Андалусия

Андалусия

Андалусия ( испанский ) | |

|---|---|

| Девиз (ы): Андалусия сама по себе, для Испании и человечества [ 1 ] («Андалусия сама по себе, для Испании и человечества») | |

| Гимн: " Белый и зеленый флаг " (Английский: «Белый и зеленый флаг» ) | |

Map of Spain with Andalusia highlighted | |

| Coordinates: 37°24′18″N 05°59′15″W / 37.40500°N 5.98750°W | |

| Country | |

| Formation | 1833 (Creation of Andalusia historic region) |

| Statute(s) of Autonomy | 1981 (First Statute) 2007 (Second Statute – in force) |

| Capital (and largest city) | Seville |

| Provinces | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Devolved government in a constitutional monarchy |

| • Body | Junta of Andalusia |

| • President | Juan Manuel Moreno (PP) |

| Legislature | Parliament of Andalusia |

| General representation | Parliament of Spain |

| Congress seats | 61 of 350 (17.4%) |

| Senate seats | 41 of 265 (15.5%) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 87,599 km2 (33,822 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 2nd |

| 17.3% of Spain | |

| Population (1 January 2023) | |

| • Total | 8,538,376 |

| • Rank | 1st 17.84% of Spain |

| Demonym(s) | Andalusian andaluz, -za[2] |

| Official language(s) | Spanish |

| GDP | |

| • Rank | 3rd |

| • Total (2022) | €180.224 billion |

| • Per capita | €21,091 (17th) |

| HDI | |

| • HDI (2021) | 0.874[4] (very high · 14th) |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) |

| Postal code prefixes | |

| ISO 3166 code | ES-AN |

| Telephone code(s) | +34 95 |

| Currency | Euro (€) |

| Official holiday | February 28 |

| Website | www |

| |

Андалусия ( Великобритания : / ˌ æ n d в L U ː S I , - Z iə// США : - ʒ ( i ) , - ʃ ( i ) / /) [ 5 ] [ 6 ] [ 7 ] Испанский : Anadalucía [andaluˈθi.a] ) является самым южным автономным сообществом на полуострове Испании . Андалусия расположена на юге иберийской полуострова , на юго -западной Европе. Это самое густонаселенное и второе по величине автономное сообщество в стране. Он официально признан исторической национальностью и национальной реальностью . [ 8 ] Территория разделена на восемь провинций : Альмерия , Кадис , Кордоба , Гранада , Хельва , Яэн , Малага и Севиль . Его столица - Севилья . Место Высокого суда Андалусии расположено в городе Гранада .

Andalusia is immediately south of the autonomous communities of Extremadura and Castilla-La Mancha; west of the autonomous community of Murcia and the Mediterranean Sea; east of Portugal and the Atlantic Ocean; and north of the Mediterranean Sea and the Strait of Gibraltar. Gibraltar shares a 1,2 километра ( 3 ~ 4 миль) наземная граница с андалузской частью провинции Кадис в восточном конце пролива Гибралтар.

The main mountain ranges of Andalusia are the Sierra Morena and the Baetic System, consisting of the Subbaetic and Penibaetic Mountains, separated by the Intrabaetic Basin. In the north, the Sierra Morena separates Andalusia from the plains of Extremadura and Castile–La Mancha on Spain's Meseta Central. To the south, the geographic subregion of Upper Andalusia lies mostly within the Baetic System, while Lower Andalusia is in the Baetic Depression of the valley of the Guadalquivir.[9]

The name Andalusia is derived from the Arabic word Al-Andalus (الأندلس), which in turn may be derived from the Vandals, the Goths or pre-Roman Iberian tribes.[10] The toponym al-Andalus is first attested by inscriptions on coins minted in 716 by the new Muslim government of Iberia. These coins, called dinars, were inscribed in both Latin and Arabic.[11][12] The region's history and culture have been influenced by the Tartessians, Iberians, Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Greeks, Romans, Vandals, Visigoths, Byzantines, Berbers, Arabs, Jews, Romanis and Castilians. During the Islamic Golden Age, Córdoba surpassed Constantinople[13][14] to be Europe's biggest city, and became the capital of Al-Andalus and a prominent center of education and learning in the world, producing numerous philosophers and scientists.[15][16] The Crown of Castile conquered and settled the Guadalquivir Valley in the 13th century. The mountainous eastern part of the region (the Emirate of Granada) was subdued in the late 15th century. Atlantic-facing harbors prospered upon trade with the New World. Chronic inequalities in the social structure caused by uneven distribution of land property in large estates induced recurring episodes of upheaval and social unrest in the agrarian sector in the 19th and 20th centuries.[17]

Andalusia has historically been an agricultural region, compared to the rest of Spain and the rest of Europe. Still, the growth of the community in the sectors of industry and services was above average in Spain and higher than many communities in the Eurozone. The region has a rich culture and a strong identity. Many cultural phenomena that are seen internationally as distinctively Spanish are largely or entirely Andalusian in origin. These include flamenco and, to a lesser extent, bullfighting and Hispano-Moorish architectural styles, both of which are also prevalent in some other regions of Spain.

Andalusia's hinterland is the hottest area of Europe, with Córdoba and Seville averaging above 36 °C (97 °F) in summer high temperatures.[18][19] These high temperatures, typical of the Guadalquivir valley are usually reached between 4 p.m. and 9 p.m. (local time),[20] tempered by sea and mountain breezes afterwards.[21] However, during heat waves late evening temperatures can locally stay around 35 °C (95 °F) until close to midnight, and daytime highs of over 40 °C (104 °F) are common.

Name

[edit]

Its present form is derived from the Arabic name for Muslim Iberia, "Al-Andalus".[22][23][24] The etymology of the name "Al-Andalus" is disputed,[25] and the extent of Iberian territory encompassed by the name has changed over the centuries.[26] Traditionally it has been assumed to be derived from the name of the Vandals. Since the 1980s, a number of proposals have challenged this contention. Halm, in 1989, derived the name from a Gothic term, *landahlauts,[27] and in 2002, Bossong suggested its derivation from a pre-Roman substrate.[25]

The Spanish place name Andalucía (immediate source of the English Andalusia) was introduced into the Spanish languages in the 13th century under the form el Andalucía.[28] The name was adopted to refer to those territories still under Moorish rule, and generally south of Castilla Nueva and Valencia, and corresponding with the former Roman province hitherto called Baetica in Latin sources. This was a Castilianization of Al-Andalusiya, the adjectival form of the Arabic language al-Andalus, the name given by the Arabs to all of the Iberian territories under Muslim rule from 711 to 1492. The etymology of al-Andalus is itself somewhat debated (see al-Andalus), but in fact it entered the Arabic language before this area came under Moorish rule.

Like the Arabic term al-Andalus, in historical contexts the Spanish term Andalucía or the English term Andalusia do not necessarily refer to the exact territory designated by these terms today. Initially, the term referred exclusively to territories under Muslim control. Later, it was applied to some of the last Iberian territories to be regained from the Muslims, though not always to exactly the same ones.[28] In the Estoria de España (also known as the Primera Crónica General) of Alfonso X of Castile, written in the second half of the 13th century, the term Andalucía is used with three different meanings:

- As a literal translation of the Arabic al-Ándalus when Arabic texts are quoted.

- To designate the territories the Christians had regained by that time in the Guadalquivir valley and in the Kingdoms of Granada and Murcia. In a document from 1253, Alfonso X styled himself Rey de Castilla, León y de toda Andalucía ("King of Castile, León and all of Andalusia").

- To designate the territories the Christians had regained by that time in the Guadalquivir valley until that date (the Kingdoms of Jaén, Córdoba and Seville – the Kingdom of Granada was incorporated in 1492). This was the most common significance in the Late Middle Ages and Early modern period.[29]

From an administrative point of view, Granada remained separate for many years even after the completion of the Reconquista[29] due, above all, to its emblematic character as the last territory regained, and as the seat of the important Real Chancillería de Granada, a court of last resort. Still, the reconquest and repopulation of Granada was accomplished largely by people from the three preexisting Christian kingdoms of Andalusia, and Granada came to be considered a fourth kingdom of Andalusia.[30] The often-used expression "Four Kingdoms of Andalusia" dates back in Spanish at least to the mid-18th century.[31][32]

Symbols

[edit]

The Andalusian emblem shows the figure of Hercules and two lions between the two pillars of Hercules that tradition situates on either side of the Strait of Gibraltar. An inscription below, superimposed on an image of the flag of Andalusia reads Andalucía por sí, para España y la Humanidad ("Andalusia for herself, Spain and Humanity"). Over the two columns is a semicircular arch in the colours of the flag of Andalusia, with the Latin words Dominator Hercules Fundator (Lord Hercules is the Founder) superimposed.[1]

The official flag of Andalusia consists of three equal horizontal stripes, coloured green, white, and green respectively; the Andalusian coat of arms is superimposed on the central stripe.[33] Its design was overseen by Blas Infante[34] and approved in the Assembly of Ronda (a 1918 gathering of Andalusian nationalists at Ronda). Blas Infante considered these to have been the colours most used in regional symbols throughout the region's history. According to him, the green came in particular from the standard of the Umayyad Caliphate and represented the call for a gathering of the populace. The white symbolised pardon in the Almohad dynasty, interpreted in European heraldry as parliament or peace. Other writers have justified the colours differently, with some Andalusian nationalists referring to them as the Arbonaida, meaning white-and-green in Mozarabic, a Romance language that was spoken in the region in Muslim times. Nowadays, the Andalusian government states that the colours of the flag evoke the Andalusian landscape as well as values of purity and hope for the future.[33]

The anthem of Andalusia was composed by José del Castillo Díaz (director of the Municipal Band of Seville, commonly known as Maestro Castillo) with lyrics by Blas Infante.[34] The music was inspired by Santo Dios, a popular religious song sung at harvest time by peasants and day labourers in the provinces of Málaga, Seville, and Huelva. Blas Infante brought the song to Maestro Castillo's attention; Maestro Castillo adapted and harmonized the traditional melody. The lyrics appeal to the Andalusians to mobilise and demand tierra y libertad ("land and liberty") by way of agrarian reform and a statute of autonomy within Spain.

