Milan

Milan

Milano (Italian) | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Milano | |

|

| |

| Coordinates: 45°28′01″N 09°11′24″E / 45.46694°N 9.19000°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | |

| Metropolitan city | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong Mayor–Council |

| • Mayor | Giuseppe Sala (EV) |

| • Legislature | Milan City Council |

| Area | |

| • Comune | 181.76 km2 (70.18 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 120 m (390 ft) |

| Population (1 January 2022)[1] | |

| • Comune | 1,371,498 |

| • Density | 7,500/km2 (20,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 4,336,121 |

| Demonym(s) | Milanese Meneghino[3] |

| GDP | |

| • Metro | €204,514 billion (2020) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code | 0039 02 |

| Website | www.comune.milano.it |

| |

| Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

Milan (/mɪˈlæn/ mil-AN, US also /mɪˈlɑːn/ mil-AHN;[5][6] Milanese: [miˈlãː] ; Italian: Milano [miˈlaːno] ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area[7] and the second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million,[8] while its metropolitan city has 3.22 million residents.[9] The urban area of Milan is the fourth-most-populous in the EU with 6.17 million inhabitants.[10] According to national sources, the population within the wider Milan metropolitan area (also known as Greater Milan) is estimated between 7.5 million and 8.2 million, making it by far the largest metropolitan area in Italy and one of the largest in the EU.[11][12] Milan is the economic capital of Italy, one of the economic capitals of Europe and a global financial centre.[13][14]

Milan is a leading alpha global city, with strengths in the fields of art, chemicals, commerce, design, education, entertainment, fashion, finance, healthcare, media (communication), services, research, and tourism.[15][16] Its business district hosts Italy's stock exchange (Italian: Borsa Italiana), and the headquarters of national and international banks and companies. In terms of GDP, Milan is the wealthiest city in Italy, having also one of the largest economies among EU cities.[17][18] Milan is viewed along with Turin as the southernmost part of the Blue Banana urban development corridor (also known as the "European Megalopolis"), and one of the Four Motors for Europe. Milan is a major international tourist destination, appearing among the most visited cities in the world, ranking second in Italy after Rome, fifth in Europe and sixteenth in the world.[19][20] Milan is a major cultural centre, with museums and art galleries that include some of the most important collections in the world, such as major works by Leonardo da Vinci.[21][22] It also hosts numerous educational institutions, academies and universities, with 11% of the national total of enrolled students.[23][24]

Founded around 590 BC[25] under the name Medhelanon by a Celtic tribe belonging to the Insubres group and belonging to the Golasecca culture, it was conquered by the ancient Romans in 222 BC, who latinized the name of the city into Mediolanum.[25][26] The city's role as a major political centre dates back to the late antiquity, when it served as the capital of the Western Roman Empire.[27] From the 12th century until the 16th century, Milan was one of the largest European cities and a major trade and commercial centre, as the capital of the Duchy of Milan, one of the greatest political, artistic and fashion forces in the Renaissance.[28][29] Having become one of the main centres of the Italian Enlightenment during the early modern period, it then became one of the most active centres during the Restoration, until its entry into the unified Kingdom of Italy. From the 20th century onwards Milan became the industrial and financial capital of Italy.[30][31]

Milan has been recognized as one of the world's four fashion capitals.[32] Many of the most famous luxury fashion brands in the world have their headquarters in the city, including: Armani, Prada, Versace, Valentino, Loro Piana and Zegna.[33][34] It also hosts several international events and fairs, including Milan Fashion Week and the Milan Furniture Fair, which are among the world's biggest in terms of revenue, visitors and growth.[35][36][37] The city is served by many luxury hotels and is the fifth most starred in the world by Michelin Guide.[38] It hosted the Universal Exposition in 1906 and 2015. In the field of sports, Milan is home to two of Europe's most successful football teams, AC Milan and Inter Milan, and one of Europe's main basketball teams, Olimpia Milano. Milan will host the Winter Olympic and Paralympic games for the first time in 2026, together with Cortina d'Ampezzo.[39][40][41]

Toponymy

[edit]

Milan was founded with the Celtic name of Medhelanon,[26][25] later latinized by the ancient Romans into Mediolanum. In Celtic language medhe- meant "middle, centre" and the name element -lanon is the Celtic equivalent of Latin -planum "plain", meant "(settlement) in the midst of the plain",[42][43] or of "place between watercourses" (Celtic medhe = "in the middle, central"; land or lan = "land"), given the presence of the Olona, Lambro, Seveso rivers and the Nirone and Pudiga streams.[44]

The Latin name Mediolanum comes from the Latin words medio (in the middle) and planus (plain).[45] However, some scholars believe that lanum comes from the Celtic root lan, meaning an enclosure or demarcated territory (source of the Welsh word llan, meaning "a sanctuary or church", ultimately cognate to English/German Land) in which Celtic communities used to build shrines.[46]

Hence Mediolanum could signify the central town or sanctuary of a Celtic tribe. Indeed, about sixty Gallo-Roman sites in France bore the name "Mediolanum", for example: Saintes (Mediolanum Santonum) and Évreux (Mediolanum Aulercorum).[47] In addition, another theory links the name to the scrofa semilanuta ("half-woolly sow") an ancient emblem of the city, fancifully accounted for in Andrea Alciato's Emblemata (1584), beneath a woodcut of the first raising of the city walls, where a boar is seen lifted from the excavation, and the etymology of Mediolanum given as "half-wool",[48] explained in Latin and in French.

According to this theory, the foundation of Milan is credited to two Celtic peoples, the Bituriges and the Aedui, having as their emblems a ram and a boar;[49] therefore "The city's symbol is a wool-bearing boar, an animal of double form, here with sharp bristles, there with sleek wool."[50] Alciato credits Ambrose for his account.[51]

History

[edit]Celtic era

[edit]

Around 590 BC[25] a Celtic tribe belonging to the Insubres group and belonging to the Golasecca culture settled the city under the name Medhelanon.[26][25] According to the legend reported by Livy (writing between 27 and 9 BC), the Gaulish king Ambicatus sent his nephew Bellovesus into northern Italy at the head of a party drawn from various Gaulish tribes; Bellovesus allegedly founded the settlement in the times of the Roman monarchy, during the reign of Tarquinius Priscus. Tarquin is traditionally recorded as reigning from 616 to 579 BC, according to ancient Roman historian Titus Livy.[52]

Medhelanon, in particular, was developed around a sanctuary, which was the oldest area of the village.[53] The sanctuary, which consisted of a wooded area in the shape of an ellipse with a central clearing, was aligned according to precise astronomical points. For this reason, it was used for religious gatherings, especially in particular celebratory moments. The sanctuary of Medhelanon was an ellipse with axes of 443 m (1,453 ft) and 323 m (1,060 ft) located near Piazza della Scala.[53] The urban planning profile was based on these early paths, and on the shape of the sanctuary, reached, in some cases, up to the 19th century and even beyond. For example, the route of the modern Corso Vittorio Emanuele, Piazza del Duomo, Piazza Cordusio and Via Broletto, which is curvilinear, could correspond to the south side of the ellipse of the ancient sanctuary of Medhelanon.[53]

One axis of the Medhelanon sanctuary was aligned towards the heliacal rising of Antares, while the other towards the heliacal rising of Capella. The latter coincided with a Celtic spring festival celebrated on 24 March, while the heliacal rising of Antares corresponded with 11 November, which opened and closed the Celtic year and which coincided with the point where the Sun rose on the winter solstice.[53] About two centuries after the creation of the Celtic sanctuary, the first residential settlements began to be built around it. Medhelanon then transformed from a simple religious center to an urban and then military centre, thus becoming a real village.[53]

The first homes were built just south of the Celtic sanctuary, near the modern Royal Palace of Milan.[53] Subsequently, with the growth of the town centre, other important buildings for the Medhelanon community were built. First, a temple dedicated to the goddess Belisama was built, which was located near the modern Milan Cathedral. Then, near the modern Via Moneta, which is located near today's Piazza San Sepolcro, a fortified building with military functions was built which was surrounded by a defensive moat.[53]

Roman times

[edit]

During the Roman Republic, the Romans, led by consul Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus, fought the Insubres and captured the settlement in 222 BC. The chief of the Insubres then submitted to Rome, giving the Romans control of the settlement.[54] The Romans eventually conquered the entirety of the region, calling the new province "Cisalpine Gaul" (Latin: Gallia Cisalpina)—"Gaul this side of the Alps"—and may have given the city its Latinized name of Mediolanum: in Gaulish *medio- meant "middle, centre" and the name element -lanon is the Celtic equivalent of Latin -planum "plain", thus *Mediolanon (Latinized as Mediolānum) meant "(settlement) in the midst of the plain".[43][55] Mediolanum became the most important center of Cisalpine Gaul and, in the wake of economic development, in 49 BC, was elevated, within the Lex Roscia, to the status of municipium.[56]

The ancient Celtic settlement was, from a topographic point of view, superimposed and replaced by the Roman one. The Roman city was then gradually superimposed and replaced by the medieval one. The urban center of Milan has therefore grown constantly and rapidly, until modern times, around the first Celtic nucleus. The original Celtic toponym Medhelanon then changed, as evidenced by a graffiti in Celtic language present on a section of the Roman walls of Milan which dates back to a period following the Roman conquest of the Celtic village, in Mesiolano.[57] In 286, the Roman Emperor Diocletian moved the capital of the Western Roman Empire from Rome to Mediolanum.[58] Diocletian himself chose to reside at Nicomedia in the Eastern Empire, leaving his colleague Maximian at Milan.

