Центр Нью-Йорка

Центр Нью-Йорка в 2010 году | |

| |

| Address | 131 W. 55th St. New York, New York United States |

|---|---|

| Owner | City of New York |

| Operator | City Center 55th Street Theater Foundation |

| Type | Performing arts center Off-Broadway (MTC) |

| Capacity | Main stage: 2,257 Stage I: 299 Stage II: 150 |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 1924 (building) 1984 (Stages I & II) |

| Years active | 1943–present |

| Architect | Harry P. Knowles and Clinton & Russell |

| Website | |

| www | |

Mecca Temple | |

New York City Landmark No. 1234

| |

| Coordinates | 40°45′50″N 73°58′46″W / 40.76389°N 73.97944°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Architectural style | Moorish |

| NRHP reference No. | 84002788[1] |

| NYCL No. | 1234 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 7, 1984 |

| Designated NYCL | April 12, 1983 |

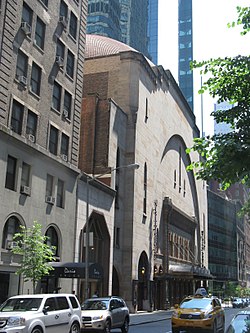

Центр Нью-Йорка (ранее известный как Храм Мекки , Городской центр музыки и драмы и Театр на 55-й улице в центре Нью-Йорка). [ 2 ] ) — центр исполнительских искусств по адресу 131 West 55th Street между Шестой и Седьмой авеню в районе Мидтаун Манхэттена в Нью-Йорке . Построенный Шрайнерами между 1922 и 1924 годами как масонский молитвенный дом, он действовал как комплекс исполнительских искусств, принадлежащий правительству Нью-Йорка . Центр города является домом для выступлений нескольких крупных танцевальных коллективов, а также Манхэттенского театрального клуба (MTC), и здесь проводятся выступления на бис! сериал музыкального театра и фестиваль «Осень танца» ежегодно.

Объект был спроектирован Гарри П. Ноулзом, Клинтоном и Расселом в стиле мавританского возрождения и разделен на две части. В южной части находится главный зал на 2257 мест на трех уровнях; Первоначально этот зал мог вместить более четырех тысяч человек, но с годами его размеры сократились. Непосредственно под главным залом находятся два небольших театра, один из которых используется MTC; они занимают то, что изначально было банкетным залом. Эта секция содержит богато украшенный фасад из песчаника с терракотовым входом в форме альфиса , а также купол диаметром около 104 футов (32 м). Северная часть гораздо проще по дизайну, с кирпичным фасадом практически без окон и содержит четыре репетиционных студии и 12-этажную офисную башню.

The Shriners decided in 1921 to construct the 55th Street building after having outgrown their previous headquarters, and the new building was dedicated on December 29, 1924. The Great Depression prompted the Shriners to downsize their activities in the 1930s and relocate out of the building entirely by 1940. New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia and New York City Council president Newbold Morris established the City Center of Music and Drama Inc. (CCMD) to operate the building as a municipal performing-arts venue, which reopened on December 11, 1943. In its early years, City Center housed the City Opera and City Ballet, as well as symphony, dance theater, drama, and art companies. After the City Opera and Ballet relocated to Lincoln Center in the 1960s, the CCMD continued to operate the building until 1976, when the City Center 55th Street Theater Foundation took over operation. City Center largely hosted dance performances during the late 20th century, although it also began hosting off-Broadway shows when the MTC moved to City Center in 1984. The venue was renovated in the 1980s and again in the 2010s.

Site

[edit]New York City Center, originally the Mecca Temple, is at 131 West 55th Street, between Sixth Avenue and Seventh Avenue, in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City.[3] The building's L-shaped land lot covers 25,153 square feet (2,336.8 m2), extending 200 feet (61 m) northward to 56th Street,[4] with frontage of 150 feet (46 m) along 55th Street and 100 feet (30 m) on 56th Street.[5][6] City Center abuts the CitySpire office building to the west and 125 West 55th Street to the east.[4][3] Immediately to the north are Carnegie Hall, Carnegie Hall Tower, Russian Tea Room, and Metropolitan Tower from west to east. Other nearby buildings include 140 West 57th Street, 130 West 57th Street, and the Parker New York hotel to the northeast, as well as the 55th Street Playhouse to the southwest and 1345 Avenue of the Americas to the southeast.[4][3]

The neighborhood was part of a former artistic hub around a two-block section of West 57th Street between Sixth Avenue and Broadway. The hub had been developed during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, following the opening of Carnegie Hall.[7][8][9] Several buildings in the area were constructed as residences for artists and musicians, such as 130 and 140 West 57th Street, the Rodin Studios, and the Osborne Apartments, as well as the demolished Sherwood Studios and Rembrandt. In addition, the area contained the headquarters of organizations such as the American Fine Arts Society, the Lotos Club, and the American Society of Civil Engineers.[10] By the 21st century, the artistic hub had largely been replaced with Billionaires' Row, a series of luxury skyscrapers around the southern end of Central Park.[11]

When the Mecca Temple was constructed in 1923, the city block had contained garages, stables, and a school.[12][13] The lots on the southern part of the building's site, at 131–133 West 55th Street, had been used by Famous Players–Lasky Corporation as a movie studio.[14][15] The two lots on the northern part of the site, at 132 and 134 West 56th Street, contained horse stables.[16][17]

Architecture

[edit]New York City Center was built by the Shriners between 1922 and 1924 as the Mecca Temple, a Masonic house of worship.[2][18] The building was designed by architects Harry P. Knowles (a Master Mason), who died before its completion, in conjunction with the firm of Clinton and Russell.[2][18] The building's design is Neo-Moorish, although sources have described the 55th Street wing as "Moresco-Baroque" and "delightfully absurd".[19] An article for the Architectural Forum characterized the Shriners' clubhouses in general as "Saracenic".[20]

The building contains a steel superstructure.[21][22][23] The roof is carried by a large 65-short-ton (58-long-ton; 59 t) girder measuring 92.5 feet (28.2 m) long and 13 feet (4.0 m) wide. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) wrote that, at the time, it was the largest piece of steel ever installed in a New York City building.[21]

Form and facade

[edit]In keeping with the Shriners' heritage, the City Center building's facade incorporates several motifs inspired by Islamic architecture.[24] Knowles had to work around the irregularly shaped site, and he needed to accommodate meeting rooms, an auditorium, and a banquet hall. As such, he placed the clubrooms and lodge rooms on the northern half of the site, which was narrower and faced 56th Street.[21][22] The northern portion of the building, at 12 stories high, is also taller than the rest of the building.[25][26] The auditorium and banquet hall were placed on the wider southern half, facing 55th Street, since these spaces were to be used much more frequently.[21][22] The southern part of the building has a tiled rooftop dome.[27]

55th Street facade

[edit]

The southern part of the building, which contains the theater, is largely clad with ashlar sandstone and contains a large pointed arch spanning nearly the entirety of the facade.[21][26] Early plans called for the facade to be laid in contrasting shades of sandstone; ultimately, the building was clad with golden Ohio sandstone. The word "Mecca" was originally inscribed at the top of the large arch.[18] The 55th Street elevation also contains multicolored glazed terracotta tiles originally manufactured by the New York Architectural Terra-Cotta Company.[24] In the early 2010s, a glass-and-steel marquee was installed above the entrance.[28]

The entrance consists of an alfiz with an arcade of nine horseshoe arches.[21][26] The arches are surrounded by a terracotta frieze with ocher, green, and blue foliate motifs. Each of the horseshoe arches in the arcade is supported by pink-veined and gray-veined granite columns and contain voussoirs made of glazed ocher tiles. The tympanum of each arch has multicolored tiles, some of which depict a scimitar and a crescent.[26][29] There are also metal lamps within the arches.[26] The entryway's design reflects the arrangement of the staircases and lobby inside.[29] The five central arches are grouped together and lead to the theater's lobby. The two horseshoe arches on either side lead to staircases that ascend to the theater's mezzanine and first balcony. On either side of the arcade are double-height sandstone arches, which connect to staircases that lead down to the basement and up to the second balcony.[26][29]

