Империализм

Империализм — это практика, теория или отношение к поддержанию или расширению власти над иностранными государствами, особенно посредством экспансионизма , используя как жесткую силу (военную и экономическую мощь), так и мягкую силу ( дипломатическую власть и культурный империализм ). Империализм фокусируется на установлении или поддержании гегемонии и более или менее формальной империи. [2] [3] [4] Хотя империализм связан с концепциями колониализма , он представляет собой отдельную концепцию, которая может применяться к другим формам экспансии и многим формам правления. [5]

Этимология и использование

[ редактировать ]Слово империализм произошло от латинского слова «империум» . [6] что означает «командовать», «быть суверенным » или просто «править». [7] Слово «империализм» впервые было использовано в 19 веке, чтобы осудить деспотический милитаризм Наполеона III и его попытки получить политическую поддержку посредством иностранных военных интервенций. [8] [9] Этот термин стал обычным явлением в нынешнем смысле в Великобритании в 1870-х годах; к 1880-м годам оно использовалось с положительным подтекстом. [10] By the end of the 19th century it was being used to describe the behavior of empires at all times and places.[11] Hannah Arendt and Joseph Schumpeter defined imperialism as expansion for the sake of expansion.[12]

The term was and is mainly applied to Western and Japanese political and economic dominance, especially in Asia and Africa, in the 19th and 20th centuries. Its precise meaning continues to be debated by scholars. Some writers, such as Edward Said, use the term more broadly to describe any system of domination and subordination organized around an imperial core and a periphery.[13] This definition encompasses both nominal empires and neocolonialism.

Versus colonialism

[edit]

The term "imperialism" is often conflated with "colonialism"; however, many scholars have argued that each has its own distinct definition. Imperialism and colonialism have been used in order to describe one's influence upon a person or group of people. Robert Young writes that imperialism operates from the centre as a state policy and is developed for ideological as well as financial reasons, while colonialism is simply the development for settlement or commercial intentions; however, colonialism still includes invasion.[15] Colonialism in modern usage also tends to imply a degree of geographic separation between the colony and the imperial power. Particularly, Edward Said distinguishes between imperialism and colonialism by stating: "imperialism involved 'the practice, the theory and the attitudes of a dominating metropolitan center ruling a distant territory', while colonialism refers to the 'implanting of settlements on a distant territory.'[16] Contiguous land empires such as the Russian, Chinese or Ottoman have traditionally been excluded from discussions of colonialism, though this is beginning to change, since it is accepted that they also sent populations into the territories they ruled.[16]: 116

Imperialism and colonialism both dictate the political and economic advantage over a land and the indigenous populations they control, yet scholars sometimes find it difficult to illustrate the difference between the two.[17]: 107 Although imperialism and colonialism focus on the suppression of another, if colonialism refers to the process of a country taking physical control of another, imperialism refers to the political and monetary dominance, either formally or informally. Colonialism is seen to be the architect deciding how to start dominating areas and then imperialism can be seen as creating the idea behind conquest cooperating with colonialism. Colonialism is when the imperial nation begins a conquest over an area and then eventually is able to rule over the areas the previous nation had controlled. Colonialism's core meaning is the exploitation of the valuable assets and supplies of the nation that was conquered and the conquering nation then gaining the benefits from the spoils of the war.[17]: 170–75 The meaning of imperialism is to create an empire, by conquering the other state's lands and therefore increasing its own dominance. Colonialism is the builder and preserver of the colonial possessions in an area by a population coming from a foreign region.[17]: 173–76 Colonialism can completely change the existing social structure, physical structure, and economics of an area; it is not unusual that the characteristics of the conquering peoples are inherited by the conquered indigenous populations.[17]: 41 Few colonies remain remote from their mother country. Thus, most will eventually establish a separate nationality or remain under complete control of their mother colony.[18]

The Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin suggested that "imperialism was the highest form of capitalism", claiming that "imperialism developed after colonialism, and was distinguished from colonialism by monopoly capitalism".[16]: 116

Age of Imperialism

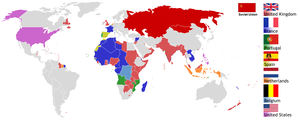

[edit]The Age of Imperialism, a time period beginning around 1760, saw European industrializing nations, engaging in the process of colonizing, influencing, and annexing other parts of the world.[19] 19th century episodes included the "Scramble for Africa."[20]

In the 1970s British historians John Gallagher (1919–1980) and Ronald Robinson (1920–1999) argued that European leaders rejected the notion that "imperialism" required formal, legal control by one government over a colonial region. Much more important was informal control of independent areas.[21] According to Wm. Roger Louis, "In their view, historians have been mesmerized by formal empire and maps of the world with regions colored red. The bulk of British emigration, trade, and capital went to areas outside the formal British Empire. Key to their thinking is the idea of empire 'informally if possible and formally if necessary.'"[22] Oron Hale says that Gallagher and Robinson looked at the British involvement in Africa where they "found few capitalists, less capital, and not much pressure from the alleged traditional promoters of colonial expansion. Cabinet decisions to annex or not to annex were made, usually on the basis of political or geopolitical considerations."[23]: 6

Looking at the main empires from 1875 to 1914, there was a mixed record in terms of profitability. At first, planners expected that colonies would provide an excellent captive market for manufactured items. Apart from the Indian subcontinent, this was seldom true. By the 1890s, imperialists saw the economic benefit primarily in the production of inexpensive raw materials to feed the domestic manufacturing sector. Overall, Great Britain did very well in terms of profits from India, especially Mughal Bengal, but not from most of the rest of its empire. According to Indian Economist Utsa Patnaik, the scale of the wealth transfer out of India, between 1765 and 1938, was an estimated $45 Trillion.[24] The Netherlands did very well in the East Indies. Germany and Italy got very little trade or raw materials from their empires. France did slightly better. The Belgian Congo was notoriously profitable when it was a capitalistic rubber plantation owned and operated by King Leopold II as a private enterprise. However, scandal after scandal regarding atrocities in the Congo Free State led the international community to force the government of Belgium to take it over in 1908, and it became much less profitable. The Philippines cost the United States much more than expected because of military action against rebels.[23]: 7–10

Because of the resources made available by imperialism, the world's economy grew significantly and became much more interconnected in the decades before World War I, making the many imperial powers rich and prosperous.[25]

Europe's expansion into territorial imperialism was largely focused on economic growth by collecting resources from colonies, in combination with assuming political control by military and political means. The colonization of India in the mid-18th century offers an example of this focus: there, the "British exploited the political weakness of the Mughal state, and, while military activity was important at various times, the economic and administrative incorporation of local elites was also of crucial significance" for the establishment of control over the subcontinent's resources, markets, and manpower.[26] Although a substantial number of colonies had been designed to provide economic profit and to ship resources to home ports in the 17th and 18th centuries, D. K. Fieldhouse suggests that in the 19th and 20th centuries in places such as Africa and Asia, this idea is not necessarily valid:[27]

Modern empires were not artificially constructed economic machines. The second expansion of Europe was a complex historical process in which political, social and emotional forces in Europe and on the periphery were more influential than calculated imperialism. Individual colonies might serve an economic purpose; collectively no empire had any definable function, economic or otherwise. Empires represented only a particular phase in the ever-changing relationship of Europe with the rest of the world: analogies with industrial systems or investment in real estate were simply misleading.[17]: 184

During this time, European merchants had the ability to "roam the high seas and appropriate surpluses from around the world (sometimes peaceably, sometimes violently) and to concentrate them in Europe".[28]

European expansion greatly accelerated in the 19th century. To obtain raw materials, Europe expanded imports from other countries and from the colonies. European industrialists sought raw materials such as dyes, cotton, vegetable oils, and metal ores from overseas. Concurrently, industrialization was quickly making Europe the centre of manufacturing and economic growth, driving resource needs.[29]

Communication became much more advanced during European expansion. With the invention of railroads and telegraphs, it became easier to communicate with other countries and to extend the administrative control of a home nation over its colonies. Steam railroads and steam-driven ocean shipping made possible the fast, cheap transport of massive amounts of goods to and from colonies.[29]

Along with advancements in communication, Europe also continued to advance in military technology. European chemists made new explosives that made artillery much more deadly. By the 1880s, the machine gun had become a reliable battlefield weapon. This technology gave European armies an advantage over their opponents, as armies in less-developed countries were still fighting with arrows, swords, and leather shields (e.g. the Zulus in Southern Africa during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879).[29] Some exceptions of armies that managed to get nearly on par with the European expeditions and standards include the Ethiopian armies at the Battle of Adwa, and the Japanese Imperial Army of Japan, but these still relied heavily on weapons imported from Europe and often on European military advisors.

Theories of imperialism

[edit]Anglophone academic studies often base their theories regarding imperialism on the British experience of Empire. The term imperialism was originally introduced into English in its present sense in the late 1870s by opponents of the allegedly aggressive and ostentatious imperial policies of British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. Supporters of "imperialism" such as Joseph Chamberlain quickly appropriated the concept. For some, imperialism designated a policy of idealism and philanthropy; others alleged that it was characterized by political self-interest, and a growing number associated it with capitalist greed.

Historians and political theorists have long debated the correlation between capitalism, class and imperialism. Much of the debate was pioneered by such theorists as John A. Hobson (1858–1940), Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950), Thorstein Veblen (1857–1929), and Norman Angell (1872–1967). While these non-Marxist writers were at their most prolific before World War I, they remained active in the interwar years. Their combined work informed the study of imperialism and its impact on Europe, as well as contributing to reflections on the rise of the military-political complex in the United States from the 1950s.

In Imperialism: A Study (1902), Hobson developed a highly influential interpretation of imperialism that expanded on his belief that free enterprise capitalism had a negative impact on the majority of the population. In Imperialism he argued that the financing of overseas empires drained money that was needed at home. It was invested abroad because of lower wages paid to the workers overseas made for higher profits and higher rates of return, compared to domestic wages. So although domestic wages remained higher, they did not grow nearly as fast as they might have otherwise. Exporting capital, he concluded, put a lid on the growth of domestic wages in the domestic standard of living. Hobson theorized that domestic social reforms could cure the international disease of imperialism by removing its economic foundation, while state intervention through taxation could boost broader consumption, create wealth, and encourage a peaceful, tolerant, multipolar world order.[31][32]

By the 1970s, historians such as David K. Fieldhouse[33] and Oron Hale could argue that "the Hobsonian foundation has been almost completely demolished."[23]: 5–6 It was not businessmen and bankers but politicians who went with the stream of the masses. The modern imperialism was primarily a political product caused by the national mass hysteria rather than by the much-abused capitalists.[34] The British experience failed to support it. Similarly, American Historian David Landes claims that businessmen were less enthusiastic about colonialism than statesmen and adventurers.[35]

However, European Marxists picked up Hobson's ideas wholeheartedly and made it into their own theory of imperialism, most notably in Vladimir Lenin's Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916). Lenin portrayed imperialism as the closure of the world market and the end of capitalist free-competition that arose from the need for capitalist economies to constantly expand investment, material resources and manpower in such a way that necessitated colonial expansion. Later Marxist theoreticians echo this conception of imperialism as a structural feature of capitalism, which explained the World War as the battle between imperialists for control of external markets. Lenin's treatise became a standard textbook that flourished until the collapse of communism in 1989–91.[36]

Some theoreticians on the non-Communist left have emphasized the structural or systemic character of "imperialism". Such writers have expanded the period associated with the term so that it now designates neither a policy, nor a short space of decades in the late 19th century, but a world system extending over a period of centuries, often going back to Colonization and, in some accounts, to the Crusades. As the application of the term has expanded, its meaning has shifted along five distinct but often parallel axes: the moral, the economic, the systemic, the cultural, and the temporal. Those changes reflect—among other shifts in sensibility—a growing unease, even great distaste, with the pervasiveness of such power, specifically, Western power.[37][33]

Walter Rodney, in his 1972 How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, proposes the idea that imperialism is a phase of capitalism "in which Western European capitalist countries, the US, and Japan established political, economic, military and cultural hegemony over other parts of the world which were initially at a lower level and therefore could not resist domination."[38] As a result, Imperialism "for many years embraced the whole world – one part being the exploiters and the other the exploited, one part being dominated and the other acting as overlords, one part making policy and the other being dependent."[38]

Imperialism has also been identified in newer phenomena like space development and its governing context.[39]

Issues

[edit]Orientalism and imaginative geography

[edit]

Imperial control, territorial and cultural, is justified through discourses about the imperialists' understanding of different spaces.[40] Conceptually, imagined geographies explain the limitations of the imperialist understanding of the societies of the different spaces inhabited by the non–European Other.[40]

In Orientalism (1978), Edward Said said that the West developed the concept of The Orient—an imagined geography of the Eastern world—which functions as an essentializing discourse that represents neither the ethnic diversity nor the social reality of the Eastern world.[41] That by reducing the East into cultural essences, the imperial discourse uses place-based identities to create cultural difference and psychologic distance between "We, the West" and "They, the East" and between "Here, in the West" and "There, in the East".[42]

That cultural differentiation was especially noticeable in the books and paintings of early Oriental studies, the European examinations of the Orient, which misrepresented the East as irrational and backward, the opposite of the rational and progressive West.[40][43] Defining the East as a negative vision of the Western world, as its inferior, not only increased the sense-of-self of the West, but also was a way of ordering the East, and making it known to the West, so that it could be dominated and controlled.[44][45] Therefore, Orientalism was the ideological justification of early Western imperialism—a body of knowledge and ideas that rationalized social, cultural, political, and economic control of other, non-white peoples.[42][16]: 116

Cartography

[edit]

One of the main tools used by imperialists was cartography. Cartography is "the art, science and technology of making maps"[46] but this definition is problematic. It implies that maps are objective representations of the world when in reality they serve very political means.[46] For Harley, maps serve as an example of Foucault's power and knowledge concept.

To better illustrate this idea, Bassett focuses his analysis of the role of 19th-century maps during the "Scramble for Africa".[47] He states that maps "contributed to empire by promoting, assisting, and legitimizing the extension of French and British power into West Africa".[47] During his analysis of 19th-century cartographic techniques, he highlights the use of blank space to denote unknown or unexplored territory.[47] This provided incentives for imperial and colonial powers to obtain "information to fill in blank spaces on contemporary maps".[47]

Although cartographic processes advanced through imperialism, further analysis of their progress reveals many biases linked to eurocentrism. According to Bassett, "[n]ineteenth-century explorers commonly requested Africans to sketch maps of unknown areas on the ground. Many of those maps were highly regarded for their accuracy"[47] but were not printed in Europe unless Europeans verified them.

Expansionism

[edit]

Imperialism in pre-modern times was common in the form of expansionism through vassalage and conquest.[citation needed]

Cultural imperialism

[edit]The concept of cultural imperialism refers to the cultural influence of one dominant culture over others, i.e. a form of soft power, which changes the moral, cultural, and societal worldview of the subordinate culture. This means more than just "foreign" music, television or film becoming popular with young people; rather that a populace changes its own expectations of life, desiring for their own country to become more like the foreign country depicted. For example, depictions of opulent American lifestyles in the soap opera Dallas during the Cold War changed the expectations of Romanians; a more recent example is the influence of smuggled South Korean drama-series in North Korea. The importance of soft power is not lost on authoritarian regimes, which may oppose such influence with bans on foreign popular culture, control of the internet and of unauthorized satellite dishes, etc. Nor is such a usage of culture recent – as part of Roman imperialism, local elites would be exposed to the benefits and luxuries of Roman culture and lifestyle, with the aim that they would then become willing participants.

Imperialism has been subject to moral or immoral censure by its critics[which?], and thus the term "imperialism" is frequently used in international propaganda as a pejorative for expansionist and aggressive foreign policy.[48]

Psychological imperialism

[edit]An empire mentality may build on and bolster views contrasting "primitive" and "advanced" peoples and cultures, thus justifying and encouraging imperialist practices among participants.[49]Associated psychological tropes include the White Man's Burden and the idea of civilizing mission (French: mission civilatrice).

Social imperialism

[edit]The political concept social imperialism is a Marxist expression first used in the early 20th century by Lenin as "socialist in words, imperialist in deeds" describing the Fabian Society and other socialist organizations.[50]Later, in a split with the Soviet Union, Mao Zedong criticized its leaders as social imperialists.[51]

Justification

[edit]

Stephen Howe has summarized his view on the beneficial effects of the colonial empires:

At least some of the great modern empires – the British, French, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and even the Ottoman – have virtues that have been too readily forgotten. They provided stability, security, and legal order for their subjects. They constrained, and at their best, tried to transcend, the potentially savage ethnic or religious antagonisms among the peoples. And the aristocracies which ruled most of them were often far more liberal, humane, and cosmopolitan than their supposedly ever more democratic successors.[52][53]

A controversial aspect of imperialism is the defense and justification of empire-building based on seemingly rational grounds. In ancient China, Tianxia denoted the lands, space, and area divinely appointed to the Emperor by universal and well-defined principles of order. The center of this land was directly apportioned to the Imperial court, forming the center of a world view that centered on the Imperial court and went concentrically outward to major and minor officials and then the common citizens, tributary states, and finally ending with the fringe "barbarians". Tianxia's idea of hierarchy gave Chinese a privileged position and was justified through the promise of order and peace.

The purportedly scientific nature of "Social Darwinism" and a theory of races formed a supposedly rational justification for imperialism. Under this doctrine, the French politician Jules Ferry could declare in 1883 that "Superior races have a right, because they have a duty. They have the duty to civilize the inferior races."[54] J. A. Hobson identifies this justification on general grounds as: "It is desirable that the earth should be peopled, governed, and developed, as far as possible, by the races which can do this work best, i.e. by the races of highest 'social efficiency'".[55] The Royal Geographical Society of London and other geographical societies in Europe had great influence and were able to fund travelers who would come back with tales of their discoveries. These societies also served as a space for travellers to share these stories.[16]: 117 Political geographers such as Friedrich Ratzel of Germany and Halford Mackinder of Britain also supported imperialism.[16]: 117 Ratzel believed expansion was necessary for a state's survival and this argument dominated the discipline of geopolitics for decades.[16]: 117 British imperialism in some sparsely-inhabited regions applied a principle now termed Terra nullius (Latin expression which stems from Roman law meaning 'no man's land'). The British settlement in Australia in the 18th century was arguably premised on terra nullius, as its settlers considered it unused by its original inhabitants. The rhetoric of colonizers being racially superior appears still to have its impact. For example, throughout Latin America "whiteness" is still prized today and various forms of blanqueamiento (whitening) are common.

Imperial peripheries benefited from economic efficiency improved through the building of roads, other infrastructure and introduction of new technologies. Herbert Lüthy notes that ex-colonial peoples themselves show no desire to undo the basic effects of this process. Hence moral self-criticism in respect of the colonial past is out of place.[56]

Environmental determinism

[edit]The concept of environmental determinism served as a moral justification for the domination of certain territories and peoples. The environmental determinist school of thought held that the environment in which certain people lived determined those persons' behaviours; and thus validated their domination. Some geographic scholars under colonizing empires divided the world into climatic zones. These scholars believed that Northern Europe and the Mid-Atlantic temperate climate produced a hard-working, moral, and upstanding human being. In contrast, tropical climates allegedly yielded lazy attitudes, sexual promiscuity, exotic culture, and moral degeneracy. The tropical peoples were believed to be "less civilized" and in need of European guidance,[16]: 117 therefore justifying colonial control as a civilizing mission. For instance, American geographer Ellen Churchill Semple argued that even though human beings originated in the tropics they were only able to become fully human in the temperate zone.[57]: 11 Across the three major waves of European colonialism (the first in the Americas, the second in Asia and the last in Africa), environmental determinism served to place categorically indigenous people in a racial hierarchy. Tropicality can be paralleled with Edward Said's Orientalism as the west's construction of the east as the "other".[57]: 7 According to Said, orientalism allowed Europe to establish itself as the superior and the norm, which justified its dominance over the essentialized Orient.[58]: 329 Orientalism is a view of a people based on their geographical location.[59]

Anti-imperialism

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2020) |

Anti-imperialism gained a wide currency after the Second World War and at the onset of the Cold War as political movements in colonies of European powers promoted national sovereignty. Some anti-imperialist groups who opposed the United States supported the power of the Soviet Union, such as in Guevarism, while in Maoism this was criticized as social imperialism.

Pan-African Movement

[edit]Pan-Africanism is a movement across Africa and the world that came as a result of imperial ideas splitting apart African nations and pitting them against each other. The Pan-African movement instead tried to reverse those ideas by uniting Africans and creating a sense of brotherhood among all African people.[60] The Pan-African movement helped with the eventual end of Colonialism in Africa.

Representatives at the 1900 Pan African Conference demanded moderate reforms for colonial African nations.[61] The conference also discussed African populations in the Caribbean and the United States and their rights. There was a total of 6 Pan-African conferences that were held and these allowed the African people to have a voice in ending colonial rule.

Imperialism by country

[edit]Rome

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2021) |

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterranean Sea in Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia, ruled by emperors.

Arabia

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

Belgium

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

United Kingdom

[edit]

England

[edit]England's imperialist ambitions can be seen as early as the 16th century as the Tudor conquest of Ireland began in the 1530s. In 1599 the British East India Company was established and was chartered by Queen Elizabeth in the following year.[17]: 174 With the establishment of trading posts in India, the British were able to maintain strength relative to other empires such as the Portuguese who already had set up trading posts in India.[17]: 174

Scotland

[edit]Between 1621 and 1699, the Kingdom of Scotland authorised several colonies in the Americas. Most of these colonies were either closed down or collapsed quickly for various reasons.

United Kingdom

[edit]Under the Acts of Union 1707, the English and Scottish kingdoms were merged, and their colonies collectively became subject to Great Britain (also known as the United Kingdom). The empire Great Britain would go on to found was the largest empire that the world has ever seen both in terms of landmass and population. Its power, both military and economic, remained unmatched for a few decades.

In 1767, the Anglo-Mysore Wars and other political activity caused exploitation of the East India Company causing the plundering of the local economy, almost bringing the company into bankruptcy.[62] By the year 1670 Britain's imperialist ambitions were well off as she had colonies in Virginia, Massachusetts, Bermuda, Honduras, Antigua, Barbados, Jamaica and Nova Scotia.[62]Due to the vast imperialist ambitions of European countries, Britain had several clashes with France. This competition was evident in the colonization of what is now known as Canada. John Cabot claimed Newfoundland for the British while the French established colonies along the St. Lawrence River and claiming it as "New France".[63] Britain continued to expand by colonizing countries such as New Zealand and Australia, both of which were not empty land as they had their own locals and cultures.[17]: 175 Britain's nationalistic movements were evident with the creation of the commonwealth countries where there was a shared nature of national identity.[17]: 147

Following the proto-industrialization, the "First" British Empire was based on mercantilism, and involved colonies and holdings primarily in North America, the Caribbean, and India. Its growth was reversed by the loss of the American colonies in 1776. Britain made compensating gains in India, Australia, and in constructing an informal economic empire through control of trade and finance in Latin America after the independence of Spanish and Portuguese colonies in about 1820.[64] By the 1840s, the United Kingdom had adopted a highly successful policy of free trade that gave it dominance in the trade of much of the world.[65] After losing its first Empire to the Americans, Britain then turned its attention towards Asia, Africa, and the Pacific. Following the defeat of Napoleonic France in 1815, the United Kingdom enjoyed a century of almost unchallenged dominance and expanded its imperial holdings around the globe. Unchallenged at sea, British dominance was later described as Pax Britannica ("British Peace"), a period of relative peace in Europe and the world (1815–1914) during which the British Empire became the global hegemon and adopted the role of global policeman. However, this peace was mostly a perceived one from Europe, and the period was still an almost uninterrupted series of colonial wars and disputes. The British Conquest of India, its intervention against Mehemet Ali, the Anglo-Burmese Wars, the Crimean War, the Opium Wars and the Scramble for Africa to name the most notable conflicts mobilised ample military means to press Britain's lead in the global conquest Europe led across the century.[66][67][68][69]

In the early 19th century, the Industrial Revolution began to transform Britain; by the time of the Great Exhibition in 1851 the country was described as the "workshop of the world".[70] The British Empire expanded to include India, large parts of Africa and many other territories throughout the world. Alongside the formal control it exerted over its own colonies, British dominance of much of world trade meant that it effectively controlled the economies of many regions, such as Asia and Latin America.[71][72] Domestically, political attitudes favoured free trade and laissez-faire policies and a gradual widening of the voting franchise. During this century, the population increased at a dramatic rate, accompanied by rapid urbanisation, causing significant social and economic stresses.[73] To seek new markets and sources of raw materials, the Conservative Party under Disraeli launched a period of imperialist expansion in Egypt, South Africa, and elsewhere. Canada, Australia, and New Zealand became self-governing dominions.[74][75]

A resurgence came in the late 19th century with the Scramble for Africa and major additions in Asia and the Middle East. The British spirit of imperialism was expressed by Joseph Chamberlain and Lord Rosebury, and implemented in Africa by Cecil Rhodes. The pseudo-sciences of Social Darwinism and theories of race formed an ideological underpinning and legitimation during this time. Other influential spokesmen included Lord Cromer, Lord Curzon, General Kitchener, Lord Milner, and the writer Rudyard Kipling.[76] After the First Boer War, the South African Republic and Orange Free State were recognised by the United Kingdom but eventually re-annexed after the Second Boer War. But British power was fading, as the reunited German state founded by the Kingdom of Prussia posed a growing threat to Britain's dominance. As of 1913, the United Kingdom was the world's fourth economy, behind the U.S., Russia and Germany.

Irish War of Independence in 1919–1921 led to the сreation of the Irish Free State. But the United Kingdom gained control of former German and Ottoman colonies with the League of Nations mandate. The United Kingdom now had a practically continuous line of controlled territories from Egypt to Burma and another one from Cairo to Cape Town. However, this period was also one of emergence of independence movements based on nationalism and new experiences the colonists had gained in the war.

World War II decisively weakened Britain's position in the world, especially financially. Decolonization movements arose nearly everywhere in the Empire, resulting in Indian independence and partition in 1947, the self-governing dominions break away from the empire in 1949, and the establishment of independent states in the 1950s. British imperialism showed its frailty in Egypt during the Suez Crisis in 1956. However, with the United States and Soviet Union emerging from World War II as the sole superpowers, Britain's role as a worldwide power declined significantly and rapidly.[77]

Canada

[edit]

In Canada, the "imperialism" (and the related term "colonialism") has had a variety of contradictory meanings since the 19th century. In the late 19th and early 20th, to be an "imperialist" meant thinking of Canada as a part of the British nation not a separate nation.[78] The older words for the same concepts were "loyalism" or "unionism", which continued to be used as well. In mid-twentieth century Canada, the words "imperialism" and "colonialism" were used in English Canadian discourse to instead portray Canada as a victim of economic and cultural penetration by the United States.[79] In twentieth century French-Canadian discourse the "imperialists" were all the Anglo-Saxon countries including Canada who were oppressing French-speakers and the province of Quebec. By the early 21st century, "colonialism" was used to highlight supposed anti-indigenous attitudes and actions of Canada inherited from the British period.

China

[edit]

China was one of the world's oldest empires. Due to its long history of imperialist expansion, China has been seen by its neighboring countries as a threat due to its large population, giant economy, large military force as well as its territorial evolution throughout history. Starting with the unification of China under the Qin dynasty, later Chinese dynasties continued to follow its form of expansions.[80]

The most successful Chinese imperial dynasties in terms of territorial expansion were the Han, Tang, Yuan, and Qing dynasties.

Denmark

[edit]Denmark–Norway (Denmark after 1814) possessed overseas colonies from 1536 until 1953. At its apex there were colonies on four continents: Europe, North America, Africa and Asia. In the 17th century, following territorial losses on the Scandinavian Peninsula, Denmark-Norway began to develop colonies, forts, and trading posts in West Africa, the Caribbean, and the Indian subcontinent. Christian IV first initiated the policy of expanding Denmark-Norway's overseas trade, as part of the mercantilist wave that was sweeping Europe. Denmark-Norway's first colony was established at Tranquebar on India's southern coast in 1620. Admiral Ove Gjedde led the expedition that established the colony. After 1814, when Norway was ceded to Sweden, Denmark retained what remained of Norway's great medieval colonial holdings. One by one the smaller colonies were lost or sold. Tranquebar was sold to the British in 1845. The United States purchased the Danish West Indies in 1917. Iceland became independent in 1944. Today, the only remaining vestiges are two originally Norwegian colonies that are currently within the Danish Realm, the Faroe Islands and Greenland; the Faroes were a Danish county until 1948, while Greenland's colonial status ceased in 1953. They are now autonomous territories.[81]

France

[edit]

During the 16th century, the French colonization of the Americas began with the creation of New France. It was followed by French East India Company's trading posts in Africa and Asia in the 17th century. France had its "First colonial empire" from 1534 until 1814, including New France (Canada, Acadia, Newfoundland and Louisiana), French West Indies (Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe, Martinique), French Guiana, Senegal (Gorée), Mascarene Islands (Mauritius Island, Réunion) and French India.

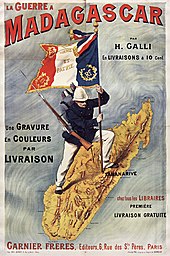

Its "Second colonial empire" began with the seizure of Algiers in 1830 and came for the most part to an end with the granting of independence to Algeria in 1962.[82] The French imperial history was marked by numerous wars, large and small, and also by significant help to France itself from the colonials in the world wars.[83] France took control of Algeria in 1830 but began in earnest to rebuild its worldwide empire after 1850, concentrating chiefly in North and West Africa (French North Africa, French West Africa, French Equatorial Africa), as well as South-East Asia (French Indochina), with other conquests in the South Pacific (New Caledonia, French Polynesia). France also twice attempted to make Mexico a colony in 1838–39 and in 1861–67 (see Pastry War and Second French intervention in Mexico).

French Republicans, at first hostile to empire, only became supportive when Germany started to build her own colonial empire. As it developed, the new empire took on roles of trade with France, supplying raw materials and purchasing manufactured items, as well as lending prestige to the motherland and spreading French civilization and language as well as Catholicism. It also provided crucial manpower in both World Wars.[84] It became a moral justification to lift the world up to French standards by bringing Christianity and French culture. In 1884 the leading exponent of colonialism, Jules Ferry declared France had a civilising mission: "The higher races have a right over the lower races, they have a duty to civilize the inferior".[85] Full citizenship rights – assimilation – were offered, although in reality assimilation was always on the distant horizon.[86] Contrasting from Britain, France sent small numbers of settlers to its colonies, with the only notable exception of Algeria, where French settlers nevertheless always remained a small minority.

The French colonial empire of extended over 11,500,000 km2 (4,400,000 sq mi) at its height in the 1920s and had a population of 110 million people on the eve of World War II.[87][88]

In World War II, Charles de Gaulle and the Free French used the overseas colonies as bases from which they fought to liberate France. However, after 1945 anti-colonial movements began to challenge the Empire. France fought and lost a bitter war in Vietnam in the 1950s. Whereas they won the war in Algeria, de Gaulle decided to grant Algeria independence anyway in 1962. French settlers and many local supporters relocated to France. Nearly all of France's colonies gained independence by 1960, but France retained great financial and diplomatic influence. It has repeatedly sent troops to assist its former colonies in Africa in suppressing insurrections and coups d'état.[89]

Education policy

[edit]French colonial officials, influenced by the revolutionary ideal of equality, standardized schools, curricula, and teaching methods as much as possible. They did not establish colonial school systems with the idea of furthering the ambitions of the local people, but rather simply exported the systems and methods in vogue in the mother nation.[90] Having a moderately trained lower bureaucracy was of great use to colonial officials.[91] The emerging French-educated indigenous elite saw little value in educating rural peoples.[92] After 1946 the policy was to bring the best students to Paris for advanced training. The result was to immerse the next generation of leaders in the growing anti-colonial diaspora centered in Paris. Impressionistic colonials could mingle with studious scholars or radical revolutionaries or so everything in between. Ho Chi Minh and other young radicals in Paris formed the French Communist party in 1920.[93]

Tunisia was exceptional. The colony was administered by Paul Cambon, who built an educational system for colonists and indigenous people alike that was closely modeled on mainland France. He emphasized female and vocational education. By independence, the quality of Tunisian education nearly equalled that in France.[94]

African nationalists rejected such a public education system, which they perceived as an attempt to retard African development and maintain colonial superiority. One of the first demands of the emerging nationalist movement after World War II was the introduction of full metropolitan-style education in French West Africa with its promise of equality with Europeans.[95][96]

In Algeria, the debate was polarized. The French set up schools based on the scientific method and French culture. The Pied-Noir (Catholic migrants from Europe) welcomed this. Those goals were rejected by the Moslem Arabs, who prized mental agility and their distinctive religious tradition. The Arabs refused to become patriotic and cultured Frenchmen and a unified educational system was impossible until the Pied-Noir and their Arab allies went into exile after 1962.[97]

In South Vietnam from 1955 to 1975 there were two competing powers in education, as the French continued their work and the Americans moved in. They sharply disagreed on goals. The French educators sought to preserving French culture among the Vietnamese elites and relied on the Mission Culturelle – the heir of the colonial Direction of Education – and its prestigious high schools. The Americans looked at the great mass of people and sought to make South Vietnam a nation strong enough to stop communism. The Americans had far more money, as USAID coordinated and funded the activities of expert teams, and particularly of academic missions. The French deeply resented the American invasion of their historical zone of cultural imperialism.[98]

Germany

[edit]

German expansion into Slavic lands begins in the 12th–13th-century (see Drang Nach Osten). The concept of Drang Nach Osten was a core element of German nationalism and a major element of Nazi ideology. However, the German involvement in the seizure of overseas territories was negligible until the end of the 19th century. Prussia unified the other states into the second German Empire in 1871. Its Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck (1862–90), long opposed colonial acquisitions, arguing that the burden of obtaining, maintaining, and defending such possessions would outweigh any potential benefits. He felt that colonies did not pay for themselves, that the German bureaucratic system would not work well in the tropics and the diplomatic disputes over colonies would distract Germany from its central interest, Europe itself.[100]

However, public opinion and elite opinion in Germany demanded colonies for reasons of international prestige, so Bismarck was forced to oblige. In 1883–84 Germany began to build a colonial empire in Africa and the South Pacific.[101][102] The establishment of the German colonial empire started with German New Guinea in 1884.[103] Within 25 years, German South West Africa had committed the Herero and Namaqua genocide in modern-day Namibia, the first genocide of the 20th century.

German colonies included the present territories of in Africa: Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, Namibia, Cameroon, Ghana and Togo; in Oceania: New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Nauru, Marshall Islands, Mariana Islands, Caroline Islands and Samoa; and in Asia: Qingdao, Yantai and the Jiaozhou Bay. The Treaty of Versailles made them mandates temporarily operated by the Allied victors.[104]Germany also lost part of the Eastern territories that became part of independent Poland as a result of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. Finally, the Eastern territories captured in the Middle Ages were torn from Germany and became part of Poland and the USSR as a result of the territorial reorganization established by the Potsdam Conference of the great powers in 1945.

Italy

[edit]

The Italian Empire (Impero italiano) comprised the overseas possessions of the Kingdom of Italy primarily in northeast Africa. It began with the purchase in 1869 of Assab Bay on the Red Sea by an Italian navigation company which intended to establish a coaling station at the time the Suez Canal was being opened to navigation.[105] This was taken over by the Italian government in 1882, becoming modern Italy's first overseas territory.[106] By the start of the First World War in 1914, Italy had acquired in Africa the colony of Eritrea on the Red Sea coast, a large protectorate and later colony in Somalia, and authority in formerly Ottoman Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (gained after the Italo-Turkish War) which were later unified in the colony of Libya.

Outside Africa, Italy possessed the Dodecanese Islands off the coast of Turkey (following the Italo-Turkish War) and a small concession in Tianjin in China following the Boxer War of 1900. During the First World War, Italy occupied southern Albania to prevent it from falling to Austria-Hungary. In 1917, it established a protectorate over Albania, which remained in place until 1920.[107] The Fascist government that came to power with Benito Mussolini in 1922 sought to increase the size of the Italian empire and to satisfy the claims of Italian irredentists.

In its second invasion of Ethiopia in 1935–36, Italy was successful and it merged its new conquest with its older east African colonies to create Italian East Africa. In 1939, Italy invaded Albania and incorporated it into the Fascist state. During the Second World War (1939–1945), Italy occupied British Somaliland, parts of south-eastern France, western Egypt and most of Greece, but then lost those conquests and its African colonies, including Ethiopia, to the invading allied forces by 1943. It was forced in the peace treaty of 1947 to relinquish sovereignty over all its colonies. It was granted a trust to administer former Italian Somaliland under United Nations supervision in 1950. When Somalia became independent in 1960, Italy's eight-decade experiment with colonialism ended.[108][109][page needed]

Japan

[edit]

For over 200 years, Japan maintained a feudal society during a period of relative isolation from the rest of the world. However, in the 1850s, military pressure from the United States and other world powers coerced Japan to open itself to the global market, resulting in an end to the country's isolation. A period of conflicts and political revolutions followed due to socioeconomic uncertainty, ending in 1868 with the reunification of political power under the Japanese Emperor during the Meiji Restoration. This sparked a period of rapid industrialization driven in part by a Japanese desire for self-sufficiency. By the early 1900s, Japan was a naval power that could hold its own against an established European power as it defeated Russia.[110]

Despite its rising population and increasingly industrialized economy, Japan lacked significant natural resources. As a result, the country turned to imperialism and expansionism in part as a means of compensating for these shortcomings, adopting the national motto "Fukoku kyōhei" (富国強兵, "Enrich the state, strengthen the military").[111]

И Япония стремилась использовать любую возможность. В 1869 году они воспользовались поражением повстанцев Республики Эдзо, чтобы окончательно присоединить остров Хоккайдо к Японии. На протяжении веков Япония считала острова Рюкю одной из своих провинций. В 1871 году произошел инцидент в Мудане : тайваньские аборигены убили 54 моряка -рюкюаня, потерпевших кораблекрушение. В то время на острова Рюкю претендовали и Цинский Китай , и Япония, и японцы интерпретировали инцидент как нападение на своих граждан. Они предприняли шаги, чтобы передать острова под свою юрисдикцию: в 1872 г. был объявлен японский домен Рюкю , а в 1874 г. было совершено ответное вторжение на Тайвань , имевшее успех. Успех этой экспедиции придал японцам смелости: даже американцы не смогли победить тайваньцев в Формозской экспедиции 1867 года. В то время мало кто серьезно об этом задумывался, но это был первый шаг в серии японского экспансионизма. Япония оккупировала Тайвань до конца 1874 года, а затем покинула его под давлением Китая, но в 1879 году она наконец аннексировала Тайвань. Острова Рюкю . В 1875 году цинский Китай послал отряд из 300 человек, чтобы подчинить себе тайваньцев, но, в отличие от японцев, китайцы были разбиты, попали в засаду, и 250 их людей были убиты; Провал этой экспедиции еще раз продемонстрировал неспособность Цинского Китая обеспечить эффективный контроль над Тайванем и послужил еще одним стимулом для японцев аннексировать Тайвань. В конце концов, трофеями победы в Первой китайско-японской войне 1894 года стал Тайвань . [112]

В 1875 году Япония провела свою первую операцию против Кореи Чосон , еще одной территории, к которой она стремилась на протяжении веков; Инцидент на острове Канхва сделал Корею открытой для международной торговли. Корея была аннексирована в 1910 году. В результате победы в русско-японской войне в 1905 году Япония отобрала у России часть острова Сахалин . Именно победа над Российской империей потрясла мир: никогда раньше азиатская нация не побеждала европейскую державу. [ сомнительно – обсудить ] , а в Японии это восприняли как подвиг. Победа Японии над Россией послужит предшественником для азиатских стран в борьбе против западных держав за деколонизацию . Во время Первой мировой войны Япония захватила арендованные Германией территории в китайской провинции Шаньдун, а также Марианские , Каролинские и Маршалловы острова и сохранила острова под мандатом Лиги наций. Поначалу Япония имела хорошие отношения с союзными державами-победительницами в Первой мировой войне, но различные разногласия и недовольство выгодами договоров охладили отношения с ними, например, американское давление вынудило ее вернуть территорию Шаньдуна. К 30-м годам экономическая депрессия, нехватка ресурсов и растущее недоверие к союзным державам заставили Японию склониться к ужесточенной милитаристской позиции. В течение десятилетия она станет ближе к Германии и Италии, вместе образуя альянс Оси. В 1931 году Япония отобрала Маньчжурию у Китая . Международная реакция осудила этот шаг, но и без того сильный скептицизм Японии в отношении стран-союзников означал, что он, тем не менее, продолжился. [113]

Во время Второй китайско-японской войны в 1937 году японские военные вторглись в центральный Китай. Также в 1938–1939 годах Япония предприняла попытку захватить территорию Советской России и Монголии, но потерпела серьёзные поражения (см. Битва на озере Хасан , Битвы на Халхин-Голе ). К этому моменту отношения с союзными державами были на самом низком уровне, и был объявлен международный бойкот Японии с целью лишить ее природных ресурсов. Военный шаг, чтобы получить к ним доступ, был сочтен необходимым, и поэтому Япония напала на Перл-Харбор , в результате чего Соединенные Штаты вступили во Вторую мировую войну. Используя свои превосходные технологические достижения в области морской авиации и современные доктрины десантной и морской войны , Япония достигла одной из самых быстрых морских экспансий в истории. К 1942 году Япония завоевала большую часть Восточной Азии и Тихого океана, включая восток Китая, Гонконг, Таиланд, Вьетнам, Камбоджу, Бирму (Мьянму), Малайзию, Филиппины, Индонезию, часть Новой Гвинеи и многие острова Тихого океана. Океан. Точно так же, как поздний успех Японии в индустриализации и победа над Российской империей рассматривались как пример среди слаборазвитых стран Азиатско-Тихоокеанского региона, японцы воспользовались этим и продвигали среди побежденных цель совместного создания антиевропейской политики. Сфера совместного процветания Большой Восточной Азии ». Этот план помог японцам заручиться поддержкой коренного населения во время своих завоеваний. [ нужна ссылка ] особенно в Индонезии. [ нужна ссылка ] Однако Соединенные Штаты имели гораздо более сильную военную и промышленную базу и победили Японию, лишив ее завоеваний и вернув ее поселенцев обратно в Японию. [114]

Нидерланды

[ редактировать ]Самый яркий пример голландского империализма касается Индонезии .

Османская империя

[ редактировать ]

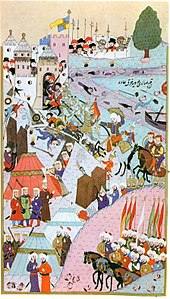

Османская империя была имперским государством, просуществовавшим с 1299 по 1922 год. В 1453 году Мехмед Завоеватель захватил Константинополь и сделал его своей столицей. В течение 16 и 17 веков, особенно на пике своего могущества во время правления Сулеймана Великолепного , Османская империя была мощной многонациональной, многоязычной империей, которая вторглась и колонизировала большую часть Юго-Восточной Европы, Западной Азии, Кавказа , Севера. Африка и Африканский Рог . Его неоднократные вторжения и жестокое обращение со славянами привели к Великому переселению сербов , спасающихся от преследований. В начале 17 в. в составе империи было 32 провинции и множество вассальных государств . Некоторые из них позже были включены в состав империи, а другим на протяжении столетий были предоставлены различные виды автономии. [115]

После длительного периода военных неудач против европейских держав Османская империя постепенно пришла в упадок , потеряв контроль над большей частью своей территории в Европе и Африке.

К 1810 году Египет стал фактически независимым. В 1821–1829 годах грекам в войне за независимость помогали Россия, Великобритания и Франция. В 1815–1914 гг. Османская империя могла существовать только в условиях острого соперничества великих держав, главным сторонником которой была Англия, особенно в Крымской войне 1853–1856 гг. против России. После поражения Османской империи в русско-турецкой войне (1877–1878 гг.) Болгария, Сербия и Черногория получили независимость, а Великобритания взяла под колониальный контроль Кипр , а Босния и Герцеговина были оккупированы и аннексированы Австро-Венгерской империей в 1908 году.

Империя объединилась с Германией в Первой мировой войне с имперскими амбициями вернуть утраченные территории, но распалась после своего решающего поражения. Кемалистское национальное движение, поддержанное Советской Россией, одержало победу в ходе турецкой войны за независимость , а стороны подписали и ратифицировали Лозаннский договор в 1923 и 1924 годах. Турецкая Республика . Была создана [116]

Португалия

[ редактировать ]

Россия

[ редактировать ]К 18 веку Российская империя распространила свой контроль на Тихий океан, мирно образовав общую границу с империей Цин и Японской империей . Это имело место в ходе большого количества военных вторжений на земли к востоку, западу и югу от него. Польско -российская война 1792 года произошла после того, как польское дворянство из Речи Посполитой написало Конституцию от 3 мая 1791 года . В результате войны восточная Польша была завоевана Императорской Россией как колония до 1918 года. Южные кампании включали серию русско-персидских войн , которые начались с Персидской экспедиции 1796 года , в результате которой Грузия стала протекторатом. Между 1800 и 1864 годами имперские армии вторглись на юг во время российского завоевания Кавказа , Мюридской войны и русско-черкесской войны . Этот последний конфликт привел к этнической чистке черкесов с их земель. Завоевание Сибири Россией произошло Сибирского ханства в XVI и XVII веках и привело к убийству русскими различных коренных племен, в том числе Дауры , коряки , ительмены , манси и чукчи . Русскую колонизацию Центральной и Восточной Европы и Сибири и обращение с местными коренными народами сравнивают с европейской колонизацией Америки, оказывая такое же негативное воздействие на коренных сибиряков, как и на коренные народы Америки. Истребление коренных сибирских племен было настолько полным, что, как говорят, сегодня существует относительно небольшая популяция, составляющая всего 180 000 человек. В этот период Российская империя эксплуатировала и подавляла казачьи превратила их в особое военное имение Сословье войска, прежде чем в конце 18 века . Затем казаки использовались в походах Императорской России против других племен. [117]

Присоединение Украины к России началось в 1654 году Переяславским соглашением . Присоединение Грузии к России в 1783 году ознаменовалось Георгиевским договором .

К 1921 году большевистские лидеры фактически восстановили государственное устройство примерно такого же размера, что и империя, но с интернационалистской идеологией: Ленин, в частности, отстаивал право на ограниченное самоопределение национальных меньшинств на новой территории. [118] Начиная с 1923 года, политика « коренизации » [коренизации] была направлена на поддержку нерусских в развитии их национальных культур в рамках социализма. Никогда официально не отменявшийся, он перестал применяться после 1932 года. [ нужна ссылка ] . После Второй мировой войны Советский Союз установил социалистические режимы по образцу тех, которые он установил в 1919–1920 годах в старой Российской империи , на территориях, оккупированных его войсками в Восточной Европе. [119] Советский Союз, а затем и Китайская Народная Республика поддерживали революционные и коммунистические движения в зарубежных странах и колониях для продвижения своих собственных интересов, но не всегда добивались успеха. [120] СССР оказал большую помощь Гоминьдану в 1926–1928 в формировании единого китайского правительства (см. Северная экспедиция ). Хотя затем отношения с СССР и ухудшились, но СССР был единственной мировой державой, оказавшей военную помощь Китаю против японской агрессии в 1937–1941 годах (см. Советско-китайский пакт о ненападении ). Победа китайских коммунистов в гражданской войне 1946—1949 опиралась на большую помощь СССР (см. Гражданская война в Китае ).

Троцкий и другие считали, что революция может добиться успеха в России только как часть мировой революции . Ленин много писал по этому вопросу и заявил, что империализм является высшей стадией капитализма . Однако после смерти Ленина Иосиф Сталин установил « социализм в одной стране » для Советского Союза, создав модель для последующих сталинистских государств, ориентированных на себя, и очистив ранние интернационалистические элементы. Интернационалистские тенденции ранней революции будут оставлены до тех пор, пока они не вернутся в структуру государства-сателлита, конкурирующего с американцами во время холодной войны . В постсталинский период конца 1950-х годов новый политический лидер Никита Хрущев оказал давление на советско-американские отношения, начав новую волну антиимпериалистической пропаганды. В своей речи на конференции ООН в 1960 году он объявил о продолжении войны с империализмом, заявив, что вскоре народы разных стран объединятся и свергнут своих империалистических лидеров. Хотя Советский Союз объявил себя антиимпериалистическим , критики утверждают, что он обладал чертами, общими для исторических империй. [122] [123] [124] Некоторые ученые считают, что Советский Союз представлял собой гибридное образование, содержащее элементы, общие как для многонациональных империй, так и для национальных государств. Некоторые также утверждали, что СССР практиковал колониализм, как и другие имперские державы, и продолжал старую российскую традицию экспансии и контроля. [124] Мао Цзэдун однажды утверждал, что Советский Союз сам стал империалистической державой , сохранив при этом социалистический фасад. Более того, идеи империализма получили широкое распространение на высших уровнях власти. Иосип Броз Тито и Милован Джилас называли внешнюю политику сталинистского СССР , такую как оккупация и экономическая эксплуатация Восточной Европы , а также его агрессивную и враждебную политику по отношению к Югославии , советским империализмом. [125] [126] Некоторые марксисты в Российской империи, а затем и в СССР, такие как Султан Галиев и Василий Шахрай , считали советский режим обновленной версией российского империализма и колониализма. [127] подавление Венгерской революции 1956 года и советско-афганская война . В качестве примеров были приведены [128] [129] [130] современный российский империализм Некоторые видят на оккупированных Россией территориях . [131]

Соединенные Штаты

[ редактировать ]

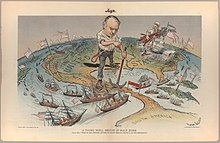

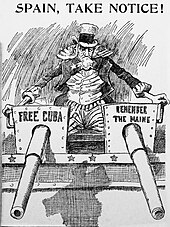

Состоящие из бывших колоний, ранние Соединенные Штаты выражали свою оппозицию империализму, по крайней мере, в форме, отличной от их собственной «Явной судьбы» , посредством такой политики, как доктрина Монро . Однако США, возможно, безуспешно пытались захватить Канаду в войне 1812 года . Соединенные Штаты добились очень значительных территориальных уступок от Мексики во время американо-мексиканской войны . Начиная с конца 19 - начала 20 века, такие политики, как Теодора Рузвельта интервенционизм в Центральной Америке и миссия Вудро Вильсона «сделать мир безопасным для демократии» [132] все это изменил. Их часто поддерживала военная сила, но чаще на них оказывали влияние из-за кулис. Это согласуется с общим представлением о гегемонии и империи исторических империй. [133] [134] В 1898 году американцы, выступавшие против империализма, создали Антиимпериалистическую лигу , чтобы противостоять аннексии США Филиппин и Кубы. Год спустя на Филиппинах разразилась война, в результате чего лидеры бизнеса, профсоюзов и правительства США осудили американскую оккупацию Филиппин, а также осудили их за гибель многих филиппинцев. [135] Американская внешняя политика была названа «рэкетом» Смедли Батлером , бывшим американским генералом, который стал представителем крайне левых сил. [136]

В начале Второй мировой войны президент Франклин Д. Рузвельт выступал против европейского колониализма, особенно в Индии. Он отступил, когда британец Уинстон Черчилль потребовал, чтобы победа в войне была главным приоритетом. Рузвельт ожидал, что Организация Объединенных Наций займется проблемой деколонизации. [137]

Некоторые описывают внутреннюю борьбу между различными группами людей как форму империализма или колониализма. Эта внутренняя форма отличается от неформального империализма США в форме политической и финансовой гегемонии. [138] Это также показало разницу в формировании Соединенными Штатами «колоний» за рубежом. [138] Благодаря обращению со своими коренными народами во время экспансии на запад, Соединенные Штаты приняли форму имперской державы еще до каких-либо попыток внешнего империализма. Эту внутреннюю форму империи назвали «внутренним колониализмом». [139] Участие в африканской работорговле и последующее обращение с 12-15 миллионами африканцев рассматривается некоторыми как более современное продолжение «внутреннего колониализма» Америки. [140] Однако этот внутренний колониализм столкнулся с сопротивлением, как и внешний колониализм, но антиколониальное присутствие было гораздо менее заметным из-за почти полного доминирования, которое Соединенные Штаты смогли утвердить как над коренными народами, так и над афроамериканцами. [141] В лекции 16 апреля 2003 года Эдвард Саид описал современный империализм в Соединенных Штатах как агрессивное средство нападения на современный Восток, заявив, что «из-за их отсталого образа жизни, отсутствия демократии и нарушения прав женщин. Западный мир во время этого процесса обращения других забывает, что просвещение и демократия — это концепции, с которыми не все согласятся». [142]

Испания

[ редактировать ]

Испанский империализм в колониальную эпоху соответствует взлету и упадку Испанской империи , которая традиционно считается возникшей в 1402 году с завоеванием Канарских островов. После успехов исследовательских морских путешествий, проведенных в эпоху Великих географических открытий , Испания выделила значительные финансовые и военные ресурсы на развитие мощного военно-морского флота, способного проводить крупномасштабные трансатлантические экспедиционные операции с целью установления и укрепления прочного имперского присутствия на больших территориях. Северная Америка, Южная Америка и географические регионы, включающие Карибский бассейн . Одновременно с одобрением и спонсорством Испании трансатлантических экспедиционных путешествий было размещение конкистадоров , которые еще больше расширили границы испанской империи за счет приобретения и развития территорий и колоний. [143]

Империализм в Карибском бассейне

[ редактировать ]

В соответствии с колониальной деятельностью конкурирующих европейских имперских держав на протяжении XV–XIX веков, испанцы были в равной степени поглощены расширением геополитической власти. Карибский бассейн служил ключевым географическим центром продвижения испанского империализма. Подобно стратегическому приоритету, который Испания отдавала достижению победы в завоеваниях Империи ацтеков и Империи инков , Испания уделяла равный стратегический акцент расширению имперского присутствия страны в Карибском бассейне.

Вторя преобладающим идеологическим взглядам на колониализм и империализм, которых придерживались европейские соперники Испании в колониальную эпоху, в том числе англичане, французы и голландцы, испанцы использовали колониализм как средство расширения имперских геополитических границ и обеспечения защиты морских торговых путей в Испании. Карибский бассейн.

Используя колониализм в том же географическом регионе, что и ее имперские соперники, Испания преследовала четкие имперские цели и установила уникальную форму колониализма в поддержку своей имперской программы. Испания уделяла значительное стратегическое внимание приобретению, добыче и экспорту драгоценных металлов (в первую очередь золота и серебра). Второй целью была евангелизация порабощенного коренного населения, проживающего в богатых полезными ископаемыми и стратегически выгодных местах. Яркими примерами этих групп коренных народов являются народы таино , населяющие Пуэрто-Рико и некоторые части Кубы. Принудительный труд и рабство были широко институционализированы на оккупированных Испанией территориях и колониях, с первоначальным упором на направление рабочей силы на горнодобывающую деятельность и связанные с ней методы добычи полудрагоценных металлов. Появление системы Энкомьенды в XVI–XVII веках в оккупированных колониях Карибского бассейна отражает постепенный сдвиг в имперских приоритетах, когда все больше внимания уделяется крупномасштабному производству и экспорту сельскохозяйственной продукции.

Научные дебаты и споры

[ редактировать ]Масштабы и масштабы участия Испании в империализме в Карибском бассейне остаются предметом научных дискуссий среди историков. Фундаментальный источник разногласий проистекает из непреднамеренного смешения теоретических концепций империализма и колониализма. Более того, существуют значительные различия в определениях и интерпретации этих терминов, изложенных историками, антропологами, философами и политологами.

Среди историков существует существенная поддержка подхода к империализму как концептуальной теории, возникшей в XVIII–XIX веках, особенно в Великобритании, пропагандируемой такими ключевыми сторонниками, как Джозеф Чемберлен и Бенджамин Дизраэли . В соответствии с этой теоретической точкой зрения, деятельность испанцев в Карибском бассейне не является компонентом выдающейся, идеологически мотивированной формы империализма. Скорее, эту деятельность точнее классифицировать как форму колониализма.

Дальнейшие расхождения среди историков можно объяснить различными теоретическими взглядами на империализм, предлагаемыми новыми академическими школами. Примечательными примерами являются культурный империализм , сторонники которого, такие как Джон Даунинг и Аннабель Среберни-Модаммади, определяют империализм как «...завоевание и контроль над одной страной более могущественной страной». [144] Культурный империализм означает масштабы процесса, выходящие за рамки экономической эксплуатации или военной силы». Более того, колониализм понимается как «… форма империализма, при которой правительством колонии управляют непосредственно иностранцы». [145]

Несмотря на расходящиеся точки зрения и отсутствие одностороннего научного консенсуса среди историков относительно империализма, в контексте испанской экспансии в Карибском бассейне в колониальную эпоху империализм можно интерпретировать как всеобъемлющую идеологическую программу, которая увековечивается через институт колониализма. . В этом контексте колониализм функционирует как инструмент, предназначенный для достижения конкретных империалистических целей.

Швеция

[ редактировать ]См. также

[ редактировать ]- Историография Британской империи

- Международные отношения, 1648–1814 гг.

- Международные отношения (1814–1919)

- Международные отношения (1919–1939)

- Список империй

- Список крупнейших империй

- Меркантилизм

- Сила делает право

- Политическая история мира

- Постколониализм

- Право завоевания

- Борьба за Африку , конец 19 века.

- Анализ западноевропейского колониализма и колонизации

- Четырнадцать очков, особенно. V и XII в 1918 году

- «Империализм, высшая стадия капитализма» Книга Ленина , 1917 год.

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ С. Гертруда Миллин , Родос , Лондон: 1933, с. 138

- ^ «Империализм» . www.britanica.com . Проверено 20 марта 2023 г.

государственная политика, практика или пропаганда расширения власти и господства, особенно путем прямого территориального приобретения или получения политического и экономического контроля над другими территориями. Поскольку он всегда предполагает использование силы, будь то военной, экономической или какой-либо более тонкой формы, империализм часто считался морально предосудительным, и этот термин часто используется в международной пропаганде для осуждения и дискредитации внешней политики противника.

- ^ «империализм» . Проверено 22 февраля 2019 г.

... политика распространения правления или власти империи или нации на зарубежные страны или приобретения и удержания колоний и зависимых территорий...

- ^ Эшкрофт, Билл; Гриффитс, Гарет; Тиффин, Хелен; Эшкрофт, Билл (2007). Постколониальные исследования: ключевые понятия . Лондон: Рутледж. п. 111. ИСБН 978-0-203-93347-3 . ОСЛК 244320058 .

В самом общем смысле империализм относится к формированию империи и, как таковой, был аспектом всех периодов истории, в которых одна нация распространяла свое господство над одной или несколькими соседними нациями.

- ^ «Империализм | Определение, история, примеры и факты | Британика» . Britannica.com . 4 июля 2023 г. Проверено 25 августа 2023 г.

- ^ «Чарльтон Т. Льюис, Элементарный латинский словарь, imperium (inp-)» . Проверено 11 сентября 2016 г.

- ^ Хоу, 13 лет

- ^ Магнуссон, Ларс (1991). Теории империализма (на шведском языке). Ход времени стр. 19. ISBN 978-91-550-3830-4 .

- ^ Штайнмец, Джордж (2014). «Империи, имперские государства и колониальные общества», Краткая энциклопедия сравнительной социологии , изд. Сасаки, Масамичи, (Лейден и Бостон: Брилл), стр. 59, http://www-personal.umich.edu/~geostein/docs/Steinmetz%202014%20Empires%20imperial%20states%20and%20colonies.pdf

- ^ Кумар, Кришан (2017). Видения империи: как пять имперских режимов сформировали мир (Нью-Джерси: Princeton University Press), стр. 16, EISBN 978-1-4008-8491-9 https://assets.press.princeton.edu/chapters/s10967. PDF

- ^ Сасаки 2014, стр. 59.

- ^ Кнорр, Клаус (1952). Шумпетер, Йозеф А.; Арендт, Ханна (ред.). «Теории империализма» . Мировая политика . 4 (3): 402–431. дои : 10.2307/2009130 . ISSN 0043-8871 . JSTOR 2009130 . S2CID 145320143 .

- ^ Эдвард В. Саид. Культура и империализм. Винтажные издательства, 1994. с. 9.

- ^ Клапп, CH (1912). «Южный остров Ванкувер». Канада. Геологическая служба. Мемуарно. 13. Оттава. дои : 10.4095/100487 . hdl : 2027/nyp.33433090753066 .

{{cite journal}}: Для цитирования журнала требуется|journal=( помощь ) - ^ Янг, Роберт (2015). Империя, колония, постколония . Джон Уайли и сыновья. п. 54. ИСБН 978-1-4051-9355-9 . OCLC 907133189 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Гилмартин, Мэри (2009). «Колониализм/Империализм» . В Галлахере, Кэролайн; Дальман, Карл; Гилмартин, Мэри; Маунтц, Элисон; Ширлоу, Питер (ред.). Ключевые понятия политической географии . стр. 115–123. дои : 10.4135/9781446279496.n13 . ISBN 9781412946728 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я Художник, Джо; Джеффри, Алекс (2009). Политическая география (2-е изд.). ISBN 978-1-4462-4435-7 .

- ^ «Империализм: исследование – Интернет-библиотека свободы» .

- ^ «Джон Хейвуд, Атлас мировой истории (1997)» .

- ^ См. Стивена Хоу, изд., The New Imperial Histories Reader (2009) Онлайн-обзор .

- ^ Р.Э. Робинсон и Джон Галлахер, Африка и викторианцы: официальное мнение империализма (1966).

- ^ Вм. Роджер Луи, Империализм (1976), с. 4.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Хейл, Орон Дж. (1971). Великая иллюзия: 1900–14 . Харпер и Роу.

- ^ Лишение собственности и развитие: очерки для Утса Патнаик . Утса Патнаик, Ариндам Банерджи, К. П. Чандрасекхар (ред.) (1-е изд.). Нью-Йорк, штат Нью-Йорк: Издательство Колумбийского университета. 2018. ISBN 9788193732915 .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: другие ( ссылка ) - ^ Кристофер, Эй Джей (1985). «Схемы британских зарубежных инвестиций в землю». Труды Института британских географов . Новая серия. 10 (4): 452–66. дои : 10.2307/621891 . JSTOR 621891 .

- ^ Джо Пейнтер (1995). Политика, география и политическая география: критическая перспектива . Э. Арнольд. п. 114 . ISBN 978-0-470-23544-7 .

- ^ Д.К. Филдхаус, «Империализм: историографический пересмотр». Обзор экономической истории , 14 № 2, 1961 г., стр. 187–209 онлайн.

- ^ Дэвид Харви, Пространства глобального капитализма: теория неравномерного географического развития (Verso, 2006), с. 91

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Адас, Майкл; Стернс, Питер Н. (2008). Турбулентный проход. Глобальная история двадцатого века (4-е изд.). Пирсон/Лонгман. стр. 54–58. ISBN 978-0-205-64571-8 .

- ^ «Хорошо начатое дело — наполовину сделано» . Убедительные карты: коллекция PJ Mode . Корнелльский университет.

- ^ Каин, Пи Джей (2007). «Капитализм, аристократия и империя: пересмотр некоторых «классических» теорий империализма». Журнал истории Империи и Содружества . 35 : 25–47. дои : 10.1080/03086530601143388 . S2CID 159660602 .

- ^ Питлинг, ГК (2004). «Глобализм, гегемонизм и британская власть: новый взгляд на Дж. А. Хобсона и Альфреда Циммерна». История . 89 (295): 381–398. дои : 10.1111/j.1468-229X.2004.00305.x .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Филдхаус, Дания (1961). « « Империализм »: историографический пересмотр». Обзор экономической истории . 14 (2): 187–209. дои : 10.1111/j.1468-0289.1961.tb00045.x . JSTOR 2593218 .

- ^ Моммзен, Вольфганг (1982). Теории империализма (тр. Фалья, PS Chicago: University of Chicago Press), стр. 72, https://archive.org/details/theoriesofimperi0000momm/page/72/mode/2up?view=theater

- ^ Моммзен, Вольфганг (1982). Теории империализма (тр. Фалья, PS Chicago: University of Chicago Press), стр. 79, https://archive.org/details/theoriesofimperi0000momm/page/78/mode/2up?view=theater

- ^ Тони Брюэр, Марксистские теории империализма: критический обзор (2002)

- ^ Праудман, Марк Ф. (2008). «Слова для ученых: семантика «империализма» ». Журнал Исторического общества . 8 (3): 395–433. дои : 10.1111/j.1540-5923.2008.00252.x .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уолтер., Родни (1972). Как Европа недоразвита Африку . Издательство Говардского университета. ISBN 978-0-9501546-4-0 . OCLC 589558 .

- ^ Алан Маршалл (февраль 1995 г.). «Развитие и империализм в космосе» . Космическая политика . 11 (1): 41–52. Бибкод : 1995СпПол..11...41М . дои : 10.1016/0265-9646(95)93233-Б . Проверено 28 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Хаббард П. и Китчин Р. Ред. Ключевые мыслители о пространстве и месте , 2-е место. Эд. Лос-Анджелес, Калифорния: Публикации Sage. 2010. с. 239.

- ^ Шарп, Дж. (2008). География постколониализма. Лос-Анджелес: Лондон: Sage Publications. стр. 16, 17.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сказал, Эдвард. «Творческая география и ее представления: ориентализация Востока», Ориентализм . Нью-Йорк: Винтаж. п. 357.

- ^ Шарп, Дж. География постколониализма . Лос-Анджелес: Лондон: Sage Publications. 2008. с. 22.

- ^ Шарп, Дж. (2008). География постколониализма. Лос-Анджелес: Лондон: Sage Publications. п. 18.

- ^ Саид, Эдвард. (1979) «Творческая география и ее представления: ориентализация Востока», Ориентализм . Нью-Йорк: Винтаж. п. 361

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Харли, Джей Би (1989). «Деконструкция карты» (PDF) . Cartographica: Международный журнал географической информации и геовизуализации . 26 (2): 1–20. дои : 10.3138/E635-7827-1757-9T53 . S2CID 145766679 . п. 2

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Бассетт, Томас Дж. (1994). «Картография и строительство империи в Западной Африке девятнадцатого века». Географическое обозрение . 84 (3): 316–335. Бибкод : 1994GeoRv..84..316B . дои : 10.2307/215456 . JSTOR 215456 . S2CID 161167051 . п. 316

- ^ «Империализм». Международная энциклопедия социальных наук , 2-е издание.