During the Augustan age Mediolanum was famous for its schools; it possessed a theatre and an amphitheatre (129.5 X 109.3 m), the third largest in Roman Italy after the Colosseum in Rome and the vast amphitheatre in Capua.[59] A large stone wall encircled the city in Caesar's time, and later was expanded in the late third century AD, by Maximian. Maximian built several gigantic monuments: the large circus (470 × 85 metres), the thermae or Baths of Hercules, a large complex of imperial palaces and other services and buildings of which few visible traces remain. Maximian increased the city area to 375 acres by surrounding it with a new, larger stone wall (about 4.5 km long) with many 24-sided towers. The monumental area had twin towers; the one included later in the construction of the convent of San Maurizio Maggiore remains 16.6 m high.

It was from Mediolanum that the Emperor Constantine issued what is now known as the Edict of Milan in AD 313, granting tolerance to all religions within the Empire, thus paving the way for Christianity to become the dominant religion of the Empire. Constantine was in Mediolanum to celebrate the wedding of his sister to the Eastern Emperor, Licinius. In 402, the Visigoths besieged the city and the Emperor Honorius moved the Imperial residence to Ravenna.[60] In 452, Attila besieged the city, but the real break with the city's Imperial past came in 539, during the Gothic War, when Uraias (a nephew of Witiges, formerly King of the Italian Ostrogoths) carried out attacks in Milan, with losses, according to Procopius, being about 300,000 men. The Lombards took Ticinum as their capital in 572 (renaming it Papia – the modern Pavia), and left early-medieval Milan to the governance of its archbishops.

Middle Ages

[edit]

After the siege of the city by the Visigoths in 402, the imperial residence moved to Ravenna. Attila, King of the Huns, sacked and devastated the city in 452 AD. In 539 the Ostrogoths conquered and destroyed Milan during the Gothic War against Byzantine Emperor Justinian I. In the summer of 569 the Lombards (from whom the name of the Italian region Lombardy derives), conquered Milan, overpowering the small Byzantine garrison left for its defence. Some Roman structures remained in use in Milan under Lombard rule.[61] Milan surrendered to Charlemagne and the Franks in 774.

The 11th century saw a reaction against the control of the Holy Roman Emperors. City-states emerged in northern Italy, an expression of the new political power of the cities and their will to fight against all feudal powers. Milan was no exception. It did not take long, however, for the Italian city-states to begin fighting each other to try to limit neighbouring powers.[62] The Milanese destroyed Lodi and continuously warred with Pavia, Cremona and Como, who in turn asked Frederick I Barbarossa for help. In a sally they captured Empress Beatrice and forced her to ride a donkey backward through the city until getting out. These brought the destruction of much of Milan in 1162.[63][64]

A period of peace followed and Milan prospered as a centre of trade due to its geographical position. During this time, the city was considered one of the largest European cities.[28] As a result of the independence that the Lombard cities gained in the Peace of Constance in 1183, Milan returned to the commune form of local government first established in the 11th century.[65][66]

In 1395, Gian Galeazzo Visconti became the first Duke of Milan upon receiving the title from Wenceslaus, King of the Romans. In 1447 Filippo Maria Visconti, Duke of Milan, died without a male heir; following the end of the Visconti line, the Ambrosian Republic was established; it took its name from St. Ambrose, the popular patron saint of the city.[67] Both the Guelph and the Ghibelline factions worked together to bring about the Ambrosian Republic in Milan. Nonetheless, the Republic collapsed when, in 1450, Milan was conquered by Francesco I of the House of Sforza, which made Milan one of the leading cities of the Italian Renaissance.[67][68] Under the House of Sforza, Milan experienced a period of great prosperity, which in particular saw the development of mulberry cultivation and silk processing.[69]

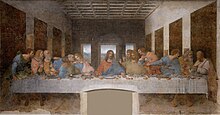

Following this economic growth, works such as the Sforza Castle (already existing in the Visconti era under the name of Porta Giovia Castle, but re-adapted, enlarged and completed by the Sforza family) and the Ospedale Maggiore were completed. The Sforzas also managed to attract to Milan personalities such as Leonardo da Vinci, who redesigned and improved the function of the navigli and painted The Last Supper, and Bramante, who worked on the church of Santa Maria presso San Satiro, on the basilica of Sant'Ambrogio and to the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie, influencing the development of the Lombard Renaissance.

Early modern

[edit]

Milan's last independent ruler, Lodovico il Moro, requested the aid of Charles VIII of France against the other Italian states, eventually unleashing the Italian Wars. The king's cousin, Louis of Orléans, took part in the expedition and realized most of Italy was virtually defenseless. This prompted him to come back a few years later in 1500, and claim the Duchy of Milan for himself, his grandmother having been a member of the ruling Visconti family. At that time, Milan was also defended by Swiss mercenaries. After the victory of Louis's successor François I over the Swiss at the Battle of Marignan, the duchy was promised to the French king François I. When the Spanish Habsburg Emperor Charles V defeated François I at the Battle of Pavia in 1525, northern Italy, which included Milan, passed to Habsburg Spain.[70]

In 1556, Charles V abdicated in favour of his son Philip II and his brother Ferdinand I. Charles's Italian possessions, including Milan, passed to Philip II and remained with the Spanish line of Habsburgs, while Ferdinand's Austrian line of Habsburgs ruled the Holy Roman Empire. The Great Plague of Milan in 1629–31, that claimed the lives of an estimated 60,000 people out of a population of 130,000, caused unprecedented devastation in the city and was effectively described by Alessandro Manzoni in his masterpiece The Betrothed. This episode was seen by many as the symbol of Spanish bad rule and decadence and is considered one of the last outbreaks of the centuries-long pandemic of plague that began with the Black Death.[71]

In 1700, the Spanish line of Habsburgs was extinguished with the death of Charles II. After his death, the War of the Spanish Succession began in 1701. In 1706, the French were defeated in Ramillies and Turin and were forced to yield northern Italy to the Austrian Habsburgs. In 1713–1714 the Treaties of Utrecht and Rastatt formally confirmed Austrian sovereignty over most of Habsburg Spain's Italian possessions including Lombardy and its capital, Milan. Napoleon invaded Italy in 1796, and Milan was declared capital of the Cisalpine Republic. Later, he declared Milan capital of the Kingdom of Italy and was crowned King of Italy in the cathedral. Once Napoleon's occupation ended, the Congress of Vienna returned Lombardy and Milan, to Austrian control in 1815.[72]

Late modern and contemporary

[edit]

On 18 March 1848 Milan effectively rebelled against Austrian rule, during the so-called "Five Days" (Italian: Le Cinque Giornate), that forced Field Marshal Radetzky to temporarily withdraw from the city. The bordering Kingdom of Piedmont–Sardinia sent troops to protect the insurgents and organised a plebiscite that ratified by a huge majority the unification of Lombardy with Piedmont–Sardinia. But just a few months later the Austrians were able to send fresh forces that routed the Piedmontese army at the Battle of Custoza on 24 July and to reassert Austrian control over northern Italy. About ten years later, however, Italian nationalist politicians, officers and intellectuals such as Cavour, Garibaldi and Mazzini were able to gather a huge consensus and to pressure the monarchy to forge an alliance with the new French Empire of Napoleon III to defeat Austria and establish a large Italian state in the region. At the Battle of Solferino in 1859 French and Italian troops heavily defeated the Austrians that retreated under the Quadrilateral line.[73] Following this battle, Milan and the rest of Lombardy were incorporated into Piedmont-Sardinia, which then proceeded to annex all the other Italian statlets and proclaim the birth of the Kingdom of Italy on 17 March 1861.

