Звездные войны (фильм)

| Звездные войны | |

|---|---|

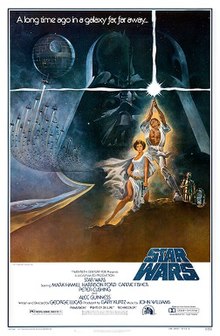

Театральный выпуск плакат Тома Юнга | |

| Режиссер | Джордж Лукас |

| Написано | Джордж Лукас |

| Производится | Гэри Курц |

| В главной роли | |

| Кинематография | Гилберт Тейлор |

| Под редакцией | |

| Музыка за | Джон Уильямс |

Производство компания | |

| Распределен | Двадцатый век-фрок |

Дата выпуска |

|

Время работы | 121 минута [ 1 ] |

| Страны | Соединенные Штаты [ 2 ] |

| Язык | Английский |

| Бюджет | 11 миллионов долларов [ 3 ] [ 4 ] |

| Театральная касса | 775,4 миллиона долларов [ 3 ] |

«Звездные войны» (позже переизданные «Звездные войны: Эпизод IV»-«Новая надежда» )-это американский эпический космический фильм 1977 года, написанный и режиссер Джордж Лукас , созданный Лукасфильмом и распространяемый по двадцатом веке . Это первый фильм, выпущенный в сериале «Звездные войны» и четвертую хронологическую главу « Скайуокеровской саги ». Установите «давным -давно» в вымышленной галактике, управляемой тиранической Галактической Империей , история следует за группой борцов за свободу, известных как альянс повстанцев , которые стремятся уничтожить новейшее оружие империи, Звезду Смерти . Когда лидер мятежника принцесса Лея похищается империей, Люк Скайуокер приобретает украденные архитектурные планы звезды Смерти и намеревается спасти ее, изучая пути метафизической силы, известной как « Сила » от мастера джедаи Оби-ван Кеноби Полем В актерский состав включают Марка Хэмилла , Харрисона Форда , Кэрри Фишер , Питера Кушинга , Алек Гиннесса , Энтони Дэниелса , Кенни Бейкера , Питера Мэйхью , Дэвида Доуса и Джеймса Эрла Джонса .

У Лукаса была идея для научно -фантастического фильма в духе Флэш -Гордона примерно в то время, когда он закончил свой первый фильм, Thx 1138 (1971), и он начал работать над лечением после выхода American Graffiti (1973). После многочисленных переписываний съемки происходили в течение 1975 и 1976 годов в местах, включая Tunsia и Elstree Studios в Хартфордшире, Англия. Лукас сформировал визуальные эффекты компании Industrial Light & Magic, чтобы помочь создать визуальные эффекты фильма. Звездные войны перенесли трудности с производством: актеры и экипаж полагали, что фильм потерпит неудачу, и он составил 3 миллиона долларов из -за бюджета из -за задержек.

Немногие были уверены в перспективах кассовых сборов фильма. Он был выпущен в небольшом количестве кинотеатров в Соединенных Штатах 25 мая 1977 года и быстро стал неожиданным блокбастером, что привело к тому, что он будет расширен до гораздо более широкого выпуска. Звездные войны открылись для положительных отзывов, похвалы за его спецэффекты. Во время первого запуска он собрал 410 миллионов долларов по всему миру, превзойдя Jaws (1975), чтобы стать самым кассовым фильмом до выхода ET The Extra Terrestrial (1982); Последующие выпуски привели к общему общению до 775 миллионов долларов. При корректировке для инфляции « Звездные войны» -второй по величине фильм в Северной Америке (за «Унесенным ветром ») и четвертым по величине фильмом всех времен . Он получил награды Академии , награды BAFTA и Saturn Awards , среди прочих. Фильм был переиздан много раз при поддержке Лукаса-в значительной степени существенно театральное «Специальное издание» 20-го годовщины-и переиздания содержали много изменений, включая новые сцены, визуальные эффекты и диалог.

Часто считается одним из величайших и самых влиятельных фильмов, когда-либо снятых, Star Wars быстро стал феноменом поп-культуры , запустив индустрию продуктов, включая романы , комиксы , видеоигры , аттракционы парка развлечений и товары, такие как игрушки, игры и одежда. Это стало одним из первых 25 фильмов, отобранных Библиотекой Конгресса Соединенных Штатов по сохранению в Национальном реестре кино в 1989 году, и ее саундтрек был добавлен в Национальный реестр записей США в 2004 году. Империя наносит удар (1980) и возвращение Джедай (1983) последовал за «Звездными войнами» , завершив оригинальную «Звездных войн» трилогию . к двум отдельным фильмам С тех пор была выпущена трилогия приквела и трилогия продолжения, в дополнение и различным телесериалам .

Сюжет

[ редактировать ]На фоне галактической гражданской войны шпионы повстанцев украли планы на Звезду Смерти , колоссальную космическую станцию, построенную Галактической империей , которая способна уничтожить целые планеты. Принцесса Лея Органа из Олдераана , тайно лидер мятежника, получила схемы, но ее корабль перехвачен и поднят имперские силы под командованием Дарта Вейдера . Лея взят в плен, но дроиды R2-D2 и C-3PO сбегают с планами, рухнув на ближайшую планету Татуина .

Дроиды захвачены Джава Трейдеры, которые продают их фермерам влаги Оуэну и Беру Ларсу и их племянникам Люком Скайуокером . В то время как Люк убирает R2-D2, он обнаруживает запись Леи, просящую помощь от бывшего союзника по имени Оби-Ван Кеноби . R2-D2 пропал без вести, и во время поиска его, Люк подвергается нападению со стороны песчаных людей . Он спасен пожилым отшельником Бен Кеноби, который вскоре показывает себя как Оби-Ван. Он рассказывает Люку о своем прошлом как одного из рыцарей -джедаев , бывших миротворцев Галактической Республики , которые привлекли мистические способности от сил , но империю охотились на почти в погибке. Люк узнает, что его отец, также джедай, сражался вместе с Оби-Ваном во время войн клонов, пока Вейдер, бывший ученик Оби-Вана, не повернулся к темной стороне силы и не убил его. своего отца Оби-Ван дает Люку световой мечи , подписного оружия джедая.

R2-D2 играет полное послание Леи, в котором она умоляет Оби-Ван принять планы Смерти Свиде Альдераану и отдать их своему отцу, коллеге-ветерану, для анализа. Первоначально Люк отказывается от предложения Оби-Вана сопровождать его в Олдераане и изучить пути силы, но у него не было выбора после того, как имперские штурмовики убивают его семью во время поиска дроидов. В поисках пути от планеты, Люка и Оби-Ван отправляются в город Мос Эйсли и нанимают Хан Соло и Чубакку , пилотов звездного сокола Миллениум .

До того, как Сокол достигнет Алдераана, командир Звезды Смерти Гранд Мофф Таркин зарегистрировал планету суперлазером станции. [ 5 ] По прибытии Сокол Звезды Смерти захвачен лучктором , но пассажиры избегают обнаружения и проникновения в станцию. Когда Оби-Ван уходит, чтобы дезактивировать тракторный луч, Люк убеждает Хана и Чубакку, чтобы помочь ему спасти Лею, которая планирует для исполнения после отказа раскрыть местоположение базы повстанцев. После отключения трактора, Оби-Ван жертвует собой в дуэли светового меча против Вейдера, что позволяет остальной группе сбежать. Используя устройство для отслеживания, размещенное на Соколе , империя обнаруживает базу повстанцев на Луне Yavin 4 .

Анализ схемы Звезды Смерти выявляет слабость в небольшом выхлопном отверстии, ведущем непосредственно к реактору станции. Люк присоединяется к эскадрильи X-Wing в отчаянном нападении на звезду смерти, в то время как Хан и Чубакка уходят, чтобы погасить долг преступлению лорду Джабба Хатт . В последующей битве Вейдер возглавляет эскадрилью бойцов и уничтожает несколько повстанческих кораблей. Хан и Чубакка неожиданно возвращаются в Сокол , сбив кораблю Вейдера с курса, прежде чем он сможет снять Люка. Руководствуясь голосом духа Оби-Вана , Люк использует силу, чтобы нацелить свои торпеды в выхлопный порт, заставляя звезду Смерти взорвать несколько минут, прежде чем он сможет стрелять на базу повстанцев. На торжественной церемонии Leia присуждает медали Люка и Хан за их героизм.

