Кембриджский университет

| |

| Английский : Кембриджский университет [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] | |

Другое имя | Канцлер, магистры и ученые Кембриджского университета |

|---|---|

| Девиз | Латынь : Отсюда свет и священная чаша. |

Девиз на английском языке | Буквально: Отсюда свет и священные зелья. Не буквально: Отсюда мы получаем просветление и драгоценные знания. |

| Type | Public research university Ancient university |

| Established | c. 1209 |

| Endowment | £2.47 billion (2023; excluding colleges)[4] (See § Endowment) |

| Budget | £2.32 billion (2022/2023; excluding colleges)[5] |

| Chancellor | The Lord Sainsbury of Turville |

| Vice-Chancellor | Deborah Prentice |

Academic staff | 5,940 (2022)[6] |

Administrative staff | 3,615 (excluding colleges)[6] |

| Students | 24,450 (2020)[7] |

| Undergraduates | 12,850 (2020) |

| Postgraduates | 11,600 (2020) |

| Location | , England |

| Campus |

|

| Colours | Cambridge Blue[10] |

| Affiliations | |

| Website | cam |

| |

— Кембриджский университет государственный университетский исследовательский университет в Кембридже , Англия. Кембриджский университет, основанный в 1209 году, является третьим старейшим постоянно действующим университетом в мире . Основание университета последовало за прибытием ученых, которые покинули Оксфордский университет и перебрались в Кембридж после спора с местными горожанами. [ 11 ] [ 12 ] Два старинных английских университета, хотя их иногда называют соперниками, имеют много общих черт и часто вместе называются Оксбриджем .

В 1231 году, через 22 года после основания, университет был признан королевской хартией , пожалованной королём Генрихом III . Кембриджский университет включает в себя 31 полуавтономный колледж и более 150 академических отделений, факультетов и других учреждений, организованных в шесть школ . Крупнейшим отделом является Отделение прессы и оценки Кембриджского университета , годовой доход которого составляет 1 миллиард фунтов стерлингов, а число учащихся достигает 100 миллионов человек. [ 13 ] Все колледжи являются самоуправляющимися учреждениями внутри университета, управляющими собственным персоналом и политикой, и все студенты обязаны иметь членство в колледже университета. Обучение на бакалавриате в Кембридже сосредоточено на еженедельных супервизиях в небольших группах в колледжах с лекциями, семинарами, лабораторными работами и иногда дальнейшим контролем, проводимыми центральными факультетами и кафедрами университета. [14][15]

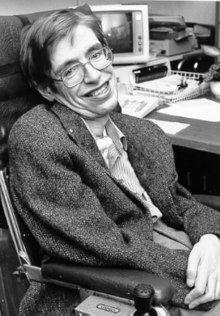

The university operates eight cultural and scientific museums, including the Fitzwilliam Museum and Cambridge University Botanic Garden. Cambridge's 116 libraries hold a total of approximately 16 million books, around nine million of which are in Cambridge University Library, a legal deposit library and one of the world's largest academic libraries. Cambridge alumni, academics, and affiliates have won 121 Nobel Prizes.[16] Among the university's notable alumni are 194 Olympic medal-winning athletes[17] and several historically iconic and transformational individuals in their respective fields, including Francis Bacon, Lord Byron, Oliver Cromwell, Charles Darwin, Rajiv Gandhi, John Harvard, Stephen Hawking, John Maynard Keynes, John Milton, Vladimir Nabokov, Jawaharlal Nehru, Isaac Newton, Sylvia Plath, Bertrand Russell, Alan Turing, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and others.

History

[edit]Founding

[edit]Prior to the founding of the University of Cambridge in 1209, Cambridge and the area surrounding it already had developed a scholarly and ecclesiastical reputation due largely to the intellectual reputation and academic contributions of monks from the nearby bishopric church in Ely. The founding of the University of Cambridge, however, was inspired largely by an incident at the University of Oxford during which three Oxford scholars, as an administration of justice in the death of a local Oxford-area woman, were hanged by town authorities without first consulting ecclesiastical authorities, who traditionally would be inclined to pardon scholars in such cases. But during this time, Oxford's town authorities were in conflict with King John. Fearing more violence from Oxford townsfolk, University of Oxford scholars began leaving Oxford for more hospitable cities, including Paris, Reading, and Cambridge. Enough scholars ultimately took residence in Cambridge to form, along with the many scholars already there, the nucleus for the new university's formation.[18][19][20]

By 1225, a chancellor of the university was appointed, and writs issued by King Henry III in 1231 established that rents in Cambridge were to be set secundum consuetudinem universitatis, according to the custom of the university, and established a panel of two masters and two townsmen to determine these. A letter from Pope Gregory IX two years later to the chancellor and the guild of scholars granted the new university ius non trahi extra, or the right not to be drawn out, for three years, meaning its members could not be summoned to a court outside of the diocese of Ely.[21]

After Cambridge was described as a studium generale in a letter from Pope Nicholas IV in 1290,[22] and confirmed as such by Pope John XXII's 1318 papal bull,[23] it became common for researchers from other European medieval universities to visit Cambridge to study or give lecture courses.[22]

Foundation of the colleges

[edit]

The 31 colleges of the present-day University of Cambridge were originally an incidental feature of the university; no college within the University of Cambridge is as old as the university itself. The colleges within the university were initially endowed fellowships of scholars. There were also institutions without endowments, called hostels, which were gradually absorbed by the colleges over the centuries, and they have left some traces, including the naming of Garret Hostel Lane and Garret Hostel Bridge, a street and bridge in Cambridge.[24]

The University of Cambridge's first college, Peterhouse, was founded in 1284 by Hugh de Balsham, the Bishop of Ely. Multiple additional colleges were founded during the 14th and 15th centuries, and colleges continued to be established during modern times, though there was a 204-year gap between the founding of Sidney Sussex in 1596 and that of Downing in 1800. The most recent college to be established is Robinson, which was built in the late 1970s. Most recently, in March 2010, Homerton College achieved full university college status, making it technically the university's newest full college.

In medieval times, many colleges were founded so that their members could pray for the souls of the founders. University of Cambridge colleges were often associated with chapels or abbeys. The colleges' focus began to shift in 1536, however, with the dissolution of the monasteries and Henry VIII's order that the university disband the canon law that governed the university's faculty[25] and stop teaching scholastic philosophy. In response, colleges changed their curricula from canon law to classics, the Bible, and mathematics.

Nearly a century later, the university found itself at the centre of a Protestant schism. Many nobles, intellectuals, and also commoners saw the Church of England as too similar to the Catholic Church and felt that it was being used by The Crown to usurp the counties' rightful powers. East Anglia emerged as the centre of what ultimately became the Puritan movement. In Cambridge, the Puritan movement was particularly strong at Emmanuel, St Catharine Hall, Sidney Sussex, and Christ's.[26] These colleges produced many nonconformist graduates who greatly influenced, by social position or preaching, some 20,000 Puritans who ultimately left England for New England and especially Massachusetts Bay Colony during the Great Migration decade of the 1630s, settling in the colonial-era Colony of Virginia and other fledgling American colonies.

Mathematics and mathematical physics

[edit]The university quickly established itself as a global leader in the study of mathematics. The university's examination in mathematics, known as the Mathematical Tripos,[27] was initially compulsory for all undergraduates studying for the Bachelor of Arts degree, the most common degree first offered at Cambridge. From the time of Isaac Newton in the late 17th century until the mid-19th century, the university maintained an especially strong emphasis on applied mathematics, and especially mathematical physics. Students awarded first class honours after completing the mathematics Tripos exam are called wranglers, and the top student among them is known as the Senior Wrangler, a position that has been described as "the greatest intellectual achievement attainable in Britain."[28]

The Cambridge Mathematical Tripos is highly competitive and has helped produce some of the most famous names in British science, including James Clerk Maxwell, Lord Kelvin, and Lord Rayleigh.[29] However, some famous students, such as G. H. Hardy, disliked the Tripos system, feeling that students were becoming too focused on accumulating high exam marks at the expense of the subject itself.

