Отступничество в исламе

| Часть серии на |

| ислам |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on Islamism |

|---|

|

|

| Islam and other religions |

|---|

| Abrahamic religions |

| Other religions |

| Islam and... |

Эта статья написана как личное размышление, личное эссе или аргументативное эссе , в котором говорится личные чувства редактора Википедии или представляет оригинальный аргумент по теме. ( Май 2024 ) |

Отступничество в исламе арабский : ردة , романизированный : Ридда или ارتداد , irtidād ) обычно определяется как отказ от ислама мусульманином ( , в мысли, словом или посредстве. Он включает в себя не только явные отречения исламской веры путем обращения в другую религию [ 1 ] или отказ от религии , [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] но также богохульство или ересь теми, кто считает себя мусульманами, [ 4 ] через любое действие или высказывание, которое подразумевает неверие, в том числе тех, кто отрицает «фундаментальный принцип или вероисповедание » ислама. [5] An apostate from Islam is known as a murtadd (مرتدّ).[1][6][7][8][9]

While Islamic jurisprudence calls for the death penalty of those who refuse to repent of apostasy from Islam,[10] what statements or acts qualify as apostasy and whether and how they should be punished, are disputed among Islamic scholars.[11][3][12] The penalty of killing of apostates is in conflict with international human rights norms which provide for the freedom of religions, as demonstrated in human rights instruments such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights provide for the freedom of religion.[13][14][15][16]

Until the late 19th century, the majority of Sunni and Shia jurists held the view that for adult men, apostasy from Islam was a crime as well as a sin, punishable by the death penalty,[3][17] but with a number of options for leniency (such as a waiting period to allow time for repentance[3][18][19][20] or enforcement only in cases involving politics),[21][22][23] depending on the era, the legal standards and the school of law. In the late 19th century, the use of legal criminal penalties for apostasy fell into disuse, although civil penalties were still applied.[3]

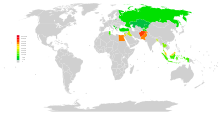

As of 2021, there were ten Muslim-majority countries where apostasy from Islam was punishable by death,[24] but legal executions are rare.[Note 1] Most punishment is extra-judicial/vigilante,[26][27] and most executions are perpetrated by jihadist and "takfiri" insurgents (al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, the GIA, and the Taliban).[10][28][29][30] Another thirteen countries have penal or civil penalties for apostates[27] – such as imprisonment, the annulment of their marriages, the loss of their rights of inheritance and the loss of custody of their children.[27]

In the contemporary Muslim world, public support for capital punishment varies from 78% in Afghanistan to less than 1% in Kazakhstan;[Note 2] among Islamic jurists, the majority of them continue to regard apostasy as a crime which should be punishable by death.[18] Those who disagree[11][3][32] argue that its punishment should be less than death, should occur in the afterlife,[33][34][35][36] (human punishment being inconsistent with Quranic injunctions against compulsion in belief),[37][38] or should apply only in cases of public disobedience and disorder (fitna).[Note 3]

Etymology and terminology

[edit]Apostasy is called irtidād (which means relapse or regress) or ridda in Islamic literature.[40] An apostate is called murtadd, which means 'one who turns back' from Islam.[41] (Another source – Oxford Islamic Studies Online – defines murtadd as "not just any kāfir (non-believer)", but "a particularly heinous type".)[42] Ridda can also refer to secession in a political context.[43] A person born to a Muslim father who later rejects Islam is called a murtadd fitri, and a person who converted to Islam and later rejects the religion is called a murtadd milli.[44][45][46] Takfir (takfeer) (Arabic: تكفير takfīr) is the act of one Muslim excommunicating another, declaring them a kafir, an apostate. The act which precipitates takfir is termed mukaffir.

Scriptural references

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (May 2024) |

Quran

[edit]The Quran references apostasy[47] (2:108, 66; 10:73; 3:90; 4:89, 137; 5:54; 9:11–12, 66; 16:06; 88:22–24) in the context of attitudes associated with impending punishment, divine anger, and the rejection of repentance for individuals who commit this act. Traditionally, these verses are thought to "appear to justify coercion and severe punishment" for apostates (according to Dale F. Eickelman),[48] including the traditional capital punishment.[49] Other scholars, by contrast, have pointed to a lack of any Quranic passage requiring the implementation of force to return apostates to Islam, nor any specific corporal punishment to apply to apostates in this world[50][51][52][Note 4] – let alone commands to kill apostates – either explicitly or implicitly.[54][55][56][57] Some verses have been cited as emphasizing mercy and a lack of compulsion with respect to religious belief (2:256; 4:137; 10:99; 11:28; 18:29; 88:21–22).[58]

Hadith

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (May 2024) |

The classical shariah punishment for apostasy comes from Sahih ("authentic") Hadith rather than the Quran.[59][60] Writing in the Encyclopedia of Islam, Heffening holds that contrary to the Quran, "in traditions [i.e. hadith], there is little echo of these punishments in the next world... and instead, we have in many traditions a new element, the death penalty."[41]

Allah's Apostle said, "The blood of a Muslim who confesses that none has the right to be worshipped but Allah and that I am His Apostle, cannot be shed except in three cases: In Qisas for murder, a married person who commits illegal sexual intercourse and the one who reverts from Islam (apostate) and leaves the Muslims."

Ali burnt some people and this news reached Ibn 'Abbas, who said, "Had I been in his place I would not have burnt them, as the Prophet said, 'Don't punish (anybody) with Allah's Punishment.' No doubt, I would have killed them, for the Prophet said, 'If somebody (a Muslim) discards his religion, kill him.'"

A man embraced Islam and then reverted back to Judaism. Mu'adh bin Jabal came and saw the man with Abu Musa. Mu'adh asked, "What is wrong with this (man)?" Abu Musa replied, "He embraced Islam and then reverted back to Judaism." Mu'adh said, "I will not sit down unless you kill him (as it is) the verdict of Allah and His Apostle."

Other hadith give differing statements about the fate of apostates;[35][61] that they were spared execution by repenting, by dying of natural causes or by leaving their community (the last case sometimes cited as an example of open apostasy that was left unpunished).[62]

A man from among the Ansar accepted Islam, then he apostatized and went back to Shirk. Then he regretted that, and sent word to his people (saying): 'Ask the Messenger of Allah [SAW], is there any repentance for me?' His people came to the Messenger of Allah [SAW] and said: 'So and so regrets (what he did), and he has told us to ask you if there is any repentance for him?' Then the Verses: 'How shall Allah guide a people who disbelieved after their Belief up to His saying: Verily, Allah is Oft-Forgiving, Most Merciful' was revealed. So he sent word to him, and he accepted Islam.

— Al-Sunan al-Sughra 37:103[63]

There was a Christian who became Muslim and read the Baqarah and the Al Imran, and he used to write for the Prophet. He then went over to Christianity again, and he used to say, Muhammad does not know anything except what I wrote for him. Then Allah caused him to die and they buried him.

A bedouin gave the Pledge of allegiance to Allah's Apostle for Islam and the bedouin got a fever where upon he said to the Prophet "Cancel my Pledge." But the Prophet refused. He came to him (again) saying, "Cancel my Pledge.' But the Prophet refused. Then (the bedouin) left (Medina). Allah's Apostle said: "Medina is like a pair of bellows (furnace): It expels its impurities and brightens and clears its good."

The Muwatta of Imam Malik offers a case were Rashidun (rightly guide) Caliph Umar admonishes a Muslim leader for not giving an apostate the opportunity to repent before being executed:

Malik related to me from Abd ar-Rahman ibn Muhammad ibn Abdullah ibn Abd al-Qari that his father said, "A man came to Umar ibn al-Khattab from Abu Musa al-Ashari. Umar asked after various people, and he informed him. Then Umar inquired, 'Do you have any recent news?' He said, 'Yes. A man has become a kafir after his Islam.' Umar asked, 'What have you done with him?' He said, 'We let him approach and struck off his head.' Umar said, 'Didn't you imprison him for three days and feed him a loaf of bread every day and call on him to tawba that he might turn in tawba and return to the command of Allah?' Then Umar said, 'O Allah! I was not present and I did not order it and I am not pleased since it has come to me!'

