Пол

Гендер включает в себя социальные, психологические, культурные и поведенческие аспекты мужчины , женщины или другой гендерной идентичности . [1] [2] В зависимости от контекста это может включать в себя пола по признаку социальные структуры (т. е. гендерные роли ) и гендерное самовыражение . [3] [4] [5] В большинстве культур используется гендерная бинарность , в которой гендер делится на две категории, и люди считаются частью одной или другой ( девочки / женщины и мальчики / мужчины ); [6] [7] [8] те, кто находится за пределами этих групп, могут подпадать под общий термин «небинарные» . В ряде обществ, помимо «мужчины» и «женщины», есть определенные полы, например, хиджры Южной Азии ; их часто называют третьим полом (и четвертым полом и т. д.). Большинство ученых согласны с тем, что гендер является центральной характеристикой социальной организации . [9]

В середине 20-го века терминологическое различие в современном английском языке (известное как различие пола и гендера ) между биологическим полом и гендером начало развиваться в академических областях психологии , сексологии и феминизма . [10] [11] редко использовалось До середины 20-го века слово «гендер» для обозначения чего-либо, кроме грамматических категорий . [3] [1] На Западе в 1970-х годах феминистская теория приняла концепцию различия между биологическим полом и социальной конструкцией гендера . Различие между гендером и полом проводится большинством современных социологов западных стран. [12][13][14] behavioral scientists and biologists,[15] many legal systems and government bodies,[16] and intergovernmental agencies such as the WHO.[17]

The social sciences have a branch devoted to gender studies. Other sciences, such as psychology, sociology, sexology, and neuroscience, are interested in the subject. The social sciences sometimes approach gender as a social construct, and gender studies particularly do, while research in the natural sciences investigates whether biological differences in females and males influence the development of gender in humans; both inform the debate about how far biological differences influence the formation of gender identity and gendered behavior. Biopsychosocial approaches to gender include biological, psychological, and social/cultural aspects.[18][19]

Etymology and usage

Derivation

The modern English word gender comes from the Middle English gender, gendre, a loanword from Anglo-Norman and Middle French gendre. This, in turn, came from Latin genus. Both words mean "kind", "type", or "sort". They derive ultimately from a Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root *ǵénh₁- 'to beget',[20] which is also the source of kin, kind, king, and many other English words, with cognates widely attested in many Indo-European languages.[21] It appears in Modern French in the word genre (type, kind, also genre sexuel) and is related to the Greek root gen- (to produce), appearing in gene, genesis, and oxygen. The Oxford Etymological Dictionary of the English Language of 1882 defined gender as kind, breed, sex, derived from the Latin ablative case of genus, like genere natus, which refers to birth.[22] The first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED1, Volume 4, 1900) notes the original meaning of gender as "kind" had already become obsolete.

History of the concept

The concept of gender, in the modern sense, is a recent invention in human history.[23] The ancient world had no basis of understanding gender as it has been understood in the humanities and social sciences for the past few decades.[23] The term gender had been associated with grammar for most of history and only started to move towards it being a malleable cultural construct in the 1950s and 1960s.[24]

Before the terminological distinction between biological sex and gender as a role developed, it was uncommon to use the word gender to refer to anything but grammatical categories.[3][1] For example, in a bibliography of 12,000 references on marriage and family from 1900 to 1964, the term gender does not even emerge once.[3] Analysis of more than 30 million academic article titles from 1945 to 2001 showed that the uses of the term "gender", were much rarer than uses of "sex", was often used as a grammatical category early in this period. By the end of this period, uses of "gender" outnumbered uses of "sex" in the social sciences, arts, and humanities.[1] It was in the 1970s that feminist scholars adopted the term gender as way of distinguishing "socially constructed" aspects of male–female differences (gender) from "biologically determined" aspects (sex).[1]

In the last two decades of the 20th century, the use of gender in academia has increased greatly, outnumbering uses of sex in the social sciences. While the spread of the word in science publications can be attributed to the influence of feminism, its use as a synonym for sex is attributed to the failure to grasp the distinction made in feminist theory, and the distinction has sometimes become blurred with the theory itself; David Haig stated, "Among the reasons that working scientists have given me for choosing gender rather than sex in biological contexts are desires to signal sympathy with feminist goals, to use a more academic term, or to avoid the connotation of copulation."[1] In 1993, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) started to use gender instead of sex to avoid confusion with sexual intercourse.[25] Later, in 2011, the FDA reversed its position and began using sex as the biological classification and gender as "a person's self-representation as male or female, or how that person is responded to by social institutions based on the individual's gender presentation."[26]

In legal cases alleging discrimination, a 2006 law review article by Meredith Render notes "as notions of gender and sexuality have evolved over the last few decades, legal theories concerning what it means to discriminate "because of sex" under Title VII have experienced a similar evolution".[27]: 135 In a 1999 law review article proposing a legal definition of sex that "emphasizes gender self-identification," Julie Greenberg writes, "Most legislation utilizes the word "sex," yet courts, legislators, and administrative agencies often substitute the word "gender" for "sex" when they interpret these statutes."[28]: 270, 274 In J.E.B. v. Alabama ex rel. T.B., a 1994 United States Supreme Court case addressing "whether the Equal Protection Clause forbids intentional discrimination on the basis of gender", the majority opinion noted that with regard to gender, "It is necessary only to acknowledge that 'our Nation has had a long and unfortunate history of sex discrimination,' id., at 684, 93 S.Ct., at 1769, a history which warrants the heightened scrutiny we afford all gender-based classifications today", and stated "When state actors exercise peremptory challenges in reliance on gender stereotypes, they ratify and reinforce prejudicial views of the relative abilities of men and women."[29]

As a grammatical category

The word was still widely used, however, in the specific sense of grammatical gender (the assignment of nouns to categories such as masculine, feminine and neuter). According to Aristotle, this concept was introduced by the Greek philosopher Protagoras.[30]

In 1926, Henry Watson Fowler stated that the definition of the word pertained to this grammar-related meaning:

"Gender...is a grammatical term only. To talk of persons...of the masculine or feminine g[ender], meaning of the male or female sex, is either a jocularity (permissible or not according to context) or a blunder."[31]

As distinct from sex

In 1945, Madison Bentley defined gender as the "socialized obverse of sex".[32][33] Simone de Beauvoir's 1949 book The Second Sex has been interpreted as the beginning of the distinction between sex and gender in feminist theory,[34][35] although this interpretation is contested by many feminist theorists, including Sara Heinämaa.[36][37]

Controversial sexologist John Money coined the term gender role,[38][39] and was the first to use it in print in a scientific trade journal in 1955.[40][41] In the seminal 1955 paper, he defined it as "all those things that a person says or does to disclose himself or herself as having the status of boy or man, girl or woman."[42]

The modern academic sense of the word, in the context of social roles of men and women, dates at least back to 1945,[43] and was popularized and developed by the feminist movement from the 1970s onwards (see Feminist theory and gender studies below), which theorizes that human nature is essentially epicene and social distinctions based on sex are arbitrarily constructed. In this context, matters pertaining to this theoretical process of social construction were labelled matters of gender.

The popular use of gender simply as an alternative to sex (as a biological category) is also widespread, although attempts are still made to preserve the distinction. The American Heritage Dictionary (2000) uses the following two sentences to illustrate the difference, noting that the distinction "is useful in principle, but it is by no means widely observed, and considerable variation in usage occurs at all levels."[44]

The effectiveness of the medication appears to depend on the sex (not gender) of the patient.

In peasant societies, gender (not sex) roles are likely to be more clearly defined.

