Королевство Италия

Королевство Италия Королевство Италия ( итальянский ) | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1861–1946 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Девиз: ФЕРТ (Девиз Савойского дома ) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Гимн: (1861–1943; 1944–27 апреля 1946 г.) Королевский марш указов («Королевский марш постановлений») (1924–1943) Giovinezza ("Youth") (1943–1944; Apr 27 1946–2 June 1946) La Leggenda del Piave ("The Legend of Piave") | |||||||||||||||||||||

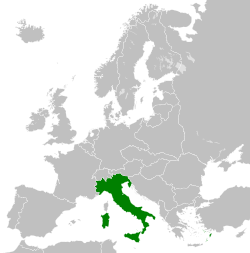

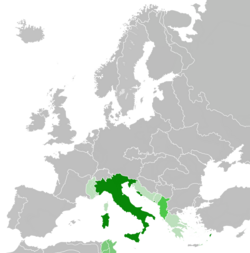

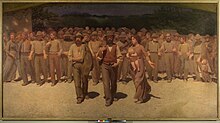

Colonies and territories held by the Italian Empire in 1939 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Largest city | Rome | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Italian | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | 96% Roman Catholicism (state religion) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Italian | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Unitary constitutional monarchy

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1861–1878 | Victor Emmanuel II | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1878–1900 | Umberto I | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1900–1946 | Victor Emmanuel III | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1946 | Umberto II | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1861 (first) | Count of Cavour | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1922–1943 | Benito Mussolini[a] | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1945–1946 (last) | Alcide De Gasperi[b] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 March 1861 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 October 1866 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 September 1870 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 May 1882 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 26 April 1915 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 28 October 1922 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 May 1939 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 27 September 1940 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 25 July 1943 | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Republic | 10 June 1946 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1861[1] | 250,320 km2 (96,650 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1936[1] | 310,190 km2 (119,770 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1861[1] | 21,777,334 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1936[1] | 42,993,602 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| GDP (PPP) | 1939 estimate | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Total | 151 billion (2.82 trillion in 2019) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Lira (₤) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Королевство Италия ( итал . Regno d'Italia , Итальянский: [ˈreɲɲo diˈtaːlja] ) — государство, существовавшее с 17 марта 1861 года, когда Виктор Эммануил II Сардинии вопросу был провозглашен королём Италии , до 10 июня 1946 года, когда монархия была упразднена в результате гражданского недовольства, которое привело к институциональному референдуму по 2 июня 1946 года . В результате возникла современная Итальянская республика . Королевство было создано путем объединения нескольких государств в ходе многолетнего процесса, получившего название Рисорджименто . На этот процесс повлияло Савойей возглавляемое Королевство Сардиния Италии , которое было одним из правовых государств-предшественников .

In 1866, Italy declared war on Austria in alliance with Prussia and, upon its victory, received the region of Veneto. Italian troops entered Rome in 1870, ending more than one thousand years of Papal temporal power. In the last two decades of the 19th century, Italy developed into a colonial power, and in 1882 it entered into a Triple Alliance with the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, following strong disagreements with France about their respective colonial expansions. Although relations with Berlin became very friendly, the alliance with Vienna remained purely formal, due in part to Italy's desire to acquire Trentino and Trieste from Austria-Hungary. As a result, Italy accepted the British invitation to join the Allied Powers during World War I, as the western powers promised territorial compensation (at the expense of Austria-Hungary) for participation that was more generous than Vienna's offer in exchange for Italian neutrality. Victory in the war gave Italy a permanent seat in the Council of the Лигу Наций , но она не получила всех обещанных территорий .

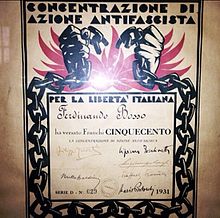

In 1922, Benito Mussolini became prime minister of Italy, ushering in an era of National Fascist Party government known as "Fascist Italy". Totalitarian rule was enforced, crushing all political opposition while promoting economic modernization, traditional values, and territorial expansion. In 1929, the Italian government reconciled with the Roman Catholic Church through the Lateran Treaties, which granted independence to the Vatican City. The following decade presided over an aggressive foreign policy, with Italy launching successful military operations against Ethiopia in 1935, Spain in 1937, and Albania in 1939. This led to economic sanctions, departure from the League of Nations, growing economic autarky, and the signing of military alliances with Germany and Japan.

Fascist Italy entered World War II as a leading member of the Axis Powers in 1940 and despite initial success, was defeated in North Africa and the Soviet Union. Allied landings in Sicily led to the fall of the Fascist regime and the new government surrendered to the Allies in September 1943. German forces occupied northern and central Italy, established the Italian Social Republic, and reappointed Mussolini as dictator. Consequentially, Italy descended into civil war, with the Italian Co-belligerent Army and resistance movement contending with the Social Republic's forces and its German allies. Shortly after the surrender of all fascist forces in Italy, civil discontent prompted an institutional referendum, which established a republic and abolished the monarchy in 1946.

Overview

[edit]Territory

[edit]

The Kingdom of Italy covered and at times exceeded the land area of present-day Italy. The Kingdom gradually extended its area through the Italian unification until 1870. In 1919 it annexed Trieste and Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol. The Triple Entente promised to grant to Italy – if the state joined the Allies in World War I – several regions, including former Austrian Littoral, western parts of former Duchy of Carniola, Northern Dalmatia and notably Zara, Šibenik and most of the Dalmatian islands (except Krk and Rab), according to the secret London Pact of 1915.[2]

After the refusal by President Woodrow Wilson to acknowledge the London Pact and the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, with the Treaty of Rapallo in 1920 Italian claims on Northern Dalmatia were abandoned. During World War II, the Kingdom gained additional territory in Slovenia (province of Lubiana) and Dalmatia (Governatorate of Dalmatia) from Yugoslavia after its breakup in 1941.[3]

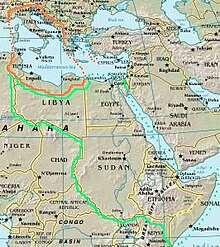

The Kingdom established and maintained until the end of World War II colonies, protectorates, military occupations and puppet states beyond its borders. These included Eritrea, Italian Somaliland, Libya, Ethiopia (annexed by Italy from 1936 to 1941), Albania (an italian protectorate since 1939), British Somaliland, part of Greece, Corsica, southern France with Monaco, Tunisia, Kosovo and Montenegro (all territories occupied in World War II) Croatia (Italian and German client state in World War II), and a 46-hectare concession from China in Tianjin (see Italian concession in Tianjin).[4] These foreign colonies and lands came under Italian control at different times and remained so over different periods.

Government

[edit]

The Kingdom of Italy was a constitutional monarchy. Executive power belonged to the monarch, who governed through appointed ministers. The legislative branch was a bicameral Parliament comprising an appointive Senate and an elective Chamber of Deputies. The kingdom maintained as its constitution the Statuto Albertino, the governing document of the Kingdom of Sardinia. In theory, ministers were responsible solely to the king. However, by this time, a king couldn't appoint a government of his choosing or keep it in office against the express will of Parliament.

Members of the Chamber of Deputies were elected through a plurality voting system in single-member districts. A candidate needed the support of 50% of votes and 25% of all enrolled voters to be elected in the first round of ballots. Seats not adjudicated on the first ballot, were filled through a runoff held shortly after the first ballots. In addition to this, there was a Council of State, which had consultative powers and decided on conflicts of jurisdiction between administrative authorities and courts, as well as on disputes between the state and its creditors. It consisted of a president, three section presidents, 24 councilors of state and the service staff, and was appointed by the king on the proposal of the Council of Ministers.

There was brief experimentation in 1882 with multi-member districts, and after World War I proportional representation was introduced with large, regional, multi-seat electoral constituencies. The Socialists became the major party, but were unable to form a government in a parliament split among the three factions of Socialists, Christian populists, and classical liberals. Elections took place in 1919, 1921 and 1924: on this last occasion, Mussolini abolished proportional representation, replacing it with the Acerbo Law, by which the party that won the largest share of votes got two-thirds of the seats, which gave the Fascist Party an absolute majority of the Chamber seats.

