Вена

Эта статья может потребовать редактирования копий для грамматики, стиля, сплоченности, тона или орфографии . ( Апрель 2024 г. ) |

Вена

| |

|---|---|

|

| |

Map of Vienna | |

Vienna highlighted in Austria | |

| Coordinates: 48°12′28″N 16°22′17″E / 48.20778°N 16.37139°E | |

| Country | Austria |

| Federal state | Vienna |

| Government | |

| • Body | State and Municipality |

| • Mayor and Governor | Michael Ludwig (SPÖ) |

| Area | |

| • Capital city, federal state and municipality | 414.78 km2 (160.15 sq mi) |

| • Land | 395.25 km2 (152.61 sq mi) |

| • Water | 19.39 km2 (7.49 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 151 (Lobau) – 542 (Hermannskogel) m (495–1,778 ft) |

| Population (2024)[3] | 2,014,614 |

| • Rank | 10th in Europe 1st in Austria |

| • Urban | 2,223,236 ("Kernzone")[2] |

| • Metro | 2,890,577 |

| • Ethnicity[4] |

|

| Demonyms | German: Wiener (m), Wienerin (f) Viennese |

| GDP | |

| • Capital city, federal state and municipality | €110.922 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code |

|

| ISO 3166 code | AT-9 |

| Vehicle registration | W |

| HDI (2021) | 0.942[7] very high · 1st of 9 |

| Seats in the Federal Council | 10 / 60

|

| GeoTLD | .wien |

| Website | wien |

| Official name | Historic Centre of Vienna |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv, vi |

| Designated | 2001 (25th session) |

| Reference no. | 1033 |

| UNESCO Region | Europe and North America |

| Endangered | 2017–present[8] |

Вена ( / v i ɛ n ə/ Век- вершину на ; [ 9 ] [ 10 ] Немецкий: Вена [viːn] ; Австро-баварский : отуг [Veɐ̯n] )-столица, самый густонаселенный город и один из федеральных государств Австрии девяти . Это город Австрии , где чуть более двух миллионов жителей. [ 11 ] [ 12 ] Его более крупный столичный район насчитывает почти 2,9 миллиона, [ 13 ] представляя почти треть населения страны. Вена является культурным , экономическим и политическим центром страны, пятым по величине городом по населению в Европейском Союзе и самым скупным из городов на реке Дунай .

Город лежит на восточном краю Венского леса ( Винервальд ), на северо -восточных предгорьях Альп , которые отделяют Вену от более западных частей Австрии, при переходе к паннонскому бассейну . Он находится на Дунайке , и проходит высокорегулируемый Венфусс ( река Венна ). Вена полностью окружена Нижней Австрией и находится около 50 км (31 миль) к западу от Словакии и ее столицы Братислава , 60 км (37 миль) к северо -западу от Венгрии и 60 км (37 миль) к югу от Моравии ( Чешская Республика ).

Когда -то кельтское поселение Ведунии было преобразовано римлянами в каструм и Канаба Виндобона ( провинция Паннония ) в 1 -м веке, и в 212 году было поднято в муниципиум с правами римского города. За этим последовало время в сфере в сфере Влияние ломбардов , а затем и паннонских аваров , когда славянки образовали большую часть населения региона. [ А ] С 8 -го века регион был урегулирован байвариями . В 1155 году Вена была основана в качестве места Бабенберга , лордов Австрии с 976 по 1278 год, и в 1221 году Вене получили права города. В 16 -м веке последующие лорды Австрии, Габсбурги , создали Вену как место императоров Священной Римской империи , за коротким исключением, до ее роспуска в 1806 году. С образованием Австрийской империи в 1804 году Вена. стал его столицей и всем его преемниками.

Throughout the modern era Vienna has been among the largest German-speaking cities in the world, being the largest in the 18th and 19th century, peaking at two million inhabitants before it was overtaken by Berlin at the beginning of the 20th century.[14][15][16] Vienna is host to many major international organizations, including the United Nations, OPEC and the OSCE. In 2001, the city center was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In July 2017, it was moved to the list of World Heritage in Danger.[17]

Vienna has been called the "City of Music"[18] due to its musical legacy, as many famous classical musicians such as Beethoven, Brahms, Bruckner, Haydn, Mahler, Mozart, Schoenberg, Schubert, Johann Strauss I and Johann Strauss II lived and worked there.[19] It played a pivotal role as a leading European music center, from the age of Viennese Classicism through the early part of the 20th century. Vienna was home to the world's first psychoanalyst, Sigmund Freud.[20] The historic center of Vienna is rich in architectural ensembles, including Baroque palaces and gardens, and the late-19th-century Ringstraße, which is lined with grand buildings, monuments, and parks.[21]

In 2024, Vienna retained its position as most livable city per the Economist Intelligence Unit, and has spent every year since 2015 in the top 2 places, bar 2021 due to the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Etymology

The place is mentioned as Οϋι[νδ]όβονα (Oui[nd]obona) in the 2nd century AD (Ptolemy, Geography, II, 14, 3); Vindobona in the 3rd century (Itinerarium Antonini Augusti 233, 8); Vindobona in the 4th century (Tabula Peutingeriana, V, 1); Vindomana ab. 400 (Notitia Dignitatum, 145, 16); Vindomina, Vendomina in the 6th century (Jordanes, De origine actibusque Getarum, 50, 264).

The English name Vienna is borrowed from the homonymous Italian name. The German name Wien comes from the name of the river Wien, mentioned ad UUeniam in 881 (Wenia- in modern writing).[22][23][24]

The name of the Roman settlement on the same emplacement is of Celtic extraction Vindobona, probably meaning "white village, white settlement" from Celtic roots, vindo-, meaning "white" (Old Irish find "white", Welsh gwyn / gwenn, Old Breton guinn "white, bright" > Breton gwenn "white"), and -bona "foundation, settlement, village",[25][26] related to Old Irish bun "base, foundation" and Welsh bon, same meaning.[26] The Celtic word vindos may reflect a widespread prehistorical cult of Vindos, a Celtic deity who survives in Irish mythology as the warrior and seer Fionn mac Cumhaill.[27][28] A variant of this Celtic name could be preserved in the Czech, Slovak, Polish and Ukrainian names of the city (Vídeň, Viedeň, Wiedeń and Відень respectively) and in that of the city's district Wieden.[29]

The name of the city in Hungarian (Bécs), Serbo-Croatian (Beč, Беч) and Ottoman Turkish (بچ, Beç) has a different, probably Slavonic origin, and originally referred to an Avar fort in the area.[30] Slovene speakers call the city Dunaj, which in other Central European Slavic languages means the river Danube, on which the city stands.

History

Duchy of Austria 1156–1453

Archduchy of Austria 1453–1485, 1490-1804

Principality of Hungary 1485–1490

Austrian Empire 1804–1867

Austria-Hungary 1867–1918

First Austrian Republic 1919–1934

Federal State of Austria 1934–1938

Nazi Germany 1938–1945

Allied-occupied Austria 1945–1955

Austria 1955–present

Roman period

In the 1st century, the Romans set up the military camp of Vindobona in Pannonia on the site of today's Vienna city center near the Danube with an adjoining civilian town to secure the borders of the Roman Empire. Construction of the legionary camp began around 97 AD. At its peak, Vindobona had a population of around 15,000 people. It was a part of a trade and communications network across the Empire. Roman emperor may have Marcus Aurelius died here in 180 AD during a campaign against the Marcomanni.

After a Germanic invasion in the second century the city was rebuilt. It served as a seat of the Roman government until the fifth century, when the population fled due to the Huns invasion of Pannonia. The city was abandoned for several centuries.

Evidence of the Romans in the city is plentiful. Remains of the military camp have been found under the city, as well as fragments of the canal system and figurines.

Middle Ages

Close ties with other Celtic peoples continued through the ages. The Irish monk Saint Colman (or Koloman, Irish Colmán, derived from colm "dove") is buried in Melk Abbey and Saint Fergil (Virgil the Geometer) served as Bishop of Salzburg for forty years. Irish Benedictines founded twelfth-century monastic settlements; evidence of these ties persists in the form of Vienna's great Schottenstift monastery (Scots Abbey), once home to many Irish monks.

In 976, Leopold I of Babenberg became count of the Eastern March, a district centered on the Danube on the eastern frontier of Bavaria. This initial district grew into the duchy of Austria. Each succeeding Babenberg ruler expanded the march east along the Danube, eventually encompassing Vienna and the lands immediately east. In 1155, Henry II, Duke of Austria moved the Babenberg family residence with the founding of the Schottenstift from Klosterneuburg in Lower Austria to Vienna.[31] From that time, Vienna remained the center of the Babenberg dynasty.[32] Hungary occupied the city between 1485 and 1490.

