Nazi Party

National Socialist German Workers' Party Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | NSDAP |

| Chairman | Anton Drexler (24 February 1920 – 29 July 1921)[1] |

| Führer | Adolf Hitler (29 July 1921 – 30 April 1945) |

| Party Minister | Martin Bormann (30 April 1945 – 2 May 1945) |

| Founded | 24 February 1920 |

| Banned | 10 October 1945 |

| Preceded by | German Workers' Party |

| Headquarters | Brown House, Munich, Germany[2] |

| Newspaper | Völkischer Beobachter |

| Student wing | National Socialist German Students' Union |

| Youth wing | Hitler Youth |

| Women's wing | National Socialist Women's League |

| Paramilitary wings | SA, SS, Motor Corps, Flyers Corps |

| Sports body | National Socialist League of the Reich for Physical Exercise |

| Overseas wing | NSDAP/AO |

| Labour wing | NSBO (1928–35), DAF (1933–45)[3] |

| Membership |

|

| Ideology | Nazism |

| Political position | Far-right[5][6] |

| Political alliance |

|

| Colours |

|

| Slogan | Deutschland erwache! ("Germany, awake!") (unofficial) |

| Anthem | "Horst-Wessel-Lied" Duration: 3 minutes and 22 seconds. |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Nazism |

|---|

The Nazi Party,[b] officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (German: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei [c] or NSDAP), was a far-right[10][11][12] political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor, the German Workers' Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei; DAP), existed from 1919 to 1920. The Nazi Party emerged from the extremist German nationalist ("Völkisch nationalist"), racist and populist Freikorps paramilitary culture, which fought against communist uprisings in post–World War I Germany.[13] The party was created to draw workers away from communism and into völkisch nationalism.[14] Initially, Nazi political strategy focused on anti–big business, anti-bourgeois, and anti-capitalist rhetoric; it was later downplayed to gain the support of business leaders. By the 1930s, the party's main focus shifted to antisemitic and anti-Marxist themes.[15] The party had little popular support until the Great Depression, when worsening living standards and widespread unemployment drove Germans into political extremism.[12]

Central to Nazism were themes of racial segregation expressed in the idea of a "people's community" (Volksgemeinschaft).[16] The party aimed to unite "racially desirable" Germans as national comrades while excluding those deemed to be either political dissidents, physically or intellectually inferior, or of a foreign race (Fremdvölkische).[17] The Nazis sought to strengthen the Germanic people, the "Aryan master race", through racial purity and eugenics, broad social welfare programs, and a collective subordination of individual rights, which could be sacrificed for the good of the state on behalf of the people. To protect the supposed purity and strength of the Aryan race, the Nazis sought to disenfranchise, segregate, and eventually exterminate Jews, Romani, Slavs, the physically and mentally disabled, homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, and political opponents.[18] The persecution reached its climax when the party-controlled German state set in motion the Final Solution – an industrial system of genocide that carried out mass murders of around 6 million Jews and millions of other targeted victims in what has become known as the Holocaust.[19]

Adolf Hitler, the party's leader since 1921, was appointed Chancellor of Germany by President Paul von Hindenburg on 30 January 1933, and quickly seized power afterwards. Hitler established a totalitarian regime known as the Third Reich and became dictator with absolute power.[20][21][22][23]

Following the military defeat of Germany in World War II, the party was declared illegal.[24] The Allies attempted to purge German society of Nazi elements in a process known as denazification. Several top leaders were tried and found guilty of crimes against humanity in the Nuremberg trials, and executed. The use of symbols associated with the party is still outlawed in many European countries, including Germany and Austria.

Name

The renaming of the German Worker's Party (DAP) to the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) was partially driven by a desire to draw upon both left-wing and right-wing ideals, with "Socialist" and "Workers'" appealing to the left, and "National" and "German" appealing to the right.[25] Nazi, the informal and originally derogatory term for a party member, abbreviates the party's name (Nationalsozialist [natsi̯oˈnaːlzotsi̯aˌlɪst]), and was coined in analogy with Sozi (pronounced [ˈzoːtsiː]), an abbreviation of Sozialdemokrat (member of the rival Social Democratic Party of Germany).[d][26] Members of the party referred to themselves as Nationalsozialisten (National Socialists), but some did occasionally embrace the colloquial Nazi (so Leopold von Mildenstein in his article series Ein Nazi fährt nach Palästina published in Der Angriff in 1934). The term Parteigenosse (party member) was commonly used among Nazis, with its corresponding feminine form Parteigenossin.[27]

Before the rise of the party, these terms had been used as colloquial and derogatory words for a backward peasant, or an awkward and clumsy person. It derived from Ignaz, a shortened version of Ignatius,[28][29] which was a common name in the Nazis' home region of Bavaria. Opponents seized on this, and the long-existing Sozi, to attach a dismissive nickname to the National Socialists.[29][30]

In 1933, when Adolf Hitler assumed power in the German government, the usage of "Nazi" diminished in Germany, although Austrian anti-Nazis continued to use the term.[26] The use of "Nazi Germany" and "Nazi regime" was popularised by anti-Nazis and German exiles abroad. Thereafter, the term spread into other languages and eventually was brought back to Germany after World War II.[30] In English, the term is not considered slang and has such derivatives as Nazism and denazification.

History

Origins and early years: 1918–1923

The Nazi Party grew out of smaller political groups with a nationalist orientation that formed in the last years of World War I. In 1918, a league called the Freier Arbeiterausschuss für einen guten Frieden (Free Workers' Committee for a good Peace)[31] was created in Bremen, Germany. On 7 March 1918, Anton Drexler, an avid German nationalist, formed a branch of this league in Munich.[31] Drexler was a local locksmith who had been a member of the militarist Fatherland Party[32] during World War I and was bitterly opposed to the armistice of November 1918 and the revolutionary upheavals that followed. Drexler followed the views of militant nationalists of the day, such as opposing the Treaty of Versailles, having antisemitic, anti-monarchist and anti-Marxist views, as well as believing in the superiority of Germans whom they claimed to be part of the Aryan "master race" (Herrenvolk). However, he also accused international capitalism of being a Jewish-dominated movement and denounced capitalists for war profiteering in World War I.[33] Drexler saw the political violence and instability in Germany as the result of the Weimar Republic being out-of-touch with the masses, especially the lower classes.[33] Drexler emphasised the need for a synthesis of völkisch nationalism with a form of economic socialism, in order to create a popular nationalist-oriented workers' movement that could challenge the rise of communism and internationalist politics.[34] These were all well-known themes popular with various Weimar paramilitary groups such as the Freikorps.

Drexler's movement received attention and support from some influential figures. Supporter Dietrich Eckart, a well-to-do journalist, brought military figure Felix Graf von Bothmer, a prominent supporter of the concept of "national socialism", to address the movement.[35] Later in 1918, Karl Harrer (a journalist and member of the Thule Society) convinced Drexler and several others to form the Politischer Arbeiter-Zirkel (Political Workers' Circle).[31] The members met periodically for discussions with themes of nationalism and racism directed against Jewish people.[31] In December 1918, Drexler decided that a new political party should be formed, based on the political principles that he endorsed, by combining his branch of the Workers' Committee for a good Peace with the Political Workers' Circle.[31][36]

On 5 January 1919, Drexler created a new political party and proposed it should be named the "German Socialist Workers' Party", but Harrer objected to the term "socialist"; so the term was removed and the party was named the German Workers' Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, DAP).[36] To ease concerns among potential middle-class supporters, Drexler made clear that unlike Marxists the party supported the middle-class and that its socialist policy was meant to give social welfare to German citizens deemed part of the Aryan race.[33] They became one of many völkisch movements that existed in Germany. Like other völkisch groups, the DAP advocated the belief that through profit-sharing instead of socialisation Germany should become a unified "people's community" (Volksgemeinschaft) rather than a society divided along class and party lines.[37] This ideology was explicitly antisemitic. As early as 1920, the party was raising money by selling a tobacco called Anti-Semit.[38]

From the outset, the DAP was opposed to non-nationalist political movements, especially on the left, including the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). Members of the DAP saw themselves as fighting against "Bolshevism" and anyone considered a part of or aiding so-called "international Jewry". The DAP was also deeply opposed to the Treaty of Versailles.[39] The DAP did not attempt to make itself public and meetings were kept in relative secrecy, with public speakers discussing what they thought of Germany's present state of affairs, or writing to like-minded societies in Northern Germany.[37]

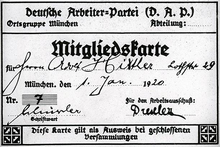

The DAP was a comparatively small group with fewer than 60 members.[37] Nevertheless, it attracted the attention of the German authorities, who were suspicious of any organisation that appeared to have subversive tendencies. In July 1919, while stationed in Munich, army Gefreiter Adolf Hitler was appointed a Verbindungsmann (intelligence agent) of an Aufklärungskommando (reconnaissance unit) of the Reichswehr (army) by Captain Mayr, the head of the Education and Propaganda Department (Dept Ib/P) in Bavaria. Hitler was assigned to influence other soldiers and to infiltrate the DAP.[40] While Hitler was initially unimpressed by the meetings and found them disorganised, he enjoyed the discussion that took place.[41] While attending a party meeting on 12 September 1919 at Munich's Sterneckerbräu, Hitler became involved in a heated argument with a visitor, Professor Baumann, who questioned the soundness of Gottfried Feder's arguments against capitalism; Baumann proposed that Bavaria should break away from Prussia and found a new South German nation with Austria. In vehemently attacking the man's arguments, Hitler made an impression on the other party members with his oratorical skills; according to Hitler, the "professor" left the hall acknowledging unequivocal defeat.[42] Drexler encouraged him to join the DAP.[42] On the orders of his army superiors, Hitler applied to join the party[43] and within a week was accepted as party member 555 (the party began counting membership at 500 to give the impression they were a much larger party).[44][45] Among the party's earlier members were Ernst Röhm of the Army's District Command VII; Dietrich Eckart, who has been called the spiritual father of National Socialism;[46] then-University of Munich student Rudolf Hess;[47] Freikorps soldier Hans Frank; and Alfred Rosenberg, often credited as the philosopher of the movement. All were later prominent in the Nazi regime.[48]