Each of the arcade's five central doorways is topped by a pair of arched windows on the mezzanine level; these windows are separated by engaged columns and surrounded by an extension of the terracotta frieze. The five center bays are flanked by blue terracotta pilasters and topped by a muqarnas cornice above the mezzanine level.[26][29] The upper portion of the 55th Street facade is relatively plain in design, except for lancet windows on the sides.[26] The uppermost part of the facade is stepped upward at its center, following the curve of the domed roof, and is topped by a large cornice with dentils. The corners are chamfered at the top; this was intended to serve as a transition between the cube-shaped lower stories and the domed roof.[21][26]

Domed roof

[edit]The theater's domed roof measures 104 ft (32 m) wide and 50 ft (15 m) tall, with 28,475 pieces of Ludowici Spanish roof tile.[27][30] Structurally, the roof is composed of four main ribs; between these are twelve smaller ribs, which are supported at their tops by a "ring" just below the top of the dome.[31] Unlike other domes in the United States, it was designed as a true sphere.[27] The lower half of each rib is composed of two chords, while the upper half is made of I-beams measuring 15 inches (380 mm) thick. The inner chord of the dome rises 37.5 feet (11.4 m) and has a diameter of 88 feet (27 m); by contrast, the outer chord has a radius of about 54 feet (16 m).[31]

The dome's outer surface consists of a 3-inch (7.6 cm) layer of a material called "Nailcrete", which was spread across metal lath; the terracotta tiles were then attached to the Nailcrete.[31] Both the 1922 and 2005 tiles for the structure were produced by Ludowici Roof Tile and colored in a varied blend of reds and ochers.[27][18] The tiles gradually narrow near the top of the dome, which also makes City Center the only structure in the Northeastern United States with a dome of graduated clay tiles.[27] The top of the dome originally was decorated with a scimitar and a crescent.[25] The roof was renovated in 2005. The refurbished roof includes a 1⁄8-inch (3.2 mm) waterproof membrane underneath each tile; a steel frame above the membrane; and 8,000 stainless-steel anchors that connect the tiles to the steel frame.[27]

56th Street facade

[edit]

The 56th Street elevation of City Center's facade was designed in a substantially different manner than that on 55th Street, as the northern part of the building was designed for a different purpose. The facade contains elements of an abstract classical style. At ground level, the facade is made of limestone and contains five arches. The outermost arches are the widest and are connected directly to stage rear, as is the center arch, which is slightly narrower. The second-outermost arches on either side are the narrowest and are flanked by lanterns on either side.[29][32]

The upper 11 stories are clad with yellow brick. The third story contains three windows, which contain sandstone moldings, balconies, and pediments.[29][32] All the decoration above the third story was made of buff-colored terracotta.[29][19] The stories above originally contained the Shriners' lodge rooms, so Knowles chose not to add windows, as was typical for office buildings of the time. Instead, on the fourth through ninth stories, the center of the facade contains six vertical piers, which are made of projecting bricks that are angled outward.[29][33] The side elevations of the northern half of the building contain even less decoration; they largely consist of brick walls with some scattered window openings.[29]

Interior

[edit]Originally, the Mecca Temple included a three-level auditorium with space for 5,000 people in total.[23][34] The building also contained a banquet room in the basement, which could fit 5,000 people, and three lodge rooms on the upper stories, which could accommodate another 3,000 people.[34] By 2010, the building contained 12 stories of offices, a main auditorium with 2,753 seats, two smaller auditoriums in the basement, and four studios.[35]

The main doorways on 55th Street lead to a ticket lobby, where gold-metal doors surrounded by ceramic tiles lead to the main auditorium.[32] In 2011, the lobbies were rearranged so that audiences entered the auditorium from the sides, rather than from the rear. The modern-day lobby is divided into outer and inner sections. The outer lobby has a bar, while the inner lobby has screens for video installations, which are changed three times a year.[28]

Main auditorium

[edit]The original seating capacity of the main auditorium is disputed but has been variously cited as 4,080[36] or 4,400.[34] According to the Boston Daily Globe, the main auditorium originally had a foyer with space for another 600 people, bringing the total capacity to 5,000.[34] These seats were spread across a ground-story orchestra level and two steeply raked balconies;[18] in contrast to the balconies, the orchestra was originally nearly flat.[37][38] Both balcony levels are supported by girders that are cantilevered from the rear of the auditorium.[39] The first balcony level is supported by a pair of diagonal girders on either end because of its unusual shape. The second balcony level, also known as the gallery, is cantilevered above the first balcony and the orchestra; the center of this level is supported by a truss measuring 92.5 feet (28.2 m) long.[38]

During the mid-20th century, the seating capacity was reduced to approximately 2,932.[40] During a 1982 renovation, City Center officials removed another 186 seats from the orchestra, reducing it to 2.746 seats.[41][42] The 1982 renovation also included raising the entire orchestra and raking the first ten rows.[40] The front rows of the rebuilt orchestra were raised 10 inches (250 mm), while the rear rows were raised by as much as 4 feet 6 inches (1.37 m).[37] City Center was again downsized in 2011 to approximately 2,250 seats.[28][43] This project involved removing six rows of seats, increasing the slope of the orchestra level, widening each seat by 2 inches, and reupholstering them in blue and green.[28]

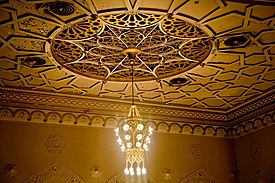

The proscenium arch and the ceiling were decorated in the Islamic style, with such motifs as stalactites and honeycombs.[18] The main auditorium's interior contained Moorish motifs such as multi-pointed stars, lancet windows, and large chandeliers hanging from molded ceiling plasterwork.[32] After the city government moved into the theater in 1943, the space was repainted white because it was easier to maintain.[28] During the mid-20th century, the auditorium was decorated in red, green, blue, and gilded rococo, but it was repainted again in beige and taupe in 1982.[37] The original color scheme was restored in 2011, along with the murals on the ceiling of the mezzanine lobby.[28][43]

The auditorium's original design focused the audience's attention at the center of the stage, but this design also created difficult sightlines; one observer likened the design to "watching a television screen".[28] Variety magazine stated that the auditorium's stage could fit 100 musicians.[36] Unlike traditional theaters, the stage originally did not have any wing space for performers;[44] even after the theater was renovated in 2011, the wing space was too small to accommodate certain types of productions,[45] To accommodate the Shriners, who frequently smoked in the Mecca Temple,[19] there was an air intake on the auditorium's roof.[31][19] Fresh air traveled from the intake to a fan and heater room above the auditorium's proscenium, and air was then distributed through the floor slabs of each level.[31] A lighting booth was also installed in the auditorium in 2011.[28]

Basement

[edit]The basement originally contained a banquet hall. This space did not contain columns. Instead, it was spanned by a set of deep lattice trusses, which were flanked by deep plate girders; these formed the floor of the auditorium.[23] The space between the trusses contained ducts that supplied fresh air to the auditorium and basement; a system of exhaust pipes for the basement; and other utilities.[46]

After an attempt in 1970 to convert City Center's basement into a cinematheque,[47] the basement became a 299-seat off-Broadway theater called The Space in 1981.[48] When The Space opened, it was only occasionally used by dance companies.[49] The Manhattan Theatre Club (MTC) moved to The Space in 1984[50][51] and divided the basement into two auditoriums.[52] As of 2022[update], MTC operates two off-Broadway spaces in the basement, known as Stage I and Stage II.[53][54] Stage I contains 299 seats, while Stage II contains 150 seats.[55] MTC also operates a coatroom, restroom, and members' lounge on the landing of the staircase between the basement and the lobby.[54]

Offices

[edit]The three lodge rooms were placed in the northern wing of the building.[18] When the Mecca Temple was converted to the City Center, the lodge rooms became rehearsal studios.[18][52] During the 1950s, scripts for the television show Your Show of Shows, starring Sid Caesar, were written in one of the offices on the sixth floor.[52] The theater's modern-day rehearsal studios occupy the upper stories.[28]

