Португальская империя

| History of Portugal |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Португальская Portuguese: Império Portuguêsимперия Европейский португальский: [ĩˈpɛ.ɾju puɾ.tuˈɣeʃ] ), также известный как Португальская Заморская ( Ultramar Português ) или Португальская Колониальная Империя ( Império Colonial Português ), состоял из заморских колоний , фабрик , а затем и заморских территорий , управляемых Королевство Португалия , а затем Республика Португалия . Это была одна из самых долгоживущих колониальных империй в европейской истории, просуществовавшая 584 года с момента Сеуты в Северной Африке в 1415 году до передачи суверенитета над Макао Китаю завоевания в 1999 году. Империя возникла в 15 веке, а с В начале 16 века она простиралась по всему миру, имея базы в Африке, Северной Америке, Южной Америке и различных регионах Азии и Океании . [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ]

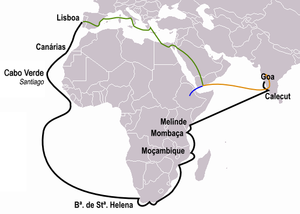

Португальская империя возникла в начале эпохи Великих географических открытий , и власть и влияние Королевства Португалия со временем распространились по всему миру. После Реконкисты португальские каравелла моряки начали исследовать побережье Африки и атлантические архипелаги в 1418–1419 годах, используя последние достижения в области навигации, картографии и морских технологий, таких как , с целью найти морской путь к источник прибыльной торговли пряностями . В 1488 году Бартоломеу Диаш обогнул мыс Доброй Надежды , а в 1498 году Васко да Гама достиг Индии. В 1500 году, то ли случайно выйдя на берег, то ли по секретному замыслу короны, Педро Альварес Кабрал достиг территории, которая впоследствии стала Бразилией .

Over the following decades, Portuguese sailors continued to explore the coasts and islands of East Asia, establishing forts and factories as they went. By 1571, a string of naval outposts connected Lisbon to Nagasaki along the coasts of Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. This commercial network and the colonial trade had a substantial positive impact on Portuguese economic growth (1500–1800) when it accounted for about a fifth of Portugal's per-capita income.

When King Philip II of Spain (Philip I of Portugal) seized the Portuguese crown in 1580, there began a 60-year union between Spain and Portugal known to subsequent historiography as the Iberian Union, although the realms continued to have separate administrations. As the King of Spain was also King of Portugal, Portuguese colonies became the subject of attacks by three rival European powers hostile to Spain: the Dutch Republic, England, and France. With its smaller population, Portugal found itself unable to effectively defend its overstretched network of trading posts, and the empire began a long and gradual decline. Eventually, Brazil became the most valuable colony of the second era of empire (1663–1825), until, as part of the wave of independence movements that swept the Americas during the early 19th century, it broke away in 1822.

The third era of empire covers the final stage of Portuguese colonialism after the independence of Brazil in the 1820s. By then, the colonial possessions had been reduced to forts and plantations along the African coastline (expanded inland during the Scramble for Africa in the late 19th century), Portuguese Timor, and enclaves in India (Portuguese India) and China (Portuguese Macau). The 1890 British Ultimatum led to the contraction of Portuguese ambitions in Africa.

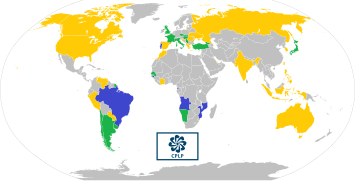

Under António Salazar (in office 1932–1968), the Estado Novo dictatorship made some ill-fated attempts to cling on to its last remaining colonies. Under the ideology of pluricontinentalism, the regime renamed its colonies "overseas provinces" while retaining the system of forced labour, from which only a small indigenous élite was normally exempt. In August 1961, the Dahomey annexed the Fort of São João Baptista de Ajudá, and in December that year India annexed Goa, Daman, and Diu. The Portuguese Colonial War in Africa lasted from 1961 until the final overthrow of the Estado Novo regime in 1974. The Carnation Revolution of April 1974 in Lisbon led to the hasty decolonization of Portuguese Africa and to the 1975 annexation of Portuguese Timor by Indonesia. Decolonization prompted the exodus of nearly all the Portuguese colonial settlers and of many mixed-race people from the colonies. Portugal returned Macau to China in 1999. The only overseas possessions to remain under Portuguese rule, the Azores and Madeira, both had overwhelmingly Portuguese populations, and Lisbon subsequently changed their constitutional status from "overseas provinces" to "autonomous regions". The Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries (CPLP) is the cultural successor of the Empire, analogous to the Commonwealth of Nations for countries formerly part of the British Empire.

History and colonisation

[edit]Background (1139–1415)

[edit]The origin of the Kingdom of Portugal lay in the reconquista, the gradual reconquest of the Iberian peninsula from the Moors.[4] After establishing itself as a separate kingdom in 1139, Portugal completed its reconquest of Moorish territory by reaching Algarve in 1249, but its independence continued to be threatened by neighbouring Castile until the signing of the Treaty of Ayllón in 1411.[5]

Free from threats to its existence and unchallenged by the wars fought by other European states, Portuguese attention turned overseas and towards a military expedition to the Muslim lands of North Africa.[6] There were several probable motives for their first attack, on the Marinid Sultanate (in present-day Morocco). It offered the opportunity to continue the Christian crusade against Islam; to the military class, it promised glory on the battlefield and the spoils of war;[7] and finally, it was also a chance to expand Portuguese trade and to address Portugal's economic decline.[6]

In 1415 an attack was made on Ceuta, a strategically located North African Muslim enclave along the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the terminal ports of the trans-Saharan gold and slave trades. The conquest was a military success, and marked one of the first steps in Portuguese expansion beyond the Iberian Peninsula,[8] but it proved costly to defend against the Muslim forces that soon besieged it. The Portuguese were unable to use it as a base for further expansion into the hinterland,[9] and the trans-Saharan caravans merely shifted their routes to bypass Ceuta and/or used alternative Muslim ports.[10]

First empire (1415–1663)

[edit]Although Ceuta proved to be a disappointment for the Portuguese, the decision was taken to hold it while exploring along the Atlantic African coast.[10] A key supporter of this policy was Infante Dom Henry the Navigator, who had been involved in the capture of Ceuta, and who took the lead role in promoting and financing Portuguese maritime exploration until his death in 1460.[11] At the time, Europeans did not know what lay beyond Cape Bojador on the African coast. Henry wished to know how far the Muslim territories in Africa extended, and whether it was possible to reach Asia by sea, both to reach the source of the lucrative spice trade and perhaps to join forces with the fabled Christian kingdom of Prester John that was rumoured to exist somewhere in the "Indies".[7][12] Under his sponsorship, soon the Atlantic islands of Madeira (1419) and Azores (1427) were reached and started to be settled, producing wheat for export to Portugal.[13]

Soon its ships were bringing into the European market highly valued gold, ivory, pepper, cotton, sugar, and slaves. The slave trade, for example, was conducted by a few dozen merchants in Lisbon. In the process of expanding the trade routes, Portuguese navigators mapped unknown parts of Africa, and began exploring the Indian Ocean. In 1487, an overland expedition by Pêro da Covilhã made its way to India, exploring trade opportunities with the Indians and Arabs, and winding up finally in Ethiopia. His detailed report was eagerly read in Lisbon, which became the best informed center for global geography and trade routes.[14]

Initial African coastline excursions

[edit]Fears of what lay beyond Cape Bojador, and whether it was possible to return once it was passed, were assuaged in 1434 when it was rounded by one of Infante Henry's captains, Gil Eanes. Once this psychological barrier had been crossed, it became easier to probe further along the coast.[15] In 1443, Infante Dom Pedro, Henry's brother and by then regent of the Kingdom, granted him the monopoly of navigation, war and trade in the lands south of Cape Bojador. Later this monopoly would be enforced by the papal bulls Dum Diversas (1452) and Romanus Pontifex (1455), granting Portugal the trade monopoly for the newly discovered lands.[16] A major advance that accelerated this project was the introduction of the caravel in the mid-15th century, a ship that could be sailed closer to the wind than any other in operation in Europe at the time.[17] Using this new maritime technology, Portuguese navigators reached ever more southerly latitudes, advancing at an average rate of one degree a year.[18] Senegal and Cape Verde Peninsula were reached in 1445.[19]

The first feitoria trade post overseas was established in 1445 on the island of Arguin, off the coast of Mauritania, to attract Muslim traders and monopolize the business in the routes travelled in North Africa. In 1446, Álvaro Fernandes pushed on almost as far as present-day Sierra Leone, and the Gulf of Guinea was reached in the 1460s.[20] The Cape Verde Islands were discovered in 1456 and settled in 1462.