Бросать

[ редактировать ]- Марк Хэмилл в роли Люка Скайуокера : молодой взрослый, воспитанный его тетей и дядей на Татуине, который мечтает о чем -то большем, чем его нынешняя жизнь. [ 6 ] [ 7 ]

- Харрисон Форд в роли Хана Соло : контрабандиста и капитан « Сокола тысячелетия» [ 8 ] [ 9 ]

- Carrie Fisher as Princess Leia Organa: Princess of the planet Alderaan, member of the Imperial Senate, and a leader of the Rebel Alliance[10]

- Peter Cushing as Grand Moff Tarkin: The commander of the Death Star[11][12]

- Alec Guinness as Ben (Obi-Wan) Kenobi: An aging Jedi Master who introduces Luke to the Force[13][14]

- Anthony Daniels as See Threepio (C3PO): A humanoid protocol droid[a][15]

- Kenny Baker as Artoo Detoo (R2-D2): An astromech droid[16]

- Peter Mayhew as Chewbacca: Han's Wookiee friend and co-pilot of the Millennium Falcon [17]

- David Prowse / James Earl Jones (voice) as Lord Darth Vader: Obi-Wan's former Jedi apprentice who fell to the dark side of the Force[18][19]

Phil Brown and Shelagh Fraser appear as Luke's Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru, respectively,[20][21] and Jack Purvis portrays the Chief Jawa.[22] Rebel leaders include Alex McCrindle as General Dodonna and Eddie Byrne as General Willard. Imperial commanders include Don Henderson as General Taggi,[b] Richard LeParmentier as General Motti, and Leslie Schofield as Commander #1. Rebel pilots are played by Drewe Henley (Red Leader, mistakenly credited as Drewe Hemley),[25] Denis Lawson (Red Two/Wedge, credited as Dennis Lawson), Garrick Hagon (Red Three/Biggs), Jack Klaff (Red Four/John "D"), William Hootkins (Red Six/Porkins), Angus MacInnes (Gold Leader, credited as Angus McInnis), Jeremy Sinden (Gold Two), and Graham Ashley (Gold Five).[26] Uncredited actors include Paul Blake as the bounty hunter Greedo,[27] Alfie Curtis as the outlaw who confronts Luke in the cantina,[c][30] and Peter Geddis as the Rebel officer who is strangled by Darth Vader.[d][33] Heavily synthesized audio recordings of John Wayne (from his earlier films) were used for the voice of Garindan, an Imperial spy.[34]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

Lucas had the idea for a space opera prior to 1971.[35] According to Mark Hamill, he wanted to make it before his 1973 coming-of-age film American Graffiti.[36] His original plan was to adapt the Flash Gordon space adventure comics and serials into films, having been fascinated by them since he was young.[37] Lucas attempted to purchase the rights, but they had already been acquired by producer Dino De Laurentiis.[38] Lucas then discovered that Flash Gordon was inspired by the John Carter of Mars book series by Edgar Rice Burroughs, the author of Tarzan. Burroughs, in turn, had been influenced by Gulliver on Mars, a 1905 science fantasy written by Edwin Arnold. Lucas took the science fantasy concept and began developing what he would later call a "space fantasy".[37]

In May 1971, Lucas persuaded the head of United Artists, David Picker, to take a chance on two of his film ideas: American Graffiti and the space opera.[39] Although Lucas signed a two-picture deal, the studio ultimately declined to produce Graffiti. Universal Pictures picked it up, and Lucas spent the next two years making the coming-of-age film, which was immensely successful.[39] In January 1973, he began working on the space opera full-time.[37] He began the process by inventing odd names for characters and places. By the time the screenplay was finalized he had discarded many of the names, but several made it into the final script and later sequels.[40] He used his early notes to compile a two-page synopsis titled Journal of the Whills, which chronicled the tale of CJ Thorpe, an apprentice "Jedi-Bendu", who was being trained by the legendary Mace Windy.[41] He felt that this story was too difficult to understand, however.[42]

Lucas began writing a 13-page treatment called The Star Wars on April 17, 1973, which had narrative parallels with Kurosawa's 1958 film The Hidden Fortress.[43] He later explained that Star Wars is not a story about the future, but rather a "fantasy" that has more in common with the Brothers Grimm than 2001: A Space Odyssey. He said his motivation for making the film was to give young people an "honest, wholesome fantasy life," of the kind his generation had. He hoped it would offer "the romance, the adventure, and the fun that used to be in practically every movie".[44]

While impressed with the innocence of the story and the sophistication of Lucas's fictional world, United Artists declined to fund the project. Lucas and Kurtz then presented the treatment to Universal Pictures, the studio that financed American Graffiti. Universal agreed it could be a successful venture, but had doubts about Lucas's ability to execute his vision.[36] Kurtz has claimed the studio's rejection was primarily due to Universal head Lew Wasserman's low opinion of science fiction, and the generally low popularity of the genre at the time.[45] Francis Ford Coppola subsequently brought the project to a division of Paramount Pictures he ran with fellow directors Peter Bogdanovich and William Friedkin, but Friedkin questioned Lucas's ability to direct the film, and both directors declined to finance it.[46] Walt Disney Productions also turned down the project.[47]

Star Wars was accepted by Twentieth Century-Fox in June 1973. Studio president Alan Ladd Jr. did not grasp the technical side of the project, but believed in Lucas's talent. Lucas later stated that Ladd invested in him, not in the film.[48] The Fox deal gave Lucas $150,000 to write and direct the film.[49] In August, American Graffiti opened to massive success, which afforded Lucas the necessary leverage to renegotiate the deal and gain control of merchandising and sequel rights.[40][48]: 19

Writing

[edit]It's the flotsam and jetsam from the period when I was twelve years old. All the books and films and comics that I liked when I was a child. The plot is simple—good against evil—and the film is designed to be all the fun things and fantasy things I remember. The word for this movie is fun.

—George Lucas, 1977[50]

Since commencing the writing process in January 1973, Lucas wrote four different screenplays for Star Wars, searching for "just the right ingredients, characters and storyline."[37] By May 1974, he had expanded the original treatment into a full, 132-page rough draft, which included elements such as the Sith, the Death Star, and a general named Annikin Starkiller.[48]: 14 [51] He then changed Starkiller to an adolescent boy, and shifted the general—who came from a family of dwarfs—into a supporting role.[48][52] Lucas envisioned the Corellian smuggler, Han Solo, as a large, green-skinned monster with gills. He based Chewbacca on his Alaskan Malamute dog, Indiana, who often acted as his "co-pilot" by sitting in the passenger seat of his car. The dog's name would later be given to the character Indiana Jones.[52][53]

Lucas completed a second draft in January 1975 entitled Adventures of the Starkiller, Episode One: The Star Wars. He had made substantial simplifications and introduced the young, farm-dwelling hero as Luke Starkiller. In this draft, Luke had several brothers. Annikin became Luke's father, a wise Jedi Knight who played a minor role at the end of the story. Early versions of the characters Han Solo and Chewbacca were present, and closely resemble those seen in the finished film.[54] This draft introduced a mystical energy field called "The Force," the concept of a Jedi turning to the dark side, and a historical Jedi who was the first to turn, and who subsequently trained the Sith. The script also included a Jedi Master with a son who trains to be a Jedi under his father's friend; this would ultimately form the basis for the finished film and, later, the original trilogy.[51][55] This version was more a fairy tale quest than the action-filled adventure story of the previous draft, and ended with a text crawl that previewed the next story in the series. According to Lucas, the second draft was over 200 pages long, which led him to split up the story into multiple films spanning multiple trilogies.[56]

While writing a third draft, Lucas claims to have been influenced by comics,[57] J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit,[58][59] Joseph Campbell's The Hero with a Thousand Faces,[60] James George Frazer's The Golden Bough,[61] and Bruno Bettelheim's The Uses of Enchantment. Author Michael Kaminski has objected to Lucas's claim regarding the Bettelheim book, arguing that it was not released until after Star Wars was filmed (J.W. Rinzler speculates that Lucas may have obtained an advance copy). Kaminski also writes that Campbell's influence on Star Wars has been exaggerated by Lucas and others, and that Lucas's second draft was "even closer to Campbell's structure" than the third.[62]

Lucas has claimed he wrote a version of the screenplay that was 250–300 pages long, which outlined the plot of the entire original trilogy. Realizing it was too lengthy for a single film, he decided to spread the story over three films.[48][63][64] This division caused problems with the first episode; Lucas had to use the ending of Return of the Jedi for Star Wars, which resulted in a Death Star being included in both films.[65][66][e] In 1975, Lucas envisioned a trilogy which would end with the destruction of the Empire, and possibly a prequel about Obi-Wan as a young man. After Star Wars became tremendously successful, Lucasfilm announced that Lucas had already written twelve more Luke Skywalker stories, which, according to Kurtz, were "separate adventures" rather than traditional sequels.[69][70][71]

