Биология сохранения

Биология сохранения это изучение сохранения природы и Земли биоразнообразия — с целью защиты видов , их среды обитания и экосистем от чрезмерных темпов вымирания и разрушения биотических взаимодействий. [1] [2] [3] Это междисциплинарный предмет, основанный на естественных и социальных науках, а также на практике управления природными ресурсами . [4] [5] [6] [7] : 478

Природоохранная этика основана на открытиях природоохранной биологии.

Происхождение

[ редактировать ]

The term conservation biology and its conception as a new field originated with the convening of "The First International Conference on Research in Conservation Biology" held at the University of California, San Diego in La Jolla, California, in 1978 led by American biologists Bruce A. Wilcox and Michael E. Soulé with a group of leading university and zoo researchers and conservationists including Kurt Benirschke, Sir Otto Frankel, Thomas Lovejoy, and Jared Diamond. The meeting was prompted due to concern over tropical deforestation, disappearing species, and eroding genetic diversity within species.[8] The conference and proceedings that resulted[2] sought to initiate the bridging of a gap between theory in ecology and evolutionary genetics on the one hand and conservation policy and practice on the other.[9]

Conservation biology and the concept of biological diversity (biodiversity) emerged together, helping crystallize the modern era of conservation science and policy.[10] The inherent multidisciplinary basis for conservation biology has led to new subdisciplines including conservation social science, conservation behavior and conservation physiology.[11] It stimulated further development of conservation genetics which Otto Frankel had originated first but is now often considered a subdiscipline as well.

Description

[edit]The rapid decline of established biological systems around the world means that conservation biology is often referred to as a "Discipline with a deadline".[12] Conservation biology is tied closely to ecology in researching the population ecology (dispersal, migration, demographics, effective population size, inbreeding depression, and minimum population viability) of rare or endangered species.[13][14] Conservation biology is concerned with phenomena that affect the maintenance, loss, and restoration of biodiversity and the science of sustaining evolutionary processes that engender genetic, population, species, and ecosystem diversity.[5][6][7][14] The concern stems from estimates suggesting that up to 50% of all species on the planet will disappear within the next 50 years,[15] which will increase poverty and starvation, and will reset the course of evolution on this planet.[16][17] Researchers acknowledge that projections are difficult, given the unknown potential impacts of many variables, including species introduction to new biogeographical settings and a non-analog climate.[18]

Conservation biologists research and educate on the trends and process of biodiversity loss, species extinctions, and the negative effect these are having on our capabilities to sustain the well-being of human society. Conservation biologists work in the field and office, in government, universities, non-profit organizations and industry. The topics of their research are diverse, because this is an interdisciplinary network with professional alliances in the biological as well as social sciences. Those dedicated to the cause and profession advocate for a global response to the current biodiversity crisis based on morals, ethics, and scientific reason. Organizations and citizens are responding to the biodiversity crisis through conservation action plans that direct research, monitoring, and education programs that engage concerns at local through global scales.[4][5][6][7] There is increasing recognition that conservation is not just about what is achieved but how it is done.[19] A "conservation acrostic" has been created to emphasize that point where C = co-produced, O = open, N = nimble, S = solutions-oriented, E = empowering, R = relational, V = values-based, A = actionable, T = transdisciplinary, I = inclusive, O = optimistic, and N = nurturing.[19]

History

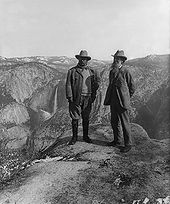

[edit]The conservation of natural resources is the fundamental problem. Unless we solve that problem, it will avail us little to solve all others.

– Theodore Roosevelt[20]

Natural resource conservation

[edit]Conscious efforts to conserve and protect global biodiversity are a recent phenomenon.[7][21] Natural resource conservation, however, has a history that extends prior to the age of conservation. Resource ethics grew out of necessity through direct relations with nature. Regulation or communal restraint became necessary to prevent selfish motives from taking more than could be locally sustained, therefore compromising the long-term supply for the rest of the community.[7] This social dilemma with respect to natural resource management is often called the "Tragedy of the Commons".[22][23]

From this principle, conservation biologists can trace communal resource based ethics throughout cultures as a solution to communal resource conflict.[7] For example, the Alaskan Tlingit peoples and the Haida of the Pacific Northwest had resource boundaries, rules, and restrictions among clans with respect to the fishing of sockeye salmon. These rules were guided by clan elders who knew lifelong details of each river and stream they managed.[7][24] There are numerous examples in history where cultures have followed rules, rituals, and organized practice with respect to communal natural resource management.[25][26]

The Mauryan emperor Ashoka around 250 BC issued edicts restricting the slaughter of animals and certain kinds of birds, as well as opened veterinary clinics.

Conservation ethics are also found in early religious and philosophical writings. There are examples in the Tao, Shinto, Hindu, Islamic and Buddhist traditions.[7][27] In Greek philosophy, Plato lamented about pasture land degradation: "What is left now is, so to say, the skeleton of a body wasted by disease; the rich, soft soil has been carried off and only the bare framework of the district left."[28] In the bible, through Moses, God commanded to let the land rest from cultivation every seventh year.[7][29] Before the 18th century, however, much of European culture considered it a pagan view to admire nature. Wilderness was denigrated while agricultural development was praised.[30] However, as early as AD 680 a wildlife sanctuary was founded on the Farne Islands by St Cuthbert in response to his religious beliefs.[7]

Early naturalists

[edit]

Natural history was a major preoccupation in the 18th century, with grand expeditions and the opening of popular public displays in Europe and North America. By 1900 there were 150 natural history museums in Germany, 250 in Great Britain, 250 in the United States, and 300 in France.[31] Preservationist or conservationist sentiments are a development of the late 18th to early 20th centuries.

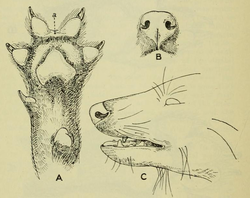

Before Charles Darwin set sail on HMS Beagle, most people in the world, including Darwin, believed in special creation and that all species were unchanged.[32] George-Louis Leclerc was one of the first naturalist that questioned this belief. He proposed in his 44 volume natural history book that species evolve due to environmental influences.[32] Erasmus Darwin was also a naturalist who also suggested that species evolved. Erasmus Darwin noted that some species have vestigial structures which are anatomical structures that have no apparent function in the species currently but would have been useful for the species' ancestors.[32] The thinking of these early 18th century naturalists helped to change the mindset and thinking of the early 19th century naturalists.

By the early 19th century biogeography was ignited through the efforts of Alexander von Humboldt, Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin.[33] The 19th-century fascination with natural history engendered a fervor to be the first to collect rare specimens with the goal of doing so before they became extinct by other such collectors.[30][31] Although the work of many 18th and 19th century naturalists were to inspire nature enthusiasts and conservation organizations, their writings, by modern standards, showed insensitivity towards conservation as they would kill hundreds of specimens for their collections.[31]

Conservation movement

[edit]The modern roots of conservation biology can be found in the late 18th-century Enlightenment period particularly in England and Scotland.[30][34] Thinkers including Lord Monboddo described the importance of "preserving nature"; much of this early emphasis had its origins in Christian theology.[34]

Scientific conservation principles were first practically applied to the forests of British India. The conservation ethic that began to evolve included three core principles: that human activity damaged the environment, that there was a civic duty to maintain the environment for future generations, and that scientific, empirically based methods should be applied to ensure this duty was carried out. Sir James Ranald Martin was prominent in promoting this ideology, publishing many medico-topographical reports that demonstrated the scale of damage wrought through large-scale deforestation and desiccation, and lobbying extensively for the institutionalization of forest conservation activities in British India through the establishment of Forest Departments.[35]

The Madras Board of Revenue started local conservation efforts in 1842, headed by Alexander Gibson, a professional botanist who systematically adopted a forest conservation program based on scientific principles. This was the first case of state conservation management of forests in the world.[36] Governor-General Lord Dalhousie introduced the first permanent and large-scale forest conservation program in the world in 1855, a model that soon spread to other colonies, as well the United States,[37][38][39] where Yellowstone National Park was opened in 1872 as the world's first national park.[40]

The term conservation came into widespread use in the late 19th century and referred to the management, mainly for economic reasons, of such natural resources as timber, fish, game, topsoil, pastureland, and minerals. In addition it referred to the preservation of forests (forestry), wildlife (wildlife refuge), parkland, wilderness, and watersheds. This period also saw the passage of the first conservation legislation and the establishment of the first nature conservation societies. The Sea Birds Preservation Act of 1869 was passed in Britain as the first nature protection law in the world[41] after extensive lobbying from the Association for the Protection of Seabirds[42] and the respected ornithologist Alfred Newton.[43] Newton was also instrumental in the passage of the first Game laws from 1872, which protected animals during their breeding season so as to prevent the stock from being brought close to extinction.[44]

One of the first conservation societies was the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, founded in 1889 in Manchester[45] as a protest group campaigning against the use of great crested grebe and kittiwake skins and feathers in fur clothing. Originally known as "the Plumage League",[46] the group gained popularity and eventually amalgamated with the Fur and Feather League in Croydon, and formed the RSPB.[47] The National Trust formed in 1895 with the manifesto to "...promote the permanent preservation, for the benefit of the nation, of lands, ... to preserve (so far practicable) their natural aspect." In May 1912, a month after the Titanic sank, banker and expert naturalist Charles Rothschild held a meeting at the Natural History Museum in London to discuss his idea for a new organisation to save the best places for wildlife in the British Isles. This meeting led to the formation of the Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves, which later became the Wildlife Trusts.