History

[edit]Mecca Temple

[edit]The City Center building on 55th Street was constructed as the Mecca Temple, the headquarters of the Shriners. The order's previous headquarters had been located at Sixth Avenue and 23rd Street since 1875.[22][56] The order began hosting large events at Carnegie Hall in 1891, but the hall banned smoking,[56] even though many Shriners enjoyed smoking large cigars during their meetings.[57] Although the Shriners moved to the 71st Regiment Armory on Park Avenue in 1905, the armory was not well-suited for theatrical productions. The Shriners also had trouble booking a theater except during the workday.[56] By 1911, the Shriners owned a converted brownstone row house at 107 West 45th Street, and they also held large meetings in the concert hall of Madison Square Garden.[58] The row house contained a grill room on the ground floor, a lounge and committee room on the second floor, executive offices on the third floor, and an assembly room on the fourth floor.[59]

Development

[edit]

By the early 1920s, the Shriners had outgrown their 45th Street location and wished to build a new headquarters prior to their 50th anniversary in 1922.[59] This prompted 1,500 Shriners to vote in favor of a new temple in April 1921.[56] The Shriners planned to fund the new temple by issuing bonds and by constructing an office building above the temple.[59] The order issued $1.5 million in bonds,[60] and its 11,080 members had purchased $1 million worth of bonds by the end of 1921, allowing the Shriners to build a standalone temple.[59] The rest of the bond issue was used to pay expenses, taxes, and interest on the mortgage loan.[60] Mecca Temple paid Yale University $400,000 for the lots at 131–135 West 55th Street in Midtown Manhattan in December 1921.[14][15] Yale, in turn, had acquired the site from William S. and Mary E. Mason three months beforehand.[57] The sale was finalized in January 1922; the Shriners hoped that their new temple would increase land values in the surrounding area.[13] The Shriners bought two stables at 133 and 135 West 56th Street from George C. Mason that April for $140,000.[16][17]

H. P. Knowles filed plans for a house of worship on 55th Street with the Manhattan Bureau of Buildings in August 1922. The structure was to cost $750,000 and was to contain a meeting hall in the basement; a three-level auditorium; three studios; and three stories of offices.[5][6] The auditorium was to contain 5,000 seats, which would allow it to be rented out for events such as concerts.[61] James Stewart & Co. was hired as the building's general contractor.[62] The Shriners hosted a parade on October 13, 1923, after which Arthur S. Tompkins, a New York state judge and the Grand Master of Masons in New York State, laid the building's cornerstone on 56th Street. At the time, the building was planned to cost $2.5 million.[63][64] The Mecca Temple received a $1 million mortgage loan from Manufacturers Trust in July 1924.[65][66] The building was dedicated on December 29, 1924, with the invocation offered by Episcopal bishop William T. Manning; contemporary sources characterized the building as a "mosque".[25][67]

Shriners usage

[edit]The Mecca Temple's auditorium first opened to the general public in May 1925, when it hosted a fashion show.[68][69] By then, the building was complete except for interior decorations and the installation of seats on the first floor.[68] John Philip Sousa's band performed in the temple's first public concert that October,[70][71] and the New York Symphony Orchestra relocated its performances to the auditorium from the Aeolian Building on 42nd Street.[72] During the 1920s, the Mecca Temple also hosted events such as a meeting of post-office workers;[73] a memorial service for American Revolutionary War military commander Casimir Pulaski;[74] and the meetings of Congregation Rodeph Sholom.[75] Unlike other Shriners temples, which were tax-exempt, mainly philanthropic concerns, the Mecca Temple earned money from renting its auditorium out, so it was not tax-exempt.[19]

By the 1930s, the Great Depression had forced many fraternal groups, such as the Shriners, to reduce the scope of their activities.[18] The Mecca Holding Company, the Mecca Temple's original owner, transferred the building's title to a group of Shriners trustees in 1933.[19] The Fides Opera Company, led by Cesare Sodero, began performing at the Mecca Temple the same year.[76] Irving Verschleiser,[a] operator of the Central Opera House on the Upper East Side, leased the building's ballroom and kitchens in 1934, with plans to convert it into the Mecca Temple Casino.[77] Aside from opera, dance, theatrical productions, and concerts, the auditorium's events in the 1930s included a Federal Theatre Project circus,[78] a protest meeting attended by over one-fifth of the city's Armenian population.[79] and a speech by former Greek prime minister Alexandros Papanastasiou.[80] Manufacturers Trust foreclosed on the building in 1937 after the Shriners failed to make mortgage payments. Verschleiser then took over the building and began operating it through his company, Mecca Temple Casino Inc.[19][81] Verschleiser failed to make a profit on the building, and the 130 West 56th Street Corporation took over in 1939.[19]

The Shriners had stopped using the building completely by 1940.[82] A writer for The New York Times reported that the auditorium had been relegated to "political oratory, all sorts of organizational harangues and resolutions, [and] second-rate prize fights".[82] Opera and ballet impresario Max Rabinoff announced in August 1941 that he would convert the auditorium into the Cosmopolitan Opera House and that he would convert the office section into the People's Art Center.[83][84] Rabinoff planned to leave the exterior intact while remodeling the interior for ballet, opera, and concerts.[84] The theater had reopened by November 1941.[85] It hosted shows such as a series of four programs by the NBC Symphony Orchestra;[85] the operettas The Gypsy Baron[86] and Beggar Student;[87] and a set of concerts to raise money for "war stamps" issued during World War II.[88]

City Center of Music and Drama operation

[edit]By 1942, the 130 West 56th Street Corporation had not paid taxes for several months, and the New York City Treasurer's office was acting as the receiver for the theater and office building.[89] That September, the New York City government bought the building for $100,000 at a foreclosure auction.[89][90] The city was offering the Mecca Temple for rent the next month.[91] Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and New York City Council president Newbold Morris began planning to convert the Mecca Temple into a theater. In March 1943, La Guardia named a committee to study these plans.[92][93] La Guardia and Morris cofounded the City Center of Music and Drama (CCMD) with tax lawyer Morton Baum, who was described as "the financial, production, and political brain that held it together".[94] The CCMD was to present opera, concerts, dance, ballet, and theatrical productions at the Mecca Temple.[95] The men wished to provide "cultural entertainment at popular prices", with tickets costing as little as $1.[96] To attract working-class audiences, La Guardia proposed that shows start at 5:30 p.m., after the end of the workday.[97]

The New York Supreme Court approved the articles of incorporation for the City Center of Music and Drama Inc. in July 1943.[97] La Guardia and Morris appointed a board of 24 people to operate the CCMD.[98] The city government hired Aymar Embury II the same month to renovate the Mecca Temple's auditorium.[99][100] City officials filed plans for the renovation with the city's Department of Buildings that August,[101] and the Board of Estimate voted to provide $65,000 for the building's renovation.[102][103] The next month, the Board of Estimate gave the CCMD a permit to stage live shows within the Mecca Temple.[104][105] Due to material shortages during World War II, the city government postponed the renovation of the theater's interior.[106] Harry Friedgut was appointed as City Center's first managing director in September 1943,[107][108] while Morris served as chairman of the CCMD.[109] The Mecca Temple was officially renamed City Center shortly afterward.[110][111] The CCMD began paying $2,000 a month in rent that October, before the theater had formally opened.[112]

Opening and early years

[edit]

City Center opened on December 11, 1943, with a concert by the New York Philharmonic and a birthday party for La Guardia.[113][114] The publicist Jean Dalrymple was appointed as volunteer director of public relations.[115][116] The first theatrical show was a revival of Rachel Crothers's play Susan and God, on December 13, 1943.[115][117] Initially, City Center presented revivals of successful Broadway shows to attract as many visitors as possible.[98] Performers who appeared at City Center between the 1940s and 1960s included Helen Hayes, Montgomery Clift, Orson Welles, Gwen Verdon, Charlton Heston, Marcel Marceau, Bob Fosse, Nicholas Magallanes, Francisco Moncion, Tallulah Bankhead, Vincent Price, Jessica Tandy, Hume Cronyn, Uta Hagen, and Christopher Walken.[118]

The newly-established New York City Opera started performing at City Center in February 1944 under director Laszlo Halasz;[119] the New York City Symphony Orchestra, led by Leopold Stokowski, debuted at City Center the next month.[120] NBC initially sponsored all of City Center's concerts and music performances.[121] The theater's first several shows were profitable, even though ticket prices were capped at $1.65.[122] By the end of the first operating season in May 1944, the theater had grossed over $414,000 from 171 performances, which had attracted 346,000 guests. City Center recorded a net profit of $844.[112][123] This prompted City Center officials to make plans for their own ballet company and repertory theater company.[124]

