San Francisco

San Francisco | |

|---|---|

| Город и округ Сан-Франциско | |

Мост Золотые Ворота и горизонт Сан-Франциско, вид со стороны мыса Марин | |

| Прозвища: | |

| Девиз(ы): | |

| Гимн: Официальная песня: Тема из Сан-Франциско («Открой свои Золотые Ворота»). Официальная баллада: « Я оставил свое сердце в Сан-Франциско ». [2] [3] | |

Интерактивная карта Сан-Франциско | |

| Координаты: 37 ° 46'39 "N 122 ° 24'59" W / 37,77750 ° N 122,41639 ° W | |

| Страна | Соединенные Штаты |

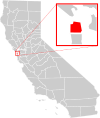

| Состояние | Калифорния |

| Графство | San Francisco |

| Метро | Сан-Франциско – Окленд – Хейворд |

| CSA | Сент-Джозеф – Сент-Фрэнсис – Окленд. |

| Миссия | 29 июня 1776 г. [4] |

| Инкорпорейтед | 16 декабря 1848 г. [5] |

| Основан | Хуан Баутиста де Анса Хосе Хоакин Морага Франсиско Палоу |

| Назван в честь | Святой Франциск Ассизский |

| Правительство | |

| • Тип | Сильный мэр-совет |

| • Тело | Наблюдательный совет |

| • Мэр | Лондонская порода ( Д ) [6] |

| • Руководители [10] | Список |

| • Члены Ассамблеи [11] [12] | Мэтт Хейни ( з ) Фил Тинг ( З ) |

| • Сенатор штата | Скотт Винер ( З ) [7] |

| • Представители США | Нэнси Пелоси ( З ) [8] Кевин Маллин ( З ) [9] |

| Область | |

| • Город и округ | 231,89 квадратных миль (600,59 км 2) 2 ) |

| • Land | 46.9 sq mi (121.48 km2) |

| • Water | 184.99 sq mi (479.11 km2) 80.00% |

| • Metro | 3,524.4 sq mi (9,128 km2) |

| Elevation | 52 ft (16 m) |

| Highest elevation | 934 ft (285 m) |

| Lowest elevation [15] (Pacific Ocean) | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population | |

| • City and county | 873,965 |

| • Estimate (2022)[16] | 808,437 |

| • Rank | 39th in North America 17th in the United States 4th in California |

| • Density | 18,634.65/sq mi (7,194.88/km2) |

| • Urban | 3,515,933 (US: 14th) |

| • Urban density | 6,843.0/sq mi (2,642.1/km2) |

| • Metro | 4,566,961 (US: 13th) |

| • CSA | 9,225,160 (US: 5th) |

| Demonym | San Franciscan[20] |

| GDP | |

| • City and county | $252.2 billion (2022) |

| • Metro | $729.1 billion (2022) |

| • CSA | $1.318 trillion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC–08:00 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC–07:00 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes[22] | List |

| Area codes | 415/628[23] |

| FIPS code | 06-67000 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 277593, 2411786 |

| Website | sf.gov |

| |

San Francisco , [24] официально город и округ Сан-Франциско — коммерческий, финансовый и культурный центр Северной Калифорнии . С населением 808 437 жителей по состоянию на 2022 год. [25] Сан-Франциско является четвертым по численности населения городом в американском штате Калифорния после Лос -Анджелеса , Сан-Диего и Сан-Хосе . Город занимает площадь 46,9 квадратных миль (121 квадратный километр). [26] в верхней части полуострова Сан-Франциско , что делает его вторым по густонаселенности крупным городом США после Нью-Йорка и пятым по густонаселенности округом США Нью-Йорка после четырех районов . Среди 92 городов США с населением более 250 000 человек Сан-Франциско занимает первое место по доходу на душу населения и шестое по совокупному доходу по состоянию на 2022 год. [27]

До европейского заселения современный город был населен Йеламу , которые говорили на языке, который сейчас называется Рамайтуш Олоне . 29 июня 1776 года поселенцы из Новой Испании основали Президио Сан-Франциско у Золотых ворот и миссию Сан-Франциско-де-Асис в нескольких милях отсюда, названные в честь Франциска Ассизского . [4] Золотая лихорадка в Калифорнии в 1849 году привела к быстрому росту, превратив незначительную деревушку в оживленный порт, сделав его крупнейшим городом на Западном побережье того времени; между 1870 и 1900 годами примерно четверть населения Калифорнии проживала в самом городе. [27] В 1856 году Сан-Франциско стал объединенным городом-графством . [28] После того, как три четверти города были разрушены землетрясением и пожаром 1906 года , [29] его быстро перестроили, и девять лет спустя он принял Панамско-Тихоокеанскую международную выставку . Во время Второй мировой войны это был главный порт для военнослужащих, военных действий отправлявшихся на Тихоокеанский театр . [30] В 1945 году в Сан-Франциско был подписан Устав ООН , учредивший Организацию Объединенных Наций , а в 1951 году Сан-Францисский договор восстановил мирные отношения между Японией и союзными державами . [31] [32] [33] После войны слияние вернувшихся военнослужащих, значительная иммиграция , либеральные взгляды, рост контркультуры битников и хиппи , сексуальная революция , движение за мир , растущее из оппозиции участию Соединенных Штатов во Вьетнамской войне , и другие факторы привели к Лето любви и движение за права геев , укрепившее Сан-Франциско как центр либерального активизма в Соединенных Штатах .

Сан-Франциско и окружающий его район залива Сан-Франциско являются глобальным центром экономической деятельности, искусства и науки. [34] [35] при поддержке ведущих университетов , [36] сектор высоких технологий , здравоохранения, финансов, страхования, недвижимости и профессиональных услуг. [37] По состоянию на 2020 год [update], мегаполис с населением 6,7 миллиона человек занимает 5-е место по ВВП (874 миллиарда долларов США) и 2-е место по ВВП на душу населения (131 082 доллара США) среди стран ОЭСР , опережая такие глобальные города , как Париж , Лондон и Сингапур . [38] [39] [40] Сан-Франциско занимает 13-е место по численности населения в статистической области США с 4,6 миллионами жителей и четвертое место по совокупному доходу и объему экономического производства с ВВП в 729 миллиардов долларов в 2022 году. [update]. [41] Более широкий объединенный статистический район Сан-Хосе-Сан-Франциско-Окленд является пятым по численности населения в стране с населением около девяти миллионов человек и третьим по величине по объему экономического производства с ВВП в 1,32 триллиона долларов в 2022 году. [update]. В том же году ВВП самого Сан-Франциско составил 252,2 миллиарда долларов, а ВВП на душу населения - 312 000 долларов. [41] Сан-Франциско занимал пятое место в мире и второе место в США в Индексе глобальных финансовых центров по состоянию на сентябрь 2023 года. [update]. [42] Несмотря на продолжающийся исход предприятий из центра Сан-Франциско, [43] [44] В городе по-прежнему расположены многочисленные компании, работающие в сфере технологий и за их пределами, включая Salesforce , Uber , Airbnb , Levi's , Gap , Dropbox и Lyft .

В 2022 году Сан-Франциско посетили более 1,7 миллиона человек из-за границы (это пятый по посещаемости город из-за границы в США после Нью-Йорка, Майами , Орландо и Лос-Анджелеса) и около 20 миллионов местных посетителей, что в общей сложности составило 21,9 миллиона человек. посетители. [45] [46] Город известен своими крутыми холмами и эклектичным сочетанием архитектуры в различных районах , а также прохладным летом, туманом и известными достопримечательностями, включая мост Золотые Ворота , канатные дороги и Алькатрас , а также Чайнатаун и Миссионер районы . . [47] В городе расположен ряд образовательных и культурных учреждений, таких как Калифорнийский университет в Сан-Франциско , Университет Сан-Франциско , Государственный университет Сан-Франциско , Музыкальная консерватория Сан-Франциско , Музей де Янга , Музей Сан-Франциско. современного искусства , Симфонический оркестр Сан-Франциско , Балет Сан-Франциско , Опера Сан-Франциско , Центр SFJAZZ и Калифорнийская академия наук . Две высшей лиги спортивные команды , « Сан-Франциско Джайентс» и « Голден Стэйт Уорриорз» , проводят свои домашние игры на территории самого Сан-Франциско. Международный аэропорт Сан-Франциско (SFO) предлагает рейсы по более чем 125 направлениям, а сеть легкорельсового транспорта и автобусов в сочетании с системами BART и Caltrain соединяет почти каждую часть Сан-Франциско с более широким регионом. [48][49]

Etymology

[edit]San Francisco, which is Spanish for "Saint Francis," takes its name from Mission San Francisco de Asís, which in turn was named after Saint Francis of Assisi. The mission received its name in 1776, when it was founded by the Spanish under the leadership of Padre Francisco Palóu. The city has officially been known as San Francisco since 1847, when Washington Allon Bartlett, then serving as the city's alcalde, renamed it from Yerba Buena (Spanish for "Good Herb"), which had been name used throughout the Spanish and Mexican eras since approximately 1776. The name Yerba Buena continues to be used in locations in the city, such as on Yerba Buena Island and in the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts and Yerba Buena Gardens.