The political unification of Italy enhanced Milan's economic dominance over northern Italy. A dense rail network, whose construction had started under Austrian patronage, was completed in a brief time, making Milan the rail hub of northern Italy and, with the opening of the Gotthard (1882) and Simplon (1906) railway tunnels, the major South European rail hub for goods and passenger transport. Indeed, Milan and Venice were among the main stops of the Orient Express that started operating from 1919.[74] Abundant hydroelectric resources allowed the development of a strong steel and textile sector and, as Milanese banks dominated Italy's financial sphere, the city became the country's leading financial centre. In May 1898, Milan was shaken by the Bava Beccaris massacre, a riot related to soaring cost of living.[75]

Milan's northern location in Italy closer to Europe, secured also a leading role for the city on the political scene. It was in Milan that Benito Mussolini built his political and journalistic careers, and his fascist Blackshirts rallied for the first time in the city's Piazza San Sepolcro; here the future Fascist dictator launched his March on Rome on 28 October 1922. During the Second World War Milan's large industrial and transport facilities suffered extensive damage from Allied bombings that often also hit residential districts.[76] When Italy surrendered in 1943, German forces occupied and plundered most of northern Italy, fueling the birth of a massive resistance guerrilla movement.[77] On 29 April 1945, the American 1st Armored Division was advancing on Milan but, before it arrived, the Italian resistance seized control of the city and executed Mussolini along with his mistress and several regime officers, that were later hanged and exposed in Piazzale Loreto, where one year before some resistance members had been executed.

During the post-war economic boom, the reconstruction effort and the Italian economic miracle attracted a large wave of internal migration (especially from rural areas of southern Italy) to Milan. The population grew from 1.3 million in 1951 to 1.7 million in 1967.[78] During this period, Milan was rapidly rebuilt, with the construction of several innovative and modernist skyscrapers, such as the Torre Velasca and the Pirelli Tower, that soon became the symbols of this new era of prosperity.[79] The economic prosperity was, however, overshadowed in the late 1960s and early 1970s during the so-called Years of lead, when Milan witnessed an unprecedented wave of street violence, labour strikes and political terrorism. The apex of this period of turmoil occurred on 12 December 1969, when a bomb exploded at the National Agrarian Bank in Piazza Fontana, killing 17 people and injuring 88.

In the 1980s, with the international success of Milanese houses (like Armani, Prada, Versace, Moschino and Dolce & Gabbana), Milan became one of the world's fashion capitals. The city saw also a marked rise in international tourism, notably from America and Japan, while the stock exchange increased its market capitalisation more than five-fold.[80] This period led the mass media to nickname the metropolis "Milano da bere", literally "Milan to be drunk".[81] But in the 1990s Milan was badly affected by Tangentopoli, a political scandal in which many politicians and businessmen were tried for corruption. The city was also affected by a severe financial crisis and a steady decline in textiles, automobile and steel production.[79] Berlusconi's Milano 2 and Milano 3 projects were the most important housing projects of the 1980s and 1990s in Milan and brought to the city new economical and social energy.

In the early 21st century Milan underwent a series of sweeping redevelopments over huge former industrial areas.[82] Two new business districts, Porta Nuova and CityLife, were built in the space of a decade, radically changing the skyline of the city. Its exhibition centre moved to a much larger site in Rho.[83] The long decline in traditional manufacturing has been overshadowed by a great expansion of publishing, finance, banking, fashion design, information technology, logistics and tourism.[84] The city's decades-long population decline seems to have partially reverted in recent years, as the comune gained about 100,000 new residents since the last census. The successful re-branding of the city as a global capital of innovation has been instrumental in its successful bids for hosting large international events such as 2015 Expo and 2026 Winter Olympics.

Geography

[edit]Topography

[edit]

Milan is located in the north-western section of the Po Valley, approximately halfway between the river Po to the south and the foothills of the Alps with the great lakes (Lake Como, Lake Maggiore and Lake Lugano) to the north, the Ticino river to the west and the Adda to the east. The city's land is flat, the highest point being at 122 m (400.26 ft) above sea level.

The administrative comune covers an area of about 181 square kilometres (70 sq mi), with a population, in 2013, of 1,324,169 and a population density of 7,315 inhabitants per square kilometre (18,950/sq mi). The Metropolitan City of Milan covers 1,575 square kilometres (608 sq mi) and in 2015 had a population estimated at 3,196,825, with a resulting density of 2,029 inhabitants per square kilometre (5,260/sq mi).[85] A larger urban area, comprising parts of the provinces of Milan, Monza e Brianza, Como, Lecco and Varese is 1,891 square kilometres (730 sq mi) wide and has a population of 5.27 million with a density of 2,783 inhabitants per square kilometre (7,210/sq mi).[10]

The concentric layout of the city centre reflects the Navigli, an ancient system of navigable and interconnected canals, now mostly covered.[86] The suburbs of the city have expanded mainly to the north, swallowing up many comuni along the roads towards Varese, Como, Lecco and Bergamo.[87] In the 21st century the Navigli region of Milan is a highly active area with a large number of residential units, bars and restaurants. It is also a well-known centre for artists.[88]

Climate

[edit]

Milan features a mid-latitude, four-season humid subtropical climate (Cfa), according to the Köppen climate classification. Milan's climate is similar to much of Northern Italy's inland plains, with hot, humid summers and cold, foggy winters. The Alps and Apennine Mountains form a natural barrier that protects the city from the major circulations coming from northern Europe and the sea.[89]

During winter daily average temperatures can fall below freezing (0 °C [32 °F]) and accumulations of snow can occur: the historic average of Milan's area is 25 centimetres (10 in) in the period between 1961 and 1990, with a record of 90 centimetres (35 in) in January 1985. In the suburbs the average can reach 36 centimetres (14 in).[90] The city receives on average seven days of snow per year.[91]

The city was often shrouded in thick cloud or fog during winter, although the removal of rice paddies from the southern neighbourhoods and the urban heat island effect have greatly reduced this occurrence since the turn of the 21st century. Occasionally, the Foehn winds cause the temperatures to rise unexpectedly: on 22 January 2012 the daily high reached 16 °C (61 °F) while on 22 February 2012 it reached 21 °C (70 °F).[92] Air pollution levels rise significantly in wintertime when cold air clings to the soil, causing Milan to be one of Europe's most polluted cities.[93][94]

Summers in Milan are hot and humidity levels are high with peak temperatures reaching above 35 °C (95 °F). Due to the high humidity, urban heat effect and lack of wind, nighttimes often remain muggy during the summer months.[95] Usually the summer enjoys clearer skies with an average of more than 13 hours of daylight:[96] when precipitation occurs though, it is more likely to be accompanied by thunderstorms and hail.[96] Springs and autumns are generally pleasant, with temperatures ranging between 10 and 20 °C (50 and 68 °F); these seasons are characterized by higher rainfall, especially in April and May.[97] Relative humidity typically ranges between 45% (comfortable) and 95% (very humid) throughout the year, rarely dropping below 27% (dry) and reaching as high as 100%.[96] Wind is generally absent: over the course of the year typical wind speeds vary from 0 to 14 km/h (0 to 9 mph) (calm to gentle breeze), rarely exceeding 29 km/h (18 mph) (fresh breeze), except during summer thunderstorms when winds can blow strong. In the spring, gale-force windstorms may happen, generated either by Tramontane blowing from the Alps or by Bora-like winds from the north. Due to its geographic location surrounded by mountains on 3 sides, Milan is among the least windy cities in Europe.[96]

| Climate data for Linate Airport, Milan (1991–2020 normals, sun 1981-2010, extremes 1946–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.7 (71.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

26.9 (80.4) |

32.4 (90.3) |

35.5 (95.9) |

36.6 (97.9) |

37.2 (99.0) |

39.3 (102.7) |

33.2 (91.8) |

28.2 (82.8) |

25.5 (77.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

39.3 (102.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

10.0 (50.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

23.9 (75.0) |

28.1 (82.6) |

30.7 (87.3) |

29.9 (85.8) |

25.5 (77.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

12.4 (54.3) |

7.4 (45.3) |

19.1 (66.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) |

5.2 (41.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

25.1 (77.2) |

24.4 (75.9) |

19.9 (67.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

3.9 (39.0) |

14.1 (57.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −0.4 (31.3) |

0.6 (33.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

8.4 (47.1) |

12.8 (55.0) |

17.2 (63.0) |

19.3 (66.7) |

18.8 (65.8) |

14.9 (58.8) |

10.2 (50.4) |

5.3 (41.5) |

0.6 (33.1) |

9.3 (48.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −15.0 (5.0) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

