Загрязнение воздуха

| Part of a series on |

| Pollution |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

Загрязнение воздуха — это загрязнение воздуха из-за присутствия в атмосфере веществ, называемых загрязнителями, которые вредны для здоровья людей и других живых существ или наносят ущерб климату или материалам. [1] Это также загрязнение внутренней или наружной среды химическими, физическими или биологическими агентами , которые изменяют естественные характеристики атмосферы. [1] Существует множество различных типов загрязнителей воздуха, таких как газы (включая аммиак , окись углерода , диоксид серы , оксиды азота , метан и хлорфторуглероды ), твердые частицы (как органические, так и неорганические) и биологические молекулы . Загрязнение воздуха может вызвать заболевания, аллергию и даже смерть людей; это также может нанести вред другим живым организмам, таким как животные и сельскохозяйственные культуры, и может нанести ущерб природной среде (например, изменение климата , истощение озонового слоя или деградация среды обитания ) или искусственной среде (например, кислотные дожди ). [2] Загрязнение воздуха может быть вызвано как деятельностью человека, так и [3] and natural phenomena.[4]

Air quality is closely related to the Earth's climate and ecosystems globally. Many of the contributors of air pollution are also sources of greenhouse emission i.e., burning of fossil fuel.[1]

Air pollution is a significant risk factor for a number of pollution-related diseases, including respiratory infections, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), stroke, and lung cancer.[5] Growing evidence suggests that air pollution exposure may be associated with reduced IQ scores, impaired cognition,[6] increased risk for psychiatric disorders such as depression[7] and detrimental perinatal health.[8] The human health effects of poor air quality are far reaching, but principally affect the body's respiratory system and the cardiovascular system.[9][10] Individual reactions to air pollutants depend on the type of pollutant a person is exposed to,[11][12] the degree of exposure, and the individual's health status and genetics.[13]

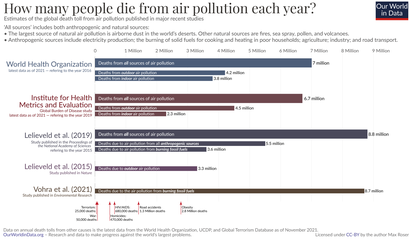

Air pollution is the largest environmental risk factor for disease and premature death[5][14] and the fourth largest risk factor overall for human health.[15] Air pollution causes the premature deaths of around 7 million people worldwide each year,[5] or a global mean loss of life expectancy (LLE) of 2.9 years,[16] and there has been no significant change in the number of deaths caused by all forms of pollution since at least 2015.[14][17][18] Outdoor air pollution attributable to fossil fuel use alone causes ~3.61 million deaths annually,[19] making it one of the top contributors to human death.[5] Anthropogenic ozone causes around 470,000 premature deaths a year and fine particulate (PM2.5) pollution around another 2.1 million.[20] The scope of the air pollution crisis is large: In 2018, WHO estimated that "9 out of 10 people breathe air containing high levels of pollutants."[21] Although the health consequences are extensive, the way the problem is handled is considered largely haphazard[22][21][23] or neglected.[14]

The World Bank has estimated that welfare losses (premature deaths) and productivity losses (lost labour) caused by air pollution cost the world economy $5 trillion per year.[24][25][26] The costs of air pollution are generally an externality to the contemporary economic system and most human activity, although they are sometimes recovered through monitoring, legislation, and regulation.[27][28]

Many different technologies and strategies are available for reducing air pollution.[29] Although a majority of countries have air pollution laws, according to UNEP, 43 percent of countries lack a legal definition of air pollution, 31 percent lack outdoor air quality standards, 49 percent restrict their definition to outdoor pollution only, and just 31 percent have laws for tackling pollution originating from outside their borders.[30] National air quality laws have often been highly effective, notably the 1956 Clean Air Act in Britain and the US Clean Air Act, introduced in 1963.[31][32] Some of these efforts have been successful at the international level, such as the Montreal Protocol,[33] which reduced the release of harmful ozone depleting chemicals, and the 1985 Helsinki Protocol,[34] which reduced sulfur emissions,[35] while others, such as international action on climate change,[36][37][38] have been less successful.

Sources of air pollution

[edit]There are many different sources of air pollution. Some air pollutants (such as nitrogen oxides) originate mainly from human activities,[39] while some (notably radon gas) come mostly from natural sources.[40] However, many air pollutants (including dust and sulfur dioxide) come from a mixture of natural and human sources.[41]

Anthropogenic (human-made) sources

[edit]

- Stationary sources include:

- fossil-fuel power plants and biomass power plants both have smoke stacks (see for example environmental impact of the coal industry)[42]

- Oil and gas sites that have methane leaks[43][44][45][46]

- burning of traditional biomass such as wood, crop waste and dung. (In developing and poor countries,[47] traditional biomass burning is the major source of air pollutants.[48][49] It is also the main source of particulate pollution in many developed areas including the UK & New South Wales.[50][51] Its pollutants include PAHs.[52])

- manufacturing facilities (factories)[53]

- a 2014 study found that in China equipment-, machinery-, and devices-manufacturing and construction sectors contributed more than 50% of air pollutant emissions.[54][better source needed] This high emission is due to high emission intensity and high emission factors in its industrial structure.[55]

- construction[56][57]

- waste incineration (incinerators as well as open and uncontrolled fires of mismanaged waste, making up about a fourth of municipal solid terrestrial waste)[58][59]

- furnaces and other types of fuel-burning heating devices[60]

- fossil-fuel power plants and biomass power plants both have smoke stacks (see for example environmental impact of the coal industry)[42]

- Mobile sources include motor vehicles, trains (particularly diesel locomotives and DMUs), marine vessels and aircraft[61] as well as rockets and re-entry of components and debris.[62] The air pollution externality of cars enters the air from the exhaust gas and car tires (including microplastics[63]). Road vehicles make a significant amount of all air pollution (typically, for example, around a third to a half of all nitrogen dioxide emissions)[64][65][66] and are a major driver of climate change.[67][68]

- Agriculture and forest management strategies using controlled burns. Practices like slash-and-burn in forests like the Amazon cause large air pollution with the deforestation.[69] Controlled or prescribed burning is a practice used in forest management, agriculture, prairie restoration, and greenhouse gas reduction.[70] Foresters can use controlled fire as a tool because fire is a natural feature of both forest and grassland ecology.[71][72] Controlled burning encourages the sprouting of some desirable forest trees, resulting in a forest renewal.[73]

There are also sources from processes other than combustion:

- Fumes from paint, hair spray, varnish, aerosol sprays and other solvents. These can be substantial; emissions from these sources was estimated to account for almost half of pollution from volatile organic compounds in the Los Angeles basin in the 2010s.[74]

- Waste deposition in landfills produces methane[75] and open burning of waste releases harmful substances.[76]

- Nuclear weapons, toxic gases, germ warfare, and rocketry are examples of military resources.[77]

- Agricultural emissions and emissions from meat production or livestock contribute substantially to air pollution[78][79]

- Fertilized farmland may be a major source of nitrogen oxides.[80]

| Food Types | Acidifying Emissions (g SO2eq per 100g protein) |

|---|---|

| Beef | |

| Cheese | |

| Pork | |

| Lamb and mutton | |

| Farmed crustaceans | |

| Poultry | |

| Farmed fish | |

| Eggs | |

| Groundnuts | |

| Peas | |

| Tofu |

Natural sources

[edit]

- Dust from natural sources, usually large areas of land with little or no vegetation.

- Methane, emitted by the digestion of food by animals, for example cattle.

- Radon gas from radioactive decay within the Earth's crust. Radon is a colorless, odorless, naturally occurring, radioactive noble gas that is formed from the decay of radium. It is considered to be a health hazard. Radon gas from natural sources can accumulate in buildings, especially in confined areas such as the basement and it is the second most frequent cause of lung cancer, after cigarette smoking.