Friedgut resigned as managing director in July 1944, citing disputes with Morris.[109] Although attendance at City Center doubled to 750,000 during the 1944–1945 season, the center recorded a net loss of $36,000, in part because of the orchestra company's large expenses.[125][126] The Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo began performing at City Center in late 1944[127] and remained there for five years.[128][129] To prevent a future mayoral administration from shuttering City Center,[130][131] the CCMD renewed its lease of the building in July 1945 for five years, paying at least $10,000 a year.[132][133] City Center planned to establish a theatrical company for the 1945–1946 season, which would present revivals of plays;[134] during that season, the center hosted 614,000 guests.[135] Officials installed an air-conditioning system in the auditorium in mid-1946.[136]

City Center remained popular in the late 1940s, with over 750,000 guests during the 1946–1947 season.[135][137] Although the city government no longer financially supported the center, City Center sold over $1 million worth of tickets per year.[135] City Center accommodated about 578,000 guests during the 1947–1948 season[138] and around 576,000 guests the following season.[139] The New York City Symphony stopped performing at City Center after that season,[140] mainly due to the theater's poor acoustics.[141] George Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein's Ballet Society became a resident organization of the CCMD in 1948 and was accordingly renamed the New York City Ballet Company.[142] The CCMD established the New York City Theater Company the same season.[98] The New York City Dance Theater performed at City Center during the 1949–1950 season,[143][144] although it did not schedule any performances afterward.[145] Despite grossing over $1.2 million from opera, ballet, theater, and dance performances during the 1949–1950 season, the CCMD recorded a net operating loss of $3,517 during that season.[146]

Lease renewals and financial issues

[edit]Several months before City Center's lease expired in 1950, musicians' labor union Local 802 had proposed buying the building for $850,000.[147] Theatrical critic Brooks Atkinson wrote that "all of the City Center's programs lose money. But the losses are not calamitous" because of the theater's relatively cheap tickets and because of various large donations.[148] Uncertainty over City Center's lease caused the 1950–1951 season to be delayed, as the CCMD could not book shows until its lease had been renewed.[149][150] After mayor William O'Dwyer pledged his support of City Center, the Board of Estimate renewed the CCMD's lease in February 1950. The CCMD agreed to cap ticket prices at $2.50, and its rent was set at 1.5 percent of its annual gross receipts.[151][152] City Center's deficit grew to over $72,000 during the 1950–1951 season.[153] By mid-1951, Baum considered hosting dramas only during the winter, as attendance was generally lower during the spring. Low patronage during the summer had already prompted him to stop staging musicals in July and August.[154]

The CCMD announced plans in March 1952 to convert one of the center's emergency-exit hallways into a visual art gallery;[155] the space would exhibit contemporary sculptures and visual art.[156] Kirstein was appointed as City Center's managing director later that year.[157] CCMD officials, citing increasing production costs asked the New York State Legislature in early 1953 to pass a law allowing the organization to lease the building for $1 annually.[158][159] The law was enacted later the same year.[160] The CCMD began raising $200,000 in April 1953 as part of its first-ever fundraiser,[161] and the Rockefeller Foundation also donated $200,000 to fund the ballet and opera companies for three years.[162][163] The 75 by 15 ft (22.9 by 4.6 m) visual-art gallery opened in September 1953;[164][165] it hosted ten exhibitions of 50 canvases per year.[166] The building needed repairs by the mid-1950s, and the city government did not always fix these issues promptly. To convince the city government to fix the leaking roof, Morris invited mayor Vincent R. Impellitteri to the City Center on a rainy night; the mayor's program soon became soaked, and the roof was fixed shortly afterward.[167][168]

The CCMD continued to lose money, recording a deficit of $225,000 for the 1953–1954 season, even as annual attendance had reached 962,000.[169] An organization called the Friends of City Center was created in January 1954, selling annual memberships to raise money.[170] The Friends sold 3,000 memberships, mostly to small-dollar donors; it was reorganized after losing $25,000.[171] The City Center Light Opera Company hosted its first performances in May 1954.[172] Kirstein resigned as City Center's managing director in January 1955 because he and the board of directors could not agree on basic policy. Whereas Kirstein wanted to spend more money to stage experimental shows, the board wished to stage more established shows and reduce its expenses.[173] The Board of Estimate voted that February to lease the building to the CCMD for $1 per year.[160] The CCMD saw an $220,000 operating loss during the 1955–1956 season, although grants and donations covered much of this cost.[174]

After the City Opera suspended the beginning of its 1957 season due to financial deficits,[175] Kirstein unsuccessfully proposed reorganizing City Center and establishing a new opera company.[176] The CCMD had received $281,000 in gifts by the end of the 1956–1957 season, saving it from insolvency, although it still operated at a net loss.[177][178] After the 1956–1957 season, City Center's drama company stopped performing for several seasons.[166] The following season, the CCMD recorded an operating deficit of over $550,000, although donations covered almost all of this deficit.[179] The Friends of City Center had 2,670 members, who paid between $10 and $1,000 per year.[171] Further losses during the 1959–1960 season prompted officials to increase the center's maximum ticket prices by mid-1960.[180]

Relocation of the ballet and opera

[edit]

As early as 1959, the CCMD was negotiating to move all of its shows from the former Mecca Temple to the newly-developed Lincoln Center on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.[181][182] The CCMD closed City Center's art gallery in May 1961, as the gallery had been unprofitable and had not attracted sponsorships. At the time, the gallery attracted 2,500 monthly visitors, and it had displayed 3,600 artworks, one-eighth of which had been sold.[183] Donors reduced the organization's operating deficit to $12,000 for the 1961–1962 season,[184] and the CCMD had a $37,500 surplus the next season, although the City Opera's losses soon eliminated this surplus.[185] In advance of the 1964 New York World's Fair, the City Ballet announced that it would move to the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center after the 1963–1964 season.[186][187] By the CCMD's 20th anniversary in December 1943, the theater had received 16 million total guests over twenty 40-week seasons.[129] During the 1963–1964 season, the CCMD recorded a net profit for the first time in 18 years, after donors covered that season's operating deficits.[188]

Meanwhile, the CCMD was still contemplating relocating its opera, light opera, and drama companies to the New York State Theater,[189] although Lincoln Center and CCMD officials could not agree on who would control that theater.[190][191] By then, Variety magazine described the original City Center on 55th Street as having "many faulty seat locations" and a shallow stage.[191] The organization ultimately agreed in January 1965 to permanently relocate its ballet and opera companies to the New York State Theater. The CCMD would relaunch its drama company and would continue to host light opera and drama at the 55th Street theater.[140][192] The CCMD became a member company of Lincoln Center in 1965[193] and signed a sublease for the New York State Theater in January 1966.[194] Although the organization recorded a $1.7 million operating deficit during the 1965–1966 season due to the costs of the second theater, this was offset by nearly $2 million in donations.[195]

Plans for 55th Street theater

[edit]The CCMD continued to subsidize the 55th Street theater after relocating its ballet and opera companies.[196] After Newbold Morris retired in 1966, Baum was appointed as the chairman of City Center's board of directors.[197] The same year, the Robert Joffrey Ballet became a resident dance company and was renamed the City Center Joffrey Ballet,[198] relocating to 55th Street that September.[199] The CCMD's drama company also resumed performances at the 55th Street theater during the 1966–1967 season, having been inactive for nine years.[200] The city government donated $500,000 for a renovation of the 55th Street building in 1967.[201] This money was used to overhaul the air-conditioning system, repaint the interior, and replace wiring.[167][201] After Baum died in early 1968, the CCMD's board appointed an executive committee to temporarily take over the organization's operations.[202] Later the same year, the CCMD appointed Norman Singer as the organization's general administrator[203] and Richard Clurman as the chairman of its board.[204][205]

