Гражданская война в США

Эта статья может оказаться слишком длинной для удобного чтения и навигации . Когда этот тег был добавлен, его читаемый размер составлял 16 000 слов. ( июль 2024 г. ) |

| Гражданская война в США | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

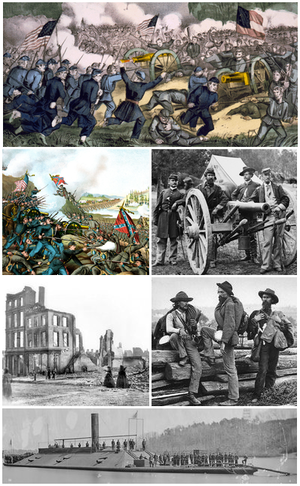

По часовой стрелке сверху: | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Воюющие стороны | |||||||||

| Командиры и лидеры | |||||||||

и другие... | и другие... | ||||||||

| Сила | |||||||||

| 2,200,000 [б] 698 000 (пик) [3] [4] | 750,000–1,000,000 [б] [5] 360 000 (пик) [3] [6] | ||||||||

| Жертвы и потери | |||||||||

| Итого: более 828 000 жертв. | Итого: более 864 000 жертв. | ||||||||

| Эта статья является частью серии статей о |

| История Соединенные Штаты |

|---|

|

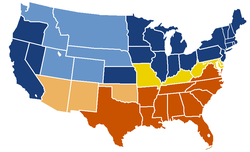

Гражданская война в США (12 апреля 1861 — 26 мая 1865; также известна под другими названиями ) — гражданская война в Соединённых Штатах между Союзом [и] («Север») и Конфедерация («Юг»), которая была образована в 1861 году штатами , вышедшими из Союза. Центральным конфликтом, приведшим к войне, был спор о том, следует ли разрешить рабству распространяться на западные территории, что приведет к появлению новых рабовладельческих государств , или запретить это делать, что, по мнению многих, поставит рабство на путь окончательного исчезновения. [16] [17]

Десятилетия споров по поводу рабства достигли апогея, когда Авраам Линкольн , выступавший против расширения рабства, победил на президентских выборах 1860 года . Семь южных рабовладельческих штатов отреагировали на победу Линкольна выходом из состава Соединенных Штатов и образованием Конфедерации. Конфедерация захватила форты США и другие федеральные активы в пределах своих границ. Война началась 12 апреля 1861 года, когда Конфедерация обстреляла форт Самтер в Южной Каролине . Волна энтузиазма по поводу войны прокатилась по Северу и Югу, поскольку резко возрос набор в армию. Еще четыре южных штата отделились после начала войны, и под руководством президента Джефферсона Дэвиса Конфедерация установила контроль над третью населения США в одиннадцати штатах. Последовали четыре года напряженных боев, в основном на юге.

В течение 1861–1862 годов на Западном театре военных действий Союз добился постоянных успехов, хотя на Восточном театре военных действий конфликт был безрезультатным. Отмена рабства стала целью войны Союза 1 января 1863 года, когда Линкольн издал Прокламацию об освобождении , которая объявила всех рабов в мятежных штатах свободными, что распространялось на более чем 3,5 миллиона из 4 миллионов порабощенных людей в стране. На западе Союз к лету 1862 года сначала уничтожил речной флот Конфедерации, затем большую часть ее западных армий и захватил Новый Орлеан . Успешная осада Виксбурга Союзом в 1863 году разделила Конфедерацию на две части у реки Миссисипи , в то время как генерала Конфедерации Роберта Ли вторжение на север провалилось в битве при Геттисберге . Успехи Запада привели к тому, что в 1864 году всеми армиями Союза командовал генерал Улисс С. Грант . Начав постоянно ужесточающуюся военно-морскую блокаду портов Конфедерации, Союз мобилизовал ресурсы и рабочую силу для нападения на Конфедерацию со всех направлений. Это привело к падению Атланты в 1864 году генералу Союза Уильяму Текумсе Шерману , за которым последовал его Марш к морю . Последние значительные сражения развернулись вокруг десятимесячной осады Петербурга , ворот столицы Конфедерации Ричмонда . Конфедераты покинули Ричмонд, и 9 апреля 1865 года Ли сдался Гранту после битвы при Аппоматтоксе , положив начало окончанию войны . [ф] Линкольн дожил до этой победы, но 14 апреля был убит .

К концу войны большая часть инфраструктуры Юга была разрушена. Конфедерация распалась, рабство было отменено, и четыре миллиона порабощенных чернокожих были освобождены. Затем раздираемая войной нация вступила в эпоху Реконструкции в попытке восстановить страну, вернуть бывшие штаты Конфедерации обратно в Соединенные Штаты и предоставить гражданские права освобожденным рабам. Эта война является одним из наиболее широко изучаемых и описанных эпизодов в истории США . Это остается предметом культурных и историографических дебатов . Особый интерес представляет сохраняющийся миф о проигранном деле Конфедерации . Война была одной из первых, где использовалась промышленная война . Широко использовались железные дороги, электрический телеграф , пароходы, броненосный военный корабль , массовое оружие. В результате войны погибло от 620 000 до 750 000 солдат, а также неопределенное количество жертв среди гражданского населения , что сделало Гражданскую войну самым смертоносным военным конфликтом в американской истории. [г] Технологии и жестокость Гражданской войны предвещали грядущие мировые войны .

Происхождение

Причины решения южных штатов об отделении были противоречивыми, но большинство ученых считают сохранение рабства главной причиной. [18] В документах об отделении нескольких отделившихся государств рабство указывается как мотив их отъезда. [16] Хотя ученые предложили дополнительные причины войны, [19] рабство было основным источником эскалации напряженности в 1850-х годах . [20] Республиканская партия была полна решимости предотвратить распространение рабства на территории, которые, после того как они будут признаны свободными штатами, дадут свободным штатам большее представительство в Конгрессе и Коллегии выборщиков. Многие южные лидеры угрожали отделением, если кандидат от республиканцев Линкольн победит на выборах 1860 года . После победы Линкольна лидеры Юга почувствовали, что разобщение было их единственным выходом, опасаясь, что потеря представительства помешает им принять законы, поддерживающие рабство. [21] [22] В своей второй инаугурационной речи в 1865 году Линкольн сказал:

рабы представляли собой особый и мощный интерес. Все знали, что этот интерес каким-то образом стал причиной войны. Укрепить, увековечить и расширить этот интерес было целью, ради которой повстанцы хотели расколоть Союз, даже посредством войны; в то время как правительство не заявляло о своем праве сделать что-либо большее, чем ограничить его территориальное расширение. [23]

Рабство

Разногласия между государствами по поводу рабства были основной причиной войны. [24] [25] Рабство вызывало споры во время разработки Конституции в 1787 году, которая из-за компромиссов в конечном итоге приобрела черты прославления и антирабства . [26] Эта проблема привела в замешательство нацию и все больше разделяла США на рабовладельческий Юг и свободный Север . Проблема усугублялась быстрой территориальной экспансией, которая неоднократно ставила вопрос о том, должна ли новая территория быть рабовладельческой или свободной. Этот вопрос доминировал в политике на протяжении десятилетий. Попытки решить этот вопрос включали Миссурийский компромисс и Компромисс 1850 года , но они лишь отложили разборки по поводу рабства. [27]

Мотивы сторонников Союза и Конфедерации не были единообразными; [28] [29] некоторые северные солдаты были равнодушны к рабству, но закономерность можно установить. [30] По мере того как война затягивалась, все больше юнионистов поддерживали отмену рабства, чтобы нанести вред Конфедерации или по моральным соображениям. [31] Солдаты Конфедерации сражались, чтобы защитить южное общество, неотъемлемой частью которого было рабство. [32] [33] Противники рабства считали его устаревшим злом, несовместимым с республиканизмом . Стратегия сил, выступающих против рабства, заключалась в том, чтобы остановить экспансию и поставить рабство на путь исчезновения. [34] Рабовладельческие интересы на Юге осудили это как нарушение их конституционных прав. [35] Поскольку значительная часть населения Юга находилась в рабстве, белые южане считали, что освобождение рабов разрушит южные семьи, общество и его экономику, при этом значительный капитал вкладывался в рабов и опасался свободного черного населения. [36] Многие южане опасались повторения резни на Гаити 1804 года . [37] [38] когда бывшие рабы убили большую часть белого населения Гаити после революции рабов . Томас Флеминг указывает на историческую фразу «болезнь общественного сознания», используемую критиками этой идеи, и предполагает, что она способствовала сегрегации в эпоху Джима Кроу . [39] These fears were exacerbated by the 1859 attempt to instigate a slave rebellion in the South.[40]