Pure mathematics at the University of Cambridge in the 19th century achieved great things, though it largely missed out on substantial developments in French and German mathematics. By the early 20th century, however, pure mathematical research at Cambridge reached the highest international standard, thanks largely to G. H. Hardy and his collaborators, J. E. Littlewood and Srinivasa Ramanujan. W. V. D. Hodge and others helped establish Cambridge as a global leader in geometry in the 1930s.

Modern period

[edit]

The Cambridge University Act 1856 formalised the university's organisational structure and introduced the study of many new subjects, including theology, history, and Modern languages.[30] Resources necessary for new courses in the arts, architecture, and archaeology were donated by Viscount Fitzwilliam of Trinity College, who also founded Fitzwilliam Museum in 1816.[31] In 1847, Prince Albert was elected the university's chancellor in a close contest with the Earl of Powis. As chancellor, Albert reformed university curricula beyond its initial focus on mathematics and classics, adding modern era history and the natural sciences. Between 1896 and 1902, Downing College sold part of its land to permit the construction of Downing Site, the university's grouping of scientific laboratories for the study of anatomy, genetics, and Earth sciences.[32] During this period, the New Museums Site was erected, including the Cavendish Laboratory, which has since moved to West Cambridge, and other departments for chemistry and medicine.[33]

The University of Cambridge began to award PhD degrees in the first third of the 20th century; the first Cambridge PhD in mathematics was awarded in 1924.[34]

The university contributed significantly to the Allies' forces in World War I with 13,878 members of the university serving and 2,470 being killed in action during the war. Teaching, and the fees it earned, nearly came to a halt during World War I, and severe financial difficulties followed. As a result, the university received its first systematic state support in 1919, and a Royal commission was appointed in 1920 to recommend that the university (but not its colleges) begin receiving an annual grant.[35] Following World War II, the university experienced a rapid expansion in applications and enrollment, partly due to the success and popularity gained by many Cambridge scientists.[36] This was not without controversies, however. For example, Cambridge researchers were accused in 2023 of helping to develop weapon systems for Iran.[37]

Parliamentary representation

[edit]The University of Cambridge was one of only two universities to hold parliamentary seats in the Parliament of England and was later one of 19 represented in the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The constituency was created by a Royal charter of 1603 and returned two members of parliament until 1950 when it was abolished by the Representation of the People Act 1948. The constituency was not a geographical area; rather, its electorate consisted of university graduates. Before 1918, the franchise was restricted to male graduates with a doctorate or MA degree.

Women's education

[edit]

For the first several centuries of its existence, as was the case broadly in England and the world, the University of Cambridge was only open to male students. The first colleges established for women were Girton College, founded by Emily Davies in 1869, Newnham College, founded by Anne Clough and Henry Sidgwick in 1872, Hughes Hall, founded in 1885 by Elizabeth Phillips Hughes as the Cambridge Teaching College for Women, Murray Edwards College, founded in 1954 by Rosemary Murray as New Hall, and Lucy Cavendish College, founded in 1965. Prior to ultimately being permitted admission to the university in 1948, female students were granted the right to take University of Cambridge exams beginning in the late 19th century.[38] Women were also allowed to study courses, take examinations, and have prior exam results recorded retroactively, dating back to 1881; for a brief period after the turn of the 20th century, this allowed the steamboat ladies to receive ad eundem degrees from the University of Dublin.[39]

In 1998, a special graduation ceremony was held in which the women who attended Cambridge before admission was allowed in 1948 were finally conferred their degrees.[40]

Beginning in 1921, women were awarded diplomas that conferred the title associated with the Bachelor of Arts degree. But since women were not yet admitted to the Bachelor of Arts degree program, they were excluded from the university's governance structure. Since University of Cambridge students must belong to a college, and since established colleges remained closed to women, women found admissions restricted to the few university colleges that had been established only for them. Darwin College, the first graduate college of the university, matriculated both male and female students from its inception in 1964 and elected a mixed fellowship. Undergraduate colleges, starting with Churchill, Clare, and King's colleges, began admitting women between 1972 and 1988. Among women's colleges at the university, Girton began admitting male students in 1979, and Lucy Cavendish began admitting men in 2021. But the other female-only colleges have remained female-only colleges as of 2023. As a result of St Hilda's College, Oxford, ending its ban on male students in 2008, Cambridge is now the only remaining university in the United Kingdom with female-only colleges; the two female-only colleges at the university are Newnham and Murray Edwards.[41][42] As of the 2019–2020 academic year, the university's male to female enrollment, including post-graduates, was nearly balanced with its total student population being 53% male and 47% female.[43]

In 2018 and later years, the university has come under some criticism and faced legal challenges over alleged sexual harassment at the university.[44][45] In 2019, for example, former student Danielle Bradford, represented by sexual harassment lawyer Ann Olivarius, sued the university for its handling of her sexual misconduct complaint. "I was told that I should think about it very carefully because making a complaint could affect my place in my department", Bradford alleged in 2019.[46] In 2020, hundreds of current and former students accused the university in a letter, citing "a complete failure" to deal with sexual misconduct complaints.[47]

Town and gown

[edit]The relationship between the university and the city of Cambridge has sometimes been uneasy. The phrase town and gown continues to be employed to distinguish between Cambridge residents (town) and University of Cambridge students (gown), who historically wore academical dress. Ferocious rivalry between Cambridge's residents and university students have periodically erupted over the centuries. During the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, strong clashes led to attacks and looting of university properties as locals contested the privileges granted by the British government to the University of Cambridge's academic staff. Residents burned university property in Market Square to the famed rallying cry "Away with the learning of clerks, away with it!".[48] Following these events, the University of Cambridge's Chancellor was given special powers allowing him to prosecute criminals and reestablish order in the city. Attempts at reconciliation between the city's residents and students followed; in the 16th century, agreements were signed to improve the quality of streets and student accommodation around the city. However, this was followed by new confrontations when the plague reached Cambridge in 1630 and colleges refused to assist those affected by the disease by locking their sites.[49]

Such conflicts between Cambridge's residents and university students have largely disappeared since the 16th century, and the university has grown as a source of enormous employment and expanded wealth in Cambridge and the region.[50] The university also has proven a source of extraordinary growth in high tech and biotech start-ups and established companies and associated providers of services to these companies. The economic growth associated with the university's high tech and biotech growth has been labeled the Cambridge Phenomenon, and has included the addition of 1,500 new companies and as many as 40,000 new jobs added between 1960 and 2010, mostly at Silicon Fen, a business cluster launched by the university in the late 20th century.[51]

Myths, legends and traditions

[edit]

Partly because of the University of Cambridge's extensive history, which now exceeds 800 years, the university has developed a large number of traditions, myths, and legends. Some are true, some are not, and some were true but have been discontinued but have been propagated nonetheless by generations of students and tour guides.

One such discontinued tradition is that of the wooden spoon, the prize awarded to the student with the lowest passing honours grade in the final examinations of the university's Mathematical Tripos. The last of these spoons was awarded in 1909 to Cuthbert Lempriere Holthouse, an oarsman of the Lady Margaret Boat Club at St John's College. It was over one metre in length and had an oar blade for a handle. It can now be seen outside the Senior Combination Room of St John's College. Since 1908, examination results have been published alphabetically within class rather than in strict order of merit, which made it difficult to ascertain the student with the lowest passing grade deserving of the spoon, leading to discontinuation of the tradition.

