistan, and Ceylon (known today as Sri Lanka), as well as head of the Commonwealth. Elizabeth reigned as a constitutional monarch through major political changes such as the Troubles in Northern Ireland, devolution in the United Kingdom, the decolonisation of Africa, and the United Kingdom's accession to the European Communities as well as its subsequent withdrawal. The number of her realms varied over time as territories gained independence and some realms became republics. As queen, Elizabeth was served by more than 170 prime ministers across her realms. Her many historic visits and meetings included state visits to China in 1986, to Russia in 1994, and to the Republic of Ireland in 2011, and meetings with five popes and fourteen US presidents.

Significant events included Elizabeth's coronation in 1953 and the celebrations of her Silver, Golden, Diamond, and Platinum jubilees in 1977, 2002, 2012, and 2022, respectively. Although she faced occasional republican sentiment and media criticism of her family—particularly after the breakdowns of her children's marriages, her annus horribilis in 1992, and the death in 1997 of her former daughter-in-law Diana—support for the monarchy in the United Kingdom remained consistently high throughout her lifetime, as did her personal popularity. Elizabeth died at the age of 96 at Balmoral Castle, and was succeeded by her eldest son, Charles III.

Early life

Elizabeth was born on 21 April 1926, the first child of Prince Albert, Duke of York (later King George VI), and his wife, Elizabeth, Duchess of York (later Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother). Her father was the second son of King George V and Queen Mary, and her mother was the youngest daughter of Scottish aristocrat Claude Bowes-Lyon, 14th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne. She was delivered at 02:40 (GMT)[1] by Caesarean section at her maternal grandfather's London home, 17 Bruton Street in Mayfair.[2] The Anglican Archbishop of York, Cosmo Gordon Lang, baptised her in the private chapel of Buckingham Palace on 29 May,[3][b] and she was named Elizabeth after her mother; Alexandra after her paternal great-grandmother, who had died six months earlier; and Mary after her paternal grandmother.[5] She was called "Lilibet" by her close family,[6] based on what she called herself at first.[7] She was cherished by her grandfather George V, whom she affectionately called "Grandpa England",[8] and her regular visits during his serious illness in 1929 were credited in the popular press and by later biographers with raising his spirits and aiding his recovery.[9]

Elizabeth's only sibling, Princess Margaret, was born in 1930. The two princesses were educated at home under the supervision of their mother and their governess, Marion Crawford.[10] Lessons concentrated on history, language, literature, and music.[11] Crawford published a biography of Elizabeth and Margaret's childhood years entitled The Little Princesses in 1950, much to the dismay of the royal family.[12] The book describes Elizabeth's love of horses and dogs, her orderliness, and her attitude of responsibility.[13] Others echoed such observations: Winston Churchill described Elizabeth when she was two as "a character. She has an air of authority and reflectiveness astonishing in an infant."[14] Her cousin Margaret Rhodes described her as "a jolly little girl, but fundamentally sensible and well-behaved".[15] Elizabeth's early life was spent primarily at the Yorks' residences at 145 Piccadilly (their town house in London) and Royal Lodge in Windsor.[16]

Heir presumptive

During her grandfather's reign, Elizabeth was third in the line of succession to the British throne, behind her uncle Edward, Prince of Wales, and her father. Although her birth generated public interest, she was not expected to become queen, as Edward was still young and likely to marry and have children of his own, who would precede Elizabeth in the line of succession.[17] When her grandfather died in 1936 and her uncle succeeded as Edward VIII, she became second in line to the throne, after her father. Later that year, Edward abdicated, after his proposed marriage to divorced American socialite Wallis Simpson provoked a constitutional crisis.[18] Consequently, Elizabeth's father became king, taking the regnal name George VI. Since Elizabeth had no brothers, she became heir presumptive. If her parents had subsequently had a son, he would have been heir apparent and above her in the line of succession, which was determined by the male-preference primogeniture in effect at the time.[19]

Elizabeth received private tuition in constitutional history from Henry Marten, Vice-Provost of Eton College,[20] and learned French from a succession of native-speaking governesses.[21] A Girl Guides company, the 1st Buckingham Palace Company, was formed specifically so she could socialise with girls her age.[22] Later, she was enrolled as a Sea Ranger.[21]

In 1939, Elizabeth's parents toured Canada and the United States. As in 1927, when they had toured Australia and New Zealand, Elizabeth remained in Britain since her father thought she was too young to undertake public tours.[23] She "looked tearful" as her parents departed.[24] They corresponded regularly,[24] and she and her parents made the first royal transatlantic telephone call on 18 May.[23]

Second World War

In September 1939, Britain entered the Second World War. Lord Hailsham suggested that Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret should be evacuated to Canada to avoid the frequent aerial bombings of London by the Luftwaffe.[25] This was rejected by their mother, who declared, "The children won't go without me. I won't leave without the King. And the King will never leave."[26] The princesses stayed at Balmoral Castle, Scotland, until Christmas 1939, when they moved to Sandringham House, Norfolk.[27] From February to May 1940, they lived at Royal Lodge, Windsor, until moving to Windsor Castle, where they lived for most of the next five years.[28] At Windsor, the princesses staged pantomimes at Christmas in aid of the Queen's Wool Fund, which bought yarn to knit into military garments.[29] In 1940, the 14-year-old Elizabeth made her first radio broadcast during the BBC's Children's Hour, addressing other children who had been evacuated from the cities.[30] She stated: "We are trying to do all we can to help our gallant sailors, soldiers, and airmen, and we are trying, too, to bear our own share of the danger and sadness of war. We know, every one of us, that in the end all will be well."[30]

In 1943, Elizabeth undertook her first solo public appearance on a visit to the Grenadier Guards, of which she had been appointed colonel the previous year.[31] As she approached her 18th birthday, Parliament changed the law so that she could act as one of five counsellors of state in the event of her father's incapacity or absence abroad, such as his visit to Italy in July 1944.[32] In February 1945, she was appointed an honorary second subaltern in the Auxiliary Territorial Service with the service number 230873.[33] She trained as a driver and mechanic and was given the rank of honorary junior commander (female equivalent of captain at the time) five months later.[34]

At the end of the war in Europe, on Victory in Europe Day, Elizabeth and Margaret mingled incognito with the celebrating crowds in the streets of London. In 1985, Elizabeth recalled in a rare interview, "... we asked my parents if we could go out and see for ourselves. I remember we were terrified of being recognised ... I remember lines of unknown people linking arms and walking down Whitehall, all of us just swept along on a tide of happiness and relief."[35][36]

During the war, plans were drawn to quell Welsh nationalism by affiliating Elizabeth more closely with Wales. Proposals, such as appointing her Constable of Caernarfon Castle or a patron of Urdd Gobaith Cymru (the Welsh League of Youth), were abandoned for several reasons, including fear of associating Elizabeth with conscientious objectors in the Urdd at a time when Britain was at war.[37] Welsh politicians suggested she be made Princess of Wales on her 18th birthday. Home Secretary Herbert Morrison supported the idea, but the King rejected it because he felt such a title belonged solely to the wife of a Prince of Wales and the Prince of Wales had always been the heir apparent.[38] In 1946, she was inducted into the Gorsedd of Bards at the National Eisteddfod of Wales.[39]

Elizabeth went on her first overseas tour in 1947, accompanying her parents through southern Africa. During the tour, in a broadcast to the British Commonwealth on her 21st birthday, she made the following pledge:[40][c]

I declare before you all that my whole life, whether it be long or short, shall be devoted to your service and the service of our great imperial family to which we all belong. But I shall not have strength to carry out this resolution alone unless you join in it with me, as I now invite you to do: I know that your support will be unfailingly given. God help me to make good my vow, and God bless all of you who are willing to share in it.

Marriage

Elizabeth met her future husband, Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, in 1934 and again in 1937.[42] They were second cousins once removed through King Christian IX of Denmark and third cousins through Queen Victoria. After meeting for the third time at the Royal Naval College in Dartmouth in July 1939, Elizabeth—though only 13 years old—said she fell in love with Philip, who was 18, and they began to exchange letters.[43] She was 21 when their engagement was officially announced on 9 July 1947.[44]

The engagement attracted some controversy. Philip had no financial standing, was foreign-born (though a British subject who had served in the Royal Navy throughout the Second World War), and had sisters who had married German noblemen with Nazi links.[45] Marion Crawford wrote, "Some of the King's advisors did not think him good enough for her. He was a prince without a home or kingdom. Some of the papers played long and loud tunes on the string of Philip's foreign origin."[46] Later biographies reported that Elizabeth's mother had reservations about the union initially and teased Philip as "the Hun".[47] In later life, however, she told the biographer Tim Heald that Philip was "an English gentleman".[48]

Before the marriage, Philip renounced his Greek and Danish titles, officially converted from Greek Orthodoxy to Anglicanism, and adopted the style Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten, taking the surname of his mother's British family.[49] Shortly before the wedding, he was created Duke of Edinburgh and granted the style His Royal Highness.[50] Elizabeth and Philip were married on 20 November 1947 at Westminster Abbey. They received 2,500 wedding gifts from around the world.[51] Elizabeth required ration coupons to buy the material for her gown (which was designed by Norman Hartnell) because Britain had not yet completely recovered from the devastation of the war.[52] In post-war Britain, it was not acceptable for Philip's German relations, including his three surviving sisters, to be invited to the wedding.[53] Neither was an invitation extended to the Duke of Windsor, formerly King Edward VIII.[54]