5.6 (42.1) |

8.4 (47.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−13.6 (7.5) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 35.9 (1.41) |

38.2 (1.50) |

42.2 (1.66) |

57.7 (2.27) |

70.3 (2.77) |

67.4 (2.65) |

44.2 (1.74) |

82.2 (3.24) |

73.4 (2.89) |

82.0 (3.23) |

112.4 (4.43) |

45.8 (1.80) |

751.7 (29.59) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4.7 | 4.5 | 5.4 | 7.2 | 8.4 | 6.6 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 5.1 | 6.6 | 8.3 | 5.7 | 72.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78.9 | 73.6 | 68.0 | 67.7 | 67.2 | 66.9 | 66.2 | 67.4 | 70.0 | 76.5 | 81.0 | 81.8 | 72.1 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 0.2 (32.4) |

0.8 (33.4) |

3.9 (39.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

11.2 (52.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

16.8 (62.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

10.1 (50.2) |

5.9 (42.6) |

1.2 (34.2) |

8.5 (47.3) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 91.4 | 108.5 | 170.0 | 178.4 | 212.3 | 247.6 | 293.2 | 237.6 | 179.3 | 116.5 | 73.3 | 67.1 | 1,975.2 |

| Source 1: NOAA NCEI[98][99] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale[100] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Malpensa Airport, Milan (1961–1990 normals, extremes 1951–present) |

|---|

Administration

[edit]Municipal government

[edit]

The legislative body of the Italian comuni is the City Council (Consiglio Comunale), which in cities with more than one million population is composed by 48 councillors elected every five years with a proportional system, at the same time of the mayoral elections. The executive body is the City Committee (Giunta Comunale), composed by 12 assessors, that is nominated and presided over by a directly elected Mayor. The current mayor of Milan is Giuseppe Sala, an independent leading a centre-left alliance led by the Democratic Party.

The municipality of Milan is subdivided into nine administrative Borough Councils (Consigli di Municipio), down from the former twenty districts before the 1999 administrative reform.[103] Each Borough Council is governed by a Council (Consiglio) and a President, elected contextually to the city Mayor. The urban organisation is governed by the Italian Constitution (art. 114), the Municipal Statute[104] and several laws, notably the Legislative Decree 267/2000 or Unified Text on Local Administration (Testo Unico degli Enti Locali).[105] After the 2016 administrative reform, the Borough Councils have the power to advise the Mayor with nonbinding opinions on a large spectrum of topics and are responsible for running most local services, such as schools, social services, waste collection, roads, parks, libraries and local commerce; in addition they are supplied with an autonomous funding to finance local activities.

Metropolitan city

[edit]

Milan is the capital of the eponymous Metropolitan city. According to the last governmental dispositions concerning administrative reorganisation, the urban area of Milan is one of the 15 Metropolitan municipalities (città metropolitane), new administrative bodies fully operative since 1 January 2015.[106] The new Metro municipalities, giving large urban areas the administrative powers of a province, are conceived for improving the performance of local administrations and to slash local spending by better co-ordinating the municipalities in providing basic services (including transport, school and social programs) and environment protection.[107] In this policy framework, the Mayor of Milan is designated to exercise the functions of Metropolitan mayor (Sindaco metropolitano), presiding over a Metropolitan Council formed by 24 mayors of municipalities within the Metro municipality. The Metropolitan City of Milan is headed by the Metropolitan Mayor (Sindaco metropolitano) and by the Metropolitan Council (Consiglio metropolitano). Since 21 June 2016, Giuseppe Sala, as mayor of the capital city, has been the mayor of the Metropolitan City.

Regional government

[edit]Milan is also the capital of Lombardy, one of the twenty regions of Italy. Lombardy is by far the most populated region of Italy, with more than ten million inhabitants, almost one sixth of the national total. It is governed by a Regional Council, composed of 80 members elected for a five-year term. On 26 March 2018, a list of candidates of the centre-right coalition, a coalition of centrist and right-wing parties, led by Attilio Fontana, largely won the regional election, defeating a coalition of socialists, liberals and ecologists and a third-party candidate from the populist Five Stars Movement. The conservatives have governed the region almost uninterruptedly since 1970. The regional council has 48 members from the centre-right coalition, 18 from the centre-left coalition and 13 from the Five Star Movement. The seat of the regional government is Palazzo Lombardia that, standing at 161.3 metres (529 feet),[108] is the fifth-tallest building in Milan.

Cityscape

[edit]Skyline

[edit]Architecture

[edit]

The architectural and artistic presence in Milan represents one of the attractions of the Lombard capital. Milan has been among the most important Italian centers in the history of architecture, has made important contributions to the development of art history, and has been the cradle of a number of modern art movements.

There are only few remains of the ancient Roman city, notably the well-preserved Colonne di San Lorenzo. During the second half of the 4th century, Saint Ambrose, as bishop of Milan, had a strong influence on the layout of the city, reshaping the centre (although the cathedral and baptistery built in Roman times are now lost) and building the great basilicas at the city gates: Sant'Ambrogio, San Nazaro in Brolo, San Simpliciano and Sant'Eustorgio, which still stand, refurbished over the centuries, as some of the finest and most important churches in Milan. Milan's Cathedral, built between 1386 and 1877, is the largest church in the Italian Republic—the larger St. Peter's Basilica is in the State of Vatican City, a sovereign state—and the third largest in the world,[109] as well as the most important example of Gothic architecture in Italy. The gilt bronze statue of the Virgin Mary, placed in 1774 on the highest pinnacle of the Duomo, soon became one of the most enduring symbols of Milan.[110]

In the 15th century, when the Sforza ruled the city, an old Viscontean fortress was enlarged and embellished to become the Castello Sforzesco, the seat of an elegant Renaissance court surrounded by a walled hunting park. Notable architects involved in the project included the Florentine Filarete, who was commissioned to build the high central entrance tower, and the military specialist Bartolomeo Gadio.[111] The alliance between Francesco Sforza and Florence's Cosimo de' Medici bore to Milan Tuscan models of Renaissance architecture, apparent in the Ospedale Maggiore and Bramante's work in the city, which includes Santa Maria presso San Satiro (a reconstruction of a small 9th-century church), the tribune of Santa Maria delle Grazie and three cloisters for Sant'Ambrogio.[112] The Counter-Reformation in the 16th to 17th centuries was also the period of Spanish domination and was marked by two powerful figures: Saint Charles Borromeo and his cousin, Cardinal Federico Borromeo. Not only did they impose themselves as moral guides to the people of Milan, but they also gave a great impulse to culture, with the creation of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, in a building designed by Francesco Maria Richini, and the nearby Pinacoteca Ambrosiana. Many notable churches and Baroque mansions were built in the city during this period by the architects, Pellegrino Tibaldi, Galeazzo Alessi and Richini himself.[113]

Empress Maria Theresa of Austria was responsible for the significant renovations carried out in Milan during the 18th century.[114] This urban and artistic renewal included the establishment of Teatro alla Scala, inaugurated in 1778, and the renovation of the Royal Palace. The late 1700s Palazzo Belgioioso by Giuseppe Piermarini and Royal Villa of Milan by Leopoldo Pollack, later the official residence of Austrian viceroys, are often regarded among the best examples of Neoclassical architecture in Lombardy.[115] The Napoleonic rule of the city in 1805–1814, having established Milan as the capital of a satellite Kingdom of Italy, took steps to reshape it accordingly to its new status, with the construction of large boulevards, new squares (Porta Ticinese by Luigi Cagnola and Foro Bonaparte by Giovanni Antonio Antolini) and cultural institutions (Art Gallery and the Academy of Fine Arts).[116] The massive Arch of Peace, situated at the bottom of Corso Sempione, is often compared to the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. In the second half of the 19th century, Milan quickly became the main industrial centre of the new Italian nation, drawing inspiration from the great European capitals that were hubs of the Second Industrial Revolution. The great Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, realised by Giuseppe Mengoni between 1865 and 1877 to celebrate Vittorio Emanuele II, is a covered passage with a glass and cast iron roof, inspired by the Burlington Arcade in London. Several other arcades such as the Galleria del Corso, built between 1923 and 1931, complement it. Another late-19th-century eclectic monument in the city is the Cimitero Monumentale graveyard, built in a Neo-Romanesque style between 1863 and 1866.