While people residing outside the San Francisco Bay Area use nicknames including "Frisco" and "San Fran", local residents in the Bay Area sometimes refer to San Francisco as "the City" or "SF";[1][50] for residents of San Francisco living in the more suburban parts of the city, "the City" generally refers to the more densely populated downtown areas around Market Street.[failed verification – see discussion] Its use, or lack thereof, is a common way for locals to distinguish long-time residents from tourists and recent arrivals. "San Fran" and "Frisco" are sometimes considered controversial as nicknames among San Francisco residents.[51][52][50]

History

[edit]Indigenous history

[edit]The earliest archeological evidence of human habitation of the territory of San Francisco dates to 3000 BCE.[53] The Yelamu group of the Ramaytush people resided in a few small villages when an overland Spanish exploration party arrived on November 2, 1769, the first documented European visit to San Francisco Bay.[54] The Ohlone name for San Francisco was Ahwaste, meaning, "place at the bay."[55] The arrival of Spanish colonists, and the implementation of their Mission system, marked the beginning of the genocide of the Ramaytush people, and the deprivation of their language and culture.[56][57][58]

Spanish era

[edit]

The Spanish Empire claimed San Francisco as part of Las Californias, a province of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The Spanish first arrived in what is now San Francisco on November 2, 1769, when the Portolá expedition led by Don Gaspar de Portolá and Juan Crespí arrived at San Francisco Bay. Having noted the strategic benefits of the area due to its large natural harbor, the Spanish dispatched Pedro Fages in 1770 to find a more direct route to the San Francisco Peninsula from Monterey, which would become part of the El Camino Real route. By 1774, Juan Bautista de Anza had arrived to the area to select the sites for a mission and presidio. The first European maritime presence in San Francisco Bay occurred on August 5, 1775, when the Spanish ship San Carlos, commanded by Juan Manuel de Ayala, became the first ship to anchor in the bay.[59]

Soon after, on March 28, 1776, Anza established the Presidio of San Francisco. On October 9, Mission San Francisco de Asís, also known as Mission Dolores, was founded by Padre Francisco Palóu.[4] In 1794, the Presidio established the Castillo de San Joaquín, a fortification on the southern side of the Golden Gate, which later came to be known as Fort Point.

In 1804, the province of Alta California was created, which included Yerba Buena ,which was the former name of San Francisco. At its peak in 1810–1820, the average population at the Mission Dolores settlement was about 1,100 people.[60]

Mexican era

[edit]

In 1821, the Californias were ceded to Mexico by Spain. The extensive California mission system gradually lost its influence during the period of Mexican rule. Agricultural land became largely privatized as ranchos, as was occurring in other parts of California. Coastal trade increased, including a half-dozen barques from various Atlantic ports which regularly sailed in California waters.[62][63]

Yerba Buena (after a native herb), a trading post with settlements between the Presidio and Mission grew up around the Plaza de Yerba Buena. The plaza was later renamed Portsmouth Square (now located in the city's Chinatown and Financial District). The Presidio was commanded in 1833 by Captain Mariano G. Vallejo.[62]

In 1833, Juana Briones de Miranda built her rancho near El Polín Spring, founding the first civilian household in San Francisco, which had previously only been comprised by the military settlement at the Presidio and the religious settlement at Mission Dolores.[61]

In 1834, Francisco de Haro became the first Alcalde of Yerba Buena. De Haro was a native of Mexico, from that nation's west coast city of Compostela, Nayarit. A land survey of Yerba Buena was made by the Swiss immigrant Jean Jacques Vioget as prelude to the city plan. The second Alcalde José Joaquín Estudillo was a Californio from a prominent Monterey family. In 1835, while in office, he approved the first land grant in Yerba Buena: to William Richardson, a naturalized Mexican citizen of English birth. Richardson had arrived in San Francisco aboard a whaling ship in 1822. In 1825, he married Maria Antonia Martinez, eldest daughter of the Californio Ygnacio Martínez.[64][a]

Yerba Buena began to attract American and European settlers; an 1842 census listed 21 residents (11%) born in the United States or Europe, as well as one Filipino merchant.[65] Following the Bear Flag Revolt in Sonoma and the beginning of the U.S. Conquest of California, American forces under the command of John B. Montgomery captured Yerba Buena on July 9, 1846, with little resistance from the local Californio population. At the end of the month, the Brooklyn arrived with a group of Mormon settlers, who had departed New York City six months earlier. Following the capture, U.S. forces appointed both José de Jesús Noé and Washington Allon Bartlett to serve as co-alcaldes (mayors), while the conquest continued on in the rest of California. Following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, Alta California was ceded from Mexico to the United States.

Post-Conquest era

[edit]

Despite its attractive location as a port and naval base, post-Conquest San Francisco was still a small settlement with inhospitable geography.[66] Its 1847 population was said to be 459.[62]

The California gold rush brought a flood of treasure seekers (known as "forty-niners," as in "1849"). With their sourdough bread in tow,[67] prospectors accumulated in San Francisco over rival Benicia,[68] raising the population from 1,000 in 1848 to 25,000 by December 1849.[69] The promise of wealth was so strong that crews on arriving vessels deserted and rushed off to the gold fields, leaving behind a forest of masts in San Francisco harbor.[70] Some of these approximately 500 abandoned ships were used at times as storeships, saloons, and hotels; many were left to rot, and some were sunk to establish title to the underwater lot. By 1851, the harbor was extended out into the bay by wharves while buildings were erected on piles among the ships. By 1870, Yerba Buena Cove had been filled to create new land. Buried ships are occasionally exposed when foundations are dug for new buildings.[71]

California was quickly granted statehood in 1850, and the U.S. military built Fort Point at the Golden Gate and a fort on Alcatraz Island to secure the San Francisco Bay. San Francisco County was one of the state's 18 original counties established at California statehood in 1850.[72] Until 1856, San Francisco's city limits extended west to Divisadero Street and Castro Street, and south to 20th Street. In 1856, the California state government divided the county. A straight line was then drawn across the tip of the San Francisco Peninsula just north of San Bruno Mountain. Everything south of the line became the new San Mateo County while everything north of the line became the new consolidated City and County of San Francisco.[73]

Entrepreneurs sought to capitalize on the wealth generated by the gold rush. Silver discoveries, including the Comstock Lode in Nevada in 1859, further drove rapid population growth.[75] With hordes of fortune seekers streaming through the city, lawlessness was common, and the Barbary Coast section of town gained notoriety as a haven for criminals, prostitution, bootlegging, and gambling.[76] Early winners were the banking industry, with the founding of Wells Fargo in 1852 and the Bank of California in 1864.

Development of the Port of San Francisco and the establishment in 1869 of overland access to the eastern U.S. rail system via the newly completed Pacific Railroad (the construction of which the city only reluctantly helped support[77]) helped make the Bay Area a center for trade. Catering to the needs and tastes of the growing population, Levi Strauss opened a dry goods business and Domingo Ghirardelli began manufacturing chocolate. Chinese immigrants made the city a polyglot culture, drawn to "Old Gold Mountain," creating the city's Chinatown quarter. By 1880, Chinese made up 9.3% of the population.[78]

The first cable cars carried San Franciscans up Clay Street in 1873. The city's sea of Victorian houses began to take shape, and civic leaders campaigned for a spacious public park, resulting in plans for Golden Gate Park. San Franciscans built schools, churches, theaters, and all the hallmarks of civic life. The Presidio developed into the most important American military installation on the Pacific coast.[79] By 1890, San Francisco's population approached 300,000, making it the eighth-largest city in the United States at the time. Around 1901, San Francisco was a major city known for its flamboyant style, stately hotels, ostentatious mansions on Nob Hill, and a thriving arts scene.[80] The first North American plague epidemic was the San Francisco plague of 1900–1904.[81]

1906 earthquake and interwar era

[edit]