Abolitionists

The abolitionists—those advocating slavery's end—were active in the decades leading up to the war. They traced their philosophical roots back to certain Puritans, who believed slavery was wrong. A Puritan writing on slavery was The Selling of Joseph, by Samuel Sewall in 1700, in which he condemned slavery and refuted justifications for it.[41][42]

The American Revolution, and the cause of liberty, added impetus to the abolitionist cause. Even in Southern states, laws were changed to limit slavery and facilitate manumission; the amount of indentured servitude dropped throughout the country. An Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves sailed through Congress with little opposition and went into effect on January 1, 1808, the first day the Constitution permitted Congress to prohibit importation of slaves. Influenced by the Revolution, many slave owners freed their slaves, but some, such as George Washington, did so only in their wills. The number of free black people as a proportion of the black population in the upper South increased from less than 1 percent to nearly 10 percent between 1790-1810.[43][44][45][46][47][48]

The establishment of the Northwest Territory as "free soil"—no slavery—would prove crucial. This territory doubled the size of the US. If those states had been slave states and voted for Lincoln's chief opponent in 1860, Lincoln would not have become president.[49][50][42]

In the decades leading up to the war, abolitionists, such as Theodore Parker, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Frederick Douglass, repeatedly used the country's Puritan heritage to bolster their cause. The anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator, invoked Puritan values over a thousand times. Parker, in urging New England congressmen to support abolition, wrote, "The son of the Puritan ... is sent to Congress to stand up for Truth and Right."[51][52] Literature spread the message; key works included Twelve Years a Slave, the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, American Slavery As It Is, and the most important: Uncle Tom's Cabin, the best-selling book of the 19th century, aside from the Bible.[53][54][55]

An unusual abolitionist was Hinton Rowan Helper, whose 1857 book, The Impending Crisis of the South: How to Meet It, "[e]ven more perhaps than Uncle Tom's Cabin ... fed the fires of sectional controversy leading up to the...War."[56] A Southerner and virulent racist, Helper was nevertheless an abolitionist because he believed, and showed with statistics, that slavery "impeded the progress and prosperity of the South, ... dwindled our commerce...into the most contemptible insignificance; sunk a large majority of our people in galling poverty and ignorance, ... [and] entailed upon us a humiliating dependence on the Free States...."[57]

By 1840 more than 15,000 people were members of abolitionist societies. Abolitionism became a popular expression of moralism and a factor that led to the war. In churches, conventions, newspapers, abolitionists advocated an immediate end to slavery.[58][59] The issue split religious groups; in 1845 the Baptists split over slavery into the Northern Baptists and Southern Baptists.[60][61]

Abolitionist sentiment was not exclusively moral. The Whig Party became opposed to slavery because it saw it as against capitalism and the free market. Whig leader William H. Seward proclaimed there was an "irrepressible conflict" between slavery and free labor, and that slavery had left the South backward and undeveloped.[62] As the Whig Party dissolved in the 1850s, the mantle of abolition fell to its successor, the Republican Party.[63]

Territorial crisis

Manifest destiny heightened the conflict over slavery. Each new territory acquired had to face the thorny question of whether to allow or disallow the "peculiar institution".[64] Between 1803-54, the US expanded significantly through purchase, negotiation, and conquest. At first, the new states were apportioned equally between slave and free states. Pro- and anti-slavery forces collided over the territories west of the Mississippi River.[65]

The Mexican–American War and its aftermath was a key territorial event in the leadup to the war.[66] As the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo finalized the conquest of northern Mexico in 1848, slaveholding interests looked forward to expanding into these lands.[67][68] Prophetically, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote that "Mexico will poison us", referring to the ensuing divisions around whether the conquered lands would end up slave or free.[69] Northern free-soil interests vigorously sought to curtail expansion of slave territory. The Compromise of 1850 over California balanced a free-soil state with a stronger federal fugitive slave law for a political settlement, after strife in the 1840s. But the states admitted following California were all free: Minnesota (1858), Oregon (1859), and Kansas (1861). In the Southern states, the question of slavery's expansion westward again became explosive.[70] The South and North drew the same conclusion: "The power to decide the question of slavery for the territories was the power to determine the future of slavery itself."[71][72] After the Utah Territory legalized slavery in 1852, the Utah War of 1857 saw Mormon settlers fighting the government.[73][74]

By 1860, four doctrines had emerged to answer the question of federal control in the territories, and all claimed they were sanctioned by the Constitution.[75] The first, represented by the Constitutional Union Party, argued that the Missouri Compromise apportionment of territory north for free soil and south for slavery should become a constitutional mandate. The failed Crittenden Compromise of 1860 was an expression of this view.[76]

The second doctrine of congressional preeminence was championed by Lincoln and the Republicans. It insisted the Constitution did not bind legislators to a policy of balance—that slavery could be excluded in a territory, as it was in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, at the discretion of Congress.[77] Thus Congress could restrict human bondage, but never establish it. The ill-fated Wilmot Proviso announced this position in 1846.[78] The Proviso was a pivotal moment, as it was the first time slavery had become a major congressional issue based on sectionalism, instead of party lines. Its support by Northern Democrats and Whigs, and opposition by Southerners, was an omen of coming divisions.[79]

Senator Stephen A. Douglas proclaimed the third doctrine: territorial or "popular" sovereignty, which asserted that settlers in a territory had the same rights as states, to allow or disallow slavery as a local matter.[80] The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 legislated this doctrine.[81] In the Kansas Territory, political conflict spawned "Bleeding Kansas", a paramilitary conflict between pro- and anti-slavery supporters. The House of Representatives voted to admit Kansas as a free state in early 1860, but its admission did not pass the Senate until January 1861, after the departure of Southern senators.[82]

The fourth doctrine was advocated by Mississippi Senator, later Confederate President, Jefferson Davis.[83] It was one of state sovereignty ("states' rights"),[84] also known as the "Calhoun doctrine",[85] named after the South Carolinian political theorist and statesman John C. Calhoun.[86] Rejecting the arguments for federal authority or self-government, state sovereignty would empower states to promote expansion of slavery as part of the federal union under the Constitution.[87] These four doctrines comprised the dominant ideologies presented to the public, before the 1860 presidential election.[88]

States' rights

A long-running dispute over the war's origin is to what extent states' rights triggered it. The consensus among historians is that the war was not fought about states' rights.[89][90][91][92] But the issue is frequently referenced in popular accounts and has traction among Southerners. Southerners advocating secession argued that just as each state had decided to join the Union, a state had the right to leave. Northerners rejected that notion as opposed to the will of the Founding Fathers, who said they were setting up a Perpetual Union.[93]

James M. McPherson points out that even if Confederates genuinely fought over states' rights, it boiled down to states' right to slavery.[92] McPherson writes:

While one or more of these interpretations remain popular among the Sons of Confederate Veterans and other Southern heritage groups, few professional historians now subscribe to them. Of all these interpretations, the states'-rights argument is perhaps the weakest. It fails to ask the question, states' rights for what purpose? States' rights, or sovereignty, was always more a means than an end, an instrument to achieve a certain goal more than a principle.[92]

States' rights was an ideology applied as a means of advancing slave state interests through federal authority.[94] Thomas Krannawitter notes the "Southern demand for federal slave protection represented a demand for an unprecedented expansion of Federal power."[95][96] Before the war, slavery advocates supported use of federal powers to enforce and extend slavery, as with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and the Dred Scott v. Sandford decision.[97][98] The faction that pushed for secession often infringed on states' rights. Because of the overrepresentation of pro-slavery factions in the federal government, many Northerners, even non-abolitionists, feared the Slave Power conspiracy.[97][98] Some Northern states resisted the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act. Eric Foner states that the act "could hardly have been designed to arouse greater opposition in the North. It overrode state and local laws...and 'commanded' individual citizens to assist, when called upon, in capturing runaways...It certainly did not reveal, on the part of slaveholders, sensitivity to states' rights."[90] According to Paul Finkelman, "the southern states mostly complained that the northern states were asserting their states' rights and that the national government was not powerful enough to counter these northern claims."[91] The Confederate Constitution "federally" required slavery to be legal in all Confederate states and claimed territories.[89][99]