Gender identity and gender roles

| Part of a series on |

| Transgender topics |

|---|

Gender identity refers to a personal identification with a particular gender and gender role in society. The term woman has historically been used interchangeably with reference to the female body, though more recently this usage has been viewed as controversial by some feminists.[45]

There are qualitative analyses that explore and present the representations of gender; however, feminists challenge these dominant ideologies concerning gender roles and biological sex. One's biological sex is often times tied to specific social roles and expectations. Judith Butler considers the concept of being a woman to have more challenges, owing not only to society's viewing women as a social category but also as a felt sense of self, a culturally conditioned or constructed subjective identity.[46] Social identity refers to the common identification with a collectivity or social category that creates a common culture among participants concerned.[47] According to social identity theory,[48] an important component of the self-concept is derived from memberships in social groups and categories; this is demonstrated by group processes and how inter-group relationships impact significantly on individuals' self perception and behaviors. The groups people belong to therefore provide members with the definition of who they are and how they should behave within their social sphere.[49]

Categorizing males and females into social roles creates a problem for some individuals who feel they have to be at one end of a linear spectrum and must identify themselves as man or woman, rather than being allowed to choose a section in between.[50] Globally, communities interpret biological differences between men and women to create a set of social expectations that define the behaviors that are "appropriate" for men and women and determine their different access to rights, resources, power in society and health behaviors.[51] Although the specific nature and degree of these differences vary from one society to the next, they still tend to typically favor men, creating an imbalance in power and gender inequalities within most societies.[52] Many cultures have different systems of norms and beliefs based on gender, but there is no universal standard to a masculine or feminine role across all cultures.[53] Social roles of men and women in relation to each other is based on the cultural norms of that society, which lead to the creation of gender systems. The gender system is the basis of social patterns in many societies, which include the separation of sexes, and the primacy of masculine norms.[52]

Philosopher Michel Foucault said that as sexual subjects, humans are the object of power, which is not an institution or structure, rather it is a signifier or name attributed to "complex strategical situation".[54] Because of this, "power" is what determines individual attributes, behaviors, etc. and people are a part of an ontologically and epistemologically constructed set of names and labels. For example, being female characterizes one as a woman, and being a woman signifies one as weak, emotional, and irrational, and incapable of actions attributed to a "man". Butler said that gender and sex are more like verbs than nouns. She reasoned that her actions are limited because she is female. "I am not permitted to construct my gender and sex willy-nilly," she said.[46] "[This] is so because gender is politically and therefore socially controlled. Rather than 'woman' being something one is, it is something one does."[46] More recent criticisms of Judith Butler's theories critique her writing for reinforcing the very conventional dichotomies of gender.[55]

Social assignment and gender fluidity

According to gender theorist Kate Bornstein, gender can have ambiguity and fluidity.[56] There are two[57][58] contrasting ideas regarding the definition of gender, and the intersection of both of them is definable as below:

The World Health Organization defines gender as "the characteristics of women, men, girls and boys that are socially constructed".[59] The beliefs, values and attitude taken up and exhibited by them is as per the agreed upon norms of the society and the personal opinion of the person is not taken into the primary consideration of assignment of gender and imposition of gender roles as per the assigned gender.[2]

The assignment of gender involves taking into account the physiological and biological attributes assigned by nature followed by the imposition of the socially constructed conduct. Gender is a term used to exemplify the attributes that a society or culture constitutes as "masculine" or "feminine". Although a person's sex as male or female stands as a biological fact that is identical in any culture, what that specific sex means in reference to a person's gender role as a man or a woman in society varies cross-culturally according to what things are considered to be masculine or feminine.[60] These roles are learned from various, intersecting sources such as parental influences, the socialization a child receives in school, and what is portrayed in the local media. Learning gender roles starts from birth and includes seemingly simple things like what color outfits a baby is clothed in or what toys they are given to play with. However, a person's gender does not always align with what has been assigned at birth. Factors other than learned behaviors play a role in the development of gender.[61]

The article Adolescent Gender-Role Identity and Mental Health: Gender Intensification Revisited focuses on the work of Heather A. Priess, Sara M. Lindberg, and Janet Shibley Hyde on whether or not girls and boys diverge in their gender identities during adolescent years. The researchers based their work on ideas previously mentioned by Hill and Lynch in their gender intensification hypothesis in that signals and messages from parents determine and affect their children's gender role identities. This hypothesis argues that parents affect their children's gender role identities and that different interactions spent with either parents will affect gender intensification. Priess and among other's study did not support the hypothesis of Hill and Lynch which stated "that as adolescents experience these and other socializing influences, they will become more stereotypical in their gender-role identities and gendered attitudes and behaviors."[62] However, the researchers did state that perhaps the hypothesis Hill and Lynch proposed was true in the past but is not true now due to changes in the population of teens in respect to their gender-role identities.

Authors of "Unpacking the Gender System: A Theoretical Perspective on Gender Beliefs and Social Relations", Cecilia Ridgeway and Shelley Correll, argue that gender is more than an identity or role but is something that is institutionalized through "social relational contexts." Ridgeway and Correll define "social relational contexts" as "any situation in which individuals define themselves in relation to others in order to act."[63] They also point out that in addition to social relational contexts, cultural beliefs plays a role in the gender system. The coauthors argue that daily people are forced to acknowledge and interact with others in ways that are related to gender. Every day, individuals are interacting with each other and comply with society's set standard of hegemonic beliefs, which includes gender roles. They state that society's hegemonic cultural beliefs sets the rules which in turn create the setting for which social relational contexts are to take place. Ridgeway and Correll then shift their topic towards sex categorization. The authors define sex categorization as "the sociocognitive process by which we label another as male or female."[63]

The failure of an attempt to raise David Reimer from infancy through adolescence as a girl after his genitals were accidentally mutilated is cited as disproving the theory that gender identity is determined solely by parenting.[64][65] Reimer's case is used by organizations such as the Intersex Society of North America to caution against needlessly modifying the genitals of unconsenting minors.[66][67] Between the 1960s and 2000, many other male newborns and infants were surgically and socially reassigned as females if they were born with malformed penises, or if they lost their penises in accidents. At the time, surgical reconstruction of the vagina was more advanced than reconstruction of the penis, leading many doctors and psychologists, including John Money who oversaw Reimer's case, to recommend sex reassignment based on the idea that these patients would be happiest living as women with functioning genitalia.[68] Available evidence indicates that in such instances, parents were deeply committed to raising these children as girls and in as gender-typical a manner as possible.[68]: 72–73 A 2005 review of these cases found that about half of natal males reassigned female lived as women in adulthood, including those who knew their medical history, suggesting that gender assignment and related social factors has a major, though not determinative, influence on eventual gender identity.[67]

In 2015, the American Academy of Pediatrics released a webinar series on gender, gender identity, gender expression, transgender, etc.[69][70] In the first lecture Sherer explains that parents' influence (through punishment and reward of behavior) can influence gender expression but not gender identity.[71] Sherer argued that kids will modify their gender expression to seek reward from their parents and society, but this will not affect their gender identity (their internal sense of self).

Societal categories

| |

|---|---|

Sexologist John Money coined the term gender role in 1955. The term gender role is defined as the actions or responses that may reveal their status as boy, man, girl or woman, respectively.[72] Elements surrounding gender roles include clothing, speech patterns, movement, occupations, and other factors not limited to biological sex. In contrast to taxonomic approaches, some feminist philosophers have argued that gender "is a vast orchestration of subtle mediations between oneself and others", rather than a "private cause behind manifest behaviours".[73]

Non-binary and third genders

Historically, most societies have recognized only two distinct, broad classes of gender roles, a binary of masculine and feminine, largely corresponding to the biological sexes of male and female.[8][74][75] When a baby is born, society allocates the child to one gender or the other, on the basis of what their genitals resemble.[60]

However, some societies have historically acknowledged and even honored people who fulfill a gender role that exists more in the middle of the continuum between the feminine and masculine polarity. For example, the Hawaiian māhū, who occupy "a place in the middle" between male and female,[76][77] or the Ojibwe ikwekaazo, "men who choose to function as women",[78] or ininiikaazo, "women who function as men".[78] In the language of the sociology of gender, some of these people may be considered third gender, especially by those in gender studies or anthropology. Contemporary Native American and FNIM people who fulfill these traditional roles in their communities may also participate in the modern, two-spirit community,[79] however, these umbrella terms, neologisms, and ways of viewing gender are not necessarily the type of cultural constructs that more traditional members of these communities agree with.[80]

The hijras of India and Pakistan are often cited as third gender.[81][82] Another example may be the muxe (pronounced [ˈmuʃe]), found in the state of Oaxaca, in southern Mexico.[83] The Bugis people of Sulawesi, Indonesia have a tradition that incorporates all the features above.[84]

