Флорида

Флорида | |

|---|---|

| Прозвище : | |

| Девиз : | |

| Гимн: « Флорида » (гимн штата), « Старики дома » (песня штата). | |

Карта Соединенных Штатов с выделенной Флоридой | |

| Страна | Соединенные Штаты |

| До государственности | Территория Флориды |

| Принят в Союз | 3 марта 1845 г ) |

| Капитал | Таллахасси |

| Крупнейший город | Джексонвилл |

| Самый большой округ или его эквивалент | Майами-Дейд |

| Крупнейшие метро и городские районы | Южная Флорида |

| Правительство | |

| • Губернатор | Рон ДеСантис ( R ) |

| • Вице-губернатор | Жанетт Нуньес (справа) |

| Законодательная власть | Законодательное собрание Флориды |

| • Верхняя палата | Сенат |

| • Нижняя палата | Палата представителей |

| судебная власть | Верховный суд Флориды |

| Сенаторы США | Марко Рубио (R) Рик Скотт (справа) |

| Делегация Палаты представителей США | 20 республиканцев 8 демократов ( список ) |

| Область | |

| • Общий | 65,758 [5] квадратных миль (170 312 км²) 2 ) |

| • Земля | 53 625 квадратных миль (138 887 км ) 2 ) |

| • Вода | 12 133 квадратных миль (31 424 км ) 2 ) 18.5% |

| • Классифицировать | 22-е |

| Размеры | |

| • Длина | 447 миль (721 км) |

| • Ширина | 361 миль (582 км) |

| Высота | 100 футов (30 м) |

| Самая высокая точка | 345 футов (105 м) |

| Самая низкая высота (Атлантический океан [6] ) | 0 футов (0 м) |

| Население (2023) | |

| • Общий | |

| • Классифицировать | 3-й |

| • Плотность | 414,8/кв. миль (160/км) 2 ) |

| • Классифицировать | 7-е место |

| • Средний доход домохозяйства | $57,700 [8] |

| • Рейтинг дохода | 34-е |

| Демон(ы) | Флоридиан из Флориды |

| Язык | |

| • Официальный язык | Английский [9] |

| • Разговорный язык |

|

| Часовые пояса | |

| Полуостров и Биг-Бенд . регион | UTC−05:00 ( восточное время ) |

| • Лето ( летнее время ) | UTC-04:00 ( ВОСТОЧНОЕ ВРЕМЯ ) |

| Панхандл к западу от реки Апалачикола | UTC−06:00 ( центральное время ) |

| • Лето ( летнее время ) | UTC−05:00 ( CDT ) |

| Аббревиатура USPS | Флорида |

| Код ISO 3166 | США-Флорида |

| Традиционная аббревиатура | Флорида. |

| Широта | От 24°27' с.ш. до 31°00' с.ш. |

| Долгота | От 80°02' з.д. до 87°38' з.д. |

| Веб-сайт | в мифлоре |

Флорида ( / ˈ f l ɒr ɪ d ə / FLORR -ih-də ) — штат в юго-восточном регионе США . Он граничит с Мексиканским заливом на западе, Алабамой на северо-западе, Джорджией на севере, Атлантическим океаном на востоке и Флоридским проливом и Кубой на юге. Около двух третей Флориды занимает полуостров между Мексиканским заливом и Атлантическим океаном . Он имеет самую длинную береговую линию в сопредельных Соединенных Штатах , простирающуюся примерно на 1350 миль (2170 км), не считая многочисленных барьерных островов . Это единственное государство, которое граничит одновременно с Мексиканским заливом и Атлантическим океаном. С населением более 21 миллиона человек это третий по численности населения штат в Соединенных Штатах и восьмое место по плотности населения по состоянию на 2020 год. Флорида занимает площадь 65 758 квадратных миль (170 310 км²). 2 ), занимая 22-е место по площади среди штатов. Агломерация Майами , окруженная городами Майами , Форт-Лодердейл и Уэст-Палм-Бич штата , является крупнейшей агломерацией с населением 6,138 миллиона человек; самый густонаселенный город — Джексонвилл . Другие крупные населенные пункты Флориды включают Тампа-Бэй , Орландо , Кейп-Корал и столицу штата Таллахасси .

Различные племена американских индейцев населяли Флориду не менее 14 000 лет. В 1513 году испанский исследователь Хуан Понсе де Леон стал первым известным европейцем, вышедшим на берег, назвав этот регион Ла Флоридой (страной цветов) ( [la floˈɾiða] ). Впоследствии Флорида стала первой территорией в континентальной части США, где на постоянной основе заселились европейцы, а поселение Сент-Огастин , основанное в 1565 году, было старейшим постоянно населенным городом. Флорида была испанской территорией, на которую Великобритания часто нападала и которую желала, прежде чем Испания уступила ее США в 1819 году в обмен на разрешение пограничного спора вдоль реки Сабина в испанском Техасе . Флорида была признана 27-м штатом 3 марта 1845 года и была основным местом проведения семинольских войн (1816–1858), самой продолжительной и масштабной из войн с американскими индейцами . Штат вышел из Союза 10 января 1861 года, став одним из семи первоначальных Конфедеративных штатов , и был вновь принят в состав Союза после Гражданской войны 25 июня 1868 года.

С середины 20 века во Флориде наблюдается быстрый демографический и экономический рост. Его экономика с валовым государственным продуктом (ВСП) в размере 1,647 триллиона долларов США является четвертой по величине среди всех штатов США и 15-й по величине в мире; Основными секторами являются туризм , гостиничный бизнес , сельское хозяйство , недвижимость и транспорт . Флорида всемирно известна своими пляжными курортами , парками развлечений , теплым и солнечным климатом и морским отдыхом; такие достопримечательности, как Мир Уолта Диснея , Космический центр Кеннеди и Майами-Бич, ежегодно привлекают десятки миллионов посетителей. Флорида — популярное место среди пенсионеров , сезонных отдыхающих , а также внутренних и международных мигрантов; здесь расположены девять из десяти наиболее быстро растущих сообществ США. Непосредственная близость штата к океану сформировала его культуру , самобытность и повседневную жизнь; его колониальная история и последовательные волны миграции отражены в африканском , европейском , коренном , латиноамериканском и азиатском влияниях. Флорида привлекла или вдохновила некоторых из самых выдающихся американских писателей, в том числе Эрнест Хемингуэй , Марджори Киннан Роулингс и Теннесси Уильямс продолжают привлекать знаменитостей и спортсменов, особенно в гольф , теннис , автогонки и водные виды спорта . Флорида считалась штатом поля битвы на президентских выборах в США , особенно в 2000 и 2016 годах .

Климат Флориды варьируется от субтропического на севере до тропического на юге. Это единственный штат, помимо Гавайев, с тропическим климатом , и единственный континентальный штат с тропическим климатом, расположенный в южной части штата, и коралловым рифом . Флорида имеет несколько уникальных экосистем, в том числе национальный парк Эверглейдс , крупнейшую тропическую дикую природу в США и одну из крупнейших в Америке . Уникальная дикая природа включает американского аллигатора , американского крокодила , американского фламинго , розовую колпицу , флоридскую пантеру , афалину и ламантина . Флоридский риф — единственный живой коралловый барьерный риф в континентальной части США и третья по величине система коралловых барьерных рифов в мире после Большого Барьерного рифа и Белизского барьерного рифа .

История

Палеоиндейцы пришли во Флориду по крайней мере 14 000 лет назад. [12] К 16 веку, самому раннему времени, о котором имеются исторические записи, основные группы людей, живших во Флориде, включали Апалачи Флоридского Панхандла , Тимукуа северной и центральной Флориды, Айс центрального Атлантического побережья и Калуса. юго-западной Флориды. [13]

Европейское прибытие

Florida was the first region of what is now the contiguous United States to be visited and settled by Europeans. The earliest known European explorers came with Juan Ponce de León. Ponce de León spotted and landed on the peninsula on April 2, 1513. He named it La Florida in recognition of the flowery, verdant landscape and because it was the Easter season, which the Spaniards called Pascua Florida (Festival of Flowers). The following day they came ashore to seek information and take possession of this new land.[14][15] The story that he was searching for the Fountain of Youth is mythical and appeared only long after his death.[16]

In May 1539, Hernando de Soto skirted the coast of Florida, searching for a deep harbor to land. He described a thick wall of red mangroves spread mile after mile, some reaching as high as 70 feet (21 m), with intertwined and elevated roots making landing difficult.[17] The Spanish introduced Christianity, cattle, horses, sheep, the Castilian language, and more to Florida.[18] Spain established several settlements in Florida, with varying degrees of success. In 1559, Don Tristán de Luna y Arellano established a settlement at present-day Pensacola, making it one of the firsts settlements in Florida, but it was mostly abandoned by 1561.

