Монархия Канады

| Король Канады | |

|---|---|

| Король Канады | |

Федеральный | |

| |

| Действующий президент | |

| |

| Карл III с 8 сентября 2022 г. | |

| Подробности | |

| Стиль | Его Величество |

| Наследник | Уильям, принц Уэльский [ 1 ] |

| Веб-сайт | canada.ca/monarchy-crown |

|

|---|

Монархия Канады в Канаде, — это форма правления олицетворяемая канадским сувереном и главой государства . Это один из ключевых компонентов канадского суверенитета , лежащий в основе конституционной федеративной структуры Канады и Вестминстерского типа парламентской демократии . [ 6 ] Монархия является основой исполнительной ( « Король в совете» ), законодательной ( «Король в парламенте» ) и судебной ( «Король на скамейке запасных» ) ветвей как федеральной , так и провинциальной юрисдикции. [ 10 ] Нынешним монархом является король Карл III , правящий с 8 сентября 2022 года. [ 17 ]

Хотя суверен принадлежит 14 другим независимым странам Содружества Наций , монархия каждой страны является отдельной и юридически отличной. [ 22 ] В результате нынешний монарх официально носит титул короля Канады , и в этом качестве он и другие члены королевской семьи выполняют государственные и частные функции внутри страны и за рубежом в качестве представителей Канады. Однако монарх — единственный член королевской семьи, имеющий какую-либо конституционную роль. Монарх живет в Соединенном Королевстве, и, хотя некоторые полномочия принадлежат только суверену, [ 23 ] Большую часть королевских правительственных и церемониальных обязанностей в Канаде выполняет представитель монарха — генерал-губернатор Канады . [ 27 ] В каждой из Канады провинций монархию представляет вице-губернатор . Поскольку территории подпадают под федеральную юрисдикцию, у каждой из них есть комиссар, а не вице-губернатор, который напрямую представляет федеральную Корону в Совете .

Вся исполнительная власть принадлежит суверену, поэтому для того, чтобы патентные грамоты и приказы совета имели юридическую силу, необходимо согласие монарха. Кроме того, монарх является членом парламента Канады, поэтому королевское согласие требуется для того, чтобы законопроекты стали законом, . Хотя власть над этими действиями исходит от канадского народа посредством конституционных соглашений демократии, [ 28 ] исполнительная власть по-прежнему принадлежит Короне и поручается сувереном правительству только от имени народа. Это подчеркивает роль Короны в защите прав, свобод и демократической системы правления канадцев, подтверждая тот факт, что «правительства являются слугами народа, а не наоборот». [ 29 ] [ 30 ] Канады Таким образом, в рамках конституционной монархии прямое участие суверена в любой из этих областей управления обычно ограничено, при этом суверен обычно осуществляет исполнительную власть только по совету и с согласия Кабинета министров Канады , а законодательные и судебные обязанности суверена в основном выполняются. через Парламент Канады, а также мировых судей и судей . [ 29 ] Однако бывают случаи, когда суверен или его представитель будут обязаны действовать напрямую и независимо в соответствии с доктриной необходимости для предотвращения действительно неконституционных действий. [ 31 ] [ 32 ] Короны В этом отношении государь и его наместники являются хранителями резервных полномочий и представляют «власть народа над правительством и политическими партиями». [ 33 ] [ 34 ] Иными словами, Корона выступает гарантом непрерывного и стабильного управления Канадой и беспартийной защитой от злоупотреблений властью . [ 37 ]

Сегодня Канаду называют «одной из старейших сохранившихся монархий в мире». [ 19 ] [ 38 ] Части того, что сейчас является Канадой, находились под монархией еще с 15 века в результате колониальных поселений и часто конкурирующих претензий, предъявляемых на территории от имени английской (а позже британской) и французской корон. [ 51 ] Монархическое правление возникло в результате колонизации Французской конкурирующих и Британской империй, за территорию в Северной Америке, и соответствующей преемственности французских и британских суверенов, правящих Новой Францией и Британской Америкой соответственно. В результате завоевания Новой Франции претензии французских монархов были прекращены, и то, что стало Британской Северной Америкой, перешло под гегемонию британской монархии, которая в конечном итоге превратилась в современную канадскую монархию. [ 54 ] За исключением Ньюфаундленда с 1649 по 1660 год , ни одна часть территории нынешней Канады не была республикой или частью республики; [ 55 ] тем не менее, были отдельные призывы к тому, чтобы страна стала единой. Однако Корона считается «укоренившейся» в правительственной структуре. [ 59 ] Институт конституционной монархии Канады иногда в просторечии называют Кленовой Короной. [ н 1 ] или Корона клёнов , [ 63 ] В Канаде развилась «узнаваемая канадская марка монархии». [ 64 ]

Хотя Канада не является частью канадской монархии ни в прошлом, ни в настоящем, она имеет еще более старую традицию наследственного вождя в некоторых коренных народах , которую сравнивают с несуверенной монархией и сегодня существует параллельно с канадской короной и правительствами отдельных групп . Все три образования являются компонентами межнациональных отношений между Короной и коренными народами в обеспечении договорных прав и обязательств, сложившихся на протяжении веков. [ нужна ссылка ]

Международные и внутренние аспекты

[ редактировать ]

15 королевств, правящим сувереном которых является король Карл III

Монарх находится в личном союзе с 14 другими королевствами Содружества состоящего из 56 членов в рамках Содружества Наций, . Поскольку он проживает [ 65 ] [ 66 ] [ 67 ] [ 68 ] в Соединенном Королевстве вице-короли ( генерал-губернатор Канады в федеральной сфере и вице-губернатор в каждой провинции) представляют суверена в Канаде и могут выполнять большую часть королевских правительственных обязанностей, даже когда монарх находится в стране. [ н 2 ] Тем не менее, монарх может выполнять канадские конституционные и церемониальные обязанности за границей. [ н 3 ] [ н 4 ]

Эволюция роли генерал-губернатора от роли одновременно представителя суверена и «агента британского правительства», который «в вопросах, считающихся «имперскими» интересами... действовал по инструкциям Британского управления по делам колоний. " [ 73 ] статус исключительно представителя монарха развился с ростом канадского национализма после окончания Первой мировой войны , кульминацией которого стало принятие Вестминстерского статута в 1931 году. [ 74 ] [ 75 ] С тех пор Корона имела как общий, так и отдельный характер: роль суверена как монарха Канады отличалась от его или ее положения как монарха любого другого королевства. [ н 3 ] [ 79 ] включая Великобританию. [ n 5 ] [ 85 ] Только канадские федеральные министры Короны могут консультировать суверена по любым вопросам канадского государства. [ n 6 ] [ 91 ] о которых суверен, когда он не в Канаде, держится в курсе посредством еженедельной связи с федеральным вице-королем. [ 92 ] Таким образом, монархия перестала быть исключительно британским институтом и в Канаде стала канадским. [ 96 ] или «одомашненный», [ 97 ] учреждение, хотя его до сих пор часто называют «британским» как на юридическом, так и на обычном языке, [ 46 ] по историческим, политическим и удобным причинам.

Это разделение иллюстрируется несколькими способами: например, суверен имеет уникальный канадский титул и, [ 98 ] страны когда он и другие члены королевской семьи выступают публично именно как представители Канады, они используют, где это возможно, канадскую символику, включая национальный флаг , уникальные королевские символы , униформу вооруженных сил , [ 103 ] и т.п., а также самолеты канадских вооруженных сил или другие транспортные средства, принадлежащие Канаде, для путешествий. [ 104 ] Попав в воздушное пространство Канады или прибыв на канадское мероприятие, проходящее за границей, канадский секретарь короля , офицеры Королевской канадской конной полиции (RCMP) и другие канадские официальные лица возьмут на себя обязанности любого из коллег из других королевств, которые ранее были сопровождение короля или другого члена королевской семьи. [ 104 ] [ 105 ]

Аналогичным образом, суверен получает средства из канадских фондов только для поддержки при выполнении своих обязанностей, когда он находится в Канаде или действует в качестве короля Канады за границей; Канадцы не платят никаких денег королю или любому другому члену королевской семьи ни в счет личного дохода, ни для содержания королевских резиденций за пределами Канады. [ 106 ] [ 107 ]

Монархия Канады имеет пять аспектов: конституционный (например, использование королевских прерогатив при созыве и роспуске парламента, предоставление королевского согласия ), национальный (произнесение тронной речи и королевского рождественского послания , раздача почестей, наград, медалями и участием в церемониях Дня памяти ), международные (монарх является главой государства в других сферах Содружества и является главой Содружество ), религиозные (слова по милости Божией в титуле монарха , Акт об урегулировании 1701 года , требующий, чтобы суверен был англиканцем, и монарх, призывающий людей «терпимо, принимать и понимать культуры, убеждения и веры»). отличается от нашей»), а также монархия благосостояния и обслуживания (что проявляется в том, что члены королевской семьи основывают благотворительные организации и поддерживают других, собирают средства на благотворительность и оказывают королевское покровительство гражданским и военным организациям ). [ 108 ]

Преемственность и регентство

[ редактировать ]Как и в других королевствах Содружества , нынешним наследником канадского престола является Уильям, принц Уэльский , за которым в линии преемственности следует его старший ребенок, принц Джордж .