Sectionalism

Sectionalism resulted from the different economies, social structure, customs, and political values of the North and South.[100][101] Regional tensions came to a head during the War of 1812, resulting in the Hartford Convention, which manifested Northern dissatisfaction with a foreign trade embargo that affected the industrial North disproportionately, the Three-Fifths Compromise, dilution of Northern power by new states, and a succession of Southern presidents. Sectionalism increased between 1800-60 as the North, which phased slavery out, industrialized, urbanized, and built prosperous farms, while the deep South concentrated on plantation agriculture based on slave labor, with subsistence agriculture for poor whites. In the 1840s and 50s, the issue of slavery split the largest religious denominations into separate Northern and Southern denominations.[102]

Historians have debated whether economic differences between the industrial North and agricultural South helped cause the war. Most historians now disagree with the economic determinism of historian Charles A. Beard in the 1920s, and emphasize that Northern and Southern economies were largely complementary. While socially different, they economically benefited each other.[103][104]

Protectionism

Slave owners preferred low-cost manual labor and free trade, while Northern manufacturing interests supported mechanized labor and protectionism, such as tariffs.[105] The Democrats in Congress, controlled by Southerners, wrote the tariff laws between 1830 and 1860, and kept reducing rates so 1857 rates were the lowest since 1816. The Republicans called for an increase in the 1860 election. These increases were enacted in 1861, after Southerners resigned their seats in Congress.[106][107] The issue was a Northern grievance, but neo-Confederates have claimed it was a Southern grievance. In 1860 and 1861 no group that proposed compromises to head off secession raised the tariff issue.[108] Pamphleteers from the North and South rarely mentioned it.[109]

Nationalism and honor

Nationalism was a powerful force in the early 19th century, with spokesmen such as Andrew Jackson and Daniel Webster. While practically all Northerners supported the Union, Southerners were split between those loyal to it, "Southern Unionists", and those loyal to the South.[110] Perceived insults to Southern collective honor included the enormous popularity of Uncle Tom's Cabin and John Brown's attempt to incite a slave rebellion in 1859.[111][112]

While the South moved towards a Southern nationalism, Northern leaders were becoming more nationally minded, and rejected splitting the Union. The Republican electoral platform of 1860 warned they regarded disunion as treason and would not tolerate it.[113] The South ignored the warnings; Southerners did not realize how ardently the North would fight for the Union.[114]

Lincoln's election

Lincoln's election in November 1860 was the final trigger for secession.[115] Southern leaders feared Lincoln would stop slavery's expansion and put it on a course toward extinction.[116] However, Lincoln would not be inaugurated until March 4, 1861, which gave the South time to secede and prepare for war during the winter of 1860-61.[117]

According to Lincoln, the American people had shown they had been successful in establishing and administering a republic, but a third challenge faced the nation: maintaining a republic based on the people's vote, in the face of an attempt to destroy it.[118]

Outbreak of the war

Secession crisis

The election of Lincoln provoked the legislature of South Carolina to call a state convention to consider secession. Before the war, South Carolina did more than any other state to advance the notion that a state had the right to nullify federal laws and even to secede. The convention unanimously voted to secede on December 20, 1860, and adopted a secession declaration. It argued for states' rights for slave owners in the South, but it complained about states' rights in the North in the form of resistance to the federal Fugitive Slave Act, claiming that Northern states were not fulfilling their obligations to assist in the return of fugitive slaves. The "cotton states" of Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas followed suit, seceding in January and February 1861.[119]

Among the ordinances of secession, those of Texas, Alabama, and Virginia specifically mentioned the plight of the "slaveholding states" at the hands of Northern abolitionists. The rest made no mention of slavery and are often brief announcements of the dissolution of ties by the legislatures.[120] However, at least four—South Carolina,[121] Mississippi,[122] Georgia,[123] and Texas[124]—passed detailed explanations of their reasons for secession, all blamed the movement to abolish slavery and its influence over the politics of the North. The Southern states believed slaveholding was a constitutional right because of the Fugitive Slave Clause. These states agreed to form a new federal government, the Confederate States of America, on February 4, 1861.[125] They took control of federal forts and other properties within their boundaries, with little resistance from outgoing President James Buchanan, whose term ended on March 4, 1861. Buchanan said the Dred Scott decision was proof the South had no reason for secession, and that the Union "was intended to be perpetual", but that "The power by force of arms to compel a State to remain in the Union" was not among the "enumerated powers granted to Congress".[126] A quarter of the US army—the entire garrison in Texas—was surrendered in February 1861 to state forces by its commanding general, David E. Twiggs, who then joined the Confederacy.[127]

As Southerners resigned their seats in the Senate and the House, Republicans were able to pass projects that had been blocked by Southern senators. These included the Morrill Tariff, land grant colleges, a Homestead Act, a transcontinental railroad,[128] the National Bank Act, the authorization of United States Notes by the Legal Tender Act of 1862, and the ending of slavery in the District of Columbia. The Revenue Act of 1861 introduced income tax to help finance the war.[129]

In December 1860, the Crittenden Compromise was proposed to re-establish the Missouri Compromise line, by constitutionally banning slavery in territories to the north of it, while permitting it to the south. The adoption of this compromise likely would have prevented the secession of the Southern states, but Lincoln and the Republicans rejected it.[130] Lincoln stated that any compromise that would extend slavery would bring down the Union.[131] A pre-war February Peace Conference of 1861 met in Washington, proposing a solution similar to that of the Compromise; it was rejected by Congress. The Republicans proposed the Corwin Amendment, an alternative compromise not to interfere with slavery where it existed, but the South regarded it as insufficient. The remaining eight slave states rejected pleas to join the Confederacy following a two-to-one no-vote in Virginia's First Secessionist Convention on April 4, 1861.[132]

On March 4, 1861, Lincoln was sworn in as president. In his inaugural address, he argued the Constitution was a more perfect union than the earlier Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, that it was a binding contract, and he called any secession "legally void".[133] He did not intend to invade Southern states, nor end slavery where it existed, but said he would use force to maintain possession of federal property,[133] including forts, arsenals, mints, and customhouses that had been seized.[134] The government would not try to recover post offices, and if resisted, mail delivery would end at state lines. Where popular conditions did not allow peaceful enforcement of federal law, US marshals and judges would be withdrawn. No mention was made of bullion lost from US mints. He stated it would be US policy "to collect the duties and imposts"; "there will be no invasion, no using of force against or among the people anywhere" that would justify an armed revolution during his administration. His speech closed with a plea for restoration of the bonds of union, famously calling on "the mystic chords of memory" binding the two regions.[133]

The Davis government of the new Confederacy sent three delegates to Washington to negotiate a peace treaty. Lincoln rejected any negotiations with Confederate agents, because he claimed that the Confederacy was not a legitimate government and that to make a treaty with it would recognize it as such.[135] Lincoln instead attempted to negotiate directly with the governors of seceded states, whose administrations he continued to recognize.[136]

Complicating Lincoln's attempts to defuse the crisis was the new Secretary of State, William Seward. Seward had been Lincoln's rival for the Republican presidential nomination. Embittered by this defeat, Seward agreed to support Lincoln's candidacy only after he was guaranteed the executive office then considered the second most powerful. In the early stages of Lincoln's presidency Seward held little regard for him, due to his perceived inexperience. Seward viewed himself as the de facto head of government, or "prime minister" behind the throne. Seward attempted to engage in unauthorized and indirect negotiations that failed.[135] Lincoln was determined to hold all remaining Union-occupied forts in the Confederacy: Fort Monroe in Virginia, Fort Pickens, Fort Jefferson, and Fort Taylor in Florida, and Fort Sumter in South Carolina.[137]

Battle of Fort Sumter

The American Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces opened fire on the Union-held Fort Sumter. Fort Sumter is located in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina.[138] Its status had been contentious for months. Outgoing President Buchanan had dithered in reinforcing the Union garrison, commanded by Major Robert Anderson. Anderson took matters into his own hands and on December 26, 1860, under the cover of darkness, sailed the garrison from the poorly placed Fort Moultrie to the stalwart island Fort Sumter.[139] Anderson's actions catapulted him to hero status in the North. An attempt to resupply the fort on January 9, 1861, failed and nearly started the war then, but an informal truce held.[140] On March 5, Lincoln was informed the fort was low on supplies.[141]

Fort Sumter proved to be one of the main challenges of the new Lincoln administration.[141] Back-channel dealing by Seward with the Confederates undermined Lincoln's decision-making; Seward wanted to pull out of the fort.[142] But a firm hand by Lincoln tamed Seward, who became one of Lincoln's staunchest allies. Lincoln decided holding the fort, which would require reinforcing it, was the only workable option. Thus, on April 6, Lincoln informed the Governor of South Carolina that a ship with food but no ammunition would attempt to supply the fort. Historian McPherson describes this win-win approach as "the first sign of the mastery that would mark Lincoln's presidency"; the Union would win if it could resupply and hold onto the fort, and the South would be the aggressor if it opened fire on an unarmed ship supplying starving men.[143] An April 9 Confederate cabinet meeting resulted in President Davis's ordering General P. G. T. Beauregard to take the fort before supplies could reach it.[144]

At 4:30 am on April 12, Confederate forces fired the first of 4,000 shells at the fort; it fell the next day. The loss of Fort Sumter lit a patriotic fire under the North.[145] On April 15, Lincoln called on the states to field 75,000 volunteer troops for 90 days; impassioned Union states met the quotas quickly.[146] On May 3, 1861, Lincoln called for an additional 42,000 volunteers for three years.[147][148] Shortly after this, Virginia, Tennessee, Arkansas, and North Carolina seceded and joined the Confederacy. To reward Virginia, the Confederate capital was moved to Richmond.[149]

Attitude of the border states

Maryland, Delaware, Missouri, and Kentucky were slave states whose people had divided loyalties to Northern and Southern businesses and family members. Some men enlisted in the Union Army and others in the Confederate Army.[150] West Virginia separated from Virginia and was admitted to the Union on June 20, 1863.[151]

Maryland's territory surrounded Washington, D.C., and could cut it off from the North.[152] It had numerous anti-Lincoln officials who tolerated anti-army rioting in Baltimore and burning of bridges, both aimed at hindering the passage of troops to the South. Maryland's legislature voted overwhelmingly (53–13) to stay in the Union, but rejected hostilities with its southern neighbors, voting to close Maryland's rail lines to prevent them from being used for war.[153] Lincoln responded by establishing martial law and unilaterally suspending habeas corpus in Maryland, along with sending in militia units from the North.[154] Lincoln took control of Maryland and the District of Columbia by seizing prominent figures, including arresting one-third of the members of the Maryland General Assembly on the day it reconvened.[153][155] All were held without trial, with Lincoln ignoring a ruling on June 1, 1861, by Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney, not speaking for the Court,[156] that only Congress could suspend habeas corpus (Ex parte Merryman). Federal troops imprisoned a prominent Baltimore newspaper editor, Frank Key Howard, after he criticized Lincoln in an editorial for ignoring Taney's ruling.[157]

In Missouri, an elected convention on secession voted to remain within the Union. When pro-Confederate Governor Claiborne F. Jackson called out the state militia, it was attacked by federal forces under General Nathaniel Lyon, who chased the governor and the rest of the State Guard to the southwestern corner of the state (see Missouri secession). Early in the war the Confederacy controlled the southern portion of Missouri through the Confederate government of Missouri but was driven out of the state after 1862. In the resulting vacuum, the convention on secession reconvened and took power as the Unionist provisional government of Missouri.[158]

Kentucky did not secede; for a time, it declared itself neutral. When Confederate forces entered the state in September 1861, neutrality ended and the state reaffirmed its Union status while maintaining slavery. During a brief invasion by Confederate forces in 1861, Confederate sympathizers and delegates from 68 Kentucky counties organized a secession convention at the Russellville Convention, formed the shadow Confederate Government of Kentucky, inaugurated a governor, and gained recognition from the Confederacy, and Kentucky was formally admitted into the Confederacy on December 10, 1861. Its jurisdiction extended only as far as Confederate battle lines in the Commonwealth, which at its greatest extent was over half the state, and it went into exile after October 1862.[159]

After Virginia's secession, a Unionist government in Wheeling asked 48 counties to vote on an ordinance to create a new state on October 24, 1861. A voter turnout of 34% approved the statehood bill (96% approving).[160] Twenty-four secessionist counties were included in the new state,[161] and the ensuing guerrilla war engaged about 40,000 federal troops for much of the war.[162][163] Congress admitted West Virginia to the Union on June 20, 1863. West Virginia provided about 20,000 soldiers to both the Confederacy and the Union.[164]

A Unionist secession attempt occurred in East Tennessee, but was suppressed by the Confederacy, which arrested over 3,000 men suspected of being loyal to the Union. They were held without trial.[165]

War

The Civil War was a contest marked by the ferocity and frequency of battle. Over 4 years, 237 named battles were fought, and many more minor actions, which were often characterized by their bitter intensity and high casualties. In his book The American Civil War, historian John Keegan writes that it "was to prove one of the most ferocious wars ever fought". In many cases, without geographic objectives, the only target was the enemy's soldier.[166]

Mobilization

As the first seven states began organizing a Confederacy, the entire US army numbered 16,000. However, Northern governors had begun to mobilize their militias.[167] The Confederate Congress authorized the new nation up to 100,000 troops sent by governors as early as February. By May, Jefferson Davis was pushing for 100,000 soldiers for one year or the duration, and that was answered in kind by the U.S. Congress.[168][169][170]

In the first year of war, both sides had more volunteers than they could effectively train and equip. After the initial enthusiasm faded, reliance on the cohort of young men who came of age every year and wanted to join was not enough. Both sides used a draft law—conscription—to encourage or force volunteering; relatively few were drafted and served. The Confederacy passed a draft law in April 1862 for men aged 18-35; overseers of slaves, government officials, and clergymen were exempt. The U.S. Congress followed in July, authorizing a militia draft within a state when it could not meet its quota with volunteers. European immigrants joined the Union Army in large numbers, including 177,000 born in Germany and 144,000 in Ireland.[171] About 50,000 Canadians served, around 2,500 of whom were black.[172]

When the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect in January 1863, ex-slaves were energetically recruited by the states and used to meet state quotas. States and local communities offered higher and higher cash bonuses for white volunteers. Congress tightened the law in March 1863. Men selected in the draft could provide substitutes or, until mid-1864, pay commutation money. Many eligibles pooled their money to cover the cost of anyone drafted. Families used the substitute provision to select which man should go into the army and which should stay home. There was much evasion and overt resistance to the draft, especially in Catholic areas. The New York City draft riots in July 1863 involved Irish immigrants who had been signed up as citizens to swell the vote of the city's Democratic political machine, not realizing it made them liable for the draft.[173] Of the 168,649 men procured for the Union through the draft, 117,986 were substitutes, leaving only 50,663 who had their services conscripted.[174]

In the North and South, the draft laws were highly unpopular. In the North, some 120,000 men evaded conscription, many fleeing to Canada, and another 280,000 soldiers deserted during the war.[175] At least 100,000 Southerners deserted, which was 10 percent of the total. Southern desertion was high because the highly localized Southern identity meant that many Southerners had little investment in the outcome of the war, with soldiers caring more about the fate of their local area than the Southern cause.[176] In the North, "bounty jumpers" enlisted to get the generous bonus, deserted, then went back to a second recruiting station under a different name to sign up for a second bonus; 141 were caught and executed.[177]

From a tiny frontier force in 1860, the Union and Confederate armies had grown into the "largest and most efficient armies in the world" within a few years. Some European observers at the time dismissed them as amateur and unprofessional,[178] but historian John Keegan concluded that each outmatched the French, Prussian, and Russian armies, and without the Atlantic, would have threatened any with defeat.[179]

Prisoners

At the start of the war, a system of paroles operated. Captives agreed not to fight until they were officially exchanged. Meanwhile, they were held in camps run by their army. They were paid, but were not allowed to perform any military duties.[180] The system of exchanges collapsed in 1863 when the Confederacy refused to exchange black prisoners. After that, about 56,000 of the 409,000 POWs died in prisons, accounting for 10% of the conflict's fatalities.[181]

Women

Historian Elizabeth D. Leonard writes that between 500 and 1000 women enlisted as soldiers on both sides of the war, disguised as men.[182]: 165, 310–11 Women served as spies, resistance activists, nurses, and hospital personnel.[182]: 240 Women served on the Union hospital ship Red Rover and nursed Union and Confederate troops at field hospitals.[183] Mary Edwards Walker, the only woman ever to receive the Medal of Honor, served in the Union Army and was given the medal for treating the wounded during the war.[184][185]

Naval tactics

The small U.S. Navy of 1861 was rapidly enlarged to 6,000 officers and 45,000 sailors in 1865, with 671 vessels, having a tonnage of 510,396.[186][187] Its mission was to blockade Confederate ports, take control of the river system, defend against Confederate raiders on the high seas, and be ready for a possible war with the British Royal Navy.[188] The main riverine war was fought in the West, where major rivers gave access to the Confederate heartland. The U.S. Navy eventually gained control of the Red, Tennessee, Cumberland, Mississippi, and Ohio rivers. In the East, the Navy shelled Confederate forts and provided support for coastal army operations.[189]

The Civil War occurred during the early stages of the industrial revolution. Many naval innovations emerged during this time, most notably the advent of the ironclad warship. It began when the Confederacy, knowing they had to match the Union's naval superiority, responded to the Union blockade by building or converting more than 130 vessels, including 26 ironclads and floating batteries.[190] Only half of these saw service. Many were equipped with ram bows, creating "ram fever" among Union squadrons wherever they threatened. In the face of overwhelming Union superiority and Union ironclad warships, they were unsuccessful.[191] The Union Navy used timberclads, tinclads, and armored gunboats. Shipyards at Cairo, Illinois, and St. Louis built new boats or modified steamboats.[192]

The Confederacy experimented with the submarine CSS Hunley, which did not work satisfactorily, and with building an ironclad ship, CSS Virginia, which was based on rebuilding a sunken Union ship, Merrimack.[193] On its first foray, on March 8, 1862, Virginia inflicted significant damage to the Union's wooden fleet, but the next day the first Union ironclad, USS Monitor, arrived to challenge it in the Chesapeake Bay. The resulting three-hour Battle of Hampton Roads was a draw, but proved ironclads were effective warships.[194] The Confederacy was forced to scuttle the Virginia to prevent its capture, while the Union built many copies of the Monitor. Lacking the technology and infrastructure to build effective warships, the Confederacy attempted to obtain warships from Great Britain. However, this failed, because Great Britain had no interest in selling warships to a nation at war with a stronger enemy, and doing so could sour relations with the US.[195]

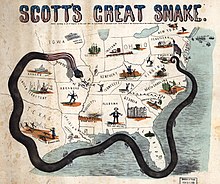

Union blockade

By early 1861, General Winfield Scott had devised the Anaconda Plan to win the war with as little bloodshed as possible, which called for blockading the Confederacy and slowly suffocating the South to surrender.[196] Lincoln adopted parts of the plan, but chose to prosecute a more active vision of war.[197] In April 1861, Lincoln announced the blockade of all Southern ports; commercial ships could not get insurance and regular traffic ended. The South blundered in embargoing cotton exports in 1861 before the blockade was effective; by the time they realized the mistake, it was too late. "King Cotton" was dead, as the South could export less than 10% of its cotton. The blockade shut down the ten Confederate seaports with railheads that moved almost all the cotton. By June 1861, warships were stationed off the principal Southern ports, and a year later nearly 300 ships were in service.[198]

Blockade runners

The Confederates began the war short on military supplies and in desperate need of arms, which the agrarian South could not provide. Arms manufactures in the industrial North were restricted by an arms embargo, keeping shipments of arms from going to the South, and ending existing and future contracts. The Confederacy looked to foreign sources for their military needs and sought out financiers and companies like S. Isaac, Campbell & Company and the London Armoury Company in Britain, who acted as purchasing agents for the Confederacy, connecting them with Britain's arms manufactures, and ultimately becoming the Confederacy's main source of arms.[199][200]

To get the arms safely to the Confederacy, British investors built small, fast, steam-driven blockade runners that traded arms and supplies brought in from Britain, through Bermuda, Cuba, and the Bahamas in return for high-priced cotton. Many were lightweight and designed for speed and could only carry a small amount of cotton back to England.[201] When the Union Navy seized a blockade runner, the ship and cargo were condemned as a prize of war and sold, with the proceeds given to the Navy sailors; the captured crewmen were mostly British, and were released.[202]

Economic impact

The Southern economy nearly collapsed during the war. There were multiple reasons for this: severe deterioration of food supplies, especially in cities; failure of Southern railroads; loss of control of the main rivers; foraging by Northern armies; and the seizure of animals and crops by Confederate armies.[203] Most historians agree the blockade was a major factor in ruining the Confederate economy; however, Wise argues blockade runners provided enough of a lifeline to allow Lee to continue fighting for additional months, thanks to fresh supplies of 400,000 rifles, lead, blankets, and boots that the homefront economy could no longer supply.[203]

Surdam argues the blockade was a powerful weapon that eventually ruined the Southern economy, at the cost of few lives in combat. Practically, the Confederate cotton crop was useless, costing the Confederacy its main source of income. Critical imports were scarce and the coastal trade was largely ended as well.[204] The measure of the blockade's success was not the few ships that slipped through, but the thousands that never tried. Merchant ships owned in Europe could not get insurance and were too slow to evade the blockade, so they stopped calling at Confederate ports.[205]

To fight an offensive war, the Confederacy purchased arms in Britain and converted British-built ships into commerce raiders. Purchasing arms involved the smuggling of 600,000 arms that enabled the Confederacy to fight on for two more years[206][207] and the commerce raiders were used in raiding U.S. Merchant Marine ships in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Insurance rates skyrocketed and the American flag virtually disappeared from international waters. However, the same ships were reflagged with European flags and continued unmolested.[191] After the war, the U.S. government demanded that Britain compensate it for the damage done by blockade runners and raiders outfitted in British ports. Britain partly acquiesced to the demand, paying the U.S. $15 million in 1871 only for commerce raiding.[208]

Dinçaslan argues another outcome of the blockade was oil's rise to prominence as a widely used and traded commodity. The already declining whale oil industry took a blow, as many old whaling ships were used in blockade efforts, such as the Stone Fleet, and Confederate raiders harassing Union whalers aggravated the situation. Oil products that had been treated mostly as lubricants, especially kerosene, started to replace whale oil used in lamps and essentially became a fuel commodity. This increased the importance of oil as a commodity, long before its eventual use as fuel for combustion engines.[209]

Diplomacy

Although the Confederacy hoped Britain and France would join them against the Union, this was never likely, and so tried to bring them in as mediators.[210][211] The Union worked to block this and threatened war if any country recognized the Confederacy. In 1861, Southerners voluntarily embargoed cotton shipments, hoping to start an economic depression in Europe, that would force Britain to enter the war to get cotton, but this did not work. Worse, Europe turned to Egypt and India for cotton, which they found superior, hindering the South's recovery after the war.[212][213]

Cotton diplomacy proved a failure as Europe had a surplus of cotton, while the 1860–62 crop failures in Europe made the North's grain exports of critical importance. It also helped to turn European opinion further away from the Confederacy. It was said that "King Corn was more powerful than King Cotton", as U.S. grain went from a quarter of the British import trade to almost half.[212] Meanwhile, the war created employment for arms makers, ironworkers, and ships to transport weapons.[213]

Lincoln's administration initially failed to appeal to European public opinion. At first, diplomats explained that the US was not committed to ending slavery and repeated legal arguments about the unconstitutionality of secession. Confederate representatives, on the other hand, started off more successfully, by ignoring slavery and instead focusing on their struggle for liberty, commitment to free trade, and the essential role of cotton in the European economy.[214] The European aristocracy was "absolutely gleeful in pronouncing the American debacle as proof that the entire experiment in popular government had failed. European government leaders welcomed the fragmentation of the ascendant American Republic."[214] However, there was still a European public with liberal sensibilities, that the U.S. sought to appeal to by building connections with the international press. As early as 1861, Union diplomats, such as Carl Schurz, realized emphasizing the war against slavery was the Union's most effective moral asset in the struggle for European public opinion. Seward was concerned an overly radical case for reunification would distress the European merchants with cotton interests; even so, Seward supported a widespread campaign of public diplomacy.[214]

U.S. minister to Britain Charles Francis Adams proved particularly adept and convinced Britain not to openly challenge the Union blockade. The Confederacy purchased warships from commercial shipbuilders in Britain. The most famous, CSS Alabama, did considerable damage and led to serious postwar disputes. However, public opinion against slavery in Britain created a political liability for politicians, where the anti-slavery movement was powerful.[215]

