Indie game

| Part of a series on the |

| Video game industry |

|---|

An indie game, short for independent video game, is a video game created by individuals or smaller development teams without the financial and technical support of a large game publisher, in contrast to most "AAA" (triple-A) games. Because of their independence and freedom to develop, indie games often focus on innovation, experimental gameplay, and taking risks not usually afforded in AAA games. Indie games tend to be sold through digital distribution channels rather than at retail due to a lack of publisher support. The term is analogous to independent music or independent film in those respective mediums.

Indie game development bore out from the same concepts of amateur and hobbyist programming that grew with the introduction of the personal computer and the simple BASIC computer language in the 1970s and 1980s. So-called bedroom coders, particularly in the United Kingdom and other parts of Europe, made their own games and used mail order to distribute their products, although they later shifted to other software distribution methods with the onset of the Internet in the 1990s, such as shareware and other file sharing distribution methods. However, by this time, interest in hobbyist programming had waned due to rising costs of development and competition from video game publishers and home consoles.

The modern take on the indie game scene resulted from a combination of numerous factors in the early 2000s, including technical, economic, and social concepts that made indie games less expensive to make and distribute but more visible to larger audiences and offered non-traditional gameplay from the current mainstream games. A number of indie games at that time became success stories that drove more interest in the area. New industry opportunities have arisen since then, including new digital storefronts, crowdfunding, and other indie funding mechanisms to help new teams get their games off the ground. There are also low-cost and open-source development tools available for smaller teams across all gaming platforms, boutique indie game publishers that leave creative freedom to the developers, and industry recognition of indie games alongside mainstream ones at major game award events.

Around 2015, the increasing number of indie games being published led to fears of an "indiepocalypse", referring to an oversupply of games that would make the entire market unprofitable. Although the market did not collapse, discoverability remains an issue for most indie developers, with many games not being financially profitable. Examples of successful indie games include Cave Story, Braid, Super Meat Boy, Terraria, Minecraft, Fez, Hotline Miami, Shovel Knight, the Five Nights at Freddy's series, Undertale, Cuphead, and Among Us.

Definition

[edit]The term "indie game" itself is based on similar terms like independent film and independent music, where the concept is often related to self-publishing and independence from major studios or distributors.[1] However, as with both indie films and music, there is no exact, widely accepted definition of what constitutes an "indie game" besides falling well outside the bounds of triple-A video game development by large publishers and development studios.[2][3][4][5] One simple definition, described by Laura Parker for GameSpot, says "independent video game development is the business of making games without the support of publishers", but this does not cover all situations.[6] Dan Pearce of IGN stated that the only consensus for what constitutes an indie game is a "I know it when I see it"-type assessment, since no single definition can capture what games are broadly considered indie.[7]

Indie games generally share certain common characteristics. One method to define an indie game is the nature of independence, which can either be:[8]

- Financial independence: In such situations, the developers have paid for the development and/or publication of the game themselves or from other funding sources such as crowd funding, and specifically without financial support of a large publisher.

- Independence of thought: In this case, the developers crafted their game without any oversight or directional influence by a third party such as a publisher.

Another means to evaluate a game as indie is to examine its development team, with indie games being developed by individuals, small teams, or small independent companies that are often specifically formed for the development of one specific game.[3][9][10] Typically, indie games are smaller than mainstream titles.[10] Indie game developers are generally not financially backed by video game publishers, who are risk-averse and prefer "big-budget games".[11] Instead, indie game developers usually have smaller budgets, usually sourcing from personal funds or via crowdfunding.[2][3][5][12][13] Being independent, developers do not have controlling interests[4] or creative limitations,[3][14][5] and do not require the approval of a publisher,[2] as mainstream game developers usually do.[15] Design decisions are thus also not limited by an allocated budget.[14] Furthermore, smaller team sizes increase individual involvement.[16]

However, this view is not all-encompassing, as there are numerous cases of games where development is not independent of a major publisher but still considered indie.[1] Some notable instances of games include:

- Journey was created by thatgamecompany, but had financial backing of Sony as well as publishing support. Kellee Santiago of thatgamecompany believes that they are an independent studio because they were able to innovate on their game without Sony's involvement.[1]

- Bastion, similarly, was developed by Supergiant Games, but with publishing by Warner Bros. Entertainment, primarily to avoid difficulties with the certification process on Xbox Live.[17] Greg Kasavin of Supergiant notes they consider their studio indie as they lack any parent company.[1][18]

- The Witness was developed by Jonathan Blow and his studio Thekla, Inc. Though self-funded and published, the game's development cost around $6 million and was priced at $40, in contrast to most indie games typically priced up to $20. Blow believed this type of game represented something between indie and AAA publishing.[19]

- No Man's Sky was developed by Hello Games, though with publishing but non-financial support from Sony; the game on release had a price equal to a typical AAA title. Sean Murray of Hello Games believes that because they are still a small team and the game is highly experimental that they consider themselves indie.[20]

- Dave the Diver was developed by Mintrocket, a thirty-person studio owned by Nexon. Despite this corporate ownership, and the studio itself stating they do not consider themselves as an indie studio, the game's approach was considered less traditional as to be considered an indie game by the industry, including being nominated for Best Indie Game at The Game Awards 2023.[21][22][23][24][25]

Yet another angle to evaluate a game as indie is from its innovation, creativity, and artistic experimentation, factors enabled by small teams free of financial and creative oversight. This definition is reflective of an "indie spirit" that is diametrically opposite of the corporate culture of AAA development, and makes a game "indie", where the factors of financial and creative independence make a game "independent".[26][2][10][16][27][28][29][30] Developers with limited ability to create graphics can rely on gameplay innovation.[31] This often leads to indie games having a retro style of the 8-bit and 16-bit generations, with simpler graphics atop the more complex mechanics.[26] Indie games may fall into classic game genres, but new gameplay innovations have been seen.[28] However, being "indie" does not imply that the game focuses on innovation.[10][32] In fact, many games with the "indie" label can be of poor quality and may not be made for profit.[5]

Jesper Juul, an associate professor at The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts that has studied the video game market, wrote in his book Handmade Pixels that the definition of an indie game is vague, and depends on different subjective considerations. Juul classified three ways games can be considered indie: those that are financially independent of large publishers, those that are aesthetically independent of and significantly different from the mainstream art and visual styles used in AAA games, and those that present cultural ideas that are independent from mainstream games. Juul however wrote that ultimately the labeling of a game as "indie" still can be highly subjective and no single rule helps delineate indie games from non-indie ones.[33]

Games that are not as large as most triple-A games, but are developed by larger independent studios with or without publisher backing and that can apply triple-A design principles and polish due to the experience of the team, have sometimes been called "triple-I" games, reflecting the middle ground between these extremes. Ninja Theory's Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice is considered a prime example of a triple-I game.[34][35] A further distinction from indie games are those considered double-A ("AA"), tending to be from mid to large-size studios ranging from 50 to 100 team members and larger than typically associated with indie games, that often work under similar practices as triple-A studios but still retain creative control of their titles from a publisher.[7][36]

Indie games are distinct from open source games. The latter are games which are developed with the intent to release the source code and other assets under an open source license. While many of the same principles used to develop open source games are the same as for indie games, open source games are not developed for commercial gain and instead as a hobbyist pursuit.[37] However, commercial sales are not a requirement for an indie game and such games can be offered as freeware, most notably with Spelunky on its original release and Dwarf Fortress, with the exception of its enhanced visual front-end version while its base version remains free.[38]

History

[edit]The onset of indie game development is difficult to track due to the broadness of what defines an indie game, and the term was not really in use until the early 2000s.[39] Until the 2000s, other terms like amateur, enthusiast, and hobbyist software or games were used to describe such software.[40] Today, terms like amateur and hobbyist development are more reflective of those that create mods for existing games,[41] or work with specific technologies or game parts rather than the development of full games.[4] Such hobbyists usually produce non-commercial products and may range from novices to industry veterans.[4]

Before home computers

[edit]There is some debate as to whether independent game development started prior to the 1977 home computer revolution with games developed for mainframe computers at universities and other large institutions. 1962's Spacewar! was not commercially financed and was made by a small team, but there was no commercial sector of the video game industry at that time to distinguish from independent works.[42]

Joyce Weisbecker, who considers herself the first indie designer, created several games for the RCA Studio II home console in 1976 as an independent contractor for RCA.[43]

Home computers (late 1970s-1980s)

[edit]When the first personal computers were released in 1977, they each included a pre-installed version of the BASIC computer language along with example programs, including games, to show what users could do with these systems. The availability of BASIC led to people trying to make their own programs. Sales of the 1978 rerelease of the book BASIC Computer Games by David H. Ahl that included the source code for over one hundred games, eventually surpassed over one million copies.[44] The availability of BASIC inspired a number of people to start writing their own games.[3][30]

Many personal computer games written by individuals or two person teams were self-distributed in stores or sold through mail order.[39] Atari, Inc. launched the Atari Program Exchange in 1981 to publish user-written software, including games, for Atari 8-bit computers.[45] Print magazines such as SoftSide, Compute!, and Antic solicited games from hobbyists, written in BASIC or assembly language, to publish as type-in listings.