Elizabeth gave birth to her first child, Prince Charles, in November 1948. One month earlier, the King had issued letters patent allowing her children to use the style and title of a royal prince or princess, to which they otherwise would not have been entitled as their father was no longer a royal prince.[55] A second child, Princess Anne, was born in August 1950.[56]

Following their wedding, the couple leased Windlesham Moor, near Windsor Castle, until July 1949,[51] when they took up residence at Clarence House in London. At various times between 1949 and 1951, Philip was stationed in the British Crown Colony of Malta as a serving Royal Navy officer. He and Elizabeth lived intermittently in Malta for several months at a time in the hamlet of Gwardamanġa, at Villa Guardamangia, the rented home of Philip's uncle Lord Mountbatten. Their two children remained in Britain.[57]

Reign

Accession and coronation

As George VI's health declined during 1951, Elizabeth frequently stood in for him at public events. When she visited Canada and Harry S. Truman in Washington, DC, in October 1951, her private secretary Martin Charteris carried a draft accession declaration in case the King died while she was on tour.[58] In early 1952, Elizabeth and Philip set out for a tour of Australia and New Zealand by way of the British colony of Kenya. On 6 February, they had just returned to their Kenyan home, Sagana Lodge, after a night spent at Treetops Hotel, when word arrived of the death of Elizabeth's father. Philip broke the news to the new queen.[59] She chose to retain Elizabeth as her regnal name,[60] and was therefore called Elizabeth II. The numeral offended some Scots, as she was the first Elizabeth to rule in Scotland.[61] She was proclaimed queen throughout her realms, and the royal party hastily returned to the United Kingdom.[62] Elizabeth and Philip moved into Buckingham Palace.[63]

With Elizabeth's accession, it seemed possible that the royal house would take her husband's name, in line with the custom for married women of the time. Lord Mountbatten advocated for House of Mountbatten, and Philip suggested House of Edinburgh, after his ducal title.[64] The British prime minister, Winston Churchill, and Elizabeth's grandmother Queen Mary favoured the retention of the House of Windsor. Elizabeth issued a declaration on 9 April 1952 that the royal house would continue to be Windsor. Philip complained, "I am the only man in the country not allowed to give his name to his own children."[65] In 1960, the surname Mountbatten-Windsor was adopted for Philip and Elizabeth's male-line descendants who do not carry royal titles.[66][67]

Amid preparations for the coronation, Princess Margaret told her sister she wished to marry Peter Townsend, a divorcé 16 years Margaret's senior with two sons from his previous marriage. Elizabeth asked them to wait for a year; in the words of her private secretary, "the Queen was naturally sympathetic towards the Princess, but I think she thought—she hoped—given time, the affair would peter out."[68] Senior politicians were against the match and the Church of England did not permit remarriage after divorce. If Margaret had contracted a civil marriage, she would have been expected to renounce her right of succession.[69] Margaret decided to abandon her plans with Townsend.[70] In 1960, she married Antony Armstrong-Jones, who was created Earl of Snowdon the following year. They divorced in 1978; Margaret did not remarry.[71]

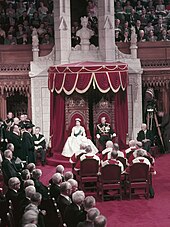

Despite Queen Mary's death on 24 March 1953, the coronation went ahead as planned on 2 June, as Mary had requested.[72] The coronation ceremony in Westminster Abbey was televised for the first time, with the exception of the anointing and communion.[73][d] On Elizabeth's instruction, her coronation gown was embroidered with the floral emblems of Commonwealth countries.[77]

Early reign

From Elizabeth's birth onwards, the British Empire continued its transformation into the Commonwealth of Nations.[78] By the time of her accession in 1952, her role as head of multiple independent states was already established.[79] In 1953, Elizabeth and Philip embarked on a seven-month round-the-world tour, visiting 13 countries and covering more than 40,000 miles (64,000 km) by land, sea and air.[80] She became the first reigning monarch of Australia and New Zealand to visit those nations.[81] During the tour, crowds were immense; three-quarters of the population of Australia were estimated to have seen her.[82] Throughout her reign, she made hundreds of state visits to other countries and tours of the Commonwealth; she was the most widely travelled head of state.[83]

In 1956, the British and French prime ministers, Sir Anthony Eden and Guy Mollet, discussed the possibility of France joining the Commonwealth. The proposal was never accepted, and the following year France signed the Treaty of Rome, which established the European Economic Community, the precursor to the European Union.[84] In November 1956, Britain and France invaded Egypt in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to capture the Suez Canal. Lord Mountbatten said that Elizabeth was opposed to the invasion, though Eden denied it. Eden resigned two months later.[85]

The governing Conservative Party had no formal mechanism for choosing a leader, meaning that it fell to Elizabeth to decide whom to commission to form a government following Eden's resignation. Eden recommended she consult Lord Salisbury, the lord president of the council. Lord Salisbury and Lord Kilmuir, the lord chancellor, consulted the British Cabinet, Churchill, and the chairman of the backbench 1922 Committee, resulting in Elizabeth appointing their recommended candidate: Harold Macmillan.[86]

The Suez crisis and the choice of Eden's successor led, in 1957, to the first major personal criticism of Elizabeth. In a magazine, which he owned and edited,[87] Lord Altrincham accused her of being "out of touch".[88] Altrincham was denounced by public figures and slapped by a member of the public appalled by his comments.[89] Six years later, in 1963, Macmillan resigned and advised Elizabeth to appoint Alec Douglas-Home as the prime minister, advice she followed.[90] Elizabeth again came under criticism for appointing the prime minister on the advice of a small number of ministers or a single minister.[90] In 1965, the Conservatives adopted a formal mechanism for electing a leader, thus relieving the Queen of her involvement.[91]

In 1957, Elizabeth made a state visit to the United States, where she addressed the United Nations General Assembly on behalf of the Commonwealth. On the same tour, she opened the 23rd Canadian Parliament, becoming the first monarch of Canada to open a parliamentary session.[92] Two years later, solely in her capacity as Queen of Canada, she revisited the United States and toured Canada.[92][93] In 1961, she toured Cyprus, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Iran.[94] On a visit to Ghana the same year, she dismissed fears for her safety, even though her host, President Kwame Nkrumah, who had replaced her as head of state, was a target for assassins.[95] Harold Macmillan wrote, "The Queen has been absolutely determined all through ... She is impatient of the attitude towards her to treat her as ... a film star ... She has indeed 'the heart and stomach of a man' ... She loves her duty and means to be a Queen."[95] Before her tour through parts of Quebec in 1964, the press reported that extremists within the Quebec separatist movement were plotting Elizabeth's assassination.[96] No assassination attempt was made, but a riot did break out while she was in Montreal; her "calmness and courage in the face of the violence" was noted.[97]

Elizabeth gave birth to her third child, Prince Andrew, in February 1960; this was the first birth to a reigning British monarch since 1857.[98] Her fourth child, Prince Edward, was born in March 1964.[99]

Political reforms and crises

The 1960s and 1970s saw an acceleration in the decolonisation of Africa and the Caribbean. More than 20 countries gained independence from Britain as part of a planned transition to self-government. In 1965, however, the Rhodesian prime minister, Ian Smith, in opposition to moves towards majority rule, unilaterally declared independence while expressing "loyalty and devotion" to Elizabeth, declaring her "Queen of Rhodesia".[100] Although Elizabeth formally dismissed him, and the international community applied sanctions against Rhodesia, his regime survived for over a decade.[101] As Britain's ties to its former empire weakened, the British government sought entry to the European Community, a goal it achieved in 1973.[102]

In 1966, the Queen was criticised for waiting eight days before visiting the village of Aberfan, where a mining disaster claimed the lives of 116 children and 28 adults. Martin Charteris said that the delay, made on his advice, was a mistake that she later regretted.[103][104]

Elizabeth toured Yugoslavia in October 1972, becoming the first British monarch to visit a communist country.[105] She was received at the airport by President Josip Broz Tito, and a crowd of thousands greeted her in Belgrade.[106]

In February 1974, British prime minister Edward Heath advised Elizabeth to call a general election in the middle of her tour of the Austronesian Pacific Rim, requiring her to fly back to Britain.[107] The election resulted in a hung parliament; Heath's Conservatives were not the largest party but could stay in office if they formed a coalition with the Liberals. When discussions on forming a coalition foundered, Heath resigned, and Elizabeth asked the Leader of the Opposition, Labour's Harold Wilson, to form a government.[108]

A year later, at the height of the 1975 Australian constitutional crisis, the Australian prime minister, Gough Whitlam, was dismissed from his post by Governor-General Sir John Kerr, after the Opposition-controlled Senate rejected Whitlam's budget proposals.[109] As Whitlam had a majority in the House of Representatives, Speaker Gordon Scholes appealed to Elizabeth to reverse Kerr's decision. She declined, saying she would not interfere in decisions reserved by the Constitution of Australia for the governor-general.[110] The crisis fuelled Australian republicanism.[109]