War loomed in late 1861 between the U.S. and Britain over the Trent affair, which began when U.S. Navy personnel boarded the British ship Trent and seized two Confederate diplomats. However, London and Washington were able to smooth this over after Lincoln released the two men.[216] Prince Albert had left his deathbed to issue diplomatic instructions to Lord Lyons during the Trent affair. His request was honored, and, as a result, the British response to the US was toned down and helped avert a war.[217] In 1862, the British government considered mediating between the Union and Confederacy, though even such an offer would have risked war with the US. British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston reportedly read Uncle Tom's Cabin three times when deciding on what his decision would be.[216]

The Union victory in the Battle of Antietam caused the British to delay this decision. The Emancipation Proclamation would increase the political liability of supporting the Confederacy. Realizing that Washington could not intervene in Mexico as long as the Confederacy controlled Texas, France invaded Mexico in 1861 and installed the Habsburg Austrian archduke Maximilian I as emperor.[218] Washington repeatedly protested France's violation of the Monroe Doctrine. Despite sympathy for the Confederacy, France's seizure of Mexico ultimately deterred it from war with the Union. Confederate offers late in the war to end slavery, in return for diplomatic recognition, were not seriously considered by London or Paris. After 1863, the Polish revolt against Russia further distracted the European powers and ensured they remained neutral.[219]

Russia supported the Union, largely because it believed that the U.S. served as a counterbalance to its geopolitical rival, the UK. In 1863, the Russian Navy's Baltic and Pacific fleets wintered in the American ports of New York and San Francisco, respectively.[220]

Eastern theater

The Eastern theater refers to the military operations east of the Appalachian Mountains, including Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, the District of Columbia, and the coastal fortifications and seaports of North Carolina.[221]

Background

Army of the Potomac

Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan took command of the Union Army of the Potomac on July 26, 1861, and the war began in earnest in 1862. The 1862 Union strategy called for simultaneous advances along four axes:[222]

- McClellan would lead the main thrust in Virginia towards Richmond.

- Ohio forces would advance through Kentucky into Tennessee.

- The Missouri Department would drive south along the Mississippi River.

- The westernmost attack would originate from Kansas.

Army of Northern Virginia

The primary Confederate force in the Eastern theater was the Army of Northern Virginia. The Army originated as the (Confederate) Army of the Potomac, which was organized on June 20, 1861, from all operational forces in Northern Virginia. On July 20 and 21, the Army of the Shenandoah and forces from the District of Harpers Ferry were added. Units from the Army of the Northwest were merged into the Army of the Potomac between March 14 and May 17, 1862. The Army of the Potomac was renamed Army of Northern Virginia on March 14. The Army of the Peninsula was merged into it on April 12, 1862.

When Virginia declared its secession in April 1861, Robert E. Lee chose to follow his home state, despite his desire for the country to remain intact and an offer of a senior Union command. Lee's biographer, Douglas S. Freeman, asserts that the army received its final name from Lee when he issued orders assuming command on June 1, 1862.[223] However, Freeman does admit that Lee corresponded with Brigadier General Joseph E. Johnston, his predecessor in army command, before that date and referred to Johnston's command as the Army of Northern Virginia. Part of the confusion results from the fact Johnston commanded the Department of Northern Virginia (as of October 22, 1861) and the name Army of Northern Virginia can be seen as an informal consequence of its parent department's name. Jefferson Davis and Johnston did not adopt the name, but it is clear the organization of units as of March 14 was the same organization that Lee received on June 1, and thus it is generally referred to today as the Army of Northern Virginia, even if that is correct only in retrospect.

On July 4 at Harper's Ferry, Colonel Thomas J. Jackson assigned Jeb Stuart to command all the cavalry companies of the Army of the Shenandoah. He eventually commanded the Army of Northern Virginia's cavalry.

Battles

In July 1861, in of the first highly visible battles, Union troops under the command of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell attacking Confederate forces led by Beauregard near Washington were repulsed at the First Battle of Bull Run.

The Union had the upper hand at first, nearly pushing Confederate forces holding a defensive position into a rout, but Confederate reinforcements under Joseph E. Johnston arrived from the Shenandoah Valley by railroad, and the course of the battle quickly changed. A brigade of Virginians under the relatively unknown brigadier general from the Virginia Military Institute, Thomas J. Jackson, stood its ground, which resulted in Jackson's receiving his famous nickname, "Stonewall".

Upon the urging of Lincoln to begin offensive operations, McClellan attacked Virginia in the spring of 1862 by way of the peninsula between the York River and James River, southeast of Richmond. McClellan's army reached the gates of Richmond in the Peninsula campaign.[224][225][226]

Also in the spring of 1862, in the Shenandoah Valley, Stonewall Jackson led his Valley Campaign. Audaciously employing rapid, unpredictable movements on interior lines, Jackson's 17,000 troops marched 646 miles (1,040 km) in 48 days and won minor battles as they successfully engaged three Union armies (52,000 men), including those of Nathaniel P. Banks and John C. Fremont, preventing them from reinforcing the Union offensive against Richmond. The swiftness of Jackson's men earned them the nickname of "foot cavalry".

Johnston halted McClellan's advance at the Battle of Seven Pines, but he was wounded in the battle, and Robert E. Lee assumed his position of command. Lee and top subordinates James Longstreet and Stonewall Jackson defeated McClellan in the Seven Days Battles and forced his retreat.[227]

The Northern Virginia Campaign, which included the Second Battle of Bull Run, ended in yet another victory for the South.[228] McClellan resisted General-in-Chief Halleck's orders to send reinforcements to John Pope's Union Army of Virginia, which made it easier for Lee's Confederates to defeat twice the number of combined enemy troops.[citation needed]

Emboldened by Second Bull Run, the Confederacy made its first invasion of the North with the Maryland Campaign. Lee led 45,000 troops of the Army of Northern Virginia across the Potomac River into Maryland on September 5. Lincoln then restored Pope's troops to McClellan. McClellan and Lee fought at the Battle of Antietam near Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17, 1862, the bloodiest single day in US military history.[227][229] Lee's army, checked at last, returned to Virginia before McClellan could destroy it. Antietam is considered a Union victory because it halted Lee's invasion of the North and provided an opportunity for Lincoln to announce his Emancipation Proclamation.[230]

When the cautious McClellan failed to follow up on Antietam, he was replaced by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside. Burnside was defeated at the Battle of Fredericksburg[231] on December 13, 1862, when more than 12,000 Union soldiers were killed or wounded during futile frontal assaults against Marye's Heights.[232] After the battle, Burnside was replaced by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker.[233]

Hooker, too, proved unable to defeat Lee's army; despite outnumbering the Confederates by more than two to one, his Chancellorsville Campaign proved ineffective, and he was humiliated in the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863.[234] Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because his risky decision to divide his army in the presence of a much larger enemy force resulted in a significant Confederate victory. Stonewall Jackson was shot in the left arm and right hand by friendly fire during the battle. The arm was amputated, but he died of pneumonia.[235] Lee famously said: "He has lost his left arm, but I have lost my right arm."[236]

The fiercest fighting of the battle—and the second bloodiest day of the Civil War—occurred on May 3 as Lee launched multiple attacks against the Union position at Chancellorsville. That same day, John Sedgwick advanced across the Rappahannock River, defeated the small Confederate force at Marye's Heights in the Second Battle of Fredericksburg, and then moved to the west. The Confederates fought a successful delaying action at the Battle of Salem Church.[237]

Gen. Hooker was replaced by Maj. Gen. George Meade during Lee's second invasion of the North, in June. Meade defeated Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1863).[238] This was the bloodiest battle and has been called the war's turning point. Pickett's Charge on July 3 is considered the high-water mark of the Confederacy because it signaled the collapse of serious Confederate threats of victory. Lee's army suffered 28,000 casualties, versus Meade's 23,000.[239]

Western theater

The Western theater refers to military operations between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River, including Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, North Carolina, Kentucky, South Carolina, Tennessee, and parts of Louisiana.[240]

Background

Army of the Tennessee and Army of the Cumberland

The primary Union forces in this theater were the Army of the Tennessee and Army of the Cumberland, named for the two rivers, Tennessee River and Cumberland River. After Meade's inconclusive fall campaign, Lincoln turned to the Western theater for new leadership. At the same time, the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg surrendered, giving the Union control of the Mississippi River, permanently isolating the western Confederacy, and producing the new leader Lincoln needed, Ulysses S. Grant.[241]