On February 27, 1975, Fox granted the film a budget of $5 million, which was later increased to $8.25 million.[48]: 17:30 Lucas then started writing with a budget in mind, conceiving the cheap, "used" look of much of the film, and—with Fox having just shut down its special effects department—reducing the number of complex special effects shots called for by the script.[72] The finalized third draft, dated August 1, 1975, was titled The Star Wars From the Adventures of Luke Starkiller. This version had most of the elements of the final plot, with only some differences in the characters and settings. It presented Luke as an only child whose father was already dead, and who was cared for by a man named Ben Kenobi.[51] This script would be rewritten for the fourth and final draft, dated January 1, 1976, and titled The Adventures of Luke Starkiller as taken from the Journal of the Whills, Saga I: The Star Wars. Lucas's friends Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck helped him revise the fourth draft into the final pre-production script.[73]

Lucas finished the screenplay in March 1976, when the crew started filming. During production, he changed Luke's surname from Starkiller to Skywalker, and changed the title first to The Star Wars, and then, finally, to Star Wars.[48][51] For the film's opening crawl, Lucas originally wrote a composition of six paragraphs with four sentences each.[49][74] He showed the draft to his friend, director Brian De Palma, who called it "gibberish" that "goes on forever."[75][76] De Palma and screenwriter Jay Cocks helped edit the crawl into its final form, which contains only four sentences.[75][77]

Casting

[edit]Lucas had a preference for casting unknown (or relatively unknown) actors,[48] which led him to select Hamill and Fisher for leading roles. Hamill was cast as Luke over Robby Benson, William Katt, Kurt Russell, and Charles Martin Smith,[78][79] while Fisher was cast as Leia over Karen Allen, Amy Irving, Terri Nunn, Cindy Williams, and Linda Purl.[80][81] Jodie Foster was offered the role, but turned it down because she was under contract with Disney.[82] Koo Stark was also considered for Leia, but was instead cast as Luke's friend Camie Marstrap, a character that did not make the final cut of the film.[83][84]

Lucas initially resisted casting Ford as Han, since Ford had previously worked with Lucas on American Graffiti, and was therefore not unknown. Instead, the director asked Ford to assist with auditions by reading lines with other actors. However, Lucas was eventually won over by Ford, and cast him as Han over many other actors who auditioned.[f]

Lucas recognized that he needed an established star to play Obi-Wan. He considered Cushing for the role, but decided the actor's lean features would be better employed as the villainous Tarkin.[91] The film's producer, Gary Kurtz, felt a strong character actor was required to convey the "stability and gravitas" of Obi-Wan.[48] Before Guinness was cast, the Japanese actor Toshiro Mifune—who stars in many Akira Kurosawa films—was considered for the role.[80] His daughter, Mika Kitagawa, said her father "had a lot of samurai pride" and turned down the roles of Obi-Wan and Vader because he thought Star Wars would employ cheap special effects and would therefore "cheapen the image of samurai".[92] Lucas credited Guinness with inspiring the cast and crew to work harder, which contributed significantly to the completion of filming.[93] Ford said he admired Guinness's preparation, professionalism and kindness towards the other actors. He recalled Guinness having "a very clear head about how to serve the story."[48] On top of his salary, Guinness received 2.25% of the film's backend grosses, which made him wealthy later in life.[94]

Daniels said he wanted the role of C-3PO after he saw a Ralph McQuarrie concept painting of the character and was struck by the vulnerability in the droid's face.[48][95] After casting Daniels for the physical performance, Lucas intended to hire another actor for the droid's voice. According to Daniels, thirty well-established actors auditioned—including Richard Dreyfuss and Mel Blanc—but Daniels received the voice role after one of the actors suggested the idea to Lucas.[96][97][98][48]

Baker (R2-D2) and Mayhew (Chewbacca) were cast largely due to their height. At 3 feet 8 inches (1.12 m), Baker was offered the role of the dimunitive droid immediately after meeting Lucas. He turned it down multiple times, however, before finally accepting it.[99] R2-D2's beeps and squeaks were made by sound designer Ben Burtt by imitating baby noises, recording his voice over an intercom, and finally mixing the sounds together using a synthesizer.[100] Mayhew initially auditioned for Vader, but Prowse was cast instead. However, when Lucas and Kurtz saw Mayhew's 7-foot-3-inch (2.21 m) stature, they quickly cast him as Chewbacca. Mayhew modeled his performance on the mannerisms of animals he observed in public zoos.[48][101][102]

Prowse was originally offered the role of Chewbacca, but turned it down, as he wanted to play the villain.[103] Prowse portrayed Vader physically, but Lucas felt his West Country English accent was inappropriate for the character, and selected James Earl Jones for Vader's voice.[66] Lucas considered Orson Welles for the voice role, but was concerned his voice would be too familiar to audiences. Jones was uncredited until 1983.[48][66][104]

Design

[edit]During pre-production, Lucas recruited several conceptual designers: Colin Cantwell, who visualized the initial spacecraft models; Alex Tavoularis, who created storyboard sketches from early scripts; and Ralph McQuarrie, who created conceptual images of characters, costumes, props, and scenery.[37] McQuarrie's paintings helped the studio visualize the film, which positively influenced their decision to fund the project.[105][106] His artwork also set the visual tone for Star Wars and the rest of the original trilogy.[37]

The trouble with the future in most futurist movies is that it always looks new and clean and shiny ... What is required for true credibility is a used future.

—George Lucas on the aesthetic of Star Wars[107]

Lucas wanted to create props and sets (based on McQuarrie's paintings) that had never before been used in science-fiction films. He hired as production designers John Barry and Roger Christian, who were then working on the film Lucky Lady (1975). Christian remembers that Lucas did not want anything in Star Wars to stand out, and "wanted it [to look] all real and used." In this "used future" aesthetic, all devices, ships, and buildings related to Tatooine and the Rebels look aged and dirty, and the Rebel ships look cobbled together in contrast to the Empire's sleeker designs.[108][109] Lucas believed this aesthetic would lend credibility to the film's fictional places, and Christian was enthusiastic about this approach.[107][110]

Barry and Christian started working with Lucas before Star Wars was funded by Fox. For several months, in a studio in Kensal Rise, England, they planned the creation of props and sets with very little money. According to Christian, the Millennium Falcon set was the most difficult to build. He wanted the interior of the ship to look like a submarine, and used inexpensive airplane scrap metal to achieve the desired effect.[110][111] Set construction later moved to Elstree Studios, where Barry created thirty sets. All nine sound stages at Elstree were needed to house the fabricated planets, starships, caves, control rooms, cantinas, and Death Star corridors. The Rebel hangar was so massive it had to be built at nearby Shepperton Studios, which contained Europe's largest sound stage at the time.[107]

Filming

[edit]In 1975, Lucas founded the visual effects company Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) after discovering that Fox's visual effects department had been shut down. ILM began its work on Star Wars in a warehouse in Van Nuys, California. Most of the visual effects used pioneering digital motion control photography developed by John Dykstra and his team, which created the illusion of size by employing small models and slowly moving cameras. The technology is now known as the Dykstraflex system.[48][112][113][114]

Visually, Lucas wanted Star Wars to have the "ethereal quality" of a fairy tale, but also "an alien look." He hoped to achieve "the seeming contradiction of [the] strange graphics of fantasy combined with the feel of a documentary."[107] His first choice for cinematographer was Geoffrey Unsworth, who had worked on 2001: A Space Odyssey. Unsworth initially accepted the job, but eventually withdrew to work on the Vincente Minnelli-directed A Matter of Time (1976).[45] Unsworth was replaced by Gilbert Taylor, who had overseen photography for Dr. Strangelove and A Hard Day's Night (both 1964). Lucas admired Taylor's work on both films, describing them as "eccentrically photographed pictures with a strong documentary flavor."[107]

Once photography was under way, Lucas and Taylor had many disputes.[45] Lucas's lighting suggestions were rejected by Taylor, who believed Lucas was overstepping his boundaries by giving specific instructions, sometimes even moving lights and cameras himself. After Fox executives complained about the soft-focus visual style of the film, Taylor changed his approach, which infuriated Lucas.[115] Kurtz said that Lucas's inability to delegate tasks resulted from his history directing low-budget films, which required him to be involved with all aspects of the production.[45] Taylor claims that Lucas avoided contact with him, which motivated the cinematographer to make his own decisions about how to shoot the film.[116][117]

Originally, Lucas envisioned Tatooine as a jungle planet, and Kurtz traveled to the Philippines to scout locations. However, the thought of spending months filming in the jungle made Lucas uncomfortable, so he made Tatooine a desert planet instead.[44] Kurtz then researched various desert locales around the globe. He ultimately decided that Southern Tunisia, on the edge of the Sahara, would make an ideal Tatooine. Principal photography began in Chott el Djerid on March 22, 1976. Meanwhile, a construction crew in nearby Tozeur spent eight weeks creating additional Tatooine locations.[107] The scenes of Luke's Tatooine home were filmed at the Hotel Sidi Driss, in Matmata.[118] Additional Tatooine scenes were shot at Death Valley in the United States.[119]