In the United Kingdom, early microcomputers such as the ZX Spectrum were popular, launching a range of "bedroom coders" which initiated the UK's video game industry.[46][47] During this period, the idea that indie games could provide experimental gameplay concepts or demonstrate niche arthouse appeal had been established.[42] Many games from the bedroom coders of the United Kingdom, such as Manic Miner (1983), incorporated the quirkiness of British humour and made them highly experimental games.[48][49] Other games like Alien Garden (1982) showed highly-experimental gameplay.[42] Infocom itself advertised its text-based interactive fiction games by emphasizing their lack of graphics in lieu of the players' imagination, at a time that graphics-heavy action games were commonplace.[42]

Shareware and chasing the console (1990s)

[edit]By the mid-1990s, the recognition of the personal computer as a viable gaming option, and advances in technology that led to 3D gaming created many commercial opportunities for video games. During the last part of the 1990s, visibility of games from these single or small team studios scene waned, since a small team could not readily compete in costs, speed and distribution as a commercial entity could. The industry had started to coalesce around video game publishers that could pay larger developers to make games and handle all the marketing and publication costs as well as opportunities to franchise game series.[47] Publishers tended to be risk averse due to high costs of production, and they would reject all small-size and too innovative concepts of small game developers.[50] The market also became fractured due to the prevalence of video game consoles, which required expensive or difficult-to-acquire game development kits typically reserved for larger developers and publishers.[30][51][42]

There were still significant developments from smaller teams that laid the basis of indie games going forward. Shareware games became a popular means to distribute demos or partially complete games in the 1980s and into the 1990s, where players could purchase the full game from the vendor after trying it. As such demos were generally free to distribute, shareware demo compilations would frequently be included in gaming magazines at that time, providing an easy means for amateur and hobbyist developers to be recognized. The ability to produce numerous copies of games, even if just shareware/demo versions, at a low cost helped to propel the idea as the PC as a gaming platform.[30][39] At the time, shareware was generally associated with hobbyist programmers, but the releases of Wolfenstein 3D in 1992 and Doom in 1993 showed the shareware route to be a viable platform for titles from mainstream developers.[42]

Rise of indie games from digital distribution (2000−2005)

[edit]

The current, common understanding of indie games on personal computer took shape in the early 2000s from several factors. Key was the availability of online distribution over the Internet, allowing game developers to sell directly to players and bypassing limitations of retail distribution and the need for a publisher.[52][39] Software technologies used to drive the growth of the World Wide Web, like Adobe Flash, were available at low cost to developers, and provided another means for indie games to grow.[31][39][53] The new interest in indie games led to middleware and game engine developers to offer their products at low or no cost for indie development,[39] in addition to open source libraries and engines.[54] Dedicated software like GameMaker Studio and tools for unified game engines like Unity and Unreal Engine removed much of the programming barriers needed for a prospective indie developer to create these games.[39] The commercial possibilities for indie games at this point helped to distinguish these games from any prior amateur game.[40]

There were other shifts in the commercial environment that were seen as drivers for the rise of indie games in the 2000s. Many of the games to be indie games of this period were considered to be the antithesis of mainstream games and which highlighted the independence of how these games were made compared to the collective of mainstream titles. Many of them took a retro-style approach to their design, art, or other factors in development, such as Cave Story in 2004, which proved popular with players.[40][55] Social and political changes also led to the use of indie games not only for entertainment purposes but to also tell a message related to these factors, something that could not be done in mainstream titles.[40] In comparing indie games to independent film and the state of their respective industries, the indie game's rise was occurring approximately at the same relative time as its market was starting to grow exponentially and be seen as a supporting offshoot of the mainstream works.[40]

Shifting industry and increased visibility (2005−2014)

[edit]

Indie games saw a large boost in visibility within the video game industry and the rest of the world starting around 2005. A key driver was the transition into new digital distribution methods with storefronts like Steam that offered indie games alongside traditional AAA titles, as well as specialized storefronts for indie games. While direct online distribution helped indie games to reach players, these storefronts allowed developers to publish, update, and advertise their games directly, and players to download the games anywhere, with the storefront otherwise handling the distribution and sales factors.[41][31][3][28][30] While Steam itself initially began heavy curation, it eventually allowed for indie publishing with its Steam Greenlight and Steam Direct programs, vastly increasing the number of games available.[39]

Further indie game growth in this period came from the departure of large publishers like Electronic Arts and Activision from their smaller, one-off titles to focus on their larger, more successful properties, leaving the indie game space to provide shorter and more experimental titles as alternatives.[56] Costs of developing AAA games had risen greatly, to an average cost of tens of millions of dollars in 2007–2008 per title, and there was little room for risks in gameplay experimentation.[57] Another driver came from discussions related to whether video games could be seen as an art form; movie critic Roger Ebert postulated in open debates that video games could not be art in 2005 and 2006, leading to developers creating indie games to specifically challenge that notion.[58]

Indie video game development saw a further boost by the use of crowdfunding as a means for indie developers to raise funds to produce a game and to determine the desire for a game, rather than risk time and investment into a game that does not sell well. While video games had used crowdfunding prior to 2012, several large indie game-related projects successfully raised millions of dollars through Kickstarter, and since then, several other similar crowdfunding options for game developers have become available. Crowdfunding eliminated some of the cost risk associated with indie game development, and created more opportunities for indie developers to take chances on new titles.[39] With more indie titles emerging during this period, larger publishers and the industry as a whole started taking notice of indie games as a significant movement within the field. One of the first examples of this was World of Goo (2008), whose developers 2D Boy had tried but failed to gain any publisher support prior to release. On release, the game was recognized at various award events including the Independent Games Festival, leading to publishers that had previously rejected World of Goo to offer to publish it.[59]

Console manufacturers also helped increase recognition of indie games in this period. By the seventh generation of consoles in 2005, each platform provided online services for players–namely Xbox Live, PlayStation Network, and Nintendo Wi-Fi Connection–which included digital game distribution. Following the increased popularity of indie games on computers, these services started publishing them alongside larger releases.[3][29] The Xbox 360 had launched in 2005 with Xbox Live Arcade (XBLA), a service that included some indie games, though these drew little attention in the first few years. In 2008, Microsoft ran its "XBLA Summer of Arcade" promotion, which included the releases of indie games Braid, Castle Crashers, and Geometry Wars: Retro Evolved 2 alongside two AAA games. While all three indie games had a high number of downloads, Braid received critical acclaim and drew mainstream media recognition for being a game developed by two people.[60][61] Microsoft continued to follow up on this promotion in the following years, bringing in more games onto XBLA such as Super Meat Boy, Limbo, and Fez.[62][63] Sony and Nintendo followed suit, encouraging indie developers to bring games onto their platforms.[60] By 2013, all three console manufacturers had established programs that allowed indie developers to apply for low-cost development toolkits and licenses to publish directly onto the console's respective storefronts following approval processes.[60] A number of "boutique" indie game publishers were founded in this period to support funding, technical support, and publishing of indie games across various digital and retail platforms.[64][65] In 2012, Journey became the first Indie game to win the Game Developers Choice Award for Game of the Year and D.I.C.E. Award for Game of the Year.[66][67]

Several other indie games were released during this period to critical and/or commercial success.[68] Minecraft (2011), the best-selling video game of all time as of 2024,[69] was originally released as an indie game[70] before its developer Mojang Studios was acquired by Microsoft in 2014 and brought into Xbox Game Studios.[71] Another indie game, Terraria, was released that same year and has become the eighth best selling video game of all time,[72] as well the highest rated game on Steam as of 2022.[73] Other successful indie games released during this time include Hotline Miami (2012),[74] Shovel Knight (2014),[75] and Five Nights at Freddy's (2014).[76] Hotline Miami inspired many to begin developing games[77] and contributed to the rise in indie game released during this time period,[78] while Shovel Knight and Five Nights at Freddy's spawned successful media franchises, with the latter becoming a cultural phenomenon.[76][79] Mobile games also became popular with indie developers, with inexpensive development tools and low-barrier storefronts with the App Store and Google Play opening in the late 2000s.[80] In 2012, a documentary, Indie Game: The Movie, was created that covers several successful games from this period.[68]

Fears regarding saturation and discoverability (2015−present)

[edit]