Under Clurman's leadership, the CCMD proposed relocating from its 55th Street theater, which officials felt was obsolete. As part of the proposed City Center Plaza, the CCMD wished to build four theaters, each with 400 to 800 seats, on the site of the third Madison Square Garden (MSG) on Eighth Avenue.[206] While negotiations for the MSG site were ongoing, CCMD officials announced in early 1970 that they would convert the 55th Street theater's basement into the City Center Cinematheque, with one or more movie theaters and a film museum.[47] In January 1971. the CCMD proposed taking over Lincoln Center's Vivian Beaumont Theater and renovating it.[207] To fund the $5.2 million cost of renovating the Beaumont, the CCMD planned to demolish the 55th Street theater and replace it with an office skyscraper containing a 3,000-seat theater.[208][209] The CCMD withdrew its plan for the Beaumont that December,[210] but it continued to contemplate the demolition of the 55th Street theater.[211][212]

City Center stopped producing drama altogether in 1969,[213][214] although Singer proposed creating a drama company in early 1972.[212] Before the 1972–1973 season began, two companies joined the CCMD: the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, which became the Alvin Ailey City Center Dance Theater,[215] and the Acting Company, which became the City Center Acting Company.[216] By October 1972, the CCMD had recorded a total deficit of $1.3 million.[217] The organization had recorded a net operating loss of $3.7 million for the 1971–1972 season, but it had not received enough grants and donations to offset these losses,[217] which grew during the next year.[218] Although the Ford Foundation gave $500,000 each to the CCMD's ballet and opera companies in early 1973, the CCMD had to drastically reduce funding for the Joffrey Ballet and for the proposed Cinematheque.[219] Later that year, the Board of Estimate extended the theater's lease for another 52 years.[220]

By the 1970s, the CCMD was subsidizing the ballet and opera at Lincoln Center, as well as the Joffrey Ballet, the Alvin Ailey Dance Theater, the Acting Company, and the Young People's Theater at 55th Street.[221][222] The CCMD also subsidized the Cinematheque, which had leased space under the Queensboro Bridge in 1973;[223][224] the Cinematheque never opened due to a lack of money.[225][226] In addition, the CCMD co-produced the American Ballet Theatre (ABT).[222] CCMD officials considered selling the 55th Street theater in 1974 to a developer who planned to erect a residential and commercial skyscraper on much of the block.[227] The 55th Street theater had hosted dance performances nearly exclusively for several years, so the CCMD planned to construct a dance theater in the proposed skyscraper.[228] Singer resigned as the organization's director that July.[222][229] By then, the center's net deficit had grown to $4 million.[222] The CCMD ultimately decided to retain the existing building in early 1975.[230]

55th Street Theater Foundation takeover

[edit]

Reorganization

[edit]A reorganization of City Center began in May 1975, when the CCMD's interim chairman created a board of governors, which in turn established separate boards of directors for the City Ballet, the City Opera, and the 55th Street theater.[221][231] The board of governors had 12 members, compared to the 41-member board of directors.[196][232] John S. Samuels III became the chairman of the board of governors the same year.[232] The CCMD concentrated its resources on the ballet and opera companies at Lincoln Center. The drama and music companies at the 55th Street theater, no longer subsidized by the CCMD, had already stopped operating.[233]

The Joffrey Ballet, the Alvin Ailey Dance Theater, the American Ballet Theatre, and the Eliot Feld Ballet proposed taking over the 55th Street theater in April 1976, alleging that the CCMD had retained control over the building while forcing the ballet companies to subsidize their own operation.[234] CCMD officials agreed to turn over the 55th Street theater's operation to the City Center 55th Street Theater Foundation, headed by these ballet companies.[235] The plan nearly failed because of disagreements between the CCMD and the dance companies,[236] but the agreement was finalized in August 1976 after months of debate.[237] Subsequently, the 55th Street building was almost entirely controlled by the 55th Street Theater Foundation, led by lawyer Howard Squadron.[55][233] The CCMD, meanwhile, focused on its Lincoln Center operations.[233]

Throughout the late 1970s, the 55th Street theater continued to be used mainly for dance performances,[238] attracting companies such as the Dance Theatre of Harlem.[239][37] City Center's resident dance companies included the Alvin Ailey, Paul Taylor, Merce Cunningham, and Martha Graham companies; this led to the center being known as "America's premier dance theatre".[55] The 55th Street Theater Foundation installed a new stage in 1978, and it began renovating the facade two years later.[239] Because the auditorium's orchestra level was nearly flat, audience members in the first twelve rows reportedly could not see dancers' feet.[37] By 1980, the 55th Street Theater Foundation was profitable, although the ABT and the Feld company had moved out.[239]

1980s

[edit]

The Theatrical Assistance Group Foundation converted City Center's basement into a 299-seat off-Broadway theater in early 1981.[48] Squadron received a $700,000 federal grant in mid-1981 to renovate the 55th Street theater,[240][55] but Samuels still wished to redevelop the 55th Street site, prompting criticism from City Center's board.[241] Samuels ultimately resigned in July 1981[242] and was succeeded by Alton Marshall,[238] who himself was succeeded by Martin J. Oppenheimer in 1983.[243][244] Meanwhile, after the 55th Street Theater Foundation had received the federal grant, the foundation announced in early 1982 that they would renovate the theater.[40] Fred Lebensold and Rothzeid, Kaiserman & Thomson designed the project, which ultimately cost $$900,000.[55] The renovation began that June.[41] To improve sightlines, City Center officials removed 186 seats, raised the orchestra level, staggered the seats in each row, and redesigned the aisles.[41][37] In addition, the lobby was expanded; the seats were re-upholstered; a wheelchair ramp was installed; decorations, including the chandeliers, were restored; and the auditorium was repainted. The refurbished theater reopened in October 1982.[41][42]

The Manhattan Theatre Club moved into City Center's basement in 1984,[50][51] and the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated City Center as a city landmark that year.[55] The same year, developer Ian Bruce Eichner proposed buying City Center's air rights to obtain additional space for his neighboring CitySpire development.[245][246] Eichner planned to pay the CCMD $11 million, of which $5.5 million would be passed along to the 55th Street Theater Foundation. According to Squadron, this would allow the foundation to expand the cramped stage; construct new storage areas; rebuild the balconies; replace the seats; and add ticket booths, bathrooms, and elevators.[44] Eichner agreed to make improvements to City Center in exchange for the additional space,[245][247] but he had not completed these renovations by 1988, prompting City Center to sue Eichner.[248][249]

Following a separate controversy over CitySpire's height, in 1988, Eichner agreed to build 7,200 square feet (670 m2) of dance studios above a pedestrian arcade at that building's base,[247] which the city approved in early 1989.[250][251] 55th Street Theater Foundation officials contended that the studios were narrow for City Center's dance companies.[252] City Center continued to host ballet and dance shows, as well as events such as the New York International Ballet Competition.[253] City Center's mezzanine was renamed after Robert Joffrey, the head of the Joffrey Ballet, in 1988.[254] In addition, City Center's executive director Anthony Micocci was considering producing musicals at the theater by the late 1980s, after the stage had been renovated.[255][213] Due to continuing disputes over the CitySpire project, the developers of that skyscraper agreed to pay the New York City government $2.1 million; some of the funding was used to renovate City Center's rehearsal rooms.[256] Starting in mid-1990, part of the auditorium was closed for restoration,[257] and Altria began sponsoring dance shows at City Center.[258]

Daykin leadership

[edit]Squadron appointed Judith Daykin as City Center's executive director in November 1991, after Micocci resigned.[259][260] The Joffrey Ballet had stopped regularly performing at City Center after 1991 due to a lack of money.[261] By the time Daykin assumed the directorship in 1992, the theater was only hosting 17 weeks of shows per year.[262] Within one year of taking over City Center, Daykin had paid off the center's $750,000 debt, and she had increased fundraising and marketing efforts for the theater.[262] Daykin initiated the Encores! Great American Musicals in Concert, which presented rarely heard musicals starting in 1994.[214][263] Daykin perceived Encores! as an experimental program that she hoped would attract new audiences.[214] Daykin was also credited for turning City Center from a rental hall into an organization that produced its own shows.[262][264] Upon City Center's 50th anniversary in 1993, it still largely hosted ballet and dance companies, including Joffrey Ballet and the Martha Graham, Alvin Ailey, Trisha Brown, and Paul Taylor dance companies; the MTC also presented off-Broadway shows there.[265]