At 5:12 am on April 18, 1906, a major earthquake struck San Francisco and northern California. As buildings collapsed from the shaking, ruptured gas lines ignited fires that spread across the city and burned out of control for several days. With water mains out of service, the Presidio Artillery Corps attempted to contain the inferno by dynamiting blocks of buildings to create firebreaks.[82] More than three-quarters of the city lay in ruins, including almost all of the downtown core.[29] Contemporary accounts reported that 498 people died, though modern estimates put the number in the several thousands.[83] More than half of the city's population of 400,000 was left homeless.[84] Refugees settled temporarily in makeshift tent villages in Golden Gate Park, the Presidio, on the beaches, and elsewhere. Many fled permanently to the East Bay. Jack London is remembered for having famously eulogized the earthquake: "Not in history has a modern imperial city been so completely destroyed. San Francisco is gone."[85]

Rebuilding was rapid and performed on a grand scale. Rejecting calls to completely remake the street grid, San Franciscans opted for speed.[86] Amadeo Giannini's Bank of Italy, later to become Bank of America, provided loans for many of those whose livelihoods had been devastated. The influential San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association or SPUR was founded in 1910 to address the quality of housing after the earthquake.[87] The earthquake hastened development of western neighborhoods that survived the fire, including Pacific Heights, where many of the city's wealthy rebuilt their homes.[88] In turn, the destroyed mansions of Nob Hill became grand hotels. City Hall rose again in the Beaux Arts style, and the city celebrated its rebirth at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in 1915.[89]

During this period, San Francisco built some of its most important infrastructure. Civil Engineer Michael O'Shaughnessy was hired by San Francisco Mayor James Rolph as chief engineer for the city in September 1912 to supervise the construction of the Twin Peaks Reservoir, the Stockton Street Tunnel, the Twin Peaks Tunnel, the San Francisco Municipal Railway, the Auxiliary Water Supply System, and new sewers. San Francisco's streetcar system, of which the J, K, L, M, and N lines survive today, was pushed to completion by O'Shaughnessy between 1915 and 1927. It was the O'Shaughnessy Dam, Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, and Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct that would have the largest effect on San Francisco.[90] An abundant water supply enabled San Francisco to develop into the city it has become today.

In ensuing years, the city solidified its standing as a financial capital; in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash, not a single San Francisco-based bank failed.[91] Indeed, it was at the height of the Great Depression that San Francisco undertook two great civil engineering projects, simultaneously constructing the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge, completing them in 1936 and 1937, respectively. It was in this period that the island of Alcatraz, a former military stockade, began its service as a federal maximum security prison, housing notorious inmates such as Al Capone, and Robert Franklin Stroud, the Birdman of Alcatraz. San Francisco later celebrated its regained grandeur with a World's fair, the Golden Gate International Exposition in 1939–40, creating Treasure Island in the middle of the bay to house it.[92]

Contemporary era

[edit]

During World War II, the city-owned Sharp Park in Pacifica was used as an internment camp to detain Japanese Americans.[93] Hunters Point Naval Shipyard became a hub of activity, and Fort Mason became the primary port of embarkation for service members shipping out to the Pacific Theater of Operations.[30] The explosion of jobs drew many people, especially African Americans from the South, to the area. After the end of the war, many military personnel returning from service abroad and civilians who had originally come to work decided to stay. The United Nations Charter creating the United Nations was drafted and signed in San Francisco in 1945 and, in 1951, the Treaty of San Francisco re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers.[94]

Urban planning projects in the 1950s and 1960s involved widespread destruction and redevelopment of west-side neighborhoods and the construction of new freeways, of which only a series of short segments were built before being halted by citizen-led opposition.[95] The onset of containerization made San Francisco's small piers obsolete, and cargo activity moved to the larger Port of Oakland.[96] The city began to lose industrial jobs and turned to tourism as the most important segment of its economy.[97] The suburbs experienced rapid growth, and San Francisco underwent significant demographic change, as large segments of the white population left the city, supplanted by an increasing wave of immigration from Asia and Latin America.[98][99] From 1950 to 1980, the city lost over 10 percent of its population.

Over this period, San Francisco became a magnet for America's counterculture movement. Beat Generation writers fueled the San Francisco Renaissance and centered on the North Beach neighborhood in the 1950s.[100] Hippies flocked to Haight-Ashbury in the 1960s, reaching a peak with the 1967 Summer of Love.[101] In 1974, the Zebra murders left at least 16 people dead.[102] In the 1970s, the city became a center of the gay rights movement, with the emergence of The Castro as an urban gay village, the election of Harvey Milk to the Board of Supervisors, and his assassination, along with that of Mayor George Moscone, in 1978.[103]

Bank of America, now based in Charlotte, North Carolina, was founded in San Francisco; the bank completed 555 California Street in 1969. The Transamerica Pyramid was completed in 1972,[104] igniting a wave of "Manhattanization" that lasted until the late 1980s, a period of extensive high-rise development downtown.[105] The 1980s also saw a dramatic increase in the number of homeless people in the city, an issue that remains today, despite many attempts to address it.[106]

The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake caused destruction and loss of life throughout the Bay Area. In San Francisco, the quake severely damaged structures in the Marina and South of Market districts and precipitated the demolition of the damaged Embarcadero Freeway and much of the damaged Central Freeway, allowing the city to reclaim The Embarcadero as its historic downtown waterfront and revitalizing the Hayes Valley neighborhood.[107]

The two recent decades have seen booms driven by the internet industry. During the dot-com boom of the late 1990s, startup companies invigorated the San Francisco economy. Large numbers of entrepreneurs and computer application developers moved into the city, followed by marketing, design, and sales professionals, changing the social landscape as once poorer neighborhoods became increasingly gentrified.[108] Demand for new housing and office space ignited a second wave of high-rise development, this time in the South of Market district.[109] By 2000, the city's population reached new highs, surpassing the previous record set in 1950. When the bubble burst in 2001 and again in 2023, many of these companies folded and their employees were laid off. Yet high technology and entrepreneurship remain mainstays of the San Francisco economy. By the mid-2000s (decade), the social media boom had begun, with San Francisco becoming a popular location for tech offices and a common place to live for people employed in Silicon Valley companies such as Apple and Google.[110]

The early 2020s featured an exodus of tech companies from Downtown San Francisco in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and struggles with homelessness and public drug use. Although some observers have raised the possibility that office vacancies and declining tax revenues could cause San Francisco to enter an economic doom loop,[111][112] other sources have refuted this broad-based characterization of the city as a whole, asserting that the issues of concern are restricted primarily to the urban core of San Francisco.[43][113] As of March 2024, Union Square was in "sorry shape" and had lost its traditional position as the Bay Area's regional shopping hub[114] to Westfield Valley Fair in San Jose.[115]

The Ferry Station Post Office Building, Armour & Co. Building, Atherton House, and YMCA Hotel are historic buildings among dozens of historical landmarks in the city, according to the National Register of Historic Places listings in San Francisco.[116]

Geography

[edit]

San Francisco is located on the West Coast of the United States, at the north end of the San Francisco Peninsula and includes significant stretches of the Pacific Ocean and San Francisco Bay within its boundaries. Several picturesque islands—Alcatraz, Treasure Island and the adjacent Yerba Buena Island, and small portions of Alameda Island, Red Rock Island, and Angel Island—are part of the city. Also included are the uninhabited Farallon Islands, 27 miles (43 km) offshore in the Pacific Ocean. The mainland within the city limits roughly forms a "seven-by-seven-mile square," a common local colloquialism referring to the city's shape, though its total area, including water, is nearly 232 square miles (600 km2).

There are more than 50 hills within the city limits.[117] Some neighborhoods are named after the hill on which they are situated, including Nob Hill, Potrero Hill, and Russian Hill.Near the geographic center of the city, southwest of the downtown area, are a series of less densely populated hills. Twin Peaks, a pair of hills forming one of the city's highest points, forms an overlook spot. San Francisco's tallest hill, Mount Davidson, is 928 feet (283 m) high and is capped with a 103-foot (31 m) tall cross built in 1934.[118] Dominating this area is Sutro Tower, a large red and white radio and television transmission tower reaching 1,811 ft (552 m) above sea level.