Between 1925 and 1943, Italy was a quasi-de jure Fascist dictatorship, as the constitution formally remained in effect without alteration while the monarchy formally accepted Fascist policies and institutions. In 1928 the Grand Council of Fascism took control of government administration, and in 1939 the Chamber of Fasces and Corporations replaced the Chamber of Deputies.

The highest state administration was divided into the following ministries, with their headquarters in Rome:

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (with the Council for Diplomatic Disputes)

- Ministry of the Interior (with the Supreme Health Council)

- Ministry of Mercy, Justice and Religious Affairs

- Ministry of Finance and Treasury

- Ministry of War (the committees for the General Staff, the Line Arms, the Royal Carabiniers, for Artillery and Engineering, for Military Health and the Supreme War and Naval Tribunal are subordinate to it)

- Ministry of the Navy (with the Supreme Navy Council)

- Ministry of Public Education (with the Higher Education Council)

- Ministry of Public Works (with the Higher Council for Public Works and the Railway Council)

- Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade (with the Mining Council and the Central Statistical Giunta)

- Ministry of Colonies (since 1937 Ministry for Italian Africa)

- Ministry for the Liberated Territories (for the territories occupied and annexed after the First World War)

- Ministry of Transport

- Ministry of Aviation

- Ministry of Education

- Ministry of Post and Telegraph

- Ministry of Labour

- Ministry of Agriculture

Due to the war, a number of other short-lived ministries were created during the First and Second World War.

The Court of Auditors of the Kingdom had an independent status.

Military structure

[edit]- King of Italy – supreme commander of the Italian Royal Army, Navy and later Air Force from 1861 to 1938 and 1943 to 1946

- First Marshal of the Empire – supreme commander of the Italian Royal Army, Air Force, Navy and the Voluntary Militia for National Security from 1938 to 1943 during the Fascist era, held by both Victor Emmanuel III and Benito Mussolini

- Regio Esercito (Royal Italian Army)

- Regia Marina (Royal Italian Navy)

- Regia Aeronautica (Royal Italian Air Force)

- Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale (Voluntary Militia for National Security also known as the "MVSN" or "Blackshirts") – militia loyal to Mussolini during the Fascist era, abolished in 1943.

Monarchs

[edit]

The King of Italy was formally the holder of state power, but he could only exercise the right of legislation in conjunction with the national parliament, and the government was de facto responsible to parliament. According to the Salic Law, the throne was inherited in the male line of the royal House of Savoy. The king and his house professed allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church. He came of age at the age of 18 and, upon assuming power, took an oath to the constitution in the presence of both chambers. According to the law of March 17, 1861, his title was: "By the grace of God and by the will of the nation, King of Italy and King of Albania (only from 1939 to 1943) and Emperor of Ethiopia (only from 1936 to 1943)". He awarded the five Orders of Knighthood of Savoy and exercised constitutional sovereign rights. He commanded the land, sea and air power; he declared wars, concluded peace, alliance, trade and other treaties, of which only those that entailed a burden on finances or a change in territory required the approval of the chambers to be effective. The king appointed to all state offices, sanctioned and promulgated the laws, which as well as the government acts had to be countersigned by the responsible ministers, and issued the decrees and regulations necessary for the execution of the laws. Justice was administered in his name, and he alone had the pardon and mitigation of punishment.

| # | Image | Name (Dates) | Period of rule | Monogram | Coats of arms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Begin | End | |||||

| 1 |  | Victor Emmanuel II Father of the Fatherland (1820–1878) | March 17 1861 | January 9 1878 |  |   |

| 2 |  | Umberto I the Good (1844–1900) | January 9 1878 | July 29 1900 |  |   |

| 3 |  | Victor Emmanuel III the Soldier King (1869–1947) | July 29 1900 | May 9 1946 |  |   |

| 4 |  | Umberto II the May King (1904–1983) | May 9 1946 | June 12 1946 |  |  |

State symbols

[edit]The first state coat of arms of the kingdom was adopted from Sardinia-Piedmont. It included the coat of arms of the House of Savoy in the middle and four Italian flags dating from 1848.

On May 4, 1870, by royal decree, two lions in gold, which now carried the shield, a crowned knight's helmet, which bore the Military Order of Savoy, the Order of the Crown of Italy, the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus and the Order of the Annunciation around its collar, were added. The motto FERT was deleted. The lions carried lances that held the national flag. From the helmet fell a royal cloak, which was supposed to protect the nation. Above the coat of arms was the star of Italy (Italian Stella d’Italia).

The newly adopted national coat of arms of 1 January 1890 removed the fur coat and the lances and the crown on the helmet was replaced by the Iron Crown of the Lombards. The whole group stood under a canopy, crowned with the Italian royal crown, above which was the banner of Italy. The flagpole was carried by a golden crowned eagle.

On 11 April 1929, Mussolini replaced the two Savoy lions with lictor's bundles. Only after his dismissal in 1944 was the old coat of arms from 1890 restored.

History

[edit]Unification process (1848–1870)

[edit]

The birth of the Kingdom of Italy was the result of efforts by Italian nationalists and monarchists loyal to the House of Savoy to establish a united kingdom encompassing the entire Italian Peninsula. Following the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the political and social Italian unification movement, or Risorgimento, emerged to unite Italy consolidating the different states of the peninsula and liberate it from foreign control. A prominent radical figure was the patriotic journalist Giuseppe Mazzini, member of the secret revolutionary society of Carbonari and founder of the influential political movement Young Italy in the early 1830s. Mazzini favoured a unitary republic and advocated a broad nationalist movement. His prolific output of propaganda helped to spread the unification movement.

The most famous member of Young Italy was the revolutionary and general Giuseppe Garibaldi, renowned for his extremely loyal followers,[5] who led the Italian republican drive for unification in Southern Italy. However, the Northern Italy monarchy of the House of Savoy in the Kingdom of Sardinia, whose government was led by Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, also had ambitions of establishing a united Italian state. In the context of the 1848 liberal revolutions that swept through Europe, an unsuccessful First Italian War of Independence, led by King Charles Albert of Sardinia, was declared on Austria. In 1855, the Kingdom of Sardinia became an ally of Britain and France in the Crimean War, giving Cavour's diplomacy legitimacy in the eyes of the great powers.[6][7] The Kingdom of Sardinia again attacked the Austrian Empire in the Second Italian War of Independence of 1859, with the aid of France, resulting in liberating Lombardy. On the basis of the Plombières Agreement, the Kingdom of Sardinia ceded Savoy and Nice to France, an event that caused the Niçard exodus, that was the emigration of a quarter of the Niçard Italians to Italy.[8]

In 1860–1861, Garibaldi led the drive for unification in Naples and Sicily (the Expedition of the Thousand),[11] while the House of Savoy troops occupied the central territories of the Italian peninsula, except Rome and part of Papal States. Teano was the site of the famous meeting of 26 October 1860 between Giuseppe Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel II, last King of Sardinia, in which Garibaldi shook Victor Emanuel's hand and hailed him as King of Italy; thus, Garibaldi sacrificed republican hopes for the sake of Italian unity under a monarchy. Cavour agreed to include Garibaldi's Southern Italy allowing it to join the union with the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1860. This allowed the Sardinian government to declare a united Italian kingdom on 17 March 1861.[12] Victor Emmanuel II then became the first king of a united Italy, and the capital was moved from Turin to Florence. The title of "King of Italy" had been out of use since the abdication of Napoleon I of France on 6 April 1814.

Following the unification of most of Italy, tensions between the royalists and republicans erupted. In April 1861, Garibaldi entered the Italian parliament and challenged Cavour's leadership, accusing him of dividing Italy, and threatened a civil war between the Kingdom in the North and his forces in the South. On 6 June 1861, the Kingdom's strongman Cavour died. During the ensuing political instability, Garibaldi and the republicans became increasingly revolutionary in tone. Garibaldi's arrest in 1862 set off worldwide controversy.[13]

In 1866, Otto von Bismarck, Minister President of Prussia, offered Victor Emmanuel II an alliance with the Kingdom of Prussia in the Austro-Prussian War. In exchange, Prussia would allow Italy to annex Austria-controlled Veneto. King Emmanuel agreed to the alliance, and the Third Italian War of Independence began. Italy fared poorly in the war with a badly-organized military against Austria, but Prussia's victory allowed Italy to annex Veneto. At this point, one major obstacle to Italian unity remained: Rome.

