Экономика Индии

| |

| Валюта | Индийская рупия (INR, ₹) |

|---|---|

| 1 апреля – 31 марта | |

Торговые организации | ВТО , ВТО , SAFTA , BIMSTEC , ВФП , БРИКС , G-20 , BIS , АБИИ , АБР и другие |

Группа стран | |

| Статистика | |

| Население | |

| ВВП | |

| Рейтинг ВВП | |

Рост ВВП |

|

ВВП на душу населения | |

Рейтинг ВВП на душу населения | |

ВВП по секторам |

|

GDP by component |

|

| |

Population below poverty line | |

| |

Labour force | |

Labour force by occupation | |

| Unemployment | |

Final consumption expenditure | |

Gross capital formation | |

| Gross savings | 31.781% of GDP (2023)[40] |

| 10-year bond 7.190% (Jan 2023)[41][42] | |

Main industries | |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods |

|

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | |

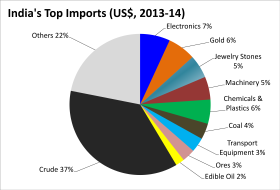

Import goods |

|

Main import partners |

|

FDI stock | |

Gross external debt |

|

| Public finances | |

| –6.4% of GDP (2022–23)[54] | |

| Revenues | |

| Expenses | |

| Economic aid |

|

(as of 19 July 2024) | |

All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

Экономика Индии представляет собой развивающуюся смешанную экономику с заметным государственным сектором в стратегических секторах. [ 5 ] экономика мира Это пятая по величине по номинальному ВВП и третья по паритету покупательной способности (ППС); По на душу населения доходу Индия заняла 136-е место по ВВП (номинальному) и 125-е место по ВВП (ППС) . [ 60 ] С момента обретения независимости в 1947 году до 1991 года сменявшие друг друга правительства следовали советской модели и продвигали протекционистскую экономическую политику с обширной советизацией , государственным вмешательством , экономикой спроса , природными ресурсами , предприятиями, управляемыми бюрократами , и экономическим регулированием . Это характеризуется как дирижизм в форме Лицензионного Раджа . [ 61 ] [ 62 ] Окончание « холодной войны» и острый кризис платежного баланса в 1991 году привели к принятию широкой экономической либерализации в Индии и индикативному планированию . [ 63 ] [ 64 ] С начала 21 века среднегодовой рост ВВП составлял от 6% до 7%. [ 5 ] В Индии около 1900 компаний государственного сектора . [ 65 ] Индийское государство полностью контролирует и владеет железными и автомобильными дорогами ; контрольный пакет акций и доля в банковской сфере , [ 66 ] страхование , [ 67 ] сельское хозяйство , [ 68 ] молочные продукты , удобрения и химикаты, [ 69 ] аэропорты , [ 70 ] ядерная , горнодобывающая, цифровизация , оборона , сталь , редкоземельные элементы, вода, электричество, нефтегазовая промышленность и электростанции, [ 71 ] и имеет существенный контроль над цифровизацией , широкополосной связью как национальной инфраструктурой , телекоммуникациями , суперкомпьютерами , космосом , портами и судоходством , [ 72 ] среди других отраслей промышленности, были фактически национализированы в середине 1950-х годов. [ 73 ] [ 61 ] [ 62 ]

Почти 70% ВВП Индии формируется за счет внутреннего потребления; [ 74 ] в мире Страна остается четвертым по величине потребительским рынком . [ 75 ] Помимо частного потребления , ВВП Индии также подпитывается государственными расходами , инвестициями и экспортом . [ 76 ] в мире В 2022 году Индия была 10-м по величине импортером и 8-м по величине экспортером . [ 77 ] Индия является членом Всемирной торговой организации с 1 января 1995 года. [78] It ranks 63rd on the Ease of doing business index and 40th on the Global Competitiveness Index.[79][80] India has one of the world's highest number of billionaires and extreme income inequality.[81][82] Economists and social scientists often consider India a welfare state.[6][8][7][9] India is officially declared a socialist state as per the constitution.[10][11] India's overall social welfare spending stood at 8.6% of GDP in 2021-22, which is much lower than the average for OECD nations.[83][84] With 586 million workers, the Indian labour force is the world's second-largest.[27]

During the 2008 global financial crisis, the economy faced a mild slowdown. India endorsed Keynesian policy and initiated stimulus measures (both fiscal and monetary) to boost growth and generate demand. In subsequent years, economic growth revived.[85]

In 2021–22, the foreign direct investment (FDI) in India was $82 billion. The leading sectors for FDI inflows were the Finance, Banking, Insurance and R&D.[86] India has free trade agreements with several nations and blocs, including ASEAN, SAFTA, Mercosur, South Korea, Japan, Australia, UAE, and several others which are in effect or under negotiating stage.[87][88] In recent years, independent economists and financial institutions have accused the government of manipulating various economic data, especially GDP growth rate.[89][90][91][92][93][94][95]

The service sector makes up more than 50% of GDP and remains the fastest growing sector, while the industrial sector and the agricultural sector employs a majority of the labor force.[96] The Bombay Stock Exchange and National Stock Exchange are some of the world's largest stock exchanges by market capitalisation.[97] India is the world's sixth-largest manufacturer, representing 2.6% of global manufacturing output.[98] Nearly 65% of India's population is rural,[99] and contributes about 50% of India's GDP.[100] India faces high unemployment, rising income inequality, and a drop in aggregate demand.[101][102] India's gross domestic savings rate stood at 29.3% of GDP in 2022.[103]

History

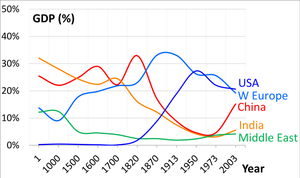

For a continuous duration of nearly 1700 years from the year 1 CE, India was the world's largest economy, constituting 35 to 40% of the world GDP.[106] The combination of protectionist, import-substitution, Fabian socialism, and social democratic-inspired policies governed India for sometime after the end of British rule. The economy was then characterised as Dirigism,[61][62] It had extensive regulation, protectionism, public ownership of large monopolies, pervasive corruption and slow growth.[63][64][107] Since 1991, continuing economic liberalisation has moved the country towards a market-based economy.[63][64] By 2008, India had established itself as one of the world's faster-growing economies.

Ancient and medieval eras

Indus Valley Civilisation

The citizens of the Indus Valley civilisation, a permanent settlement that flourished between 2800 BCE and 1800 BCE, practised agriculture, domesticated animals, used uniform weights and measures, made tools and weapons, and traded with other cities. Evidence of well-planned streets, a drainage system, and water supply reveals their knowledge of urban planning, which included the first-known urban sanitation systems and the existence of a form of municipal government.[108]

West Coast

Maritime trade was carried out extensively between southern regions of India and Southeast Asia and West Asia from early times until around the fourteenth century CE. Both the Malabar and Coromandel Coasts were the sites of important trading centres from as early as the first century BCE, used for import and export as well as transit points between the Mediterranean region and southeast Asia.[109] Over time, traders organised themselves into associations which received state patronage. This state patronage for overseas trade came to an end by the thirteenth century CE, when it was largely taken over by the local Parsi, Jewish, Syrian Christian, and Muslim communities, initially on the Malabar and subsequently on the Coromandel coast.[110]

Silk Route

Other scholars suggest trading from India to West Asia and Eastern Europe was active between the 14th and 18th centuries.[111][112][113] During this period, Indian traders settled in Surakhani, a suburb of greater Baku, Azerbaijan. These traders built a Hindu temple, which suggests commerce was active and prosperous for Indians by the 17th century.[114][115][116][117]

Further north, the Saurashtra and Bengal coasts played an important role in maritime trade, and the Gangetic plains and the Indus valley housed several centres of river-borne commerce. Most overland trade was carried out via the Khyber Pass connecting the Punjab region with Afghanistan and onward to the Middle East and Central Asia.[118] Although many kingdoms and rulers issued coins, barter was prevalent. Villages paid a portion of their agricultural produce as revenue to the rulers, while their craftsmen received a part of the crops at harvest time for their services.[119]

Mughal, Rajput, and Maratha eras (1526–1820)

The Indian economy was the largest and most prosperous throughout world history and would continue to be under the Mughal Empire, up until the 18th century.[120] Sean Harkin estimates that China and India may have accounted for 60 to 70 percent of world GDP in the 17th century. The Mughal economy functioned on an elaborate system of coined currency, land revenue and trade. Gold, silver and copper coins were issued by the royal mints which functioned on the basis of free coinage.[121] The political stability and uniform revenue policy resulting from a centralized administration under the Mughals, coupled with a well-developed internal trade network, ensured that India–before the arrival of the British–was to a large extent economically unified, despite having a traditional agrarian economy characterised by a predominance of subsistence agriculture.[122] Agricultural production increased under Mughal agrarian reforms,[120] with Indian agriculture being advanced compared to Europe at the time, such as the widespread use of the seed drill among Indian peasants before its adoption in European agriculture,[123] and possibly higher per-capita agricultural output and standards of consumption than 17th century Europe.[124]

The Mughal Empire had a thriving industrial manufacturing economy, with India producing about 25% of the world's industrial output up until 1750,[125] making it the most important manufacturing center in international trade.[126] Manufactured goods and cash crops from the Mughal Empire were sold throughout the world. Key industries included textiles, shipbuilding, and steel, and processed exports included cotton textiles, yarns, thread, silk, jute products, metalware, and foods such as sugar, oils and butter.[120] Cities and towns boomed under the Mughal Empire, which had a relatively high degree of urbanization for its time, with 15% of its population living in urban centres, higher than the percentage of the urban population in contemporary Europe at the time and higher than that of British India in the 19th century.[127]

In early modern Europe, there was significant demand for products from Mughal India, particularly cotton textiles, as well as goods such as spices, peppers, indigo, silks, and saltpeter (for use in munitions).[120] European fashion, for example, became increasingly dependent on Mughal Indian textiles and silks. From the late 17th century to the early 18th century, Mughal India accounted for 95% of British imports from Asia, and the Bengal Subah province alone accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia.[128] In contrast, there was very little demand for European goods in Mughal India, which was largely self-sufficient.[120] Indian goods, especially those from Bengal, were also exported in large quantities to other Asian markets, such as Indonesia and Japan.[129] At the time, Mughal Bengal was the most important center of cotton textile production.[130]

In the early 18th century the Mughal Empire declined, as it lost western, central and parts of south and north India to the Maratha Empire, which integrated and continued to administer those regions.[131] The decline of the Mughal Empire led to decreased agricultural productivity, which in turn negatively affected the textile industry.[132] The subcontinent's dominant economic power in the post-Mughal era was the Bengal Subah in the east., which continued to maintain thriving textile industries and relatively high real wages.[133] However, the former was devastated by the Maratha invasions of Bengal[134][135] and then British colonization in the mid-18th century.[133] After the loss at the Third Battle of Panipat, the Maratha Empire disintegrated into several confederate states, and the resulting political instability and armed conflict severely affected economic life in several parts of the country – although this was mitigated by localised prosperity in the new provincial kingdoms.[131] By the late eighteenth century, the British East India Company had entered the Indian political theatre and established its dominance over other European powers. This marked a determinative shift in India's trade, and a less-powerful effect on the rest of the economy.[136]

British era (1793–1947)

There is no doubt that our grievances against the British Empire had a sound basis. As the painstaking statistical work of the Cambridge historian Angus Maddison has shown, India's share of world income collapsed from 22.6% in 1700, almost equal to Europe's share of 23.3% at that time, to as low as 3.8% in 1952. Indeed, at the beginning of the 20th century, "the brightest jewel in the British Crown" was the poorest country in the world in terms of per capita income.

From the beginning of the 19th century, the British East India Company's gradual expansion and consolidation of power brought a major change in taxation and agricultural policies, which tended to promote commercialisation of agriculture with a focus on trade, resulting in decreased production of food crops, mass impoverishment and destitution of farmers, and in the short term, led to numerous famines.[139] The economic policies of the British Raj caused a severe decline in the handicrafts and handloom sectors, due to reduced demand and dipping employment.[140] After the removal of international restrictions by the Charter of 1813, Indian trade expanded substantially with steady growth.[141] The result was a significant transfer of capital from India to England, which, due to the colonial policies of the British, led to a massive drain of revenue rather than any systematic effort at modernisation of the domestic economy.[142] The economy of the Indian subcontinent was the largest in the world for most of recorded history up until the onset of colonialism in early 19th century.[138][143][144]

Under British rule, India's share of the world economy declined from 24.4% in 1700 down to 4.2% in 1950. India's GDP (PPP) per capita was stagnant during the Mughal Empire and began to decline prior to the onset of British rule.[143] India's share of global industrial output declined from 25% in 1750 down to 2% in 1900.[125] At the same time, United Kingdom's share of the world economy rose from 2.9% in 1700 up to 9% in 1870. The British East India Company, following their conquest of Bengal in 1757, had forced open the large Indian market to British goods, which could be sold in India without tariffs or duties, compared to local Indian producers who were heavily taxed, while in Britain protectionist policies such as bans and high tariffs were implemented to restrict Indian textiles from being sold there, whereas raw cotton was imported from India without tariffs to British factories which manufactured textiles from Indian cotton and sold them back to the Indian market. British economic policies gave them a monopoly over India's large market and cotton resources.[151][152][153] India served as both a significant supplier of raw goods to British manufacturers and a large captive market for British manufactured goods.[154]

British territorial expansion in India throughout the 19th century created an institutional environment that, on paper, guaranteed property rights among the colonisers, encouraged free trade, and created a single currency with fixed exchange rates, standardised weights and measures and capital markets within the company-held territories. It also established a system of railways and telegraphs, a civil service that aimed to be free from political interference, a common-law, and an adversarial legal system.[155] This coincided with major changes in the world economy – industrialisation, and significant growth in production and trade. However, at the end of colonial rule, India inherited an economy that was one of the poorest in the developing world,[156] with industrial development stalled, agriculture unable to feed a rapidly growing population, a largely illiterate and unskilled labour force, and extremely inadequate infrastructure.[157]

The 1872 census revealed that 91.3% of the population of the region constituting present-day India resided in villages.[158] This was a decline from the earlier Mughal era, when 85% of the population resided in villages and 15% in urban centers under Akbar's reign in 1600.[159] Urbanisation generally remained sluggish in British India until the 1920s, due to the lack of industrialisation and absence of adequate transportation. Subsequently, the policy of discriminating protection (where certain important industries were given financial protection by the state), coupled with the Second World War, saw the development and dispersal of industries, encouraging rural-urban migration, and in particular, the large port cities of Bombay, Calcutta and Madras grew rapidly. Despite this, only one-sixth of India's population lived in cities by 1951.[160]

The effect of British rule on India's economy is a controversial topic. Leaders of the Indian independence movement and economic historians have blamed colonial rule for India's poor economic performance following independence and argued that the wealth required for Britain's industrial development was derived from wealth taken from India. At the same time, right-wing historians have countered that India's poor economic performance was due to various sectors being in a state of growth and decline due to changes brought in by colonialism and a world that was moving towards industrialisation and economic integration.[161]

Several economic historians have argued that real wage decline occurred in the early 19th century, or possibly beginning in the very late 18th century, largely as a result of British imperialism. According to Prasannan Parthasarathi and Sashi Sivramkrishna, the grain wages of Indian weavers were likely comparable to that of their British counterparts and their average income was around five times the subsistence level, which was comparable to advanced parts of Europe.[162][163] However they concluded that due to the scarcity of data, it was hard to draw definitive conclusions and that more research was required.[126][163] It has also been argued that India went through a period of deindustrialization in the latter half of the 18th century as an indirect outcome of the collapse of the Mughal Empire.[125]

Pre-liberalisation period (1947–1991)

Indian economic policy after independence was influenced by the colonial experience, which was seen as exploitative by Indian leaders exposed to the planned economy of the Soviet Union.[157] Domestic policy tended towards protectionism, with a strong emphasis on import substitution industrialisation, economic interventionism, a large government-run public sector, business regulation, and central planning,[164] while trade and foreign investment policies were relatively liberal.[165] Five-Year Plans of India resembled central planning in the Soviet Union. Steel, mining, machine tools, telecommunications, insurance, and power plants, among other industries, were effectively nationalised in the mid-1950s.[73] The Indian economy of this period is characterised as Dirigism.[61][62]

Never talk to me about profit, Jeh, it is a dirty word.

— Nehru, India's Fabian Socialism-inspired first prime minister to industrialist J. R. D. Tata, when Tata suggested state-owned companies should be profitable[168]

Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, along with the statistician Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, formulated and oversaw economic policy during the initial years of the country's independence. They expected favourable outcomes from their strategy, involving the rapid development of heavy industry by both public and private sectors, and based on direct and indirect state intervention, rather than the more extreme Soviet-style central command system.[169][170] The policy of concentrating simultaneously on capital- and technology-intensive heavy industry and subsidising manual, low-skill cottage industries was criticised by economist Milton Friedman, who thought it would waste capital and labour, and retard the development of small manufacturers.[171]

I cannot decide how much to borrow, what shares to issue, at what price, what wages and bonus to pay, and what dividend to give. I even need the government's permission for the salary I pay to a senior executive.

— J. R. D. Tata, on the Indian regulatory system, 1969[168]

Since 1965, the use of high-yielding varieties of seeds, increased fertilisers and improved irrigation facilities collectively contributed to the Green Revolution in India, which improved the condition of agriculture by increasing crop productivity, improving crop patterns and strengthening forward and backward linkages between agriculture and industry.[172] However, it has also been criticised as an unsustainable effort, resulting in the growth of capitalistic farming, ignoring institutional reforms and widening income disparities.[173]

In 1984, Rajiv Gandhi promised economic liberalization, he made V. P. Singh the finance minister, who tried to reduce tax evasion and tax receipts rose due to this crackdown although taxes were lowered. This process lost its momentum during the later tenure of Mr. Gandhi as his government was marred by scandals.

Post-liberalisation period (since 1991)

The collapse of the Soviet Union, which was India's major trading partner, and the Gulf War, which caused a spike in oil prices, resulted in a major balance-of-payments crisis for India, which found itself facing the prospect of defaulting on its loans.[174] India asked for a $1.8 billion bailout loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which in return demanded de-regulation.[175]

In response, the Narasimha Rao government, including Finance Minister Manmohan Singh, initiated economic reforms in 1991. The reforms did away with the Licence Raj, reduced tariffs and interest rates and ended many public monopolies, allowing automatic approval of foreign direct investment in many sectors.[176] Since then, the overall thrust of liberalisation has remained the same, although no government has tried to take on powerful lobbies such as trade unions and farmers, on contentious issues such as reforming labour laws and reducing agricultural subsidies.[177] This has been accompanied by increases in life expectancy, literacy rates, and food security, although urban residents have benefited more than rural residents.[178]

From 2010, India has risen from ninth-largest to the fifth-largest economies in the world by nominal GDP in 2019 by surpassing UK, France, Italy and Brazil.[179]

India started recovery in 2013–14 when the GDP growth rate accelerated to 6.4% from the previous year's 5.5%. The acceleration continued through 2014–15 and 2015–16 with growth rates of 7.5% and 8.0% respectively. For the first time since 1990, India grew faster than China which registered 6.9% growth in 2015.[needs update] However the growth rate subsequently decelerated, to 7.1% and 6.6% in 2016–17 and 2017–18 respectively,[180] partly because of the disruptive effects of 2016 Indian banknote demonetisation and the Goods and Services Tax (India).[181]

India is ranked 63rd out of 190 countries in the World Bank's 2020 ease of doing business index, up 14 points from the last year's 100 and up 37 points in just two years.[182] In terms of dealing with construction permits and enforcing contracts, it is ranked among the 10 worst in the world, while it has a relatively favourable ranking when it comes to protecting minority investors or getting credit.[183] The strong efforts taken by the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP) to boost ease of doing business rankings at the state level is said to affect the overall rankings of India.[184]

COVID-19 pandemic and aftermath (2020–present)

During the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous rating agencies downgraded India's GDP predictions for FY21 to negative figures,[185][186] signalling a recession in India, the most severe since 1979.[187][188] The Indian Economy contracted by 6.6 percent which was lower than the estimated 7.3 percent decline.[189] In 2022, the ratings agency Fitch Ratings upgraded India's outlook to stable similar to S&P Global Ratings and Moody's Investors Service's outlooks.[190] In the first quarter of financial year 2022–2023, the Indian economy grew by 13.5%.[191]

Data

This article needs to be updated. (October 2023) |

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2022 (with IMF staff estimates in 2023–2028). Inflation below 5% is in green.[192] The annual unemployment rate is extracted from the World Bank, although the International Monetary Fund finds them unreliable.[193] [194]

| Year | GDP (in Bil. US$PPP) |

GDP per capita (in US$ PPP) |

GDP (in Bil. US$nominal) |

GDP per capita (in US$ nominal) |

GDP growth (real) |

Inflation rate (in Percent) |

Unemployment (in Percent) |

Government debt (in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 371.9 | 532.0 | 189.4 | 271.0 | n/a | n/a | ||

| 1981 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1982 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1983 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1984 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1985 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1986 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1987 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1988 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1989 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1990 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1991 | 6.8% | 75.3% | ||||||

| 1992 | ||||||||

| 1993 | ||||||||

| 1994 | ||||||||

| 1995 | ||||||||

| 1996 | ||||||||

| 1997 | ||||||||

| 1998 | ||||||||

| 1999 | ||||||||

| 2000 | ||||||||

| 2001 | ||||||||

| 2002 | ||||||||

| 2003 | ||||||||

| 2004 | ||||||||

| 2005 | ||||||||

| 2006 | ||||||||

| 2007 | ||||||||

| 2008 | ||||||||

| 2009 | ||||||||

| 2010 | ||||||||

| 2011 | ||||||||

| 2012 | ||||||||

| 2013 | ||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | ||||||||

| 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||

| 2020 | ||||||||

| 2021 | ||||||||

| 2022 | ||||||||

| 2023 | ||||||||

| 2024 | n/a | |||||||

| 2025 | n/a | |||||||

| 2026 | n/a | |||||||

| 2027 | n/a | |||||||

| 2028 | n/a |

Sectors

Agriculture, forest, and fishing

Agriculture and allied sectors like forestry, logging and fishing accounted for 18.4% of the GDP,[17] the sector employed 51.2 crore persons or 45.5% of the workforce in India are employed in agriculture.[199][200] India is major agriculture producing country and has the most arable land in the world followed by the United States.[201] However, agricultural output lags far behind its potential.[202] Agriculture's contribution to GDP has steadily declined from 1951 to 2023, shifting from 52% to 15% of India's GDP[203][204] yet it is still the country's largest employment provider sector .[199] Crop-yield-per-unit-area of all crops has grown since 1950, due to the special emphasis placed on agriculture in the five-year plans and steady improvements in irrigation, technology, application of modern agricultural practices and provision of agricultural credit and subsidies since the Green Revolution in India. However, international comparisons reveal the average yield in India is generally 30% to 50% of the highest average yield in the world.[205] The states of Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Bihar, West Bengal, Gujarat and Maharashtra are key contributors to Indian agriculture.

India receives an average annual rainfall of 1,208 millimetres (47.6 in) and a total annual precipitation of 4,000 billion cubic metres, with the total utilisable water resources, including surface and groundwater, amounting to 1,123 billion cubic metres.[206] 546,820 square kilometres (211,130 sq mi) of the land area, or about 39% of the total cultivated area, is irrigated.[207] India's inland water resources and marine resources provide employment to nearly 6 million people in the fisheries sector. In 2023, according to the Ministry of Fisheries, India is the 3rd largest fish producing and 2nd largest aquaculture producing nation in the world.

India is the largest producer of milk, jute and pulses, and has the world's largest cattle population with 303 million animals in 2023.[209] It is the second-largest producer of rice, wheat, sugarcane, cotton and groundnuts, as well as the second-largest fruit and vegetable producer, accounting for 10.9% and 8.6% of the world fruit and vegetable production, respectively, but only for 1% of global fruits and vegetables trade. India is also the second-largest producer and the largest consumer of silk, producing 77,000 tonnes (76,000 long tons; 85,000 short tons) in 2005.[210] India is the second-largest exporter of cashew kernels and cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL). Foreign exchange earned by the country through the export of cashew kernels during FY 2023 reached 356M$. 76,624 tonnes (75,414 long tons; 84,464 short tons) of kernels were exported during 2023.[211] There are about 600 cashew processing units in Kollam, Kerala.[208]

India's foodgrain production stagnant at approximately 316 megatonnes (311 million long tons; 348 million short tons) during 2020–21.[212] India exports several agriculture products, such as Basmati rice, wheat, cereals, spices, fresh fruits, dry fruits, cotton, tea, coffee, milk products and other cash crops to the Asian, African and other countries.[213]

The low productivity in India is a result of several factors.Over-regulation of agriculture has increased costs, price risks and uncertainty, and governmental intervention in labour, land, and credit are hurting the market. Infrastructure such as rural roads, electricity, ports, food storage, retail markets and services remain inadequate.[214] The average size of land holdings is very small, with 70% of holdings being less than one hectare (2.5 acres) in size.[215] Irrigation facilities are inadequate, as revealed by the fact that only 46% of the total cultivable land was irrigated as of 2016,[update][207] resulting in farmers still being dependent on rainfall, specifically the monsoon season, which is often inconsistent and unevenly distributed across the country.[216] In an effort to bring an additional 20,000,000 hectares (49,000,000 acres) of land under irrigation, various schemes have been attempted, including the Accelerated Irrigation Benefit Programme (AIBP) which was provided ₹800 billion (equivalent to ₹1.2 trillion or US$14 billion in 2023) in the Union Budget.[217] Farming incomes are also hampered by lack of food storage and distribution infrastructure; a third of India's agricultural production is lost from spoilage.[218]

Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSME)

India began its first few steps during the years 1978-80 when early conditions for SMEs or entrepreneurship were hostile too. 63 million MSMEs in India which contribute 35% to the country’s GDP provides employment to 111.4 million persons and accounts for more than 40% of India’s exports and are hailed as the ‘growth engines’ of the economy.China has been creating 16,000-18,000 new enterprises per day for the last 5 years. When you compare that with India, it is about 1000-1100 per day.[219]

Micro and small enterprises have the potential to resolve India’s unemployment crisis provided the constraints impeding the growth of the sector are resolved.According to Annual MSME Report 2021-22, over 90 per cent of India’s 6.3 crore MSMEs are in the micro-segment. Within the micro sector, 62 per cent firms are self-employments which no workers, another 32 per cent have two or three workers and just 6-7 per cent have four workers or above (up to 19).[220] In 2023, SME IPOs set a record-breaking year with 179 listings.

In Budget 2023, The government has implemented a number of reforms aimed at boosting MSMEs' growth in India while also improving their international competitiveness.[221]

Mining, resources, and chemicals

Mining

India has, in 2022, a reported 1,319 mines of which reporting mines for metallic minerals were estimated at 545 and non-metallic minerals at 775.[222]

Mining contributed to 1,75% of GDP and employed directly or undirecly 11 million people in 2021.[223] India's mining industry was the fourth-largest producer of minerals in the world by volume, and eighth-largest producer by value in 2009.[224] In 2013, it mined and processed 89 minerals, of which four were fuel, three were atomic energy minerals, and 80 non-fuel.[225] The public sector accounted for 68% of mineral production by volume in 2011–12.[226] India has the world's fourth-largest natural resources, with the mining sector contributing 11% of the country's industrial GDP and 2.5% of total GDP.

Nearly 50% of India's mining industry, by output value, is concentrated in eight states: Odisha, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka. Another 25% of the output by value comes from offshore oil and gas resources.[226] India operated about 3,000 mines in 2010, half of which were coal, limestone and iron ore.[227] On output-value basis, India was one of the five largest producers of mica, chromite, coal, lignite, iron ore, bauxite, barite, zinc and manganese; while being one of the ten largest global producers of many other minerals.[224][226] India was the fourth-largest producer of steel in 2013,[228] and the seventh-largest producer of aluminium.[229]

India's mineral resources are vast.[230] However, its mining industry has declined – contributing 2.3% of its GDP in 2010 compared to 3% in 2000, and employed 2.9 million people – a decreasing percentage of its total labour. India is a net importer of many minerals including coal. India's mining sector decline is because of complex permit, regulatory and administrative procedures, inadequate infrastructure, shortage of capital resources, and slow adoption of environmentally sustainable technologies.[226][231]

Iron and steel

India surpassed Japan as the second largest steel producer in January 2019.[232] As per worldsteel, India's crude steel production in 2018 was at 106.5 tonnes (104.8 long tons; 117.4 short tons), 4.9% increase from 101.5 tonnes (99.9 long tons; 111.9 short tons) in 2017, which means that India overtook Japan as the world's second largest steel production country.

According to data presented by PIB(FY2021-22), there are more than 900 steel plants in India that produce crude steel. These are owned by PSUs, large-scale companies as well as small and medium enterprises (SMEs). In the year 2021–22, the total capacity of these plants stood at 154.06 million tonnes.[233]

The total market value of the Indian steel sector stood at US$57.8 billion in 2011 and is predicted to touch US$95.3 billion by 2016.Growth of crude steel production in India has not kept pace with the growth in capacity of production, according to the report. As per this report, steel sector contributes 2 per cent to India's GDP and employs half a million people directly and 2 million people indirectly. The Indian steel sector has been vibrant, growing at a compounded rate of 6% year-on-year.[234]

Petroleum

Petroleum products and chemicals are a major contributor to India's industrial GDP, and together they contribute over 34% of its export earnings. India hosts many oil refinery and petrochemical operations developed with help of Soviet technology such as Barauni Refinery and Gujarat Refinery, it also includes the world's largest refinery complex in Jamnagar that processes 1.24 million barrels of crude per day.[235] By volume, the Indian chemical industry was the third-largest producer in Asia, and contributed 5% of the country's GDP. India is one of the five-largest producers of agrochemicals, polymers and plastics, dyes and various organic and inorganic chemicals.[236] Despite being a large producer and exporter, India is a net importer of chemicals due to domestic demands.[237] India's chemical industry is extremely diversified and estimated at $178 billion.[238]

Chemicals and fertilizer

The chemical industry contributed $163 billion to the economy in FY18 and is expected to reach $300–400 billion by 2025.[239][240] The industry employed 17.33 million people (4% of the workforce) in 2016.[241]

At present, 57 large fertilizer units are manufacturing a wide number of nitrogen fertilizers. These include 29 urea-producing units and 9 ammonia sulfate-producing units as a by-product. Besides, there are 64 small-scale producing units of single super phosphate.[242]

According to the latest data released by the WTO, India has emerged as the second largest exporter of agrochemicals in the world. The rank was sixth, 10 years ago.The Indian agrochemical industry fetches valuable trade surplus every year. The trade surplus sharply increased from Rs. 8,030 crores in 2017–18 to Rs. 28,908 crores in the last fiscal. India's agrochemicals export has doubled in the last 6 years from $2.6 bn in 2017–18 to $5.4 bn in the last financial year according to the data recently released by Ministry of Commerce. It has grown at an impressive CAGR of 13% which is among the highest in the manufacturing sector.[243]

Millions of farmers in over 130 countries trust Indian agrochemicals for their high quality and affordable prices, said an industry observer. With the global agrochemicals market estimated at $78 billion, predominantly comprising post-patent products, India is rapidly becoming a preferred global hub for sourcing such agrochemicals. To bolster domestic production and reduce imports, the Crop Care Federation of India (CCFI) has recommended specific measures to the Government of India.[244]

Transportation

Railways and Logistics

The Indian Railways contributes to ~3% of the country's gross domestic product (GDP) and has social obligations pegged at $5.3 billion annually.[245] Indian Railways revenue has grown at 5% CAGR in the past 5 years but profitability has reduced drastically in the past 4 years, due to growing infrastructure and modernization expenses. With a workforce of 1.31 million people, the IR is also one of the country's largest employers. The railways is a major contributor to jobs, GDP, and mobility.[246]

Indian Railways has decided to revise its 2022–23 rolling stock production plan upwards. The Ministry's new plan targets the production of 8,429 units for the coming financial year. Production for 2022–23 has been raised by 878 units from the earlier planned 7,551, according to the revised targets.[247] Indian Railways has targeted to manufacture 475 new Vande Bharat trainsets for the next four years as a part of its modernization plan.[248] It is about Rs 40,000 crore($5 billion) business opportunity that would also create 15,000 jobs and several spin-off benefits.[249] Indian Railway's CORE aims to electrify all of its broad gauge network by 31 March 2024.[250] The entire electrified mainline rail network in India uses 25 kV AC; DC is used only for metros.As of July 2023, India currently has 90% of total train tracks fully electrified.[251]

Under the eleventh Five Year Plan of India (2007–12), the Ministry of Railways started constructing a new Dedicated Freight Corridor (DFC) in two long routes, namely the Eastern and Western freight corridors.[252] The two routes cover a total length of 3,260 kilometres (2,030 mi), with the Eastern Dedicated Freight Corridor stretching from Ludhiana in Punjab to Dankuni in West Bengal and the Western Dedicated Freight Corridor from Jawaharlal Nehru Port in Mumbai (Maharashtra) to Dadri in Uttar Pradesh.[253] The DFC will generate around 42,000 jobs and provide long term employment to many people in public sector and private sector.[citation needed]

Rapid Transit

India is developing modern mass rapid transit systems to meet present and future urban requirements. A modern metro rail system is already in place in the cities of Navi Mumbai, Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore, Kolkata, Hyderabad, Kochi, Gurgaon, Jaipur, Noida, Pune, Nagpur, Kanpur, Ahmedabad and Lucknow. Similar mass transit systems are intended for Agra, Bhopal, Indore, Surat, Patna, Bhubaneswar Tri-city, Chandigarh Tri-city, Gwalior, Mysore, Nashik, Prayagraj, Varanasi, Ranchi, Thane and Trivandrum. Former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee has been credited with success of the metro systems in India and every metro has followed Delhi Metro model generating lot of real estate wealth in India specially in smaller cities like Gurgaon and Noida. For Elevated corridor, there is no need for land acquisition as pillars are built above Median strip of a road.[254][citation needed] Land prices in tier-II cities such as Lucknow, Patna, Jaipur, Ahmedabad, Pune, Kochi, and Coimbatore have gone up by almost 8-10 percent following the introduction of a metro corridor in these cities, an assessment by JLL has said.[255]

India is also developing modern RRTS system to replace the old MRTS system which will provide connectivity in Delhi Metropolitan Area and Mumbai Metropolitan Region which will serve the suburbs of these big cities at 80–100 km of distance from city center.[citation needed]

Aviation

India is the fourth-largest civil aviation market in the world recording an air traffic of 158 million passengers in 2017.[256][257] The market is estimated to have 800 aircraft by 2020, which would account for 4.3% of global volumes,[258] and is expected to record annual passenger traffic of 520 million by 2037.[257] IATA estimated that aviation contributed $30 billion to India's GDP in 2017, and supported 7.5 million jobs – 390,000 directly, 570,000 in the value chain, and 6.2 million through tourism.[257]

As of 2024, There are 75 new airports have been built in the last ten years, taking the total count to 149 airports (include helipads and aerodromes). Government vision is to take this milestone 149 to 220 airports in the next 5 to 7 years and Government of India has a Rs 1 lakh crore capex plan to spend on Airport infrastructure. [259]

IT and telecommunications

Datacenter and Cloud

India has emerged as the leading data centre hub in the Asia-Pacific region (excluding China), surpassing established players like Singapore, Australia, South Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong in installed capacity. This reflects the escalating demand for data services in one of the world’s fastest-growing major economies. With a current installed capacity of 950 MW and projections indicating an additional 850 MW by 2026, India is poised to solidify its position as a key player in the Asia-Pacific data centre landscape.[260]

In Hyderabad, The largest datacenter is spread over 1. 31 lakh square feet, the proposed rated-4 (tier-4) data centre will be equipped with 1,600 racks and powered by 18MW of electricity.[261]

India’s overall public cloud services market is projected to hit US $13 billion by 2026, expanding at a CAGR of 23.1% in 2021-26. The market’s revenue totaled US $2.8 billion for the first half of 2022.[262]

Telecommunications

The telecommunication sector generated ₹2.20 trillion (US$26 billion) in revenue in 2014–15, accounting for 1.94% of total GDP.[263] India is the second-largest market in the world by number of telephone users (both fixed and mobile phones) with 1.053 billion subscribers as of 31 August 2016.[update] It has one of the lowest call-tariffs in the world, due to fierce competition among telecom operators. India has the world's third-largest Internet user-base. As of 31 March 2016,[update] there were 342.65 million Internet subscribers in the country.[264] India's telecommunication industry is the world's second largest by the number of mobile phone, smartphone, and internet users. It is the world's 24th-largest oil producer and the third-largest oil consumer.[265]

Industry estimates indicate that there are over 554 million TV consumers in India as of 2012.[update][266] India is the largest direct-to-home (DTH) television market in the world by number of subscribers. As of May 2016,[update] there were 84.80 million DTH subscribers in the country.[267]

Defence and energy

Defence

With strength of over 1.3 million active personnel, Indian Army is the third-largest military force and the largest volunteer army. Defence expenditure was pegged at US$70.12 billion for fiscal year 2022–23 and, increased 9.8% than previous fiscal year.[268] India is the world's second largest arms importer; between 2016 and 2020, it accounted for 9.5% of the total global arms imports.[269] India exported military hardware worth ₹159.2 billion (US$1.9 billion) in the financial year 2022–23, the highest ever and a notable tenfold increase since 2016–17.[270]

Diversified Energy sector

Primary energy consumption of India is the third-largest after China and US with 5.3% global share in the year 2015.[271] Coal and crude oil together account for 85% of the primary energy consumption of India. India's oil reserves meet 25% of the country's domestic oil demand.[272][273] As of April 2015,[update] India's total proven crude oil reserves are 763.476 megatonnes (751.418 million long tons; 841.588 million short tons), while gas reserves stood at 1,490 billion cubic metres (53 trillion cubic feet).[274] Oil and natural gas fields are located offshore at Ashoknagar Oil Field, Bombay High, Krishna Godavari Basin, Mangala Area and the Cauvery Delta, and onshore mainly in the states of West Bengal, Assam, Gujarat and Rajasthan. India is the fourth-largest consumer of oil and net oil imports were nearly ₹8.2 trillion (US$98 billion) in 2014–15,[274] which had an adverse effect on the country's current account deficit. The petroleum industry in India mostly consists of public sector companies such as Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC), Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited (HPCL), Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited (BPCL) and Indian Oil Corporation Limited (IOCL). There are some major private Indian companies in the oil sector such as Reliance Industries Limited (RIL) which operates the world's largest oil refining complex.[275]

India became the world's third-largest producer of electricity in 2013 with a 4.8% global share in electricity generation, surpassing Japan and Russia.[276] By the end of calendar year 2015, India had an electricity surplus with many power stations idling for want of demand.[277] The utility electricity sector had an installed capacity of 303 GW as of May 2016[update] of which thermal power contributed 69.8%, hydroelectricity 15.2%, other sources of renewable energy 13.0%, and nuclear power 2.1%.[278] India meets most of its domestic electricity demand through its 106 gigatonnes (104 billion long tons; 117 billion short tons) of proven coal reserves.[279] India is also rich in certain alternative sources of energy with significant future potential such as solar, wind and biofuels (jatropha, sugarcane). India's dwindling uranium reserves stagnated the growth of nuclear energy in the country for many years.[280] Recent discoveries in the Tummalapalle belt may be among the top 20 natural uranium reserves worldwide,[281][282][283][needs update] and an estimated reserve of 846,477 tonnes (833,108 long tons; 933,081 short tons) of thorium[284] – about 25% of world's reserves – are expected to fuel the country's ambitious nuclear energy program in the long-run. The Indo-US nuclear deal has also paved the way for India to import uranium from other countries.[285]

Infrastructure and constructions

This article needs to be updated. (June 2023) |

India's infrastructure and transport sector contributes about 5% of its GDP. India has a road network of over 5,472,144 kilometres (3,400,233 mi) as of 31 March 2015,[update] the second-largest road network in the world only behind United States. At 1.66 km of roads per square kilometre of land (2.68 miles per square mile), the quantitative density of India's road network is higher than that of Japan (0.91) and United States (0.67), and far higher than that of China (0.46), Brazil (0.18) or Russia (0.08).[286] Qualitatively, India's roads are a mix of modern highways and narrow, unpaved roads, and are being improved.[287] As of 31 March 2015,[update] 87.05% of Indian roads were paved.[286] It is upgrading its infrastructure. As of May 2014,[update] India had completed over 22,600 kilometres (14,000 mi) of 4- or 6-lane highways, connecting most of its major manufacturing, commercial and cultural centres.[288] India's road infrastructure carries 60% of freight and 87% of passenger traffic.[289]

India has a coastline of 7,500 kilometres (4,700 mi) with 13 major ports, 15 big private ports and 60 operational non-major ports, which together handle 95% of the country's external trade by volume and 70% by value (most of the remainder handled by air).[290] Kandla Port, New Kandla is the largest public port established in early 1960's, while Mundra is the largest private sea port.[291] The airport infrastructure of India includes 125 airports,[292] of which 66 airports are licensed to handle both passengers and cargo.[293] India has multiple global infrastructure companies such as Adani Group, JSW Infrastructure, Larsen & Toubro etc.

The construction industry contributed $288 billion (13% of GDP) and employed 60.42 million people (14% of the workforce) in 2016.[241] The construction and real estate sector ranks third among the 14 major sectors in terms of direct, indirect, and induced effects in all sectors of the economy.[294]

The real estate sector will provide huge business opportunities, employment and big avenues for startup ecosystem. The 2023 Union budget of India also focused significantly on infrastructure with nearly ₹10 trillion direct investment of central government.[295]

Finance and trade

Banking and financial services

The financial services industry contributed $809 billion (37% of GDP) and employed 14.17 million people (3% of the workforce) in 2016, and the banking sector contributed $407 billion (19% of GDP) and employed 5.5 million people (1% of the workforce) in 2016.[241] The Indian money market is classified into the organised sector, comprising private, public and foreign-owned commercial banks and cooperative banks, together known as 'scheduled banks'; and the unorganised sector, which includes individual or family-owned indigenous bankers or money lenders and non-banking financial companies.[296] The unorganised sector and microcredit are preferred over traditional banks in rural and sub-urban areas, especially for non-productive purposes such as short-term loans for ceremonies.[297]

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi nationalised 14 banks in 1969, followed by six others in 1980, and made it mandatory for banks to provide 40% of their net credit to priority sectors including agriculture, small-scale industry, retail trade and small business, to ensure that the banks fulfilled their social and developmental goals. Since then, the number of bank branches has increased from 8,260 in 1969 to 72,170 in 2007 and the population covered by a branch decreased from 63,800 to 15,000 during the same period. The total bank deposits increased from ₹59.1 billion (equivalent to ₹2.8 trillion or US$34 billion in 2023) in 1970–71 to ₹38.31 trillion (equivalent to ₹96 trillion or US$1.2 trillion in 2023) in 2008–09. Despite an increase of rural branches – from 1,860 or 22% of the total in 1969 to 30,590 or 42% in 2007 – only 32,270 of 500,000 villages are served by a scheduled bank.[298][299]

India's gross domestic savings in 2006–07 as a percentage of GDP stood at a high 32.8%.[300] More than half of personal savings are invested in physical assets such as land, houses, cattle, and gold.[301] The government-owned public-sector banks hold over 75% of total assets of the banking industry, with the private and foreign banks holding 18.2% and 6.5% respectively.[66] Since liberalisation, the government has approved significant banking reforms. While some of these relate to nationalised banks – such as reforms encouraging mergers, reducing government interference and increasing profitability and competitiveness – other reforms have opened the banking and insurance sectors to private and foreign companies.[272][302]

Retail

The retail industry, excluding wholesale, contributed $793 billion (10% of GDP) and employed 35 million people (8% of the workforce) in 2020. The industry is the second largest employer in India, after agriculture.[303][304][305][306] The Indian retail market is estimated to be US$600 billion and one of the top-five retail markets in the world by economic value. India has one of the fastest-growing retail markets in the world,[307][308] and is projected to reach $1.3 trillion by 2020.[309][310] India has retail market worth $1.17 trillion, which contributes over 10% of India's GDP. It also has one of the world's fastest growing e-commerce markets.[311] The e-commerce retail market in India was valued at $32.7 billion in 2018, and is expected to reach $71.9 billion by 2022.[312]

India's retail industry mostly consists of local mom-and-pop stores, owner-staffed shops and street vendors. Retail supermarkets are expanding, with a market share of 4% in 2008.[313] In 2012, the government permitted 51% FDI in multi-brand retail and 100% FDI in single-brand retail. However, a lack of back-end warehouse infrastructure and state-level permits and red tape continue to limit growth of organised retail.[314] Compliance with over thirty regulations such as "signboard licences" and "anti-hoarding measures" must be made before a store can open for business. There are taxes for moving goods from state to state, and even within states.[313]

Industries

Tourism

The World Travel & Tourism Council calculated that tourism generated ₹15.24 trillion (US$180 billion) or 9.4% of the nation's GDP in 2017 and supported 41.622 million jobs, 8% of its total employment. The sector is predicted to grow at an annual rate of 6.9% to ₹32.05 trillion (US$380 billion) by 2028 (9.9% of GDP).[315] Over 10 million foreign tourists arrived in India in 2017 compared to 8.89 million in 2016, recording a growth of 15.6%.[316] The tourism industry contributes about 9.2% of India's GDP and employs over 42 million people.[317] India earned $21.07 billion in foreign exchange from tourism receipts in 2015.[318] International tourism to India has seen a steady growth from 2.37 million arrivals in 1997 to 8.03 million arrivals in 2015. Bangladesh is the largest source of international tourists to India, while European Union nations and Japan are other major sources of international tourists.[319][320] Less than 10% of international tourists visit the Taj Mahal, with the majority visiting other cultural, thematic and holiday circuits.[321] Over 12 million Indian citizens take international trips each year for tourism, while domestic tourism within India adds about 740 million Indian travellers.[319] India has a fast-growing medical tourism sector of its health care economy, offering low-cost health services and long-term care.[322][323] In October 2015, the medical tourism sector was estimated to be worth US$3 billion. It is projected to grow to $7–8 billion by 2020.[324] In 2014, 184,298 foreign patients traveled to India to seek medical treatment.[325]

Films, entertainment and music industry

The Indian cinema industry is expected to garner a revenue of around Rs 16,198 crore by 2026, of which Rs 15,849 would be Box office revenue and the rest Rs 349 crore from advertising, the report added.[326] India's Recorded Music industry (which is a key sub-segment) is making steady progress at a CAGR of 13.6 percent, thanks to streaming models.[326]

Security markets

The development of Indian security markets began with the launch of the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) in July 1875 and the Ahmedabad Stock Exchange in 1894. Since then, 22 other exchanges have traded in Indian cities. In 2014, India's stock exchange market became the 10th largest in the world by market capitalisation, just above those of South Korea and Australia.[328] India's two major stock exchanges, BSE and the National Stock Exchange of India, had a market capitalisation of US$1.71 trillion and US$1.68 trillion as of February 2015,[update] according to the World Federation of Exchanges, which grew to $3.36 trillion and $3.31 trillion respectively by September 2021.[329][330]

The initial public offering (IPO) market in India has been small compared to NYSE and NASDAQ, raising US$300 million in 2013 and US$1.4 billion in 2012. Ernst & Young stated[331] that the low IPO activity reflects market conditions, slow government approval processes, and complex regulations. Before 2013, Indian companies were not allowed to list their securities internationally without first completing an IPO in India. In 2013, these security laws were reformed and Indian companies can now choose where they want to list first: overseas, domestically, or both concurrently.[332] Further, security laws have been revised to ease overseas listings of already-listed companies, to increase liquidity for private equity and international investors in Indian companies.[331]

Foreign trade and investment

Foreign trade

India's foreign trade by year

| Year | Exports (in USD billion) | Imports (in USD billion) | Trade Deficit (in USD billion) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022[333] | 458.3 | 725.4 | -267.2 |

| 2021 | 420 | 612 | -192 |

| 2020 | 314.31 | 467.19 | -158.88 |

| 2019 | 330.07 | 514.07 | -184 |

| 2018 | 303.52 | 465.58 | -162.05 |

| 2017 | 275.8 | 384.3 | -108.5 |

| 2016 | 262.3 | 381 | -118.7 |

| 2015 | 310.3 | 447.9 | -137.6 |

| 2014 | 318.2 | 462.9 | -144.7 |

| 2013 | 313.2 | 467.5 | -154.3 |

| 2012 | 298.4 | 500.4 | -202.0 |

| 2011 | 299.4 | 461.4 | -162.0 |

| 2010 | 201.1 | 327.0 | -125.9 |

| 2009 | 168.2 | 274.3 | -106.1 |

| 2008 | 176.4 | 305.5 | -129.1 |

| 2007 | 112.0 | 100.9 | 11.1 |

| 2006 | 76.23 | 113.1 | -36.87 |

| 2005 | 69.18 | 89.33 | -20.15 |

| 2004 | 57.24 | 74.15 | -16.91 |

| 2003 | 48.3 | 61.6 | -13.3 |

| 2002 | 44.5 | 53.8 | -9.3 |

| 2001 | 42.5 | 54.5 | -12.0 |

| 2000 | 43.1 | 60.8 | -17.7 |

| 1999 | 36.3 | 50.2 | -13.9 |

Until the liberalisation of 1991, India was largely and intentionally isolated from world markets, to protect its economy and to achieve self-reliance. Foreign trade was subject to import tariffs, export taxes and quantitative restrictions, while foreign direct investment (FDI) was restricted by upper-limit equity participation, restrictions on technology transfer, export obligations and government approvals; these approvals were needed for nearly 60% of new FDI in the industrial sector. The restrictions ensured that FDI averaged only around $200 million annually between 1985 and 1991; a large percentage of the capital flows consisted of foreign aid, commercial borrowing and deposits of non-resident Indians.[334] India's exports were stagnant for the first 15 years after independence, due to general neglect of trade policy by the government of that period; imports in the same period, with early industrialisation, consisted predominantly of machinery, raw materials and consumer goods.[335] Since liberalisation, the value of India's international trade has increased sharply,[336] with the contribution of total trade in goods and services to the GDP rising from 16% in 1990–91 to 47% in 2009–10.[337][338] Foreign trade accounted for 48.8% of India's GDP in 2015.[339] Globally, India accounts for 1.44% of exports and 2.12% of imports for merchandise trade and 3.34% of exports and 3.31% of imports for commercial services trade.[338] India's major trading partners are the European Union, China, United States and United Arab Emirates.[340] In 2006–07, major export commodities included engineering goods, petroleum products, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, gems and jewellery, textiles and garments, agricultural products, iron ore and other minerals. Major import commodities included crude oil and related products, machinery, electronic goods, gold and silver.[341] In November 2010, exports increased 22.3% year-on-year to ₹851 billion (equivalent to ₹1.9 trillion or US$23 billion in 2023), while imports were up 7.5% at ₹1.25 trillion (equivalent to ₹2.8 trillion or US$34 billion in 2023). The trade deficit for the same month dropped from ₹469 billion (equivalent to ₹1.2 trillion or US$14 billion in 2023) in 2009 to ₹401 billion (equivalent to ₹900 billion or US$11 billion in 2023) in 2010.[342]

India is a founding-member of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and its successor, the WTO. While participating actively in its general council meetings, India has been crucial in voicing the concerns of the developing world. For instance, India has continued its opposition to the inclusion of labour, environmental issues and other non-tariff barriers to trade in WTO policies.[343]

India secured 43rd place in competitiveness index.[344]

Balance of payments

Since independence, India's balance of payments on its current account has been negative. Since economic liberalisation in the 1990s, precipitated by a balance-of-payment crisis, India's exports rose consistently, covering 80.3% of its imports in 2002–03, up from 66.2% in 1990–91.[345] However, the global economic slump followed by a general deceleration in world trade saw the exports as a percentage of imports drop to 61.4% in 2008–09.[346] India's growing oil import bill is seen as the main driver behind the large current account deficit,[347] which rose to $118.7 billion, or 11.11% of GDP, in 2008–09.[348] Between January and October 2010, India imported $82.1 billion worth of crude oil.[347] The Indian economy has run a trade deficit every year from 2002 to 2012, with a merchandise trade deficit of US$189 billion in 2011–12.[349] Its trade with China has the largest deficit, about $31 billion in 2013.[350]

India's reliance on external assistance and concessional debt has decreased since liberalisation of the economy, and the debt service ratio decreased from 35.3% in 1990–91 to 4.4% in 2008–09.[351] In India, external commercial borrowings (ECBs), or commercial loans from non-resident lenders, are being permitted by the government for providing an additional source of funds to Indian corporates. The Ministry of Finance monitors and regulates them through ECB policy guidelines issued by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) under the Foreign Exchange Management Act of 1999.[352] India's foreign exchange reserves have steadily risen from $5.8 billion in March 1991 to ₹38,832.21 billion (US$540 billion) in July 2020.[353][354] In 2012, United Kingdom announced an end to all financial aid to India, citing the growth and robustness of Indian economy.[355][356]

India's current account deficit reached an all-time high in 2013.[357] India has historically funded its current account deficit through borrowings by companies in the overseas markets or remittances by non-resident Indians and portfolio inflows. From April 2016 to January 2017, RBI data showed that, for the first time since 1991, India was funding its deficit through foreign direct investment inflows. The Economic Times noted that the development was "a sign of rising confidence among long-term investors in Prime Minister Narendra Modi's ability to strengthen the country's economic foundation for sustained growth".[358]

Foreign direct investment

This section needs to be updated. (October 2015) |

| Rank | Country | Inflows (million US$) |

Inflows (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mauritius | 50,164 | 42.00 |

| 2 | Singapore | 11,275 | 9.00 |

| 3 | US | 8,914 | 7.00 |

| 4 | UK | 6,158 | 5.00 |

| 5 | Netherlands | 4,968 | 4.00 |

As the third-largest economy in the world in PPP terms, India has attracted foreign direct investment (FDI).[360] During the year 2011, FDI inflow into India stood at $36.5 billion, 51.1% higher than the 2010 figure of $24.15 billion. India has strengths in telecommunication, information technology and other significant areas such as auto components, chemicals, apparels, pharmaceuticals, and jewellery. Despite a surge in foreign investments, rigid FDI policies[361] were a significant hindrance. Over time, India has adopted a number of FDI reforms.[360] India has a large pool of skilled managerial and technical expertise. The size of the middle-class population stands at 300 million and represents a growing consumer market.[362]

India liberalised its FDI policy in 2005, allowing up to a 100% FDI stake in ventures. Industrial policy reforms have substantially reduced industrial licensing requirements, removed restrictions on expansion and facilitated easy access to foreign technology and investment. The upward growth curve of the real-estate sector owes some credit to a booming economy and liberalised FDI regime. In March 2005, the government amended the rules to allow 100% FDI in the construction sector, including built-up infrastructure and construction development projects comprising housing, commercial premises, hospitals, educational institutions, recreational facilities, and city- and regional-level infrastructure.[363] Between 2012 and 2014, India extended these reforms to defence, telecom, oil, retail, aviation, and other sectors.[364][365]

From 2000 to 2010, the country attracted $178 billion as FDI.[366] The inordinately high investment from Mauritius is due to routing of international funds through the country given significant tax advantages – double taxation is avoided due to a tax treaty between India and Mauritius, and Mauritius is a capital gains tax haven, effectively creating a zero-taxation FDI channel.[367] FDI accounted for 2.1% of India's GDP in 2015.[339]

As the government has eased 87 foreign investment direct rules across 21 sectors in the last three years, FDI inflows hit $60.1 billion between 2016 and 2017 in India.[368][369]

Outflows

Since 2000, Indian companies have expanded overseas, investing FDI and creating jobs outside India. From 2006 to 2010, FDI by Indian companies outside India amounted to 1.34 per cent of its GDP.[370] Indian companies have deployed FDI and started operations in United States,[371] Europe and Africa.[372] The Indian conglomerate Tata Group is United Kingdom's largest manufacturer and private-sector employer.[373][374]

Remittances

In 2015, a total of US$68.91 billion was made in remittances to India from other countries, and a total of US$8.476 billion was made in remittances by foreign workers in India to their home countries. UAE, US, and Saudi Arabia were the top sources of remittances to India, while Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal were the top recipients of remittances from India.[375] Remittances to India accounted for 3.32% of the country's GDP in 2015.[339]

Mergers and acquisitions

Between 1985 and 2018 20,846 deals have been announced in, into (inbound) and out of (outbound) India. This cumulates to a value of US$618 billion. In terms of value, 2010 has been the most active year with deals worth almost 60 bil. USD. Most deals have been conducted in 2007 (1,510).[376]

Here is a list of the top 10 deals with Indian companies participating:

| Acquiror Name | Acquiror Mid Industry | Acquiror Nation | Target Name | Target Mid Industry | Target Nation | Value of Transaction ($mil) |

| Petrol Complex Pte Ltd | Oil & Gas | Singapore | Essar Oil Ltd | Oil & Gas | India | 12,907.25 |

| Vodafone Grp Plc | Wireless | United Kingdom | Hutchison Essar Ltd | Telecommunications Services | India | 12,748.00 |

| Vodafone Grp PLC-Vodafone Asts | Wireless | India | Idea Cellular Ltd-Mobile Bus | Wireless | India | 11,627.32 |

| Bharti Airtel Ltd | Wireless | India | MTN Group Ltd | Wireless | South Africa | 11,387.52 |

| Bharti Airtel Ltd | Wireless | India | Zain Africa BV | Wireless | Nigeria | 10,700.00 |

| BP PLC | Oil & Gas | United Kingdom | Reliance Industries Ltd-21 Oil | Oil & Gas | India | 9,000.00 |

| MTN Group Ltd | Wireless | South Africa | Bharti Airtel Ltd | Wireless | India | 8,775.09 |

| Shareholders | Other Financials | India | Reliance Inds Ltd-Telecom Bus | Telecommunications Services | India | 8,063.01 |

| Oil & Natural Gas Corp Ltd | Oil & Gas | India | Hindustan Petro Corp Ltd | Petrochemicals | India | 5,784.20 |

| Reliance Commun Ventures Ltd | Telecommunications Services | India | Reliance Infocomm Ltd | Telecommunications Services | India | 5,577.18 |

Currency

• EXCHANGE RATES

| Year | INR₹ per US$ (annual average)[377] |

INR₹ per Pound(£) (annual average)[378] |

|---|---|---|

| 1947 | 3.31 | 13.33 |

| 1950 | 4.76 | — |

| 1967 | 7.50 | 17.76 |

| 1975 | 9.4058 | — |

| 1980 | 7.88 | — |

| 1985 | 12.364 | — |

| 1987 | — | 21.18 |

| 1990 | 17.4992 | 31.07 |

| 1995 | 32.4198 | 51.17 |

| 2000 | 44.9401 | 67.99 |

| 2005 | 44.1000 | 80.15 |

| 2010 | 45.7393 | 70.65 |

| 2015 | 64.05 | 98.0101 |

| 2016 | 67.09 | 90.72 |

| 2017 | 64.14 | 87.56 |

| 2018 | 69.71 | 98.51 |

| 2019 | 70.394 | 95.06 |

| 2020 | 72.97 | 100.05 |

| 2021 | 74.98 | 101.56 |

| 2022 | 81.35 | 96.23 |

| 2023 | 81.94 | 100.95 |

The Indian rupee (₹) is the only legal tender in India, and is also accepted as legal tender in neighbouring Nepal and Bhutan, both of which peg their currency to that of the Indian rupee. The rupee previously was divided into 100 paise, which no longer exist. The highest-denomination banknote is the ₹2,000 note until 30 September 2023 after which it will be scrapped and ₹500 note will become the highest denomination; the lowest-denomination coin in circulation is the ₹1 coin.[380] In 2017, demonetisation was announced in which ₹500 and ₹1000 notes were withdrawn and new ₹500 notes were issued. India's monetary system is managed by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the country's central bank.[381] Established on 1 April 1935 and nationalised in 1949, the RBI serves as the nation's monetary authority, regulator and supervisor of the monetary system, banker to the government, custodian of foreign exchange reserves, and as an issuer of currency. It is governed by a central board of directors, headed by a governor who is appointed by the Government of India.[382] The benchmark interest rates are set by the Monetary Policy Committee.

The rupee was linked to the British pound from 1927 to 1946, and then to US dollar until 1975 through a fixed exchange rate. It was devalued in September 1975 and the system of fixed par rate was replaced with a basket of four major international currencies: the British pound, US dollar, the Japanese yen and the Deutsche Mark.[383] In 1991, after the collapse of its largest trading partner, the Soviet Union, India faced the major foreign exchange crisis and the rupee was devalued by around 19% in two stages on 1 and 2 July. In 1992, a Liberalized Exchange Rate Mechanism (LERMS) was introduced. Under LERMS, exporters had to surrender 40 percent of their foreign exchange earnings to the RBI at the RBI-determined exchange rate; the remaining 60% could be converted at the market-determined exchange rate. In 1994, the rupee was convertible on the current account, with some capital controls.[384]

After the sharp devaluation in 1991 and transition to current account convertibility in 1994, the value of the rupee has been largely determined by market forces. The rupee has been fairly stable during the decade 2000–2010. In October 2022, rupee touched an all-time low 83.29 to US dollar.[385] [386]

Income and consumption

This article needs to be updated. (March 2022) |

India's gross national income per capita had experienced high growth rates since 2002. It tripled from ₹19,040 in 2002–03 to ₹53,331 in 2010–11, averaging 13.7% growth each of these eight years, with peak growth of 15.6% in 2010–11[389] and, growth in the inflation-adjusted per-capita income of the nation slowed to 5.6% in 2010–11, down from 6.4% in the previous year. These consumption levels are on an individual basis.[390] The average family income in India was $6,671 per household in 2011.[391]

According to 2011 census data, India has about 330 million houses and 247 million households. The household size in India has dropped in recent years, the 2011 census reporting 50% of households have four or fewer members, with an average of 4.8 members per household including surviving grandparents.[392][393] These households produced a GDP of about $1.7 trillion.[394] Consumption patterns note: approximately 67% of households use firewood, crop residue, or cow-dung cakes for cooking purposes; 53% do not have sanitation or drainage facilities on premises; 83% have water supply within their premises or 100 metres (330 ft) from their house in urban areas and 500 metres (1,600 ft) from the house in rural areas; 67% of the households have access to electricity; 63% of households have landline or mobile telephone service; 43% have a television; 26% have either a two- or four-wheel motor vehicle. Compared to 2001, these income and consumption trends represent moderate to significant improvements.[392] One report in 2010 claimed that high-income households outnumber low-income households.[395]

New World Wealth publishes reports tracking the total wealth of countries, which is measured as the private wealth held by all residents of a country. According to New World Wealth, India's total wealth increased from $3,165 billion in 2007 to $8,230 billion in 2017, a growth rate of 160%. India's total wealth decreased by 1% from $8.23 trillion in 2017 to $8.148 trillion in 2018, making it the sixth wealthiest nation in the world. There are 20,730 multimillionaires (7th largest in the world)[397] and 118 billionaires in India (3rd largest in the world). With 327,100 high net-worth individuals (HNWI), India is home to the 9th highest number of HNWIs in the world. Mumbai is the wealthiest Indian city and the 12th wealthiest in the world, with a total net worth of $941 billion in 2018. Twenty-eight billionaires reside in the city, ranked ninth worldwide.[398] As of December 2016,[update] the next wealthiest cities in India were Delhi ($450 billion), Bengaluru ($320 billion), Hyderabad ($310 billion), Kolkata ($290 billion), Chennai ($200 billion), and Gurugram ($110 billion).[399][400]

The Global Wealth Migration Review 2019 report, published by New World Wealth, found that 5,000 HNWI's emigrated from India in 2018, or about 2% of all HNWIs in the country. Australia, Canada, and United States were among the top destination countries.[401] The report also projected that private wealth in India would grow by around 180% to reach $22,814 billion by 2028.[398]

Poverty

In May 2014, the World Bank reviewed and proposed revisions to its poverty calculation methodology of 2005 and purchasing-power-parity basis for measuring poverty. According to the revised methodology, the world had 872.3 million people below the new poverty line, of which 179.6 million lived in India. With 17.5% of the total world's population, India had a 20.6% share of the world's poorest in 2013.[402] According to a 2005–2006 survey,[403] India had about 61 million children under the age of 5 who were chronically malnourished. A 2011 UNICEF report stated that between 1990 and 2010, India achieved a 45 percent reduction in mortality rates under the age of 5, and now ranks 46th of 188 countries on this metric.[404]

Since the early 1960s, successive governments have implemented various schemes to alleviate poverty, under central planning, that have met with partial success.[405] In 2005, the government enacted the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), guaranteeing 100 days of minimum wage employment to every rural household in all the districts of India.[406] In 2011, it was widely criticised and beset with controversy for corrupt officials, deficit financing as the source of funds, poor quality of infrastructure built under the programme, and unintended destructive effects.[407][408][409] Other studies suggest that the programme has helped reduce rural poverty in some cases.[410][411] Yet other studies report that India's economic growth has been the driver of sustainable employment and poverty reduction, though a sizeable population remains in poverty.[412][413] India lifted 271 million people out of poverty between 2006 and 2016, recording the fastest reductions in the multidimensional poverty index values during the period with strong improvements in areas such as assets, cooking fuel, sanitation, and nutrition.[414]

On the 2019 Global Hunger Index India ranked 102nd (out of 117 countries), being categorized as 'serious' in severity.

Employment

Agricultural and allied sectors accounted for about 52% of the total workforce in 2009–10. While agriculture employment has fallen over time in percentage of labour employed, services which include construction and infrastructure have seen a steady growth accounting for 20.3% of employment in 2012–13.[415] Of the total workforce, 7% is in the organised sector, two-thirds of which are in the government-controlled public sector.[416] About 51.2% of the workforce in India is self-employed.[415] According to a 2005–06 survey, there is a gender gap in employment and salaries. In rural areas, both men and women are primarily self-employed, mostly in agriculture. In urban areas, salaried work was the largest source of employment for both men and women in 2006.[417]

Unemployment