- Smoke and carbon monoxide from wildfires. During periods of active wildfires, smoke from uncontrolled biomass combustion can make up almost 75% of all air pollution by concentration.[82]

- Vegetation, in some regions, emits environmentally significant amounts of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) on warmer days. These VOCs react with primary anthropogenic pollutants – specifically, NOx, SO2, and anthropogenic organic carbon compounds – to produce a seasonal haze of secondary pollutants.[83] Black gum, poplar, oak and willow are some examples of vegetation that can produce abundant VOCs. The VOC production from these species result in ozone levels up to eight times higher than the low-impact tree species.[84]

- Volcanic activity, which produces sulfur, chlorine, and ash particulates.[85]

Emission factors

[edit]

Air pollutant emission factors are reported representative values that aim to link the quantity of a pollutant released into the ambient air to an activity connected with that pollutant's release.[2][86][87][88] The weight of the pollutant divided by a unit weight, volume, distance, or time of the activity generating the pollutant is how these factors are commonly stated (e.g., kilograms of particulate emitted per tonne of coal burned). These criteria make estimating emissions from diverse sources of pollution easier. Most of the time, these components are just averages of all available data of acceptable quality, and they are thought to be typical of long-term averages.

The Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants identified pesticides and other persistent organic pollutants of concern. These include dioxins and furans which are unintentionally created by combustion of organics, like open burning of plastics, and are endocrine disruptors and mutagens.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency has published a compilation of air pollutant emission factors for a wide range of industrial sources.[89] The United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, and many other countries have published similar compilations, as well as the European Environment Agency.[90][91][92][93]

Pollutants

[edit]

An air pollutant is a material in the air that can have many effects on humans and the ecosystem.[94] The substance can be solid particles, liquid droplets, or gases, and often takes the form of an aerosol (solid particles or liquid droplets dispersed and carried by a gas).[95] A pollutant can be of natural origin or man-made. Pollutants are classified as primary or secondary. Primary pollutants are usually produced by processes such as ash from a volcanic eruption.

Other examples include carbon monoxide gas from motor vehicle exhausts or sulfur dioxide released from factories. Secondary pollutants are not emitted directly. Rather, they form in the air when primary pollutants react or interact. Ground level ozone is a prominent example of a secondary pollutant. Some pollutants may be both primary and secondary: they are both emitted directly and formed from other primary pollutants.

Primary pollutants

[edit]Pollutants emitted into the atmosphere by human activity include:

- Ammonia: Emitted mainly by agricultural waste. Ammonia is a compound with the formula NH3. It is normally encountered as a gas with a characteristic pungent odor. Ammonia contributes significantly to the nutritional needs of terrestrial organisms by serving as a precursor to foodstuffs and fertilizers. Ammonia, either directly or indirectly, is also a building block for the synthesis of many pharmaceuticals. Although in wide use, ammonia is both caustic and hazardous.[96] In the atmosphere, ammonia reacts with oxides of nitrogen and sulfur to form secondary particles.[97]

- Carbon dioxide (CO2): Carbon dioxide is a natural component of the atmosphere, essential for plant life and given off by the human respiratory system.[98] It is potentially lethal at very high concentrations (typically 100 times "normal" atmospheric levels).[99][100] Although the World Health Organization recognizes CO2 as a climate pollutant, it does not include the gas in its Air Quality Guidelines or set recommended targets for it.[101] Because of its role as a greenhouse gas, CO2 has been described as "the worst climate pollutant".[102] Statements such as this refer to its long-term atmospheric effects rather than shorter-term effects on such things as human health, food crops, and buildings. This question of terminology has practical consequences, for example, in determining whether the U.S. Clean Air Act (which is designed to improve air quality) is deemed to regulate CO2 emissions.[103] That issue was resolved in the United States by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which specifically amended the Clean Air Act "to define the carbon dioxide produced by the burning of fossil fuels as an 'air pollutant.'"[104] CO2 currently forms about 410 parts per million (ppm) of Earth's atmosphere, compared to about 280 ppm in pre-industrial times,[105] and billions of metric tons of CO2 are emitted annually by burning of fossil fuels.[106] CO2 increase in Earth's atmosphere has been accelerating.[107] CO2 is an asphyxiant gas and not classified as toxic or harmful in general.[108] Workplace exposure limits exist in places like UK (5,000 ppm for long-term exposure and 15,000 ppm for short-term exposure).[100] Natural disasters like the limnic eruption at Lake Nyos can result in a sudden release of huge amount of CO2 as well.[109]

- Carbon monoxide (CO): CO is a colorless, odorless, toxic gas.[110] It is a product of combustion of fuel such as natural gas, coal or wood. Vehicular exhaust contributes to the majority of carbon monoxide let into the atmosphere. It creates a smog type formation in the air that has been linked to many lung diseases and disruptions to the natural environment and animals.

- Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs): Emitted from goods that are now prohibited from use; harmful to the ozone layer. These are gases emitted by air conditioners, freezers, aerosol sprays, and other similar devices. CFCs reach the stratosphere after being released into the atmosphere.[111] They interact with other gases here, causing harm to the ozone layer. UV rays are able to reach the Earth's surface as a result of this. This can result in skin cancer, eye problems, and even plant damage.[112]

- Nitrogen oxides (NOx): Nitrogen oxides, particularly nitrogen dioxide, are expelled from high temperature combustion, and are also produced during thunderstorms by electric discharge. They can be seen as a brown haze dome above or a plume downwind of cities. Nitrogen dioxide is a chemical compound with the formula NO2. It is one of several nitrogen oxides. One of the most prominent air pollutants, this reddish-brown toxic gas has a characteristic sharp, biting odor.

- Odors: Such as from garbage, sewage, and industrial processes.

- Particulate matter/particles (PM), also known as particulates, atmospheric particulate matter (APM), or fine particles, are microscopic solid or liquid particles suspended in a gas.[113] Aerosol is a mixture of particles and gas. Volcanoes, dust storms, forest and grassland fires, living plants, and sea spray are all sources of particles. Aerosols are produced by human activities such as the combustion of fossil fuels in automobiles, power plants, and numerous industrial processes.[114] Averaged worldwide, anthropogenic aerosols – those made by human activities – currently account for approximately 10% of the atmosphere. Increased levels of fine particles in the air are linked to health hazards such as heart disease,[115] altered lung function and lung cancer. Particulates are related to respiratory infections and can be particularly harmful to those with conditions like asthma.[116]

- Persistent organic pollutants, which can attach to particulates. Persistent organic pollutants are organic compounds that are resistant to environmental degradation due to chemical, biological, or photolytic processes (POPs). As a result, they've been discovered to survive in the environment, be capable of long-range transmission, bioaccumulate in human and animal tissue, biomagnify in food chains, and pose a major threat to human health and the ecosystem.[117]

- Persistent free radicals connected to airborne fine particles are linked to cardiopulmonary disease.[118][119]

- Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs): a group of aromatic compounds formed from the incomplete combustion of organic compounds including coal and oil and tobacco.[120]

- Radioactive pollutants: Produced by nuclear explosions, nuclear events, war explosives, and natural processes such as the radioactive decay of radon.

- Sulfur oxides (SOx): particularly sulfur dioxide, a chemical compound with the formula SO2. SO2 is produced by volcanoes and in various industrial processes. Coal and petroleum often contain sulfur compounds, and their combustion generates sulfur dioxide. Further oxidation of SO2, usually in the presence of a catalyst such as NO2, forms H2SO4, and thus acid rain is formed. This is one of the causes for concern over the environmental impact of the use of these fuels as power sources.

- Toxic metals, such as lead and mercury, especially their compounds.

- Volatile organic compounds (VOC): VOCs are both indoor and outdoor air pollutants.[121] They are categorized as either methane (CH4) or non-methane (NMVOCs). Methane is an extremely efficient greenhouse gas which contributes to enhanced global warming. Other hydrocarbon VOCs are also significant greenhouse gases because of their role in creating ozone and prolonging the life of methane in the atmosphere. This effect varies depending on local air quality. The aromatic NMVOCs benzene, toluene and xylene are suspected carcinogens and may lead to leukemia with prolonged exposure. 1,3-butadiene is another dangerous compound often associated with industrial use.