In the United States, the Forest Reserve Act of 1891 gave the President power to set aside forest reserves from the land in the public domain. John Muir founded the Sierra Club in 1892, and the New York Zoological Society was set up in 1895. A series of national forests and preserves were established by Theodore Roosevelt from 1901 to 1909.[49][50] The 1916 National Parks Act, included a 'use without impairment' clause, sought by John Muir, which eventually resulted in the removal of a proposal to build a dam in Dinosaur National Monument in 1959.[51]

In the 20th century, Canadian civil servants, including Charles Gordon Hewitt[52] and James Harkin, spearheaded the movement toward wildlife conservation.[53]

In the 21st century professional conservation officers have begun to collaborate with indigenous communities for protecting wildlife in Canada.[54] Some conservation efforts are yet to fully take hold due to ecological neglect.[55][56][57] For example in the USA, 21st century bowfishing of native fishes, which amounts to killing wild animals for recreation and disposing of them immediately afterwards, remains unregulated and unmanaged.[48]

Global conservation efforts

[edit]In the mid-20th century, efforts arose to target individual species for conservation, notably efforts in big cat conservation in South America led by the New York Zoological Society.[58] In the early 20th century the New York Zoological Society was instrumental in developing concepts of establishing preserves for particular species and conducting the necessary conservation studies to determine the suitability of locations that are most appropriate as conservation priorities; the work of Henry Fairfield Osborn Jr., Carl E. Akeley, Archie Carr and his son Archie Carr III is notable in this era.[59][60][61] Akeley for example, having led expeditions to the Virunga Mountains and observed the mountain gorilla in the wild, became convinced that the species and the area were conservation priorities. He was instrumental in persuading Albert I of Belgium to act in defense of the mountain gorilla and establish Albert National Park (since renamed Virunga National Park) in what is now Democratic Republic of Congo.[62]

By the 1970s, led primarily by work in the United States under the Endangered Species Act[63] along with the Species at Risk Act (SARA) of Canada, Biodiversity Action Plans developed in Australia, Sweden, the United Kingdom, hundreds of species specific protection plans ensued. Notably the United Nations acted to conserve sites of outstanding cultural or natural importance to the common heritage of mankind. The programme was adopted by the General Conference of UNESCO in 1972. As of 2006, a total of 830 sites are listed: 644 cultural, 162 natural. The first country to pursue aggressive biological conservation through national legislation was the United States, which passed back to back legislation in the Endangered Species Act[64] (1966) and National Environmental Policy Act (1970),[65] which together injected major funding and protection measures to large-scale habitat protection and threatened species research. Other conservation developments, however, have taken hold throughout the world. India, for example, passed the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972.[66]

In 1980, a significant development was the emergence of the urban conservation movement. A local organization was established in Birmingham, UK, a development followed in rapid succession in cities across the UK, then overseas. Although perceived as a grassroots movement, its early development was driven by academic research into urban wildlife. Initially perceived as radical, the movement's view of conservation being inextricably linked with other human activity has now become mainstream in conservation thought. Considerable research effort is now directed at urban conservation biology. The Society for Conservation Biology originated in 1985.[7]: 2

By 1992, most of the countries of the world had become committed to the principles of conservation of biological diversity with the Convention on Biological Diversity;[67] subsequently many countries began programmes of Biodiversity Action Plans to identify and conserve threatened species within their borders, as well as protect associated habitats. The late 1990s saw increasing professionalism in the sector, with the maturing of organisations such as the Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management and the Society for the Environment.

Since 2000, the concept of landscape scale conservation has risen to prominence, with less emphasis being given to single-species or even single-habitat focused actions. Instead an ecosystem approach is advocated by most mainstream conservationists, although concerns have been expressed by those working to protect some high-profile species.

Ecology has clarified the workings of the biosphere; i.e., the complex interrelationships among humans, other species, and the physical environment. The burgeoning human population and associated agriculture, industry, and the ensuing pollution, have demonstrated how easily ecological relationships can be disrupted.[68]

The last word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant: "What good is it?" If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. If the biota, in the course of aeons, has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.

Concepts and foundations

[edit]Measuring extinction rates

[edit]Extinction rates are measured in a variety of ways. Conservation biologists measure and apply statistical measures of fossil records,[1][69] rates of habitat loss, and a multitude of other variables such as loss of biodiversity as a function of the rate of habitat loss and site occupancy[70] to obtain such estimates.[71] The Theory of Island Biogeography[72] is possibly the most significant contribution toward the scientific understanding of both the process and how to measure the rate of species extinction. The current background extinction rate is estimated to be one species every few years.[73] Actual extinction rates are estimated to be orders of magnitudes higher.[74] While this is important, it's worth noting that there are no models in existence that account for the complexity of unpredictable factors like species movement, a non-analog climate, changing species interactions, evolutionary rates on finer time scales, and many other stochastic variables.[75][18]

The measure of ongoing species loss is made more complex by the fact that most of the Earth's species have not been described or evaluated. Estimates vary greatly on how many species actually exist (estimated range: 3,600,000–111,700,000)[76] to how many have received a species binomial (estimated range: 1.5–8 million).[76] Less than 1% of all species that have been described beyond simply noting its existence.[76] From these figures, the IUCN reports that 23% of vertebrates, 5% of invertebrates and 70% of plants that have been evaluated are designated as endangered or threatened.[77][78] Better knowledge is being constructed by The Plant List for actual numbers of species.

Systematic conservation planning

[edit]Systematic conservation planning is an effective way to seek and identify efficient and effective types of reserve design to capture or sustain the highest priority biodiversity values and to work with communities in support of local ecosystems. Margules and Pressey identify six interlinked stages in the systematic planning approach:[79]

- Compile data on the biodiversity of the planning region

- Identify conservation goals for the planning region

- Review existing conservation areas

- Select additional conservation areas

- Implement conservation actions

- Maintain the required values of conservation areas

Conservation biologists regularly prepare detailed conservation plans for grant proposals or to effectively coordinate their plan of action and to identify best management practices (e.g.[80]). Systematic strategies generally employ the services of Geographic Information Systems to assist in the decision-making process. The SLOSS debate is often considered in planning.

Conservation physiology: a mechanistic approach to conservation

[edit]Conservation physiology was defined by Steven J. Cooke and colleagues as:[11]

An integrative scientific discipline applying physiological concepts, tools, and knowledge to characterizing biological diversity and its ecological implications; understanding and predicting how organisms, populations, and ecosystems respond to environmental change and stressors; and solving conservation problems across the broad range of taxa (i.e. including microbes, plants, and animals). Physiology is considered in the broadest possible terms to include functional and mechanistic responses at all scales, and conservation includes the development and refinement of strategies to rebuild populations, restore ecosystems, inform conservation policy, generate decision-support tools, and manage natural resources.

Conservation physiology is particularly relevant to practitioners in that it has the potential to generate cause-and-effect relationships and reveal the factors that contribute to population declines.

Conservation biology as a profession

[edit]The Society for Conservation Biology is a global community of conservation professionals dedicated to advancing the science and practice of conserving biodiversity. Conservation biology as a discipline reaches beyond biology, into subjects such as philosophy, law, economics, humanities, arts, anthropology, and education.[5][6] Within biology, conservation genetics and evolution are immense fields unto themselves, but these disciplines are of prime importance to the practice and profession of conservation biology.

Conservationists introduce bias when they support policies using qualitative description, such as habitat degradation, or healthy ecosystems. Conservation biologists advocate for reasoned and sensible management of natural resources and do so with a disclosed combination of science, reason, logic, and values in their conservation management plans.[5] This sort of advocacy is similar to the medical profession advocating for healthy lifestyle options, both are beneficial to human well-being yet remain scientific in their approach.