The nearby San Andreas and Hayward Faults are responsible for much earthquake activity, although neither physically passes through the city itself. The San Andreas Fault caused the earthquakes in 1906 and 1989. Minor earthquakes occur on a regular basis. The threat of major earthquakes plays a large role in the city's infrastructure development. The city constructed an auxiliary water supply system and has repeatedly upgraded its building codes, requiring retrofits for older buildings and higher engineering standards for new construction.[119] However, there are still thousands of smaller buildings that remain vulnerable to quake damage.[120] USGS has released the California earthquake forecast which models earthquake occurrence in California.[121]

San Francisco's shoreline has grown beyond its natural limits. Entire neighborhoods such as the Marina, Mission Bay, and Hunters Point, as well as large sections of the Embarcadero, sit on areas of landfill. Treasure Island was constructed from material dredged from the bay as well as material resulting from the excavation of the Yerba Buena Tunnel through Yerba Buena Island during the construction of the Bay Bridge. Such land tends to be unstable during earthquakes. The resulting soil liquefaction causes extensive damage to property built upon it, as was evidenced in the Marina district during the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.[122] A few natural lakes and creeks (Lake Merced, Mountain Lake, Pine Lake, Lobos Creek, El Polin Spring) are within parks and remain protected in what is essentially their original form, but most of the city's natural watercourses, such as Islais Creek and Mission Creek, have been partially or completely culverted and built over. Since the 1990s, however, the Public Utilities Commission has been studying proposals to daylight or restore some creeks.[123]

Neighborhoods

[edit]

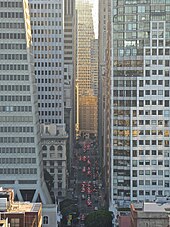

The historic center of San Francisco is the northeast quadrant of the city anchored by Market Street and the waterfront. Here the Financial District is centered, with Union Square, the principal shopping and hotel district, and the Tenderloin nearby. Cable cars carry riders up steep inclines to the summit of Nob Hill, once the home of the city's business tycoons, and down to the waterfront tourist attractions of Fisherman's Wharf, and Pier 39, where many restaurants feature Dungeness crab from a still-active fishing industry. Also in this quadrant are Russian Hill, a residential neighborhood with the famously crooked Lombard Street; North Beach, the city's Little Italy and the former center of the Beat Generation; and Telegraph Hill, which features Coit Tower. Abutting Russian Hill and North Beach is San Francisco's Chinatown, the oldest Chinatown in North America.[124][125][126][127] The South of Market, which was once San Francisco's industrial core, has seen significant redevelopment following the construction of Oracle Park and an infusion of startup companies. New skyscrapers, live-work lofts, and condominiums dot the area. Further development is taking place just to the south in Mission Bay area, a former railroad yard, which now has a second campus of the University of California, San Francisco and Chase Center, which opened in 2019 as the new home of the Golden State Warriors.[128]

West of downtown, across Van Ness Avenue, lies the large Western Addition neighborhood, which became established with a large African American population after World War II. The Western Addition is usually divided into smaller neighborhoods including Hayes Valley, the Fillmore, and Japantown, which was once the largest Japantown in North America but suffered when its Japanese American residents were forcibly removed and interned during World War II. The Western Addition survived the 1906 earthquake with its Victorians largely intact, including the famous "Painted Ladies," standing alongside Alamo Square. To the south, near the geographic center of the city is Haight-Ashbury, famously associated with 1960s hippie culture.[129] The Haight is now[timeframe?] home to some expensive boutiques[130][better source needed] and a few controversial chain stores,[131] although it still retains[timeframe?][citation needed] some bohemian character.

North of the Western Addition is Pacific Heights, an affluent neighborhood that features the homes built by wealthy San Franciscans in the wake of the 1906 earthquake. Directly north of Pacific Heights facing the waterfront is the Marina, a neighborhood popular with young professionals that was largely built on reclaimed land from the Bay.[132]

In the southeast quadrant of the city is the Mission District—populated in the 19th century by Californios and working-class immigrants from Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Scandinavia. In the 1910s, a wave of Central American immigrants settled in the Mission and, in the 1950s, immigrants from Mexico began to predominate.[133] In recent years, gentrification has changed the demographics of parts of the Mission from Latino, to twenty-something professionals. Noe Valley to the southwest and Bernal Heights to the south are both increasingly popular among young families with children. East of the Mission is the Potrero Hill neighborhood, a mostly residential neighborhood that features sweeping views of downtown San Francisco. West of the Mission, the area historically known as Eureka Valley, now popularly called the Castro, was once a working-class Scandinavian and Irish area. It has become North America's first gay village, and is now the center of gay life in the city.[134] Located near the city's southern border, the Excelsior District is one of the most ethnically diverse neighborhoods in San Francisco. The Bayview-Hunters Point in the far southeast corner of the city is one of the poorest neighborhoods, though the area has been the focus of several revitalizing and urban renewal projects.

The construction of the Twin Peaks Tunnel in 1918 connected southwest neighborhoods to downtown via streetcar, hastening the development of West Portal, and nearby affluent Forest Hill and St. Francis Wood. Further west, stretching all the way to the Pacific Ocean and north to Golden Gate Park lies the vast Sunset District, a large middle-class area with a predominantly Asian population.[135]

The northwestern quadrant of the city contains the Richmond, a mostly middle-class neighborhood north of Golden Gate Park, home to immigrants from other parts of Asia as well as many Russian and Ukrainian immigrants. Together, these areas are known as The Avenues. These two districts are each sometimes further divided into two regions: the Outer Richmond and Outer Sunset can refer to the more western portions of their respective district and the Inner Richmond and Inner Sunset can refer to the more eastern portions.

Many piers remained derelict for years until the demolition of the Embarcadero Freeway reopened the downtown waterfront, allowing for redevelopment. The centerpiece of the port, the Ferry Building, while still receiving commuter ferry traffic, has been restored and redeveloped as a gourmet marketplace.

Climate

[edit]

San Francisco has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csb), characteristic of California's coast, with moist winters and dry summers.[136] San Francisco's weather is strongly influenced by the cool currents of the Pacific Ocean on the west side of the city, and the water of San Francisco Bay to the north and east. This moderates temperature swings and produces a remarkably mild year-round climate with little seasonal temperature variation.[137]

Among major U.S. cities, San Francisco has the coolest daily mean, maximum, and minimum temperatures for June, July, and August.[138]During the summer, rising hot air in California's interior valleys creates a low-pressure area that draws winds from the North Pacific High through the Golden Gate, which creates the city's characteristic cool winds and fog.[139] The fog is less pronounced in eastern neighborhoods and during the late summer and early fall. As a result, the year's warmest month, on average, is September, and on average, October is warmer than July, especially in daytime.

Temperatures reach or exceed 80 °F (27 °C) on an average of only 21 and 23 days a year at downtown and San Francisco International Airport (SFO), respectively.[140] The dry period of May to October is mild to warm, with the normal monthly mean temperature peaking in September at 62.7 °F (17.1 °C).[140] The rainy period of November to April is slightly cooler, with the normal monthly mean temperature reaching its lowest in January at 51.3 °F (10.7 °C).[140] On average, there are 73 rainy days a year, and annual precipitation averages 23.65 inches (601 mm).[140] Variation in precipitation from year to year is high. Above-average rain years are often associated with warm El Niño conditions in the Pacific while dry years often occur in cold water La Niña periods. In 2013 (a "La Niña" year), a record low 5.59 in (142 mm) of rainfall was recorded at downtown San Francisco, where records have been kept since 1849.[140] Snowfall in the city is very rare, with only 10 measurable accumulations recorded since 1852, most recently in 1976 when up to 5 inches (13 cm) fell on Twin Peaks.[141][142]

The highest recorded temperature at the official National Weather Service downtown observation station[b] was 106 °F (41 °C) on September 1, 2017.[144] During that hot spell, the warmest ever night of 71 °F (22 °C) was also recorded.[145] The lowest recorded temperature was 27 °F (−3 °C) on December 11, 1932.[146]

During an average year between 1991 and 2020, San Francisco recorded a warmest night at 64 °F (18 °C) and a coldest day at 49 °F (9 °C).[140] The coldest daytime high since the station's opening in 1945 was recorded in December 1972 at 37 °F (3 °C).[140]

As a coastal city, San Francisco will be heavily affected by climate change. As of 2021[update], sea levels are projected to rise by as much as 5 feet (1.5 m), resulting in periodic flooding, rising groundwater levels, and lowland floods from more severe storms.[147]