The tumultuous period of early 20th century brought several, radical innovations in Milanese architecture. Art Nouveau, also known as Liberty in Italy, is recognisable in Palazzo Castiglioni, built by architect Giuseppe Sommaruga between 1901 and 1903.[117] Other examples include Hotel Corso,[117] Casa Guazzoni with its wrought iron and staircase, and Berri-Meregalli house, the latter built in a traditional Milanese Art Nouveau style combined with elements of neo-Romanesque and Gothic revival architecture, regarded as one of the last such types of architecture in the city.[118] A new, more eclectic form of architecture can be seen in buildings such as Castello Cova, built the 1910s in a distinctly neo-medieval style, evoking the architectural trends of the past.[119] An important example of Art Deco, which blended such styles with Fascist architecture, is the huge Central railway station inaugurated in 1931.[120]

The post-World War II period saw rapid reconstruction and fast economic growth, accompanied by a nearly two-fold increase in population. In the 1950s and 1960s, a strong demand for new residential and commercial areas drove to extreme urban expansion, that has produced some of the major milestones in the city's architectural history, including Gio Ponti's Pirelli Tower (1956–60), Velasca Tower (1956–58), and the creation of brand new residential satellite towns, as well as huge amounts of low-quality public housings. In recent years, de-industrialization, urban decay and gentrification led to a vast urban renewal of former industrial areas, that have been transformed into modern residential and financial districts, notably Porta Nuova in downtown Milan and FieraMilano in the suburb of Rho. In addition, the old exhibition area is being completely reshaped according to the Citylife regeneration project, featuring residencial areas, museums, an urban park and three skyscrapers designed by international architects, and after whom they are named: the 202-metre (663-foot) Isozaki Arata—when completed, the tallest building in Italy,[121] the twisted Hadid Tower,[122] and the curved Libeskind Tower.[123]

Two business districts dominate Milan's skyline: Porta Nuova in the north-east (boroughs No. 9 and 2) and CityLife (borough No. 8) in the north-west part of the commune. The tallest buildings include the Unicredit Tower at 231 m (though only 162 m without the spire), and the 209 m Allianz Tower, a 50-story tower.

Parks and gardens

[edit]

The largest parks in the central area of Milan are Sempione Park, at the north-western edge, and Montanelli Gardens, situated north-east of the city. English-style Sempione Park, built in 1890, contains the Civic Arena, the Civic Aquarium of Milan (which is the third oldest aquarium in Europe[124]), a steel lattice panoramic tower, an art exhibition centre, a Japanese garden and a public library.[125] The Montanelli gardens, created in the 18th century, hosts the Natural History Museum of Milan and a planetarium.[126] Slightly away from the city centre, heading east, Forlanini Park is characterised by a large pond and a few preserved shacks which remind of the area's agricultural past.[127] In recent years Milan's authorities pledged to develop its green areas: they planned to create twenty new urban parks and extend the already existing ones, and announced plans to plant three million trees by 2030.[citation needed]

Also notable is Monte Stella ("Starmount"), also informally called Montagnetta di San Siro ("Little mountain of San Siro"), an artificial hill and surrounding city park in Milan. The hill was created using the debris from the buildings that were bombed during World War II, as well as from the last remnants of the Spanish walls of the city, demolished in the mid 20th century. Even at only 25 m (82 ft) height, the hill provides a panoramic view of the city and hinterland, and in a clear day, the Alps and Apennines can be distinguished from atop. A notable area of the park is called "Giardino dei Giusti" (Garden of the Just), which is a memorial to distinguished opponents of genocide and crimes against humanity; each tree in the garden is dedicated to one such person. Notable people who have been dedicated a tree in the Giardino dei Giusti include Moshe Bejski, Andrej Sakharov, Svetlana Broz, and Pietro Kuciukian.

The Orto Botanico di Brera a botanical garden located behind Palazzo Brera at Via Brera 28 in the center of Milan, is another major park in the city. The garden consists primarily of rectangular flower-beds, trimmed in brick, with elliptical ponds from the 18th century, and specula and greenhouse from the 19th century (now used by the Academy of Fine Arts). It contains one of the oldest Ginkgo biloba trees in Europe, as well as mature specimens of Firmiana platanifolia, Juglans nigra, Pterocarya fraxinifolia, and Tilia.

In addition, even though Milan is located in one of the most urbanised regions of Italy, it is surrounded by a belt of green areas and features numerous gardens even in its very centre. The farmlands and woodlands north (Parco Nord Milano since 1975) and south (Parco Agricolo Sud Milano since 1990) of the urban area have been protected as regional parks.[128][129] West of the city, the Parco delle Cave (Sand pit park) has been established on a neglected site where gravel and sand used to be extracted, featuring artificial lakes and woods.[130]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1861 | 267,621 | — |

| 1871 | 290,518 | +8.6% |

| 1881 | 354,045 | +21.9% |

| 1901 | 538,483 | +52.1% |

| 1911 | 701,411 | +30.3% |

| 1921 | 818,161 | +16.6% |

| 1931 | 960,682 | +17.4% |

| 1936 | 1,115,794 | +16.1% |

| 1951 | 1,274,187 | +14.2% |

| 1961 | 1,582,474 | +24.2% |

| 1971 | 1,732,068 | +9.5% |

| 1981 | 1,604,844 | −7.3% |

| 1991 | 1,369,295 | −14.7% |

| 2001 | 1,256,211 | −8.3% |

| 2011 | 1,242,123 | −1.1% |

| 2021 | 1,371,498 | +10.4% |

| Istat historical data 1861–2021[131] | ||

The official estimated population of the City of Milan was 1,378,689 as of 31 December 2018, according to ISTAT, the official Italian statistical agency,[132] up by 136,556 from the 2011 census, or a growth of about 11%. At the same date 3,250,315 people lived in Milan province-level municipality.[133] The population of Milan today is lower than its historical peak. With rapid industrialization in post-war years, the population of Milan peaked at 1,743,427 in 1973.[134] Thereafter, during the following decades, about one third of the population moved to the outer belt of suburbs and new satellite settlements that grew around the city proper.

Milan is home to the second-largest Far East Asian community in Europe after Paris, with the Philippines and China, making up about a quarter of its foreign population (around 70,000 out of 261,000 in 2023). Another 3,500 foreigners come from other East Asian countries.[135]

Today, Milan's conurbation extends well beyond the borders of the city proper and of its special-status provincial authority: its contiguous built-up urban area was home to 5.27 million people in 2015,[10] while its wider metropolitan area, the largest in Italy and fourth largest in the EU, is estimated to have a population of more than 8.2 million.[12]

Foreign residents

[edit]Nationality held by residents as of 2023[136]

As of 2021, some 261,277 foreign residents lived in the municipality of Milan,[137] representing 19.2% of the total resident population. These figures suggest that the immigrant population has more than doubled in the last 15 years.[138] After World War II, Milan experienced two main waves of immigration: the first, dating from the 1950s to the early 1970s, saw a large influx of migrants from poorer and rural areas within Italy; the second, starting from the late 1980s, has been characterized by the preponderance of foreign-born immigrants.[139]

The early period coincided with the so-called Italian economic miracle of postwar years, an era of extraordinary growth based on rapid industrial expansion and great public works, that brought to the city a large influx of over 400,000 people, mainly from rural and underdeveloped Southern Italy.[79]

Immigrants came mainly from Africa (in particular Eritreans, Egyptians, Moroccans, Senegalese and Nigerian), and the former socialist countries of Eastern Europe (notably Albanians, Romanians, Ukrainians, Macedonians, Moldovans, and Russians), in addition to a growing number of Asians (in particular Chinese, Sri Lankans and Filipinos) and Latin Americans (Mainly South Americans). At the beginning of the 1990s, Milan already had a population of foreign-born residents of approximately 58,000 (or 4% of the then population), that rose rapidly to over 117,000 by the end of the decade (about 9% of the total).[140]

Decades of continuing high immigration have made the city one of the most cosmopolitan and multicultural in Italy. Milan notably hosts the oldest and largest (along with Prato) Chinese community in Italy, with around 32,500 people in 2023, excluding Italians of Chinese descent such as immigrants who have acquired Italian citizenship or their descendants. Situated in the 8th district, and centered on Via Paolo Sarpi, an important commercial avenue, the Milanese Chinatown was originally established in the 1920s by immigrants from Wencheng County, in the Zhejiang, and used to operate small textile and leather workshops.[141]

Milan has also a substantial English-speaking community (around 3,500 US citizens, British, Irish and Australian expatriates, excluding double-citizens), and several English schools and English-language publications, such as Hello Milano, Where Milano and Easy Milano.[136]

Religion

[edit]

Milan's population, like that of Italy as a whole, is mostly Catholic.[142][143] It is the seat of the Archdiocese of Milan. Greater Milan is also home to Protestant, Eastern Orthodox, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Sikh and Buddhist communities.[144][145][146][147][148]

Milan has been a Christian-majority city since the late Roman Empire.[149] Its religious history was marked by the figure of St. Ambrose, whose heritage includes the Ambrosian Rite (Italian: Rito ambrosiano), used by some five million Catholics in the greater part of the Archdiocese of Milan,[150] which consider the largest in Europe.[151] The Rite varies slightly from the canonical Roman Rite liturgy, with differences in the mass, liturgical year (Lent starts four days later than in the Roman Rite), baptism, rite of funerals, priest clothes and sacred music (use of the Ambrosian chant rather than Gregorian).[152]

In addition, the city is home to the largest Orthodox community in Italy. Lombardy is the seat of at least 78 Orthodox parishes and monasteries, the vast majority of them located in the area of Milan.[153] The main Romanian Orthodox church in Milan is the Catholic church of Our Lady of Victory (Chiesa di Santa Maria della Vittoria), currently granted for use to the local Romanian community.[154] Similarly, the point of reference for the followers of the Russian Orthodox Church is the Catholic church of San Vito in Pasquirolo.[155][156]

The Jewish community of Milan is the second largest in Italy after Rome, with about 10,000 members, mainly Sephardi.[157] The main city synagogue, Hechal David u-Mordechai Temple, was built by architect Luca Beltrami in 1892.