Army of Tennessee

The primary Confederate force in the Western theater was the Army of Tennessee. The army was formed on November 20, 1862, when General Braxton Bragg renamed the former Army of Mississippi. While the Confederate forces had successes in the Eastern theater, they were defeated many times in the West.[240]

Battles

The Union's key strategist and tactician in the West was Ulysses S. Grant, who won victories at Forts Henry (February 6, 1862) and Donelson (February 11 to 16, 1862), earning him the nickname of "Unconditional Surrender" Grant. With these victories the Union gained control of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers.[242] Nathan Bedford Forrest rallied nearly 4,000 Confederate troops and led them to escape across the Cumberland. Nashville and central Tennessee thus fell to the Union, leading to attrition of local food supplies and livestock and a breakdown in social organization.[citation needed]

Confederate general Leonidas Polk's invasion of Columbus ended Kentucky's policy of neutrality and turned it against the Confederacy. Grant used river transport and Andrew Hull Foote's gunboats of the Western Flotilla, to threaten the Confederacy's "Gibraltar of the West" at Columbus, Kentucky. Although rebuffed at Belmont, Grant cut off Columbus. The Confederates, lacking their gunboats, were forced to retreat and the Union took control of west Kentucky and opened Tennessee in March 1862.[243]

At the Battle of Shiloh, in Shiloh, Tennessee in April 1862, the Confederates made a surprise attack that pushed Union forces against the river as night fell. Overnight, the Navy landed reinforcements, and Grant counterattacked. Grant and the Union won a decisive victory—the first battle with the high casualty rates that would occur repeatedly.[244] The Confederates lost Albert Sidney Johnston, considered their finest general before the emergence of Lee.[245]

One of the early Union objectives was to capture the Mississippi River to cut the Confederacy in half. The Mississippi was opened to Union traffic to the southern border of Tennessee with the taking of Island No. 10 and New Madrid, Missouri, and then Memphis, Tennessee.[246]

In April 1862, the Union Navy captured New Orleans.[246] "The key to the river was New Orleans, the South's largest port [and] greatest industrial center."[247] U.S. Naval forces under Farragut ran past Confederate defenses south of New Orleans. Confederate forces abandoned the city, giving the Union a critical anchor in the deep South,[248] which allowed Union forces to move up the Mississippi. Memphis fell to Union forces on June 6, 1862, and became a key base for further advances south along the Mississippi. Only the fortress city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, prevented Union control of the entire river.[249]

Bragg's second invasion of Kentucky in the Confederate Heartland Offensive included initial successes such as Kirby Smith's triumph at the Battle of Richmond and the capture of the Kentucky capital of Frankfort on September 3, 1862.[250] However, the campaign ended with a meaningless victory over Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell at the Battle of Perryville. Bragg was forced to end his attempt at invading Kentucky and retreat, due to lack of logistical support and infantry recruits.[251] Bragg was narrowly defeated by Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans at the Battle of Stones River in Tennessee, the culmination of the Stones River Campaign.[252]

Naval forces assisted Grant in the long, complex Vicksburg Campaign that resulted in the Confederates surrendering at the Battle of Vicksburg in July 1863, which cemented Union control of the Mississippi and is one of the turning points of the war.[253][254]

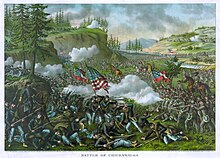

The one clear Confederate victory in the West was the Battle of Chickamauga. After Rosecrans' successful Tullahoma Campaign, Bragg, reinforced by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's corps, defeated Rosecrans, despite the defensive stand of Maj. Gen. George Henry Thomas.[citation needed]

Rosecrans retreated to Chattanooga, which Bragg then besieged in the Chattanooga Campaign. Grant marched to the relief of Rosecrans and defeated Bragg at the Third Battle of Chattanooga,[255] eventually causing Longstreet to abandon his Knoxville Campaign and driving Confederate forces out of Tennessee and opening a route to Atlanta and the heart of the Confederacy.[256]

Trans-Mississippi theater

Background

The Trans-Mississippi theater refers to military operations west of the Mississippi, encompassing most of Missouri, Arkansas, most of Louisiana, and the Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma. The Trans-Mississippi District was formed by the Confederate States Army to better coordinate Ben McCulloch's command of troops in Arkansas and Louisiana, Sterling Price's Missouri State Guard, as well as the portion of Earl Van Dorn's command that included the Indian Territory and excluded the Army of the West. The Union's command was the Trans-Mississippi Division, or the Military Division of West Mississippi.[257]

Battles

The first battle of the Trans-Mississippi theater was the Battle of Wilson's Creek (August 1861). The Confederates were driven from Missouri early in the war as a result of the Battle of Pea Ridge.[259]

Extensive guerrilla warfare characterized the trans-Mississippi region, as the Confederacy lacked the troops and logistics to support regular armies that could challenge Union control.[260] Roving Confederate bands such as Quantrill's Raiders terrorized the countryside, striking military installations and civilian settlements.[261] The "Sons of Liberty" and "Order of the American Knights" attacked pro-Union people, elected officeholders, and unarmed uniformed soldiers. These partisans could not be driven out of Missouri, until an entire regular Union infantry division was engaged. By 1864, these violent activities harmed the nationwide antiwar movement organizing against the re-election of Lincoln. Missouri not only stayed in the Union, but Lincoln took 70 percent of the vote to win re-election.[262]

Small-scale military actions south and west of Missouri sought to control Indian Territory and New Mexico Territory for the Union. The Battle of Glorieta Pass was the decisive battle of the New Mexico Campaign. The Union repulsed Confederate incursions into New Mexico in 1862, and the exiled Arizona government withdrew into Texas. In the Indian Territory, civil war broke out within tribes. About 12,000 Indian warriors fought for the Confederacy but fewer for the Union.[263] The most prominent Cherokee was Brigadier General Stand Watie, the last Confederate general to surrender.[264]

After the fall of Vicksburg in July 1863, Jefferson Davis informed General Kirby Smith in Texas that he could expect no further help from east of the Mississippi. Although he lacked resources to beat Union armies, he built up a formidable arsenal at Tyler, along with his own Kirby Smithdom economy, a virtual "independent fiefdom" in Texas, including railroad construction and international smuggling. The Union, in turn, did not directly engage him.[265] Its 1864 Red River Campaign to take Shreveport, Louisiana, failed and Texas remained in Confederate hands throughout the war.[266]

Lower Seaboard theater

Background

The Lower Seaboard theater refers to military and naval operations that occurred near the coastal areas of the Southeast as well as the southern part of the Mississippi. Union Naval activities were dictated by the Anaconda Plan.[267]

Battles

One of the earliest battles was fought at Port Royal Sound (November 1861), south of Charleston. Much of the war along the South Carolina coast concentrated on capturing Charleston. In attempting to capture Charleston, the Union military tried two approaches: by land over James or Morris Islands or through the harbor. However, the Confederates were able to drive back each attack. A famous land attack was the Second Battle of Fort Wagner, in which the 54th Massachusetts Infantry took part. The Union suffered a serious defeat, losing 1,515 soldiers while the Confederates lost only 174. However, the 54th was hailed for its valor, which encouraged the general acceptance of the recruitment of African American soldiers into the Union Army, which reinforced the Union's numerical advantage.[268]

Fort Pulaski on the Georgia coast was an early target for the Union navy. Following the capture of Port Royal, an expedition was organized with engineer troops under the command of Captain Quincy A. Gillmore, forcing a Confederate surrender. The Union army occupied the fort for the rest of the war after repairing it.[269]

In April 1862, a Union naval task force commanded by Commander David D. Porter attacked Forts Jackson and St. Philip, which guarded the river approach to New Orleans from the south. While part of the fleet bombarded the forts, other vessels forced a break in the obstructions in the river and enabled the rest of the fleet to steam upriver to the city. A Union army force commanded by Major General Benjamin Butler landed near the forts and forced their surrender. Butler's controversial command of New Orleans earned him the nickname "Beast".[270]

The following year, the Union Army of the Gulf commanded by Major General Nathaniel P. Banks laid siege to Port Hudson for nearly eight weeks, the longest siege in US military history. The Confederates attempted to defend with the Bayou Teche Campaign but surrendered after Vicksburg. These surrenders gave the Union control over the Mississippi.[271]

