Multiple sclerosis

This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources, specifically: references that do not meet Wikipedia's guidelines for medical content, or are excessively dated, are contained in this article. (July 2022) |  |

| Multiple sclerosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Multiple cerebral sclerosis, multiple cerebro-spinal sclerosis, disseminated sclerosis, encephalomyelitis disseminata |

| |

| CD68-stained tissue shows several macrophages in the area of a demyelinated lesion caused by MS. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

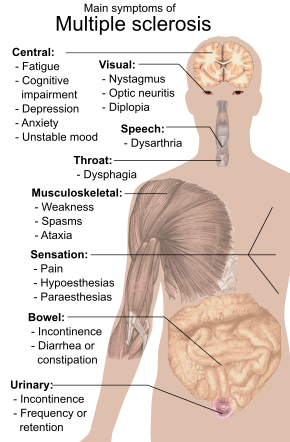

| Symptoms | Variable, including almost any neurological symptom or sign, with autonomic, visual, motor, and sensory problems being the most common.[1] |

| Usual onset | Age 20–50[2] |

| Duration | Long term[3] |

| Causes | Unknown[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and medical tests[5] |

| Treatment | |

| Frequency | 0.032% (world) |

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease in which the insulating covers of nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord are damaged.[3] This damage disrupts the ability of parts of the nervous system to transmit signals, resulting in a range of signs and symptoms, including physical, mental, and sometimes psychiatric problems.[1][8][9] Symptoms include double vision, vision loss, eye pain, muscle weakness, and loss of sensation or coordination.[3][10][11] MS takes several forms, with new symptoms either occurring in isolated attacks (relapsing forms) or building up over time (progressive forms).[12][13] In relapsing forms of MS, between attacks, symptoms may disappear completely, although some permanent neurological problems often remain, especially as the disease advances.[13] In progressive forms of MS, bodily function slowly deteriorates once symptoms manifest and will steadily worsen if left untreated.[14]

While its cause is unclear, the underlying mechanism is thought to be either destruction by the immune system or failure of the myelin-producing cells.[4] Proposed causes for this include immune dysregulation, genetics, and environmental factors, such as viral infections.[15][16][8][17] MS is usually diagnosed based on the presenting signs and symptoms and the results of supporting medical tests.[5]

No cure for multiple sclerosis is known.[18] Current treatments are aimed at mitigating inflammation and resulting symptoms from acute flares and prevention of further attacks with disease-modifying medications.[8][19] Physical therapy[7] and occupational therapy,[20] along with patient-centered symptom management, can help with people's ability to function. The long-term outcome is difficult to predict; better outcomes are more often seen in women, those who develop the disease early in life, those with a relapsing course, and those who initially experienced few attacks.[21]

Multiple sclerosis is the most common immune-mediated disorder affecting the central nervous system.[22] Nearly one million people in the United States had MS in 2022,[23] and in 2020, about 2.8 million people were affected globally, with rates varying widely in different regions and among different populations.[24] The disease usually begins between the ages of 20 and 50 and is twice as common in women as in men.[2] MS was first described in 1868 by French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot.[25]

The name "multiple sclerosis" is short for multiple cerebro-spinal sclerosis, which refers to the numerous glial scars (or sclerae – essentially plaques or lesions) that develop on the white matter of the brain and spinal cord.[25]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

As multiple sclerosis (MS) lesions can affect any part of the central nervous system, a person with MS can have almost any neurological symptom or sign referable to the central nervous system.

Fatigue[26] is one of the most common symptoms of MS.[27][28] Some 65% of people with MS experience fatigue symptomatology, and of these, some 15–40% report fatigue as their most disabling MS symptom.[29]

Autonomic, visual, motor, and sensory problems are also among the most common symptoms.[1]

The specific symptoms are determined by the locations of the lesions within the nervous system, and may include focal loss of sensitivity and/or changes in sensation in the limbs, such as feeling tingling, pins and needles, or numbness; limb motor weakness/pain, blurred vision,[30] pronounced reflexes, muscle spasms, difficulty with ambulation (walking), difficulties with coordination and balance (ataxia); problems with speech[31] or swallowing, visual problems (optic neuritis manifesting as eye pain & vision loss,[32] or nystagmus manifesting as double vision), fatigue, and bladder and bowel difficulties (such as urinary and/or fecal incontinence or retention), among others.[1] When multiple sclerosis is more advanced, walking difficulties can occur and the risk of falling increases.[33][19][34]

Difficulties thinking and emotional problems such as depression or unstable mood are also common.[1][35] The primary deficit in cognitive function that people with MS experience is slowed information-processing speed, with memory also commonly affected, and executive function less commonly. Intelligence, language, and semantic memory are usually preserved, and the level of cognitive impairment varies considerably between people with MS.[36][37][38]

Uhthoff's phenomenon, a worsening of symptoms due to exposure to higher-than-usual temperatures, and Lhermitte's sign, an electrical sensation that runs down the back when bending the neck, are particularly characteristic of MS, although may not always be present.[1] Another presenting manifestation that is rare but highly suggestive of a demyelinating process such as MS is bilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia, where the patient experiences double vision when attempting to move their gaze to the right & left.[39]

Some 60% or more of MS patients find their symptoms, particularly including fatigue,[40] are affected by changes in body temperature.[41][42][43]

Measures of disability

[edit]The main measure of disability and severity is the expanded disability status scale (EDSS), with other measures such as the multiple sclerosis functional composite being increasingly used in research.[44][45][46] EDSS is also correlated with falls in people with MS.[10] While it is a popular measure, EDSS has been criticized for some of its limitations, such as relying too much on walking.[47][10]

Disease course

[edit]Prodromal phase

[edit]MS may have a prodromal phase in the years leading up to its manifestation, characterized by psychiatric issues, cognitive impairment, and increased use of healthcare.[48][49]

Onset

[edit]The condition begins in 85% of cases as a clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) over a number of days with 45% having motor or sensory problems, 20% having optic neuritis,[32] and 10% having symptoms related to brainstem dysfunction, while the remaining 25% have more than one of the previous difficulties.[5] Regarding optic neuritis as the most common presenting symptom, people with MS notice sub-acute loss of vision, often associated with pain worsening on eye movement, and reduced colour vision. Early diagnosis of MS-associated optic neuritis helps timely initiation of targeted treatments. However, it is crucial to adhere to established diagnostic criteria when treating optic neuritis due to the broad range of alternative causes, such as neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), and other autoimmune or infectious conditions. The course of symptoms occurs in two main patterns initially: either as episodes of sudden worsening that last a few days to months (called relapses, exacerbations, bouts, attacks, or flare-ups) followed by improvement (85% of cases) or as a gradual worsening over time without periods of recovery (10–15% of cases).[2] A combination of these two patterns may also occur[13] or people may start in a relapsing and remitting course that then becomes progressive later on.[2]

Relapses

[edit]Relapses are usually unpredictable, occurring without warning.[1] Exacerbations rarely occur more frequently than twice per year.[1] Some relapses, however, are preceded by common triggers and they occur more frequently during spring and summer.[50] Similarly, viral infections such as the common cold, influenza, or gastroenteritis increase their risk.[1] Stress may also trigger an attack.[51]

Many events have been found not to affect rates of relapse requiring hospitalization including vaccination,[52][53] breast feeding,[1] physical trauma,[54] and Uhthoff's phenomenon.[50]

Pregnancy

[edit]Many women with MS who become pregnant experience lower symptoms[55][56][57] and fewer relapses.[56][58] During the first months after delivery, the risk increases.[1] Overall, pregnancy does not seem to influence long-term disability.[1]

Causes

[edit]Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disease with a combination of genetic and environmental causes underlying it. Both T-cells and B-cells are involved, although T-cells are often considered to be the driving force of the disease. The causes of the disease are not fully understood. The Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) has been shown to be directly present in the brain of most cases of MS and the virus is transcriptionally active in infected cells.[59][60] EBV nuclear antigens are believed to be involved in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis, but not all people with MS have signs of EBV infection.[15] Dozens of human peptides have been identified in different cases of the disease, and while some have plausible links to infectious organisms or known environmental factors, others do not.[61]

Immune dysregulation

[edit]Failure of both central and peripheral nervous system clearance of autoreactive immune cells is implicated in the development of MS.[15] The thymus is responsible for the immune system's central tolerance, where autoreactive T-cells are killed without being released into circulation. Via a similar mechanism, autoreactive B-cells in the bone marrow are killed. Some autoreactive T-cells & B-cells may escape these defense mechanisms, which is where peripheral immune tolerance defenses take action by preventing them from causing disease. However, these additional lines of defense can still fail.[15][19] Further detail on immune dysregulation's contribution to MS risk is provided in the pathophysiology section of this article as well as the standalone article on the pathophysiology of MS.

Infectious agents

[edit]Early evidence suggested the association between several viruses with human demyelinating encephalomyelitis, and the occurrence of demyelination in animals caused by some viral infections.[62] One such virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), can cause infectious mononucleosis and infects about 95% of adults, though only a small proportion of those infected later develop MS.[63][16][64][60] A study of more than 10 million US military members compared 801 people who developed MS to 1,566 matched controls who did not develop MS. The study found a 32-fold increased risk of developing MS after infection with EBV. It did not find an increased risk after infection with other viruses, including the similar cytomegalovirus. These findings strongly suggest that EBV plays a role in MS onset, although EBV alone may be insufficient to cause it.[16][64]

The nuclear antigen of EBV, which is the most consistent marker of EBV infection across all strains,[65] has been identified as a direct source of autoreactivity in the human body. These antigens appear to be more likely to promote autoimmune responses in a person who also has a vitamin D deficiency. The exact nature of this relationship is poorly understood.[66][15]

Genetics

[edit]

MS is not considered a hereditary disease, but several genetic variations have been shown to increase its risk.[67] Some of these genes appear to have higher expression levels in microglial cells than expected by chance.[68] The probability of developing MS is higher in relatives of an affected person, with a greater risk among those more closely related.[8] An identical twin of an affected individual has a 30% chance of developing MS, 5% for a nonidentical twin, 2.5% for a sibling, and an even lower chance for a half sibling.[1][8][69] If both parents are affected, the risk in their children is 10 times that of the general population.[2] MS is also more common in some ethnic groups than others.[70]

Specific genes that have been linked with MS include differences in the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system—a group of genes on chromosome 6 that serves as the major histocompatibility complex (MHC).[1] The contribution of HLA variants to MS susceptibility has been known since the 1980s,[71] and this same region has also been implicated in the development of other autoimmune diseases, such as type 1 diabetes and systemic lupus erythematosus.[71] The most consistent finding is the association between higher risk of developing multiple sclerosis and the MHC allele DR15, which is present in 30% of the U.S. and Northern European population.[15][1] Other loci exhibit a protective effect, such as HLA-C554 and HLA-DRB1*11.[1] HLA differences account for an estimated 20 to 60% of the genetic predisposition.[71] Genome-wide association studies have revealed at least 200 variants outside the HLA locus that affect the risk of MS.[72]

Geography

[edit]

The prevalence of MS from a geographic standpoint resembles a gradient, with MS being more common in people who live farther from the equator (e.g. those who live in northern regions of the world), although exceptions exist.The cause of this geographical pattern is not clear, although exposure to ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation and vitamin D levels have been proposed as potential explanations.[73][15] As such, those who live in northern regions of the world are thought to have less exposure to UVB radiation and subsequently lower levels of vitamin D, which is a known risk factor for developing MS.[15] Inversely, those who live in areas of relatively higher sun exposure and subsequently increased UVB radiation have a decreased risk of developing MS.[15] While the north–south gradient of incidence is decreasing,[74] as of 2010, it is still present.[73]

MS is more common in regions with northern European populations,[1] so the geographic variation may simply reflect the global distribution of these high-risk populations.[2]

A relationship between season of birth and MS lends support to this idea, with fewer people born in the Northern Hemisphere in November compared to May being affected later in life.[75]

Environmental factors may play a role during childhood, with several studies finding that people who move to a different region of the world before the age of 15 acquire the new region's risk of MS. If migration takes place after age 15, the persons retain the risk of their home country.[1][76] Some evidence indicates that the effect of moving may still apply to people older than 15.[1]

There are some exceptions to the above mentioned geographic pattern. These include ethnic groups that are at low risk and that live far from the equator such as the Sami, Amerindians, Canadian Hutterites, New Zealand Māori,[77] and Canada's Inuit,[73] as well as groups that have a relatively high risk and that live closer to the equator such as Sardinians,[73] inland Sicilians,[78] Palestinians, and Parsi.[77]

Impact of temperature

[edit]MS symptoms may increase if body temperature is dysregulated.[79][80][81] Fatigue is particularly effected.[40][41][42][43][82][83][84][85]

Other

[edit]Smoking may be an independent risk factor for MS.[86] Stress may also be a risk factor, although the evidence to support this is weak.[76] Association with occupational exposures and toxins—mainly organic solvents[87]—has been evaluated, but no clear conclusions have been reached.[76] Vaccinations were studied as causal factors; most studies, though, show no association.[76][88] Several other possible risk factors, such as diet and hormone intake, have been evaluated, but evidence on their relation with the disease is "sparse and unpersuasive".[86] Gout occurs less than would be expected and lower levels of uric acid have been found in people with MS. This has led to the theory that uric acid is protective, although its exact importance remains unknown.[89] Obesity during adolescence and young adulthood is a risk factor for MS.[90]

Pathophysiology

[edit]

Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disease, primarily mediated by T-cells.[15] The three main characteristics of MS are the formation of lesions in the central nervous system (also called plaques), inflammation, and the destruction of myelin sheaths of neurons. These features interact in a complex and not yet fully understood manner to produce the breakdown of nerve tissue, and in turn, the signs and symptoms of the disease.[1] Damage is believed to be caused, at least in part, by attack on the nervous system by a person's own immune system.[1]

Immune dysregulation

[edit]As briefly detailed in the causes section of this article, MS is currently thought to stem from a failure of the body's immune system to kill off autoreactive T-cells & B-cells.[15] Currently, the T-cell subpopulations that are thought to drive the development of MS are autoreactive CD8+ T-cells, CD4+ helper T-cells, and TH17 cells. These autoreactive T-cells produce substances called cytokines that induce an inflammatory immune response in the CNS, leading to the development of the disease.[15] More recently, however, the role of autoreactive B-cells has been elucidated. Evidence of their contribution to the development of MS is implicated through the presence of oligoclonal IgG bands (antibodies produced by B-cells) in the CSF of patients with MS.[15][19] The presence of these oligoclonal bands has been used as supportive evidence in clinching a diagnosis of MS.[91] As similarly described before, B-cells can also produce cytokines that induce an inflammatory immune response via activation of autoreactive T-cells.[15][92] As such, higher levels of these autoreactive B-cells is associated with increased number of lesions & neurodegeneration as well as worse disability.[15]

Another cell population that is becoming increasingly implicated in MS are microglia. These cells are resident to & keep watch over the CNS, responding to pathogens by shifting between pro- & anti-inflammatory states. Microglia have been shown to be involved in the formation of MS lesions and have been shown to be involved in other diseases that primarily affect the CNS white matter. Although, because of their ability to switch between pro- & anti-inflammatory states, microglia have also been shown to be able to assist in remyelination & subsequent neuron repair.[15] As such, microglia are thought to be participating in both acute & chronic MS lesions, with 40% of phagocytic cells in early active MS lesions being proinflammatory microglia.[15]

Lesions

[edit]

The name multiple sclerosis refers to the scars (sclerae – better known as plaques or lesions) that form in the nervous system. These lesions most commonly affect the white matter in the optic nerve, brain stem, basal ganglia, and spinal cord, or white matter tracts close to the lateral ventricles.[1] The function of white matter cells is to carry signals between grey matter areas, where the processing is done, and the rest of the body. The peripheral nervous system is rarely involved.[8]

To be specific, MS involves the loss of oligodendrocytes, the cells responsible for creating and maintaining a fatty layer—known as the myelin sheath—which helps the neurons carry electrical signals (action potentials).[1] This results in a thinning or complete loss of myelin, and as the disease advances, the breakdown of the axons of neurons. When the myelin is lost, a neuron can no longer effectively conduct electrical signals.[8] A repair process, called remyelination, takes place in early phases of the disease, but the oligodendrocytes are unable to completely rebuild the cell's myelin sheath.[93] Repeated attacks lead to successively less effective remyelinations, until a scar-like plaque is built up around the damaged axons.[93] These scars are the origin of the symptoms and during an attack magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) often shows more than 10 new plaques.[1] This could indicate that some number of lesions exist, below which the brain is capable of repairing itself without producing noticeable consequences.[1] Another process involved in the creation of lesions is an abnormal increase in the number of astrocytes due to the destruction of nearby neurons.[1] A number of lesion patterns have been described.[94]

Inflammation

[edit]Apart from demyelination, the other sign of the disease is inflammation. Fitting with an immunological explanation, the inflammatory process is caused by T cells, a kind of lymphocytes that plays an important role in the body's defenses.[8] T cells gain entry into the brain as a result of disruptions in the blood–brain barrier. The T cells recognize myelin as foreign and attack it, explaining why these cells are also called "autoreactive lymphocytes".[1]

The attack on myelin starts inflammatory processes, which trigger other immune cells and the release of soluble factors like cytokines and antibodies. A further breakdown of the blood-brain barrier, in turn, causes a number of other damaging effects, such as swelling, activation of macrophages, and more activation of cytokines and other destructive proteins.[8] Inflammation can potentially reduce transmission of information between neurons in at least three ways.[1] The soluble factors released might stop neurotransmission by intact neurons. These factors could lead to or enhance the loss of myelin, or they may cause the axon to break down completely.[1]

Blood–brain barrier

[edit]The blood–brain barrier (BBB) is a part of the capillary system that prevents the entry of T cells into the central nervous system. It may become permeable to these types of cells secondary to an infection by a virus or bacteria. After it repairs itself, typically once the infection has cleared, T cells may remain trapped inside the brain.[8][95] Gadolinium cannot cross a normal BBB, so gadolinium-enhanced MRI is used to show BBB breakdowns.[96]

MS fatigue

[edit]The pathophysiology and mechanisms causing MS fatigue are not well understood.[97][98][99] MS fatigue can be affected by body heat,[79][81] and this may differentiate MS fatigue from other primary fatigue.[40][41][85] Fatigability (loss of strength) may increase perception of fatigue, but the two measures warrant independent assessment in clinical studies.[100]

Diagnosis

[edit]

Multiple sclerosis is typically diagnosed based on the presenting signs and symptoms, in combination with supporting medical imaging and laboratory testing.[5] It can be difficult to confirm, especially early on, since the signs and symptoms may be similar to those of other medical problems.[1][101]

McDonald criteria

[edit]The McDonald criteria, which focus on clinical, laboratory, and radiologic evidence of lesions at different times and in different areas, is the most commonly used method of diagnosis[102] with the Schumacher and Poser criteria being of mostly historical significance.[103] The McDonald criteria states that patients with multiple sclerosis should have lesions which are disseminated in time (DIT) and disseminated in space (DIS), i.e. lesions which have appeared in different areas in the brain and at different times.[91] Below is an abbreviated outline of the 2017 McDonald Criteria for diagnosis of MS.

- At least 2 clinical attacks with MRI showing 2 or more lesions characteristic of MS.[91]

- At least 2 clinical attacks with MRI showing 1 lesion characteristic of MS with clear historical evidence of a previous attack involving a lesion at a distinct location in the CNS.[91]

- At least 2 clinical attacks with MRI showing 1 lesion characteristic of MS, with DIT established by an additional clinical attack at a distinct CNS site or by MRI showing an old MS lesion.[91]

- 1 clinical attack with MRI showing at least 2 lesions characteristic of MS, with DIT established by an additional attack, by MRI showing old MS lesion(s), or presence of oligoclonal bands in CSF.[91]

- 1 clinical attack with MRI showing 1 lesion characteristic of MS, with DIS established by an additional attack at a different CNS site or by MRI showing old MS lesion(s), and DIT established by an additional attack, by MRI showing old MS lesion(s), or presence of oligoclonal bands in CSF.[91]

As of 2017[update], no single test (including biopsy) can provide a definitive diagnosis.[104]

MRI

[edit]Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and spine may show areas of demyelination (lesions or plaques). Gadolinium can be administered intravenously as a contrast agent to highlight active plaques, and by elimination, demonstrate the existence of historical lesions not associated with symptoms at the moment of the evaluation.[105][106]

Central vein signs (CVSs) have been proposed as a good indicator of MS in comparison with other conditions causing white lesions.[107][108][109][110] One small study found fewer CVSs in older and hypertensive people.[111] Further research on CVS as a biomarker for MS is ongoing.[112]

Cerebrospinal fluid (lumbar puncture)

[edit]Testing of cerebrospinal fluid obtained from a lumbar puncture can provide evidence of chronic inflammation in the central nervous system. The cerebrospinal fluid is tested for oligoclonal bands of IgG on electrophoresis, which are inflammation markers found in 75–85% of people with MS.[105][113]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]Several diseases present similarly to MS.[114][115] Medical professionals use a patient's specific presentation, history, and exam findings to make an individualized differential. Red flags are findings that suggest an alternate diagnosis, although they do not rule out MS. Red flags include a patient younger than 15 or older than 60, less than 24 hours of symptoms, involvement of multiple cranial nerves, involvement of organs outside of the nervous system, and atypical lab and exam findings.[114][115]

In an emergency setting, it is important to rule out a stroke or bleeding in the brain.[115] Intractable vomiting, severe optic neuritis,[32] or bilateral optic neuritis[32] raises suspicion for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD).[116] Infectious diseases that may look similar to multiple sclerosis include HIV, Lyme disease, and syphilis. Autoimmune diseases include neurosarcoidosis, lupus, Guillain-Barré syndrome, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and Behçet's disease. Psychiatric conditions such as anxiety or conversion disorder may also present in a similar way. Other rare diseases on the differential include CNS lymphoma, congenital leukodystrophies, and anti-MOG-associated myelitis.[114][115]

Types and variants

[edit]

Several phenotypes (commonly termed "types"), or patterns of progression, have been described. Phenotypes use the past course of the disease in an attempt to predict the future course. They are important not only for prognosis, but also for treatment decisions.

The International Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of MS describes four types of MS (revised in 2013) in what is known as the Lublin classification:[117][118]

- Clinically isolated syndrome (CIS)

- Relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS)

- Primary progressive MS (PPMS)

- Secondary progressive MS (SPMS)

CIS can be characterised as a single lesion seen on MRI which is associated with signs and/or symptoms found in MS. Due to the McDonald criteria, it does not completely fit the criteria to be diagnosed as MS, hence being named "clinically isolated syndrome". CIS can be seen as the first episode of demyelination in the central nervous system. To be classified as CIS, the attack must last at least 24 hours and be caused by inflammation or demyelination of the central nervous system.[1][119] Patients who suffer from CIS may or may not go on to develop MS, but 30 to 70% of persons who experience CIS will later develop MS.[120]

RRMS is characterized by unpredictable relapses followed by periods of months to years of relative quiet (remission) with no new signs of disease activity. Deficits that occur during attacks may either resolve or leave problems, the latter in about 40% of attacks and being more common the longer a person has had the disease.[1][5] This describes the initial course of 80% of individuals with MS.[1]

PPMS occurs in roughly 10–20% of individuals with the disease, with no remission after the initial symptoms.[5][121] It is characterized by progression of disability from onset, with no, or only occasional and minor, remissions and improvements.[13] The usual age of onset for the primary progressive subtype is later than of the relapsing-remitting subtype. It is similar to the age that secondary progressive usually begins in RRMS, around 40 years of age.[1]

SPMS occurs in around 65% of those with initial RRMS, who eventually have progressive neurologic decline between acute attacks without any definite periods of remission.[1][13] Occasional relapses and minor remissions may appear.[13] The most common length of time between disease onset and conversion from RRMS to SPMS is 19 years.[122]

Special courses

[edit]Independently of the types published by the MS associations, regulatory agencies such as the FDA often consider special courses, trying to reflect some clinical trials results on their approval documents. Some examples could be "highly active MS" (HAMS),[123] "active secondary MS" (similar to the old progressive-relapsing)[124] and "rapidly progressing PPMS".[125]

Also, deficits always resolving between attacks is sometimes referred to as "benign" MS,[126] although people still build up some degree of disability in the long term.[1] On the other hand, the term malignant multiple sclerosis is used to describe people with MS having reached significant level of disability in a short period.[127]

An international panel has published a standardized definition for the course HAMS.[123]

Variants

[edit]Atypical variants of MS have been described; these include tumefactive multiple sclerosis, Balo concentric sclerosis, Schilder's diffuse sclerosis, and Marburg multiple sclerosis. Debate remains on whether they are MS variants or different diseases.[128] Some diseases previously considered MS variants, such as Devic's disease, are now considered outside the MS spectrum.[129]

Management

[edit]Although no cure for multiple sclerosis has been found, several therapies have proven helpful. Several effective treatments can decrease the number of attacks and the rate of progression.[23] The primary aims of therapy are returning function after an attack, preventing new attacks, and preventing disability. Starting medications is generally recommended in people after the first attack when more than two lesions are seen on MRI.[130]

The first approved medications used to treat MS were modestly effective, though were poorly tolerated and had many adverse effects.[3] Several treatment options with better safety and tolerability profiles have been introduced,[23] improving the prognosis of MS.

As with any medical treatment, medications used in the management of MS have several adverse effects. Alternative treatments are pursued by some people, despite the shortage of supporting evidence of efficacy.

Initial management of acute flare

[edit]During symptomatic attacks, administration of high doses of intravenous corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone, is the usual therapy,[1] with oral corticosteroids seeming to have a similar efficacy and safety profile.[131] Although effective in the short term for relieving symptoms, corticosteroid treatments do not appear to have a significant impact on long-term recovery.[132][133] The long-term benefit is unclear in optic neuritis as of 2020.[134][32] The consequences of severe attacks that do not respond to corticosteroids might be treatable by plasmapheresis.[1]

Chronic management

[edit]Relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis

[edit]Multiple disease-modifying medications were approved by regulatory agencies for RRMS; they are modestly effective at decreasing the number of attacks.[135] Interferons[136] and glatiramer acetate are first-line treatments[5] and are roughly equivalent, reducing relapses by approximately 30%.[137] Early-initiated long-term therapy is safe and improves outcomes.[138][139]

Treatment of CIS with interferons decreases the chance of progressing to clinical MS.[1][140][141] Efficacy of interferons and glatiramer acetate in children has been estimated to be roughly equivalent to that of adults.[142] The role of some newer agents such as fingolimod,[143] teriflunomide, and dimethyl fumarate,[144] is not yet entirely clear.[145] Making firm conclusions about the best treatment is difficult, especially regarding the long‐term benefit and safety of early treatment, given the lack of studies directly comparing disease-modifying therapies or long-term monitoring of patient outcomes.[146]

The relative effectiveness of different treatments is unclear, as most have only been compared to placebo or a small number of other therapies.[147] Direct comparisons of interferons and glatiramer acetate indicate similar effects or only small differences in effects on relapse rate, disease progression, and MRI measures.[148] There is high confidence that natalizumab, cladribine, or alemtuzumab are decreasing relapses over a period of two years for people with RRMS.[149] Natalizumab and interferon beta-1a (Rebif) may reduce relapses compared to both placebo and interferon beta-1a (Avonex) while Interferon beta-1b (Betaseron), glatiramer acetate, and mitoxantrone may also prevent relapses.[147] Evidence on relative effectiveness in reducing disability progression is unclear.[147] There is moderate confidence that a two-year treatment with natalizumab slows disability progression for people with RRMS.[149] All medications are associated with adverse effects that may influence their risk to benefit profiles.[147][149]

Ublituximab was approved for medical use in the United States in December 2022.[150]

Medications

[edit]Overview of medications available for MS.[151]

| Medication | Compound | Producer | Use | Efficacy (annualized relapse reduction rate) | Annualized relapse rate (ARR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avonex | Interferon beta-1a | Biogen | Intramuscular | 30% | 0.25 |

| Rebif | Interferon beta-1a | Merck Serono | Subcutaneous | 30% | 0.256 |

| Extavia | Interferon beta-1b | Bayer Schering | Subcutaneous | 30% | 0.256 |

| Copaxone | Glatiramer acetate | Teva Pharmaceuticals | Subcutaneous | 30% | 0.3 |

| Aubagio | Teriflunomide | Genzyme | Oral | 30% | 0.35 |

| Plegridy | Interferon beta-1a | Biogen | Subcutaneous | 30% | 0.12 |

| Tecfidera | Dimethyl fumarate | Biogen | Oral | 50% | 0.15 |

| Vumerity | Diroximel fumarate | Biogen | Oral | 50% | 0.11-0.15 |

| Gilenya | Fingolimod | Oral | 50% | 0.22-0.25 | |

| Zeposia | Ozanimod | [better source needed] | Oral | 0.18-0.24 | |

| Kesimpta | Ofatumumab | Subcutaneous | 70% | 0.09-0.14 | |

| Mavenclad | Cladribine | Oral | 70% | 0.1-0.14 | |

| Lemtrada | Alemtuzumab | Intravenous | 70% | 0.08 | |

| Ocrevus | Ocrelizumab | Intravenous | 70% | 0.09 |

Progressive multiple sclerosis

[edit]In 2011, mitoxantrone was the first medication approved for secondary progressive MS.[152] In this population, tentative evidence supports mitoxantrone moderately slowing the progression of the disease and decreasing rates of relapses over two years.[153][154]

New approved medications continue to emerge in modern medicine. In March 2017, the FDA approved ocrelizumab as a treatment for primary progressive MS in adults, the first drug to gain that approval,[155][156][157] with requirements for several Phase IV clinical trials.[158] It is also used for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis, to include clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting disease, and active secondary progressive disease in adults.[157] According to a 2021 Cochrane review, ocrelizumab may reduce worsening of symptoms for primary progressive MS and probably increases unwanted effects but makes little or no difference to the number of serious unwanted effects.[159]

In 2019, siponimod and cladribine were approved in the United States for the treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS).[155] Subsequently, ozanimod was approved in 2020, and ponesimod was approved in 2021, which were both approved for management of CIS, relapsing MS, and SPMS in the U.S., and RRMS in Europe.[160]

Adverse effects

[edit]

The disease-modifying treatments have several adverse effects. One of the most common is irritation at the injection site for glatiramer acetate and the interferons (up to 90% with subcutaneous injections and 33% with intramuscular injections).[136][161] Over time, a visible dent at the injection site, due to the local destruction of fat tissue, known as lipoatrophy, may develop.[161] Interferons may produce flu-like symptoms;[162] some people taking glatiramer experience a post-injection reaction with flushing, chest tightness, heart palpitations, and anxiety, which usually lasts less than thirty minutes.[163] More dangerous but much less common are liver damage from interferons,[164] systolic dysfunction (12%), infertility, and acute myeloid leukemia (0.8%) from mitoxantrone,[153][165] and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy occurring with natalizumab (occurring in 1 in 600 people treated).[5][166]

Fingolimod may give rise to hypertension and slowed heart rate, macular edema, elevated liver enzymes, or a reduction in lymphocyte levels.[143][145] Tentative evidence supports the short-term safety of teriflunomide, with common side effects including: headaches, fatigue, nausea, hair loss, and limb pain.[135] There have also been reports of liver failure and PML with its use and it is dangerous for fetal development.[145] Most common side effects of dimethyl fumarate are flushing and gastrointestinal problems.[144][167][145] While dimethyl fumarate may lead to a reduction in the white blood cell count there were no reported cases of opportunistic infections during trials.[168]

Associated symptoms

[edit]Both medications and neurorehabilitation have been shown to improve some symptoms, though neither changes the course of the disease.[169] Some symptoms have a good response to medication, such as bladder spasticity, while others are little changed.[1] Equipment such as catheters for neurogenic bladder dysfunction or mobility aids can be helpful in improving functional status.

A multidisciplinary approach is important for improving quality of life; however, it is difficult to specify a 'core team' as many health services may be needed at different points in time.[1] Multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs increase activity and participation of people with MS but do not influence impairment level.[170] Studies investigating information provision in support of patient understanding and participation suggest that while interventions (written information, decision aids, coaching, educational programmes) may increase knowledge, the evidence of an effect on decision making and quality of life is mixed and low certainty.[171] There is limited evidence for the overall efficacy of individual therapeutic disciplines,[172][173] though there is good evidence that specific approaches, such as exercise,[174][175][176][177] and psychological therapies are effective.[178] Cognitive training, alone or combined with other neuropsychological interventions, may show positive effects for memory and attention though firm conclusions are not possible given small sample numbers, variable methodology, interventions and outcome measures.[179] The effectiveness of palliative approaches in addition to standard care is uncertain, due to lack of evidence.[180] The effectiveness of interventions, including exercise, specifically for the prevention of falls in people with MS is uncertain, while there is some evidence of an effect on balance function and mobility.[181] Cognitive behavioral therapy has shown to be moderately effective for reducing MS fatigue.[182] The evidence for the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for chronic pain is insufficient to recommend such interventions alone, however their use in combination with medications may be reasonable.[183]

Non-pharmaceutical

[edit]There is some evidence that aquatic therapy is a beneficial intervention.[184]

The spasticity associated with MS can be difficult to manage because of the progressive and fluctuating course of the disease.[185] Although there is no firm conclusion on the efficacy in reducing spasticity, PT interventions can be a safe and beneficial option for patients with multiple sclerosis. Physical therapy including vibration interventions, electrical stimulation, exercise therapy, standing therapy, and radial shock wave therapy (RSWT), were beneficial for limiting spasticity, helping limit excitability, or increasing range of motion.[186]

Alternative treatments

[edit]Over 50% of people with MS may use complementary and alternative medicine, although percentages vary depending on how alternative medicine is defined.[187] Regarding the characteristics of users, they are more frequently women, have had MS for a longer time, tend to be more disabled and have lower levels of satisfaction with conventional healthcare.[187] The evidence for the effectiveness for such treatments in most cases is weak or absent.[187][188] Treatments of unproven benefit used by people with MS include dietary supplementation and regimens,[187][189][190] vitamin D,[191] relaxation techniques such as yoga,[187] herbal medicine (including medical cannabis),[187][192][193] hyperbaric oxygen therapy,[194] self-infection with hookworms, reflexology, acupuncture,[187][195] and mindfulness.[196] Evidence suggests vitamin D supplementation, irrespective of the form and dose, provides no benefit for people with MS; this includes for measures such as relapse recurrence, disability, and MRI lesions while effects on health‐related quality of life and fatigue are unclear.[197] There is insufficient evidence supporting high-dose biotin[198][199][200] and some evidence for increased disease activity and higher risk of relapse with its use.[201] A recent review of the effectiveness of Cannabis and Cannabinoids (2022) found that compared with placebo nabiximols probably reduce the severity of spasticity in the short term.[202]

Prognosis

[edit]The availability of treatments that modify the course of multiple sclerosis beginning in the 1990s, known as disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), has improved prognosis. These treatments can reduce relapses and slow progression, but there is no cure.[23][203]

The prognosis of MS depends on the subtype of the disease, and there is considerable individual variation in the progression of the disease.[204] In relapsing MS, the most common subtype, a 2016 cohort study found that after a median of 16.8 years from onset, one in ten needed a walking aid, and almost two in ten transitioned to secondary progressive MS, a form characterized by more progressive decline.[23] With treatments available in the 2020s, relapses can be eliminated or substantially reduced. However, "silent progression" of the disease still occurs.[203][205]

In addition to secondary progressive MS (SPMS), a small proportion of people with MS (10–15%) experience progressive decline from the onset, known as primary progressive MS (PPMS). Most treatments have been approved for use in relapsing MS; there are fewer treatments with lower efficacy for progressive forms of MS.[206][203][23] The prognosis for progressive MS is worse, with faster accumulation of disability, though with considerable individual variation.[206] In untreated PPMS, the median time from onset to requiring a walking aid is estimated as seven years.[23] In SPMS, a 2014 cohort study reported that people required a walking aid after an average of five years from onset of SPMS, and were chair or bed-bound after an average of fifteen years.[207]

After diagnosis of MS, characteristics that predict a worse course are male sex, older age, and greater disability at the time of diagnosis; female sex is associated with a higher relapse rate.[208] Currently, no biomarker can accurately predict disease progression in every patient.[204] Spinal cord lesions, abnormalities on MRI, and more brain atrophy are predictive of a worse course, though brain atrophy as a predictor of disease course is experimental and not used in clinical practice.[208] Early treatment leads to a better prognosis, but a higher relapse frequency when treated with DMTs is associated with a poorer prognosis.[204][208] A 60-year longitudinal population study conducted in Norway found that those with MS had a life expectancy seven years shorter than the general population. Median life expectancy for RRMS patients was 77.8 years and 71.4 years for PPMS, compared to 81.8 years for the general population. Life expectancy for men was five years shorter than for women.[209]

Epidemiology

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (July 2022) |

MS is the most common autoimmune disorder of the central nervous system.[22] The latest estimation of the total number of people with MS was 2.8 million globally, with a prevalence of 36 per 100,000 people. Moreover, prevalence varies widely in different regions around the world.[24] In Africa, there are five people per 100,000 diagnosed with MS, compared to South East Asia where the prevalence is nine per 100,000, 112 per 100,000 in the Americas, and 133 per 100,000 in Europe.[210]

Increasing rates of MS may be explained simply by better diagnosis.[2] Studies on populational and geographical patterns have been common[211] and have led to a number of theories about the cause.[17][76][86]

MS usually appears in adults in their late twenties or early thirties but it can rarely start in childhood and after 50 years of age.[2][102] The primary progressive subtype is more common in people in their fifties.[121] Similarly to many autoimmune disorders, the disease is more common in women, and the trend may be increasing.[1][212] As of 2020, globally it is about two times more common in women than in men, and the ratio of women to men with MS is as high as 4:1 in some countries.[213][medical citation needed] In children, it is even more common in females than males,[1] while in people over fifty, it affects males and females almost equally.[121]

History

[edit]Medical discovery

[edit]

Robert Carswell (1793–1857), a British professor of pathology, and Jean Cruveilhier (1791–1873), a French professor of pathologic anatomy, described and illustrated many of the disease's clinical details, but did not identify it as a separate disease.[214] Specifically, Carswell described the injuries he found as "a remarkable lesion of the spinal cord accompanied with atrophy".[1] Under the microscope, Swiss pathologist Georg Eduard Rindfleisch (1836–1908) noted in 1863 that the inflammation-associated lesions were distributed around blood vessels.[215][216]

The French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893) was the first person to recognize multiple sclerosis as a distinct disease in 1868.[214] Summarizing previous reports and adding his own clinical and pathological observations, Charcot called the disease sclerose en plaques.

Diagnosis history

[edit]The first attempt to establish a set of diagnostic criteria was also due to Charcot in 1868. He published what now is known as the "Charcot Triad", consisting in nystagmus, intention tremor, and telegraphic speech (scanning speech).[217] Charcot also observed cognition changes, describing his patients as having a "marked enfeeblement of the memory" and "conceptions that formed slowly".[25]

Diagnosis was based on Charcot triad and clinical observation until Schumacher made the first attempt to standardize criteria in 1965 by introducing some fundamental requirements: Dissemination of the lesions in time (DIT) and space (DIS), and that "signs and symptoms cannot be explained better by another disease process".[217] The DIT and DIS requirement was later inherited by the Poser and McDonald criteria, whose 2017 revision is in use.[217][204]

During the 20th century, theories about the cause and pathogenesis were developed and effective treatments began to appear in the 1990s.[1] Since the beginning of the 21st century, refinements of the concepts have taken place. The 2010 revision of the McDonald criteria allowed for the diagnosis of MS with only one proved lesion (CIS).[218]

In 1996, the US National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) (Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials) defined the first version of the clinical phenotypes that is in use. In this first version they provided standardized definitions for four MS clinical courses: relapsing-remitting (RR), secondary progressive (SP), primary progressive (PP), and progressive relapsing (PR). In 2010, PR was dropped and CIS was incorporated.[218] Three years later, the 2013 revision of the "phenotypes for the disease course" were forced to consider CIS as one of the phenotypes of MS, making obsolete some expressions like "conversion from CIS to MS".[219] Other organizations have proposed later new clinical phenotypes, like HAMS (Highly Active MS).[220]

Historical cases

[edit]

There are several historical accounts of people who probably had MS and lived before or shortly after the disease was described by Charcot.

A young woman called Halldora who lived in Iceland around 1200 suddenly lost her vision and mobility but recovered them seven days after. Saint Lidwina of Schiedam (1380–1433), a Dutch nun, may be one of the first clearly identifiable people with MS. From the age of 16 until her death at 53, she had intermittent pain, weakness of the legs and vision loss: symptoms typical of MS.[221] Both cases have led to the proposal of a "Viking gene" hypothesis for the dissemination of the disease.[222]

Augustus Frederick d'Este (1794–1848), son of Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex and Lady Augusta Murray and a grandson of George III of the United Kingdom, almost certainly had MS. D'Este left a detailed diary describing his 22 years living with the disease. His diary began in 1822 and ended in 1846, although it remained unknown until 1948. His symptoms began at age 28 with a sudden transient visual loss (amaurosis fugax) after the funeral of a friend. During his disease, he developed weakness of the legs, clumsiness of the hands, numbness, dizziness, bladder disturbance and erectile dysfunction. In 1844, he began to use a wheelchair. Despite his illness, he kept an optimistic view of life.[223][224] Another early account of MS was kept by the British diarist W. N. P. Barbellion, pen name of Bruce Frederick Cummings (1889–1919), who maintained a detailed log of his diagnosis and struggle.[224] His diary was published in 1919 as The Journal of a Disappointed Man.[225] Charles Dickens, a keen observer, described possible bilateral optic neuritis with reduced contrast vision and Uhthoff phenomenon in the main female character of Bleak House (1852–1853), Esther Summerville.[226]

Research

[edit]Epstein-Barr virus

[edit]As of 2022, the pathogenesis of MS as it relates to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is actively investigated, as are disease-modifying therapies; understanding of how risk factors combine with EBV to initiate MS is sought. Whether EBV is the only cause of MS might be better understood if an EBV vaccine is developed and shown to prevent MS as well.[16]

Even though a variety of studies showed the connection between an EBV infection and a later development of multiple sclerosis, the mechanisms behind this correlation are not completely clear, and several theories have been proposed to explain the relationship between the two diseases. It is thought that the involvement of EBV-infected B-cells (B lymphocytes)[227] and the involvement of anti-EBNA antibodies, which appear to be significantly higher in multiple sclerosis patients, play a crucial role in the development of the disease.[228] This is supported by the fact that treatment against B-cells, e.g. ocrelizumab, reduces the symptoms of multiple sclerosis: annual relapses appear less frequently and the disability progression is slower.[229] A 2022 Stanford University study has shown that during an EBV infection, molecular mimicry can occur, where the immune system will produce antibodies against the EBNA1 protein, which at the same time is able to bind to GlialCAM in the myelin. Additionally, they observed a phenomenon which is uncommon in healthy individuals but often detected in multiple sclerosis patients – B-cells are trafficking to the brain and spinal cord, where they are producing oligoclonal antibody bands. A majority of these oligoclonal bands do have an affinity to the viral protein EBNA1, which is cross-reactive to GlialCAM. These antibodies are abundant in approximately 20–25% of multiple sclerosis patients and worsen the autoimmune demyelination which leads consequently to an pathophysiologocal exacerbation of the disease. Furthermore, the intrathecal oligoclonal expansion with a constant somatic hypermutation is unique in multiple sclerosis when compared to other neuroinflammatory diseases. In the study there was also the abundance of antibodies with IGHV 3–7 genes measured, which appears to be connected to the disease progress. Antibodies which are IGHV3–7-based are binding with a high affinity to EBNA1 and GlialCAM. This process is actively thriving the demyelination. It is probable that B-cells, expressing IGHV 3–7 genes entered the CSF and underwent affinity maturation after facing GlialCAM, which led consequently to the production of high affinity anti-GlialCAM antibodies. This was additionally shown in the EAE mouse model where immunization with EBNA1 lead to a strong B-cell response against GlialCAM, which worsened the EAE.[230]

Human endogenous retroviruses

[edit]Two members of the human endogenous retroviruses-W (HERV-W) family, namely, ERVWE1 and MS-associated retrovirus (MSRV), may be co-factors in MS immunopathogenesis. HERVs constitute up to 8% of the human genome; most are epignetically silent, but can be reactivated by exogenous viruses, proinflammatory conditions and/or oxidative stress.[231][232][233]

Medications

[edit]Medications that influence voltage-gated sodium ion channels are under investigation as a potential neuroprotective strategy because of hypothesized role of sodium in the pathological process leading to axonal injury and accumulating disability. There is insufficient evidence of an effect of sodium channel blockers for people with MS.[234]

Pathogenesis

[edit]MS is a clinically defined entity with several atypical presentations. Some auto-antibodies have been found in atypical MS cases, giving birth to separate disease families and restricting the previously wider concept of MS.

Anti-AQP4 autoantibodies were found in neuromyelitis optica (NMO), which was previously considered a MS variant. A spectrum of diseases named NMOSD (NMO spectrum diseases) or anti-AQP4 diseases has been accepted.[235] Some cases of MS were presenting anti-MOG autoantibodies, mainly overlapping with the Marburg variant. Anti-MOG autoantibodies were found to be also present in ADEM, and a second spectrum of separated diseases is being considered. This spectrum is named inconsistently across different authors, but it is normally something similar to anti-MOG demyelinating diseases.[235]

A third kind of auto-antibodies is accepted. They are several anti-neurofascin auto-antibodies which damage the Ranvier nodes of the neurons. These antibodies are more related to the peripheral nervous demyelination, but they were also found in chronic progressive PPMS and combined central and peripheral demyelination (CCPD, which is considered another atypical MS presentation).[236]

In addition to the significance of auto-antibodies in MS, four different patterns of demyelination have been reported, opening the door to consider MS as a heterogeneous disease.[237]

Biomarkers

[edit]

Since disease progression is the result of degeneration of neurons, the roles of proteins showing loss of nerve tissue such as neurofilaments, tau, and N-acetylaspartate are under investigation.[239][240]

Improvement in neuroimaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET) or MRI carry a promise for better diagnosis and prognosis predictions. Regarding MRI, there are several techniques that have already shown some usefulness in research settings and could be introduced into clinical practice, such as double-inversion recovery sequences, magnetization transfer, diffusion tensor, and functional magnetic resonance imaging.[241] These techniques are more specific for the disease than existing ones, but still lack some standardization of acquisition protocols and the creation of normative values.[241] This is particularly the case for proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy, for which a number of methodological variations observed in the literature may underlie continued inconsistencies in central nervous system metabolic abnormalities, particularly in N-acetyl aspartate, myoinositol, choline, glutamate, GABA, and GSH, observed for multiple sclerosis and its subtypes.[242] There are other techniques under development that include contrast agents capable of measuring levels of peripheral macrophages, inflammation, or neuronal dysfunction,[241] and techniques that measure iron deposition that could serve to determine the role of this feature in MS, or that of cerebral perfusion.[241]

COVID-19

[edit]The hospitalization rate was found to be higher among individuals with MS and COVID-19 infection, at 10%, while the pooled infection rate is estimated at 4%. The pooled prevalence of death in hospitalized individuals with MS is estimated as 4%.[243]

Metformin

[edit]A 2019 study on rats and a 2024 study on mice showed that a first-line medication for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, metformin, could promote remyelination.[244][245] The promising drug is currently being researched on humans in the Octopus trials, a multi-arm, multi-stage trial, focussed on testing existing drugs for other conditions on patients with MS.[246] Currently, clinical trials on humans are ongoing in Belgium, for patients with non-active progressive MS,[247] in the U.K., in combination with clemastine for the treatment of relapsing remitting MS,[248] and Canada, for MS patients up to 25 years old.[249][250]

Other emerging theories

[edit]One emerging hypothesis, referred to as the hygiene hypothesis, suggests that early-life exposure to infectious agents helps to develop the immune system and reduces susceptibility to allergies and autoimmune disorders. The hygiene hypothesis has been linked with MS and microbiome hypotheses.[251]

It has also been proposed that certain bacteria found in the gut use molecular mimicry to infiltrate the brain via the gut–brain axis, initiating an inflammatory response and increasing blood-brain barrier permeability. Vitamin D levels have also been correlated with MS; lower levels of vitamin D correspond to an increased risk of MS, suggesting a reduced prevalence in the tropics – an area with more Vitamin D-rich sunlight – strengthening the impact of geographical location on MS development.[252] MS mechanisms begin when peripheral autoreactive effector CD4+ T cells get activated and move into the CNS. Antigen-presenting cells localize the reactivation of autoreactive effector CD4-T cells once they have entered the CNS, attracting more T cells and macrophages to form the inflammatory lesion.[253][medical citation needed] In MS patients, macrophages and microglia assemble at locations where demyelination and neurodegeneration are actively occurring, and microglial activation is more apparent in the normal-appearing white matter of MS patients.[254] Astrocytes generate neurotoxic chemicals like nitric oxide and TNFα, attract neurotoxic inflammatory monocytes to the CNS, and are responsible for astrogliosis, the scarring that prevents the spread of neuroinflammation and kills neurons inside the scarred area.[255][better source needed]

In 2024, scientists shared research on their findings of ancient migration to northern Europe from the Yamnaya area of culture,[256] tracing MS-risk gene variants dating back around 5,000 years.[257][258] The MS-risk gene variants protected ancient cattle herders from animal diseases,[259] but modern lifestyles, diets and better hygiene, have allowed the gene to develop, resulting in the higher risk of MS today.[260]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as Compston A, Coles A (October 2008). "Multiple sclerosis". Lancet. 372 (9648): 1502–1517. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7. PMID 18970977. S2CID 195686659.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Milo R, Kahana E (March 2010). "Multiple sclerosis: geoepidemiology, genetics and the environment". Autoimmunity Reviews. 9 (5): A387-94. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2009.11.010. PMID 19932200.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "NINDS Multiple Sclerosis Information Page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 19 November 2015. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nakahara J, Maeda M, Aiso S, Suzuki N (February 2012). "Current concepts in multiple sclerosis: autoimmunity versus oligodendrogliopathy". Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 42 (1): 26–34. doi:10.1007/s12016-011-8287-6. PMID 22189514. S2CID 21058811.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Tsang BK, Macdonell R (December 2011). "Multiple sclerosis- diagnosis, management and prognosis". Australian Family Physician. 40 (12): 948–955. PMID 22146321. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ Liu Z, Liao Q, Wen H, Zhang Y (June 2021). "Disease modifying therapies in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis". Autoimmunity Reviews. 20 (6): 102826. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2021.102826. PMID 33878488. S2CID 233325057.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Alphonsus KB, Su Y, D'Arcy C (April 2019). "The effect of exercise, yoga and physiotherapy on the quality of life of people with multiple sclerosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis". Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 43: 188–195. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2019.02.010. PMID 30935529. S2CID 86669723.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Compston A, Coles A (April 2002). "Multiple sclerosis". Lancet. 359 (9313): 1221–1231. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08220-X. PMID 11955556. S2CID 14207583.

- ^ Murray ED, Buttner EA, Price BH (2012). "Depression and Psychosis in Neurological Practice". In Daroff R, Fenichel G, Jankovic J, Mazziotta J (eds.). Bradley's neurology in clinical practice (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-0434-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Piryonesi SM, Rostampour S, Piryonesi SA (April 2021). "Predicting falls and injuries in people with multiple sclerosis using machine learning algorithms". Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 49: 102740. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2021.102740. PMID 33450500. S2CID 231624230.

- ^ Mazumder R, Murchison C, Bourdette D, Cameron M (25 September 2014). "Falls in people with multiple sclerosis compared with falls in healthy controls". PLOS ONE. 9 (9): e107620. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j7620M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107620. PMC 4177842. PMID 25254633.

- ^ Baecher-Allan C, Kaskow BJ, Weiner HL (February 2018). "Multiple Sclerosis: Mechanisms and Immunotherapy". Neuron. 97 (4): 742–768. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.021. PMID 29470968. S2CID 3499974.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f [medical citation needed]Lublin FD, Reingold SC (April 1996). "Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of New Agents in Multiple Sclerosis". Neurology. 46 (4): 907–911. doi:10.1212/WNL.46.4.907. PMID 8780061. S2CID 40213123.

- ^ Loma I, Heyman R (September 2011). "Multiple sclerosis: pathogenesis and treatment". Current Neuropharmacology. 9 (3): 409–416. doi:10.2174/157015911796557911. PMC 3151595. PMID 22379455.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Ward M, Goldman MD (August 2022). "Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of Multiple Sclerosis". Continuum. 28 (4): 988–1005. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000001136. PMID 35938654. S2CID 251375096.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Aloisi F, Cross AH (October 2022). "MINI-review of Epstein-Barr virus involvement in multiple sclerosis etiology and pathogenesis". Journal of Neuroimmunology. 371: 577935. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2022.577935. PMID 35931008. S2CID 251152784.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ашерио А., Мангер К.Л. (апрель 2007 г.). «Экологические факторы риска рассеянного склероза. Часть I: роль инфекции» . Анналы неврологии . 61 (4): 288–299. дои : 10.1002/ana.21117 . ПМИД 17444504 . S2CID 7682774 .

- ^ «Информационная страница NINDS по рассеянному склерозу» . Национальный институт неврологических расстройств и инсульта . 19 ноября 2015 года. Архивировано из оригинала 13 февраля 2016 года . Проверено 6 марта 2016 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Макгинли, член парламента, Гольдшмидт, Рэй-Грант, А.Д. (февраль 2021 г.). «Диагностика и лечение рассеянного склероза: обзор». ДЖАМА . 325 (8): 765–779. дои : 10.1001/jama.2020.26858 . ПМИД 33620411 . S2CID 232019589 .

- ^ Куинн Э, Хайнс С.М. (июль 2021 г.). «Вмешательства трудотерапии при рассеянном склерозе: обзорный обзор». Скандинавский журнал профессиональной терапии . 28 (5): 399–414. дои : 10.1080/11038128.2020.1786160 . hdl : 10379/16066 . ПМИД 32643486 . S2CID 220436640 .

- ^ Вайншенкер Б.Г. (1994). «Естественное течение рассеянного склероза». Анналы неврологии . 36 (Дополнение): S6-11. дои : 10.1002/ana.410360704 . ПМИД 8017890 . S2CID 7140070 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Берер К., Кришнамурти Дж. (ноябрь 2014 г.). «Микробный взгляд на аутоиммунитет центральной нервной системы». Письма ФЭБС . 588 (22): 4207–13. Бибкод : 2014FEBSL.588.4207B . дои : 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.007 . ПМИД 24746689 . S2CID 2772656 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Макгинли, член парламента, Гольдшмидт, Рэй-Грант, А.Д. (февраль 2021 г.). «Диагностика и лечение рассеянного склероза: обзор». ДЖАМА . 325 (8): 765–779. дои : 10.1001/jama.2020.26858 . ПМИД 33620411 . S2CID 232019589 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Лейн Дж., Нг Х.С., Пойзер С., Лукас Р.М., Тремлетт Х. (июль 2022 г.). «Заболеваемость рассеянным склерозом: систематический обзор изменений с течением времени по географическим регионам» . Мультсклер, связанное с расстройством . 63 : 103932. дои : 10.1016/j.msard.2022.103932 . ПМИД 35667315 . S2CID 249188137 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Кланет М (июнь 2008 г.). «Жан-Мартен Шарко. 1825 по 1893 год» . Международный журнал MS . 15 (2): 59–61. ПМИД 18782501 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 30 марта 2019 года . Проверено 21 октября 2010 г.

* Шарко Ж (1868). «Гистология рассеянного склероза». Gazette des Hopitaux, Париж . 41 :554–5. - ^ «ТикТок — сделай свой день» . www.tiktok.com .

- ^ "Усталость" . Летчворт-Гарден-Сити, Соединенное Королевство: Фонд рассеянного склероза.

- ^ Мур Х., Наир К.П., Бастер К., Миддлтон Р., Палинг Д., Шаррак Б. (август 2022 г.). «Усталость при рассеянном склерозе: исследование на основе регистров MS в Великобритании». Рассеянный склероз и связанные с ним заболевания . 64 : 103954. doi : 10.1016/j.msard.2022.103954 . ПМИД 35716477 .

- ^ Бакалиду Д., Джаннопапас В., Джаннопулос С. (июль 2023 г.). «Мысли об усталости у пациентов с рассеянным склерозом» . Куреус . 15 (7): e42146. дои : 10.7759/cureus.42146 . ПМЦ 10438195 . ПМИД 37602098 .

- ^ «Знаки МС» . Вебмд . Архивировано из оригинала 30 сентября 2016 года . Проверено 7 октября 2016 г.

- ^ Плотас П., Наноси В., Кантанис А., Циамаки Е., Пападопулос А., Цапара А. и др. (июль 2023 г.). «Речевой дефицит при рассеянном склерозе: описательный обзор существующей литературы» . Европейский журнал медицинских исследований . 28 (1):252.doi : 10.1186 /s40001-023-01230-3 . ПМЦ 10364432 . ПМИД 37488623 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Петцольд А., Фрейзер К.Л., Абегг М., Алругани Р., Альшоуэйр Д., Альваренга Р. и др. (декабрь 2022 г.). «Диагностика и классификация неврита зрительного нерва» (zip) . «Ланцет». Неврология . 21 (12): 1120–1134. дои : 10.1016/s1474-4422(22)00200-9 . ПМИД 36179757 . S2CID 252564095 . Проверено 9 мая 2024 г.

- ^ Кэмерон М.Х., Нильсагард Ю. (2018). «Равновесие, походка и падения при рассеянном склерозе». Баланс, походка и падения . Справочник по клинической неврологии. Том. 159. стр. 237–250. дои : 10.1016/b978-0-444-63916-5.00015-x . ISBN 978-0-444-63916-5 . ПМИД 30482317 .

- ^ Гасеми Н., Разави С., Никзад Э. (январь 2017 г.). «Рассеянный склероз: патогенез, симптомы, диагностика и клеточная терапия» . Клеточный журнал . 19 (1): 1–10. дои : 10.22074/cellj.2016.4867 . ПМК 5241505 . ПМИД 28367411 .

- ^ Чен М.Х., Уайли Г.Р., Сандрофф Б.М., Дакоста-Агуайо Р., ДеЛука Дж., Дженова Х.М. (август 2020 г.). «Нейральные механизмы, лежащие в основе состояния умственной усталости при рассеянном склерозе: пилотное исследование». Журнал неврологии . 267 (8): 2372–2382. дои : 10.1007/s00415-020-09853-w . ПМИД 32350648 .

- ^ Ореха-Гевара К, Аюсо Бланко Т, Бриева Руис Л, Эрнандес Перес Ма, Мека-Лаллана В, Рамио-Торрента Л (2019). «Когнитивные дисфункции и оценки при рассеянном склерозе» . Границы в неврологии . 10 :581 дои : 10.3389/fneur.2019.00581 . ПМК 6558141 . ПМИД 31214113 .

- ^ Калб Р., Бейер М., Бенедикт Р.Х., Шарвет Л., Костелло К., Файнштейн А. и др. (ноябрь 2018 г.). «Рекомендации по когнитивному скринингу и лечению рассеянного склероза» . Рассеянный склероз . 24 (13): 1665–1680. дои : 10.1177/1352458518803785 . ПМК 6238181 . ПМИД 30303036 .

- ^ Бенедикт Р.Х., член парламента Амато, ДеЛука Дж., Гертс Дж.Дж. (октябрь 2020 г.). «Когнитивные нарушения при рассеянном склерозе: клиническое лечение, МРТ и терапевтические возможности» . «Ланцет». Неврология . 19 (10): 860–871. дои : 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30277-5 . ПМЦ 10011205 . ПМИД 32949546 . S2CID 221744328 .

- ^ Зайнал Абидин Н., Туан Джаффар Т.Н., Ахмад Таджудин Л.С. (март 2023 г.). «Наклоненная двусторонняя межъядерная офтальмоплегия как раннее проявление рассеянного склероза» . Куреус . 15 (3): e36835. дои : 10.7759/cureus.36835 . ПМЦ 10147486 . ПМИД 37123672 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Горячо и обеспокоено: как жара ухудшает симптомы рассеянного склероза» . Летчворт-Гарден-Сити, Соединенное Королевство: Фонд рассеянного склероза.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Кристоянни А., Бибб Р., Дэвис С.Л., Джей О., Барнетт М., Эванджелоу Н. и др. (17 января 2018 г.). «Температурная чувствительность при рассеянном склерозе: обзор ее влияния на сенсорные и когнитивные симптомы» . Температура . 5 (3): 208–223. дои : 10.1080/23328940.2018.1475831 . ПМК 6205043 . ПМИД 30377640 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Теплочувствительность» .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Температурная чувствительность» . Летчворт-Гарден-Сити, Соединенное Королевство: Фонд рассеянного склероза.

- ^ Курцке Дж. Ф. (ноябрь 1983 г.). «Оценка неврологических нарушений при рассеянном склерозе: расширенная шкала статуса инвалидности (EDSS)» . Неврология . 33 (11): 1444–52. дои : 10.1212/WNL.33.11.1444 . ПМИД 6685237 .

- ^ Член парламента Амато, Понциани Дж. (август 1999 г.). «Количественная оценка нарушений при рассеянном склерозе: обсуждение используемых шкал». Рассеянный склероз . 5 (4): 216–9. дои : 10.1177/135245859900500404 . ПМИД 10467378 . S2CID 6763447 .

- ^ Рудик Р.А., Каттер Г., Рейнгольд С. (октябрь 2002 г.). «Функциональный комплекс рассеянного склероза: новый показатель клинических результатов исследований рассеянного склероза». Рассеянный склероз . 8 (5): 359–65. дои : 10.1191/1352458502ms845oa . ПМИД 12356200 . S2CID 31529508 .

- ^ ван Мюнстер CE, Уитдехааг BM (март 2017 г.). «Оценка результатов клинических исследований рассеянного склероза» . Препараты ЦНС . 31 (3): 217–236. дои : 10.1007/s40263-017-0412-5 . ПМЦ 5336539 . ПМИД 28185158 .

- ^ Махани Н., Тремлетт Х. (август 2021 г.). «Продром рассеянного склероза» . Обзоры природы. Неврология . 17 (8): 515–521. дои : 10.1038/s41582-021-00519-3 . ПМЦ 8324569 . ПМИД 34155379 .

- ^ Марри РА (декабрь 2019 г.). «Все больше доказательств продромального периода рассеянного склероза». Обзоры природы. Неврология . 15 (12): 689–690. дои : 10.1038/s41582-019-0283-0 . ПМИД 31654040 . S2CID 204887642 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Татару Н., Видаль С., Декавел П., Бергер Э., Румбах Л. (2006). «Ограниченное влияние летней жары во Франции (2003 г.) на госпитализацию и рецидивы рассеянного склероза». Нейроэпидемиология . 27 (1): 28–32. дои : 10.1159/000094233 . ПМИД 16804331 . S2CID 20870484 .

- ^ Хисен С., Мор Д.С., Хуитинга И., Берг Ф.Т., Гааб Дж., Отте С. и др. (март 2007 г.). «Регуляция стресса при рассеянном склерозе: современные проблемы и концепции». Рассеянный склероз . 13 (2): 143–148. дои : 10.1177/1352458506070772 . ПМИД 17439878 . S2CID 8262595 .

- ^ Конфаврё К., Суисса С., Саддье П., Бурдес В., Вукусич С. (февраль 2001 г.). «Прививки и риск рецидива рассеянного склероза. Группа по изучению вакцин при рассеянном склерозе» . Медицинский журнал Новой Англии . 344 (5): 319–326. дои : 10.1056/NEJM200102013440501 . ПМИД 11172162 .

- ^ Гримальди Л., Папейкс С., Хамон Ю., Бушар А., Морид Ю., Бенишу Дж. и др. (октябрь 2023 г.). «Вакцины и риск госпитализации при обострении рассеянного склероза». JAMA Неврология . 80 (10): 1098–1104. дои : 10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.2968 . PMC 10481324. PMID 37669073 .

- ^ Мартинелли В. (2000). «Травма, стресс и рассеянный склероз». Неврологические науки . 21 (4 Приложение 2): S849–S852. дои : 10.1007/s100720070024 . ПМИД 11205361 . S2CID 2376078 .

- ^ Добсон Р., Дассан П., Робертс М., Джованнони Дж., Нельсон-Пирси К., Брекс, Пенсильвания (апрель 2019 г.). «Консенсус Великобритании по поводу беременности при рассеянном склерозе: рекомендации Ассоциации британских неврологов». Практическая неврология . 19 (2): 106–114. doi : 10.1136/practneurol-2018-002060 . ПМИД 30612100 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Варите Г, Закарявичене Ю, Рамашаускайте Д, Лаужикене Д, Арлаускене А (январь 2020 г.). «Беременность и рассеянный склероз: обновленная информация о стратегии лечения, модифицирующей заболевание, и обзор влияния беременности на активность заболевания» . Медицина . 56 (2): 49. doi : 10.3390/medicina56020049 . ПМК 7074401 . ПМИД 31973138 .

- ^ «Беременность, роды, грудное вскармливание и РС» .

- ^ https://www.msaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/pregnancy-and-ms-2020.pdf#:~:text=Fatigue%20is%20often%20a%20problem,далее% 20способствует%20%20повышению%20усталости . [ только URL ]

- ^ Серафини Б., Розикарелли Б., Франчиотта Д., Мальоцци Р., Рейнольдс Р., Чинкве П. и др. (ноябрь 2007 г.). «Дисрегуляция вирусной инфекции Эпштейна-Барра в головном мозге при рассеянном склерозе» . Журнал экспериментальной медицины . 204 (12): 2899–2912. дои : 10.1084/jem.20071030 . ПМК 2118531 . ПМИД 17984305 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хассани А., Корбой-младший, Аль-Салам С., Хан Г. (2018). «Вирус Эпштейна-Барра присутствует в мозге в большинстве случаев рассеянного склероза и может поражать не только В-клетки» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 13 (2): e0192109. Бибкод : 2018PLoSO..1392109H . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0192109 . ПМЦ 5796799 . ПМИД 29394264 .

- ^ Луттеротти А., Хейворд-Кеннеке Х., Соспедра М., Мартин Р. (2021). «Антиген-специфическая иммунная толерантность в перспективных подходах к рассеянному склерозу и как донести их до пациентов» . Границы в иммунологии . 12 : 640935. дои : 10.3389/fimmu.2021.640935 . ПМК 8019937 . ПМИД 33828551 .

- ^ Гилден Д.Х. (март 2005 г.). «Инфекционные причины рассеянного склероза» . «Ланцет». Неврология . 4 (3): 195–202. дои : 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)01017-3 . ПМК 7129502 . ПМИД 15721830 .

- ^ Солдан СС, премьер-министр Либерман (январь 2023 г.). «Вирус Эпштейна-Барра и рассеянный склероз» . Обзоры природы. Микробиология . 21 (1): 51–64. дои : 10.1038/s41579-022-00770-5 . ПМЦ 9362539 . ПМИД 35931816 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бьёрневик К., Кортезе М., Хили Б.С., Куле Дж., Мина М.Дж., Ленг Ю. и др. (январь 2022 г.). «Продольный анализ показывает высокую распространенность вируса Эпштейна-Барра, связанного с рассеянным склерозом». Наука . 375 (6578): 296–301. Бибкод : 2022Sci...375..296B . дои : 10.1126/science.abj8222 . ПМИД 35025605 . S2CID 245983763 . См. краткое изложение BBC. Архивировано 25 апреля 2022 года в Wayback Machine от 13 апреля 2022 года.

- ^ Мюнц С. (май 2004 г.). «Ядерный антиген 1 вируса Эпштейна-Барра: от иммунологически невидимого к многообещающей мишени для Т-клеток» . Журнал экспериментальной медицины . 199 (10): 1301–1304. дои : 10.1084/jem.20040730 . ПМК 2211815 . ПМИД 15148332 .

- ^ Миклеа А., Банью М., Чан А., Хопнер Р. (6 мая 2020 г.). «Краткий обзор воздействия витамина D на рассеянный склероз» . Границы в иммунологии . 11 : 781. дои : 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00781 . ПМК 7218089 . ПМИД 32435244 .

- ^ Даймент Д.А., Эберс Г.К., Садовник А.Д. (февраль 2004 г.). «Генетика рассеянного склероза». «Ланцет». Неврология . 3 (2): 104–10. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.334.1312 . дои : 10.1016/S1474-4422(03)00663-X . ПМИД 14747002 . S2CID 16707321 .

- ^ Скин Н.Г., Грант С.Г. (2016). «Идентификация уязвимых типов клеток при основных заболеваниях головного мозга с использованием одноклеточных транскриптомов и обогащения типов клеток, взвешенных по экспрессии» . Границы в неврологии . 10:16 . дои : 10.3389/fnins.2016.00016 . ПМК 4730103 . ПМИД 26858593 .

- ^ Хасан-Смит Дж., Дуглас М.Р. (октябрь 2011 г.). «Эпидемиология и диагностика рассеянного склероза». Британский журнал больничной медицины . 72 (10): М146-51. doi : 10.12968/hmed.2011.72.Sup10.M146 . ПМИД 22041658 .