There is a movement in conservation biology suggesting a new form of leadership is needed to mobilize conservation biology into a more effective discipline that is able to communicate the full scope of the problem to society at large.[81] The movement proposes an adaptive leadership approach that parallels an adaptive management approach. The concept is based on a new philosophy or leadership theory steering away from historical notions of power, authority, and dominance. Adaptive conservation leadership is reflective and more equitable as it applies to any member of society who can mobilize others toward meaningful change using communication techniques that are inspiring, purposeful, and collegial. Adaptive conservation leadership and mentoring programs are being implemented by conservation biologists through organizations such as the Aldo Leopold Leadership Program.[82]

Approaches

[edit]Conservation may be classified as either in-situ conservation, which is protecting an endangered species in its natural habitat, or ex-situ conservation, which occurs outside the natural habitat.[83] In-situ conservation involves protecting or restoring the habitat. Ex-situ conservation, on the other hand, involves protection outside of an organism's natural habitat, such as on reservations or in gene banks, in circumstances where viable populations may not be present in the natural habitat.[83]

The conservation of habitats like forest, water or soil in its natural state is crucial for any species depending in it to thrive. Instead of making the whole new environment looking alike the original habitat of wild animals is less effective than preserving the original habitats. An approach in Nepal named reforestation campaign has helped increase the density and area covered by the original forests which proved to be better than creating entirely new environment after original one is let to lost. Old Forests Store More Carbon than Young Ones as proved by latest researches, so it is more crucial to protect the old ones. The reforestation campaign launched by Himalayan Adventure Therapy in Nepal basically visits the old forests in periodic basis which are vulnerable to loss of density and the area covered due to unplanned urbanization activities. Then they plant the new saplings of same tree families of that existing forest in the areas where the old forest has been lost and also plant those saplings to the barren areas connected to the forest. This maintains the density and area covered by the forest.

Also, non-interference may be used, which is termed a preservationist method. Preservationists advocate for giving areas of nature and species a protected existence that halts interference from the humans.[5] In this regard, conservationists differ from preservationists in the social dimension, as conservation biology engages society and seeks equitable solutions for both society and ecosystems. Some preservationists emphasize the potential of biodiversity in a world without humans.

Ecological monitoring in conservation

[edit]Ecological monitoring is the systematic collection of data relevant to the ecology of a species or habitat at repeating intervals with defined methods.[84] Long-term monitoring for environmental and ecological metrics is an important part of any successful conservation initiative. Unfortunately, long-term data for many species and habitats is not available in many cases.[85] A lack of historical data on species populations, habitats, and ecosystems means that any current or future conservation work will have to make assumptions to determine if the work is having any effect on the population or ecosystem health. Ecological monitoring can provide early warning signals of deleterious effects (from human activities or natural changes in an environment) on an ecosystem and its species.[84] In order for signs of negative trends in ecosystem or species health to be detected, monitoring methods must be carried out at appropriate time intervals, and the metric must be able to capture the trend of the population or habitat as a whole.

Long-term monitoring can include the continued measuring of many biological, ecological, and environmental metrics including annual breeding success, population size estimates, water quality, biodiversity (which can be measured in many way, i.e. Shannon Index), and many other methods. When determining which metrics to monitor for a conservation project, it is important to understand how an ecosystem functions and what role different species and abiotic factors have within the system.[86] It is important to have a precise reason for why ecological monitoring is implemented; within the context of conservation, this reasoning is often to track changes before, during, or after conservation measures are put in place to help a species or habitat recover from degradation and/or maintain integrity.[84]

Another benefit of ecological monitoring is the hard evidence it provides scientists to use for advising policy makers and funding bodies about conservation efforts. Not only is ecological monitoring data important for convincing politicians, funders, and the public why a conservation program is important to implement, but also to keep them convinced that a program should be continued to be supported.[85]

There is plenty of debate on how conservation resources can be used most efficiently; even within ecological monitoring, there is debate on which metrics that money, time and personnel should be dedicated to for the best chance of making a positive impact. One specific general discussion topic is whether monitoring should happen where there is little human impact (to understand a system that has not been degraded by humans), where there is human impact (so the effects from humans can be investigated), or where there is data deserts and little is known about the habitats' and communities' response to human perturbations.[84]

The concept of bioindicators / indicator species can be applied to ecological monitoring as a way to investigate how pollution is affecting an ecosystem.[87] Species like amphibians and birds are highly susceptible to pollutants in their environment due to their behaviours and physiological features that cause them to absorb pollutants at a faster rate than other species. Amphibians spend parts of their time in the water and on land, making them susceptible to changes in both environments.[88] They also have very permeable skin that allows them to breath and intake water, which means they also take any air or water-soluble pollutants in as well. Birds often cover a wide range in habitat types annually, and also generally revisit the same nesting site each year. This makes it easier for researchers to track ecological effects at both an individual and a population level for the species.[89]

Many conservation researchers believe that having a long-term ecological monitoring program should be a priority for conservation projects, protected areas, and regions where environmental harm mitigation is used.[90]

Ethics and values

[edit]Conservation biologists are interdisciplinary researchers that practice ethics in the biological and social sciences. Chan states[91] that conservationists must advocate for biodiversity and can do so in a scientifically ethical manner by not promoting simultaneous advocacy against other competing values.

A conservationist may be inspired by the resource conservation ethic,[7]: 15 which seeks to identify what measures will deliver "the greatest good for the greatest number of people for the longest time."[5]: 13 In contrast, some conservation biologists argue that nature has an intrinsic value that is independent of anthropocentric usefulness or utilitarianism.[7]: 3, 12, 16–17 Aldo Leopold was a classical thinker and writer on such conservation ethics whose philosophy, ethics and writings are still valued and revisited by modern conservation biologists.[7]: 16–17

Conservation priorities

[edit]

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has organized a global assortment of scientists and research stations across the planet to monitor the changing state of nature in an effort to tackle the extinction crisis. The IUCN provides annual updates on the status of species conservation through its Red List.[92] The IUCN Red List serves as an international conservation tool to identify those species most in need of conservation attention and by providing a global index on the status of biodiversity.[93] More than the dramatic rates of species loss, however, conservation scientists note that the sixth mass extinction is a biodiversity crisis requiring far more action than a priority focus on rare, endemic or endangered species. Concerns for biodiversity loss covers a broader conservation mandate that looks at ecological processes, such as migration, and a holistic examination of biodiversity at levels beyond the species, including genetic, population and ecosystem diversity.[94] Extensive, systematic, and rapid rates of biodiversity loss threatens the sustained well-being of humanity by limiting supply of ecosystem services that are otherwise regenerated by the complex and evolving holistic network of genetic and ecosystem diversity. While the conservation status of species is employed extensively in conservation management,[93] some scientists highlight that it is the common species that are the primary source of exploitation and habitat alteration by humanity. Moreover, common species are often undervalued despite their role as the primary source of ecosystem services.[95][96]

While most in the community of conservation science "stress the importance" of sustaining biodiversity,[97] there is debate on how to prioritize genes, species, or ecosystems, which are all components of biodiversity (e.g. Bowen, 1999). While the predominant approach to date has been to focus efforts on endangered species by conserving biodiversity hotspots, some scientists (e.g)[98] and conservation organizations, such as the Nature Conservancy, argue that it is more cost-effective, logical, and socially relevant to invest in biodiversity coldspots.[99] The costs of discovering, naming, and mapping out the distribution of every species, they argue, is an ill-advised conservation venture. They reason it is better to understand the significance of the ecological roles of species.[94]

Biodiversity hotspots and coldspots are a way of recognizing that the spatial concentration of genes, species, and ecosystems is not uniformly distributed on the Earth's surface.[100] For example, "... 44% of all species of vascular plants and 35% of all species in four vertebrate groups are confined to 25 hotspots comprising only 1.4% of the land surface of the Earth."[101]

Those arguing in favor of setting priorities for coldspots point out that there are other measures to consider beyond biodiversity. They point out that emphasizing hotspots downplays the importance of the social and ecological connections to vast areas of the Earth's ecosystems where biomass, not biodiversity, reigns supreme.[102] It is estimated that 36% of the Earth's surface, encompassing 38.9% of the worlds vertebrates, lacks the endemic species to qualify as biodiversity hotspot.[103] Moreover, measures show that maximizing protections for biodiversity does not capture ecosystem services any better than targeting randomly chosen regions.[104] Population level biodiversity (mostly in coldspots) are disappearing at a rate that is ten times that at the species level.[98][105] The level of importance in addressing biomass versus endemism as a concern for conservation biology is highlighted in literature measuring the level of threat to global ecosystem carbon stocks that do not necessarily reside in areas of endemism.[106][107] A hotspot priority approach[108] would not invest so heavily in places such as steppes, the Serengeti, the Arctic, or taiga. These areas contribute a great abundance of population (not species) level biodiversity[105] and ecosystem services, including cultural value and planetary nutrient cycling.[99]

Those in favor of the hotspot approach point out that species are irreplaceable components of the global ecosystem, they are concentrated in places that are most threatened, and should therefore receive maximal strategic protections.[109] This is a hotspot approach because the priority is set to target species level concerns over population level or biomass.[105][failed verification] Species richness and genetic biodiversity contributes to and engenders ecosystem stability, ecosystem processes, evolutionary adaptability, and biomass.[110] Both sides agree, however, that conserving biodiversity is necessary to reduce the extinction rate and identify an inherent value in nature; the debate hinges on how to prioritize limited conservation resources in the most cost-effective way.