By the late 1990s, the center's Encores! series had become popular.[266][267] According to Daykin, the Encores! series attracted people "who probably hadn't been here in 20 years, if they weren't dance fans".[267] City Center continued to host visiting dance companies like the ABT, which resumed performances there in 1996;[268] it also operated a dance-education program for middle-school students, which served 5,000 pupils per year by 1999.[269] The auditorium had been renovated, but The New York Times reported in 1999 that City Center needed to spend between $8 million and $10 million on repairing the mechanical systems. In addition, the dome was leaking and needed another $3 million in repairs.[18] After Raymond A. Lamontagne succeeded Howard Squadron as the chairman of City Center's board in early 1999, Lamontagne announced that he would create an endowment fund for the center.[270]

Largely because of the changes that Daykin had instituted, the theater was hosting shows 40 weeks per year by 2000. At that point, City Center had a $10 million annual budget, 38 full-time staff members, and hundreds of part-time staff, even as its production costs were increasing.[262] Because City Center's staff were part of a labor union, it cost $200,000 per week to produce a show there, compared to $60,000 for a non-unionized theater such as the Joyce Theater.[258] Consequently, The New York Times wrote in 2003 that City Center was "no longer affordable for many [dance] companies",[271] though the ABT and the Alvin Ailey and Paul Taylor dance companies continued to perform there.[272] The upper balcony was rarely open.[273]

Shuler leadership and renovation

[edit]

In 2003, former Joffrey Ballet dancer Arlene Shuler became president and CEO of City Center.[272] Shuler quickly renamed the venue New York City Center, expanded the board of directors, hired development and marketing teams, and increased the center's annual budget to $12 million.[258] She also launched the Fall for Dance Festival, which sold dance tickets for $10, to attract both audiences and dance companies.[273][274] City Center hired architecture firm Helpern Architects and contractor Nicholson & Galloway in 2005 to repair the theater's leaky roof for $2.8 million.[27] At the end of that year, City Center formed a partnership with the neighboring Carnegie Hall.[275][276] The partnership would have allowed the venues to host each other's dance, music, and theater programs; at the time, City Center was still mostly a rental venue.[277] To accommodate these new programs, Shuler had planned to renovate City Center between 2007 and 2008 for $150 million.[275][276]

The partnership with Carnegie Hall was canceled in early 2007, prompting Shuler to delay City Center's renovation;[277] by mid-2008, Shuler planned to begin renovations at the end of the next year.[278] Shuler also expanded the Encores! program and continued to host dance and off-Broadway shows at City Center, although the Times wrote in 2009 that "Fall for Dance has redefined the theater's identity".[279] A $75 million renovation of City Center finally began in March 2010.[35] Designed by Ennead Architects LLP, the work included improved sightlines, improved seating, and a new canopy, as well as restoration of historical elements.[35] To accommodate the theater's 2010–2011 theatrical season work, contractors renovated the center in two phases during 2010 and 2011.[35] The renovation was completed in October 2011 with a ceremony led by mayor Michael Bloomberg.[43][280]

Just before the theater reopened, the Alvin Ailey Dance Theater signed a contract to become City Center's main dance company.[281][282] Two dance and ballet companies left City Center in the early 2010s.[45][282] The Paul Taylor Dance Company left City Center in 2011,[283] and ABT departed the following year, citing City Center's small wing space.[45] City Center temporarily suspended in-person shows in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City.[284] This affected two of the theater's most popular programs;[285] the Encores! series was suspended for two years,[286] while Fall for Dance was held virtually in 2020.[284] After Shuler resigned as City Center's president in 2021,[287][288] Michael S. Rosenberg was appointed as City Center's new director in September 2022.[285][289]

Management and governance

[edit]City Center of Music and Drama Inc.

[edit]The 55th Street theater was originally controlled by the City Center of Music and Drama Inc. (CCMD),[104][105] which the city government established in July 1943.[95] The City Center for Music and Drama Inc. is the organizational parent of the New York City Ballet and was formerly also the parent company of the New York City Opera,[290] which was liquidated in 2013.[291] During its first two decades, the CCMD was largely synonymous with the 55th Street theater, which for the most part was its only location.[196] The CCMD temporarily operated the International Theatre on Columbus Circle during the 1948–1949 season.[292][293] In January 1965, the CCMD became a member company of Lincoln Center.[193] In subsequent years, the CCMD used other venues such as the ANTA Theatre.[294]

Several of the CCMD's constituent companies are no longer affiliated with City Center or no longer exist. The New York City Symphony performed there from 1944 to about 1948,[140][141] and the New York City Dance Theater only performed at the 55th Street theater during the 1949–1950 season.[145] The City Center Art Gallery operated between 1953 and 1961.[183] Another former constituent company was the City Center Cinematheque, which was proposed in 1970[47] but never formally opened.[225][226]

55th Street Theater Foundation

[edit]The City Center 55th Street Theater Foundation took over the 55th Street theater in August 1976,[235] subleasing the theater from the CCMD.[37] The foundation rents out the main auditorium to various performers and leases the basement space to the Manhattan Theatre Club.[52]

New York City Center Inc., a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization established in 1976, controls the theater. As of 2023[update], Michael S. Rosenberg is listed as the president and CEO of New York City Center Inc.[295][296] For the fiscal year that ended in June 2020, the organization recorded $21,340,158 in revenue and $23,620,235 in expenses, for a total net loss of $2,280,077.[296]

Programming

[edit]Upon the theater's 75th anniversary in 2018, The New York Times characterized City Center as "a multidisciplinary space for artists in theater, dance and music".[297] From the 1940s to the 1960s, the City Center's resident companies included the CCMD's opera, symphony, drama, dance, and ballet companies,[52] Since the late 20th century, City Center has hosted a variety of dance performances each season.[279] It also hosts events including the Fall for Dance Festival and Encores!.[52]

Dance

[edit]In 2004, New York City Center introduced the annual Fall for Dance Festival.[273][274] The festival attracted many young adults, as well as those that had never previously been to City Center or seen dance performances.[298] The theater has also hosted events such as the New York City edition of the Vail International Dance Festival, which began in 2016.[299]

The New York City Center Choreography Fellowship, established during the 2011–2012 season, accepts three fellows per season.[300] Fellows receive a stipend, are given access to rehearsal space, and receive administrative support from City Center officials.[300][301]

Theatre

[edit]New York City Center launched its first Encores! Great American Musicals in Concert productions in 1994.[302][303] In its early years, Encores! presented musicals such as Du Barry Was a Lady and Pal Joey.[266][267] The program earned numerous theatrical awards, including from the New York Drama Critics' Circle and the Outer Critics Circle;[270] In 2000, the American Theatre Wing presented a Tony Honors for Excellence in Theatre award to City Center for the Encores! series.[304][305] The New York Times described Encores! in 2001 as a "major guardian of America's musical-theater heritage".[306] Under the tenure of Jack Viertel, who directed the series from 2001 to 2019, several Encores! productions transferred to Broadway during the 2000s and 2010s, including After Midnight, The Apple Tree, Finian's Rainbow, and Gypsy.[307] As of 2019, the series is directed by Lear deBessonet.[308]

Encores! Off-Center, dedicated to hosting rarely-heard off-Broadway musicals, premiered in mid-2013.[309] Composer Jeanine Tesori served as the series's first artistic director,[310] while Anne Kauffman has directed the series since 2019.[311] City Center and Jazz at Lincoln Center launched a partnership during the 2011–2012 season, starting with the show Cotton Club Parade.[312][313] These shows are presented separately from the Encores! series.[313]

Former programs

[edit]The New Dramatists Committee and City Center formed the Elinor Morgenthau Players and Playwrights Workshop in April 1951, with funding from the family of former U.S. Treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr., whose wife Elinor had been on the CCMD's board.[314][315] The workshop opened in October 1951 and was headquartered on three stories of the City Center building.[316] The workshop itself consisted of 50 regular members and 50 alternate members, who were divided into three groups. Half of the regular members created their own plays and presented them at City Center, while the other regular members and the alternates studied plays by established playwrights.[317]

In celebration of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Centennial, he City Center co-sponsored "Cinémathèque at the Metropolitan Museum", which showed seventy films dating from the medium's first 75 years from July 29 to September 3, 1970.[318] The films were selected by Cinémathèque Française founder and director Henri Langlois, from its archive of more than 50,000 films.[319] The Met exhibition had led to the creation of the City Center Cinematheque, although the CCMD's film division was never formally opened.[226]

See also

[edit]- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c White, Norval & Willensky, Elliot (2000). AIA Guide to New York City (4th ed.). New York: Three Rivers Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-8129-3107-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "131 West 55 Street, 10019". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on February 28, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Shriners to Build Fine Club on West 55th St.: Structure Will Cost $750,000 To Build, According to Estimate Made by Architect". New-York Tribune. August 5, 1922. p. 13. ProQuest 576693437.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "New Mecca Temple Home; Building in West Fifty-Fifth Street Will Cost $750,000". The New York Times. August 5, 1922. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2023. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (May 9, 1999). "Streetscapes /57th Street Between Avenue of the Americas and Seventh Avenue; High and Low Notes of a Block With a Musical Bent". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ "Steinway Hall" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 13, 2001. pp. 6–7. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project (1939). New York City Guide. New York: Random House. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.)