In 1564–1565, there was a French settlement at Fort Caroline, in present Duval County, which was destroyed by the Spanish.[19] Today a reconstructed version of the fort stands in its location within Jacksonville.

In 1565, the settlement of St. Augustine (San Agustín) was established under the leadership of admiral and governor Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, creating what would become the oldest, continuously occupied European settlements in the continental U.S. and establishing the first generation of Floridanos and the Government of Florida.[20] Spain maintained strategic control over the region by converting the local tribes to Christianity. The marriage between Luisa de Abrego, a free black domestic servant from Seville, and Miguel Rodríguez, a white Segovian, occurred in 1565 in St. Augustine. It is the first recorded Christian marriage in the continental United States.[21]

Some Spanish married or had unions with Pensacola, Creek, or African women, both slave and free, and their descendants created a mixed-race population of mestizos and mulattoes. The Spanish encouraged slaves from the Thirteen Colonies to come to Florida as a refuge, promising freedom in exchange for conversion to Catholicism. King Charles II of Spain issued a royal proclamation freeing all slaves who fled to Spanish Florida and accepted conversion and baptism. Most went to the area around St. Augustine, but escaped slaves also reached Pensacola. St. Augustine had mustered an all-black militia unit defending Spanish Florida as early as 1683.[22]

The geographical area of Spanish claims in La Florida diminished with the establishment of English settlements to the north and French claims to the west. English colonists and buccaneers launched several attacks on St. Augustine in the 17th and 18th centuries, razing the city and its cathedral to the ground several times. Spain built the Castillo de San Marcos in 1672 and Fort Matanzas in 1742 to defend Florida's capital city from attacks, and to maintain its strategic position in the defense of the Captaincy General of Cuba and the Spanish West Indies.

In 1738, the Spanish governor of Florida Manuel de Montiano established Fort Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose near St. Augustine, a fortified town for escaped slaves to whom Montiano granted citizenship and freedom in return for their service in the Florida militia, and which became the first free black settlement legally sanctioned in North America.[23][24]

In 1763, Spain traded Florida to the Kingdom of Great Britain for control of Havana, Cuba, which had been captured by the British during the Seven Years' War. The trade was done as part of the 1763 Treaty of Paris which ended the Seven Years' War. Spain was granted Louisiana from France due to their loss of Florida. A large portion of the Florida population left, taking along large portions of the remaining Indigenous population with them to Cuba.[25] The British soon constructed the King's Road connecting St. Augustine to Georgia. The road crossed the St. Johns River at a narrow point called Wacca Pilatka, now the core of Downtown Jacksonville, and formerly referred to by the British name "Cow Ford", reflecting the fact that cattle were brought across the river there.[26][27][28]

The British divided and consolidated the Florida provinces (Las Floridas) into East Florida and West Florida, a division the Spanish government kept after the brief British period.[29] The British government gave land grants to officers and soldiers who had fought in the French and Indian War in order to encourage settlement. In order to induce settlers to move to Florida, reports of its natural wealth were published in England. A number of British settlers who were described as being "energetic and of good character" moved to Florida, mostly coming from South Carolina, Georgia and England. There was also a group of settlers who came from the colony of Bermuda. This was the first permanent English-speaking population in what is now Duval County, Baker County, St. Johns County and Nassau County. The British constructed good public roads and introduced the cultivation of sugar cane, indigo and fruits, as well as the export of lumber.[30][31]

The British governors were directed to call general assemblies as soon as possible in order to make laws for the Floridas, and in the meantime they were, with the advice of councils, to establish courts. This was the first introduction of the English-derived legal system which Florida still has today, including trial by jury, habeas corpus and county-based government.[30][31] Neither East Florida nor West Florida sent any representatives to Philadelphia to draft the Declaration of Independence. Florida remained a Loyalist stronghold for the duration of the American Revolution.[32]

Spain regained both East and West Florida after Britain's defeat in the Revolutionary War and the subsequent Treaty of Versailles in 1783, and continued the provincial divisions until 1821.[33]

Statehood and Indian removal

Defense of Florida's northern border with the United States was minor during the second Spanish period. The region became a haven for escaped slaves and a base for Indian attacks against U.S. territories, and the U.S. pressed Spain for reform.

Americans of English and Scots Irish descent began moving into northern Florida from the backwoods of Georgia and South Carolina. Though technically not allowed by the Spanish authorities and the Floridan government, they were never able to effectively police the border region and the backwoods settlers from the United States would continue to immigrate into Florida unchecked. These migrants, mixing with the already present British settlers who had remained in Florida since the British period, would be the progenitors of the population known as Florida Crackers.[34]

These American settlers established a permanent foothold in the area and ignored Spanish authorities. The British settlers who had remained also resented Spanish rule, leading to a rebellion in 1810 and the establishment for ninety days of the so-called Free and Independent Republic of West Florida on September 23. After meetings beginning in June, rebels overcame the garrison at Baton Rouge (now in Louisiana) and unfurled the flag of the new republic: a single white star on a blue field. This flag would later become known as the "Bonnie Blue Flag".

In 1810, parts of West Florida were annexed by the proclamation of President James Madison, who claimed the region as part of the Louisiana Purchase. These parts were incorporated into the newly formed Territory of Orleans. The U.S. annexed the Mobile District of West Florida to the Mississippi Territory in 1812. Spain continued to dispute the area, though the United States gradually increased the area it occupied. In 1812, a group of settlers from Georgia, with de facto support from the U.S. federal government, attempted to overthrow the Floridan government in the province of East Florida. The settlers hoped to convince Floridians to join their cause and proclaim independence from Spain, but the settlers lost their tenuous support from the federal government and abandoned their cause by 1813.[35]

Traditionally, historians argued that Seminoles based in East Florida began raiding Georgia settlements and offering havens for runaway slaves. The United States Army led increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish territory, including the 1817–1818 campaign against the Seminole Indians by Andrew Jackson that became known as the First Seminole War. The United States now effectively controlled East Florida. Control was necessary according to Secretary of State John Quincy Adams because Florida had become "a derelict open to the occupancy of every enemy, civilized or savage, of the United States, and serving no other earthly purpose than as a post of annoyance to them."[36]

More recent historians describe that after U.S. independence, settlers in Georgia increased pressure on Seminole lands, and skirmishes near the border led to the First Seminole War (1816–19). The United States purchased Florida from Spain by the Adams-Onis Treaty (1819) and took possession in 1821. The Seminole were moved out of their rich farmland in northern Florida and confined to a large reservation in the interior of the Florida peninsula by the Treaty of Moultrie Creek (1823). Passage of the Indian Removal Act (1830) led to the Treaty of Payne's Landing (1832), which called for the relocation of all Seminole to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma).[37] Some resisted, leading to the Second Seminole War, the bloodiest war against Native Americans in United States history. By 1842, most Seminoles and Black Seminoles, facing starvation, were removed to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. Perhaps fewer than 200 Seminoles remained in Florida after the Third Seminole War (1855–1858), having taken refuge in the Everglades, from where they never surrendered to the US. They fostered a resurgence in traditional customs and a culture of staunch independence.[38]

Florida had become a burden to Spain, which could not afford to send settlers or troops due to the devastation caused by the Peninsular War. Madrid, therefore, decided to cede the territory to the United States through the Adams–Onís Treaty, which took effect in 1821.[39] President James Monroe was authorized on March 3, 1821, to take possession of East Florida and West Florida for the United States and provide for initial governance.[40] On behalf of the U.S. government, Andrew Jackson, whom Jacksonville is named after, served as a military commissioner with the powers of governor of the newly acquired territory for a brief period.[41] On March 30, 1822, the U.S. Congress merged East Florida and part of West Florida into the Florida Territory.[42]

By the early 1800s, Indian removal was a significant issue throughout the southeastern U.S. and also in Florida. In 1830, the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act and as settlement increased, pressure grew on the U.S. government to remove the Indians from Florida. Seminoles offered sanctuary to blacks, and these became known as the Black Seminoles, and clashes between whites and Indians grew with the influx of new settlers. In 1832, the Treaty of Payne's Landing promised to the Seminoles lands west of the Mississippi River if they agreed to leave Florida. Many Seminole left at this time.

Some Seminoles remained, and the U.S. Army arrived in Florida, leading to the Second Seminole War (1835–1842). Following the war, approximately 3,000 Seminole and 800 Black Seminole were removed to Indian Territory. A few hundred Seminole remained in Florida in the Everglades.

On March 3, 1845, only one day before the end of President John Tyler's term in office, Florida became the 27th state,[43] admitted as a slave state and no longer a sanctuary for runaway slaves. Initially its population grew slowly.[44]

As European settlers continued to encroach on Seminole lands, the United States intervened to move the remaining Seminoles to the West. The Third Seminole War (1855–58) resulted in the forced removal of most of the remaining Seminoles, although hundreds of Seminole Indians remained in the Everglades.[45]

The first settlements and towns in South Florida were founded much later than those in the northern part of the state. The first permanent European settlers arrived in the early 19th century. People came from the Bahamas to South Florida and the Keys to hunt for treasure from the ships that ran aground on the treacherous Great Florida Reef. Some accepted Spanish land offers along the Miami River. At about the same time, the Seminole Indians arrived, along with a group of runaway slaves. The area was affected by the Second Seminole War, during which Major William S. Harney led several raids against the Indians. Most non-Indian residents were soldiers stationed at Fort Dallas. It was the most devastating Indian war in American history, causing almost a total loss of population in Miami.

After the Second Seminole War ended in 1842, William English re-established a plantation started by his uncle on the Miami River. He charted the "Village of Miami" on the south bank of the Miami River and sold several plots of land. In 1844, Miami became the county seat, and six years later a census reported there were ninety-six residents in the area.[46] The Third Seminole War was not as destructive as the second, but it slowed the settlement of southeast Florida. At the end of the war, a few of the soldiers stayed.

Civil War and Reconstruction

American settlers began to establish cotton plantations in north Florida, which required numerous laborers, which they supplied by buying slaves in the domestic market. By 1860, Florida had only 140,424 people, of whom 44% were enslaved. There were fewer than 1,000 free African Americans before the American Civil War.[47]

On January 10, 1861, nearly all delegates in the Florida Legislature approved an ordinance of secession,[48][49] declaring Florida to be "a sovereign and independent nation"—an apparent reassertion to the preamble in Florida's Constitution of 1838, in which Florida agreed with Congress to be a "Free and Independent State". The ordinance declared Florida's secession from the Union, allowing it to become one of the founding members of the Confederate States.

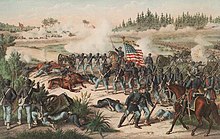

The Confederacy received little military help from Florida; the 15,000 troops it offered were generally sent elsewhere. Instead of troops and manufactured goods, Florida did provide salt and, more importantly, beef to feed the Confederate armies. This was particularly important after 1864, when the Confederacy lost control of the Mississippi River, thereby losing access to Texas beef.[50][51] The largest engagements in the state were the Battle of Olustee, on February 20, 1864, and the Battle of Natural Bridge, on March 6, 1865. Both were Confederate victories.[52] The war ended in 1865.

Following the American Civil War, Florida's congressional representation was restored on June 25, 1868, albeit forcefully after Reconstruction and the installation of unelected government officials under the final authority of federal military commanders. After the Reconstruction period ended in 1876, white Democrats regained power in the state legislature. In 1885, they created a new constitution, followed by statutes through 1889 that disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites.[53]

In the pre-automobile era, railroads played a key role in the state's development, particularly in coastal areas. In 1883, the Pensacola and Atlantic Railroad connected Pensacola and the rest of the Panhandle to the rest of the state. In 1884 the South Florida Railroad (later absorbed by Atlantic Coast Line Railroad) opened full service to Tampa. In 1894 the Florida East Coast Railway reached West Palm Beach; in 1896 it reached Biscayne Bay near Miami. Numerous other railroads were built all over the interior of the state.

20th century

Florida's economy has been based primarily upon agricultural products such as citrus fruits, strawberries, nuts, sugarcane and cattle.[54] The boll weevil devastated cotton crops during the early 20th century.[55][56]

Until the mid-20th century, Florida was the least-populous state in the southern United States. In 1900, its population was only 528,542, of whom nearly 44% were African American, the same proportion as before the Civil War.[57] Forty thousand blacks, roughly one-fifth of their 1900 population levels in Florida, left the state in the Great Migration. They left due to lynchings and racial violence and for better opportunities in the North and the West.[58] Disfranchisement for most African Americans in the state persisted until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s gained federal legislation in 1965 to enforce protection of their constitutional suffrage.

In response to racial segregation in Florida, a number of protests occurred in Florida during the 1950s and 1960s as part of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1956–1957, students at Florida A&M University organized a bus boycott in Tallahassee to mimic the Montgomery bus boycott and succeeded in integrating the city's buses.[59] Students also held sit-ins in 1960 in protest of segregated seating at local lunch counters, and in 1964 an incident at a St. Augustine motel pool, in which the owner poured acid into the water during a demonstration, influenced the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.[60]

Economic prosperity in the 1920s stimulated tourism to Florida and related development of hotels and resort communities. Combined with its sudden elevation in profile was the Florida land boom of the 1920s, which brought a brief period of intense land development. In 1925, the Seaboard Air Line broke the FEC's southeast Florida monopoly and extended its freight and passenger service to West Palm Beach; two years later it extended passenger service to Miami. Devastating hurricanes in 1926 and 1928, followed by the Great Depression, brought that period to a halt. Florida's economy did not fully recover until the military buildup for World War II.

In 1939, Florida was described as "still very largely an empty State."[61] Subsequently, the growing availability of air conditioning, the climate, and a low cost of living made the state a haven. Migration from the Rust Belt and the Northeast sharply increased Florida's population after 1945.

In the 1960s, many refugees from Cuba, fleeing Fidel Castro's communist regime, arrived in Miami at the Freedom Tower, where the federal government used the facility to process, document and provide medical and dental services for the newcomers. As a result, the Freedom Tower was also called the "Ellis Island of the South".[62] In recent decades, more migrants have come for the jobs in a developing economy.

21st century

With a population of more than 18 million, according to the 2010 census, Florida is the most populous state in the southeastern United States and the third-most populous in the United States.[63] The population of Florida has boomed in recent years with the state being the recipient of the largest number of out-of-state movers in the country as of 2019.[64] Florida's growth has been widespread, as cities throughout the state have continued to see population growth.[65]

In 2012, the killing of Trayvon Martin, a young black man, by George Zimmerman in Sanford drew national attention to Florida's stand-your-ground laws, and sparked African American activism, including the Black Lives Matter movement.[66]

After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico in September 2017, a large population of Puerto Ricans began moving to Florida to escape the widespread destruction. Hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans arrived in Florida after Maria dissipated, with nearly half of them arriving in Orlando and large populations also moving to Tampa, Fort Lauderdale, and West Palm Beach.[67]

A handful of high-profile mass shootings have occurred in Florida in the 21st century. In June 2016, a gunman killed 49 people at a gay nightclub in Orlando. It is the deadliest incident in the history of violence against LGBT people in the United States, as well as the deadliest terrorist attack in the U.S. since the September 11 attacks in 2001, and it was the deadliest mass shooting by a single gunman in U.S. history until the 2017 Las Vegas shooting. In February 2018, 17 people were killed in a school shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, leading to new gun control regulations at both the state and federal level.[68]

On June 24, 2021, a condominium in Surfside, Florida, near Miami collapsed, killing at least 97 people.[69] The Surfside collapse is tied with the Knickerbocker Theatre collapse as the third-deadliest structural engineering failure in United States history, behind the Hyatt Regency walkway collapse and the collapse of the Pemberton Mill.[70][71]

Geography

Much of Florida is on a peninsula between the Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic Ocean and the Straits of Florida. Spanning two time zones, it extends to the northwest into a panhandle, extending along the northern Gulf of Mexico. It is bordered on the north by Georgia and Alabama, and on the west, at the end of the panhandle, by Alabama. It is the only state that borders both the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. Florida also is the southernmost of the 48 contiguous states, Hawaii being the only one of the fifty states reaching farther south. Florida is west of the Bahamas and 90 miles (140 km) north of Cuba. Florida is one of the largest states east of the Mississippi River, and only Alaska and Michigan are larger in water area. The water boundary is 3 nautical miles (3.5 mi; 5.6 km) offshore in the Atlantic Ocean[72] and 9 nautical miles (10 mi; 17 km) offshore in the Gulf of Mexico.[72]

At 345 feet (105 m) above mean sea level, Britton Hill is the highest point in Florida and the lowest highpoint of any U.S. state.[73] Much of the state south of Orlando lies at a lower elevation than northern Florida, and is fairly level. Much of the state is at or near sea level. Some places, such as Clearwater have promontories that rise 50 to 100 ft (15 to 30 m) above the water. Much of Central and North Florida, typically 25 mi (40 km) or more away from the coastline, have rolling hills with elevations ranging from 100 to 250 ft (30 to 76 m). The highest point in peninsular Florida (east and south of the Suwannee River), Sugarloaf Mountain, is a 312-foot (95 m) peak in Lake County.[74] On average, Florida is the flattest state in the United States.[75]

Lake Okeechobee, the largest lake in Florida, is the tenth-largest natural freshwater lake among the 50 states of the United States and the second-largest natural freshwater lake contained entirely within the contiguous 48 states, after Lake Michigan.[76] The longest river within Florida is the St. Johns River, at 310 miles (500 km) long. The drop in elevation from its headwaters South Florida to its mouth in Jacksonville is less than 30 feet (9.1 m).