The argument has been made (by the Fiqh Council of North America, among others) that the hadiths above – traditionally cited as proof that apostates from Islam should be punished by death – have been misunderstood. In fact (the council argues), the victims were executed for changing their allegiances to the armies fighting the Muslims (i.e. for treason), not for their personal beliefs.[64] As evidence, they point to two hadith, each from a different "authentic" (sahih) Sunni hadith collection[Note 5] where Muhammad calls for the death of apostates or traitors. The wording of the hadith are almost identical, but in one, the hadith ends with the phrase "one who reverts from Islam and leaves the Muslims", and in the other it ends with "one who goes forth to fight Allah and His Apostle" (in other words, the council argues the hadith were likely reports of the same incident but had different wording because "reverting from Islam" was another way of saying "fighting Allah and His Apostle"):

Allah's Apostle said, "The blood of a Muslim who confesses that none has the right to be worshipped but Allah and that I am His Apostle, cannot be shed except in three cases: In Qisas for murder, a married person who commits illegal sexual intercourse and the one who reverts from Islam (apostate) and leaves the Muslims."

Allah's Apostle said: "The blood of a Muslim man who testifies that there is no god but Allah and that Muhammad is Allah's Apostle should not lawfully be shed except only for one of three reasons: a man who committed fornication after marriage, in which case he should be stoned; one who goes forth to fight Allah and His Apostle, in which case he should be killed or crucified or exiled from the land; or one who commits murder for which he is killed."

Definition of apostasy in Islam

[edit]Scholars of Islam differ as to what constitutes apostasy in that religion and under what circumstances an apostate is subject to the death penalty. [note?]

Conditions of apostasy in classical Islam

[edit]Al-Shafi'i listed three necessary conditions to pass capital punishment on a Muslim for apostasy in his Kitab al-Umm. (In the words of Frank Griffel) these are:

- "first, the apostate had to once have had faith (which, according to Al-Shafi'i's definition, means publicly professing all tenets of Islam);

- secondly, there had to follow unbelief (meaning the public declaration of a breaking-away from Islam), (having done these two the Muslim is now an unbeliever but not yet an apostate and thus not eligible for punishment);[Note 6]

- "third, there had to be the omission or failure to repent after the apostate was asked to do so."[66][65]

Three centuries later, Al-Ghazali wrote that one group, known as "secret apostates" or "permanent unbelievers" (aka zandaqa), should not be given a chance to repent, eliminating Al-Shafi'i's third condition for them although his view was not accepted by his Shafi'i madhhab.[67][65]

Characteristics

[edit]Describing what qualifies as apostasy Christine Schirrmacher writes

there is widespread consensus that apostasy undoubtedly exists where the truth of the Koran is denied, where blasphemy is committed against God, Islam, or Muhammad, and where breaking away from the Islamic faith in word or deed occurs. The lasting, willful non-observance of the five pillars of Islam, in particular the duty to pray, clearly count as apostasy for most theologians. Additional distinguishing features are a change of religion, confessing atheism, nullifying the Sharia as well as judging what is allowed to be forbidden and judging what is forbidden to be allowed. Fighting against Muslims and Islam (Arabic: muḥāraba) also counts as unbelief or apostasy;[68]

Kamran Hashemi classifies apostasy or unbelief in Islam into three different "phenomena":[69]

- Converting from Islam to another religion (or abandoning religion altogether),[69][70][71][3] also described as "explicit" apostasy.[3] (Hashemi gives the example of Abdul Rahman, an Afghan who was arrested in February 2006 and threatened with the death penalty in a lower court in Kabul for converting to Christianity).[72]

- Blaspheming (sabb)[69] (by a Muslim) against God, Islam, its laws or its prophet,[40][73] which can be defined, in practice, as any objection to the authenticity of Islam, its laws or its prophet.[69][74]

- Heresy;[69] or "implicit" apostasy (by a Muslim),[3] where the alleged apostate does not formally renounce Islam,[71] but has (in the eyes of their accusers) verbally denied some principle of belief prescribed by Qur'an or a Hadith; deviated from approved Islamic tenets (ilhad).[71] (Accusations of heresy, or takfir, often involve public thinkers and theologians – Mahmoud Mohammed Taha, Nasr Abu Zayd, Hashem Aghajari – but can involve the collective takfir of a large group and mass killings[75] – takfir of Algerians who did not support the Armed Islamic Group of Algeria in 1997, takfir of Shia by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi in 2005).[76]

Issues in defining heresy

[edit]

While identifying someone who publicly converted to another religion as an apostate was straightforward, determining whether a diversion from orthodox doctrine qualified as heresy, blasphemy, or something permitted by God could be less so. Traditionally, Islamic jurists did not formulate general rules for establishing unbelief, instead, compiled sometimes lengthy lists of statements and actions which in their view implied apostasy or were incompatible with Islamic "theological consensus".[3] Al-Ghazali,[77] for example, devoting "chapters to dealing with takfir and the reasons for which one can be accused of unbelief" in his work Faysal al-Tafriqa bayn al-Islam wa-l-Zandaqa ("The Criterion of Distinction between Islam and Clandestine Unbelief").[78][79]

Some heretical or blasphemous acts or beliefs listed in classical manuals of Islamic jurisprudence and other scholarly works (i.e. works written by Islamic scholars) that allegedly demonstrate apostasy include:

- to deny the obligatory character of something considered obligatory by ijma (legal consensus of Islamic scholars);[80][81]

- revile, question, wonder, doubt, mock, and/or deny the existence of God or Muhammad, or that Muhammad was sent by God;[80][81]

- belief that things in themselves or by their nature have a cause independent of the will of God;[80][81]

- to assert the createdness of the Quran and/or to translate the Quran in any language other than Arabic;[82]

- According to some to ridicule Islamic scholars or address them in a derisive manner, to reject the validity of sharīʿah courts;[82]

- Some also say to pay respect to non-Muslims, to celebrate Nowruz the Iranian New Year;[82]

- Though disputed to express uncertainty such as "'I do not know why God mentioned this or that in the Quran'...";[83]

- Some also say include for the wife of an Islamic scholar to curse her husband;[83]

- to make a declaration of prophethood; i.e., for someone to declare that they are a prophet or messenger. In the early history of Islam, following Muhammad's death, this act was automatically deemed to be proof of apostasy—because Islam teaches Muhammad was the last prophet, there could be no more after him.[84] This view is alleged to be the basis of the rejection of Ahmadi Muslims as apostates from Islam.[84][85][86]

While there are numerous requirements for a Muslim to avoid being an apostate, it is also an act of apostasy, in Shāfiʿī te doctrine and other schools of Islamic jurisprudence, for a Muslim to accuse or describe another devout Muslim of being an unbeliever,[87] based on the hadith where Muhammad is reported to have said: "If a man says to his brother, 'You are an infidel,' then one of them is right."[88][89] Historian Bernard Lewis writes that in "religious polemic" of early Islamic times, it was common for one scholar to accuse another of apostasy, but attempts to bring an alleged apostate to justice (have them executed) were very rare.[90]

The tension between desire to cleanse Islam of heresy and fear of inaccurate takfir is suggested in the writings of some of the leading Islamic scholars. Al-Ghazali "is often credited with having persuaded theologians", in his Fayal al-tafriqa, "that takfir is not a fruitful path and that utmost caution is to taken in applying it", but in other writing, he made sure to condemn as beyond the pale of Islam "philosophers and Ismaili esotericists". Ibn Hazm and Ibn Taymiyyah also "warned against unbridled takfir" while takfiring "specific categories" of theological opponents as "unbelievers".[91] Gilles Kepel writes that "used wrongly or unrestrainedly, this sanction would quickly lead to discord and sedition in the ranks of the faithful. Muslims might resort to mutually excommunicating one another and thus propel the Ummah to complete disaster."[92]

The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), for example, takfired all those who opposed its policy of exterminating and enslaving members of the Yazidi religion. According to one source, Jamileh Kadivar, the majority of the "27,947 terrorist deaths" ISIL has been responsible for (as of 2020) have been Muslims it regards "as kafir",[Note 7] as ISIL gives fighting alleged apostates a higher priority than fighting self-professed non-Muslims—Jews, Christians, Hindus, etc.[94] An open letter to ISIL by 126 Islamic scholars includes as one of its points of opposition to ISIL: "It is forbidden in Islam to declare people non-Muslim unless he (or she) openly declares disbelief".[95]

There is general agreement among Muslims that the takfir and mass killings of alleged apostates perpetrated not only by ISIL but also by the Armed Islamic Group of Algeria and Abu Musab al-Zarqawi's jihadis[76] were wrong, but there is less unanimity in other cases, such as what to do in a situation where self-professed Muslim(s) – post-modernist academic Nasr Abu Zayd or the Ahmadiyya movement – disagree with their accusers on an important doctrinal point. (Ahmadi quote a Muslim journalist, Abdul-Majeed Salik, claiming that, "all great and eminent Muslims in the history of Islam as well as all the sects in the Muslim world are considered to be disbelievers, apostates, and outside the pale of Islam according to one or the other group of religious leaders".)[Note 8] In the case of the Ahmadiyya – who are accused by mainstream Sunni and Shia of denying the basic tenet of the Finality of Prophethood (Ahmadis state they believe Mirza Ghulam Ahmad is a mahdi and a messiah)[97] – the Islamic Republic of Pakistan has declared in Ordinance XX of the Second Amendment to its Constitution, that Ahmadis are non-Muslims and deprived them of religious rights. Several large riots (1953 Lahore riots, 1974 Anti-Ahmadiyya riots) and a bombing (2010 Ahmadiyya mosques massacre) have killed hundreds of Ahmadis in that country. Whether this is unjust takfir or applying sharia to collective apostasy is disputed.[98]

- Overlap with blasphemy

The three types (conversion, blasphemy and heresy) of apostasy may overlap – for example some "heretics" were alleged not to be actual self-professed Muslims, but (secret) members of another religion, seeking to destroy Islam from within. (Abdullah ibn Mayun al-Qaddah, for example, "fathered the whole complex development of the Ismaili religion and organisation up to Fatimid times," was accused by his different detractors of being (variously) "a Jew, a Bardesanian and most commonly as an Iranian dualist")[99] In Islamic literature, the term "blasphemy" sometimes also overlaps with kufr ("unbelief"), fisq (depravity), isa'ah (insult), and ridda (apostasy).[100][101] Because blasphemy in Islam included rejection of fundamental doctrines,[47] blasphemy has historically been seen as an evidence of rejection of Islam, that is, the religious crime of apostasy. Some jurists believe that blasphemy automatically implies a Muslim has left the fold of Islam.[102] A Muslim may find himself accused of being a blasphemer, and thus an apostate on the basis of one action or utterance.[103][104]

- Collective apostasy

In collective apostasy, a self-proclaimed Islamic group/sect are declared to be heretics/apostates. Groups treated as collective apostates include zindiq, sometimes Sufis, and more recently Ahmadis and Bahais.[105] As described above, the difference between legitimate Muslim sects and illegitimate apostate groups can be subtle and Muslims have not agreed on where the line dividing them lies. According to Gianluca Parolin, "collective apostasy has always been declared on a case-by-case basis".[105]

- Fetri and national apostates

Among Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and others in Ja'fari fiqh, a distinction is made between "fetri" or "innate" apostates who grew up Muslims and remained Muslim after puberty until converting to another religion, and "national apostates" – essentially people who grew up non-Muslim and converted to Islam. "National apostates" are given a chance to repent, but "innate apostates are not.[106]

- Children raised in apostasy

Orthodox apostasy fiqh can be problematic for someone who was raised by a non-Muslim (or non-Muslims) but has an absentee Muslim parent, or was raised by an apostate (or apostates) from Islam. A woman born to a Muslim parent is considered an apostate if she marries a non-Muslim,[107][108] even if her Muslim parent did not raise her and she has always practiced another religion; and whether or not they know anything about Islam, by simply practicing the (new) religion of their parent(s) they become apostates (according to the committee of fatwa scholars at Islamweb.net).[109]

- Contemporary issues of defining apostasy

In the 19th, 20th and 21 century issues affecting shariʿah on apostasy include modern norms of freedom of religion,[3] the status of members of Baháʼí (considered unbeliever/apostates in Iran) and Ahmadi faiths (considered appostates from Islam in Pakistan and elsewhere),[3] those who "refuse to judge or be judged according to the shariʿah,"[3] and more recently the status of Muslims authorities and governments that do not implement classical shariʿah law in its completeness.

Punishment

[edit]

There are differences of opinion among Islamic scholars about whether, when and especially how apostasy in Islam should be punished.[11][3][41]

From 11th century onwards, apostasy of Muslims from Islam was forbidden by Islamic law, earlier apostasy law was only applicable if a certain number of witnesses testify which for the most past was impossible.[110][111][112] Apostasy was punishable by death and also by civil liabilities such as seizure of property, children, annulment of marriage, loss of inheritance rights.[3] (A subsidiary law, also applied throughout the history of Islam, forbade non-Muslims from proselytizing Muslims to leave Islam and join another religion,[113][114][110][111][112] because it encouraged Muslims to commit a crime). Starting in the 19th century the legal code of many Muslim states no longer included apostasy as a capital crime, and to compensate some Islamic scholars called for vigilante justice of hisbah to execute the offenders (see Apostasy in Islam#Colonial era and after).

In contemporary times the majority of Islamic jurists still regard apostasy as a crime deserving the death penalty, (according to Abdul Rashied Omar),[18] although "a growing body of Islamic jurists" oppose this,[Note 9] (according to Javaid Rehman)[11][3][32] as inconsistent with "freedom of religion" as expressed in the Quranic injunctions Quran 88:21-88:22[37] and Quran 2:256 ("there is no compulsion in religion");[25] and a relic of the early Islamic community when apostasy was desertion or treason.[38]

Still others support a "centrist or moderate position" of executing only those whose apostasy is "unambiguously provable" such as if two just Muslim eyewitnesses testify; and/or reserving the death penalty for those who make their apostacy public. According to Christine Schirrmacher, "a majority of theologians" embrace this stance.[115]

Who qualifies for judgement for the crime of apostasy

[edit]As mentioned above, there are numerous doctrinal fine points outlined in fiqh manuals whose violation should render the violator an apostate, but there are also hurdles and exacting requirements that spare (self-proclaimed) Muslims conviction for apostasy in classical fiqh.

One motive for caution is that it is an act of apostasy (in Shafi'i and other fiqh) for a Muslim to accuse or describe another innocent Muslim of being an unbeliever,[87] based on the hadith where Muhammad is reported to have said: "If a man says to his brother, 'You are an infidel,' then one of them is right."[116][117]

According to sharia, to be found guilty the accused must at the time of apostasizing be exercising free will, an adult, and of sound mind,[3] and have refused to repent when given a time period to do so (not all schools include this last requirement). The free will requirement excludes from judgement those who embraced Islam under conditions of duress and then went back to their old religion, or Muslims who converted to another religion involuntarily, either force or as concealment (Taqiyya or Kitman) out of fear of persecution or during war.[118][119]

Some of these requirements have served as "loopholes" to exonerate apostates (apostasy charges against Abdul Rahman, were dropped on the grounds he was "mentally unfit").[120]

Death penalty

[edit]In classical Islamic jurisprudence

[edit]Traditional Sunnī and Shīʿa Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) and their respective schools (maḏāhib) agree on some issues—that male apostates should be executed, and that most but not all perpetrators should not be given a chance to repent; among the excluded are those who practice sorcery (subhar), treacherous heretics (zanādiqa), and "recidivists".[3] They disagree on issues such as whether women can be executed,[121][122][123] whether apostasy is a violation of "the rights of God",[3][124] whether apostates who were born Muslims may be spared if they repent,[3] whether conviction requires the accused be a practicing Muslim,[3] or whether it is enough to simply intend to commit apostasy rather than actually doing it.[3]

- Ḥanafī school – recommends three days of imprisonment before the execution, although the delay before killing the apostates is not mandatory. Apostasy from Islam is not considered a hudud crime.[125] Unlike in other schools, it is not obligatory to call on the apostate to repent.[3] Apostate males are to be killed, while apostate females are to be held in solitary confinement and beaten every three days till they recant and return to Islam.[126] The death penalty for apostasy from Islam is limited for those who cause aggravated robbery or grand larceny (ḥirābah) after leaving Islam, not for converting to another religion.[127]

- Mālikī school – allows up to ten days for recantation, after which the apostates must be killed. Apostasy from Islam is considered a hudud crime.[125] Both male and female apostates deserve the death penalty for leaving Islam, according to the traditional view of the Mālikī school.[123] Unlike other schools, the apostates must have a history of being "good" (i.e., practicing) Muslims.[3]

- Shāfiʿī school – waiting period of three days is required to allow the apostates time to repent and return to Islam. Failing repentance, death penalty is the recommended form of punishment for both male and female apostates for leaving Islam.[123] Apostasy from Islam is not considered a hudud crime.[125]

- Ḥanbalī school – waiting period not necessary, but may be granted. Apostasy from Islam is considered a hudud crime.[125] Death penalty is the traditional form of punishment for both male and female apostates for leaving Islam.[123]

- Jaʿfari or Imāmī school – Male apostates must be executed, while female apostates must be held in solitary confinement until they repent and return to Islam.[123][126] Apostasy from Islam is considered a hudud crime.[125] The "mere intention of unbelief" without expression qualifies as apostasy.[3] Unlike the other schools, repentance will not save a defendant from execution, unless they are "national apostates" who were not born Muslims but converted to Islam before apostasizing, although it is disputed by some Muslim scholars. "Innate" apostates, who grew up Muslims and remained Muslim after puberty and until converting to another religion, should be executed.[3][106]

Vigilante application

[edit]In contemporary situations where apostates, (or alleged apostates), have ended up being killed, it is usually not be through the formal criminal justice system, especially when "a country's law does not punish apostasy." It is not uncommon in some countries for "vigilante" Muslims to kill or attempt to kill apostates or alleged apostates (or force them to flee the country).[14] In at least one case, the high profile execution of Mahmud Muhammad Taha, the victim was legally executed and the government made clear he was being executed for apostasy, but the technical "legal basis" for his killing was another crime or crimes,[14] namely "heresy, opposing the application of Islamic law, disturbing public security, provoking opposition against the government, and re-establishing a banned political party."[128] When post-modernist professor Nasr Abu Zayd was found to be an apostate by an Egyptian court, it meant only an involuntary divorce from his wife (who did not want to divorce), but it put the proverbial target on his back and he fled to Europe.[14][129]

Civil liabilities

[edit]In Islam, apostasy has traditionally had both criminal and civil penalties. In the late 19th century, when the use of criminal penalties for apostasy fell into disuse, civil penalties were still applied.[3] The punishment for the criminal penalties such as murder includes death or prison, while [3][130] In all madhhabs of Islam, the civil penalties include:

- (a) the property of the apostate is seized and distributed to his or her Muslim relatives;

- (b) his or her marriage annulled (faskh) (as in the case of Nasr Abu Zayd);

- (1) if they were not married at the time of apostasy they could not get married[131]

- (c) any children removed and considered ward of the Islamic state.[3]

- (d) In case the entire family has left Islam, or there are no surviving Muslim relatives recognized by Sharia, the apostate's inheritance rights are lost and property is liquidated by the Islamic state (part of fay, الْفيء).

- (e) In case the apostate is not executed – such as in case of women apostates in Hanafi school – the person also loses all inheritance rights.[35][36][not specific enough to verify] Hanafi Sunni school of jurisprudence allows waiting till execution, before children and property are seized; other schools do not consider this wait as mandatory but mandates time for repentance.[3]

- Social liabilities

The conversion of a Muslim to another faith is often considered a "disgrace" and "scandal" as well as a sin,[132] so in addition to penal and civil penalties, loss of employment,[132] ostracism and proclamations by family members that they are "dead", is not at all "unusual".[133] For those who wish to remain in the Muslim community but who are considered unbelievers by other Muslims, there are also "serious forms of ostracism". These include the refusal of other Muslims to pray together with or behind a person accused of kufr, the denial of the prayer for the dead and burial in a Muslim cemetery, boycott of whatever books they have written, etc.[134]

Supporters and opponents of death penalty

[edit]- Support among contemporary preachers and scholars

"The vast majority of Muslim scholars both past as well as present" consider apostasy "a crime deserving the death penalty", according to Abdul Rashided Omar, writing circa 2007.[18] Some notable contemporary proponents include:

- Abul A'la Maududi (1903–1979), who "by the time of his death had become the most widely read Muslim author of our time", according to one source.

- Mohammed al-Ghazali (1917–1996), considered an Islamic "moderate"[136] and "preeminent" faculty member of Egypt's preeminent Islamic institution – Al Azhar University − as well as a valuable ally of the Egyptian government in its struggle against the "growing tide of Islamic fundamentalism",[137] was "widely credited" with contributing to the 20th century Islamic revival in the largest Arabic country, Egypt.[138] (Al-Ghazali was on record as declaring all those who opposed the implementation of sharia law to be apostates who should ideally be punished by the state, but "when the state fails to punish apostates, somebody else has to do it".[139][138]

- Yusuf al-Qaradawi (b. 1926), another "moderate" Islamist,[140] chairman of the International Union of Muslim Scholars,[141] who as of 2009 was "considered one of the most influential" Islamic scholars living.[142][143][144]

- Zakir Naik, Indian Islamic televangelist and preacher,[145] whose Peace TV channel, reaches a reported 100 million viewers,[146][147] and whose debates and talks are widely distributed,[148][149][147] supports the death penalty only for those apostates who "propagate the non-Islamic faith and speak against Islam" as he considers it treason.[150][148]

- Muhammad Saalih Al-Munajjid, a Syrian Islamic scholar, considered a respected scholar in the Salafi movement (according to Al Jazeera);[151] and founder of the fatwa website IslamQA,[152] one of the most popular Islamic websites, and (as of November 2015 and according to Alexa.com) the world's most popular website on the topic of Islam generally (apart from the website of an Islamic bank).[153][154][155]

- Opposing the death penalty for apostasy

- Mahmud Shaltut, Grand Imam of Al-Azhar (1958–1963).[156]

- Ahmed el-Tayeb, Grand Imam of Al-Azhar (2010–Present) and Grand Mufti of Egypt (2002–2003). [citation needed]

- Ali Gomaa, Grand Mufti of Egypt (2003–2013).[157][158]

- Mohsen Kadivar, Director of Department of Philosophy and Theology - Center of Scientific and Cultural Publishing, Tehran (1998–2003) and Professor Duke University (2009–).[159][160]

- Hossein-Ali Montazeri, Grand Ayatollah and Deputy Supreme Leader of Iran (1985-1989).[161]

- Hussein Esmaeel al-Sadr, Grand Ayatollah.[162]

- Taha Jabir Alalwani (1935–2016), founder and former chairman of the Fiqh Council of North America.[163]

- Intisar Rabb, faculty director of the Program in Islamic Law at Harvard Law School. [citation needed]

- Javed Ahmad Ghamidi, a Pakistani Muslim theologian, Quran scholar. Ghamidi, Javed (26 March 2023), ارتداد اور توہین رسالت کا قانون

- Tariq Ramadan, Professor of contemporary Islamic studies at St Antony's College, Oxford and the Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Oxford [citation needed]

- Reza Aslan, an Iranian-American scholar of religious studies and writer. [citation needed]

- Jonathan A.C. Brown, Associate professor at Georgetown University's Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service and Alwaleed bin Talal Chair of Islamic Civilization at Georgetown University. [citation needed]

- Rudolph F. Peters, Professor of Islamic Law at the University of Amsterdam. [citation needed]

- Khaled Abou El Fadl, Omar and Azmeralda Alfi Distinguished Professor of Law at the UCLA School of Law.

- S. A. Rahman, 5th Chief Justice of Pakistan (1968). [citation needed]

- Yaşar Nuri Öztürk, Professor of Islamic Philosophy at Istanbul University (2008). Öztürk, Yaşar Nuri (26 March 2023), Allah ile Aldatmak (PDF)

Rationale, arguments, criticism for and against killing apostates

[edit]The question of whether apostates should be killed, has been "a matter for contentious dispute throughout Islamic history".[164]

- For the death penalty

Throughout Islamic history the Muslim community, scholars, and schools of fiqh have agreed that scripture prescribes this penalty; scripture must take precedence over reason or modern norms of human rights, as Islam is the one true religion; "no compulsion in religion" (Q.2:256) does not apply to this punishment; apostasy is "spiritual and cultural" treason; it hardly ever happens and so is not worth talking about.

- Abul A'la Maududi said that among early Muslims, among the schools of fiqh both Sunni and Shia, among scholars of shari'ah "of every century ... available on record", there is unanimous agreement that the punishment for apostate is death, and that "no room whatever remains to suggest" that this penalty has not "been continuously and uninterruptedly operative" through Islamic history; evidence from early texts that Muhammad called for apostates to be killed, and that companions of the Prophet and early caliphs ordered beheadings and crucifixions of apostates and has never been declared invalid over the course of the history of Islamic theology (Christine Schirrmacher).[132]

- "Many hadiths", not just "one or two", call for the killing of apostates (Yusuf al-Qaradawi).[165][166]

- Verse Q.2:217 – "hindering ˹others˺ from the Path of Allah, rejecting Him, and expelling the worshippers from the Sacred Mosque is ˹a˺ greater ˹sin˺ in the sight of Allah" – indicates the punishment for apostasy from Islam is death (Mohammad Iqbal Siddiqi),[167] Quranic verses in general "appear to justify coercion and severe punishment" for apostates (Dale F. Eickelman).[48]

- If this doctrine is called into question, what's next? Ritual prayer (salat)? Fasting (sawm)? Even Muhammad's mission? (Abul A'la Maududi).[168]

- It "does not merit discussion" because [the advocates maintain] apostasy from Islam is so rare (Ali Kettani),[169] (Mahmud Brelvi);[170][171] before the modern era, there was virtually no apostasy from Islam (Syed Barakat Ahmad).[172]

- The punishment is "rarely invoked" because there are numerous qualifications or ways for the apostate to avoid death (to be found guilty they must openly reject Islam, have made their decision without coercion, be aware of the nature of their statements, be an adult, be completely sane, refused to repent, etc.) (Religious Tolerance website).[173]

- The verse only forbids compulsion to believe "things that are wrong", when it comes to accepting the truth, compulsion is allowed (Peters and Vries explaining a traditional view).[Note 10]

- Others maintain that verse Q.2:256 has been "abrogated", i.e. according to classical Quranic scholars it has been overruled/cancelled by verses of Quran revealed later, (in other words, compulsion was not allowed in the very earliest days of Islam but this was changed by divine revelation a few years later) (Peters and Vries explaining traditional view).[175]

- Because "the social order of every Moslem society is Islam", apostasy constitutes "an offense" against that social order, "that may lead in the end to the destruction of this order" (Muhammad Muhiy al-Din al-Masiri).[176]

- Apostasy is usually "a psychological pretext for rebellion against worship, traditions and laws and even against the foundations of the state", and so "is often synonymous with the crime of high treason ... " (Muhammad al-Ghazali).[177]

- Against death penalty

Arguments against the death penalty include: that some scholars throughout Islamic history have opposed that punishment for apostasy; that it constitutes a form of compulsion in faith, which the Quran explicitly forbids in Q.2.256 and other verses, and that these override any other scriptural arguments; and especially that the death penalty in hadith and applied by Muhammad was for treasonous/seditious behavior, not for a change in personal belief.