Expansion of sugarcane in Madeira started in 1455, using advisers from Sicily and (largely) Genoese capital to produce the "sweet salt" rare in Europe. Already cultivated in Algarve, the accessibility of Madeira attracted Genoese and Flemish traders keen to bypass Venetian monopolies. Slaves were used, and the proportion of imported slaves in Madeira reached 10% of the total population by the 16th century.[21] By 1480 Antwerp had some seventy ships engaged in the Madeira sugar trade, with the refining and distribution concentrated in Antwerp. By the 1490s Madeira had overtaken Cyprus as a producer of sugar.[22] The success of sugar merchants such as Bartolomeo Marchionni would propel the investment in future travels.[23]

In 1469, after prince Henry's death and as a result of meagre returns of the African explorations, King Afonso V granted the monopoly of trade in part of the Gulf of Guinea to merchant Fernão Gomes.[24] Gomes, who had to explore 100 miles (160 km) of the coast each year for five years, discovered the islands of the Gulf of Guinea, including São Tomé and Príncipe and found a thriving alluvial gold trade among the natives and visiting Arab and Berber traders at the port then named Mina (the mine), where he established a trading post.[25] Trade between Elmina and Portugal grew throughout a decade. During the War of the Castilian Succession, a large Castilian fleet attempted to wrest control of this lucrative trade, but were decisively defeated in the 1478 Battle of Guinea, which firmly established an exclusive Portuguese control. In 1481, the recently crowned João II decided to build São Jorge da Mina in order to ensure the protection of this trade, which was held again as a royal monopoly. The equator was crossed by navigators sponsored by Fernão Gomes in 1473 and the Congo River by Diogo Cão in 1482. It was during this expedition that the Portuguese first encountered the Kingdom of Kongo, with which it soon developed a rapport.[26] During his 1485–86 expedition, Cão continued to Cape Cross, in present-day Namibia, near the Tropic of Capricorn.[27]

In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the southern tip of Africa and reached Great Fish River on the coast of Africa,[28] proving false the view that had existed since Ptolemy that the Indian Ocean was land-locked. Simultaneously Pêro da Covilhã, traveling secretly overland, had reached Ethiopia, suggesting that a sea route to the Indies would soon be forthcoming.[29]

As the Portuguese explored the coastlines of Africa, they left behind a series of padrões, stone crosses engraved with the Portuguese coat of arms marking their claims,[30] and built forts and trading posts. From these bases, they engaged profitably in the slave and gold trades. Portugal enjoyed a virtual monopoly on the African seaborne slave trade for over a century, importing around 800 slaves annually. Most were brought to the Portuguese capital Lisbon, where it is estimated black Africans came to constitute 10 percent of the population.[31]

Treaty of Tordesillas (1494)

[edit]

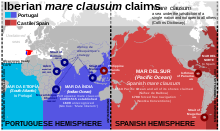

Christopher Columbus's 1492 discovery for Spain of the New World, which he believed to be Asia, led to disputes between the Spanish and the Portuguese.[32] These were eventually settled by the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, which divided the world outside of Europe in an exclusive duopoly between the Portuguese and the Spanish along a north–south meridian 370 leagues, or 970 miles (1,560 km), west of the Cape Verde islands.[33] However, as it was not possible at the time to correctly measure longitude, the exact boundary was disputed by the two countries until 1777.[34]

The completion of these negotiations with Spain is one of several reasons proposed by historians for why it took nine years for the Portuguese to follow up on Dias's voyage to the Cape of Good Hope, though it has also been speculated that other voyages were in fact taking place in secret during this time.[35][36] Whether or not this was the case, the long-standing Portuguese goal of finding a sea route to Asia was finally achieved in a ground-breaking voyage commanded by Vasco da Gama.[37]

The Portuguese enter the Indian Ocean

[edit]

The squadron of Vasco da Gama left Portugal in 1497, rounded the Cape and continued along the coast of East Africa, where a local pilot was brought on board who guided them across the Indian Ocean, reaching Calicut, the capital of the kingdom ruled by Zamorins, also known as Kozhikode) in south-western India in May 1498.[38] The second voyage to India was dispatched in 1500 under Pedro Álvares Cabral. While following the same south-westerly route as Gama across the Atlantic Ocean, Cabral made landfall on the Brazilian coast. This was probably an accidental discovery, but it has been speculated that the Portuguese secretly knew of Brazil's existence and that it lay on their side of the Tordesillas line.[39] Cabral recommended to the Portuguese King that the land be settled, and two follow up voyages were sent in 1501 and 1503. The land was found to be abundant in pau-brasil, or brazilwood, from which it later inherited its name, but the failure to find gold or silver meant that for the time being Portuguese efforts were concentrated on India.[40] In 1502, to enforce its trade monopoly over a wide area of the Indian Ocean, the Portuguese Empire created the cartaz licensing system, granting merchant ships protection against pirates and rival states.[41]

Profiting from the rivalry between the ruler of Kochi and the Zamorin of Calicut, the Portuguese were well-received and seen as allies, as they obtained a permit to build the fort Immanuel (Fort Kochi) and a trading post that was the first European settlement in India. They established a trading center at Tangasseri, Quilon (Coulão, Kollam) city in (1503) in 1502, which became the centre of trade in pepper,[42] and after founding manufactories at Cochin (Cochim, Kochi) and Cannanore (Canonor, Kannur), built a factory at Quilon in 1503. In 1505 King Manuel I of Portugal appointed Francisco de Almeida first Viceroy of Portuguese India, establishing the Portuguese government in the east. That year the Portuguese also conquered Kannur, where they founded St. Angelo Fort, and Lourenço de Almeida arrived in Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka), where he discovered the source of cinnamon.[43] Although Cankili I of Jaffna initially resisted contact with them, the Jaffna kingdom came to the attention of Portuguese officials soon after for their resistance to missionary activities as well as logistical reasons due to its proximity with Trincomalee harbour among other reasons.[44] In the same year, Manuel I ordered Almeida to fortify the Portuguese fortresses in Kerala and within eastern Africa, as well as probe into the prospects of building forts in Sri Lanka and Malacca in response to growing hostilities with Muslims within those regions and threats from the Mamluk sultan.[45]

A Portuguese fleet under the command of Tristão da Cunha and Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Socotra at the entrance of the Red Sea in 1506 and Muscat in 1507. Having failed to conquer Ormuz, they instead followed a strategy intended to close off commerce to and from the Indian Ocean.[46] Madagascar was partly explored by Cunha, and Mauritius was discovered by Cunha whilst possibly being accompanied by Albuquerque.[47] After the capture of Socotra, Cunha and Albuquerque operated separately. While Cunha traveled India and Portugal for trading purposes, Albuquerque went to India to take over as governor after Almeida's three-year term ended. Almeida refused to turn over power and soon placed Albuquerque under house arrest, where he remained until 1509.[48]

Although requested by Manuel I to further explore interests in Malacca and Sri Lanka, Almeida instead focused on western India, in particular the Sultanate of Gujarat due to his suspicions of traders from the region possessing more power. The Mamlûk Sultanate sultan Al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghawri along with the Gujarati sultanate attacked Portuguese forces in the harbor of Chaul, resulting in the death of Almeida's son. In retaliation, the Portuguese fought and destroyed the Mamluks and Gujarati fleets in the sea Battle of Diu in 1509.[49]

Along with Almeida's initial attempts, Manuel I and his council in Lisbon had tried to distribute power in the Indian Ocean, creating three areas of jurisdiction: Albuquerque was sent to the Red Sea, Diogo Lopes de Sequeira to South-east Asia, seeking an agreement with the Sultan of Malacca, and Jorge de Aguiar followed by Duarte de Lemos were sent to the area between the Cape of Good Hope and Gujarat.[50] However, such posts were centralized by Afonso de Albuquerque after his succession and remained so in subsequent ruling.[51]

-

Portuguese discoveries and explorations: first arrival places and dates; main Portuguese spice trade routes (blue)

-

16th century Portuguese illustration from the Códice Casanatense, depicting a Portuguese nobleman with his retinue in India

-

16th century heavy Portuguese carrack.

Trade with Maritime Asia, Africa and the Indian Ocean

[edit]Goa, Malacca and Southeast Asia

[edit]

By the end of 1509, Albuquerque became viceroy of the East Indies with the capital at Velha Goa, after the Cape route was discovered by Vasco da Gama. In contrast to Almeida, Albuquerque was more concerned with strengthening the navy,[52] as well as being more compliant with the interests of the kingdom.[53] His first objective was to conquer Goa, due to its strategic location as a defensive fort positioned between Kerala and Gujarat, as well as its prominence for Arabian horse imports.[49]

The initial capture of Goa from the Bijapur sultanate in 1510 was soon countered by the Bijapuris, but with the help of Hindu privateer Timoji, on November 25 of the same year it was recaptured.[54][55] In Goa, Albuquerque began the first Portuguese mint in India in 1510.[56] He encouraged Portuguese settlers to marry local women, built a church in honor of St. Catherine (as it was recaptured on her feast day), and attempted to build rapport with the Hindus by protecting their temples and reducing their tax requirements.[55] The Portuguese maintained friendly relations with the south Indian Emperors of the Vijayanagara Empire.[57]

In April 1511, Albuquerque sailed to Malacca on the Malay Peninsula,[58] the largest spice market of the period.[59] Though the trade was largely dominated by the Gujarati, other groups such as the Turks, Persians, Armenians, Tamils and Abyssinians traded there.[59] Albuquerque targeted Malacca to impede the Muslim and Venetian influence in the spice trade and increase that of Lisbon.[60] By July 1511, Albuquerque had captured Malacca and sent Antonio de Abreu and Francisco Serrão (along with Ferdinand Magellan) to explore the Indonesian archipelago.[61]

The Malacca peninsula became the strategic base for Portuguese trade expansion with China and Southeast Asia. A strong gate, called the A Famosa, was erected to defend the city and remains.[62] Learning of Siamese ambitions over Malacca, Albuquerque immediately sent Duarte Fernandes on a diplomatic mission to the Kingdom of Siam (modern Thailand), where he was the first European to arrive, establishing amicable relations and trade between both kingdoms.[63][64]