Climate

The climate of Florida is tempered somewhat by the fact that no part of the state is distant from the ocean. North of Lake Okeechobee, the prevalent climate is humid subtropical (Köppen: Cfa), while areas south of the lake (including the Florida Keys) have a true tropical climate (Köppen: Aw, Am, and Af).[77] Mean high temperatures for late July are primarily in the low 90s Fahrenheit (32–34 °C). Mean low temperatures for early to mid-January range from the low 40s Fahrenheit (4–7 °C) in north Florida to above 60 °F (16 °C) from Miami on southward. With an average daily temperature of 70.7 °F (21.5 °C), it is the warmest state in the U.S.[78][79]

In the summer, high temperatures in the state rarely exceed 100 °F (37.8 °C). Several record cold maxima have been in the 30s °F (−1 to 4 °C) and record lows have been in the 10s (−12 to −7 °C). These temperatures normally extend at most a few days at a time in the northern and central parts of Florida. South Florida rarely dips below freezing.[80] The hottest temperature ever recorded in Florida was 109 °F (43 °C), which was set on June 29, 1931, in Monticello. The coldest temperature was −2 °F (−19 °C), on February 13, 1899, just 25 miles (40 km) away, in Tallahassee.[81][82]

Due to its subtropical and tropical climate, Florida rarely receives measurable snowfall.[83] On rare occasions, a combination of cold moisture and freezing temperatures can result in snowfall in the farthest northern regions like Jacksonville, Gainesville or Pensacola. Frost, which is more common than snow, sometimes occurs in the panhandle.[84] The USDA Plant hardiness zones for the state range from zone 8a (no colder than 10 °F or −12 °C) in the inland western panhandle to zone 11b (no colder than 45 °F or 7 °C) in the lower Florida Keys.[85] Fog also occurs all over the state or climate of Florida.[86]

| Average high and low temperatures for various Florida cities | ||||||||||||

| °F | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

| Jacksonville[87] | 65/42 | 68/45 | 74/50 | 79/55 | 86/63 | 90/70 | 92/73 | 91/73 | 87/69 | 80/61 | 74/51 | 67/44 |

| Miami[88] | 76/60 | 78/62 | 80/65 | 83/68 | 87/73 | 89/76 | 91/77 | 91/77 | 89/76 | 86/73 | 82/68 | 78/63 |

| Orlando[89] | 71/49 | 74/52 | 78/56 | 83/60 | 88/66 | 91/72 | 92/74 | 92/74 | 90/73 | 85/66 | 78/59 | 73/52 |

| Pensacola[90] | 61/43 | 64/46 | 70/51 | 76/58 | 84/66 | 89/72 | 90/74 | 90/74 | 87/70 | 80/60 | 70/50 | 63/45 |

| Tallahassee[91] | 64/39 | 68/42 | 74/47 | 80/52 | 87/62 | 91/70 | 92/72 | 92/72 | 89/68 | 82/57 | 73/48 | 66/41 |

| Tampa[92] | 70/51 | 73/54 | 77/58 | 81/62 | 88/69 | 90/74 | 90/75 | 91/76 | 89/74 | 85/67 | 78/60 | 72/54 |

| °C | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

| Jacksonville | 18/6 | 20/7 | 23/10 | 26/13 | 30/17 | 32/21 | 33/23 | 33/23 | 31/21 | 27/16 | 23/11 | 19/7 |

| Miami | 24/16 | 26/17 | 27/18 | 28/20 | 31/23 | 32/24 | 33/25 | 33/25 | 32/24 | 30/23 | 28/20 | 26/17 |

| Orlando | 22/9 | 23/11 | 26/13 | 28/16 | 31/19 | 33/22 | 33/23 | 33/23 | 32/23 | 29/19 | 26/15 | 23/11 |

| Pensacola | 16/6 | 18/8 | 21/11 | 24/14 | 29/19 | 32/22 | 32/23 | 32/23 | 31/21 | 27/16 | 21/10 | 17/7 |

| Tallahassee | 18/4 | 20/6 | 23/8 | 27/11 | 31/17 | 33/21 | 33/22 | 33/22 | 32/20 | 28/14 | 23/9 | 19/5 |

| Tampa | 21/11 | 23/12 | 25/14 | 27/17 | 31/21 | 32/23 | 32/24 | 33/24 | 32/23 | 29/19 | 26/16 | 22/12 |

Florida's nickname is the "Sunshine State", but severe weather is a common occurrence in the state. Central Florida is known as the lightning capital of the United States, as it experiences more lightning strikes than anywhere else in the country.[93] Florida has one of the highest average precipitation levels of any state,[94] in large part because afternoon thunderstorms are common in much of the state from late spring until early autumn.[95] A narrow eastern part of the state including Orlando and Jacksonville receives between 2,400 and 2,800 hours of sunshine annually. The rest of the state, including Miami, receives between 2,800 and 3,200 hours annually.[96]

Florida leads the United States in tornadoes per area (when including waterspouts),[97] but they do not typically reach the intensity of those in the Midwest and Great Plains. Hail often accompanies the most severe thunderstorms.[98]

Hurricanes pose a severe threat each year from June 1 to November 30, particularly from August to October. Florida is the most hurricane-prone state, with subtropical or tropical water on a lengthy coastline. Of the category 4 or higher storms that have struck the United States, 83% have either hit Florida or Texas.[99]

From 1851 to 2006, Florida was struck by 114 hurricanes, 37 of them major—category 3 and above.[99] It is rare for a hurricane season to pass without any impact in the state by at least a tropical storm.[100]

In 1992, Florida was the site of what was then the costliest weather disaster in U.S. history, Hurricane Andrew, which caused more than $25 billion in damages when it struck during August; it held that distinction until 2005, when Hurricane Katrina surpassed it, and it has since been surpassed by six other hurricanes. Andrew is the second-costliest hurricane in Florida's history.[101]

Fauna

Florida is host to many types of wildlife, including:

- Marine mammals: bottlenose dolphin, short-finned pilot whale, North Atlantic right whale, West Indian manatee

- Mammals: Florida panther, northern river otter, mink, eastern cottontail rabbit, marsh rabbit, raccoon, striped skunk, squirrel, white-tailed deer, Key deer, bobcats, red fox, gray fox, coyote, wild boar, Florida black bear, nine-banded armadillos, Virginia opossum

- Reptiles: eastern diamondback and pygmy rattlesnakes, gopher tortoise, green and leatherback sea turtles,[102] brown anoles, and eastern indigo snake. In 2012, there were about one million American alligators and 1,500 crocodiles.[103]

- Birds: peregrine falcon,[104] bald eagle, American flamingo,[105] crested caracara, snail kite, osprey, white and brown pelicans, sea gulls, whooping and sandhill cranes, roseate spoonbill, American white ibis, Florida scrub jay (state endemic), and others. One subspecies of wild turkey, Meleagris gallopavo osceola, is found only in Florida.[106] The state is a wintering location for many species of eastern North American birds.

- As a result of climate change, there have been small numbers of several new species normally native to cooler areas to the north: snowy owls, snow buntings, harlequin ducks, and razorbills. These have been seen in the northern part of the state.[107]

- Invertebrates: carpenter ants, termites, American cockroach, Africanized bees, the Miami blue butterfly, and the grizzled mantis.

Florida also has more than 500 nonnative animal species and 1,000 nonnative insects found throughout the state.[108] Some exotic species living in Florida include the Burmese python, green iguana, veiled chameleon, Argentine black and white tegu, peacock bass, mayan cichlid, lionfish, White-nosed coati, rhesus macaque, vervet monkey, Cuban tree frog, cane toad, Indian peafowl, monk parakeet, tui parakeet, and many more. Some of these nonnative species do not pose a threat to any native species, but some do threaten the native species of Florida by living in the state and eating them.[109]

Flora

The state has more than 26,000 square miles (67,000 km2) of forests, covering about half of the state's land area.[110]

There are about 3,000 different types of wildflowers in Florida.[111] This is the third-most diverse state in the union, behind California and Texas, both larger states.[112] In Florida, wild populations of coconut palms extend up the East Coast from Key West to Jupiter Inlet, and up the West Coast from Marco Island to Sarasota. Many of the smallest coral islands in the Florida Keys are known to have abundant coconut palms sprouting from coconuts deposited by ocean currents. Coconut palms are cultivated north of south Florida to roughly Cocoa Beach on the East Coast and the Tampa Bay area on the West Coast.[113]

On the east coast of the state, mangroves have normally dominated the coast from Cocoa Beach southward; salt marshes from St. Augustine northward. From St. Augustine south to Cocoa Beach, the coast fluctuates between the two, depending on the annual weather conditions.[107] All three mangrove species flower in the spring and early summer. Propagules are produced from late summer through early autumn.[114] Florida mangrove plant communities covered an estimated 430,000 to 540,000 acres (1,700 to 2,200 km2) in Florida in 1981. Ninety percent of the Florida mangroves are in southern Florida, in Collier, Lee, Miami-Dade and Monroe Counties.

Reef

The Florida Reef is the only living coral barrier reef in the continental United States.[115] It is also the third-largest coral barrier reef system in the world, after the Great Barrier Reef and the Belize Barrier Reef.[116] The reef lies a little bit off of the coast of the Florida Keys. A lot of the reef lies within John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, which was the first underwater park in the United States.[117] The park contains a lot of tropical vegetation, marine life, and seabirds. The Florida Reef extends into other parks and sanctuaries as well including Dry Tortugas National Park, Biscayne National Park, and the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Almost 1,400 species of marine plants and animals, including more than 40 species of stony corals and 500 species of fish, live on the Florida Reef.[118] The Florida Reef, being a delicate ecosystem like other coral reefs, faces many threats including overfishing, plastics in the ocean, coral bleaching, rising sea levels, and changes in sea surface temperature.

Environmental issues

Florida is a low per capita energy user.[119] As of 2008[update], it is estimated that approximately 4% of energy in the state is generated through renewable resources.[120] Florida's energy production is 6% of the U.S. total energy output, while total production of pollutants is lower, with figures of 6% for nitrogen oxide, 5% for carbon dioxide, and 4% for sulfur dioxide.[120] Wildfires in Florida occur at all times of the year.[121]

All potable water resources have been controlled by the state government through five regional water authorities since 1972.[122]

Red tide has been an issue on the southwest coast of Florida, as well as other areas. While there has been a great deal of conjecture over the cause of the toxic algae bloom, there is no evidence that it is being caused by pollution or that there has been an increase in the duration or frequency of red tides.[123] Red tide is now killing off wildlife or Tropical fish and coral reefs putting all in danger.[124]

The Florida panther is close to extinction. A record 23 were killed in 2009, mainly by automobile collisions, leaving about 100 individuals in the wild. The Center for Biological Diversity and others have therefore called for a special protected area for the panther to be established.[125] Manatees are also dying at a rate higher than their reproduction.[126] American flamingos are rare to see in Florida due to being hunted in the 1900s, where it was to a point considered completely extirpated. Now the flamingos are reproducing toward making a comeback to South Florida since it is adamantly considered native to the state and also are now being protected.[127][128]

Much of Florida has an elevation of less than 12 feet (3.7 m), including many populated areas. Therefore, it is susceptible to rising sea levels associated with global warming.[129] The Atlantic beaches that are vital to the state's economy are being washed out to sea due to rising sea levels caused by climate change. The Miami beach area, close to the continental shelf, is running out of accessible offshore sand reserves.[130] Elevated temperatures can damage coral reefs, causing coral bleaching. The first recorded bleaching incident on the Florida Reef was in 1973. Incidents of bleaching have become more frequent in recent decades, in correlation with a rise in sea surface temperatures. White band disease has also adversely affected corals on the Florida Reef.[131]

Geology

The Florida peninsula is a porous plateau of karst limestone sitting atop bedrock, known as the Florida Platform.

The largest deposits of potash in the United States are found in Florida.[133] The largest deposits of rock phosphate in the country are found in Florida.[133] Most of this is in Bone Valley.[134]

Extended systems of underwater caves, sinkholes and springs are found throughout the state and supply most of the water used by residents.[135] The limestone is topped with sandy soils deposited as ancient beaches over millions of years as global sea levels rose and fell. During the last glacial period, lower sea levels and a drier climate revealed a much wider peninsula, largely savanna.[136] While there are sinkholes in much of the state, modern sinkholes have tended to be in West-Central Florida.[137][138] Everglades National Park covers 1,509,000 acres (6,110 km2), throughout Dade, Monroe, and Collier counties in Florida.[139] The Everglades, an enormously wide, slow-flowing river encompasses the southern tip of the peninsula. Sinkhole damage claims on property in the state exceeded a total of $2 billion from 2006 through 2010.[140] Winter Park Sinkhole, in central Florida, appeared May 8, 1981. It was approximately 350 feet (107 m) wide and 75 feet (23 m) deep. It was one of the largest recent sinkholes to form in the United States. It is now known as Lake Rose.[141] The Econlockhatchee River (Econ River for short) is an 54.5-mile-long (87.7 km)[142] north-flowing blackwater tributary of the St. Johns River, the longest river in the U.S. state of Florida. The Econ River flows through Osceola, Orange, and Seminole counties in Central Florida, just east of the Orlando Metropolitan Area (east of State Road 417). It is a designated Outstanding Florida Waters.[143]

Earthquakes are rare because Florida is not located near any tectonic plate boundaries.[144]

Regions

Cities and towns

The largest metropolitan area in the state as well as the entire southeastern United States is the Miami metropolitan area, with about 6.06 million people. The Tampa Bay area, with more than 3.02 million, is the second-largest; the Orlando metropolitan area, with more than 2.44 million, is third; and the Jacksonville metropolitan area, with more than 1.47 million, is fourth.[145]

Florida has 22 Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) defined by the United States Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Forty-three of Florida's 67 counties are in an MSA.

The legal name in Florida for a city, town or village is "municipality". In Florida there is no legal difference between towns, villages and cities.[146]

Florida is a highly urbanized state, with 89 percent of its population living in urban areas in2000, compared to 79 percent across the U.S.[147]

In 2012, 75% of the population lived within 10 miles (16 km) of the coastline.[148]

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Jacksonville  Miami | 1 | Jacksonville | Duval | 949,611 | 11 | Pembroke Pines | Broward | 171,178 |  Tampa  Orlando |

| 2 | Miami | Miami-Dade | 442,241 | 12 | Hollywood | Broward | 153,067 | ||

| 3 | Tampa | Hillsborough | 384,959 | 13 | Gainesville | Alachua | 141,085 | ||

| 4 | Orlando | Orange | 307,573 | 14 | Miramar | Broward | 134,721 | ||

| 5 | St. Petersburg | Pinellas | 258,308 | 15 | Coral Springs | Broward | 134,394 | ||

| 6 | Hialeah | Miami-Dade | 223,109 | 16 | Palm Bay | Brevard | 119,760 | ||

| 7 | Port St. Lucie | St. Lucie | 204,851 | 17 | West Palm Beach | Palm Beach | 117,415 | ||

| 8 | Tallahassee | Leon | 196,169 | 18 | Clearwater | Pinellas | 117,292 | ||

| 9 | Cape Coral | Lee | 194,016 | 19 | Lakeland | Polk | 112,641 | ||

| 10 | Fort Lauderdale | Broward | 182,760 | 20 | Pompano Beach | Broward | 112,046 | ||

Demographics

Population

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1830 | 34,730 | — | |

| 1840 | 54,477 | 56.9% | |

| 1850 | 87,445 | 60.5% | |

| 1860 | 140,424 | 60.6% | |

| 1870 | 187,748 | 33.7% | |

| 1880 | 269,493 | 43.5% | |

| 1890 | 391,422 | 45.2% | |

| 1900 | 528,542 | 35.0% | |

| 1910 | 752,619 | 42.4% | |

| 1920 | 968,470 | 28.7% | |

| 1930 | 1,468,211 | 51.6% | |

| 1940 | 1,897,414 | 29.2% | |

| 1950 | 2,771,305 | 46.1% | |

| 1960 | 4,951,560 | 78.7% | |

| 1970 | 6,789,443 | 37.1% | |

| 1980 | 9,746,324 | 43.6% | |

| 1990 | 12,937,926 | 32.7% | |

| 2000 | 15,982,378 | 23.5% | |

| 2010 | 18,801,310 | 17.6% | |

| 2020 | 21,538,187 | 14.6% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 22,610,726 | 5.0% | |

| Sources: 1910–2020[152] | |||

The U.S. Census Bureau estimated that the population of Florida was 21,477,737 on July 1, 2019, a 14.24% increase since the 2010 United States census.[153] The population of Florida in the 2010 census was 18,801,310.[154] Florida was the seventh fastest-growing state in the U.S. in the 12-month period ending July 1, 2012.[155] In 2010, the center of population of Florida was located between Fort Meade and Frostproof. The center of population has moved less than 5 miles (8 km) to the east and approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) to the north between 1980 and 2010 and has been located in Polk County since the 1960 census.[156] The population exceeded 19.7 million by December 2014, surpassing the population of the state of New York for the first time, making Florida the third most populous state.[157][158] The Florida population was 21,477,737 residents or people according to the U.S. Census Bureau's 2019 Population Estimates Program.[159] By the 2020 census, its population increased to 21,538,187.

In 2010, undocumented immigrants constituted an estimated 5.7% of the population. This was the sixth highest percentage of any U.S. state.[160][b] There were an estimated 675,000 illegal immigrants in the state in 2010.[161] Florida has banned sanctuary cities.[162]

The top countries of origin for Florida's immigrants were Cuba, Haiti, Colombia, Mexico and Jamaica in 2018.[163]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 25,959 homeless people in Florida.[164][165]

| Racial composition | 1970[166] | 1990[166] | 2000[167] | 2010[168] | 2020[169][170] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 6.6% | 12.2% | 16.8% | 22.5% | 26.5% |

| Black or African American alone | 15.3% | 13.6% | 14.6% | 16.0% | 15.1% |

| Asian alone | 0.2% | 1.2% | 1.7% | 2.4% | 3.0% |

| Native American alone | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

| Two or more races | — | — | 2.3% | 2.5% | 16.5% |

| White alone, not Hispanic or Latino | 77.9% | 73.2% | 65.4% | 57.9% | 51.5% |

| White alone | 84.2% | 83.1% | 78.0% | 75.0% | 57.7% |

In 2010, 6.9% of the population (1,269,765) considered themselves to be of only American ancestry (regardless of race or ethnicity).[171][172] Many of these were of English or Scotch-Irish descent, whose families have lived in the state for so long they choose to identify as having "American" ancestry or do not know their ancestry.[173][174][175][176][177][178] In the 1980 United States census, the largest ancestry group reported in Florida was English with 2,232,514 Floridians claiming they were of English or mostly English American ancestry.[179] Some of their ancestry dated to the original thirteen colonies.

As of 2010[update], those of (non-Hispanic white) European ancestry accounted for 57.9% of Florida's population. Out of the 57.9%, the largest groups were 12.0% German (2,212,391), 10.7% Irish (1,979,058), 8.8% English (1,629,832), 6.6% Italian (1,215,242), 2.8% Polish (511,229), and 2.7% French (504,641).[171][172] White Americans of all European backgrounds are present in all areas of the state. In 1970, non-Hispanic whites constituted nearly 80% of Florida's population.[180] Those of English and Irish ancestry are present in large numbers in all the urban/suburban areas across the state. Some native white Floridians, especially those who have descended from long-time Florida families, may refer to themselves as "Florida crackers"; others see the term as a derogatory one. Like whites in most other states of the southern U.S., they descend mainly from English and Scots-Irish settlers, as well as some other British American settlers.[181]

As of 2010, those of Hispanic or Latino ancestry accounted for 22.5% (4,223,806) of Florida's population. Out of the 22.5%, the largest groups were 6.5% (1,213,438) Cuban, and 4.5% (847,550) Puerto Rican.[151] Florida's Hispanic population includes large communities of Cuban Americans in Miami and Tampa, Puerto Ricans in Orlando and Tampa, and Mexican/Central American migrant workers. The Hispanic community continues to grow more affluent and mobile. Florida has a large and diverse Hispanic population, with Cubans and Puerto Ricans being the largest groups in the state. Nearly 80% of Cuban Americans live in Florida, especially South Florida where there is a long-standing and affluent Cuban community.[182] Florida has the second-largest Puerto Rican population after New York, as well as the fastest-growing in the U.S.[183] Puerto Ricans are more widespread throughout the state, though the heaviest concentrations are in the Orlando area of Central Florida.[184] Florida has one of the largest and most diverse Hispanic/Latino populations in the country, especially in South Florida around Miami, and to a lesser degree Central Florida. Aside from the dominant Cuban and Puerto Rican populations, there are also large populations of Mexicans, Colombians, Venezuelans and Dominicans, among numerous other groups, as most Latino groups have sizable numbers in the state.

As of 2010[update], those of African ancestry accounted for 16.0% of Florida's population, which includes African Americans. Out of the 16.0%, 4.0% (741,879) were West Indian or Afro-Caribbean American.[171][172][151] During the early 1900s, black people made up nearly half of the state's population.[185] In response to segregation, disfranchisement and agricultural depression, many African Americans migrated from Florida to northern cities in the Great Migration, in waves from 1910 to 1940, and again starting in the later 1940s. They moved for jobs, better education for their children and the chance to vote and participate in society. By 1960, the proportion of African Americans in the state had declined to 18%.[186] Conversely, large numbers of northern whites moved to the state.[187] Today, large concentrations of black residents can be found throughout Florida. Aside from blacks descended from African slaves brought to the southern U.S., there are also large numbers of blacks of West Indian, recent African, and Afro-Latino immigrant origins, especially in the Miami/South Florida area.[188] Florida has the largest West Indian population of any state, originating from many Caribbean countries, with Haitian Americans being the most numerous.

In 2016, Florida had the highest percentage of West Indians in the United States at 4.5%, with 2.3% (483,874) from Haitian ancestry, 1.5% (303,527) Jamaican, and 0.2% (31,966) Bahamian, with the other West Indian groups making up the rest.[189]

As of 2010[update], those of Asian ancestry accounted for 2.4% of Florida's population.[171][172]

As of 2011, Florida contains the highest percentage of people over 65 (17.3%) in the U.S.[190] There were 186,102 military retirees living in the state in 2008.[191] About two-thirds of the population was born in another state, the second-highest in the U.S.[192]

In 2020, Hispanic and Latinos of any race(s) made up 26.5% of the population, while Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders made up 0.1% of all Broward County residents.[193]

Languages

In 1988, English was affirmed as the state's official language in the Florida Constitution. Spanish is also widely spoken, especially as immigration has continued from Latin America.[194] About 20% percent of the population speaks Spanish as their first language, while 27% speaks a mother language other than English. More than 200 first languages other than English are spoken at home in the state.[195][196]

The most common languages spoken in Florida as a first language in 2010 are:[195]

- 73% English

- 20% Spanish

- 2% Haitian Creole

- Other languages less than 1% each

Religion

Florida is mostly Christian (70%),[197] although there is a large irreligious and relatively significant Jewish community. Protestants account for almost half of the population, but the Catholic Church is the largest single denomination in the state mainly due to its large Hispanic population and other groups like Haitians. Protestants are very diverse, although Baptists, Methodists, Pentecostals and nondenominational Protestants are the largest groups. Smaller Christian groups include The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and Jehovah's Witnesses. There is also a sizable Jewish community in South Florida. This is the largest Jewish population in the southern U.S. and the third-largest in the U.S. behind those of New York and California.[198]

In 2010, the three largest denominations in Florida were the Catholic Church, the Southern Baptist Convention, and the United Methodist Church.[199]

The Pew Research Center survey in 2014 gave the following religious makeup of Florida:[200]

Governance

The basic structure, duties, function, and operations of the government of the State of Florida are defined by the Florida Constitution, which establishes the basic law of the state and guarantees various rights and freedoms of the people. As with the American federal government and all other state governments, Florida's government consists of three separate branches: executive, legislative, and judicial. The legislature enacts bills, which, if signed by the governor, become law.

The Florida Legislature comprises the Florida Senate, which has 40 members, and the Florida House of Representatives, which has 120 members. The governor of Florida is Ron DeSantis. The Florida Supreme Court consists of a chief justice and six justices.

Florida has 67 counties. Some reference materials may show only 66 because Duval County is consolidated with the City of Jacksonville. There are 379 cities in Florida (out of 411) that report regularly to the Florida Department of Revenue, but there are other incorporated municipalities that do not. The primary revenue source for cities and counties is property tax; properties with unpaid taxes are subject to tax sales, which are held at the county level in May and are highly popular, due to the extensive use of online bidding sites.

The state government's primary revenue source is sales tax. Florida is one of eight states that do not impose a personal income tax.

There were 800 federal corruption convictions from 1988 to 2007, more than any other state.[201]

In a 2020 study, Florida was ranked as the 11th hardest state for citizens to vote in.[202] In April 2022, the legislature passed and the governor signed a new election law prohibiting Floridians from using ranked-choice voting in all federal, state and municipal elections.[203]

Florida retains the death penalty. Authorized methods of execution include the electric chair and lethal injection.[204]

Elections history

From 1952 to 1964, most voters were registered Democrats, but the state voted for the Republican presidential candidate in every election except for 1964. The following year, Congress passed and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, providing for oversight of state practices and enforcement of constitutional voting rights for African Americans and other minorities in order to prevent the discrimination and disenfranchisement which had excluded most of them for decades from the political process.

From the 1930s through much of the 1960s, Florida was essentially a one-party state dominated by white conservative Democrats, who together with other Democrats of the Solid South, exercised considerable control in Congress. They have gained slightly less federal money from national programs than they have paid in taxes.[205] Since the 1970s, conservative white voters in the state have largely shifted from the Democratic to the Republican Party. Though the majority of registered voters in Florida were Democrats,[206] it continued to support Republican presidential candidates through 2004, except in 1976 and 1996, when the Democratic nominee was from the South.

In the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections, Barack Obama carried the state as a northern Democrat, attracting high voter turnout, especially among the young, independents, and minority voters, of whom Hispanics comprise an increasingly large proportion. 2008 marked the first time since 1944, when Franklin D. Roosevelt carried the state for the fourth time, that Florida was carried by a Northern Democrat for president.

The first post-Reconstruction era Republican elected to Congress from Florida was William C. Cramer in 1954 from Pinellas County on the Gulf Coast,[207] where demographic changes were underway. In this period, African Americans were still disenfranchised by the state's constitution and discriminatory practices; in the 19th century, they had made up most of the Republican Party. Cramer built a different Republican Party in Florida, attracting local white conservatives and transplants from northern and midwestern states. In 1966, Claude R. Kirk Jr. was elected as the first post-Reconstruction Republican governor, in an upset election.[208] In 1968, Edward J. Gurney, also a white conservative, was elected as the state's first post-reconstruction Republican US senator.[209] In 1970, Democrats took the governorship and the open US Senate seat and maintained dominance for years.

Florida is sometimes considered a bellwether state in presidential elections because every candidate who won the state from 1996 until 2016 won the election.[210] The 2020 election broke that streak when Donald Trump won Florida but lost the election.

In 1998, Democratic voters dominated areas of the state with a high percentage of racial minorities and transplanted white liberals from the northeastern United States, known colloquially as "snowbirds".[211] South Florida and the Miami metropolitan area became dominated by both racial minorities and white liberals. Because of this, the area has consistently voted as one of the most Democratic areas of the state. The Daytona Beach area is similar demographically and the city of Orlando has a large Hispanic population, which has often favored Democrats. Republicans, made up mostly of white conservatives, have dominated throughout much of the rest of Florida, including Jacksonville and the panhandle and particularly in the more rural and suburban areas. This is characteristic of its voter base throughout the Deep South.[211]

The fast-growing I-4 corridor area, which runs through Central Florida and connects the cities of Daytona Beach, Orlando, and Tampa/St. Petersburg, has had a fairly even breakdown of Republican and Democratic voters. The area has often been seen as a merging point of the conservative northern portion of the state and the liberal southern portion, making it the biggest swing area in the state. Since the late 20th century, the voting results in this area, containing 40% of Florida voters, has often determined who will win the state in federal presidential elections.[212]

Historically, the Democratic Party maintained an edge in voter registration, both statewide and in the state's three most populous counties, Miami-Dade County, Broward County, and Palm Beach County.[213][when?]

2000–present

In 2000, George W. Bush won the U.S. presidential election by a margin of 271–266 in the Electoral College.[214] Of the 271 electoral votes for Bush, 25 were cast by electors from Florida.[215] The Florida results were contested and a recount was ordered by the court, with the results settled in a Supreme Court decision, Bush v. Gore.

Reapportionment following the 2010 United States census gave the state two more seats in the House of Representatives.[216] The legislature's redistricting, announced in 2012, was quickly challenged in court, on the grounds that it had unfairly benefited Republican interests. In 2015, the Florida Supreme Court ruled on appeal that the congressional districts had to be redrawn because of the legislature's violation of the Fair District Amendments to the state constitution passed in 2010; it accepted a new map in early December 2015.

The political make-up of congressional and legislative districts has enabled Republicans to control the governorship and most statewide elective offices, and 17 of the state's 27 seats in the 2012 House of Representatives.[217] Florida has been listed as a swing state in presidential elections since 1952, voting for the losing candidate only twice in that period of time.[218]

In the closely contested 2000 election, the state played a pivotal role.[214][215][219][220][221][222] Out of more than 5.8 million votes for the two main contenders Bush and Al Gore, around 500 votes separated the two candidates for the all-decisive Florida electoral votes that landed Bush the election win. Florida's felony disenfranchisement law is more severe than most European nations or other American states. A 2002 study in the American Sociological Review concluded that "if the state's 827,000 disenfranchised felons had voted at the same rate as other Floridians, Democratic candidate Al Gore would have won Florida—and the presidency—by more than 80,000 votes."[223]

In 2008, delegates of both the Republican Florida primary election and Democratic Florida primary election were stripped of half of their votes when the conventions met in August due to violation of both parties' national rules.

In the 2010 elections, Republicans solidified their dominance statewide, by winning the governor's mansion, and maintaining firm majorities in both houses of the state legislature. They won four previously Democratic-held seats to create a 19–6 Republican majority delegation representing Florida in the federal House of Representatives.

In 2010, more than 63% of state voters approved the initiated Amendments 5 and 6 to the state constitution, to ensure more fairness in districting. These have become known as the Fair District Amendments. As a result of the 2010 United States Census, Florida gained two House of Representative seats in 2012.[216] The legislature issued revised congressional districts in 2012, which were immediately challenged in court by supporters of the above amendments.

The court ruled in 2014, after lengthy testimony, that at least two districts had to be redrawn because of gerrymandering. After this was appealed, in July 2015 the Florida Supreme Court ruled that lawmakers had followed an illegal and unconstitutional process overly influenced by party operatives, and ruled that at least eight districts had to be redrawn. On December 2, 2015, a 5–2 majority of the Court accepted a new map of congressional districts, some of which was drawn by challengers. Their ruling affirmed the map previously approved by Leon County Judge Terry Lewis, who had overseen the original trial. It particularly makes changes in South Florida. There are likely to be additional challenges to the map and districts.[224]

| Party | Registered voters | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | 5,257,407 | 39.14% | |

| Democratic | 4,300,964 | 32.02% | |

| Unaffiliated | 3,507,230 | 26.11% | |

| Minor parties | 365,009 | 2.72% | |

| Total | 13,430,610 | 100.00% | |

According to The Sentencing Project, the effect of Florida's felony disenfranchisement law is such that in 2014, "[m]ore than one in ten Floridians—and nearly one in four African-American Floridians—are [were] shut out of the polls because of felony convictions", although they had completed sentences and parole/probation requirements.[226]

The state switched back to the GOP in the 2016 presidential election, and again in 2020, when Donald Trump headed the party's ticket both times. 2020 marked the first time Florida sided with the eventual loser of the presidential election since 1992.

In the 2018 elections, the ratio of Republican to Democratic representation fell from 16:11 to 14:13. The U.S. Senate election between Democratic incumbent senator Bill Nelson and then governor Rick Scott was close, with 49.93% voting for the incumbent and 50.06% voting for the former governor. Republicans also held onto the governorship in a close race between Republican candidate Ron DeSantis and Democratic candidate Andrew Gillum, with 49.6% voting for DeSantis and 49.3% voting for Gillum. In 2022, incumbent Governor DeSantis won reelection by a landslide against Democrat Charlie Crist. The unexpectedly large margin of victory led many pundits to question Florida's perennial status as a swing state, and instead identify it as a red state.[227]

In November 2021, for the first time in Florida's history, the total number of registered Republican voters exceeded the number of registered Democrats.[228]

Statutes

In 1972, the state made personal injury protection auto insurance mandatory for drivers, becoming the second in the U.S. to enact a no-fault insurance law.[229] The ease of receiving payments under this law is seen as precipitating a major increase in insurance fraud.[230] Auto insurance fraud was the highest in the U.S. in 2011, estimated at close to $1 billion.[231] Fraud is particularly centered in the Miami-Dade and Tampa areas.[232][233][234]

Capital punishment is applied in Florida.[235] If a person committing a predicate felony directly contributed to the death of the victim then the person will be charged with murder in the first degree. The only two sentences available for that statute are life imprisonment and the death penalty.[236][237] If a person commits a predicate felony, but was not the direct contributor to the death of the victim then the person will be charged with murder in the second degree. The maximum prison term is life.[236][237] In 1995, the legislature modified Chapter 921 to provide that felons should serve at least 85% of their sentence.[238][239]

Florida approved its lottery by amending the constitution in 1984. It approved slot machines in Broward and Miami-Dade County in 2004. It has disapproved casinos (outside of sovereign Seminole and Miccosukee tribal areas) three times: 1978, 1986, and 1994.[240]

Taxation

Tax is collected by the Florida Department of Revenue.

Economy

The economy of the state of Florida is the fourth-largest in the United States, with a $1.647 trillion gross state product (GSP) as of 2024.[241] If Florida were a sovereign nation (2024), it would rank as the world's 15th-largest economy according to the International Monetary Fund, ahead of Spain and behind South Korea.[241][242][243] In the 20th century, tourism, industry, construction, international banking, biomedical and life sciences, healthcare research, simulation training, aerospace and defense, and commercial space travel have contributed to the state's economic development.[244]

Tourism is a large portion of Florida's economy. Florida is home to the world's most visited theme park, the Magic Kingdom.[245] Florida is also home to the largest single-site employer in the United States, Walt Disney World.[246] PortMiami is the largest passenger port in the world and one of the largest cargo ports in the United States.[247] Beach towns have many visitors too as Florida is known around the world for its beaches.

Agriculture is another large part of the Florida economy. Florida is the number one grower of oranges for juice,[248] mangoes,[249] fresh tomatoes,[250] sugar,[251] sweet corn, green beans,[252] beans, cucumbers, watermelons, and more.[253] Florida is also the second biggest producer of strawberries, avocadoes, grapefruit, and peppers in the U.S.[253][254]

Other large sectors of Florida's economy include finance, government and military (especially in Jacksonville and Pensacola),[255] healthcare, aerospace (especially in the Space Coast), mining (especially for phosphate in Bone Valley), fishing, trade, real estate, and tech (especially in Miami, Orlando, and Tampa in the 2020s).

Healthcare

There were 2.7 million Medicaid patients in Florida in 2009. The governor has proposed adding $2.6 billion to care for the expected 300,000 additional patients in 2011.[256] The cost of caring for 2.3 million clients in 2010 was $18.8 billion.[257] This is nearly 30% of Florida's budget.[258] Medicaid paid for 60% of all births in Florida in 2009. The state has a program for those not covered by Medicaid.

In 2013, Florida refused to participate in providing coverage for the uninsured under the Affordable Care Act, colloquially called Obamacare. The Florida legislature also refused to accept additional Federal funding for Medicaid, although this would have helped its constituents at no cost to the state. As a result, Florida is second only to Texas in the percentage of its citizens without health insurance.[259]

In 2022, the largest hospital network in Florida is HCA Healthcare[260] and the second largest is AdventHealth.[261][262]In 2023, the largest hospitals in Florida were Jackson Memorial Hospital, AdventHealth Orlando, Tampa General Hospital, UF Health Shands Hospital and Baptist Hospital of Miami.[263]

Mayo Clinic hosts one of its three major U.S. campuses in Jacksonville. The practice specializes in treating difficult cases through tertiary care and destination medicine.

Architecture

Florida has the largest collection of Art Deco and Streamline Moderne buildings, both in the United States and in the entire world, most of which are located in the Miami metropolitan area, especially Miami Beach's Art Deco District, constructed as the city was becoming a resort destination.[264] A unique architectural design found only in Florida is the post-World War II Miami Modern, which can be seen in areas such as Miami's MiMo Historic District.[265]

Being of early importance as a regional center of banking and finance, the architecture of Jacksonville displays a wide variety of styles and design principles. Many of the state's earliest skyscrapers were constructed in Jacksonville, dating as far back as 1902,[266] and last holding a state height record from 1974 to 1981.[267] The city is endowed with one of the largest collections of Prairie School buildings outside of the Midwest.[268] Jacksonville is also noteworthy for its collection of Mid-Century modern architecture.[269]

Some sections of the state feature architectural styles including Spanish revival, Florida vernacular, and Mediterranean Revival.[270] A notable collection of these styles can be found in St. Augustine, the oldest continuously occupied European-established settlement within the borders of the United States.[271]

Education

In 2020, Florida was ranked the third best state in the U.S. for K-12 education, outperforming other states in 15 out of 18 metrics in Education Week's 2020 Quality Counts report.[272] In terms of K-12 Achievement, which measures progress in areas such as academic excellence and graduation rates, the state was graded "B−" compared to a national average of C.[272] Florida's higher education was ranked first and pre-K-12 was ranked 27th best nationwide by U.S. News & World Report.[273]

Primary and secondary education

Florida spent $8,920 for each student in 2016, and was 43rd in the U.S. in expenditures per student.[274]

Florida's primary and secondary school systems are administered by the Florida Department of Education. School districts are organized within county boundaries. Each school district has an elected Board of Education that sets policy, budget, goals, and approves expenditures. Management is the responsibility of a Superintendent of schools.

The Florida Department of Education is required by law to train educators in teaching English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL).[275]

While Florida's public schools suffer from more than 5,000 unoccupied teacher positions, according to Karla Hernández, teacher and president of United Teachers of Dade, decisions made by the DeSantis administration will make the situation worse. She referred to its blocking of an Advanced Placement African American studies course,[276] book bans and removing some lessons in courses as "really scary moments in the state of Florida".[277]

In 2023, the state of Florida approved a public school curriculum including videos produced by conservative advocacy group PragerU, likening climate change skeptics to those who fought Communism and Nazism, implying renewable energy harms the environment, and saying global warming occurs naturally.[278] DeSantis has called climate change "leftwing stuff".[278]

In August 2023, restrictions have been placed on the teaching of Shakespearean plays and literature by Florida teachers in order to comply with state law.[279][280][281]

Higher education

The State University System of Florida was founded in 1905, and is governed by the Florida Board of Governors. During the 2019 academic year, 346,604 students attended one of these twelve universities.[282] In 2016, Florida charged the second lowest tuition in the U.S. for four-year programs, at $26,000 for in-state students and $86,000 for out-of-state students; this compares with an average of $34,800 for in-state students.[283]

As of 2020, three Florida universities are among the top 10 largest universities by enrollment in the United States: The University of Central Florida in Orlando (2nd), the University of Florida in Gainesville (4th), and Florida International University in Miami (8th).

The Florida College System comprises 28 public community and state colleges with 68 campuses spread out throughout the state. In 2016, enrollment exceeded 813,000 students.[284]

The Independent Colleges and Universities of Florida is an association of 30 private, educational institutions in the state.[285] This Association reported that their member institutions served more than 158,000 students in the fall of 2020.[286]

The University of Miami in Coral Gables is one of the top private research universities in the U.S. Florida's first private university, Stetson University in DeLand, was founded in 1883.

As of 2023, three universities in Florida are members of the Association of American Universities: University of Florida, University of Miami and University of South Florida.[287]

Transportation

Highways

Florida's highway system contains 1,495 mi (2,406 km) of interstate highway, and 10,601 mi (17,061 km) of non-interstate highway, such as state highways and U.S. Highways. Florida's interstates, state highways, and U.S. Highways are maintained by the Florida Department of Transportation.[288]

In 2011, there were about 9,000 retail gas stations in the state. Floridians consumed 21 million gallons of gasoline daily in 2011, ranking it third in national use behind California and Texas.[289]As of 2024, motorists in Florida have one of the highest rates of car insurance in the U.S.[290][291] 24% are uninsured.[292]

Drivers between 15 and 19 years of age averaged 364 car crashes a year per ten thousand licensed Florida drivers in 2010. Drivers 70 and older averaged 95 per 10,000 during the same time frame. A spokesperson for the non-profit Insurance Institute stated "Older drivers are more of a threat to themselves."[293]

Intercity bus travel, which utilizes Florida's highway system, is provided by Greyhound, Megabus, and Amtrak Thruway.