Leading into 2015, there was concern that the rise of easy-to-use tools to create and distribute video games could lead to an oversupply of video games, which was termed the "indiepocalypse".[84] This perception of an indiepocalypse is not unanimous; Jeff Vogel stated in a talk at GDC 2016 that any downturn was just part of the standard business cycle. The size of the indie game market was estimated in March 2016 to be at least $1 billion per year for just those games offered through Steam.[85] Mike Wilson, Graeme Struthers and Harry Miller, the co-founders of indie publisher Devolver Digital, stated in April 2016 that the market in indie games is more competitive than ever but continues to appear healthy with no signs of faltering.[86] Gamasutra said that by the end of 2016, while there had not be any type of catastrophic collapse of the indie game market, there were signs that the growth of the market had significantly slowed and that it has entered a "post-indiepocalypse" phase as business models related to indie games adjust to these new market conditions.[87]

While there has not been any type of collapse of the indie game field since 2015, there are concerns that the market is far too large for many developers to get noticed. Very few selected indie titles get wide coverage in the media, and are typically referred to as "indie darlings". In some cases, indie darlings are identified through consumer reactions that praise the game rather than direct industry influence, leading to further coverage; examples of such games include Celeste and Untitled Goose Game.[88] However, there are also times where the video game media may see a future title as a success and position it as an indie darling before its release, only to have the game fail to make a strong impression on players, such as in the case of No Man's Sky and Where the Water Tastes Like Wine.[88][89]

Discoverability has become an issue for indie developers as well. With the Steam distribution service allowing any developer to offer their game with minimal cost to them, there are thousands of games being added each year, and developers have come to rely heavily on Steam's discovery tools – methods to tailor catalog pages to customers based on past purchases – to help sell their titles.[90] Mobile app stores have had similar problems with large volumes of offers but poor means for discovery by consumers in the late 2010s.[80] Several indie developers have found it critical to have a good public relations campaign across social media and to interact with the press to make sure a game is noticed early on in its development cycle to get interest and maintain that interest through release, which adds to costs of development.[91][92]

Several games during this time have still seen success, including games that were referred to as "indie darlings."[88] Some of the most popular indie games from this time were primarily popularized over social media and spawned cultural phenomena, such as Undertale (2015) and Among Us (2018),[93][9] with the later being one of the most popular games during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021 with half a billion players.[9] A similar example is Lethal Company, which released in 2023 and was popularized through internet culture, becoming one of the most played games of 2023.[8] More commercially successful games from this time include Stardew Valley,[6] Hollow Knight,[94] and Cuphead.[95]

Other regions

[edit]Indie games are generally associated with Western regions, specifically with North American, European, and Oceanic areas. However, other countries have had similar expansions of indie games that have intersected with the global industry.

Japanese doujin soft

[edit]In Japan, the doujin soft community has generally been treated as a hobbyist activity up through the 2010s. Computers and bedroom coding had taken off similarly in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but the computer market was quickly overwhelmed by consoles. Still, hobbyist programmers continued to develop games. One area that Japan had focused on were game development kits, specialized software that would allow users to create their own games. A key line of these were produced by ASCII Corporation, which published ASCII, a hobbyist programming magazine that users could share their programs with. Over time, ASCII saw the opportunity to publish game development kits, and by 1992, released the first commercial version of the RPG Maker software. While the software cost money to obtain, users could release completed games with it as freeware or commercial products, which established the potential for a commercial independent games market by the early 2000s, aligning with the popularity of indie games in the West.[96]

Like other Japanese fan-created works in other media, doujin games were often built from existing assets and did not receive much respect or interest from consumers, and instead were generally made to be played and shared with other interested players and at conventions. Around 2013, market forces began to shift with the popularity of indie games in the Western regions, bringing more interest to doujin games as legitimate titles. The Tokyo Game Show first offered a special area for doujin games in 2013 with support from Sony Interactive Entertainment who had been a promoter of Western indie games in prior years, and has expanded that since.[97] The distinction between Japanese-developed doujin games and indie games is ambiguous - the use of the term usually refers to if their popularity formed in Western or Eastern markets before the mid-2010s, and if they are made with the aim of selling large copies or just as a passion project; the long-running bullet hell Touhou Project series, developed entirely by one-man independent developer ZUN since 1995, has been called both indie and doujinshi.[98][99] Meanwhile, despite being Japanese-developed, Cave Story is primarily referred to as an "indie game" because of its success in the Western market. It is one of the most influential indie games, also contributing to the resurgence of the Metroidvania genre.[100][101][102] Doujin games also got a strong interest in Western markets after some English-speaking groups translated various titles with permission for English release, most notably with Recettear: An Item Shop's Tale, the first such doujin to be published on Steam in 2010.[103][104]

Mikhail Fiadotau, a lecturer in video game studies at Tallinn University, identified three primary distinctions between the established doujin culture and the Western idea of indie games. From a conceptual view, indie games generally promote independence and novelty in thought, while doujin games tend to be ideas shared by a common group of people and tend to not veer from established concepts (such as strong favoritism towards the well-established RPG genre). From a genealogical standpoint, the nature of doujin dates back as far as the 19th century, while the indie phenomena is relatively new. Finally, only until recently, doujin games tended to only be talked about in the same circles as other doujin culture (fan artwork and writing) and rarely mixed with commercial productions, whereas indie games have shared the same stage with AAA games.[105][106]

Development

[edit]Many of the same basic concepts behind video game development for mainstream titles also apply to indie game development, particularly around the software development aspects. Key differences lie in how the development of the game ties in with the publisher or lack thereof.

Development teams

[edit]

There is no definitive size for how big an independent game development studio might be. Several successful indie games, such as the Touhou Project series, Axiom Verge, Cave Story, Papers, Please, and Spelunky, were developed by a single person, though often with support of artists and musicians for those assets.[107] More common are small teams of developers, from two to a few dozen, with additional support from external artists. While it is possible for development teams to be larger, with this comes a higher cost overhead of running the studio, which may be risky if the game does not perform well.[108]

Indie teams can arise from many different directions. One common path recently includes student projects, developed as prototypes as part of their coursework, which the students then take into a commercial opportunity after graduating from school. Examples of such games are And Yet It Moves,[109] Octodad: Dadliest Catch,[110] Risk of Rain,[111] and Outer Wilds.[112] In some cases, students may drop out of school to pursue the commercial opportunity or for other reasons; Vlambeer's founders, for example, had started to develop a commercial game while still in school and dropped out when the school demanded rights to the game.[113]

Another route for indie development teams comes from experienced developers in the industry who either voluntarily leave to pursue indie projects, typically due to creative burnout from the corporate process, or resulting from termination from the company. Examples of games from such groups include FTL: Faster Than Light,[114] Papers, Please,[115] Darkest Dungeon,[116] and Gone Home.[117]

Yet another route is simply those with little to no experience in the games industry, although they may have computer-programming skills and experience, and they may come in with ideas and fresh perspectives for games, with ideas that are generally more personable and close to their hearts. These developers are usually self-taught and thus may not have certain disciplines of typical programmers, thereby allowing for more creative freedom and new ideas.[118] However, some may see amateur work less favorably than those that have had experience, whether from school or from the industry, relying on game development toolkits rather than programming languages, and they may associate such titles as amateur or hobbyist.[119] Some such amateur-developed games have found great success. Examples of these include Braid,[120] Super Meat Boy,[121] Dwarf Fortress,[122] and Undertale.[123]

Typically, a starting indie-game studio will be primarily programmers and developers. Art assets including artwork and music may be outsourced to work-for-hire artists and composers.[124]

Development tools

[edit]For development of personal computer games, indie games typically rely on existing game engines, middleware and game development kits to build their titles, lacking the resources to build custom engines.[26] Common game engines include Unreal Engine and Unity, but there are numerous others as well. Small studios that do not anticipate large sales are generally afforded reduced prices for mainstream game engines and middleware. These products may be offered free, or be offered at a substantial royalty discount that only increases if their sales exceed certain numbers.[125] Indie developers may also use open source software (such as Godot) or by taking advantage of homebrew libraries, which are freely available but may lack technically-advanced features compared to equivalent commercial engines.[126][127][128]

Prior to 2010, development of indie games on consoles was highly restrictive due to costly access to software development kits (SDKs), typically a version of the console with added debugging features that would cost several thousands of dollars and come with numerous restrictions on its use to prevent trade secrets related to the console from being leaked. Console manufacturers may have also restricted sales of SDKs to only certain developers that met specific criteria, leaving potential indie developers unable to acquire them.[129] When indie games became more popular by 2010, the console manufacturers as well as mobile device operating system providers released special software-based SDKs to build and test games first on personal computers and then on these consoles or mobile devices. These SDKs were still offered at commercial rates to larger developers, but reduced pricing was provided to those who would generally self-publish via digital distribution on the console or mobile device's storefront, such as with the ID@Xbox program or the iOS SDK.

