Максимилиен Робеспирре

Максимилиен Робеспирре | |

|---|---|

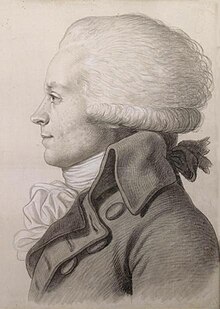

в 1790 , Музей Карнавалета | |

| Член комитета общественной безопасности | |

| В офисе 27 июля 1793 г. - 27 июля 1794 г. | |

| Предшествует | Томас-аугустин де гаспарин |

| Преуспевает | Жак Николас Билд-Варенн |

| В офисе 25 марта 1793 - 3 апреля 1793 г. Член комитета общей обороны | |

| 24 -й президент Национального съезда | |

| В офисе 4 июня 1794 - 19 июня 1794 г. | |

| Предшествует | Клод-Антуан Приер-Дуерноа |

| Преуспевает | Эли Лакост |

| В офисе 22 августа 1793 - 7 сентября 1793 г. | |

| Предшествует | Мари-Жан швыряет Софисес |

| Преуспевает | Жак-Николас Билд-Варенн |

| Заместитель Национального конвенции | |

| В офисе 20 сентября 1792 - 27 июля 1794 г. | |

| Избирательный округ | Париж |

| Заместитель Национального собрания | |

| В офисе 9 июля 1789 - 30 сентября 1791 года | |

| Избирательный округ | Артуа |

| Заместитель Национального собрания | |

| В офисе 17 июня 1789 - 9 июля 1789 г. | |

| Избирательный округ | Артуа |

| Заместитель общего Для третьего поместья | |

| В офисе 6 мая 1789 - 16 июня 1789 г. | |

| Избирательный округ | Артуа |

| Президент Jacobin Club | |

| В офисе 31 марта - 3 июня 1790 года | |

| В офисе 7 августа - 28 августа 1793 г. | |

| Личные данные | |

| Рожденный | Максимилиен Франсуа Мари Исидор де Робеспирре 6 мая 1758 г. Arras , Artois, королевство Франция |

| Умер | 10 Thermidor, год II 28 июля 1794 года (в возрасте 36 лет) Place de la révolution , Paris, France |

| Причина смерти | Исполнение гильотином |

| Политическая партия | Гора (1792–1794) |

| Другие политические принадлежность | Jacobin Club (1789–1794) |

| Альма -матер | Парижский университет |

| Профессия |

|

| Подпись | |

| Часть политической серии |

| Республиканство |

|---|

|

|

| Часть серии на |

| Радикализм |

|---|

| Часть серии на |

| Либерализм |

|---|

|

Максимилиен Франсуа Мари Исидор де Робеспирре ( Французский: [maksimiljɛ̃ ʁɔbɛspjɛʁ] ; 6 мая 1758 - 10 Термидор, год II 28 июля 1794 года) был французским адвокатом и государственным деятелем, который широко признан одной из самых влиятельных и противоречивых фигур французской революции . Робеспирре горячо проводил кампанию за права голоса всех людей и их беспрепятственное поступление в Национальную гвардию . [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] Кроме того, он выступал за право на ходатайство , право нести оружие в самообороне и отмену атлантической работорговли . [ 4 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ] Он был радикальным лидером якобина , который стал известен в качестве члена Комитета общественной безопасности , административного органа Первой Французской Республики . Его наследие оказало большое влияние на его фактическое или воспринимаемое участие в репрессиях противников революции, но на то время известно своим прогрессивным взглядам.

Будучи одним из выдающихся членов Парижской коммуны , Робеспьер был избран в качестве заместителя на Национальной конвенции в начале сентября 1792 года. Он присоединился к радикальным Монтагнардсам , левой фракции . Тем не менее, он столкнулся с критикой за то, что якобы пытался создать либо триумвират , либо диктатуру . [ 7 ] В апреле 1793 года Робесперре выступил с мобилизацией армии Санс-Кулот , стремящейся обеспечить соблюдение революционных законов и устранение любых контрреволюционных элементов. Этот звонок привел к вооруженному восстанию 31 мая - 2 июня 1793 года . 27 июля он был назначен членом комитета общественной безопасности .

Робеспирре столкнулся с растущим разочарованием среди прочего, отчасти из-за политически мотивированного насилия, выступающего за Монтагнардами . Все чаще члены Конвенции повернулись против него, и обвинения накапливались на 9 термидоре . Робеспирре был арестован и доставлен в тюрьму. Приблизительно 90 человек, в том числе Робеспирре, были выполнены без испытаний в последующие дни, отмечая начало термидорской реакции . [ 8 ]

Фигура, глубоко разногласия в течение его жизни, взгляды и политику Робеспьера продолжают вызывать противоречие. [ 9 ] [ 10 ] [ 11 ] Академический и популярный дискурс настойчиво участвуют в дебатах, связанных с его наследием и репутацией. [ 12 ] [ 13 ] [ 14 ]

Ранний период жизни

[ редактировать ]

Максимилиен де Робеспирре был крещен 6 мая 1758 года в Аррасе , Артуа . [ А ] Его отец, Франсуа Максимилиен Бартелеми де Робеспирре, адвокат, женился на Жаклин Маргарите Карраул, дочери пивовара, в январе 1758 года. Максимилиен, старший из четырех детей, родился четыре месяца спустя. Его братьями и сестрами были Шарлотта Робеспирре , [ B ] Генриетта Робеспирре, [ C ] и Августин Робеспирре . [ 18 ] [ 19 ] Мать Робеспирре умерла 16 июля 1764 года, [ 20 ] После доставки мертворожденного сына в 29 лет. Смерть его матери, благодаря мемуарам Шарлотты, которые, как полагают, оказали серьезное влияние на молодого Робеспьера. Около 1767 года по неизвестным причинам его отец оставил детей. [ D ] Две его дочери были воспитаны их отцовской (девичьей) тетями и двумя его сыновьями их бабушкой и дедушкой по материнской линии. [ 21 ]

Демонстрируя грамотность в раннем возрасте, Максимилиен начал свое образование в Коллеге Арра , когда ему было всего восемь. [ 22 ] В октябре 1769 года, рекомендованный епископом Луи-Хилером де Конзи , он получил стипендию в престижном коллеге Луис-ле-группе в Париже. Среди его сверстников были Камилла Десмулинс и Станислас Фрерон . Во время обучения он получил глубокое восхищение Римской Республикой и риторическими навыками Цицерона , Катона и Люциуса Юрия Брута . В 1776 году он получил первый приз за риторику .

Его признательность за классику вдохновила его стремиться к римским добродетелям, особенно воплощению Руссо . гражданского солдата [ 23 ] [ 24 ] Робеспирре был привлечен к концепциям влиятельной философы относительно политических реформ, изложенных в его работе, противоречивая социальным . Связываясь с Руссо, он считал общую волю народа основой политической легитимности . [ 25 ] Видение Робеспьера революционной добродетели и его стратегии создания политической власти через прямую демократию можно проследить до идеологий Монтескье и Мабли . [ 26 ] [ E ] В то время как некоторые утверждают, что Robespierre по совпадению встретился с Руссо до кончины последнего, другие утверждают, что этот рассказ был апокрифическим . [ 30 ] [ 31 ] [ 32 ]

Ранняя политика

[ редактировать ]

Во время своего трехлетнего изучения права в Сорбонне Робеспьер отличился академически, кульминацией которого стал выпускной в июле 1780 года, где он получил специальный приз из 600 ливров за свои исключительные академические достижения и образцовое поведение. [ 33 ] Принятый в коллегию адвокатов , он был назначен одним из пяти судей в местном уголовном суде в марте 1782 года. Однако Робеспьер вскоре подал в отставку из -за его этического дискомфорта по рассмотрению дел о капитале, вытекающих из его противодействия смертной казни .

Robespierre was elected to the literary Academy of Arras in November 1783.[ 34 ] В следующем году Академия Мец удостоила его медали за его эссе, размышляющее об коллективном наказании , таким образом, установив его как литературную фигуру . [ 35 ] (Pierre Louis de Lacretelle and Robespierre shared the prize.)

В 1786 году Робеспирре страстно рассмотрел неравенство до закона , критикуя унижения, с которыми сталкиваются незаконные или естественные дети , а затем осуждая практики, такие как Lettres de Cachet (тюремное заключение без судебного разбирательства) и маргинализация женщин в академических кругах. [ 36 ] Общий круг Робеспьера расширился, чтобы включить влиятельные фигуры, такие как адвокат Марман Герман , офицер и инженер Лазаре Карно и учитель Джозеф Фуше , все они будут иметь значение в его более поздних начинаниях. [ 37 ] His role as the secretary of the Academy of Arras connected him with François-Noël Babeuf, a revolutionary land surveyor in the region.