The Parliament of Andalusia voted unanimously in 1983 that the preamble to the Statute of Autonomy recognise Blas Infante as the Father of the Andalusian Nation (Padre de la Patria Andaluza),[35] which was reaffirmed in the reformed Statute of Autonomy submitted to popular referendum 18 February 2007. The preamble of the present 2007 Statute of Autonomy says that Article 2 of the present Spanish Constitution of 1978 recognises Andalusia as a nationality. Later, in its articulation, it speaks of Andalusia as a "historic nationality" (Spanish: nacionalidad histórica). It also cites the 1919 Andalusianist Manifesto of Córdoba describing Andalusia as a "national reality" (realidad nacional), but does not endorse that formulation. Article 1 of the earlier 1981 Statute of Autonomy defined it simply as a "nationality" (nacionalidad).[36]

The national holiday, Andalusia Day, is celebrated on 28 February,[37] commemorating the 1980 autonomy referendum.

The honorific title of Hijo Predilecto de Andalucía ("Favourite Son of Andalusia") is granted by the Autonomous Government of Andalusia to those whose exceptional merits benefited Andalusia, for work or achievements in natural, social, or political science. It is the highest distinction given by the Autonomous Community of Andalusia.[38]

Geography

[edit]The Sevillian historian Antonio Domínguez Ortiz wrote that:

one must seek the essence of Andalusia in its geographic reality on the one hand, and on the other in the awareness of its inhabitants. From the geographic point of view, the whole of the southern lands is too vast and varied to be embraced as a single unit. In reality there are not two, but three Andalusias: the Sierra Morena, the Valley [of the Guadalquivir] and the [Cordillera] Penibética[39]

Location

[edit]Andalusia has a surface area of 87,597 square kilometres (33,821 sq mi), 17.3% of the territory of Spain. Andalusia alone is comparable in extent and in the variety of its terrain to any of several of the smaller European countries. To the east is the Mediterranean Sea; to the west Portugal and the Gulf of Cádiz (Atlantic Ocean); to the north the Sierra Morena constitutes the border with the Meseta Central; to the south, the self-governing[40] British overseas territory of Gibraltar and the Strait of Gibraltar separate it from Morocco.

Climate

[edit]

Andalusia is home to the hottest and driest climates in Spain, with yearly average rainfall around 150 millimetres (5.9 in) in Cabo de Gata, as well as some of the wettest ones, with yearly average rainfall above 2,000 millimetres (79 in) in inland Cádiz.[42] In the west, weather systems sweeping in from the Atlantic ensure that it is relatively wet and humid in the winter, with some areas receiving copious amounts. Contrary to what many people think, as a whole, the region enjoys above-average yearly rainfall in the context of Spain.[43]

Andalusia sits at a latitude between 36° and 38° 44' N, in the warm-temperate region. In general, it experiences a hot-summer Mediterranean climate, with dry summers influenced by the Azores High, but subject to occasional torrential rains and extremely hot temperatures.[41][44] In the winter, the tropical anticyclones move south, allowing cold polar fronts to penetrate the region. Still, within Andalusia there is considerable climatic variety. From the extensive coastal plains one may pass to the valley of the Guadalquivir, barely above sea level, then to the highest altitudes in the Iberian peninsula in the peaks of the Sierra Nevada. In a mere 50 km (31 mi) one can pass from the subtropical coast of the province of Granada to the snowy peaks of Mulhacén. Andalusia also includes both the dry Tabernas Desert in the province of Almería and the Sierra de Grazalema Natural Park in the province of Cádiz, which experiences one of highest rainfall in Spain.[45][46][47]

Annual rainfall in the Sierra de Grazalema has been measured as high as 4,346 millimetres (171.1 in) in 1963, the highest ever recorded for any location in Iberia.[48] Andalusia is also home to the driest place in Europe, the Cabo de Gata, with only 156 millimetres (6.1 in) of rain per year.[49][50]

In general, as one goes from west to east, away from the Atlantic, there is less precipitation.[48] "Wet Andalusia" includes most of the highest points in the region, above all the Sierra de Grazalema but also the Serranía de Ronda in western Málaga. The valley of the Guadalquivir has moderate rainfall. The Tabernas Desert in Almería has less than 300 millimetres (12 in) annually.[47] Much of "dry Andalusia" has more than 300 sunny days a year.[51]

The average temperature in Andalusia throughout the year is over 16 °C (61 °F). Averages in the cities range from 15.1 °C (59.2 °F) in Baeza to 19.2 °C (66.6 °F) in Seville. However, a small region on the Mediterranean coast of Almeria and Granada provinces have average annual temperature over 20 °C (68 °F).[52] Much of the Guadalquivir valley and the Mediterranean coast has an average of about 18 °C (64 °F). The coldest month is January when Granada at the foot of the Sierra Nevada experiences an average temperature of 6.4 °C (43.5 °F). The hottest are July and August, with an average temperature of 28.5 °C (83.3 °F) for Andalusia as a whole. Córdoba is the hottest provincial capital, followed by Seville.[53]

The Guadalquivir valley has experienced some of the highest temperatures recorded in Europe, with a maximum of 47.6 °C (117.7 °F) recorded at La Rambla, Córdoba (14 August 2021).[54] The mountains of Granada and Jaén have the coldest temperatures in southern Iberia, but do not reach continental extremes (and, indeed are surpassed by some mountains in northern Spain). In the cold snap of January 2005, Santiago de la Espada (Jaén) experienced a temperature of −21 °C (−6 °F) and the ski resort at Sierra Nevada National Park—the southernmost ski resort in Europe—dropped to −18 °C (0 °F). Sierra Nevada Natural Park has Iberia's lowest average annual temperature, (3.9 °C or 39.0 °F at Pradollano) and its peaks remain snowy practically year-round.

| Location | Coldest month | April | Warmest month | October |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almería | 16.9 °C (62.4 °F)/ 8.3 °C (46.9 °F) | 24.1 °C (75.4 °F)/ 15.3 °C (59.5 °F) | 31.0 °C (87.8 °F)/ 22.4 °C (72.3 °F) | 24.5 °C (76.1 °F)/ 16.3 °C (61.3 °F) |

| Cádiz | 16.0 °C (60.8 °F)/ 9.4 °C (48.9 °F) | 19.9 °C (67.8 °F)/ 13.7 °C (56.7 °F) | 27.9 °C (82.2 °F)/ 22.0 °C (71.6 °F) | 23.4 °C (74.1 °F)/ 17.3 °C (63.1 °F) |

| Córdoba | 14.9 °C (58.8 °F)/ 3.6 °C (38.5 °F) | 22.8 °C (73.0 °F)/ 9.3 °C (48.7 °F) | 36.9 °C (98.4 °F)/ 19.0 °C (66.2 °F) | 25.1 °C (77.2 °F)/ 13.0 °C (55.4 °F) |

| Granada | 12.6 °C (54.7 °F)/ 1.1 °C (34.0 °F) | 19.5 °C (67.1 °F)/ 6.8 °C (44.2 °F) | 34.2 °C (93.6 °F)/ 17.7 °C (63.9 °F) | 22.6 °C (72.7 °F)/ 10.1 °C (50.2 °F) |

| Huelva | 16.2 °C (61.2 °F)/ 5.9 °C (42.6 °F) | 22.0 °C (71.6 °F)/ 10.3 °C (50.5 °F) | 32.7 °C (90.9 °F)/ 18.9 °C (66.0 °F) | 24.9 °C (76.8 °F)/ 14.1 °C (57.4 °F) |

| Jaén | 12.1 °C (53.8 °F)/ 5.1 °C (41.2 °F) | 19.0 °C (66.2 °F)/ 10.0 °C (50.0 °F) | 33.7 °C (92.7 °F)/ 21.4 °C (70.5 °F) | 21.9 °C (71.4 °F)/ 13.8 °C (56.8 °F) |