- How can it be claimed that there was a consensus among scholars or community (ijma) from the beginning of Islam in favor of capital punishment when a number of companions of Muhammad and early Islamic scholars (Ibn al-Humam, al-Marghinani, Ibn Abbas, Sarakhsi, Ibrahim al-Nakh'i) opposed the execution of murtadd? (Mirza Tahir Ahmad)[178]

- In addition there have been a number of prominent ulema (though a minority) over the centuries who argued against the death penalty for apostasy in some way, such as ...

- The Maliki jurist Abu al-Walid al-Baji (d. 474 AH) held that apostasy was liable only to a discretionary punishment (known as ta'zir) and so might not require execution.[156]

- The Hanafi jurist Al-Sarakhsi (d. 483 AH/ 1090 CE)[179][180] and Imam Ibnul Humam (d. 681 AH/ 1388 CE)[181] and Abd al-Rahman al-Awza'i (707–774 CE),[182] all distinguished between non-seditious religious apostasy on the one hand and treason on the other, with execution reserved for treason.

- Ibrahim al-Nakhaʿī (50 AH/670 – 95/96 AH/717 CE) and Sufyan al-Thawri (97 AH/716 CE – 161 AH/778 CE) as well as the Hanafi jurist Sarakhsi (d. 1090), believed that an apostate should be asked to repent indefinitely (which would be incompatible with being sentenced to death).[156][183]

- In addition there have been a number of prominent ulema (though a minority) over the centuries who argued against the death penalty for apostasy in some way, such as ...

- There are problems with the scriptural basis for sharia commanding the execution of apostates.

- Quran (see Quran above)

- Compulsion in faith is "explicitly" forbidden by the Quran ('Abd al-Muta'ali al-Sa'idi);[184] Quranic statements on freedom of religion – 'There is no compulsion in religion. The right path has been distinguished from error' (Q.2:256) (and also 'Whoever wants, let him believe, and whoever wants, let him disbelieve,' (Q.18:29) – are "absolute and universal" statement(s) (Jonathan A.C. Brown),[55] (Grand Mufti Ali Gomaa),[157] "general, overriding principle(s)" (Khaled Abou El Fadl)[185] of Islam, and not abrogated by hadith or the Sword Verse (Q.9:5), and there can be little doubt capital punishment for apostasy is incompatible with this principle – after all, if someone has the threat of death hanging over their head in a matter of faith, it cannot be said that there is "no compulsion or coercion" in their belief (Tariq Ramadan).[186]

- Neither verse Q.2:217, (Mirza Tahir Ahmad),[187] nor any other Quranic verse say anything to indicate an apostate should be punished in the temporal world, aka dunyā (S. A. Rahman),[188] (W. Heffening),[189] (Wael Hallaq),[190][53] (Grand Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri);[161] the verses only indicate that dangerous, aggressive apostates should be killed (Mahmud Shaltut)[156] (e.g. "If they do not withdraw from you, and offer you peace, and restrain their hands, take them and kill them wherever ye come upon them" Q.4:90), (Peters and Vries describing argument of Islamic Modernists).[191][192]

- Another verse condemning apostasy – Q.4:137, "Those who believe then disbelieve, then believe again, then disbelieve and then increase in their disbelief – God will never forgive them nor guide them to the path" – makes no sense if apostasy is punished by death, because killing apostates "would not permit repeated conversion from and to Islam" (Louay M. Safi),[58] (Sisters in Islam).[193]

- Hadith and Sunnah (see hadith above)

- "According to most established juristic schools, a hadith can limit the application of a general Qur'anic statement, but can never negate it", so the hadith calling for execution cannot abrogate the "There is no compulsion in religion" verse (Q.2:256) (Louay M. Safi).[Note 11]

- The Prophet Muhammad did not call for the deaths of contemporaries who left Islam (Mohamed Ghilan)[194] – for example, apostates like "Hishâm and 'Ayyash", or converts to Christianity, such as "Ubaydallah ibn Jahsh" – and since what The Prophet did is by definition part of the Sunnah of Islam, this indicates "that one who changes her/his religion should not be killed" (Tariq Ramadan).[186]

- another reason not to use the hadith(s) stating “whoever changes his religion kill him” as the basis for law is that it is not among the class of hadith eligible to be used as the basis for "legal rulings binding upon all Muslims for all times" (Muhammad al-Shawkani (1759–1834 CE));[194] as their authenticity is not certain (Wael Hallaq);[190] the hadith are in a category relying "on only one authority (khadar al-ahad) and were not widely known amongst the Companions of the Prophet," and so ought not abrogate Quranic verses of tolerance (Peters and Vries describing argument of Islamic Modernists).[195]

- The hadith(s) "calling for apostates to be killed" are actually referring to "what can be considered in modern terms political treason", not change in personal belief (Mohamed Ghilan),[194] (Adil Salahi),[Note 12] or collective conspiracy and treason against the government (Enayatullah Subhani),[197] (Mahmud Shaltut);[Note 13] and in fact, translating the Islamic term ridda as simply "apostasy" – a standard practice – is really an error, as ridda should be defined as "the public act of political secession from the Muslim community" (Jonathan Brown).[198]

- Quran (see Quran above)

- The punishment or lack for apostasy should reflect the circumstances of the Muslim community which is very different now then when the death penalty was established;

- Unlike some other sharia laws, those on how to deal with apostates from Islam are not set in stone but should be adjusted according to circumstances based on what best serves the interests of society. In the past, the death penalty for leaving Islam "protected the integrity of the Muslim community", but today this goal is no longer met by punishing apostasy (Jonathan Brown).[198]

- The "premise and reasoning underlying the sunna rule of death penalty for apostasy were valid in the historical context" where 'disbelief is equated with high treason' because citizenship was 'based on belief in Islam', but doesn't apply today (Abdullahi An-Na'im, et al.);[199][200] the prescription of death penalty for apostasy found in hadith was aimed at prevention of aggression against Muslims and sedition against the state (Mahmud Shaltut);[156] it's a man-made rule enacted in the early Islamic community to prevent and punish the equivalent of desertion or treason (John Esposito);[38] it is probable that the punishment was prescribed by Muhammad during early Islam to combat political conspiracies against Islam and Muslims, those who desert Islam out of malice and enmity towards the Muslim community, and is not intended for those who simply change their belief, converting to another religion after investigation and research (Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri).[161]

- The concept of apostasy as treason is not so much part of Islam, as part of the pre-modern era when classical Islamic fiqh was developed, and when "every religion was a 'religion of the sword'" (Reza Aslan);[201] and every religion "underpinned the political and social order within ... the states they established" (Jonathan Brown);[198] "This was also an era in which religion and the state were one unified entity. ... no Jew, Christian, Zoroastrian, or Muslim of this time would have considered his or her religion to be rooted in the personal confessional experiences of individuals. ... Your religion was your ethnicity, your culture, and your social identity... your religion was your citizenship."[201]

- For example, the Holy Roman Empire had its officially sanctioned and legally enforced version of Christianity; the Sasanian Empire had its officially sanctioned and legally enforced version of Zoroastrianism; in China at that time, Buddhist rulers fought Taoist rulers for political ascendancy (Reza Aslan);[201] Jews who abandoned the God of Israel to worship other deities "were condemned to stoning" (Jonathan Brown).[198]

- Transcending tribalism with religious (Islamic) unity could mean prevention of civil war in Muhammad's era, so to violate religious unity meant violating civil peace (Mohamed Ghilan).[194]

- Capital punishment for apostasy is a time-bound command, applying only to those Arabs who denied the truth even after having Muhammad himself explain and clarify it to them (Javed Ahmad Ghamidi).[202]

- Now the only reason to kill an apostate is to eliminate the danger of war, not because of their disbelief (Al-Kamal ibn al-Humam 861 AH/1457 CE);[181] these days, the number of apostates is small, and does not politically threaten the Islamic community (Christine Schirrmacher describing the "liberal" position on apostasy);[115] it should be enforced only if apostasy becomes a mechanism of public disobedience and disorder (fitna) (Ahmet Albayrak).[39]

- In Islamic history, laws calling for severe penalties against apostasy (and blasphemy) have not been used to protect Islam, but "almost exclusively" to either eliminate "political dissidents" or target "vulnerable religious minorities" (Javaid Rehman),[203] which is hardly something worthy of imitating.