В августе 1788 года король Людовик XVI объявил о новых выборах для всех провинций и вызвал Генерал поместья в совокупности 1 мая 1789 года, направленную на решение проблемы финансовых и налоговых и налоговых проблем Франции. Участвуя в дискуссиях по выбору французского правительства провинции, Робеспьер выступал в своем обращении к стране Артуа , который возвращается к прежнему способу выборов членами провинциальных поместья, не сможет адекватно представлять народ Франции в новом поместье -Общий . В своем избирательном районе Робеспьер начал отстаивать свое влияние в политике благодаря своему уведомлению жителей сельской местности в 1789 году, нацеливаясь на местные власти и оказывая поддержку сельским избирателям. [ f ] This move solidified his position among the country's electors. On 26 April 1789, Robespierre secured his place as one of 16 deputies representing French Flanders in the Estates-General.[ 39 ] [ G ]

6 июня Робеспьер произнес свою первую речь, нацеленную на иерархическую структуру церкви. [ 40 ] [ 41 ] Его страстное ораторское искусство побудило наблюдателей прокомментировать: «Этот молодой человек еще не является неопытным; не подозревая, когда прекратить, но обладает красноречием, которое отличает его от остальных». [ 42 ] К 13 июня Робеспьер присоединился к депутатам, которые позже объявили о себе Национальным собранием , утверждая представительство для 96% нации. [ 43 ] On 9 July, the Assembly relocated to Paris and began deliberating a new constitution and taxation system. On 13 July, the National Assembly proposed reinstating the "bourgeois militia" in Paris to quell the unrest.[ 44 ] [ 45 ] На следующий день население потребовало оружие и штурмовал как остр, так и в Бастилии . Местная милиция перешла в Национальную гвардию , [ 46 ] шаг, который дистанцировал наиболее бедных граждан от активного участия. [ 47 ] Во время обсуждений и ссоры с Лалли-Толлендалом , который выступал за право и порядок , Робеспьер напомнил гражданам об их «недавней защите свободы», которая парадоксально ограничила их доступ к нему. [ 48 ] [ 49 ] [ 50 ]

In October, alongside Louvet, Robespierre supported Maillard following the Women's March on Versailles.[ 51 ] Первоначально группа женских протестующих передала относительно примирительное послание, однако их ряды вскоре были подкреплены более военизированными и опытными мужскими фракциями при достижении Версаля. [ 52 ] В то время как Учредительное Ассамблея рассмотрело избирательное право переписи мужчин 22 октября, Робеспьер и несколько избранных депутатов выступили против предварительных условий для голосования и удержания. [ 53 ] Through December and January Robespierre notably drew attention from marginalized groups, particularly Protestants, Jews,[ 54 ] individuals of African descent, domestic servants, and actors.[ 55 ] [ 56 ]

Как частый оратор в Ассамблее, Робеспьер отстаивал идеалы, инкапсулированные в Декларации прав человека и гражданина (1789) и выступал за конституционные положения, изложенные в Конституции 1791 года . Однако, по словам Малкольма Крука , его взгляды редко получали поддержку большинства среди других депутатов. [ 35 ] [ 57 ] Несмотря на его приверженность демократическим принципам, Робеспьер настойчиво надел культуру и сохранил тщательно ухоженную внешность с порошкообразными, свернутыми и ароматными волосами. [ 58 ] [ 59 ] Some accounts described him as "nervous, timid, and suspicious".[ 60 ] [ 61 ] Мадам де Стаэль изобразила Робеспирре как кого -то «очень преувеличенного в его демократических принципах» и «сохранила самые абсурдные предложения с прохладой, которая имела вид убеждения». [ 62 ] В октябре он взял на себя роль судьи в Версальском трибунале.

Якобин клуб

[ редактировать ]1789–1790

[ редактировать ]

После 5 октября Женский марш на Версале и насильственное перемещение короля и национального собрания из Версаля в Париж, Робеспьер жил в 30 Rue de Saintonge в Ле -Мараисе , округе с относительно богатыми жителями. [ 64 ] Он разделил квартиру на третьем этаже с Пьером Виллиерс , который был его секретарем в течение нескольких месяцев. [ 65 ] Робеспирре связан с новым обществом друзей Конституции , широко известного как Jacobin Club. Первоначально эта организация ( клуб Бретон ) состояла только заместителями из Бриттани, но после того, как Национальное собрание переехало в Париж, группа признала не депутаты. Среди этих 1200 человек Робесперре нашел сочувствующую аудиторию. Равенство перед законом было ключевым камнем идеологии якобин. Начиная с октября и продолжая до января, он выступил с несколькими выступлениями в ответ на предложения о квалификации имущества для голосования и владения офисом в соответствии с предлагаемой конституцией. Это была позиция, которую он энергично выступал, выступив в речи 22 октября. Положение, которое он получил от Руссо :

"Суверенитет находится у людей, во всех людях народа. Поэтому каждый человек имеет право участвовать в принятии закона, который его управляет и в управлении общественным блага, что является его собственным. Если нет, это не правда что все люди равны по правам, что каждый человек является гражданином. [ 66 ] "

Во время продолжающихся дебатов о избирательном праве Робесперр закончил свою речь от 25 января 1790 года с тупым утверждением о том, что «все французы должны быть допустимы на все публичные должности без каких -либо других различий, чем у добродетелей и талантов». [ 67 ] 31 марта 1790 года Робеспирре был избран их президентом. [ 68 ] 28 апреля Робеспьер предложил разрешить равное число офицеров и солдат в военном суде . [ 69 ] Робеспирре поддержал сотрудничество всех национальных охранников в общей федерации 11 мая. [ 70 ] 19 июня он был избран секретарем Национального собрания. В июле Робеспирре потребовал «братского равенства» в зарплатах. [ 71 ] До конца года его считали одним из лидеров маленького тела крайнего левого. Робеспирре был одним из «тридцати голосов». [ 72 ]

5 декабря Робеспирре произнес речь по срочной теме Национальной гвардии. [ 73 ] [ 74 ] [ 75 ] «Быть вооруженным для личной защиты - это право каждого человека, чтобы быть вооруженным для защиты свободы, а существование общего отца - это право каждого гражданина». [ 76 ] Робеспирре придумал знаменитый девиз " Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité ", добавив слово братство на флагах Национальной гвардии. [ H ] [ 78 ] [ 79 ]

1791

[ редактировать ]

В 1791 году Робесперр произнес 328 речей, почти по одному в день. 28 января Робесперре обсудила на Ассамблее Организация Национальной гвардии , [ 80 ] В течение трех лет горячая тема во французских газетах. [ 81 ] В начале марта провинциальные ополченцы были отменены, а парижская департамент была размещена над коммуной во всех вопросах общего порядка и безопасности. 27 и 28 апреля Робесперре выступил против планов реорганизовать Национальную гвардию и ограничить ее членство активными гражданами , что считалось слишком аристократическим. [ 82 ] [ 83 ] Он потребовал восстановления Национальной гвардии на демократической основе, отменить использование украшений и разрешить равное число офицеров и солдат в военном суде . [ 84 ] Он чувствовал, что Национальная гвардия должна стать инструментом защиты свободы и больше не представляет угрозы. [ 85 ] В том же месяце Робеспьер опубликовал брошюру, в которой он утверждал, что дело об универсальном избирательном праве мужественности . [ 86 ]

15 мая Учредительное собрание объявило полное и равное гражданство для всех цветных людей . В дебатах Робеспьер сказал: «Я чувствую, что я здесь, чтобы защитить права людей; я не могу согласиться на какую -либо поправку и прошу, чтобы этот принцип был принят полностью». Он спустился из рострумы в середине повторяющихся аплодисментов левого и всех трибунов. [ 87 ] 16–18 мая, когда начались выборы, Робесперре предложил и принес предложение, что ни один заместитель, который сидел в Учредительном собрании, не мог сидеть в последующем законодательном собрании . [ 88 ] Тактическая цель этого самооплачивающего постановления состояла в том, чтобы заблокировать амбиции старых лидеров Якобинса, Антуан Барнаве , Адриена Дюпорта и Александра де Ламета , [ 89 ] стремление создать конституционную монархию, примерно похожие на моназок Англии. [ 90 ] [ я ] 28 мая Робеспьер предложил всем французам, которые должны быть объявлены активными гражданами и имеют право на голосование. [ 86 ] 30 мая он произнес речь о том, как отменить смертную казнь без успеха. [ 92 ] На следующий день Робеспьер напал на Аббе Рэйнана , который отправил адрес, критикующий работу Ассамблеи и требуя восстановления королевской прерогативы .

10 июня Робеспьер выступил с речью о штате полиции и предложил уволить офицеров. [ 85 ] 11 июня 1791 года он был избран или назначен в качестве (заменителя) обвинителя. Робеспирре принял функцию « общественного обвинителя » в преступном трибунале, подготовленном обвинениями и обеспечивая защиту. [ 93 ] [ J ] Два дня спустя L'Ami Du Roi , роялистская брошюра, назвал Робеспьере «адвокатом для бандитов, мятежников и убийц». [ 73 ] 15 июня Pétion de Villeneuve стал президентом «Friminel Criminel Criminel» после того, как Дюпорт отказался работать с Робеспирре. [ 96 ] [ 97 ]

Людовика XVI После неудачного перелета в Варенс , Ассамблея отстранила короля от своих обязанностей 25 июня. С 13 по 15 июля Ассамблея обсудила восстановление короля и его конституционные права. [ 98 ] Робеспирре объявил в клубе Jacobin 13 июля: «Нынешняя французская конституция - это республика с монархом. [ 99 ] Поэтому она не монархия, ни республика. Она оба ". [ 100 ]

17 июля Бейли и Лафайет объявили запрет на сборование, за которым следует военное положение . [ 101 ] [ 102 ] После резни Чемпиона де Марса власти заказали многочисленные аресты. Робеспирре, который посещал клуб Якобин, не вернулся на Рю Сейнтонге, где он поселился, и спросил Лорана Лекоинтре , знает ли он патриота возле Туильри, который мог бы поставить его на ночь. Лекоинтр предложил дом Душпы и отвез его туда. [ 103 ] Морис Дюшлей , кабинета директоров и горячий поклонник, жил на 398 Rue Saint-Honoré возле Tuileries . Через несколько дней Робеспирре решил переехать навсегда. [ 104 ]