| Jerez | 16.2 °C (61.2 °F)/ 5.2 °C (41.4 °F) | 22.2 °C (72.0 °F)/ 9.8 °C (49.6 °F) | 33.5 °C (92.3 °F)/ 18.7 °C (65.7 °F) | 25.5 °C (77.9 °F)/ 13.7 °C (56.7 °F) |

| Málaga | 16.8 °C (62.2 °F)/ 7.4 °C (45.3 °F) | 21.4 °C (70.5 °F)/ 11.1 °C (52.0 °F) | 30.8 °C (87.4 °F)/ 21.1 °C (70.0 °F) | 24.1 °C (75.4 °F)/ 15.0 °C (59.0 °F) |

| Seville | 16.0 °C (60.8 °F)/ 5.7 °C (42.3 °F) | 23.4 °C (74.1 °F)/ 11.1 °C (52.0 °F) | 36.0 °C (96.8 °F)/ 20.3 °C (68.5 °F) | 26.0 °C (78.8 °F)/ 14.4 °C (57.9 °F) |

| Tarifa | 15.1 °C (59.2 °F)/ 10.9 °C (51.6 °F) | 17.3 °C (63.1 °F)/ 13.0 °C (55.4 °F) | 24.5 °C (76.1 °F)/ 20.0 °C (68.0 °F) | 20.6 °C (69.1 °F)/ 16.7 °C (62.1 °F) |

Terrain

[edit]

Mountain ranges affect climate, the network of rivers, soils and their erosion, bioregions, and even human economies insofar as they rely on natural resources.[56] The Andalusian terrain offers a range of altitudes and slopes. Andalusia has the Iberian peninsula's highest mountains and nearly 15 percent of its terrain over 1,000 metres (3,300 ft). The picture is similar for areas under 100 metres (330 ft) (with the Baetic Depression), and for the variety of slopes.

The Atlantic coast is overwhelmingly beach and gradually sloping coasts; the Mediterranean coast has many cliffs, above all in the Malagan Axarquía and in Granada and Almería.[57] This asymmetry divides the region naturally into Upper Andalusia (two mountainous areas) and Lower Andalusia (the broad basin of the Guadalquivir).[58]

The Sierra Morena separates Andalusia from the plains of Extremadura and Castile–La Mancha on Spain's Meseta Central. Although sparsely populated, this is not a particularly high range, and its highest point, the 1,323-metre (4,341 ft) peak of La Bañuela in the Sierra Madrona, lies outside of Andalusia. Within the Sierra Morena, the gorge of Despeñaperros forms a natural frontier between Castile and Andalusia.

The Baetic Cordillera consists of the parallel mountain ranges of the Cordillera Penibética near the Mediterranean coast and the Cordillera Subbética inland, separated by the Surco Intrabético. The Cordillera Subbética is quite discontinuous, offering many passes that facilitate transportation, but the Penibético forms a strong barrier between the Mediterranean coast and the interior.[59] The Sierra Nevada, part of the Cordillera Penibética in the province of Granada, has the highest peaks in Iberia: El Mulhacén at 3,478 metres (11,411 ft) and El Veleta at 3,392 metres (11,129 ft).

Lower Andalusia, the Baetic Depression, the basin of the Guadalquivir, lies between these two mountainous areas. It is a nearly flat territory, open to the Gulf of Cádiz in the southwest. Throughout history, this has been the most populous part of Andalusia.

Hydrography

[edit]

Andalusia has rivers that flow into both the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. Flowing to the Atlantic are the Guadiana, Odiel-Tinto, Guadalquivir, Guadalete, and Barbate. Flowing to the Mediterranean are the Guadiaro, Guadalhorce, Guadalmedina, Guadalfeo, Andarax (also known as the Almería) and Almanzora. Of these, the Guadalquivir is the longest in Andalusia and fifth longest on the Iberian peninsula, at 657 kilometres (408 mi).[60]

The rivers of the Atlantic basin are characteristically long, run through mostly flat terrain, and have broad river valleys. As a result, at their mouths are estuaries and wetlands, such as the marshes of Doñana in the delta of the Guadalquivir, and wetlands of the Odiel. In contrast, the rivers of the Mediterranean Basin are shorter, more seasonal, and make a precipitous descent from the mountains of the Baetic Cordillera. Their estuaries are small, and their valleys are less suitable for agriculture. Also, being in the rain shadow of the Baetic Cordillera means that they receive a lesser volume of water.[58]

The following hydrographic basins can be distinguished in Andalusia. On the Atlantic side are the Guadalquivir basin; the Andalusian Atlantic Basin with the sub-basins Guadalete-Barbate and Tinto-Odiel; and the Guadiana basin. On the Mediterranean side is the Andalusian Mediterranean Basin and the upper portion of the basin of the Segura.[61]

Soils

[edit]The soils of Andalusia can be divided into three large areas: the Sierra Morena, Cordillera Subbética, and the Baetic Depression and the Surco Intrabético.[62]

The Sierra Morena, due to its morphology and the acidic content of its rocks, developed principally relatively poor, shallow soils, suitable only for forests. In the valleys and in some areas where limestone is present, deeper soils allowed farming of cereals suitable for livestock. The more complicated morphology of the Baetic Cordillera makes it more heterogeneous, with the most heterogeneous soils in Andalusia. Very roughly, in contrast to the Sierra Morena, a predominance of basic (alkaline) materials in the Cordillera Subbética, combined with a hilly landscape, generates deeper soils with greater agricultural capacity, suitable to the cultivation of olives.[63]

Finally, the Baetic Depression and the Surco Intrabético have deep, rich soils, with great agricultural capacity. In particular, the alluvial soils of the Guadalquivir valley and plain of Granada have a loamy texture and are particularly suitable for intensive irrigated crops.[64] In the hilly areas of the countryside, there is a double dynamic: the depressions have filled with older lime-rich material, developing the deep, rich, dark clay soils the Spanish call bujeo, or tierras negras andaluzas, excellent for dryland farming. In other zones, the whiter albariza provides an excellent soil for vineyards.[65]

Despite their marginal quality, the poorly consolidated soils of the sandy coastline of Huelva and Almería have been successfully used in recent decades for hothouse cultivation under clear plastic of strawberries, raspberries, blueberries, and other fruits.

Flora

[edit]

Biogeographically, Andalusia forms part of the Western Mediterranean subregion of the Mediterranean Basin, which falls within the Boreal Kingdom. Five floristic provinces lie, in whole or in part, within Andalusia: along much of the Atlantic coast, the Lusitanian-Andalusian littoral or Andalusian Atlantic littoral; in the north, the southern portion of the Luso-Extremaduran floristic province; covering roughly half of the region, the Baetic floristic province; and in the extreme east, the Almerian portion of the Almerian-Murcian floristic province and (coinciding roughly with the upper Segura basin) a small portion of the Castilian-Maestrazgan-Manchegan floristic province. These names derive primarily from past or present political geography: "Luso" and "Lusitanian" from Lusitania, one of three Roman provinces in Iberia, most of the others from present-day Spanish provinces, and Maestrazgo being a historical region of northern Valencia.

In broad terms, the typical vegetation of Andalusia is Mediterranean woodland, characterized by leafy xerophilic perennials, adapted to the long, dry summers. The dominant species of the climax community is the holly oak (Quercus ilex). Also abundant are cork oak (Quercus suber), various pines, and Spanish fir (Abies pinsapo). Due to cultivation, olive (Olea europaea) and almond (Prunus dulcis) trees also abound. The dominant understory is composed of thorny and aromatic woody species, such as rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), thyme (Thymus), and Cistus. In the wettest areas with acidic soils, the most abundant species are the oak and cork oak, and the cultivated Eucalyptus. In the woodlands, leafy hardwoods of genus Populus (poplars, aspens, cottonwoods) and Ulmus (elms) are also abundant; poplars are cultivated in the plains of Granada.[66]

The Andalusian woodlands have been much altered by human settlement, the use of nearly all of the best land for farming, and frequent wildfires. The degraded forests become shrubby and combustible garrigue. Extensive areas have been planted with non-climax trees such as pines. There is now a clear conservation policy for the remaining forests, which survive almost exclusively in the mountains.

Fauna

[edit]

The biodiversity of Andalusia extends to its fauna as well. More than 400 of the 630 vertebrate species extant in Spain can be found in Andalusia. Spanning the Mediterranean and Atlantic basins, and adjacent to the Strait of Gibraltar, Andalusia is on the migratory route of many of the numerous flocks of birds that travel annually from Europe to Africa and back.[67]

The Andalusian wetlands host a rich variety of birds. Some are of African origin, such as the red-knobbed coot (Fulica cristata), the purple swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio), and the greater flamingo (Phoenicopterus roseus). Others originate in Northern Europe, such as the greylag goose (Anser anser). Birds of prey (raptors) include the Spanish imperial eagle (Aquila adalberti), the griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus), and both the black and red kite (Milvus migrans and Milvus milvus).

Among the herbivores, are several deer (Cervidae) species, notably the fallow deer (Dama dama) and roe deer (Capreolus capreolus); the European mouflon (Ovis aries musimon), a feral sheep; and the Spanish ibex (Capra pyrenaica, which despite its scientific name is no longer found in the Pyrenees). The Spanish ibex has recently been losing ground to the Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia), an invasive species from Africa, introduced for hunting in the 1970s. Among the small herbivores are rabbits—especially the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus)—which form the most important part of the diet of the carnivorous species of the Mediterranean woodlands.

The large carnivores such as the Iberian wolf (Canis lupus signatus) and the Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus) are quite threatened, and are limited to the Sierra de Andújar, inside of Sierra Morena, Doñana and Despeñaperros. Stocks of the wild boar (Sus scrofa), on the other hand, have been well preserved because they are popular with hunters. More abundant and in varied situations of conservation are such smaller carnivores as otters, dogs, foxes, the European badger (Meles meles), the European polecat (Mustela putorius), the least weasel (Mustela nivalis), the European wildcat (Felis silvestris), the common genet (Genetta genetta), and the Egyptian mongoose (Herpestes ichneumon).[68]

Other notable species are Acherontia atropos (a variety of death's-head hawkmoth), Vipera latasti (a venomous snake), and the endemic (and endangered) fish Aphanius baeticus.

Protected areas

[edit]

Andalusia has many unique ecosystems. In order to preserve these areas in a manner compatible with both conservation and economic exploitation, many of the most representative ecosystems have been given protected status.[69][70]

The various levels of protection are encompassed within the Network of Protected Natural Spaces of Andalusia (Red de Espacios Naturales Protegidos de Andalucía, RENPA) which integrates all protected natural spaces located in Andalusia, whether they are protected at the level of the local community, the autonomous community of Andalusia, the Spanish state, or by international conventions. RENPA consists of 150 protected spaces, consisting of two national parks, 24 natural parks, 21 periurban parks (on the fringes of cities or towns), 32 natural sites, two protected countrysides, 37 natural monuments, 28 nature reserves, and four concerted nature reserves (in which a government agency coordinates with the owner of the property for its management), all part of the European Union's Natura 2000 network. Under the international ambit are the nine Biosphere Reserves, 20 Ramsar wetland sites, four Specially Protected Areas of Mediterranean Importance and two UNESCO Geoparks.[71]

In total, nearly 20 percent of the territory of Andalusia lies in one of these protected areas, which constitute roughly 30 percent of the protected territory of Spain.[71] Among these many spaces, some of the most notable are the Sierras de Cazorla, Segura y Las Villas Natural Park, Spain's largest natural park and the second largest in Europe, the Sierra Nevada National Park, Doñana National Park and Natural Park, the Tabernas Desert, and the Cabo de Gata-Níjar Natural Park, the largest terrestrial-maritime reserve in the European Western Mediterranean Sea.

History

[edit]

The geostrategic position of Andalusia, at the southernmost tip of Europe, between Europe and Africa and between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, has made it a hub for various civilizations since the Metal Ages. Its wealth of minerals and fertile land, combined with its large surface area, attracted settlers from the Phoenicians to the Greeks, who influenced the development of early cultures like Los Millares, El Argar, and Tartessos. These early Andalusian societies played a vital role in the region's transition from prehistory to protohistory.

With the Roman conquest, Andalusia became fully integrated into the Roman world as the prosperous province of Baetica, which contributed emperors like Trajan and Hadrian to the Roman Empire. During this time, Andalusia was a key economic center, providing resources and cultural contributions to Rome. Even after the Germanic invasions of Iberia by the Vandals and Visigoths, the region retained much of its Roman cultural and political significance, with figures such as Saint Isidore of Seville maintaining Andalusia's intellectual heritage.

In 711, the Umayyad conquest of Hispania marked a major cultural and political shift, as Andalusia became a focal point of al-Andalus, the Muslim-controlled Iberian Peninsula. The city of Córdoba emerged as the capital of al-Andalus and one of the most important cultural and economic centers of the medieval world. The height of Andalusian prosperity came during the Caliphate of Córdoba, under rulers like Abd al-Rahman III and Al-Hakam II, when the region became known for its advancements in science, philosophy, and architecture. However, the 11th century brought internal divisions with the fragmentation of al-Andalus into taifas—small, independent kingdoms—which allowed the Reconquista to push southwards. By the late 13th century, much of Andalusia had been reconquered by the Crown of Castile, led by monarchs like Ferdinand III of Castile, who captured the fertile Guadalquivir valley. The last Muslim kingdom, the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, held out until its defeat in 1492, marking the completion of the Reconquista.

In the centuries following the Reconquista, Andalusia played a central role in Spain's exploration and colonization of the New World. Cities like Seville and Cádiz became major hubs for transatlantic trade. However, despite its global influence during the Spanish Empire, Andalusia experienced economic decline due to a combination of military expenditures and failed industrialization efforts in the 17th and 18th centuries. In the modern era, Andalusia became part of Spain's movement towards autonomy, culminating in its designation as an autonomous community in 1981. Despite its rich history, the region faces challenges in overcoming economic disparities and aligning with the wealthier parts of the European Union.

Government and politics

[edit]

Andalusia is one of the 17 autonomous communities of Spain. The Regional Government of Andalusia (Spanish: Junta de Andalucía) includes the Parliament of Andalusia, its chosen president, a Consultative Council, and other bodies.

The Autonomous Community of Andalusia was formed in accord with a referendum of 28 February 1980[72] and became an autonomous community under the 1981 Statute of Autonomy known as the Estatuto de Carmona. The process followed the Spanish Constitution of 1978, still current as of 2009, which recognizes and guarantees the right of autonomy for the various regions and nationalities of Spain. The process to establish Andalusia as an autonomous region followed Article 151 of the Constitution, making Andalusia the only autonomous community to take that particular course. That article was set out for regions like Andalusia that had been prevented by the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War from adopting a statute of autonomy during the period of the Second Spanish Republic.

Article 1 of the 1981 Statute of Autonomy justifies autonomy based on the region's "historical identity, on the self-government that the Constitution permits every nationality, on outright equality to the rest of the nationalities and regions that compose Spain, and with a power that emanates from the Andalusian Constitution and people, reflected in its Statute of Autonomy".[73]

In October 2006 the constitutional commission of the Cortes Generales (the national legislature of Spain), with favorable votes from the left-of-center Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE), the leftist United Left (IU) and the right-of-center People's Party (PP), approved a new Statute of Autonomy for Andalusia, whose preamble refers to the community as a "national reality" (realidad nacional):

The Andalusianist Manifesto of Córdoba described Andalusia as a national reality in 1919, whose spirit the Andalusians took up outright through the process of self-government recognized in our Magna Carta. In 1978 the Andalusians broadly backed the constitutional consensus. Today, the Constitution, in its Article 2, recognizes Andalusia as a nationality as part of the indissoluble unity of the Spanish nation.[36]

— Andalusian Statute of Autonomy on Wikisource, in Spanish

On 2 November 2006 the Spanish Chamber Deputies ratified the text of the Constitutional Commission with 306 votes in favor, none opposed, and 2 abstentions. This was the first time a Spanish Organic Law adopting a Statute of Autonomy was approved with no opposing votes. The Senate, in a plenary session of 20 December 2006, ratified the referendum to be voted upon by the Andalusian public 18 February 2007.

The Statute of Autonomy spells out Andalusia's distinct institutions of government and administration. Chief among these is the Andalusian Autonomous Government (Junta de Andalucía). Other institutions specified in the Statute are the Defensor del Pueblo Andaluz (literally "Defender of the Andalusian People", basically an ombudsperson), the Consultative Council, the Chamber of Accounts, the Audiovisual Council of Andalusia, and the Economic and Social Council.

The Andalusian Statute of Autonomy recognizes Seville as the autonomy's capital. The Andalusian Autonomous Government is located there. The region's highest court, the High Court of Andalusia (Tribunal Superior de Justicia de Andalucía) is not part of the Autonomous Government, and has its seat in Granada.

Autonomous Government

[edit]

The Andalusian Autonomous Government (Junta de Andalucía) is the institution of self-government of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia. Within the government, the President of Andalusia is the supreme representative of the autonomous community, and the ordinary representative of the Spanish state in the autonomous community. The president is formally named to the position by the Monarch of Spain and then confirmed by a majority vote of the Parliament of Andalusia. In practice, the monarch always names a person acceptable to the ruling party or coalition of parties in the autonomous region. In theory, were the candidate to fail to gain the needed majority, the monarch could propose a succession of candidates. After two months, if no proposed candidate could gain the parliament's approval, the parliament would automatically be dissolved and the acting president would call new elections.[74] On 18 January 2019 Juan Manuel Moreno was elected as the sixth president of Andalusia.[75]

The Council of Government, the highest political and administrative organ of the Community, exercises regulatory and executive power.[76] The President presides over the council, which also includes the heads of various departments (Consejerías). In the current legislature (2008–2012), there are 15 of these departments. In order of precedence, they are Presidency, Governance, Economy and Treasury, Education, Justice and Public Administration, Innovation, Science and Business, Public Works and Transportation, Employment, Health, Agriculture and Fishing, Housing and Territorial Planning, Tourism, Commerce and Sports, Equality and Social Welfare, Culture, and Environment.

The Parliament of Andalusia, its Autonomic Legislative Assembly, develops and approves laws and elects and removes the President.[77] Elections to the Andalusian Parliament follow a democratic formula through which the citizens elect 109 representatives. After the approval of the Statute of Autonomy through Organic Law 6/1981 on 20 December 1981, the first elections to the autonomic parliament took place 23 May 1982. Further elections have occurred in 1986, 1990, 1994, 1996, 2000, 2004, and 2008.

The current (2008–2012) legislature includes representatives of the PSOE-A (Andalusian branch of the left-of-center PSOE), PP-A (Andalusian branch of the right-of-center PP) and IULV-CA (Andalusian branch of the leftist IU).[78]

Judicial power

[edit]The High Court of Andalusia (Tribunal Superior de Justicia de Andalucía) in Granada is subject only to the higher jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of Spain. The High Court is not an organ of the Autonomous Community, but rather of the Judiciary of Spain, which is unitary throughout the kingdom and whose powers are not transferred to the autonomous communities. The Andalusian territory is divided into 88 legal/judicial districts (partidos judiciales).[79]

Administrative divisions

[edit]Provinces

[edit]

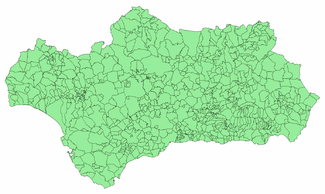

Andalusia consists of eight provinces. The latter were established by Javier de Burgos in the 1833 territorial division of Spain. Each of the Andalusian provinces bears the same name as its capital:[80]

| Province | Capital | Population | Density | Municipalities | Legal districts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almería | 753,920 | 85.9/km2 (222/sq mi) | 102 municipalities | 8 | |

| Cádiz | 1,250,539 | 168.1/km2 (435/sq mi) | 44 municipalities | 14 | |

| Córdoba | 773,997 | 56.2/km2 (146/sq mi) | 75 municipalities | 12 | |

| Granada | 930,181 | 73.5/km2 (190/sq mi) | 170 municipalities | 9 | |

| Huelva | 530,824 | 52.4/km2 (136/sq mi) | 79 municipalities | 6 | |

| Jaén | 620,242 | 45.9/km2 (119/sq mi) | 97 municipalities | 10 | |

| Málaga | 1,751,600 | 239.7/km2 (621/sq mi) | 102 municipalities | 11 | |

| Seville | 1,957,210 | 139.4/km2 (361/sq mi) | 105 municipalities | 15 |

Andalusia is traditionally divided into two historical subregions: Upper Andalusia or Eastern Andalusia (Andalucía Oriental), consisting of the provinces of Almería, Granada, Jaén, and Málaga, and Lower Andalusia or Western Andalusia (Andalucía Occidental), consisting of the provinces of Cádiz, Córdoba, Huelva and Seville.

Comarcas and mancomunidades

[edit]

Within the various autonomous communities of Spain, comarcas are comparable to shires (or, in some countries, counties) in the English-speaking world. Unlike in some of Spain's other autonomous communities, under the original 1981 Statute of Autonomy, the comarcas of Andalusia had no formal recognition, but, in practice, they still had informal recognition as geographic, cultural, historical, or in some cases administrative entities. The 2007 Statute of Autonomy echoes this practice, and mentions comarcas in Article 97 of Title III, which defines the significance of comarcas and establishes a basis for formal recognition in future legislation.[81]

The current statutory entity that most closely resembles a comarca is the mancomunidad, a freely chosen, bottom-up association of municipalities intended as an instrument of socioeconomic development and coordination between municipal governments in specific areas.[80][82]

Municipalities and local entities

[edit]

Beyond the level of provinces, Andalusia is further divided into 774 municipalities (municipios).[80] The municipalities of Andalusia are regulated by Title III of the Statute of Autonomy, Articles 91–95, which establishes the municipality as the basic territorial entity of Andalusia, each of which has legal personhood and autonomy in many aspects of its internal affairs. At the municipal level, representation, government and administration is performed by the ayuntamiento (municipal government), which has competency for urban planning, community social services, supply and treatment of water, collection and treatment of waste, and promotion of tourism, culture, and sports, among other matters established by law.[83]

In conformity with the intent to devolve control as locally as possible, in many cases, separate nuclei of population within municipal borders each administer their own interests. These are variously known as pedanías ("hamlets"), villas ("villages"), aldeas (also usually rendered as "villages"), or other similar names.[80]

Demographics

[edit]Andalusia ranks first by population among the 17 autonomous communities of Spain. The estimated population at the beginning of 2023 was 8,538,376. The population is concentrated, above all, in the provincial capitals and along the coasts, so that the level of urbanization is quite high; half the population is concentrated in the 28 cities of more than 50,000 inhabitants. The population is aging, although the process of immigration is countering the inversion of the population pyramid.[84]

Main cities

[edit]| Rank | Province | Pop. | Rank | Province | Pop. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Seville  Málaga |

1 | Seville | Seville | 684,025 | 11 | Jaén | Jaén | 111,888 |  Córdoba  Granada |

| 2 | Málaga | Málaga | 586,384 | 12 | Cádiz | Cádiz | 111,811 | ||

| 3 | Córdoba | Córdoba | 323,763 | 13 | Roquetas de Mar | Almería | 106,510 | ||

| 4 | Granada | Granada | 230,595 | 14 | San Fernando | Cádiz | 93,927 | ||

| 5 | Jerez de la Frontera | Cádiz | 213,231 | 15 | Mijas | Málaga | 91,691 | ||

| 6 | Almería | Almería | 200,578 | 16 | El Ejido | Almería | 89,975 | ||

| 7 | Marbella | Málaga | 156,295 | 17 | El Puerto de Santa María | Cádiz | 89,813 | ||

| 8 | Huelva | Huelva | 142,532 | 18 | Chiclana de la Frontera | Cádiz | 88,709 | ||

| 9 | Dos Hermanas | Seville | 138,981 | 19 | Fuengirola | Málaga | 85,598 | ||

| 10 | Algeciras | Cádiz | 123,639 | 20 | Vélez-Málaga | Málaga | 85,377 | ||

Population change

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 3,544,769 | — |

| 1910 | 3,800,299 | +7.2% |

| 1920 | 4,221,686 | +11.1% |

| 1930 | 4,627,148 | +9.6% |

| 1940 | 5,255,120 | +13.6% |

| 1950 | 5,647,244 | +7.5% |

| 1960 | 5,940,067 | +5.2% |

| 1970 | 5,991,076 | +0.9% |

| 1981 | 6,441,149 | +7.5% |

| 1991 | 6,940,542 | +7.8% |

| 2001 | 7,357,558 | +6.0% |

| 2011 | 8,371,270 | +13.8% |

| 2021 | 8,484,804 | +1.4% |

| 2023 | 8,538,376 | +0.6% |

| Source: INE | ||

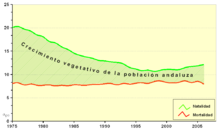

At the end of the 20th century, Andalusia was in the last phase of demographic transition. The death rate stagnated at around 8–9 per thousand, and the population came to be influenced mainly by birth and migration.[86] In 1950, Andalusia had 20.04 percent of the national population of Spain. By 1981, this had declined to 17.09 percent. Although the Andalusian population was not declining in absolute terms, these relative losses were due to emigration great enough to nearly counterbalance having the highest birth rate in Spain. Since the 1980s, this process has reversed on all counts,[87] and as of 2009, Andalusia has 17.82 percent of the Spanish population.[88] The birth rate is sharply down, as is typical in developed economies, although it has lagged behind much of the rest of the world in this respect. Furthermore, prior emigrants have been returning to Andalusia. Beginning in the 1990s, others have been immigrating in large numbers as well, as Spain has become a country of net immigration.[87]

At the beginning of the 21st century, statistics show a slight increase in the birth rate, due in large part to the higher birth rate among immigrants.[89][90] The result is that as of 2009, the trend toward rejuvenation of the population is among the strongest of any autonomous community of Spain, or of any comparable region in Europe.[88]

Structure

[edit]

At the beginning of the 21st century, the population structure of Andalusia shows a clear inversion of the population pyramid, with the largest cohorts falling between ages 25 and 50.[91] Comparison of the population pyramid in 2008 to that in 1986 shows:

- A clear decrease in the population under the age of 25, due to a declining birth rate.

- An increase in the adult population, as the earlier, larger cohort born in the "baby boom" of the 1960s and 1970s reach adulthood. This effect has been exacerbated by immigration: the largest contingent of immigrants are young adults.

- A further increase in the adult population, and especially the older adult population, due to increased life expectancy.

As far as composition by sex, two aspects stand out: the higher percentage of women in the elderly population, owing to women's longer life expectancy, and, on the other hand, the higher percentage of men of working age, due in large part to a predominantly male immigrant population.[88]

Immigration

[edit]In 2005, 5.35 percent of the population of Andalusia were born outside of Spain. This is a relatively low number for a Spanish region, the national average being three percentage points higher. The immigrants are not evenly distributed among the Andalusian provinces: Almería, with a 15.20 percent immigrant population, is third among all provinces in Spain, while at the other extreme Jaén is only 2.07 percent immigrants and Córdoba 1.77 percent. The predominant nationalities among the immigrant populations are Moroccan (92,500, constituting 17.79 percent of the foreigners living in Andalusia) and British (15.25 percent across the region). When comparing world regions rather than individual countries, the single largest immigrant block is from the region of Latin America, outnumbering not only all North Africans, but also all non-Spanish Western Europeans.[92] Demographically, this group has provided an important addition to the Andalusian labor force.[89][90]

| Foreign Population by Nationality[93] | Number | % |

| 2022 | ||

| TOTAL FOREIGNERS | 741,378 | |

| EUROPE | 342,463 | |

| EUROPEAN UNION | 206,934 | |

| OTHER EUROPE | 135,529 | |

| AFRICA | 211,443 | |

| SOUTH AMERICA | 102,938 | |

| CENTRAL AMERICA | 30,160 | |

| NORTH AMERICA | 11,446 | |

| ASIA | 41,811 | |

| OCEANIA | 573 | |

| Instituto Nacional de Estadística | ||

Economy

[edit]Andalusia is traditionally an agricultural area, but the service sector (particularly tourism, retail sales, and transportation) now predominates. The once booming construction sector, hit hard by the 2009 recession, was also important to the region's economy. The industrial sector is less developed than most other regions in Spain.

Between 2000 and 2006 economic growth per annum was 3.72%, one of the highest in the country. Still, according to the Spanish Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE), the GDP per capita of Andalusia (€17,401; 2006) remains the second lowest in Spain, with only Extremadura lagging behind.[94] The Gross domestic product (GDP) of the autonomous community was 160.6 billion euros in 2018, accounting for 13.4% of Spanish economic output. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was 20,500 euros or 68% of the EU27 average in the same year.[95]

| Andalusia | Almería | Cádiz | Córdoba | Granada | Huelva | Jaén | Málaga | Seville | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP (thousands of €) | 154,011,654 | 14,124,024 | 21,430,772 | 13,000,521 | 16,403,614 | 9,716,037 | 10,036,091 | 31,331,122 | 37,969,433 |

| GDP per capita (€) | 18,360 | 20,054 | 17,284 | 16,422 | 17,919 | 18,699 | 15,481 | 19,229 | 19,574 |

| Workers | 2,990,143 | 286,714 | 387,174 | 264,072 | 309,309 | 196,527 | 220,877 | 607,255 | 718,215 |

| GDP (%) | 100 | 9.17 | 13.92 | 8.44 | 10.65 | 6.31 | 6.52 | 20.34 | 24.65 |

Primary sector

[edit]The primary sector, despite adding the least of the three sectors to the regional GDP, remains important, especially when compared to typical developed economies. The primary sector produces 8.26 percent of regional GDP, 6.4 percent of its GVA and employs 8.19 percent of the workforce.[97][98][better source needed] In monetary terms it could be considered a rather uncompetitive sector, given its level of productivity compared to other Spanish regions.[citation needed] In addition to its numeric importance relative to other regions, agriculture and other primary sector activities have strong roots in local culture and identity.

The primary sector is divided into a number of subsectors: agriculture, commercial fishing, animal husbandry, hunting, forestry, mining, and energy.

Agriculture, husbandry, hunting, and forestry

[edit]

For many centuries, agriculture dominated Andalusian society, and, with 44.3 percent of its territory cultivated and 8.4 percent of its workforce in agriculture as of 2016 it remains an integral part of Andalusia's economy.[99] However, its importance is declining, like the primary and secondary sectors generally, as the service sector is increasingly taking over.[100] The primary cultivation is dryland farming of cereals and sunflowers without artificial irrigation, especially in the vast countryside of the Guadalquivir valley and the high plains of Granada and Almería-with a considerably lesser and more geographically focused cultivation of barley and oats. Using irrigation, maize, cotton and rice are also grown on the banks of the Guadalquivir and Genil.[101]

The most important tree crops are olives, especially in the Subbetic regions of the provinces of Córdoba and Jáen, where irrigated olive orchards constitute a large component of agricultural output.[102] There are extensive vineyards in various zones such as Jerez de la Frontera (sherry), Condado de Huelva, Montilla-Moriles and Málaga. Fruits—mainly citrus fruits—are grown near the banks of the Guadalquivir; almonds, which require far less water, are grown on the high plains of Granada and Almería.[103]

In monetary terms, by far the most productive and competitive agriculture in Andalusia is the intensive forced cultivation of strawberries, raspberries, blueberries, and other fruits grown under hothouse conditions under clear plastic, often in sandy zones, on the coasts, in Almería and Huelva.[104]

Organic farming has recently undergone rapid expansion in Andalusia, mainly for export to European markets but with increasing demand developing in Spain.[105]

Andalusia has a long tradition of animal husbandry and livestock farming, but it is now restricted mainly to mountain meadows, where there is less pressure from other potential uses. Andalusians have a long and colourful history of dog breeding that can be observed throughout the region today. The raising of livestock now plays a semi-marginal role in the Andalusian economy, constituting only 15 percent of the primary sector, half the number for Spain taken as a whole.[106]

"Extensive" raising of livestock grazes the animals on natural or cultivated pastures, whereas "intensive" raising of livestock is based in fodder rather than pasture. Although the productivity is higher than with extensive techniques, the economics are quite different. While intensive techniques now dominate in Europe and even in other regions of Spain, most of Andalusia's cattle, virtually all of its sheep and goats, and a good portion of its pigs are raised by extensive farming in mountain pastures. This includes the Black Iberian pigs that are the source of Jamón ibérico. Andalusia's native sheep and goats present a great economic opportunity in a Europe where animal products are generally in strong supply, but the sheep and goat meat, milk, and leather (and the products derived from these) are relatively scarce. Dogs are bred not just as companion animals, but also as herding animals used by goat and sheep herders.

Hunting remains relatively important in Andalusia, but has largely lost its character as a means of obtaining food. It is now more of a leisure activity linked to the mountain areas and complementary to forestry and the raising of livestock.[107] Dogs are frequently used as hunting companions to retrieve killed game.

The Andalusian forests are important for their extent—50 percent of the territory of Andalusia—and for other less quantifiable environmental reasons, such as their value in preventing erosion, regulating the flow of water necessary for other flora and fauna. For these reasons, there is legislation in place to protect the Andalusian forests.[108] The value of forest products as such constitutes only 2 percent of agricultural production. This comes mostly from cultivated species—eucalyptus in Huelva and poplar in Granada—as well as naturally occurring cork oak in the Sierra Morena.[109]

Fishing

[edit]

Fishing is a longstanding tradition on the Andalusian coasts. Fish and other seafood have long figured prominently in the local diet and in the local gastronomic culture: fried fish (pescaito frito in local dialect), white prawns, almadraba tuna, among others. The Andalusian fishing fleet is Spain's second largest, after Galicia, and Andalusia's 38 fishing ports are the most of any Spanish autonomous community.[110] Commercial fishing produces only 0.5 percent of the product of the regional primary sector by value, but there are areas where it has far greater importance. In the province of Huelva it constitutes 20 percent of the primary sector, and locally in Punta Umbría 70 percent of the work force is involved in commercial fishing.[111]

Failure to comply with fisheries laws regarding the use of trawling, urban pollution of the seacoast, destruction of habitats by coastal construction (for example, alteration of the mouths of rivers, construction of ports), and diminution of fisheries by overexploitation[112] have created a permanent crisis in the Andalusian fisheries, justifying attempts to convert the fishing fleet. The decrease in fish stocks has led to the rise of aquaculture, including fish farming both on the coasts and in the interior.[113]

Mining

[edit]

Despite the general poor returns in recent years, mining retains a certain importance in Andalusia. Andalusia produces half of Spain's mining product by value. Of Andalusia's production, roughly half comes from the province of Huelva. Mining for precious metals at Minas de Riotinto in Huelva (see Rio Tinto Group) dates back to pre-Roman times; the mines were abandoned in the Middle Ages and rediscovered in 1556. Other mining activity is coal mining in the Guadiato valley in the province of Córdoba; various metals at Aznalcóllar in the province of Seville, and iron at Alquife in the province of Granada. In addition, limestone, clay, and other materials used in construction are well distributed throughout Andalusia.[114]

Secondary sector: industry

[edit]The Andalusian industrial sector has always been relatively small. Nevertheless, in 2007, Andalusian industry earned 11.979 million euros and employed more than 290,000 workers. This represented 9.15 percent of regional GDP, far below the 15.08 the secondary sector represents in the economy of Spain as a whole.[115] By analyzing the different subsectors of the food industry Andalusian industry accounts for more than 16% of total production. In a comparison with the Spanish economy, this subsector is virtually the only food that has some weight in the national economy with 16.16%. Lies far behind the manufacturing sector of shipping materials just over 10% of the Spanish economy. Companies like Cruzcampo (Heineken Group), Puleva, Domecq, Santana Motors or Renault-Andalusia, are exponents of these two subsectors. Of note is the Andalusian aeronautical sector, which is second nationally only behind Madrid and represents approximately 21% of total turnover in terms of employment, highlighting companies like Airbus, Airbus Military, or the newly formed Aerospace Alestis. On the contrary it is symptomatic of how little weight the regional economy in such important sectors such as textiles or electronics at the national level.[citation needed]

Andalusian industry is also characterized by a specialization in industrial activities of transforming raw agricultural and mineral materials. This is largely done by small enterprises without the public or foreign investment more typical of a high level of industrialization.

Tertiary sector: services

[edit]

In recent decades the Andalusian tertiary (service) sector has grown greatly, and has come to constitute the majority of the regional economy, as is typical of contemporary economies in developed nations.[116][100] In 1975 the service sector produced 51.1 percent of local GDP and employed 40.8 percent of the work force. In 2007, this had risen to 67.9 percent of GDP and 66.42 percent of jobs. This process of "tertiarization" of the economy has followed a somewhat unusual course in Andalusia.[117] This growth occurred somewhat earlier than in most developed economies and occurred independently of the local industrial sector. There were two principal reasons that "tertiarization" followed a different course in Andalusia than elsewhere:

1. Andalusian capital found it impossible to compete in the industrial sector against more developed regions, and was obligated to invest in sectors that were easier to enter.

2. The absence of an industrial sector that could absorb displaced agricultural workers and artisans led to the proliferation of services with rather low productivity. This unequal development compared to other regions led to a hypertrophied and unproductive service sector, which has tended to reinforce underdevelopment, because it has not led to large accumulations of capital.[117][118]

Tourism in Andalusia

[edit]

Due in part to the relatively mild winter and spring climate, the south of Spain is attractive to overseas visitors–especially tourists from Northern Europe. While inland areas such as Jaén, Córdoba and the hill villages and towns remain relatively untouched by tourism, the coastal areas of Andalusia have heavy visitor traffic for much of the year.

Among the autonomous communities, Andalusia is second only to Catalonia in tourism, with nearly 30 million visitors every year. The principal tourist destinations in Andalusia are the Costa del Sol and (secondarily) the Sierra Nevada. As discussed above, Andalusia is one of the sunniest and warmest places in Europe, making it a center of "sun and sand" tourism,[119] but not only it. Around 70 percent of the lodging capacity and 75 percent of the nights booked in Andalusian hotels are in coastal municipalities. The largest number of tourists come in August—13.26 percent of the nights booked throughout the year—and the smallest number in December—5.36 percent.

On the west (Atlantic) coast are the Costa de la Luz (provinces of Huelva and Cádiz), and on the east (Mediterranean) coast, the Costa del Sol (provinces of Cádiz y Málaga), Costa Tropical (Granada and part of Almería) and the Costa de Almería. In 2004, the Blue Flag beach program of the non-profit Foundation for Environmental Education recognized 66 Andalusian beaches and 18 pleasure craft ports as being in a good state of conservation in terms of sustainability, accessibility, and quality.[citation needed] Nonetheless, the level of tourism on the Andalusian coasts has been high enough to have a significant environmental impact, and other organizations—such as the Spanish Ecologists in Action (Ecologistas en Acción) with their description of "Black Flag beaches"[120] or Greenpeace[121]—have expressed the opposite sentiment. Still, Hotel chains such as Fuerte Hotels have ensured that sustainability within the tourism industry is one of their highest priorities.[122][123][124]

Together with "sand and sun" tourism, there has also been a strong increase in nature tourism in the interior, as well as cultural tourism, sport tourism, and conventions.[citation needed] One example of sport and nature tourism is the ski resort at Sierra Nevada National Park.

As for cultural tourism, there are hundreds of cultural tourist destinations: cathedrals, castles, forts, monasteries, and historic city centers and a wide variety of museums.

It can be highlighted that Spain has seven of its 42 cultural UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Andalucia:

- Alhambra, Generalife and Albayzín, Granada (1984,1994)

- Antequera Dolmens Site (2016)

- 10th Century Caliphate City of Medina Azahara (2018)

- Cathedral, Alcázar and Archivo de Indias in Seville (1987)

- Historic centre of Córdoba (1984,1994)

- Renaissance Monumental Ensembles of Úbeda and Baeza (2003)

- Rock Art of the Mediterranean Basin on the Iberian Peninsula (1998)

Further, there are the Lugares colombinos, significant places in the life of Christopher Columbus:[125] Palos de la Frontera, La Rábida Monastery, and Moguer) in the province of Huelva. There are also archeological sites of great interest: the Roman city of Italica, birthplace of Emperor Trajan and (most likely) Hadrian or Baelo Claudia near Tarifa.

Andalusia was the birthplace of such great painters as Velázquez and Murillo (Seville) and, more recently, Picasso (Málaga); Picasso is memorialized by his native city at the Museo Picasso Málaga and Natal House Foundation; the Casa de Murillo was a house museum 1982–1998, but is now mostly offices for the Andalusian Council of Culture. The CAC Málaga (Museum of Modern Art) Archived 20 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine is the most visited museum of Andalusia[126] and has offered exhibitions of artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Jake and Dinos Chapman, Gerhard Richter, Anish Kapoor, Ron Mueck or Rodney Graham. Malaga is also located part of the private Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection at Carmen Thyssen Museum.

There are numerous other significant museums around the region, both of paintings and of archeological artifacts such as gold jewelry, pottery and other ceramics, and other works that demonstrate the region's artisanal traditions.

The Council of Government has designated the following "Municipios Turísticos": in Almería, Roquetas de Mar; in Cádiz, Chiclana de la Frontera, Chipiona, Conil de la Frontera, Grazalema, Rota, and Tarifa; in Granada, Almuñécar; in Huelva, Aracena; in Jaén, Cazorla; in Málaga, Benalmádena, Fuengirola, Nerja, Rincón de la Victoria, Ronda, and Torremolinos; in Seville, Santiponce.

Monuments and features

[edit]- Alcazaba, Almería

- Cueva de Menga, Antequera (Málaga)

- El Torcal, Antequera (Málaga)

- Medina Azahara, Córdoba

- Mosque–Cathedral, Córdoba

- Mudejar Quarter, Frigiliana (Málaga)

- Alhambra, Granada

- Palace of Charles V, Granada

- Charterhouse, Granada

- Albayzín, Granada

- La Rabida Monastery, Palos de la Frontera (Huelva)

- Castle of Santa Catalina, Jaén

- Jaén Cathedral, Jaén

- Úbeda and Baeza, Jaén

- Alcazaba, Málaga

- Buenavista Palace, Málaga

- Málaga Cathedral, Málaga

- Puente Nuevo, Ronda (Málaga)

- Caves of Nerja, Nerja (Málaga)

- Ronda Bullring, Ronda (Málaga)

- Giralda, Seville

- Torre del Oro, Seville

- Plaza de España, Seville

- Seville Cathedral, Seville

- Alcázar of Seville, Seville

- Almonaster la Real Mosque, Almonaster la Real (Huelva)

Unemployment

[edit]The unemployment rate stood at 25.5% in 2017 and was one of the highest in Spain and Europe.[127]

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unemployment rate (in %) |

12.6% | 12.8% | 17.7% | 25.2% | 27.8% | 30.1% | 34.4% | 36.2% | 34.8% | 31.5% | 28.9% | 25.5% |

Infrastructure

[edit]Transport

[edit]

As in any modern society, transport systems are an essential structural element of the functioning of Andalusia. The transportation network facilitates territorial coordination, economic development and distribution, and intercity transportation.[128]

In urban transport, underdeveloped public transport systems put pedestrian traffic and other non-motorized traffic are at a disadvantage compared to the use of private vehicles. Several Andalusian capitals—Córdoba, Granada and Seville—have recently been trying to remedy this by strengthening their public transport systems and providing a better infrastructure for the use of bicycles.[129] There are now three rapid transit systems operating in Andalucia – the Seville Metro, Málaga Metro and Granada Metro. Cercanías commuter rail networks operate in Seville, Málaga and Cádiz.

For over a century, the conventional rail network has been centralized on the regional capital, Seville, and the national capital, Madrid; in general, there are no direct connections between provincial capitals. High-speed AVE trains run from Madrid via Córdoba to Seville and Málaga, from which a branch from Antequera to Granada opened in 2019. Further AVE routes are under construction.[130] The Madrid-Córdoba-Seville route was the first high-velocity route in Spain (operating since 1992). Other principal routes are the one from Algeciras to Seville and from Almería via Granada to Madrid.

Most of the principal roads have been converted into limited access highways known as autovías. The Autovía del Este (Autovía A-4) runs from Madrid through the Despeñaperros Natural Park, then via Bailén, Córdoba, and Seville to Cádiz, and is part of European route E05 in the International E-road network. The other main road in the region is the portion of European route E15, which runs as the Autovia del Mediterráneo along the Spanish Mediterranean coast. Parts of this constitute the superhighway Autopista AP-7, while in other areas it is Autovía A-7. Both of these roads run generally east–west, although the Autovía A-4 turns to the south in western Andalusia.

Other first-order roads include the Autovía A-48 roughly along the Atlantic coast from Cádiz to Algeciras, continuing European route E05 to meet up with European route E15; the Autovía del Quinto Centenario (Autovía A-49), which continues west from Seville (where the Autovía A-4 turns toward the south) and goes on to Huelva and into Portugal as European route E01; the Autovía Ruta de la Plata (Autovía A-66), European route E803, which roughly corresponds to the ancient Roman 'Silver Route' from the mines of northern Spain, and runs north from Seville; the Autovía de Málaga (Autovía A-45), which runs south from Córdoba to Málaga; and the Autovía de Sierra Nevada (Autovía A-44), part of European route E902, which runs south from Jaén to the Mediterranean coast at Motril.

As of 2008 Andalusia has six public airports, all of which can legally handle international flights. The Málaga Airport is dominant, handling 60.67 percent of passengers[131] and 85 percent of its international traffic.[132] The Seville Airport handles another 20.12 percent of traffic, and the Jerez Airport 7.17 percent, so that these three airports account for 87.96 percent of traffic.[131]

Málaga Airport is the international airport that offers a wide variety of international destinations. It has a daily link with twenty cities in Spain and over a hundred cities in Europe (mainly in Great Britain, Central Europe and the Nordic countries but also the main cities of Eastern Europe: Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Sofia, Riga or Bucharest), North Africa, Middle East (Riyadh, Jeddah and Kuwait) and North America (New York, Toronto and Montreal).

The main ports are Algeciras (for freight and container traffic) and Málaga for cruise ships. Algeciras is Spain's leading commercial port, with 60,000,000 tonnes (66,000,000 short tons) of cargo in 2004.[133] Seville has Spain's only commercial river port. Other significant commercial ports in Andalusia are the ports of the Bay of Cádiz, Almería and Huelva.

The Council of Government has approved a Plan of Infrastructures for the Sustainability of Transport in Andalusia (PISTA) 2007–2013, which plans an investment of 30 billion euros during that period.[134]

Energy infrastructure

[edit]

The lack of high-quality fossil fuels in Andalusia has led to a strong dependency on petroleum imports. Still, Andalusia has a strong potential for the development of renewable energy, above all wind energy. The Andalusian Energy Agency established in 2005 by the autonomous government, is a new governmental organ charged with the development of energy policy and provision of a sufficient supply of energy for the community.[128]

The infrastructure for production of electricity consists of eight large thermal power stations, more than 70 hydroelectric power plants, two wind farms, and 14 major cogeneration facilities. Historically, the largest Andalusian business in this sector was the Compañía Sevillana de Electricidad, founded in 1894, absorbed into Endesa in 1996. The Solar power tower PS10 was built by the Andalusian firm Abengoa in Sanlúcar la Mayor in the province of Seville, and began operating in March 2007. It is the largest existing solar power facility in Europe.[135] Smaller solar power stations, also recent, exist at Cúllar and Galera, Granada, inaugurated by Geosol and Caja Granada. Two more large thermosolar facilities, Andasol I y II, planned at Hoya de Guadix in the province of Granada are expected to supply electricity to half a million households.[136] The Plataforma Solar de Almería (PSA) in the Tabernas Desert is an important center for the exploration of the solar energy.[137]

The largest wind power firm in the region is the Sociedad Eólica de Andalucía, formed by the merger of Planta Eólica del Sur S.A. and Energía Eólica del Estrecho S.A.

The Medgaz gas pipeline directly connects the Algerian town of Béni Saf to Almería.[138]

Education

[edit]

As throughout Spain, basic education in Andalusia is free and compulsory. Students are required to complete ten years of schooling, and may not leave school before the age of 16, after which students may continue on to a baccalaureate, to intermediate vocational education, to intermediate-level schooling in arts and design, to intermediate sports studies, or to the working world.

Andalusia has a tradition of higher education dating back to the Modern Age and the University of Granada, University of Baeza, and University of Osuna.

As of 2009,[update] there were ten private or public universities in Andalusia. University studies are structured in cycles, awarding degrees based on ECTS credits in accord with the Bologna process, which the Andalusian universities are adopting in accord with the other universities of the European Higher Education Area.

Healthcare

[edit]

Responsibility for healthcare jurisdictions devolved from the Spanish government to Andalusia with the enactment of the Statute of Autonomy. Thus, the Andalusian Health Service (Servicio Andaluz de Salud) currently manages almost all public health resources of the Community, with such exceptions as health resources for prisoners and members of the military, which remain under central administration.

Science and technology

[edit]According to the Outreach Program for Science in Andalusia, Andalusia contributes 14 percent of Spain's scientific production behind only Madrid and Catalonia among the autonomous communities,[139] even though regional investment in research and development (R&D) as a proportion of GDP is below the national average.[140] The lack of research capacity in business and the low participation of the private sector in research has resulted in R&D taking place largely in the public sector.

The Council of Innovation, Science and Business is the organ of the autonomous government responsible for universities, research, technological development, industry, and energy. The council coordinates and initiates scientific and technical innovation through specialized centers an initiatives such as the Andalusian Center for Marine Science and Technology (Centro Andaluz de Ciencia y Tecnología Marina) and Technological Corporation of Andalusia (Corporación Tecnológica de Andalucía).

Within the private sphere, although also promoted by public administration, technology parks have been established throughout the Community, such as the Technological Park of Andalucia (Parque Tecnológico de Andalucía) in Campanillas on the outskirts of Málaga, and Cartuja 93 in Seville. Some of these parks specialize in specific sector, such as Aerópolis in aerospace or Geolit in food technology. The Andalusian government deployed 600,000 Ubuntu desktop computers in their schools.

Media

[edit]Andalusia has international, national, regional, and local media organizations, which are active gathering and disseminating information (as well as creating and disseminating entertainment).

The most notable is the public Radio y Televisión de Andalucía (RTVA), broadcasting on two regional television channels, Canal Sur and Canal Sur 2, four regional radio stations, Canal Sur Radio, Canal Fiesta Radio, Radio Andalucía Información and Canal Flamenco Radio, as well as various digital signals, most notably Canal Sur Andalucía available on cable TV throughout Spain.[141]

Newspapers

[edit]Different newspapers are published for each Andalusian provincial capital, comarca, or important city. Often, the same newspaper organization publishes different local editions with much shared content, with different mastheads and different local coverage. There are also popular papers distributed without charge, again typically with local editions that share much of their content.

No single Andalusian newspaper is distributed throughout the region, not even with local editions. In eastern Andalusia the Diario Ideal has editions tailored for the provinces of Almería, Granada, and Jaén. Grupo Joly is based in Andalucia, backed by Andalusian capital, and publishes eight daily newspapers there. Efforts to create a newspaper for the entire autonomous region have not succeeded (the most recent as of 2009 was the Diario de Andalucía). The national press (El País, El Mundo, ABC, etc.) include sections or editions specific to Andalusia.

Public television

[edit]

Andalusia has two public television stations, both operated by Radio y Televisión de Andalucía (RTVA):

- Canal Sur first broadcast on 28 February 1989 (Andalusia Day).

- Canal Sur 2 first broadcast 5 June 1998. Programming focuses on culture, sports, and programs for children and youth.

In addition, RTVA also operates the national and international cable channel Canal Sur Andalucía, which first broadcast in 1996 as Andalucía Televisión.

Radio

[edit]There are four public radio stations in the region, all operated by RTVA:

- Canal Sur Radio, first broadcast October 1988.

- Radio Andalucía Información, first broadcast September 1998.

- Canal Fiesta Radio, first broadcast January 2001.

- Canal Flamenco Radio, first broadcast 29 September 2008.

Art and culture

[edit]

The patrimony of Andalusia has been shaped by its particular history and geography, as well as its complex flows of population. Andalusia has been home to a succession of peoples and civilizations, many very different from one another, each impacting the settled inhabitants. The ancient Iberians were followed by Celts, Phoenicians and other Eastern Mediterranean traders, Romans, migrating Germanic tribes, Arabs or Berbers. All have shaped the Spanish patrimony in Andalusia, which was already diffused widely in the literary and pictorial genre of the costumbrismo andaluz.[142][143]

In the 19th century, Andalusian culture came to be widely viewed as the Spanish culture par excellence, in part thanks to the perceptions of romantic travellers. In the words of Ortega y Gasset: