сомалийцы

сомалийцы 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒆𐒖 Сумальда | |||

|---|---|---|---|

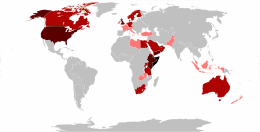

Традиционная территория, населенная сомалийской этнической группой. | |||

| Общая численность населения | |||

25,8 миллиона [1]  | |||

| Регионы со значительной численностью населения | |||

| Африканский Рог | |||

| 18,143,378 (2023) [2] [3] | |||

| 4,581,793 (2007) [4] | |||

| 2,780,502 (2019) [5] | |||

| 560,000 (2024) [6] | |||

| 500,000 (2014) [7] | |||

| 176,645 (2021) [8] | |||

| 164,723 (2022) [9] –221,000 (2020) [10] | |||

| 112,000 (2020) [11] | |||

| 101,000 [12] | |||

| 68,290 [13] [14] | |||

| 66,000 [15] | |||

| 65,550 [16] | |||

| 60,295 [17] | |||

| 51,536 [18] | |||

| 43,196 [19] | |||

| 39,737 [20] | |||

| 27,000–40,000 [21] | |||

| 34,000–67,500 [22] [23] | |||

| 24,647 [24] | |||

| 21,000 [11] –200,000 [25] | |||

| 21,210 [26] | |||

| 18,401 [27] | |||

| 9,349 [28] | |||

| 7,101 [29] | |||

| 7,025 [30] | |||

| 5,518 [31] | |||

| |||

| Языки | |||

| Сомали | |||

| Религия | |||

| ислам (сунниты) | |||

| Родственные этнические группы | |||

| Афар • Сахо • Оромо • Рандеву • Кушиты [42] | |||

Сомалийский Somali: Soomaalida, Osmanya: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒆𐒖, Wadaadнарод سٝومَالِدْاَ ) — кушитская этническая группа, обитающая на Африканском Роге. [43] [44] которые имеют общее происхождение, культуру и историю. Восточно -кушитский сомалийский язык является общим родным языком этнических сомалийцев, которые являются частью кушитской ветви афроазиатской языковой семьи, и они преимущественно мусульмане-сунниты . [45] [46] занимаемую одной этнической группой Составляя одну из крупнейших этнических групп на континенте, они занимают одну из самых обширных территорий в Африке, . [47]

По мнению большинства ученых, древняя Земля Пунт и ее коренные жители составляли часть этногенеза сомалийского народа. Говорят, что это древнее историческое королевство является местом происхождения значительной части их культурных традиций и предков. [48] [49] [50] [51] Сомалийцы разделяют многие исторические и культурные черты с другими кушитскими народами , особенно с равнинными восточно-кушитскими народами, особенно с афарами и сахо . [52]

Этнические сомалийцы в основном сконцентрированы в Сомали (около 17,6 миллиона человек). [53] Сомалиленд (5,7 миллиона), [54] Эфиопия (4,6 миллиона), [4] Кения (2,8 миллиона), [5] и Джибути (534 000). [55] Сомалийские диаспоры также встречаются в некоторых частях Ближнего Востока , Северной Америки , Западной Европы , Великих африканских озер региона , Южной Африки и Океании .

Этимология

Самаале , древнейший общий предок нескольких сомалийских кланов , обычно считается источником этнонима сомали . Другая теория состоит в том, что название происходит от слов soo и maal , которые вместе означают «иди и дои». Эта интерпретация различается в зависимости от региона: северные сомалийцы подразумевают, что это относится к верблюжьему молоку. [56] Южные сомалийцы используют транслитерацию « са' маал », которая относится к коровьему молоку. [57] Это отсылка к повсеместному скотоводству сомалийского народа. [58] Другая правдоподобная этимология предполагает, что термин «сомали» происходит от арабского слова «богатый» ( zāwamāl ), что снова относится к сомалийскому богатству скота. [59] [60]

Альтернативно, этноним сомали , как полагают, произошел от аутомоли (асмахов), группы воинов из древнего Египта , описанных Геродотом . Считается, что Асмах — это их египетское имя, а Автомоли — греческое производное от еврейского слова Смали (что означает «на левой стороне»). [61]

В танском китайском документе 9-го века нашей эры упоминается северное побережье Сомали, которое тогда было частью более широкого региона в Северо-Восточной Африке, известного как Барбария , в отношении этого региона варваров ( кушитов ). жителей [62] — as Po-pa-li . [63] [64]

Первое четкое письменное упоминание прозвища « сомали» относится к началу 15 века нашей эры, во время правления эфиопского императора Йешака I , который поручил одному из своих придворных чиновников сочинить гимн, прославляющий военную победу над султанатом Ифат . [65] Симур также был древним псевдонимом Харари для сомалийского народа. [66]

Сомалийцы в подавляющем большинстве предпочитают демоним «сомали» неправильному «сомалийцу», поскольку первый является эндонимом, а второй — экзонимом с двойными суффиксами. [67] Гипероним « термина сомалиец» в геополитическом смысле — Хорнер , а в этническом смысле — кушит . [68]

История

| История Сомали |

|---|

|

| История Сомалиленда |

|---|

|

Происхождение сомалийского народа, которое, как ранее предполагалось, происходило из Южной Эфиопии с 1000 г. до н.э. или с Аравийского полуострова в одиннадцатом веке, теперь опровергнуто новыми археологическими и лингвистическими исследованиями, которые помещают первоначальную родину сомалийского народа в Сомалиленд регион . , из которого делается вывод, что сомалийцы являются коренными жителями Африканского Рога на протяжении последних 7000 лет. [69]

Древние наскальные рисунки , которым около 5000 лет (по оценкам), были найдены в Сомалиленд регионе . Эти гравюры изображают раннюю жизнь на этой территории. [70] Самый известный из них — комплекс Лаас-Гил . Он содержит некоторые из самых ранних известных наскальных изображений на африканском континенте и множество тщательно продуманных скотоводческих эскизов фигур животных и людей. В других местах, например в регионе Дхамбалин , изображение человека на лошади считается одним из самых ранних известных примеров конного охотника. [70]

Надписи были найдены под многими наскальными рисунками, но археологам до сих пор не удалось расшифровать эту форму древнего письма. [71] В каменном веке со промышленными своими здесь процветали культуры Дойан и Харгейсан предприятиями и фабриками. [72]

Древнейшие свидетельства погребальных обычаев на Африканском Роге происходят из кладбищ в Сомали, датируемых 4-м тысячелетием до нашей эры . [73] Каменные орудия из Джалело стоянки в Сомали считаются важнейшим связующим звеном, свидетельствующим об универсальности во палеолита времена между Востоком и Западом . [74]

В древности предки сомалийцев были важным звеном на Африканском Роге, связывающим торговлю региона с остальным древним миром. Сомалийские моряки и купцы были основными поставщиками ладана , мирры и специй считали ценной роскошью , предметов роскоши, которые древние египтяне , финикийцы , микенцы и вавилоняне . [75] [76]

По мнению большинства ученых, древняя Земля Пунт и ее коренные жители составляли часть этногенеза сомалийского народа. [48] [49] [50] [51] Древние пунтиты — народ, имевший тесные связи с фараонским Египтом во времена фараона Сахуре и царицы Хатшепсут . Пирамидальные сооружения , храмы и древние дома из тесаного камня, разбросанные по всей территории Сомали, возможно, относятся к этому периоду. [77]

В классической древности макробианцы , которые , возможно, были предками аутомоли или древних сомалийцев, основали мощное племенное королевство, которое управляло значительной частью современной Сомали . Они славились своим долголетием и богатством и считались «самыми высокими и красивыми из всех людей». [78] Макробиане были воинами-пастухами и мореплавателями. Согласно рассказу Геродота, император Ахеменидов Камбис II после завоевания Египта в 525 г. до н.э. отправил послов в Макробию, принося роскошные подарки царю Макробии, чтобы побудить его подчиниться. Макробианский правитель, избранный на основании своего роста и красоты, вместо этого ответил вызовом своему персидскому коллеге в виде лука без тетивы: если бы персам удалось его натянуть, они имели бы право вторгнуться в его страну; но до тех пор им следует благодарить богов за то, что макробианцы так и не решили вторгнуться в их империю. [78][79] The Macrobians were a regional power reputed for their advanced architecture and gold wealth, which was so plentiful that they shackled their prisoners in golden chains.[79]

Several ancient city-states, such as Opone, Essina, Sarapion, Nikon, Malao, Damo and Mosylon near Cape Guardafui, which competed with the Sabaeans, Parthians and Axumites for the wealthy Indo-Greco-Roman trade, also flourished in Somalia.[80]

Islam was introduced to the area early on by the first Muslims of Mecca fleeing prosecution during the first Hejira with Masjid al-Qiblatayn being built before the Qiblah faced towards Mecca. The town of Zeila's two-mihrab Masjid al-Qiblatayn dates to the 7th century, and is one of the oldest mosques in Africa.[81]

Consequently the Somalis were some of the earliest non-Arabs that converted to Islam.[82] The peaceful conversion of the Somali population by Somali Muslim scholars in the following centuries, the ancient city-states eventually transformed into Islamic Mogadishu, Berbera, Zeila, Barawa, Hafun and Merca, which were part of the Berberi civilization. The city of Mogadishu came to be known as the City of Islam,[83] and controlled the East African gold trade for several centuries.[84]

The Sultanate of Ifat, led by the Walashma dynasty with its capital at Zeila, ruled over parts of what is now eastern Ethiopia, Djibouti and Somaliland. The historian al-Umari records that Ifat was situated near the Red Sea coast, and states its size as 15 days travel by 20 days travel. Its army numbered 15,000 horsemen and 20,000 foot soldiers. Al-Umari also credits Ifat with seven "mother cities": Belqulzar, Kuljura, Shimi, Shewa, Adal, Jamme and Laboo.[85]

In the Middle Ages, several powerful Somali empires dominated the regional trade including the Ajuran Sultanate, which excelled in hydraulic engineering and fortress building,[86] the Adal Sultanate, whose general Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (Ahmed Gurey) was the first commander to use cannon warfare on the continent during Adal's conquest of the Ethiopian Empire,[87] and the Sultanate of the Geledi, whose military dominance forced governors of the Omani empire north of the city of Lamu to pay tribute to the Somali Sultan Ahmed Yusuf.[88] The Harla, an early group who inhabited parts of Somalia, Tchertcher and other areas in the Horn, also erected various tumuli.[89] These masons are believed to have been ancestral to the Somalis ("proto-Somali").[90]

Berbera was the most important port in the Horn of Africa between the 18th–19th centuries.[91] For centuries, Berbera had extensive trade relations with several historic ports in the Arabian Peninsula. Additionally, the Somali and Ethiopian interiors were very dependent on Berbera for trade, where most of the goods for export arrived from. During the 1833 trading season, the port town swelled to over 70,000 people, and upwards of 6,000 camels laden with goods arrived from the interior within a single day. Berbera was the main marketplace in the entire Somali seaboard for various goods procured from the interior, such as livestock, coffee, frankincense, myrrh, acacia gum, saffron, feathers, ghee, hide (skin), gold and ivory.[92] Historically, the port of Berbera was controlled indigenously between the mercantile Reer Ahmed Nur and Reer Yunis Nuh sub-clans of the Habar Awal.[93]

According to a trade journal published in 1856, Berbera was described as “the freest port in the world, and the most important trading place on the whole Arabian Gulf.”:

“The only seaports of importance on this coast are Feyla [Zeila] and Berbera; the former is an Arabian colony, dependent of Mocha, but Berbera is independent of any foreign power. It is, without having the name, the freest port in the world, and the most important trading place on the whole Arabian Gulf. From the beginning of November to the end of April, a large fair assembles in Berbera, and caravans of 6,000 camels at a time come from the interior loaded with coffee, (considered superior to Mocha in Bombay), gum, ivory, hides, skins, grain, cattle, and sour milk, the substitute of fermented drinks in these regions; also much cattle is brought there for the Aden market.”[94]

As a tributary of Mocha, which in turn was part of the Ottoman possessions in Western Arabia, the port of Zeila had seen several men placed as governors over the years. The Ottomans based in Yemen held nominal authority of Zeila when Sharmarke Ali Saleh, who was a successful and ambitious Somali merchant, purchased the rights of the town from the Ottoman governor of Mocha and Hodeida.[95]

Allee Shurmalkee [Ali Sharmarke] has since my visit either seized or purchased this town, and hoisted independent colours upon its walls; but as I know little or nothing save the mere fact of its possession by that Soumaulee chief, and as this change occurred whilst I was in Abyssinia, I shall not say anything more upon the subject.[96]

However, the previous governor was not eager to relinquish his control of Zeila. Hence in 1841, Sharmarke chartered two dhows (ships) along with fifty Somali Matchlock men and two cannons to target Zeila and depose its Arab Governor, Syed Mohammed Al Barr. Sharmarke initially directed his cannons at the city walls which frightened Al Barr's followers and caused them to abandon their posts and succeeded Al Barr as the ruler of Zeila. Sharmarke's governorship had an instant effect on the city, as he maneuvered to monopolize as much of the regional trade as possible, with his sights set as far as Harar and the Ogaden.[97][98]

In 1845, Sharmarke deployed a few matchlock men to wrest control of neighboring Berbera from that town's then feuding Somali local authorities.[99][100][101] Sharmarke's influence was not limited to the Somali coast as he had allies and influence in the interior of the Somali country, the Danakil coast and even further afield in Abyssinia. Among his allies were the Kings of Shewa. When there was tension between the Amir of Harar Abu Bakr II ibn `Abd al-Munan and Sharmarke, as a result of the Amir arresting one of his agents in Harar, Sharmarke persuaded the son of Sahle Selassie, ruler of Shewa, to imprison on his behalf about 300 citizens of Harar then resident in Shewa, for a length of two years.[102]

In the late 19th century, after the Berlin Conference had ended, the Scramble for Africa reached the Horn of Africa. Increasing foreign influence in the region culminated in the creation of the first Darawiish, an armed resistance movement calling for the independence from the European powers.[103][104] The Dervish had their leaders, Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, Haji Sudi and Sultan Nur Ahmed Aman, who sought a state in the Nugaal[105] and began one of the longest African conflicts in modern history.[106][107]

The news of the incident that sparked the 21 year long Dervish rebellion, according to the consul-general James Hayes Sadler, was spread or as he claimed was concocted by Sultan Nur of the Habr Yunis. The incident in question was that of a group of Somali children who were converted to Christianity and adopted by the French Catholic Mission at Berbera in 1899. Whether Sultan Nur experienced the incident first hand or whether he was told of it is not clear but what is known is that he propagated the incident in June 1899, precipitating the religious rebellion of the Dervishes.[108]

The Dervish movement successfully stymied British forces four times and forced them to retreat to the coastal region.[109] As a result of its successes against the British, the Dervish movement received support from the Ottomans and Germans. The Ottoman government also named Hassan Emir of the Somali nation,[110] and the German government promised to officially recognise any territories the Dervishes were to acquire.[111]

After a quarter of a century of military successes against the British, the Dervishes were finally defeated by Britain in 1920 in part due to the successful deployment of the newly-formed Royal Air Force by the British government.[112]

Majeerteen Sultanate was founded in the early-1700s and rose to prominence in the following century, under the reign of the resourceful Boqor (King) Osman Mahamuud.[113] His Kingdom controlled Bari Karkaar, Nugaaal, and also central Somalia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Majeerteen Sultanate maintained a robust trading network, entered into treaties with foreign powers, and exerted strong centralized authority on the domestic front.[114][115]

The Majeerteen Sultanate was nearly dismantled in the late-1800s by a power struggle between Boqor Osman Mahamuud and his ambitious cousin, Yusuf Ali Kenadid who founded the Sultanate of Hobyo in 1878. Initially Kenadid wanted to seize control of the neighbouring Sultanate. However, he was unsuccessful in this endeavour, and was eventually forced into exile in Yemen.[116] Both sultanates maintained written records of their activities, which still exist.[117]

In late 1888, Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid entered into a treaty with the Italian government, making his Sultanate of Hobyo an Italian protectorate known as Italian Somalia. His rival Boqor Osman Mahamuud was to sign a similar agreement vis-a-vis his own Majeerteen Sultanate the following year. In signing the agreements, both rulers also hoped to exploit the rival objectives of the European imperial powers so as to more effectively assure the continued independence of their territories.[118] The Italians, for their part, were interested in the territories mainly because of its ports specifically Port of Bosaso which could grant them access to the strategically important Suez Canal and the Gulf of Aden.[119] The terms of each treaty specified that Italy was to steer clear of any interference in the Sultanates' respective administrations.[118] In return for Italian arms and an annual subsidy, the Sultans conceded to a minimum of oversight and economic concessions.[120] The Italians also agreed to dispatch a few ambassadors to promote both the Sultanates' and their own interests.[118] The new protectorates were thereafter managed by Vincenzo Filonardi through a chartered company.[120] An Anglo-Italian border protocol was later signed on 5 May 1894, followed by an agreement in 1906 between Cavalier Pestalozza and General Swaine acknowledging that Baran fell under the Majeerteen Sultanate's administration.[118] With the gradual extension into northern Somalia of Italian colonial rule, both Kingdoms were eventually annexed in the early 20th century.[121] However, unlike the southern territories, the northern sultanates were not subject to direct rule due to the earlier treaties they had signed with the Italians.[122]

Following World War II, Britain retained control of both British Somaliland and Italian Somalia as protectorates. In 1945, during the Potsdam Conference, the United Nations granted Italy trusteeship of Italian Somalia, but only under close supervision and on the condition — first proposed by the Somali Youth League (SYL) and other nascent Somali political organizations, such as Hizbia Digil Mirifle Somali (HDMS) and the Somali National League (SNL) — that Somalia achieve independence within ten years.[123][124] British Somalia remained a protectorate of Britain until 1960.[125]

To the extent that Italy held the territory by UN mandate, the trusteeship provisions gave the Somalis the opportunity to gain experience in political education and self-government. These were advantages that British Somaliland, which was to be incorporated into the new Somali Republic state, did not have. Although in the 1950s British colonial officials attempted, through various administrative development efforts, to make up for past neglect, the protectorate stagnated. The disparity between the two territories in economic development and political experience would cause serious difficulties when it came time to integrate the two parts.[126]

Meanwhile, in 1948, under pressure from their World War II allies and to the dismay of the Somalis,[127] the British ceded official control of the Haud (an important Somali grazing area that was brought under British protection via treaties with the Somalis in 1884 and 1886) and the Ogaden to Ethiopia, based on a treaty they signed in 1897 in which the British ceded Somali territory to the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik in exchange for his help against raids by Somali clans.[128] Britain included the proviso that the Somali nomads would retain their autonomy, but Ethiopia immediately claimed sovereignty over them.[123] This prompted an unsuccessful bid by Britain in 1956 to purchase back the Somali lands it had turned over.[123] The British government also granted administration of the almost exclusively Somali-inhabited[129] Northern Frontier District (NFD) to the Kenyan government despite an informal plebiscite demonstrating the overwhelming desire of the region's population to join the newly formed Somali Republic.[130]

| History of Djibouti |

|---|

|

| Prehistory |

| Antiquity |

|

| Middle Ages |

|

| Colonial period |

|

| Modern period |

| Republic of Djibouti |

A referendum was held in neighboring Djibouti (then known as French Somaliland) in 1958, on the eve of Somalia's independence in 1960, to decide whether or not to join the Somali Republic or to remain with France. The referendum turned out in favour of a continued association with France, largely due to a combined yes vote by the sizable Afar ethnic group and resident Europeans.[131] There was also widespread vote rigging, with the French expelling thousands of Somalis before the referendum reached the polls.[132] The majority of those who voted no were Somalis who were strongly in favour of joining a united Somalia, as had been proposed by Mahmoud Harbi, Vice President of the Government Council. Harbi was killed in a plane crash two years later.[131] Djibouti finally gained its independence from France in 1977, and Hassan Gouled Aptidon, a Somali who had campaigned for a yes vote in the referendum of 1958, eventually wound up as Djibouti's first president (1977–1991).[131]

British Somaliland became independent on 26 June 1960 as the State of Somaliland, and the Trust Territory of Somalia (the former Italian Somalia) followed suit five days later.[133] On 1 July 1960, the two territories united to form the Somali Republic, albeit within boundaries drawn up by Italy and Britain.[134][135] A government was formed by Abdullahi Issa Mohamud and Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal other members of the trusteeship and protectorate governments, with Haji Bashir Ismail Yusuf as president of the Somali National Assembly, Aden Abdullah Osman Daar as the president of the Somali Republic and Abdirashid Ali Shermarke as Prime Minister (later to become president from 1967 to 1969). On 20 July 1961 and through a popular referendum, the people of Somalia ratified a new constitution, which was first drafted in 1960. The constitution was rejected by the people of Somaliland.[136] In 1967, Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal became Prime Minister, a position to which he was appointed by Shermarke.

On 15 October 1969, while paying a visit to the northern town of Las Anod, Somalia's then President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was shot dead by one of his own bodyguards. His assassination was quickly followed by a military coup d'état on 21 October 1969 (the day after his funeral), in which the Somali Army seized power without encountering armed opposition — essentially a bloodless takeover. The putsch was spearheaded by Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, who at the time commanded the army.[137]

Alongside Barre, the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) that assumed power after President Sharmarke's assassination was led by Lieutenant Colonel Salaad Gabeyre Kediye and Chief of Police Jama Korshel. The SRC subsequently renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic,[138][139] dissolved the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution.[140]

The revolutionary army established large-scale public works programs and successfully implemented an urban and rural literacy campaign, which helped dramatically increase the literacy rate. In addition to a nationalization program of industry and land, the new regime's foreign policy placed an emphasis on Somalia's traditional and religious links with the Arab world, eventually joining the Arab League (AL) in 1974.[141] That same year, Barre also served as chairman of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the predecessor of the African Union (AU).[142]

Demographics

Clans

Somalis are ethnically of Cushitic ancestry, but have genealogical traditions of descent from various patriarchs associated with the spread of Islam.[143] Being one tribe, they are segmented into various clan groupings, which are important kinship units that play a central part in Somali culture and politics. Clan families are patrilineal, and are divided into clans, primary lineages or subclans, and dia-paying kinship groups. The lineage terms qabiil, qolo, jilib and reer are often interchangeably used to indicate the different segmentation levels. The clan represents the highest kinship level. It owns territorial properties and is typically led by a clan-head or Sultan. Primary lineages are immediately descended from the clans, and are exogamous political units with no formally installed leader. They comprise the segmentation level that an individual usually indicates he or she belongs to, with their founding patriarch reckoned to between six and ten generations.[144]

The five major clan families are the traditionally nomadic pastoralist Dir, Isaaq, Darod, Hawiye and the sedentary agropastoralist Rahanweyn.[144] Minor Somali clans include Asharaf.[145]

The Dir, Hawiye, Gardere (Gaalje'el, Degodia, Garre), Hawadle and Ajuran trace agnatic origins to the patriarch Samaale.[146][147] The Darod have separate paternal traditions of descent through Abdirahman bin Isma'il al-Jabarti (Sheikh Darod), who is said to have Banu Hashim origins through Aqiil Abu Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib. He arrived at a later date from the Arabian Peninsula in the 10th or 11th centuries.[148] Sheikh Darod is asserted to have married a woman from the Dir (while some accounts say Hawiye[149][150]), thus establishing matrilateral ties with the Samaale family.[146] The Isaaq clan trace paternal descent to the Islamic leader Ishaaq bin Ahmed al-Hashimi (Sheikh Isaaq). The Digil & Mirifle (Rahanweyn) trace their ancestry back to the patriarch Sab. Both Samaale and Sab are supposed to have descended from a common ancestor with origins in the Arabian Peninsula.[146] Contemporary genetic studies indicate that Somalis in general do not possess any noticeable Arab ancestry.[151][152][153] The traditions of descent from noble elite forefathers who settled on the littoral are debated, although they are based on early Arab documents and northern folklore.[154][155][156]

A comprehensive genealogy of Somali clans can be found in Abbink (2009), providing detailed family trees and historical background information.[157]

The tombs of the founders of Darod, Dir and Isaaq as well as the Abgaal subclan of Hawiye are all located in northern Somalia. Tradition holds this area as the ancestral homeland of the Somali people.[145]

Kinship

The traditional political unit among the Somali people has been kinships.[155] Dia-paying groups are groupings of a few small lineages, each consisting of a few hundred to a few thousand members. They trace their foundation to between four and eight generations. Members are socially contracted to support each other in jural and political duties, including paying or receiving dia or blood compensation (mag in Somali).[144] Compensation is obligatory in regards to actions committed by or against a dia-paying group, including blood-compensation in the event of damage, injury or death.[155][158][159]

Social stratification

Within traditional Somali society (as in other ethnic groups of the Horn of Africa and the wider region), there has been social stratification.[160][161][162] According to the historian Donald Levine, these comprised high-ranking clans, low-ranking clans, caste groups, and slaves.[163] This rigid hierarchy and concepts of lineal purity contrast with the relative egalitarianism in clan leadership and political control.[161]

Nobles constituted the upper tier and were known as bilis. They consist of individuals of ethnic Somali ancestral origin, and have been endogamous.[164]

The lower tier was designated as Sab, and was distinguished by its heterogeneous constitution and agropastoral lifestyle as well as some linguistic and cultural differences. A third Somali caste strata was made up of artisanal groups, which were endogamous and hereditary.[146] Among the caste groups, the Midgan were traditionally hunters and circumcision performers.[165][166] The Tumal (also spelled Tomal) were smiths and leatherworkers, and the Yibir (also spelled Yebir) were the tanners and magicians.[167][168]

According to the anthropologist Virginia Luling, the artisanal caste groups of the north closely resembled their higher caste kinsmen, being generally Caucasoid like other ethnic Somalis.[169] Although ethnically indistinguishable from each other, state Mohamed Eno and Abdi Kusow, upper castes have stigmatized the lower ones.[170]

Outside of the Somali caste system were slaves of Bantu origin and physiognomy.[171] Their distinct physical features and occupations differentiated them from Somalis and positioned them as inferior within the social hierarchy.[172][173]

Marriage

Among Somali clans, in order to strengthen alliance ties, marriage is often to another ethnic Somali from a different clan. According to I. M. Lewis, of 89 marriages initiated by men of the Dhulbahante clan, 55 (62%) were therefore with women of Dhulbahante subclans other than those of their husbands; 30 (33.7%) were with women of adjacent clans of other clan families (Isaaq, 28; Hawiye, 3); and 3 (4.3%) were with women of other clans of the Darod clan family (Majerteen 2, Ogaden 1).[174]

Such exogamy is always followed by the dia-paying group and usually adhered to by the primary lineage, whereas marriage to lineal kin falls within the prohibited range.[175] These traditional strictures against consanguineous marriage ruled out the patrilateral first cousin marriages that are favored by Arab Bedouins and specially approved by Islam. These marriages were practiced to a limited degree by certain northern Somali subclans.[174] In areas inhabited by diverse clans, such as the southern Mogadishu area, endogamous marriages also served as a means of ensuring clan solidarity in uncertain socio-political circumstances.[176] This inclination was further spurred on by intensified contact with Arab society in the Gulf, wherein first cousin marriage was preferred. Although politically expedient, such endogamous marriage created tension with the traditional principles within Somali culture.[177]

In 1975, the most prominent government reforms regarding family law in a Muslim country were set in motion in the Somali Democratic Republic, which put women and men, including husbands and wives, on complete equal footing.[178] The 1975 Somali Family Law gave men and women equal division of property between the husband and wife upon divorce and the exclusive right to control by each spouse over his or her personal property.[179]

FGM is almost universal in Somalia, and many women undergo infibulation, the most extreme form of female genital mutilation.[180] According to a 2005 WHO estimate, about 97.9% of Somalia's women and girls underwent FGM. This was at the time the world's highest prevalence rate of the procedure.[181]

Religion

According to data from the Pew Research Center, the creed breakdown of Muslims in the Somali-majority Djibouti is as follows: 77% adhere to Sunnism, 8% are non-denominational Muslim, 2% are Shia and 13% declined to answer, and a further report inclusive of Somali Region stipulating 2% adherence to a minority sect (e.g. Ibadism, Quranism etc.).[182] In the neighboring country of Somalia, 99.8% of the population is Muslim according to the Pew Research Center.[183] The majority belong to the Sunni branch of Islam and the Shafi'i school of Islamic jurisprudence.[184] Sufism, the mystical sect of Islam, is also well established, with many local jama'a (zawiya) or congregations of the various tariiqa or Sufi orders.[185] The constitution of Somalia likewise defines Islam as the state religion of the Federal Republic of Somalia, and Islamic sharia law as the basic source for national legislation. It also stipulates that no law that is inconsistent with the basic tenets of Shari'a can be enacted.[186]There are some nobles who believe with great pride that they are of Arabian ancestry, and trace their stirp to Muhammad's lineage of Quraysh and those of his companions. Although they do not consider themselves culturally Arabs, except for the shared religion, their presumed noble Arabian origins genealogically unite them.[187] The purpose behind claiming genealogical traditions of descent from the Arabian Peninsula is used to reinforce one's lineage and the various associated patriarchs with the spread of Islam.[143]

Languages

The Somali language (Af-Soomaali) is a member of the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic family. Its nearest relatives are the Afar and Saho languages.[189] Somali is the best documented of the Cushitic languages[190] with academic studies dating from the 19th century.

The exact number of speakers of Somali is unknown. One source estimates that there are 16.3 million speakers of Somali within Somalia and 25.8 million speakers globally.[191][192] Recent estimates had approximately 24 million speakers of Somali, spread in Greater Somalia of which around 17 million resided in Somalia.[193] The Somali language is spoken by ethnic Somalis in Greater Somalia and the Somali diaspora.

Somali dialects are divided into three main groups: Northern, Benadiri, and Maay. Northern Somali (or Northern-Central Somali) forms the basis for Standard Somali. Benadiri (also known as Coastal Somali) is spoken on the Benadir coast from Adale to south of Merca, including Mogadishu, as well as in the immediate hinterland. The coastal dialects have additional phonemes which do not exist in Standard Somali. Maay is principally spoken by the Digil and Mirifle (Rahanweyn) clans in the southwestern areas of Somalia.[194]

A number of writing systems have been used over the years for transcribing the Somali language. Of these, the Somali Latin alphabet is the most widely used, and has been the official writing script in Somalia since the government of former President of Somalia Mohamed Siad Barre formally introduced it in October 1972.[195] The script was developed by the Somali linguist Shire Jama Ahmed specifically for the Somali language. It uses all letters of the Latin alphabet, except p, v, and z. Besides the Latin script, other orthographies that have been used for centuries for writing Somali include the long-established Arabic script and Wadaad writing. Other writing systems developed in the twentieth century including the Osmanya, Borama and Kaddare scripts, which were invented by Osman Yusuf Kenadid, Abdurahman Sheikh Nuur and Hussein Sheikh Ahmed Kaddare respectively.[196]

In addition to Somali, Arabic, which is also an Afro-Asiatic tongue, is an official national language in Somalia and Djibouti. Many Somalis speak it due to millennia-old ties with the Arab world, the far-reaching influence of the Arabic media, and religious education.[197] Somalia and Djibouti are also both members of the Arab League.[44][198]

Culture

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Somalia |

|---|

| Culture |

| People |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Politics |

The culture of Somalia is an amalgamation of traditions developed independently and through interaction with neighbouring and far away civilizations, such as other parts of Northeast Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, India and Southeast Asia.[199]

The textile-making communities in Somalia are a continuation of an ancient textile industry, as is the culture of wood carving, pottery and monumental architecture that dominates Somali interiors and landscapes. The cultural diffusion of Somali commercial enterprise can be detected in its cuisine, which contains Southeast Asian influences. Due to the Somali people's passionate love for and facility with poetry, Somalia has often been referred to by scholars as a "Nation of Poets" and a "Nation of Bards" including, among others, the Canadian novelist Margaret Laurence.[200]

According to Canadian novelist and scholar Margaret Laurence, who originally coined the term "Nation of Poets" to describe the Somali Peninsular, the Eidagale clan were viewed as "the recognized experts in the composition of poetry" by their fellow Somali contemporaries:

Among the tribes, the Eidagalla are the recognized experts in the composition of poetry. One individual poet of the Eidagalla may be no better than a good poet of another tribe, but the Eidagalla appear to have more poets than any other tribe. "if you had a hundred Eidagalla men here," Hersi Jama once told me, "And asked which of them could sing his own gabei ninety-five would be able to sing. The others would still be learning."[201]

All of these traditions, including festivals, martial arts, dress, literature, sport and games such as Shax, have immensely contributed to the enrichment of Somali heritage.

Music

Somalis have a rich musical heritage centered on traditional Somali folklore. Most Somali songs are pentatonic. That is, they only use five pitches per octave in contrast to a heptatonic (seven note) scale, such as the major scale. At first listen, Somali music might be mistaken for the sounds of nearby regions such as Ethiopia, Sudan or Arabia, but it is ultimately recognizable by its own unique tunes and styles. Somali songs are usually the product of collaboration between lyricists (midho), songwriters (laxan) and singers (Codka or "voice").[202]

Musicians and bands

- Aar Maanta – UK-based Somali singer, composer, writer and music producer.

- Abdi Sinimo – Prominent Somali artist and inventor of the Balwo musical style.

- Abdullahi Qarshe – Somali musician, poet and playwright known for his innovative styles of music, which included a wide variety of musical instruments such as the guitar, piano and oud.

- Ali Feiruz – Somali musician from Djibouti; part of the Radio Hargeisa generation of Somali artists.

- Dur-Dur – Somali band active during the 1980s and 1990s in Somalia, Djibouti and Ethiopia.

- Hasan Adan Samatar – popular male artist during the 1970s and 80s.

- Hibo Nuura – popular Somali singer.

- Jonis Bashir – Somali-Italian actor and singer

- Khadija Qalanjo – popular Somali singer in the 1970s and 1980s.

- K'naan – award-winning Somali-Canadian hip hop artist.

- Magool (2 May 1948 – 19 March 2004) – prominent Somali singer considered in Somalia as one of the greatest entertainers of all time.

- Maryam Mursal (born 1950) – Somali musician, composer and vocalist whose work has been produced by the record label Real World.

- Mohammed Mooge – Prominent Somali artist from the Radio Hargeisa generation.

- Poly Styrene – Somali-British punk rock singer; best known as being the lead singer of X Ray Spex.

- Saado Ali Warsame – Somali singer-songwriter and modern Qaraami exponent.

- Waaberi – Somalia's foremost musical group that toured through several countries in Northeast Africa and Asia, including Egypt, Sudan and China.

- Waayaha Cusub – Somali music collective. Organized the international Reconciliation Music Festival in 2013 in Mogadishu.

Cinema and theatre

Growing out of the Somali people's rich storytelling tradition, the first few feature-length Somali films and cinematic festivals emerged in the early 1960s, immediately after independence. Following the creation of the Somali Film Agency (SFA) regulatory body in 1975, the local film scene began to expand rapidly. Hassan Sheikh Mumin was considered one of the most prolific and early playwrights and composers in Somali literature. Mumin's most important work is Shabeel Naagood (1965), a piece that touches on the social position of women, urbanization, changing traditional practices, and the importance of education during the early pre-independence period. Although the issues it describes were later to some degree redressed, the work remains a mainstay of Somali literature.[203] Shabeel Naagood was translated into English in 1974 under the title Leopard Among the Women by the Somali Studies pioneer Bogumił W. Andrzejewski, who also wrote the introduction. Mumin composed both the play itself and the music used in it.[204] The piece is regularly featured in various school curricula, including Oxford University, which first published the English translation under its press house.

During one decisive passage in the play, the heroine, Shallaayo, laments that she has been tricked into a false marriage by the Leopard in the title:

"Women have no share in the encampments of this world

And it is men who made these laws, to their own advantage.

By God, by God, men are our enemies, though we ourselves nurtured them

We suckled them at our breasts, and they maimed us:

We do not share peace with them."

The Somali filmmaker Ali Said Hassan concurrently served as the SFA's representative in Rome. In the 1970s and early 1980s, popular musicals known as riwaayado were the main driving force behind the Somali movie industry.

Epic and period films as well as international co-productions followed suit, facilitated by the proliferation of video technology and national television networks. Said Salah Ahmed during this period directed his first feature film, The Somali Darwish (The Somalia Dervishes), devoted to the Dervish movement. In the 1990s and 2000s, a new wave of more entertainment-oriented movies emerged. Referred to as Somaliwood, this upstart, youth-based cinematic movement has energized the Somali film industry and in the process introduced innovative storylines, marketing strategies and production techniques. The young directors Abdisalam Aato of Olol Films and Abdi Malik Isak are at the forefront of this quiet revolution.[205]

Art

Somalis have old visual art traditions, which include pottery, jewelry and wood carving. In the medieval period, affluent urbanites commissioned local wood and marble carvers to work on their interiors and houses. Intricate patterns also adorn the mihrabs and pillars of ancient Somali mosques. Artistic carving was considered the province of men, whereas the textile industry was mainly that of women. Among the nomads, carving, especially woodwork, was widespread and could be found on the most basic objects such as spoons, combs and bowls. It also included more complex structures, such as the portable nomadic house, the aqal. In the last several decades, traditional carving of windows, doors and furniture have given way to workshops employing electrical machinery, which deliver the same results in a far shorter time period.[206]

Additionally, henna is an important part of Somali culture. It is worn by Somali women on their hands, arms, feet and neck during wedding ceremonies, Eid, Ramadan and other festive occasions. Somali henna designs are similar to those in the Arabian peninsula, often featuring flower motifs and triangular shapes. The palm is also frequently decorated with a dot of henna and the fingertips are dipped in the dye. Henna parties are usually held before the wedding takes place. Somali women have likewise traditionally applied kohl (kuul) to their eyes.[207] Usage of the eye cosmetic in the Horn region is believed to date to the ancient Land of Punt.[208]

Sports

Football is the most popular sport amongst Somalis. Important competitions are the Somalia League and Somalia Cup. The Ocean Stars is Somalia's multi-ethnic national team.[209]

Basketball is also played in the country. The FIBA Africa Championship 1981 was hosted in Mogadishu from 15 to 23 December December 1981, during which the national basketball team received the bronze medal.[210] The squad also takes part in the basketball event at the Pan Arab Games. Other team sports include badminton, baseball, table tennis, and volleyball.[209]

In the martial arts, Faisal Jeylani Aweys and Mohamed Deq Abdulle also took home a silver medal and fourth place, respectively, at the 2013 Open World Taekwondo Challenge Cup in Tongeren. The Somali National Olympic committee has devised a special support program to ensure continued success in future tournaments.[211] Additionally, Mohamed Jama has won both world and European titles in K1 and Thai Boxing.[212] Other individuals sports include judo, boxing, athletics, weight lifting, swimming, rowing, fencing and wrestling.[209] Somalis have also produced many world-class distance runners like their neighboring countries with Mo Farah, Abdi Bile and Mohammed Ahmed.

Attire

Traditionally, Somali men typically wear the macawis. It is a sarong that is worn around the waist. On their heads, they often wrap a colorful turban or wear the koofiyad, which is an embroidered fez.[213]

Due to Somalia's proximity to and close ties with the Arabian Peninsula, many Somali men also wear the jellabiya (jellabiyad or qamiis). The costume is a long white garment common in the Arab world.[214]

During regular, day-to-day activities, Somali women usually wear the guntiino. It is a long stretch of cloth tied over the shoulder and draped around the waist. The cloth is usually made out of alandi, which is a textile that is common in the Horn region and some parts of North Africa. The garment can be worn in different styles. It can also be made with other fabrics, including white cloth with gold borders. For more formal settings, such as at weddings or religious celebrations like Eid, women wear the dirac. It is a long, light, diaphanous voile dress made of silk, chiffon, taffeta or saree fabric. The gown is worn over a full-length half-slip and a brassiere. Known as the gorgorad, the underskirt is made out of silk and serves as a key part of the overall outfit. The dirac is usually sparkly and very colorful, the most popular styles being those with gilded borders or threads.[213]

Married women tend to wear headscarves referred to as shaash. They also often cover their upper body with a shawl, which is known as garbasaar. Unmarried or young women, however, do not always cover their heads. Traditional Arabian garb, such as the jilbab and abaya, is also commonly worn.[213]

Additionally, Somali women have a long tradition of wearing gold jewelry, particularly bangles. During weddings, the bride is frequently adorned in gold. Many Somali women by tradition also wear gold necklaces and anklets.[213]

Ethnic flag

The Somali flag is an ethnic flag conceived to represent ethnic Somalis.[215] It was created in 1954 by the Somali scholar Mohammed Awale Liban, after he had been selected by the labour trade union of the Trust Territory of Somalia to come up with a design.[216] Upon independence in 1960, the flag was adopted as the national flag of the nascent Somali Republic.[217] The five-pointed Star of Unity in the flag's center represents the Somali ethnic group inhabiting the five territories in Greater Somalia.[217][218]

Cuisine

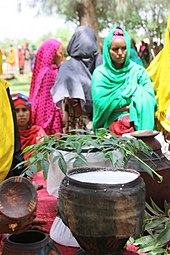

The Somali staple food comes from their livestock, however, the Somali cuisine varies from region to region and consists of a fusion of diverse culinary influences. In the interiors, the cuisine is mainly local with usage of Ethiopian grains and vegetables while in the coast it is the product of Somalia's rich tradition of trade and commerce. Despite the variety, there remains one thing that unites the various regional cuisines: all food is served halal. There are therefore no pork dishes, alcohol is not served, nothing that died on its own is eaten, and no blood is incorporated.[219]

Breakfast (quraac) is an important meal for Somalis, some drink tea (shahie or shaah) others coffee (qaxwa or bun). The tea is often in the form of haleeb shai (Yemeni milk tea) in the north. The main dish is typically a pancake-like bread (canjeero or canjeelo) similar to Ethiopian injera, but smaller and thinner, or muufo a Somali flat bread traditionally baked on a clay oven. These breads might also be eaten with a stew (maraqe) or soup at lunch or dinner.[220] Qado or lunch is often elaborate, varieties of bariis (rice), the most popular being basmati are usually served as the main dish alongside goat, lamb or fish. Spices like cumin, cardamom, cloves, cinnamon, and garden sage are used to aromatize these different rice delicacies. Somalis eat dinner as late as 9 pm. During Ramadan, supper is often served after Tarawih prayers; sometimes as late as 11 pm.[219]

In some regions, xalwo (halva) is a popular confection eaten during festive occasions such as Eid celebrations or wedding receptions. It is made from sugar, corn starch, cardamom powder, nutmeg powder and ghee. Peanuts are also sometimes added to enhance texture and flavor.[221] After meals, homes are traditionally perfumed using frankincense (lubaan) or incense (cuunsi), which is prepared inside an incense burner referred to as a dabqaad.

Literature

Somali scholars have for centuries produced many notable examples of Islamic literature ranging from poetry to Hadith. With the adoption of the Latin alphabet in 1972 to transcribe the Somali language, numerous contemporary Somali authors have also released novels, some of which have gone on to receive worldwide acclaim. Most of the early Somali literature is in the Arabic script and Wadaad writing.[222] This usage was limited to Somali clerics and their associates, as sheikhs preferred to write in the liturgical Arabic language. Various such historical manuscripts in Somali nonetheless exist, which mainly consist of Islamic poems (qasidas), recitations and chants.[223] Among these texts are the Somali poems by Sheikh Uways and Sheikh Ismaaciil Faarah. The rest of the existing historical literature in Somali principally consists of translations of documents from Arabic.[224]

Authors and poets

- Elmi Boodhari (1908–1940) – Early 20th century poet and pioneer in the genre of Somali love poems. He is popularly known by Somalis as the King of romance (Boqorki Jacaylka)[225]

- Abdillahi Diiriye Guled - Literary scholar and discoverer of the Somali prosodic system

- Ali Bu'ul (Cali Bucul) – 19th century poet, military leader and sultan, many of the most well known geeraar (short styled poems recited on a horse) came from his tongue and are still known today.

- Mohamed Ibrahim Warsame 'Hadrawi' – songwriter, philosopher, and Somali Poet Laureate; also dubbed the Somali Shakespeare.

- Hassan Sheikh Mumin – 20th century poet, playwright, broadcaster, actor and composer.

- Nuruddin Farah (born 1943) – Somali writer and winner of the 1998 Neustadt International Prize for Literature.

- Abdillahi Suldaan Mohammed Timacade (1920–1973) – prominent Somali poet known for his nationalist poems such as Kana siib Kana Saar.

- Mohamud Siad Togane (born 1943) – Somali-Canadian poet, professor, and political activist.

- Maxamed Daahir Afrax – Somali novelist and playwright. Afrax has published several novels and short stories in Somali and Arabic, and has also written two plays, the first being Durbaan Been ah ("A Deceptive Drum"), which was staged in Somalia in 1979. His major contribution in the field of theatre criticism is Somali Drama: Historical and Critical Study (1987).

- Gaarriye (1949–2012) – Somali poet, most notable for his famous poem Hagarlaawe.

- Nadifa Mohamed – Somali novelist. Winner of the 2010 Betty Trask Prize.

- Musa Haji Ismail Galal (1917–1980) – was a Somali writer, scholar, linguist, historian and polymath

- Farah Mohamed Jama Awl – Somali author best known for his historical fiction novels.

- Diriye Osman – Somali writer and visual artist. Winner of the 2014 Polari First Book Prize.

- Sofia Samatar – Somali professor and writer. Winner of the 2014 World Fantasy Award.

Law

Somalis for centuries have practiced a form of customary law, which they call xeer. Xeer is a polycentric legal system where there is no monopolistic agent that determines what the law should be or how it should be interpreted. It is assumed to have developed exclusively in the Horn of Africa since approximately the 7th century. Given the dearth of loan words from foreign languages within the xeer's nomenclature, the customary law appears to have evolved in situ.[226]

Xeer is defined by a few fundamental tenets that are immutable and which closely approximate the principle of jus cogens in international law: payment of blood money (locally referred to as diya or mag), assuring good inter-clan relations by treating women justly, negotiating with "peace emissaries" in good faith, and sparing the lives of socially protected groups (e.g. children, women, the pious, poets and guests), family obligations such as the payment of dowry, and sanctions for eloping, rules pertaining to the management of resources such as the use of pasture land, water, and other natural resources, providing financial support to married female relatives and newlyweds, donating livestock and other assets to the poor.[227] The Xeer legal system also requires a certain amount of specialization of different functions within the legal framework. Thus, one can find odayal (judges), xeer boggeyaal (jurists), guurtiyaal (detectives), garxajiyaal (attorneys), murkhaatiyal (witnesses) and waranle (police officers) to enforce the law.[228]

Architecture

| Somali architecture |

|---|

|

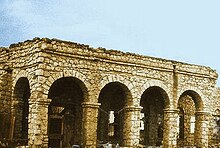

Somali architecture is a rich and diverse tradition of engineering and designing. It involves multiple different construction types, such as stone cities, castles, citadels, fortresses, mosques, mausoleums, towers, tombs, tumuli, cairns, megaliths, menhirs, stelae, dolmens, stone circles, monuments, temples, enclosures, cisterns, aqueducts, and lighthouses. Spanning the ancient, medieval and early modern periods in Greater Somalia, it also includes the fusion of Somali architecture with Western designs in contemporary times.[229]

In ancient Somalia, pyramidical structures known in Somali as taalo were a popular burial style. Hundreds of these dry stone monuments are found around the country today. Houses were built of dressed stone similar to the ones in Ancient Egypt.[77] There are also examples of courtyards and large stone walls enclosing settlements, such as the Wargaade Wall.

The peaceful introduction of Islam in the early medieval era of Somalia's history brought Islamic architectural influences from Arabia and Persia. This had the effect of stimulating a shift in construction from drystone and other related materials to coral stone, sundried bricks, and the widespread use of limestone in Somali architecture. Many of the new architectural designs, such as mosques, were built on the ruins of older structures. This practice would continue over and over again throughout the following centuries.[230]

Geographic distribution

Somalis constitute the largest ethnic group in Somalia, at approximately 85% of the nation's inhabitants.[44] They also comprise around 60% of the inhabitants in Djibouti.[231]

Civil strife in the early 1990s greatly increased the size of the Somali diaspora, as many of the best educated Somalis left for the Middle East, Europe and North America.[232] In Canada, the cities of Toronto, Ottawa, Calgary, Edmonton, Montreal, Vancouver, Winnipeg and Hamilton all harbor Somali populations. Statistics Canada's 2006 census ranks people of Somali descent as the 69th largest ethnic group in Canada.[233]

UN migration estimates of the international migrant stock 2015 suggest that 1,998,764 people from Somalia were living abroad.[234][235]

While the distribution of Somalis per country in Europe is hard to measure because the Somali community on the continent has grown so quickly in recent years, the Office for National Statistics estimates that 98,000 people born in Somalia were living in the United Kingdom in 2016.[236] This includes secondary migration of Somalis from mainland European countries.[237] Somalis in Britain are largely concentrated in the cities of London, Sheffield, Bristol, Birmingham, Cardiff, Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, and Leicester, with London alone accounting for roughly 78% of Britain's Somali population in 2001.[238] There are also significant Somali communities in continental Europe such as Sweden: 63,853 (2016);[13] Norway: 42,217 (2016);[19] the Netherlands: 39,465 (2016);[20] Germany: 33,900 (2016);[17] Denmark: 21,050 (2016);[26] and Finland: 20,007 (2017).[24]

In the United States, Minneapolis, Saint Paul, Columbus, San Diego, Seattle, Washington, D.C., Houston, Atlanta, Los Angeles, Portland, Denver, Nashville, Green Bay, Lewiston, Portland, Maine and Cedar Rapids have the largest Somali populations.

An estimated 20,000 Somalis emigrated to the U.S. state of Minnesota in the mid-1990s and the Twin Cities (Minneapolis and Saint Paul) now have the highest population of Somalis in North America.[239] The city of Minneapolis hosts hundreds of Somali-owned and operated businesses offering a variety of products, including leather shoes, jewelry and other fashion items, halal meat, and hawala or money transfer services. Community-based video rental stores likewise carry the latest Somali films and music.[240] The number of Somalis has especially surged in the Cedar-Riverside area of Minneapolis.

There is a sizable Somali community in the United Arab Emirates. Somali-owned businesses line the streets of Deira, the Dubai city centre,[241] with only Iranians exporting more products from the city at large.[242] Internet cafés, hotels, coffee shops, restaurants and import-export businesses are all testimony to the Somalis' entrepreneurial spirit. Star African Air is also one of three Somali-owned airlines which are based in Dubai.[241]

Besides their traditional areas of inhabitation in Greater Somalia, a Somali community mainly consisting of entrepreneurs, academics, and students also exists in Egypt.[243][244] In addition, there is an historical Somali community in the general Sudan area. Primarily concentrated in the north and Khartoum, the expatriate community mainly consists of students as well as some businesspeople.[245] More recently, Somali entrepreneurs have established themselves in Kenya, investing over $1.5 billion in the Somali enclave of Eastleigh alone.[246] In South Africa, Somali businesspeople also provide most of the retail trade in informal settlements around the Western Cape province.[247]

Notable individuals of the diaspora

- Abdulrahim Abby Farah Undersecretary General of the United Nations 1979–1990, Permanent Representative of Somalia to the United Nations 1965–1972.

- Abdusalam H. Omer – Somali economist and politician. Former Foreign Affairs Minister of Somalia and Governor of the Central Bank of Somalia.

- Abdi Yusuf Hassan – Somali politician, diplomat and journalist. Former director of IRIN and UNHCR Head of External and Media Relations in Southwest and Central Asia.

- Ahmed Hussen – Somali lawyer. Minister of Immigration of Canada. President of the Canadian Somali Congress.

- Abdulqawi Yusuf – Prominent Somali international lawyer and current president of the International Court of Justice.

- Abdirahim Hussein Mohamed – Somali politician. Elected Chairman of the Helsinki Centre Youth in 2007 and chairman of the Moniheli cooperation network for multicultural organizations.

- Abdirashid Duale – award-winning Somali entrepreneur, philanthropist, and the CEO of the multinational enterprise Dahabshiil.

- Adan Mohammed – Somali banker, entrepreneur and politician. He previously served as the managing director of Barclays Bank in East and West Africa and is currently the Cabinet Secretary for Industrialization of Kenya.

- Ali Said Faqi – Somali scientist and the leading researcher on the design and interpretation of toxicology studies at the MPI research center in Mattawan, Michigan.

- Amina Moghe Hersi – Award-winning Somali entrepreneur that has launched several multimillion-dollar projects in Kampala, Uganda, such as the Oasis Centre luxury mall and the Laburnam Courts. She also runs Kingstone Enterprises Limited, one of the largest distributors of cement and other hardware materials in Kampala.

- Amina Mohamed – Somali lawyer and politician. Former Chairman of the International Organization for Migration and the World Trade Organisation's General Council, and current Secretary for Foreign Affairs of Kenya.

- Ayaan and Idyl Mohallim – Somali twin fashion designers and owners of the Mataano brand.

- Ayaan Hirsi Ali – Feminist and atheist activist, writer and politician known for her views critical of Islam and female circumcision.

- Ayub Daud – Somali international footballer who plays as a forward/attacking midfielder for FC Crotone on loan from Juventus.

- Faisal Hawar – Somali engineer and entrepreneur. Chairman of the International Somalia Development Foundation and the Maakhir Resource Company.

- Halima Ahmed – Somali political activist with the Youth Rehabilitation Center and prospective candidate in the Federal Parliament of Somalia.

- Halima Aden – Somali american model. minnesota first woman to wear a hijab in Miss Minnesota USA pageant

- Hanan Ibrahim – Somali social activist. Received the Queen's Award for Voluntary Service in 2004 and was made an MBE in 2010.

- Hassan Abdillahi – Somali journalist. President of Ogaal Radio, the largest Somali community station in Canada.

- Hibaaq Osman – Somali political strategist. Founder and Chairperson of the ThinkTank for Arab Women, the Dignity Fund, and Karama.

- Hodan Ahmed – Somali political activist and Senior Program Officer at the National Democratic Institute.

- Hodan Nalayeh – Somali media executive and entrepreneur. President of the Cultural Integration Agency and the Vice President of Sales & Programming Development of Cameraworks Productions International.

- Idil Ibrahim – Somali American film director, writer and producer. Founder of Zeila Films.

- Ilhan Omar – Somali American politician, the first Somali Member of Congress in the United States. Omar currently represents Minnesota's 5th congressional district.

- Iman Mohamed Abdulmajid – international fashion icon, supermodel, actress and entrepreneur; professionally known as Iman.

- Jawahir Ahmed – Somali American model. Served as Miss Somalia in 2013 Miss United Nations USA pageant.

- Leila Abukar – Somali-Australian political activist. Recipient of Centenary Medal.

- Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed (Farmajo) – Somali politician and diplomat. Former Prime Minister of Somalia and founder of the Tayo Political Party.

- Mo Farah – Somali-British Olympic gold medalist and world champion long distance runner.

- Musse Olol – Somali American social activist. Recipient of the 2011 Director's Community Leadership Award.

- Mustafa Mohamed – Somali-Swedish long-distance runner who mainly competes in the 3,000-meter steeplechase. Won gold in the 2006 Nordic Cross Country Championships and at the 1st SPAR European Team Championships in Leiria, Portugal, in 2009. Beat the 31-year-old Swedish record in 2007.

- Nathif Jama Adam – Somali banker and politician. Former senior vice president and the head of the Sharjah Islamic Bank's Investments & International Banking Division, and Governor of Garissa County.

- Shadya Yasin – Somali-Canadian social activist, poet and teacher.

- Omar Abdi Ali – Somali entrepreneur, accountant, financial consultant, philanthropist, and specialist on Islamic finance. Was formerly CEO of Dar al-Maal al-Islami (DMI Trust), which under his management increased its assets from $1.6 billion to $4.0 billion. He is currently the chairman and founder of the multinational real estate corporation Integrated Property Investments Limited and its sister company Quadron investments.

- Rageh Omaar – Somali-British television news presenter and writer. Formerly a BBC news correspondent in 2009, he moved to a new post at Al Jazeera English, where he currently presents the nightly weekday documentary series Witness.

- Sulekha Ali, a Somali-Canadian musician.

- Waris Dirie – Somali model, author, actress, and social activist. UN Special Ambassador from 1997 to 2003.

- Yasmin Warsame – Somali-Canadian model who was named "The Most Alluring Canadian" in a poll by Fashion magazine.

- Zahra Abdulla – Somali politician in Finland and member of the Helsinki City Council representing the Green League.

Генетика

Однородительские линии

Согласно исследованиям Y-хромосомы Sanchez et al. (2005), Кручиани и др. (2004, 2007), сомалийцы по отцовской линии тесно связаны с другими афро-азиатскоязычными группами Северо-Восточной Африки . [151] [248] [152] Помимо большей части Y-ДНК у сомалийцев, E1b1b (ранее E3b) гаплогруппа также составляет значительную часть отцовской ДНК эфиопов , суданцев , египтян , берберов , североафриканских арабов , а также многих средиземноморских народов. [248] [249] Санчес и др. (2005) наблюдали субклад E-M78 E1b1b1a примерно в 70,6% выборок сомалийских мужчин. [151] По данным Кручиани и др. (2007), присутствие этой субгаплогруппы в регионе Рога может представлять собой следы древней миграции из Египта / Ливии . [Примечание 1] [152]

После гаплогруппы E1b1b второй наиболее часто встречающейся гаплогруппой Y-ДНК среди сомалийцев является западноазиатская гаплогруппа T (M184). [250] Клада наблюдается более чем у 10% сомалийских мужчин в целом. [151] с пиковой частотой среди членов клана Сомалийский Дир в Джибути (100%) [251] и сомалийцы в Дире-Даве (82,4%), городе, где проживает большинство населения Дира . [252] Гаплогруппа T, как и гаплогруппа E1b1b, также обычно встречается среди других популяций Северо-Восточной Африки, Магриба , Ближнего Востока и Средиземноморья. [253]

У сомалийцев время до самого недавнего общего предка (TMRCA) оценивалось в 4000–5000 лет (2500 до н.э. ) для кластера γ гаплогруппы E-M78 и в 2100–2200 лет (150 до н.э.) для сомалийских T-M184 . носителей [151]

Глубокий субклад E-Y18629 обычно встречается у сомалийцев и имеет дату образования 3700 лет назад (за несколько лет до настоящего времени) и TMRCA 3300 лет назад. [254]

Согласно исследованиям мтДНК Холдена (2005) и Ричардса и др. (2006), значительная часть материнских линий сомалийцев состоит из гаплогруппы M1 в размере более 20%. [255] [256] Эта митохондриальная клада распространена среди эфиопов и жителей Северной Африки, особенно египтян и алжирцев . [257] [258] Считается, что M1 возник в Азии. [259] где его родительская клада M представляет большинство линий мтДНК. [260] Также считается, что эта гаплогруппа, возможно, коррелирует с афро-азиатской языковой семьей: [256] Кроме того, сомалийцы и другие популяции Африканского Рога также несут значительную долю материнских линий L, связанных с Африкой к югу от Сахары.

«Мы проанализировали вариации мтДНК примерно у 250 человек из Ливии, Сомали и Конго/Замбии как представителей трех интересующих регионов. Наши первоначальные результаты указывают на резкий скачок частот M1, который обычно не распространяется на страны Африки к югу от Сахары. наши образцы из Северной и особенно Восточной Африки содержали частоты M1 более 20%, наши образцы из стран к югу от Сахары почти полностью состояли только из гаплогрупп L1 или L2. Кроме того, внутри гаплогруппы M1 существовала значительная однородность. история небольшого смешения между этими регионами может означать более недавнее происхождение M1 в Африке, поскольку более старые линии более разнообразны и широко распространены по своей природе и могут быть признаком обратной миграции в Африку с Ближнего Востока». [256]

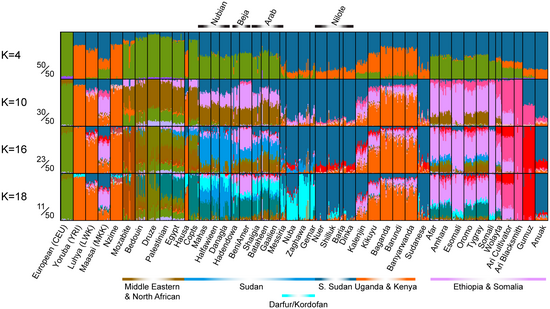

Аутосомное происхождение

Исследования показывают, что у сомалийцев есть смесь коренных африканских предков, уникальных и автохтонных для Африканского Рога , а также предков, происходящих в результате неафриканской обратной миграции. Согласно исследованию аутосомной ДНК , проведенному Hodgson et al. (2014), афро-азиатские языки, вероятно, были распространены по Африке и Ближнему Востоку за счет предкового населения, несущего недавно выявленный неафриканский генетический компонент, который исследователи называют «этиосомалийским». Этот компонент сегодня наиболее распространен среди афроазиатскоязычного населения Африканского Рога. Пика частоты он достигает среди этнических сомалийцев, представляющих большую часть их предков. Эфио-сомалийский компонент наиболее тесно связан с неафриканским генетическим компонентом Магриби и, как полагают, отделился от всех других неафриканских предков по крайней мере 23 000 лет назад. На этом основании исследователи предполагают, что первоначальная эфиосомалийская популяция, носительница(и), вероятно, прибыла в доземледельческий период с Ближнего Востока, перейдя в северо-восточную Африку через Синайский полуостров . Затем население, вероятно, разделилось на две ветви: одна группа направилась на запад, в сторону Магриба , а другая — на юг, в сторону Рога. [261] Анализ древней ДНК показывает, что эти основополагающие предки в регионе Хорн родственны таковым у неолитических земледельцев южного Леванта . [262]

Более того, по данным Hodgson et al. как африканское происхождение (эфиопское), так и неафриканское происхождение (эфио-сомалийское) в кушитскоязычном населении значительно отличается от всех соседних африканских и неафриканских предков сегодня. Общая генетическая родословная кушитских и семитоязычных популяций на Африканском Роге представляет собой предков, не встречающихся за пределами популяций ТСЖ. Исследователи утверждают:

«Африканское эфиопское происхождение жестко ограничено популяциями ТСЖ и, вероятно, представляет собой автохтонную популяцию ТСЖ. Неафриканское происхождение в ТСЖ, которое в первую очередь приписывается новому предполагаемому эфиосомалийскому компоненту происхождения, значительно отличается от всех соседних не-африканских предков. Африканские предки в Северной Африке, Леванте и Аравии». [263]

Более того, Ходжсон и др. (2014) уточняет:

«Мы обнаруживаем, что большая часть неафриканского происхождения в ТСЖ может быть отнесена к отдельному компоненту этиосомалинского происхождения неафриканского происхождения, который наиболее часто встречается в кушитских и семитоязычных популяциях ТСЖ». [264]

Молинаро, Людовика и др. в 2019 году охарактеризовали неафриканское происхождение эфиопских сомалийцев как происходящее от неолитических групп Анатолии (аналогично тунисским евреям). [265] Али А.А., Аалто М., Йонассон Дж. и др. (2020) с использованием анализа главных компонентов показало, что примерно 60% сомалийцев имеют восточноафриканское происхождение и 40% - западноевразийское. [266]

сомалийские исследования

Научный термин для исследования, касающегося сомалийцев и Великого Сомали, — сомалийские исследования . Он состоит из нескольких дисциплин, таких как антропология , социология , лингвистика , историография и археология . Эта область опирается на старые сомалийские хроники , записи и устную литературу, а также письменные отчеты и традиции о сомалийцах от исследователей и географов Африканского Рога и Ближнего Востока. С 1980 года видные учёные -сомалисты со всего мира также ежегодно собираются для проведения Международного конгресса сомалийских исследований.

См. также

Примечания

- ^ Кручиани и др. В 2007 году термин «Северо-Восточная Африка» использовался для обозначения Египта и Ливии, как показано в Таблице 1 исследования. До Cruciani et al. 2007 , Семино и др. Ошибка harvnb 2004 г Восточная Африка как возможное место происхождения E-M78, на основе испытаний в Эфиопии. Это произошло из-за высокой частоты и разнообразия линий E-M78 в регионе Эфиопии. Однако Кручиани и др. 2007 г. смогли изучить больше данных, в том числе о популяциях из Северной Африки, которые не были представлены в исследовании Semino et al. Ошибка harvnb 2004 года и обнаружило доказательства того, что линии E-M78, составляющие значительную часть некоторых популяций в этом регионе, были относительно молодыми ветвями (см. E-V32 ниже). Поэтому они пришли к выводу, что «Северо-Восточная Африка» была вероятным местом происхождения E-M78, основываясь на «периферийном географическом распределении наиболее производных субгаплогрупп по отношению к северо-востоку Африки, а также на результатах количественного анализа UEP и разнообразия микросателлитов». . Итак, согласно Кручиани и др. 2007 г. E-M35, родительская клада E-M78, возникла в Восточной Африке, впоследствии распространилась в Северо-Восточную Африку, а затем произошла «обратная миграция» хромосом E-M215, которые приобрели мутацию E-M78. Кручиани и др. Поэтому в 2007 году отмечают это как свидетельство существования «коридора двунаправленной миграции» между Северо-Восточной Африкой (по их данным, Египтом и Ливией) с одной стороны и Восточной Африкой с другой. Авторы полагают, что было «по крайней мере 2 эпизода между 23,9–17,3 тыс. лет назад и 18,0–5,9 тыс. лет назад».

Ссылки

- ^ включая Сомалиленд

- ^ «Сомали, распространение по всему миру» . Проверено 16 июля 2023 г.

- ^ «Открытые данные Всемирного банка» . Архивировано из оригинала 30 ноября 2023 года . Проверено 4 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Льюис, IM (1998). Народы Африканского Рога: Сомали, Афар и Сахо . Красное Море Пресс. ISBN 978-1-56902-104-0 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Таблица 2.2 Процентное распределение основных этнических групп: 2007 г.» (PDF) . Сводный и статистический отчет по результатам переписи населения и жилищного фонда 2007 года . Комиссия по переписи населения. п. 16. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 25 марта 2009 года . Проверено 21 апреля 2020 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Перепись населения и жилищного фонда Кении, том IV, 2019 год: Распределение населения по социально-экономическим характеристикам» . Национальное статистическое бюро Кении. Декабрь 2019. с. 423 . Проверено 24 марта 2020 г.

- ^ [1] – Joshuaproject.net

- ^ Грамер, Робби (17 марта 2017 г.). «Вертолет Apache обстрелял лодку, полную сомалийских беженцев, бегущих из Йемена» . Внешняя политика . Проверено 24 апреля 2020 г.

- ^ Статистика этнической принадлежности 2021 года в Англии и Уэльсе, перепись 2021 года. «Население Сомали в Англии и Уэльсе в 2021 году» . Проверено 14 июня 2024 г.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: числовые имена: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ Бюро переписи населения США. «Опрос американского сообщества – оценки на 1 год – таблица B04006» . data.census.gov .

- ^ «Файл А с подробными демографическими и жилищными характеристиками переписи 2020 года будет опубликован 25 мая» . Бюро переписи населения США . Министерство торговли США. 25 мая 2023 г. Проверено 7 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Население иммигрантов и эмигрантов по странам происхождения и назначения» . www.migrationpolicy.org . 10 февраля 2014 г. Архивировано из оригинала 14 апреля 2021 г. Проверено 16 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ «Этнолог Объединенных Арабских Эмиратов» . Этнолог . Проверено 21 февраля 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Статистика Швеции – родившиеся за границей и родившиеся в Швеции» .

- ^ Клейст, Н. (2018). Группы сомалийской диаспоры в Швеции . Делми.

- ^ PeopleGroups.org. «PeopleGroups.org – Сомали из Танзании» . Peoplegroups.org . Проверено 18 декабря 2018 г.

- ^ «Профиль переписи населения, перепись 2021 года – этническое или культурное происхождение – Канада [страна]» . 8 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Количество иностранцев в Германии по странам происхождения» . Статистика.

- ^ «Беженцы в Уганде по странам происхождения, 2024 г.» . Статистика . Проверено 8 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Иммигранты и норвежцы, рожденные от родителей-иммигрантов» .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Население; пол, возраст, происхождение и поколение, 1 января» . CBS StatLine . Статистическое управление Нидерландов.

- ^ Джинна, Захира. «Строимся на враждебной земле: понимание сомалийской идентичности, интеграции, средств к существованию и рисков в Йоханнесбурге» (PDF) . Журнал социологии Soc Anth, 1 (1–2): 91–99 (2010) . Издательство КРЭ . Проверено 6 марта 2014 г.

- ^ «Этнолог Саудовской Аравии» . Этнолог . Проверено 12 июля 2017 г. .

- ^ PeopleGroups.org. «PeopleGroups.org – Сомали из Саудовской Аравии» . Peoplegroups.org . Проверено 18 декабря 2018 г. [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Статистика Финляндии» . stat.fi.

- ^ Миграционное агентство ООН. «Миграционный фонд в Египте 2022» (PDF) . Международная организация по миграции (МОМ) . Проверено 12 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Статбанк Дании» . statbank.dk .

- ^ «Таблица 5. Происхождение по штатам и территориям обычного проживания, количество человек – 2016(a)(b)» . Австралийское статистическое бюро. 20 июля 2017 года . Проверено 4 августа 2017 г.

- ^ «Демографическая статистика ИСТАТ» . Tuttitalia Иностранные граждане к 2022 году . Проверено 2 июля 2024 г.

- ^ «Население на начало 2002–2021 года по подробной национальности» . Статистика Австрии . Проверено 2 марта 2021 г.

- ^ «Федеральное статистическое управление» . Архивировано из оригинала 17 апреля 2017 года.

- ^ УВКБ ООН (1 августа 2018 г.). «Информационный бюллетень по Турции» . unhcr.org .

- ^ «Сомалийцы в Замбии стремятся к лучшему руководству» . www.hiiraan.com . Проверено 18 октября 2018 г.

- ^ «Замбия: Сомалийская община в Замбии пожертвовала 35 грузовиков для вывоза мусора» . LusakaTimes.com . 10 января 2018 года . Проверено 18 октября 2018 г.

- ^ Хертоген, Дж. «Жители иностранного происхождения в Бельгии» .

- ^ УВКБ ООН (1 августа 2018 г.). «Информационный бюллетень по Эритрее» . Унхр .

- ^ Чармарке, Хусейн (2013). «Использование социальных сетей, Тахрииб (миграция) и расселение сомалийских беженцев во Франции» . Убежище . 29 (1): 43–52. дои : 10.25071/1920-7336.37505 .

- ^ Фахр, Алхан (15 июля 2012 г.). «Снова небезопасно» . Дейли Чан . Проверено 10 ноября 2013 г.

- ^ УВКБ ООН (1 августа 2015 г.). «Информационный бюллетень о Малайзии» . Унхр .

- ^ УВКБ ООН (1 февраля 2016 г.). «Информационный бюллетень по Индонезии» . Унхр .

- ^ «Профили этнических групп» . stats.govt.nz .

- ^ «Население, обычно проживающее и присутствующее в штате, которое говорит дома на другом языке, кроме английского или ирландского, с 2011 по 2016 год по месту рождения, языку общения, возрастной группе и году переписи населения - StatBank - данные и статистика» . www.cso.ie. Проверено 12 июля 2017 г. .