Мадам Роланд назвала Петио де Вильневе, Франсуа Бузот и Робеспьера в качестве трех неподкупных патриотов в попытке почтить их чистоту принципов, их скромные способы жизни и их отказ от взяток. [ 105 ] Его стойкое соблюдение и защита взглядов, которые он выразил, принесли ему прозвище . [ 106 ] [ 107 ] [ k ] По словам его друга, хирург Джозеф Соубербиель , Иоахим Вилат , [ Цитация необходима ] и дочь DuPlay Элисабет, Робеспьер общалась с старшей дочерью DuPlay Eléonore , но его сестра Шарлотта энергично отрицала это; Его брат Августин отказался жениться на ней. [ 108 ] [ 109 ] [ 110 ] [ 111 ] [ нужно разъяснения ]

3 сентября французская конституция 1791 года была принята, десять дней спустя королем. [ 112 ] 30 сентября, в день роспуска Ассамблеи, Робеспьер выступил против Жана Ле Часовня , который хотел провозглашать прекращение революции и ограничить свободу выражения мнений . [ 113 ] [ L ] Ему удалось получить какое -либо требование для проверки из гарантии конституции свободы выражения мнений: «Свобода каждого человека говорить, писать, печатать и публиковать свои мысли, без сочинений не приходится подвергаться цензуре или проверке до их публикация ... " [ 114 ] Пеция и Робеспер были возвращены в триумф в свои дома. [ м ] 16 октября Робеспьер выступил с речью в Аррасе; Через неделю в Бешенун , маленький город, который он хотел поселиться. Он отправился на собрание Общества друзей Конституции , которое проходило по воскресеньям. 28 ноября он вернулся в клуб Якобин, где встретился с триумфальным приемом. Коллот Д'Арбоис отдал свой стул Робеспирре, который председательствовал в тот вечер. 5 декабря он выступил с речью об организации Гарде Национального , которое он считал уникальным учреждением, родившимся от идеалов Французской революции. [ 115 ] 11 декабря Робесперре был наконец установлен как « Accucusatur Public ». [ 116 ] В январе 1791 года Робеспирре продвигал эту идею не только Национальной гвардии, но и людей, которые должны были быть вооружены. [ 117 ] [ 118 ] Якобинс решил, что его речь не будет напечатана. [ 119 ]

Оппозиция войне с Австрией

[ редактировать ]

Декларация Пиллниц (27 августа 1791 года) из Австрии и Пруссии предупредила народа Франции не причинять вреда Луи XVI, или эти нации «вмешались в военном отношении». Brissot сплотил поддержку Законодательного собрания. Как Жан-Поль Марат , Жорж Дантон и Робеспьер не были избраны в новом законодательном органе благодаря постановлению самоотрески, оппозиционная политика часто происходила за собранием. 18 декабря 1791 года Робеспирре выступил в якобинском клубе против Декларации войны. [ 121 ] Робеспирре предупредил от угрозы диктатуры, вытекающей из войны:

Если это кесары , каталины или Cromwells , они захватывают силу для себя. Если они являются безразличными придворными, не заинтересованы в том, чтобы делать добро, но опасно, когда они стремятся нанести вред, они возвращаются, чтобы положить свою власть за ноги своего хозяина и помогают ему возобновить произвольную власть при условии, что они становятся его главными слугами. [ 122 ]

В конце декабря, Гуадет председатель Ассамблеи, предположил, что война будет выгодой для нации и повысит экономику. Он призвал Францию объявить войну против Австрии . Марат и Робеспир против него выступили против, утверждая, что победа создаст диктатуру, в то время как поражение восстановит короля его бывшим способностям. [ 123 ]

Самая экстравагантная идея, которая может возникнуть в главе политика, состоит в том, чтобы поверить, что людям достаточно вторгаться в чужую страну, чтобы заставить ее принять свои законы и их конституцию. Никто не любит вооруженных миссионеров ... Декларация прав человека ... не является молниеносным болтом, который одновременно поражает каждый трон ... Я далеко не утверждаю, что наша революция в конечном итоге не повлияет на судьбу Мир ... но я говорю, что это не будет сегодня (2 января 1792 года). [ 124 ]

Эта оппозиция со стороны ожидаемых союзников раздражала Жирондин, и война стала главной точкой спора между фракциями. В своей третьей выступлении на войне Робеспьер возразил 25 января 1792 года в клубе Якобин, «Война революционной войны должна вестись со свободными предметами и рабами от несправедливой тирании, а не по традиционным причинам защиты династий и расширяющихся границ ...» Робеспьер утверждал, что такая война может способствовать только силу контрреволюции, поскольку она будет играть в руки тех, кто выступал против суверенитета народа . Риски цезаризма были ясны: «В проблемных периодах истории генералы часто стали арбитрами судьбы их стран». [ 125 ] Робеспирре уже знал, что он проиграл, так как не смог собрать большинство. Его речь, тем не менее, была опубликована и отправлена во все клубы и якобинские общества Франции. [ 126 ]

10 февраля 1792 года Робеспьер произнес речь о том, как спасти государство и свободу и не использовал слово «война». Он начал с того, что уверял свою аудиторию, что все, что он намеревался сделать, было строго конституционным. Затем он продолжал выступать за конкретные меры для укрепления, не столько национальную защиту, сколько силы, на которые можно было бы опираться, чтобы защитить революцию. [ 127 ] Робеспирре продвигал народную армию, постоянно под оружием и способствовал навязывать свою волю на Feuillants и Girondins в конституционном кабинете Луи XVI и законодательного собрания. [ 128 ] Якобинс решил изучить свою речь, прежде чем решить, следует ли ее напечатать. [ 129 ] [ n ]

15 февраля Робеспьер не смог избрать в городской совет ( Conseil Général ); [ 131 ] В тот же день состоялась установка Суда по уголовным делам Департамента Парижа. [ 132 ] Для Робеспирре это была неблагодарная позиция как «общественного обвинителя»; Это означало, что его не разрешили в бар, прежде чем присяжные вынесли свой приговор . [ 133 ] Робесперре отвечал за координацию местной и федеральной полиции в департаменте и участках. [ 134 ]

26 марта Гуаде обвинил Робеспирре в суевериях, полагаясь на Божественное Провидение . [ 135 ] Вскоре после того, как Робеспер был обвинен Бриссо и Гуадетом в «пытаться стать идолом народа». [ 136 ] Будучи против войны, Робеспирре также был обвинен в том, что он выступал в качестве секретного агента для « Австрийского комитета ». [ 137 ] Гирондинс запланировал стратегии, чтобы превзойти влияние Робеспьере среди якобинов. [ 138 ] 27 апреля, в рамках своей речи, отвечающей на обвинения Бриссо и Гуадет против него, он угрожал покинуть якобинс, утверждая, что предпочел продолжить свою миссию в качестве обычного гражданина. [ 139 ]

17 мая Робеспьер опубликовал первый выпуск своей еженедельной периодической конституции Le Défenseur de la ( Защитник Конституции ). В этой публикации он раскритиковал Бриссо и выразил свой скептицизм по поводу военного движения. [ 140 ] [ 141 ] Период, напечатанный его соседом Николасом, служил нескольким целям: печатать свои речи, противостоять влиянию Королевского суда в государственной политике и защищать его от обвинений в лидерах Жиронда; [ 142 ] Для Альберта Собула ее целью было озвучить экономические и демократические интересы более широких масс в Париже и защитить их права. [ 143 ]

Мятежная коммуна Парижа, 1792

[ редактировать ]Апрель по июль 1792 года

[ редактировать ]

Когда законодательное собрание объявило войну против Австрии 20 апреля 1792 года, Робеспьер заявил, что французы должны вооружаться, будь то сражаться за границей или предотвратить деспотизм дома. [ 144 ] Изолированный Робеспьер ответил, работая над тем, чтобы уменьшить политическое влияние класса офицера и короля. 23 апреля Робеспьер потребовал того, что Маркиз де Лафайетт , глава армии центра , ушел вниз. Спорив о благополучии обычных солдат, Робеспьер призвал новые акции смягчить доминирование класса офицера аристократической и роялистской эколевой воинством и консервативной национальной гвардией. [ O ] Наряду с другими якобинами он призвал создать « армей -revolutionnaire » в Париже, состоящий не менее 20 000–23 000 человек, [ 146 ] [ 147 ] Чтобы защитить город, «Свобода» (революция), поддерживать порядок и обучать членов демократическим и республиканским принципам, идею, которую он одолжил у Жана-Жака Руссо . [ 148 ] [ 149 ] По словам Жана Джарса , он считал это еще более важным, чем право на удар . [ Цитация необходима ] [ 84 ]

29 мая 1792 года Ассамблея распустила конституционную гвардию , подозревая его роялистов и контрреволюционных симпатий. В начале июня 1792 года Робесперре предложил конец монархии и подчинение Ассамблеи в общую волю . [ 150 ] Монархия столкнулась с абортной демонстрацией 20 июня . [ 151 ] [ 152 ]

Поскольку французские силы потерпели катастрофические поражения и серию дефектов в начале войны, Робеспьер и Марат боялись возможности военного переворота . [ 153 ] Один из них возглавлял Лафайет, глава Национальной гвардии, которая в конце июня выступала за подавление клуба Якобин. Робеспирре публично напал на него в ужасных терминах:

"Генерал, в то время как в середине вашего лагеря вы объявили мне войну, которую вы до сих пор избавили от врагов нашего государства, в то время как вы осудили меня как врага свободы армии, национальной гвардии и нации в письмах, опубликованных Ваши купленные документы, я думал, что я только оспаривает общее ... но еще не диктатор Франции, арбитра государства ». [ 154 ]

2 июля Ассамблея уполномочила Национальную гвардию отправиться на фестиваль Федерации 14 июля, обходя королевское вето. 11 июля Якобинс выиграл чрезвычайное голосование в «Некаливающемся Ассамблее», объявив нацию в опасности и подготовив всех парижцев с помощью пик в Национальной гвардии. [ 155 ] 15 июля Биллауд-Варенн в Jacobin Club изложил программу для следующего восстания: депортация бурбонов и «врагов людей», очищение Национальной гвардии, выборы конвенции, «передача Королевский вето народу »и освобождение от самых бедных от налогообложения. 24 июля было сформировано «Центральное офис координации», и разделы получили право на «постоянную» сессию. [ 156 ] [ 157 ]

25 июля, согласно логографу , Карно продвигал использование пиков и предоставляется каждому гражданину. [ 158 ] 29 июля Робеспирре призвал к показанию короля и выборы конвенции. [ 159 ] [ 160 ] В конце июля Манифест Брансуика начал промегаться по Парижу. Это часто называли незаконным и оскорбительным для национального суверенитета . Авторство часто выступало под сомнение. [ 161 ]

Август 1792

[ редактировать ]

1 августа Ассамблея проголосовала за предложение Карно, обеспечивая распространение пик для всех граждан, за исключением бродяги. [ 162 ] [ 163 ] [ 164 ] К 3 августа мэр и 47 секций требовали удаления короля. 5 августа Робеспирре раскрыл открытие плана, чтобы король сбежал в Шато де Гайлон . [ 165 ] Связываясь с позицией Робеспьера, почти все разделы в Париже сплотились за свержение короля и выпустили решающий ультиматум. [ 166 ] Бриссо призвал сохранение Конституции, выступая против свержения короля и выборов нового собрания. [ 167 ] 7 августа Pétion предложил помочь Robespierre в содействии отъезду Fédérés, чтобы успокоить столицу, предложив их более эффективную службу на передовой. [ 168 ] Одновременно Совет министров рекомендовал арестовать Дантона, Марата и Робеспьера, если они посещают клуб Якобин. [ 169 ]

9 августа комиссионные из нескольких секций собрались в ратуше. Примечательно отсутствовали Марат, Робеспьер и Талфиен. Распад муниципального совета города произошел в полночь. Сульпис-гугенин , видная фигура среди санс-кулоттов Сант -Антуина , была назначена предварительным президентом Сообщества восстания.

В ранние часы ( пятница, 10 августа ) 30 000 Fédérés (волонтеры, родом из сельской местности) и Sans-Culottes (воинствующие граждане из Парижа) организовали успешное нападение на Tuileries. [ 170 ] Робеспирре считал это триумфом для «пассивных» (не голосов) граждан. Ассамблея, охваченная событиями, приостановила короля и санкционировала выборы национальной конвенции, чтобы вытеснить свою власть. [ 171 ] Ночью 11 августа. Робеспирре занял должность в Парижской коммуне, представляя раздел де Пикес , его жилой район. [ 172 ] Управляющий комитет выступал за соблюдение конвенции, отобранного через универсальное избирательное право мужского пола , [ 173 ] поручено создать новое правительство и ограничить Францию. Несмотря на веру Камилле Десмулинс в том, что суматоха завершилась, Робесперре утверждала, что она отмечена лишь началом. К 13 августа Робеспирре открыто выступил против подкрепления департаментов . [ 174 ] Впоследствии Дантон пригласил его присоединиться к Совету юстиции. Робеспирре опубликовал двенадцатое и последнее издание конституции Le Défenseur de la , служа отчетом и политическим заветом. [ 175 ] [ 176 ]

16 августа Робеспьер подал ходатайство в Законодательное собрание, одобренное Парижской коммуной, призывающей создать предварительный революционный трибунал, специально предназначенный для работы с воспринимаемыми «предателями» и « врагами людей ». На следующий день он был назначен одним из восьми судей для этого трибунала. Однако, ссылаясь на отсутствие беспристрастности, Робесперре отказался председательствовать в этом. [ 177 ] [ P ] Это решение вызвало критику. [ 179 ] [ 180 ]

Прусская армия нарушила французскую границу 19 августа. Чтобы укрепить защиту, вооруженные участки Парижа были интегрированы в 48 батальонов Национальной гвардии под командованием Сантерре . Ассамблея постановила, что все священники, не относящиеся к приюту, должны покинуть Париж в течение недели и покинуть страну в течение двух недель. [ 181 ] 28 августа Ассамблея заказала комендантский час на следующие два дня. [ 182 ] Городские ворота были закрыты; Все общение со страной было остановлено. По поручению министра юстиции Дантон тридцать комиссарам из секций было приказано обыска в каждом подозреваемом доме для оружия, боеприпасов, мечей, вагонов и лошадей. [ 183 ] [ 184 ] «В результате этой инквизиции более 1000« подозреваемых »были добавлены к огромному объему политических заключенных, уже ограниченных в тюрьмах и монастырях города». [ 185 ] Марат и Робеспир оба не нравились Кондорсет , который предположил, что « враги народа » принадлежали всей нации и должны были судить конституционно по его имени. [ 186 ] 30 августа временный министр внутренних дел Роланд и Гуаде пытались подавить влияние коммуны, потому что разделы исчерпали обыски. Ассамблея, уставая от давления, объявила об коммуне незаконной и предложила организацию общинных выборов. [ 187 ]

Робеспирре больше не хотел сотрудничать с Бриссо и Роландом . В воскресенье утром 2 сентября члены коммуны, собравшиеся в ратуше, чтобы пройти выборы депутатов на национальный конгресс, решили сохранить свои места и арестовать Роланд и Бриссо. [ 188 ] [ 189 ]

Национальное собрание

[ редактировать ]Выборы

[ редактировать ]

2 сентября начались выборы Французских национальных конгрессов 1792 года . Париж организовал свою защиту, но он столкнулся с отсутствием оружия для тысяч добровольцев. Дантон произнес речь в Ассамблее и, возможно, ссылаясь на швейцарских заключенных: «Мы просим, чтобы любой, кто отказывается служить лично, или сдать свое оружие, наказан смертью». [ 190 ] [ 191 ] Его речь действовала как призыв к прямым действиям среди граждан, а также удар по внешнему врагу. [ 192 ] Вскоре начались сентябрьские убийства . [ 193 ] Робеспирре и Мануэль , государственный прокурор , ответственный за полицейскую администрацию, посетили тюрьму храмовой тюрьмы , чтобы проверить безопасность королевской семьи. [ 194 ]

В Париже подозреваемые кандидаты Джирондина и Роялистов были бойкотированы; [ 195 ] Робесперр внес свой вклад в неспособность Бриссо (и его коллеги по бриссотинам и кондорсе) быть избранным в Париже. [ 196 ] По словам Шарлотты Робеспирре , ее брат перестал разговаривать со своим бывшим другом, мэром Петом де Вильневе . Пеция была обвинена в заметном потреблении Desmoulins, [ 197 ] и, наконец, сплотился в Бриссо. [ 198 ] 5 сентября Робесперр был избран заместителем на Национальный конгресс, но Дантон и коллот Д'Арбоис получили больше голосов, чем Робеспьер. [ Q ] Мадам Роланд написала другу: «Мы под ножом Робеспьер и Марат, тех, кто будет возбуждать людей». [ 199 ] Выборы не были триумфом для Монтанд -Якобинс, которые они ожидали, но в течение следующих девяти месяцев они постепенно устраняли своих противников и получили контроль над конвенцией. [ 200 ]

21 сентября пети был избран президентом Конвенции. Монтандарные якобинс и корделиеры взяли высокие скамейки в задней части бывшего Salle du Manège , давая им этикетку Montagnards («Гора»); Под ними были « манежа » Жирондеров, умеренных республиканцев. Большинство, которую равнина была сформирована независимыми (как барер , Камбон и Карно ), но доминировала радикальной горой. [ 201 ] 25 и 26 сентября Барбару и Жиронст Ласурс обвинили Робеспьер в желании сформировать диктатуру. [ 202 ] Ходили слухи, что Робеспьер, Марат и Дантон замышляли создать триумвират , чтобы спасти Первую Французскую Республику , хотя нет никаких доказательств, подтверждающих это утверждение.