San Francisco falls under the USDA 10b Plant hardiness zone, though some areas, particularly downtown, border zone 11a.[148][149]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) | 81 (27) | 87 (31) | 94 (34) | 97 (36) | 103 (39) | 99 (37) | 98 (37) | 106 (41) | 102 (39) | 86 (30) | 76 (24) | 106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 67.1 (19.5) | 71.8 (22.1) | 76.4 (24.7) | 80.7 (27.1) | 81.4 (27.4) | 84.6 (29.2) | 80.5 (26.9) | 83.4 (28.6) | 90.8 (32.7) | 87.9 (31.1) | 75.8 (24.3) | 66.4 (19.1) | 94.0 (34.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 57.8 (14.3) | 60.4 (15.8) | 62.1 (16.7) | 63.0 (17.2) | 64.1 (17.8) | 66.5 (19.2) | 66.3 (19.1) | 67.9 (19.9) | 70.2 (21.2) | 69.8 (21.0) | 63.7 (17.6) | 57.9 (14.4) | 64.1 (17.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 52.2 (11.2) | 54.2 (12.3) | 55.5 (13.1) | 56.4 (13.6) | 57.8 (14.3) | 59.7 (15.4) | 60.3 (15.7) | 61.7 (16.5) | 62.9 (17.2) | 62.1 (16.7) | 57.2 (14.0) | 52.5 (11.4) | 57.7 (14.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 46.6 (8.1) | 47.9 (8.8) | 48.9 (9.4) | 49.7 (9.8) | 51.4 (10.8) | 53.0 (11.7) | 54.4 (12.4) | 55.5 (13.1) | 55.6 (13.1) | 54.4 (12.4) | 50.7 (10.4) | 47.0 (8.3) | 51.3 (10.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 40.5 (4.7) | 42.0 (5.6) | 43.7 (6.5) | 45.0 (7.2) | 48.0 (8.9) | 50.1 (10.1) | 51.6 (10.9) | 52.9 (11.6) | 52.0 (11.1) | 49.9 (9.9) | 44.9 (7.2) | 40.7 (4.8) | 38.8 (3.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 29 (−2) | 31 (−1) | 33 (1) | 40 (4) | 42 (6) | 46 (8) | 47 (8) | 46 (8) | 47 (8) | 43 (6) | 38 (3) | 27 (−3) | 27 (−3) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.40 (112) | 4.37 (111) | 3.15 (80) | 1.60 (41) | 0.70 (18) | 0.20 (5.1) | 0.01 (0.25) | 0.06 (1.5) | 0.10 (2.5) | 0.94 (24) | 2.60 (66) | 4.76 (121) | 22.89 (581) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.2 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 6.8 | 4.0 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 7.9 | 11.6 | 71.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 80 | 77 | 75 | 72 | 72 | 71 | 75 | 75 | 73 | 71 | 75 | 78 | 75 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 185.9 | 207.7 | 269.1 | 309.3 | 325.1 | 311.4 | 313.3 | 287.4 | 271.4 | 247.1 | 173.4 | 160.6 | 3,061.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 61 | 69 | 73 | 78 | 74 | 70 | 70 | 68 | 73 | 71 | 57 | 54 | 69 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Source 1: NOAA (sun 1961–1974)[140][150][151][152] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Met Office (humidity),[153] Weather Atlas (UV)[154] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

[edit]

Historically, tule elk were present in San Francisco County, based on archeological evidence of elk remains in at least five different Native American shellmounds: at Hunter's Point, Fort Mason, Stevenson Street, Market Street, and Yerba Buena.[155][156] Perhaps the first historical observer record was from the De Anza Expedition on March 23, 1776. Herbert Eugene Bolton wrote about the expedition camp at Mountain Lake, near the southern end of today's Presidio: "Round about were grazing deer, and scattered here and there were the antlers of large elk."[157] Also, when Richard Henry Dana Jr. visited San Francisco Bay in 1835, he wrote about vast elk herds near the Golden Gate: on December 27 ."..we came to anchor near the mouth of the bay, under a high and beautifully sloping hill, upon which herds of hundreds and hundreds of red deer [note: "red deer" is the European term for "elk"], and the stag, with his high branching antlers, were bounding about...," although it is not clear whether this was the Marin side or the San Francisco side.[158]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1848 | 1,000 | — |

| 1849 | 25,000 | +2400.0% |

| 1852 | 34,776 | +39.1% |

| 1860 | 56,802 | +63.3% |

| 1870 | 149,473 | +163.1% |

| 1880 | 233,959 | +56.5% |

| 1890 | 298,997 | +27.8% |

| 1900 | 342,782 | +14.6% |

| 1910 | 416,912 | +21.6% |

| 1920 | 506,676 | +21.5% |

| 1930 | 634,394 | +25.2% |

| 1940 | 634,536 | +0.0% |

| 1950 | 775,357 | +22.2% |

| 1960 | 740,316 | −4.5% |

| 1970 | 715,674 | −3.3% |

| 1980 | 678,974 | −5.1% |

| 1990 | 723,959 | +6.6% |

| 2000 | 776,733 | +7.3% |

| 2010 | 805,235 | +3.7% |

| 2020 | 873,965 | +8.5% |

| 2023 | 808,988 | −7.4% |

| https://www.sfchronicle.com/sf/article/s-f-exodus-population-recovery-data-18564064.php | ||

The 2020 United States census showed San Francisco's population to be 873,965, an increase of 8.5% from the 2010 census.[16] With roughly one-quarter the population density of Manhattan, San Francisco is the second-most densely populated large American city, behind only New York City among cities greater than 200,000 population, and the fifth-most densely populated U.S. county, following only four of the five New York City boroughs.

San Francisco is part of the five-county San Francisco–Oakland–Hayward, CA Metropolitan Statistical Area, a region of 4.7 million people (13th most populous in the U.S.), and has served as its traditional demographic focal point. It is also part of the greater 14-county San Jose-San Francisco-Oakland, CA Combined Statistical Area, whose population is over 9.6 million, making it the fifth-largest in the United States as of 2018[update].[159][failed verification]

Race, ethnicity, religion, and languages

[edit]

As of the 2020[update] census, the racial makeup and population of San Francisco included: 361,382 Whites (41.3%), 296,505 Asians (33.9%), 46,725 African Americans (5.3%), 86,233 Multiracial Americans (9.9%), 6,475 Native Americans and Alaska Natives (0.7%), 3,476 Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders (0.4%) and 73,169 persons of other races (8.4%). There were 136,761 Hispanic or Latino residents of any race (15.6%).

San Francisco is a majority minority city, as non-Hispanic White residents comprise less than half of the population; in 1940 they formed 92.5% of the population.[160]

In 2010, residents of Chinese ethnicity constituted the largest single ethnic minority group in San Francisco at 21% of the population; other large Asian groups include Filipinos (5%) and Vietnamese (2%), with Japanese, Koreans and many other Asian and Pacific Islander groups represented in the city.[161] The population of Chinese ancestry is most heavily concentrated in Chinatown and the Sunset and Richmond Districts. Filipinos are most concentrated in SoMa and the Crocker-Amazon; the latter neighborhood shares a border with Daly City, which has one of the highest concentrations of Filipinos in North America.[161][162] The Tenderloin District is home to a large portion of the city's Vietnamese population as well as businesses and restaurants, which is known as the city's Little Saigon.[161]

The principal Hispanic groups in the city were those of Mexican (7%) and Salvadoran (2%) ancestry. The Hispanic population is most heavily concentrated in the Mission District, Tenderloin District, and Excelsior District.[163] The city's percentage of Hispanic residents is less than half of that of the state.

African Americans constituted about 5% of San Francisco's population in 2020; their share of the city's population has been decreasing since the 1970s.[164] The majority of the city's Black residents live in the neighborhoods of Bayview-Hunters Point, Visitacion Valley, and the Fillmore District.[163] There are smaller Black communities in Diamond Heights, Glen Park, and Mission District.

The city has long been home to a significant Jewish community; in 2018 Jewish Americans made up an estimated 10% (80,000) of the city's population. It the third-largest Jewish community in proportional terms in the United States, behind only those of New York City, and Los Angeles, respectively, and it is also relatively young compared to other major U.S. cities.[165] The Jewish community resides throughout the city, but the Richmond District is home to an ethnic enclave of mostly Russian Jews.[166] The Fillmore District was formerly a mostly Jewish neighborhood from the 1920s until the 1970s, when many of its Jewish residents moved to other neighborhoods of the city as well as the suburbs of nearby Marin County.[167]

Source: U.S. Census and IPUMS USA[168] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

According to a 2018 study by the Jewish Community Federation of San Francisco, Jews make up 10% (80,000) of the city's population, making Judaism the second-largest religion in San Francisco after Christianity.[165] A prior 2014 study by the Pew Research Center, the largest religious groupings in San Francisco's metropolitan area are Christians (48%), followed by those of no religion (35%), Hindus (5%), Jews (3%), Buddhists (2%), Muslims (1%) and a variety of other religions have smaller followings. According to the same study by the Pew Research Center, about 20% of residents in the area are Protestant, and 25% professing Roman Catholic beliefs. Meanwhile, 10% of the residents in metropolitan San Francisco identify as agnostics, while 5% identify as atheists.[170][171]

As of 2010[update], 55% (411,728) of San Francisco residents spoke only English at home, while 19% (140,302) spoke a variety of Chinese (mostly Taishanese and Cantonese[172][173]), 12% (88,147) Spanish, 3% (25,767) Tagalog, and 2% (14,017) Russian. In total, 45% (342,693) of San Francisco's population spoke a language at home other than English.[174]

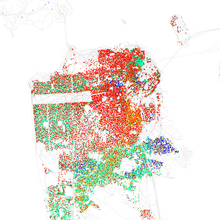

Ethnic clustering

[edit]San Francisco has several prominent Chinese, Mexican, and Filipino neighborhoods including Chinatown and the Mission District. Research collected on the immigrant clusters in the city show that more than half of the Asian population in San Francisco is either Chinese-born (40.3%) or Philippine-born (13.1%), and of the Mexican population 21% were Mexican-born, meaning these are people who recently immigrated to the United States.[175] Between the years of 1990 and 2000, the number of foreign-born residents increased from 33% to nearly 40%.[175] During this same time period, the San Francisco metropolitan area received 850,000 immigrants, ranking third in the United States after Los Angeles and New York.[175]

Education, households, and income

[edit]

Of all major cities in the United States, San Francisco has the second-highest percentage of residents with a college degree, second only to Seattle. Over 44% of adults have a bachelor's or higher degree.[177]San Francisco had the highest rate at 7,031 per square mile, or over 344,000 total graduates in the city's 46.7 square miles (121 km2).[178]

San Francisco has the highest estimated percentage of gay and lesbian individuals of any of the 50 largest U.S. cities, at 15%.[179]San Francisco also has the highest percentage of same-sex households of any American county, with the Bay Area having a higher concentration than any other metropolitan area.[180]

San Francisco ranks third of American cities in median household income[181] with a 2007 value of $65,519.[182] Median family income is $81,136.[182]An emigration of middle-class families has left the city with a lower proportion of children than any other large American city,[183] with the dog population cited as exceeding the child population of 115,000, in 2018.[184]The city's poverty rate is 12%, lower than the national average.[185]Homelessness has been a chronic problem for San Francisco since the early 1970s.[186]The city is believed to have the highest number of homeless inhabitants per capita of any major U.S. city.[187][188]

There are 345,811 households in the city, out of which: 133,366 households (39%) were individuals, 109,437 (32%) were opposite-sex married couples, 63,577 (18%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 21,677 (6%) were unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 10,384 (3%) were same-sex married couples or partnerships. The average household size was 2.26; the average family size was 3.11. 452,986 people (56%) lived in rental housing units, and 327,985 people (41%) lived in owner-occupied housing units.The median age of the city population is 38 years.

San Francisco declared itself a sanctuary city in 1989, and city officials strengthened the stance in 2013 with its 'Due Process for All' ordinance. The law declared local authorities could not hold immigrants for immigration offenses if they had no violent felonies on their records and did not currently face charges."[189] The city issues a Resident ID Card regardless of the applicant's immigration status.[190]

Homelessness

[edit]

Homelessness in San Francisco emerged as a major issue in the late 20th century and remains a growing problem in modern times.[191]

8,035 homeless people were counted in San Francisco's 2019 point-in-time street and shelter count. This was an increase of more than 17% over the 2017 count of 6,858 people. 5,180 of the people were living unsheltered on the streets and in parks.[192] 26% of respondents in the 2019 count identified job loss as the primary cause of their homelessness, 18% cited alcohol or drug use, and 13% cited being evicted from their residence.[192] The city of San Francisco has been dramatically increasing its spending to service the growing population homelessness crisis: spending jumped by $241 million in 2016–17 to total $275 million, compared to a budget of just $34 million the previous year. In 2017–18 the budget for combatting homelessness stood at $305 million.[193] In the 2019–2020 budget year, the city budgeted $368 million for homelessness services. In the proposed 2020–2021 budget the city budgeted $850 million for homelessness services.[194]

In January 2018 a United Nations special rapporteur on homelessness, Leilani Farha, stated that she was "completely shocked" by San Francisco's homelessness crisis during a visit to the city. She compared the "deplorable conditions" of the homeless camps she witnessed on San Francisco's streets to those she had seen in Mumbai.[193] In May 2020, San Francisco officially sanctioned homeless encampments.[195]

Crime

[edit]This article needs to be updated. (March 2024) |

San Francisco's violent crime rate is low compared to other major cities, though many residents are still concerned about it.[196]

In 2011, 50 murders were reported, which is 6.1 per 100,000 people.[197] There were about 134 rapes, 3,142 robberies, and about 2,139 assaults. There were about 4,469 burglaries, 25,100 thefts, and 4,210 motor vehicle thefts.[198] The Tenderloin area has the highest crime rate in San Francisco: 70% of the city's violent crimes, and around one-fourth of the city's murders, occur in this neighborhood. The Tenderloin also sees high rates of drug abuse, gang violence, and prostitution.[199] Another area with high crime rates is the Bayview-Hunters Point area. In the first six months of 2015 there were 25 murders compared to 14 in the first six months of 2014. However, the murder rate is still much lower than in past decades.[200] That rate, though, did rise again by the close of 2016. According to the San Francisco Police Department, there were 59 murders in the city in 2016, an annual total that marked a 13.5% increase in the number of homicides (52) from 2015.[201] The city has also gained a reputation for car break-ins, with over 19,000 car break-ins occurring in 2021.[202]

During the first half of 2018, human feces on San Francisco sidewalks were the second-most-frequent complaint of city residents, with about 65 calls per day. The city has formed a "poop patrol" to attempt to combat the problem.[203]

In January 2022, CBS News reported that a single suspect was "responsible for more than half of all reported hate crimes against the API community in San Francisco last year," and that he "was allowed to be out of custody despite the number of charges against him."[204]

Several street gangs have operated in the city over the decades, including MS-13,[205] the Sureños and Norteños in the Mission District.[206]

African-American street gangs familiar in other cities, including the Bloods, Crips and their sets, have struggled to establish footholds in San Francisco,[207] while police and prosecutors have been accused of liberally labeling young African-American males as gang members.[208]

Criminal gangs with shot callers in China, including Triad groups such as the Wo Hop To, were active in San Francisco in the 20th century.[209] According to statistics released by SFPD in April 2024, the crime figures were down in the first 100 days of the year, namely in terms of robberies, burglaries and larceny.[210]

Economy

[edit]

The city has a diversified service economy, with employment spread across a wide range of professional services, including tourism, financial services, and (increasingly) high technology.[212] In 2016, approximately 27% of workers were employed in professional business services; 14% in leisure and hospitality; 13% in government services; 12% in education and health care; 11% in trade, transportation, and utilities; and 8% in financial activities.[212] In 2019, GDP in the five-county San Francisco metropolitan area grew 3.8% in real terms to $592 billion.[213][214] Additionally, in 2019 the 14-county San Jose–San Francisco–Oakland combined statistical area had a GDP of $1.086 trillion,[214] ranking 3rd among CSAs, and ahead of all but 16 countries. As of 2019[update], San Francisco County was the 7th highest-income county in the United States (among 3,142), with a per capita personal income of $139,405.[215] Marin County, directly to the north over the Golden Gate Bridge, and San Mateo County, directly to the south on the Peninsula, were the 6th and 9th highest-income counties respectively.

The legacy of the California gold rush turned San Francisco into the principal banking and finance center of the West Coast in the early twentieth century.[216] Montgomery Street in the Financial District became known as the "Wall Street of the West," home to the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, and the site of the now-defunct Pacific Coast Stock Exchange.[216] Bank of America, a pioneer in making banking services accessible to the middle class, was founded in San Francisco and in the 1960s, built the landmark modern skyscraper at 555 California Street for its corporate headquarters, since relocated to Charlotte, North Carolina. Many large financial institutions, multinational banks, and venture capital firms are based in or have regional headquarters in the city. With over 30 international financial institutions,[217] six Fortune 500 companies,[218] and a large supporting infrastructure of professional services—including law, public relations, architecture and design—San Francisco is designated as an Alpha(-) World City.[219] The 2017 Global Financial Centres Index ranked San Francisco as the sixth-most competitive financial center in the world.[220]

Beginning in the 1990s, San Francisco's economy diversified away from finance and tourism towards the growing fields of high tech, biotechnology, and medical research.[221] Technology jobs accounted for just 1 percent of San Francisco's economy in 1990, growing to 4 percent in 2010 and an estimated 8 percent by the end of 2013.[222] San Francisco became a center of Internet start-up companies during the dot-com bubble of the 1990s and the subsequent social media boom of the late 2000s (decade).[223] Since 2010, San Francisco proper has attracted an increasing share of venture capital investments as compared to nearby Silicon Valley, attracting 423 financings worth US$4.58 billion in 2013.[224][225][226] In 2004, the city approved a payroll tax exemption for biotechnology companies[227] to foster growth in the Mission Bay neighborhood, site of a second campus and hospital of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Mission Bay hosts the UCSF Medical Center, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences, and Gladstone Institutes,[228] as well as more than 40 private-sector life sciences companies.[229]

According to academic Rob Wilson, San Francisco is a global city, a status that pre-dated the city's popularity during the California gold rush.[231] However, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to high office vacancy rates and the closure of many retail and tech businesses in the downtown core of San Francisco.[232][233] Attributed causes include a shift to remote work in the technology and professional services sectors, as well as high levels of homelessness, drug use, and crime in areas around downtown San Francisco, such as the Tenderloin and Mid-Market neighborhoods.[234][235]

The top employer in San Francisco is the city government itself, employing 5.6% (31,000+ people) of the city's workforce, followed by UCSF with over 25,000 employees.[236] The largest private-sector employer is Salesforce, with 8,500 employees, as of 2018[update].[237] Small businesses with fewer than 10 employees and self-employed firms made up 85% of city establishments in 2006,[238] and the number of San Franciscans employed by firms of more than 1,000 employees has fallen by half since 1977.[239] The growth of national big box and formula retail chains into the city has been made intentionally difficult by political and civic consensus. In an effort to buoy small privately owned businesses in San Francisco and preserve the unique retail personality of the city, the Small Business Commission started a publicity campaign in 2004 to keep a larger share of retail dollars in the local economy,[240] and the Board of Supervisors has used the planning code to limit the neighborhoods where formula retail establishments can set up shop,[241] an effort affirmed by San Francisco voters.[242] However, by 2016, San Francisco was rated low by small businesses in a Business Friendliness Survey.[243]

Like many U.S. cities, San Francisco once had a significant manufacturing sector employing nearly 60,000 workers in 1969, but nearly all production left for cheaper locations by the 1980s.[244] As of 2014[update], San Francisco has seen a small resurgence in manufacturing, with more than 4,000 manufacturing jobs across 500 companies, doubling since 2011. The city's largest manufacturing employer is Anchor Brewing Company, and the largest by revenue is Timbuk2.[244]

As of the first quarter of 2022[update], the median value of homes in San Francisco County was $1,297,030. It ranked third in the U.S. for counties with highest median home value, behind Nantucket, Massachusetts and San Mateo County, California.[245]

Technology

[edit]

San Francisco became a hub for technological driven economic growth during the internet boom of the 1990s, and still holds an important position in the world city network today.[175][246] Intense redevelopment towards the "new economy" makes business more technologically minded. Between the years of 1999 and 2000, the job growth rate was 4.9%, creating over 50,000 jobs in technology firms and internet content production.[175] However, the technology industry has become geographically dispersed.[247][248]

In the second technological boom driven by social media in the mid-2000s, San Francisco became a location for companies such as Apple, Google, Ubisoft, Facebook, and Twitter to base their tech offices and for their employees to live.[249]

Tourism and conventions

[edit]

Tourism is one of San Francisco's most important private-sector industries, accounting for more than one out of seven jobs in the city.[221][250] The city's frequent portrayal in music, film, and popular culture has made the city and its landmarks recognizable worldwide. In 2016, it attracted the fifth-highest number of foreign tourists of any city in the United States.[251] More than 25 million visitors arrived in San Francisco in 2016, adding US$9.96 billion to the economy.[252]With a large hotel infrastructure and a major convention facility in the Moscone Center, San Francisco is a popular destination for annual conventions and conferences.[253]

Some of the most popular tourist attractions in San Francisco, as noted by the Travel Channel, include the Golden Gate Bridge and Alamo Square Park, home to the famous "Painted Ladies." Both of these locations were often used as landscape shots for the hit American television sitcom Full House. There is also Lombard Street, known for its "crookedness" and extensive views. Tourists also visit Pier 39, which offers dining, shopping, entertainment, and views of the bay, sunbathing California sea lions, the Aquarium of the Bay, and the famous Alcatraz Island.[254]

San Francisco also offers tourists varied nightlife in its neighborhoods.[255][256]

The new Terminal Project at Pier 27 opened September 25, 2014, as a replacement for the old Pier 35.[257] Itineraries from San Francisco usually include round-trip cruises to Alaska and Mexico.

A heightened interest in conventioneering in San Francisco, marked by the establishment of convention centers such as Yerba Buena, acted as a feeder into the local tourist economy and resulted in an increase in the hotel industry: "In 1959, the city had fewer than thirty-three hundred first-class hotel rooms; by 1970, the number was nine thousand; and by 1999, there were more than thirty thousand."[258] The commodification of the Castro District has contributed to San Francisco's tourist economy.[259]

Arts and culture

[edit]

Although the Financial District, Union Square, and Fisherman's Wharf are well known around the world, San Francisco is also characterized by its numerous culturally rich streetscapes featuring mixed-use neighborhoods anchored around central commercial corridors to which residents and visitors alike can walk.[citation needed] Because of these characteristics,[original research?] San Francisco is ranked the "most walkable" city in the United States by Walkscore.com.[260] Many neighborhoods feature a mix of businesses, restaurants and venues that cater to the daily needs of local residents while also serving many visitors and tourists. Some neighborhoods are dotted with boutiques, cafés and nightlife such as Union Street in Cow Hollow, 24th Street in Noe Valley, Valencia Street in the Mission, Grant Avenue in North Beach, and Irving Street in the Inner Sunset. This approach especially has influenced the continuing South of Market neighborhood redevelopment with businesses and neighborhood services rising alongside high-rise residences.[261][failed verification]

Since the 1990s, the demand for skilled information technology workers from local startups and nearby Silicon Valley has attracted white-collar workers from all over the world and created a high standard of living in San Francisco.[263] Many neighborhoods that were once blue-collar, middle, and lower class have been gentrifying, as many of the city's traditional business and industrial districts have experienced a renaissance driven by the redevelopment of the Embarcadero, including the neighborhoods South Beach and Mission Bay. The city's property values and household income have risen to among the highest in the nation,[264][265][266] creating a large and upscale restaurant, retail, and entertainment scene. According to a 2014 quality of life survey of global cities, San Francisco has the highest quality of living of any U.S. city.[267] However, due to the exceptionally high cost of living, many of the city's middle and lower-class families have been leaving the city for the outer suburbs of the Bay Area, or for California's Central Valley.[268] By June 2, 2015, the median rent was reported to be as high as $4,225.[269] The high cost of living is due in part to restrictive planning laws which limit new residential construction.[270]

The international character that San Francisco has enjoyed since its founding is continued today by large numbers of immigrants from Asia and Latin America. With 39% of its residents born overseas,[239] San Francisco has numerous neighborhoods filled with businesses and civic institutions catering to new arrivals. In particular, the arrival of many ethnic Chinese, which began to accelerate in the 1970s, has complemented the long-established community historically based in Chinatown throughout the city and has transformed the annual Chinese New Year Parade into the largest event of its kind on the West Coast.

With the arrival of the "beat" writers and artists of the 1950s and societal changes culminating in the Summer of Love in the Haight-Ashbury district during the 1960s, San Francisco became a center of liberal activism and of the counterculture that arose at that time. The Democrats and to a lesser extent the Green Party have dominated city politics since the late 1970s, after the last serious Republican challenger for city office lost the 1975 mayoral election by a narrow margin. San Francisco has not voted more than 20% for a Republican presidential or senatorial candidate since 1988.[271] In 2007, the city expanded its Medicaid and other indigent medical programs into the Healthy San Francisco program,[272] which subsidizes certain medical services for eligible residents.[273][274][275]

Since 1993, the San Francisco Department of Public Health has distributed 400,000 free syringes every month aimed at reducing HIV and other health risks for drug users, as well as providing disposal sites and services.[276][277][278]

San Francisco also has had a very active environmental community. Starting with the founding of the Sierra Club in 1892 to the establishment of the non-profit Friends of the Urban Forest in 1981, San Francisco has been at the forefront of many global discussions regarding the environment.[279][280] The 1980 San Francisco Recycling Program was one of the earliest curbside recycling programs.[281] The city's GoSolarSF incentive promotes solar installations and the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission is rolling out the CleanPowerSF program to sell electricity from local renewable sources.[282][283] SF Greasecycle is a program to recycle used cooking oil for conversion to biodiesel.[284]

The Sunset Reservoir Solar Project, completed in 2010, installed 24,000 solar panels on the roof of the reservoir. The 5-megawatt plant more than tripled the city's 2-megawatt solar generation capacity when it opened in December 2010.[285][286]

LGBT

[edit]

San Francisco has long had an LGBT-friendly history. It was home to the first lesbian-rights organization in the United States, Daughters of Bilitis; the first openly gay person to run for public office in the United States, José Sarria; the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California, Harvey Milk; the first openly lesbian judge appointed in the U.S., Mary C. Morgan; and the first transgender police commissioner, Theresa Sparks. The city's large gay population has created and sustained a politically and culturally active community over many decades, developing a powerful presence in San Francisco's civic life.[287] Survey data released in 2015 by Gallup places the proportion of LGBT adults in the San Francisco metro area at 6.2%, which is the highest proportion of the 50 most populous metropolitan areas as measured by the polling organization.[288]

One of the most popular destinations for gay tourists internationally, the city hosts San Francisco Pride, one of the largest and oldest pride parades. San Francisco Pride events have been held continuously since 1972. The events are themed and a new theme is created each year.[289] In 2013, over 1.5 million people attended, around 500,000 more than the previous year.[290] Pink Saturday is an annual street party held the Saturday before the pride parade, which coincides with the Dyke march.

The Folsom Street Fair (FSF) is an annual BDSM and leather subculture street fair that is held in September, endcapping San Francisco's "Leather Pride Week."[291] It started in 1984 and is California's third-largest single-day, outdoor spectator event and the world's largest leather event and showcase for BDSM products and culture.[292]

Performing arts

[edit]

San Francisco's War Memorial and Performing Arts Center hosts some of the most enduring performing arts companies in the country. The War Memorial Opera House houses the San Francisco Opera, the second-largest opera company in North America[293] as well as the San Francisco Ballet, while the San Francisco Symphony plays in Davies Symphony Hall. Opened in 2013, the SFJAZZ Center hosts jazz performances year round.[294]

The Fillmore is a music venue located in the Western Addition. It is the second incarnation of the historic venue that gained fame in the 1960s, housing the stage where now-famous musicians such as the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, Led Zeppelin, and Jefferson Airplane first performed, fostering the San Francisco Sound.[295] It closed its doors in 1971 with a final performance by Santana and reopened in 1994 with a show by the Smashing Pumpkins.[296]

San Francisco has a large number of theaters and live performance venues. Local theater companies have been noted for risk taking and innovation.[297] The Tony Award-winning non-profit American Conservatory Theater (A.C.T.) is a member of the national League of Resident Theatres. Other local winners of the Regional Theatre Tony Award include the San Francisco Mime Troupe.[298]San Francisco theaters frequently host pre-Broadway engagements and tryout runs,[299] and some original San Francisco productions have later moved to Broadway.[300]

Museums

[edit]

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) houses 20th century and contemporary works of art. It moved to its current building in the South of Market neighborhood in 1995 and attracted more than 600,000 visitors annually.[301] SFMOMA closed for renovation and expansion in 2013. The museum reopened on May 14, 2016, with an addition, designed by Snøhetta, that has doubled the museum's size.[302]

The Palace of the Legion of Honor holds primarily European antiquities and works of art at its Lincoln Park building modeled after its Parisian namesake. The de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park features American decorative pieces and anthropological holdings from Africa, Oceania and the Americas, while Asian art is housed in the Asian Art Museum. Opposite the de Young stands the California Academy of Sciences, a natural history museum that also hosts the Morrison Planetarium and Steinhart Aquarium. Located on Pier 15 on the Embarcadero, the Exploratorium is an interactive science museum. The Contemporary Jewish Museum is a non-collecting institution that hosts a broad array of temporary exhibitions. On Nob Hill, the Cable Car Museum is a working museum featuring the cable car powerhouse, which drives the cables.[303] Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts was founded in 1998 and is part of the California College of the Arts.[304]

Sports

[edit]

Major League Baseball's San Francisco Giants have played in San Francisco since moving from New York in 1958. The Giants play at Oracle Park, which opened in 2000.[305] The Giants won World Series titles in 2010, 2012, and in 2014. The Giants have boasted stars such as Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, and Barry Bonds (MLB's career home run leader). In 2012, San Francisco was ranked No. 1 in a study that examined which U.S. metro areas have produced the most Major Leaguers since 1920.[306]

The San Francisco 49ers of the National Football League (NFL) began playing in 1946 as an All-America Football Conference (AAFC) league charter member, moved to the NFL in 1950 and into Candlestick Park in 1971. The team left San Francisco in 2014, moving approximately 50 miles south to Santa Clara, and began playing its home games at Levi's Stadium,[307][308] The 49ers have won five Super Bowl titles between 1982 and 1995.

The NBA's Golden State Warriors have played in the San Francisco Bay Area since moving from Philadelphia in 1962. The Warriors played as the San Francisco Warriors, from 1962 to 1971, before being renamed the Golden State Warriors prior to the 1971–1972 season in an attempt to present the team as a representation of the whole state of California, which had already adopted "The Golden State" nickname.[309] The Warriors' arena, Chase Center, is located in San Francisco.[310] After winning two championships in Philadelphia, they have won five championships since moving to the San Francisco Bay Area,[311] and made five consecutive NBA Finals from 2015 to 2019, winning three of them. They won again in 2022, the franchise's first championship while residing in San Francisco proper.

At the collegiate level, the San Francisco Dons compete in NCAA Division I. Bill Russell led the Dons basketball team to NCAA championships in 1955 and 1956. There is also the San Francisco State Gators, who compete in NCAA Division II.[312] Oracle Park hosted the annual Fight Hunger Bowl college football game from 2002 through 2013 before it moved to Santa Clara.

There are a handful of lower-league soccer clubs in San Francisco playing mostly from April – June.

| Club | Founded | Venue | League | Tier level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Farolito | 1985 | Boxer Stadium | NPSL | 4 |

| San Francisco City FC | 2001 | Kezar Stadium | USL League Two | 4 |

| San Francisco Glens SC | 1961 | Skyline College | USL League Two | 4 |

| SF Elite Metro | 2017 | Negoesco Stadium | NISA Nation | 5 |

The Bay to Breakers footrace, held annually since 1912, is best known for colorful costumes and a celebratory community spirit.[313] The San Francisco Marathon attracts more than 21,000 participants.[314] The Escape from Alcatraz triathlon has, since 1980, attracted 2,000 top professional and amateur triathletes for its annual race.[315] The Olympic Club, founded in 1860, is the oldest athletic club in the United States. Its private golf course has hosted the U.S. Open on five occasions. San Francisco hosted the 2013 America's Cup yacht racing competition.[316]

With an ideal climate for outdoor activities, San Francisco has ample resources and opportunities for amateur and participatory sports and recreation. There are more than 200 miles (320 km) of bicycle paths, lanes and bike routes in the city.[317]San Francisco residents have often ranked among the fittest in the country.[318] Golden Gate Park has miles of paved and unpaved running trails as well as a golf course and disc golf course.Boating, sailing, windsurfing and kitesurfing are among the popular activities on San Francisco Bay, and the city maintains a yacht harbor in the Marina District.

San Francisco also has had Esports teams, such as the Overwatch League's San Francisco Shock. Established in 2017,[319] they won two back-to-back championship titles in 2019 and 2020.[320][321]

Parks and recreation

[edit]

Several of San Francisco's parks and nearly all of its beaches form part of the regional Golden Gate National Recreation Area, one of the most visited units of the National Park system in the United States with over 13 million visitors a year. Among the GGNRA's attractions within the city are Ocean Beach, which runs along the Pacific Ocean shoreline and is frequented by a vibrant surfing community, and Baker Beach, which is located in a cove west of the Golden Gate Bridge, as well as the California Academy of Sciences, a research institute and natural history museum.

The Presidio of San Francisco is the former 18th century Spanish military base, which today is one of the city's largest parks and home to numerous museums and institutions. Also within the Presidio is Crissy Field, a former airfield that was restored to its natural salt marsh ecosystem. The GGNRA also administers Fort Funston, Lands End, Fort Mason, and Alcatraz. The National Park Service separately administers the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park – a fleet of historic ships and waterfront property around Aquatic Park.[citation needed]

There are more than 220 parks maintained by the San Francisco Recreation & Parks Department.[323] The largest and best-known city park is Golden Gate Park,[324] which stretches from the center of the city west to the Pacific Ocean. Once covered in native grasses and sand dunes, the park was conceived in the 1860s and was created by the extensive planting of thousands of non-native trees and plants. The large park is rich with cultural and natural attractions such as the Conservatory of Flowers, Japanese Tea Garden and San Francisco Botanical Garden.[citation needed]