Проблема зла

| Часть серии о |

| Философия религии |

|---|

| Указатель статей по философии религии |

| Часть серии о |

| Теодицея |

|---|

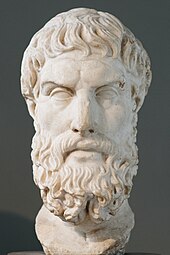

Проблема зла – это философский вопрос о том, как примирить существование зла и страданий со всемогущим , всеблагим и всеведущим Богом . [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] В настоящее время существуют различные определения этих понятий. Самое известное изложение проблемы принадлежит греческому философу Эпикуру . Его популяризировал Дэвид Юм .

Помимо философии религии , проблема зла также важна для теологии и этики . Есть также много дискуссий о зле и связанных с ним проблемах в других философских областях, таких как светская этика , [ 4 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ] и эволюционная этика . [ 7 ] [ 8 ] Но, как обычно понимают, проблема зла ставится в богословском контексте. [ 2 ] [ 3 ]

Ответы на проблему зла традиционно делятся на три типа: опровержения, защиты и теодицеи .

The problem of evil is generally formulated in two forms: the logical problem of evil and the evidential problem of evil. The logical form of the argument tries to show a logical impossibility in the coexistence of a god and evil,[2][9] while the evidential form tries to show that given the evil in the world, it is improbable that there is an omnipotent, omniscient, and a wholly good god.[3] Concerning the evidential problem, many theodicies have been proposed. One accepted theodicy is to appeal to the strong account of the compensation theodicy. This view holds that the primary benefit of evils, in addition to their compensation in the afterlife, can reject the evidential problem of evil.[10] The problem of evil has been extended to non-human life forms, to include suffering of non-human animal species from natural evils and human cruelty against them.[11]

According to scholars, most philosophers see the logical problem of evil as having been fully rebutted by various defenses.[12][13][14]

Definitions

[edit]Evil

[edit]A broad concept of evil defines it as any and all pain and suffering,[15] yet this definition quickly becomes problematic. Marcus Singer says that a usable definition of evil must be based on the knowledge that: "If something is really evil, it can't be necessary, and if it is really necessary, it can't be evil".[16]: 186 According to John Kemp, evil cannot be correctly understood on "a simple hedonic scale on which pleasure appears as a plus, and pain as a minus".[17][15] The National Institute of Medicine says pain is essential for survival: "Without pain, the world would be an impossibly dangerous place".[18][19]

While many of the arguments against an omni-God are based on the broadest definition of evil, "most contemporary philosophers interested in the nature of evil are primarily concerned with evil in a narrower sense".[20] The narrow concept of evil involves moral condemnation, and is applicable only to moral agents capable of making independent decisions, and their actions; it allows for the existence of some pain and suffering without identifying it as evil.[21]: 322 Christianity is based on "the salvific value of suffering".[22]

Philosopher Eve Garrard suggests that the term evil cannot be used to describe ordinary wrongdoing, because "there is a qualitative and not merely a quantitative difference between evil acts and other wrongful ones; evil acts are not just very bad or wrongful acts, but rather ones possessing some specially horrific quality".[21]: 321 Calder argues that evil must involve the attempt or desire to inflict significant harm on the victim without moral justification.[15]

Evil takes on different meanings when seen from the perspective of different belief systems, and while evil can be viewed in religious terms, it can also be understood in natural or secular terms, such as social vice, egoism, criminality, and sociopathology.[23] John Kekes writes that an action is evil if "(1) it causes grievous harm to (2) innocent victims, and it is (3) deliberate, (4) malevolently motivated, and (5) morally unjustifiable".[24]

Omni-qualities

[edit]Omniscience is "maximal knowledge".[25] According to Edward Wierenga, a classics scholar and doctor of philosophy and religion at the University of Massachusetts, maximal is not unlimited but limited to "God knowing what is knowable".[26]: 25 This is the most widely accepted view of omniscience among scholars of the twenty-first century, and is what William Hasker calls freewill-theism. Within this view, future events that depend upon choices made by individuals with free will are unknowable until they occur.[27]: 104, 137 [25]: 18–20

Omnipotence is maximal power to bring about events within the limits of possibility, but again maximal is not unlimited.[28] According to the philosophers Hoffman and Rosenkrantz: "An omnipotent agent is not required to bring about an impossible state of affairs... maximal power has logical and temporal limitations, including the limitation that an omnipotent agent cannot bring about, i.e., cause, another agent's free decision".[28]

Omnibenevolence sees God as all-loving. If God is omnibenevolent, he acts according to what is best, but if there is no best available, God attempts, if possible, to bring about states of affairs that are creatable and are optimal within the limitations of physical reality.[29]

Defenses and theodicies

[edit]Responses to the problem of evil have occasionally been classified as defences or theodicies although authors disagree on the exact definitions.[2][3][30] Generally, a defense refers to attempts to address the logical argument of evil that says "it is logically impossible – not just unlikely – that God exists".[3] A defense does not require a full explanation of evil, and it need not be true, or even probable; it need only be possible, since possibility invalidates the logic of impossibility.[31][9]

A theodicy, on the other hand, is more ambitious, since it attempts to provide a plausible justification – a morally or philosophically sufficient reason – for the existence of evil. This is intended to weaken the evidential argument which uses the reality of evil to argue that the existence of God is unlikely.[3][32]

Secularism

[edit]In philosopher Forrest E. Baird's view, one can have a secular problem of evil whenever humans seek to explain why evil exists and its relationship to the world.[33] He adds that any experience that "calls into question our basic trust in the order and structure of our world" can be seen as evil,[33] therefore, according to Peter L. Berger, humans need explanations of evil "for social structures to stay themselves against chaotic forces".[34]

Formulation

[edit]The problem of evil refers to the challenge of reconciling the existence of evil and suffering with our view of the world, especially but not exclusively, with belief in an omnipotent, omnibenevolent, and omniscient God who acts in the world.[3][32][35][36][37]

The problem of evil may be described either experientially or theoretically.[3] The experiential problem is the difficulty in believing in a concept of a loving God when confronted by evil and suffering in the real world, such as from epidemics, or wars, or murder, or natural disasters where innocent people become victims.[38][39][40] Theoretically, the problem is usually described and studied by religion scholars in two varieties: the logical problem and the evidential problem.[3]

One of the earliest statements of the problem is found in early Buddhist texts. In the Majjhima Nikāya, the Buddha (6th or 5th century BCE) states that if a God created sentient beings, then due to the pain and suffering they feel, he is likely to be an evil God.[41]

Logical problem of evil

[edit]

The problem of evil possibly originates from the Greek philosopher Epicurus (341–270 BCE).[42] Hume summarizes Epicurus's version of the problem as follows: "Is [god] willing to prevent evil, but not able? then is he impotent. Is he able, but not willing? then is he malevolent. Is he both able and willing? whence then is evil?"[43][44]

The logical argument from evil is as follows:

P1. If an omnipotent, omnibenevolent and omniscient god exists, then evil does not.

P2. There is evil in the world.

C1. Therefore, an omnipotent, omnibenevolent and omniscient god does not exist.

This argument is of the form modus tollens: if its premise (P1) is true, the conclusion (C1) follows of necessity. To show that the first premise is plausible, subsequent versions tend to expand on it, such as this modern example:[3]

P1a. God exists.

P1b. God is omnipotent, omnibenevolent and omniscient.

P1c. An omnipotent being has the power to prevent that evil from coming into existence.

P1d. An omnibenevolent being would want to prevent all evils.

P1e. An omniscient being knows every way in which evils can come into existence, and knows every way in which those evils could be prevented.

P1f. A being who knows every way in which an evil can come into existence, who is able to prevent that evil from coming into existence, and who wants to do so, would prevent the existence of that evil.

P1. If there exists an omnipotent, omnibenevolent and omniscient God, then no evil exists.

P2. Evil exists (logical contradiction).

Both of these arguments are understood to be presenting two forms of the 'logical' problem of evil. They attempt to show that the assumed premises lead to a logical contradiction that cannot all be correct. Most philosophical debate has focused on the suggestion that God would want to prevent all evils and therefore cannot coexist with any evils (premises P1d and P1f), but there are existing responses to every premise (such as Plantinga's response to P1c), with defenders of theism (for example, St. Augustine and Leibniz) arguing that God could exist and allow evil if there were good reasons.