Hitler later claimed to be the seventh party member. He was, in fact, the seventh executive member of the party's central committee[49] and he would later wear the Golden Party Badge number one. Anton Drexler drafted a letter to Hitler in 1940—which was never sent—that contradicts Hitler's later claim:

No one knows better than you yourself, my Führer, that you were never the seventh member of the party, but at best the seventh member of the committee... And a few years ago I had to complain to a party office that your first proper membership card of the DAP, bearing the signatures of Schüssler and myself, was falsified, with the number 555 being erased and number 7 entered.[50]

Although Hitler initially wanted to form his own party, he claimed to have been convinced to join the DAP because it was small and he could eventually become its leader.[51] He consequently encouraged the organisation to become less of a debating society, which it had been previously, and more of an active political party.[52] Normally, enlisted army personnel were not allowed to join political parties. In this case, Hitler had Captain Karl Mayr's permission to join the DAP. Further, Hitler was allowed to stay in the army and receive his weekly pay of 20 gold marks a week.[53] Unlike many other members of the organisation, this continued employment provided him with enough money to dedicate himself more fully to the DAP.[54]

Hitler's first DAP speech was held in the Hofbräukeller on 16 October 1919. He was the second speaker of the evening, and spoke to 111 people.[55] Hitler later declared that this was when he realised he could really "make a good speech".[37] At first, Hitler spoke only to relatively small groups, but his considerable oratory and propaganda skills were appreciated by the party leadership. With the support of Anton Drexler, Hitler became chief of propaganda for the party in early 1920.[56] Hitler began to make the party more public, and organised its biggest meeting yet of 2,000 people on 24 February 1920 in the Staatliches Hofbräuhaus in München. Such was the significance of this particular move in publicity that Karl Harrer resigned from the party in disagreement.[57] It was in this speech that Hitler enunciated the twenty-five points of the German Workers' Party manifesto that had been drawn up by Drexler, Feder and himself.[58] Through these points he gave the organisation a much bolder stratagem[56] with a clear foreign policy (abrogation of the Treaty of Versailles, a Greater Germany, Eastern expansion and exclusion of Jews from citizenship) and among his specific points were: confiscation of war profits, abolition of unearned incomes, the State to share profits of land and land for national needs to be taken away without compensation.[59] In general, the manifesto was antisemitic, anti-capitalist, anti-democratic, anti-Marxist and anti-liberal.[60] To increase its appeal to larger segments of the population, on the same day as Hitler's Hofbräuhaus speech on 24 February 1920, the DAP changed its name to the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei ("National Socialist German Workers' Party", or Nazi Party).[61][62][e] The name was intended to draw upon both left-wing and right-wing ideals, with "Socialist" and "Workers'" appealing to the left, and "National" and "German" appealing to the right.[65] The word "Socialist" was added by the party's executive committee (at the suggestion of Rudolf Jung), over Hitler's initial objections,[f] in order to help appeal to left-wing workers.[67]

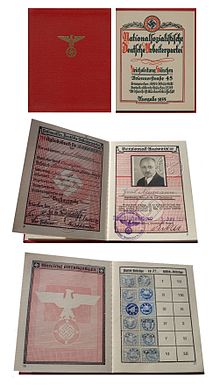

In 1920, the Nazi Party officially announced that only persons of "pure Aryan descent [rein arischer Abkunft]" could become party members and if the person had a spouse, the spouse also had to be a "racially pure" Aryan. Party members could not be related either directly or indirectly to a so-called "non-Aryan".[68] Even before it had become legally forbidden by the Nuremberg Laws in 1935, the Nazis banned sexual relations and marriages between party members and Jews.[69] Party members found guilty of Rassenschande ("racial defilement") were persecuted heavily. Some members were even sentenced to death.[70]

Hitler quickly became the party's most active orator, appearing in public as a speaker 31 times within the first year after his self-discovery.[71] Crowds began to flock to hear his speeches.[72] Hitler always spoke about the same subjects: the Treaty of Versailles and the Jewish question.[60] This deliberate technique and effective publicising of the party contributed significantly to his early success,[60] about which a contemporary poster wrote: "Since Herr Hitler is a brilliant speaker, we can hold out the prospect of an extremely exciting evening".[73][page needed] Over the following months, the party continued to attract new members,[49] while remaining too small to have any real significance in German politics.[74] By the end of the year, party membership was recorded at 2,000,[72] many of whom Hitler and Röhm had brought into the party personally, or for whom Hitler's oratory had been their reason for joining.[75]

Hitler's talent as an orator and his ability to draw new members, combined with his characteristic ruthlessness, soon made him the dominant figure. However, while Hitler and Eckart were on a fundraising trip to Berlin in June 1921, a mutiny broke out within the party in Munich. Members of its executive committee wanted to merge with the rival German Socialist Party (DSP).[76] Upon returning to Munich on 11 July, Hitler angrily tendered his resignation. The committee members realised that his resignation would mean the end of the party.[77] Hitler announced he would rejoin on condition that he would replace Drexler as party chairman, and that the party headquarters would remain in Munich.[78] The committee agreed, and he rejoined the party on 26 July as member 3,680. Hitler continued to face some opposition within the NSDAP, as his opponents had Hermann Esser expelled from the party and they printed 3,000 copies of a pamphlet attacking Hitler as a traitor to the party.[78] In the following days, Hitler spoke to several packed houses and defended himself and Esser to thunderous applause.[79]

Hitler's strategy proved successful; at a special party congress on 29 July 1921, he replaced Drexler as party chairman by a vote of 533 to 1.[79] The committee was dissolved, and Hitler was granted nearly absolute powers in the party as its sole leader.[79] He would hold the post for the remainder of his life. Hitler soon acquired the title Führer ("leader") and after a series of sharp internal conflicts it was accepted that the party would be governed by the Führerprinzip ("leader principle"). Under this principle, the party was a highly centralised entity that functioned strictly from the top down, with Hitler at the apex. Hitler saw the party as a revolutionary organisation, whose aim was the overthrow of the Weimar Republic, which he saw as controlled by the socialists, Jews and the "November criminals", a term invented to describe alleged elements of society who had 'betrayed the German soldiers' in 1918. The SA ("storm troopers", also known as "Brownshirts") were founded as a party militia in 1921 and began violent attacks on other parties.

For Hitler, the twin goals of the party were always German nationalist expansionism and antisemitism. These two goals were fused in his mind by his belief that Germany's external enemies—Britain, France and the Soviet Union—were controlled by the Jews and that Germany's future wars of national expansion would necessarily entail a war of annihilation against them.[80][page needed] For Hitler and his principal lieutenants, national and racial issues were always dominant. This was symbolised by the adoption as the party emblem of the swastika. In German nationalist circles, the swastika was considered a symbol of an "Aryan race" and it symbolised the replacement of the Christian Cross with allegiance to a National Socialist State.

The Nazi Party grew significantly during 1921 and 1922, partly through Hitler's oratorical skills, partly through the SA's appeal to unemployed young men, and partly because there was a backlash against socialist and liberal politics in Bavaria as Germany's economic problems deepened and the weakness of the Weimar regime became apparent. The party recruited former World War I soldiers, to whom Hitler as a decorated frontline veteran could particularly appeal, as well as small businessmen and disaffected former members of rival parties. Nazi rallies were often held in beer halls, where downtrodden men could get free beer. The Hitler Youth was formed for the children of party members. The party also formed groups in other parts of Germany. Julius Streicher in Nuremberg was an early recruit and became editor of the racist magazine Der Stürmer. In December 1920, the Nazi Party had acquired a newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter, of which its leading ideologist Alfred Rosenberg became editor. Others to join the party around this time were Heinrich Himmler and World War I flying ace Hermann Göring.

Adoption of Italian fascism: The Beer Hall Putsch

On 31 October 1922, a fascist party with similar policies and objectives came into power in Italy, the National Fascist Party, under the leadership of the charismatic Benito Mussolini. The Fascists, like the Nazis, promoted a national rebirth of their country, as they opposed communism and liberalism; appealed to the working-class; opposed the Treaty of Versailles; and advocated the territorial expansion of their country. Hitler was inspired by Mussolini and the Fascists, beginning to adopt elements of the Fascist's and Mussolini for the Nazi Party and himself.[81] The Italian Fascists also used a straight-armed Roman salute and wore black-shirted uniforms; Hitler would later borrow their use of the straight-armed salute as a Nazi salute.

When the Fascists took control of Italy through their coup d'état called the "March on Rome", Hitler began planning his own coup less than a month later.[81] In January 1923, France occupied the Ruhr industrial region as a result of Germany's failure to meet its reparations payments. This led to economic chaos, the resignation of Wilhelm Cuno's government and an attempt by the German Communist Party (KPD) to stage a revolution. The reaction to these events was an upsurge of nationalist sentiment. Nazi Party membership grew sharply to about 20,000,[82] compared to the approximate 6,000 at the beginning of 1923.[83] By November 1923, Hitler had decided that the time was right for an attempt to seize power in Munich, in the hope that the Reichswehr (the post-war German military) would mutiny against the Berlin government and join his revolt. In this, he was influenced by former General Erich Ludendorff, who had become a supporter—though not a member—of the Nazis.[84]

On the night of 8 November, the Nazis used a patriotic rally in a Munich beer hall to launch an attempted putsch ("coup d'état"). This so-called Beer Hall Putsch attempt failed almost at once when the local Reichswehr commanders refused to support it. On the morning of 9 November, the Nazis staged a march of about 2,000 supporters through Munich in an attempt to rally support. The two groups exchanged fire, after which 15 putschists, four police officers, and a bystander lay dead.[85][86][87] Hitler, Ludendorff and a number of others were arrested and were tried for treason in March 1924. Hitler and his associates were given very lenient prison sentences. While Hitler was in prison, he wrote his semi-autobiographical political manifesto Mein Kampf ("My Struggle").