Secondary pollutants

[edit]Secondary pollutants include:

- Ground level ozone (O3): Ozone is created when NOx and VOCs mix. It is a significant part of the troposphere.[122] It's also an important part of the ozone layer, which can be found in different sections of the stratosphere. Photochemical and chemical reactions involving it fuel many of the chemical activities that occur in the atmosphere during the day and night. It is a pollutant and a component of smog that is produced in large quantities as a result of human activities (mostly the combustion of fossil fuels).[123]

- Peroxyacetyl nitrate (C2H3NO5): similarly formed from NOx and VOCs.

- Photochemical smog: particles are formed from gaseous primary contaminants and chemicals.[124] Smog is a type of pollution that occurs in the atmosphere. Smog is caused by a huge volume of coal being burned in a certain region, resulting in a mixture of smoke and sulfur dioxide.[125] Modern smog is usually caused by automotive and industrial emissions, which are acted on in the atmosphere by UV light from the sun to produce secondary pollutants, which then combine with the primary emissions to generate photochemical smog.

Other pollutants

[edit]There are many other chemicals classed as hazardous air pollutants. Some of these are regulated in the USA under the Clean Air Act and in Europe under numerous directives (including the Air "Framework" Directive, 96/62/EC, on ambient air quality assessment and management, Directive 98/24/EC, on risks related to chemical agents at work, and Directive 2004/107/EC covering heavy metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in ambient air).[126][127]

| To display all pages, subcategories and images click on the "►": |

|---|

- Before flue-gas desulfurization was installed, the emissions from this power plant in New Mexico contained excessive amounts of sulfur dioxide.

- Thermal oxidisers are air pollution abatement options for hazardous air pollutants (HAPs), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and odorous emissions.

- This video provides an overview of a NASA study on the human fingerprint on global air quality.

Exposure

[edit]The risk of air pollution is determined by the pollutant's hazard and the amount of exposure to that pollutant. Air pollution exposure can be measured for a person, a group, such as a neighborhood or a country's children, or an entire population. For example, one would want to determine a geographic area's exposure to a dangerous air pollution, taking into account the various microenvironments and age groups. This can be calculated[128] as an inhalation exposure. This would account for daily exposure in various settings, e.g. different indoor micro-environments and outdoor locations. The exposure needs to include different ages and other demographic groups, especially infants, children, pregnant women, and other sensitive subpopulations.[128]

For each specific time that the subgroup is in the setting and engaged in particular activities, the exposure to an air pollutant must integrate the concentrations of the air pollutant with regard to the time spent in each setting and the respective inhalation rates for each subgroup, playing, cooking, reading, working, spending time in traffic, etc. A little child's inhaling rate, for example, will be lower than that of an adult. A young person engaging in strenuous exercise will have a faster rate of breathing than a child engaged in sedentary activity. The daily exposure must therefore include the amount of time spent in each micro-environmental setting as well as the kind of activities performed there. The air pollutant concentration in each microactivity/microenvironmental setting is summed to indicate the exposure.[128]

For some pollutants such as black carbon, traffic related exposures may dominate total exposure despite short exposure times since high concentrations coincide with proximity to major roads or participation in (motorized) traffic.[129] A large portion of total daily exposure occurs as short peaks of high concentrations, but it remains unclear how to define peaks and determine their frequency and health impact.[130]

In 2021, the WHO halved its recommended guideline limit for tiny particles from burning fossil fuels. The new limit for nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is 75% lower.[131] Growing evidence that air pollution—even when experienced at very low levels—hurts human health, led the WHO to revise its guideline (from 10 μg/m3 to 5 μg/m3) for what it considers a safe level of exposure of particulate pollution, bringing most of the world—97.3 percent of the global population—into the unsafe zone.[132]

Indoor air quality

[edit]

A lack of ventilation indoors concentrates air pollution where people often spend the majority of their time. Radon (Rn) gas, a carcinogen, is exuded from the Earth in certain locations and trapped inside houses. Building materials including carpeting and plywood emit formaldehyde (H-CHO) gas. Paint and solvents give off volatile organic compounds (VOCs) as they dry. Lead paint can degenerate into dust and be inhaled.[133][134]

Intentional air pollution is introduced with the use of air fresheners, incense, and other scented items. Controlled wood fires in cook stoves and fireplaces can add significant amounts of harmful smoke particulates into the air, inside and out.[133][134] Indoor pollution fatalities may be caused by using pesticides and other chemical sprays indoors without proper ventilation. Also the kitchen in a modern produce harmful particles and gases, with equipment like toasters being one of the worst sources.[135]

Carbon monoxide poisoning and fatalities are often caused by faulty vents and chimneys, or by the burning of charcoal indoors or in a confined space, such as a tent.[136] Chronic carbon monoxide poisoning can result even from poorly-adjusted pilot lights. Traps are built into all domestic plumbing to keep sewer gas and hydrogen sulfide, out of interiors. Clothing emits tetrachloroethylene, or other dry cleaning fluids, for days after dry cleaning.

Though its use has now been banned in many countries, the extensive use of asbestos in industrial and domestic environments in the past has left a potentially very dangerous material in many localities. Asbestosis is a chronic inflammatory medical condition affecting the tissue of the lungs. It occurs after long-term, heavy exposure to asbestos from asbestos-containing materials in structures. Those with asbestosis have severe dyspnea (shortness of breath) and are at an increased risk regarding several different types of lung cancer. As clear explanations are not always stressed in non-technical literature, care should be taken to distinguish between several forms of relevant diseases. According to the World Health Organization,[137] these may be defined as asbestosis, lung cancer, and peritoneal mesothelioma (generally a very rare form of cancer, when more widespread it is almost always associated with prolonged exposure to asbestos).

Biological sources of air pollution are also found indoors, as gases and airborne particulates. Pets produce dander, people produce dust from minute skin flakes and decomposed hair, dust mites in bedding, carpeting and furniture produce enzymes and micrometre-sized fecal droppings, inhabitants emit methane, mold forms on walls and generates mycotoxins and spores, air conditioning systems can incubate Legionnaires' disease and mold, and houseplants, soil and surrounding gardens can produce pollen, dust, and mold. Indoors, the lack of air circulation allows these airborne pollutants to accumulate more than they would otherwise occur in nature.

Indoor air pollution can pose a significant health risk. According to EPA reports, the concentrations of many air pollutants can be two to five times higher in indoor air than in outdoor air. Indoor air pollutants can be up to 100 times higher in some cases than they are inside. People can spend up to 90% of their time indoors, according to the american lung association (alp); the us consumer product safety commission (cpsc) 2012; and the us environmental protection agency 2012a.[138]

When gathering data on exposures, the clinician should consider the following potential sources of indoor air pollution. Indoor contaminants that may be present include asbestos, biologic agents, building materials, radon, tobacco smoke, and wood stoves, gas ranges, or other heating systems.[138]

Health effects

[edit]Even at levels lower than those considered safe by United States regulators, exposure to three components of air pollution, fine particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide and ozone, correlates with cardiac and respiratory illness.[139] In 2020, pollution (including air pollution) was a contributing factor to one in eight deaths in Europe, and was a significant risk factor for pollution-related diseases including heart disease, stroke and lung cancer.[140] The health effects caused by air pollution may include difficulty in breathing, wheezing, coughing, asthma[141] and worsening of existing respiratory and cardiac conditions. These effects can result in increased medication use, increased doctor or emergency department visits, more hospital admissions and premature death.[128][better source needed]

