Боинг 747

| Боинг 747 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Боинг 747-200 Иберии (1980 г.) | |

| Роль | Широкофюзеляжный реактивный авиалайнер |

| Национальное происхождение | Соединенные Штаты |

| Производитель | Коммерческие самолеты Боинг |

| Первый полет | 9 февраля 1969 г. |

| Введение | 22 января 1970 г. , с Pan Am. |

| Статус | В грузовом сервисе; в ограниченном пассажирском сообщении |

| Primary users | Atlas Air |

| Produced | 1968–2023 |

| Number built | 1,574 (including prototype) |

| Variants | |

| Developed into | |

Boeing 747 — дальнемагистральный широкофюзеляжный авиалайнер, разработанный и производившийся компанией Boeing Commercial Airplanes в США в период с 1968 по 2023 год. После появления Боинга 707 в октябре 1958 года Pan Am захотела создать реактивный самолет. В 2 + 1 ⁄ 2 раза больше его размера, чтобы снизить стоимость места на 30%. В 1965 году Джо Саттер вышел из программы разработки 737 , чтобы спроектировать 747. В апреле 1966 года компания Pan Am заказала 25 самолетов Boeing 747-100, а в конце 1966 года компания Pratt & Whitney согласилась разработать двигатель JT9D — турбовентиляторный двигатель с большим двухконтурным режимом . 30 сентября 1968 года первый Боинг 747 был вывезен из построенного по индивидуальному заказу завода в Эверетте в мире , крупнейшего по объему здания . Первый полет Боинга 747 состоялся 9 февраля 1969 года, а в декабре того же года Боинг 747 был сертифицирован. Он поступил на вооружение компании Pan Am 22 января 1970 года. Боинг 747 был первым самолетом, получившим название «Jumbo Jet» и первым широкофюзеляжным авиалайнером.

Боинг 747 — четырехмоторный реактивный самолет , первоначально оснащенный двигателями Pratt & Whitney JT9D турбовентиляторными , затем двигателями General Electric CF6 и Rolls-Royce RB211 для исходных вариантов. Имея десять сидений в ряд, он обычно вмещает 366 пассажиров в трех классах обслуживания . Он имеет выраженную стреловидность крыла 0,85 Маха (490 узлов; 900 км/ч) 37,5°, что позволяет развивать крейсерскую скорость , а его тяжелый вес поддерживается четырьмя основными опорами шасси, каждая из которых оснащена четырехколесной тележкой . Частичный двухпалубный самолет был спроектирован с приподнятой кабиной, чтобы его можно было преобразовать в грузовой самолет путем установки передней грузовой двери, поскольку первоначально предполагалось, что в конечном итоге его вытеснят сверхзвуковые транспортные самолеты .

Boeing introduced the -200 in 1971, with uprated engines for a heavier maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) of 833,000 pounds (378 t) from the initial 735,000 pounds (333 t), increasing the maximum range from 4,620 to 6,560 nautical miles [nmi] (8,560 to 12,150 km; 5,320 to 7,550 mi). It was shortened for the longer-range 747SP in 1976, and the 747-300 followed in 1983 with a stretched upper deck for up to 400 seats in three classes. The heavier 747-400 with improved RB211 and CF6 engines or the new PW4000 engine (the JT9D successor), and a two-crew glass cockpit, was introduced in 1989 and is the most common variant. After several studies, the stretched 747-8 was launched on November 14, 2005, with new General Electric GEnx engines, and was first delivered in October 2011. The 747 is the basis for several government and military variants, such as the VC-25 (Air Force One), E-4 Emergency Airborne Command Post, Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, and some experimental test aircraft such as the YAL-1 and SOFIA airborne observatory.

Initial competition came from the smaller trijet widebodies: the Lockheed L-1011 (introduced in 1972), McDonnell Douglas DC-10 (1971) and later MD-11 (1990). Airbus competed with later variants with the heaviest versions of the A340 until surpassing the 747 in size with the A380, delivered between 2007 and 2021. Freighter variants of the 747 remain popular with cargo airlines. The final 747 was delivered to Atlas Air in January 2023 after a 54-year production run, with 1,574 aircraft built. As of December 2023[update], 64 Boeing 747s (4.1%) have been lost in accidents and incidents, in which a total of 3,746 people have died.

Development

[edit]Background

[edit]

In 1963, the United States Air Force started a series of study projects on a very large strategic transport aircraft. Although the C-141 Starlifter was being introduced, officials believed that a much larger and more capable aircraft was needed, especially to carry cargo that would not fit in any existing aircraft. These studies led to initial requirements for the CX-Heavy Logistics System (CX-HLS) in March 1964 for an aircraft with a load capacity of 180,000 pounds (81.6 t) and a speed of Mach 0.75 (430 kn; 800 km/h), and an unrefueled range of 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) with a payload of 115,000 pounds (52.2 t). The payload bay had to be 17 feet (5.18 m) wide by 13.5 feet (4.11 m) high and 100 feet (30 m) long with access through doors at the front and rear.[1]

The desire to keep the number of engines to four required new engine designs with greatly increased power and better fuel economy. In May 1964, airframe proposals arrived from Boeing, Douglas, General Dynamics, Lockheed, and Martin Marietta; engine proposals were submitted by General Electric, Curtiss-Wright, and Pratt & Whitney. Boeing, Douglas, and Lockheed were given additional study contracts for the airframe, along with General Electric and Pratt & Whitney for the engines.[1]

The airframe proposals shared several features. As the CX-HLS needed to be able to be loaded from the front, a door had to be included where the cockpit usually was. All of the companies solved this problem by moving the cockpit above the cargo area; Douglas had a small "pod" just forward and above the wing, Lockheed used a long "spine" running the length of the aircraft with the wing spar passing through it, while Boeing blended the two, with a longer pod that ran from just behind the nose to just behind the wing.[2][3] In 1965, Lockheed's aircraft design and General Electric's engine design were selected for the new C-5 Galaxy transport, which was the largest military aircraft in the world at the time.[1] Boeing carried the nose door and raised cockpit concepts over to the design of the 747.[4]

Airliner proposal

[edit]The 747 was conceived while air travel was increasing in the 1960s.[5] The era of commercial jet transportation, led by the enormous popularity of the Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8, had revolutionized long-distance travel.[5][6] In this growing jet age, Juan Trippe, president of Pan American Airways (Pan Am), one of Boeing's most important airline customers, asked for a new jet airliner 2+1⁄2 times size of the 707, with a 30% lower cost per unit of passenger-distance and the capability to offer mass air travel on international routes.[7] Trippe also thought that airport congestion could be addressed by a larger new aircraft.[8]

In 1965, Joe Sutter was transferred from Boeing's 737 development team to manage the design studies for the new airliner, already assigned the model number 747.[9] Sutter began a design study with Pan Am and other airlines to better understand their requirements. At the time, many thought that long-range subsonic airliners would eventually be superseded by supersonic transport aircraft.[10] Boeing responded by designing the 747 so it could be adapted easily to carry freight and remain in production even if sales of the passenger version declined.[11]

In April 1966, Pan Am ordered 25 Boeing 747-100 aircraft for US$525 million[12][13] (equivalent to $3.8 billion in 2023 dollars). During the ceremonial 747 contract-signing banquet in Seattle on Boeing's 50th Anniversary, Juan Trippe predicted that the 747 would be "…a great weapon for peace, competing with intercontinental missiles for mankind's destiny".[14] As launch customer,[15][16] and because of its early involvement before placing a formal order, Pan Am was able to influence the design and development of the 747 to an extent unmatched by a single airline before or since.[17]

Design effort

[edit]Ultimately, the high-winged CX-HLS Boeing design was not used for the 747, although technologies developed for their bid had an influence.[18] The original design included a full-length double-deck fuselage with eight-across seating and two aisles on the lower deck and seven-across seating and two aisles on the upper deck.[19][20] However, concern over evacuation routes and limited cargo-carrying capability caused this idea to be scrapped in early 1966 in favor of a wider single deck design.[15] The cockpit was therefore placed on a shortened upper deck so that a freight-loading door could be included in the nose cone; this design feature produced the 747's distinctive "hump".[21] In early models, what to do with the small space in the pod behind the cockpit was not clear, and this was initially specified as a "lounge" area with no permanent seating.[22] (A different configuration that had been considered to keep the flight deck out of the way for freight loading had the pilots below the passengers, and was dubbed the "anteater".)[23]

One of the principal technologies that enabled an aircraft as large as the 747 to be drawn up was the high-bypass turbofan engine.[24] This engine technology was thought to be capable of delivering double the power of the earlier turbojets while consuming one-third less fuel. General Electric had pioneered the concept but was committed to developing the engine for the C-5 Galaxy and did not enter the commercial market until later.[25][26] Pratt & Whitney was also working on the same principle and, by late 1966, Boeing, Pan Am and Pratt & Whitney agreed to develop a new engine, designated the JT9D to power the 747.[26]

The project was designed with a new methodology called fault tree analysis, which allowed the effects of a failure of a single part to be studied to determine its impact on other systems.[15] To address concerns about safety and flyability, the 747's design included structural redundancy, redundant hydraulic systems, quadruple main landing gear and dual control surfaces.[27] Additionally, some of the most advanced high-lift devices used in the industry were included in the new design, to allow it to operate from existing airports. These included Krueger flaps running almost the entire length of the wing's leading edge, as well as complex three-part slotted flaps along the trailing edge of the wing.[28][29] The wing's complex three-part flaps increase wing area by 21% and lift by 90% when fully deployed compared to their non-deployed configuration.[30]