- ^ "Society House of the American Society of Civil Engineers" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 16, 2008. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 23, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ Scher, Robin (July 19, 2016). "'Round 57th Street: New York's First Gallery District Continues (for Now) to Weather Endless Changes in the Art World". ARTnews. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Stable Block Changes Call Sharp Attention: Mecca Temple and Five Apart- Ments in Fifty-Fifth Street". The New York Times. March 25, 1923. p. RE2. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 103126048.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1983, p. 4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Yale Sells West 55th St. Realty to Mecca Temple: Property Extending Through Block Will Be Improved With a Mosque". New-York Tribune. December 26, 1921. p. 16. ProQuest 576510677.

- ^ Перейти обратно: a b «Йельский университет продает землю масонскому ордену: храм в Мекке в Нью-Йорке для строительства мечети за 1 500 000 долларов». Хартфорд Курант . 28 декабря 1921 г. с. 12. ISSN 1047-4153 . ПроКвест 556999075 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Мистические храмы увеличиваются за 2 000 000 долларов» . Нью-Йорк Трибьюн . 21 апреля 1922 г. с. 9. ПроКвест 576583809 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Шрайнерс расширяет сайт» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 21 апреля 1922 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж Грей, Кристофер (11 апреля 1999 г.). «Уличные пейзажи / Центр города; от храма Шрайнерс в Мекке до Мекки искусств» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2023 года . Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Комиссия по сохранению достопримечательностей 1983 , с. 7.

- ^ Грин, Герберт М. (сентябрь 1926 г.). «Планировка братских построек» . Архитектурный форум . Том. 45, нет. 3. п. 141.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Комиссия по сохранению достопримечательностей 1983 , с. 5.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Служба национальных парков 1984 , с. 6.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Американский архитектор и архитектура 1925 , с. 173.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Комиссия по сохранению достопримечательностей, 1983 г. , стр. 5–6.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Святители посвящают новый дом в Мекке; дворяне со всех концов страны здесь для открытия мечети стоимостью 2 500 000 долларов» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 30 декабря 1924 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 августа 2021 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я Служба национальных парков 1984 , с. 2.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Коллинз, Гленн (25 марта 2005 г.). «Починим протекающую крышу, и что за крыша!» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 6 марта 2023 года . Проверено 3 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я Погребин, Робин (10 октября 2011 г.). «Обратный отсчет в центре города по мере приближения открытия» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 5 марта 2023 года . Проверено 5 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я Комиссия по сохранению достопримечательностей 1983 , с. 6.

- ^ Ганье, Николь (август 2005 г.). «Кровля на заказ: чудо крыши». Традиционное здание . Клем Лабин.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Американский архитектор и архитектура 1925 , с. 175.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Служба национальных парков 1984 , с. 3.

- ^ Комиссия по сохранению достопримечательностей, 1983 , стр. 6–7.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Батчелдер, Роджер (28 декабря 1924 г.). «5000 святилищ пройдут маршем по 5-й авеню: завтрашнее открытие храма в Мекке соберет дворян из многих штатов». Бостон Дейли Глоуб . п. 29. ПроКвест 498083004 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Погребин, Робин (16 марта 2010 г.). «Центр города начнет реконструкцию стоимостью 75 миллионов долларов» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 14 декабря 2020 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Опера и концерт: Храм в Новой Мекке, штат Нью-Йорк, в поле для концертов». Разнообразие . Том. 78, нет. 7. 1 апреля 1925 г. с. 23. ПроКвест 1505651409 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г «Превращение городского театра в первоклассное танцевальное пространство» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 29 августа 1982 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2023 года . Проверено 3 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Американский архитектор и архитектура 1925 , с. 177.

- ^ Американский архитектор и архитектура 1925 , стр. 177, 180.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Лоусон, Кэрол (16 марта 1982 г.). «Комплект ремонта центра города к лету» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2023 года . Проверено 3 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Берман Александр, Дженис (5 октября 1982 г.). «Новый вид на обновленный центр города». Новостной день . п. С19. ISSN 2574-5298 . ПроКвест 993226250 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Киссельгофф, Анна (5 октября 1982 г.). «Центр нового города: место, где можно увенчать танец; оценка» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 августа 2021 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Новек, Джоселин (30 октября 2011 г.). «Центр города вновь открывается после ремонта стоимостью 56 миллионов долларов» . Стандартный динамик . стр. С2. Архивировано из оригинала 5 марта 2023 года . Проверено 5 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Подробный план расширения центра города» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 30 октября 1984 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 августа 2021 года . Проверено 4 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Кэттон, Пиа (24 октября 2012 г.). «Американский театр балета покинет центр города» . Уолл Стрит Джорнал . ISSN 0099-9660 . Архивировано из оригинала 29 октября 2012 года . Проверено 5 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Американский архитектор и архитектура 1925 , стр. 173, 175.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Томпсон, Ховард (14 февраля 1970 г.). «Кинотеатр в центре города, спроектированный с использованием архивов синематеки» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 марта 2023 года . Проверено 3 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Танцевальный зонтик открывается» . Новостной день . 31 марта 1981 г. с. 123. Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2023 года . Проверено 3 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Фридман, Сэмюэл Г. (8 августа 1984 г.). «Тесный театральный клуб ищет место в центре города» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2023 года . Проверено 4 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гусов, Мел (24 октября 1984 г.). «Манхэттенский театральный клуб переезжает в центр города» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2023 года . Проверено 4 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Основная сцена переходит на центральную сцену» . Новостной день . 21 октября 1984 г. с. 130. Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2023 года . Проверено 4 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Майерс, Эрик (12 июля 2007 г.). «Дворец для народа» . Афиша . Архивировано из оригинала 6 марта 2023 года . Проверено 5 марта 2023 г.

- ^ «Карты рассадки» . Центр Нью-Йорка . Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2023 года . Проверено 4 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Спланируйте свой визит» . Манхэттенский театральный клуб . 28 сентября 2022 года. Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2023 года . Проверено 4 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Ботто и Митчелл 2002 , с. 302.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Комиссия по сохранению достопримечательностей 1983 , с. 3.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Комиссия по сохранению достопримечательностей 1983 , с. 16.

- ^ «Шрайнерс планируют собственный дом» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 15 июня 1911 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д «Здесь святители планируют построить мечеть за 2 000 000 долларов; храм в Мекке заплатит 400 000 долларов за участок на Западной 55-й улице - здание обойдется в 1 500 000 долларов» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 25 декабря 1921 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Комиссия по сохранению достопримечательностей 1983 , с. 17.

- ^ «Театр в храме Мекки». Рекламный щит . Том. 35, нет. 33. 18 августа 1923. с. 11. ПроКвест 1031716636 .

- ^ Американский архитектор и архитектура 1925 , с. 178.

- ^ «Храмовники на месте новой мечети; присутствуют на закладке краеугольного камня дома стоимостью 2 500 000 долларов для храма в Мекке» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 14 октября 1923 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ «Камень храмовой мечети в Мекке, заложенный Томпкинсом». Нью-Йорк Трибьюн . 14 октября 1923 г. с. 15. ПроКвест 1237297553 .

- ^ «Последние сделки в сфере недвижимости». Нью-Йорк Таймс . 15 июля 1924 г. с. 32. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 103363044 .