The Portuguese empire pushed further south and proceeded to discover Timor in 1512. Jorge de Meneses discovered New Guinea in 1526, naming it the "Island of the Papua".[65] In 1517, João da Silveira commanded a fleet to Chittagong,[66] and by 1528, the Portuguese had established a settlement in Chittagong.[67] The Portuguese eventually based their center of operations along the Hugli River, where they encountered Muslims, Hindus, and Portuguese deserters known as Chatins.[68]

China and Japan

[edit]

Jorge Alvares was the first European to reach China by sea, while the Romans were the first overland via Asia Minor.[69][70][71][72] He was also the first European to discover Hong Kong.[73][74] In 1514, Afonso de Albuquerque, the Viceroy of the Estado da India, dispatched Rafael Perestrello to sail to China in order to pioneer European trade relations with the nation.[75][76]

In their first attempts at obtaining trading posts by force, the Portuguese were defeated by the Ming Chinese at the Battle of Tunmen in Tamão or Tuen Mun. In 1521, the Portuguese lost 2 ships at the Battle of Sincouwaan in Lantau Island. The Portuguese also lost 2 ships at Shuangyu in 1548 where several Portuguese were captured and near the Dongshan Peninsula. In 1549 two Portuguese junks and Galeote Pereira were captured. During these battles the Ming Chinese captured weapons from the defeated Portuguese which they then reverse engineered and mass-produced in China such as matchlock musket arquebuses which they named bird guns and breech-loading swivel guns which they named as Folangji (Frankish) cannon because the Portuguese were known to the Chinese under the name of Franks at this time. The Portuguese later returned to China peacefully and presented themselves under the name Portuguese instead of Franks in the Luso-Chinese agreement (1554) and rented Macau as a trading post from China by paying annual lease of hundreds of silver taels to Ming China.[77]

Despite initial harmony and excitement between the two cultures, difficulties began to arise shortly afterwards, including misunderstanding, bigotry, and even hostility.[78] The Portuguese explorer Simão de Andrade incited poor relations with China due to his pirate activities, raiding Chinese shipping, attacking a Chinese official, and kidnappings of Chinese. He based himself at Tamao island in a fort. The Chinese claimed that Simão kidnapped Chinese boys and girls to be molested and cannibalized.[79] The Chinese sent a squadron of junks against Portuguese caravels that succeeded in driving the Portuguese away and reclaiming Tamao. As a result, the Chinese posted an edict banning men with Caucasian features from entering Canton, killing multiple Portuguese there, and driving the Portuguese back to sea.[80][81]

After the Sultan of Bintan detained several Portuguese under Tomás Pires, the Chinese then executed 23 Portuguese and threw the rest into prison where they resided in squalid, sometimes fatal conditions. The Chinese then massacred Portuguese who resided at Ningbo and Fujian trading posts in 1545 and 1549, due to extensive and damaging raids by the Portuguese along the coast, which irritated the Chinese.[80] Portuguese pirating was second to Japanese pirating by this period. However, they soon began to shield Chinese junks and a cautious trade began. In 1557 the Chinese authorities allowed the Portuguese to settle in Macau, creating a warehouse in the trade of goods between China, Japan, Goa and Europe.[80][82]

Spice Islands (Moluccas) and Treaty of Zaragoza

[edit]

Portuguese operations in Asia did not go unnoticed, and in 1521 Magellan arrived in the region and claimed the Philippines for Spain. In 1525, Spain under Charles V sent an expedition to colonize the Moluccas islands, claiming they were in his zone of the Treaty of Tordesillas, since there was no set limit to the east. The expedition of García Jofre de Loaísa reached the Moluccas, docking at Tidore. With the Portuguese already established in nearby Ternate, conflict was inevitable, leading to nearly a decade of skirmishes. A resolution was reached with the Treaty of Zaragoza in 1529, attributing the Moluccas to Portugal and the Philippines to Spain.[84] The Portuguese traded regularly with the Bruneian Empire from 1530 and described the capital of Brunei as surrounded by a stone wall.

South Asia, Persian Gulf and Red Sea

[edit]

The Portuguese empire expanded into the Persian Gulf, contesting control of the spice trade with the Ajuran Empire and the Ottoman Empire. In 1515, Afonso de Albuquerque conquered the Huwala state of Hormuz at the head of the Persian Gulf, establishing it as a vassal state. Aden, however, resisted Albuquerque's expedition in that same year and another attempt by Albuquerque's successor Lopo Soares de Albergaria in 1516. In 1521 a force led by António Correia captured Bahrain, defeating the Jabrid King, Muqrin ibn Zamil.[85] In a shifting series of alliances, the Portuguese dominated much of the southern Persian Gulf for the next hundred years. With the regular maritime route linking Lisbon to Goa since 1497, the island of Mozambique became a strategic port, and there was built Fort São Sebastião and a hospital. In the Azores, the Islands Armada protected the ships en route to Lisbon.[86]

In 1534, Gujarat faced attack from the Mughals and the Rajput states of Chitor and Mandu. The Sultan Bahadur Shah of Gujarat was forced to sign the Treaty of Bassein with the Portuguese, establishing an alliance to regain the country, giving in exchange Daman, Diu, Mumbai and Bassein. It also regulated the trade of Gujarati ships departing to the Red Sea and passing through Bassein to pay duties and allow the horse trade.[87] After Mughal ruler Humayun had success against Bahadur, the latter signed another treaty with the Portuguese to confirm the provisions and allowed the fort to be built in Diu. Shortly afterward, Humayun turned his attention elsewhere, and the Gujarats allied with the Ottomans to regain control of Diu and lay siege to the fort. The two failed sieges of 1538 and 1546 put an end to Ottoman ambitions, confirming the Portuguese hegemony in the region,[87][88] as well as gaining superiority over the Mughals.[89] However, the Ottomans fought off attacks from the Portuguese in the Red Sea and in the Sinai Peninsula in 1541, and in the northern region of the Persian Gulf in 1546 and 1552. Each entity ultimately had to respect the sphere of influence of the other, albeit unofficially.[90][91]

Sub-Saharan Africa

[edit]

After a series of prolonged contacts with Ethiopia, the Portuguese embassy made contact with the Ethiopian (Abyssinian) Kingdom led by Rodrigo de Lima in 1520.[92][93] This coincided with the Portuguese search for Prester John, as they soon associated the kingdom as his land.[94] The fear of Turkish advances within the Portuguese and Ethiopian sectors also played a role in their alliance.[92][95] The Adal Sultanate defeated the Ethiopians in the battle of Shimbra Kure in 1529, and Islam spread further in the region. Portugal responded by aiding king Gelawdewos with Portuguese soldiers and muskets. Though the Ottomans responded with support of soldiers and muskets to the Adal Sultanate, after the death of the Adali sultan Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi in the battle of Wayna Daga in 1543, the joint Adal-Ottoman force retreated.[96][97][98]

The Portuguese also made direct contact with the Kongolose vassal state Ndongo and its ruler Ngola Kiljuane in 1520, after the latter requested missionaries.[99] Kongolese king Afonso I interfered with the process with denunciations, and later sent a Kongo mission to Ndongo after the latter had arrested the Portuguese mission that came.[99] The growing official and unofficial slave trading with Ndongo strained relations between Kongo and the Portuguese, and even had Portuguese ambassadors from Sao Tome support Ndongo against the Kingdom of Kongo.[100][101] However, when the Jaga attacked and conquered regions of Kongo in 1568, Portuguese assisted Kongo in their defeat.[102] In response, the Kongo allowed the colonization of Luanda Island; Luanda was established by Paulo Dias de Novais in 1576 and soon became a slave port.[102][103] De Novais' subsequent alliance with Ndongo angered Luso-Africans who resented the influence from the Crown.[104] In 1579, Ndongo ruler Ngola Kiluanje kia Ndamdi massacred Portuguese and Kongolese residents in the Ndongo capital Kabasa under the influence of Portuguese renegades. Both the Portuguese and Kongo fought against Ndongo, and off-and-on warfare between the Ndongo and Portugal would persist for decades.[105]

In east-Africa, the main agents acting on behalf of the Portuguese Crown, exploring and settling the territory of what would become Mozambique were the prazeiros, to whom vast estates around the Zambezi river were leased by the King as a reward for their services. Commanding vast armies of chikunda warrior-slaves, these men acted as feudal-like lords, either levying tax from local chieftains, defending them and their estates from marauding tribes, participating in the ivory or slave trade, and becoming involved in the politics of the Kingdom of Mutapa, to the point of installing client kings upon its throne.