The Nazi Party was banned on 9 November 1923; however, with the support of the nationalist Völkisch-Social Bloc (Völkisch-Sozialer Block), it continued to operate under the name "German Party" (Deutsche Partei or DP) from 1924 to 1925.[88] The Nazis failed to remain unified in the DP, as in the north, the right-wing Volkish nationalist supporters of the Nazis moved to the new German Völkisch Freedom Party, leaving the north's left-wing Nazi members, such as Joseph Goebbels retaining support for the party.[88]

Rise to power: 1925–1933

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2017) |

Pardoned by the Bavarian Supreme Court, Hitler was released from prison on 20 December 1924, against the state prosecutor's objections.[89] On 16 February 1925, Hitler convinced the Bavarian authorities to lift the ban on the NSDAP and the party was formally refounded on 26 February 1925, with Hitler as its undisputed leader. It was at this time Hitler began referring to himself as "der Führer".[90] The new Nazi Party was no longer a paramilitary organisation and disavowed any intention of taking power by force. In any case, the economic and political situation had stabilised and the extremist upsurge of 1923 had faded, so there was no prospect of further revolutionary adventures. Instead, Hitler intended to alter the party's strategy to achieving power through what he called the "path of legality".[91] The Nazi Party of 1925 was divided into the "Leadership Corps" (Korps der politischen Leiter) appointed by Hitler and the general membership (Parteimitglieder). The party and the SA were kept separate and the legal aspect of the party's work was emphasised. In a sign of this, the party began to admit women. The SA and the SS members (the latter founded in 1925 as Hitler's bodyguard, and known originally as the Schutzkommando) had to all be regular party members.[92][93]

In the 1920s the Nazi Party expanded beyond its Bavarian base. At this time, it began surveying voters in order to determine what they were dissatisfied with in Germany, allowing Nazi propaganda to be altered accordingly.[94] Catholic Bavaria maintained its right-wing nostalgia for a Catholic monarch;[citation needed] and Westphalia, along with working-class "Red Berlin", were always the Nazis' weakest areas electorally, even during the Third Reich itself. The areas of strongest Nazi support were in rural Protestant areas such as Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg, Pomerania and East Prussia. Depressed working-class areas such as Thuringia also produced a strong Nazi vote, while the workers of the Ruhr and Hamburg largely remained loyal to the Social Democrats, the Communist Party of Germany or the Catholic Centre Party. Nuremberg remained a Nazi Party stronghold, and the first Nuremberg Rally was held there in 1927. These rallies soon became massive displays of Nazi paramilitary power and attracted many recruits. The Nazis' strongest appeal was to the lower middle-classes—farmers, public servants, teachers and small businessmen—who had suffered most from the inflation of the 1920s, so who feared Bolshevism more than anything else. The small business class was receptive to Hitler's antisemitism, since it blamed Jewish big business for its economic problems. University students, disappointed at being too young to have served in the War of 1914–1918 and attracted by the Nazis' radical rhetoric, also became a strong Nazi constituency. By 1929, the party had 130,000 members.[95]

The party's nominal Deputy Leader was Rudolf Hess, but he had no real power in the party. By the early 1930s, the senior leaders of the party after Hitler were Heinrich Himmler, Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Göring. Beneath the Leadership Corps were the party's regional leaders, the Gauleiters, each of whom commanded the party in his Gau ("region"). Goebbels began his ascent through the party hierarchy as Gauleiter of Berlin-Brandenburg in 1926. Streicher was Gauleiter of Franconia, where he published his antisemitic newspaper Der Stürmer. Beneath the Gauleiter were lower-level officials, the Kreisleiter ("county leaders"), Zellenleiter ("cell leaders") and Blockleiter ("block leaders"). This was a strictly hierarchical structure in which orders flowed from the top and unquestioning loyalty was given to superiors. Only the SA retained some autonomy. Being composed largely of unemployed workers, many SA men took the Nazis' socialist rhetoric seriously. At this time, the Hitler salute (borrowed from the Italian fascists) and the greeting "Heil Hitler!" were adopted throughout the party.

The Nazis contested elections to the national parliament (the Reichstag) and to the state legislature (the Landtage) from 1924, although at first with little success. The "National Socialist Freedom Movement" polled 3% of the vote in the December 1924 Reichstag elections and this fell to 2.6% in 1928. State elections produced similar results. Despite these poor results and despite Germany's relative political stability and prosperity during the later 1920s, the Nazi Party continued to grow. This was partly because Hitler, who had no administrative ability, left the party organisation to the head of the secretariat, Philipp Bouhler, the party treasurer Franz Xaver Schwarz and business manager Max Amann. The party had a capable propaganda head in Gregor Strasser, who was promoted to national organizational leader in January 1928. These men gave the party efficient recruitment and organizational structures. The party also owed its growth to the gradual fading away of competitor nationalist groups, such as the German National People's Party (DNVP). As Hitler became the recognised head of the German nationalists, other groups declined or were absorbed. In the late 1920s, seeing the party's lack of breakthrough into the mainstream, Goebbels proposed that instead of focusing all of their propaganda in major cities where there was competition from other political movements, they should instead begin holding rallies in rural areas where they would be more effective.[96]

Despite these strengths, the Nazi Party might never have come to power had it not been for the Great Depression and its effects on Germany. By 1930, the German economy was beset with mass unemployment and widespread business failures. The Social Democrats and Communists were bitterly divided and unable to formulate an effective solution: this gave the Nazis their opportunity and Hitler's message, blaming the crisis on the Jewish financiers and the Bolsheviks, resonated with wide sections of the electorate. At the September 1930 Reichstag elections, the Nazis won 18% of the votes and became the second-largest party in the Reichstag after the Social Democrats. Hitler proved to be a highly effective campaigner, pioneering the use of radio and aircraft for this purpose. His dismissal of Strasser and his appointment of Goebbels as the party's propaganda chief were major factors. While Strasser had used his position to promote his own leftish version of national socialism, Goebbels was completely loyal to Hitler, and worked only to improve Hitler's image.

The 1930 elections changed the German political landscape by weakening the traditional nationalist parties, the DNVP and the DVP, leaving the Nazis as the chief alternative to the discredited Social Democrats and the Zentrum, whose leader, Heinrich Brüning, headed a weak minority government. The inability of the democratic parties to form a united front, the self-imposed isolation of the Communists and the continued decline of the economy, all played into Hitler's hands. He now came to be seen as de facto leader of the opposition and donations poured into the Nazi Party's coffers. Some major business figures, such as Fritz Thyssen, were Nazi supporters and gave generously[97] and some Wall Street figures were allegedly involved,[citation needed] but many other businessmen were suspicious of the extreme nationalist tendencies of the Nazis and preferred to support the traditional conservative parties instead.[98]

In 1931 the Nazi Party altered its strategy to engage in perpetual campaigning across the country, even outside of election time.[99] During 1931 and into 1932, Germany's political crisis deepened. Hitler ran for president against the incumbent Paul von Hindenburg in March 1932, polling 30% in the first round and 37% in the second against Hindenburg's 49% and 53%. By now the SA had 400,000 members and its running street battles with the SPD and Communist paramilitaries (who also fought each other) reduced some German cities to combat zones. Paradoxically, although the Nazis were among the main instigators of this disorder, part of Hitler's appeal to a frightened and demoralised middle class was his promise to restore law and order. Overt antisemitism was played down in official Nazi rhetoric, but was never far from the surface. Germans voted for Hitler primarily because of his promises to revive the economy (by unspecified means), to restore German greatness and overturn the Treaty of Versailles and to save Germany from communism. On 24 April 1932, the Free State of Prussia elections to the Landtag resulted in 36% of the votes and 162 seats for the NSDAP.

On 20 July 1932, the Prussian government was ousted by a coup, the Preussenschlag; a few days later at the July 1932 Reichstag election the Nazis made another leap forward, polling 37% and becoming the largest party in parliament by a wide margin. Furthermore, the Nazis and the Communists between them won 52% of the vote and a majority of seats. Since both parties opposed the established political system and neither would join or support any ministry, this made the formation of a majority government impossible. The result was weak ministries governing by decree. Under Comintern directives, the Communists maintained their policy of treating the Social Democrats as the main enemy, calling them "social fascists", thereby splintering opposition to the Nazis.[g] Later, both the Social Democrats and the Communists accused each other of having facilitated Hitler's rise to power by their unwillingness to compromise.

Chancellor Franz von Papen called another Reichstag election in November, hoping to find a way out of this impasse. The electoral result was the same, with the Nazis and the Communists winning 50% of the vote between them and more than half the seats, rendering this Reichstag no more workable than its predecessor. However, support for the Nazis had fallen to 33.1%, suggesting that the Nazi surge had passed its peak—possibly because the worst of the Depression had passed, possibly because some middle-class voters had supported Hitler in July as a protest, but had now drawn back from the prospect of actually putting him into power. The Nazis interpreted the result as a warning that they must seize power before their moment passed. Had the other parties united, this could have been prevented, but their shortsightedness made a united front impossible. Papen, his successor Kurt von Schleicher and the nationalist press magnate Alfred Hugenberg spent December and January in political intrigues that eventually persuaded President Hindenburg that it was safe to appoint Hitler as Reich Chancellor, at the head of a cabinet including only a minority of Nazi ministers—which he did on 30 January 1933.

Ascension and consolidation

In Mein Kampf, Hitler directly attacked both left-wing and right-wing politics in Germany.[h] However, a majority of scholars identify Nazism in practice as being a far-right form of politics.[101][page needed] When asked in an interview in 1934 whether the Nazis were "bourgeois right-wing" as alleged by their opponents, Hitler responded that Nazism was not exclusively for any class and indicated that it favoured neither the left nor the right, but preserved "pure" elements from both "camps" by stating: "From the camp of bourgeois tradition, it takes national resolve, and from the materialism of the Marxist dogma, living, creative Socialism".[102]

The votes that the Nazis received in the 1932 elections established the Nazi Party as the largest parliamentary faction of the Weimar Republic government. Hitler was appointed as Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933.

The Reichstag fire on 27 February 1933 gave Hitler a pretext for suppressing his political opponents. The following day he persuaded the Reich's President Paul von Hindenburg to issue the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended most civil liberties. The NSDAP won the parliamentary election on 5 March 1933 with 44% of votes, but failed to win an absolute majority. After the election, hundreds of thousands of new members joined the party for opportunistic reasons, most of them civil servants and white-collar workers. They were nicknamed the "casualties of March" (German: Märzgefallenen) or "March violets" (German: Märzveilchen).[103] To protect the party from too many non-ideological turncoats who were viewed by the so-called "old fighters" (alte Kämpfer) with some mistrust,[103] the party issued a freeze on admissions that remained in force from May 1933 to 1937.[104]

On 23 March, the parliament passed the Enabling Act of 1933, which gave the cabinet the right to enact laws without the consent of parliament. In effect, this gave Hitler dictatorial powers. Now possessing virtually absolute power, the Nazis established totalitarian control as they abolished labour unions and other political parties and imprisoned their political opponents, first at wilde Lager, improvised camps, then in concentration camps. Nazi Germany had been established, yet the Reichswehr remained impartial. Nazi power over Germany remained virtual, not absolute.

| Election | Votes | Seats | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | +/– | No. | +/– | ||

| May 1924 (as National Socialist Freedom Movement) |

1,918,300 | 6.5 (No. 6) | 32 / 472

|

Hitler in prison | ||

| December 1924 (as National Socialist Freedom Movement) |

907,300 | 3.0 (No. 8) | 14 / 493

|

Hitler released from prison | ||

| May 1928 | 810,100 | 2.6 (No. 9) | 12 / 491

|

|||

| September 1930 | 6,409,600 | 18.3 (No. 2) | 107 / 577

|

After the financial crisis | ||

| July 1932 | 13,745,000 | 37.3 (No. 1) | 230 / 608

|

After Hitler was candidate for presidency | ||

| November 1932 | 11,737,000 | 33.1 (No. 1) | 196 / 584

|

|||

| March 1933 | 17,277,180 | 43.9 (No. 1) | 288 / 647

|

During Hitler's term as Chancellor of Germany | ||

After taking power: intertwining of party and state

The Nazis embarked on a campaign of Gleichschaltung (coordination) to exert their control over all aspects of German government and society. During June and July 1933, all competing parties were either outlawed or dissolved themselves and subsequently the Law Against the Formation of Parties of 14 July 1933 legally established the Nazi Party's monopoly. On 1 December 1933, the Law to Secure the Unity of Party and State entered into force, which was the base for a progressive intertwining of party structures and state apparatus.[106] By this law, the SA—actually a party division—was given quasi-governmental authority and their Stabschef became a cabinet minister without portfolio. By virtue of the 30 January 1934 Law on the Reconstruction of the Reich, the Länder (states) lost their sovereignty and were demoted to administrative divisions of the Reich government. Effectively, they lost most of their power to the Gaue that were originally just regional divisions of the party, but took over most competencies of the state administration in their respective sectors.[107]

During the Röhm Purge of 30 June to 2 July 1934 (also known as the "Night of the Long Knives"), Hitler disempowered the SA's leadership—most of whom belonged to the Strasserist (national revolutionary) faction within the NSDAP—and ordered them killed. He accused them of having conspired to stage a coup d'état, but it is believed that this was only a pretense to justify the suppression of any intraparty opposition. The purge was executed by the SS, assisted by the Gestapo and Reichswehr units. Aside from Strasserist Nazis, they also murdered anti-Nazi conservative figures like former chancellor von Schleicher.[108] After this, the SA continued to exist but lost much of its importance, while the role of the SS grew significantly. Formerly only a sub-organisation of the SA, it was made into a separate organisation of the NSDAP in July 1934.[109]

Upon the death of President Hindenburg on 2 August 1934, Hitler merged the offices of party leader, head of state and chief of government in one, taking the title of Führer und Reichskanzler by passage of the Law Concerning the Head of State of the German Reich. The Chancellery of the Führer, officially an organisation of the Nazi Party, took over the functions of the Office of the President (a government agency), blurring the distinction between structures of party and state even further. The SS increasingly exerted police functions, a development which was formally documented by the merger of the offices of Reichsführer-SS and Chief of the German Police on 17 June 1936, as the position was held by Heinrich Himmler who derived his authority directly from Hitler.[110] The Sicherheitsdienst (SD, formally the "Security Service of the Reichsführer-SS") that had been created in 1931 as an intraparty intelligence became the de facto intelligence agency of Nazi Germany. It was put under the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) in 1939, which then coordinated SD, Gestapo and criminal police, therefore functioning as a hybrid organisation of state and party structures.[111]

| Election | Votes | % | Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| November 1933 | 39,655,224 | 92.1 | 661 / 661

|

| 1936 | 44,462,458 | 98.8 | 741 / 741

|

| 1938 | 44,451,092 | 99.0 | 813 / 813

|

Defeat and abolition

Officially, Nazi Germany lasted only 12 years. The Instrument of Surrender was signed by representatives of the German High Command at Berlin, on 8 May 1945, when the war ended in Europe.[112] The party was formally abolished on 10 October 1945 by the Allied Control Council, followed by the process of denazification along with trials of major war criminals before the International Military Tribunal (IMT) in Nuremberg.[113] Part of the Potsdam Agreement called for the destruction of the Nazi Party alongside the requirement for the reconstruction of the German political life.[114] In addition, the Control Council Law no. 2 Providing for the Termination and Liquidation of the Nazi Organization specified the abolition of 52 other Nazi affiliated and supervised organisations and outlawed their activities.[115] The denazification was carried out in Germany and continued until the onset of the Cold War.[116][page needed][117]

Between 1939 and 1945, the Nazi Party led regime, assisted by collaborationist governments and recruits from occupied countries, was responsible for the deaths of at least eleven million people,[118][119] including 5.5 to 6 million Jews (representing two-thirds of the Jewish population of Europe),[19][120][121] and between 200,000 and 1,500,000 Romani people.[122][123] The estimated total number includes the killing of nearly two million non-Jewish Poles,[123] over three million Soviet prisoners of war,[124] communists, and other political opponents, homosexuals, the physically and mentally disabled.[125][126]

Political programme

The National Socialist Programme was a formulation of the policies of the party. It contained 25 points and is therefore also known as the "25-point plan" or "25-point programme". It was the official party programme, with minor changes, from its proclamation as such by Hitler in 1920, when the party was still the German Workers' Party, until its dissolution.

Party composition

Command structure

Top leadership

At the top of the Nazi Party was the party chairman ("Der Führer"), who held absolute power and full command over the party. All other party offices were subordinate to his position and had to depend on his instructions. In 1934, Hitler founded a separate body for the chairman, Chancellery of the Führer, with its own sub-units.

Below the Führer's chancellery was first the "Staff of the Deputy Führer", headed by Rudolf Hess from 21 April 1933 to 10 May 1941; and then the "Party Chancellery" (Parteikanzlei), headed by Martin Bormann.

Following Hitler's suicide on 30 April 1945, Bormann would be named as Party Minister, which gave him the top position in the Nazi Party itself;[127] unlike Hitler, however, Bormann would not have a leadership role over the government of Nazi Germany.[127] Bormann, whose fate would remain unknown for several decades, would soon afterwards commit suicide as well on 2 May 1945 while trying flee Berlin around the time Soviet Union forces captured the city.[128][129] his remains were first identified in 1972, then again in 1998 through DNA testing.[130][131]

Reichsleiter

Directly subjected to the Führer were the Reichsleiter ("Reich Leader(s)"—the singular and plural forms are identical in German), whose number was gradually increased to eighteen. They held power and influence comparable to the Reich Ministers' in Hitler's Cabinet. The eighteen Reichsleiter formed the "Reich Leadership of the Nazi Party" (Reichsleitung der NSDAP), which was established at the so-called Brown House in Munich. Unlike a Gauleiter, a Reichsleiter did not have individual geographic areas under their command, but were responsible for specific spheres of interest.