- ^ «Участок, занимаемый рестораном на 34-й Западной улице, продан». «Нью-Йорк Геральд», «Нью-Йорк Трибьюн» . 16 июля 1924 г. с. 22. ПроКвест 1112741808 .

- ^ «3000 святилищ помогают освятить мечеть в Мекке: арабский храм за 2 000 000 долларов на Западной 55-й улице, сцена впечатляющих обрядов парада знати масонского ордена перед службой. Выступают мэр Филадельфии Мюррей Халберт и судья Томпкин». «Нью-Йорк Геральд», «Нью-Йорк Трибьюн» . 30 декабря 1924 г. с. 8. ПроКвест 1113085593 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Храмовая мечеть Мекки открылась на выставке: новая аудитория святителей считается самой большой в городе» . «Нью-Йорк Геральд», «Нью-Йорк Трибьюн» . 19 мая 1925 г. с. 15. ПроКвест 1113071210 .

- ^ «Водевиль: Шоу стиля Шрайнерс — одежда и вещи». Разнообразие . Том. 79, нет. 1. 20 мая 1925. с. 31. ПроКвест 1505686880 .

- ^ «Соуза открывает новый храмовый зал в Мекке; отмечает третье столетие своей группы концертом в огромном зале» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 12 октября 1925 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ «Сусу встречают на концерте данью и подарками: известный капельмейстер открывает зал храма в Мекке в своем единственном появлении на Манхэттене в этом сезоне» . Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . 12 октября 1925 г. с. 10. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1112989740 .

- ^ «Снижается высокая стоимость концертной музыки; New York Symphony сокращает расходы на 10 и 20 процентов в сериях следующего сезона» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 2 апреля 1925 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ «Почтовые служащие благодарят Конгресс за повышение заработной платы». «Нью-Йорк Геральд», «Нью-Йорк Трибьюн» . 5 апреля 1925 г. с. 14. ПроКвест 1112918434 .

- ^ «Честь Пуласки завтра; прокламация мэра требует почтить память героя 1776 года» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 10 октября 1929 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ «Покидает временный дом; община Родефа Шолома проводит последнюю храмовую службу в Мекке» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 30 сентября 1929 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ «Новая группа планирует популярную оперу; труппа Фидес включает 57 музыкантов из оркестра Метрополитен» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 11 сентября 1933 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2023 года . Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Аренда в храме в Мекке: Verschleisser будет управлять бальным залом - проблема переезда ковров». Нью-Йорк Таймс . 5 апреля 1934 г. с. 40. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 101049399 .

- ^ «Дети-гости в цирке WPA; 4000 больных молодых людей в восторге от 3-часового шоу в храме в Мекке» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 24 декабря 1936 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2023 года . Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ «Убитого архиепископа оплакивают 3000 человек; армянский митинг протеста в храме в Мекке охраняется полицией и армией ашеров» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 29 января 1934 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2023 года . Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ «Греков призывают поддержать республику; Папанастасиу сомневается, что плебисцит по вопросу о монархии состоится этой осенью» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 8 сентября 1935 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2023 года . Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Служба национальных парков 1984 , с. 7.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брэкер, Милтон (12 декабря 1953 г.). «Центр города отмечает свое 10-летие; Феррер играет вместе с Вагнером и Моррисом на праздновании, дополненном большим тортом» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 марта 2023 года . Проверено 2 марта 2023 г.

- ^ «Опера в храме в Мекке; здание будет переоборудовано к осени – Центр искусств в Храме-Храме» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 13 августа 1941 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2023 года . Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Началась реконструкция храма в Мекке». Христианский научный монитор . 16 августа 1941 г. с. 9. ПроКвест 513630113 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Даунс, Олин (5 ноября 1941 г.). «Стокски открывает симфоническую серию; оркестр NBC звучит в первой из четырех программ в Cosmopolitan Opera House» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2023 года . Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Нс (20 июня 1942 г.). «Здесь представлен «Цыганский барон». Музыкальные и театральные деятели Центральной Европы слышат оперетту Штрауса» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2023 года . Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Штраус, Ноэль (26 сентября 1942 г.). « Здесь представлен «Нищий студент»; в оперном театре «Космополитен» поставлена трехактная оперетта Карла Миллокера» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2023 года . Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Штраус, Ноэль (18 мая 1942 г.). «Концерт дан за военные марки; проведен третий из серии под руководством мэра и городской WPA при поддержке группы музыкантов» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2023 года . Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Заявка на покупку храма в Мекке городом под залогом» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 2 сентября 1942 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2023 года . Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ «Город лишил права собственности храма в Мекке» . Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . 2 сентября 1942 г. с. 25. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1320076853 .

- ^ «Храм в Мекке сдается в аренду городом». Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . 5 октября 1942 г. с. 23. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1284467995 .

- ^ «План музыкального центра в храме в Мекке; мэр и представители искусств обсуждают предложение Морриса» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 6 марта 1943 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2023 года . Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ «Музыкальный центр Мэра Пианнинга в храме в Мекке: назначит комитеты для изучения планов создания «храма» муниципального искусства ». Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . 6 марта 1943 г. с. 6А. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1267871292 .

- ^ «Мортон Баум, юрист, мертв; основатель City Center в 43-м году; его называли «финансовым, производственным и политическим мозгом» художественного учреждения» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 8 февраля 1968 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 марта 2023 года . Проверено 2 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Мэр раскрывает планы открыть храм в Мекке как музыкальный центр: объявляет, что 40-недельный сезон начнется этой осенью с концертно-опера-фестиваля, а затем будет играть; низкие цены на вход будут правилом». Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . 22 июля 1943 г. с. 1. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1267875722 .

- ^ «Центр откроется 11 декабря; Филармония выступит на официальном открытии городского проекта» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 11 ноября 1943 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2023 года . Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Комиссия по сохранению достопримечательностей 1983 , с. 8.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Зинссер, Уильям К. (21 февраля 1950 г.). «Репертуарный театр Нью-Йорка: будущее прекрасных трупп музыки, балета и драмы ждет решения города». Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . п. 18. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1326037218 .

- ^ «Город реконструирует аудиторию Мекки; архитектор рисует планы по обновлению нового гражданского центра музыки и драмы» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 23 июля 1943 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ «Музыкальный центр может быть готов к 1 октября: реконструкция храма в Мекке начнется через две недели: корпорация мэров». Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . 23 июля 1943 г. с. 9. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1267876483 .

- ^ «Изменить храм в Мекке; городские документы планируют изменить новый музыкальный центр» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 4 августа 1943 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ «65 000 долларов проголосовали за ремонт храма в Мекке: сметная комиссия 11 против 5 утверждает фонд для подготовки музыкально-драматического центра» . Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . 13 августа 1943 г. с. 8. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1322118418 .

- ^ «Харт говорит, что расследование ничего не будет стоить; расследование режима Ла Гуардиа сэкономит городу большую сумму, - утверждает он» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 13 августа 1943 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Музыкальный центр получает отзывное разрешение; сметная комиссия проголосовала за новую городскую аудиторию» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 24 сентября 1943 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Разрешение на храм в Мекке выдано центру города: запланирована 40-недельная программа драмы, музыки и оперы». Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . 24 сентября 1943 г. с. 16. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1269853372 .

- ^ «Приоритеты нарушают реконструкцию храма в Мекке: но музыкально-драматический центр может открыться в ноябре после некоторого косметического ремонта». Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . 23 сентября 1943 г. с. 19. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1268029308 .

- ^ «Человек из Джерси возглавляет городской музыкальный центр; мэр объявил Гарри Фридгута руководителем культурного проекта» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 13 сентября 1943 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2023 года . Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ «Фридгут назначен директором музыкального центра Нового города: развлечения в храме Мечеа Slart около 1 ноября». Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . 13 сентября 1943 г. с. 8. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1267877310 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Сообщается, что директор городского центра увольняется; говорят, что он поссорился с руководством из-за политики» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 5 июля 1944 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2023 года . Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ «Храм в Мекке переименован в центр Нью-Йорка: корпорация берет на себя управление развлечениями» . Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . 20 октября 1943 г. с. 17. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1319897239 .

- ^ «Городской театральный центр меняет название». Нью-Йорк Амстердам Новости . 20 ноября 1943 г. с. 21. ПроКвест 226101923 .