Missionary expeditions

[edit]

In 1542, Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier arrived in Goa at the service of King John III of Portugal, in charge of an Apostolic Nunciature. At the same time Francisco Zeimoto, António Mota, and other traders arrived in Japan for the first time. According to Fernão Mendes Pinto, who claimed to be in this journey, they arrived at Tanegashima, where the locals were impressed by firearms, that would be immediately made by the Japanese on a large scale.[106] By 1570 the Portuguese bought part of a Japanese port where they founded a small part of the city of Nagasaki,[107] and it became the major trading port in Japan in the triangular trade with China and Europe.[108]

Guarding its trade from both European and Asian competitors, Portugal dominated not only the trade between Asia and Europe, but also much of the trade between different regions of Asia and Africa, such as India, Indonesia, China, and Japan. Jesuit missionaries, followed the Portuguese to violently and forcefully spread Catholicism[109][110] to Asia and Africa with mixed success.[111]

Colonization efforts in the Americas

[edit]Canada

[edit]

Based on the Treaty of Tordesillas, the Portuguese Crown, under the kings Manuel I, John III and Sebastian, also claimed territorial rights in North America (reached by John Cabot in 1497 and 1498). To that end, in 1499 and 1500, João Fernandes Lavrador explored Greenland and the north Atlantic coast of Canada, which accounts for the appearance of "Labrador" on topographical maps of the period.[112] Subsequently, in 1500–1501 and 1502, the brothers Gaspar and Miguel Corte-Real explored what is today the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, and Greenland, claiming these lands for Portugal. In 1506, King Manuel I created taxes for the cod fisheries in Newfoundland waters.[citation needed] Around 1521, João Álvares Fagundes was granted donatary rights to the inner islands of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and also created a settlement on Cape Breton Island to serve as a base for cod fishing. Pressure from natives and competing European fisheries prevented a permanent establishment and it was abandoned five years later. Several attempts to establish settlements in Newfoundland over the next half-century also failed.[113]

Brazil

[edit]Within a few years after Cabral arrived from Brazil, competition came along from France. In 1503, an expedition under the command of Gonçalo Coelho reported French raids on the Brazilian coasts,[114] and explorer Binot Paulmier de Gonneville traded for brazilwood after making contact in southern Brazil a year later.[115] Expeditions sponsored by Francis I along the North American coast directly violated of the Treaty of Tordesilhas.[116] By 1531, the French had stationed a trading post off of an island on the Brazilian coast.[116]

The increase in brazilwood smuggling from the French led João III to press an effort to establish effective occupation of the territory.[117] In 1531, a royal expedition led by Martim Afonso de Sousa and his brother Pero Lopes went to patrol the whole Brazilian coast, banish the French, and create some of the first colonial towns – among them São Vicente, in 1532.[118] Sousa returned to Lisbon a year later to become governor of India and never returned to Brazil.[119][120] The French attacks did cease to an extent after retaliation led to the Portuguese paying the French to stop attacking Portuguese ships throughout the Atlantic,[116] but the attacks would continue to be a problem well into the 1560s.[121]

Upon de Sousa's arrival and success, fifteen latitudinal tracts, theoretically to span from the coast to the Tordesillas limit, were decreed by João III on 28 September 1532.[119][122] The plot of the lands formed as a hereditary captaincies (Capitanias Hereditárias) to grantees rich enough to support settlement, as had been done successfully in Madeira and Cape Verde islands.[123] Each captain-major was to build settlements, grant allotments and administer justice, being responsible for developing and taking the costs of colonization, although not being the owner: he could transmit it to offspring, but not sell it. Twelve recipients came from Portuguese gentry who become prominent in Africa and India and senior officials of the court, such as João de Barros.[124]

Of the fifteen original captaincies, only two, Pernambuco and São Vicente, prospered.[125] Both were dedicated to the crop of sugar cane, and the settlers managed to maintain alliances with Native Americans. The rise of the sugar industry came about because the Crown took the easiest sources of profit (brazilwood, spices, etc.), leaving settlers to come up with new revenue sources.[126] The establishment of the sugar cane industry demanded intensive labor that would be met with Native American and, later, African slaves.[127] Deeming the capitanias system ineffective, João III decided to centralize the government of the colony in order to "give help and assistance" to grantees. In 1548 he created the first General Government, sending in Tomé de Sousa as first governor and selecting a capital at the Bay of All Saints, making it at the Captaincy of Bahia.[128][129]

Tomé de Sousa built the capital of Brazil, Salvador, at the Bay of All Saints in 1549.[130] Among de Sousa's 1000 man expedition were soldiers, workers, and six Jesuits led by Manuel da Nóbrega.[131] The Jesuits would have an essential role in the colonization of Brazil, including São Vicente, and São Paulo, the latter which Nóbrega co-founded.[132] Along with the Jesuit missions later came disease among the natives, among them plague and smallpox.[133] Subsequently, the French would resettle in Portuguese territory at Guanabara Bay, which would be called France Antarctique.[134] While a Portuguese ambassador was sent to Paris to report the French intrusion, Joao III appointed Mem de Sá as new Brazilian governor general, and Sá left for Brazil in 1557.[134] By 1560, Sá and his forces had expelled the combined Huguenot, Scottish Calvinist, and slave forces from France Antarctique, but left survivors after burning their fortifications and villages. These survivors would settle Gloria Bay, Flamengo Beach, and Parapapuã with the assistance of the Tamoio natives.[135]

The Tamoio had been allied with the French since the settlement of France Antarctique, and despite the French loss in 1560, the Tamoio were still a threat.[136] They launched two attacks in 1561 and 1564 (the latter event was assisting the French), and were nearly successful with each.[137][138] By this time period, Manuel de Nóbrega, along with fellow Jesuit José de Anchieta, took part as members of attacks on the Tamoios and as spies for their resources.[136][137] From 1565 through 1567 Mem de Sá and his forces eventually destroyed France Antarctique at Guanabara Bay. He and his nephew, Estácio de Sá, then established the city of Rio de Janeiro in 1567, after Mem de Sá proclaimed the area "São Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro" in 1565.[139] By 1575, the Tamoios had been subdued and essentially were extinct,[136] and by 1580 the government became more of an ouvidor general rather than the ouvidores.[140]

Iberian Union, Protestant rivalry, and colonial stasis (1580–1663)

[edit]

In 1580, King Philip II of Spain invaded Portugal after a crisis of succession brought about by King Sebastian of Portugal's death during a disastrous Portuguese attack on Alcácer Quibir in Morocco in 1578. At the Cortes of Tomar in 1581, Philip was crowned Philip I of Portugal, uniting the two crowns and overseas empires under Spanish Habsburg rule in a dynastic Iberian Union.[141] At Tomar, Philip promised to keep the empires legally distinct, leaving the administration of the Portuguese Empire to Portuguese nationals, with a Viceroy of Portugal in Lisbon seeing to his interests.[142] Philip even had the capital moved to Lisbon for a two-year period (1581–83) due to it being the most important city in the Iberian peninsula.[143] All the Portuguese colonies accepted the new state of affairs except for the Azores, which held out for António, a Portuguese rival claimant to the throne who had garnered the support of Catherine de Medici of France in exchange for the promise to cede Brazil. Spanish forces eventually captured the islands in 1583.[144]

The Tordesillas boundary between Spanish and Portuguese control in South America was then increasingly ignored by the Portuguese, who pressed beyond it into the heart of Brazil,[142] allowing them to expand the territory to the west. Exploratory missions were carried out both ordered by the government, the "entradas" (entries), and by private initiative, the "bandeiras" (flags), by the "bandeirantes".[145] These expeditions lasted for years venturing into unmapped regions, initially to capture natives and force them into slavery, and later focusing on finding gold, silver and diamond mines.[146]

However, the union meant that Spain dragged Portugal into its conflicts with England, France and the Dutch Republic, countries which were beginning to establish their own overseas empires.[147] The primary threat came from the Dutch, who had been engaged in a struggle for independence against Spain since 1568. In 1581, the Seven Provinces gained independence from the Habsburg rule, leading Philip II to prohibit commerce with Dutch ships, including in Brazil where Dutch had invested large sums in financing sugar production.[148]

Spanish imperial trade networks now were opened to Portuguese merchants, which was particularly lucrative for Portuguese slave traders who could now sell slaves in Spanish America at a higher price than could be fetched in Brazil.[149] In addition to this newly acquired access to the Spanish asientos, the Portuguese were able to solve their bullion shortage issues with access to the production of the silver mining in Peru and Mexico.[150] Manila was also incorporated into the Macau-Nagasaki trading network, allowing Macanese of Portuguese descent to act as trading agents for Philippine Spaniards and use Spanish silver from the Americas in trade with China, and they later drew competition with the Dutch East India Company.[151]

In 1592, during the war with Spain, an English fleet captured a large Portuguese carrack off the Azores, the Madre de Deus, which was loaded with 900 tons of merchandise from India and China estimated at half a million pounds (nearly half the size of English Treasury at the time).[152] This foretaste of the riches of the East galvanized English interest in the region.[153] That same year, Cornelis de Houtman was sent by Dutch merchants to Lisbon, to gather as much information as he could about the Spice Islands.[151][154]

The Dutch eventually realized the importance of Goa in breaking up the Portuguese empire in Asia. In 1583, merchant and explorer Jan Huyghen van Linschoten (1563 – 8 February 1611), formerly the Dutch secretary of the Archbishop of Goa, had acquired information while serving in that position that contained the location of secret Portuguese trade routes throughout Asia, including those to the East Indies and Japan. It was published in 1595 and then greatly expanded the next year as his Itinerario.[155][156] Dutch and English interests used this new information, leading to their commercial expansion, including the foundation of the English East India Company in 1600, and the Dutch East India Company in 1602. These developments allowed the entry of chartered companies into the East Indies.[157][158]

The Dutch took their fight overseas, attacking Spanish and Portuguese colonies and beginning the Dutch–Portuguese War, which would last for over sixty years (1602–1663). Other European nations, such as Protestant England, assisted the Dutch Empire in the war. The Dutch attained victories in Asia and Africa with assistance of various indigenous allies, eventually wrenching control of Malacca, Ceylon, and São Jorge da Mina. The Dutch also had regional control of the lucrative sugar-producing region of northeast Brazil as well as Luanda, but the Portuguese regained these territories after considerable struggle.[159][160]

Meanwhile, in the Persian Gulf region, the Portuguese also lost control of Ormuz by a joint alliance of the Safavids and the English in 1622, and Oman under the Al-Ya'arubs would capture Muscat in 1650.[161] The 1625 Battle off Hormuz, one of the most important of the Portuguese–Safavid wars, would result in a draw.[162] They would continue to use Muscat as a base for repetitive incursions within the Indian Ocean, including capturing Fort Jesus in 1698.[163] In Ethiopia and Japan in the 1630s, the ousting of missionaries by local leaders severed influence in the respective regions.[164][165]

Second empire (1663–1822)

[edit]

The loss of colonies was one of the reasons that contributed to the end of the personal union with Spain. In 1640 John IV was proclaimed King of Portugal and the Portuguese Restoration War began. Even before the war's final resolution, the crown established the Overseas Council, conceived in 1642 on the short-lived model of the Council of India (1604–1614), and established in 1643, it was the governing body for most of the Portuguese overseas empire. The exceptions were North Africa, Madeira, and the Azores. All correspondence concerning overseas possessions were funneled through the council. When the Portuguese court fled to Brazil in 1807, following the Napoleonic invasion of Iberia, Brazil was removed from the jurisdiction of the council. It made recommendations concerning personnel for the administrative, fiscal, and military, as well as bishops of overseas dioceses.[166] A distinguished seventeenth-century member was Salvador de Sá.[167]

In 1661 the Portuguese offered Bombay and Tangier to England as part of a dowry, and over the next hundred years the English gradually became the dominant trader in India, gradually excluding the trade of other powers. In 1668 Spain recognized the end of the Iberian Union and in exchange Portugal ceded Ceuta to the Spanish crown.[168]

After the Portuguese were defeated by the Indian rulers Chimnaji Appa of the Maratha Empire[169][170] and by Shivappa Nayaka of the Keladi Nayaka Kingdom[171] and at the end of confrontations with the Dutch, Portugal was only able to cling onto Goa and several minor bases in India, and managed to regain territories in Brazil and Africa, but lost forever to prominence in Asia as trade was diverted through increasing numbers of English, Dutch and French trading posts. Thus, throughout the century, Brazil gained increasing importance to the empire, which exported brazilwood and sugar.[146]

Minas Gerais and the gold industry

[edit]In 1693, gold was discovered at Minas Gerais in Brazil. Major discoveries of gold and, later, diamonds in Minas Gerais, Mato Grosso and Goiás led to a "gold rush", with a large influx of migrants.[172] The village became the new economic center of the empire, with rapid settlement and some conflicts. This gold cycle led to the creation of an internal market and attracted a large number of immigrants. By 1739, at the apex of the mining boom, the population of Minas Gerais was somewhere between 200,000 and 250,000.[173]

The gold rush considerably increased the revenue of the Portuguese crown, who charged a fifth of all the ore mined, or the "fifth". Diversion and smuggling were frequent, along with altercations between Paulistas (residents of São Paulo) and Emboabas (immigrants from Portugal and other regions in Brazil), so a whole set of bureaucratic controls began in 1710 with the captaincy of São Paulo and Minas Gerais. By 1718, São Paulo and Minas Gerais became two captaincies, with eight vilas created in the latter.[174][175] The crown also restricted the diamond mining within its jurisdiction and to private contractors.[175] In spite of gold galvanizing global trade, the plantation industry became the leading export for Brazil during this period; sugar constituted at 50% of the exports (with gold at 46%) in 1760.[173]

Africans became the largest group of people in Minas Gerais. Slaves labeled as 'Minas' and 'Angolas' rose in high demand during the boom. The Akan within the 'Minas' group had a reputation to have been experts in extrapolating gold in their native regions, and became the preferred group. In spite of the high death rate associated with the slaves involved in the mining industry, the owners that allowed slaves that extracted above the minimum amount of gold to keep the excesses, which in turn led to the possibility of manumission. Those that became free partook in artisan jobs such as cobblers, tailors, and blacksmiths. In spite of free blacks and mulattoes playing a large role in Minas Gerais, the number of them that received marginalization was greater there than in any other region in Brazil.[176]

Gold discovered in Mato Grosso and Goiás sparked an interest to solidify the western borders of the colony. In the 1730s contact with Spanish outposts occurred more frequently, and the Spanish threatened to launch a military expedition in order to remove them. This failed to happen and by the 1750s the Portuguese were able to implant a political stronghold in the region.[177]

In 1755 Lisbon suffered a catastrophic earthquake, which together with a subsequent tsunami killed between 40,000 and 60,000 people out of a population of 275,000.[178] This sharply checked Portuguese colonial ambitions in the late 18th century.[179]

According to economic historians, Portugal's colonial trade had a substantial positive impact on Portuguese economic growth, 1500–1800. Leonor Costa et al. conclude:

intercontinental trade had a substantial and increasingly positive impact on economic growth. In the heyday of colonial expansion, eliminating the economic links to empire would have reduced Portugal's per capita income by roughly a fifth. While the empire helped the domestic economy it was not sufficient to annul the tendency towards decline in relation to Europe's advanced core which set in from the 17th century onwards.[180]

Pombaline and post-Pombaline Brazil

[edit]

Unlike Spain, Portugal did not divide its colonial territory in America. The captaincies created there functioned under a centralized administration in Salvador, which reported directly to the Crown in Lisbon. The 18th century was marked by increasing centralization of royal power throughout the Portuguese empire. The Jesuits, who protected the natives against slavery, were brutally suppressed by the Marquis of Pombal, which led to the dissolution of the order in the region by 1759.[181] Pombal wished to improve the status of the natives by declaring them free and increasing the mestizo population by encouraging intermarriage between them and the white population. Indigenous freedom decreased in contrast to its period under the Jesuits, and the response to intermarriage was lukewarm at best.[182] The crown's revenue from gold declined and plantation revenue increased by the time of Pombal, and he made provisions to improve each. Although he failed to spike the gold revenue, two short-term companies he established for the plantation economy drove a significant increase in production of cotton, rice, cacao, tobacco, and sugar. Slave labor increased as well as involvement from the textile economy. The economic development as a whole was inspired by elements of the Enlightenment in mainland Europe.[183] However, the diminished influence from states such as the United Kingdom increased the Kingdom's dependence upon Brazil.[184]

Encouraged by the example of the United States of America, which had won its independence from Britain, the colonial province of Minas Gerais attempted to achieve the same objective in 1789. However, the Inconfidência Mineira failed, its leaders were arrested, and of the participants in the insurrections, the one of lowest social position, Tiradentes, was hanged.[185] Among the conspiracies led by the African population was the Bahian revolt in 1798, led primarily by João de Deus do Nascimento. Inspired by the French Revolution, leaders proposed a society without slavery, food prices would be lowered, and trade restriction abolished. Impoverished social conditions and a high cost of living were among reasons of the revolt. Authorities diffused the plot before major action began; they executed four of the conspirators and exiled several others to the Atlantic Coast of Africa.[186] Several more smaller-scale slave rebellions and revolts would occur from 1801 and 1816 and fears within Brazil were that these events would lead to a "second Haiti".[187]

In spite of the conspiracies, the rule of Portugal in Brazil was not under serious threat. Historian A. R. Disney states that the colonists did not until the transferring of the Kingdom in 1808 assert influence of policy changing due to direct contact,[188] and historian Gabriel Paquette mentions that the threats in Brazil were largely unrealized in Portugal until 1808 because of effective policing and espionage.[189] More revolts would occur after the arrival of the court.[190]

Brazilian Independence

[edit]

In 1808, Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Portugal, and Dom João, prince regent in place of his mother, Queen Maria I, ordered the transfer of the royal court to Brazil. In 1815 Brazil was elevated to the status of Kingdom, the Portuguese state officially becoming the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves (Reino Unido de Portugal, Brasil e Algarves), and the capital was transferred from Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro, the only instance of a European country being ruled from one of its colonies. There was also the election of Brazilian representatives to the Cortes Constitucionais Portuguesas (Portuguese Constitutional Courts), the Parliament that assembled in Lisbon in the wake of the Liberal Revolution of 1820.[191]

Although the royal family returned to Portugal in 1821, the interlude led to a growing desire for independence amongst Brazilians. In 1822, the son of Dom João VI, then prince-regent Dom Pedro I, proclaimed the independence of Brazil on September 7, 1822, and was crowned Emperor of the new Empire of Brazil. Unlike the Spanish colonies of South America, Brazil's independence was achieved without significant bloodshed.[192][193]

Third empire (1822–1999)

[edit]

At the height of European colonialism in the 19th century, Portugal had lost its territory in South America and all but a few bases in Asia. During this phase, Portuguese colonialism focused on expanding its outposts in Africa into nation-sized territories to compete with other European powers there. Portugal pressed into the hinterland of Angola and Mozambique, and explorers Serpa Pinto, Hermenegildo Capelo and Roberto Ivens were among the first Europeans to cross Africa west to east.[194][195]

British Ultimatum and end of Portuguese monarchy (1890–1910)

[edit]

Проект по соединению двух колоний, « Розовая карта» , был главной целью португальской политики в 1880-х годах. [ 196 ] Однако эта идея была неприемлема для британцев, у которых были свои собственные стремления к созданию прилегающей британской территории, простирающейся от Каира до Кейптауна . Британский ультиматум 1890 года был предъявлен королю Португалии Карлушу I , и «Розовая карта» подошла к концу. [ 196 ]

Реакцией короля на ультиматум воспользовались республиканцы. [ 196 ] 1 февраля 1908 года король Карлуш и принц Луиш Филипе были убиты в Лиссабоне двумя португальскими революционерами-республиканцами, Альфредо Луишем да Коштой и Мануэлем Буисой . Брат Луиша Филипе, Мануэль, стал королем Португалии Мануэлем II . Два года спустя, 5 октября 1910 года, он был свергнут и бежал в изгнание в Англию в Фулвелл-Парк, Твикенхем недалеко от Лондона, и Португалия стала республикой . [ 197 ]

Первая мировая война

[ редактировать ]В 1914 году Германская империя сформулировала планы по узурпации Анголы из-под контроля Португалии. [ 198 ] Последовали стычки между португальскими и немецкими солдатами, в результате которых с материка было отправлено подкрепление. [ 199 ] Основной целью этих солдат было вернуть себе треугольник Кионга на севере Мозамбика, территорию, порабощенную Германией. В 1916 году, после того как Португалия интернировала немецкие корабли в Лиссабоне, Германия объявила Португалии войну. Португалия последовала этому примеру и вступила в Первую мировую войну. [ 200 ] В начале войны Португалия в основном занималась снабжением союзников, находящихся во Франции. В 1916 году произошло только одно нападение на территорию Португалии, на Мадейру . [ 201 ] В 1917 году одним из действий, предпринятых Португалией, была помощь Великобритании в ее лесной промышленности, необходимой для военных действий. Совместно с Канадским лесным корпусом португальские сотрудники создали инфраструктуру лесозаготовок в районе, который сейчас называют « Португальским камином ». [ 202 ]

На протяжении 1917 года Португалия отправляла контингенты войск на фронт союзников во Франции. В середине года Португалия понесла первые потери в Первой мировой войне. В португальской Африке Португалия и британцы вели многочисленные сражения против немцев как в Мозамбике, так и в Анголе. Позже в том же году подводные лодки снова вошли в воды Португалии и еще раз атаковали Мадейру, потопив несколько португальских кораблей. До начала 1918 года Португалия продолжала сражаться на союзном фронте против Германии, включая участие в печально известной битве при Ла-Лисе . [ 203 ] С приближением осени Германия добилась успеха как в португальской Африке, так и против португальских судов, потопив несколько кораблей. После почти трёх лет боевых действий (с точки зрения Португалии) Первая мировая война закончилась перемирием, подписанным Германией. На Версальской конференции Португалия восстановила контроль над всей своей утраченной территорией, но не сохранила владения (по принципу uti possidetis ) территориями, полученными в ходе войны, за исключением Кионги — портового города в современной Танзании . [ 204 ]

Португальские территории в Африке, возможно, включали современные государства Кабо-Верде , Сан-Томе и Принсипи , Гвинею-Бисау , Анголу и Мозамбик . [ 205 ]

Деколонизация (1954–1999)

[ редактировать ]

После Второй мировой войны в империях европейских держав начали набирать обороты движения за деколонизацию. Последовавшая за этим холодная война также создала нестабильность среди португальского населения за рубежом, поскольку Соединенные Штаты и Советский Союз соперничали за расширение своих сфер влияния. После предоставления независимости Индии Великобританией в 1947 году и решения Франции разрешить включение своих анклавов в Индии в состав новой независимой страны, на Португалию было оказано давление с целью сделать то же самое. [ 206 ] Этому сопротивлялся Антониу де Оливейра Салазар , пришедший к власти в 1933 году. Салазар отклонил просьбу в 1950 году премьер-министра Индии Джавахарлала Неру вернуть анклавы, рассматривая их как неотъемлемую часть Португалии. [ 207 ] В следующем году в конституцию Португалии были внесены поправки, изменившие статус колоний на заморские провинции. В 1954 году местное восстание привело к свержению португальских властей в индийских анклавах Дадра и Нагар-Хавели . Существование оставшихся португальских колоний в Индии становилось все более несостоятельным, и Неру пользовался поддержкой почти всех внутриполитических партий Индии, а также Советского Союза и его союзников. В 1961 году, вскоре после восстания против португальцев в Анголе, Неру приказал индийской армии войти в Гоа , Даман и Диу , которые были быстро захвачены и официально аннексированы в следующем году. Салазар отказался признать передачу суверенитета, полагая, что территории просто оккупированы. Провинция Гоа продолжала быть представлена в Национальном собрании Португалии до 1974 года. [ 208 ]

Вспышка насилия в феврале 1961 года в Анголе стала началом конца португальской империи в Африке. Офицеры португальской армии в Анголе придерживались мнения, что она не сможет справиться военным путем с вспышкой партизанской войны и поэтому переговоры следует начать с движениями за независимость. Однако Салазар публично заявил о своей решимости сохранить империю в целостности, и к концу года там было размещено 50 000 солдат. В том же году крошечный португальский форт Сан-Жуан-Баптиста-де-Ажуда в Уиде , остаток западноафриканской работорговли, был аннексирован новым правительством Дагомеи (ныне Бенин ), получившим независимость от Франции. Беспорядки распространились из Анголы на Гвинею, которая восстала в 1963 году, и Мозамбик в 1964 году. [ 208 ]

По словам одного историка, португальские правители не желали удовлетворять требования своих колониальных подданных (в отличие от других европейских держав) отчасти потому, что португальская элита считала, что «У Португалии не хватает средств для проведения успешной «стратегии выхода» (сродни «неоколониальной» стратегии выхода). подхода, которому следуют британцы, французы или бельгийцы)», и отчасти из-за отсутствия «свободных и открытых дебатов [в диктаторском государстве Салазара] о затратах на поддержание империи вопреки преобладавшему антиколониальному консенсусу в ООН с начала 1960-х годов». [ 209 ] Рост советского влияния среди военных (МИД) и рабочего класса Движения дас Армадас , а также цена и непопулярность португальской колониальной войны (1961–1974 гг.), в ходе которой Португалия сопротивлялась зарождающимся националистическим партизанским движениям в некоторых странах. его африканские территории, в конечном итоге привели к краху режима Estado Novo в 1974 году. Известная как « Революция гвоздик », один из первых актов правительства под руководством МИД, которое затем пришло к власти – Хунты национального спасения ( Junta de Salvação Nacional ) – должен был положить конец войнам и договориться о выводе Португалии из своих африканских колоний. Эти события вызвали массовый исход португальских граждан с африканских территорий Португалии (в основном из Анголы и Мозамбика ), в результате чего появилось более миллиона португальских беженцев – реторнадо . [ 210 ] Новые правящие власти Португалии также признали Гоа и другие территории португальской Индии, на которые вторглись вооруженные силы Индии , как индийские территории. Претензии Бенина на Сан-Жуан-Баптиста-де-Ажуда были приняты Португалией в 1974 году. [ 211 ]

гражданские войны в Анголе и Мозамбике Сразу же вспыхнули , когда новые коммунистические правительства, сформированные бывшими повстанцами (и поддерживаемые Советским Союзом, Кубой и другими коммунистическими странами), боролись против повстанческих группировок, поддерживаемых такими странами, как Заир , Южная Африка и Соединенные Штаты. Штаты. [ 212 ] Восточный Тимор также провозгласил независимость в 1975 году, совершив исход многих португальских беженцев в Португалию, который также был известен как реторнадо . Однако Восточный Тимор почти сразу же подвергся вторжению Индонезии , которая позже оккупировала его до 1999 года. Референдум, спонсируемый Организацией Объединенных Наций, привел к тому, что большинство восточнотиморцев проголосовали за независимость, которая, наконец, была достигнута в 2002 году. [ 213 ]

В 1987 году Португалия подписала Совместную китайско-португальскую декларацию с Китайской Народной Республикой, определяющую процесс и условия передачи суверенитета над Макао , ее последним оставшимся заморским владением. Хотя этот процесс был аналогичен соглашению между Соединенным Королевством и Китаем двумя годами ранее относительно Гонконга , передача Португалии Китаю была встречена меньшим сопротивлением, чем Великобритания в отношении Гонконга, поскольку Португалия уже признала Макао китайской территорией под управлением Португалии. Администрация в 1979 году. [ 214 ] В соответствии с соглашением о передаче Макао будет управляться в соответствии с политикой « одна страна, две системы» , в рамках которой он сохранит высокую степень автономии и сохранит свой капиталистический образ жизни в течение как минимум 50 лет после передачи, до 2049 года . 20 декабря 1999 года в Макао официально ознаменовало конец Португальской империи и конец колониализма в Азии. [ 215 ]

Наследие

[ редактировать ]

В настоящее время Сообщество португалоязычных стран (CPLP) является культурным и межправительственным преемником Империи. [ 216 ]

Макао был возвращен Китаю 20 декабря 1999 года в соответствии с условиями соглашения, заключенного между Китайской Народной Республикой и Португалией двенадцатью годами ранее. Тем не менее, португальский язык остается одним из официальных языков кантонского китайского языка в Макао. [ 217 ]

В настоящее время Азорские острова и Мадейра (последняя управляет необитаемыми Дикими островами ) являются единственными заморскими территориями , которые остаются политически связанными с Португалией. Хотя Португалия начала процесс деколонизации Восточного Тимора в 1975 году, в 1999–2002 годах ее иногда считали последней оставшейся колонией Португалии, поскольку индонезийское вторжение в Восточный Тимор не было оправдано Португалией. [ 218 ]

В восьми бывших колониях Португалии официальным языком является португальский . Вместе с Португалией они теперь являются членами Сообщества португалоязычных стран , общая площадь которых составляет 10 742 000 км. 2 , или 7,2% суши Земли (148 939 063 км 2 ). [ 219 ] По состоянию на 2023 год в составе СПЯС насчитывалось 32 ассоциированных наблюдателя, что отражает глобальный охват и влияние бывшей португальской империи. Более того, двенадцать стран или регионов-кандидатов подали заявки на членство в СПЯС и ожидают одобрения. [ 220 ]

Сегодня португальский является одним из основных языков мира, занимает шестое место в общем зачете, на нем говорят около 240 миллионов человек по всему миру. [ 221 ] Это третий по распространенности язык в Северной и Южной Америке, в основном благодаря Бразилии, хотя значительные сообщества португалоязычных населения также существуют в таких странах, как Канада, США и Венесуэла. Кроме того, существует множество креольских языков на основе португальского языка , в том числе тот, который используется народом кристанг в Малакке . [ 222 ]

Например, поскольку португальские купцы, по-видимому, были первыми, кто привез сладкий апельсин в Европу , в нескольких современных индоевропейских языках этот фрукт назван в их честь. Некоторые примеры: албанский портокалл , болгарский портокал ( портокал ), греческий πορτοκάλι ( портокали ), македонский ( портокал ) , персидский апельсин ( портокал ) и румынский портокал. портокал [ 223 ] [ 224 ] Родственные имена можно найти на других языках, таких как арабский البرتقال ( буртукал ), ფორთოხალი ( португальский ) , турецкий портакал и амхарский биртукан. грузинский [ 223 ] Кроме того, в южно-итальянских диалектах (например, неаполитанском ) апельсин — это портогалло или пуртуалло , буквально «португальский (один)», в отличие от стандартного итальянского аранча .

Учитывая его международное значение, Португалия и Бразилия возглавляют движение за включение португальского языка в число официальных языков Организации Объединенных Наций . [ 225 ]

-

Карта Сообщества португалоязычных стран ; государства-члены (синий), ассоциированные наблюдатели (зеленый) и официально заинтересованные страны и территории (золотой)

-

Фактическое имущество

Исследования

Области влияния и торговли

Претензии на суверенитет

Торговые посты

Основные морские исследования, маршруты и зоны влияния -

Столп Васко да Гамы в Малинди , Кения.

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Португальская колониальная архитектура

- Указ об изгнании

- Эволюция Португальской империи

- Гоанская инквизиция

- Список тем о Португальской империи на Востоке

- Лузотропизм

- Преследование евреев и мусульман Мануэлем I Португальским

- Португальские армады

- Португальский в Африке

- Португальская инквизиция

- Португальские изобретения

- Португальский суринамский

- Магелланов пролив

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Пейдж и Зонненбург 2003 , с. 481

- ^ Броки 2008 , с. xv

- ^ Хуанг и Морриссетт 2008 , с. 894

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 301

- ^ Ньюитт 2005 , стр. 15–17.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ньюитт 2005 , с. 19

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Боксер 1969 г. , с. 19

- ^ Абернети , с. 4

- ^ Ньюитт 2005 , с. 21

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Диффи и Виниус 1977 , с. 55

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 56: Генри, выходец из Португалии 15-го века, был вдохновлен как религиозными, так и экономическими факторами.

- ^ Андерсон 2000 , с. 50

- ^ Коутс 2002 , с. 60

- ^ Л.С. Ставрианос, Мир с 1500 года: глобальная история (1966), стр. 92–93.

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 68

- ^ Даус 1983 , с. 33

- ^ Боксер 1969 , с. 29

- ^ Рассел-Вуд 1998 , с. 9

- ^ Родригес 2007 , с. 79

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 469

- ^ Годиньо, В.М. Открытия и мировая экономика , Аркадия, 1965, Том 1 и 2, Лиссабон.

- ^ Понтинг 2000 , с. 482

- ^ Дэвис 2006 , с. 84

- ^ Бетанкур и Курто 2007 , с. 232

- ^ Уайт 2005 , с. 138

- ^ Ганн и Дуиньян 1972 , с. 273

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 156

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 161.

- ^ Андерсон 2000 , с. 59

- ^ Ньюитт 2005 , с. 47

- ^ Андерсон 2000 , с. 55

- ^ Макалистер 1984 , стр. 73–75.

- ^ Бетанкур и Курто 2007 , с. 165

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 174

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 176

- ^ Боксер 1969 , с. 36

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 176–185.

- ^ Скаммелл , с. 13

- ^ Макалистер 1984 , с. 75

- ^ Макалистер 1984 , с. 76

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 274, 320–323.

- ^ «Тангассери, Коллам, голландский Килон, Керала» . Керала Туризм . Архивировано из оригинала 14 мая 2014 г. Проверено 1 сентября 2014 г.

- ^ Бетанкур и Курто 2007 , с. 207

- ^ Абеасингхе 1986 , с. 2

- ^ Дисней 2009b , с. 128

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 233, 235.

- ^ Макмиллан 2000 , с. 11

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 237–239.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дисней, 2009b , стр. 128–129.

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 245–247.

- ^ Субраманьям 2012 , стр. 67–83

- ^ Дисней 2009b , с. 129

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 238

- ^ Шастры 2000 , стр. 34–45

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дисней 2009b , с. 130

- ^ де Соуза 1990 , с. 220

- ^ Мехта 1980 , с. 291

- ^ Риклефс 1991 , с. 23

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кратоска 2004 , стр. 98.

- ^ Гипулу, 2011 , стр. 301–302.

- ^ Ньюитт 2005 , с. 78

- ^ Оой 2009 , с. 202

- ^ Лах 1994 , стр. 520–521

- ^ Энциклопедия народов Азии и Океании Барбары А. Уэст. Издательство «Информационная база», 2009. с. 800

- ^ Куанчи, Макс; Робсон, Джон (2005). Исторический словарь открытия и исследования островов Тихого океана . Пугало Пресс. п. хiii. ISBN 978-0-8108-6528-0 .

- ^ де Сильва Джаясурия, с. 86

- ^ Харрис, Джонатан Гил (2015). Первый Фирангис . Книжная компания Алеф. п. 225. ИСБН 978-93-83064-91-5 . [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ де Сильва Джаясурия, с. 87

- ^ Твитчетт, Денис Криспин; Фэрбанк, Джон Кинг (1978). Кембриджская история Китая . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 336. ИСБН 978-0-521-24333-9 .

- ^ Эдмондс, Ричард Л., изд. (сентябрь 2002 г.). Китай и Европа с 1978 года: европейская перспектива . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-52403-2 .

- ^ Уорд, Джеральд В.Р. (2008). Энциклопедия материалов и техник Grove в искусстве . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 37. ИСБН 978-0-19-531391-8 .

- ^ Глисон, Кэрри (2007). Биография чая . Издательская компания Крэбтри. п. 12. ISBN 978-0-7787-2493-3 .

- ^ Гонконг и Макао 14. Эндрю Стоун, Пьера Чен, Chung Wah Chow Lonely Planet, 2010. стр. 20–21.

- ^ Гонконг и Макао. Жюль Браун Rough Guides, 2002. стр. 195

- ^ «Португальцы на Дальнем Востоке» . Algarvedailynews.com. Архивировано из оригинала 30 января 2013 г. Проверено 18 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ « Открытие Португалии в Китае» на выставке» . www.china.org.cn . Архивировано из оригинала 15 мая 2022 г. Проверено 3 мая 2013 г.

- ^ с. 343–344, Денис Криспин Твитчетт, Джон Кинг Фэрбенк, Кембриджская история Китая, Том 2; Том 8. Архивировано 13 декабря 2022 г. в Wayback Machine , Cambridge University Press, 1978 г., ISBN 0-521-24333-5

- ^ «Когда Португалия правила морями | История и археология | Журнал Смитсоновского института» . Смитсонианмаг.com. Архивировано из оригинала 25 декабря 2012 г. Проверено 18 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ Иисус 1902 , с. 5

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Додж 1976 , с. 226

- ^ Уайтвей 1899 , с. 339

- ^ Дисней 2009b , стр. 175, 184.

- ^ Леупп, Гэри П. (2003). Межрасовая близость в Японии . Международная издательская группа «Континуум» . п. 35. ISBN 978-0-8264-6074-5 .

- ^ Оой 2004 , с. 1340

- ^ Хуан Коул, Священное пространство и священная война, IB Tauris, 2007, стр. 37

- ^ О'Фланаган 2008 , с. 125

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пирсон 1976 , стр. 74–82.

- ^ Малекандатил 2010 , стр. 116–118

- ^ Мэтью 1988 , с. 138

- ^ Уяр, Месут; Дж. Эриксон, Эдвард (2003). Военная история османов: от Османа до Ататюрка . АВС-КЛИО. ISBN 0275988767 .

- ^ Д. Жоау де Кастро. Путешествие дона Стефано де Гамы из Гоа в Суэц в 1540 году с намерением сжечь турецкие галеры в этом порту. Архивировано 14 октября 2006 г. в Wayback Machine (том 6, глава 3, eText) . )

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Абир, с. 86

- ^ Аппиа; Гейтс, с. 130

- ^ Чесворт; Томас п. 86

- ^ Ньюитт (2004), с. 86

- ^ Блэк, с. 102

- ^ Стэплтон 2013 , с. 121

- ^ Коэн, стр. 17–18.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Мэнколл 2007 , с. 207

- ^ Торнтон 2000 , стр. 100–101.

- ^ Хейвуд и Торнтон 2007 , с. 83

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Стэплтон 2013 , с. 175

- ^ Гудвин, с. 184

- ^ Хейвуд и Торнтон 2007 , с. 86

- ^ Манколл 2007 , стр. 208–211

- ^ Пейси, Арнольд (1991). Технологии в мировой цивилизации: тысячелетняя история . МТИ Пресс. ISBN 978-0-262-66072-3 .

- ^ Ёсабуро Такэкоси, «Экономические аспекты истории цивилизации Японии», ISBN 0-415-32379-7 .

- ^ Дисней 2009b , с. 195

- ^ К. Блумер, Кристин (2018). Одержимый Богородицей: индуизм, католицизм и марианское владение в Южной Индии . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 14. ISBN 9780190615093 .

- ^ Дж. Руссо, Дэвид (2000). Американская история с глобальной точки зрения: интерпретация . Издательская группа Гринвуд. п. 314. ИСБН 9780275968960 .

Англиканская церковь была «государственной церковью» в колониях, как это, бесспорно, было в Англии, и как Римско-католическая церковь была в соседних Испанской и Португальской империях.

- ^ Бетанкур и Курто 2007 , стр. 262–265

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 464

- ^ Дисней 2009a , с. 116

- ^ Сельдь и Сельдь 1968 , с. 214

- ^ Меткалф (2006), с. 60

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Пикетт и Пикетт 2011 , с. 14

- ^ Марли 2008 , с. 76

- ^ Марли 2008 , стр. 76–78.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б де Оливейра Маркес 1972 , с. 254

- ^ Марли 2008 , с. 78

- ^ Марли 2005 , стр. 694–696.

- ^ Марли 2008 , с. 694

- ^ Диффи и Виниус 1977 , стр. 310

- ^ де Абреу, Жоао Капистрано (1998). Главы колониальной истории Бразилии 1500–1800 гг . пер. Артур Иракель. Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 35, 38–40. ISBN 978-0-19-802631-0 . Проверено 10 июля 2012 г.

- ^ де Оливейра Маркес 1972 , стр. 255–56

- ^ де Оливейра Маркес 1972 , с. 255

- ^ Бетанкур и Курто 2007 , стр. 111–119

- ^ Локхарт 1983 , стр. 190–191.

- ^ Бэйквелл 2009 , с. 496

- ^ Махони 2010 , с. 246

- ^ Рассел-Вуд 1968 , с. 47

- ^ Ковш 2000 , с. 185

- ^ Меткалф (2005), стр. 36–37.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Марли 2008 , с. 86

- ^ Марли 2008 , с. 90

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Трис 2000 , с. 31

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Марли 2008 , стр. 91–92.

- ^ Меткалф (2005), с. 37

- ^ Марли 2008 , с. 96

- ^ Шварц 1973 , с. 41

- ^ Камен 1999 , с. 177

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бояджян 2008 , с. 11

- ^ Галлахер 1982 , с. 8

- ^ Андерсон 2000 , стр. 104–105.

- ^ Боксер 1969 , с. 386

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бетанкур и Курто 2007 , стр. 111, 117

- ^ Андерсон 2000 , с. 105

- ^ Томас 1997 , с. 159

- ^ Локхарт 1983 , с. 250

- ^ Ньюитт 2005 , с. 163

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дисней 2009b , с. 186

- ^ Смит, Роджер (1986). «Типы кораблей раннего Нового времени, 1450–1650 гг.» . Библиотека Ньюберри. Архивировано из оригинала 20 июля 2008 г. Проверено 8 мая 2009 г.

- ^ Пуга, Рожерио Мигель (декабрь 2002 г.). «Присутствие «португальцев» в Макао и Японии в навигациях Ричарда Хаклюта » . Бюллетень португальских/японских исследований . 5 : 81–116. ISSN 0874-8438 . Архивировано из оригинала 30 марта 2023 г. Проверено 26 марта 2022 г. - через Redalyc .

- ^ Лах 1994 , стр. 200.

- ^ Ван Линшотен, Ян Гюйген (1596), Itinerario, Частое путешествие Шипварта (на голландском языке), Амстердам: Корнелис Клас.

- ^ Бернелл, Артур Кок; и др., ред. (1885), Путешествие Джона Гюйгена ван Линшотена в Ост-Индию... , Лондон: Общество Хаклюта .

- ^ Кроу, Джон А. (1992). Эпос Латинской Америки (4-е изд.). Беркли и Лос-Анджелес, Калифорния: Издательство Калифорнийского университета. п. 241 . ISBN 978-0-520-07723-2 . Проверено 10 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Боуэн, HV ; Линкольн, Маргарет; Ригби, Найджел, ред. (2002). Миры Ост-Индской компании . Бойделл и Брюэр. п. 2. ISBN 978-1-84383-073-3 . Проверено 10 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Дисней 2009b , стр. 73–74, 168–171, 226–231.

- ^ Чарльз Р. Боксер, Голландцы в Бразилии, 1624–1654 . Оксфорд: Clarendon Press 1957.

- ^ Дисней 2009b , с. 169

- ^ Уиллем Флор, «Отношения Голландии с Персидским заливом», в книге Лоуренса Г. Поттера (редактор), «Персидский залив в истории» (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), стр. 240.

- ^ Дисней 2009b , с. 350

- ^ Олсон, Джеймс Стюарт, изд. (1991). Исторический словарь европейского империализма . Гринвуд Пресс. п. 204. ИСБН 978-0313262579 . Проверено 27 августа 2017 г.

- ^ Гудман, Грант К., изд. (1991). Япония и голландцы 1600-1853 гг . Рутледж. п. 13. ISBN 978-0700712205 . Проверено 27 августа 2017 г.

- ^ Фрэнсис А. Дутра. «Заморский совет (Португалия)» в Энциклопедии латиноамериканской истории и культуры , том. 4, стр. 254–255. Нью-Йорк: Сыновья Чарльза Скрибнера 1996.

- ^ Фрэнсис А. Дутра, «Сальвадор Коррейя де Са и Бенавидес» в Энциклопедии латиноамериканской истории и культуры , том. 5, с. 2. Нью-Йорк: Сыновья Чарльза А. Скрибнера, 1996.

- ^ Коуэнс, Джон, изд. (2003). Ранняя современная Испания: документальная история . Издательство Пенсильванского университета. п. 180. ИСБН 0-8122-1845-0 . Проверено 10 июля 2012 г.

- ^ История конкана Александра Кида Нэрна, стр. 84–85.

- ^ Ахмед 2011 , с. 330

- ^ Обзор португальских исследований ISSN 1057-1515 (Baywolf Press), с. 35

- ^ Боксер 1969 , с. 168

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дисней, 2009b , стр. 268–269.

- ^ Бетелл 1985 , с. 203

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дисней, 2009b , стр. 267–268.

- ^ Дисней 2009b , стр. 273–275.

- ^ Дисней 2009b , с. 288

- ^ Козак и Чермак 2007 , с. 131

- ^ Рамасами, С.М.; Выступаю, CJ; Сивакумар, Р.; и др., ред. (2006). Геоматика в цунами . Издательство Новой Индии. п. 8. ISBN 978-81-89422-31-8 . Проверено 10 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Коста, Леонор Фрейре; Пальма, Нуно; Рейс, Хайме (2015). «Великий побег? Вклад империи в экономический рост Португалии, 1500–1800 гг.» . Европейский обзор экономической истории . 19 (1): 1–22. дои : 10.1093/ereh/heu019 . hdl : 10400.5/26870 .

- ^ Дисней 2009a , стр. 298–302.

- ^ Дисней 2009b , стр. 288–289.

- ^ Дисней 2009b , стр. 277–279, 283–284.

- ^ Пакетт, с. 67

- ^ Бетелл 1985 , стр. 163–164.

- ^ Дисней 2009b , стр. 296–297.

- ^ Пакетт, с. 104

- ^ Дисней 2009b , с. 298

- ^ Пекетт, с. 106

- ^ Пекетт, стр. 106–114.

- ^ Бетелл 1985 , стр. 177–178.

- ^ Ангус, Уильям, изд. (1837). История Англии: от римского вторжения до воцарения королевы Виктории I. Глазго. стр 254–255 . . Проверено 10 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Левин, Роберт М. (2003). История Бразилии . Пэлгрейв Макмиллан. стр. 59–61. ISBN 978-1-4039-6255-3 . Проверено 10 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Ньюитт 1995 , стр. 335–336.

- ^ Коррадо 2008 , с. 18

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Лиссабон 2008 , с. 134

- ^ Уиллер 1998 , стр. 48–61.