Boeing agreed to deliver the first 747 to Pan Am by the end of 1969. The delivery date left 28 months to design the aircraft, which was two-thirds of the normal time.[31] The schedule was so fast-paced that the people who worked on it were given the nickname "The Incredibles".[32] Developing the aircraft was such a technical and financial challenge that management was said to have "bet the company" when it started the project.[15] Due to its massive size, Boeing subcontracted the assembly of subcomponents to other manufacturers, most notably Northrop and Grumman (later merged into Northrop Grumman in 1994) for fuselage parts and trailing edge flaps respectively, Fairchild for tailplane ailerons,[33] and Ling-Temco-Vought (LTV) for the empennage.[34][35]

Production plant

[edit]

As Boeing did not have a plant large enough to assemble the giant airliner, they chose to build a new plant. The company considered locations in about 50 cities,[36] and eventually decided to build the new plant some 30 miles (50 km) north of Seattle on a site adjoining a military base at Paine Field near Everett, Washington.[37] It bought the 780-acre (320 ha) site in June 1966.[38]

Developing the 747 had been a major challenge, and building its assembly plant was also a huge undertaking. Boeing president William M. Allen asked Malcolm T. Stamper, then head of the company's turbine division, to oversee construction of the Everett factory and to start production of the 747.[39] To level the site, more than four million cubic yards (three million cubic meters) of earth had to be moved.[40] Time was so short that the 747's full-scale mock-up was built before the factory roof above it was finished.[41] The plant is the largest building by volume ever built, and has been substantially expanded several times to permit construction of other models of Boeing wide-body commercial jets.[37]

Flight testing

[edit]

Before the first 747 was fully assembled, testing began on many components and systems. One important test involved the evacuation of 560 volunteers from a cabin mock-up via the aircraft's emergency chutes. The first full-scale evacuation took two and a half minutes instead of the maximum of 90 seconds mandated by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), and several volunteers were injured. Subsequent test evacuations achieved the 90-second goal but caused more injuries. Most problematic was evacuation from the aircraft's upper deck; instead of using a conventional slide, volunteer passengers escaped by using a harness attached to a reel.[42] Tests also involved taxiing such a large aircraft. Boeing built an unusual training device known as "Waddell's Wagon" (named for a 747 test pilot, Jack Waddell) that consisted of a mock-up cockpit mounted on the roof of a truck. While the first 747s were still being built, the device allowed pilots to practice taxi maneuvers from a high upper-deck position.[43]

In 1968, the program cost was US$1 billion[44] (equivalent to $6.7 billion in 2023 dollars). On September 30, 1968, the first 747 was rolled out of the Everett assembly building before the world's press and representatives of the 26 airlines that had ordered the airliner.[45] Over the following months, preparations were made for the first flight, which took place on February 9, 1969, with test pilots Jack Waddell and Brien Wygle at the controls[46][47] and Jess Wallick at the flight engineer's station. Despite a minor problem with one of the flaps, the flight confirmed that the 747 handled extremely well. The 747 was found to be largely immune to "Dutch roll", a phenomenon that had been a major hazard to the early swept-wing jets.[48]

Issues, delays and certification

[edit]

During later stages of the flight test program, flutter testing showed that the wings suffered oscillation under certain conditions. This difficulty was partly solved by reducing the stiffness of some wing components. However, a particularly severe high-speed flutter problem was solved only by inserting depleted uranium counterweights as ballast in the outboard engine nacelles of the early 747s.[49] This measure caused anxiety when these aircraft crashed, for example El Al Flight 1862 at Amsterdam in 1992 with 622 pounds (282 kg) of uranium in the tailplane (horizontal stabilizer).[50][51]

The flight test program was hampered by problems with the 747's JT9D engines. Difficulties included engine stalls caused by rapid throttle movements and distortion of the turbine casings after a short period of service.[52] The problems delayed 747 deliveries for several months; up to 20 aircraft at the Everett plant were stranded while awaiting engine installation.[53] The program was further delayed when one of the five test aircraft suffered serious damage during a landing attempt at Renton Municipal Airport, the site of Boeing's Renton factory. The incident happened on December 13, 1969, when a test aircraft was flown to Renton to have test equipment removed and a cabin installed. Pilot Ralph C. Cokely undershot the airport's short runway and the 747's right, outer landing gear was torn off and two engine nacelles were damaged.[54][55] However, these difficulties did not prevent Boeing from taking a test aircraft to the 28th Paris Air Show in mid-1969, where it was displayed to the public for the first time.[56] Finally, in December 1969, the 747 received its FAA airworthiness certificate, clearing it for introduction into service.[57]

The huge cost of developing the 747 and building the Everett factory meant that Boeing had to borrow heavily from a banking syndicate. During the final months before delivery of the first aircraft, the company had to repeatedly request additional funding to complete the project. Had this been refused, Boeing's survival would have been threatened.[16][58] The firm's debt exceeded $2 billion, with the $1.2 billion owed to the banks setting a record for all companies. Allen later said, "It was really too large a project for us."[59] Ultimately, the gamble succeeded, and Boeing held a monopoly in very large passenger aircraft production for many years.[60]

Entry into service

[edit]

On January 15, 1970, First Lady Pat Nixon christened Pan Am's first 747 at Dulles International Airport in the presence of Pan Am chairman Najeeb Halaby.[61] Instead of champagne, red, white, and blue water was sprayed on the aircraft. The 747 entered service on January 22, 1970, on Pan Am's New York–London route;[62] the flight had been planned for the evening of January 21, but engine overheating made the original aircraft (Clipper Young America, registration N735PA) unusable. Finding a substitute delayed the flight by more than six hours to the following day when Clipper Victor (registration N736PA) was used.[63][64] The 747 enjoyed a fairly smooth introduction into service, overcoming concerns that some airports would not be able to accommodate an aircraft that large.[65] Although technical problems occurred, they were relatively minor and quickly solved.[66]

Improved 747 versions

[edit]

After the initial 747-100, Boeing developed the -100B, a higher maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) variant, and the -100SR (Short Range), with higher passenger capacity.[67] Increased maximum takeoff weight allows aircraft to carry more fuel and have longer range.[68] The -200 model followed in 1971, featuring more powerful engines and a higher MTOW. Passenger, freighter and combination passenger-freighter versions of the -200 were produced.[67] The shortened 747SP (special performance) with a longer range was also developed, and entered service in 1976.[69]

The 747 line was further developed with the launch of the 747-300 on June 11, 1980, followed by interest from Swissair a month later and the go-ahead for the project.[70]: 86 The 300 series resulted from Boeing studies to increase the seating capacity of the 747, during which modifications such as fuselage plugs and extending the upper deck over the entire length of the fuselage were rejected. The first 747-300, completed in 1983, included a stretched upper deck, increased cruise speed, and increased seating capacity. The -300 variant was previously designated 747SUD for stretched upper deck, then 747-200 SUD,[71] followed by 747EUD, before the 747-300 designation was used.[72] Passenger, short range and combination freighter-passenger versions of the 300 series were produced.[67]

In 1985, development of the longer range 747-400 began.[73] The variant had a new glass cockpit, which allowed for a cockpit crew of two instead of three,[74] new engines, lighter construction materials, and a redesigned interior. Development costs soared, and production delays occurred as new technologies were incorporated at the request of airlines. Insufficient workforce experience and reliance on overtime contributed to early production problems on the 747-400.[15] The -400 entered service in 1989.[75]

In 1991, a record-breaking 1,087 passengers were flown in a 747 during a covert operation to airlift Ethiopian Jews to Israel.[76] Generally, the 747-400 held between 416 and 524 passengers.[77] The 747 remained the heaviest commercial aircraft in regular service until the debut of the Antonov An-124 Ruslan in 1982; variants of the 747-400 surpassed the An-124's weight in 2000. The Antonov An-225 Mriya cargo transport, which debuted in 1988, remains the world's largest aircraft by several measures (including the most accepted measures of maximum takeoff weight and length); one aircraft has been completed and was in service until 2022. The Scaled Composites Stratolaunch is currently the largest aircraft by wingspan.[78]

Further developments

[edit]

After the arrival of the 747-400, several stretching schemes for the 747 were proposed. Boeing announced the larger 747-500X and -600X preliminary designs in 1996.[79] The new variants would have cost more than US$5 billion to develop,[79] and interest was not sufficient to launch the program.[80] In 2000, Boeing offered the more modest 747X and 747X stretch derivatives as alternatives to the Airbus A38X. However, the 747X family was unable to attract enough interest to enter production. A year later, Boeing switched from the 747X studies to pursue the Sonic Cruiser,[81] and after the Sonic Cruiser program was put on hold, the 787 Dreamliner.[82] Some of the ideas developed for the 747X were used on the 747-400ER, a longer range variant of the 747-400.[83]

After several variants were proposed but later abandoned, some industry observers became skeptical of new aircraft proposals from Boeing.[84] However, in early 2004, Boeing announced tentative plans for the 747 Advanced that were eventually adopted. Similar in nature to the 747-X, the stretched 747 Advanced used technology from the 787 to modernize the design and its systems. The 747 remained the largest passenger airliner in service until the Airbus A380 began airline service in 2007.[85]

On November 14, 2005, Boeing announced it was launching the 747 Advanced as the Boeing 747-8.[86] The last 747-400s were completed in 2009.[87] As of 2011[update], most orders of the 747-8 were for the freighter variant. On February 8, 2010, the 747-8 Freighter made its maiden flight.[88] The first delivery of the 747-8 went to Cargolux in 2011.[89][90] The first 747-8 Intercontinental passenger variant was delivered to Lufthansa on May 5, 2012.[91] The 1,500th Boeing 747 was delivered in June 2014 to Lufthansa.[92]

In January 2016, Boeing stated it was reducing 747-8 production to six per year beginning in September 2016, incurring a $569 million post-tax charge against its fourth-quarter 2015 profits. At the end of 2015, the company had 20 orders outstanding.[93][94] On January 29, 2016, Boeing announced that it had begun the preliminary work on the modifications to a commercial 747-8 for the next Air Force One presidential aircraft, then expected to be operational by 2020.[95]

On July 12, 2016, Boeing announced that it had finalized an order from Volga-Dnepr Group for 20 747-8 freighters, valued at $7.58 billion (~$9.44 billion in 2023) at list prices. Four aircraft were delivered beginning in 2012. Volga-Dnepr Group is the parent of three major Russian air-freight carriers – Volga-Dnepr Airlines, AirBridgeCargo Airlines and Atran Airlines. The new 747-8 freighters would replace AirBridgeCargo's current 747-400 aircraft and expand the airline's fleet and will be acquired through a mix of direct purchases and leasing over the next six years, Boeing said.[96]

End of production

[edit]On July 27, 2016, in its quarterly report to the Securities and Exchange Commission, Boeing discussed the potential termination of 747 production due to insufficient demand and market for the aircraft.[97] With a firm order backlog of 21 aircraft and a production rate of six per year, program accounting had been reduced to 1,555 aircraft.[98] In October 2016, UPS Airlines ordered 14 -8Fs to add capacity, along with 14 options, which it took in February 2018 to increase the total to 28 -8Fs on order.[99][100] The backlog then stood at 25 aircraft, though several of these were orders from airlines that no longer intended to take delivery.[101]

On July 2, 2020, it was reported that Boeing planned to end 747 production in 2022 upon delivery of the remaining jets on order to UPS and the Volga-Dnepr Group due to low demand.[102] On July 29, 2020, Boeing confirmed that the final 747 would be delivered in 2022 as a result of "current market dynamics and outlook" stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, according to CEO David Calhoun.[103] The last aircraft, a 747-8F for Atlas Air registered N863GT, rolled off the production line on December 6, 2022,[104] and was delivered on January 31, 2023.[105] Boeing hosted an event at the Everett factory for thousands of workers as well as industry executives to commemorate the delivery.[106]

Design

[edit]

The Boeing 747 is a large, wide-body (two-aisle) airliner with four wing-mounted engines. Its wings have a high sweep angle of 37.5° for a fast, efficient cruise speed[21] of Mach 0.84 to 0.88, depending on the variant. The sweep also reduces the wingspan, allowing the 747 to use existing hangars.[15][107] Its seating capacity is over 366 with a 3–4–3 seat arrangement (a cross section of three seats, an aisle, four seats, another aisle, and three seats) in economy class and a 2–3–2 layout in first class on the main deck. The upper deck has a 3–3 seat arrangement in economy class and a 2–2 layout in first class.[108]

Raised above the main deck, the cockpit creates a hump. This raised cockpit allows front loading of cargo on freight variants.[21] The upper deck behind the cockpit provides space for a lounge and/or extra seating. The "stretched upper deck" became available as an alternative on the 747-100B variant and later as standard beginning on the 747-300. The upper deck was stretched more on the 747-8. The 747 cockpit roof section also has an escape hatch from which crew can exit during the events of an emergency if they cannot do so through the cabin.

The 747's maximum takeoff weight ranges from 735,000 pounds (333 t) for the -100 to 970,000 pounds (440 t) for the -8. Its range has increased from 5,300 nautical miles (9,800 km; 6,100 mi) on the -100 to 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) on the -8I.[109][110]

The 747 has redundant structures along with four redundant hydraulic systems and four main landing gears each with four wheels; these provide a good spread of support on the ground and safety in case of tire blow-outs. The main gear are redundant so that landing can be performed on two opposing landing gears if the others are not functioning properly.[111] The 747 also has split control surfaces and was designed with sophisticated triple-slotted flaps that minimize landing speeds and allow the 747 to use standard-length runways.[112]

For transportation of spare engines, the 747 can accommodate a non-functioning fifth-pod engine under the aircraft's port wing between the inner functioning engine and the fuselage.[113][114] The fifth engine mount point was also used by Virgin Orbit's LauncherOne program to carry an orbital-class rocket to cruise altitude where it was deployed.[115][116]

Operational history

[edit]After the aircraft's introduction with Pan Am in 1970, other airlines that had bought the 747 to stay competitive began to put their own 747s into service.[117] Boeing estimated that half of the early 747 sales were to airlines desiring the aircraft's long range rather than its payload capacity.[118][119] While the 747 had the lowest potential operating cost per seat, this could only be achieved when the aircraft was fully loaded; costs per seat increased rapidly as occupancy declined. A moderately loaded 747, one with only 70 percent of its seats occupied, used more than 95 percent of the fuel needed by a fully occupied 747.[120] Nonetheless, many flag-carriers purchased the 747 due to its prestige "even if it made no sense economically" to operate. During the 1970s and 1980s, over 30 regularly scheduled 747s could often be seen at John F. Kennedy International Airport.[121]

The recession of 1969–1970, despite having been characterized as relatively mild, greatly affected Boeing. For the year and a half after September 1970, it only sold two 747s in the world, both to Irish flag carrier Aer Lingus.[122][123] No 747s were sold to any American carrier for almost three years.[59] When economic problems in the US and other countries after the 1973 oil crisis led to reduced passenger traffic, several airlines found they did not have enough passengers to fly the 747 economically, and they replaced them with the smaller and recently introduced McDonnell Douglas DC-10 and Lockheed L-1011 TriStar trijet wide bodies[124] (and later the 767 and Airbus A300/A310 twinjets). Having tried replacing coach seats on its 747s with piano bars in an attempt to attract more customers, American Airlines eventually relegated its 747s to cargo service and in 1983 exchanged them with Pan Am for smaller aircraft;[125] Delta Air Lines also removed its 747s from service after several years.[126] Later, Delta acquired 747s again in 2008 as part of its merger with Northwest Airlines, although it retired the Boeing 747-400 fleet in December 2017.[127]

International flights bypassing traditional hub airports and landing at smaller cities became more common throughout the 1980s, thus eroding the 747's original market.[128] Many international carriers continued to use the 747 on Pacific routes.[129] In Japan, 747s on domestic routes were configured to carry nearly the maximum passenger capacity.[130]

Variants

[edit]The 747-100 with a range of 4,620 nautical miles (8,556 km), was the original variant launched in 1966. The 747-200 soon followed, with its launch in 1968. The 747-300 was launched in 1980 and was followed by the 747-400 in 1985. Ultimately, the 747-8 was announced in 2005. Several versions of each variant have been produced, and many of the early variants were in production simultaneously. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) classifies variants using a shortened code formed by combining the model number and the variant designator (e.g. "B741" for all -100 models).[131]

747-100

[edit]

The first 747-100s were built with six upper deck windows (three per side) to accommodate upstairs lounge areas. Later, as airlines began to use the upper deck for premium passenger seating instead of lounge space, Boeing offered an upper deck with ten windows on either side as an option. Some early -100s were retrofitted with the new configuration.[132] The -100 was equipped with Pratt & Whitney JT9D-3A engines. No freighter version of this model was developed, but many 747-100s were converted into freighters as 747-100(SF).[133] The first 747-100(SF) was delivered to Flying Tiger Line in 1974.[134] A total of 168 747-100s were built; 167 were delivered to customers, while Boeing kept the prototype, City of Everett.[135] In 1972, its unit cost was US$24M[136] (174.8M today).

747SR

[edit]Responding to requests from Japanese airlines for a high-capacity aircraft to serve domestic routes between major cities, Boeing developed the 747SR as a short-range version of the 747-100 with lower fuel capacity and greater payload capability. With increased economy class seating, up to 498 passengers could be carried in early versions and up to 550 in later models.[67] The 747SR had an economic design life objective of 52,000 flights during 20 years of operation, compared to 24,600 flights in 20 years for the standard 747.[137] The initial 747SR model, the -100SR, had a strengthened body structure and landing gear to accommodate the added stress accumulated from a greater number of takeoffs and landings.[138] Extra structural support was built into the wings, fuselage, and the landing gear along with a 20% reduction in fuel capacity.[139]

The initial order for the -100SR – four aircraft for Japan Air Lines (JAL, later Japan Airlines) – was announced on October 30, 1972; rollout occurred on August 3, 1973, and the first flight took place on August 31, 1973. The type was certified by the FAA on September 26, 1973, with the first delivery on the same day. The -100SR entered service with JAL, the type's sole customer, on October 7, 1973, and typically operated flights within Japan.[38] Seven -100SRs were built between 1973 and 1975, each with a 520,000-pound (240 t) MTOW and Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7A engines derated to 43,000 pounds-force (190 kN) of thrust.[140]

Following the -100SR, Boeing produced the -100BSR, a 747SR variant with increased takeoff weight capability. Debuting in 1978, the -100BSR also incorporated structural modifications for a high cycle-to-flying hour ratio; a related standard -100B model debuted in 1979. The -100BSR first flew on November 3, 1978, with first delivery to All Nippon Airways (ANA) on December 21, 1978. A total of 20 -100BSRs were produced for ANA and JAL.[141] The -100BSR had a 600,000 pounds (270 t) MTOW and was powered by the same JT9D-7A or General Electric CF6-45 engines used on the -100SR. ANA operated this variant on domestic Japanese routes with 455 or 456 seats until retiring its last aircraft in March 2006.[142]

In 1986, two -100BSR SUD models, featuring the stretched upper deck (SUD) of the -300, were produced for JAL.[143] The type's maiden flight occurred on February 26, 1986, with FAA certification and first delivery on March 24, 1986.[144] JAL operated the -100BSR SUD with 563 seats on domestic routes until their retirement in the third quarter of 2006. While only two -100BSR SUDs were produced, in theory, standard -100Bs can be modified to the SUD certification.[141] Overall, 29 Boeing 747SRs were built.[145]

747-100B

[edit]

The 747-100B model was developed from the -100SR, using its stronger airframe and landing gear design. The type had an increased fuel capacity of 48,070 US gal (182,000 L), allowing for a 5,000-nautical-mile (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) range with a typical 452-passenger payload, and an increased MTOW of 750,000 lb (340 t) was offered. The first -100B order, one aircraft for Iran Air, was announced on June 1, 1978. This version first flew on June 20, 1979, received FAA certification on August 1, 1979, and was delivered the next day.[146] Nine -100Bs were built, one for Iran Air and eight for Saudi Arabian Airlines.[147][148] Unlike the original -100, the -100B was offered with Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7A, CF6-50, or Rolls-Royce RB211-524 engines. However, only RB211-524 (Saudia) and JT9D-7A (Iran Air) engines were ordered.[149] The last 747-100B, EP-IAM was retired by Iran Air in 2014, the last commercial operator of the 747-100 and -100B.[150]

747SP

[edit]

The development of the 747SP stemmed from a joint request between Pan American World Airways and Iran Air, who were looking for a high-capacity airliner with enough range to cover Pan Am's New York–Middle Eastern routes and Iran Air's planned Tehran–New York route. The Tehran–New York route, when launched, was the longest non-stop commercial flight in the world. The 747SP is 48 feet 4 inches (14.73 m) shorter than the 747-100. Fuselage sections were eliminated fore and aft of the wing, and the center section of the fuselage was redesigned to fit mating fuselage sections. The SP's flaps used a simplified single-slotted configuration.[151][152] The 747SP, compared to earlier variants, had a tapering of the aft upper fuselage into the empennage, a double-hinged rudder, and longer vertical and horizontal stabilizers.[153] Power was provided by Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7(A/F/J/FW) or Rolls-Royce RB211-524 engines.[154]

The 747SP was granted a type certificate on February 4, 1976, and entered service with launch customers Pan Am and Iran Air that same year.[152] The aircraft was chosen by airlines wishing to serve major airports with short runways.[155] A total of 45 747SPs were built,[135] with the 44th 747SP delivered on August 30, 1982. In 1987, Boeing re-opened the 747SP production line after five years to build one last 747SP for an order by the United Arab Emirates government.[152] In addition to airline use, one 747SP was modified for the NASA/German Aerospace Center SOFIA experiment.[156] Iran Air is the last civil operator of the type; its final 747-SP (EP-IAC) was retired in June 2016.[157][158]

747-200

[edit]

While the 747-100 powered by Pratt & Whitney JT9D-3A engines offered enough payload and range for medium-haul operations, it was marginal for long-haul route sectors. The demand for longer range aircraft with increased payload quickly led to the improved -200, which featured more powerful engines, increased MTOW, and greater range than the -100. A few early -200s retained the three-window configuration of the -100 on the upper deck, but most were built with a ten-window configuration on each side.[159] The 747-200 was produced in passenger (-200B), freighter (-200F), convertible (-200C), and combi (-200M) versions.[160]

The 747-200B was the basic passenger version, with increased fuel capacity and more powerful engines; it entered service in February 1971.[71] In its first three years of production, the -200 was equipped with Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7 engines (initially the only engine available). Range with a full passenger load started at over 5,000 nmi (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) and increased to 6,000 nmi (11,000 km; 6,900 mi) with later engines. Most -200Bs had an internally stretched upper deck, allowing for up to 16 passenger seats.[161] The freighter model, the 747-200F, had a hinged nose cargo door and could be fitted with an optional side cargo door,[71] and had a capacity of 105 tons (95.3 tonnes) and an MTOW of up to 833,000 pounds (378 t). It entered service in 1972 with Lufthansa.[162] The convertible version, the 747-200C, could be converted between a passenger and a freighter or used in mixed configurations,[67] and featured removable seats and a nose cargo door.[71] The -200C could also be outfitted with an optional side cargo door on the main deck.[163]

The combi aircraft model, the 747-200M (originally designated 747-200BC), could carry freight in the rear section of the main deck via a side cargo door. A removable partition on the main deck separated the cargo area at the rear from the passengers at the front. The -200M could carry up to 238 passengers in a three-class configuration with cargo carried on the main deck. The model was also known as the 747-200 Combi.[71] As on the -100, a stretched upper deck (SUD) modification was later offered. A total of 10 747-200s operated by KLM were converted.[71] Union de Transports Aériens (UTA) also had two aircraft converted.[citation needed]

After launching the -200 with Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7 engines, on August 1, 1972, Boeing announced that it had reached an agreement with General Electric to certify the 747 with CF6-50 series engines to increase the aircraft's market potential. Rolls-Royce followed 747 engine production with a launch order from British Airways for four aircraft. The option of RB211-524B engines was announced on June 17, 1975.[149] The -200 was the first 747 to provide a choice of powerplant from the three major engine manufacturers.[164] In 1976, its unit cost was US$39M (208.8M today).

A total of 393 of the 747-200 versions had been built when production ended in 1991.[165] Of these, 225 were -200B, 73 were -200F, 13 were -200C, 78 were -200M, and 4 were military.[166] Iran Air retired the last passenger 747-200 in May 2016, 36 years after it was delivered.[167] As of July 2019[update], five 747-200s remain in service as freighters.[168]

747-300

[edit]

The 747-300 features a 23-foot-4-inch-longer (7.11 m) upper deck than the -200.[72] The stretched upper deck (SUD) has two emergency exit doors and is the most visible difference between the -300 and previous models.[169] After being made standard on the 747-300, the SUD was offered as a retrofit, and as an option to earlier variants still in-production. An example for a retrofit were two UTA -200 Combis being converted in 1986, and an example for the option were two brand-new JAL -100 aircraft (designated -100BSR SUD), the first of which was delivered on March 24, 1986.[70]: 68, 92

The 747-300 introduced a new straight stairway to the upper deck, instead of a spiral staircase on earlier variants, which creates room above and below for more seats.[67] Minor aerodynamic changes allowed the -300's cruise speed to reach Mach 0.85 compared with Mach 0.84 on the -200 and -100 models, while retaining the same takeoff weight.[72] The -300 could be equipped with the same Pratt & Whitney and Rolls-Royce powerplants as on the -200, as well as updated General Electric CF6-80C2B1 engines.[67]

Swissair placed the first order for the 747-300 on June 11, 1980.[170] The variant revived the 747-300 designation, which had been previously used on a design study that did not reach production. The 747-300 first flew on October 5, 1982, and the type's first delivery went to Swissair on March 23, 1983.[38] In 1982, its unit cost was US$83M (262.1M today). Besides the passenger model, two other versions (-300M, -300SR) were produced. The 747-300M features cargo capacity on the rear portion of the main deck, similar to the -200M, but with the stretched upper deck it can carry more passengers.[154][171] The 747-300SR, a short range, high-capacity domestic model, was produced for Japanese markets with a maximum seating for 584.[172] No production freighter version of the 747-300 was built, but Boeing began modifications of used passenger -300 models into freighters in 2000.[173]

A total of 81 747-300 series aircraft were delivered, 56 for passenger use, 21 -300M and 4 -300SR versions.[174] In 1985, just two years after the -300 entered service, the type was superseded by the announcement of the more advanced 747-400.[175] The last 747-300 was delivered in September 1990 to Sabena.[67][176] While some -300 customers continued operating the type, several large carriers replaced their 747-300s with 747-400s. Air France, Air India, Japan Airlines, Pakistan International Airlines, and Qantas were some of the last major carriers to operate the 747-300. On December 29, 2008, Qantas flew its last scheduled 747-300 service, operating from Melbourne to Los Angeles via Auckland.[177] In July 2015, Pakistan International Airlines retired their final 747-300 after 30 years of service.[178] Mahan Air was the last passenger operator of the Boeing 747-300. In 2022, their last 747-300M was leased by Emtrasur Cargo. The 747-300M was later seized by the US Department of Justice and scrapped in 2024.[citation needed] As of 2024, TransAVIAExport, a Belarusian cargo airline operates one Boeing 747-300F.[citation needed] As of 2024, a former Saudia 747-300 is used for VVIP transport, operated by the Saudi Arabian Government.[citation needed]

747-400

[edit]

The 747-400 is an improved model with increased range. It has wingtip extensions of 6 ft (1.8 m) and winglets of 6 ft (1.8 m), which improve the type's fuel efficiency by four percent compared to previous 747 versions.[179] The 747-400 introduced a new glass cockpit designed for a flight crew of two instead of three, with a reduction in the number of dials, gauges and knobs from 971 to 365 through the use of electronics. The type also features tail fuel tanks, revised engines, and a new interior. The longer range has been used by some airlines to bypass traditional fuel stops, such as Anchorage.[180] A 747-400 loaded with 126,000 pounds (57,000 kg) of fuel flying 3,500 miles (3,000 nmi; 5,600 km) consumes an average of 5 US gallons per mile (12 L/km).[181][182] Powerplants include the Pratt & Whitney PW4062, General Electric CF6-80C2, and Rolls-Royce RB211-524.[183] As a result of the Boeing 767 development overlapping with the 747-400's development, both aircraft can use the same three powerplants and are even interchangeable between the two aircraft models.[184]

The -400 was offered in passenger (-400), freighter (-400F), combi (-400M), domestic (-400D), extended range passenger (-400ER), and extended range freighter (-400ERF) versions. Passenger versions retain the same upper deck as the -300, while the freighter version does not have an extended upper deck.[185] The 747-400D was built for short-range operations with maximum seating for 624. Winglets were not included, but they can be retrofitted.[186][187] Cruising speed is up to Mach 0.855 on different versions of the 747-400.[183]

The passenger version first entered service in February 1989 with launch customer Northwest Airlines on the Minneapolis to Phoenix route.[188] The combi version entered service in September 1989 with KLM, while the freighter version entered service in November 1993 with Cargolux. The 747-400ERF entered service with Air France in October 2002, while the 747-400ER entered service with Qantas,[189] its sole customer, in November 2002. In January 2004, Boeing and Cathay Pacific launched the Boeing 747-400 Special Freighter program,[190] later referred to as the Boeing Converted Freighter (BCF), to modify passenger 747-400s for cargo use. The first 747-400BCF was redelivered in December 2005.[191]

In March 2007, Boeing announced that it had no plans to produce further passenger versions of the -400.[192] However, orders for 36 -400F and -400ERF freighters were already in place at the time of the announcement.[192] The last passenger version of the 747-400 was delivered in April 2005 to China Airlines. Some of the last built 747-400s were delivered with Dreamliner livery along with the modern Signature interior from the Boeing 777. A total of 694 of the 747-400 series aircraft were delivered.[135] At various times, the largest 747-400 operator has included Singapore Airlines,[193] Japan Airlines,[193] and British Airways.[194][195] As of July 2019[update], 331 Boeing 747-400s were in service;[168] there were only 10 Boeing 747-400s in passenger service as of September 2021.

747 LCF Dreamlifter

[edit]

The 747-400 Dreamlifter[196] (originally called the 747 Large Cargo Freighter or LCF[197]) is a Boeing-designed modification of existing 747-400s into a larger outsize cargo freighter configuration to ferry 787 Dreamliner sub-assemblies. Evergreen Aviation Technologies Corporation of Taiwan was contracted to complete modifications of 747-400s into Dreamlifters in Taoyuan. The aircraft flew for the first time on September 9, 2006, in a test flight.[198] Modification of four aircraft was completed by February 2010.[199] The Dreamlifters have been placed into service transporting sub-assemblies for the 787 program to the Boeing plant in Everett, Washington, for final assembly.[196] The aircraft is certified to carry only essential crew with no passengers.[200]

747-8

[edit]

Boeing announced a new 747 variant, the 747-8, on November 14, 2005. Referred to as the 747 Advanced prior to its launch, the 747-8 uses similar General Electric GEnx engines and cockpit technology to the 787. The variant is designed to be quieter, more economical, and more environmentally friendly. The 747-8's fuselage is lengthened from 232 feet (71 m) to 251 feet (77 m),[201] marking the first stretch variant of the aircraft.

The 747-8 Freighter, or 747-8F, has 16% more payload capacity than its predecessor, allowing it to carry seven more standard air cargo containers, with a maximum payload capacity 154 tons (140 tonnes) of cargo.[202] As on previous 747 freighters, the 747-8F features a flip up nose-door, a side-door on the main deck, and a side-door on the lower deck ("belly") to aid loading and unloading. The 747-8F made its maiden flight on February 8, 2010.[203][204] The variant received its amended type certificate jointly from the FAA and the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) on August 19, 2011.[205] The -8F was first delivered to Cargolux on October 12, 2011.[206]

The passenger version, named 747-8 Intercontinental or 747-8I, is designed to carry up to 467 passengers in a 3-class configuration and fly more than 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at Mach 0.855. As a derivative of the already common 747-400, the 747-8I has the economic benefit of similar training and interchangeable parts.[207] The type's first test flight occurred on March 20, 2011.[208] The 747-8 has surpassed the Airbus A340-600 as the world's longest airliner, a record it would hold until the 777X, which first flew in 2020. The first -8I was delivered in May 2012 to Lufthansa.[209] The 747-8 has received 155 total orders, including 106 for the -8F and 47 for the -8I as of June 2021[update].[135] The final 747-8F was delivered to Atlas Air on January 31, 2023, marking the end of the production of the Boeing 747 series.[105]

Government, military, and other variants

[edit]

- VC-25 – This aircraft is the U.S. Air Force very important person (VIP) version of the 747-200B. The U.S. Air Force operates two of them in VIP configuration as the VC-25A. Tail numbers 28000 and 29000 are popularly known as Air Force One, which is technically the air-traffic call sign for any United States Air Force aircraft carrying the U.S. president.[210] Partially completed aircraft from Everett, Washington, were flown to Wichita, Kansas, for final outfitting by Boeing Military Airplane Company.[211] Two new aircraft, based around the 747-8, are being procured which will be designated as VC-25B.[212]

- E-4B – This is an airborne command post designed for use in nuclear war. Three E-4As, based on the 747-200B, with a fourth aircraft, with more powerful engines and upgraded systems delivered in 1979 as an E-4B, with the three E-4As upgraded to this standard.[213][214] Formerly known as the National Emergency Airborne Command Post (referred to colloquially as "Kneecap"), this type is now referred to as the National Airborne Operations Center (NAOC).[214][215]

- Survivable Airborne Operations Center - In April 2024, Sierra Nevada Corporation was awarded a contract to develop and build the Survivable Airborne Operations Center aircraft to replace the Boeing E-4 NAOC. Five 747-8Is were purchased from Korean Air for conversion, with the contract calling for nine in total.[216][217]

- YAL-1 – This was the experimental Airborne Laser, a planned component of the U.S. National Missile Defense.[218]

- Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) – Two 747s were modified to carry the Space Shuttle orbiter. The first was a 747-100 (N905NA), and the other was a 747-100SR (N911NA). The first SCA carried the prototype Enterprise during the Approach and Landing Tests in the late 1970s. The two SCA later carried all five operational Space Shuttle orbiters.[219]

- C-33 – This aircraft was a proposed U.S. military version of the 747-400F intended to augment the C-17 fleet. The plan was canceled in favor of additional C-17s.[220]

- KC-25/33 – A proposed 747-200F was also adapted as an aerial refueling tanker and was bid against the DC-10-30 during the 1970s Advanced Cargo Transport Aircraft (ACTA) program that produced the KC-10 Extender. Before the 1979 Iranian Revolution, Iran bought four 747-100 aircraft with air-refueling boom conversions to support its fleet of F-4 Phantoms.[221] There is a report of the Iranians using a 747 Tanker in H-3 airstrike during Iran–Iraq War.[222] It is unknown whether these aircraft remain usable as tankers. Since then there have been proposals to use a 747-400 for that role.[223]

- 747F Airlifter – Proposed US military transport version of the 747-200F intended as an alternative to further purchases of the C-5 Galaxy. This 747 would have had a special nose jack to lower the sill height for the nose door. System tested in 1980 on a Flying Tiger Line 747-200F.[224]

- 747 CMCA – This "Cruise Missile Carrier Aircraft" variant was considered by the U.S. Air Force during the development of the B-1 Lancer strategic bomber. It would have been equipped with 50 to 100 AGM-86 ALCM cruise missiles on rotary launchers. This plan was abandoned in favor of more conventional strategic bombers.[225]

- MC-747 – Two separate studies from the 1970s and 2005, the first by Boeing and the second by ATK and BAE Systems, to horizontally store up to four Peacekeeper ICBMs or seven Minutemen above bomb bay-like doors in the first study,[226][227] and to vertically store twelve Minutemen or 32 JDAM-equipped conventional missiles for launch from in situ tubes in the second.[228][229]

- 747 AAC – A Boeing study under contract from the USAF for an "airborne aircraft carrier" for up to 10 Boeing Model 985-121 "microfighters" with the ability to launch, retrieve, re-arm, and refuel. Boeing believed that the scheme would be able to deliver a flexible and fast carrier platform with global reach, particularly where other bases were not available. Modified versions of the 747-200 and Lockheed C-5A were considered as the base aircraft. The concept, which included a complementary 747 AWACS version with two reconnaissance "microfighters", was considered technically feasible in 1973.[230]

- Evergreen 747 Supertanker – A Boeing 747-200 modified as an aerial application platform for fire fighting using 20,000 US gallons (76,000 L) of firefighting chemicals.[231]

- Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) – A former Pan Am Boeing 747SP modified to carry a large infrared-sensitive telescope, in a joint venture of NASA and DLR. High altitudes are needed for infrared astronomy, to rise above infrared-absorbing water vapor in the atmosphere.[232][233]

- A number of other governments also use the 747 as a VIP transport, including Bahrain, Brunei, India, Iran, Japan, Kuwait, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates. Several Boeing 747-8s have been ordered by Boeing Business Jet for conversion to VIP transports for several unidentified customers.[234]

Proposed variants

[edit]Boeing has studied a number of 747 variants that have not gone beyond the concept stage.

747 trijet

[edit]During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Boeing studied the development of a shorter 747 with three engines, to compete with the smaller Lockheed L-1011 TriStar and McDonnell Douglas DC-10. The center engine would have been fitted in the tail with an S-duct intake similar to the L-1011's. Overall, the 747 trijet would have had more payload, range, and passenger capacity than both of them. However, engineering studies showed that a major redesign of the 747 wing would be necessary. Maintaining the same 747 handling characteristics would be important to minimize pilot retraining. Boeing decided instead to pursue a shortened four-engine 747, resulting in the 747SP.[235]

747-500

[edit]In January 1986, Boeing outlined preliminary studies to build a larger, ultra-long haul version named the 747-500, which would enter service in the mid- to late-1990s. The aircraft derivative would use engines evolved from unducted fan (UDF) (propfan) technology by General Electric, but the engines would have shrouds, sport a bypass ratio of 15–20, and have a propfan diameter of 10–12 feet (3.0–3.7 m).[236] The aircraft would be stretched (including the upper deck section) to a capacity of 500 seats, have a new wing to reduce drag, cruise at a faster speed to reduce flight times, and have a range of at least 8,700 nmi; 16,000 km, which would allow airlines to fly nonstop between London, England and Sydney, Australia.[237]

747 ASB

[edit]Boeing announced the 747 ASB (Advanced Short Body) in 1986 as a response to the Airbus A340 and the McDonnell Douglas MD-11. This aircraft design would have combined the advanced technology used on the 747-400 with the foreshortened 747SP fuselage. The aircraft was to carry 295 passengers over a range of 8,000 nmi (15,000 km; 9,200 mi).[238] However, airlines were not interested in the project and it was canceled in 1988 in favor of the 777.

747-500X, -600X, and -700X

[edit]

Boeing announced the 747-500X and -600X at the 1996 Farnborough Airshow.[79] The proposed models would have combined the 747's fuselage with a new wing spanning 251 feet (77 m) derived from the 777. Other changes included adding more powerful engines and increasing the number of tires from two to four on the nose landing gear and from 16 to 20 on the main landing gear.[239]

The 747-500X concept featured a fuselage length increased by 18 feet (5.5 m) to 250 feet (76 m), and the aircraft was to carry 462 passengers over a range up to 8,700 nautical miles (16,100 km; 10,000 mi), with a gross weight of over 1.0 Mlb (450 tonnes).[239] The 747-600X concept featured a greater stretch to 279 feet (85 m) with seating for 548 passengers, a range of up to 7,700 nmi (14,300 km; 8,900 mi), and a gross weight of 1.2 Mlb (540 tonnes).[239] A third study concept, the 747-700X, would have combined the wing of the 747-600X with a widened fuselage, allowing it to carry 650 passengers over the same range as a 747-400.[79] The cost of the changes from previous 747 models, in particular the new wing for the 747-500X and -600X, was estimated to be more than US$5 billion.[79] Boeing was not able to attract enough interest to launch the aircraft.[80]

747X and 747X Stretch

[edit]As Airbus progressed with its A3XX study, Boeing offered a 747 derivative as an alternative in 2000; a more modest proposal than the previous -500X and -600X that retained the 747's overall wing design and add a segment at the root, increasing the span to 229 ft (69.8 m).[240] Power would have been supplied by either the Engine Alliance GP7172 or the Rolls-Royce Trent 600, which were also proposed for the 767-400ERX.[241] A new flight deck based on the 777's would be used. The 747X aircraft was to carry 430 passengers over ranges of up to 8,700 nmi (16,100 km; 10,000 mi). The 747X Stretch would be extended to 263 ft (80.2 m) long, allowing it to carry 500 passengers over ranges of up to 7,800 nmi (14,400 km; 9,000 mi).[240] Both would feature an interior based on the 777.[242] Freighter versions of the 747X and 747X Stretch were also studied.[243]

Like its predecessor, the 747X family was unable to garner enough interest to justify production, and it was shelved along with the 767-400ERX in March 2001, when Boeing announced the Sonic Cruiser concept.[81] Though the 747X design was less costly than the 747-500X and -600X, it was criticized for not offering a sufficient advance from the existing 747-400. The 747X did not make it beyond the drawing board, but the 747-400X being developed concurrently moved into production to become the 747-400ER.[244]

747-400XQLR

[edit]After the end of the 747X program, Boeing continued to study improvements that could be made to the 747. The 747-400XQLR (Quiet Long Range) was meant to have an increased range of 7,980 nmi (14,780 km; 9,180 mi), with improvements to boost efficiency and reduce noise.[245][246] Improvements studied included raked wingtips similar to those used on the 767-400ER and a sawtooth engine nacelle for noise reduction.[247] Although the 747-400XQLR did not move to production, many of its features were used for the 747 Advanced, which was launched as the 747-8 in 2005.[248]

Operators

[edit]In 1979, Qantas became the first airline in the world to operate an all Boeing 747 fleet, with seventeen aircraft.[249]

As of July 2019[update], there were 462 Boeing 747s in airline service, with Atlas Air and British Airways being the largest operators with 33 747-400s each.[250]

The last US passenger Boeing 747 was retired from Delta Air Lines in December 2017. The model flew for almost every American major carrier since its 1970 introduction.[251] Delta flew three of its last four aircraft on a farewell tour, from Seattle to Atlanta on December 19 then to Los Angeles and Minneapolis/St Paul on December 20.[252]

As the IATA forecast an increase in air freight from 4% to 5% in 2018 fueled by booming trade for time-sensitive goods, from smartphones to fresh flowers, demand for freighters is strong while passenger 747s are phased out. Of the 1,544 produced, 890 are retired; as of 2018[update], a small subset of those which were intended to be parted-out got $3 million D-checks before flying again. Young -400s were sold for 320 million yuan ($50 million) and Boeing stopped converting freighters, which used to cost nearly $30 million. This comeback helped the airframer financing arm Boeing Capital to shrink its exposure to the 747-8 from $1.07 billion in 2017 to $481 million in 2018.[253]

In July 2020, British Airways announced that it was retiring its 747 fleet.[254][255] The final British Airways 747 flights departed London Heathrow on October 8, 2020.[256][257]

Orders and deliveries

[edit]| Year | Total | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orders | 1,573 | – | – | 5 | 1 | – | 13 | 6 | 18 | 6 | 2 | 13 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 16 | 53 |

| Deliveries | 1,573 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 14 | 9 | 18 | 19 | 24 | 31 | 9 | – | 8 | 14 | 16 | 14 |

| Year | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | 1996 | 1995 | 1994 | 1993 | 1992 | 1991 | 1990 | 1989 | 1988 | 1987 | 1986 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orders | 46 | 10 | 4 | 17 | 16 | 26 | 35 | 15 | 36 | 56 | 32 | 16 | 2 | 23 | 31 | 122 | 56 | 49 | 66 | 84 |

| Deliveries | 13 | 15 | 19 | 27 | 31 | 25 | 47 | 53 | 39 | 26 | 25 | 40 | 56 | 61 | 64 | 70 | 45 | 24 | 23 | 35 |

| Year | 1985 | 1984 | 1983 | 1982 | 1981 | 1980 | 1979 | 1978 | 1977 | 1976 | 1975 | 1974 | 1973 | 1972 | 1971 | 1970 | 1969 | 1968 | 1967 | 1966 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orders | 42 | 23 | 24 | 14 | 23 | 49 | 72 | 76 | 42 | 14 | 20 | 29 | 29 | 18 | 7 | 20 | 30 | 22 | 43 | 83 |

| Deliveries | 24 | 16 | 22 | 26 | 53 | 73 | 67 | 32 | 20 | 27 | 21 | 22 | 30 | 30 | 69 | 92 | 4 | – | – | – |

Boeing 747 orders and deliveries (cumulative, by year):

Orders

Deliveries

Orders and deliveries through to the end of February 2023.

Model summary

[edit]| Model Series | ICAO code[131] | Deliveries | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 747-100 | B741 / BSCA[a] | 167 | 205 |

| 747-100B | 9 | ||

| 747-100SR | B74R | 29 | |

| 747SP | B74S | 45 | 45 |

| 747-200B | B742[b] | 225 | 393 |

| 747-200C | 13 | ||

| 747-200F | 73 | ||

| 747-200M | 78 | ||

| 747 E-4A | 3 | ||

| 747-E4B | 1 | ||

| 747-300 | B743 | 56 | 81 |

| 747-300M | 21 | ||

| 747-300SR | 4 | ||

| 747-400 | B744 / BLCF[c] | 442 | 694 |

| 747-400ER | 6 | ||

| 747-400ERF | 40 | ||

| 747-400F | 126 | ||

| 747-400M | 61 | ||

| 747-400D | B74D | 19 | |

| 747-8I | B748 | 48 | 155 |

| 747-8F | 107 | ||

| 747 Total | 1,573 | ||

- ^ BSCA refers to 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, used by NASA.

- ^ B742 includes the VC-25, two 747-200Bs modified for the U.S. Air Force.

- ^ BLCF refers to the 747-400LCF Dreamlifter, used to transport components for the Boeing 787 Dreamliner program.

Orders and deliveries through to the end of February 2023.

Accidents and incidents

[edit]As of November 2023[update], the 747 has been involved in 173 aviation accidents and incidents,[258] including 64 hull losses (52 in-flight accidents),[259] causing 3,746 fatalities.[260] There have been several hijackings of Boeing 747s, such as Pan Am Flight 73, a 747-100 hijacked by four terrorists, causing 20 deaths.[261] The 747 also fell victim to three mid-air bombings, two of which resulted in fatalities and hull losses, Air India Flight 182 in 1985, and Pan Am Flight 103 in 1988.[262][263][264]

Few crashes have been attributed to 747 design flaws. The Tenerife airport disaster resulted from pilot error and communications failure, while the Japan Air Lines Flight 123 and China Airlines Flight 611 crashes stemmed from improper aircraft repair due to a tailstrike. The fatal crash of Korean Air Flight 801, a 747-300 was caused due to pilot fatigue and Korean Airlines overworking their pilots. United Airlines Flight 811, which suffered an explosive decompression mid-flight on February 24, 1989, led the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) to issue a recommendation that the Boeing 747-100 and 747-200 cargo doors similar to those on the Flight 811 aircraft be modified to those featured on the Boeing 747-400. Korean Air Lines Flight 007 was shot down by a Soviet fighter aircraft in 1983 after it had strayed into Soviet territory, causing US President Ronald Reagan to authorize the then-strictly-military global positioning system (GPS) for civilian use.[265] South African Airways Flight 295, a 747-200M Combi, which crashed on 28 November 1987 due to an inflight fire, led to the mandate of adding fire-suppression systems on board Combi variants.[266][267]

The lack of adequate warning systems combined with flight crew error led to a preventable crash of Lufthansa Flight 540 in November 1974, which was the first fatal crash of a 747,[268][269] while an instrument malfunction leading to lack of situational awareness led to the crash of Air India Flight 855 on New Years Day in 1978.[270][271] A series of design deficiencies caused the destruction of TWA Flight 800, where a 747-100 exploded in mid-air on July 17, 1996, probably due to sparking electrical wires inside the fuel tank.[272] This finding led the FAA to adopt a rule in July 2008 requiring installation of an inerting system in the center fuel tank of most large aircraft, after years of research into solutions. At the time, the new safety system was expected to cost US$100,000 to $450,000 per aircraft and weigh approximately 200 pounds (91 kg).[273] Two 747-200F freighters - China Airlines Flight 358 in December 1991 and El Al Flight 1862 in October 1992, crashed after the fuse pins for an engine(no. 3) broke off shortly after take-off due to metal fatigue, and instead of simply dropping away from the wing, the engine knocked off the adjacent engine and damaged the wing.[274] Following these crashes, Boeing issued a directive to examine and replace all fuse pins found to be cracked.

Other incidents did not result in any hull losses, but the planes suffered certain damages and were put back into service after repair. On July 30, 1971, Pan Am Flight 845 struck approach lighting system structures while taking off from San Francisco for Tokyo, Japan; the plane dumped fuel and landed back. The cause was pilot error with improper calculations, and the plane was repaired and returned to service.[275] On June 24, 1982, British Airways Flight 9, a Boeing 747-200, registration G-BDXH, flew through a cloud of volcanic ash and dust from the eruption of Mount Galunggung, suffering an all engine flameout; the crew restarted the engines and successfully landed at Jakarta. The volcanic ash caused windscreens to be sandblasted along with engine damage and paint rip-off; the plane was repaired with engines replaced and returned to service.[276] On December 11, 1994, on board Philippine Airlines Flight 434 from Manila to Tokyo via Cebu, a bomb exploded under a seat, killing one passenger; the plane landed safely at Okinawa despite damage to the plane's controls. The bomber, Ramzi Yousef, was caught on 7 February 1995 in Islamabad, Pakistan, and the plane was repaired, but converted for cargo use.[277]

Preserved aircraft

[edit]Aircraft on display

[edit]

As increasing numbers of "classic" 747-100 and 747-200 series aircraft have been retired, some have been used for other uses such as museum displays. Some older 747-300s and 747-400s were later added to museum collections.

- 20235/001 – 747-121 registration N7470 City of Everett, the first 747 and prototype, is at the Museum of Flight, Seattle, Washington.[278]

- 19651/025 – 747-121 registration N747GE at the Pima Air & Space Museum, Tucson, Arizona, US.[279]

- 19778/027 – 747-151 registration N601US nose at the National Air and Space Museum, Washington, D.C.[280]

- 19661/070 – 747-121(SF) registration N681UP preserved at a plaza on Jungong Road, Shanghai, China.[citation needed]

- 19896/072 – 747-132(SF) registration N481EV at the Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum, McMinnville, Oregon, US.[281][282]

- 20107/086 – 747-123 registration N905NA, a NASA Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, at the Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas, US.[283][284]

- 20269/150 – 747-136 registration G-AWNG nose at Hiller Aviation Museum, San Carlos, California.[285]

- 20239/160 – 747-244B registration ZS-SAN nicknamed Lebombo, at the South African Airways Museum Society, Rand Airport, Johannesburg, South Africa.[286]

- 20541/200 – 747-128 registration F-BPVJ at Musée de l'Air et de l'Espace, Paris, France.[287]

- 20770/213 – 747-2B5B registration HL7463 at Jeongseok Aviation Center, Jeju, South Korea.[288]

- 20713/219 - 747-212B(SF) registration N482EV at the Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum, McMinnville, Oregon, US.[citation needed]

- 20825/223 - 747-200 registration SX-OAB at the site of Ellinikon International Airport, Athens, Greece. After over 20 years sitting at the closed airport, it was moved to a permanent location within the boundaries of the airport and put on display as part of the ongoing regeneration work.[289]

- 21134/288 – 747SP-44 registration ZS-SPC at the South African Airways Museum Society, Rand Airport, Johannesburg, South Africa.[290]

- 21549/336 – 747-206B registration PH-BUK at the Aviodrome, Lelystad, Netherlands.[291]

- 21588/342 – 747-230B(M) registration D-ABYM preserved at Technik Museum Speyer, Germany.[citation needed]

- 21650/354 – 747-2R7F/SCD registration G-MKGA preserved at Cotswold Airport, UK as an event space.[292]

- 22145/410 – 747-238B registration VH-EBQ at the Qantas Founders Outback Museum, Longreach, Queensland, Australia.[293]

- 22455/515 – 747-256BM registration EC-DLD Lope de Vega nose at the National Museum of Science and Technology, A Coruña, Spain.

- 23223/606 – 747-338 registration VH-EBU at Melbourne Avalon Airport, Avalon, Victoria, Australia. VH-EBU is an ex-Qantas airframe formerly decorated in the Nalanji Dreaming livery, currently in use as a training aircraft and film set.[294][295]

- 23719/696 – 747-451 registration N661US at the Delta Flight Museum, Atlanta, Georgia, US. This particular plane was the first 747-400 in service, as well as the prototype.[296]

- 24354/731 – 747-438 registration VH-OJA at Shellharbour Airport, Albion Park Rail, New South Wales, Australia.[297]

- 21441/306 - SOFIA - 747SP-21 registration N747NA at Pima Air and Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona, US. Former Pan Am and United Airlines 747SP bought by NASA and converted into a flying telescope, for astronomy purposes. Named Clipper Lindbergh.[298][299]

Other uses

[edit]

Upon its retirement from service, the 747 which was number two in the production line was dismantled and shipped to Hopyeong, Namyangju, Gyeonggi-do, South Korea where it was re-assembled, repainted in a livery similar to that of Air Force One and converted into a restaurant. Originally flown commercially by Pan Am as N747PA, Clipper Juan T. Trippe, and repaired for service following a tailstrike, it stayed with the airline until its bankruptcy. The restaurant closed by 2009,[300] and the aircraft was scrapped in 2010.[301]

A former British Airways 747-200B, G-BDXJ,[302] is parked at the Dunsfold Aerodrome in Surrey, England and has been used as a movie set for productions such as the 2006 James Bond film, Casino Royale.[303] The airplane also appears frequently in the television series Top Gear, which is filmed at Dunsfold.

The Jumbo Stay hostel, using a converted 747-200 formerly registered as 9V-SQE, opened at Arlanda Airport, Stockholm in January 2009.[304][305]

A former Pakistan International Airlines 747-300 was converted into a restaurant by Pakistan's Airports Security Force in 2017.[306] It is located at Jinnah International Airport, Karachi.[307]

The wings of a 747 have been repurposed as roofs of a house in Malibu, California.[308][309][310][311]

In 2023, a 747-200B originally operated by Lufthansa as a combi aircraft bearing the registration D-ABYW and named Berlin, and later by Lufthansa Cargo and other airlines as a full freighter, was opened as a Coach outlet store at Freeport A'Famosa Outlet Mall in Malacca, Malaysia.[citation needed]

Specifications

[edit]

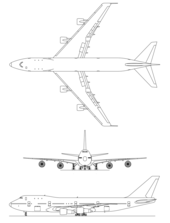

At the top: 747-100 (dorsal, cross-section, and front views). Side views, in descending order: 747SP, 747-100, 747-400, 747-8I, and 747LCF.

| Модель | 747СП [ 312 ] | 747-100 [ 312 ] | 747-200Б [ 312 ] | 747-300 [ 312 ] | 747-400 [ 313 ] | 747-8 [ 314 ] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Экипаж кабины | Трое (капитан, первый помощник, бортинженер ) | Два (капитан, первый помощник) | ||||

| Типичные сиденья | 276 (25F, 57J, 194Y) | 366 (32F, 74J, 260Y) | 400 (34F, 76J, 290Y) | 416 (23F, 78J, 315Y) | 467 (24F, 87J, 356Y) | |

| Лимит выхода [ а ] [ 315 ] | 400 | 440/550 | 550/660 | 495/605 | ||

| Груз | 3900 куб футов (110 м 3 ) | 6190 куб футов (175 м 3 ), 30× LD1 | 5655 куб футов (160,1 м 3 ) | 6345 куб футов (179,7 м 3 ) | ||

| Длина | 184 футов 9 дюймов (56,3 м) | 231 футов 10 дюймов (70,7 м) | 250 футов 2 дюйма (76,25 м) | |||

| Ширина кабины | 239,5 дюйма (6,08 м) [ 313 ] | |||||

| Размах крыльев | 195 футов 8 дюймов (59,6 м) | 211 футов 5 дюймов (64,4 м) | 224 фута 7 дюймов (68,5 м) | |||

| Площадь крыла | 5500 кв. футов (511 м 2 ) 2 ) | 5650 кв. футов (525 м ) 2 ) [ 316 ] | 5960 кв. футов (554 м 2 ) 2 ) [ 317 ] | |||

| Стреловидность крыла | 37.5° [ 318 ] [ 319 ] [ 320 ] | |||||

| Соотношение сторон | 7 | 7.9 | 8.5 | |||

| Высота хвоста | 65 футов 5 дюймов (19,9 м) | 63 фута 5 дюймов (19,3 м) | 63 фута 8 дюймов (19,4 м) | 63 фута 6 дюймов (19,4 м) | ||

| МВВ [ 321 ] | 630 000–696 000 фунтов (285,8–315,7 т) |

735 000–750 000 фунтов (333,4–340,2 т) |

775 000–833 000 фунтов (351,5–377,8 т) |

875 000–910 000 фунтов (396,9–412,8 т) [ 322 ] |

975 000–987 000 фунтов 442,3–447,7 т | |

| ОЙ [ 321 ] | 325 660–336 870 фунтов (147,72–152,80 т) |

358 000–381 480 фунтов (162,39–173,04 т) |

376 170–388 010 фунтов (170,63–176,00 т) |

384 240–402 700 фунтов (174,29–182,66 т) |

394 088–412 300 фунтов (178,755–187,016 т) |

485 300 фунтов (220,1 т) |

| Топливо емкость [ 321 ] |

48 780–50 360 галлонов США (184 700–190 600 л) |

47 210–48 445 галлонов США (178 710–183 380 л) |

52 035–52 410 галлонов США (196 970–198 390 л) |

53 985–63 705 галлонов США (204 360–241 150 л) |

63 034 галлона США (238 610 л) | |

| ТРДД (×4) | Pratt & Whitney JT9D или Rolls-Royce RB211 или General Electric CF6 | PW4000 / CF6 / RB211 | ГЭнкс-2B67 | |||

| Упор (×4) | 46 300–54 750 фунтов силы (206,0–243,5 кН) |

43 500–51 600 фунтов силы (193–230 кН) |

46 300–54 750 фунтов силы (206,0–243,5 кН) |

46 300–56 900 фунтов силы (206–253 кН) |

56 750–63 300 фунтов силы (252,4–281,6 кН) |

66 500 фунтов силы (296 кН) |

| ММо [ 315 ] | 0,92 Маха | 0,9 Маха | ||||

| Крейсерская скорость | эконом. 907 км/ч (490 узлов; 564 миль в час), макс. 939 км / ч (507 узлов; 583 миль в час) [ 323 ] [ 324 ] | 0,855 Маха (504 узла; 933 км/ч; 580 миль в час) | ||||

| Диапазон | 5830 миль (10800 км; 6710 миль) [ б ] |

4620 миль (8560 км; 5320 миль) [ с ] |

6560 миль (12 150 км; 7 550 миль) [ с ] |

6330 миль (11720 км; 7280 миль) [ д ] |

7285–7670 морских миль (13 492–14 205 км; 8 383–8 826 миль) [ и ] |

7730 миль (14320 км; 8900 миль) [ ж ] [ 325 ] |

| Снимать | 9250 футов (2820 м) | 10 650 футов (3250 м) | 10 900 футов (3300 м) | 10 900 футов (3300 м) | 10700 футов (3300 м) | 10 200 футов (3100 м) |

Культурное влияние

[ редактировать ]

После своего дебюта Боинг 747 быстро приобрел культовый статус. Самолет вошел в культурный лексикон как оригинальный Jumbo Jet — термин, придуманный авиационными СМИ для описания его размера. [ 326 ] а также получила прозвище Королева Небес . [ 327 ] Летчик-испытатель Дэвид П. Дэвис охарактеризовал его как «самый впечатляющий самолет с рядом исключительно хороших качеств». [ 328 ] : 249 и похвалил его систему управления полетом как «поистине выдающуюся» из-за ее дублирования. [ 328 ] : 256

Снявшись более чем в 300 фильмах, [ 329 ] Боинг 747 — один из наиболее широко изображаемых гражданских самолетов, и многие считают его одним из самых знаковых в истории кино. [ 330 ] Он появлялся в таких фильмах, как фильмы-катастрофы «Аэропорт 1975» и «Аэропорт 77» , а также в фильмах «Воздушный силы один» , «Крепкий орешек 2» и «Решение руководителя» . [ 331 ] [ 332 ]

Супервспышка 1974 года , одна из самых интенсивных вспышек торнадо в зарегистрированной истории, первоначально была названа Тедом Фудзитой «гигантской» вспышкой торнадо из-за даты ее возникновения (4 марта 1974 года), что добавляло день к дате ее возникновения. месяц может привести к номеру модели 747 «гигантского реактивного самолета». [ важность? ] [ 333 ]

См. также

[ редактировать ]Связанные разработки

Связанные списки

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Нортон 2003, стр. 5–12.

- ^ Модель Boeing CX-HLS , Корпоративный архив Boeing, 1963/64.

Модели Boeing C-5A и Lockheed (корейские); следующая страница . - ^ «Lockheed C-5 Galaxy, партнеры по свободе». Архивировано 14 декабря 2007 года в Wayback Machine NASA , 2000 год, см. изображения в «Вкладе Лэнгли в C-5». Проверено: 17 декабря 2007 г.

- ^ Дженкинс 2000, стр. 12–13.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Норрис и Вагнер 1997, с. 13.

- ^ «Галерея мультимедийных изображений Boeing 707» . Компания Боинг. Архивировано из оригинала 11 января 2012 года . Проверено 8 декабря 2007 г.

- ^ Брэнсон, Ричард (7 декабря 1998 г.). «Пилот эпохи реактивных самолетов» . Время . Архивировано из оригинала 11 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 11 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ «Новаторы: Хуан Триппе» . В погоне за Солнцем . ПБС. Архивировано из оригинала 8 мая 2006 года.

- ^ Саттер 2006, стр. 80–84.

- ^ «Авиаперелеты, сверхзвуковое будущее?» BBC News , 17 июля 2001 г. Дата обращения: 9 декабря 2007 г.

- ^ Слуцкен, Ховард (7 ноября 2017 г.). «Как гигантский реактивный самолет Boeing 747 изменил путешествия» . CNN . Проверено 8 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ «Заказан лайнер на 490 мест» . Льюистон Морнинг Трибьюн . Айдахо. Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 14 апреля 1966 г. с. 1.

- ^ «Pan Am заказывает гигантские самолеты» . Новости Дезерета . Солт-Лейк-Сити, Юта. УПИ. 14 апреля 1966 г. с. А1.

- ^ Саймонс, Грэм (2014). Airbus A380: история . Перо и меч. п. 31. ISBN 978-1-78303-041-5 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Румерман, Джуди. «Боинг 747». Комиссия по столетию полетов США, 2003 г. Дата обращения: 30 апреля 2006 г.