Nazi Party offices

The Nazi Party had a number of party offices dealing with various political and other matters. These included:

- Rassenpolitisches Amt der NSDAP (RPA): "NSDAP Office of Racial Policy"

- Außenpolitische Amt der NSDAP (APA): "NSDAP Office of Foreign Affairs"

- Kolonialpolitisches Amt der NSDAP (KPA): "NSDAP Office of Colonial Policy"

- Wehrpolitisches Amt der NSDAP (WPA): "NSDAP Office of Military Policy"

- Amt Rosenberg (ARo): "Rosenberg Office"

Paramilitary groups

In addition to the Nazi Party proper, several paramilitary groups existed which "supported" Nazi aims. All members of these paramilitary organisations were required to become regular Nazi Party members first and could then enlist in the group of their choice. An exception was the Waffen-SS, considered the military arm of the SS and Nazi Party, which during the Second World War allowed members to enlist without joining the Nazi Party. Foreign volunteers of the Waffen-SS were also not required to be members of the Nazi Party, although many joined local nationalist groups from their own countries with the same aims. Police officers, including members of the Gestapo, frequently held SS rank for administrative reasons (known as "rank parity") and were likewise not required to be members of the Nazi Party.

A vast system of Nazi Party paramilitary ranks developed for each of the various paramilitary groups. This was part of the process of Gleichschaltung with the paramilitary and auxiliary groups swallowing existing associations and federations after the Party was flooded by millions of membership applications.[132]

The major Nazi Party paramilitary groups were as follows:

- Schutzstaffel (SS): "Protection Squadron" (both Allgemeine SS and Waffen-SS)

- Sturmabteilung (SA): "Storm Division"

- Nationalsozialistisches Fliegerkorps (NSFK): "National Socialist Flyers Corps"

- Nationalsozialistisches Kraftfahrerkorps (NSKK): "National Socialist Motor Corps"

The Hitler Youth was a paramilitary group divided into an adult leadership corps and a general membership open to boys aged fourteen to eighteen. The League of German Girls was the equivalent group for girls.

Affiliated organisations

Certain nominally independent organisations had their own legal representation and own property, but were supported by the Nazi Party. Many of these associated organisations were labour unions of various professions. Some were older organisations that were nazified according to the Gleichschaltung policy after the 1933 takeover.

- Reich League of German Officials (union of civil servants, predecessor to German Civil Service Federation)

- German Labour Front (DAF)

- National Socialist German Doctors' League

- National Socialist League for the Maintenance of the Law (NSRB, 1936–1945, earlier National Socialist German Lawyers' League)

- National Socialist War Victim's Care (NSKOV)

- National Socialist Teachers League (NSLB)

- National Socialist People's Welfare (NSV)

- Reich Labour Service (RAD)

- German Faith Movement

- German Colonial League (RKB)

- German Red Cross

- Kyffhäuser League

- Technical Emergency Relief (TENO)

- Reich's Union of Large Families

- Reichsluftschutzbund (RLB)

- Reichskolonialbund (RKB)

- Bund Deutscher Osten (BDO)

- German American Bund

The employees of large businesses with international operations such as Deutsche Bank, Dresdner Bank, and Commerzbank were mostly party members.[133] All German businesses abroad were also required to have their own Nazi Party Ausland-Organization liaison men, which enabled the party leadership to obtain updated and excellent intelligence on the actions of the global corporate elites.[134][page needed]

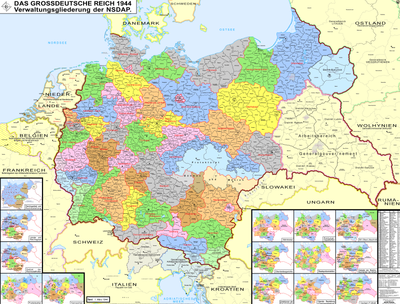

Regional administration

For the purpose of centralisation in the Gleichschaltung process, a rigidly hierarchal structure was established in the Nazi Party, which it later carried through in the whole of Germany in order to consolidate total power under the person of Hitler (Führerstaat). It was regionally sub-divided into a number of Gaue (singular: Gau) headed by a Gauleiter, who received their orders directly from Hitler. The name (originally a term for sub-regions of the Holy Roman Empire headed by a Gaugraf) for these new provincial structures was deliberately chosen because of its mediaeval connotations. The term is approximately equivalent to the English shire.

While the Nazis maintained the nominal existence of state and regional governments in Germany itself, this policy was not extended to territories acquired after 1937. Even in German-speaking areas such as Austria, state and regional governments were formally disbanded as opposed to just being dis-empowered.

After the Anschluss a new type of administrative unit was introduced called a Reichsgau. In these territories the Gauleiters also held the position of Reichsstatthalter (Reich Governor) thereby formally combining the spheres of both party and state offices. The establishment of this type of district was subsequently carried out for any further territorial annexations of Germany both before and during World War II. Even the former territories of Prussia were never formally re-integrated into what was then Germany's largest state after being re-taken in the 1939 Polish campaign.

The Gaue and Reichsgaue (state or province) were further sub-divided into Kreise (counties) headed by a Kreisleiter, which were in turn sub-divided into Zellen (cells) and Blöcke (blocks), headed by a Zellenleiter and Blockleiter respectively.

A reorganisation of the Gaue was enacted on 1 October 1928. The given numbers were the official ordering numbers. The statistics are from 1941, for which the Gau organisation of that moment in time forms the basis. Their size and populations are not exact; for instance, according to the official party statistics the Gau Kurmark/Mark Brandenburg was the largest in the German Reich.[135][page needed] By 1941, there were 42 territorial Gaue for Greater Germany.[i] Of these, 10 were designated as Reichsgaue: 7 of them for Austria, one for the Sudetenland (annexed from Czechoslovakia) and two for the areas annexed from Poland and the Free City of Danzig after the joint invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in 1939 at the onset of World War II.[136] Getting the leadership of the individual Gaue to co-operate with one another proved difficult at times since there was constant administrative and financial jockeying for control going on between them.[137]

The first table below describes the organizational structure for the Gaue that existed before their dissolution in 1945.[138] Information on former Gaue (that were either renamed, or dissolved by being divided or merged with other Gaue) is provided in the second table.[139]

Nazi Party Gaue

| Nr. | Gau | Headquarters | Area (km2) | Inhabitants (1941) | Gauleiter |

| 01 | Baden-Alsace | Strasbourg | 23,350 | 2,502,023 | Robert Heinrich Wagner from 22 March 1941 |

| 02 | Bayreuth, renaming of Gau Bayerische Ostmark 2 June 1942 | Bayreuth | 29,600 | 2,370,658 | Hans Schemm (1933–1935) Fritz Wachtler (1935–1945) Ludwig Ruckdeschel from 19 April 1945 |

| 03 | Berlin | Berlin | 884 | 4,338,756 | Joseph Goebbels from 1 October 1928 |

| 04 | Danzig-Westpreußen | Danzig | 26,057 | 2,287,394 | Albert Forster from 10 October 1939 |

| 05 | Düsseldorf | Düsseldorf | 2,672 | 2,261,909 | Friedrich Karl Florian from 1 August 1930 |

| 06 | Essen | Essen | 2,825 | 1,921,326 | Josef Terboven from 1 August 1928 |

| 07 | Franken, renaming of Gau Mittelfranken 21 April 1933 | Nuremberg | 7,618 | 1,077,216 | Julius Streicher (1929–1940) Hans Zimmermann (1940–1942) Karl Holz from 19 March 1942 |

| 08 | Halle-Merseburg | Halle an der Saale | 10,202 | 1,578,292 | Walter Ernst (1925–1926) Paul Hinkler (1926–1931) Rudolf Jordan (1931–1937) Joachim Albrecht Eggeling from 20 April 1937 |

| 09 | Hamburg | Hamburg | 747 | 1,711,877 | Josef Klant (1925–1926) Albert Krebs (1926–1928) Hinrich Lohse (1928–1929) Karl Kaufmann from 15 April 1929 |

| 10 | Hessen-Nassau | Frankfurt | 15,030 | 3,117,266 | Jakob Sprenger from 1 January 1933 |

| 11 | Kärnten | Klagenfurt | 11,554 | 449,713 | Hans Mazenauer (1926–1927) Hugo Herzog (1927–1933) Hans vom Kothen (1933) Hubert Klausner (1933–1936) Peter Feistritzer (1936–1938) Hubert Klausner (1938–1939) Franz Kutschera (1939–1941) Friedrich Rainer from 27 November 1941 |

| 12 | Köln-Aachen | Köln | 8,162 | 2,432,095 | Joseph Grohé from 1 June 1931 |

| 13 | Kurhessen, renaming of Gau Hessen-Nord 1934 | Kassel | 9,200 | 971,887 | Walter Schultz (1925–1928) Karl Weinrich (1928–1943) Karl Gerland from 6 November 1943 |

| 14 | Magdeburg-Anhalt, renaming of Gau Anhalt-Provinz Sachsen Nord 1 October 1928 | Dessau | 13,910 | 1,820,416 | Gustav Hermann Schmischke (1926–1927) Wilhelm Friedrich Loeper (1927–1935) with a short replacement by Paul Hofmann from August to December 1932 Joachim Albrecht Eggeling (1935–1937) Rudolf Jordan from 20 April 1937 |

| 15 | Mainfranken, renaming of Gau Unterfranken 30 July 1935 | Würzburg | 8,432 | 840,663 | Otto Hellmuth from 1 October 1928 |

| 16 | Mark Brandenburg, renaming of Gau Kurmark 1 January 1939 |

Berlin | 38,278 | 3,007,933 | Wilhelm Kube (1933–1936) Emil Stürtz from 7 August 1936 |

| 17 | Mecklenburg, renaming of Gau Mecklenburg-Lübeck 1 April 1937 |

Schwerin | 15,722 | 900,427 | Friedrich Hildebrandt from 1925 with a short replacement by Herbert Albrecht (July 1930 – January 1931) |

| 18 | Moselland | Koblenz | 11,876 | 1,367,354 | Gustav Simon from 24 January 1941 |

| 19 | München-Oberbayern | Munich | 16,411 | 1,938,447 | Adolf Wagner (1930–1944) Paul Giesler from 12 April 1944 |

| 20 | Niederdonau, renaming of Gau Niederösterreich 21 May 1938 |

Nominal capital: Krems, District Headquarters: Vienna | 23,502 | 1,697,676 | Leopold Eder (1926–1927) Josef Leopold (1927–1938) Hugo Jury from 21 May 1938 |

| 21 | Niederschlesien | Breslau | 26,985 | 3,286,539 | Karl Hanke from 27 January 1941 |

| 22 | Oberdonau, renaming of Gau Oberösterreich 22 May 1938 |

Linz | 14,216 | 1,034,871 | Albert Proksch (1926–1927) Andreas Bolek (1927–1934) Rudolf Lengauer (1934–1935) Oscar Hinterleitner (1935) August Eigruber from 22 May 1938 |

| 23 | Oberschlesien | Kattowitz | 20,636 | 4,341,084 | Fritz Bracht from 27 January 1941 |

| 24 | Ost-Hannover, renaming of Gau Lüneburg-Stade 1 October 1928 |

Buchholz, after 1 April 1937 Lüneburg | 18,006 | 1,060,509 | Otto Telschow from 27 March 1925 |

| 25 | Ostpreußen | Königsberg | 52,731 | 3,336,777 | Wilhelm Stich (1925–1926) Bruno Gustav Scherwitz (1926–1927) Hans Albert Hohnfeldt (1927–1928) Erich Koch from 1 October 1928 |

| 26 | Pommern | Stettin | 38,409 | 2,393,844 | Theodor Vahlen (1925–1927) Walther von Corswant (1927–1931) Wilhelm Karpenstein (1931–1934) Franz Schwede-Coburg from 21 July 1934 |

| 27 | Sachsen | Dresden | 14,995 | 5,231,739 | Martin Mutschmann from 27 March 1925 |

| 28 | Salzburg | Salzburg | 7,153 | 257,226 | Karl Scharizer (1932–1934) Anton Wintersteiger (1934–1938) Friedrich Rainer (1938–1941) Gustav Adolf Scheel from 27 November 1941 |

| 29 | Schleswig-Holstein | Kiel | 15,687 | 1,589,267 | Hinrich Lohse from 27 March 1925 |

| 30 | Schwaben | Augsburg | 10,231 | 946,212 | Karl Wahl from 1 October 1928 |

| 31 | Steiermark | Graz | 17,384 | 1,116,407 | Walther Oberhaidacher (1928–1934) Georg Bilgeri (1934–1935) Sepp Helfrich (1936–1938) Siegfried Uiberreither from 25 May 1938 |

| 32 | Sudetenland (also known as Sudetengau) | Reichenberg | 22,608 | 2,943,187 | Konrad Henlein from 1 October 1938 |

| 33 | Südhannover-Braunschweig | Hannover | 14,553 | 2,136,961 | Bernhard Rust (1928–1940) Hartmann Lauterbacher from 8 December 1940 |

| 34 | Thüringen | Weimar | 15,763 | 2,446,182 | Artur Dinter (1925–1927) Fritz Sauckel from 30 September 1927 |

| 35 | Tirol-Vorarlberg | Innsbruck | 13,126 | 486,400 | Franz Hofer from 25 May 1938 |

| 36 | Wartheland (also known as Warthegau), renaming of Gau Posen (29 January 1940) | Posen | 43,905 | 4,693,722 | Arthur Karl Greiser from 21 October 1939 |

| 37 | Weser-Ems | Oldenburg | 15,044 | 1,839,302 | Carl Röver (1928–1942) Paul Wegener from 26 May 1942 |

| 38 | Westfalen-Nord | Münster | 14,559 | 2,822,603 | Alfred Meyer from 31 January 1931 |

| 39 | Westfalen-Süd | Bochum | 7,656 | 2,678,026 | Josef Wagner (1931–1941) Paul Giesler (1941–1943) Albert Hoffmann from 26 January 1943 |

| 40 | Westmark | Saarbrücken | 14,713 | 1,892,240 | Josef Bürckel (1940–1944) Willi Stöhr from 29 September 1944 |

| 41 | Wien | Vienna | 1,216 | 1,929,976 | Walter Rentmeister (1926–1928) Eugen Werkowitsch (1928–1929) Robert Derda (1929) Alfred Frauenfeld (1930–1933) Leopold Tavs (1937–1938) Odilo Globocnik (1938–1939) Josef Bürckel (1939–1940) Baldur von Schirach from 8 August 1940 |

| 42 | Württemberg-Hohenzollern | Stuttgart | 20,657 | 2,974,373 | Eugen Munder (1925–1928) Wilhelm Murr from 1 February 1928 |

| 43 | Auslandsorganisation (also known as NSDAP/AO) | Berlin | Hans Nieland (1932–1933) Ernst Wilhelm Bohle from 17 February 1934 |

Later Gaue:

- Flanders, existed from 15 December 1944 (Gauleiter in German exile: Jef van de Wiele)

- Wallonia, existed from 8 December 1944 (Gauleiter in German exile: Léon Degrelle)

Gaue dissolved before 1945

The numbering is not based on any official former ranking, but merely listed alphabetically. Gaue that were simply renamed without territorial changes bear the designation RN in the column "later became." Gaue that were divided into more than one Gau bear the designation D in the column "later became." Gaue that were merged with other Gaue (or occupied territory) bear the designation M in the column "together with."

| Nr. | Gau | in existence | later became | together with | Gauleiter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Anhalt | 1925–1926 | Anhalt-Provinz Sachsen Nord (1 September 1926) |

Magdeburg & Elbe-Havel M | from 17 July 1925 to 1 September 1926 Gustav Hermann Schmischke |

| 02 | Anhalt-Provinz Sachsen Nord | 1926–1928 | Magdeburg-Anhalt (1 October 1928) RN |

see above table | |

| 03 | Baden | 1925–1941 | Baden-Elsaß (22 March 1941) |

Alsace M | from 25 March 1925 to 22 March 1941 Robert Heinrich Wagner |

| 04 | Bayerische Ostmark | 1933–1942 | Bayreuth (2 June 1942) RN |

see above table | |

| 05 | Berlin-Brandenburg | 1926–1928 | Berlin & Brandenburg (II) (1 October 1928) D |

from 26 October 1926 to 1 October 1928 Joseph Goebbels | |

| 06 | Brandenburg (I) | 1925–1926 | Potsdam (February 1926) RN |

from 5 November 1925 to February 1926 Walter Klaunig | |

| 07 | Brandenburg (II) | 1928–1933 | Kurmark (6 March 1933) |

Ostmark M | from 1 October 1928 to 1930 Emil Holtz, then from 18 October 1930 to 16 March 1933 Ernst Schlange |

| 08 | Burgenland | 1935–1938 | Niederdonau & Steiermark (1 October 1938) D |

from May 1935 to 1 October 1938 Tobias Portschy | |

| 09 | Danzig | 1926–1939 | Danzig-Westpreußen (10 October 1939) |

Westpreußen M | from 11 March 1926 to 20 June 1928 Hans Albert Hohnfeldt, then from 20 August 1928 to 1 March 1929 Walter Maass, then from 1 March 1929 to 30 September 1930 Erich Koch, then from 15 October 1930 to 10 October 1939 Albert Forster |

| 10 | Elbe-Havel | 1925–1926 | Anhalt-Provinz Sachsen Nord (1 September 1926) |

Anhalt & Magdeburg M | from 25 November 1925 to 1 September 1926 Alois Bachschmid |

| 11 | Göttingen | 1925 | Hannover-Süd (December 1925) RN |

from 27 March 1925 to December 1925 Ludolf Haase | |

| 12 | Groß-Berlin | 1925–1926 | Berlin-Brandenburg (26 October 1926) |

Potsdam M | from 27 March 1925 to 20 June 1926 Ernst Schlange, then from 20 June 1926 to 26 October 1926 Erich Schmiedicke |

| 13 | Groß-München ("Traditionsgau") | 1929–1930 | München-Oberbayern (15 November 1930) |

Oberbayern M | from 1 November 1929 to 15 November 1930 Adolf Wagner |

| 14 | Ганновер-Брауншвейг | 1925 | Ганновер Норт (December 1925) RN |

с 22 марта 1925 г. по декабрь 1925 г. Бернхард Руст | |

| 15 | Ганновер Норт | 1925–1928 | Южный Ганновер-Брауншвейг и Везер Эмс (1 октября 1928 г.) Д. |

с декабря 1925 г. по 30 сентября 1928 г. Бернхард Руст | |

| 16 | Ганновер Юг | 1925–1928 | Южный Ганновер-Брауншвейг (1 октября 1928 г.) |

Ганновер-Норд М | с декабря 1925 г. по 30 сентября 1928 г. Людольф Хаазе |

| 17 | Харцгау | 1925–1926 | Магдебург (апрель 1926 г.) РН |

с августа 1925 г. по апрель 1926 г. Людвиг Фирек | |

| 18 | Гессен-Дармштадт | 1927–1933 | Гессен-Нассау (1 января 1933 г.) |

Гессен-Нассау-Зюд М | с 1 марта 1927 г. по 9 января 1931 г. Фридрих Рингсхаузен , затем Петер Гемайндер до 30 августа 1931 г., затем Карл Ленц до 15 декабря 1932 г. |

| 19 | Гессен-Нассау-Север | 1925–1934 | Курхессен (1934) РН |

см. таблицу выше | |

| 20 | Гессен-Нассау-Юг | 1925–1932 | Гессен-Нассау (1 января 1933 г.) |

Гессен-Дармштадт М | с 1 апреля 1925 по 22 сентября 1926 года Антон Хазельмайер , затем с 1 октября 1926 по 1 апреля 1927 года Карл Линдер , затем с 1 апреля 1927 по 1 января 1933 года Якоб Шпренгер с кратковременной заменой Карлом Линдером (август 1932 — декабрь 1932) |

| 21 | Кобленц-Трир | 1931–1941 | Мозельланд (24 января 1941 г.) |

Люксембург М | с 1 июня 1931 г. по 24 января 1941 г. Густав Симон. |

| 22 | Кёльн | 1925 | Рейнланд-Юг (27 марта 1925 г.) РН |

с 22 февраля 1925 г. по 27 марта 1925 г. Генрих Хааке | |

| 23 | Курмарк | 1933–1939 | Марк Бранденбург (1 января 1939 г.) РН |

см. таблицу выше | |

| 24 | Люнебург-Штаде | 1925–1928 | Ост-Ганновер (1 октября 1928 г.) РН |

см. таблицу выше | |

| 25 | Магдебург | 1926 | Провинция Анхальт Саксония Север (1 сентября 1926 г.) |

останавливаться & Эльба-Гавел М |

с апреля 1926 г. по 1 сентября 1926 г. Людвиг Фирек. |

| 26 | Мекленбург-Любек | 1925– 1937 | Мекленбург (1 апреля 1937 г.) РН |

см. таблицу выше | |

| 27 | Средняя Франкония | 1929–1933 | Франкен (21 апреля 1933 г.) РН |

см. таблицу выше | |

| 28 | Средняя Франкония-Запад | 1928–1929 | Средняя Франкония (1 марта 1929 г.) |

Нюрнберг-Фюрт-Эрланген М | с 1 октября 1928 г. по 1 марта 1929 г. Вильгельм Гримм. |

| 29 | Нижняя Бавария (I) | 1925–1926 | Нижняя Бавария-Верхний Пфальц (I) (декабрь 1926 г.) |

Оберпфальц (I) М | с февраля 1925 г. по декабрь 1926 г. Грегор Штрассер |

| 30 | Нижняя Бавария (II) | 1928–1932 | Нижняя Бавария-Верхний Пфальц (II) (1 апреля 1932 г.) |

Верхний Пфальц (II) M | с 1 октября 1928 по 1 марта 1929 Грегор Штрассер , затем с 1 марта 1929 по 1 апреля 1932 Отто Эрберсдоблер , затем с 1 апреля 1932 по 17 августа 1932 Франц Майерхофер |

| 31 | Нижняя Бавария-Верхний Пфальц (I) | 1926–1928 | Верхний Пфальц (II) и Нижняя Бавария (II) (1 октября 1928 г.) Д. |

с декабря 1926 г. по 1 октября 1928 г. Грегор Штрассер. | |

| 32 | Нижняя Бавария-Верхний Пфальц (II) | 1932–1933 | Баварская остмарка (19 января 1933 г.) |

Оберфранкен М | с 17 августа 1932 г. по 13 января 1933 г. Франц Майерхофер. |

| 33 | Нижняя Австрия | 1926–1938 | Нидердонау (21 мая 1938 г.) РН |

см. таблицу выше | |

| 34 | Северная Бавария | 1925–1928 | Средняя Франкония-Запад, Нюрнберг-Фюрт, Верхняя Франкония и Нижняя Франкония (1 октября 1928 г.) Д. |

со 2 апреля 1925 г. по 1 октября 1928 г. Юлиус Штрайхер. | |

| 35 | Нюрнберг-Фюрт-Эрланген | 1925–1929 | Средняя Франкония (1 марта 1929 г.) |

Средняя Франкония-Запад M | со 2 апреля 1925 г. по 1 марта 1929 г. Юлиус Штрайхер. |

| 36 | Верхняя Бавария | 1928–1930 | Мюнхен-Верхняя Бавария (15 ноября 1930 г.) |

Большой Мюнхен М | с 1 октября 1928 г. по 1 ноября 1930 г. Фриц Рейнхардт. |

| 37 | Верхняя Бавария-Швабия | 1926–1928 | Верхняя Бавария и Швабия (1 октября 1928 г.) Д. |

с 16 сентября 1926 по май 1927 года Герман Эссер , затем с 1 июня 1928 по 1 октября 1928 года Фриц Рейнхардт | |

| 38 | Верхняя Франкония | 1929–1933 | Баварская остмарка (19 января 1933 г.) |

Нижняя Бавария-Верхний Пфальц (II) M | с 1 марта 1929 г. по 19 января 1933 г. Ганс Шемм |

| 39 | Верхняя Австрия | 1926–1938 | Обердонау (22 мая 1938 г.) РН |

см. таблицу выше | |

| 40 | Оберпфальц (I) | 1925–1926 | Нижняя Бавария-Верхний Пфальц (I) (декабрь 1926 г.) |

Нижняя Бавария (I) M | неизвестный |

| 41 | Оберпфальц (II) | 1928–1932 | Нижняя Бавария-Верхний Пфальц (II) (17 августа 1932 г.) |

Нижняя Бавария (II) М | с 1 октября 1928 по 1 ноября 1929 Адольф Вагнер , затем с 1 ноября 1929 по июнь 1930 Франц Майерхофер , затем с июня 1930 по ноябрь 1930 Эдмунд Гейнс , затем с 15 ноября 1930 по 17 августа 1932 Франц Майерхофер |

| 42 | Остмарк | 1928–1933 | Курмарк (6 марта 1933 г.) |

Бранденбург (II) М | со 2 января 1928 г. по 6 марта 1933 г. Вильгельм Кубе. |

| 43 | Остсаксен | 1925–1926 | Саксония (16 мая 1926 г.) |

Саксония М | с 22 мая 1925 г. по 16 мая 1926 г. Антон Госс |

| 44 | Пфальц-Саар | 1935–1936 | Саарпфальц (13 января 1936 г.) РН |

с 1 марта 1935 г. по 13 января 1936 г. Йозеф Бюркель | |

| 45 | Они обладают | 1939–1940 | Вартеланд (29 января 1940 г.) РН |

см. таблицу выше | |

| 46 | Потсдам | 1926 | Берлин-Бранденбург (26 октября 1926 г.) |

Большой Берлин М | с февраля по июнь 1926 г. Вальтер Клауниг |

| 47 | Рейнланд | 1926–1931 | Кёльн-Аахен и Кобленц-Трир (1 июня 1931 г.) Д. |

с июля 1926 г. по 1 июня 1931 г. Роберт Лей | |

| 48 | Рейнланд-Норд | 1925–1926 | Рур (7 марта 1926 г.) |

Вестфалия (I) М | с марта 1925 по июль 1925 Аксель Рипке , затем с июля 1925 по 7 марта 1926 Карл Кауфман . |

| 49 | Рейнланд Юг | 1925–1926 | Рейнланд (июль 1926 г.) РН |

27 марта 1925 г. — 1 июня 1925 г. Генрих Хааке , затем с июля 1925 г. по июль 1926 г. Роберт Лей. | |

| 50 | Райнпфальц | 1925–1935 | Пфальц-Саар (1 марта 1935 г.) |

Саар М | с февраля 1925 по 13 марта 1926 года Фридрих Вамбсгансс , затем с февраля 1926 по 1 марта 1935 года Йозеф Бюркель. |

| 51 | Рейн-Рур | 1926 | Рур (июль 1926 г.) РН |

с 7 марта 1926 г. по 20 июня 1926 г. Карл Кауфманн | |

| 52 | Рур («Гросгау Рур») |

1926–1928 | Дюссельдорф , Есть & Вестфалия (II) (1 октября 1928 г.) Д. |

с 20 июня 1926 г. по 1 октября 1928 г. Карл Кауфманн | |

| 53 | Удалять | 1926–1935 | Пфальц-Саар (1 марта 1935 г.) |

Райнпфальц М | с 30 мая 1926 по 8 декабря 1926 Вальтер Юнг , затем с 8 декабря 1926 по 21 апреля 1929 Якоб Юнг , затем с 21 апреля 1929 по 30 июля 1929 Густав Штебе (исполняющий обязанности), затем с 30 июля 1929 по 1 сентября 1931 Адольф Эреке , затем с 15 сентября 1931 г. по 6 мая 1933 г. Карл Брюк , затем с 6 мая 1933 г. по 1 марта 1935 г. Йозеф Бюркель. |

| 54 | Саарпфальц | 1936–1940 | Вестмарк (7 декабря 1940 г.) |

Лоррейн М | с 13 января 1936 г. по 7 декабря 1940 г. Йозеф Бюркель |

| 55 | Силезия | 1935–1941 | Нижняя Силезия и Верхняя Силезия (27 января 1941 г.) Д. |

с 15 марта 1925 г. по 4 декабря 1934 г. Гельмут Брюкнер , затем с 12 декабря 1934 г. по 9 января 1941 г. Йозеф Вагнер. | |

| 56 | Тироль | 1932–1938 | Тироль-Форарльберг (22 мая 1938 г.) |

Форарльберг М | с 1 ноября 1932 по июль 1934 Франц Хофер , затем с 28 июля 1934 по 1 февраля 1935 Фридрих Платтнер , затем с 15 августа 1935 по 11 марта 1938 Эдмунд Кристоф |

| 57 | Нижняя Франкония | 1928–1935 | Главная Франкония (30 июля 1935 г.) РН |

см. таблицу выше | |

| 58 | Форарльберг | 1932–1938 | Тироль-Форарльберг (22 мая 1938 г.) |

Тироль М | с 12 марта 1938 г. по 22 мая 1938 г. Антон Планкенштейнер |

| 59 | Вестфалия (I) | 1925–1926 | Рур (7 марта 1926 г.) |

Рейнланд-Норд М | с 27 марта 1925 г. по 7 марта 1926 г. Франц Пфеффер фон Саломон. |

| 60 | Вестфалия (II) | 1928–1931 | Вестфалия-Север и Южная Вестфалия (1 января 1931 г.) Д. |

с 1 октября 1928 г. по 1 января 1931 г. Йозеф Вагнер. | |

| 61 | Вестгау | 1928–1932 | Зальцбург , Тироль и Форарльберг (1 июля 1932 г.) Д. |

с 1 октября 1928 по 1931 год Генрих Зуске , затем с 1931 по 1 июля 1932 года Рудольф Ридель. |

Дочерние организации за рубежом

Ночь в Швейцарии

Нерегулярное швейцарское отделение нацистской партии также создало в этой стране ряд партийных организаций , большинство из которых названы в честь своих региональных столиц. В их число входили Гау Базель - Золотурн , Гау Шаффхаузен , Гау Люцерн , Гау Берн и Гау Цюрих . [ 140 ] [ 141 ] [ 142 ] Гау Остшвайц (Восточная Швейцария) объединил территории трёх кантонов: Санкт-Галлен , Тургау и Аппенцелль . [ 143 ]

Членство

Общее членство

Общий состав нацистской партии в основном состоял из городских и сельских низших слоев среднего класса . 7% принадлежали к высшему классу, еще 7% были крестьянами , 35% были промышленными рабочими и 51% относились к тому, что можно охарактеризовать как средний класс. В начале 1933 года, незадолго до назначения Гитлера на пост канцлера, в партии было недостаточно представлено «рабочих», которые составляли 30% членов, но 46% немецкого общества. И наоборот, служащие (19% членов и 12% немцев), самозанятые (20% членов и 10% немцев) и государственные служащие (15% членов и 5% населения Германии) имели присоединились в пропорциях, превышающих их долю в общей численности населения. [ 144 ] Эти члены были связаны с местными отделениями партии, которых в 1928 году насчитывалось 1378 по всей стране. В 1932 году их число возросло до 11 845, что отражает рост партии в этот период. [ 144 ]

Когда нацистская партия пришла к власти в 1933 году, она насчитывала более 2 миллионов членов. В 1939 году общее число членов выросло до 5,3 миллиона человек, из которых 81% составляли мужчины, а 19% - женщины. Она продолжала привлекать еще больше людей, и к 1945 году партия достигла своего пика в 8 миллионов человек, из которых 63% составляли мужчины, а 37% - женщины (около 10% 80-миллионного населения Германии). [ 4 ] [ 145 ]

Военное членство

Нацистских членов с военными амбициями поощряли вступать в Ваффен-СС, но большое их количество было зачислено в Вермахт , а еще больше было призвано на службу после начала Второй мировой войны. Ранние правила требовали, чтобы все члены Вермахта были аполитичными, а любой нацистский член, вступивший в 1930-е годы, должен был выйти из нацистской партии.

Однако вскоре это постановление было отменено, и полноправные члены нацистской партии служили в Вермахте, особенно после начала Второй мировой войны. В резервы Вермахта также поступило большое количество высокопоставленных нацистов: Рейнхард Гейдрих и Фриц Тодт присоединились к Люфтваффе , а также Карл Ханке , служивший в армии.

Британский историк Ричард Дж. Эванс писал, что младшие офицеры армии были склонны быть особенно ревностными национал-социалистами, причем треть из них присоединилась к нацистской партии к 1941 году. которые были созданы с целью воспитания войск для «истребительной войны» против Советской России. [ 146 ] Среди высших офицеров к 1941 году 29% были членами НСДАП. [ 147 ]

Студенческое членство

В 1926 году партия сформировала специальное подразделение для привлечения студентов, известное как Национал-социалистическая лига немецких студентов (NSDStB). Группа преподавателей университетов — Национал-социалистическая лига преподавателей университетов Германии (NSDDB) — также существовала до июля 1944 года.

Женское членство

Национал -социалистическая женская лига была женской организацией партии и к 1938 году насчитывала около 2 миллионов членов.

Членство за пределами Германии

Члены партии, проживавшие за пределами Германии, были объединены в Аусландскую организацию ( НСДАП/АО , «Иностранная организация»). Организация ограничивалась только так называемыми « имперскими немцами » (гражданами Германской империи); и «этническим немцам» ( Volksdeutsche ), не имевшим немецкого гражданства, не разрешили присоединиться.

Согласно указу Бенеша № 16/1945 Сб. Членство граждан Чехословакии в нацистской партии каралось лишением свободы на срок от пяти до двадцати лет.

Немецкое сообщество

Deutsche Gemeinschaft — филиал нацистской партии, основанный в 1919 году и созданный для немцев со статусом Volksdeutsche . [ 148 ] Ее не следует путать с послевоенной правой Deutsche Gemeinschaft , основанной в 1949 году.

Среди известных участников: [ 149 ] [ нужна страница ]

- Освальд Менгин ( Вена )

- Герман Нойбахер, ответственный за вторжение в Югославию.

- Рудольф Мач ( Вена )

- Артур Зейсс-Инкварт ( Вена )

Партийная символика

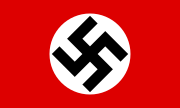

- Нацистские флаги : Нацистская партия использовала обращенную вправо свастику в качестве своего символа, а красный и черный цвета, как говорили, символизировали Blut und Boden («кровь и почва»). Другое определение флага описывает цвета как представляющие идеологию национал-социализма, свастику, представляющую арийскую расу и арийскую националистическую программу движения; белый, представляющий арийскую расовую чистоту; и красный цвет представляет социалистическую программу движения. Черный, белый и красный на самом деле были цветами старого флага Северо-Германской Конфедерации (изобретенного Отто фон Бисмарком на основе прусских цветов, черно-белого и красного, используемых северными немецкими государствами). В 1871 году, с основанием Германского Рейха, флаг Северо-Германской Конфедерации стал German Reichsflagge («флаг Рейха»). Черный, белый и красный стали цветами националистов в последующей истории (например, Первая мировая война и Веймарская республика ).

- Дизайн Parteiflagge с диском со свастикой в центре служил партийным флагом с 1920 года . В период с 1933 года (когда нацистская партия пришла к власти) по 1935 год он использовался как национальный флаг ( Nationalflagge ) и торговый флаг ( Handelsflagge ), но взаимозаменяем с черно-бело-красным горизонтальным триколором . В 1935 году черно-бело-красный горизонтальный триколор был (снова) отменен, а флаг со смещенной от центра свастикой и диском был учрежден в качестве национального флага и оставался таковым до 1945 года. Флаг с центральным диском продолжал использоваться. используется после 1935 года, но исключительно как Parteiflagge , флаг партии.

- Немецкий орел : Нацистская партия использовала традиционного немецкого орла , стоящего на вершине свастики внутри венка из дубовых листьев. Он также известен как «Железный орел». Когда орел смотрит на свое левое плечо, он символизирует нацистскую партию и называется Партейадлер . Напротив, когда орел смотрит на свое правое плечо, он символизирует страну ( Рейх ) и поэтому его называли Рейхсадлером . После того, как нацистская партия пришла к национальной власти в Германии, они заменили традиционную версию немецкого орла модифицированным партийным символом по всей стране и во всех ее учреждениях.

Звания и знаки отличия

Слоганы и песни

- нацистские лозунги: « Зиг Хайль ! »; « Хайль Гитлер »

- Нацистский гимн: Хорст-Вессель-Лиед

Результаты выборов

Немецкий Рейхстаг

| Год выборов | Голоса | % | Выиграно мест | +/– | Примечания |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1928 | 810,127 | 2.6 | 12 / 491

|

||

| 1930 | 6,379,672 | 18.3 | 107 / 577

|

||

| июль 1932 г. | 13,745,680 | 37.3 | 230 / 608

|

||

| ноябрь 1932 г. | 11,737,021 | 33.1 | 196 / 584

|

Последние свободные и честные выборы. | |

| Март 1933 г. | 17,277,180 | 43.9 | 288 / 647

|

Полусвободные, но сомнительные выборы. Последние многопартийные оспариваемые выборы. | |

| ноябрь 1933 г. | 39,655,224 | 92.1 | 661 / 661

|

Единственная юридическая сторона. | |

| 1936 | 44,462,458 | 98.8 | 741 / 741

|

Единственная юридическая сторона. | |

| 1938 | 44,451,092 | 99.0 | 813 / 813

|

Единственная юридическая сторона. |

Президентские выборы

| Год выборов | Кандидат | Первый раунд | Второй раунд | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Голоса | % | Место | Голоса | % | Место | ||

| 1925 | поддержал Людендорфа (1,1%) | поддержал Гинденбурга (48,3%) | |||||

| 1932 | Адольф Гитлер | 11,339,446 | 30.1 | 2-й | 13,418,547 | 36.8 | 2-й |

Народный день Гданьска

| Год выборов | Голоса | % | Выиграно мест | +/– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1927 | 1,483 | 0.8 | 1 / 72

|

|

| 1930 | 32,457 | 16.4 | 12 / 72

|

|

| 1933 | 107,331 | 50.1 | 38 / 72

|

|

| 1935 | 139,423 | 59.3 | 43 / 72

|

См. также

- Деловое сотрудничество с нацистской Германией

- Сотрудничество с нацистской Германией и фашистской Италией.

- Глоссарий нацистской Германии

- Список книг о нацистской Германии

- Список компаний, причастных к Холокосту

- Список лидеров и должностных лиц нацистской партии

- Массовые самоубийства в нацистской Германии в 1945 году.

- Неонацизм

- Китайско-германское сотрудничество (1926–1941)

- Партия Социалистического Рейха

- Фольксштурм

Ссылки

Информационные примечания