The filmmakers experienced many problems in Tunisia. Production fell behind schedule in the first week due to malfunctioning props and electronic breakdowns.[48][120][121] The radio-controlled R2-D2 models functioned poorly.[44] The left leg of Anthony Daniels's C-3PO costume shattered, injuring his foot.[122] A rare winter rainstorm struck the country, which further disrupted filming.[123][124] After two and a half weeks in Tunisia, production moved to Elstree Studios in London for interior scenes.[118][121]

Kurtz has described Lucas as a shy "loner" who does not enjoy working with a large cast and crew. According to Carrie Fisher, he gave very little direction to the actors, and when he did, it usually consisted of the words "faster" and "more intense".[48] Laws in Britain stipulated that filming had to finish by 5:30 pm, unless Lucas was in the middle of a shot, in which case he could ask the crew to stay an extra 15 minutes.[49] However, his requests were usually turned down. Most of the British crew considered Star Wars a children's film, and the actors sometimes did not take the project seriously. Kenny Baker later confessed that he thought the film would be a failure.[48]

According to Taylor, it was impossible to light the Elstree sets in the conventional way. He was forced to break open the walls, ceilings and floors, placing quartz lamps inside the openings he created. This lighting system gave Lucas the ability to shoot in almost any direction without extensive relighting.[123] In total, filming in Britain took fourteen and a half weeks.[118] While visiting an English travel agency, Lucas saw a poster depicting Tikal, Guatemala, and decided to use the location for the moon Yavin 4.[125] The scenes of the Rebel base on Yavin were filmed in the local Mayan temples. The animation of the Death Star plans shown at the base were created by computer programmer Larry Cuba, using the GRASS programming language. It is the only digital computer animation utilized in the original version of Star Wars.[126] The visual simulation of Yavin 4 orbiting its mother planet was created on the Scanimate analog computer. All the other computer monitors and targeting displays in the film featured simulated computer graphics, which were generated using pre-digital animation methods, such as hand-drawn backlight animation.[127][128]

Although Obi-Wan did not die in the final version of the script, Alec Guinness disliked the character's dialogue and said he begged Lucas to kill him off.[129] Lucas, however, claimed he added Obi-Wan's death because the character served no purpose after his duel with Vader.[130][131]

At Fox, Alan Ladd endured scrutiny from board members over the film's complex screenplay and rising budget.[48][121] After the filmmakers requested more than the original $8 million budget, Kurtz said the executives "got a bit scared." According to Kurtz, the filmmaking team spent two weeks drafting a new budget.[45] With the project behind schedule, Ladd told Lucas he had to finish production within a week or it would be shut down. The crew split into three units, led by Lucas, Kurtz, and production supervisor Robert Watts. Under the new system, they met the studio's deadline.[48][121]

The screenplay originally featured a human Jabba the Hutt, but the character was removed due to budget and time constraints.[100] The idea of Jabba being an alien did not arise until work began on the 1979 Star Wars re-release.[132] Lucas would later claim he had wanted to superimpose a stop-motion creature over a human actor; he accomplished a similar effect with computer-generated imagery (CGI) in the 1997 Special Edition.[133][134] According to Greedo actor Paul Blake, his character was created as a result of Lucas having to cut the Jabba scene.[135]

During production, the cast attempted to make Lucas laugh or smile, as he often appeared depressed. At one point, the project became so demanding that Lucas was diagnosed with hypertension and exhaustion and was warned to reduce his stress level.[48][121] Post-production was equally stressful due to increasing pressure from the studio. Another obstacle arose when Hamill's face became visibly scarred after a car accident, which restricted re-shoots featuring Luke.[121]

Post-production

[edit]Star Wars was originally slated for release on December 25, 1976, but production delays pushed it back to mid-1977.[136] Editor John Jympson began cutting the film while Lucas was still filming in Tunisia; as Lucas noted, the editor was in an "impossible position" because Lucas had not explained any of the film's material to him. When Lucas viewed Jympson's rough cut, he felt the editor's selection of takes was questionable.[137] He felt Jympson did not fully understand the film nor Lucas's style of filmmaking, and he continued to disapprove of Jympson's editing as time went by.[138] Halfway through production, Lucas fired Jympson and replaced him with Paul Hirsch, Richard Chew, and his then-wife, Marcia Lucas. The new editing team felt Jympson's cut lacked excitement, and they sought to inject more dynamism into the film.[48][139]

Jympson's rough cut of Star Wars (often called the "Lost Cut") differed significantly from the final version. Author David West Reynolds describes Jympson's version as "more leisurely paced", and estimates that it contained 30–40% different footage from the final cut. Although most of the differences relate to extended scenes or alternate takes, there were also scenes which were completely removed to accelerate the pace of the narrative.[140] The most notable of these were a series from Tatooine, when Luke is first introduced. Set in the city of Anchorhead, the scenes depicted Luke's everyday life among his friends, and showed how their lives are affected by the space battle above the planet. These scenes also introduced Biggs Darklighter, Luke's closest friend who leaves to join the Rebellion.[141] Hirsch said the scenes were removed because they presented too much information in the first few minutes of the film, and they created too many storylines for the audience to follow.[142] The removal of the Anchorhead scenes also helped distinguish Star Wars from Lucas's previous film; Alan Ladd called the deleted scenes "American Graffiti in outer space".[141] Lucas also wanted to shift the narrative focus to C-3PO and R2-D2 at the beginning of the film. He explained that having "the first half hour of the film be mainly about robots was a bold idea."[143][144]

Meanwhile, ILM was struggling to achieve unprecedented special effects. The company had spent half its budget on four shots that Lucas deemed unacceptable.[121] With hundreds of shots remaining, ILM was forced to finish a year's work in six months. To inspire the visual effects team, Lucas spliced together clips of aerial dogfights from old war films. These kinetic segments helped the team understand his vision for scenes in Star Wars.[48]

Sound designer Ben Burtt had created a library of sounds that Lucas referred to as an "organic soundtrack". Blaster sounds were created by modifying the noise of a steel cable being struck while under tension. Lightsaber sound effects were a combination of the hum of movie projector motors and interference caused by a television set on a shieldless microphone. Burtt discovered the latter accidentally while searching for a buzzing, sparking sound to add to the projector-motor hum.[145] For Chewbacca's speech, Burtt combined the sounds of four bears, a badger, a lion, a seal, and a walrus.[146] Burtt achieved Vader's breathing noise by breathing through the mask of a scuba regulator; this process inspired the idea of Vader being a burn victim.[147][148]

In February 1977, Lucas screened an early cut of the film for Fox executives, several director friends, and Roy Thomas and Howard Chaykin of Marvel Comics, who were preparing a Star Wars comic book. The cut had a different crawl from the finished version and used Prowse's voice for Vader. It also lacked most special effects; hand-drawn arrows took the place of blaster beams, and footage of World War II dogfights replaced space battles between TIE fighters and the Millennium Falcon.[149] Several of Lucas's friends failed to understand the film, and their reactions disappointed Lucas. Steven Spielberg enjoyed it, however, and believed the lack of enthusiasm from others was due to the absence of finished special effects. In contrast, Ladd and the other studio executives loved the film; production executive Gareth Wigan described the experience as the "most extraordinary day of [his] life." Lucas, who was accustomed to negative reactions from executives, found the experience shocking and rewarding.[48]

Ladd reluctantly agreed to release an extra $50,000 in funding.[150] The unit also completed additional studio footage for the Mos Eisley cantina sequence.[151]

Star Wars was completed less than a week before its May 25, 1977, release date. With all of the film's elements coming together just in time, Lucas described the work as not so much finished, but "abandoned".[152] Star Wars began production with a budget of $8 million; the total budget eventually reached $11 million.[153]

Soundtrack

[edit]Lucas initially planned to use pre-existing music for Star Wars, rather than an original score. Since the film portrayed alien worlds, he believed recognizable music was needed to create a sense of familiarity. He hired John Williams as a music consultant, and showed him a collection of orchestral pieces he intended to use for the soundtrack.[154] After Williams convinced Lucas that an original score would be preferable, Lucas tasked him with creating it. A few of the composer's finished pieces were influenced by Lucas's initial orchestral selections. The "Main Title Theme" was inspired by the theme from the 1942 film Kings Row (scored by Erich Wolfgang Korngold), and the "Dune Sea of Tatooine" was influenced by the music of Bicycle Thieves (scored by Alessandro Cicognini). Lucas later denied he ever considered using pre-existing music for the film.[155][156]

Over a period of 12 days in March 1977, Williams and the London Symphony Orchestra recorded the Star Wars score.[48] The soundtrack was released as a double LP in 1977 by 20th Century Fox Records.[157][158] That year, the label also released The Story of Star Wars, an audio drama adaptation of the film utilizing some of its music, dialogue, and sound effects.[159][160]

In 2005, the American Film Institute chose the Star Wars soundtrack as the best film score of all time.[161]

Cinematic and literary allusions

[edit]Before creating Star Wars, Lucas had hoped to make a Flash Gordon film, but was unable to obtain the rights. Star Wars features many elements ostensibly derived from Flash Gordon, such as the conflict between rebels and imperial forces; the fusion of mythology and futuristic technology; the wipe transitions between scenes; and the text crawl at the beginning of the film.[162][better source needed] Lucas also reportedly drew from Joseph Campbell's book The Hero with a Thousand Faces and Akira Kurosawa's 1958 film The Hidden Fortress.[38][162][163] Robey has also suggested that the Mos Eisley cantina brawl was influenced by Kurosawa's Yojimbo (1961), and that the scene in which Luke and his friends hide in the floor of the Millenium Falcon was derived from that film's sequel, Sanjuro (1962).[162]

Star Wars has been compared to Frank Herbert's Dune book series in multiple ways.[38][164][better source needed] Both have desert planets: Star Wars has Tatooine, while Dune has Arrakis, which is the source of a longevity spice. Star Wars, meanwhile, makes references to spice mines and a spice freighter. Jedi mind tricks in Star Wars have been compared to "The Voice", a controlling ability used by the Bene Gesserit in Herbert's novels. Luke's Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru are moisture farmers; on Arrakis, dew collectors are used by Fremen to collect and recycle small amounts of water.[better source needed][165] Herbert reported that David Lynch, director of the 1984 film Dune, "had trouble with the fact that Star Wars used up so much of Dune." Herbert and Lynch found "sixteen points of identity" between the two universes, and argued that these similarities could not be a coincidence.[166]

Writing for Starwars.com in 2013, Bryan Young noted many similarities between Lucas's space opera and the World War II film The Dam Busters (1955). In Star Wars, Rebel ships assault the Death Star by diving into a trench and attempting to fire torpedoes into a small exhaust port; in Dam Busters, British bombers fly along heavily defended reservoirs and aim bouncing bombs at dams to cripple the heavy industry of Germany (also, Star Wars cinematographer Gilbert Taylor filmed the special effects sequences in Dam Busters).[167] Lucas used clips from both Dam Busters and 633 Squadron to illustrate his vision for dogfights in Star Wars.[168]

Journalist and blogger Martin Belam has pointed out similarities between the Death Star's docking bay and the docking bay on the space station in 2001.[169] In 2014, Young observed a number of parallels between Lucas's space opera and Fritz Lang's 1927 film Metropolis.[170] Star Wars has also been compared to The Wizard of Oz (1939).[96]

Marketing

[edit]

While the film was in production, a logo was commissioned from Dan Perri, a title sequence designer who had worked on The Exorcist (1973) and Taxi Driver (1976). Perri created a logotype consisting of block-capital letters filled with stars and leaning towards a vanishing point. The graphic was designed to follow the same perspective as the opening text crawl. Ultimately, Perri's logo was not used for the film's opening title sequence, although it was used widely in pre-release print advertising and on cinema marquees.[171][172]

The logotype eventually selected for on-screen use originated in a promotional brochure that was distributed by Fox to cinema owners in 1976. The brochure was designed by Suzy Rice, a young art director at the Los Angeles advertising agency Seiniger Advertising. On a visit to ILM in Van Nuys, Rice was instructed by Lucas to produce a "very fascist" logo that would intimidate the viewer. Rice employed an outlined and modified Helvetica Black typeface in her initial version. After some feedback from Lucas, Rice joined the S and T of STAR and the R and S of WARS. Kurtz was impressed with Rice's composition and selected it over Perri's design for the film's opening titles, after flattening the pointed tips of the letter W. The Star Wars logo became one of the most recognizable designs in cinema, though Rice was not credited in the film.[171]

For the film's US release, Fox commissioned a promotional poster from the advertising agency Smolen, Smith and Connolly. The agency contracted the freelance artist Tom Jung, and gave him the phrase "good over evil" as a starting point. His poster, known as Style 'A', depicts Luke standing in a heroic pose, brandishing a shining lightsaber above his head. Leia is slightly below him, and a large image of Vader's helmet looms behind them. Some Fox executives considered this poster "too dark" and commissioned the Brothers Hildebrandt, a pair of well-known fantasy artists, to modify it for the UK release. When Star Wars opened in British theaters, the Hildebrandts' Style 'B' poster was used on cinema billboards. Fox and Lucasfilm later decided to promote the film with a less stylized and more realistic depiction of the lead characters, and commissioned a new design from Tom Chantrell. Two months after Star Wars opened, the Hildebrandts' poster was replaced by Chantrell's Style 'C' version in UK cinemas.[g]

Fox gave Star Wars little marketing support beyond licensed T-shirts and posters. The film's marketing director, Charley Lippincott, had to look elsewhere for promotional opportunities. He secured deals with Marvel Comics for a comic book adaptation and with Del Rey Books for a novelization. A fan of science fiction, Lippincott used his contacts to promote the film at San Diego Comic-Con and elsewhere within the science-fiction community.[48][45]

Release

[edit]MPAA rating

[edit]When Star Wars was submitted to the Motion Picture Association of America's rating board, the votes for the rating were evenly split between G and PG. In an unusual move, Fox requested the stricter PG rating, in part because it believed the film was too scary for young children, but also because it feared teenagers would perceive the G rating as "uncool". Lucasfilm marketer Charley Lippincott supported Fox's position after witnessing a five-year-old at the film's preview become upset by a scene in which Darth Vader chokes a Rebel captain. Although the board initially opted for the G rating, it reneged after Fox's request and applied the PG rating.[177]

First public screening

[edit]On May 1, 1977, the first public screening of Star Wars was held at Northpoint Theatre in San Francisco,[178][179] where American Graffiti had been test-screened four years earlier.[180][181]

Premiere and initial release

[edit]

Lucas wanted the film released in May, on the Memorial Day weekend. According to Fox executive Gareth Wigan, "Nobody had ever opened a summer film before school was out." Lucas, however, hoped the school-term release would build word-of-mouth publicity among children.[182] Fox ultimately decided on a release date of May 25, the Wednesday before the holiday weekend. Very few theaters, however, wanted to show Star Wars. To encourage exhibitors to purchase the film, Fox packaged it with The Other Side of Midnight, a film based on a bestselling book. If a theater wanted to show Midnight, it was required to show Star Wars as well.[48]

Lucas's film debuted on Wednesday, May 25, 1977, in 32 theaters. Another theater was added on Thursday, and ten more began showing the film on Friday.[152] On Wednesday, Lucas was so absorbed in work—approving advertising campaigns and mixing sound for the film's wider-release version—that he forgot the film was opening that day.[183] His first glimpse of its success occurred that evening, when he and Marcia went out for dinner on Hollywood Boulevard. Across the street, crowds were lining up outside Mann's Chinese Theatre, waiting to see Star Wars.[121][184]

Two weeks after its release, Lucas's film was replaced by William Friedkin's Sorcerer at Mann's because of contractual obligations. The theater owner moved Star Wars to a less-prestigious location after quickly renovating it.[185] After Sorcerer failed to meet expectations, Lucas's film was given a second opening at Mann's on August 3. Thousands of people attended a ceremony in which C-3PO, R2-D2 and Darth Vader placed their footprints in the theater's forecourt.[186][48] By this time, Star Wars was playing in 1,096 theaters in the United States.[187] Approximately 60 theaters played the film continuously for over a year. In May 1978, Lucasfilm distributed "Birthday Cake" posters to those theaters for special events on the one-year anniversary of the film's release.[188][189] Star Wars premiered in the UK on December 27, 1977. News reports of the film's popularity in America caused long lines to form at the two London theaters that first offered the film; it became available in 12 large cities in January 1978, and additional London theaters in February.[190]

On opening day I ... did a radio call-in show ... this caller, was really enthusiastic and talking about the movie in really deep detail. I said, "You know a lot about the film." He said, "Yeah, yeah, I've seen it four times already."

—Gary Kurtz, on when he realized Star Wars had become a cultural phenomenon[191]

The film immediately broke box office records.[186] Three weeks after it opened, Fox's stock price had doubled to a record high. Prior to 1977, the studio's highest annual profit was $37 million. In 1977, it posted a profit of $79 million.[48] Lucas had instantly become very wealthy. His friend, director Francis Ford Coppola, sent a telegram to his hotel asking for money to finish his film Apocalypse Now.[183] Cast members became instant household names, and even technical crew members, such as model makers, were asked for autographs.[48] When Harrison Ford visited a record store to buy an album, enthusiastic fans tore half his shirt off.[183]

Lucas had been certain Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind would outperform his space opera at the box office. Before Star Wars opened, Lucas proposed to Spielberg that they trade 2.5% of the profit on each other's films. Spielberg accepted, believing Lucas's film would be the bigger hit. Spielberg still receives 2.5% of the profits from Star Wars.[192]

Box office

[edit]Star Wars remains one of the most financially successful films of all time. It earned over $2.5 million in its first six days ($12.9 million in 2023 dollars).[193] According to Variety's weekly box office charts, it was number one at the US box office for its first three weeks. It was dethroned by The Deep, but gradually added screens and returned to number one in its seventh week, building up to $7-million weekends as it entered wide release ($35.2 million in 2023 dollars) and remained number one for the next 15 weeks.[3] It replaced Jaws as the highest-earning film in North America just six months into release,[194] eventually grossing over $220 million during its initial theatrical run ($1.11 billion in 2023 dollars).[195] Star Wars entered international release towards the end of the year, and in 1978 added the worldwide record to its domestic one,[196] earning $314.4 million in total.[3] Its biggest international market was Japan, where it grossed $58.4 million.[197]

On July 21, 1978, while still showing in 38 theaters in the US, the film expanded into a 1,744 theater national saturation windup of release and set a new U.S. weekend record of $10,202,726.[198][199][200] The gross prior to the expansion was $221,280,994. The expansion added a further $43,774,911 to take its gross to $265,055,905. Reissues in 1979 ($22,455,262), 1981 ($17,247,363), and 1982 ($17,981,612) brought its cumulative gross in the U.S. and Canada to $323 million,[201][202] and extended its global earnings to $530 million.[203] In doing so, it became the first film to gross $500 million worldwide,[204] and remained the highest-grossing film of all time until E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial broke that record in 1983.[205]

The release of the Special Edition in 1997 was the highest-grossing reissue of all-time with a gross of $138.3 million, bringing its total gross in the United States and Canada to $460,998,007, reclaiming the all-time number one spot.[206][3][207][208] Internationally, the reissue grossed $117.2 million, with $26 million from the United Kingdom and $15 million from Japan.[197] In total, the film has grossed over $775 million worldwide.[3]

Adjusted for inflation, it had earned over $2.5 billion worldwide at 2011 prices,[209] which saw it ranked as the third-highest-grossing film at the time, according to Guinness World Records.[210] At the North American box office, it ranks second behind Gone with the Wind on the inflation-adjusted list.[211]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]Star Wars received many positive reviews upon its release. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times called the film "an out-of-body experience".[212] Vincent Canby of The New York Times described it as "the most elaborate ... most beautiful movie serial ever made".[213] A. D. Murphy of Variety called the film "magnificent" and said Lucas had succeeded in his attempt to create the "biggest possible adventure fantasy" based on the serials and action epics of his childhood.[214] Writing for The Washington Post, Gary Arnold gave the film a positive review, calling it "a new classic in a rousing movie tradition: a space swashbuckler."[215] Star Wars was not without its detractors, however. Pauline Kael of The New Yorker said "there's no breather in the picture, no lyricism", and no "emotional grip".[216] John Simon of New York magazine also panned the film, writing, "Strip Star Wars of its often striking images and its highfalutin scientific jargon, and you get a story, characters, and dialogue of overwhelming banality."[217]

In the UK, Barry Norman of Film... called the movie "family entertainment at its most sublime", which combines "all the best-loved themes of romantic adventure".[218] The Daily Telegraph's science correspondent Adrian Berry said that Star Wars "is the best such film since 2001 and in certain respects it is one of the most exciting ever made". He described the plot as "unpretentious and pleasantly devoid of any 'message'".[219]

Gene Siskel, writing for the Chicago Tribune, said, "What places it a sizable cut above the routine is its spectacular visual effects, the best since Stanley Kubrick's 2001."[220][221] Andrew Collins of Empire magazine awarded the film five out of five and said, "Star Wars' timeless appeal lies in its easily identified, universal archetypes—goodies to root for, baddies to boo, a princess to be rescued and so on—and if it is most obviously dated to the 70s by the special effects, so be it."[222] In his 1977 review, Robert Hatch of The Nation called the film "an outrageously successful, what will be called a 'classic,' compilation of nonsense, largely derived but thoroughly reconditioned. I doubt that anyone will ever match it, though the imitations must already be on the drawing boards."[223] In a more critical review, Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader stated, "None of these characters has any depth, and they're all treated like the fanciful props and settings."[224] Peter Keough of the Boston Phoenix said, "Star Wars is a junkyard of cinematic gimcracks not unlike the Jawas' heap of purloined, discarded, barely functioning droids."[225]

In a 1978 appearance on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, scientist Carl Sagan called attention to the overwhelming whiteness of the human characters in the film.[226] Actor Raymond St. Jacques echoed Sagan's complaint, writing that "the terrifying realization ... [is] that black people (or any ethnic minority for that matter) shall not exist in the galactic space empires of the future."[227][h][i] Writing in the African-American newspaper New Journal and Guide, Walter Bremond claimed that due to his black garb and his being voiced by a black actor, the villainous Vader reinforces a stereotype that "black is evil".[231][234]

The film continues to receive critical acclaim from contemporary critics. On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 93% of 137 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 8.8/10. The website's consensus reads: "A legendarily expansive and ambitious start to the sci-fi saga, George Lucas opened our eyes to the possibilities of blockbuster filmmaking and things have never been the same."[235] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 90 out of 100, based on 24 critics.[236] In his 1997 review of the film's 20th-anniversary release, Michael Wilmington of the Chicago Tribune gave the film four out of four stars, calling it "[a] grandiose and violent epic with a simple and whimsical heart".[237] A San Francisco Chronicle staff member described the film as "a thrilling experience".[238] In 2001 Matt Ford of the BBC awarded the film five out of five stars and wrote, "Star Wars isn't the best film ever made, but it is universally loved."[239] CinemaScore reported that audiences for the film's 1999 re-release gave the film a "A+" grade.[240]

Accolades

[edit]Star Wars won many awards after its release, including six Academy Awards, two BAFTA Awards, one Golden Globe Award, three Grammy Awards, one Hugo Award, and thirteen Saturn Awards. Additionally, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences gave a Special Achievement Academy Award to Ben Burtt, and granted a Scientific and Engineering Award to John Dykstra, Alvah J. Miller, and Jerry Jeffress for the development of the Dykstraflex camera system.[241][242]

| Organization | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[243] | Best Picture | Gary Kurtz | Nominated |

| Best Director | George Lucas | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Alec Guinness | Nominated | |

| Best Original Screenplay | George Lucas | Nominated | |

| Best Art Direction | John Barry, Norman Reynolds, Leslie Dilley and Roger Christian | Won | |

| Best Costume Design | John Mollo | Won | |

| Best Film Editing | Paul Hirsch, Marcia Lucas and Richard Chew | Won | |

| Best Original Score | John Williams | Won | |

| Best Sound | Don MacDougall, Ray West, Bob Minkler and Derek Ball | Won | |

| Best Visual Effects | John Stears, John Dykstra, Richard Edlund, Grant McCune and Robert Blalack | Won | |

| Special Achievement Academy Award | Ben Burtt | Won | |

| Scientific and Engineering Award | John Dykstra, Alvah J. Miller and Jerry Jeffress | Won | |

| American Music Awards | Favorite Pop/Rock Album | John Williams | Nominated |

| BAFTA Awards[244] | Best Film | Gary Kurtz | Nominated |

| Best Costume Design | John Mollo | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | Paul Hirsch, Marcia Lucas and Richard Chew | Nominated | |

| Best Original Music | John Williams | Won | |

| Best Production Design | John Barry | Nominated | |

| Best Sound | Sam Shaw, Robert Rutledge, Gordon Davidson, Gene Corso, Derek Ball, Don MacDougall, Bob Minkler, Ray West, Michael Minkler, Les Fresholtz, Richard Portman and Ben Burtt | Won | |

| Directors Guild of America Awards | Outstanding Directing – Feature Film | George Lucas | Nominated |

| Golden Globe Awards[245] | Best Motion Picture – Drama | Gary Kurtz | Nominated |

| Best Director | George Lucas | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | Alec Guinness | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | John Williams | Won | |

| Grammy Awards[246] | Best Instrumental Composition | John Williams | Won |

| Best Original Score Written for a Motion Picture or a Television Special | John Williams | Won | |

| Best Pop Instrumental Performance | John Williams | Won | |

| Hugo Awards[247] | Best Dramatic Presentation | George Lucas | Won |

| Saturn Awards[248] | Best Science Fiction Film | Gary Kurtz | Won |

| Best Director | George Lucas | Won | |

| Best Actor | Harrison Ford | Nominated | |

| Mark Hamill | Nominated | ||

| Best Actress | Carrie Fisher | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Alec Guinness | Won | |

| Peter Cushing | Nominated | ||

| Best Writing | George Lucas | Won | |

| Best Costume Design | John Mollo | Won | |

| Best Make-up | Rick Baker and Stuart Freeborn | Won | |

| Best Music | John Williams | Won | |

| Best Special Effects | John Dykstra and John Stears | Won | |

| Best Art Direction | Norman Reynolds and Leslie Dilley | Won | |

| Best Cinematography | Gilbert Taylor | Won | |

| Best Editing | Paul Hirsch, Marcia Lucas and Richard Chew | Won | |

| Best Set Decoration | Roger Christian | Won | |

| Best Sound | Ben Burtt and Don MacDougall | Won | |

| Writers Guild of America Awards | Best Original Screenplay | George Lucas | Nominated |