Economic values and natural capital

[edit]

Conservation biologists have started to collaborate with leading global economists to determine how to measure the wealth and services of nature and to make these values apparent in global market transactions.[111] This system of accounting is called natural capital and would, for example, register the value of an ecosystem before it is cleared to make way for development.[112] The WWF publishes its Living Planet Report and provides a global index of biodiversity by monitoring approximately 5,000 populations in 1,686 species of vertebrate (mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians) and report on the trends in much the same way that the stock market is tracked.[113]

This method of measuring the global economic benefit of nature has been endorsed by the G8+5 leaders and the European Commission.[111] Nature sustains many ecosystem services[114] that benefit humanity.[115] Many of the Earth's ecosystem services are public goods without a market and therefore no price or value.[111] When the stock market registers a financial crisis, traders on Wall Street are not in the business of trading stocks for much of the planet's living natural capital stored in ecosystems. There is no natural stock market with investment portfolios into sea horses, amphibians, insects, and other creatures that provide a sustainable supply of ecosystem services that are valuable to society.[115] The ecological footprint of society has exceeded the bio-regenerative capacity limits of the planet's ecosystems by about 30 percent, which is the same percentage of vertebrate populations that have registered decline from 1970 through 2005.[113]

The ecological credit crunch is a global challenge. The Living Planet Report 2008 tells us that more than three-quarters of the world's people live in nations that are ecological debtors – their national consumption has outstripped their country's biocapacity. Thus, most of us are propping up our current lifestyles, and our economic growth, by drawing (and increasingly overdrawing) upon the ecological capital of other parts of the world.

WWF Living Planet Report[113]

The inherent natural economy plays an essential role in sustaining humanity,[116] including the regulation of global atmospheric chemistry, pollinating crops, pest control,[117] cycling soil nutrients, purifying our water supply,[118] supplying medicines and health benefits,[119] and unquantifiable quality of life improvements. There is a relationship, a correlation, between markets and natural capital, and social income inequity and biodiversity loss. This means that there are greater rates of biodiversity loss in places where the inequity of wealth is greatest[120]

Although a direct market comparison of natural capital is likely insufficient in terms of human value, one measure of ecosystem services suggests the contribution amounts to trillions of dollars yearly.[121][122][123][124] For example, one segment of North American forests has been assigned an annual value of 250 billion dollars;[125] as another example, honey bee pollination is estimated to provide between 10 and 18 billion dollars of value yearly.[126] The value of ecosystem services on one New Zealand island has been imputed to be as great as the GDP of that region.[127] This planetary wealth is being lost at an incredible rate as the demands of human society is exceeding the bio-regenerative capacity of the Earth. While biodiversity and ecosystems are resilient, the danger of losing them is that humans cannot recreate many ecosystem functions through technological innovation.

Strategic species concepts

[edit]Keystone species

[edit]Some species, called a keystone species form a central supporting hub unique to their ecosystem.[128] The loss of such a species results in a collapse in ecosystem function, as well as the loss of coexisting species.[5] Keystone species are usually predators due to their ability to control the population of prey in their ecosystem.[128] The importance of a keystone species was shown by the extinction of the Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas) through its interaction with sea otters, sea urchins, and kelp. Kelp beds grow and form nurseries in shallow waters to shelter creatures that support the food chain. Sea urchins feed on kelp, while sea otters feed on sea urchins. With the rapid decline of sea otters due to overhunting, sea urchin populations grazed unrestricted on the kelp beds and the ecosystem collapsed. Left unchecked, the urchins destroyed the shallow water kelp communities that supported the Steller's sea cow's diet and hastened their demise.[129] The sea otter was thought to be a keystone species because the coexistence of many ecological associates in the kelp beds relied upon otters for their survival. However this was later questioned by Turvey and Risley,[130] who showed that hunting alone would have driven the Steller's sea cow extinct.

Indicator species

[edit]An indicator species has a narrow set of ecological requirements, therefore they become useful targets for observing the health of an ecosystem. Some animals, such as amphibians with their semi-permeable skin and linkages to wetlands, have an acute sensitivity to environmental harm and thus may serve as a miner's canary. Indicator species are monitored in an effort to capture environmental degradation through pollution or some other link to proximate human activities.[5] Monitoring an indicator species is a measure to determine if there is a significant environmental impact that can serve to advise or modify practice, such as through different forest silviculture treatments and management scenarios, or to measure the degree of harm that a pesticide may impart on the health of an ecosystem.

Government regulators, consultants, or NGOs regularly monitor indicator species, however, there are limitations coupled with many practical considerations that must be followed for the approach to be effective.[131] It is generally recommended that multiple indicators (genes, populations, species, communities, and landscape) be monitored for effective conservation measurement that prevents harm to the complex, and often unpredictable, response from ecosystem dynamics (Noss, 1997[132]: 88–89 ).

Umbrella and flagship species

[edit]An example of an umbrella species is the monarch butterfly, because of its lengthy migrations and aesthetic value. The monarch migrates across North America, covering multiple ecosystems and so requires a large area to exist. Any protections afforded to the monarch butterfly will at the same time umbrella many other species and habitats. An umbrella species is often used as flagship species, which are species, such as the giant panda, the blue whale, the tiger, the mountain gorilla and the monarch butterfly, that capture the public's attention and attract support for conservation measures.[5] Paradoxically, however, conservation bias towards flagship species sometimes threatens other species of chief concern.[133]

Context and trends

[edit]Conservation biologists study trends and process from the paleontological past to the ecological present as they gain an understanding of the context related to species extinction.[1] It is generally accepted that there have been five major global mass extinctions that register in Earth's history. These include: the Ordovician (440 mya), Devonian (370 mya), Permian–Triassic (245 mya), Triassic–Jurassic (200 mya), and Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (66 mya) extinction spasms. Within the last 10,000 years, human influence over the Earth's ecosystems has been so extensive that scientists have difficulty estimating the number of species lost;[134] that is to say the rates of deforestation, reef destruction, wetland draining and other human acts are proceeding much faster than human assessment of species. The latest Living Planet Report by the World Wide Fund for Nature estimates that we have exceeded the bio-regenerative capacity of the planet, requiring 1.6 Earths to support the demands placed on our natural resources.[135]

Holocene extinction

[edit]

Conservation biologists are dealing with and have published evidence from all corners of the planet indicating that humanity may be causing the sixth and fastest planetary extinction event.[136][137][138] It has been suggested that an unprecedented number of species is becoming extinct in what is known as the Holocene extinction event.[139] The global extinction rate may be approximately 1,000 times higher than the natural background extinction rate.[140] It is estimated that two-thirds of all mammal genera and one-half of all mammal species weighing at least 44 kilograms (97 lb) have gone extinct in the last 50,000 years.[130][141][142][143] The Global Amphibian Assessment[144] reports that amphibians are declining on a global scale faster than any other vertebrate group, with over 32% of all surviving species being threatened with extinction. The surviving populations are in continual decline in 43% of those that are threatened. Since the mid-1980s the actual rates of extinction have exceeded 211 times rates measured from the fossil record.[145] However, "The current amphibian extinction rate may range from 25,039 to 45,474 times the background extinction rate for amphibians."[145] The global extinction trend occurs in every major vertebrate group that is being monitored. For example, 23% of all mammals and 12% of all birds are Red Listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), meaning they too are threatened with extinction. Even though extinction is natural, the decline in species is happening at such an incredible rate that evolution can simply not match, therefore, leading to the greatest continual mass extinction on Earth.[146] Humans have dominated the planet and our high consumption of resources, along with the pollution generated is affecting the environments in which other species live.[146][147] There are a wide variety of species that humans are working to protect such as the Hawaiian Crow and the Whooping Crane of Texas.[148] People can also take action on preserving species by advocating and voting for global and national policies that improve climate, under the concepts of climate mitigation and climate restoration. The Earth's oceans demand particular attention as climate change continues to alter pH levels, making it uninhabitable for organisms with shells which dissolve as a result.[140]

Status of oceans and reefs

[edit]Global assessments of coral reefs of the world continue to report drastic and rapid rates of decline. By 2000, 27% of the world's coral reef ecosystems had effectively collapsed. The largest period of decline occurred in a dramatic "bleaching" event in 1998, where approximately 16% of all the coral reefs in the world disappeared in less than a year. Coral bleaching is caused by a mixture of environmental stresses, including increases in ocean temperatures and acidity, causing both the release of symbiotic algae and death of corals.[149] Decline and extinction risk in coral reef biodiversity has risen dramatically in the past ten years. The loss of coral reefs, which are predicted to go extinct in the next century, threatens the balance of global biodiversity, will have huge economic impacts, and endangers food security for hundreds of millions of people.[150] Conservation biology plays an important role in international agreements covering the world's oceans[149] and other issues pertaining to biodiversity.

Эти прогнозы, несомненно, покажутся экстремальными, но трудно представить, как такие изменения не произойдут без фундаментальных изменений в человеческом поведении.

Джей Би Джексон [17] : 11463

Океанам угрожает закисление из-за увеличения уровня CO 2 . Это самая серьезная угроза для обществ, которые в значительной степени полагаются на природные ресурсы океана . Вызывает обеспокоенность то, что большинство всех морских видов не смогут развиваться или акклиматизироваться в ответ на изменения в химии океана. [151]

Перспективы предотвращения массового вымирания кажутся маловероятными, когда «90% всех крупных (в среднем около 50 кг) тунцов, марлиновых и акул открытого океана обитают в океане». [17] как сообщается, пропали. Учитывая научный обзор текущих тенденций, прогнозируется, что в океане останется мало выживших многоклеточных организмов , и только микробы останутся доминировать в морских экосистемах . [17]

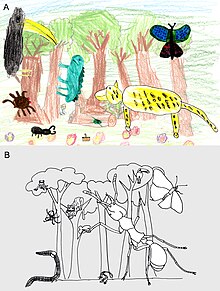

Группы, кроме позвоночных

[ редактировать ]Серьезную озабоченность также вызывают таксономические группы , которые не получают такой же степени социального внимания и не привлекают средств, как позвоночные. К ним относятся грибные (в том числе лишайниковообразующие виды), [152] беспозвоночные (особенно насекомые [15] [153] [154] ) и растительные сообщества [155] где представлена подавляющая часть биоразнообразия. Сохранение грибов и сохранение насекомых, в частности, имеют решающее значение для природоохранной биологии. Являясь микоризными симбионтами, а также разрушителями и переработчиками, грибы необходимы для устойчивости лесов. [152] Значение насекомых в биосфере огромно, поскольку по видовому богатству они превосходят все другие группы живых существ . Наибольшая масса биомассы на суше содержится в растениях, которые поддерживаются за счет отношений с насекомыми. Этой огромной экологической ценности насекомых противостоит общество, которое часто негативно реагирует на этих эстетически «неприятных» существ. [156] [157]

Одной из проблем в мире насекомых, которая привлекла внимание общественности, является загадочный случай исчезновения медоносных пчел ( Apis mellifera ). Медоносные пчелы оказывают незаменимую экологическую услугу посредством опыления, поддерживая огромное разнообразие сельскохозяйственных культур. Использование меда и воска получило широкое распространение во всем мире. [158] Внезапное исчезновение пчел, покидающих пустые ульи, или синдром распада семей (CCD) не являются редкостью. Однако за 16-месячный период с 2006 по 2007 год 29% из 577 пчеловодов в Соединенных Штатах сообщили о потерях CCD почти в 76% своих семей. Эта внезапная демографическая потеря численности пчел создает нагрузку на сельскохозяйственный сектор. Причина такого массового снижения озадачивает ученых. вредители , пестициды и глобальное потепление . В качестве возможных причин рассматриваются [159] [160]

Еще одним ярким событием, которое связывает природоохранную биологию с насекомыми, лесами и изменением климата, является горного соснового жука ( Dendroctonus ponderosae ) эпидемия в Британской Колумбии , Канада, которая заразила 470 000 км2 территории. 2 (180 000 квадратных миль) лесных земель с 1999 года. [106] Правительство Британской Колумбии подготовило план действий для решения этой проблемы. [161] [162]

Это воздействие [ эпидемия соснового жука ] превратило лес из небольшого чистого поглотителя углерода в крупный чистый источник углерода как во время, так и сразу после вспышки. В худший год последствия вспышки жуков в Британской Колумбии были эквивалентны 75% среднегодовых прямых выбросов лесных пожаров по всей Канаде в 1959–1999 годах.

—Курц др и . [107]

Биология сохранения паразитов

[ редактировать ]Значительная часть видов паразитов находится под угрозой исчезновения. Некоторые из них уничтожаются как вредители человека или домашних животных; однако большинство из них безвредны. Паразиты также составляют значительную часть глобального биоразнообразия, учитывая, что они составляют значительную часть всех видов на Земле. [163] что делает их все более распространенным природоохранным интересом. Угрозы включают сокращение или фрагментацию принимающего населения, [164] или исчезновение видов-хозяев. Паразиты сложно вплетены в экосистемы и пищевые сети, тем самым играя ценную роль в структуре и функционировании экосистем. [165] [163]

Угрозы биоразнообразию

[ редактировать ]Сегодня существует множество угроз биоразнообразию. Аббревиатура, которую можно использовать для обозначения главных угроз современного HIPPO, означает «потеря среды обитания, инвазивные виды, загрязнение окружающей среды, человеческое население и чрезмерный вылов». [166] Основными угрозами биоразнообразию являются разрушение среды обитания (например, вырубка лесов , расширение сельского хозяйства , развитие городов ) и чрезмерная эксплуатация (например, торговля дикими животными ). [134] [167] [168] [169] [170] [171] [172] [173] [174] Фрагментация среды обитания также создает проблемы, поскольку глобальная сеть охраняемых территорий покрывает лишь 11,5% поверхности Земли. [175] Серьезным последствием фрагментации и отсутствия связанных между собой охраняемых территорий является сокращение миграции животных в глобальном масштабе. [176] Учитывая, что миллиарды тонн биомассы ответственны за круговорот питательных веществ по Земле, сокращение миграции является серьезным вопросом для природоохранной биологии. [177] [178]

Человеческая деятельность прямо или косвенно связана почти со всеми аспектами нынешнего спазма вымирания.

Уэйк и Фреденбург [136]

Однако деятельность человека не обязательно должна наносить непоправимый вред биосфере. Благодаря управлению сохранением и планированию биоразнообразия на всех уровнях, от генов до экосистем, есть примеры, когда люди устойчиво сосуществуют с природой. [179] Даже несмотря на нынешние угрозы биоразнообразию, мы можем улучшить нынешнее состояние и начать все заново.

Многие угрозы биоразнообразию, включая болезни и изменение климата, проникают внутрь границ охраняемых территорий, делая их «не очень защищенными» (например, Йеллоустонский национальный парк ). [180] Изменение климата , например, часто называют серьезной угрозой в этом отношении, поскольку существует петля обратной связи между вымиранием видов и выбросом углекислого газа в атмосферу . [106] [107] Экосистемы хранят и перерабатывают большое количество углерода, который регулирует глобальные условия. [181] В настоящее время произошли серьезные климатические изменения, а изменения температуры затрудняют выживание некоторых видов. [166] Последствия глобального потепления создают катастрофическую угрозу массового вымирания глобального биологического разнообразия. [182] По прогнозам, еще множество видов столкнутся с беспрецедентным уровнем риска исчезновения из-за увеличения численности населения, изменения климата и экономического развития в будущем. [183] Защитники природы утверждают, что не все виды можно спасти, и им приходится решать, какие усилия следует приложить для защиты. Эта концепция известна как консервационная сортировка. [166] По оценкам, к 2050 году угроза исчезновения составит от 15 до 37 процентов всех видов. [182] или 50 процентов всех видов в течение следующих 50 лет. [15] Нынешние темпы вымирания сегодня в 100–100 000 раз выше, чем в последние несколько миллиардов лет. [166]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Прикладная экология

- Птичья обсерватория

- Виды, требующие сохранения

- Экологическое вымирание

- Генофонд

- Генетическая эрозия

- Генетическое загрязнение

- Сохранение на месте

- Коренные народы: экологические выгоды

- Список основных тем по биологии

- Список биологических сайтов

- Список тем по биологии

- Список природоохранных организаций

- Список тем сохранения

- Взаимность и сохранение

- Природная среда

- Охрана природы

- Природоохранные организации по странам

- Охраняемая территория

- Региональный Красный список

- Возобновляемый ресурс

- Реставрационная экология

- Тирания маленьких решений

- Экономия воды

- Биология благополучия

- Болезнь дикой природы

- Управление дикой природой

- Всемирный центр мониторинга охраны природы

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Сахни, С.; Бентон, MJ (2008). «Восстановление после самого глубокого массового вымирания всех времен» . Труды Королевского общества B: Биологические науки . 275 (1636): 759–65. дои : 10.1098/rspb.2007.1370 . ПМЦ 2596898 . ПМИД 18198148 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Суле, Майкл Э.; Уилкокс, Брюс А. (1980). Биология сохранения: эволюционно-экологическая перспектива . Сандерленд, Массачусетс: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-800-1 .

- ^ Соуле, Майкл Э. (1986). «Что такое биология сохранения?» (PDF) . Бионаука . 35 (11). Американский институт биологических наук: 727–34. дои : 10.2307/1310054 . JSTOR 1310054 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Соул, Майкл Э. (1986). Природоохранная биология: наука о дефиците и разнообразии . Синауэр Ассошиэйтс. п. 584. ИСБН 978-0-87893-795-0 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж Хантер, Малкольм Л. (1996). Основы биологии сохранения . Оксфорд: Блэквелл Наука. ISBN 978-0-86542-371-8 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Меффе, Гэри К.; Марта Дж. Грум (2006). Принципы биологии сохранения (3-е изд.). Сандерленд, Массачусетс: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-518-5 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н Ван Дайк, Фред (2008). Биология сохранения: основы, концепции, приложения (2-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Springer-Verlag . дои : 10.1007/978-1-4020-6891-1 . hdl : 11059/14777 . ISBN 9781402068904 . ОСЛК 232001738 .

- ^ Дж. Дуглас. 1978. Биологи призывают американский фонд сохранить природу. Природа Том. 275, 14 сентября 1978. Кэт Уильямс. 1978. Естественные науки. Новости науки. 30 сентября 1978 года.

- ^ Организация самой встречи также повлекла за собой преодоление разрыва между генетикой и экологией. Суле был генетиком-эволюционистом, работавшим с генетиком пшеницы сэром Отто Франкелем над продвижением природоохранной генетики как новой в то время области. Джаред Даймонд , который предложил Уилкоксу идею конференции, был обеспокоен применением теории экологии сообщества и биогеографии островов к сохранению природы. Уилкокс и Томас Лавджой , которые вместе инициировали планирование конференции в июне 1977 года, когда Лавджой получил начальное финансирование от Всемирного фонда дикой природы , считали, что на ней должны быть представлены как генетика, так и экология. Уилкокс предложил использовать новый термин «биология сохранения» , дополняющий концепцию Франкеля и изобретение «генетики сохранения», чтобы охватить применение биологических наук в целом к сохранению. Впоследствии Суле и Уилкокс составили повестку дня встречи, которую они совместно организовали 6–9 сентября 1978 г., под названием « Первая международная конференция по исследованиям в области природоохранной биологии». , в котором в программе описывалось: «Цель этой конференции — ускорить и облегчить развитие новой строгой дисциплины, называемой биологией сохранения — междисциплинарной области, черпающей свои идеи и методологию в основном из популяционной экологии, экологии сообществ, социобиологии, популяционной генетики и репродуктивная биология». Включение на встречу тем, связанных с разведением животных, отражало участие и поддержку со стороны зоопарков и сообществ по разведению животных в неволе.

- ^ Карейва, Питер; Марвье, Мишель (ноябрь 2012 г.). «Что такое наука о сохранении природы?» . Бионаука . 62 (11): 962–969. дои : 10.1525/bio.2012.62.11.5 . ISSN 1525-3244 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кук, С.Дж.; Сак, Л.; Франклин, CE; Фаррелл, AP; Бердалл, Дж.; Викельски, М.; Чоун, СЛ (2013). «Что такое физиология сохранения? Перспективы все более интегрированной и важной науки» . Физиология сохранения . 1 (1): кот001. дои : 10.1093/conphys/cot001 . ПМЦ 4732437 . ПМИД 27293585 .

- ^ Уилсон, Эдвард Осборн (2002). Будущее жизни . Бостон: Литтл, Браун. ISBN 978-0-316-64853-0 . [ нужна страница ]

- ^ Кала, Чандра Пракаш (2005). «Использование коренными народами, плотность населения и сохранение находящихся под угрозой исчезновения лекарственных растений на охраняемых территориях Индийских Гималаев». Биология сохранения . 19 (2): 368–78. дои : 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00602.x . JSTOR 3591249 . S2CID 85324142 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сахни, С.; Бентон, MJ; Ферри, Пенсильвания (2010). «Связь между глобальным таксономическим разнообразием, экологическим разнообразием и распространением позвоночных на суше» . Письма по биологии . 6 (4): 544–7. дои : 10.1098/rsbl.2009.1024 . ПМК 2936204 . ПМИД 20106856 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Ко, Лиан Пин; Данн, Роберт Р.; Содхи, Навджот С.; Колвелл, Роберт К.; Проктор, Хизер С.; Смит, Винсент С. (2004). «Сосуществование видов и кризис биоразнообразия». Наука . 305 (5690): 1632–4. Бибкод : 2004Sci...305.1632K . дои : 10.1126/science.1101101 . ПМИД 15361627 . S2CID 30713492 .

- ^ Оценка экосистемы тысячелетия (2005). Экосистемы и благополучие человека: синтез биоразнообразия. Институт мировых ресурсов, Вашингтон, округ Колумбия. [1]

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Джексон, JBC (2008). «Экологическое вымирание и эволюция в дивном новом океане» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 105 (Приложение 1): 11458–65. Бибкод : 2008PNAS..10511458J . дои : 10.1073/pnas.0802812105 . ПМК 2556419 . ПМИД 18695220 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фитцпатрик, Мэтью С.; Харгроув, Уильям В. (1 июля 2009 г.). «Проекция моделей распространения видов и проблема неаналогового климата» . Биоразнообразие и сохранение . 18 (8): 2255–2261. дои : 10.1007/s10531-009-9584-8 . ISSN 1572-9710 . S2CID 16327687 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кук, С.Дж.; Майклс, С.; Нюбоер, Э.А.; Шиллер, Л.; Литлчайлд, DBR; Ханна, Делавэр; Робишо, CD; Мердок, А.; Рош, Д.; Соройе, П.; Вермэр, JC (31 мая 2022 г.). «Переосмысление сохранения» . PLOS Устойчивое развитие и трансформация . 1 (5): e0000016. дои : 10.1371/journal.pstr.0000016 . ISSN 2767-3197 .

- ^ Теодор Рузвельт, Обращение к Конвенции о глубоководных путяхМемфис, Теннесси, 4 октября 1907 г.

- ^ «Защита и сохранение биоразнообразия» . ffem.fr . Архивировано из оригинала 18 октября 2016 г. Проверено 11 октября 2016 г.

- ^ Хардин Дж. (декабрь 1968 г.). «Трагедия общин» . Наука . 162 (3859): 1243–8. Бибкод : 1968Sci...162.1243H . дои : 10.1126/science.162.3859.1243 . ПМИД 5699198 .

- ^ Также считается следствием эволюции, когда индивидуальный отбор предпочтительнее группового. Недавние обсуждения см.: Кей CE (1997). «Окончательная трагедия общин». Консервировать. Биол . 11 (6): 1447–8. дои : 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1997.97069.x . S2CID 1397580 .

и Уилсон Д.С., Уилсон Э.О. (декабрь 2007 г.). «Переосмысление теоретических основ социобиологии» (PDF) . Q Преподобный Биол . 82 (4): 327–48. дои : 10.1086/522809 . ПМИД 18217526 . S2CID 37774648 . Архивировано из оригинала 26 марта 2009 г. - ^ Мейсон, Рэйчел и Джудит Рамос. (2004). Традиционные экологические знания тлинкитов о промысле нерки в районе Сухого залива, Соглашение о сотрудничестве между Департаментом внутренней службы национальных парков и якутатским племенем тлинкитов, Заключительный отчет (FIS) проекта 01-091, Якутат, Аляска. «Традиционные экологические знания тлинкитов о промысле нерки в районе Сухого залива» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 25 февраля 2009 г. Проверено 7 января 2009 г.

- ^ Мерфри, Маршалл В. (22 мая 2009 г.). «Стратегические основы общинного управления природными ресурсами: польза, расширение прав и возможностей и сохранение». Биоразнообразие и сохранение . 18 (10): 2551–2562. дои : 10.1007/s10531-009-9644-0 . ISSN 0960-3115 . S2CID 23587547 .

- ^ Уилсон, Дэвид Алек (2002). Дарвиновский собор: эволюция, религия и природа общества . Чикаго: Издательство Чикагского университета. ISBN 978-0-226-90134-3 .

- ^ Примак, Ричард Б. (2004). Учебник по биологии сохранения, 3-е изд . Синауэр Ассошиэйтс. стр. 320стр . ISBN 978-0-87893-728-8 .

- ^ Гамильтон, Э. и Х. Кэрнс (ред.). 1961. Платон: собрание диалогов. Издательство Принстонского университета, Принстон, Нью-Джерси

- ↑ Библия, Левит, 25:4-5.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Эванс, Дэвид (1997). История охраны природы в Великобритании . Нью-Йорк: Рутледж. ISBN 978-0-415-14491-9 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Фарбер, Пол Лоуренс (2000). Нахождение порядка в природе: натуралистическая традиция от Линнея до Э.О. Вильсона . Балтимор: Издательство Университета Джонса Хопкинса. ISBN 978-0-8018-6390-5 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Мадер, Сильвия (2016). Биология . Нью-Йорк, штат Нью-Йорк: McGraw Hill Education. п. 262. ИСБН 978-0-07-802426-9 .

- ^ «Введение в биологию охраны природы и биогеографию» . web2.uwindsor.ca .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Клойд, Эл. (1972). Джеймс Бернетт, лорд Монбоддо . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 196. ИСБН 978-0-19-812437-5 .

- ^ Стеббинг, EP (1922) Леса Индии, том. 1, стр. 72-81.

- ^ Бартон, Грег (2002). Империя лесного хозяйства и истоки энвайронментализма . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 48. ИСБН 978-1-139-43460-7 .

- ^ МУТИЯ, С. (5 ноября 2007 г.). «Жизнь для лесного хозяйства» . Индус . Ченнаи, Индия. Архивировано из оригинала 8 ноября 2007 года . Проверено 9 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Клегхорн, Хью Фрэнсис Кларк (1861). Леса и сады Южной Индии (оригинал Мичиганского университета, оцифровано от 10 февраля 2006 г.). Лондон: WH Аллен. OCLC 301345427 .

- ^ Беннетт, Бретт М. (2005). «Ранние истории охраны природы в Бенгалии и Британской Индии: 1875-1922» . Журнал Азиатского общества Бангладеш . 50 (1–2). Азиатское общество Бангладеш: 485–500. ISSN 1016-6947 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2012 г.

- ^ Хейнс, Обри (1996). Йеллоустонская история: история нашего первого национального парка: том 1, исправленное издание . Йеллоустонская ассоциация естествознания, истории образования.

- ^ Г. Байенс; М.Л. Мартинес (2007). Прибрежные дюны: экология и охрана . Спрингер. п. 282.

- ^ Макел, Джо (2 февраля 2011 г.). «Защита морских птиц в Бемптон-Клиффс» . Новости Би-би-си .

- ^ Ньютон А. 1899. Торговля шлейфами: заимствованные шлейфы. «Таймс» 28 января 1876 г.; и Торговля шлейфом. The Times, 25 февраля 1899 г. Перепечатано Обществом защиты птиц, апрель 1899 г.

- ^ Ньютон А. 1868. Зоологический аспект законов игры. Обращение к Британской ассоциации , раздел D, август 1868 г. Перепечатано [nd] Обществом защиты птиц.

- ^ «Вехи» . РСПБ . Проверено 19 февраля 2007 г.

- ^ Пенна, Энтони Н. (1999). Щедрость природы: исторические и современные экологические перспективы . Армонк, Нью-Йорк: Я Шарп . п. 99 . ISBN 978-0-7656-0187-2 .

- ^ «История РСПБ» . РСПБ . Проверено 19 февраля 2007 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Лакманн, Алек Р.; Беляк-Лакманн, Эвелина С.; Джейкобсон, Рид И.; Эндрюс, Аллен Х.; Батлер, Малкольм Г.; Кларк, Марк Э. (30 августа 2023 г.). «Тенденции добычи, роста и продолжительности жизни, а также динамика популяции показывают, что традиционные предположения об управлении красной лошадью (виды Moxostoma) в Миннесоте не подтверждаются» . Экологическая биология рыб . дои : 10.1007/s10641-023-01460-8 . ISSN 1573-5133 .

- ^ «Теодор Рузвельт и охрана природы - Национальный парк Теодора Рузвельта (Служба национальных парков США)» . nps.gov . Проверено 4 октября 2016 г.

- ^ «Экологическая хронология 1890–1920 годов» . рунет.edu . Архивировано из оригинала 23 февраля 2005 г.

- ^ Дэвис, Питер (1996). Музеи и природная среда: роль музеев естествознания в сохранении биологической природы . Лондон: Издательство Лестерского университета. ISBN 978-0-7185-1548-5 .

- ^ «Хроно-биографический очерк: Чарльз Гордон Хьюитт» . люди.wku.edu . Проверено 7 мая 2017 г.

- ^ Фостер, Джанет (1 января 1998 г.). Работа на благо дикой природы: начало охраны дикой природы в Канаде . Университет Торонто Пресс. ISBN 978-0-8020-7969-5 .

- ^ Чекко, Лейланд (19 апреля 2020 г.). «Вклад коренных народов помогает спасти своенравного медведя гризли от необдуманного убийства» . Хранитель . Проверено 23 апреля 2020 г.

- ^ Лакманн, Алек Р.; Эндрюс, Аллен Х.; Батлер, Малкольм Г.; Беляк-Лакманн, Эвелина С.; Кларк, Марк Э. (23 мая 2019 г.). «Большеротый буйвол Ictiobus cyprinellus устанавливает рекорд пресноводной костистости, поскольку улучшенный возрастной анализ показывает столетнее долголетие» . Коммуникационная биология . 2 (1): 197. дои : 10.1038/s42003-019-0452-0 . ISSN 2399-3642 . ПМК 6533251 . ПМИД 31149641 .

- ^ Райпел, Эндрю Л.; Саффариния, Парса; Вон, Кэрин С.; Неспер, Ларри; О'Рейли, Кэтрин; Парисек, Кристина А.; Миллер, Мэтью Л.; Мойл, Питер Б.; Фанг, Нанн А.; Белл-Тилкок, Миранда; Айерс, Дэвид; Дэвид, Соломон Р. (декабрь 2021 г.). «Прощай, «грубая рыба»: сдвиг парадигмы в сохранении местных рыб» . Рыболовство . 46 (12): 605–616. дои : 10.1002/fsh.10660 . ISSN 0363-2415 .

- ^ Скарнеккья, Деннис Л.; Шули, Джейсон Д.; Лакманн, Алек Р.; Райдер, Стивен Дж.; Рике, Деннис К.; Макмаллен, Джозеф; Ганус, Дж. Эрик; Стеффенсен, Кирк Д.; Крамер, Николас В.; Шаттук, Закари Р. (декабрь 2021 г.). «Программа восстановления спортивной рыбы как источник финансирования для управления и мониторинга боуфишинга и мониторинга коммерческого рыболовства во внутренних водоемах» . Рыболовство . 46 (12): 595–604. дои : 10.1002/fsh.10679 . ISSN 0363-2415 .

- ^ А. Р. Рабиновиц, «Ягуар: битва одного человека за создание первого в мире заповедника ягуаров» , Arbor House, Нью-Йорк, штат Нью-Йорк (1986)

- ^ Карр, Марджори Харрис; Карр, Арчи Фэйрли (1994). Натуралист во Флориде: праздник Эдема . Нью-Хейвен, Коннектикут: Издательство Йельского университета. ISBN 978-0-300-05589-4 .

- ^ «Хроно-биографический очерк: (Генри) Фэрфилд Осборн-младший» . wku.edu .

- ^ «История вирунгов» . котф.edu . Проверено 10 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Экли, К., 1923. В самой яркой Африке, Нью-Йорк, Doubleday. 188-249.

- ^ Закон США об исчезающих видах (7 USC § 136, 16 USC § 1531 и последующие) 1973 года, Вашингтон, округ Колумбия, Типография правительства США

- ^ «16 Кодекс США § 1531 – Выводы Конгресса и декларация целей и политики» . ЛИИ/Институт правовой информации .

- ^ «Издательство правительства США — FDsys — Просмотр публикаций» . frwebgate.access.gpo.gov .

- ^ Краусман, Пол Р.; Джонсингх, AJT (1990). «Образование в области охраны природы и дикой природы в Индии». Бюллетень Общества дикой природы . 18 (3): 342–7. JSTOR 3782224 .

- ^ «Официальная страница Конвенции о биологическом разнообразии» . Архивировано из оригинала 27 февраля 2007 года.

- ^ Гор, Альберт (1992). Земля на волоске: экология и человеческий дух . Бостон: Хоутон Миффлин. ISBN 978-0-395-57821-6 .

- ^ Риган, Хелен М.; Лупия, Ричард; Дриннан, Эндрю Н.; Бургман, Марк А. (2001). «Валюта и темпы вымирания». Американский натуралист . 157 (1): 1–10. дои : 10.1086/317005 . ПМИД 18707231 . S2CID 205983813 .

- ^ Маккензи, Дэррил И.; Николс, Джеймс Д.; Хайнс, Джеймс Э.; Натсон, Мелинда Г.; Франклин, Алан Б. (2003). «Оценка занятости участка, колонизации и местного вымирания при несовершенном обнаружении вида». Экология . 84 (8): 2200–2207. дои : 10.1890/02-3090 . hdl : 2027.42/149732 . JSTOR 3450043 .

- ^ Балмфорд, Эндрю; Грин, Рис Э.; Дженкинс, Мартин (2003). «Измерение изменяющегося состояния природы» (PDF) . Тенденции в экологии и эволюции . 18 (7): 326–30. дои : 10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00067-3 .

- ^ Макартур, Р.Х. ; Уилсон, Э.О. (2001). Теория островной биогеографии . Принстон, Нью-Джерси: Издательство Принстонского университета. ISBN 978-0-691-08836-5 .

- ^ Рауп ДМ (1991). «Кривая гибели морских видов фанерозоя». Палеобиология . 17 (1): 37–48. Бибкод : 1991Pbio...17...37R . дои : 10.1017/S0094837300010332 . ПМИД 11538288 . S2CID 29102370 .

- ^ Себальос, Херардо; Эрлих, Пол Р.; Барноски, Энтони Д.; Гарсиа, Андрес; Прингл, Роберт М.; Палмер, Тодд М. (01 июня 2015 г.). «Ускоренная гибель видов, вызванная деятельностью человека: на пороге шестого массового вымирания» . Достижения науки . 1 (5): e1400253. Бибкод : 2015SciA....1E0253C . дои : 10.1126/sciadv.1400253 . ISSN 2375-2548 . ПМК 4640606 . ПМИД 26601195 .

- ^ Брун, Филипп; Тюллер, Вильфрид; Шовье, Йоханн; Пеллиссье, Лоик; Вюэст, Рафаэль О.; Ван, Чжихэн; Циммерманн, Никлаус Э. (январь 2020 г.). «Сложность модели влияет на прогнозы распределения видов в условиях изменения климата» . Журнал биогеографии . 47 (1): 130–142. дои : 10.1111/jbi.13734 . ISSN 0305-0270 . S2CID 209562589 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Уилсон, Эдвард О. (2000). «О будущем природоохранной биологии» . Биология сохранения . 14 (1): 1–3. дои : 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.00000-e1.x . S2CID 83906221 .

- ^ «Статистика Красного списка МСОП (2006 г.)» . Архивировано из оригинала 30 июня 2006 года.

- ^ МСОП не разделяет находящихся под угрозой исчезновения от находящихся под угрозой исчезновения или находящихся под угрозой исчезновения. Для целей этой статистики

- ^ Маргулес ЧР, Пресси РЛ (май 2000 г.). «Систематическое планирование сохранения» (PDF) . Природа . 405 (6783): 243–53. дои : 10.1038/35012251 . ПМИД 10821285 . S2CID 4427223 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 25 февраля 2009 г.

- ^ «План действий по сохранению земноводных» (PDF) . 04 июля 2007 г. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 4 июля 2007 г. Проверено 29 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Манолис Дж.К., Чан К.М., Финкельштейн М.Е., Стивенс С., Нельсон С.Р., Грант Дж.Б., Домбек член парламента (2009). «Лидерство: новый рубеж в природоохранной науке». Консервировать. Биол . 23 (4): 879–86. дои : 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01150.x . ПМИД 19183215 . S2CID 36810103 .

- ^ «Программа лидерства Альдо Леопольда» . Институт окружающей среды Вудса Стэнфордского университета. Архивировано из оригинала 17 февраля 2007 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кала, Чандра Пракаш (2009). «Сохранение лекарственных растений и развитие предпринимательства». Лекарственные растения - Международный журнал фитомедицины и смежных отраслей . 1 (2): 79–95. дои : 10.5958/j.0975-4261.1.2.011 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Спеллерберг, Ян Ф. (18 августа 2005 г.). Мониторинг экологических изменений . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-1-139-44547-4 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Линденмайер, Дэвид Б.; Лавери, Тайрон; Шееле, Бен К. (01 декабря 2022 г.). «Почему нам нужно инвестировать в крупномасштабные долгосрочные программы мониторинга в области ландшафтной экологии и природоохранной биологии» . Текущие отчеты по ландшафтной экологии . 7 (4): 137–146. дои : 10.1007/s40823-022-00079-2 . hdl : 1885/312385 . ISSN 2364-494X . S2CID 252889110 .

- ^ Родригес-Гонсалес, Патрисия Мария; Альбукерке, Антониу; Мартинес-Альмарса, Мигель; Диас-Дельгадо, Рикардо (01 ноября 2017 г.). «Долгосрочный мониторинг для управления сохранением: уроки из тематического исследования, объединяющего дистанционное зондирование и полевые подходы в пойменных лесах» . Журнал экологического менеджмента . Пьеге и Ламуру «Расширение пространственных и временных масштабов для биофизической диагностики и устойчивого управления реками». 202 (Часть 2): 392–402. дои : 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.01.067 . ISSN 0301-4797 . ПМИД 28190693 .

- ^ Бургер, Джоанна (июль 2006 г.). «Биоиндикаторы: обзор их использования в экологической литературе 1970–2005 гг.» . Экологические биоиндикаторы . 1 (2): 136–144. дои : 10.1080/15555270600701540 . ISSN 1555-5275 .

- ^ Макдональд, Н. (2002). Руководство для учителей Frogwatch: лягушки как индикаторы здоровья экосистемы .

- ^ Бегазо, А. (2022). Птицы как индикаторы здоровья экосистемы . Проверено 14 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Суле, Майкл Э.; Терборг, Джон (октябрь 1999 г.). «Сохранение природы в региональном и континентальном масштабах — научная программа для Северной Америки» . Бионаука . 49 (10): 809–817. дои : 10.2307/1313572 . ISSN 1525-3244 . JSTOR 1313572 .

- ^ Чан, Кай, Массачусетс (2008). «Ценность и пропаганда природоохранной биологии: кризисная дисциплина или дисциплина в условиях кризиса?» . Биология сохранения . 22 (1): 1–3. дои : 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00869.x . ПМИД 18254846 .

- ^ «Красный список видов, находящихся под угрозой исчезновения» МСОП . Архивировано из оригинала 27 июня 2014 г. Проверено 20 октября 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вие, Дж.К.; Хилтон-Тейлор, К.; Стюарт, С.Н., ред. (2009). Дикая природа в меняющемся мире – анализ Красного списка исчезающих видов МСОП 2008 г. (PDF) . Гланд, Швейцария: МСОП. п. 180 . Проверено 24 декабря 2010 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Молнар, Дж.; Марвье, М.; Карейва, П. (2004). «Сумма больше частей». Биология сохранения . 18 (6): 1670–1. дои : 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00l07.x .

- ^ Гастон, Кей Джей (2010). «Оценка распространенных видов». Наука . 327 (5962): 154–155. Бибкод : 2010Sci...327..154G . дои : 10.1126/science.1182818 . ПМИД 20056880 . S2CID 206523787 .

- ^ Кернс, Кэрол Энн (2010). «Сохранение биоразнообразия» . Знания о природном образовании . 3 (10): 7.

- ^ «Центр биоразнообразия и охраны природы | AMNH» . Американский музей естественной истории . Проверено 29 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Удачи, Гэри В.; Дейли, Гретхен К.; Эрлих, Пол Р. (2003). «Разнообразие населения и экосистемные услуги». Тенденции в экологии и эволюции . 18 (7): 331–6. дои : 10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00100-9 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Карейва, Питер; Марвье, Мишель (2003). «Сохранение холодных точек биоразнообразия». Американский учёный . 91 (4): 344–51. дои : 10.1511/2003.4.344 .

- ^ Поссингем, Хью П.; Уилсон, Керри А. (август 2005 г.). «Усиление тепла в горячих точках» . Природа . 436 (7053): 919–920. дои : 10.1038/436919а . ISSN 1476-4687 .

- ^ Майерс, Норман; Миттермайер, Рассел А.; Миттермайер, Кристина Г.; да Фонсека, Густаво АБ; Кент, Дженнифер (2000). «Горячие точки биоразнообразия для приоритетов сохранения». Природа . 403 (6772): 853–8. Бибкод : 2000Natur.403..853M . дои : 10.1038/35002501 . ПМИД 10706275 . S2CID 4414279 .

- ^ Андервуд Э.К., Шоу М.Р., Уилсон К.А. и др. (2008). Сомерс М. (ред.). «Защита биоразнообразия, когда деньги имеют значение: максимизация рентабельности инвестиций» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 3 (1): e1515. Бибкод : 2008PLoSO...3.1515U . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0001515 . ПМК 2212107 . ПМИД 18231601 .

- ^ Леру С.Дж., Шмигелов ФК (февраль 2007 г.). «Согласование биоразнообразия и важность эндемизма». Консервировать. Биол . 21 (1): 266–8, обсуждение 269–70. дои : 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00628.x . ПМИД 17298533 . S2CID 1394295 .

- ^ Найду Р., Балмфорд А., Костанца Р. и др. (июль 2008 г.). «Глобальное картирование экосистемных услуг и приоритетов сохранения» . Учеб. Натл. акад. наук. США . 105 (28): 9495–500. Бибкод : 2008PNAS..105.9495N . дои : 10.1073/pnas.0707823105 . ПМЦ 2474481 . ПМИД 18621701 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Вуд CC, Gross MR (февраль 2008 г.). «Элементарные природоохранные единицы: информирование о риске исчезновения без указания целей защиты» (PDF) . Консервировать. Биол . 22 (1): 36–47. дои : 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00856.x . ПМИД 18254851 . S2CID 23211536 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 1 октября 2018 г. Проверено 5 января 2009 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Бег, SW (2008). «Изменение климата: нарушение экосистемы, углерод и климат». Наука . 321 (5889): 652–3. дои : 10.1126/science.1159607 . ПМИД 18669853 . S2CID 206513681 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Курц, Вашингтон; Даймонд, CC; Стинсон, Г.; Рэмпли, Дж.Дж.; Нилсон, ET; Кэрролл, Алабама; Эбата, Т.; Сафраньик, Л. (2008). «Горный сосновый жук и влияние лесного углерода на изменение климата». Природа . 452 (7190): 987–90. Бибкод : 2008Natur.452..987K . дои : 10.1038/nature06777 . ПМИД 18432244 . S2CID 205212545 .

- ^ Глобальный фонд охраны природы. Архивировано 16 ноября 2007 г. в Wayback Machine. Это пример финансирующей организации, которая исключает «холодные точки» биоразнообразия из своей стратегической кампании.

- ^ «Горячие точки биоразнообразия» . Архивировано из оригинала 22 декабря 2008 г.