The human health effects of poor air quality are far reaching, but principally affect the body's respiratory system and the cardiovascular system. Individual reactions to air pollutants depend on the type of pollutant a person is exposed to, the degree of exposure, and the individual's health status and genetics.[128] The most common sources of air pollution include particulates, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide. Children aged less than five years who live in developing countries are the most vulnerable population in terms of total deaths attributable to indoor and outdoor air pollution.[142] Under the Clean Air Act, U.S. EPA sets limits on certain air pollutants, including setting limits on how much can be in the air anywhere in the United States.[143] New research demonstrates that the biological and health outcomes of mixed exposures (Example PM + Ozone) could be significantly greater than individual exposures.[144]

Air pollution has both acute and chronic effects on human health, affecting a number of different systems and organs. It ranges from minor upper respiratory irritation to chronic respiratory and heart disease, lung cancer, acute respiratory infections in children and chronic bronchitis in adults, aggravating pre-existing heart and lung disease, or asthmatic attacks. Short and long term exposures have been linked with premature mortality and reduced life expectancy.[145] Diseases that develop from persistent exposure to air pollution are environmental health diseases, which develop when a health environment is not maintained.[146]

Mortality

[edit]

The World Health Organization estimated in 2014 that every year air pollution causes the premature death of some 7 million people worldwide.[5] Studies published in March 2019 indicated that the number may be around 8.8 million.[148] A 2022 review concluded that air pollution was responsible for 6.67 (5.90–7.49) million premature deaths in 2019. It concluded that since 2015 little real progress against (superordinate) pollution, which remained at ~9 million earlier deaths, can be identified.[149][14] Causes of deaths include strokes, heart disease, COPD, lung cancer, and lung infections.[5]

Urban outdoor air pollution is estimated to cause 1.3 million deaths worldwide per year.[150] Children are particularly at risk due to the immaturity of their respiratory organ systems.[151] In 2015, outdoor air pollution, mostly by PM2.5, was estimated to lead to 3.3 (95% CI 1.61–4.81) million premature deaths per year worldwide, predominantly in Asia.[79]In 2021, the WHO reported that outdoor air pollution was estimated to cause 4.2 million premature deaths worldwide in 2016.[152]

A 2020 study indicates that the global mean loss of life expectancy (LLE; similar to YPLL) from air pollution in 2015 was 2.9 years, substantially more than, for example, 0.3 years from all forms of direct violence, albeit a significant fraction of the LLE is unavoidable.[16] Communities with the most exceptional aging have low ambient air pollution, suggesting a link between air pollution levels and longevity.[153]

A study published in 2022 in GeoHealth concluded that eliminating energy-related fossil fuel emissions in the United States would prevent 46,900–59,400 premature deaths each year and provide $537–$678 billion in benefits from avoided PM2.5-related illness and death.[154]A study published in 2023 in Science focused on sulfur dioxide emissions by coal power plants (coal PM2.5) and concluded that "exposure to coal PM2.5 was associated with 2.1 times greater mortality risk than exposure to PM2.5 from all sources."[155] From 1999 to 2020, a total of 460,000 deaths in the US were attributed to coal PM2.5.[155]

By region

[edit]India and China have the highest death rate due to air pollution.[156][157] India also has more deaths from asthma than any other nation according to the World Health Organization. In 2019, 1.6 million deaths in India were caused by air pollution.[158] In December 2013, air pollution was estimated to kill 500,000 people in China each year.[159] There is a positive correlation between pneumonia-related deaths and air pollution from motor vehicle emissions.[160]

Annual premature European deaths caused by air pollution are estimated at 430,000[161] to 800,000.[148] An important cause of these deaths is nitrogen dioxide and other nitrogen oxides (NOx) emitted by road vehicles.[161] In a 2015 consultation document the UK government disclosed that nitrogen dioxide is responsible for 23,500 premature UK deaths per annum.[162] Across the European Union, air pollution is estimated to reduce life expectancy by almost nine months.[163]

Guidelines

[edit]The US EPA has estimated that limiting ground-level ozone concentration to 65 parts per billion (ppb), would avert 1,700 to 5,100 premature deaths nationwide in 2020 compared with the 75 ppb standard. The agency projected the more protective standard would also prevent an additional 26,000 cases of aggravated asthma, and more than a million cases of missed work or school.[164][165] Following this assessment, the EPA acted to protect public health by lowering the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for ground-level ozone to 70 ppb.[166]

A 2008 economic study of the health impacts and associated costs of air pollution in the Los Angeles Basin and San Joaquin Valley of Southern California shows that more than 3,800 people die prematurely (approximately 14 years earlier than normal) each year because air pollution levels violate federal standards. The number of annual premature deaths is considerably higher than the fatalities related to auto collisions in the same area, which average fewer than 2,000 per year.[167][168][169] A 2021 study found that outdoor air pollution is associated with substantially increased mortality "even at low pollution levels below the current European and North American standards and WHO guideline values" shortly before the WHO adjusted its guidelines.[170][171]

Major causes

[edit]

The largest cause is air pollution generated by fossil fuel combustion[173] – mostly the production and use of cars, electricity production, and heating.[174] A study by Greenpeace estimates there are 4.5 million annual premature deaths worldwide because of pollutants released by high-emission power stations and vehicle exhausts.[175]

Diesel exhaust (DE) is a major contributor to combustion-derived particulate matter air pollution. In several human experimental studies, using a well-validated exposure chamber setup, DE has been linked to acute vascular dysfunction and increased thrombus formation.[176][177]

A study concluded that PM2.5 air pollution induced by the contemporary free trade and consumption by the 19 G20 nations causes two million premature deaths annually, suggesting that the average lifetime consumption of about ~28 people in these countries causes at least one premature death (average age ~67) while developing countries "cannot be expected" to implement or be able to implement countermeasures without external support or internationally coordinated efforts.[178][172]

Primary mechanisms

[edit]The WHO estimates that in 2016, ~58% of outdoor air pollution-related premature deaths were due to ischaemic heart disease and stroke.[152] The mechanisms linking air pollution to increased cardiovascular mortality are uncertain, but probably include pulmonary and systemic inflammation.[179]

Contemporary annual deaths

[edit]A 2021 study by scientists of U.K. and U.S. universities that uses a high spatial resolution model and an updated concentration-response function concluded that 10.4 million global excess deaths in 2012 and 8.7 million in 2018 – or a fifth[dubious – discuss] – were due to air pollution generated by fossil fuel combustion, significantly higher than earlier estimates and with spatially subdivided mortality impacts.[180][173]

According to the WHO, air pollution accounts for 1 in 8 deaths worldwide.[181]

Cardiovascular disease

[edit]According to the Global Burden of Disease Study, air pollution is responsible for 19 percent of all cardiovascular deaths.[182][183] A 2022 review of over 50 studies carried out between 2010 and 2021 found strong evidence linking both short- and long-term exposure to air pollution with cardiovascular disease mortality and morbidity, stroke, blood pressure, and ischemic heart diseases (IHD).[183]

Air pollution is a leading risk factor for stroke, particularly in developing countries where pollutant levels are highest.[184] A systematic analysis of 17 different risk factors in 188 countries found air pollution is associated with nearly one in three strokes (29 percent) worldwide (33.7 percent of strokes in developing countries versus 10.2 percent in developed countries).[184][185] A 2007 study found that in women, air pollution is not associated with hemorrhagic but with ischemic stroke.[186] Air pollution was found to be associated with increased incidence and mortality from coronary stroke in a cohort study in 2011.[187] Associations are believed to be causal and effects may be mediated by vasoconstriction, low-grade inflammation and atherosclerosis.[188] Other mechanisms such as autonomic nervous system imbalance have also been suggested.[189][190]

Lung disease

[edit]Research has demonstrated increased risk of developing asthma[191] and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)[192] from increased exposure to traffic-related air pollution. Air pollution has been associated with increased hospitalization and mortality from asthma and COPD.[193][194] COPD includes diseases such as chronic bronchitis and emphysema.[195] The risk of lung disease from air pollution is greatest for the following groups of people: infants and young children, whose normal breathing is faster than that of older children and adults; the elderly; those who work outside or spend a lot of time outside; and those who have heart or lung disease.[196]