30 сентября Робесперре выступал за несколько законов; Регистрация браков, рождений и захоронения была отозвана из церкви. 29 октября Лувет де Куврай напал на Робеспьера. [ 203 ] Он обвинил его в управлении Парижом « Консель Жанрал » и в том, что он ничего не сделал, чтобы остановить сентябрьскую резню; Вместо этого, по его словам, он использовал его, чтобы выбрать больше монтандарков; [ 204 ] Предположительно, выплачивая сентябрьскими моделями за получение большего количества голосов. [ 205 ] Робеспирре, который был болен, получила неделю, чтобы ответить. 5 ноября Робеспьер защитил себя, Jacobin Club и своих сторонников:

На якобинах я тренируюсь, если мы хотим верить своим обвинителям, деспотизм мнения, который можно рассматривать как не что иное, как предшественник диктатуры. Во -первых, я не знаю, что такое диктатура мнения, прежде всего в обществе свободных людей ... если только это не описывает не что иное, как естественное принуждение принципов. Это принуждение вряд ли принадлежит человеку, который их излучает; Это принадлежит универсальной причине и всем людям, которые хотят слушать его голос. Это принадлежит моим коллегам из Учредительного собрания , патриотам Законодательного собрания, всем гражданам, которые неизменно будут защищать дело свободы. Опыт, несмотря на Людовик XVI и его союзников, доказало, что мнение «Якобинс» и «Популярные клубы» были мнениями французской нации; Ни один гражданин не сделал их, и я не сделал ничего, кроме того, чтобы разделить в них. [ 206 ]

Овернув обвинения на своих обвинителях, Робеспьер доставил одну из самых известных линий французской революции на Ассамблею:

Я не буду напоминать вам, что единственным объектом спора, разделяющего нас, состоит в том, что вы инстинктивно защищали все действия новых министров, и мы, принципов; Что вы, казалось, предпочитали власть, и мы равенство ... почему вы не преследовали в судебном порядке в коммуне , законодательном собрании, участках Парижа, собраниях кантонов и всех, кто нас подражал? Ибо все это было незаконным, столь же незаконным, как революция, как падение монархии и Бастилии , столь же незаконно, как и сама свобода ... граждане, вы хотите революцию без революции? Что это за дух преследования, который направил себя против тех, кто освободил нас от цепей? [ 207 ]

После того, как он опубликовал свою речь « Максимилиен Робеспирре и его роялисты (обвинение) », Лувет больше не был допущен в клуб Jacobin. [ 208 ] Кондорсет считал французскую революцию религией и считал, что у Робеспьера были все характеристики лидера секты , [ 209 ] [ 210 ] или культ . [ 211 ] [ r ] Как хорошо знали его противники, у Робеспирре была сильная база поддержки среди женщин Парижа, называемых трикотеатами (вязальщицы). [ 213 ] [ 214 ] По словам Мур, «он [Робеспирре] отказывается от офисов, в которых он может служить, берет тех, где он может управлять; появляется, когда он может сделать фигуру, исчезает, когда другие занимают сцену». [ 215 ]

Казнь Людовика XVI

[ редактировать ]

После единодушного заявления Конвенции Французской Республики 21 сентября 1792 года была создана комиссия для изучения доказательств против бывшего короля, в то время как комитет законодательства Конвенции рассмотрел юридические аспекты любого будущего судебного разбирательства. [ 216 ] 20 ноября мнение резко повернулось к Луи после обнаружения секретного кеша 726 документов, состоящих из связи Луи с банкирами и министрами. [ 217 ] По предложению Клода Базира , Дантониста, национальное собрание постановило, что осуществили Луи XVI . его члены [ 218 ] 28 декабря Робеспирре попросили повторить свою речь о судьбе короля в клубе Jacobin. 14 января 1793 года король был единогласно признан виновным в заговоре и нападениях на общественную безопасность. [ 219 ]

15 января призыв на референдум был побежден 424 голосами на 287, который возглавлял Робеспьер. 16 января голосование начало определять приговор короля; Робеспирре горячо работал, чтобы обеспечить казнь короля. Якобинс успешно победил окончательную апелляцию Джирондинс к помилованию. [ 220 ] 20 января половина депутатов проголосовала за немедленную смерть. На следующий день Людовик XVI был гильотизирован.

После исполнения короля, Робеспирре, Дантона и Монтагнардов под влиянием, затмевав Жирондинс . [ 221 ]

Март/апрель 1793 года

[ редактировать ]

24 февраля Конвенция постановила первую, хотя и безуспешную , леви , вызвав восстания в сельской Франции. Протестующие, поддерживаемые Enragés , обвинили Girondins в подстрекательстве к беспорядкам и растущим ценам. [ 221 ] В начале марта 1793 года началась война в Вендее и войне Пиренеев . Тем временем население австрийских Нидерландов , которые были терроризированы армией Санс-Кулоттов , сопротивлялись французскому вторжению . [ 222 ]

Вечером 9 марта толпа собралась за пределами съезда, выкрикивая угрозы и призывая к удалению всех «предательских» депутатов, которые не смогли проголосовать за казнь короля. 12 марта 1793 года предварительный революционный трибунал был создан ; Три дня спустя Конвенция назначила Фукье-Тинвилля в качестве обвиняемого общественности и Флеурио-Глес в качестве его помощника. Робеспирре не был восторженным и боялся, что он может стать политическим инструментом фракции. [ 223 ] Робеспирре полагал, что все учреждения плохие, если они не основаны на предположении, что люди хороши, а их магистраты развратимы. [ 224 ]

11 марта Чарльз Франсуа Дюмурье обратился к Ассамблее Брюссель, извинившись за действия французских комиссаров и солдат. [ 225 ] Дюмурье пообещал австрийцам, что французская армия покинет Бельгию к концу марта без разрешения конвенции. [ 226 ] Он призвал герцога Чартрес присоединиться к своему плану договориться о мире, распустить конвенцию, восстановить французскую конституцию 1791 года и конституционную монархию , а также освободить Мари-Антунетту и ее детей. [ 227 ] [ 228 ] Лидеры якобина были совершенно уверены, что Франция приблизилась к военному перевороту, установленному Дюмуризом и поддерживаемой Джирондинсом.

25 марта Робеспьер стал одним из 25 членов комитета общей обороны для координации военных действий. [ 229 ] Робеспьер призвал к удалению Думуриза, который, в его глазах, стремился стать бельгийским диктатором или начальником государственного происхождения, а Дюмурес был арестован. [ 230 ] Он потребовал, чтобы родственники короля покинули Францию, но Мария-Антунетта должна судить. [ 231 ] Он говорил о энергичных мерах по спасению конвенции, но покинул комитет в течение нескольких дней. Марат начал способствовать более радикальному подходу войны с Жиронннами. [ 232 ] Montagnards начал активную кампанию против Джирондинс после выхода генерала Дюмуриза, который отказался сдаться революционному трибуналу. [ 233 ] 3 апреля Робеспьер объявил перед конвенцией, что вся война была подготовленной игрой между Думурисом и Бриссо, чтобы свергнуть республику. [ 234 ]

6 апреля Комитет общественной безопасности был установлен по предложению Maximin Isnard , поддерживаемого Жоржом Дантоном. Комитет состоял из девяти заместителей из равнины и дантонистов, но нет Джиронндин или Робеспирристы. [ 235 ] Как один из первых актов комитета, Марат, президент Jacobin Club, призвал к изгнанию двадцати двух Жироннсов. [ 236 ] Робеспирре, который не был избран, был пессимистичным в отношении перспектив парламентских действий и сказал якобинам, что необходимо поднять армию Санс-Кулоттов для защиты Парижа и арестовать неклояльных депутатов. [ 237 ] По словам Робеспирре: людей и их врагов были только две партии: люди и их враги . [ 238 ] 10 апреля Робеспьер обвинил Дюмуриза в речи: «Он и его сторонники нанесли смертельный удар по публичному удаче, предотвращая циркуляцию назначения в Бельгии». [ 239 ] Речи Робеспьера в апреле 1793 года отражают растущую радикализацию. «Я прошу секции поднять армию, достаточно большую, чтобы сформировать ядро революционной армии, которая привлечет всех безлотков из департаментов, чтобы уничтожить повстанцев ...» [ 240 ] [ 241 ] Подозревая дальнейшую измену, Робеспьер пригласил Конвенцию проголосовать за смертную казнь против любого, кто предложит переговоры с врагом. [ 242 ] Марат был заключен в тюрьму, призывающую к военному трибуналу, а также отстранению от Конвенции. [ 243 ] 15 апреля люди снова были вторглись люди из секций, требуя удаления тех Жирондинс, которые защищали короля. До 17 апреля Конвенция обсуждала декларацию прав человека и гражданина 1793 года , политический документ, который предшествовал первой конституции республиканцев 1793 года . 18 апреля коммуна объявила о восстании против конвенции после ареста Марата. 19 апреля Робесперр выступил против статьи 7 о равенстве перед законом ; 22 апреля в конвенции обсуждались статья 29 о праве сопротивления . [ 244 ] 24 апреля Робеспьер представил свою версию с четырьмя статьями справа от собственности . [ s ] Он фактически ставил под сомнение индивидуальное право на владение, [ 247 ] и выступал за прогрессивный налог и братство между людьми всех наций. [ 240 ] Робесперр объявил себя против аграрного права.

Май 1793 года

[ редактировать ]1 мая 1793 года, по словам депутата Джирондина Жак-Антуина Дулаура , 8000 вооруженных мужчин окружили конвенцию и угрожали не уйти, если потребовали чрезвычайные меры (достойная зарплата и максимум на цены на продовольствие ) не были приняты. [ 248 ] [ 249 ] 4 мая Конвенция согласилась поддержать семьи солдат и моряков, которые покинули свой дом, чтобы сражаться с врагом. Робеспирре настаивал вперед со своей стратегией классовой войны. [ 250 ] 8 и 12 мая в клубе Якобин Робеспьер подтвердил необходимость основания революционной армии, которая будет искать зерно, будет финансироваться за счет налогов на богатых, и будет предназначена для победы над аристократами и контрреволюционерами. Он сказал, что общественные квадраты должны использоваться для производства оружия и пиков. [ 251 ] В середине мая Марат и коммуна поддерживали его публично и тайно. [ 252 ] Конвенция решила организовать комиссию по расследованию двенадцати членов с очень сильным большинством Джирондина. [ 253 ] Жак Хеберт , редактор Le Père Duchesne , был арестован после нападения или призвания к смерти двадцати двух Жирондин. На следующий день коммуна потребовала, чтобы Эберт был освобожден.