Vienna became at the turn to the 16th century the seat of the Aulic Council[33] and subsequently later in the 16th century of the Habsburg emperors of the Holy Roman Empire with an interruption between at the turn to the 17th century until 1806, becoming an important center in the empire.[34]

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Christian forces twice stopped Ottoman armies outside Vienna, in the 1529 siege of Vienna and the 1683 Battle of Vienna. The Great Plague of Vienna ravaged the city in 1679, killing nearly a third of its population.[35]

Austrian Empire and early 20th century

In 1804, during the Napoleonic Wars, Vienna became the capital of the newly formed Austrian Empire. The city continued to play a major role in European and world politics, including hosting the Congress of Vienna in 1814–15. The city also saw major uprisings against Habsburg rule in 1848, which were suppressed. After the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, Vienna remained the capital of what became the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The city functioned as a center of classical music, for which the title of the First Viennese School (Haydn/Mozart/Beethoven) is sometimes applied.

During the latter half of the 19th century, Vienna developed what had previously been the bastions and glacis into the Ringstraße, a new boulevard surrounding the historical town and a major prestige project. Former suburbs were incorporated, and the city of Vienna grew dramatically. In 1918, after World War I, Vienna became capital of the Republic of German-Austria, and then in 1919 of the First Republic of Austria.

From the late-19th century to 1938, the city remained a center of high culture and of modernism. A world capital of music, Vienna played host to composers such as Johannes Brahms, Anton Bruckner, Gustav Mahler, and Richard Strauss. The city's cultural contributions in the first half of the 20th century included, among many, the Vienna Secession movement in art, the Second Viennese School, the architecture of Adolf Loos, the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein, and the Vienna Circle.

Red Vienna

The city of Vienna became the center of socialist politics from 1919 to 1934, a period referred to as Red Vienna (Das rote Wien). After a new breed of socialist politicians won the local elections they engaged in a brief but ambitious municipal experiment.[36] Social democrats had won an absolute majority in the May 1919 municipal election and commanded the city council with 100 of the 165 seats. Jakob Reumann was appointed by the city council as city mayor.[37] The theoretical foundations of so-called Austromarxism were established by Otto Bauer, Karl Renner, and Max Adler.[38]

Red Vienna is perhaps most well known for its Gemeindebauten, public housing buildings. Between 1925 and 1934, over 60,000 new apartments were built in the Gemeindebauten. Apartments were assigned on the basis of a point system favoring families and less affluent citizens.[39]

July Revolt and Civil War

In July 1927, after three nationalist far-right paramilitary members were acquitted of the killing of two social democratic Republikanischer Schutzbund members, a riot broke out in the city. The protestors, enraged by the decision, set the Palace of Justice ablaze. The police attempted to end the revolt with force and killed at least 84 protestors, with 5 policemen also dying.[40] In 1933, right-wing Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss dissolved the parliament, essentially letting him run the country as a dictatorship, banned the Communist Party and severely limited the influence of the Social Democratic Party. This led to a civil war between the right-wing government and socialist forces the following year, which started in Linz and quickly spread to Vienna. Socialist members of the Republikanischer Schutzbund barricaded themselves inside the housing estates and exchanged fire with the police and paramilitary groups. The fighting in Vienna ended after the Austrian Armed Forces shelled the Karl Marx-Hof, a civilian housing estate, and the Schutzbund surrendered.[41]

Anschluss and World War II

On 15 March 1938, three days after German troops had first entered Austria, Adolf Hitler arrived in Vienna. 200,000 Austrians greeted him at the Heldenplatz, where he held a speech from a balcony in the Neue Burg, in which he announced that Austria would be absorbed into Nazi Germany. The persecution of Jews started almost immediately, Viennese Jews were harassed and hounded, their homes and businesses plundered. Some were forced to scrub pro-independence slogans off the streets. This culminated in the Kristallnacht, a nationwide pogrom against the Jews carried out by the Schutzstaffel and the Sturmabteilung, with support of the Hitler Youth and German civilians. All synagogues and prayer houses in the city were destroyed, bar the Stadttempel, due to its proximity to residential buildings.[42][43] Vienna lost its status as a capital to Berlin, as Austria had ceased to exist. The few resistors in the city were arrested.

Adolf Eichmann held office in the expropriated Palais Rothschild and organized the expropriation and persecution of the Jews. Of the almost 200,000 Jews in Vienna, around 120,000 were driven to emigrate and around 65,000 were killed. After the end of the war, the Jewish population of Vienna was only about 5,000.[44][45][46][47]

In 1942 the city suffered its first air raid, carried out by the Soviet air force. Only after the Allies had taken Italy did the next raids commence. From March 17, 1944, 51 air raids were carried out in Vienna. Targets of the bombings were primarily the city's oil refineries. However, around a third of the city center was destroyed, and culturally important buildings such as the State Opera and the Burgtheater were burned, and the Albertina was heavily damaged. These air raids lasted until March 1945, just before the Soviet troops started the Vienna offensive.

The Red Army, who had previously marched through Hungary, first entered Vienna on 6 April. They first attacked the eastern and southern suburbs, before moving on to the western suburbs. By the 8th they had the center of the city surrounded. The following day the Soviets started with the infiltration of the city center. Fighting continued for a few more days until the Soviet Navy’s Danube Flotilla naval force arrived with reinforcements. The remaining defending soldiers surrendered that same day.

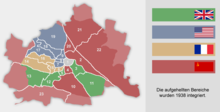

Four-power Vienna

After the war, Vienna was part of Soviet-occupied Eastern Austria until September 1945. That month, Vienna was divided into sectors by the four powers: the US, the UK, France, and the Soviet Union and supervised by an Allied Commission. The four-power occupation of Vienna differed in one key respect from that of Berlin: the central area of the city, known as the first district, constituted an international zone in which the four powers alternated control on a monthly basis. The city was policed by the four powers on a day-to-day basis, the "four soldiers in a jeep" method, which had one soldier from each power sitting together, was relied upon. The four powers all had separate headquarters, the Soviets in Palais Epstein next to the Parliament, the French in Hotel Kummer on Mariahilferstraße, the Americans in the National Bank, and the British in Schönnbrunn Palace. The division of the city was not comparable to that of Berlin. Although the borders between the sectors were marked, travel between them was freely possible.

During the 10 years of the four-power occupation, Vienna was a hotbed for international espionage between the Western and Eastern blocs, who distrusted one another deeply. The city, just like the rest of the country and Western Europe, had an economic upturn due to the Marshall Plan.

The atmosphere of four-power Vienna is the background for Graham Greene's screenplay for the film The Third Man (1949). The film's theme music was composed and performed by Viennese musician Anton Karas using a zither. Later he adapted the screenplay as a novel and published it. Occupied Vienna is also depicted in the 1991 Philip Kerr novel, A German Requiem.

Austrian State Treaty and subsequent sovereignty

The four-power control of Vienna lasted until the Austrian State Treaty was signed in May 1955 and came into force on 27 July 1955. By October, all soldiers had left the country. That year, after years of reconstruction and restoration, the State Opera and the Burgtheater, both on the Ringstraße, reopened to the public.

In the Autumn of 1956, Vienna accepted many Hungarian refugees, who had fled Hungary after an attempted revolution. The city experienced another wave of refugees after the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia in 1968, as well as after the collapse of Yugoslavia in 1991.

In 1972 the construction of the Donauinsel and the excavation of the New Danube began. In the same decade, Austrian Chancellor Bruno Kreisky inaugurated the Vienna International Centre, a new area of the city created to host international institutions. Vienna has regained much of its former international stature by hosting international organisations, such as the United Nations.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1637 | 60,000 | — |

| 1683 | 90,000 | +50.0% |

| 1710 | 113,800 | +26.4% |

| 1754 | 175,460 | +54.2% |

| 1783 | 247,753 | +41.2% |

| 1793 | 271,800 | +9.7% |

| 1830 | 401,200 | +47.6% |

| 1840 | 469,400 | +17.0% |

| 1850 | 551,300 | +17.4% |

| 1857 | 683,000 | +23.9% |

| 1869 | 900,998 | +31.9% |

| 1880 | 1,162,591 | +29.0% |

| 1890 | 1,430,213 | +23.0% |

| 1900 | 1,769,137 | +23.7% |

| 1910 | 2,083,630 | +17.8% |

| 1923 | 1,918,720 | −7.9% |

| 1934 | 1,935,881 | +0.9% |

| 1939 | 1,770,938 | −8.5% |

| 1951 | 1,616,125 | −8.7% |

| 1961 | 1,627,566 | +0.7% |

| 1971 | 1,619,885 | −0.5% |

| 1981 | 1,531,346 | −5.5% |

| 1991 | 1,539,848 | +0.6% |

| 2001 | 1,550,123 | +0.7% |

| 2011 | 1,714,227 | +10.6% |

| 2021 | 1,926,960 | +12.4% |

| Source for 1869-2021:[48] | ||

| Country of birth | Population as of 31 December 2022 |

|---|---|

| 88,715 | |

| 65,650 | |

| 60,513 | |

| 50,036 | |

| 48,741 | |

| 40,054 | |

| 39,327 | |

| 34,285 | |

| 25,084 | |

| 24,145 |

Because of the industrialization and migration from other parts of the Empire, the population of Vienna increased sharply during its time as the capital of Austria-Hungary (1867–1918). In 1910, Vienna had more than two million inhabitants and was the third largest city in Europe after London and Paris.[50] Around the start of the 20th century, Vienna was the city with the second-largest Czech population in the world (after Prague).[51] After World War I, many Czechs and Hungarians returned to their ancestral countries, resulting in a decline in the Viennese population. After World War II, the Soviets used force to repatriate key workers of Czech, Slovak and Hungarian origins to return to their ethnic homelands to further the Soviet bloc economy.[citation needed] The population of Vienna generally stagnated or declined through the remainder of the 20th century, not demonstrating significant growth again until the census of 2000. In 2020, Vienna's population remained significantly below its reported peak in 1916.

Under the Nazi regime, 65,000 Jews were deported and murdered in concentration camps by Nazi forces; approximately 130,000 fled.[52]

By 2001, 16% of people living in Austria had nationalities other than Austrian, nearly half of whom were from former Yugoslavia;[53][54] the next most numerous nationalities in Vienna were Turks (39,000; 2.5%), Poles (13,600; 0.9%) and Germans (12,700; 0.8%).

As of 2012[update], an official report from Statistics Austria showed that more than 660,000 (38.8%) of the Viennese population have full or partial migrant background, mostly from Ex-Yugoslavia, Turkey, Germany, Poland, Romania and Hungary.[12][55]

From 2005 to 2015 the city's population grew by 10.1%.[56] According to UN-Habitat, Vienna could be the fastest growing city out of 17 European metropolitan areas until 2025 with an increase of 4.65% of its population, compared to 2010.[57]

| Background | Nos. |

|---|---|

| Native born | 970,900 |

| 1st generation migration background | 739,500 |

| 2nd generation migration background | 242,900 |

| Total | 1,953,300 |

Religion

Religion in Vienna (2021)[59]

According to the 2021 census, 49.0% of Viennese were Christian. Among them, 31,8% were Catholic, 11,2% were Eastern Orthodox, and 3,7% were Protestant, mostly Lutheran, 34.1% had no religious affiliation, 14.8% were Muslim, and 2% were of other religions, including Jewish.[60] One sources estimates that Vienna's Jewish community is of 8,000 members meanwhile another suggest 15,000.[61][62]

Based on information provided to city officials by various religious organizations about their membership, Vienna's Statistical Yearbook 2019 reports in 2018 an estimated 610,269 Roman Catholics, or 32.3% of the population, and 200,000 (10.4%) Muslims, 70,298 (3.7%) Orthodox, 57,502 (3.0%) other Christians, and 9,504 (0.5%) other religions.[63] A study conducted by the Vienna Institute of Demography estimated the 2018 proportions to be 34% Catholic, 30% unaffiliated, 15% Muslim, 10% Orthodox, 4% Protestant, and 6% other religions.[64][65]

As of the spring of 2014, Muslims made up 30% of the total proportion of schoolchildren in Vienna.[66][67]

Vienna is the seat of the Metropolitan Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Vienna, in which is also vested the exempt Ordinariate for Byzantine-Rite Catholics in Austria; its Archbishop is Cardinal Christoph Schönborn. Many Catholic Churches in central Vienna feature performances of religious or other music, including masses sung to classical music and organ. Some of Vienna's most significant historical buildings are Catholic churches, including the St. Stephen's Cathedral (Stephansdom), Karlskirche, Peterskirche and the Votivkirche. On the banks of the Danube, there is a Buddhist Peace Pagoda, built in 1983 by the monks and nuns of Nipponzan Myohoji.

Geography

Vienna is located in northeastern Austria, at the easternmost extension of the Alps in the Vienna Basin. The earliest settlement, at the location of today's inner city, was south of the meandering Danube while the city now spans both sides of the river. Elevation ranges from 151 to 542 m (495 to 1,778 ft). The city has a total area of 414.65 square kilometers (160.1 sq mi), making it the largest city in Austria by area.

Climate

Vienna has a borderline oceanic (Köppen: Cfb) and humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfb), with some parts of the urban core being warm enough for a humid subtropical (Köppen: Cfa) classification.

The city has warm, showery summers, with average high temperatures ranging between 25 to 27 °C (77 to 81 °F) and a record maximum exceeding 38 °C (100 °F). Winters are relatively dry and cold with average temperatures at about freezing point. Spring is variable and autumn cool, with a chance of snow in November.

Precipitation is generally moderate throughout the year, averaging around 600 mm (23.6 in) annually, with considerable local variations, the Vienna Woods region in the west being the wettest part (700 to 800 mm (28 to 31 in) annually) and the flat plains in the east being the driest part (500 to 550 mm (20 to 22 in) annually). Snow in winter is common, even if not so frequent compared to the Western and Southern regions of Austria.

| Climate data for Vienna (Hohe Warte) 1991–2020, extremes 1775–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.7 (65.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

29.5 (85.1) |

34.0 (93.2) |

36.5 (97.7) |

39.5 (103.1) |

38.4 (101.1) |

34.0 (93.2) |

27.8 (82.0) |

21.7 (71.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

39.5 (103.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.5 (38.3) |

6.5 (43.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

17.2 (63.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

25.1 (77.2) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.1 (79.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

14.3 (57.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.1 (34.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

6.9 (44.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

16.3 (61.3) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.6 (70.9) |

16.6 (61.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

6.2 (43.2) |

1.8 (35.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −1.3 (29.7) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

2.6 (36.7) |

6.7 (44.1) |

10.7 (51.3) |

14.7 (58.5) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

12.0 (53.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

7.2 (45.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −23.8 (−10.8) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

−16.3 (2.7) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

3.2 (37.8) |

6.9 (44.4) |

6.5 (43.7) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−14.3 (6.3) |

−20.7 (−5.3) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 42.1 (1.66) |

38.1 (1.50) |

51.6 (2.03) |

41.8 (1.65) |

78.9 (3.11) |

70.0 (2.76) |

77.7 (3.06) |

69.1 (2.72) |

64.1 (2.52) |

46.9 (1.85) |

46.0 (1.81) |

46.8 (1.84) |

673.1 (26.50) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 15.9 (6.3) |

13.6 (5.4) |

5.2 (2.0) |

1.1 (0.4) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (0.2) |

3.2 (1.3) |

10.8 (4.3) |

50.2 (19.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.7 | 7.1 | 8.7 | 6.5 | 9.4 | 8.4 | 8.9 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 7.6 | 8.6 | 96.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1.0 cm) | 11.4 | 8.8 | 3.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 6.2 | 31.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 14:00) | 73.4 | 64.9 | 57.7 | 51.6 | 54.6 | 54.4 | 53.3 | 52.8 | 58.4 | 66.2 | 74.3 | 76.6 | 61.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 70.2 | 104.9 | 155.1 | 216.5 | 248.3 | 260.5 | 273.6 | 266.3 | 191.7 | 129.9 | 67.7 | 57.1 | 2,041.8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 26.4 | 37.5 | 43.0 | 54.1 | 54.4 | 56.3 | 58.6 | 62.1 | 52.2 | 40.0 | 25.1 | 22.6 | 44.4 |

| Source 1: Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics[68] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows),[69] wien.orf.at[70] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Vienna (Innere Stadt) 1991–2020, extremes 1961–2020 |

|---|

| Climate data for Vienna (Hohe Warte) 1961–1990[i] |

|---|

- ^ Afternoon humidity measured at 14:00 local time

Districts and enlargement

Districts

| No. | District | Coat of arms |

Area (km2) |

Population (2023) |

Density per km2 |

Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Innere Stadt | 2.869 | 16,538 | 5,764 |

| |

| 2 | Leopoldstadt | 19.242 | 110,100 | 5,707 |

| |

| 3 | Landstraße | 7.403 | 98,398 | 13,292 |

| |

| 4 | Wieden | 1.776 | 33,155 | 18,668 |

| |

| 5 | Margareten | 2.012 | 54,400 | 27,038 |

| |

| 6 | Mariahilf | 1.455 | 31,386 | 21,571 |

| |

| 7 | Neubau | 1.608 | 31,513 | 19,598 |

| |

| 8 | Josefstadt | 1.090 | 24,499 | 22,476 |

| |

| 9 | Alsergrund | 2.976 | 41,631 | 13,989 |

| |

| 10 | Favoriten | 31.823 | 220,324 | 6,923 |

| |

| 11 | Simmering | 23.256 | 110,559 | 4,754 |

| |

| 12 | Meidling | 8.103 | 101,714 | 12,556 |

| |

| 13 | Hietzing | 37.713 | 55,505 | 1,472 |

| |

| 14 | Penzing | 33.760 | 98,161 | 2,908 |

| |

| 15 | Rudolfsheim-Fünfhaus | 3.918 | 76,381 | 19,495 |

| |

| 16 | Ottakring | 8.673 | 102,770 | 11,849 |

| |

| 17 | Hernals | 11.396 | 56,671 | 4,973 |

| |

| 18 | Währing | 6.347 | 51,395 | 8,098 |

| |

| 19 | Döbling | 24.944 | 75,400 | 3,023 |

| |

| 20 | Brigittenau | 5.710 | 85,930 | 15,049 |

| |

| 21 | Floridsdorf | 44.443 | 186,233 | 4,190 |

| |

| 22 | Donaustadt | 102.299 | 220,794 | 2,158 |

| |

| 23 | Liesing | 32.061 | 121,303 | 3,784 |

|

Vienna is composed of 23 districts (Bezirke). Administrative district offices in Vienna, called Magistratische Bezirksämter, serve functions similar to those in the other Austrian states (called Bezirkshauptmannschaften), the officers being subject to the mayor of Vienna; with the notable exception of the police, which is under federal supervision.