Milan hosts also one of the largest Muslim communities in Italy,[158] and the city saw the construction of the country's first new mosque featuring a dome and minaret, since the destruction of the ancient mosques of Lucera in the year 1300. In 2014 the City Council agreed on the construction of a new mosque amid bitter political debate, since it is strenuously opposed by right-wing parties such as the Northern League.[159] As of 2018, the Muslim population is estimated at around 9% of the city's population.[160]

Currently, accurate statistics on the Hindu and Sikh presence in Milan metro area are not available; however, various sources estimate that about 40% of the total Indian population living in Italy, or about 50,000 individuals, reside in Lombardy,[161][162] where a number of Hindu and Sikh temples exist and where they form the largest such communities in Europe after the ones in Britain.[163]

Economy

[edit]

Milan is the economic capital of Italy[13] and is a global financial centre. Milan is, together with London, Hamburg, Frankfurt, Munich and Paris, one of the six European economic capitals.[14] Milan is the capital of the Lombardy region in northern Italy and is the wealthiest city in Italy.[166] Milan and Lombardy had a GDP of €400 billion ($493 billion) and €650 billion ($801 billion), respectively, in 2017.[167] It is a member of the Blue Banana corridor and of the Four Motors for Europe among Europe's economic leaders. Milan's hinterland is Italy's largest industrial area. Milan's GDP per capita of about €49,500 (US$55,600) ranks among Italy's highest.[168]

Whereas Rome is Italy's political and cultural capital, Milan is the country's industrial and financial heart. With a 2019 GDP estimated at €207.4 billion,[169] the province of Milan generates approximately 10% of the national GDP; while the economy of the Lombardy region generates approximately 19.5% of Italy's GDP (or an estimated €400 billion in 2021,[170] roughly the size of Belgium). The province of Milan is home to about 45% of businesses in the Lombardy region and more than 8 percent of all businesses in Italy, including three Fortune 500 companies.[171]

According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, Milan was the 11th-most-expensive city in Europe and the 22nd-most-expensive city in the world in 2019,[172] while the well-known Via Monte Napoleone is Europe's most expensive street and the second-most-expensive street in the world after Fifth Avenue in New York City (2023).[165]

Since the late 1800s, the area of Milan has been a major industrial and manufacturing centre. Alfa Romeo automobile company and Falck steel group employed thousands of workers in the city until the closure of their sites in Arese in 2004 and Sesto San Giovanni in 1995. Other global industrial companies, such as Edison, Prysmian Group, Riva Group, Saras, Saipem and Techint, maintain their headquarters and significant employment in the city and its suburbs. Other relevant industries active in metro Milan include chemicals (e.g. Mapei, Versalis, Tamoil Italy), home appliances (e.g. Candy), hospitality (UNA Hotels & Resorts), food & beverages (e.g. Bertolli, Campari), machinery, medical technologies (e.g. Amplifon, Bracco), plastics and textiles. The construction (e.g. Webuild), retail (e.g. Esselunga, La Rinascente) and utilities (e.g. A2A, Edison S.p.A., Snam, Sorgenia) sectors are also large employers in the Greater Milan.

Milan is Italy's largest financial hub. The main national insurance companies and banking groups (for a total of 198 companies) and over forty foreign insurance and banking companies are located in the city,[173] as well as a number of asset management companies, including Anima Holding, Azimut Holding, ARCA SGR and Eurizon Capital. The Associazione Bancaria Italiana representing the Italian banking system, and Milan Stock Exchange (225 companies listed on the stock exchange) are both located in the city. Porta Nuova, the main business district of Milan and one of the most important in Europe, hosts the Italian headquarters of numerous global companies, such as Accenture, AXA, Bank of America, BNP Paribas, Celgene, China Construction Bank, Deutsche Bank, FM Global, Herbalife, Amazon, Iliad, KPMG, Maire Tecnimont, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Panasonic, Pirelli, Ubisoft, Shire, Tata Consultancy Services, Telecom Italia, UniCredit, UnipolSai.

Other large multinational service companies, such as Allianz, Generali, Alleanza Assicurazioni and PricewaterhouseCoopers, have their headquarters in the CityLife business district, a new 900-acre-wide (3.6 km2) development project designed by prominent modernist architects Zaha Hadid, Daniel Liebskind and Arata Isozaki.

The city is home to numerous media and advertising agencies, national newspapers and telecommunication companies, including both the public service broadcaster RAI and private television companies like Mediaset and Sky Italia. In addition, it hosts the headquarters of the largest Italian publishing companies, such as Feltrinelli, Giunti Editore, Messaggerie Italiane, Mondadori, RCS Media Group and Rusconi Libri. Milan has also seen a rapid increase in the presence of IT companies, with both domestic and international companies such as Altavista, Google, Italtel, Lycos, Microsoft,[174] Virgilio and Yahoo! establishing their Italian operations in the city.

Milan is one of the fashion capitals of the world, where the sector can count on 12,000 companies, 800 show rooms and 6,000 sales outlets; the city hosts the headquarters of global fashion houses such as Armani, Dolce & Gabbana, Luxottica, Prada, Versace, Valentino, Zegna and four weeks a year are dedicated to fashion events.[173] The city is also a global hub for event management and trade fairs. Fiera Milano operates the most important trade fair organiser in Italy and the world's fourth-largest[164] exhibition hall in Rho, were international exhibitions like Milan Furniture Fair, EICMA, EMO take place on 400,000 square metres of exhibition areas with more than 4 million visitors in 2018.[175]

Tourism

[edit]

Tourism is an increasingly important part of the city's economy: with 8.81 million registered international arrivals in 2018 (up 9.92% on the previous year), Milan ranked as the world's 15th-most-visited city.[177] One source has 56% of international visitors to Milan are from Europe, 44% of the city's tourists are Italian, and 56% are from abroad.[176] The most important European Union markets are the United Kingdom (16%), Germany (9%) and France (6%).[176] Most of the visitors who come from the United States to the city go on business matters, while Chinese and Japanese tourists mainly take up the leisure segment.[176] Milan is one of the international tourism destinations, appearing among the forty most visited cities in the world, ranking second in Italy after Rome, fifth in Europe and sixteenth in the world.[19][20]

The city boasts several popular tourist attractions, such as the Milan Cathedral and Piazza del Duomo, the Teatro alla Scala, the San Siro Stadium, the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, the Castello Sforzesco, the Pinacoteca di Brera and the Via Montenapoleone. Most tourists visit sights[178] such as Milan Cathedral, the Castello Sforzesco and the Teatro alla Scala; however, other main sights such as the Basilica di Sant'Ambrogio, the Navigli and the Brera district are less visited and prove to be less popular.[179] The city also has numerous hotels, including the ultra-luxurious Town House Galleria, which is the world's first seven-star hotel according to Société Générale de Surveillance (five-star superior luxury according to state law, however) and one of The Leading Hotels of the World.[180]

Culture

[edit]

Museums and art galleries

[edit]

Milan is home to many cultural institutions, museums and art galleries, that account for about a tenth of the national total of visitors and receipts.[181] The Pinacoteca di Brera is one of Milan's most important art galleries. It contains one of the foremost collections of Italian painting, including masterpieces such as the Brera Madonna by Piero della Francesca. The Castello Sforzesco hosts numerous art collections and exhibitions, especially statues, ancient arms and furnitures, as well as the Pinacoteca del Castello Sforzesco, with an art collection including Michelangelo's last sculpture, the Rondanini Pietà, Andrea Mantegna's Trivulzio Madonna and Leonardo da Vinci's Codex Trivulzianus manuscript. The Castello complex also includes The Museum of Ancient Art, The Furniture Museum, The Museum of Musical Instruments and the Applied Arts Collection, The Egyptian and Prehistoric sections of the Archaeological Museum and the Achille Bertarelli Print Collection (Civica Raccolta delle Stampe Bertarelli).

Milan's figurative art flourished in the Middle Ages, and with the Visconti family being major patrons of the arts, the city became an important centre of Gothic art and architecture (Milan Cathedral being the city's most formidable work of Gothic architecture). Leonardo worked in Milan from 1482 until 1499. He was commissioned to paint the Virgin of the Rocks for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception and The Last Supper for the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie.[182]

The city was affected by the Baroque in the 17th and 18th centuries, and hosted numerous formidable artists, architects and painters of that period, such as Caravaggio and Francesco Hayez, which several important works are hosted in Brera Academy. The Museum of Risorgimento is specialised on the history of Italian unification Its collections include iconic paintings like Baldassare Verazzi's Episode from the Five Days and Francesco Hayez's 1840 Portrait of Emperor Ferdinand I of Austria. The Triennale is a design museum and events venue located in Palazzo dell'Arte, in Sempione Park. It hosts exhibitions and events highlighting contemporary Italian design, urban planning, architecture, music and media arts, emphasising the relationship between art and industry.

Milan in the 20th century was the epicentre of the futurist artistic movement. Filippo Marinetti, the founder of Italian Futurism wrote in his 1909 "Manifesto of Futurism" (in Italian, Manifesto Futuristico), that Milan was "grande...tradizionale e futurista" ("grand...traditional and futuristic", in English). Umberto Boccioni was also an important Futurism artist who worked in the city. Today, Milan remains a major international hub of modern and contemporary art, with numerous modern art galleries. The Modern Art Gallery, situated in the Royal Villa, hosts collections of Italian and European painting from the 18th to the early 20th centuries.[183][184][185] The Museo del Novecento, situated in the Palazzo dell'Arengario, is one of the most important art galleries in Italy about 20th-century art; of particular relevance are the sections dedicated to Futurism, Spatialism and Arte povera. In the early 1990s architect David Chipperfield was invited to convert the premises of the former Ansaldo Factory into a Museum. Museo delle Culture (MUDEC) opened in April 2015.[186] The Gallerie di Piazza Scala, a modern and contemporary museum located in Piazza della Scala in the Palazzo Brentani and the Palazzo Anguissola, hosts 195 artworks from the collections of Fondazione Cariplo with a strong representation of nineteenth-century Lombard painters and sculptors, including Antonio Canova and Umberto Boccioni. A new section was opened in the Palazzo della Banca Commerciale Italiana in 2012. Other private ventures dedicated to contemporary art include the exhibiting spaces of the Prada Foundation and HangarBicocca. The Nicola Trussardi Foundation is renewed for organising temporary exhibition in venues around the city. Milan is also home to many public art projects, with a variety of works that range from sculptures to murals to pieces by internationally renowned artists, including Arman, Kengiro Azuma, Francesco Barzaghi, Alberto Burri, Pietro Cascella, Maurizio Cattelan, Leonardo da Vinci, Giorgio de Chirico, Kris Ruhs, Emilio Isgrò, Fausto Melotti, Joan Miró, Carlo Mo, Claes Oldenburg, Igor Mitoraj, Gianfranco Pardi, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Arnaldo Pomodoro, Carlo Ramous, Aldo Rossi, Aligi Sassu, Giuseppe Spagnulo and Domenico Trentacoste.

Music

[edit]

Milan is a major national and international centre of the performing arts, most notably opera. The city hosts La Scala operahouse, considered one of the world's most prestigious,[188] having throughout history witnessed the premieres of numerous operas, such as Nabucco by Giuseppe Verdi in 1842, La Gioconda by Amilcare Ponchielli, Madama Butterfly by Giacomo Puccini in 1904, Turandot by Puccini in 1926, and more recently Teneke, by Fabio Vacchi in 2007. Other major theatres in Milan include the Teatro degli Arcimboldi, Teatro Dal Verme, Teatro Lirico and formerly the Teatro Regio Ducale. The city is also the seat of a renowned symphony orchestra and musical conservatory, and has been, throughout history, a major centre for musical composition: numerous famous composers and musicians such as Gioseppe Caimo, Simon Boyleau, Hoste da Reggio, Verdi, Giulio Gatti-Casazza, Paolo Cherici and Alice Edun lived and worked in Milan. The city is also the birthplace of many modern ensembles and bands, including I Camaleonti, Camerata Mediolanense, Gli Spioni, Dynamis Ensemble, Elio e le Storie Tese, Krisma, Premiata Forneria Marconi, Quartetto Cetra, Stormy Six, Le Vibrazioni and Lacuna Coil.

Fashion and design

[edit]

Milan is widely regarded as a global capital in industrial design, fashion and architecture.[189] In the 1950s and 60s, as the main industrial centre of Italy and one of Europe's most dynamic cities, Milan became a world capital of design and architecture. There was such a revolutionary change that Milan's fashion exports accounted for US$726 million in 1952, and by 1955 that number grew to US$72.5 billion.[190] Modern skyscrapers, such as the Pirelli Tower and the Torre Velasca were built, and artists such as Bruno Munari, Lucio Fontana, Enrico Castellani and Piero Manzoni gathered in the city.[191] Today, Milan is still particularly well known for its high-quality furniture and interior design industry. The city is home to FieraMilano, Europe's largest permanent trade exhibition, and Salone Internazionale del Mobile, one of the most prestigious international furniture and design fairs.[192]

Milan is also regarded as one of the fashion capitals of the world, along with New York City, Paris and London.[193] Milan is synonymous with the Italian prêt-à-porter industry,[194] as many of the most famous Italian fashion brands, such as Valentino, Versace, Prada, Armani and Dolce & Gabbana, are headquartered in the city. Numerous international fashion labels also operate shops in Milan. Furthermore, the city hosts the Milan Fashion Week twice a year, one of the most important events in the international fashion system.[195] Milan's main upscale fashion district, quadrilatero della moda, is home to the city's most prestigious shopping streets (Via Monte Napoleone, Via della Spiga, Via Sant'Andrea, Via Manzoni and Corso Venezia), in addition to Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, one of the world's oldest shopping malls.[196] The term sciura encapsulates the look and culture of fashionable, elderly Milanese women.

Languages and literature

[edit]

In the late 18th century and throughout the 19th, Milan was an important centre for intellectual discussion and literary creativity. The Enlightenment found here a fertile ground. Cesare, Marquis of Beccaria, with his famous Dei delitti e delle pene, and Count Pietro Verri, with the periodical Il Caffè were able to exert a considerable influence over the new middle-class culture.

In the first years of the 19th century, the ideals of the Romantic movement made their impact on the cultural life of the city and its major writers debated the primacy of Classical versus Romantic poetry. Additionally, Giuseppe Parini and Ugo Foscolo published their most important works, and were admired by younger poets as masters of ethics, as well as of literary craftsmanship.

In the third decade of the 19th century, Alessandro Manzoni wrote his novel I Promessi Sposi, considered the manifesto of Italian Romanticism, which found in Milan its centre; in the same period Carlo Porta, reputed the most renowned local vernacular poet, wrote his poems in Lombard Language. The periodical Il Conciliatore published articles by Silvio Pellico, Giovanni Berchet, Ludovico di Breme, who were both Romantic in poetry and patriotic in politics.

After the Unification of Italy in 1861, Milan retained a sort of central position in cultural debates. New ideas and movements from other countries of Europe were accepted and discussed: thus Realism and Naturalism gave birth to prewar Italian movement of Verismo in Southern Italy, its greatest Verista novelist Giovanni Verga formed in Sicily who wrote his most important books in Milan.

In addition to Italian, approximately 2 million people in Northern Italy can speak the Milanese dialect or other Western Lombard variation.[199]

Media

[edit]

Milan is an important national and international media centre. Corriere della Sera, founded in 1876, is one of the oldest Italian newspapers, and it is published by Rizzoli, as well as La Gazzetta dello Sport, a daily dedicated to coverage of various sports and currently considered the most widely read daily newspaper in Italy. Other local dailies are the general broadsheets Il Giorno, Il Giornale, the Catholic newspaper Avvenire, and Il Sole 24 Ore, a daily business newspaper owned by Confindustria (the Italian employers' federation). Free daily newspapers include Leggo and Metro. Milan is also home to many architecture, art and fashion periodicals, including Abitare, Casabella, Domus, Flash Art, Gioia, Grazia and Vogue Italia. Panorama and Oggi, two of Italy's most important weekly news magazines, are also published in Milan.