A study conducted in 1960–1961 in the wake of the Great Smog of 1952 compared 293 London residents with 477 residents of Gloucester, Peterborough, and Norwich, three towns with low reported death rates from chronic bronchitis. All subjects were male postal truck drivers aged 40 to 59. Compared to the subjects from the outlying towns, the London subjects exhibited more severe respiratory symptoms (including cough, phlegm, and dyspnea), reduced lung function (FEV1 and peak flow rate), and increased sputum production and purulence. The differences were more pronounced for subjects aged 50 to 59. The study controlled for age and smoking habits, so concluded that air pollution was the most likely cause of the observed differences.[197]More studies have shown that air pollution exposure from traffic reduces lung function development in children[198] and lung function may be compromised by air pollution even at low concentrations.[199]

It is believed that much like cystic fibrosis, by living in a more urban environment serious health hazards become more apparent. Studies have shown that in urban areas people experience mucus hypersecretion, lower levels of lung function, and more self-diagnosis of chronic bronchitis and emphysema.[200]

COPD comprises a spectrum of clinical disorders that include emphysema, bronchiectasis, and chronic bronchitis. COPD risk factors are both genetic and environmental. Elevated particle pollution contributes to the exacerbation of this disease and likely its pathogenesis.[201]

Cancer (lung cancer)

[edit]

Around 300,000 lung cancer deaths were attributed globally in 2019 to exposure to fine particulate matter, PM2.5, contained in air pollution.[204]

A review of evidence regarding whether ambient air pollution exposure is a risk factor for cancer in 2007 found solid data to conclude that long-term exposure to PM2.5 (fine particulates) increases the overall risk of non-accidental mortality by 6% per a 10 μg/m3 increase. Exposure to PM2.5 was also associated with an increased risk of mortality from lung cancer (range: 15–21% per 10 μg/m3 increase) and total cardiovascular mortality (range: 12–14% per a 10 μg/m3 increase).[205]

The review further noted that living close to busy traffic appears to be associated with elevated risks of these three outcomes – increase in lung cancer deaths, cardiovascular deaths, and overall non-accidental deaths. The reviewers also found suggestive evidence that exposure to PM2.5 is positively associated with mortality from coronary heart diseases and exposure to SO2 increases mortality from lung cancer, but the data was insufficient to provide solid conclusions.[205] Another investigation showed that higher activity level increases deposition fraction of aerosol particles in human lung and recommended avoiding heavy activities like running in outdoor space at polluted areas.[206]

In 2011, a large Danish epidemiological study found an increased risk of lung cancer for people who lived in areas with high nitrogen oxide concentrations. In this study, the association was higher for non-smokers than smokers.[207] An additional Danish study, also in 2011, likewise noted evidence of possible associations between air pollution and other forms of cancer, including cervical cancer and brain cancer.[208]

A study presented in 2022 outlined the biological basis for how air pollution causes cancer.[204]

Kidney disease

[edit]In 2021, a study of 163,197 Taiwanese residents over the period of 2001–2016 estimated that every 5 μg/m3 decrease in the ambient concentration of PM2.5 was associated with a 25% reduced risk of chronic kidney disease development.[209] According to a chord study involving 10,997 atherosclerosis patients, higher PM 2.5 exposure is associate with increased albuminuria.[210]

Fertility

[edit]NO2

[edit]In women undergoing IVF treatment, increases in NO2 both at the patient's address and by the IVF lab were significantly associated with a lower live birth rate.[211]

In the general population, there is a significant increase in miscarriage rate in women exposed to NO2 compared to the non-exposed group.[211]

CO

[edit]CO exposure is significantly associated with stillbirth in the second and third trimester.[211]

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

[edit]Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) have been associated with reduced fertility. Benzo(a)pyrene (BaP) is a well-known PAH and carcinogen which is often found in exhaust fumes and cigarette smoke.[212] PAHs have been reported to administer their toxic effects through oxidative stress by increasing the production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) which can result in inflammation and cell death. More long-term exposure to PAHs can result in DNA damage and reduced repair.[213]

Exposure to BaP has been reported to reduce sperm motility and increasing the exposure worsens this effect. Research has demonstrated that more BaPs were found in men with reported fertility issues compared to men without.[214]

Studies have shown that BaPs can affect folliculogenesis and ovarian development by reducing the number of ovarian germ cells via triggering cell death pathways and inducing inflammation which can lead to ovarian damage.[215]

Particulate matter

[edit]Particulate matter (PM) refers to the collection of solids and liquids suspended in the air. These can be harmful to humans when exposed to in day-to-day life, and more research has shown that these effects may be more extensive than first thought; particularly on male fertility. Within the spectrum of PM there are different weights, such as PM2.5 which are tiny particles of 2.5 microns in width or smaller, compared with PM10 which are classified as 10 microns in diameter or less.

In a study based in California it was found that as exposure to PM2.5 increased sperm motility decreased and morphology became more abnormal. Similarly, in Poland exposure to PM2.5 and PM10 lead to an increase in the percentage of cells with immature chromatin (DNA that has not fully developed or has developed abnormally).[216]

In Turkey, a study looked at the fertility of men who work as toll collectors and are therefore exposed to high levels of traffic pollutants daily. Traffic pollution often has high levels of PM10 alongside carbon monoxide and nitrous oxides.[216] In this study group there were significant differences in sperm count and motility when compared to a control group with limited air pollution exposure.

In women, whilst overall effects on fertility did not seem significant there was an association was found between increased exposure to PM10 and early miscarriage. Exposure to smaller particulate matter, PM2.5, was seen to have an effect on conception rates in women undergoing IVF but not with live birth rates.[211]

Ground-level ozone pollution

[edit]Ground-level ozone (O3), when in high concentrations, is regarded as an air pollutant and is often found in smog in industrial areas. O3 is largely produced by chemical reactions involving NOx gases (nitrous oxides, especially from combustion) and volatile organic compounds in the presence of sunlight.

There is limited research about the effect that ozone pollution has on fertility.[211] At present, there is no evidence to suggest that ozone exposure poses a deleterious effect on spontaneous fertility in either females or males. However, there have been studies which suggest that high levels of ozone pollution, often a problem in the summer months, exert an effect on in vitro fertilisation (IVF) outcomes. Within an IVF population, NOx and ozone pollutants were linked with reduced rates of live birth.[211]

While most research on this topic is focused on the direct human exposure of air pollution, other studies have analysed the impact of air pollution on gametes and embryos within IVF laboratories. Multiple studies have reported a marked improvement in embryo quality, implantation and pregnancy rates after IVF laboratories have implemented air filters in a concerted effort to reduce levels of air pollution.[217] Therefore, ozone pollution is considered to have a negative impact on the success of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) when occurring at high levels.

Ozone is thought to act in a biphasic manner where a positive effect on live birth is observed when ozone exposure is limited to before IVF embryo implantation.[218] Conversely, a negative effect is demonstrated upon exposure to ozone after embryo implantation.[219]

Retrospective and prospective studies evaluating the effect of several traffic pollutants (of which ground-level ozone is one) highlighted a significant decrease in live birth rates and miscarriages.[217]

In terms of male fertility, ozone is reported to cause a significant decrease in sperm concentration measured in semen after exposure.[220] Similarly, sperm vitality, the proportion of alive spermatozoa in a sample, was demonstrated to be diminished in a handful of studies.[219] This demonstrates that ozone air pollution exhibits a significantly negative effect of air pollution on this parameter. However, findings on the effect of ozone exposure on male fertility are somewhat discordant, highlighting the need for further research.[219]

Children

[edit]In the United States, despite the passage of the Clean Air Act in 1970, in 2002 at least 146 million Americans were living in non-attainment areas – regions in which the concentration of certain air pollutants exceeded federal standards.[221] These dangerous pollutants are known as the criteria pollutants, and include ozone, particulate matter, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, and lead. Protective measures to ensure children's health are being taken in cities such as New Delhi, India, where buses now use compressed natural gas to help eliminate the "pea-soup" smog.[222] A 2015 study in Europe has found that exposure to ultrafine particles can increase blood pressure in children.[223] In a 2018 WHO report, polluted air leads to the poisoning of millions of children under the age of 15, resulting in the death of some six hundred thousand children annually.[224]

Prenatal exposure

[edit]Prenatal exposure to polluted air has been linked to a variety of neurodevelopmental disorders in children. For example, exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) was associated with reduced IQ scores and symptoms of anxiety and depression.[225] They can also lead to detrimental perinatal health outcomes that are often fatal in developing countries.[8] A 2014 study found that PAHs might play a role in the development of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[226]

Researchers have begun to find evidence for air pollution as a risk factor for autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In Los Angeles, children who were living in areas with high levels of traffic-related air pollution were more likely to be diagnosed with autism between three–five years of age.[227] The connection between air pollution and neurodevelopmental disorders in children is thought to be related to epigenetic dysregulation of the primordial germ cells, embryo, and fetus during a critical period. Some PAHs are considered endocrine disruptors and are lipid soluble. When they build up in adipose tissue, they can be transferred across the placenta.[228] Air pollution has been associated with the prevalence of preterm births.[229]

Infants

[edit]Ambient levels of air pollution have been associated with preterm birth and low birth weight. A 2014 WHO worldwide survey on maternal and perinatal health found a statistically significant association between low birth weights (LBW) and increased levels of exposure to PM2.5. Women in regions with greater than average PM2.5 levels had statistically significant higher odds of pregnancy resulting in a low-birth weight infant even when adjusted for country-related variables.[230] The effect is thought to be from stimulating inflammation and increasing oxidative stress.

A study by the University of York found that in 2010 exposure to PM2.5 was strongly associated with 18% of preterm births globally, which was approximately 2.7 million premature births. The countries with the highest air pollution associated preterm births were in South and East Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, and West sub-Saharan Africa.[231] In 2019, ambient particulate matter pollution in Africa resulted in at least 383,000 early deaths, according to new estimates of the cost of air pollution in the continent. This increased from 3.6% in 1990 to around 7.4% of all premature deaths in the area.[232][233][234]

The source of PM2.5 differs greatly by region. In South and East Asia, pregnant women are frequently exposed to indoor air pollution because of wood and other biomass fuels being used for cooking, which are responsible for more than 80% of regional pollution. In the Middle East, North Africa and West sub-Saharan Africa, fine PM comes from natural sources, such as dust storms.[231] The United States had an estimated 50,000 preterm births associated with exposure to PM2.5 in 2010.[231]

A study between 1988 and 1991 found a correlation between sulfur dioxide (SO2) and total suspended particulates (TSP) and preterm births and low birth weights in Beijing. A group of 74,671 pregnant women, in four separate regions of Beijing, were monitored from early pregnancy to delivery along with daily air pollution levels of sulfur Dioxide and TSP (along with other particulates). The estimated reduction in birth weight was 7.3 g for every 100 μg/m3 increase in SO2 and 6.9 g for each 100 μg/m3 increase in TSP. These associations were statistically significant in both summer and winter, although, summer was greater. The proportion of low birth weight attributable to air pollution, was 13%. This is the largest attributable risk ever reported for the known risk factors of low birth weight.[235] Coal stoves, which are in 97% of homes, are a major source of air pollution in this area.

Brauer et al. studied the relationship between air pollution and proximity to a highway with pregnancy outcomes in a Vancouver cohort of pregnant woman using addresses to estimate exposure during pregnancy. Exposure to NO, NO2, CO, PM10 and PM2.5 were associated with infants born small for gestational age (SGA). Women living less than 50 meters away from an expressway or highway were 26% more likely to give birth to a SGA infant.[236]

"Clean" areas

[edit]

Even in areas with relatively low levels of air pollution, public health effects can be significant and costly, since a large number of people breathe in such pollutants. A study published in 2017 found that even in areas of the U.S. where ozone and PM2.5 meet federal standards, Medicare recipients who are exposed to more air pollution have higher mortality rates.[237]

A 2005 scientific study for the British Columbia Lung Association showed that a small improvement in air quality (1% reduction of ambient PM2.5 and ozone concentrations) would produce $29 million in annual savings in the Metro Vancouver region in 2010.[238] This finding is based on health valuation of lethal (death) and sub-lethal (illness) affects. A study published in 2022 found that rural population in India, like those in urban areas, are also exposed to high levels of air pollution.[239]

In 2020, scientists found that the boundary layer air over the Southern Ocean around Antarctica is 'unpolluted' by humans.[240]

Central nervous system

[edit]Data is accumulating that air pollution exposure also affects the central nervous system.[241]

Air pollution increases the risk of dementia in people over 50 years old.[242] Childhood indoor air pollution may negatively affect cognitive function and neurodevelopment.[243][244] Prenatal exposure may also affect neurodevelopment.[245][246] Studies show that air pollution is associated with a variety of developmental disabilities, oxidative stress, and neuro-inflammation and that it may contribute to Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease.[244]

Researchers at the University of Rochester Medical Center found that early exposure to air pollution causes the same changes in the brain as autism and schizophrenia. This study was published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, in June 2014. It also showed that air pollution also affected short-term memory, learning ability, and impulsivity. Lead researcher Deborah Cory-Slechta said that:

When we looked closely at the ventricles, we could see that the white matter that normally surrounds them hadn't fully developed. It appears that inflammation had damaged those brain cells and prevented that region of the brain from developing, and the ventricles simply expanded to fill the space. Our findings add to the growing body of evidence that air pollution may play a role in autism, as well as in other neurodevelopmental disorders.

Exposure to fine particulate matter can increase levels of cytokines - neurotransmitters produced in response to infection and inflammation that are also associated with depression and suicide. Pollution has been associated with inflammation of the brain, which may disrupt mood regulation. According to a study of Washington DC's American University, heightened PM2.5 levels are linked to more self-reported depressive symptoms, and increases in daily suicide rates.[247]

In a study of mice, air pollution also has a larger negative impact on males than on females.[248][249][250]

In 2015, experimental studies reported the detection of significant episodic (situational) cognitive impairment from impurities in indoor air breathed by test subjects who were not informed about changes in the air quality. Researchers at the Harvard University and SUNY Upstate Medical University and Syracuse University measured the cognitive performance of 24 participants in three different controlled laboratory atmospheres that simulated those found in "conventional" and "green" buildings, as well as green buildings with enhanced ventilation. Performance was evaluated objectively using the widely used Strategic Management Simulation software simulation tool, which is a well-validated assessment test for executive decision-making in an unconstrained situation allowing initiative and improvisation. Significant deficits were observed in the performance scores achieved in increasing concentrations of either volatile organic compounds (VOCs) or carbon dioxide, while keeping other factors constant. The highest impurity levels reached are not uncommon in some classroom or office environments.[251][252] Higher PM2.5 and CO2 concentrations were shown to be associated with slower response times and reduced accuracy in tests.[253]

Agricultural effects

[edit]Various studies have estimated the impacts of air pollution on agriculture, especially ozone. A 2020 study showed that ozone pollution in California may reduce yields of certain perennial crops such as table grapes by as much as 22% per year, translating into economic damages of more than $1 billion per year.[254] After air pollutants enter the agricultural environment, they not only directly affect agricultural production and quality, but also enter agricultural waters and soil.[255] The COVID-19 induced lockdown served as a natural experiment to expose the close links between air quality and surface greenness. In India, the lockdown induced improvement in air quality, enhanced surface greenness and photosynthetic activity, with the positive response of vegetation to reduce air pollution was dominant in croplands.[256] On the other hand, agriculture in its traditional form is one of the primary contributors to the emission of trace gases like atmospheric ammonia.[257]

Economic effects

[edit]Air pollution costs the world economy $5 trillion per year as a result of productivity losses and degraded quality of life, in a 2016 joint study by the World Bank and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington.[24][25][26] These productivity losses are caused by deaths due to diseases caused by air pollution. One out of ten deaths in 2013 was caused by diseases associated with air pollution and the problem is getting worse. The problem is even more acute in the developing world. "Children under age 5 in lower-income countries are more than 60 times as likely to die from exposure to air pollution as children in high-income countries."[24][25] The report states that additional economic losses caused by air pollution, including health costs[258] and the adverse effect on agricultural and other productivity were not calculated in the report, and thus the actual costs to the world economy are far higher than $5 trillion. A study published in 2022 found "a strong and significant connection between air pollution and construction site accidents" and that "a 10-ppb increase in NO2 levels increases the likelihood of an accident by as much as 25 percent".[259]

Other effects

[edit]Artificial air pollution may be detectable on Earth from distant vantage points such as other planetary systems via atmospheric SETI – including NO2 pollution levels and with telescopic technology close to today. It may also be possible to detect extraterrestrial civilizations this way.[260][261][262]

Historical disasters

[edit]The world's worst short-term civilian pollution crisis was the 1984 Bhopal Disaster in India.[263] Leaked industrial vapours from the Union Carbide factory, belonging to Union Carbide, Inc., U.S.A. (later bought by Dow Chemical Company), killed at least 3787 people and injured from 150,000 to 600,000. The United Kingdom suffered its worst air pollution event when the 4 December Great Smog of 1952 formed over London. In six days more than 4,000 died and more recent estimates put the figure at nearer 12,000.[264]

An accidental leak of anthrax spores from a biological warfare laboratory in the former USSR in 1979 near Yekaterinburg (formerly Sverdlovsk) is believed to have caused at least 64 deaths.[265] The worst single incident of air pollution to occur in the US occurred in Donora, Pennsylvania, in late October 1948, when 20 people died and over 7,000 were injured.[266]

Reduction and regulation

[edit]Global depletion of the surrounding air pollution will require valiant leadership, a surplus of combined resources from the international community, and extensive societal changes.[267] Pollution prevention seeks to prevent pollution such as air pollution and could include adjustments to industrial and business activities such as designing sustainable manufacturing processes (and the products' designs)[268] and related legal regulations as well as efforts towards renewable energy transitions.[269][270]

Efforts to reduce particulate matter in the air may result in better health.[271]

The 9-Euro-Ticket scheme in Germany which allowed people to buy a monthly pass allowing use on all local and regional transport (trains, trams and busses) for 9 euro (€) for one month of unlimited travel saved 1.8 million tons of CO2 emissions during its three-month implementation from June to August 2022.[272]

Pollution control

[edit]

Various pollution control technologies and strategies are available to reduce air pollution.[273][274] At its most basic level, land-use planning is likely to involve zoning and transport infrastructure planning. In most developed countries, land-use planning is an important part of social policy, ensuring that land is used efficiently for the benefit of the wider economy and population, as well as to protect the environment.[275] Stringent environmental regulations, effective control technologies and shift towards the renewable source of energy also helping countries like China and India to reduce their sulfur dioxide pollution.[276]

Titanium dioxide has been researched for its ability to reduce air pollution. Ultraviolet light will release free electrons from material, thereby creating free radicals, which break up VOCs and NOx gases. One form is superhydrophilic.[277]

Pollution-eating nanoparticles placed near a busy road were shown to absorb toxic emission from around 20 cars each day.[278]

Energy transition

[edit]Since a large share of air pollution is caused by combustion of fossil fuels such as coal and oil, the reduction of these fuels can reduce air pollution drastically. Most effective is the switch to clean power sources such as wind power, solar power, hydro power which do not cause air pollution.[279] Efforts to reduce pollution from mobile sources includes expanding regulation to new sources (such as cruise and transport ships, farm equipment, and small gas-powered equipment such as string trimmers, chainsaws, and snowmobiles), increased fuel efficiency (such as through the use of hybrid vehicles), conversion to cleaner fuels, and conversion to electric vehicles.

A very effective means to reduce air pollution is the transition to renewable energy. According to a study published in Energy and Environmental Science in 2015 the switch to 100% renewable energy in the United States would eliminate about 62,000 premature mortalities per year and about 42,000 in 2050, if no biomass were used. This would save about $600 billion in health costs a year due to reduced air pollution in 2050, or about 3.6% of the 2014 U.S. gross domestic product.[279] Air quality improvement is a near-term benefit among the many societal benefits from climate change mitigation.

Alternatives to pollution

[edit]

There are now practical alternatives to the principal causes of air pollution:

- Strategic substitution of air pollution sources in transport with lower-emission or, during the lifecycle, emission-free forms of public transport[280][281] and bicycle use and infrastructure (as well as with remote work, reductions of work, relocations, and localizations)

- Phase-out of fossil fuel vehicles is a critical component of a shift to sustainable transport; however, similar infrastructure and design decisions like electric vehicles may be associated with similar pollution for production as well as mining and resource exploitation for large numbers of needed batteries as well as the energy for their recharging[282][283]

- Areas downwind (over 20 miles) of major airports have more than double total particulate emissions in air than other areas, even when factoring in areas with frequent ship calls, and heavy freeway and city traffic like Los Angeles.[284] Aviation biofuel mixed in with jetfuel at a 50/50 ratio can reduce jet derived cruise altitude particulate emissions by 50–70%, according to a NASA led 2017 study (however, this should imply ground level benefits to urban air pollution as well).[285]

- Ship propulsion and idling can be switched to much cleaner fuels like natural gas. (Ideally a renewable source but not practical yet)

- Combustion of fossil fuels for space heating can be replaced by using ground source heat pumps and seasonal thermal energy storage.[286]

- Electricity generated from the combustion of fossil fuels can be replaced by nuclear and renewable energy. Heating and home stoves, which contribute significantly to regional air pollution, can be replaced with a much cleaner fossil fuel, such as natural gas, or, preferably, renewables, in poor countries.[287][288]

- Motor vehicles driven by fossil fuels, a key factor in urban air pollution, can be replaced by electric vehicles. Though lithium supply and cost is a limitation, there are alternatives. Herding more people into clean public transit such as electric trains can also help. Nevertheless, even in emission-free electric vehicles, rubber tires produce significant amounts of air pollution themselves, ranking as 13th worst pollutant in Los Angeles.[289]

- Reducing travel in vehicles can curb pollution. After Stockholm reduced vehicle traffic in the central city with a congestion tax, nitrogen dioxide and PM10 pollution declined, as did acute pediatric asthma attacks.[290]

- Biodigesters can be utilized in poor nations where slash and burn is prevalent, turning a useless commodity into a source of income. The plants can be gathered and sold to a central authority that will break them down in a large modern biodigester, producing much needed energy to use.[291]

- Induced humidity and ventilation both can greatly dampen air pollution in enclosed spaces, which was found to be relatively high inside subway lines due to braking and friction and relatively less ironically inside transit buses than lower sitting passenger automobiles or subways.[292]

Control devices

[edit]

The following items are commonly used as pollution control devices in industry and transportation. They can either destroy contaminants or remove them from an exhaust stream before it is emitted into the atmosphere.

- Particulate control

- Mechanical collectors (dust cyclones, multicyclones)

- Electrostatic precipitators: An electrostatic precipitator (ESP), or electrostatic air cleaner, is a particulate collection device that removes particles from a flowing gas (such as air), using the force of an induced electrostatic charge. Electrostatic precipitators are highly efficient filtration devices that minimally impede the flow of gases through the device, and can easily remove fine particulates such as dust and smoke from the air stream.

- Baghouses: Designed to handle heavy dust loads, a dust collector consists of a blower, dust filter, a filter-cleaning system, and a dust receptacle or dust removal system (distinguished from air cleaners which utilize disposable filters to remove the dust).

- Particulate scrubbers: A wet scrubber is a form of pollution control technology. The term describes a variety of devices that use pollutants from a furnace flue gas or from other gas streams. In a wet scrubber, the polluted gas stream is brought into contact with the scrubbing liquid, by spraying it with the liquid, by forcing it through a pool of liquid, or by some other contact method, so as to remove the pollutants.

- Scrubbers

- NOx control

- LO-NOx burners

- Selective catalytic reduction (SCR)

- Selective non-catalytic reduction (SNCR)

- NOx scrubbers

- Exhaust gas recirculation

- Catalytic converter (also for VOC control)

- VOC abatement

- Acid gas/SO2 control

- Mercury control

- Sorbent injection technology

- Electro-catalytic oxidation (ECO)

- K-Fuel

- Dioxin and furan control

- Miscellaneous associated equipment

- Source capturing systems

- Continuous emissions monitoring systems (CEMS)

Monitoring

[edit]Spatiotemporal monitoring of air quality may be necessary for improving air quality, and thereby the health and safety of the public, and assessing impacts of interventions.[293] Such monitoring is done to different extents with different regulatory requirements with discrepant regional coverage by a variety of organizations and governance entities such as using a variety of technologies for use of the data and sensing such mobile IoT sensors,[294][295] satellites,[296][297][298] and monitoring stations.[299][300] Some websites attempt to map air pollution levels using available data.[301][302][303]

Air quality modeling

[edit]Numerical models either on a global scale using tools such as GCMs (general circulation models coupled with a pollution module) or CTMs (Chemical transport model) can be used to simulate the levels of different pollutants in the atmosphere. These tools can have several types (Atmospheric model) and different uses. These models can be used in forecast mode which can help policy makers to decide on appropriate actions when an air pollution episode is detected. They can also be used for climate modeling including evolution of air quality in the future, for example the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) provides climate simulations including air quality assessments in their reports (latest report accessible through their site).

Regulations

[edit]

In general, there are two types of air quality standards. The first class of standards (such as the U.S. National Ambient Air Quality Standards and E.U. Air Quality Directive[304]) set maximum atmospheric concentrations for specific pollutants. Environmental agencies enact regulations which are intended to result in attainment of these target levels. The second class (such as the North American air quality index) take the form of a scale with various thresholds, which is used to communicate to the public the relative risk of outdoor activity. The scale may or may not distinguish between different pollutants.

Canada

[edit]In Canada, air pollution and associated health risks are measured with the Air Quality Health Index (AQHI).[305] It is a health protection tool used to make decisions to reduce short-term exposure to air pollution by adjusting activity levels during increased levels of air pollution.

The AQHI is a federal program jointly coordinated by Health Canada and Environment Canada. However, the AQHI program would not be possible without the commitment and support of the provinces, municipalities and NGOs. From air quality monitoring to health risk communication and community engagement, local partners are responsible for the vast majority of work related to AQHI implementation. The AQHI provides a number from 1 to 10+ to indicate the level of health risk associated with local air quality. Occasionally, when the amount of air pollution is abnormally high, the number may exceed 10. The AQHI provides a local air quality current value as well as a local air quality maximums forecast for today, tonight and tomorrow and provides associated health advice.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | + |

| Risk: | Low (1–3) | Moderate (4–6) | High (7–10) | Very high (above 10) |

As it is now known that even low levels of air pollution can trigger discomfort for the sensitive population, the index has been developed as a continuum: The higher the number, the greater the health risk and need to take precautions. The index describes the level of health risk associated with this number as 'low', 'moderate', 'high' or 'very high', and suggests steps that can be taken to reduce exposure.[306]

| Health risk | Air Quality Health Index | Health messages[307] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| At risk population | General population | ||

| Low | 1–3 | Enjoy your usual outdoor activities. | Ideal air quality for outdoor activities |

| Moderate | 4–6 | Consider reducing or rescheduling strenuous activities outdoors if you are experiencing symptoms. | No need to modify your usual outdoor activities unless you experience symptoms such as coughing and throat irritation. |

| High | 7–10 | Reduce or reschedule strenuous activities outdoors. Children and the elderly should also take it easy. | Consider reducing or rescheduling strenuous activities outdoors if you experience symptoms such as coughing and throat irritation. |

| Very high | Above 10 | Avoid strenuous activities outdoors. Children and the elderly should also avoid outdoor physical exertion and should stay indoors. | Reduce or reschedule strenuous activities outdoors, especially if you experience symptoms such as coughing and throat irritation. |

The measurement is based on the observed relationship of nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ground-level ozone (O3) and particulates (PM2.5) with mortality, from an analysis of several Canadian cities. Significantly, all three of these pollutants can pose health risks, even at low levels of exposure, especially among those with pre-existing health problems.

When developing the AQHI, Health Canada's original analysis of health effects included five major air pollutants: particulates, ozone, and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), as well as sulfur dioxide (SO2), and carbon monoxide (CO). The latter two pollutants provided little information in predicting health effects and were removed from the AQHI formulation.

The AQHI does not measure the effects of odour, pollen, dust, heat or humidity.

Germany

[edit]TA Luft is the German air quality regulation.[308]

Governing urban air pollution

[edit]In Europe, Council Directive 96/62/EC on ambient air quality assessment and management provides a common strategy against which member states can "set objectives for ambient air quality in order to avoid, prevent or reduce harmful effects on human health and the environment ... and improve air quality where it is unsatisfactory".[309]

In July 2008, in the case Dieter Janecek v. Freistaat Bayern, the European Court of Justice ruled that under this directive[309] citizens have the right to require national authorities to implement a short term action plan that aims to maintain or achieve compliance to air quality limit values.[310][311]

This important case law appears to confirm the role of the EC as centralised regulator to European nation-states as regards air pollution control. It places a supranational legal obligation on the UK to protect its citizens from dangerous levels of air pollution, furthermore superseding national interests with those of the citizen.

In 2010, the European Commission (EC) threatened the UK with legal action against the successive breaching of PM10 limit values.[312] The UK government has identified that if fines are imposed, they could cost the nation upwards of £300 million per year.[313]

In March 2011, the Greater London Built-up Area remained the only UK region in breach of the EC's limit values, and was given three months to implement an emergency action plan aimed at meeting the EU Air Quality Directive.[314] The City of London has dangerous levels of PM10 concentrations, estimated to cause 3000 deaths per year within the city.[315] As well as the threat of EU fines, in 2010 it was threatened with legal action for scrapping the western congestion charge zone, which is claimed to have led to an increase in air pollution levels.[316]

In response to these charges, mayor of London Boris Johnson has criticised the current need for European cities to communicate with Europe through their nation state's central government, arguing that in future "A great city like London" should be permitted to bypass its government and deal directly with the European Commission regarding its air quality action plan.[314]

This can be interpreted as recognition that cities can transcend the traditional national government organisational hierarchy and develop solutions to air pollution using global governance networks, for example through transnational relations. Transnational relations include but are not exclusive to national governments and intergovernmental organisations,[317] allowing sub-national actors including cities and regions to partake in air pollution control as independent actors.

Global city partnerships can be built into networks, for example the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, of which London is a member. The C40 is a public 'non-state' network of the world's leading cities that aims to curb their greenhouse emissions.[318] The C40 has been identified as 'governance from the middle' and is an alternative to intergovernmental policy.[319] It has the potential to improve urban air quality as participating cities "exchange information, learn from best practices and consequently mitigate carbon dioxide emissions independently from national government decisions".[318] A criticism of the C40 network is that its exclusive nature limits influence to participating cities and risks drawing resources away from less powerful city and regional actors.

Indigenous people

[edit]Because Indigenous people[320] frequently experience a disproportionate share of the effects of environmental degradation and climate change, even while they have made very little contribution to the processes causing these changes, environmental justice is especially important to them. Indigenous peoples have been marginalized and their lands and resources have been exploited as a result of historical and continuing colonization, institutional injustices, and inequality.