In addition to these traditionally recognized third genders, many cultures now recognize, to differing degrees, various non-binary gender identities. People who are non-binary (or genderqueer) have gender identities that are not exclusively masculine or feminine. They may identify as having an overlap of gender identities, having two or more genders, having no gender, having a fluctuating gender identity, or being third gender or other-gendered. Recognition of non-binary genders is still somewhat new to mainstream Western culture,[85] and non-binary people may face increased risk of assault, harassment, and discrimination.[86]

Measurement of gender identity

Two instruments incorporating the multidimensional nature of masculinity and femininity have dominated gender identity research: The Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI) and the Personal Attributes Questionnaire (PAQ).[87] Both instruments categorize individuals as either being sex typed (males report themselves as identifying primarily with masculine traits, females report themselves as identifying primarily with feminine traits), cross sex-typed (males report themselves as identifying primarily with feminine traits, females report themselves as identifying primarily with masculine traits), androgynous (either males or females who report themselves as high on both masculine and feminine traits) or undifferentiated (either males or females who report themselves as low on both masculine and feminine traits).[88] Twenge (1997) noted that men are generally more masculine than women and women generally more feminine than men, but the association between biological sex and masculinity/femininity is waning.[89]

Biological factors and views

Some gendered behavior is influenced by prenatal and early life androgen exposure. This includes, for example, gender normative play, self-identification with a gender, and tendency to engage in aggressive behavior.[90] Males of most mammals, including humans, exhibit more rough and tumble play behavior, which is influenced by maternal testosterone levels. These levels may also influence sexuality, with non-heterosexual persons exhibiting sex atypical behavior in childhood.[91]

The biology of gender became the subject of an expanding number of studies over the course of the late 20th century. One of the earliest areas of interest was what became known as "gender identity disorder" (GID) and which is now also described as gender dysphoria. Studies in this, and related areas, inform the following summary of the subject by John Money. He stated:

The term "gender role" appeared in print first in 1955. The term gender identity was used in a press release, 21 November 1966, to announce the new clinic for transsexuals at The Johns Hopkins Hospital. It was disseminated in the media worldwide, and soon entered the vernacular. The definitions of gender and gender identity vary on a doctrinal basis. In popularized and scientifically debased usage, sex is what you are biologically; gender is what you become socially; gender identity is your own sense or conviction of maleness or femaleness; and gender role is the cultural stereotype of what is masculine and feminine. Causality with respect to gender identity disorder is sub-divisible into genetic, prenatal hormonal, postnatal social, and post-pubertal hormonal determinants, but there is, as yet, no comprehensive and detailed theory of causality. Gender coding in the brain is bipolar. In gender identity disorder, there is discordance between the natal sex of one's external genitalia and the brain coding of one's gender as masculine or feminine.[92]

Although causation from the biological—genetic and hormonal—to the behavioral has been broadly demonstrated and accepted, Money is careful to also note that understanding of the causal chains from biology to behavior in sex and gender issues is very far from complete.[93] Money had previously stated that in the 1950s, American teenage girls who had been exposed to androgenic steroids by their mothers in utero exhibited more traditionally masculine behavior, such as being more concerned about their future career than marriage, wearing pants, and not being interested in jewelry.[94][95]

There are studies concerning women who have a condition called congenital adrenal hyperplasia, which leads to the overproduction of the masculine sex hormone, androgen. These women usually have ordinary female appearances (though nearly all girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) have corrective surgery performed on their genitals). However, despite taking hormone-balancing medication given to them at birth, these females are statistically more likely to be interested in activities traditionally linked to males than female activities. Psychology professor and CAH researcher Dr. Sheri Berenbaum attributes these differences to an exposure of higher levels of male sex hormones in utero.[96]

Non-human animals

In non-human animal research, gender is commonly used to refer to the biological sex of the animals.[1] According to biologist Michael J. Ryan, gender identity is a concept exclusively applied to humans.[97] Also, in a letter Ellen Ketterson writes, "[w]hen asked, my colleagues in the Department of Gender Studies agreed that the term gender could be properly applied only to humans, because it involves one's self-concept as man or woman. Sex is a biological concept; gender is a human social and cultural concept."[98] However, Poiani (2010) notes that the question of whether behavioural similarities across species can be associated with gender identity or not is "an issue of no easy resolution",[99] and suggests that mental states, such as gender identity, are more accessible in humans than other species due to their capacity for language.[100] Poiani suggests that the potential number of species with members possessing a gender identity must be limited due to the requirement for self-consciousness.[101]

Jacques Balthazart suggests that "there is no animal model for studying sexual identity. It is impossible to ask an animal, whatever its species, to what sex it belongs."[102] He notes that "this would imply that the animal is aware of its own body and sex, which is far from proved", despite recent research demonstrating sophisticated cognitive skills among non-human primates and other species.[103] Hird (2006) has also stated that whether or not non-human animals consider themselves to be feminine or masculine is a "difficult, if not impossible, question to answer", as this would require "judgements about what constitutes femininity or masculinity in any given species". Nonetheless, she asserts that "non-human animals do experience femininity and masculinity to the extent that any given species' behaviour is gender segregated."[104]

Despite this, Poiani and Dixson emphasise the applicability of the concept of gender role to non-human animals[99] such as rodents[105] throughout their book.[106] The concept of gender role has also been applied to non-human primates such as rhesus monkeys.[107][108]

Feminist theory and gender studies

| Part of a series on |

| Feminist philosophy |

|---|

|

Biologist and feminist academic Anne Fausto-Sterling rejects the discourse of biological versus social determinism and advocates a deeper analysis of how interactions between the biological being and the social environment influence individuals' capacities.[109]

The philosopher and feminist Simone de Beauvoir applied existentialism to women's experience of life: "One is not born a woman, one becomes one."[110] In context, this is a philosophical statement. However, it may be analyzed in terms of biology—a girl must pass puberty to become a woman—and sociology, as a great deal of mature relating in social contexts is learned rather than instinctive.[111]

Within feminist theory, terminology for gender issues developed over the 1970s. In the 1974 edition of Masculine/Feminine or Human, the author uses "innate gender" and "learned sex roles",[112] but in the 1978 edition, the use of sex and gender is reversed.[113]By 1980, most feminist writings had agreed on using gender only for socioculturally adapted traits.

Gender studies is a field of interdisciplinary study and academic field devoted to gender, gender identity and gendered representation as central categories of analysis. This field includes Women's studies (concerning women, feminity, their gender roles and politics, and feminism), Men's studies (concerning men, masculinity, their gender roles, and politics), and LGBT studies.[114]Sometimes Gender studies is offered together with Study of Sexuality.These disciplines study gender and sexuality in the fields of literature and language, history, political science, sociology, anthropology, cinema and media studies, human development, law, and medicine.[115]It also analyses race, ethnicity, location, nationality, and disability.[116][117]

In gender studies, the term gender refers to proposed social and cultural constructions of masculinities and femininities. In this context, gender explicitly excludes reference to biological differences, to focus on cultural differences.[118] This emerged from a number of different areas: in sociology during the 1950s; from the theories of the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan; and in the work of French psychoanalysts like Julia Kristeva, Luce Irigaray, and American feminists such as Judith Butler. Those who followed Butler came to regard gender roles as a practice, sometimes referred to as "performative".[119]

Charles E. Hurst states that some people think sex will, "...automatically determine one's gender demeanor and role (social) as well as one's sexual orientation" (sexual attractions and behavior).[120] Gender sociologists believe that people have cultural origins and habits for dealing with gender. For example, Michael Schwalbe believes that humans must be taught how to act appropriately in their designated gender to fill the role properly, and that the way people behave as masculine or feminine interacts with social expectations. Schwalbe comments that humans "are the results of many people embracing and acting on similar ideas".[121] People do this through everything from clothing and hairstyle to relationship and employment choices. Schwalbe believes that these distinctions are important, because society wants to identify and categorize people as soon as we see them. They need to place people into distinct categories to know how we should feel about them.