- Executing apostates is a violation of the human right to freedom of religion, and somewhat hypocritical for a religion that enthusiastically encourages non-Muslims to apostatize from their current faith and convert to Islam (Non-Muslims and liberal Muslims).

Middle way

[edit]At least some conservative jurists and preachers have attempted to reconcile following the traditional doctrine of death for apostasy while addressing the principle of freedom of religion. Some of whom argue apostasy should have a lesser penalty than death.[33][34][35][36]

At a 2009-human rights conference at Mofid University in Qom, Iran, Ayatollah Mohsen Araki, stated that "if an individual doubts Islam, he does not become the subject of punishment, but if the doubt is openly expressed, this is not permissible." As one observer (Sadakat Kadri) noted, this "freedom" has the advantage that "state officials could not punish an unmanifested belief even if they wanted to".[204]

Zakir Naik, the Indian Islamic televangelist and preacher[145] takes a less strict line (mentioned above), stating that only those Muslims who "propagate the non-Islamic faith and speak against Islam" after converting from Islam should be put to death.[150][148]

While not speaking to the issue of executing apostates, Dar al-Ifta al-Misriyyah, an Egyptian Islamic advisory, justiciary and governmental body, issued a fatwa in the case of an Egyptian Christian convert to Islam but "sought to return to Christianity", stating: "Those who embraced Islam voluntarily and without coercion cannot later deviate from the public order of society by revealing their act of apostasy because such behavior would discourage other people from embracing Islam." (The Egyptian court followed the fatwa.)[205]

In practice: historical impact

[edit]From the Middle Ages to the early modern period

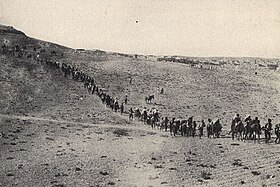

[edit]The charge of apostasy has often been used by religious authorities to condemn and punish skeptics, dissidents, and minorities in their communities.[51] From the earliest times of the history of Islam, the crime of apostasy and execution for apostasy has driven major events in the development of the Islamic religion. For example, the Ridda wars (civil wars of apostasy) shook the Muslim community in 632–633 AD, immediately after the death of Muhammad.[51][206] These sectarian wars caused the split between the two major sects of Islam: Sunnis and Shias, and numerous deaths on both sides.[207][208] Sunni and Shia sects of Islam have long accused each other of apostasy.[209]

The charge of apostasy dates back to the early history of Islam with the emergence of the Kharijites in the 7th century CE.[210] The original schism between Kharijites, Sunnis, and Shias among Muslims was disputed over the political and religious succession to the guidance of the Muslim community (Ummah) after the death of Muhammad.[210] From their essentially political position, the Kharijites developed extreme doctrines that set them apart from both mainstream Sunni and Shia Muslims.[210] Shias believe ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib is the true successor to Muhammad, while Sunnis consider Abu Bakr to hold that position. The Kharijites broke away from both the Shias and the Sunnis during the First Fitna (the first Islamic Civil War);[210] they were particularly noted for adopting a radical approach to takfīr (excommunication), whereby they declared both Sunni and Shia Muslims to be either infidels (kuffār) or false Muslims (munāfiḳūn), and therefore deemed them worthy of death for their perceived apostasy (ridda).[210][211][212]

Modern historians recognize that the Christian populations living in the lands invaded by the Arab Muslim armies between the 7th and 10th centuries AD suffered religious persecution, religious violence, and martyrdom multiple times at the hands of Arab Muslim officials and rulers;[213][214][215][216] many were executed under the Islamic death penalty for defending their Christian faith through dramatic acts of resistance such as refusing to convert to Islam, repudiation of the Islamic religion and subsequent reconversion to Christianity, and blasphemy towards Muslim beliefs.[214][215][216] Notable Christian converts to Islam who reportedly reverted to Christianity and were executed under the Islamic death penalty for this reason include "Kyros", who was executed by burning in 769 CE, “Holy Elias” in 795 CE, and “Holy Bacchus” in 806 CE.[217] The martyrdoms of forty-eight Christian martyrs that took place in the Emirate of Córdoba between 850 and 859 CE[218] are recorded in the hagiographical treatise written by the Iberian Christian and Latinist scholar Eulogius of Córdoba.[214][215][216] The Martyrs of Córdoba were executed under the rule of Abd al-Rahman II and Muhammad I, and Eulogius' hagiography describes in detail the executions of the martyrs for capital violations of Islamic law, including apostasy and blasphemy.[214][215][216]

Historian David Cook writes that "it is only with the 'Abbasi caliphs al-Mu'taṣim (218–28 AH/833–42 CE) and al-Mutawakkil (233–47 /847–61) that we find detailed accounts" of apostates and what was done with them. Prior to that, in the Umayyad and early Abbasid periods, measures to defend Islam from apostasy "appear to have mostly remained limited to intellectual debates"[219] He also states that "the most common category of apostates" – at least of apostates who converted to another religion – "from the very first days of Islam" were "Christians and Jews who converted to Islam and after some time" reconverted back to their former faith.[220]

Some sources emphasize that executions of apostates have been "rare in Islamic history".[25] According to historian Bernard Lewis, in "religious polemic" in the "early times" of Islam, "charges of apostasy were not unusual", but the accused were seldom prosecuted, and "some even held high offices in the Muslim state". Later, "as the rules and penalties of the Muslim law were systematized and more regularly enforced, charges of apostasy became rarer."[90] When action was taken against an alleged apostate, it was much more likely to be "quarantine" than execution, unless the innovation was "extreme, persistent and aggressive".[90] Another source, legal historian Sadakat Kadri, argues execution was rare because "it was widely believed" that any accused apostate "who repented by articulating the shahada [...] had to be forgiven" and their punishment delayed until after Judgement Day. This principle was upheld "even in extreme situations", such as when an offender adopted Islam "only for fear of death" and their sincerity seemed highly implausible. It was based on the hadith that Muhammad had upbraided a follower for killing a raider who had uttered the shahada.[Note 14]

The New Encyclopedia of Islam also states that after the early period, with some notable exceptions, the practice in Islam regarding atheism or various forms of heresy, grew more tolerant as long as it was a private matter. However heresy and atheism expressed in public may well be considered a scandal and a menace to a society; in some societies they are punishable, at least to the extent the perpetrator is silenced. In particular, blasphemy against God and insulting Muhammad are major crimes.[223]

In contrast, historian David Cook maintains the issue of apostasy and punishment for it was not uncommon in Islamic history. However, he also states that prior to 11th century execution seems rare he gives an example of a Jew who had converted to Islam and used the threat of reverting to Judaism in order to gain better treatment and privilege.[224]

Zindīq (often a "blanket phrase" for "intellectuals" under suspicion of having abandoned Islam" or freethinker, atheist or heretic who conceal their religion),[225] experienced a wave of persecutions from 779 to 786. A history of those times states:[223]

"Tolerance is laudable", the Spiller (the Caliph Abu al-Abbās) had once said, "except in matters dangerous to religious beliefs, or to the Sovereign's dignity."[223] Al-Mahdi (d. 169/785) persecuted Freethinkers, and executed them in large numbers. He was the first Caliph to order composition of polemical works to in refutation of Freethinkers and other heretics; and for years he tried to exterminate them absolutely, hunting them down throughout all provinces and putting accused persons to death on mere suspicion.[223]

The famous Sufi mystic of 10th-century Iraq, Mansur Al-Hallaj was officially executed for possessing a heretical document suggesting hajj pilgrimage was not required of a pure Muslim (i.e. killed for heresy which made him an apostate), but it is thought he would have been spared execution except that the Caliph at the time Al-Muqtadir wished to discredit "certain figures who had associated themselves" with al-Hallaj.[226] (Previously al-Hallaj had been punished for talking about being at one with God by being shaved, pilloried and beaten with the flat of a sword. He was not executed because the Shafi'ite judge had ruled that his words were not "proof of disbelief."[226])

In 12th-century Iran, al-Suhrawardi along with followers of Ismaili sect of Islam were killed on charges of being apostates;[51] in 14th-century Syria, Ibn Taymiyyah declared Central Asian Turko-Mongol Muslims as apostates due to the invasion of Ghazan Khan;[227] in 17th-century India, Dara Shikoh and other sons of Shah Jahan were captured and executed on charges of apostasy from Islam by his brother Aurangzeb although historians agree it was more political than a religious execution.[228]

Colonial era and after

[edit]

From around 1800 up until 1970, there were only a few cases of executions of apostates in the Muslim world, including the strangling of a woman in Egypt (sometime between 1825 and 1835), and the beheading of an Armenian youth in the Ottoman Empire in 1843.[3] Western powers campaigned intensely for a prohibition on the execution of apostates in the Ottoman Empire. British envoy to the court of Sultan Abdulmejid I (1839–1861), Stratford Canning, led diplomatic representatives from Austria, Russia, Prussia, and France in a "tug of war" with the Ottoman government.[231] In the end (following the execution of the Armenian), the Sublime Porte agreed to allow "complete freedom of Christian missionaries" to try to convert Muslims in the Empire.[3] The death sentence for apostasy from Islam was abolished by the Edict of Toleration, and substituted with other forms of punishment by the Ottoman government in 1844. The implementation of this ban was resisted by religious officials and proved difficult.[232][233] A series of edicts followed during the Ottoman Tanzimat period, such as the 1856 Reform Edict.

This was also the time that Islamic modernists like Muhammad Abduh (d. 1905) argued that to be executed, it was not enough to be an apostate, the perpetrator had to pose a real threat to public safety.[164] Islamic scholars like Muhammad Rashid Rida (d. 1935) and Muhammad al Ghazzali (d. 1996), on the other hand, asserted that public, explicit apostasy automatically tened public order and hence; punishable by death. These scholars reconciled the Qur'anic verse "There is no compulsion in religion.." by arguing that freedom of religion in Islam doesn't extend for Muslims who seek to change their religion. Other authors like 'Abd al-Muta'ali al-Sa'idi, S.A. Rahman, etc assert that capital punishment for apostasy is contradictory to freedom of religion and need to be banished.[234]

Efforts to convert Muslims to other religions were extremely unpopular with the Muslim community. Despite these edicts on apostasy, there was constant pressure on non-Muslims to convert to Islam, and apostates from Islam continued to be persecuted, punished and threatened with execution, particularly in eastern and Levant parts of the then Ottoman Empire.[232] The Edict of Toleration ultimately failed when Sultan Abdul Hamid II assumed power, re-asserted pan-Islamism with sharia as Ottoman state philosophy, and initiated Hamidian massacres in 1894 against Christians, particularly the Genocides of Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians, and crypto-Christian apostates from Islam in Turkey (Stavriotes, Kromlides).[236][237][238][not specific enough to verify]

In the colonial era, the death penalty for apostasy was abolished in Islamic countries that had come under Western rule or in places, such as the Ottoman Empire, Western powers could apply enough pressure to abolish it.[3] Writing in the mid 1970s, Rudolph Peters and Gert J. J. De Vries stated that "apostasy no longer falls under criminal law"[3] in the Muslim world, but that some Muslims (such as 'Adb al-Qadir 'Awdah) were preaching that "the killing of an apostate" had "become a duty of individual Moslems" (rather than a less important collective duty in hisbah doctrine) and giving advice on how to plead in court after being arrested for such a murder to avoid punishment.[239]

Some (Louay M. Safi), have argued that this situation, with the adoption of "European legal codes ... enforced by state elites without any public debate", created an identification of tolerance with foreign/alien control in the mind of the Muslim public, and rigid literalist interpretations (such as the execution of apostates), with authenticity and legitimacy. Autocratic rulers "often align themselves with traditional religious scholars" to deflect grassroots discontent, which took the form of angry pious traditionalists.[58]

In practice in the recent past

[edit]While as of 2004 apostasy from Islam is a capital offence in only eight majority-Muslim states,[229] in other states that do not directly execute apostates, apostate killing is sometimes facilitated through extrajudicial killings performed by the apostate's family, particularly if the apostate is vocal.[Note 15] In some countries, it is not uncommon for "vigilante" Muslims to kill or attempt to kill apostates or alleged apostates, in the belief they are enforcing sharia law that the government has failed to.

Background

[edit]More than 20 Muslim-majority states have laws that punish apostasy by Muslims to be a crime some de facto other de jure.[229] As of 2014, apostasy was a capital offense in Afghanistan, Brunei, Mauritania, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.[229] Executions for religious conversion have been infrequent in recent times, with four cases reported since 1985: one in Sudan in 1985; two in Iran, in 1989 and 1998; and one in Saudi Arabia in 1992.[229][25] In Mauritania, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Yemen apostasy laws have been used to charge persons for acts other than conversion.[229] In addition, some predominantly Islamic countries without laws specifically addressing apostasy have prosecuted individuals or minorities for apostasy using broadly-defined blasphemy laws.[241] In many nations, the Hisbah doctrine of Islam has traditionally allowed any Muslim to accuse another Muslim or ex-Muslim for beliefs that may harm Islamic society, i.e. violate the norms of sharia (Islamic law). This principle has been used in countries such as Egypt, Pakistan and others to bring blasphemy charges against apostates.[242][243]

The source of most violence or threats of violence against apostate has come from outside of state judicial systems in the Muslim world in recent years, either from extralegal acts by government authorities or from other individuals or groups operating unrestricted by the government.[244][page needed] There has also been social persecution for Muslims converting to Christianity. For example, the Christian organisation Barnabas Fund reports:

The field of apostasy and blasphemy and related "crimes" is thus obviously a complex syndrome within all Muslim societies which touches a raw nerve and always arouses great emotional outbursts against the perceived acts of treason, betrayal and attacks on Islam and its honour. While there are a few brave dissenting voices within Muslim societies, the threat of the application of the apostasy and blasphemy laws against any who criticize its application is an efficient weapon used to intimidate opponents, silence criticism, punish rivals, reject innovations and reform, and keep non-Muslim communities in their place.[245][unreliable source?]

Similar views are expressed by the non-theistic International Humanist and Ethical Union.[246] Author Mohsin Hamid points out that the logic of widely accepted claim that anyone helping an apostate is themselves an apostate, is a powerful weapon in spreading fear among those who oppose the killings (in at least the country of Pakistan). It means that a doctor who agrees to treat an apostate wounded by attacker(s), or a police officer who has agreed to protect that doctor after they have been threatened is also an apostate – "and on and on".[247]

Contemporary reformist/liberal Muslims such as Quranist Ahmed Subhy Mansour,[248] Edip Yuksel, and Mohammed Shahrour have suffered from accusations of apostasy and demands to execute them, issued by Islamic clerics such as Mahmoud Ashur, Mustafa Al-Shak'a, Mohammed Ra'fat Othman and Yusif Al-Badri.[249]

Apostate communities

[edit]- Christian apostates from Islam

Regarding Muslim converts to Christianity, Duane Alexander Miller (2016) identified two different categories:

- 'Muslims followers of Jesus Christ', 'Jesus Muslims' or 'Messianic Muslims' (analogous to Messianic Jews), who continue to self-identify as 'Muslims', or at least say Islam is (part of) their 'culture' rather than religion, but "understand themselves to be following Jesus as he is portrayed in the Bible".

- 'Christians from a Muslim background' (abbreviated CMBs), also known as 'ex-Muslim Christians', who have completely abandoned Islam in favour of Christianity.

Miller introduced the term 'Muslim-background believers' (MBBs) to encompass both groups, adding that the latter group are generally regarded as apostates from Islam, but orthodox Muslims' opinions on the former group is more mixed (either that 'Muslim followers of Jesus' are 'heterodox Muslims', 'heretical Muslims' or 'crypto-Christian liars').[250]

- Atheist apostates from Islam

Writing in 2015, Ahmed Benchemsi argued that while Westerners have great difficulty even conceiving of the existence of an Arab atheist, "a generational dynamic" is underway with "large numbers" of young people brought up as Muslims "tilting away from ... rote religiosity" after having "personal doubts" about the "illogicalities" of the Quran and Sunnah.[251] Immigrant apostates from Islam in Western countries "converting" to Atheism have often gathered for comfort in groups such as Women in Secularism, Ex-Muslims of North America, Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain,[252] sharing tales of the tension and anxieties of "leaving a close-knit belief-based community" and confronting "parental disappointment", "rejection by friends and relatives", and charges of "trying to assimilate into a Western culture that despises them", often using terminology first uttered by the LGBT community – "'coming out,' and leaving 'the closet'".[252] Atheists in the Muslim world maintain a lower profile, but according to the Editor-in-chief of FreeArabs.com:

When I recently searched Facebook in both Arabic and English, combining the word ‘atheist’ with names of different Arab countries I turned up over 250 pages or groups, with memberships ranging from a few individuals to more than 11,000. And these numbers only pertain to Arab atheists (or Arabs concerned with the topic of atheism) who are committed enough to leave a trace online.[251]

Public opinion

[edit]A survey based on face-to-face interviews conducted in 80 languages by the Pew Research Center between 2008 and 2012 among thousands of Muslims in many countries, found varied views on the death penalty for those who leave Islam to become an atheist or to convert to another religion.[31] In some countries (especially in Central Asia, Southeast Europe, and Turkey), support for the death penalty for apostasy was confined to a tiny fringe; in other countries (especially in the Arab world and South Asia) majorities and large minorities support the death penalty.

In the survey, Muslims who favored making Sharia the law of the land were asked for their views on the death penalty for apostasy from Islam.[31] The results are summarized in the table below. (Note that values for Group C have been derived from the values for the other two groups and are not part of the Pew report.)[31]

|

|

|

Overall, the figures in the 2012 survey suggest that the percentage of Muslims in the countries surveyed who approve the death penalty for Muslims who leave Islam to become an atheist or convert to another religion varies widely, from 0.4% (in Kazakhstan) to 78.2% (in Afghanistan).[31] The Governments of the Gulf Cooperation Council (Saudi Arabia, UAE, Oman, Qatar, Bahrain and Kuwait) did not permit Pew Research to survey nationwide public opinion on apostasy in 2010 or 2012. The survey also did not include China, India, Syria, or West African countries such as Nigeria.

By country

[edit]The situation for apostates from Islam varies markedly between Muslim-minority and Muslim-majority regions. In Muslim-minority countries "any violence against those who abandon Islam is already illegal". But in Muslim-majority countries, violence is sometimes "institutionalised", and (at least in 2007) "hundreds and thousands of closet apostates" live in fear of violence and are compelled to live lives of "extreme duplicity and mental stress."[253]

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

[edit]Laws prohibiting religious conversion run contrary[254] to Article 18 of the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states the following:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.[255]

Afghanistan, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan and Syria voted in favor of the Declaration.[255] The governments of other Muslim-majority countries have responded by criticizing the Declaration as an attempt by the non-Muslim world to impose their values on Muslims, with a presumption of cultural superiority,[256][257] and by issuing the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam—a joint declaration of the member states of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference made in 1990 in Cairo, Egypt.[258][259] The Cairo Declaration differs from the Universal Declaration in affirming Sharia as the sole source of rights, and in limits of equality and behavior[260][page needed][261][262] in religion, gender, sexuality, etc.[259][263] Islamic scholars such as Muhammad Rashid Rida in Tafsir al-Minar, argue that the "freedom to apostatize", is different from freedom of religion on the grounds that apostasy from Islam infringes on the freedom of others and the respect due the religion of Islamic states.[3]

Literature and film

[edit]Films and documentaries

[edit]- Leaving the Faith – Former Muslims (2014) – for Deutsche Welle

- Ex-Muslim: Leaving Religion (2015) – Benjamin Zand for BBC News

- Islam's Non-Believers (2016) – Deeyah Khan for Fuuse

- Among Nonbelievers (2015) – Dorothée Forma for HUMAN

- Non-believers: Freethinkers on the Run (2016) – Dorothée Forma for HUMAN

- Rescuing Ex-Muslims: Leaving Islam (2016) – Poppy Begum for Vice News

- Diary of a Pakistani Atheist (2017) – Mobeen Azhar for BBC World Service[264]

- Becoming Ex-Muslim: The secret group for Aussies who've left their faith (2017) – Patrick Abboud for The Feed

Books by ex-Muslims

[edit]- Qureshi, Nabeel (2014). Seeking Allah, Finding Jesus: A Devout Muslim Encounters Christianity. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0310515029.

- Ham, Boris van der; Benhammou, Rachid (2018). Nieuwe Vrijdenkers: 12 voormalige moslims vertellen hun verhaal (New Freethinkers: 12 Former Muslims Tell Their Story). Amsterdam: Prometheus. p. 209. ISBN 978-9044636840.

- Hirsi Ali, Ayaan (2007). Infidel: My Life (Mijn Vrijheid). Simon & Schuster UK. ISBN 978-0743295031.

- Hirsi Ali, Ayaan (2011). Nomad: From Islam to America. Simon & Schuster UK. ISBN 978-1847398185.

- Al-Husseini, Waleed (2017). The Blasphemer: The Price I Paid for Rejecting Islam (Blasphémateur ! : les prisons d'Allah). New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1628726756.

- Jami, Ehsan (2007). Het recht om ex-moslim te zijn (The Right to Be an Ex-Muslim). Kampen: Uitgeverij Ten Have. ISBN 978-9025958367.

- Mohammed, Yasmine (2019). From Al Qaeda to Atheism: The Girl Who Would Not Submit. Free Hearts Free Minds. ISBN 978-1724790804.

- Rizvi, Ali Amjad (2016). The Atheist Muslim: A Journey from Religion to Reason. New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1250094445.

- Saleem, Aliyah; Mughal, Fiyaz (2018). Leaving Faith Behind: The journeys and perspectives of people who have chosen to leave Islam. London: Darton, Longman & Todd. p. 192. ISBN 978-0232533644.

- Sultan, Harris (2018). The Curse of God: Why I Left Islam. Gordon Centre, Australia: Xilbris. ISBN 978-1984502124.[265]

- Warraq, Ibn (2003). Leaving Islam: Apostates Speak Out. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1591020684.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ From 1985 to 2006, only four individuals were officially executed for apostasy from Islam by governments, "one in Sudan in 1985; two in Iran, in 1989 and 1998; and one in Saudi Arabia in 1992."[25] These were sometimes charged with unrelated political crimes.

- ^ Pew Research Center taken from 2008 and 2012.[31]

- ^ Ahmet Albayrak writes in The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia that regarding apostasy as a wrongdoing is not a sign of intolerance of other religions, and it is not aimed at one's freedom to choose a religion or one's freedom to leave Islam and embrace another faith, on the contrary, it is more correct to say that the punishment is imposed as a safety precaution when conditions warrant the imposition of it, for example, the punishment is imposed if apostasy becomes a mechanism of public disobedience and disorder (fitna).[39]

- ^ Legal historian Wael Hallaq writes that "nothing in the law governing apostates and apostasy derives from the letter" of the Quran.[53]

- ^ (two of the Kutub al-Sittah or the six most important collections of hadith for Sunni Muslims)

- ^ for example Ibn Taymiyya wrote "not everyone who falls into unbelief becomes an unbeliever" Laysa kull man waqaʿa fi l-kufr ṣāra kāfir.[65]

- ^ killings have been directly by ISIL or through affiliated groups, from its inception in 2014 to 2020 according to Jamileh Kadivar based on estimates from Global Terrorism Database, 2020; Herrera, 2019; Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights & United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) Human Rights Office, 2014; Ibrahim, 2017; Obeidallah, 2014; 2015[93]

- ^ according to one "well known Muslim journalist of the Indo-Pak subcontinent, Maulana Abdul-Majeed Salik", "All great and eminent Muslims in the history of Islam as well as all the sects in the Muslim world are considered to be disbelievers, apostates, and outside the pale of Islam according to one or the other group of religious leaders. In the realm of the Shariah [religious law] and tariqat [path of devotion], not a single sect or a single family has been spared the accusations of apostasy."[96]

- ^ More recently, a growing body of Islamic jurists have relied on Quranic verses which advocate absolute freedom of religion.[citation needed]

- ^ «Наконец, выдвигается аргумент, что убийство отступника должно рассматриваться как принуждение в религии, что было запрещено в K 2: 256, хотя этот стих традиционно интерпретировался по -другому». Сноска 38: «Согласно некоторым классическим ученым, этот стих был абограммирован более поздними стихами. Однако нынешняя интерпретация этого стиха заключалась в том, что он запрещает принуждение к неправильным вещам (батиль), но не принудительно принять истину» [ 174 ]

- ^ См. Уважение Аль-Шатиби, Аль-Муафакат (Бейрут, Ливан: Дорогой Аль-М'Рефа, ND), Vol. 3, с. 15–26; цитируется в [ 58 ]

- ^ «Сунна, которая согласуется с Кораном, оставляет за собой смертную казнь для тех, кто отступил и изменялся против мусульман» [ 196 ]

- ^ Рецепт смертной казни в отношении отступничества, обнаруженный в хадисе [ 156 ]