Several small skirmishes but no major battles were fought in Florida. The biggest was the Battle of Olustee in early 1864.[citation needed]

Pacific Coast theater

The Pacific Coast theater refers to military operations on the Pacific Ocean and in the states and Territories west of the Continental Divide.[272]

Conquest of Virginia

At the beginning of 1864, Lincoln made Grant commander of all Union armies. Grant made his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac and put Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman in command of most of the western armies. Grant understood the concept of total war and believed, along with Lincoln and Sherman, that only the utter defeat of Confederate forces and their economic base would end the war.[273] This was total war not in killing civilians, but in taking provisions and forage and destroying homes, farms, and railroads, that Grant said "would otherwise have gone to the support of secession and rebellion. This policy I believe exercised a material influence in hastening the end."[274]

Grant devised a coordinated strategy that would strike at the entire Confederacy from multiple directions. Generals Meade and Benjamin Butler were ordered to move against Lee near Richmond, General Franz Sigel was to attack the Shenandoah Valley, General Sherman was to capture Atlanta and march to the Atlantic Ocean, Generals George Crook and William W. Averell were to operate against railroad supply lines in West Virginia, and Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks was to capture Mobile, Alabama.[275]

Grant's Overland Campaign

Grant's army set out on the Overland Campaign intending to draw Lee into a defense of Richmond, where they would attempt to pin down and destroy the Confederate army. The Union army first attempted to maneuver past Lee and fought several battles, notably at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor. These resulted in heavy losses on both sides and forced Lee's Confederates to fall back repeatedly.[276] At the Battle of Yellow Tavern, the Confederates lost Jeb Stuart.[277]

An attempt to outflank Lee from the south failed under Butler, who was trapped inside the Bermuda Hundred river bend. Each battle resulted in setbacks for the Union that mirrored those they had suffered under prior generals, though unlike them, Grant chose to fight on rather than retreat. Grant was tenacious and kept pressing Lee's Army of Northern Virginia back to Richmond. While Lee was preparing for an attack on Richmond, Grant unexpectedly turned south to cross the James River and began the protracted Siege of Petersburg, where the two armies engaged in trench warfare for over nine months.[278]

Sheridan's Valley Campaign

Grant finally found a commander, General Philip Sheridan, aggressive enough to prevail in the Valley campaigns of 1864. Sheridan was repelled at the Battle of New Market Confederate Gen. John C. Breckinridge. The Battle of New Market was the Confederacy's last major victory and included a charge by teenage VMI cadets. After redoubling his efforts, Sheridan defeated Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early in a series of battles, including a decisive defeat at the Battle of Cedar Creek. Sheridan then proceeded to destroy the agricultural base of the Shenandoah Valley, a strategy similar to the tactics Sherman later employed in Georgia.[279]

Sherman's March to the Sea

Meanwhile, Sherman maneuvered from Chattanooga to Atlanta, defeating Confederate Generals Joseph E. Johnston and John Bell Hood. The fall of Atlanta on September 2, 1864, guaranteed the reelection of Lincoln.[280] Hood left the Atlanta area to swing around and menace Sherman's supply lines and invade Tennessee in the Franklin–Nashville Campaign. Union Maj. Gen. John Schofield defeated Hood at the Battle of Franklin, and George H. Thomas dealt Hood a massive defeat at the Battle of Nashville, effectively destroying Hood's army.[281]

Leaving Atlanta, and his base of supplies, Sherman's army marched, with no destination set, laying waste to about 20% of the farms in Georgia in his "March to the Sea". He reached the Atlantic at Savannah, Georgia, in December 1864. Sherman's army was followed by thousands of freed slaves; there were no major battles along the march. Sherman turned north through South Carolina and North Carolina, to approach the Confederate Virginia lines from the south, increasing the pressure on Lee's army.[282]

The Waterloo of the Confederacy

Lee's army, thinned by desertion and casualties, was now much smaller than Grant's. One last Confederate attempt to break the Union hold on Petersburg failed at the decisive Battle of Five Forks on April 1. The Union now controlled the entire perimeter surrounding Richmond–Petersburg, completely cutting it off from the Confederacy. Realizing the capital was now lost, Lee's army and the Confederate government were forced to evacuate. The Confederate capital fell on April 2–3, to the Union XXV Corps, composed of black troops. The remaining Confederate units fled west after a defeat at Sayler's Creek on April 6.[283]

End of the war

Lee did not intend to surrender, but planned to regroup at Appomattox Station, where supplies were to be waiting, and then continue the war. Grant chased Lee and got in front of him, so that when Lee's army reached the village of Appomattox Court House, they were surrounded. After an initial battle, Lee decided the fight was hopeless, and surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to Grant on April 9, 1865, during a conference at the McLean House.[286][287] In an untraditional gesture and as a sign of Grant's respect and anticipation of peacefully restoring Confederate states to the Union, Lee was permitted to keep his sword and horse, Traveller. His men were paroled, and a chain of Confederate surrenders began.[288]

On April 14, 1865, Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer. Lincoln died early the next morning. Lincoln's vice president, Andrew Johnson, was unharmed, because his would-be assassin, George Atzerodt, lost his nerve, so Johnson was immediately sworn in as president.

Meanwhile, Confederate forces across the South surrendered, as news of Lee's surrender reached them.[289] On April 26, the same day Sergeant Boston Corbett killed Booth at a tobacco barn, Johnston surrendered nearly 90,000 troops of the Army of Tennessee to Sherman at Bennett Place, near present-day Durham, North Carolina. It proved to be the largest surrender of Confederate forces. On May 4, all remaining Confederate forces in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana east of the Mississippi, under the command of Lt. General Richard Taylor, surrendered.[290] Confederate president Davis was captured in retreat at Irwinville, Georgia on May 10.[291]

The final land battle was fought on May 13, 1865, at the Battle of Palmito Ranch in Texas.[292][293][294] On May 26, 1865, Confederate Lt. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, acting for Edmund Smith, signed a military convention surrendering Confederate forces in the Trans-Mississippi Department.[295][296] This date is often cited by contemporaries and historians as the effective end date of the war.[1][2] On June 2, with most of his troops having already gone home, a reluctant Kirby Smith had little choice but to sign the official surrender document.[297][298] On June 23, Cherokee leader and Brig. General Stand Watie became the last Confederate general to surrender his forces.[299][300]

On June 19, 1865, Union Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger announced General Order No. 3, bringing the Emancipation Proclamation into effect in Texas and freeing the last slaves of the Confederacy.[301] The anniversary of this date is now celebrated as Juneteenth.[302]

The naval part of the war ended more slowly. It had begun on April 11, two days after Lee's surrender, when Lincoln proclaimed that foreign nations had no further "claim or pretense" to deny equality of maritime rights and hospitalities to U.S. warships and, in effect, that rights extended to Confederate ships to use neutral ports as safe havens from U.S. warships should end.[303][304] Having no response to Lincoln's proclamation, President Johnson issued a similar proclamation dated May 10, more directly stating that the war was almost at an end and insurgent cruisers still at sea, and prepared to attack U.S. ships, should not have rights to do so through use of safe foreign ports or waters.[305] Britain finally responded on June 6, by transmitting a letter from Foreign Secretary John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, to the Lords of the Admiralty withdrawing rights to Confederate warships to enter British ports and waters.[306] U.S. Secretary of State Seward welcomed the withdrawal of concessions to the Confederates.[307] Finally, on October 18, Russell advised the Admiralty that the time specified in his June message had elapsed and "all measures of a restrictive nature on vessels of war of the United States in British ports, harbors, and waters, are now to be considered as at an end".[308] Nonetheless, the final Confederate surrender was in Liverpool, England where James Iredell Waddell, the captain of CSS Shenandoah, surrendered the cruiser to British authorities on November 6.[309]

Legally, the war did not end until August 20, 1866, when President Johnson issued a proclamation that declared "that the said insurrection is at an end and that peace, order, tranquillity, and civil authority now exist in and throughout the whole of the United States of America".[310][311][312]

Union victory and aftermath

The causes of the war, reasons for its outcome, and even its name are subjects of lingering contention. The North and West grew rich while the once-rich South became poor for a century. The national political power of the slaveowners and rich Southerners ended. Historians are less sure about the results of postwar Reconstruction, especially regarding the second-class citizenship of the freedmen and their poverty.[313]