Hurst comments that in a society where we present our genders so distinctly, there can often be severe consequences for breaking these cultural norms. Many of these consequences are rooted in discrimination based on sexual orientation. Gays and lesbians are often discriminated against in our legal system because of societal prejudices.[122][123][124] Hurst describes how this discrimination works against people for breaking gender norms, no matter what their sexual orientation is. He says that "courts often confuse sex, gender, and sexual orientation, and confuse them in a way that results in denying the rights not only of gays and lesbians, but also of those who do not present themselves or act in a manner traditionally expected of their sex".[120] This prejudice plays out in our legal system when a person is judged differently because they do not present themselves as the "correct" gender.

Andrea Dworkin stated her "commitment to destroying male dominance and gender itself" while stating her belief in radical feminism.[125]

Political scientist Mary Hawkesworth addresses gender and feminist theory, stating that since the 1970s the concept of gender has transformed and been used in significantly different ways within feminist scholarship. She notes that a transition occurred when several feminist scholars, such as Sandra Harding and Joan Scott, began to conceive of gender "as an analytic category within which humans think about and organize their social activity". Feminist scholars in Political Science began employing gender as an analytical category, which highlighted "social and political relations neglected by mainstream accounts". However, Hawkesworth states "feminist political science has not become a dominant paradigm within the discipline".[126]

American political scientist Karen Beckwith addresses the concept of gender within political science arguing that a "common language of gender" exists and that it must be explicitly articulated in order to build upon it within the political science discipline. Beckwith describes two ways in which the political scientist may employ 'gender' when conducting empirical research: "gender as a category and as a process." Employing gender as a category allows for political scientists "to delineate specific contexts where behaviours, actions, attitudes and preferences considered masculine or feminine result in particular political outcomes". It may also demonstrate how gender differences, not necessarily corresponding precisely with sex, may "constrain or facilitate political" actors. Gender as a process has two central manifestations in political science research, firstly in determining "the differential effects of structures and policies upon men and women," and secondly, the ways in which masculine and feminine political actors "actively work to produce favorable gendered outcomes".[127]

With regard to gender studies, Jacquetta Newman states that although sex is determined biologically, the ways in which people express gender is not. Gendering is a socially constructed process based on culture, though often cultural expectations around women and men have a direct relationship to their biology. Because of this, Newman argues, many privilege sex as being a cause of oppression and ignore other issues like race, ability, poverty, etc. Current gender studies classes seek to move away from that and examine the intersectionality of these factors in determining people's lives. She also points out that other non-Western cultures do not necessarily have the same views of gender and gender roles.[128] Newman also debates the meaning of equality, which is often considered the goal of feminism; she believes that equality is a problematic term because it can mean many different things, such as people being treated identically, differently, or fairly based on their gender. Newman believes this is problematic because there is no unified definition as to what equality means or looks like, and that this can be significantly important in areas like public policy.[129]

Social construction of sex hypotheses

The World Health Organization states "As a social construct, gender varies from society to society and can change over time."[130] Sociologists generally regard gender as a social construct. For instance, sexologist John Money suggests the distinction between biological sex and gender as a role.[72] Moreover, Ann Oakley, a professor of sociology and social policy, says "the constancy of sex must be admitted, but so also must the variability of gender."[131] Lynda Birke, a feminist biologist, maintains "'biology' is not seen as something which might change."[132]

However, there are scholars who argue that sex is also socially constructed. For example, gender studies writer Judith Butler states that "perhaps this construct called 'sex' is as culturally constructed as gender; indeed, perhaps it was always already gender, with the consequence that the distinction between sex and gender turns out to be no distinction at all."[133]

She continues:

It would make no sense, then, to define gender as the cultural interpretation of sex, if sex is itself a gender-centered category. Gender should not be conceived merely as the cultural inscription of meaning based on a given sex (a juridical conception); gender must also designate the very apparatus of production whereby the sexes themselves are established. [...] This production of sex as the pre-discursive should be understood as the effect of the apparatus of cultural construction designated by gender.[134]

Butler argues that "bodies only appear, only endure, only live within the productive constraints of certain highly gendered regulatory schemas,"[135] and sex is "no longer as a bodily given on which the construct of gender is artificially imposed, but as a cultural norm which governs the materialization of bodies."[136]

With regard to history, Linda Nicholson, a professor of history and women's studies, argues that the understanding of human bodies as sexually dimorphic was historically not recognised. She states that male and female genitals were considered inherently the same in Western society until the 18th century. At that time, female genitals were regarded as incomplete male genitals, and the difference between the two was conceived as a matter of degree. In other words, there was a belief in a gradation of physical forms, or a spectrum.[137] Scholars such as Helen King, Joan Cadden, and Michael Stolberg have criticized this interpretation of history.[138] Cadden notes that the "one-sex" model was disputed even in ancient and medieval medicine,[139] and Stolberg points out that already in the sixteenth century, medicine had begun to move towards a two-sex model.[140]

In addition, drawing from the empirical research of intersex children, Anne Fausto-Sterling, a professor of biology and gender studies, describes how the doctors address the issues of intersexuality. She starts her argument with an example of the birth of an intersexual individual and maintains "our conceptions of the nature of gender difference shape, even as they reflect, the ways we structure our social system and polity; they also shape and reflect our understanding of our physical bodies."[141] Then she adds how gender assumptions affects the scientific study of sex by presenting the research of intersexuals by John Money et al., and she concludes that "they never questioned the fundamental assumption that there are only two sexes, because their goal in studying intersexuals was to find out more about 'normal' development."[142] She also mentions the language the doctors use when they talk with the parents of the intersexuals. After describing how the doctors inform parents about the intersexuality, she asserts that because the doctors believe that the intersexuals are actually male or female, they tell the parents of the intersexuals that it will take a little bit more time for the doctors to determine whether the infant is a boy or a girl. That is to say, the doctors' behavior is formulated by the cultural gender assumption that there are only two sexes. Lastly, she maintains that the differences in the ways in which the medical professionals in different regions treat intersexual people also give us a good example of how sex is socially constructed.[143] In her Sexing the Body: gender politics and the construction of sexuality, she introduces the following example:

A group of physicians from Saudi Arabia recently reported on several cases of XX intersex children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), a genetically inherited malfunction of the enzymes that aid in making steroid hormones. [...] In the United States and Europe, such children, because they have the potential to bear children later in life, are usually raised as girls. Saudi doctors trained in this European tradition recommended such a course of action to the Saudi parents of CAH XX children. A number of parents, however, refused to accept the recommendation that their child, initially identified as a son, be raised instead as a daughter. Nor would they accept feminizing surgery for their child. [...] This was essentially an expression of local community attitudes with [...] the preference for male offspring.[144]

Thus it is evident that culture can play a part in assigning gender, particularly in relation to intersex children.[143]

Psychology and sociology

Many of the more complicated human behaviors are influenced by both innate factors and by environmental ones, which include everything from genes, gene expression, and body chemistry, through diet and social pressures. A large area of research in behavioral psychology collates evidence in an effort to discover correlations between behavior and various possible antecedents such as genetics, gene regulation, access to food and vitamins, culture, gender, hormones, physical and social development, and physical and social environments.[145]

A core research area within sociology is the way human behavior operates on itself, in other words, how the behavior of one group or individual influences the behavior of other groups or individuals. Starting in the late 20th century, the feminist movement has contributed extensive study of gender and theories about it, notably within sociology but not restricted to it.[146]

Social theorists have sought to determine the specific nature of gender in relation to biological sex and sexuality,[147][148] with the result being that culturally established gender and sex have become interchangeable identifications that signify the allocation of a specific 'biological' sex within a categorical gender.[148] The second wave feminist view that gender is socially constructed and hegemonic in all societies, remains current in some literary theoretical circles, Kira Hall and Mary Bucholtz publishing new perspectives as recently as 2008.[149]

As the child grows, "...society provides a string of prescriptions, templates, or models of behaviors appropriate to the one sex or the other,"[150] which socialises the child into belonging to a culturally specific gender.[151] There is huge incentive for a child to concede to their socialisation with gender shaping the individual's opportunities for education, work, family, sexuality, reproduction, authority,[152] and to make an impact on the production of culture and knowledge.[153] Adults who do not perform these ascribed roles are perceived from this perspective as deviant and improperly socialized.[154]

Some believe society is constructed in a way that splits gender into a dichotomy via social organisations that constantly invent and reproduce cultural images of gender. Joan Acker believed gendering occurs in at least five different interacting social processes:[155]

- The construction of divisions along the lines of gender, such as those produced by labor, power, family, the state, even allowed behaviors and locations in physical space

- The construction of symbols and images such as language, ideology, dress and the media, that explain, express and reinforce, or sometimes oppose, those divisions

- Interactions between men and women, women and women and men and men that involve any form of dominance and submission. Conversational theorists, for example, have studied the way that interruptions, turn taking and the setting of topics re-create gender inequality in the flow of ordinary talk

- The way that the preceding three processes help to produce gendered components of individual identity, i.e., the way they create and maintain an image of a gendered self

- Gender is implicated in the fundamental, ongoing processes of creating and conceptualising social structures.