In its May 30, 1977, issue, Time named Star Wars the "Movie of the Year". The publication said it was a "big early supporter" of the vision which would become Star Wars. In an article intended for the cover of the issue, Time's Gerald Clarke wrote that Star Wars is "a grand and glorious film that may well be the smash hit of 1977, and certainly is the best movie of the year so far. The result is a remarkable confection: a subliminal history of the movies, wrapped in a riveting tale of suspense and adventure, ornamented with some of the most ingenious special effects ever contrived for film." Each of the subsequent films of the Star Wars saga has appeared on the magazine's cover.[249]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (1998) – #15[250]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills (2001) – #27[251]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains (2003):

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes (2004):

- "May the Force be with you." – #8[253]

- AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores (2005) – #1[161]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers (2006) – #39[254]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) (2007) – #13[255]

- AFI's 10 Top 10 (2008) – #2 Sci-Fi Film[256]

American Film Institute[257]

Star Wars was voted the second most popular film by Americans in a 2008 nationwide poll conducted by the market research firm Harris Interactive.[258] It has also been featured in several high-profile audience polls: In 1997, it ranked as the 10th Greatest American Film on the Los Angeles Daily News Readers' Poll;[259] in 2002, Star Wars and its sequel The Empire Strikes Back were voted the greatest films ever made in Channel 4's 100 Greatest Films poll;[260] in 2011, it ranked as Best Sci-Fi Film on Best in Film: The Greatest Movies of Our Time, a primetime special aired by ABC that ranked the best films as chosen by fans, based on results of a poll conducted by ABC and People magazine; and in 2014, the film placed 11th in a poll undertaken by The Hollywood Reporter, which balloted every studio, agency, publicity firm, and production house in the Hollywood region.[261]

In 2008, Empire magazine ranked Star Wars at 22nd on its list of the "500 Greatest Movies of All Time". In 2010, the film ranked among the "All-Time 100" list of the greatest films as chosen by Time film critic Richard Schickel.[262][263]

Lucas's screenplay was selected by the Writers Guild of America as the 68th greatest of all time.[264] In 1989, the United States Library of Congress named Star Wars among its first selections to the National Film Registry as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant"; at the time, it was the most recent film to be selected and it was the only film from the 1970s to be chosen.[265] Although Lucas declined to provide the Library with a workable copy of the original film upon request (instead offering the Special Edition), a viewable scan was made of the original copyright deposit print.[266][267] In 1991, Star Wars was one of the first 25 films inducted into the Producers Guild of America's Hall of Fame for setting "an enduring standard for American entertainment."[268] The soundtrack was added to the United States National Recording Registry 15 years later (in 2004).[269] The lack of a commercially available version of the 1977 original theatrical edit of the film since early '80s VHS releases has spawned numerous restorations by disgruntled fans over the years, such as Harmy's Despecialized Edition.[270]

In addition to the film's multiple awards and nominations, Star Wars has also been recognized by the American Film Institute on several of its lists. The film ranks first on 100 Years of Film Scores,[161] second on Top 10 Sci-Fi Films,[256] 15th on 100 Years ... 100 Movies[250] (ranked 13th on the updated 10th-anniversary edition),[255] 27th on 100 Years ... 100 Thrills,[251] and 39th on 100 Years ... 100 Cheers.[254] In addition, the quote "May the Force be with you" is ranked eighth on 100 Years ... 100 Movie Quotes,[253] and Han Solo and Obi-Wan Kenobi are ranked as the 14th and 37th greatest heroes respectively on 100 Years ... 100 Heroes & Villains.[252]

Post-release

[edit]Theatrical re-releases

[edit]

Star Wars was re-released theatrically in 1978, 1979, 1981, and 1982.[271] The subtitles Episode IV and A New Hope were added for the 1981 re-release.[272][273][j] The subtitles brought the film into line with its 1980 sequel, which was released as Star Wars: Episode V—The Empire Strikes Back.[274] Lucas claims the subtitles were intended from the beginning, but were dropped for Star Wars to avoid confusing audiences.[275] Kurtz said they considered calling the first film Episode III, IV, or V.[276] Hamill claims that Lucas's motivation for starting with Episode IV was to give the audience "a feeling that they'd missed something". Another reason Lucas began with Episodes IV–VI, according to Hamill, was because they were the most "commercial" sections of the larger overarching story.[277][71] Michael Kaminski, however, points out that multiple early screenplay drafts of Star Wars carried an "Episode One" subtitle, and that early drafts of Empire were called "Episode II".[71]

In 1997, Star Wars was digitally remastered with some altered scenes for a theatrical re-release, dubbed the "Special Edition". In 2010, Lucas announced that all six previously released Star Wars films would be scanned and transferred to 3D for a theatrical release, but only 3D versions of the prequel trilogy were completed before the franchise was sold to Disney in 2012.[278] In 2013, Star Wars was dubbed into Navajo, making it the first major motion picture dubbed into the Navajo language.[279][280]

Special Edition

[edit]

After ILM began to create CGI for Steven Spielberg's 1993 film Jurassic Park, Lucas decided that digital technology had caught up to his "original vision" for Star Wars.[48] For the film's 20th anniversary in 1997, Star Wars was digitally remastered with some altered scenes and re-released to theaters, along with The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, under the campaign title Star Wars Trilogy: Special Edition. This version of Star Wars runs 124 minutes.

The Special Edition contains visual shots and scenes that were unachievable in the original film due to financial, technological, and time constraints.[48] The process of creating the new visual effects was explored in the documentary Special Effects: Anything Can Happen, directed by Star Wars sound designer Ben Burtt.[281] Although most changes are minor or cosmetic in nature, many fans and critics believe that Lucas degraded the film with the additions.[282][283][284] A particularly controversial change in which a bounty hunter named Greedo shoots first when confronting Han Solo has inspired T-shirts bearing the phrase "Han shot first".[285][286]

Star Wars required extensive recovery of misplaced footage and restoration of the whole film before Lucas's Special Edition modifications could be attempted. In addition to the negative film stock commonly used for feature films, Lucas had also used Color Reversal Internegative (CRI) film, a reversal stock subsequently discontinued by Kodak. Although it theoretically was of higher quality, CRI deteriorated faster than negative stocks. Because of this, the entire composited negative had to be disassembled, and the CRI portions cleaned separately from the negative portions. Once the cleaning was complete, the film was scanned into the computer for restoration. In many cases, entire scenes had to be reconstructed from their individual elements. Digital compositing technology allowed the restoration team to correct for problems such as misalignment of mattes and "blue-spill".[287]

In 1989, the 1977 theatrical version of Star Wars was selected for preservation by the National Film Registry of the United States Library of Congress.[265] 35 mm reels of the 1997 Special Edition were initially presented for preservation because of the difficulty of transferring from the original prints, but it was later revealed that the Library possessed a copyright deposit print of the original theatrical release.[266] By 2015, this copy had been transferred to a 2K scan, now available to be viewed by appointment.[267] Shortly after the release of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, director Gareth Edwards claimed he viewed a 4K restoration of the original theatrical version of Star Wars, created by Disney. The company has never confirmed its existence, however.[288][289]

Home media

[edit]In the United States, France, West Germany, Italy and Japan, parts of or the whole film were released on Super 8.[290] Clips were also released for the Movie Viewer toy projector by Kenner Products in cassettes featuring short scenes.[291][292]

Star Wars was released on Betamax,[293] CED,[294] LaserDisc,[295] Video 2000, and VHS[296][297] during the 1980s and 1990s by CBS/Fox Video. The final issue of the original theatrical release (pre-Special Edition) on VHS occurred in 1995, as part of a "Last Chance to Own the Original" campaign, and was available as part of a trilogy set or as a standalone purchase.[298] The film was released for the first time on DVD on September 21, 2004, in a box set with The Empire Strikes Back, Return of the Jedi, and a bonus disc of supplementary material. The films were digitally restored and remastered, and more changes were made by Lucas (in addition to those made for the 1997 Special Edition). The DVD features a commentary track from Lucas, Fisher, Burtt and visual effects artist Dennis Muren. The bonus disc contains the documentary Empire of Dreams: The Story of the Star Wars Trilogy, three featurettes, teaser and theatrical trailers, TV spots, image galleries, an exclusive preview of Episode III: Revenge of the Sith, a playable Xbox demo of the LucasArts game Star Wars: Battlefront, and a making-of documentary about the Episode III video game.[299] The set was reissued in December 2005 as a three-disc limited edition without the bonus disc.[300]

The trilogy was re-released on separate two-disc limited edition DVD sets from September 12 to December 31, 2006, and again in a limited edition box set on November 4, 2008;[301] the original theatrical versions of the films were added as bonus material. The release was met with criticism because the unaltered versions were from the 1993 non-anamorphic LaserDisc masters, and were not re-transferred using modern video standards. This led to problems with colors and digital image jarring.[302]

All six existing Star Wars films were released by 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment on Blu-ray on September 16, 2011, in three different editions. A New Hope was available in both a box set of the original trilogy[303][304] and with the other five films in the set Star Wars: The Complete Saga, which includes nine discs and over 40 hours of special features.[305] The original theatrical versions of the films were not included in the box set. New changes were made to the films, provoking mixed responses.[306]

On April 7, 2015, Walt Disney Studios, Twentieth Century Fox, and Lucasfilm jointly announced the digital releases of the six existing Star Wars films. Fox released A New Hope for digital download on April 10, 2015, while Disney released the other five films.[307][308] Disney reissued A New Hope on Blu-ray, DVD, and for digital download on September 22, 2019.[309] Additionally, all six films were available for 4K HDR and Dolby Atmos streaming on Disney+ upon the service's launch on November 12, 2019.[310] This version of A New Hope was also released by Disney in a 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray box set on March 31, 2020.[311]

Merchandising

[edit]Little Star Wars merchandise was available for several months after the film's debut, as only Kenner Products had accepted marketing director Charles Lippincott's licensing offers. Kenner responded to the sudden demand for toys by selling boxed vouchers in its "empty box" Christmas campaign. Television commercials told children and parents that vouchers contained in a "Star Wars Early Bird Certificate Package" could be redeemed for four action figures between February and June 1978.[48] Jay West of the Los Angeles Times said that the boxes in the campaign "became the most coveted empty box[es] in the history of retail."[312] In 2012, the Star Wars action figures were inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame.[313]

The novelization of the film was published as Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker in December 1976, six months before the film was released. The credited author was George Lucas, but the book was revealed to have been ghostwritten by Alan Dean Foster. Marketing director Charles Lippincott secured the deal with Del Rey Books to publish the novelization in November 1976. By February 1977, a half million copies had been sold.[48] Foster also wrote the sequel novel Splinter of the Mind's Eye (1978) to be adapted as a low-budget film if Star Wars was not a financial success.[314]

Marvel Comics also adapted the film as the first six issues of its licensed Star Wars comic book, with the first issue sold in April 1977. The comic was written by Roy Thomas and illustrated by Howard Chaykin. Like the novelization, it contained certain elements, such as the scene with Luke and Biggs, that appeared in the screenplay but not in the finished film.[149] The series was so successful that, according to comic book writer Jim Shooter, it "single-handedly saved Marvel".[315] From January to April 1997, Dark Horse Comics, which had held the comic rights to Star Wars since 1991, published a comic book adaptation of the "Special Edition" of the film, written by Bruce Jones with art by Eduardo Barreto and Al Williamson; 36 years later, the same company published The Star Wars, an adaptation of the plot from Lucas's original rough draft screenplay, from September 2013 to May 2014.[316]

Lucasfilm adapted the story for a children's book-and-record set. Released in 1979, the 24-page Star Wars read-along book was accompanied by a 33+1⁄3 rpm 7-inch phonograph record. Each page of the book contained a cropped frame from the movie with an abridged and condensed version of the story. The record was produced by Buena Vista Records, and its content was copyrighted by Black Falcon, Ltd., a subsidiary of Lucasfilm "formed to handle the merchandising for Star Wars."[317] The Story of Star Wars was a 1977 record album presenting an abridged version of the events depicted in Star Wars, using dialogue and sound effects from the original film. The recording was produced by George Lucas and Alan Livingston, and was narrated by Roscoe Lee Browne. The script was adapted by E. Jack Kaplan and Cheryl Gard.[159][160]

An audio CD boxed set of the Star Wars radio series was released in 1993, containing the original 1981 radio drama along with the radio adaptations of the sequels, The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi.[318]

Legacy and influence

[edit]Ford, who subsequently starred in the Indiana Jones series (1981–2023), Blade Runner (1982), and Witness (1985), told the Daily Mirror that Star Wars "boosted" his career.[319][better source needed] The film also spawned the Star Wars Holiday Special, which debuted on CBS on November 17, 1978, and is often considered a failure; Lucas himself disowned it.[320] The special was never aired again after its original broadcast, and it has never been officially released on home video. However, many bootleg copies exist, and it has consequently become something of an underground legend.[321]

In popular culture

[edit]Star Wars and its subsequent film installments have been explicitly referenced and satirized across a wide range of media. Hardware Wars, released in 1978, was one of the first fan films to parody Star Wars. It received positive critical reaction, earned over $1 million, and is one of Lucas's favorite Star Wars spoofs.[322][323][324][325] Writing for The New York Times, Frank DeCaro said, "Star Wars littered pop culture of the late 1970s with a galaxy of space junk."[326] He cited Quark (a short-lived 1977 sitcom that parodies the science fiction genre)[326] and Donny & Marie (a 1970s variety show that featured a 10-minute musical adaptation of Star Wars guest starring Daniels and Mayhew)[327] as "television's two most infamous examples."[326] Mel Brooks's Spaceballs, a satirical comic science-fiction parody, was released in 1987 to mixed reviews.[328] Lucas permitted Brooks to make a spoof of the film under "one incredibly big restriction: no action figures."[329] In the 1990s and 2000s, animated comedy TV series Family Guy,[330] Robot Chicken,[331] and The Simpsons[332] produced episodes satirizing the film series. A Nerdist article published in 2021 argues that "Star Wars is the most influential film of all time" partly on the basis that "if all copies ... suddenly vanished, we could more or less recreate the film ... using other media," including parodies.[333]

Many elements of Star Wars are prominent in popular culture. Darth Vader, Han Solo, and Yoda were all named in the top twenty of the British Film Institute's "Best Sci-Fi Characters of All-Time" list.[334] The expressions "Evil empire" and "May the Force be with you" have become part of the popular lexicon.[335] A pun on the latter phrase ("May the Fourth") has led to May 4 being regarded by many fans as an unofficial Star Wars Day.[336] To commemorate the film's 30th anniversary in May 2007, the United States Postal Service issued a set of 15 stamps depicting the characters of the franchise. Approximately 400 mailboxes across the country were also designed to look like R2-D2.[337]

Star Wars and Lucas are the subject of the 2010 documentary film The People vs. George Lucas, which explores filmmaking and fandom as they pertain to the film franchise and its creator.[338]

Cinematic influence

[edit]In his book The Great Movies, Roger Ebert called Star Wars "a technical watershed" that influenced many subsequent films. It began a new generation of special effects and high-energy motion pictures. The film was one of the first films to link genres together to invent a new, high-concept genre for filmmakers to build upon.[108] Along with Steven Spielberg's Jaws, it shifted the film industry's focus away from the more personal filmmaking of the 1970s towards fast-paced, big-budget blockbusters for younger audiences.[48][339][340]

Filmmakers who have been influenced by Star Wars include J. J. Abrams, James Cameron, Dean Devlin, Gareth Edwards,[341] Roland Emmerich, David Fincher, Peter Jackson, John Lasseter,[342] Damon Lindelof, Christopher Nolan, Ridley Scott, John Singleton, Kevin Smith,[108] and Joss Whedon. Lucas's "used future" concept was employed in Scott's Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982); Cameron's Aliens (1986) and The Terminator (1984); and Jackson's The Lord of the Rings trilogy.[108] Nolan cited Star Wars as an influence when making Inception (2010).[343]

Some critics have complained that Star Wars, as well as Jaws, "ruined" Hollywood by shifting its focus from "sophisticated" films such as The Godfather, Taxi Driver, and Annie Hall to films about spectacle and juvenile fantasy.[344] On a 1977 episode of Sneak Previews, Gene Siskel said he hoped Hollywood would continue to cater to audiences who enjoy "serious pictures".[345] Peter Biskind claimed that Lucas and Spielberg "returned the 1970s audience, grown sophisticated on a diet of European and New Hollywood films, to the simplicities of the pre-1960s Golden Age of movies ... They marched backward through the looking-glass."[344][183] In contrast, Tom Shone wrote that through Star Wars and Jaws, Lucas and Spielberg did not betray cinema, but instead "plugged it back into the grid, returning it ... to its roots as a carnival sideshow, a magic act, one big special effect", which amounted to "a kind of rebirth."[340]