In 1977, Elizabeth marked the Silver Jubilee of her accession. Parties and events took place throughout the Commonwealth, many coinciding with her associated national and Commonwealth tours. The celebrations re-affirmed Elizabeth's popularity, despite virtually coincident negative press coverage of Princess Margaret's separation from her husband, Lord Snowdon.[111] In 1978, Elizabeth endured a state visit to the United Kingdom by Romania's communist leader, Nicolae Ceaușescu, and his wife, Elena,[112] though privately she thought they had "blood on their hands".[113] The following year brought two blows: the unmasking of Anthony Blunt, former Surveyor of the Queen's Pictures, as a communist spy and the assassination of Lord Mountbatten by the Provisional Irish Republican Army.[114]

According to Paul Martin Sr., by the end of the 1970s, Elizabeth was worried the Crown "had little meaning for" Pierre Trudeau, the Canadian prime minister.[115] Tony Benn said Elizabeth found Trudeau "rather disappointing".[115] Trudeau's supposed republicanism seemed to be confirmed by his antics, such as sliding down banisters at Buckingham Palace and pirouetting behind Elizabeth's back in 1977, and the removal of various Canadian royal symbols during his term of office.[115] In 1980, Canadian politicians sent to London to discuss the patriation of the Canadian constitution found Elizabeth "better informed ... than any of the British politicians or bureaucrats".[115] She was particularly interested after the failure of Bill C-60, which would have affected her role as head of state.[115]

Perils and dissent

During the 1981 Trooping the Colour ceremony, six weeks before the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer, six shots were fired at Elizabeth from close range as she rode down The Mall, London, on her horse, Burmese. Police later discovered the shots were blanks. The 17-year-old assailant, Marcus Sarjeant, was sentenced to five years in prison and released after three.[116] Elizabeth's composure and skill in controlling her mount were widely praised.[117] That October, Elizabeth was the subject of another attack while on a visit to Dunedin, New Zealand. Christopher John Lewis, who was 17 years old, fired a shot with a .22 rifle from the fifth floor of a building overlooking the parade but missed.[118] Lewis was arrested, but instead of being charged with attempted murder or treason was sentenced to three years in jail for unlawful possession and discharge of a firearm. Two years into his sentence, he attempted to escape a psychiatric hospital with the intention of assassinating Charles, who was visiting the country with Diana and their son Prince William.[119]

From April to September 1982, Elizabeth's son Andrew served with British forces in the Falklands War, for which she reportedly felt anxiety[120] and pride.[121] On 9 July, she awoke in her bedroom at Buckingham Palace to find an intruder, Michael Fagan, in the room with her. In a serious lapse of security, assistance only arrived after two calls to the Palace police switchboard.[122] After hosting US president Ronald Reagan at Windsor Castle in 1982 and visiting his California ranch in 1983, Elizabeth was angered when his administration ordered the invasion of Grenada, one of her Caribbean realms, without informing her.[123]

Intense media interest in the opinions and private lives of the royal family during the 1980s led to a series of sensational stories in the press, pioneered by The Sun tabloid.[124] As Kelvin MacKenzie, editor of The Sun, told his staff: "Give me a Sunday for Monday splash on the Royals. Don't worry if it's not true—so long as there's not too much of a fuss about it afterwards."[125] Newspaper editor Donald Trelford wrote in The Observer of 21 September 1986: "The royal soap opera has now reached such a pitch of public interest that the boundary between fact and fiction has been lost sight of ... it is not just that some papers don't check their facts or accept denials: they don't care if the stories are true or not." It was reported, most notably in The Sunday Times of 20 July 1986, that Elizabeth was worried that Margaret Thatcher's economic policies fostered social divisions and was alarmed by high unemployment, a series of riots, the violence of a miners' strike, and Thatcher's refusal to apply sanctions against the apartheid regime in South Africa. The sources of the rumours included royal aide Michael Shea and Commonwealth secretary-general Shridath Ramphal, but Shea claimed his remarks were taken out of context and embellished by speculation.[126] Thatcher reputedly said Elizabeth would vote for the Social Democratic Party—Thatcher's political opponents.[127] Thatcher's biographer John Campbell claimed "the report was a piece of journalistic mischief-making".[128] Reports of acrimony between them were exaggerated,[129] and Elizabeth gave two honours in her personal gift—membership in the Order of Merit and the Order of the Garter—to Thatcher after her replacement as prime minister by John Major.[130] Brian Mulroney, Canadian prime minister between 1984 and 1993, said Elizabeth was a "behind the scenes force" in ending apartheid.[131][132]

In 1986, Elizabeth paid a six-day state visit to the People's Republic of China, becoming the first British monarch to visit the country.[133] The tour included the Forbidden City, the Great Wall of China, and the Terracotta Warriors.[134] At a state banquet, Elizabeth joked about the first British emissary to China being lost at sea with Queen Elizabeth I's letter to the Wanli Emperor, and remarked, "fortunately postal services have improved since 1602".[135] Elizabeth's visit also signified the acceptance of both countries that sovereignty over Hong Kong would be transferred from the United Kingdom to China in 1997.[136]

By the end of the 1980s, Elizabeth had become the target of satire.[137] The involvement of younger members of the royal family in the charity game show It's a Royal Knockout in 1987 was ridiculed.[138] In Canada, Elizabeth publicly supported politically divisive constitutional amendments, prompting criticism from opponents of the proposed changes, including Pierre Trudeau.[131] The same year, the elected Fijian government was deposed in a military coup. As monarch of Fiji, Elizabeth supported the attempts of Governor-General Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau to assert executive power and negotiate a settlement. Coup leader Sitiveni Rabuka deposed Ganilau and declared Fiji a republic.[139]

Turbulent years

In the wake of coalition victory in the Gulf War, Elizabeth became the first British monarch to address a joint meeting of the United States Congress in May 1991.[140]

In November 1992, in a speech to mark the Ruby Jubilee of her accession, Elizabeth called 1992 her annus horribilis (a Latin phrase, meaning "horrible year").[141] Republican feeling in Britain had risen because of press estimates of Elizabeth's private wealth—contradicted by the Palace[e]—and reports of affairs and strained marriages among her extended family.[146] In March, her second son, Prince Andrew, separated from his wife, Sarah; her daughter, Princess Anne, divorced Captain Mark Phillips in April;[147] angry demonstrators in Dresden threw eggs at Elizabeth during a state visit to Germany in October;[148] and a large fire broke out at Windsor Castle, one of her official residences, in November. The monarchy came under increased criticism and public scrutiny.[149] In an unusually personal speech, Elizabeth said that any institution must expect criticism, but suggested it might be done with "a touch of humour, gentleness and understanding".[150] Two days later, John Major announced plans to reform the royal finances, drawn up the previous year, including Elizabeth paying income tax from 1993 onwards, and a reduction in the civil list.[151] In December, Prince Charles and his wife, Diana, formally separated.[152] At the end of the year, Elizabeth sued The Sun newspaper for breach of copyright when it published the text of her annual Christmas message two days before it was broadcast. The newspaper was forced to pay her legal fees and donated £200,000 to charity.[153] Elizabeth's solicitors had taken successful action against The Sun five years earlier for breach of copyright after it published a photograph of her daughter-in-law the Duchess of York and her granddaughter Princess Beatrice.[154]

In January 1994, Elizabeth broke the scaphoid bone in her left wrist as the horse she was riding at Sandringham tripped and fell.[155] In October 1994, she became the first reigning British monarch to set foot on Russian soil.[f] In October 1995, she was tricked into a hoax call by Montreal radio host Pierre Brassard impersonating Canadian prime minister Jean Chrétien. Elizabeth, who believed that she was speaking to Chrétien, said she supported Canadian unity and would try to influence Quebec's referendum on proposals to break away from Canada.[160]

In the year that followed, public revelations on the state of Charles and Diana's marriage continued.[161] In consultation with her husband and John Major, as well as the Archbishop of Canterbury (George Carey) and her private secretary (Robert Fellowes), Elizabeth wrote to Charles and Diana at the end of December 1995, suggesting that a divorce would be advisable.[162]

In August 1997, a year after the divorce, Diana was killed in a car crash in Paris. Elizabeth was on holiday with her extended family at Balmoral. Diana's two sons, Princes William and Harry, wanted to attend church, so Elizabeth and Philip took them that morning.[163] Afterwards, for five days, the royal couple shielded their grandsons from the intense press interest by keeping them at Balmoral where they could grieve in private,[164] but the royal family's silence and seclusion, and the failure to fly a flag at half-mast over Buckingham Palace, caused public dismay.[132][165] Pressured by the hostile reaction, Elizabeth agreed to return to London and address the nation in a live television broadcast on 5 September, the day before Diana's funeral.[166] In the broadcast, she expressed admiration for Diana and her feelings "as a grandmother" for the two princes.[167] As a result, much of the public hostility evaporated.[167]

In October 1997, Elizabeth and Philip made a state visit to India, which included a controversial visit to the site of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre to pay her respects. Protesters chanted "Killer Queen, go back",[168] and there were demands for her to apologise for the action of British troops 78 years earlier.[169] At the memorial in the park, she and Philip laid a wreath and stood for a 30‑second moment of silence.[169] As a result, much of the fury among the public softened, and the protests were called off.[168] That November, the royal couple held a reception at Banqueting House to mark their golden wedding anniversary.[170] Elizabeth made a speech and praised Philip for his role as consort, referring to him as "my strength and stay".[170]

In 1999, as part of the process of devolution in the United Kingdom, Elizabeth formally opened newly established legislatures for Wales and Scotland: the National Assembly for Wales at Cardiff in May,[171] and the Scottish Parliament at Edinburgh in July.[172]

Dawn of the new millennium

On the eve of the new millennium, Elizabeth and Philip boarded a vessel from Southwark, bound for the Millennium Dome. Before passing under Tower Bridge, she lit the National Millennium Beacon in the Pool of London using a laser torch.[173] Shortly before midnight, she officially opened the Dome.[174] During the singing of Auld Lang Syne, Elizabeth held hands with Philip and British prime minister Tony Blair.[175] Following the 9/11 attacks in the United States, Elizabeth, breaking with tradition, ordered the American national anthem to be played during the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace to express her solidarity with the country.[176][177]

In 2002, Elizabeth marked her Golden Jubilee, the 50th anniversary of her accession. Her sister and mother died in February and March, respectively, and the media speculated on whether the Jubilee would be a success or a failure.[178] Princess Margaret's death shook Elizabeth; her funeral was one of the rare occasions where Elizabeth openly cried.[179] Elizabeth again undertook an extensive tour of her realms, beginning in Jamaica in February, where she called the farewell banquet "memorable" after a power cut plunged King's House, the official residence of the governor-general, into darkness.[180] As in 1977, there were street parties and commemorative events, and monuments were named to honour the occasion. One million people attended each day of the three-day main Jubilee celebration in London,[181] and the enthusiasm shown for Elizabeth by the public was greater than many journalists had anticipated.[182]

In 2003, Elizabeth sued the Daily Mirror for breach of confidence and obtained an injunction which prevented the outlet from publishing information gathered by a reporter who posed as a footman at Buckingham Palace.[183] The newspaper also paid £25,000 towards her legal costs.[184] Though generally healthy throughout her life, in 2003 she had keyhole surgery on both knees. In October 2006, she missed the opening of the new Emirates Stadium because of a strained back muscle that had been troubling her since the summer.[185]

In May 2007, citing unnamed sources, The Daily Telegraph reported that Elizabeth was "exasperated and frustrated" by the policies of Tony Blair, that she was concerned the British Armed Forces were overstretched in Iraq and Afghanistan, and that she had raised concerns over rural and countryside issues with Blair.[186] She was, however, said to admire Blair's efforts to achieve peace in Northern Ireland.[187] She became the first British monarch to celebrate a diamond wedding anniversary in November 2007.[188] On 20 March 2008, at the Church of Ireland St Patrick's Cathedral, Armagh, Elizabeth attended the first Maundy service held outside England and Wales.[189]

Elizabeth addressed the UN General Assembly for a second time in 2010, again in her capacity as Queen of all Commonwealth realms and Head of the Commonwealth.[190] The UN secretary-general, Ban Ki-moon, introduced her as "an anchor for our age".[191] During her visit to New York, which followed a tour of Canada, she officially opened a memorial garden for British victims of the 9/11 attacks.[191] Elizabeth's 11-day visit to Australia in October 2011 was her 16th visit to the country since 1954.[192] By invitation of the Irish president, Mary McAleese, she made the first state visit to the Republic of Ireland by a British monarch in May 2011.[193]

Diamond Jubilee and milestones

The 2012 Diamond Jubilee marked 60 years since Elizabeth's accession, and celebrations were held throughout her realms, the wider Commonwealth, and beyond. She and Philip undertook an extensive tour of the United Kingdom, while their children and grandchildren embarked on royal tours of other Commonwealth states on her behalf.[194] On 4 June, Jubilee beacons were lit around the world.[195] On 18 December, the Queen became the first British sovereign to attend a peacetime Cabinet meeting since George III in 1781.[196]

Elizabeth, who opened the Montreal Summer Olympics in 1976, also opened the 2012 Summer Olympics and Paralympics in London, making her the first head of state to open two Olympic Games in two countries.[197] For the London Olympics, she portrayed herself in a short film as part of the opening ceremony, alongside Daniel Craig as James Bond.[198] On 4 April 2013, she received an honorary BAFTA award for her patronage of the film industry and was called "the most memorable Bond girl yet" at a special presentation at Windsor Castle.[199]

In March 2013, the Queen stayed overnight at King Edward VII's Hospital as a precaution after developing symptoms of gastroenteritis.[201] A week later, she signed the new Charter of the Commonwealth.[202] That year, because of her age and the need for her to limit travelling, she chose not to attend the biennial Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting for the first time in 40 years. She was represented at the summit in Sri Lanka by Prince Charles.[203] On 20 April 2018, the Commonwealth heads of government announced that Charles would succeed her as Head of the Commonwealth, which the Queen stated as her "sincere wish".[204] She underwent cataract surgery in May 2018.[205] In March 2019, she gave up driving on public roads, largely as a consequence of a car accident involving her husband two months earlier.[206]

On 21 December 2007, Elizabeth surpassed her great-great-grandmother, Queen Victoria, to become the longest-lived British monarch, and she became the longest-reigning British monarch and longest-reigning queen regnant and female head of state in the world on 9 September 2015.[207] She became the oldest living monarch after the death of King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia on 23 January 2015.[208] She later became the longest-reigning current monarch and the longest-serving current head of state following the death of King Bhumibol of Thailand on 13 October 2016,[209] and the oldest current head of state on the resignation of Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe on 21 November 2017.[210] On 6 February 2017, she became the first British monarch to commemorate a sapphire jubilee,[211] and on 20 November that year, she was the first British monarch to celebrate a platinum wedding anniversary.[212] Philip had retired from his official duties as the Queen's consort in August 2017.[213]

Pandemic and widowhood

On 19 March 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United Kingdom, Elizabeth moved to Windsor Castle and sequestered there as a precaution.[214] Public engagements were cancelled and Windsor Castle followed a strict sanitary protocol nicknamed "HMS Bubble".[215]

On 5 April, in a televised broadcast watched by an estimated 24 million viewers in the United Kingdom,[216] Elizabeth asked people to "take comfort that while we may have more still to endure, better days will return: we will be with our friends again; we will be with our families again; we will meet again."[217] On 8 May, the 75th anniversary of VE Day, in a television broadcast at 9 pm—the exact time at which her father had broadcast to the nation on the same day in 1945—she asked people to "never give up, never despair".[218] In 2021, she received her first and second COVID-19 vaccinations in January and April respectively.[219]

Prince Philip died on 9 April 2021, after 73 years of marriage, making Elizabeth the first British monarch to reign as a widow or widower since Queen Victoria.[220] She was reportedly at her husband's bedside when he died,[221] and remarked in private that his death had "left a huge void".[222] Due to the COVID-19 restrictions in place in England at the time, Elizabeth sat alone at Philip's funeral service, which evoked sympathy from people around the world.[223] In her Christmas broadcast that year, which was ultimately her last, she paid a personal tribute to her "beloved Philip", saying, "That mischievous, inquiring twinkle was as bright at the end as when I first set eyes on him."[224]

Despite the pandemic, Elizabeth attended the 2021 State Opening of Parliament in May,[225] the 47th G7 summit in June,[226] and hosted US president Joe Biden at Windsor Castle. Biden was the 14th US president that the Queen had met.[227] In October 2021, Elizabeth cancelled a planned trip to Northern Ireland and stayed overnight at King Edward VII's Hospital for "preliminary investigations".[228] On Christmas Day 2021, while she was staying at Windsor Castle, 19-year-old Jaswant Singh Chail broke into the gardens using a rope ladder and carrying a crossbow with the aim of assassinating Elizabeth in revenge for the Amritsar massacre. Before he could enter any buildings, he was arrested and detained under the Mental Health Act. In 2023, he pleaded guilty to attempting to injure or alarm the sovereign.[229]

Platinum Jubilee and beyond

Elizabeth's Platinum Jubilee celebrations began on 6 February 2022, marking 70 years since her accession.[230] In her accession day message, she renewed her commitment to a lifetime of public service, which she had originally made in 1947.[231]

Later that month, Elizabeth fell ill with COVID-19 along with several family members, but she only exhibited "mild cold-like symptoms" and recovered by the end of the month.[232][233] She was present at the service of thanksgiving for her husband at Westminster Abbey on 29 March,[234] but was unable to attend both the annual Commonwealth Day service that month[235] and the Royal Maundy service in April, because of "episodic mobility problems".[236] In May, she missed the State Opening of Parliament for the first time in 59 years. (She did not attend the state openings in 1959 and 1963 as she was pregnant with Prince Andrew and Prince Edward, respectively.)[237]

The Queen was largely confined to balcony appearances during the public jubilee celebrations, and she missed the National Service of Thanksgiving on 3 June.[238] On 13 June, she became the second-longest reigning monarch in history (among those whose exact dates of reign are known), with 70 years and 127 days on the throne—surpassing King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand.[239] On 6 September, she appointed her 15th British prime minister, Liz Truss, at Balmoral Castle in Scotland. This was the only occasion on which Elizabeth received a new prime minister at a location other than Buckingham Palace.[240] No other British monarch appointed as many prime ministers.[241] The Queen's last public message was issued on 7 September, in which she expressed her sympathy for those affected by the Saskatchewan stabbings.[242]

Elizabeth did not plan to abdicate,[243] though she took on fewer public engagements in her later years and Prince Charles performed more of her duties.[244] She told Canadian governor-general Adrienne Clarkson in a meeting in 2002 that she would never abdicate, saying, "It is not our tradition. Although, I suppose if I became completely gaga, one would have to do something."[245] In June 2022, Elizabeth met the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, who "came away thinking there is someone who has no fear of death, has hope in the future, knows the rock on which she stands and that gives her strength."[246]

Death

On 8 September 2022, Buckingham Palace stated, "Following further evaluation this morning, the Queen's doctors are concerned for Her Majesty's health and have recommended she remain under medical supervision. The Queen remains comfortable and at Balmoral."[247][248] Her immediate family rushed to Balmoral.[249][250] She died peacefully at 15:10 BST at the age of 96.[251][252][253] Her death was announced to the public at 18:30,[254][255] setting in motion Operation London Bridge and, because she died in Scotland, Operation Unicorn.[256][257] Elizabeth was the first monarch to die in Scotland since James V in 1542.[258] Her death certificate recorded her cause of death as "old age".[252][259] However, biographer Gyles Brandreth also reported that Elizabeth was battling multiple myeloma,[260] a form of bone marrow cancer, when she died.[261]

On 12 September, Elizabeth's coffin was carried up the Royal Mile in a procession to St Giles' Cathedral, where the Crown of Scotland was placed on it.[262] Her coffin lay at rest at the cathedral for 24 hours, guarded by the Royal Company of Archers, during which around 33,000 people filed past it.[263] On 13 September, the coffin was flown to RAF Northolt in west London to be met by Liz Truss, before continuing its journey by road to Buckingham Palace.[264] On 14 September, her coffin was taken in a military procession to Westminster Hall, where Elizabeth lay in state for four days. The coffin was guarded by members of both the Sovereign's Bodyguard and the Household Division. An estimated 250,000 members of the public filed past the coffin, as did politicians and other public figures.[265][266] On 16 September, Elizabeth's children held a vigil around her coffin, and the next day her eight grandchildren did the same.[267][268]

Elizabeth's state funeral was held at Westminster Abbey on 19 September, which marked the first time a monarch's funeral service was held at the Abbey since George II in 1760.[269] More than a million people lined the streets of central London,[270] and the day was declared a holiday in several Commonwealth countries. In Windsor, a final procession involving 1,000 military personnel took place, which 97,000 people witnessed.[271][270] Elizabeth's fell pony and two royal corgis stood at the side of the procession.[272] After a committal service at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, Elizabeth was interred with her husband Philip in the King George VI Memorial Chapel later the same day, in a private ceremony attended by her closest family members.[ 273 ] [ 271 ] [ 274 ] [ 275 ]

Наследие

Убеждения, деятельность и интересы

Элизабет редко давала интервью, и о ее политических взглядах было мало что известно, которые она не выражала открыто публично. Спрашивать или раскрывать точку зрения монарха противоречит традиции. Когда Times журналист Пол Рутледж спросил ее о забастовке шахтеров 1984–85 годов во время королевского тура по офисам газеты, она ответила, что «все дело в одном человеке» (отсылка к Артуру Скаргиллу ), [ 276 ] с чем Рутледж не согласился. [ 277 ] Рутледжа широко раскритиковали в средствах массовой информации за то, что он задал этот вопрос, и заявил, что он не знал о протоколах. [ 277 ] После референдума о независимости Шотландии в 2014 году было слышно , как премьер-министр Дэвид Кэмерон заявил, что Элизабет довольна результатом. [ 278 ] Возможно, она опубликовала публичное закодированное заявление о референдуме, сказав одной женщине за пределами Балморал-Кёрк, что надеется, что люди «очень тщательно» подумают о результате. Позже выяснилось, что Кэмерон специально попросила ее выразить свою обеспокоенность. [ 279 ]

Элизабет имела глубокое чувство религиозного и гражданского долга и серьезно отнеслась к своей коронационной клятве . [ 280 ] Помимо своей официальной религиозной роли верховного правителя установленной англиканской церкви , она поклонялась вместе с этой церковью и национальной церковью Шотландии . [ 281 ] Она продемонстрировала поддержку межконфессиональных отношений и встретилась с лидерами других церквей и религий, включая пять пап: Пия XII , Иоанна XXIII , Иоанна Павла II , Бенедикта XVI и Франциска . [ 282 ] Личная заметка о ее вере часто упоминается в ее ежегодном Рождественском послании, транслируемом Содружеству. В 2000 году она сказала: [ 283 ]

Для многих из нас наши убеждения имеют фундаментальное значение. Для меня учение Христа и моя личная ответственность перед Богом создают основу, в которой я пытаюсь вести свою жизнь. Я, как и многие из вас, в трудные времена черпал большое утешение из слов и примера Христа.

Элизабет была покровительницей более 600 организаций и благотворительных организаций. [ 284 ] По оценкам Фонда благотворительной помощи , за время своего правления Елизавета помогла собрать более 1,4 миллиарда фунтов стерлингов для своего покровительства. [ 285 ] Ее основные интересы в свободное время включали конный спорт и собак, особенно ее вельш-корги пемброк . [ 286 ] Ее пожизненная любовь к корги началась в 1933 году с Дуки , первого из многих королевских корги . [ 287 ] Время от времени можно было наблюдать сцены непринужденной, неформальной домашней жизни; время от времени она и ее семья вместе готовили еду, а потом мыли посуду. [ 288 ]

Изображение в СМИ и общественное мнение

В 1950-х годах, будучи молодой женщиной в начале своего правления, Елизавету изображали гламурной «сказочной королевой». [ 289 ] После травм Второй мировой войны наступило время надежд, период прогресса и достижений, знаменующее «новую елизаветинскую эпоху ». [ 290 ] Обвинение лорда Олтринчема в 1957 году в том, что ее речи звучали как речи « чопорной школьницы», было крайне редкой критикой. [ 291 ] В конце 1960-х годов попытки изобразить более современный образ монархии были предприняты в телевизионном документальном фильме « Королевская семья» и в трансляции по телевидению вступления принца Чарльза в должность принца Уэльского . [ 292 ] Элизабет также ввела другие новые практики; ее первая королевская прогулка, встречающаяся с обычными представителями общественности, состоялась во время турне по Австралии и Новой Зеландии в 1970 году. [ 293 ] В ее гардеробе сформировался узнаваемый, фирменный стиль, основанный больше на функциональности, чем на моде. [ 294 ] На публике она носила в основном однотонные пальто и декоративные шляпы, что позволяло ее легко заметить в толпе. [ 295 ] К концу ее правления почти треть британцев видели или встречались с Елизаветой лично. [ 296 ]

На серебряном юбилее Елизаветы в 1977 году толпы и празднования были полны энтузиазма; [ 297 ] но в 1980-х годах публичная критика королевской семьи усилилась, поскольку личная и трудовая жизнь детей Елизаветы оказалась под пристальным вниманием средств массовой информации. [ 298 ] Ее популярность упала до минимума в 1990-е годы. Под давлением общественного мнения она впервые стала платить подоходный налог, и Букингемский дворец был открыт для публики. [ 299 ] Хотя поддержка республиканизма в Британии казалась выше, чем когда-либо на памяти живущих, республиканская идеология по-прежнему оставалась точкой зрения меньшинства, а сама Элизабет имела высокие рейтинги одобрения. [ 300 ] Критика была сосредоточена на институте самой монархии и поведении более широкой семьи Елизаветы, а не на ее собственном поведении и действиях. [ 301 ] Недовольство монархией достигло своего апогея после смерти Дианы, принцессы Уэльской, хотя личная популярность Елизаветы, а также общая поддержка монархии восстановились после ее прямой телетрансляции на весь мир через пять дней после смерти Дианы. [ 302 ]

В ноябре 1999 года референдум в Австралии о будущем австралийской монархии отдал предпочтение ее сохранению, а не косвенно избранному главе государства. [ 303 ] Многие республиканцы считали, что личная популярность Елизаветы способствовала выживанию монархии в Австралии. В 2010 году премьер-министр Джулия Гиллард отметила, что в Австралии к Елизавете испытывают «глубокую привязанность» и что новый референдум по монархии следует подождать до окончания ее правления. [ 304 ] Преемник Гиллард, Малкольм Тернбулл , который возглавил республиканскую кампанию в 1999 году, также считал, что австралийцы не будут голосовать за то, чтобы стать республикой при ее жизни. [ 305 ] «Она была выдающимся главой государства, — сказал Тернбулл в 2021 году, — и, честно говоря, я думаю, что в Австралии больше елизаветинцев, чем монархистов». [ 306 ] Аналогичным образом, на референдумах в Тувалу в 2008 году и в Сент-Винсенте и Гренадинах в 2009 году избиратели отклонили предложения о создании республик. [ 307 ]

Опросы общественного мнения в Великобритании в 2006 и 2007 годах выявили сильную поддержку монархии. [ 308 ] а в 2012 году, в год бриллиантового юбилея Элизабет, ее рейтинг одобрения достиг 90 процентов. [ 309 ] Ее семья снова оказалась под пристальным вниманием в последние несколько лет ее жизни из-за связи ее сына Эндрю с осужденными за сексуальные преступления Джеффри Эпштейном и Гислен Максвелл , его иска с Вирджинией Джуффре на фоне обвинений в сексуальных непристойностях, а также ее внука Гарри и его жены Меган . Выход из рабочей королевской семьи и последующий переезд в США. [ 310 ] Однако опросы в Великобритании во время Платинового юбилея показали поддержку сохранения монархии. [ 311 ] и личная популярность Элизабет оставалась высокой. [ 312 ] По состоянию на 2021 год она оставалась третьей женщиной в мире, которой больше всего восхищаются, согласно ежегодному опросу Gallup : ее 52 появления в списке означают, что она входила в первую десятку больше, чем любая другая женщина в истории опроса. [ 313 ]

Элизабет изображалась в различных средствах массовой информации многими известными художниками, в том числе художниками Пьетро Аннигони , Питером Блейком , Чинве Чуквуого-Роем , Теренсом Кунео , Люсьеном Фрейдом , Рольфом Харрисом , Дэмиеном Херстом , Джульет Паннетт и Тай-Шаном Ширенбергом . [ 314 ] [ 315 ] Среди известных фотографов Элизабет были Сесил Битон , Юсуф Карш , Анвар Хусейн , Энни Лейбовиц , лорд Личфилд , Терри О'Нил , Джон Суоннелл и Дороти Уайлдинг . Первая официальная портретная фотография Элизабет была сделана Маркусом Адамсом в 1926 году. [ 316 ]

Титулы, стили, почести и оружие

Названия и стили

Елизавета имела множество званий и почетных воинских должностей по всему Содружеству , была владетельницей многих орденов в своих странах и получала почести и награды со всего мира. В каждом из своих королевств у нее был отдельный титул, который следовал аналогичной формуле: Королева Сент-Люсии и ее других королевств и территорий в Сент-Люсии , королева Австралии и ее других королевств и территорий в Австралии и т. д. Ее также называли Защитник Веры .

Оружие

С 21 апреля 1944 года и до ее вступления на престол герб Елизаветы представлял собой ромб с королевским гербом Соединенного Королевства , отличавшийся этикеткой из трех серебряных точек , в центре которой была изображена роза Тюдоров , а на первой и третьей - крест Святого Георгия. . [ 317 ] После своего вступления на престол она унаследовала различные гербы, которые ее отец держал как суверен, с измененным изображением короны. Елизавета также владела королевскими штандартами и личными флагами для использования в Великобритании , Канаде , Австралии , Новой Зеландии , Ямайке и других странах. [ 318 ]

Проблема

| Имя | Рождение | Свадьба | Дети | Внуки | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Дата | Супруг | ||||

| Карл III | 14 ноября 1948 г. | 29 июля 1981 г. Разведен 28 августа 1996 г.

|

Леди Диана Спенсер | Уильям, принц Уэльский | |

| Принц Гарри, герцог Сассекский | |||||

| 9 апреля 2005 г. | Камилла Паркер Боулз | Никто | |||

| Анна, королевская принцесса | 15 августа 1950 г. | 14 ноября 1973 г. Разведен 23 апреля 1992 г.

|

Марк Филлипс | Питер Филлипс |

|

| Зара Тиндалл |

| ||||

| 12 декабря 1992 г. | Тимоти Лоуренс | Никто | |||

| Принц Эндрю, герцог Йоркский | 19 февраля 1960 г. | 23 июля 1986 г. Разведен 30 мая 1996 г.

|

Сара Фергюсон | Принцесса Беатрис, г-жа Эдоардо Мапелли Моцци | Сиенна Мапелли Моцци |

| Принцесса Евгения, миссис Джек Бруксбанк |

| ||||

| Принц Эдвард, герцог Эдинбургский | 10 марта 1964 г. | 19 июня 1999 г. | Софи Рис-Джонс | Леди Луиза Маунтбаттен-Виндзор | Никто |

| Джеймс Маунтбаттен-Виндзор, граф Уэссекса | Никто | ||||

Родословная

| Предки Елизаветы II [ 319 ] |

|---|

См. также

- Финансы британской королевской семьи

- Дом Елизаветы II

- Список вещей, названных в честь Елизаветы II

- Список юбиляров Елизаветы II

- Список особых адресов Елизаветы II

- Королевские эпонимы в Канаде

- Список обложек журнала Time (1920-е , 1940-е , 1950-е , 2010-е)

Примечания

- ↑ Будучи монархом, Елизавета была Верховным губернатором англиканской церкви . Она также была членом Шотландской церкви .

- ^ Ее крестными родителями были: король Георг V и королева Мария; лорд Стратмор; Принц Артур, герцог Коннахтский и Страттернский (ее двоюродный дедушка по отцовской линии); Принцесса Мария, виконтесса Ласселлес (ее тетя по отцовской линии); и леди Эльфинстон (ее тетя по материнской линии). [ 4 ]

- ↑ Часто цитируемая речь была написана Дермотом Моррой , журналистом The Times . [ 41 ]

- ^ Телевизионное освещение коронации сыграло важную роль в повышении популярности средства массовой информации; количество телевизионных лицензий в Соединенном Королевстве удвоилось до 3 миллионов, [ 74 ] и многие из более чем 20 миллионов британских зрителей впервые смотрели телевизор в домах своих друзей или соседей. [ 75 ] В Северной Америке записанные передачи смотрели почти 100 миллионов зрителей. [ 76 ]

- ↑ Список богатых людей Sunday Times за 1989 год поставил ее на первое место в списке с заявленным состоянием в 5,2 миллиарда фунтов стерлингов (примерно 12,6 миллиарда фунтов стерлингов по состоянию на 2023 год). [ 142 ] но в него входили государственные активы, такие как Королевская коллекция , которые не принадлежали ей лично. [ 143 ] В 1993 году Букингемский дворец назвал оценку в 100 миллионов фунтов стерлингов «сильно завышенной». [ 144 ] В 1971 году Джок Колвилл , ее бывший личный секретарь и директор ее банка Coutts , оценил ее состояние в 2 миллиона фунтов стерлингов (что эквивалентно примерно 15 миллионам фунтов стерлингов в 1993 году). [ 142 ] ). [ 145 ]

- ↑ Единственный предыдущий государственный визит британского монарха в Россию совершил король Эдуард VII в 1908 году. Король никогда не выходил на берег и встречался с Николаем II на королевских яхтах у балтийского порта на территории нынешнего Таллинна , Эстония. [ 156 ] [ 157 ] Во время четырехдневного визита , считавшегося одним из самых важных зарубежных поездок за время правления Елизаветы, [ 158 ] они с Филиппом посетили мероприятия в Москве и Санкт-Петербурге . [ 159 ]

Ссылки

Цитаты

- ^ «№ 33153» , «Лондонская газета» , 21 апреля 1926 г., стр. 1

- ^ Брэдфорд 2012 , с. 22; Брандрет 2004 , с. 103; Марр 2011 , с. 76; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 2–3; Лейси 2002 , стр. 75–76; Робертс 2000 , с. 74

- ^ Хоуи 2002 , с. 40

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , с. 103; Хоуи 2002 , с. 40

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , с. 103

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , с. 12

- ^ Уильямсон 1987 , с. 205

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , с. 15

- ^ Лейси 2002 , с. 56; Николсон 1952 , с. 433; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 14–16.

- ^ Кроуфорд 1950 , с. 26; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 20; Шокросс 2002 , с. 21

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , с. 124; Лейси 2002 , стр. 62–63; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 24, 69.

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , стр. 108–110; Лейси 2002 , стр. 159–161; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 20, 163.

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , стр. 108–110.

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , с. 105; Лейси 2002 , с. 81; Шоукросс 2002 , стр. 21–22

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , стр. 105–106.

- ^ Кроуфорд 1950 , стр. 14–34; Хилд, 2007 г. , стр. 7–8; Уорик, 2002 г. , стр. 35–39.

- ^ Бонд 2006 , с. 8; Лейси 2002 , с. 76; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 3

- ^ Лейси 2002 , стр. 97–98.

- ^ Марр 2011 , стр. 78, 85; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 71–73.