Looking at gender through a Foucauldian lens, gender is transfigured into a vehicle for the social division of power. Gender difference is merely a construct of society used to enforce the distinctions made between what is assumed to be female and male, and allow for the domination of masculinity over femininity through the attribution of specific gender-related characteristics.[156] "The idea that men and women are more different from one another than either is from anything else, must come from something other than nature... far from being an expression of natural differences, exclusive gender identity is the suppression of natural similarities."[157]

Gender conventions play a large role in attributing masculine and feminine characteristics to a fundamental biological sex.[158] Socio-cultural codes and conventions, the rules by which society functions, and which are both a creation of society as well as a constituting element of it, determine the allocation of these specific traits to the sexes. These traits provide the foundations for the creation of hegemonic gender difference. It follows then, that gender can be assumed as the acquisition and internalisation of social norms. Individuals are therefore socialized through their receipt of society's expectations of 'acceptable' gender attributes that are flaunted within institutions such as the family, the state and the media. Such a notion of 'gender' then becomes naturalized into a person's sense of self or identity, effectively imposing a gendered social category upon a sexed body.[157]

The conception that people are gendered rather than sexed also coincides with Judith Butler's theories of gender performativity. Butler argues that gender is not an expression of what one is, but rather something that one does.[159] It follows then, that if gender is acted out in a repetitive manner it is in fact re-creating and effectively embedding itself within the social consciousness. Contemporary sociological reference to male and female gender roles typically uses masculinities and femininities in the plural rather than singular, suggesting diversity both within cultures as well as across them.

The difference between the sociological and popular definitions of gender involve a different dichotomy and focus. For example, the sociological approach to "gender" (social roles: female versus male) focuses on the difference in (economic/power) position between a male CEO (disregarding the fact that he is heterosexual or homosexual) to female workers in his employ (disregarding whether they are straight or gay). However the popular sexual self-conception approach (self-conception: gay versus straight) focuses on the different self-conceptions and social conceptions of those who are gay/straight, in comparison with those who are straight (disregarding what might be vastly differing economic and power positions between female and male groups in each category). There is then, in relation to definition of and approaches to "gender", a tension between historic feminist sociology and contemporary homosexual sociology.[160]

Gender as biopsychosocial

According to Alex Iantaffi, Meg-John Barker, and others, gender is biopsychosocial. This is because it is derived from biological, psychological, and social factors,[161][18] with all three factors feeding back into each other to form a person's gender.[18]

Biological factors such as sex chromosomes, hormones, and anatomy play a significant role in the development of gender. Hormones such as testosterone and estrogen also play a crucial role in shaping gender identity and expression. Anatomy, including genitalia and reproductive organs, can also influence one's gender identity and expression.[162]

Psychological factors such as cognition, personality, and self-concept also contribute to gender development. Gender identity emerges around the age of two to three years. Gender expression, which refers to the outward manifestation of gender, is influenced by cultural norms, personal preferences, and individual differences in personality.[163]

Social factors such as culture, socialization, and institutional practices shape gender identity and expression.

In some English literature, there is also a trichotomy between biological sex, psychological gender, and social gender role. This framework first appeared in a feminist paper on transsexualism in 1978.[1][164]

Legal status

A person's gender can have legal significance. In some countries and jurisdictions there are same-sex marriage laws.[165]

Transgender people

The legal status of transgender people varies greatly around the world. Some countries have enacted laws protecting the rights of transgender individuals, but others have criminalized their gender identity or expression.[166] Many countries now legally recognize sex reassignments by permitting a change of legal gender on an individual's birth certificate.[167]

Intersex people

For intersex people, who according to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies",[168] access to any form of identification document with a gender marker may be an issue.[169] For other intersex people, there may be issues in securing the same rights as other individuals assigned male or female; other intersex people may seek non-binary gender recognition.[170]

Non-binary and third genders

Some countries now legally recognize non-binary or third genders, including Canada, Germany,[171] Australia, New Zealand, India and Pakistan. In the United States, Oregon was the first state to legally recognize non-binary gender in 2017,[172] and was followed by California and the District of Columbia.[173][174]

Gender and society

Languages

- Grammatical gender is a property of some languages in which every noun is assigned a gender, often with no direct relation to its meaning. For example, the word for "girl" is muchacha (grammatically feminine) in Spanish,[171] Mädchen (grammatically neuter) or the older Maid (grammatically feminine)[175] in German, and cailín (grammatically masculine) in Irish.[171]

- The term "grammatical gender" is often applied to more complex noun class systems. This is especially true when a noun class system includes masculine and feminine as well as some other non-gender features like animate, edible, manufactured, and so forth. An example of the latter is found in the Dyirbal language. Other gender systems exist with no distinction between masculine and feminine; examples include a distinction between animate and inanimate things, which is common to, amongst others, Ojibwe,[176] Basque and Hittite; and systems distinguishing between people (whether human or divine) and everything else, which are found in the Dravidian languages and Sumerian.

- A sample of the World Atlas of Language Structures by Greville G Corbett found that fewer than half of the 258 languages sampled have any system of grammatical gender.[177] Of the remaining languages that feature grammatical gender, over half have more than the minimum requirement of two genders.[177] Grammatical gender may be based on biological sex (which is the most common basis for grammatical gender), animacy, or other features, and may be based on a combination of these classes.[178] One of the four genders of the Dyirbal language consists mainly of fruit and vegetables.[179] Languages of the Niger-Congo language family can have as many as twenty genders, including plants, places, and shapes.[180]

- Many languages include terms that are used asymmetrically in reference to men and women. Concern that current language may be biased in favor of men has led some authors in recent times to argue for the use of a more gender-neutral vocabulary in English and other languages.[181]

- Several languages attest the use of different vocabulary by men and women, to differing degrees. See, for instance, Gender differences in Japanese. The oldest documented language, Sumerian, records a distinctive sub-language, Emesal, only used by female speakers.[182] Conversely, many Indigenous Australian languages have distinctive registers with a limited lexicon used by men in the presence of their mothers-in-law (see Avoidance speech).[183] As well, quite a few sign languages have a gendered distinction due to boarding schools segregated by gender, such as Irish Sign Language.[184]

- Several languages such as Persian[171] or Hungarian are gender-neutral. In Persian the same word is used in reference to men and women. Verbs, adjectives and nouns are not gendered. (See Gender-neutrality in genderless languages).

- Several languages employ different ways to refer to people where there are three or more genders, such as Navajo[185]

Science

Historically, science has been portrayed as a masculine pursuit in which women have faced significant barriers to participate.[186] Even after universities began admitting women in the 19th century, women were still largely relegated to certain scientific fields, such as home science, nursing, and child psychology.[187] Women were also typically given tedious, low-paying jobs and denied opportunities for career advancement.[187] This was often justified by the stereotype that women were naturally more suited to jobs that required concentration, patience, and dexterity, rather than creativity, leadership, or intellect.[187] Although these stereotypes have been dispelled in modern times, women are still underrepresented in prestigious "hard science" fields such as physics, and are less likely to hold high-ranking positions,[188] a situation global initiatives such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 5 are trying to rectify.[189]

Religion

Эта тема включает внутренние и внешние религиозные вопросы, такие как пол Бога и мифы о создании божеств о человеческом поле, ролях и правах (например, руководящие роли, особенно посвящение женщин , сегрегация по признаку пола , гендерное равенство , брак, аборт, гомосексуализм ).

В даосизме Инь и Ян считаются женским и мужским началом соответственно. Тайцзиту и концепция периода Чжоу затрагивают семейные и гендерные отношения. Инь – это женщина, а Ян – мужчина. Они сочетаются друг с другом как две части единого целого. Мужское начало приравнивалось к солнцу: деятельному, яркому, сияющему; женское начало соответствует луне: пассивное, затененное и отражающее. Таким образом, «мужская жесткость уравновешивалась женской мягкостью, мужские действия и инициатива — женской выносливостью и потребностью в завершении, а мужское лидерство — женской поддержкой». [190]

В иудаизме Бог традиционно описывается в мужском роде, но в мистической традиции Каббалы представляет женский Шхина аспект сущности Бога. [191] Однако иудаизм традиционно считает , что Бог совершенно бесплотен и, следовательно, не является ни мужчиной, ни женщиной. Несмотря на концепции пола Бога, традиционный иудаизм уделяет большое внимание людям, следующим традиционным гендерным ролям иудаизма, хотя многие современные конфессии иудаизма стремятся к большему эгалитаризму. Более того, традиционная еврейская культура признает как минимум шесть полов . [192] [193]

В христианстве Бог традиционно описывается мужским родом, а Церковь исторически описывалась женским родом. С другой стороны, христианское богословие во многих церквях проводит различие между мужскими образами Бога (Отца, Царя, Бога-Сына) и реальностью, которую они обозначают, которая выходит за рамки гендера и в совершенстве воплощает все добродетели как мужчин, так и женщин, что может можно увидеть через доктрину Imago Dei . В Новом Завете Иисус несколько раз упоминает Святой Дух с местоимением мужского рода, то есть Иоанна 15:26, среди других стихов. Следовательно, Отец , Сын и Святой Дух (т. е. Троица ) упоминаются с местоимением мужского рода; хотя точное значение мужественности христианского триединого Бога оспаривается. [194]

В индуизме одной из нескольких форм индуистского бога Шивы является Ардханаришвара (буквально полуженский бог). В этой составной форме левая половина тела представляет шакти (энергию, силу) в форме богини Парвати (иначе ее супруги), а правая половина представляет Шиву. В то время как Парвати считается причиной пробуждения камы (желания), Шива является разрушителем концепции. Символически Шива пронизан силой Парвати, а Парвати пронизана силой Шивы. [195]

Этот миф отражает присущую древнему индуизму точку зрения, согласно которой каждый человек несет в себе как женские, так и мужские компоненты, которые являются скорее силами, чем полом, и что это гармония между созидательным и уничтожающим, сильным и мягким, активным и разрушительным. пассив, который делает настоящего человека. Свидетельства гомосексуализма, бисексуальности, андрогинности, множественных сексуальных партнеров и открытого представления сексуальных удовольствий можно найти в таких произведениях искусства, как храмы Кхаджурахо, которые, как полагают, были приняты в преобладающих социальных рамках. [196]

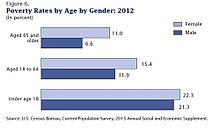

Бедность

Гендерное неравенство наиболее распространено среди женщин, живущих в условиях бедности. Многие женщины должны взять на себя всю ответственность за домашнее хозяйство, поскольку они должны заботиться о семье. Часто это может включать в себя такие задачи, как обработка земли, измельчение зерна, доставка воды и приготовление пищи. [197] Кроме того, женщины с большей вероятностью будут получать низкие доходы из-за гендерной дискриминации, поскольку мужчины с большей вероятностью будут получать более высокую заработную плату, иметь больше возможностей и в целом иметь больший политический и социальный капитал, чем женщины. [198] Примерно 75% женщин мира не могут получить банковские кредиты из-за нестабильной работы. [197] Это показывает, что среди населения мира много женщин, но лишь немногие представляют мировое богатство. Во многих странах финансовый сектор в значительной степени пренебрегает женщинами, хотя они играют важную роль в экономике, как отметила Нена Стоилькович в D+C Development andсотрудничестве . [199] В 1978 году Диана М. Пирс ввела термин «феминизация бедности» , чтобы описать проблему более высокого уровня бедности среди женщин. [200] Женщины более уязвимы к хронической бедности из-за гендерного неравенства в распределении доходов, владении собственностью, кредите и контроле над заработанным доходом. [201] Распределение ресурсов обычно имеет гендерную предвзятость внутри домохозяйств и продолжается на более высоком уровне в отношении государственных учреждений. [201]

Гендер и развитие (GAD) – это целостный подход к оказанию помощи странам, где гендерное неравенство не способствует улучшению социального и экономического развития. Это программа, направленная на гендерное развитие женщин, чтобы расширить их возможности и снизить уровень неравенства между мужчинами и женщинами. [202]

Крупнейшее исследование дискриминации трансгендерного сообщества, проведенное в 2013 году, показало, что трансгендерное сообщество в четыре раза чаще живет в крайней бедности (доход менее 10 000 долларов в год), чем цисгендерные люди . [203] [204]

Общая теория деформации

Согласно общей теории напряжения , исследования показывают, что гендерные различия между людьми могут привести к экстернализованному гневу, который может привести к вспышкам насилия. [205] Эти насильственные действия, связанные с гендерным неравенством, можно измерить, сравнивая районы с насилием и районами, где нет насилия. [205] Отмечая независимые переменные (насилие по соседству) и зависимую переменную (индивидуальное насилие), можно проанализировать гендерные роли. [206] Напряжение в общей теории напряжения — это удаление положительного стимула и/или введение отрицательного стимула, который может создать отрицательный эффект (напряжение) внутри человека, который направлен либо внутрь (депрессия/вина), либо направлен вовне. (гнев/разочарование), которое зависит от того, винит ли человек себя или свое окружение. [207] Исследования показывают, что хотя мужчины и женщины с одинаковой вероятностью реагируют на напряжение гневом, причины гнева и способы борьбы с ним могут сильно различаться. [207]

Мужчины склонны возлагать вину за несчастья на других и поэтому выражать чувство гнева вовне. [205] Женщины обычно усваивают свой гнев и вместо этого склонны винить себя. [205] Женский внутренний гнев сопровождается чувством вины, страха, тревоги и депрессии. [206] Женщины рассматривают гнев как признак того, что они каким-то образом потеряли контроль, и поэтому беспокоятся, что этот гнев может привести к тому, что они причинят вред другим и/или испортят отношения. На другом конце спектра мужчины меньше озабочены разрушением отношений и больше сосредоточены на использовании гнева как средства подтверждения своей мужественности. [206] Согласно общей теории напряжения, мужчины с большей вероятностью будут проявлять агрессивное поведение, направленное на других, из-за внешнего гнева, тогда как женщины будут направлять свой гнев на себя, а не на других. [207]

Экономическое развитие

Гендер и особенно роль женщин широко признаны жизненно важными для вопросов международного развития . [208] Это часто означает сосредоточение внимания на гендерном равенстве, обеспечении участия , но включает понимание различных ролей и ожиданий полов в сообществе. [209]

Изменение климата

Гендер является темой, вызывающей растущее беспокойство в политике и науке в области изменения климата . [210] Как правило, гендерные подходы к изменению климата касаются гендерно-дифференцированных последствий изменения климата , а также неравных возможностей адаптации и гендерного вклада в изменение климата. Более того, пересечение изменения климата и гендера поднимает вопросы относительно сложных и пересекающихся властных отношений, вытекающих из этого. Однако эти различия в большинстве случаев обусловлены не биологическими или физическими различиями, а формируются социальным, институциональным и правовым контекстом. Следовательно, уязвимость является не столько внутренней чертой женщин и девочек, сколько продуктом их маргинализации. [211] Рёр [212] отмечает, что, хотя Организация Объединенных Наций официально взяла на себя обязательства по учету гендерной проблематики , на практике гендерное равенство не достигается в контексте политики в области изменения климата. Это отражается в том факте, что в дискуссиях и переговорах по вопросам изменения климата в основном доминируют мужчины. [213] [214] [215] Некоторые ученые-феминистки считают, что в дебатах об изменении климата не только доминируют мужчины, но и в первую очередь формируются «мужские» принципы, что ограничивает дискуссии об изменении климата перспективой, сосредоточенной на технических решениях. [214] Такое восприятие изменения климата скрывает субъективность и соотношение сил, которые на самом деле определяют политику и науку в области изменения климата, что приводит к явлению, которое Туана [214] термин «эпистемическая несправедливость».Аналогично, МакГрегор [213] свидетельствует о том, что, рассматривая изменение климата как проблему «жесткого» естественнонаучного поведения и естественной безопасности, оно удерживается в традиционных сферах гегемонной мужественности. [213] [215]

Социальные сети

В 2010 году Forbes опубликовал статью, в которой сообщалось, что 57% пользователей Facebook — женщины, что объясняется тем фактом, что женщины более активны в социальных сетях. В среднем у женщин на 8% больше друзей, и на их долю приходится 62% постов, которыми делятся через Facebook. [216] Другое исследование, проведенное в 2010 году, показало, что в большинстве западных культур женщины тратят больше времени на отправку текстовых сообщений, чем на мужчин, а также проводят больше времени в социальных сетях как способ общения с друзьями и семьей. [217]

Исследование, проведенное в 2013 году, показало, что более 57% фотографий, размещенных на сайтах социальных сетей, были сексуальными и были созданы с целью привлечь внимание. [218] При этом 58% женщин и 45% мужчин не смотрят в камеру, что создает иллюзию отстраненности. [218] Другими факторами, которые следует учитывать, являются позы на фотографиях, например, женщины, лежащие в подчиненной позе или даже трогающие себя по-детски. [218]

Девочки-подростки обычно используют социальные сети как инструмент для общения со сверстниками и укрепления существующих отношений; мальчики, с другой стороны, склонны использовать социальные сети как инструмент для поиска новых друзей и знакомых. [219] Более того, сайты социальных сетей позволили людям по-настоящему выразить себя, поскольку они могут создать идентичность и общаться с другими людьми, которые могут общаться. [220] Сайты социальных сетей также предоставили людям доступ к созданию пространства, где они будут чувствовать себя более комфортно в отношении своей сексуальности. [220] Недавние исследования показали, что социальные сети становятся все более сильной частью медиакультуры молодых людей, поскольку через социальные сети рассказывается более интимные истории, которые переплетаются с гендером, сексуальностью и отношениями. [220]

Исследования показали, что почти все подростки США (95%) в возрасте от 12 до 17 лет находятся в сети, по сравнению с только 78% взрослых. Из этих подростков 80% имеют профили в социальных сетях по сравнению с 64% интернет-пользователей в возрасте 30 лет и старше. По данным исследования Kaiser Family Foundation, подростки в возрасте от 11 до 18 лет проводят в среднем более полутора часов в день за компьютером и 27 минут в день на посещении социальных сетей, т.е. на последнюю приходится около четверть ежедневного использования компьютера. [221]

Исследования показали, что пользователи-женщины, как правило, публикуют более «милые» фотографии, в то время как участники-мужчины чаще публикуют свои фотографии во время занятий. Женщины в США также склонны публиковать больше фотографий друзей, в то время как мужчины чаще публикуют ссылки на спортивные темы и юмористические ссылки. Исследование также показало, что мужчины публикуют больше упоминаний об алкоголе и сексе. [221] Однако, если посмотреть на сайт знакомств для подростков, роли поменялись: женщины упоминали сексуальные темы значительно чаще, чем мужчины. Мальчики делятся большей личной информацией, а девочки более консервативны в отношении публикуемой личной информации. Между тем мальчики чаще ориентируются на технологии, спорт и юмор в информации, которую они размещают в своем профиле. [222]

Исследования 1990-х годов показали, что представители разных полов проявляют в онлайн-взаимодействии определенные черты, такие как активность, привлекательность, зависимость, доминирование, независимость, сентиментальность, сексуальность и покорность. [223] Несмотря на то, что эти черты продолжают проявляться через гендерные стереотипы, недавние исследования показывают, что это уже не обязательно так. [224]

См. также

Ссылки

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Хейг, Дэвид (апрель 2004 г.). «Неумолимый рост гендера и упадок пола: социальные изменения в академических званиях, 1945–2001» (PDF) . Архив сексуального поведения . 33 (2): 87–96. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.359.9143 . дои : 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000014323.56281.0d . ПМИД 15146141 . S2CID 7005542 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 15 июня 2012 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Что мы подразумеваем под «полом» и «гендером»?» . Всемирная организация здравоохранения . Архивировано из оригинала 30 января 2017 года . Проверено 26 ноября 2015 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Удри, Дж. Ричард (ноябрь 1994 г.). «Природа гендера» (PDF) . Демография . 31 (4): 561–573. дои : 10.2307/2061790 . JSTOR 2061790 . ПМИД 7890091 . S2CID 38476067 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 29 июня 2021 года.

- ^ Линдквист, Анна; Сенден, Мари Густавссон; Ренстрем, Эмма А. (2 октября 2021 г.). «Что вообще такое гендер: обзор вариантов операционализации гендера» . Психология и сексуальность . 12 (4): 332–344. дои : 10.1080/19419899.2020.1729844 . S2CID 213397968 .

- ^ Бейтс, Нэнси; Чин, Маршалл; Беккер, Тара, ред. (2022). Измерение пола, гендерной идентичности и сексуальной ориентации . Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Издательство национальных академий. дои : 10.17226/26424 . ISBN 978-0-309-27510-1 . ПМИД 35286054 . S2CID 247432505 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 мая 2023 года.

- ^ Сигельман, Кэрол К.; Райдер, Элизабет А. (2017). Человеческое развитие на протяжении всей жизни . Cengage Обучение. п. 385. ИСБН 978-1-337-51606-8 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 августа 2021 года . Проверено 4 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Мэддукс, Джеймс Э.; Уинстед, Барбара А. (2019). Психопатология: основы современного понимания . Рутледж. ISBN 978-0-429-64787-1 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 августа 2021 года . Проверено 4 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кевин Л. Надаль, Энциклопедия психологии и гендера Sage (2017, ISBN 1483384276 ), с. 401: «Большинство культур в настоящее время строят свои общества на основе понимания гендерной бинарности — двух гендерных категорий (мужчины и женщины). Такие общества делят свое население на основе биологического пола, присвоенного людям при рождении, чтобы начать процесс гендерной социализации».

- ^ Хайнеманн, Изабель (2012). Изобретая современную американскую семью: семейные ценности и социальные изменения в Соединенных Штатах 20-го века . Кампус Верлаг. п. 36. ISBN 978-3-593-39640-8 . Архивировано из оригинала 27 августа 2021 года . Проверено 28 июля 2021 г.

- ^ Хаусман, Бернис (1995). Изменение пола: транссексуализм, технологии и идея пола . Соединенное Королевство: Издательство Университета Дьюка. п. 95. ИСБН 0822316927 .

- ^ Жермон, Дж. (2009). «Деньги и производство гендера» . Пол . Нью-Йорк: Пэлгрейв Макмиллан. стр. 23–62. дои : 10.1057/9780230101814_2 . ISBN 978-1-349-37508-0 .

- ^ Киммел, Майкл С. (2017). Гендерное общество (Шестое изд.). Нью-Йорк. п. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-026031-6 . OCLC 949553050 .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: отсутствует местоположение издателя ( ссылка ) - ^ Линдси, Линда Л. (2010). «Глава 1. Социология гендера» (PDF) . Гендерные роли: социологический взгляд . Пирсон. ISBN 978-0-13-244830-7 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 5 апреля 2015 года.

- ^ Палуди, Мишель Антуанетта (2008). Психология женщин на работе: проблемы и решения для нашей женской рабочей силы . АВС-КЛИО. п. 153. ИСБН 978-0-275-99677-2 . Архивировано из оригинала 20 октября 2021 года . Проверено 30 августа 2021 г.

- ^ О'Халлоран, Керри (2020). Сексуальная ориентация, гендерная идентичность и международное право прав человека: перспективы общего права . Лондон. стр. 22–28, 328–329. ISBN 978-0-429-44265-0 . OCLC 1110674742 .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: отсутствует местоположение издателя ( ссылка ) - ^ «Гендер: определения» . www.euro.who.int . Архивировано из оригинала 25 сентября 2021 года . Проверено 22 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Янтафи, Алекс (2017). Как понять свой пол: практическое руководство по изучению того, кто вы есть . Издательство Джессики Кингсли. ISBN 978-1785927461 .

- ^ Кнудсон-Мартин, Кармен; Махони, Энн Рэнкин (март 2009 г.). «Введение в специальный раздел «Гендерная сила в культурном контексте: изучение жизненного опыта пар» . Семейный процесс . 48 (1): 5–8. дои : 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01263.x . ПМИД 19378641 .

- ^ Ринге, Дональд А. (2006). От протоиндоевропейского к протогерманскому . Оксфорд: Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 61. ИСБН 978-1-4294-9182-2 . OCLC 170965273 . Архивировано из оригинала 17 февраля 2022 года . Проверено 16 октября 2021 г.

- ^ «Gen» Архивировано 19 октября 2009 года в Wayback Machine . Ваш словарь.com

- ^ Скит, Уолтер Уильям (1882). Этимологический словарь английского языка . Оксфорд: Кларендон Пресс. п. 230.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Холмс, Брук (2012). "Введение". Гендер: античность и ее наследие . Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 1–2. ISBN 978-0195380828 .

Оказывается, то, что мы называем гендером, появилось сравнительно недавно. Дело не в том, что люди в Древней Греции и Риме не говорили, не думали и не спорили о категориях мужского и женского, мужского и женского, а также о природе и степени половых различий. Они поступали [способами] одновременно похожими на наши и сильно отличающимися от них. Проблема в том, что у них не было концепции гендера, которая стала настолько влиятельной в гуманитарных и социальных науках за последние четыре десятилетия.

- ^ Холмс, Брук (2012). "Введение". Гендер: античность и ее наследие . Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 3–4. ISBN 978-0195380828 .

Понятие гендера, как я только что сказал, появилось недавно. Так что же это такое и откуда оно взялось? Симона де Бовуар, как известно, написала: «Женщиной не рождаются, а становятся женщиной». 1960-е годы.

- ^ «Руководство по изучению и оценке гендерных различий при клинической оценке лекарств» (PDF) . Управление по контролю за продуктами и лекарствами . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 6 апреля 2015 года . Проверено 3 августа 2014 г.

- ^ «Оценка данных с разбивкой по полу в клинических исследованиях медицинского оборудования – Руководство для промышленности и персонала Управления по контролю за продуктами и лекарствами» . Управление по контролю за продуктами и лекарствами США . 22 августа 2014 года. Архивировано из оригинала 9 августа 2014 года . Проверено 26 февраля 2019 г.

- ^ Рендер, Мередит (декабрь 2006 г.). «Мизогиния, андрогинность и сексуальные домогательства: половая дискриминация в гендерно-деконструированном мире» . Гарвардский журнал права и гендера . 29 :99–150 . Проверено 24 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Гринберг, Джули А. (1999). «Определение мужчины и женщины: интерсексуальность и столкновение между законом и биологией» . Обзор права штата Аризона . 41 : 265–328. ССНР 896307 .

- ^ «JEB, Истец против АЛАБАМА ex rel. TB» Институт правовой информации . Корнеллская юридическая школа . Проверено 24 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Аристотель (1954), Риторика , перевод Робертса, Уильяма Риса, Минеола, Нью-Йорк: Дувр , стр. 127, ISBN 978-0-486-43793-4 , OCLC 55616891 ,

Четвертое правило — соблюдать классификацию существительных Протагора на мужские, женские и неодушевленные.

- ^ Современное использование английского языка Фаулером , 1926: стр. 211.

- ^ Бентли, Мэдисон (апрель 1945 г.). «Здравомыслие и опасность в детстве» . Американский журнал психологии . 58 (2): 212–246. дои : 10.2307/1417846 . ISSN 0002-9556 . JSTOR 1417846 . Проверено 17 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Хорли, Джеймс; Кларк, Январь (2016). Опыт, значение и идентичность в сексуальности: психосоциальная теория сексуальной стабильности и изменений . Спрингер. п. 24. ISBN 978-1-137-40096-3 . Архивировано из оригинала 17 августа 2021 года . Проверено 17 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Витт, Шарлотта Э. (2011). Феминистская метафизика: исследования онтологии пола, гендера и идентичности . Спрингер. п. 48. ИСБН 978-90-481-3782-4 . OCLC 780208834 . Архивировано из оригинала 17 февраля 2022 года . Проверено 6 сентября 2021 г.

- ^ Батлер, Джудит , «Секс и гендер во втором поле Симоны де Бовуар» в Йельских французских исследованиях , № 72 (1986), стр. 35–49.

- ^ Хейнямаа, Сара (1997). «Что такое женщина? Батлер и Бовуар об основах полового различия» . Гипатия . 12 (1): 20–39. дои : 10.1111/j.1527-2001.1997.tb00169.x . S2CID 143621442 . Проверено 8 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Виверос Вигоя, Мара (2016). Диш, Лиза; Хоксворт, Мэри (ред.). «Пол/Гендер» . Academic.oup.com . дои : 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199328581.013.42 . Проверено 24 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ Брюингтон, Келли (2006). «Пионер Хопкинса в области гендерной идентичности» . Балтимор Сан . Архивировано из оригинала 13 апреля 2010 года . Проверено 7 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ Голди, профессор кафедры английского языка Терри; Голди, Терри (2014). Человек, который изобрел гендер: использование идей Джона Мани . ЮБК Пресс. ISBN 978-0-7748-2794-2 .

- ^ Деньги, Дж. (1994). «Понятие о расстройстве гендерной идентичности в детском и подростковом возрасте после 39 лет» . Журнал секса и супружеской терапии . 20 (3): 163–177. дои : 10.1080/00926239408403428 . ISSN 0092-623X . ПМИД 7996589 .

- ^ Дрешер, Джек (31 марта 2010 г.). «Транссексуализм, расстройство гендерной идентичности и DSM» . Журнал психического здоровья геев и лесбиянок . 14 (2): 109–122. дои : 10.1080/19359701003589637 . ISSN 1935-9705 .

- ^ Деньги, Джон ; Хэмпсон, Джоан Дж; Хэмпсон, Джон (октябрь 1955 г.). «Исследование некоторых основных сексуальных концепций: доказательства человеческого гермафродитизма». Бык. Хосп Джонса Хопкинса . 97 (4): 301–19. ПМИД 13260820 .

Под термином «гендерная роль» мы подразумеваем все те вещи, которые человек говорит или делает, чтобы раскрыть себя как имеющий статус мальчика или мужчины, девочки или женщины соответственно. Оно включает, помимо прочего, сексуальность в смысле эротики. Гендерная роль оценивается по следующим критериям: общие манеры поведения, манера поведения и манера поведения, игровые предпочтения и развлекательные интересы; спонтанные темы разговоров в разговорах без подсказки и случайных комментариях; содержание снов, мечтаний и фантазий; ответы на косвенные запросы и проективные тесты; свидетельства эротических практик и, наконец, собственные ответы человека на прямой запрос.

- ^ « пол , сущ.» Оксфордский онлайн-словарь английского языка . Оксфордский словарь английского языка. п. Смысл 3(б). Архивировано из оригинала 21 июля 2017 года . Проверено 5 января 2017 г.

- ^ Примечание по использованию: Пол , Архивировано 21 марта 2006 г. в Wayback Machine. Словарь английского языка американского наследия , четвертое издание (2000 г.).

- ↑ Миккола, Мари (12 мая 2008 г.). «Феминистские взгляды на секс и гендер». Архивировано 25 января 2020 года в Wayback Machine Стэнфордского университета.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Батлер (1990)

- ^ Сноу, Д.А. и Оливер, ЧП (1995). «Социальные движения и коллективное поведение: социально-психологические аспекты и соображения», стр. 571–600 в книге Карен Кук, Гэри А. Файна и Джеймса С. Хауса (ред.) «Социологические перспективы социальной психологии» . Бостон: Аллин и Бэкон.

- ^ Тайфель, Х. и Тернер, Дж.К. (1986). «Социальная идентичность межгрупповых отношений», стр. 7–24 в книге С. Уорчела и У. Г. Остина (ред.) . Психология межгрупповых отношений . Чикаго: Нельсон-Холл. ISBN 0-8185-0278-9 .