Publishers

[edit]While most indie games lack a publisher with the developer serving in that role, a number of publishers geared towards indie games have been established since 2010, also known as boutique game publishers; these include Raw Fury, Devolver Digital, Annapurna Interactive, Finji, and Adult Swim Games. There also have been a number of indie developers that have grown large enough on their own to also support publishing for smaller developers, such as Chucklefish, Coffee Stain Studios, and Team17. These boutique publishers, having experience in making indie games themselves, typically will provide necessary financial support and marketing but have little to no creative control on developers' product as to maintain the "indie" nature of the game. In some cases, the publisher may be more selective of the type of games it supports; Annapurna Interactive sought games that were "personal, emotional and original".[64][130]

Funding

[edit]The lack of a publisher requires an indie developer to find means to fund the game themselves. Existing studios may be able to rely on past funds and incoming revenue, but new studios may need to use their own personal funds ("bootstrapping"), personal or bank loans, or investments to cover development costs,[13][130][131] or building community support while in development.[132][133]

More recently, crowd-funding campaigns, both reward-based and equity-based, have been used to obtain the funds from interested consumers before development begins in earnest. While using crowd-funding for video games took off in 2012, its practice has significantly waned as consumers became wary of campaigns that failed to deliver on promised goods. A successful crowd-funded campaign now typically requires significant development work and costs associated with this before the campaign is launched, in order to demonstrate that the game will likely be completed in a timely manner and draw in funds.[134]

Another mechanism offered through digital distribution is the early access model, in which interested players can buy playable beta versions of the game to provide software testing and gameplay feedback. Those consumers become entitled to the full game for free on release, while others may have to pay a higher price for the final game. This can provide funding midway though development, but like with crowd-funding, consumers expect a game that is near completion, so significant development and costs will likely need to have been invested already.[135] Minecraft was considered an indie game during its original development, and was one of the first titles to successfully demonstrate this approach to funding.[136]

More recently, a number of dedicated investor-based indie game funds have been established such as the Indie Fund. Indie developers can submit applications requesting grants from these funds. The money is typically provided as a seed investment to be repaid through game royalties.[133] Several national governments, through their public arts agencies, also have made similar grants available to indie developers.[137]

Distribution

[edit]Prior to digital distribution, hobbyist programmers typically relied on mail order to distribute their product. They would place ads in local papers or hobbyist computer magazines such as Creative Computing and Byte and, once payment was received, fulfill orders by hand, making copies of their game to cassette tape, floppy disc, or CD-ROM along with documentation. Others would provide copies to their local computer store to sell. In the United Kingdom, where personal computer game development took off in the early 1980s, a market developed for game distributors that handled the copying and distribution of games for these hobbyist programmers.[48] In Japan, doujinshi conventions like Comiket, the largest fan convention in the world, have allowed independent developers to sell and promote their physical products since its inauguration in 1975, allowing game series like Touhou Project and Fate to spread in popularity and dominate the convention for years.[138][139][140]

As the media shifted to higher-capacity formats and with the ability for users to make their own copies of programs, the simple mail order method was threatened since one person could buy the game and then make copies for their friends. The shareware model of distribution emerged in the 1980s accepting that users would likely make copies freely and share these around. The shareware version of the software would be limited, and require payment to the developer to unlock the remaining features. This approach became popular with hobbyist games in the early 1990s, notably with the releases of Wolfenstein 3D and ZZT, "indie" games from fledgling developers id Software and Tim Sweeney (later founder of Epic Games), respectively. Game magazines started to include shareware games on pack-in demo discs with each issue, and as with mail-order, companies arose that provided shareware sampler discs and served to help with shareware payment and redemption processing. Shareware remained a popular form of distribution even with availability of bulletin board systems and the Internet.[141] By the 2000s, indie developers relied on the Internet as their primary distribution means as without a publisher, it was nearly impossible to stock an indie game at retail, the mail order concept having long since died out.[41]

Continued Internet growth led to dedicated video game sites that served as repositories for shareware and other games, indie and mainstream alike, such as GameSpy's FilePlanet.[142] A new issue had arisen for larger mainstream games that featured multiplayer elements, in that updates and patches could easily be distributed through these sites but making sure all users were equally informed of the updates was difficult, and without the updates, some players would be unable to participate in multiplayer modes. Valve built the Steam software client originally to serve these updates automatically for their games, but over time, it became a digital storefront that users could also purchase games through.[143] For indie games, Steam started curating third-party titles (including some indies) onto the service by 2005, later adding Steam Greenlight in 2012 that allowed any developer to propose their game for addition onto the service to the userbase, and ultimately replacing Greenlight with Steam Direct in 2017 where any developer can add their game to the service for a small fee.

While Steam remains the largest digital storefront for personal computer distribution, a number of other storefronts have since opened. For example, Itch.io, established in 2013, has been more focused on serving indie games over mainstream ones, providing the developers with store pages and other tools to help with marketing. Other services act more as digital retailers, giving tools to the indie developer to be able to accept and redeem online purchases and distribute the game, such as Humble Bundle, but otherwise leaving the marketing to the developer.[144]

On consoles, the distribution of an indie game is handled by the console's game store, once the developer has been approved by the console manufacturer. Similarly, for mobile games, the distribution of the game is handled by the app store provider once the developer has been approved to release apps on that type of device. In either case, all aspects of payment, redemption and distribution are handled at the manufacturer/app store provider level.[145]

A recent trend for some of the more popular indies is a limited physical release, typical for console-based versions. The distributor Limited Run Games was formed to produce limited runs of games, most commonly successful indie titles that have a proven following that would have a market for a physical edition. These versions are typically produced as special editions with additional physical products like art books, stickers, and other small items in the game's case. Other such distributors include Super Rare Games, Special Reserve Games, and Strictly Limited Games.

In nearly all cases with digital distribution, the distribution platform takes a revenue cut of each sale with the rest of the sale going to the developer, as a means to pay for the costs of maintaining the digital storefront.

Industry

[edit]Most indie games do not make a significant profit, and only a handful have made large profits.[146] Instead, indie games are generally seen as a career stepping stone rather than a commercial opportunity.[52] The Dunning–Kruger effect has been shown to apply to indie games: some people with little experience have been able to develop successful games from the start, but for most, it takes upwards of ten years of experience within the industry before one regularly starts making games with financial success. Most in the industry caution that indie games should not be seen a financially-rewarding career for this reason.[147]

The industry perception towards indie games have also shifted, making the tactics of how to develop and market indie games difficult in contrast to AAA games. In 2008, a developer could earn around 17% of a game's retail price, and around 85% if sold digitally.[31] This can lead to the appearance of more "risky" creative projects.[31] Furthermore, the expansion of social websites has introduced gaming to casual gamers.[3] Recent years have brought the importance of drawing social media influencers to help promote indie games as well.[148]

There is contention as to how prominent indie video game development is in the video game industry.[27] Most games are not widely known or successful, and mainstream media attention remains with mainstream titles.[149][3] This can be attributed to a lack of marketing for indie games,[149] but indie games can be targeted at niche markets.[10][30]

Industry recognition of indie games through awards has grown significantly over time. The Independent Games Festival was established in 1998 to recognize the best of indie games, and since its first event in 1999 has been held in conjunction with the Game Developers Conference in the first part of each year alongside the Game Developers Choice Awards (GDCA).[150] However, it was not until 2010 when indie games were seen as similar competition to major gaming awards, with the 2010 GDCA recognizing games like Limbo, Minecraft, and Super Meat Boy among AAA titles.[151] Since then, indie games have frequently been included in award nominations alongside AAA games in the major awards events like the GDCA, the D.I.C.E. Awards, The Game Awards, and the BAFTA Video Games Awards. Indie games like What Remains of Edith Finch, Outer Wilds, Untitled Goose Game, Hades, Inscryption, and Vampire Survivors have been awarded various Game of the Year awards.[152][153][154][155][156][157]

Community

[edit]

Indie developers are generally considered a highly collaborative community with development teams sharing knowledge between each other, providing testing, technical support, and feedback, as generally indie developers are not in any direct competition with each other once they have achieved funding for their project. Indie developers also tend to be open with their target player community, using beta testing and early access to get feedback, and engaging users regularly through storefront pages and communication channels such as Discord.[158]

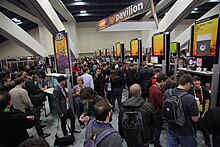

Indie game developers can be involved with various indie game trade shows, such as Independent Games Festival, held alongside the Game Developers Conference, and IndieCade held prior to the annual E3 convention.[2][159] The Indie Megabooth was established in 2012 as a large showcase at various trade shows to allow indie developers to show off their titles. These events act as intermediaries between indie developers and the larger industry, as they allow for indie developers to connect with larger developers and publishers for business opportunities, as well as to get word of their games out to the press prior to release.[160]

Game jams, including Ludum Dare, the Indie Game Jam, the Nordic Game Jam, and the Global Game Jam, are typically annual competitions in which game developers are given a theme, concept and/or specific requirements and given a limited amount of time, on the order of a few days, to come up with a game prototype to submit for review and voting by judges, with the potential to win small cash prizes.[161][162][163][164] Companies can also have internal game jams as a means to relieve stress which may generate ideas for future games, as has notably been the case for developer Double Fine and its Amnesia Fortnight game jams. The structure of such jams can influence whether the end games are more experimental or serious, and whether they are to be more playful or more expressive.[165] While many game jam prototypes go no further, some developers have subsequently expanded the prototype into a full release after the game jam into successful indie games, such as Superhot, Super Time Force, Gods Will Be Watching, Hollow Knight, Surgeon Simulator, and Goat Simulator.[166]

Impact and popularity

[edit]Indie games are recognized for helping to generate or revitalize video game genres, either bringing new ideas to stagnant gameplay concepts or creating whole new experiences. The expansion of roguelikes from ASCII, tile-based hack-and-slash games to a wide variety of so-called "rogue-lites" that maintain the roguelike procedural generation and permadeath features bore out directly from indie games Strange Adventures in Infinite Space (2002) and its sequel Weird Worlds: Return to Infinite Space (2005), Spelunky (2008), The Binding of Isaac (2011), FTL: Faster Than Light (2012) and Rogue Legacy (2012).[167] In turn, new takes on the roguelike genre were inspired by Slay the Spire (2019), which popularized the roguelike deck-building game,[168] and Vampire Survivors (2022), which led to numerous "bullet heaven" or reverse bullet hell games using roguelike mechanics.[169] Metroidvanias resurged following the releases of Cave Story (2004) and Shadow Complex (2009).[102] Stardew Valley (2016) created a resurgence in life simulation games.[170] Art games have gained attention through indie developers with early indie titles such as Samorost (2003)[171] and The Endless Forest (2005).[172]

The following table lists indie games that have reported total sales over one million copies, based on the last reported sales figures. These results exclude downloaded copies for games that had transitioned to a free-to-play model such as Rocket League, or copies sold after acquisition by a larger publisher and no longer being considered an indie game, such as Minecraft.

| Игра |

|

Выпускать | Разработчик | Издатель | Примечания |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Шахтерское ремесло | 60 | 2011 | Можанг | Можанг | К октябрю 2014 года Microsoft приобрела Mojang. [ 173 ] С тех пор Minecraft продал более 200 миллионов экземпляров к маю 2020 года. [ 174 ] |

| Террария | 58.7 | 2011 | Повторная логика | Re-Logic, 505 игр | По состоянию на июль 2024 г. [ 175 ] [ 176 ] |

| ЧЕЛОВЕК: Перепасть | 30 | 2016 | Без тормозных игр | Кривая цифровое | По состоянию на июль 2021 г. [ 177 ] |

| Стартовая долина | 30 | 2016 | Группа | Обеспокоенный , смех | По состоянию на февраль 2024 года [ 178 ] |

| Check Crashers | 20 | 2008 | Бегемот | Бегемот | По состоянию на август 2019 года [ 179 ] |

| Мод Гарри | 20 | 2006 | Facepunch Studios | Клапан | По состоянию на сентябрь 2021 года [ 180 ] |

| Симулятор силовой промывки | 12 | 2022 | Фантастический | Square Enix Collective | По состоянию на апрель 2024 года [ 181 ] |

| Падшие ребята | 11 | 2020 | Mediatonic | Вернуть цифровой | По состоянию на декабрь 2020 года. Включает только продажи на персональных компьютерах, а не на консолях, [ 182 ] и до его приобретения Epic Games и преобразования игры в бесплатный титул в июне 2022 года. [ 183 ] |

| Ракетная лига | 10.5 | 2015 | Psyonix | Psyonix | По состоянию на апрель 2017 года и не включает бесплатные копии, предоставленные в рамках ранней PlayStation Plus . В 2019 году Psyonix был приобретен Epic Games , а в 2020 году игра перешла, чтобы бесплатно играть . [ 184 ] |

| Валхейм | 10 | 2021 | Студии Железных Ворот | Кофейное пятно издательство | По состоянию на апрель 2022 года, все еще в раннем доступе [ 185 ] |

| Ржавчина | 9 | 2018 | Facepunch Studios | Facepunch Studios | По состоянию на декабрь 2019 года [ 186 ] |

| Чашка | 6 | 2017 | Студия MDHR | Студия MDHR | По состоянию на июль 2020 года [ 187 ] |

| Удовлетворительно | 5.5 | 2019 | Студия кофейных пятен | Кофейное пятно издательство | По состоянию на январь 2024 года, все еще в раннем доступе [ 188 ] |

| Subnautica | 5.2 | 2018 | Неизвестные миры развлечения | Неизвестные миры развлечения | По состоянию на январь 2020 года бесплатные копии дисконтирования от рекламных предложений [ 189 ] |

| Связывание Исаака | 5 | 2011 | Edmund McMillen / nicalis | Эдмунд Макмиллен/Никалис | Включает в себя как версию на основе Flash (которая продала только 3 миллиона по состоянию на июль 2014 года), так и обязательство Isaac: Rebirth . [ 190 ] |

| Документы, пожалуйста | 5 | 2013 | 3909 LLC | 3909 LLC | С августа 2023 года [ 191 ] |

| Слизи ранчо | 5 | 2017 | Мономи Парк | Мономи Парк | По состоянию на январь 2022 года [ 192 ] |

| Бит Сэйбер | 4 | 2019 | Бить игры | Бить игры | По состоянию на февраль 2021 года [ 193 ] |

| Горячая линия Майами | 4 | 2012 | Деннатонские игры | Вернуть цифровой | По состоянию на апрель 2023 года только продажи для версии Steam. [ 194 ] |

| Риск дождя 2 | 4 | 2020 | Hopoo Games | Gearbox Publishing | По состоянию на март 2021 года, включает только продажи для Steam версии. [ 195 ] |

| Мертвые клетки | 3.5 | 2018 | Движение близнецы | Движение близнецы | По состоянию на ноябрь 2020 года [ 196 ] |

| Фактор | 3.5 | 2020 | Создайте программное обеспечение | Создайте программное обеспечение | По состоянию на декабрь 2022 года, включает продажи во время раннего доступа с февраля 2016 года. [ 197 ] |

| Культ ягнца | 3.5 | 2022 | Массивный монстр | Вернуть цифровой | По состоянию на январь 2024 года [ 198 ] |

| Среди нас | 3.2 | 2018 | Инслот | Инслот | По состоянию на декабрь 2020 года только продажи для версии Nintendo Switch. Игра продается на других платформах, но также доступна в качестве бесплатного приложения для мобильных платформ. [ 199 ] |

| Бастион | 3 | 2011 | Supergiant Games | Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment /Supergiant Games | По состоянию на январь 2015 года [ 200 ] |

| Глубокий рок Галактик | 3 | 2020 | Ghost Ship Games | Кофейное пятно издательство | По состоянию на ноябрь 2021 г. [ 201 ] |

| Войдите в Ганджон | 3 | 2016 | Dodge Roll | Вернуть цифровой | По состоянию на январь 2020 года [ 202 ] |

| Подвешенный | 3 | 2010 | Playdead | Playdead | По состоянию на июнь 2013 года [ 203 ] |

| Риск дождя | 3 | 2013 | Hopoo Games | Посмеиваться | По состоянию на апрель 2019 года [ 204 ] |

| Полый рыцарь | 2.8 | 2017 | Командная вишня | Командная вишня | По состоянию на февраль 2019 года [ 205 ] |

| Рыцарь лопат | 2.6 | 2014 | Яхт -клубные игры | Яхт -клубные игры | По состоянию на сентябрь 2019 года [ 206 ] |

| Симулятор коз | 2.5 | 2014 | Студия кофейных пятен | Студия кофейных пятен | По состоянию на январь 2015 года [ 207 ] |

| Темное подземелье | 2 | 2016 | Red Hook Studios | Red Hook Studios | По состоянию на апрель 2020 года [ 208 ] |

| Поместья лорды | 2 | 2024 | Славянская магия | Капюшона лошадь | По состоянию на май 2024 года, достигнуто в течение трех недель после раннего доступа [ 209 ] [ 210 ] |

| Супер -матт | 2 | 2016 | Superhot Team | Superhot Team | По состоянию на май 2019 года [ 211 ] |

| Супер мясной мальчик | 2 | 2010 | Командное мясо | Командное мясо | По состоянию на апрель 2014 года [ 212 ] |

| Battlebit Remastered | 1.8 | 2023 | Сержанкидоки, Виласкис и Теликидхарс | Сержант | По состоянию на июль 2023 г. [ 213 ] |

| Dyson Sphere Program | 1.7 | 2021 | Молодочная студия | Gamera Game | По состоянию на сентябрь 2021 года, все еще в раннем доступе [ 214 ] |

| Убить шпиль | 1.5 | 2017 | Мегакрит | Скромный пакет | По состоянию на март 2019 года [ 215 ] |

| Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP | 1.5 | 2011 | Superbrothers , Капибара | Капибарские игры | По состоянию на июль 2013 года [ 216 ] |