Упадок Короны и воцарение

[ редактировать ]После смерти монарха происходит немедленное и автоматическое правопреемство наследника покойного государя; [ 111 ] отсюда и фраза: « Король мертв. Да здравствует король ». [ 112 ] [ 113 ] Никакого подтверждения или дальнейших церемоний не требуется. Федеральный кабинет министров и государственная служба следуют Руководству по официальным процедурам правительства Канады при выполнении различных формальностей, связанных с переходом. [ 114 ]

По обычаю, о вступлении на престол нового монарха публично объявляет губернатора совет генерал- , который собирается в Ридо-холле сразу после смерти предыдущего монарха. [ 114 ] С момента принятия Вестминстерского статута считалось «конституционно неуместным», чтобы прокламации о присоединении Канады были одобрены британским указом в совете. [ 77 ] поскольку с тех пор монарх вступил на канадский трон в соответствии с канадским законодательством. В честь вступления на престол Карла III, первого с момента создания Канадского геральдического управления в 1989 году, Главный герольд зачитал королевскую прокламацию вслух. Если парламент находится на сессии, премьер-министр объявит о кончине короны и предложит совместное обращение с выражением симпатии и лояльности новому монарху. [ 114 ]

Далее следует период траура , во время которого портреты недавно умершего монарха задрапируют черной тканью, а сотрудники правительственных домов носят черные нарукавные повязки . В Руководстве по официальным процедурам правительства Канады говорится, что премьер-министр несет ответственность за созыв парламента, внесение парламентской резолюции о лояльности и соболезновании новому монарху и организацию поддержки этого предложения лидером официальной оппозиции . [ 109 ] [ 115 ] Затем премьер-министр предложит закрыть парламент. [ 109 ] [ 115 ] Канадская радиовещательная корпорация регулярно обновляет план «трансляции национального значения», объявляя о кончине суверена и освещая последствия, во время которого все регулярные программы и реклама отменяются, а дежурные комментаторы участвуют в круглосуточной трансляции новостей. режим. [ 109 ] Поскольку похороны канадских монархов, а также их супруг проходят в Соединенном Королевстве, [ 116 ] Поминальные услуги проводятся федеральным правительством и правительством провинций по всей Канаде. [ 116 ] [ 117 ] Подобные церемонии могут быть проведены и для других недавно умерших членов королевской семьи. День похорон государя, скорее всего, станет федеральным праздником. [ 109 ] [ 118 ]

Новый монарх коронуется в Соединенном Королевстве по древнему ритуалу, который не является обязательным для правления суверена. [ н 7 ] Согласно Федеральному закону о толковании , [ 114 ] Смерть монарха не затрагивает должностных лиц, занимающих федеральные должности под властью Короны, и они не обязаны снова приносить присягу на верность . [ 119 ] Однако в некоторых провинциях те, кто занимает должности Короны, должны принести присягу новому суверену. [ 120 ] Все ссылки в федеральном законодательстве на предыдущих монархов, будь то мужского (например , Его Величество ) или женского (например, Королева ) рода, продолжают означать правящего суверена Канады, независимо от его или ее пола. [ 121 ] Это потому, что согласно общему праву Корона никогда не умирает . После того, как человек вступает на трон, он или она обычно продолжает править до самой смерти. [ н 8 ]

Правовые аспекты наследования

[ редактировать ]

Отношения между королевствами Содружества таковы, что любое изменение правил наследования соответствующих корон требует единогласного согласия всех королевств. Наследование регулируется законами, такими как Билль о правах 1689 года , Акт об урегулировании 1701 года и Акты о союзе 1707 года .

Король Эдуард VIII отрекся от престола в 1936 году, и любые его возможные будущие потомки были исключены из линии преемственности. [ 122 ] Британское правительство в то время, желая ускорить процесс, чтобы избежать неприятных дебатов в парламентах доминионов, предложило правительствам доминионов Британского Содружества – тогда Австралии, Новой Зеландии, Ирландского Свободного Государства , Южно-Африканского Союза и Канада — считается, что тот, кто был монархом Великобритании, автоматически становится монархом соответствующего Доминиона. Как и в случае с другими правительствами Доминиона, канадский кабинет министров, возглавляемый премьер-министром Уильямом Лайоном Маккензи Кингом , отказался принять эту идею и подчеркнул, что законы о наследовании являются частью канадского законодательства и, поскольку Вестминстерский статут 1931 года запрещает Великобритании принимать законы. для Канады, в том числе в отношении правопреемства, [ 123 ] их изменение требовало запроса и согласия Канады на то, чтобы британское законодательство ( Закон о декларации Его Величества об отречении от престола, 1936 г. ) стало частью канадского законодательства. [ 124 ] Сэр Морис Гвайер , первый парламентский советник Великобритании, отразил эту позицию, заявив, что Акт об урегулировании является частью закона в каждом доминионе. [ 124 ] Таким образом, Соборный Приказ ПК 3144 [ 125 ] был издан, в котором выражалась просьба Кабинета министров и согласие на то, чтобы Закон Его Величества об отречении от престола 1936 года стал частью законов Канады, а Закон о престолонаследии 1937 года дал парламентскую ратификацию этому действию, объединив Закон об урегулировании и Закон о королевских браках 1772 года в канадское законодательство. [ 126 ] [ 127 ] Последнее было признано Кабинетом министров в 1947 году частью канадского законодательства. [ n 9 ] [ 128 ] Министерство иностранных дел включило все законы, касающиеся наследования, в свой список законов канадского законодательства.

Верховный суд Канады единогласно заявил в Справке о патриации 1981 года , что Билль о правах 1689 года «несомненно имеет силу как часть законодательства Канады». [ 130 ] [ 131 ] Кроме того, в деле О'Донохью против Канады (2003 г.) Верховный суд Онтарио установил, что Акт об урегулировании 1701 г. является «частью законов Канады», а правила наследования «по необходимости включены в Конституцию Канады». Канада". [ 132 ] Другое постановление Верховного суда Онтарио, вынесенное в 2014 году, повторило дело 2003 года, заявив, что Акт об урегулировании «является имперским статутом, который в конечном итоге стал частью законодательства Канады». [ 133 ] Отклонив апелляцию по этому делу, Апелляционный суд Онтарио заявил, что «правила наследования являются частью конституции Канады и включены в нее». [ 134 ]

На заседании Специального объединенного комитета по конституции во время процесса принятия канадской конституции в 1981 году Джон Манро спросил тогдашнего министра юстиции Жана Кретьена о «выборочных упущениях» в Законе о престолонаследии 1937 года , о кончине Закона о Короне 1901 года , Закона о печатях , Закона о генерал-губернаторе и Закона о королевском стиле и титулах 1953 года. , из приложения к Закону о Конституции 1982 года . В ответ Кретьен заявил, что приложение к Закону о Конституции 1982 года не является исчерпывающим, подчеркнув, что в разделе 52 (2) Закона о Конституции 1982 года говорится: «[t] Конституция Канады включает [...] законы и приказы, относящиеся к графику» и «[когда] вы используете слово «включает» [...] это означает, что если когда-либо есть что-то, связанное с канадской конституцией как ее часть, оно должно было быть там или могло быть там оно покрыто, поэтому нам не нужно перенумеровывать [sic] тех, о которых вы упоминаете». [ 135 ] На том же заседании заместитель генерального прокурора Барри Стрейер заявил: «Статья 52(2) не является исчерпывающим определением Конституции Канады, поэтому, хотя в перечне перечислены определенные вещи, которые явно являются частью конституции, это не означают, что нет других вещей, которые являются частью конституции [...] [График] не является исчерпывающим списком». [ 135 ]