Several commercial broadcast television networks have their national headquarters in the Milan conurbation, including Mediaset Group (owner of Canale 5, Italia 1, Iris and Rete 4), Telelombardia and MTV Italy. National radio stations based in Milan include Radio Deejay, Radio 105 Network, R101 (Italy), Radio Popolare, RTL 102.5, Radio Capital and Virgin Radio Italia.

Cuisine

[edit]

Like most cities in Italy, Milan has developed its own local culinary tradition, which, as it is typical for North Italian cuisines, uses more frequently rice than pasta, butter than vegetable oil and features almost no tomato or fish. Milanese traditional dishes includes cotoletta alla milanese, a breaded veal (pork and turkey can be used) cutlet pan-fried in butter (similar to Viennese Wiener Schnitzel). Other typical dishes are cassoeula (stewed pork rib chops and sausage with Savoy cabbage), ossobuco (braised veal shank served with a condiment called gremolata), risotto alla milanese (with saffron and beef marrow), busecca (stewed tripe with beans), mondeghili (meatballs made with leftover meat fried in butter) and brasato (stewed beef or pork with wine and potatoes).

Season-related pastries include chiacchiere (flat fritters dusted with sugar) and tortelli (fried spherical cookies) for Carnival, colomba (glazed cake shaped as a dove) for Easter, pane dei morti ("bread of the (Day of the) Dead", cookies flavoured with cinnamon) for All Souls' Day and panettone for Christmas. The salame Milano, a salami with a very fine grain, is widespread throughout Italy. Renowned Milanese cheeses are gorgonzola (from the namesake village nearby), mascarpone, used in pastry-making, taleggio and quartirolo.

The comune of San Colombano al Lambro, located about 40 kilometres (25 mi) south-east of Milan, is home to the Denominazione di origine controllata (DOC) wine which includes 100 hectares (250 acres) producing a single red wine. The finished wine must attain a minimum alcohol level of 11% to be labelled with the San Colombano DOC designation.[200]

Milan is well known for its world-class restaurants and cafés, characterised by innovative cuisine and design.[201] As of 2014[update], Milan has 157 Michelin-selected places, including three 2-Michelin-starred restaurants;[202] these include Cracco, Sadler and il Luogo di Aimo e Nadia.[203] Many historical restaurants and bars are found in the historic centre, the Brera and Navigli districts. One of the city's oldest surviving cafés, Caffè Cova, was established in 1817.[204] In total, Milan has 15 cafés, bars and restaurants registered among the Historical Places of Italy, continuously operating for at least 70 years.[205]

Sport

[edit]

Milan hosted matches at the FIFA World Cup in 1934 and 1990 and the UEFA European Championship in 1980, and more recently held the 2003 World Rowing Championships, the 2009 World Boxing Championships, and some games of the Men's Volleyball World Championship in 2010 and the final games of the Women's Volleyball World Championship in 2014. In 2018, Milan hosted the World Figure Skating Championships. Milan will host the 2026 Winter Olympics as well as the 2026 Winter Paralympics jointly with Cortina d'Ampezzo.

Milan, along with Manchester, is one of only two cities in Europe that is home to two European Cup/Champions League winning teams: Serie A football clubs AC Milan and Inter. They are two of the most successful clubs in the world of football in terms of international trophies. Both teams have also won the FIFA Club World Cup (formerly the Intercontinental Cup). With a combined ten Champions League titles, Milan is only second to Madrid as the city with the most European Cups. Both teams play at the UEFA 5-star-rated Giuseppe Meazza Stadium, more commonly known as the San Siro, that is one of the biggest stadiums in Europe, with a seating capacity of over 80,000.[206] The Meazza Stadium has hosted four European Cup/Champions League finals, most recently in 2016, when Real Madrid defeated Atlético Madrid 5–3 in a penalty shoot-out. A third team, Brera Calcio, plays in Prima Categoria, the seventh tier of Italian football.[207] Another team, Milano City FC (a successor of Bustese Calcio),[208] plays in Serie D, the fourth level.

Milan is one of the host cities of the EuroBasket 2022. There are currently four professional Lega Basket clubs in Milan: Olimpia Milano, Pallacanestro Milano 1958, Società Canottieri Milano and A.S.S.I. Milano. Olimpia is the most decorated basketball club in Italy, having won 27 Italian League championships, six Italian National Cups, one Italian Super Cup, three European Champions Cups, one FIBA Intercontinental Cup, three FIBA Saporta Cups, two FIBA Korać Cups and many junior titles. The team play at the Mediolanum Forum, with a capacity of 12,700, where it has been hosted the final of the 2013–14 Euroleague. In some cases the team also plays at the PalaDesio, with a capacity of 6,700.

Milan is also home to Italy's oldest American football team: Rhinos Milano, who have won five Italian Super Bowls. The team plays at the Velodromo Vigorelli, with a capacity of 8,000. Another American football team that use the same venue is the Seamen Milano, who joined the professional European League of Football in 2023. Milan has also two cricket teams: Milano Fiori, currently competing in the second division, and Kingsgrove Milan, who won the Serie A championship in 2014. Amatori Rugby Milano, the most decorated rugby team in Italy, was founded in Milan in 1927. The Monza Circuit, located near Milan, hosts the Formula One Italian Grand Prix.[209] The circuit is located inside the Royal Villa of Monza park. It is one of the world's oldest car racing circuits. The capacity for the Formula One races is currently over 113,000. It has hosted an Formula One race nearly every year since the first year of competition, with the exception of 1980.

In road cycling, Milan hosts the start of the annual Milan–San Remo classic one-day race and the annual Milano–Torino one day race. Milan is also the traditional finish for the final stage of the Giro d'Italia, which, along with the Tour de France and the Vuelta a España, is one of cycling's three Grand Tours.

Education

[edit]

Milan is a major global centre of higher education teaching and research and has the second-largest concentration of higher education institutes in Italy after Rome. Milan's higher education system includes 7 universities, 48 faculties and 142 departments, with 185,000 university students enrolled in 2011 (approximately 11 percent of the national total)[23] and the largest number of university graduates and postgraduate students (34,000 and more than 5,000, respectively) in Italy.[212]

Universities

[edit]The University of Milan (also known as the "State University") founded in 1924,[213] is the largest public teaching and research university in the city.[214] The University of Milan is the sixth-largest university in Italy, with approximately 60,000 enrolled students and a teaching staff of 2,500.[215] Most relevant academics are in the fields of medicine, law and politics and sustainability. Notable alumni such as former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and Nobel laureates earned their degree at University of Milan.

University of Milano-Bicocca, established in 1998 is the city's newest institution of higher education in science and technology. Built over a once industrial area, today enrolls more than 30,000 students, of which more than 60% are female.[216] As its older parent institute, it is one of the most sought-after location for medical students.[217] It ranks as the 82nd-best young college on over 300 institutions in the 2020 Times Higher Education World University Rankings.[218]

The Polytechnic University of Milan is the city's oldest university, founded in 1863. With over 40,000 students, it is the largest technical university in Italy.[219] According to the QS World University Rankings for the subject area 'Engineering & Technology', it ranked in 2022 as the 13th best in the world.[220] It ranked 6th worldwide for Design, 9th for Civil and Structural Engineering, 9th for Mechanical, Aerospace Engineering and 7th for Architecture.[220] It is the best university in Italy.[210]

Catholic University of the Sacred Heart is the largest private teaching university in Europe[221] and the largest Catholic University in the world with 42,000 enrolled students.[222][223] Agostino Gemelli University Polyclinic serves as the teaching hospital for the medical school of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore and owes its name to the university founder, the Franciscan friar, physician and psychologist Agostino Gemelli.[224]

Bocconi University is a private management and finance university established in 1902, ranking as the best university in Italy in its fields, and as one of the best in the world. In 2020, QS World University Rankings (viewed as one of the three most-widely read university rankings in the world) ranked the university seventh worldwide and third in Europe in business and management studies,[225] as well as first in economics and econometrics outside the US and the UK.[226] Financial Times ranked it the sixth-best business school in Europe in 2018.[227] Bocconi University also ranks as the fifth-best one-year MBA course in the world, according to the Forbes 2017 ranking.[228]

Vita-Salute San Raffaele University is a private teaching medical university linked to the San Raffaele Hospital.[229]