| Амнезия: темный спуск | 1.4 | 2010 | Фрикционные игры | Фрикционные игры | По состоянию на сентябрь 2012 года [ 217 ] |

| Магка | 1.3 | 2011 | Arrowhead Game Studios | Парадокс интерактивный | По состоянию на январь 2012 года [ 218 ] |

| Срывать | 1.1 | 2022 | Tuxedo Labs | Tuxedo Labs | С марта 2023 года [ 219 ] |

| Балатро | 1 | 2024 | Localthunk | PlayStack | С марта 2024 года. [ 220 ] |

| Расщеплять | 1 | 2023 | Blobfish | Blobfish | По состоянию на март 2023 года, который включает в себя продажи во время раннего доступа в 2022 году. [ 221 ] |

| Рулетка из бакшота | 1 | 2024 | Mike Klubnika | Критический рефлекс | По состоянию на апрель 2024 года [ 222 ] |

| Селеста | 1 | 2018 | Очень нормальные игры | Очень нормальные игры | С марта 2020 года [ 223 ] |

| Предупреждение о содержании | 1 | 2024 | Форест, Зорро, Уилнил, Филипп, Тэпен | Landfall Games | По состоянию на апрель 2024 года не включает 6,6 миллиона единиц, заявленных во время бесплатного запуска игры [ 224 ] |

| Основной хранитель | 1 | 2022 | Пугсторм | Fireshine Games | По состоянию на июль 2022 года [ 225 ] |

| Дэйв дайвер | 1 | 2023 | Майор | Нексон | По состоянию на июль 2023 г. [ 226 ] |

| Deep Rock Galactic: выживший | 1 | 2024 | Funday Games | Призрачная судоходство издательство | С марта 2024 года [ 227 ] |

| Дрейг | 1 | 2023 | Черные соляные игры | Команда17 | По состоянию на октябрь 2023 года [ 228 ] |

| Пыль: хвост элизии | 1 | 2012 | Скромные сердца | Microsoft Studios | По состоянию на март 2014 года [ 229 ] |

| Он сделал | 1 | 2012 | Polytron Corporation | Лестница | По состоянию на январь 2014 года [ 230 ] |

| Firewatch | 1 | 2016 | Кампо Санто | Panic Inc. | По состоянию на январь 2017 года [ 231 ] |

| Серый | 1 | 2018 | Nomada Studio | Вернуть цифровой | По состоянию на апрель 2020 года [ 232 ] |

| Аид | 1 | 2020 | Supergiant Games | Supergiant Games | По состоянию на сентябрь 2020 года. Включает 700 000 продаж в раннего доступа период [ 233 ] |

| Инсципция | 1 | 2021 | Игры Даниэля Маллинса | Вернуть цифровой | По состоянию на январь 2022 года [ 234 ] |

| Герой петли | 1 | 2021 | Четыре квартала | Вернуть цифровой | По состоянию на декабрь 2021 года [ 235 ] |

| Лунный засадок | 1 | 2018 | Цифровое солнце | 11 битных студий | По состоянию на июнь 2020 года [ 236 ] |

| Убийство | 1 | 2020 | Дома | Дома | По состоянию на декабрь 2022 года [ 237 ] |

| Пицца башня | 1 | 2023 | Пицца | По состоянию на январь 2024 года. [ 238 ] | |

| Rimworld | 1 | 2018 | Людион Студии | Людион Студии | По состоянию на август 2020 года [ 239 ] |

| Сифу | 1 | 2022 | Sloclap | Sloclap | С марта 2022 года. [ 240 ] |

| Спираль | 1 | 2020 | Громовые лотосные игры | Громовые лотосные игры | По состоянию на декабрь 2021 года [ 241 ] |

| Skul: The Hero Slayer | 1 | 2021 | Игры левша | Neowiz | По состоянию на январь 2022 года [ 242 ] |

| Томас был один | 1 | 2012 | Майк Бителл | Майк Бителл | По состоянию на апрель 2014 года [ 243 ] |

| Тимберборн | 1 | 2021 | Механизмом | Механизмом | По состоянию на сентябрь 2023 года [ 244 ] |

| Транзистор | 1 | 2014 | Supergiant Games | Supergiant Games | По состоянию на декабрь 2015 года [ 245 ] |

| Гнездо | 1 | 2015 | Тоби Фокс | Тоби Фокс | По состоянию на октябрь 2018 года [ 246 ] |

| Распаковка | 1 | 2021 | Ведьма пум | Скромные игры | С ноября 2022 года [ 247 ] |

| Без названия Goose Game | 1 | 2019 | Дом | Panic Inc. | По состоянию на декабрь 2019 года [ 248 ] |

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Даттон, Фред (2012-04-18). "Что такое инди?" Полем Еврогамер . Архивировано с оригинала 2016-03-07 . Получено 2016-03-04 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Гнаде, Майк (15 июля 2010 г.). "Что такое инди -игра?" Полем Журнал Indie Game . Архивировано с оригинала 27 сентября 2013 года . Получено 9 января 2011 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Гриль, Хуан (30 апреля 2008 г.). «Состояние инди -игры» . Гамасутра . Архивировано из оригинала 7 декабря 2013 года . Получено 14 января 2011 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Макдональд, Дэн (3 мая 2005 г.). «Понимание" независимого " . Игровой туннель . Архивировано из оригинала 15 июня 2009 года . Получено 18 января 2011 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Томсен, Майкл (25 января 2011 г.). «Инди -бредое: игровая категория, которая не существует» . Магнитный Архивировано из оригинала 22 февраля 2014 года . Получено 4 декабря 2012 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Паркер, Лаура (2011-02-13). «Рост инди -разработчика» . Gamepot . Архивировано с оригинала 2016-03-21 . Получено 2016-03-04 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Пирс, Дэн (9 июля 2021 г.). «Мнение:« Инди »потеряло свое значение» . Магнитный Архивировано из оригинала 12 июля 2021 года . Получено 23 июля 2021 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Гриль, Хуан (2008-04-30). «Состояние инди -игры» . Гамасутра . Архивировано из оригинала 2015-12-13 . Получено 2016-03-04 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в McGuire & Jenkins 2009 , с. 27; Moore & Novak 2010 , с. 272; Бейтс 2004 , с. 252;

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Кэрролл, Рассел (14 июня 2004 г.). "Инди -инновации?" Полем GameTunnel . Архивировано из оригинала 15 июня 2009 года . Получено 7 февраля 2011 года .

- ^ Марсело Принс, Питер Рот (2004-12-21). «Издатели видеоигр делают большие ставки на игры с большими бюджетами» . Wall Street Journal Online . Получено 2013-07-01 .

Затраты на развитие и маркетинг сделали индустрию видеоигр «чрезвычайно не склонны к риску, [...] издатели в значительной степени сосредоточены на создании продолжений успешных названий или игр на основе фильмов или персонажей комиксов, которые рассматриваются как менее рискованные». Мы больше не зеленые светильники, которые будут маленькими или средним размером игр. [...] "

[ Постоянная мертвая ссылка ] - ^ McGuire & Jenkins 2009 , p. 27; Moore & Novak 2010 , с. 272; Бейтс 2004 , с. 252; Iuppa & Borst 2009 , p. 10

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Паркер, Лора (14 февраля 2011 г.). «Рост инди -разработчика» . Gamepot . Архивировано с оригинала 8 ноября 2012 года . Получено 4 декабря 2012 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Келли, Кевин (17 марта 2009 г.). «SXSW 2009: быть инди -успешным в индустрии видеоигр» . Джойстик . Архивировано из оригинала 21 октября 2012 года . Получено 4 февраля 2011 года .

- ^ Bethke 2003 , p. 102

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Кроссли, Роб (19 мая 2009 г.). «Indie Game Studios 'всегда будет более креативным » . McV . Архивировано из оригинала 5 июня 2009 года . Получено 18 января 2011 года .

- ^ Кук, Дэйв (13 мая 2014 г.). «Почему Supergiant отказался от издателей для выпуска Transistor - интервью» . VG247 . Архивировано с оригинала 8 сентября 2015 года . Получено 26 апреля 2016 года .

- ^ Винчестер, Херни (14 ноября 2011 г.). «Разработчик бастионов говорит о инди -публикации» . ПК Геймер . Архивировано с оригинала 24 сентября 2015 года . Получено 26 августа 2015 года .

- ^ Кондитт, Джессика (21 января 2016 г.). «Путешествие во времени с создателем« косичка »Джонатана Блоу» . Engadget . AOL Tech . Архивировано с оригинала 21 января 2016 года . Получено 21 января 2016 года .

- ^ Камен, Мэтт (2016-03-04). «Ни один мужчина небо, режиссер:« Все для проволоки, мы работаем всю ночь » » . Wired UK . Архивировано с оригинала 2016-03-05 . Получено 2016-03-04 .

- ^ Сигер, Хирун (30 июня 2023 г.). «Дейв, дайвер, холодная RPG о рыбалке и суши, является одной из самых больших историй успеха в паре 2023 года» . Gamesradar . Архивировано из оригинала 11 июля 2023 года . Получено 14 ноября 2023 года .

- ^ Ngan, Liv (11 июля 2023 г.). «Инди -RPG и Sushi Restaurant Sim Dave Diver достигает 1 млн продаж» . Еврогамер . Архивировано из оригинала 18 июля 2023 года . Получено 14 ноября 2023 года .

- ^ Spangler, Тодд (13 ноября 2023 г.). «Номинации на премию Game Awards 2023: Алан Уэйк 2, Baldur's Gate 3 возглавляют пакет с по восемью номинами каждый» . Разнообразие . Архивировано с оригинала 13 ноября 2023 года . Получено 14 ноября 2023 года .

- ^ Роу, Вилла (14 ноября 2023 г.). «Номинанты на премию Game Awards раскрывают самую большую слепую пятно события» . Обратный . Bustle Digital Group . Архивировано из оригинала 14 ноября 2023 года . Получено 15 ноября 2023 года .

- ^ «Кейли взвешивает дебаты о Дэйве Дайвере, квалифицируемом на лучшую инди -игру» . 27 ноября 2023 года. Архивировано с оригинала 27 ноября 2023 года . Получено 27 ноября 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Гарда, Мария Б.; RASCARCRYK, PAWEL (октябрь 2016 г.). «Независит ли каждая инди -игра? На пути к концепции независимой игры». Истории игры . 16 (1). ISSN 1604-7982 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Диаманте, Винс (7 марта 2007 г.). «GDC: будущее инди -игр» . Гамасутра . Архивировано из оригинала 7 декабря 2013 года . Получено 18 января 2011 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Персонал Gamasutra (4 октября 2007 г.). «Q & A: независимые создатели игры о важности инди -движения» . Гамасутра . Архивировано из оригинала 7 декабря 2013 года . Получено 25 февраля 2011 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный McGuire & Jenkins 2009 , с. 27

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Коббетт, Ричард (19 сентября 2010 г.). "Инди -игра в будущем?" Полем Techradar . п. 1. Архивировано из оригинала 23 декабря 2010 года . Получено 24 февраля 2011 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Ирвин, Мэри Джейн (20 ноября 2008 г.). «Разработчики инди -игры поднимаются» . Форбс . Архивировано из оригинала 17 мая 2019 года . Получено 10 января 2011 года .

- ^ Diamante, Винсент (6 марта 2007 г.). «GDC: анализ инноваций в инди -играх» . Гамасутра . Архивировано из оригинала 5 декабря 2017 года . Получено 4 декабря 2012 года .

- ^ Кунзельман, Кэмерон (15 января 2020 г.). "Что это действительно значит быть инди -игрой?" Полем Порок . Архивировано с оригинала 15 января 2020 года . Получено 15 января 2020 года .

- ^ Кларк, Райан (8 сентября 2015 г.). «5 мифов о индипокалипсисе» . Гамасутра . Архивировано из оригинала 15 декабря 2017 года . Получено 14 декабря 2017 года .

- ^ Ньюман, Джаред (31 марта 2017 г.). «Как itch.io стал инди -игрой для ПК - и антитезой Steam» . ПК Мир . Архивировано с оригинала 26 февраля 2018 года . Получено 14 декабря 2017 года .

- ^ Стили, Александр; Remneland-Wikhamn, Björn (2021). «Видеоигра как Agencement и изображение новых игр: работа разработчиков инди -видеоигр». Культура и организация : 1–14.

- ^ Iuppa, Ник; Борст, Терри; Симпсон, Крис (2012). Средняя разработка игры: создание независимых серьезных игр и симуляций от начала до конца . CRC Press . п. 10

- ^ Jacevic, Милан (2018). Инди -игра: фильм: The Paper - документальные фильмы и подполе независимых игр . Материалы Digra 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Коббетт, Ричард (22 сентября 2017 г.). «От Shareware Superstars до Steam Gold Rush: как инди завоевала ПК» . ПК Геймер . Архивировано из оригинала 9 сентября 2021 года . Получено 25 сентября 2017 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Паркер, Фелан (2013). Изучение инди -игры год одиннадцать . Материалы Digra 2013: дефраггирование игровых исследований. Цифровая ассоциация исследований .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в McGuire & Jenkins 2009 , с. 27

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Juul, Jesper (15 ноября 2019 г.). «Инди -взрыв, который продолжается в течение 30 лет (дай или возьми)» . Многоугольник . Архивировано с оригинала 15 ноября 2019 года . Получено 15 ноября 2019 года .

- ^ Эдвардс, Бендж (2017-10-27). «Заново открытие истории« Потерянная первая женщина -дизайнер видеоигр » . Быстрая компания . Архивировано из оригинала 2017-11-09 . Получено 2017-10-27 .

- ^ МакКракен, Гарри (29 апреля 2014 г.). «Пятьдесят лет базового, язык программирования, который сделал компьютеры личным» . Время . Архивировано с оригинала 5 февраля 2016 года . Получено 24 августа 2020 года .

- ^ «Представление обмена программы Atari» . Программный программный каталог Atari Exchange . Лето 1981. С. 1–2 . Получено 7 ноября 2020 года .

- ^ «Смерть кодера спальни» . Хранитель . 24 января 2004 года. Архивировано с оригинала 30 сентября 2019 года . Получено 30 сентября 2019 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Изуши, Хиро; Aoyama, Yuko (2006). «Эволюция отрасли и перекрестные навыки: сравнительный анализ индустрии видеоигр в Японии, Соединенных Штатах и Великобритании». Окружающая среда и планирование а . 38 (10): 1843–1861. Bibcode : 2006enpla..38.1843i . doi : 10.1068/a37205 . S2CID 143373406 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Бейкер, Крис (6 августа 2010 г.). «Sinclair ZX80 и рассвет« сюрреалистической »британской игровой индустрии» . Проводной . Архивировано из оригинала 26 июля 2019 года . Получено 30 сентября 2019 года .

- ^ Донлан, Кристиан (26 июля 2012 г.). «Маниакальный шахтер 360: пересмотр классики» . Еврогамер . Архивировано с оригинала 30 сентября 2019 года . Получено 30 сентября 2019 года .

- ^ Марсело Принс, Питер Рот (2004-12-21). «Издатели видеоигр делают большие ставки на игры с большими бюджетами» . Wall Street Journal Online . Получено 2013-07-01 .

Затраты на развитие и маркетинг сделали индустрию видеоигр «чрезвычайно не склонны к риску, [...] издатели в значительной степени сосредоточены на создании продолжений успешных названий или игр на основе фильмов или персонажей комиксов, которые рассматриваются как менее рискованные». Мы больше не зеленые светильники, которые будут маленькими или средним размером игр. [...] "

[ Постоянная мертвая ссылка ] - ^ Чандлер 2009 , с. XXI

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Iuppa & Borst 2009 , p. 10

- ^ Чан, Хи Хун (18 марта 2021 г.). «Отслеживание растягивающихся корней сохранения вспышки» . Порок . Архивировано из оригинала 7 августа 2021 года . Получено 18 марта 2021 года .

- ^ Блейк, Майкл (22 июня 2011 г.). «ПК Gaming: обреченные? Или Zdoomed? - некоторые из самых полезных компьютерных игр были созданы инди -разработчиками, использующими код с открытым исходным кодом» . Магнитный Архивировано из оригинала 21 февраля 2014 года . Получено 25 сентября 2017 года .

- ^ Муллис, Стив (4 ноября 2013 г.). «Март Индии: панк -рокеры видеоигр» . ЭНЕРГЕТИЧЕСКИЙ ЯДЕРНЫЙ РЕАКТОР . Архивировано из оригинала 18 июля 2021 года . Получено 18 июля 2021 года .

- ^ «Независимый бум развития игры: интервью со Стефани Бариш, генерального директора Indiecade» . Нью -Йоркская кинокадемия . 22 октября 2014 года. Архивировано с оригинала 15 октября 2019 года . Получено 15 октября 2019 года .

- ^ Такацуки, Йо (27 декабря 2007 г.). «Стоимость головной боли для разработчиков игр» . Би -би -си . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2020 года . Получено 31 августа 2020 года .

- ^ Берман, Джошуа (13 ноября 2009 г.). "Может ли DIY вытеснить стрелка от первого лица?" Полем New York Times . Архивировано из оригинала 23 декабря 2019 года . Получено 20 января 2020 года .

- ^ Майсур, Сахана (2 января 2009 г.). «Как мир GOO стал одним из инди -видеоигр 2008 года» . Венчурная бит . Архивировано с оригинала 12 сентября 2019 года . Получено 29 января 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Роуз, Майк (19 ноября 2013 г.). «Как Инди оказало влияние на поколение игровых приставок» . Гамасутра . Архивировано из оригинала 1 октября 2020 года . Получено 26 августа 2020 года .