In 1870, Prussia went to war with France, igniting the Franco-Prussian War. To keep the large Prussian Army at bay, France abandoned its positions in Rome – which protected the remnants of the Papal States and Pius IX – to fight the Prussians. Italy benefited from Prussia's victory against France by taking over the Papal States from French authority. The Kingdom of Italy captured Rome after several battles and guerrilla-like warfare by Papal Zouaves and official troops of the Holy See against the Italian invaders. Italy's unification was completed and its capital moved to Rome. Victor Emmanuel, Garibaldi, Cavour, and Mazzini are remembered as Italy's Four Fathers of the Fatherland.[9]

Garibaldi was elected in 1871 in his home city of Nice to the French National Assembly, where he tried to promote the cession of the city from France to the newborn Italian unitary state. He was prevented from speaking,[14] which led the Garibaldini to riots called the "Niçard Vespers".[15][16] Fifteen of the Nice rebels were tried and sentenced.[17]

Economic conditions in united Italy were poor.[18] The country lacked industry and transportation facilities, and suffered from extreme poverty (especially in the Mezzogiorno) and high illiteracy. Only a small wealthy elite had the right to vote. The unification movement relied largely on foreign powers' support and continued to do so afterwards. Following the capture of Rome in 1870 from French forces of Napoleon III, Papal troops, and Zouaves, relations between Italy and the Vatican remained sour for the next sixty years, with the Popes declaring themselves to be prisoners in the Vatican. The Roman Catholic Church frequently protested the anti-clerical actions of the secular Italian governments, refused to meet with envoys from the King, and urged Roman Catholics not to vote in Italian elections.[19] Not until 1929 was the Roman question resolved and positive relations restored between the Kingdom of Italy and the Vatican, after the signing of the Lateran Pacts.

Some of the states that had been targeted for unification (terre irredente), Trentino-Alto Adige and the Julian March, did not join the Kingdom of Italy until 1918 after Italy defeated Austria-Hungary in the First World War. For this reason, historians sometimes describe the unification period as continuing past 1871, including activities during the late 19th century and the First World War (1915–1918), and reaching completion only with the Armistice of Villa Giusti on 4 November 1918. This more expansive view of the unification is presented at the Central Museum of the Risorgimento.[20][21]

Unifying multiple bureaucracies

[edit]

A major challenge for the prime ministers of the new Kingdom of Italy was integrating the political and administrative systems of the seven different major components under a unified set of policies. The different regions were proud of their traditions and could not easily be fitted into the Sardinian model. Cavour started planning for integration, but died before it was fully developed – indeed, the challenge is thought to have hastened his death. The regional administrative bureaucracies followed the Napoleonic precedent, so their harmonization was relatively straightforward. The next challenge was to develop a parliamentary legislative system. Cavour and most liberals up and down the peninsula highly admired the British system, which became the model for Italy.

Harmonizing the Army and Navy was much more complex, chiefly because the systems of recruiting soldiers and selecting and promoting officers were so different and grandfathered exceptions to the general system persisted for decades. The disorganization helps explain the dismal performance of the Italian navy in the 1866 war.

Uniformizing the diverse education systems also proved complicated. Shortly before his death, Cavour appointed Francesco De Sanctis as minister of education, an eminent scholar from the University of Naples who proved an able and patient administrator. The addition of Veneto in 1866 and Rome in 1870 further complicated the challenges of bureaucratic coordination.[22]

Economy

[edit]

Italy has a long history of different coinage types. Italian unification highlighted the confusion of the pre-unification Italian monetary system which was mostly based on silver monometallism and therefore in contrast with the gold monometallism in force in the Kingdom of Sardinia and in the major European nations.[23] To reconcile the various monetary systems it was decided to opt for bimetallism, taking inspiration from the French franc model, from which the dimensions of the coins and the exchange rate of 1 to 15.50 between gold and silver were taken. The Italian monetary system, however, differed from the French one in two aspects: silver coins could be exchanged in unlimited quantities with the State, but limited quantities between private individuals and it was decided to mint coins that nominally had 900‰ fine silver, but which in fact they contained 835‰ so as to approach the real exchange rate between gold and silver which was approximately 1 to 14.38.[24] Exactly four months after the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, the government introduced the new national currency, the Italian lira. The legal tender of the new currency was established by the Royal Decree of 17 July 1861 which specified the exchange of pre-unification coins into lire and the fact that local coins continued to be legal tender in their respective provinces of origin.[25]

In the entire period from 1861 to 1940, Italy experienced considerable economic growth despite several economic crises and the First World War. Unlike most modern nations, where industrialization was undertaken by large corporations, industrial growth in Italy was mostly due to small and medium-sized family businesses.

Political unification did not automatically bring about economic integration, because of the sharp contrasts in culture, politics, and economic practices among the various regions. Italy managed to industrialize in several steps, although the country remained the most backward economy among the great powers (except for the Russian Empire) and was very dependent on foreign trade, especially the international markets through which it imported coal and exported grain.

After unification, Italy had a predominantly agricultural society, with 60 percent of the labor force employed in agriculture. Advances in technology increased export opportunities for Italian agricultural produce after a period of crisis in the 1880s. With industrialization, the proportion employed in agriculture fell below 50% around the turn of the century. However, not everyone benefited from these developments, as southern agriculture in particular suffered from the hot arid climate, while in the north malaria hampered cultivation of low-lying areas on the Adriatic coast.

The government's focus on foreign and military policy in the early years of the state led to the neglect of agriculture, which declined after 1873. The Italian parliament initiated an investigation in 1877, which lasted eight years and blamed the lack of mechanization and modern farming techniques, and the failure of landowners to develop their lands. In addition, most farm laborers were temporary inexperienced short-term workers (braccianti). Farmers without a steady income were forced to subsist on meager food. Disease spread rapidly and a major cholera epidemic killed at least 55,000 people. Government action was blocked by strong political and economic opposition from the large landowners. Another commission of inquiry in 1910 found similar problems.

Around 1890 there was also an overproduction crisis in the Italian wine industry, almost the only successful sector in agriculture. In the 1870s and 1880s, viticulture in France suffered from a crop failure caused by insects, and Italy became the largest wine exporter in Europe. After France's recovery in 1888, Italian wine exports collapsed, causing a wave of unemployment and bankruptcies.

From the 1860s, Italy invested heavily in the development of railways, with its rail network more than tripling between 1861 and 1872, then doubling again by 1890. Gio. Ansaldo & C. from the former Kingdom of Sardinia provided the first Italian built locomotives with the FS Class 113 and the later FS Class 650. The first railway section on the island of Sicily was inaugurated on 28 April 1863 with the Palermo–Bagheria line. By 1914 the Italian railway had around 17,000 km of railways.