26 мая, после недели молчания, Робеспьер произнес одно из самых решительных выступлений в своей карьере. [ 254 ] Он призвал джакобинский клуб «поставить себя в восстание против коррумпированных депутатов». [ 255 ] Иснард заявил, что на съезд не будет влиять какое -либо насилие и что Париж должен был уважать представителей из других мест во Франции. [ 256 ] Конвенция решила, что Робеспирре не будет услышана. Атмосфера стала чрезвычайно взволнованной. Некоторые депутаты были готовы убить, если Иснард осмелился объявить гражданскую войну в Париже; Президента попросили отказаться от его места.

28 мая слабый Робесперре дважды извинялся из -за своего физического состояния, но все еще атаковал Бриссо за его королевство. [ 257 ] [ 258 ] Робеспирре покинул съезд после аплодисментов с левой стороны и отправился в ратушу. [ 232 ] Там он призвал к вооруженному восстанию против большинства конвенции. «Если коммуна не совпадает с людьми, она нарушает свою самую священную обязанность», - сказал он. [ 259 ] Во второй половине дня коммуна потребовала создания революционной армии Санс-Кулоттов в каждом городе Франции, в том числе 20 000 человек для защиты Парижа. [ 260 ] [ 255 ] [ 261 ]

29 мая Робеспьер был занят в подготовке общественного разума. Он напал на Чарльза Джин Мари Барбару , но признался, что почти отказался от своей политической карьеры из -за его тревог . [ 232 ] Делегаты, представляющие тридцать три из парижских секций, сформировали комитет по восстановлению. [ 262 ] Они объявили себя в состоянии восстания, распустили Генеральный совет коммуны и немедленно восстановили его, заставив его принять новую клятву; Франсуа Ханриот был избран комендантом-журналом Парижской национальной гвардии. Сен-Just был добавлен в комитет общественной безопасности; Couthon стал секретарем.

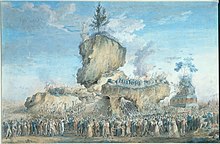

The next day, the tocsin in the Notre-Dame was rung and the city gates were closed; the Insurrection of 31 May – 2 June began. Hanriot was ordered to fire a cannon on the Pont-Neuf as a sign of alarm. Around ten in the morning, 12,000 armed citizens appeared to protect the Convention against the arrest of Girondin deputies.

On 1 June, the Commune gathered over the course of the day and devoted it to the preparation of a great movement. The Comité insurrectionnel ordered Hanriot to surround the Convention "with a respectable armed force".[263] In the evening, 40,000 men surrounded the building to force the arrest. Marat led the attack on the representatives, who had voted against the execution of the King and since then paralyzed the Convention.[264][236] The Commune decided to petition the Convention. The Convention decided to allow men to carry arms on days of crisis and pay them for each day and promised to indemnify the workers for the interruption in the past four days.[265]

Unsatisfied with the result, the Commune demanded and prepared a "Supplement" to the revolution. Hanriot offered (or was ordered) to march the National Guard from the town hall to the National Palace.[266] The next morning a large force of armed citizens (some estimated 80,000 or 100,000, but Danton spoke of only 30,000)[267] surrounded the Convention with artillery. "The armed force", Hanriot said, "will retire only when the Convention has delivered to the people the deputies denounced by the Commune."[268] The Girondins believed they were protected by the law, but the people in the galleries called for their arrest. Twenty-two Girondins were seized.[269]

The Montagnards now had control of the Convention.[270] The Girondins, going to the provinces, joined the counter-revolution.[271]

During the insurrection, Robespierre had scrawled a note in his memorandum-book:

What we need is a single will (il faut une volonté une). It must be either republican or royalist. If it is to be republican, we must have republican ministers, republican newspapers, republican deputies, a republican government. ... The internal dangers come from the middle classes; to defeat the middle classes we must rally the people. ... The people must ally themselves with the Convention, and the Convention must make use of the people.[272][273]

On 3 June, the Convention decided to split up the land belonging to Émigrés and sell it to farmers. On 12 June, Robespierre announced his intention to resign due to health issues.[274] On 13 July, Robespierre defended the plans of Le Peletier to teach revolutionary ideas in boarding schools.[275][t] On the following day, the Convention rushed to praise Marat – who had been murdered in his bathtub – for his fervor and revolutionary diligence. Opposing Pierre-Louis Bentabole, Robespierre simply called for an inquiry into the circumstances of Marat's death.[277] On 17 or 22 July the property of the Émigres were expropriated by decree; proofs of ownership had to be collected and burnt.

-

Journées des 31 Mai, 1er et 2 Juin 1793, an engraving of the Convention surrounded by National Guards.

-

The uprising of the Parisian sans-culottes from 31 May to 2 June 1793. The scene takes place in front of the Deputies Chamber in the Tuileries. The depiction shows Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles and Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud.

-

François Hanriot chef de la section des Sans-Culottes (Rue Mouffetard); drawing by Gabriel in the Carnavalet Museum

Reign of Terror

[edit]

The French government confronted significant internal challenges as the provincial cities rebelled against the more radical revolutionaries in Paris. Marat and Le Peletier were assassinated, instilling fear in Robespierre and other prominent figures for their own safety. Corsica formally seceded from France and sought protection from the British government. In July, France teetered on the brink of civil war, besieged by aristocratic uprisings in Vendée and Brittany, by federalist revolts in Lyon, Le Midi, and Normandy, and confronted with hostility from across Europe and foreign factions.[278][279][280]

June and July 1793

[edit]At the end of June, Robespierre launched an attack on Jacques Roux, portraying him as a foreign agent, which led to Roux's expulsion from the Jacobin Club. On 13 July, the day Marat was assassinated, Robespierre voiced support for Louis-Michel le Peletier's proposals to introduce revolutionary concepts into schools.[275] He also condemned the initiatives of the Parisian radicals, known as the Enragés, who exploited rising inflation and food shortages to incite unrest among the Paris sections.[5]

On 27 July 1793, Robespierre finally joined the Committee, replacing Thomas-Augustin de Gasparin. This marked Robespierre's second stint in an executive position to oversee the war effort. While Robespierre was generally considered the most recognizable member of the Committee, it operated without a hierarchical structure.[281]

August 1793

[edit]On 4 August, the Convention promulgated the French Constitution of 1793.[u] However, by the end of August, the rebellious cities of Marseille, Bordeaux, and Lyon had not yet accepted the new Constitution. French historian Soboul suggests that Robespierre opposed its implementation before the rebellious départements had acknowledged it.[283] By mid-September, the Jacobin Club proposed that the Constitution should not be published, arguing that the general will was absent, despite an overwhelming majority favoring it.[284]

On 21 August, Robespierre was elected as president of the Convention.[285] Two days later, on 23 August Lazare Carnot was appointed to the committee and the provisional government introduced the Levée en masse against the enemies of the republic. Couthon proposed a law punishing any person who sold assignats at less than their nominal value with twenty years imprisonment in chains. Robespierre was particularly concerned with ensuring the virtue of public officials.[286] He had dispatched his brother Augustin, also a representative, and sister Charlotte to Marseille and Nice to quell the federalist insurrection.[287]

September 1793

[edit]On 4 September, the sans-culottes once again stormed the Convention, demanding stricter measures against rising prices, even though the circulating assignats had doubled in the preceding months.[288] They also called for the establishment of a system of terror to eradicate counter-revolution.

During the session on 5 September 1793, Robespierre yielded the chair to Thuriot, as he needed to attend the Committee of Public Safety to supervise the report on the constitution of the revolutionary army.[289] On that day's session, the Convention decided to form a revolutionary army of 6,000 men in Paris upon a proposal by Chaumette supported by Billaud and Danton.[290] Barère, representing the Committee of Public Safety, introduced a decree that was promptly passed, establishing a paid armed force of 6,000 men and 1,200 gunners "tasked with crushing counter-revolutionaries, enforcing revolutionary laws and public safety measures decreed by the National Convention, and safeguarding provisions."[240]

The Committee of General Security, responsible for rooting out crimes and preventing domestic counter-revolution, began overseeing the National Gendarmerie and financial matters. A decree was issued for the arrest of all foreigners in the country. On 8 September, banks and exchange offices were shuttered to curb the circulation of counterfeit assignats and the outflow of capital,[291] with investments in foreign countries punishable by death.

On 11 September, the authority of the Committee of Public Safety was extended for one month. Robespierre threw his support behind Hanriot in the Jacobin Club and voiced opposition to the appointment of Lazare Carnot on 23 August to the committee, citing Carnot's non-membership in the Jacobin Club and his refusal to endorse the events of 31 May.[292][293] Robespierre also called for the punishment of the leaders involved in the Bordeaux conspiracy.

Jacques Thuriot resigned on 20 September due to irreconcilable differences with Robespierre, becoming one of his more vocal opponents.[294] The Revolutionary Tribunal underwent reorganization, being divided into four sections, with two sections always active simultaneously. On 29 September, the Committee introduced the price controls, particularly in the area supplying Paris.[295] According to historian Augustin Cochin, shops were emptied within a week due to these measures.[296]

On 1 October, the Convention resolved to eradicate the "brigands" in the Vendée before the month's end.

October 1793

[edit]On 3 October, Robespierre perceived the Convention as split into two factions: those aligned with the people, and those he deemed conspirators.[297] He defended seventy-three Girondins "as useful",[298] but over twenty were subsequently brought to trial. He criticized Danton, who had declined a seat on the Committee of Public Safety, advocating instead for a stable government capable of resisting the Committee's directives.[299] Danton, who had been dangerously ill for a few weeks,[300] withdrew from politics and departed for Arcis-sur-Aube.[301] By 8 October, the Convention resolved to arrest Brissot and the Girondins.

On 10 October, the Convention officially recognised the Committee of Public Safety as the supreme "Revolutionary Government",[302][better source needed] a designation that was solidified on 4 December.[303] Despite the overwhelming popularity of the Constitution and its drafting, which bolstered support for the Montagnards, the Convention indefinitely suspended it on 10 October until a future peace could be achieved.[304] The Committee of Public Safety transformed into a war cabinet with unprecedented authority over the economy and the political life of the nation. However, it remained accountable to the Convention for any legislative measures and could be replaced at any time.[305]

On 12 October, amid accusations by Hébert implicating Marie-Antoinette's engaging in incest with her son, Robespierre shared a meal with staunch supporters including Barère, Saint-Just, and Joachim Vilate. During the discussion, Robespierre, visibly incensed, broke his plate with his fork and denounced Hébert as an "imbécile".[306][307][308] The verdict on the former queen was delivered by the jury of the Revolutionary Tribunal on 16 October at four o'clock in the morning, and she was guillotined at noon.[309] Courtois reportedly discovered Marie-Antoinette's will among Robespierre's papers, concealed beneath his bed.[310]

On 25 October, the Revolutionary government faced accusations of inaction.[311] Several members of the Committee of General Security, aided by armées revolutionnaires, were dispatched to quell active resistance against the Revolution in the provinces.[312] Robespierre's landlord, Maurice Duplay, became a member of the Revolutionary Tribunal. On 31 October, Brissot and twenty-one other Girondins were guillotined.[313]

November 1793

[edit]On the morning of 14 November, François Chabot allegedly barged into Robespierre's room, dragging him from bed with accusations of counter-revolution and a foreign conspiracy. Chabot waved a hundred thousand livres in assignat notes, claiming that a group of royalist plotters had given it to him to buy votes.[314][315] Chabot was arrested three days later; Courtois urged Danton to return to Paris immediately.

On 25 November, the remains of the Comte de Mirabeau were removed from the Pantheon and replaced with those of Jean-Paul Marat.[316] Robespierre initiated this change upon discovering that Mirabeau had secretly conspired with the court of Louis XVI in his final months.[317] At the end of November, under intense emotional pressure from Lyonnaise women, who protested and gathered 10,000 signatures, Robespierre proposed the establishment of a secret commission to examine the cases of the Lyon rebels and investigate potential injustices.

December 1793

[edit]On 3 December, Robespierre accused Danton in the Jacobin Club of feigning an illness to emigrate to Switzerland.[citation needed] Danton, according to him, showed too often his vices and not his virtue. Robespierre was stopped in his attack. The gathering was closed after applause for Danton.[318] On 4 December, by the Law of Revolutionary Government, the independence of departmental and local authorities came to an end when extensive powers of the Committee of Public Safety were codified. Submitted by Billaud and implemented within 24 hours, the law was a drastic decision against the independence of deputies and commissionaires on a mission; coordinated action among the sections became illegal.[319] On 5 December, the journalist Camille Desmoulins launched a new journal, Le Vieux Cordelier. He defended Danton, attacked the de-Christianisers, and later compared Robespierre with Julius Caesar as dictator.[320] Robespierre made a counterproposal of setting up a Committee of Justice to examine some of the cases under the Law of Suspects.[321] Seventy-three deputies who had voted against the insurrection on 2 June were allowed to take their seats in the Convention.[322] On 6 December, Robespierre warned in the Convention against the dangers of dechristianization, and attacked "all violence or threats contrary to the freedom of religion".

On 12 December, Robespierre attacked the wealthy foreigner Cloots in the Jacobin club of being a Prussian spy.[323] Robespierre denounced the "de-Christianisers" as foreign enemies. The Indulgents mounted an attack on the Committee of Public Safety, accusing them of being murderers.[324] Desmoulins addressed Robespierre directly, writing, "My dear Robespierre... my old school friend... Remember the lessons of history and philosophy: love is stronger, more lasting than fear."[325][326]

On 25 December, provoked by Desmoulins' insistent challenges, Robespierre produced his "Report on the Principles of Revolutionary Government".[321] Robespierre replied to the plea for an end to the Terror, justifying the collective authority of the National Convention, administrative centralisation, and the purging of local authorities. He said he had to avoid two cliffs: indulgence and severity. He could not consult the 18th-century political authors, because they had not foreseen such a course of events. He protested against the various factions that he believed threatened the government, such as the Hébertists and Dantonists.[327][328] Robespierre strongly believed that the strict legal system was still necessary:

The theory of the revolutionary government is as new as the revolution from which this government was born. This theory may not be found in the books of the political writers who were unable to predict the Revolution, nor in the law books of the tyrants...

The goal of a constitutional government is the protection of the Republic; that of a revolutionary government is the establishment of the Republic.

The Revolution is the war waged by liberty against its foes—but the Constitution is the régime of victorious and peaceful freedom.

The Revolutionary Government will need to put forth extraordinary activity, because it is at war. It is subject to no constant laws, since the circumstances under which it prevails are those of a storm, and change with every moment. This government is obliged unceasingly to disclose new sources of energy to oppose the rapidly changing face of danger.[329]

Robespierre would suppress chaos and anarchy: "the Government has to defend itself" [against conspirators] and "to the enemies of the people it owes only death".[330][331][332] According to R.R. Palmer and Donald C. Hodges, this was the first important statement in modern times of a philosophy of dictatorship.[333][334] Others[who?] see it as a natural consequence of political instability and conspiracy.

February and March 1794

[edit]In his Report on the Principles of Political Morality of 5 February 1794, Robespierre praised the revolutionary government and argued that terror and virtue were necessary:

If the spring of popular government in time of peace is virtue, the springs of popular government in revolution are at once virtue and terror: virtue, without which terror is fatal; terror, without which virtue is powerless. Terror is nothing other than justice, prompt, severe, inflexible; it is therefore an emanation of virtue; it is not so much a special principle as it is a consequence of the general principle of democracy applied to our country's most urgent needs.

It has been said that terror is the principle of despotic government. Does your government therefore resemble despotism? Yes, as the sword that gleams in the hands of the heroes of liberty resembles that with which the henchmen of tyranny are armed. Let the despot govern by terror his brutalized subjects; he is right, as a despot. Subdue by terror the enemies of liberty, and you will be right, as founders of the Republic. The government of the revolution is liberty's despotism against tyranny. Is force made only to protect crime? And is the thunderbolt not destined to strike the heads of the proud?[335]

To punish the oppressors of humanity is clemency; to forgive them is barbarity.[336]

Aulard sums up the Jacobin train of thought: "All politics, according to Robespierre, must tend to establish the reign of virtue and confound vice. He reasoned thus: those who are virtuous are right; error is a corruption of the heart; error cannot be sincere; error is always deliberate."[337][338] According to the German journalist K.E. Oelsner, Robespierre behaved "more like a leader of a religious sect than of a political party. He can be eloquent but most of the time he is boring, especially when he goes on too long, which is often the case."[339]

From 13 February to 13 March 1794, Robespierre had withdrawn from active business on the Committee due to illness.[67] Robespierre seems to have suffered from acute physical and mental exhaustion, exacerbated by an austere personal regime, according to McPhee. Saint-Just was elected president of the Convention for the next two weeks. On 19 February, Robespierre decided to return to the Duplays.[340]

In early March, in a speech at the Cordeliers Club, Hébert attacked both Robespierre and Danton as being too soft. Hébert used the latest issue of Le Père Duchesne to criticise Robespierre. There were queues and near-riots at the shops and in the markets; there were strikes and threatening public demonstrations. Some of the Hébertistes and their friends were calling for a new insurrection.[341] Robespierre managed to acquire a small army of secret agents, which reported to him.[342]

A majority of the Committee decided that the ultra-left Hébertists would have to perish or their opposition within the committee would overshadow the other factions due to its influence in the Commune of Paris. Robespierre also had personal reasons for disliking the Hébertists for their "bloodthirstiness" and atheism, which he associated with the old aristocracy.[343] On the night of 13–14 March, Hébert and 18 of his followers were arrested as the agents of foreign powers. On 15 March, Robespierre reappeared in the Convention.[v] The next day, Robespierre denounced a petition demanding that all merchants should be excluded from public offices whilst the war lasted.[345] Subsequently, he joined Saint-Just in his attacks on Hébert.[346] The leaders of the "armées révolutionnaires" were denounced by the Revolutionary Tribunal as accomplices of Hébert.[347] Their armies were dissolved on 27 March. Robespierre protected Hanriot, the commander of the Paris National Guards, and Pache.[348][w] Around twenty people, including Hébert, Cloots and De Kock), were guillotined on the evening of 24 March. On 25 March, Condorcet was arrested, as he was seen as an enemy of the Revolution; he committed suicide two days later.