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , с. 124; Кроуфорд 1950 , с. 85; Лейси 2002 , с. 112; Марр 2011 , с. 88; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 51; Шокросс 2002 , с. 25

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Ее Величество Королева: Молодость и образование» , Royal Household, 29 декабря 2015 г., заархивировано из оригинала 7 мая 2016 г. , получено 18 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ Марр 2011 , с. 84; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 47

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пимлотт 2001 , с. 54

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пимлотт 2001 , с. 55

- ^ Уорвик 2002 , с. 102

- ^ Гуди, Эмма (21 декабря 2015 г.), «Королева Елизавета, королева-мать» , Королевская семья , Королевский двор, заархивировано из оригинала 7 мая 2016 г. , получено 18 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ Кроуфорд 1950 , стр. 104–114; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 56–57.

- ^ Кроуфорд 1950 , стр. 114–119; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 57

- ^ Кроуфорд 1950 , стр. 137–141.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Детский час: Принцесса Елизавета» , Архив BBC , 13 октября 1940 г., заархивировано из оригинала 27 ноября 2019 г. , получено 22 июля 2009 г.

- ^ «Ранняя общественная жизнь» , Royal Household, заархивировано из оригинала 28 марта 2010 г. , получено 20 апреля 2010 г.

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , с. 71

- ^ «№ 36973» , The London Gazette (Приложение), 6 марта 1945 г., стр. 1315

- ^

- Брэдфорд 2012 , с. 45; Лейси 2002 , стр. 136–137; Марр 2011 , с. 100; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 75;

- «№ 37205» , The London Gazette (Приложение), 31 июля 1945 г., стр. 3972

- ^ Бонд 2006 , с. 10; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 79

- ^

- «Королева помнит День Победы 1945 года» , The Way We Were (интервью), интервью Годфри Талбота , BBC Radio 4 , 8 мая 1985 года , получено 4 апреля 2024 года – через YouTube ;

- Запись The Way We Were Radio Times о проекте BBC Genome Project

- ^ «Королевские планы победить национализм» , BBC News , 8 марта 2005 г., заархивировано из оригинала 8 февраля 2012 г. , получено 15 июня 2010 г.

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 71–73.

- ^ «Горседд бардов» , Национальный музей Уэльса, заархивировано из оригинала 18 мая 2014 г. , получено 17 декабря 2009 г.

- ^ Фишер, Конни (20 апреля 1947 г.), «Речь королевы по случаю ее 21-летия» , Королевская семья , Королевское хозяйство, заархивировано из оригинала 3 января 2017 г. , получено 18 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ Атли, Чарльз (июнь 2017 г.), «Мой дедушка написал речь принцессы» , The Oldie , заархивировано из оригинала 31 мая 2022 г. , получено 8 сентября 2022 г.

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , стр. 132–139; Лейси 2002 , стр. 124–125; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 86

- ^ Бонд 2006 , с. 10; Брандрет 2004 , стр. 132–136, 166–169; Лейси 2002 , стр. 119, 126, 135.

- ^ Хилд 2007 , с. 77

- ^ Эдвардс, Фил (31 октября 2000 г.), «Настоящий принц Филипп» , Channel 4 , заархивировано из оригинала 9 февраля 2010 г. , получено 23 сентября 2009 г.

- ^ Кроуфорд 1950 , с. 180

- ^

- Дэвис, Кэролайн (20 апреля 2006 г.), «Филип, единственный постоянный человек в ее жизни» , The Telegraph , Лондон, заархивировано из оригинала 9 января 2022 г. , получено 23 сентября 2009 г .;

- Брандрет 2004 , с. 314

- ^ Хилд 2007 , с. XVIII

- ^ Хои 2002 , стр. 55–56; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 101, 137.

- ^ «№ 38128» , «Лондонская газета» , 21 ноября 1947 г., стр. 5495

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «60 фактов о годовщине бриллиантовой свадьбы» , Royal Household, 18 ноября 2007 г., заархивировано из оригинала 3 декабря 2010 г. , получено 20 июня 2010 г.

- ^ Хоуи 2002 , с. 58; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 133–134.

- ^ Хоуи 2002 , с. 59; Петропулос 2006 , с. 363

- ^ Брэдфорд 2012 , с. 61

- ^

- Патентное письмо, 22 октября 1948 г.;

- Хоуи 2002 , стр. 69–70; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 155–156.

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , с. 163

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , стр. 226–238; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 145, 159–163, 167.

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , стр. 240–241; Лейси 2002 , с. 166; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 169–172.

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , стр. 245–247; Лейси 2002 , с. 166; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 173–176; Шокросс 2002 , с. 16

- ^ Баусфилд и Тоффоли 2002 , с. 72; Брэдфорд 2002 , с. 166; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 179; Шокросс 2002 , с. 17

- ^ Митчелл 2003 , с. 113

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 178–179.

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 186–187.

- ^ Сомс, Эмма (1 июня 2012 г.), «Эмма Сомс: Как Черчилли, мы гордимся тем, что выполняем свой долг» , The Telegraph , Лондон, заархивировано из оригинала 2 июня 2012 г. , получено 12 марта 2019 г.

- ^ Брэдфорд 2012 , с. 80; Брандрет, 2004 г. , стр. 253–254; Лейси 2002 , стр. 172–173; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 183–185.

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 297–298.

- ^ «№ 41948» , The London Gazette (Приложение), 5 февраля 1960 г., стр. 1003

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , стр. 269–271.

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , стр. 269–271; Лейси 2002 , стр. 193–194; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 201, 236–238.

- ^ Бонд 2006 , с. 22; Брандрет 2004 , с. 271; Лейси 2002 , с. 194; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 238; Шокросс 2002 , с. 146

- ^ «Принцесса Маргарет: Брак и семья» , Royal Household, заархивировано из оригинала 6 ноября 2011 г. , получено 8 сентября 2011 г.

- ^ Брэдфорд 2012 , с. 82

- ^ «50 фактов о коронации королевы» , Royal Household, 25 мая 2003 г., заархивировано из оригинала 7 февраля 2021 г. , получено 18 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , с. 207

- ^ Бриггс 1995 , стр. 420 и далее. ; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 207; Робертс 2000 , с. 82

- ^ Лейси 2002 , с. 182

- ^ Лейси 2002 , с. 190; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 247–248.

- ^ Марр 2011 , с. 272

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , с. 182

- ^ «Содружество: подарки королеве» , Royal Collection Trust , заархивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2016 г. , получено 20 февраля 2016 г.

- ^

- «Австралия: Королевские визиты» , Royal Household, 13 октября 2015 г., заархивировано из оригинала 1 февраля 2019 г. , получено 18 апреля 2016 г .;

- Валланс, Адам (22 декабря 2015 г.), «Новая Зеландия: Королевские визиты» , Королевская семья , Королевский двор, заархивировано из оригинала 22 марта 2019 г. , получено 18 апреля 2016 г .;

- Марр 2011 , с. 126

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , с. 278; Март 2011 г. , с. 126; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 224; Шокросс 2002 , с. 59

- ^ Кэмпбелл, Софи (11 мая 2012 г.), «Бриллиантовый юбилей королевы: шестьдесят лет королевских турне» , The Telegraph , заархивировано из оригинала 10 января 2022 г. , получено 20 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ Томсон, Майк (15 января 2007 г.), «Когда Великобритания и Франция почти поженились» , BBC News , заархивировано из оригинала 23 января 2009 г. , получено 14 декабря 2009 г.

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , с. 255; Робертс 2000 , с. 84

- ^ Марр 2011 , стр. 175–176; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 256–260; Робертс 2000 , с. 84

- ^ Лейси 2002 , с. 199; Шокросс 2002 , с. 75

- ^

- Альтринчем в журнале National Review , цитируется по

- Брандрет 2004 , с. 374; Робертс 2000 , с. 83

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , с. 374; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 280–281; Шокросс 2002 , с. 76

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хардман 2011 , с. 22; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 324–335; Робертс 2000 , с. 84

- ^ Робертс 2000 , с. 84

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Королева и Канада: Королевские визиты» , Royal Household, заархивировано из оригинала 4 мая 2010 г. , получено 12 февраля 2012 г.

- ^ Брэдфорд 2012 , с. 114

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , с. 303; Шокросс 2002 , с. 83

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Макмиллан 1972 , стр. 466–472.

- ^ Дюбуа, Поль (12 октября 1964 г.), «Демонстрации в субботу в Квебеке» , The Gazette , стр. 1, заархивировано 23 января 2021 года , получено 6 марта 2010 года.

- ^ Баусфилд и Тоффоли 2002 , с. 139

- ^ «Королевское генеалогическое древо и линия преемственности» , BBC News , 4 сентября 2017 г., заархивировано из оригинала 11 марта 2021 г. , получено 13 мая 2022 г.

- ^ «№ 43268» , The London Gazette , 11 марта 1964 г., стр. 2255

- ^ Уильямс, Кейт (18 августа 2019 г.), «По мере возвращения Короны, следите за этими вехами» , The Guardian , заархивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2021 г. , получено 5 июля 2021 г.

- ^ Бонд 2006 , с. 66; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 345–354.

- ^ Брэдфорд, 2012 , стр. 123, 154, 176; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 301, 315–316, 415–417.

- ^ «Аберфанская катастрофа: сожаление королевы после трагедии» , BBC News , 10 сентября 2022 г., заархивировано из оригинала 23 ноября 2022 г. , получено 20 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ «Как съемки агонии Аберфана для The Crown показали, что деревня все еще находится в травме» , The Guardian , 17 ноября 2019 г., заархивировано из оригинала 21 декабря 2022 г. , получено 20 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Хоуи 2022 , с. 58

- ^ «Большие толпы в Белграде приветствуют королеву Елизавету» , The New York Times , 18 октября 1972 г., заархивировано из оригинала 6 июня 2022 г. , получено 8 сентября 2022 г.

- ^ Брэдфорд 2012 , с. 181; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 418

- ^ Брэдфорд 2012 , с. 181; Марр 2011 , с. 256; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 419; Шокросс 2002 , стр. 109–110.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бонд 2006 , с. 96; Марр 2011 , с. 257; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 427; Шокросс 2002 , с. 110

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 428–429.

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , с. 449

- ^ Хардман 2011 , с. 137; Робертс 2000 , стр. 88–89; Шокросс 2002 , с. 178

- ^ Элизабет своим сотрудникам, цитируется по Shawcross 2002 , p. 178

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 336–337, 470–471; Робертс 2000 , стр. 88–89.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Хейнрикс, Джефф (29 сентября 2000 г.), «Трюдо: ящик-монархист», National Post , Торонто, стр. Б12

- ^ «Фэнтезийный убийца королевы заключен в тюрьму» , BBC News , 14 сентября 1981 г., заархивировано из оригинала 28 июля 2011 г. , получено 21 июня 2010 г.

- ^ Лейси 2002 , с. 281; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 476–477; Шокросс 2002 , с. 192

- ^ Макнилли, Хэмиш (1 марта 2018 г.), «Документы разведки подтверждают покушение на королеву Елизавету в Новой Зеландии» , The Sydney Morning Herald , заархивировано из оригинала 26 июня 2019 г. , получено 1 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Эйндж Рой, Элеонора (13 января 2018 г.), « « Черт ... я промахнулся »: невероятная история того дня, когда королеву чуть не застрелили» , The Guardian , заархивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2018 г. , получено 1 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Бонд 2006 , с. 115; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 487

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , с. 487; Шокросс 2002 , с. 127

- ^ Лейси 2002 , стр. 297–298; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 491

- ^ Бонд 2006 , с. 188; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 497

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 488–490.

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , с. 521

- ^

- Хардман, 2011 г. , стр. 216–217; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 503–515; см. также

- Нил 1996 , стр. 195–207; Шокросс 2002 , стр. 129–132.

- ^

- Тэтчер Брайану Уолдену , цитируется по Neil 1996 , стр. 207;

- Нил, цитата из Wyatt 1999 , дневник от 26 октября 1990 г.

- ^ Кэмпбелл 2003 , с. 467

- ^ Хардман 2011 , стр. 167, 171–173.

- ^ Робертс 2000 , с. 101; Шокросс 2002 , с. 139

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Геддес, Джон (2012), «День, когда она вступила в бой», Maclean's (Специальное памятное издание), стр. 72

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б МакКуин, Кен; Требл, Патриция (2012), «Драгоценность в короне», Maclean's (Специальный памятный выпуск), стр. 43–44.

- ^ «Королева достигает королевской цели: посетить Китай» , The New York Times , 13 октября 1986 г., заархивировано из оригинала 6 июня 2022 г. , получено 8 сентября 2022 г.

- ^ BBC Books 1991 , стр. 181

- ^ Хардман 2019 , с. 437

- ^ Богерт, Кэрролл Р. (13 октября 1986 г.), «Королева Елизавета II прибыла в Пекин с 6-дневным визитом» , The Washington Post , ISSN 0190-8286 , заархивировано из оригинала 26 марта 2023 г. , получено 12 октября 2022 г.

- ^ Лейси 2002 , стр. 293–294; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 541

- ^ Хардман 2011 , стр. 82–83; Лейси 2002 , с. 307; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 522–526.

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 515–516.

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , с. 538

- ^ Фишер, Конни (24 ноября 1992 г.), «Речь Annus horribilis» , Королевская семья , Королевское хозяйство, заархивировано из оригинала 3 января 2017 г. , получено 18 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Соединенного Королевства Показатели дефлятора валового внутреннего продукта соответствуют «согласованному ряду» MeasuringWorth, представленному в Томас, Райланд; Уильямсон, Сэмюэл Х. (2024), «Какой тогда был ВВП Великобритании?» , MeasuringWorth , получено 15 июля 2024 г.

- ^ «Список богатых: изменение лица богатства» , BBC News , 18 апреля 2013 г., заархивировано из оригинала 6 ноября 2020 г. , получено 23 июля 2020 г.

- ^

- Лорд Эйрли , лорд-камергер , цитируется в

- Хоуи 2002 , с. 225; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 561

- ^

- «Оценка богатства королевы в 2 миллиона фунтов стерлингов, скорее всего, будет точной» , The Times , 11 июня 1971 г., стр. 1 ;

- Пимлотт 2001 , с. 401

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 519–534.

- ^ Лейси 2002 , с. 319; Марр 2011 , с. 315; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 550–551.

- ^ Стенглин, Дуглас (18 марта 2010 г.), «Немецкое исследование пришло к выводу, что в результате бомбардировки Дрездена союзниками погибло 25 000 человек» , USA Today , заархивировано из оригинала 15 мая 2010 г. , получено 19 марта 2010 г.

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , с. 377; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 558–559; Робертс 2000 , с. 94; Шокросс 2002 , с. 204

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , с. 377

- ^ Брэдфорд 2012 , с. 229; Лейси 2002 , стр. 325–326; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 559–561.

- ^ Брэдфорд 2012 , с. 226; Хардман 2011 , с. 96; Лейси 2002 , с. 328; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 561

- ^ Пимлотт 2001 , с. 562

- ^ «Королева угрожает подать в суд на газету» , Associated Press News , Лондон, 3 февраля 1993 г., заархивировано из оригинала 7 апреля 2022 г. , получено 27 декабря 2021 г.

- ^ «Королева сломала запястье в результате несчастного случая при езде» , Associated Press News , 17 января 1994 г., заархивировано из оригинала 31 августа 2022 г. , получено 1 сентября 2022 г.

- ^

- «Елизавета II посетит Россию в октябре» , Evansville Press , Associated Press, 15 июля 1994 г., стр. 2, заархивировано из оригинала 6 июня 2022 года , получено 8 сентября 2022 года ;

- Томашевский 2002 , стр. 22.

- ^ Слоан, Венди (19 октября 1994 г.), «Не все прощено, поскольку королева совершает поездку по безцарской России» , The Christian Science Monitor , Москва, заархивировано из оригинала 5 сентября 2022 г. , получено 8 сентября 2022 г.

- ^ «Британская королева в Москве» , United Press International , Москва, 17 октября 1994 г., заархивировано из оригинала 12 марта 2022 г. , получено 8 сентября 2022 г.

- ^ де Ваал, Томас (15 октября 1994 г.), «Визит королевы: поднимая облака прошлого», The Moscow Times

- ^

- «Алло! Алло! Иси Королева. Кто это?» , The New York Times , 29 октября 1995 г., заархивировано из оригинала 6 июня 2022 г. , получено 8 сентября 2022 г .;

- «Королева стала жертвой радиомистификации» , The Independent , 28 октября 1995 г., заархивировано из оригинала 3 июня 2022 г. , получено 8 сентября 2022 г.

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , с. 356; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 572–577; Робертс 2000 , с. 94; Шокросс 2002 , с. 168

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , с. 357; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 577

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , с. 358; Хардман 2011 , с. 101; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 610

- ^ Бонд 2006 , с. 134; Брандрет 2004 , с. 358; Марр 2011 , с. 338; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 615

- ^ Бонд 2006 , с. 134; Брандрет 2004 , с. 358; Лейси, 2002 г. , стр. 6–7; Пимлотт 2001 , с. 616; Робертс 2000 , с. 98; Шокросс 2002 , с. 8

- ^ Брандрет 2004 , стр. 358–359; Лейси, 2002 г. , стр. 8–9; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 621–622.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бонд 2006 , с. 134; Брандрет 2004 , с. 359; Лейси, 2002 г. , стр. 13–15; Пимлотт 2001 , стр. 623–624.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Индийская группа отменяет протест, принимает сожаления королевы» , Амритсар, Индия: CNN, 14 октября 1997 г., заархивировано из оригинала 3 мая 2021 г. , получено 3 мая 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бернс, Джон Ф. (15 октября 1997 г.), «В Индии королева склоняет голову во время резни в 1919 году» , The New York Times , заархивировано из оригинала 17 мая 2013 г. , получено 12 февраля 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фишер, Конни (20 ноября 1997 г.), «Речь королевы по случаю ее золотой годовщины свадьбы» , Королевская семья , Королевский двор, заархивировано из оригинала 10 января 2019 г. , получено 10 февраля 2017 г.

- ^ Гиббс, Джеффри (27 мая 1999 г.), «День валлийской короны с песней» , The Guardian , заархивировано из оригинала 20 сентября 2022 г. , получено 16 сентября 2022 г.