Each Christmas Eve, The Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols, sung by the Choir of King's College, are broadcast globally on BBC World Service television and radio and syndicated to hundreds of additional radio stations in the U.S. and elsewhere. The radio broadcast has been a national Christmas Eve tradition since 1928, though the festival has existed since 1918 and the celebration itself originated even earlier at Truro Cathedral in Cornwall in 1880.[52] The first television broadcast of the festival was in 1954.[53][54]

Locations and buildings

[edit]

Buildings

[edit]The university occupies a central location within the city of Cambridge. University of Cambridge students represent approximately 20 percent of the town's population, which was 145,674 as of 2021, resulting in a lower age demographic in the city.[55]

Most of the university's older colleges are located near the city centre, through which River Cam flows. Students and others traditionally punt on the River Cam, which provides views of the university's buildings that surround the river.[56]

A few of the notable University of Cambridge buildings are King's College Chapel;[57] the history faculty building[58] designed by James Stirling; and the New Court and Cripps Buildings at St John's College.[59] The brickwork of several colleges is notable: Queens' College has some of the earliest patterned brickwork in England[60] and the brick walls of St John's College are examples of English bond, Flemish bond, and Running bond.[61]

Sites

[edit]The university is divided into several sites, which house the university's various departments, including:[62]

The university's School of Clinical Medicine is based in Addenbrooke's Hospital, where medical students undergo their three-year clinical placement period after obtaining their BA degree.[63] The West Cambridge site is undergoing a major expansion and will host new buildings and fields for university sports.[64] Since 1990, Cambridge Judge Business School, on Trumpington Street, provides management education courses and is consistently ranked among the top 20 business schools in the world by Financial Times.[65]

Many of the sites are quite close together, and the area around Cambridge is reasonably flat. Furthermore, students are not permitted to hold car park permits except under special circumstances. For these reasons, of the favourite modes of transport for students is the bicycle; an estimated one-fifth of journeys in the city are made by bike..[66]

Notable locations

[edit]The University of Cambridge and its constituent colleges include many notable locations, some of which are iconic or of historical, academic, religious, and cultural significance, including:

- Bridge of Sighs, Cambridge

- Cambridge University Botanic Garden

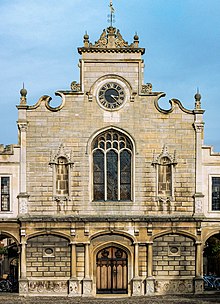

- Church of St Mary the Great, Cambridge

- Downing Site

- Fenner's

- Goldie Boathouse

- King's College Chapel, Cambridge

- Lady Mitchell Hall

- Mathematical Bridge

- Nevile's Court, Trinity College, Cambridge

- Sidgwick Site

- St Bene't's Church

- The Backs

- Trinity College Chapel, Cambridge

- West Cambridge

Organisation and administration

[edit]

Cambridge is a collegiate university, which means that its colleges are self-governing and independent, each with its own property, endowments, and income. Most colleges bring together academics and students from a broad range of disciplines. Each faculty, school, or department at the university includes academics affiliated with differing colleges.

The college faculties are responsible for giving lectures, arranging seminars, performing research, and determining the syllabi for teaching, all of which is overseen by the university's general board. Together with the central administration headed by the Vice-Chancellor, the college faculties make up the University of Cambridge. Facilities such as libraries are provided on all these levels by the university. The Cambridge University Library is the university's largest and primary library. Squire Law Library is the primary library for the university's students of law. Individual colleges each maintain a multi-discipline library designed for each college's respective undergraduates. College libraries tend to operate 24/7 and their usage in generally restricted to members of the college. Conversely, libraries operated by departments are generally open to all students of the university, regardless of subject.

The university is legally structured as an exempt charity and a common law corporation. Its corporate titles include the Chancellor, Masters, and Scholars of the University of Cambridge.[67]

Colleges

[edit]

The colleges are self-governing institutions with their own endowments and property, each founded as components of the university. All students and most academics are attached to a college. The colleges' importance lies in the housing, welfare, social functions, and undergraduate teaching they provide. All faculties, departments, research centres, and laboratories belong to the university, which arranges lectures and awards degrees but undergraduates receive their overall academic supervision within the colleges through small group teaching sessions, which often include just one student; though in many cases students go to other colleges for supervision if the teaching fellows at their college do not specialise in a student's particular area of academic focus. Each college appoints its own teaching staff and fellows, both of whom are members of a university department. The colleges also decide which undergraduates to admit to the university, in accordance with university standards and regulations.

Cambridge has 31 colleges, two of which, Murray Edwards and Newnham, admit women only. The other colleges are mixed. Darwin was the first college to admit both men and women. In 1972, Churchill, Clare, and King's were the first previously all-male colleges to admit female undergraduates. In 1988, Magdalene became the last all-male college to accept women.[68] Clare Hall and Darwin admit only postgraduates, and Hughes Hall, St Edmund's, and Wolfson admit only mature undergraduate and graduate students who are 21 years or older on the date of their matriculation. Lucy Cavendish, which was previously a women-only mature college, began admitting both men and women in 2021.[69] All other colleges admit both undergraduate and postgraduate students without any age restrictions.

Colleges are not required to admit students in all subjects; some colleges choose not to offer subjects such as architecture, art history, or theology, but most offer a complete range of academic specialties and related courses. Some colleges maintain a relative strength and associated reputation for expertise in certain academic disciplines. Churchill, for example, has a reputation for its expertise and focus on the sciences and engineering, in part due to the requirement imposed by Winston Churchill upon the college's founding that 70% of its students studied mathematics, engineering, and the sciences.[70] Other colleges have more informal academic focus and even demonstrate ideological focus, such as King's, which is known for its left-wing political orientation,[71] and Robinson and Churchill, both of which have a reputation for academic focus on sustainability and environmentalism.[72]

Costs to students for room and board vary considerably from college to college.[73][74] Similarly, the investment in student education by each college at the university varies widely between the colleges.[75]

Three theological colleges at the university, Westcott House, Westminster College, and Ridley Hall Theological College, are members of the Cambridge Theological Federation and associated in partnership with the university.[76]

The University of Cambridge's 31 colleges are:[77]

Christ's

Christ's Churchill

Churchill Clare

Clare Clare Hall

Clare Hall Corpus Christi

Corpus Christi Darwin

Darwin Downing

Downing Emmanuel

Emmanuel Fitzwilliam

Fitzwilliam Girton

Girton Gonville & Caius

Gonville & Caius Homerton

Homerton Hughes Hall

Hughes Hall Jesus

Jesus King's

King's Lucy Cavendish

Lucy Cavendish Magdalene

Magdalene Murray Edwards

Murray Edwards Newnham

Newnham Pembroke

Pembroke Peterhouse

Peterhouse Queens'

Queens' Robinson

Robinson Selwyn

Selwyn Sidney Sussex

Sidney Sussex St Catharine's

St Catharine's St Edmund's

St Edmund's St John's

St John's Trinity

Trinity Trinity Hall

Trinity Hall Wolfson

Wolfson

Schools, faculties and departments

[edit]

In addition to the 31 colleges, the university maintains over 150 departments, faculties, schools, syndicates, and other academic institutions.[78] Members of these are usually members of one of the colleges, and responsibility for the entire academic programme of the university is divided among them.

The university has a department dedicated to providing continuing education, the Institute of Continuing Education, which is based primarily in Madingley Hall, a 16th-century manor house in Cambridgeshire. Its award-bearing programmes include both undergraduate certificates and part-time master's degrees.[79]

A school in the University of Cambridge is a broad administrative grouping of related faculties and other units. Each has an elected supervisory body known as a Council, composed of representatives of the various constituent bodies. The University of Cambridge maintains six such schools:[80]

- Arts and Humanities

- Biological Sciences

- Clinical Medicine

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Physical Sciences

- Technology

Teaching and research at the university is organised by faculties. The faculties have varying organisational substructures that partly reflect their respective histories and the university's operational needs, which may include a number of departments and other institutions. A small number of bodies called syndicates hold responsibility for teaching and research, including for the University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate, the University Press, and the University Library.

Central administration

[edit]Chancellor and Vice-Chancellor

[edit]

The Chancellor of the university is limitless term position that is mainly ceremonial and is held currently by David Sainsbury, Baron Sainsbury of Turville, who succeeded the Duke of Edinburgh following his retirement on his 90th birthday in June 2011. Lord Sainsbury was nominated by the nomination board.[81][82][83][84] The election took place on 14 and 15 October 2011[84] with Sainsbury taking 2,893 of the 5,888 votes cast, and winning on the election's first count.

The current vice-chancellor is Deborah Prentice, who began her role in July 2023.[85] While the Chancellor's office is ceremonial, the Vice-Chancellor serves as the university's de facto principal administrative officer. The university's internal governance is carried out almost entirely by Regent House augmented by some external representation from the Audit Committee and four external members of the University's Council.[86]

Senate and the Regent House

[edit]

The university Senate consists of all holders of the MA or higher degrees and is responsible for electing the Chancellor and the High Steward. Until 1950 when the Cambridge University constituency was abolished, it was also responsible for electing two members of the House of Commons. Prior to 1926, the university Senate was the university's governing body, fulfilling the functions that Regent House has provided since.[87] Regent House is the university's governing body, comprising all resident senior members of the university and the colleges, the Chancellor, the High Steward, the Deputy High Steward, and the Commissary.[88] Public representatives of Regent House are the two Proctors, elected to serve for one year terms upon their nominations by the colleges.

Council and General Board

[edit]

Although the University Council is the university's principal executive and policy-making body, the Council reports to, and is held accountable by, Regent House through a variety of checks and balances. The council is obliged to advise Regent House on matters of general concern to the university, which it does by publishing notices to the Cambridge University Reporter, the university's official journal.[89] In March 2008, Regent House voted to increase from two to four the number of external members on the council,[90][91] and this was approved by Her Majesty the Queen in July 2008.[92]

The General Board of the Faculties is responsible for the university's academic and educational policies[93] and is accountable to the council for its management of these affairs.

Faculty boards are accountable to the general board; other boards and syndicates are accountable either to the general board or to the council. Under this organizational structure, the university's various arms are kept under supervision of both the central administration and Regent House.[94]

Finances

[edit]Endowment

[edit]The Cambridge University Endowment Fund is the main vehicle of investment for the University.[95] In the fiscal year ending 31 July 2023, the university group, excluding colleges, reported a total endowment of £3.736 billion.[96] The figure includes both restricted and unrestricted funds. When reported strictly using Statements of Recommended Practice (SORPs) guidelines, which accounted for only donations that meet certain criteria among non-profit organizations in the UK, endowment reserve stood at £2.469 billion.[96] The 31 colleges reported collective endowment reserve of £4.582 billion.

Benefactions and fundraising

[edit]In the fiscal year ending 31 July 2023, the central university, excluding colleges, reported total consolidated income of £2.518 billion, of which £569.5 million was from research grants and contracts.[5] In July 2022, the Dear World, Yours Cambridge Campaign for the university and colleges concluded, raising a total of £2.217 billion in commitments.[5]

The university maintains multiple scholarship programs. The Stormzy Scholarship for Black UK Students covers tuition costs for two students and maintenance grants for up to four years.[97]

In 2000, Bill Gates of Microsoft donated US$210 million through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to endow Gates Cambridge Scholarships for students from outside the United Kingdom to pursue full-time postgraduate study at Cambridge.[98]

In October 2021, the university suspended its £400m collaboration with the United Arab Emirates, citing allegations that UAE was involved in illegal hacking of the university's computer and storage systems using NSO Group's Pegasus software. UAE also was behind the leak of over 50,000 phone numbers, including hundreds belonging to British citizens. Stephen Toope, the university's outgoing Vice-Chancellor, said the decision to suspend its collaboration with UAE also was a result of additional revelations about UAE's Pegasus software hacking.[99]

Bonds

[edit]The University of Cambridge borrowed £350 million in October 2012 by issuing 40-year security bonds,[100] whose interest rate is approximately 0.6 percent higher than the British government's 40-year bond.[101]

Affiliations and memberships

[edit]The University of Cambridge is a member of the Russell Group of research-led British universities, the G5, the League of European Research Universities, the International Alliance of Research Universities, and it is part of the so-called golden triangle of research intensive universities in the south of England.[102] It is also closely linked to the high tech business cluster known as Silicon Fen and is part of Cambridge University Health Partners, Europe's largest academic health science centre.

Academic profile

[edit]Admissions

[edit]| 2023[103] | 2022[104] | 2021[105] | 2020[106] | 2019[107] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applications | 21,445 | 22,470 | 22,795 | 20,426 | 19,359 |

| Offer Rate (%) | 21.2 | 18.9 | 18.7 | 23.1 | 24.3 |

| Enrols | 3,557 | 3,544 | 3,660 | 3,997 | 3,528 |

| Yield (%) | 78.1 | 83.6 | 85.9 | 84.9 | 75.2 |

| Applicant/Enrolled Ratio | 6.03 | 6.34 | 6.23 | 5.11 | 5.49 |

| Average Entry Tariff[108] | — | — | 209 | 207 | 205 |

Process

[edit]

Admission to the University of Cambridge is extremely competitive. In 2022, for instance, around 15% of applicants were admitted.[113][114] In 2021, Cambridge introduced an over-subscription clause to its offers of admission, which also permits the university to withdraw acceptances if too many students meet its selective entrance criteria. The clause can be invoked in the event of circumstances outside the reasonable control of the university. The clause was introduced following a record number of A-level pupils who obtained the highest grades from teacher assessment, which was introduced due to the cancellation of A-level examinations during the COVID-19 pandemic.[115][116]

The university's standard offer for most courses is set at A*AA,[117][118] with A*A*A for science courses, or equivalent in other examination systems, e.g. 7,6,6 or 7,7,6 in IB. Due to a high proportion of applicants receiving the highest school grades, an interview process was introduced as a component of consideration for admission. Interviews are performed by College Fellows, who evaluate candidates on unexamined factors including potential for original thinking and creativity.[119] Prior to 2020 these interviews were normally held in person but moved online during the COVID-19 pandemic and have, at most colleges, remained online since.[120] For exceptional candidates, a matriculation offer is sometimes offered, requiring only two A-levels at grade E or above. Sutton Trust maintains that the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge recruit disproportionately from eight schools, which account for 1,310 Oxbridge places over three years contrasted with 1,220 from 2,900 other schools.[121]

Strong applicants who are not successful in being admitted to their chosen college at the university may be placed in the Winter Pool, where they can be considered for admission to other university colleges, which maintains consistency throughout the colleges, some of which receive more applicants than others.

Undergraduate applications are processed through UCAS, and the deadline for their submission currently is mid-October in the year before prior to beginning. Until the 1980s, candidates for all subjects were required to take special entrance examinations,[122] which have since been replaced by additional tests for some subjects, such as the Thinking Skills Assessment and Cambridge Law Test.[123] The university has at times considered reintroducing an admissions exam for all subjects.[124]

Graduate admission is first decided by the faculty or department responsible for the applicant's respective academic subject. An offer of acceptance effectively guarantees admission to the university, though not necessarily the applicant's preferred choice of college.[125]

Winter pool

[edit]The Winter Pool or inter-College Pool is part of the undergraduate application process intended to ensure that the best applicants are offered admission.[126] Approximately 20–25% of undergraduate admissions are awarded through the Pool. Each college can place applicants in the Winter Pool. These applicants' applications are then considered by Admissions Tutors or Directors of Studies during the pool, which takes place over three days in January prior to the release of the university's admissions decisions.[127]

For each subject, colleges create an ordered list of the pooled applicants they seek to admit, and take turns choosing applicants. Colleges with specific student requirements, such as mature colleges and women-only colleges, are given priority over applicants eligible for their colleges. Some applicants are selected from the pool by the college that originally pooled them.[127] Once all the colleges have selected as many applicants as they need, the pool ends. Some applicants are then interviewed a second time by the colleges before final admissions decisions are made.

Colleges can pool any candidate, either because the college has no space but believes the applicant is strong enough to get a place, or because the college wants to compare that applicant to other pooled applicants. Most applicants in the pool are pooled at their original college's discretion, but some candidates meet the compulsory pooling criteria.[128]

There were, as of the 2020–21 admissions cycle, only two grounds for compulsory pooling. For post-qualified applicants, their achieved grades at A level or equivalent and, for applicants with overseas interviews, an interview score of at least eight is achieved in all interviews. The second criterion does not apply to medicine applicants.[129] Previously, AS-Level UMS have been used as pooling criteria, but after A-levels became linear this was discontinued.[129]

| Qualification Type | Minimum grades | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| A-Levels | A*A*A* | For science applicants, at least three A*s must be in science/maths subjects |

| International Baccalaureate | 43 points overall with 776 at higher level or

42 points overall with 777 at higher level |

For science applicants, at least two 7s must be in science/maths subjects |

| Scottish Advanced Highers | A1A1A1 | For science applicants, at least 3 A1s must be in science/maths subjects |

As of 2012, there is only one specifically identified category for pooled applicants, which is known as S, meaning that the application is in special need of reassessment. This is used when candidates whose initial interview scores are of questionable accuracy, such as when a candidate received very different scores from different interviewers, experienced technical issues with interviews conducted over the internet, or was impacted by significant extenuating circumstances such as illness or the loss of a family member.[129]

Pooled applicants who are fished by a college may be offered a place immediately or may be invited for an interview. In 2020, just 89 applicants were invited for second interviews, 34 of whom received offers of admission.[127]

Each year, approximately 3,500 applicants receive offers from their preference college and a further 1,000 to 1,100 applicants are offered admission by another college through the pool. On average, one in five applicants is pooled and around one in four pooled applicants receives an offer of admission.[127]

Statistics released by the university show that some colleges regularly receive particularly high numbers of applicants, and these colleges tend to take fewer applicants from the pool. Other colleges regularly draw a greater proportion of their undergraduate intake from the pool.[130]

Access

[edit]

Public debate in the United Kingdom exists over whether admissions processes used at the University of Oxford and Cambridge are entirely merit-based and fair, whether enough students from state schools are encouraged to apply, and whether these students are offered sufficient admission. In 2020–21, 71% of all successful applicants were from state schools[133] compared to approximately 93% of all students in the UK who attended state schools and 82% of post-16 students[134]).

Critics have argued that the relative lower percent of state school applicants with the required grades for admission to Cambridge and Oxford has had a negative impact on Oxford and Cambridge's collective reputation, though both universities have encouraged pupils from state schools to apply to help redress the perceived imbalance.[135] Others counter that government pressure to increase state school admissions constitutes inappropriate social engineering.[136][137] The proportion of undergraduates drawn from independent schools has dropped over the years, constituting, as of 2020, 26% of total admissions among the university's 3,436 applicants from independent schools compared to 23% of the 9,237 applications from state schools.[138] Cambridge, together with Oxford and Durham, was among those universities that adopted formulae in 2009 to rate the GCSE performance of schools, using data from the Department for Children, Schools and Families, and took this into account when assessing university applicants.[139]

With the release of admissions figures, The Guardian reported in 2013 that ethnic minority candidates had lower success rates in individual subjects even when they had the same grades as white applicants. The university was criticised for what was seen as institutional discrimination against ethnic minority applicants in favour of white applicants. The university denied the claims of institutional discrimination, stating the figures did not take into account other variables.[140] A subsequent article reported that, in the years 2010 to 2012, ethnic minority applicants to medicine with 3 A* grades or higher were 20% less likely to gain admission than white applicants with similar grades. The university refused to provide figures for a wider range of subjects, claiming that assembling and releasing such information was excessively costly.[141]

Given the competitive nature of gaining admission to the University of Cambridge, a number of educational consultancies have emerged to offer support with the application process. Some claim they can improve chances for admission, though these claims have never been independently verified. None of these companies are affiliated with or endorsed by the University of Cambridge. The university informs applicants that all necessary information regarding the application process is publicly available through the university and none of these services is providing any insight not already publicly available to applicants.[142]

The University of Cambridge has been criticised for admitting a lower percentage of Black students, though many apply. Of the 31 colleges at Cambridge, six of them admitted fewer than 10 Black or mixed race students between 2012 and 2016.[143] Similar criticism exists over a relatively lower admission rate for white working class applicants; in 2019, only 2% of admitted students were white working class.[144]

In January 2021, Cambridge created foundation courses for disadvantaged students.[145] While the usual entry requirements are A*AA in A-Levels, the one-year foundation course has 50 places for students who achieve BBB.[146] If successful on the course, students receive a recognised CertHE qualification and can progress to degrees in the arts, humanities, and social sciences at the university.[145] Candidates include those who have been in care, who are estranged from their families, who have missed significant periods of learning because of health issues, those from low-income backgrounds, and those from schools with few students attending universities.[145]

Teaching

[edit]

The University of Cambridge academic year is divided into three academic terms determined by the statutes of the university.[147] Michaelmas term lasts from October to December; the Lent term last from January to March; and the Easter term last from April to June.

Within these terms, undergraduate teaching takes place during eight-week periods called full terms. According to university statutes, it is a requirement during these periods that all students live within three miles of the Church of St Mary the Great, which this is known as keeping term. Students eligible for graduation must fulfill this condition for nine terms (three years) while pursuing a Bachelor of Arts or twelve terms (four years) when pursuing a Master of Science, engineering, or mathematics degree.[148]

These terms are shorter than those of many other British universities.[149] Undergraduates are also expected to prepare heavily in the three holidays known as the Christmas, Easter, and Long Vacation holiday periods, which are referred to by the university as vacations rather than holidays; students vacate the premises during these periods but are still expected to be pursuing studies and assignments.

The Tripos exam involves a mixture of lectures organised by the university department) and supervised and organised by the colleges. Science subjects involve laboratory sessions organised by the departments. The relative importance of these methods of teaching varies according to the needs of the subject. Supervisions are typically weekly hour-long sessions in which small groups of students, usually between one and three students, who meet with a member of the teaching staff or with a doctoral student. Students are normally required to complete an assignment in advance of this supervision, which they then discuss with the supervisor during the session. The assignment is often an essay on a subject assigned by the supervisor, or a problem sheet set by the lecturer. Depending on the subject and college, students sometimes receive between one and four supervisory sessions each week.[150] This pedagogical system is often cited as being unique to Oxford, where supervisions are known as tutorials,[151] and Cambridge and is sometimes credited with the exceptional nature generally associated with the education at these two world-renowned universities.

A tutor named William Farish developed the concept of grading students' work quantitatively at the University of Cambridge in 1792.[152]

Research

[edit]The University of Cambridge has research departments and teaching faculties in nearly every academic discipline, and ll research and lectures are conducted by university departments. The colleges are charged with giving or arranging most supervisions, student accommodation, and funding most extracurricular activities. During the 1990s, the University of Cambridge added a substantial number of new specialist research laboratories on several sites around the city, and major expansion continues.[153] From 2000 to 2006, the University of Cambridge maintained a research partnership with MIT in the United States, known as the Cambridge–MIT Institute, which was discontinued after evolving into what is now called the CMI Partnership Programme.

Graduation tradition and ceremony

[edit]

The university's governing body Regent House manages and votes on graduations. A formal meeting of Regent House, known as a congregation, is held for this purpose,[154] which is typically the final act during which all university procedures for undergraduate and graduate students and other degrees are finalised. After degrees are approved, candidates for graduation are required to request their respective college presents them during commencement congregation.

Graduates receiving an undergraduate degree wear the academic dress to which they are entitled prior to graduating; for example, most students becoming Bachelor of Arts graduates wear undergraduate gowns and not BA gowns. Graduates receiving a post-graduate degree wear the academic dress that they were entitled to before graduating if their first degree was also from the University of Cambridge; if their first degree was from another university, they wear the academic dress of the degree that they are about to receive. The BA gown without the strings is worn if the graduate is 24 years old or younger, and the MA gown without strings is worn if the graduate is 24 years old or older.[155] Graduates are presented their degrees in Senate House by each respective college in order of foundation or recognition by the university, except for the university's royal colleges.

During the University of Cambridge's congregation ceremony, graduands are brought forth by the Praelector of their respective college, who takes them by the right hand and presents them to the vice-chancellor to receive the degree they have earned. The Praelector presents graduands with the following Latin statement, substituting "____" with the name of the degree and substituting "woman" for "man" if the graduate is female:

"Dignissima domina, Domina Procancellaria et tota Academia praesento vobis hunc virum quem scio tam moribus quam doctrina esse idoneum ad gradum assequendum _____; idque tibi fide mea praesto totique Academiae.

The Latin statement translates in English as, "Most worthy Vice-Chancellor and the whole University, I present to you this man whom I know to be suitable as much by character as by learning to proceed to the degree of ____; for which I pledge my faith to you and to the whole University."

After presentation, the graduate is called by name and kneels before the vice-chancellor and proffers their hands to the vice-chancellor, who clasps them and then confers the degree through the following Latin statement, known as the Trinitarian formula (in nomine Patris), which may be omitted at the request of the graduand:

"Auctoritate mihi commissa admitto te ad gradum ____, in nomine Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti, which translates in English as: "By the authority committed to me, I admit you to the degree of ____, in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit."

The new graduate then rises, bows, and leaves the Senate House through the Doctor's door in Senate House Passage, where they receive their degree certificate.[154]

For the Cambridge Master of Arts, the degree is not awarded by merit of study, but by right following six years and one term after matriculation.

Libraries and museums

[edit]

The University of Cambridge has 116 libraries.[156] Cambridge University Library, which holds over eight million volumes, is the central research library. It is a legal deposit library, which entitles it to request a free copy of every book published in the UK and Ireland.[157]

In addition to the University Library and its dependents, almost every faculty or department has a specialised library; for example, the History Faculty's Seeley Historical Library houses in excess of 100,000 books. Every college also maintains a library, partly for the purpose of undergraduate teaching; older colleges often possess many early books and manuscripts in a separate library. For example, Trinity College's Wren Library houses over 200,000 books printed before 1800 and Corpus Christi College's Parker Library has over 600 medieval manuscripts, representing one of the largest such collections in the world. Churchill Archives Centre on the campus of Churchill College houses the official papers of former British prime ministers Winston Churchill and Margaret Thatcher.

The university operates eight arts, cultural, and scientific museums, and a botanical garden.[158] Fitzwilliam Museum is the art and antiquities museum; Kettle's Yard is the university's contemporary art gallery; the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology houses the university's collections of local antiquities along with archaeological and ethnographic artefacts from around the world; Cambridge University Museum of Zoology houses a wide range of zoological specimens from around the world and is known for its iconic finback whale skeleton that hangs outside the museum. Cambridge University Museum of Zoology also holds specimens collected by Charles Darwin, an 1831 University of Cambridge alumnus. Other museums include the Museum of Classical Archaeology, Whipple Museum of the History of Science, Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, the university's geology museum, which displays some of Darwin's geological specimens and equipment (Darwin had studied under Adam Sedgwick, and wrote "I a geologist" in a notebook in 1838), and Polar Museum, part of the Scott Polar Research Institute, which is dedicated to Captain Scott and his men and focuses on the exploration of the Polar Regions.

Cambridge University Botanic Garden, created in 1831, is the university's botanical garden.

Publishing and assessments

[edit]The university's publishing arm, Cambridge University Press & Assessment, is the oldest printer and publisher in the world and the second largest university press in the world.[159][160] It is also the largest department of the university by financial income, reporting income above £800 million.[161]

The university established its Local Examination Syndicate in 1858, now known as Cambridge University Press & Assessment after its merger with Cambridge University Press. It is the largest assessment agency in Europe. Cambridge University Press & Assessment plays a leading role in researching, developing, and delivering assessments around the world.[162]

Awards

[edit]The University of Cambridge issues a number of prestigious awards and prizes annually to accomplished University of Cambridge faculty and students. It also issues some awards to those of varying global academic accomplishment regardless of whether their recipient is affiliated with the University of Cambridge. Some of these awards and prizes rank among the world's most estimable academic and intellectual accomplishments. Among the most prominent of them are:

- Adam Smith Prize, awarded annually to the university's top-performing student in economics

- Adams Prize, awarded annually by University of Cambridge mathematics faculty to a UK resident in recognition of distinguished research in mathematics

- Browne Medal, awarded annually to students who win the Latin and Greek poetry competition

- Carus Greek Testament Prizes, a prize issued to winners of an annual competition of the university's undergraduate and graduate in Greek translation of New Testament passeges

- Chancellor's Gold Medal, a prize issued to winners of the university's annual poetry competition

- Porson Prize, a prize for students who develop the best Greek composition

- Raymond Horton-Smith Prize, awarded annually to the University of Cambridge Medical School student for the best medical school thesis

- Seatonian Prize, awarded annually for the best English language poem on a sacred subject

- Senior Wrangler, awarded annually to the university's top performing student on the Part II of Mathematical Tripos[28]

- Thirlwall Prize, awarded every other year for the best essay about British literature or history

- Thomas Bond Sprague Prize, awarded annually to the top performing Part III of the Mathematical Tripos student in the areas of probability, statistics, finance and optimization.

- Tyson Medal, awarded annually to the top astronomy student

- Mayhew Prize, awarded annually to the top performing Part III of the Mathematical Tripos student in areas of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics (DAMTP)

Reputation and rankings

[edit]| National rankings | |

|---|---|

| Complete (2025)[163] | 1 |

| Guardian (2025)[164] | 3 |

| Times / Sunday Times (2024)[165] | 3 |

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU (2024)[166] | 4 |

| QS (2025)[167] | 5 |

| THE (2024)[168] | 5 |

Due to its age[169][170] and its social and academic status,[171][172] the University of Cambridge is considered to be one of Britain's most prestigious or elite universities[173][174][175] and to form, along with the University of Oxford, a top two that stand above other UK universities in this regard.[169][171][172][176]

The University of Cambridge is routinely ranked among the world's top five universities, and has sometimes been ranked as the world's best. As of 2024, the University of Cambridge is ranked the second-best university in the world behind the MIT and the best university in Europe by QS Rankings.[177] ARWU ranks Cambridge the fourth-best university in the world as of 2024 behind Harvard, Stanford, and MIT.[178] Times Higher Education ranks Cambridge third-best in the world (tied with Stanford) in its 2023 rankings behind Oxford and Harvard.[179]

In April 2022, QS Rankings ranked Cambridge's programmes among the world's best. Cambridge's Arts and Humanities program is ranked second-best in the world. The University of Cambridge's Engineering and Technology program is ranked second-best in the world. Its Life Sciences and Medicine program is ranked fourth-best in the world. Its Natural Sciences program is ranked third-best in the world. Its Social Sciences and Management program is ranked fourth-best in the world.[180]

In 2011, Times Higher Education recognised the University of Cambridge as one of the world's six super brands in its "World Reputation Rankings" along with Berkeley, Harvard, MIT, Oxford, and Stanford.[181]

The University of Cambridge has been highly ranked by most international and UK league tables. It was ranked the best university in the world by QS World University Rankings in both their 2010–11 and 2011–12 rankings.[182][183]

In 2006, a Thomson Scientific study reported that the University of Cambridge had the highest research paper output of any British university and ranked first in research production as assessed by total paper citation count in ten of 21 major British research fields.[184] An evidence-based study published the same year showed that the University of Cambridge won a larger proportion (6.6%) of total British research grants and contracts than any other university, ranking first in three out of four major measured discipline fields.[185]

Student life

[edit]Formal halls and May balls

[edit]

One privilege of student life at the University of Cambridge is the opportunity to attend formal dinners at a student's respective college, known as Formal Hall that are held regularly during academic terms and daily at some of the university's colleges. During Formal Hall, students typically sit down for a meal in their gowns while fellows and sometimes guests eat separately at a so-called High Table. The beginning and end of the function is usually marked with grace, which is said in Latin. Special Formal Halls are organised for Christmas and the Commemoration of Benefactors.[186]

After the exam period, May Week is held during which it is customary to celebrate by attending May Balls, which are all-night lavish parties held in the colleges where food, drinks, and entertainment are provided. So-called Suicide Sunday, the first day of May Week, is a popular date for garden parties.[187]

JCR and MCR

[edit]In addition to university-wide representation, students can participate in their own college student unions, which are known as Junior Combination Room (JCR) for undergraduates and Middle Combination Room (MCR) for post-graduates. These serve as a link between college staff and members and include officers elected annually between the fellow students; individual JCR and MCRs also report to Cambridge Students' Union, which offers training courses for some of the positions within the body.[188]

Societies

[edit]

Numerous student-run societies exist at the University of Cambridge designed to encourage students who share common passions or interests to periodically meet or discuss these interests. As of 2010[update], there were 751 registered societies at the university.[189] In addition to these, individual colleges often promote their own societies and sports teams.

Although technically independent from the university, Cambridge Union, a globally-renowned debate organization and the oldest debate organization in the world, offers students high-level debate and public speaking experience. Drama societies include the Amateur Dramatic Club (ADC) and the comedy club Footlights, whose alumni include many well-known show business personalities. The university's Chamber Orchestra, composed entirely of university students, offers a range of orchestra programs, including symphonies.

Sports

[edit]

Rowing is one of the most popular sports at the University of Cambridge, and there are competitions between colleges, notably the bumps races. The University of Cambridge's rowing competition against Oxford is known as the Boat Race. Varsity matches against Oxford also exist in other sports, including cricket, rugby, chess, and tiddlywinks. Athletes who representing the university in a varsity match are entitled to a Blue or a Half Blue, depending on the sport and other criteria.[190]

The University of Cambridge Sports Centre opened in August 2013. Phase one included a sports hall, a fitness suite, a strength and conditioning room, a multi-purpose room, and Eton and Rugby fives courts. Phase two of its development included five glass-backed squash courts and a team training room. Future phases include indoor and outdoor tennis courts and a swimming pool.[191]

The university also has an athletic track at Wilberforce Road, an indoor cricket school, and Fenner's, the cricket ground for Cambridge University Cricket Club.

The university has an ice hockey club called Cambridge University Ice Hockey Club

The Hawks' Club is a private members' club for the university's leading sportsmen.[190] The Ospreys are the equivalent female club.

Student newspapers and radio

[edit]Cambridge's oldest student newspaper is Varsity. Established in 1947, notable figures who have edited the newspaper include Jeremy Paxman, BBC media editor Amol Rajan, and Vogue international editor Suzy Menkes. The student newspaper also has featured the early writings of Zadie Smith, who appeared in Varsity's literary anthology offshoot The Mays, Robert Webb, Tristram Hunt, and Tony Wilson.

Varsity has a circulation of 9,000 and is the only student publication published weekly. News stories from Varsity have appeared in The Guardian, The Times, The Sunday Times, The Daily Telegraph, The Independent, and i.

Other student publications include The Cambridge Student, which is funded by Cambridge Students' Union and is published fortnightly, The Tab, and The Mays Founded by two University of Cambridge students in 2009, The Tab is an online media outlet featuring light-hearted features content. The Mays is a literary anthology including student prose, poetry, and visual art from both University of Cambridge and Oxford students. Founded in 1992 by three Cambridge students, the anthology publishes once a year and is overseen by Varsity Publications Ltd., the same body responsible for Varsity. Another literary journal, Notes, is published roughly twice per term. Additionally, many colleges have their own student-run publications.

The student radio station, Cam FM, is run jointly by University of Cambridge and Anglia Ruskin University students. The station holds an FM licence (frequency 97.2 MHz), and hosts a mixture of music, talk, and sports shows.

Student Union

[edit]All students at the University of Cambridge are represented by Cambridge Students' Union, which was founded in 2020 as a merger of two student unions, Cambridge University Students' Union (CUSU) and the Graduate Union (GU). CUSU previously represented all University students, and GU represented graduate students.[192][193]

The eight most important positions in Cambridge Students' Union are occupied by sabbatical officers.[194] In 2020, the sabbatical officers were elected with a turnout of 20.88% of the whole student body.[195]

In 2021, Cambridge Students' Union launched a petition opposing the financial collaboration between the university and the government of United Arab Emirates that was worth £400m. The Union cited a "values gap" and threat to "academic freedom and institutional autonomy" following the release of internal UAE documents. Citing UAE's history of violating international human rights laws, it warned that university staff were vulnerable under the partnership to repression by gender, sexuality, or freedom of expression.[196]

In 2023, 72% of the Students' Union voted in favour of hosting talks regarding the removal of all animal products from cafes and canteens operated by the university's catering services. The students backed vegan food in response to threats to the climate and biodiversity. The vote is non-binding since the university controls the catering service. The vote was supported by the student chapter of Plant-Based Universities.[197] After the vote, Darwin College decided to serve only vegan food at its May Ball in 2023.[198]

Politics

[edit]A protest in Cambridge with an attendance of over a thousand students and residents – the city's largest demonstration – called on the University of Cambridge to divest from Israel over Israel's actions in the Gaza Strip during the Israel–Hamas war.[199][200] Students and staff also walked out of lectures in protest over the same issues.[201]

Students and staff at the University of Cambridge wrote an open letter to the university, with more than 1,400 signatories, demanding it acknowledge the "slaughter of innocent Palestinians", "sever financial ties with Israel" as it had with Russia following the invasion of Ukraine, and demanding it investigate its financial ties with arms manufacturers that potentially supplied to Israel, mentioning, among others, Plasan and Caterpillar.[199][202]

Notable alumni and academics

[edit]The University of Cambridge has produced many distinguished alumni in various fields. As of 2020,[203][204] 70 alumni have won Nobel Prizes. As of 2019, Cambridge alumni, faculty members, and researchers have won 11 Fields Medals and seven Turing Awards.

Highly notable University of Cambridge alumni by specialty include:

Education

[edit]Notable alumni in academia include the founders and early professors of Harvard University, including John Harvard himself; Emily Davies, founder of Girton College at Cambridge, the first residential higher education institution for women, and John Haden Badley, founder of the first mixed-sex public school (i.e. private) in England; Anil Kumar Gain, 20th century mathematician and founder of the Vidyasagar University in Bengal, Siram Govindarajulu Naidu, founder and vice chancellor of Sri Venkateswara University; and Menachem Ben-Sasson, president of Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel.

Humanities, music, and art

[edit]

In the humanities, Greek studies were inaugurated at the University of Cambridge in the early sixteenth century by Desiderius Erasmus; contributions to the field were made by Richard Bentley and Richard Porson. John Chadwick was associated with Michael Ventris in the decipherment of Linear B. The Latinist A. E. Housman taught at the university but is more widely known for his contributions as a poet. Simon Ockley made a significant contribution to Arabic Studies.

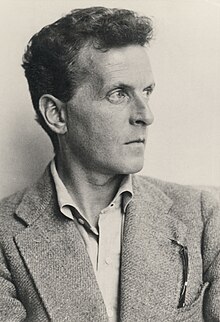

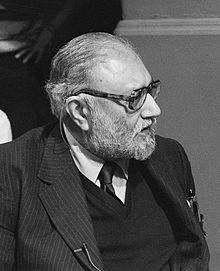

University of Cambridge academics include economists such as John Maynard Keynes, Thomas Malthus, Alfred Marshall, Milton Friedman, Joan Robinson, Piero Sraffa, Ha-Joon Chang, and Amartya Sen. Notable philosophers include Francis Bacon, Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Leo Strauss, George Santayana, G. E. M. Anscombe, Karl Popper, Bernard Williams, Allama Muhammad Iqbal, and G. E. Moore. Notable alumni historians include Thomas Babington Macaulay, Frederic William Maitland, Lord Acton, Joseph Needham, E. H. Carr, Hugh Trevor-Roper, Rhoda Dorsey, E. P. Thompson, Eric Hobsbawm, Quentin Skinner, Niall Ferguson, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., and Karl Schweizer.

Notable alumni in religion include Rowan Williams, the former Archbishop of Canterbury and his predecessors; William Tyndale, the biblical translator; Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer, and Nicholas Ridley, known as the Oxford martyrs from the place of their execution; Benjamin Whichcote and the Cambridge Platonists; William Paley, the Christian philosopher known primarily for formulating the teleological argument for the existence of God; William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson, largely responsible for the abolition of the slave trade; Evangelical churchman Charles Simeon; John William Colenso, the bishop of Natal who interpreted Scripture and its relations with native peoples that seemed dangerously radical at the time; John Bainbridge Webster and David F. Ford, theologians; and six winners of the Templeton Prize, the highest accolade in the world associated with the study of religion.

Notable University of Cambridge alumni in the field of musical composition include Ralph Vaughan Williams, Charles Villiers Stanford, William Sterndale Bennett, Orlando Gibbons and, more recently, Alexander Goehr, Thomas Adès, John Rutter, Julian Anderson, Judith Weir, and Maury Yeston. The university has also produced world-renowned instrumentalists and conductors, including Colin Davis, John Eliot Gardiner, Roger Norrington, Trevor Pinnock, Andrew Manze, Richard Egarr, Mark Elder, Richard Hickox, Christopher Hogwood, Andrew Marriner, David Munrow, Simon Standage, Endellion Quartet, and Fitzwilliam Quartet. Although the university in music predominantly for its contributions to choral music, university alumni in popular music include members of contemporary bands such as Radiohead, Hot Chip, Procol Harum, Clean Bandit, Sports Team songwriter and entertainer Jonathan King, Henry Cow, and the singer-songwriter Nick Drake.

Artists Quentin Blake, Roger Fry, Rose Ferraby, and Julian Trevelyan, sculptors Antony Gormley, Marc Quinn, and Anthony Caro, and photographers Antony Armstrong-Jones, Cecil Beaton, and Mick Rock are each University of Cambridge alumni.

Literature

[edit]

Writers to have studied at the university include the Elizabethan dramatist Christopher Marlowe, his fellow University Wits, Thomas Nashe, and Robert Greene, arguably the first professional authors in England, and John Fletcher who collaborated with Shakespeare on The Two Noble Kinsmen, Henry VIII, and the lost Cardenio and succeeded him as house playwright for The King's Men. Samuel Pepys matriculated in 1650, known for his diary, the original manuscripts of which are now housed in the Pepys Library at Magdalene College. Lawrence Sterne, whose novel Tristram Shandy is judged to have inspired many modern narrative devices and styles. In the following century, the novelists W. M. Thackeray, author of Vanity Fair, Charles Kingsley, author of Westward Ho! and Water Babies, and Samuel Butler, remembered for The Way of All Flesh and Erewhon, are all University of Cambridge alumni.

Ghost story writer M. R. James served as provost of King's College from 1905 to 1918. Novelist Amy Levy was the first Jewish woman to attend the university. Modernist writers to have attended the university include E. M. Forster, Rosamond Lehmann, Vladimir Nabokov, Christopher Isherwood, and Malcolm Lowry. Playwright J. B. Priestley, physicist and novelist C. P. Snow, and children's writer A. A. Milne are each early 20th century alumni of the university. They were followed by postmodernists Patrick White, J. G. Ballard, and early postcolonial writer E. R. Braithwaite. More recently, alumni include comedy writers Douglas Adams, Tom Sharpe and Howard Jacobson, the popular novelists A. S. Byatt, Salman Rushdie, Nick Hornby, Zadie Smith, Louise Dean, Robert Harris, and Sebastian Faulks, action writers Michael Crichton, David Gibbins, and Jin Yong, and contemporary playwrights and screenwriters, including Julian Fellowes, Stephen Poliakoff, Michael Frayn, and Peter Shaffer, as well as musical theatre writers Toby Marlow and Lucy Moss.

Within poetry, University of Cambridge alumni include the poets Edmund Spenser, author of The Faerie Queene, metaphysical poets John Donne, who wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls, George Herbert and Andrew Marvell, and John Milton, who is renowned for Paradise Lost, Restoration poet and playwright John Dryden, pre-romantic poet Thomas Gray best known his Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, William Wordsworth, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, whose joint work Lyrical Ballads is often cited as marking the beginning of the Romantic movement, later Romantics including Lord Byron and the post-romantic Lord Tennyson, authors of the best known carpe diem poems, including Robert Herrick known for "To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time" with the first line "Gather ye rosebuds while ye may", and Andrew Marvell, who authored "To His Coy Mistress", classical scholar and lyric poet A. E. Housman, war poets Siegfried Sassoon and Rupert Brooke, modernist T. E. Hulme, confessional poets Ted Hughes, Sylvia Plath, and John Berryman, and, more recently, Cecil Day-Lewis, Joseph Brodsky, Kathleen Raine, and Geoffrey Hill.

At least nine Poets Laureate graduated from the University of Cambridge. University alumni have also made notable contributions to literary criticism, having produced, among others, F. R. Leavis, I. A. Richards, C. K. Ogden, and William Empson, often collectively known as the Cambridge Critics, the Marxists Raymond Williams, sometimes regarded as the founding father of cultural studies, and Terry Eagleton, author of Literary Theory: An Introduction, the most successful academic book ever published, the aesthetician Harold Bloom, new historicist Stephen Greenblatt, and biographical writers including Lytton Strachey, a central figure in the Bloomsbury Group, Peter Ackroyd, and Claire Tomalin.

Actors and directors who attended the University of Cambridge include Ian McKellen, Eleanor Bron, Miriam Margolyes, Derek Jacobi, Michael Redgrave, James Mason, Emma Thompson, Stephen Fry, Hugh Laurie, John Cleese, John Oliver, Freddie Highmore, Eric Idle, Graham Chapman, Graeme Garden, Tim Brooke-Taylor, Bill Oddie, Simon Russell Beale, Tilda Swinton, Thandie Newton, Georgie Henley, Rachel Weisz, Sacha Baron Cohen, Tom Hiddleston, Sara Mohr-Pietsch, Eddie Redmayne, Dan Stevens, Jamie Bamber, Lily Cole, David Mitchell, Robert Webb, Richard Ayoade, Mel Giedroyc, and Sue Perkins. Directors Mike Newell, Robert Icke, Sam Mendes, Simon McBurney, Peter Hall, Trevor Nunn, Stephen Frears, Paul Greengrass, Chris Weitz, and John Madden each are alumni of the university.

Mathematics and sciences

[edit]

Isaac Newton, who conducted many of his experiments on the grounds of Trinity College, ranks among the most famed University of Cambridge alumni. Other alumni of the university include Francis Bacon, who developed the scientific method of inquiry, mathematicians John Dee and Brook Taylor, pure mathematicians G. H. Hardy, John Edensor Littlewood, Mary Cartwright, and Augustus De Morgan; Michael Atiyah, a geometry specialist; William Oughtred, inventor of the logarithmic scale; John Wallis, first to explain the law of acceleration; Srinivasa Ramanujan, a genius who made substantial contributions to mathematical analysis, number theory, infinite series, and continued fractions; and James Clerk Maxwell, who brought about the second great unification of physics (the first being accredited to Newton) with his classical theory of electromagnetic radiation. In 1890, mathematician Philippa Fawcett, a University of Cambridge student, registered the highest score in the Cambridge Mathematical Tripos exams but as a woman was then ineligible to claim the title Senior Wrangler.