If God lacks any one of these qualities – omniscience, omnipotence, or omnibenevolence – then the logical problem of evil can be resolved. Process theology and open theism are modern positions that limit God's omnipotence or omniscience (as defined in traditional theology) based on free will in others.

Evidential problem of evil

[edit]The evidential problem of evil (also referred to as the probabilistic or inductive version of the problem) seeks to show that the existence of evil, although logically consistent with the existence of God, counts against or lowers the probability of the truth of theism.[45] Both absolute versions and relative versions of the evidential problems of evil are presented below.

A version by William L. Rowe:

- There exist instances of intense suffering which an omnipotent, omniscient being could have prevented without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse.

- An omniscient, wholly good being would prevent the occurrence of any intense suffering it could, unless it could not do so without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse.

- (Therefore) There does not exist an omnipotent, omniscient, wholly good being.[3]

Another by Paul Draper:

- Gratuitous evils exist.

- The hypothesis of indifference, i.e., that if there are supernatural beings they are indifferent to gratuitous evils, is a better explanation for (1) than theism.

- Therefore, evidence prefers that no god, as commonly understood by theists, exists.[46]

Skeptical theism is an example of a theistic challenge to the premises in these arguments.

Problem of evil and animal suffering

[edit]

The problem of evil has also been extended beyond human suffering, to include suffering of animals from cruelty, disease and evil.[11] One version of this problem includes animal suffering from natural evil, such as the violence and fear faced by animals from predators, natural disasters, over the history of evolution.[48] This is also referred to as the Darwinian problem of evil,[49][50] after Charles Darwin who wrote in 1856: "What a book a Devil's chaplain might write on the clumsy, wasteful, blundering low & horridly cruel works of nature!", and in his later autobiography said: "A being so powerful and so full of knowledge as a God who could create the universe, is to our finite minds omnipotent and omniscient, and it revolts our understanding to suppose that his benevolence is not unbounded, for what advantage can there be in the sufferings of millions of the lower animals throughout almost endless time? This very old argument from the existence of suffering against the existence of an intelligent first cause seems to me a strong one".[51][52]

The second version of the problem of evil applied to animals, and avoidable suffering experienced by them, is one caused by some human beings, such as from animal cruelty or when they are shot or slaughtered. This version of the problem of evil has been used by scholars including John Hick to counter the responses and defenses to the problem of evil such as suffering being a means to perfect the morals and greater good because animals are innocent, helpless, amoral but sentient victims.[11][53][54] Scholar Michael Almeida said this was "perhaps the most serious and difficult" version of the problem of evil.[50] The problem of evil in the context of animal suffering, states Almeida, can be stated as:[55][note 1]

- God is omnipotent, omniscient and wholly good.

- The evil of extensive animal suffering exists.

- Necessarily, God can actualize an evolutionary perfect world.

- Necessarily, God can actualize an evolutionary perfect world only if God does actualize an evolutionary perfect world.

- Necessarily, God actualized an evolutionary perfect world.

- If #1 is true then either #2 or #5 is true, but not both. This is a contradiction, so #1 is not true.

Secular responses

[edit]While the problem of evil is usually considered to be a theistic one, Peter Kivy says there is a secular problem of evil that exists even if one gives up belief in a deity; that is, the problem of how it is possible to reconcile "the pain and suffering human beings inflict upon one another".[56] Kivy writes that all but the most extreme moral skeptics agree that humans have a duty to not knowingly harm others. This leads to the secular problem of evil when one person injures another through "unmotivated malice" with no apparent rational explanation or justifiable self-interest.[56]: 486, 491

There are two main reasons used to explain evil, but according to Kivy, neither are fully satisfactory.[56] The first explanation is psychological egoism – that everything humans do is from self-interest. Bishop Butler has countered this asserting pluralism: human beings are motivated by self-interest, but they are also motivated by particulars – that is particular objects, goals or desires – that may or may not involve self-interest but are motives in and of themselves and may, occasionally, include genuine benevolence.[56]: 481–482 For the egoist, "man's inhumanity to man" is "not explainable in rational terms", for if humans can be ruthless for ruthlessness' sake, then egoism is not the only human motive.[56]: 484 Pluralists do not fare better simply by recognizing three motives: injuring another for one of those motives could be interpreted as rational, but hurting for the sake of hurting, is as irrational to the pluralist as the egoist.[56]: 485

Amélie Rorty offers a few examples of secular responses to the problem of evil:[23]

Evil as necessary

[edit]According to Michel de Montaigne and Voltaire, while character traits such as wanton cruelty, partiality and egoism are an innate part of the human condition, these vices serve the "common good" of the social process.[23]: xiii For Montaigne, the idea of evil is relative to the limited knowledge of human beings, not to the world itself or to God. He adopts what philosophers Graham Oppy and N. N. Trakakis refer to as a "neo-Stoic view of an orderly world" where everything is in its place.[57]

This secular version of the early coherentist response to the problem of evil, (coherentism asserts that acceptable belief must be part of a coherent system), can be found, according to Rorty, in the writings of Bernard de Mandeville and Sigmund Freud. Mandeville says that when vices like greed and envy are suitably regulated within the social sphere, they are what "spark[s] the energy and productivity that make progressive civilization possible". Rorty asserts that the guiding motto of both religious and secular coherentists is: 'Look for the benefits gained by harm and you will find they outweigh the damage'."[23]: xv

Economic theorist Thomas Malthus stated in a 1798 essay on the question of population over-crowding, its impact on food availability, and food's impact on population through famine and death, that it was: "Necessity, that imperious, all pervading law of nature, restrains them within the prescribed bounds [...] and man cannot by any means of reason escape from it".[58]: 2 He adds: "Nature will not, indeed cannot be defeated in her purposes."[58]: 412 According to Malthus, nature and the God of nature, cannot be seen as evil in this natural and necessary process.[59]

Evil as the absence of good

[edit]Paul Elmer More says that, to Plato, evil resulted from the human failure to pay sufficient attention to finding and doing good: evil is an absence of good where good should be. More says Plato directed his entire educational program against the "innate indolence of the will" and the neglect of a search for ethical motives "which are the true springs of our life".[60]: 256–257 Plato asserted that it is the innate laziness, ignorance and lack of attention to pursuing good that, in the beginning, leads humans to fall into "the first lie, of the soul" that then often leads to self-indulgence and evil.[60]: 259 According to Joseph Kelly,[61] Clement of Alexandria, a neo-Platonist in the 2nd-century, adopted Plato's view of evil.[60]: 256, 294, 317 The fourth-century theologian Augustine of Hippo also adopted Plato's view. In his Enchiridion on Faith, Hope and Love, Augustine maintained that evil exists as an "absence of the good".[62]

Schopenhauer emphasized the existence of evil and its negation of the good. Therefore, according to Mesgari Akbar and Akbari Mohsen, he was a pessimist.[63] He defined the "good" as coordination between an individual object and a definite effort of the will, and he defined evil as the absence of such coordination.[63]

Deny problem exists

[edit]Theophrastus, the Greek Peripatetic philosopher and author of Characters,[64] a work that explores the moral weaknesses and strengths of 30 personality types in the Greece of his day, thought that the nature of 'being' comes from, and consists of, contraries, such as eternal and perishable, order and chaos, good and evil; the role of evil is thereby limited, he said, since it is only a part of the whole which is overall, good.[65] According to Theophrastus, a world focused on virtue and vice was a naturalistic social world where the overall goodness of the universe as a whole included, of necessity, both good and evil, rendering the problem of evil non-existent.[23]: xv

David Hume traced what he asserted as the psychological origins of virtue but not the vices. Rorty says: "He dispels the superstitious remnants of a Manichean battle: the forces of good and evil warring in the will"; concluding instead that human beings project their own subjective disapproval onto events and actions.[23]: 282

Evil as illusory

[edit]A modern version of this view is found in Christian Science which asserts that evils such as suffering and disease only appear to be real but, in truth, are illusions.[66] The theologians of Christian Science, states Stephen Gottschalk, posit that the Spirit is of infinite might; mortal human beings fail to grasp this and focus instead on evil and suffering that have no real existence as "a power, person or principle opposed to God".[67]

The illusion theodicy has been critiqued for denying the reality of crimes, wars, terror, sickness, injury, death, suffering and pain to the victim.[67] Further, adds Millard Erickson, the illusion argument merely shifts the problem to a new problem, as to why God would create this "illusion" of crimes, wars, terror, sickness, injury, death, suffering and pain; and why God does not stop this "illusion".[68]

Moral rationalism

[edit]"In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries rationalism about morality was repeatedly used to reject strong divine command theories of ethics".[69] Such moral rationalism asserts that morality is based on reason.[70] Rorty refers to Immanuel Kant as an example of a "pious rationalist".[23]: xv According to Shaun Nichols, "The Kantian approach to moral philosophy is to try to show that ethics is based on practical reason".[70] The problem of evil then becomes, "how [it is] possible for a rational being of good will to be immoral".[23]: xiii

Kant wrote an essay on theodicy criticizing it for attempting too much without recognizing the limits of human reason.[71] Kant did not think he had exhausted all possible theodicies, but did assert that any successful one must be based on nature rather than philosophy.[72] While a successful philosophical theodicy had not been achieved in his time, added Kant, he asserted there was no basis for a successful anti-theodicy either.[73]

Evil God challenge

[edit]One resolution to the problem of evil is that God is not good. The evil God challenge thought experiment explores whether an evil God is as likely to exist as a good God. Dystheism is the belief that God is not wholly good. Maltheism is the belief in an evil god.

Peter Forrest has stated:

The anti-God that I take seriously is the malicious omnipotent omniscient being, who, it is said, creates so that creatures will suffer, because of the joy this suffering gives It. This may be contrasted with a different idea of anti-God, that of an evil being that seeks to destroy things of value out of hatred or envy. An omnipotent, omniscient being would not be envious. Moreover, destructive hatred cannot motivate creation. For these two reasons I find that rather implausible. My case holds, however, against that sort of anti-God as well as the malicious one. The variety of anti-Gods alerts us to the problem of positing any character to God, whether benign, indifferent, or malicious. There are many such character traits we could hypothesize. Why not a God who creates as a jest? Or a God who loves drama? Or a God who, adapting Haldane's quip, is fond of beetles? Or, more seriously, a God who just loves creating regardless of the joy or suffering of creatures?[74]

Catholic Response

[edit]The Catholic Church believes good things include power and knowledge, and that only the misuse of power and knowledge is evil. Consequently, the church believes God could not be evil or become evil if he is omnipotent and omniscient, since these qualities spring from omnibenevolence. As the Roman Catechism puts it:

For by acknowledging God to be omnipotent, we also of necessity acknowledge Him to be omniscient, and to hold all things in subjection to His supreme authority and dominion. When we do not doubt that He is omnipotent, we must be also convinced of everything else regarding Him, the absence of which would render His omnipotence altogether unintelligible. Besides, nothing tends more to confirm our faith and animate our hope than a deep conviction that all things are possible to God; for whatever may be afterwards proposed as an object of faith, however great, however wonderful, however raised above the natural order, is easily and without hesitation believed, once the mind has grasped the knowledge of the omnipotence of God. Nay more, the greater the truths which the divine oracles announce, the more willingly does the mind deem them worthy of belief. And should we expect any favour from heaven, we are not discouraged by the greatness of the desired benefit, but are cheered and confirmed by frequently considering that there is nothing which an omnipotent God cannot effect.[75]

Disavowal of theodicy

[edit]This position argues from a number of different directions that the theodicy project is objectionable. Toby Betenson writes that the central theme of all anti-theodicies is that: "Theodicies mediate a praxis that sanctions evil".[76] A theodicy may harmonize God with the existence of evil, but it can be said that it does so at the cost of nullifying morality. Most theodicies assume that whatever evil there is exists for the sake of some greater good. However, if that is so, then it appears humans have no duty to prevent it, for in preventing evil they would also prevent the greater good for which the evil is required. Even worse, it seems that any action can be rationalized, for if one succeeds in performing an evil act, then God has permitted it, and so it must be for the greater good. From this line of thought one may conclude that, as these conclusions violate humanity's basic moral intuitions, no greater good theodicy is true, and God does not exist. Alternatively, one may point out that greater good theodicies lead humanity to see every conceivable state of affairs as compatible with the existence of God, and in that case the notion of God's goodness is rendered meaningless.[77][78][79][80]

Betenson also says there is a "rich theological tradition of anti-theodicy".[76] For many theists, there is no seamless theodicy that provides all answers, nor do 21st-century theologians think there should be. As Felix Christen, Fellow at Goethe University, Frankfurt, says, "When one considers human lives that have been shattered to the core, and, in the face of these tragedies [ask] the question 'Where is God?' [...] we would do well to stand with [poet and Holocaust survivor] Nelly Sachs as she says, 'We really don't know'."[81] Contemporary theodiceans, such as Alvin Plantinga, describe having doubts about the enterprise of theodicy "in the sense of providing an explanation of precise reasons why there is evil in the world". Plantinga's ultimate response to the problem of evil is that it is not a problem that can be solved. Christians simply cannot claim to know the answer to the "Why?" of evil. Plantinga stresses that this is why he does not proffer a theodicy but only a defense of the logic of theistic belief.[82]: 33

Atheistic viewpoint

[edit]From an atheistic viewpoint, the problem of evil is solved in accordance with the principle of Occam's razor: the existence of evil and suffering is reconciled with the assumption that an omnipotent, omnibenevolent, and omniscient God exists by assuming that no God exists.

David Hume's formulation of the problem of evil in Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion is this:

[God's] power we allow [is] infinite: Whatever he wills is executed: But neither man nor any other animal are happy: Therefore he does not will their happiness. His wisdom is infinite: He is never mistaken in choosing the means to any end: But the course of nature tends not to human or animal felicity: Therefore it is not established for that purpose. Through the whole compass of human knowledge, there are no inferences more certain and infallible than these. In what respect, then, do his benevolence and mercy resemble the benevolence and mercy of men?[83]

Theistic arguments

[edit]The problem of evil is acute for monotheistic religions such as Christianity, Islam, and Judaism that believe in a God who is omnipotent, omniscient and omnibenevolent;[84][85] but the question of why evil exists has also been studied in religions that are non-theistic or polytheistic, such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism.[32][86] Excepting the classic primary response of suffering as redemptive as not being a full theodicy, John Hick writes that theism has traditionally responded to the problem within three main categories: the common freewill theodicy, the soul making theodicy, and the newer process theology.[87]: 79

Cruciform theodicy

[edit]Cruciform theodicy is not a full theodical system in the same manner that Soul-making theodicy and Process theodicy are, so it does not address all the questions of "the origin, nature, problem, reason and end of evil."[88]: 145 It is, instead, a thematic trajectory. Historically, it has been and remains the primary Christian response to the problem of evil.[87]: 79–80

In cruciform theodicy, God is not a distant deity. In the person of Jesus, James Cone states that a suffering individual will find that God identifies himself "with the suffering of the world".[89]

This theodicy sees incarnation as the "culmination of a series of things Divine love does to unite itself with material creation" to first share in that suffering and demonstrate empathy with it, and second to recognize its value and cost by redeeming it.[90] This view asserts that an ontological change in the underlying structure of existence has taken place through the life and death of Jesus, with its immersion in human suffering, thereby transforming suffering itself. Philosopher and Christian priest Marilyn McCord Adams offers this as a theodicy of "redemptive suffering" in which personal suffering becomes an aspect of Christ's "transformative power of redemption" in the world. In this way, personal suffering does not only have value for one's self, it becomes an aspect of redeeming others.[90]: ix [88]: 158–168

For the individual, there is an alteration in the thinking of the believer as they come to see existence in this new light. For example, "On July 16, 1944 awaiting execution in a Nazi prison and reflecting on Christ's experience of powerlessness and pain, Dietrich Bonhoeffer penned six words that became the clarion call for the modern theological paradigm: 'Only the suffering God can help'."[88]: 146

This theodicy contains a special concern for the victims of the world, and stresses the importance of caring for those who suffer at the hands of injustice.[88]: 146–148 Soelle says that Christ's willingness to suffer on behalf of others means that his followers must themselves serve as "God's representatives on earth" by struggling against evil and injustice and being willing to suffer for those on the "underside of history".[91]

Animal suffering

[edit]In response to arguments concerning natural evil and animal suffering, Christopher Southgate, a trained research biochemist and a Senior Lecturer of Theology and Religion at the University of Exeter, has developed a "compound evolutionary theodicy."[92]: 711 Southgate uses three methods of analyzing good and harm to show how they are inseparable and create each other.[93]: 128 First, he says evil is the consequence of the existence of good: free will is a good, but the same property also causes harm. Second, good is a goal that can only be developed through processes that include harm. Third, the existence of good is inherently and constitutively inseparable from the experience of harm or suffering.[93]: 41–46

Robert John Russell summarizes Southgate's theodicy as beginning with an assertion of the goodness of creation and all sentient creatures.[93]: 15 Next Southgate argues that Darwinian evolution was the only way God could create such goodness. "A universe with the sort of beauty, diversity, sentience and sophistication of creatures that the biosphere now contains" could only come about by the natural processes of evolution.[92]: 716 Michael Ruse points out that Richard Dawkins has made the same claim concerning evolution:

Dawkins [...] argues strenuously that selection and only selection can [produce adaptedness]. No one – and presumably this includes God – could have gotten adaptive complexity without going the route of natural selection [...] The Christian positively welcomes Dawkins's understanding of Darwinism. Physical evil exists, and Darwinism explains why God had no choice but to allow it to occur. He wanted to produce design like effects (including humankind) and natural selection is the only option open.[92]: 714

According to Russell and Southgate, the goodness of creation is intrinsically linked to the evolutionary processes by which such goodness is achieved, and these processes, in turn, inevitably come with pain and suffering as intrinsic to them.[92]: 716 In this scenario, natural evils are an inevitable consequence of developing life.[92]: 716 Russell goes on to say that the physical laws that undergird biological development, such as thermodynamics, also contribute to "what is tragic" and "what is glorious" about life.[92]: 715 "Gravity, geology, and the specific orbit of the moon lead to the tidal patterns of the Earth's oceans and thus to both the environment in which early life evolved and in which tsunamis bring death and destruction to countless thousands of people".[92]: 717–718

Holmes Rolston III says nature embodies 'redemptive suffering' as exemplified by Jesus. "The capacity to suffer through to joy is a supreme emergent and an essence of Christianity... The whole evolutionary upslope is a lesser calling of this kind".[94] He calls it the 'cruciform creation' where life is constantly struggling through its pain and suffering toward something higher. Rolston says that within this process, there is no real waste as life and its components are "forever conserved, regenerated, redeemed".[95]

Bethany N. Sollereder, Research Fellow at the Laudato Si' Research Institute at Campion Hall, specializes in theology concerning evolution; she writes that evolving life has become increasingly complex, skilled and interdependent. As it has become more intelligent and has increased its ability to relate emotionally, the capacity to suffer has also increased.[96]: 6 Southgate describes this using Romans 8:22 which says "the whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth" since its beginning. He says God responds to this reality by "co-suffering" with "every sentient being in creation".[92]: 716–720

Southgate's theodicy rejects any 'means to an end' argument that says the evolution of any species justifies the suffering and extinction of any prior species that led to it, and he affirms that "all creatures which have died, without their full potential having been realized, must be given fulfillment elsewhere".[93]: 63 Russell asserts that the only satisfactory understanding of that "elsewhere" is the eschatological hope that the present creation will be transformed by God into the New Creation, with its new heaven and new earth.[92]: 718–720

Critique

[edit]Heaven

[edit]In what Russell describes as a "blistering attack by Wesley Wildman" on Southgate's theodicy, Wildman asserts that "if God really is to create a heavenly world of 'growth and change and relationality, yet no suffering', that world and not this world would be the best of all possible worlds, and a God that would not do so would be 'flagrantly morally inconsistent'."[97]: 290 [92]: 724

Southgate has responded with what he calls an extension of the original argument: "that this evolutionary environment, full as it is of both competition and decay, is the only type of creation that can give rise to creaturely selves".[93]: 90 That means "our guess must be that though heaven can eternally preserve those selves subsisting in suffering-free relationship, it could not give rise to them in the first place".[92]: 720 [93]: 90

Randomness

[edit]Thomas F. Tracy offers a two-point critique: "The first is the problem of purpose: can evolutionary processes, in which chance plays so prominent a role, be understood as the context of God's purposive action? The second is the problem of the pervasiveness of suffering and death in evolution".[98]

According to John Polkinghorne, the existence of chance does not negate the power and purposes of a Creator because "it is entirely possible that contingent processes can, in fact, lead to determined ends".[99]: 317–318 But in Polkinghorne's theology, God is not a "Puppetmaster pulling every string", and his purposes are therefore general.[99]: 317 Francisco J. Ayala adds that this means "God is not the explicit designer of each facet of evolution".[100][92]: 714 For Polkinghorne, it is sufficient theologically to assume that "the emergence of some form of self-conscious, God-conscious being" was an aspect of divine purpose from the beginning whether God purposed humankind specifically or not.[99]: 317–318

Polkinghorne also links the existence of human freedom to the flexibility created by randomness in the quantum world.[101] Richard W. Kropf asserts that free will has its origins in the "evolutionary ramifications" of the existence of chance as part of the process, thereby providing a "causal connection" between natural evil and the possibility of human freedom: one cannot exist without the other.[102]: 2, 122 Polkinghorne writes this means that "there is room for independent action in order for creatures to be themselves and "make themselves" in evolution, which therefore makes room for suffering and death.[99]: 318–319

A world in which creatures 'make themselves' can be held to be a greater good than a ready-made world would have been, but it has an inescapable cost. Evolutionary processes will not only yield great fruitfulness, but they will also necessarily involve ragged edges and blind alleys. Genetic mutation will not only produce new forms of life, but it will also result in malignancy. One cannot have the one without the other. The existence of cancer is an anguishing fact about creation but it is not gratuitous, something that a Creator who was a bit more competent or a bit less callous could easily have avoided. It is part of the shadow side of creative process... The more science helps us to understand the processes of the world, the more we see that the good and the bad are inextricably intertwined... It is all a package deal.[99]: 318

Other responses to animal suffering and natural evil

[edit]Others have argued:

- That natural evils are the result of the fall of man, which corrupted the perfect world created by God.[103] Theologian David Bentley Hart argues that "natural evil is the result of a world that's fallen into death" and says that "in Christian tradition, you don't just accept 'the world as it is'" but "you take 'the world as it is' as a broken, shadowy remnant of what it should have been." Hart's concept of the human fall, however, is an atemporal fall: "Obviously, wherever this departure from the divine happened, or whenever, it didn't happen within terrestrial history," and "this world, as we know it, from the Big Bang up until today, has been the world of death."[104][105][106]

- That forces of nature are neither "goods" nor "evils". They just are. Nature produces actions vital to some forms of life and lethal to others.[107] Other life forms cause diseases, but for the disease, hosts provide food, shelter and a place to reproduce which are necessary things for life and are not by their nature evil.[108]: 170

- That natural evils are the result of natural laws[109] Williams points out that all the natural laws are necessary for life, and even death and natural disaster are necessary aspects of a developing universe.[note 2]

- That natural evils provide humanity with a knowledge of evil which makes their free choices more significant than they would otherwise be, and so their free will more valuable[110] or

- That natural evils are a mechanism of divine punishment for moral evils that humans have committed, and so the natural evil is justified.[111]

Free will defense

[edit]The problem of evil is sometimes explained as a consequence of free will.[112][113] Free will is a source of both good and of evil, since with free will comes the potential for abuse. People with free will make their own decisions to do wrong, states Gregory Boyd, and it is they who make that choice, not God.[112] Further, the free will argument asserts that it would be logically inconsistent for God to prevent evil by coercion because then human will would no longer be free.[112][113]

The key assumption underlying the free-will defense is that a world containing creatures who are significantly free is innately more valuable than one containing no free creatures. The sort of virtues and values that freedom makes possible – such as trust, love, charity, sympathy, tolerance, loyalty, kindness, forgiveness and friendship – are virtues that cannot exist as they are currently known and experienced without the freedom to choose them or not choose them.[114]: 30 Augustine proffered a theodicy of freewill in the fourth century, but the contemporary version is best represented by Alvin Plantinga.

Plantinga offers a free will defense, instead of a theodicy, that began as a response to three assertions raised by J. L. Mackie.[82] First, Mackie asserts "there is no possible world" in which the "essential" theistic beliefs Mackie describes can all be true. Either believers retain a set of inconsistent beliefs, or believers can give up "at least one of the 'essential propositions' of their faith".[115]: 90, 97–98 Second, there is Mackie's statement that an all powerful God, in creating the world, could have made "beings who would act freely, but always go right", and third is the question of what choices would have been logically available to such a God at creation.[115]: 98

Plantinga built his response beginning with Gottfried Leibniz' assertion that there were innumerable possible worlds available to God before creation.[82]: 38 Leibniz introduced the term theodicy in his 1710 work Essais de Théodicée sur la bonté de Dieu, la liberté de l'homme et l'origine du mal ("Theodicic Essays on the Benevolence of God, the Free will of man, and the Origin of Evil") where he argued that this is the best of all possible worlds that God could have created.

Plantinga says mankind lives in the actual world (the world God actualized), but that God could have chosen to create (actualize) any of the possibilities including those with moral good but no moral evil. The catch, Plantinga says, is that it is possible that factors within the possible worlds themselves prevented God from actualizing any of the worlds containing moral goodness and no moral evil. Plantinga refers to these factors as the nature of "human essences" and "transworld depravity".[114]: 51–53

Across the various possible worlds (transworld) are all the variations of possible humans, each with their own "human essence" (identity): core properties essential to each person that makes them who they are and distinguishes them from others. Every person is the instantiation of such an essence. This "transworld identity" varies in details but not in essence from world to world.[114]: 50–51 This might include variations of a person (X) who always chooses right in some worlds. If somewhere, in some world, (X) ever freely chooses wrong, then the other possible worlds of only goodness could not be actualized and still leave (X) fully free.[116]: 184 There might be numerous possible worlds which contained (X) doing only morally good things, but these would not be worlds that God could bring into being, because (X) would not be free in those worlds to make the wrong choice.[116]: 187–188

An all knowing God would know "in advance" that there are times when "no matter what circumstances" God places (X) in, as long as God leaves (X) free, (X) will make at least one bad choice. Plantinga terms this "transworld depravity".[116]: 186 Therefore, if God wants (X) to be a part of creation, and free, then it could mean that the only option such a God would have would be to have an (X) who goes wrong at least once in a world where such wrong is possible. (X)'s free choice determined the world available for God to create.[116]: 187–188

"What is important about transworld depravity is that if a person suffers from it, then it wasn't within God's power to actualize any world in which that person is significantly free but does no wrong".[114]: 48 Plantinga extends this to all human agents noting, "clearly it is possible that everybody suffers from transworld depravity".[116]: 186 This means creating a world with moral good, no moral evil, and truly free persons was not an option available to God. The only way to have a world free of moral evil would be "by creating one without significantly free persons".[116]: 189

Critique

[edit]Most philosophers accept Plantinga's free-will defense and see the logical problem of evil as having been fully rebutted, according to Chad Meister, Robert Adams, and William Alston.[12][117][118] William L. Rowe, in referring to Plantinga's argument, has written that "granted incompatibilism, there is a fairly compelling argument for the view that the existence of evil is logically consistent with the existence of the theistic God".[119] In Arguing About Gods, Graham Oppy offers a dissent; while he acknowledges that "[m]any philosophers seem to suppose that [Plantinga's free-will defense] utterly demolishes the kinds of 'logical' arguments from evil developed by Mackie", he also says "I am not sure this is a correct assessment of the current state of play".[120] Among contemporary philosophers, most discussion on the problem of evil currently revolves around the evidential problem of evil, namely that the existence of God is unlikely, rather than logically impossible.[121]

Critics of the free will response have questioned whether it accounts for the degree of evil seen in this world. One point in this regard is that while the value of free will may be thought sufficient to counterbalance minor evils, it is less obvious that it outweighs the negative attributes of evils such as rape and murder. Another point is that those actions of free beings which bring about evil very often diminish the freedom of those who suffer the evil; for example the murder of a young child prevents the child from ever exercising their free will. In such a case the freedom of an innocent child is pitted against the freedom of the evil-doer, it is not clear why God would remain unresponsive and passive.[122] Christopher Southgate asserts that a freewill defense cannot stand alone as sufficient to explain the abundance of situations where humans are deprived of freewill. It requires a secondary theory.[93]: 42

Another criticism is that the potential for evil inherent in free will may be limited by means which do not impinge on that free will. God could accomplish this by making moral actions especially pleasurable, or evil action and suffering impossible by allowing free will but not allowing the ability to enact evil or impose suffering.[123] Supporters of the free will explanation state that would then no longer be free will.[112][113] Critics respond that this view seems to imply it would be similarly wrong to try to reduce suffering and evil in these ways, a position which few would advocate.[124]

Natural evil

[edit]A third challenge to the free will defence is natural evil, evil which is the result of natural causes (e.g. a child suffering from a disease, mass casualties from a volcano).[125] Criticism of natural evil posits that even if for some reason an all-powerful and all-benevolent God tolerated evil human actions in order to allow free will, such a God would not be expected to also tolerate natural evils because they have no apparent connection to free will.[112][113] Patricia A. Williams says differentiating between moral and natural evil is common but, in her view, unjustified. "Because human beings and their choices are part of nature, all evils are natural".[108]: 169

Advocates of the free will response propose various explanations of natural evils. Alvin Plantinga[2][126] references Augustine of Hippo,[127] writing of the possibility that natural evils could be caused by supernatural beings such as Satan.[128] Plantinga emphasizes that it is not necessary that this be true, it is only necessary that this possibility be compatible with the argument from freewill.[126]: 58 There are those who respond that Plantinga's freewill response might address moral evil but not natural evil.[129] Some scholars, such as David Griffin, state that free will, or the assumption of greater good through free will, does not apply to animals.[130][131] In contrast, a few scholars, while accepting that "free will" applies in a human context, have posited an alternative "free creatures" defense, stating that animals too benefit from their physical freedom though that comes with the cost of dangers they continuously face.[132]

The "free creatures" defense has also been criticized, in the case of caged, domesticated and farmed animals who are not free and many of whom have historically experienced evil and suffering from abuse by their owners. Further, even animals and living creatures in the wild face horrendous evils and suffering – such as burns and slow death after natural fires or other natural disasters or from predatory injuries – and it is unclear, state Bishop and Perszyk, why an all-loving God would create such free creatures prone to intense suffering.[132]

Process theodicy

[edit]"Process theodicy reframes the debate on the problem of evil" by acknowledging that, since God "has no monopoly on power, creativity, and self-determination", God's power and ability to influence events are, of necessity, limited by human creatures with wills of their own.[88]: 143 This concept of limitation is one of the key aspects of process theodicy.[88]: 143 The God of process theology had all options available before actualizing the creation that exists, and chose voluntarily to create free persons knowing the limitations that would impose: he must not unilaterally intervene and coerce a certain outcome because that would violate free will.[87]: 93 God's will is only one factor in any situation, making that will "variable in effectiveness", because all God can do is try to persuade and influence the person in the best direction, and make sure that possibility is available.[87]: 98–100 Through knowledge of all possibilities, this God provides "ideal aims to help overcome [evil] in light of (a) the evil that has been suffered and (b) the range of good possibilities allowed by that past".[87]: 93

Process theology's second key element is its stressing of the "here and now" presence of God. God becomes the Great Companion and Fellow-Sufferer where the future is realized hand-in-hand with the sufferer.[88]: 143 The God of process theology is a benevolent Providence that feels a person's pain and suffering.[87]: 93 According to Wendy Farley, "God labors in every situation to mediate the power of compassion to suffering" by enlisting free persons as mediators of that compassion.[133] Freedom and power are shared, therefore, responsibility must be as well. Griffin quotes John Hick as noting that "the stirring summons to engage on God's side in the never-ending struggle against the evils of an intractable world" is another key characteristic of process theology.[134]

Critique

[edit]A hallmark of process theodicy is its conception of God as persuasive rather than coercive.[135]: 179 Nancy Frankenberry asserts that this creates an either-or dichotomy – either God is persuasive or coercive – whereas lived experience has an "irreducible ambiguity" where it seems God can be both.[135]: 180–181

Since the 1940s, process theodicy has also been "dogged by the problem of 'religious adequacy' of its concept of God" and doubts about the 'goodness' of its view of God.[135]: 186 It has not resolved all the old questions concerning the problem of evil,[136] while it has raised new ones concerning "the nature of divine power, the meaning of God's goodness, and the realistic assessment of what we may reasonably hope for by way of creative advance".[135]: 196

"Greater good" responses

[edit]The greater good defense is more often argued in response to the evidential version of the problem of evil,[137] while the free will defense is often discussed in the context of the logical version.[138] Some solutions propose that omnipotence does not require the ability to actualize the logically impossible. "Greater good" responses to the problem make use of this insight by arguing for the existence of goods of great value which God cannot actualize without also permitting evil, and thus that there are evils he cannot be expected to prevent despite being omnipotent.

Skeptical theologians argue that, since no one can fully understand God's ultimate plan, no one can assume that evil actions do not have some sort of greater purpose.[139]

Skeptical theism

[edit]"According to skeptical theism, if there were a god, it is likely that he would have reasons for acting that are beyond [human] ken, ... the fact that we don't see a good reason for X does not justify the conclusion that there is no good reason for X".[140] One standard of sufficient reason for allowing evil is by asserting that God allows an evil in order to prevent a greater evil or cause a greater good.[141] Pointless evil, then, is an evil that does not meet this standard; it is an evil God permitted where there is no outweighing good or greater evil. The existence of such pointless evils would lead to the conclusion there is no benevolent god.[142]: 79 The skeptical theist asserts that humans can't know that such a thing as pointless evil exists, that humans as limited beings are simply "in the dark" concerning the big picture on how all things work together. "The skeptical theist's skepticism affirms certain limitations to [human] knowledge with respect to the realms of value and modality" (method).[143]: 6, 8 "Thus, skeptical theism purports to undercut most a posteriori arguments against the existence of God".[140]

Skeptical theism questions the first premise of William Rowe's argument: "There exist instances of intense suffering which an omnipotent, omniscient being could have prevented without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse"; how can that be known?[143]: 11–12 John Schellenberg's argument of divine hiddenness,[143]: 13–14 and the first premise of Paul Draper's Hypothesis of Indifference, which begins "Gratuitous evil exists", are also susceptible to questions of how these claimed concepts can be genuinely known.[143]: 15–18

Critique

[edit]Skeptical theism is criticized by Richard Swinburne on the basis that the appearance of some evils having no possible explanation is sufficient to agree there can be none, (which is also susceptible to the skeptic's response); and it is criticized on the basis that, accepting it leads to skepticism about morality itself.[144]

Hidden reasons

[edit]The hidden reasons defense asserts the logical possibility of hidden or unknown reasons for the existence of evil as not knowing the reason does not necessarily mean that the reason does not exist.[2][3] This argument has been challenged with the assertion that the hidden reasons premise is as plausible as the premise that God does not exist or is not "an almighty, all-knowing, all-benevolent, all-powerful". Similarly, for every hidden argument that completely or partially justifies observed evils it is equally likely that there is a hidden argument that actually makes the observed evils worse than they appear without hidden arguments, or that the hidden reasons may result in additional contradictions.[2][145] As such, from an inductive viewpoint hidden arguments will neutralize one another.[2]

A sub-variant of the "hidden reasons" defense is called the "PHOG" – profoundly hidden outweighing goods – defense.[145] The PHOG defense, states Bryan Frances, not only leaves the co-existence of God and human suffering unanswered, but raises questions about why animals and other life forms have to suffer from natural evil, or from abuse (animal slaughter, animal cruelty) by some human beings, where hidden moral lessons, hidden social good, and other possible hidden reasons do not apply.[145]

Soul-making or Irenaean theodicy

[edit]The soul-making (or Irenaean) theodicy is named after the 2nd-century Greek theologian Irenaeus whose ideas were adopted in Eastern Christianity.[146] It has been modified and advocated in the twenty-first century by John Hick.[146] Irenaen theodicy stands in sharp contrast to the Augustinian. For Augustine, humans were created perfect but fell, and thereafter continued to choose badly of their own freewill. In Irenaeus' view, humans were not created perfect, but instead, must strive continuously to move closer to it.[147]

The key points of a soul-making theodicy begin with its metaphysical foundation: that "(1) The purpose of God in creating the world was soul-making for rational moral agents".[148] (2) Humans choose their responses to the soul-making process thereby developing moral character. (3) This requires that God remain hidden, otherwise freewill would be compromised. (4) This hiddenness is created, in part, by the presence of evil in the world. (5) The distance of God makes moral freedom possible, while the existence of obstacles makes meaningful struggle possible. (6) The result of beings who complete the soul-making process is "a good of such surpassing value" that it justifies the means. (7) Those who complete the process will be admitted to the kingdom of God where there will be no more evil.[148] Hick argues that, for suffering to have soul-making value, "human effort and development must be present at every stage of existence including the afterlife".[87]: 132, 138

C. S. Lewis developed a theodicy that began with freewill and then accounts for suffering caused by disease and natural disasters by developing a version of the soul-making theodicy. Nicholas Wolterstorff has raised challenges for Lewis's soul-making theodicy. Erik J. Wielenberg draws upon Lewis's broader corpus beyond The Problem of Pain but also, to a lesser extent, on the thought of two other contemporary proponents of the soul-making theodicy, John Hick and Trent Dougherty, in an attempt to make the case that Lewis's version of the soul-making theodicy has depth and resilience.[149]

Critique

[edit]The Irenaean theodicy is challenged by the assertion that many evils do not promote spiritual growth, but can instead be destructive of the human spirit. Hick acknowledges that this process often fails in the actual world.[150] Particularly egregious cases known as horrendous evils, which "[constitute] prima facie reason to doubt whether the participant's life could (given their inclusion in it) be a great good to him/her on the whole," have been the focus of recent work in the problem of evil.[151] Horrendous suffering often leads to dehumanization, and its victims become angry, bitter, vindictive, depressed and spiritually worse.[152]

Yet, life crises are a catalyst for change that is often positive.[153] Neurologists Bryan Kolb and Bruce Wexler indicate this has to do with the plasticity of the brain. The brain is highly plastic in childhood development, becoming less so by adulthood once development is completed. Thereafter, the brain resists change.[154]: 5–9 The neurons in the brain can only make permanent changes "when the conditions are right" because the brain's development is dependent upon the stimulation it receives.[155]: 7 [154]: 13 When the brain receives the powerful stimulus that experiences like bereavement, life-threatening illness, the trauma of war and other deeply painful experiences provide, a prolonged and difficult internal struggle, where the individual completely re-examines their self-concept and perceptions of reality, reshapes neurological structures.[154]: 6–7 [156]: 4 The literature refers to turning points,[157] defining moments,[158] crucible moments,[159] and life-changing events.[160] These are experiences that form a catalyst in an individual's life so that the individual is personally transformed, often emerging with a sense of learning, strength and growth, that empowers them to pursue different paths than they otherwise would have.[156]: 2

Стив Грегг признает, что многие человеческие страдания не приносят заметного блага и что большее благо не полностью охватывает каждый случай. «Тем не менее, тот факт, что страдания временны и часто справедливо карают, исправляют, освящают и облагораживают, выступает как один из важных аспектов библейского мировоззрения, который несколько смягчает неразрешимую в противном случае проблему боли». [161]

Вторая критика утверждает, что, если бы это было правдой, что Бог допустил зло, чтобы способствовать духовному росту, было бы разумно ожидать, что зло непропорционально постигло бы тех, у кого плохое духовное здоровье, таких как декадентские богатые, которые, кажется, часто наслаждаются жизнью в роскоши. изолированы от зла, тогда как многие благочестивые бедны и хорошо знакомы с мирским злом. [ 162 ] На примере Франциска Ассизского . Г. К. Честертон утверждает, что, вопреки «современному мнению», богатство осуждается в христианском богословии именно по той причине, что богатство изолирует от зла и страданий, а также от духовного роста, который может произвести такой опыт Честертон объясняет, что Франциск преследовал бедность «так же, как люди безумно искали золото», потому что сопутствующие ей страдания — это путь к благочестию. [ 163 ] : 32, 89–90

Дж. Стэнли Кейн утверждает, что человеческий характер можно развивать непосредственно конструктивными и заботливыми способами любви, и неясно, почему Бог считает или допускает зло и страдания как необходимые или предпочтительные пути духовного роста. [ 146 ] : 376–379 Хик утверждает, что страдание необходимо не только для достижения некоторых конкретных добродетелей, но и что «...тот, кто достиг добра, встретив искушение и в конечном итоге преодолев его, и, таким образом, правильно сделав [ответственный] выбор в конкретных ситуациях, хорош в более богатый и ценный смысл, чем тот, который был бы создан ab initio в состоянии невинности или добродетели. В первом случае, который представляет собой действительные моральные достижения человечества, доброта человека содержит в себе силу преодоленных искушений. стабильность, основанная на накоплении правильных решений, а также позитивный и ответственный характер, который возникает в результате вложения дорогостоящих личных усилий». [ 150 ] : 255

Однако добродетели, определенные как результат «сотворения души», могут оказаться ценными только в мире, где уже существуют зло и страдания. Например, готовность пожертвовать собой, чтобы спасти других от преследований, добродетельна, потому что преследования существуют. Точно так же готовность пожертвовать свою еду тем, кто голодает, ценна, потому что голод существует. Если бы не было преследований и голода, не было бы оснований считать эти действия добродетельными. Если добродетели, развитые посредством сотворения души, ценны только там, где существует страдание, тогда неясно, что было бы потеряно, если бы страдания не существовало. [ 164 ] К. Робер Месле говорит, что такое обсуждение предполагает, что добродетели имеют лишь инструментальную ценность, а не внутреннюю ценность. [ 165 ]

Душевное примирение проблемы зла, утверждает Криган, не может объяснить необходимость или обоснование зла, причиняемого животным, и связанных с этим страданий животных, потому что «нет никаких доказательств того, что страдания улучшают характер животных или являются доказательством сотворения души в них». [ 152 ] Хик проводит различие между страданиями животных и людей, основываясь на «нашей способности творчески предвидеть будущее». [ 150 ] : 314

Загробная жизнь

[ редактировать ]Фома Аквинский предложил теодицею загробной жизни , чтобы решить проблему зла и оправдать существование зла. [ 166 ] Предпосылка этой теодицеи заключается в том, что загробная жизнь бесконечна, человеческая жизнь коротка, и Бог допускает зло и страдания, чтобы судить и даровать вечный рай или ад на основе человеческих моральных действий и человеческих страданий. [ 166 ] [ 167 ] [ 168 ] Фома Аквинский говорит, что загробная жизнь — это высшее благо, оправдывающее зло и страдания в нынешней жизни. [ 166 ] радости Христианский писатель Рэнди Алкорн утверждает, что небесные компенсируют страдания на земле. [ 169 ]

Стивен Мейтцен назвал это теодицеей «Небеса поглощают все» и утверждает, что она ложна, поскольку смешивает компенсацию и оправдание. [ 167 ] [ 170 ] Эта теодическая точка зрения основана на принципе, согласно которому при справедливом Боге «ни одно невинное существо не терпит страданий, которые не компенсируются счастьем на каком-то более позднем этапе (например, в загробной жизни)», но, согласно традиционной точке зрения, у животных нет загробной жизни. [ 171 ] [ 172 ]

Аргумент Майнцена был отвергнут Сейедом Джаабером Мусавирадом на основании убедительной аргументации теодицеи компенсации. Можно предложить две версии теодицеи компенсации. Основываясь на слабой интерпретации, которая учитывает только компенсацию в загробной жизни, эта критика была бы приемлемой, но на основе сильной точки зрения, которая учитывает как «компенсацию в загробной жизни», так и «основные выгоды от зла» (даже если они не больше), Теодицею компенсации можно защитить. [ 173 ]

Зло не настоящее

[ редактировать ]Во втором веке христианские богословы пытались примирить проблему зла со всемогущим, всезнающим и всеблагим Богом, отрицая существование зла. Среди этих богословов Климент Александрийский предложил несколько теодицей, одна из которых называлась «теорией лишений зла», которая была принята впоследствии. [ 61 ] Другой — более современная версия «отрицания зла», предложенная Христианской наукой, в которой восприятие зла описывается как форма иллюзии. [ 66 ]

Лишение теории зла

[ редактировать ]Ранняя версия «отрицания зла» называется «теорией лишений зла», названной так потому, что она описывала зло как форму «недостатка, потери или лишений». Одним из первых сторонников этой теории был Климент Александрийский, живший во II веке, который, по словам Джозефа Келли, [ 61 ] заявил, что «поскольку Бог полностью добр, он не мог создать зло; но если Бог не создал зла, то оно не может существовать». Зло, по мнению Климента, не существует как положительное, а существует как отрицательное или как «недостаток добра». [ 61 ] Идею Климента критиковали за ее неспособность объяснить страдания в мире, если бы зла не существовало. Ученые-гностики также задавали ему вопрос, почему Бог не создал существ, которые «не лишены добра». Климент попытался ответить на эти вопросы онтологически через дуализм, идею, обнаруженную в школе Платона. [ 62 ] то есть путем представления двух реальностей: одной Бога и Истины, другой человеческого и воспринимаемого опыта. [ 174 ]

Богослов четвертого века Августин Гиппонский принял теорию лишений и в своей «Энхиридионе о вере, надежде и любви » утверждал, что зло существует как «отсутствие добра». [ 62 ] Бог — духовное (не телесное) Существо, которое властно над другими меньшими существами, потому что Бог создал материальную реальность ex nihilo . Взгляд Августина на зло основан на причинном принципе, согласно которому каждая причина превосходит ее последствия. [ 175 ] : 43 Бог по своей природе превосходит свое творение, и «все, что создает Бог, хорошо». [ 175 ] : 40–42 Каждое существо хорошо, но «некоторые лучше других». [ 175 ] : 44 Однако созданные существа также имеют склонность к изменчивости и разложению, поскольку они были созданы из ничего. Они подвержены предрассудкам, исходящим из личной точки зрения: люди заботятся о том, что влияет на них самих, и не видят, как их лишения могут способствовать общему благу. Для Августина зло, когда оно относится к материальному творению Бога, относится к лишениям, отсутствию добра, « там, где добро могло бы быть ». [ 175 ] : 44 Зло — это не субстанция, существующая сама по себе, отдельно от природы всего Существа. [ 176 ] Это отсутствие добра является актом воли, «преступным отказом от бесконечной щедрости, предлагаемой Богом, в пользу бесконечно худшей пищи», свободно выбранной волей человека. [ 175 ] : 46

Бен Пейдж и Макс Бейкер-Хитч отмечают, что, хотя существует множество философов, которые открыто защищают теорию лишений , она также, по-видимому, выведена из функционального анализа добра, который является широко распространенной точкой зрения в современной философии. [ 177 ] [ 178 ]

Критика

[ редактировать ]Эта точка зрения подвергалась критике как семантическая: замена определения зла «потерей добра», «проблемы зла и страданий» на «проблему потери добра и страданий» не решает проблему с теоретической точки зрения. ни с экспериментальной точки зрения. [ 179 ] Ученые, критикующие теорию лишений, заявляют, что убийства, изнасилования, террор, боль и страдания являются реальными событиями жизни жертвы, и их нельзя отрицать как простое «отсутствие добра». [ 180 ] Августин, утверждает Перейра, признавал существование страдания и осознавал, что теория лишений не является решением проблемы зла. [ 179 ]

Зло как иллюзорное

[ редактировать ]Альтернативная современная версия теории лишений принадлежит христианской науке , которая утверждает, что такое зло, как страдания и болезни, только кажется реальным, но на самом деле это иллюзии, а на самом деле зла не существует. [ 66 ] Теологи христианской науки, как утверждает Стивен Готшалк, утверждают, что Дух обладает бесконечной мощью, смертные люди не могут этого понять и вместо этого сосредотачиваются на зле и страданиях, которые не имеют реального существования как «сила, личность или принцип, противостоящие Богу». . [ 67 ]

Иллюзорная версия теодицеи теории лишений подвергалась критике за отрицание реальности преступлений, войн, террора, болезней, травм, смерти, страданий и боли жертвы. [ 67 ] Далее, добавляет Миллард Эриксон, аргумент иллюзии просто переводит проблему на новую проблему: почему Бог создал эту «иллюзию» преступлений, войн, террора, болезней, травм, смерти, страданий и боли; и почему Бог не останавливает эту «иллюзию». [ 68 ]

Поворот столов

[ редактировать ]Другой подход к проблеме зла состоит в том, чтобы перевернуть ситуацию, предположив, что любой аргумент, основанный на зле, является самоопровержимым, поскольку его заключение потребует ложности одной из его предпосылок. Один ответ, называемый защитной реакцией, заключался в том, чтобы указать, что утверждение «зло существует» подразумевает этический стандарт, относительно которого определяется моральная ценность, а затем доказать, что тот факт, что такой универсальный стандарт вообще существует, подразумевает существование Бог. [ 181 ]

Пандеизм

[ редактировать ]Пандеизм — это современная теория, объединяющая деизм и пантеизм и утверждающая, что Бог создал Вселенную, но во время творения стал Вселенной. [ 182 ] В пандеизме Бог не является контролирующей небесной силой, способной ежечасно вмешиваться в земные дела. Больше не существуя «сверху», Бог не может вмешаться сверху, и его нельзя винить за то, что он не сделал этого. Бог в пандеизме был всемогущим и всеблагим, но в форме вселенной уже не является всемогущим и всеблагожелательным. [ 183 ] : 76–77

Связанные вопросы

[ редактировать ]Филип Ирвинг Митчелл, директор Университетской программы почестей Баптистского университета Далласа, предлагает список того, что он называет проблемами, которые не являются строго частью проблемы зла, но все же связаны с ней:

- Зло и демоническое : Митчелл пишет, что, учитывая веру в сверхъестественные силы, характерную для всех трех монотеистических религий, какое отношение эти убеждения имеют к злу?

- Политика теодицеи : служит ли объяснение причин зла и страданий оправданием угнетения со стороны сильных или освобождения бессильных? [ 34 ] : 59

- Ужасное зло : Холокост, жестокое обращение с детьми и изнасилования, крайняя форма шизофрении, пытки, массовый геноцид и т. д. Стоит ли вообще говорить об оправдании таких зверств? Какую надежду на восстановление и исцеление можно дать выжившим?

- Суд Божий . Многие теодические дискуссии сосредотачиваются на «невинных» страданиях и переживаниях глубокого зла, игнорируя при этом ошибки, общие для отдельных людей, идей, систем убеждений и социальных структур. Можно ли понимать зло как Божий суд над грехом и злом?

- Сокрытость Бога : Божественная сокрытость Бога (deus absconditus) иногда считается разновидностью теодицеи. Почему часто кажется, что Бог не отвечает открыто и явно на зло (или добро) бесспорным образом?

- Метафизическое зло : Что такое зло? В чем его происхождение и суть? [ 33 ]

Экзистенциальная проблема зла

[ редактировать ]Экзистенциальная проблема спрашивает, каким образом опыт страдания соотносится с вопросами теодицеи и каким образом теодицея вредит или помогает в переживании страдания? Дэн Аллендер и Тремпер Лонгман отмечают, что страдания порождают внутренние вопросы о Боге, выходящие за рамки философских, например: заботится ли Бог или кто-либо еще о том, от чего я страдаю каждый день? [ 184 ] : 24, 45, 135

Литература и искусство

[ редактировать ]Митчелл говорит, что литература, посвященная проблеме зла, предлагает смесь как универсального применения, так и конкретной драматизации конкретных случаев, художественных и научно-популярных, с религиозными и светскими взглядами. Такие работы, как «Доктор Фауст» Кристофера Марлоу ; «Потерянный рай» Джона Мильтона ; «Очерк человека» Поупа Александра ; Кандид Вольтера ; Фауст Гете ; « In Memoriam AHH » Теннисона ; «Братья Карамазовы» Федора Достоевского ; Четыре квартета Элиота Т. С. ; «Чума Камю » ; «Ночь » Эли Визеля ; «Святая твердь и на время» Энни Диллард ; и «Книга скорби» Уолтера Вангерина-младшего предлагают понимание того, как можно понять проблему зла. [ 33 ] [ 185 ] [ 56 ]

Хотя художница Корнелия ван Вурст сначала заявляет, что «художники думают о мире не с точки зрения хорошего и плохого, а больше с точки зрения: что мы можем из этого сделать?», она также приводит пример картины Пабло Пикассо 1935 года . гравюра «Минотавромахия» , в настоящее время находящаяся в Эшмоловском музее , где маленькая девочка держит свой маленький сияющий свет, чтобы противостоять злому Минотавру войны. [ 186 ] Франциска Рейнигер говорит, что искусство, изображающее подавляющее зло Холокоста, стало противоречивым. На картине Лолы Либер-Шварц « Убийство Матильды Либер, ее дочерей Лолы и Берты и детей Берты Иче (Ицхака) и Марилки, январь 1942 года » изображена семья, лежащая мертвая на заснеженной земле возле деревни с нацистом и его собака уходит с места происшествия. Его лица не видно. Сцена холодная и мертвая, в живых остались только преступник и, возможно, одна из его жертв, ребенок, цепляющийся за свою мать. Никто не знает, кто был свидетелем этого события и каково могло быть их отношение к этим событиям, но само искусство представляет собой изображение проблемы зла. [ 187 ]

См. также

[ редактировать ]Примечания и ссылки

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Никола Криган представила логические и доказательные версии проблемы зла применительно к страданиям животных. [ 48 ]

- ^ «Когда звезды горят, взрываются и умирают, тяжелые элементы рождаются и распространяются, питая жизнь. Когда первые живые организмы умирают, они освобождают место для более сложных и начинают процесс естественного отбора. Когда организмы умирают, новая жизнь питается на них... источники [естественного] зла заключаются в атрибутах, настолько ценных, что мы даже не рассматриваем возможность их устранения, чтобы искоренить зло». [ 108 ] : 169, 179

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Тулинг, Кари Х. (2020). «Часть 1: Является ли Бог Создателем и источником всего сущего, включая зло?» . В Тулинге, Кари Х. (ред.). Размышление о Боге: еврейские взгляды . Серия JPS «Основной иудаизм». Линкольн и Филадельфия : Издательство Университета Небраски / Еврейское издательское общество . стр. 3–64. дои : 10.2307/j.ctv13796z1.5 . ISBN 978-0-8276-1848-0 . LCCN 2019042781 . S2CID 241611417 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Стэнфордская энциклопедия философии, « Проблема зла », Майкл Тули.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л Интернет-энциклопедия философии, « Доказательная проблема зла », Ник Тракакис.

- ^ Николас Дж. Ренггер, Моральное зло и международные отношения , в SAIS Review 25:1, зима/весна 2005 г., стр. 3–16.

- ^ Питер Киви, Билли Мелвилла и светская проблема зла: червь в зародыше , в The Monist (1980), 63

- ^ Кекес, Джон (1990). Столкновение со злом . Принстон: Принстон, UP. ISBN 978-0-691-07370-5 .

- ^ Тимоти Андерс, Эволюция зла (2000)

- ^ Беккер, Лоуренс К.; Беккер, Шарлотта Б. (2013). Энциклопедия этики . Рутледж. стр. 147–149. ISBN 978-1-135-35096-3 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Интернет-энциклопедия философии, « Логическая проблема зла », Джеймс Р. Биб.

- ^ Мусавирад, Сейед Джаабер (2 июля 2022 г.). «Теория компенсации и проблема зла: новая защита» . Европейский журнал философии религии . 14 (2). дои : 10.24204/ejpr.2022.3357 . ISSN 1689-8311 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Питер ван Инваген (2008). Проблема Зла . Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 120, 123–126, контекст: 120–133. ISBN 978-0-19-954397-7 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Мейстер, Чад (2009). Введение в философию религии . Тейлор и Фрэнсис. п. 134. ИСБН 9781134141791 .

- ^ Ховард-Снайдер, Дэниел; О'Лири-Хоторн, Джон (1998). «Трансмировая святость и защита свободной воли Плантинги». Международный журнал философии религии. 44 (1): 1–21. два : 10.1023/A:1003210017171 . ISSN 1572-8684 .

- ^ Олстон, Уильям П. (1991). «Индуктивный аргумент зла и когнитивное состояние человека». Философские перспективы. 5: 29–67. дои : 10.2307/2214090 . ISSN 1758-2245 . JSTOR 2214090 . S2CID 16744068 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Колдер, Тодд (26 ноября 2013 г.). «Понятие зла» . Стэнфордская энциклопедия философии . Стэнфордский университет . Проверено 17 января 2021 г.

- ^ Маркус Г. Сингер, Маркус Г. Сингер (апрель 2004 г.). «Понятие зла» . Философия . 79 (308). Издательство Кембриджского университета: 185–214. дои : 10.1017/S0031819104000233 . JSTOR 3751971 . S2CID 146121829 .

- ^ Кемп, Джон (25 февраля 2009 г.). «Боль и зло» . Философия . 29 (108): 13. дои : 10.1017/S0031819100022105 . S2CID 144540963 . Проверено 8 января 2021 г.

- ^ Комитет по развитию исследований, ухода и образования в области боли, Медицинский институт (США). «Облегчение боли в Америке: план преобразования профилактики, ухода, образования и исследований» . Книжная полка NCBI . Издательство национальных академий (США) . Проверено 21 февраля 2021 г.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ «Отзывы» . Гуманный обзор . 2 (5–8). Э. Белл: 374. 1901.

- ^ Колдер, Тодд К. (2007). «Является ли теория лишений зловещими мертвецами?» . Американский философский ежеквартальный журнал . 44 (4): 371–381. JSTOR 20464387 .