On 29 March, Danton met again with Robespierre privately.[353] On 30 March the two committees decided to arrest Danton and Desmoulins.[354] On 31 March, Saint-Just publicly attacked both. In the Convention, criticism was voiced against the arrests, which Robespierre silenced with "whoever trembles at this moment is guilty."[355] Legendre suggested that "before you listen to any report, you send for the prisoners, and hear them". Robespierre replied, "It would be violating the laws of impartiality to grant to Danton what was refused to others, who had an equal right to make the same demand. This answer silenced at once all solicitations in his favour."[356] No friend of the Dantonists dared speak up in case he too should be accused of putting friendship before virtue.[357]

April 1794

[edit]

Danton, Desmoulins, and several others faced trial from 3 to 5 April before the Revolutionary Tribunal, presided over by Martial Herman. Described as more politically charged than criminally focused, the trial proceeded in an irregular manner.[358] Hanriot had been informed not to arrest the president and the "public accuser" of the Revolutionary Tribunal.[359] The accusations of theft, corruption, and the scandal involving the French East India Company paved the way for Danton's downfall,[360] accusing him of conspiracy with count Mirabeau, Marquis de Lafayette, the Duke of Orléans and Dumouriez.[361] In Robespierre's eyes, the Dantonists had ceased to be true patriots, instead prioritizing personal and foreign interests over the nation's welfare.[358] Following Robespierre's advice, a decree was accepted to present Saint-Just's account on Danton's alleged royalist tendencies at the tribunal, effectively ending further debates and restraining any further insults to justice by the accused.[362]

Fouquier-Tinville asked the tribunal to order the defendants who "confused the hearing" and insulted "National Justice" to the guillotine. Desmoulins struggled to accept his fate and accused Robespierre, the Committee of General Security, and the Revolutionary Tribunal. He was dragged up the scaffold by force.

On the last day of their trial, Desmoulins's wife, Lucile Desmoulins, was imprisoned. She was accused of organising a revolt against the patriots and the tribunal to free her husband and Danton. She admitted to having warned the prisoners of a course of events as in September 1792, and that it was her duty to revolt against it. Robespierre was not only his school friend but also had witnessed at their marriage in December 1790, together with Pétion and Brissot.[363][364][67] Following the executions of Danton and Desmoulins on 5 April, Robespierre had a partial withdrawal from public life. He did not reappear until 7 May. The withdrawal may have been an indication of health issues.[363]

On 1 April, Lazare Carnot proposed the provisional executive council of six ministers be suppressed and the ministries be replaced by twelve Committees reporting to the Committee of Public Safety.[365] The proposal was unanimously adopted by the National Convention and set up by Martial Herman on 8 April. On 3 April, Fouché was invited to Paris. On 9 April, he appeared in the Convention; in the evening he visited Robespierre at home. On 12 April, his report was discussed in the Convention; according to Robespierre, it was incomplete.[366] When Barras and Fréron paid a visit to Robespierre, they were received in an extremely unfriendly manner.[367] At the request of Robespierre, the Convention ordered the transfer of the ashes of Jean-Jacques Rousseau to the Panthéon.

On 22 April, Malesherbes, a lawyer who had defended the king and the deputés Isaac René Guy le Chapelier and Jacques Guillaume Thouret, four times elected president of the Constituent Assembly, were taken to the scaffold.[368] The decree of 8 May suppressed the revolutionary courts and committees in the provinces and brought all political cases for trial in the capital.[369] The police bureau, directed by Martial Herman, became a serious rival of the Committee of General Security after a month.[370] Payan, even advised Robespierre to get rid of the Committee of General Security, saying it broke the unity of action of the government.[368]

June 1794

[edit]On 10 June, Georges Couthon introduced the Law of 22 Prairial to liberate the Revolutionary Tribunals from Convention control while severely restricting suspects' ability to defend themselves. The law significantly expanded the scope of charges, criminalizing virtually any criticism of the government.[371] Legal defence was sidelined in favor of efficiency and centralisation, as all assistance for defendants before the revolutionary tribunal was outlawed.[372] The Tribunal transformed into a court of condemnation, denying suspects the right to counsel and offering only two verdicts: complete acquittal or death, often based more on jurors' moral convictions than evidence.[373][374] Within three days, 156 people were sent in batches to the guillotine, including all the members of Parlement of Toulouse.[375][376] On 11 July, shopkeepers, craftsmen, and others were temporarily released from prison due to overcrowding, with over 8,000 "suspects" initially confined by the start of Thermidor Year II, according to François Furet.[377] Paris saw a doubling of death sentences.[378]

Abolition of slavery

[edit]

Robespierre's stance on abolition exhibits certain contradictions, prompting doubts about his intentions regarding slavery.[379][380][381][382]

On 13 May 1791, he opposed the inclusion of the term "slaves" in a law, vehemently denouncing the slave trade.[383] He emphasized that slavery contradicted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.[382] On 15 May 1791, the Constituent Assembly granted citizenship to "all people of colour born of free parents".[384] Robespierre passionately argued in the Assembly against the Colonial Committee, which was composed predominantly of plantation owners and slaveholders in the Caribbean.[385] The colonial lobby contented that granting political rights to black individuals would lead to France losing her colonies. In response, Robespierre asserted, "We should not compromise the interests humanity holds most dear, the sacred rights of a significant number of our fellow citizens," later exclaiming, "Perish the colonies, if it will cost you your happiness, your glory, your freedom. Perish the colonies!"[383][386] Robespierre expressed fury at the assembly's decision to grant "constitutional sanction to slavery in the colonies", and advocating for equal political rights regardless of skin colour.[387] Despite the decree, the colonial whites refused to comply the decree,[388] leading them to contemplate separation from France thereafter.

Robespierre did not advocate for the immediate abolition of slavery. However, proponents of slavery in France viewed Robespierre as a "bloodthirsty innovator" and accused him of conspiring to surrender French colonies to England.[386] On 4 April 1792, Louis XVI affirmed the Jacobin decree, which granted equal political rights to free blacks and mulattoes in Saint-Domingue.[389] On 2 June 1792, the National Assembly appointed a three-man Civil Commission, led by Léger Félicité Sonthonax, to travel to Saint-Domingue and ensure the enforcement of the 4 April decree. However, the commission eventually issued a proclamation of general emancipation that included black slaves.[390] Robespierre condemned the slave trade in a speech before the Convention in April 1793.[391]

Ask a merchant of human flesh what is property; he will answer by showing you that long coffin he calls a ship... Ask a gentleman [the same] who has lands and vassals... and he will give you almost the identical ideas.

Babeuf urged Chaumette to spearhead efforts to persuade the Convention to adopt the seven additional articles proposed by Maximilien Robespierre on 24 April 1793, regarding the scale and scope of property rights, to be incorporated into the new Declaration of Rights.[393] On 3 June 1793, Robespierre attended a Jacobin meeting to lend support for a decree aimed at ending slavery.[394] On 4 June 1793, a delegation of sans-culottes and men of colour, led by Chaumette, presented a petition to the Convention requesting the general emancipation of the blacks in the colonies. The abolition of slavery was officially included into the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1793.[246] The radical 1793 constitution, championed by Robespierre and the Montagnards, was ratified in August through a national referendum. It granted universal suffrage to French men and explicitly condemned slavery. However, the French Constitution of 1793 was never put in effect.

Starting in August, former slaves in St Domingue were granted "all the rights of French citizens". In August 1793, an increasing number of slaves in St Domingue initiated a Haitian Revolution against slavery and colonial domination.[395] Robespierre, however, prioritized the rights of free people of color over those of the enslaved.[396] On 31 October 1793, slavery was officially abolished in St Domingue. Robespierre criticised the actions of the former governor of Saint-Domingue Sonthonax and Étienne Polverel, who initially had freed slaves in Haïti, but then proposed arming them.[397] Robespierre also cautioned the Committee against relying on white individuals to govern the colony.[398] In 1794 the National Convention passed a decree abolishing slavery in all the colonies.[399][400] On the day following the emancipation decree, Robespierre addressed the Convention, lauding the French as pioneers to "summon all men to equality and liberty, and their full rights as citizens". Although Robespierre mentioned slavery twice in his speech, he did not specifically reference the French colonies.[401] Despite petitions from the slaveholding delegation, the Convention resolved to fully endorse the decree. However, its implementation and application were limited to St Domingue (1793), Guadeloupe (December 1794) and French Guiana.[402][403]

The National Convention declares the abolition of negro slavery in all the Colonies; consequently it decrees that all men, without distinction of color, domiciled in the Colonies, are French citizens, and will enjoy all the rights assured by the constitution.[404]

Robespierre's stance on the decree of 16 Pluviose year II regarding the emancipation of the slaves remains a topic of contention. French historian Claude Mazauric interpreted Robespierre's cautious approach in February 1794 toward the abolition decree as an attempt to avoid controversy.[405] On 11 April 1794, the decree underwent alterations,[406] with Robespierre endorsing orders to ratify it.[407] This decree significantly bolstered the Republic's popularity among black individuals in St. Domingue, many of whom had already liberated themselves and sought military alliances to safeguard their freedom.[387] In May 1794, Toussaint Louverture aligned with the French after the Spanish declined to take actions against slavery and in repelling the English. Following the events of 9–10 Thermidor, an anti-slavery campaign emerged targeting Robespierre. Critics accused him of attempting to perpetuate slavery, despite its abolition by the Convention on 4 February 1794, following the precedent set by Sonthonax's abolition decree in August 1793 in St. Domingue.[408]

Cult of the Supreme Being

[edit]