( Трон государя слева) и трон королевской супруги (справа) за креслом спикера - все сделано в 2017 году - во временной палате Сената .

|

Лесли Зайнс заявила в публикации 1991 года « Конституционные изменения в Содружестве» , что, хотя наследование престола Канады было предусмотрено общим правом и Актом об урегулировании 1701 года , они не были частью канадской конституции, которая «не содержит правил для престолонаследия». [ 136 ] Ричард Топороски, три года спустя писавший для Монархической лиги Канады , заявил: «В нашем законе нет другого положения, кроме Акта об урегулировании 1701 года , которое предусматривает, что королем или королевой Канады должно быть то же лицо, что и король или королева Соединенного Королевства. Если бы британский закон был изменен, а мы не изменили наш закон [...], лицо, предусмотренное новым законом, стало бы королем или королевой, по крайней мере, в некоторых сферах Содружества. Канада бы продолжайте с человеком, который стал бы монархом по предыдущему закону». [ 137 ]

Канада, как и другие государства Содружества, присоединилась к Пертскому соглашению 2011 года , в котором предлагались изменения в правилах, регулирующих наследование, с целью устранения предпочтений мужчин и устранения дисквалификации, возникающей в результате брака с католиком. В результате канадский парламент принял Закон о престолонаследии 2013 года , который дал согласие страны на законопроект о престолонаследии , находившийся в то время на рассмотрении парламента Соединенного Королевства. Отклонив оспаривание закона на том основании, что изменение порядка наследования в Канаде потребует единогласного согласия всех провинций в соответствии со статьей 41(a) Конституционного акта 1982 года , судья Верховного суда Квебека Клод Бушар постановил, что Канада «не должны изменить свои законы и свою конституцию, чтобы правила наследования британских королевских особ были изменены и вступили в силу», а конституционная конвенция обязала Канаду иметь линию наследования, симметричную линиям наследования в других Содружестве. сферы. [ 138 ] [ 139 ] Решение было поддержано Апелляционным судом Квебека . [ 140 ] Верховный суд Канады отказался рассматривать апелляцию в апреле 2020 года. [ 141 ]

Исследователь-конституционал Филипп Лагассе утверждает, что в свете Закона о престолонаследии 2013 года и постановлений суда, поддерживающих этот закон, раздел 41(a) Закона о Конституции 1982 года требует внесения поправки в конституцию, принятой с единогласного согласия провинциях, применяется только к «должности королевы», но не к тому, кто занимает эту должность, и поэтому «отмена принципа симметрии с Соединенным Королевством может быть осуществлена с помощью общего процедуры внесения поправок, или даже только Парламентом в соответствии со статьей 44 Закона о Конституции 1982 года ». [ 141 ] [ 142 ]

Тед МакВинни , другой ученый-конституционист, утверждал, что будущее правительство Канады могло бы начать процесс постепенного упразднения монархии после смерти Елизаветы II «тихо и без помпы, просто не сумев юридически провозгласить какого-либо преемника королевы в отношении Канада". По его словам, это будет способом обойти необходимость внесения поправки в конституцию, которая потребует единогласного согласия федерального парламента и всех законодательных собраний провинций. [ 143 ] Однако Ян Холлоуэй, декан юридического факультета Университета Западного Онтарио , раскритиковал предложение Маквинни за незнание мнений провинций и высказал мнение, что его реализация «противоречит простой цели тех, кто создал нашу систему управления». [ 144 ]

Некоторые аспекты правил наследования оспаривались в судах. Например, согласно положениям Билля о правах 1689 года и Акта об урегулировании 1701 года , католикам запрещено наследовать трон; этот запрет дважды подтверждался канадскими судами: один раз в 2003 году и еще раз в 2014 году. [ 149 ] Ученый-правовед Кристофер Корнелл из юридической школы Дедмана SMU пришел к выводу, что «запрет на то, чтобы канадский монарх был католиком, хотя и носит дискриминационный характер, является совершенно, если не фундаментальным, конституционным» и что, если этот запрет «будет изменен или отменен, он будет иметь должно быть достигнуто политически и законодательно через другое многостороннее соглашение, подобное Пертскому соглашению, а не судебным путем через суд». [ 150 ]

Регентство

[ редактировать ]В Канаде нет законов, разрешающих регентство , если суверен несовершеннолетний или ослабленный; [ 92 ] ни один из них не был принят канадским парламентом, и с 1937 года сменявшие друг друга кабинеты министров давали понять, что Закон о регентстве Соединенного Королевства не применим к Канаде, [ 92 ] Поскольку канадский кабинет министров не требовал иного, когда закон был принят в том же году и снова в 1943 и 1953 годах. Поскольку патентная грамота 1947 года , выданная королем Георгом VI, разрешает генерал-губернатору Канады осуществлять почти все полномочия монарха в отношении Ожидается, что вице-король Канады продолжит действовать как личный представитель монарха, а не какой-либо регент, даже если монарх является ребенком или недееспособным. [153]

This has led to the question of whether the governor general has the ability to remove themselves and appoint their viceregal successor in the monarch's name. While Lagassé argued that appears to be the case,[142] both the Canadian Manual of Official Procedures, published in 1968, and the Privy Council Office took the opposite opinion.[154][155] Lagassé and Patrick Baud claimed changes could be made to regulations to allow a governor general to appoint the next governor general;[156] Christopher McCreery, however, criticised the theory, arguing it is impractical to suggest that a governor general would remove him or herself on ministerial advice,[157] with the consequence that, if a prolonged regency occurred, it would remove one of the checks and balances in the constitution.[158] The intent expressed whenever the matter of regency came up among Commonwealth realm heads of government was that the relevant parliament (other than the United Kingdom's) would pass a bill if the need for a regency arose and the pertinent governor-general would already be empowered to grant royal assent to it.[159] The governor general appointing their successor is not a power that has been utilized to date.[142]

Foreign visits

[edit]The following state and official visits to foreign countries have been made by the monarch as the sovereign of Canada (sometimes representing other realms on the same visit):

| Visit to | Date | Monarch of Canada | Received by | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 July 1936 | King Edward VIII | President Albert Lebrun | Official[163] | |

| 7–11 June 1939 | King George VI | President Franklin D. Roosevelt | State[164][165][166] | |

| 17 October 1957 | Queen Elizabeth II | President Dwight D. Eisenhower | State[170] | |

| 26 June 1959 | Official[171][172] | |||

| 6 July 1959 | Governor William Stratton | State[175] | ||

| 6 June 1984 | President François Mitterrand | Official[179] | ||

| 1994 | Official[172][178] | |||

| 6 June 2004 | President Jacques Chirac | Official[180][172] | ||

| 9 April 2007 | Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin | Official[181] | ||

| 6 July 2010 | Governor David Paterson | Official[166][182] |

Federal and provincial aspects

[edit]

The origins of Canadian sovereignty lie in the early 17th century, during which time the monarch in England fought with parliament there over who had ultimate authority, culminating in the Glorious Revolution in 1688 and the subsequent Bill of Rights, 1689, which, as mentioned elsewhere in this article, is today part of Canadian constitutional law. This brought to Canada the British notion of the supremacy of parliament—of which the monarch is a part—and it was carried into each of the provinces upon the implementation of responsible government. That, however, was superseded when the Charter of Rights and Freedoms (within the Constitution Act, 1982) introduced into Canada the American idea of the supremacy of the law.[183] Still, the King remains the sovereign of Canada.[n 10][185]

Canada's monarchy was established at Confederation, when its executive government and authority were declared, in section 9 of the Constitution Act, 1867, to continue and be vested in the monarch. Placing such power, along with legislative power, with the tangible, living Queen, rather than the abstract and inanimate Crown, was a deliberate choice by the framers of the constitution.[186] Still, the Crown is the foundation of the country[187][188] as "the very centre of [Canada's] constitution and democracy."[187] Although Canada is a federation, the Canadian monarchy is unitary throughout all jurisdictions in the country,[189] the sovereignty of the different administrations being passed on through the overreaching Crown itself as a part of the executive, legislative, and judicial operations in each of the federal and provincial spheres[190] and the headship of state being a part of all equally.[189] The Crown thus links the various governments into a federal state,[8] while it is simultaneously also "divided" into 11 legal jurisdictions, or 11 "crowns"—one federal and 10 provincial[191]—with the monarch taking on a distinct legal persona in each.[n 11][n 12] As such, the constitution instructs that any change to the position of the monarch or his or her representatives in Canada requires the consent of the Senate, the House of Commons, and the legislative assemblies of all the provinces.[194] The Crown, being shared and balanced,[188] provides the bedrock upon which all of Canada's different regions and peoples can live together peacefully[195] and was said by David E. Smith, in 2017, to be the "keystone of the constitutional architecture" of Canada.[196]

The Crown is located beyond politics, existing to give authority to and protect the constitution and system of governance.[187] Power, therefore, rests with an institution that "functions to safeguard it on behalf of all its citizens", rather than any singular individual.[197] The sovereign and his representatives typically "act by 'not acting'"[n 13]—holding power, but, not exercising it—both because they are unelected figures and to maintain their neutrality, "deliberately, insistently, and resolutely",[199] in case they have to be an impartial arbiter in a constitutional crisis and ensure that normal democratic discourse can resume.[202] Consequently, the Crown performs two functions:[203] as a unifying symbol and a protector of democratic rights and freedoms,[188] "tightly woven into the fabric of the Canadian constitution."[203]

At the same time, a number of freedoms granted by the constitution to all other Canadians are denied to, or limited for, the monarch and the other senior members of the royal family: freedom of religion, freedom of expression, freedom to travel, freedom to choose a career, freedom to marry, and freedom of privacy and family life.[204]

While the Crown is empowered by statute and the royal prerogative, it also enjoys inherent powers not granted by either.[205] The Court of Appeal of British Columbia ruled in 1997 that "the Crown has the capacities and powers of a natural person"[206] and its actions as a natural person are, as with the actions of any natural person, subject to judicial review.[207] Further, it was determined in R. v Secretary of State for Health the ex parte C that, "as a matter of capacity, no doubt, [the Crown] has power to do whatever a private person can do. But, as an organ of government, it can only exercise those powers for the public benefit, and for identifiably 'governmental' purposes within limits set by the law."[208] Similarly, use of the royal prerogative is justiciable,[209] though, only when the "subject matter affects the rights or legitimate expectations of an individual".[210]

The governor general is appointed by the monarch on the advice of his federal prime minister and the lieutenant governors are appointed by the governor general on the advice of the federal prime minister. The commissioners of Canada's territories are appointed by the federal governor-in-council, at the recommendation of the minister of Crown–Indigenous relations, but, as the territories are not sovereign entities, the commissioners are not personal representatives of the sovereign. The Advisory Committee on Vice-Regal Appointments, which may seek input from the relevant premier and provincial or territorial community, proposes candidates for appointment as governor general, lieutenant governor, and commissioner.[211][212]

Sovereign immunity

[edit]It has been held since 1918 that the federal Crown is immune from provincial law.[213] Constitutional convention has also held that the Crown in right of each province is outside the jurisdiction of the courts in other provinces. This view, however, has been questioned.[214]

Lieutenant governors do not enjoy the same immunity as the sovereign in matters not relating to the powers of the viceregal office, as decided in the case of former Lieutenant Governor of Quebec Lise Thibault, who had been accused of misappropriating public funds.[215]

Personification of the Canadian state

[edit]As the living embodiment of the Crown,[121][216] the sovereign is regarded as the personification of the Canadian state[n 14][230] and is meant to represent all Canadians, regardless of political affiliation.[231] As such, he, along with his or her viceregal representatives, must "remain strictly neutral in political terms".[95]

The person of the reigning sovereign thus holds two distinct personas in constant coexistence, an ancient theory of the "King's two bodies"—the body natural (subject to infirmity and death) and the body politic (which never dies).[232] The Crown and the monarch are "conceptually divisible but legally indivisible [...] The office cannot exist without the office-holder",[n 15][78] so, even in private, the monarch is always "on duty".[221] The terms the state, the Crown,[234] the Crown in Right of Canada, His Majesty the King in Right of Canada (French: Sa Majesté le Roi du chef du Canada),[235] and similar are all synonymous and the monarch's legal personality is sometimes referred to simply as Canada.[223][236]

The king or queen of Canada is thus the employer of all government officials and staff (including the viceroys, judges, members of the Canadian Forces, police officers, and parliamentarians),[n 16] the guardian of foster children (Crown wards), as well as the owner of all state lands (Crown land), buildings and equipment (Crown held property),[238] state owned companies (Crown corporations), and the copyright for all government publications (Crown copyright).[239] This is all in his or her position as sovereign, and not as an individual; all such property is held by the Crown in perpetuity and cannot be sold by the sovereign without the proper advice and consent of his or her ministers.

The monarch is at the apex of the Canadian order of precedence and, as the embodiment of the state, is also the focus of oaths of allegiance,[n 17][243] required of many of the aforementioned employees of the Crown, as well as by new citizens, as by the Oath of Citizenship. Allegiance is given in reciprocation to the sovereign's Coronation Oath,[244] wherein he or she promises to govern the people of Canada "according to their respective laws and customs".[245]

Head of state

[edit]Although it has been argued that the term head of state is a republican one inapplicable in a constitutional monarchy such as Canada, where the monarch is the embodiment of the state and thus cannot be head of it,[221] the sovereign is regarded by official government sources,[249] judges,[250] constitutional scholars,[223][251] and pollsters as the head of state,[252] while the governor general and lieutenant governors are all only representatives of, and thus equally subordinate to, that figure.[253] Some governors general, their staff, government publications,[223] and constitutional scholars like Ted McWhinney and C.E.S. Franks have,[254][255] however, referred to the position of governor general as that of Canada's head of state;[256][257] though, sometimes qualifying the assertion with de facto or effective;[261] Franks has hence recommended that the governor general be named officially as the head of state.[255] Still others view the role of head of state as being shared by both the sovereign and his viceroys.[265] Since 1927, governors general have been received on state visits abroad as though they were heads of state.[266]

Officials at Rideau Hall have attempted to use the Letters Patent, 1947, as justification for describing the governor general as head of state. However, the document makes no such distinction,[267] nor does it effect an abdication of the sovereign's powers in favour of the viceroy,[92] as it only allows the governor general to "act on the Queen's behalf".[268][269] D. Michael Jackson, former Chief of Protocol of Saskatchewan, argued that Rideau Hall had been attempting to "recast" the governor general as head of state since the 1970s and doing so preempted both the Queen and all of the lieutenant governors.[253] This caused not only "precedence wars" at provincial events (where the governor general usurped the lieutenant governor's proper spot as most senior official in attendance)[270][271] and Governor General Adrienne Clarkson to accord herself precedence before the Queen at a national occasion,[272] but also constitutional issues by "unbalancing [...] the federalist symmetry".[189][273] This has been regarded as both a natural evolution and as a dishonest effort to alter the constitution without public scrutiny.[267][274]

In a poll conducted by Ipsos-Reid following the first prorogation of the 40th parliament on 4 December 2008, it was found that 42 per cent of the sample group thought the prime minister was head of state, while 33 per cent felt it was the governor general. Only 24 per cent named the Queen as head of state,[252] a number up from 2002, when the results of an EKOS Research Associates survey showed only 5 per cent of those polled knew the Queen was head of state (69 per cent answered that it was the prime minister).[275]

Arms

[edit]

The Arms of His Majesty the King in Right of Canada is the arms of dominion of the Canadian monarch and, thus, equally the official coat of arms of Canada[276][277] and a symbol of national sovereignty.[278] It is closely modelled after the royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom, with French and distinctive Canadian elements replacing or added to those derived from the British version, which was employed in Canada before the granting of the Canadian arms in 1921.[279]

The royal standard is the monarch's official flag, which depicts the royal arms in banner form.[280] It takes precedence above all other flags in Canada—including the national flag and those of the other members of the royal family[44]—and is typically flown from buildings, vessels, and vehicles in which the sovereign is present (although exceptions have been made for its use when the monarch is not in attendance). The royal standard is never flown at half-mast because there is always a sovereign: when one dies, his or her successor becomes the sovereign instantly. Elements of the royal arms have also been incorporated into the governor general's flag; similarly, the flags of the lieutenant governors employ the shields of the relevant provincial coat of arms.

Federal constitutional role

[edit]Canada's constitution is based on the Westminster parliamentary model, wherein the role of the King is both legal and practical, but not political.[95] The sovereign is vested with all the powers of state, collectively known as the royal prerogative,[281] leading the populace to be considered subjects of the Crown.[282] However, as the sovereign's power stems from the people[30][283] and the monarch is a constitutional one, he or she does not rule alone, as in an absolute monarchy. Instead, the Crown is regarded as a corporation sole, with the monarch being the centre of a construct in which the power of the whole is shared by multiple institutions of government[187]—the executive, legislative, and judicial[9]—acting under the sovereign's authority,[223][284] which is entrusted for exercise by the politicians (the elected and appointed parliamentarians and the ministers of the Crown generally drawn from among them) and the judges and justices of the peace.[29] The monarchy has thus been described as the underlying principle of Canada's institutional unity and the monarch as a "guardian of constitutional freedoms"[48][241] whose "job is to ensure that the political process remains intact and is allowed to function."[95]

The Great Seal of Canada "signifies the power and authority of the Crown flowing from the sovereign to [the] parliamentary government"[285] and is applied to state documents such as royal proclamations and letters patent commissioning Cabinet ministers, senators, judges, and other senior government officials.[286] The "lending" of royal authority to Cabinet is illustrated by the great seal being entrusted by the governor general, the official keeper of the seal, to the minister of innovation, science, and economic development, who is ex officio the registrar general of Canada.[286] Upon a change of government, the seal is temporarily returned to the governor general and then "lent" to the next incoming registrar general.[285]

The Crown is the pinnacle of the Canadian Armed Forces, with the constitution placing the monarch in the position of commander-in-chief of the entire force, though the governor general carries out the duties attached to the position and also bears the title of Commander-in-Chief in and over Canada.[287]

Executive (King-in-Council)

[edit]

The government of Canada—formally termed His Majesty's Government[288]—is defined by the constitution as the King acting on the advice of his Privy Council;[291] what is technically known as the King-in-Council,[8] or sometimes the Governor-in-Council,[121] referring to the governor general as the King's stand-in, though, a few tasks must be specifically performed by, or bills that require assent from, the King.[294] One of the main duties of the Crown is to "ensure that a democratically elected government is always in place,"[264] which means appointing a prime minister to thereafter head the Cabinet[295]—a committee of the Privy Council charged with advising the Crown on the exercise of the royal prerogative.[290] The monarch is informed by his viceroy of the swearing-in and resignation of prime ministers and other members of the ministry,[295] remains fully briefed through regular communications from his Canadian ministers, and holds audience with them whenever possible.[246] By convention, the content of these communications and meetings remains confidential so as to protect the impartiality of the monarch and his representative.[95][296] The appropriateness and viability of this tradition in an age of social media has been questioned.[297][298]

In the construct of constitutional monarchy and responsible government, the ministerial advice tendered is typically binding,[299] meaning the monarch reigns but does not rule,[300] the Cabinet ruling "in trust" for the monarch.[301] This has been the case in Canada since the Treaty of Paris ended the reign of the territory's last absolute monarch, King Louis XV of France. However, the royal prerogative belongs to the Crown and not to any of the ministers[303] and the royal and viceroyal figures may unilaterally use these powers in exceptional constitutional crisis situations (an exercise of the reserve powers),[n 18] thereby allowing the monarch to make sure "the government conducts itself in compliance with the constitution";[264] he and the viceroys being guarantors of the government's constitutional, as opposed to democratic, legitimacy and must ensure the continuity of such.[304] Use of the royal prerogative in this manner was seen when the Governor General refused his prime minister's advice to dissolve Parliament in 1926 and when, in 2008, the Governor General took some hours to decide whether or not to accept her Prime Minister's advice to prorogue Parliament to avoid a vote of non-confidence.[305][306] The prerogative powers have also been used numerous times in the provinces.[305]

The royal prerogative further extends to foreign affairs, including the ratification of treaties, alliances, international agreements, and declarations of war,[307] the accreditation of Canadian high commissioners and ambassadors and receipt of similar diplomats from foreign states,[308][309] and the issuance of Canadian passports,[310] which remain the sovereign's property.[311] It also includes the creation of dynastic and national honours,[312] though only the latter are established on official ministerial advice.

Parliament (King-in-Parliament)

[edit]

All laws in Canada are the monarch's and the sovereign is one of the three components of the Parliament of Canada[313][314]—formally called the King-in-Parliament[8]—but, the monarch and viceroy do not participate in the legislative process, save for royal consent, typically expressed by a minister of the Crown,[315] and royal assent, which is necessary for a bill to be enacted as law. Either figure or a delegate may perform this task and the constitution allows the viceroy the option of deferring assent to the sovereign.[316]

The governor general is further responsible for summoning the House of Commons, while either the viceroy or monarch can prorogue and dissolve the legislature, after which the governor general usually calls for a general election. This element of the royal prerogative is unaffected by legislation "fixing" election dates, as An Act to Amend the Canada Elections Act specifies that it does not curtail the Crown's powers.[317] The new parliamentary session is marked by either the monarch, governor general, or some other representative reading the Speech from the Throne.[318] Members of Parliament must recite the Oath of Allegiance before they may take their seat. Further, the official opposition is traditionally dubbed as His Majesty's Loyal Opposition,[321] illustrating that, while its members are opposed to the incumbent government, they remain loyal to the sovereign (as personification of the state and its authority).[322]

The monarch does not have the prerogative to impose and collect new taxes without the authorization of an act of Parliament. The consent of the Crown must, however, be obtained before either of the houses of Parliament may even debate a bill affecting the sovereign's prerogatives or interests and no act of Parliament binds the King or his rights unless the act states that it does.[323]

Courts (King-on-the-Bench)

[edit]

The sovereign is responsible for rendering justice for all his subjects and is thus traditionally deemed the fount of justice[324] and his position in the Canadian courts formally dubbed the King on the Bench.[8] The Arms of His Majesty in Right of Canada are traditionally displayed in Canadian courtrooms,[325] as is a portrait of the sovereign.[326] The badge of the Supreme Court also bears a St. Edward's Crown to symbolize the source of the court's authority.

The monarch does not personally rule in judicial cases; this function of the royal prerogative is instead performed in trust and in the King's name by officers of His Majesty's court.[324] Common law holds the notion that the sovereign "can do no wrong": the monarch cannot be prosecuted in his own courts—judged by himself—for criminal offences under his own laws.[327] Canada inherited the common law version of Crown immunity from British law.[328] However, over time, the scope of said immunity has been steadily reduced by statute law. With the passage of relevant legislation through the provincial and federal parliaments, the Crown in its public capacity (that is, lawsuits against the King-in-Council), in all areas of Canada, is now liable in tort, as any normal person would be.[328] In international cases, as a sovereign and under established principles of international law, the King of Canada is not subject to suit in foreign courts without his express consent.[329]

Within the royal prerogative is also the granting of immunity from prosecution,[330] mercy, and pardoning offences against the Crown.[331][332] Since 1878, the prerogative of pardon has always been exercised upon the recommendation of ministers.[333]

The Crown and Indigenous peoples

[edit]

Included in Canada's constitution are the various treaties between the Crown and Canada's First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples, who, like the Māori and the Treaty of Waitangi in New Zealand,[334] generally view the affiliation as being not between them and the ever-changing Cabinet, but instead with the continuous Crown of Canada, as embodied in the reigning sovereign,[335] meaning the link between monarch and Indigenous peoples in Canada will theoretically last for "as long as the sun shines, grass grows, and rivers flow."[336][337]

The association stretches back to the first decisions between North American Indigenous peoples and European colonialists and, over centuries of interface, treaties were established concerning the monarch and indigenous nations. The only treaties that survived the American Revolution are those in Canada, which date to the beginning of the 18th century. Today, the main guide for relations between the monarchy and Canadian First Nations is King George III's Royal Proclamation of 1763;[338][339] while not a treaty, it is regarded by First Nations as their Magna Carta or "Indian bill of rights",[339][340] as it affirmed native title to their lands and made clear that, though under the sovereignty of the Crown, the aboriginal bands were autonomous political units in a "nation-to-nation" association with non-native governments,[341][342] with the monarch as the intermediary.[343] The agreements with the Crown are administered by aboriginal law and overseen by the minister of Crown-Indigenous relations.[344][345]

I have greatly appreciated the opportunity to discuss [...] the vital process of reconciliation in this country—not a one-off act, of course, but an ongoing commitment to healing, respect and understanding [...] with indigenous and non-indigenous peoples across Canada committing to reflect honestly and openly on the past and to forge a new relationship for the future.[346]

Prince Charles, Prince of Wales, 2022

The link between the Crown and Indigenous peoples will sometimes be symbolically expressed through ceremony.[347] Gifts have been frequently exchanged and aboriginal titles have been bestowed upon royal and viceregal figures since the early days of indigenous contact with the Crown.[352] As far back as 1710, Indigenous leaders have met to discuss treaty business with royal family members or viceroys in private audience and many continue to use their connection to the Crown to further their political aims;[353] public ceremonies attended by the monarch or another member of the royal family have been employed as a platform on which to present complaints, witnessed by both national and international cameras.[356] Following country-wide protests, beginning in 2012, and the close of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2015, focus turned toward rapprochement between the nations in the nation-to-nation relationship.[363]

Hereditary chiefs

[edit]The hereditary chiefs are leaders within First Nations who represent different houses or clans and whose chieftaincies are passed down intergenerationally; most First Nations have a hereditary system.[364] The positions are rooted in traditional models of Indigenous governance that predate the colonization of Canada[365][366] and are organized in a fashion similar to the occidental idea of monarchy.[371] Indeed, early European explorers often considered territories belonging to different aboriginal groups to be kingdoms—such as along the north shore of the St. Lawrence River, between the Trinity River and the Isle-aux-Coudres, and the neighbouring "kingdom of Canada", which stretched west to the Island of Montreal[372]—and the leaders of these communities were referred to as kings,[353] particularly those chosen through heredity.[373][374]

Today, the hereditary chiefs are not sovereign; according to the Supreme Court of Canada, the Crown holds sovereignty over the whole of Canada, including reservation and traditional lands.[378] However, by some interpretations of case law from the same court, the chiefs have jurisdiction over traditional territories that fall outside of band-controlled reservation land,[379][380] beyond the elected band councils established by the Indian Act.[381][382] Although recognized by, and accountable to, the federal Crown-in-Council (the Government of Canada), band chiefs do not hold the cultural authority of hereditary chiefs, who often serve as knowledge-keepers, responsible for the upholding of a First Nation's traditional customs, legal systems, and cultural practices.[385] When serving as Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia, Judith Guichon postulated that the role of hereditary chiefs mirrored that of Canada's constitutional monarch, being the representative of "sober second thought and wisdom, not the next political cycle; but, rather, enduring truths and the evolution of our nation through generations."[370] For these reasons, the Crown maintains formal relations with Canada's hereditary chiefs, including on matters relating to treaty rights and obligations.[386]

Cultural role

[edit]Royal presence and duties

[edit]

Members of the royal family have been present in Canada since the late 18th century, their reasons including participating in military manoeuvres, serving as the federal viceroy, or undertaking official royal tours, which "reinforce [the] country's collective heritage".[387] At least one royal tour has been conducted every year between 1957 and 2018.[388]

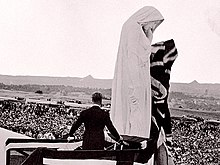

The "welfare and service" function of the monarchy is regarded as an important part of the modern monarchy's role and demonstrates a significant change to the institution in recent generations, from a heavily ceremonialized, imperial crown to a "more demotic and visible" head of state "interacting with the general population far beyond confined court circles."[389] As such, a prominent feature of tours are royal walkabouts; a tradition initiated in 1939 by Queen Elizabeth when she was in Ottawa and broke from the royal party to speak directly to gathered veterans.[390][391] Usually important milestones, anniversaries, or celebrations of Canadian culture will warrant the presence of the monarch,[390] while other members of the royal family will be asked to participate in lesser occasions. A household to assist and tend to the monarch forms part of the royal party.

Official duties involve the sovereign representing the Canadian state at home or abroad, or her relations as members of the royal family participating in government organized ceremonies either in Canada or elsewhere;[n 19][413] sometimes these individuals are employed in asserting Canada's sovereignty over its territories.[n 20] The advice of the Canadian Cabinet is the impetus for royal participation in any Canadian event, though, at present, the Chief of Protocol and his staff in the Department of Canadian Heritage are, as part of the State Ceremonial and Canadian Symbols Program,[415][416] responsible for orchestrating any official events in or for Canada that involve the royal family.[417]

Conversely, unofficial duties are performed by royal family members for Canadian organizations of which they may be patrons, through their attendance at charity events, visiting with members of the Canadian Forces as colonel-in-chief, or marking certain key anniversaries.[409][410] The invitation and expenses associated with these undertakings are usually borne by the associated organization.[409] In 2005, members of the royal family were present at a total of 76 Canadian engagements, as well as several more through 2006 and 2007.[418] In the period between 2019 and 2022, they carried out 53 engagements, the number reduced, and all through the latter year and a half being virtual, because of restrictions in place during the COVID-19 pandemic.[419] The various viceroys took part in 4,023 engagements through 2019 and 2020, both in-person and virtually.[420]

Apart from Canada, the King and other members of the royal family regularly perform public duties in the other 14 Commonwealth realms in which the King is head of state. This situation, however, can mean the monarch and/or members of the royal family will be promoting one nation and not another; a situation that has been met with criticism.[n 21]

Symbols, associations, and awards

[edit]The main symbol of the monarchy is the sovereign himself,[187] described as "the personal expression of the Crown in Canada,"[422] and his image is thus used to signify Canadian sovereignty and government authority—his image, for instance, appearing on currency, and his portrait in government buildings.[241] The sovereign is further both mentioned in and the subject of songs, loyal toasts, and salutes.[423] A royal cypher, appearing on buildings and official seals, or a crown, seen on provincial and national coats of arms, as well as police force and Canadian Forces regimental and maritime badges and rank insignia, is also used to illustrate the monarchy as the locus of authority,[424] the latter without referring to any specific monarch.

Since the days of King Louis XIV,[425] the monarch is the fount of all honours in Canada and the orders,[425][426] decorations, and medals form "an integral element of the Crown."[425] Hence, the insignia and medallions for these awards bear a crown, cypher, and/or portrait of the monarch. Similarly, the country's heraldic authority was created by Queen Elizabeth II and, operating under the authority of the governor general, grants new coats of arms, flags, and badges in Canada. Use of the royal crown in such symbols is a gift from the monarch showing royal support and/or association and requires his approval before being added.[424][427]

Members of the royal family also act as ceremonial colonels-in-chief, commodores-in-chief, captains-general, air commodores-in-chief, generals, and admirals of various elements of the Canadian Forces, reflecting the Crown's relationship with the country's military through participation in events both at home and abroad.[n 22] The monarch also serves as the Commissioner-in-Chief, and Prince Edward and Princess Anne as Honorary Deputy Commissioners, of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.[428]

A number of Canadian civilian organizations have association with the monarchy, either through their being founded via a royal charter, having been granted the right to use the prefix royal before their name, or because at least one member of the royal family serves as a patron. In addition to The Prince's Trust Canada, established by Charles III when Prince of Wales, some other charities and volunteer organizations have also been founded as gifts to, or in honour of, some of Canada's monarchs or members of the royal family, such as the Victorian Order of Nurses, a gift to Queen Victoria for her Diamond Jubilee in 1897; the Canadian Cancer Fund, set up in honour of King George V's Silver Jubilee in 1935; and the Queen Elizabeth II Fund to Aid in Research on the Diseases of Children. A number of awards in Canada are likewise issued in the name of previous or present members of the royal family. Further, organizations will give commemorative gifts to members of the royal family to mark a visit or other important occasion. All Canadian coins bear the image of the monarch reigning at the time of the coin's production, with an inscription, Dei gratia Rex (often abbreviated to DG Rex), a Latin phrase translated to English as, "by the grace of God, king".[429] During the reign of a female monarch, rex is replaced with regina, which is Latin for 'queen'.

Throughout the 1970s, symbols of the monarch and monarchy were slowly removed from the public eye. For instance, the Queen's portrait was seen less in public schools and the Royal Mail became Canada Post. Smith attributed this to the attitude the government of the day held toward Canada's past;[430] though, it never raised the policy in public or during any of the constitutional conferences held that decade.[137] Andrew Heard argued, however, that dispensing with such symbols was necessary to facilitate the simultaneous increasing embrace of the monarch as Queen of Canada.[431] Emblems such as the Royal Coat of Arms remained, however, and others, such as the monarch's royal standard, were created. With the later developments of the governor general's flag, foundation of the Canadian Heraldic Authority, royal standards for other members of the royal family, and the like, Canada, along with New Zealand, is one of the two realms that have "paid the greatest attention to the nationalization of the visual symbols of the monarchy."[432]

Significance to Canadian identity

[edit]In his 2018 book, The Canadian Kingdom: 150 Years of Constitutional Monarchy, Jackson wrote that "the Canadian manifestation of the monarchy is not only historical and constitutional, it is political, cultural, and social, reflecting, and contributing to, change and evolution in Canada's governance, autonomy, and identity."[64] Since at least the 1930s,[433] supporters of the Crown have held the opinion that the monarch is a unifying focal point for the nation's "historic consciousness"—the country's heritage being "unquestionably linked with the history of monarchy"[387]—and Canadian patriotism, traditions, and shared values,[387] "around which coheres the nation's sense of a continuing personality".[434] This infusion of monarchy into Canadian governance and society helps strengthen Canadian identity[387] and distinguish it from American identity,[435] a difference that has existed since at least 1864, when it was a factor in the Fathers of Confederation choosing to keep constitutional monarchy for the new country in 1866.[436] Former Governor General Vincent Massey articulated in 1967 that the monarchy "stands for qualities and institutions which mean Canada to every one of us and which, for all our differences and all our variety, have kept Canada Canadian."[437]

I want the Crown in Canada to represent everything that is best and most admired in the Canadian ideal. I will continue to do my best to make it so during my lifetime.[438]

Elizabeth II, 1973

But, Canadians were, through the late 1960s to the 2000s, encouraged by federal and provincial governments to "neglect, ignore, forget, reject, debase, suppress, even hate, and certainly treat as foreign what their parents and grandparents, whether spiritual or blood, regarded as the basis of Canadian nationhood, autonomy, and history", including the monarchy.[439] resulting in a disconnect between the Canadian populace and their monarch.[436] Former Governor General Roland Michener said in 1970 that anti-monarchists claimed the Canadian Crown is foreign and incompatible with Canada's multicultural society,[292] which the government promoted as a Canadian identifier, and Lawrence Martin called in 2007 for Canada to become a republic in order to "re-brand the nation".[440] However, Michener also stated, "[the monarchy] is our own by inheritance and choice, and contributes much to our distinctive Canadian identity and our chances of independent survival amongst the republics of North and South America."[292] Journalist Christina Blizzard emphasized in 2009 that the monarchy "made [Canada] a haven of peace and justice for immigrants from around the world",[441] while Michael Valpy contended in 2009 that the Crown's nature permitted non-conformity amongst its subjects, thereby opening the door to multiculturalism and pluralism.[46] Johnston described the Crown as providing "space for our values and beliefs as Canadians."[188]

In media and popular culture

[edit]Painting and sculpture

[edit]Aside from official artworks, such as monuments and portraits commissioned by government bodies, Canadian painters have, by their own volition or for private organizations, created more expressive, informal depictions of Canada's monarchs and other members of the royal family, ranging from fine art to irreverent graffiti. For example, the English-Canadian artist Frederic Marlett Bell-Smith produced The Artist Painting Queen Victoria in 1895, which now resides at the National Gallery of Canada. At Library and Archives Canada is the painting The Unveiling of the National War Memorial, capturing the dedication of the monument, in Ottawa, by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in 1939; though, the artist is unknown.[442]

Hilton Hassell depicted Princess Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth II) square dancing at Rideau Hall in 1951 and a portrait of Elizabeth II by Lorena Ziraldo, of Ottawa, was featured in the Hill Times and Ottawa Citizen.

Charles Pachter, from Toronto, fashioned the painting Noblesse Oblige in 1972, which shows Queen Elizabeth II, in her Guards Regiment uniform and saluting, as she did during Trooping the Colour ceremonies, except atop a moose instead of her horse, Burmese. Despite great controversy when it was first exhibited,[443] it "has become a Canadian cultural image; the people's image".[443][444] Pachter, subsequently made numerous variations on the theme,[445] including Queen & Moose (1973)[446] and The Queen on a Moose (1988).[447] The artist said, "there was an amazing symmetry of putting the sovereign of her northern realm (Canada) on an animal who is the 'monarch of the north, awkward but majestic'".[443] Pachter made similar pieces showing Elizabeth's son, Prince Charles (now King Charles III) and his wife, Camilla, standing alongside a moose[444] and Charles's son, Prince William, and his wife, Catherine, with Canadian wildlife, such as a moose and a squirrel.[448] For Elizabeth II's Diamond Jubilee, Pachter created a series of fake postage stamps using all his paintings that include members of the royal family,[443] which he called "my branded images for Canada."[449] Some were featured on accessory items sold at the Hudson's Bay Company.[449]

Portraits of Elizabeth II hung in several hockey arenas across Canada after her accession in 1952. One was in place in Maple Leaf Gardens until the early 1970s, when owner Harold Ballard had it removed to construct more seating, stating, "if people want to see pictures of the Queen, they can go to an art gallery."[450] Three large portraits of Elizabeth II were created for Winnipeg Arena, on display there from the building's opening in 1955 to 1999.[454]

At the time of the sesquicentennial of Confederation in 2017, Vancouver Island-based[455] artist Timothy Hoey created a "Canada 150" version of his decade-long "O Canada" project, painting 150 Canadian icons in acrylic paint on 20.3 by 25.4 centimetre (eight by 10 inch) boards.[456][457] Among them are numerous depictions of Queen Elizabeth II with other Canadian icons, such as beavers, Cheezies, the Grey Cup,[456] the Stanley Cup,[457] a bottle of beer (O Canada Liz Enjoying Some Wobbly-Pops),[458] Rush (O Canada Closer to the Heart), the Hudson's Bay point blanket,[458] the Trans-Canada Highway, a birch canoe, a buckskin jacket, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police uniform, a Montreal Canadiens hockey sweater, and so on.[456] Hoey had previously painted Elizabeth, in formal attire and tiara, holding a hockey stick in front of a Hudson's Bay point blanket; the work titled O-Canada Liz.[459] In 2021, he depicted the Queen in a decorative hat, uniform of the Vancouver Canucks from the 1978–1979 season, and full goaltender equipment.[460]

The also exist wax sculptures of Queen Elizabeth II in private museums, such as the Royal London Wax Museum in Victoria, British Columbia, and the Wax Museum of History in Niagara Falls, Ontario.[461]

Television

[edit]The television series Rideau Hall, starring Bette MacDonald, was produced by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and aired for one season in 2002. Its premise was a brash, one-hit wonder disco artist being appointed governor general on the advice of a republican prime minister.[462][463]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Canadian comedian Scott Thompson regularly played a parody of Queen Elizabeth II in a Canadian context on the sketch comedy television show The Kids in the Hall,[464] as well as in other productions, such as The Queen's Toast: A Royal Wedding Special[465] and Conan. Thompson also voiced a portrayal of Queen Elizabeth II in Canada in the animated television show Fugget About It, in the episode "Royally Screwed".[466]

The Canadian monarchy was parodied in "Royal Pudding", the third episode of the 15th season of the animated television show South Park, which first aired on 11 May 2011.[467] The opening focuses on a spoof of the wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton,[468][469] featuring caricatures of Queen Elizabeth II; Prince William, Prince of Wales; and Catherine, Princess of Wales. Specific mention is made of "the Queen of Canada" and "the Canadian royal family".[470] The show subsequently, in the second episode of the 26th season, "The Worldwide Privacy Tour", parodied the Duke and Duchess of Sussex as a prince of Canada and "the wife", who, after hostile treatment at the funeral of the late Queen of Canada, go on national television and a world tour demanding people and the media not pay attention to them and branding themselves as victims.[471]

Royal family and house

[edit]

The Canadian royal family is the group of people who are comparatively closely related to the country's monarch and,[472] as such, belong to the House of Windsor and owe their allegiance specifically to the reigning king or queen of Canada.[473] There is no legal definition of who is or is not a member of the royal family; though, the Government of Canada's website lists "working members of the royal family".[474]

Unlike in the United Kingdom, the monarch is the only member of the royal family with a title established through Canadian law and is styled by convention as His/Her Majesty,[475] as would be a queen consort. Otherwise, the remaining family members are, as a courtesy, styled and titled as they are in the UK,[475] according to letters patent issued there,[476][477] with additional French translations.[478]

Those in the royal family are distant relations of the Belgian, Danish, Greek, Norwegian, Spanish, and Swedish royal families and,[479] given the shared nature of the Canadian monarch, are also members of the British royal family. While Canadian and foreign media often refer to them as the "British royal family",[480][481] the Canadian government considers it inappropriate, as they are family members of the Canadian monarch.[482] Further, in addition to the few Canadian citizens in the royal family,[n 23] the sovereign is considered Canadian,[490] and those among his relations who do not meet the requirements of Canadian citizenship law are considered Canadian, which entitles them to Canadian consular assistance and the protection of the King's armed forces of Canada when they are in need of protection or aid outside of the Commonwealth realms,[473] as well as, since 2013, substantive appointment to the Order of Canada and Order of Military Merit.[491][492][493] Beyond formalities, members of the royal family have, on occasion, been said by the media and non-governmental organizations to be Canadian,[n 24] have declared themselves to be Canadian,[n 25] and some past members have lived in Canada for extended periods as viceroy or for other reasons.[n 26]

According to the Canadian Royal Heritage Trust, Prince Edward Augustus, Duke of Kent and Strathearn—due to his having lived in Canada between 1791 and 1800 and fathering Queen Victoria—is the "ancestor of the modern Canadian royal family".[505] Nonetheless, the concept of the Canadian royal family did not emerge until after the passage of the Statute of Westminster in 1931, when Canadian officials only began to overtly consider putting the principles of Canada's new status as an independent kingdom into effect.[508] Initially, the monarch was the only member of the royal family to carry out public ceremonial duties solely on the advice of Canadian ministers; King Edward VIII became the first to do so when in July 1936 he dedicated the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France.[n 19] Over the decades, however, the monarch's children, grandchildren, cousins, and their respective spouses began to also perform functions at the direction of the Canadian Crown-in-Council, representing the monarch within Canada or abroad, in a role specifically as members of the Canadian royal family.[509]

However, it was not until October 2002 when the term Canadian royal family was first used publicly and officially by one of its members: in a speech to the Nunavut legislature at its opening, Queen Elizabeth II stated: "I am proud to be the first member of the Canadian royal family to be greeted in Canada's newest territory."[510][511] Princess Anne used it again when speaking at Rideau Hall in 2014,[512] as did the now King Charles in Halifax the same year.[513] Also in 2014, then-Premier of Saskatchewan Brad Wall called Prince Edward a member of the Canadian royal family.[514] By 2011, both Canadian and British media were referring to "Canada's royal family" or the "Canadian royal family".[519]

While Heard observed in 2018 that no direct legal action has, so far, created a Canadian royal family,[520] he also asserted that the Canadian Heraldic Authority creating uniquely Canadian standards for members of the royal family other than the monarch was a symbolic "localization of the royal family";[521] Sean Palmer agreed, stating the banners are a sign the country has taken "'ownership' not only of the Queen of Canada, but of the other members of her family as well" and that doing so was another formal affirmation of the concept of a Canadian royal family "as distinct as the Queen of Canada is from the Queen of the United Kingdom".[511] Jai Patel and Sally Raudon also noted, in 2019, that the purpose of these heraldic banners was to recognize the owners' roles as members of the Canadian royal family.[522]

Federal residences and royal household

[edit]Buildings across Canada reserved by the Crown for the use of the monarch and his viceroys are called Government House, but may be customarily known by some specific name. The sovereign's and governor general's official residences are Rideau Hall in Ottawa and the Citadelle in Quebec City.[n 27][534] Each holds pieces from the Crown Collection.[535] Though neither was used for their intended purpose, Hatley Castle in British Columbia was purchased in 1940 by the federal government for the use of George VI and his family during the Second World War[536] and the Emergency Government Headquarters, built between 1959 and 1961 at CFS Carp and decommissioned in 1994, included a residential apartment for the sovereign or governor general in the case of a nuclear attack.[537]

British royalty have also owned homes and land in Canada in a private capacity: Edward VIII owned Bedingfield Ranch, near Pekisko, Alberta;[538] and Princess Margaret owned Portland Island, which was given to her by British Columbia in 1958. She offered it back to the province on permanent loan in 1961, which was accepted in 1966, and the island and surrounding waters eventually became Princess Margaret Marine Park.[539]

In addition to a maître d’hôtel, chefs, footmen, valets, dressers, pages, aides-de-camp (drawn from the junior officers of the armed forces), equerries, and others at Rideau Hall,[540] the King appoints various people to his Canadian household to assist him in carrying out his official duties on behalf of Canada. Along with the Canadian secretary to the King,[417] the monarch's entourage includes the equerry-in-waiting to the King, the King's police officer, two ladies-in-waiting for the Queen,[541] the King's honorary physician, the King's honorary dental surgeon, and the King's honorary nursing officer[542]—the latter three being drawn from the Canadian Forces.[152] Prince Edward, Duke of Edinburgh, also has a Canadian private secretary and his wife,[543] Sophie, Duchess of Edinburgh, a lady-in-waiting.[544] Royal Canadian Air Force VIP aircraft are provided by 412 Transport Squadron.

There are three household regiments specifically attached to the royal household—the Governor General's Foot Guards, the Governor General's Horse Guards, and the Canadian Grenadier Guards. There are also three chapels royal, all in Ontario:[545] Mohawk Chapel in Brantford; Christ Church Royal Chapel, near Deseronto; and St Catherine's Chapel in Massey College, in Toronto. Though not a chapel royal, St Bartholomew's Anglican Church, located across MacKay Street from Rideau Hall, is regularly used by governors general and their families and sometimes by the sovereign and other visiting royalty, as well as by staff, their families, and members of the Governor General's Foot Guards, for whom the church serves as a regimental chapel.[546]

Security

[edit]The Royal Canadian Mounted Police is tasked with providing security to the sovereign, the governor general (starting from when he or she is made governor general-designate[547]), and other members of the royal family; as outlined in the RCMP Regulations, the force "has a duty to protect individuals designated by the minister of public safety, including certain members of the royal family when visiting."[548] The RCMP's provision of service is determined based on threat and risk assessment, the seniority of the individual in terms of precedence and.[n 28] for members of the royal family, the nature of the royal tour—i.e. an official tour by the King or on behalf of the King or a working or private visit.[548] The governor general receives round-the-clock security from the Governor General Protection Detail,[550] part of the Personal Protection Group, based at Rideau Hall.

History

[edit]From colonies to independence

[edit]The Canadian monarchy can trace its ancestral lineage back to the kings of the Angles and the early Scottish kings and through the centuries since the claims of King Henry VII in 1497 and King Francis I in 1534; both being blood relatives of the current Canadian monarch. Former Prime Minister Stephen Harper said of the Crown that it "links us all together with the majestic past that takes us back to the Tudors, the Plantagenets, Magna Carta, habeas corpus, petition of rights, and English common law."[551] Though the first French and British colonizers of Canada interpreted the hereditary nature of some indigenous North American chieftainships as a form of monarchy,[555] it is generally accepted that Canada has been a territory of a monarch or a monarchy in its own right only since the establishment of the French colony of Canada in the early 16th century;[47] according to historian Jacques Monet, the Canadian Crown is one of the few that have survived through uninterrupted succession since before its inception.[53]

After the Canadian colonies of France were, via war and treaties, ceded to the British Crown, and the population was greatly expanded by those loyal to George III fleeing north from persecution during and following the American Revolution, British North America was in 1867 confederated by Queen Victoria to form Canada as a kingdom in its own right.[557] By the end of the First World War, the increased fortitude of Canadian nationalism inspired the country's leaders to push for greater independence from the King in his British Council, resulting in the creation of the uniquely Canadian monarchy through the Statute of Westminster, which was granted royal assent in 1931.[74][558] Only five years later, Canada had three successive kings in the space of one year, with the death of George V, the accession and abdication of Edward VIII, and his replacement by George VI.

From 1786 through to the 1930s, members of the royal family toured Canada, including Prince William (later King William IV); Prince Edward, Duke of Kent; Prince Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII); Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn; John Campbell, Marquess of Lorne, and Princess Louise; Prince Leopold; Princess Marie-Louise; Prince George, Duke of Cornwall and York (later King George V), and Princess Victoria (later Queen Mary); Prince Arthur (son of the Duke of Connaught); Princess Patricia; Prince Albert (later King George VI); Prince Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII); Prince George, Duke of Kent; and Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester.[559]

The Canadian Crown

[edit]