- ^ Берман, Джошуа (15 ноября 2009 г.). "Может ли DIY вытеснить стрелка от первого лица?" Полем New York Times . Архивировано с оригинала 6 сентября 2015 года . Получено 23 сентября 2015 года .

- ^ Грубб, Джефф (14 февраля 2012 г.). «Как продажи первого дня Fez по сравнению с хитами Braid, Limbo и других XBLA» . Венчурная бит . Архивировано из оригинала 9 августа 2014 года . Получено 15 октября 2019 года .

- ^ Чаплин, Хизер (27 августа 2008 г.). «Кошачья кошачья кошачья кошачья удара по неожиданным причинам» . ЭНЕРГЕТИЧЕСКИЙ ЯДЕРНЫЙ РЕАКТОР . Архивировано с оригинала 27 марта 2019 года . Получено 4 февраля 2011 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Смит, Грэм (5 марта 2018 г.). «Бутик -издатели - это будущее рынка инди -игр» . GamesIndustry.Biz . Архивировано из оригинала 16 августа 2020 года . Получено 26 августа 2020 года .

- ^ Вебстер, Эндрю (4 апреля 2018 г.). «Издатели Indie Game - это новые инди -рок -лейблы» . Грава . Архивировано с оригинала 4 апреля 2018 года . Получено 4 апреля 2018 года .

- ^ «Архив - 13 -й ежегодный награды за разработчиками игр» . Разработчики игр. Награды . 2021-04-23. Архивировано из оригинала 2022-06-23 . Получено 2022-06-29 .

- ^ «Детали категории наград» . www.interactive.org . Архивировано из оригинала 2022-04-13 . Получено 2022-06-29 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Фабер, Том (15 июля 2019 г.). «Кошки, рак и умственные сбои: неожиданные радости инди -игр» . Финансовые времена . Архивировано из оригинала 19 сентября 2019 года . Получено 1 октября 2019 года .

- ^ «Minecraft становится первой видеоигры, чтобы достичь 300 -метровых продаж» . 2023-10-16 . Получено 2024-07-15 .

- ^ Планкетт, Люк (4 января 2011 г.). «Почему Minecraft так чертовски популярен» . Котаку . Архивировано с оригинала 9 января 2011 года . Получено 4 февраля 2011 года .

- ^ Молина, Бретт (15 сентября 2014 г.). «Microsoft, чтобы приобрести производитель Minecraft» Mojang за 2,5 млрд долларов » . USA сегодня . Архивировано с оригинала 7 сентября 2017 года . Получено 5 сентября 2017 года .

- ^ Сирани, Джордан (2024-07-11). «10 бестселлеров-видеоигр всех времен» . Магнитный Получено 2024-07-15 .

- ^ Остлер, Энн-Мари (2022-08-30). «Terraria может быть самой рецензируемой Steam-игрой, с более чем миллионами обзоров и 97% положительным рейтингом» . Gamesradar . Получено 2024-07-15 .

- ^ Гордон, Льюис (2022-10-25). «Десять лет спустя горячая линия Майами остается тошнотворной, ультрафилентной классикой» . Зуль . Получено 2024-07-15 .

- ^ Матар, Джо (26 июня 2019 г.). «Рыцарь -лопат: инди -шедевр» . Логовой гик . Архивировано из оригинала 1 декабря 2021 года . Получено 14 сентября 2021 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Брей, Бетси; Кларк, MJ; Ван, Синтия (2020). Инди -игры в цифровую эпоху . Bloomsbury Publishing . п. 74. ISBN 978-1501356438 .

- ^ Аргуэлло, Диего Николас (2022-10-26). «Горячая линия ультра-насилия Майами повлияла на игры в течение десятилетия» . Грава . Получено 2024-07-15 .

- ^ Коркоран, Нина (2023-03-08). «Горячая линия Майами и рост техно в ультра-насильственных видеоиграх» . Pitchfork . Получено 2024-07-15 .

- ^ «Глубокий: Yacht Club становится прозрачным с номерами продаж» . www.gamedeveloper.com . Получено 2024-07-15 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Райт, Стивен (28 сентября 2018 г.). "Слишком много видеоигр. Что теперь?" Полем Многоугольник . Архивировано с оригинала 24 октября 2019 года . Получено 15 октября 2019 года .

- ^ Макалун, Алисса (10 января 2018 г.). «7672 игры попали в Steam только в 2017 году, говорит Steam Spy» . Гамасутра . Архивировано с оригинала 11 января 2018 года . Получено 10 января 2018 года .

- ^ Кальвин, Алекс (14 января 2019 г.). «Сейчас в Steam насчитывается более 27 000 игр» . ПК Games Insider.biz . Архивировано с оригинала 15 января 2019 года . Получено 14 января 2019 года .

- ^ Кальвин, Алекс (2 января 2020 г.). «В 2019 году было выпущено более 8 000 игр в 2019 году» . Pcgamesinsider.biz . Архивировано из оригинала 2 января 2020 года . Получено 2 января 2020 года .

- ^ Трансплантат, Крис (10 декабря 2015 г.). «5 тенденций, которые определили игровую индустрию в 2015 году» . Гамасутра . Архивировано с оригинала 11 декабря 2015 года . Получено 10 декабря 2015 года .

- ^ Wawro, Алекс (15 марта 2016 г.). «Разработчики делятся настоящими разговорами о выживании последнего« индипокалипсиса » » . Гамасутра . Архивировано из оригинала 19 августа 2017 года . Получено 15 марта 2016 года .

- ^ Пирсон, Дэн (13 апреля 2016 г.). «Каждый год был лучше, чем последний. Процветает - лучший способ выразить это» . GamesIndustry.Biz . Архивировано с оригинала 16 апреля 2016 года . Получено 13 апреля 2016 года .

- ^ Трансплантат, Крис (13 декабря 2016 г.). «5 тенденций, которые определили игровую индустрию в 2016 году» . Гамасутра . Архивировано с оригинала 14 декабря 2016 года . Получено 13 декабря 2016 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Bycer, Джош (15 октября 2019 г.). «Проблема инди -игры пьедестал» . Гамасутра . Архивировано с оригинала 14 октября 2019 года . Получено 15 октября 2019 года .

- ^ Манси, Джули (15 августа 2017 г.). «Год спустя ни одно небо человека - и его эволюция - стоит изучить» . Проводной . Архивировано из оригинала 18 августа 2017 года . Получено 17 августа 2017 года .

- ^ Валентина, Ревекка (19 июля 2019 г.). «Индии в Steam делают ставки на обнаружение» . GamesIndustry.Biz . Архивировано из оригинала 4 октября 2019 года . Получено 15 октября 2019 года .

- ^ Запад, Даниэль (8 сентября 2015 г.). « Хорошо» недостаточно - выпуск инди -игры в 2015 году » . Гамасутра . Архивировано с оригинала 15 октября 2019 года . Получено 15 октября 2019 года .

- ^ Нельсон, Xalavier Jr. (12 марта 2019 г.). «Каково это выпустить инди -игру в 2019 году» . Многоугольник . Архивировано из оригинала 27 февраля 2020 года . Получено 15 октября 2019 года .

- ^ Диас, Ана (17 октября 2020 г.). «Занимайся любовью, а не войной: пять лет« подтеяль » » . ЭНЕРГЕТИЧЕСКИЙ ЯДЕРНЫЙ РЕАКТОР . Архивировано из оригинала 18 октября 2020 года . Получено 2023-11-12 .

- ^ Уокер, Алекс (2018-07-05). «Hollow Knight продал более 1 миллиона копий на ПК» . Kotaku Australia . Получено 2024-03-27 .

- ^ Грубб, Джефф (30 сентября 2019 г.). «Cuphead превосходит 5 миллионов проданных копий» . Венчурная бит . Архивировано из оригинала 16 января 2020 года . Получено 28 января 2020 года .

- ^ Ито, Кенджи (2005). Возможности некоммерческих игр: случай любителей ролевых игр в Японии . Труды конференции Digra 2005: Изменение взглядов - миры в игре. Цифровая ассоциация исследований .

- ^ Эллисон, Кара (1 октября 2014 г.). "Dōjin Nation: действительно ли в Японии существуют ли игры« инди -инди »?» Полем Хранитель . Архивировано из оригинала 1 февраля 2020 года . Получено 1 февраля 2020 года .

- ^ PCGamer (24 ноября 2014 г.). "The story of the Touhou sensation" . ПК Геймер . Архивировано из оригинала 17 июля 2021 года . Retrieved 17 July 2021 .

- ^ "『UNDERTALE』トビー・フォックス×『東方』ZUN×Onion Games木村祥朗鼎談──自分が幸せでいられる道を進んだらこうなった──同人の魂、インディーの自由を大いに語る" (in Japanese). 19 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.