During the Fascist dictatorship, enormous sums were invested in new technological achievements, especially in military technology. But large sums of money were also spent on prestige projects such as the construction of the new Italian ocean liner SS Rex, which set a transatlantic sea voyage record of four days in 1933, and the development of the seaplane Macchi-Castoldi M.C.72, which was the world's fastest seaplane in 1933. In 1933, Italo Balbo completed a flight across the Atlantic in a seaplane to the World's Fair in Chicago. The flight symbolized the power of the Fascist leadership and the industrial and technological progress the state had made under the Fascists.

| Measure | 1861 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1945 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP in billion US dollars | 37.995 | 41.814 | 46.690 | 52.863 | 60.114 | 85.285 | 96.757 | 119.014 | 155.424 | 114.422 |

Industrialization

[edit]

During the 1860s and 1870s, Italian manufacturing was backward and small-scale, while the oversized agrarian sector was the backbone of the national economy. The country lacked large coal and iron deposits.[28] In the 1880s, a severe farm crisis led to the introduction of more modern farming techniques in the Po Valley,[29] while from 1878 to 1887 protectionist policies were introduced with the aim of establishing a base of heavy industry.[30]

In the 1880s industrialisation moved into high gear, which lasted until 1912/13 and reached its peak under Giolitti. Industrial plants soon clustered around areas of hydropower energy.[31] Between 1887 and 1911 hydroelectricity became the main source of energy, with over sixty plants constructed.[32] From 1881 to 1887, Italy's textile, mechanical, steel, iron, and chemical industries grew by an average 4.6 percent annually.[33] The backbone of the industrial boom was, next to the labor force, institutions of higher learning such as the Politecnico founded in Milan in 1863 by Francesco Brioschi and the Technical School for Engineers in Turin established four years earlier.

Steelworks were established with state and private capital, notably from the Credito Mobiliare: in 1884 in Terni and in 1897 in Piombino using iron-ore from Elba. The relative backwardness of the south continued to be a central problem for the state. Various solutions were proposed for the so-called "southern question" by Francesco Saverio Nitti, Gaetano Salvemini and Sidney Sonnino, but the government only acted in special problem areas such as Naples.[34] The ILVA group of Genoa, with the political and financial backing of the Italian state, built the Bagnoli steel plant as part of the 1904 law for the development of Naples, prepared by economist and later prime minister Nitti. In 1898, in order to make the steel-industry completely independent from foreign coal imports, the Neapolitan engineer Ernesto Stassano invented the Stassano furnace, the first indirect-arc electric furnace. By 1917, Italian iron and steel plants operated 88 indirect-arc furnaces, manufactured by Stassano, Bassanese and Angelini.[35]

In 1899 the automobile industry commenced when Giovanni Agnelli bought the designs and patents of the Ceirano brothers and founded the Fiat automobile works. In 1906 another automobile factory was built in the Portello district of Milan for the French entrepreneur Alexandre Darracq and the headquarters of his Italian branch Società Anonima Italiana Darracq. In 1910, the company brought the first successful model onto the market with the 24 HP and the brand name ALFA on the radiator grille. While automobiles were only affordable by few its popularity and fascination rose rapidly, and one of the first sports car racing events in the world, the Targa Florio, held annually in the mountains of Sicily was established in 1906.

In the financial sector, Prime Minister Giolitti was mainly concerned with increasing pensions and restructuring the state budget, though proceeding with great caution. The government secured the support of large companies and banks. Most criticism the project came from conservatives, with a majority of the public supporting the soundness of public finances. The state budget, which from 1900 had an annual income of around 50 million lire, was to be additionally strengthened by the nationalization of the railways.

In March 1905, after serious labor unrest among railroad workers, Giolitti resigned due to illness, and suggested his fellow party member Alessandro Fortis to the king as his successor. On March 28, Victor Emmanuel III appointed Fortis as the new prime minister, making him the first Jewish head of government worldwide. With Law 137 of April 22, 1905, he sanctioned the nationalization of the railways through a public recruitment process under the control of the Court of Audit and the supervision of the Ministries of Public Works and Finance. At the same time, the telephone system was nationalized.[36] The Fortis government remained in office until the beginning of 1906. It was followed from February 8 to May 29 by a brief government under Sidney Sonnino. Finally, Giolitti entered his third term. In this he dealt mainly with the economic situation in southern Italy, due both to long-term demographic and economic factors, as well as natural disasters such as the eruption of Vesuvius in 1906 and the earthquake in Messina, Calabria, and Palmi in 1908. Entire villages were depopulated and centuries-old regional cultures disappeared.[36] Nevertheless, there was a slight economic upswing in the south afterwards. The government, which had initially discouraged emigration to avoid labor shortages, now gave its approval to the emigration of hundreds of thousands of Italians from the south. This was motivated by fear of increasing social tensions and monetary instability.

In 1906 the government lowered the national interest tax rate from 5% to 3.75%. This move eased the burden on the state's required finances, reduced the fears of state bondholders, and encouraged the growth of heavy industry. The subsequent budget surplus made it possible to finance major government work projects which massively reduced unemployment, such as the completion of the Simplon Tunnel in 1906. Shortly after the railway began its triumphal march through Switzerland, each region wanted its own north-south connection and with the construction of the railway tunnels on the Gotthard 14,998 km (1872–1880), Simplon 19,803 km (1898–1906) and Lötschberg 14,612 km (1907–1913), three major Alpine crossings were realized that were important for Switzerland and neighboring European countries. The workforce of these monumental projects were largely Italians: at the Gotthard tunnel 90% of miners came from northern Italy, while at the Lötschberg tunnel 97% were Italian, chiefly from the south.

In addition to the now completed nationalization of the railways, the planned nationalization of insurance was tackled and thetrade war with France, which had lasted since 1887, ended. Giolitti thereby interrupted Crispi's pro-German foreign policy and thus enabled the export of fruit, vegetables and wine to France. He also boosted the cultivation of sugar beets and their processing in the Po Valley and encouraged heavy industry to gain a foothold in the south as well. However, the latter was not very successful. In 1908, some laws limiting working hours for women and children up to 12 hours were passed with the support of the Socialist MPs.[36] Special laws for the disadvantaged regions of the south followed. However, their implementation mostly failed due to the resistance of the large landowners. Nevertheless, there was a significant improvement in the economic situation of smallholders.

In 1911, 55.4% of the Italian population worked in agriculture and 26.9% in industry.[37]

- The Terni steel plant est. 1884 (picture of 1912)

- Hydroelectric plant on the Adda river built in 1906

- Monument in memory of the workers that died mining the Simplon Tunnel, next to the Iselle di Trasquera railway station, dated 29 May 1905

Social changes and mass emigration

[edit]

Strong social tensions came to light, Italy's social legislation took last place in Europe,[38] the socialists were opposed not only to social policy but also to colonial expansion. Prime Minister Francesco Crispi financed the colonial policy with tax increases and austerity measures. The internal political differences culminated in the Bava Beccaris massacre in Milan. There, on May 7, 1898, there were mass demonstrations against rising bread prices. General Fiorenzo Bava-Beccaris, after the state of siege was declared, fired artillery and rifles at the crowd.[39] Depending on the information, between 82 and 300 people were killed.[40][41] King Umberto I congratulated the general in a telegram and awarded him a medal. This made him enemies, and in 1900 he, who had been king for 22 years, was shot in Monza by the anarchist Gaetano Bresci.

His successor was Victor Emmanuel III politically dominant however was Giolitti, who was initially Minister of the Interior from 1901 to 1903, then prime minister from 1903 with interruptions until 1914 (and often also Minister of the Interior at the same time). He dominated or shaped Italian politics to such an extent that one speaks of the Giolitti era. He was willing to make concessions to the reformist and revolutionary movements and promoted industrialization. It is true that state subsidies for private health insurance were introduced in 1886 and the first compulsory accident insurance was introduced in 1898,[42] but it was Giolitti that introduced state social insurance in 1912 based on the German model. He also reformed the right to vote so that there were no more property limits and the number of eligible voters rose to 8 million men. Unemployment insurance came into being as early as 1919, eight years before Germany.[43]

In the 1880s there were serious industrial disputes, and around 1889 repression against the Partito Operaio (Labour Party) began, so that the aim was to unite all socialist organizations in the country in one party. The Fasci Siciliani, short for "Fasci siciliani dei lavoratori", Italian Sicilian Workers' Union was perceived as the "first act of Italian socialism". The movement, led by Prime Minister Crispi, was crushed after harsh military operations. The industrial workers managed to organize in 1892 in the Partito dei Lavoratori Italiani (Italian Workers' Party), which in 1893 was renamed Partito Socialista Italiano (Italian Socialist Party). Prime Minister Francesco Crispi pushed through exceptional laws against the Socialists from 1894, but they were ultimately unsuccessful. In 1901 his successor Giovanni Giolitti tried to integrate the party, which had won 32 seats in the elections, into the government, but the latter refused. But from 1908 to 1912 there was cooperation with the bourgeois left until radical syndicalism prevailed. In 1912 the Partito Socialista Riformista Italiano split off, which for patriotic reasons agreed to the War against the Ottomans. In 1917, the majority of socialist deputies became pro-war, but the party leadership continued to oppose the war.