District residents in Vienna (Austrians as well as EU citizens with permanent residence here) elect a District Assembly (Bezirksvertretung). City hall has delegated maintenance budgets, e.g., for schools and parks, so that the districts are able to set priorities autonomously. Any decision of a district can be overridden by the city assembly (Gemeinderat) or the responsible city councilor (amtsführender Stadtrat).

Enlargement

The heart and historical city of Vienna, a large part of today's Innere Stadt, was a fortress surrounded by fields to defend itself from potential attackers. In 1850, Vienna with the consent of the emperor annexed 34 surrounding villages,[74] called Vorstädte, into the city limits (districts no. 2 to 8, after 1861 with the separation of Margareten from Wieden no. 2 to 9). Consequently, the walls were razed after 1857,[75] making it possible for the city center to expand.

In their place, a broad boulevard called the Ringstraße was built, along which imposing public and private buildings, monuments, and parks were created by the start of the 20th century. These buildings include the Rathaus (town hall), the Burgtheater, the University, the Parliament, the twin museums of natural history and fine art, and the Staatsoper. It is also the location of the New Wing of the Hofburg, the former imperial palace, and the Imperial and Royal War Ministry finished in 1913. The mainly Gothic Stephansdom is located at the center of the city, on Stephansplatz. The Imperial-Royal Government set up the Vienna City Renovation Fund (Wiener Stadterneuerungsfonds) and sold many building lots to private investors, thereby partly financing public construction works.

From 1850 to 1890, city limits in the West and the South mainly followed another wall called Linienwall at which a road toll called the Liniengeld was charged. Outside this wall from 1873 onwards a ring road called The Gürtel was built. In 1890 it was decided to integrate 33 suburbs (called Vororte) beyond that wall into Vienna by 1 January 1892[76] and transform them into districts no. 11 to 19 (district no. 10 had been constituted in 1874); hence the Linienwall was torn down beginning in 1894.[77] In 1900, district no. 20, Brigittenau, was created by separating the area from the 2nd district.

From 1850 to 1904, Vienna had expanded only on the eastern bank of the Danube, following the main branch before the regulation of 1868–1875, i.e., the Old Danube of today. In 1904, the 21st district was created by integrating Floridsdorf, Kagran, Stadlau, Hirschstetten, Aspern and other villages on the left bank of the Danube into Vienna, and in 1910 Strebersdorf followed. On 15 October 1938, the Nazis created Great Vienna with 26 districts by merging 97 towns and villages into Vienna, 80 of which were returned to surrounding Lower Austria in 1954.[76] Since then Vienna has had 23 districts.

Industries are located mostly in the southern and eastern districts. The Innere Stadt is situated away from the main flow of the Danube, but is bounded by the Donaukanal ("Danube canal"). Vienna's second and twentieth districts are located between the Donaukanal and the Danube. Across the Danube, where the Vienna International Centre is located (districts 21–22), and in the southern areas (district 23) are the newest parts of the city.

Politics

Political history

In the provinces represented in the Imperial Council, men had had universal suffrage at the national level since 1907. Mayor Karl Lueger of the Christian Social Party prevented the adoption of this right to vote in municipal council elections, which excluded many working-class people. The first elections in which all adult men and women were entitled to vote took place in 1919 after the end of the monarchy. Since 1919, the Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ) has provided the mayor in all free elections and the Vienna City Council (the city parliament) has had a Social Democratic majority.

On November 10, 1920, the day on which the Federal Constitution of Austria came into force, which defined Vienna as a separate federal state and made its separation from Lower Austria possible. Since then, the mayor of Vienna has also been the governor of the state, the city senate the state government and the municipal council the state parliament. Vienna was used as the seat of the Lower Austrian government until 1997 when they moved to St. Pölten.

From 1934 to 1945, during the period of Austrofascist and Nazi, no democratic elections were held and the city was run as a dictatorship. During this time the SPÖ was banned and many of its members were imprisoned. Vienna's city constitution was reinstated in 1945.

The city has enacted many social democratic policies. The Gemeindebauten are social housing assets that are well integrated into the city architecture outside the inner district. The low rents enable comfortable accommodation and good access to the city amenities. Many of the projects were built after World War II on vacant lots that were destroyed by bombing during the war. The city took particular pride in building them to a high standard. The social housing in Vienna provides living for more than 500,000 people.[78]

Government

In the 1996 City Council election, the SPÖ lost its overall majority in the 100-seat chamber, winning 43 seats and 39.15% of the vote. The SPÖ had held an outright majority at every free municipal election since 1919. In 1996, the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), which won 29 seats (up from 21 in 1991), beat the ÖVP into third place for the second time running. From 1996 to 2001, the SPÖ governed Vienna in a coalition with the ÖVP. In 2001 the SPÖ regained the overall majority with 52 seats and 46.91% of the vote; in October 2005, this majority was increased further to 55 seats (49.09%). In the 2010 city council elections the SPÖ lost their overall majority again and consequently forged a coalition with the Green Party – the first SPÖ/Green coalition in Austria.[79] This coalition was maintained following the 2015 election. Following the 2020 election, the SPÖ forged a coalition with NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum. The next elections will take place in 2025.

Current government

The latest elections were held on 11 October 2020. It resulted in an SPÖ-NEOS coalition and Michael Ludwig was re-elected as mayor.

- SPÖ: 46

- NEOS: 8

- ÖVP: 22

- Greens: 16

- FPÖ: 8

| Party | Votes | % | +/– | Seats | +/– |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ) | 301,967 | 41.62 | +2.03 | 46 | +2 |

| Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) | 148,238 | 20.43 | +11.19 | 22 | +15 |

| The Greens – The Green Alternative (GRÜNE) | 107,397 | 14.80 | +2.96 | 16 | +6 |

| NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum (NEOS) | 54,173 | 7.47 | +1.31 | 8 | +3 |

| Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) | 51,603 | 7.11 | –23.68 | 8 | –26 |

| Other | 62,132 | 8.56 | +6.19 | 0 | +0 |

| Total | 725,510 | 100 | – | 100 | 0 |

Economy

Vienna generates 28.6% of Austria's GDP, making it the highest performing regional economy of the country. It has a GDP per capita of 53,000€ as of 2021. The service sector dominates Vienna's economy. The unemployment rate in Vienna is 9.6% as of 2022, which is the highest of all the states.[80] The private service sector provides 75% of all jobs.[81] The city improved its position from 2012 on the ranking of the most economically powerful cities reaching number nine on the list in 2015.[82][83] Of the top 500 Austrian firms measured by turnover, 203 are headquartered in Vienna.[81] As of 2015, 175 international firms maintained offices in Vienna.[84]

Since the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, Vienna has expanded its position as a gateway to Eastern Europe. 300 international companies have their Eastern European headquarters in Vienna, including Hewlett-Packard, Henkel, Baxalta, and Siemens.[85]

Annually since 2004, approximately 8,300 new companies have been founded in Vienna.[86] The majority of these companies are operating in fields of industry-oriented services, wholesale trade as well as information and communications technologies and new media.[87] Vienna makes efforts to establish itself as a start-up hub.[citation needed]

Since 2012, the city has hosted the annual Pioneers Festival, the largest start-up event in Central Europe with 2,500 international participants taking place at Hofburg Palace. Tech Cocktail, an online portal for the start-up scene, has ranked Vienna sixth among the top ten start-up cities worldwide.[88][89][90]

The cultivation and production of wines within the city borders have a high socio-cultural value.

Research and development

Life sciences are a major research and development sector in Vienna. The Vienna Life Science Cluster is Austria's major hub for life science research, education and business. Throughout Vienna, five universities and several basic research institutes form the academic core of the hub with more than 12,600 employees and 34,700 students. Here, more than 480 medical device, biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies with almost 23,000 employees generate around 12 billion euros in revenue (2017). This corresponds to more than 50% of the revenue generated by life science companies in Austria (22.4 billion euros).[91][92][needs update]

Vienna is home to Boehringer Ingelheim, Octapharma, Ottobock and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company.[93] However, there is also a growing number of start-up companies in the life sciences and Vienna was ranked first in the 2019 PeoplePerHour Startup Cities Index.[94] Companies such as Apeiron Biologics, Hookipa Pharma, Marinomed, mySugr, Themis Bioscience and Valneva operate a presence in Vienna and regularly hit the headlines internationally.[95] Vienna also houses the headquarters of the Central European Diabetes Association, a cooperative international medical research association.

To facilitate tapping the economic potential of the multiple facets of the life sciences at Austria's capital, the Austrian Federal Ministry for Digital and Economic Affairs and the local government of the City of Vienna have joined forces. Since 2002, the LISAvienna platform has been available as a central contact point. It provides free business support services at the interface of the Austrian federal promotional bank, Austria Wirtschaftsservice and the Vienna Business Agency and collects data that inform policy making.[96] The main academic hotspots in Vienna are the Life Science Center Muthgasse with the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU), the Austrian Institute of Technology, the University of Veterinary Medicine, the AKH Vienna with the MedUni Vienna and the Vienna Biocenter.[97] Central European University, a graduate institution expelled from Budapest in the midst of a Hungarian government steps to take control of academic and research organizations, welcomes the first class of students to its new Vienna campus in 2019.[98]

Information technologies

The Viennese sector for information and communication technologies is comparable in size with the sector in Helsinki, Milan, or Munich, and ranks among Europe's largest locations for information technology. In 2012 8,962 information technology businesses with a workforce of 64,223 were located in the Vienna Region. The main products are instruments and appliances for measuring, testing and navigation as well as electronic components. More than two-thirds of the enterprises provide IT services. Among the biggest IT firms in Vienna are Kapsch, Beko Engineering & Informatics, air traffic control experts Frequentis, Cisco Systems Austria, Hewlett-Packard, Microsoft Austria, IBM Austria and Samsung Electronics Austria.[99][100]

The U.S. technology corporation Cisco runs its Entrepreneurs in Residence program for Europe in Vienna in cooperation with the Vienna Business Agency.[101][102]

The British company UBM has rated Vienna one of the Top 10 Internet Cities worldwide, by analyzing criteria like connection speed, WiFi availability, innovation spirit and open government data.[103]

Conferences

In 2022, the International Congress and Convention Association (ICCA) ranked Vienna 1st in the world for association meetings.[104] The Union of International Associations (UIA) ranked Vienna 5th in the world for 2019 with 306 international meetings, behind Singapore, Brussels, Seoul and Paris.[105] The city's largest conference center, the Austria Center Vienna (ACV) has a total capacity for around 22,800 people and is situated next to the United Nations Office at Vienna.[106] Other centers are the Messe Wien Exhibition & Congress Center (up to 3,000 people) and the Hofburg Palace (up to 4,900 people).

Tourism

There were 17.3 million overnight stays in Vienna in 2023. The top ten incoming markets in 2023 were Germany, the rest of Austria, the United States, Italy, the United Kingdom, Spain, France, Poland, Switzerland, and Romania.[107]

Urban planning

Vienna regularly hosts urban planning conferences and is often used as a case study by urban planners.[108] The highest wooden skyscraper in the world, "HoHo Wien", was built within 3 years, starting in 2015.[109] In recent years a syndicate housing movement has established itself in Vienna, Linz, Salzburg, and Innsbruck.[110]

In 2011, 74.3% of Viennese households were connected to broadband, and 79% were in possession of a computer. According to the broadband strategy of the city, full broadband coverage will be reached by 2020.[99][100]

Vienna Central Station

The new Vienna Central Station (Hauptbahnhof) was opened in October 2014.[111] Construction began in June 2007 and was due to last until December 2015. The station is served by 1,100 trains with 145,000 passengers. There is a shopping center with approximately 90 shops and restaurants.

In the vicinity of the station, a new district is emerging with 550,000 m2 (5,920,000 sq ft) office space and 5,000 apartments until 2020.[112][113][114]

Smart City Wien

The mayor of Vienna announced the Smart City Wien initiative in March 2011 after the Austrian Climate and Energy Fund decided to fund a project under the same heading. The Vienna city administration engaged with a broad range of stakeholders and published the Smart City Wien action plan.[115]

Seestadt Aspern

Seestadt Aspern in Vienna's Donaustadt district is one of the largest urban expansion projects of Europe. A 5-hectare artificial lake, offices, apartments, and a subway station within walking distance are supposed to attract 20,000 new citizens when construction is completed in 2028.[116][117]

Culture

Classical Music, theater, and opera

Art and culture have had a long tradition in Vienna, including theater, opera, classical music and fine arts. The Burgtheater is considered one of the premier theaters in the German-speaking world alongside its branch, the Akademietheater. The Volkstheater and the Theater in der Josefstadt also enjoy good reputations. There is also a multitude of smaller theaters, in many cases devoted to less mainstream forms of the performing arts, such as modern or experimental plays, as well as cabaret.

The city is also home to a number of opera houses, including the Theater an der Wien, the Staatsoper and the Volksoper, the latter being devoted to the typical Viennese operetta. Classical concerts are performed at venues such as the Wiener Musikverein, home of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra known across the world for its annual, widely broadcast "New Year's Concert", as well as the Wiener Konzerthaus, home of the internationally renowned Vienna Symphony. Many concert venues offer concerts aimed at tourists, featuring popular highlights of Viennese music, particularly the works of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Johann Strauss I, and Johann Strauss II.

Notable classical musicians born in Vienna include Louie Austen, Alban Berg, Fritz Kreisler, Joseph Lanner, Arnold Schoenberg, Franz Schubert, Johann Strauss I, Johann Strauss II and Anton Webern.

Famous classical musicians who moved to the city to work were Kurt Adler, Johann Joseph Fux, Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, Ferdinand Ries, Johann Sedlatzek, Antonio Salieri, Carl Czerny, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Franz Liszt, Franz von Suppé, Anton Bruckner, Johannes Brahms, and Gustav Mahler.

Operas that premiered in the capital include Fidelio, Die Fledermaus, The Gypsy Baron, The Magic Flute, and The Marriage of Figaro.

Up until 2005, the Theater an der Wien hosted premieres of musicals, but since 2006 (a year dedicated to the 250th anniversary of Mozart's birth), has devoted itself to opera again, becoming a stagione opera house offering one new production each month. Since 2012, Theater an der Wien has taken over the Wiener Kammeroper, a historical small theater in the first district of Vienna seating 300 spectators, turning it into its second venue for smaller-sized productions and chamber operas created by the young ensemble of Theater an der Wien (JET). Before 2005 the most successful musical was Elisabeth, which was later translated into several languages and performed all over the world. The Wiener Taschenoper is dedicated to stage music of the 20th and 21st century. The Haus der Musik ("House of Music") opened in the year 2000.

The Vienna's English Theater (VET) is an English theater in Vienna. It was founded in 1963 and is located in the 8th Vienna's district. It is the oldest English-language theater in continental Europe.

Popular Music

Vienna has also produced some well-known pop music artists. Pioneers of Austropop, Georg Danzer, Rainhard Fendrich, Wolfgang Ambros, and Peter Cornelius all hail from the capital. Willi Resetarits lived in the city from the age of three. The internationally best-known Viennese artist was Falco, whose song ”Rock Me Amadeus” is the only German-language song to reach number 1 on the American Billboard Hot 100, which it held for three weeks in 1986. His other hits, such as “Der Kommissar” and “Jeanny” also charted internationally. The founder of the American jazz fusion band Weather Report and Miles Davis collaborator, Joe Zawinul, was born in Vienna and studied music at the Conservatory of Vienna.

Current artists include Rapper RAF Camora, who grew up in the district of Rudolfsheim-Fünfhaus and often emphasizes his ties to his home in his lyrics, as well as hip-hop-musician Yung Hurn and indie pop band Wanda.

Multiple popular songs have been written about Vienna, such as "Vienna" (1977) by Billy Joel, "Vienna" (1981) by Ultravox, and "Vienna Calling" by Falco.

The Wienerlied is a unique song genre from Vienna. They are sung in Viennese dialect and often center around the city. There are approximately 60,000 – 70,000 Wienerlieder.

Every year the Donauinsel stages the Donauinselfest, the largest open-air music festival in the world, with approximately 3 million attendees over three days.[118] The festival is organized by the SPÖ Wien and is free to enter.[119] The Vienna Jazz Festival has taken place almost every year since 1991 and has featured artists such as Nina Simone, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, and Ravi Shankar.

Cinema

Films set in Vienna include Amadeus, Before Sunrise, The Third Man, The Living Daylights and Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation.

Notable actors born in Vienna include Hedy Lamarr, Christoph Waltz, Christiane Hörbiger, Eric Pohlmann, Boris Kodjoe, Christine Buchegger, Senta Berger and, Christine Ostermayer. Filmmakers include Michael Haneke and Fritz Lang, and Billy Wilder, who lived in Vienna during his teenage years.

Vienna's cinemas include the Apollo Kino and Cineplexx Donauzentrum and many English language cinemas, including the Haydn Kino, Artis International and the Burg Kino, screens The Third Man, a 1949 film set in Vienna, three times a week.

Every October since 1960 the city has staged the Viennale, an international film festival which screens several different genres of films, including premieres.

Literature

Notable writers from Vienna include Carl Julius Haidvogel, Karl Leopold von Möller, and Stefan Zweig.

Writers who lived and worked in Vienna include Ingeborg Bachmann, Thomas Bernhard, Elias Canetti, Ernst von Feuchtersleben, Elfriede Jelinek, Franz Kafka, Karl Kraus, Robert Musil, Arthur Schnitzler, and Bertha von Suttner.

Science

Scientists and intellectuals who were born, lived or worked in Vienna include:

- Biology: Konrad Lorenz, Karl von Frisch, Max Perutz

- Computer Science: Heinz Zemanek

- Chemistry: Karl Kordesch, Walter Kohn, Carl and Gerti Cori, Richard Kuhn

- Economics: Austrian School of Economics, Eugen Böhm von Bawerk, Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich August von Hayek, Rudolf Hilferding

- Engineering: Viktor Kaplan, Robert Adler, Paul Eisler, Siegfried Marcus

- Jurisprudence: Hans Kelsen, Karl Renner

- Mathematics: Kurt Gödel

- Medicine: Ignaz Semmelweis, Ferdinand von Hebra, Karl Landsteiner, Hans Asperger, Carl von Rokitansky, Julius Wagner-Jauregg, Robert Bárány, Theodor Billroth, Karl Koller

- Philosophy: Karl Popper, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Paul Feyerabend, Moritz Schlick

- Physics: Lise Meitner, Erwin Schrödinger, Wolfgang Pauli, Ludwig Boltzmann, Victor Franz Hess, Ernst Mach, Christian Doppler, Josef Stefan, Anton Zeilinger

- Psychology: Sigmund Freud, Alfred Adler, Viktor Frankl

- Sociology: Karl Polanyi, Otto Bauer, Max Adler

Museums

The majority of museums in Vienna are located in an area on the border of Innere Stadt and Neubau in the center of the city, from the museums inside the Hofburg to the MuseumsQuartier, with the twin Naturhistorisches and Kunsthistorisches Museum in between. This area is home to many museums such as:

- In and around the Hofburg:

- Imperial Treasury: a collection of European treasures, such as the Imperial Regalia of the Holy Roman Emperor and the Imperial Crown of Austria

- Sisi Museum: dedicated to Empress Elisabeth of Austria, it allows visitors to view the imperial apartments.

- Weltmuseum Wien: an anthropological museum, which houses many ethnographic objects from Africa, America, Asia and Oceania, such as Moctezuma's headdress.

- House of Austrian History

- Globe Museum

- Esperanto Museum and Collection of Planned Languages

- Austrian National Library

- Ephesos Museum

- Albertina: an art museum featuring approximately 65,000 drawings and 1 million old master prints, with works from Leonardo da Vinci, Claude Monet and Albrecht Dürer. Young Hare by Dürer is perhaps the most well-known painting in the museum.

- On Maria-Theresien-Platz: Two almost identical buildings were completed in 1891 and opened by Emperor Franz Joseph I.

- Kunsthistorisches Museum: an art museum featuring paintings from artists such as Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Caravaggio, Albrecht Dürer, Raphael, Rembrandt, Titian and Vermeer. Notable works exhibited in the museum include The (Great) Tower of Babel and The Hunters in the Snow (both Bruegel),

- Naturhistorisches Museum: A natural history museum with 30 million objects in its collection, of which 100,000 are on display. A notable exhibit is the Venus of Willendorf, a 25,000-year-old statue found in Austria.

- In the MuseumsQuartier: The former imperial stalls were converted to a group of museums in the late 1990s and opened in 2001.

- MUMOK (Museum of Modern Art): a modern and contemporary art museum housing works from Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Pablo Picasso.

- Leopold Museum: a collection of modern Austrian art with works from Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt, as well as works of the Vienna Secession, Viennese Modernism and Austrian Expressionism.

- Kunsthalle Wien

- ZOOM Kindermuseum

- Architekturzentrum Wien

The Österreichische Galerie Belvedere at the Belvedere presents art from Austria from the Middle Ages through the Baroque to the early 20th century, including The Kiss, Gustav Klimt's most famous work. It also houses the Baroque Museum with Franz Xaver Messerschmidt's famous character heads. In 2011, Belvedere 21 (formerly 21er Haus) was reopened in its immediate vicinity as a branch of contemporary art.

The Vienna Museum documents the history of Vienna with temporary exhibitions and a permanent presentation and presents the memorials to Ludwig van Beethoven, Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Franz Schubert and Johann Strauss. Other branches of the museum include the Hermesvilla in the Lainzer Tiergarten, the Vienna Clock Museum, the Roman Museum and the Prater Museum.

The former imperial summer residence at Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna's most visited attraction, is functionally set up as a museum with the palace's showrooms and the Imperial Carriage Museum.

The Museum of Military History in the Arsenal is the leading museum of the Austrian Armed Forces and documents the history of the Austrian military with exhibits including weapons, armour, tanks, aircraft, uniforms, battle flags, paintings, medals and decorations, photographs, battleship models and documents.

Other museums in the city include:

- House of Music: a music museum in the former palace of Archduke Charles, where Otto Nicolai, founder of the Vienna Philharmonic, once lived.

- Haus des Meeres: a public aquarium in a WWII flak tower.

- Museum of Art Fakes

- KunstHausWien

- Museum of Applied Arts

- Liechtenstein Museum

- Sigmund Freud Museum: a museum about Freuds' life at his old residence.

- Mozarthaus Vienna

- Liechtenstein Museum

- Jewish Museum Vienna: founded in 1896, the oldest of its kind.

- Money Museum: owned by the Austrian National Bank

- Museum of illusions

Architecture

A variety of architectural styles have been preserved in Vienna, including Romanesque architecture and Baroque architecture. Art Nouveau has left many architectural traces in Vienna. The Secession building, Karlsplatz Stadtbahn Station, and the Kirche am Steinhof by Otto Wagner rank among the best-known examples of Art Nouveau in the world.

The Wiener Moderne shunned the use of extraneous adornment. Architect Adolf Loos is responsible for the Looshaus (1909), the Kärntner Bar (1908), and the Steiner House (1910).

The Hundertwasserhaus by Friedensreich Hundertwasser, designed to counter the clinical look of modern architecture, is one of Vienna's most popular tourist attractions. Hundertwasser also designed the KunstHausWien and the District Heating Plant in Alsergrund.

In the 1990s, a number of quarters were adapted and extensive building projects were implemented in the areas around Donaustadt and Wienerberg. Vienna has seen numerous architectural projects completed which combine modern architectural elements with old buildings, such as the remodeling and revitalization of the old Gasometer in 2001.

The DC Towers are located on the northern bank of the Danube and were completed in 2013.[120][121]

Places of worship

Due to the prevalence of Christianity in the city, most places of worship are churches and cathedrals. Most notable are:

- St. Rupert's Church (ca. 800), the presumed oldest church in the city.

- St. Stephen's Cathedral (1137), the Gothic mother church of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Vienna, one of the city's most recognizable symbols. It sits in the Stephansplatz in the center of town and is a popular tourist attraction.

- Schottenkirche (12th century), founded by Irish Benedictine monks as the parish church of the Schottenstift.

- Maria am Gestade (1414), it is one of the oldest churches in the city and an example of Gothic architecture.

- Capuchin Church (1632), it contains the Imperial Crypt, where many members of the Habsburg family are buried.

- Karlskirche (1737), it sits in the Karlsplatz and is a popular tourist attraction.

- Peterskirche (early 18th century), it sits just off the Graben and is a popular tourist attraction.

- Votivkirche (1879), this church on the Ring was built as a thanks to God after Emperor Franz Joseph survived an assassination attempt in 1853.

- St. Francis of Assisi Church (1910), a Basilica-style church on the bank of the Danube on the Mexikoplatz, it is administered by the Order of the Holy Trinity.

Other churches include the Augustinian Church, the Church of St. Maria Rotunda, the Church of St. Leopold, the Franciscan Church, the Jesuit Church and the Minoritenkirche.

Vienna's biggest mosque is the Vienna Islamic Center in Kaisermühlen, which is financed by the Muslim World League. The mosque has a 32-meter-high minaret and a 16-meter-high dome with a 20-meter radius.[122] There are over 100 further mosques in the city.[123]

Before the November pogroms of 1938, there were 24 synagogues and 78 prayer houses in the city. Only one synagogue, the Stadttempel, survived.[124]

Ball dances

The first balls in Vienna were held in the 18th century. The ball season runs during Carnival from 11 November to Shrove Tuesday. Many balls are held in the Hofburg, Rathaus and Musikverein. Guests adhere to a strict dress code, men wear black or white tie while women wear a ball gown. Debutants of the ball wear white.[125]

The balls are opened with dances, traditionally including a Viennese waltz, at around 22:00, and close at about 05:00 the next morning. Food served at the balls includes sausages with bread or Gulaschsoups.

Notable Viennese balls include the Vienna Opera Ball, the Vienna Ball of Sciences, the Wiener Akademikerball and the Hofburg SIlvesterball.

The Wiener Akademikerball in the Hofburg has attracted lots of controversy for being a gathering for far-right politicians and groups. The ball is hosted by the FPÖ, the right-wing populist party of Austria and has attracted multiple right-wing and far-right personalities, such as Martin Sellner and Marie Le Pen. Since 2008, there have been annual demonstrations by various organizations against the ball. Former leader of the FPÖ Heinz-Christian Strache compared the anti-fascist protesters to a Nazi mob, claiming the ball goers were "new Jews".[126][127]

Language

Vienna is part of the Austro-Bavarian language area, in particular Central Bavarian (Mittelbairisch).[128] The Viennese dialect takes many loanword from languages of the former Habsburg Monarchy, especially Czech. The dialect differs from the west of Austria in its pronunciation and grammar. Features typical of Viennese German include Monophthongization, the transformation of a diphthong into a monophtong (German heiß (hot) into Viennese haas) and the lengthening of vowels (Heeaasd, i bin do ned bleeed, wooos waaasn ii, wea des woooa (Standard German Hörst du, ich bin doch nicht blöd, was weiß denn ich, wer das war): "Listen, I'm not stupid; what do I know, who that was?"). Speakers of the dialect tend to avoid the genetive case.[129]

LGBT

Vienna is considered the center of LGBTQ+ life in Austria.[130] The city has an action plan against homophobic discrimination and, since 1998, has had an anti-discrimination unit within the city's administration.[131] The city has several cafés, bars and clubs frequented by LGBTQ+ people. Among the most prominent is Café Savoy, which is a traditional coffee house built in 1896. In 2015, the city introduced traffic lights with same-sex couples before hosting the Eurovision Song Contest that year, which attracted media attention internationally.[132] Vienna's Pride Parade is held every June. In 2019, when the pride parade also hosted Europride, it attracted 500.000 visitors.[133]

Education

Universities

- Academy of Fine Arts Vienna

- Central European University

- Diplomatic Academy of Vienna

- Medical University of Vienna

- University of Applied Arts Vienna

- University of Applied Sciences Campus Vienna

- University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna

- University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna

- University of Vienna

- Vienna University of Economics and Business

- University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna

- University of Applied Sciences Technikum Wien

- TU Wien

- Webster Vienna Private University

- Sigmund Freud Private University

International schools

- Amadeus International School Vienna

- American International School Vienna

- Danube International School Vienna

- International Christian School of Vienna

- Japanese International School in Vienna

- Lauder Business School

- Lycée Français de Vienne

- SAE Vienna

- Vienna International School

Green spaces

Parks

On the southeastern outer border of the Ringstraße is the Stadtpark. The park covers an area of about 28 acres and is split in half by the Wien river. It contains monuments to various Viennese artists, most notably the gilded bronze monument of Johann Strauß II.[134] On the other side of the Ring is the Burggarten, just behind the Hofburg, which features a monument to Mozart as well as a greenhouse. On the other side of the Hofburg is the Volksgarten, home to a small-scale replica of the Temple of Hephaestus and a cultivated flower garden. On the other side of the road, in front of the Rathaus, is the Rathauspark, which hosts the Christmas Christkindlmarkt.

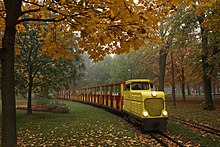

The Prater is a large public park in Leopoldstadt. Within the park is the Wurstelprater (which is commonly referred to as just “the Prater”), a public amusement park which contains the Wiener Riesenrad, a 64.75 meter tall Ferris Wheel, as well as various rides, roller coasters, carousels and a Madame Tussauds.[134] The rest of the park is covered in by the forest. The Hauptallee, a wide, car-free alley lined with horse chestnut trees, runs through the park.[135] Eliud Kipchoge broke the marathon distance record on this road in the INEOS 1:59 Challenge in October 2019.[136] The Prater also is home to the Liliputbahn, a railway line primarily used by tourists, and a planetarium.[137][138] It was the location of the 1873 Vienna World's Fair.[139] In 1931, the Ernst-Happel-Stadion, formerly known as the Praterstadion, was opened in the Prater.[140][141]

The Lobau, a floodplain in the southeast of the city, is a part of the wider Danube-Auen National Park. It is used for recreation and has many nudist areas. It is home to multiple species of animals:[142]

- Mammals: beavers, deer, European hares, Eurasian water shrews

- Reptiles: European pond turtles, Slow worm, Grass snake

- Amphibians: European tree frogs, European fire-bellied toad

- Fish: Pigo, Rhodeus, White-finned gudgeon

- Birds: Grey herons, Cormorants, Common kingfishers, White-tailed eagles

In the west of the city is the Lainzer Tiergarten, a 24.5km² public nature reserve, of which 19.5 km² is woodland.[143] The park was created in 1561 by Emperor Ferdinand I, who used it as a private hunting ground. After the fall of the monarchy, the Austrian government declared it a public nature reserve. Since 1973, admission has been free of charge. The reserve is home to many wild boar, fallow deer, red deer, European mouflons, as well as 18 species of bats.[144]

The grounds of the imperial Schönbrunn Palace contain an 18th-century park which includes the Schönbrunn Zoo, which was founded in 1752, making it the world's oldest zoo still in operation.[145] The zoo is one of the few to house giant pandas.[146] The park also features the Palmenhaus Schönbrunn, a large greenhouse with around 4,500 plant species.

The Augarten in Leopoldstadt, on the border of Brigittenau, is a 129-acre French Baroque-style public park open during the day. The park is home to flower gardens and multiple tree-lined avenues. The park was opened in 1775 by Joseph II and is surrounded by a wall with five gates, which are shut at night. The baroque Palais Augarten, in the south of the park, is home to the Vienna Boys' Choir. Towering over the park are two anti-aircraft Flak Towers, built by the Nazis in 1944. After the war, as the towers were unable to be destroyed, they were left standing and are now empty and serve no purpose, though various other such towers in the city were repurposed, such as the Haus des Meeres in Esterhazy Park.

The Donauinsel, part of Vienna's flood defences, is a 21.1 km (13.1 mi) long artificial island between the Danube and New Danube dedicated to leisure activities. It was constructed from 1972 to 1988 as a measure for flood protection.[147] Sporting amenities, such as volleyball courts, playgrounds, skate spots, dog parks, and multiple toilet facilities, some with showers, are available on the island. In order to turn the island into a green space, about 1.8 million trees and shrubs plus about 170 hectares of forest were planted.[148] A few hundred Japanese cherry trees were planted as a symbol of friendship between Austria and Japan. Animals on the island include sand lizards and Danube crested newts.[149]

The Donaupark is a 63-hectare park in Kaisermühlen, Donaustadt, between the New Danube and the Old Danube, next to the Vienna International Centre. The park features the Donauturm, the tallest structure in Austria at 252 meters, as well as a 40-meter tall steel cross, erected in 1983 on the occasion of a holy mass held by Pope John Paul II during his visit to Austria. In the park is the Latin America-Caribbean Square, which features memorials to multiple Latin American figures such as Salvador Allende, Simón Bolívar, and Che Guevara.

Other parks include the Türkenschanzpark, the Schweizergarten, and the Waldmüllerpark.

Cemeteries

Vienna is home to 55 cemeteries, 46 of which are run by the city, the others by religious communities.[150]

Самое большое кладбище в городе - Венское центральное кладбище ( Zentralfriedhof ). Он имеет 2,4 км² с более чем 330 000 могил и около 3 000 000 последователей. Он был открыт в 1874 году и содержит католические, протестантские, мусульманские и еврейские секторы. Примечательные погребения включают Людвига Ван Бетховен , Фалько , Бруно Крейски , Хеди Ламарра , а также каждого умершего президента со времен Второй мировой войны. Олень, барсуки , мартенс и, в частности, европейские хомяки бродят по парку, есть растения, растущие вокруг надгробий . На территории кладбища есть многочисленные мемориалы, такие как жертвы революций 1848 года и июльское восстание 1927 года и для жертв нацистского режима .

Теперь закрытое кладбище Св. Маркса содержит могилу Вольфганга Амадея Моцарта . Другие включают в себя кладбища Гринзинга и Хитзинга, а также еврейское кладбище в Росли.

Дунай

Вена является крупнейшим городом на Дуная , который проходит с севера, через город и на юго-востоке. В Вене река разделена на 4 части:

- Главный Дунай является самым широким из них и используется в основном для доставки.

- Neue Donau (новый Дунай) - это побочный канал на востоке реки. Он был построен в 1972 году для мер по защите от наводнения и отделен от Дунайка искусственным Donauinsel . Он работает около 21 километра. Река течет медленнее, чем основной дунай и может использоваться для водных видов спорта, таких как плавание , гребля или парусный спорт . Моторные лодки запрещены в этой части реки.

- Альте Донау (Старый Дунай) - это озеро к востоку от нового Дунака, которое отрезает Кайзермюлена от остальной части города. Озеро является центром для пловцов в Вене, со свободно доступными пирсами и пляжами. Моторные лодки и педало разрешены на озере и могут быть сданы в аренду у близлежащих продавцов. [ 151 ]

- Донауканал распадается и возвращается в дунай недалеко от южного и северного края города. В отличие от главной реки, она течет через центр города. Сам водный путь используется в основном лодками, в то время как пути по обе стороны Донауканала регулярно используются пешеходами , бегунами и велосипедистами . [ 152 ] [ 153 ]

Спорт

Футбол

Город является домом для многочисленных футбольных клубов . Двумя крупнейшими командами являются FK Austria Wien (21 австрийские названия Bundesliga и рекордные 27-кратные победители Cup ), которые играют на The Generali Arena на Fanoriten, и Sk Rapid Wien (рекорд 32 Бундеслига австрийских титула ), которые играют на стадионе Allianz на Пензинг. Самая старая команда в Австрии, Первая Вена ФК и Флориддорфер А.С. оба играют в 2. Лига , и футбольная команда спортивного клуба Винера , одного из старейших клубов легкой атлетики в стране, играют на австрийском региональном востоке, на востоке, на Востоке Австрийского региона, на востоке, на Востоке Австрийского региона, на востоке, на востоке Австрии, на востоке, на востоке Австрии, на востоке, на востоке Австрии Регионалга, на востоке , на Востоке Австрии Регионал. Третья дивизия.

Стадион Эрнста-Хаппеля является крупнейшим стадином в Австрии с 50 865 местами и является домашним стадином футбольной команды Австрии . В нем приняли участие несколько финалов Лиги Кубка Европы/чемпионов ( 1963–64 , 1986–87 , 1989–90 , 1994–95 ), а также семь игр на евро 2008 года , в том числе финал , в котором испании победа 1–0 1–0 над Германией .

Другие виды спорта

Другие спортивные клубы включают викингов Вена ( американский футбол ), которая выиграла титул Eurobowl 4 раза подряд в период с 2004 по 2007 год и прошел идеальный сезон в 2013 году. Hotvolleys Vienna ( волейбол ), Вена Wanderers ( бейсбол ), которая выиграла Чемпионат австрийской бейсбольной лиги 2012 и 2013 годов и Венские столицы ( хоккей с шайбой ). Европейская федерация гандбола (EHF) со штаб -квартирой в Вене. Есть также три клуба регби в городе; Вена Селтик , самый старый регби -клуб в Австрии, RC Donau и Stade Viennois.

В дополнение к командным видам спорта, Вена также предлагает широкий спектр отдельных видов спорта. Пути в Prater или в Donauinsel являются популярными маршрутами бега. Венский городской марафон , который привлекает более 10 000 участников каждый год, обычно происходит в мае. Велосипедисты могут выбирать из более чем 1000 километров велосипедных дорожек и многочисленных горных велосипедных дорожек в Венских горах. Поля для гольфа доступны на Винерберге или в Пратере.

Турнир Vienna Open Tennis проводился в городе с 1974 года. Матчи разыгрываются на хардкруах в помещении в Stadthalle Wiener .

Город Вена также управляет двумя лыжными склонами на Хохен-Ванде и на куклах.

Кулинарные специальности

Еда

Вена хорошо известна Wiener Schnitzel , котлетой телятины (Kalbsschnitzel) (иногда также приготовленной из свинины ( Schweinsschnitzel ) или курицы ( Hühnerchnitzel )), которая избита плоской, покрывается мукой, яйцами и хлебными трубами и жареным в поясненном масле . Он доступен практически в каждом ресторане, который подает венскую кухню и может быть съедена горячей или холодной. Традиционный «Wiener Schnitzel», хотя и является котлетой телятины. Другие примеры венской кухни включают Тафельспитц (очень наклоненная говядина), которая традиционно подается с герёстете Эрдепфель (вареного картофеля, пюре с вилкой и впоследствии жареным) и соусом для лошадей, Apfelkren (смесь хорни, сливки и яблока) и шниттауса (смеси хорни, сливок и яблока) и шниттла ( смеси хорных, кремо Соус из лука, приготовленный с майонезом и несвежним хлебом).

Вена имеет давнюю традицию производства тортов и десертов. К ним относятся Apfelstrudel (Hot Apple Strudel), Milchrahmstrudel (молочный штрудель), палатсчинкен (сладкие блины) и Knödel (пельмени), часто наполненные фруктами, такими как абрикосы ( Marillenknödel ). Sachertorte , деликатно влажный шоколадный торт с абрикосовым джемом, созданным The Sacher Hotel , всемирно известен.

Зимой маленькие уличные стойки продают традиционные марони (горячие каштаны) и картофельные оладьи .

Колбасы популярны и доступны у уличных продавцов ( Würstelstand ) в течение дня и до ночи. Колбаса, известная как Винер (немецкий для Венцев) в США и в Германии, называется Франкфуртером в Вене. Другими популярными колбасами являются Burenwurst (грубая говядина и свиная колбаса, обычно кипячена), Käsekrainer (пряная свиная с небольшими кусочками сыра) и Bratwurst (белая свиная колбаса). Большинство из них могут быть заказаны «MIT Brot» (с хлебом) или в виде «хот -дога» (фарширован в длинном рулете). Горчица - это традиционная приправа, которая обычно предлагается в двух сортах: «Süß» (Sweet) или «Scharf» (острый).

Вена заняла 10 -е место в веганских европейских городах в исследовании альтернативного путешественника. [ 154 ]

Naschmarkt . является постоянным рынком для фруктов, овощей, специй, рыбы и мяса

Напитки

Вена, наряду с Барселоной , Братиславой , Канберрой , Кейптауном , Парижем, Прагой, Сантьяго и Варшавкой , является одним из немногих оставшихся мировых столичных городов со своими собственными виноградниками. [ 155 ] Вино подается в небольших венских пабах, известных как эйуригер . Вино часто пьян как спритцер («G'spritzter») с блестящей водой. Grüner Veltliner , сухое белое вино, является наиболее широко культивируемым вином в Австрии. [ 156 ] Еще одним вином, очень типичным для региона, является «Gemischter Satz», который, как правило, представляет собой смесь различных видов, собранных с одного виноградников. [ 157 ]

Пиво следующее по важности для вина. Венна имеет единую большую пивоварню, Ottakringer и более десяти пивоваренных заводов . Самым популярным напитком Ottakringers является « Отакрингер Хеллес» , пиво с содержанием алкоголя на 5,2%. « Бейсл » - это типичный маленький австрийский паб, из которого в Вене много.

Местные безалкогольные напитки, такие как Almdudler, популярны по всей стране в качестве альтернативы алкогольным напиткам, размещая их на главных местах вместе с американскими коллегами, такими как Coca-Cola с точки зрения доли рынка. Другими популярными напитками являются Spezi , смесь колы и апельсинового лимонада и Frucade , немецкого газированного апельсинового напитка.

Венское кафе

Венская кофейня ( Каффихаус ) восходит к австро-венгерской империи. Венская интеллигенция относилась к Венским кафе как к гостиной. [ 158 ] Первое веновое кафе было открыто в 1685 году армянским бизнесменом Йоханнесом Диодато. Культура кафе процветала в Вене в начале 19 -го века. [ 159 ] Известными посетителями были политические деятели Джозеф Сталин , Адольф Гитлер , Леон Троцкий и Джозип Броз Тито , которые все жили в Вене в 1913 году, а также ученых, писателей и художников, таких как Зигмунд Фрейд , Стефан Цвейг , Эгон Шил и Густав Климт . [ 160 ]

Примечательные кофейни включают:

- Café Central : часто посещается Гитлером, Сталином, Тито, Троцким и Цвейгом

- Кафе Ландтманн : часто посещается Фрейдом

- Кафе Sacher: часть отеля Sacher

Эйуригер

Вена-один из немногих крупных городов с собственным винодельческим регионом . Это вино продается в тавернах, так называемой эйуригере , местными виноделами в течение вегетационного периода. Вино часто подается как шорле , смесь вина и газированной воды . Еда простая и домашняя, обычно состоит из свежего хлеба, обычно полумель , с местными холодными и сырами, или спреда . Геригеры особенно многочисленны в районах Доблинг ( Гринцинг , Неустифт А.М. Уолде , Нуслиф , Салманнсдорф , Сиверенг ), Флориддорф (Stammersdorf, Strebersdorf), Lieing ( Mauer ) и фаворита (Oberlaa). [ 161 ]

Транспорт

Общественный транспорт

Вена имеет обширную сеть общественного транспорта. Он состоит в основном из сети Wiener Linien (метро, трамвай и автобусных линий) и линий S-Bahn, принадлежащих к австрийским федеральным железным дорогам (ÖBB) . По состоянию на 2023 год 32% населения города используют общественный транспорт в качестве основного способа транзита. [ 162 ]

U-Bahn

Система Vienna Metro состоит из пяти строк ( U1 , U2 , U3 , U4 , U6 ) с U5 в настоящее время строится. В настоящее время метро обслуживает 109 станций и охватывает расстояние 83,1 километра. [ 163 ] Службы проходят с 05:00 до 01:00 с интервалами от двух до пяти минут в течение дня и до восьми минут после 20:00. В пятницу и субботу вечера и по вечерам перед праздником, они работают 24-часовым сервисом с 15-минутными интервалами. [ Цитация необходима ]

| Линия | Цвет | Маршрут | Длина | Станции |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Красный | Оберлаа - Леопольдау | 19,2 км (11,9 миль) | 24 | |

| Фиолетовый | Шоттентор - Seestadt | 16,7 км (10,4 мили) | 20 | |

| Апельсин | Отакринга - кипячение | 13,5 км (8,4 мили) | 21 | |

| Зеленый | Hütteldorf - Heiligenstadt | 16,5 км (10,3 мили) | 20 | |

| Коричневый | Зибенхартен - Флориддорф | 17,4 км (10,8 мили) | 24 |

-

Логотип

-

U2 пересекает Дунай

-

Вход в Nestroyplatz

-

Интерьер станции Крио

Автобусы