Эфталиты

Эфталиты | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Империя: 440–560 гг. [ 1 ] Княжества в Тохаристане и Гиндукуше до 710 г. [ 2 ] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

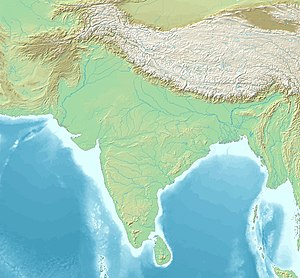

Территория Империи Гефталитов, около 500 г. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Статус | Кочевая империя | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Капитал | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Общие языки |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Религия | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Историческая эпоха | Поздняя античность | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Учредил | Империя: 440-е гг. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Упразднено | 560 [ 1 ] Княжества в Тохаристане и Гиндукуше до 710 г. [ 2 ] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Эфталиты , ( бактрийский : ηβοδαλο , латинизированный: Эбодало ) [ 11 ] иногда называемые Белыми гуннами (также известными как Белые гунны , по -ирански — Спец Кён , а по -санскритски — Света-хуна ), [ 12 ] [ 13 ] — народ, живший в Средней Азии в V-VIII веках нашей эры, входивший в большую группу иранских гуннов . [ 14 ] [ 15 ] Они сформировали империю Имперских Эфталитов и имели важное военное значение с 450 г. н.э., когда они победили кидаритов , до 560 г. н.э., когда объединенные силы Первого Тюркского каганата и Сасанидской империи разгромили их. [ 1 ] [ 16 ] После 560 г. н. э. они основали «княжества» в районе Тохаристана , под сюзеренитетом западных тюрков (в районах к северу от Окса ) и Сасанидской империи (в районах к югу от Окса ), до Тохара Ябгуса. вступил во владение в 625 году. [ 16 ]

Имперские эфталиты, обосновавшиеся в Бактрии , расширялись на восток до Таримской котловины , на запад до Согдианы и на юг через Афганистан , но никогда не выходили за пределы Гиндукуша , который был занят алчонскими гуннами , ранее ошибочно считавшимися продолжением эфталитов. . [ 17 ] Они представляли собой племенную конфедерацию и включали как кочевые, так и оседлые городские общины. Они входили в состав четырех основных государств, известных под общим названием Ксион (ксиониты) или Хуна , им предшествовали кидариты и алхон , а на смену им пришли гунны Незак и Первый Тюркский каганат. Все эти гуннские народы часто были связаны с гуннами , вторгшимися в Восточную Европу в тот же период, и / или их называли «гуннами», но ученые не пришли к единому мнению относительно какой-либо такой связи.

Оплотом эфталитов был Тохаристан (современный южный Узбекистан и северный Афганистан ) на северных склонах Гиндукуша , а их столица, вероятно, находилась в Кундузе , придя [ нужны разъяснения ] с востока, возможно, из района Бадахшана . [ 16 ] К 479 г. эфталиты завоевали Согдиану и оттеснили кидаритов на восток, а к 493 г. захватили часть Джунгарии и Таримской котловины (на территории современного Северо-Западного Китая ). Алчонские гунны , которых раньше путали с эфталитами, распространились на Северную Индию . также [ 18 ]

Источники по истории эфталитов немногочисленны, и мнения историков различаются. Списка королей не существует, и историки не уверены, как возникла эта группа и на каком языке они первоначально говорили. Похоже, они называли себя Эбодало (ηβοδαλο, отсюда Гефтал ), часто сокращая Эб (ηβ), имя, которое они писали бактрийским шрифтом на некоторых своих монетах. [ 19 ] [ 20 ] [ 21 ] [ 22 ] Происхождение названия «эфталиты» неизвестно, оно может происходить либо от хотанского слова *Hitala, означающего «сильный», [ 23 ] от гипотетического согдийского * Heβtalīt , множественного числа от * Heβtalak , [ 24 ] или от предполагаемого среднеперсидского *haftāl «Семь [ 25 ] Ал ». [ 26 ] [ а ] [ б ]

Имя и этнонимы

[ редактировать ]

Эфталиты называли себя Эбодал , как видно на печати одного из первых эфталитских царей с надписью бактрийским письмом :

пах бвго

эбодал ббго

« Ябгу (Господь) эфталитов»

Он носит сложную лучистую корону и королевские ленты. Конец V – начало VI века нашей эры. [ 3 ] [ 17 ] [ 27 ] [ 28 ]

Эфталиты называли себя Эбодал ( бактрийский : ![]() , греческое письмо: ηβοδαλο ) в своих надписях, которое обычно сокращали до

, греческое письмо: ηβοδαλο ) в своих надписях, которое обычно сокращали до ![]() ( ηβ , «Eb») в их чеканке. [ 29 ] [ 27 ] Важная и уникальная печать, хранящаяся в частной коллекции профессора доктора Амана ур Рахмана и опубликованная Николасом Симс-Уильямсом в 2011 году. [ 30 ] изображен ранний гефталитский правитель с круглым безбородым лицом и раскосыми миндалевидными глазами, носящий лучистую корону с одним полумесяцем и обрамленный бактрийского письма легендой ηβοδαλο ββγο («Господин [ Ябгу ] эфталитов»). [ 31 ] [ с ] Печать датируется концом V – началом VI веков нашей эры. [ 3 ] [ 27 ] Этническое название «Эбодало» и титул «Эбодало Ябгу» также были обнаружены в современных бактрийских документах царства Роб, описывающих административные функции при эфталитах. [ 33 ] [ 34 ]

( ηβ , «Eb») в их чеканке. [ 29 ] [ 27 ] Важная и уникальная печать, хранящаяся в частной коллекции профессора доктора Амана ур Рахмана и опубликованная Николасом Симс-Уильямсом в 2011 году. [ 30 ] изображен ранний гефталитский правитель с круглым безбородым лицом и раскосыми миндалевидными глазами, носящий лучистую корону с одним полумесяцем и обрамленный бактрийского письма легендой ηβοδαλο ββγο («Господин [ Ябгу ] эфталитов»). [ 31 ] [ с ] Печать датируется концом V – началом VI веков нашей эры. [ 3 ] [ 27 ] Этническое название «Эбодало» и титул «Эбодало Ябгу» также были обнаружены в современных бактрийских документах царства Роб, описывающих административные функции при эфталитах. [ 33 ] [ 34 ]

Византийские греческие источники называли их гефталитами ( Ἐφθαλῖται ), [ 35 ] Абдель или Авдель . Для армян эфталиты были Hephthal , Hep't'al и Tetal и иногда отождествлялись с кушанами . Для персов эфталиты — это гефтал, гефтель и евталс. Для арабов эфталитами были Хайтал , Хетал , Хейтал , Хайетал , Хейателиты , (аль-)Хаятила ( هياطلة ), и иногда идентифицированные как турки . [ 8 ] По мнению Зеки Велиди Тогана форма Haytal 1985) , ( первый период была технической ошибкой для Ha btal , поскольку арабский -b- и арабских источниках в похож на -y- . в персидских [ 36 ]

В китайских хрониках эфталитов называют Yàndàiyílìtuó ( китайский : 厭帶夷栗陀 ), или в более обычной сокращенной форме, Yedā 嚈噠 , а в Книге Ляна 635 года — Хуа 滑 . [ 37 ] [ 38 ] Последнее имя получило различные латинизации , включая Yeda , Ye-ta , Ye-tha ; Йе-да и Янда . Соответствующие кантонские и корейские имена Yipdaat и Yeoptal ( корейский : 엽달 ), которые сохраняют аспекты среднекитайского произношения ( IPA [ʔjɛpdɑt] ) лучше, чем современное мандаринское произношение, более соответствуют греческому эфталиту . Некоторые китайские летописцы предполагают, что корень Hephtha- (как в Yàndaiyílìtuó или Yedā ) технически был титулом, эквивалентным «императору», тогда как Хуа было названием доминирующего племени. [ 39 ]

В древней Индии такие имена, как эфталит, были неизвестны. Эфталиты были частью или ответвлением народа, известного в Индии как гуны или турушки . [ 40 ] хотя эти имена могли относиться к более широким группам или соседним народам. В древнем санскритском тексте Правишьясутра упоминается группа людей по имени Хавитарас, но неясно, обозначает ли этот термин эфталитов. [ 41 ] Индейцы также использовали выражение «Белые гунны» ( Света Хуна ). для обозначения эфталитов [ 42 ]

Географическое происхождение и расширение

[ редактировать ]Согласно новейшим исследованиям, оплотом эфталитов всегда был Тохаристан на северных склонах Гиндукуша , на территории современного южного Узбекистана и северного Афганистана . [ 43 ] Их столица, вероятно, находилась в Кундузе , который был известен ученому XI века аль-Бируни как Вар-Вализ , возможное происхождение одного из имен, данных китайцами эфталитам: 滑 ( Среднекитайский ( ZS ) * ɦˠuat̚ > стандартный Китайский : Хуа ). [ 43 ]

Эфталиты, возможно, пришли с Востока, через горы Памира , возможно, из района Бадахшана . [ 43 ] Альтернативно, они могли мигрировать из Алтая среди волн вторжения гуннов. [ 44 ]

После своей экспансии на запад или юг эфталиты поселились в Бактрии и вытеснили гуннов Алхона , которые распространились на Северную Индию. Эфталиты вступили в контакт с Сасанидской империей и участвовали в военной помощи Перозу I в захвате трона у его брата Хормизда III . [ 43 ]

Позже, в конце V века, эфталиты распространились на обширные территории Средней Азии и заняли Таримскую впадину до Турфана , взяв под свой контроль территорию у жужжан , которые собирали тяжелую дань с городов-оазисов, но были в настоящее время ослабевает под натиском китайской династии Северная Вэй . [ 45 ]

Происхождение и характеристики

[ редактировать ]Было несколько теорий относительно происхождения эфталитов, включая иранскую. [ 51 ] [ 52 ] [ 53 ] и алтайский [ 54 ] [ 55 ] [ 56 ] [ 57 ] [ 58 ] [ 59 ] теории являются основными. Самая известная теория в настоящее время, по-видимому, состоит в том, что эфталиты изначально имели тюркское происхождение, а затем переняли бактрийский язык. [ 60 ]

По мнению большинства учёных-специалистов, эфталиты приняли бактрийский язык в качестве своего официального языка, так же, как кушаны это сделали после своего расселения в Бактрии / Тохаристане . [ 58 ] Бактрийский язык был восточноиранским языком , но был написан греческим алфавитом , остатком Греко-Бактрийского царства в III–II веках до нашей эры. [ 58 ] Бактрийский язык , помимо того, что был официальным языком, был также языком местного населения, которым правили эфталиты. [ 61 ] [ 52 ]

Эфталиты писали свои монеты на бактрийском языке , титулы, которые они носили, были бактрийскими, например XOAΔHO или Шао, [ 62 ] и вероятно китайского происхождения, такие как Ябгу , [ 34 ] имена правителей-эфталитов, приведенные в Фирдоуси » « Шахнаме , иранские, [ 62 ] а надписи на драгоценных камнях и другие свидетельства показывают, что официальным языком элиты эфталитов был восточноиранский. [ 62 ] В 1959 году Кадзуо Эноки предположил, что эфталиты, вероятно, были индоевропейскими (восточными) иранцами , произошедшими из Бактрии / Тохаристана , основываясь на том, что древние источники обычно располагали их в районе между Согдией и Гиндукушем , а эфталиты имели некоторые иранские особенности. [ 63 ] Ричард Нельсон Фрай осторожно принял гипотезу Эноки, одновременно подчеркнув, что эфталиты «вероятно, представляли собой смешанную орду». [ 64 ] Согласно Энциклопедии Ираника и Энциклопедии Ислама , эфталиты, возможно, произошли на территории современного Афганистана . [ 5 ] [ 65 ]

Некоторые ученые, такие как Марквар и Груссе, предположили протомонгольское происхождение. [ 66 ] Ю Тайшань проследил происхождение эфталитов до Сяньбэя и далее до Когурё . [ 67 ]

Другие ученые, такие как де ла Васьер , на основе недавней переоценки китайских источников предполагают, что эфталиты изначально имели тюркское происхождение, а затем приняли бактрийский язык сначала для административных целей, а, возможно, позже в качестве родного языка — согласно Резахани (2017) , этот тезис, по-видимому, является «самым заметным в настоящее время». [ 68 ] [ 69 ] [ д ]

По сути, эфталиты могли быть конфедерацией разных народов, говорящих на разных языках. По словам Ричарда Нельсона Фрая :

Just as later nomadic empires were confederations of many peoples, we may tentatively propose that the ruling groups of these invaders were, or at least included, Turkic-speaking tribesmen from the east and north, although most probably the bulk of the people in the confederation of Chionites and then Hephhtalites spoke an Iranian language. In this case, as normal, the nomads adopted the written language, institutions, and culture of the settled folks.[61]

Relation to European Huns

[edit]According to Martin Schottky, the Hephthalites apparently had no direct connection with the European Huns, but may have been causally related with their movement. The tribes in question deliberately called themselves "Huns" in order to frighten their enemies.[78] On the contrary, de la Vaissière considers that the Hepthalites were part of the great Hunnic migrations of the 4th century CE from the Altai region that also reached Europe, and that these Huns "were the political, and partly cultural, heirs of the Xiongnu".[79][80][81] This massive migration was apparently triggered by climate change, with aridity affecting the mountain grazing grounds of the Altay Mountains during the 4th century CE.[82] According to Amanda Lomazoff and Aaron Ralby, there is a high synchronicity between the "reign of terror" of Attila in the west and the southern expansion of the Hephthalites, with extensive territorial overlap between the Huns and the Hephthalites in Central Asia.[83]

The 6th-century Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea (History of the Wars, Book I. ch. 3), related them to the Huns in Europe, but insisted on cultural and sociological differences, highlighting the sophistication of the Hephthalites:

The Ephthalitae Huns, who are called White Huns [...] The Ephthalitae are of the stock of the Huns in fact as well as in name, however, they do not mingle with any of the Huns known to us, for they occupy a land neither adjoining nor even very near to them; but their territory lies immediately to the north of Persia [...] They are not nomads like the other Hunnic peoples, but for a long period have been established in a goodly land... They are the only ones among the Huns who have white bodies and countenances which are not ugly. It is also true that their manner of living is unlike that of their kinsmen, nor do they live a savage life as they do; but they are ruled by one king, and since they possess a lawful constitution, they observe right and justice in their dealings both with one another and with their neighbors, in no degree less than the Romans and the Persians[84]

Chinese chronicles

[edit]The Hephthalites were first known to the Chinese in 456 CE, when a Hephthalite embassy arrived at the Chinese court of the Northern Wei.[89] The Chinese used various names for the Hephthalites, such as Hua (滑), Ye-tha-i-li-to (simp. 厌带夷栗陁, trad. 厭帶夷粟陁) or more briefly Ye-da (嚈噠).[90][91] Ancient imperial Chinese chronicles give various explanations about the origins of the Hephthalites:[92][93][94]

- They were descendants "of the Gaoju or the Da Yuezhi" according to the earliest chronicles such as the Book of Wei or the History of the Northern Dynasties.[92]

- They were descendants "of the Da Yuezhi tribes", according to many later chronicles.[92]

- The ancient historian Pei Ziye conjectured that the "Hua" (滑) may be descendants of a Jushi general of the 2nd century CE because that general was named "Bahua" (八滑). This etymological fantasy was adopted by the Book of Liang (Volume 30 and Volume 54).[92][95]

- Another etymological fantasy appeared in the Tongdian, reporting an account by the traveller Wei Jie according to which the Hephthalites may have been the descendants of the Kangju because a Kangju general of the Eastern Han happened to be named "Yitian".[92]

Kazuo Enoki made a first groundbreaking analysis of the Chinese sources in 1959, suggesting that the Hephthalites were a local tribe of the Tokharistan (Bactria) region, with their origin in the nearby Western Himalayas.[92] He also used as an argument the presence of numerous Bactrian names among the Hephthalites, and the fact that the Chinese reported that they practiced polyandry, a well-known West Himalayan cultural trait.[92]

According to a recent reappraisal of the Chinese sources by de la Vaissière (2003), only the Turkic Gaoju origin of the Hephthalites should be retained as indicative of their primary ethnicity, and the mention of the Da Yuezhi only stems from the fact that, at the time, the Hephthalites had already settled in the former Da Yuezhi territory of Bactria, where they are known to have used the Eastern Iranian Bactrian language.[96] The earliest Chinese source on this encounter, the near-contemporary chronicles of the Northern Wei (Weishu) as quoted in the later Tongdian, reports that they migrated southward from the Altai region circa 360 CE:

The Hephthalites are a branch of the Gaoju (高車, "High Carts") or the Da Yuezhi, they originated from the north of the Chinese frontier and came down south from the Jinshan (Altai) mountains [...] This was 80 to 90 years before Emperor Wen (r. 440–465 CE) of the Northern Wei (i.e. circa 360 CE)

嚈噠國,或云高車之別種,或云大月氏之別種。其原出於塞北。自金山而南。[...] 至後魏 文帝時已八九十年矣

The Gaoju (高車 lit. "High Cart"), also known as Tiele,[97] were early Turkic speakers related to the earlier Dingling,[98][99] who were once conquered by the Xiongnu.[100][101] Weishu also mentioned the linguistic and ethnic proximity between the Gaoju and the Xiongnu.[102] De la Vaissière proposes that the Hephthalites had originally been one Oghuric-speaking tribe who belonged the Gaoju/Tiele confederation.[89][103][104] This and several later Chinese chronicles also report that the Hephthalites may have originated from the Da Yuezhi, probably because of their settlement in the former Da Yuezhi territory of Bactria.[89] Later Chinese sources become quite confused about the origins of the Hephthalites, and this may be due to their progressive assimilation of Bactrian culture and language once they settled there.[105]

According to the Beishi, describing the situation in the first half of the 6th century CE around the time Song Yun visited Central Asia, the language of the Hephthalites was different from that of the Rouran, Gaoju or other tribes of Central Asia, but that probably reflects their acculturation and adoption of the Bactrian language since their arrival in Bactria in the 4th century CE.[106] The Liangshu and Liang Zhigongtu do explain that the Hephthalites originally had no written language and adopted the hu (local, "Barbarian") alphabet, in this case, the Bactrian script.[106]

Overall, de la Vaissière considers that the Hephthalites were part of the great Hunnic migrations of the 4th century CE from the Altai region that also reached Europe and that these Huns "were the political, and partly cultural, heirs, of the Xiongnu".[79]

Appearance

[edit]

The Hepthalites appear in several mural paintings in the area of Tokharistan, especially in banquet scenes at Balalyk tepe and as donors to the Buddha in the ceiling painting of the 35-meter Buddha at the Buddhas of Bamyan.[77] Several of the figures in these paintings have a characteristic appearance, with belted jackets with a unique lapel of their tunic being folded on the right side, a style which became popular under the Hephthalites,[109] the cropped hair, the hair accessories, their distinctive physionomy and their round beardless faces.[110] The figures at Bamyan must represent the donors and potentates who supported the building of the monumental giant Buddha.[110] These remarkable paintings participate "to the artistic tradition of the Hephthalite ruling classes of Tukharistan".[76][77]

The paintings related to the Hephthalites have often been grouped under the appellation of "Tokharistan school of art",[111] or the "Hephthalite stage in the History of Central Asia Art".[112] The paintings of Tavka Kurgan, of very high quality, also belong to this school of art, and are closely related to other paintings of the Tokharistan school such as Balalyk tepe, in the depiction of clothes, and especially in the treatment of the faces.[107]

This "Hephthalite period" in art, with the caftans with a triangular collar folded on the right, the particular cropped hairstyle, the crowns with crescents, have been found in many of the areas historically occupied and ruled by the Hephthalites, in Sogdia, Bamyan (modern Afghanistan), or in Kucha in the Tarim Basin (modern Xinjiang, China). This points to a "political and cultural unification of Central Asia" with similar artistic styles and iconography, under the rule of the Hephthalites.[113]

History

[edit]

The Hephthalites were a vassal state to the Rouran Khaganate until the beginning of the 5th century.[114] There were close contacts between them, although they had different languages and cultures, and the Hephthalites borrowed much of their political organization from Rourans.[8] In particular, the title "Khan", which according to McGovern was original to the Rourans, was borrowed by the Hephthalite rulers.[8] The reason for the migration of the Hephthalites southeast was to avoid a pressure of the Rourans.

The Hephthalites became a significant political entity in Bactria around 450 CE, or sometime before.[18] It has been commonly assumed that the Hephthalites formed a third wave of migrations into Central Asia, after the Chionites (who arrived circa 350 CE) and the Kidarites (who arrived from around 380 CE), but recent studies suggest that instead there may have been a single massive wave of nomadic migrations around 350–360 CE, the "Great Invasion", triggered by climate change and the onset of aridity in the grazing grounds of the Altay region, and that these nomadic tribes vied for supremacy thereafter in their new territories in Southern Central Asia.[82][115] As they rose to prominence, the Hephthalites displaced the Kidarites and then the Alchon Huns, who expanded into Gandhara and Northern India.

The Hephthalites also entered into conflict with the Sasanians. The reliefs of the Bandian complex seem to show the initial defeat of the Hephthalites against the Sasanians in 425 CE, and then their alliance with them, from the time of Bahram V (420-438 CE), until they invaded Sasanian territory and destroyed the Bandian complex in 484 CE.[118][117]

In 456–457 a Hephthalite embassy arrived in China, during the reign of Emperor Wen of the Northern Wei.[82] By 458 they were strong enough to intervene in Persia.

Around 466 they probably took Transoxianan lands from the Kidarites with Persian help but soon took from Persia the area of Balkh and eastern Kushanshahr.[58] In the second half of the fifth century they controlled the deserts of Turkmenistan as far as the Caspian Sea and possibly Merv.[119] By 500 they held the whole of Bactria and the Pamirs and parts of Afghanistan. In 509, they captured Sogdia and they took 'Sughd' (the capital of Sogdiana).[75]

To the east, they captured the Tarim Basin and went as far as Urumqi.[75]

Around 560 CE their empire was destroyed by an alliance of the First Turkic Khaganate and the Sasanian Empire, but some of them remained as local rulers in the region of Tokharistan for the next 150 years, under the suzerainty of the Western Turks, followed by the Tokhara Yabghus.[58][75] Among the principalities which remained in Hephthalite hands even after the Turkic overcame their territory were: Chaganian, and Khuttal in the Vakhsh Valley.[75]

Ascendancy over the Sasanian Empire (442–c.530 CE)

[edit]

(ηβ "ēb") in front of the crown of Peroz I, abbreviation of ηβοδαλο "ĒBODALO", for "Hepthalites".[29]

(ηβ "ēb") in front of the crown of Peroz I, abbreviation of ηβοδαλο "ĒBODALO", for "Hepthalites".[29]

before the face of Khavad.[e][121] First half of the 6th century CE.

before the face of Khavad.[e][121] First half of the 6th century CE.The Hephthalites were originally vassals of the Rouran Khaganate but split from their overlords in the early fifth century. The next time they were mentioned was in Persian sources as foes of Yazdegerd II (435–457), who from 442, fought 'tribes of the Hephthalites', according to the Armenian Elisee Vardaped.

In 453, Yazdegerd moved his court east to deal with the Hephthalites or related groups.

In 458, a Hephthalite king called Akhshunwar helped the Sasanian Emperor Peroz I (458–484) gain the Persian throne from his brother.[122] Before his accession to the throne, Peroz had been the Sasanian for Sistan in the far east of the Empire, and therefore had been one of the first to enter into contact with the Hephthalites and request their help.[123]

The Hephthalites may have also helped the Sasanians to eliminate another Hunnic tribe, the Kidarites: by 467, Peroz I, with Hephthalite aid, reportedly managed to capture Balaam and put an end to Kidarite rule in Transoxiana once and for all.[124] The weakened Kidarites had to take refuge in the area of Gandhara.

Victories over the Sasanian Empire (474–484 CE)

[edit]Later, however, from 474 CE, Peroz I fought three wars with his former allies the Hephthalites. In the first two, he himself was captured and ransomed.[18] Following his second defeat, he had to offer thirty mules loaded with silver drachms to the Hephthalites, and also had to leave his son Kavad as a hostage.[123] The coinage of Peroz I in effect flooded Tokharistan, taking precedence over all other Sasanian issues.[125]

In the third battle, at the Battle of Herat (484), he was vanquished by the Hepthalite king Kun-khi, and for the next two years the Hephthalites plundered and controlled the eastern part of the Sasanian Empire.[122][126] Perozduxt, the daughter of Peroz, was captured and became a lady as the Hephtalite court, as Queen of king Kun-khi.[126] She became pregnant and had a daughter who would later marry her uncle Kavad I.[123] From 474 until the middle of the 6th century, the Sasanian Empire paid tribute to the Hephthalites.

Bactria came under formal Hephthalite rule from that time.[3] Taxes were levied by the Hephthalites over the local population: a contract in the Bactrian language from the archive of the Kingdom of Rob, has been found, which mentions taxes from the Hephthalites, requiring the sale of land in order to pay these taxes. It is dated to 483/484 CE.[3]

Hephthalite coinage

[edit]With the Sasanian Empire paying a heavy tribute, from 474, the Hephthalites themselves adopted the winged, triple-crescent crowned Peroz I as the design for their coinage.[18] Benefiting from the influx of Sasanian silver coins, the Hephthalites did not develop their own coinage: they either minted coins with the same designs as the Sasanians, or simply countermarked Sasanian coins with their own symbols.[3] They did not inscribe the name of their ruler, contrary to the habit of the Alchon Huns or the Kidarites before them.[3] Exceptionally, one coin type deviates from the Sasanian design, by showing the bust of a Hepthalite prince holding a drinking cup.[3] Overall, the Sasanians paid "an enormous tribute" to the Hephthalites, until the 530s and the rise of Khosrow I.[82]

Protectors of Kavad

[edit]Following their victory over Peroz I, the Hepthalites became protectors and benefactors of his son Kavad I, as Balash, a brother of Peroz took the Sasanian throne.[123] In 488, a Hepthalite army vanquished the Sasaniana army of Balash, and was able to put Kavad I (488–496, 498–531) on the throne.[123]

In 496–498, Kavad I was overthrown by the nobles and clergy, escaped, and restored himself with a Hephthalite army. Joshua the Stylite reports numerous instances in which Kavadh led Hepthalite ("Hun") troops, in the capture of the city of Theodosiupolis of Armenia in 501–502, in battles against the Romans in 502–503, and again during the siege of Edessa in September 503.[122][127][128]

Hephthalites in Tokharistan (466 CE)

[edit]Around 461–462 CE, an Alchon Hun ruler named Mehama is known to have been based in Eastern Tokharistan, possibly indicating a partition of the region between the Hephthalites in western Tokharistan, centered on Balkh, and the Alchon Huns in eastern Tokharistan, who would then go on to expand into northern India.[131] Mehama appears in a letter in the Bactrian language he wrote in 461–462 CE, where he describes himself as "Meyam, King of the people of Kadag, the governor of the famous and prosperous King of Kings Peroz".[131] Kadag is Kadagstan, an area in southern Bactria, in the region of Baghlan. Significantly, he presents himself as a vassal of the Sasanian Empire king Peroz I, but Mehama was probably later able to wrestle autonomy or even independence as Sasanian power waned and he moved into India, with dire consequences for the Gupta Empire.[131][132][133]

The Hepthalites probably expanded into Tokharistan following the destruction of the Kidarites in 466. The presence of the Hepthalites in Tokharistan (Bactria) is securely dated to 484 CE, date of a tax receipt from the Kingdom of Rob mentioning the need to sell some land in order to pay Hephthalite taxes.[134] Two documents were also found, with dates from the period from 492 to 527 CE, mentioning taxes paid to Hephthalite rulers. Another, undated documents, mentions scribal and judiciary functions under the Hephthalites:

Sartu, the son of Hwade-gang, the prosperous Yabghu of the Hepthalite people (ebodalo shabgo); Haru Rob, the scribe of the Hephthalite ruler (ebodalo eoaggo), the judge of Tokharistan and Gharchistan.

— Document of the Kingdom of Rob.[135]

Hephthalite conquest of Sogdiana (479 CE)

[edit]

The Hephthalites conquered the territory of Sogdiana, beyond the Oxus, which was incorporated into their Empire.[137] They may have conquered Sogdiana as early as 479 CE, as this is the date of the last known embassy of the Sogdians to China.[137][138] The account of the Liang Zhigongtu also seems to record that from around 479 CE, the Hephthalites occupied the region of Samarkand.[138] Alternatively, the Hephthalites may have occupied Sogdia later in 509 CE, as this is the date of the last known embassy from Samarkand to the Chinese Empire, but this might not be conclusive as several cities, such as Balkh or Kobadiyan, are known to have sent embassies to China as late as 522 CE, while under Hephthalite control.[138] As early as 484, the famous Hephthalite ruler Akhshunwar, who defeated Peroz I, held a title that may be understood as Sogdian: "’xs’wnd’r" ("power-holder").[138]

The Hephthalites may have built major fortified Hippodamian cities (rectangular walls with an orthogonal network of streets) in Sogdiana, such as Bukhara and Panjikent, as they had also in Herat, continuing the city-building efforts of the Kidarites.[138] The Hephthalites probably ruled over a confederation of local rulers or governors, linked through alliance agreements. One of these vassals may have been Asbar, ruler of Vardanzi, who also minted his own coinage during the period.[139]

The wealth of the Sasanian ransoms and tributes may have been reinvested in Sogdia, possibly explaining the prosperity of the region from that time.[138] Sogdia, at the center of a new Silk Road between China to the Sasanian Empire and the Byzantine Empire became extremely prosperous under its nomadic elites.[140] The Hephthalites took on the role of major intermediary on the Silk Road, after their great predecessor the Kushans, and contracted local Sogdians to carry on the trade of silk and other luxury goods between the China Empire and the Sasanian Empire.[141]

Because of the Hephthalite occupation of Sogdia, the original coinage of Sogdia came to be flooded by the influx of Sasanian coins received as a tribute to the Hephthalites. This coinage then spread along the Silk Road.[137] The symbol of the Hephthalites appears on the residual coinage of Samarkand, probably as a consequence of the Hephthalite control of Sogdia, and becomes prominent in Sogdian coinage from 500 to 700 CE, including in the coinage of their indigenous successors the Ikhshids (642-755 CE), ending with the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana.[142][143]

Tarim Basin (circa 480–550 CE)

[edit]In the late 5th century CE they expanded eastward through the Pamir Mountains, which are comparatively easy to cross, as did the Kushans before them, due to the presence of convenient plateaus between high peaks.[152] They occupied the western Tarim Basin (Kashgar and Khotan), taking control of the area from the Rourans, who had been collecting heavy tribute from the oasis cities, but were now weakening under the assaults of the Chinese Northern Wei dynasty.[45] In 479 they took the east end of the Tarim Basin, around the region of Turfan.[45][153] In 497–509, they pushed north of Turfan to the Urumchi region.[153] In the early years of the 6th century, they were sending embassies from their dominions in the Tarim Basin to the Northern Wei dynasty.[45][153] They were probably in contact with Li Xian, the Chinese Governor of Dunhuang, who is known for having furnished his tomb with a Western-style ewer probably made in Bactria.[153]

The Hephthalites continued to occupy the Tarim Basin until the end of their Empire, circa 560 CE.[45][154]

As the territories ruled by the Hephthalites expanded into Central Asia and the Tarim Basin, the art of the Hephthalites, characterized by the clothing and hairstyles of the figures being represented, also came to be used in the areas they ruled, such as Sogdiana, Bamyan or Kucha in the Tarim Basin (Kizil Caves, Kumtura Caves, Subashi reliquary).[144][48][155] In these areas appear dignitaries with caftans with a triangular collar on the right side, crowns with three crescents, some crowns with wings, and a unique hairstyle. Another marker is the two-point suspension system for swords, which seems to have been an Hephthalite innovation, and was introduced by them in the territories they controlled.[144] The paintings from the Kucha region, particularly the swordsmen in the Kizil Caves, appear to have been made during Hephthalite rule in the region, circa 480–550 CE.[144][156] The influence of the art of Gandhara in some of the earliest paintings at the Kizil Caves, dated to circa 500 CE, is considered as a consequence of the political unification of the area between Bactria and Kucha under the Hephthalites.[157] Some words of the Tocharian languages may have been adopted from the Hephthalites in the 6th century CE.[158]

The early Turks of the First Turkic Khaganate then took control of the Turfan and Kucha areas from around 560 CE, and, in alliance with the Sasanian Empire, became instrumental in the fall of the Hepthalite Empire.[159]

Hephthalite embassies to Liang China (516–526 CE)

[edit]

An illustrated account of a Hepthalite (滑, Hua) embassy to the Chinese court of the Southern Liang in the capital Jingzhou in 516–526 CE is given in Portraits of Periodical Offering of Liang, originally painted by Pei Ziye or the future Emperor Yuan of Liang while he was a Governor of the Province of Jingzhou as a young man between 526 and 539 CE,[160] and of which an 11th-century Song copy is preserved.[161][162][163] The text explains how small the country of the Hua was when they were still vassals of the Rouran Khaganate, and how they later moved to "Moxian", possibly referring to their occupation of Sogdia, and then conquered numerous neighbouring country, including the Sasanian Empire:[161][164][165][166][f]

When the Suolu (Northern Wei) entered (the Chinese frontier) and settled in the (valley of the river) Sanggan (i.e. in the period 398–494 CE), the Hua was still a small country and under the rule of the Ruirui. In the Qi period (479–502 CE), they left (their original area) for the first time and shifted to Moxian (possibly Samarkand), where they settled.[167] Growing more and more powerful in the course of time, the Hua succeeded in conquering the neighbouring countries such as Bosi (Sasanid Persia), Panpan (Tashkurgan?), Jibin (Kashmir), Wuchang (Uddiyana or Khorasan), Qiuci (Kucha), Shule (Kashgar), Yutian (Khotan) and Goupan (Karghalik), and expanded their territory by a thousand li...[166]

— "Hua" paragraph in Portraits of Periodical Offering of Liang.[161]

The Portraits of Periodical Offering of Liang mentions that no envoys from the Hephthalites came before 516 to the southern court, and it was only in that year that a Hephthalite King named Yilituo Yandai (姓厭帶名夷栗陁) sent an ambassador named Puduoda[] (蒲多达[], possibly a Buddhist name "Buddhadatta" or "Buddhadāsa").[162][168] In 520, another ambassador named Fuheliaoliao (富何了了) visited the Liang court, bringing a yellow lion, a white marten fur coat and Persian brocade as present.[162][168] Another ambassador named Kang Fuzhen (康符真), followed with presents as well (in 526 CE according to the Liangshu).[162][168] Their language had to be translated by the Tuyuhun.[168]

In Portraits of Periodical Offering of Liang, the Hepthalithes are treated as the most important foreign state, as they occupy the leading position, at the front of the column of foreign ambassadors, and have by far the largest descriptive text.[169] The Hepthalites were, according to the Liangshu (Chap.54), accompanied in their embassy by three states: Humidan (胡蜜丹), Yarkand (周古柯, Khargalik) and Kabadiyan (呵跋檀).[170] The envoys from right to left were: the Hephthalites (滑/嚈哒), Persia (波斯), Korea (百濟), Kucha (龜茲), Japan (倭), Malaysia (狼牙脩), Qiang (鄧至), Yarkand (周古柯, Zhouguke, "near Hua"),[170] Kabadiyan (呵跋檀 Hebatan, "near Hua"),[170] Kumedh (胡蜜丹, Humidan, "near Hua"),[170] Balkh (白題, Baiti, "descendants of the Xiongnu and east of the Hua"),[170] and finally Merv (末).[169][161][171]

Most of the ambassadors from Central Asia are shown wearing heavy beards and relatively long hair, but, in stark contrast, the Hephthalite ambassador, as well as the ambassador from Balkh, are clean-shaven and bare-headed, and their hair is cropped short.[172] These physical characteristics are also visible in many of the Central Asian seals of the period.[172]

Other embassies

[edit]Overall, Chinese chronicles recorded twenty-four Hephthalite embassies: the first embassy in 456, and the others from 507 to 558 CE (including fifteen to the Northern Wei until the end of this dynasty in 535, and five to the Southern Liang in 516–541).[173][174] The last three are mentioned in the Zhoushu, which records that the Hepththalites had conquered Anxi, Yutian (Hotan region in Xinjiang) and more than twenty other countries, and that they sent embassies to the Chinese court of the Western Wei and Northern Zhou in 546, 553 and 558 CE respectively, after what the Hepthalites were "crushed by the Turks" and embassies stopped.[175]

The Hephthalites also requested and obtained a Christian bishop from the Patriarch of the Church of the East Mar Aba I circa 550 CE.[176]

Buddhas of Bamiyan (544–644 CE)

[edit]The complex of the Buddhas of Bamiyan was developed under Hephthalite rule.[87][88][179] After the dissolution of their empire in 550-560, the Hephthalites continued to rule in the geographical areas corresponding to Tokharistan and today's northern Afghanistan,[1][180][181] and particularly held a series of castles on the roads to Bamiyan.[182] Carbon dating of the structural components of the Buddhas has determined that the smaller 38 m (125 ft) "Eastern Buddha" was built around 570 CE (544–595 CE with 95% probability), while the larger 55 m (180 ft) "Western Buddha" was built around 618 CE (591–644 CE with 95% probability).[85] This corresponds to the period soon before or after the major defeat of the Hephthalites against the combined forces of Western Turk and Sasanian Empire (557 CE), or the following period during which they regrouped south of the Oxus as Principalities, but essentially before the Western Turks finally overran the region to form the Tokhara Yabghus (625 CE).

Among the most famous paintings of the Buddhas of Bamyan, the ceiling of the smaller Eastern Buddha represents a solar deity on a chariot pulled by horses, as well as ceremonial scenes with royal figures and devotees.[177] The god is wearing a caftan in the style of Tokhara, boots, and is holding a lance, he is "The Sun God and a Golden Chariot Rising in Heaven".[183] His representation is derived from the iconography of the Iranian god Mithra, as revered in Sogdia.[183] He is riding a two-wheeled golden charriot, pulled by four horses.[183] Two winged attendants are standing to the side of the charriot, wearing a Corinthian helmet with a feather, and holding a shield.[183] In the top portion are wind gods, flying with a scarf held in both hands.[183] This great composition is unique, and has no equivalent in Gandhara or India, but there are some similarities with the painting of Kizil or Dunhuang.[183]

The central image of the Sun God on his golden chariot is framed by two lateral rows in individuals: Kings and dignitaries mingling with Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.[110] One of the personages, standing behind a monk in profile, much be the King of Bamyan.[110] He wears a crenelated crown with single crescent and korymbos, a round-neck tunic and a Sasanian headband.[110] Several of the figures, either royal couples, crowned individuals or richly dressed women, have the characteristic appearance of the Hephthalites of Tokharistan, with belted jackets with a unique lapel of their tunic being folded on the right side, the cropped hair, the hair accessories, their distinctive physionomy and their round beardless faces.[77][110][184] These figures must represent the donors and potentates who supported the building of the monumental giant Buddha.[110] They are gathered around the Seven Buddhas of the past and Maitreya.[185] The individuals in this painting are very similar to the individuals depicted in Balalyk Tepe, and they may be related to the Hepthalites.[77][186] They participate "to the artistic tradition of the Hephthalite ruling classes of Tukharestan".[187]

These murals disappeared with the destruction of the statues by the Taliban in 2001.[110]

Hephthalite royals on the tombs of Sogdian traders

[edit]The Tomb of Wirkak is the tomb of a 6th-century Sogdian trader established in China, and discovered in Xi'an.[188] It seems that depictions of Hephthalite rulers are omnipresent in the pictorial decorations of the tomb, as royal figures with elaborate Sasanian-type crowns appearing in their palaces, nomadic yurts or while hunting.[188] Hephthalites rulers are shown short-haired, wearing tunics, and are often depicted together with their female consort.[188] The Sogdian trader Wirkak may therefore have primarily dealt with the Hephthalites during his young years (he was around 60 when the Hephthalites were finally destroyed by the alliance of the Sasanians and the Turks between 556 and 560 CE).[189] The Hephthalites also appear in four panels of the Miho funerary couch (c.570 CE) with somewhat caricatural features, and characteristics of vassals to the Turks.[190] On the contrary, the depictions in the tombs of later Sogdian traders, such as the Tomb of An Jia (who was 24 years younger than Wirwak), already show the omnipresence of the Turks of the First Turkic Khaganate, who were probably his main trading partners during his active life.[189]

End of the Empire and fragmentation into Hephthalite Principalities (560–710 CE)

[edit]

After Kavad I, the Hephthalites seem to have shifted their attention away from the Sasanian Empire, and Kavad's successor Khosrow I (531–579) was able to resume an expansionist policy to the east.[123] According to al-Tabari, Khosrow I managed, through his expansionsit policy, to take control of "Sind, Bust, Al-Rukkhaj, Zabulistan, Tukharistan, Dardistan, and Kabulistan" as he ultimately defeated the Hephthalites with the help of the First Turkic Khaganate.[123]

In 552, the Göktürks took over Mongolia, formed the First Turkic Khaganate, and by 558 reached the Volga. Circa 555–567,[g] the Turks of the First Turkic Khaganate and the Sasanians under Khosrow I allied against the Hephthalites and defeated them after an eight-day battle near Qarshi, the Battle of Gol-Zarriun, perhaps in 557.[h][193]

These events put an end to the Hephthalite Empire, which fragmented into semi-independent Principalities, paying tribute to either the Sasanians or the Turks, depending on the military situation.[1][180] After the defeat, the Hephthalites withdrew to Bactria and replaced king Gatfar with Faghanish, the ruler of Chaghaniyan. Thereafter, the area around the Oxus in Bactria contained numerous Hephthalites principalities, remnants of the great Hephthalite Empire destroyed by the alliance of the Turks and the Sasanians.[194] They are reported in the Zarafshan valley, Chaghaniyan, Khuttal, Termez, Balkh, Badghis, Herat and Kabul, in the geographical areas corresponding to Tokharistan and today's northern Afghanistan.[1][180][195] They also held a series of castles on the roads to Bamiyan.[196] Extensive Hephthalite kurghan necropoli have been excavated all over the region, as well as a possible one in the Bamiyan valley.[197]

The Sasanians and Turks established a frontier for their zones of influence along the Oxus river, and the Hephthalite Principalities functioned as buffer states between two Empires.[180] But when the Hephthalites chose Faghanish as their king in Chaganiyan, Khosrow I crossed the Oxus and put the Principalities of Chaghaniyan and Khuttal under tribute.[180]

When Khosrow I died in 579, the Hephthalites of Tokharistan and Khotan took advantage of the situation to rebel against the Sasanians, but their efforts were obliterated by the Turks.[180] By 581 or before, the western part of the First Turkic Khaganate separated and became the Western Turkic Khaganate. In 588, triggering the First Perso-Turkic War, the Turkic Khagan Bagha Qaghan (known as Sabeh/Saba in Persian sources), together with his Hephthalite subjects, invaded the Sasanian territories south of the Oxus, where they attacked and routed the Sasanian soldiers stationed in Balkh, and then proceeded to conquer the city along with Talaqan, Badghis, and Herat.[198] They were finally repelled by the Sasanian general Vahram Chobin.[180]

Raids into the Sasanid Empire (600–610 CE)

[edit]Circa 600, the Hephthalites were raiding the Sasanian Empire as far as Ispahan (Spahan) in central Iran. The Hephthalites issued numerous coins imitating the coinage of Khosrow II, adding on the obverse a Hephthalite signature in Sogdian and a Tamgha symbol ![]() .

.

Circa 616/617 CE the Göktürks and Hephthalites raided the Sasanian Empire, reaching the province of Isfahan.[199] Khosrow recalled Smbat IV Bagratuni from Persian Armenia and sent him to Iran to repel the invaders. Smbat, with the aid of a Persian prince named Datoyean, repelled the Hephthalites from Persia, and plundered their domains in eastern Khorasan, where Smbat is said to have killed their king in single combat. Khosrow then gave Smbat the honorific title Khosrow Shun ("the Joy or Satisfaction of Khosrow"), while his son Varaztirots II Bagratuni received the honorific name Javitean Khosrow ("Eternal Khosrow").[200]

Western Turk takeover (625 CE)

[edit]

From 625 CE, the territory of the Hephthalites from Tokharistan to Kabulistan was taken over by the Western Turks, forming an entity ruled by Western Turk nobles, the Tokhara Yabghus.[180] The Tokhara Yabghus or "Yabghus of Tokharistan" (Chinese: 吐火羅葉護; pinyin: Tǔhuǒluó Yèhù), were a dynasty of Western Turk sub-kings, with the title "Yabghus", who ruled from 625 CE south of the Oxus river, in the area of Tokharistan and beyond, with some smaller polities surviving in the area of Badakhshan until 758 CE. Their legacy was extended to the southeast until the 9th century CE, with the Turk Shahis and the Zunbils.

Arab invasion (c.651 CE)

[edit]Circa 650 CE, during the Arab conquest of the Sasanian Empire, the Sasanian Empire ruler Yazdegerd III was trying to regroup and gather forces around Tokharistan and was hoping to obtain the help of the Turks, after his defeat to the Arabs in the Battle of Nihâvand (642 CE).[204] Yazdegerd was initially supported by the Hephthalite Principality of Chaghaniyan, which sent him troops to aid him against the Arabs. But when Yazdegerd arrived in Merv (in what is today's Turkmenistan) he demanded tax from the Marzban of Marw, losing his support and making him ally with the Hephthalite ruler of Badghis, Nezak Tarkan. The Hepthalite ruler of Badghis allied with the Marzban of Merv attack Yazdegerd and defeated him in 651.[204] Yazdegerd III barely escaped with his life but was murdered in the vicinity of Merv soon after, and the Arabs managed to capture the city of Merv the same year.[204]

In 652 CE, following the Siege of Herat (652) to which the Hephthalites participated, the Arabs captured the cities of northern Tokharistan, Balkh included, and the Hepthalites principalities were forced to pay tribute and accept Arab garrisons.[204] The Hephthalites again rebelled in 654 CE, leading to the Battle of Badghis.

In 659, Chinese chronicles still mentioned the "Hephtalite Tarkans" (悒達太汗 Yida Taihan, probably related to "Nezak Tarkan"), as some of the rulers in Tokharistan who remained theoretically subjects to the Chinese Empire, and whose main city was Huolu 活路 (modern Mazār-e Sherif, Afghanistan).[205][206]

The city of Merv became the base of the Arabs for their Central Asian operations.[204] The Arabs weakened during the 4-year civil war leading to the establishment of the Umayyad Caliphate in 661, but they were able to continue their expansion after that.[204]

Hephthalite revolts against the Ummayad Caliphate (689–710 CE)

[edit]

. Circa 700 CE.

. Circa 700 CE.Circa 689 CE, the Hephthalite ruler of Badghis and the Arab rebel Musa ibn Abd Allah ibn Khazim, son of the Zubayrid governor of Khurasan Abd Allah ibn Khazim al-Sulami, allied against the forces of the Umayyad Caliphate.[207] The Hepthalites and their allies captured Termez in 689, repelled the Arabs, and occupied the whole region of Khorasan for a brief period, with Termez as the capital, described by the Arabs as "the headquarters of the Hephthalites" (dār mamlakat al-Hayāṭela).[208][209] The Arabs of the Umayyad Caliphate under Yazid ibn al-Muhallab re-captured Termez in 704.[207][205] Nezak Tarkan, the ruler of the Hephthalites of Badghis, led a new revolt in 709 with the support of other principalities as well as his nominal ruler, the Yabghu of Tokharistan.[208] In 710, Qutaiba ibn Muslim was able to re-establish Muslim control over Tokharistan and captured Nezak Tarkan who was executed on al-Hajjaj's orders, despite promises of pardon, while the Yabghu was exiled to Damascus and kept there as a hostage.[210][211][212]

In 718 CE, Chinese chronicles still mention the Hephthalites (悒達 Yida) as one of the polities under the suzerainty of the Turkic Tokhara Yabghus, capable of providing 50,000 soldiers at the service of its overlord.[205] Some remnants, not necessarily dynastic, of the Hephthalite confederation would be incorporated into the Göktürks, as an Old Tibetan document, dated to the 8th century, mentioned the tribe Heb-dal among 12 Dru-gu tribes ruled by Eastern Turkic khagan Bug-chor, i.e. Qapaghan Qaghan[213] Chinese chronicles report embassies from the "Hephtalite kingdom" as late as 748 CE.[205][214]

Military and weapons

[edit]

The Hephthalites were considered to be a powerful military force.[216] Depending on sources, their main weapon was the bow, the mace or the sword.[216] Judging from their military achievements, they probably had a strong cavalry.[216] In Persia, according to the 6th-century Armenian chronicler Lazar Parpetsi:

Even in time of peace the mere sight or mention of a Hephthalite terrified everybody, and there was no question of going to war openly against one, for everybody remembered all too clearly the calamities and defeats inflicted by the Hephthalites on the king of the Aryans and on the Persians.[216]

"Hunnic" designs in weaponry are known to have influenced Sasanian designs during the 6th–7th century CE, just before the Islamic invasions.[217] The Sasanians adopted Hunnish nomadic designs for straight iron swords and their gold-covered scabbards.[217] This is particularly the case of two-straps suspension design, in which straps of different lengths were attached to a P-shaped projection on the scabbard, so that the sword could be held sideways, making it easier to draw, especially when on horseback.[217] The two-point suspension system for swords is considered to have been introduced by the Hephthalites in Central Asia and in the Sasanian Empire and is a marker of their influence, and the design was generally introduced by them in the territories they controlled.[144] The first example of two-suspension sword in Sasanian art occurs in a relief of Taq-i Bustan dated to the time of Khusro II (590–628 CE), and is thought to have been adopted from the Hepthalites.[144]

Swords with ornate cloisonné designs and two-straps suspensions, as found in the paintings of Penjikent and Kizil and in archaeological excavations, may be versions of the daggers produced under Hephthalite influence.[218] Weapons with Hunnic designs are depicted in the "Cave of the Painters" in the Kizil Caves, in a mural showing armoured warriors and dated to the 5th century CE.[215] Their sword guards have typical Hunnish designs of rectangle or oval shapes with cloisonné ornamentation.[215] The Gyerim-ro dagger, found in a tomb in Korea, is a 5-6th century highly decorated dagger and scabbard of "Hunnic" two-straps suspension design, introduced by the Hephthalites in Central Asia.[219] The Gyerim-ro dagger is thought to have reached Korea either through trade or as a diplomatic gift.[220]

Lamellar helmets were also popularized by the steppe nomads, and were adopted by the Sasanian Empire when they took control of former Hephthalite territory.[221] This type of helmet appears in sculptures on pillar capitals at Ṭāq-e Bostān and Behistun, and on the Anahita coinage of Khosrow II (r. 590–628 CE).[221]

Religion and culture

[edit]

They were said to practice polyandry and artificial cranial deformation. Chinese sources said they worshiped 'foreign gods', 'demons', the 'heaven god' or the 'fire god'. The Gokturks told the Byzantines that they had walled cities. Some Chinese sources said that they had no cities and lived in tents. Litvinsky tries to resolve this by saying that they were nomads who moved into the cities they had conquered. There were some government officials but central control was weak and local dynasties paid tribute.[224]

According to Song Yun, the Chinese Buddhist monk who visited the Hephthalite territory in 540 and "provides accurate accounts of the people, their clothing, the empresses and court procedures and traditions of the people and he states the Hephthalites did not recognize the Buddhist religion and they preached pseudo gods, and killed animals for their meat."[7] It is reported that some Hephthalites often destroyed Buddhist monasteries but these were rebuilt by others. According to Xuanzang, the third Chinese pilgrim who visited the same areas as Song Yun about 100 years later, the capital of Chaghaniyan had five monasteries.[62]

According to historian André Wink, "...in the Hephthalite dominion Buddhism was predominant but there was also a religious sediment of Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism."[9] Balkh had some 100 Buddhist monasteries and 30,000 monks. Outside the town was a large Buddhist monastery, later known as Naubahar.[62]

There were Christians among the Hephthalites by the mid-6th century, although nothing is known of how they were converted. In 549, they sent a delegation to Aba I, the patriarch of the Church of the East, asking him to consecrate a priest chosen by them as their bishop, which the patriarch did. The new bishop then performed obeisance to both the patriarch and the Sasanian king, Khosrow I. The seat of the bishopric is not known, but it may have been Badghis–Qadištan, the bishop of which, Gabriel, sent a delegate to the synod of Patriarch Ishoyahb I in 585.[226] It was probably placed under the metropolitan of Herat. The church's presence among the Hephthalites enabled them to expand their missionary work across the Oxus. In 591, some Hephthalites serving in the army of the rebel Bahram Chobin were captured by Khosrow II and sent to the Roman emperor Maurice as a diplomatic gift. They had Nestorian crosses tattooed on their foreheads.[10][227]

Hephthalite seals

[edit]

Several seals found in Bactria and Sogdia have been attributed to the Hephthalites.

- The "Hephthalite Yabghu seal" shows a Hephthalite ruler with a radiate crown, royal ribbons and a beardless face, with the Bactrian script title "Ebodalo Yabghu" (

ηβοδαλο ββγο, "The Lord of the Hephthalites"), and has been dated to the end of the 5th century-early 6th century CE.[3][27][34] This important seal was published by Judith A. Lerner and Nicholas Sims-Williams in 2011.[233]

ηβοδαλο ββγο, "The Lord of the Hephthalites"), and has been dated to the end of the 5th century-early 6th century CE.[3][27][34] This important seal was published by Judith A. Lerner and Nicholas Sims-Williams in 2011.[233] - Stamp seal (BM 119999) in the British Museum shows two facing figures, one bearded and wearing the Sasanian dress, and the other without facial hair and wearing a radiate crown, both being adorned with royal ribbons. This seal was initially dated to 300–350 CE and attributed to the Kushano-Sasanians,[231][234] but has been more recently attributed to the Hephthalites,[229] and dated to the 5th–6th century CE.[230] Paleographically, the seal can be attributed to the 4th century or first half of the 5th century.[235]

- The "Seal of Khingila" shows a beardless ruler with radiate crown and royal ribbons, wearing a single-lapel caftan, in the name of Eškiŋgil (εϸχιγγιλο), which could correspond to one of the rulers named Khingila (χιγγιλο), or may be a Hunnic title meaning "Companion of the Sword", or even "Companion of the God of War".[236][237]

Local populations under the Hephthalites

[edit]The Hephthalites governed a confederation of various people, many of whom were probably of Iranian descent, speaking an Iranian language.[238] Several cities, such as Balkh, Kobadiyan and possibly Samarkand, were allowed to send regional embassies to China while under Hephthalite control.[138] Several portraits of regional ambassadors from the territories occupied by the Hephthalites (Tokharistan, Tarim Basin) are known from Chinese paintings such as the Portraits of Periodical Offering of Liang, originally painted in 526–539 CE.[166] They were at that time under the overlordship of the Hephthalites, who led the embassies to the Southern Liang court in the early 6th century CE.[169][170] A century later, under the Tang dynasty, portraits of the local people of Tokharistan were again illustrated in The Gathering of Kings, circa 650 CE. Etienne de la Vaissière has estimated the local population of each major oasis in Tokharistan and Western Turkestan during the period to around several hundreds of thousands each, while the major oasis of the Tarim Basin are more likely to have had populations ranging in the tens of thousands each.[239]

-

Kabadiyan ambassador to the Chinese court of Emperor Yuan of Liang in his capital Jingzhou in 516–520 CE. Portraits of Periodical Offering of Liang, 11th century Song copy. He accompanied the Hephthalite ambassador to China.

-

Kumedh ambassador to the Chinese court of Emperor Yuan of Liang in his capital Jingzhou in 516–520 CE. Portraits of Periodical Offering of Liang, 11th century Song copy.

-

Ambassador from Kucha (龜茲國 Qiuci-guo), one of the main Tocharian cities in the Tarim Basin, visiting the Chinese Southern Liang court in Jingzhou circa 516–520 CE. Portraits of Periodical Offering of Liang, 11th century Song copy.

-

Ambassadors from Kabadiyan (阿跋檀), Balkh (白題國) and Kumedh (胡密丹), visiting the court of the Tang dynasty. The Gathering of Kings (王会图), circa 650 CE

The Alchon Huns (formerly considered as a branch of the Hephthalites) in South Asia

[edit]Алчонские гунны , которые вторглись в северную Индию и были известны там как « хуны », долгое время считались частью или подразделением эфталитов или их восточной ветвью, но теперь их склонны рассматривать как отдельное образование. которые, возможно, были перемещены в результате поселения эфталитов в Бактрии. [241][242][243] Историки, такие как Беквит , ссылаясь на Этьена де ла Васьера , говорят, что эфталиты не обязательно были одним и тем же, что и гунны ( Света Хуна ). [ 244 ] По мнению де ла Вэсьера, эфталиты не идентифицируются напрямую в классических источниках наряду с гуннами. [ 245 ] Первоначально они базировались в бассейне реки Окс в Центральной Азии и установили свой контроль над Гандхарой в северо-западной части Индийского субконтинента примерно к 465 году нашей эры. [ 246 ] Оттуда они распространились по различным частям северной, западной и центральной Индии .

В Индии этих вторгшихся людей называли Хунами , или «Света Хуна» ( Белые гунны ) на санскрите . [ 40 ] Хуны упоминаются в нескольких древних текстах, таких как Рамаяна , Махабхарата , Пураны Калидаса и Рагхувамша . [ 247 ] Первые гуны , вероятно, кидариты , первоначально были побеждены императором Скандагуптой из Империи Гуптов в V веке нашей эры. [ 248 ] В начале VI века нашей эры Алчон-Хун -Хунас, в свою очередь, захватили часть Империи Гуптов, которая находилась к их юго-востоку, и завоевали Центральную и Северную Индию . [ 8 ] Гупта-император Бханугупта победил гуннов под командованием Тораманы в 510 году, а его сын Михиракула был отброшен Яшодхарманом в 528 году нашей эры. [ 249 ] [ 250 ] Хуны Нарасимхагуптой были изгнаны из Индии царями Ясодхарманом и . в начале VI века [ 251 ] [ 252 ]

Возможные потомки

[ редактировать ]Ряд групп мог произойти от эфталитов. [ 253 ] [ 254 ]

- Авары: высказывались предположения, что паннонские авары были гефталитами, которые отправились в Европу после своего краха в 557 году нашей эры, но это не подтверждается должным образом археологическими или письменными источниками. [ 255 ]

- Пуштуны: Эфталиты, возможно, внесли свой вклад в этногенез пуштунов . Ю. Советский историк-афганист В. Ганьковский констатировал: «Пуштуны возникли как союз преимущественно восточноиранских племен, который стал исходным этническим слоем пуштунского этногенеза, начиная с середины первого тысячелетия н. э., и связан с распадом конфедерации эфталитов». [ 256 ] Согласно «Кембриджской истории Ирана», потомками эфталитов являются пуштуны . [ 257 ]

- Дуррани: Дуррани- пуштуны в Афганистане до 1747 года назывались «Абдали». По мнению лингвиста Георга Моргенштирна , их племенное имя Абдали может иметь «какое-то отношение» к эфталиту. [ 258 ] Эту гипотезу поддержал историк Айдогды Курбанов , который указал, что после распада конфедерации эфталитов они, вероятно, ассимилировались с различными местными популяциями и что абдали могут быть одним из племен эфталитского происхождения. [ 8 ]

- Халадж: Люди Халаджа впервые упоминаются в VII–IX веках в районе Газни , Калати-Гилджи и Забулистана на территории современного Афганистана . Они говорили на халадж-тюркском языке . Аль-Хорезми упоминал их как оставшееся племя эфталитов. Однако, по мнению лингвиста Симса-Уильямса , археологические документы не подтверждают предположение о том, что Халаджи были преемниками эфталитов. [ 261 ] тогда как, по мнению историка В. Минорского , халаджи «возможно, были лишь политически связаны с эфталитами». Некоторые из халаджей были позже пуштунизированы , после чего превратились в пуштунское племя гильджи . [ 262 ]

- Канджина: племя саков, связанное с индоиранскими кумиджи. [ 263 ] [ 264 ] и вошли в состав эфталитов. Канджины, возможно, были тюркизированы позже, поскольку аль-Хорезми назвал их «канджинскими турками». Однако Босворт и Клосон утверждали, что аль-Хорезми просто использовал слово «турки» «в расплывчатом и неточном смысле». [ 265 ]

- Карлуки: (или карлугиды ), как сообщается, поселились в Газни и Забулистане, современный Афганистан, в тринадцатом веке. Многие мусульманские географы из-за путаницы отождествляли «Карлуков» Халлух ~ Харлух с «Халаджес» Халаджем , поскольку эти два имени были похожи и эти две группы жили рядом друг с другом. [ 266 ] [ 267 ]

- Абдал — имя, связанное с эфталитами. Это альтернативное название народа айну .

- По мнению Орхана Кёпрюлю , Абдал Турецкий мог происходить от гефталитов. Альберт фон Ле Кок упоминает отношения между Абдалами из Аданы и Эйнусом из Восточного Туркестана , поскольку у них есть некоторые общие слова, и они оба называют себя абдалами и говорят между собой на одном языке. [ 268 ] Некоторые абдаловские элементы можно встретить также в составе азербайджанцев , туркмен (ата, чоудур , эрсары , сарык ), казахов, узбеков-локайцев, тюрков и волжских булгар ( савиров ). [ 269 ]

Эфталитские правители

[ редактировать ]| История Центральной Азии |

|---|

|

- Ахшунвар , около 458 г. н.э.

- Кун-хи, около 484 г. н.э. [ 126 ]

- Яндай Илитуо, около 516 г. н.э. (известен только по китайскому имени Яндай Или Чао) [ 162 ] [ 163 ]

- Хваде-банда (известна только из архивов Королевства Роб ). [ 33 ]

- Гадфар/Гатифар, около 567–568 гг. н.э. [ 270 ]

- Фаганиш (568-) (правящий в Чаганиане )

- Незак Таркан (около 650–710 гг.)

См. также

[ редактировать ]- История Афганистана

- Скрытые люди

- Кидариты (красные гунны)

- Алчон Хунны

- Kushan Empire

- Ксиониты

- Незак гунны

- Иранские гунны

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ де ла Васьер предлагает лежащий в основе тюркский Йети-Ал , позже переведенный на иранский Хафт-Ал.

- ^ де ла Васьер также процитировал Симса-Вильямса, который отметил, что начальное η- ē бактрийской формы ηβοδαλο Ēbodālo исключает этимологию, основанную на иранском хафте и, следовательно, гипотетическом базовом тюркском йети «семь».

- ^ Подобные короны известны и на других печатях, таких как печать «Кедир, хазарухт» («Кедир Хилиарх » ), датированная Симсом-Вильямсом последней четвертью V века нашей эры на основании палеографии надписи. [ 32 ] Ссылка на точные данные: Sundermann, Hintze & de Blois (2009) , с. 218, примечание 14

- ^ де ла Васьер (2012) отметил, что «[недавно опубликованная печать] дает титул лорда Самарканда пятого века как« короля гуннов-огларов »». [ 70 ] (ваго оглар(с)о – йонано). См. печать и это прочтение надписи у Ганса Баккера (2020: 13, примечание 17) со ссылкой на Сим-Уильямса (2011: 72-74). [ 71 ] Считается, что слово «оглар» происходит от тюркского слова «оул-лар» > «олар » «сыновья; князья» плюс иранский суффикс прилагательного -g. [ 72 ] В качестве альтернативы, что менее вероятно, «Огларг» может соответствовать «Валкону» и, следовательно, алчонским гуннам , хотя печать ближе к типам монет Кидаритов . [ 72 ] На другой печати, найденной в Кашмире, написано «ολαρ(γ)ο» (печать AA2.3). [ 71 ] Кашмирская печать была опубликована Гренетом, ур Рахманом и Симсом-Уильямсом (2006:125-127), которые сравнили ολαργο Уларг на печати с этнонимом οιλαργανο «народ Виларга », засвидетельствованным в бактрийском документе, написанном в 629 году нашей эры. [ 73 ] Стиль печатей родственен кидаритам , а титул «Кушаншах», как известно, исчез вместе с кидаритами. [ 74 ]

- ^ Jump up to: а б Смотрите другой пример (с описанием монеты). [ 120 ]

- ^ Аналогичный отчет о возвышении и завоеваниях Хуа появляется в Ляншу ( том 54 ).

- ^ Датировка войны разная: 560–565 гг. (Гумилев, 1967); 555 (Старк, 2008, Altturkenzeit, 210); 557 ( Ираника, «Хосров II» ); 558–561 ( Бивар , «Эфталиты»); 557–563 ( Баумер 2018 , стр. 174 ); 557–561 ( Синор 1990 , стр. 301); 560–563 ( Литвинский 1996 , с. 143); 562–565 ( Кристиан 1998 , стр. 252); в. 565 ( Grousset 1970 , стр. 82); 567 (Шаванн, 1903 г., Документы, 236 и 229)

- ↑ Майкл Дж. Декер утверждает, что битва произошла в 563 году. [ 192 ]

- ^ Лучевая корона сравнима с короной царя на печати « Ябгу эфталитов » . [ 228 ]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Бенджамин, Крейг (16 апреля 2015 г.). Кембриджская всемирная история: Том 4, Мир с государствами, империями и сетями, 1200 г. до н.э. – 900 г. н.э. Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 484. ИСБН 978-1-316-29830-5 .

- ^ Николсон, Оливер (19 апреля 2018 г.). Оксфордский словарь поздней античности . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 708. ИСБН 978-0-19-256246-3 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж к Альрам и др. 2012–2013 гг . Экспонат: 10. Эфталиты в Бактрии. Архивировано 29 марта 2016 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ Альрам 2008 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Бивар, АДХ «Эфталиты» . Энциклопедия Ираника . Проверено 8 марта 2017 г.

- ^ Южный, Марк Р.В. (2005). Заразительные связи: передача экспрессивных высказываний в идишских эхо-фразах . Издательская группа Гринвуд. п. 46. ИСБН 9780275980870 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Китайские путешественники в Афганистане» . Абдул Хай Хабиби . alamahabibi.com. 1969 год . Проверено 9 августа 2012 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Курбанов 2010 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Аль-Хинд, Создание индо-исламского мира: Раннесредневековая Индия . Андре Винк, с. 110. Э.Дж. Брилл.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Дэвид Уилмшерст (2011). Церковь мучеников: история Церкви Востока . Издательство Восток и Запад. стр. 77–78.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Дэни, Литвинский и Замир Сафи 1996 , с. 177 .

- ^ Дигнас, Беате; Зима, Энгельберт (2007). Рим и Персия в поздней античности: соседи и соперники . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 97. ИСБН 978-0-521-84925-8 .

- ^ Голсуорси, Адриан (2009). Падение Запада: смерть римской сверхдержавы . Орион. ISBN 978-0-297-85760-0 .

- ^ Резахани, Ходадад (25 апреля 2014 г.). «Эфталиты» . Иранология.com . Проверено 5 октября 2023 г.

- ^ Шоттки, Мартин (20 августа 2020 г.), "HUNS" , Encyclepaedia Iranica Online , Брилл , получено 5 октября 2023 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Резахани 2017а , с. 208.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Альрам 2014 , с. 279.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Маас 2015 , с. 287

- ^ Резахани 2017 , с. 213 .

- ^ Резахани 2017 , с. 217 .

- ^ Альрам 2014 , стр. 278–279.

- ^ Уитфилд, Сьюзен (2018). Шелк, рабы и ступы: материальная культура Шелкового пути . Издательство Калифорнийского университета. п. 185. ИСБН 978-0-520-95766-4 .

- ^ Бэйли, HW (1979) Словарь Хотан-Сака . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 482

- ^ Гариб Б. (1995) Согдийский словарь . Тегеран, Иран: Публикации Фархангана. п. xvi

- ^ Курбанов 2010 , с. 27.

- ^ цитата: «Семь ариев». Трамбле , 28Теофилакта в книге Этьена де ла Вэсьера, «Возвращение к турецким экскурсиям » в книге «От Самарканда до Стамбула: Hommages à Pierre Chuvin II» , Париж, CNRS Editions, 2015, стр.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Резахани 2017а , с. 208. «Печать с надписью ηβοδαλο ββγο, «Ябгу/правитель Хефтала», показывает местную, бактрийскую форму их имени, Эбодал, которая на их монетах обычно сокращается до ηβ»

- ^ Резахани 2017 , с. 214 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Хайдеманн, Стефан (2015). «Эфталитовые драхмы, отчеканенные в Балхе. Клад, последовательность и новое прочтение» (PDF) . Нумизматическая хроника . 175 : 340.

- ^ Лернер и Симс-Уильямс 2011 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Lerner & Sims-Williams 2011 , стр. 83–84, Печать AA 7 (Hc007). «Самое поразительное — глаза миндалевидные и раскосые…»

- ^ Лернер 2010 , Табличка I Рис.7.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Переводы Николаса Симса-Уильямса , цитируемые в Соловьев, Сергей (20 января 2020 г.). Аттила Каган гуннов из рода Вельсунгов . Литры. п. 313. ИСБН 978-5-04-227693-4 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Резахани 2017 , с. 135.

- ^ Резахани 2017a , с. 209.

- ^ Курбанов, Айдогды. (2013) «Исчезли эфталиты или нет?» в Study and Documenta Turcologica , 1 . Издательство Клужского университета. стр. 88 из 87-94

- ^ Балог 2020 , стр. 44–47 .

- ^ Теобальд, Ульрих (26 ноября 2011 г.). «Либо 嚈噠, эфталиты, либо белые гунны» . ChinaKnowledge.de .

- ^ Эноки, К. (декабрь 1970 г.). «Лян ши-гун-ту о происхождении и миграции хуа или эфталитов». Журнал Восточного общества Австралии . 7 (1–2): 37–45.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Александр Берзин. «История буддизма в Афганистане» . Изучайте буддизм .

- ^ Динеш Прасад Саклани (1998). Древние сообщества Гималаев . Индус Паблишинг. п. 187. ИСБН 978-81-7387-090-3 .

- ^ Дэни, Литвинский и Замир Сафи 1996 , с. 169 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Резахани 2017a , стр. 208–209.

- ^ Кагеяма 2016 , с. 200.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Миллуорд 2007 , стр. 30–31 .

- ^ Курбанов 2010 , стр. 135–136.

- ^ Бернард, П. «ДелбарджинЭЛЬБАРЖЕН» . Энциклопедия Ираника .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Ilyasov 2001 , pp. 187–197.

- ^ Дэни, Литвинский и Замир Сафи 1996 , с. 183 .

- ^ Лернер и Симс-Уильямс 2011 , с. 36.

- ^ Эноки 1959 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Синор, Денис (1990). «Создание и роспуск Тюркской империи». Кембриджская история ранней Внутренней Азии, том 1 . Издательство Кембриджского университета . п. 300 . ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9 . Проверено 19 августа 2017 г.

- ^ «Asia Major, том 4, часть 1» . Институт истории и филологии Академии Синика Университета Индианы. 1954 год . Проверено 19 августа 2017 г.

- ^ М.А. Шабан (1971). «Хурасан во времена арабского завоевания». В CE Босворте (ред.). Иран и ислам в память о покойном Владимире Минорском . Издательство Эдинбургского университета. п. 481. ИСБН 0-85224-200-Х .

- ^ Кристиан, Дэвид (1998). История России, Внутренней Азии и Монголии . Оксфорд: Бэзил Блэквелл. п. 248.

- ^ Курбанов 2010 , с. 14.

- ^ Адас, Майкл (2001). Сельскохозяйственные и скотоводческие общества в древней и классической истории . Издательство Университета Темпл. п. 90. ИСБН 978-1-56639-832-9 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Баумер 2018 , стр. 97–99.

- ^ Талбот, Тамара Абельсон Райс (Миссис Дэвид (1965). Древнее искусство Центральной Азии . Темза и Гудзон. стр. 93. ISBN 978-0-19-520001-0 .

- ^ Резахани 2017 , с. 135 . «Предположение о том, что эфталиты изначально были тюркского происхождения и лишь позже приняли бактрийский язык в качестве своего административного и, возможно, родного языка (де ла Вайсьер 2007: 122), кажется, наиболее заметным в настоящее время».

- ^ Jump up to: а б Фрай 2002 , с. 49 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Литвинский 1996 , стр. 138–154.

- ^ Эноки 1959 , стр. 23–28.

- ^ Фрай, Р. «ЦЕНТРАЛЬНАЯ АЗИЯ III. В доисламские времена» . Энциклопедия Ираника .

- ^ Г. Амброс; П.А. Эндрюс; Л. Базен; А. Гёкальп; Б. Флемминг; и др. «Турки», в Энциклопедии ислама , онлайн-издание, 2006 г.

- ^ Эноки 1959 , стр. 17–18.

- ^ Ю Тайшань (2011). «История племени еда (эфталитов): Дальнейшие вопросы» . Евразийские исследования . Я : 66–119.

- ^ Резахани 2017 , с. 135. «Предположение о том, что эфталиты изначально были тюркского происхождения и лишь позже приняли бактрийский язык в качестве своего административного и, возможно, родного языка (де ла Вайсьер 2007: 122), кажется, наиболее заметным в настоящее время».

- ^ де ла Васьер 2003 , стр. 119–137.

- ^ де ла Васьер, 2012 , с. 146 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Баккер, Ханс Т. (12 марта 2020 г.). Алхан: гунны в Южной Азии . Бархуис. п. 13, примечание 17. ISBN 978-94-93194-00-7 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Ван, Сян (август 2013 г.). «Исследование кидаритов: пересмотр документальных источников» . Архив Евразии Медии Аеви . 19 : 286.

- ^ Грене, Франц; твой Милосерднейший, Аман; Симс-Уильямс, Николас (2006). «Гуннский кушаншах» . Журнал искусства и археологии Внутренней Азии . 1 : 125–131. дои : 10.1484/J.JIAAA.2.301930 .

- ^ Курбанов, Айдогды (2013а). «Некоторые сведения, относящиеся к истории искусства эфталитовского времени (IV-VI вв. н.э.) в Средней Азии и Соседних странах» . Исиму . 16 : 99–112.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Хайэм, Чарльз (14 мая 2014 г.). Энциклопедия древних азиатских цивилизаций . Издательство информационной базы. стр. 141–142. ISBN 978-1-4381-0996-1 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Курбанов 2010 , с. 67.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Азарпай, Гитти; Беленицкий, Александр М.; Маршак, Борис Ильич; Дрезден, Марк Дж. (1981). Согдийская живопись: живописный эпос в восточном искусстве . Издательство Калифорнийского университета. С. 92 – 93 . ISBN 978-0-520-03765-6 .

- ^ Шоттки, М. «Иранские гунны» . Энциклопедия Ираника .

- ^ Jump up to: а б де ла Васьер 2003 , с. 122.

- ^ де ла Васьер, 2012 , стр. 144–155. «Гунны, вне всякого сомнения, являются политическими и этническими наследниками старой империи хунну»

- ^ Космо, Никола Ди; Маас, Майкл (26 апреля 2018 г.). Империи и обмены в Евразии поздней античности: Рим, Китай, Иран и Степь, ок. 250–750 . Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 196–197. ISBN 978-1-108-54810-6 .

В 2005 году Этьен де ла Васьер в своей плодотворной статье использовал некоторые новые или малоизвестные источники, чтобы доказать, что хунну на самом деле называли себя «гуннами» и что после распада их империи значительная часть северных хунну остался в Алтайском крае. В середине IV века оттуда ушли две большие группы гуннов: одна на юг, в земли севернее Персии (кидариты, алханы, эфталиты), а другая на запад, в Европу. Хотя утверждение о том, что имперские и постимперские хунну, гуннские династии к северу и востоку от Сасанидов и европейские гунны напрямую связаны, хотя и основано на ограниченных источниках, хорошо аргументировано.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д де ла Васьер, 2012 , стр. 144–146.

- ^ Ломазофф, Аманда; Ралби, Аарон (август 2013 г.). Атлас военной истории . Саймон и Шустер. п. 246. ИСБН 978-1-60710-985-3 .

- ^ Прокопий, История войн . Книга I, гл. III, «Персидская война»

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Бленсдорф, Катарина; Надо, Мари-Жозе; Гроутс, Питер М.; Хюльс, Матиас; Пфеффер, Стефани; Тиманн, Лаура (2009). «Датировка статуй Будды – AMS 14

С

Датирование органических материалов » (PDF) . В Петцете, Майкле (ред.). Гигантские Будды Бамиана. Охрана останков (PDF) . Памятники и места. Том 19. Берлин: Бэсслер. стр. 235, таблица 4. ISBN 978-3-930388-55-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 17 ноября 2020 г. .Восточный Будда: 549–579 гг. н.э. (диапазон 1 σ, вероятность 68,2%) 544–595 гг. н.э. (диапазон 2 σ, вероятность 95,4%). Западный Будда: 605 г. н.э. – 633 г. н.э. (диапазон 1 σ, 68,2%) 591 г. н.э. – 644 г. н.э. (диапазон 2 σ, вероятность 95,4%).

- ^ Азарпай, Гитти; Беленицкий, Александр М.; Маршак, Борис Ильич; Дрезден, Марк Дж. (1981). Согдийская живопись: живописный эпос в восточном искусстве . Издательство Калифорнийского университета. С. 92 – 93 . ISBN 978-0-520-03765-6 .

... будут доказывать их связь с художественной традицией правящих классов гефталитов в Тухаристане , переживших падение власти эфталитов в 557 году нашей эры.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Лю, Синьжу (9 июля 2010 г.). Шелковый путь в мировой истории . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 64. ИСБН 978-0-19-979880-3 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Литвинский 1996 , с. 158.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с де ла Васьер 2003 , с. 121.

- ^ Ду Ю , Тонгдянь "Том 193", листы 5b-6a

- ^ » Британская энциклопедия (11-е изд.). 1911 год

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г де ла Васьер 2003 , стр. 119–122, Приложение 1.

- ^ Эноки 1959 , стр. 1–14.

- ^ Курбанов 2010 , стр. 2–32.