| Measure | 1861 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1946 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population in millions | 22.182 | 25.766 | 28.437 | 30.947 | 32.475 | 34.565 | 37.837 | 40.703 | 43.787 | 45.380 |

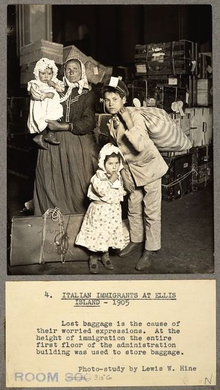

The state reaction to the drastic social changes came very late, because the social elites, landowners in the south and industrialists in the north, refused for a long time and often relied on the work of the church, which had dominated the social systems since the Middle Ages. However, it was no longer supported by an adequate municipal or guild system. The population of Italy increased from 18.3 million in 1800 to 24.7 in 1850, finally to 33.8 in 1900.[45] Nevertheless, Italy's share of the population of Europe continued to fall. On the one hand, this was due to its developmental deficit and, on the other hand, to the fact that from about 1852 there was a large-scale mass emigration. By 1985, around 29 million people had been recorded. From 1876 to around 1890, most came from the north, especially from Venetia (17.9%), Friuli-Venezia Giulia (16.1%) and Piedmont (12.5%). After that, Italians from the south increasingly emigrated. From 1876 to 1915, more than 14 million people emigrated chiefly for south and north America, of which 8.3 million came from the northern half, including 2.7 million alone from the northeast and from the southern half 5.6 million emigrated.[46] The main destinations were the United States of America, in which the descendants of the Italians (Italian Americans) today represent the third largest European immigrant group after Germans and Irish with a population share of 6%, along with Argentina (Italian Argentines), Brazil (Italian Brazilians) and Uruguay (Italian Uruguayans). Many also emigrated to Canada, Australia and other Latin American countries.

The main reason for emigration was widespread poverty, especially among the rural population. Up until the 1950s, parts of Italy remained a rural, agrarian, and pre-modern society, with agricultural conditions not suitable for keeping farmers in the country, particularly in the northeast and south.[47] The extent of emigration can be explained on the one hand by the decline of agriculture and the sharp conflicts, which were exacerbated by the preservation of old structures and the lack of capital as well as by large landowners and half-tenancy. At the same time, the hesitant industrialization in the fast-growing cities hardly offered enough jobs. In addition, domestic consumption was low, especially since the fiscalism that was believed to be necessary to expand infrastructure continued to weigh on incomes. After all, the companies were equipped with only little capital compared to the foreign ones. Therefore, the government set up high tariff barriers from 1878 to 1887 and pursued a protectionist policy intended to protect the still weak textile and heavy industry in the development phase. France in turn responded to the protective tariff policy with corresponding counter-tariffs.

While industrialization was promoted and infrastructure expanded in the north, the government in the south supported the latifundia, whereby in both cases the protagonists of heavy industry and agriculture were able to assert their influence in the north and south. In central Italy there was a different system for the peasants. Land could be leased here and they could keep a relatively large amount, so there was less migration from this part of the country than from other parts. There was less migration from large cities, but there was a major exception to this. Naples was the capital of the Kingdom of Naples and later of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies for six hundred years and in 1861 became simply a city in the united Italy. As a result, many bureaucratic jobs were lost and there was a lot of unemployment. Due to a cholera epidemic in the 1880s, many people also decided to leave the city. In the south the unification abolished the feudal system that had survived since the middle ages. However, this did not mean that the farmers now got their own land that they could work on. Many remained without property and plots became smaller and smaller and thus more unproductive after lands were divided among heirs. Another reason was the overpopulation, especially in the south (Mezzogiorno). After unification southern Italy established access to running water and medical care in hospitals for the first time. This reduced infant mortality and, together with what had been the highest birth rate in Europe for a long time, led to an increase in population, which in turn forced many young southern Italians to emigrate at the beginning of the 20th century.

Currency policy caused major problems, because during the Franco-Prussian War Italy also suspended free convertibility. Now the gold standard prevailed, which ensured that banknotes could only be issued in a fixed proportion to the gold reserves. It was expected that this would stabilize currency relations through the gold automatism, whereby the respective central banks had to adhere to strict rules. If a currency became weaker, this led to a gold outflow in the direction of the stronger currency, with the result that the banknote issue had to be reduced in line with the reduced gold reserves. This raised interest rates and lowered prices. In contrast, in the country where gold was flocking, this created more paper money in circulation, lowering interest rates and raising prices. At a certain point, the flow of gold reversed, the balance of payments settled, and the currency stabilized. Even if the central banks often did not comply with the guidelines, the system was successful because people trusted that money and gold could be exchanged at any time. By linking the Latin Monetary Union, founded in 1865 and based on bimetallism, i.e. gold and silver coins, and thus the lira to gold, the government was able to create so much trust that foreign investment capital after Italy came. Treasury Secretary Sidney Sonnino also tried to put a strain on large fortunes in the same way as consumption was put under pressure, but he failed due to conservative opposition. With the overcoming of the economic crisis from 1896, it was nevertheless possible to achieve a balanced budget.

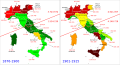

- Italian emigration per region from 1876 to 1900 and from 1901 to 1915

- Map of the Italian diaspora in the world

Southern question and Italian diaspora

[edit]Italy's population remained severely divided between wealthy elites and impoverished workers, especially in the South. An 1881 census found that over 1 million southern day-laborers were chronically under-employed and likely to become seasonal emigrants to sustain themselves economically.[48] Southern peasants, as well as small landowners and tenants, often were in a state of conflict and revolt throughout the late 19th century.[49] There were exceptions to the generally poor economic condition of agricultural workers of the South, as some regions near cities such as Naples and Palermo as well as along the Tyrrhenian Sea coast.[48] From the 1870s onward, intellectuals, scholars and politicians examined the economic and social conditions of Southern Italy (Il Mezzogiorno), a movement known as Meridionalismo ("Meridionalism"). For example, the 1910 Commission of Inquiry into the South indicated that the Italian government thus far had failed to ameliorate the severe economic differences. The limited voting rights only to those with sufficient property allowed rich landowners to exploit the poor.[50]

The transition from a peninsula divided into several states to a unified Italy was not smooth for the south (the Mezzogiorno). The path to unification and modernization created a divide between Northern and Southern Italy. People condemned the South for being "backwards" and barbaric, when in truth, compared to Northern Italy, "where there was backwardness, the lag, never excessive, was always more or less compensated by other elements".[51] Of course, there had to be some basis for singling out the South like Italy did. The entire region south of Naples was afflicted with numerous deep economic and social liabilities.[52] However, many of the South's political problems and its reputation of being "passive" or lazy (politically speaking) was due to the new government (that was born out of Italy's want for development) that alienated the South and prevented the people of the South from any say in important matters. However, on the other hand, transportation was difficult, soil fertility was low with extensive erosion, deforestation was severe, many businesses could stay open only because of high protective tariffs, large estates were often poorly managed, most peasants had only very small plots, and there was chronic unemployment and high crime rates.[53]

Cavour decided the basic problem was poor government, and believed that could be remedied by strict application of the Piedmonese legal system. The main result was an upsurge in brigandage, which turned into a bloody civil war that lasted almost ten years. The insurrection reached its peak mainly in Basilicata and northern Apulia, headed by the brigands Carmine Crocco and Michele Caruso.[54] With the end of the southern riots, there was a heavy outflow of millions of peasants in the Italian diaspora, especially to the United States and South America. Others relocated to the northern industrial cities such as Genoa, Milan and Turin, and sent money home.[53]

The first Italian diaspora began around 1880, two decades after the Unification of Italy, and ended in the 1920s to the early 1940s with the rise of Fascist Italy.[55] Poverty was the main reason for emigration, specifically the lack of land as mezzadria sharecropping flourished in Italy, especially in the South, and property became subdivided over generations. Especially in Southern Italy, conditions were harsh.[55] Until the 1860s to 1950s, most of Italy was a rural society with many small towns and cities and almost no modern industry in which land management practices, especially in the South and the northeast, did not easily convince farmers to stay on the land and to work the soil.[47]

Another factor was related to the overpopulation of Southern Italy as a result of the improvements in socioeconomic conditions after Unification.[56] That created a demographic boom and forced the new generations to emigrate en masse in the late 19th century and the early 20th century, mostly to the Americas.[57] The new migration of capital created millions of unskilled jobs around the world and was responsible for the simultaneous mass migration of Italians searching for "work and bread" (Italian: pane e lavoro, Italian: [ˈpaːne e llaˈvoːro]).[58]

The Unification of Italy broke down the feudal land system, which had survived in the south since the Middle Ages, especially where land had been the inalienable property of aristocrats, religious bodies or the king. The breakdown of feudalism, however, and redistribution of land did not necessarily lead to small farmers in the south winding up with land of their own or land they could work and make profit from. Many remained landless, and plots grew smaller and smaller and so less and less productive, as land was subdivided amongst heirs.[47]

Between 1860 and World War I, 9 million Italians left permanently of a total of 16 million who emigrated, most travelling to North or South America.[59] The numbers may have even been higher; 14 million from 1876 to 1914, according to another study. Annual emigration averaged almost 220,000 in the period 1876 to 1900, and almost 650,000 from 1901 through 1915. Prior to 1900 the majority of Italian immigrants were from northern and central Italy. Two-thirds of the migrants who left Italy between 1870 and 1914 were men with traditional skills. Peasants were half of all migrants before 1896.[57]

The bond of the emigrants with their mother country continued to be very strong even after their departure. Many Italian emigrants made donations to the construction of the Altare della Patria (1885–1935), a part of the monument dedicated to King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy, and in memory of that, the inscription of the plaque on the two burning braziers perpetually at the Altare della Patria next to the tomb of the Italian Unknown Soldier, reads Gli italiani all'estero alla Madre Patria ("Italians abroad to the Motherland").[60] The allegorical meaning of the flames that burn perpetually is linked to their symbolism, which is centuries old, since it has its origins in classical antiquity, especially in the cult of the dead.[61] A fire that burns eternally symbolizes that the memory, in this case of the sacrifice of the Unknown Soldier and the bond of the country of origin, is perpetually alive in Italians, even in those who are far from their country, and will never fade.[61]

Education

[edit]

In Italy a state school system or education system has existed since 1859, when the Legge Casati (Casati Act) mandated educational responsibilities for the forthcoming Italian state (Italian unification took place in 1861).

The Casati Act made primary education (scuola elementare) compulsory, and had the goal of increasing literacy. This law gave control of primary education to the single towns, of secondary education to the provinces, and the universities were managed by the State. Even with the Casati Act and compulsory education, in rural (and southern) areas children often were not sent to school (the rate of children enrolled in primary education would reach 90% only after 70 years) and the illiteracy rate (which was nearly 80% in 1861) took more than 50 years to halve.

The next important law concerning the Italian education system was the Legge Gentile. This act was issued in 1923, thus when Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party were in power. In fact, Giovanni Gentile was appointed the task of creating an education system deemed fit for the fascist system. The compulsory age of education was raised to 14 years, and was somewhat based on a ladder system: after the first five years of primary education, one could choose the scuola media, which would give further access to the liceo and other secondary education, or the 'avviamento al lavoro' (work training), which was intended to give a quick entry into the low strates of the workforce. The reform enhanced the role of the Liceo Classico, created by the Casati Act in 1859 (and intended during the Fascist era as the peak of secondary education, with the goal of forming the future upper classes), and created the Technical, Commercial and Industrial institutes and the Liceo Scientifico. The influence of Gentile's Italian idealism was great,[62] and he considered the Catholic religion to be the "foundation and crowning" of education.

Liberal era of politics (1870–1914)

[edit]

After unification, Italy's politics favored liberalism:[a] the liberal-conservative right (destra storica or Historical Right) was regionally fragmented[b] and liberal-conservative prime minister Marco Minghetti only held on to power by enacting revolutionary and left-leaning policies (such as the nationalization of railways) to appease the opposition.

Agostino Depretis

[edit]In 1876, Minghetti was ousted and replaced by liberal Agostino Depretis, who began the long Liberal Period. The Liberal Period was marked by corruption, government instability, continued poverty in Southern Italy and the use of authoritarian measures by the Italian government.

Depretis began his term as prime minister by initiating an experimental political notion known as trasformismo ("transformism"). The theory of trasformismo was that a cabinet should select a variety of moderates and capable politicians from a non-partisan perspective. In practice, trasformismo was authoritarian and corrupt as Depretis pressured districts to vote for his candidates if they wished to gain favourable concessions from Depretis when in power. The results of the Italian general election of 1876 resulted in only four representatives from the right being elected, allowing the government to be dominated by Depretis. Despotic and corrupt actions are believed to be the key means by which Depretis managed to keep support in Southern Italy. Depretis put through authoritarian measures, such as banning public meetings, placing "dangerous" individuals in internal exile on remote penal islands across Italy and adopting militarist policies. Depretis enacted controversial legislation for the time, such as abolishing arrest for debt and making elementary education free and compulsory while ending compulsory religious teaching in elementary schools.[63]

In 1887, Francesco Crispi became prime minister and began focusing government efforts on foreign policy. Crispi worked to build Italy as a great world power through increased military expenditures, advocacy of expansionism[64] and trying to win the favor of Germany. Italy joined the Triple Alliance, which included both Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1882 and which remained officially intact until 1915. While helping Italy develop strategically, he continued trasformismo and became authoritarian, once suggesting the use of martial law to ban opposition parties.[65] Despite being authoritarian, Crispi put through liberal policies such as the Public Health Act of 1888 and established tribunals for redress against abuses by the government.[66]

Francesco Crispi

[edit]Francesco Crispi was prime minister for a total of six years, from 1887 until 1891 and again from 1893 until 1896. Historian R. J. B. Bosworth says of his foreign policy:

Crispi pursued policies whose openly aggressive character would not be equaled until the days of the Fascist regime. Crispi increased military expenditure, talked cheerfully of a European conflagration, and alarmed his German or British friends with signs of preventative attacks on his enemies. His policies were ruinous for Italy's trade with France and, more humiliatingly, for colonial ambitions in Eastern Africa. Crispi's lust for territory there was thwarted when on 1 March 1896, the armies of Ethiopian Emperor Menelik routed Italian forces at Adowa [...] an unparalleled disaster for a modern army. Crispi, whose private life (he was perhaps a trigamist) and personal finances [...] were objects of perennial scandal, went into dishonorable retirement.[67]

Crispi greatly admired the United Kingdom, but was unable to get British assistance for his aggressive foreign policy and turned instead to Germany.[68] Crispi also enlarged the army and navy and advocated expansionism as he sought Germany's favor by joining the Triple Alliance which included both Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1882. It remained officially intact until 1915 and prevented hostilities between Italy and Austria, which controlled border regions that Italy claimed.

Colonialism

[edit]

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Italy emulated the Great Powers in acquiring colonies, especially in the scramble to take control of Africa that took place in the 1870s. Italy was weak in military and economic resources compared to Britain, France and Germany. Still, it proved difficult due to popular resistance. It was unprofitable due to high military costs and the lesser economic value of spheres of influence remaining when Italy began to colonize. Britain was eager to block French influence and assisted Italy in gaining territory of the Red Sea.[69]

Several colonial projects were undertaken by the government. These were done to gain the support of Italian nationalists and imperialists, who wanted to rebuild a Roman Empire. Italy had already large settlements in Alexandria, Cairo and Tunis. Italy first attempted to gain colonies through negotiations with other world powers to make colonial concessions, but these negotiations failed. Italy also sent missionaries to uncolonized lands to investigate the potential for Italian colonization. The most promising and realistic of these were parts of Africa. Italian missionaries had already established a foothold at Massawa (in present-day Eritrea) in the 1830s and had entered deep into the Ethiopian Empire.[70]

The beginning of colonialism came in 1885, shortly after the fall of Egyptian rule in Khartoum, when Italy landed soldiers at Massawa in East Africa. In 1888, Italy annexed Massawa by force, creating the colony of Italian Eritrea. The Eritrean ports of Massawa and Assab handled trade with Italy and Ethiopia. The trade was promoted by the low duties paid on Italian trade. Italy exported manufactured products and imported coffee, beeswax and hides.[71] At the same time, Italy occupied territory on the south side of the horn of Africa, forming what would become Italian Somaliland.

The Treaty of Wuchale, signed in 1889, stated in the Italian language version that Ethiopia was to become an Italian protectorate, while the Ethiopian Amharic language version stated that the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik II could go through Italy to conduct foreign affairs. This happened presumably due to the mistranslation of a verb, which formed a permissive clause in Amharic and a mandatory one in Italian.[72] When the differences in the versions came to light, in 1895 Menelik II abrogated the treaty and abandoned the agreement to follow Italian foreign policy.[73] Because of the Ethiopian refusal to abide by the Italian version of the treaty and despite economic handicaps at home, the Italian government decided on a military solution to force Ethiopia to abide by the Italian version of the treaty. In doing so, they believed that they could exploit divisions within Ethiopia and rely on tactical and technological superiority to offset any inferiority in numbers. As a result, Italy and Ethiopia came into confrontation, in what was later to be known as the First Italo-Ethiopian War.[74]

The Italian army failed on the battlefield and was overwhelmed by a huge Ethiopian army at the Battle of Adwa. At that point, the Italian invasion force was forced to retreat into Eritrea. The war formally ended with the Treaty of Addis Ababa in 1896, which abrogated the Treaty of Wuchale, recognizing Ethiopia as an independent country. The failed Ethiopian campaign was one of the few military victories scored by the Africans against an imperial power at this time.[75]

From 2 November 1899 to 7 September 1901, Italy participated as part of the Eight-Nation Alliance forces during the Boxer Rebellion in China. On 7 September 1901, a concession in Tientsin was ceded to Italy by the Qing Dynasty. On 7 June 1902, the concession was taken into Italian possession and administered by an Italian consul.

In 1911, Italy declared war on the Ottoman Empire and invaded Tripolitania, Fezzan and Cyrenaica. These provinces together formed what became known as Libya. The war ended only one year later, but the occupation resulted in acts of discrimination against Libyans, such as the forced deportation of Libyans to the Tremiti Islands in October 1911. By 1912, one-third of these Libyan refugees had died from a lack of food and shelter.[76] The annexation of Libya led nationalists to advocate Italian domination of the Mediterranean Sea by occupying Greece and the Adriatic Sea coastal region of Dalmatia.[77]

Giovanni Giolitti

[edit]

In 1892, Giovanni Giolitti became Prime Minister of Italy for his first term. Although his first government quickly collapsed one year later, Giolitti returned in 1903 to lead Italy's government during a fragmented period until 1914. Giolitti had spent his earlier life as a civil servant and then took positions within the cabinets of Crispi. Giolitti was the first long-term Italian Prime Minister because he mastered the political concept of trasformismo by manipulating, coercing and bribing officials to his side. In elections during Giolitti's government, voting fraud was common. Giolitti helped improve voting only in well-off, more supportive areas while attempting to isolate and intimidate poor areas where opposition was strong.[78] Southern Italy was in terrible shape before and during Giolitti's tenure as Prime Minister: four-fifths of southern Italians were illiterate, and the dire situation there ranged from problems of large numbers of absentee landlords to rebellion and even starvation.[79] Corruption was such a large problem that Giolitti himself admitted that there were places "where the law does not operate at all".[80]

In 1911, Giolitti's government sent forces to occupy Libya. While the success of the Libyan War improved the status of the nationalists, it did not help Giolitti's administration as a whole. The government attempted to discourage criticism by speaking about Italy's strategic achievements and inventiveness of their military in the war: Italy was the first country to use the airship for military purposes and undertook aerial bombing on the Ottoman forces.[81] The war radicalized the Italian Socialist Party, and anti-war revolutionaries called for violence to bring down the government. Elections were held in 1913, and Giolitti's coalition retained an absolute majority in the Chamber of Deputies, while the Radical Party emerged as the largest opposition bloc. The Italian Socialist Party gained eight seats and was the largest party in Emilia-Romagna.[82] Giolitti's coalition did not endure long after the election, and he was forced to resign in March 1914. Giolitti later returned as Prime Minister only briefly in 1920, but the era of liberalism was effectively over in Italy.

The 1913 and 1919 elections saw gains made by Socialist, Catholic and nationalist parties at the expense of the traditionally dominant Liberals and Radicals, who were increasingly fractured and weakened as a result.

World War I and failure of the liberal state (1915–1922)

[edit]

Italy entered into the First World War in 1915 with the aim of completing national unity: for this reason, the Italian intervention in the First World War is also considered the Fourth Italian War of Independence,[83] in a historiographical perspective that identifies in the latter the conclusion of the unification of Italy.[84][85]

The war forced the decision whether to honor the alliance with Germany and Austria. For six months Italy remained neutral, as the Triple Alliance was only for defensive purposes. Italy took the initiative in entering the war in spring 1915, despite strong popular and elite sentiment in favor of neutrality. Italy was a large, poor country whose political system was chaotic, its finances were heavily strained, and its army was very poorly prepared.[86] The Triple Alliance meant little either to Italians or Austrians – Vienna had declared war on Serbia without consulting Rome. Prime Minister Antonio Salandra and Foreign Minister Sidney Sonnino negotiated with both sides in secret for the best deal, and got one from the Entente, which was quite willing to promise large slices of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, including the Tyrol and Trieste, as well as making Albania a protectorate. Russia vetoed giving Italy Dalmatia. Britain was willing to pay subsidies and loans to get 36 million Italians as new allies who threatened the southern flank of Austria.[87]

When the Treaty of London was announced in May 1915, there was an uproar from antiwar elements. Reports from around Italy showed the people feared war, and cared little about territorial gains. Rural folk saw war as a disaster, like drought, famine or plague. Businessmen were generally opposed, fearing heavy-handed government controls and taxes, and loss of foreign markets. Reversing the decision seemed impossible, for the Triple Alliance did not want Italy back, and the king's throne was at risk. Pro-war supporters mobbed the streets. The fervor for war represented a bitterly hostile reaction against politics as usual, and the failures, frustrations, and stupidities of the ruling class.[88][89] Benito Mussolini created the newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia, which at first attempted to convince socialists and revolutionaries to support the war.[90] The Allied Powers, eager to draw Italy to the war, helped finance the newspaper.[91] Later, after the war, this publication would become the official newspaper of the Fascist movement.

Italy entered the war with an army of 875,000 men, but the army was poorly led and lacked heavy artillery and machine guns, their war supplies having been largely depleted in the war of 1911–12 against Turkey. Italy proved unable to prosecute the war effectively, as fighting raged for three years on a very narrow front along the Isonzo River, where the Austrians held the high ground. In 1916, Italy declared war on Germany, which provided significant aid to the Austrians. Some 650,000 Italian soldiers died and 950,000 were wounded, while the economy required large-scale Allied funding to survive.[92][93]

Before the war the government had ignored labor issues, but now it had to intervene to mobilize war production. With the main working-class Socialist party reluctant to support the war effort, strikes were frequent and cooperation was minimal, especially in the Socialist strongholds of Piedmont and Lombardy. The government imposed high wage scales, as well as collective bargaining and insurance schemes.[94] Many large firms expanded dramatically. Inflation doubled the cost of living. Industrial wages kept pace but not wages for farm workers. Discontent was high in rural areas since so many men were taken for service, industrial jobs were unavailable, wages grew slowly and inflation was just as bad.[95]

The Italian victory,[96][97][98] which was announced by the Bollettino della Vittoria and the Bollettino della Vittoria Navale, marked the end of the war on the Italian Front, secured the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and was chiefly instrumental in ending the First World War less than two weeks later. More than 651,000 Italian soldiers died on the battlefields.[99] The Italian civilian deaths were estimated at 589,000 due to malnutrition and food shortages.[100]

As the war came to an end, Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando met with British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of France Georges Clemenceau and United States President Woodrow Wilson in Versailles to discuss how the borders of Europe should be redefined to help avoid a future European war. The talks provided little territorial gain to Italy as Wilson promised freedom to all European nationalities to form their nation-states. As a result, the Treaty of Versailles did not assign Dalmatia and Albania to Italy as had been promised in the Treaty of London. Furthermore, the British and French decided to divide the German overseas colonies into their mandates, with Italy receiving none. Italy also gained no territory from the breakup of the Ottoman Empire. Despite this, Orlando agreed to sign the Treaty of Versailles, which caused uproar against his government. The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919) and the Treaty of Rapallo (1920) allowed the annexation of Trentino Alto-Adige, the Julian March, Istria, Kvarner as well as the Dalmatian city of Zara.

Furious over the peace settlement, the Italian nationalist poet Gabriele D'Annunzio led disaffected war veterans and nationalists to form the Free State of Fiume in September 1919. His popularity among nationalists led him to be called Il Duce ("The Leader"), and he used black-shirted paramilitary in his assault on Fiume. The leadership title of Duce and the blackshirt paramilitary uniform would later be adopted by the Fascist movement of Benito Mussolini. The demand for the Italian annexation of Fiume spread to all sides of the political spectrum, including Mussolini's Fascists.[101]

The subsequent Treaty of Rome (1924) led to the annexation of the city of Fiume to Italy. Italy's lack of territorial gain led to the outcome being denounced as a mutilated victory. The rhetoric of mutilated victory was adopted by Mussolini and led to the rise of Italian fascism, becoming a key point in the propaganda of Fascist Italy. Historians regard mutilated victory as a "political myth", used by fascists to fuel Italian imperialism and obscure the successes of liberal Italy in the aftermath of World War I.[102] Italy also gained a permanent seat in the League of Nations's executive council.

Fascist regime, World War II, and Civil War (1922–1946)

[edit]Rise of Fascism into power

[edit]

Benito Mussolini created the Fasci di Combattimento or Combat League in 1919. It was originally dominated by patriotic socialist and syndicalist veterans who opposed the pacifist policies of the Italian Socialist Party. This early Fascist movement had a platform more inclined to the left, promising social revolution, proportional representation in elections, women's suffrage (partly realized in 1925) and dividing rural private property held by estates.[103][104] They also differed from later Fascism by opposing censorship, militarism and dictatorship.[105]

At the same time, the so-called Biennio Rosso (red biennium) took place in the two years following the war in a context of economic crisis, high unemployment and political instability. The 1919–20 period was characterized by mass strikes, worker manifestations as well as self-management experiments through land and factory occupations. In Turin and Milan, workers councils were formed and many factory occupations took place under the leadership of anarcho-syndicalists. The agitations also extended to the agricultural areas of the Padan plain and were accompanied by peasant strikes, rural unrests and guerilla conflicts between left-wing and right-wing militias. Thenceforth, the Fasci di Combattimento (forerunner of the National Fascist Party, 1921) successfully exploited the claims of Italian nationalists and the quest for order and normalization of the middle class. In October 1922, Mussolini took advantage of a general strike to announce his demands to the Italian government to give the Fascist Party political power or face a coup. With no immediate response, a group of 30,000 Fascists began a long trek across Italy to Rome (the March on Rome), claiming that Fascists were intending to restore law and order. The Fascists demanded Prime Minister Luigi Facta's resignation and that Mussolini be named to the post. Although the Italian Army was far better armed than the Fascist militias, the liberal system and King Victor Emmanuel III were facing a deeper political crisis. The King was forced to choose which of the two rival movements in Italy would form the government: Mussolini's Fascists, or the marxist Italian Socialist Party. He selected the Fascists.

Mussolini formed a coalition with nationalists and liberals, and in 1923 passed the electoral Acerbo Law, which assigned two-thirds of the seats to the party that achieved at least 25% of the vote. The Fascist Party used violence and intimidation to achieve the threshold in the 1924 election, thus obtaining control of Parliament. Socialist deputy Giacomo Matteotti was assassinated after calling for a nullification of the vote. The parliament opposition responded to Matteotti's assassination with the Aventine Secession.

Over the next four years, Mussolini eliminated nearly all checks and balances on his power. On 24 December 1925, he passed a law that declared he was responsible to the king alone, making him the sole person able to determine Parliament's agenda. Local governments were dissolved, and appointed officials (called podestà) replaced elected mayors and councils. In 1928, all political parties were banned, and parliamentary elections were replaced by plebiscites in which the Grand Council of Fascism nominated a single list of 400 candidates. Christopher Duggan argues that his regime exploited Mussolini's popular appeal and forged a cult of personality that served as the model that was emulated by dictators of other fascist regimes of the 1930s.[106]

In summary, historian Stanley G. Payne says that Fascism in Italy was:

- A primarily political dictatorship. The Fascist Party itself had become almost completely bureaucratized and subservient to, not dominant over, the state itself. Big business, industry, and finance retained extensive autonomy, particularly in the early years. The armed forces also enjoyed considerable autonomy. ... The Fascist militia was placed under military control. The judicial system was left largely intact and relatively autonomous as well. The police continued to be directed by state officials and were not taken over by party leaders, nor was a major new police elite created. There was never any question of bringing the Church under overall subservience. Sizable sectors of Italian cultural life retained extensive autonomy, and no major state propaganda-and-culture ministry existed. The Mussolini regime was neither especially sanguinary nor particularly repressive.[107]

End of the Roman question

[edit]

During the unification of Italy in the mid-19th century, the Papal States resisted incorporation into the new nation. The nascent Kingdom of Italy invaded and occupied Romagna (the eastern portion of the Papal States) in 1860, leaving only Latium in the pope's domains. Latium, including Rome itself, was occupied and annexed in 1870. For the following sixty years, relations between the Papacy and the Italian government were hostile, and the status of the pope became known as the "Roman question".The Lateran Treaty was one component of the Lateran Pacts of 1929, agreements between the Kingdom of Italy under King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy and the Holy See under Pope Pius XI to settle the question. The treaty and associated pacts were signed on 11 February 1929.[108] The treaty recognized Vatican City as an independent state under the sovereignty of the Holy See. The Italian government also agreed to give the Roman Catholic Church financial compensation for the loss of the Papal States.[109] In 1948, the Lateran Treaty was recognized in the Constitution of Italy as regulating the relations between the state and the Catholic Church.[110] The treaty was significantly revised in 1984, ending the status of Catholicism as the sole state religion.

Foreign politics

[edit]

Lee identifies three major themes in Mussolini's foreign policy. The first was a continuation of the foreign-policy objectives of the preceding Liberal regime. Liberal Italy had allied itself with Germany and Austria, and had great ambitions in the Balkans and North Africa. Ever since it had been badly defeated in Ethiopia in 1896, there was a strong demand for seizing that country. Second was a profound disillusionment after the heavy losses of the First World War; the small territorial gains from Austria were not enough to compensate. Third was Mussolini's promise to restore the pride and glory of the Roman Empire.[111]

Italian Fascism is based upon Italian nationalism and in particular seeks to complete what it considers as the incomplete project of Risorgimento by incorporating Italia Irredenta (unredeemed Italy) into the state of Italy.[112][113] To the east of Italy, the Fascists claimed that Dalmatia was a land of Italian culture.[114] To the south of Italy, the Fascists claimed Malta, which belonged to the United Kingdom, and Corfu, which belonged to Greece, to the north claimed Italian Switzerland, while to the west claimed Corsica, Nice and Savoy, which belonged to France.[115][116]

Legend: